STUDY

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

European Added Value Unit

PE 558.773 - September 2015

Bringing transparency,

coordination and

convergence to

corporate tax policies

in the European Union

I - Assessment of the magnitude of

aggressive corporate tax planning

PE 558.773 1

Bringing transparency, coordination

and convergence to corporate tax

policies in the European Union

Part I: Assessment of the magnitude of

aggressive corporate tax planning

Research paper

by Dr Robert Dover, Dr Benjamin Ferrett, Daniel

Gravino, Professor Erik Jones and Silvia Merler

This study has been written at the request of the European Added Value Unit of the

Directorate for Impact Assessment and European Added Value, within the Directorate-

General for Parliamentary Research Services (DG EPRS) for the European Parliament’s

Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) in relation with the legislative

own-initiative Report of Co-Rapporteurs Luděk Niedermayer and Anneliese Dodds,

MEPs.

Abstract

This paper assesses the loss of tax revenue to the EU through aggressive corporate tax

planning to be around 50-70 billion euro per annum. On an assumption of no base from

sources other than profit shifting, then this figure jumps to 160-190 billion euro. The

paper presents the methodology used and the country-by-country calculations on

which these figures are based. It describes the common tools used in aggressive

planning, and the impacts these have on tax revenue, concluding with an assessment of

the inefficiencies created by individual tax arrangements for large multinational

companies in the European Union.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 2

AUTHORS

This study has been written by Dr Robert Dover, Dr Benjamin Ferrett, Daniel Gravino,

Professor Erik Jones and Silvia Merler, at the request of the European Added Value

Unit of the Directorate for Impact Assessment and European Added Value, within the

Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services (DG EPRS) of the General

Secretariat of the European Parliament.

RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATORS

Risto Nieminen, Stanislas de Finance, European Added Value Unit of the Directorate for

Impact Assessment and European Added Value, within the Directorate–General for

Parliamentary Research Services of the Secretariat of the European Parliament.

To contact the Unit, please email EPRS-EuropeanAd[email protected].eu

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

This document is available on the internet at: www.europarl.eu/thinktank

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and

do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorized, provided

the source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy.

Manuscript completed in September 2015. Brussels © European Union, 2015.

PE: 558.773

ISBN 978-92-823-7991-2

doi:10.2861/386200

QA-04-15-644-EN-N

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 3

Table of Contents

Executive summary ....................................................................................................................... 4

Chapter 1 – How much do aggressive corporate tax planning and tax evasion cost the

EU as lost tax income? What is the cost of corporate tax evasion and aggressive tax

avoidance at EU-level? .................................................................................................................. 7

1. Background ...................................................................................................................... 8

2. Country-by-country analysis ......................................................................................... 9

2.1. Shifting from national to European level, and consequential losses ...................... 11

3. Calculations of tax loss.................................................................................................. 13

3.1. Country-level indicators ............................................................................................... 13

Chapter 2 – What is the potential EU added value of addressing this lack of

transparency, coordination and convergence at EU level? .................................................... 17

1. Background .................................................................................................................... 17

2. Definition of tax avoidance .......................................................................................... 18

2.1. Theoretical background ................................................................................................ 18

3. Income shifting .............................................................................................................. 19

3.1. The relative advantages of common and separate tax jurisdictions....................... 25

3.2. Structural considerations.............................................................................................. 26

Chapter 3 – Macro-economic impact at single Member State level. What are the

channels through which spillovers operate? What are the spillover effects, within as

well as outside of the EU?........................................................................................................... 29

1. Background .................................................................................................................... 30

2. The net-effect of spillover activities ............................................................................ 30

2.1. Base spillovers through relocation .............................................................................. 32

2.2. Base spillovers through profit shifting ....................................................................... 32

2.3. Strategic spillovers......................................................................................................... 33

Chapter 4 – Do tax deals lead to collective (in)efficiency? ..................................................... 34

1. Background .................................................................................................................... 34

2. Inefficiencies................................................................................................................... 35

2.1. Organisational inefficiency........................................................................................... 35

2.2. Productive inefficiency ................................................................................................. 35

2.3. Informational inefficiency ............................................................................................ 35

2.4. Inefficient public goods provision............................................................................... 36

2.5. Summary of inefficiencies ............................................................................................ 36

References ..................................................................................................................................... 37

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 4

Executive summary

Aggressive tax planning and tax avoidance are the ostensibly legal practices of working

within a tax code, but using often sophisticated business and accountancy practices to

minimise a company’s tax liability. By contrast, tax evasion is the illegal practice of partial

or non-payment of taxes due. Presented like this, the two broad concepts of evasion and

avoidance appear as a binary. This is illusory: frequently aggressive tax planning is

prosecuted by tax authorities, and it becomes a matter for courts to decide whether the

practices were merely aggressive or in breach of the legal code. Similarly, it is for tax

authorities and legislators to work together to refine their systems and dispositions

towards prosecution. There is – therefore – much in the way of interpretation in this

public policy area.

We estimate that revenue losses for the EU as a result of corporate tax avoidance could

amount to around 50-70 billion euro, representing the sum lost to profit shifting. We

think this figure represents a lower-end estimate of lost revenue. If, however, we include

other tax regime issues, such as special tax arrangements, inefficiencies in collection and

other practices, we estimate that revenue losses for the EU due to corporate tax avoidance

could amount to around 160-190 billion euro, again a conservative estimate. We have

assessed the corporate income tax efficiency to be 75 per cent. This contrasts with the

IMF’s assessment of 86 per cent. The data and calculations used are provided in the

annexes to this report. These percentage figures do not represent the amounts that could

be expected to be recovered by the various tax authorities. A certain percentage of these

sums would be excessively expensive or technically difficult to collect, and would thus

remain uncollected. Similarly, our calculations do not include estimates for activities

within the shadow economy (which would themselves amount to evasion) that, if

factored in, would add substantially to these figures.

Our assessment is that if a complete solution to the problem of base erosion and profit

shifting were available and implementable across the EU, it would have an estimated

positive impact of 0.2 per cent of the total tax revenues of the Member States. The Annual

Macroeconomic Database of the European Commission (AMECO) calculates that the total

tax revenues collected over the EU as a whole were 5.74 trillion euro in 2011 (which is the

latest year for which such figures are available). This means a comprehensive solution

would add another 11.5 billion euro in revenues. While we believe that the calculation

on which this estimate is based is robust, we also believe that this figure is likely to be at

the lower end of what could reasonably be expected to be recovered through EU-level

regulation.

There is considerable empirical evidence that the Member States engage in strategic

competition when comes to setting taxes (essentially by adjusting the effective rate) and

to recovery practices (the latitude afforded to businesses in complying with the tax code).

Nonetheless, there are divergent views within the academic literature as to whether such

competition exists, and what impact it has if it does. Compounding the effects of this

empirically observable competition are the substantial differences in the published

estimates for lost tax revenue. These differences are the result of the absence of accepted

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 5

benchmarks for assessment, and of the radically different methodologies used by the

various governmental, academic and private accountancy institutions making the

assessments. For example, the most common – and largest – difference between

methodologies is the inclusion or not of tax allowances (for capital investment or staff

development) in the calculation of lost tax revenue; such inclusions serve to inflate the

stated calculation of tax revenue ‘lost’. Nevertheless, it would be useful to have, at EU

level, a coherent conceptual framework for building consistent and reliable benchmarks

to be used when assessing the impact of aggressive tax planning and tax avoidance

across the Member States and the EU. This would provide a firmer platform on which to

assess the different tax systems and rules prevalent across the EU, and in reducing the

opacity in the tax systems and arrangements. This opacity is fuelling strategic

competition among the Member States, and is reducing the effective tax rates levied on

businesses operating in the EU.

The reduction in ‘effective tax rates’ has a positive correlation with attracting foreign

direct investment (FDI). It does have to be recognised, however, that some forms of FDI

do not amount in a net gain to the recipient country, and that other forms (such as long-

term loans) are only weakly linked to FDI. Some studies have suggested that the

reduction in effective tax rates has similarly resulted in a reduction in government

investment in public services. These studies are highly contested and often do not take

into account the natural fluctuations contained within the economic cycle. The presence

of such studies may suggest that there is only a slight positive correlation between

reducing ‘effective tax rates’ and attracting FDI.

There is some evidence that businesses effectively pass on increased business taxes

through wage negotiations. The evidence is interesting because it also suggested that

wages did not rise, but that employment levels dropped. One academic study found that

once the cost of labour was factored in, every 1 euro reduction in corporation tax only

saved business 53 cents owing to an offset effect.

Aggressive tax-planning is increasingly occurring through spillovers. The main channels

through which spillovers occur are: base spillovers through relocation; base spillovers

through profit-shifting; and strategic spillovers (seen most commonly with highly mobile

capital and the registration of intellectual property). Currently the most effective

framework within which to discuss spillovers is via examples of individual countries: we

provide the contrasting examples of Germany, Ireland and the UK in the report.

As with revenue losses, measurements of ‘bottom-line’ figures for profit shifting are

complicated and contested. Those who have sought to measure profit shifting have only

been able to focus on the tax jurisdiction failing to recover funds, rather than on the

whole balance, which would necessarily include the recipient tax jurisdiction. As a

consequence, assessments of whole-picture net gains or losses are largely absent in

published assessments. As per the previous paragraph, we are able to compare and

evaluate the efforts of several Member States in this regard. We have made an assessment

that the net loss to the EU amounts to 50-70 billion euro per annum, a sum that would

justify the additional cost of EU-level regulation.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 6

The problem of the ease of reallocating taxable income via accounting mechanisms is

overstated. If reallocation via accounting were easy, there would be no benefit in

relocating real business activities to low-tax countries. We can observe empirically that

relocation is the predominant practice, and studies suggest that a 10 per cent reduction in

effective tax rate can produce a 30 per cent uplift in FDI, albeit with some caveats

regarding how the FDI is assessed and what its true impact is.

There is a great deal of tax competition between Member States, which has become

strategic and outward-facing in nature. Econometric data point to a trend whereby if one

country reduces its effective tax rate by 1 per cent, there is a commensurate downward

shift of 0.7 per cent among its key competitors. This means that lack of coordination at EU

level could lead to a race to the bottom. Accepting that the assessment of an effective tax

rate occurs ex post, further investigation is always required to validate the hypothesis

that a response occurs.

Individualised tax arrangements between major multinational enterprises and tax

authorities lead to four types of possible inefficiencies. These inefficiencies are the result

of both nominal and real effects of tax deals. They arise from aggressive tax strategies

based on transfer pricing and profit shifting, but they also arise from the impact of tax

deals on the location and pattern of investment.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 7

Chapter 1 – How much do aggressive corporate tax

planning and tax evasion cost the EU as lost tax income?

What is the cost of corporate tax evasion and aggressive

tax avoidance at EU-level?

Key findings

- We estimate that revenue losses for the EU due to corporate tax avoidance through profit

shifting are estimated to amount to around 50-70 billion euro.

- If, however, we assume no base from sources other than profit shifting, we estimate that

revenue losses for the EU due to corporate tax avoidance amount to around 160-190 billion

euro. This would encompass special tax arrangements, inefficiencies in collection and other

practices. The data and calculations used are provided in the annexes.

- It should be recognised that these figures do not represent the amounts that could be

expected to be recovered. Some percentage of these sums would be excessively expensive

or technically difficult to collect.

- We have assessed the corporate income tax efficiency to be 75 per cent. This contrasts with

the IMF’s assessment of 86 per cent.

- These figures do not include estimates for activities within the shadow economy (which

would themselves amount to evasion) that, if factored in, would add substantially to the

figures above.

- There is considerable empirical evidence that the Member States engage in strategic

competition when setting taxes and also in recovery practices. Compounding the effects of

this competition are the substantial differences in published estimates for lost tax revenues,

the result of an absence of accepted benchmarks for assessment and of the range of

radically different methodologies used by the various governmental, academic and private

accountancy institutions making the assessments. It should be noted that the difference

between tax evasion and tax avoidance is not a binary. There is a great deal of

interpretation between businesses, accountants, legislators and judicial authorities on these

questions.

- A common EU approach and methodology could help address the lack of operational

agreement between institutions. The relaunch of the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax

Base (CCCTB) could offer an effective solution to some of these problems.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 8

1. Background

On 10 May 2013 EurActiv, an online media on EU affairs, quoted European Council

President Herman Van Rompuy as saying that ‘every year around 1 trillion euro is lost in

EU Member States because of tax evasion and tax avoidance’. A similar figure is

presented on the European Commission’s Taxation and Customs Union website.

1

These

figures possibly reflect the findings of a report prepared by Murphy (2012).

2

A close look

at the report shows that, of the estimated loss of 1 trillion euro, 150 billion euro can be

attributed to tax avoidance (the minimisation of tax liability within the legal code),

resolvable through cost-effective regulatory and enforcement measures, whilst the

remaining loss of 850 billion euro is the result of tax evasion (the illegal non-payment or

under-payment of tax). While EU-level regulation can help mitigate the impact of

avoidance in a cost-effective way, only Member State-level responses (some of which will

be coordinated) can usefully address the problem of evasion.

That said, the reliability of the 1 trillion euro headline figure is open to question.

Although there is substantial evidence that tax avoidance and evasion impose significant

revenue losses, most economists agree that estimating those losses with any precision is a

challenge.

3

Existing estimates based on a macro approach (most of which are published

by NGOs) attract considerable public attention, but are difficult to interpret because of

the drawbacks associated with some of the measurement concepts. Moreover, many of

these published estimates include tax-reliefs (for capital investment, staff development

and so on) in the ‘lost revenue’. This is a highly questionable practice as these allowances

are designed to spur economic growth and, therefore, increase receipts in the medium

term. The inclusion of such allowances in these meta-figures also reduces the amount of

revenue that Member States could be expected to collect with more effective regulation

and collection. The calculations concerning what lost revenue can reasonably be

recovered rely on settled methodologies of calculating loss, and on the understanding

that only a proportion of lost revenues not attributed to allowances can affordably be

collected.

4

1

http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/taxation/tax_fraud_evasion/a_huge_problem/index_en.htm.

2

Murphy, R. (2012), ‘Closing the European Tax Gap’, a report for the Progressive Alliance of

Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament.

3

See, for example, Fuest, C. and Riedel, N. (2009), ‘Tax evasion, tax avoidance and tax expenditures

in developing countries: a review of literature,’ Report prepared for the UK Department for

International Development, Oxford: Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation; Hines, J.R.

(2014), ‘How serious is the problem of base erosion and profit shifting?’, Canadian Tax Journal, no. 2,

pp. 443-53; IMF (2014), ‘Spillovers in international corporate taxation’, IMF policy paper,

International Monetary Fund, May 2014; Maria Theresia Evers, Ina Meier, and Christoph Spengel

(2014), ‘Transparency in Financial Reporting: Is Country-by-Country Reporting suitable to combat

international profit shifting?’, ZEW Discussion Paper, http://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-

docs/dp/dp14015.pdf.

4

An example of this – essentially based on the same sets of data – are the British Government’s

figure for the corporation tax gap in 2012-13 of GBP 3.9 billion, to be compared with Murphy’s

estimate of GPB 12 billion.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 9

Part of the problem is institutional and part is conceptual. Aggressive tax planning is a

legitimate practice in most countries. Moreover, firms argue that such aggressive tax

planning is not only part of their responsibility to shareholders, but also that it frees up

resources for investment and, thus, for economic growth. The sophistication of tax

planners in devising complex tax plans has largely been ahead that of government tax

authorities and the judiciary. Adding an extraterritorial dimension to tax planning has

allowed companies to shift their taxable profits to states where they will receive more

favourable tax treatment. A key characteristic of deliberative tax planning is the

reduction of current or future tax liabilities through strictly legal arrangements that can

be seen to contradict the intention behind the original law.

5

Aggressive tax planning involves the exploitation of technicalities and technical

weaknesses in a fiscal regime, or working with multiple tax regimes to identify loopholes,

gaps and terminological mismatches that allow for the reduction of tax liabilities. While

such practices let companies exploit gaps in international tax law, they are not illegal, but

rather ‘entrepreneurial’, with a political component in individual countries influencing as

to whether these practices are to be viewed as ‘acceptable’ within ethical, moral or

political frames of reference. There is no unitary or universally accepted distinction

between ‘acceptable’ and ‘aggressive’ tax planning.

6

The absence of such a unitary model

has allowed for a far greater quantum of activity to avoid tax across the Union than

would otherwise have been the case. In practical terms, a Europeanised response is the

only practical response to such issues (in terms of both organisation and of

implementation).

2. Country-by-country analysis

The most useful approach to begin an analysis of European tax loss is to use a country-

by-country analysis. Such analyses usually build on specific tax avoidance practices

rather than on an overview of phenomena such as aggressive corporate tax planning or

tax evasion. For example, according to Bach (2013), the annual revenue loss due to profit

shifting in Germany (explored later in conceptual terms) amounts to about

90 billion euro. ‘If the revenue from corporate taxation in Germany is divided by the

corporate income figures from the national accounts, companies’ average tax burden for

the period 2001 to 2008 is 21 per cent. This rate is considerably lower than the statutory

tax rates for this period (but is not out of line with prevailing business tax rates across the

developed world). The reason for this is that tax-reported profits were well below

macroeconomic profits. This tax gap in 2007 was something in the order of at least

120 billion euro, or almost five per cent of GDP. The high level of tax losses is significant.

By broadening the tax base as part of the corporate tax reform of 2008, the tax gap has

5

Adapted from European Commission (2012) Recommendation of 06.12.2012 on aggressive tax

planning,

http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/resources/documents/taxation/tax_fraud_evasion/c_2012

_8806_en.pdf.

6

See Evers, Meier and Spengel (2014).

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 10

diminished significantly, but it was still at about 90 billion euro, or 3.7 per cent of GDP.’

7

That estimate is controversial. Heckemeyer and Spengel, for example, provide several

reasons to believe that Bach has overestimated the amount of the revenue loss; according

to their own calculations, the actual figure is likely to be less than 10 billion euro.

8

Another illustration comes from the United Kingdom. On the basis of a model presented

in his report ‘The Missing Billions’, Richard Murphy (2008) assesses that tax avoidance by

the largest 700 companies in the UK has cost the Inland Revenue some GBP 12 billion in

lost corporate income tax (CIT) (the current equivalent of circa 16.9 billion euro).

9

The

Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation (2012) criticised Murphy’s approach in

its report ‘The Tax Gap for Corporation Tax’. Specifically, the authors argued that

Murphy’s approach tells us more about the differences in tax and financial accounting for

corporate income and profits than it does about the absolute value of the revenue loss.

10

These illustrations reveal the importance of establishing reliable benchmarks and the

magnitude of financial implications of aggressive tax planning or tax avoidance. It is at

this point that the effects of the different institutional arrangements between nations and,

similarly, the individual national conceptual conventions become most apparent, as

radically different assessments and calculations are possible using the same evidence

base. The point is often made in the literature; suffice here to cite a recent description of

the methods used in popular estimation techniques: ‘For instance, taxable income or

respectively tax payments in absence of tax avoidance are approximated by using profits

from financial accounts multiplied by the statutory tax rate, company profits from

national accounts or foreign capital stocks multiplied by a deemed return and an average

tax rate. The differences between the actual tax payments or taxable profits and the proxy

for benchmark profits/tax payments in absence of tax avoidance can therefore not be

clearly attributed to profit shifting activity but rather capture conceptual differences

between the compared measures. This makes these figures difficult to interpret.’

11

7

The 2008 reforms came in several forms: the rate of corporation tax was reduced from 25 per cent

to 15 per cent, but there remained a ‘solidarity surcharge’ of 5.5 per cent. The average trade tax base

rate would now be 14 per cent (with local variations). The effective tax rate was estimated to be

29.8 per cent after the reforms. The tax cuts announced in the reforms were partly paid for through

reductions in allowances and deductions, but also with incentives for corporations to file in

Germany (indicating an assumption of increased tax revenues). In addition to the reduction of

corporate tax rates, there were new rules on interest-capping and change-of-control, and new

regulations for transfer-pricing. For the pricing estimate, see S. Bach (2013),

‘Unternehmensbesteuerung: Hohe Gewinne – mäßige Steuereinnahmen’, DIW Wochenbericht, pp. 3-

12.

8

J. H. Heckemeyer and C. Spengel (2008), ‘Ausmaß der Gewinnverlagerung multinationaler

Unternehmen – empirische Evidenz und Implikationen für die deutsche Steuerpolitik,

Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik’, Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik, vol. 9(1), p. 54.

9

R. Murphy (2008), ‘The Missing Billions: The UK Tax Gap’, Trades Union Congress: London.

10

Michael P. Devereux, Judith Freedman and John Vella (2012), ‘The Tax Gap for Corporation Tax’,

Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation: Oxford.

11

Adapted from Clemens Fuest, Christoph Spengel, Katharina Finke, Jost Heckemeyer, Hannah

Nusser (2013), ‘Profit Shifting and ‘Aggressive’ Tax Planning by Multinational Firms: Issues and

Options for Reform’.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 11

2.1. Shifting from national to European level, and consequential losses

As we shift from national to European level, we need to consider interactions across

national jurisdictions. There are a large number of research studies that assess the

significance of corporate tax avoidance and the impact that international tax incentives

have on avoidance strategies. For the purposes of this report, we have selected studies

that have passed a peer-review threshold and which can therefore be considered to have

been robustly challenged by the academic community. Huizinga and Laeven support the

assertion that the profits reported by European subsidiaries of multinational enterprises

(MNEs) often depend on specific tax incentives and on the potential for profit shifting

within the multinational group. Thus, European level action and regulation would serve

to reduce some of the incentives that currently exist for profit shifting within MNEs. As

Egger, Eggert and Winner reveal, the result is not only a redistribution of tax revenue but

also a reduction in overall tax payments, both in absolute terms and in relation to firms

that operation within only one national jurisdiction, owing to the effect that these tax

competition incentives have on prevailing tax rates. We suggest that there would likely

be reduced tax competition, and therefore reduced market-distorting incentives, were

European-level action to be introduced.

12

The challenge is to estimate this net revenue loss. Again, while there is substantial reason

to believe that aggressive tax planning takes place, very little is actually known about

what the impact of aggressive tax planning will be on net revenue loss, precisely because

it is neither in the interest of the businesses concerned, nor of their accountants, to reveal

the amount of corporate tax that has been avoided by taking planned steps. Recent

empirical research builds on extrapolations of the volume of profit shifting across

jurisdictions, and yet such approaches are likely to overestimate the gross losses within

countries and the net loss at European level, because of assumptions built into the

extrapolations that are based on figures of a small number of very large, listed MNEs.

13

Our research leads us to conclude that the relaunch of the Common Consolidated

Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB) in June 2015 offers an elegant solution to the complicated

issues pertaining to corporate taxation in the EU. If the Commission is able to conclude its

negotiations successfully, there is every reason to believe that that the CCCTB will reduce

the transaction costs for businesses operating across borders and, by having the force of

law (rather than the status of voluntary undertakings), also to minimise the opportunity

for them to avoid corporate taxes by exploiting gaps between individual national codes.

One empirical study that attempts to shed light on revenue losses is Hines’ recent

research report, published in 2014.

14

Some of the latest evidence suggests that the semi-

elasticity of income reporting is roughly 0.4, which means that a corporation that

operates in a jurisdiction with a 25 per cent tax rate, and that has the opportunity to

reallocate some of its taxable income to another jurisdiction that has a 15 per cent tax rate,

12

Ibid.

13

Ibid.

14

Hines, J.R. (2014). ‘How serious is the problem of base erosion and profit shifting?’, Canadian Tax

Journal, no. 2, pp. 443-53.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 12

will typically arrange its financial and other affairs to reallocate 4 per cent of its income to

the lower-rate country. For various reasons, discussed below, even this 4 per cent figure

may overstate the potential tax revenue income by eradicating base erosion and profit

shifting, but, on its own terms, the potential tax revenue from 4 per cent of pre-tax

incomes of multinational corporations make a limited but valuable contribution to the

government finances of most countries.

15

On average, a member country of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) in 2011 generated 8.8 per cent of its total revenue from taxes on

corporate profits, only a portion of which represented taxes on multinational

corporations. As an illustrative estimate, 2 per cent would be two tenths of 1 per cent of

tax revenue – even if one were to double or quintuple this figure, it would amount to less

than 1 per cent of tax revenue. From this standpoint, it appears that even a complete

solution to the problem of having the tax base erode and the profits shifted to another

jurisdiction – were one available and implementable – would have little direct impact on

government finances.

16

To support his arguments, Hines notes that:

- The fact that governments of countries with high tax rates collect considerable

revenue from taxing the profits of their resident multinational corporations is in

itself an indication that tax avoidance is neither as easy nor as cost-effective as some

fear it is. If firms were able to organise their affairs in ways that would easily

redistribute pre-tax earnings in high-tax locations to alternative locations with zero

or very low tax rates, then most would surely do so, and even those corporations

without an international business presence would quickly establish operations in

foreign locations with lower tax rates in order to reduce their tax obligations. That

multinational corporations still seek to shift a proportion of their profits indicates to

us that a new European regulatory regime should place appropriate costs on MNCs

and, thereby, price out a reasonable proportion of profit-shifting for tax avoidance

purposes.

- If it were easy to reallocate taxable income via accounting tools, there would be no

benefit in locating real business activities in low-tax countries. The profit-

maximising strategy would be to locate business activity wherever it generates the

highest pre-tax profits, and use financial or other means to reallocate taxable income

to an affiliate located in a zero-tax location.

- Further evidence is available from the location of foreign business activities. Studies

consistently show that multinational firms locate more employment, property, plant

and equipment in locations with lower tax rates, and less in locations with higher tax

rates. Some of this movement can, in some instances, be accounted for by a lower

cost base in the recipient nation.

- Finally, there is evidence from the use of tax haven affiliates by multinational

corporations. Tax havens are those countries that have the lowest tax rates, and so

are the destinations of choice (if one has unfettered choice) for profits to be

15

Ibid.

16

Ibid.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 13

reallocated from high-tax countries. From 2002 to 2008, only 20 per cent of large

German multinational firms had tax haven affiliates. A majority of German firms did

not reallocate taxable income to tax havens, since they had no method of doing so,

given the absence of legal presence in those countries or the deterrent of prevailing

norms that mitigate against the practice.

Is it possible that corporate tax evasion and aggressive tax planning at EU-level is less

significant than generally assumed? In order to analyse this further, we need to unpack

the conceptual issues around tax evasion and tax avoidance and then generate some

preliminary estimates based on that conceptual reorganisation. Before doing so, however,

it is opportune to provide some rough estimates based on preliminary calculations.

3. Calculations of tax loss

Using public finance and national accounts data from Eurostat and the European

Commission’s publications on taxation trends in the EU, it is possible to obtain data on

corporate income tax (CIT) revenues, CIT rates and operating surplus (‘profits’) that can

be used to estimate the extent to which international tax planning may affect EU Member

States’ CIT revenues. Following the IMF’s report on spillovers, we propose a two-tier

approach.

17

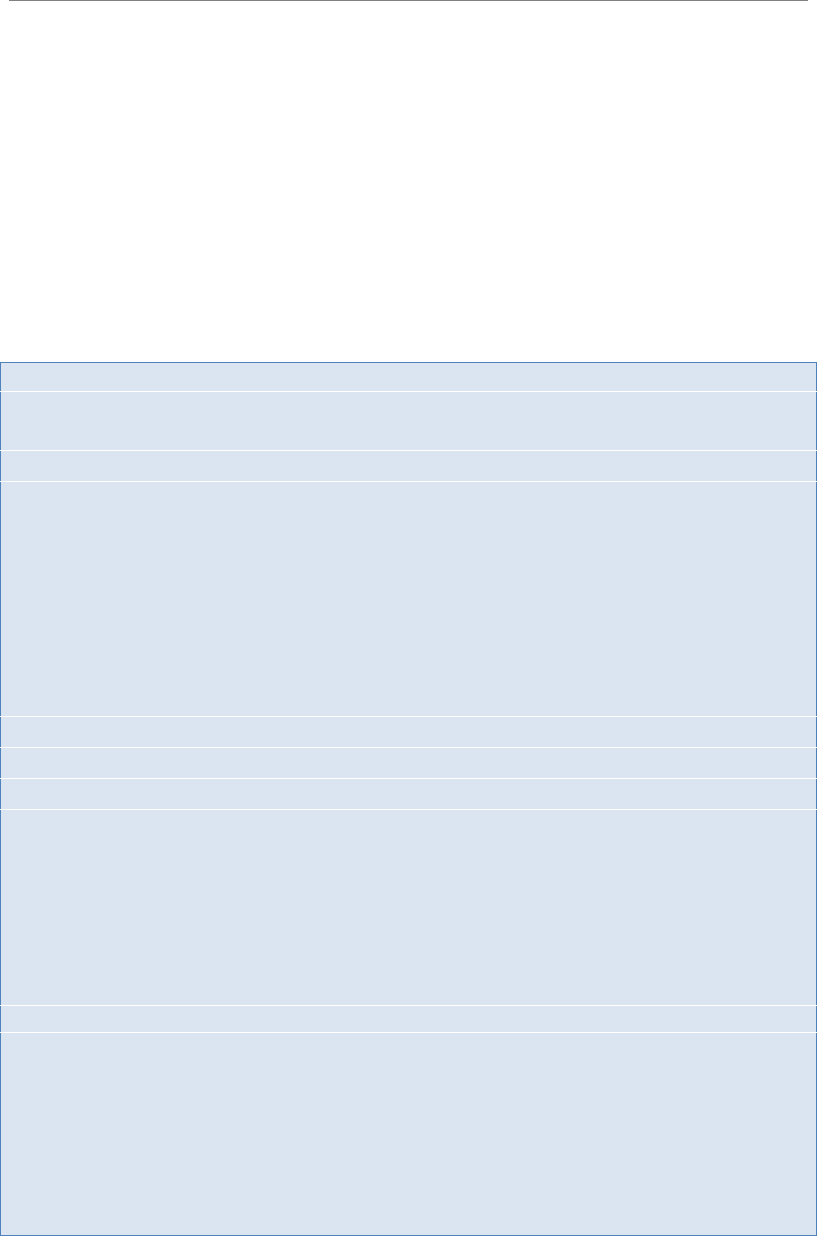

3.1. Country-level indicators

At the first level, we have constructed country-level indicators of CIT efficiency (Eff

i

):

where Rev

i

is the actual CIT revenue of country i, Rate

i

is the CIT rate and Base

i

is the

‘theoretical’ tax base. The further Eff

i

lies below one (unity), the less efficient is the CIT

system in raising revenue in relation to the benchmark. This may reflect special tax

incentives and efficiency, but it also reflects profit shifting.

At the second level, to gain insight into which (and how much) Member States lose/gain

from profit shifting, we have constructed an indicator of ‘revenue without profit shifting’

(RWS

i

):

where is the average efficiency rate for the entire sample, which enables us to

eliminate (in a crude way) the base effects from sources other than profit shifting. The

17

International Monetary Fund (2014), ‘Spillovers in international corporate taxation’, IMF Policy

Paper.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 14

difference between ‘revenue without profit shifting’ (RWS

i

) and the ‘actual revenue’

(Rev

i

) could be interpreted as the loss/gain from profit shifting.

Importantly, it should be noted that there are three available measures of the operating

surplus (which is the measure for the theoretical tax base – surplus being the sum of

money that governments’ seek corporation tax for), namely: (i) gross operating surplus

(GOS); (ii) net operating surplus (NOS) not adjusted for imputed compensation for self-

employed workers (who are treated for tax purposes as being external contractors and,

therefore, not subject to payroll taxes, pensions and so on); and (iii) NOS adjusted for

imputed compensation for self-employed workers.

This gross operating surplus (GOS) is somewhat more inclusive than the standard

conceptualisation of a corporate income tax base insofar as it does not allow for the

subtraction of asset depreciation, interest payments or other provisions, which commonly

include allowances to reduce corporation tax for capital investment or staff development,

or for other measures determined to be both a business and a social good. Moreover, tax

treatment of losses across periods of assessment can create differences between the GOS

that appears as accrued in national accounts, as opposed to the corporate income tax base

that is relevant for tax assessment purposes. So the simple equation of income versus

expenditure, which gives rise to an operating surplus, rarely equates to the actual surplus

that is declared after allowances and deductions are factored in. Hence, it is reasonable to

expect the efficiency (Eff

i

) of the tax system relative to this corporate income tax base to be

reduced (i.e. below 1, or unity). This is why we subtract depreciation from the GOS to

create a net operating surplus (NOS). Calculations using this figure should bring us

closer to the ‘true’ corporate income tax base. Like earnings before interest and tax, NOS

is closer to tax accounting than national income accounting. Debates about different

forms of accounting standards and methods formed part of Parliament’s work in the

previous parliamentary session as part of the work stream associated with the

Transatlantic Legislators’ Dialogue. In the accompanying MS Excel sheet, in which we

presents our calculations, there are estimates for NOS inclusive of compensation to self-

employed (Computations (NOS not adj. SE) (2)) and NOS adjusted for the compensation

to self-employed (Computations (NOS adj. SE) (2)). We seek to rely on the latter estimate

because our revenue data is ‘taxes on the income or profits of corporations’, which

excludes the income of self-employed persons, whose surplus above costs is taxed as

personal income rather than as business profit, which would therefore be subject to

corporation tax.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 15

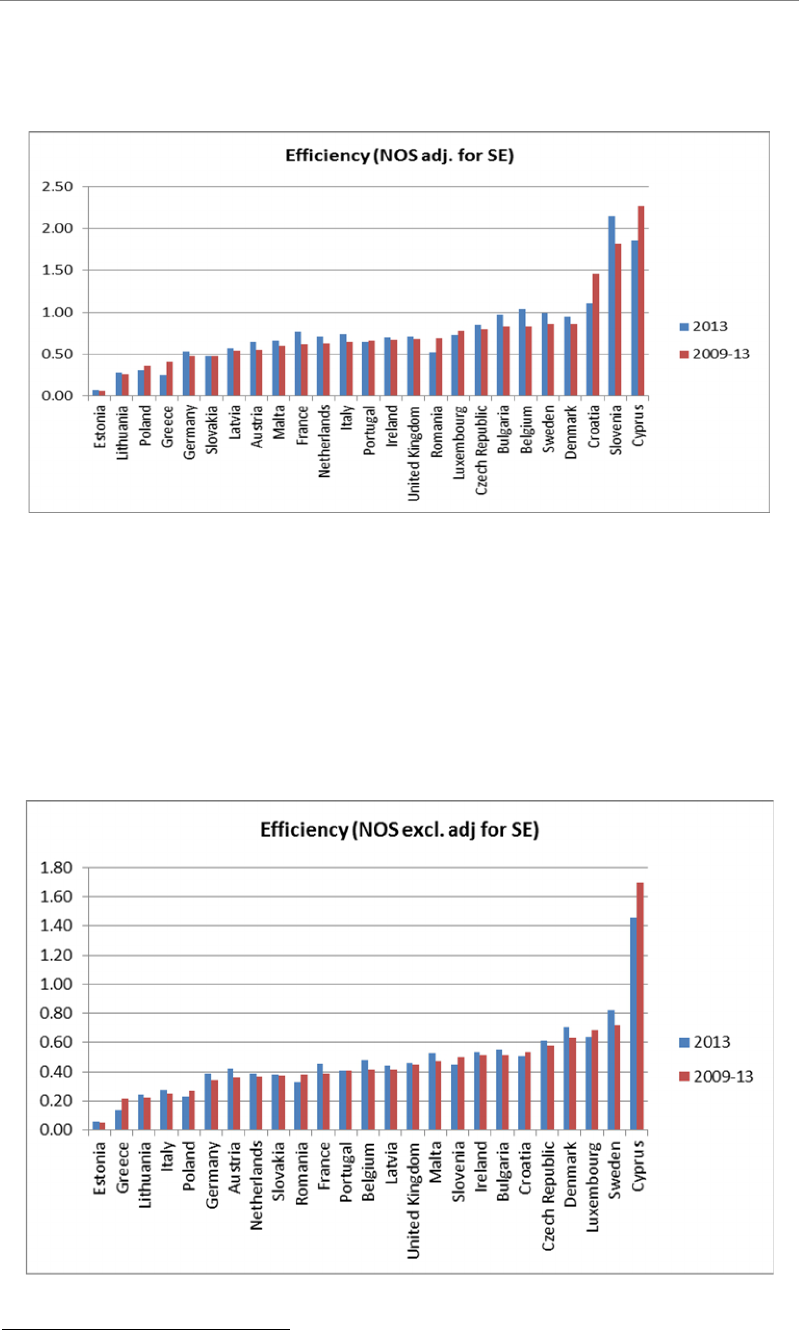

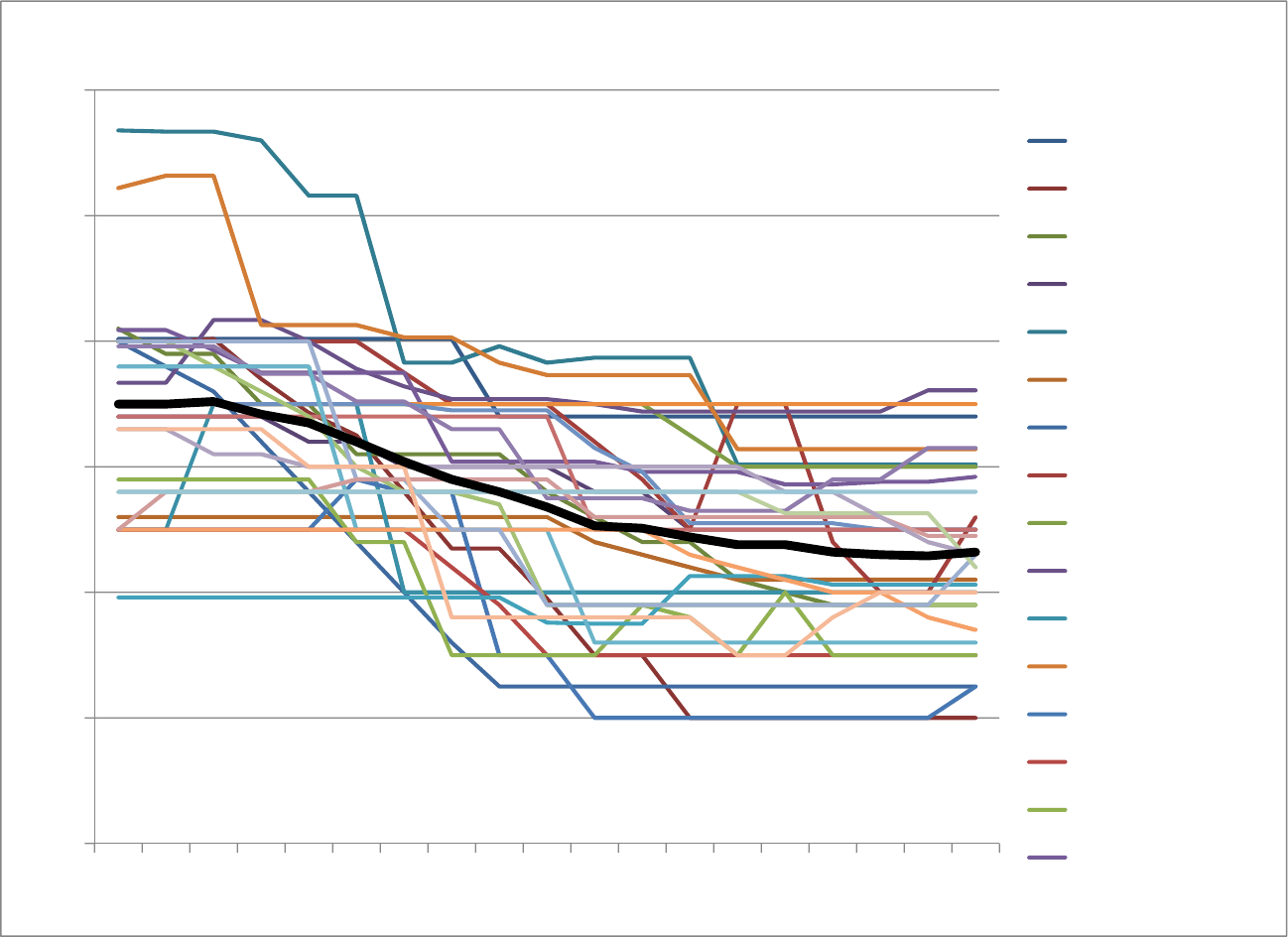

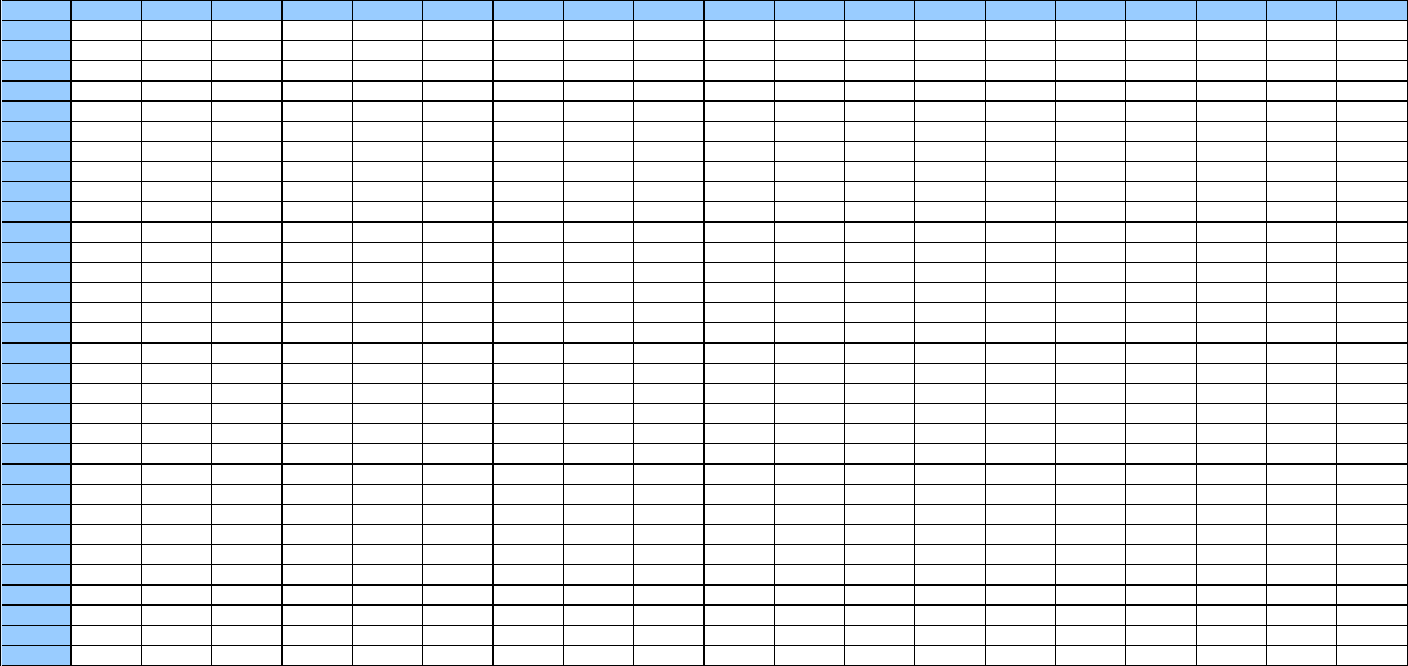

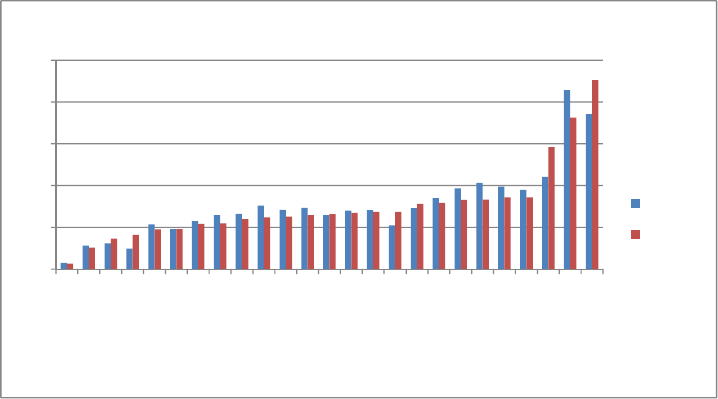

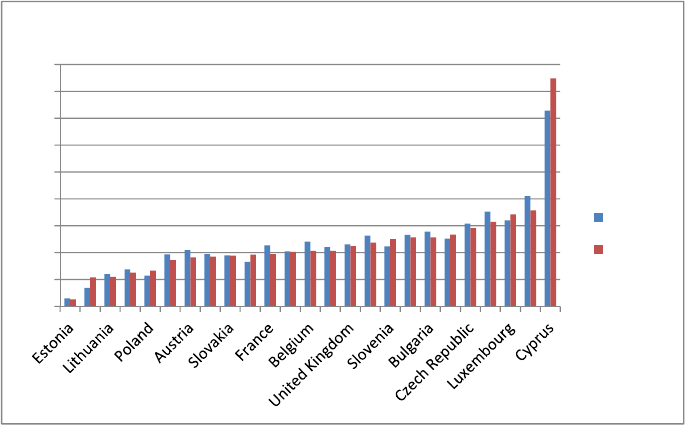

Estimates based on NOS adj. for SE yield the following CIT efficiencies:

As a benchmark, we think it is useful to compare these results to similar estimates based

on GOS presented by the IMF (2014).

18

The mean CIT efficiency is around 75 per cent (if

we estimate this over the period 2009-2013; see sheet (Computations (NOS adj. SE) (2)) in

red). (It should be noted that Spain, Hungary and Finland are excluded owing to a lack of

available data.) This is comparable to the figure given in footnote 134 in the IMF study,

whereby they report an average efficiency at 86 per cent. Note that while the implicit CIT

base is smaller than NOS, the variation between individual countries is large.

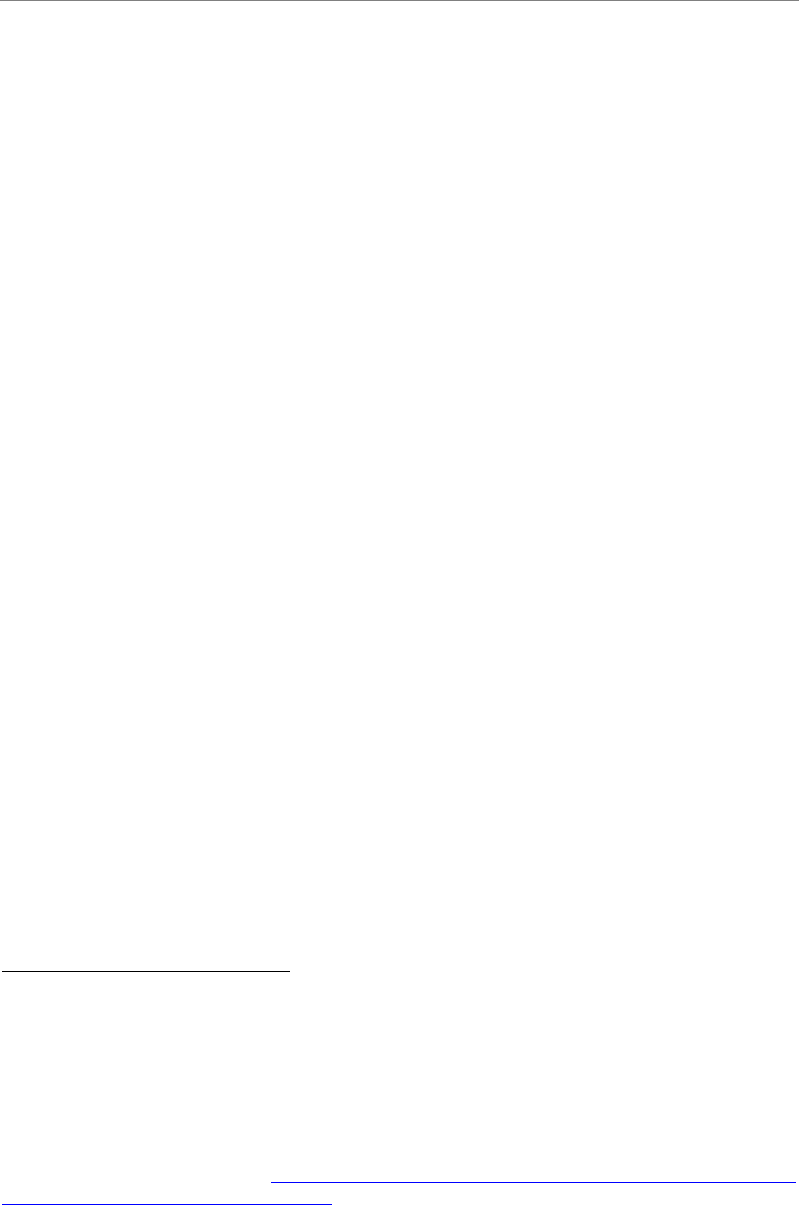

Estimates based on NOS not adj. for SE yield the following CIT efficiencies:

These results are similar to those presented in the IMF’s 2014 report.

18

IMF (2014), p. 66.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 16

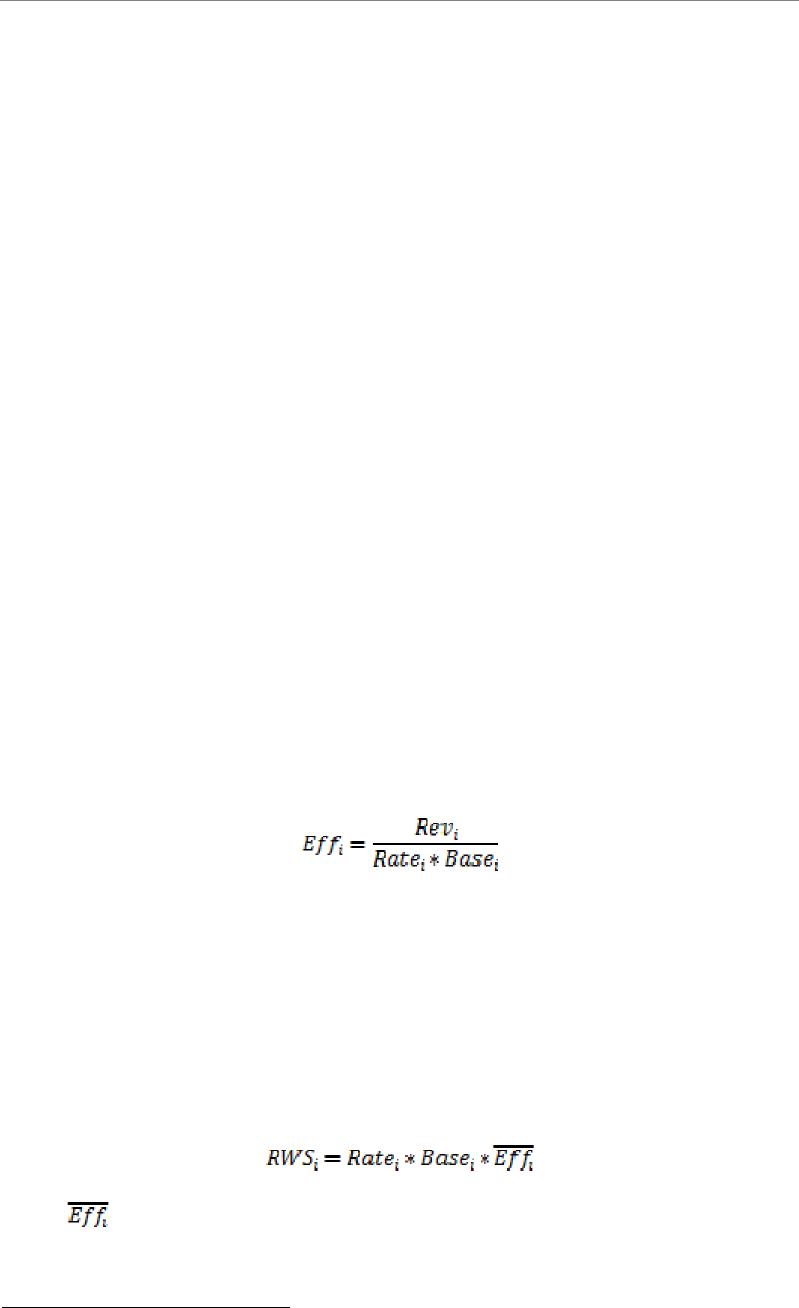

We make two calculations for revenue losses. One is in line with IMF (2014) as described

above, whereby we calculate a variable called revenue without profit shifting (RWS).

Here we assume – the average efficiency rate for the entire sample to be equivalent

to 75 per cent. Therefore estimated revenue losses for the EU due to tax avoidance from

corporate taxation could then amount to around 50-70 billion euro (see sheet

(Computations (NOS adj. SE) (2)) in blue). If, however, we assume that profit shifting is

the only source, then we estimate that revenue losses for the EU due to tax avoidance

from corporate taxation could amount to around 160-190 billion euro (see sheet

(Computations (NOS adj. SE) (2)) in green). This is close to the estimate of around

150 billion euro presented in Murphy (2012). However, we assume that this is likely to be

an over-estimate, given that the differences between ‘revenue without profit shifting’ and

the ‘actual revenue’ could be the result of other factors: (i) cross-country differences in

compliance and enforcement; (ii) strategic responses to the tax policies of other countries

(international tax competition); or (iii) differences between ‘assumed’ and ‘true’ tax base.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 17

Chapter 2 – What is the potential EU added value of

addressing this lack of transparency, coordination and

convergence at EU level?

Key findings

- The establishment of a coherent conceptual, EU-wide framework for consistent and reliable

benchmarks for assessing the impact of aggressive tax planning and tax avoidance across

Member States and the EU would increase transparency.

- This would provide a firmer platform upon which to assess (a) the different tax systems and

rules prevalent across the EU, and (b) the revenue that is lost between Member States.

- Current opacity in the tax systems and arrangements across the EU is fueling strategic

competition amongst Member States, and is deteriotating the effective corporate tax rates.

- The local reduction in effective tax rates in individual Member States has a positive

correlation with attracting foreign direct investment.

- One study suggest that the competition in tax rates – which has resulted in an approximate

reduction of 15 per cent in the statutory corporate tax rate across a sample of OECD

countries – is associated with a reduction of 0.6-1.1 per cent of GDP in government

investment into public services, equating to 81-161 billion euro.

- The added value of transparency, coordination and convergence would come from the

potential to eliminate excessively low corporate income tax rates across all Member States,

thereby raising tax revenues and thus the potential for increased funding for public services.

1. Background

Corporate tax planning is understood to refer to the financial analysis carried out by

companies to achieve their goals in the most tax-efficient manner possible. Over recent

years, tax planning has received substantial media attention and is now once again at the

fore of the European policy debate in response to what some consider to be – in some

cases – abusive tax avoidance by MNEs. Indeed, the Commission’s competition authority

has asked the governments of countries such as the Netherlands, Luxembourg and

Ireland to explain their tax system rulings and to give details on assurances given to

several specific companies, including Abbott Laboratories, Amazon, Apple, Facebook,

Google, Microsoft, and Starbucks.

19

As recently as March 2015 the Commission presented

19

Barker, A., Smyth, J. and Steinglass, M. (2013), ‘Brussels probes multinationals’ tax deals’,

Financial Times, 11 Sep. 2013; Smyth, J., Steinglass, M. And Houlder, V. (2013), ‘Looking into

sweetheart tax deals’, Financial Times, 11 Sep. 2013.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 18

new plans on a mandatory information exchange as a means of tackling corporate tax

avoidance and harmful tax competition.

20

Differing tax rates and systems across countries (see Box 1 below) have given MNEs the

opportunity to employ different strategies, allowing them to reduce their tax bills

significantly. There is ample evidence that MNEs have been arranging their affairs in a

tax sensitive – or tax ‘efficient’ – manner. They have done this in several ways, but the

strategies used can broadly be categorised into two groups:

(i) locating the enterprise in a jurisdiction with low tax rates; and/or

(ii) shifting earnings or profits to low-tax jurisdictions.

Group (i) is self-explanatory while group (ii) encompasses controlled transactions by

MNEs to shift earning across countries. For instance, they may shift income into low tax

jurisdictions from jurisdictions with higher taxes in order to minimise payments. In this

sense, MNEs are accused of engaging in tax avoidance and, in some cases, evasion.

2. Definition of tax avoidance

An important distinction must be made between tax planning and tax evasion. Tax

planning (or, if defined loosely, tax avoidance) is legal (and includes strategies such as

shifting net revenues to low-tax jurisdictions while taking deductions for loss in high-tax

countries, exploiting any inconsistencies across national legislative frameworks,

including reporting calendars that make it possible to minimise tax obligations by

delaying the repatriation of earnings), while tax evasion is illegal (and takes the form of

non-payment by making false or no declarations about income to tax authorities). The

remainder of these notes focus on tax avoidance.

Another important contribution regarding transparency could be the establishment of a

coherent conceptual framework for reliable benchmarks for assessing the impact of

aggressive tax planning and tax avoidance across Member States and the EU as a whole.

2.1. Theoretical background

The original treatment of tax competition focused on interactions across a wider economy

consisting of multiple identical tax jurisdictions. Theorists have focused on how

policymakers compete to attract capital – which is the most mobile productive factor. The

models they used were game-theoretical (Cournot-Nash models), and the conclusion

they drew was widely accepted: if you can tax those productive factors that are relatively

less mobile, like labour, then it makes no sense to impose taxes on those factors that can

20

European Commission (2015), ‘Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 2011/16/EU

as regards mandatory automatic exchange of information in the field of taxation’, COM(2015)0135,

2015/0068 (CNS).

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 19

move out of the jurisdiction easily. This is the so-called ‘zero tax result’, which implies a

‘race to the bottom’ in terms of corporate income tax rates.

21

Such early modelling of tax competition quickly moved into more extreme conclusions. If

it makes no sense to tax mobile factors, then it might be attractive to offer a negative tax

or subsidy to attract mobile factors (again, like capital) to move from one jurisdiction to

the next. The Belgian notional interest rate reduction (notionele interestaftrek) is a good

illustration of this.

22

Such subsidies do not need to be market distorting in order to be

effective. On the contrary, they could help overcome market failures by providing access

to information about investment opportunities, human capital, growth prospects and

other relevant factors. By creating incentives for firms to relocate across jurisdictions,

policymakers could be helping those firms to exploit unrealised opportunities. The net

result of such redistribution of activity would be to improve welfare in the aggregate.

23

Whether such arguments find empirical support is one question; whether they influence

policy is another. Economists dispute the welfare consequences of tax competition. They

tend to agree, however, that tax competition exists. Policymakers use both statutory tax

rates and firm-specific exemptions to attract highly mobile capital from high-value

businesses. There is more controversy over which jurisdictions are most actively engaged

in the competition. For example, smaller economies, which have a lower ability to tax

immobile factors because they have a smaller pool of more highly mobile labour, would

be expected to be more aggressive in seeking to create tax advantages. Hence, scholars

such as Bucovetsky and Wilson have constructed models of asymmetric tax competition,

where large countries with market power have positive corporate income taxes while

smaller countries either have no taxes or engage in some form of subsidy to attract

capital.

24

Such arguments have obvious implications for discussions about tax policy in

the ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ countries of the European Union.

3. Income shifting

21

Zodrow, George R., and Peter Mieszkowski (1983) ‘The Incidence of the Property Tax: The

Bene

fit View versus the New View’, in Zodrow, George R. (ed.),

Local Provision of Public Services:

The Tiebout Model after Twenty-Five Years, Academic Press, New York, NY, pp. 109–129 ; Zodrow,

George R. (2006), ‘Capital Mobility and Source-Based Taxation of Capital Income in Small Open

Economies’, International Tax and Public Finance, vol. 13(2–3), pp. 269–294; Razin, Assaf, and Efraim

Sadka (1991) ‘International Tax Competition and Gains from Tax Harmonization’, Economics Letters

no. 37 (1), pp. 69–76.

22

For an explanation, see ‘Notionele interestaftrek: uniek en innoverend belastingvoordeel in

België,’ FOD Financien, http://financien.belgium.be/nl/ondernemingen/vennootschapsbelasting

/belastingvoordelen/notionele_interestaftrek/.

23

Gordon, Roger H., and A. Lans Bovenberg (1996), ‘Why is Capital So Immobile Internationally?

Possible Explanations and Implications for Capital Income Taxation.’ American Economic Review,

vol. 86(5), pp. 1057–1075.

24

Bucovetsky, Sam, and John D. Wilson (1991), ‘Tax Competition with Two Tax Instruments’,

Regional Science and Urban Economics, vol. 21(3), pp. 333–350; Baldwin, Richard, and Paul Krugman

(2004), ‘Agglomeration, Integration and Tax Harmonization’, European Economic Review, vol. 48(1),

pp. 1–23.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 20

Firm specific subsidies are one instrument in tax competition, deductions and other

favourable treatment regimes are another. Hence, the difference between statutory tax

rates (meaning overall) and marginal tax rates (meaning once deductions and other

favourable treatment measures are taken into account) is important in models for tax

competition. This distinction will also play a role in shifting income across jurisdictional

boundaries.

25

There is a large amount of empirical research suggesting that MNEs are

readily able to reallocate profits to respond to tax differentials through the use of transfer

pricing mechanisms, inter-company transfers and transactions, licensing fees and so on,

and there is evidence that this practice is becoming widespread.

26

Since the turn of the century, the focus in the literature has been on the increasing

importance of competition in statutory tax rates, due to the relative ease of shifting

profits. Marginal tax rates become less important to tax competition in this context.

Scholars like Devereux, Lockwood and Redoano (2008) and Haufler and Schjelderup

(2000) have constructed models for tax competition that demonstrate that lowering

statutory tax rates whilst increasing marginal tax rates can have desirable results,

particularly if the companies in question have an element of foreign ownership.

27

These

early models focused on income shifting through transfer pricing. Later studies were able

to replicate these results in models where companies were able to reallocate debt in a

straightforward way, and in models in which firms are differentially mobile, with the

more mobile firm generating higher profits.

28

Such findings are important not simply because they help us understand how tax

revenue is distributed across jurisdictions, but also because of the implications that this

redistribution of tax revenues has for the provision of public services. Infrastructure

appears to be particularly hard hit. Gomes and Pouget (2008) provide evidence (taken

from 21 OECD nations

29

over a period running from 1966 to 2002) that tax competition

has reduced infrastructure spending wherever statutory tax rates have come down.

25

Zodrow, George R. (2010) ‘Capital Mobility and Capital Tax Competition’, National Tax Journal,

vol. 63(4), pp. 865–902.

26

Altshuler, Rosanne, and Harry Grubert (2006), ‘Governments and Multinational Corporations in

the Race to the Bottom,’ Tax Notes, vol. 110(8), pp. 459–474; Altshuler, Rosanne, and Harry Grubert

(2002), ‘Repatriation Taxes, Repatriation Strategies, and Multinational Financial Policy’, Journal of

Public Economics, vol. 87(1), pp. 73–107; Hines, James R., Jr. (1999), ‘Lessons from Behavioral

Responses to International Taxation’, National Tax Journal, no. 52 (2), pp. 305–322.; Desai, Mihir, C.

Fritz Foley and James R. Hines, Jr. (2004), ‘Foreign Direct Investment in a World of Multiple Taxes’,

Journal of Public Economics, vol. 88(12), pp. 2727–2744.; Desai, Mihir, C. Fritz Foley, and James R.

Hines, Jr. (2006), ‘The Demand for Tax Haven Operations,’ Journal of Public Economics, vol. 90(3),

513–531.

27

Haufler, A and Schjelderup, G (2000), ‘Corporate tax systems and cross country profit shifting,

Oxford Economic Papers, vol. 52(2), pp.306-325; Devereux, Michael P., Ben Lockwood, and Michela

Redoano (2008), ‘Do Countries Compete over Corporate Tax Rates?,’ Journal of Public Economics, vol.

92(5–6), pp. 1210–1235.

28

Fuest, Clemens, and Thomas Hemmelgarn (2005), ‘Corporate Tax Policy, Foreign Firm

Ownership and Thin Capitalization,’ Regional Science and Urban Economics, vol. 35(5), pp. 508–

526; Fuest, Clemens, and Becker, Johannes (2005), ‘Does Germany collect revenue from taxing the

normal return to capital?, Fiscal Studies, 2005, vol. 26(4), pp. 491-511.

29

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy,

Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, UK, US.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 21

Specifically, they estimate that the 15 per cent decline in statutory corporate income tax

rates across the OECD correlates with a reduction in public investment of 0.6–1.1 per cent

of gross domestic product (GDP).

30

OECD GDP was worth USD 42 trillion dollars in

2008; implying a reduction in public investment of between USD 250 billion and USD 462

billion that year alone. The latest figures available from the OECD puts GDP at a

USD 47.48 trillion

31

, which implies on the same extrapolation a reduction of USD 285-

522 billion.

Where there are significant possibilities for tax avoidance, there is less incentive for tax

competition across jurisdictions. MNEs that can avoid paying tax are unlikely to be

influenced by tax incentives. This means that relatively high tax rates are going to have

less influence on the distribution of economic activity across jurisdictions. It also means

that any distortions in accounting practices will result more from efforts at overall tax

avoidance than from efforts to shift profits or earnings from one jurisdiction to the next.

32

By implication, governments have to tackle two different challenges at once. First, they

have to eliminate the opportunities for firms to avoid tax payments through aggressive

tax planning and, second, they have to coordinate efforts across jurisdictions to ensure

that tax reforms do not create incentives for firms to move activity from one jurisdiction

to the next. Such efforts include the coordination of rules for the treatment of transfer

pricing, limits on tax deductions and other forms of special treatment, and treaties

designed to limit opportunities for avoidance. Much of this coordination takes place

within the context of the OECD.

33

30

Gomes, Pedro, and Francois Pouget (2008), Corporate Tax Competition and the Decline of Public

Investment,’ ECB Working Paper Series No. 928, European Central Bank, Frankfurt, Germany.

31

OECD, Gross Domestic Product – as Stated in Dollars, June 2015 - http://www.oecd-

ilibrary.org/economics/gross-domestic-product-in-us-dollars-2014-5_gdp-cusd-table-2014-5-en

32

Zodrow, George R. (2010), ‘Capital Mobility and Capital Tax Competition.’ National Tax Journal,

vol. 63(4), pp. 865–902.

33

European Commission (1997), ‘Towards Tax Co-Ordination in the European Union: A Package to

Tackle Harmful Tax Competition’, COM (97)0495, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-

content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:51997DC0495&from=EN; OECD (1998), ‘Harmful Tax

Competition: An Emerging Global Issue’, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development, Paris, France; OECD (2000), ‘Towards Global Tax Cooperation: Progress in

Identifying and Eliminating Harmful Tax Practices’, Report to the 2000 Ministerial Council Meeting

and Recommendations by the Committee on Fiscal Affairs, Organisation for Economic Co-

operation and Development, Paris, France; Nicodème, G. (2006) ‘Corporate Tax Competition and

Coordination in the European Union: What Do We Know? Where Do We Stand?, European

Commission, Economic Papers no. 250, June 2006,

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication718_en.pdf.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 22

Box 1: National corporate income tax systems

The two principles that frame most national corporate income tax systems are ‘source of

profits’ and ‘residence of business’:

- ‘Source of profits’ refers in broad terms to the location where investments are made

and activity takes place. This is usually ascertained by physical presence. Legislators

establish thresholds for use by tax authorities in assessing where labor and capital is

said to work, where sales or other transactions are made, and where profits should be

booked. A firm that crosses these thresholds is deemed to create a permanent

establishment and, hence, incur tax liabilities. These liabilities are exclusive where tax

regimes are territorial – which is called the ‘exemption method’ in Europe. In other

words, activity should only be taxed in the jurisdiction that is regarded as its ‘source’.

- If ‘source of profits’ is based on physical presence, ‘residence of business’ is based on

legal status. A firm is ‘resident’ in that place where it has its primary activity. Once that

residence is established, it is possible for ‘home’ tax authorities to lay claim on the

firm’s worldwide income or earnings. Here too the taxation should be exclusive. The

challenge is to deal with any overlap in jurisdictions, otherwise firms would be

subjected to taxation twice (or more often) on the same activity. Legislators deal with

such potential overlap through the negotiation of bilateral tax treaties that establish

how tax obligations will be distributed across competing jurisdictions.

These two principles can be reconciled through treaty negotiation. The problem is that such

tax treaties have often been negotiated without coordination from one agreement to the

next. Hence there are significant complications across bilateral tax arrangements. Moreover,

these complications have increased as the ‘physical’ location of economic activity has

become more difficult to establish. As firms rely increasingly in intellectual property to

generate earnings, and on information technology to engage in transactions, the

establishment of physical presence or principal activity has become more difficult (IMF,

2014). Multinational enterprises are adept at exploiting any resulting ambiguities as part of

their tax planning. Hence national tax authories need not only to eliminate distortions across

bilateral tax arrangements, but also to improve their applicability in a new economic

environment.

Tax competition can take place through the implementation or enforcement of tax policy

as well as through the setting of statutory tax rates or the legislation of special tax

treatment. Hence, as Altshuler and Grubert argue, differential treatment of tax avoidance

(or tax planning) is another area of competition.

34

Where tax authorities believe that they

can maximise revenues or attract additional economic activity, they may facilitate the

efforts of MNEs to reduce their overall tax obligations through aggressive tax planning.

34

Altshuler, Rosanne, and Harry Grubert (2006) ‘Governments and Multinational Corporations in

the Race to the Bottom.’ Tax Notes, vol. 110(8), pp. 459–474.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 23

Box 2: Profit shifting strategies

There are many tax avoidance strategies than can be discussed in this note. Here we focus

on the more important and popular practices.

- Transfer pricing

Transfer pricing has to do with the potential mispricing of natural resources or intellectual

property rights so that costs are assigned to high-tax jurisdicctions and revenues are

attributed to low tax jurisdictions. Affiliates of the same MNE trade amongst themselves and

charge a price for these transactions, which affects the allocation of the MNE’s income

across jurisdictions (see, e.g., Hines 2014). The transaction does not need to be related to

the principal activity of the firm. All that is required is a remunerated exchange between

subsidiaries. So long as the charge is recorded in the high-tax jurisdiction and the payment is

received in the low-tax jurisdiction, the overall tax liabilities of the multinational enterprise

will decrease.

The ‘double Irish’ is a good illustration of this practice. The ‘double Irish’ refers to a tax

avoidance strategy that uses payments between different units or subsidiaries within a

multinational corporation to shift income from a higher-tax jurisdiction to a lower-tax

jurisdiction. This is possible insofar as Irish tax law does not penalise or restrict transfer

pricing. This creates an incentive for MNEs to create two distinct entities, one that is resident

and taxed in Ireland and another that is resident in Ireland but taxed in another jurisdiction

with lower taxes. The entity taxed in Ireland will absorb the charges associated with the use

of the firm’s intellectual property and use those to reduce its Irish tax liabilities; the entity

taxed elsewhere will receive the royalties from the use of the firm’s intellectual property and

pay taxes on those revenues in the lower tax jurisdiction. As a result of this two-entity

structure, the overall obligations of the MNE are reduced.

Tax authorities are well aware of the perverse incentives that give rise to transfer pricing. In

response, they try to legislate requirements that intra-firm transactions should be made at

the prices that would apply if they were to take place between different firms or at one step

removed. Such requirements are more easily enforced for widely traded commodities than

they are for intellectual property rights and other intangibles. The challenge for legislators is

to come up with standards that are transparent and enforceable without creating new

distortions in the distribution of economic activity. The implicit cost-benefit calculation is

that the measures designed to eliminate transfer pricing should not do more damage than

the practice of tax avoidance or tax planning.

Once again, the challenge is to find an adequate measurement of the impact of tax

avoidance. Some researchers, like Clausing (2003) or Heckemey and Overesche (2013), find

evidence to suggest that there is significant abuse of intra-company transactions by US

multinationals for reasons related to transfer pricing; researchers like Swenson (2001), by

contrast, find that practices like transfer pricing are not very responsive to cross-country tax

differentials. This suggests that the overall impact of transfer pricing could be small.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 24

Box 2: Profit shifting strategies (cont.)

The challenge is to generalise across economic sectors. Transfer pricing in manufacturing is

likely to be less important than in areas where ‘arm’s length’ or one-step-removed

transactions are less likely to generate ‘objective’ market prices. This includes not only

intellectual property, but also much of the trade in business-to-business and financial

services.

- Location of intangible assets

Differences in corporate income tax rates can also have an impact on the ‘location’ of

intangible assets. For example, there is some evidence to suggest that firms will file for

patents more frequently in jurisdictions with lower corporate income tax rates. This will alter

not only the overall volume of patents filed in a given jurisidictions but also the relative size

of intangible assets on the balance sheets of firms within that jurisdicution (Karkinsky and

Riedel, 2012; Grubert 2003; Dischinger and Riedel, 2011).

- Intra-company debt shifting

The differential treatment of interest expenses can also have an impact on tax liabilities.

Hence an MNE could organise loans from subsidiaries or other entities in jurisdictions where

interest expenses are given a lower rate of deduction to subsidiaries or other entities in

jurisdictions where interest expenses have a higher rate of deduction. Provided that the

taxable revenues in the two places are equivalent, the result will be a reduction in overall tax

obligations. With entities in multiple jurisdictions, it would be possible to use loans at

different rates of interest across entities located in each of the jurisdictions in order to

minimise the tax obligations of the MNE as a whole. There is significant empirical support to

suggest this practice is widespread (De Mooij 2011).

- Deferral of repatriation of profits

MNEs can hold earnings in tax jurisdictions with low marginal or effective tax rates until

there is a good reason to repatriate those earnings. In doing so, the MNE can defer payment

of tax. If there is the prospect that the home country will introduce a tax holiday or some

other incentive for repatriation in the near future, then the deferral can lower tax

obligations overall. There is significant evidence that US MNEs engage in this practice

generally and that many benefited from the one-year low-tax repratriation window

introduced in 2005 (Dharmapala et al., 2011; Marples and Gravelle, 2011).

- Treaty shopping

A final consideration is that MNEs may take advantage of the differences between bilateral

tax agreements in order to minimise their obligations, such as their obligations to

shareholders. For example, it may make sense to pay dividends to shareholders in markets

where they will receive more favourable tax treatment. The result would be a reduction in

net tax accrual.

Bringing Transparency, Coordination and Convergence to corporate Tax Policies in the EU

PE 558.773 25

A second major area where action at EU level can add value is in the raising of important

themes for consideration both within and across Member States. Below are highlighted

some of those themes that have received most attention in the academic literature. They

are important as they set the stage for answering two final questions concerning the

relative advantage of common tax jurisdictions, and structural variables impact on

corporation tax.

3.1. The relative advantages of common and separate tax jurisdictions

A first theme is the relative advantages to be garnered from common and separate tax

jurisdictions. The question for the European Union is whether the creation of an

overarching tax jurisdiction would lead to a more even distribution of economic activity

across Member States (and hence a greater equalisation of their respective tax bases). This

question draws in part from the observation that while tax rates have declined across

Europe, the revenues collected via corporate income taxation have remained roughly

stable in consequence of the modest economic growth rates.

35

This stability may in part

be the result of greater coordination of favourable tax treatments (which create a

distinction between statutory and marginal tax rates), in part to a more even

redistribution of economic activity. Research by Timothy Goodspeed suggests that both

factors may have been at work across OECD countries in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

36

By extrapolation, greater efforts at fiscal integration and tax coordination within the EU

could offer significant welfare gains.

Other scholars (such as Genschel et al.) focus instead on the institutional context of tax

competition.

37

They present evidence to suggest that tax competition is stronger in the EU

than in the rest of the world as a result of the pressure generated via market integration

and enlargement. This pressure is not unmitigated, and the combination of coordination

measures undertaken within the Council of Ministers and the tax jurisprudence of the

European Court of Justice could potentially reduce it. Nevertheless, the net effect of

European integration has been the acceleration of tax competition across Member States.

Moreover, studies of EU tax policy show how the Commission has fostered the

emergence of two functionally differentiated policy arenas of closer market integration

and evolving areas of community law, dealing with different definitions of tax problems

and operating with modes of governance that suits the Commission’s own internal

logic.

38

This structure constrains the ability of European institutions to mitigate tax

competition among Member States. A more coherent European approach to tax policy

could generate additional welfare gains as a consequence.

35

Nicodème, G. (2006) op. cit.

36

Goodspeed, Timothy (1999), ‘Tax Competition and Tax Structure in Open Federal Economies:

Evidence from OECD Countries with Implications for the European Union’, ZEW Discussion Paper

no. 99-40.

37

Genschel, P., Kemmerling, A. and E. Seils (2011), ‘Accelerating downhill: how the EU shapes

corporate tax competition in the Single market’, Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 49( 3),

pp.585-606.

38

Kraemer, U. S. and C. M. Radaelli (2008), ‘Governance Areas in the EU direct tax policy’, JCMS

2008, vol. 46(2), pp.315-336.

Part I - Assessment of the magnitude of aggressive tax planning

PE 558.773 26

These issues are relevant to other major European projects such as the completion of the

internal market and the development of a European capital markets union. For example,

standard models suggest that the increase in capital mobility would lead to downward

pressure on corporate income taxes in the EU. Research by Krogstrup (2006) suggests that

there is some merit to this claim.

39

Such research also makes it possible to make a

quantitative assessment of the importance of tax competition pressures within the

internal market. Studies have found that the increase in capital mobility may have

reduced corporate taxation by as much as 20 per cent between 1980 and 2001 across the

EU. The result, while not a ‘race to the bottom’, suggests that incentives that remain for

MNEs to engage in avoidance strategies exist, and that these could be mitigated by cost-

effective regulation.

3.2. Structural considerations

A second theme relates to the relative ease with which firms or workers respond to

differences in tax rates depending on the situation, by which we mean large structural