1

PPP-60

Lisa Shaheen, Editor-in-Chief, Pest Control Magazine

Kevin Kilbane, Features Reporter, News-Sentinel

Josh Boyd, Assistant Professor, Purdue Department of Communication

Jane Natt, Assistant Professor, Purdue Department of Communication

Dan Skinner, General Manager, WBAA Public Radio

Chris Morisse, News Director, WLFI-TV

Wayne Falda, Staff Writer, South Bend Tribune

Arlene Blessing, Developmental Editor and Designer,

Purdue Pesticide Programs

Purdue Pesticide Programs

Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service

COMMUNICATING

WITH THE NEWS MEDIA

Sending a Clear, Concise,

Consistent Message

FRED WHITFORD

Coordinator, Purdue Pesticide Programs

2

3

Introduction

As a society we expect the media to tell us everything we need to know

about issues and events that impact our lives. But the goal of the media is to

present the facts and report each story in a way that will help us decide for

ourselves what impact it might have or what value it holds.

Reporters are seldom experts on the subjects they report; most rely on

information provided by their sources. Much of what they write for print,

television, and radio is based on what they are told by experts or others

close to the subject: people like yourself.

Reporters call you for information that will

enhance their reporting, and seldom if

ever will you nd yourself in confrontation

with them. Speaking with the local media

offers you an opportunity to provide useful

information and to convey the positive

inuence your organization has on the

community. Your contribution to news

stories reminds people that your company

exists; that you employ local people and

pay taxes; and that you are an integral part

of the community.

You might be asked to explain the local

effect of a specic national issue. It might

be a story on Japanese beetles or on

controlling mosquitoes to guard against an

outbreak of West Nile Virus; or it may be a

human-interest story on how your business

is sponsoring an adopt-a-pet program in

conjunction with the local humane shelter. You might be asked to comment

on any number of topics—health, water quality, scientic advances—and

how they affect your business and the community. Your participation

gives you a voice in what will be reported to the public, and you may be

the only expert who can explain the signicance of an issue and the local

ramications it might have.

Some interviews can be difcult; they might involve controversial issues

on which two or more entrenched adversaries are standing their ground.

Reporters basically want your opinion and perspective. For example, do

pesticides pose a risk to children when used in or around an elementary

school? Do farm chemicals pose a threat to the local surface water supply?

Why does your company use pesticides when there are clear alternatives?

Express your views simply and concisely; help the reporter to present the

story in a way that will allow the public to weigh the information and form

their own opinions.

4

5

View working with the media as an opportunity. Your organization might

exist just ne without them, but what if a crisis occurs? Building positive

relationships with the media when business is uneventful helps establish

rapport that will serve you well in times less fortunate.

Understanding that reporters play an important role in informing the public is

the rst step in building a successful partnership. Providing timely, accurate,

helpful information both in critical situations and in the mundane can

enhance that partnership and the credibility of your organization.

The purpose of this publication is to help you understand the role of the

media in American society, how news is processed, and how to put your best

foot forward during an interview. Your expressiveness—your clear, concise

answers to reportersʼ questions—can help the media deliver accurate,

interesting, educational information.

When Information Becomes Newsworthy

You have an interest in what is happening not only in your community but

also nationally and around the world. Local news offers in-depth coverage

of issues close to home. Headlines can range from property taxes to

education to what can and canʼt be done in the community. National news,

on the other hand, covers events of national or global importance; it might

focus on what a senator is doing or saying or how the United Nations voted.

Trade magazines, although national in focus, may publish information from

interviews with pertinent experts in your community.

News must generate interest to produce a prot. Reporters and journalists

are limited by time and space, so they must decide what is of greatest

interest to their subscribers, listeners, and viewers—that is, what will attract

an audience and hold its attention. The “attractor” captures the interested

audience that in turn attracts advertisers.

The mediaʼs decision on what is news and how best to present it sets

the tone of the story, be it front-page coverage with a big headline and a

photograph or a brief mention in a newscast. How the story is “framed”

inuences what readers and viewers feel or think about a specic issue or

event. Deciding what is news and how to report it is called

agenda setting

and framing.

Factors that determine whether information or an event becomes news:

• Does it affect a lot of people?

• Will the report right a wrong?

• Is the story/event/information compelling?

• Is there a human-interest angle?

• Is it timely?

4

5

• Are people talking about it?

• Will it affect my wallet either positively or negatively?

• Does it have entertainment value?

• Does it tap into the fears or aspirations of the audience?

• Is there a clear-cut underdog for whom we can “cheer”?

• Is it unique?

• Is there an appealing photo or graphic, or is there audio footage that

will make the story engaging?

Speaking with Authority,

Condence, and Compassion

The news industry—television, newspapers, magazines, radio, the Internet—

faces unique challenges. Journalists must research, synthesize, and write

the news under time constraints uncommon to most other professionals.

Most of us are unaccustomed to the rapid exchange of information

necessitated by journalists with a deadline; but an understanding of media

constraints will help you realize how your position may be compromised,

why errors occur, and why scientic principles are sometimes reported

inaccurately. Your genuine respect for reporters and their obligations will

create goodwill, and they will come to rely on you as a source they can trust

not only for accurate information but for courtesy as well.

The media have to know their audience, and they have to consistently feed

the audience valuable information to make it grow. The bottom line is that

the audience has to be interested enough to subscribe to a publication or to

purchase it continually at the newsstand, or to watch the news consistently

on television or listen to it on the radio. The audience has to be interested;

itʼs really all about advertising revenues tied to reading, viewing, and

listening. Ratings ultimately govern what advertisers and other contributors

will pay.

Reporters have to supply all the facts, knowing that their story will get

condensed into a 15-second television or radio sound bite. In most cases,

short stories have more appeal, so the media try to produce brief news items

that not only grab the audienceʼs attention but also foster understanding.

The journalistʼs age, education, and experience inuence how a story is

reported. Journalists hired into small media markets may be starting their

rst job after college—or high school—and the disparity in education and

experience between these individuals and seasoned professionals denitely

affects how the news is presented. Interpretation of complex scientic,

medical, political, and/or social topics varies, depending on the reporterʼs

credentials.

Good reporters, experienced or not, rely on experts to provide the facts

and put them into context. They often must break through scientic jargon

and condense mountains of information just to pique and maintain public

6

7

interest. You can help by presenting the

facts as simply as possible when you are

interviewed.

Reporters struggle continually to meet

deadlines. There is erce competition

among newspapers, radio and television

stations, and trade publications to be the

rst to report breaking news or exclusive

stories, but some contend that the scoop

is not nearly as vital as reporting the story

completely and accurately.

The goal of most reporters is to present

a balanced news report. Generally, they

interview people on each side of an issue

and present the facts so that the public

can draw their own conclusions. But when

a tight schedule or an imminent deadline

prevents it, reporters have to choose

between dropping a story and reporting it

without input from all perspectives.

Why Talk to Them?

The question often arises, Why would I want to subject myself to a media

interview? Well, for one thing, if youʼve done your homework it is an

opportunity to have your message heard. It is a way to reach the public,

and itʼs free advertising! Speaking with the media allows you to help set the

public agenda. The public relies on professional opinions for answers to

media questions, and youʼre the professional!

6

7

Express your own opinions or the position of your organization to raise

public awareness of the topic, issue, or problem at hand; share important

facts with the public to prevent or squelch unsubstantiated or false

information. This enhances your own public image and that of your business

or organization; and in certain situations it may allow you to publicly defend

yourself and set the record straight. Refer reporters to other experts who

may be able to answer questions that you cannot.

Interviews Start with Your Questions

Not everyone is cut out to deal effectively with the media, and you must

decide for yourself whether granting an interview is the right thing to do.

Many professionals mistakenly believe that “being interviewed” just means

answering questions, but actually it requires thorough preparation.

When you are contacted by the media, ask questions and write down the

name of the caller and his afliation. In deciding whether you will or will not

participate, keep in mind that you will be speaking as an expert

through

the reporter

to a larger audience. If you choose to be interviewed, ask for

time to collect your thoughts and return the call. Then take a few minutes to

organize what you want to say, but respect the deadline implicitly. Offer your

perspective clearly, concisely, and engagingly.

Ask the reporter questions such as the following.

What questions will you be asking?

Good reporters will explain what kind of information they expect from you.

They want to deliver an accurate report from various perspectives in a way

that will capture their audience, so jot down their questions and take the time

to prepare your answers.

Do not let the prestige of being asked for an interview cloud your judgment;

decide in all honesty whether you should speak to the reporter or decline

the opportunity. The media will respect your decision if you tell them that you

really are not knowledgeable on a subject.

Whom do you represent, and why are you doing this piece?

If you are unfamiliar with a reporter who contacts you, ask whom he or

she represents and take the time to conrm the response. If you recognize

the afliate as a fringe publication noted for misquoting or otherwise

misrepresenting its sources, you might want to decline the interview. It is

important to know if there is an agenda already in place, i.e., whether the

reporter expects you to put the nail in the cofn or whether the interview

could turn hostile. Donʼt put yourself in a position to be used—or abused!

8

9

Who is the audience?

It is important to know your audience and to understand how they already

feel about the subject at hand. Are their opinions valid? Is there a general

misunderstanding that needs to be cleared up? Will they be expecting you to

reinforce their beliefs or to counter their argument? You might reach a group

of 18-year-olds with one approach, but a middle-aged or senior audience

might require a different slant.

Will others be interviewed?

It may be important to know if the reporter will be consulting others on the

issue as well. Maybe you are the only person being interviewed, but in most

cases individuals with various points of view are asked to comment. In other

cases multiple sources within an organization may be contacted.

It is important to know who has been or may be interviewed from your own

organization, particularly if your rm has a press liaison whose job is to

coordinate interviews with the media. Knowing who will be interviewed—both

inside and outside your own organization—often reveals the true intent of

the reporter and may inuence your decision to participate or to decline the

invitation.

Have you followed our established procedures

for securing interviews?

In large organizations there may be specic procedures for assisting the

media. If that is the case with your rm, politely ask the reporter to follow

protocol.

What is your deadline?

Most television and radio reporters work on stories that will be broadcast

the very same day, so they need a quick interview. Those covering

breaking news need immediate, straightforward information. If you cannot

accommodate them, refer them to someone who can answer their questions

factually and quickly.

Do you expect to consult with me continually as a source for

background information, and do you intend to quote me?

Journalists donʼt always conduct interviews just to get information they can

quote, so make sure you know whether the reporter expects to use you as a

contact source, a background source, or a main source.

Contact Source.

There are times when it is appropriate to provide the

names of other contacts rather than answer questions. Declining an offer

to speak with reporters is justiable and prudent when you are being asked

to address something outside your expertise. When possible, suggest

8

9

individuals or organizations that the reporter may contact. If your referrals

are good ones, this approach may lay the groundwork for future media

interaction. Consider it an investment in good media relations.

Background Source.

Reporters often interview background sources to gain

a better understanding of the subject they are covering. Information gathered

in context aids the reporter in asking more in-depth and pertinent questions,

in composing the story logically, and in developing a unique angle.

When you are interviewed as a background source, it is very important

to use everyday language; jargon and acronyms used by experts on the

subject may be meaningless to the target audience. If there is time, prepare

a one-page hard copy of your comments for the reporter.

Background sources are commonly unsung heroes who never see their

names or photographs in print nor witness their voices heard. But if you

provide information that is easily understood, you may end up being quoted

or interviewed as an expert. Never state anything “off the record” because

nothing ever is! Even if a reporter assures you that what you say will be kept

condential, donʼt risk it; and if you are not authorized to represent your

organization on the subject at hand, refer the reporter to someone who is.

Main Source.

You become a main (quotable) source when you can

demonstrate your expertise on a subject and back it up with research or

experience or both. You must clearly understand the ne points of the issue

and be able to dene its relative importance.

How much time will the interview take?

If the interview is for a feature story or one that doesnʼt have an immediate

deadline, it is appropriate to ask for an appointment. The worst time to do an

interview is when you have other things on your mind, so allow enough time

in your schedule to answer questions without feeling rushed.

If you are asked to tape a confrontational interview for broadcast, it is very

important to set a time limit for the taping session—and stick to it. Otherwise

you may be asked the same question again and again until you give an

answer the reporter likes. In most cases, 30 minutes is plenty of time for

taping comments that will be edited for broadcast.

If you are short on time when a reporter calls, tell the person that you have

time for just two or three questions and offer to schedule an appointment

to discuss the issue further; then schedule an interview for a mutually

convenient day and time—and make sure you keep the appointment. The

reporter will appreciate your effort to accommodate the request and will feel

free to contact you in the future.

10

11

Will the interview be live?

Having a microphone in front of you during a live radio or TV program can

be intimidating. Ask the reporter for his questions in advance; and if the

interview is tape-delayed, you may ask the reporter to repeat a question so

that you can give a better answer.

Are you going to take photographs and/or videos?

If the answer is yes, ask yourself, How do I look? and What image will I

portray? If the image you conjure is negative, improve your appearance

before the interview, and for video footage pay close attention to your body

language as well.

How much detail do you want?

If a reporter wants something concise, respond in as few words as possible.

Typically, reporters look for basic information; but it is important to include

in your response all of the information you deem crucial, regardless of

simplicity and time constraints. If the reporter is working on a long news

piece, she will ask for more detail and allow you to expound on the subject.

How much do you already know about this issue?

If the reporter isnʼt familiar with the topic of discussion, ask if she would like

an overview before asking her questions.

May I suggest a location for the interview?

If the reporter is coming to you, choose a location where you feel

comfortable. Suggest a spot that will enhance the interview: a test plot, for

example, if you are discussing an agricultural pest problem.

What is the correct spelling of your name?

No matter how rushed the reporter seems, youʼll both benet by verifying

each otherʼs name and numbers prior to the interview.

Ask the reporter to provide all numbers where he

might be reached for follow-up, listing them in order of

preference; ask for his e-mail address as well. These

details become critical when trying to reach broadcast

reporters who are continually on the go; and they can

save you valuable time, help you meet deadlines, and

afford you an opportunity to be heard.

10

11

May I provide names of additional contacts?

Feel free to mention others who might be able to contribute to the story; it

will demonstrate your sincere interest and the reporter will be grateful for the

leads. Perhaps more important, the reporter will remember that you were a

generous contributor and call you again “next time.”

Is there something specic on which you want me to

comment during the interview?

If the reporter wants you to comment on something such as a press release,

an article, a legal notice, etc., insist on seeing it in advance. Never comment

on something you are handed during the interview unless you are already

familiar with it.

Delivering Your Message

Todayʼs well-informed public expects the person being interviewed to

answer reportersʼ questions clearly, truthfully, and professionally, so never

underestimate the importance of a

question. All questions

are important to the person

who is asking and to the

audience heʼs reaching, and

they deserve the best answer

you can possibly provide. It is

important to remember that

the media are your conduits

to the public, so treat them

with respect. Effective

communication with

the media and the

public requires

experience in

being interviewed

and answering

questions. To

effectively communicate your

message, you must

• demonstrate knowledge on the topic.

• be enthusiastic about the topic.

• clearly communicate the core message.

If during an interview the reporterʼs questions are not leading you in the

direction that you believe is most important to the audience, take the

initiative to interject information. For instance, after addressing a question

thoroughly, add a transitional phrase and take 20 or 30 seconds to comment

12

13

from your own perspective. There is a host of phrases that you use every

day to interject information into conversation, so use those that come

naturally to you—perhaps one of these:

• Itʼs also important to keep in mind that . . .

• Let me add that . . .

• You might also want to know that . . .

But do not use this approach to avoid answering the reporterʼs questions;

the audience will resent your being evasive. Do use it to offer a valuable

perspective that the audience may not recognize if you donʼt take the

initiative.

• Go beyond yes and no answers, depending on the circumstances; that

is, answer each question with the level of detail necessary to make it

clear in context, but donʼt digress or run on.

• Back your statements with facts.

• Talk freely without having to explain every word.

• Use an analogy to make your point.

• Convey your personal beliefs or position on the subject if answering

from your own perspective. If answering on behalf of an organization,

you must convey the consensus.

• Repeat key points that the audience should remember.

• Suggest other avenues that the reporter may not have known to

pursue.

One of the most important aspects of giving a good interview is to use

common language: words that come naturally to you. Donʼt use jargon and

scientic terms that the reporter and the audience may not know. Your goal

is to communicate, that is, to raise awareness and broaden the audienceʼs

level of knowledge on the subject. Jargon and unfamiliar terminology may

confuse the audience and

cause them to miss the point.

Both the reporter and the

audience must understand

your message: One out of two

wonʼt do!

There are no perfect scripts

or how-to steps for answering

reportersʼ questions, but it

is important that you feel

comfortable with your own

responses. Using your own

words and examples will go

a long way in gaining—and

maintaining—the mediaʼs

condence in you as a

professional.

12

13

The Golden Rules

Following are additional points to remember when speaking with the media.

• There are unfriendly interviews, and there are friendly interviews,

but what you must remember is this: You are addressing an

“invisible” audience that deserves clear, concise information from

your perspective. The demeanor of the reporter—professional or

otherwise—never relieves you of your obligation to the audience.

• The media are the eyes and ears of the public. What you say to

them does matter, and it reects directly on the company, agency, or

association that you represent.

• If you are unsure of your ability to deal with the media, then donʼt.

• Donʼt dodge the media. Help them if you can; but if you cannot, tell

them so. And always thank them for calling.

• Return phone calls promptly to facilitate strict media deadlines. If

they report that you didnʼt return their calls, it will have a negative

connotation.

• Let the reporter nish each question without interruption. Interrupting

conveys defensiveness and may result in misunderstanding.

• Answer the question asked, but lead the reporter in a different direction

if you think something important is being overlooked.

• Always assume that the microphone is on and the tape is running, even

if the reporter leaves the room for a minute. Never let down your guard.

Even comments made while equipment is being disassembled or as

you are walking the reporter out of the building can be reported. Use

these “informal” time spans to reinforce your key points. Assume that

the interview is still in progress until all equipment is put away and the

reporter is gone.

• Never fall into the common trap of starting your answer by agreeing

with something with which you disagree! In other words, donʼt get

hooked by the reporterʼs lead-in. For example, the reporter might say,

We all know that college is overpriced because of wasteful overhead,

so how can we look to the university for cost-effective research

innovation? If you do not agree with the lead comment, donʼt say,

Yes, but . . . . Instead, state your disagreement and then address the

14

15

question. For example, you might respond by saying, Actually, when

you consider the multiple services provided by colleges and their value

to society and future generations, college is a tremendous value for

the money; and the focus within the college environment is on leading

edge technology as well as cost management.

• You can typically take a few seconds to formulate your answer

without appearing worried or evasive, but you need to look

thoughtful during that time; and donʼt pause before every question.

• Donʼt talk or speculate on things outside your expertise.

• Use your scientic knowledge to increase your credibility. If the

point is clearly science-based, state it that way. For instance,

say “Science shows . . . ” rather than, “I think . . . .” The

latter can be misconstrued as personal opinion.

• Many times scientists try too hard to sound

unbiased. For example, even when the vast

majority of accepted work shows a common

conclusion, they may feel it is necessary

to mention every other study, data point, or

speculation. Their answer becomes muddled

because they try to include every tidbit of

information. Remember that you are being

interviewed for your expert opinion. Only when

there is truly no denitive answer should you

bring up other possibilities.

• If you use hand gestures in everyday conversation, donʼt stie them

during an interview. Gesturing helps some people feel at ease and has

a favorable effect on the animation of their voice.

• Avoid saying, No comment. The public may view it as a ploy to evade

the truth.

• The importance of brevity is monumental. If you spend more than

20–30 seconds answering a question, youʼre babbling. Answer simply

and get to the point. If reporters want more information, they will ask

additional questions.

• Once youʼve completed your answer, wait for the reporter to ask

another question. Donʼt let awkward silence overcome your common

sense; i.e., donʼt repeat yourself or try to make conversation to ll the

gap. It is the

reporterʼs

job to use up the clock!

• Watch the reporterʼs facial expressions to detect when he wants to ask

another question.

• Never give a ll-in-the-blank response to a reporterʼs question.

Complete each sentence. If you leave thoughts dangling, you may

be inadvertently misquoted. It is difcult for reporters to shape their

reports around incomplete thoughts, so guard against them; and never

say what you donʼt want repeated. Assume that everything you say is

on the record.

• Say it correctly the rst time. Once you say it wrong, itʼs hard to make it

right.

• Thereʼs a time to smile and a time to be serious. Make sure you know

the difference.

14

15

• Courtesy helps the public feel more relaxed. Be polite and make eye

contact with the reporter when answering questions.

• Be honest and forthright. People will sense your sincerity and trust you.

• Never discredit those with opposing opinions when answering

reportersʼ questions: it is unprofessional. If you have information that

refutes an opposing view, present it tactfully and positively. Never

“attack” the other person.

• Donʼt try to impress the media. Your purpose in an interview is to get

your message out. Think in advance about what you want to say, and

jot down a list of key words or phrases to use in answering questions.

The list should be memorized or at least unobtrusive.

• Never let your emotions override your technical expertise and common

sense. Losing your temper turns the audience off and the media on—

and you come off looking like the bad guy.

• Provide reporters your ofce, home, and cell phone numbers in case

they need to reach you for additional comments or clarication.

• Assume that after youʼve made your comments your words no longer

belong to you: they belong to the reporter. Do not insult the reporter

by asking to proofread his draft. If he offers you the opportunity,

thatʼs ne; in fact, trade magazine writers often do. But never offer

constructive criticism unless you are asked. If the story is complicated,

you might offer to listen while the reporter reads his notes back to you

for accuracy. Stress that you wonʼt mind if he needs to contact you with

additional questions or comments or for clarication.

• Relax and remember that in all likelihood you know the topic better

than the person asking the questions—and better than the intended

audience.

Tips on Working with the Media

Television Interviews.

The following tips apply if you have a

scheduled interview and time to plan your wardrobe.

• Wear professional clothes

in conservative colors. Avoid stark

white, deep reds, and blues as well

as bold prints, stripes, and dots.

• Do not wear large jewelry since it can

reect studio lighting undesirably.

Glasses can be a problem as well, so

ask the set crew to make sure there is

no glare before taping.

• Do not wear sunglasses or light-

sensitive glasses.

• Women should wear only their

normal amount of makeup. If you use

lipstick, avoid frosts and bright colors.

Avoid blue, lavender, and green eye

shadow.

16

17

• Make sure that your shoes are clean—and shined, if applicable.

• Wear something that will easily accommodate the microphone; a jacket

with a lapel is best.

• Assume that the microphone is always on, even during breaks.

• Look at the person asking the questions, and answer in conversation. It

looks unnatural—even impolite—to address the camera instead of the

person who is interviewing you.

• Do not look at people walking around in the studio. Stay focused on the

person asking the questions.

• Stay alert even if the reporter hesitates: the camera may still be rolling.

• Use only those hand gestures and facial expressions that come

naturally to you. Too much movement conveys nervousness.

Radio Interviews in Your Own Ofce.

Ask the ofce staff to hold

your calls, and close your door to shut out ofce conversation

and background noise. Turn off the radio, television, intercom, air

conditioner—anything that makes a sound. The reporter may ask

you to say something before the interview begins to make sure the recording

equipment is picking up your voice satisfactorily.

• Avoid the “ums” and “ahs” of audible thought that can creep into the

voids as you consider a response to the reporterʼs question. These are

distracting to the listener and may cast a negative impact on what you

have to say.

• You may nd it helpful to stand up and loosen your tie (if you happen

to be wearing one) just before the interview; freeing the diaphragm and

throat in this manner can enhance the quality of your delivery.

• Speak naturally and use proper English. Donʼt use words that youʼre

not sure how to pronounce. Poor grammar and mispronunciation will

undermine your credibility.

• Make sure you know the interviewerʼs name and how to pronounce

it. This is especially important during

a live radio talk show. Never risk the

embarrassment of referring to the

host incorrectly. It will jeopardize

your credibility with regular listeners.

After all, if you canʼt get the hostʼs

name right, why should they take you

seriously?

16

17

Telephone Interviews for Radio Broadcast.

When doing a live radio

interview over the telephone it is important to turn off your radio. This is

necessary for several reasons. If you are listening to the radio station

on which your voice is being broadcast, a high-pitched squeal known as

feedback may result. If the radio station is using a delay system, you will

hear your own voice on the radio a few seconds after you speak; this will

be disorienting to you and distracting to the radio audience. Consider the

following as well:

• Ask the person conducting the interview if the telephone that you are

using is transmitting quality audio. If not, switch to a different phone.

Portable phones sometimes buzz or fade in and out as you move

around.

• If you have call-waiting on your telephone, turn it off for the interview

if possible. Otherwise, an incoming call may block the audio between

your phone and the radio station, creating a silent interruption, that is, a

gap in the transmission of your voice.

• Keep the mouthpiece of the telephone about an inch from your mouth

and speak at normal volume to avoid distorting the audio.

• Focus on the interview. Find a quiet place where you can close the

door to block out noise and distraction. Ask coworkers not to disturb

you during the interview. If there is a second phone in the room, set it

to divert calls, or turn off its ringer; turn off pagers and cell phones.

Cell Phone Interviews.

Donʼt do a cell phone interview from

any location unless there is absolutely no other way, and never

conduct a cell phone interview while driving: clarity and safety are

the reasons why. Ask the caller to allow you to nd a place to pull

over and return the call from a landline phone. This will eliminate

the nuisance of your signal fading in and out or your losing it completely, and

you wonʼt have to take your mind off the road.

18

19

In-Studio Radio Interviews

.

There are several things to consider

when doing in-studio radio interviews:

• Some microphones are more sensitive than others, so ask

your interviewer how to speak into the one provided. In

general, hold the microphone about the width of your st (4–5 inches)

away from your mouth, and always keep it directly in front of your

mouth when turning your head from side to side or moving about the

interview area.

• Avoid clearing your throat while the

microphone is on. Ask to have a glass of

water available, but donʼt drink anything that

contains caffeine either before or during the

interview (it dries the mouth). Use a cough

drop prior to the interview if you anticipate

that coughing might be a problem, but do not

go on the air with anything in your mouth.

• Donʼt make noise; for example, donʼt wear

jewelry that might rattle or clink as you move

or as it hits hard surfaces such as chair

arms, desktops, tabletops, and microphones.

If you have a nervous habit such as tapping

the table, clicking an ink pen, cracking your

knuckles, or rocking back and forth in your chair, be particularly careful

not to do it on the air: even the slightest noise may be picked up by the

microphone, and nervous motion is distracting. Donʼt risk having these

things detract from what you have to say.

Newspaper Interviews.

Newspapers require more details and

information than other media.

• Give reporters your business card to assure that your name

will be spelled correctly in the article.

• Be prepared with background information and data on the interview

topic.

• If you are not the best authority on the topic, ask permission to bring

someone else who can contribute to the interview. In general, reporters

welcome additional sources.

• If you will be photographed, dress in bright colors and avoid busy

patterns as well as dark blue and black suits.

Trade Magazine Interviews.

Respect journalists' commitment to

fair reporting.

• Refrain from mentioning products by name. Magazines try

to remain unbiased, and it puts the reporter in an awkward position if

you reference specic products and services during the interview. Use

brand names only when asked about specic products.

• Offer to provide photographs and other visual aids if the interview is

being conducted over the phone.

18

19

Only Part of What Is Said Will Be Used

You might be upset when only a few lines of your contribution to a big

story actually get published or when you get only 15 seconds of air time

out of an hour-long taping. But you must recognize that news stories are

seldom based on the views of any one person. So while your initial reaction

might be, What! Thatʼs all he used out of all I told him? remember that he

contacted you, that he considers you a key source, and that heʼll call you

again next time.

Good reporters research their topics from various perspectives—public,

government, expert, and industry—and the truth is, only a small portion of

the information you provide will ever be broadcast or appear in print. Even

the most thorough reporter concentrates on the segment that he feels will

have the greatest impact on his audience.

The Misquote or Out-of-Context Quote

The misquote and the out-of-context quote represent an important aspect

of interviewing that professionals tend to forget or dismiss. Read, watch, or

listen—whatever it takes—but nd out how the information you provide will

ultimately be reported to the public.

Let reporters know that you appreciate their level of professionalism,

their fairness in reporting, and/or their writing style; and emphasize your

availability for consultation on future stories.

What should you do when you have been misquoted

or quoted out-of-context?

This is an important question because consumers tend to believe what they

see in print. But one statement written out-of-context can change the whole

direction of a story, rendering it misleading or wrong. Reporters often use

quotes or comments from their sources to emphasize a point, and thatʼs ne

if they get it right; it is when they

donʼt

that the story can take a bad turn.

Misquotes and comments out-of-context are generally unintentional.

Perhaps the reporter didnʼt fully understand or didnʼt write down exactly

what you said. Maybe she twisted your words just a little bit to put a spin

on the story and, in the process, shifted their meaning. Or maybe the

comment in question seems out-of-context to you but claries the subject

for the audience. Itʼs also possible that the reporter took your comments

out-of-context and therefore conveyed them incorrectly without realizing it.

Regardless what the case may be, you have many options when a statement

needs correcting, so think it through before you make the call.

20

21

Speak with the Reporter

If a misquote compromises your integrity or raises other ethical issues,

you have a legitimate concern and it is both important and appropriate to

contact the reporter. But, when you call, give him the benet of the doubt;

he probably was not out to get you, so assume that the message somehow

got mixed up in translation. Most misquotes result from the reporter's

misunderstanding of the issue. Explain your concern in detail and discuss

what kind of follow-up action is necessary to correct the mistake. If you and

the reporter cannot agree on remediation, contact his immediate supervisor

or the ombudsman within his organization.

Write to the Reporter

If after an interview you fear that your perspectives will not be represented

appropriately in the nal story, do not hesitate to write a brief, cordial, follow-

up letter thanking the reporter for the opportunity to be interviewed and

restating your most important points. It may or may not make a difference

in how the story comes out, but it will become a written record of your

perspectives that might be helpful later if you are misrepresented in the

report. If your perspective has been misrepresented, donʼt hesitate to write

a letter to the reporterʼs afliate to set the record straight. Use courteous

language, get right to the point, and mail your letter within 48 hours of

realizing the problem. A professional letter commands a response, whereas

a letter to the editor either gets published or it doesnʼt.

Protection of Information Sources

Hardly a day goes by when we donʼt read or hear a story that begins like

this: A government ofcial close to the situation told us that . . . .

There is a code of ethics among journalists to protect their sourcesʼ

identities. Sources sometimes have delicate information that they feel should

be disclosed, but they know that going public with it could endanger their

livelihood or their reputation—or worse. Unnamed sources can often provide

valuable background information, give a story some direction, and name

other sources who can verify their claims; so by protecting the sourcesʼ

identity, the reporter has access to information that might otherwise be

suppressed.

The United States Supreme Court ruled in 1972 that the names of sources

used by reporters are not absolutely protected by the First Amendment. If a

judge so orders, reporters may be legally bound to provide a sourceʼs name,

to turn over all pertinent notes and documents, and, if subpoenaed, to testify

before a federal grand jury or participate in a civil lawsuit.

On the other hand, many states have passed “limited shield laws” that

protect reporters from having to disclose a sourceʼs identity. They are

required to disclose the identity of a source only when there is a compelling

20

21

reason to do so; that is, when the reporterʼs information is clearly relevant, or

when the information cannot be obtained any other way.

Most professional reporters will not base a story on one sourceʼs comments

unless they have worked with the person for many years and know rsthand

that he is accurate and trustworthy. The reporter can use leads provided by

the unnamed source to contact individuals who are knowledgeable on the

subject. Checking and rechecking is the only way to verify information.

Sending News Releases to the Press

Normally, press reporters contact us when they need information. But

business, industry, government, and trade associations can initiate media

contact by sending out news releases on information they believe is

interesting and newsworthy.

News releases can be used effectively in generating publicity on any subject:

new products or services, a change in leadership, employee news, etc. In

other cases, an organization might use a news release to inform the public

that its employees are volunteering time for a community project, or that the

company is donating goods and services to help a local charity, or that it is

deeding a piece of property to the community as a wildlife sanctuary. A news

release thatʼs exciting and unique represents a “free story” to the media.

News releases are important avenues by which the media can develop

topics for their market. Research indicates that 50 percent of all copy in a

newspaper originates as a news release. Itʼs easier for reporters to use a

news release as a starting point than to go looking for items of interest for

their daily newscast or newspaper or for their monthly magazine. By doing a

little follow-up reporting and adding a photograph or two and a few quotes,

they have a great story that otherwise might have been missed.

Competing for Attention

While the information in your news release may be of great interest to you, it

arrives as just one more sheet of paper on the reporterʼs desk. Many news

organizations receive 200 news releases a day!

If youʼre going to spend valuable time writing a news release, do it right the

rst time. Remember, itʼs not how many news releases you send, itʼs whether

your message reaches the public. Most news releases are tossed in the bin

because they

• read more like advertising (media

charge

for advertising and run the

news for

free);

• contain hype words and phrases such as

revolutionary, the best,

fantastic, terric,

etc.;

22

23

• are of limited interest to the reporter;

• are not newsworthy;

• are not in an appropriate format;

• donʼt have lead paragraphs that

quickly convey the content;

• are poorly written and contain

numerous spelling and

grammatical errors;

• leave out pertinent facts and details;

or

• contain too much jargon or too many

abbreviations, making them difcult to

read.

Remember that you and the journalists youʼre

contacting may interpret the term

news

very differently,

much as scientists and reporters differ in their perception of

probability

and

fact.

Always try to write press releases in the style most commonly used by

the media youʼre addressing.

Writing an Effective News Release: Less Is More

News releases that are well written and targeted for specic media outlets

have a reasonably good chance of being used, whereas poorly written

generic releases do not. And since news releases are intended for reporters

and assignment editors, it is important to ask yourself what they want to

know.

If the journalist doesnʼt quickly recognize how the information in a news

release would benet his readers/viewers/listeners, it wonʼt make the cut. So

if you canʼt write a news release that lends itself to easy interpretation, youʼre

wasting the journalistʼs time as well as your own.

22

23

How to Write a News Release

Every news release is skimmed, initially, and only those that captivate the

reporter get a second look. Try to limit each news release to one page (never

more than two). Some organizations distribute a brief news release, initially,

and write a longer version to provide reporters who call for more information.

Consider the following tips when writing your own news release.

• Use the inverted pyramid theory to help reporters recognize the

importance of a news release:

If I read the first sentence, I know the thrust of the story.

The second sentence tells me more, and even if that

is all there is, I recognize the significance of

the story. Succeeding sentences and

paragraphs add information.

I can stop at any point

and know the

story.

• Use company letterhead (8 1/2 by 11 inches).

• Type the words NEWS RELEASE in capital letters at the top left-hand

side.

• Type FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE at the top right-hand corner unless

there is a compelling reason for the journalist to hold the information

until a certain time or date. The holding of a news release is called an

embargo

and should be used sparingly; if applicable, indicate the date

after which the story should be run.

• Type CONTACT INFORMATION beneath NEWS RELEASE. The

contact person has to be easily reachable. Preferably it should be

the person who writes the release; but, if not, designate someone

who is wholly knowledgeable on the subject. List a second contact in

case the primary person is unavailable. Provide each contactʼs name,

position, phone numbers (day and night, landline, and cell), pager and

fax numbers, and e-mail address (but donʼt list the e-mail addresses

unless you know that they are checked frequently for messages).

• Write in journalistic style: short sentences and paragraphs; active

voice; present tense. The text should be typed and double-spaced.

• The headline should be centered on the page and should be a single

phrase that conveys the main point of the news release. For example,

a poor news release headline might read, RISE UP! Rewritten, it

could read, ART MUSEUM TOUR TO RAISE MONEY FOR CHILD

ADVOCACY CENTER. Which one conveys the clearer message to the

reporter? Which one has a headline that says NEWS!

24

25

• The lead paragraph is absolutely the most important paragraph of

the news release; it conveys the

who, what, when, where, why,

and

sometimes

how

or

how much

. Using the preferred headline above for a

news release on the child advocacy center, the lead paragraph can be

outlined:

Dateline: WESTLAFAYETTE,IN,November30,2002

Who: Localbusinesses

What: Fund-raiserforchildAdvocacycenter

Where: ArtMuseum,123MainStreet,

WestLafayette,Indiana

Why: Toprovidecounselingforabused

childrenundertheageof14

HowMuch: $50perperson(donation)

The paragraph could then be written as follows:

Local businesses will sponsor a special evening tour of the Art Museum, 123

Main Street, at 6:30 p.m., November 30. A donation of $50 per person will go to

the Lafayette Child Advocacy Center to fund counseling programs for abused

children under the age of 14. For tickets call Tom Jones, (765) 123-4567.

• The second and third paragraphs can add details such as quotes,

facts, and gures. Imagine a reporter who has two news releases. One

cites statistics, quotes experts, gives phone numbers for the experts,

and provides the website for statistics used in the release. The other

states basic facts but offers little else. Both may interest the reporter,

but which one do you think the reporter would be inclined to use?

• The nal paragraph of the news release, sometimes called the

boilerplate,

is one or two sentences that briey describe the pertinent

association, agency, university, or company. It can also inform the

reporter where to go for more details, perhaps with web addresses or

phone numbers for the experts quoted.

• If the text is more than one page, center —MORE— on the bottom of

the rst page and make sure the top left-hand corner of the second

page contains the same contact information as the rst page, along

with an abbreviated headline and “p. 2.” Lastly, try not to carry a

sentence onto another page lest the pages get separated; this is

especially important in the last paragraph of the release.

• The pound signs ### or —30— should be centered underneath your

last line of text to indicate to the reporter that this is the end of the news

release; an alternative is to type —END—.

24

25

Sending a News Release

There are literally thousands of places to send news releases, so focus

on the media outlets that would be most interested in your story. If itʼs

something that affects a particular industry, a trade magazine might be a

perfect t. If itʼs something that might be of interest to the community (e.g.,

eliminating yellowjackets), a local television talk show might be good. Or,

if someone has been hired or promoted, the local newspaper might be

an ideal choice. But donʼt assume that your story is of interest to only one

segment of the news media. Send it to all that you think might be even

remotely interested. Let them decide what they want to run. Yours may be

the next story they use!

Call the media that youʼve identied as potential recipients of your news

release and determine who should receive the information. Call that person

to see whether they prefer U.S. mail, e-mail, or fax. One word of caution:

Sending news releases by e-mail is popular, but it poses some difculties. A

news release should never be sent as an e-mail attachment due to the risk

of computer viruses; also, the person who receives it may not have software

that is compatible with yours. Compact discs are more desirable.

If your news release is about an event that you would like the media to

attend, send it two to four weeks in advance. This will allow the person

in charge of assignments to schedule reporters, photographers, and

equipment. Donʼt forget to take pictures, and video or tape record the event.

The tapes can be used to complement a news release following the event if

no media attend. Remember, however, that a news release after the event

has occurred must be sent immediately thereafter to be newsworthy. Save

photos and tapes for promotion of future events. If sending a photograph

with the press release, always provide the date and location where the

photo was taken as well as names (spelled correctly!) of the photographer

and the people in the picture. If a journalist has to search for this information,

the photo likely will not make it into the publication. If a reporter gets an

angry call from someone whose name was misspelled or who was not

identied in a photo as a result of inaccuracies in a press release, the

journalist is not likely to publish photos or information from that source in the

future. It is surprising how keen a journalistʼs memory can be!

Working with the Media During a Crisis

Communication during a crisis is one of the most complex forms of

communication there is. Pressure cooker stories—pesticide spills, vehicular

accidents, sh kills, lawsuits, workplace violence, res, oods, etc.—

denitely stir public interest.

People want information about a crisis as quickly as possible. They want

to know what to do or how to protect themselves. Their only access to

26

27

pertinent information may be through the media, which places tremendous

pressure on reporters to verify what has taken place and what harm it has

caused.

During a crisis, however, loyal media contacts (e.g., re, police, hospital

personnel) may be too busy dealing with it to grant an interview. This makes

it difcult for reporters to access information when the public wants it most;

and this is where the organization involved in the crisis can play an important

role in disseminating information. The media turns to the organizationʼs

spokesperson for the facts.

Handling a crisis properly means that bad news concerning your

organization needs to come from you. Some organizations donʼt want to

share bad news for fear of tarnishing their image. However, the public tends

to like cover-ups even less than they like bad news. Stonewalling and partial

truths that put the company image ahead of community safety trigger public

outrage that may be more damaging and long-lived than the effects of the

crisis itself.

The Crisis Communication Plan:

Preparing for the Unexpected

“Crisis” is dened as a signicant business or community disruption (that)

stimulates extensive media coverage. The resulting public scrutiny may

affect your organizationʼs normal operations and may also have a political,

legal, nancial, or governmental impact.

During a crisis, information is often transmitted live from the scene. News

coverage may extend into weeks or months until the problem is resolved,

and public condence in your organization may teeter between positive and

negative as the public hears and reads about the incident. Positive public

perception may hinge on whether or not you are truthful and whether you

have placed the interests of your organization above those of the community.

Thatʼs why it is important—in fact, critical—that you develop a Crisis

Communication Plan, that is, a blueprint that describes how your

organization will deal with the media if and when a crisis occurs. The Crisis

Communication Plan is the communication component of an emergency

response plan developed by industry and local services (e.g., police, re,

hospitals). Preplanning for an emergency facilitates responding to an actual

crisis and dealing with the media.

A Model Crisis Communication Plan

The Crisis Communication Plan for most businesses is a one- to two-page

document that outlines company policy on dealing with the media; it directs

personnel to relay accurate up-to-date information rst and foremost during

a crisis. The following is a model that you may use as a guide in writing your

own Crisis Communication Plan.

26

27

5 Easy Steps to Generate a

Crisis Communication Plan . . .

Step 1. Express your company philosophy on working within the community.

General Principles.

This organization cares about the community. We hire local people,

purchase many of the products we use from local businesses, and have every intention

of building an organization that the community will be proud to have in it midst. All of our

operations are completed in a safe, professional manner.

We shall inform the public in a timely manner of any emergency or crisis that occurs

within our operation. We will disclose the facts and make every effort to minimize any

negative impact that the crisis may impose.

Step 2. Designate and train specic employees to communicate with the media.

Policy A.

Company employees are not to speak with the media during a crisis unless

instructed to do so by a member of the Crisis Management Team.

Policy B.

A designated media spokesperson shall be responsible for relaying timely,

accurate, up-to-date, and sensitive information to the media. All media and public

inquiries during a crisis must be referred to the media spokesperson (name the person)

for response.

Policy C.

The Crisis Communication Plan will be updated annually.

Policy D.

The Crisis Communication Plan and the companyʼs emergency response plan

will be activated simultaneously.

28

29

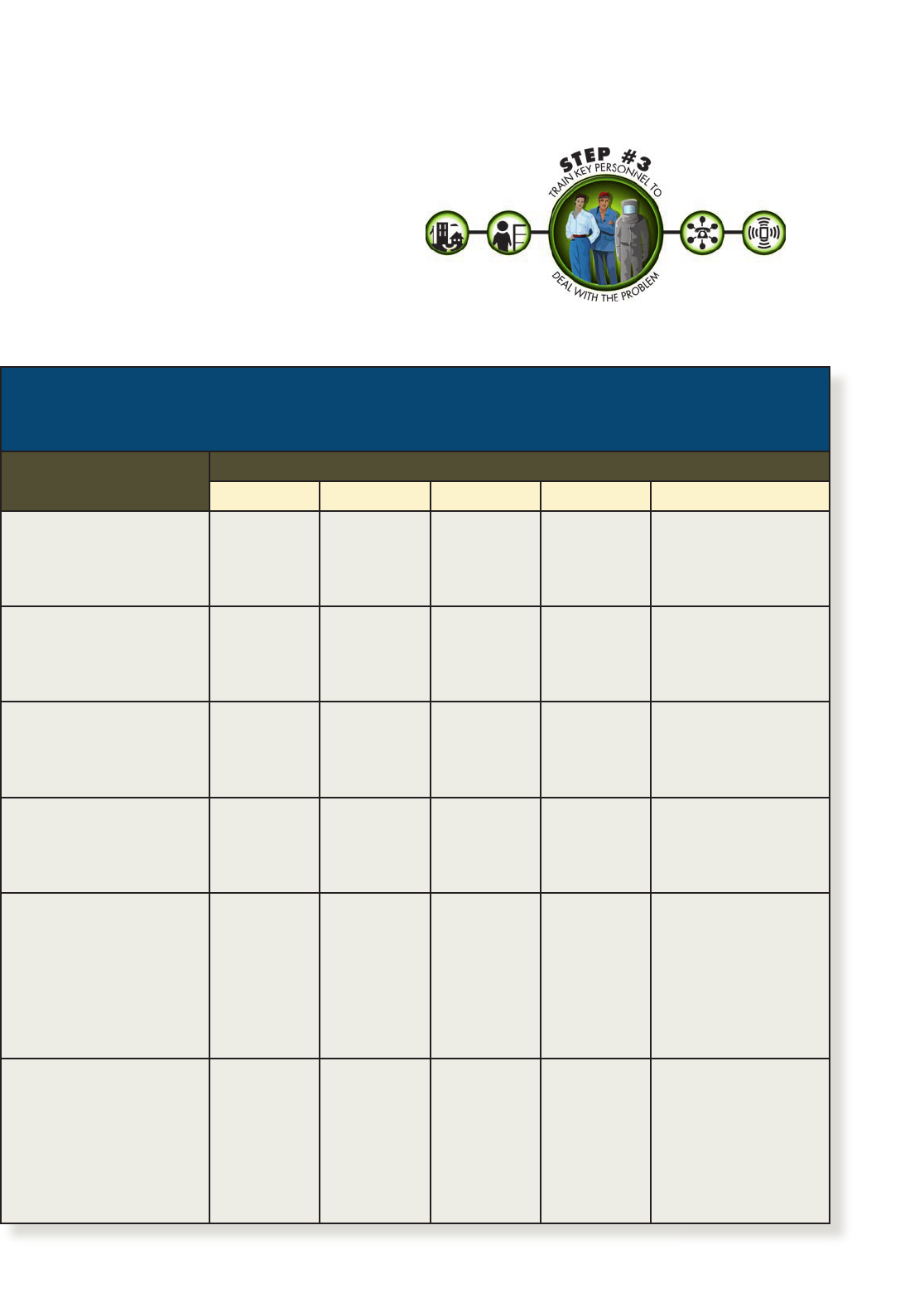

~~~ CRISIS MANAGEMENT TEAM ~~~

Order in Which to Call

(Enter Names)

Phone Numbers and E-mail Addresses

Day Evening Cellular Pager E-mail

1. Primary Spokesperson:

2. Alternate Spokesperson:

3. President or CEO:

4. Safety Director/Trainer:

5. Department Manager(s):

6. Key Employee(s):

Step 3. Develop and train a Crisis Management Team to take

charge during a crisis. Team members must be available 24

hours a day, 7 days a week.

28

29

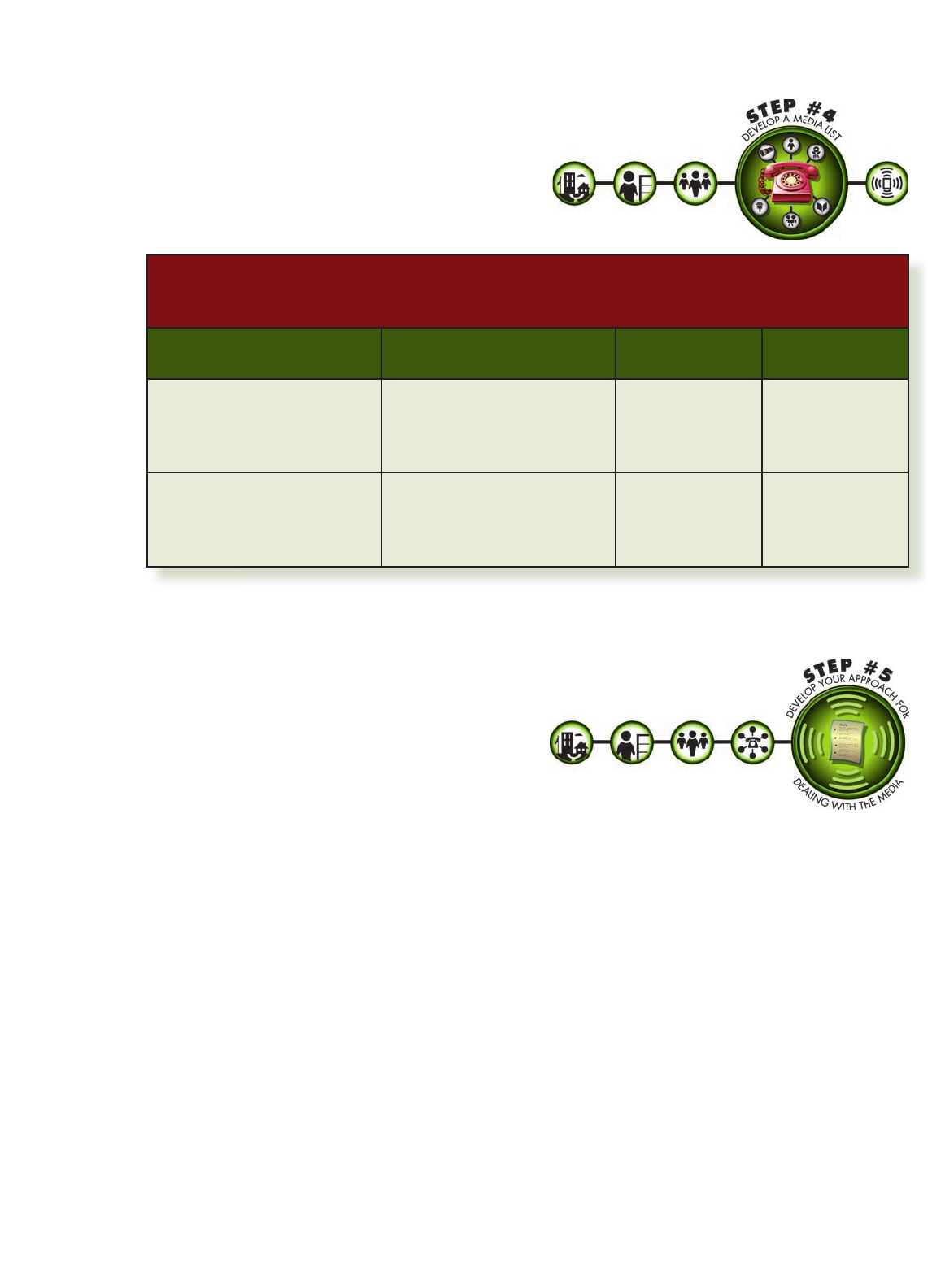

~~~ MEDIA CONTACTS ~~~

Media to Contact

(Enter Station or Newspaper) News Desk Editor Daytime Phone Evening Phone

Local Television:

Local Radio:

Step 4. Develop a list of media representatives

to contact during a crisis.

Step 5. Develop a step-by-step approach—a Crisis Communication Plan—

for dealing with the media during a crisis.

• Handle the emergency according to the organizationʼs emergency response plan

and simultaneously activate the Crisis Communication Plan.

• Notify the spokesperson of the emergency and what is currently known about it.

• Activate the Crisis Management Team through the spokesperson or safety

personnel.

• Notify all employees of the emergency. Inform them that all calls are to be logged

and that all questions must be directed to the spokesperson.

• Have the spokesperson review the facts and inform media contacts of the crisis.

• Keep the spokesperson and the Crisis Management Team apprised of all

activities regarding the crisis.

• Provide the media only the facts that are currently known about the crisis. If a

reporter poses a question that cannot be answered immediately, take his name

and phone numbers and call him as information becomes available.

• Initiate a press conference if necessary. You may want to call a press conference

to answer questions or explain details that cannot be easily addressed in a news

release. For example, maybe you donʼt know exactly how the crisis will unfold, but

you can inform reporters of actions underway to control the situation.

30

31

The Message Must be Clear, Concise, and Consistent

Respond quickly during a crisis. In the event of a life-threatening situation

or an environmental spill, rst contact the local Emergency Management

Agency and ask their personnel to notify the general public. They have the

capability to get the word out quickly. Then go ahead and contact the local

media. If they are already on top of it they will tell you so.

During the initial contact with the media, you need to provide basic

information: what happened, whom it affects, and what action the public

needs to take. Provide instructions on meeting with your media contact

person.

While these initial phone calls are being made, have someone set up an

emergency crisis center where your spokesperson can address the media

and where families of those affected by the crisis can gather. These should

be separate locations, if possible, to allow privacy for the families.

Provide information equally to all media. Deal with the issue up-front to avoid

misrepresentation and misinterpretation of the facts. Most companies have

their spokesperson read a prepared statement to brief the media; after the

30

31

brieng, reporters are given the opportunity to ask questions. Be ready to

handle the following inquiries.

• How did it happen?

• When did it happen?

• What is the risk to the public or the environment?

• How long will the risk last?

• Have the proper authorities been notied?

• Was anyone hurt or anything damaged?

• What is being done to control/correct the problem?

• Are there any special precautions that the public should take?

It is always best to tell the media that the information provided is all that

is known at the moment and that follow-up information will be provided as

the issue unfolds. Answer questions to the best of your ability, but donʼt

speculate or address hypothetical scenarios. It may be helpful to have

members of the Crisis Management Team present to help eld media

questions; they sometimes have the knowledge or expertise to answer

inquiries that the media spokesperson cannot.

A useful preparation activity for dealing with a crisis is to

have scientic

backup information at hand in usable form.

You may have mountains of

support information, but volume can work against you if you have to try to

locate it or sort through it on a momentʼs notice.

When answering questions, be sure to remember the following points:

• Stay calm and avoid confrontation. Never argue or lose your

composure. If a question contains words you dislike, donʼt repeat them.

Politely correct hostile or inaccurate remarks in your answer and avoid

assigning blame.

• If anyone has been injured or killed, rst express your sincere personal

condolences; your expression should be one of caring, not guilt.

• Make sure your answers are easy to understand. Donʼt use technical

terminology or jargon unless you are prepared to explain it.

• Donʼt be led into unfamiliar territory. Keep the interview on track by

emphasizing the points that you want to make.

• Never say, No comment. It only invites speculation on what you havenʼt

said.

• Donʼt say anything “off the record.” There is no legal obligation for a

reporter to keep anything off the record. If you have a comment that

you donʼt want publicized, donʼt say it.

32

33

Conclusion

The framers of the U.S. Constitution clearly understood the importance of

the media, freedom of speech, and an uncensored press in a democracy.

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states, “Congress shall

make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free

exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or the press; or the

right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government

for a redress of grievances.”

A democracy needs an open and free press unhindered by government

regulations and legal challenges. The media in most situations cannot be

told what to say, how to present it, what words to use, or what to cover as

news. The media are free to disseminate information. This is important

because citizens must trust that the information they receive is accurate and

uncensored.

The media report international, national, regional, and local events and

play a critical role in educating the public. They deliver information that we

need to act on and information that we need in order to better understand

the world in which we live. Their reporting contributes to and inuences

government policies, industry practices, and public perception.

32

33

It is the media who decide what fraction of available information is

presented, how an issue is portrayed (e.g., confrontational, fairly, balanced),

and the amount of resources devoted to a specic item. The media act as

information lters. They search for information, sift through it, and relay to

the public what is currently newsworthy. News is ltered through the camera

lenses and pens of those who bring the information into our living rooms,

workplaces, and vehicles.

Since news outlets have limited amounts of airtime and page space, only

a small fraction of a dayʼs events is ever presented. Reporters and editors

must decide when information becomes news based on what is capturing

public interest and what is important at the moment.

Itʼs a judgment call as to when information is news and what is of interest

to the reader or listener. For example, trade magazine editors might list ten

items they deem important, but they may have only enough space to cover

seven items—so three items donʼt make the cut. However, that doesnʼt mean

that the information in the excluded three is unimportant; it just means that

somebody had to decide what to cut, and did. Another person or committee

might choose to use all three and cut a different three. Itʼs a judgment call.

What makes the news is reective of the reporter. A reporter might sit

through a three-hour county commissionersʼ meeting, but it would be

ludicrous for him to report everything that was addressed. Instead, she must

consider what topic is most important and to whom, what the public needs to

know about it, and where to refer them for additional information.

A television reporter might allocate 90 seconds to a story, while a newspaper

might publish it on the front page of the local section. In essence, it is the

reporter who decides what is newsworthy. Thus, the media decide what we

read in newspapers and magazines, what we see on TV, and what we hear

on the radio. They turn information into news!

Working with the media does not have to be stressful or confrontational.

Most reporters are professional, ethical journalists: their job is to report the

news. The person who agrees to give an interview—thatʼs you!—has to

understand how best to respond to their request for information.

34

35

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Steve Adduci for his artwork that so effectively illustrates the text,

and thanks to the following individuals who gave of their time and expertise

in reviewing and contributing to this publication:

Jeffrey Courtright, Department of Communication, Illinois State

University

Skip Davis, WKOA, Lafayette, Indiana

Marie Dick, Department of Speech Communication, Southwest State

University

Beth Forbes, Agricultural Communication Service, Purdue University

Charles Franklin, Ofce of Pesticide Programs, Communication

Services Branch, United States Environmental Protection Agency

Paul Guillebeau, Department of Entomology, University of Georgia

Gary Hamlin, Government and Public Affairs, Dow AgroSciences

Dean Kruckeberg, Department of Communication Studies, University

of Northern Iowa

Oscar Nagler, Agricultural Communication Service, Purdue University

Tom Neltner, President, Improving Kidsʼ Environment

George Oliver, Global Leader Human Health and Assessment, Dow

AgroSciences

This publication was partially supported by the United States Environmental

Protection Agency.

36

The information given herein is supplied with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no

endorsement by the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service is implied.

It is the policy of the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service, David C. Petritz, Director, that all persons

shall have equal opportunity and access to the programs and facilities without regard to race, color, sex, religion,

national origin, age, marital status, parental status, sexual orientation, or disability. Purdue University is an Af-

rmative Action employer.

New 3/03