%0-"=)41<)<1>-#-87:<%0-"=)41<)<1>-#-87:<

'74=5- =5*-: 7?%7:<1+4-

"=)41<)<1>-)<)6)4A;1;.7:-)4<0#-;-):+0$<-8*A$<-8"=)41<)<1>-)<)6)4A;1;.7:-)4<0#-;-):+0$<-8*A$<-8

@)584-7.!0-675-6747/1+)46<-:8:-<)<176@)584-7.!0-675-6747/1+)46<-:8:-<)<176

$=-76):7

&61>-:;1<A7.$A,6-A=;<:)41)

;=-576):70-)4<06;?/7>)=

)61+-=441+3

&61>-:;1<A7.$A,6-A=;<:)41)

2)61+-/=441+3;A,6-A-,=)=

$)6,:)(-;<

&61>-:;1<A7.$A,6-A=;<:)41)

;0?-;</5)14+75

7447?<01;)6,),,1<176)4?7:3;)<0<<8;6;=?7:3;67>)-,=<9:

!):<7.<0-):,17>);+=4):1;-);-;75576;-:1)<:1+ =:;16/75576;"=)6<1<)<1>-"=)41<)<1>-

758):)<1>-)6,1;<7:1+)4-<07,747/1-;75576;)6,<0-$7+1)4$<)<1;<1+;75576;

#-+755-6,-,!1<)<176#-+755-6,-,!1<)<176

76):7$=441+3(-;<$"=)41<)<1>-)<)6)4A;1;.7:-)4<0#-;-):+0$<-8*A$<-8

@)584-7.!0-675-6747/1+)46<-:8:-<)<176

%0-"=)41<)<1>-#-87:<

0<<8;,717:/

%01;7?%7:<1+4-1;*:7=/0<<7A7=.7:.:--)6,78-6)++-;;*A<0-%0-"=)41<)<1>-#-87:<)< $&(7:3;<0);

*--6)++-8<-,.7:16+4=;17616%0-"=)41<)<1>-#-87:<*A)6)=<07:1B-,),5161;<:)<7:7. $&(7:3;7:57:-

16.7:5)<17684-);-+76<)+<6;=?7:3;67>)-,=

"=)41<)<1>-)<)6)4A;1;.7:-)4<0#-;-):+0$<-8*A$<-8@)584-7."=)41<)<1>-)<)6)4A;1;.7:-)4<0#-;-):+0$<-8*A$<-8@)584-7.

!0-675-6747/1+)46<-:8:-<)<176!0-675-6747/1+)46<-:8:-<)<176

*;<:)+<*;<:)+<

!0-675-6747/1+)4;<=,1-;0)>-*--6+:1<19=-,?0-6)6)4A<1+)+<1>1<1-;)6,16<-:;-+<176?1<0<0-

=6,-:816616/80147;780A4)+3+4):1<A%01;5-<07,747/1+)4,1;+=;;1768)8-:,-;+:1*-;,)<))6)4A;1;16

0-:5-6-=<1+16<-:8:-<1>-80-675-6747/A)<)5)6)/-5-6<;<:)<-/1-;<:)6;+:18<8:-8):)<176+7,16/

80147;780A)8841+)<176<)*416/+76+-8<5)8;)6,1+:7;7.<(7:,)6,,)<))6)4A;1;8:7+-;;-;

:-,=+<176,1;84)A)6,+76+4=;176,:)?16/>-:1C+)<176):-144=;<:)<-,-+76;<:=+<176:-+76;<:=+<176

)6,:-7:/)61;)<1767.<0-5-;;=*<0-5-;=;16/01-:):+01+)40-),16/;<A4-;<7878=4)<-<0-6)>1/)<176

8)6-)6,80147;7801+)4<-6-<;)+<-,);)6)4A<1+0773;%01;8)8-:0);7=<416-,,)<))6)4A;1;16

0-:5-6-=<1+16<-:8:-<1>-80-675-6747/A16+4=,16/<0-=;-7.$(7:,)6,1<;.=6+<176)41<A?01+0?);

;=887:<-,*A7<0-:,)<),1;84)A;<:)<-/1-;<7-60)6+-,)<)>1;=)41;)<176)6,>-:1C+)<176%-+0619=-;

,-;+:1*-,):-<:)6;.-::)*4-<77<0-:9=)41<)<1>-5-<07,747/1-;

-A?7:,;-A?7:,;

9=)41<)<1>-:-;-):+080-675-6747/1+)416<-:8:-<)<1760-:5-6-=<1+;:1/7=:

:-)<1>-75576;1+-6;-:-)<1>-75576;1+-6;-

%01;?7:31;41+-6;-,=6,-:):-)<1>-75576;<<:1*=<176 76+755-:+1)4$0):-413-6<-:6)<176)4

1+-6;-

%01;07?<7):<1+4-1;)>)14)*4-16%0-"=)41<)<1>-#-87:<0<<8;6;=?7:3;67>)-,=<9:>741;;

The Qualitative Report 2022 Volume 27, Number 4, 1040-1057

https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5249

Qualitative Data Analysis for Health Research:

A Step-by-Step Example of Phenomenological Interpretation

Sue Monaro

1, 2

, Janice Gullick

2

, and Sandra West

2

1

Department of Vascular Surgery, Concord Repatriation General Hospital, Sydney, Australia

2

Susan Wakil School of Nursing & Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine and Health,

University of Sydney, Australia

Phenomenological studies have been critiqued when analytic activities and

intersection with the underpinning philosophy lack clarity. This methodological

discussion paper describes data analysis in hermeneutic interpretive

phenomenology. Data management strategies (transcript preparation, coding,

philosophy application, tabling/concept maps, and Microsoft Word) and data

analysis processes (reduction, display, and conclusion drawing/verification) are

illustrated. Deconstruction, reconstruction, and reorganisation of

themes/subthemes using hierarchical heading styles to populate the navigation

pane and philosophical tenets acted as analytic hooks. This paper has outlined

data analysis in hermeneutic interpretive phenomenology, including the use of

MS Word and its functionality, which was supported by other data display

strategies to enhance data visualisation and verification. Techniques described

are transferrable to other qualitative methodologies.

Keywords: qualitative research, phenomenological interpretation,

hermeneutics, rigour

Aim

This paper aims to provide examples of data analysis strategies in hermeneutic

interpretive phenomenological research to inform clinical knowledge and practice. There are

few published examples of step-by-step analytical processes within the methodological

literature for interpretative phenomenology. The described examples are grounded in concepts

shared across qualitative methodologies yet are focussed on activities and assumptions

congruent with the phenomenological tradition.

Background

Clinical researchers are increasingly using qualitative research as a way to access

understanding of complex illness experiences. There is an expanding range of qualitative

methodologies with variation in their techniques, complexities, and acceptability. These

methodologies typically generate large volumes of data and researchers often struggle to

describe the granular detail of their data analysis. The process and reporting of data analysis

must be rigorous if findings are to be publishable and considered a trustworthy basis for clinical

practice/systems improvement. The overarching methodological approaches to primary

qualitative research continue to be distinguishable as either descriptive or interpretative.

Descriptive qualitative research, where the research is not necessarily grounded within

a particular philosophy or prescriptive methodology, includes both thematic analysis (e.g.,

Miles & Huberman, 1984), and qualitative content analysis (e.g., Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). While

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1041

it is necessary to give an account of the analytic lens used to examine the data (Caelli et al.,

2003), for example, detailing the theoretical or discipline-based assumptions about the

phenomenon of interest that may be drawn from literature (Sandelowski, 2010), the researcher

then tends to stay closer to the data (Sandelowski, 2000) using lower inference interpretation

to describe common experiences. However, even in thematic description some level of

abstraction is required to establish such themes, along with a need to describe the personal

positioning of the researcher (their personal history, presuppositions and motives) that may

influence interpretation (Jootun et al., 2009).

Interpretative qualitative research (including the theory-building methodology of

Grounded Theory) uses methodologies that harness a theory or philosophy congruent with the

research paradigm to provide a vehicle for the abstraction of data; for example, the application

of symbolic interactionism within Grounded Theory or the existential philosophies of Merleau-

Ponty (1945/1962) or Heidegger (1927/1996) within phenomenology. Given that a theoretical

or philosophical lens establishes assumptions about how a phenomenon will be explored and

influences the types of questions we ask of participants, theory and philosophy are ideally

incorporated at the outset of a study. As analytical tools, philosophy and theory can also be

used as either a deductive analytic framework (Gullick et al., 2020) or to refine and reframe

the understanding of inductively derived themes (Gullick, Monaro, & Stewart, 2016; Sheils,

Mason, & Gullick, 2019) and can even be employed retrospectively to help the researcher

explain patterns emerging from data.

The debate about phenomenological research persists to some extent because of the

frequently weak published descriptions of the analytical approach used in phenomenology and

the often-cursory attention paid to the philosophical lens claimed by authors (Gullick & West,

2019, Paley, 2005, 2018). To assist, scholars such as Benner (1994) and van Manen (2016)

have suggested steps in the interpretive phenomenological research process. Both offer

simplified structures of philosophical thought in their seminal texts; for example, Benner

(1994) republished Victoria Leonard’s 1989 “Heideggerian phenomenological perspective on

the concept of a person” to provide a simplified overview, while van Manen’s existential

domains of corporeality, spatiality, temporality, and relationality capture and simplify

important elements of existentialist thought. Benner suggests identification of a “paradigm

case” where a strong example of a certain way of being-in-the-world is identified, then used as

a comparator to other cases through a thematic analysis. These methods have the benefit of

practicality for novice researchers yet their application in nursing research is often reductionist.

Smith et al. (2009) also provide a six-step approach to the method known as IPA (Interpretive

Phenomenological Analysis), but this has been vigorously criticised in scholarly discourse,

refuting its place as an interpretative/hermeneutic method (Giorgi, 2011; Paley, 2016). One

critique is that Smith et al.’s work seeks a psychological understanding of a particular person’s

life experiences, and so differs vastly from the existential analysis that philosophically-based

interpretive phenomenology offers in understanding the fundamental nature of human

situations (van Manen, 2018).

Philosophy forms the basis for sound interpretive phenomenology and ideally, the

philosopher is chosen to align to the research problem. Heidegger (1927/1996), for example,

explores one’s embeddedness in-the-world alongside others and his temporal understanding of

the world is framed by a sense of finitude. Merleau-Ponty (1962) offers an analysis of

experience as “embodied” and so is useful to researchers of illness and injury. Gadamer (1960)

“Truth and Method,” is another frequently used framing for phenomenology with a focus on

language as a means to cocreate meaning in a fusion of horizons between the researcher and

the researched. Published descriptions of the techniques and strategies needed to conduct and

analyse interpretive phenomenology are often lacking in granular detail – perhaps because

specific strategies are frequently shaped by the particulars of a project and its data. Core

1042 The Qualitative Report 2022

concepts in phenomenological nursing research have been well illustrated (Tuohy et al., 2013).

Mackey (2005) established the importance of the philosophical and methodological

foundations on which the method is built. Others have explored the ties between the operational

elements of an interpretive phenomenological study and the philosophical tradition (Frechette

et al. 2020).

As interpretive phenomenology is widely used but difficult to learn and teach, the aim

of this methodological discussion paper is to describe one research team’s application of

interpretive phenomenology using an existential philosophical lens. Papers such as this, which

provide more detailed descriptions of analytical processes, may assist clinical researchers using

phenomenology in finding a way through the analytic maze to become more systematic and

transparent about their methods.

Method

This methodological discussion, used as a vehicle in an interpretive phenomenological

project that explored patient and family experiences of decision-making in the face of major

amputation; a complex phenomenological analysis of a large data set reported within a doctoral

thesis (Monaro, 2018). The authors have clinical backgrounds in acute care nursing. The

doctoral student and advanced practice nurse (SM) and nurse academic supervisors (SW and

JG) have expertise in the application of qualitative methods, and more specifically interpretive

phenomenology, to understand the lived experience of illness. They have a particular interest

in progressing the practical application of Heideggerian phenomenology to health research in

ways that promote both philosophical and methodological integrity.

The granular techniques developed are not the only possible approach but provide some

strategies to tackle phenomenological analysis. While the research steps within a qualitative

project should be driven by the methodology, ethical considerations and the practicalities of

generating data about a phenomenon, Miles and Huberman’s “concurrent flows of activity”

provide a useful structure for the organisation of our discussion of methods in this paper (1984,

p. 21). Their seminal text describes process domains of data reduction, data display, and

conclusion drawing/verification that can be applied across a range of qualitative methodologies

and collectively contribute to a researcher’s analytic choices. While later versions of this text

have been published (Miles et al., 2014, 2019) and expand on thematic analytic method, these

were not used pre-emptively as an analytic tool for this phenomenological study. The original

1984 version provided a simple organising structure as a vehicle for this present discussion.

An overview of these “concurrent flows of activity” applicable to all qualitative methods

provide a foundation for our later granular explanation.

Concurrent flows of activity in all qualitative research

Data reduction

Data reduction is a continuous process extending from establishing the research design

(i.e., deciding what framework to use and what research questions to ask), through to the

transformation of findings into publication. Data reduction processes include determining

which chunks of data to code through initial allocation of a label to organise data, identifying

and choosing to explore patterns between data elements, and processes of simplifying,

summarising, and focussing interrogations of the data. These multiple reductive processes

support the emerging development and critical interrogation of themes that contribute to

understanding (Miles & Huberman, 1984).

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1043

Data display

Data display refers to the ways in which data are organised into forms that are more

compact and accessible so the researcher can see patterns in the data and then can either draw

clear, justifiable conclusions or be guided by the data display towards further analytic steps

(Miles & Huberman, 1984). Data display, which may take the form of coding trees, mind maps

(paper-based or digital), cardboard index cards, tables, diagrams, and/or text with headings and

subheadings, is understood as a key element and indeed a cornerstone to rigorous analysis.

Qualitative research software programmes are designed to support analyses by

providing tools for data organisation and display. Software packages offer benefits (e.g., easy

filing and coding of large data sets and storage of references and memos), yet there are also

limitations for phenomenology (Goble et al., 2012). There has long been concern that when

using software, researchers may be seduced by the prioritisation of coding and conflate

achieving a fully-coded data set with completion of analysis (Bong, 2002; Goble et al., 2012).

The use of software should therefore be guided by the research questions and the chosen

theoretical/philosophical framework (Jackson & Bazely, 2019). Similarly, it should be

recognised that not all methodologies follow the same analytic patterns, which necessarily

shape researcher interaction with the data (Atherton & Elsmore, 2007). Additionally, in

interpretive qualitative methods where analytical uncertainty is a necessary stage of researcher

reflexivity, the lure of a simplified structuring of data may provide a false certainty about

interpretation.

Methodologies with highly systematic analytic processes such as Grounded Theory

may lend themselves to data management software. However, in approaches such as

interpretive phenomenology, it may de-emphasise the importance of writing and rewriting as a

priority for a developing philosophical explanation (van Manen, 2003). There is also a danger

of software fragmenting the data and increasing the risk of data elements being concealed so

that possible links with other data elements are hidden during phenomenological interpretation

(Goble et al. 2012). We argue here though, that there may be advantages to using simple data

display technologies that allow a methodical way of organising and visualising emerging ideas,

particularly for large, complex data sets.

Conclusion drawing and Verification

Conclusion drawing includes determination of early conclusions (hopefully held lightly

and sceptically) that are then either refuted or developed into increasingly explicit and

grounded understandings (Miles & Huberman, 1984). These conclusions may lead to further

reframing/sampling, changing direction in analytic thinking, or, finally, proposing a rich and

thick (Dibley, 2011) comprehensive description or interpretation of findings.

Verification may take the form of revisiting field notes/interview transcripts to check a

point made, through to lengthy review between colleagues to argue for or against elements of

the interpretation (Miles & Huberman, 1984). Member checking (where conclusions are

presented to participants to confirm the validity of findings) is a feature of some methodologies

for example, Collaizi’s descriptive phenomenology (Collaizi, 1978, p. 6), but has been

challenged as both impractical and problematic if a participant does not recognise their

individual experience in an abstracted, theorised synthesis of participant experiences (Morse,

2015). Member checking is not a feature of interpretive phenomenology, although in a

longitudinal study there is an opportunity to seek clarification or accuracy of wording within a

transcript from an individual participant or explore how a developing understanding of the

experiences of others resonates with an individual participant. This need to consider the fit of

member checking with the study’s epistemological stance is important (Birt et al., 2016), and

1044 The Qualitative Report 2022

its application to synthesised, analysed data in interpretive phenomenology is argued to be

redundant and inconsistent with, for example, Heideggerian philosophy (McConnell-Henry et

al., 2011).

Most qualitative approaches have published criteria for rigour that guide method-

specific strategies for data verification – for example, Elo et al.’s (2014) “Focus on

trustworthiness” in qualitative content analysis, or the de Witt and Ploeg (2006) framework for

rigour in interpretive phenomenological nursing research.

Analysing a hermeneutic phenomenological study: An example of an analytical process

Hermeneutics is a method and theory of interpretation of written records that can be

traced back to the writings of Aristotle. Hermeneutic interpretation was fleshed out in the early

1800s by Ast (Dilthey, 1976) as an iterative movement between the “parts” (e.g., small

segments of data, or elements relating to an individual) and the “whole” (e.g., data from across

a whole sample or elements of greater context such as one’s society and culture).

The hermeneutic phenomenological study that provides the vehicle for this paper

explored 19 cases of critical limb-threatening ischaemia (CLTI) by analysing semi-structured

interview data from 14 people with CLTI and 13 family members who were making decisions

about major amputation (Monaro, 2018; Monaro, Gullick, & West, 2019; Monaro, West, &

Gullick, 2021)). Heidegger’s (1927/1996) articulation of the “parts” and the “whole” from an

existential philosophical perspective requires application of his existentials; moving back and

forth between a person’s Being (for example, being-with-others, spatiality, temporality, being-

towards death) and what is being asked about Being (e.g., our study of an illness experience).

The use of these existential philosophical domains in providing “analytic hooks” in

phenomenology have been described in detail (Gullick & West, 2019; Gullick et al., 2020).

Due to Heidegger’s relative neglect of the body (Aho, 2010), the philosophy of

Heidegger (1927/1996) (exploring one’s being-in-the-world) was complemented by the

philosophy of Merleau-Ponty (1968) (exploring the intertwining physical and existential body),

which provided a different analytic lens to uncover the embodied disruption of CLTI (Monaro,

Gullick, & West, 2019). The developing interpretation then explored the making of decisions

about amputation in a changed body and the subsequent relationship to “Being,” situated in a

familial, relational, social, and cultural context.

We have used Miles and Huberman’s (1984) concurrent flows of activity: data

reduction, data visualisation, drawing conclusions, and verification in the following sections,

where we attempt to describe these mechanics of analysis in detail. We note that, in reality, the

steps described sometimes cross these artificial boundaries and the activities are iterative in

nature and commonly grow in complexity over the life of the study.

Reducing Data

The research problem, identified through practical experience and a critical review of

the literature, initially encompassed broader patient experiences of CLTI but directed the

inquiry towards making subsequent decisions about amputation. Decisions were made about

inclusion/exclusion criteria to guide purposive sampling of patients and their significant others

and the timing of and rationale for longitudinal interviews. An interview guide focused on these

conversational style encounters to elicit narratives that unveiled an ontological understanding

of the body with CLTI in the face of its tasks.

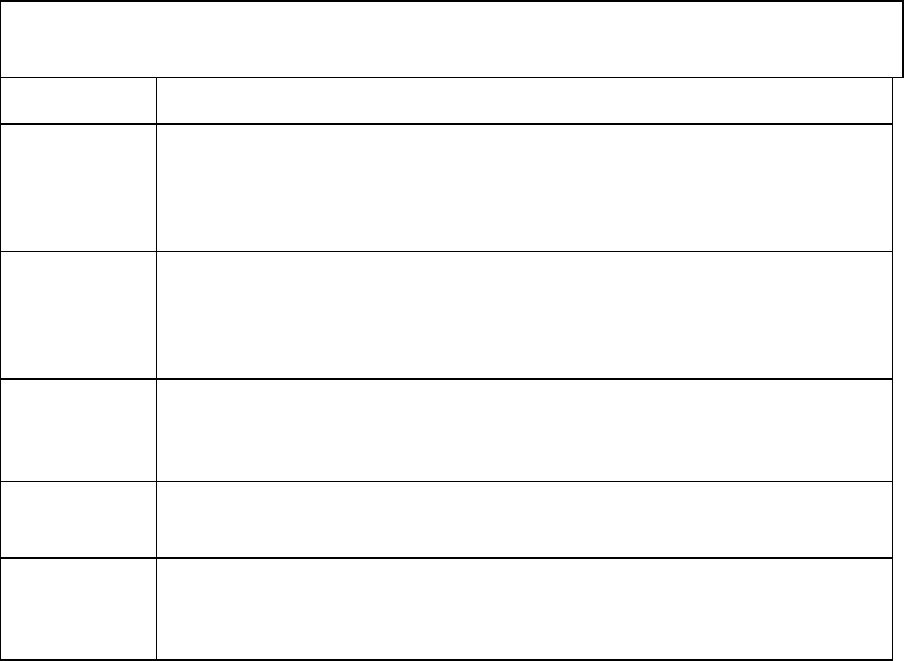

Data analysis commenced with reading and screening verbatim transcripts that had been

formatted for data tracking (Table 1), and immediate ideas about small parts of data were

captured by highlighting any words, phrases, and sentences of interest with handwritten notes.

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1045

Data were reduced by collecting text with similar initial codes and clumping these using early

category and subcategory labels. All data considered in any way relevant were coded, while

parts of the story that were unrelated to the experience and its broader context were put aside

(for example, initial ice-breaking conversations about the weather). Data were then cleaned,

with repetitions and mis-starts removed without changing the meaning/nuance of the data.

Superior exemplars were selected, duplicate quotes deleted, and a narrative style interpretation

woven through to include interpretive philosophical touchpoints. A version of the initial coded

data was retained so that a sense of “saturation” of themes could be revisited and reported.

Table 1

Data Management - *Transcript preparation

1. Verbatim transcription of digital voice file to a Microsoft Word file with transcript marked by

line numbers and participant responses designated by individual codes to link participant to

exemplar

2. Transcript checked against the digital voice file for accuracy and notation of non-verbal

communication, which was inserted in parentheses

3. Where the subject had referred to an object or concept by “it” or “thing,” the object or concept

was specified in parentheses

4. Where the subject had referred to another person as “they” or “them” or had used the person’s

name, the person was specified by inserting their relationship to the subject in parentheses

5. Gender-specific references, e.g., “her” and “she” to surgeons, changed to masculine because of

the possibility of identification of individual surgeons due to the low number of female vascular

surgeons

6. Redundant or repeated words and phrases deleted if they did not add meaning or emphasis, e.g.,

“um”, “you know,” “ah.”

Much of this early data coding was clinically oriented (reflecting the naïve

understanding of the novice clinician-researcher), and an effort was then made to use language

more relevant to the philosophical touchpoints and the patient and family experience. Van

Manen’s (1997) four domains of corporeality, temporality, relationality and spatiality were

useful as an entree to philosophical thinking. They functioned as deductive analytical “hooks,”

allowing initial inductively coded data to be more selectively organised into data blocks. The

main document containing blocks of data was separated into four Word files, one for each of

van Manen’s domains, making these sections less unwieldly to work with.

As the doctoral student became increasingly sensitised to this phenomenological

theming, Victoria Leonard's (1989) work: “A Heideggerian phenomenological perspective on

the concept of the person,” was used to assist with deeper conceptual application and language

for a novice philosophical researcher. The data was further reduced using this framework which

loosely organises substantive Heideggerian concepts.

As the researchers began to immerse themselves into the primary philosophical texts of

Merleau-Ponty and Heidegger and their understanding grew, the further reduction of the

existentially-derived data blocks (see van Manen, 2003, then Leonard, 1989) were rescreened

by reviewing words, phrases and quotes as the specificity of the philosophical lens was

increased. This allowed additional reduction into philosophically-derived foci that captured

and targeted both Merleau-Ponty’s (1945/1962, 1968) and Heidegger’s (1927/1996) important

philosophical ideas.

The work of analytic reduction therefore involved a backwards and forwards approach

that saw both a deconstruction of the texts and their situated meanings and then reconstruction

through a philosophically-derived interpretation that reflected the lived experience of the

individual against a larger, contextual historical/cultural perspective (Rescher, 1997). The list

1046 The Qualitative Report 2022

of philosophically-derived themes was continually interrogated, extended, collapsed and

intellectually challenged until they were reduced to a refined yet cohesive and interlinked set

of explanatory themes. Table 2 provides a detailed outline of these steps illustrated by examples

from the study and linking of the analysis process with de Witt and Ploeg’s (2006) criteria for

rigour. In the final phase of data reduction, we decided which findings would be included in

the thesis and which might sit outside of that dissertation for separate publication.

Table 2

Data Analysis - Interpretative processes and steps

Process

Steps and Examples from study

Stage 1: Initial data reduction of individual transcripts

A.

Coding prepared transcripts

for points of immediate

interest.

Label identified points in transcript with “sticky”/

handwritten notes.

B.

Collating early meanings

with attention to individual

contexts (conclusion

drawing & data

verification).

Separate Word file with exemplars of early inductive

meanings cut & pasted under category headings.

Exemplars labelled with participant code & line

number to ensure traceability (verification).

C.

Document early analytical

thinking (conclusion

drawing).

Writing a description of initial analytical thinking

using explanatory text to provide both context &

background for exemplars (conclusion drawing).

Stage 2: Initial application of the philosophical lens

A.

Seeking ways to organise &

visualise data categorised

under philosophical concepts

of interest (data reduction

& display).

Began constructing a table of analytical ideas from all

transcripts & aligning with Merleau-Ponty (MP) &

Heideggerian (H) concepts. Large data volume was

difficult to manage & the table approach was

discontinued.

Use of qualitative software considered but decided

against due to concern about fragmentation & loss of

visibility of the large volume of data.

B.

Organise selected data by

analytical “hooks”

(philosophically derived

foci) (data reduction &

data display).

Create a separate Word file for each the van Manen’s

(1997) four existentials as these capture important

philosophical ideas/domains of MP & H:

Corporeality, temporality, relationality, spatiality

(analytic hooks).

C.

Use the conceptual framing

of Victoria Leonard (1989)

as an entrée to Heideggerian

philosophy.

Rework data using the framework: The person as

having a world / The person as a being for whom

things have significance & value / The person as self-

interpreting / The person as embodied /The person in

time.

D.

Use of specific MP or H

philosophical lenses to

rescreen within the above

data blocks (data reduction

& verification).

Review words, phrases & quotes using an MP & H

philosophical lens – Data associated with changes to

the body were explored through MP, while the

remainder of data were explored through an H lens.

Stage 3: Emergence & extension of an analytical structure

A.

Use multiple hierarchical

levels of headings of Word

navigation pane tool to

develop a philosophically

guided sense &

The emergence of nine parts of the experience:

Creeping decay (MP), Unclear boundaries of the body

(MP), Changed boundaries of the body (MP) & space

for living (H), Being towards death (H), No choice

(H), Delay as a deficient mode of concern (H),

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1047

understanding of the whole

& parts of the data (see

Figure 1) (data display).

Turning point/clearing (H), Difficulty with open

conversations (H), & Being alongside (H) in a world

of amputation.

B.

Re-check of all transcripts

using new key ideas to locate

any overlooked data (data

verification).

Overlooked data assigned to part(s).

C.

Develop a written narrative

to (a) explain, expand &

refine each area identified &

(b) establish concreteness of

emerging findings (De Witt

& Ploeg 2006) (conclusion

drawing & data reduction).

(a) Word file with the navigation pane selected from

the “View” tab allowed data visualisation of themes

(headings) & sub themes (levels of subheadings) to

organise meaningful units of analysis in the findings

section.

(b) Include participant’s context (e.g., significant

other, living environment, disease trajectory) at the

start of each participant exemplar as part of the

“whole” against which an exemplar (a part) could be

examined (Figure 1).

Stage 4: Challenging analytical thinking & data organisation

A

Support the criterion of

openness (de Witt & Ploeg

2006) by using mind

mapping of areas to

challenge current thinking &

explore analytical links

between key thematic blocks

(data display).

Hand drawn mind maps and schematics make visible

the important stages of thinking & analysis (Figure 3).

Process

Steps and examples from the study

B.

Reorganise initial ordering of

data according to philosopher

etc., re-order & regroup data

to enhance linkages & allow

a more

temporally/chronologically

coherent narrative (data

reduction, conclusion

drawing). Sections may

either expand or collapse,

changing the number of

themes.

Reduced data into seven sections: The body with

CLTI, Being-towards-death, Talking about CLTI,

Making decisions about CLTI, Being alongside, The

changed body & space for living, & The chaos of

hospitalisation.

Further development of the narrative to connect the

philosophical interpretation to exemplars &

participant contexts.

C

Link related areas to form

consolidated blocks (data

reduction).

Consolidation of the experience of CLTI: including:

1. The body with CLTI & Being-towards-death.

2. Dealing with CLTI: including Talking about CLTI

& Making decisions about CLTI.

3. The experience of major amputation: including

Being alongside, The changed body & space for

living & The chaos of hospitalisation.

D.

Compare original analysis

document against refined

analysis to ensure no loss or

overlooking of key findings

during data reduction (data

verification).

Returned to original analysis document that used van

Manen’s four existential concepts & checked against

the subheadings (in navigation plan) to re-check for

any unintentionally omitted data.

Stage 5: Deeper refinement of analysis

1048 The Qualitative Report 2022

A.

Extract/separate findings

outside of current decision-

making interests (a

phenomenon of interest &

focus of research problem).

Parts extracted for possible later publication: (1)

Recovery & rehabilitation (2) Chaos of

hospitalisation.

B.

Look for negative cases &/or

outliers across themes, an

established criterion for

rigour (Benner) (data

verification).

To acknowledge the multiple truths accepted within

an interpretive paradigm & to draw links between the

contexts that underpin diverse cases.

C.

Linking of thematic parts,

i.e., extremes of diverse

findings that may exist along

a continuum (conclusion

drawing).

Linking of parts, e.g., talking about CLTI versus

retreating to silence.

D.

Reorganising & re-titling

parts (data reduction).

The final four parts related to decision-making: (1)

Embodied CLTI (2) Being towards death (3) Being-

with (4) Turning – these became separate findings

chapters in the thesis.

Stage 6: Preparing final documentation of the research for dissemination

A.

De-identification (data

display).

Linking: 1) Pseudonyms (linked patient & family

participants allocated pseudonyms paired with

matching letters to assist the reader (e.g., Mel &

Michael). Unique stories that could reveal participant

identity considered.

B.

Final rewriting & analysis

(data reduction, display &

conclusion drawing).

Simultaneously using the navigation pane to view

parts against the whole. Automatically generated table

of contents (using heading function in Word) to view

the whole.

C.

Congruence with further

criteria for rigour in

interpretive phenomenology

(de Witt & Ploeg (2006), see

Table 3)

(data verification)

Consolidated criteria for

Reporting Qualitative

research (COREQ) used to

report in thesis and other

publications (data

verification).

Activities informed by De Witt & Ploeg (2006) -

rereading to ensure a balance between the

philosophical interpretation & the participants’

voices. The interweaving of the philosophy with the

findings: Provision of verbatim quotes from the

existential philosophical texts (MP & H) supported

the interpretation. Further grounding of the

interpretation through carefully paraphrased concepts

from the philosophical texts to make the ideas

accessible to readers who are not conversant with the

dense philosophies used. This paraphrasing also

challenges the researcher to question the depth of

their understanding. Ensuring upon final reading by

the research team, that all interpretative meanings

generated resonates & is supported by exemplars.

COREQ (Tong et al., 2007) – Specific criteria within

the domains of Research team & reflexivity; Study

design; and Analysis and findings either reported or

exclusions justified with references. COREQ

Checklist appended to thesis.

D

Actualisation – looking for

further realisation of the

resonance of the study

findings (data verification).

Dissemination of findings through conferences &

research publications: feedback from conference

attendees & peer-reviewers of manuscripts compels

the researcher to re-examine & make further

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1049

refinements to the interpretation before publication

&/or thesis examination.

Displaying Data

Seeking ways to organise and display data categorised under philosophical concepts of

interest, we began to visualise data by constructing a table in Microsoft Word. However, due

to the volume of textual data from the study’s 42 interviews, this tabling became a difficult

format to manage and was aborted. The possibility of using qualitative software was considered

but not pursued due to concerns about fragmentation and the loss of visibility of the large

volume of data.

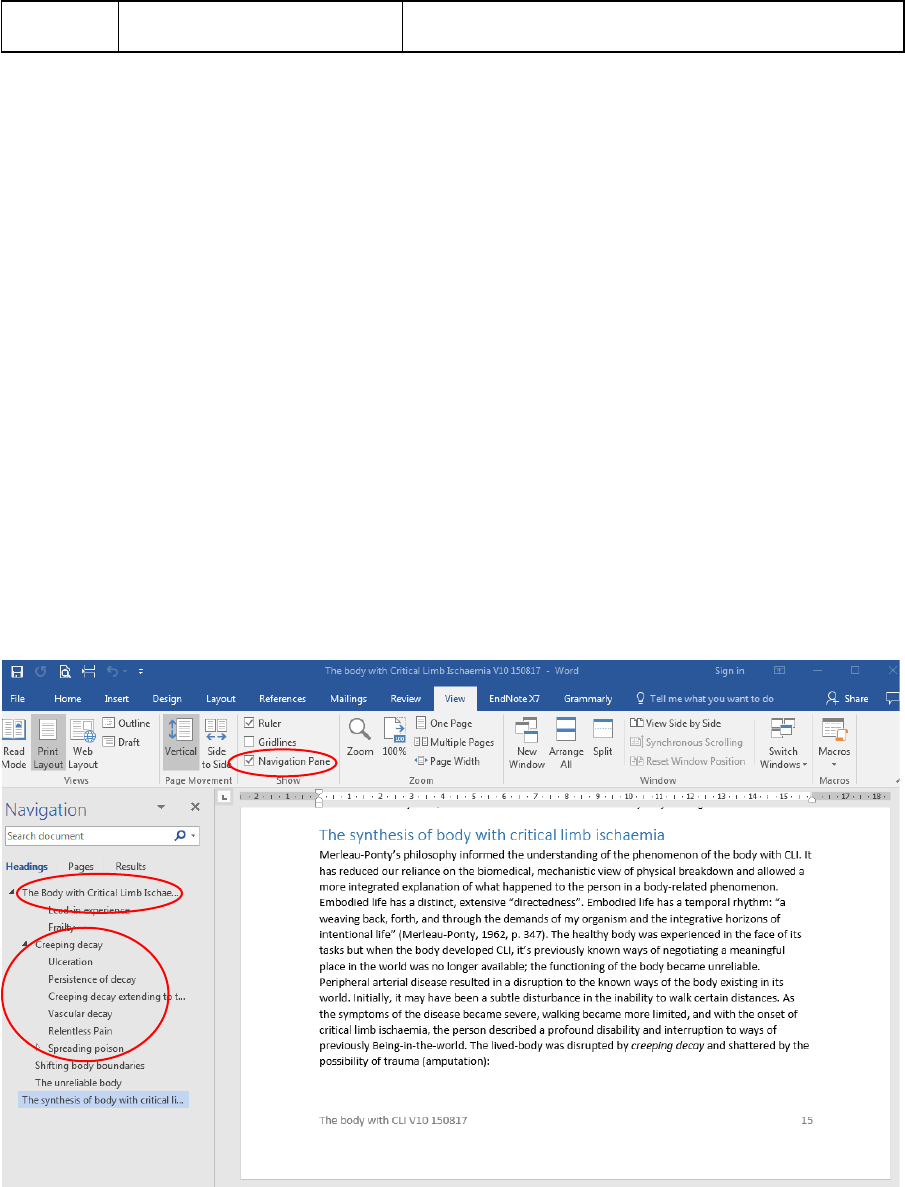

A Microsoft Word (.docx) document with the navigation pane selected (from the “View”

tab) allowed data visualisation of themes and subthemes (previously formatted using the

heading function in “Styles”), so they appeared in hierarchical order in the navigation pane

(Figure 1). The document contained multiple headings within hierarchical levels. For example,

heading one was a theme and heading two a subtheme. Further breakdown of the parts meant

that within some themes, there might have been subthemes down to level five or six. This data

display allowed organisation of the data through visual clumping under these early theme

headings (common ideas from raw data grouped under subheadings) that displayed on the left

of the screen as a table of hierarchical content. 198 pages of themed participant quotes resulted.

Figure 1

Microsoft Word Navigation pane: Parts versus the whole (Monaro, 2018)

This visual format of the navigation pane facilitated seamless movement across a large

document to, for example, quickly paste new data into an existing theme by simply clicking

that heading in the navigation pane. It also facilitated the easy moving of whole sections of text

to different parts of the document by dragging a subheading in the navigation plane to a new

placement. As data analysis became more sophisticated, visualising the heading structures

enabled a philosophically guided sense and understanding of the “whole” (tabulated thematic

1050 The Qualitative Report 2022

list) and “parts” of the data (see Figure 1). This visualisation revealed that a restructure of the

ideas was required to clarify the chronology and temporality of the CLTI experience. This

provided context and ensured that the reconfiguration of sections was congruent with the parts

against the whole. An early philosophical interpretation was then progressed between

researchers using the “Insert Comment” function under the “Review” tab in Word to visualise

emerging philosophical codes/rationale.

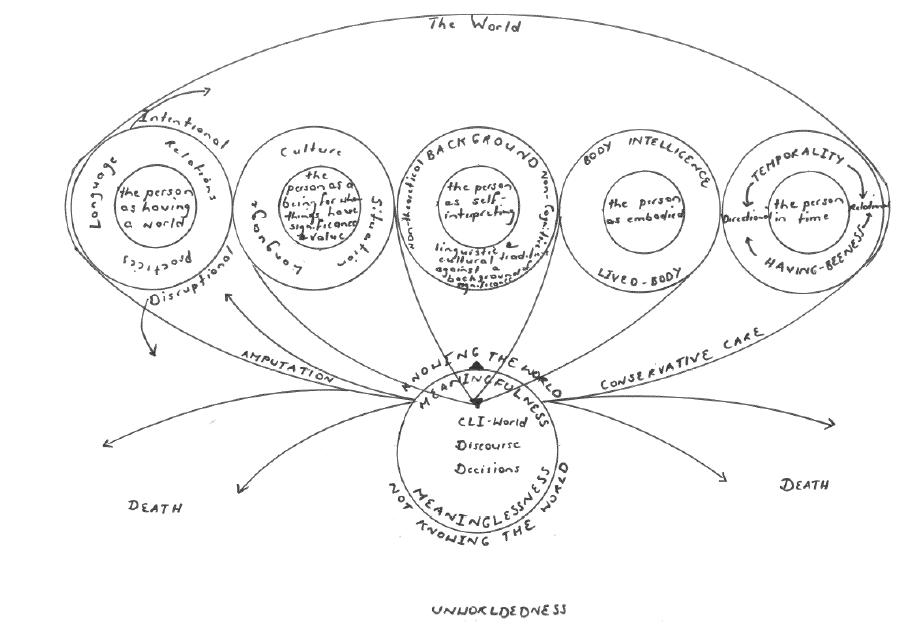

To assist the application of Leonard's (1989) summary of Heideggerian ideas, her

conceptual work as it related to this themed data set was developed as a figure (Figure 2): the

person as having a world; the person as a being for whom things have significance and value;

the person as self-interpreting; the person as embodied; and the person in time.

Figure 2

Superimposing Leonard’s (1989) “Heideggerian concepts of the person” on the experience

of CLTI ) (Monaro, 2018)

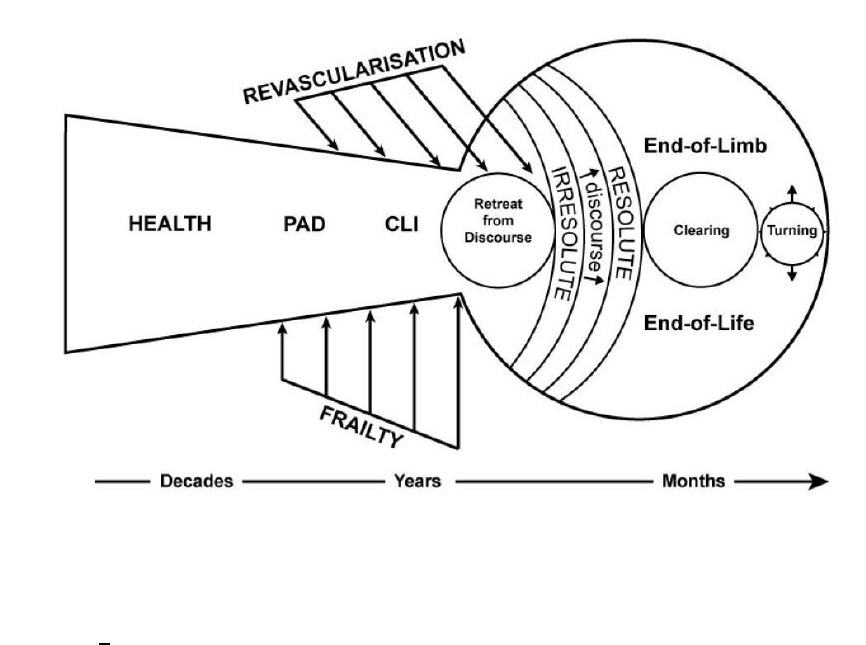

Mind mapping was employed to draw out and connect ideas, challenge thinking, and explore

analytical links between key thematic blocks (data display). These hand-drawn mind maps

made visible the important stages of thinking and analysis: Figure 3 illustrates a representation

of the temporality of disease progression. The process of mind mapping initiated thinking

which linked the text (data) to the guiding framework for philosophical sensitivity. These mind

maps were included in the methods section of the thesis.

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1051

Figure 3

Temporality of disease progression and making treatment decisions (Monaro, 2018)

Drawing (Tentative) Conclusions

The process of conclusion-drawing was tentative and iterative and required thorough

immersion in both the language and stories generated by the participants. Conclusion drawing

spanned the life cycle of analysis – it began during transcription and then continued with

repeated listening to recorded interviews while reading the transcripts. Such immersion

required not only data familiarity but also a philosophically-informed response to the semantics

(the meaning and intentions of participants words) and the syntax (the way words were

arranged) (Gullick et al., 2017).

The analysis document containing the organised quotes (supported by the navigation

pane) (Figure 1) was further developed by inserting initial descriptive analytic thinking using

explanatory text to provide context and background to participant exemplars. This became

richer and more nuanced as the staged theorising progressed (informed by van Manen, then

Leonard, then Merleau-Ponty and Heidegger, enabled by mind-mapping).

The process of working with the “parts” and the “whole” supported early conclusion

drawing as individual words were considered against the context of a sentence, then parts of a

participant’s interview were interpreted against the whole of their interview. As part of the

“whole” against which an exemplar (a part) could be examined, each participant’s exemplar

was preceded by relevant context (e.g., significant other, living environment, disease

trajectory). The whole of the participant’s interview was then interpreted against what was

understood about the individual’s health condition, their family, and their social world and

culture.

Each interview was also considered against the whole of the other participants’

aggregated data. Thus, the parts and the whole of the data were entered and re-entered to

interpret the person and their family's experience. Collecting data at two references points: soon

after the possibility of amputation had been raised (an interim understanding), and six months

after it had been experienced (a more comprehensive temporal understanding), also facilitated

further consideration of the “parts” and the “whole” relevant to this experience.

1052 The Qualitative Report 2022

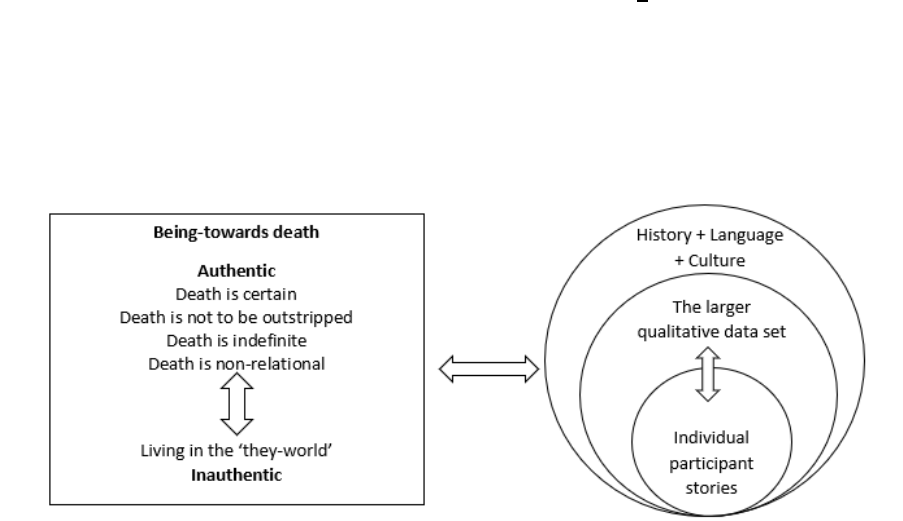

A structure for philosophically-informed conclusion drawing emerged from this

process of moving between the parts and whole. Figure 4 illustrates this for two sections of the

analysis by showing how hermeneutic interpretation moves between the embodied disruption

of CLTI and Heidegger’s philosophical structures of Being-with; a temporal sense of being

already situated in the world, among others, with a sense of projected Being-towards (for

example, the Heideggerian concept of Being-towards-death) (Monaro et al., 2021).

Figure 4

Analysis of Dasein with CLTI and Being-towards death (adapted (Monaro et al., 2021 and

reproduced with permission).

An Application of Data Verification to Support Rigour

Processes for verification also spanned the cycle of analysis, ensuring the credibility of

the research process. The initial, pre-reflexive ideas arising out of the data through early coding

were initially generated independently by the group and consolidated by consensus. Data

exemplars that had been cut and pasted from transcripts were labelled with the participant code

and line number to ensure traceability. Pseudonyms were allocated to enhance the humanistic

tone of the text and we used pseudonyms beginning with the same letter for linked participants

(e.g., Michael and Mel) to make family connections easier to recognise.

After key concepts were themed, several iterations of document comparison occurred

to capture any overlooked data/findings during data reduction: raw transcripts against original

analysis, original analysis document against refined analysis (using the search function in

word), and analysis using Van Manen’s four existential concepts against the thematic structure

in the final navigation pane.

In a further expression of data verification, the 32-item Consolidated criteria for

Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) reporting checklist (Tong et al. 2007) allowed

reflection on elements of rigour expected for publication. However, not all points were relevant

to phenomenological research, and these were thoughtfully rebutted.

Finally, a methods-specific framework provided the final structure to verification, as

we sought congruence with de Witt and Ploeg’s (2006) criteria for trustworthiness in

interpretive phenomenological nursing research. These criteria and their application are

detailed in Table 3.

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1053

Table 3

Criteria for rigour (de Witt & Ploeg, 2006)

Criteria

Demonstration

Balanced

integration

The balance between the philosophical interpretation and the participants’ voices;

further grounding of the interpretation through carefully paraphrasing concepts

from the philosophical texts to make the ideas accessible to readers who are not

conversant with the dense philosophies. This paraphrasing also challenged the

researcher to question the depth of their understanding.

Openness

Every time a research-related decision was made (e.g., data collection, changes to

the analytical process, emerging ethical issues), they were documented in an audit

trail. The developing philosophical understanding and the processes for getting

there were exhaustively described in the thesis and subsequent publications,

including the use of mind maps.

Concreteness

The data was considered in a way that was useful to practice – (the philosophical

lens did not obliterate the clinicians apriori understanding and communication of

the world of amputation). Enough context was provided to allow an informed

reading of the data by others.

Resonance

The wording of themes allowed an intuitive grasp of the embodied meaning of

something (for example, “creeping decay” to describe the impact of deteriorating

peripheral ischaemia on the fleshiness of the body).

Actualisation

We looked for further realisation of the resonance of the interpretation through

preliminary dissemination. We used feedback from conference attendees and

peer-reviewers of manuscripts which compelled us to re-examine and refine the

interpretation before final publication and/or thesis examination.

Discussion

The work of Miles and Huberman (1984) provided a useful framing for this paper and

supported the idea that there is more that unites strong qualitative approaches than divides. It

allowed us to explain the reduction of data from initial narrowing of the research interest to a

research problem and articulating the sampling strategy, through to refinement of final themes

and decisions about what and how to publish. It provided the opportunity to communicate the

value of visual aids in displaying data to share ideas and enabled an explanation of the

navigation pane as a simple but effective analytic tool for high-level analysis of a large and

complex data set. Many of our verification strategies were common to other qualitative

approaches and are described in qualitative reporting guidelines. The doctoral work that

provided the vehicle for this paper started with the intentional use of Heideggerian philosophy,

which required an eventual deep familiarity. This can be challenging for novice researchers

who are simultaneously developing an understanding of general methodological rigour. In this

case, a gradual introduction to philosophical thinking using the work of van Manen (2017) and

Leonard (1989) provided an early establishment of assumptions, philosophical sensitivity, and

a gentle immersion into these complex ideas. Growing expertise in applying Heidegger’s

(1927/1996) and Merleau-Ponty’s (1945/1962, 1968) philosophies then provided analytical

hooks on which to frame a nuanced philosophical interpretation. It is recommended that

researchers who are new to interpretive phenomenology seek supervision and support from

philosophical/methodological experts.

1054 The Qualitative Report 2022

Implications for Practice

Research into complex illness experiences using philosophically-based, interpretative

qualitative methods is challenging to novice clinical researchers. Phenomenology has specific

considerations related to the philosophical framework which underpins interpretation. Clear

and detailed articulations of such processes have been explained. Our use of Microsoft Word

and the functionalities of the navigation pane generated by hierarchical heading styles,

comments, and search functions provided techniques to manage and interpret large volumes of

complex and diverse data. Mind maps are particularly useful data visualisation devices which

increase the transparency of the analytic process. We have confirmed the value of Miles and

Huberman’s (1984) seminal text and have applied it to describe our analytical techniques and,

in so doing, have provided granular guidance to clinicians commencing research using

interpretive qualitative methodologies. Given the subjective, context-bound nature of

qualitative research (acknowledged as a strength), the importance of a clear and extensive

description of the research activities and processes of analysis is vital to help readers determine

the strength and trustworthiness of their work to inform clinical practice. Many of the

approaches described here are transferrable to a range of descriptive and interpretative

qualitative methods. Establishing the specific criteria for rigour within one’s chosen

methodology and wrestling in a supportive manner with the underpinning philosophy or theory

allows rigour to be fully realised.

References

Aho, K. A. (2010). Heidegger's neglect of the body. SUNY Press.

Atherton, A., & Elsmore, P. (2007). Structuring qualitative enquiry in management and

organization research: A diologue on the merits of using software for qualitative data

analysis. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management, 2(1), 62-77.

https://doi.org/10.1108/17465640710749117

Benner, P. (1994). Interpretive phenomenology: Embodiment, caring, and ethics in health and

illness. SAGE.

Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to

enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research,

26(13), 1802-1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

Bong, S. A. (2002). Debunking myths in qualitative data analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social

Research, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-3.2.849

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in descriptive

qualitative research. International Journal of Nursing Methods. 2(2), 1-13.

https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690300200201

Collaizi, P. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In R. Valle & M.

King (Eds.), Existential-phenomenological alternatives for psychology (pp. 48-71).

Oxford University Press.

de Witt, L., & Ploeg, J. (2006). Critical appraisal of rigour in interpretive phenomenological

nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55(2), 215-229.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03898.x

Dibley, L. (2011). Analyzing narrative data using McCormack’s lenses. Nurse Researcher,

18(3), 13-19. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2011.04.18.3.13.c8458

Dilthey, W. (1976). W. Dilthey, selected writings (H. P. Rickman, Ed., Trans.). Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative

content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1).

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1055

https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced

Nursing, 62(1), 107-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Frechette, J., Bitzas, V., Aubry, M., Kilpatrick, K., & Lavoie-Tremblay, M. (2020). Capturing

lived experience: Methodological considerations for interpretive phenomenological

inquiry. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920907254.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1960). Truth and method. The Crossroad Publishing Company.

Giorgi, A. (2011). IPA and science: A response to Jonathan Smith. Journal of

Phenomenological Psychology, 42(2), 195-216.

https://doi.org/10.1163/156916211X599762

Goble, E., Austin, W., Larsen, D., Kreitzer, L., & Brintnell, E. S. (2012). Habits of mind and

the split-mind effect: When computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software is used

in phenomenological research. Paper presented at the Forum Qualitative

Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research.

Gullick, J., Krivograd, M., Taggart, S., Brazete, S., Panaretto, L., & Wu, J. (2017). A

phenomenological construct of caring among spouses following acute coronary

syndrome. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 20(3), 393-404. doi:

10.1007/s11019-017-9759-0.

Gullick, J., Monaro, S., & Stewart, G. (2016). Compartmentalising time and space: A

phenomenological interpretation of the temporal experience of commencing

haemodialysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(21-22), 3382-3395. doi:

10.1111/jocn.13697

Gullick, J., & West, S. (2019). Heideggerian hermeneutic phenomenology as method:

Modelling analysis through a metasynthesis of articles on being-towards-death.

Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 23(1), 87-105.

Gullick, J., Wu, J., Reid, C., Tembo, A. C., Shishehgar, S., & Conlon, L. (2020). Heideggerian

structures of Being-with in the nurse–patient relationship: modelling phenomenological

analysis through qualitative meta-synthesis. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy,

23(4), 645-664.

Heidegger, M. (1927/1996). Being and time: A translation of Sein and Zeit (J. Stanbaugh,

Trans.). State University of New York Press.

Jackson, K., & Bazely, P. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with NVIVO. SAGE.

Jootun, D., McGhee, G., & Marland, G. (2009). Reflexivity: Promoting rigour in qualitative

research. Nursing Standard, 23(23), 42-46.

https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2009.02.23.23.42.c6800

Leonard, V. (1989). A Heideggerian phenomenologic perspective on the concept of the person.

Advances in Nursing Science, 11(4), 40-55. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-

198907000-00008

Mackey, S. (2005). Phenomenological nursing research: methodological insights derived from

Heidegger's interpretive phenomenology. International Journal of Nursing Studies,

42(2), 179-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.011

McConnell-Henry, T., Chapman, Y., & Francis, K. (2011). Member checking and

Heideggerian phenomenology: A redundant component. Nurse researcher, 18(2).

https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2011.01.18.2.28.c8282

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945/1962). Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, Trans.). Librairie

Gallimard.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisible. Northwestern University Press.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data:

Toward a shared craft. Educational Researcher, 13(5), 20-30.

1056 The Qualitative Report 2022

https://doi.org/10.2307/1174243

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods

sourcebook (3rd ed). SAGE.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: A methods

sourcebook (4

th

ed.). Sage.

Monaro, S. (2018). Grappling with making decisions about amputation for Critical Limb

Ischaemia: the patient and family experience. (PhD), The University of Sydney,

Sydney. Retrieved from https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/20199

Monaro, S., Gullick, G., & West, S. (2019). The body with Chronic limb-threatening

ischaemia: A phenomenologically derived understanding. Journal of Clinical Nursing,

29 (7-8), 1276-1289.

Monaro, S., West, S., & Gullick, J. (2021). Chronic limb‐threatening ischaemia and reframing

the meaning of ‘end’. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(5-6), 687-700.

Morse, J. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry.

Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212-1222.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315588501

Paley, J. (2005). Phenomenology as rhetoric. Nursing Inquiry, 12(2), 106-116.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2005.00263.x

Paley, J. (2016). Phenomenology as qualitative research: A critical analysis of meaning

attribution. Routledge.

Paley, J. (2018). Phenomenology and qualitative research: Amedeo Giorgi's hermetic

epistemology. Nursing Philosophy, e12212.

Rescher, N. (1997). Objectivity: The obligations of impersonal reason. University of Notre

Dame Press.

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and

analysis techniques in mixed‐method studies. Research in Nursing & Health, 23(3),

246-255. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240x(200006)23:3<246::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-h

Sandelowski, M. (2010). What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in

Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77-84. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20362

Sheils, S., Mason, S., & Gullick, J. (2019). Acceptability of External Jugular Venepuncture for

Patients with Liver Disease and Difficult Venous Access. Journal of the Association of

Vascular Access, 24(2), 9. Smith, J., Flower, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative

phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative

research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International

Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349-357.

https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Tuohy, D., Cooney, A., Dowling, M., Murphy, K., & Sixsmith, J. (2013). An overview of

interpretive phenomenology as a research methodology. Nurse Researcher, 20(6).

https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2013.07.20.6.17.e315

van Manen, M. (2003). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive

pedagogy. The Althouse Press.

van Manen, M. (2017). Phenomenology in its original sense. Qualitative Health Research,

27(6), 1-16. https://doi/10.1177/1049732317699381

van Manen, M. (2018). Rebuttal rejoinder: Present IPA for what it is – interpretative

psychological analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 28(12), 1959-1968.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318795474

van Manen, M. (1997). From meaning to method. Qualitative Health Research, 7(3), 345-369.

https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239700700303

van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in

Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, and Sandra West 1057

phenomenological research and writing. Routledge.

Author Note

The authors, Sue Monaro (https://orcid.org/my-orcid?orcid=0000-0002-4172-4932),

Janice Gullick, and Sandra West, work in the Susan Wakil School of Nursing and Midwifery

in the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the University of Sydney, Australia. This body of

work arises from a PhD that used phenomenology to explore the patient and family experience

of chronic limb-threatening ischaemia. The research team has collaborated on other projects

and have created a community of practice for qualitative research in clinical settings.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Sue Monaro, Level 3

West Cardiovascular Ambulatory Care, Concord Repatriation General Hospital, Concord, New

South Wales, 2138, Australia. Email: sue.monaro@health.nsw.gov.au

Copyright 2022: Sue Monaro, Janice Gullick, Sandra West, and Nova Southeastern

University.

Article Citation

Monaro, S., Gullick, J., & West, S. (2022). Qualitative data analysis for health research: A

step-by-step example of phenomenological interpretation. The Qualitative Report,

27(4), 1040-1057. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5249