September-October 2019 MILITARY REVIEW16

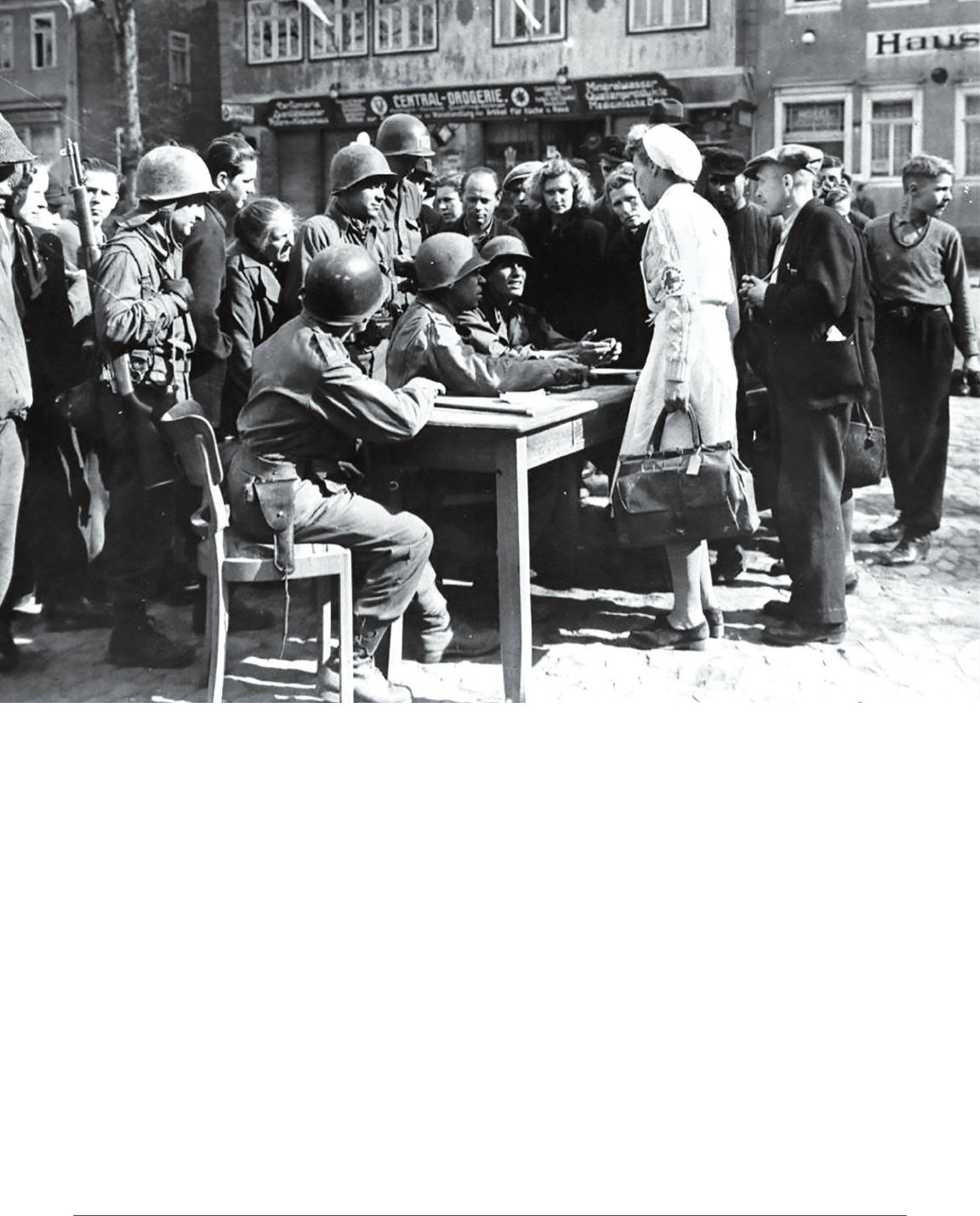

A military government “spearhead” (I Detachment) of the 3rd U.S. Army answers German civilian questions in April 1945 at an outdoor oce in

the town square of Schleusingen, Germany. I Detachments moved in the wake of division advances to immediately begin the process of civilian

stabilization and normalization. (Photo from book, e U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany 1944-1946, by Earl F. Ziemke)

ree Perspectives on

Consolidating Gains

Lt. Gen. Mike Lundy, U.S. Army

Col. Richard Creed, U.S. Army

Col. Nate Springer, U.S. Army

Lt. Col. Sco Pence, U.S. Army

MILITARY REVIEW September-October 2019

W

inning bales while losing wars is an

expensive waste of lood and treasure.

Armies that win bales without folowing

through to consolidate taical gains tend to lose wars,

and the U.S. Army has experience on both sides of the

historical ledger in this regard. While consolidation of

gains has been a consistent military necessity, it remains

one of the most misunderstood features of our warght-

ing doctrine. Many strugle to understand the relation-

ship between the strategic role, the responsibilities of

the various echelons, and the aions required across the

range of military operations. As the requirement and

term “consolidate gains” is relatively new to our doc-

trine, this article seeks to clarify what it means and en-

compasses. To do so, it aproaches consolidating gains

from three perectives: the taician, the operational

artist, and the strategist. By considering the perective

of each level of warfare, one may beer understand how

echelons and their subordinate formations consolidate

gains in mutualy suporting and interdependent ways.

How the Army

Contributes to Winning

e U.S. Army contributes to achieving national

objectives through its four unique strategic roles:

shaping the security environment, preventing con-

ict, prevailing in large-scale combat operations

(LSCO), and consolidating gains. ese strategic roles

represent the interelated and continuous purposes

for which the Army conducts operations across the

competition continuum as a part of the joint force.

Successful consolidation of gains is an inherent part

of achieving enduring success in each of the other

three roles in competition and conict.

e operational environment is a competition

continuum among nation-states. e pulicly released

Sumary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy describes

the requirement to defeat one peer adversary while

detering another.

1

e National Defense Strategy also

adresses other things the joint force and the Army

must continue to do. While the Army focuses on

readiness to deter and defeat a revanchist Russia, a

revisionist China, a roue North Korea, and an Iran

seeking regional hegemony, it also must continue to dis-

rupt terorism abroad to protect the homeland while

continuing to full oligations to security partners in

Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. A large part of the

Consolidating Operational Gains

in the European eater during

World War II

“e workhorses of military government on the

move were the I detachments [‘Spear Detach-

ments’] composed of three or four ocers apiece,

ve enlisted men, and two jeeps with trailers. ese

detachments represented the occupation to the

Germans, at once the harbingers of a new order

and the only stable inuence in a world turned

upside down. ey arranged for the dead in the

streets to be buried, restored rationing, put police

back on the streets, and if possible got the electric-

ity and water working. ey provided care for the

displaced persons and military government courts

for the Germans. … Since, in an opposed ad-

vance, predicting when specic localities would be

reached was impossible, the armies sent out spear-

head detachments in the rst wave—I detachments

whose pinpoint assignments were east of the Rhine.

eir job was to move with the divisions in the front.”

—Earl F. Ziemke, “e Rhineland Campaign,” chap.

XII in e U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germa-

ny, 1944-1946 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government

Printing Oce, 2003), 186.

September-October 2019 MILITARY REVIEW

Total Army remains engaged in security force as-

sistance, counterinsurgency, counterterorism, and

stability-related missions, the focus of which is to

consolidate gains in suport of host-nation govern-

ments. Consolidation of gains in present-day Iraq

and Afghanistan is inherently the purpose of the

advise-and-assist missions for which security force

assistance brigades were designed.

While recognizing that the U.S. Army consoli-

dates gains during competition, during conict, and

aer LSCO, this article focuses on consolidation of

gains within the context of the Army’s third strategic

role: prevail in large-scale combat. Armed conict

against a peer adversary is likely to encompass mul-

tiple corps in large geographical areas inhabited by

signicant populations. Any conict is also likely to

require ground forces to defeat enemy forces in or-

der to reealish the sovereign control of an aly or

partner’s land and population. is would be an im-

mense undertaking and requires thinking about how

to simultaneously consolidate gains from the boom

up and top down. Consolidating gains during LSCO

looks dierent at each stage of the operation and

from each level of warfare.

2

e consolidation area is an important feature of

LSCO at the taical level. Field Manual (FM) 3-0,

Operations, explicitly identied the consolidation

area to solve an age-old prolem during operations.

3

Army forces consistently strugle with securing the

ground between brigades advancing in the close area

and the division and corps rear boundaries, particu-

larly during oensive operations when the size of ar-

eas of operation (AOs) expand. Maintaining tempo

in the close and deep areas requires that the division

and corps suport areas be secured as the lines of

communication lengthen. However, this leaves the

prolem of defeating bypassed forces and securing

key terain and population centers to be solved in

ad hoc fashion. “e typical solution was to assign

combat power from brigades commied to oper-

ations in the close and deep areas to the maneuver

enhancement brigade (MEB).”

4

is proved satis-

factory during short-duration simulations as long as

the division bypassed only smal enemy formations.

“Actual experience against Iraqi forces during the

rst few months of Operation Iraqi Freedom [2003]

indicated this aproach entails signicant risk” in

Extract from TIME magazine

“How Disbanding the Iraqi

Army Fueled ISIS”

By Mark ompson

29 May 2015

“General Ray Odierno, [former] Army chief of sta, says the

U.S. could have weeded Saddam Hussein’s loyalists from the

Iraqi army while keeping its structure, and the bulk of its forc-

es, in place. ‘We could have done a lot beer job of sorting

through that and keeping the Iraqi army together,’ he told

TIME on ursday. ‘We struggled for years to try to put it

back together again.’ e decision to dissolve the Iraqi army

robbed Baghdad’s post-invasion military of some of its best

commanders and troops. … it also drove many of the sud-

denly out-of-work Sunni warriors into alliances with a Sunni

insurgency that would eventually mutate into ISIS [Islamic

State of Iraq and Syria]. Many former Iraqi military ocers

and troops, trained under Saddam, have spent the last 12

years in Anbar Province baling both U.S. troops and Bagh-

dad’s Shi’ite-dominated security forces, Pentagon ocials

say. ‘Not reorganizing the army and police immediately were

huge strategic mistakes,’ said [General] Jack Keane, a retired

Army vice chief of sta and architect of the ‘surge’ of 30,000

additional U.S. troops into Iraq in 2007. ‘We began to slowly

put together a security force, but it took far too much time

and that gave the insurgency an ability to start to rise.’”

To view the complete article, visit hps://time.com/3900753/

isis-iraq-syria-army-united-states-military/.

19MILITARY REVIEW September-October 2019

CONSOLIDATING GAINS

the real world, where not accounting for both the ene-

my’s wil and means to continue a conict resulted in a

wel-resourced insurgency in a maer of months.

5

FM 3-0 emphasizes that an “enemy cannot be alowed

time to reconstitute new forms of resistance to protract

the conict and undo our initial baleeld gains.”

6

is is

based upon experience that indicates consolidating gains

requires more combat power than what is required for

the initial taical defeat of enemy forces in the eld. is

in turn must drive planners at the operational and stra-

tegic levels to account for the need for these aditional

forces. If not, a short-war planning mindset using “mini-

mum force” risks the ability to consolidate gains taicaly,

operationaly, and strategicaly.

Deliberately wrien to empower operational plan-

ners and commanders to anticipate aditional force re-

quirements, FM 3-0 provides an expanded description

of the operational framework and the consolidation

area in chapter 1. While consolidate gains aivities

are adressed throughout FM 3-0, chapter 8 is sinu-

larly dedicated to the topic. It says consolidation of

gains are “aivities to make enduring any temporary

operational success and set the conditions for a stale

environment alowing for a transition of control to

legitimate authorities.” e chapter concludes with a

review of the theater army, corps, division, and brigade

combat teams (BCTs) in operations and the distinctive

roles they play in consolidating gains.

7

e folowing perectives expand upon the last

section of chapter 8 by describing the considerations

and responsibilities for consolidating gains at each of

three levels of warfare. Instead of explicitly identify-

ing the echelon (brigade, corps, division, eld army,

or theater army), we start with the taician, advance

to the operational artist, and then conclude with the

strategist. e intent is to provide insight on consoli-

dation of gains for the warghting professionals at the

level for which they are responsile, not necessarily

the type of headquarters or rank.

e Tactician’s View

ose ho hae won ictoies are fa more numerous than

those ho hae used the to avantage.

—Polybius

8

e taician focuses on bales and engagements,

aranging forces and capabilities in time and space to

achieve military objectives. e point of departure for

thinking about consolidating gains at the taical level

is clearly understanding that the means for doing so is

decisive aion: the execution of oensive, defensive,

and stability tasks in the ever-changing context of a

particular operation and operational environment.

e goal is defeating the enemy, accounting for al his

capabilities to resist, and ensuring unrelenting pressure

that grants him no respite or oportunity to recover

the means to resist. Corps and divisions assign AOs,

objectives, and ecic taical tasks for their subor-

dinate echelons. While initialy they must focus on

the defeat of enemy forces, the ultimate objective is to

consolidate gains in a way that ensures the enemy no

longer has the means or wil to continue the conict

while maintaining a frienly position of relative ad-

vantage. Divisions and corps have a critical, mutualy

interdependent role in making this hapen.

While limited contingency operations over the

last twenty years saw corps headquarters function

as joint task forces or land component commands,

during large-scale ground combat operations, corps

ght as taical formations. Corps provide com-

mand and control (C2) and shape the operational

environment for multiple divisions, functional and

multifunctional brigades, and BCTs. e corps plans,

enales, and manages consolidation of gains with its

subordinate formations while anticipating future op-

erations and continuously adjusting to developments

in the close and deep areas. As LSCO concludes in a

part of the corps AO, the corps headquarters assigns

responsibility, usualy a division but in some cases

one or more BCTs, to consolidate gains in that AO.

When LSCO is largely concluded throughout the

corps AO, it reorganizes the AOs of its subordinate

echelons in a way that enales the most rapid consol-

idation of gains with the capabilities availale.

A corps consolidation area is comprised of the phys-

ical terain that was formerly part of its subordinate

division consolidation areas, which the corps assumed

responsibility for as it shied the division rear bound-

aries forward to maintain tempo during oensive

operations. e division assigned the corps consolida-

tion area may be a unit that was ecicaly dedicated

to and deployed for the task or one that was folowing

in suport of the close ght, or it may be a division

that was already commied that remains focused on

September-October 2019 MILITARY REVIEW20

defeating enemy remnants and bypassed forces. As

the corps enjoys success and its AO expands, a larger

proportion of its combat power may be commied to

consolidate gains. e commitment of combat power

to consolidate gains should enale tempo and is not

intended to draw forces away from the ghts in the

close and deep areas. is means that taical and op-

erational level planners need to anticipate the amount

of combat power necessary to simultaneously defeat

the enemy in the close and deep areas while consoli-

dating gains in their AOs. Accounting for the required

aditional forces during operational planning and force

ow development prior to conict is essential. Again,

a short-war, minimum-force planning mentality at the

strategic and operational level wil likely result in insuf-

cient forces to maintain oensive tempo and continu-

ously consolidate gains to win decisively.

Because divisions begin to consolidate gains in their

own consolidation areas, their decisive-aion focus

is heavily weighted toward oensive tasks designed to

defeat al remaining enemy forces in the eld and se-

cure key terain that is likely to encompass population

centers. is means that when corps ealish consoli-

dation areas, particularly when they assume responsi-

bility for division consolidation areas as frienly forces

advance, their focus in terms of consolidating gains is

likely to be broader and emphasize stability tasks, area

security, and governance. e divisions should have

already consolidated gains to some degree, particularly

in terms of defeating enemy remnants and bypassed

forces. Successful consolidation of gains at the division

level creates security conditions more amenale to a

higher level of focus on populations, infrastructure, and

governance at the corps level because there are few or

no enemies le to contest frienly forces in an AO.

For the taician, consolidating gains at the di-

vision level is initialy dicult to distinuish from

other LSCO for a couple of reasons. e rst is that

it represents a transition within a portion of the AO

that might not be readily aparent. e second rea-

son is that ealishing security within a portion of an

AO requires defeating enemy remnants and bypassed

forces through decisive aion, and that is likely to

require oensive operations, which dier only in scale

from what a BCT was doing previously. When an AO

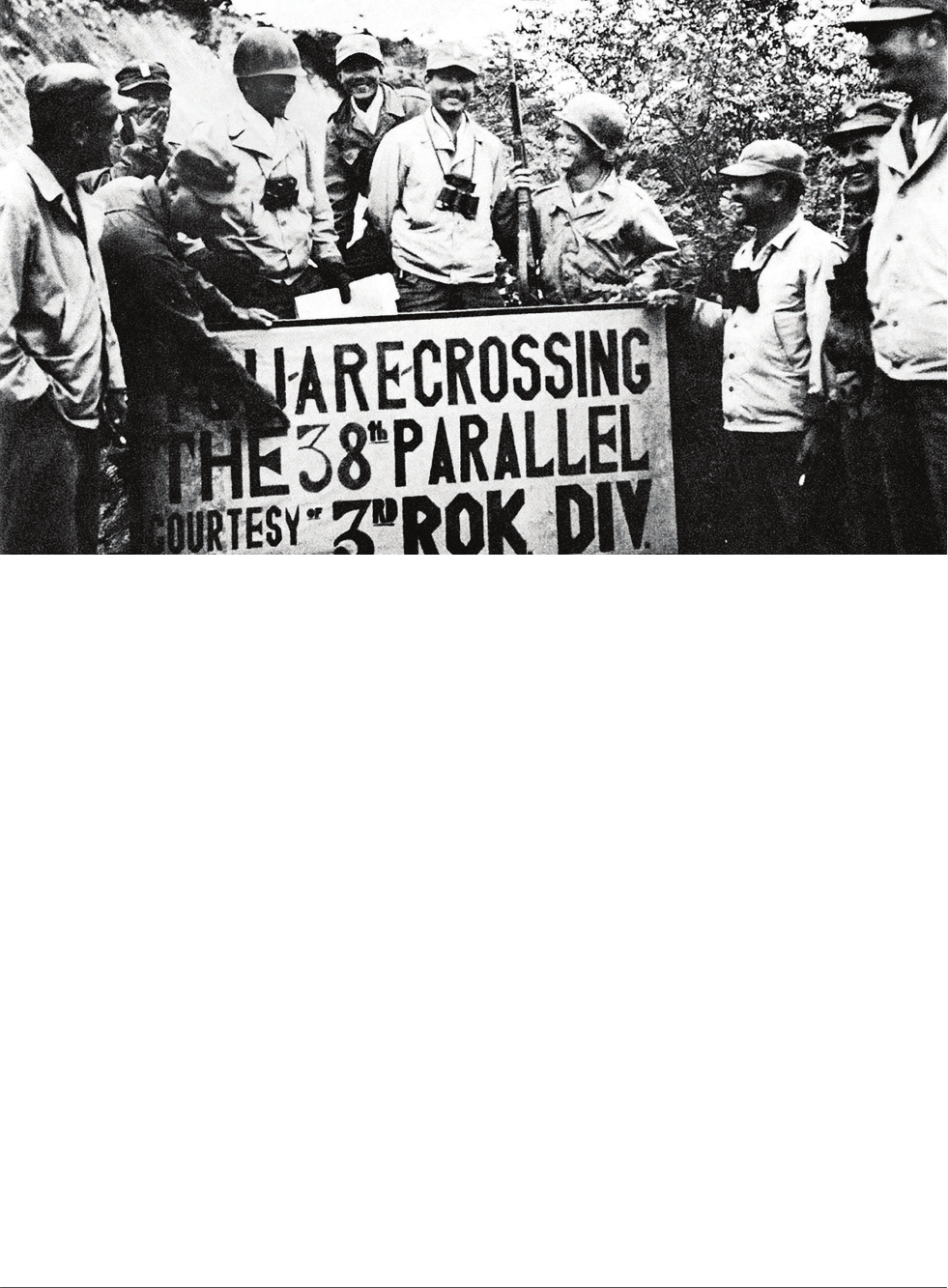

Members of a UN public health and welfare detachment, a com-

posite allied force, meet at a crossing point on the 38th parallel

circa early October 1950. For more information, see the sidebar

on page 21. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Army Special Operations

Command History Oce)

MILITARY REVIEW September-October 2019

is designated a consolidation area, the BCT assigned

to it may already be there, so consolidating gains

becomes a form of exploitation and pursuit by forces

already in contact with the enemy. If an uncommied

BCT is assigned an AO to consolidate gains, the tran-

sition is more explicit even if the assigned tasks do not

change. In either case, taical planners must antici-

pate what aditional capabilities the division should

provide the BCT to facilitate area security, secure

key terain, and control the local population. Some

of those capabilities are likely to be under control of

the corps and must be task-organized down into the

division for use by the BCT.

In al cases, every eort should be made to ac-

count for the requirement to consolidate gains early

in the planning process so that adequate aditional

combat power is availale to consolidate gains with-

out diverting forces from other purposes and losing

tempo. Similar to how the corps aproaches consol-

idating gains, the division may pass an uncommied

BCT forward into the close area to maintain tempo

and momentum and assign an already commied

BCT consolidate gains related tasks in its AO. is

aproach avoids the complexities of a relief in place

while in contact and generaly saves time but ads

the complexity of a forward passage of lines requir-

ing detailed planning and rehearsals.

e BCT entrusted with the division consolida-

tion area enales the division’s MEB to focus on the

security and C2 of the suport area(s) and enaling

operations in the close and deep areas. MEBs are

task organized with engineer and military police

units to facilitate maneuver suport while securing

routes and sustainment sites from mid-level threats.

eir focus is enaling the desired tempo of opera-

tions in the close and deep areas, not consolidating

gains achieved in those areas.

e easiest way to think of the division consolida-

tion area is as another close ght area with a dierent

purpose. FM 3-0 states that a division consolidation

area requires at least one BCT to be responsile for

it as an assigned area of operations.

9

No smaler force

can hanle the task because the BCT is the rst

element capale of controling airspace and employ-

ing combined arms across an AO. As an operation

progresses, multiple BCTs may be employed to

consolidate gains within the division AO, particularly

Consolidating Gains in Korea

Following a successful UN amphibious counteroensive

in September 1950, the invading North Korean military

was forced back north out of South Korea and even-

tually across the Yalu River into China. Accompanying

the Allied forces as they crossed the 38th parallel were

public health and welfare detachments whose mission

was to administer military government in occupied

areas. However, the existence of these detachments

was short-lived, as Chinese forces crossed the Yalu and

drove UN forces back below the 38th parallel. ese

detachments were subsequently replaced by Unit-

ed Nations Civil Assistance Corps, Korea (UNCACK)

teams, which provided civil aairs support in the south

with the stated missions of helping to “prevent disease,

starvation, and unrest,” to “safeguard the security of the

rear areas,” and “to assure that front line action could go

on without interruption by unrest in the rear.” Guidance

given to these units was oen vague. One UNCACK of-

cer later recounted that the only guidance he received

in two years of service was, “Your orders are to see what

needs to be done and do what you can.”

For more on the public health and welfare detach-

ments and UNCACK teams, see “Same Organiza-

tion, Four Dierent Names: U.S. Army Civil Aairs

in Korea 1950-1953,” U.S. Army Special Operations

Command History Oce, hps://www.soc.mil/AR-

SOF_History/articles/v7n1_same_org_four_names_

page_1.html.

September-October 2019 MILITARY REVIEW22

toward the successful conclusion of large-scale ground

combat operations. Successful consolidation of gains

ultimately denies the enemy the time, space, and psy-

chological breathing space to reorganize for continued

resistance. At the taical level, consolidating gains is

the preventative that kils the seeds of insurgency.

History shows that successfuly consolidating

gains requires a much broader aproach than simply

assigning aditional stability tasks to existing subordi-

nate formations. ey lack the ecialized capabilities

to comprehensively consolidate gains in an enduring

manner because it is simply not what they are designed

to do; they are built for LSCO. Our Army adressed

this prolem eectively in the past. During World War

II, the United States realized that it would need to

set conditions for the governance of the teritories it

liberated in Europe and the Pacic.

By the D-Day landings in 1944, the U.S. Army had

assessed governance aptitude and expertise amongst

its ranks and identied 7,500 U.S. military personnel

to train in the United States as the cadre for military

governance in liberated areas. ey were placed into

governance detachments assigned directly to corps

and division commanders during combat operations

for the purpose of consolidating gains directly behind

the close area. Governance detachments reeab-

lished civil administration, cared for sick and injured

locals, registered the local population, assisted refu-

gees and displaced persons, colected weapons and

contraband, organized local citizens for the cleanup

of their communities, and reealished basic services

to the cities, towns, and vilages occupied by Alied

forces to the best of their ability.

For the taician, the goal is to continuously create

and then exploit positions of relative advantage that

facilitate the achievement of military objectives that

suport the political end state of a campaign. Al ef-

forts to consolidate gains ultimately suport that goal;

therefore, they must be synchronized and integrated

into the campaign plan itself.

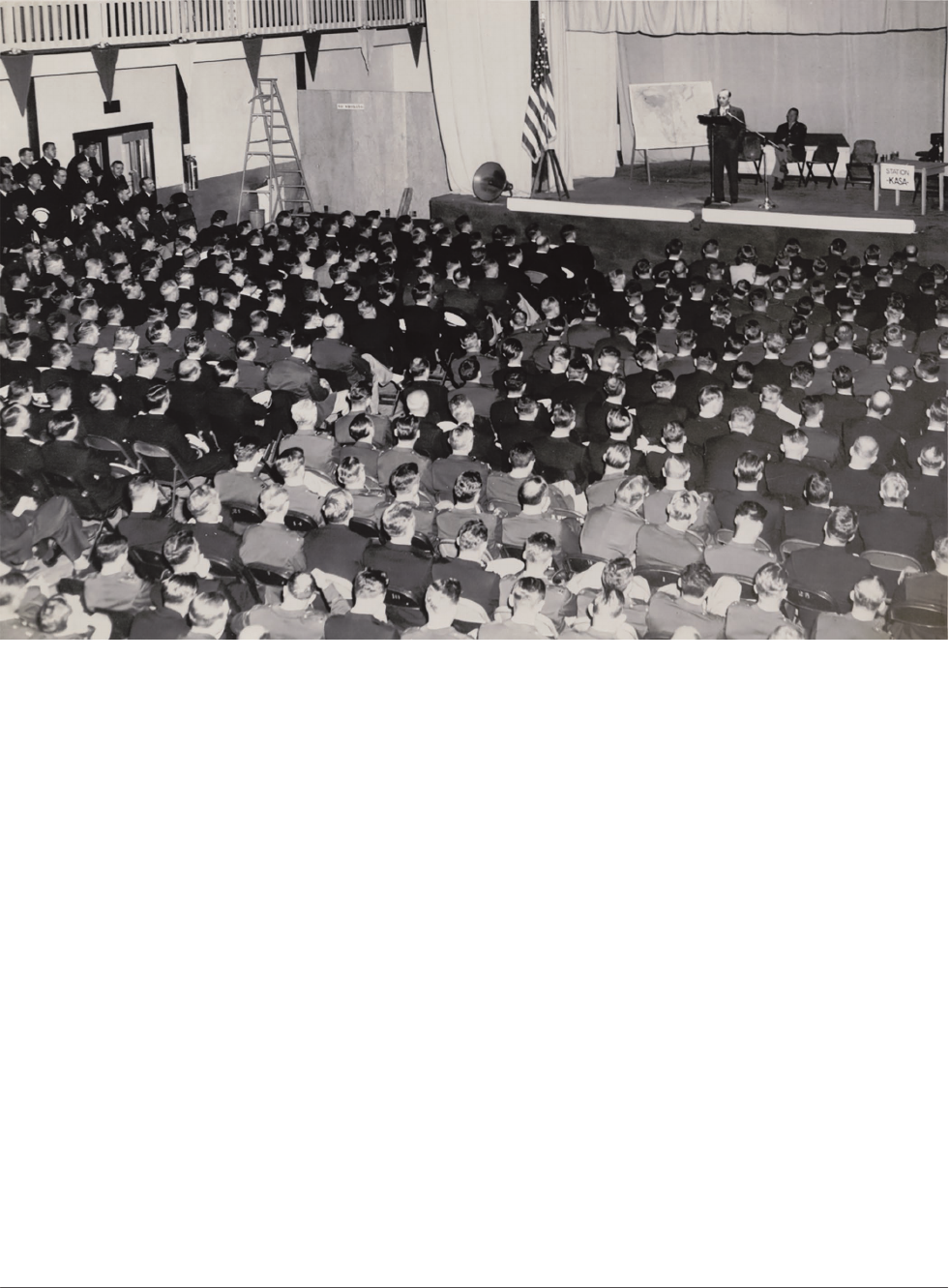

Army and Navy Civil Aairs Staging Area (CASA) ocers listen to a

civilian speaker on stage with a large map of Asia at an assembly in the

spring of 1945 in Presidio of Monterey, California. (Photo courtesy of

the U.S. Army via the National Archives)

23MILITARY REVIEW September-October 2019

CONSOLIDATING GAINS

e Operational Artist’s View

Operational artists design military campaigns

to achieve strategic goals. They consider the em-

ployment of military forces and the arangement

of tactical efforts in time, space, and purpose to

achieve strategic objectives. Folowing the initialy

successful invasion of Iraq in 2003, the joint force

learned many valuale lessons about the importance

of rapily consolidating gains. The first and perhaps

most important lesson was adequately determining

the required means (forces) to accomplish not only

the tasks required to defeat enemy forces in the field

but also those required to estalish physical control

of the entire country. Identifying and deploying the

necessary capabilities to defeat al potential forms

of enemy resistance should be a fundamental part of

any operational aproach seeking to end a war with

an enduring and decisive outcome. This requires

breaking the enemy’s wil to resist.

Consolidating gains was and remains critical to

aacking the enemy’s wil. Part of breaking the wil to

resist is denying the availale means to resist, which

means kiling or capturing its reular and ireular

forces and separating them from the population, seiz-

ing control of weapons and munitions, and controling

the population in a

way that maintains

order and security

without creating incentives for further resistance.

is provides incontrovertile evidence of defeat

and removes the hope upon which those who would

mount a protraed resistance feed. It generaly has a

sobering eect on the population, particularly when

done quickly, an eect that endures if the means that

secure a population and enforce its orderly behavior

improve or do not excessively interfere with the eco-

nomic and personal lives of the people.

Planning to consolidate gains is integral to pre-

vailing in armed conict. Any campaign that does

not account for the requirement to consolidate gains

is either a punitive expedition or likely to result in a

protraed war. e planning must therefore account

for the desired end state of military operations and

work backward. It should determine how much dam-

age to infrastructure is acceptale and desirale, what

is required to physicaly secure the relevant terain

and populations, and what resources are availale

among both Army forces and our coalition alies. It

needs to account for al the potential means of enemy

resistance to ensure the

defeat of the enemy

Col. Nate Springer,

U.S. Army, is a recent

graduate of the Advanced

Strategic Leadership

Studies Program through

the School of Advanced

Military Studies (SAMS),

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

He holds an MA in security

studies from the Naval

Postgraduate School, an

MMAS from the Command

and General Sta College,

and an MA in strategic

studies from SAMS. He pre-

viously served as executive

ocer to the commanding

general, Combined Arms

Center, and commander

of 1st Squadron, 32nd

Cavalry, 101st Airborne

Division. His assignments

include multiple tours in

Iraq and Afghanistan.

Col. Richard Creed,

U.S. Army, is the director

of the Combined Arms

Doctrine Directorate at

Fort Leavenworth and one

of the authors of FM 3-0,

Operations. He holds a BS

from the United

States Military Academy,

an MS from the School

of Advanced Military

Studies, and an MS from

the Army War College. His

assignments include tours

in Germany, Korea, Bosnia,

Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Lt. Gen. Michael D.

Lundy, U.S. Army, is the

commanding general of the

U.S. Army Combined Arms

Center and the comman-

dant of the Command and

General Sta College on

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

He holds an MS in strategic

studies and is a graduate

of the Command and

General Sta College and

the Army War College. He

previously served as the

commanding general of the

U.S. Army Aviation Center

of Excellence at Fort Rucker,

Alabama, and he has de-

ployed to Haiti, Bosnia, Iraq,

and Afghanistan.

Lt. Col. Sco Pence,

U.S. Army, is the executive

ocer to the commanding

general, Combined Arms

Command. He holds a BA

in organizational psychol-

ogy from the University

of Michigan, an MBA from

Webster University, and

an MMAS in operational

art from the School for

Advanced Military Studies.

His previous assignments

include commander, 5th

Squadron, 73rd Cavalry,

82nd Airborne Division;

baalion and brigade

operations ocer in the

173rd Airborne Brigade;

and assistant S3 and HHC

commander of the 75th

Ranger Regiment.

September-October 2019 MILITARY REVIEW24

in detail. Planning should also determine, based upon

the availale resources, where and when to accept risk

in terms of balancing the need to consolidate gains

against maintaining the desired tempo of an operation.

Consolidating gains throughout the operation may

require a slower tempo but result in a shorter conict,

while a high-tempo operation that quickly achieves

taical success may result in a longer conict because

signicant parts of the enemy forces and population

not engaged or inuenced by the initial bales may

retain both the means and wil to resist.

e Roman general Scipio Africanus is an exam-

ple of a successful operational artist in ancient times

who understood the importance of consolidating

gains. During the Second Punic War, he designed the

campaigns against Hannibal’s Carthaginian armies

and their Spanish alies while the authorities in Rome

decided the overal strategy. In 208 BC, although

outnumbered, he launched an initial assault to seize

the critical port of Cartagena, Spain, and with it the

base of suplies and reinforcements for Hannibal’s

movement from North Africa to the Italian penin-

sula. Folowing the seizure of Cartagena, he showed

mercy to the vanquished Spanish troops and built a

reputation for baleeld diplomacy. Scipio made ef-

fective use of the slow reaion of other Carthaginian

forces in Spain. While maintaining a defense around

the perimeter of Cartagena, he alocated sucient

forces to eectively administer the population. He

found work for the captured artisans and set free al

of the residents that agreed to suport his cause. His

enlightened and innovative leadership resulted in a

stale and secure environment that protected non-

combatants as a means to achieve Rome’s strategic

aim of denying Spain as an enemy base of opera-

tions.

10

Without eective consolidation measures in

Cartagena, Scipio would not have been ale to control

the gains he had won. News of his aions folowing

the seizure of Cartagena won over three of the most

powerful tribes in Spain and gave Scipio a numerical

advantage against the Carthaginians. Months later,

he routed the Carthaginians at the Bale of Baecula.

Historian B. H. Lidel Hart noted, “Scipio, more than

any other great captain, seems to have graed the

truth that the fruits of victory lie in the aer years of

p e a c e .”

11

ese timeless historical lessons are ignored

at our peril, and the striking similarities between con-

icts over time should inform our eorts today.

Campaign planners designate forces to consol-

idate gains and advocate for strategic-level leaders

to alocate the resources necessary to achieve objec-

tives. Candor and mutual understanding criticaly

impact this dialoue. Strategic leaders must make

resource alocation decisions based upon wel-in-

formed operational-level planner estimates and in-

formed by the actual operational environment in the

context of our doctrine, not the potentialy faulty

assumptions that underpin a desire for easy victories.

Understanding the population in the area of opera-

tions is a critical step toward avoiding faulty assump-

tions. Cheap and easy victories where populations do

not play a significant role in the conflict are not the

historic norm and are virtualy impossile against

capale enemy nation-states.

A Strategist’s View

In the philosophy of a there is no pinciple more sound

than this: that the peranence of peace deends, in large

degree, upon the magnanimity of the icto.

—Col. I. L. Hunt, Civil Aairs Ocer, World War I

12

e military strategist is most concerned with

creating multiple options and conditions that place

the United States in positions of relative advan-

tage. When considering ends, ways, and means, the

strategist needs to consider, and reconsider, con-

solidating gains before, during, and aer a conict.

Military governance is a good example of potential

strategic-level consideration to consolidate gains

mentioned earlier. roughout most of American

military history, a lack of forethought about military

governance at the strategic level has made the consol-

idation of gains during and aer large-scale combat

markely more dicult. e reality is that military

governance has been an unavoidale component of

American military intervention going back to the

Indian Wars of the nineteenth century.

ere has been an ongoing debate, rekinled from

one campaign to the next, about what the U.S. military’s

proper role should be in the administration of gover-

nance to civilian populations under its control. e

prewar debates center on whether the military should

25MILITARY REVIEW September-October 2019

CONSOLIDATING GAINS

execute such a task or if governance should be le to

professional bureaucrats. Regarless of the debate, and

whether the military does or does not want to execute

governance operations during large-scale combat, the

military nds itself governing out of necessity both

during and aer conicts even if it is rarely, if ever,

labeled as such. In most cases, this hapens because there

is no other government entity present to do the job in

the rst place. e Second World War is one of the few

examples of strategists linking military governance and

consolidating gains to enduring strategic outcomes.

Folowing the surender of Germany, the Oce

of Military Government United States (OMGUS) in

the American Zone was ealished to command and

control al governance operations. Control of gover-

nance detachments shied from taical commanders

to OMGUS. Once military governance detachments

were under the control of the post-surender terito-

rial C2 structure of OMGUS, U.S. governance eorts

were beer streamlined and coordinated with the

German governmental system maximizing eciency

with German counterparts at the local, regional, and

national levels. e alignment of U.S. governance de-

tachments with the German governmental structure in

the post-combat phase was imperative and accelerated

reoring Germans to power at every level, crucialy

removing the U.S. Army from the governance side of

the street as soon as possile.

e debate between the ecacy of the land, sea, or

air power is realy one of consolidating gains. People

transit through the air and sea. ey live on land. e

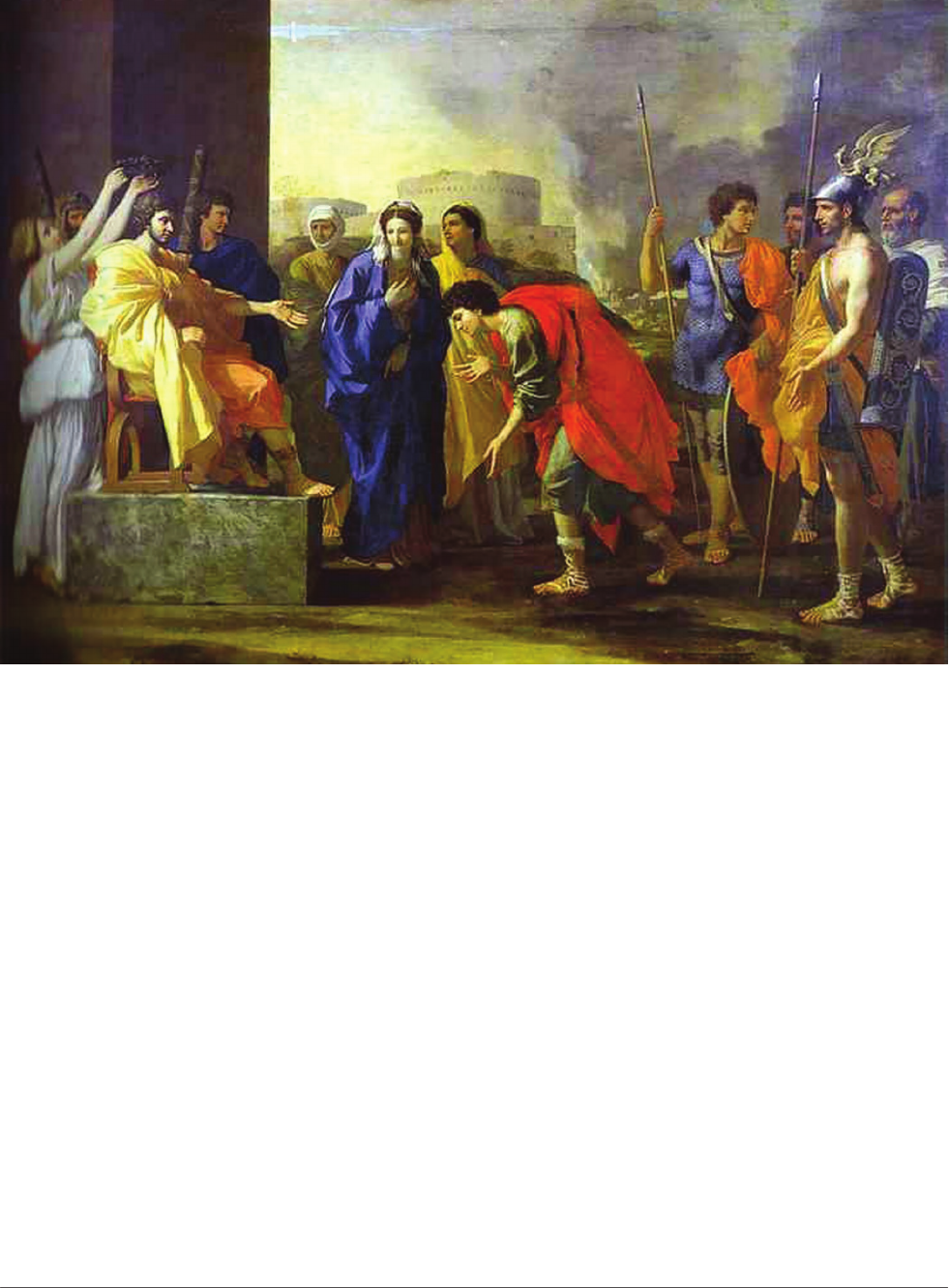

Scipio’s Noble Deed (1640), painting, by Nicholas Poussin. Roman

general Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus conquered the port of

Carthage located in what is today southern Spain. One widely retold

anecdote that emerged from this conquest was his reputed return of

a beautiful young captive woman unravished to her family and an-

cé. is gesture reportedly promoted his reputation among the local

conquered population for justice and mercy, which facilitated their

acquiescence to his rule and their cooperation. e reputed event

became emblematic of his shrewd diplomatic approach to stabilizing

and consolidating Roman gains in a series of campaigns that eventually

cleared the way for his eventual conquest of Carthage itself. (Painting

originally from Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Digital/me-

chanical reproduction via Wikimedia Commons)

September-October 2019 MILITARY REVIEW26

initial U.S. strategy in Vietnam (1965–1968) was to

use air power to bomb targets in North Vietnam in

order to force the North Vietnamese to the negotiat-

ing tale.

13

Although the bombing imposed great suf-

fering and material damage, the failure of the Army

of the Repulic of Vietnam and U.S. ground forces to

consolidate taical gains in ways that earned popular

suport ceded those gains.

e execution of military government has proven an

inescapale, crucial aect of war that the U.S. military,

ecicaly the Army, must consider. e U.S. military

must plan and prepare for the execution of military

governance before, during, and aer combat operations.

is planning deserves the same, or perhaps greater,

level of professional forethought than combat operations

received. Failure to do so results in the type of ad hoc

aproach that charaerized our experiences in Iraq.

Conclusion

e U.S. Army has consolidated gains, with varying

degrees of success, throughout its history. It did so in the

Indian Wars, aer the Civil War during Reconstruction,

during the Spanish-American War, during World

War II and Korea, and in Vietnam, Haiti, Iraq, and

Afghanistan. e success of consolidation-of-gains op-

erations shaped how those wars and conicts are viewed

today. How we plan for, execute, and folow through

with consolidating gains in our generation wil deter-

mine not just the strategic advantages of the Nation but

dene the way history judges our aions.

By placing the reader in the shoes of the taician, the

operational artist, and the strategist, this article sought

to provide a clearer understanding about consolida-

tion-of-gains operations. e release of FM 3-0 in 2017

and the professional discussion that folowed enaled an

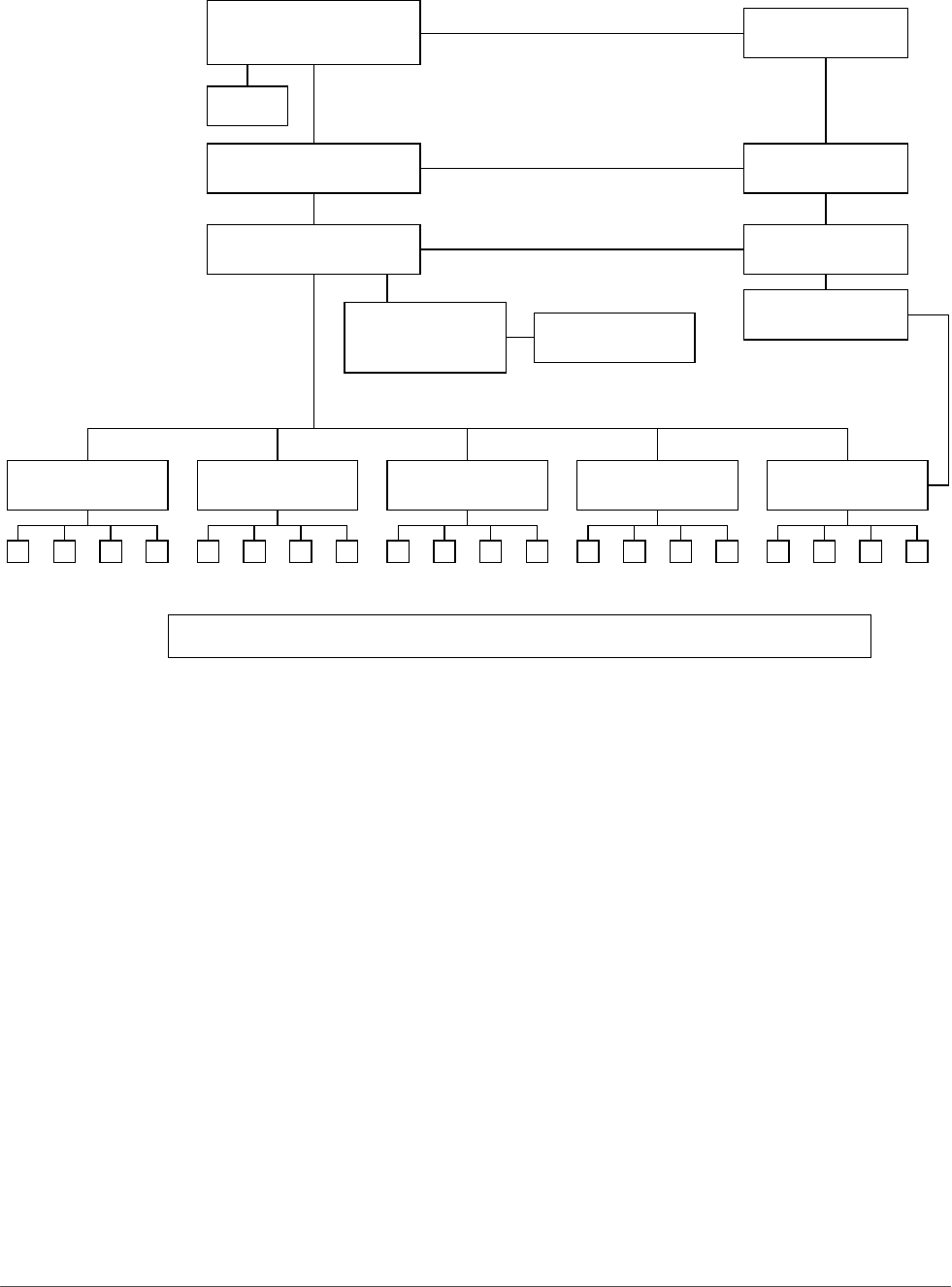

OMG

Bavaria

OMG

Wuerttemberg-Baden

OMG

Greater Hesse

OMG

Bremen

OMG

Berlin District

Laenderrat

OMG–Oce of Military Government USFET G-5–U.S. Forces in the European theater civil aairs-military government section

Coordinating

committee

Control sta

Control council

Berlin

Kommandatura

Oce of military government

(United States)

Deputy military

governor

Military governor

also theater commander

Regional government

coordinating oce

Liaison and security oces of Landkreis and Stadtkreis level

USFET

G-5

U.S. Military Government Relationships aer 1 April 1946

(Figure from e U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany 1944-1946, Earl F. Ziemke)

27MILITARY REVIEW September-October 2019

CONSOLIDATING GAINS

apreciation of how the Army strategic roles contribute

to the joint defense of the Nation, identied organiza-

tional gaps, and began to change the Army. Military pro-

fessionals must engage in thoughtful reection and study

of how we consolidate gains on the baleeld if we are

to prevail in future conicts. We welcome the insightful

professional discussion that ensues.

Notes

1. Department of Defense, Summary of the National Defense

Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American

Military’s Competitive Edge (Washington, DC: U.S. Government

Publishing Oce [GPO], 2018), 6.

2. Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO,

6 October 2017), chap. 8.

3. Ibid., 1-35.

4. Mike Lundy and Rich Creed, “e Return of U.S. Army Field

Manual 3-0, Operations,” Military Review 97, no. 6 (November-De-

cember 2017): 19.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. FM 3-0, Operations, chap. 8.

8. Polybius, “Book X,” e Histories of Polybius, 6.36, accessed on

26 May 2019, hp://penelope.uchicago.edu/ayer/E/Roman/Texts/

Polybius/10*.html.

9. FM 3-0, Operations, 8-6.

10. Polybius, “Book X,” 2.7–2.9.

11. B. H. Liddell Hart, Scipio Africanus: Greater than Napoleon (La

Vergne, TN: BN Publishing, 1926), 45.

12. I. L. Hunt, American Military Government of Occupied

Germany, 1918-1920: Report of the Ocer in Charge of Civil Aairs,

ird Army and American Forces in Germany (Washington, DC: U.S.

Government Printing Oce, 1943), vii, accessed 2 July 2019, hps://

history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/resmat/interwar_years/american_

military_government_of_occupied_germany_1918-1920.pdf.

13. John T. McNaughton, Dra Memorandum for Secretary of

Defense Robert S. McNamara, “Annex–Plan for Action for South

Vietnam,” in e Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, vol. 3 (Washington,

DC: Department of Defense, 24 March 1965), accessed 1 July 2019,

hps://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon3/doc253.htm.

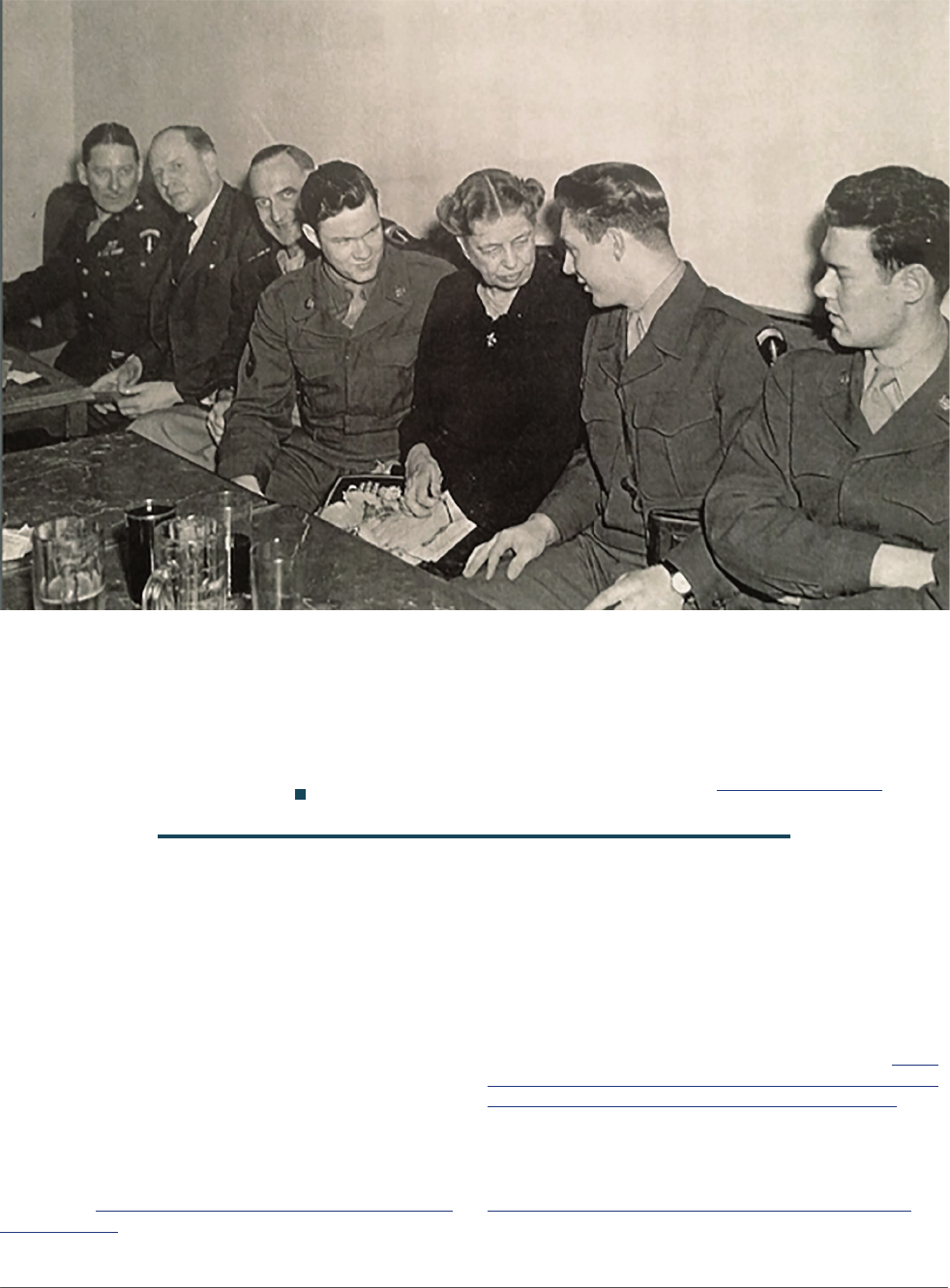

Sgt. Verlan Gunnell (second from right) speaks with Eleanor Roosevelt

(third from right) in this photograph from World War II. Also pictured

(from le) are Brig. Gen. James Edmunds, administrative ocer of the

Oce of Military Government, United States (OMGUS); Ambassador

Robert Murphy, political adviser of OMGUS; Lt. Gen. Lucius Clay,

deputy military governor of OMGUS; Richard Jones; and Sgt. Jay

Campbell (far right). (Photo submied by the Gunnell family via e

Preston Citizen/e Herald Journal, hps://www.hjnews.com/)

September-October 2019 MILITARY REVIEW28

For more on consolidating gains, Military Review recommends

the previously published article “e Particular Circumstances of

Time and Place” by retired U.S. Army Col. David Hunter-Chester.

e author, a trained historian, compares the U.S. occupation of

Japan with the coalition occupation of Iraq, while also drawing on

his personal experience working with the Coalition Provisional

Authority in Baghdad, to show why U.S. plans and policies for oc-

cupying any country should be tailored to the situation. To view

this article from the May-June 2016 edition of Military Review,

visit hps://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/

Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20160630_art010.pdf.

Military Review also recommends the previously published article

“Government versus Governance” by U.S. Army Maj. Jennifer Jant-

zi-Schlichter. e author asserts that there are two main reasons

that the U.S. military has been unable to achieve success in building

sustainable governments in Iraq and Afghanistan: the U.S. military

has failed to dierentiate between government and governance;

and it does not eectively train and educate its personnel on how

to execute this task. To view this article from the November-De-

cember 2018 edition of Military Review, visit hps://www.armyu-

press.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/ND-18/

Jantzi-Schlichter-Govt-Governance.pdf.

For those interested in older examples of successful consolidation of

gains in U.S. military history, Military Review recommends the pre-

viously published article “Expeditionary Land Power: Lessons from

the Mexican-American War” by U.S. Army Maj. Nathan A. Jennings.

e author details the planning and execution of a campaign by

Gen. Wineld Sco that is considered by many historians to be a

textbook example of how consolidation of gains were eectively

incorporated into an overall invasion and occupation plan. To view

this article from the January-February 2017 edition of Military Re-

view, visit hps://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/

Archives/English/MilitaryReview_2017228_art010.pdf.