Australia as a modern migration state: Past and present

Background paper to the World Development Report 2023: Migrants, Refugees, and Societies

April 2023

Mary Crock and Chris Parsons*

Abstract

Australia is one of relatively few nations able to regulate closely who enters and leaves. It has done so by the confluence of

accidents of geography, population, and history. In the modern era, this has played out in policies and laws that vest

government with extraordinary control over economic migration, with granular precision over which migrants should be

admitted to fill vacancies in specific occupations. This paper presents an overview of immigration to Australia. The paper

begins by describing current trends, highlighting the crisis engendered by the loss of skilled labor during and after the

COVID-19 pandemic. It then reviews Australia’s regulatory history, highlighting strengths and weaknesses of the policy

landscape and the state apparatus that has guided matters relating to immigration control. In so doing, it emphasizes key

triumphs and shortcomings in the policy regime. It sketches the main channels of entry to Australia and documents key

trends, presenting recent and relevant research, including that of government-appointed inquiries. The paper concludes with

some policy recommendations.

Keywords: Migration, migration policy, refugees, Australia

* Mary Crock is Professor of Public Law and Co-Director of the Sydney Centre for International Law at the University of Sydney, e-

mail: mary.crock@sydney.edu.au. Chris Parsons is an Associate Professor in the Economics Department at the University of Western

Australia, e-mail: christopher.parsons@uwa.edu.au. This paper serves as a background paper to the World Development Report 2023,

Migrants, Refugees, and Societies. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors.

They do not necessarily represent the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated

organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The authors thank Çaglar Özden

and the World Bank Australia Country Office for valuable discussion and feedback.

2

Introduction

Australia is often championed for her successful migration programs and flourishing multiculturalism. As a classical

migration state (Gamlen and Sherrell 2022), Australia has experienced consistently high population and economic growth

because of its targeted intake programs. Australia’s federal apparatus has proved to be resilient, dynamic, and responsive.

The unique powers vested in Australia’s Immigration Minister allow national migration policies to be changed swiftly in

response to changing economic circumstances.

This paper tells the story of a country undergoing seismic economic shocks brought about by external events. Of particular

note is the country’s increasing reliance on temporary migration, whether to fill immediate vacancies or as a step in a

staggered process toward achieving permanent residence or Australian citizenship. Temporary migrants now make up

approximately 7 percent of the workforce (Mackay, Coates, and Sherrell 2022). As this paper will show, this trend stands

in sharp contrast to historical preferences to grant migrants immediate permanent residence.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a huge impact on migration. At the height of the pandemic, Australia emerged as one of the

most restrictive countries on the planet, preventing virtually all movements into and across the country. Much of the

responsibility for controlling the spread of the virus and movement within the country was passed to the state and territory

governments. Western Australia lifted its travel restrictions only on March 3, 2022, after more than 700 days of isolation.

Policies related to the support (or lack of support) of migrants affected by stay-at-home orders figured for many migrants

in their decisions to leave the country. As a direct result of the pandemic, more than half a million temporary visa holders

chose to exit.

1

The pandemic left Australia in something of a crisis, with chronic skills shortages despite low unemployment

rates. The election of a new government in May 2022 ushered in a period of change and with it a growing understanding of

the residual effects of pandemic-era migration policies.

Net overseas migration (NOM) to Australia in the 2020–21 financial year fell by 88,800, the country’s largest net outflow

since World War I.

2

There were 281,000 fewer migrants in June 2021 than in the preceding financial year.

3

During this

period, immigration decreased by 71 percent, but was partially offset by a 25 percent decrease in emigration. The shrinkage

was experienced in every state and territory but felt most keenly in the powerhouse states of New South Wales and Victoria.

4

Border closures cast Australia’s reliance on temporary migrants into sharp relief. Migration in every temporary visa category

declined: students, temporary skilled, working holiday makers,

5

and other temporary workers, particularly from China and

India. Despite their economic importance, most temporary migrants were excluded from federal support payments. Unlike

other Western democracies, Australia made no attempt to assist stranded students.

6

Declines in migrant arrivals were

exacerbated by an uptick in departures of permanent residents and citizens. Counterintuitively, the lockdown period was

not used to process visa applications. In May 2022, incoming Minister for Immigration Andrew Giles revealed a processing

backlog of nearly one million visa applications.

7

Australia’s population growth has been remarkably resilient, growing at an average of 1.4 percent annually over the last

four decades.

8

During 2020–21, however, population growth was a meagre 0.2 percent, the lowest in over a century, and

accounted for by natural increase alone.

9

Domestic fertility rates also fell to a record low in 2020,

10

and previous “fertility

assumptions” pertaining to migrants had to be revised. Australia’s reliance on migration to grow its population is reflected

in census data from 2021 that show that nearly 50 percent of Australians in that year were either born overseas or had a

parent born overseas.

11

For the first time in recorded history, in the 12 months to June 2021, combined populations in all capital cities and territories

fell with the outflow of migrants and internal migration to regional areas.

12

The regions have attempted to attract talent by

offering higher wages and swifter paths to permanency for migrants. Pandemic fears, cost of living pressures, and the

increased ability to work from home seem to have driven the exodus from big cities. Regional population growth overtook

capital city growth in every part of the country except Western Australia, whose economy boomed (leading the world,

according to S&P) throughout the pandemic, in part fuelled by record iron ore prices.

13

The 2022–23 budget, released on March 29, 2022, forecast net overseas migration to grow by 41,000 during the 2021–22

financial year (which in Australia spans July 1 to June 30), increasing to 180,000 during 2022–23, before rising to some

3

235,000 per year in 2024–25 and after.

14

In recognition that it will take years before Australia returns to “business as usual,”

a raft of policies were introduced to plug resulting skill shortages, guided by a desire to drive the increase in predicted

migrant numbers predominantly through the “skilled” channel, and including an expanded apprenticeship program. The

country’s international borders reopened on November 1, 2021, resulting in Australia welcoming 130,000 international

students, 190,000 tourists, 70,000 skilled migrants, and 10,000 working holiday makers.

15

The surge was spurred by visa

fee refunds to international students and working holiday makers entering the country between 19 January 2022 and March

19, 2022 (students) and April 19, 2022 (working holiday makers).

16

Nonreciprocal 30 percent increases in country caps for

working holiday makers were also introduced in tandem with 12,500 additional visas for workers under the Pacific Australia

Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme and a new Australian Agriculture Visa.

Immigration remains a matter for concern, although the latest figures provide cause for some optimism. In the 12 months

to April 2022, net overseas migration fell, because total departures (606,710) outstripped total arrivals (573,930) by more

than 30,000.

17

In the financial year to June 30, 2022 however, it had risen to a net gain of 171,000 individuals.

18

While

skilled migration is expected to plug some of the skills shortfall, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) in their latest Economic Outlook (2022, Vol. 2, Issue 2) argues that any uptick in skilled migration

will not “be sufficient to materially alleviate the tightness in the [Australian] labour market.”

The drop in migrants has been accompanied by the federal government’s policy response of notably omitting public

universities from receiving pandemic-related economic relief packages.

19

An embrace of “remote” learning deprived

students of “on-campus” education and their education suffered. Myriad universities, given their ever-increasing

overreliance upon international student fees, introduced stringent austerity measures, which resulted in a significant decrease

in university employment.

20

Given changes in global labor demand and supply, it remains far from clear whether forecast job vacancies will be filled by

Australian university graduates, not least due to the proliferation of jobs in non-tradeable services (Pritchett 2006). Indeed,

it seems more likely that such service positions will be filled by students working part-time while studying, as opposed to

once they have graduated; having invested significantly in their tertiary education, they are likely to seek higher-status jobs.

It has therefore been argued that the majority of future job vacancies will need to be filled by migrants, by increased labor

force participation rates, or by drawing white-collar workers into “lower skilled” jobs, which would like prove problematic

from employers’ perspectives.

21

In 2023, the number of temporary migrants in Australia was estimated at nearly 2 million.

22

With most of these in employment of some kind, the statistics suggest an extraordinary level of reliance on temporary

workers within the country’s overall workforce.

A chronic shortage of skills pervaded Australia’s local labor markets in mid-2022. Only Canada was in a worse situation.

23

The quarterly job vacancies survey showed that job vacancies increased by 13.8 percent between the February and May

quarters 2022.

24

By May 2022, the total number of job vacancies in Australia reached 480,100, compared to a total of

548,100 unemployed people nationwide. In other words, for each vacancy across the country, there are only 1.14

unemployed persons, which is the lowest such ratio since the series began in May 1980. Some 25.2 percent of all businesses

in Australia in June 2022 reported at least one unfilled vacancy, with the situation felt most acutely in administrative and

support services (38.3 percent); public administration and safety (37.9 percent); electricity, gas, water, and waste services

(34.5 percent); accommodation and food services (34 percent); and construction (30.3 percent).

25

In concert with rising

input costs and global inflation pressures, these labor shortages have also brought about the demise of businesses. For

example, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission reported 1,284 construction companies going under during

the 2021–22 financial year, and 605 comparable companies folding within the first quarter of 2023.

26

To put into context the huge shifts in migration Australia is experiencing, the section that follows presents a brief account

of Australia’s immigration history and system of government. The third section examines Australia’s complex and at times,

contradictory administrative architecture. The discussion then addresses in turn the main categories of migration—family,

humanitarian, and economic—and examines immigration enforcement in light of Australia’s visa cancellation and detention

regimes. In each instance, the paper highlights policy successes and failures. It concludes by making some recommendations

for future policy making.

Appendix A provides a list of major Australian legislation and court cases concerning migration.

4

History

Australia is a country that has been, and continues to be, shaped by its experience of, and approach to, immigration. Although

home to more than 500 unique Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations before colonization, British colonialists refused

to acknowledge or engage with the justice claims of the indigenous inhabitants. The fiction that Australia was “terra

nullius,” a land belonging to no one,

27

provided the basis for a full-blown enterprise in socially engineered nation-building

that failed to acknowledge or accommodate the rights of the country’s indigenous peoples. The many and egregious

historical injustices to Australia’s First Nations peoples (Reynolds 2018) underlie the initiative taken by the Labor

government in 2022–23 to conduct a referendum in 2023 to amend the Australian Constitution to provide for an indigenous

Voice to the Federal Parliament.

Concerns about race meant that close attention was paid to who was admitted and counted as societal members,

notwithstanding the irony in the first settlements being established as penal establishments.

28

As the colonies multiplied

across the continent, concern about creating societies in the image of the white Anglo-Saxon motherland became a unifying

feature. While travel between the colonies was unremarkable for some, the ability to move became a privilege for unwanted

minorities—whether or not they had been born in Australia or were British Imperial subjects. Each colony answered directly

and independently to England, creating its own immigration laws.

Exclusion of non-indigenous persons of color began with the Chinese. The discovery of gold in the 1850s, in Victoria,

witnessed so many Chinese miners and businessmen arrive that by 1858, they made up 20 percent of Victoria’s population

(Galligan and Roberts (2004, 50–51). The Victorian government responded by passing the world’s first legislation to restrict

immigration on the basis of race,

29

limiting the number of Chinese passengers who could be brought in any one vessel to

one for every 10 tonnes of registered tonnage.

30

New South Wales passed similar laws subjecting Chinese migrants to poll

taxes and quotas in 1861.

31

In the decades that followed, the various colonies introduced and then repealed similar legislative

measures in response to the ebb and flow of Chinese prospectors as gold reserves were discovered and depleted [see Choi

(1975, 21–27) and Doulman and Lee (2008, 36ff)].

The British Imperial government was aware of the offence caused by overtly racist enactments within sections of white rule

of the empire: when its commercial interests were affected, it refused the Royal Assent to such legislation.

32

This was the

fate when the local parliament in the colony of South Australia attempted to pass the Coloured Immigrants Restriction Act

1896 (Imperial) No. 672 in 1896, expanding anti-Chinese legislation to expressly prevent the admission of all non-white

people.

33

The various colonies responded by passing legislation that allowed for the exclusion of persons of color, yet made

no express mention of race or color. The exclusionary ruse was to impose a language/literacy test as a precondition for

entry. This device, referred to as the “Natal test,” probably originated in Massachusetts as a device for excluding Irish

settlers from the franchise (see Lake and Reynolds 2008).

Australia’s system of government

The Commonwealth of Australia was created in 1901 through legislation passed by the British Parliament. It became a

founding member of the Commonwealth group of nations. The six most populous colonies became states while the Northern

Territory and the Australian Capital Territory (created to house the nation’s capital) were declared territories. The British

monarch remains Australia’s titular head of state, represented locally by the Governor-General. In 1901, the Australian

Constitution was proclaimed by Governor-General Lord Hopetoun, appointed by Queen Victoria. Australia’s Federal

Parliament consists of two chambers modelled on the United Kingdom and “New World” (US and Canadian) systems of

representative government. Members of the House of Representatives are elected to represent electorates across each state

and territory. Members of the (upper chamber) Senate are elected on the basis of proportional representation across states

and territories. Voting is compulsory and is now close to universal.

Section 51 of the Constitution sets out the matters in respect of which the Federal Parliament can make legislation: anything

not mentioned remains the province of the states and territories. Critically, section 51 includes powers to make laws with

respect to immigration and emigration, and naturalization and aliens. Of equal significance, the Constitution makes no

mention of Australian citizenship as a constitutional right. Indeed, no attempt was made to articulate rights in individual

Australians beyond references to free trade and commerce between states and freedom of religion.

5

Post Federation immigration

The colonies’ desire to speak with one voice on immigration is thought to have been a driving force for federation in 1901.

By then the white population had grown to four million. With the American Civil War a recent memory, Australia’s founders

were keen to create their “new” country in a particular image. Anxious to avoid the socially divisive effects of slavery, the

new country was to be White and Free. After establishing the machinery of government, the first order of business for the

new Federal Parliament was to legislate for the removal of Pacific Island laborers who had been brought in to work the cane

fields in Queensland (Act No 16). The second step was to ensure that only white Anglo-Saxon people would be allowed to

immigrate. The Natal dictation test was a central feature of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (Act No 17) that followed.

Although racially neutral on its face, the dictation test empowered immigration officials to subject undesirable “immigrants”

to one or more 50-word tests, first in English and later in any European language. As Alfred Deakin, Australia’s second

Prime Minister stated in 1905: “The object of applying the language test is not to allow persons to enter the Commonwealth

but to keep them out” (Jupp 2001, 47) [see also Armit (1988) and Rivett (1975)]. The dictation test was also used to deport

migrants who remained subject to the test until deemed to have been absorbed into the community. British immigration was

favored throughout this period, to populate lands “cleared of natives” (Jupp 2001, 47). Whereas 78 percent of the population

heralded from the British Isles in 1901, by the outbreak of World War II, more than 99 percent of Australia was “white.”

The push to create a free society was reflected in a sometimes controversial policy to insist that migrant workers be strictly

brought in as permanent residents (Crock and Berg 2011, chapters 2 and 9). After passage of the Contract Immigrants Act

in 1905 it became almost as difficult to bring in temporary workers as it was to import migrants of color (Layman 1996).

World War II highlighted Australia’s defence vulnerabilities. First Minister for Immigration, Arthur Caldwell, implemented

mass migration policies using the rallying cry of “Populate or Perish.” No longer could the country rely solely upon the

United Kingdom to provide sufficient numbers of whites, so following World War II, a large number of European migrants

were “assisted” to come to Australia.

34

Asian nationals who had sheltered in Australia during the war years were

unceremoniously removed—a measure supported by the High Court under the Constitution’s Defence power (O’Keefe v

Caldwell, 594–5). Non-British migrants were accommodated by altering the meaning of “white.” Following lobbying by

prominent members of the Jewish community, Caldwell admitted some 2,000 Jewish refugees, instituting what later

developed into a humanitarian intake program. Through the International Refugee Organisation, Australia eventually

welcomed some 170,000 persons displaced by European conflict. While Asians continued to be deported, Australia

welcomed Germans and Italians—once sworn enemies—because of their skin color (Neuman 2004).

The White Australia Policy remained in force until 1972, although it began to weaken in the 1960s. Permanent migration

was the norm throughout the mass migration era following World War II. It remained the favored approach for economic

migration until the 1990s, when Australia responded to the call for liberalization of temporary labor in the Uruguay Round

of trade liberalization talks and the entry into force, in 1995, of the General Agreement in Trade of Services (GATS). This

multilateral legal platform for the international trade in services included a Decision on Negotiations on Movement of

Natural Persons (GATS Mode IV) and led to the establishment of a Negotiating Group on the Movement of Natural Persons

within the World Trade Organization. Australia was one of six countries to submit a schedule of commitments that included

amending its laws and policies to facilitate the admission of temporary workers.

35

Historical echoes in modern migration law and politics

The significance of Australia’s backstory is two-fold. First, the failure to provide for an Australian citizenship in the

Constitution has made migrants’ transition to permanent status in the country uniquely uncertain. It was only in 1948 that

Federal Parliament passed laws to formally create Australian citizenship. Over the years, Parliament has expanded and

contracted the criteria for citizenship by birth, descent, adoption, and conferral (Rubenstein 2017). Because the Constitution

set nothing in stone, tenure rights remained unclear for persons who were not citizens but could not be described as “aliens”

in the country. Certain long-term British nationals were held to be nonremovable in 2001 (Re Patterson; Ex parte Taylor

2001). As recently as 2020, Australia’s High Court ruled unconstitutional attempts to deport non-citizens who could show

that they were members of Australia’s indigenous communities (Love v Commonwealth and Thoms v Commonwealth).

The second legacy of this history lies in the embedded acceptance that controlling immigration to Australia is part of the

natural order of things; that it is the job of government and an integral marker of Australian sovereignty. As one of the first

6

High Court Justices, Isaacs J, noted in 1923: “The history of this country and its development has been, and must inevitably

be, largely the story of its policy with respect to population from abroad. That naturally involves the perfect control of the

subject of immigration, both as to encouragement and restriction with all their incidents” (R v Macfarlane; Ex parte

O’Flanagan and O’Kelly at 557).

In fact, Australia is one of relatively few nations able to regulate closely who enters and leaves. It has done so by the

confluence of accidents of geography, population, and history. In the modern era, this has played out in policies and laws

that vest government with extraordinary control over economic migration, with granular precision over which migrants

should be admitted to fill vacancies in specific occupations (see discussion in the sixth section on economic migration).

Politicians’ belief in the primacy of their power has also manifest in extraordinary battles between the Executive and the

Judiciary over who should have the final say in popularist and contested areas such as the deportation of criminal permanent

residents and the treatment of refugees and asylum-seekers. The contest between these two arms of government may explain

some of the more extreme measures adopted by Australia to deter irregular migration of any kind, including mandatory

detention and the removal of refugees to foreign countries for processing and resettlement (Crock and Berg 2011, chapter

19).

The success enjoyed by the politicians in asserting their control over law and policy may help to explain, at least in part, the

politicization of migration law in Australia in recent years. On the one hand, criticisms of policies and practices were used

in opposition to frame charges of political incompetence in government (Crock and Ghezelbash 2010). On the other hand,

muscular prosecutions of hard-line policies—often in disregard of human rights and international law, and in manifest harm

to migrants—were used to deliver political and electoral gains. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the use of the

migration portfolio as a proving ground for promotion to the highest political office. No fewer than three recent Prime

Ministers or aspirants to that position (Tony Abbott, Scott Morrison, and Peter Dutton) used periods as Ministers for

Immigration to build their leadership credentials.

36

The evolution of migration policy and administrative processes

Australia offers an interesting case study of how immigration has been used to build a modern nation. The story is one of

staggered advances. The early focus on race left little room for economic policy analysis. The migration program was based

on bilateral agreements with source countries that sometimes saw whole villages (of acceptable ethnicity) targeted as

potential migrants.

Even after the dictation test was abandoned in 1958 with the passage of the Migration Act, the system was characterized by

policy opacity and sweeping powers vested in officials well-described as “angels and arrogant gods” (Martin 1988). The

country began to take a more reflective approach in the 1960s, a decade when greater thought was given to the relationship

between family, economic, and humanitarian migration. The 1972 election forced the issue: the abolition of color and race

as selection criteria with the abolition of the White Australia Policy exponentially increased the range of persons eligible

for consideration. Of equal importance were changes to accountability mechanisms in the form of a new Federal Court,

“merits review” bodies such as the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), and laws that made it easier and cheaper to

challenge migration decisions. “Rightless” migrants acquired a voice (Crock and Berg 2011, chapter 18). By the end of the

1980s, modernization and democratization processes would affect every aspect of the program. Although there was a long

period when active attempts were made to ground policy in social science and economic research, in recent decades,

politicians have turned away from evidence-based policies. The discussion that follows examines key aspects of the modern

processes for managing migration, highlighting both successful aspects of the system and those of more questionable value.

7

Box 1. The need to strengthen the evidence base for migration analyses

Until 1996, the internal research capacity for conducting migration analyses within the Australian government was world

class. Despite the adoption of a policy to destroy individual census records immediately after processing—in great contrast

to other Anglo-Saxon countries (Hull 2007)—the data available to researchers have consistently been of high quality. The

body of data has comprised weighted samples and full 100 percent census data, administrative flow data, and various

administrative datasets at both the state and federal levels.

This research capacity was reduced in and after 1996 (Jupp 2002), as progressively less data were released for researchers

to analyze. While the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey—the first nationally

representative longitudinal household survey of the country—has been conducted almost every year since 2001 under the

auspices of the Melbourne Institute—with wave 20 having just been released— this is of limited use to migration researchers

given the paucity of migrants in the sample. The Australian Census Longitudinal Data (ACLD) links a representative 5

percent sample of the Australian population over time, from 2006 to 2016. Recognizing the ever-growing importance of the

delineation between temporary and permanent migrants, the Australian Census and Temporary Entrants Integrated Dataset

(ACTEID) links the Australian census with Australian government temporary visa holder data, while the Australian Census

and Migrants Integrated Dataset (ACMID) links the census with Australian government permanent migrant data. The

Business Longitudinal Analysis Data Environment (BLADE) provides data on all active businesses in Australia between

the 2001–02 and 2018–19 financial years, by linking tax, trade, and intellectual property data from various surveys

conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). LEED (the Linked Employer-Employee Dataset) in turn links

BLADE with employee information deriving from Personal Income Tax data.

Above all, MADIP, the ambitious Multi-Agency Data Integration Project, established in 2015 and further developed

between 2017 and 2020 through the Data Integration Partnership for Australia (DIPA), aims to provide sponsored users

with access to a broad range of linked administrative datasets, including data on individuals’ health, education, government

payments, income and taxation, and employment, as well as their census data. Notably, MADIP comprises a full count of

the population of Australia. MADIP therefore promises to provide researchers data of a quality perhaps unseen outside

Nordic countries, although teething problems remain, and it will likely be some time before these data can be used in

rigorous research with which to guide policy.

While administrative data have been made available to researchers and while state-of-the-art data are available, the evidence

base on which policy should be based remains deficient as of 2023. The prospects going forward however, are promising,

as researchers are given ever better access to high-quality data. The Queensland Centre for Population Research currently

stands out in this regard. On the governmental side, the establishment of the Centre of Population under the Treasury

Department in 2020 represents a significant step toward bolstering suitable capacity within government.

Codification of decision making

Perhaps the most striking change to Australian immigration processes occurred in 1989, one year after a major inquiry into

migration policy and law saw the tabling of the report of the Committee to Advise on Australia’s Immigration Policies

(CAAIP) (Crock and Berg 2011, chapter 5 [5.21]). The CAAIP Report (1998) contained many recommendations similar to

those made by earlier bodies, which had also criticized the breath of discretion given to officials and the lack of a clear

appeals system. These earlier reports had observed the potential for corrupt and arbitrary decisions making and influence

peddling by the Minister (Administrative Review Council 1985, Report No 25, [81]–[82]; Australian Human Rights

Commission 2001, Report No 13, [197], [316]). In 1989, the sweeping powers vested in immigration officials were replaced

with regulations. These codified into law myriad criteria that had been developed to select various classes of migrants. The

year 1989 therefore marked the beginning of the transformation of migration laws, from a tiny act spanning barely a dozen

pages [(Migration Act 1958 (Austl)], to a legislative leviathan that today constitutes one of the most complex and

voluminous pieces of Australian legislation [see Migration Act 1958 (Austl)[Migration Regulations 2004 (Austl)]. While

migration law suddenly became more certain in 1989, such that migrants meeting entry criteria nominally acquired rights,

regulations could nonetheless be rapidly changed without immediate involvement of Parliament.

At this time, considerable debate occurred around the question of residual discretion in the administrative process. Pressure

from politicians led to the retention of special powers for the Minister for Immigration to intervene so as to make more

8

favorable application decisions. Over time, these “non-reviewable, non-compellable” powers have proliferated (Liberty

Victoria’s Right Advocacy Project 2017). They have been expanded to provide Ministers with over-ride powers to cancel

as well as to confer status. The era of “angels and arrogant gods” reemerged in January 2022 when the visa of tennis great,

Novak Djokovic, was cancelled when he sought to enter the country—in the absence of a COVID-19 vaccination—to defend

his Australian Open title (Higgins 2022).

The modern laws in Australia also reflect significant changes made in September 1994, in response to the growing power

struggle between the executive and the judiciary. If one objective in codifying immigration law in 1989 was to articulate

policy and stop judicial activism, the measure failed. Judicial review applications increased (exponentially). In 1994, the

law was changed to create a binary (supposedly automated) system of lawful versus unlawful status. The central idea was

to focus all attention on eligibility for a visa, the so-called universal visa requirement. A visa carries with it rights to be in

Australia (with or without conditions on matters such as work rights). The absence of a visa means that a person must be

detained and removed as quickly as possible. As discussed in the section on economic migration, this apparently simple

idea has resulted in prolonged uncertainty and even endemic cruelty at times.

The 1994 amendments led to the first full-scale attempt to openly restrict the ability of the courts to review migration

decisions. The automation of enforcement processes altogether removed the courts from arrest and detention processes. This

marked the point at which migration law was segregated from mainstream administrative law. The attempt was largely

unsuccessful in discouraging judicial review applications. Overt hostilities between Parliament and the Judiciary over time,

however, meant that migration cases came to shape (and deform) notions of administrative justice in Australia. Mandatory

immigration detention, couched in terms of the country’s human rights record, represents a major point of criticism and

inflection point of societal division (Crock and Berg 2011, chapters 19, 20). In recent decades, Australia has profited greatly

from advances in computing technology. It pioneered systems for tracing the movement and legal status of people in

Australia and overseas. For those engaged in practice or management of migration, “Legend.com” provides extraordinary

point-in-time access to every law and policy dating back to 1994.

Privatization of selection processes

The codification of migration policy reflected a systemic change in thinking about immigration within government and the

community more generally. The portfolio has been the subject of a great many reviews over the years, the outcomes of

which have been reflected in policies and practices in each program area. A pivotal structural reform in the 1990s was to

overhaul the operating model of the immigration bureaucracy to export or privatize many of the functions that traditionally

had been performed “in-house.” Processes for determining the health of prospective migrants were delegated for example,

to private doctors appointed as medical officers of the Commonwealth. The changes restricted scope for compassionate

decision making because migration officials were denied the ability to “go behind” assessments made by private bodies.

Although some bodies instituted internal appeal mechanisms, this could not compensate for the tight rules set by

government.

If one objective was to reduce the opportunity for administrative and judicial appeals, the changes also meant that the

government was no longer required to employ staff with diverse specializations within the Department. of Immigration

Privatization also saw more thought being given to which Australian bodies exhibit natural expertise in particular fields in

matters such as the assessment of migrants’ skills and qualifications to work in specific occupations (see section on

economic migration). One aspect of this trend was the rise of private companies to run immigration detention centres.

Privatization has worked well in areas such as health and economic migration. In the context of law enforcement

(immigration detention) and offshore processing, it has increased the potential for corruption, systemic incompetence and

neglect, and abuse of human rights (see Australian County Report for Global Detention Project 2022).

9

The securitization of immigration

One final trend is worthy of mention. However remote from the 2001 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States, Australia

was deeply affected by the perceived global threat of terrorism. Successive changes made to the law since that time reflected

a conflation of issues around border control, irregular maritime migration, and terrorism. Many of these developments are

discussed in the section on planned humanitarian migration. The electoral power of equating boat people, border control,

and security threats was seen most forcefully in the 2013 federal election. The restoration of a conservative Coalition

government saw the creation of a new super portfolio of Home Affairs. This consolidated those areas of government dealing

with immigration, customs, and national and international security. The then-new Minister for Home Affairs (Peter Dutton

MP) was vested with more individual power than any Minister other than the Prime Minister in any time in Australian

history. This concentration of power was heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic when aligned with bio-security

legislation. Quick to close its borders to international travellers and migrants alike, Australia became one of the most

restrictive countries on the planet. As noted, the policies adopted have had an ongoing impact on the country’s population

and economy.

Family migration

Declining birth rates in Australia motivated the relaxation of the family reunification program in June 1978. Concurrently,

the government implemented the predecessor of today’s Points Based System (PBS), the Numerical Multifactor Assessment

System (NUMAS), based on a Canadian model. Introduced on January 1, 1979, the NUMAS distinguished along social,

educational, and economic lines to determine “general eligibility,” increasingly discriminating in favor of “human capital.”

Importantly, NUMAS did not apply to family reunion or refugee admission.

Family migration is probably the most universal and immutable aspect of migration around the world, reflected in the

foundational right in international law to marry and found a family (Art 23 ICCPR) (Guendelsberger 1988). Australian

policy has always been generous in allowing for the sponsorship by citizens and permanent residents of certain close family

members on the basis of relationship. Between 1983 and 1997, therefore, family reunification was employed as a “hook”

for aspects of economic migration through a “concessional” category within the program. This allowed nondependent

children, working-age parents, and brothers and sisters of Australian citizens and permanent residents to gain extra points

in the points-based visa categories (see Crock 1998, 94–97). Today, the family program comprises four main subgroupings:

partner, child, parent, and a miscellaneous category for aged dependent relatives, remaining relatives, orphaned family, and

“carers.”

Australia classifies migrants in the family category as only those individuals who have been issued family-related visas.

Family members of persons issued with economic or humanitarian visas are instead counted against those categories under

the label of “secondary visa applicants.” In many European countries, this cohort is counted separately as family migrants.

The result is that family migration in Australia features even more prominently in practice than the reported statistics

suggest.

The single biggest policy change in Australian migration in recent years has been the shift from permanent to temporary

migration. With this has come a growing preference for “try-before-you-buy” visas that facilitate movement from temporary

to permanent status. Interestingly, it was in the partner stream of the family category that this trend began (in 1989) and

took root. As concern about the economics of migration developed, the family category within the overall program shrank

(see Crock and Berg 2011, chapters 7 and 8).

10

Box 2. The changing composition of additional flows of permanent migrants to Australia

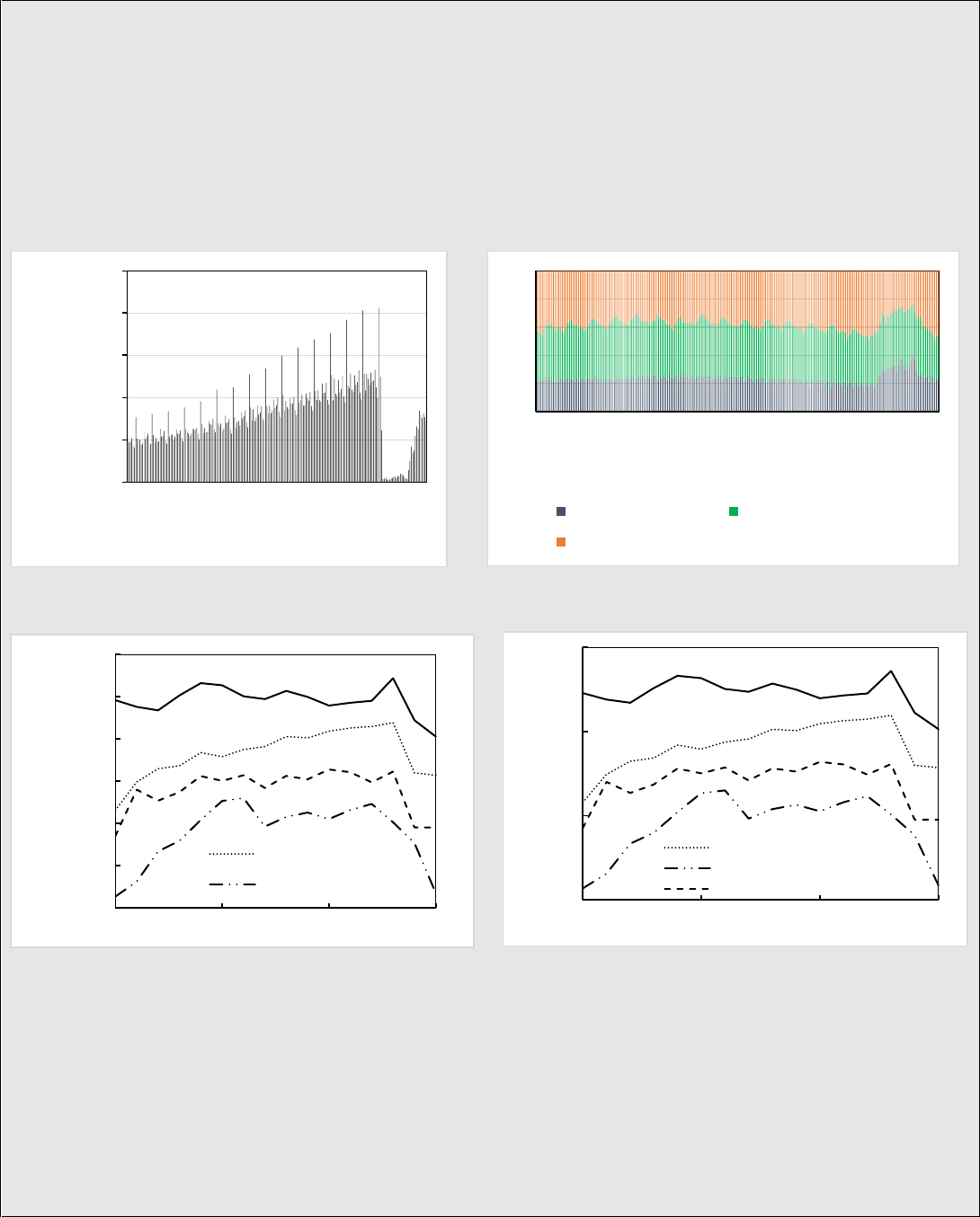

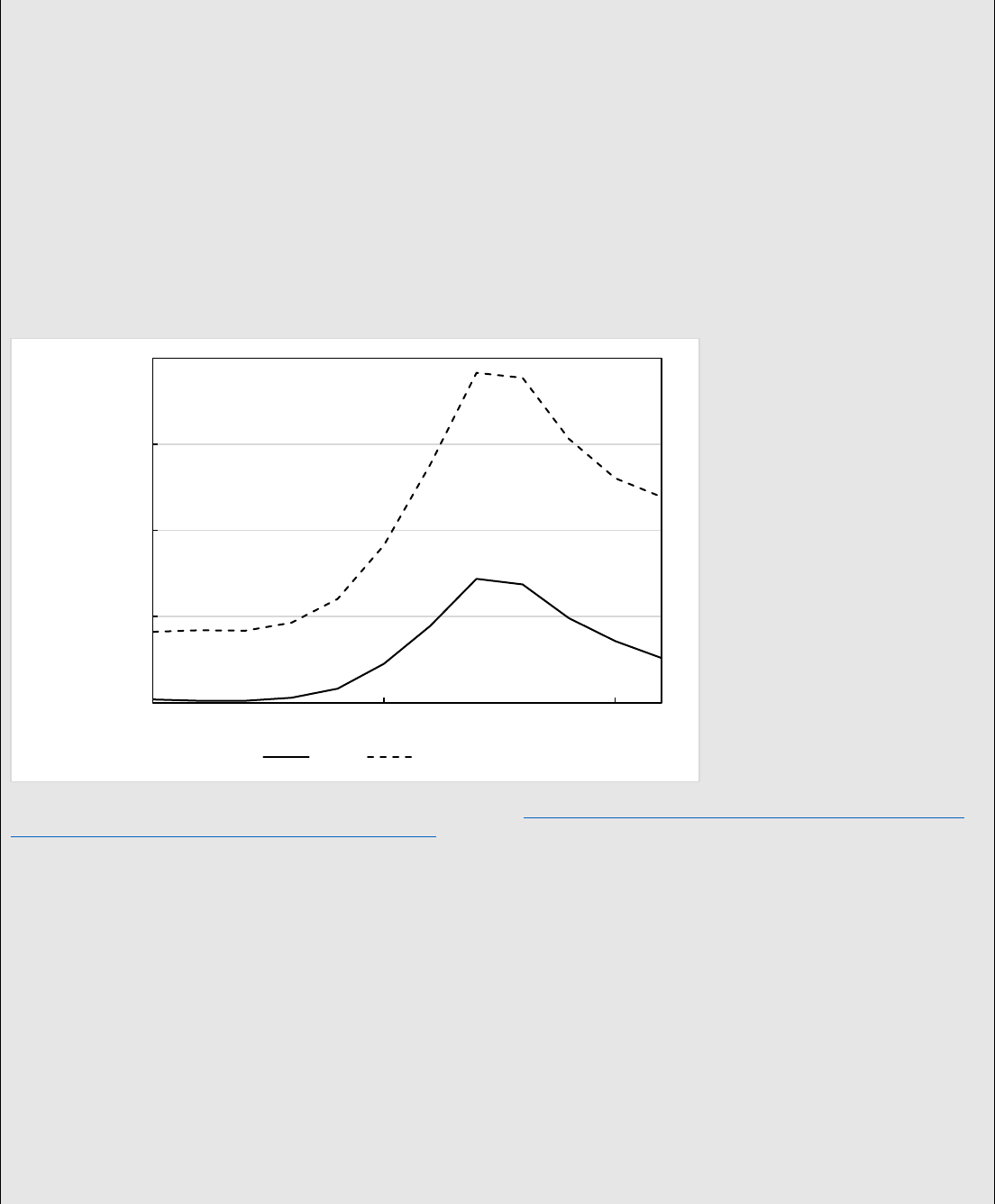

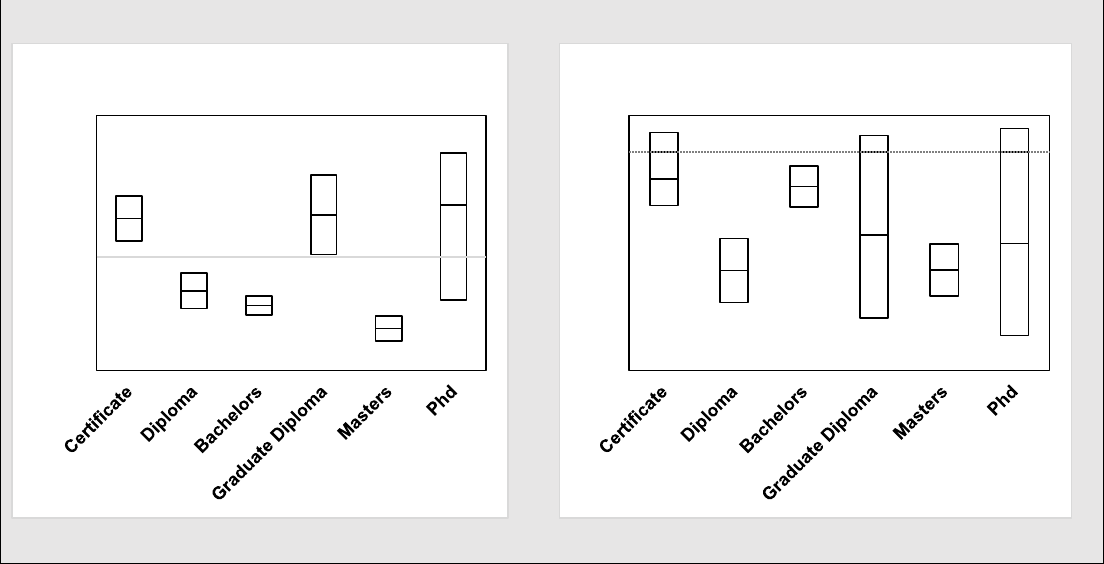

Figure B2.1 plots changes in the entry channel and skill composition of migration over time. Panels a and b, constructed

using the most recently released figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), show the overall volumes of

monthly permanent additions to Australia since July 2004, together with the disaggregation of these aggregate numbers

by entry channel.

Figure B2.1. Changes in the entry channel and skill composition of migration over time

a. Number of permanent visas, 2004-22 b. Composition of permanent visas, 2004-22

c. Human capital content of migration flows by entry d. High-skilled migration by entry channel, 1995--2010

channel, 1995—2010

Sources: Australia Bureaus of Statistics (ABS) for panels a and b; Kerr et al. 2017 for panels c and d.

Note: Panels a and b exclude “Special eligibility” permanent visas, while the data for December 2022 are provisional. Panels c and d

are taken from Kerr et al. (2017), based on 100 percent administrative data from 1996 when the series began to be collected.

The granularity of these data allow one to construct a consistent measure of skill over the period, in effect based on the

top three tiers of the 2008 International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO), including in the period before the

in

troduction of the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) in 2006: namely, (1)

managers, senior officials, and legislators; (2) professionals; and (3) technicians and associate professionals (see Czaika

and Parsons 2017 for further details). Unsurprisingly, panel c shows that a higher proportion of high-skilled workers enter

the country through the skill channel. Even though family members of economic and humanitarian visa holders count

against those categories, at the beginning of the time series, more highly skilled migrants entered Australia through the

family channel than through any other channel (panel d).

0

50000

100000

150000

200000

250000

7/1/2004

7/1/2005

7/1/2006

7/1/2007

7/1/2008

7/1/2009

7/1/2010

7/1/2011

7/1/2012

7/1/2013

7/1/2014

7/1/2015

7/1/2016

7/1/2017

7/1/2018

7/1/2019

7/1/2020

7/1/2021

7/1/2022

Total Permanent Visas

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

7/1/2004

7/1/2005

7/1/2006

7/1/2007

7/1/2008

7/1/2009

7/1/2010

7/1/2011

7/1/2012

7/1/2013

7/1/2014

7/1/2015

7/1/2016

7/1/2017

7/1/2018

7/1/2019

7/1/2020

7/1/2021

7/1/2022

Share Family Visas Share Skilled Visas

Share Other Visas

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1996 2001 2006 2011

Human Capital Content

of Migration Flows (%)

Family Channel

Humanitarian

Channel

0.3

0.5

0.7

0.9

1996 2001 2006 2011

Human Capital Content

of Migration Flows (%)

Family Channel

Humanitarian Channel

Nonprogram Channel

11

Planned humanitarian migration

Although the humanitarian program is a small and separate part of Australia’s migration intake, it has played a significant

role over time by literally changing the face of the country. Australia has made room in its planning for migrants displaced

by war, conflict, and disasters for almost as long as it has had organized programs. Following World War II, the admission

of persons displaced by conflict became a cornerstone of its population policy. After the abolition of the White Australia

Policy in 1972, the intake became more diverse (Neumann 2015). It was the aftermath of another war that ushered in the

most dramatic change, however.

After the fall of Saigon in 1975, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese fled the country (Parsons and Vézina 2018).

Australians had fought alongside these fugitives, so when boats began arriving in the country carrying Vietnamese refugees

they were treated with compassion. In July 1979, Prime Minister Malcom Fraser made the valiant decision, consulting

neither the cabinet nor the public, to welcome large volumes of Vietnamese refugees. In 1979, 14,000 were admitted, with

70,000 welcomed during his prime ministership. Between 1980 and 1983, Asian migration was made Australia’s top

migration priority. The White Australia Policy was consigned to history and the foundations of multicultural Australia laid.

Nevertheless, unauthorized maritime arrivals continue to engender fear that persists in influencing migration policy.

Australia responded to the revolution in Hungary by opening its doors to 14,000 Hungarians in 1957. After the Soviets

invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, 6,000 Czechs received visas. The 1970s witnessed the country respond to persons in need

outside of Europe, first from Chile in 1973 following the overthrow of the Allende government and later from Lebanon.

Some 16,000 displaced Lebanese had been accepted by 1980. An enquiry by the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign

Affairs and Defence in 1977 led to the creation of the Humanitarian Settlement scheme to oversee social integration

programs.

The scheme is characterized by a coordinated approach to providing language, education, health, and other services to

humanitarian arrivals. The program was tested and matured in the pressure of ensuring the integration over Indochinese

refugees from the conflict in Vietnam and later Cambodia. It has changed through time as the government has commissioned

private actors to deliver programs under contract.

A confusing aspect of Australia’s humanitarian program is that frequent reference is made to the country’s admission of

“refugees.” Australia is party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol, which lifted

the geographic and temporal limitations on the Convention. The word “refugee” has a specific meaning under the Refugee

Convention and thus under international law (see Hathaway and Foster 2014). In short, it is only persons physically in

Australia or under Australia’s care and control who attract legal obligations under this instrument. Critically, the Convention

does not require any country to run refugee resettlement programs. It does oblige state parties to refrain from sending those

meeting the definition of a refugee to places where they may face persecution for one of the five reasons stipulated in the

Convention (race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion). Persons claiming to

be refugees are referred to as “asylum-seekers.” This category is discussed in the seventh section of this paper on Australia

and asylum-seekers.

Over the years, Australia has looked increasingly to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the

global agency responsible for refugees, for assistance in identifying worthy candidates for admission. In 2022, the UNHCR

identified more than 100 million “persons of concern” (POC) displaced by human conflict. Of these huge numbers, the

agency identifies through its field operations a modest number of POC (generally fewer than 100,000), which the agency

proposes for resettlement in third countries. It is from this cohort that Australia often draws candidates for its planned

program. Australia is one of very few countries to cooperate in this manner with the UNHCR.

As explored in the seventh section, Australia’s treatment of Convention refugees and asylum-seekers has become

increasingly dissonant with its approach to migrants in its humanitarian program. Its treatment of asylum-seekers and

Convention refugees has become a consistent point of criticism when Australia is reviewed for its adherence to human rights

principles.

12

Although Australia’s humanitarian intake is advertised as non-discriminatory, there has been selective generosity in the

cohorts chosen for admission. After 2014, for example, an emphasis was placed on the selection of Christians at risk of

persecution. The ascendance of the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2021 saw the introduction of special visas for persons

evacuated by Australia and its allies. Afghans holding visas in Australia were given automatic 12-month extensions and

granted permission to lodge Refugee and Humanitarian visas (Class XB) onshore. These visas usually require individuals

to be offshore. Persons fleeing the conflict in Ukraine were also granted special visas allowing them to enter and remain in

Australia—with the possibility of conversion to permanent stay.

Box 3. Australian (birthplace) diversity and economic prosperity

The demise of the White Australia Policy was cemented by Prime Minister Fraser’s response to the unfolding humanitarian

catastrophe in Vietnam. Because refugees often represent new additions to host populations,

a

Australia’s Humanitarian

Settlement scheme has contributed significantly to the birthplace diversity of Australian migrants and the country’s push

toward multiculturalism. Despite the publication of the 1988 Fitzgerald Report, which placed greater emphasis on pivoting

away from humanitarian migration in general, the formation of migrant networks compounded earlier humanitarian numbers

from previously banned origins. The Keating government (1991–96) further placed emphasis on Australia’s role in the Asia-

Pacific region. Australia therefore continued to welcome large numbers of migrants from countries previously excluded.

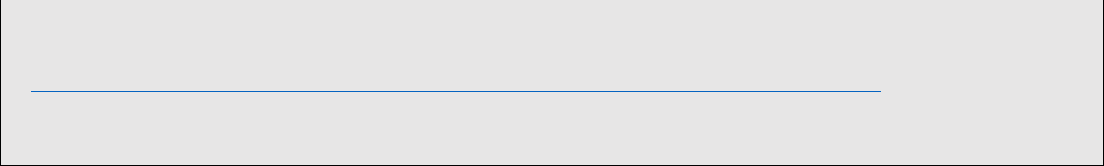

The “Asianisation” of migration to Australia since that time has been remarkable; between 1971 and 2006 the numbers of

Asians in Australia grew almost tenfold, as shown in figure B3.1.

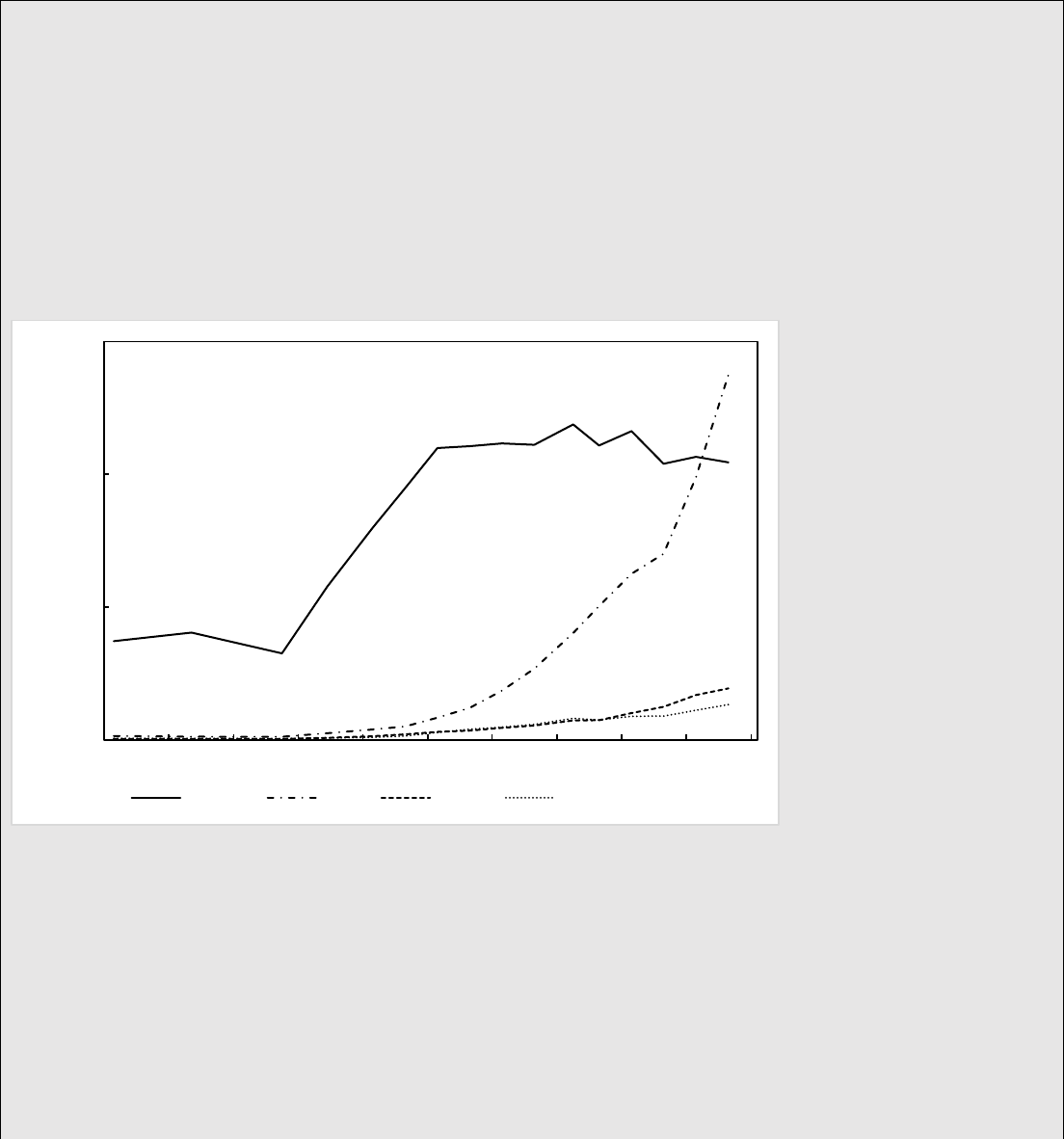

Figure B3.1. Growth of Asian migrants to Australia, 1920–2020

Source: Various censuses.

Watershed moments in Australia’s economic fortune are often associated with reforms introduced by Labor Prime Minister

Bob Hawke and then Treasurer, Paul Keating. The pair is credited with implementing key economic reforms, including the

introduction of a floating exchange rate mechanism; Medicare (universal health care); a Prices and Incomes Accord; the

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum; financial deregulation; the Family Assistance Scheme; the Sex

Discrimination Act; and a superannuation pension scheme for all. The passage of the Australia Act 1986 (Austl) removed

the remaining vestiges of British jurisdiction from Australia’s legal system. A key trend that sometimes omitted from this

narrative is the dramatic and sustained rise in migrant diversity over the period, as measured by migrant birthplace

fractionalization (splintering) or polarization (clustering).

In the workplace, diversity within teams can be viewed as a “double-edged sword” (Horwitz and Horwitz 2007, 111).

Cultural differences between workers may yield productivity gains within teams, especially in the context of collaboratively

0.0E+00

1.0E+06

2.0E+06

3.0E+06

1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

Europe Asia Africa The Americas

13

solving complex problems. Lazear (1999), for example, in the context of birthplace diversity, argues that firms’ decision to

hire workers from myriad origins is a function of how correlated knowledge is across countries. On the flipside, migrant

diversity can result in inferior economic outcomes should, for example, cultural differences foster distrust (Guiso et al. 2004

Nunn and Wantchekon 2011) or erode social capital (Alesina and La Ferrera 2000).

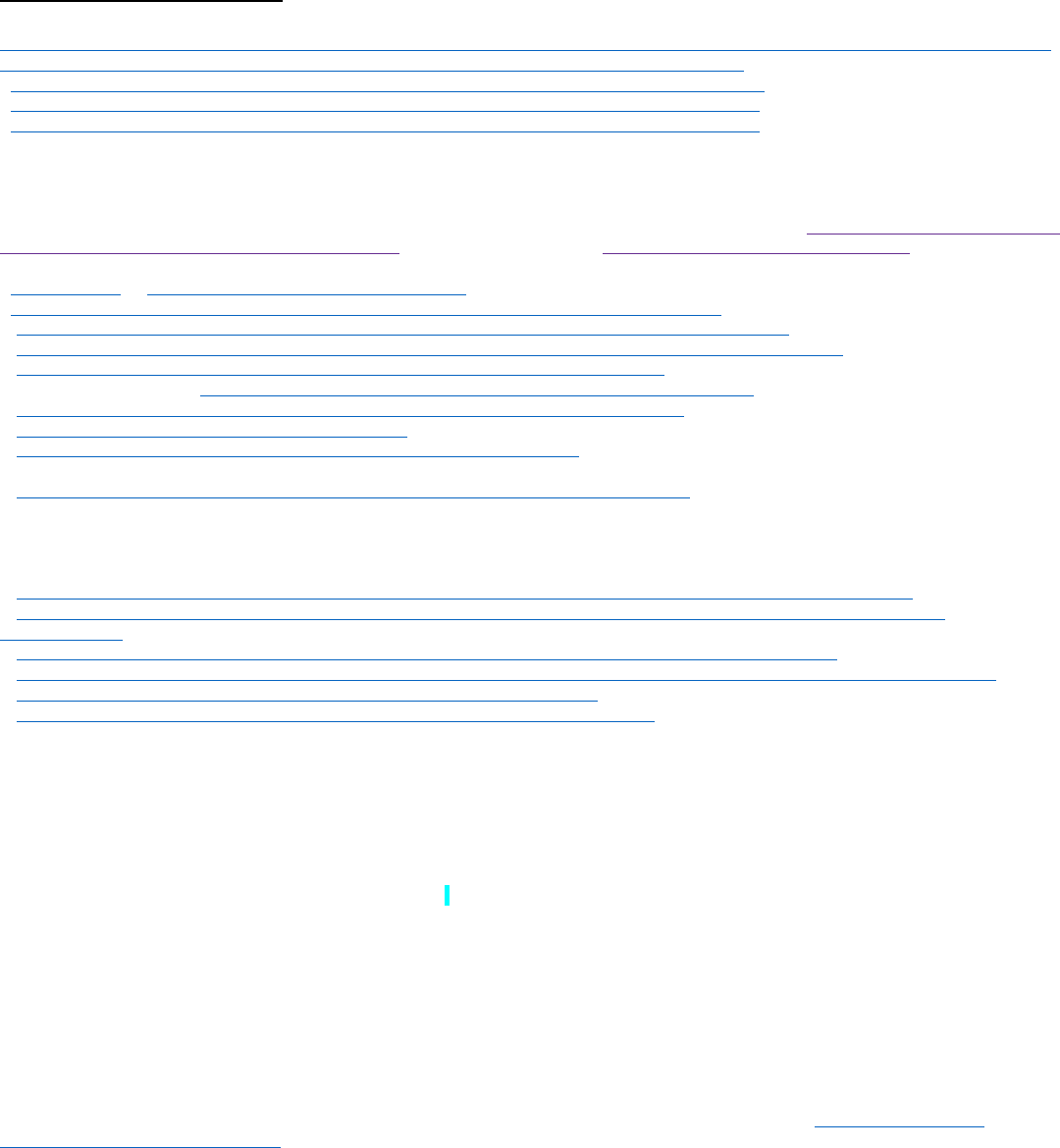

In the only study of its kind, Vernon (2018) examines the economic consequences of migrant birthplace fractionalization

(splintering) and polarization (clustering) on the economic fortunes of Australian industries between 1981 and 2016, as

measured by income per worker. Figure B3.2 shows the change in migrant birthplace fractionalization between 1981 and

2016, based on harmonized data pertaining to 89 origin countries. Harmonization is required because Australian censuses

capture migrants from a varying number of origin countries over time. Notably, fractionalization increased in every SA4

local government area with the exceptions of the Yorke Peninsula and the Barossa Valley.

b

Across a broad range of

econometric specifications Vernon finds consistently that migrant birthplace fractionalization is positively associated with

increases in income per worker, while migrant birthplace polarization is negatively associated.

Figure B3.2 Change in migrant birthplace fractionalization in Australia, 1981–2016

Source: Vernon 2018.

Note: Fractionalisation is defined as =

∑

(

1 −

)

=1

, the probability that two immigrants come from different birthplaces.

For example, a value of 0.7 represents a 70 percent probability of selecting two immigrants born in different places. SA4 = Statistical

Area Level 4.

Exploring the heterogeneity of the results across industries, Vernon finds that the negative effects of migrant birthplace

polarization (which is often associated with tension and miscommunication between groups) manifest in all three industrial

sectors: primary (raw materials extraction and production); secondary (manufacturing); and tertiary (services). By contrast,

the positive effects of migrant birthplace fractionalization (typically associated with knowledge diversification and complex

problem solving) are driven exclusively by work performed in tertiary service industries. Indeed, it is also in the tertiary

sector that the negative influence of migrant birthplace polarization is felt most acutely.

Further disaggregating the results by migrants’ skill levels as captured by their levels of education, Vernon finds that it is

only high-skilled diversity in the tertiary sector that results in significant “spillovers.” The analysis suggests that a one

standard deviation increase in tertiary sector fractionalization increases income per worker by almost 5 percent. Taking the

two heterogeneity results in tandem, Vernon argues that because only skilled diversity in the tertiary sector has a positive

income effect across the entire industry, “the industry and skill distinctions are complementary and…immigrant

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

-0.04 0 0.04 0.08 0.12 0.16 0.2 0.24 0.28 0.32 0.36 0.4

Frequency

Change in Immigrant Fractionalisation (SA4)

14

fractionalisation may be relatively more of a productive attribute among high-skilled workers within services.” Finally,

exploring the mechanisms at play that undergird his analysis, Vernon, in a supplementary analysis, argues that the effects

of birthplace diversity are at least in part transmitted through improvements in labor productivity and that cultural

differences between groups wane over time through subsequent generations, presumably because of integration.

a. These additions are along the extensive margin (Bahar, Parsons, and Vézina 2022).

b. SA4 areas as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics refers to an area defined on the basis of commuting data whereby

individuals work and live in the same areas. They are comparable to US commuting zones.

c. The benchmark regressions of these specifications are corroborated by causal results based on a shift-share identification strategy.

Economic migration

The program for the admission of migrants on economic grounds is the area where policy and practice have changed most

markedly over the years. This section bundles discussion of employment-based categories, business migration, foreign

students, tourists, and other visitors. Modern laws and policies stand in sharp contrast to the radical simplicity of the White

Australia era, when little or no attention was given to migrant attributes beyond skin color and ethnicity. Discrimination

today is based upon an individual’s net worth in terms of wealth (as a business migrant); occupation; and wage-earning

position for a sponsoring employer. High-value migrants are more likely to be offered immediate permanent residence. For

others, the norm has been temporary visas with varying capacities to transition to permanence over time.

A paradigm shift in Australia’s migration policy occurred following the publication of the 1988 CAAIP report discussed

earlier. The report demarcated Australia’s change in focus toward “economic rationalism”:

37

away from manufacturing and

toward attracting human capital and raising “immigrant quality.” The report advocated professionalizing the Immigration

Department and switching to a rules-based system of selection—one freer from lobbying and less prone to bureaucratic and

ministerial discretion, while remaining focused on skills (as opposed to family reunion and humanitarian intakes). The report

further recommended reducing refugee numbers, and abandoning reliance on periodic amnesties to regularize the status of

unlawful non-citizens. The modern era in economic migration policy in Australia can be dated back to this report. The move

to codify policy was matched by a more economically literate approach to policy formulation—and more thoughtful

consideration of which authority is best placed to assess the suitability of potential migrants. By 1998, the skill stream

accounted for most of the visas granted under the Migration Programme.

The other major policy change occurred in 1995 with the introduction of a simplified temporary immigration system in the

form of the two- to four-year 457 (Business Long-Term) visa. Temporary (though long-stay) migration emerged as a new

tool through which migration could be tailored to suit the requirements of the Australian economy dynamically. Until this

time, migration to Australia was largely favored to be permanent by both the government and incoming migrants. From this

time onward, there would exist a segment of society, those “Not Quite Australian” (Mares 2016), who paid taxes but could

not vote, draw benefits, or access Medicare, amounting to many who would never be offered permanent residency (see

Crock and Berg 2011, chapter 9). In-need skills defined by shortage lists are regularly revised.

38

Over time, employers and

regional governments have become increasingly involved in the process to ensure that the incoming skills match the current

demands of the nation as well as local economies.

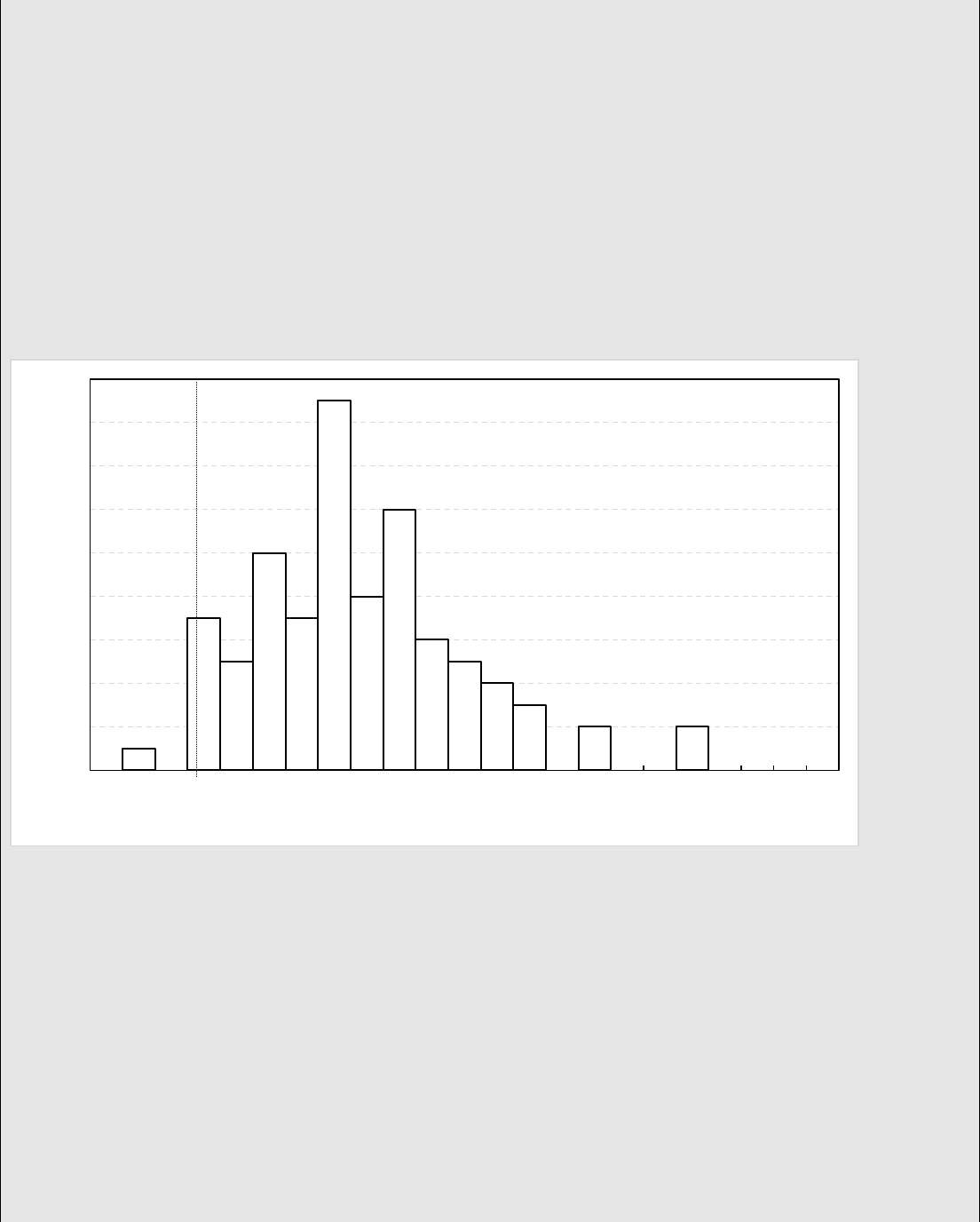

Box 4. An economic assessment of two-step migration

Without question, the shift from admitting permanent settlers only to an ever-increasing reliance upon temporary, try-before-

you-buy migration represents the greatest seismic shift in recent Australian immigration policy. Approximately 7 percent

of the workforce comprises temporary workers, while over the past two decades, approximately 50,000 additional temporary

workers have been added to the stock (Mackey, Coates, and Sherrell 2022). Gregory (2015) estimates that the ratio of

temporary to permanent visas each year to be approximately three to one.

Until the mid-90s, migration to Australia was premised on permanency and predicated on planned arrivals being funnelled

through skill, family, and humanitarian channels, or applications for skilled independents through the Points Based System

(PBS), the modern-day representation of what began life as the Numerical Multifactor Assessment System. Increasingly

over time, the PBS has sought to select skilled individuals on the basis of their human capital and individuals’ economic

and employment viability. Notably, the supply-side mechanism of the PBS did not match incoming skilled migrants to

15

specific job vacancies, whereas today, all temporary working visas are employer sponsored. This in turn however, has

resulted in a two-step or staggered process of migration to the country where an individual first enters on a temporary basis

before subsequently applying for “PR” (permanent residency) status and in turn citizenship, should indeed the visa subclass

they entered the country on permit that possibility. Whereas temporary or non-permanent migration was actively

discouraged to Australia when it was considered a “settler country,” today, temporary visas are not subject to quotas, while

permanent numbers are strictly capped.

Cobb-Clark (2003) has suggested that the shift away from direct migration to two-step indirect migration has resulted in

remarkable employment gains for the country. Given that most pathways to permanency are through employer sponsorship,

or else studying—often with the specific intent to remain in Australia as a permanent resident afterward—it indeed seems

intuitive that superior employment outcomes should have resulted. In a recent assessment of Australia’s two-step

immigration policy, however, Gregory (2015) provides a nuanced perspective—one that recognizes the changing nature of

new arrivals to the country relative to the existing migrant stock. Turning away from unlinked quinquennial census data that

suitably capture permanent additions, Gregory (2015) rather analyses (male) pseudo-cohort monthly employment data from

Australia’s Labour Force Survey, which are superior in also including temporary migrants experience during their early

(temporary) years. In doing so, Gregory moves beyond relying only upon descriptive statistics to essentially comparing

monthly cohorts over time, before and after the shift in policy system.

Under the traditional regime, between 1981 and 1985, 40 percent of those who had arrived by January 1981 were employed,

with more than 60 percent being employed within 9 months of arrival. Employment levelled off at about 70 percent after 4

years, finally plateauing at about 80 percent after 8 years of arrival. These numbers are indicative of a relatively smooth and

swift integration process. In comparison with the 2001 to 2005 period under the new regime however, Gregory highlights

three distinct periods: the first four years after arrival, which is characterized by significantly lower employment rates; a

period of comparable employability from four to six years; and a final period after six years, which is characterized by

notably higher employment rates.

Gregory further highlights that all significant employment changes take place within the group of migrants heralding from

so-called non-English-speaking countries, the group with the lowest employment rates, as opposed to changes occurring

within groups. This suggests that the changing composition of incoming migrant flows between English and non-English-

speaking groups underpins Gregory’s findings. For students from non-English-speaking countries—70 percent of whom

originate from China and India, the group most affected by student visa growth—there are definitive and large full-time

employment differences between the old and new policy systems. Finally, in making the distinction between full- and part-

time employment, Gregory highlights that under the current indirect system, full-time employment is 30 percent to 60

percent less likely than when compared to under the old regime and that only one-third of non–-English-speaking male

migrants hold down a full-time job. As such, Gregory concludes that labor market integration today takes place via part-

time employment as opposed to from the unemployment pool as it once did.

Employment-based migration

The migration program in Australia has long been divided into supply-based (independent) permanent economic migration

and demand-based (employer-sponsored) temporary migration. Australia was one of the first countries to adopt the

Canadian device of awarding points against various attributes as an assessment device. Over time, it has refined the points

test device to give the government detailed control over who is deemed worthy of a temporary or permanent visa.

A feature that unifies most supply and demand categories in the program is the mechanism for selecting migrants based on

occupation, skills, and experience. A single reference point is used for classifying all occupations: The Australian and New

Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO), compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. ANZSCO

provides common groupings of every occupation from laborer to specialist medical practitioner. It also catalogues the

qualifications, skills, and/or experience that are required to work in each position. ANZSCO is used by migration officials

and by domestic agencies tasked with accrediting persons in designated jobs (see Parsons et al. 2020 for additional details).

Critically, labor market vacancies are also catalogued using this classification of occupations. It is a system that vests the

Australian government with extraordinary control over the selection of “skilled” migrants, meaning it is difficult to describe

the system as anything approximating a “free market.” If an occupation is not listed, an employer will generally be powerless

16

to sponsor an individual—no matter how important they are for their business. The system is one that delivers high labor

market participation rates for migrants.

Since 2001, the federal government has used labor market data to create various lists that act as both preconditions for visa

applications and mechanisms to give preference to certain applicants (whose occupations are in short supply). In the early

days, attempts were made to link educational programs to the skills shortages list. This created problems because sham

educational institutions were created in fields such as cooking and hairdressing. This led to abuse of the program and abuse

of potential migrants—and no clear economic gain to Australia. The lists have subsequently been refined and extended to

cover all aspects of economic migration, temporary as well as permanent. Over time, the term “skilled” has become a proxy

term for “needed migrant.” The system is one that can appear to place equal value on the skills of a welder and those of a

specialist brain surgeon. Concessions are made to accommodate regional needs.

Independent (permanent) migration

The points test first introduced in 1979 bears little resemblance to the system in place in 2023, except that age (capped at

45), educational qualifications, work experience, and English-language proficiency still feature prominently. Two

significant changes have been made. First, and perhaps most significant, is the requirement that applicants have their

qualifications and experience assessed by relevant accreditation bodies before making any form of application. Relevant

assessment bodies are identified against every occupation listed on the Skilled Occupations Lists, published in the

Government Gazette. Applicants must also test for language proficiency before applying. The Pre-Application Skills

Assessment system slows the application process for migrants. However, it has reduced problems that used to arise around

the recognition of overseas qualifications—at least with respect to primary applicants for skilled visas.

The second change to the points-based visas (made in 2010) is that the system has been moved to an Expression of Interest

(EoI) process that occurs online. There are still “pass marks” that indicate who has a chance of succeeding. Formal

applications can only be made, however, if the Minister issues an invitation to apply. The system allows the government to

pool applications and then issue invitations to the top applicants each quarter according to job vacancies in particular

occupations. Hence the entry point for an EoI can be 65 for everyone, but then engineers may require 80 points and medical

practitioners 90 points. Concessions (lower scores) apply where applicants want to live in a regional area (defined by

postcode). The system is opaque for applicants, but highly responsive for government policy makers. To deal with problems

of applicants inflating their claims, a Public Interest Criterion (PIC 4020) operates to block any applications for three years

should a person be unable to substantiate their claims, or if they submit a bogus document.

Employer-sponsored migration

The new normal in economic migration in Australia is that most applicants begin their migration journey on temporary

visas, all of which are necessarily employee sponsored. Permanent status is available to high-net-worth migrants attracting

salaries above $A180,000.

Since 1999, there has been a steady move toward unified regulations that preference young (under 45), highly skilled

individuals who are “job ready” to work in Australia. As noted, the explosion in temporary workers has been one of the

most remarkable transformations to occur in the labor market in the modern era. Although generally yielding good outcomes

for employers—for example, keeping labor costs lower—issues surrounding the abuse of workers have proliferated. The

degree of concern showed about abuse of migrant workers, however, represents a key point of political difference The issue

spawned a series of inquiries and myriad policy changes over two decades.

The most used vehicle for temporary skills shortage visas (referred to as TSS visa) is now the subclass 482 visa—previously

the 457 visa. The regime involves three steps: government approval of the business sponsoring an applicant; nomination of

a position listed as an approved occupation, meeting salary and other requirements; and determination that an applicant has

the skills and experience to perform the job specified. Workers can be vulnerable at each stage. Where an employer goes

bankrupt or otherwise loses approval to sponsor, migrant workers will lose their visas unless they can find another employer

willing to sponsor them. Workers were initially given only 28 days to do this. This period was extended to 90 days in 2008

and reduced to 60 days in 2017.

17

The position to be filled by a migrant worker raises issues around the protection of local workers and the abuse of those

brought in to perform work. A decade of controversy has delivered policies that specify minimum salary levels for specific

occupations and require sponsors to undertake labor market testing to demonstrate that local workers cannot be found.

Attempts have been made to make salary floors stick, by implementing rules that prevent employers (at risk of losing

sponsoring rights) from deducting items from salaries such as visa costs, accommodation, and other items. The requirement

that sponsors engage in labor market testing seems to be a political gesture, especially because the list system is supposed

to be predicated on known vacancies in the labor market. Interestingly, in 2017, the government dropped previous

requirements that sponsors demonstrate a commitment to training local workers to fill needed positions. Instead, employers

were required to pay money into a “Skilling Australia Fund” vaunted as a vehicle for funding apprenticeships. It is not clear

that this has created the resource promised. Big employers seem to have found ways to avoid making the contributions

because of carve-outs in the legislation for repeat players and high-income earners.

Other issues identified as problems include the relationship between temporary and permanent occupation lists, which limit

the ability of lower-skilled workers to progress to permanent status. Businesses are only likely to be able to sponsor a visa

if they are large sufficiently large. Many small and medium enterprises (SMEs), for example, are reliant upon specific

temporary workers: working holiday makers in the case of SMEs in the construction sector, for example. A separate

Temporary Activity (subclass 408) visa was used by the Australian government to allow migrants to remain in Australia on

a temporary basis during the COVID-19 pandemic.

39

Concerns with the proliferation of temporary visas was a significant

factor in the decision of the Labor government in 2022 to institute an inquiry into the operation of the visa system that it

described as “broken.”

40

Business migration

One area where competition between countries to attract migrants is keenest is in the field of business. It was Labor Prime

Minister Paul Keating who in 1993 introduced a visa class that would allow individuals to migrate on the basis of investing

in government securities. At that juncture, the visa required applicants to invest, but also demonstrate a record of

achievement in investing as a form of business. Programs have typically targeted individuals as business owners and as

senior executives with established records of achievement in business. Over time, the program has involved points testing

(now unfavored) and transitioned to align with other economic visa programs with try-before-you-buy visas that facilitate

the transition from temporary to permanent status. The business visa categories are arguably the most relaxed of all the

streams in terms of occupational qualifications and experience. The emphasis is upon wealth creation. Nowhere is this more

apparent than with the Special Investor Visas. Using an EoI system, these have given priority to individuals with the

resources to invest large amounts of money (at least $A5 million and up to $A15 million) in a designated business or fund.

Concessions made for business migrants include relaxed criteria for visa cancellations following the failure of a business

venture within three years of visa grant. Applicants are only required to show that they made a genuine attempt to establish

and run a business.

Box 5. The labor market impact of (high) skilled migration

Despite the large volumes of both temporary and permanent migration to Australia, there is a startling paucity of evidence

analyzing the labor market impacts of this migration. This lack of evidence is all the more stark given the importance of a

strong evidence base in informing policy and the ongoing data revolution. As Boucher, Breunig, and Karmel (2022) lament

in their recent overview, while a veritable cornucopia of studies continue to be produced in other countries that examine

various facets of the economic impact of migration on natives the outcomes for nationals, implementing ever-more stringent

econometric methods, it is simply not the case that those findings can be applied to the idiosyncratic case of Australia. This

is because of the high percentage of foreign-born individuals in the population (29.7 percent, according to Boucher, Breunig,