MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES:

Their Effects on Crime, Sentencing Disparities,

and Justice System Expenditures

rr2002-1e

Thomas Gabor, Professor

Department of Criminology

University of Ottawa

Nicole Crutcher

Carleton University

Research and Statistics Division

Department of Justice Canada

January 2002

The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the Department of Justice Canada.

Research and Statistics Division i

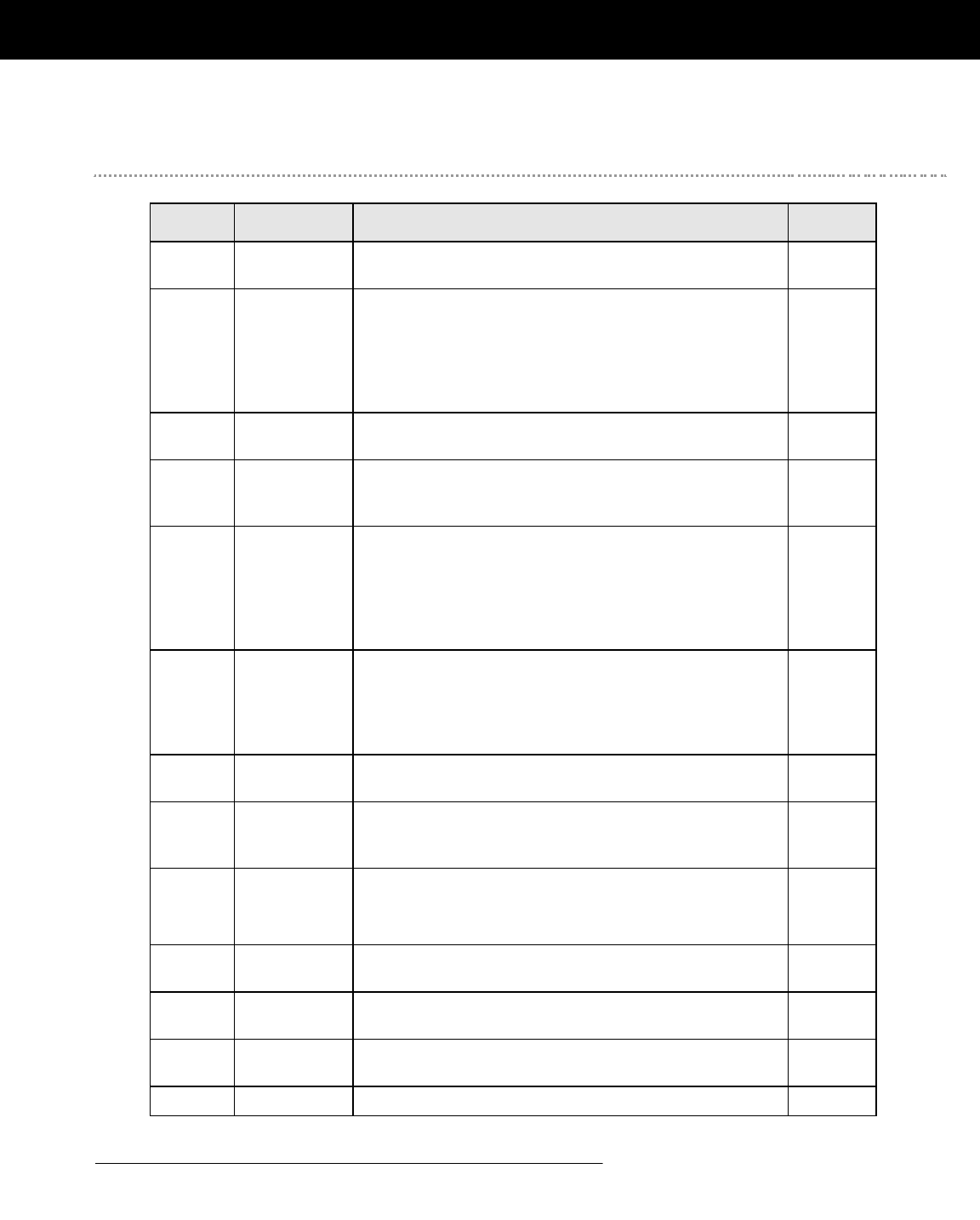

Page

Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................iii

1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................................1

2.0 Scope of the Review......................................................................................................................3

3.0 Some Theoretical and Conceptual

Issues............................................................................................................................................5

4.0 Can Offenders be Deterred?..........................................................................................................7

4.1 The Rational Choice Perspective ..........................................................................................7

4.2Offender Characteristics ......................................................................................................7

4.3 Evidence on Deterrence and Incapacitation ........................................................................8

4.3.1 Deterrence ................................................................................................................8

4.3.2 Incapacitation ..........................................................................................................9

5.0 The Impact of Mandatory Minimum

Sentences....................................................................................................................................11

5.1 General Mandatory Sentencing Laws ................................................................................11

5.2 Mandatory Sentences for Firearm Offences ......................................................................13

5.3 Mandatory Sentences for Impaired Driving ......................................................................15

5.4 Mandatory Sentences for Drug Offences ............................................................................17

5.5 Estimating the Effects of Hypothetical Mandatory Sentences ............................................18

6.0 Mandatory Penalties and Sentencing

Disparities..................................................................................................................................21

6.1 General Disparities and the Shift from Judicial to Prosecutorial Discretion ....................21

6.2 Racial Disparity ..................................................................................................................22

6.3 Effects of Mandatory Sentences on Other Groups ..............................................................23

7.0 The Economic Impact of Mandatory

Sentences....................................................................................................................................25

7.1 Court Costs ........................................................................................................................25

7.2 Effects on Prison Populations ............................................................................................25

8.0 Other Issues................................................................................................................................27

9.0 Conclusions................................................................................................................................29

9.1 Deterrence and Incapacitation ..........................................................................................29

9.2 General Mandatory Sentencing Laws ................................................................................30

9.3 Mandatory Sentences for Firearms Offences ......................................................................30

Table of Contents

MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES

ii Research and Statistics Division

9.7 Sentencing Disparity ..........................................................................................................31

9.8 Some Adverse Effects of Mandatory Sentences ..................................................................31

9.9 Concluding Remarks ..........................................................................................................32

References..........................................................................................................................................35

APPENDIX A: Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the 2001 Criminal Code..........................................41

APPENDIX B:Private Members’ Bills from 1999-200119....................................................................43

T

he authors would like to express their gratitude to

David Daubney, Phyllis MacRae, Ivan Zinger, Dan

Antonowicz, and Julian Roberts for all their advice

and assistance during the preparation of this report.

Acknowledgements

Research and Statistics Division iii

I

t has been said that mandatory punishments are as

old as civilization itself. The biblical lex talionis– an

eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth – was mandatory,

leaving little room for clemency or mitigation of

punishment. Mandatory penalties were also enshrined

in early Anglo-Saxon law, prescribing set fines for every

conceivable form of harm (Wallace, 1993). In the United

States, mandatory minimum sentences (MMS) date back

to 1790 and, since the 1950s, have evoked considerable

ambivalence. In American federal law today, over 60

statutes contain MMS, although only four, covering drug

and weapons offences, are used with any frequency

(Wallace, 1993).

By 1999, The Criminal Code of Canadacontained 29

offences carrying MMS (Appendix A). Nineteen of these

offences were created in 1995 with the enactment of Bill

C-68, a package of firearms legislation. MMS appear to

be increasing in popularity with Members of Parliament,

as shown by the number of private members’ bills

introduced in the 1999 session (Appendix B). This review

was prompted by the increasing interest in MMS, as well

as by the controversy surrounding them. The principal

aim was to assess the effects of MMS through a review of

relevant social science and legal literature.

Several arguments have been advanced in favour of

MMS. Proponents believe that these penalties act as a

general or specific deterrent; that is, they dissuade

potential offenders from offending or actual offenders

from re-offending. They also claim that MMS prevent

crime by incapacitating or removing the offender from

society. Furthermore, MMS may serve a denunciatory or

educational purpose, by communicating society’s

condemnation of given acts. Moreover, MMS are

thought to reduce sentencing disparity.

Opponents assert that MMS have little or no deterrent or

denunciatory effect. They also maintain that the rigid

penalty structure limits judicial discretion, thereby

preventing the imposition of just sentences.

Furthermore, there is the concern that the rigidity of

MMS may result in some grossly disproportionate

sentences. In addition, opponents assert that MMS can

make it difficult to convict defendants in cases where the

penalty is perceived as unduly harsh. Moreover, there is

a concern about the fiscal consequences of these

penalties, as they may increase the burden on

prosecutorial resources and produce substantial

increases in prison populations. Finally, MMS may

exacerbate racial/ethnic biases in the justice system if

they are applied disproportionately to minority groups.

The primary aim of this review was to assess the

utilitarian aspects of MMS; that is, the crime preventive,

fiscal, and social consequences of MMS, as well as

impediments to their implementation. This review did

not consider constitutional/Charter issues raised by

these penalties.

1.0 Introduction

Research and Statistics Division 1

T

his review covered the period from 1980 to 2000

inclusive, although several earlier studies were

included due to their salience. The databases

searched included Current Contents, Soc Abstracts,

PsycINFO, and Legal Trac. Dozens of key words were

used in the searches including various combinations of

the following: mandatory sentences, mandatory

minimum penalties, deterrence, incapacitation,

denunciation, homicide, murder, impaired driving,

drugs, firearms, crimes, offences, disparity, capital

punishment.

Materials cited in this report included empirical studies,

as well as commentaries by jurists and prosecutors with

extensive first-hand experience with cases eligible for or

resulting in the imposition of a MMS.

2.0 Scope of the Review

Research and Statistics Division 3

A

principal aim of this review was to assess the

utilitarian aspects of MMS; that is, the potential

crime preventive benefits of such penalties. As

indicated in Section 1.0, these benefits can arise through

incapacitation, general or specific deterrence,

denunciation, or education (i.e., raising awareness and

sensitization). Since penalties already tend to exist in

areas where MMS are introduced (e.g., murder,

firearms-related crimes, impaired driving),

demonstrating that a given MMS has an absolute

deterrent or incapacitation effect is insufficient.

Sentences for robbery, for example, had a potential

preventive effect prior to the introduction of sentence

enhancements (MMS in addition to the primary offence)

for using a firearm in robberies and other offences.

Thus, the marginalor additional benefit of MMS over

previous penalties must be established (Shavell, 1992).

These marginal preventive effects, in turn, can exist only

if MMS actually increase the certainty and/or severity of

punishment. If their perceived severity results in fewer

guilty pleas and more cases proceeding to trial, the

certainty and celerity of their imposition may be

diminished relative to sentences imposed previously.

Also, MMS do not guarantee that sentence severity will

increase, as sentences under a previous sentencing

regime may have typically exceeded the minimum

penalty introduced. These concerns underscore the

necessity of examining the implementation of MMS, as

marginal benefits cannot accrue if MMS are

circumvented at the prosecutorial stage or fail to result

in more certain and severe punishment. This review,

therefore, devotes considerable attention to issues in the

implementation of MMS.

Even where the marginal preventive effects of MMS are

demonstrated, a further difficulty arises with regard to

the explanation of these effects. If a “three strikes” law,

such as that enacted in California, is accompanied by a

sharp decline in felonies over a period of several years,

to which utilitarian doctrine do we attribute this finding?

It is difficult to distinguish whether the law has proven

effective due to deterrence, incapacitation, moral

condemnation/sensitization, or some combination of

these factors. Few studies try to empirically determine

the relative importance of these explanations. As a

result, our focus here will be on the impact of MMS,

rather than on explaining any effects observed.

An additional issue is that MMS apply to a wide range of

sanctions internationally, from mandatory license

restrictions and fines for impaired driving to mandatory

life sentences and even the death penalty for certain

categories of murder. Thus, sweeping statements about

the utility of MMS are problematic. Sentences of varying

degrees of severity ought to be considered separately.

Accordingly, impaired driving, drug, and firearms

offences are discussed in different sections of this

report.

3.0 Some Theoretical and Conceptual

Issues

Research and Statistics Division 5

While MMS may serve political ends (placating public

indignation about one or more serious crimes) and

retributive goals, deterrence is presumably an important

aspect of such penalties. Incapacitation alone, whether

for retributive or utilitarian reasons, may ultimately

prove far too costly to sustain MMS. If there is no

deterrent effect, the correctional system is likely to face

a crisis due to the continual growth of the prison

population. Deterrence offers the hope that any short-

term increases in the prison population produced by

MMS will be offset by long-term reductions arising from

declining crime rates.

A number of recent developments and studies in the

field shed light on the potential deterrent effect of prison

sentences. Most of these studies relate to legal sanctions

and incarceration in general; they do not tend to

distinguish between mandatory and other types of

penalties.

4.1The Rational Choice Perspective

The deterministic view that social, biological, and

psychological forces shaped behaviour was dominant

throughout most of the 20th century. While some

criminality undoubtedly is an expression of pure rage

and often involves impaired judgment due to intoxicants

(Wolfgang, 1958; Innes, 1986), an important

development in criminological theorizing over the past

two decades has been the emergence of the rational

choiceperspective (Siegel and McCormick, 1999). While

not assuming complete rationality (Harding, 1990),

proponents regard offenders as active decision-makers,

rather than simply as passive actors responding to

adverse social conditions and psychological needs.

Offender decision-making encompasses a whole range

of choices, aside from the decision to commit a crime.

Offenders are seen as deciding on the timing and

location of their offences, choosing specific targets

(whether people or premises), and making decisions

about the means (e.g., weapons) they will use to commit

their offences. Documented patterns in different crimes

show that crimes are not merely committed in a random

fashion. Dozens of case studies, often involving

interviews with offenders, display their decision-making

processes and decision criteria (Clarke, 1997). Studies

also show that many offenders are anything but

indifferent to the risks, including imprisonment,

associated with their crimes (Brown, 1997; Gabor et al.,

1987). In this context, risk usually refers to the

likelihood of arrest and punishment, rather than its

severity. Furthermore, studies in this area show that

much crime is committed by a larger pool of individuals

responding to situational factors (e.g., opportunities,

risks, and transient motives) favourable to crime, rather

than simply a smaller group of hardcore offenders

(Gabor, 1994).

4.2Offender Characteristics

A series of studies appears to contradict the view of

offenders as rational and of crime as largely

opportunistic as they suggest that:

1) Among the strongest correlates of

criminality are antisocial attitudes and

associates, a history of antisocial

behaviour, and antisocial personality,

indicating that offenders are strongly

predisposed to committing their crimes

(Gendreau et al., 1992; Simourd and

Andrews, 1994);

2) Only a small proportion of incarcerated

offenders are “calculators”, carefully

weighing the costs and benefits of their

crimes (Benaquisto, 2000);

3) Many offenders would prefer to go to

prison than face community sanctions

and do not differentiate between a prison

sentence of three and five years (Spelman,

1995; Petersilia and Deschenes, 1994;

Crouch, 1993; Petersilia, 1990);

4) Incarceration does not appear to reduce

re-offending as offenders receiving

custodial sanctions have recidivism rates

similar to those receiving community

dispositions (Gendreau et al., 1999).

The apparent contradictions between the rational

choice perspective and the more pessimistic studies just

cited might be reconciled by the fact that the former

applies to a wider pool of offenders and potential

offenders, whereas the latter deal with re-offending

among a more intractable group of offenders, many of

whom have been previously incarcerated. Some

evidence does show that those who have been

previously punished are the most likely to recidivate

(Greenfield, 1985). Thus, criminal sanctions may

exercise a greater deterrent effect in relation to those

4.0 Can Offenders be Deterred?

Research and Statistics Division 7

with limited previous justice system contacts.

Incapacitation, on the other hand, may be more

effective than the threat of sanctions in dealing with the

smaller, hardcore, persistent criminal element that is

responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime.

Put negatively, deterrents will be relatively ineffective in

dealing with hardcore offenders and incapacitation

policies may be wasteful in dealing with those (the

population at large) who may commit crimes only

occasionally and who respond to the mere threat of

sanctions and moral persuasion (von Hirsch et al., 1999).

The “offender population” is certainly not monolithic

and a key, largely unresolved issue is the proportion of

different types of offenders who are, in fact, intractable.

It may be that the distribution of hardcore versus

occasional offenders is offence specific. For example,

more robbers than impaired drivers may qualify as

hardcore, committed offenders.

4.3Evidence on Deterrence and

Incapacitation

Research on the deterrent and incapacitative effects of

punishment in general can shed some light on the

potential preventive effects of MMS. One issue is

whether minimum penalties are actually imposed

consistently and hence increase the certainty of

punishment. Also, assuming that MMS increase

sentence length, do potential or actual offenders

differentiate between sentences of, say, five and seven

years in their decision to commit a crime? Legal

sanctions that dissuade the general population from

offending are referred to as general deterrents, while

those dissuading actual offenders from repeating their

crimes are called specific deterrents. Furthermore, do

lengthier sentences continue to provide preventive

benefits through incapacitation; or, might they provide

diminishing returns, as incapacitated individuals age

and other offenders replace them in the illicit

marketplace?

4.3.1Deterrence

There is a voluminous research literature on these

matters. Criminal sanctions have been found to carry

some deterrent and incapacitative effects (Canadian

Sentencing Commission, 1987; Nagin, 1998); however,

these effects vary according to a number of factors,

including:

1. The nature of the crime. Deterrent effects

may be crime-specific. One study, for

example, found that the increased

certainty of arrest helped lower the

burglary rate, while larceny rates were

unaffected by police efforts (Zedlewski,

1983);

2. The target group.The link between the

certainty of punishment and crime rates

may also vary according to criminal

history or race (Greenfield, 1985; Wu and

Liska, 1993). More persistent offenders

and those who have been punished in the

past are less likely to be deterred by the

threat of punishment and each

ethnic/racial group tends to respond to

the arrest probability of members of that

group, rather than to society-wide arrest

probabilities;

3. Moral prohibitions associated with the

behaviour.Those who will experience

shame or embarrassment as a result of

their involvement in a crime are less likely

to commit that crime (Grasmick, Bursik,

and Arneklev, 1993);

4. Knowledge of the pertinent sanction. The

public has little knowledge of the nature

and severity of criminal sanctions,

including those offences carrying MMS

(Canadian Sentencing Commission, 1987).

The awareness of legislative change, such

as the introduction of a MMS, is an

obvious prerequisite to its marginal

deterrent effect;

5. The certainty of punishment.Some

studies show that crime rates decline with

an increase in the probability of arrest

(Tittle and Rowe, 1974; Marvell and

Moody, 1996);

6. The celerity or swiftness of punishment

(Howe and Brandau, 1988). While little

evidence exists in relation to this factor,

learning theories suggest that the more

swiftly punishment follows a crime, the

lower the likelihood that the crime will be

repeated;

7. The severity of the sanction.While some

studies show that tough sanctions carry a

deterrent effect (Green, 1986), the

evidence relating to this factor is mixed at

best;

8. Perceptions of the risk of incurring the

sanction(Klepper and Nagin, 1989).

Generally, those who believe they are

likely to be caught and punished will be

less likely to commit a criminal act.

MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES

8 Research and Statistics Division

The many factors shaping the potential deterrent effect

of criminal sanctions preclude simplistic, sweeping

generalizations affirming the presence or absence of a

deterrent effect. The evidence bearing on the issue of

deterrence is very complex and incomplete. Hence,

extreme positions either denying the existence of any

deterrent effect of legal sanctions or suggesting that

everyone can be deterred reflect entrenched ideological

positions, rather than the empirical evidence.

The research on both sentence certainty and severity are

relevant to MMS and, on balance, the evidence suggests

that severity may be less critical to deterrence than

initiatives boosting the certainty of punishment (Miller

and Anderson, 1986; von Hirsch et al., 1999). In fact,

these elements often operate at cross-purposes as actors

within the criminal justice system have been known to

circumvent laws they believe are draconian by failing to

charge or by refusing to convict guilty defendants (Ross,

1982). Thus, excessively harsh penalties may undermine

the certainty of punishment by reducing the risk of

incarceration. Conversely, increases in the certainty of

imprisonment can produce compensating reductions in

sentence lengths. A US study of incarceration in six

states found that, for drug offences and robbery, an

increase in one was compensated for by reductions in

the other (Cohen and Canela-Cacho, 1994). As prison

capacity, at any time, is finite, increasing the rate of

incarceration for one group of offenders may necessitate

shorter sentences or early releases of other offenders.

There may be important lessons here with regard to

MMS.

As MMS often apply to repeat offenders, research on

specific deterrence, the extent to which known offenders

respond to the threat and experience of punishment, is

particularly relevant. The high recidivism rates

generally found among former prisoners and studies of

the impact of custodial sanctions on young offenders

leave little room for optimism regarding specific

deterrence (Siegel and McCormick, 1999:). The specific

deterrent effect may be limited, but it is not nil. A study

of career armed robbers who had abandoned their life in

crime revealed that one of the key factors underlying

their decision was a desire to avoid further incarceration

(Gabor et al., 1987). For some offenders, at least, there

may be a point at which they tire of punishment and its

associated privations.

A survey of 1,000 convicted felons suggests that even

serious offenders do not become completely inured to

the effects of punishment (Horney and Marshall, 1992).

The study revealed that subjects with higher arrest ratios

(self-reported arrests to self-reported crimes) also

reported higher risk perceptions, indicating that active

offenders may learn from their offending experience. In

turn, those believing that they face higher risks in

lawbreaking have been found to commit fewer crimes

(Nagin, 1999).

Public awareness of sanctions is also critical to their

value as a deterrent. People will not be deterred by a

sanction about which they have little knowledge. The

Canadian Sentencing Commission’s (1987) research

suggests a lack of awareness of sentencing laws and

practices in Canada, especially in relation to MMS. The

Latimer case illustrates this point as the jury was

unaware that murder in this country carries a mandatory

life sentence.

4.3.2Incapacitation

At first glance, estimating the crime preventive effects of

incapacitating offenders appears simple enough. The

average annual number of offences per offender must be

multiplied by the number of people in custody.

Unfortunately, the problem is complex, owing in part to

enormous variations in the estimation of individual

offending rates. Estimates using arrest records range

between 8 and 14 index crimes per year on the street,

while estimates from self-report studies demonstrate a

greater variation still. Robbers are estimated to average

between 5 and 75 robberies per year and burglars are

estimated to commit an average of 14 to 50 burglaries

per year (Nagin, 1999). Zimring and Hawkins (1995)

report that estimates of the number of crimes prevented

per year in prison ranges from 3 to 187. Even the low-

end estimates suggest that incapacitation prevents large

numbers of crimes.

Nagin points out, however, that the averages are skewed

by a small number of individuals who commit

extraordinarily high numbers of offences. Visher (1986),

for example, found that five percent of robbers

committed 180 or more robberies per year. Thus,

incapacitating the remaining 90% to 95% of offenders

will yield a much lower crime preventive benefit than

that suggested by the mean offence rate. Then there are

issues of diminishing returns with age, offender

replacement in relation to offences meeting a demand

(e.g., drug dealing) and those committed in groups, and

the possibility that incapacitation merely delays rather

than disrupts criminal careers (Vitiello, 1997).

It has been estimated that, in 1975, 32.9% of potential

violent offences were prevented nationally (in the US)

due to incapacitation alone (Cohen and Canela-Cacho,

1994). By 1989, the near 200% increase in prison

inmates, according to these authors, had prevented just

an additional 9% of violent offences, for a total of 41.9%

Research and Statistics Division 9

of potential offences. The marginal benefits of

imprisonment decline with age and once most of the

high rate offenders have been confined. A study

applying a mathematical model estimating the effects of

incarceration has corroborated this point by finding that

crime levels are quite insensitive to the size of the prison

population (Greene, 1988).

The most cost effective method of incapacitation would

involve the allocation of prison resources more

selectively, through the early identification of the most

active offender group – selective incapacitation.

Selective incapacitation, however, has drawn fierce

criticism on both ethical and pragmatic grounds. From

an ethical standpoint, sentencing exclusively according

to risk is said to violate fundamental legal principles by

allocating punishment on the basis of expected future

behaviour (Dershowitz, 1973), undermines

proportionality in sentencing (Capune, 1988), and

would likely be applied disproportionately to various

social groups (e.g., minorities, the young) (Capune,

1988; Gabor, 1985).

Practically speaking, the prediction enterprise is

essentially unable to identify high-rate career offenders

prospectively (in advance) (Petersilia, 1980; Greenberg

and Larkin, 1998). Also, studies attempting to predict

offender risk tend to have false positive rates (i.e., over-

predictions of dangerousness) of over 50% (Auerhahn,

1999). Furthemore, it is believed that many high-rate

offenders are already incapacitated under existing

sentencing practices, thereby limiting the potential

gains under a selective incapacitation policy (Beres and

Griffith, 1998; Nagin, 1998). In any event, MMS tend to

adopt a collectiverather than selectiveincapacitation

approach, as they are usually triggered by specific or

repeat offences, rather than offender-specific risk-

related attributes.

Finite prison space has implications for both

incapacitation and deterrent effects. As it is difficult to

simultaneously increase both the rate of incarceration

and the length of prison sentences, the respective

benefits of each must be considered. One study has

found that a sentencing regime involving shorter

sentences (one year) for a large offender base (all

convicted persons) is more efficient than one involving

longer sentences (four years) applied to a smaller

offender base (repeat felons) (Petersilia and Greenwood,

1978). The crime preventive yield of both strategies was

estimated to be the same, although the cost of the latter

strategy would be far more substantial in terms of the

size of the prison population.

MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES

10 Research and Statistics Division

M

andatory sentencing laws can apply to an

entire class of offences (e.g., felonies) or to just

one category of crime. In Canada, MMS apply

to both first and second degree murder, high treason,

impaired driving and related offences, various firearms

offences, betting/bookmaking, and living off the avails

of child prostitution (Appendix A). Laws applying to a

broad class of offenders are discussed in the next

section. The research literature on firearms, impaired

driving, and drug offences is examined in separate

sections due to the level of attention accorded these

offences in discussions of mandatory sentencing.

While murder carries a mandatory life sentence in

Canada, systematic evaluations of the impact of the

MMS introduced in 1976 have been conspicuously

absent. Weighing the merits of MMS relative to the

death penalty and other sanctions existing prior to 1976

would be a complex undertaking, given the confounding

influence of the capital punishment moratorium prior to

its abolition. We suggest that the case of murder be

taken up elsewhere, given the extensive literature on the

subject and the absence of MMS for murder in most

jurisdictions – including most of those with capital

punishment. While the death penalty is usually

discretionary, mandatory death penalty statutes persist

in a number of US states for life-term prisoners who

commit murder. These statutes are designed to deter

those who need an added disincentive to committing

murder as they are already serving life sentences.

Many of these statutes have been repealed by state

legislatures or struck down by state courts in keeping

with various US Supreme Court decisions since its

landmark Furmanv. Georgiaruling in 1972 (Galbo,

1985). The gradual disappearance of mandatory death

statutes, both before and after Furman, was due to “jury

nullification” (i.e., juries preferred to acquit guilty

defendants rather than impose the death penalty) and

the failure of MMS to consider mitigating individual or

offence-related factors. From the Furmanruling in 1972

to 1987, the US Supreme Court had struck down every

mandatory death penalty statute it had ruled on and has

all but explicitly deemed them unconstitutional

(Bowers, 1988). Furthermore, from an international

perspective, there is a world-wide trend toward the

abolition of capital punishment (Radelet and Borg,

2000).

5.1General Mandatory Sentencing

Laws

Gainsborough and Mauer (2000) have pointed out that

during the national decline in crime from 1991 to 1998,

US states with the greatest increases in the rate of

incarceration (often due to MMS) tended to experience

the most modest declines in crime. States with above

average increases in their incarceration rates increased

their use of prison by an average of 72% and experienced

a 13% decline in crime, while “below average” states

increased their use of prison by 30% and saw their crime

rates decline by 17%. While these findings cast doubt on

the overall preventive effect of incarceration, the

authors do acknowledge that, nationally, crime did

decline in the 1990s with increasing incarceration rates.

They did not rule out the possibility that the increased

use of incarceration may have played a role in this

decline, in addition to economic and other factors.

Further muddying this analysis was the finding that

increasing incarceration rates throughout most of the

1980s were accompanied by increases in crime.

Among the best known and most thoroughly evaluated

laws prescribing MMS has been the California “Three-

Strikes” law enacted in March, 1994. This law calls for a

MMS of 25 years to life in prison for offenders convicted

of any felony (roughly equivalent to indictable offences

in Canada) following two prior convictions for serious

crimes. The law also increases the prison sentence for

second-strike offenders, requires consecutive prison

sentences for multiple-count convictions, and limits

good-time credits to 20% following the first strike. These

laws have proliferated and assumed various

incarnations across the US, although many are modelled

on the California version. They are based on criminal

career research, beginning in the 1970s, pointing to the

disproportionate involvement in violence of a hardcore

group of chronic offenders (e.g., Wolfgang, Figlio, and

Sellin, 1972). The policy implications of these studies

appeared clear: the incapacitation of these chronic

offenders could occasion major reductions in crime.

Projections by researchers at Rand Corporation lent

optimism to the California law (Greenwood et al., 1996).

They calculated that a fully implemented Three-Strikes

law would reduce serious felonies by between 22 and 34

percent. Furthermore, the Rand researchers noted that

5.0 The Impact of Mandatory Minimum

Sentences

Research and Statistics Division 11

this expected reduction was based solely on its

incapacitation effect and did not consider its potential

deterrent effect.

Stolzenberg and D’Alessio (1997) evaluated the impact

of the law on the rates of serious (index) crimes in

California's ten largest cities. While the rate of these

crimes across these cities dropped by 15% from the 9-

year pre-implementation period to the 20-month post-

implementation period, a time-series analysis

conducted by the authors suggests that this reduction

was due to a declining trend in these offences already

underway before the law was enacted. The authors did

find a significant effect in one of the ten jurisdictions. It

is also noteworthy that the drop in index crimes in the

post-implementation period exceeded by a wide margin

the drop in petty theft during the same period. Petty

theft served as a control as it was expected to be

unaffected by the legislation. While the findings

appeared to provide mixed support for the Three-Strikes

law, the authors speculated about its limited effect on

serious crime. One explanation offered was that

California’s sentencing system already called for

enhanced (longer) sentences for repeat offenders;

therefore, many high-risk offenders were already behind

bars prior to the new law’s enactment. Secondly, the

authors conjectured that the third strike will often occur

at an age when criminal careers are on the decline,

thereby limiting the law’s impact.

Another short-term analysis of the impact of California’s

Three Strikes law indicated that major crime dropped

more sharply in the state than it did nationwide (Vitiello,

1997). In the first year of the law (1994), crime in the

state dropped by 4.9%, compared to 2% in the US as a

whole. In the second year, California's major crime rate

dropped by 7% as opposed to a 1% reduction

nationwide. While these findings are noteworthy, no

systematic attempt has been made to examine the role

played by the law as opposed to economic and

demographic factors.

Austin (1993) found that in four states with sentencing

guidelines and enhancements (Pennsylvania, Florida,

Minnesota, and Washington), the crime trends were

similar to national trends. Wichiraya (1996) examined

31 states that have implemented some sentencing

enhancements and found no significant declines in

crime rates in most of these states and even increases in

a few cases. Maxwell (1999) notes, however, that such

studies should not be interpreted as an indication of the

failure of MMS to reduce crime rates. As MMS apply to

only a fraction of those entering the justice system, they

are likely to only marginally affect crime rates. As of

August, 1998, of the 22 states adopting Three-Strikes

laws, six or less individuals had been sentenced under

these laws in eight states (Schultz, 2000). Only in

California have these laws been applied to a sizable

group of offenders. Furthermore, 85% of those

convicted under California’s law were nonviolent or

drug offenders, thereby limiting the laws ability to

prevent violent crime.

A spate of fatalities in Western Australia, stemming from

car pursuits often involving young offenders with stolen

vehicles, resulted in the enactment of the Crime (Serious

and Repeat Offenders) Sentencing Act 1992 (Broadhurst

and Loh, 1993). The most controversial aspect of the

Act was an 18-month mandatory prison term for those

convicted four times within a period of 18 months for a

violent offence or convicted seven times, with the

seventh being for a serious offence. The sentence was

both mandatory and indeterminate, as release following

the 18-month period required approval by the Supreme

Court, in the case of juveniles, and by the Governor, in

the case of adults.

The authors first provided a general critique of the Act,

arguing that it offended the principle of proportionality

by relying excessively on the offender’s criminal record,

embraced preventive detention, and adopted the

dubious strategy of selective incapacitation. Due to the

poor quality of Western Australian juvenile offending

records, the authors asserted that accurate estimates of

the number of individuals likely to be subject to the

legislation were not possible. Using South Australian

data, it was predicted that between 1.3% and 3.2% of the

juvenile population would be subject to the Actwithin 12

months of its implementation. South Australian cohort

data indicated that there was no empirical basis to the

idea that the four or seven offence threshold triggering

the legislation would capture the most persistent

offenders. Sixteen months following its

implementation, only two offenders had been sentenced

under the Act. The authors attributed its lack of

application to the vagueness of the Actregarding the

meaning of a prior offence and reluctance on the part of

key players in the justice system to enforce it. The

infrequent application of the Actmakes it unlikely that,

as enforced, it could yield a significant incapacitation

effect. Also, observed declines in car thefts and chases

around the introduction of the law were found to be

short lived and were viewed as resulting from changes in

police practices and factors other than a deterrent effect.

Morgan (2000), also in Western Australia, examined the

impact of a 12-month MMS for a third home burglary

offence. Enacted in November, 1996, the law was not

accompanied by a significant reduction in reported

home burglary offences when the pre-intervention

MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES

12 Research and Statistics Division

(1991-96) and post-intervention (1997-98) periods were

compared. Although claims have been made that just a

small proportion of those serving these MMS and

subsequently released committed a further burglary,

Morgan asserts that these claims were based on an

analysis with a very small sample (57 cases) and plagued

by other methodological flaws.

Chief Justice Rehnquist (1993) of the US Supreme Court

has observed that MMS allocate scarce prison space to

low-level criminals (e.g., the “mules” in drug trafficking)

for long periods, rather than those directing criminal

activity. Hence, the costs of these penalties are

substantial and their benefits, in terms of crime

reduction, are few.

To summarize, the evidence was mixed in terms of the

effectiveness of more general mandatory sentencing

laws such as “Three Strikes.” Some studies show modest

crime preventive effects. California’s Three Strikes

legislation has been the most extensively researched of

these initiatives. While that state experienced a sharper

decline than other states following the law’s

implementation, communities in California showed

inconsistent effects. Also, studies comparing states with

and without such a law showed no difference in their

crime trends. Reasons given for the lack of a more

pronounced effect of such sweeping laws include their

inconsistent application, the small number of

individuals to whom these laws apply, and the

possibility that the most serious and persistent offenders

already tend to be serving long sentences under existing

legislation.

5.2Mandatory Sentences for Firearm

Offences

Over half of the mandatory sentencing provisions in

Canada deal with firearms offences. These provisions

were first introduced in 1977 and have been amended

with the enactment of Bill C-68 in December, 1995.

Section 85 of the Criminal Codecalls for a one-year

minimum penalty for using a firearm during the

commission of an offence and a three-year MMS for

subsequent convictions. These penalties are to be

served consecutively to any other sanction imposed for

the primary offence. Bill C-68 introduced ten four-year

minimum sentences for serious crimes, such as

manslaughter, sexual assault, robbery, and kidnapping

(Appendix A).

Surveys of armed robbers conducted in Western

Australia suggest that gun robbers consider the threat of

punishment in general and MMS in particular (Harding,

1990). Harding found that 73% of his small sample of 15

gun robbers had actively considered the possibility of

being caught. Two-thirds of the gun robbers

interviewed stated that they thought about the

consequences of carrying a weapon and all but one said

that they knew weapon use carried a longer maximum

penalty in Western Australia. Gun robbers were more

likely to be aware of the penalties and to consider the

consequences of their crimes than were robbers not

using firearms, suggesting that such individuals might

be most responsive to MMS. Notwithstanding this

rationality, Harding found that virtually all the gun

robbers said that they would carry a gun next time they

committed a robbery. This study revealed an interesting

divergence, seen in many contexts, between perceptions

of risk and behaviour. Just as smokers may persist in

their habit despite their awareness of the risks, offenders

reflecting on the risks of using a gun may nevertheless

continue to use firearms due to habit, the sense of

security they afford, or other reasons. Thus, awareness

of penal sanctions (including MMS) is no guarantee that

offender behaviour will be modified by them.

The 1977 legislation imposing a one-year MMS for use of

a firearm during an offence was accompanied by a

decrease in the proportion of homicides and robberies

in which firearms were used (Scarff, 1983). However,

the Scarff evaluation study was fraught with a number of

methodological shortcomings and acknowledged that

there may have been a compensating increase or

displacement to homicides and robberies not involving

firearms (Gabor,1994b).

A study by Meredith, Steinke, and Palmer (1994)

assessed the application of the one-year MMS provided

for under Section 85. The study relied on data from the

Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) regarding

charges laid under Section 85 and the sentences

imposed for those convicted. The authors called for

caution in the interpretation of their findings due to a

number of limitations of the database (e.g., missing

records, under-representation of dual/hybrid and

summary offences, differing reporting practices among

police departments). The study revealed that

approximately two-thirds of the charges laid under

Section 85 were stayed, withdrawn, or dismissed. The

primary offence in half the cases was robbery and the

sentence imposed most frequently for convictions under

Section 85 was a one-year period of incarceration. The

average prison sentence imposed was 16.4 months

where the Section 85 offence was imposed consecutively

to the primary offence. In some cases, the firearms

offence was imposed concurrently to the substantive

offence. No quantitative analysis was undertaken to

determine the effect of the MMS on sentence length;

Research and Statistics Division 13

however, police, Crown prosecutors, and judges

interviewed in the study believed the effect was minimal

or none at all. The interviews also showed that there

were no written policies to guide police in laying charges

under Section 85.

In the 1970s, a number of American states enacted MMS

for firearms offences. Several studies examined the 1975

Massachusetts Bartley-Fox Amendment that provided

for a one-year MMS for illegally carrying a firearm (Beha,

1977a; Beha, 1977b; Deutsch and Alt, 1977; Pierce and

Bowers, 1990; and Rossman et al., 1980). The

assessments of the Amendment were mixed. While Beha

found little evidence of a preventive effect, Pierce and

Bowers found that homicides, gun assaults, and armed

robberies declined, but other assaults and robberies

increased – a possible substitution effect. Deutsch and

Alt's evaluation revealed a decline in robberies and

assaults committed with firearms, while failing to show

an effect for homicide. They did not explore the

possibility of a displacement to similar crimes

committed without guns. Many of these studies were

characterized by short follow-up periods (e.g., six

months). Tonry (1992) has suggested that some of

Bartley-Fox's shortcomings may have been due to the

greater selectivity of the police in their searches

following the Amendment. In addition, the Amendment

was accompanied by a major increase in the number of

firearm confiscations (without arrest), as well as in case

dismissals and acquittals. By undermining the certainty

of punishment, these factors may have jointly lessened

the effect of the law.

The Michigan Felony Firearms Statute of 1977 provided

for a two-year minimum sentence for possession of a

firearm during the commission of a felony to be served

consecutively to the primary offence. Evaluations of this

legislation revealed little evidence of a deterrent effect

(Heumann and Loftin, 1979; Loftin, Heumann and

McDowall, 1983). There was evidence that the statute

was circumvented both by increases in case dismissals

and by the tendency of the courts to undermine its

intent by imposing the same overall sentence as was the

case prior to its introduction.

McDowall, Loftin and Wiersema (1992) analyzed the

effects of MMS for firearms offences in six American

municipalities – Detroit, Jacksonville, Tampa, Miami,

Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh. Aside from undertaking

separate analyses in these cities, the authors pooled the

results from these cities to obtain an estimate of the

impact of these laws across the six jurisdictions.

According to the authors, the laws had sufficient

common elements to justify combining the data from

the six cities. Each law required judges to impose a

specific sentence for an offence involving a gun and

prohibited mitigating devices, such as suspended

sentences and parole. In addition, each of these laws

was accompanied by a major publicity campaign. The

authors compared gun and non-gun homicides,

assaults, and robberies to ascertain the impact of these

laws, using sophisticated time-series designs that

monitored the rates of these crimes from 54 to 150

months prior to each law.

The separate analyses yielded mixed results. Gun

homicides decreased in all six cities, significantly in four

and insignificantly in two. Gun assaults declined in two

cities and some effect was observed for armed robbery in

two other cities. In the pooled analysis, a very strong

effect was observed for gun homicide across the six

cities, while little change was observed for non-gun

homicide. There was no evidence that gun assaults were

prevented by the statutes and there was some evidence

that these laws may have prevented armed robberies

from increasing as non-gun robberies increased

following their enactment while gun robbery rates

remained unchanged. Thus, the MMS seemed to have a

preventive effect with regard to gun homicide and,

possibly, armed robbery. The authors acknowledge that

caution must be exercised in drawing conclusions from

this study as the cities included were not necessarily

representative of those adopting MMS for gun-related

crimes. Also, no comparisons were made with cities

without such laws to determine whether gun-related

violence declined nationally, rather than as a result of

the MMS.

An Arizona firearm sentence enhancement law enacted

in 1974 was followed by highly significant reductions in

gun robberies in two large counties, with no evidence of

displacement to other robberies or property crimes

(McPheters, Mann, and Schlagenhauf, 1984). The

authors also found no significant gun robbery reduction

in five other southwestern cities used as controls. They

nevertheless noted that the reduction might have been

due to a return of robbery rates to historical trends after

they peaked in the two years prior to the law.

Marvell and Moody (1995) conducted regression

analyses to assess the effects of firearm sentence

enhancements on prison populations and crime across

the 49 US states that have passed such laws. The study

found no consistent effect on prison populations and no

significant impact on gun homicide. There was also no

evidence of a shift to other homicides. There was little

evidence overall that other crimes were affected by these

laws. In just three of the states did these laws appear to

produce more imprisonment the year following

implementation, along with less crime and gun use.

MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES

14 Research and Statistics Division

Such analyses are confounded by many other social and

policy-related factors influencing both incarceration

rates and gun use in crime. Furthermore, the firearm

laws in the various states took many forms, making

generalizations difficult.

To summarize, MMS for firearms offences show

promise, although the findings are inconsistent or

unclear. In Canada, a major evaluation of the one-year

mandatory prison sentence for the commission of a

crime with a firearm, introduced in 1977, indicated that

a modest decrease in the proportion of homicides and

robberies involving a firearm had occurred. There was

some evidence, however, that there was a displacement

or shift to offences committed by other weapons. This

evaluation was plagued by a number of serious

methodological shortcomings that preclude more

definitive statements about the law’s impact. Another

study found that the one-year MMS has been applied

inconsistently and has not increased sentence length as

judges appear to provide a “going rate” for crimes. Thus,

judges do not appear to regard the one-year MMS as an

enhancement or add-on to the sentence imposed for the

primary offence.

In several American jurisdictions, similar laws have been

accompanied by reductions in gun homicides and/or

robberies. The most extensively researched law was

Massachusetts’ Bartley-Fox Amendment, which called

for a one-year mandatory prison term for carrying a gun

illegally. The evidence was mixed on the impact of this

Amendment on crime. It has been suggested that

adaptive behaviour by the police may have undermined

the law, as searches of suspects became more selective

and informal remedies (e.g., the confiscation of guns

without charges) became more commonplace.

An Australian study was particularly discouraging for

proponents of MMS and deterrence in general, for this

category of offender at least. Gun robbers in that study

indicated that they would continue to use firearms in

their offences despite their knowledge of mandatory

terms for criminal gun use and despite their

consideration of the consequences of their crimes.

5.3Mandatory Sentences for

Impaired Driving

In Canada, impaired driving infractions carry a

minimum penalty of 14 days for a second conviction and

90 days for any subsequent conviction. While MMS in

this area have proliferated in North America since 1980,

few evaluations have assessed them directly.

There are indications that those committing this

infraction may be sensitive to the certainty of

punishment, as police crackdowns have been quite

successful in reducing incidents of this offence

(Sherman, 1990). Furthermore, research in which

impaired driving scenarios were presented to subjects

has shown that persons who perceived that sanctions

were more certain or severe reported lower probabilities

of their engaging in the behaviour (Nagin and

Paternoster, 1993). At the same time, Taxman and

Piquero (1998) have found that treatment-oriented

sentences for impaired driving offenders may reduce

recidivism rates more than punitive sentences. For first-

time offenders, these investigators found that less

formal punishment (e.g., probation terms in which

convictions are expunged if successfully completed) was

the most effective in deterring impaired driving. In

general, isolating the effects of punishment versus

treatment is rendered difficult by the infrequency of

incapacitation for impaired drivers, as well as the fact

that punitive sanctions often include education and

treatment measures (Yu, 1994).

Nienstedt (1990) attempted to isolate the effects of a

tough law from the effects of the publicity

accompanying it using a sophisticated research design.

The law in question was enacted in Arizona in 1982 and

called for MMS, as well as a prohibition on diversion and

plea bargaining in the case of impaired driving

infractions. Five months before the enactment of the

law, major media campaigns were initiated in Phoenix

and Tucson, Arizona’s two largest cities. Aside from

advertisements in both the electronic and print media,

the media campaign generated a flurry of articles and

programs on the subject. The impaired driving initiative

was also publicized through posters, billboards,

brochures, and bumper stickers. The publicity not only

featured the legislation that was about to be introduced

but promised increased resources for traffic

enforcement. No additional resources were actually

allocated. The study revealed that the reduction of

accidents, including those involving alcohol, was much

greater following the publicity campaign than after the

enactment of the impaired driving law. Furthermore,

once the effect of the publicity was statistically

controlled, the law’s effect on accidents vanished. An

analysis of the law’s implementation showed that court

backlogs undermined the law’s prohibition of plea

bargaining, as impaired driving offences were routinely

reduced to loitering. The author concluded that

publicity campaigns may be a less costly and more

effective alternative to largely symbolic MMS.

Grasmick, Burski Jr., and Arneklev (1993) examined the

relative importance of legal sanctions and moral

Research and Statistics Division 15

prohibitions in curtailing impaired driving. They noted

that moral crusades in the 1980s, spearheaded by groups

such as MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving) and

SADD (Students Against Drunk Driving), underscored

the growing unacceptability of this activity. The

researchers randomly sampled 332 Oklahoma City

adults in 1982 and another 314 adults in 1990, probing

their level of impaired driving, the shame associated

with it, and their anticipated embarrassment if caught.

The surveys revealed a significant decrease, from 1982 to

1990, in the number of respondents who had driven

drunk in the last five years and who indicated they

would do so in the future. Anticipated feelings of shame

or remorse increased significantly. There was also an

increase in the perceived certainty and severity of legal

sanction, as well as some increase in the perceived

certainty of embarrassment. While the threat of legal

sanctions was found to be an important deterrent,

anticipated shame was determined to be the primary

deterrent.

Kenkel (1993) used data derived from the 1985 Health

Interview Survey (US) to determine whether self-

reported drinking and impaired driving patterns were

related to state laws governing these behaviours. Nearly

12,000 males and 16,000 females participated in the

survey. State laws, including MMS, were found to have a

deterrent effect upon heavy drinking and impaired

driving. States with tougher laws, more sobriety checks,

and heavier taxes in relation to alcohol were

characterized by lower levels of these behaviours.

Kingsnorth, Alvis and Gavia (1993) examined whether

increases in the severity of penalties for impaired driving

in Sacramento, California affected recidivism rates.

Over 400 cases were examined for each of three years –

1980, 1984, and 1988. In 1980, there were no written

court policies in dealing with impaired driving

infractions. In 1984, MMS were introduced, including a

combination of fines, jail time or license restriction,

probation for a first offence, and a mandatory jail

sentence and other enhancements for subsequent

convictions. In 1988, the fines, financial penalties and

other provisions became more severe than in 1984. The

authors found that recidivism rates over the ten-year

study period (1980-90) did not decline with the

increasing severity of penalties.

Yu (1994) examined the files of almost fourteen

thousand New York State drivers with an impaired

driving conviction record in order to identify the

sanctions most likely to exercise a deterrent effect. The

author found that increases in fines reduced recidivism

significantly. Yu found that license withdrawals, which

were mandatory but could vary in length, did not show

an effect on recidivism. He conjectured that license

actions imposed fewer consequences on impaired

drivers, as these measures would not necessarily prevent

them from driving. Yu further found that the celerity or

swiftness of punishment was not an important factor, as

the intervals between arrest and conviction tended to be

long. Also, he speculated that impaired driving was a

unique offence in that repeat offenders, by virtue of their

substance abuse, did not respond to swift punishment.

Grube and Kearney (1983) evaluated the impact of a

two-day mandatory jail sentence, enacted in 1979 in

Yakima County (Washington) for anyone convicted of

impaired driving. They found that alcohol involvement

in fatal accidents occurring in the county did not change

significantly following the introduction of the MMS; nor

was such involvement lower in the county than in the

state as a whole. One reason cited for the apparent

failure of the law to reduce the role of alcohol in fatal

accidents was the finding that 40% of residents were

unaware of the mandatory penalty.

Ross and Voas (1990) assessed the effects of sentence

severity on impaired driving in the neighbouring cities

of New Philadelphia and Cambridge, Ohio in May, 1985.

The cities were similar economically and

demographically. In Cambridge, impaired drivers were

dealt with more traditionally – their jail sentences rarely

exceeded the state minimum of three days and their

sentences were usually served in education-oriented

weekend camps rather than in the county jail. By

contrast, in New Philadelphia, the sole judge imposed a

“standard” jail term of 15 days, a $750 fine, and a six-

month license restriction on first offenders. Surveys

conducted in the two cities indicated that New

Philadelphia residents did perceive the certainty and

severity of penalties to be greater than in Cambridge.

Despite the differences in both actual and expected

punishments, no significant differences were found in

the levels of impaired driving in the two cities as

indicated by random breath tests. A study of court files

indicated that the re-conviction rate, too, was similar in

both cities and therefore unaffected by the harsher

penalties in New Philadelphia. The authors concluded

that increasing sentence severity did not serve as a

deterrent without a concomitant increase in the

certainty of punishment.

To summarize, the deterrent effects of MMS for

impaired driving are especially difficult to assess as

these legislative initiatives are usually accompanied by

educational campaigns. In addition, legal sanctions are

often accompanied by treatment for alcohol abuse.

Research attempting to isolate the effects of legal

sanctions has found that people are more likely to

MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES

16 Research and Statistics Division

respond to the shame associated with impaired driving

than to the threat of punishment per se, although the

level of shame is undoubtedly influenced by sanctions

and publicity campaigns. Overall, the evidence in this

area holds out more hope for vigorous law enforcement

and the certainty of punishment than for tough

sentences. Studies indicate that MMS and sanctions of

increasing severity do not reduce recidivism rates or

alcohol-related accidents. One author has noted that

impaired driving often involves substance abuse which,

in turn, cannot be adequately dealt with through

punishments alone.

5.4Mandatory Sentences for Drug

Offences

The most extreme manifestation of MMS for drug

offences can be seen in Malaysia. In 1975, the Malaysian

Parliament imposed a mandatory life sentence for drug

trafficking and, in 1983, a mandatory death penalty was

introduced for this crime (Harring, 1991). Over 200

death sentences were imposed between 1985 and 1989.

However, the conviction rate has declined by 30%

during those years and many charges are being dropped

by the police and Public Prosecutor. In many cases,

charges are being used as leverage to gain the

cooperation of defendants. Also, in 1989, appellate

judges began to reduce death sentences to life. The

judiciary has developed a number of legal devices to

spare defendants from the death sentence, including

their conviction for drug possession rather than

trafficking. The author asserts that the Malaysian

experience demonstrates the limitations of a “drug war”

model in dealing with the drug problem. Despite over

100 executions and many more death sentences

imposed, as well as more aggressive tactics by police,

drug use and trafficking remain serious social problems.

This case provides another illustration of adaptive

behaviour on the part of actors within the justice system

in circumventing a law regarded as excessively harsh,

inflexible, and overly cumbersome to enforce.

In the United States, the Anti-Drug Abuse Actsof 1986

and 1988 prescribed harsh minimum penalties at the

federal level (Spencer, 1995). In 1986, a 5 to 40-year

sentence, without probation or parole, was mandated

for first offenders convicted of possession with intent to

distribute small quantities of designated substances.

The sentence was 10 years to life for larger quantities.

The 1988 Amendments increased MMS, imposed these

sentences for even smaller quantities, and prescribed

especially tough sentences for first-time offenders

possessing crack and other cocaine-based substances.

Congressional debates revealed a view of drug offenders

as essentially non-human and as not responding to

deterrents. As a consequence, the focus of legislation

turned to long-term incapacitation. Surveys in the 1990s

indicate that illicit drug use remains at a high level in the

US – there are about 12.5 million cocaine, hallucinogen,

and heroin users annually – and many crimes continue

to be drug-related. At the same time, Spencer notes that

convictions and the length of sentences have increased

sharply for drug offenders between 1980 and 1990, while

the average length of sentences for other crimes has

decreased. In 1990, the majority of federal prisoners

serving MMS were first-time offenders. Furthermore,

many were low-level, non-violent individuals. From a

utilitarian perspective, the federal system appears to be

incarcerating the wrong people; individuals who are

easily replaced in the illicit market. Spencer argues that

low-level drug offenders may not even consider

imprisonment as punitive, due to the privations they

experience in the community.

Some of the most sophisticated research in this area has

been undertaken at the Rand Corporation (Caulkins et

al., 1997). Through various mathematical models, Rand

researchers compared the cost effectiveness of various

drug prevention/control strategies, including lengthy

MMS. Their analyses considered the cost of each

strategy and the expected yield in terms of both drug

consumption and crime reductions. Their conclusion

was that conventional sentences imposed on dealers are

more cost effective than long MMS reserved for fewer

offenders and that treating heavy users is more cost

effective than either approach in lowering drug use or

drug-related crime. MMS were found to be the most

cost effective strategy only in the case of the highest-

level dealers; however, the low thresholds at which MMS

tend to kick in means that these laws are more likely to

ensnare low-level offenders. Also, high-level dealers are

more likely to avoid MMS, as they are in a better position

to have information to trade for an exemption from

these penalties. Finally, these investigators note that the

time horizon of evaluations is critical, as MMS become

less cost effective over time.

Hansen (1999) asserts that the tide is turning against

MMS for drug infractions. He notes that they have done

little to reduce crime or to put large-scale dealers out of

business. Rather, they have filled prisons with young.

low-level, non-violent individuals at great cost to

taxpayers. Hansen points out that, in Massachusetts,

84% of inmates serving mandatory drug sentences are

first-time offenders.

Two Milwaukee field studies, involving interviews with

street gang leaders and members, shed some light on the

potential impact of severe and mandatory penalties for

Research and Statistics Division 17

drug offences (Hagedorn, 1994). These studies reveal

that gangs involved in dealing drugs are anything but a

monolith. In fact, most gang members are involved

intermittently in this activity, financial rewards tend to

be modest (one-third earned about the minimum wage),

and most of these dealers would opt for a conventional

lifestyle and work, if that option was available. Others

sell to support their habits and just a fraction of gang

members are committed to selling drugs as a career.

MMS fail to discriminate between these hardcore drug

dealers and those who feel compelled to sell due to an

addiction or difficulties encountered in participating

steadily in the work force. The implication is that

employment opportunities, more accessible drug

treatment, and alternative sentences would be

preferable to the “iron fist of the war on drugs.”

Harsh MMS and the “drug war” approach in general

show little effect in relation to drug offences. Judges

routinely circumvent the “mandatory” death sentences

for drug trafficking in Malaysia and the tough MMS in

the US have imprisoned mostly low-level, nonviolent

offenders. MMS do not appear to influence drug

consumption or drug-related crime in any measurable

way. A variety of research methods concludes that

treatment-based approaches are more cost effective

than lengthy prison terms. MMS are blunt instruments

that fail to distinguish between low and high-level, as

well as hardcore versus transient drug dealers.

Optimally, it would appear that tough sentences should

be reserved for hardcore, high-level dealers, while

treatment may be more appropriate for addicted dealers

and employment opportunities may be more cost

effective in relation to part-time dealers who are

underemployed.

5.5Estimating the Effects of

Hypothetical Mandatory

Sentences

Brown (1998) assessed the potential impact of MMS

through an analysis of the characteristics of a national

sample of 613 offenders released from New Zealand

prisons during 1986. These offenders had been either

released halfway through their sentences on parole or at

two-thirds of sentence on remission. A subsequent two

and one-half year follow-up suggested that the marginal

incapacitation effects of additional confinement during

the post-release period would have been modest. Just

five percent of the sample were convicted for a serious

offence during the follow-up period. Furthermore,

three-quarters of these individuals had been imprisoned

for non-violent offences – offences that would not have

predicted the serious offences of those who did

recidivate nor have warranted additional confinement.

In Franklin County, Ohio, investigators studied the

criminal records of 342 individuals arrested for violent

felonies in 1973 to determine whether that offence could

have been prevented by a five-year MMS for a previous

juvenile or adult felony conviction (Van Dine, Dinitz,

and Conrad, 1979). Over half of these offenders were

found to have no previous felony conviction. According

to the authors’ calculations, a five-year MMS imposed

for violent felonies in the five years leading up to 1973

would have reduced the 1973 felony rate in the county

by just 1% to 4%. A re-calculation of the figures, using

more generous assumptions, yielded a 15% reduction in

the felony rate (Boland, 1978). The Ohio study

underscored the notion that, each year, many new

offenders come to the attention of the justice system. In

Michigan, Johnson (1978) further found that only about

24% of those arrested for violent offences had a previous

violent felony conviction. Harsh incapacitation policies

would be most effective where most crime was confined

to a relatively small and specialized (e.g., exclusively

violent) offender group.

In a Swedish study of all persons born in 1953 and living

in the Stockholm area in 1963, Andersson (1993)

estimated the crime preventive effect that would be

achieved if a two-year MMS was imposed for anysecond

criminal offence. He concluded that 28% of all

sentences for crimes would be prevented, while the

prison population would increase by 500%. Such a

policy would bring Sweden near the top of the list of

nations in terms of its per capita prison population

(Mathiesen, 1998). Furthermore, Mathiesen contends

that the preventive effect would be far more modest as

Andersson’s calculation fails to account for undetected

offenders, the substitution of prevented crimes by

others, the adverse effects of incarceration on post-

release behaviour, and the entry into crime by new

cohorts of offenders.

One major concern with MMS based exclusively on the

commission of a set number of designated offences (i.e.,

collective incapacitation) is that they are applied to

individuals across the entire risk spectrum. Hence, false

positives, the false assumption that those receiving such

penalties will repeat their crimes if not incarcerated,

tend to be problematic. Even if we accept Andersson’s

very liberal estimates of crime preventive gains from

blanket MMS for all second offenders, a 28% reduction

in known crimes would require a five-fold increase of

Sweden's prison population – an increase from 5,200 to

26,000 inmates. Many low risk offenders would be

MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES

18 Research and Statistics Division

ensnared in the web of such sweeping legislation,

exacting a massive economic and human toll.

The inefficiency and costs seemingly associated with

collective incapacitation strategies have led

investigators to project the preventive effects of

sentencing strategies that would consider individual risk

factors. A subsequent study by Andersson revealed that

if a MMS was also imposed on the basis of criminal

history and prior drug use/offence data, 44.5% of those