FISCAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT

|

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

FISCAL POLICY

How to Improve the Financial

Oversight of Public Corporations

NOTES

5

NOVEMBER 2016

©2016 International Monetary Fund

Cover Design: IMF Multimedia Services

Composition: AGS, an RR Donnelley Company

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Joint Bank-Fund Library

Names: Allen, Richard, 1944 December 13- | Alves, Miguel. | International Monetary Fund. Fiscal Affairs Department.

Title: How to improve the financial oversight of public corporations / this note was prepared by Richard Allen and Miguel Alves.

Other titles: Fiscal policy, how to improve the financial oversight of public corporations | How to notes (International Monetary

Fund) ; 5

Description: [Washington, DC] : Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund, 2016. | How to notes / International

Monetary Fund ; 5 | November 2016. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781475551983

Subjects: LCSH: Corporate governance—Quality control. | Corporations--Evaluation.

ISBN 978-1-47555-198-3 (paper)

DISCLAIMER: Fiscal Affairs Department (FAD) How-To Notes offer practical advice from IMF staff members to policymakers

on important fiscal issues. The views expressed in FAD How-To Notes are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent

the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Publication orders may be placed online, by fax, or through the mail:

International Monetary Fund, Publication Services

PO Box 92780, Washington, DC 20090, U.S.A.

Tel.: (202) 623-7430 Fax: (202) 623-7201

Email: [email protected]

www.imf bookstore.org

1International Monetary Fund | November 2016

Public corporations, otherwise known as state-owned

enterprises (SOEs), are commercial entities owned or

controlled by the government. In this note we discuss the

legal, institutional, and procedural arrangements that gov-

ernments need in order to oversee the nancial operations

of their public corporations, ensure accountability for

the performance of these corporations, and manage the

scal risks they present. In particular, governments should

focus their surveillance on public corporations that are

large in relation to the economy, create scal risks, are not

protable, are unstable nancially, or are heavily depen-

dent on government subsidies or guarantees.

e purpose of the note is to:

• Clarify the definition and classification of public

corporations, and explain why their supervision is

important to manage a range of potential fiscal risks;

• Propose a policy and a legal and institutional frame-

work for the financial oversight of public corpora-

tions, and tests of their economic and social viability;

• Set out the range of financial controls and approvals

over public corporations that should be exercised by

the government, and indicators for reporting and

monitoring their financial performance and quasi-

fiscal activities; and

• Recommend a checklist of key measures that a

government should consider taking to effectively

manage and oversee public corporations’ finances,

and the possible sequencing of these reforms.

Introduction

Many studies have highlighted how failures of public

corporations

1

can result in huge economic and scal

is note was prepared by Richard Allen and Miguel Alves. e

authors would like to thank Ould Abdallah, Virginia Alonso Albar-

ran, David Amaglobeli, M. Astou Diouf, Israel Fainboim, Suzanne

Flynn, Andrea Gamba, Gavin Gray, Alessandro Gullo, Richard

Hughes, Yasemin Hürcan, Tom Josephs, Yugo Koshima, Ngouana

Lonkeng, Paulo Lopes, Erik Lundback, Maria Mendez, Ken Miy-

ajima, Mario Pessoa, Xavier Rame, Carolina Renteria, Christiane

Roehler, Rani Selyodewanti, Niamh Sheridon, Jongsoon Shin,

Alejandro Simone, S. Sriramachandran, Eivind Tandberg, Aminata

Toure, Hui Tong, Karla Vasquez, and Philppe Wingender for their

helpful comments and suggestions.

1

is note focuses on the oversight of nonnancial public corpo-

rations, as dened in the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics Manual

costs. A recent survey by Bova and others (2016), for

example, analyzes a series of episodes in which contin-

gent liabilities materialized over the period 1990–2014.

e study concluded that the maximum cost of those

episodes involving public corporations was 15.1 percent

of GDP, and the average cost was 3 percent of GDP.

Public corporations were the second-largest category of

scal risk after the nancial sector (which includes many

state-controlled companies). Moreover, the number of

episodes involving public corporations and their average

scal cost doubled between the 1990s and the 2000s.

In order to contain such risks, an eective regime

for the nancial supervision and oversight

2

of public

corporations should be put in place. is is important

for several reasons:

• First, despite the large-scale privatizations that began

in the 1980s, companies owned by the govern-

ment continue to account for a significant share of

economic activity and, in many countries, the bulk

of public sector assets and liabilities (Figures 1 and

2). Kowalski and others (2013) show that the market

value of public corporations accounts for over 11

percent of the market capitalization of listed compa-

nies worldwide, and is even higher in many emerging

markets (for example, Brazil, 18 percent; India, 22

percent; China, 44 percent). Another study shows

that the share of public corporations among Fortune

Global 500 companies has grown from 9 percent

in 2005 to 23 percent in 2014, driven primarily by

Chinese public corporations (PWC 2015). Even in

regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, where the public

corporation sector is smaller, substantial fiscal risks

may arise, and issues relating to privatization and

resource revenue management can be important.

2014. Due to the specicity of banking supervision and regulatory

standards that apply both to private and state-owned banks, these two

types of public corporation are not covered in this note. Nevertheless,

many of the note’s ndings and recommendations also apply to nan-

cial institutions such as state-owned commercial banks and develop-

ment banks, which can present signicant scal risks for government.

For this reason, their nancial performance should be monitored by

both the Ministry of Finance and the relevant nancial regulator.

2

Oversight of public corporations by government covers many

issues other than nance—for example, the monitoring of public

corporations’ compliance with their legal mandate, management of

personnel, security issues, and nonnancial performance.

HOW TO IMPROVE THE FINANCIAL OVERSIGHT OF

PUBLIC CORPORATIONS

2

FISCAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT HOWTO NOTES

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

• Second, inefficient or poorly managed public corpo-

rations can impose substantial economic and fiscal

costs. The existence of public corporations is usually

justified by an intention to address potential market

failures—for example, the companies are considered

natural monopolies, or they operate in markets that

are protected from competition for strategic or social

reasons. However, in the absence of strong perfor-

mance incentives, public corporations also often

produce at high costs, overcharge customers, and

under-provide often essential services such as power,

water, and telecommunications.

• Third, loss-making public corporations can be a

persistent drag on public finances in the form of

government guarantees, subsidies, loans, or capital

injections. Public corporations that approach

or enter bankruptcy often see their liabilities

assumed by government, even where those liabili-

ties are not explicitly guaranteed. A recent survey

found that public corporations were perceived

by IMF staff to be second only to the central

government budget as a source of fiscal risk (IMF

2012). This impression is confirmed by Bova and

others (2016) in the study noted above (see also

IMF 2016).

• Fourth, many public corporations are pressured or

mandated to fulfill political objectives and engage

in quasi-fiscal activities that bear little relationship

to their core commercial operations and for which

the companies are not compensated from the

budget, especially in less-developed countries. Such

quasi-fiscal activities include, for example, public

service obligations that are below cost-recovery, price

regulations that imply cross-subsidies, ancillary oper-

ations outside the public corporation’s core mandate,

or excessive employment levels.

• Finally, public corporations can be used as a mech-

anism for circumventing traditional fiscal controls,

and as a conduit for financial corruption (Allen

and Vani 2013). Governments have used public

corporations to conduct fiscal operations off-budget

or channel political favors and patronage to private

individuals and enterprises. These activities under-

mine the integrity of countries’ public administra-

tion, their financial management systems, and the

commercial incentives of the companies themselves.

It should be noted that the structure and economic

character of public corporations have changed quite

radically in the past three decades. Traditionally, many

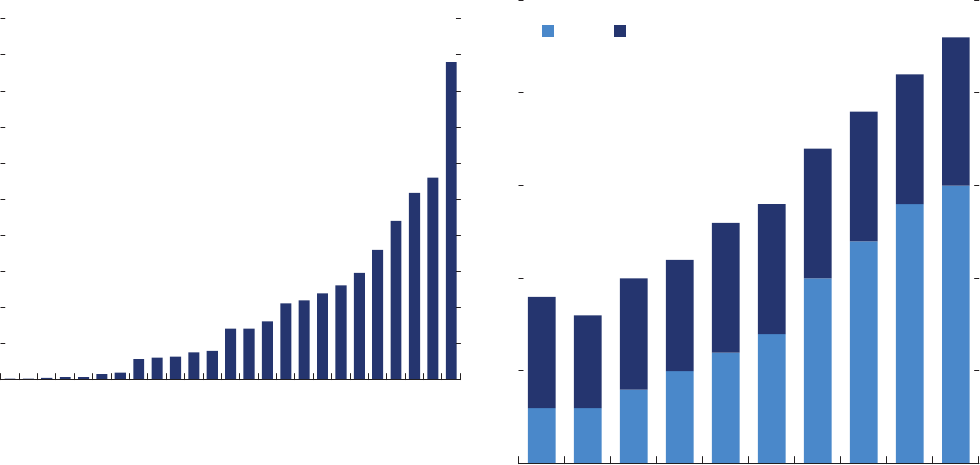

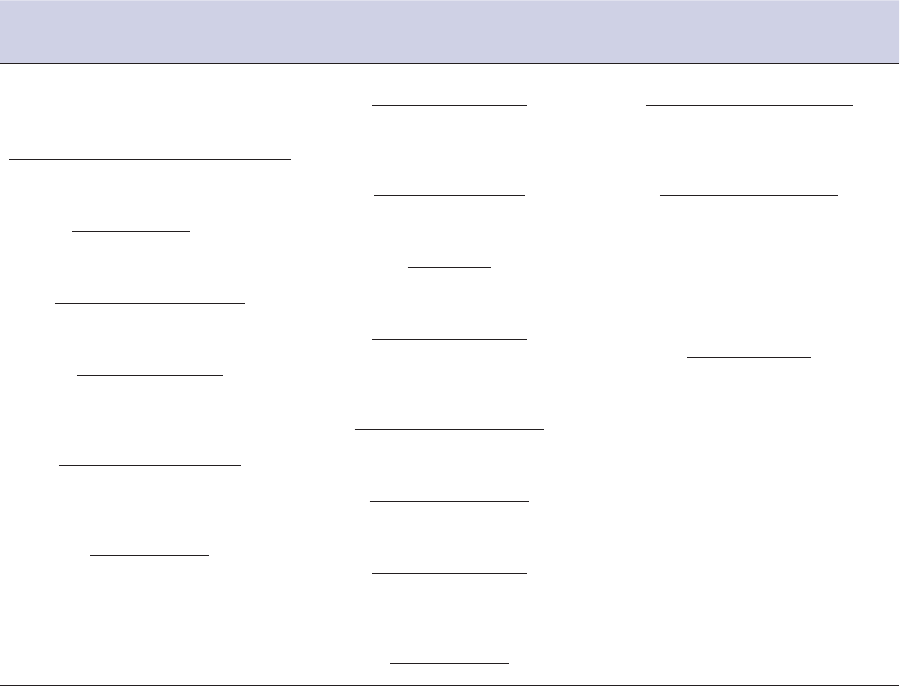

Figure 1. Market Capitalization of Listed State-Owned

Enterprises

(Percent of gross national income)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Germany

Italy

Ireland

Turkey

United States

Japan

South Africa

Belgium

Austria

United Kingdom

Greece

Korea

France

Switzerland

Sweden

Finland

Global

Indonesia

Czech Republic

Poland

Brazil

India

Norway

Russia

China

Source: Kowalski and others (2013).

Figure 2. State-Owned Enterprises as a Percentage of

Global 500

3% 3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

10%

12%

14%

15%

6%

5%

6%

6%

7%

7%

7%

7%

7%

8%

0

5

10

15

20

25

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

China Rest of the World

Source: PWC (2013).

3

HOW TO IMPROVE THE FINANCIAL OVERSIGHT OF PUBLIC CORPORATIONS

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

public corporations were natural monopolies. How-

ever, as a result of technological changes, many natural

monopolies have disappeared. For instance, such

sectors as electricity distribution (due to the opening

of the market to competition in many countries) and

telecommunications (due to the growth of the Inter-

net and the use of cellular phones, etc.) are no longer

natural monopolies. Many of the largest public corpo-

rations now operate in the oil, gas, copper, and other

mineral sectors, and some are only legal monopolies

rather than natural ones.

In this note, we discuss the essential building

blocks of an eective framework for the nancial

oversight of public corporations. ese elements

include a comprehensive set of denitions and classi-

cations that conforms with international standards;

a mechanism by which governments can review peri-

odically the status of public corporations to ensure

that they are commercially and economically viable;

a policy framework that determines the ownership

of public corporations, and their legal and institu-

tional status; a robust system of nancial controls and

approvals; and arrangements for measuring and moni-

toring public corporations’ nancial performance and

their quasi-scal activities. In addition, the note rec-

ommends measures that governments should take to

enhance their capacity for overseeing the nances of

public corporations—and how such reforms should

be sequenced.

Denition and Classication of Public

Corporations

Public corporations can take a diverse range of legal

and organizational forms, and the terminology used

by countries to dene such entities can also cause

confusion. Public corporations are known by many

dierent names—state-owned enterprises, state-owned

entities, state enterprises, parastatals, publicly owned

corporations, government business enterprises, crown

corporations, and nonprot organizations (World Bank

2006, 2014; Allen and Vani 2013). In some cases,

government entities may be legally incorporated as an

enterprise but be largely or entirely engaged in non-

commercial activity; in other cases, entities established

as government agencies may be primarily or wholly

engaged in commercial activity. In many countries, the

legal and commercial distinction between public cor-

porations and other public entities engaging in service

delivery, regulatory, or quasi-commercial functions is

blurred.

3

It is important to ensure that the denition

and classication of public corporations and other

public entities are clear, transparent, and, to the extent

possible, in line with international standards.

Countries should identify and classify public cor-

porations based on their economic nature. Specically,

the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics Manual 2014

(GFSM 2014)

4

denes corporations as “entities that

are capable of generating a prot or other nancial

gain for their owners, are recognized by law as separate

legal entities from their owners, and are set up for

purposes of engaging in market production” (GFSM

2014, paragraph 2.31).

5

A corporation is classied as a

public corporation if it is controlled by the government

(paragraph 2.107). Public corporations in turn can be

classied as nonnancial or nancial corporations,

6

depending on the nature of their primary activity

(paragraphs 2.113–2.116). Public corporations may be

under the control of either central or subnational gov-

ernments. Control, which is interpreted broadly as the

ability to determine the general corporate policy of the

3

A recent study of the United Kingdom, for example, found that

in 2014, more than 3,000 government companies were registered—a

number that has been increasing—but there is no unied and reliable

source of information on these companies (National Audit Oce

2015). In Egypt, public corporations comprise “economic authorities”

and “public sector enterprises.” e distinction between these two

categories lies with their legal status rather than their commercial

nature. Economic authorities are controlled by the government, which

approves their budgets and, ultimately, covers any losses, while public

sector enterprises have more operational autonomy, are controlled

by boards of directors, and are grouped under government holding

companies. In Cyprus, a generic category termed “nongovernmental

organizations” covers a wide range of entities, including regulatory

and sponsorship bodies, non-prot-making educational and cultural

entities, and nancial and nonnancial corporations, which may take

the legal form of either statutory entities or state-owned enterprises.

4

roughout this note, references to the GFSM 2014 framework

also apply to the GFSM 2001 framework. Both versions of the Man-

ual provide a broadly consistent treatment of public corporations’

classication. e treatment of public corporations in the 1986

version of the Manual was more limited.

5

Dierent, and somewhat more stringent, denitions of public

corporations have been proposed by the OECD’s updated Guidelines

on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises (OECD 2015)

and international public sector accounting standards (IPSAS). For

example, the denition contained in IPSAS 1 (Presentation of

Financial Statements) requires a government business enterprise

(equivalent to a public corporation) “to sell goods and services, in

the normal course of business to other entities at a prot or full cost

recovery” (our emphasis).

6

Examples of nonnancial public corporations are national

airlines, electricity companies, and railways. e category could also

include nonprot organizations engaged in market production, such

as hospitals, schools, or colleges. Financial corporations are those

engaged in providing nancial services, such as banks, insurance

companies, and pension fund services.

4

FISCAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT HOWTO NOTES

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

entity, may be assessed by analyzing eight indicators, as

proposed in Box2.2 of GFSM 2014.

7

A government-controlled entity that is legally estab-

lished as an enterprise may not be a public corporation,

from an economic standpoint. Entities that are controlled

by the government should be classied as public cor-

porations only if they are market producers—namely, if

they provide all or most of their output at prices that are

economically signicant. Although there is no precise

numerical formula for determining whether prices

are “economically signicant,” the orientation of an

entity toward market production can be assessed by the

so-called market test. GFSM 2014 proposes that a unit

be classied as a market producer if the value of its sales

(excluding both taxes and subsidies not directly linked to

the volume or value of the output) averages at least half

of the production costs (broadly dened as the sum of the

compensation of employees, use of goods and services,

consumption of xed capital, and a return on capital),

over a period of at least three years. In practice, however,

diculties of valuation may arise. In sectors such as util-

ities, nuclear energy production, or weapons production,

for example, prices are often dicult to determine or are

not strongly linked with production costs.

8

Reviewing the Status of Public Corporations

Policy goals associated with the establishment of

public corporations may be achieved in a more e-

cient way. For example, a tax and regulatory frame-

work enshrined in law may be a more ecient and

transparent way to ensure that the government receives

its fair share of hydrocarbon revenues, while reducing

legal uncertainty for investors. Similarly, providing

targeted subsidies may be a more ecient means of

making energy more aordable for consumers than

7

ese eight indicators include, for example, ownership of the

majority of the voting interest, control of the board or other governing

body, and control of key committees of the public corporation, any

of which would be sucient to determine government control. How-

ever, in most cases, a decision on the source of control may require

judgment and an assessment of a wider range of indicators. A similar

framework, comprising ve indicators to assess the commercial orien-

tation and scal risks of public enterprises, was proposed earlier by the

Fiscal Aairs Department of the IMF (see IMF 2005, 2007).

8

Governments sometimes undertake scal or quasi-scal activities

(including the securitization of assets, borrowing, etc.) using special

purpose vehicles (SPVs). e classication criteria described above

also apply to SPVs, but the special nature of these activities, and the

fact that some of them may be established in a dierent country,

requires some elaboration. See GFSM 2014, paragraphs 2.136–

2.138, for further guidance.

setting up a public corporation. Legislation should

require the government to carry out a full assessment

of the costs and benets of each alternative in order to

inform policymakers whenever a proposal to establish a

new public corporation is put forward.

In addition to undertaking a critical assessment of the

economic case for establishing new public corporations,

governments should review periodically the status and

viability of existing public corporations. Table 1 sets

out a stylized framework for undertaking such reviews.

Governments should take into account both the eco-

nomic performance of each entity (for example, whether

it is actually or potentially protable, and whether

market conditions are favorable) and its relevance from

a strategic or a national security point of view. Such a

policy assessment, in turn, may depend on, among other

things, the government’s political orientation regarding

issues such as the role of the market and state owner-

ship. Reviews of the status of public corporations should

also take account of the social context. For example, if a

public corporation is a candidate for corporatization or

privatization, the impact on income distribution should

be considered, given that privatization often results in

large employment losses in the short term. Even when

privatization is not a viable policy option, public corpo-

rations can still be exposed to market discipline through

partial listing procedures.

Policy, Legal, and Institutional Frameworks for

Public Corporations

An eective framework for the nancial oversight of

public corporations requires a clearly dened owner-

ship policy backed by strong legal and institutional

arrangements.

9

In some countries, the laws and regula-

tions governing business enterprises will provide much

9

A similar framework has been applied by the International Bud-

get Partnership in several recent studies—see, for example, e State

Table 1. Framework for Reviewing the Status of

Public Enterprises

Policy or Strategic Relevance

Low High

Commercial Viability

Low

Close down

Convert into a noncommercial

government entity

High

Privatize

Retain as a public corporation, monitor

closely operations and finances

5

HOW TO IMPROVE THE FINANCIAL OVERSIGHT OF PUBLIC CORPORATIONS

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

of the required legal framework for public corpora-

tions. Such laws include those related to the structure

and powers of the management board, requirements

on nancial reporting, and independent audit arrange-

ments. However, for public corporations these laws

need to be supplemented by a public sector–specic

oversight framework that denes the respective goals,

powers, and responsibilities of the corporation, the

Ministry of Finance, and any line ministries involved.

is framework’s three main components are described

below. e interactions with nancial institutions (for

example, the potential domino eect of the nancial

collapse of a public corporation) and ties with other

countries (for example, through foreign shareholding)

should be taken into account in the institutional and

legal framework for public corporations.

Ownership Policy

e government should develop and publish a

comprehensive ownership policy for its corporations.

e ownership policy should provide a clear state-

ment of the state’s policy and nancial objectives as

shareholder in each company or group of companies,

which may be a mix of nancial, economic, and social

objectives.

10

It should also state how the government

intends to exercise its ownership rights; the main

functions carried out by the government as owner

of public corporations; the objectives and mandate

of each public corporation; the organization of the

ownership function; the relationship between nancial

and nonnancial oversight; and the main principles

and policies to be followed, such as ensuring a level

playing eld between public corporations and the

private sector. e ownership policy should refer to the

constitution, laws, regulations, codes, and other docu-

ments that dene the ownership rights of the state. On

nancial oversight, the policy should explicitly address

the following elements: planning or budgeting require-

ments; reporting requirements; pricing and taris; div-

idend policy; nancial assistance from the government,

of the Art of State-Owned Enterprises in Brazil, June 2014, and similar

studies of Korea and South Africa.

10

In Sweden, for example, the government’s overall objective is

“to create value for the owners”; in Norway, the state requires SOEs

“to take corporate responsibility and uphold our basic values in an

exemplary manner”; in the United Kingdom, the objective is “to

ensure that Government’s shareholdings deliver sustained, positive

returns…within the policy, regulatory and customer parameters set

by the government, acting as an eective and intelligent share-

holder.” Examples quoted in OECD (2010).

including guarantees; and contractual commitments.

e policy should also ensure that all these elements

are included in the government’s nancial monitoring

and reporting framework. More detailed guidance and

examples of ownership policies can be found in OECD

(2010).

11

Legal Framework

To establish clearly the respective roles of the gov-

ernment and its corporations in the area of nancial

management, many countries have found it helpful

to prepare a framework law on public corporations.

Such a law may be self-standing (for example, New

Zealand, Philippines), or it may comprise a chapter of

the public nance law (South Africa, Spain). e legal

framework should include the following elements:

1. A clear definition of a public corporation. If there

is a special legal form of incorporation only applied

to public corporations, then the law should define

the parameters of this legal form. If public corpo-

rations are incorporated according to commercial

law, then the legal framework should refer to these

laws and clarify whether they apply in their entirety

or include some special provisions for public

corporations;

2. A clear definition of the financial oversight func-

tion, whether this role would be carried out by the

Ministry of Finance, a sector ministry in consulta-

tion with the Ministry of Finance, or possibly an

independent agency (as in the Swedish model);

3. A statement of the powers of the government

to receive, comment on, and approve the finan-

cial plans, financial targets, and annual financial

statements of public corporations; set financial

performance targets; and respond to requests by

public corporations for compensation of public

sector obligations, capital injections, borrowing, or

government guarantees;

4. A statement of the public reporting requirements

for all corporations, including a full annual financial

statement

12

(containing a statement of operations,

a cash flow statement, and a balance sheet) pre-

pared in accordance with national or international

accounting standards;

11

e OECD Guidelines provide examples of how ownership

policies are exercised in a range of countries, including Finland,

France, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

12

Probably also full quarterly statements for large, listed compa-

nies, for example, in accordance with stock exchange requirements.

FISCAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT HOWTO NOTES

6 International Monetary Fund | November 2016International Monetary Fund | November 2016

5. A requirement for the government to publish an

annual report on whether public corporations are

achieving their policy and financial objectives, and

complying with their obligations to prepare regular

and timely financial reports; and

6. A requirement for the annual accounts of the public

corporation to be audited by a reputable, indepen-

dent auditing body that is recognized internation-

ally, and to publish the audit report.

13

e role of the sector ministry and the public

corporation’s management board, in terms of exercis-

ing its responsibilities for planning and managing the

entity’s resources, also needs to be clearly dened in

law (OECD 2015).

14

e sector ministry should be

responsible for policy issues related to that sector, but

it should not be involved in the strategic planning of

individual public corporations, especially if there exist

private sector competitors that are regulated under the

same policy framework. e governance framework

should be based on the “arm’s length” principle of

managing public corporations, which distinguishes the

functions of ownership and management. Management

boards should be allowed to exercise their responsi-

bilities without interference or pressure from their

respective line ministry. Where such independence can-

not be guaranteed, as is the case in many less-advanced

economies, the Ministry of Finance may need to

employ stronger oversight of the nancial performance

of public corporations.

Finally, the legal framework for public corpora-

tions should include sanctions to ensure that the

provisions are enforceable and eective. In particu-

lar, sanctions may be necessary to meet nancial or

operational performance targets, in cases of nancial

distress or insolvency, or in serious cases of fraud

and nancial mismanagement. Such sanctions may

assume various degrees of severity, ranging from addi-

tional reporting requirements (for example, monthly

13

Audit standards vary from country to country, and depend on

the legal status of the public corporation. If the public corporation

is subject to commercial law, audit requirements are likely to be

prescribed. e right to decide on who should audit a public cor-

poration may rest with the country’s supreme audit institution, the

Ministry of Finance, or the public corporation itself.

14

Public corporations may take a variety of legal forms. Some of

these entities may not include a management board in their gover-

nance structure. In some countries, public corporations have been

converted into corporations with modern board structures, with the

aim of ensuring the independence of the public corporations’ day-to-

day management from the government’s ownership functions.

rather than quarterly reports), imposition of addi-

tional controls (for example, over sta recruitment,

pay, or major investment decisions); administrative

measures (for example, steps to dismiss or suspend

members of the management board); or, ultimately,

imposition by the government of direct control over

a public corporation’s day-to-day operations. In some

countries, sanctions may be applied to members of

the public corporation’s management board or indi-

viduals in government who have been charged with

the oversight of public corporations.

Institutional Framework

Because shareholders have the right to approve

public corporations’ corporate and nancial plans and

dividend policies, and to receive nancial reports, the

ownership and nancial oversight functions overlap

with each other. For this reason, some countries have

chosen to locate both the ownership and nancial

oversight functions in a central agency, often the Min-

istry of Finance, the Treasury, or the Presidency (exam-

ples are Brazil and Sweden). Other countries apply a

more decentralized ownership model or a mixture of

the centralized and decentralized models. e latter

approaches include:

• In some countries, shares in public corporations

are held by an autonomous agency, or by a holding

company or investment company. Examples include

Austria (Österreichische Industrieholding AG),

China (SASAC), Finland (Solidium Oy), France

(APE), Kenya (Government Investment Corpo-

ration, GIC), Malaysia (Khazanah), Peru (FON-

AFE), Singapore (Temasek), and Spain (SEPI). The

management board of the holding company may

include representatives of the Ministry of Finance

(for example, Austria, Finland, Malaysia, Singapore).

The holding company model has the advantage of

putting in charge professional asset managers with

relevant private sector skills, who can actively man-

age the portfolio of public corporations. It also helps

to insulate the portfolio of public corporations from

political interference. Nevertheless, it requires some

prerequisites to be in place, such as the harmoniza-

tion of legal frameworks surrounding ownership and

oversight of public corporations, and the adoption

in law and publication of a comprehensive corporate

governance framework.

• In other countries, Ministry of Finance staff often

lack sufficient sector knowledge to exercise effective

7

HOW TO IMPROVE THE FINANCIAL OVERSIGHT OF PUBLIC CORPORATIONS

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

e Public Finance Management Act of 1999 and

Treasury regulations require public enterprises to submit

on an annual basis: (1) strategic plans, (2) nancial

plans, and (3) risk management plans.

e Department of Public Enterprises (DPE) enters

into a Shareholder Compact (a form of Performance

Agreement) with six of the largest commercial state

enterprises, in which key performance indicators and

other performance data are formalized. e DPE is

responsible for approving signicant transactions into

which the enterprise enters. e Minister of the DPE

is also responsible for nominating the board mem-

bers of most public enterprises, who must then be

approved by the Cabinet.

Source: Adapted from IMF (2016, Box A1.5).

Public enterprises are required to submit multiyear

budgets to the DPE at least one month before the start

of their nancial year. e National Treasury imposes

annual limits on the borrowing, guarantees, and other

contingent liabilities of the enterprises.

e Fiscal Liability Committee in the National

Treasury advises the Minister on short- and medi-

um-term contingent liabilities and guarantees related

to public enterprises.

Public enterprises are required to prepare annual

nancial statements in line with generally accepted

accounting practices within ve months of the

end of each year. ey are also required to submit

quarterly nancial reports to the DPE, or the super-

vising ministry when they are not subject to DPE

oversight.

oversight of a public corporation.

15

In such cases,

line ministries often assume the policy/ownership

role, subject to a framework established and super-

vised by the Ministry of Finance or some other cen-

tral agency. Such a model is prevalent in countries

with a large and diverse portfolio of public corpo-

rations, where full centralization of the ownership

function may be difficult. Examples include Mexico,

South Africa, and Thailand. These decentralized

approaches call for close coordination between the

Ministry of Finance and the ministry or agency that

holds the shares.

Analyzing the nancial performance of public cor-

porations requires specialized and advanced skills that

in many countries are vested in a dedicated oversight

unit. In some advanced economies and middle-

income countries, this unit is located in the Ministry

of Finance, as for example in Chile, France, New

Zealand, South Africa, and Sweden; or in the Prime

Minister’s Oce, as in Finland; or in the Ministry of

Planning, as in Brazil. In less-advanced economies,

which frequently lack expertise in corporate nance

15

ere are exceptions, however. In Honduras, for example, a

Directorate of the Secretariat of Finance (the Ministry of Finance)

provides nancial oversight of public corporations. e Directorate

produces quarterly reports on the nancial performance and human

resources of public corporations, using a range of indicators, and

advises the government on policies for public corporations.

and other required skills, the case for centralizing

resources in a single entity such as the Ministry of

Finance is strong. e monitoring units require a mix

of expertise in nancial analysis, corporate governance,

corporate nance, and law, and their sta may repre-

sent or support the representatives of the government

on the boards of public corporations. Box 1 provides

an example of how the central oversight mechanism

works in South Africa.

Public corporation monitoring units frequently

publish annual monitoring reports on the nancial

and operational performance of the public corporation

sector and the scal risks they create.

16

e tasks of the

16

For South Africa, see Analysis of the Financial Performance

of State-Owned Enterprises (http://www.gov.za/documents/analy-

sis-nancial-performance-state-owned-enterprises); for Lithuania,

Annual Review of Lithuanian State-Owned Commercial Assets (http://

www.euroinvestor.dk/pdf/cse/11176061_17359.pdf); for Fin-

land, Annual Report of the State’s Ownership Steering (http://vnk.

/documents/10616/1221497/2014_OO+vuosikertomus_eng.

pdf/1f84341c-ddb7-4a04-9de6-3fb50013c606); for France, French

State as Shareholder (http://www.economie.gouv.fr/les/les/

directions_services/agence-participations-etat/Documents/Rap-

ports-de-l-Etat-actionnaire/2013/Overview_2013.pdf); for Brazil,

Prole of State Companies (Perl das Empresas Estatais) (http://

www.planejamento.gov.br/assuntos/empresas-esatais/publicacoes/

perl-dasempresas-estasais); for New Zealand, Annual Portfo-

lio Report (http://www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/commercial/

portfolio/reporting/annual/2013/apr-13.pdf); and, for Sweden,

Annual Report: State-Owned Companies (http://www.govern-

ment.se/contentassets/0126b664c843479d8696d1be546fe4b6/

annual-report-state-owned-companies-2014).

Box 1. Central Oversight of Public Enterprises in South Africa

8

FISCAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT HOWTO NOTES

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

monitoring unit include analyzing the nancial plans of

public corporations, setting appropriate nancial targets,

monitoring performance against quarterly and annual

nancial reports, and assessing the cost and impact of

public service obligations and other quasi-scal activ-

ities. e unit may also advise the government on the

appointment of board members and on decisions of

whether to provide the company with more capital

or increase the annual dividend, in accordance with

the government’s ownership policy. Monitoring units

need to work closely with the macroeconomic unit and

the budget oce of the Ministry of Finance to ensure

that any transfers provided to public corporations

made through the budget,

17

together with government

guarantees and the cost of public service obligations,

are correctly estimated and disclosed in the budget, the

medium-term scal strategy, or a scal risk statement.

Central Financial Control and Approvals

In exercising their ownership functions, governments

need to strike a balance between maximizing the opera-

tional autonomy of public corporations and minimizing

scal risks to government. Although nancial control

mechanisms vary from country to country, they typically

include some or all of the following elements:

• Financial and policy objectives: Good financial man-

agement depends critically on a clear and opera-

tional statement of the government’s financial and

policy objectives related to each public corporation.

The former may be expressed in terms of the public

corporation’s dividend, profit, return on equity, or

other indicators discussed below. The latter may

include the maintenance of universal access to

infrastructure services, provision of certain strategic

outputs, or provision of services at below market

prices, all of which should be compensated through

transfers from the government’s budget;

• Financial plans: The ownership of the majority of

the voting interest gives the government a veto

power on all major decisions regarding corporate

policy and financial plans.

18

When assessing a public

17

Some governments (for example, Turkey in the 1990s) have

issued bonds to cover the losses or quasi-scal activities of public

corporations, without making transfers through the budget. Such

practices are nontransparent and can be prevented by appropriate

provisions in the public nance law.

18

In countries where the government owns “golden shares” or

share purchase options in public corporations, these powers can also

be exercised when the government is a minority shareholder.

corporation’s financial plan, governments should

ensure that, among other things, (1) financial tar-

gets, prices and tariffs, capital levels, and targets for

dividends are appropriate; (2) the balance between

commercial objectives and any public service obliga-

tions is adequate; (3) investment plans take govern-

ment priorities and related activities into account;

(4) financial and operational risks are actively

managed; and (5)public corporations do not create

subsidiaries as a means of transferring the control of

public assets to private interests;

• Borrowing: The government—in some countries

with the formal approval of the legislature—may

establish ceilings on the borrowing of public cor-

porations as a whole and/or individually to limit

the contingent liability to government itself and the

impact on the wider economy;

• Guarantees: Governments in some cases either

prohibit entirely or strictly control the issuance of

guarantees by public corporations to third parties, as

this impairs the government’s equity in the corpora-

tion and is typically more expensive than extending

the guarantee directly from government;

• Sale/pledging of assets: Public corporations’ nonfinan-

cial assets, such as land or buildings, are often pro-

vided to them by the government free of charge (in

some cases, the legal ownership of the assets remains

with the government, rather than with the public

corporation itself). For this reason, and to protect

its equity in the corporation, the government may

restrict the sale of these assets or their use as collat-

eral in financial transactions. It may similarly restrict

the pledging or securitization of future revenue

streams;

• Mergers/acquisitions: Given the impact that mergers

and acquisitions may have in terms of the public

corporations’ operations and finances, as well as the

environment for competition, governments typi-

cally require their approval before a corporation can

merge with or acquire another enterprise; and

• Corporate governance: public corporations should

establish professional management and a strong

corporate governance framework that can operate

effectively without government interference, in line

with international standards (OECD 2015). While

the government, as owner, has a direct responsibility

for selecting board members, the selection of chief

executive officers and other key personnel should

be performed by the board without government

interference. Because of operational autonomy

9

HOW TO IMPROVE THE FINANCIAL OVERSIGHT OF PUBLIC CORPORATIONS

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

considerations, the formal feedback (and reporting

of potential risks) to the government should be

undertaken by the management board, rather than

by personnel of the public corporations concerned.

19

In addition, all public corporations should establish

an audit committee and a well-functioning internal

audit regime.

Monitoring Public Corporations’ Financial

Performance

Financial Reporting and Auditing Standards

Monitoring the nancial performance of public

corporations is greatly facilitated if public corporations

follow International Financial Reporting Standards

(IFRS) for nancial reporting and auditing. Compliance

with IFRS

20

ensures a high-quality source of primary

data on public corporations, including for the purposes

of their nancial oversight. By providing a true and

fair view on the accounting for assets and liabilities,

IFRS enhances the reliability of nancial information,

which is also more readily understood and comparable,

both domestically and worldwide. Independent audit

of public corporations’ nancial statements, conducted

in line with the International Standards on Auditing,

further enhances their reliability and is an important

prerequisite of sound nancial governance, especially for

large public corporations. In less-advanced economies,

the adoption of IFRS and contracting of international

accounting rms can involve large costs that may exceed

their nancial resources. In such cases, a prudent policy

may be to require only the largest public corporations—

or those with a substantial exposure to scal risk—to

comply with IFRS and international audit standards.

Compliance with IFRS also facilitates the consol-

idation of nancial data on public corporations with

19

Boards may need to be given guidance on issues such as

(1) how management autonomy can be assured, (2)how manage-

ment skills can be developed and sustained, (3) how board members

should be selected and remunerated, and (4) how to avoid pressures

to exempt certain public corporations from good governance princi-

ples in cases where vested interests are strong.

20

Depending on the country, the corporate legal framework may

require reporting rules other than IFRS. In some jurisdictions, only

listed companies are required to comply with IFRS, while other

corporations have to comply with national or regional standards (see

PwC, “IFRS Adoption by Country,” at http://www.pwc.com/us/en/

issues/ifrs-reporting/publications/ifrs-status-country.html for more

information). Recently, the IPSAS Board revised the applicability of

IPSAS, making these standards applicable for enterprises other than

commercial public sector entities.

data on the general government sector in countries

that follow IPSAS, GFSM 2014, or related standards.

Under IFRS, the recording of government support to

public corporations should reect the economic nature

of the transaction, rather than its instrumental or legal

form. is is consistent with the treatment prescribed

in IPSAS and GFSM 2014, thus allowing for an

accurate elimination of intra-governmental transactions

and stock holdings, for the purpose of consolidating

nancial statements. Particular attention should be

paid to so-called nancial transactions such as capital

injections, loans, and debt assumptions. If these trans-

actions create a true nancial claim of the govern-

ment on the public corporation, then they should be

regarded as purchases of nancial assets by the govern-

ment and not count against its reported surplus/decit.

If not, they should be recorded as capital transfers with

a positive impact on the net worth of the public corpo-

ration and a negative impact on the government’s sur-

plus/decit and net worth. GFSM2014 (Figures A3.1

and A3.2) presents decision trees to help determine the

economic nature of nancial transactions, which are

broadly consistent with IFRS/IPSAS.

Public Corporation Monitoring Reports

Monitoring reports on public corporations should

summarize the overall nancial performance of the

sector as well as provide information on individual

companies. Well-designed reports (note 16 has links

to good examples from several countries, and Box 2

outlines an example from Sweden) usually encompass

ve main sections:

• An overview of the sector and highlights of public

corporation activities during the year, including

information on policy decisions or transactions that

had a material impact on the financial position of

the sector;

• A full list of the companies owned by the government,

broken down by industry, size, and type of ownership

(for example, majority- or minority-owned companies,

strategic companies, or candidates for privatization);

• An overview of how the government has exercised

its ownership policy, including the appointment of

board members, dividend policy, organizational and

governance arrangements, and the announcement of

financial and public policy targets;

21

21

In Brazil, the government prepared a guidance manual (Manual

do Conselheiro de Administracao) for members of the management

10

FISCAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT HOWTO NOTES

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

1. Financial overview

2. Events in brief

3. Ownership issues

a. Ownership model

b. Company cases

c. Nominations to company boards

d. Financial targets

e. Sustainability business models

f. Public policy targets

g. Remuneration and terms of employment

h. Company portfolio, including its valuation

i. Eect of company divestments and dividends in

government nances

4. Individual company data

a. Description of company’s mandate and

operations

Source: Department for Innovation and State-Owned

Companies (2015).

b. Summary of activities in 2014

c. Targets (nancial, sustainability, and public

policy)

d. Performance review

e. Summary nancial information (abridged

income statement and balance sheet, key ratios,

reporting performance)

f. Panel charts (state ownership, gender

distribution, and one performance indicator)

5. General information

a. State’s ownership policy

b. Accounting principles and denitions

c. Legislation

d. Summary of changes in executive boards

e. Assessment of reporting practices

f. Guidelines for reporting

g. Guidelines for terms of employments for senior

executives

h. Management responsibility for companies

• Special topics, including a more thorough explana-

tion of issues related to the government’s ownership

policy: for example, changes in the policy frame-

work for public corporations, remuneration policy,

the valuation of companies, issues of organization

and management, and the impact of public corpo-

rations on government finances and the economy

more broadly; and

• Information on individual companies, comprising

a summary of their operations, abridged financial

statements, and indicators of financial performance

for the current year and previous years. The report

should also provide a list of board members, key

personnel, and auditors, as well as information on

the government’s shareholding and financial targets,

if applicable, together with data on key performance

indicators. This information could draw on a central

database of public corporations at the national and

subnational levels.

boards appointed by the Ministry of Planning. is manual covers

issues related to governance, coordination between the board and the

government, the role and responsibilities of management and board

members, conicts of interest, and remuneration. See http://www.

planejamento.gov.br/assuntos/empresas-estatais/publicacoes/manual-

do-conselheiro-de-administracao-dest-mp.pdf/view.

Indicators of Public Corporations’ Financial

Health

Analysis of the nancial performance of public cor-

porations should include a range of indicators of the

protability, risks, and nancial relations with the gov-

ernment. e choice of specic indicators depends on

country circumstances, including the type of industry a

public corporation is representing, the level of risk, and

comparability with the private sector. However, nan-

cial surveillance by the government typically focuses on

indicators of:

• Financial performance as measured by indicators

such as the profit margin (earnings/revenue), the

return on equity (earnings/equity), and the return

on assets (earnings/assets);

• Financial risk as measured by indicators such as

liquidity (current assets/current liabilities), leverage

(assets/equity), solvency (liabilities/revenue), or the

probability of default;

22

22

ere is a broad range of indicators of rm default risk, such as

Altman (1968) Z-Score measures, Ohlson (1980) O-Score measures,

and Black-Scholes-Merton (1973) default probabilities, which take

into account broader rm characteristics such as protability and

size. In the case of public corporations, for which an implicit bailout

guarantee often exists, this probability of default can be used to

measure the implicit risk.

Box 2. Content of Sweden’s 2014 Annual Report of State-Owned Companies

11

HOW TO IMPROVE THE FINANCIAL OVERSIGHT OF PUBLIC CORPORATIONS

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

• Transactions with the government

23

in the form of

dividends, taxes, grants, compensation for qua-

si-fiscal activities (see below), and other subsidies;

changes in government equity holdings in the

public corporation;

24

and guarantees given or

called; and

• Foreign linkages as measured by indicators such as

the relative weight of debt to foreign creditors, the

currency composition of debt, or the hedging of

currency risk.

23

Ideally, comprehensive information on these transactions should

be included in the government’s annual nancial statements and

other scal reports.

24

Government equity holdings are reected in the government’s

balance sheet and may represent a substantial share of the assets and

liabilities under its control. Explaining the changes in equity hold-

ings requires a disclosure of transactions, valuation changes, or other

economic ows related to those assets and liabilities.

Table 2 provides examples of the specic indicators

monitored by the Australian government.

25

From a scal risk management perspective, the anal-

ysis of individual company information is as important

as aggregated data for the public corporation sector.

26

25

Another good example is Indonesia, where the ownership

entity uses eight nancial indicators to assess the nancial health of

nonnancial public enterprises. ese indicators include: the return

on equity, the return on investment, the ratio of current assets to

current liabilities, inventory turnover, total asset turnover, and the

equity to total asset ratio. A weighted average of the indicators is also

constructed in order to classify enterprises as “healthy,” “less than

healthy,” and “not healthy.”

26

It would be good practice for a summary of scal risks from

the public corporation sector (drawn from relevant monitoring

reports) to be included in any wider scal risk statement produced

by the country. Bachmair (2016) presents a framework for the

quantication, management, and mitigation of risks stemming from

government guarantees and on-lending, and demonstrates how it is

applied in Colombia, Indonesia, Sweden, and Turkey.

Table 2. Australia: Financial Performance Indicators for Government Enterprises

Financial performance

(indication of the commercial viability of the

enterprise)

Financial risk

(information on the risk of an enterprise not

being able to meet its financial obligations)

Transactions with government

(impact of the transactions with the

government in the enterprise’s finances)

Profit before tax =

Revenue – Total expenses (excluding income tax)

Operating profit margin =

Earnings before interest and tax from operation

Operating revenue

Cost Recovery =

Operating revenue

x 100

Operating expenses

Return on operating assets =

Earnings before interest and tax

Average operating assets

x 100

Return on total equity =

Operating profit after tax

Average total equity

x 100

Return on equity based on operating assets

and liabilities =

Operating profit after tax

Average equity based on

x 100

operating assets and liabilities

Operating cash flow to sales =

Operating cash flow

Operating revenue

x 100

Debt to equity =

Debt

x 100

Equity based on operating

assets and liabilities

Debt to operating assets =

Debt

x 100

Average operating assets

Total liabilities to equity =

Total liabilities

Total equity

x 100

Operating liabilities to equity =

Operating liabilities

x 100

Equity based on operating

assets and liabilities

Interest Coverage =

Earnings before interest and tax

Gross interest expense

Current ratio =

Current operating assets

x 100

Current operating liabilities

Leverage ratio =

Total operating assets

x 100

Equity based on operating

assets and liabilities

Short term debt coverage =

Operating cash flow

Current liabilities

x 100

Dividend to equity =

Dividend paid or provided for

x 100

Average equity based on operating

assets and liabilities

Divident payout ratio =

Dividends paid or provided for

Operating profit after tax

x 100

Income tax expense =

the value of income tax or income tax-

equivalent expenses payable to government

Grants revenue ratio =

Grants to cover

deficits in operations

Revenue

x 100

Public service obligations =

the sum of payments by governments to public

corporations for the specific noncommercial

activities that they direct public corporations

to undertake

Source: Australian Government, Productivity Commission, “Financial Performance of Government Trading Enterprises” (http://www.pc.gov.au/research/

completed/government-trading-enterprises).

12

FISCAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT HOWTO NOTES

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

e segmentation of public corporations according

to risk can be done through a composite indicator

1

(for example, a linear combination of business ratios,

weighted by coecients) or a simple count of the

number of indicators on which the enterprise exceeds

an established (safe) threshold. e government can

also stipulate that a public corporation be considered

a high-risk entity if a particular indicator reaches a

level that imposes an unacceptable scal risk. Enter-

prises with higher risk should be subject to a stricter

oversight regime (more frequent reporting, stricter

targets, tighter controls, etc.) and should be required

to implement risk-mitigating measures.

Source: IMF (2016, Table 3).

1

Eorts to build composite indicators of risk of individual

enterprises have a long history. One early example is the Z-Score,

which measures the probability that an enterprise will go bank-

rupt in the next two to three years. See Altman 2000, 2005.

In a recent paper (IMF 2016, Table 3), the IMF

has proposed a number of measures and techniques

to mitigate the risks arising from public corporations;

they can be summarized as follows:

• Direct controls to limit fiscal exposure, for exam-

ple, by reducing the size of the public corporation

sector, or by imposing caps on the liabilities that

public corporations can accumulate;

• Regulations and charges to reduce risky activities,

for example, by holding public corporation boards

to account for financial performance; and

• The transfer or sharing of risks, for example, by

introducing explicit no-bailout clauses.

e government should consider provisioning for

those risks that are not mitigated. is could take the

form of expensing the costs of expected subsidies (for

example, compensation for quasi-scal activities) in

the budget, or setting aside nancial assets to meet the

costs of potential restructuring of public corporations.

Given that the prots of public corporations are not

fungible, the likelihood of scal risks materializing

from their activities (in the form of higher subsidies,

increased borrowing costs, or outright bailouts) depends

on individual companies’ performance. In this sense, the

government should assess the nancial performance of

each public corporation, segment them according to the

level of risk, and apply appropriate levels of control and

risk-mitigating measures to each segment (see Box 3).

Taking account of their macro-criticality, larger pub-

lic corporations should be subject to stricter oversight

regimes, even if the level of risk they pose is low (the

indicators most commonly used for measuring the size

of public corporations include the level of sales, assets

or liabilities, or income tax paid). Special challenges in

monitoring performance and risk may arise where a

public corporation has a complex corporate structure

that involves a large number of subsidiaries and shell

corporations, and where the information provided by

the parent company is unreliable or nontransparent.

Quasi-Fiscal Activities

Quasi-scal activities are operations carried out by

public corporations to further a public policy objec-

tive that worsens their nancial position relative to a

strictly commercial prot-maximizing level. Quasi-

scal activities can take a variety of forms, the most

common of which include:

• Public service obligations: charging less than commer-

cial cost (cost-recovering) prices for the provision

of goods and services to the general public or target

groups (for example, setting artificially low prices

for public utilities, such as energy and water, thus

providing an implicit subsidy to consumers);

• Noncore functions: obligations imposed by the gov-

ernment for the public corporation to provide goods

and services, or undertake capital investments, that

are unrelated to their core functions;

• Subsidized purchases: paying above commercial prices

to particular suppliers of goods and services or assets

(for example, agricultural inventories purchased

from domestic farmers);

• “Super-dividends”: withdrawal of own funds in excess

of the distributable income of the accounting year,

normally as a consequence of sales of assets or pay-

ments out of accumulated reserves; and

• Pricing for short-term budget revenue purposes: set-

ting a higher price for goods and services so as to

increase a public corporation’s profits and divi-

Box 3. Fiscal Risks Related to Public Corporations: Segmentation and Mitigating Measures

13International Monetary Fund | November 2016

HOW TO IMPROVE THE FINANCIAL OVERSIGHT OF PUBLIC CORPORATIONS

Transportation services in the European Union

(EU), typically engage in three dierent types of pub-

lic service obligations:

• Obligations to operate a service (for example, a

low-density branch line) or a particular service level

(for example,services at night or on weekends/

holidays);

• Obligations to transport customers at specified fare

levels (a regulated fare structure below cost recovery

or with restrictions on fare increases); and

• Obligations to offer concessional fares to specific

groups, such as students, the elderly, disabled riders,

military personnel, civil servants, etc.

Under EU legislation, government units must

establish a public service contract with any passenger

transport operator that has been granted an exclusive

right of operation, or compensation for public service

obligations, or both. ese contracts mandatorily:

Sources: World Bank (2011); and European Union (2007).

• Define in a clear way the public service obligations

with which the operator needs to comply, and the

geographic areas concerned.

• Establish, in an objective and transparent manner,

the basis on which compensation payments, if

any, are to be calculated, and the nature and

extent of any exclusive rights granted, in a way

that prevents overcompensation and distortion of

competition.

• Determine the arrangements for the allocation

between the operator and the public authority of

(1)costs connected with the provision of services,

and (2) revenue from the sale of tickets.

For contracts awarded without competitive tender-

ing, the legislation further stipulates that the com-

pensation should not exceed the net nancial cost of

contractual obligations. To increase transparency and

avoid cross-subsidies, the legislation also requires that

accounts of public services be separated from accounts

of other (noncompensated) activities.

dends in the short term, even if this risks reducing

the company’s market share and its profits in the

medium term.

e cost of delivering public service obligations

and subsidized purchases should be fully funded

through the budget, and it should be disclosed sepa-

rately in the nancial statements of both the gov-

ernment and the public corporation. is disclosure

of information should describe the type of activity;

the rationale for performing it through the public

corporation, rather than directly through the state

budget; the opportunity cost of the activity; and

the mechanism designed to compensate the public

corporation for the negative impact on its nancial

position, if applicable. Such an approach is trans-

parent and holds the government accountable for

the performance of its companies and the delivery

of public services. It also prevents the government

from using public corporations to hide activities that

are essentially scal, by requiring their full costs to

be recognized in the budget and the government’s

nancial statements. In addition, disclosure allows

for comparisons with the nancial performance and

eciency of private corporations that are competing

in the same markets as public corporations. Box 4

presents examples of how public service obligations

in the transport sector are disclosed and managed in

the European Union.

ere are several methods of estimating the costs

of quasi-scal activities, depending on their nature.

27

For targeted reduced-tari regimes or above-market-

price payments to suppliers, the cost of the quasi-scal

activity can be estimated as the dierence between sales

of output at observable market prices and the prices

specied by the government for the specic target

groups. Other types of public service obligation, such

as obligations to operate low-density transportation

services (for example, little-used bus or rail routes,

or night/weekend/holiday services) or generalized

low-tari regimes, where market prices are not directly

observable, can be estimated through indirect methods,

for example, using the actual cost of providing the

27

e literature refers to dierent methods for such estimations

(see, for example, OECD 2010, Box 1.10). While there is no

preferred method, the government should develop an approach that

removes inconsistencies in measuring the nancial performance of

public corporations.

Box 4. EU Regulatory Framework for Public Service Obligations in the Transportation Sector

14

FISCAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT HOWTO NOTES

International Monetary Fund | November 2016

Example A: Reduced rail tariff for students

e government requests that the Public Railway

Corporation transport college students from the

Central Station to the University Station at a quarter

of the regular fare ($1 per trip). In 2015, the Railway

Corporation sold 23,000 student fare tickets.

Cost of 2015 quasi-scal activity = $17,250 =

23,000 × $0.75 (assumes a price elasticity equal to zero)

Example B: Subsidized bus route to a rural

community

e government requests that the Public Bus

Corporation maintain in operation a loss-making

route between the capital city and a rural community,

without raising fares charged to passengers. e gov-

ernment allowed the corporation to borrow in order to

cover the underlying decit, and it has agreed to pay

compensation sucient for the corporation to achieve

a nancial surplus on this route comparable to the

surplus obtained on other routes it operates. Details

of the operations of the loss-making route in 2015

were as follows: operating costs, $56 million; interest

paid, $4 million; ticket sales, $20 million. e average

surplus obtained on other routes was 10 percent of

ticket sales.

Estimated economic cost of 2015 quasi-scal

activity (millions) = $40 = $56 + $4 – $20

Compensation paid in 2015 (millions) = $46 =

($56 + $4) × 1.1 -– $20

Example C: Super-dividend from national energy

company

e Board of the National Energy Company (totally

owned by government) determined the distribution of

$100 million in dividends, in relation to the opera-

tions of 2015. e $100 million resulted from a dis-

tributable income of $60 million, a sale of land of $30

million, and a draw down on accumulated reserves of

$10 million.

Cost of 2015 quasi-scal activity (millions): $40 =

$30 + $10

e government accounts should record this

amount as a nancial transaction (exchange of equity

for cash), rather than as revenue.

additional noncommercial services. “Super-dividends”

can be measured by the amount in excess of distrib-

utable income

28

that has been paid by the public cor-

poration as a dividend to government. Box 5 provides

illustrative examples of the estimation of quasi-scal

activity costs.

Building Capacity for Overseeing Public

Corporations

Putting in place a system for overseeing public

corporations that meets all the requirements discussed

above can be challenging for developing or emerg-

ing market economies, and takes time and resources.

Advanced economies have spent many years building

and rening these systems. In less-advanced economies,

28

Equivalent to the net result of current activity (“continuing”

under IFRS), before distribution and income tax, excluding any

exceptional transactions generating holding gains or losses.

a cautious step-by-step approach is required. In many

countries, however, ineciencies and scal risks are

concentrated in a relatively small number of public

corporations, which should be subject to the most

intensive monitoring. Moreover, many of the “best

practice” solutions discussed above have a substan-

tial cost and require a high degree of competence

within the government and the public corporations.

Some of these reforms may not be practicable in the

short term in low-capacity countries. In such cases,

a risk-based and sequenced approach to building an

oversight regime for public corporations is strongly

recommended. Table 3 provides a checklist of the main

elements of such a system and a possible prioritization

of the underlying reforms:

• In the short term (up to one year), the government

could ensure that a full inventory of public sector

entities with commercial or quasi-commercial func-

tions is taken and that these entities are classified

according to the latest international standards

Box 5. Illustrative Examples of Quasi-Fiscal Activity Cost Estimation

HOW TO IMPROVE THE FINANCIAL OVERSIGHT OF PUBLIC CORPORATIONS

15International Monetary Fund | November 2016

(GFSM2001/2014); that a basic reporting frame-

work for public corporations that are high risk or

have a large fiscal or budgetary impact is established;

and that the role and responsibilities of the Pres-

ident’s Office, the Ministry of Finance, and line

ministries participating in the oversight of public

corporations are determined.

• In the medium term (up to three years), the legal

framework relating to public corporations could

be established (or revised), providing the Ministry

Table 3. Implementation of an Oversight Regime for Public Corporations

System Elements Suggested Prioritization

Short Term Medium Term Long Term

1. Definition/classification/status of public corporations

1.1 Inventory of public corporations •

1.2 Classification of public corporations in line with GFSM 2001/2014 •

1.3 Periodic review of classification and optimal status of public corporations •

2. Broad ownership policy, comprising:

2.1 Government’s objectives as owner of public corporations •

2.2 Organization of ownership function •

2.3 Mandate of entities exercising ownership role •

2.4 Main principles and policies to be followed •

2.5 Information disclosure requirements •

2.6 Dividend policy •

2.7 Modalities for financial assistance from the state •

2.8 Policy on quasi-fiscal activities •

3. Disclosure of mandate for each public corporation •

4. Legal framework for public corporations •

5. Public corporation oversight unit in Ministry of Finance, with the following functions:

5.1 Advice on financial support to public corporations •

5.2 Analysis of financial health of public corporations •

5.3 Estimation of fiscal and budgetary impact of public corporations •

5.4 Advice on appointment of board members •

5.5 Advice on annual dividends •

5.6 Central financial controls and approvals •

5.7 Monitoring of financial reports and performance indicators •

5.8 Drafting of annual public corporation monitoring reports •

5.9 Estimation of costs of current and future quasi-fiscal activities •

6. Central financial control and approvals, comprising:

6.1 Review and approval of financial plans •

6.2 Approval of new borrowing and of concession of guarantees •

6.3 Approval of sales or pledging of assets •

6.4 Approval of mergers or acquisitions •

6.5 Review staffing and remuneration policies •

7. Publication of annual Public Corporation Monitoring Report, comprising:

7.1 An overview of the sector and highlights of activities •

7.2 A full list of companies owned by government •

7.3 Information on individual public corporations’ financial performance, public

service obligations, fiscal risks, etc.

•