Performance Audit of

the San Diego Housing

Commission’s Homelessness

Services Contract

Management

Finding 1

SDHC follows its policies and procedures for contract

procurement, but can improve its process to identify sole sourced

contractors’ potential confl icts of interest.

Finding 2

SDHC ensures contracted homelessness services programs follow

best practices through contract design, ongoing administration,

and compliance monitoring.

Finding 3

The City lacks documented processes for repairs at City-owned

or leased homelessness facilities, causing persistent unsafe and

unsanitary conditions at some locations.

MARCH 2023 | OCA-23-07

Andy Hanau

, City Auditor

Danielle Knighten, Deputy City Auditor

Joseph Picek Principal Performance Auditor

Andrew Reeves, Performance Auditor

OCA-23-07 March 2023

Performance Audit of the San Diego Housing Commission’s

Homelessness Services Contract Management

Source: OCA generated based on review of procurement

documentation for 29 sampled contracts.

Finding 2: SDHC ensures contracted homelessness

services programs follow best practices through

contract design, ongoing

administration, and

compliance monitoring. We found that SDHC ensures

programs follow best practices, including use of a

trauma-informed care approach; incorporation of

Housing First policies; having an exit, grievance, and

appeals process and policy; obtaining and incorporating

client feedback; and collecting and using data to monitor

performance. SDHC ensures adherence to these best

practices through contract design, ongoing contract

administration, and annual compliance monitoring.

We also found that SDHC followed best practices in

performance management, but systemwide limitations

make it difficult for programs to achieve community

targets. For example, staffing issues plagued providers in

recent years, limiting their ability to provide in-depth case

management services. SDHC is trying to address this

systemwide issue in a variety of ways, including a

partnership with San Diego City College for workforce

training and development and

a salary study to

determine if homelessness service staff are adequately

compensated. Additionally, COVID-19 policies made it

difficult for contractors to achieve performance targets.

Why OCA Did This Study

Addressing homelessness is a major challenge and top

priority for the City of San Diego. At the time of the last

count, 4,801 individuals

were experiencing

homelessness within the City. Contractors perform many

of the City’s homelessness services, such as operating

storage centers, rapid re-housing programs, shelters,

transitional housing, permanent supportive housing,

safe parking, and outreach. These contracts are mostly

administered by the San Diego Housing Commission

(SDHC). Our objectives were to: (1) Determine whether

SDHC procures homelessness services contracts

according to leading practices; (2) Determine whether

SDHC adequately monitors contract compliance; and (3)

Determine whether SDHC holds contractors accountable

for following best practices in providing homelessness

services.

What OCA Found

We found that generally SDHC followed best practices in

the procurement, administration, and monitoring of

homelessness services contracts. We also found that the

City lacks a documented process for addressing

maintenance requests at homelessness services sites.

Finding 1: SDHC follows its policies and procedures

for contract procurement, but

can improve its

process to identify sole sourced contractors’

potential conflicts of interest. We found that SDHC

followed its procurement policy while obtaining

contracts, but did not follow its conflict of interest policy

for sole sourced contracts. This increases the risk that

potential conflicts are not identified and prevented.

We found that in 29 sampled contracts, the contracts

followed the authorized procurement path, were

evaluated according to policy, and were approved by the

appropriate authority. Competitive procurements

included Statements for Public D

isclosure, but sole

source procurements did not. This was caused by a

procurement policy that did not include a requirement

for Statements for Public D

isclosure, while SDHC’s

conflict of interest policy requires these for all contracts

over $50,000.

Office of the City Auditor

Report Highlights

OCA-23-07 March 2023

What OCA Recommends

We make four recommendations to improve SDHC’s

procurement practices and improve the City’s process for

completing maintenance requests at facilities where the

City is responsible for maintenance and repairs:

• SDHC should develop an Administrative Regulation

requiring

collection of Statements for Public

Disclosure for sole source contractors.

• SDHC should include the requirement for collecting

Statements for Public Disclosure in a future

procurement policy revision.

• HSSD should work with stakeholders to perform

inspections of all homelessness services sites where

the City is responsible for maintenance and complete

any identified maintenance needs.

• HSSD should develop a documented City procedure

for tracking maintenance requests between

providers, SDHC, and City departmen

ts. This

procedure should include required information,

estimated timelines, and communication of progress

to all stakeholders.

SDHC agreed to implement both of its

recommendations. Although HSSD indicated agreement

with its recommendations, it is unclear if HSSD will take

the necessary actions to address the issues we identified.

For more information, contact Andy Hanau, City Auditor

at (619) 533-3165.

Finding 3:

The City lacks documented processes for

repairs at City-

owned or leased homelessness

facilities, causing persistent unsafe and unsanitary

conditions at some locations. We found a lack of

documented City process resulted in delayed repairs at

some City-owned or leased homelessness facilities. We

observed disrepair at sites, including shelters, a safe

parking lot, and the Homelessness Response Center.

Some examples of disrepair were moldy ADA-showers, a

ripped privacy mesh, and a broken HVAC system.

Maintenance requests we reviewed showed broken

outlets and falling ceiling panels. Some issues were

reported on consecutive reports with no information on

remediation.

SDHC’s contracts require contractors to report any

maintenance or repair needs to SDHC. SDHC has a

process for receiving, evaluating, and submitting

maintenance and repair requests to the City through the

H

omelessness Strategies and Solutions Department

(HSSD). However, HSSD does not have a documented

process for receiving and submitting maintenance and

services requests to those responsible for performing

maintenance.

As a new department, HSSD is responsible for ensuring

homelessness policies are carried out by various City

departments. In this role, HSSD has the opportunity to

evaluate existing process and implement an improved

procedure.

Office of the City Auditor

Report Highlights

Source: OCA generated based on maintenance request, observation, and interviews.

March 2, 2023

Honorable Mayor, City Council, and Audit Committee Members

City of San Diego, California

Transmitted herewith is a performance audit report of the San Diego Housing Commission’s

homelessness services contract management. This report was conducted in accordance with

the City Auditor’s Fiscal Year 2022 Audit Work Plan, and the report is presented in accordance

with City Charter Section 39.2. Audit Objectives, Scope, and Methodology are presented in

Appendix B. Management’s responses to our audit recommendations are presented starting on

page 44 of this report. Per Government Auditing Standards Section 9.52, our response to

Management’s comments is on page 49.

We would like to thank staff from the San Diego Housing Commission, Homelessness Strategies

and Solutions Department, and program contractors for their assistance and cooperation

during this audit. All of their valuable time and efforts spent on providing us information is

greatly appreciated. The audit staff members responsible for this audit report are Andrew

Reeves, Joseph Picek, and Danielle Knighten.

Respectfully submitted,

Andy Hanau

City Auditor

cc: Honorable City Attorney, Mara Elliot

Eric Dargan, Chief Operating Officer

Paola Avila, Chief of Staff, Mayor’s Office

Kristina Peralta, Deputy Chief Operating Officer of Neighborhood Services

Christiana Gauger, Chief Compliance Officer

Jeff Davis, Interim President & Chief Executive, San Diego Housing Commission

Hafsa Kaka, Director, Homelessness Strategies and Solutions Department

Charles Modica, Independent Budget Analyst

Jessica Lawrence, Director of Policy, Mayor’s Office

OFFICE OF THE CITY AUDITOR

600 B STREET, SUITE 1350 ● SAN DIEGO, CA 92101

PHONE (619) 533-3165 ● CityAuditor@sandiego.gov

TO REPORT FRAUD, WASTE, OR ABUSE, CALL OUR FRAUD HOTLINE (866) 809-3500

Table of Contents

Background ................................................................................................................ 1

Audit Results ............................................................................................................ 10

Finding 1: SDHC follows its policies and procedures for contract

procurement, but can improve its process to identify sole sourced

contractors’ potential conflicts of interest. ................................................. 10

Recommendation 1.1–1.2 .......................................................................... 14

Finding 2: SDHC ensures contracted homelessness services programs

follow best practices through contract design, ongoing administration,

and compliance monitoring. .......................................................................... 15

Finding 3: The City lacks documented processes for repairs at City-owned

or leased homelessness facilities, causing persistent unsafe and

unsanitary conditions at some locations. .................................................... 30

Recommendations 3.1–3.2 ......................................................................... 36

Appendix A: Definition of Audit Recommendation Priorities ............................ 38

Appendix B: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology ............................................... 39

Appendix C: Categories of Homelessness Services .............................................. 42

Appendix D: Sample Contracts ............................................................................... 43

Management Response (SDHC) ………………………………………………………………..… 44

Management Response (HSSD) …………………………………………………………….……. 47

City Auditor’s Comments to HSSD’s Management Response ……………….………. 49

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 1

Background

Like many cities across California and the United States,

addressing homelessness is a major challenge and a top priority

for the City of San Diego (City). On February 24, 2022, the

Regional Taskforce on Homelessness (RFTH) counted 4,801

individuals experiencing homelessness

1

within the City.

2

Almost

2,500 of those counted were unsheltered—a 9 percent increase

from 2020. In October 2022, RTFH published a report that found

that over the prior year, 11,861 individuals experiencing

homelessness in the region were successfully housed. This

indicates that regional efforts are finding success. However,

during the same time period, 15,327 individuals reported

experiencing homelessness for the first time; thus, the region

continues to face challenges to ending homelessness.

Over the past several years, the City experienced additional

challenges in its homelessness response. From late 2016 to mid-

2018, a Hepatitis A outbreak resulted in 589 cases and 20

deaths. The outbreak disproportionately affected individuals

experiencing homelessness, who accounted for 49 percent of

cases and 70 percent of deaths. In 2020, COVID-19 impacted the

City’s efforts to end homelessness. In response, the City opened

Operation Shelter to Home at the San Diego Convention Center

to provide shelter beds with physical distancing. On March 5,

2021, Mayor Todd Gloria announced plans to wind down

Operation Shelter to Home and to re-open shelters with new

social distancing guidelines.

Prior to COVID-19, the Office of the City Auditor (OCA) conducted

an audit of the City’s efforts to address homelessness. The audit

found that at the time, the City had made strategic

improvements, but needed additional planning, coordination,

1

An individual or family is defined as experiencing homelessness if they: (1) lack a fixed, regular, and adequate

nighttime residence; (2) will imminently lose their primarily nighttime residence; or (3) are fleeing, or are

attempting to flee, domestic violence.

2

The 2023 Point-in-Time count took place on January 26, 2023, and data was not yet available at the time of

report issuance.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 2

oversight, and improved outreach to better address

homelessness.

3

The City funds a wide

variety of homelessness

programs, with

contractors operating

many of these services.

Combined, the City and the San Diego Housing Commission

(SDHC) budgeted over $170 million on homelessness services in

fiscal year (FY)2023. Funding for homelessness services comes

from a variety of sources, including the City General Fund, State

funds, federal funds, and other revenues. Some of these funds

are used directly by the City to fund homelessness services

programs; however, most of the funds are managed by SDHC

through Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs). SDHC then

procures contractors to provide most homelessness services.

Exhibit 1 shows an overview of how San Diego funds and

administers homelessness services.

Exhibit 1

Funding for Homelessness Services Flows from a Variety of Sources, through Multiple

Agencies, and Ends with Contractors and Direct Services

*$500,000 is administered by San Diego County.

Note: More detailed information on the types of programs can be found in Appendix C.

Source: OCA generated based on information from the Independent Budget Analyst’s Report 22-20,

published July 2022.

3

The full audit, published in February 2020, can be found here.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 3

Funding is allocated to different groups of programs that

cover all aspects of the housing and homelessness response.

Programs funded include direct homelessness services, such

as shelter and rapid rehousing, as well as related programs,

such as federal voucher support, landlord engagement, and

construction of new affordable housing. As displayed in

Exhibit 2, only services that are contracted by SDHC and are

directly related to assisting individuals currently experiencing

homelessness were included in the scope of this audit.

Exhibit 2

SDHC Participates in a Wide Variety of Activities that Help Address Homelessness,

but Not All Are Covered by this Audit

Note: Coordinated outreach, family reunification, and safe parking programs were administered by

SDHC at some point in FY2018 to FY2022. These programs are currently administered by the City.

Source: OCA generated based on audit scope and contract sample selection.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 4

The City is part of a

regional homelessness

response.

In 2019, the partnership of RTFH, SDHC, the Mayor’s Office,

and City Council released the Community Action Plan on

Homelessness for the City of San Diego. The plan’s vision is

for regional partners to work creatively and collaboratively to

quickly create a path to safe and affordable housing and

services for individuals who experience homelessness. The

report recognized that homelessness is a regional issue and

does not stay within the limits of the City. Therefore, multiple

public agencies provide homelessness services or administer

funding related to homelessness within the San Diego

Continuum of Care.

4

Exhibit 3 summarizes the relationship

between these agencies.

Exhibit 3

Functional Areas of Focus for San Diego Homelessness Agencies

Source: Community Action Plan on Homelessness, page 37.

4

A Continuum of Care (CoC) is a regional or local planning body that coordinates housing and services funding

for homeless families and individuals.

RTFH SDHC City - Mayor's Office City Council

Coordination with

Mainstream

Resources

Budget Authority

Alignment and

Coordination of City

Departments

Legislative Authority

Coordinated Entry Policy Guidance

HMIS Data Analysis

and Reporting

Housing-Pipeline

Development

Engagement of People

with Lived Experience

Project Management

Support for

Implementation Team

and Leadership

Council

Convening Stakeholders

Identification of Political Issues/Barriers

Coodination and Collaboration with Key Stakeholders, Business, and Philanthropy

Communications

Collaboration with County Resources

Subject Matter Expertise: Policy Development

and Program Design

Operations for Funded Programs

Budget and Legislative Recommendations

Functional Areas of Focus

Leadership-Implementation Team

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 5

The Regional Task Force on Homelessness coordinates activities

between jurisdictions. It is the lead agency for the Continuum of

Care, administers other State and federal funding, administers

the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) and

Coordinated Entry,

5

and conducts federally required activities,

such as system performance review and housing inventory

tracking. RTFH released a Regional Action Plan in September

2022 that identifies resource gaps and is designed to align all

stakeholders under one vision. The plan also adopts a set of core

principles, identifies system priorities, and establishes a sense of

urgency.

The San Diego Housing Commission administers City of San

Diego, State, and federal funds for transitional and permanent

supportive housing to address homelessness among families,

seniors, veterans, and individuals. It also creates low-income and

supportive housing, provides direct services, recommends and

implements policy, and trains and provides technical assistance

for the network.

The Mayor’s Office and the Homelessness Strategies and

Solutions Department (HSSD) develop and execute policy, issue

Requests for Proposal (RFPs), administer funding allocated to

SDHC and other contractors, and identify City property for use in

addressing homelessness. Since 2022, HSSD also administers

contracts for street outreach, safe parking, and family

reunification. Other City departments also have operations that

are related to the City’s homelessness response. For example,

the San Diego Police Department’s Homeless Outreach Team

(HOT) conducts street outreach, the Environmental Services

Department participates in encampment abatements, and the

Department of Real Estate and Airport Management (DREAM)

manages some owned and leased properties used by

homelessness services contractors.

The Housing Authority of the City of San Diego (Housing

Authority), which consists of the nine members of the City

Council, provides budget authority and policy direction as a

5

The Coordinated Entry System (CES) functions throughout the San Diego region and connects individuals

experiencing homelessness with the most appropriate and available housing options.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 6

means to oversee City and SDHC activities, approves contracts,

and funds pilot programs. SDHC is governed by the Housing

Authority, which has final authority over SDHC’s budget and

major policy changes.

SDHC’s contract

management process

has strict protocols for

contract procurement,

administration, and

compliance monitoring.

Most of the City’s contracts related to homelessness services are

administered by SDHC. SDHC’s contract management process,

summarized in Exhibit 4, consists of three parts: (1)

procurement, (2) contract administration, and (3) compliance

monitoring.

Exhibit 4

SDHC Follows a Detailed Process of Contract Management, from Solicitation to

Annual Compliance Monitoring

Source: OCA generated based on information from SDHC.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 7

SDHC’s Procurement Policy sets requirements for procurement

to ensure that SDHC’s purchasing and contracting functions

promote administrative flexibility and efficiency. The policy also

maintains prudent internal controls and compliance with

applicable statutes and regulations.

The procurement policy lays out specific requirements and

restrictions on this process, such as:

Which contracts require a formal solicitation process

based on a monetary threshold;

When sole source procurement is allowed;

How contracts are evaluated; and

How and by whom contracts are approved depending

on the monetary amount.

After SDHC selects a contractor, the contract moves into the

contract administration stage with the Homeless Housing

Innovations team (HHI). Contract administration involves the

ongoing monitoring of contractor performance, technical and

programmatic assistance, and the monitoring and collection of

data.

Some examples of contract administration conducted by HHI

include:

Annual trainings to cover critical changes to fiscal

procedures, broad changes to program guidelines, and

more;

On-site visits to participate in Joint Hazard Assessment

Teams (JHAT) and observe shelter conditions for health

and safety hazards;

Technical assistance to help problem-solve issues, such

as interagency coordination and the planning and

execution of client housing goals;

Online meetings with program staff to discuss and

train on financial tracking and specific program

guidelines; and

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 8

Monthly data reporting using the Data Collection Tool

(DCT), which includes enrollment levels, performance

metrics, basic demographics, and program staffing.

SDHC’s Equity and Compliance Assurance team performs annual

sub-recipient monitoring by looking at program outcomes and

requirements. To perform monitoring, staff complete the

following:

Program policies and procedures review;

Participant files review, including review of the intake

process, case management papers, and exit

documents for a sample of participant files;

Annual facility reviews for minimum habitability

requirements;

6

and

Desk review of inspections and maintenance,

necessary permits, and other operational

documentation.

Audit Scope and

Objectives

The scope of this audit was homelessness services contracts

administered by SDHC that started during FY2018 through

FY2022. Programs within scope covered $63.8 million of SDHC’s

$128 million homelessness budget in FY2022. The scope did not

include contracts administered by HSSD because HSSD had not

administered any homelessness services contracts for longer

than a year during the scope period. However, HSSD and other

City departments—including General Services Facilities Division

(Facilities) and DREAM—are involved in maintenance conducted

at City-owned and leased properties used by homelessness

services providers.

The objectives of the audit were to:

1. Determine whether SDHC procures homelessness services

contracts according to leading practices;

2. Determine whether SDHC adequately monitors contract

compliance; and

6

SDHC staff informed us that on-site compliance monitoring was temporarily suspended due to the COVID-19

pandemic, but that SDHC is planning out how to restart in-person reviews.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 9

3. Determine whether SDHC holds contractors accountable

for following best practices in providing homelessness

services.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 10

Audit Results

Finding 1: SDHC follows its policies and procedures for

contract procurement, but can improve its process to

identify sole sourced contractors’ potential conflicts of

interest.

A key step to effective provision of contracts is a strong procurement policy, which should

protect the public interest by awarding contracts that represent the best overall value and

protect against conflicts of interest. We found that the San Diego Housing Commission (SDHC)

generally follows its contract procurement policies and procedures with one specific

exception. In reviewed sole sourced contracts, SDHC did not obtain Statements of Public

Disclosure—which provide information on ownership and leadership interests—as prescribed

in its internal conflict of interest policy. SDHC confirmed that it typically does not collect

Statements of Public Disclosure for sole sourced contracts, which accounted for 42 of 93

homelessness services contracts during FY2018 through FY2022, totaling over $70 million in

contract value. This increases the risk that potential conflicts are not identified and prevented.

We recommend that SDHC update its procedures for sole sourced contracts to require this

disclosure.

SDHC followed its

procurement policy

while obtaining

contracts, but did not

follow its separate

conflict of interest

policy for sole sourced

contracts.

As mentioned in the Background, SDHC’s Statement of

Procurement Policy describes the requirements and procedural

steps for SDHC to procure homelessness services contractors.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

requires that public housing agencies, including SDHC, adopt a

procurement policy that conforms with federal law and includes

recommended best practices. SDHC adopted such a policy,

which was approved by the Housing Authority of the City of San

Diego, effective January 31, 2017. To determine the extent to

which SDHC followed this policy, we reviewed:

Cost analyses and independent cost estimates for

awarded contracts;

Evaluation scores for contractor proposals;

Sole source justifications to determine eligibility of sole

sourced contracts;

Contractor proposals to determine if they included

required conflict of interest documents; and

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 11

Records from the SDHC Board of Commissioners and

the Housing Authority of the City of San Diego to

determine whether the contracts were appropriately

approved.

We tested a sample of 29 contracts

7

during FY2018 through

FY2022. The contracts covered a variety of service providers and

intervention types. We separated the contracts into three

groups, including:

The housing group, which contained 6 contracts

covering 6 separate permanent supportive housing

and rapid re-housing programs totaling $24 million;

The shelter and transitional housing group, which

contained 18 contracts covering 9 separate emergency

shelter and bridge shelter programs totaling $124

million; and

The support group, which contained 5 support

contracts covering 4 separate safe parking, family

reunification, and storage center programs totaling

$13 million.

Our sample covered $160 million of the $187 million in

homelessness services contract value in our scope. Our sample

also covered 10 of the 24 homelessness services contractors

8

awarded contracts during the scope period, including 9 of the

top 10 contractors by total awards.

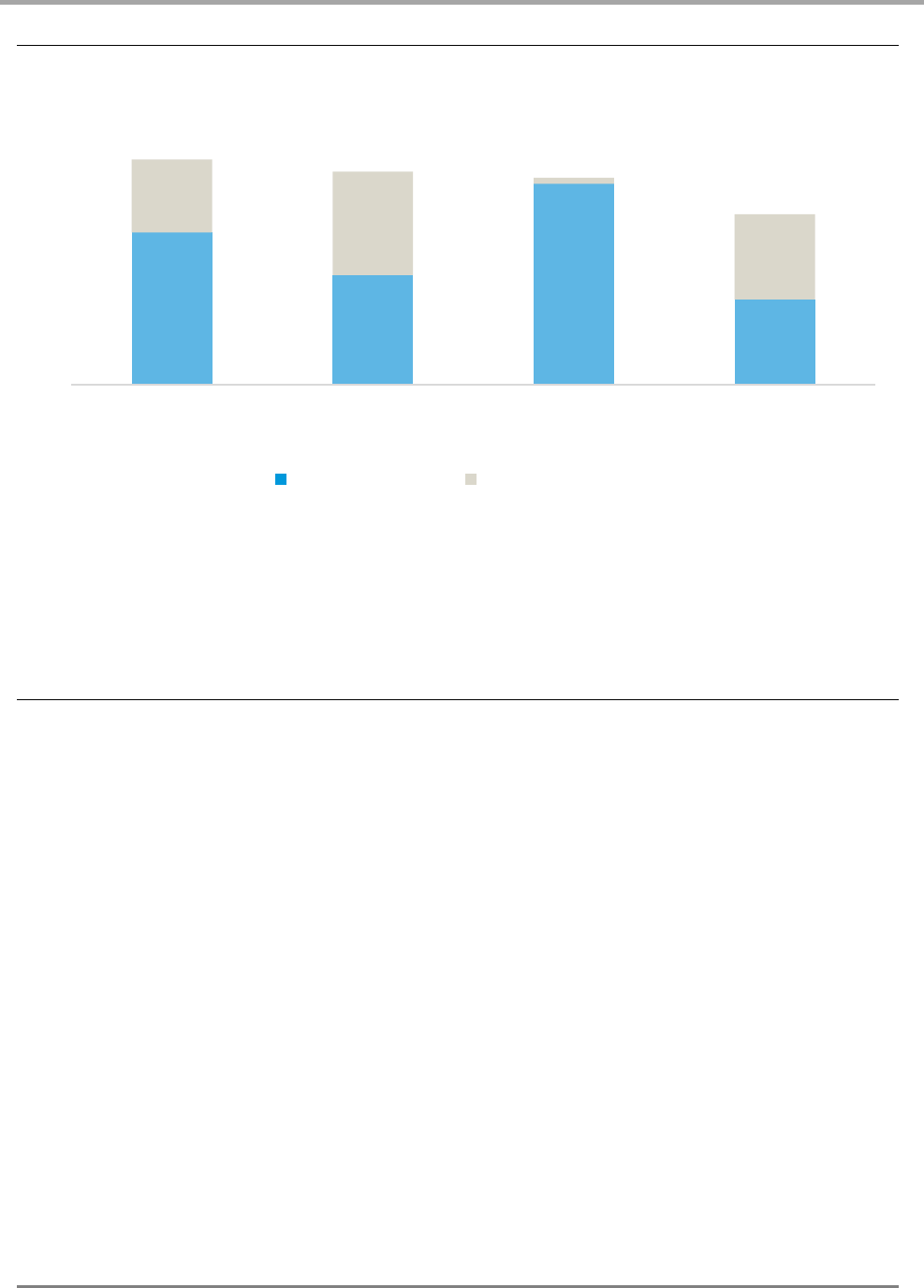

We found the following, which is summarized in Exhibit 5:

Reviewed contracts followed the authorized

procurement path. This helps provide assurance that

public funds are only committed after following a

proper procurement process, including ensuring

reasonable cost.

7

We requested documentation for 30 contracts. After receiving documents, one was an option and not a full

contract. Contracts were randomly selected out of 94 weighted by contract value. This is not a statistically

significant random sample and cannot be extrapolated to all contracts. Appendix C contains the description of

sample programs, including name, provider, contract amount, and start/end date. See Appendix B for more

details on audit procedures.

8

Of these contractors, 12 received less than $1 million over the scope period.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 12

Reviewed contracts were evaluated in accordance with

policy. This helps provide assurance that contracts are

awarded to the best proposal.

Reviewed competitive procurements included

Statements for Public Disclosure. This helps provide

assurance that contractors do not have a conflict of

interest.

Reviewed sole source procurements did not include

Statements for Public Disclosure. SDHC confirmed that

these were not collected for sole source procurements

during the audit scope. This creates a potential for

contractor conflict of interest.

Reviewed contracts were approved by the appropriate

authority. This helps ensure accountability and good

stewardship of public funds.

Exhibit 5

SDHC Generally Followed Procedures for Procurement Outside of One Aspect

Source: OCA generated based on review of procurement documentation for 29 sampled contracts.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 13

SDHC required sole sourced contracts to provide a written

justification and meet the prescribed conditions for use.

Justifications for our sampled contracts included the Hepatitis A

outbreak, the COVID-19 pandemic, and maintaining a continuity

of care for affected individuals. As stated above, sole sourced

contracts in our sample were approved by the appropriate

authority (i.e., the SDHC CEO, Board of Commissioners, or the

Housing Authority of the City of San Diego).

SDHC’s procurement

policy does not require

Statements for Public

Disclosure for sole

sourced contracts.

Conflict of interest policies help prevent the erosion of trust that

can occur if a government employee were to put their own

interests ahead of the public’s interests. Therefore, SDHC does

not allow its employees or agents to participate in the award or

administration of a contract if a conflict—real or apparent—

would be involved. To ensure SDHC identifies all conflicts of

interest, the SDHC Conflict of Interest Policy states that

contractors receiving an award of $50,000 or more must submit

a Statement for Public Disclosure. Statements of Public

Disclosure require names of charitable organizations’ leadership

in order to identify potential conflicts of interest with SDHC’s

procurement procedures. We reviewed competitive

procurements that required these statements; however, SDHC

staff stated they typically do not require these statements for

sole sourced contracts. Consequently, during our analysis of

sample procurement documents, we found that SDHC collected

these disclosures for all competitive procurements but approved

all sample sole sourced contracts without the required

disclosure statements. While SDHC policies mention other

controls

9

to prevent fraud, sole sourced contracts present a

higher risk for conflicts of interest. This makes it especially

important for SDHC to require Statements for Public Disclosure

on sole sourced contracts in addition to competitively bid

contracts.

9

SHDC Procurement Policy Section 3.4 allows the CEO, or their designee, to establish Administrative

Regulations that will facilitate appropriate review of procurement-related actions. SDHC should use this tool to

quickly establish a process to obtain Statements for Public Disclosure for sole-sourced contracts.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 14

Recommendation 1.1

The San Diego Housing Commission should issue an

Administrative Regulation to require Statements for Public

Disclosure for sole source contracts in accordance with its

Conflict of Interest Policy and collect required statements for all

current and future contracts over $50,000.

(Priority 2)

Recommendation 1.2

When the San Diego Housing Commission next updates its

Statement of Procurement Policy, it should require Statements

for Public Disclosure for sole source contracts in accordance

with its Conflict of Interest Policy.

(Priority 2)

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 15

Finding 2: SDHC ensures contracted homelessness

services programs follow best practices through contract

design, ongoing administration, and compliance

monitoring.

Once a contract is awarded, contract administration is important to maintain performance.

Best practices in the operations of homelessness services programs ensure persons

experiencing homelessness receive a consistent and coordinated minimum standard of care.

We found that SDHC ensures contracted programs follow best practices across all aspects of

contract administration.

To test SDHC’s controls for securing compliance with these standards, we reviewed

documents from our sample of 29 contracts relating to five areas of best practice, across three

different aspects of contract administration. Documents we reviewed included:

Signed contracts between SDHC and contractors;

Data Collection Tools (DCTs)

10

; and

Annual Compliance Monitoring Reports.

Additionally, we conducted 15 site visits of programs and conducted interviews with program

staff. Exhibit 6 summarizes our findings.

10

Contracts require a monthly data collection tool that reviews progress on the contract metrics and provides a

narrative section for program staff to explain any shortcomings or barriers that may prevent them from

achieving the target.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 16

Exhibit 6

SDHC Ensures Programs Follow Regional and National Best Practices Across Aspects

of Contract Administration

Source: OCA generated from review of 29 sampled contracts and monitoring documents.

SDHC requires trauma-

informed care

procedures and

monitors contractor

compliance with this

requirement.

For a program to be considered trauma-informed, it must realize

the widespread impact of trauma, recognize the signs and

symptoms of trauma in clients, and respond by integrating

knowledge about trauma into policies and practices. Continuum

of Care (CoC) standards state that programs need to use a

trauma-informed approach and must incorporate the principles

of trauma-informed care in their written policies and

procedures, and in staff training protocols.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 17

Overall, we found that SDHC ensures contractors incorporate

trauma-informed care principles. Contracts we reviewed

included language requiring the use of trauma-informed care.

Program staff training logs we reviewed also showed evidence

that staff attended trainings on trauma-informed care. To learn

more about staff experience, we surveyed 67 contractor staff

11

to determine if they agreed with statements about trauma-

informed topics. Topics included training, knowledge, physical

environment, and crisis procedures. As shown in Exhibit 7, we

found that staff generally agreed with these statements, with no

more than five staff disagreeing with any given statement.

Finally, while conducting site visits, we observed that sites

generally had trauma-informed environments.

Exhibit 7

Staff Believe Their Work is Providing Trauma-Informed Care that is Flexible to Meet

the Clients’ Needs

Source: OCA generated based on survey responses.

11

We provided the survey either during auditor site visits or through an online link. We received 67 responses

from staff at multiple agencies and programs. See Appendix B for more details on our site visits.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 18

SDHC also reviews policies and procedures for evidence that a

program is ground in trauma-informed care. The monitoring

reports we analyzed demonstrated that SDHC reviewed program

policies and procedures for trauma-informed care.

SDHC requires Housing

First procedures and

monitors contractor

compliance with this

requirement.

Housing First prioritizes rapid placement and stabilization in

permanent housing without service participation requirements

or preconditions for entry. California State law requires

recipients of State funding to adopt guidelines and regulations to

include Housing First policies. Additionally, CoC Community

Standards recommend programs have a Housing First approach.

This approach incorporates other best practices, such as harm

reduction, and can be used in all phases of the homeless

housing and services system.

The SDHC contracts we analyzed required programs to have

Housing First principles. We also saw evidence of SDHC assisting

programs in following Housing First principles. For example, in

meeting notes for monthly DCT review, we saw evidence that

SDHC staff provided technical assistance on participant

immigration status and joined case conferencing to assist with

the housing of four undocumented households. Program staff

also stated that SDHC worked with them to ensure referred

clients would meet a funder’s income verification and addressed

the issue before it was escalated.

Throughout the lifetime of the contract, SDHC monitors a

program’s adherence to Housing First. Specifically, during the

annual compliance monitoring process, SDHC staff checked for

Housing First principles. In the program review procedures, staff

check client intake paperwork and program files against a

number of Housing First test steps. Staff review the intake

paperwork for additional screening, make sure participation in

services is voluntary, and ensure no requirements for sobriety.

SDHC requires client

feedback procedures

and monitors

contractor compliance

with this requirement.

CoC standards expect programs to engage participants in

ongoing program evaluation, solicit feedback on program

services quality, and make improvements based on input. To

help programs meet this requirement, SDHC contracts require

each program’s policies contain a way for clients to provide

feedback. Specifically, FY2022 contracts require the collection of

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 19

client satisfaction data and quarterly reports to SDHC. The

reports should include how findings were incorporated into

service delivery and program design.

Program staff described changes that directly resulted from

client feedback, including a new donation area, elimination of a

laundry schedule, and creation of a clean and sober area of a

shelter. We observed kiosks that SDHC installed to obtain

anonymous feedback from participants. At the kiosks,

participants are asked about their overall stay, safety,

cleanliness, and more. SDHC staff stated that they discuss any

issues or suggestions in meetings with providers. As a result of

client feedback, staff described positive changes at the

Homelessness Response Center, including refresher trainings

and improved staffing for the busiest times. During annual

monitoring, the SDHC compliance team reviews program

policies and procedures for compliance with client feedback

requirements and discusses with the program examples of

feedback that are being incorporated.

SDHC requires exit

policies, monitors

contractor compliance

with this requirement,

and is working with

contractors to

standardize policies.

While programs are aiming to get participants into permanent

housing, circumstances require that programs also have a

process for involuntary exit or termination of services. There is

no one best exit policy, but national and regional best practice

agencies describe aspects including:

The process must include written notice and a formal

review process.

Rules should be designed to help individuals get into

permanent housing and should be centered around

safety, terminating assistance only in the most severe

cases.

In most instances, terminations should not mean

permanent bans. However, shelters can have different

standards for termination of assistance and could

permanently ban participants who violate rules or

create dangerous situations.

Any terminations or bans should not prohibit entry

into other supportive services in the area.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 20

The most recent SDHC contracts we reviewed require that

programs have policies around grievances, progressive conflict

resolution, and client appeals. The contracts also require that

programs give participants a service agreement, which includes

violations that lead to immediate terminations. SDHC and

program staff both stated that they were in conversations

around standardizing the exit policy to create consistency across

the system.

To monitor these policies throughout the lifetime of the contract,

SDHC collects information on exits due to noncompliance with

its monthly and annual data collection tool (DCT). Of the 39 DCTs

we reviewed that measured negative outcomes, only 2 showed a

failure to meet the goal.

During the annual monitoring process, SDHC staff check the

program’s policies and procedures for the contract

requirements. Staff also review client files to see if terminated

clients were given due process. In the monitoring reports we

analyzed, SDHC reported 142 client files as involuntarily exited

and all client files contained evidence of due process.

SDHC designs contracts

to meet local standards

on program data

collection and

performance

management.

Homelessness services program evaluation is important for

determining if services are impactful. Evaluations track program

performance and allow for mid-course corrections. CoC

Community Standards expect that all programs regularly review

program data throughout the year to support ongoing program

decision-making and use this data to make improvements.

Additionally, CoC Community Standards recommend programs

discuss data regularly among staff and other stakeholders to

strategize activities for improvement.

SDHC contracts meet this standard

12

in a variety of ways,

including:

Requiring the use of a Homeless Management

Information System (HMIS);

Establishing performance metrics and targets;

12

We analyzed contracts over our entire scope period for language surrounding the different topics, but the

language of the bullets is from FY2022 contracts.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 21

Requiring contractors participate in compliance and

performance monitoring and improvement activities;

Requiring documentation of program progress

through monthly and term-end reports; and

Establishing possibility of a performance improvement

plan if contract benchmarks are not met.

Systemwide limitations

make it difficult for

programs to achieve

community targets.

For specific contracts, SDHC and RTFH staff informed us that

performance metric targets are based off of regional goal-setting

documents, such as the Community Action Plan and CoC

Community Standards, funder-specific requirements, and

analyses of past performance. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic,

many of these targets are out-of-date and do not fully capture

the current environment for contractors. SDHC staff stated that

RTFH plans to engage with regional stakeholders on program

goals this year.

For our sample of 29 contracts, we analyzed performance

metrics for different programs in three different groups:

permanent housing, emergency shelter, and support services.

13

Each program has different metrics and targets based on the

type and size of the program. We reviewed annual data

collection tools and combined different metrics into five broad

categories

14

:

Persons Served: How many individuals the program

served. For example, a storage center’s goal may be to

serve 500 unique individuals in one year.

Occupancy/Utilization: Rate at which beds or case

management slots were filled. For example, an

emergency shelter’s goal may be to be at least 95

percent occupied, on average, for a contract year.

Positive Outcome: Rate at which participants

achieved permanent or other longer-term housing

OR the number of households housed. For example,

13

We analyzed some contracts that did not end up in groups because they did not last a full fiscal year or did

not have applicable target metrics.

14

To standardize the results, we analyzed whether the program achieved its goal each year (or was within 10

percent of achieving its goal). For example, a program’s goal could be to move 100 individuals into permanent

housing. If the program housed at least 90 individuals, we would count it as successful; housing less than 90

individuals would count as unsuccessful.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 22

a rapid re-housing program’s goal may be to house 56

persons in one year.

Negative Outcome: Rate at which participants

were involuntarily exited from the program. For

example, an emergency shelter’s goal may be to exit

less than 20 percent of participants for non-

compliance with program rules.

Returns to Homelessness: Rate at which

participants who were housed returned to

homelessness within the next 6–24 months. For

example, a rapid re-housing project may have a goal

that 85 percent of participants who positively exited

are still permanently housed after 12 months.

Below, we present results of our analyses separated into the

different groups of programs: permanent housing, emergency

shelter, and support services. Following the results of our

analyses, we go into detail on external factors—such as staffing

shortages, high housing prices, and COVID-19—that contributed

to vendor underperformance.

Permanent Housing

The permanent housing group contains the permanent

supportive housing programs and rapid re-housing programs,

totaling 5 of the 29 sampled contracts. As shown in Exhibit 8,

the permanent housing group generally succeeded in achieving

goals for positive outcomes but had mixed results on persons

served.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 23

Exhibit 8

Permanent Housing Programs Generally Achieved Targets for Positive Outcomes, but

Returned Mixed Results on Persons Served

Note: Each contract may not report on all metrics, or a specific contract year may not have a target

for that metric. In these cases, we did not analyze the performance of that program year.

Additionally, COVID-19 impacted contractor performance. For more information, see below section

titled “COVID-19 related policies made it difficult for contractors to achieve performance targets.”

Source: OCA generated from review of 5 sampled permanent housing contracts and annual data

collection tools.

Shelter

The shelter group contains the different emergency shelter and

bridge shelter contracts, totaling 16 of the 29 sample contracts.

As shown in Exhibit 9, the shelters succeeded in achieving their

goals for negative outcomes. However, they returned mixed

results on occupancy/utilization goals, and failed to meet targets

for positive outcomes and avoiding returns to homelessness

around half the time.

7

10

2 2

5

2

1 1

Persons Served Positive Outcome Avoiding Negative

Outcome

Avoiding Return to

Homelessness

Total Years

Successful Years Unsuccessful Years

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 24

Exhibit 9

Shelters Achieved Negative Outcome Goals but Often Missed Targets

for Positive Outcomes

Note: Each contract may not report on all metrics, or a specific contract year may not have a target

for that metric. In these cases, we did not analyze the performance of that program year.

Additionally, COVID-19 impacted contractor performance. For more information, see below section

titled “COVID-19 related policies made it difficult for contractors to achieve performance targets.”

Source: OCA generated from review of 16 sampled shelter contracts and annual data collection

tools.

Support Services

The support services group contains the safe parking program,

family reunification program, and the storage connect centers,

totaling 4 of the 29 sample contracts. These programs met

negative outcome goals, returned mixed results on persons

served goals, and failed to meet occupancy/utilization goals.

Exhibit 10 shows the results of this group’s analysis.

25

18

33

14

12

17

1

14

Occupancy/Utilization Positive Outcome Avoiding Negative

Outcome

Avoiding Return to

Homelessness

Total Years

Successful Years Unsuccessful Years

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 25

Exhibit 10

Support Programs Showed Mixed Results on Goals Related to Persons Served

Note: Each contract may not report on all metrics, or a specific contract year may not have a target

for that metric. In these cases, we did not analyze the performance of that program year.

Additionally, COVID-19 impacted contractor performance. For more information, see below section

titled “COVID-19 related policies made it difficult for contractors to achieve performance targets.”

Source: OCA generated from review of 4 sampled support services contracts and annual data

collection tools.

Staffing and housing

inventory shortages

impacted contractor

performance.

As mentioned above, external factors contributed to low

performance. Staffing issues plagued providers in recent years,

limiting their ability to provide in-depth case management

services. While contracts require programs to provide

appropriate staffing levels, SDHC staff understand contractors

may not have the funding necessary to learn the root cause of

staffing shortages. Therefore, SDHC is trying to address this

systemwide issue in a variety of ways. SDHC partners with San

Diego City College to operate the Homelessness Program for

Engaged Educational Resources. This program provides

specialized education, training, and job placement assistance to

develop the workforce needed for homelessness programs and

services.

Staffing shortages are likely exacerbated by relatively low wages.

Program management noted that due to wages, staff compete

with participants for housing resources. Recently, SDHC

commissioned a salary study which showed a majority of

6

2

3

2

Persons Served Occupancy/Utilization Avoiding Negative Outcome

Total Years

Successful Years Unsuccessful Years

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 26

frontline homelessness staff cannot afford even a one-bedroom

unit without being cost-burdened. The report recommended

that SDHC and the City collaborate to find funding to shift from

minimum wage to living wage as the benchmark for comparing

wages.

Contractors also underperformed on positive outcomes due to

system-wide limitations with the high price of housing in the

area, low availability of permanent supportive housing, and low

rental vacancy rates. Additionally, program staff stated that

“returns to homelessness” does not fully reflect program

performance. Staff often have little to no insight into a

participant’s actions and circumstances once they exit the

program. For instance, shelter programs are not modeled to

provide case management after individuals exit the program. All

of these factors may impact performance against metrics and

make it difficult to achieve targets that might be achievable in

other parts of the country or region.

COVID-19 related policies

made it difficult for

contractors to achieve

performance targets.

Finally, program narratives provided on DCTs and program

underperformance over time demonstrate the impact of COVID-

19 on operations. The related policies made it more difficult for

participants to gain employment and affordable housing, and

lowered occupancy rates due to quarantine units and closure of

upstream referral locations. Despite these restrictions, programs

still reported performance against original contract goals.

Exhibit 11 shows the rate at which programs achieved their

goals during the five years in our scope period.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 27

Exhibit 11

Program Performance Declined During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Source: OCA generated from review of 24 sample program’s annual data collection tools from

FY2018 through FY2022.

Our analysis showed that some programs experienced large

shifts in occupancy or persons served during this time. The

Family Reunification Program went from serving 103 percent of

its goal in FY2019 to serving only 36 percent of its goal in FY2021.

Transitional housing program staff mentioned that many

referrals to their program come through the court system.

However, since COVID-19, referrals have had difficulty obtaining

the necessary proof of chronic alcoholism needed to enroll in

the program. Shelter staff voiced similar concerns, stating that

COVID-19 policies lowered the number of spaces that could be

occupied. Finally, according to SDHC, persons served for rapid

re-housing programs declined during COVID-19 due to the

shifting need toward longer-term rental assistance to prevent

returns to homelessness. As the region continues recovering

from the pandemic, targets and performance should continue to

be analyzed within the context of these external factors.

73%

81%

76%

60%

52%

FY2018 FY2019 FY2020 (First Year

Affected by

COVID-19)

FY2021 FY2022

Goal Completion

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 28

SDHC followed best

practices in

performance

management, but its

ability to change

providers is limited by a

low number of bid

respondents.

Throughout the lifetime of a contract, programs should be

evaluated with a mixed methods approach that includes

information about how the programs are implemented as well

as data on client outcomes. The National Association of State

Procurement Officials recommends monitoring performance by:

Collecting and analyzing information needed to

evaluate supplier performance;

Monitoring and providing feedback to the supplier

about performance standards;

Identifying critical areas for improvement; and

Implementing agreed-upon steps to remedy issues.

According to SDHC staff, their first course of action when

approaching an underperforming program is to compare

performance to other similar programs and the system at large.

Staff use the recommended mixed methods approach when

comparing across the system. Contracts require a monthly data

collection tool that reviews progress on the contract metrics and

provides a narrative section for program staff to explain any

shortcomings or barriers that may prevent them from achieving

the target. We observed during an update meeting and learned

from interviews that SDHC staff meet with program staff

regularly regarding performance targets and that the narrative

section is helpful to explain any sort of challenges or information

that are not captured by the metrics. Additionally, SDHC staff

monitor program staff vacancies to assess program

performance in context. SDHC and program staff informed us

that SDHC staff participate in case conferencing to try and

contribute to solutions for clients with specific barriers or

challenges. Program staff stated that this level of involvement

can be helpful and goes beyond the participation of other

funders.

To support this ongoing performance management effort,

SDHC’s compliance team evaluates policies and procedures for

multiple aspects. The compliance team reviews documents and

interviews staff for evidence that a program has the necessary

data systems to collect information, documents project

outcomes, and adheres to RTFH’s performance standards and

requirements. Additionally, we reviewed monitoring reports for

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 29

evidence of fiscal controls to make sure program expenses and

administrative costs were allowable, reasonable, and

documented.

According to SDHC, competitive bids often return a small

number of respondents and this requires SDHC to try and work

with the contractors it has, rather than be punitive. Out of the

contracts we reviewed that were competitively awarded, there

was an average of 137 vendors notified and only 4 respondents.

We interviewed staff from the City of Sacramento and the City

and County of San Francisco about procurement outreach and

found that while the number of respondents in San Diego was

comparatively low, neither city indicated conducting any

additional outreach beyond what SDHC currently performs.

Overall, we found that SDHC ensures contractors follow best

practices by having checks at the contract design stage,

administering contracts on an ongoing basis, and monitoring

compliance through an annual process. Therefore, we have no

recommendations for this finding. It is important for

administration of homelessness contracts to continue to use

best practices to ensure good stewardship of public funds and

maximize performance.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 30

Finding 3: The City lacks documented processes for

repairs at City-owned or leased homelessness facilities,

causing persistent unsafe and unsanitary conditions at

some locations.

We found a lack of documented City processes resulted in delayed repairs at some City-owned

or leased homelessness facilities.

15

We observed disrepair at sites, including shelters, a safe

parking lot, and the Homelessness Response Center. We did not observe similar conditions at

sites owned or leased by the contractor or the San Diego Housing Commission (SDHC). We

also reviewed maintenance requests submitted to the City by providers and SDHC that were

not addressed in a timely fashion—with potentially hazardous situations lasting for months.

At City-owned and leased sites, SDHC’s contracts require contractors to report any

maintenance or repair needs to SDHC. SDHC has a process for receiving, evaluating, and

submitting maintenance and repair requests to the City through the Homelessness Strategies

and Solutions Department (HSSD). However, HSSD does not have a documented process for

receiving and submitting maintenance and service requests to those responsible for

performing maintenance.

Additionally, service providers may be unaware of the status of their maintenance and repair

requests because the City does not have a process for providing information on the status of

these requests. This can lead to deterioration of facilities and damaged trust between the

service providers and their clients.

Areas of homelessness

facilities are unsafe,

unclean, and in

disrepair.

Throughout the course of the audit, we conducted a number of

site visits at program facilities from sampled contracts.

16

These

visits occurred at both City-owned or leased sites and sites

owned or leased by the contractor or SDHC. We found that sites

where maintenance was fully the contractor’s responsibility were

in good repair. However, we observed unsafe or unclean

conditions at sites where the City was partially responsible for

maintenance. Some examples of disrepair were moldy ADA-

showers, as shown in Exhibit 12, a ripped privacy mesh at the

Golden Hall shelter, a broken HVAC system at a sprung shelter, a

15

The audit covered programs administered by SDHC from FY2018 to FY2022. Ten of these programs were

located at City-owned or leased facilities. These programs included the safe parking program, whose contract is

administered by HSSD as of July 1, 2022.

16

The sites visited were part of our value-weighted random sample of contracts and are not necessarily

representative of all sites.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 31

broken window at the Homelessness Resource Center, and a

broken streetlight at a safe parking site.

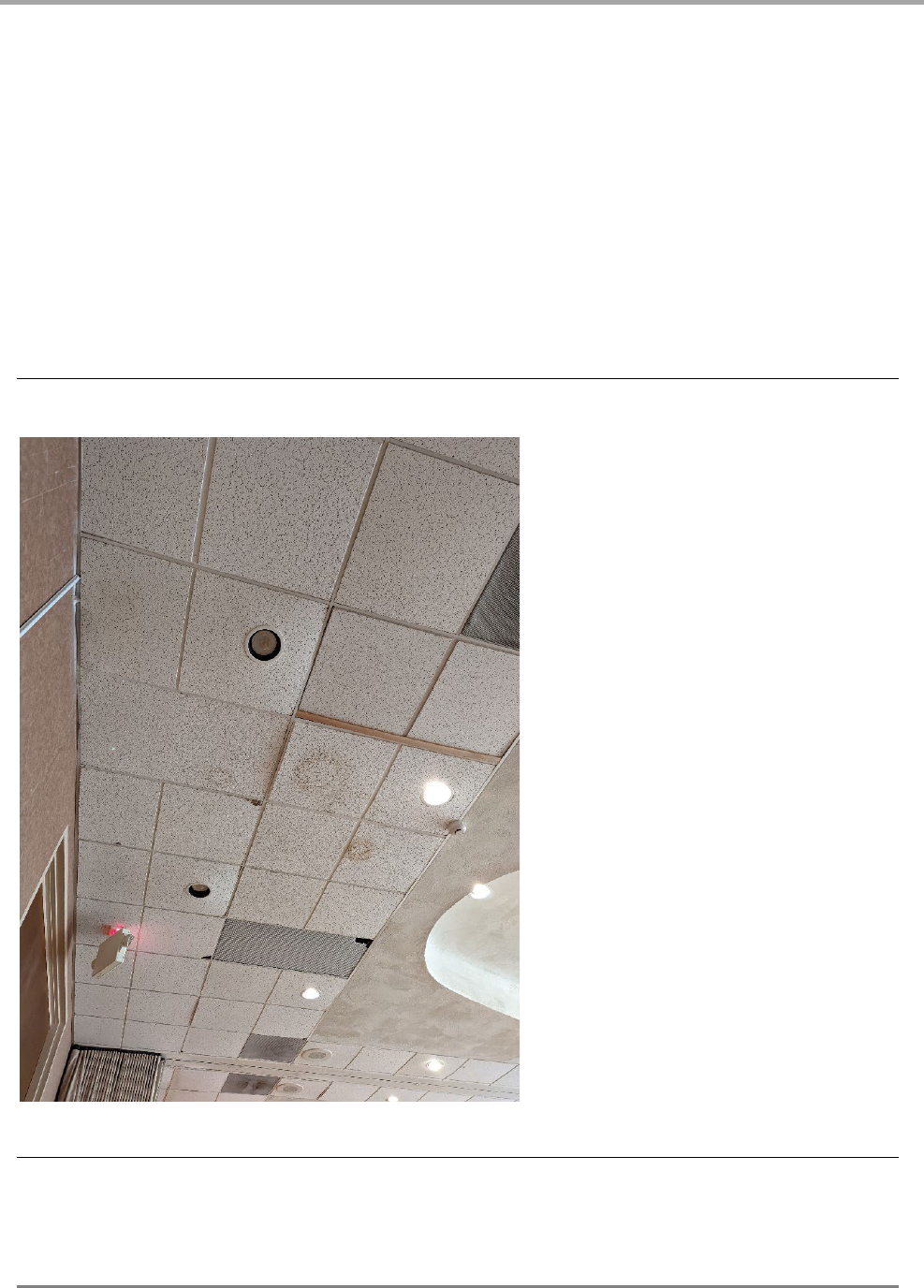

Exhibit 12

Mold in an ADA Shower at Golden Hall Resulted in Closure of the Shower, Leaving

Only One ADA Shower for at Least Two Months

Source: Photographed by OCA during site visit at Golden Hall on October 28, 2022.

Additionally, we reviewed Joint Hazard Assessment Team (JHAT)

reports,

17

which included observations of missing cover plates

on light poles, exposed wires, and falling ceiling panels. Some of

these issues were reported on consecutive JHAT reports with no

information regarding remediation.

17

JHAT observations are monthly or bi-monthly observations from SDHC, City staff, and site staff.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 32

The City is responsible

for some maintenance

and repairs at City-

owned and leased

properties.

At City-owned facilities, the party responsible for completing

repairs varies by location and program. Uncertainty and

disagreements over the responsible party can lead to delays in

fixing the problem. Additionally, there are different agreements

that make establishing the responsible party unclear. For

example, the Memorandum of Understanding for Bridge

Shelters between SDHC and the City states that SDHC is

responsible for ensuring maintenance of porta-potties or

modular restrooms, while the City is responsible for structural

maintenance and repairs.

City staff informed us that determining responsibility between

City departments also causes delays. For example, auditors

noticed a broken streetlight that caused a safety risk at a safe

parking facility. When asked about the status, City staff said the

repair was delayed due to “back and forth” between two City

departments on who was responsible for both fixing the light

and clearing brush necessary to access the light. While HSSD

staff notified the appropriate party to complete the repair, staff

could not confirm when the repair happened.

From a contractor perspective, SDHC contracts establish the

contractor as the responsible party to keep the site clean and

maintained and require the contractor to notify SDHC of any

issues that require repair. In addition, license agreements may

provide an additional assignment of responsibility. For example,

the license agreement between Father Joe’s Villages and the City

for Golden Hall establishes Father Joe’s Villages as the

responsible party for waste, damage, or destruction.

In our interviews, we learned there is disagreement between a

contractor and the City regarding who should be responsible for

“vandalism” conducted by shelter residents. While license

agreements might establish the contractor as the responsible

party, program staff informed us that it is difficult to control

actions of shelter residents if they do not have a say in who

resides in their facility.

18

For example, as a result of a JHAT assessment, a service request

for a broken outlet—pictured in Exhibit 13—was submitted to

18

Shelter residents are assigned by SDHC through a central coordinated intake process.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 33

City staff on August 23, 2022. City staff deemed it to be

vandalism and therefore did not request a work order as the

contractor is responsible for addressing vandalism. However,

the City could not provide documentation of the determination

or of its notification of the determination to SDHC or the service

provider. According to program staff, the outlet was fixed on

January 18, 2023 by a third party contracted by the City.

Exhibit 13

A Broken Outlet Remained Unfixed for Almost Five Months

Source: Maintenance request submitted by SDHC on August 23, 2022.

While initially deemed as the responsibility of the contactor, City

staff ultimately took responsibility after the issue persisted for

almost five months. Although the City has the ability to obtain

payment from the contractor for fixing these issues, City staff

stated that the City has not pursued payment.

The City does not have

a documented process

for receiving

maintenance requests

from SDHC or

contractors.

A lack of process documentation could lead to some

maintenance issues falling through the cracks. In practice,

maintenance requests originate from JHAT site visits or

contractor reports and are reported to SDHC, which receives,

evaluates, and forwards them to HSSD and the Department of

Real Estate and Airport Management. The requests then get

forwarded to the appropriate department or vendor and follow

the appropriate party’s internal process. Based on interviews

with SDHC and City departments, we found that there is a lack of

process documentation establishing contact department,

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 34

timelines, and communication of progress and task completion.

Additionally, when we asked for the status of two service

requests submitted by SDHC with lengthy timelines, City staff

were unable to identify the status of the request to determine

whether it was completed. This lack of process—and the

resulting delays in fixes—caused the disrepair we observed.

Additionally, the delays risk straining the relationship between

the contractor and program participants.

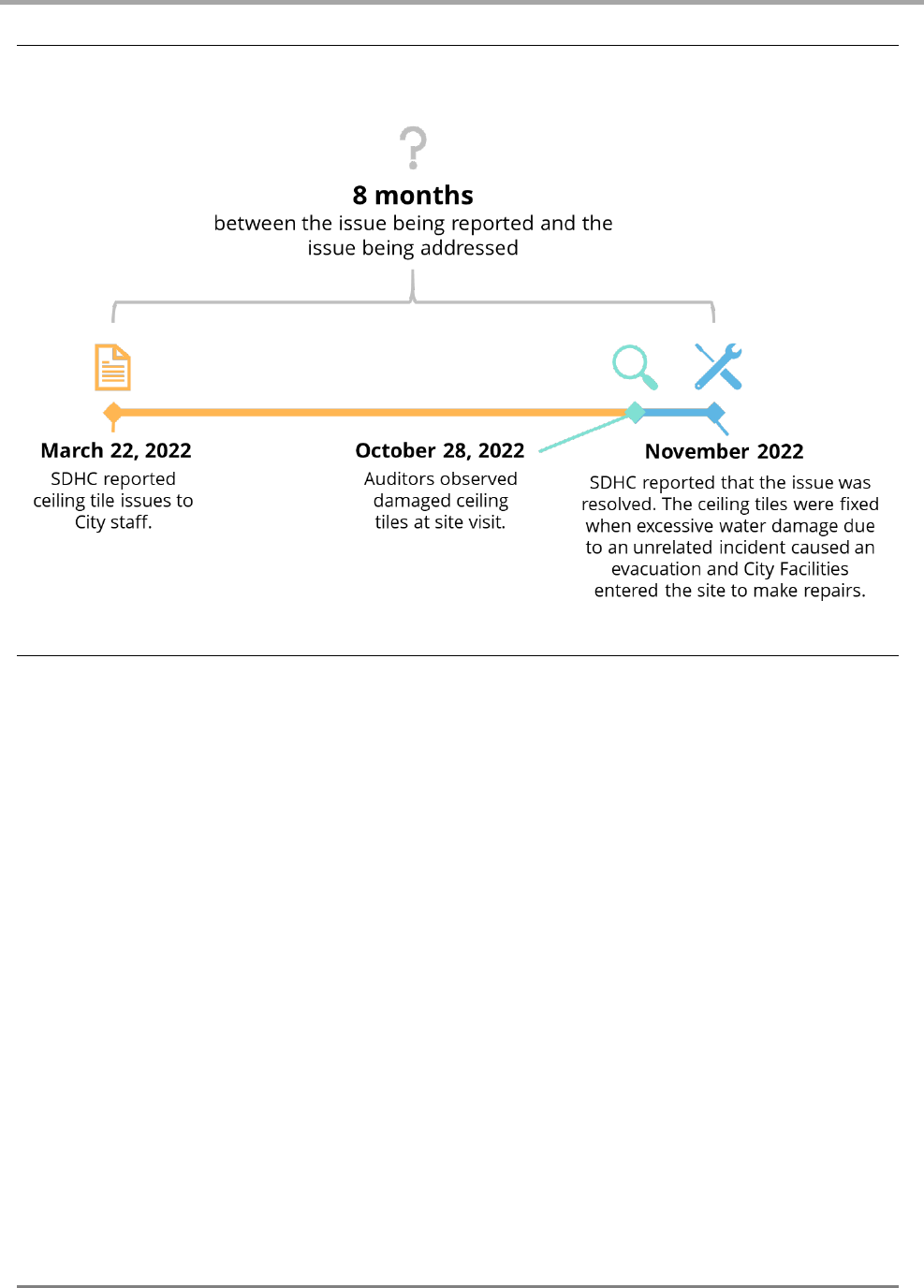

For example, Exhibits 14 and 15 show the damaged ceiling tiles

we observed at a shelter, and the lengthy timeline of their repair.

Exhibits 14

Damaged Ceiling Tiles Create a Potentially Hazardous Situation

Source: Photographed by OCA during site visit at Golden Hall on October 28, 2022.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 35

Exhibit 15

Unsafe Shelter Conditions Persisted for 8 Months After the City Received a

Maintenance Request

Source: OCA generated based on maintenance request, observation, and interviews.

As mentioned in the Background, the Community Action Plan on

Homelessness assigns the Mayor’s Office with the responsibility

of coordinating City departments’ response to homelessness. A

2021 consultant memorandum found that HSSD needs to

strengthen internal partnerships across City departments and

teams. Additionally, the memorandum detailed a need for

additional documentation and clarification of the City’s policies

and procedures.

As a new department, HSSD is tasked with serving as the liaison

to homelessness services agencies and is responsible for

ensuring homelessness policies are carried out by various City

departments. As the coordinating department for the City, HSSD

could add value by tracking requests that span different

agencies and City departments. In this role, HSSD has the

opportunity to evaluate existing process and implement an

improved procedure that would help ensure accountability from

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 36

the City for maintenance and repairs that are the City’s

responsibility.

HSSD has already made progress in this area. Staff provided

draft procedures for an SDHC-administered homelessness

facility that detailed roles and contact points for different

vendors. Additionally, HSSD is rolling out a “text bot” that helps

track service requests across the different agencies. These draft

procedures are a good first step, but are not applicable to all

sites, and should be properly approved. Once fully developed for

use at all sites and approved, HSSD should distribute the

procedures to all stakeholders.

Delayed repairs lead to

damaged facilities and

broken trust between

service providers and

individuals

experiencing

homelessness.

City facilities deteriorate when repairs are delayed. For example,

when a roof leak required relocation of residents at Golden Hall,

the Department of General Services Facilities Division stated that

it identified many additional repairs that it was not aware of. As

a result, the City needed to conduct significant repairs while the

residents were relocated.

Additionally, lengthy timelines for repairing facilities can damage

trust between shelter residents and service providers. Since

residents may not know who is responsible for repairs at a

shelter, they may blame the contractor for the delays. This can

lead to damaged trust, which is counterproductive to the

relationship-building required for contractors to encourage

participation in programs intended to assist individuals

experiencing homelessness and bring them into permanent

housing.

Recommendation 3.1

In order to address existing maintenance issues, the

Homelessness Strategies and Solutions Department should

coordinate with providers, the San Diego Housing Commission,

and relevant City departments to perform an inspection of all

homelessness services sites for which the City is responsible for

maintenance and repairs, and complete any identified repairs

and maintenance at those sites.

(Priority 2)

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 37

Recommendation 3.2

In order to address future maintenance issues at sites where the

City is responsible for maintenance and repairs, the

Homelessness Strategies and Solutions Department should

establish a procedure to track maintenance requests between

providers, the San Diego Housing Commission (SDHC), and

relevant City departments. This procedure should contain

required information for service requests, correct routing

procedure for requests, estimated timelines for repair, and

communication of progress and task completion to SDHC and

service providers.

(Priority 2)

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 38

Appendix A: Definition of Audit

Recommendation Priorities

DEFINITIONS OF PRIORITY 1, 2, AND 3

AUDIT RECOMMENDATIONS

The Office of the City Auditor maintains a priority classification scheme for audit

recommendations based on the importance of each recommendation to the City, as described

in the table below. While the City Auditor is responsible for providing a priority classification for

recommendations, it is the City Administration’s responsibility to establish a target date to

implement each recommendation taking into consideration its priority. The City Auditor

requests that target dates be included in the Administration’s official response to the audit

findings and recommendations.

Priority Class

19

Description

1

Fraud or serious violations are being committed.

Significant fiscal and/or equivalent non-fiscal losses are occurring.

Costly and/or detrimental operational inefficiencies are taking

place.

A significant internal control weakness has been identified.

2

The potential for incurring significant fiscal and/or equivalent non-

fiscal losses exists.

The potential for costly and/or detrimental operational

inefficiencies exists.

The potential for strengthening or improving internal controls

exists.

3

Operation or administrative process will be improved.

19

The City Auditor is responsible for assigning audit recommendation priority class numbers. A

recommendation which clearly fits the description for more than one priority class shall be assigned the higher

priority.

Performance Audit of SDHC’s Homelessness Services Contract Management

OCA-23-07 Page 39

Appendix B: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology