Software Requirements

SEI Curriculum Module SEI-CM-19-1.2

January 1990

John W. Brackett

Boston University

Software Engineering Institute

Carnegie Mellon University

This work was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense.

Approved for public release. Distribution unlimited.

The Software Engineering Institute (SEI) is a federally funded research and development center, operated by Carnegie

Mellon University under contract with the United States Department of Defense.

The SEI Education Program is developing a wide range of materials to support software engineering education. A

curriculum module identifies and outlines the content of a specific topic area, and is intended to be used by an instructor

in designing a course. A support materials package includes materials helpful in teaching a course. Other materials

under development include model curricula, textbooks, educational software, and a variety of reports and proceedings.

SEI educational materials are being made available to educators throughout the academic, industrial, and government

communities. The use of these materials in a course does not in any way constitute an endorsement of the course by the

SEI, by Carnegie Mellon University, or by the United States government.

SEI curriculum modules may be copied or incorporated into other materials, but not for profit, provided that appropriate

credit is given to the SEI and to the original author of the materials.

Comments on SEI educational publications, reports concerning their use, and requests for additional information should

be addressed to the Director of Education, Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania 15213.

Comments on this curriculum module may also be directed to the module author.

John W. Brackett

Department of Electrical, Computer

and System Engineering

Boston University

44 Cummington St.

Boston, MA 02215

Copyright 1990 by Carnegie Mellon University

This technical report was prepared for the

SEI Joint Program Office

ESD/AVS

Hanscom AFB, MA 01731

The ideas and findings in this report should not be construed as an official DoD position.

It is published in the interest of scientific and technical information exchange.

Review and Approval

This report has been reviewed and is approved for publication.

FOR THE COMMANDER

Karl H. Shingler

SEI Joint Program Office

191211090

Software Requirements

Acknowledgements Contents

Dieter Rombach, of the University of Maryland, played an

Capsule Description 1

invaluable role in helping me organize this curriculum

Philosophy 1

module. He reviewed many drafts. Lionel Deimel, of the

Objectives 4

SEI, was of great assistance in clarifying my initial drafts.

Douglas T. Ross, one of the true pioneers in software

Prerequisite Knowledge 4

engineering, taught me much of what I know about soft-

Module Content 5

ware requirements definition.

Outline 5

Annotated Outline 5

Teaching Considerations 15

Suggested Course Types 15

Teaching Experience 15

Suggested Reading Lists 15

Bibliography 17

SEI-CM-19-1.2 iii

Software Requirements

Module Revision History

Version 1.2 (January 1990) Minor revisions and corrections

Version 1.1 (December 1989) Revised and expanded bibliography; other minor changes

Approved for publication

Version 1.0 (December 1988) Draft for public review

iv SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

pendent of the specific techniques used. The mate-

Capsule Description

rial presented here should be considered prerequisite

to the study of specific requirements methodologies

This curriculum module is concerned with the defi-

and representation techniques.

nition of software requirements—the software engi-

neering process of determining what is to be pro-

Software Requirements has been developed in con-

duced—and the products generated in that defini-

junction with Software Specification: A Framework

tion. The process involves all of the following:

[Rombach90] and uses the conceptual framework

and terminology presented in that module. This ter-

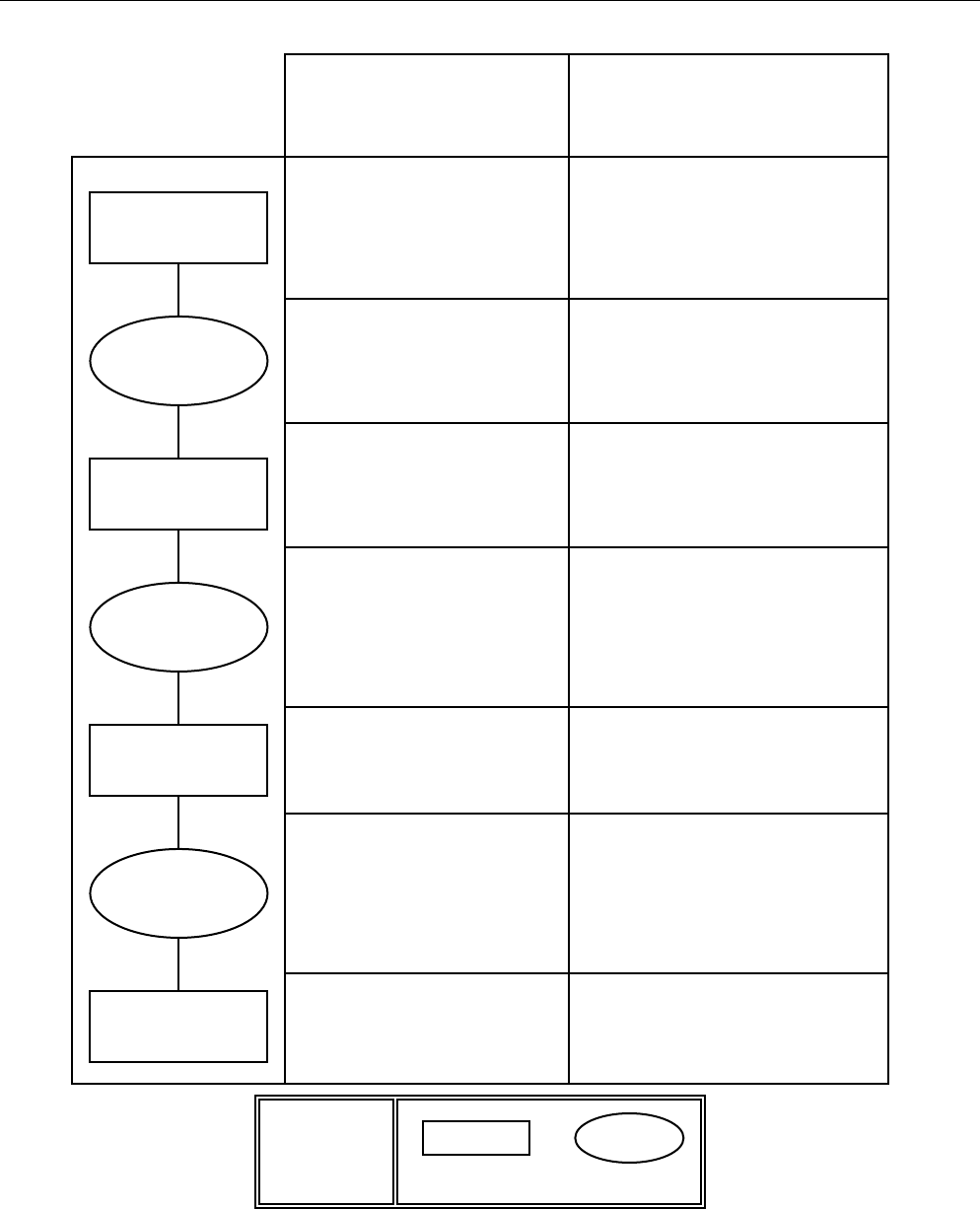

• requirements identification

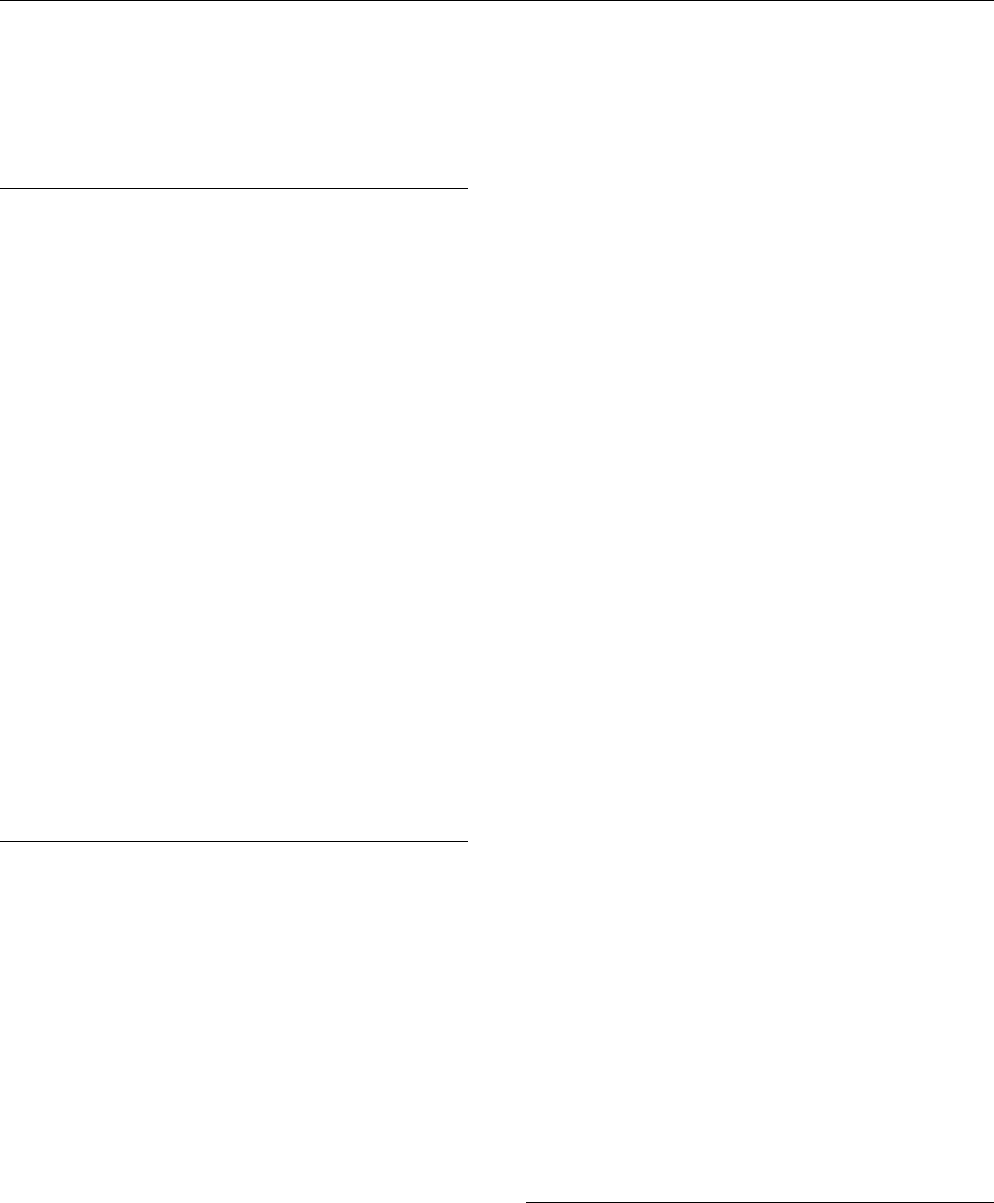

minology is summarized in Figure 1. Both modules

• requirements analysis

identify two products of the software requirements

• requirements representation

process: customer/user-oriented software require-

ments (“C-requirements”) and developer-oriented

• requirements communication

software requirements (“D-requirements”). The

• development of acceptance criteria and

principal objective of these documents is the

procedures

achievement of agreement on what is to be pro-

The outcome of requirements definition is a precur-

duced. Their form, however, is largely determined

sor of software design.

by the communication needs of the diverse partic-

ipants in the requirements process. The develop-

ment of the D-requirements refines and augments

the C-requirements, in order to provide the informa-

Philosophy

tion required to support software design and subse-

quent validation of the developed software against

the requirements.

The subject of software requirements is often given

far less attention in software engineering education

Because of the dependence of this module on

than software design, even though its importance is

Software Specification: A Framework, that curricu-

widely recognized. For example, Brooks

[Brooks87]

lum module should be read before studying this one.

has written:

This module reflects two strong opinions of the au-

The hardest single part of building a software

thor:

system is deciding precisely what to build. No

other part of the conceptual work is as difficult

• The software requirements definition

as establishing the detailed technical require-

process is highly dependent upon the

ments, including all the interfaces to people, to

previous steps in the system develop-

machines, and to other software systems. No

ment process.

part of the work so cripples the resulting system

• The prime objective of the requirements

if done wrong. No other part is more difficult

definition process is to achieve agree-

to rectify later.

ment on what is to be produced.

The purpose of this module is to provide a compre-

Where the overall system requirements have been

hensive view of the field of software requirements in

determined and the decision has been made that cer-

order that the subject area can be more widely

tain system functions are to be performed by soft-

taught. The module provides the material needed to

ware, the software requirements process is highly

understand the requirements definition process and

constrained by previous systems engineering work.

the products produced by it. It emphasizes what

In this situation, requirements are obtained largely

must be done during requirements definition, inde-

SEI-CM-19-1.2 1

Software Requirements

Existing

Life-cycle

Terminology

Terminology

Used in this Module

Market Analysis

Systems Analysis

Business Planning

Systems Engineering

Context Analysis

Market Needs

Business Needs

Demands

System Requirements

Needs Product

Requirements Analysis

Requirements Definition

System Specification

C(ustomer/User-oriented)-

Requirements Process

Requirements

Requirements Definition

Requirements Document

Requirements Specification

Functional Specification

C - Requirements Product

Specification D(eveloper-oriented)-

Requirements Process

Behavioral Specification

System Specification

Functional Specification

Specification Document

Requirements Specification

D - Requirements Product

Software Needs

Customer/User

Oriented Software

Requirements

Developer

Oriented Software

Requirements

Design Design Process

LEGEND

Processes Products

Figure 1. Life-cycle terminology used in this module.

2 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

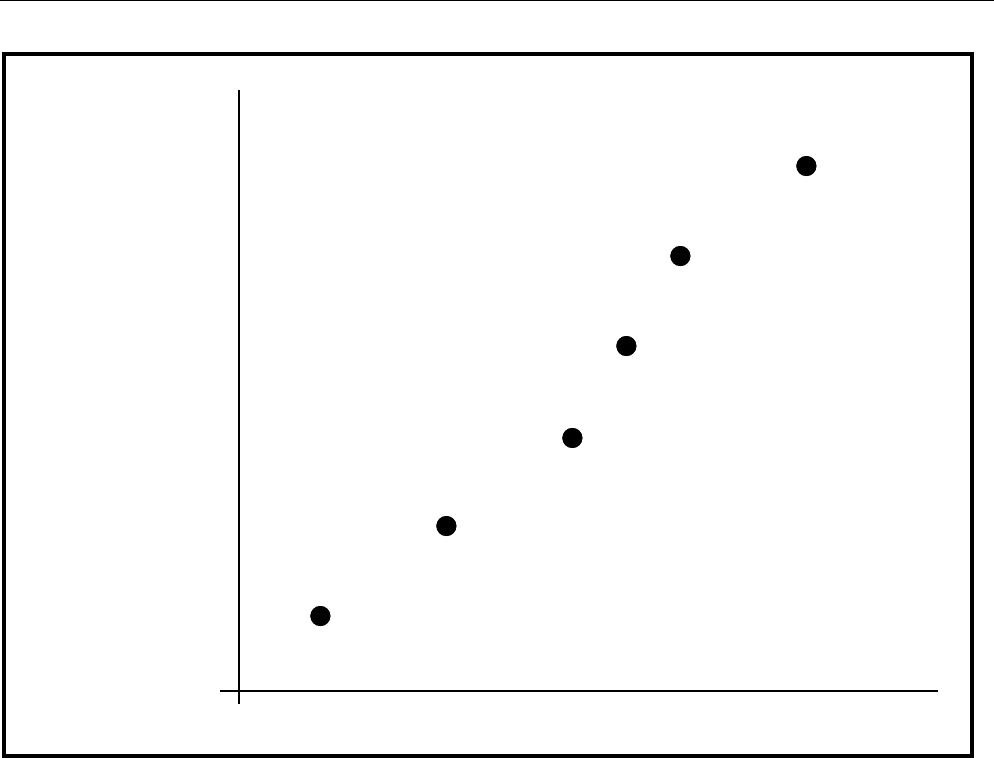

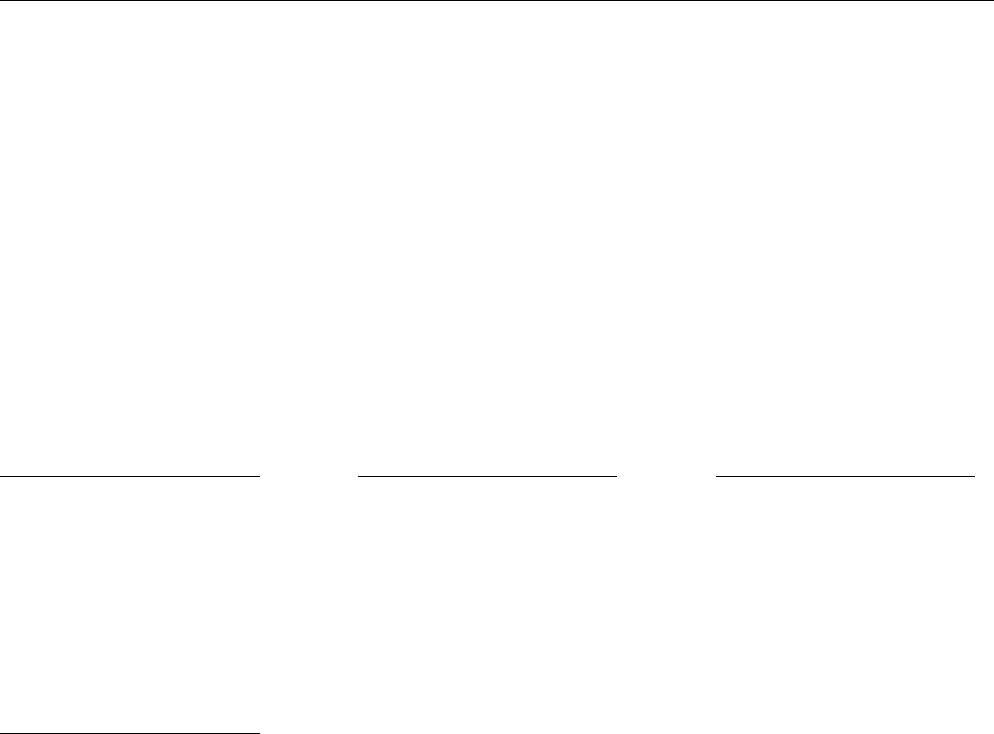

Environment

for the

Software

Requirements

Definition

Process

Unconstrained

Highly

Constrained

Decision

Support

System

Corporate

Accounting

System

Manufacturers

Operating

System

Enhancements to

Corporate Accounting

System

Airliner Flight

Control

System

Missile

Guidance

System

% of Requirements Gathered from People

Figure 2. Sources of requirements.

by analyzing documents. (A typical example is the Requirements products have three, sometimes com-

requirements definition for software to control a spe- peting, objectives:

cific hardware device.)

1. To achieve agreement regarding the re-

quirements between system developers,

Where there are few constraints imposed by the en-

customers, and end-users.

vironment in which the software will operate and

there may be many opinions on desired software

2. To provide the basis for software design.

functionality, requirements definition primarily in-

3. To support verification and validation.

volves eliciting requirements from people. (A typi-

During C-requirements development, the first objec-

cal example is the requirements definition needed to

tive is paramount. Later in the life cycle, the other

build decision support software for use by a group of

two objectives increase in importance.

managers.)

Figure 2 suggests how the fraction of requirements

elicited from people increases as constraints on the

software requirements process decrease.

The fact that the prime objective of the requirements

definition process is to achieve agreement on what is

to be produced makes it mandatory that the products

of the process serve to communicate effectively with

the diverse participants.

SEI-CM-19-1.2 3

Software Requirements

Objectives

The following is a list of possible objectives for in-

struction based upon this module. The objectives for

any particular unit of instruction may include all of

these or consist of some subset of this list, depend-

ing upon the nature of the unit and the backgrounds

of the students.

Comprehension

• The student will be able to describe the

products produced by requirements defi-

nition, the type of information each

should contain, and the process used to

produce the products.

Synthesis

• The student will be able to develop a

plan for conducting a requirements defi-

nition project requiring a small team of

analysts.

• The student will be able to perform re-

quirements definition as part of a team

working with a small group of end-users.

Evaluation

• The student will be able to evaluate criti-

cally the completeness and utility, for a

particular audience, of requirements doc-

uments upon which software design is to

be based.

Prerequisite Knowledge

Familiarity with the terms and concepts of the soft-

ware engineering life cycle.

4 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

Module Content

c. Key contents

Outline

4. Developer-oriented software requirements

I. Introduction to Software Requirements

a. Objectives

1. What are requirements?

b. Relative importance of specification

attributes

2. The requirements definition process

c. Key contents

3. Process participants and their roles

IV. Techniques and Tools for Performing Software

4. The products of requirements definition

Requirements Definition

II. The Software Requirements Definition Process

1. Techniques for eliciting requirements from

1. Requirements identification

people

a. Software needs as input to requirements

2. Modeling techniques

definition

3. Representative requirements definition methods

b. Elicitation from people

a. Structured Analysis and SADT

c. Deriving software requirements from system

b. DSSD

requirements

c. SREM/DCDS

d. Task analysis to develop user interface

requirements

d. NRL/SCR

2. Identification of software development

4. Computer support tools for model development

constraints

a. Method-specific tools

3. Requirements analysis

b. Non–method-specific tools

a. Assessment of potential problems

5. Computer support tools for prototyping

b. Classification of requirements

c. Evaluation of feasibility and risks

4. Requirements representation

Annotated Outline

a. Use of models

b. Roles for prototyping

I. Introduction to Software Requirements

5. Requirements communication

1. What are requirements?

6. Preparation for validation of software

There are many definitions of requirements, which

requirements

differ in their emphasis. The IEEE software engi-

7. Managing the requirements definition process

neering glossary [IEEE83] defines requirement as:

III. Software Requirements Products

(1) A condition or capability needed by a user to

solve a problem or achieve an objective. (2) A

1. Results of requirements definition

condition or capability that must be met or pos-

a. Functional requirements

sessed by a system or system component to sat-

isfy a contract, standard, specification, or other

b. Non-functional requirements

formally imposed document. The set of all re-

c. Inverse requirements (what the software shall

quirements forms the basis for subsequent de-

not do)

velopment of the system or system component.

d. Design and implementation constraints

Abbott [Abbott86] defines requirement as:

2. Standards for requirements documents

any function, constraint, or other property that

must be provided, met, or satisfied to fill the

3. Customer/user-oriented software requirements

needs of the system’s intended user(s).

a. Objectives

For projects in which the software development is

b. Relative importance of specification

highly constrained by prior system engineering

attributes

work, the second IEEE definition is most applicable.

SEI-CM-19-1.2 5

Software Requirements

In less constrained environments, the first IEEE de- engineers, who evolve the C-requirements product

finition or Abbott’s definition is appropriate. into the D-requirements product; managers; and ver-

ification and validation (V&V) personnel.

Requirements cover not only the desired function-

ality of a system or software product, but also ad- Requirements analysts act as catalysts in identifying

dress non-functional issues (e.g., performance, inter- requirements from the information gathered from

face, and reliability requirements), constraints on the many sources, in structuring the information (per-

design (e.g., operating in conjunction with existing haps by building models), and in communicating

hardware or software), and constraints on the imple- draft requirements to different audiences. Since

mentation (e.g., cost, must be programmed in Ada). there is a variety of participants involved in the re-

The process of determining requirements for a sys- quirements definition process, requirements must be

tem is referred to as requirements definition. presented in alternative, but consistent, forms that

are understandable to different audiences.

Our concern in this module is with software

4. The products of requirements definition

requirements, those requirements specifically related

to software systems or to the software components

The outcome of requirements definition is the for-

of larger systems. Where software is a component

mulation of functional requirements, non-functional

of another system, software requirements can be dis-

requirements, and design and implementation con-

tinguished from the system requirements of the

straints. These requirements and constraints must be

larger artifact.

represented in a manner fulfilling the information

needs of different audiences.

Software Specification: A Framework [Rombach90]

describes several different software evolution (life-

The following are the principal objectives of re-

cycle) models and notes that the commonalities

quirements products:

among these models are the types of products they

• To achieve agreement on the require-

eventually produce. The products shown in Figure 1

ments. Requirements definition, the proc-

are assumed to be produced on a project, irrespec-

ess culminating in the production of re-

tive of how the products get built. Although the

quirements products, is a communications-

requirements on a small project may be defined in-

intensive one that involves the iterative

formally and briefly, a definition of what the soft-

elicitation and refinement of information

ware development process will produce is required

from a variety of sources, usually includ-

in all life-cycle models.

ing end-users with divergent perceptions

2. The requirements definition process

of what is needed. Frequent review of the

evolving requirements by persons with a

The requirements definition process comprises these

variety of backgrounds is essential to the

steps:

convergence of this iterative process. Re-

• Requirements identification

quirements documents must facilitate com-

munication with end-users and customers,

• Identification of software development

as well as with software designers and per-

constraints

sonnel who will test the software when de-

• Requirements analysis

veloped.

• Requirements representation

• To provide a basis for software design.

• Requirements communication

Requirements documents must provide

• Preparation for validation of software re-

precise input to software developers who

quirements

are not experts in the application domain.

However, the precision required for this

These steps, which are not necessarily performed in

purpose is frequently at odds with the need

a strictly sequential fashion, are described and dis-

for requirements documents to facilitate

cussed in Section II.

communication with other people.

3. Process participants and their roles

• To provide a reference point for soft-

ware validation. Requirements docu-

[Rombach90] describes classes of project partici-

ments are used to perform software valida-

pants and their responsibilities. Rombach distin-

tion, i.e., to determine if the developed

guishes between customers, who contract for the

software satisfies the requirements from

software project, and end-users, who will install,

which it was developed. Requirements

operate, use, and maintain the system incorporating

must be stated in a measurable form, so

the software. Customers are assumed to be respon-

tests can be developed to show un-

sible for acceptance of the software. Other par-

ambiguously whether each requirement

ticipants he defines are: requirements analysts, who

has been satisfied [Boehm84a].

develop the C-requirements product; specification

6 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

In formulating requirements, it is important for the e.g., where software is embedded in a larger

analyst to maintain his role as analyst and avoid be- hardware system (an embedded system), system-

coming a designer. Of two requirements purporting level documentation frequently provides the con-

to represent the same need, the better one is that text for software requirements definition. This

which allows the designer greater latitude. This ad- documentation, which serves as software needs,

vice is difficult to heed, both because users and cus- typically covers system requirements, the alloca-

tomers often state particular design solutions as tion of system functions to software, and the de-

“needs” and because it is usually easier to postulate scription of interfaces between hardware and soft-

a solution in lieu of understanding what is really ware.

needed by users or customers. The analyst’s objec-

When a software product is being developed for a

tive should always be to maximize the options avail-

heterogeneous audience (e.g., a database manager

able to the designer. This objective can be well-

or a spreadsheet package), software needs will

illustrated by a simple example from another

typically contain the results of a market analysis

domain. The statement “the customer requires an

and a list of important product features. Since

automobile” provides the problem-solver with fewer

information provided in software needs differs so

options than “the customer needs a means to get to

widely, requirements definition must usually in-

Cleveland.”

clude an understanding of the environment in

II. The Software Requirements Definition Process

which the software will operate and how the soft-

ware will interact with that environment.

The steps in software requirements definition and the

management of the process are discussed below.

b. Elicitation from people

1. Requirements identification

An essential step in most requirements definition

projects is elicitation of requirements-related in-

Requirements identification is the step of require-

formation from end-users, subject-matter experts,

ments definition during which software require-

and customers. Elicitation is the process per-

ments are elicited from people or derived from sys-

formed by analysts for gathering and understand-

tem requirements [Davis82, Martin88, Powers84].

ing information [Leite87]. Elicitation involves

An important precursor to requirements definition is

fact-finding, validating one’s understanding of the

the context analysis process, which precedes re-

information gathered, and communicating open

quirements definition. (See Figure 1.)

issues for resolution.

a. Software needs as input to requirements

Fact-finding uses mechanisms such as interviews,

definition

questionnaires, and observation of the operational

environment of which the software will become a

Context analysis [Ross77b] documents why soft-

part.

ware is to be created and why certain technical,

operational, and economic feasibilities establish

Validation involves creating a representation of

boundary conditions for the software develop-

the elicitation results in a form that will focus

ment process. According to Ross, context anal-

attention on open issues and that can be reviewed

ysis should answer the following questions:

with those who provided information. Possible

• Why is the software to be created?

representations include summary documents,

usage scenarios, prototype software [Boehm84b],

• What is the environment of the software

and models.

to be created?

• What are the technical, operational, and

Some type of explicit approval to proceed with

economic boundary conditions that an

requirements definition completes the elicitation

acceptable software implementation

process. The audiences who must approve the

must satisfy?

requirements should agree that all relevant infor-

mation sources have been contacted.

Context analysis for software to be developed for

internal company use is frequently called business

c. Deriving software requirements from system

planning or systems analysis. In any case, we

requirements

will refer to the product of context analysis as

software needs.

Requirements are created for embedded software

based upon the system requirements for the sys-

Software needs can take significantly different

tem or system component in which the software is

forms depending upon the context of system de-

embedded. Traceability techniques are used to

velopment. In many situations, software needs

communicate how the software requirements re-

will be very informal and will provide little de-

late to the system requirements, since the cus-

tailed information for beginning requirements de-

tomer is usually more familiar with the system

finition. For a highly constrained environment,

SEI-CM-19-1.2 7

Software Requirements

requirements. Because functions are allocated to It is frequently useful also to assess requirements

software and hardware before software require- regarding stability; a stable requirement addresses

ments definition begins, most of the functions the a need that is not expected to change during the

software is to perform will not be derived through life of the software. Knowing that a requirement

requirements elicitation from end-users or cus- may change facilitates developing a software de-

tomers. sign that isolates the potential impact of the

change.

d. Task analysis to develop user interface

c. Evaluation of feasibility and risks

requirements

Assessment of feasibility involves technical feasi-

User Interface Development [Perlman88] de-

bility (i.e, can the requirements be met with cur-

scribes methods for user interface evaluation that

rent technology?), operational feasibility (i.e, can

also apply to determining software requirements

the software be used by the existing staff in its

concerned with human interaction. Analyzing the

planned environment?), and economic feasibility

tasks the user must perform should result in a de-

(i.e., are the costs of system implementation and

tailed understanding of how a person is supposed

use acceptable to the customer?) [Ross77b].

to use the proposed software.

4. Requirements representation

2. Identification of software development

constraints

Requirements representation is the step of require-

ments definition during which the results of require-

During this step, constraints on the software devel-

ments identification are portrayed. Requirements

opment process are identified. Typical constraints

have traditionally been represented in a purely tex-

include cost, the characteristics of the hardware to

tual form. Increasingly, however, techniques such

which the software must interface, existing software

as model building and prototyping, which demand

with which the new software must operate, fault tol-

more precision in their description, are being used.

erance objectives, and portability requirements.

Only software solutions satisfying the requirements

a. Use of models

and implemented within the restrictions imposed by

the constraints are acceptable.

Models are built during requirements definition to

define specific characteristics of the software (i.e.,

3. Requirements analysis

the functions it will perform and the interfaces to

its environment) in a form that can be more easily

Requirements are generally gathered from diverse

understood and analyzed than a textual descrip-

sources, and much analysis (requirements analysis)

tion. A good model:

is usually needed before the results of requirements

definition are adequate for the customer to commit

• Reduces the amount of complexity that

to proceeding with further software development.

must be comprehended at one time.

“Adequate,” in this context, means there is per-

• Is inexpensive to build and modify

ceived to be an acceptable level of risk regarding

compared to the real thing.

technical and cost feasibility and an acceptable level

• Facilitates the description of complex

of risk regarding the completeness, correctness, and

aspects of the real thing.

lack of ambiguity in the results.

Most requirements methods include the develop-

The principal steps in requirements analysis, which

ment of models of some type to portray the results

are frequently iterated until all issues are resolved,

of requirements elicitation and to facilitate the re-

are:

quirements analysis process. An important moti-

vation for building models during requirements

a. Assessment of potential problems

definition is the belief that the model notation—

and computer support tools supporting the nota-

This is the process step during which require-

tion—help the analyst identify potential problems

ments are assessed for feasibility and for prob-

early in the requirements definition process.

lems such as ambiguity, incompleteness, and in-

consistency. Software requirements for em-

b. Roles for prototyping

bedded software must be verified to ensure they

are consistent with the system requirements.

Prototyping is frequently used to provide early

feedback to customers and end-users and to im-

b. Classification of requirements

prove communication of requirements between

users and system developers. Many users find it

Requirements should be classified into priority

difficult to visualize how software will perform in

categories such as mandatory, desirable, and in-

their environment if they have only a non-

essential. “Mandatory” means that the software

executable description of requirements. A proto-

will not be acceptable to the customer unless

these requirements are met in an agreed manner.

8 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

type can be an effective mechanism to convey a proposed acceptance criteria and the techniques to

sense of how the system will work. Hands-on use be used during the software validation process, such

of a prototype is particularly valuable if a system as execution of a test plan to determine that the crite-

has to be used by a wide variety of users, not all ria have been met [Collofello88a].

of whom have participated in the requirements

7. Managing the requirements definition process

definition process. Although a prototype is not a

substitute for a thorough written specification, it

Requirements definition can present a major project

allows representation of the effect of require-

management challenge. Nearly all cost and schedule

ments—certain kinds of requirements, at any rate

estimating approaches assume that the requirements

—with an immediacy not matched by its more

are defined and can be used to estimate roughly the

static counterpart. Of course, not all elements of

size of the project. The effort for a requirements

a system can be captured in a prototype at a

project is related to the total development man-

reasonable cost.

months, and the effort rises in proportion to the

number of divergent sources from which require-

In many situations, users do not understand the

ments information must be gathered and reconciled.

required functionality well enough to completely

For example, an application that must support five

articulate their needs to analysts. A prototype

different classes of users with significantly different

based on the information obtained during require-

expectations about the capabilities to be provided

ments elicitation is often very useful in refining

could easily involve a requirements definition proc-

the required functionality [Gomaa81]. Models de-

ess that is five times more difficult than the cor-

veloped after requirements elicitation can be use-

responding process for a homogeneous group of

ful in deciding what functionality to include in

users.

such a prototype.

The complexity of requirements definition rises as a

Boehm [Boehm86] describes possible roles of

function of project duration. The longer a project

prototyping to minimize development risks due to

goes on, the more likely it is that the software envi-

incomplete requirements. Clapp [Clapp87] de-

ronment, customers, and end-users will change. A

scribes the uses of prototypes during requirements

large application, whose total development will re-

definition to assess technology risks and to assess

quire several people working for a number of years,

whether a user interface can be developed that

will involve a complex requirements definition proc-

will allow the designated personnel to operate the

ess that does not terminate when design and imple-

system effectively. Modeling methods are of lit-

mentation begin. Requirements changes will be re-

tle help in determining the requirements for user

quested throughout the development cycle and must

interfaces. Development of prototypes of alter-

be evaluated for their cost and schedule impact on

native user interfaces is usually required to obtain

the work already performed or underway.

meaningful feedback from customers and users.

If the technical feasibility of meeting essential re-

It is difficult to identify the optimum effort to devote

quirements is in question, developing prototypes

to requirements definition before undertaking soft-

incorporating key algorithms can provide results

ware design. Determining this effort involves an

that are not otherwise available.

assessment of the risk involved in assuming that the

requirements are defined adequately to proceed.

5. Requirements communication

There will be a negative impact on the cost and

Requirements communication is the step in which schedule of subsequent life-cycle phases if all the

results of requirements definition are presented to requirements have not been identified or if they have

diverse audiences for review and approval. The fact not been stated with adequate precision.

that users and analysts are frequently expert in their

III. Software Requirements Products

own areas but inexperienced in each other’s domains

1. Results of requirements definition

makes effective communication particularly diffi-

cult. The result of requirements communication is

The format in which the results of the requirements

frequently a further iteration through the require-

definition process should be presented depends upon

ments definition process in order to achieve agree-

the information needs of different audiences. End-

ment on a precise statement of requirements.

users prefer a presentation that uses an application-

oriented vocabulary, while software designers re-

6. Preparation for validation of software

quire more detail and a precise definition of

requirements

application-specific terminology. However, require-

During this step, the criteria and techniques are es-

ments, no matter how presented, fall into four

tablished for ensuring that the software, when pro-

classes [Ross77b]:

duced, meets the requirements. The customer and

• Functional requirements

software developers must reach agreement on the

• Non-functional requirements

SEI-CM-19-1.2 9

Software Requirements

2. Standards for requirements documents

• Inverse requirements

• Design and implementation constraints

The two most widely referenced standards relevant

to producing requirements documents are

a. Functional requirements

U. S. Department of Defense Standard 2167A,

Military Standard for Defense System Software

A functional requirement specifies a function that

Development [DoD88] and IEEE Standard 830, IEEE

a system or system component (i.e., software)

Guide to Software Requirements Specifications

must be capable of performing.

[IEEE84]. The IEEE standard describes the neces-

Functional requirements can be stated from either

sary content and qualities of a good requirements

a static or dynamic perspective. The dynamic

document and presents a recommended outline.

perspective describes the behavior of a system or

Section 2 of the outline can be considered a template

system component in terms of the results pro-

for customer/user-oriented requirements and section

duced by executing the system under specified

3 a template for developer-oriented requirements.

circumstances. Functional requirements stated

Even if a company standard for documentation for-

from an external, dynamic perspective are fre-

mat is to be used, the IEEE standard provides a good

quently written in terms of externally observable

checklist of the items that should be included.

states; for example, the functions capable of being

3. Customer/user-oriented software requirements

performed by an automobile cruise control system

are different when the system is turned on from

This section describes important characteristics of

when it is disabled. Functional requirements

C-requirements products.

stated from a static perspective describe the func-

tions performed by each entity and the way each

a. Objectives

interacts with other entities and the environment.

C-requirements provide to the customer, who

b. Non-functional requirements

contracts for the software project and must accept

the resulting software, a description of the func-

Non-functional requirements are those relating to

tional requirements, non-functional requirements,

performance, reliability, security, maintainability,

inverse requirements, and design constraints ade-

availability, accuracy, error-handling, capacity,

quate to commit to software development.

ability to be used by specific class of users, an-

“Adequate” means there is an acceptable level of

ticipated changes to be accommodated, accepta-

risk regarding technical and cost feasibility and an

ble level of training or support, or the like. They

acceptable level of risk regarding the complete-

state characteristics of the system to be achieved

ness, correctness, and lack of ambiguity in the

that are not related to functionality. In a real-time

C-requirements. Acceptance criteria are usually

system, performance requirements may be of cri-

developed in parallel with C-requirements.

tical importance, and functional requirements

may need to be sacrificed in order to achieve min-

b. Relative importance of specification

imally acceptable performance.

attributes

c. Inverse requirements (what the software shall

Rombach describes the desirable attributes of

not do)

specification products in general; the relative im-

portance of these attributes depends upon the

Inverse requirements describe the constraints on

specification product. C-requirements must be

allowable behavior. In many cases, it is easier to

understandable to the customer—and hence by

state that certain behavior must never occur than

end-users, who typically review the requirements

to state requirements guaranteeing acceptable be-

before they are approved by the customer. They

havior in all circumstances. Software safety and

must therefore be written using the application

security requirements are frequently stated in this

vocabulary. Although understandability is the

manner [Leveson86, Leveson87].

most important attribute of the C-requirements,

there must be adequate precision for complete-

d. Design and implementation constraints

ness, correctness, consistency, and freedom from

Design constraints and implementation con-

ambiguity to be evaluated by analysts, users, and

straints are boundary conditions on how the re-

customers.

quired software is to be constructed and imple-

c. Key contents

mented. They are givens of the development

within which the designer must work. Examples

The critical components of C-requirements are

of design constraints include the fact that the soft-

described below.

ware must run using a certain database system or

that the software must fit into the memory of a

512Kbyte machine.

10 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

formation for the purposes of software

(i) Software functionality

development. Acceptance tests are usually devel-

Functionality and overall behavior of the soft-

oped in parallel with D-requirements.

ware to be developed must be presented from a

customer/user viewpoint. C-requirements can

C-requirements and D-requirements for em-

use a language other than natural English that

bedded software are frequently combined into one

allows the use of the application vocabulary. A

document that is reviewed by technical represen-

prototype illustrating proposed software func-

tatives of the customer who have the expertise to

tionality may accompany C-requirements, but

review material whose principal audience is

the conclusions drawn from the evaluation by

designers and implementors and who can verify

customers and end-users should be stated ex-

the consistency of the C- with the D-

plicitly.

requirements. The customer is usually much

more concerned with the C-requirements for the

(ii) Information definition and relationships

total system. In cases where the requirements

risks the customer will accept are very low—in a

The information to be processed and stored,

software system for airliner flight control, for ex-

and the relationships between different types of

ample—a separate verification and validation

information, must be defined. Entity-Relation-

contractor may be employed by the customer to

ship diagrams [Flavin81, Shlaer88] are fre-

verify, independently of the project team, that the

quently used for this purpose.

D-requirements are consistent with the system re-

(iii) Critical non-functional requirements

quirements and are adequate to allow the team to

proceed with software implementation.

(iv) Critical design constraints

b. Relative importance of specification

(v) Acceptance criteria

attributes

4. Developer-oriented software requirements

D-requirements must be usable by designers and

D-requirements are usually produced by refining and

implementors without an in-depth knowledge of

augmenting the C-requirements. As an example,

the application vocabulary and without direct

consider the description of the requirements for a

contact with customers and end-users. Therefore,

scientific computation. The C-requirements might

many aspects of the requirements must be more

contain the equation to be solved and the numerical

detailed than in the C-requirements, wherein the

tolerance required, whereas the D-requirements

application vocabulary is expected to provide a

would also contain the algorithm for solving the

common foundation of understanding among the

equation within the stated tolerance. During design,

customer and end-users. Application-specific in-

implementation of the specific algorithm would be

formation is frequently assumed by those who

chosen.

produce C-requirements, since it is inherent in un-

derstanding the terminology used. Precision in

In many cases, an updated version of the C-

the D-requirements is essential, and less use of

requirements is developed during the creation of the

the application vocabulary—even at the cost of

D-requirements, as issues are resolved and more in-

reduced understandability by application area ex-

formation is obtained from the customer, end-users,

perts—is usually required in order to achieve it.

and “experts” in the application field. D-

requirements products may exist at various levels of

c. Key contents

the software refinements process for the entire sys-

tem, subsystem, or modules.

The critical components of D-requirements are

described below.

For a highly constrained system, where there is little

requirements elicitation from people, only D-

(i) Software functionality

requirements are usually produced.

Functionality must be presented from the view-

Important characteristics of D-requirements products

point of the software developer and must be

are described below.

sufficient in precision and detail for software

design.

a. Objectives

(ii) Information in C-requirements

D-requirements provide to the developer a de-

scription of the functional requirements, non-

No significant information appearing in the C-

functional requirements, inverse requirements,

requirements may be omitted in preparing the

and design constraints adequate to design and im-

D-requirements.

plement the software. “Adequate” means there is

(iii) Interfaces to hardware/external systems

an acceptable level of risk regarding the com-

pleteness, consistency, and correctness of the in-

(iv) Critical non-functional requirements

SEI-CM-19-1.2 11

Software Requirements

ods are intended to be useful in a variety of appli-

(v) Critical design constraints

cation areas and are referred to here as “system

(vi) Acceptance criteria and acceptance tests

modeling methods.” For example, SADT [Ross85]

IV. Techniques and Tools for Performing Software

has been applied to understanding how functions are

Requirements Definition

performed manually in an organization and to build-

ing models showing the functions of a combined

The objective of this section is to introduce some of the

hardware/software system. However, there is also a

techniques and computer support tools most likely to

role for other types of models in requirements defi-

be used during requirements definition, but it is not

nition, such as physical models (the layout of an

intended to be a comprehensive description.

assembly line to be automated) and simulation

models (the actions proposed to take place on an

1. Techniques for eliciting requirements from

automated assembly line).

people

Specification languages that are not graphically

Techniques used in a variety of fields for gathering

oriented have been proposed as an alternative to the

information from people with different opinions

graphically-oriented modeling languages widely

(such as questionnaires and interviews) are relevant

used during requirements definition. None, how-

to defining software requirements. Davis [Davis83]

ever, has received significant usage for producing

and Powers [Powers84] cover most of the relevant

customer/user-oriented requirements and few have

methods.

been used by other than their developers to produce

In order to facilitate the elicitation of requirements, a

developer-oriented requirements. One exception is

variety of techniques have been developed that in-

the NRL/SCR requirements method [Heninger80],

volve the participation of analysts, end-users, and

which is not graphically oriented and which has

customers in intensive working sessions over a

been applied to major projects.

period of several days. The objective is to speed up

Unfortunately, the developers of system modeling

the negotiations between users with divergent

methods have used inconsistent terminology to de-

opinions, to provide analysts with an in-depth under-

scribe their modeling approaches. It is usually diffi-

standing of software needs, and to complete a draft

cult to understand what information can be

of the most important requirements. The analysts

represented easily using the modeling method and to

may develop models or prototypes during these ses-

what class of problems the approach is most ap-

sions for review with the users. The best known of

plicable. White [White87] has done a thorough com-

these techniques is Joint Application Development

parison of what can be represented using the most

Technique (JAD), developed by IBM.

common model-building techniques. Pressman

Frequent review of the work of analysts by cus-

[Pressman87] surveys the following modeling meth-

tomers and users facilitates agreement on require-

ods and tools, which are among those described be-

ments. An incremental process for reviewing

low: Structured Analysis, Real-Time Structured

models and accelerating the convergence of the re-

Analysis, Data Structured Systems Development,

quirements elicitation process has been formalized

SADT, SREM/DCDS, and PSL/PSA. Davis

in the Reader-Author Cycle of the SADT method-

[Davis88] surveys techniques for specifying the ex-

ology [Marca88]. The SADT approach is applicable

ternal behavior of systems and compares alternative

to any model-building technique.

approaches, including two formal specification lan-

guages.

Walk-throughs [Freedman82] can be used to help

determine the consistency and completeness of

A majority of modeling methods support describing

evolving requirements and to ensure that there is a

a system in terms of several of the following charac-

common understanding among analysts, users, and

teristics:

customers of the implications of requirements.

• Interfaces to external entities. Since any

Yourdon [Yourdon89b] describes how to conduct

model can describe only a well-defined

walk-throughs using models built during require-

subject area, the model-building notation

ments definition. Technical reviews [Collofello88b]

must allow a precise description of what is

can be utilized to assess the status of the require-

to be included in the system of interest and

ments definition process.

how that system interfaces to external en-

tities. In the case of a software system, the

2. Modeling techniques

external entities typically are hardware,

Nearly all requirements definition techniques devel-

other software, and people. The ability to

op some type of model to structure the information

describe precisely the model interfaces is

gathered during requirements elicitation and to de-

particularly important in requirements de-

scribe the functionality and behavior of software to

finition, since there may be divergent

meet the requirements. Most of the modeling meth-

opinions among customers and users

12 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

regarding the scope of the software to be depiction of data transformations and functional

developed in response to the requirements. decomposition. It incorporates the concept of a

context diagram, which shows the external en-

• Functions to be performed. All model-

tities that provide information to the system or

ing methods widely used in requirements

receive information from the system.

definition support the description of sys-

tem functions, but they differ in how they

Structured Analysis is probably the most widely

describe the conditions under which func-

used graphically-oriented requirements definition

tions are performed. For software that

technique. It is described in a number of books,

must react to external events (i.e., real-

including DeMarco [DeMarco79], Gane and Sar-

time software), one must be able to de-

son [Gane79], and McMenamins and Palmer

scribe precisely the events that cause a

[McMenamins84]. The emphasis of the method is

function to be performed.

primarily on producing customer/user-oriented re-

• Data Transformations. Modeling meth-

quirements.

ods that emphasize functions performing

SADT (Structured Analysis and Design

data transformations, such as Structured

Technique) [Ross85, Wallace87, Marca88] is a su-

Analysis, are widely used in requirements

perset of Structured Analysis and was the first

definition for business data processing ap-

graphically-oriented method developed for use in

plications.

performing requirements definition. Among its

• Structure of input/output data. The

features are the use of interrelated multiple

structure of input and output data is

models to represent a system from the viewpoints

modeled in requirements definition tech-

of different participants in the requirements defi-

niques that are designed to deal with com-

nition process [Leite88] and the ability to describe

plex information, such as Data Structured

the states of data [Marca82]. A subset similar to

Systems Development (the Warnier-Orr

Structured Analysis is known by the name IDEF.

methodology) [Orr81]. Typically, the

Also part of the method are procedures for con-

structure of the information is assumed to

ducting reviews of evolving models and team-

be hierarchical. Such a model assists the

oriented techniques for performing analysis and

analyst in understanding what items of in-

design. The emphasis of the method is primarily

formation must be generated to produce a

on producing customer/user-oriented require-

required report or screen display.

ments.

• Relationships among information. If the

In Real-Time Structured Analysis, a state-

requirements indicate the software is to

diagrammatic representation is used to extend

handle a significant number of items of in-

Structured Analysis to facilitate the description of

formation that are associated through com-

system behavior. Alternative notations have been

plex relationships, information models can

proposed by Hatley [Hatley87] and by Ward and

be used to show graphically the relation-

Mellor [Ward85]. A consolidation of these two

ships between data objects. The most

notations into a new notation called the Extended

widely used information modeling tech-

Systems Modeling Language has been proposed

niques [Flavin81] are Entity-Relationship

[Bruyn88]. An alternative notation for describing

(E-R) models and logical data models

the states of a real-time system, Statecharts, has

using the Curtice and Jones notation

been developed by Harel [Harel88a].

[Curtice82].

• System behavior. To model behavior as a

b. DSSD

system reacts to a sequence of externally-

DSSD (Data Structured Software Development)

generated events requires representing the

(the Warnier-Ross Methodology) [Orr81] devel-

time sequence of inputs. Behavioral

ops software requirements by focusing on the

models are essential to the development of

structure of input and output data. It assists the

requirements for real-time systems.

analyst in identifying key information objects and

3. Representative requirements definition methods

operations on those objects. The principal appli-

cation of this graphically-oriented approach has

The following four groups of methods are the most

been in the area of data processing systems.

frequently used in the United States. Each involves

the production of a model for requirements represen-

c. SREM/DCDS

tation. In Europe, the Jackson System Development

SREM (Software Engineering Requirements

method [Sutcliffe88] is also frequently used.

Methodology) [Alford77] was originally developed

a. Structured Analysis and SADT

for performing requirements definition for very

large embedded systems having stringent perfor-

This group of methods emphasizes the graphic

SEI-CM-19-1.2 13

Software Requirements

mance requirements. With the addition of exten- prototyping on personal computers, widely used

sions to support distributed concurrent systems, tools are Hypercard on the Apple Macintosh and

the name has been changed to the Distributed Dan Bricklin’s Demo II Program on the IBM PC.

Computer Design System [Alford85]. The em- Statemate [Harel88b] supports the development on a

phasis of SREM/DCDS is primarily on producing workstation of a combined user interface prototype

developer-oriented requirements. and an essential functionality prototype through the

use of an executable model that describes the func-

d. NRL/SCR

tionality and behavior of the system

The NRL/SCR (Naval Research Laboratory Soft-

ware Cost Reduction) requirements method

[Heninger80] is oriented toward embedded sys-

tems and produces developer-oriented require-

ments. It differs from the methods listed above

by being a “black box” requirements method, in

which requirements are stated in terms of input

and output data items and externally visible char-

acteristics of the system state. The method is in-

tended to separate clearly design issues from re-

quirements issues, and it is sufficiently different

in its assumptions from the other methods that it

is worthy of detailed study. The work of Mills

[Mills86] is based on similar assumptions.

4. Computer support tools for model development

Tools for use on personal computers and worksta-

tions to support the most widely used modeling

methods are evolving rapidly, and published infor-

mation on available tools is outdated within a few

months of publication. The best sources of current

information are the exhibitions associated with

major conferences such as the International Con-

ference on Software Engineering and CASExpo.

a. Method-specific tools

Computer support tools designed for notations

used by specific methods are commercially avail-

able for all the modeling methods listed above

except SREM/DCDS and NRL/SCR. Tools are

also available to support the development of in-

formation models using both the ERA notation

and the Curtice and Jones notation.

b. Non–method-specific tools

Tools that are not specific to the notation of a

particular modeling method fall into two categor-

ies: tools that can be user-customized to represent

the notation, objects, and relationships specific to

a given modeling method; and tools that require a

translation between the notation of the modeling

method and the notation required by the tool.

PSL/PSA (Problem Statement Language/Problem

Statement Analyzer) [Teichroew77], which was

the first widely available computer tool to support

requirements analysis, is in the second category.

5. Computer support tools for prototyping

Available computer tools to support prototyping are

rapidly increasing in capability. For user interface

14 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

Teaching Considerations

Because most students have no experience in dealing

Suggested Course Types

with customer and end-user issues, they learn most

by producing C-requirements.

The material presented in this module is intended to

be used in one of three ways:

The author’s software system design course uses

IEEE Guide for Software Requirement Specifica-

1. As background material for teachers pre-

tions

[IEEE84] to define the outline and content of

paring software engineering courses.

the C-requirements document. Techniques for re-

2. As material for a course containing a

quirements definition must be taught in enough de-

series of lectures on software require-

tail for students to apply them. In practice, this

ments.

means emphasizing one technique for each step of

3. As material for a teacher planning a soft-

the process, even though it would desirable to ex-

ware requirements definition project

pose the student to a wide variety of techniques.

course.

The author currently teaches the details of

The author is currently using the module material to

• Information modeling using the Curtice

teach a course, Software System Design, in the soft-

and Jones notation

[Curtice82].

ware engineering master’s degree program at Boston

• Real-Time Structured Analysis

[Hatley-

University. Of the 26 lectures, 10 are on system and

87].

software requirements, and 16 are on architectural

• Support tools associated with the above.

design.

Since producing models is not the principal objec-

While on the faculty of the Wang Institute, the au-

tive of requirements definition, emphasis in the

thor supervised project courses in which teams of

course and in the instructor’s review of the project

4-5 students performed requirements definition proj-

documents must be given to non-functional require-

ects for external customers

[Brackett88].

ments, the handling of unexpected events, and de-

sign constraints.

The following projects have been used in teaching

Software System Design:

Teaching Experience

• The requirements for the first automatic

In the author’s experience, it is difficult, if not im-

teller machine (assuming the project was

possible, to convey adequately the principal con-

conducted in 1977).

cepts in this module without having the students un-

• The requirements for the software to

dertake some type of requirements definition project.

control 5 elevators in a 50-story building.

Nearly all students, even those with 3-5 years of in-

As the major assignment in the course, each has

dustrial experience, lack any experience in perform-

been adequately done to the C-requirements level by

ing requirements definition. Therefore, survey

teams of three to four students in about four weeks.

courses are likely only to introduce the student to the

To continue to the D-requirements level would re-

need to specify software requirements and to some

quire about an additional four weeks.

of the modeling and prototyping techniques fre-

quently used.

A requirements definition project requires adequate

calendar time for the student to produce a C-

Suggested Reading Lists

requirements document, the teacher to provide de-

tailed feedback on it, and the student to prepare a

The following lists categorize items in the bibliog-

second (or third!) iteration. Each iteration should

raphy by applicability.

define the requirements more completely and

precisely, while reducing the number of design solu-

Instructor Essential: This is a small set of readings

tions the students identify as requirements. Follow-

intended to provide, in conjunction with this module,

ing the completion of C-requirements, D-

the basic information an instructor needs to prepare a

requirements should be developed, if time permits.

series of lectures on software requirements.

SEI-CM-19-1.2 15

Software Requirements

Instructor Recommended: These readings provide * Those readings marked with “*” are suitable for

the instructor with additional material and, if time use by students in a graduate-level course including

permits, should be reviewed in conjunction with the a series of lectures on software requirements.

Instructor Essential items.

† Possible textbooks are indicated with “†”.

Detailed: These readings have been included to pro-

No single book suitable both for an information-

vide access to the literature on specific topics or to

systems–oriented course and a real-time–oriented

materials that are secondary sources to those listed

course can be recommended.

under the Instructor Essential or Instructor

Recommended categories.

Paper Categories

Instructor Essential Detailed Detailed (cont.)

Davis88 Abbott86 IEEE83

IEEE84* Alford77 Kowall88*†

Alford85 Leite87

Martin88*

one of

{

Powers84*†

Boehm84b* Leite88

Pressman87*†

Boehm86* Leveson86*

one of

{

Sommerville89*†

Brackett88 Leveson87

Bruyn88 Marca82

Collofello88a Marca88*

Collofello88b McMenamins84*

Instructor Recommended

Curtice82* Mills86

Boehm84a*

Davis82* Orr81

Brooks87*

Davis83*† Perlman88

Clapp87*

DeMarco79* Ross85

Flavin81*

DoD88 Shlaer88

Hatley87*†

one of

Freedman82 Sutcliffe88

{

Ward85*†

Gane79* Teichroew77*

Heninger80

Gause89 Wallace87

Rombach90

Gomaa81* Ward89

Ross77b*

Gomaa89* White87

Yourdon89a

Harel88a Yourdon89b

Harel88b*

16 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

Bibliography

Abbott86 Alford85

Abbott, R. J. An Integrated Approach to Software Alford, M. “SREM at the Age of Eight: The Distri-

Development. New York: John Wiley, 1986. buted Computing Design System.” Computer 18, 4

(April 1985), 36-46.

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

SREM/DCDS has been used primarily on very large

government contracts, but the supporting tools

PART 1: REQUIREMENTS

make it unsuitable for use in an academic course.

2 Requirements Discussion

They are difficult to learn and somewhat difficult to

3 Requirements Document Outline

install.

PART 2: SYSTEM SPECIFICATION

Boehm84a

4 Discussion

Boehm, B. W. “Verifying and Validating Software

5 Behavioral Specification Outline

Requirements and Design Specifications.” IEEE

6 Procedures Manual

Software 1, 1 (Jan. 1984), 75-88.

7 Administrative Manual

An excellent survey article, which is understandable

PART 3: DESIGN

by students.

8 Design Discussion

9 System Design Documentation

Boehm84b

10 Component Documentation: Specification and

Design

Boehm, B. W., T. E. Gray, and T. Seewaldt.

“Prototyping vs. Specifying: A Multi-Project Exper-

Appendix: Abstraction and Specification

iment.” Proc. 7th Intl. Conf. Software Eng. New

References

York: IEEE, 1984, 473-484.

Index

Abstract: In this experiment, seven software teams

This is a general software engineering text, organ-

developed versions of the same small-size (2000-

ized as a collection of annotated outlines for tech-

4000 source instruction) application software prod-

nical documents important to the development and

uct. Four teams used the Specifying approach.

maintenance of software. The outline of Abbott’s

Three teams used the Prototyping approach.

requirements document differs from [IEEE84], and

The main results of the experiment were:

the instructor may find it useful to compare the dif-

Prototyping yielded products with roughly

ferences. The process of requirements definition is

equivalent performance, but with about 40%

not explained in detail, so this book is not an ade-

less code and 45% less effort.

quate stand-alone text for a series of lectures on

software requirements.

The prototyped products rated somewhat

lower on functionality and robustness, but

higher on ease of use and ease of learning.

Alford77

Alford, M. “A Requirements Engineering Method-

Specifying produced more coherent designs

and software that was easier to integrate.

ology for Real-Time Processing Requirements.”

IEEE Trans. Software Eng. SE-3, 1 (Jan. 1977),

The paper presents the experimental data support-

ing these and a number of additional conclusions.

60-69.

Abstract: This paper describes a methodology for

Boehm86

the generation of software requirements for large,

Boehm, B.W. “A Spiral Model of Software Devel-

real-time unmanned weapons systems. It describes

opment and Enhancement.” ACM Software Engi-

what needs to be done, how to evaluate the interme-

diate products, and how to use automated aids to

neering Notes 11, 4 (Aug. 1986), 14-24.

improve the quality of the product. An example is

This paper, reprinted from the proceedings of the

provided to illustrate the methodology steps and

March 1985 International Workshop on the Soft-

their products and the benefits. The results of some

ware Process and Software Environments, presents

experimental applications are summarized.

Boehm’s spiral model. The author’s description

This paper should be read in conjunction with

from the introduction:

[Alford85] and [Davis88].

SEI-CM-19-1.2 17

Software Requirements

The spiral model of software development and en-

13-1.1, Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie

hancement presented here provides a new

Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa., Dec. 1988.

framework for guiding the software process. Its

major distinguishing feature is that it creates a risk-

Capsule Description: Software verification and

driven approach to the software process, rather

validation techniques are introduced and their ap-

than a strictly specification-driven or prototype-

plicability discussed. Approaches to integrating

driven process. It incorporates many of the

these techniques into comprehensive verification

strengths of other models, while resolving many of

and validation plans are also addressed. This cur-

their difficulties.

riculum module provides an overview needed to un-

derstand in-depth curriculum modules in the verifi-

Brackett88

cation and validation area.

Brackett, J. W. “Performing Requirements Analysis

Project Courses for External Customers.” In Issues

Collofello88b

in Software Engineering Education, R. Fairley and

Collofello, J. S. The Software Technical Review

P. Freeman, eds. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1988,

Process. Curriculum Module SEI-CM-3-1.5, Soft-

56-63.

ware Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon Univer-

sity, Pittsburgh, Pa., June 1988.

Brooks87

Capsule Description: This module consists of a

Brooks, F. “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accidents

comprehensive examination of the technical review

of Software Engineering.” Computer 20, 4 (April

process in the software development and mainte-

1987), 10-19.

nance life cycle. Formal review methodologies are

analyzed in detail from the perspective of the review

participants, project management and software

Bruyn88

quality assurance. Sample review agendas are also

Bruyn, W., R. Jensen, D. Keskar, and P. T. Ward.

presented for common types of reviews. The objec-

“ESML: An Extended Systems Modeling Language

tive of the module is to provide the student with the

Based on the Data Flow Diagram.” ACM Software

information necessary to plan and execute highly

Engineering Notes 13, 1 (Jan. 1988), 58-67.

efficient and cost effective technical reviews.

Abstract: ESML (Extended Systems Modeling

Language) is a new system modeling language

Curtice82

based on the Ward-Mellor and Boeing structured

Curtice, R. and P. Jones. Logical Data Base Design.

methods techniques, both of which have proposed

New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1982.

certain extensions of the DeMarco data flow

diagram notation to capture control and timing in-

This book introduces a data modeling notation that

formation. The combined notation has a broad

is easily taught to students and that facilitates

range of mechanisms for describing both com-

decomposing a large data model into smaller sub-

binatorial and sequential control logic.

models. However, the text is not oriented toward

using data models during requirements definition.

This paper should be read in conjunction with

[Ward89].

Davis82

Davis, G. B. “Strategies for Information Require-

Clapp87

ments Determination.” IBM Systems J. 21, 1 (1982),

Clapp, J. “Rapid Prototyping for Risk Management.”

4-30.

Proc. COMPSAC 87. Washington, D. C.: IEEE

Computer Society Press, 1987, 17-22.

Abstract: Correct and complete information re-

quirements are key ingredients in planning or-

Abstract: Rapid prototyping is useful for control-

ganizational information systems and in implement-

ling risks in the development and upgrade of deci-

ing information system applications. Yet, there has

sion support systems. These risks derive from un-

been relatively little research on information re-

certainty about what the system should do, how its

quirements determination, and there are relatively

capabilities should be achieved, how much it will

few practical, well-formulated procedures for ob-

cost, and how long it will take to complete. This

taining complete, correct information requirements.

paper describes uses of rapid prototyping for risk

Methods for obtaining and documenting informa-

management and summarizes lessons learned from

tion requirements are proposed, but they tend to be

their use. . . .

presented as general solutions rather than alter-

native methods for implementing a chosen strategy

Collofello88a

of requirements determination. This paper identi-

fies two major levels of requirements: the organiza-

Collofello, J. S. Introduction to Software Verifica-

tional information requirements reflected in a

tion and Validation. Curriculum Module SEI-CM-

18 SEI-CM-19-1.2

Software Requirements

planned portfolio of applications and the detailed Module N: Forms Design and Report Design

information requirements to be implemented in a Module O: Decision Tables and Decision Trees

specific application. The constraints on humans as

A text for a first undergraduate course in analysis

information processors are described in order to

and design, based on three case studies. Each of the

explain why “asking” users for information re-

case studies is taken through the steps of problem

quirements may not yield a complete, correct set.

definition, feasibility study, analysis, system design,

Various strategies for obtaining information re-

detailed design. The main emphasis of the book is

quirements are explained. Examples are given of

on analysis rather than design. The book is oriented

methods that fit each strategy. A contingency ap-

toward business applications and primarily makes

proach is then presented for selecting an informa-

use of Structured Analysis and Structured Design.

tion requirements determination strategy. The con-

The case studies may provide a useful basis for

tingency approach is explained both for defining or-

class discussions.

ganizational information requirements and for de-

fining specific, detailed requirements in the devel-

opment of an application.

Davis88

Davis, A. “A Comparison of Techniques for the

Davis83

Specification of External System Behavior.” Comm.

ACM 31, 9 (Sept. 1988), 1098-1115.

Davis, W. S. Systems Analysis and Design. Read-