Strategy for

New India @ 75

November 2018

iii

I

ndia is on the cusp of a major transformation. Change has been in the making over the last four years.

The economy is nally moving out of the negative legacies of the past, specially the reckless credit

expansion. India has regained its position as the fastest growing large economy in the world. This is

highly commendable. However, to meet the rising aspirations of our young population, India needs to

achieve and sustain a high rate of GDP growth for the next three decades. There will be several milestones

in this long and arduous journey. The rst of these milestones will be in 2022 when India celebrates the 75th

anniversary of its independence. The government’s goal is for India to be a USD 4.0 trillion economy when we

celebrate the platinum jubilee of our independence.

Moreover, the Prime Minister has given his clarion call for establishing a New India by 2022. The ‘Strategy for

New India @ 75’ captures three key messages from the Prime Minister. First, development must become a

mass movement, in which every Indian recognizes her role and also experiences the tangible benets accruing

to her in the form of better ease of living. Collective effort and resolve will ensure that we achieve a New India

by 2022 just like independence was achieved within ve years of Mahatma Gandhi giving his call of Quit India

in 1942. The direct implication of ensuring rapid growth with inclusion is that policymaking will have to be

rooted in Indian ground realities and emphasize the welfare of all in both design and implementation.

Second, development strategy should help achieve broad-based economic growth to ensure balanced

development across all regions and states and across sectors. This implies embracing new technologies

fostering innovation and upskilling. We will have to focus on the necessary modernization of our agriculture

and mainstreaming of regions such as the North East, hilly states and the 115 Aspirational Districts. The direct

outcome of this will be improved regional and inter-personal equity and elimination of dualism that has so

far characterised our economy. We will put in place an economy that is predominantly formal, rule-driven and

facilitates investment and innovation.

Third, the strategy when implemented, will bridge the gap between public and private sector performance.

The Prime Minister has focused on putting in place a ‘development state’ in place of the ‘soft state’ that this

government had inherited. In this context, the government has focused on the efcient delivery of public

services, rooting out corruption and black economy, formalizing the economy and expanding the tax base,

improving the ease of doing business, nursing the stressed commercial banking sector back to a healthy state,

and stopping leakages through direct benet transfers and widespread use of the JAM trinity.

Preface

Strategy for

New India @ 75

iv

Efcient, transparent and accountable governance has come to be recognized as this government’s USP. This

will ensure that India will not only achieve its ambitious goals for 2022, but also go on to become one of the

two largest economies in the world by 2047, when we celebrate the centenary of our independence.

‘Strategy for New India @ 75’ has identied 41 different areas that require either a sharper focus on

implementing the agship schemes already in place or a new design and initiative to achieve India’s true

potential. Each chapter summarizes the current status of the sector, takes full cognizance of the progress

made thus far and spells out the objectives. It then identies the binding constraints and proposes measures

to address these constraints. It is our hope that this new approach will provide an inventory of readily

implementable measures for the government departments and agencies both in the central and state

governments. The focus of the strategy is to further improve the policy environment in which private investors

and other stakeholders can contribute their fullest towards achieving the goals set out for New India 2022.

We have followed a deeply participative approach in preparing the strategy. The process started with a series

of consultations with all possible stakeholders. Each area vertical in NITI Aayog had in depth consultations

with all three groups of stakeholders, viz., business persons, academics including scientists, and government

ofcials. This was followed by consultations held by NITI Aayog with seven sets of stakeholders that included

scientists and innovators, farmers, civil society organizations, think tanks, labour representatives and trade

unions, as well as industry representatives (Lists at Annex 1 and 2).

Each chapter draft was sent to the respective line ministry for their inputs, suggestions and comments.

The completed draft document was circulated to all the States and Union Territories. As many as 23 States

and 4 Union Territories sent detailed and well considered comments and suggestions. These have helped

in improving the draft by reecting state specic features in various chapters. This exercise has further

strengthened NITI Aayog’s efforts at cooperative federalism. It will also encourage us to collaborate with the

states to develop state specic development blueprints.

With these extensive consultations and inputs, the strategy reects ground realities and a collective consensus

on addressing the challenges and achieving the goals for a New India. The attempt is to present a set of ideas

that can provide the basis for a constructive public-private-personal partnership and promote centre-state

cooperation. We hope that the document will also help to build the trust required among all stakeholders for

making development into a mass movement.

I would like to thank NITI Aayog members Dr. V. K. Saraswat, Dr. Ramesh Chand and Dr. Vinod K. Paul for their

leadership and invaluable inputs at every stage of the process. This document would not have been possible

v

without the contribution of NITI Aayog CEO, Amitabh Kant and senior ofcials of NITI Aayog. I would like to

thank Additional Secretaries Yaduvendra Mathur and R. P. Gupta; Senior Advisers Sunita Sanghi and Srikara

Naik; Advisers Alok Kumar, Anil Srivastava, Anna Roy, Ashok K. Jain, J. P. Mishra, Jitendra Kumar, Maninder

Kaur Dwivedi, Praveen Mahto, Ravinder Goyal, S. S. Ganapathy, U. K. Sharma, Vikram Singh Gaur, Yogesh Suri;

Senior Consultants C. Muralikrishna Kumar, Rakesh Ranjan and Sujeet Samaddar and Ofcer on Special Duty

Sanyukta Samaddar.

This task would not have been completed without the help of a dedicated team of experts attached to the

Vice Chairman’s ofce, led by Ramgopal Agarwala and Dhiraj Nayyar. The team consisted of Urvashi Prasad,

Ranveer Nagaich, Devashish Dhar, Atisha Kumar, Chinmaya Goyal, Vaibhav Kapoor and Ajit Pai. Tara Nair

provided crucial editing inputs.

Preparing the strategy is only the rst step towards India’s economic transformation. The foresighted framers of

our celebrated Constitution have set the enormous challenge of simultaneously completing India’s triple transition

across social, political and economic elds. India is one of the very few countries that have taken on this historical

challenge of completing the three transitions together. Having successfully taken forward the social and political

transitions, India is now within sight of completing its economic transition as well. This will see per capita incomes

rising from about USD 1,900 in 2017-18 to around USD 3,000 in 2022-23. As outlined in this Strategy Document,

successfully completing our economic transition will enable us to achieve freedom from squalor, illiteracy,

corruption, poverty, malnutrition and poor connectivity for the common Indian.

By 2022, New India will provide a solid foundation for clean, inclusive, sustained and sustainable growth for

the next three decades. The ‘Strategy for New India @ 75’ reects our preparedness to make this transition. Its

recommendations are practical and detailed to facilitate time-bound implementation. All levels of government

must work together to achieve the vision of New India. Working together as ‘Team India’ will ensure prosperity

for all while protecting our environment and promoting the emergence of an innovative eco-system, propelling

India to the front ranks of the global economy.

Dr. Rajiv Kumar

Vice Chairman

NITI Aayog

vii

Introduction 1

Drivers

1. Growth 7

2. Employment and Labour Reforms 12

3. Technology and Innovation 16

4. Industry 20

5. Doubling Farmers’ Income (I): Modernizing Agriculture 25

6. Doubling Farmers’ Income (II): Policy & Governance 30

7. Doubling Farmers’ Income (III): Value Chain & Rural Infrastructure 36

8. Financial Inclusion 41

9. Housing for All 45

10. Travel, Tourism and Hospitality 49

11. Minerals 54

Infrastructure

12. Energy 61

13. Surface Transport 66

14. Railways 70

15. Civil Aviation 75

16. Ports, Shipping and Inland Waterways 80

17. Logistics 85

18. Digital Connectivity 88

19. Smart Cities for Urban Transformation 92

20. Swachh Bharat Mission 96

21. Water Resources 100

22. Sustainable Environment 104

Inclusion

23. School Education 111

Table of Contents

Strategy for

New India @ 75

viii

24. Higher Education 116

25. Teacher Education and Training 121

26. Skill Development 124

27. Public Health Management and Action 129

28. Comprehensive Primary Health Care 133

29. Human Resources for Health 137

30. Universal Health Coverage 142

31. Nutrition 146

32. Gender 150

33. Senior Citizens, Persons with Disability and Transgender Persons 155

34. Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs),

Other Tribal Groups and Minorities 161

Governance

35. Balanced Regional Development: Transforming Aspirational Districts 169

36. The North-East Region 173

37. Legal, Judicial and Police Reforms 178

38. Civil Services Reforms 183

39. Modernizing City Governance for Urban Transformation 187

40. Optimizing the Use of Land Resources 191

41. Data Led Governance and Policy Making 195

Annex 1 199

Annex 2 205

Table of Contents

ix

List of Figures

1.1 India’s real GDP growth 8

2.1 Share of workforce employed in agriculture 13

3.1 Steps taken to promote science, technology and innovation in India 16

4.1 Manufacturing as a share of GDP, 2011-12 to 2017-18 21

6.1 Price spread between farm harvest prices and retail prices for select agricultural

commodities, 2015-16 31

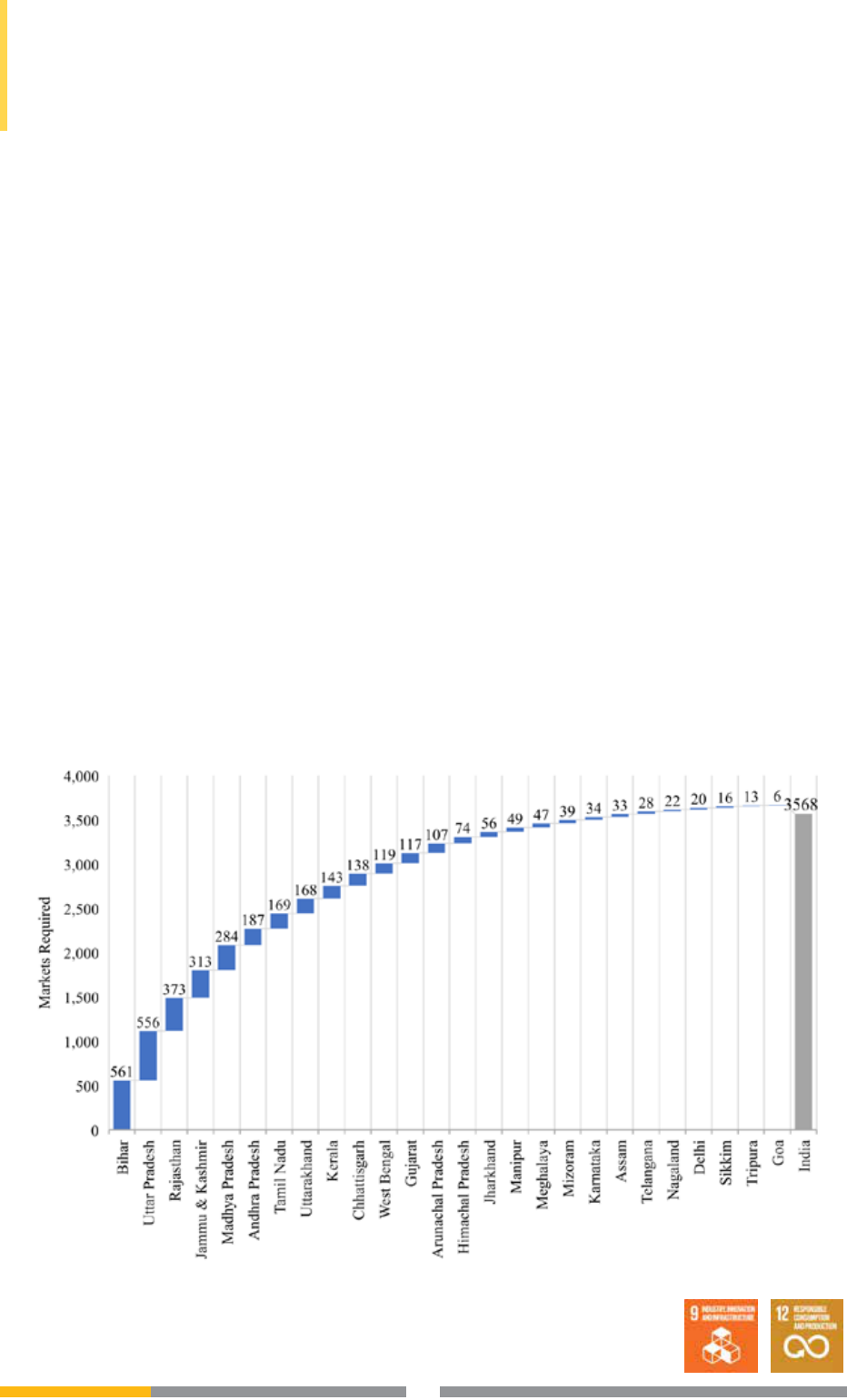

7.1 Additional markets required by 2022-23 36

8.1 Distribution of household savings across physical and nancial assets 42

8.2 Growth in unied payment interface (UPI) usage 42

9.1 Multi-pronged approach to resolving constraints in the ‘Housing for All’ scheme 46

10.1 Contribution of travel and tourism in India, 2016 49

11.1 India’s share in world production, 2015 55

12.1 Strategies for improving the energy sector in India 63

13.1 Total number of registered vehicles in India 66

14.1 Growth of Indian Railways,1950-51 to 2013-14 71

15.1 Passenger trafc by scheduled carriers, 2007-08 to 2016-17 75

15.2 Freight Transported by air, 2007-08 to 2016-17 76

16.1 Operating cost comparison in transporting cargo through various modes 81

16.2 Pillars of the Sagarmala programme 81

18.1 Increase in internet users and online penetration in India 88

19.1 Four paradigms to leverage Smart Cities Mission 93

20.1 Improvement in

Swachh Bharat Mission

(Gramin) coverage 97

21.1 Status on average annual water availability 100

22.1 Strategies for achieving sustainable environment 105

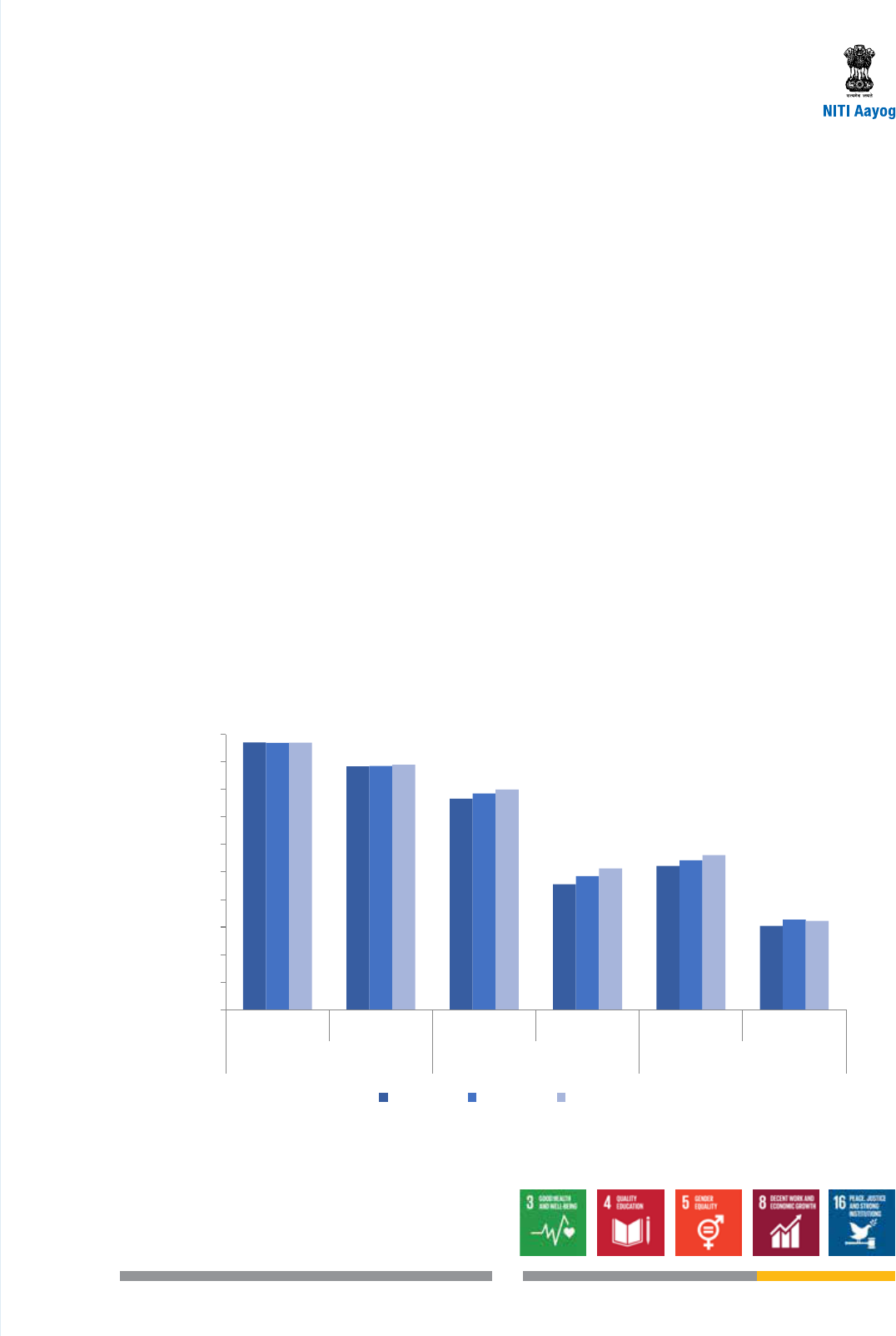

23.1 Gross and net enrolment ratios for elementary, secondary and senior secondary 111

Strategy for

New India @ 75

x

List of Figures

23.2 Learning outcomes from ASER survey 2016 for rural areas 112

24.1 Gross Enrolment Ratio in higher education, 2016-17 117

24.2 UGC’s graded autonomy regulations for universities 118

26.1 Workforce that has undergone formal skill training 125

27.1 Preventable risk factors are the biggest contributors to the disease burden, 2016 130

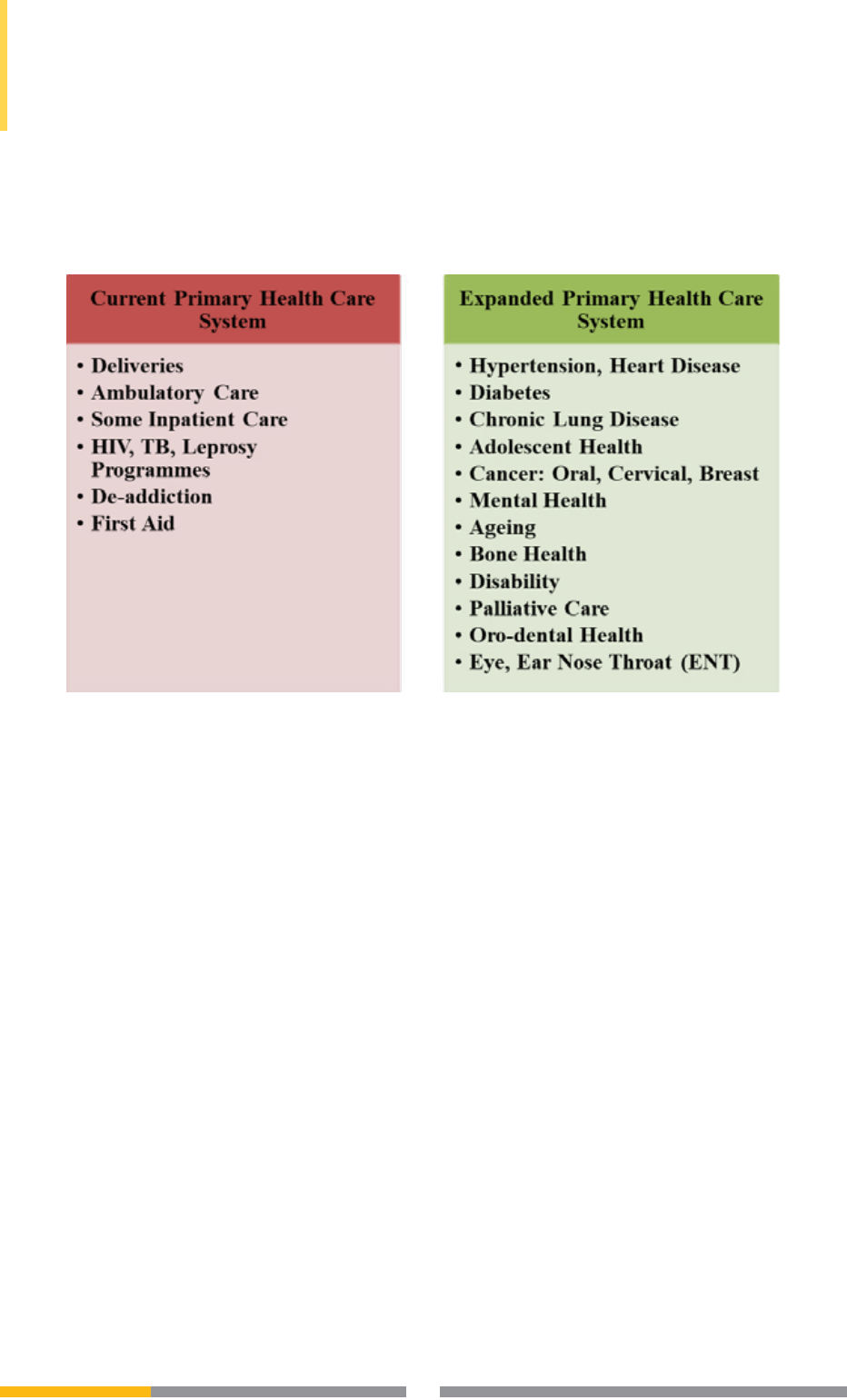

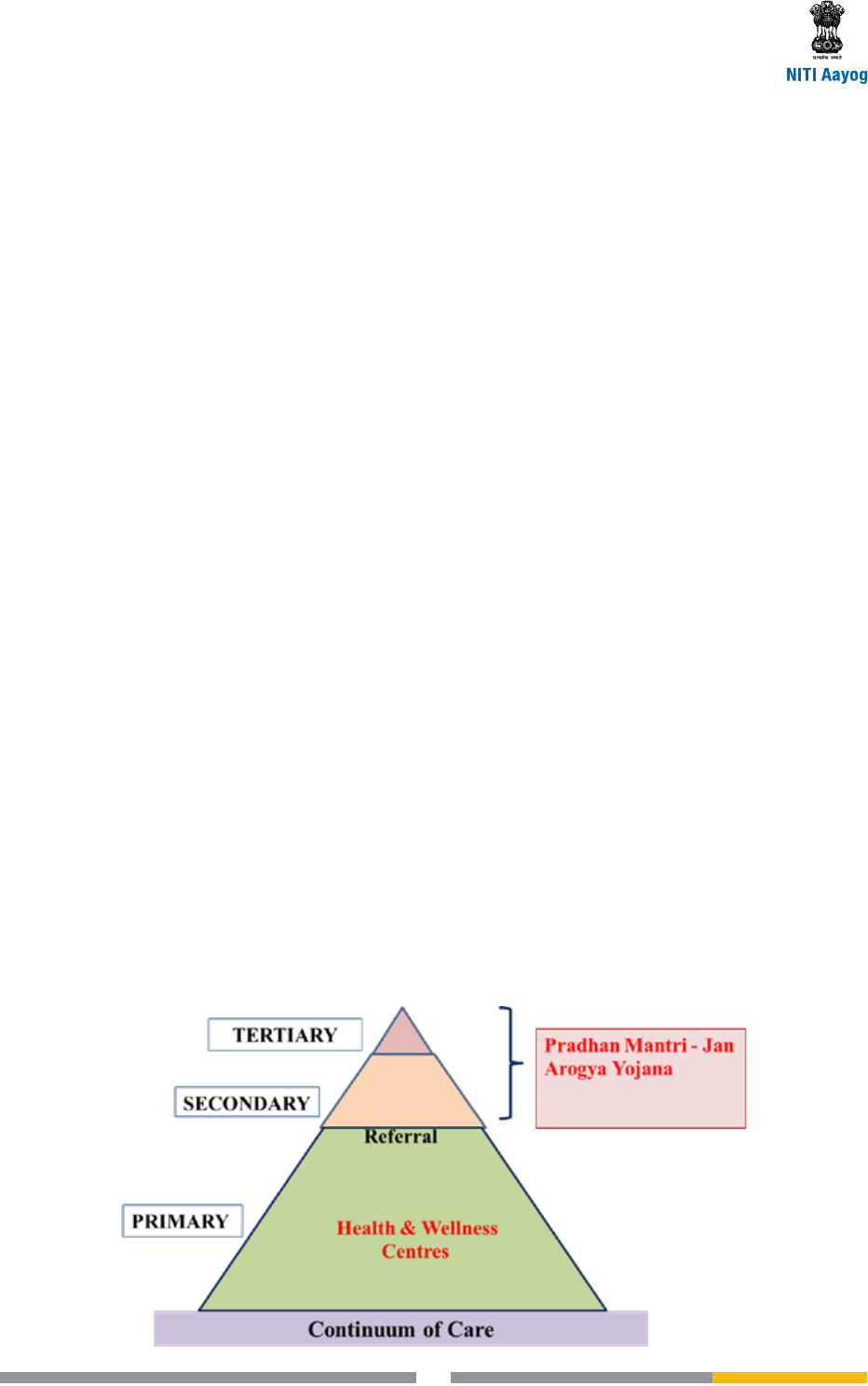

28.1 Additional services to be provided under the New India primary care system 134

28.2 Revamped primary health system for New India 135

29.1 Shortfall of specialists in government health centres compared to the

requirement based on existing infrastructure 138

29.2 Sanctioned posts of specialists vacant 138

30.1 Pillars of universal health coverage 143

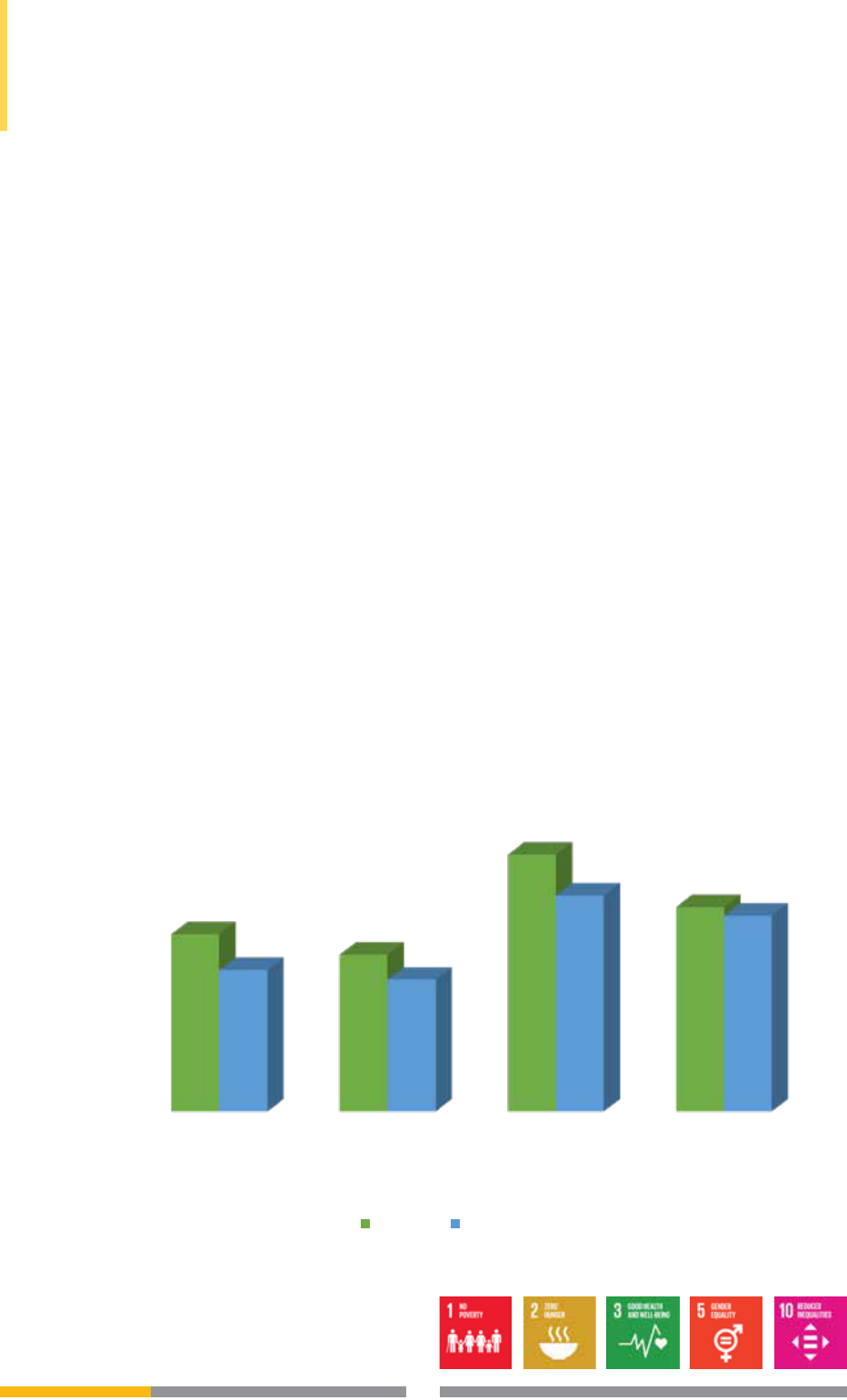

31.1 Key nutritional indicators in India 146

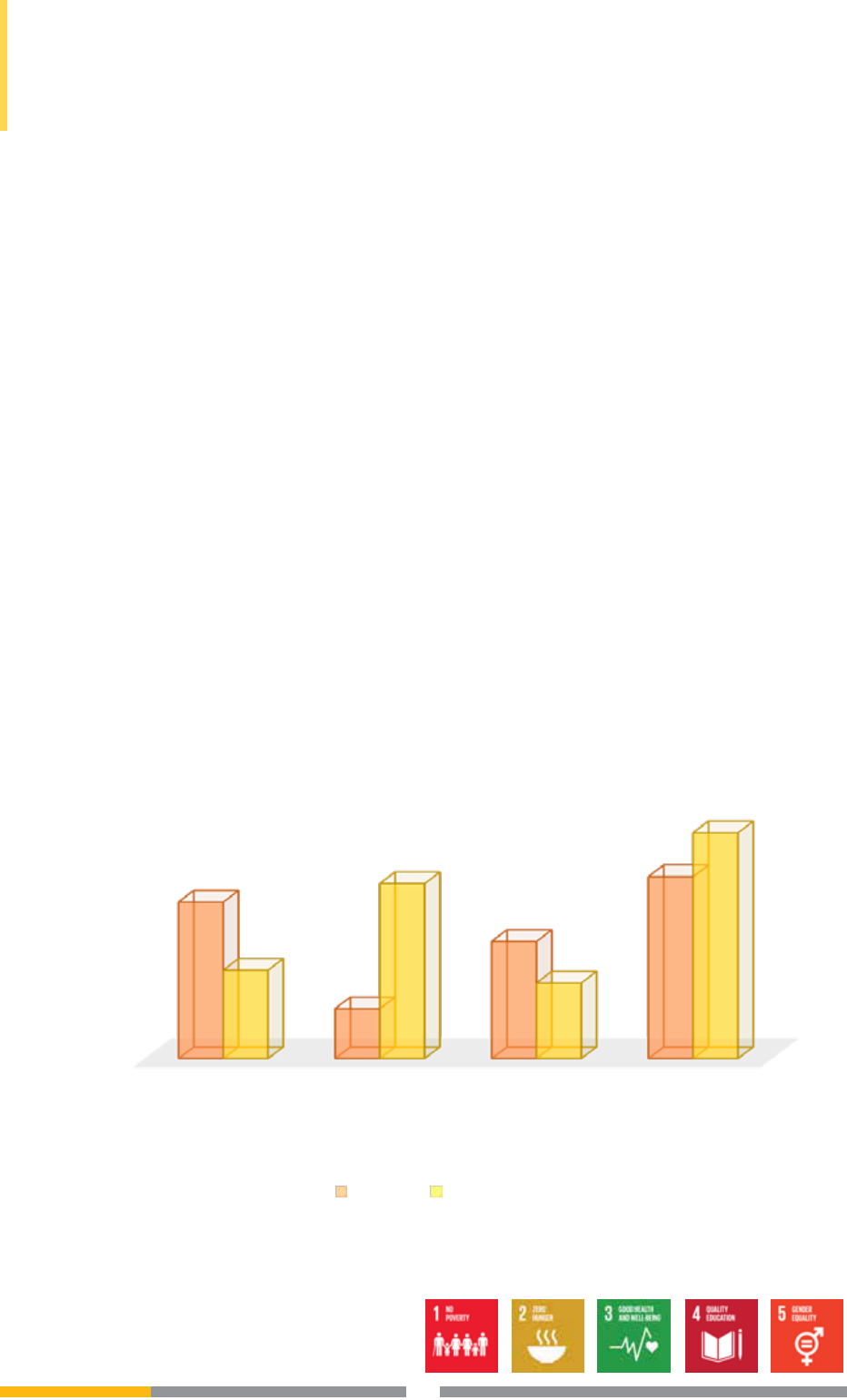

32.1 Progress with respect to gender-related indicators 150

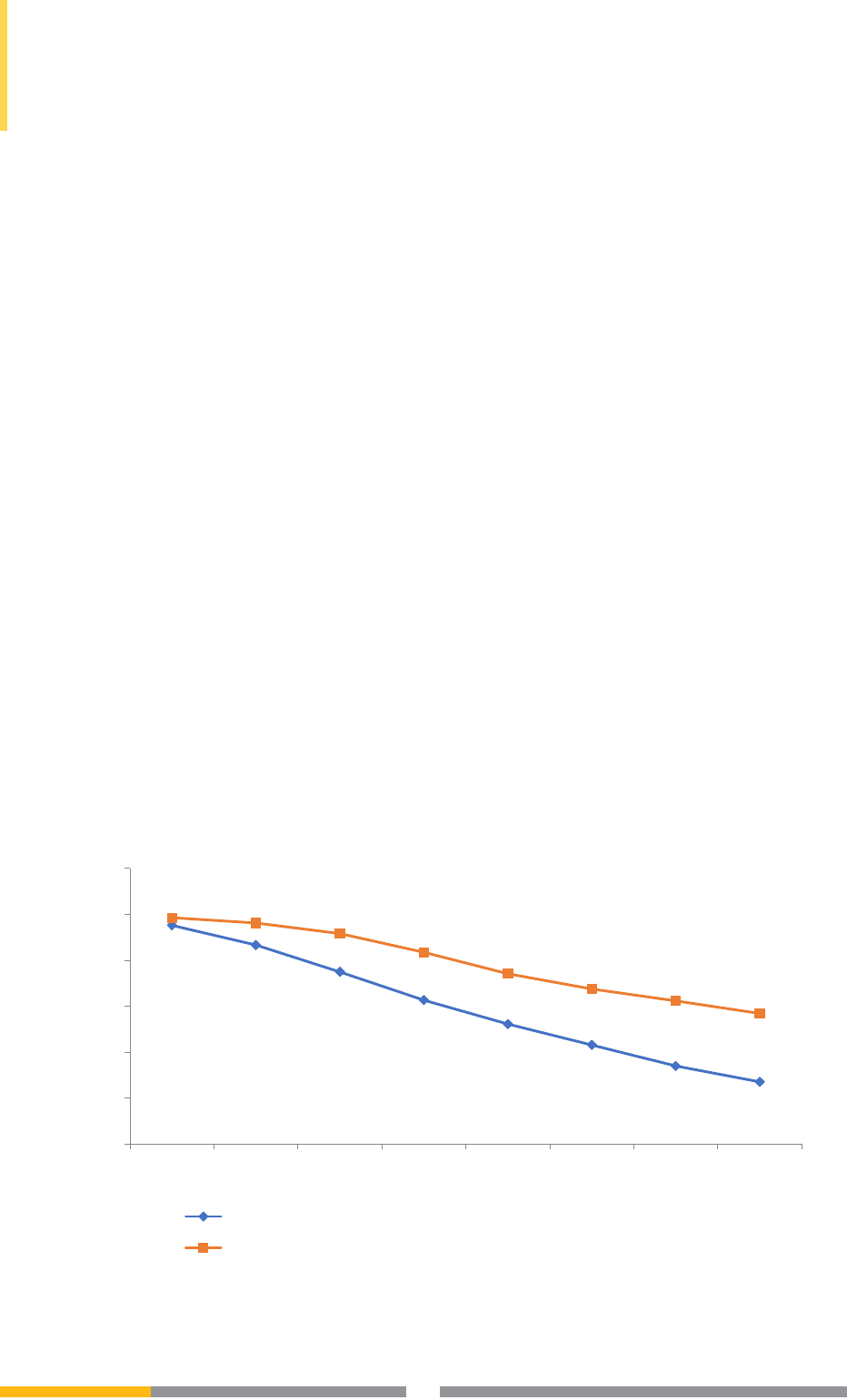

32.2 Female labour force participation 151

32.3 Examples of indicators that could be used for developing the gender-based

index and ranking states 153

33.1 School attendance of children with disabilities between 5-19 years 156

33.2 Literacy status of PwDs 157

33.3 Allocation and expenditure pertaining to the Department of Empowerment of

Persons with Disabilities 157

34.1 Workforce participation rate 164

34.2 Out of school children by religious group 165

35.1 Illustration of how the ADP converges stakeholders’ efforts in the prevention of stunting 171

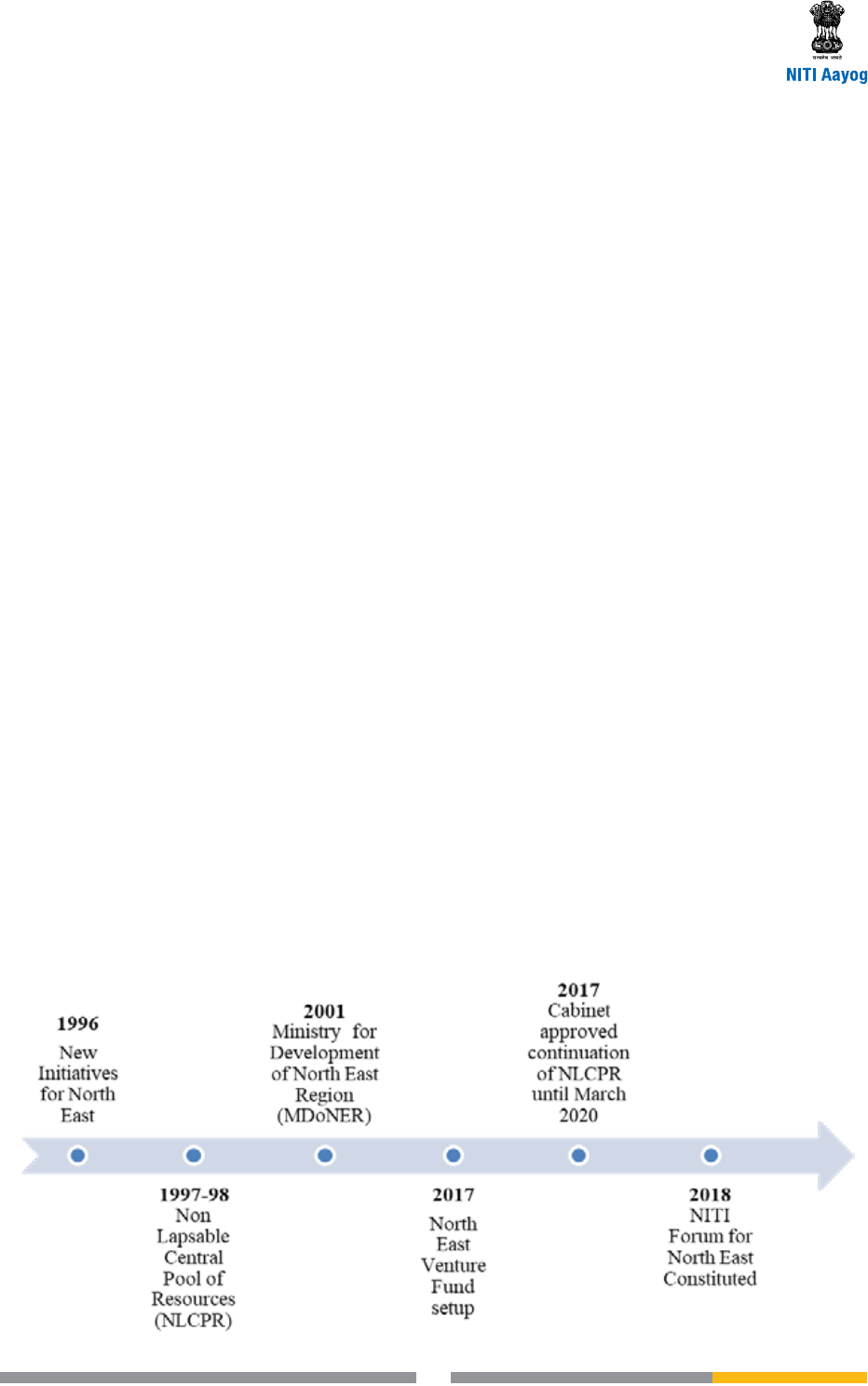

36.1 Per capita NSDP for north-east states, 2015-16 173

36.2 Per capita NSDP for north-east states, 2004-05 174

xi

List of Tables

List of Figures

36.3 Timeline of government initiatives for the development of north-east region 175

39.1 Key strategies to improve urban governance by 2022-23 188

40.1 Land use across different uses in India, 1990-91 to 2013-14 191

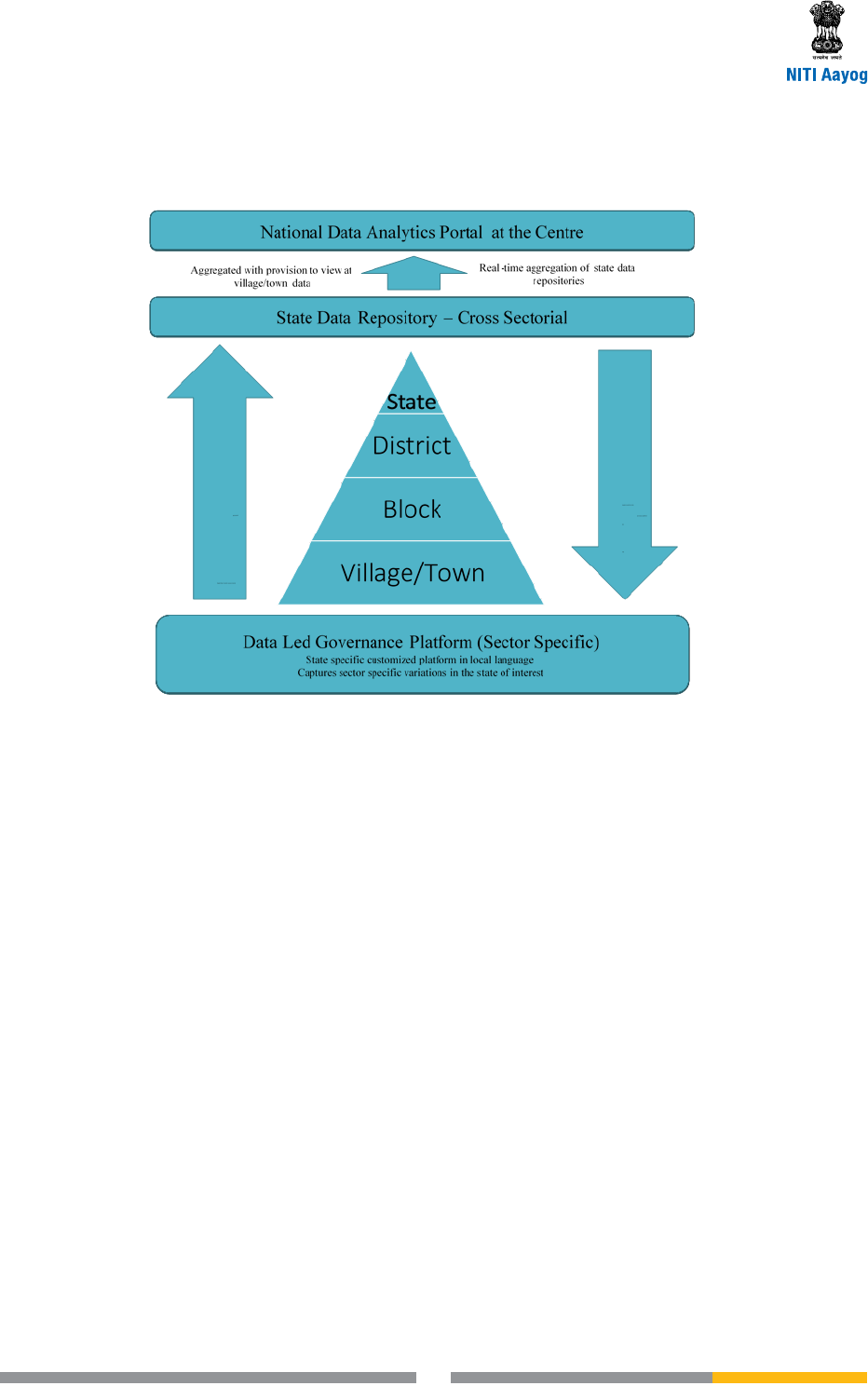

41.1 Framework for achieving transparent governance 197

7.1 Gaps in cold-chain development 37

23.1 Prole of public schools with low enrolment 114

34.1 Incidence of poverty across social groups 161

34.2 Literacy rate among social groups 162

34.3 Literacy Rate among minority communities 164

35.1 Core dimensions of ADP and their weightage 171

1

O

n August 15, 2022, independent India will turn 75. In the lifespan of nations, India is still young.

The best is surely yet to come. India’s youthful and aspirational population deserves a rapid

transformation of the economy, which can deliver double-digit growth, jobs and prosperity to all.

A strong foundation has been laid in the last four years. While there is every room for condence,

there is none for complacency. A surge of energy, untiring effort and an unshakeable resolve on the part of the

government, private sector and every individual citizen can achieve this transformation in the next ve years.

Seventy years ago, similar energy, effort and resolve from all Indians freed the country from colonial rule within

ve years of the launch of the Quit India movement in 1942. Then, like now, foundations had been laid but a

committed acceleration of effort was necessary. The Prime Minister’s call for

Sankalp Se Siddhi

is a clarion call

for a radical transformation for a New India by 2022-23.

The government has to be in the vanguard of the transformation of the Indian economy. However, the

government’s role must be dened correctly. This Strategy document attempts to do this. The document is

being framed in a context where a re-imagination of governance is taking place. We need a ‘development

state’ that focuses sharply on the difcult and accountable delivery of key public goods and services. There is

an ongoing effort to achieve an optimum level of public-private partnership. Policies have been put in place

for more efcient delivery of public goods and services such as health, education, power, urban water supply

and connectivity. In this context, a deliberate effort is being made to cut red tape and end burdensome over-

regulation for promoting entrepreneurship and private investment. Also, in an effort to align the ‘Strategy

for New India @ 75’ with India’s commitment to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, each

chapter is mapped to the relevant goals. India is currently putting in place a ‘development state’ guided by the

philosophy of

Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas

.

The purpose of this document, ‘Strategy for New India @ 75’, is to dene clear objectives for 2022-23 in a

diverse range of 41 areas that recognize the progress already made; and challenges that remain; identify

binding constraints in specic sectors; and suggest the way forward for achieving the stated objectives.

The Strategy document has disaggregated the 41 sectors under four sections: drivers, infrastructure,

inclusion and governance. The rst section on drivers focuses on the engines of economic performance – in

macroeconomic terms with chapters on growth and employment. The section also discusses strategies for

the doubling of farmers’ incomes; boosting Make in India; upgrading the science, technology and innovation

eco-system; and promoting sunrise sectors like ntech and tourism. An annual rate of growth of 9 per cent

Introduction

Strategy for

New India @ 75

2

by 2022-23 is essential for generating sufcient jobs and achieving prosperity for all. Four key steps, among

others have been spelled out for achieving this GDP growth rate. These are:

a. Increase the investment rate as measured by gross xed capital formation (GFCF) from present 29 per

cent to 36 per cent of GDP by 2022. About half of this increase must come from public investment

which is slated to increase from 4 per cent to 7 per cent of GDP. Government savings have to move into

positive territory. This sharp increase in investment-to-GDP ratio will require signicantly higher resource

mobilization efforts as elaborated in the chapter on Growth.

b. In agriculture, emphasis must shift to converting farmers to ‘agripreneurs’ by further expanding

e-National Agriculture Markets (e-NAMs) and replacing the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee

(APMC) Act with the Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (APLM) Act. The creation of a unied

national market, a freer export regime and abolition of the Essential Commodities Act are essential for

boosting agricultural growth.

c. A strong push would be given to ‘Zero Budget Natural Farming’ (ZBNF) techniques that reduce costs,

improve land quality and increase farmers’ incomes. This is a tested method for putting environment

carbon back into the land. Therefore, ZBNF allows India to signicantly contribute to reducing the global

carbon footprint.

d. To ensure maximum employment creation, codication of labour laws must be completed and a massive

effort must be made to upscale apprenticeships.

The second section on infrastructure deals with the physical foundations of growth. A lot of progress has been

made across all infrastructure sectors. This is crucial to enhancing the competitiveness of Indian business as

also ensuring the citizens’ ease of living. Three key steps, among others, are:

a. Expediting the establishment of the Rail Development Authority (RDA), which is already approved. RDA

will advise or make informed decisions on an integrated, transparent and dynamic pricing mechanism

for the railways. Investment in railways will be ramped up, including by monetising existing railway

assets.

b. The share of freight transported by coastal shipping and inland waterways will be doubled. Initially,

viability gap funding will be provided until the infrastructure is fully developed. An IT-enabled platform

would be developed for integrating different modes of transport and promoting multi-modal and

digitised mobility.

c. With the completion of the

Bharat Net

programme in 2019, all 2.5 lakh

gram panchayats

will be digitally

connected. In the next phase the last mile connectivity to the individual villages will be completed. The

aim will be to deliver all government services at the state, district, and

gram panchayat

level digitally by

2022-23, thereby eliminating the digital divide.

3

The section on inclusion deals with the urgent task of investing in the capabilities of all of India’s citizens. The

three themes in this section revolve around the various dimensions of health, education and mainstreaming

of traditionally marginalized sections of the population. While there are multiple dimensions and pathways

contained in the chapters in this section, four key steps, among others, are:

a. Successfully implementing the

Ayushman

Bharat programme including the establishment of 150,000

health and wellness centres across the country, and rolling out the

Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya

Abhiyaan

.

b. Upgrading the quality of the school education system and skills, including the creation of a new

innovation ecosystem at the ground level by establishing at least 10,000 Atal Tinkering Labs by 2020.

c. As already done in rural areas, affordable housing in urban areas will be given a huge push to improve

workers’ living conditions and ensure equity while providing a strong impetus to economic growth.

d. Implementing strategies to achieve regional equity by focusing on the North-East region and successfully

rolling out the Aspirational Districts Programme.

The nal section on governance delves deep into how the tasks/business of government can be streamlined

and reformed to achieve better outcomes. It involves a sharp focus on ensuring accountability and a shift to

performance-based evaluation. The government will revamp its data systems and analysis so that all policy

interventions and decision-making are based on evidence and real-time data. This will yield efcient and

targeted delivery of services and justice to those who need them the most. Three key steps, among others, are:

a. Implementing the recommendations of the Second Administrative Reforms Commission as a prelude

to appointing a successor for designing reforms in the changing context of emerging technologies and

growing complexity of the economy.

b. A new autonomous body, viz., the Arbitration Council of India, may be set up to grade arbitral

institutions and accredit arbitrators to make the arbitration process cost effective and speedy, and to pre-

empt the need for court intervention.

c. The scope of

Swachh Bharat Mission

may be expanded to cover initiatives for landlls, plastic waste and

municipal waste and generating wealth from waste.

To achieve the goals of New India in 2022-23, it is important for the private sector, civil society and even

individuals to draw up their own strategies to complement and supplement the steps the government intends

to take. With the available tools of 21st century technology, it should be possible to truly create a mass

movement for development. With the

Sankalp

of all Indians, India will have

Siddhi

.

DRIVERS

7

Objectives

• Steadily accelerate the gross domestic product

(GDP) growth rate to achieve a target of about

8 per cent during 2018-23 (

note that this target

has been set to catalyse policy action and

does not represent a forecast

). This will raise

the economy’s size in real terms from USD 2.7

trillion in 2017-18 to nearly USD 4 trillion by

2022-23. Besides having rapid growth, which

reaches 9-10 per cent by 2022-23, it is also

necessary to ensure that growth is inclusive,

sustained, clean and formalized.

• The investment rate should be raised from 29

per cent to 36 per cent of GDP which has been

achieved in the past, by 2022-23.

• Exports of goods and services combined should

be increased from USD 478 billion in 2017-18

to USD 800 billion by 2022-23.

Current Situation

Economic growth in India has been broadly on

an accelerating path. It is likely to be the fastest

growing major economy in the world in the

medium-term.

The share of manufacturing in India’s GDP is low

relative to the average in low and middle-income

countries. It has not increased in any signicant

measure in the quarter century after economic

liberalization began in 1991. Within manufacturing,

growth has often been highest in sectors that are

relatively capital intensive, such as automobiles and

pharmaceuticals. This stems from India’s inability to

capitalize fully on its inherent labour and skill cost

advantages to develop large-scale labour intensive

manufacturing. Complex land and labour laws have

also played a notable part in this outcome. There

is a need to increase the pace of generating good

quality jobs to cater to the growing workforce, their

rising aspirations and to absorb out-migration of

labour from agriculture.

The positive news is that high growth rate has been

achieved with strong macroeconomic fundamentals

including low and stable rates of ination and

a falling scal decit. However, along with

macroeconomic stability, the sufcient condition for

escalating growth is to continue with the structural

reforms that address the binding constraints for a

more robust supply-side response.

Constraints

Overall, growth can be accelerated by a number

of measures across different policy areas, which

have been detailed in different chapters of this

strategy for 2022-23. This chapter focuses on the

macroeconomic drivers of growth.

Way Forward

1. Raising investment rates to 36 per cent by

2022-23

• To raise the rate of investment (gross xed

capital formation as a share of GDP) from about

29 per cent in 2017-18 to about 36 per cent

of GDP by 2022-23, a slew of measures will

be required to boost both private and public

investment.

1. Growth

Strategy for

New India @ 75

8

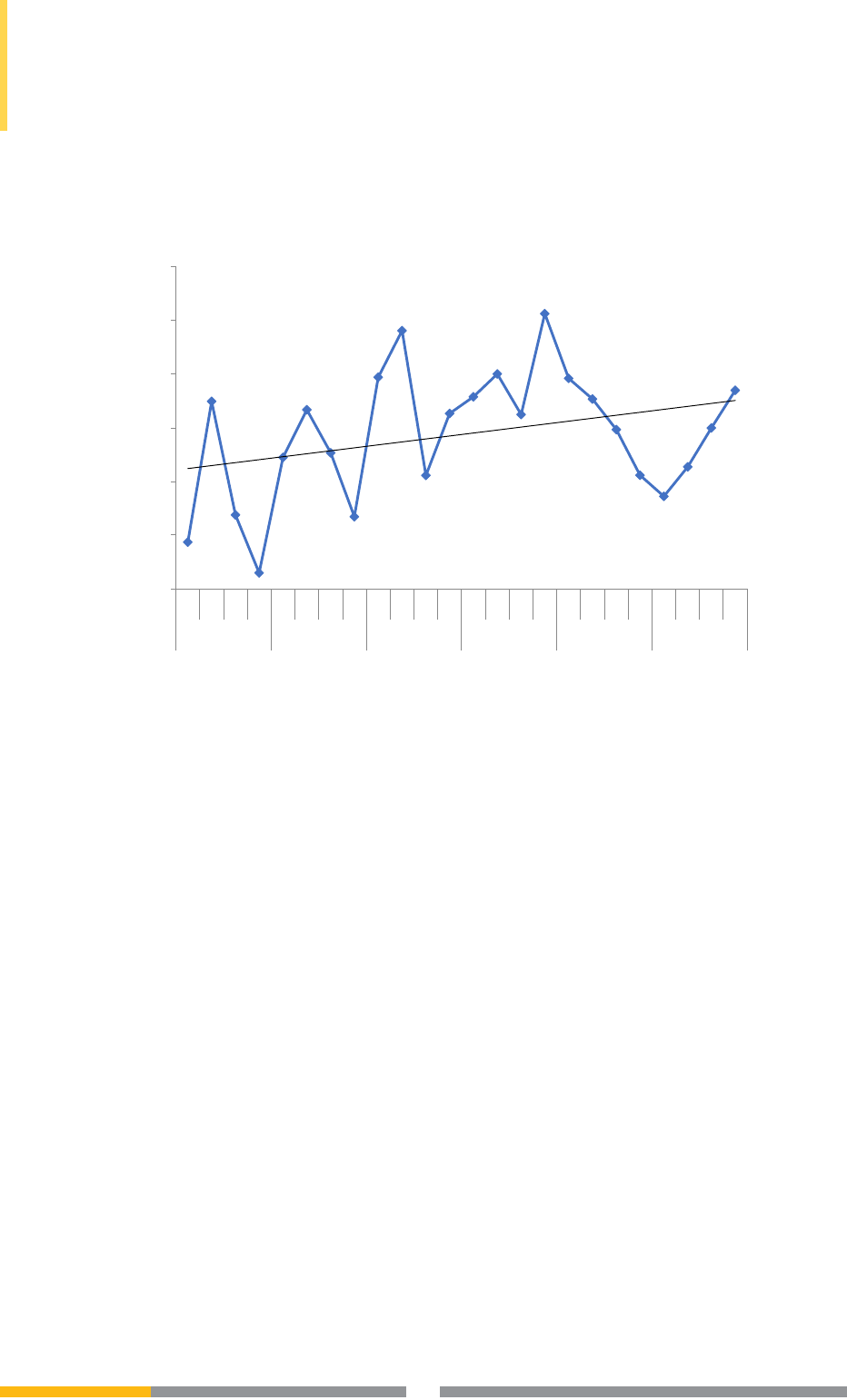

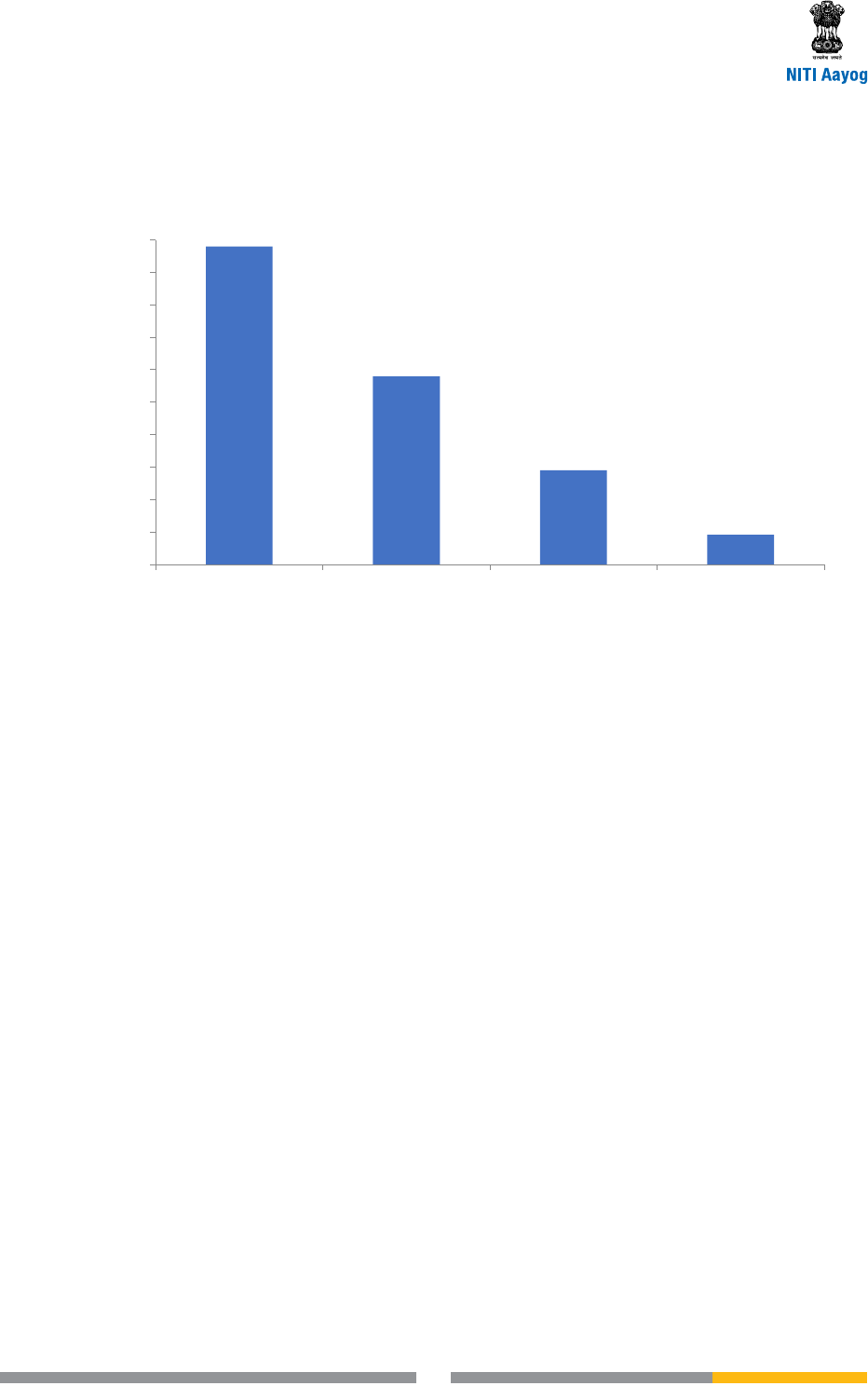

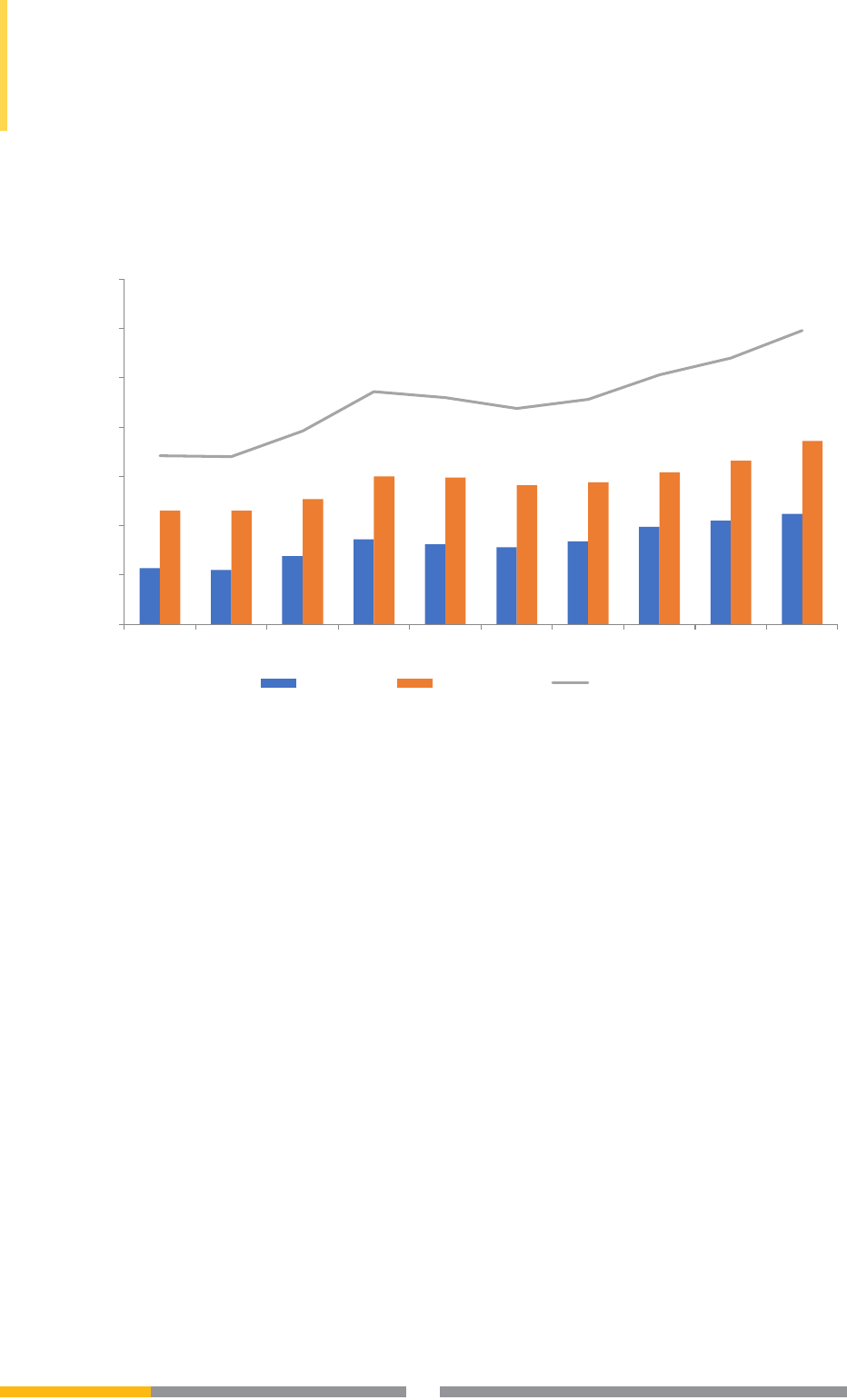

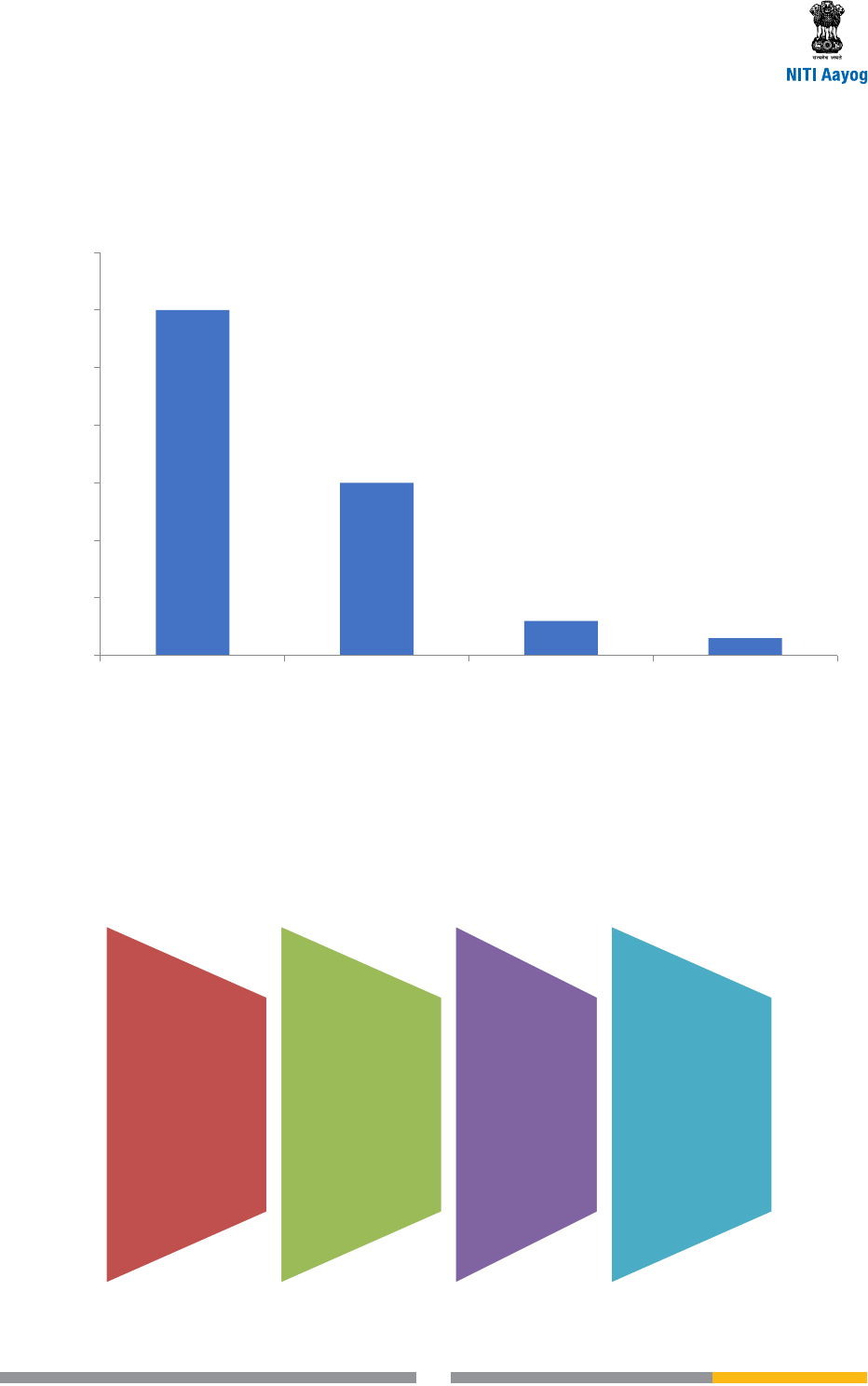

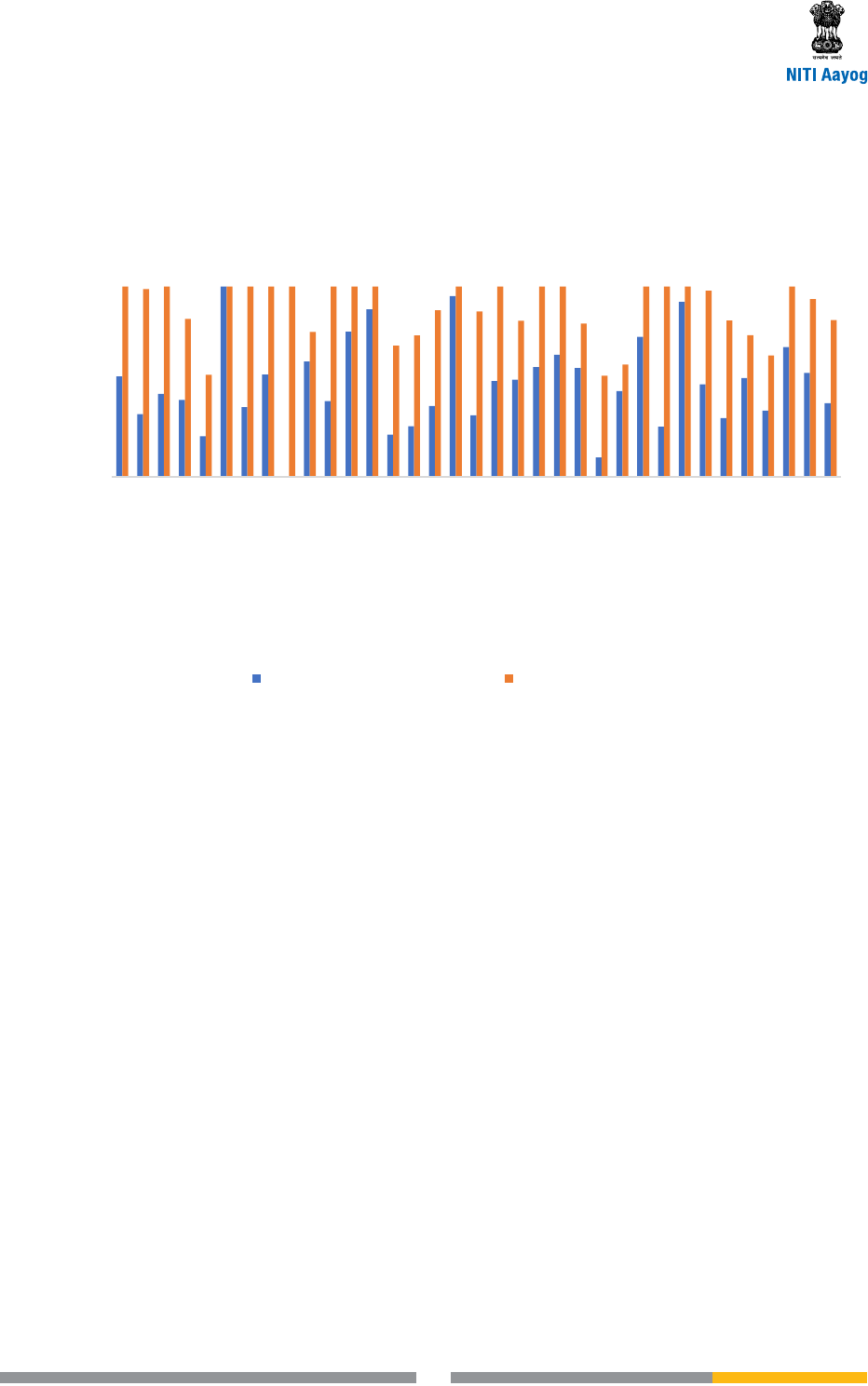

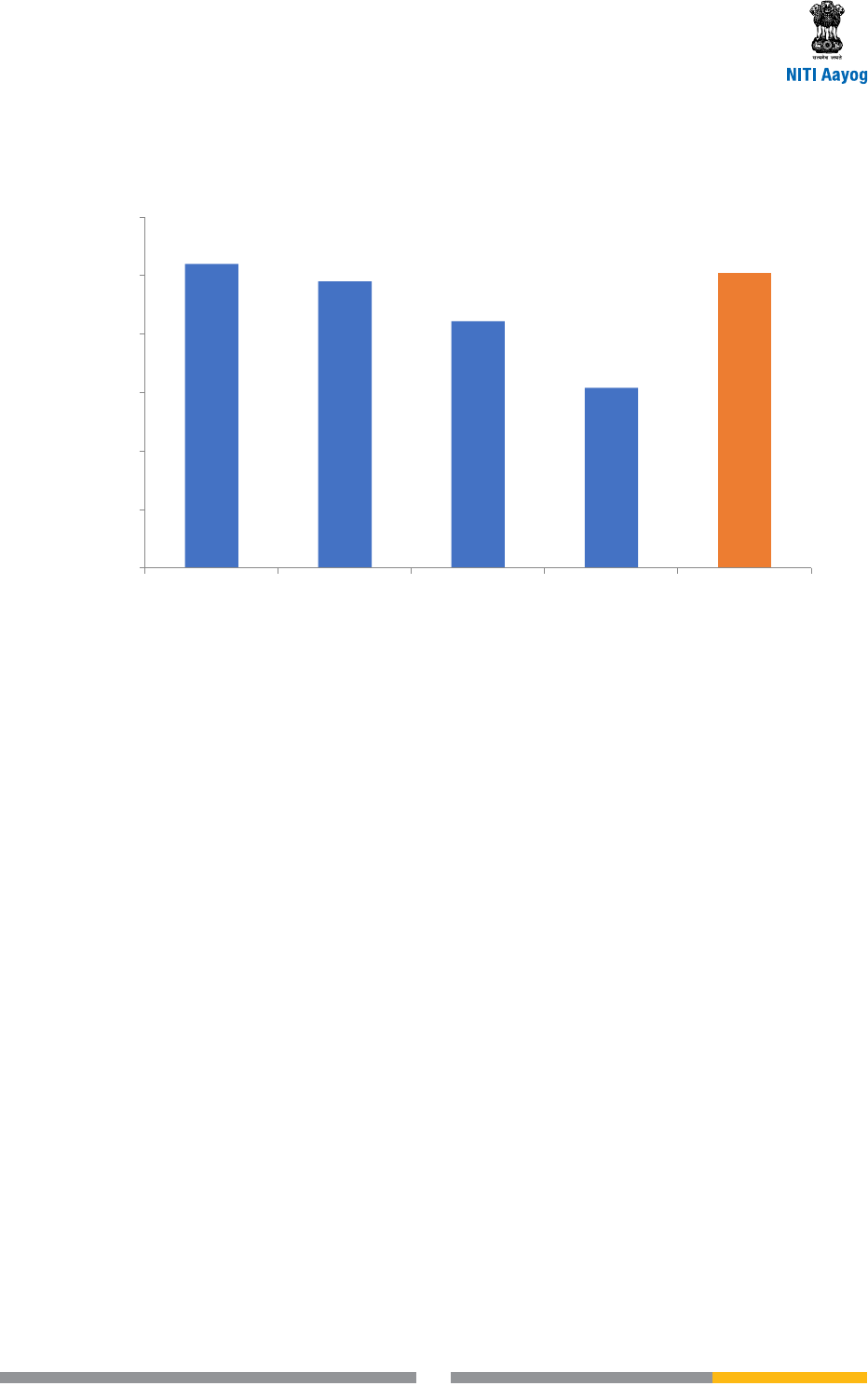

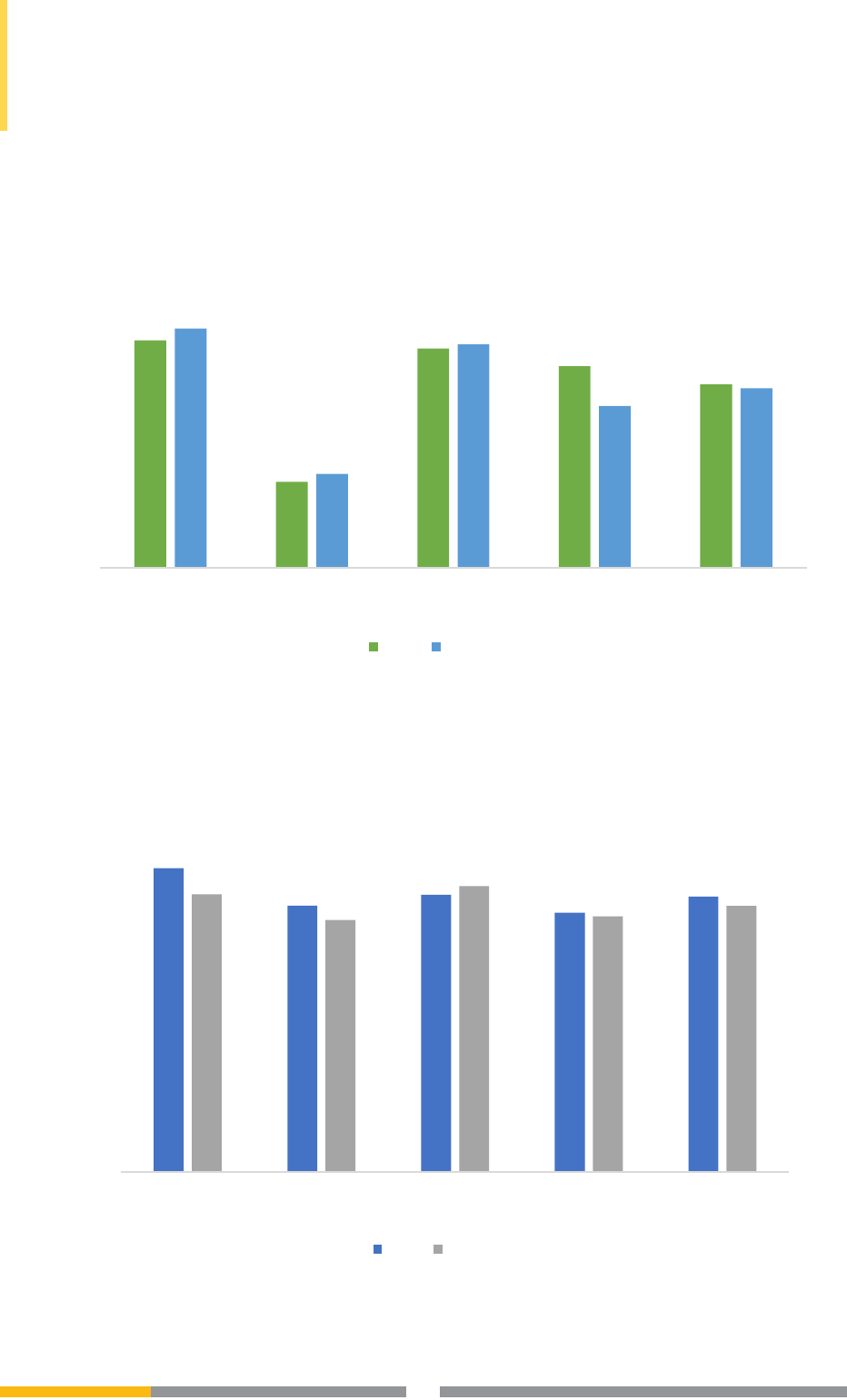

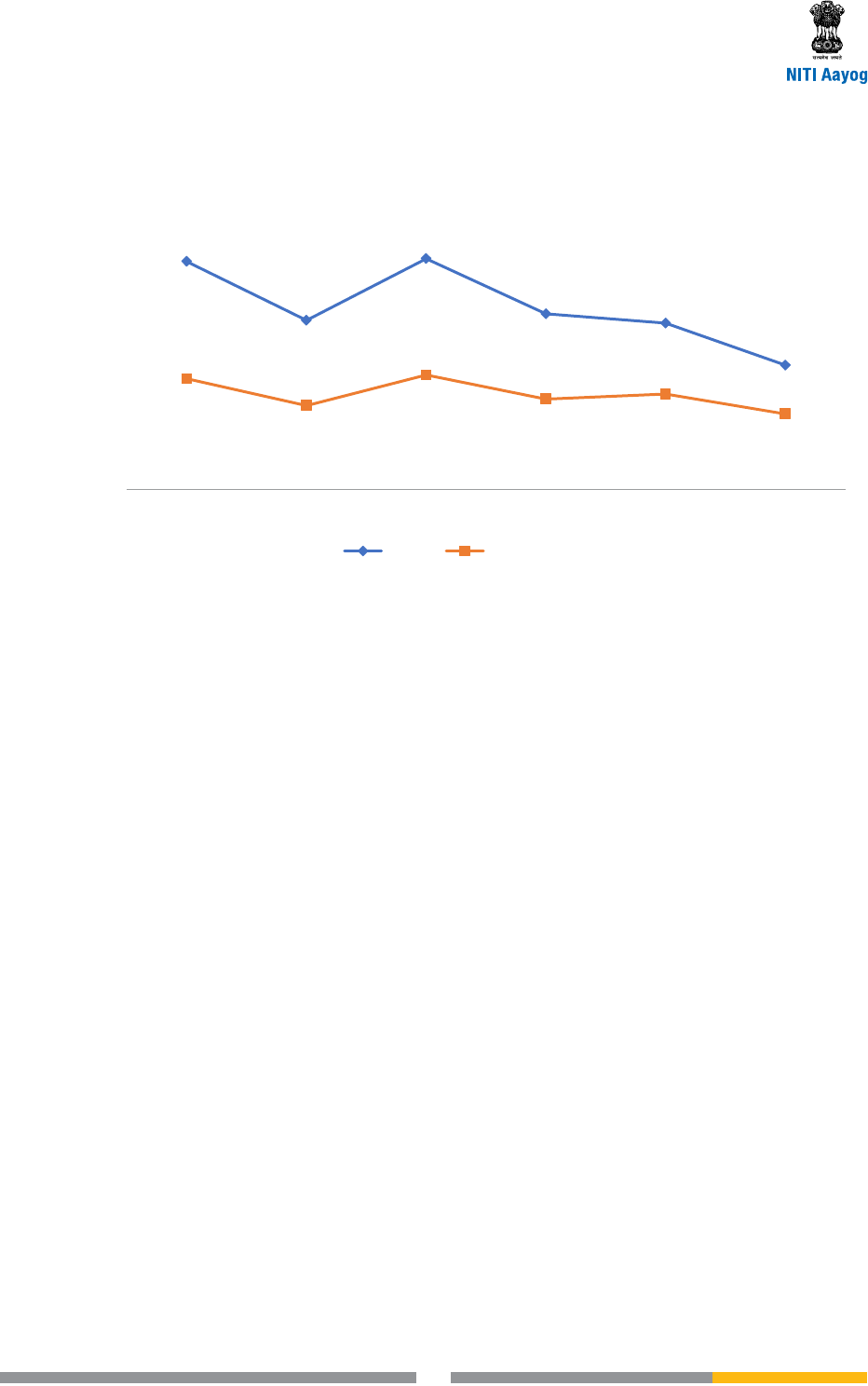

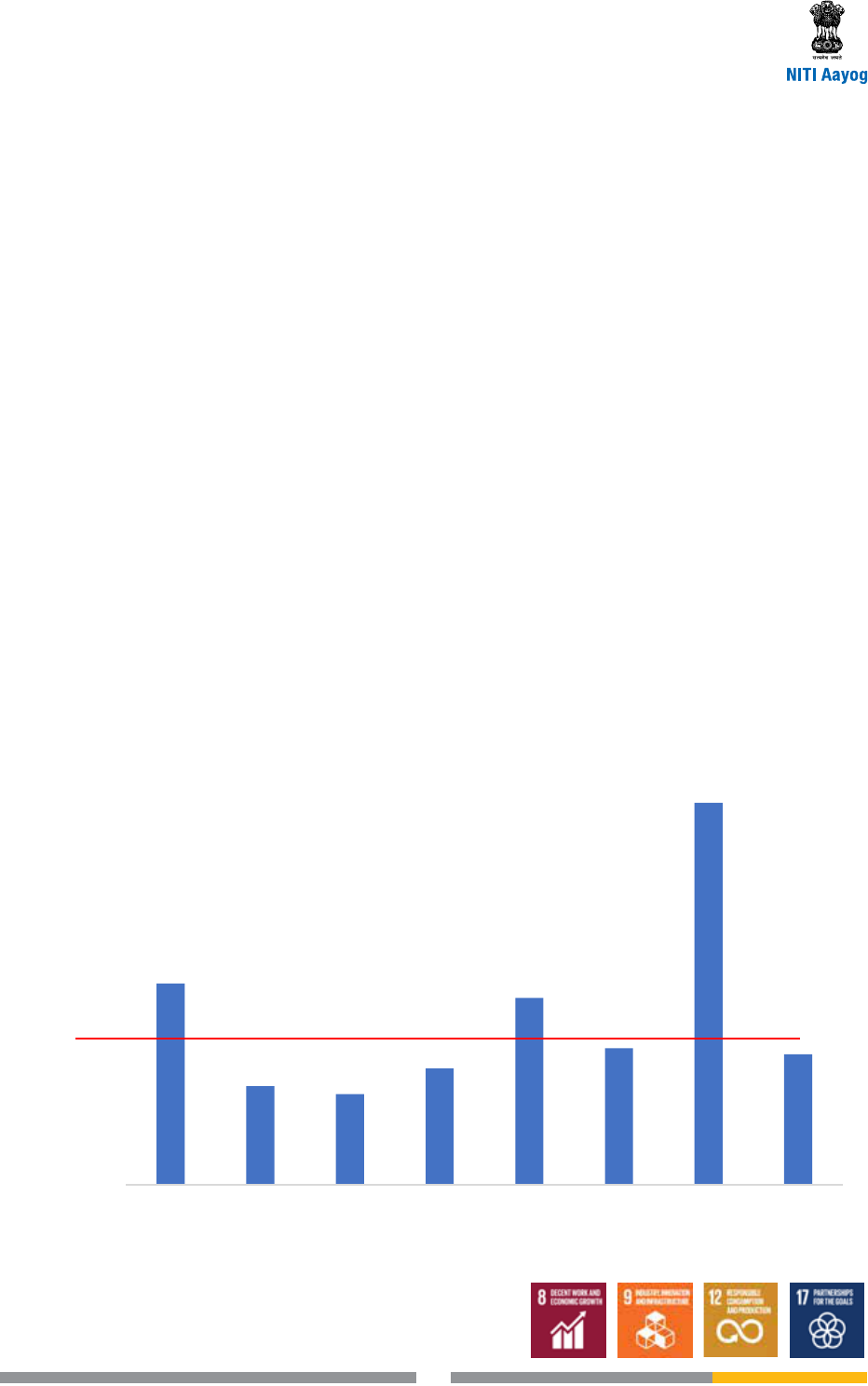

Figure 1.1: India’s real GDP growth

4%

5%

6%

7%

8%

9%

10%

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4

2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18

Real GDP Growth (%)

• India’s tax-GDP ratio of around 17 per cent

is half the average of OECD countries (35

per cent) and is low even when compared to

other emerging economies like Brazil (34 per

cent), South Africa (27 per cent) and China

(22 per cent). To enhance public investment,

India should aim to increase its tax-GDP

ratio to at least 22 per cent of GDP by 2022-

23. Demonetization and GST will contribute

positively to this critical effort. In addition,

efforts need to be made to rationalize direct

taxes for both corporate tax and personal

income tax. Simultaneously, there is a need to

ease the tax compliance burden and eliminate

direct interface between taxpayers and tax

ofcials using technology.

• In 2016-17, the share of government (central

and state combined) capital expenditure in

total budget expenditure was 16.2 per cent,

1

and government’s contribution to xed capital

formation was close to 4 per cent of GDP. This

needs to be increased to at least 7 per cent of

GDP by 2022-23 through greater orientation

of expenditure towards productive assets, and

minimizing the effective revenue decit.

• States could also undertake greater mobilization

of own taxes such as property tax, and taking

specic steps to improve administration of GST

to increase tax collections.

• Two areas in which higher public investment

will easily be absorbed are housing and

infrastructure. Investment in housing,

especially in urban areas, will create very large

multiplier effects in the economy. Investment

in physical infrastructure will address long-

standing deciencies faced by the economy.

Sector-specic measures are mentioned in

corresponding chapters.

• The government has taken signicant measures

to attract foreign direct investment by easing

caps on the extent of permissible stake holding

Source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation

9

and the norms of approval. By 2022-23, the

government may consider further liberalizing

FDI norms across sectors. Domestic savings

can be complemented by attracting foreign

investment in bonds and government securities.

Regulatory limits can be relaxed for rupee

denominated debt.

• The government should continue to exit central

public sector enterprises (CPSEs) that are not

strategic in nature. Inefcient CPSEs surviving

on government support distort entire sectors

as they operate without any real budget

constraints. The government’s exit will attract

private investment and contribute to the

exchequer, enabling higher public investment.

For larger CPSEs, the goal should be to create

widely held companies by ofoading stake to

the public to create entities where no single

promoter has control. This will both improve

management efciency and allow government

to monetize its holdings with substantial

contribution to public nances.

• Private investment needs be encouraged in

infrastructure through a renewed public-private

partnership (PPP) mechanism on the lines

suggested by the Kelkar Committee.

2. Macroeconomic stability through prudent

scal and monetary policies

• Sustained high growth requires macroeconomic

stability, which is being achieved through a

combination of prudent scal and monetary

policies.

• The government has targeted a gradual

lowering of the government debt-to-GDP ratio.

It will help reduce the relatively high interest

cost burden on the government budget, bring

the size of India’s government debt closer to

that of other emerging market economies, and

improve the availability of credit for the private

sector in the nancial markets.

• But even as lowering of debt and limiting scal

decit are important, the government should

be exible in its approach towards setting

annual targets based on prevailing economic

conditions. This approach is enshrined in

the existing Fiscal Responsibility and Budget

Management (FRBM) architecture that has built

in exibility in the form of adequately dened

“escape and buoyancy” clauses. Targets should

take cognizance of the stage of the business

cycle and scal decit and borrowing targets

should not be set in isolation.

• The effective revenue decit should be

brought down as rapidly as possible. Capital

expenditure incurred for the health and

education sectors, which in effect builds

human capital, should be excluded from

estimates of revenue expenditure. This will

increase government savings.

• One of the major institutional reforms of recent

years has been to statutely mandate the RBI

to maintain “... price stability while keeping in

mind the objective of growth”. Ination needs

to be contained within the stated target range

of 2 per cent to 6 per cent. Ination targeting

provides a reasonably exible policy framework

which is in line with global best practices and

can respond appropriately to supply shocks.

• Policy should be directed to minimize volatility

in the nominal exchange rate.

3. Efcient nancial intermediation

• Efcient functioning of the nancial markets is

crucial to maintain high growth in the economy.

There is a need to deepen nancial markets

with easier availability of capital, greater use

Strategy for

New India @ 75

10

of nancial markets to channel savings and

an improved risk-assessment framework for

lending to avoid a situation of large-scale non-

performing assets in the banking sector.

• Governance reforms in public sector banks require,

apart from the establishment of independent and

commercially driven bank boards, performance

assessment of executives and increased exibility

in human resources policy.

• The Gujarat International Finance and Tech

City (GIFT) should be leveraged to push the

envelope on nancial sector liberalization. It

is an opportunity to onshore trading in rupees

and other derivatives, which currently happens

outside India for regulatory reasons. If GIFT

succeeds, liberalization can be extended to the

rest of the country.

• Enable alternative (to banks) sources of credit

for India’s long-term investment needs.

The bond market needs deepening through

liberalization of regulations and continued scal

consolidation.

4. Focus on exports and manufacturing

• India needs to remain globally competitive,

particularly in the production and exports of

manufactured, including processed agricultural,

goods. The following reforms would help in

improving the competitiveness:

o A focused effort on making the logistics

sector more efcient is needed.

o Power tariff structures may be rationalized

to ensure global competitiveness of Indian

industries.

o Import tariffs that seek to promote

indigenous industry should come with

measures to raise productivity which will

provide the ability to compete globally.

• Improve connectivity by accelerating the

completion of announced infrastructure

projects. Enhancing physical connectivity will

help reduce delivery times and improve global

connectivity and the reach of our exporters. By

2022-23, we should complete projects that are

already underway such as the Delhi-Mumbai

Industrial Corridor (DMIC) and Dedicated Freight

Corridors.

• Work with states to ease labour and land

regulations. In particular, we should introduce

exibility in labour provisions across sectors. All

state governments should speedily implement

xed term employment (FTE) that has now been

extended to cover all sectors.

• The government has recently established

a dedicated fund of INR 5,000 crore for

enhancing 12 “Champion Services Sectors”.

Among others, these include IT & ITeS, tourism,

medical value travel and audio visual services.

Given the signicant role of services exports in

maintaining India’s balance of payments, the

government should continue to focus on these

sectors.

• Strengthen the governance and technical

capabilities of Export Promotion Councils

(EPCs) by subjecting them to a well-dened,

performance-based evaluation. Performance

evaluations of EPCs could be based on

increasing the share of Indian exports in

product markets covered by these EPCs. Those

EPCs unable to achieve mutually agreed upon

targets for increasing market shares could be

closed down or re-structured.

• Explore closer economic integration within

South Asia and the emerging economies of

South East Asia particularly Cambodia, Laos,

Myanmar and Vietnam, using the existing

Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal (BBIN) and

11

the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral

Technical and Economic Co-operation (BIMSTEC)

frameworks.

o Building the physical infrastructure and

putting in place measures to facilitate

seamless cross-border movement of

goods in the North-East region would

help accelerate integration and promote

exports.

5. Employment generation

• The necessary condition for employment

generation is economic growth. Achieving

the growth targets by implementing the

development strategy outlined in this document

can generate sufcient jobs for new entrants

into the labour force, as well as those migrating

out of agriculture. A large part of jobs would

hopefully be generated in labour-intensive

manufacturing sectors, construction and

services. In addition, the employability of labour

needs to be enhanced by improving health,

education and skilling outcomes and a massive

expansion of the apprenticeship scheme.

________________________________________

1

Source: RBI.

Strategy for

New India @ 75

12

Objectives

• Complete codication of central labour laws

into four codes by 2019.

• Increase female labour force participation to at

least 30 per cent by 2022-23.

• Disseminate publicly available data, collected

through rigorous household and enterprise

surveys and innovative use of administrative

data on a quarterly basis by 2022-23.

• Encourage increased formalization of the labour

force by reforming labour laws, easing of

industrial relations and ensuring of fair wages,

working conditions and social security through

signicant productivity improvements in the

economy.

Current Situation

To capitalize on its demographic dividend, India

must create well-paying, high productivity jobs. Of

India’s total workforce of about 52 crore, agriculture

employed nearly 49 per cent while contributing

only 15 per cent of the GVA. Comprehensive

modernization of agriculture and allied sectors are

needed urgently. In contrast, only about 29 per cent

of China’s workforce was employed in agriculture

(Figure 2.1).

1

Industry and services accounted

for 13.7 and 37.5 per cent of employment while

making up for 23 per cent and 62 per cent of GVA,

respectively.

2

A signicant number of workers, currently employed

in agriculture, will move out in search of jobs in

other areas. This will be in addition to the new

entrants to the labour force as a result of population

growth. By some estimates, the Indian economy

will need to generate nearly 70 lakh jobs annually

to absorb the net addition to the workforce. Taking

into account the shift of labour force from low

productivity employment, 80-90 lakhs new jobs will

be needed in the coming years.

Micro and small-sized rms as well as informal

sector rms dominate the employment landscape

in India. As per the National Sample Survey (NSS)

73rd round, for the period 2015-16, there were

6.34 crore unincorporated non-agricultural micro,

small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the

country engaged in different economic activities

providing employment to 11.10 crore workers. A

large majority of these rms are in the unorganized

sector. By some estimates, India’s informal sector

employs approximately 85 per cent of all workers.

3

India also exhibits a low and declining female

labour force participation rate. The female labour

force participation rate in India was 23.7 per cent in

2011-12

4

compared to 61 per cent in China, 56 per

cent in the United States.

5

Recognizing the high cost of compliance with

existing labour regulations and the complexity

generated by various labour laws at the central

and state levels, the central government has

recently introduced policies to make compliance

easier and more effective. They are also simplifying

and rationalizing the large and often overlapping

2. Employment and Labour Reforms

13

49%

29%

14.50%

4.60%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

50%

India China Brazil South Africa

Share of Workforce Employed in

Agriculture (%)

Figure 2.1: Share of workforce employed in agriculture

Source: NSSO; World Bank

number of labour laws. These measures include

moving licensing and compliance processes

online, simplifying procedures and permitting

self-certication in larger number of areas. One of

the government’s key initiatives is to rationalize 38

central labour laws into four codes, namely wages,

safety and working conditions, industrial relations,

and social security and welfare. Of the four codes,

the one on wages has been introduced in the Lok

Sabha and is under examination. The other three

codes are at the pre-legislative consultation stage

and should be completed urgently.

The government has put in place several schemes

to help generate employment. These include the

Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment

Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS),

MUDRA Yojana

,

Prime Minister’s Employment Generation

Programme and

Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Protsahan

Yojana

. Additional initiatives aid job creation

through providing skill development, easing access

to credit and addressing sector specic constraints.

The government also made the EPFO premium

portable so that workers can change jobs without

fear of losing their provident fund benets.

The government has recently made publicly

available the data on employment collected by the

Employment Provident Fund Organization (EPFO),

Employees’ State Insurance Corporation (ESIC)

and National Pension Scheme (NPS). With MOSPI

collecting employment data through its enterprises

and household surveys – particularly the Periodic

Labour Force Survey – and the focus on improving

payroll data, the effort is to vastly improve

availability of reliable employment data and release

it on a regular basis.

Constraints

• Productivity across all sectors. A large

share of India’s workforce is employed in

low productivity activities with low levels of

Strategy for

New India @ 75

14

remuneration. This is especially true of the

informal sector where wages can be one

twentieth of those in rms producing the same

goods or services but in the formal sector.

6

• Protection and social security. A large number

of workers that are engaged in the unorganized

sector are not covered by labour regulations

and social security. This dualistic nature of the

labour market in India may be a result of the

complex and large number of labour laws that

make compliance very costly. In 2016, there

were 44 labour laws under the statute of the

central government. More than 100 laws fall

under the jurisdiction of state governments.

7

The multiplicity and complexity of laws makes

compliance and enforcement difcult.

• Skills. According to the India Skill Report 2018,

only 47 per cent of those coming out of higher

educational institutions are employable.

8

• Employment data. We currently lack timely

and periodic estimates of the work force.

This lack of data prevents us from rigorously

monitoring the employment situation and

assessing the impact of various interventions to

create jobs.

Way Forward

1. Enhance skills and apprenticeships

• The Labour Market Information System (LMIS)

is important for identifying skill shortages,

training needs and employment created. The

LMIS should be made functional urgently.

• Ensure the wider use of apprenticeship

programmes by all enterprises. This may require

an enhancement of the stipend amount paid

by the government for sharing the costs of

apprenticeships with employers.

2. Labour law reforms

• Complete the codication of labour laws at the

earliest.

• Simplify and modify labour laws applicable

to the formal sector to introduce an optimum

combination of exibility and security.

• Make the compliance of working conditions

regulations more effective and transparent.

• The National Policy for Domestic Workers

needs to be brought in at the earliest to

recognize their rights and promote better

working conditions.

3. Enhance female labour force participation

• Ensure the implementation of and employers’

adherence to the recently passed Maternity

Benet (Amendment) Act, 2017, and the

Sexual Harassment of Women at Work Place

(Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act. It is

also important to ensure implementation of these

legislations in the informal sector. Further details

may be found in the chapter on Gender.

• Ensure that skills training programmes and

apprenticeships include women.

4. Improve data collection on employment

• Ensure that data collection for the Periodic

Labour Force Survey (PFLS) of households

initiated in April 2017 is completed as per

schedule and data disseminated by 2019.

• Conduct an annual enterprise survey using the

goods and service tax network (GSTN) as the

sample frame.

• Increase the use of administrative data viz.

EPFO, ESIC and the NPS to track regularly the

state of employment while adjusting for the

formalization of the workforce.

15

5. Ease industrial relations to encourage

formalization

• Increase severance pay, in line with global best

practices.

• Overhaul the labour dispute resolution system

to resolve disputes quickly, efciently, fairly and

at low cost.

• Strengthen labour courts/tribunals for timely

dispute resolution and set a time frame for

different disputes.

6. Wages

• Make compliance with the national oor level

minimum wage mandatory.

• Expand the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, to

cover all jobs.

• Enforce the payment of wages through cheque

or

Aadhaar

-enabled payments for all.

7. Working conditions and social security

• Enact a comprehensive occupational health and

safety legislation based on risk assessment,

employer-worker co-operation, and effective

educational, remedial and sanctioning. Workers

housing on site will help to improve global

competitiveness of Indian industry, along with

enhancing workers’ welfare.

• Enhance occupational safety and health (OSH)

in the informal sector through capacity building

and targeted programmes.

• Ensure compulsory registration of all

establishments to ensure better monitoring of

occupational safety as well as recreation and

sanitation facilities.

• Enhance transparency in the labour inspection

system by allowing online complaints and

putting in place a standardized and clear

mechanism.

________________________________________

1

2017 OECD Economic Survey of India; NSSO.

2

Sectoral Contribution to GVA calculated using data from MOSPI’s Second Advance Estimates. Industry consists of manufacturing,

mining and quarrying and electricity, gas, water supply& other utility services. The services sector consists of trade, hotels, transport,

communication and services related to broadcasting; construction; nancial, real estate and professional services; and public admin-

istration, defence and other services.

3

OECD India Policy Brief, Education and Skills. Accessed May 15, 2018.

https://www.oecd.org/policy-briefs/India-Improving-Quality-of-Education-and-Skills-Development.pdf.

4

NSSO 68th Round (2011-12). Female labour force participation rate calculated using usual principal status, covering both urban and

rural areas.

5

World Development Indicators database, World Bank. Accessed May 16, 2018.

6

Data from Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) and NSS, cited in the Annual Economic Survey, 2015-16

http://indiabudget.nic.in/es2015-16/echapvol1-10.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2018.

7

Ministry of Labour and Employment, India.

http://labour.nic.in/about-ministry. Accessed May 15, 2018.

8

India Skill Report 2018.

Strategy for

New India @ 75

16

Objectives

• India should be among the top 50 countries in

the Global Innovation Index by 2022-23.

1

• Five of our scientic research institutions should

be amongst the top 100 in the world.

• India should aim to spend at least 2 per cent

of gross domestic product (GDP) on R&D with

equal contributions from the public and private

sector.

Current Situation

Recognizing the crucial role of technology and inno-

vation in economic development, India’s policy mak-

ers have taken several initiatives to promote science,

technology and innovation (see gure below).

Various schemes have been launched to attract,

nurture and retain young researchers and women

scientists in the eld of scientic research. Some

important achievements in the eld of science and

technology are enumerated below.

3. Technology and Innovation

TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION

OBJECTIVE:

By 2022-23:

India should be among the top 50 countries in the Global Innovation Index.

i

Ten of our scientific research institutions should be amongst the top 100 in the world.

India should aim to spend at least 2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) on R&D with

equal contributions from the public and private sector.

CURRENT SITUATION

Recognizing the crucial role of technology and innovation in economic development, India’s policy

makers have taken several initiatives over the last decade and a half to promote science, technology

and innovation (see figure below):

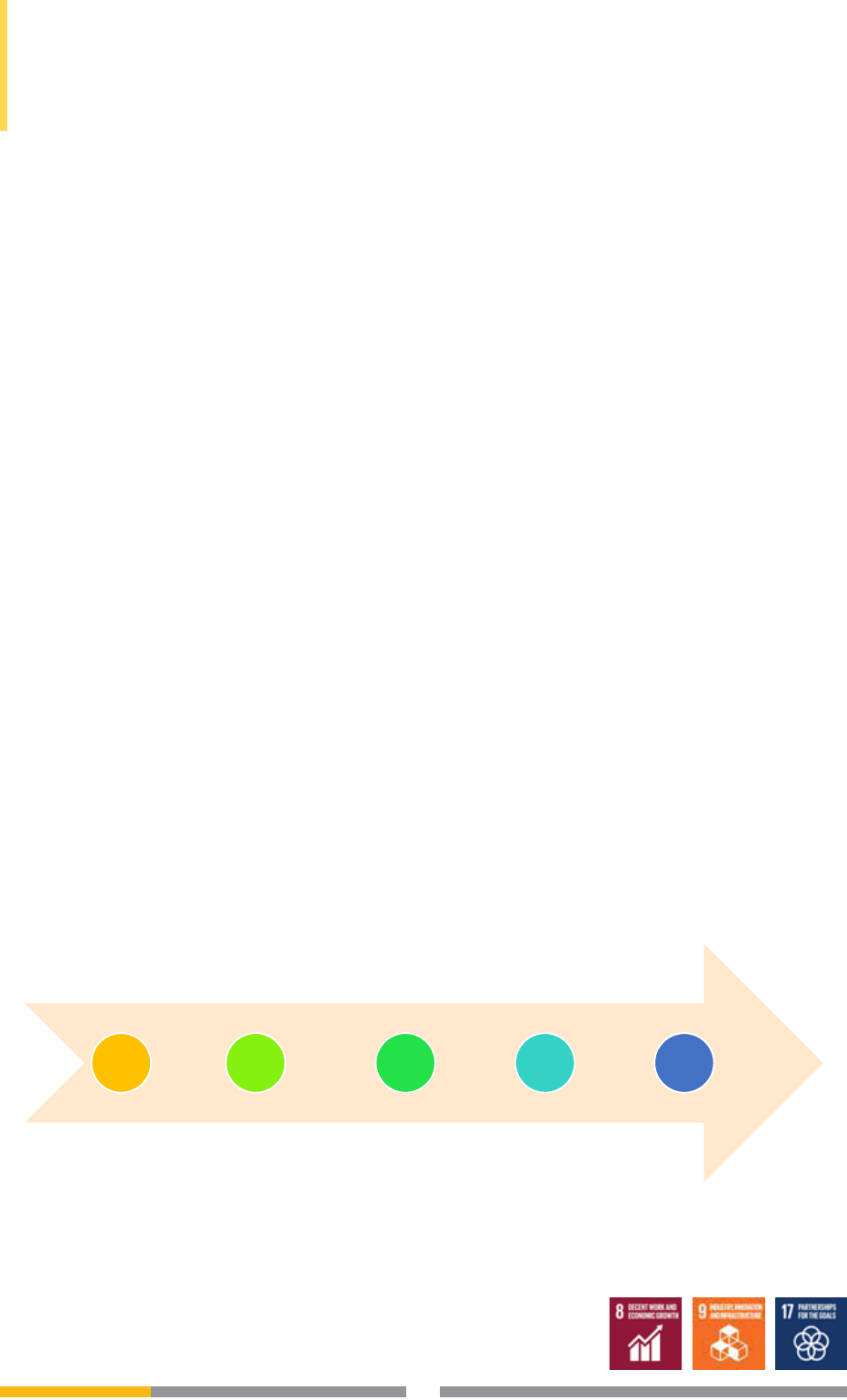

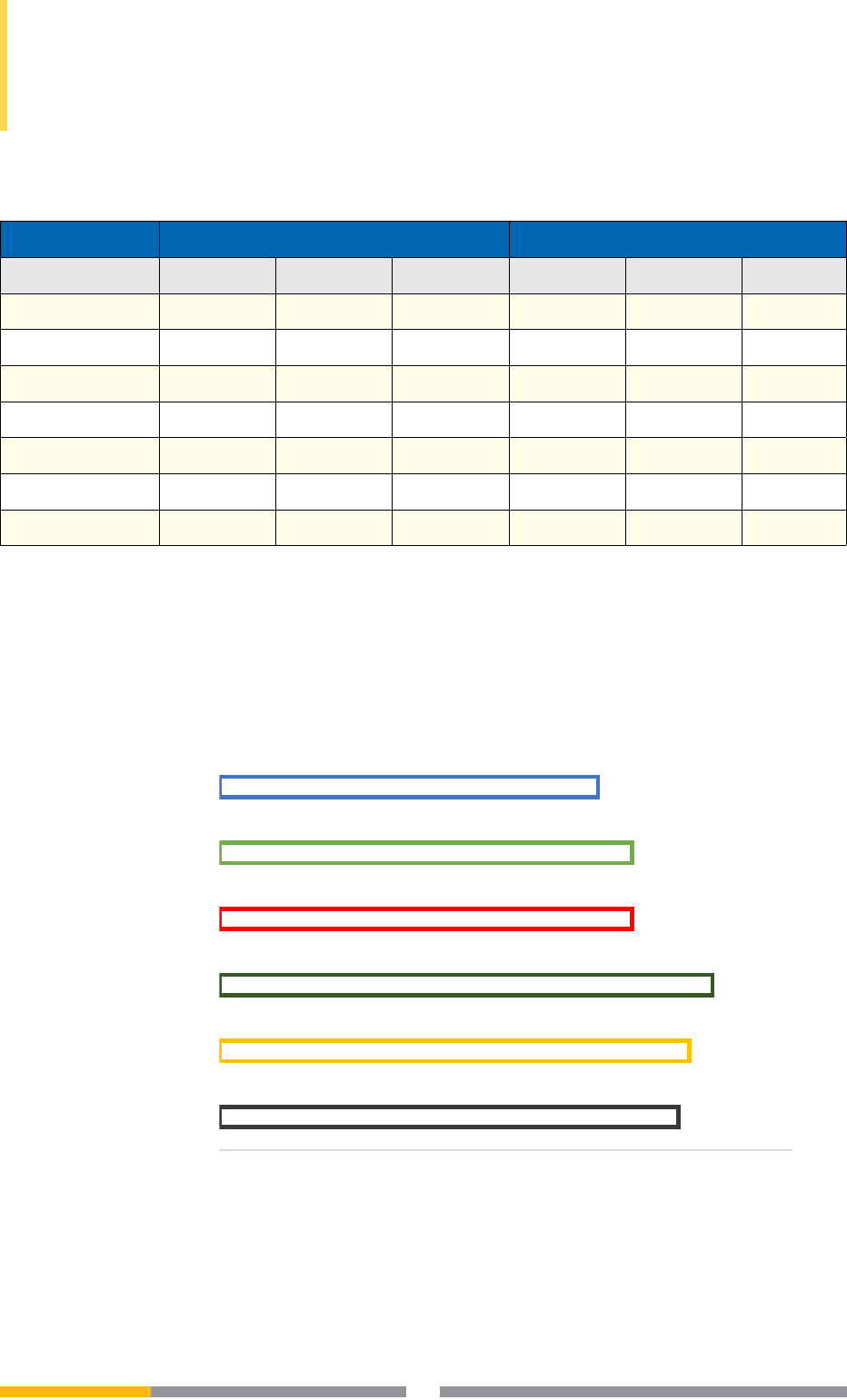

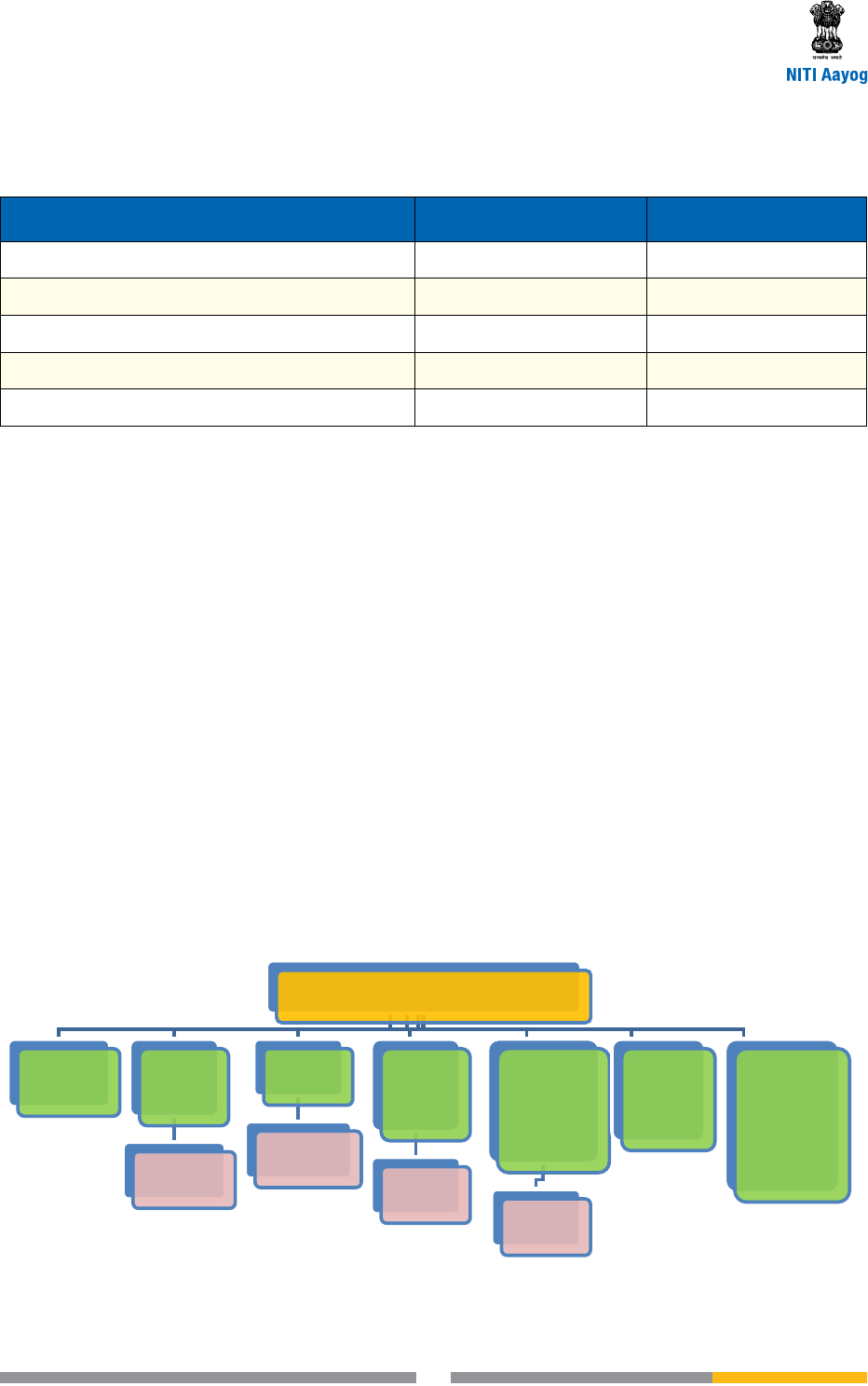

Figure 1: Steps taken to promote science, technology and innovation in India

Various schemes have been launched to attract, nurture and retain young researchers and women

scientists in the field of scientific research. Some important achievements in the field of science and

technology are enumerated below:

First, India has become a major destination for outsourced R&D activities. We currently have

more than 1,100 R&D centres set up by multi-national companies (MNCs) such as IBM,

Google, Microsoft, Intel, Lupin, Wockhardt, etc. These R&D centres cover areas including

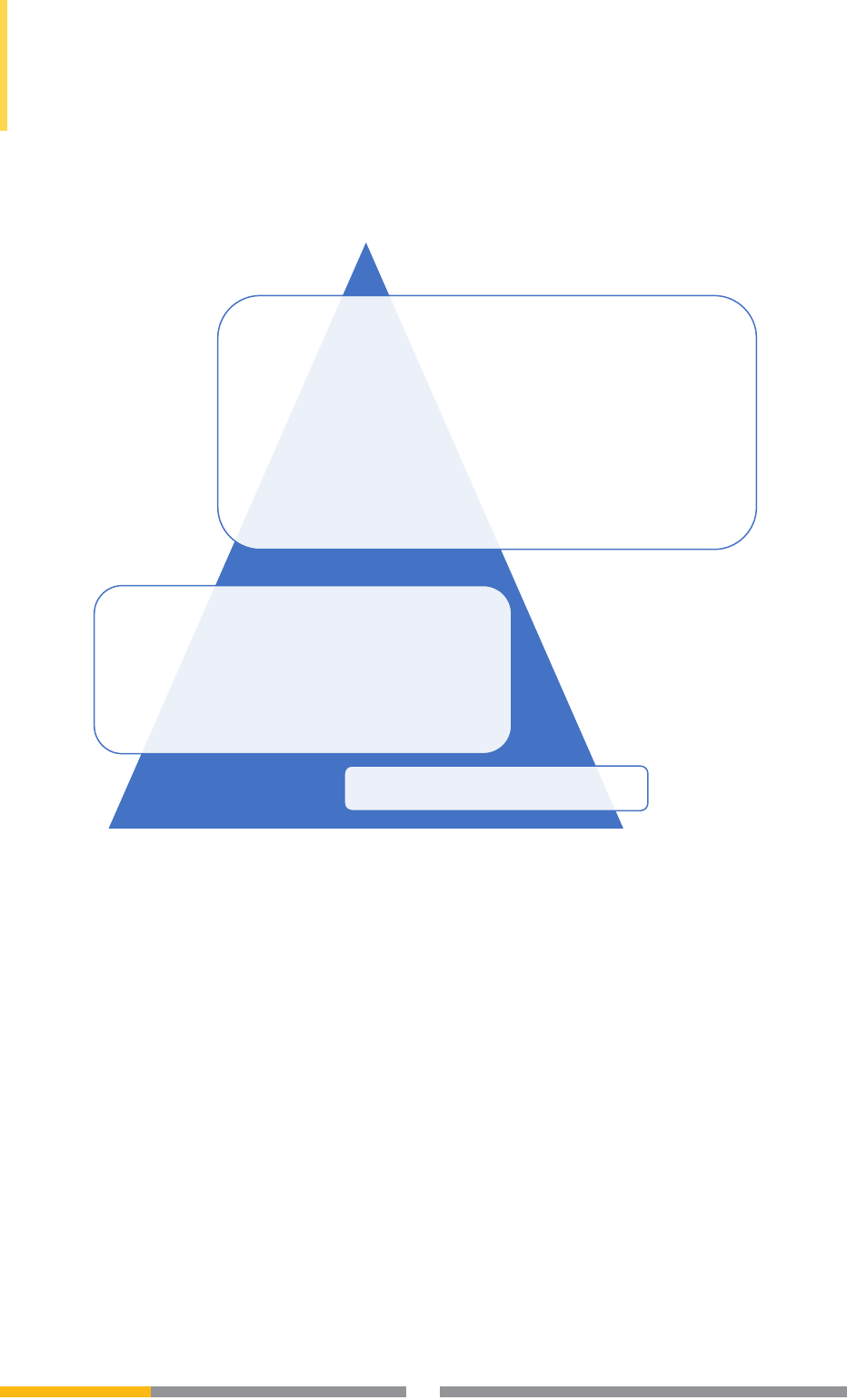

1971

Department of Science and

Technology established.

Promotes basic research

via:

• Research funding schemes

through Science and

Engineering Research

Board (SERB) and other

in-house programmes

• Autonomous Institutions

(AIs) under DST were set

up

2000

National

Innovation

Foundation was

set up to fund

grassroots

innovations

2003

Science and

Technology

Policy brought

together Science

and Technology

2013

Science,

Technology and

Innovation (STI)

Policy formulated.

2016

Atal Innovation

Mission

launched

Figure 3.1: Steps taken to promote science, technology and innovation in India

17

• India has become a major destination for

outsourced R&D activities. We currently have

more than 1,100 R&D centres set up by multi-

national companies (MNCs) such as IBM, Google,

Microsoft, Intel, Lupin, Wockhardt, etc. These

R&D centres cover areas including information

and communication technologies, biotechnology,

and aerospace, automotive, chemicals and

materials technology. India’s relatively strong

intellectual property regime will facilitate its

emergemce as a major R&D centre.

• Indian scientists are at the forefront of some

global groundbreaking work. Recent contribu-

tions by Indian scientists to frontier research

and technology have been encouraging. For

example, 37 Indian scientists from nine Indian

institutions played a key role in the discovery

of gravitational waves that received the Physics

Nobel prize in 2017. Indian scientists also

contributed to the discovery of a neutron star

merger at Laser Interferometer Gravitational

Wave Observatory (LIGO), USA.

• The development of Brahmos, advanced air

defence supersonic interceptor missiles, diverse

missiles and rocket systems, remotely piloted

vehicles, light combat aircraft, etc., are brilliant

examples of India’s progress in strategic and

defence technologies.

• India now ranks amongst a handful of nations

that have credible capabilities in the eld of

space technology. The upgrading from SLV to

ASLV and PSLV to GSLV, the rst moon orbiter

project Chandrayan-1, Mars Orbiter Mission

and the recent simultaneous launch of 104

satellites are India’s signicant achievements.

• India is now the third largest country in

terms of the number of start-ups. This

number is expected to rise exponentially

in the coming years. The government has

set up the Atal Innovation Mission (AIM)

to transform radically the innovation,

entrepreneurship and start-up ecosystem of

the country.

While India has improved in most areas of

technology, it is also necessary to recognize the

challenges that we need to overcome to become an

innovation led society.

Constraints

• Low R&D expenditure, especially from the private

sector, is a key challenge facing the innovation

ecosystem in India. The latest R&D Statistics

2

released by the National Science and Technology

Management Information System (NSTMIS) of

the Department of Science and Technology (DST)

show that while R&D expenditure in India tripled

in the period from 2004-05 to 2014-15, its size

as a percentage of GDP remained at 0.7 per cent.

This is very low compared to the 2 per cent and

1.2 per cent spent by China (for 2015) and Brazil

(for 2014) respectively.

3

Countries like Israel

spend as much as 4.3 per cent of their GDP on

R&D. Furthermore, while the share of the private

sector in R&D investment in most technologically

advanced countries is as high as 65 per cent to

75 per cent, it is only about 30 per cent in India.

• The number of scientic R&D professionals

in India at 218 per million population is

distressingly low compared to China’s 1,113

and USA’s 4,019.

• The link between research, higher education

and industry is weak and nascent. It needs to

be strengthened and put on a rm platform.

• Our education system has so far not focused on

cultivating a scientic temperament at an early

age. Even at the later stages of an aspiring sci-

Strategy for

New India @ 75

18

entist’s career, the lack of career opportunities

in basic sciences leads to the diversion of po-

tential researchers to other rewarding sectors.

• “Lab to Land” time is too long. Renowned public

funded institutions like the Council of Scientic

& Industrial Research (CSIR), Defence Research

and Development Organization (DRDO), Bhabha

Atomic Research Centre (BARC), Indian Council

of Medical Research (ICMR), Indian Council

of Agricultural Research (ICAR) Indian Space

Research Organisation (ISRO), Indira Gandhi

Centre for Atomic Research (IGCAR) etc., along

with prominent universities across the country,

have developed many frontline technologies.

However, the rate of transfer of these

technologies to industry and for societal benets

is low.

• The adoption of indigenous innovations by

Indian industry is not very encouraging.

Frequent violation of Preferential Market Access

(PMA) is an issue leading to large-scale imports

of foreign products and services.

• The public procurement system is heavily

biased in favour of experienced and established

products and technologies. This strongly

discourages new and innovative technologies

offered by start-ups, who do not get much-

needed support from government procurement.

• There has been poor progress in the

development and deployment of affordable

technologies for rural areas, particularly in

agriculture, agro-processing, micro irrigation, etc.

The Way Forward

• An empowered body is needed to steer

holistically the management of science in the

country. Its scope will include science education

and scientic research as well as coordinating

and guiding various science initiatives. The

proposed body will help in pursuing inter-

ministerial, inter-disciplinary research besides

breaking silos among various scientic

departments/agencies.

• The major weaknesses of public funded

R&D and technology institutions like CSIR,

DRDO, BARC, ICMR and ISRO are their poor

marketing skills and information dissemination.

Some measures for enhancing technology

commercialization by public funded institutions

are provided below:

o Value addition centres may be set up in

each of these institutions for (i) up-scaling

technologies, (ii) improving technologies

from Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 4 to

TRL 6/7, (iii) demonstrating industrial scale

pilot production, (iv) coordinating with in-

vestors to incubate entrepreneurs, (v) bridg-

ing the gap between industry and technolo-

gy development teams, (vi) enabling formal

technology transfer, (vii) enabling commer-

cialization and marketing and (viii) providing

technology support during production.

o DST should create a National Technology

Data Bank in coordination with all publicly

funded R&D institutions. This will provide a

central database for technologies that are

ready for deployment or under development.

o Public funded research institutions

should consider shifting their focus to the

development and deployment of socially

relevant technologies in areas such as

clean drinking water, sanitation, energy,

affordable healthcare, organic farming, etc.

These technologies have large potential for

commercialization.

• Measures related to government procurement

include the following:

19

o In all government procurements,

international competitive bidding for both

products and services should be resorted

to only when Indian manufacturers are

unable to supply products/services of

comparable international quality. This will

promote the Make in India initiative.

o Quarterly workshops may be organised for

creating awareness among procurement

managers of various ministries/

departments/state governments/CPSUs,

about the DIPP’s Public Procurement Order

2017 (which aims to promote Make in

India products/services).

o To adopt innovative technologies,

experts/scientic practitioners should be

mandatorily included on board/committees

related to government procurement. All

RFP/RFQ documents should include a

suitable clause in this regard.

o In order to promote procurement of goods/

services developed by Indian start-ups,

preference in the technical evaluation could

be provided to them.

• To bring vibrancy to frugal innovations, a non-

lapsable “District Innovation Fund” with a corpus

of about INR 2 crore in each district may be creat-

ed and used to promote grass root innovations.

• AIM has already launched Atal New India

Challenges in partnership with ve ministries

to create products from technologies and

prototypes in areas of national importance

such as solid waste management, water and

wastewater management as well as road and

rail transport. These, along with Atal Incubation

Centres (AICs) will also provide the platform

for promoting frugal innovation. More such

challenges will be launched in partnership with

ministries and support will be provided to these

ministries to adopt the resultant innovations.

• AIM has set up over 1000 Atal Tinkering Labs

(ATLs) around the country covering over 625

districts. It is aimed to take this number to

at least 5,000 by 2019 and 10,000 by 2020.

Further expansion will be considered based on

the outcomes of the rst phase.

• To promote entrepreneurship and startups, AIM

is supporting AICs across the country including

at Tier II/III locations. These include existing

and new incubation centres. It is expected that

more than 100 world-class incubation centres

will be up and running by 2020.

• Foreign collaborators, consultants, visiting

faculty, adjunct scientists, etc., need to be

involved in pursuing R&D in the emerging areas

of basic sciences such as nano-technology,

stem cell research, astronomy, genetics, next

generation genomics, drug discovery, etc. DST, in

collaboration with Indian Missions abroad, may

identify discipline wise foreign experts who can

collaborate with Indian scientists to take basic

research in these areas to the next level.

• The Higher Education Commission once set

up may consider giving credits for innovation

and start-ups and also setting up online

entrepreneurial development courses in colleges

and universities.

________________________________________

1

Published by World Intellectual Property Organization jointly with Cornell University and INSEAD.

2

Source: http://www.nstmis-dst.org/Statistics-Glance-2017-18.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2018.

3

World Bank Statistics.

Strategy for

New India @ 75

20

Objectives

• Double the current growth rate of the manufac-

turing sector by 2022.

• Promote in a planned manner the adoption of

the latest technology advancements, referred to

as ‘Industry 4.0’, that will have a dening role

in shaping the manufacturing sector in 2022.

Current Situation

India is the fth largest manufacturer in the world

with a gross value added (GVA) of INR 21,531.47

billion in 2017-18 (2nd advance estimate for

2017-18 at 2011-12 prices). The sector registered

a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around

7.7 per cent between 2012-13 and 2017-18.

1

The government has taken several initiatives to

promote manufacturing. Among these are the

Make in India Action Plan aimed at increasing

the manufacturing sector’s contribution to 25 per

cent of GDP by 2020,

2

the Start-up India initia-

tive to promote entrepreneurship and nurture

innovation, and the Micro Units Development

and Refinance Agency (MUDRA) and Stand-up

India to facilitate access to credit. It has also un-

dertaken massive recapitalisation of public sector

banks

3

to ease availability of credit to micro,

small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Besides,

it has undertaken major infrastructure projects,

such as the setting up of industrial corridors, to

boost manufacturing.

The Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion

(DIPP) has been engaging with states/UTs to

enhance the ease of doing business. Following

concerted efforts of the government, the World

Bank ranked India 100th among 190 countries

in the Ease of Doing Business (EODB) in 2018.

This was a jump of 34 positions since 2014.

While these indices are useful for comparison,

actual improvement in EODB will come only with

greater coordination between the centre and

states.

The foreign direct investment (FDI) regime has been

substantially liberalized, signicantly improving

India’s rank in terms of annual FDI inows from 14

in 2010 to 9 in 2017. However, India receives only

25 per cent of the FDI that China gets and only 10

per cent of what the USA receives. FDI inows into

the manufacturing sector reached about 35 per cent

of total FDI.

4

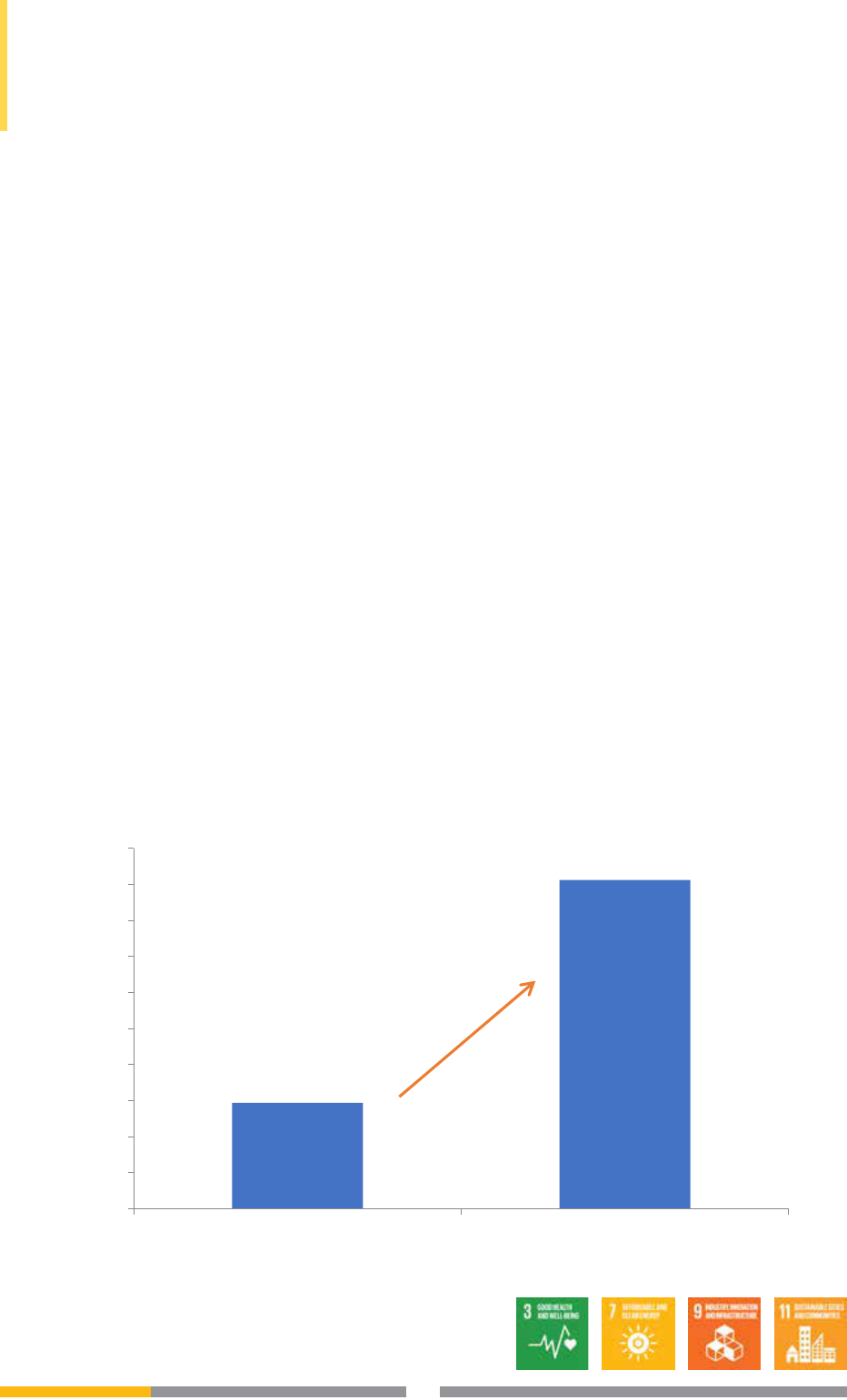

Manufacturing as a percentage of the gross

domestic product has remained at about 16 per

cent. Improvement are evident in recent quarters,

where manufacturing growth at 6.9 per cent and

8.1 per cent in Q2 and Q3 2017-18 (year-on-year

as compared to 2016-17) outpaced GDP growth.

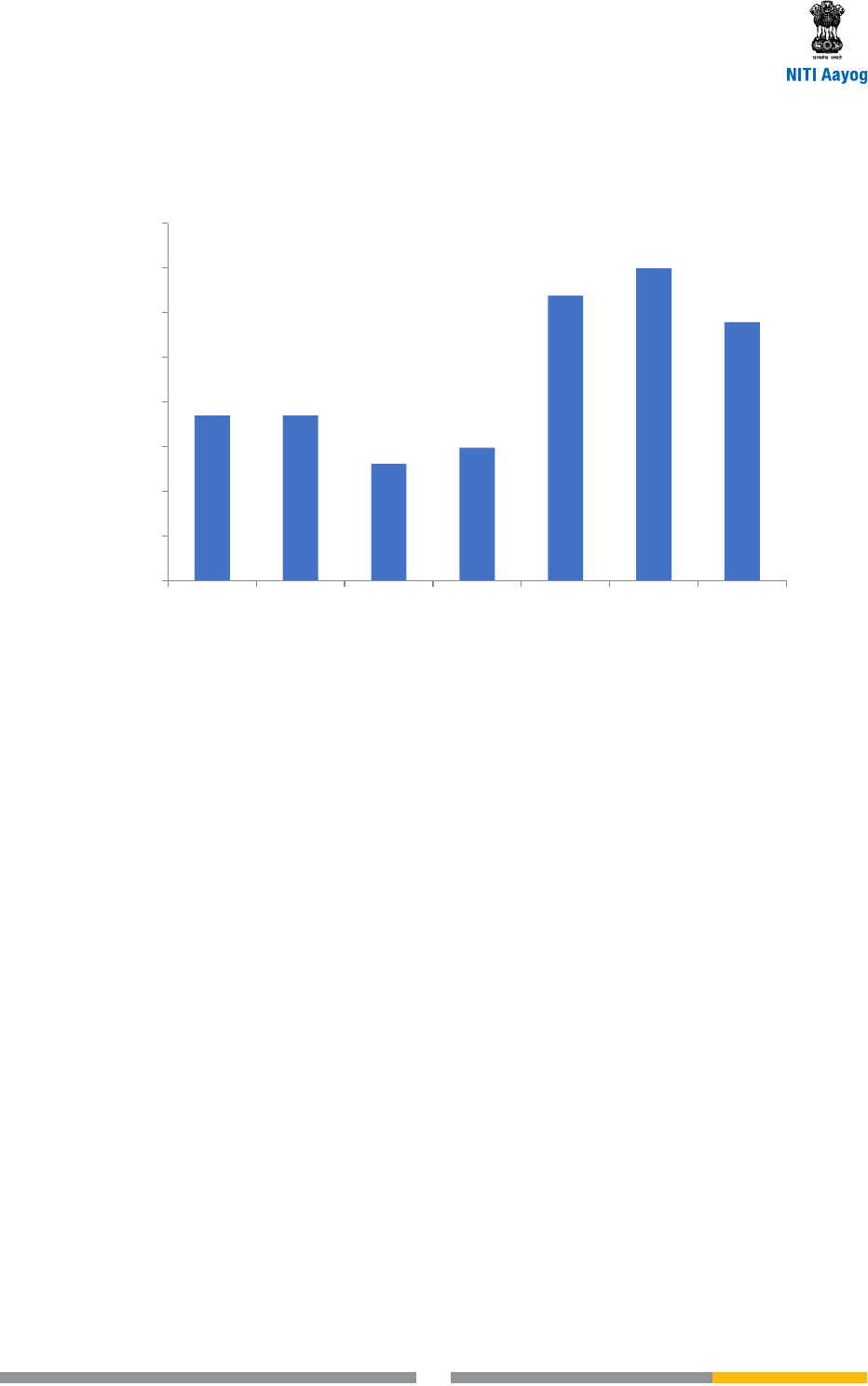

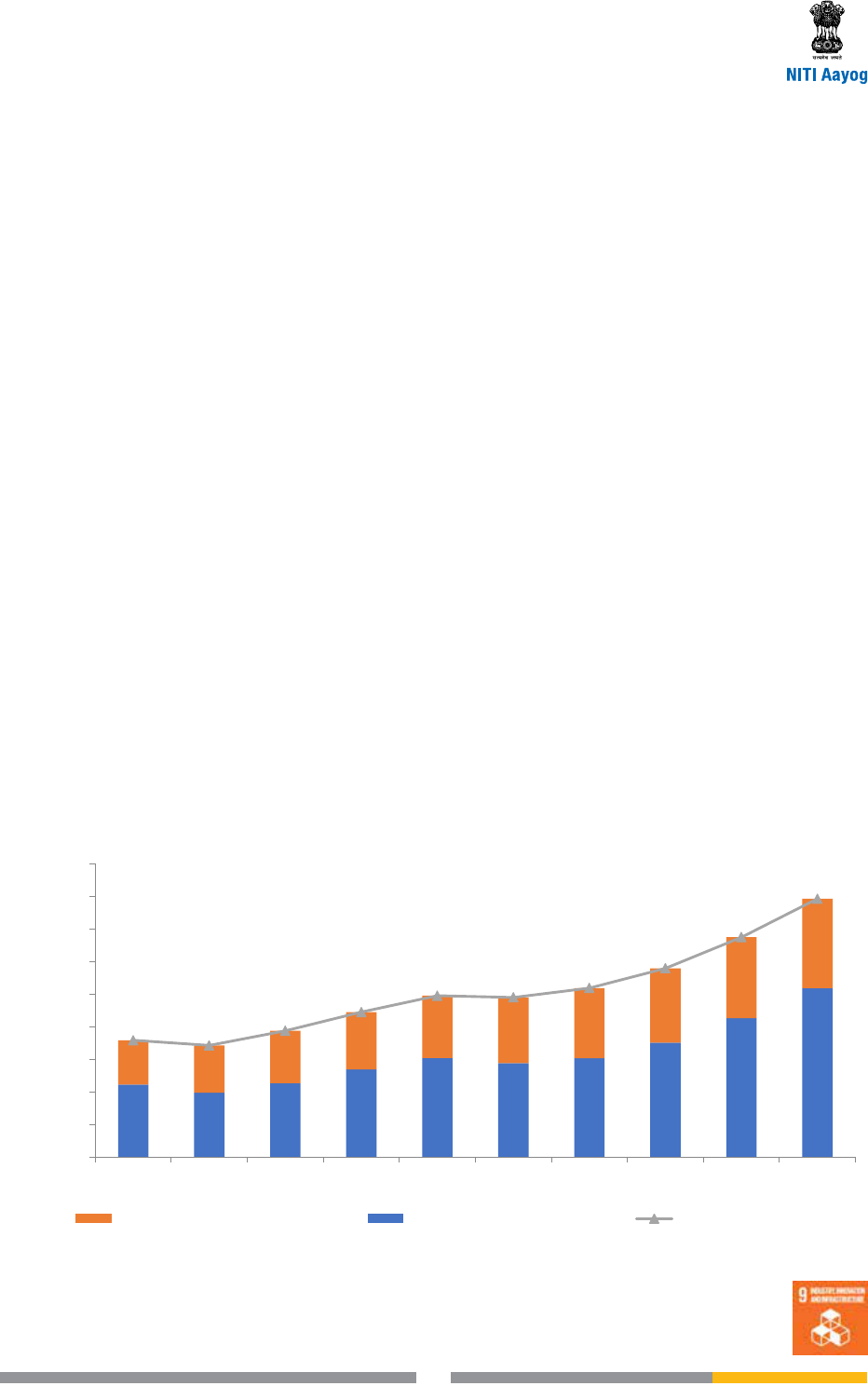

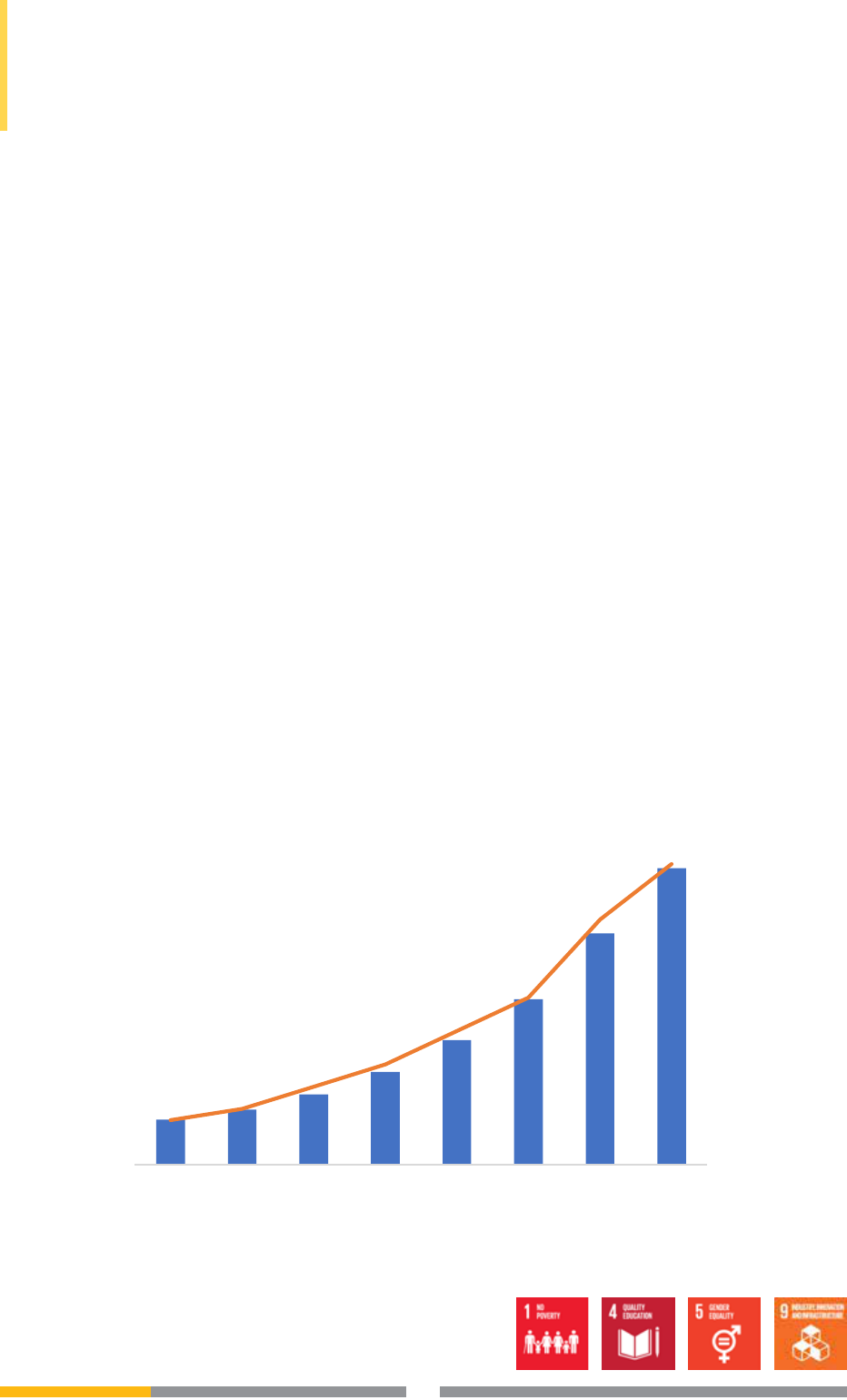

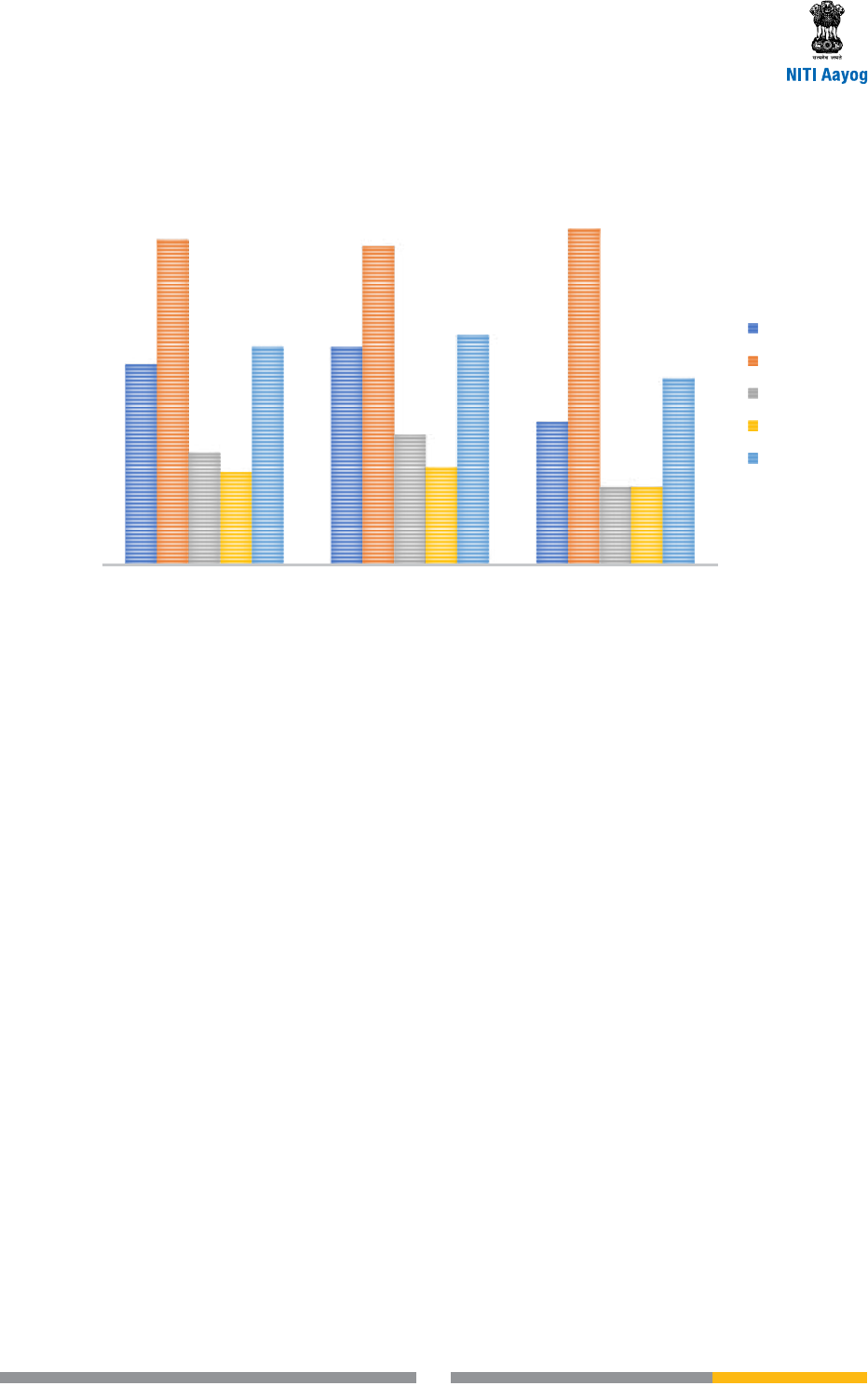

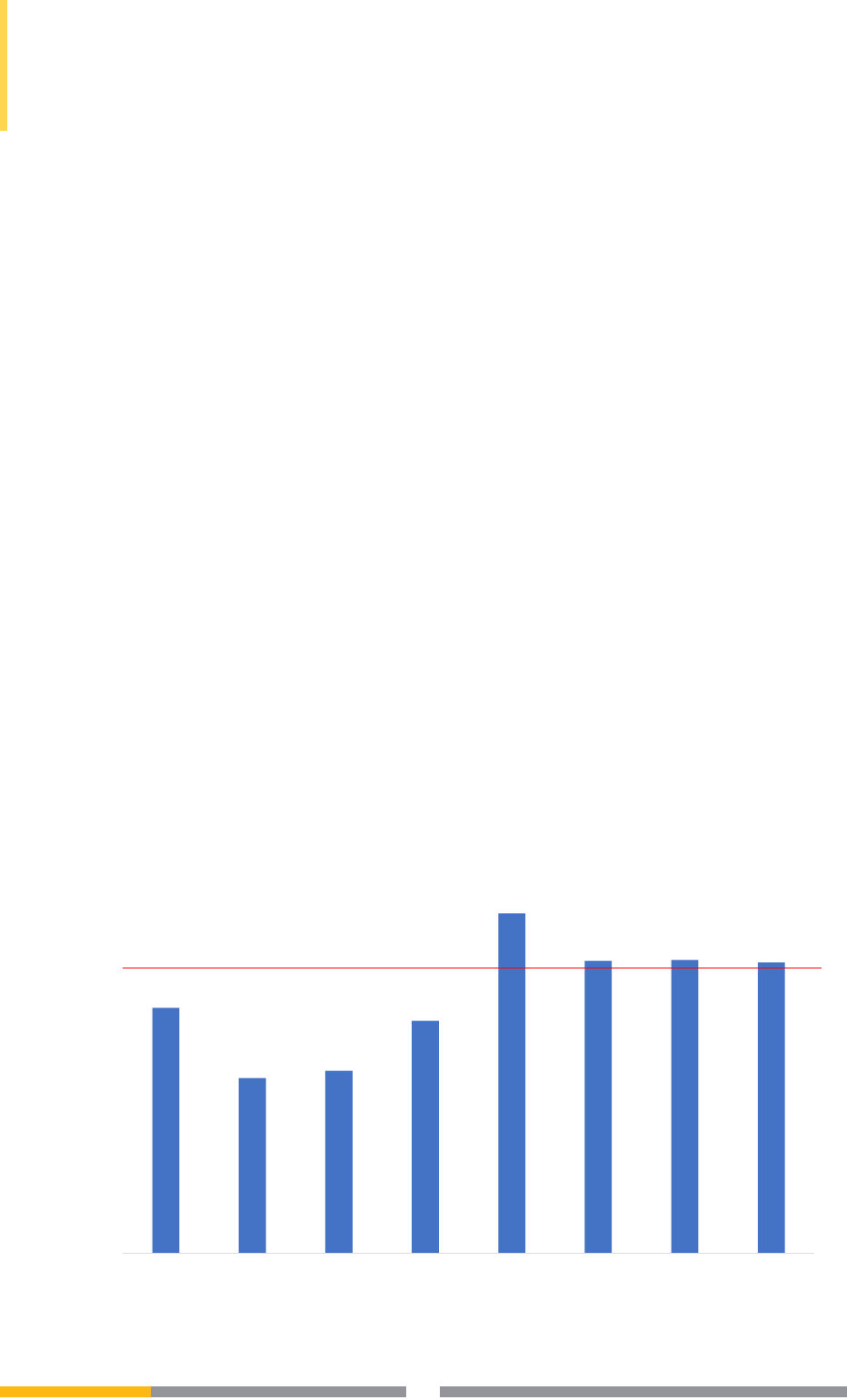

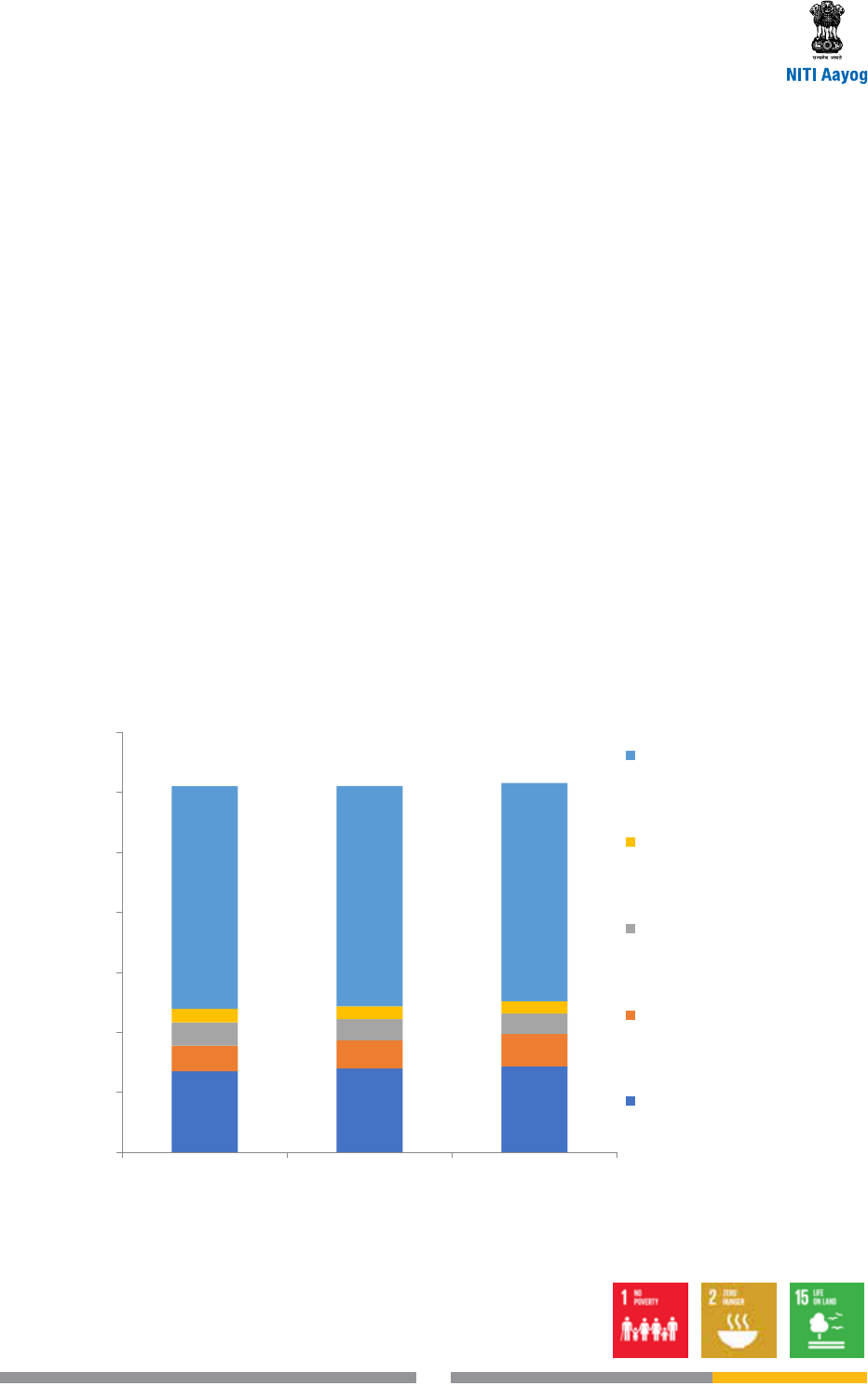

Figure 4.1 shows the trend in manufacturing as a

percentage of GVA from 2011-12 until 2017-18.

Constraints

The main constraints on achieving the objectives set

for India’s industry in 2022-23 are the following:

4. Industry

21

improvements in our global EODB rank, it

continues to be a drag on the system. This is

also true of investment conditions in the states.

Getting construction permits, enforcing con-

tracts, paying taxes, starting a business and

trading across borders continue to constrain

doing business.

Way Forward

Demand generation, augmentation of industrial

infrastructure and promotion of MSMEs

• The government can play a crucial role in

creating domestic manufacturing capabilities by

leveraging proposed public procurement and

projects. Mega public projects such as

Sagar-

mala, Bharatmala

, industrial corridors, and the

Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana

(PMAY) can stimu-

late domestic manufacturing activities provided

the projects are suitably structured and demand

is aggregated strategically. This should be

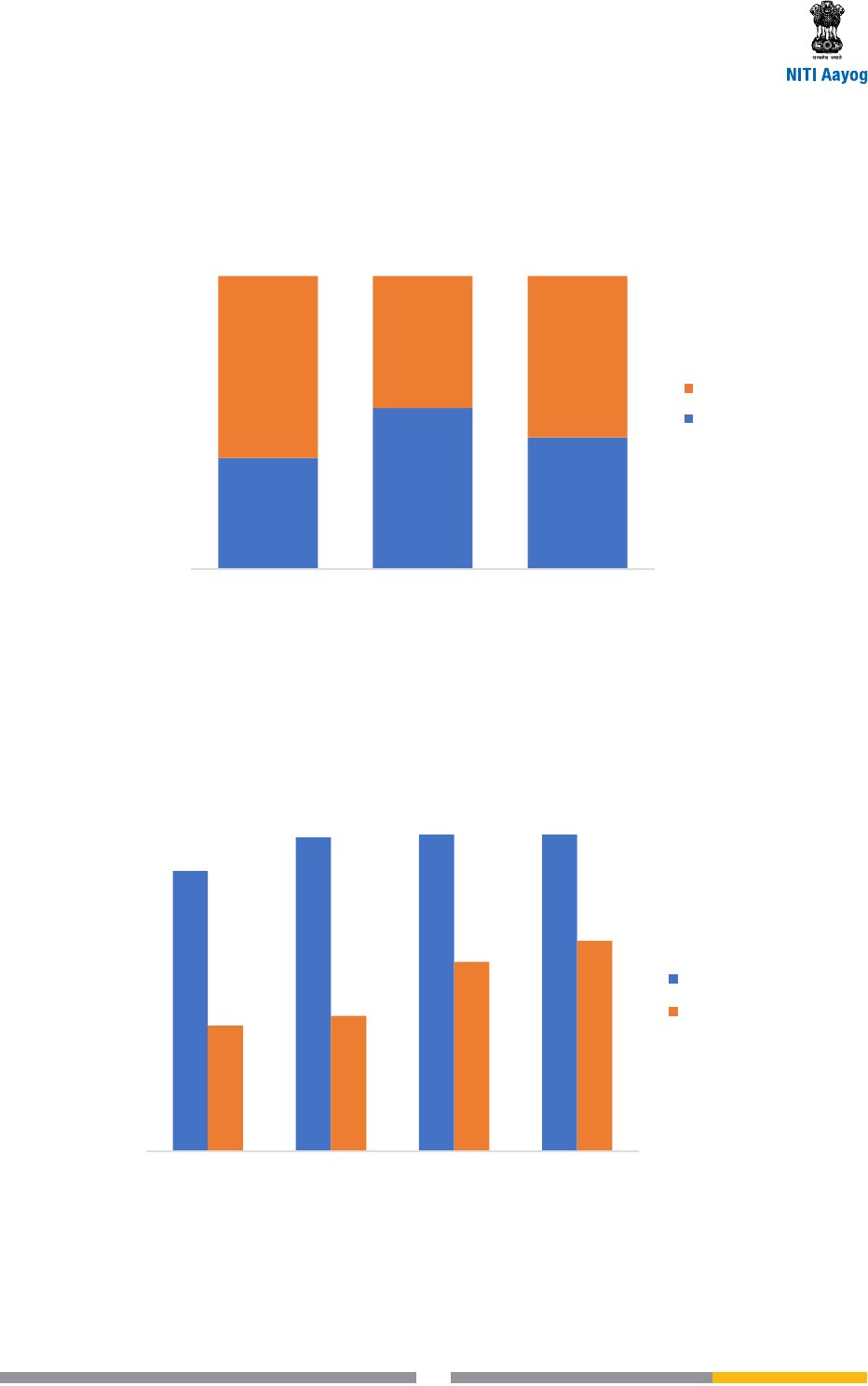

Figure 4.1: Manufacturing as a share of GDP, 2011-12 to 2017-18

16.1%

16.1%

15.9%

16.0%

16.7%

16.8%

16.6%

15%

16%

16%

16%

16%

16%

17%

17%

17%

2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18

(2nd AE)

Share of GDP (%)

Source: MoSPI

• Regulatory uncertainty: Regulatory risks and

policy uncertainty in the past have dented

investor condence.

• Investment: There has been a cyclical slow-

down in fresh investment since 2011-12.

• Technology adoption: The adoption of new

technologies like articial intelligence, data

analytics, machine-to-machine communications,

robotics and related technologies, collectively

called “Industry 4.0”, are a bigger challenge

for SMEs than for organized large-scale manu-

facturing. Data security, reliability of data and

stability in communication/transmission also

pose challenges to technology adoption.

• Exports and insufcient domestic demand:

There has been no export driven industrial

growth. Domestic demand alone may not be ad-

equate for sustained, high value manufacturing.

• Challenges to doing business: Despite recent

Strategy for

New India @ 75

22

accompanied by simplication of the regulatory

process. The Madhepura Electric Locomotive

Project, a joint venture between the Indian

Railways and the French multinational Alstom,

provides a good example of how mega projects

can be leveraged to boost domestic production.

The project enabled effective transfer of tech-

nology and the availability of state-of-the-art

locomotives for the railways. The Madhepura

model is replicable in the defence, aerospace,

railways and shipping sectors.

• Set up a portal to monitor projects beyond a

given threshold so that any roadblocks are

identied and addressed on a real time basis.

State governments should be encouraged or

incentivized to contribute data to this portal.

NITI Aayog’s Development Monitoring and Eval-

uation Ofce (DMEO) can help set up the portal.

An inter-ministerial body with representatives

of state governments and project promoters (as

special invitees) may be constituted.

• Efforts should be made to develop self-sufcient

clusters of manufacturing competence, with

Cluster Administrative Authorities empowered

to provide single window clearances to en-

trepreneurs and investors. Industrial corridors

should address the lack of infrastructure and

logistics. Logistics will need to be supplemented

with warehousing and other elements of the

manufacturing supply chain.

• NITI Aayog could work with states to prepare

manufacturing clusters and develop export

strategies based on their sector competitive-

ness and resource strengths. A cluster should

have supporting industries and infrastructure. It

should also develop a local brand and distribu-

tion channel through an e-commerce platform.

A Cluster Administration Ofce should be given

the responsibility to award factory permissions

and compliances.

• For India to become the world’s workshop, we

should encourage further FDI in manufacturing,

particularly when it is supported with buybacks

and export orders.

• Streamline discretionary powers vested at

different levels of governance by adopting

digitized processes and making all approvals

electronic in a transparent, time bound manner.

• Disruptive technology, while leading to job

losses in traditional areas, also presents new

job opportunities. A greater connect between

government-industry-academia is required to

identify the changing requirements in manufac-

turing and prepare an employable workforce. In

the context of employability of engineers, there

is a need for thorough review of standards of

engineering education and its linkages with

industry.

• E-commerce can be the driver of overall eco-

nomic growth over the next decade through

its impact on generating demand, expanding

manufacturing, employment generation and

greater transparency. A Committee, chaired

by CEO, NITI Aayog examined issues related

to the e-commerce industry

5

. It made recom-

mendations for the sector’s growth including

increasing internet access, digitizing payments,

further improving transportation infrastructure,

logistics and distributed warehousing support.

These may be examined for implementation at

the earliest.

• Harmonize Indian quality standards with global

standards in many sectors. Lack of harmoniza-

tion has affected Indian exports and prevented

the leveraging of trade agreements adequately.

23

For e.g., the medical device industry would

benet greatly from conformity to standards

that are essential for new products to be

acceptable to doctors and patients abroad.

The issues of regulations and standards setting

are also intertwined. The following initiative is

required in this regard:

o Task the Bureau of Indian Standards and

Quality Council of India with assessing

the improvements in standards and

productivity required to achieve global

standards.

• Address the following issues in respect of

MSMEs:

o Setting up of mega parks and manufac-

turing clusters in labour intensive sectors

with common facilities to reduce costs and

improve quality. It is also recommended

that state governments should set up plug

and play parks (atted factories) to ensure

international productivity standards.

o Workers of industrial units in the new

mega parks should have decent accommo-

dation within reasonable proximity of the

work place.

o An expert committee should examine

sector-specic pain points and make its

recommendations within three months.

o The Department of Public Enterprises

(DPE) should ensure registration of all

public sector units (PSUs) on the Trade

Receivables Discounting System (TREDS)

portal.

o Initiate a small business research

programme in some select ministries for

encouraging R&D in MSMEs.

Industry 4.0

• Launch a major initiative to push industry to

adopt Industry 4.0. Industry 4.0 is characterized

by increasing digitization and interconnection of

products, value chains and business models. It

will signicantly impact sectors like automobile,

pharmaceuticals, chemicals and nancial ser-

vices and will result in operational efciencies,

cost control and revenue growth. Experts feel

that emerging markets like India could benet

tremendously from the adoption of Industry 4.0

practices.

• In his 2018 Budget Speech, the Finance

Minister mandated NITI Aayog to initiate a

national programme directing India’s efforts

on Articial Intelligence

6

. On a similar note,

NITI Aayog could organize a discussion on

“Industry 4.0,” inviting leading manufacturing

companies from various sectors including

automobile/auto components, electrical and

electronics, chemicals, cement/steel, etc.,

along with concerned ministries to discuss

plans for adopting Industry 4.0.

• The Indian Institute of Science, a few select In-

dian Institutes of Technology (IITs), National In-

stitutes of Technology (NITs) and other premier

engineering colleges should create specialized

training programmes on ‘Smart Manufacturing’

to address the shortage of high-tech human

resources.

• The Department of Heavy Industry (DHI) should

develop the Central Manufacturing Technology

Institute (CMTI), Bangalore, as a Centre of

Excellence for pursuing R&D in Industry 4.0

technologies and systems. The Department

of Science & Technology should spearhead

industry-academia R&D projects on cyber

physical systems.

Strategy for

New India @ 75

24

• The development of industries that produce

the key building blocks forming the basis of

Industry 4.0 could be incentivized. Incentives

could be focused on MSMEs that manufacture

products including sensors, actuators, drives,

synchronous motors, communication systems,

computer displays, and auxiliary electromechan-

ical systems. Similarly, industries adopting In-

dustry 4.0 standards could be provided support

for a xed period of time.

• Reliability, stability and integrity of smart man-

ufacturing systems can be increased by creating

Indian standards for the systems and sub-sys-

tems for adoption by manufacturers.

Ease of doing business

• Introduce a “single window” system in all states

that provides a single point of contact between

investor and government and facilitates all

required licences and approvals. It should be

based on stakeholder consultation.

• For efcient approval/inspection process, devel-

op a system of accountability for major stake-

holders like inspection bodies, testing labs, etc.

• For geographical planning and ease of

environmental clearances, adopt the system

of using Geographic Information System (GIS)

based maps at all levels to create pre-approved

land banks for manufacturing facilities. This

is already being practiced in some states. In

such designated land banks, standards can

be clearly laid down in advance relating to (i)

environmental requirements (ii) building bye-

laws, and (iii) safety and other norms.

• Replicate in other states the Gujarat Pollution

Control Board (GPCB) Environmental Audit

Scheme based on third party certication.

• To strengthen third party certication systems,

develop suitable accreditation agencies.

• Ensure the seamless integration of the

Shram

Suvidha

portal and state agencies’ portals.

________________________________________

1

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation data Accessed April 30, 2018.

2

Make in India website. Accessed April 30, 2018. http://www.makeinindia.com/about.

3

http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=171900. Accessed April 30, 2018.

4

http://dipp.nic.in/sites/default/les/FDI_FactSheet_21February2018.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2018.

5

http://pib.nic.in/newsite/mbErel.aspx?relid=169011. Accessed April 27, 2018.

6

http://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ub2018-19/bs/bs.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2018.

25

Objectives