High-Quality Curriculum

Implementation

Summer 2020

Connecting What to Teach with How to Teach It

The Potential of a High-Quality Curriculum

1

INTRODUCTION

The Potential of a High-Quality Curriculum

Research confirms what effective educators

and policymakers know from practice: that

the implementation of a “high-quality”

curriculum – one that is aligned to rigorous

state standards – leads to notable learning

gains for students.

1,2

Yet, only 40% of

teachers report that they are using curricula

that are “high-quality and well aligned to

learning standards.”

3

In a study of math

curriculum usage that included 6,000 schools

and over 1,200 teachers across six states,

researchers reported that just 25% of

teachers used the textbook in nearly all their

lessons for all essential activities, including

in-class exercises, practice problems, and

homework problems. They also found that

teachers received 0.8 to 1.4 days, on

average, of professional development

tailored to the curriculum they were using.

Even a curriculum highlighted as being

among those with the most support

provided a total of only 1.6 days.

4

In light of these findings, many districts and

states have made the adoption of high-

quality curriculum a priority and have

marshaled considerable resources to this

end. A number of national organizations –

including Chiefs for Change, The Education

Trust, and The Aspen Institute – have called

for the adoption of high-quality curriculum to

ensure that all students have the opportunity

to learn in an academically rigorous

classroom.

This is a much-needed reform. It is especially

critical for low-income students and students

of color who too often attend schools with

low-quality curriculum and learning

materials. Without high-quality instructional

materials, students are not challenged to

work at a level that meets expectations for

their grade level and often spend time on

irrelevant or disconnected activities and

assignments.

5

As a result, low-income

students and students of color are less likely

to be given opportunities to think and

problem-solve in more complex ways or

reach the depth of knowledge necessary to

meet state standards for college and career

readiness.

In districts that lack a high-quality

curriculum, teachers are forced to try to fill

the gaps – spending hours looking for, or

developing their own, resources or activities

to better align to rigorous state standards.

1

Chingos, Matthew, and Grover Whitehurst. 2012. “Choosing Blindly: Instructional Materials, Teacher

Effectiveness, and the Common Core.” Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution.

2

Jackson, C. Kirabo and Alexey Makarin. 2016. “Simplifying Teaching: A Field Experiment with Online Off-the-Shelf

Lessons.” National Bureau of Economic Statistics, Working Paper No. 22398.

3

Educators for Excellence. Voices from the Classroom, 2020. e4e.org/teachersurvey.

4

Kane, Tom and David Blazer. March 2019. “Learning by the Book.” Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard

University.

5

TNTP. 2017. “The Opportunity Myth: What students can show us about how school is letting them down – and

how they can fix it.” Brooklyn, NY: TNTP.

2

This investment of time can be substantial.

For example, 70% of teachers in Tennessee

report spending more than four hours per

week creating or sourcing instructional

materials.

6

The challenge of supplementing a low-

quality curriculum is daunting even for

experienced, highly skilled teachers. It can be

overwhelming for inexperienced or less

skilled teachers. Recent research on the

quality of supplemental curricular materials

available on three popular websites found

fewer than 10% were “exceptional or highly

likely to contribute to a quality curriculum.”

7

Amy Drury – a second grade teacher at

Barrera Veterans Elementary School in

Somerset Independent School District (ISD),

located just south of San Antonio, Texas,

described a disjointed approach before the

adoption of a new curriculum. “Before, we

would have to fit various things together on

our own,” she said. “Too often there was a

disconnect between what we were teaching

and what the standards were. We often

ended up using piecemeal resources.”

Introducing a new high-quality curriculum

offers the potential to address these

challenges. High-quality instructional

materials are designed to engage students in

a deeper level of learning, create a focused

direction, and help teachers make

connections across grade levels. This saves

teachers from having to fit things together

on their own or fill in gaps that may exist

between the curriculum and the adopted

state standards.

Faydra Alexander, director of leadership

development in the Algiers Charter in New

Orleans, puts it this way: “Using high-quality

curricula is key to helping our students think

in a more complex way and access the type

of reading, writing, computing, and problem-

solving they will face in college and beyond.

We need to prepare our students for that.”

A high-quality curriculum provides more

coherence and connection in the sequencing

of learning between grade levels. Robert

Pondiscio of the Fordham Institute

highlighted the potential impact. “An

excellent education is not just what gets

taught today,” he said. “It’s the cumulative

effect of a coherent, thoughtfully sequenced,

and knowledge-rich curriculum that

broadens and deepens over time, within and

across grade levels.”

8

6

Tennessee Department of Education. 2019. “Tennessee Educator Survey.” Retrieved from:

https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/education/data/2019-survey/Lessons_District_Leaders_Infographic.pdf

7

Polikoff, Morgan and Amber Northern. December 2019. “The Supplemental Curriculum Bazaar.” Education Next.

8

Pondiscio, Robert. January 2020. “Digging in the dirt for quality curriculum.” Washington, D.C. Fordham Institute.

The Potential of a High-Quality Curriculum

Implementation Challenges

3

Implementation Challenges

Identifying and selecting a high-quality

curriculum is the first step, but implementing

it well is just as important. “I've never said

it's just about curriculum,” Baltimore City

Public Schools CEO Dr. Sonja Santelises said.

“What I've said is if you don't have a strong

curriculum, you're not even starting in the

right place.” She describes the adoption of a

knowledge-rich curriculum as “the first half

of chapter one.“

9

While districts and curriculum providers offer

a range of upfront training and some

additional professional development

sessions during the year for teachers, even

the best training on a new curriculum

provides limited opportunities for teachers

to plan and refine how to use the materials.

Curriculum developers cannot anticipate or

address all of the challenges that will arise

once teachers begin using the resources with

their students.

Less experienced teachers and new teachers,

in particular, might not understand the

content at the depth necessary to effectively

teach it. Teachers often do not know how to

locate and use curricular resources or whom

to ask for help. For example, being able to

identify where the curriculum might not be

fully aligned to expectations in a state

standard, or how to support students who

are above or below grade level, requires

significant content and instructional

knowledge.

9

Pondiscio, Robert. November 2019. “Curriculum advocates: Prepare for a long, hard struggle.” Washington, D.C.

Fordham Institute.

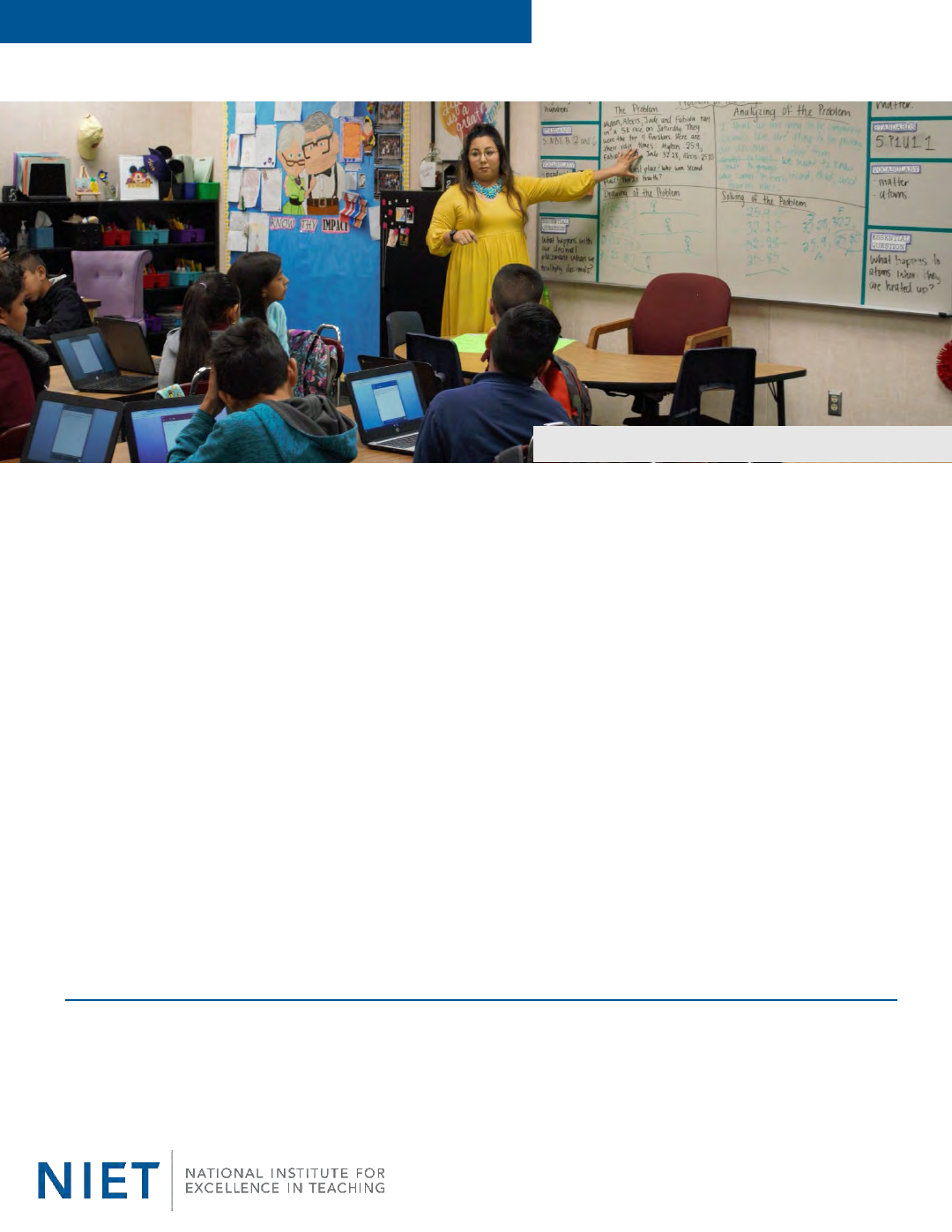

Michael Anderson School, Avondale, Arizona

4

Teachers with students below grade level

face an even bigger set of concerns with

high-quality instructional materials. In these

classrooms, teachers must work even harder

to create strategies or build scaffolds for

their students to successfully use the new

materials. Districts and schools with

significant numbers of students below grade

level need to prioritize the inclusion of

supports for these students in selecting a

new curriculum and create professional

learning that helps them to use these

supports in their classroom. These schools

require significant ongoing investment from

the district to ensure that teachers have the

help they need.

In addition, many principals are not

adequately prepared to provide coaching on

the curriculum, and district systems for

ongoing professional learning are often

disconnected from curriculum training. These

challenges in implementation contribute to a

lack of impact on classroom teaching and

student outcomes. As Executive Director of

the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education

Policy Dr. David Steiner points out, high-

quality curriculum without teacher supports

is not going to have a positive impact.

“Availability isn’t usage, and usage ‘in some

fashion’ isn’t going to move the needle on

student outcomes,” he said.

10

High-quality curriculum sets the course for

deeper learning and requires commensurate

improvements in instructional skills to deliver

rich, engaging lessons. To truly achieve

equitable outcomes for students, adopting a

high-quality curriculum cannot be a stand-

alone goal. The curriculum must be

implemented in conjunction with ongoing,

job-embedded learning for teachers to

understand how to adapt their teaching to

the demands of the new curriculum. If we

expect teachers to utilize the curriculum

every day, we have to create a professional

learning environment where teachers and

school leaders are always talking about,

planning, and designing instruction with the

curriculum.

The introduction of a strong curriculum

provides a key opportunity to restructure

professional learning to better support the

use of high-quality materials alongside

effective teaching practices. This

restructuring requires teamwork among

multiple stakeholders at every level of the

system, including district curriculum leaders,

principals, coaches, teacher leaders, and

teachers. Success in this work also involves

communicating to parents the new

expectations embedded in the curriculum

and supporting them to reinforce their child’s

learning at home.

10

Steiner, David. November 2019. “Staying on the shelf: Why rigorous new curricula aren’t being used.”

Washington, D.C.: Fordham Institute.

Implementation Challenges

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lessons Learned

5

Blending Curriculum and

Instructional Support:

Lessons Learned

For 20 years, NIET has worked with district

partners across the country to improve

classroom instruction. We have learned that

the most effective professional learning

blends support for “what” is being taught

with “how” it is being taught.

Katrina Harris – a fourth grade teacher at

Queensborough Leadership Academy in

Caddo Parish Public Schools, a high-poverty

district located in northwest Louisiana –

knows firsthand the power of blending these

supports. “It’s about taking the intended

curriculum activities and understanding the

alignment among the learning objectives,

standards, and assessment, and then making

instructional decisions that help students to

reach the learning goal,” Harris said. Caddo

Parish uses the common language of NIET’s

instructional rubric to help marry the “what”

and the “how” to maximize teachers’

success. Teachers receive feedback on the

instructional strategies that help students

own their learning to grow in their

understanding of content.

Katrina also noted: “Teachers need to make

effective use of academic feedback, student

grouping, student differentiation, and other

instructional practices that enable us to

deliver the content in ways that support

student success. When coaching and support

for curriculum and pedagogy are done

together, it makes more sense to a teacher. It

doesn’t feel like two separate decisions; it

feels like one. You may not label them as

‘curriculum’ or ‘pedagogy,’ but you intuitively

understand it’s good teaching.”

Working with NIET partner districts like

Caddo, we have seen firsthand how more

demanding instructional materials require

significant improvements in classroom

teaching to enable students to master

higher-level content. That is why we are so

committed to creating the conditions

necessary for every teacher to have access to

a high-quality curriculum and the

instructional support that equips them to use

those materials to accelerate student

learning.

”

When coaching and support for

curriculum and pedagogy are done

together, it makes more sense to a

teacher. It doesn’t feel like two separate

decisions; it feels like one. You may not

label them as ‘curriculum’ or ‘pedagogy,’

but you intuitively understand it’s good

teaching

.

—Katrina Harris, Fourth Grade Teacher

6

This paper outlines the lessons we have

learned with our partners as they have

adopted and implemented high-quality

curricula in their schools, particularly those

serving large numbers of low-income

students. These six key lessons for

implementing a high-quality curriculum are:

1. Focus on leaders first.

2. Create time, structures, and formal roles

to support ongoing, school-based

collaborative professional learning.

3. Adopt a research-based instructional

rubric to guide conversations about

teaching and learning with the

curriculum.

4. Anchor coaching and feedback in the

curriculum.

5. Recognize the stages of curriculum

implementation and what teachers need

to progress to higher stages.

6. Ensure that districts work closely with

schools to plan for, communicate, and

implement school-based professional

learning that blends support for

curriculum and instructional practice.

While the selection process for a new

curriculum is critical to success, the lessons

we share here focus exclusively on the

challenge of implementing that new

curriculum to maximize student learning. We

also discuss how educators can continue to

grow in curriculum implementation after the

initial push.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lessons Learned

Katrina Harris, Caddo Parish, Louisiana

7

1. Focus on leaders first.

Truly understanding curriculum and its

connection to standards and assessment is

complex and time-consuming work. If school

leaders and their leadership team members

do not understand the curriculum deeply,

they will not be effective in supporting

teachers to do the same.

Following a decision about what curriculum

to implement, districts must provide

sufficient time for school leaders and their

leadership team members to understand the

curriculum and its alignment with other

elements of the broader instructional

system, including standards, instruction,

assessment, and evaluation and feedback.

The investment leaders make in this early

stage, before bringing the new curriculum

into schools and classrooms, will pay

dividends as other structures and systems

are put in place to support implementation.

First, upfront training on the curriculum itself

is essential to ensure leaders understand the

scope and sequence, layout, and decision

points within the curriculum. Unfortunately,

most districts do not provide much more

than one day on this initial training.

11

“Teachers need at least 2-3 full days of

upfront training and a handful of ongoing

touchpoints throughout the year to take on

their new curriculum,” said Rebecca Kockler,

consultant and former assistant

superintendent for academics at the

Louisiana Department of Education. “This

training should also be led by someone who

is truly expert in the curriculum.”

Introductory training must then be followed

by opportunities for collaborative work at all

levels – district leaders, school leaders,

coaches, and teachers. Several weeks or

even months of leader engagement with the

curriculum create a foundation of knowledge

that is critical as the new curriculum is rolled

out to teachers. This learning establishes the

foundation for leaders to embed the

curriculum in school systems and structures

and continue to build on this knowledge

throughout the year. “It’s not just that they

know the curriculum, but that they know

how to uphold the expectation that the

curriculum is taught,” Kockler said. “That is

an action orientation that is critical but rarely

exists.”

11

Kane, Thomas and David Blazer. March 2019. “Learning by the Book.” Center for Education Policy Research,

Harvard University.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 1

8

As a new curriculum is introduced to

teachers, many may be resistant to changing

their teaching approach and adopting the

new materials. Having used other materials

and resources for years, teachers may be

concerned about completely abandoning

familiar materials and often simply choose a

few ideas or strategies from the new

curriculum to supplement their existing

lessons. Having teacher leaders and other

school leaders discuss the rationale and

strengths of the new materials is an

important strategy for supporting teachers in

implementing the new curriculum with

fidelity.

As part of the training for district and school

leaders, an important investment is to set

aside the time to understand the “big

picture” or arc of the curriculum and how it

connects to adopted standards and current

assessments. This investment in reviewing

alignment within the instructional system

enhances district and school leaders’ ability

to analyze and address potential gaps among

these elements, areas where the curriculum

might not reach the level of rigor of the

standards, or where additional resources and

supports might be needed for students who

are significantly above or below grade-level

expectations.

Of course, opportunities to work

collaboratively with peers to deepen

knowledge of the curriculum “arc” and its

impact on the instructional system should

not be a one-time event but continue in

professional learning opportunities

throughout the year. NIET partner districts

and schools use teacher leader roles and

weekly team meeting structures to ensure

curriculum implementation is effective and

aligned to all elements they use to make

decisions for individual teachers and

students.

One such partner is DeSoto Parish Schools,

located 40 miles south of Shreveport in

Mansfield, Louisiana. DeSoto has been

recognized for its sustained growth, moving

from a district ranking of 45th to 12th in the

state. The district brings together district

instructional leaders, school leaders, and

teacher leaders to develop plans for how to

maximize curriculum usage within the

instructional system of the district. This

includes weekly professional learning in each

school.

Teacher leaders, called master teachers in

DeSoto and other NIET partner districts,

serve as members of the school leadership

team, guide weekly professional learning

teams, and coach in classrooms, putting

them in a critical role for successful

curriculum implementation. The district-level

planning meetings ensure principals and

teacher leaders are well-versed and

comfortable with the new curriculum before

supporting teachers in using it.

Master Teacher Jessica Parker at North

DeSoto Upper Elementary School shared her

experience. “The district gave us permission,

and the time and space, to grapple with the

curriculum,” she said. “Then, we worked

together to figure out how to effectively use

the curriculum to address the needs we were

seeing in classrooms.”

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 1

9

Monthly master teacher meetings provide an

ongoing opportunity to dig into curricular

needs with attention to improving

instructional practices based in part on

student work analysis.

This investment of time is also important in

other districts. Goshen Community Schools, a

northern Indiana school district with a large

number of English language learners, adopted

a new writing curriculum for grades K-8 at the

start of the 2019-20 school year. To ensure

that teachers and school leaders are

comfortable with the new materials, the

district conducts weekly professional learning

for teacher leaders and principals. These

weekly, 90-minute district-level meetings are

modeled on the school-based professional

learning system that has been in place in all

Goshen schools for the past nine years.

“It has been invaluable to have time

allocated by the district to learn how the

new writing curriculum can be integrated

into weekly professional development

sessions. As a teacher leader, it’s essential for

me to fully understand the new materials in

order to support the classroom teachers in

my school,” said Lauren Moore, a master

teacher at West Goshen Elementary, which

has improved from a D to an A rating on the

Indiana state report card. “I’m grateful to

have the opportunity to collaborate and

learn from the other teacher leaders and

principals in my district to ensure that our

students are receiving the best instruction.”

Through this collaborative work, school

leadership teams build a common

understanding of when it is (and is not)

appropriate to make adjustments or

instructional decisions while remaining

within the curriculum. Marvin Rainey, a

district-based instructional coach who serves

as executive master teacher in Caddo Parish,

noted, “Having consistent messaging to

teachers was really important as challenges

in classrooms started to arise. Scheduled,

monthly, hourlong meetings helped master

teachers from across schools to stay on the

same page, discuss adjustments that needed

to be made, and work through problems

together. This strengthened the coherence

and consistency of curriculum

implementation districtwide while being

responsive to the realities teachers were

facing in their classrooms over the course of

the year.”

These ongoing, collaborative learning

structures for all levels of leadership also

regularly elevate areas where additional

coherence is needed to ensure teachers have

what they need to align expectations with

the resources they have, the data they are

gathering, and the feedback they are

receiving.

”

This strengthened the coherence and

consistency of curriculum

implementation districtwide while

being responsive to the realities

teachers were facing in their classrooms

over the course of the year.

—Marvin Rainey, Instructional Coach

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 1

10

2. Create time, structures,

and formal roles to

support ongoing,

collaborative professional

learning at the school

level.

Effective school-based, job-embedded

professional learning requires creating time

and space for teachers to work

collaboratively. This time must be structured

so it focuses on supporting teachers to

address specific student needs. This is best

done when schools create formal roles for

school-based instructional leaders to guide

this learning, such as the master teacher

positions described in this report.

Teacher leaders, who may maintain roles as

classroom teachers while taking on

instructional leadership responsibilities, are

uniquely positioned to support their peers

and build capacity and buy-in for successful

implementation of a new curriculum. Their

content knowledge across multiple grades

and subjects provides essential expertise in

supporting teachers to deliver instruction

using a new curriculum in classrooms.

In school systems supported by NIET, there

are multiple teacher leadership positions,

and these individuals are members of the

school leadership team. For example,

teacher leaders who are released from all or

most regular classroom duties are called

instructional coaches or master teachers, as

mentioned earlier. Master teachers serve on

the school leadership team, design and lead

collaborative professional learning, and

observe and provide feedback on classroom

practice for classroom teachers in their

building. Master teachers typically support

about 20 classroom teachers, although this

varies based on school context and budgets.

Teacher leaders who remain “teachers of

record” for one or more of their own classes

of students are mentor teachers. Mentor

teachers are released several hours each

week to work with a group of colleagues,

supporting collaborative learning teams and

providing individual classroom coaching, in

addition to joining the school leadership

team.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 2

Principal Marco French (right) and Instructional

Coach Marvin Rainey, Caddo Parish, Louisiana

11

Amber Simpson – former master teacher in

Somerset ISD, Texas, and current NIET Senior

Program Specialist – explained: “Teacher

leaders were very involved in the committees

that were established to evaluate new

curriculum resource options. Once the new

curriculum resource was determined,

upfront training took place over the summer

and during professional development days in

the fall. Teacher leaders took that curriculum

work and brought it into existing professional

learning structures. The focus of weekly

collaborative learning meetings is on

pedagogy through the content – the coupling

of strong instructional practices with the new

curriculum.”

School Leadership Teams

Creating school-level leadership teams that

include teacher leaders who serve alongside

principals broadens the curriculum

knowledge of the leadership team as a whole

and supports school leaders’ work to align

standards, curriculum, instruction,

assessment, and evaluation and feedback.

While this can look different based on school

contexts, NIET has found that collaborative

weekly professional learning teams and

follow-up coaching for teachers require the

following: 1) time embedded in the school

day, 2) structures to guide the work, and 3)

instructional leadership capacity to support

the kind of sustained, applied learning

necessary to impact teacher instruction.

School leadership teams also must meet

weekly to monitor and adjust plans for

professional learning teams.

“In order to support teachers in the next

learning cycle, leadership teams need to

understand what the support looks and

sounds like in the curriculum and what it will

look and sound like in weekly collaborative

learning teams,” Executive Master Teacher

Nicole Bolen from DeSoto Parish Schools

said. School leadership team meetings

provide the opportunity for school leaders

and teacher leaders to develop this

understanding and plan how to facilitate this

learning in collaborative professional

learning meetings.

Collaborative Professional Learning Teams

To engage in focused problem-solving around

the use of a high-quality curriculum,

collaborative teams need regular time to

meet every week for 60-90 minutes, and

school leaders need to protect that time

from competing demands. While principal

support is crucial, teams are often more

successful when led by trained and effective

teacher leaders who implement the new

curriculum in classrooms themselves and can

show evidence of improved student learning.

“If teachers are struggling with the

curriculum as written, a teacher leader might

teach the curriculum in a classroom, try out

the lessons, break down some of the

important pieces, then bring back that work

to the weekly collaborative learning team

meeting and show how it impacted student

achievement,” Bolen said. “They have to help

teachers understand what this looks and

sounds like and what student learning should

be.”

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 2

12

Researchers have found that collaborative

teams have a positive impact on student

achievement when they “focus on a specific

student learning need over a period of time

and shift to an emphasis on figuring out an

instructional solution that produces a

detectable improvement in learning, not just

trying out a variety of instructional

activities.”

12

Ensuring teacher leaders have

the expertise and skills to successfully lead

professional learning teams is critical,

particularly since professional learning so

often lacks a designated leader, clear

expectations, or an explicit connection to a

teacher’s specific classroom challenges.

13

Gadsden Elementary School District #32,

near the border with Mexico in San Luis,

Arizona, has strong, collaborative leadership

teams across the district, which can help

facilitate seamless implementation of

districtwide initiatives. “We recently shifted

to a new literacy program,” Professional

Development Coordinator Vanessa Gonzalez

said. “Because we already had strong

structures for professional learning and a

system of ongoing follow-up, the

implementation of this new curriculum has

been smooth. The weekly collaborative

learning teams create a structure for the new

curriculum to be taught to teachers.” This

approach is showing impact, with five of

Gadsden’s schools earning an A in 2018-19

from the state, many for the first time.

Protocols for Professional Learning

Teams are also more successful when the

leader is trained to use protocols to guide a

process of identifying student learning

difficulties, developing new learning that

connects curriculum with instructional

strategies, and analyzing student work for

evidence of impact. The use of protocols

enables school leaders to monitor

professional learning, hold teacher leaders

accountable for successfully carrying out

their new role and responsibilities, and

provide support and training for teacher

leaders to do their job well.

One example is NIET’s Steps for Effective

Learning protocol, which provides

instructional leaders with a systematic

process to ensure that the valuable time

teachers spend in collaborative team

meetings is focused, productive, and useful.

The steps help leaders facilitate meetings

that are well planned and tied to specific

student needs identified through data,

introduce instructional strategies grounded

in the curriculum, support teachers to plan

how they will apply this learning in their

classroom, and include a plan for measuring

the impact on student learning. The Steps for

Effective Learning are also used by leadership

teams to identify and address challenges

teachers are facing in curriculum

implementation.

12

Gallimore, Ronald, Bradley A. Ermeling, William M. Saunders, and Claude Goldenberg. May 2009. “Moving the

learning of teaching closer to practice: Teacher education implications of school-based inquiry teams.” University

of Chicago Press, The Elementary School Journal; 109(5), 537-553.

13

NIET. 2012. “Beyond Job-Embedded: Ensuring Good Professional Development Gets Results.” Santa Monica, CA:

NIET.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 2

13

The school leadership team at

Queensborough Leadership Academy in

Caddo, for example, used the Steps for

Effective Learning to structure their

classroom observations to understand

whether teachers were making the

instructional changes necessary to support

the deeper student learning and

expectations in the curriculum. By reviewing

student work and observing classrooms, the

leadership team identified (Step 1: identify

the need) that teachers were not teaching to

the level of the exemplar in the curriculum or

as required to meet state standards and

expectations on the assessment.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 2

IDENTIFY

problem or

need

OBTAIN

new teacher

learning aligned to

student need and

formatted for

classroom

application

EVALUATE

the impact on

student

performance

DEVELOP

new teacher

learning with

support in the

classroom

APPLY

new teacher

learning to

the

classroom

Steps for Effective Learning

During curriculum implementation, the Steps for Effective Learning can help leadership

teams target their support for teachers in the following ways:

• Target student

need

s using

evidence (e.g.,

pre-test) that is

clear, specific,

high-quality, and

measurable in

student outcomes

• Connect student

learning on the

curriculum with

instructional

strategies

• Use credible

sources

• Use

curriculum-

aligned

strategies with

proven impact

on student

learning

• Deepen learning

of the curriculum

through

demonstration,

modeling,

practice, team

teaching, and

peer coaching

with subsequent

analysis of

student work

• Practice with

s

upport from

observations,

peer coaching,

and self-

reflection;

student work

provides

formative

assessment

• Analyze

s

tudent work

and

assessments

(e.g., post-

test) to

determine

next steps

14

Queensborough’s principal, Marco French,

explained, “The responses teachers were

accepting weren’t at the depth of the

exemplar, the academic vocabulary wasn’t

there, and students were writing simpler

sentences with reduced vocabulary. Students

were being rated as proficient when they

were not meeting the level of the exemplar.

As a result, the level of rigor wasn’t there.”

This was happening across multiple

classrooms, so the leadership team planned

a professional learning cycle focused on

“incorporating exemplars in lesson delivery”

(Step 2: obtain new learning). During

professional learning meetings, teacher

leaders supported classroom teachers to

plan how to practice this instructional skill

using the curriculum for an upcoming lesson

(Step 3: develop new learning).

They followed up after the meeting with

classroom-level coaching for each teacher as

they delivered the lesson (Step 4: apply new

learning) and supported students at different

levels of learning to master the content.

Leaders used observations and student work

to evaluate whether the professional

learning resulted in teachers effectively

delivering the lesson and the impact on

student learning (Step 5: evaluate the

impact). This process was essential in

demonstrating to teachers that they could

support their students to work with the new

curriculum, including, most importantly,

students who were below grade level.

Using a protocol helps both teachers and

school leaders build their collective expertise

and create coherence in the ways they assess

curriculum implementation, identify and

diagnose problems, and provide feedback.

Teacher leaders play an important role in

helping principals analyze what should be

happening in each classroom and what

students are engaged in. Working as a team

builds a greater level of expertise in knowing

if students are on track to be successful in

mastering the content across grade levels

and subject areas. “Principals don’t have to

be experts in every grade and content area,”

Principal French said. “They do need to be

aware of the structure of the curriculum and

capable of accessing resources in order to

point teachers in the right direction. Their

leadership team as a whole needs to carry

this consistency into professional learning.”

Creating the time, structures, and formal

roles for teacher leaders to support

professional learning at the school level

ensures classroom teachers have someone

who knows the challenges they face and can

offer learning tied to their context every

week. The school leadership team members

learn alongside one another, build trust in

each other, get on the same page, and

continually build their collective knowledge.

School leadership team members model

being lead learners and take the difficult step

of “going first” in understanding the new

curriculum and the challenges it will present

to teachers and students. Their knowledge of

the specific challenges of curriculum

implementation and student learning in that

school makes teachers more likely to engage

in productive, collaborative professional

learning.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 2

15

3. Adopt a research-based

instructional rubric to

guide conversations about

teaching and learning.

As districts and schools implement a new

high-quality curriculum, having a shared vision

and common language for describing,

discussing, and collaborating around excellent

instruction is critical. Without a shared

understanding and language for instructional

practice, teachers receive inconsistent and

conflicting feedback, and leaders struggle to

help them grow in their practice. This is

particularly problematic when a new

curriculum is being introduced that requires

significant shifts in instructional practice.

Districts need to think about what tools or

processes they have in place to describe and

measure curriculum implementation in

classrooms; how these tools are used across

different staff roles and content areas; and

whether they are sufficient to help to build

systems, share goals, and monitor curriculum

implementation over time.

A high-quality curriculum typically requires

more advanced teaching practices. This

presents an opportunity to reset expectations

around classroom instruction and develop the

necessary supports for teachers to build their

instructional knowledge and skills.

NIET district partners cite the adoption of an

instructional rubric as a significant advantage

in their work to support teachers in

strengthening their instructional practices to

effectively use high-quality instructional

materials. The instructional rubric (Appendix

A) provides a common language for

describing, observing, discussing, and

planning effective instruction. It facilitates

work to improve classroom practices – such

as the use of questioning, providing

academic feedback, and lesson structure and

pacing – that are necessary to support

student learning.

In addition, it equips instructional leaders

within and across schools to use a consistent

approach and common language to share

ideas and grow their professional practice

together. “Everyone is comfortable in what

the indicators look and sound like in the

classroom,” Assistant Superintendent Kellie

Duguid, in Avondale Elementary School

District #44 near Phoenix, Arizona, said.

“Our content-specific collaborative teams

talk about curriculum along with standards

and assessment, all the components

together, within the framework of the

instructional rubric. The instructional rubric

gives us a common language and lens to

support professional learning.”

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 3

”

Our content-specific collaborative teams

talk about curriculum along with

standards and assessment, all the

components together, within the

framework of the instructional rubric.

The instructional rubric gives us a

common language and lens to support

professional learning.

—Kellie Duguid, Assistant Superintendent

16

Using an instructional rubric helps teachers

discuss how an instructional decision or skill,

such as the use of academic feedback,

supports students to better achieve the

depth of knowledge required to master a

learning standard. The rubric also provides a

structure for addressing content-specific or

curricular issues that are challenging

teachers in the classroom.

For example, Master Teacher Jessica Parker

and her colleagues at North DeSoto Upper

Elementary School in Louisiana identified the

rubric indicator “academic feedback” as an

area needing improvement across a number

of fourth and fifth grade classrooms as

teachers were implementing a new English

language arts curriculum. Teachers were

providing feedback to students that was at a

surface level and not soliciting the kind of

deeper thinking necessary for students to

master the lesson’s objectives. Other

teachers needed support in engaging their

students to provide high-quality,

academically focused feedback to each other,

another expectation in the new ELA

curriculum.

Parker structured weekly professional

learning for a group of fourth and fifth grade

ELA teachers around improving academic

feedback to strengthen a specific upcoming

lesson in the curriculum. The new ELA

curriculum required students to engage in

deeper analysis and comparison of texts, and

this required teachers to strengthen their

ability to facilitate deeper engagement,

thinking, and collaboration among students.

Teachers also needed to improve their ability

to monitor student work, provide strong

feedback during class, and adjust based on

the feedback they were getting from

students.

To address these needs, the professional

learning team meeting was designed for

teachers to share examples of student work

illustrating the need for better academic

feedback, discuss research illustrating why

academic feedback is important to student

learning, and learn how strong academic

feedback can clarify goals and support

students in understanding the criteria for

success. The group discussed the differences

between high-quality, academically focused

feedback and more general feedback.

Teachers analyzed their use of academic

feedback in a specific lesson and how they

might have strengthened it to be more

actionable and personalized. Working in

small groups, they reviewed an upcoming

lesson and planned specifically where they

could strengthen students’ understanding

through more effective use of academic

feedback. They ended the meeting by

planning time for fourth and fifth grade

teachers to observe each other’s classroom

teaching and see firsthand how their peers

were delivering this lesson.

The professional learning team in this

example used the instructional rubric to

guide a discussion around the specific ways

that teachers could adjust their instruction to

better deliver an upcoming lesson.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 3

17

Through this work, teachers strengthened

their understanding of how important

instructional practice is to maximizing the

impact of curriculum activities and materials

on student learning.

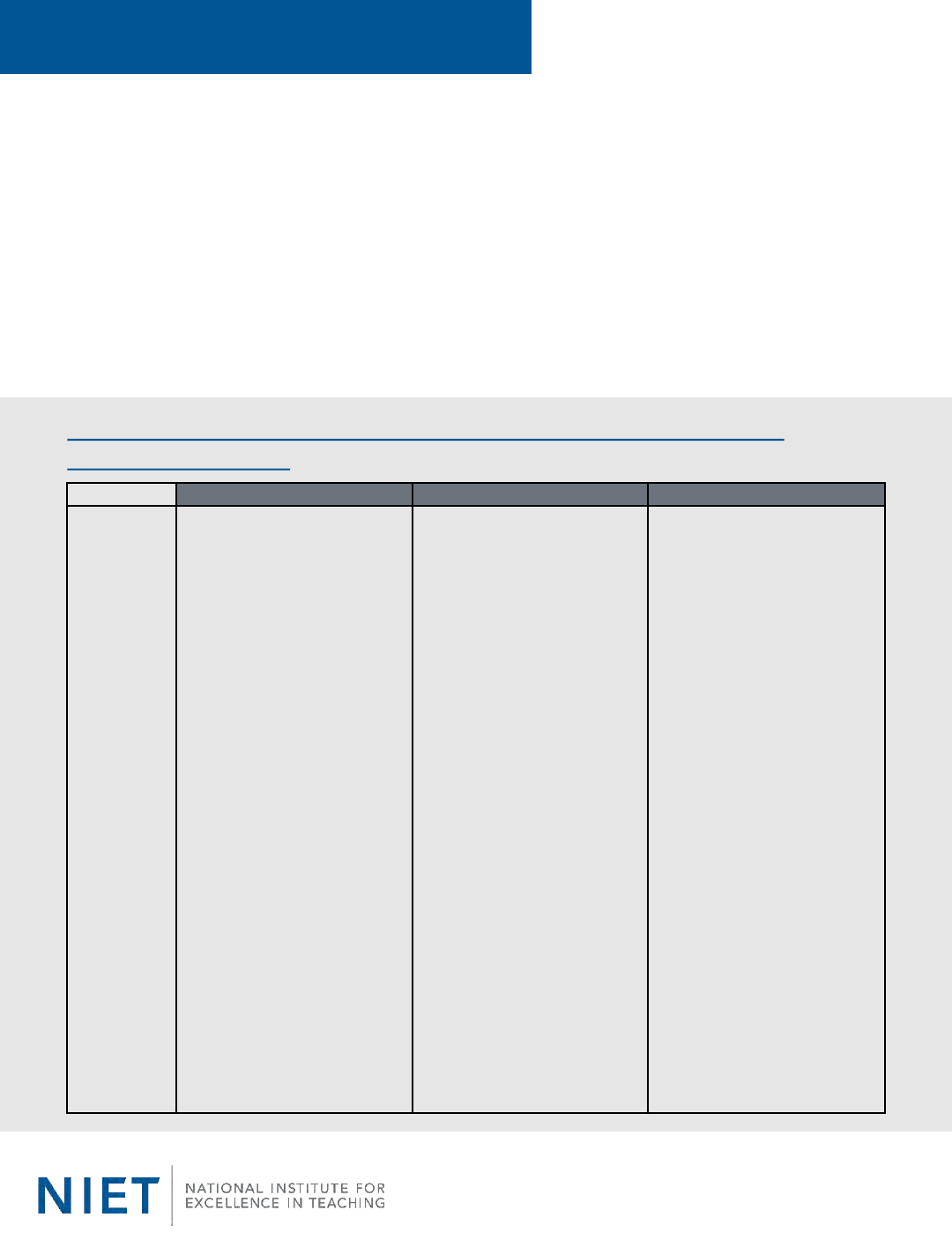

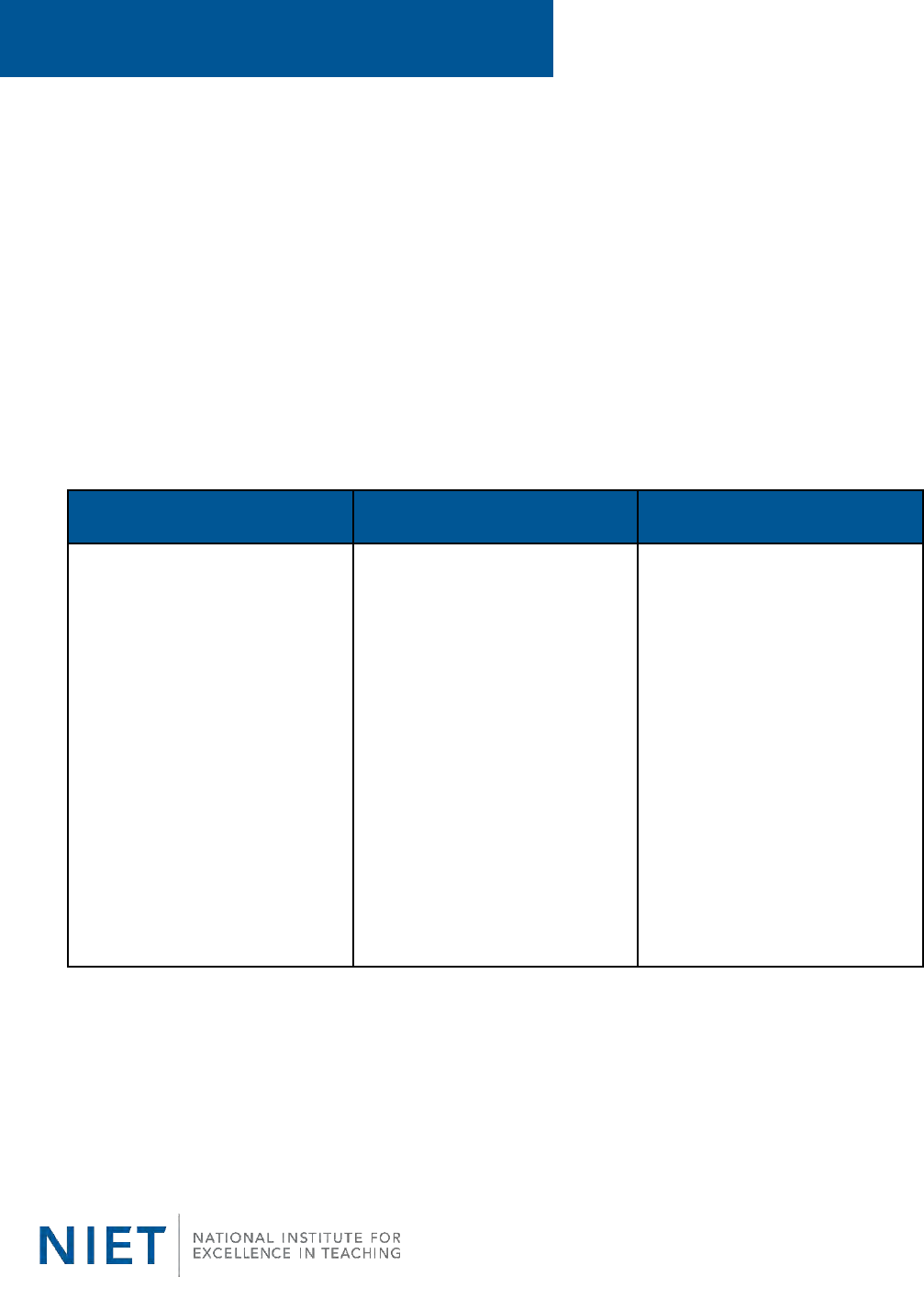

Below is a description of the indicator

“academic feedback” on the NIET Teaching

Standards Rubric at different levels of

effectiveness. This descriptive language

enables coaches and leaders to provide

detailed, consistent feedback to teachers as

they work to improve their instruction and

build a common understanding of

expectations. To unlock the power of a high-

quality curriculum, teacher practice needs to

begin to move beyond “proficient” into the

higher levels of practice described as

“exemplary” in the instructional rubric.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 3

Example of an indicator in the NIET Teaching Standards Rubric:

Academic Feedback

Exemplary Proficient Unsatisfactory

Academic

Feedback

• Oral and written

feedback is consistently

academically focused,

frequent, and high-

quality.

• Feedback is frequently

given during guided

practice and homework

review.

• The teacher circulates

to prompt student

thinking, assess each

student’s progress, and

provide individual

feedback.

• Feedback from students

is regularly used to

monitor and adjust

instruction.

• The teacher engages

students in giving

specific and high-quality

feedback to one

another.

• Oral and written

feedback is mostly

academically focused,

frequent, and mostly

high-quality.

• Feedback is sometimes

given during guided

practice and homework

review.

• The teacher circulates

during instructional

activities to support

engagement and

monitor student work.

• Feedback from students

is sometimes used to

monitor and adjust

instruction.

• The quality and

timeliness of feedback

are inconsistent.

• Feedback is rarely given

during guided practice

and homework review.

• The teacher circulates

during instructional

activities but monitors

mostly behavior.

• Feedback from students

is rarely used to monitor

or adjust instruction.

18

Professional learning should marry the

“what” and the “how” by utilizing the

developmental language of a common

instructional rubric in the context of specific

lessons or components of the curriculum. For

instance, in the example above, Parker

focused on building the teachers’ skills to

provide high-quality academic feedback in

the context of specific fourth and fifth grade

lessons from the curriculum. Teachers could,

therefore, see how to apply their improved

instructional skills (“the how”) to their

content (“the what”). Similarly, in some

states and districts, the use of content-

specific “look fors” or questions provides an

additional layer of guidance in implementing

a new curriculum. These “look fors” include

indicators that help measure whether the

teacher is using the new curriculum and how

their lessons address grade-level standards.

For example, a curriculum “look for”

resource might ask: 1) “Is a high-quality text

that is at or above grade level expectations

being used?” or 2) “Are questions and tasks

text-specific, and do they accurately address

the analytical thinking required by the grade-

level standards?”

14, 15

These companion

resources help to maintain a focus on the

specific content being taught in each lesson

of the new curriculum and its alignment to

standards for student learning. Together with

the instructional rubric, this support helps

teachers plan and deliver learning for their

students.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 3

14

Achieve the Core. August 2018. “Instructional Practice Guide for ELA/Literature Grades 3-12.”

15

Lee, L. E., Smith, K. S., & Lancashire, H. 2020. “Guide and checklists for a school leader’s walkthrough during

literacy instruction in grades 4–12 (REL 2020–018).” Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of

Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational

Laboratory Southeast.

DeSoto Parish, Louisiana

19

4. Anchor coaching and

feedback in the

curriculum.

Coaching is an essential part of instructional

improvement, enabling principals and

instructional leaders to work one-on-one

with an individual classroom teacher,

observe instruction, and provide real-time

feedback. When coaching during curriculum

implementation, it is essential to provide

clear and consistent feedback targeted to

where teachers are in their own learning.

Simply visiting a classroom to see if the

curriculum is being used is not enough.

Leaders and coaches must deeply know the

curriculum in order to connect their

instructional feedback to specific resources

and lessons. Support, especially during

curriculum implementation, must be

differentiated by the teacher, both in terms

of subject matter and also intensity and

duration.

A high-quality curriculum places new

demands on teaching, including the use of

more complex texts, scaffolded supports for

students, and greater emphasis on

differentiating instruction. For example,

Louisiana’s ELA curriculum, “Guidebooks,”

includes the text for each unit and links to

related readings, related standards, and

sample research projects.

Each unit includes descriptions of activities,

handouts, lesson scripts, and examples of

student work, as well as links to resources

like assessments and videos. A strong ELA

curriculum with this level of support seeks to

build students’ background knowledge –

which research has shown is crucial to strong

reading competency

16

– and to build

knowledge across grade levels.

In mathematics, a high-quality curriculum

teaches the content at a conceptual level. As

one highly rated curriculum provider in math

explains, “It’s not enough for students to

know the process for solving a problem; they

need to understand why that process works.

…This builds students’ knowledge logically

and thoroughly to help them achieve deep

understanding.”

17

Content is organized in a

logical progression across multiple years,

enabling teachers to know what students

have learned in prior years and what to

prepare them for in the next grade level. A

high-quality math curriculum offers

suggested questions, activities that

encourage students to problem-solve, and

other teacher resources embedded in each

lesson and unit. It also provides resources for

parents to support students at home, such as

key vocabulary and connections to prior

learning. Knowing how to maximize the

benefits of these varied resources is a new

challenge for many teachers that coaches

can address.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 4

16

Willingham, Daniel T. 2006. “How Knowledge Helps.” American Educator. Washington, D.C.: American

Federation of Teachers.

17

Eureka Math. Retreived from: www.greatminds.org/math/about-eureka

20

To meet the demands of a top-rated

curriculum and bring all students up to the

new expectations for learning, teachers need

additional support to understand why certain

skills or strategies are being employed, how

to best facilitate them, and when to enhance

the materials to meet specific student needs.

Coaching might include co-planning, diving

into the curriculum together, or team

teaching and providing feedback. The

support must be more intense for those

teachers who struggle, especially those who

need targeted support to increase their

content expertise.

Chinle Unified School District in Arizona used

to be among the lowest-performing Native

American reservation districts and is now the

highest-performing reservation district.

Although they are outperforming similar

districts, they still have many academic

challenges. In order to meet these

challenges, Chinle invested in creating

teacher leadership positions (“academic

coaches”) in every school and adopted a

more demanding curriculum in ELA and

math. Academic Coach Melissa Martin

explained her coaching role: “Our job as

academic coaches is to help teachers work

out how to make learning happen, how their

students can master each standard, how to

stretch their higher-performing students, and

how to support those who are struggling. We

help them build their knowledge of the

content in the curriculum and then work

through, step by step, how to help every

student to master it, based on their specific

needs. The rigor has changed. The way we

ask students to think is at a higher level.”

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 4

Chinle Unified School District, Arizona

21

To provide this level of support and coaching,

schools and districts need trained teacher

leaders and a system of school-based

professional learning that prioritizes the time

and resources to ensure that professional

learning translates to the classroom. Teacher

leaders and the principal, in particular, must

demonstrate through their feedback that

they understand and value the curriculum

and that using it well is important. No matter

the reason a school leader may visit a

classroom, it is important to anchor any

feedback or support in the curriculum.

Principal French, from Caddo Parish in

Louisiana, is intentional about making that

connection. “If I’m giving instructional ideas

outside of the curriculum, I’m almost

working against it,” he said. “I need examples

and tips from the curriculum or that connect

to the curriculum in an important way that

shows how instructional practice and

curriculum are braided together. Sometimes

it’s just a coaching tip straight from the

curriculum. I can support a teacher by

noting, ‘Here’s a good idea that came from

the curriculum.’ That builds teacher buy-in

because I am showing I understand and value

the curriculum.”

Anchoring feedback in the curriculum also

addresses potential challenges or resistance

from teachers. For example, Clarece

Johnson, a master teacher at

Queensborough Leadership Academy, found,

“When you’re told to do the curriculum as

written, it can give teachers a false sense of,

‘Well, I don’t really have to dig into this and

understand it.’ When, in fact, they really do.”

Intensive, one-on-one coaching is particularly

important in low-performing schools, where

teachers will need additional support in

helping students who are significantly below

grade level. The use of a high-quality

curriculum provided to every school relieves

instructional leaders of the overwhelming

responsibility of designing and supporting

multiple curricula or lesson planning on their

own and enables them to focus on building

content knowledge, improving teacher

practice, and analyzing the effect of

instructional strategies on student learning.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 4

Caddo Parish, Louisiana

22

5. Recognize the stages of

curriculum

implementation and what

teachers need to progress

to higher stages.

NIET is working with district leaders in

Jefferson Parish Schools in Louisiana to

develop tools, processes, and training for

school leaders to gauge where individual

teachers are in the progression of learning on

a new, more rigorous curriculum and

determine how to best target support for

each teacher based on their needs. Using

classroom observations, a teacher survey,

and follow-up consultations with school

leaders, Jefferson’s cadre of six district-level

instructional coaches, called executive

master teachers, are supporting school

leadership teams to identify each teacher’s

level of expertise with the curriculum and

design individual support plans.

Their analysis includes both content

knowledge and instructional practices in

order to pinpoint specific areas for

improvement that connect to student

learning needs. For example, in a middle

school English language arts class, classroom

observation and follow-up coaching with the

teacher found that student work was not

meeting grade-level standards. This

particular teacher’s pacing was off, and he

had skipped parts of several lessons he

thought would not be engaging for his

students. His coach spoke with him about

why he had skipped certain lessons, what

purpose they served, and how he could have

covered that material in an engaging way

with his students. Together they pulled up

the standards and looked at his students’

work and where it was falling short. Through

this process, the teacher and his coach

reviewed why the skills in those lessons were

essential for his students to master,

adjustments he could make to lesson pacing

to cover them, and engagement strategies

that worked with his students.

NIET’s Teacher Learning Progression on

Curriculum outlines connections between

curriculum and instructional skills at various

levels of expertise. Maria Held, Jefferson

Parish executive master teacher, explained

how it is being used in her school: “We use

the curriculum progression alongside the

instructional rubric because we want to

move teachers in areas of both practices and

their knowledge of curriculum. A carefully

implemented support plan that addresses a

teacher’s stage in curriculum learning will

help teachers to understand how

instructional practices enable them to

support students to master grade-level

content at the depth of knowledge needed

for academic success.”

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 5

23

Leaders in Rapides Parish in central Louisiana

are working to support teachers with specific

instructional practices based on where they

are in learning the content of the new

curriculum. For example, during a classroom

observation, the leadership team found that

a middle school math teacher was providing

strong overall instruction, but she was not

effectively differentiating instruction for

students that were struggling or providing

extensions to the learning for students who

were ready for additional challenges. In

providing feedback to this teacher, it became

clear that she was not accessing

supplemental curriculum resources and

strategies.

With coaching from the leadership team, she

was able to incorporate additional

curriculum resources to better differentiate

her support to meet individual student

needs. For example, she used small group

pullouts for those students who were

performing above proficiency in order to

extend their learning. By providing those

students with additional real-world examples

and requiring them to represent those

examples mathematically, she was able to

advance their thinking and problem-solving

above grade level.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 5

Teacher Learning Progression on Curriculum

24

For her students who had not yet mastered

the grade-level content, she used

remediation resources provided in the

curriculum to anticipate where her students

might struggle and what interventions she

could plan ahead of time. She grouped these

students based on their specific needs and

used strategies from the curriculum

resources during the lesson to enable them

to work on grade-level assignments. With

these supports and continued practice,

students were able to master grade-level

material. This teacher took her practice to a

higher level of effectiveness by improving her

ability to differentiate instruction for

individual students. On the curriculum

progression, she was moving toward

“emerging differentiation.”

Nikki Snow, master teacher at Alma Redwine

Elementary School in Rapides, explained how

she is blending support for curriculum and

instruction when she coaches teachers: “We

have been focusing on how to get our

students to lead discussions, to work

together collaboratively in groups to

complete tasks, and to create a student-led

environment. The last stage of the

curriculum progression is to have student-led

learning, and this fit in perfectly with what

we have been trying to achieve. Teachers are

not being asked to do anything extra, but

they can apply these strategies with the

content that they are already teaching in the

classroom.” School leaders in Rapides Parish

can speak to the impact this approach has

made to improving instruction and advancing

student learning.

“We are building a stronger path which

equips our teachers with the necessary tools

for designing and delivering learning

opportunities that are continuously

differentiated and student-led,” said Alma

Redwine Elementary School Principal Dr.

LaQuanta Jones. “This higher level of

practice requires a deeper understanding of

the content and resources in the curriculum

and the instructional practices needed to be

successful in supporting learning for each

individual student.”

As with the instructional rubric, this

progression illustrates that teacher

instructional practice needs to move toward

the exemplary level in order to realize the full

potential of high-quality instructional

materials. For example, more demanding

curricula require teachers to support

students to take ownership of their own

learning and to engage in thinking and

problem-solving with their peers, described

in the curriculum progression as “student-led

learning.”

In addition to using a learning progression as

a coaching tool, it is also useful as an overall

guide during the introduction of a new

curriculum. Teachers will need time before

the school year starts to understand changes

that the new curriculum will require in

routines, structures, scheduling, grading, and

assessments.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 5

25

With that basic understanding, teachers can

focus on how the new content aligns with

student learning standards and build their

understanding of why the curriculum is

structured the way it is and how this

supports student learning. At this stage of

learning, teachers make connections

between the content of the curriculum and

instructional practices, such as lesson

structure and pacing, questioning, and

activities and materials that will support

deeper student learning. They increase their

understanding of what student work should

look like at different levels of proficiency.

With a growing understanding of what needs

to be taught and why, teachers build their

ability to deliver effective lessons. As

described in the example above, this

increased expertise enables teachers to

better differentiate learning, such as

providing scaffolds to students who are not

mastering learning objectives to enable them

to build the skills and knowledge necessary

to achieve grade-level performance

expectations. As teachers increase their

knowledge and skills using a new curriculum

and the supplemental resources it provides,

they are more equipped to differentiate

instruction so that every student receives

support to learn the material presented.

In the early stages of implementing a new

curriculum, weekly collaborative learning

meetings offer the opportunity to support

groups of teachers who are focused on

building similar skills and knowledge.

“Everything we do in our district is grounded

in our model of professional learning that

provides for a culture of collaboration and

common language for improving instruction

using a high-quality curriculum,” said Duguid

from Avondale Elementary School District.

“Pedagogy goes hand in hand with

curriculum, and with stronger instructional

skills, our teachers can more actively engage

students in more challenging content.”

At Wildflower Accelerated Academy in

Goodyear, Arizona, leaders are identifying

issues that individual teachers might be

struggling with in the curriculum and how to

support teachers to improve during

professional learning and through coaching.

“We start by asking, ‘What is in the

curriculum?’ Then we look at the science

behind how students read, for example,” said

Dr. Araceli Montoya, principal of Wildflower

Accelerated Academy. “Through our

professional learning block, we support

teachers to become more proficient with the

instructional content and how to best teach

the material to their students. Within

months we saw improvements in

classrooms.”

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 5

”

Through our professional learning

block, we support teachers to become

more proficient with the instructional

content and how to best teach the

material to their students. Within

months we saw improvements in

classrooms.

—Araceli Montoya, Principal

26

6. Ensure that districts

work closely with schools

to plan for, communicate,

and implement school-

based professional

learning that blends

support for curriculum

and instructional practice.

Districts have the distinct role of creating a

vision for equity and high expectations for all

students. A new curriculum is a critical tool

in advancing that goal, but adopting a new

curriculum does not happen in a vacuum. A

range of other initiatives continue in each

school, and practices, materials, and

activities associated with the old curriculum

often persist. District leaders play a critical

part in communicating what to stop doing,

even as they are communicating what to

start, and in determining how a new

curriculum will be integrated with other

initiatives.

Assessment is a particularly important area

for district review with a new curriculum. For

example, existing interim assessments might

not align with the new learning in the

curriculum, and this will need to be updated.

District instructional staff must understand

and be able to explain how shifts in state

standards are reflected in the new

curriculum, assessments, and expectations

for classroom instructional practice. They

need to be able to weave that knowledge

into the support they are giving to schools.

Districts also need to consider that schools

struggling to reach academic goals, including

those serving larger numbers of low-income

students and students of color, will need

more support using the new curriculum.

"This year, we began implementing a new

high-quality curriculum that is helping us to

build our understanding of what student

success needs to look like,” Principal Dexter

Murphy of Maynard Elementary School in

Knox County Schools, Tennessee, said. “As

principal, a pivotal part of my role is that of a

lead learner, focused on how to better

support our instructional coaches, teachers,

and students through the lens of curriculum

and student work. District support and

resources have been really important as we

embark on this work.”

In addition to creating coherence among

different components of instruction, district

leaders need to create coherence among the

individuals and organizations supporting the

schools. With new curriculum comes new

service providers who are in and out of

classrooms. This can lead to a lot of “noise”

and competing programs. Districts can create

coherence by purposefully planning and

promoting coordination among the variety of

service providers operating in schools. They

can further build this coherence by breaking

down silos and strengthening coordination

among district-level leaders who are

supporting schools.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 6

27

School-based Professional Learning

Structures

As the new curriculum is introduced, it needs

to be clear to schools how it will align with

and be delivered through existing

instructional improvement systems and

supports, or how schools should realign

those instructional supports to support the

new curriculum. Researcher Heather Hill

summarized the need for districts to review

and reset expectations and structures for

professional learning: “Professional learning

time should focus on developing teachers’

expertise with specific curriculum materials.

Pivoting to such a focus will be no small feat,

especially considering the patchwork of

materials (e.g., from the internet or

supplemental sources) teachers use, and

considering also the lack of well-established

protocols and routines for teachers’ study of

materials together.”

18

Districts play the lead role in supporting

schools to create professional learning

structures that enable teachers to increase

their instructional skills and knowledge in

order to deliver the curriculum and support

diverse learners to master standards. “It is

important that we support our teachers with

professional development, quality

instructional coaching, and opportunities to

collaborate with their peers to ensure they

are informed decision-makers in relation to

curriculum implementation and application,”

explained Dr. Elizabeth Lackey, early

childhood education supervisor in Knox

County Schools. “These structures, when

coupled with a high-quality curriculum,

provide teachers with the essential tools to

meet the needs of their students.”

By creating stronger connections and deeper

alignment between district supports and

initiatives, the district strengthens the ability

of school leaders to take ownership and

actively determine how to best achieve

district goals in their own school. Keith

Burton, chief academic officer in Caddo

Parish, described the challenge: “If the

district does not clearly articulate how

learning on the new curriculum and support

for instruction should be tied together,

school leaders will tend to separate them,

which causes dissonance and competing

priorities, even if the work is complementary.

The new curriculum can feel like a separate

initiative, leading principals to say, ‘I have

curriculum here and instructional support

over here, what do you want me to focus

on?’ Or principals might focus on curriculum

during classroom walk-throughs but not

make connections to curriculum

implementation in teacher evaluations and

feedback.”

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 6

18

Hill, Heather and Kathleen Lynch. November 2019. “STEM Professional Development That Works.” Washington,

D.C. ARISE.

”

These structures, when coupled with a

high-quality curriculum, provide

teachers with the essential tools to meet

the needs of their students.

—Elizabeth Lackey, Early Childhood

Education Supervisor

28

District leadership is critical in creating a

coherent vision for this new approach to

professional learning, identifying the

resources to make it possible at the school

level, clearly communicating how district

systems and initiatives support this work,

and prioritizing it through ongoing district

investments in training and support.

Common tools and protocols, funding for

teacher leadership positions, and

investments in release time for collaborative

learning all require strategic use of existing

resources to sustain the work.

Focusing on Student-Centered Practices

A high-quality curriculum requires a shift

toward more student-centered practices

across the system. To achieve this shift,

districts need to standardize and

communicate a common understanding of

what exemplary student work looks like

using the new curriculum. “All of our

principals engage in reflective conversations

with district leaders multiple times

throughout the year,” DeSoto Parish

Executive Master Teacher Nicole Bolen said.

“These conversations center around student

work and how it aligns to the outcomes we

expect to see using a high-quality curriculum.

Sometimes our focus is on a misalignment

with assessments, or on how we are pacing

ourselves to reach goals.”

Teacher observations and feedback should

reflect this shift from a focus on teacher

practice to looking primarily at student work

and outcomes that result from those

practices.

Blending Curriculum and Instructional

Support: Lesson 6

Goshen Community Schools, Indiana

29

“We took a whole year and retrained

everyone to see through that lens,” said

Kathy Noel, director of student learning in

DeSoto Parish Schools. “District leaders

worked with principals and master teachers

to ask: In a classroom where the teacher is