Interagency Land Acquisition Conference

UNIFORM APPRAISAL

STANDARDS FOR FEDERAL

LAND ACQUISITIONS

2016

The Yellow Book is available in an enhanced electronic version and in

print from The Appraisal Foundation. Please visit these links to purchase

your copy today!

Yellow Book Electronic PDF Edition

Yellow Book in Print (available mid-February 2017)

Interagency Land Acquisition Conference

UNIFORM APPRAISAL

STANDARDS FOR FEDERAL

LAND ACQUISITIONS

2016

e

PDF EDITION

Interagency Land Acquisition Conference

UNIFORM APPRAISAL

STANDARDS FOR FEDERAL

LAND ACQUISITIONS

2016

The Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions have been developed, revised,

approved, adopted and promulgated on behalf of the Interagency Land Acquisition Conference.

The Conference is solely and exclusively responsible for the content of the Standards. The

Appraisal Foundation provided editing and technical assistance to the Standards, but neither

undertakes nor assumes any responsibility whatsoever for the content of the Standards. The

Appraisal Foundation has published the Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land

Acquisitions on behalf of the Conference and in cooperation with the United States Department

of Justice.

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-0-09892208-8-0

The Appraisal Foundation is the nation’s foremost authority on the valuation profession. The

organization sets the Congressionally authorized standards and qualications for real estate

appraisers, and provides voluntary guidance on recognized valuation methods and techniques

for all valuation professionals. This work advances the profession by ensuring that appraisals are

independent, consistent, and objective.

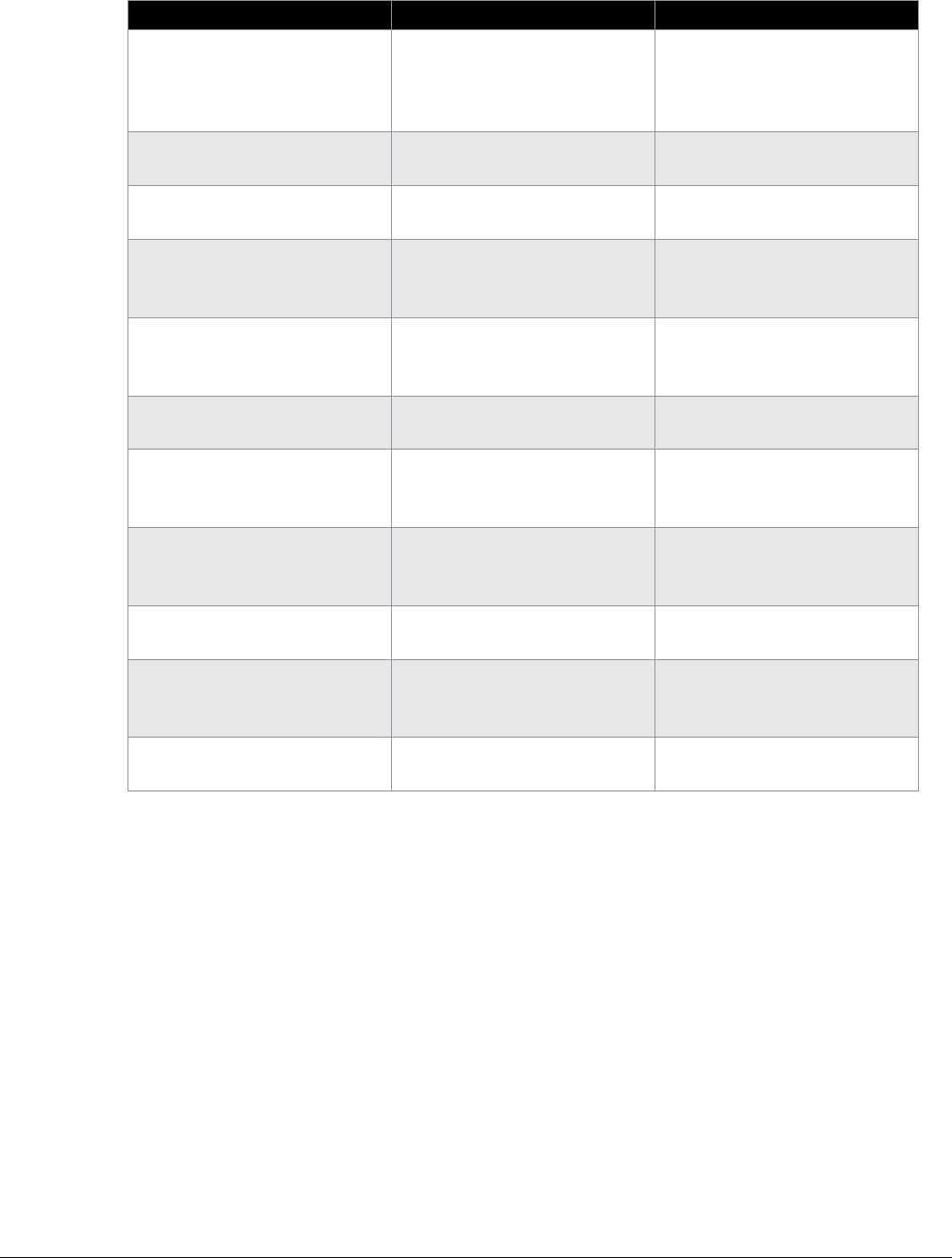

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Table of Contents I

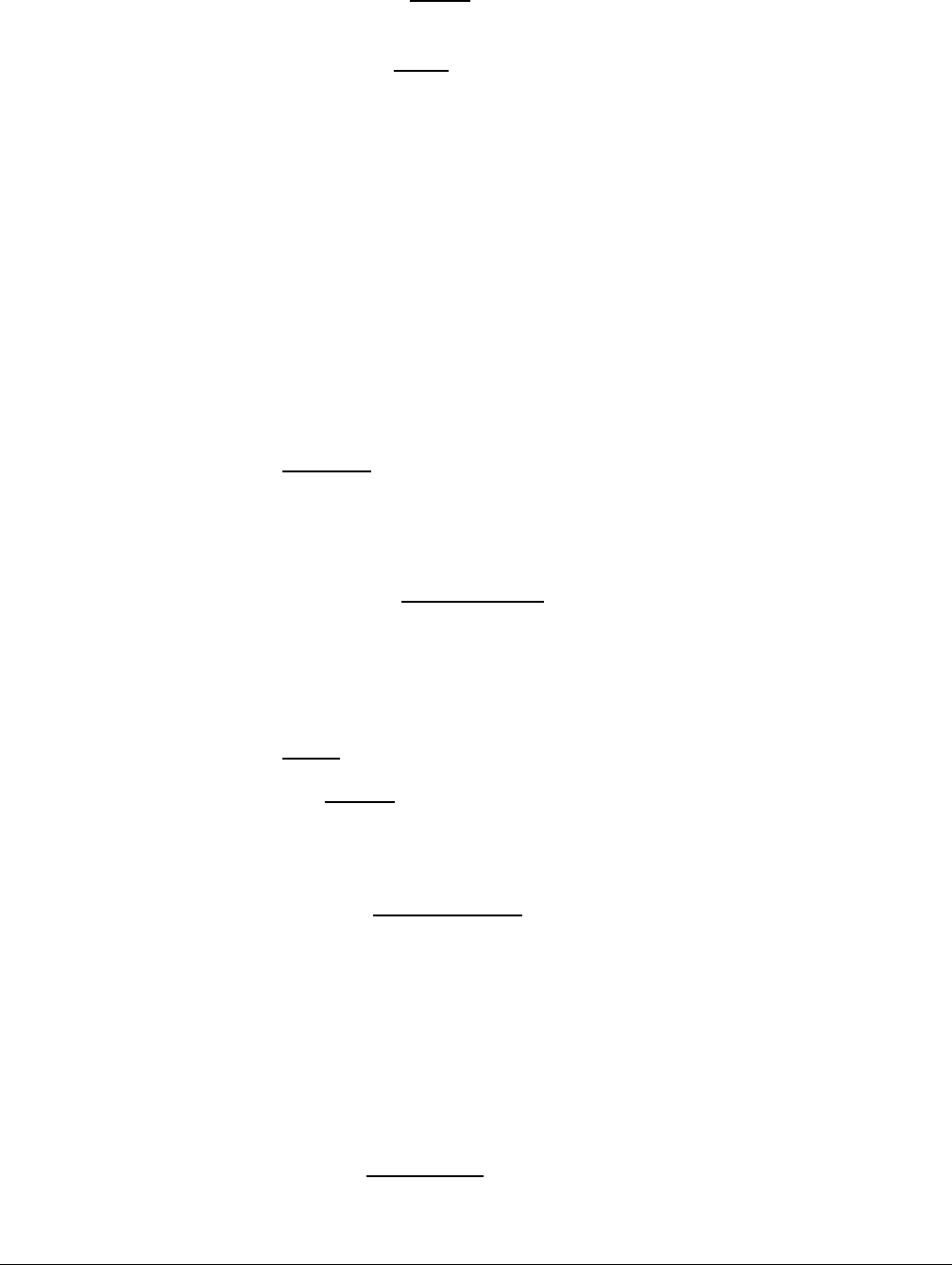

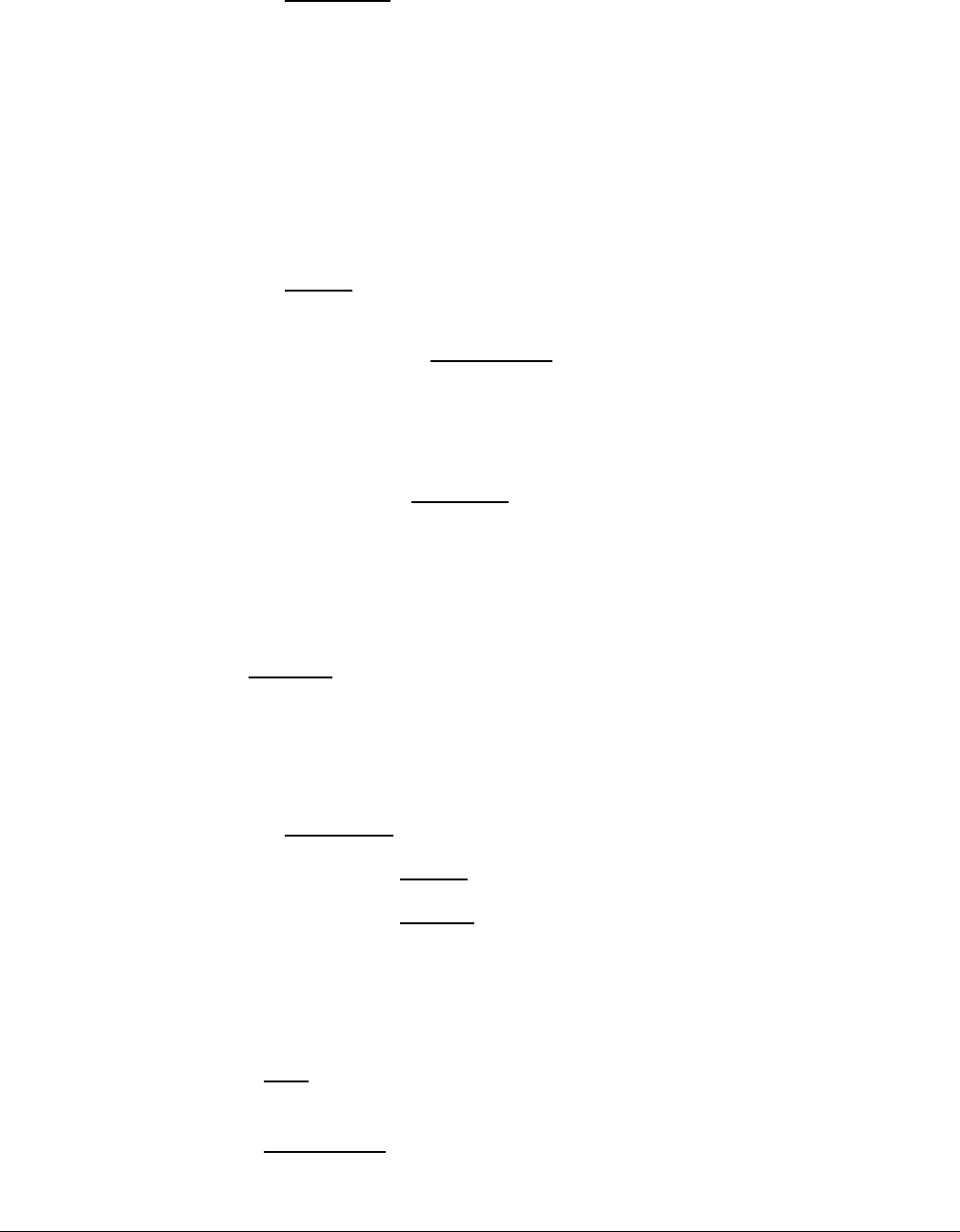

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

0. INTRODUCTORY MATERIAL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

0.1. Purpose . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

0.2. Governing Principles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

0.3. Scope . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

0.4. About the Sixth Edition to the “Yellow Book.” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

0.5. Policy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

1. APPRAISAL DEVELOPMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

1.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

1.2. Problem Identication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

1.2.1. Client . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

1.2.2. Intended Users . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

1.2.3. Intended Use. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

1.2.4. Type of Opinion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

1.2.5. Eective Date.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

1.2.6. Relevant Characteristics of the Subject Property. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

1.2.6.1. Property Interest(s) to be Appraised . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.2.6.2.Legal Description . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.2.6.3. Property Inspections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

1.2.6.4. Contacting Landowners . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

1.2.7. Assignment Conditions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.2.7.1. Instructions, Hypothetical Conditions, Extraordinary Assumptions. . . . . . . .13

1.2.7.2. Jurisdictional Exceptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

1.2.7.3. Special Rules and Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

1.2.7.3.1. Larger Parcel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

1.2.7.3.2. Unit Rule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

1.2.7.3.3. Government Project Inuence and the “Scope of the Project” Rule 16

1.2.7.3.4. Before and After Rule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

1.2.7.3.5. Damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

1.2.7.3.6. Benets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

1.2.8. Scope of Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

1.3. Data Collection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

1.3.1. Property Data.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

1.3.1.1. Land . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

1.3.1.2. Improvements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

1.3.1.3. Zoning and Land Use Controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Table of ContentsII

1.3.1.4. Use History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

1.3.1.5. Sales History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

1.3.1.6. Rental History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

1.3.1.7. Assessed Value and Annual Tax Load . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

1.4. Data Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

1.4.1. Area and Neighborhood Analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

1.4.2. Marketability Studies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

1.4.3. Highest and Best Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

1.4.4. Denition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

1.4.5. Four Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

1.4.5.1. Economic Use. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

1.4.6. Larger Parcel Analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

1.4.7. Highest and Best Use Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

1.5. Application of Approaches to Value. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

1.5.1. Land Valuation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

1.5.1.1. Sales Comparison Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

1.5.1.2. Subdivision Development Method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

1.5.1.3. Ground Leases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

1.5.2. Sales Comparison Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26

1.5.2.1. Prior Sales of Subject Property . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26

1.5.2.2. Selection and Verication of Sales . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26

1.5.2.3. Adjustment Process. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

1.5.2.4. Sales Requiring Extraordinary Verication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28

1.5.3. Cost Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

1.5.3.1. Critical Elements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

1.5.3.1.1. Reproduction and Replacement Costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

1.5.3.1.2. Depreciation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

1.5.3.1.3. Entrepreneurial Prot . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .35

1.5.3.1.4. Unit Rule. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

1.5.4. Income Capitalization Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

1.5.4.1. Market Rent . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .35

1.5.4.2. Comparable Leases. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

1.5.4.3. Expense Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

1.5.4.4. Direct Capitalization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

1.5.4.5. Yield Capitalization (Discounted Cash-Flow [DCF] Analysis). . . . . . . . . .36

1.6. The Reconciliation Process and Final Opinion of Value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

1.7. Partial Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

1.7.1. Before and After Rule (Federal Rule) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

1.7.1.1. Damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .38

1.7.1.2. Benets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .38

1.7.1.3. Osetting of Benets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

1.7.1.4. Takings Plus Damages Procedure (State Rule) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

1.8. Leasehold Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

1.8.1. Market Rent and Highest and Best Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Table of Contents III

1.8.2. Leasehold Estate Acquired . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .40

1.8.3. Larger Parcel Concerns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

1.9. Temporary Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

1.9.1. Temporary Construction Easements (TCEs) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .42

1.9.2. Temporary Inverse Takings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

1.10. Acquisitions Involving Natural Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

1.10.1. The Unit Rule. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

1.10.2. Highest and Best Use Considerations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .44

1.10.3. Special Considerations for Minerals Properties. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

1.10.4. Special Considerations for Forested Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

1.10.5. Water Rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

1.11. Special Considerations in Appraisals for Inverse Condemnations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

1.12. Special Considerations in Appraisals for Federal Land Exchanges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .50

1.13. Supporting Experts Opinions and Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

1.14. Appraisers as Expert Witnesses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

1.15. Condentiality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .54

2. APPRAISAL REPORTING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

2.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56

2.2. Appraisal Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56

2.2.1. Oral Appraisal Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56

2.2.2. Restricted Appraisal Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56

2.2.3. Compliance with Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure . . . . . . . . . . . 57

2.2.4. Electronic Transmission of Appraisal Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57

2.2.5. Draft Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57

2.3. Content of Appraisal Report . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57

2.3.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

2.3.1.1. Title Page. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

2.3.1.2. Letter of Transmittal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

2.3.1.3. Table of Contents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

2.3.1.4. Appraiser’s Certication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

2.3.1.5. Executive Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

2.3.1.6. Photographs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

2.3.1.7. Statement of Assumptions and Limiting Conditions . . . . . . . . . . . . . .59

2.3.1.8. Description of Scope of Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .60

2.3.2. Factual Data—Before Acquisition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

2.3.2.1. Legal Description. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

2.3.2.2. Area, City, and Neighborhood Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .61

2.3.2.3. Property Data. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .61

2.3.2.3.1. Site. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

2.3.2.3.2. Improvements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62

2.3.2.3.3. Fixtures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

2.3.2.3.4. Use History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

2.3.2.3.5. Sales History. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Table of ContentsIV

2.3.2.3.6. Rental History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

2.3.2.3.7. Assessed Value and Annual Tax Load. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

2.3.2.3.8. Zoning and Other Land Use Regulations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

2.3.3. Data Analysis and Conclusions – Before Acquisition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

2.3.3.1. Highest and Best Use. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

2.3.3.1.1. Four Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

2.3.3.1.2. Larger Parcel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .65

2.3.3.2. Land Valuation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

2.3.3.2.1. Sales Comparison Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .65

2.3.3.2.2. Subdivision Development Method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .65

2.3.3.3. Cost Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .66

2.3.3.4. Sales Comparison Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

2.3.3.5. Income Capitalization Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .67

2.3.3.6. Reconciliation and Final Opinion of Market Value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .68

2.3.4. Factual Data—After Acquisition (Partial Acquisitions Only) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .68

2.3.4.1. Legal Description. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

2.3.4.2. Neighborhood Factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .68

2.3.4.3. Property Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .69

2.3.4.3.1. Site. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

2.3.4.3.2. Improvements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .69

2.3.4.3.3. Fixtures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

2.3.4.3.4. History. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

2.3.4.3.5. Assessed Value and Tax Load . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

2.3.4.3.6. Zoning and Other Land Use Regulations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

2.3.5. Data Analysis and Conclusions—After Acquisition (Partial Acquisitions Only) . . . . .69

2.3.5.1. Analysis of Highest and Best Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

2.3.5.2. Land Valuation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

2.3.5.3. Cost Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .70

2.3.5.4. Sales Comparison Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

2.3.5.5. Income Capitalization Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .70

2.3.5.6. Reconciliation and Final Opinion of Market Value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .70

2.3.6. Acquisition Analysis (Partial Acquisitions Only) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

2.3.6.1. Recapitulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

2.3.6.2. Allocation and Damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .71

2.3.6.3. Special Benets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .71

2.3.7. Exhibits and Addenda . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .71

2.4. Reporting Requirements for Leasehold Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .72

2.4.1. Property Rights Appraised . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .72

2.4.2. Improvements Description . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

2.4.3. Highest and Best Use and Larger Parcel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .72

2.5. Project Appraisal Reports. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Table of Contents V

3. APPRAISAL REVIEW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

3.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .80

3.1.1. Government Review Appraisers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

3.1.2. Contract Review Appraisers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .81

3.1.3. Rebuttal Experts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

3.2. Types of Appraisal Reviews . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

3.3. Problem Identication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .83

3.3.1. Client . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .84

3.3.2. Intended Users . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

3.3.3. Intended Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

3.3.4. Type of Opinion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

3.3.5. Eective Date . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .84

3.3.6. Subject of the Assignment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

3.3.7. Assignment Conditions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .85

3.4. Responsibilities of the Review Appraiser . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .85

3.5. Review Appraiser Expressing an Opinion of Value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .86

3.6. Review Appraiser’s Use of Information Not Available to Appraiser . . . . . . . . . . . . . .86

3.7. Review Reporting Requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

3.8. Certication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .88

4. LEGAL FOUNDATIONS FOR APPRAISAL STANDARDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

4.1. Introduction to Legal Foundations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .89

4.1.1. Requirement of Just Compensation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

4.1.2. Market Value: The Measure of Just Compensation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

4.1.3. Federal Law Controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .90

4.1.4. Dening Property Interests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

4.1.5. About the Sixth Edition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .92

4.2. Market Value Standard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .92

4.2.1. Market Value Denition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .93

4.2.1.1. Date of Value. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

4.2.1.2. Exposure on the Open, Competitive Market . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .95

4.2.1.3. Willing and Reasonably Knowledgeable Buyers and Sellers. . . . . . . . . . .95

4.2.1.4. All Available Economic Uses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

4.2.2. The Unit Rule. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

4.2.2.1. Ownership Interests (the Undivided Fee) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

4.2.2.2. Physical Components . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

4.2.2.2.1. Existing Government Improvements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .98

4.2.2.3. Allocations and Administrative Payments Under the Uniform Act . . . . . . .98

4.2.2.4. Departure from the Unit Rule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

4.2.3. Objective Market Evidence; Conjectural and Speculative Evidence . . . . . . . . . . . 99

4.2.4. Renements of Market Value Standard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

4.2.5. Special Rules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

4.2.6. Exceptions to Market Value Standard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Table of ContentsVI

4.3. Highest and Best Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

4.3.1. Highest and Best Use Denition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

4.3.2. Criteria for Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

4.3.2.1. All Possible Uses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

4.3.2.2. Market Demand . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .104

4.3.2.3. Economic Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

4.3.2.4. Zoning and Permits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

4.3.2.4.1. Exceptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

4.3.3. Larger Parcel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

4.3.4. Criteria for Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

4.3.4.1. Unity of Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

4.3.4.2. Unity of Ownership (Title). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

4.3.4.3. Physical Unity (Contiguity or Proximity) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

4.3.4.4. Legal Instructions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 116

4.3.4.5. Special Considerations in Partial Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

4.3.4.6. Special Considerations in Riparian Land Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

4.3.4.7. Special Considerations in Land Exchanges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

4.3.4.8. Special Considerations in Inverse Takings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

4.4. Valuation Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

4.4.1. The Three Approaches to Value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

4.4.2. Sales Comparison Approach. Under federal law. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119

4.4.2.1. Comparability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

4.4.2.2. Adjustments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

4.4.2.3. Sales Verication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

4.4.2.4. Transactions Requiring Extraordinary Care. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

4.4.2.4.1. Prior Sales of the Same Property . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

4.4.2.4.2. Transactions with Potential Nonmarket Motivations . . . . . . . . 124

4.4.2.4.3. Exchanges of Property . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

4.4.2.4.4. Sales that Include Personal Property . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

4.4.2.4.5. Contingency Sales . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

4.4.2.4.6. Oers, Listings, Contracts, and Options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

4.4.2.4.7. Sales After the Date of Valuation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

4.4.3. Cost Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

4.4.3.1. Foundations of the Cost Approach. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132

4.4.3.2. Value of the Land (Site) as if Vacant. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

4.4.3.3. Reproduction Cost and Replacement Cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

4.4.3.4. Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .135

4.4.3.5. Entrepreneurial Incentive and Entrepreneurial Prot . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135

4.4.3.6. Unit Rule and the Cost Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .136

4.4.4. Income Capitalization Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136

4.4.4.1. Applications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

4.4.4.2. Income to Be Considered . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 140

4.4.4.3. Capitalization Rate or Discount Rate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .140

4.4.4.4. Unit Rule Implications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141

4.4.4.5. Further Guidance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Table of Contents VII

4.4.5. Subdivision Valuation and the Development Method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142

4.4.5.1. Reasonable Probability of Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

4.4.5.2. Application to Undeveloped Land . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

4.4.5.3. Credible Cost Estimate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

4.4.5.4. Availability of Comparable Sales . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145

4.5. Project Inuence. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145

4.5.1. The Scope of the Project Test . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146

4.5.2. Application of the Scope of the Project Rule. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

4.5.3. Legal Instructions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

4.5.4. Impact on Market Value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

4.5.5. Limits of the Scope of the Project Rule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

4.5.6. Further Guidance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

4.6. Partial Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

4.6.1. The Federal Rule: Before and After Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152

4.6.1.1. Larger Parcel Determination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

4.6.2. Damage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154

4.6.2.1. Compensable (Severance) Damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155

4.6.2.2. Necessary Support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156

4.6.2.3. Non-Compensable (Consequential) Damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

4.6.3. Benets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

4.6.4. Exceptions to the Federal Rule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .165

4.6.4.1. Taking Plus Damages (the “State Rule”) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

4.6.5. Easement Valuation Issues. In general terms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .168

4.6.5.1. Dominant Easement Interests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

4.6.5.1.1. “Going Rates” and Nonmarket Considerations. . . . . . . . . . . 171

4.6.5.1.2. Temporary Easements. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

4.6.5.1.3. Sale or Disposal of Easements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

4.6.5.2. Lands Encumbered by Easements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172

4.6.5.3. Appurtenant Easements to the Servient Estate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172

4.7. Leaseholds and Other Temporary Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174

4.7.1. Leaseholds. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175

4.7.2. Temporary Inverse Takings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177

4.8. Natural Resources Acquisitions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178

4.8.1. Unit Rule and Natural Resources. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178

4.8.2. Highest and Best Use and Natural Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179

4.8.3. Valuation Approaches for Mineral Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 180

4.8.4. Timber . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182

4.8.5. Water Rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183

4.9. Inverse Takings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .184

4.10. Land Exchanges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185

4.11. Special Rules. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187

4.11.1. Riparian Lands and the Federal Navigational Servitude . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187

4.11.2. Federal Grazing Permits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 195

4.11.3. Streets, Rail Corridors, Infrastructure, and Public Facilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . 195

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Table of ContentsVIII

4.11.3.1. Streets, Highways, Roads, and Alleys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .196

4.11.3.2. Corridors and Rights of Way . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 198

4.11.3.3. Substitute-Facility Compensation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199

4.12. Appraisers’ Use of Supporting Experts’ Opinions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

4.13. Common Purpose (Roles and Responsibilities) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203

4.13.1. Appraisers and Other Experts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203

4.13.2. Government Agency Sta . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .205

4.13.3. Landowners . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 206

4.13.4. Attorneys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 206

APPENDIX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 207

A. Appraisal Report Documentation Checklist. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 208

B. Recommended Appraisal Report Format for Total Acquisition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 212

C. Recommended Appraisal Report Format for Partial Acquisitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214

D. Recommended Project Appraisal Report Format . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 216

E. Extraordinary Verication of Sales . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .218

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 220

INDEX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Foreword 1

FOREWORD

This is the sixth edition of the Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions, known to many

as the Yellow Book. The valuation of real estate in federal acquisitions—serving public purposes that range

from national parks and public buildings to infrastructure and national security needs—must satisfy not only

appraisal industry standards authorized by Congress, but also the command of the Fifth Amendment to

the U.S. Constitution: that no property shall “be taken for public use, without just compensation.” Sound

appraisals are vital to ensure that government acquisitions do justice to both the individual whose property is

taken and the public which must pay for it. These federal Standards, frequently cited in legislation and court

rulings, have guided the appraisal process in the valuation of real estate in federal acquisitions since their

original publication by the Interagency Land Acquisition Conference in 1971.

The Attorney General formed the Interagency Land Acquisition Conference in 1968. Since its inception,

the Conference has been “fueled by the common purpose and dedication” of its participants—any and all

federal agencies that acquire property for public uses. Their shared objectives are to promulgate uniform,

fair, and ecient appraisal standards for federal acquisitions; to identify and nd the best solutions to

the problems incident to acquiring land for public purposes; and to consider all acquisition-related

matters with the twin aims of protecting the public interest and ensuring fair and equitable treatment of

landowners whose property is aected by public projects.

The Conference is chaired by the Assistant Attorney General for the Environment and Natural Resources

Division, Department of Justice, and Andrew M. Goldfrank, Chief of the Division’s Land Acquisition

Section, serves as Conference Executive.

In updating the Standards for the rst time in 16 years, we incorporated relevant new appraisal

methodology and theory, integrated new case law, and ensured appropriate consistency with professional

appraisal standards. The content is also restructured and revised for clarity and readability, resulting in

practical and understandable guidance for appraisers, attorneys, and the general public. The nal text

reects the contributions of the Conference agencies’ representatives, who shared valuable insights and

suggestions on the previous Standards and commented on drafts of the sixth edition.

The Appraisal Foundation provided technical assistance in preparing these Standards for publication. To

ensure the Yellow Book is easily available to all interested users, The Appraisal Foundation is publishing

this 2016 edition in both print and electronic forms under a cooperative agreement with the Department

of Justice. A free electronic version is also available on the Department of Justice website.

I commend the sixth edition of the Yellow Book to all readers as the foremost authority on real estate

valuation in federal eminent domain, and an indispensable resource for the appraisal of property for all

types of federal acquisitions. And, I would like to single out for special recognition appraisal unit chief

Brian Holly, MAI, and trial attorney Georgia Garthwaite, of the Department of Justice, who led the eort

that resulted in this sixth edition of the Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions, with

the assistance of Mr. Goldfrank.

John C. Cruden, Chair

Interagency Land Acquisition Conference

December 6, 2016

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Acknowledgments2

The Interagency Land Acquisition Conference gratefully acknowledges the important

contributions of the following individuals.

United States Department of Justice

Jennifer Campbell, Supervisory Paralegal

Eric Chiapponi, Review Appraiser

Hannah Flesch, Paralegal

Kristine Hartley, Review Appraiser

Jacqueline Hyatt, Law Clerk

Daniel Kastner, Trial Attorney

Kristin Muenzen, Trial Attorney

Erica Pencak, Trial Attorney

Wade Schroeder, Review Appraiser

Michelle Sellers, Paralegal

Lucy Shepherd, Sta Assistant

Moriah Sulc, Paralegal

Reade Wilson, Trial Attorney

General Services Administration

Nicholas Huord, Chief Appraiser

United States Army Corps of Engineers

Mary Arndt, Chief Appraiser

United States Forest Service

Jerry Sanchez, Chief Appraiser

United States Department of the Interior

Timothy Hansen, Chief Appraiser

United States Department of the Navy

Mark Worthen, Chief Appraiser

The Appraisal Foundation

Magdalene Vasquez, Editor

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Introductory Material 3

0. INTRODUCTORY MATERIAL

0.1. Purpose. The purpose of the Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions (Standards) is to

promote fairness, uniformity, and eciency in the appraisal of real property in federal acquisitions. Just

compensation must be paid for property acquired for public purposes, whether by voluntary purchase,

land exchange, or the power of eminent domain. Landowners should be treated equitably no matter

which agency is acquiring their land. The use of public funds compels ecient, cost-eective practices.

The same goals of uniformity, eciency, and fair treatment of those aected by public projects underlie

the Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970 (hereinafter

Uniform Act).

1

The Uniform Act applies to federal acquisitions as well as many state and local

government acquisitions involving federal funds.

In federal acquisitions, the purpose of an appraisal—whether prepared for the government or a

landowner—is to develop an opinion of market value that can be used to determine just compensation

under federal law. As a result, appraisals in federal acquisitions face dierent—and often more rigorous—

valuation problems and standards than those typically encountered in appraisals for other purposes,

such as private sales, tax, mortgage, rate-making, or insurance. These Standards set forth the guiding

principles, legal requirements, and practical implications for the appraisal of property in all types of

federal acquisitions.

These Standards may need to be modied to meet specic requirements of agency programs, special

legislation, or negotiated agreements between agencies and landowners.

2

Any such modications to these

Standards require specic written instructions from the acquiring agency, as do modications to comply

with court rulings or stipulations between parties in litigation.

Legal questions often arise when applying these Standards to the facts of a specic appraisal assignment,

requiring appropriate written legal instructions. Appraisers and agency counsel should work closely to

ensure legal instructions not only are legally correct, but also adequately address the valuation problem

to be solved. Federal agencies are also encouraged to consult with the U.S. Department of Justice on

challenging legal and valuation issues, regardless of whether condemnation is anticipated. Appropriate

legal instructions can resolve doubt about the proper method of valuation or the application of particular

rules to specic factual situations. If these Standards are properly applied, under sound legal instructions,

1 The Uniform Act, also called the URA, is discussed throughout these Standards. The Uniform Act addresses two principal areas:

• Real Property Acquisition policies set out agency appraisal criteria and negotiation obligations in order to encourage acquisitions by agreement, avoid

litigation, ensure consistent treatment for landowners across federal programs, and promote public condence in federal property acquisition practices.

• Relocation Assistance policies are designed to ensure uniform, fair, and equitable treatment of those who are displaced by government programs and

projects, and to minimize the hardships displaced persons may face as a result of programs and projects intended to benet the public as a whole.

Federal regulations direct agencies to implement the Uniform Act in an ecient, cost-eective manner, and specically reference these appraisal

Standards at 49 C.F.R. § 24.103. In turn, these appraisal Standards presume full compliance with all applicable provisions of the Uniform Act and

related regulations. The full Uniform Act is codied at 42 U.S.C. §§ 4601 to 4655, and enforced by federal regulations at 49 C.F.R. Part 24.

2 Some federal agencies have adopted appraisal and/or appraisal review handbooks or manuals that may modify these Standards to meet other criteria

for specic acquisition programs.

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Introductory Material4

the resulting appraisal will be a credible, reliable, and accurate opinion of market value that can be used

for purposes of just compensation.

0.2. Governing Principles. Federal acquisitions entail dierent appraisal standards than other types

of property transactions because they involve payment of just compensation. As the measure of just

compensation is a question of substantive right “grounded upon the Constitution of the United States,”

just compensation must be determined under federal common law—that is, case law.

3

Federal case law

holds that just compensation must reect basic principles of fairness and justice for both the individual

whose property is taken and the public which must pay for it. To achieve this, an objective and practical

standard was required, and the Supreme Court has long adopted

the concept of market value to measure just compensation. As a

result, just compensation is measured by the market value of the

property taken. “To award [a landowner] less would be unjust to

him; to award him more would be unjust to the public.”

4

Most of the case law on just compensation stems from the federal

exercise of eminent domain, but the resulting practical, objective

rules for determining market value have been adopted in numerous federal statutes, rules and regulations,

and programs and agency policies. As a result, the federal eminent domain-based valuation requirements

reected in these Standards apply to all types of federal acquisitions.

5

And because these Standards

require appraisers to provide an opinion of market value and not just compensation, they also apply to

the appraisal of property for many types of government transactions that require a reliable determination

of market value without reference to just compensation, such as land exchanges under the Federal Land

Policy and Management Act (FLPMA).

6

Certain types of transactions may require exceptions to specic valuation rules contained in these

Standards—for example, to comply with special legislation—but the underlying principles of just

compensation remain in force. In addition, while just compensation does not exceed market value fairly

determined, Congress has the power to allow or require the United States to pay more than the just

compensation required under the Fifth Amendment. For example, under the Uniform Act, people and

businesses displaced by public projects receive moving and relocation expenses in addition to the market-

value-based just compensation received for the acquisition.

Just compensation is determined under federal rather than state law. Appraisers must apply federal

law throughout the process of opining on market value, recognizing that federal and state laws dier

in important respects. Most appraisals for federal acquisitions involve straightforward application of

established law to the facts. But some valuation problems require nuanced legal instructions to address

complicated or undecided questions of law. These Standards address both routine and complex legal

issues that arise in federal acquisitions.

3 United States v. Miller, 317 U.S. 369, 380 (1943); see Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803).

4 Bauman v. Ross, 167 U.S. 548, 574 (1897).

5 Similarly, the appraisal requirements set forth in the Uniform Act regulations “are necessarily designed to comply with . . . Federal eminent domain

based appraisal requirements.” 49 C.F.R. app. A § 24.103(a).

6 See Sections 1.12 and 4.10 for a discussion of special considerations arising in the appraisal of property for federal land exchanges under FLPMA, 43

U.S.C. § 1716, and other statutes.

“. . . nor shall private property

be taken for public use, without

just compensation.”

— U.S. Constitution,

amendment v

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Introductory Material 5

Where just compensation is concerned, a reliable process is

necessary to ensure a just result. For federal acquisition purposes,

the appraisal process must result in opinions of market value

that are credible, reliable, and accurate. These federal Standards

governing the appraisal process protect against allowing

“mere speculation and conjecture to become a guide for the

ascertainment of value—a thing to be condemned in business

transactions as well as in judicial ascertainment of truth.”

7

0.3. Scope. These Standards cover the following areas:

(1) Appraisal Development

(2) Appraisal Reporting

(3) Appraisal Review

(4) Legal Foundations

Section 1: Appraisal Development sets forth the standards

that must be followed in developing an appraisal for federal acquisition purposes to ensure a

credible, reliable, and accurate valuation that reects just compensation mandated by the United

States Constitution. Section 1 derives from generally accepted professional appraisal standards

and federal law. Competent development of an appraisal under these Standards requires an

understanding of applicable law, described in Section 4: Legal Foundations and Guidance.

Section 2: Appraisal Reporting presents the content and documentation required for

appraisals developed in compliance with these Standards and applicable law. Section 2 also

includes a recommended appraisal report format. Agencies may modify these documentation

and formatting requirements in certain circumstances to ensure appropriate exibility to

accomplish agency program goals.

Section 3: Appraisal Review addresses technical and administrative reviews of appraisals by

appraisers and non-appraisers, and is derived from generally accepted appraisal review standards

and federal law and regulations. The purpose of Section 3 is to ensure that appraisals used by the

government in its land acquisitions are credible, reliable and accurate and have been conducted

in an unbiased, objective, and thorough manner, in accordance with applicable law.

Section 4: Legal Foundations explains the federal law that dictates these appraisal Standards,

which apply to appraisals for all federal acquisitions involving the measure of just compensation.

Federal case law, cited throughout the section, has long held that market value is normally

the measure of just compensation; the rare departures from the market value standard are

also discussed. Appraisers who make market value appraisals for federal acquisitions must

understand and apply federal law in the development, reporting, and review of appraisals in

federal acquisitions. Section 4 also includes a discussion of the legal standards that apply to many

recurring valuation problems, as well as guidance on specialized appraisal issues that are unique

to federal acquisitions.

7 Olson v. United States, 292 U.S. 246, 257 (1934).

“[O]ur cases have

set forth a clear and

administrable rule for

just compensation: ‘The

Court has repeatedly held

that just compensation

normally is to be

measured by ‘the market

value of the property at

the time of the taking.’”

— Horne v. Dep’t of Agric.,

135 S. Ct. 2419, 2432

(2015) (quoting United

States v. 50 Acres of Land

(Duncanville), 469 U.S. 24,

29 (1984))

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Introductory Material6

As a whole, these Standards aim to encourage uniform, reliable, and fair approaches to appraisal

problems, and to ensure consistent, eective practices for evaluating appraisal reports for federal

acquisition purposes. Nothing in these Standards is intended to limit the scope of appraisal

investigations or to undermine the independence and objectivity of appraisers engaged in

providing opinions of market value for just compensation purposes.

With appropriate modications, these Standards—or rather, portions of these Standards—may

be applied to valuations for non-acquisition purposes, such as appraisals for conveyance, sale, or

other disposals of federal property. Some rules that must be followed in valuing real property for

federal acquisition purposes are inapt or impossible to apply to federal disposals. As discussed

in Section 1.2.8, these Standards do not prohibit adapting these valuation rules to address the

distinct challenges of appraising federal property for disposal purposes.

0.4. About the Sixth Edition to the “Yellow Book.” In this sixth edition, the Uniform Appraisal

Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions have been updated to reect developments in appraisal

methodology and theory, case law, and other federal requirements since the fth edition was

published in 2000. These Standards have also been restructured for clarity, convenience, and

consistency with professional appraisal standards, as appropriate.

The four-part structure is designed to follow the appraisal process, from development, to

reporting, to review, while the nal section explains the legal foundations for the appraisal

development, reporting, and review requirements, and provides practical examples of how the

underlying law applies to actual valuation problems in federal acquisitions. This sixth edition

is also broadly consistent with the structure of the current Uniform Standards of Professional

Appraisal Practice (USPAP) and federal regulations implementing the Uniform Relocation

Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970 (Uniform Act or URA).

The sixth edition’s structure reects the evolution of USPAP (which did not exist in early

editions of these Standards) as the congressionally authorized minimum standards for the

appraisal profession. It also continues the fth edition’s focus on the practical eects of federal

valuation requirements on appraisals in federal acquisitions.

8

Broadly speaking, this sixth

edition incorporates previous editions as follows:

Section 1: Appraisal Development addresses the appraisal process and the scope of work appropriate

for appraisals in federal acquisitions, integrating appraisal development topics from the fth

edition’s Parts A, B, C, and D with USPAP’s Scope of Work Rule (created since the fth edition);

Section 2: Appraisal Reporting incorporates the contents of the fth edition’s Part A, Data

Documentation and Appraisal Reporting Standards;

8 Recognizing that the vast majority of federal acquisitions are accomplished by voluntary means, the fth edition placed technical appraisal

requirements up front. Previous editions led o with discussion of federal law on valuation issues, primarily focusing on eminent domain

litigation. To reduce confusion, topics in this sixth edition are organized by number, unlike the lettered subparts in earlier editions. A detailed

cross-reference table is included in the Appendix.

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Introductory Material 7

Section 3: Appraisal Review incorporates the contents of the fth edition’s Part C, Standards for

the Review of Appraisals; and

Section 4: Legal Foundations integrates and updates the topics in the fth edition’s Part B, Legal

Basis for Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions, and several legal topics previously

in Part D as miscellaneous. Of particular note, the fth edition’s lengthy Part D-9, Comparable

Sales Requiring Extraordinary Verication and Treatment, is now addressed in Section 1.5.2.4,

and the legal foundations for these heightened requirements are explained in Section 4.4.2.4. A

verication checklist is also included in the Appendix.

0.5. Policy. In acquiring real property, or any interest in real

property, the United States will impartially protect the interests

of the public and ensure the fair and equitable treatment

of those whose property is needed for public purposes. As a

general policy, the United States bases its property acquisitions

on appraisals of market value, the standard adopted

by the courts as the practical, objective measure of just

compensation.

“[I]t is the duty of the state,

in the conduct of the inquest

by which the compensation is

ascertained, to see that it is just,

not merely to the individual

whose property is taken but to

the public which is to pay for it.”

— Bauman v. Ross, 167 U.S. 548,

574 (1897)

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Appraisal Development8

1.1. Introduction. These Standards reect the application of the appraisal process to valuation

assignments for federal property acquisitions. The goal of every appraisal prepared under these

Standards is a well-supported opinion of market value that is credible, reliable, and accurate.

These requirements and rules are set forth to ensure that the appraiser’s opinion of market

value can be used for purposes of just compensation under the United States Constitution.

The appraisal process provides a logical framework for the identication and proper solution

of an appraisal problem. The general steps of the appraisal process are:

• Problem identication

• Scope of work

• Data collection

• Data analysis

• Application of approaches to value

• Reconciliation and nal opinion of market value

• Report of opinion of market value

The rst step in the appraisal process is to identify the appraisal problem to be solved. To do

so, the appraiser and the client

9

must address seven critical assignment elements presented in

Section 1.2. This discussion summarizes each of the seven elements and in particular addresses

the assignment conditions associated with appraisals prepared for federal property acquisitions.

The special legal rules and methods required under these Standards are identied and briey

addressed. This section is intended to assist appraisers and agencies in determining the

appropriate scope of work for each appraisal assignment.

Section 1 also addresses the next four steps in the appraisal process. Section 1.3 addresses data

collection concerning the subject property and the market, respectively. Section 1.4 addresses

data analysis, including highest and best use, and larger parcel and market analysis. Section

1.5 addresses the application of the approaches to value including land valuation, the sales

comparison approach, the income capitalization approach, and the cost approach. Section 1.6

addresses the reconciliation process and the nal opinion of market value. Section 1 also contains

appraisal development requirements specic to certain types of federal acquisitions including

partial acquisitions, leasehold acquisitions, temporary acquisitions, natural resources acquisitions,

inverse takings, and federal land exchanges. Finally, Section 1 provides guidance concerning the

use of reports by other experts and the appraiser’s responsibilities in litigation.

Section 1 is generally consistent with Standard 1 of USPAP, but provides more in-depth

discussion of each topic to address the heightened requirements for appraisals prepared for

just compensation purposes. These Standards do not cover all of the valuation problems that

9 See Section 1.2.1 for discussion concerning the client.

1. APPRAISAL DEVELOPMENT

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Appraisal Development 9

might be encountered in the appraisal of real property for government acquisitions. Instead,

the Standards address the fundamental scope of work issues associated with preparing sound

appraisals for federal agencies. Proper application of the scope of work will ensure that federal

agencies obtain appraisals that are credible, reliable, and accurate and result in uniform, fair

treatment of property owners during the acquisition process.

The acquisition of private property by government agencies can create dicult and complex

valuation problems, the solutions to which must be developed with great care. It is critical that in

those instances when proposed acquisitions are complex, high value, sensitive, or controversial or

when the matter must be referred to the Department of Justice for litigation, the full scope of work

described in these Standards must be applied. In other assignments, it is appropriate to modify

the scope of work when the acquisition is noncomplex and/or to ensure the cost of the appraisal

is consistent with the requirements of the client agency. Under no circumstances may the scope of

work result in an appraisal that does not meet the minimum requirements under the Uniform Act.

1.2. Problem Identication. The problem identication process ensures that the appraiser

identies and understands the critical assignment elements associated with developing an

appraisal for federal acquisition purposes under these Standards. Federal appraisal requirements

are often dierent than those of private clients, and the appraiser must fully understand and

comply with these requirements.

The scope of work

10

must address seven critical assignment elements for each appraisal assignment:

• Client

• Intended users

• Intended use

• Type and denition of value

• Eective date

• Relevant characteristics about the subject property

• Assignment conditions

1.2.1. Client. The client is the party or parties engaging an appraiser in an assignment. The client is

the appraiser’s primary contact and provides all of the information about the assignment. Most

importantly, the client is the entity to whom the appraiser owes condentiality. The client must

be established before the appraiser begins the assignment. Under these Standards, the client is

the federal agency that is requesting the appraisal.

1.2.2. Intended Users. All intended users of an appraisal must be identied at the outset of the

assignment. Intended users often include not only the client agency but also other federal,

state, or local agencies. In appraisals for land exchanges, discussed in more detail in Section

1.12, intended users may include landowners. In appraisals for acquisitions referred to the

Department of Justice for condemnation litigation purposes, the intended users may include

10 The ApprAisAl FoundATion, uniForm sTAndArds oF proFessionAl ApprAisAl prAcTice (USPAP) 17-18 (2016-2017) [hereinafter USPAP].

See Scope of Work Rule and Standards Rule 1-2.

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Appraisal Development10

the federal court, landowners, and their counsel. The appraiser must fully identify and

understand who the intended users are before initiating the appraisal assignment.

1.2.3. Intended Use. The intended use of the appraisal is one of the most important elements of

the problem identication process. In most assignments, the intended use of the appraisal is

to assist the client agency in its determination of the amount to be paid as just compensation

for the property rights acquired or conveyed. In those cases that have been referred to the

Department of Justice for litigation, the intended use will be to assist government’s trial counsel

and the court in determining market value for the purpose of just compensation.

1.2.4. Type of Opinion. In all assignments for federal acquisitions under these Standards, the type

of opinion to be developed is market value. It is imperative that the appraiser utilize the correct

denition of market value. In all federal acquisitions except leasehold acquisitions, appraisers

must use the following federal denition of market value:

11

Appraisers should not link opinions of value under these Standards to a specic opinion of

exposure time, unlike appraisal assignments for other purposes under USPAP Standards Rule

1-2(c). This requires a jurisdictional exception to USPAP because, as discussed in Section 4.2.1.2,

the federal denition of market value already presumes that the property was exposed on the

open market for a reasonable length of time, given the character of the property and its market.

Similarly, estimates of marketing time are not appropriate for just compensation purposes, and

must not be included in appraisal reports prepared under these Standards.

12

While estimates

of marketing time may be appropriate in other contexts and are often required by relocation

companies, mortgage lenders, and other users, “provid[ing] a reasonable marketing time

opinion exceeds the normal information required for the conduct of the appraisal process”

13

and is beyond the scope of the appraisal assignment under these Standards.

1.2.5. Eective Date. The eective date of value for the assignment is dependent on the intended

use, which depends on the legal nature of the acquisition and is further discussed in Section

4.2.1.1. In most direct acquisitions (such as voluntary purchases), the eective date of value

will be as near as possible to the date of the acquisition—typically the date of nal inspection.

In “quick-take” condemnations under the Declaration of Taking Act, the date of value is the

earlier of (1) the date the United States les a declaration of taking and deposits estimated

compensation with the court, or (2) the date the government enters into possession of the

property. In “complaint-only” straight condemnations under the General Condemnation

11 See Section 4.2.1 for the legal basis for this denition.

12 Marketing time refers to the period of time it would take to sell the appraised property, after the eective date of value, at its appraised value.

13 USPAP, Advisory Opinion 7, Marketing Time Opinions.

Denition of Market Value

Market value is the amount in cash, or on terms reasonably equivalent to cash, for which in

all probability the property would have sold on the eective date of value, after a reasonable

exposure time on the open competitive market, from a willing and reasonably knowledgeable

seller to a willing and reasonably knowledgeable buyer, with neither acting under any

compulsion to buy or sell, giving due consideration to all available economic uses of the property.

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Appraisal Development 11

Act in which no declaration of taking is led, there may be two valuation dates: the rst date

will likely be the date of nal inspection; the second date is when the appraiser is asked to

form a new opinion of value (a new appraisal assignment) eective as of the date of trial.

In inverse takings, the date of value is the date of taking, typically established by the court.

When necessary, the client must provide the appraiser with a legal instruction regarding the

appropriate eective date of value and the legal basis for the date to be used in the assignment.

For assignments in which the eective date of value is prior to the date of the report, the

appraiser should consult USPAP guidance regarding retrospective value opinions.

14

The

identication of the eective date of value does not preclude consideration of market data

after that date. Comparable sales and rentals occurring after the eective date of value may be

considered (see Section 4.4.2.4.7). Market data after the eective date of value that conrms

market trends identied as of the eective date of value may also be considered.

1.2.6. Relevant Characteristics of the Subject Property. The subject property is the property

that is being appraised.

15

In the context of these Standards the term may refer to the property

that is the larger parcel. In developing an appraisal under these Standards the appraiser must

complete a comprehensive study of the physical, legal, and economic characteristics of the

subject property as well as the neighborhood and market in which it is located.

1.2.6.1. Property Interest(s) to be Appraised. It is the responsibility of the acquiring agency to

provide the appraiser with an accurate description of the property interest(s) to be appraised in

each assignment.

Often, the property interest being acquired and appraised is the fee simple estate. This is so

even when the real estate has been divided into multiple estates with dierent owners. This is

an application of the unit rule, which will be discussed in greater detail in Section 1.2.7.3.2 and

4.2.2. Federal agencies can also acquire something less than the fee simple interest in property,

for example by excluding easements for roads and utilities, mineral rights, water rights, or mineral

leases. Agencies can also acquire partial interests such as permanent and temporary easements,

rights of entry, and leaseholds. The appraiser must fully understand the nature of the estate(s) to

be acquired, and request legal instructions if clarication is needed, for each assignment.

1.2.6.2. Legal Description. It is the responsibility of the agency to provide the appraiser with an

accurate legal description of the subject property prior to initiating the assignment. If the

assignment is a partial acquisition, the appraiser should receive both a legal description of

the larger parcel and a legal description of the remainder property, or alternatively, a legal

description of the area to be acquired and/or encumbered. Since the larger parcel is determined

by the appraiser as part of the highest and best use analysis, it is possible that a legal description

for the larger parcel must be developed at that point in the appraisal development process.

The appraiser should verify the legal description (1) on the ground during a physical inspection

of the property; (2) with the owner of the property (if possible); (3) by comparing it with aerial

or other maps available in city, county, or other governmental oces; and (4) by comparing it

14 USPAP, Advisory Opinion 34, Retrospective and Prospective Value Opinions.

15 Subject Property, The dicTionAry oF reAl esTATe ApprAisAl (6th ed. 2015).

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Appraisal Development12

with public records in the recorder’s, auditor’s, assessor’s, tax collector’s, or other appropriate

city or county oces. If the appraiser discovers a signicant error or inconsistency, the

appraiser should consult the client for clarication before proceeding with the appraisal.

1.2.6.3. Property Inspections. The appraiser must personally inspect the subject property in every

assignment. Appraisers should recognize that they may have only one opportunity to physically

inspect the property and should ensure that they have collected all information required to

identify all property characteristics (land and improvements) that inuence value.

In partial acquisitions in which the appraiser’s inspection precedes the acquisition, the

appraiser should request that the agency stake the portion(s) of the property to be acquired

before the inspection so that the impact of the acquisition on the remainder can be visualized.

If the appraiser’s inspection occurs after construction of the government’s project begins (most

commonly in Declaration of Taking cases), the appraiser must learn about the property as it

existed before the taking to ensure that the property characteristics inuencing value before the

taking are properly accounted for.

16

In acquisitions of such large or inaccessible properties that

a physical on-the-ground inspection may be impossible or not useful, the client may modify the

scope of work to allow for an aerial inspection of the property.

In most assignments, the appraiser should also conduct a physical inspection of all properties

used as sales or rental comparables. The level of detail of these inspections is dependent on

the complexity of the appraisal problem to be solved. Physical inspection of all properties

used as sales or rental comparables is required for any appraisal being prepared for the U.S.

Department of Justice for litigation purposes.

1.2.6.4. Contacting Landowners. During the course of inspecting the subject property, the

appraiser is expected to meet with the property owner or, in the owner’s absence, the owner’s

agent or representative. If a property owner is represented by legal counsel, all owner contact

and property inspections must be arranged through the owner’s attorney, unless the attorney

specically authorizes the appraiser to make direct contact with the owner. Owners are

generally a prime source of detailed information concerning the history, management, and

operation of the property.

Under the Uniform Act, the owner or the owner’s designated representative must be given an

opportunity to accompany the acquiring agency’s appraiser during the appraiser’s inspection

of the property.

17

1.2.7. Assignment Conditions. In developing an appraisal under these Standards, appraisers must

understand the special assignment conditions associated with the valuation of property being

acquired by federal agencies. These special assignment conditions include the use of instructions,

hypothetical conditions, extraordinary assumptions, and jurisdictional exceptions from USPAP as

well as the special rules and methods required in these appraisals.

16 J.D. eATon, reAl esTATe VAluATion in liTigATion 272-73 (2d ed. 1995) [hereinafter eATon].

17 42 U.S.C. § 4651(2).

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Appraisal Development 13

1.2.7.1. Instructions, Hypothetical Conditions, Extraordinary Assumptions. Application

of these Standards may require instructions from the acquiring agency. For example, agency

instructions can provide clarication about the legal description of the property to be appraised

and/or the property rights being acquired. Agency instructions that result in assumptions,

hypothetical conditions, or extraordinary assumptions that impact the appraisal process or the

appraisal results should be carefully considered before being issued. An appraiser cannot make

an assumption or accept an instruction that is unreasonable or misleading, nor can an appraiser

make an assumption that corrupts the credibility of the opinion of market value

18

or alters the

scope of work required by the appraiser’s contract. For example, it is improper (unless specically

instructed otherwise) for an appraiser to make an assumption that the property being appraised is

free of contamination when there is evidence from the property inspection or the past use of the

property that contamination may exist. Instructions should always be in writing, retained in the

appraiser’s workle, and included in the addenda of the report.

Hypothetical Conditions. “A hypothetical condition

19

may be used in an assignment only if:

• use of the hypothetical condition is clearly required for legal purposes, for purposes of

reasonable analysis, or for purposes of comparison;

• use of the hypothetical condition results in a credible analysis; and

• the appraiser complies with the disclosure requirements set forth in USPAP for hypothetical

conditions.”

20

The appraiser must always consult with the client and/or counsel before employing a

hypothetical condition. If utilization of a hypothetical condition is required by the facts or

nature of the acquisition, then written legal instructions must be provided to the appraiser

and included within the appraisal report. The appraiser must also comply with USPAP

requirements regarding disclosure and impact on the value conclusion.

21

Extraordinary Assumptions. “An extraordinary assumption

22

may be used in an

assignment only if:

• it is required to properly develop credible opinions and conclusions;

• the appraiser has a reasonable basis for the extraordinary assumption;

• use of the extraordinary assumption results in a credible analysis; and

• the appraiser complies with the disclosure requirements set forth in USPAP for extraordinary

assumptions.”

23

18 See Section 4.4 (Valuation Process).

19 “Hypothetical conditions are contrary to known facts about physical, legal, or economic characteristics of the subject property; or about

conditions external to the property, such as market conditions or trends; or about the integrity of data used in an analysis.” USPAP, Denitions, 3.

20 USPAP, Comment to Standards Rule 1-2(g), 19.

21 USPAP, Standards Rule 2-2(a)(xi), (b)(xi), 25, 27.

22 “Extraordinary assumptions presume as fact otherwise uncertain information about physical, legal, or economic characteristics of the

subject property; or about conditions external to the property, such as market conditions or trends; or about the integrity of data used in an

analysis.” USPAP, Comment to Extraordinary Assumption, 3.

23 USPAP, Comment to Standards Rule 1-2(f), 19.

Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions / Appraisal Development14

It is improper for an appraiser to classify conclusions reached after investigation and analysis

as assumptions. For example, after proper investigation and analysis, an appraiser can conclude

that a probability of rezoning for the subject property exists, but it would be improper to

assume such a probability. The appraiser must also comply with USPAP requirements regarding

disclosure and impact on the value conclusion.

Circumstances arise in which a legal instruction is necessary to properly complete the

appraisal assignment. Examples of situations in which a legal instruction may be required

include: unity of title questions in a larger parcel analysis, scope of the government’s project

questions, compensability of damages questions, special benets questions, and eective date

of value questions. Resolving questions such as these is a proper role for agency counsel (and

Department of Justice trial attorneys) and appraisers must follow their guidance. In situations

where the legal outcome is uncertain, counsel may direct the appraiser to develop a dual

premise appraisal.

1.2.7.2. Jurisdictional Exceptions. While these Standards generally conform to USPAP,

24

in certain

instances it is necessary to invoke USPAP’s Jurisdictional Exception Rule to comply with

federal law relating to the valuation of real estate for just compensation purposes. Areas of