CONSUMER

PRODUCT SAFETY

OVERSIGHT

Opportunities Exist to

Strengthen

Coordination and

Increase Efficiencies

and Effectiveness

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2014

GAO-15-52

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-15-52, a report to

congressional committees

November 2014

CONSUMER PRODUCT SAFETY OVERSIGHT

Opportunities Exist to Strengthen Coordination and

Increase Efficiencies and Effectiveness

Why GAO Did This Study

The oversight of consumer product

safety is a complex system involving

many federal agencies. As part of a

mandate that requires GAO to identify

federal programs, agencies, offices,

and initiatives with duplicative goals or

activities, GAO reviewed federal

oversight of consumer product safety.

This review examines (1) which federal

agencies oversee consumer product

safety and their roles and

responsibilities; (2) the extent and

effects of any fragmentation or overlap

in the oversight of consumer products;

and (3) collaboration among agencies

to address any negative effects of

fragmentation or overlap.

To assess the involvement of multiple

agencies in the oversight of consumer

product safety, GAO conducted a

multiagency survey and reviewed laws

and regulations, and past GAO work.

GAO also interviewed federal agency

officials and consumer and industry

groups.

What GAO Recommends

Congress should consider (1)

transferring oversight of the markings

of toy, look-alike, and imitation firearms

from NIST to CPSC, and (2)

establishing a formal collaboration

mechanism to address comprehensive

oversight and inefficiencies related to

fragmentation and overlap. Also, GAO

recommends that the Coast Guard and

CPSC establish a formal coordination

mechanism. CPSC, the Department of

Homeland Security, and NIST agreed

with GAO’s matters and

recommendation; other agencies

neither agreed nor disagreed.

What GAO Found

GAO identified eight agencies that have direct oversight responsibilities for

consumer product safety: the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC),

Department of Housing and Urban Development, Environmental Protection

Agency, Food and Drug Administration, National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration (NHTSA), Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Pipeline and

Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, and the U.S. Coast Guard (within the

Department of Homeland Security). All eight agencies conduct regulatory

activities to promote consumer product safety, such as rulemaking, standard

setting, risk assessment, enforcement, and product recalls. In addition, at least

12 other agencies play a support role in consumer product safety in various

areas, such as public health and law enforcement.

Oversight of consumer product safety is fragmented across agencies, and

jurisdiction overlaps or is unclear for certain products. In some cases, agencies

regulate different components of or carry out different regulatory activities for the

same product, or jurisdiction for a product can change depending on where or

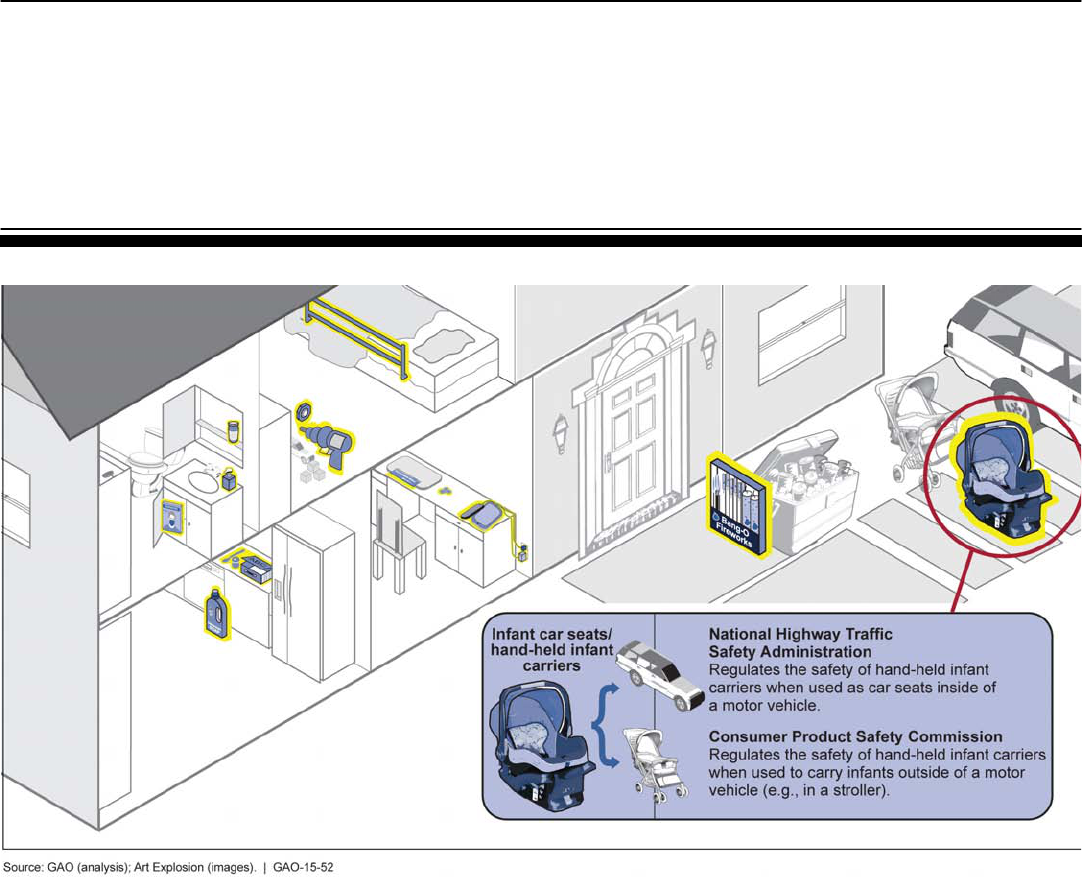

how it is used. For example, NHTSA regulates hand-held infant carriers when

used as car seats, but CPSC regulates the carriers when used outside of motor

vehicles. Agencies reported that the involvement of multiple agencies with

various expertise can help ensure more comprehensive oversight by addressing

a range of safety concerns. However, agencies also noted some inefficiencies,

including the challenges of sharing information across agencies and challenges

related to jurisdiction. For example, GAO found that the jurisdiction for some

recreational boating products can be unclear and the potential exists for

confusion regarding agency responsibility for addressing product safety hazards.

Coast Guard officials said they work informally with CPSC when the need arises

but that these interactions are infrequent. Without a more formal coordination

mechanism to address jurisdictional uncertainties some potential safety hazards

may go unregulated. In addition, the Department of Commerce’s National

Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) oversees the markings of toy and

imitation firearms to distinguish them from real firearms, which may be an

inefficient use of resources because it does not leverage NIST’s primary

expertise related to scientific measurement. According to NIST, this function

may be better administered by CPSC, which oversees the safety and

performance of toys. However, this would require a statutory change.

Agencies reported that they collaborate to address specific consumer product

safety topics, but GAO did not identify a formal mechanism for addressing such

issues more comprehensively. Independent agencies, such as CPSC, are not

subject to the Office of Management and Budget’s planning and review process

for executive agencies. Additionally, no single entity or mechanism exists to help

the agencies that collectively oversee consumer product safety. GAO has

identified issues for agencies to consider in collaborating, such as clarifying roles

and including all relevant participants. Because no mechanism exists to help

agencies collectively address crosscutting issues, agencies may miss

opportunities to leverage resources and address challenges, including those

related to fragmentation and overlap identified in this report.

View GAO-15-52. For more information,

contact Alicia Puente Cackley, 202-512-8678,

cackleya@gao.gov

Page i GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

Letter 1

Background 2

Multiple Agencies Oversee Various Aspects of Consumer Product

Safety 8

Fragmented and Overlapping Oversight Can Help Agencies

Leverage Expertise but Also Creates Inefficiencies 15

Agencies Report Coordinating on Specific Activities but Lack a

Mechanism to Facilitate Comprehensive Oversight 38

Conclusions 46

Matters for Congressional Consideration 47

Recommendation 47

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 47

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 52

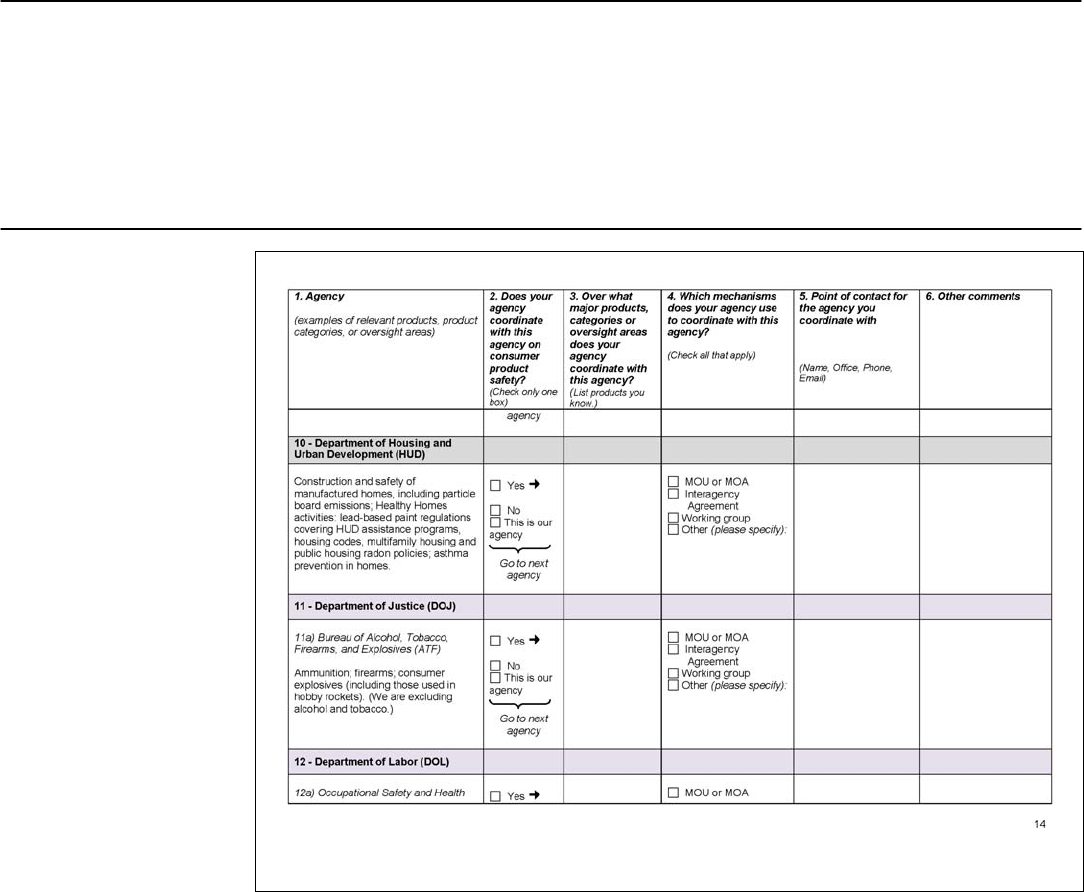

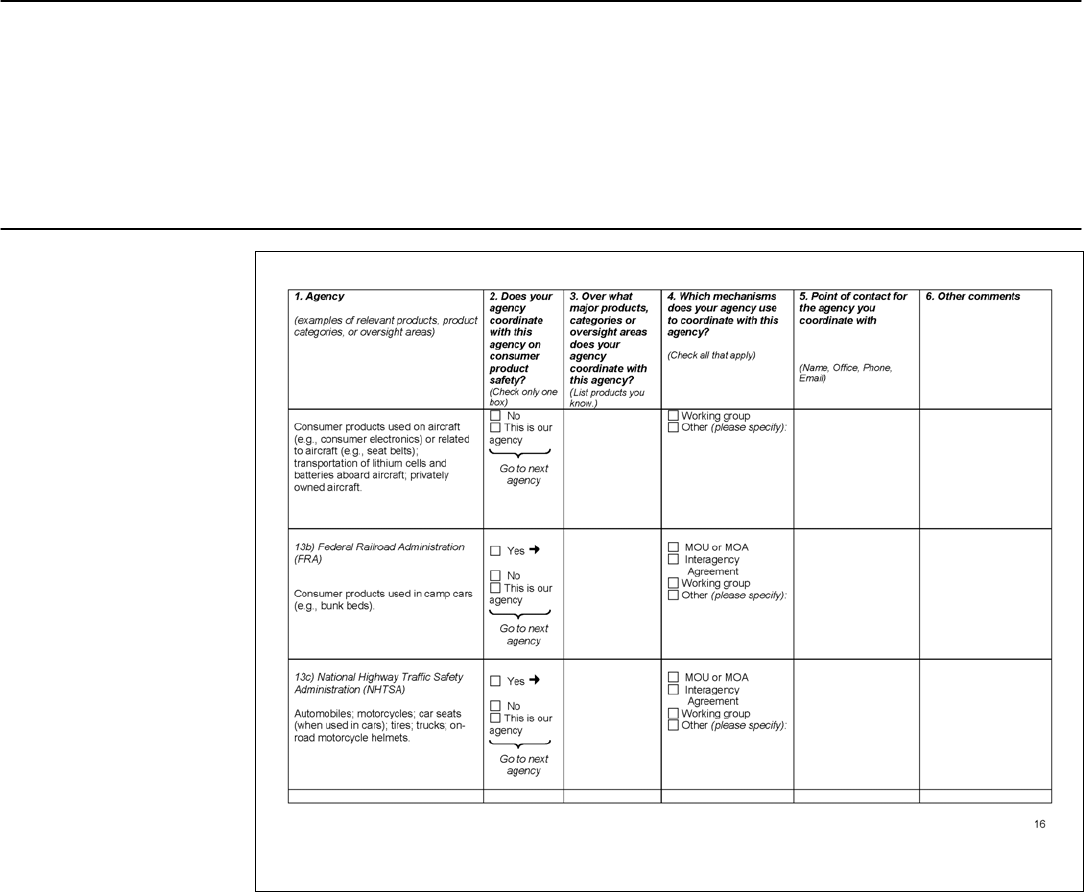

Appendix II Consumer Product Safety Oversight Questionnaire 57

Appendix III Agencies That Indirectly Support Consumer Product Safety

Oversight 81

Appendix IV Full Text for Figure 2 Presentation of Examples of Consumer

Products Regulated by More Than One Agency 84

Appendix V Comments from the Consumer Product Safety Commission 94

Appendix VI Comments from the Department of Homeland Security 96

Appendix VII GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 98

Contents

Page ii GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

Related GAO Products 99

Tables

Table 1: Eight Agencies with a Direct Oversight Role for

Consumer Product Safety 9

Table 2: Select Mechanisms for Interagency Collaboration and

Their Definitions 40

Table 3: Twelve Agencies with an Indirect Oversight Role for

Consumer Product Safety 81

Figures

Figure 1: Definitions of Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication 7

Figure 2: Examples of Consumer Products Regulated by More

Than One Agency 16

Figure 3: Coordination between Eight Regulatory Agencies on

Consumer Product Safety Activities 39

Figure 4: Drugs and Other Products with Child-Resistant

Packaging 84

Figure 5: Soaps and Detergents 85

Figure 6: Toy Laser Guns 86

Figure 7: Consumer Fireworks 87

Figure 8: Mobile Phones and Other Wireless Devices 88

Figure 9: Adult Portable Bed Rails 89

Figure 10: Food Contact Articles 90

Figure 11: Lithium Batteries 91

Figure 12: Infant Car Seats/Hand-held Infant Carriers 92

Figure 13: Respirators 93

Page iii GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

Abbreviations

ATF Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

CBP Customs and Border Protection

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CPSA Consumer Product Safety Act

CPSC Consumer Product Safety Commission

CPSIA Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

FAA Federal Aviation Administration

FCC Federal Communications Commission

FDA Food and Drug Administration

FEMA Federal Emergency Management Agency

FTC Federal Trade Commission

GPRA Government Performance and Results Act of 1993

GPRAMA GPRA Modernization Act of 2010

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

HRSA Health Resources and Services Administration

HUD Department of Housing and Urban Development

MOA memorandum of agreement

MOU memorandum of understanding

NCHS National Center for Health Statistics

NHTSA National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

NIEHS National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

NIH National Institutes of Health

NIOSH National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

NRC Nuclear Regulatory Commission

NTSB National Transportation Safety Board

OIRA Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs

OMB Office of Management and Budget

OSHA Occupational Safety and Health Administration

PHMSA Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

November 19, 2014

Congressional Committees

The oversight of consumer product safety is a complex system that

evolved over time and involves a number of federal agencies. Further, as

globalization and technological advances expand the range of products

available in U.S. markets, the challenge of regulating the thousands of

product types has become increasingly complex. The Consumer Product

Safety Commission (CPSC) is charged with protecting the public from

unreasonable risk of injury or death associated with the use of thousands

of types of consumer products. However, many other federal agencies

also have various roles and responsibilities related to consumer product

safety oversight. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

(NHTSA), U.S. Coast Guard (Coast Guard), Food and Drug

Administration (FDA), and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),

among others, have jurisdiction over products such as automobiles and

other on-road vehicles and their equipment, including tires; boats; drugs;

cosmetics; medical devices; and pesticides. These agencies conduct a

wide range of regulatory activities to oversee these products, such as risk

assessment, rulemaking, and enforcement.

As the fiscal pressures facing the nation continue, so too does the need

for federal agencies and Congress to improve the efficiency and

effectiveness of government programs and activities.

1

1

GAO, 2014 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap,

and Duplication and Achieve Other Financial Benefits, GAO-14-343SP (Washington, D.C.:

Apr. 8, 2014).

As part of a

mandate that requires GAO to identify federal programs, agencies,

offices, and initiatives with duplicative goals and activities within

departments and government-wide, GAO reviewed federal oversight of

consumer product safety. Specifically, this review examines (1) which

federal agencies oversee consumer product safety and their roles and

responsibilities, (2) the extent and effects of fragmentation, overlap, or

duplication, if any, in the oversight of consumer products, and (3) how do

consumer product safety oversight agencies coordinate their activities

and to what extent does that address any identified negative effects of

fragmentation, overlap, or duplication.

Page 2 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

To address these objectives, we reviewed relevant laws and regulations,

as well as literature and our past reports on consumer product safety;

fragmentation, overlap, and duplication; and mechanisms for interagency

collaboration (see a list of related GAO products at the end of this report).

To identify agencies that conduct consumer product safety oversight and

to delineate their roles and responsibilities, we reviewed the following

sources: (1) laws related to consumer product safety, as well as Federal

Register notices for proposed and final rulemaking from August 2008 to

October 2013; (2) the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s web link

to federal agencies with jurisdiction over consumer products; (3) our past

reports; and (4) agency members of CPSC-identified interagency working

groups. We then disseminated a questionnaire to the agencies we

identified to (1) confirm their roles and responsibilities and (2) identify any

other relevant agencies with whom they coordinate. We also asked

questions about what types of statutory authority the agency has, its

mission, other agencies with which it coordinates, barriers to coordination,

and knowledge of any potential fragmentation, overlap, or duplication in

oversight. We disseminated 33 questionnaires in total and obtained and

analyzed at least one response from each of the 33 entities. We also

interviewed federal agency officials and industry groups to gather

information on the extent of fragmentation, overlap, and duplication, their

benefits and challenges, and how coordination may help to address any

negative effects. Appendix I contains a detailed description of our scope

and methodology and appendix II is a reprint of the questionnaire we sent

to the agencies.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2013 to November 2014

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The existing system for consumer product safety, like many other federal

programs and policies, has evolved in a piecemeal fashion. New laws and

agencies have been established over time, resulting in a patchwork

system with different agencies having different regulatory and

enforcement authorities for different consumer products. Consumer

product safety activities can include setting standards and conducting

enforcement, product recalls, rulemaking, and risk assessment. Below is

Background

Page 3 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

a brief overview of some of the key laws that provide agencies with the

authority to conduct consumer product safety oversight.

Pre-Consumer Product Safety Act (CPSA) laws:

• Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, first enacted in 1938 to

replace the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, provides FDA with

various public health responsibilities, including to ensure the safety

and effectiveness of medical products—drugs, biologics, and medical

devices—and safety of cosmetics marketed in the United States.

2

• Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act provides for the

federal regulation of pesticides. While various versions of a federal

pesticide statute have been in place since 1910, Congress enacted

substantial amendments to the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and

Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) in 1972.

The

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended, mandates FDA

to, among other things, conduct pre-market reviews of the safety of all

new drugs, as well as pre-market approval of some medical devices.

3

Under the current version of

FIFRA, pesticides must generally be registered (licensed) by EPA

before they may be sold or distributed in the United States. EPA may

register a pesticide if it finds, among other things, that use of the

pesticide will not generally cause unreasonable adverse effects on the

environment. When EPA registers a pesticide, it approves directions

for use of the pesticide, which must appear on the product label and

be followed by users of the pesticide.

• The National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 established

an agency which, under the Highway Safety Act of 1970, later

became the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

4

2

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, ch. 675, 52 Stat. 1040 (1938); Pure Food and

Drugs Act, ch. 3915, 34 Stat. 768 (1906). The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act has

been amended and expanded multiple times since 1938.

The National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act authorizes NHTSA

3

Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act, Pub. L. No. 92-516, 86 Stat. 998

(1972). The general definition of pesticide in the statute includes “any substance or

mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, repelling, or mitigating any

pest.” 7 U.S.C. § 136(u).

4

Highway Safety Act of 1970, Pub. L. No. 91-605, 84 Stat. 1713 (1970); National Traffic

and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, Pub. L. No. 89-563, 80 Stat. 718 (1966).

Page 4 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

to, among other things, promulgate federal safety standards for motor

vehicles and equipment.

• The Federal Boat Safety Act of 1971 authorizes the Coast Guard

(within the Department of Homeland Security) to, among other things,

establish minimum safety standards for recreational vessels and

associated equipment and to require the installation or use of such

equipment.

5

CPSA and post-CPSA laws:

The act was created to improve boating safety, to

authorize the establishment of national construction and performance

standards for boats and associated equipment, and to encourage

greater uniformity of boating laws and regulations among states and

the federal government.

The CPSA, first enacted in 1972, establishes CPSC and consolidates

federal safety regulatory activity relating to consumer products within

the agency.

6

5

Federal Boat Safety Act, Pub. L. No. 92-75, 85 Stat. 213 (1971).

CPSC is authorized to protect the public against

unreasonable risks of injury associated with consumer products in

general, and also to administer other laws such as those governing

fabric flammability, hazardous substances, child-resistant packaging,

6

Consumer Product Safety Act, Pub. L. No. 92-573, 86 Stat. 1207 (1972). CPSA explicitly

excludes from CPSC’s jurisdiction various products that are covered by other agencies

under other laws. See footnote 12 for more detail.

Page 5 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

refrigerators, pool and spa safety, and toy safety.

7

Congress enacted

the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA) in 2008 to

strengthen CPSC’s authority to enforce safety standards and provide

greater public access to product safety information.

8

• The Toxic Substances Control Act, first enacted in 1976, authorizes

EPA to obtain more information on chemicals and to regulate those

chemicals that EPA determines pose unreasonable risks to human

health or the environment.

9

The act authorizes EPA to review

chemicals already in commerce as well as chemicals yet to enter

commerce.

10

In addition, under the Toxic Substances Control Act,

EPA can regulate the manufacture (including import), processing,

distribution in commerce, use, or disposal of “chemical substances”

and “mixtures,” including for use as or as part of a consumer product.

7

These additional laws include: (1) the Flammable Fabrics Act, which among other things,

authorizes CPSC to prescribe flammability standards for clothing, upholstery, and other

fabrics (Act of June 30, 1953, ch. 164, 67 Stat. 111 (1953)); (2) the Federal Hazardous

Substances Act, which establishes the framework for the regulation of substances that are

toxic, corrosive, combustible, or otherwise hazardous (Pub. L. No. 86-613, 74 Stat. 372

(1960)); (3) the Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970, which authorizes CPSC to

prescribe special packaging requirements to protect children from injury resulting from

handling, using, or ingesting certain drugs and other household substances (Pub. L. No.

91-601, 84 Stat. 1670 (1970)); (4) the Refrigerator Safety Act of 1956, which mandates

CPSC to prescribe safety standards for household refrigerators to ensure that the doors

can be opened easily from the inside (Act of August 2, 1956, c. 890, 70 Stat. 953); (5) the

Virginia Graeme Baker Pool and Spa Safety Act of 2007, which establishes mandatory

safety standards for swimming pool and spa drain covers, as well as a grant program to

provide states with incentives to adopt pool and spa safety standards (Pub. L. No. 110-

140, Tit. XIV, 121 Stat. 1492, 1794 (2007)); (6) the Children’s Gasoline Burn Prevention

Act of 2008, which establishes safety standards for child-resistant closures on all portable

gasoline containers (Pub. L. No. 110-278, 122 Stat. 2602 (2008)); and (7) the Child Safety

Protection Act of 1994, which requires the banning or labeling of toys that pose a choking

risk to small children and the reporting of certain choking incidents to CPSC (Pub. L. No.

103-267, 108 Stat. 722 (1994)).

8

Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act, Pub. L. No. 110-314, 122 Stat. 3016 (2008).

CPSA was further amended in 2011 to provide CPSC with greater authority and discretion

in enforcing current consumer product safety laws. Pub. L. No. 112-28, 125 Stat. 273

(2011).

9

Toxic Substances Control Act, Pub. L. No. 94-469, 90 Stat. 2003 (1976).

10

Existing chemicals are composed of those that were in commerce in 1979 when EPA

began reviewing chemicals, as well as those listed for commercial use after that time.

Page 6 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

CPSA defines a consumer product, for purposes of CPSC’s jurisdiction,

as “any article, or component part thereof, produced or distributed (i) for

sale to a consumer for use in or around a permanent or temporary

household or residence, a school, in recreation, or otherwise, or (ii) for the

personal use, consumption or enjoyment of a consumer in or around a

permanent or temporary household or residence, a school, in recreation,

or otherwise,” subject to a number of exclusions.

11

By statute, certain

categories of products that are regulated by other agencies are excluded

from the definition of “consumer product,” and therefore CPSC does not

have jurisdiction over them.

12

For purposes of our report, because we are

looking at consumer products broadly rather than solely those in CPSC’s

jurisdiction, we use the broader definition of “consumer product,” without

the statutory exclusions. We include in our purview motor vehicles,

pesticides, cosmetics, and some other products that CPSA excludes from

its definition of a consumer product.

13

In 2010, Congress directed us to identify programs, agencies, offices, and

initiatives with duplicative goals and activities within departments and

government-wide and report to Congress annually.

14

11

Pub. L. No. 92-573, § 3(a)(1), 86 Stat. at 1208 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §

2052(a)(5)).

Since March 2011,

we have issued annual reports to Congress in response to this

12

CPSA excludes from the definition of “consumer product” certain items, including any

article which is not customarily produced or distributed for sale to, or use or consumption

by, or enjoyment of, a consumer; tobacco and tobacco products; motor vehicles or motor

vehicle equipment; pesticides as defined by the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and

Rodenticide Act; any article which if sold would be subject to the firearm tax imposed by

26 U.S.C. § 4181, or any component of such article; aircraft, aircraft engines, propellers,

or appliances; boats and certain related equipment subject to Coast Guard regulation;

drugs, devices, or cosmetics under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; and food

under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 15 U.S.C. § 2052(a)(5).

13

Our broad definition of “consumer product” does not include financial products, alcohol,

tobacco, and food. We have conducted prior work on fragmentation, overlap, and

duplication in federal food safety oversight. See, for example, GAO, Federal Food Safety

Oversight: Food Safety Working Group Is a Positive First Step but Governmentwide

Planning Is Needed to Address Fragmentation, GAO-11-289 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 18,

2011). We have a forthcoming report on fragmentation, overlap, and duplication in the

financial regulatory system. We excluded tobacco and alcohol because of the unique

regulatory structure for these products.

14

Pub. L. No. 111-139, § 21, 124 Stat. 8, 29 (2010) (codified at 31 U.S.C. § 712 note).

Definition of a Consumer

Product

Overview of GAO’s

Fragmentation, Overlap,

and Duplication Work

Page 7 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

requirement.

15

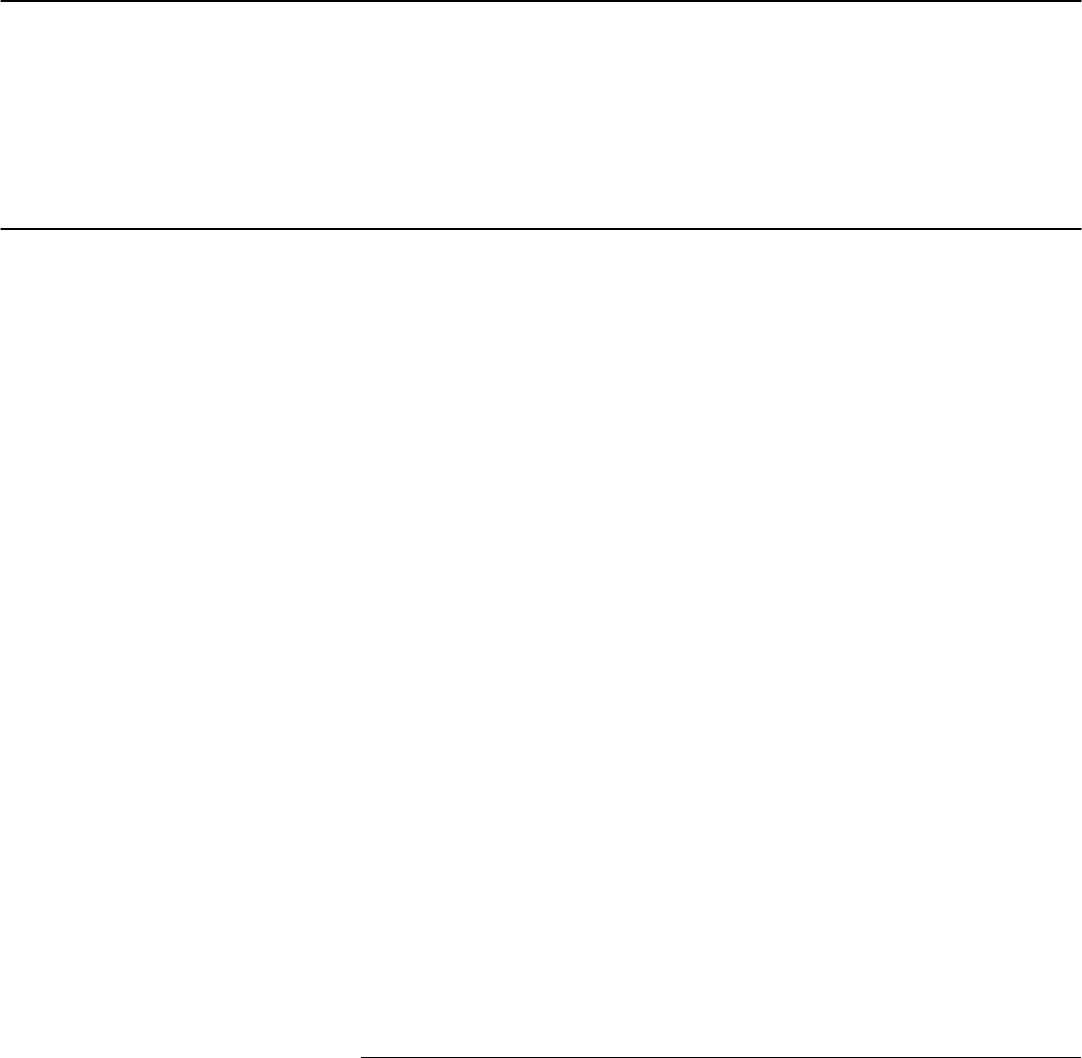

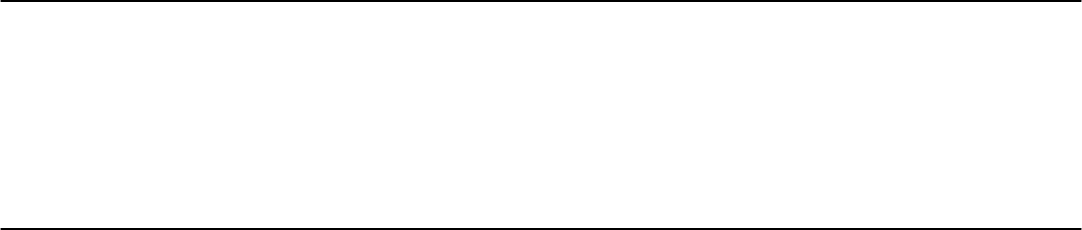

Figure 1: Definitions of Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication

The annual reports describe areas in which we found

evidence of fragmentation, overlap, or duplication among federal

programs. The annual reports define fragmentation, overlap, and

duplication as shown in figure 1.

15

For more information on GAO’s work on fragmentation, overlap, and duplication in the

federal government, see GAO-14-343SP; GAO, 2013 Annual Report: Actions Needed to

Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Other Financial Benefits,

GAO-12-279SP (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 9, 2013); 2012 Annual Report: Opportunities to

Reduce Duplication, Overlap and Fragmentation, Achieve Savings, and Enhance

Revenue, GAO-12-342SP (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 28, 2012); and Opportunities to

Reduce Potential Duplication in Government Programs, Save Tax Dollars, and Enhance

Revenue, GAO-11-318SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 1, 2011).

Page 8 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

We identified 8 agencies that have direct oversight responsibility for

various aspects of consumer product safety, based on our analyses of

data collected from our questionnaire and interviews with agency officials.

In addition, we identified at least 12 other agencies that have an indirect

role in consumer product safety oversight.

16

We distinguished agencies

with direct versus indirect responsibility by whether they perform certain

regulatory activities, as well as by how the agencies self-identified in their

interviews.

Eight agencies reported that they have direct oversight responsibilities for

consumer product safety: the Coast Guard; CPSC; Department of

Housing and Urban Development (HUD); EPA; FDA; NHTSA; Nuclear

Regulatory Commission (NRC); and Pipeline and Hazardous Materials

Safety Administration (PHMSA). We considered an agency to have a

direct oversight role if it met two criteria: (1) in its response to our

questionnaire, the agency noted having statutory authority over consumer

product safety through one or more of five regulatory activities—

rulemaking, standard setting, enforcement, risk assessment, and product

recalls; and (2) in subsequent interviews and follow-up discussions, the

agency confirmed that it views itself as having a role in overseeing the

safety of consumer products.

17

We describe the oversight roles of these

agencies in table 1. Some of these agencies oversee products, whereas

others oversee components that might be found within a product (e.g.,

chemical substances or radioactive materials).

16

In addition, the remaining agencies (13 of the 33) were characterized as not having a

role in consumer product safety oversight.

17

We used the information from the interviews, in addition to the questionnaires, as criteria

for categorizing an agency as having a direct role because several agencies told us in

interviews that they are not consumer product safety oversight agencies, even though

they initially noted having regulatory authority for consumer product safety in their

questionnaire responses.

Multiple Agencies

Oversee Various

Aspects of Consumer

Product Safety

Eight Agencies Have

Direct Oversight

Responsibility for

Consumer Product Safety

Page 9 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

Table 1: Eight Agencies with a Direct Oversight Role for Consumer Product Safety

Agency

Role of the agency as it relates to

consumer product safety

Examples of consumer products that the

agency regulates

Coast Guard The Coast Guard regulates safety

standards for recreational boats.

All original equipment installed on boats; limited

equipment installed after purchase (inboard

engines, outboard engines, stern drive units, and

inflatable life jackets)

Consumer Product Safety Commission

(CPSC)

CPSC oversees consumer products

produced or distributed in the United

States for sale to, or use by, consumers

in or around a residence or school or in

recreation or otherwise.

Toys, cribs, power tools that are used by

consumers, lighters, and household products

Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD)

HUD mitigates lead-based paint hazards

in federally assisted housing. It also

establishes federal standards for the

design and construction of

manufactured homes.

Structural materials in manufactured homes such

as particle board, plywood, drywall, steel frames,

and windows

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) EPA conducts risk assessments of

pesticides and registers them for use in

the United States. It also evaluates and

manages risks of chemicals.

Insect repellents, toilet bowl

sanitizers/disinfectants, ant traps, and flea

powder

Some household products such as window

cleaners; flame retardants used in furniture and

electronics ; and formaldehyde emissions from

composite wood products (e.g., kitchen cabinets)

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) FDA is responsible for ensuring the

safety, efficacy, and security of human

and veterinary drugs, biological

products, medical devices, and

electronic products that emit radiation.

FDA also ensures the safety of

cosmetics. Additionally, FDA regulates

food and tobacco products, but are

outside the scope of this study.

Prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs,

contact lenses, breast pumps, cosmetics such as

lipstick and eye liner, cell phones, and toy laser

products

National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration (NHTSA)

NHTSA sets and enforces safety

performance standards for motor

vehicles and motor vehicle equipment.

Motor vehicles, motor vehicle equipment such as

tires and motorcycle helmets, and child restraint

systems (when sold for use in vehicles)

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) NRC licenses and regulates civilian use

of certain radioactive materials.

Consumer products that contain NRC-regulated

materials such as tritium watches, smoke

detectors, and electron tubes.

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials

Safety Administration (PHMSA)

PHMSA ensures that hazardous

materials are packaged and handled

safely during transportation.

Hazardous materials (such as consumer

fireworks, lithium batteries, and compressed gas)

in transport

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO 15-52

Note: Some agencies have broader responsibilities than those listed in the table, which focuses on

aspects of each agency’s work that relate to consumer product safety.

These eight agencies conduct a range of regulatory activities related to

consumer product safety, including rulemaking, standard setting,

enforcement, risk assessment, and product recalls.

Page 10 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

• Rulemaking, standard setting, and enforcement. All eight agencies

reported conducting rulemaking, standard-setting, and enforcement

activities. As an example of rulemaking, CPSC recently issued a final

rule establishing a safety standard for strollers and infant carriages.

18

CPSC issued the rule in response to a provision of the Consumer

Product Safety Improvement Act, which required CPSC to promulgate

consumer product safety standards for durable infant or toddler

products.

19

• Risk assessment. Six of the eight agencies reported conducting risk

assessments, whereas PHMSA did not and the Coast Guard reported

that its authority in this area is unclear.

The rule incorporates by reference the most recent

voluntary standard developed by ASTM International, a standard-

setting organization. The standard includes requirements for improved

test methods of various parts (e.g., brakes, wheels) and warning label

clarifications. In an example of enforcement, PHMSA inspects

consumer commodity shipments. PHMSA staff stated that they

coordinate with other agencies to identify where hazardous

substances are coming from and where they are going. In another

enforcement example, under the Toxic Substances Control Act, EPA

can initiate civil actions to seize an imminently hazardous substance,

mixture, or any article containing such a substance or mixture.

20

18

Safety Standard for Carriages and Strollers, 79 Fed. Reg. 13,208 (Mar. 10, 2014).

As an example of risk

assessment, EPA recently conducted an assessment for a flea and

tick pet collar using the insecticide propoxur. EPA’s risk assessment

found, in some but not all use scenarios, unacceptable risks to

children from exposure to propoxur pet collars. EPA noted that small

children may ingest pesticide residues when they touch a treated cat

19

Pub. L. No. 110-314, § 104, 122 Stat. at 3028 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §

2056a).

20

CPSC provided additional information on its risk assessment authorities, which it

approaches in two ways. First, the agency noted that it is inferred that it would assess the

risks associated with consumer products in order to implement the CPSA. For CPSC to

issue a consumer product safety rule under section 7 of CPSA, CPSC must determine

that the rule is reasonably necessary to prevent or reduce an unreasonable risk of

injury. 15 U.S.C. § 2056(a). CPSC also conducts traditional chemical risk assessments

under the Federal Hazardous Substances Act to determine whether a substance meets

the definition of a “hazardous substance.” See 15 U.S.C. §§ 1261, 1262. We have done

prior work on CPSC’s ability to stay generally informed about new risks associated with

consumer products and use available information to identify product hazards. See GAO,

Consumer Product Safety Commission: Agency Faces Challenges in Responding to New

Product Risks, GAO 13-150 (Washington D.C.: Dec. 20, 2012).

Page 11 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

or dog and subsequently put their hands in their mouths. EPA and the

manufacturers agreed to do a voluntary cancellation of the product

based on concerns that the residue on animals can be dangerous for

children.

21

• Product recalls. Six of the eight agencies reported having regulatory

authority to recall certain products under their jurisdiction, whereas

NRC and PHMSA did not. As an example of a product recall, an

official from the Coast Guard noted that the agency works with

manufacturers and conducts between 10 and 20 recall campaigns

annually of recreational boats, equipment originally installed on boats,

and limited equipment installed after purchase. The Coast Guard

officials recently worked with Honda, which has stopped

manufacturing personal watercraft, when the company found it had a

problem with boats it manufactured from 2002 through 2008. The

manufacturer is now recalling these boats for possible fuel tank

failure. The Coast Guard stated that it does not actually conduct the

recalls but records the recalls and monitors the progress that the

manufacturer completes in the performance of the recalls. According

to the agency, once regulatory noncompliance or a substantial risk

defect is discovered, the manufacturer normally voluntarily registers

the recall campaign with the Coast Guard and performs the recall in

accordance with statutory requirements and the Coast Guard

regulations regarding recall notification.

The Coast Guard noted that its authority to conduct risk

assessments is unclear. A Coast Guard official explained that

statutory authority allows the Coast Guard to establish whether,

according to their reasonable and prudent judgment, a defect creates

a substantial risk of personal injury.

22

21

Under the cancellation agreement, manufacturers are allowed to produce the pet collars

until April 1, 2015, and will not be allowed to distribute the products after April 1, 2016.

The agency determined that this agreement, which phases out use of the product, would

be the best way to remove the product from the market expeditiously.

By statute, the manufacturer

is required to notify the first purchaser, subsequent purchasers if

known to the manufacturer, and the dealers and distributors. Based

on the progress reports submitted to the Coast Guard by the

manufacturer, the Coast Guard decides when it is practical to close

the recall campaign. According to the agency, the Coast Guard has

the authority to require a manufacturer to perform a recall, but this

authority has rarely been used.

22

46 U.S.C. § 4310; 33 C.F.R. pt. 179.

Page 12 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

In addition to the regulatory activities listed earlier, agencies reported

other oversight activities they undertake. Specifically, CPSC noted that it

can also collect data and conduct informational campaigns. NHTSA also

stated that it can conduct consumer informational programs. For example,

NHTSA noted the New Car Assessment Program, under which it

conducts vehicle crash and rollover tests to encourage manufacturers to

make safety improvements to new vehicles and provide the public with

information on the relative safety of vehicles (e.g., through a safety rating

using a five-star scale). Additionally, EPA noted its statutory authority to

conduct licensing of pesticides under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide,

and Rodenticide Act, as amended.

Based on our analyses of information obtained through the

questionnaires and interviews with agency officials, we identified at least

12 agencies that play an indirect role in the oversight of consumer

product safety. We categorized an agency as having an indirect role if it

met one of two criteria: (1) it did not conduct any of the five regulatory

activities described in the previous section, but described other activities

that supported consumer product safety oversight; or (2) it initially

described a role in regulating consumer products, but in subsequent

interviews, did not self-identify as a consumer product safety oversight

agency.

23

23

For example, although the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention initially noted regulatory authorities in their

questionnaire responses, the agencies specified in interviews that they regulate the safety

of products used in the workplace, and as such did not see their role as pertaining to

consumer products but rather employee safety. The Federal Communications

Commission noted a role regulating maximum levels of radiofrequency emissions from

radio devices, but considered its role to be one of measurement expertise, not product

safety. In addition, the National Institute of Standards and Technology noted a regulatory

role over one item, toy guns, but primarily considered itself a nonregulatory agency. Thus

we categorized these agencies as having an indirect rather than direct role.

An indirect role can include such activities as conducting

underlying research to support regulatory activities and providing public

health expertise, among others. We describe the overall work of these

agencies and the specific roles that they play in relation to consumer

product safety in detail in appendix III. The 12 agencies are the National

Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); Federal Communications

Commission (FCC); Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA);

National Institutes of Health (NIH); Health Resources and Services

Administration (HRSA); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

At Least 12 Agencies Play

an Indirect Role in

Consumer Product Safety

Oversight

Page 13 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

(CDC); Federal Aviation Administration (FAA); National Transportation

Safety Board (NTSB); Occupational Safety and Health Administration

(OSHA); U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP); Bureau of Alcohol,

Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF); and Federal Trade

Commission (FTC).

These 12 agencies supported product safety in at least one of the

following areas: (1) public health expertise; (2) law enforcement; (3)

workplace safety; (4) transportation safety; and (5) other activities.

• Public health expertise. NIH, HRSA, and CDC reported providing

public health expertise. For example, the National Institute of

Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), within NIH, manages the

National Toxicology Program, which studies substances in the

environment, including substances used in personal care products,

household products, foods, and dietary supplements, to identify any

potential harm they might cause to human health. One example of a

substance over which NIH and CPSC have coordinated is diisononyl

phthalate (DINP). Phthalates are a group of chemicals used to make

plastics more flexible and more difficult to break. The National

Toxicology Program has provided CPSC with access to its scientific

expertise and research on DINP. It also served on and provided

DINP-related analysis to the Chronic Hazard Advisory Panel on DINP.

This panel advised CPSC on whether DINP in consumer products

poses a chronic hazard.

• Law enforcement. CBP, ATF, and FTC reported involvement in law

enforcement. For example, FTC investigates and can take action

against companies that engage in unfair or deceptive acts or practices

in or affecting commerce, which can include making deceptive safety

claims. One example where FTC has played a role in consumer

product safety is through an administrative action it took against a

manufacturer that falsely claimed that football mouth guards prevent

concussions. FTC’s settlement order with the manufacturer prohibits

the company and its owner from, among other things, misrepresenting

the health benefits of any mouth guard or other athletic equipment

designed to protect the brain from injury. FTC has also taken other

actions related to the safety of consumer products. For example, it

has challenged several after-market braking devices that called

themselves antilock brake systems (ABS) but that did not, in fact,

function as well as factory-installed antilock brakes.

• Workplace Safety. CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety

and Health (NIOSH) and OSHA reported responsibilities for workplace

Page 14 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

safety. For example, NIOSH conducts and publishes research on the

occupational hazards associated with the use of tools (such as nail

guns) and materials (such as spray foam insulation and methylene

chloride). NIOSH’s research focuses on worker safety, but consumers

may benefit because they may purchase the same products for use in

and around the home. In the case of nail guns, NIOSH stated that it

had identified causes of worker injuries, developed recommendations

to improve worker safety, and published the information in a variety of

media and formats, including a joint publication with OSHA, to make it

widely available. Sometimes, a manufacturer may end up making

improvements to a product as a result of NIOSH’s research, which

may enhance consumer safety. NIOSH also conducts rulemaking,

standard setting, and product recalls of respirators for use by workers,

which also may be purchased by consumers.

• Transportation safety. FAA and NTSB reported responsibilities for

transportation safety. For example, NTSB investigates every civil

aviation accident in the United States and significant accidents in

other modes of transportation—railroad, highway, marine, and

pipeline. As part of its investigations, NTSB makes safety

recommendations to other federal agencies on a variety of topics,

including their oversight of any specific consumer products involved in

the accidents. In the past, NTSB has made recommendations to

NHTSA to improve the visibility of brake and turn lights and to modify

performance and testing requirements for passenger-side air bags.

More recently, NTSB has made recommendations to FAA to improve

the safety of amateur-built aircraft.

• Other activities. NIST, FCC, and FEMA’s U.S. Fire Administration

reported involvement in other activities that support consumer product

safety oversight. For example, with the increasing use of

nanomaterials, NIST stated that it has collaborated with CPSC to

measure and better understand the release of nanotechnology-based

products and exposure pathways. According to NIST, in these

collaborations, it has provided unique measurement expertise, for

example, for determining the quantities and properties of

nanoparticles released from flooring finishes and interior paints and

their subsequent airborne concentrations.

Page 15 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

We found that oversight of consumer product safety is fragmented across

multiple agencies with some overlap occurring—for example, when

agencies regulate different uses of the same product. We did not find

specific cases of duplication in oversight. Fragmentation and overlap can

help provide more comprehensive oversight by allowing agencies to

leverage one another’s expertise, resources, and authorities, but they can

also create inefficiencies. In particular, NIST’s role as regulator for the

markings of toy and imitation firearms may be an inefficient use of

resources because it may not leverage the agency’s primary mission and

expertise, which are related to scientific measurement. In addition,

because of potential jurisdictional uncertainty regarding whether some

recreational boating equipment should be regulated by the Coast Guard

or CPSC, the potential exists for some hazards to not be adequately

addressed.

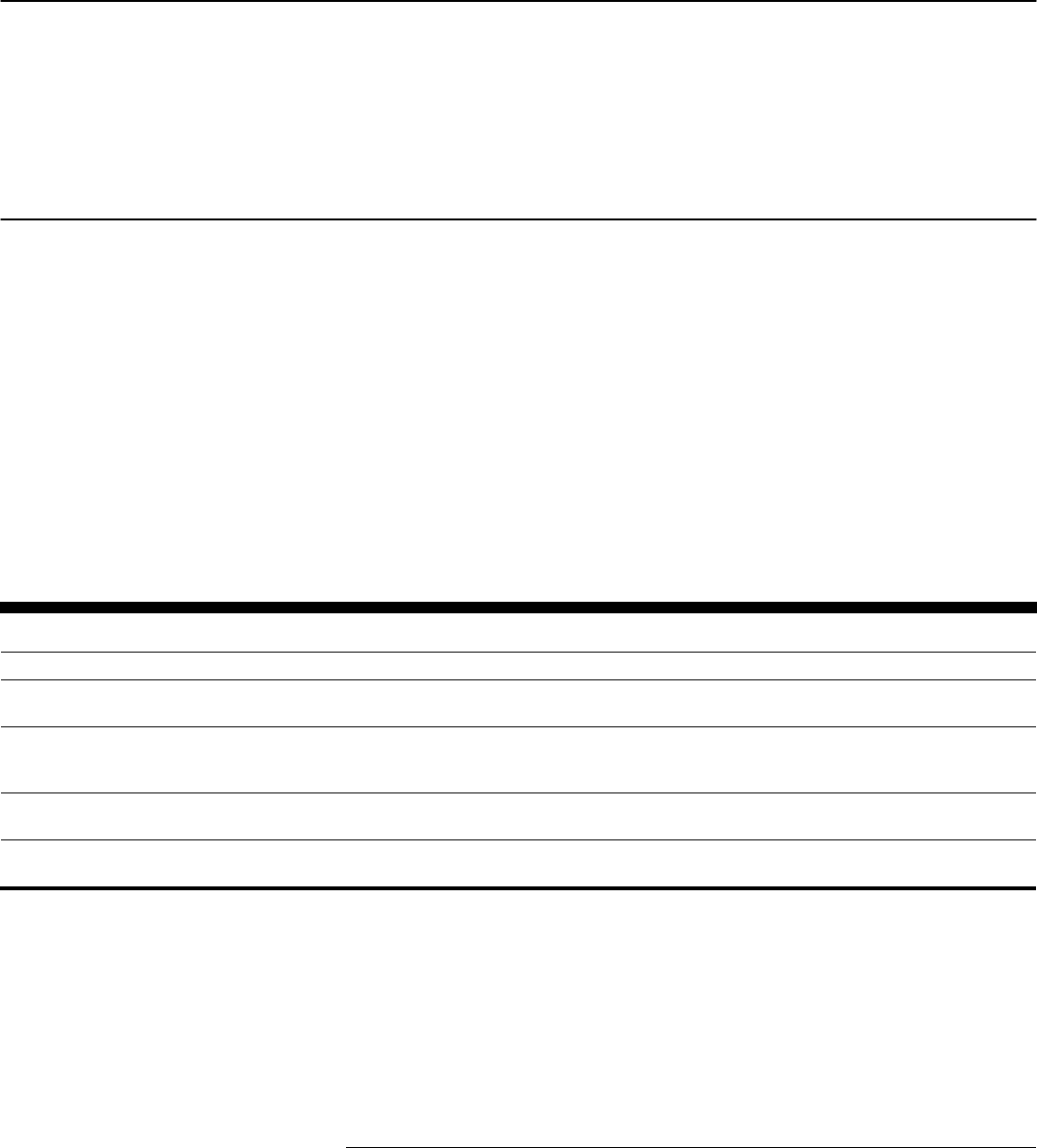

Federal regulatory oversight of consumer product safety is fragmented

across multiple agencies, and some overlap occurs among these

agencies based on their statutory authorities for certain products. The

agencies we surveyed and interviewed provided several examples of

regulatory oversight involving multiple agencies, including scenarios in

which agencies regulate different components of the same product,

regulate different uses of a product, or administer different regulatory

oversight activities for the same product.

24

We did not find specific cases

of duplication in oversight. Figure 2 contains examples of consumer

products regulated by more than one agency. (See app. IV for a full-text

presentation of the examples in fig. 2).

24

In addition to the examples included in this section of the report, agencies provided

other examples of potential fragmentation or overlap in the oversight of consumer product

safety in their questionnaire responses. For example, HUD noted in its questionnaire

response that while it oversees manufactured—or factory-built—homes, FEMA orders

large quantities of manufactured homes. In an interview, HUD said that FEMA orders

these homes for use in areas affected by disasters and that FEMA may set additional

requirements for their use. CPSC officials noted overlap in their questionnaire response in

the area of chemical regulation and that this regulation in general involves several

different agencies because chemicals, such as flame retardants, are used in a wide range

of products and in different settings.

Fragmented and

Overlapping

Oversight Can Help

Agencies Leverage

Expertise but Also

Creates Inefficiencies

Oversight Is Fragmented,

and Jurisdictions Overlap

When Multiple Agencies

Regulate the Same

Product, Its Components,

or Its Uses

Page 16 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

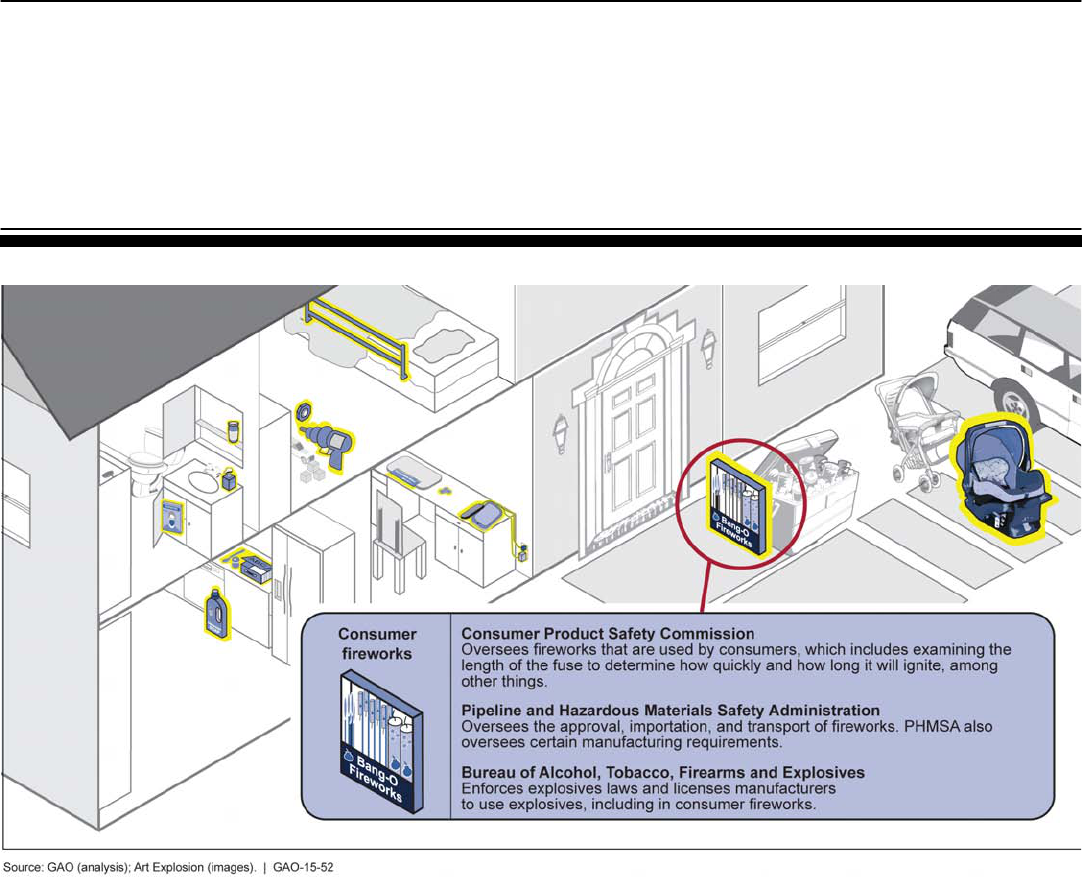

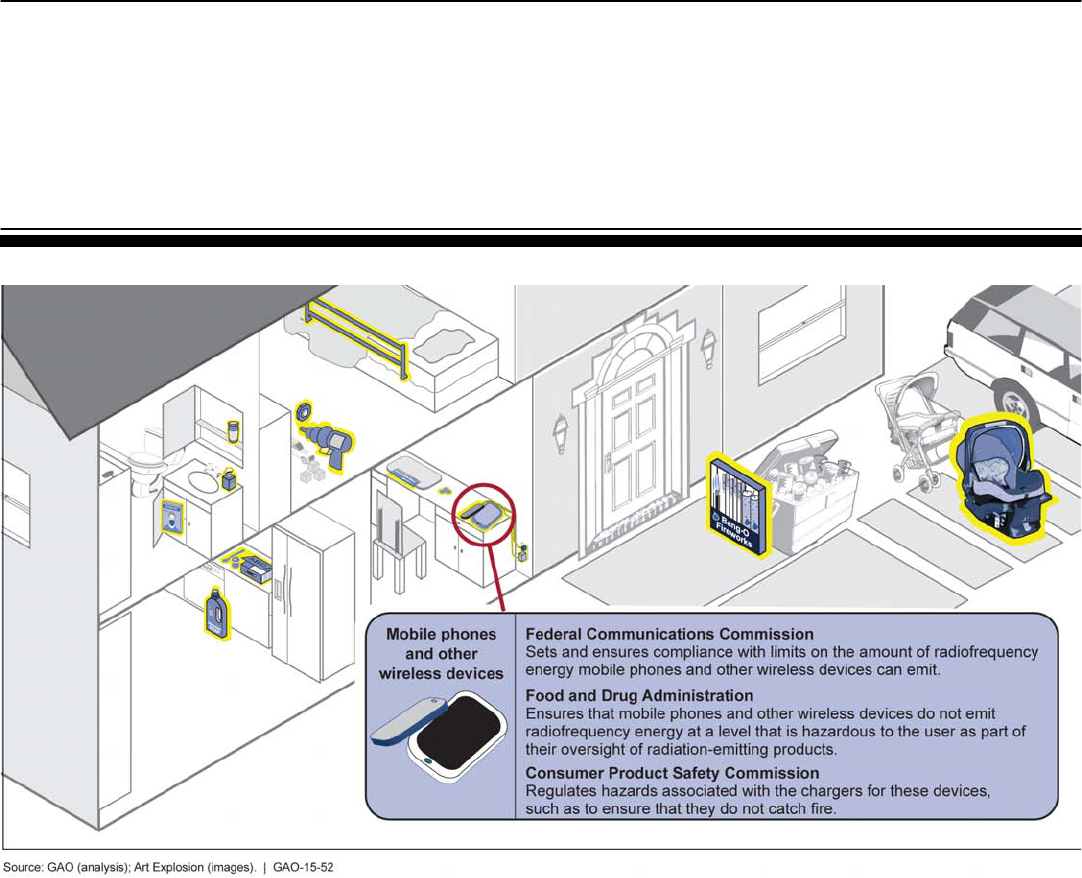

Figure 2: Examples of Consumer Products Regulated by More Than One Agency

Source: GAO (analysis); Art Explosion (images). | GAO-15-52

ABC

ABC

ATF - Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

CDC-NIOSH - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National

Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

CPSC - Consumer Product Safety Commission

EPA - Environmental Protection Agency

FCC - Federal Communications Commission

FDA - Food and Drug Administration

NHTSA - National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

NIST - National Institute of Standards and Technology

PHMSA - Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration

RESPIRATORS

Quantity:

5

Product

Drugs and other products with child-resistant packaging

Soaps and detergents

Toy laser guns

Consumer fireworks

Mobile phones/wireless devices

Adult portable bed rails

Food contact articles

Lithium batteries

Infant car seats/hand-held carriers

Respirators

CPSC FDA PHMSA NIST ATFEPA

Regulatory or oversight agency

FCC NHTSA

CDC-

NIOSH

Interactive

Directions: Hover over consumer products (in blue) or table text for additional information.

Page 17 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

In the following examples, agencies regulate different components of a

product, which can result in fragmentation and overlap.

• Articles or equipment that come into contact with food (CPSC,

FDA): FDA regulates substances making up the surfaces of products,

such as spoons, drinking glasses, and lunch boxes, that come into

contact with and can potentially leach into food.

25

In contrast, CPSC

regulates the parts of food containers or preparation articles that do

not come into contact with food, as well as certain chemical

substances.

26

In 1976, CPSC and FDA signed a memorandum of understanding

(MOU) that outlines each agency’s jurisdiction over food contact

articles and equipment. According to FDA, the agency began working

with CPSC in 2012 to update the MOU to reflect the agency’s current

An example of a product with overlapping regulation is

spoons intended for use by infants. The substances making up the

portion of the spoon that comes into contact with the food would

generally be regulated by FDA to ensure the safety of substances in

the spoon that may migrate into the food. However, if the spoon had a

plastic coating, it could also be subject to CPSC’s limits on the use of

certain phthalates in children’s products. In another example, in 2010,

CPSC issued a voluntary recall of about 12 million drinking glasses

because the designs on the outside of the glasses contained

cadmium, a substance that can cause adverse health effects.

25

Articles classified as “food” under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act are

excluded from the definition of “consumer products” under CPSA and are therefore

excluded from CPSC’s jurisdiction. 15 U.S.C. § 2052(a)(5)(I) (CPSA definition of

“consumer product,” excluding “food”); 21 U.S.C. § 321(f) (the Federal Food, Drug, and

Cosmetic Act definition of “food”). According to FDA, articles having food contact surfaces,

such as food containers, and products used for eating, cooking, and preparing food, from

which there is migration of a substance from the contact surface to the food, are

considered food “components” and thus “food” within the meaning of the Federal Food,

Drug and Cosmetic Act and subject to regulation by FDA. See 21 U.S.C. § 321(f).

26

CPSC also regulates mechanical hazards (e.g., a broken pan handle) and the proper

functioning of a product to prevent contaminated or spoiled food (e.g., slow cookers or

refrigerators that fail to perform at proper temperatures).

Page 18 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

authorities but did not continue with this effort due to other priorities.

27

However, according to FDA, the lack of an updated MOU does not

indicate any coverage gap in the regulatory oversight of food contact

articles. CPSC staff also noted that while their overall authorities for

consumer product safety have changed since the MOU was first

signed—for example, CPSC received the authority in 2008 to limit the

use of phthalates in children’s products—the MOU still reflects

CPSC’s current jurisdiction over food contact articles.

28

• Toy laser products (CPSC, FDA): FDA has jurisdiction over

radiation-emitting products, including oversight responsibilities for

ensuring manufacturers’ compliance with applicable safety

performance standards and certification requirements.

29

For example,

FDA can require that manufacturers incorporate safety features,

warnings, and instructions for safe use. FDA’s jurisdiction potentially

overlaps with CPSC’s for toy laser products, as CPSC regulates

safety standards and testing requirements for children’s products,

including toys.

30

27

Both CPSA and the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act have been amended since

1976, when the MOU was signed, resulting in changes and additional authority. For

example, the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 provided FDA with

the authority to establish a food contact notification process, which according to FDA, is

the primary means by which FDA regulates food additives that are also food contact

substances. Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997, Pub. L. No. 105-

115, § 309, 111 Stat. 2296, 2354 (1997) (amending 21 U.S.C. § 348).

For example, CPSC regulates toys to ensure that

they do not contain small parts children could swallow and that the

28

Pub. L. No. 110-314, § 108, 122 Stat. at 3036 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §

2057c).

29

21 U.S.C. §§ 360hh-360ss.

30

See 15 U.S.C. § 2056b. However, CPSC does not have the authority to regulate a risk

of injury associated with electronic product radiation emitted from an electronic product. 15

U.S.C. § 2080(a). Thus, FDA has authority over a toy laser product that presents a

radiation hazard. According to FDA, LASER stands for Light Amplification by the

Stimulated Emission of Radiation. One type of laser consists of a sealed tube, containing

a pair of mirrors, and a laser medium that is excited by some form of energy to produce

visible light or invisible ultraviolet or infrared radiation. Other examples of products that

incorporate lasers are compact disc and DVD players, fax machines, laser pointers, bar

code scanners, cutting and welding tools, and laser speed detectors.

Page 19 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

lead content of the paint is below the required threshold.

31

Examples

of toy laser products include “light sabers,” toy guns with mounted

lasers for taking aim, and tops that project laser beams while they

spin. In June 2013, FDA proposed laser safety regulations specific to

toy laser products marketed to children that would restrict the amount

of radiation emitted by toy lasers to the lowest laser class limits.

32

FDA and CPSC indicated that they did not coordinate on the

proposed rule for toy laser products, but according to FDA officials,

the agencies collaborated on a draft guidance document concerning

this rule that was issued in August 2013.

33

Regulatory jurisdiction for some products changes depending on where or

how the product is used, which can result in overlapping oversight, as in

the following examples.

FDA also noted that the

agency has organized a multiagency Laser Communications Working

Group to educate consumers about laser safety.

• Infant car seats/hand-held infant carriers (CPSC, NHTSA): Infant

car seats can be used to protect a child inside a moving vehicle, but

some (which are also called hand-held infant carriers) can also be

31

CPSC regulations ban any toy or other article intended for use by children under 3 years

of age that presents a choking, aspiration, or ingestion hazard because of small parts. 16

C.F.R. § 1500.18(a)(9). Additionally, all children’s products, including toys, must not

contain a concentration of lead greater than 0.009 percent (90 parts per million) in paint or

any similar surface coatings. CPSIA mandated CPSC to modify its regulations to lower the

concentration of lead in paint that is permissible from 0.06 percent (600 ppm) to 0.009

percent (90 ppm), effective August 14, 2009, and this limit is subject to periodic ongoing

review by CPSC. Pub. L. No. 110-314, § 101(f), 122 Stat. at 3020 (codified at 15 U.S.C. §

1278a(f)); 16 C.F.R. § 1303.1.

32

Laser Products; Proposed Amendment to Performance Standard, 78 Fed. Reg. 37,723

(June 24, 2013). FDA is proposing to amend 21 C.F.R. § 1040.11 by adding a new

paragraph which would restrict to Class 1 under any conditions of operation, maintenance,

service, or failure, any laser products that are made or promoted as children’s toys for use

by children under 14 years of age. FDA is proposing this amendment to ensure children

will not be harmed by laser radiation under any conditions including disassembly or

breakage. Because the class of the laser within the toy could be higher than the class of

the toy product itself, the amendment aims to protect children from unanticipated harmful

exposure.

33

In this guidance issued to the industry in August 2013, FDA indicated that the whole toy

needs to be certified as a laser product, unless the part of the toy that can emit laser light

is removable and can emit laser light independently when separated from the other parts

of the toy, in which case only that laser-emitting part would need to be certified. Minimizing

Risk for Children’s Toy Laser Products; Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug

Administration Staff; Availability, 78 Fed. Reg. 48,172 (Aug. 7, 2013).

Page 20 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

used to carry an infant outside of a vehicle and can attach to strollers.

CPSC regulates hazards associated with the use of infant carriers

outside of a motor vehicle, including soft infant carriers, framed

carriers worn on caregivers’ backs, and hand-held infant carriers, as

part of their jurisdiction over durable infant and toddler products.

Overlap with NHTSA occurs with hand-held infant carriers that are

also used as car seats and are therefore considered “motor vehicle

equipment” for the purpose of NHTSA’s jurisdiction. For example,

infant car seats sold for purposes that include motor vehicle use are

considered child-restraint systems and must be certified as meeting

federal motor vehicle safety standards.

34

In December 2013, CPSC

issued a final rule, which incorporated an existing voluntary standard

for hand-held infant carriers.

35

• Adult portable bed rails (CPSC, FDA): CPSC and FDA regulate

portable bed rails for adult use. These are rails that are not part of a

bed’s original design, but can be installed against or adjacent to adult

beds to protect people from falling and to assist them as they get in

and out of bed. Jurisdiction depends on whether the adult portable

For example, this standard includes

warning label requirements to address suffocation and restraint-

related hazards, as well as testing procedures to ensure that the

carrier handle automatically locks. NHTSA and CPSC indicated that

they had coordinated on the rulemaking. For example, CPSC said that

the agency had worked with NHTSA to assess the effectiveness of

existing standards for hand-held infant carriers and to ensure that the

warning label to address strangulation hazards does not interfere with

NHTSA’s label for air bags.

34

Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 213 (codified at 49 C.F.R. § 571.213).

35

78 Fed. Reg. 73,415 (Dec. 6, 2013) (codified at 16 C.F.R. pt. 1225). Under Section 104

of CPSIA, CPSC is required to issue mandatory standards based on voluntary standards

for certain durable infant and toddler products, including infant carriers. 15 U.S.C. §

2056a. Voluntary standards are generally determined by standard-setting organizations,

with input from government representatives and industry groups, and are also referred to

as “consensus standards.” Under CPSIA, CPSC is required to work with various

stakeholders and experts to examine and assess the effectiveness of existing voluntary

standards for durable infant or toddler products and establish mandatory standards that

are substantially the same as or more stringent than the voluntary standards for such

products. In 2012, GAO reported on manufacturers’ compliance with voluntary industry

standards, including CPSC’s ability to encourage compliance with voluntary standards and

other authorities in this regard. See GAO, Consumer Product Safety Commission: A More

Active Role in Voluntary Standards Development Should Be Considered, GAO-12-582

(Washington, D.C.: May 21, 2012).

Page 21 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

bed rails constitute medical devices.

36

• Soaps, cleaners, and other household products (CPSC, EPA,

FDA): Jurisdiction over soaps, cleaners, and other household

products depends on whether the product is formulated and marketed

as a soap, cosmetic, drug, or pesticide, resulting in jurisdictional

fragmentation and overlap. FDA regulates cosmetics and drugs;

CPSC regulates household products, such as household cleaners,

(including soap but excluding certain items, such as drugs, cosmetics,

FDA has jurisdiction over adult

portable bed rails considered to be medical devices, and CPSC

regulates adult portable bed rails that do not meet the definition of

such devices. FDA noted that for consumers, there is little difference

between the adult portable bed rails regulated by FDA or CPSC in

terms of the physical product. FDA and CPSC have been working with

manufacturers, health care practitioners, and consumer

representatives since 2013, to develop a voluntary consensus

standard for adult portable bed rails through an organization that

develops standards (ASTM International). This voluntary standard

would apply to all portable adult bed rails whether they are regulated

by FDA or CPSC and should help ensure that there are no gaps in

oversight of the safety of portable bed rails for adult use. The effort to

establish a voluntary standard for bed rails was ongoing as of

September 2014. CPSC and FDA also noted that they maintain an

interagency working group that addresses the issues associated with

adult portable bed rails. While this working group’s primary focus is

the development of the voluntary standard, CPSC and FDA said the

group also exchanges technical information and compliance

challenges to improve regulatory oversight.

36

Section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act defines a device, in part, as

an instrument intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or in the

cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, or intended to affect the structure or

function of the body. 21 U.S.C. § 321(h).

Page 22 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

and pesticides);

37

and EPA regulates pesticides and certain chemicals

that may also be contained in soaps, cleaners, and other household

products.

38

Body-cleansing products that do not meet FDA’s definition

of “soap” but contain detergents and are used for cosmetic purposes

are typically considered cosmetics under FDA’s jurisdiction. FDA

considers antibacterial or antimicrobial cleansing products to be drugs

under its jurisdiction, even though they contain the chemical Triclosan,

which is also regulated by EPA when used as a pesticide in other

products.

39

37

FDA defines “soap” to mean articles that meet the following conditions: (1) the bulk of

the nonvolatile matter in the product consists of an alkali salt of fatty acids and the

product’s detergent properties are due to the alkali-fatty acid compounds, and (2) the

product is labeled, sold, and represented only as soap. 21 C.F.R. § 701.20. Products that

meet this definition of soap are excluded from the definition of “cosmetic” in the Federal

Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and are regulated by CPSC. 21 U.S.C. § 321(i) (excluding

soap from the definition of “cosmetic” under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act).

The CPSA excludes “cosmetics,” as that term is defined in the Federal Food, Drug, and

Cosmetic Act, from the definition of a “consumer product” under CPSC’s jurisdiction. 15

U.S.C. § 2052(a)(5)(H). However, according to CPSC officials, the agency could use its

authorities under the CPSA and the Federal Hazardous Substances Act to address any

hazards associated with soaps that do not meet the definition of a cosmetic.

CPSC has authority over products that are labeled and

sold only as soap and that have specified chemical properties that

exclude them from FDA’s jurisdiction. With respect to other household

cleaners, while FDA regulates the detergents used in cosmetics,

CPSC has authority over cleansers that are not cosmetics or

38

In addition to regulating pesticides under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and

Rodenticide Act, EPA, under the Toxic Substances Control Act, regulates “chemical

substances” and “mixtures” of chemical substances. Certain items are excluded from the

Toxic Substances Control Act’s definition of “chemical substance,” including but not limited

to pesticides, foods, drugs, and cosmetics. 15 U.S.C. § 2602(2)(B). According to EPA,

soaps, cleaners, and other household products may consist of or contain chemical

substances and mixtures that are regulated under the Toxic Substances Control Act.

Additionally, as noted above, EPA said that under the Toxic Substances Control Act, it can

regulate the manufacture (including import), processing, distribution in commerce, use, or

disposal of chemical substances and mixtures, including for use as or as part of a

consumer product. Such consumer products could include the items described in this

section (toy laser products, infant car seats, bed rails, fireworks, and wireless devices),

except food contact articles, which are excluded from the Toxic Substances Control Act’s

definition of chemical substance. See 15 U.S.C. § 2602(2)(B)(vi).

39

Triclosan is an antimicrobial active ingredient contained in a variety of products where it

acts to slow or stop the growth of bacteria, fungi, and mildew. There are currently 20

antimicrobial registrations, which EPA regulates under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide,

and Rodenticide Act. Triclosan is also an active ingredient in antibacterial hand soaps,

and toothpastes and as such, is considered by FDA to be an over-the-counter drug under

regulation by FDA under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Page 23 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

pesticides, such as laundry or dishwashing detergents. In addition,

EPA staff noted that its jurisdiction overlaps with CPSC’s with respect

to some household cleaners, such as window cleaners. Even if the

cleaners are not marketed as pesticides, EPA may still regulate

certain chemicals contained in them. EPA also noted that they work

with CPSC and other agencies when their jurisdictions overlap to

share information and determine how to address a particular product

hazard.

40

In addition, agencies can conduct different regulatory oversight activities

for the same product, but requirements can overlap.

• Fireworks (ATF, CPSC, PHMSA): CPSC oversees fireworks that are

used by consumers, which includes examining the length of the fuse

to determine how quickly and how long it will ignite, among other

things. PHMSA regulates the approval, importation, and transport of

fireworks based on its authority to regulate the transportation of

hazardous materials. PHMSA staff noted that some overlap exists

between CPSC’s and PHMSA’s manufacturing requirements for

fireworks. They explained that both sets of requirements have been

incorporated into industry standards (standard 87-1 of the American

Pyrotechnic Association), which PHMSA in turn has incorporated into

its regulations governing the approval and transport of fireworks.

Additionally, ATF enforces explosives laws and licenses

manufacturers to use explosives, including in consumer fireworks.

• Mobile phones and other wireless devices (FCC, FDA): FCC and

FDA share regulatory responsibilities for mobile phones and other

wireless devices. Although FCC does not directly regulate the safety

of mobile phones and wireless devices, it sets limits on the amount of

radiofrequency energy these devices can emit and certifies that

40

EPA officials noted that the agency receives notification under the Toxic Substances

Control Act from potential manufacturers when they plan to begin manufacture of a new

chemical substance (i.e., those substances that are not already on the list of chemicals

included in the Toxic Substances Control Act), including when such chemical substance

may be used in consumer products. EPA can take action to prevent any unreasonable

risks from consumer uses. Additionally, the Toxic Substances Control Act authorizes EPA

to work with a federal agency with overlapping jurisdiction to determine whether an

unreasonable risk “may be prevented or reduced to a sufficient extent” by action taken

under the other agency’s laws. 15 U.S.C. § 2608(a).

Page 24 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

devices sold in the United States comply with FCC requirements.

41

According to FDA, the agency, as part of its oversight of radiation-

emitting products, ensures that mobile phones and other wireless

devices do not emit radiofrequency energy at a level that is hazardous

to the user. FDA also stated that as a health expert agency, its

expertise was significant in developing the radiofrequency exposure

limits from which the FCC radiofrequency emission limits are derived,

and it is FDA that would have the jurisdiction to determine whether a

product is unsafe.

42

For example, while FDA does not review the

safety of mobile phone devices before they are marketed, it can

require manufacturers to replace or recall mobile phones that are

shown to emit radiofrequency energy at a level that is hazardous. As

we previously reported, FCC said it relies heavily on the guidance and

recommendations of federal health and safety agencies when

determining the appropriate exposure limit for radiofrequency

energy.

43

As we discuss in the next section of this report, FDA, FCC,

and other agencies are part of the Radiofrequency Interagency Work

Group, which works to share information and research on

radiofrequency energy-related issues.

Agency officials, as well as a consumer group and industry expert, told us

that the involvement of multiple agencies with various areas of expertise

can help ensure more comprehensive oversight of a product. Consumer

product safety encompasses complex topics and often requires a range

of expertise to address the breadth of products and potential safety

hazards (e.g., manufacturing, transport, effects on the environment, or

use in different settings). As a result, it may be impractical for any single

agency to oversee consumer product safety alone. For example, CPSC

staff noted that in the area of nanomaterials, no single agency has the

41

According to FCC, the agency specifically certifies that devices sold in the United States

comply with FCC requirements regarding maximum Specific Absorption Rates (SAR) to

which humans can be exposed by devices that emit radiofrequency energy.

42

We previously noted that at high power levels, radiofrequency energy can heat

biological tissue and cause damage. Though mobile phones operate at power levels well

below the level at which this thermal effect occurs, the question of whether long-term

exposure to radiofrequency energy emitted from mobile phones can cause other types of

adverse health effects, such as cancer, has been the subject of research and debate.

GAO, Telecommunications: Exposure and Testing Requirements for Mobile Phones

Should Be Reassessed, GAO-12-771 (Washington, D.C.: July 24, 2012).

43

GAO-12-771.

Current Structure Helps

Provide More

Comprehensive Oversight

but Also Creates Some

Inefficiencies

Page 25 GAO-15-52 Consumer Product Safety Oversight

resources to tackle the potential human health and environmental risks.

Moreover, some agencies noted that each agency brings a different

mission or focus to addressing consumer product safety problems. For

example, CPSC staff noted that while CPSC and EPA both conduct risk

assessments as part of their oversight of generators, EPA’s focus is on

how much pollution a generator emits into the environment, while CPSC

focuses on the safety implications of how consumers use generators

around their homes. CPSC staff noted that risk assessments from other

agencies can serve as an additional check on their own safety

assessments.

As part of providing more comprehensive oversight of consumer product

safety within a fragmented and overlapping regulatory structure, agencies

noted that they leverage one another’s expertise, resources, and statutory