1

Best Management Practices for Crime

Prevention Through Environmental

Design in Natural Landscapes

2

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Puget Sound Energy with a grant secured by Forterra.

Contributions include:

Christina Pfeiffer, Horticulture Consultant & Educator

Charlie Vogelheim, Forterra

Kathleen Wolf, University of Washington

Lisa Ciecko, City of Seattle

Michael Yadrick, City of Seattle

Ina Penberthly, City of Kirkland

Publication Date

February 2019

Photos and images provided by Christina Pfeiffer

3

Contents

Publication Date ................................................................................................................................................................. 2

Background .......................................................................................................................................................................... 4

CPTED Basics ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4

CPTED Goals for Natural Area Vegetation Managment ..................................................................................... 6

Natural Area Planting for CPTED ................................................................................................................................. 6

Plant Selection and Placement.................................................................................................................................... 6

Edge Friendly Plants ...................................................................................................................................................... 7

Thoughtful Placement for Trees .............................................................................................................................. 10

Thicket Forming Plants to Steer Away from Edges ............................................................................................ 12

Resources for More Information on Native Plant Identification and Characteristics: ............................... 12

Protecting New Edge Plantings during Establishment ........................................................................................ 12

Natural Area Pruning for CPTED ................................................................................................................................ 14

Introduction to Pruning ............................................................................................................................................. 15

General Pruning Principles to Meet Natural Area CPTED and Habitat Objectives ................................... 20

Species-Specific Considerations ............................................................................................................................... 21

Natural Area Maintenance for CPTED ...................................................................................................................... 27

General Maintenance.................................................................................................................................................. 28

Invasive/Unwanted Plants .......................................................................................................................................... 28

Planning .......................................................................................................................................................................... 28

Challenges and Opportunities for Vegetation Management ................................................................................. 28

Social Dimensions of CPTED........................................................................................................................................ 30

Social Dimension CPTED Principles ....................................................................................................................... 30

Social Dimension CPTED Recommendations for Natural Areas .................................................................... 31

Glossary ............................................................................................................................................................................. 33

References ......................................................................................................................................................................... 35

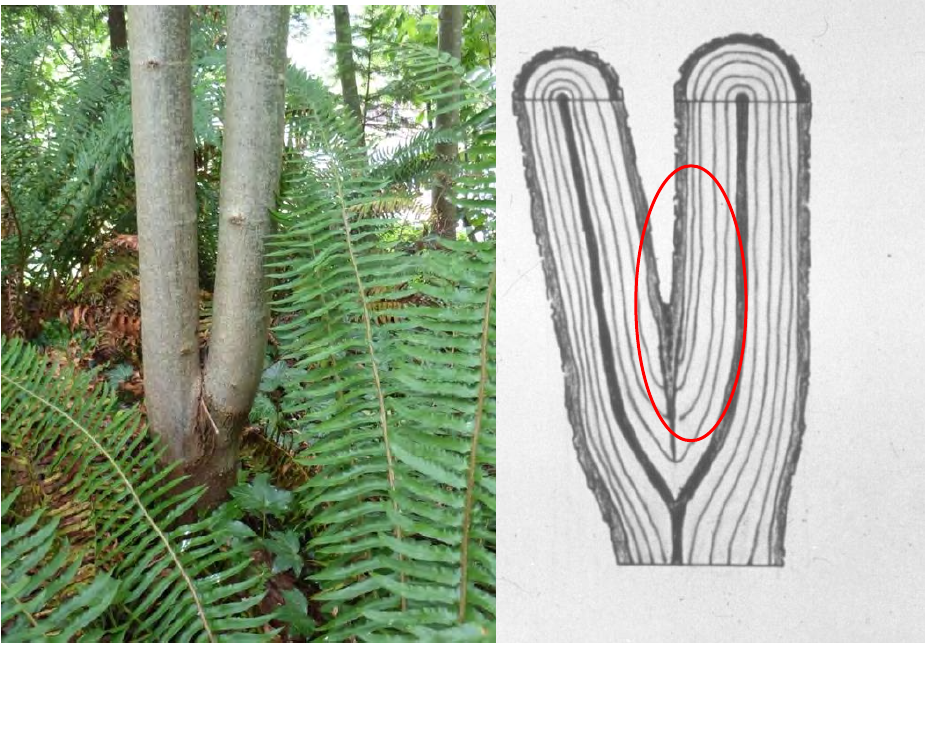

Appendix 1: Tree Training Cue Card ......................................................................................................................... 36

4

Background

The Green Cities Partnerships are a coordinated effort to restore, manage, and maintain the natural

areas within urban centers around the Puget Sound region. In these partnerships, city government, local

organizations, and community members work together so that their community can benefit from healthy

and sustainable habitats within their city.

Residents do not experience urban natural areas in the same way. A narrow trail with dense vegetation

may feel adventurous to one person and dangerous to another. Research has noted that there are

conflicting views of urban vegetation (Wolf 2010). It is valued as an environmental asset yet can be

readily implicated in providing cover for illegal or undesirable activity. Current science offers data and

insights into both aspects. Managers of natural areas have the challenge of both maintaining and restoring

healthy native habitat while ensuring that visitors are safe and that they also feel safe. There are many

public safety issues beyond the scope of either urban or landscape design solutions. There are not any

absolute solutions, we do know that proper planning, design (plant selection and placement in ecological

restoration and habitat enhancement projects), and maintenance can help to reduce perceived and real

threats to public safety.

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) is an approach to deterring crime that was

developed for the urban built environment. Based off the principle of designing spaces that reduce the

opportunity and desirability for criminal acts, effectively applied CPTED principles can also make spaces

feel more comfortable and safer to visitors. With thoughtful planting, intentional pruning, and careful

weed removal, these principles can also be applied to managed natural areas.

While there is a lot written on applying CPTED principles to the built environment, little is written on

applying them to the natural environment. This document was created to provide Green City Partners

the best management practices for effective application of CPTED within their managed spaces. We

intend for this to be a helpful guide for both project managers at the planning level, and for ground

crews and volunteers working in the park and greenspaces.

CPTED Basics

The principles of CPTED date back to work in the 1970’s on urban design of non-natural built spaces. A

multidisciplinary approach emerged that focused on using physical design elements to help deter crime

in urban centers. After decades of installations and test cases the First Generation principles were

expanded to Second Generation CPTED, which incorporates social and psychological theories

(described later in this manual).

The main principles of First Generation CPTED are:

Natural surveillance. Sight lines, the ability to see and to be seen characterized by spaces

with a lack of obstructions or blind corners, and the creation of spaces that foster ease of social

interaction.

Natural access control. Design features which facilitate wayfinding through spaces and clearly

define entrances and exits.

Territorial reinforcement. The use of elements that identify specific functions of a site and

provide visual indicators of what the place and its users are about.

Maintenance. A visual message of care, attention and stewardship that can discourage

undesired activity.

5

The concerns for public safety in urban built spaces are also present in urban natural areas that residents

visit. Site damage from inappropriate uses, vandalism, encampments, property damage, and incidents of

crime beset some of our green spaces and CPTED approaches are increasingly employed to address

them. There are greenspaces in cities that are intended to be relatively “wild” and are without concerns

for visitor experience. This document gives suggestions on how to manage vegetation along trails and

natural area edges so that these public spaces align to CPTED principles.

A basic tenet for sustainable landscape design that can be applied to meeting CPTED goals is “right plant,

right place.” This means choosing plant species with the appropriate natural adaptations, growth habit,

and mature size for the location. Trails that are well planned use well-placed sight lines and views to

guide visitors through the site. Placing smaller scale plants at the front edges of planting areas or more

formal planting beds provides an enhanced sense of space and greater depth of view into the plantings.

Strategically placed trees can add definition to entrances and boundaries. Combining the basic principles

of landscape design with the CPTED principles offers opportunities to achieve safety goals while

preserving the amenities and benefits provided by naturalized vegetation.

Figure 1: Placing smaller scale plants at the front edges of planting areas provides a sense of open space and

greater depth of view through the area (left). Large shrubs and trees planted too close to trail edges (right) leads

to extensive pruning demands, often resulting in hard walls of clipped vegetation that detract from the visual

experience and sense of safety.

6

CPTED Goals for Natural Area Vegetation Management

Traditional CPTED recommendations often discuss installing lighting, cameras, and fencing in spaces as a

way to prevent unwanted activities. This guide focuses only how to install and manage vegetation in

accordance to CPTED principles. Given these principles, goals for landscape management of urban green

spaces that preserve the naturalistic character while providing for people’s personal safety are:

Trees with high canopy. Trees provide some of the greatest contributions toward

environmental quality, habitat, and aesthetics than any other plant form. Urban areas planted

with trees that have a high branching structure allowing for strong sight lines are associated with

greater sense of safety and lower crime rates.

View corridors. Open sight lines provide the ability to see and be seen at main entry points,

along trails, and in other critical locations integral to natural surveillance.

Vegetation with transparency. Plantings which are open and composed of plants with varied

heights will allow for visibility through the vegetation and reduce opportunities for concealment.

Well maintained settings. Providing a more intentioned level of care for trails, main

entrances, and other critical locations will not only help manage vegetation for needed clearance

and visibility, but also helps maintain a positive sense of attention and community.

Natural Area Planting for CPTED

Plant Selection and Placement

Random placement of native trees, shrubs, ferns and groundcovers

without consideration of their position to trail edges and sight lines

will create future maintenance problems. The same is true for

allowing naturalized native plant seedlings that will grow too large for

a given location to remain where they are. The concept of “right

plant, right place” pays immense dividends when applied to the edges

of natural area planting projects. Arrange plants according to their

size, growth, and habit, as well as their natural adaptations for soil,

light, and moisture conditions. Take lessons from observations of

plant combinations in more mature plantings which could be

successfully applied to new plantings.

Poorly designed plantings cannot always be remedied with pruning.

Good plant placement in relation to trails can reduce or even

eliminate the need for future pruning. A small sapling conifer or a

small rose shrub will eventually command a very large area and can

overwhelm trails and block sight lines. By the time they grow to a

problematic size, it will be too late to make adjustments, and a costly

plant removal is likely the only option.

Figure 2: Spreading, multi-stem shrubs and

brambles like thimbleberry (left) can quickly

overtake trail edges and require a lot of effort to

maintain clearance and visibility. They should not

be planted or allowed to spread within several

feet of trail edges

7

Edge Friendly Plants

Place the lowest growing species closest to the edges, within 5 feet of the forest or trail edge. Combine

ferns and shrubs with carpeting groundcovers. The edge zone is a good area to introduce a variety of

woodland perennials for added visual interest and to serve as “living mulch”. If goals include preventing

people from entering sites or preventing weeds, edge friendly plants can be planted densely to create a

clear boundary or to shade out potential weeds. Following is a selected list of edge-friendly choices.

Follow these basic tenets when installing a new set of plants:

Place low growing species near trail edges

Place larger shrubs and trees with an ample setback from trails and from each other (see following

guidelines), at least 5 feet.

Keep densely growing plants away from trail and forest edges.

Adjust the placement of evergreen trees and shrubs to accommodate different visibility needs within

the site:

o Corners and entries need a broader view corridor

o Trails are more inviting and safer when maintained with a sense of open space and good views

of what is ahead.

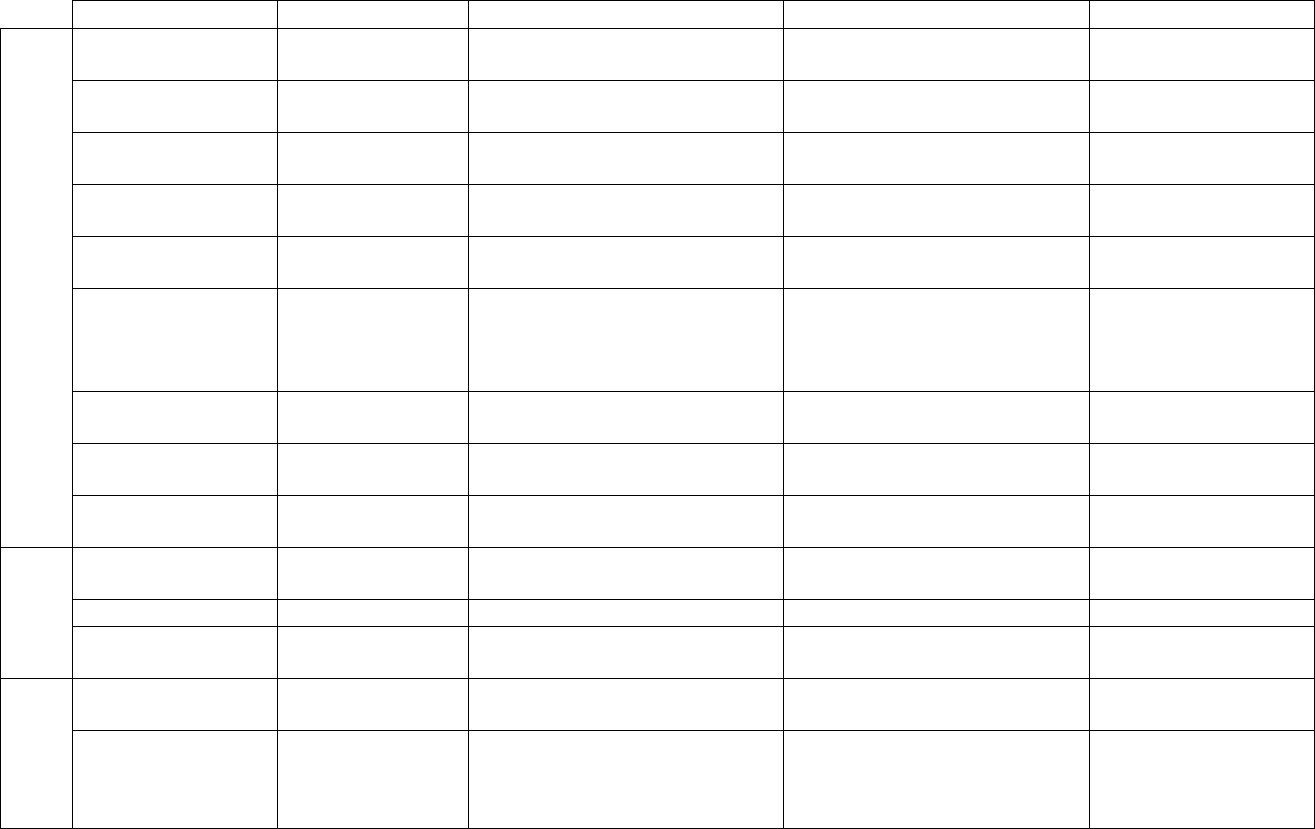

Figure 3: A sketch showing ideal plant placement along a forested

edge or trailside. Low groundcovers grow within the first 5 feet of the

trail corridor, medium sized shrubs grow sparsely at least 5 feet back,

and trees are growing 10 feet back from the trail with branches

trimmed up to 10 feet.

Figure 4: This corner bed at the intersection of two trails is planted

with sword fern, low companion plants, and widely spaced tall conifers,

allowing for a broad area of view.

8

Table 1: Edge-Friendly Plants to plant along trails and forest edges that require clear lines of sight.

Common Name

Botanical Name

Type / size

Habitat

Notes

Low profile, spreading groundcovers

Kinnikinick

Arctostaphylos uva-

ursi

Woody evergreen, 8” tall

spreading mat.

Sun to light shade. Slopes.

Well-drained soil.

Broad-leaf sedum

Sedum

spathulifolium

Evergreen perennial, 4” height.

Sun to light shade. Slopes.

Rocky edges. Well-drained soil.

Plant in early spring.

Narrow-leaf sedum

Sedum divergens

Evergreen perennial, 4” height.

Sun to light shade. Slopes.

Rocky edges. Well-drained soil.

Plant in early spring.

Beach strawberry

Fragaria chiloensis

Evergreen perennial 6” height,

spreading.

Sun to light shade. Slopes.

Well-drained soil.

Woodland

strawberry

Fragaria vesca

Evergreen perennial, 8” height.

Carpeting.

Damp to dry open woodland.

Wood sorrel

Oxalis oregana

Deciduous perennial, 6” height.

Dense, aggressive carpet can

outcompete weeds and other

low plants.

Damp woods beneath large

trees.

Plant in early spring

when in leaf.

False lily-of-the-

valley

Maianthemum

dilatatum

Deciduous perennial, 4” height.

Dense carpet.

Damp woodland beneath large

trees.

Plant in early spring

when in leaf.

Fringecup

Tellima grandiflora

Evergreen perennial, 4” height

with taller flower stalks. .

Damp to dry woodland.

Piggyback plant

Tolmiea menziesii

Evergreen perennial, 4” height.

Spreading.

Moist woods and stream sides.

Ferns

Sword fern

Polystichum

munitum

3 to 5’ height and spread.

Woodland sun to shade.

Drought tolerant.

Deer fern

Blechnum spicant

1 to 3’ height.

Moist to damp soils.

Licorice fern

Polypodium

glycyrrhiza

1’ height.

Moist mossy banks, rock, and

logs.

Graminoids

Wood rushes

Luzula spp.

1 to 2’ height.

Merten’s sedge

Carex mertensii

2 to 3’ height.

9

Shrubs

Low Oregon grape

Mahonia nervosa

Evergreen shrub with prickly

leaves, 1 to 3’ height. Spreads by

underground stems.

Open woodland shade, well

drained soils. Slopes.

Can be slow to

establish. Plant closely

with herbaceous

companions for

shelter to improve

establishment.

Shrubby cinquefoil

Potentilla fruticosa

Deciduous shrub up to 3’ x 3’.

Open sun and damp soil.

Deciduous Herbaceous

Perennials

Vanilla leaf

Achlys triphylla

Deciduous. 1’ height. Carpeting.

Dappled shade.

Pacific bleeding

heart

Dicentra formosa

Deciduous. 1’ height. Spreading.

Dappled shade.

Fairy bell

Disporum smithii

Deciduous. 1’ height.

Dappled shade.

False Solomon’s seal

Maianthemum

racemosum

Deciduous. 3’ height.

Dappled shade.

Combines well with

sword fern.

Dwarf false

Solomon’s seal

Maianthemum

stellatum

Deciduous. 1’ height.

Dappled shade.

Oregon iris

Iris tenax

Deciduous. 8 to 18” height.

Sun to light shade. Damp to dry

soils.

Wood rush

Luzula campestris

Evergreen. 2’ height. Spreading.

Shade.

Combines well with

sword fern.

Common Name

Botanical Name

Type / size

Habitat

Notes

10

A quick note on maintenance: Deciduous perennials may not be visible during winter months after the

foliage dies down. Beware of adding thick wood chip mulch where perennial groundcovers are dormant,

as it can readily smother them. Apply a couple inches or less of mulch as needed around perennials

when they are visible.

Thoughtful Placement for Trees

Trees provide greater contributions toward environmental quality, habitat and aesthetics than any other

plant form. Trees are long lived and their placement in relation to trails and infrastructure is especially

important for long-term sustainability and safety.

Planting trees too close to trail edges can create problems with visibility, greater pruning demands, trunk

wounds, and disruption of trail surfaces as buttress roots grow and expand. Tree wounds (including

pruning wounds) are vulnerable to disease and eventual decay. New wood grows around injured areas

which can reduce longevity and lead to future structural problems. Planting trees too close together can

also lead to future problems; it creates competition, which can result in stunted growth or a heavy lean

toward sunlight along trail openings. Proper placement can reduce the potential for tree injuries as well

as the need to move or remove a tree that grows too large for its placement.

Planting trees at closer density is sometimes used to account for potential transplant loss. This method

can be helpful provided someone follows up to remove or transplant crowded trees. There may be

reluctance to remove mature crowded trees in the future. As an alternative, it can be helpful to plan for

monitoring of tree establishment and to follow up with replacement planting as needed.

As a rule, the larger the mature size of the species, the greater the space needed between each tree and

from built edges.

The following table provides information on potential mature sizes and optimal spacing for commonly

planted native trees in the Puget Sound region.

11

Table 2: Recommendations for planting native trees in natural areas

Common Name

Botanical Name

Habitat

Potential canopy radius

Minimal spacing on-

center*

Conifers

True firs

Abies spp.

Sun.

10-15 feet. Horizontal

branching habit.

10-15 feet.

Douglas fir

Pseudotsuga menziesii

Full Sun.

15 – 25 feet.

15 feet .

Western red

cedar

Thuja plicata

Sun to light shade. Prefers moist

soil.

15-25 feet. Typically

retains lower branches.

20-feet from trails and

structures.

Western hemlock

Tsuga heterophylla

Sun to light shade.

15-20 feet.

15-feet.

Sitka spruce

Picea sitchensis

Sun. Moist soils.

10-15 feet.

10 feet.

Shore pine

Pinus contorta var.

contorta

Sun. Drought tolerant.

8-12 feet, often irregular

form.

8 feet.

Large

Deciduous

Trees

Black cottonwood

Populus trichocarpa

Sun. Prefers moist soil. Large trees

are hazards.

10-15 feet.

15 feet.

Bigleaf maple

Acer macrophyllum

Sun to part shade.

15-50 feet.

15 - 20 feet.

Red alder

Alnus rubra

Sun.

10-20 feet.

10 feet.

Medium

Deciduou

s Trees

Pacific dogwood

Cornus nuttallii

Shade.

10-15 feet.

10 feet.

Bitter cherry

Prunus emarginata

Sun to partial shade.

10-15 feet.

10 feet.

Cascara

Rhamnus purshiana

Sun to shade.

10-15 feet.

10 feet.

Small

Deciduous

Trees

Vine maple

Acer circinatum

Sun to deep shade.

10-15 feet.

6 – 10 feet.

Western

serviceberry

Amelanchier alnifolia

Sun to part shade.

8-12 feet.

6 – 10 feet.

Scouler’s willow

Salix scouleriana

Sun. Damp to dry soil.

8 – 20 feet.

6 – 10 feet.

*On center spacing refers to the distance center to center between tree trunks and between the trees and built edges such as trails, fences,

buildings or parking areas. Some organizations use a standard 10-foot setback from trails for tree planting. This allows room for both the basal

growth of the trunk and for the canopy spread of lower branches on young trees. As trees grow taller, the lowest branches can be gradually

removed until the lowest lateral branches are above trail clearance height. There are less likely to be any pruning concerns for trees planted

farther back from the trail than their anticipated potential canopy radius.

12

Thicket Forming Plants to Steer Away from Edges

Large multi-stem shrubs and brambles which grow wider through underground stems and/or readily

root from branches touching the ground offer great habitat but are poorly suited for use close to trail

edges. Their rapid dense annual growth can quickly overwhelm trail edges, require constant

maintenance, and create visibility problems within a few years of planting. Some may send new growth

up through trails, constraining them, ruining trail tread and causing footpaths to creep (See Figure 2).

Their small size at planting can be deceiving. These types of plants are best planted where they have

plenty of room to spread without crowding trails and other edges. Give them a healthy setback from

trail edges to reduce pruning needs and protect important sight lines.

Table 3: Thicket forming plants to avoid planting along forest edges.

Common Name

Botanical Name

Height

Notes

Bramble

s

Native roses

Rosa spp.

3 - 10 feet.

Salmonberry

Rubus spectabilis

3 – 10 feet.

Thimbleberry

Rubus parviflorus

3 – 8 feet.

Shrubs

Tall Oregon grape

Mahonia aquifolium

3 – 10 feet.

Growth habit can be more tree-

like in shade or spreading multi-

stem habit in open areas.

Snowberry

Symphoricarpos albus

1.5 – 7 feet.

Douglas spirea

Spiraea douglasii

3 – 7 feet.

Red stem dogwood

Cornus sericea

7-15 feet

tall by wide

Shrub willows

Salix species

5 – 15 feet

tall and

wide.

Resources for More Information on Native Plant Identification and

Characteristics:

Krukeburg. A. 1996. Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest, 2

nd

ed. University of Washington

Press.

Pojar J and A. MacKinnon. 2004. Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Washington, Oregon, British

Columbia & Alaska, revised. Lone Pine Press.

Washington Native Plant Society Plants. 2018. www.wnps.org/plants.

Protecting New Edge Plantings during Establishment

Until they have had enough time to grow and cover the ground, new plantings along trails are vulnerable

to being damaged by foot traffic. Here are some useful approaches to protecting them:

13

Take advantage of existing stumps or fallen logs. Placing new groundcovers, ferns,

perennials and other low growing plants close to existing stumps or logs will provide some

shelter and protection.

Place sturdy wood stakes near young trees. A stake may be a good idea in locations

where the setback distance from the trail isn’t enough to protect young trees from potential

trampling. Stakes can be milled wood or made of sturdy branches. Don’t tie trees to stakes, just

place stakes near enough to prevent the tree from being stepped on.

Interpretive signage. Simply worded signs such as “New plants growing, please stay off” can

help inform the public about staying on trails and about the purpose for the temporary fences.

Strategically placed large woody debris. Arrange small logs and large fallen branches in a

random fashion along the trail edge and near young plants. This technique can also help define

the boundary between a trail and planting beds where it may not be clear. Materials need to be

large enough to deflect foot traffic while also blending in as a natural element. Use this as a last

resort as decomposing woody material can cover trail tread and lead to maintenance and

drainage concerns.

These techniques also convey the two CPTED principles of territorial markers and evidence of

maintenance.

Figure 5: Strategically placed large woody debris like the log in this photo help protect new plantings from trampling.

14

Natural Area Pruning for CPTED

Good stewardship is necessary where native trees and shrubs meet the edges of trails, roads, parking

lots, and adjacent property. These

plantings provide important environmental functions, including wildlife habitat and storm water

interception. They are generally expected to look natural, not manicured. They should not interrupt

lines of sight, making the space feel unsafe.

The choice of pruning methods not only affects the look, but also impacts how often pruning will be

needed, the density of new growth after pruning, and how well the plants fulfill their environmental

functions.

The common practice of shearing and tipping branches along boundary edges typically results dense

growth at that edge, which is the opposite intent of this action and it demands more frequent pruning.

Pruning according to the natural habit of each plant type will prevent this. The benefits include:

Maintenance of open vegetation structure near trails and other edges of natural areas.

The look of being "untouched by human hands".

Preserved habitat functions of edge plants.

Optimal environmental functions in the interception and infiltration of rainfall.

Less future pruning!

Figure 6: Two examples of interpretive signage.

15

Introduction to Pruning

How Woody Plants Grow

Understanding a few principles of how plants grow is a vital first step toward effective pruning practices.

Plant Physiology Related to Pruning

Growth concentrates at the highest point of the plant. Growth in height and length originate at the

apical buds located at branch tips. Apical dominance is the suppression of growth in lateral buds and

branches below the growing branch tip. This is largely controlled by plant growth regulators called

auxins which are concentrated at the highest points in the plant. The farther down the stem, the less

auxin and the less shoot suppression. We can see the effects of apical dominance when a stem bends

over in a strong arc; auxins and apical dominance move to the high point of the arc, releasing the growth

of vertical stems from that point. Pruning can change the location of apical dominance, whether

productive or unproductive for management goals.

Wounds do not heal. New layers of wood grow to surround woody stems each growing season. This

growth originates from the bright green layer of cambium cells just below the bark. This is also where

the xylem and phloem cells that move water and other materials through the plant are located.

Wounds, including pruning cuts, will remain in that year’s layer wood for the life of the plant. They do

not heal, but grow new layers of wood around and over the injured area. Old wounds, particularly larger

wounds, can become future locations of decay. In addition, dormant buds may jump into action to

provide replacement shoots and leaf area.

Natural Growth Habit

The size and form of each plant species is determined by genetics and environmental conditions.

Particularly in natural area plantings, pruning that matches the natural form and structure of the species

will produce the best results in the long run. Take a good look at how the plant grows for clues on how

to best prune it:

Trees have a permanent architecture of a main trunk, large scaffold limbs and lateral branches. Many

conifers mature with a strong central leader while deciduous trees lose their central leader as they

develop a broader spreading branch structure at maturity.

Shrubs may be multi-stemmed with new stems originating from the roots or tree-like with one to a few

well branched main stems. Cane growers form thickets of long, thin stems (Rosa spp., Rubus spp). Most

shrub species will regenerate well with new growth from the roots.

Pruning and Seasonal Growth Cycles

Pruning can be done year round take advantage of but it is important to use seasonal growth cycles to

meet your pruning goals.

Dormant season pruning (December through March) will promote vigorous shoot growth. Energy

reserves are at their peak. Plant structure and pruning needs are easy to see. This is the time of year for

hard pruning to stimulate strong new growth. As a general rule, the harder the pruning at this time of

year, the stronger the response. Modest pruning at this time of year is useful for training young plants

and for maintaining form. If managing size or avoiding the development of excess shoot growth from

dormant buds (watersprouts and suckers) is important, avoid pruning in winter and prune lightly in

summer instead.

16

As the growing season progresses, the main flow of energy shifts away from growing points and toward

storing carbohydrates in the stems and roots. There is generally less available moisture and less shoot

expansion in the latter half of the growing season.

Summer pruning (about mid-July through September) results in a subdued growth response. This is an

optimal time for light pruning to remove problem branches and to manage size. Heavy pruning in

summer can harm plant health and should be avoided on valued plants. Avoid pruning live branches

during periods of high heat or if plants are drought stressed.

Light pruning that removes about one-quarter or less of live tissue as well as the removal of dead

branches can be done just about any time of year without significant impact to plant growth responses.

Bird nesting season in this region is typically March through June. Avoiding heavy pruning during this

period meets both the goals of vegetation management and avoiding nesting season disturbances.

Types of Pruning Cuts and Growth Response

Productive Pruning Cuts

Using a combination of reduction and removal cuts will reduce the overall branch density, allowing

greater light and air circulation through the canopy. This approach is useful for maintaining some

“transparency” though plantings. Healthy plants will respond to the injury of a pruning cut with new

growth. Choose the right cut at the right location to promote new growth that meets your pruning

objectives.

Reduction Cuts shorten the length of a stem by cutting to a lateral branch

large enough to serve as the new, shorter leader. Choose a lateral branch that

is at least one-third the diameter of main stem.

Resulting growth response:

Apical dominance is maintained with the selected new leader.

New growth tends to be more moderate and natural form is preserved

while size is reduced.

NOTE: If a reduction cut is made at a lateral that is too small in

diameter, the growth response will be like that from a heading or

topping cut.

Removal Cuts are used to remove an entire branch at its point of attachment.

These cuts are made at the branch collar on trees and larger shrubs, and down to

the root crown for multi-stem shrubs and cane plants.

Resulting growth response:

Natural plant structure is maintained.

On trees and large shrubs, depending on which branches are removed,

the canopy will be higher or less dense.

A ring of callus (woundwood) develops around the circumference and

eventually over the face of the pruning cut.

New shoots will grow from the root crown area.

Figure 7: Example of a

reduction cut.

Figure 8: Example

of a removal cut

17

Removal cuts are often on large weight-bearing branches. Use the Branch Collar Cut to reduce injury to

the plant:

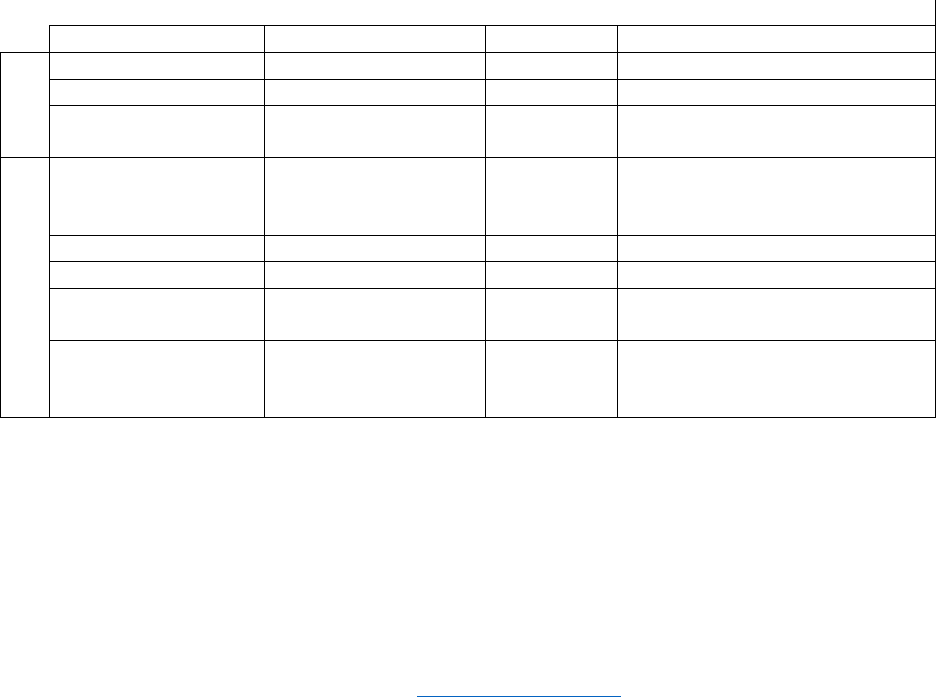

Figure 9: Example of branch collar cuts. The finish cut is placed at C—D to keep the branch collar intact.

The result is a smaller diameter wound and better callus growth than a cut made flush to the trunk. Cut

A—B is critical to remove the weight of the branch and avoid tearing of the bark into the branch collar.

(Diagram: USDA Forest Service)

In general, expect new growth to emerge nearby the cut. If cuts are concentrated near branch ends, so

will new shoots. If a long branch from a multi-stem shrub is pruned back to the ground, new growth

will emerge from the roots or base of the plant. When a tree branch is removed at the trunk, new

growth will be in the form new wood growing around the wound, and in certain species, from nearby

dormant buds.

18

Counter-Productive Pruning Habits

Shearing, heading and topping cuts are often considered easiest and quickest. However, they are all

generally counterproductive to CPTED and habitat planting objectives. In the long run, plants that are

sheared, headed or topped will demand greater management attention than plant which are pruned to

their natural structure.

Heading Cuts lop the ends off of branches near buds or randomly.

Shearing is a form of making heading cuts.

Resulting growth response:

Apical dominance in the stem is broken.

Initially size reduction is likely to be short lived as vigorous new

shoots develop near the cut end.

Branch density increases

Natural plant structure is lost.

A topping cut is a heading cut made to stems and trunks greater than 2 years

old and/or ½-inch diameter.

Resulting growth response:

Apical dominance is broken.

Vigorous growth from existing and dormant buds near the cut.

New shoots are weakly attached.

Natural plant structure is lost.

Tree architecture is permanently damaged.

Poor to no callus wood is formed.

Cut ends remain exposed to the elements and are prone to future decay.

Figure 10: Example of a

heading cut. Next season’s

growth will vigorously emerge

from the bud close to the cut

Figure 11: Example

of a topping cut.

Figure 12: Growth response of topping and heading cuts.

19

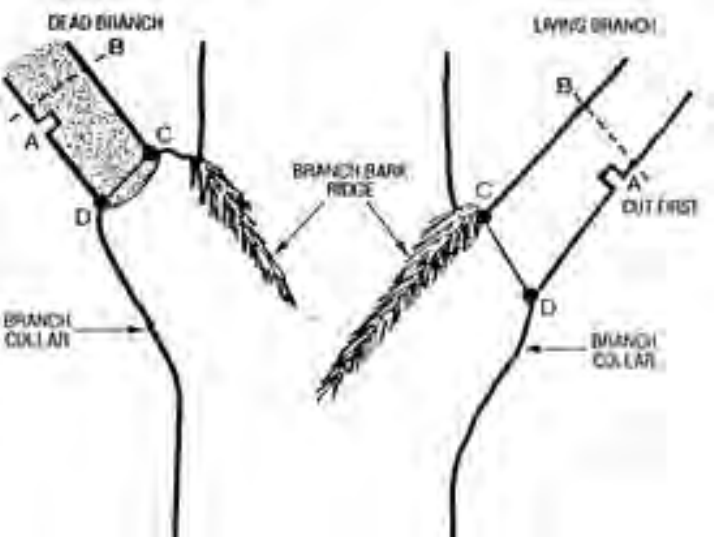

Pruning Tools and Uses

By-pass (scissor) style blades on hand pruners, loppers, and pole pruner heads provide the best quality

finish cuts for pruning. Anvil style blades have a straight blade that cuts against a flat metal anvil which

can crush and damage plant tissue.

Handheld Tools: A set of sharp loppers, hand pruners, and a

small pruning saw can effectively handle many important

pruning tasks along trails. Use:

Hand pruners for branches up to ¾-inch diameter.

Loppers for branches up 1.5-inch diameter,

sometimes larger depending on the size of the

cutting head.

A pruning saw with tri-edged teeth that cut on the

pull stroke. This type of hand saw can be amazingly

effective at removing branches up to a few inches in

diameter.

Pole tools: These are valuable to extend your reach without needing a ladder. They can also be useful

to reach into beds to make small cuts without having to step in. Some have extendable pole lengths.

Due to safety concerns, pole tools should only be used by trained staff and not offered as a tool to

volunteers.

Long-arm pruners have a cutting head similar to hand pruners, which is activated with a pistol

grip at the base of the pole.

Pole pruners typically have a larger cutting head with capacity similar to loppers and are

operated with a pull cord.

Pole saws are useful for removing low hanging tree branches. They can be awkward to handle

and don’t work well for making reduction cuts.

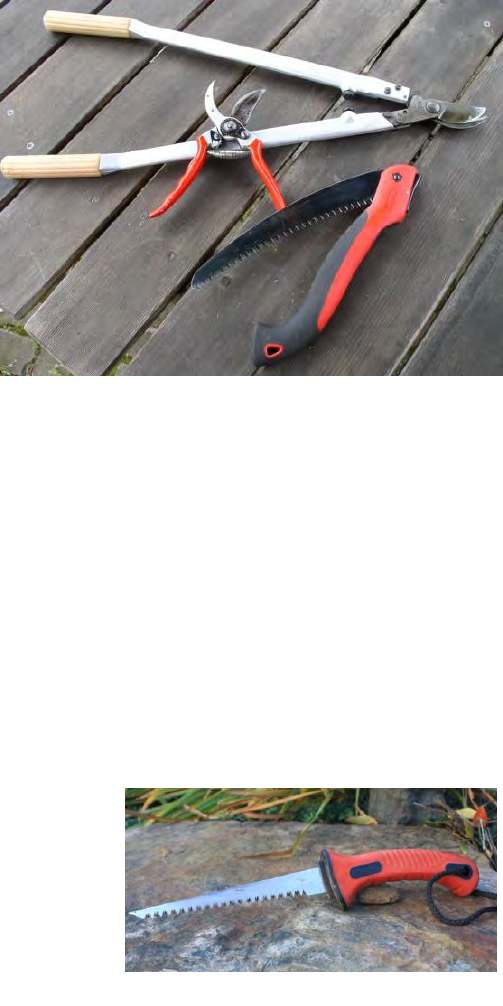

A specially designed root saw has a strong stiff blade and tri-edged teeth

for cutting roots and branches at soil grade. It is useful for cutting out

stems and root crowns to reduce the spread of multi-stem, colonizing

shrubs and cane growers along trail edges.

While not initially considered a pruning tool, a sharp shovel is useful for removing dense growth of multi-

stem, colonizing shrubs and cane growers along trail edges. Digging out and/or transplanting plants that

are too large or crowding trail edges is more effective and long lasting than pruning alone.

Power equipment including chainsaws, string trimmers, and mowers used by trained operators may be

needed for work on larger scale plants and areas. Volunteers should not be using powertools.

Figure 13: Common pruning tools from left to right:

Loppers, hand pruners, and a pruning saw.

Figure 14: Example of a root saw.

20

General Pruning Principles to Meet Natural Area CPTED and Habitat

Objectives

Following are three guidelines to meet the goals for safe and productive natural areas:

1. Avoid shearing and heading cuts in line with the width of the trail

It creates dense growth at that boundary and reduces visibility and sight lines.

Frequent pruning is needed to manage resulting dense new growth.

This technique results in the look and function of a tightly manicured hedge.

Species which are intolerant of shearing will gradually die back.

Repeated shearing and heading can compound drought stress impacts.

Consider plant replacement or renovation pruning every 10 years or so.

Provides low quality bird habitat.

2. Remove plants which are too large for their location and encourage plant types that are

the right size for that location.

Pruning cannot fix a plant that grows too large for the given location.

Remove seedlings of large growing plants that crop up in locations where they will block sight

lines or grow into the trail.

Native plants dug up during the dormant season may be transplanted to better locations at the

same time.

Figure 15: Example of CPTED unfriendly trailside plant maintenance.

Dense hedge-like shrubs from

repeated shearing provide no

lines of sight around trail

bends or within natural areas

making the trail feel unsafe

and unnatural.

21

3. Use reduction and removal cuts to keep branches clear of trail edges.

Thinning branches out helps maintains both size and open-density allowing for natural aesthetic

and some lines of sight through shrubs.

Pruning cuts should be intentional and well placed to match natural form.

Less frequent pruning is needed when this is done correctly.

This technique preserves the normal look and function of native plant species.

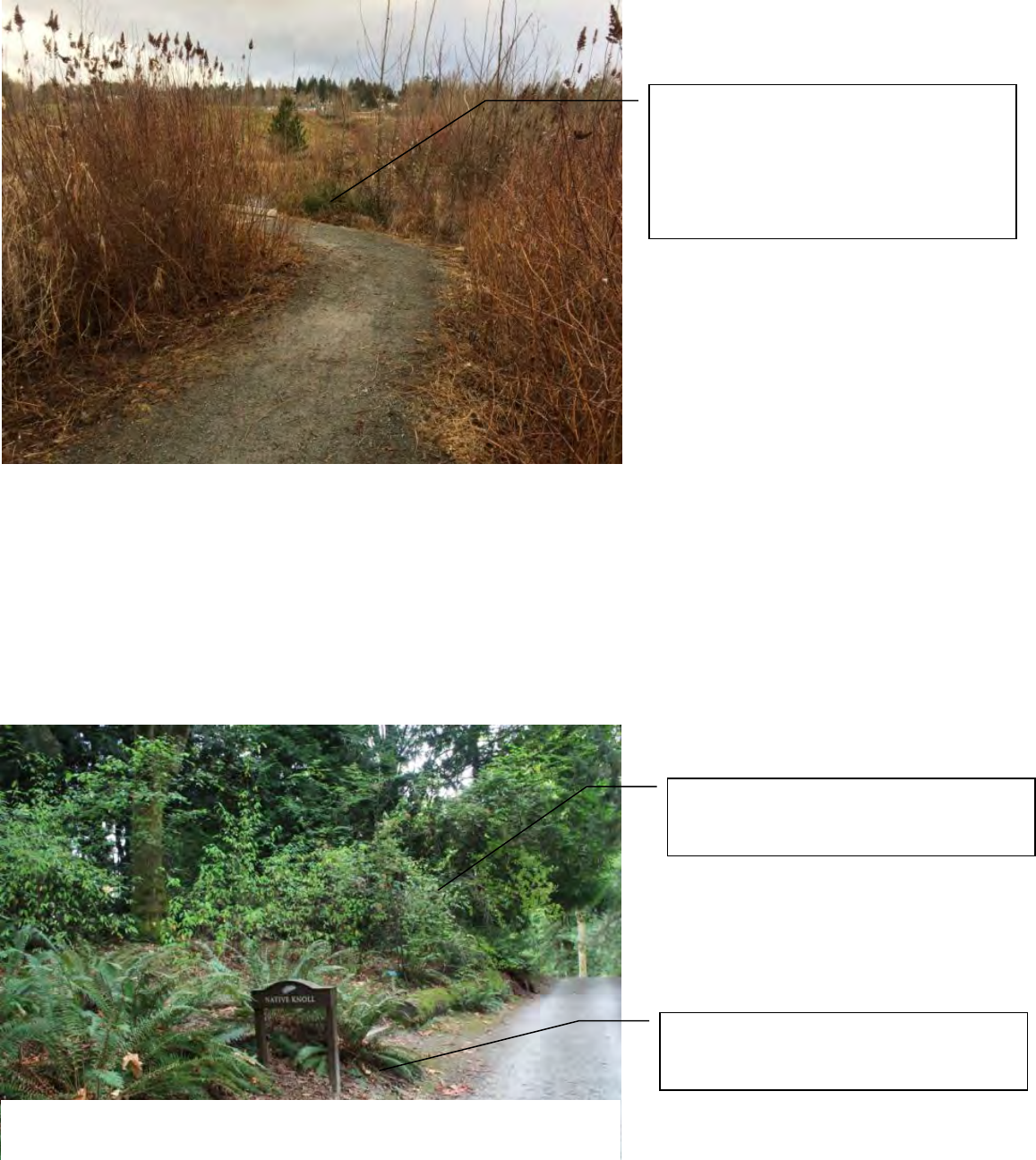

Figure 16: Example of a trail with dense and large plants growing too close to the

edge.

Removal of the hardhack at this bend in

the trail and replacement planting with

lower growing species would improve

sight lines and greatly reduce ongoing

pruning needs.

Figure 17: Example of a well-planted and a well maintained forested edge for

meeting CPTED principles

Shrubs pruned to natural form and for

trail clearance.

Area closest to the trail is maintained with

low growing plant species.

22

Species-Specific Considerations

Ferns and Perennials

When ferns and larger perennials grow over trail edges,

transplanting them to a location farther back from the edge

is the most effective long-term solution. Transplanting is best

while ferns are still dormant in the early spring. Consider

dividing ferns if transplanting.

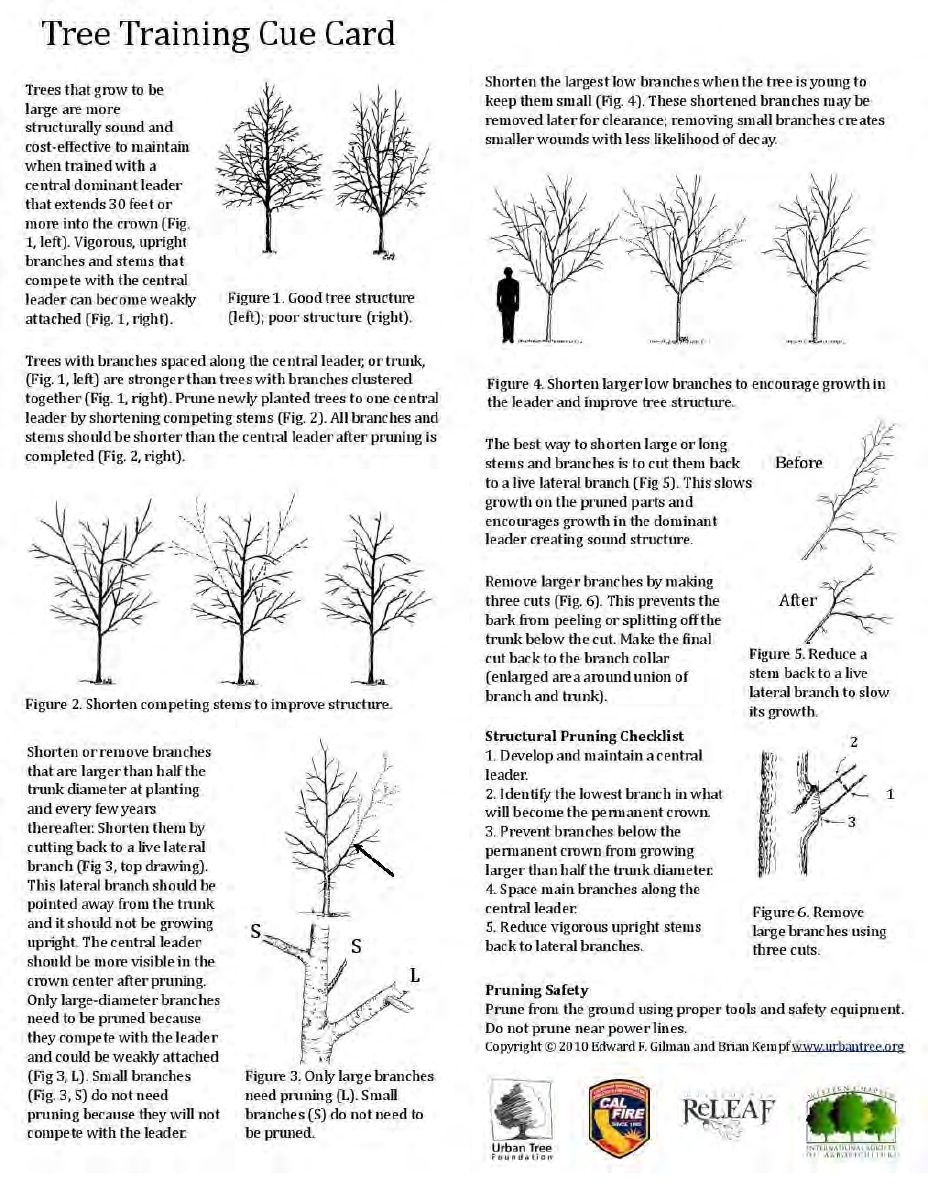

Cane-like Shrubs

These are mostly thicket-forming plants with thin, upright

stems which can grow up to 5 or 6-feet tall.

As a group, they should not be planted or allowed grow

within 6-feet of trail edges (see previous sections on planting

for more information). They are tolerant of hard pruning and

cutting all the growth down to ground. However, pruning to

manage size in these locations is difficult at best. Rather than

pruning these plants along trail edges, it is best to dig them

out and replant that zone with smaller scale plants.

Examples include Rosa species, Rubus species, and hardhack

(Spirea douglasii)

Multi-stem Shrubs

Some shrubs generate new stems from the root system. These can grow in distinct clumps (mock

orange, western azalea) or spread via underground stems (snowberry, Oregon grape). The stems of

some species may develop a more tree-like growth habit (red-flowering currant, red huckleberry) and

can be pruned as described for trees. Multi-stem shrubs can have arching stems (oceanspray, oso-berry)

or generally vertical stems (tall Oregon grape, western serviceberry).

Examples Include:

Salal

Evergreen huckleberry

Tall Oregon grape

Low Oregon grape

Silk-tassel bush

Western serviceberry

Red-osier dogwood

Oceanspray

Mock-orange

Western azalea

Twinberry

Oso-berry

Red huckleberry

High bush cranberry

Western blackhaw

Shrubby cinquefoil

Gooseberry

Devil’s club

Shrub willows

Figure 18: This thicket of native rose is aggressively growing

into the trail and blocking sight lines. Removing this shrub

and replanting with something lower will open up the trail

and create a safer space.

23

The key common characteristic for pruning multi-stem shrubs is that they all generate new stem growth

from their roots.

Use reduction and removal cuts for trail clearance and to maintain open-density.

Remove strongly leaning or overhanging stems by cutting them back to ground

level. When stems are cut to a location several feet back from the trail edge, pruning should

not be needed for another three to five years, about the time it takes for new stem growth

from the roots to reach the trail edge.

Staged renovation of older shrubs can be done to reduce overall size and improve

sightlines. Remove the largest and oldest stems and retain smaller younger stems. Fifty-percent

or more of the live stems can be removed with this method. At the time of pruning, the

remaining stems should be smaller than the desired boundaries to allow some room for growth.

Severely overgrown plantings can be started over through drastic renovation by cutting

entire plants down to soil grade during the dormant season. This is helpful when growth has

gotten too dense for effective selective pruning.

Some species can be managed for size by cutting them back to ground level

periodically when the overall height of the planting reaches the maximum desired height and

would exceed that height the next growing season. This can be done with power equipment for

large scale beds. This technique can be effective for red-stem dogwood, snowberry, twinberry,

tall Oregon grape, and salal.

Figure 19: Pruning a multi-stem shrub for visibility

BEFORE AFTER

TRAIL TRAIL

1. Identify the branches that are blocking the

trail and critical sight lines.

2. Remove entire branches to soil line or close

to the soil line on a major branch.

3. Avoid leaving stubs, these are like short

topping cuts that may produce multiple

shoots.

24

Tree-like shrubs

These may have a single main trunk or a clump of multiple trunks with a growth habit more similar to

trees. They are generally best pruned as described for trees. Some species are tolerant of renovation

pruning.

Examples: red-flowering currant, western rhododendron.

Trees

Because of their close proximity to people, trees growing near trails and other highly occupied areas

need some extra attention not typically needed for trees farther within natural areas.

Two important pruning practices for young trees are:

1. Early training for future overhead clearance over trails. By gradually removing the lowest

branches when they are less than two-inches in diameter, trees will develop a stronger trunk and branch

structure. Cut branches from all the way around the trunk. Place cuts at the branch collar and don’t

leave stubs. The remaining branch area after pruning should cover at least two-thirds of the total height

of the tree.

Figure 20: When the ends of low tree branches are clipped off near the trail edge (left), the growth gets denser near those pruning cuts. After

repeated clipping, stubbed off branches on conifers often die. When lower branches are removed early (right), the small pruning wounds close

over quickly and sight lines around the tree are kept open.

25

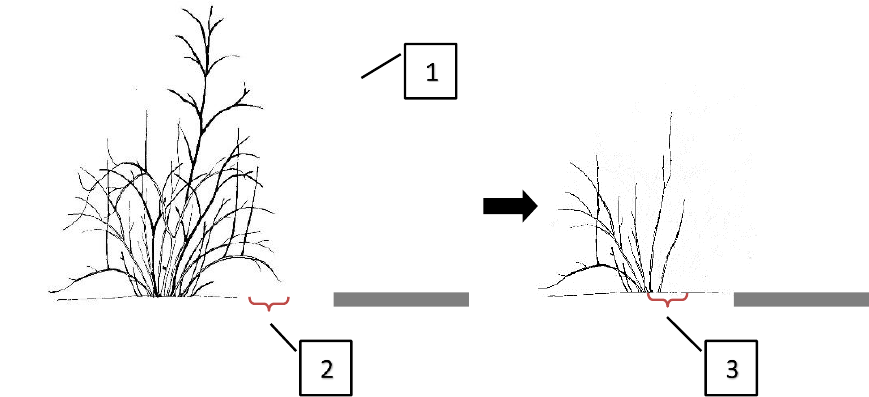

2. Correcting co-dominant leaders. This is a common point of structural failure due to the weak

connection resulting from the embedded bark between multiple leaders. It is a concern for deciduous

trees and conifers alike, whether the trunks divide at ground level or higher up. The resulting crowded

growth is also problematic for maintaining desired open canopy density near trails. Look for and correct

co-dominant and multiple leaders at planting and during the early years of establishment when hand

pruners and small saws can be used to remove the extra leaders.

Ultimately, providing a planting setback of at least 10-feet from trails for most species of trees will help

avoid most future problems and pruning demands.

Figure 21: The tree on the left has been allowed to grow with two co-dominant leaders. As the leaders grow,

embedded bark between the leaders (right) weakens their structure leading to early tree failure. Correcting co-

dominant leaders early can prevent this.

26

Conifer trees:

Conifers have a strong pyramidal shape when young. Branches can die back from excess shade. They will

not break new growth from older stems and are not tolerant of hard pruning.

Figure 22: Pruning is needed for the tree branches overhanging the trail (left, yellow dashed lines. The two branches were pruned at the branch

collar (right) with a pole saw. No future pruning of this same tree for clearance should be needed.

27

Broadleaf trees:

Evergreen Pacific madrone and deciduous broadleaf trees generally develop with a strong central leader

while young and develop a broad spreading crown with age. Like with many shrubs, they readily break

new growth from dormant buds in older stems. Leaving branch stubs often leads to clusters of vigorous

shoot growth as seen after topping and heading cuts; place cuts at branch collars and well-sized lateral

branches to avoid this problem.

Broadleaf trees in the

Pacific Northwest region

generally prefer full sun.

They can sometimes send

large leaders at angles to

“follow” the light and lean

into trails when growing

near forested edges and

are competing with

nearby trees for sunlight.

When this occurs with

trees such as alders,

willows, it is usually most

effective to remove

severely leaning young

trees back to the base.

This can also serve to

release other plants

growing nearby the trail.

Pacific madrone is an

exception in this regard,

as a leaning, but strong,

growth habit is common

to the species.

Maintain low

growing vegetation

next to trail.

Remove severely

leaning trees. Cut at

ground level.

Maintain low

growing vegetation

next to trail.

Remove severely

leaning trees. Cut at

ground level.

Figure 23: Sometimes severely leaning trees that block trails cannot be saved with

pruning and must be removed.

28

Natural Area Maintenance for CPTED

General Maintenance

Well-maintained natural areas indicate care and create a sense of ownership. Address vandalism and

garbage promptly. Locations where there is a visible presence of care and attention are less likely to

appeal to criminal elements and they will make visitors feel safer.

Well-cared for areas with good lines of sight will attract more visitors and will reduce potential for

criminal activity.

Invasive/Unwanted Plants

Learning to recognize unwanted species when they are young and easily extracted from the ground is a

vital management tactic. At the very least, they should be removed before they have the chance to

flower and start producing seeds.

Common invasive trees and shrubs that establish in natural areas include English holly (Ilex aquifolium),

cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus), Portuguese laurel (Prunus lusitanica), European mountain ash

(Sorbus aucuparia), English hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), butterfly bush (Buddleia davidii), and

Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius). They compete with desired vegetation and create shrubby

monocultures if left to grow too long. Consult with local counties or conservation districts for

recommendations for best management practices for removal.

Although they are not invasive species, seedlings of some of our native trees and shrubs can become

weeds when they crop up in locations where they might smother out desirable plants or aggressively

encroach into trails and critical sight lines. Black cottonwood, red alder, salmonberry, and hardhack are

examples of native species which often seed into openings in woodland areas and which can result in

conflicts. These and any other larger growing native species which spread or seed into “low vegetation”

zones should be removed while they are small (less than an inch trunk diameter for trees).

Herbicides (applied by a certified professional) may be a useful tool for removing large quantities of

unwanted vegetation.

Planning

Following the recommendations in this guide for proper planting will not only create natural spaces that

feel safer and more inviting, but can also reduce the amount of maintenance required. For example,

more thoughtful planning and pruning of shrubs can ultimately result in fewer and quicker pruning needs.

Proper placement and translocating of plants may eliminate the need for pruning maintenance

altogether.

Challenges and Opportunities for Vegetation Management

Breaking from routines and trying new and unfamiliar methods pose challenges for individuals and work

teams alike. The new method may feel counter-intuitive to what they are accustomed to or like it does

not fit in the scope of a work plan.

Each natural area site has its own set of conditions and stewardship challenges that may not neatly fit

into the examples and recommendations included in this manual. These basic techniques can be built

into the routine stewardship for a wide range of conditions and situations. The following are

recommendations for incorporating these techniques into a workplan:

29

Start small. Choose a manageable spot to do some trial and error practice to fine tune the optimal

methods for your site and work team. Build on what’s successful in incremental steps toward a larger

scale.

Keep records of the dates, the time required, and the tools used. Take before and after photos

the day of work and then again later in the growing season. Also take photos of areas not addressed or

done with existing techniques. Photo records are easy to take and are incredibly informative. By

tracking the data and using the photos for reference, you will have good information to guide future

work efforts and to train others.

Communication and education is vital. Training in the planting and stewardship methods for

CPTED in natural areas is critically important for success, especially for incoming workers, volunteers,

and seasonal staff who are likely to be unfamiliar with the techniques. Ongoing communication and

training are also important for more seasoned workers to reinforce use of preferred methods, build on

lessons of past efforts, and to foster greater coordination for consistent results throughout a work

team.

Be patient. At first, the tasks of selective pruning and organizing plants by future size for trailside areas

can appear too time consuming or expensive to be worth the effort. The field experience of those

utilizing the kinds of methods covered in this manual validate the proactive approaches to plant

placement, pruning, and selective plant removal along trailside plantings. As with many new jobs, it can

be a bit more difficult and time consuming the first time through. This is the value of beginning with a

small area or a single component. After the initial years of changing over to selective pruning and plant

removal along trail edges, the frequency and amount of work required will be reduced. In addition, the

character of the plantings will develop more naturally and be somewhat more self-sustaining over time

as the plantings mature.

30

Social Dimensions of CPTED

The earliest authors of CPTED, and related ideas about crime and security, emphasized that within built

environments people’s psychological response and related behaviors were influenced by physical

features. The recommendations for planting, pruning, and maintenance of native vegetation presented

thus far address these ideas by guiding how to manipulate natural areas’ physical features for CPTED.

However, social dimensions of public spaces also have a strong influence on the intended and undesired

activities that happen there. Introduced later, Second Generation CPTED encouraged practitioners to

reconsider the social ecology origins of CPTED, including sociological and psychological dimensions of

people in public space.

Second Generation CPTED practices are meant to discourage crime, while at the same time

encouraging legitimate use of an environment. Criminal behavior research shows that certainty of being

caught is a major deterrence for criminals, less so the severity of the punishment. Given the complexity

of crime and undesirable behavior, thinking about the social dimensions of a place should always be a

part of the CPTED process.

Crime prevention success requires community help. In her 1961 book Jane Jacobs interpreted many

facets of city life and urban planning practices. She coined the term ‘eyes on the street’, noting that

‘public peace’ was not kept primarily by the police, but by the ‘intricate, almost unconscious, network of

voluntary controls and standards among the people themselves, and enforced by the people themselves.’

Social Dimension CPTED Principles

The main principles of 2nd Generation CPTED are:

Social Cohesion. The goal is to support places where there exists a mutual respect and

appreciation for both the similarities and differences between people and groups within a site

user population. This includes attention to the conditions and operations that recognize,

support, and celebrate community diversity. Nurturing increased levels of formal and informal

social control through relationships of users and nearby residents who have different

backgrounds produces positive esteem and place attachment.

Community Connectivity. Achieving connectivity means nurturing partnerships within the

community. Such connections serve as the foundation to coordinate activities and programs

with and between government and nongovernment agencies. A more empowered, well-

connected, and integrated community will have a stronger sense of place. This connectivity can

help to encourage and maintain community self-policing.

Community Culture. This is present when community members come together and share a

sense of place that contributes to positive expressions of ownership and territoriality. A strong

sense of community can encourage the neighborhood to adopt positive outlooks and behaviors,

including self-policing. Shared culture is expressed as people work on setting up and participating

in festivals, cultural events, youth clubs, and commemorating significant local community events

and people.

Threshold Capacity. Neighborhoods and places can be regarded as ecosystems. Pressures

and drivers of change are constant and resulting changes can encourage or inhibit negative

behavior. When neighborhood ecosystems exceed their threshold capacity, this is referred to as

the tipping point. Place perceptions can tip from a positive outlook (despite modest levels of

negative activity) to a sense of decline or threat, and vice versa.

31

Inclusion and Community Participation. Inclusive community participation is crucial to the

effectiveness of CPTED. Within inclusive, healthy, and safe communities, people are able to

generate and implement practical ideas to improve and enhance a place. Participation includes

continued engagement with place users and the nearby community to do local safety audits of

perceived problems, conflict resolution, and work to enhance social interactions. Inclusion also

involves equal access to all for amenities and services.

Natural Surveillance. In addition to considering sight lines, view obstructions or blind

corners, this includes the intentional presence of people as informal monitors of a place.

Surveillance occurs by designing settings, activities and programs that welcome people to a

space in ways that maximize visibility of users and fosters positive social interaction among

legitimate users. Potential offenders feel increased scrutiny and perceive increased risk.

Activity Support. Activity support increases the use of a place for safe activities with the

intent of increasing the opportunities to detect criminal and undesirable activities. This

compares to natural surveillance which is casual and does not include any guidance for people to

watch out for criminal activity. By placing signs or equipment for certain activities (such as

‘caution children playing’ signs) users will be more involved and pay closer attention to what

should be happening around them. They will be more tuned in to who is and isn’t likely to be

within a space and what looks suspicious.

Social Dimension CPTED Recommendations for Natural Areas

While, most of these recommendations apply to natural area land managers at the program level,

residents can advocate and organize for the following recommendations to happen within their own

community’s natural areas.

Conduct a Social CPTED Audit for a Site. Assess the current conditions, programs and

activities that encourage positive behavior within a site, and develop a plan to sustain what

works and add additional opportunities. The audit can include access points, trails, site facilities

(such as benches, picnic shelters and restrooms), locations where programs occur, and popular

natural attractions.

Provide Positive Guidance for Site Activity. A social audit can help managers to identify

key trouble areas and visualize how to introduce more social dimensions of CPTED. For

instance, law enforcement assistance may be needed to correct existing trouble spots. Then

currently positive situations can be reinforced and new social dynamics introduced through

vegetation and other site management.

Plan Programs and Activities. Recurring and special events can foster inclusion and maintain

a steady sense of ‘eyes on the park.’ Examples include environmental education and bioblasts.

And with increased attention to the relationship of nature experiences and human health, a

variety of health improvement programs are possible: schedule group walks or hikes; initiate

Park Rx (a parks prescription program), Walk with a Doc, or forest bathing. Consider cultural

diversity and equity in planning and implementation.

Integrate Local Policies of Equity and Environmental Justice. Local governments have

recently launched equity and justice policies that include nature and urban greening. The values

represented by these initiatives can be expressed in site planning, design and management.

Optimize Social Contacts in Access and Trails. Ecological assessments often propose

ecosystem units within a parcel for specific management practices. In a similar way a social audit

can suggest how to guide users across a site in a managed way so there are frequent and

distributed social encounters. Access locations and trail development can reinforce visitor

32

density and interactions across the entire site. Discourage social trails that promote unobserved

activity.

Support Placemaking and Promote Features for Visitor Appeal. Conduct an

assessment of elements that are popular for visitors, such as promontories, water edges, wildlife

viewing locations, or unique features (such as large trees) and orient trails to welcome visitors

and provide comfortable access. Intentional placement of park furniture, such as benches or

picnic tables, guides user flow and distribution across a site. Encourage legitimate spaces for

lingering. This creates an ambience that unsettles negative behavior and nuisances by supporting

natural surveillance.

Monitor Thresholds in Management. Examples of a tipping point in residential

neighborhoods are the number of derelict or unoccupied buildings. The tipping point moves

from the expected cycling of business use to a place image of decline. In natural areas excessive

amounts of graffiti, trash or unkempt and abused facilities may signal thresholds. Networks of

informal trails not only signal unexpected encounters, but can also lead to confusion in users’

wayfinding. The result is a sense of uncertainty, even fear when in a natural area.

Support ‘Friends Of’ Groups. Engage nearby residents, civic organizations and school groups

in site planning, as well as vegetation management and ecological restoration activities. The

Green Cities Partnerships program is a great example of this. This helps to set up the

partnership relationships and organization connections that encourage positive site use. It can

also build a community alarm system, so that the neighborhood responds quickly to any

emerging negative site uses.

Promote Civic Environmental Stewardship. Involving and engaging the community in

stewarding natural areas provides more opportunities for surveillance, and ensures a more

maintained setting. Stewardship roles can include both volunteers and green jobs, such as

summer programs for youth. Stewardship programs that welcome people of diverse

backgrounds nurtures broader place attachment and awareness about natural settings and actual

crime incidence.

33

Glossary

Apical buds: Buds located at the tip of a branch.

Apical dominance: The phenomenon by which the central leader is dominant over the lateral

branches, allowing the plant to grow vertically.

Auxin: A plant hormone that regulates plant growth.

Branch collar: The ring around the base of a branch where it shoots out from a larger branch, which is

typically wider in diameter than the rest of the branch.

Branch collar cut: A pruning cut placed above the branch collar in order to create a smaller surface

area wound, which can prevent excess water loss and tree stress.

Buttress roots: The lateral surface roots that aid in stabilizing a tree.

Callus: A hard formation of new tissue over and around a wound

Cambium: Vascular tissue that divides to produce xylem and phloem and is responsible for increasing

the girth of plant stems and branches.

Cane growers: Shrubs with annual growth or “canes” emerging from a central root crown. Canes may

or may not be perennial.

Central leader: A dominant stem located more or less in the center of the crown.

Co-dominant leaders: When a tree has two leaders that are similar in height and diameter and

originate from the same point.

Colonizing shrub: Shrubs that are able to colonize adjacent areas with new stems that grow up from a

spreading root system.

Deciduous perennial: A plant that dies back at some point in the year, typically fall or winter, and re-

sprouts from its roots during the next growing season.

Dormant (dormancy): A period during the year when activity is temporarily stopped to conserve

energy when environmental conditions are not right for a plant to grow. For most plants in the Pacific

northwest, this period happens during the late fall and early winter.

Finish cut: The cut that completes the removal of a branch.

Growth habit: The shape, growth rate, mature size, and branching structure of a tree without pruning.

Heading cut: A type of pruning cut that severs a shoot or stem that is no more than one year old,

back to a bud; cutting a stem back to a lateral branch less than one-third the diameter of the cut stem;

cutting a stem of any diameter to a node (the assumed position of a bud).

Heavy pruning: Removing more than 50% of live foliage on young trees, 25% on medium-aged trees,

and 10% on mature trees at one time.

Lateral branch: A stem growing from an older and larger stem.

Light Pruning: Removing less than about 20% of the foliage on young trees, 10% of the foliage on

medium-aged trees, or 5% of the foliage on mature trees.

34

Line of sight: A straight line along which an observer has an unobstructed view.

Mature tree: A tree that has reached at least 75% of its final height and spread, but is not declining due

to old age.

Monoculture: When one species is severely dominant in a given area. This can lead to weakened

ecosystem resilience.

Open vegetation structure: A structure of a shrub with lots of space between branches, promoting

healthy growth and allowing some lines of sight through the shrub.

Perennial: A plant that persists for many growing seasons. See also deciduous perennial.

Phloem: Vascular tissue that transports energy produces in the leaves to other parts of the plant.

Pruning: removal of plant parts.

Reduction cut: A type of pruning cut that shortens the length of a branch or stem back to a live lateral

branch large enough to assume apical dominance – this is typically at least one-third the diameter of the

cut stem; cutting back a stem to an existing, smaller, lateral branch that is large enough to prevent bark

death on the retained lateral branch.

Removal cut: A pruning cut that removes a branch back to the trunk or parent stem just beyond the

branch collar.

Renovation pruning: Cutting a shrub back to the ground in order to encourage healthy, vigorous

growth in the next growing period.

Root crown: The base of the trunk where roots and trunk merge that becomes swollen as trees grow.

Scaffold limb: A permanent branch that is among the largest in diameter on the tree.

Shearing: Shaping a plant with heading cuts to branches that are no more than one year old to form a

defined, smooth surface.

Social ecology: The study of the relationships within and between the environment and people with a

focus on social, cultural, physical, institutional, and cultural contexts of these relationships.

Suckers: Fast growing shoots that develop from the roots of a plant or the trunk below the root collar.

Tipping: Similar to topping except heading cuts are made through smaller-diameter branches on the

edges of the crown.

Topping: An inappropriate pruning technique used to reduce the size of a tree by making heading cuts

through a stem more than 2 years old. It destroys tree architecture and causes discoloration and decay

on cut branches.

View Corridors: Open spaces that provide unobstructed lines of sight.

Water sprouts: Fast growing shoots that develop from dormant buds on a tree’s trunk or branches.

Wound wood: a very tough, woody tissue that grows behind a callus and replaces it in that position.

When wound wood closes wounds, then normal wood continues to form.

Xylem: Vascular tissue that moves water and nutrients up the stem of the plant from the roots.

35

References

Cozens, P. & T. Love. 2015. A review and current status of Crime Prevention through Environmental

Design (CPTED). Journal of Planning Literature 30, 4: 393-412.

Cleveland, G. & G. Saville, G. 1997. 2nd generation CPTED: An antidote to the social Y2K virus of urban

design. Paper presented at the 2nd Annual International CPTED Conference. Orlando, FL, December

14–16.

Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

Koonts, D.W. Design Approaches to CPTEDin Natural Area Parks - Case Study: Lower Kinnear Park.

Accessed 10 February 2019: https://botanicgardens.uw.edu/wp-

content/uploads/sites/7/2016/11/2017_CPTED-Lower-Kinnear.pdf

Landscaping for Wildlife

Seattle list of native plants best for natural area edges

Wolf, K.L. 2010. Crime and Fear - A Literature Review. Accessed 10 February 2019: Green Cities:

Good Health, University of Washington: http://depts.washington.edu/hhwb/Thm_Crime.html.

36

Appendix 1: Tree Training Cue Card