Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage

within the Greater

Charlotte Harbor Region

Cooperative Agreement between the

Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program

and the

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Fish and Wildlife Research Institute

Produced by Grantee: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Fish and Wildlife Research Institute

100 Eighth Ave. Southeast

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

Submitted by: Kevin Madley, Jim Krolick, and Bill Sargent

Prepared for: Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program

Submitted to: Catherine Corbett

The Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program is a partnership of citizens, elected

officials, resource managers and commercial and recreational resource users working

to improve the water quality and ecological integrity of the greater Charlotte Harbor

watershed. A cooperative decision-making process is used within the program to

address diverse resource management concerns in the 4,400 square mile study area.

Many of these partners also financially support the Program, which, in turn, affords

the Program opportunities to fund projects such as this. The entities that have

financially supported the program include the following:

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Southwest Florida Water Management District

South Florida Water Management District

Florida Department of Environmental Protection

Florida Coastal Zone Management Program

Peace River/Manasota Regional Water Supply Authority

Polk, Sarasota, Manatee, Lee, Charlotte, DeSoto and Hardee Counties

Cities of Sanibel, Cape Coral, Fort Myers, Punta Gorda, North Port, Venice and Fort

Myers Beach

and the Southwest Florida Regional Planning Council.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................................ 4

LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................................... 4

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 6

METHODS........................................................................................................................ 8

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION....................................................................................... 9

LIST OF PROJECT DELIVERABLES....................................................................... 12

LITERATURE CITED .................................................................................................. 13

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

4

List of Tables

Table 1. Acreages and percents of propeller scarred seagrass habitat by segments in the

greater Charlotte Harbor region.

List of Figures

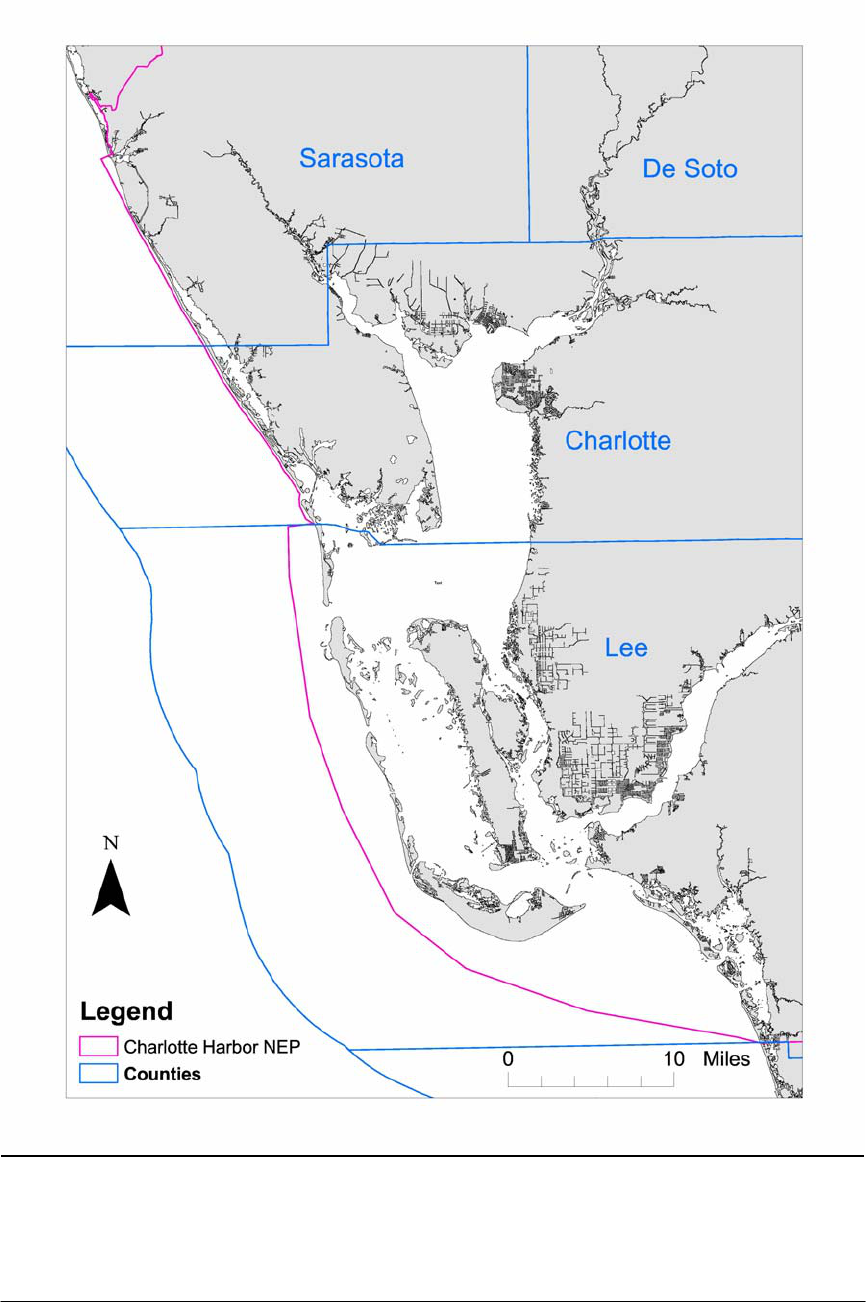

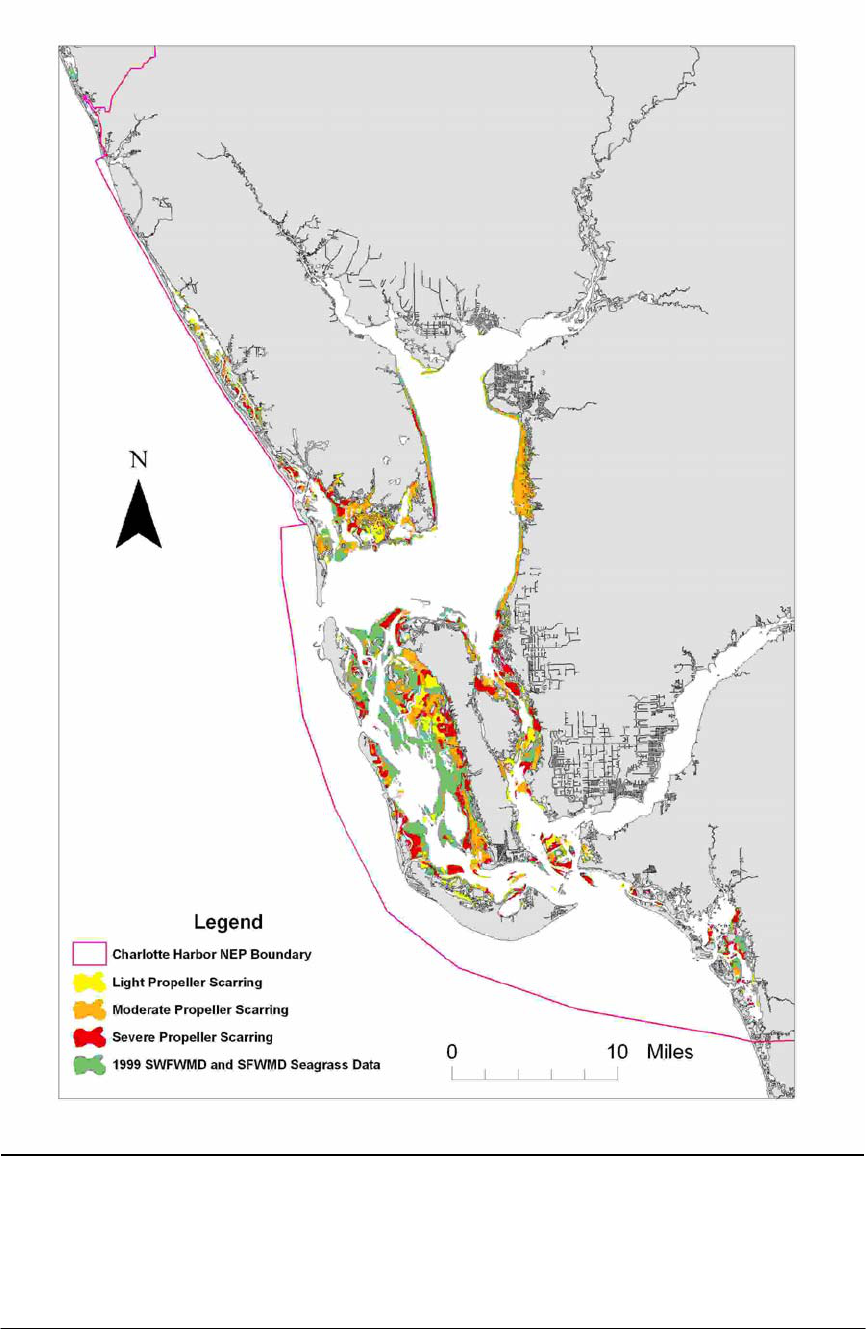

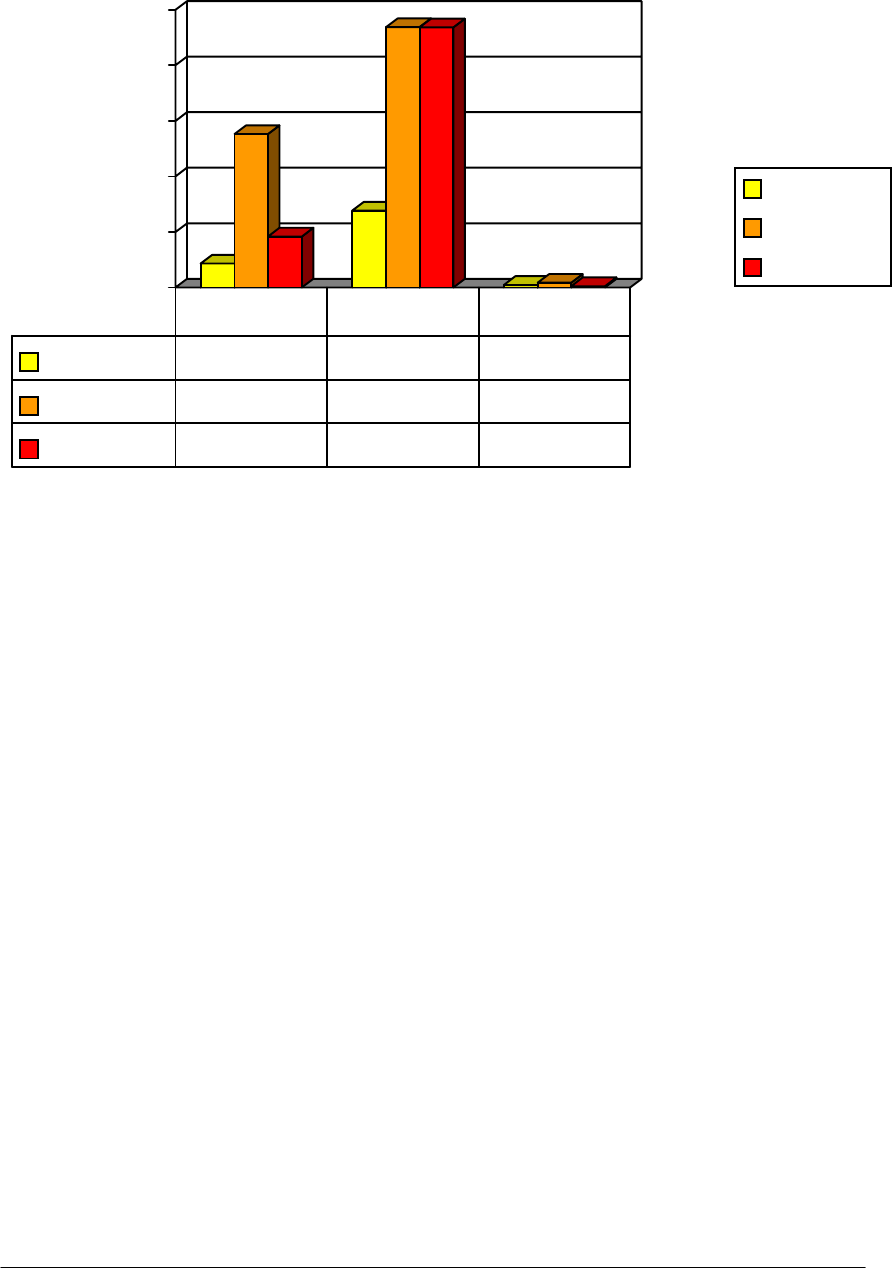

Figure 1. Coastal boundary of Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program.

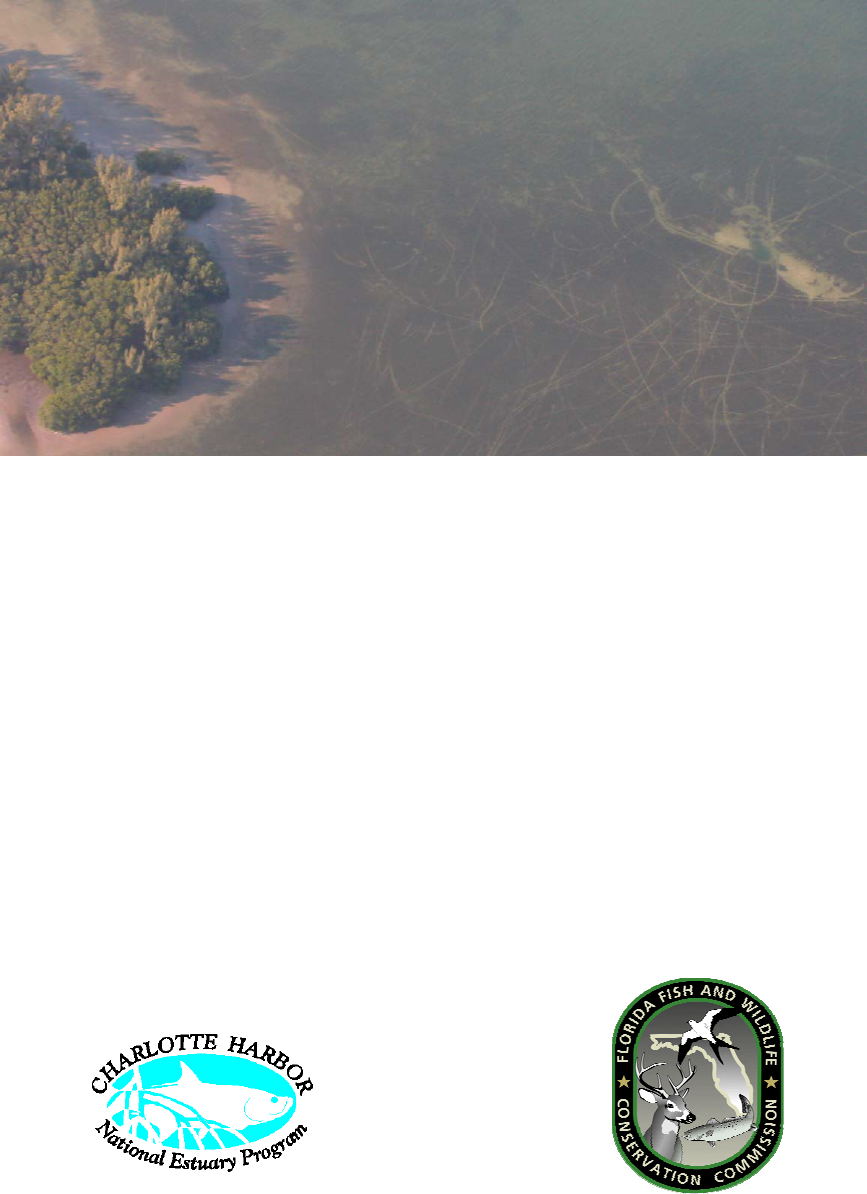

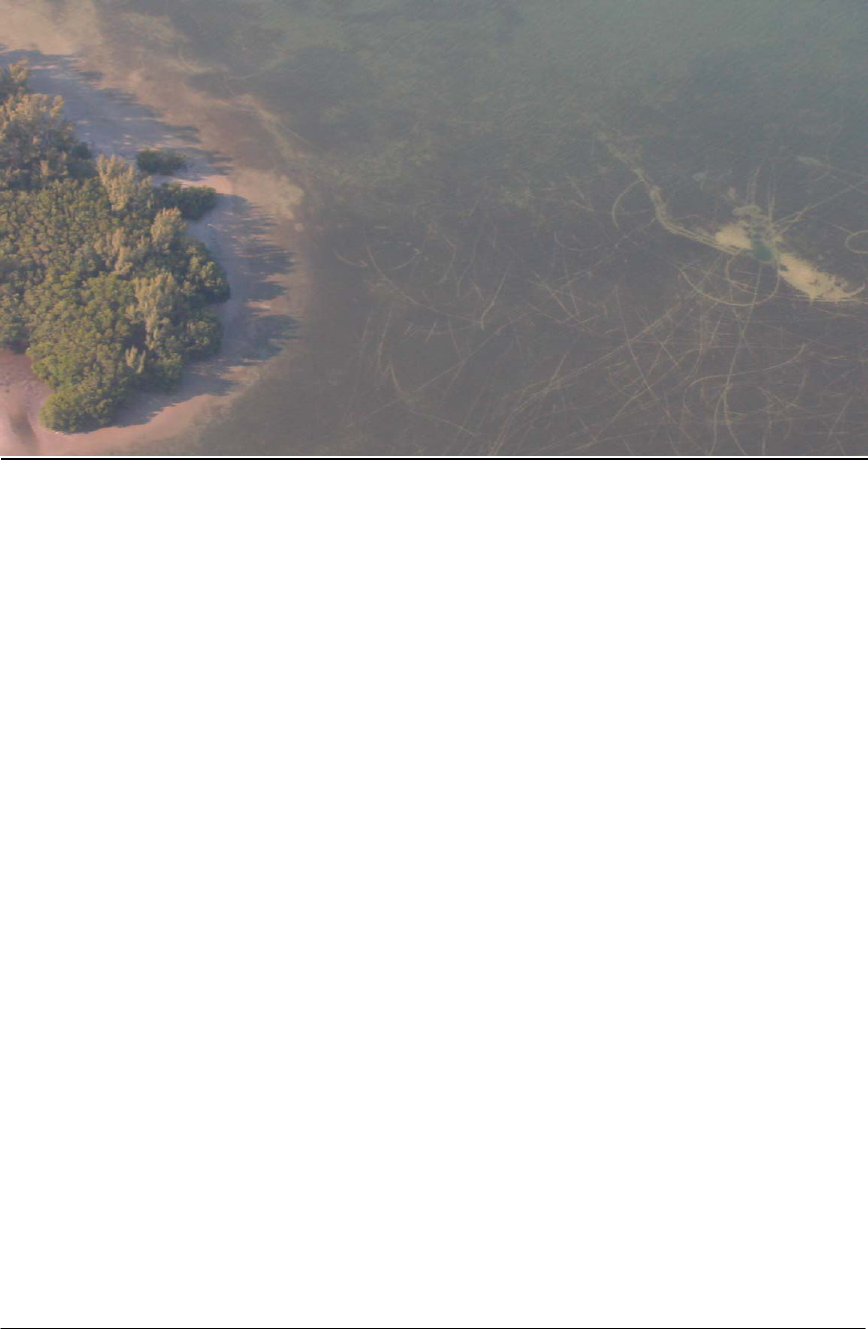

Figure 2. Example of a seagrass meadow in Charlotte Harbor with moderate and severe

propeller scarring.

Figure 3. Close-up example of a propeller scars in a seagrass meadow in Charlotte

Harbor. This example shows a location where scars from a twin prop vessel cross a scar

from a single prop vessel.

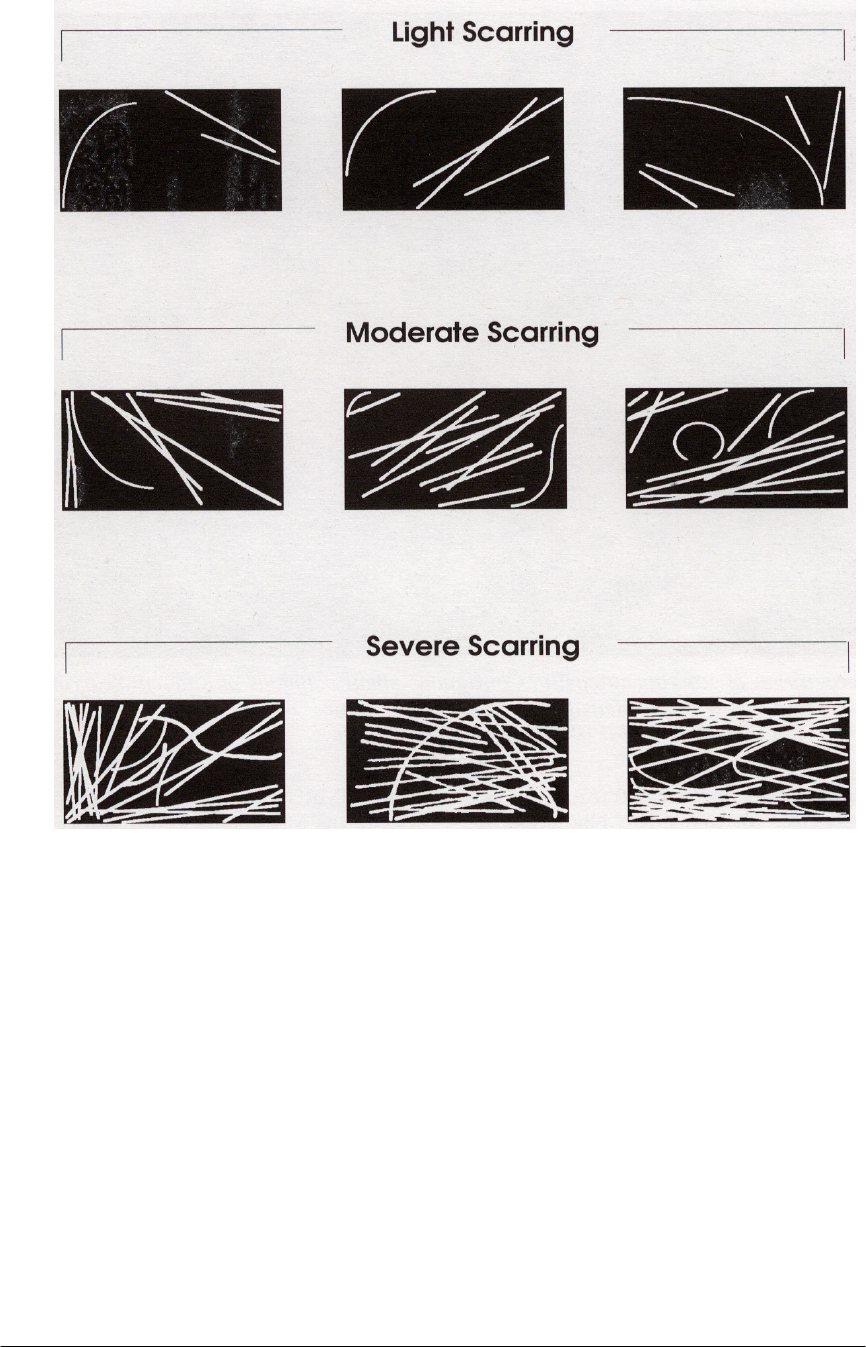

Figure 4. Diagrammatic representation of the three categories of estimated scarring

intensity used as a guide for the delineation and classification of propeller scarred

habitats (from Sargent et al. 1995). Black space within each block represents seagrasses,

and white marks represent scarring. Light scarring is defined as the presence of scars in

less than 5 percent of the delineated polygon, moderate scarring is the presence of scars

in 5 to 20 percent of the polygon, and severe scarring as the presence of scars in more

than 20 percent of the polygon.

Figure 5. Map of propeller scarred seagrass polygons produced during this study.

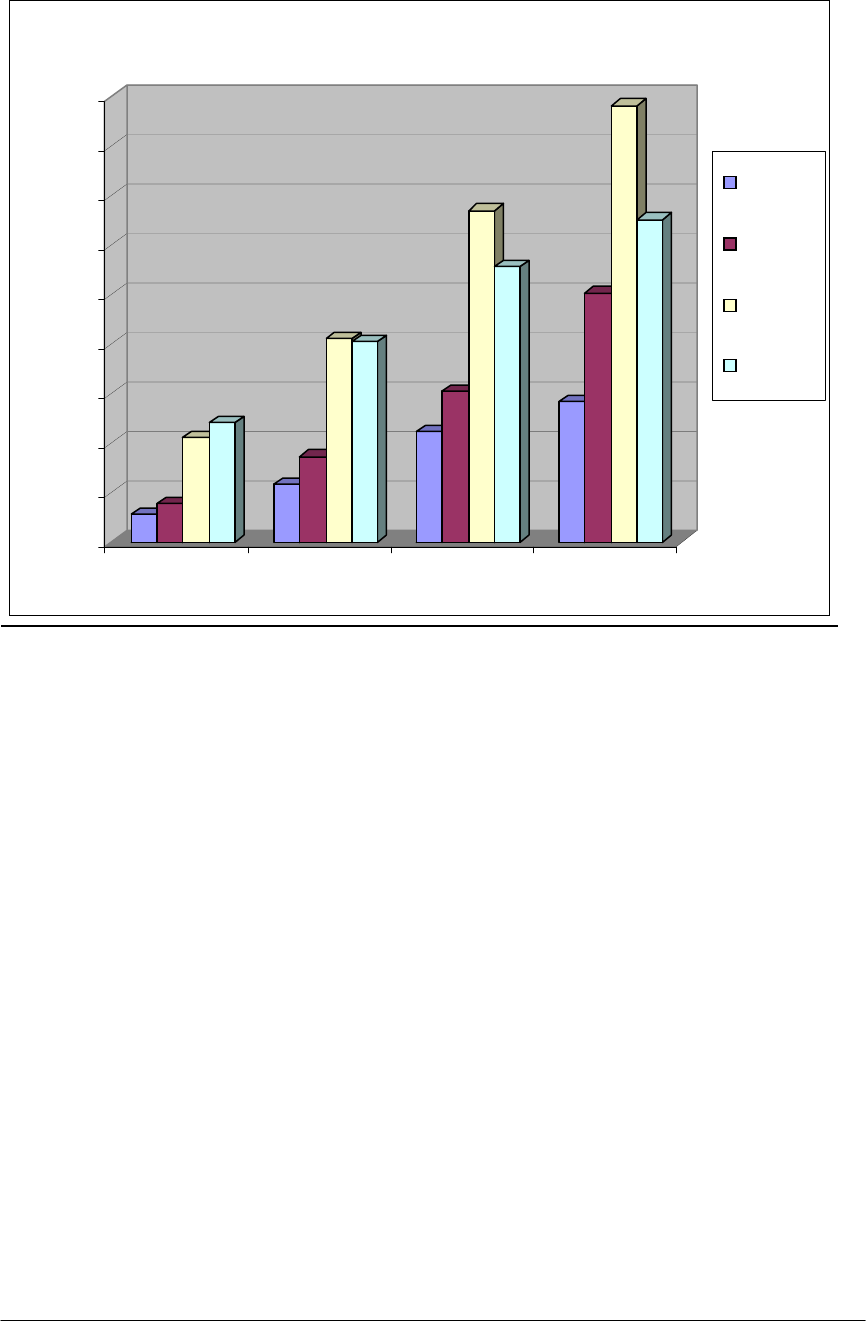

Figure 6. Population trends for the four coastal counties surrounding the Charlotte

Harbor National Estuary Program boundaries.

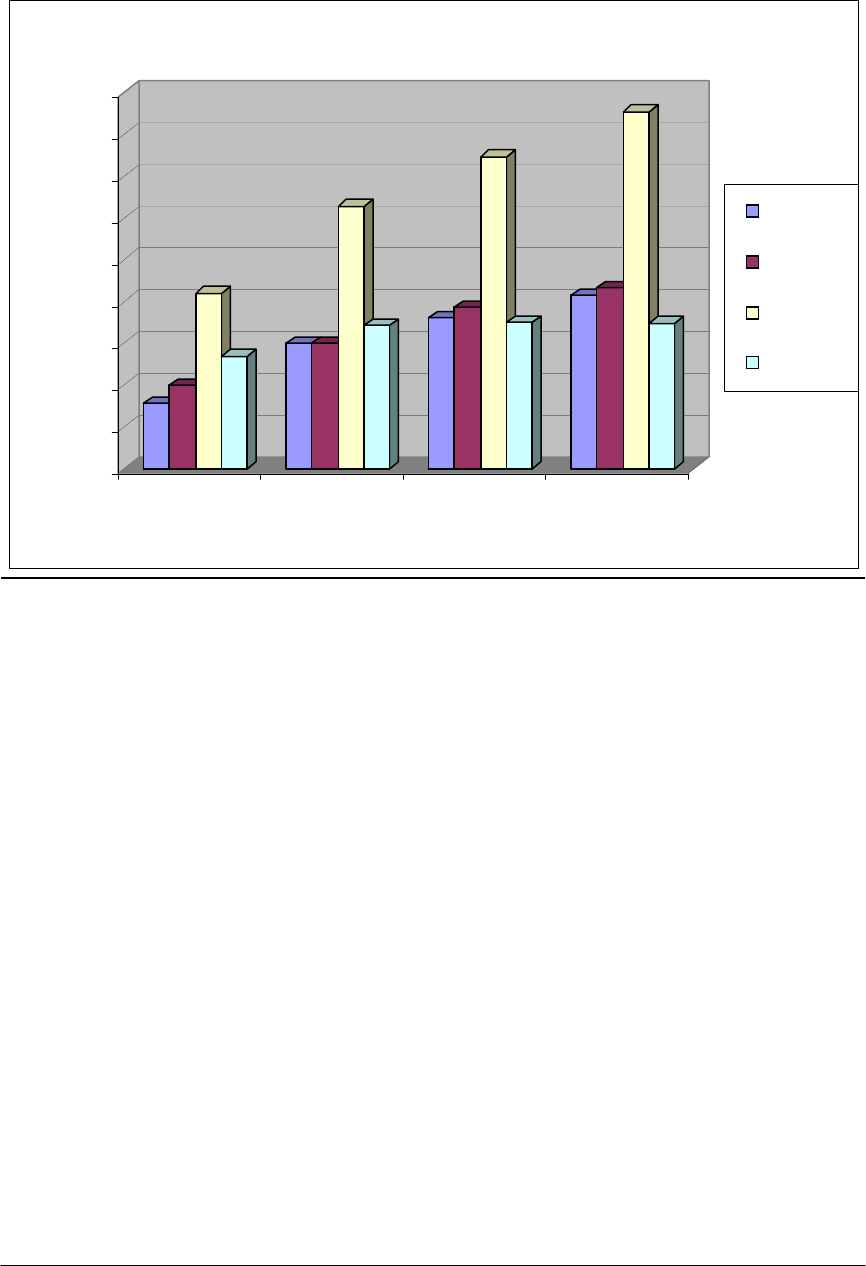

Figure 7. Numbers of registered watercraft (recreational and commercial) for the four

coastal counties surrounding the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program boundaries.

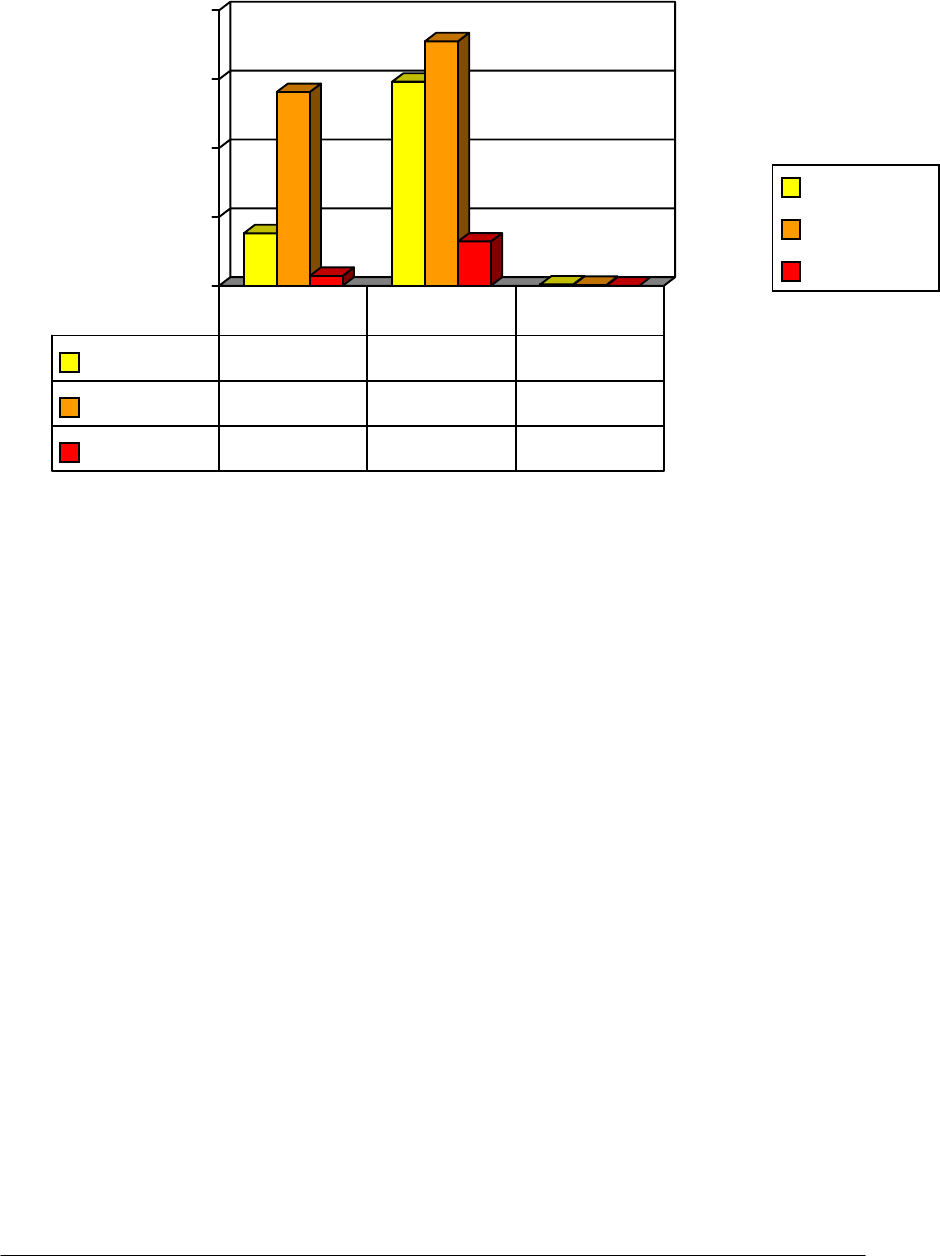

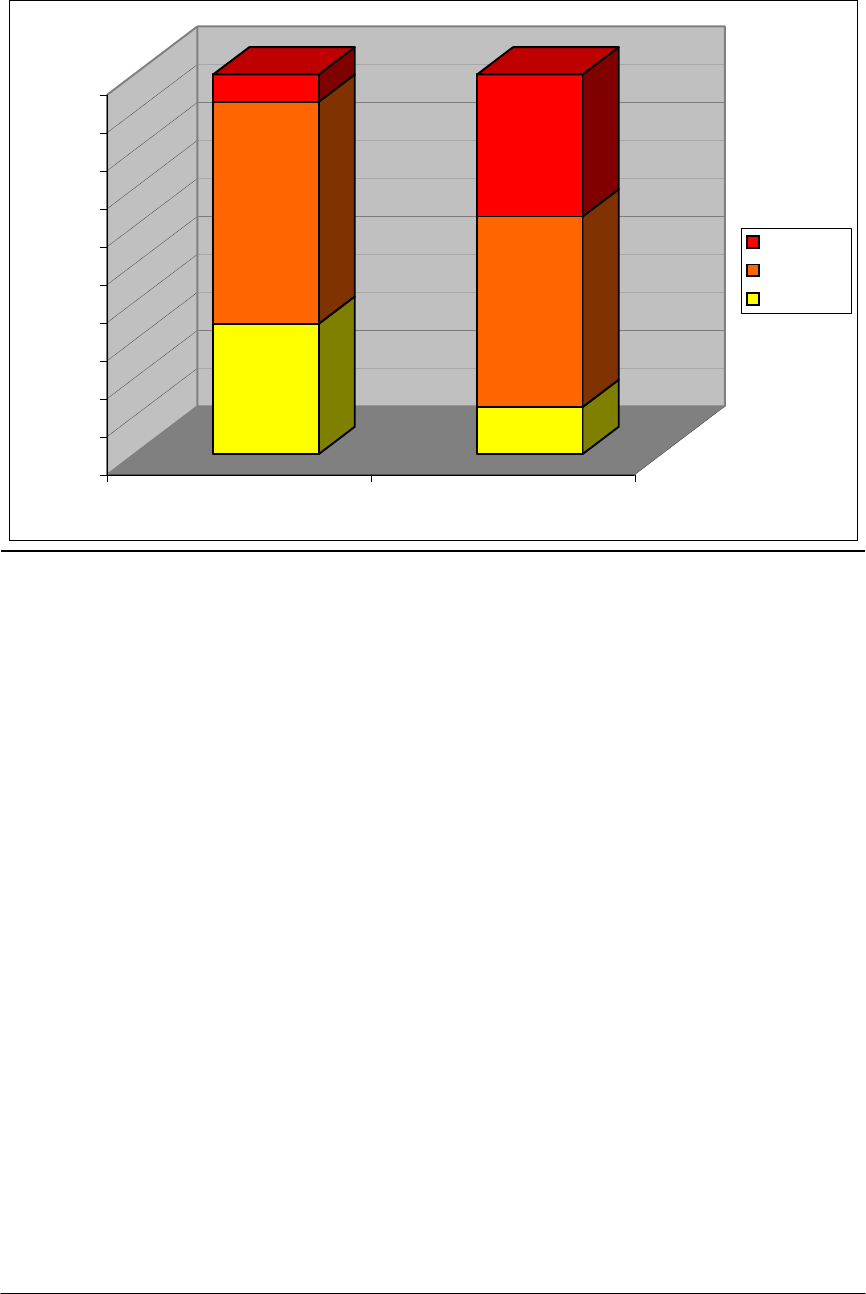

Figure 8. Amounts of propeller scar impacted seagrass habitat in 1993 per severity

category within each county of the study area. The sum is 21,816 acres. Note:

calculations for Sarasota county acreages were limited to the portion of the county within

the Charlotte Harbor NEP Boundary.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

5

Figure 9. Amounts of propeller scar impacted seagrass habitat in 2003 per severity

category within each county of the study area. The sum is 30,064 acres. Note:

calculations for Sarasota county acreages were limited to the portion of the county within

the Charlotte Harbor NEP Boundary.

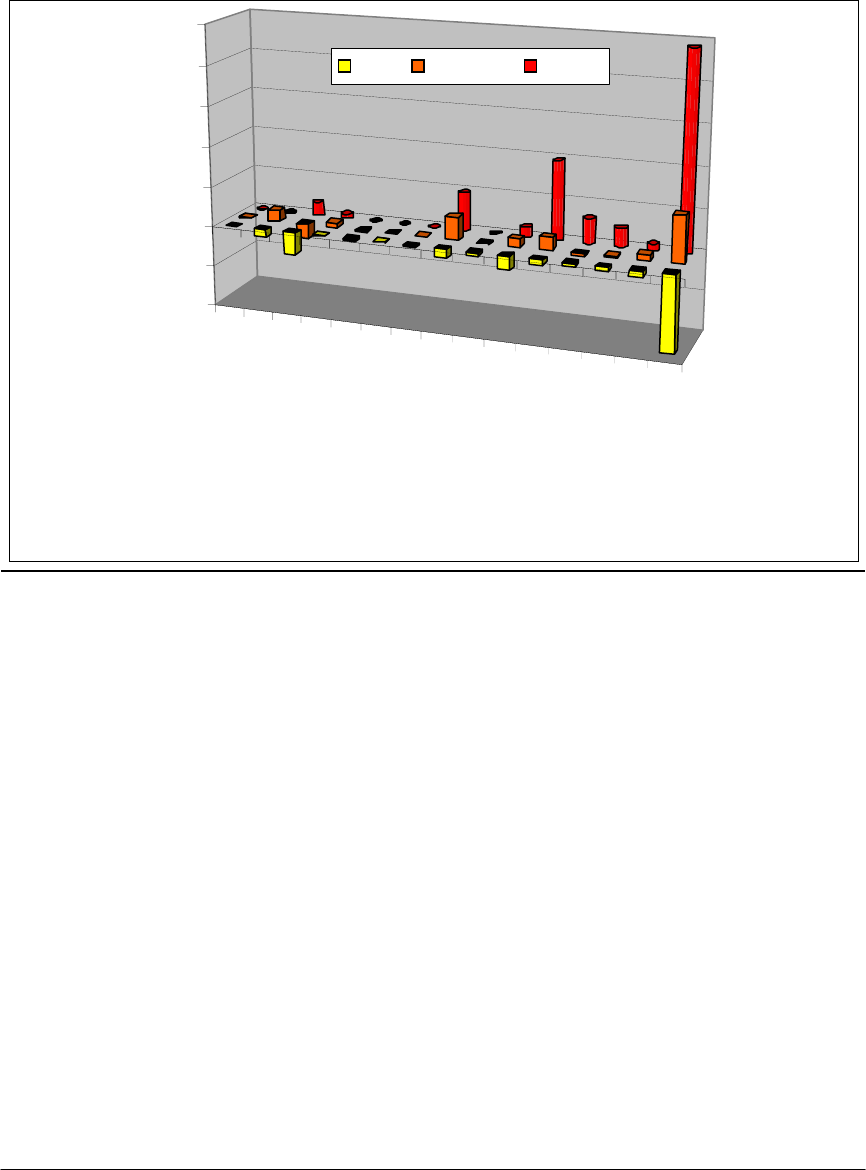

Figure 10. Amounts of seagrass habitat classified as severely or moderately scarred

increased between 1993 and 2003. However, lightly scarred seagrass habitat declined in

area between the same time period. The values in the columns represent actual acres of

habitat in each category as measured within the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary

Program boundary. The total scarred areas increased from 21,816 acres in 1993 to

30,064 in 2003.

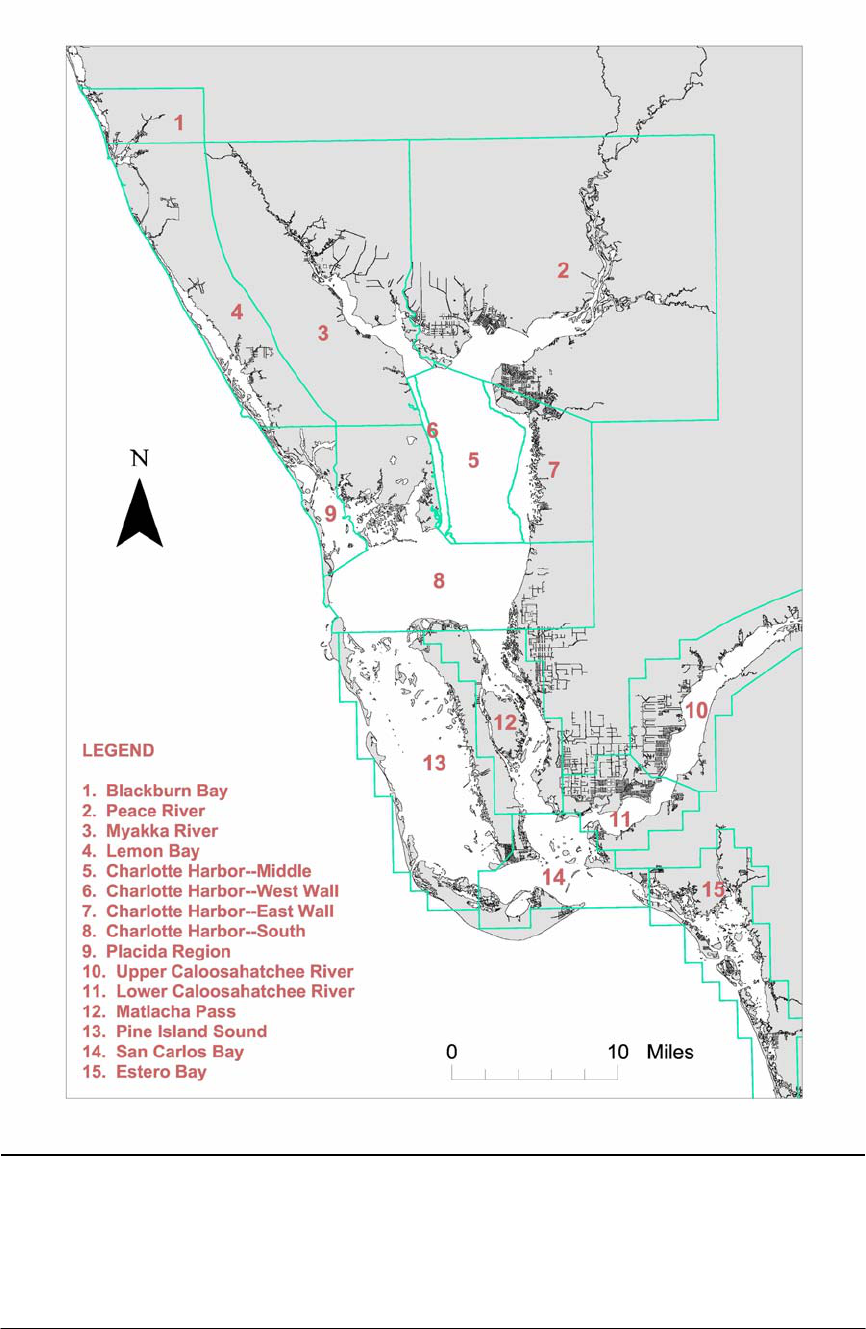

Figure 11. Locations and names of segments created for tracking and reporting of

seagrass coverage in the greater Charlotte Harbor area.

Figure 12. Comparison of propeller scarred seagrass habitat by segments in the greater

Charlotte Harbor region. Total acreages per segment are represented by three component

categories: Lightly scarred habitat, Moderately scarred habitat, and Severely scarred

habitat.

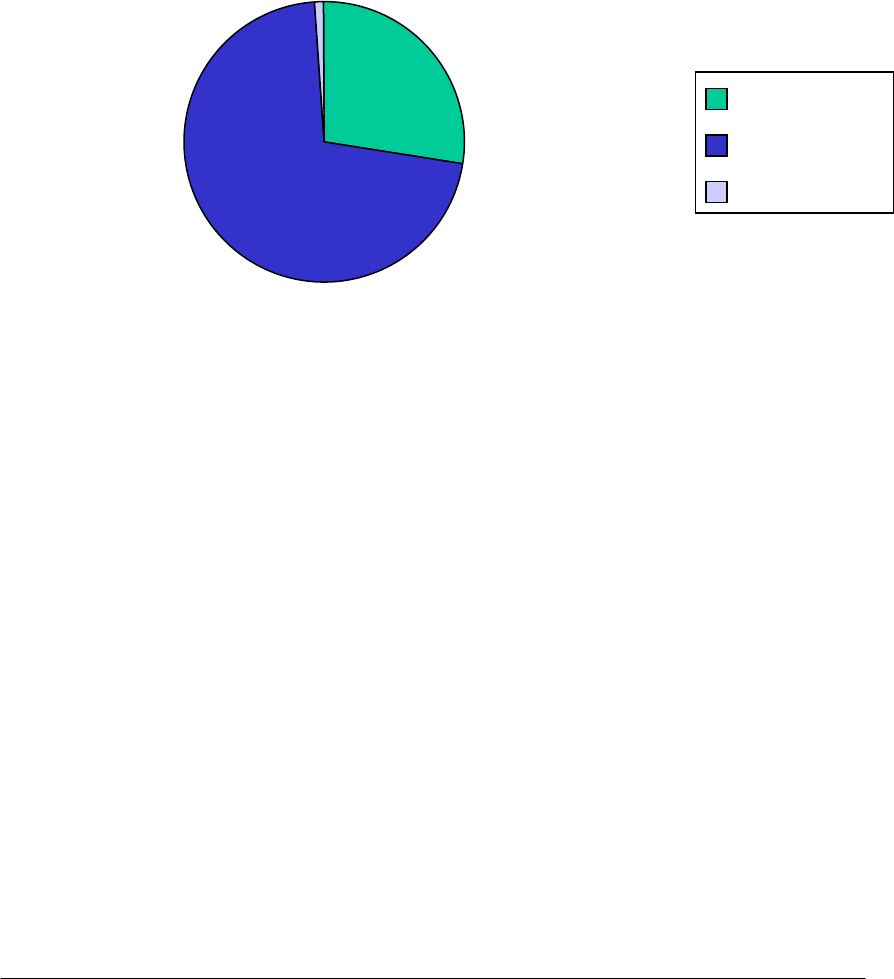

Figure 13. Percentages of scarred seagrass habitat within the Charlotte Harbor National

Estuary Program. Acres of scarred habitat per county are Lee County = 21,507, Charlotte

County = 8236, and Sarasota County = 321. Note: Sarasota county values are limited to

the portion within the NEP boundary.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

6

Introduction

The Fish and Wildlife Research Institute (FWRI) of the Florida Fish and Wildlife

Conservation Commission (FWC) performed this assessment of extent and severity of

boat propeller scars in seagrass habitats under cooperative agreement with the Charlotte

Harbor National Estuary Program (Charlotte Harbor NEP). Data compiled by the Florida

Marine Research Institute for the 1995 report Scarring of Florida’s Seagrasses:

Assessment and Management Options (Sargent, F.J, et al.) found that Charlotte Harbor

has been one of the most severely scarred areas of Florida. This document reports on a

project that serves as an update to the 1995 work for the coastal portion of the Charlotte

Harbor NEP study area and provides area resource managers with an analysis of the

current extent, location and severity of boat propeller scarring. The survey area

encompassed all estuarine waters within the Charlotte Harbor NEP boundary (Figure 1).

Submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) is an integral part of the Charlotte Harbor

estuarine system and an important natural resource that performs a number of significant

functions. For example, seagrasses help to maintain water clarity, stabilize bottom

sediments, provide habitat for many fishes, crustaceans, and shellfish, and they make up

the food for many marine animals. Most importantly, these areas are the nursery grounds

for most of Charlotte Harbor’s recreationally and commercially important fisheries. The

Charlotte Harbor NEP’s Management Conference developed 2 goals specific to the

preservation and restoration of submerged aquatic vegetation within the greater Charlotte

Harbor watershed:

FW-2: Meet the stated objectives for the target extent, location, and quality of the

following habitats in the Charlotte Harbor NEP study area:

a) native submerged aquatic vegetation should be maintained and

restored at a total extent and quality no less than caused by natural

variation; …

and

FW-3: Reduce propeller damage to seagrass beds, identified from the 1992-1993

baseline data, within the Charlotte Harbor NEP area by the year 2010. Reduce all

severely scarred areas to light scarring and reduce 70 percent or more of the

moderately scarred areas to light scarring.

The Greater Charlotte Harbor region has experienced a 29 % decrease in seagrass

coverage since the 1940s (Harris et al, 1983). This seagrass loss is mostly within the

southern portion of the study area and is believed to have originated from various causes,

such as Sanibel Causeway Island construction, Intercoastal Waterway dredging activities,

changes to water flow and quality characteristics (Harris et al, 1983). Boat propeller

scars are also a cause of seagrass loss in the Charlotte Harbor system. Lee and Charlotte

counties ranked 3

rd

and 4

th

among 31 coastal counties for the amount of scarred seagrass

in data collected in the early 1990’s (Sargent et al. 1995). As the amount of people

settling in the coastal counties and the number of registered vessels continue to increase,

the Charlotte Harbor NEP stakeholders need to know how the increase in boating activity

may be affecting the SAV of the Charlotte Harbor region.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

7

Propeller scarring of seagrasses usually occurs when boaters motor through water

that is shallower than the drafts of their boats. The propellers tear some combination of

the seagrass leaves, stems and roots, managing at times to remove the sediments, creating

unvegetated, linear troughs of varying lengths (Figures 2 and 3). The amount of

destruction from a scar-producing event depends on water depth and the size, speed, and

path of the vessel. Some vessels create scars in areas at low tide that would not do so at

high tides. Although linear features are most often associated with the term “prop scar,”

some areas of seagrass habitats have been completely denuded by repeated scarring. In

other instances, a linear scar can become a larger feature if the sediments are scoured to

undercut the seagrass bed. This erosion can result in detachment of large sections of

seagrasses that then float away leaving behind patches of bare sediment wider than the

original prop scar.

Sargent et al. (1995) listed nine situations that account for the vast majority of

prop scars:

1) when boaters misjudge water depth and accidentally scar seagrass beds;

2) when boaters who lack navigational charts or the skill to use them stray from

marked channels and accidentally scar seagrass beds;

3) when boaters intentionally leave marked channels to take shortcuts through

shallow seagrass beds, knowing that seagrass beds may be scarred;

4) when boaters carelessly navigate in shallow seagrass beds because they

believe scars heal quickly;

5) when inexperienced boaters engage in recreational or commercial endeavors

over shallow seagrass flats, thinking that their boat’s designed draft is not

deep enough to scar seagrasses or that the design will prevent damage to their

boat;

6) when boaters overload their vessels, causing deeper drafts than the boaters

realize;

7) when boaters anchor over shallow seagrass beds, where their boats swing at

anchor and scar seagrasses;

8) when boaters intentionally prop-dredge to create a channel, and;

9) when inexperienced boaters, ignorant of the benefits of seagrasses accept and

mimic local boating behavior that disregards negative impacts to the

environment.

Seagrass habitats are especially susceptible to prop scarring because they exist in shallow

depths, generally less than 2 meters (6.6 feet). Sunlight is needed by seagrasses for

photosynthesis, thus the affinity of the plants for shallow locations. Averaging only 2.1

meters (7 feet) in depth, Charlotte Harbor is relatively shallow and susceptible for high

levels of prop scarred habitat (Stoker 1986).

The slowest Florida seagrass species to recover from prop scar damage, turtle

grass (Thalassia testudinum Banks ex König), reportedly regrows into the scarred area

within a range of 2-8 years in Florida (Dawes and Andorfer, 2002) with complete

recovery reaching 10 years (Lewis and Estevez, 1988). Areas subject to repeated boat

impacts may never have the opportunity to recover. Because seagrass habitats are known

to be critical feeding and sheltering areas for wading birds, juvenile finfish, and shellfish,

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

8

cumulative scar damage results in reduction of valuable habitat. Decreasing productive

habitat for wildlife to use may affect the condition of wildlife populations.

Methods

The methods used for this study follow those described in the 1995 report by Sargent

et al. that were used to survey and map propeller scars around the coastline of Florida,

including the Charlotte Harbor region. A combination of analysis of aerial photography

and field observations during low elevation flights were used to collect the propeller scar

extent and severity data, which was then converted into maps using a geographic

information system (GIS). The process involved five main steps:

1) Collection and standardization of aerial photography appropriate for evaluating

the seafloor within the study area.

2) Creation of draft maps through digital delineation of polygons that represent

locations and degree of propeller scarred areas seen in the digital imagery.

3) Flights over the study area to edit the draft maps produced from Step 2.

4) Edits to the draft maps based on field observations in Step 3.

5) Quality control and assurance measures of the final maps with a geographic

information system (GIS).

Descriptions of each of those five process steps follows:

1) Aerial photography of the entire study area was gathered, scanned, and

georeferenced. Collection of the photography was originally funded by the Southwest

Florida Water Management District (i.e. photographs from Venice through the northern

tip of Pine Island) and the South Florida Water Management District (i.e. photographs

from the northern tip of Pine Island through Estero Bay) for the specific reason of

mapping SAV extent. The1:24,000 scale, natural color photography was flown in

December of 1999. Mosaics were created from the scanned imagery, then converted to

MrSID compression formats to decrease file sizes and allow for easier use of the

imagery.

2) Delineation of the scarred habitat polygons was performed with ArcGIS 8.3

software. An image analyst was able to view the digital imagery and create polygons “on

top” of the images. The polygons were coded as Light Scarring, Moderate Scarring, or

Severe Scarring as illustrated in Figure 4.

3) After creating the draft maps showing polygons of scarred areas, flights were

arranged for flying above the study area to evaluate the draft maps. The three flight

surveys were conducted from light, fixed-wing aircraft (Cessna 172 from Andersen

Aviation, LLC at Charlotte County Airport) during April and May of 2004. Flight

altitudes varied from 1,000 to 1,500 feet. Flight speeds were maintained at 80-90 mph.

Hardcopy map atlases were created so the flight researchers could easily view and edit

the draft polygons as the flights proceeded.

4) Edits to the existing polygons were marked on the maps, then these edits were

copied into the digital map using ArcGIS 8.3 software.

5) Several procedures were used to standardize this data with the data used in the

Sargent et al. (1995) project. First, using the ERASE function in ArcGIS, a shoreline

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

9

layer from the FWC Marine Resources GIS was used to erase any portions of the scar

polygons that overlapped with a land feature. This step was necessary to eliminate any

polygon edges that would be coincident with the pre-existing shoreline of a larger scale

(i.e. 1:40,000). Next, both the Sargent et al. 1995 data and the data created during this

project were intersected with the 1999 seagrass data layers previously existing from

projects of the SWFWMD and the SFWMD. With the ArcGIS INTERSECT function,

only those portions of the scarred habitat polygons that are coincident with a portion of a

seagreass habitat polygon remain. As a result, the remaining scarred habitat polygons

contain only area that is seagrass habitat as known to exist from the seagrass mapping

efforts of the SFWMD and the SWFWMD. A map of the scar polygons is shown in

Figure 5.

It should be noted that by using the 1999 seagrass data to standardize the Sargent et

al. 1995 data, in effect, we re-calculated the Sargent et al. data for the Charlotte Harbor

NEP area. Thus, the acreage calculations, county rankings, etc. in the Sargent et al. study

did not directly transfer to this study. This was necessary to be able to perform a reliable

trend analysis for the amount of scarred habitat between the two studies.

Results and Discussion

Florida continues to be a popular destination for people re-locating from other parts

of the world. The population of coastal counties in Florida continues to swell (Figure 6),

with predictions for even more rapid growth during the next two decades when the “baby

boomer generation” reaches retirement ages.

Associated with a growing population is the growing use of the natural resources of

Florida’s unique coastal areas. The amount of registered boats within the coastal area of

the Charlotte Harbor NEP have more than doubled within each county, except Sarasota,

in the period from 1980 to 2000 (Figure 7). Those numbers account for county

registered vehicles only; many more boaters travel from outside the coastal counties to

recreate among the seagrass habitats within the Charlotte Harbor NEP.

The scarred seagrass habitat in the 1993 results for Charlotte County, Lee County and

the small portion of Sarasota County within the Charlotte Harbor NEP boundary

amounted to 21,816 acres (Figure 8). In contrast, the amount of scarred seagrass habitat

in the 2004 analyses increased to 30,064 acres (Figure 9). Results from this study

indicate that the amount of seagrass habitat that has been affected by propeller scarring

has increased 38% from 1993 to 2003. The amount of severely scarred seagrass habitat

has increased 71%, while the amount of lightly scarred seagrass has declined 50%

(Figure 10). Presumably, the decrease in lightly scarred area results from habitats that

have been classified as light scarring in the previous study that are now contained within

the areas classified as moderately and severely scarred.

For purposes of assessing status and trends of seagrass coverage within the Charlotte

Harbor NEP boundary in another research effort, Charlotte Harbor NEP and FWC staff

reported seagrass coverage by seagrass segments. The locations and names of the

segments are illustrated in Figure 8. For this study, those same segments were used to

assess the propeller scarred habitat data (Table 1; Figure 12). Trends in the percent

gains/losses of scarred habitat should be reviewed with caution, especially for the river

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

10

segments. For instance, trends in the Lower Caloosahatchee River segment indicate a

100% decline in scarred habitat; however, the actual loss of SAV in the entire segment

accounts for the 100% decline, not a decline in boating activity. Thus, changes in

coverage of seagrass habitat in a segment may be partially responsible for changes in the

percent gains or losses for the segments.

The amount of scarred habitat in Lee County is 14,312 acres compared to 7,443 acres

in Charlotte County (Figure 13). While Lee County has nearly twice as much scarred

seagrass habitat as Charlotte County, it should be considered that Lee County contains

more than twice the amount of seagrass habitat as Charlotte County. Trend analyses by

counties indicate that the amount of scarred seagrass habitat increased from 28% to 43%

in Lee County and from 52% to 58% for Charlotte County.

Examinations of prop scar prevalence indicate areas around docks, marinas, channel

edges, oyster bars, and mangrove islands are exceptionally susceptible to repeat scarring.

These are areas that draw vessels on repeat trips and often over very shallow water. For

example, the researchers in this project noticed that the edges of many mangrove islands

and oyster bars were heavily scarred from boats using them as navigational aides to

maneuver through the estuary. Likewise, channel edges are often locations of severe

scarring because a high percentage of boats travel the channels with a minority of them

actually missing the deepwater and scaring the channel edges.

Assessing the locations, extents, and severity of scarred habitats is an initial step in

the process of conservation measures for these areas. Next, decisions must be made on

what, how, and when steps need to proceed for reduction or elimination of the impacts to

the seagrass habitat. Management considerations for reducing the impacts of propeller

scarring fall within four categories: boater education, channel markers and other signage,

enforcement, and limited-motoring zones. Discussion of each of the four options is

included here as provided in Florida Seagrass Manager’s Toolkit (Florida Fish and

Wildlife Conservation Commission 2003):

(1) Boater Education

Efforts to educate boaters on the locations of shallow seagrass beds—and the importance

of seagrasses to estuarine fish and shellfish communities—have been undertaken by

many local governments, the FWC, FDEP, several National Estuary Programs and

Estuarine Research Reserves, and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. “Boaters

Guides,” which include bathymetric charts showing the locations of shallow seagrass

beds and other sensitive aquatic habitats, along with text explaining the importance of

those habitats, have been developed for Apalachicola Bay, Biscayne Bay, Charlotte

Harbor, Choctawhatchee Bay, Citrus County, Indian River Lagoon, Lake Worth Lagoon,

Lee County, Saint Joseph Bay, Tampa Bay, and the Upper Florida Keys. Many of these

guides can be downloaded from the FMRI website

(http://www.floridamarine.org/products/products.asp) and are distributed in printed form

by a number of organizations in the vicinity of each waterbody. Educational signs, which

have been erected at a number of boat ramps, have also been used to provide information

on the locations and importance of sensitive aquatic habitats in the vicinity of the ramps.

The Citizens Advisory Committees (CACs) associated with several National Estuary

Programs have implemented boater education programs in an effort to reduce boating

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

11

impacts to seagrass meadows and their inhabitants, including manatees. In the Tampa

Bay region, multi-stakeholder users groups (e.g., the Cockroach Bay Users Group, at

http://cbug.org) have been established for some portions of the bay where seagrass

scarring has been particularly intense. One focus of these groups has been an effort to

identify potential nonregulatory management actions that might be used to provide better

protection for existing seagrass beds.

(2) Channel Markers and Other Signage

Efforts to provide more effective marking of navigation channels have been used in many

parts of the state to reduce scarring caused by boaters who inadvertently motor onto

shallow vegetated flats. Because seagrass beds in shallow waters can also be impacted by

the erosive effects of boat wakes and pressure waves, signage designating slow-speed or

no-wake zones has also been used as a protective measure in the vicinity of shallow

grassbeds. In many cases channel marking and other signage has been used in

combination with motor exclusion or caution zones to protect heavily-scarred areas, a

multi-pronged approach that is described in more detail below.

(3) Enforcement of Boating Regulations

Experience suggests that many boaters will voluntarily obey regulations designed to

protect seagrass resources, particularly if those regulations are developed through an

inclusive, consensus-based process that includes an adequate level of public input. The

results also suggest, however, that a certain percentage of boaters may tend to overlook,

misunderstand or ignore such regulations. Consistent presence of enforcement personnel

in areas of heavy boating activity appears to be one of the more effective tools available

for reducing the potential impacts of this portion of the boating community on shallow

seagrass habitats (Sargent et al. 1995). Sargent et al. (1995) also noted that mapping and

monitoring of managed areas are essential for evaluating the effectiveness of

management efforts, and suggested that regional or statewide management plans might be

needed to provide adequate protection for large areas of seagrass habitat that fall within

the jurisdictions of multiple local governments.

(4) Designation of Internal Combustion No-Entry or Slow-Speed Zones

Smith (1998) summarized 11 boating management areas that had been established in

Florida prior to 1998 for the purpose of seagrass protection:

• Merritt Island NWR, No Entry Zone, Brevard County

• No Motor Power Zones Lee County

• Virginia Key, No Entry Zone, Miami-Dade County

• Pansy Bayou, No Entry Zone, Sarasota County

• J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge, No Entry Zone, Lee County

• John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, No Combustion Motor Operation Zones,

Monroe County

• Lignumvitae Key State Botanical Site, No Combustion Motor Operation Zones,

Monroe County

• Gulf Islands GeoPark, Combustion Motor Exclusion Zones. Pinellas County

• Weedon Island Aquatic Management Area, Combustion Motor Exclusion and Shallow

Water Caution Zones, Pinellas County

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

12

• Fort DeSoto Wetland and Aquatic Habitat Management Area, Combustion Motor

Exclusion and Shallow Water Caution Zones, Pinellas County

• Cockroach Bay Aquatic Preserve, Combustion Motor Exclusion Zones, Hillsborough

County

More recently, the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

(http://www.fknms.nos.noaa.gov) has designated a number of combustion motor

exclusion and other protective zones to reduce boating impacts to seagrass and coral reef

habitats in areas under its jurisdiction.

For additional information on how these four management options may be used,

please refer to Sargent et al. 1995 and the Florida Seagrass Manager’s Toolkit (Florida

Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 2003). Both of these documents have been

provided in digital format to the Charlotte Harbor NEP, as well as being available from

the seagrass pages of the FWC website (http://research.myfwc.com/).

List of Project Deliverables

1) Aerial imagery mosaics covering the all of the estuaries in the Charlotte Harbor NEP

boundary.

2) 1995 statewide propeller scar report (Sargent et al.) in digital format,

3) Seagrass Manager’s Toolkit in digital format,

4) Prop scar locations and severity quick-reference pdf maps,

5) GIS data:

a) 2003 prop scar habitat locations and severity,

b) county boundaries,

c) Charlotte Harbor NEP boundary,

d) Charlotte Harbor NEP seagrass subbasins,

e) seagrass habitat locations,

f) shoreline,

g) marine facilities,

h) aids-to-navigation,

i) bathymetry.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

13

Literature Cited

Dawes, C., and J. Andorfer. 2002 Production of rhizome meristems by Thalassia

testudinum. Pp. 185-197 in Greening, H.S. (ed.) 2002. Seagrass Management: It’s Not

Just Nutrients! Aug. 22-24, 2000; Tampa Bay Estuary Program. St. Petersburg, FL.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2003. Florida Seagrass Manager’s

Toolkit. Fish and Wildlife Research Institute website.

http://research.myfwc.com/features/view_article.asp?id=23202

Harris, B.A., K.D. Haddad, K.A. Steidinger and J.A. Huff. 1983. Assessment of

Fisheries Habitat: Charlotte Harbor and Lake Worth, Florida, Final Report, Florida

Department of Natural Resources. Available from Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation

Commission-Florida Marine Research Institute, St. Petersburg, FL.

Lewis, R.R., III, and E. Estevez. 1988. The ecology of Tampa Bay, Florida: an estuarine

profile. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv. Biol. Rep. 85 (7.18). 132 p.

Sargent, F.J., T.J. Leary, D.W. Crewz, and C.R. Kruer. 1995. Scarring of Florida’s

seagrasses: assessment and management options. FMRI Tech. Rep. TR-1. Fish and

Wildlife Research Institute, St. Petersburg, Florida. 37 p. plus appendices.

Stoker, Y.E. 1986. Water Quality of the Charlotte Harbor Estuarine System, Florida.

November 1982 through October 1984. Open File Report 85-563. Prepared in

cooperation with the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation. U.S. Geological

Survey, Tallahassee, FL.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

14

1993 Acres 2003 Acres

Gains/Losses

(Acres)

Gains/Losses

(Percent)

Cowpen Slough/Blackburn Bay

Light

14 2 -12 -88%

Moderate

6 41 35 582%

Severe

044NA

Lemon Bay

Light

100 122 23 23%

Moderate

157 390 233 148%

Severe

111 339 227 204%

Placida Region

Light

697 32 -666 -95%

Moderate

453 871 417 92%

Severe

8 518 510 6350%

Peace River

Light

210 44 -165 -79%

Moderate

86 23 -64 -74%

Severe

000NA

Myakka River

Light

166 72 -94 -57%

Moderate

26 54 28 108%

Severe

044NA

East Wall Charlotte Harbor

Light

373 0 -373 -100%

Moderate

2,021 2,558 537 27%

Severe

68 19 -49 -72%

Middle Charlotte Harbor

Light

1 32 31 5106%

Moderate

123 63 -60 -49%

Severe

000NA

West Wall Charlotte Harbor

Light

303 2 -301 -99%

Moderate

21 324 303 1430%

Severe

0 319 319 NA

South Charlotte Harbor

Light

876 719 -157 -18%

Moderate

2,867 2,714 -153 -5%

Severe

190 1,434 1,244 654%

Pine Island Sound

Light

1,946 1,718 -227 -12%

Moderate

4,543 5,178 634 14%

Severe

798 4,714 3,915 490%

Matlacha Pass

Light

986 567 -419 -42%

Moderate

645 1,789 1,143 177%

Severe

73 1,979 1,906 2608%

San Carlos Bay

Light

565 364 -200 -35%

Moderate

745 802 56 8%

Severe

190 1,120 931 491%

Lower Caloosahatchee River

Light

113 0 -113 -100%

Moderate

77 0 -77 -100%

Severe

2 0 -2 -100%

Upper Caloosahatchee River

Light

0000

Moderate

0000

Severe

0000

Estero Bay

Light

1,144 57 -1,087 -95%

Moderate

976 272 -704 -72%

Severe

136 806 669 490%

Total Scarred Seagrass Habitat

21,817 30,064 8,247 38%

Table 1. Acreages and percents of propeller scarred seagrass habitat by subbasins in the

greater Charlotte Harbor region.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

15

Figure 1. Coastal boundary of Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

16

Figure 2. Example of a seagrass meadow in Charlotte Harbor with moderate and severe

propeller scarring.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

17

Figure 3. Close-up example of a propeller scars in a seagrass meadow in Charlotte

Harbor. This example shows a location where scars from a twin prop vessel cross a scar

from a single prop vessel.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

18

Figure 4 . Diagrammatic representation of the three categories of estimated scarring

intensity used as a guide for the delineation and classification of propeller scarred

habitats (from Sargent et al. 1995). Black space within each block represents seagrasses,

and white marks represent scarring. Light scarring is defined as the presence of scars in

less than 5 percent of the delineated polygon, moderate scarring is the presence of scars

in 5 to 20 percent of the polygon, and severe scarring as the presence of scars in more

than 20 percent of the polygon.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

19

Figure 5. Map of propeller scarred seagrass polygons produced during this study.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

20

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

400,000

450,000

1970 1980 1990 2000

County Population Trends

Charlotte

Collier

Lee

Sarasota

Figure 6. Population trends for the four coastal counties surrounding the Charlotte

Harbor National Estuary Program boundaries.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

21

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

35,000

40,000

45,000

1980-81 1992-93 1998-99 2001-02

Years

Registered Watercraft

Charlotte

Collier

Lee

Sarasota

Figure 7. Numbers of registered watercraft (recreational and commercial) for the four

coastal counties surrounding the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program boundaries.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

22

Figure 8. Amounts of propeller scar impacted seagrass habitat in 1993 per severity

category within each county of the study area. The sum is 21,816 acres. Note:

calculations for Sarasota county acreages were limited to the portion of the county within

the Charlotte Harbor NEP Boundary.

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

Light

Moderate

Severe

Light

1,529 5,925 39

Moderate

5,628 7,098 21

Severe

286 1,288 2

Charlotte Lee Sarasota

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

23

Figure 9. Amounts of propeller scar impacted seagrass habitat in 2003 per severity

category within each county of the study area. The sum is 30,064 acres. Note:

calculations for Sarasota county acreages were limited to the portion of the county within

the Charlotte Harbor NEP Boundary.

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

Light

Moderate

Severe

Light

869 2,768 95

Moderate

5,527 9,374 176

Severe

1,840 9,365 50

Charlotte Lee Sarasota

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

24

7,492

12,747

1,577

3,732

15,077

11,255

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1993 2003

Severe

Moderate

Light

Figure 10. Amounts of seagrass habitat classified as severely or moderately scarred

increased between 1993 and 2003. However, lightly scarred seagrass habitat declined in

area between the same time period. The values in the columns represent actual acres of

habitat in each category as measured within the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary

Program boundary. The total scarred areas increased from 21,816 acres in 1993 to

30,064 in 2003.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

25

Figure 11. Locations and names of segments created for tracking and reporting of

seagrass coverage in the greater Charlotte Harbor area.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

26

B

l

a

c

k

b

u

r

n

B

a

y

E

a

s

t

W

a

l

l

C

h

a

r

l

o

t

.

.

E

s

t

e

r

o

B

a

y

L

e

m

o

n

B

a

y

L

o

w

e

r

C

a

l

o

o

s

a

h

a

t

.

.

.

M

i

d

d

l

e

C

h

a

r

l

o

t

t

e

H

.

.

.

M

y

a

k

k

a

R

i

v

e

r

M

a

t

l

a

c

h

a

P

a

s

s

P

e

a

c

e

R

i

v

e

r

P

l

a

c

i

d

a

R

e

g

i

o

n

P

i

n

e

I

s

l

a

n

d

S

o

u

n

d

S

o

u

t

h

C

h

a

r

l

o

t

t

e

H

.

.

.

S

a

n

C

a

r

l

o

s

B

a

y

W

e

s

t

W

a

l

l

C

h

a

r

l

o

t

.

.

T

O

T

A

L

-4,000

-2,000

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

Acres

Light Moderate Severe

Figure 12. Comparison of propeller scarred seagrass habitat by segments in the greater

Charlotte Harbor region. Total acreages per segment are represented by three component

categories: Lightly scarred habitat, Moderately scarred habitat, and Severely scarred

habitat.

Assessment of Boat Propeller Scar Damage December 2004

within the Greater Charlotte Harbor Region

Report by Fish and Wildlife Research Institute to the Charlotte Harbor NEP

27

Figure 13. Percentages of scarred seagrass habitat within the Charlotte Harbor National

Estuary Program. Acres of scarred habitat per county are Lee County = 21,507, Charlotte

County = 8236, and Sarasota County = 321. Note: Sarasota county values are limited to

the portion within the NEP boundary.

Charlotte

27%

Lee

72%

Sarasota

1%

Charlotte

Lee

Sarasota