REPORT TO CONGRESS

REDUCING BARRIERS TO FURNISHING SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER (SUD)

SERVICES USING TELEHEALTH AND REMOTE PATIENT MONITORING FOR

PEDIATRIC POPULATIONS UNDER MEDICAID

FINAL REPORT

As Required by section 1009(d) of the

Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment

for Patients and Communities Act (Pub. L. 115-271)

May 15, 2020

Section 1009(d) of the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act required the Secretary of

Health and Human Services (HHS), acting through the Administrator of the Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), to issue this final report. The Office of the Assistant

Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) and their contractor RTI International prepared

this final report in consultation with CMS. While this report includes programs and cites to laws

administered by federal agencies, it is not a federal endorsement of specific programs. All

research included in this report was completed in 2019 prior to the COVID-19 national public

health emergency.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

CONTENTS

Section Page

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...........................................................................................................ES-1

Background ..................................................................................................................................1

Purpose and Scope ......................................................................................................................2

Data and Methods .......................................................................................................................5

Data Collection .....................................................................................................................5

Environmental Scan ................................................................................................... 5

Case Studies ............................................................................................................... 8

Data Analysis ......................................................................................................................10

Results .......................................................................................................................................12

Overview of Environmental Scan Results ..........................................................................12

Environmental Scan and Discussion Results by Question .................................................14

What Are the Best Practices, Barriers and Potential Solutions for Using

Services Delivered Via Telehealth to Diagnose and Provide Services

and Treatment for Children With SUD, Including OUD? (Research

Question #1) ................................................................................................ 14

What Are the Differences, If Any, in Furnishing Services and Treatment for

Children With SUD Using Services Delivered Via Telehealth and

Using Services Delivered in Person? (Research Question #2) ..................... 18

Delivery of Pediatric Behavioral Health Treatment via Telehealth ...................................23

Program Examples ................................................................................................... 23

Policy and Reimbursement Considerations .......................................................................26

Telehealth Policies that Influence Delivery of SUD Treatment ............................... 26

Medicare and Medicaid Coverage ........................................................................... 29

Federal Models and Programs to Support Telehealth ............................................ 33

Privacy and Confidentiality Considerations ............................................................. 35

Key Informant Discussions ........................................................................................................38

Overview of Key Informant Discussion Results .................................................................38

What Are the Best Practices, Common Barriers and Potential Solutions for Using

Services Delivered via Telehealth to Diagnose and Provide Services and

Treatment for Children with SUD, Including OUD (Research Question 1)? .............38

Best Practices ........................................................................................................... 38

Detailed Best Practices Emphasized by Key Informants.......................................... 41

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

Barriers and Solutions .............................................................................................. 43

What Are the Differences, If Any, in Furnishing Services and Treatment for

Children with SUD Using Services Delivered via Telehealth and Using

Services Delivered in Person? (Research Question 2) ..............................................48

Utilization rates, costs and avoidable inpatient admissions and

readmissions ................................................................................................ 48

Quality and Satisfaction ........................................................................................... 49

Case Studies ...............................................................................................................................52

Case Study Programs .........................................................................................................52

Case Study 1: The Medical University of South Carolina’s Telehealth

Outreach Program ....................................................................................... 52

Case Study 2: University of Kansas Medical Center’s Telehealth ROCKS

Schools, Rural Outreach for Children of Kansas .......................................... 55

Case Study Results by Question .........................................................................................62

What Are the Best Practices, Barriers and Potential Solutions for Using

Services Delivered Via Telehealth to Diagnose and Provide Services

and Treatment for Children With SUD, Including OUD? (Research

Question #1) ................................................................................................ 62

What Are the Differences, If Any, in Furnishing Services and Treatment for

Children With SUD Using Services Delivered Via Telehealth and

Using Services Delivered in Person? (Research Question #2) ..................... 64

Discussion ..................................................................................................................................67

Best Practices: ....................................................................................................................67

Videoconferencing ................................................................................................... 67

Support Staff ............................................................................................................ 68

School-based Models ............................................................................................... 68

Barriers, Solutions and Information Gaps..........................................................................68

Quality and Fidelity .................................................................................................. 68

Patient Safety ........................................................................................................... 69

Acceptance of a Telehealth Program....................................................................... 69

Financing .................................................................................................................. 69

Consent for Services ................................................................................................ 70

Cost Studies ............................................................................................................. 70

Summary ............................................................................................................................70

References ...............................................................................................................................R-1

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

APPENDIXES

Key Informant Interview Guide ............................................................................................. A-1

Case Study Interview Guides ..................................................................................................B-1

EXHIBITS

Summary of Evidence from Available Literature .................................................................................. 12

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

ES-1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

Section 1009(d) of the SUPPORT Act requires the Secretary of the Department of Health and

Human Services, acting through the Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS), to provide a report to Congress identifying best practices and potential solutions

for reducing barriers to using services delivered via telehealth to furnish services and treatment

for substance use disorder (SUDs) among pediatric populations under Medicaid. The Office of

the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) and their contractor Research

Triangle Institute (RTI) International drafted this final report in consultation with CMS.

Although generally telehealth has become more prevalent in the last decade, uptake is not yet

widespread (Bashshur, Shannon, Bashshur, & Yellowlees, 2016; Benavides-Vaello, Strode, &

Sheeran, 2013; Dorsey & Topol, 2016), particularly among pediatric populations with SUD.

Understanding the barriers to the use of telehealth and best practices to overcome these barriers

among the pediatric population is critical to increasing access to SUD services for this

population.

Methods

RTI conducted an environmental scan, interviewed key researchers, clinicians, and healthcare

administrator informants via phone, and conducted two in-person case studies to identify best

practices, barriers and potential solutions for using services delivered via telehealth to diagnose

and provide services for pediatric patients with SUD. Differences in service provision for

children with SUD using services delivered via telehealth and using services delivered in person

were also explored with respect to utilization rates; costs; avoidable inpatient admissions and

readmissions; quality of care; and patient, family, and provider satisfaction.

Results

Best Practices

Best practices are still evolving and emerging; however, there are a few general principles for

telehealth applicable to behavioral health, including the need for organizational readiness,

engagement of clinical and administrative staff, investment in technology, efforts to increase

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

ES-2

technology acceptance, and support of ongoing service delivery. Key informants also mentioned

workforce shortages, balancing face-to-face and telehealth sessions, having a designated

telehealth coordinator, and engagement of families, specifically.

Barriers

The environmental scan revealed that the lack of technology investment and technology

acceptance are barriers to the provision of services via telehealth. Ongoing service delivery,

capacity issues, licensing and credentialing requirements can also be challenging. Key

informants added that barriers often exist due to state limits and restrictions on reimbursement

for telehealth services. They also noted workforce shortages and concerns about the loss of non-

verbal cues or other SUD-related cues are barriers (e.g., the patient’s smell, hygiene, or visual

indicators of self-harm). A specific barrier that emerged in the case studies were state laws that

prohibited prescribing any controlled substances for students in a school-based clinic other than

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications.

Potential Solutions

Identification of systems and processes to support coordination within and across organizations

may help address the barriers associated with capacity and ongoing service development. The

key informants stressed the value of having a dedicated telehealth program coordinator to

facilitate solutions to common barriers, and the importance of site-based staff to support

telehealth programs was emphasized in the case studies. Initiatives to increase technology access

(e.g., broadband internet) and decrease technology costs may help address barriers to service

delivery. Training of clinical and administrative staff and patients may also improve technology

acceptance.

Utilization Rates

The environmental scan showed that utilization rates may be higher at schools with versus

without services delivered via telehealth for students with special health care needs and in rural

areas versus urban areas. The case studies showed that the telehealth program representatives

feel that their patients are much more likely to persist in treatment than face-to-face patients,

with one program reporting a 90% completion rate. Further study is needed to obtain more robust

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

ES-3

estimates of the net changes in health care utilization associated with telehealth-delivered mental

health or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) services.

Costs

Information specific to the total cost of care and treatment was limited. Few studies provided any

quantifiable results on the costs of telehealth models. While case study participants also did not

have formal economic data available, they noted that payers and other providers had not reported

excess costs or use of other services among their patients. They also noted that, beyond near-

term health care cost savings, they felt strongly that their programs would ultimately save society

resources by reducing inefficient use of misapplied community resources (e.g., teacher time) and

reducing the long-term costs associated with untreated pediatric disorders. On average, the

program representatives believe that the cost of their services delivered via telehealth was equal

to that of in-person services, even including some fixed technology costs.

Avoidable Inpatient Admissions and Readmissions

There was limited information in the environmental scan about how telehealth for pediatric

patients with SUD impacts avoidable inpatient admissions and readmissions. Results are varied

with respect to whether telehealth interventions increase or decrease use of urgent or emergency

care.

Quality of Care

Overall, the quality of telehealth care is similar to that of face-to-face care, both generally and in

behavioral health, specifically. Case study participants felt that the quality of their programs was

as good as or better than face-to-face delivery.

Patient, Family and Provider Satisfaction

Telehealth use and satisfaction is influenced by both pediatric patients’ and their caregivers’

access to technology, knowledge of available resources, and willingness to interact with the

technology, all factors that may be influenced by the potential user’s educational,

socioeconomic, health, and other personal characteristics. Key informants agreed that telehealth

as a modality for pediatric SUDs is often preferred by patients over traditional encounters.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

ES-4

Telehealth satisfaction and uptake is also influenced by provider factors such as training and

technology acceptance.

The environmental scan also yielded examples of programs that demonstrate the potential

advantages of providing services via telehealth, including the reduction of unnecessary patient

transfers, improved access to services through school-based care, and provision of training,

expertise, and/or certification opportunities to providers in areas that are relevant to the patients

they are treating.

Many of the resources reviewed in the environmental scan called for regulatory changes to

promote the uptake of telehealth delivery methods to treat SUDs. The scan identified a number

of policies, many of which support the use of telehealth more generally and were not unique to

pediatric patients with SUD. Those policies that did specifically address telehealth service

delivery methods emphasized the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) and medication

assisted treatment (MAT). Policies governing privacy and protection of personal data influence

telehealth models, particularly for pediatric patients and their parents and for sensitive care areas

like SUD and mental health.

Medicaid coverage for services delivered via telehealth varies by state according to factors such

as the setting where the patient is located, types of services, provider type, and whether the

service was delivered synchronously or asynchronously. Some states restrict reimbursement for

services delivered via telehealth for behavioral health issues. All states providing Medicaid-

covered services delivered via telehealth include some form of coverage and reimbursement for

certain mental health services.

Discussion/Conclusion

Much of the evidence base for the use of telehealth with pediatric patients comes from treatment

of mental disorders, which provides valuable lessons learned and next steps forward. Overall,

programs are successfully providing quality services to patients who may not otherwise have

access. Many questions remain, however, around best practices in different settings with

different pediatric patient disorders, optimal staffing and financial viability.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

ES-5

[This page intentionally left blank]

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

1

BACKGROUND

Substance use disorder (SUD) among the pediatric population (ages up to 21) has been

identified as a significant public health concern. As of 2018, an estimated 3.7 percent of

adolescents aged 12 to 17, and 12.9 percent of young adults aged 18 to 20, had an SUD

(SAMHSA, 2019). Substance use during adolescence is associated with short- and long-term

negative effects on functioning and well-being. Brain development may be delayed or altered

with consequences that can persist throughout adulthood (Chassin et al., 2010; Eiden et al., 2016;

Squeglia, Jacobus, & Tapert, 2009; Tapert, Caldwell, & Burke, 2004). Substance using

adolescents are more likely to experience worse mental health and have behavioral problems (Ali

et al., 2015; Bouvier et al., 2019; Poon, Turpyn, Hansen, Jacangelo, & Chaplin, 2016; Schuler,

Vasilenko, & Lanza, 2015; Trim, Meehan, King, & Chassin, 2007; Volkow, Baler, Compton, &

Weiss, 2014) and to have poorer academic outcomes (Heradstveit, Skogen, Hetland, & Hysing,

2017; Kelly et al., 2015). Adolescents with early onset heavy substance use are most likely to

remain heavy users as they transition into adulthood (Derefinko et al., 2016; Winters et al.,

2018). Despite evidence for the effectiveness of many different treatment modalities for

adolescents (Nelson, Ryzin, & Dishion, 2015; Wu, Zhu, & Swartz, 2016), only 14.1 percent

received any form of SUD treatment. Among all adolescents with an SUD, those with opioid use

disorder (OUD) are the least likely to receive treatment (Winters et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2016).

Adolescents face many barriers to accessing treatment, including stigma, which may prevent

adolescents or their guardians from seeking help; logistical limitations, such as a lack of

transportation or locally available specialty treatment providers; and financial limitations, such as

being uninsured or underinsured. Among many strategies to reduce barriers to treatment access,

telehealth models of service delivery have the promise of expanding access, improving treatment

engagement and retention, enhancing the clinical outcomes of evidence-based services, and

reducing costs (Bashshur et al., 2016; Benavides-Vaello et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2016).

Although generally telehealth has become more prevalent in the last decade, its it has not

been adopted widely across all patient groups (Bashshur et al., 2016; Benavides-Vaello et al.,

2013; Dorsey & Topol, 2016), particularly pediatric patients. Much of the existing work on

barriers and facilitators to telehealth to support SUD treatment focuses on the adult population.

Common barriers to telehealth implementation for a general patient population include staff and

patient acceptance; cost and reimbursement; workflow challenges; and technology

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

2

availability/connectivity (Myers et al., 2017). Additionally, providers often experience barriers

related to ensuring privacy, confidentiality, and security; initial setup costs; and other technical

difficulties that can potentially compromise confidentiality.

While many telehealth considerations apply equally to adult and pediatric populations,

there are some potential differences. For example, pediatric patients may be more likely to

embrace technology. Recent surveys from the Pew Foundation have pointed to adult technology

and social media use remaining stagnant and teen use increasing (Pew Research Center, 2018,

2019a). Meanwhile, privacy while living with family or roommates can be a concern for

pediatric patients. In contrast, stigma about receiving mental health or substance use disorder

(MH/SUD) services may be lessened when delivered via telehealth. However, there is some

evidence that parents’ willingness to access mental health services is more influenced by stigma

when the services are delivered via telehealth (Polaha, Williams, Heflinger, & Studts, 2015).

Financing is another potential barrier to telehealth for the pediatric population. While Medicaid

and the Children’s Health Insurance Program are the main coverage sources for behavioral

health coverage and treatment of SUD for the pediatric population (Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services, n.d.-a), Medicaid-covered services delivered via telehealth vary by state.

Although variation in coverage across states is also a challenge for providers serving adults, it

can exacerbate the existing workforce challenges for pediatric patients with MH/SUD who need

services from providers with specialized training. Understanding the barriers to the use of

telehealth and best practices to overcome these barriers among the pediatric population is critical

to increasing access to SUD services delivered via telehealth for this group.

PURPOSE AND SCOPE

The goal of this work is to gain a greater understanding of contextual factors influencing

the use of telehealth for SUD services for pediatric populations, with a focus on services funded

by Medicaid. For the purposes of this work, the term pediatric refers to individuals up to the age

of 21. Telehealth refers to synchronous and asynchronous provider-to-provider and provider-to-

patient services (RTI International, 2017, September 15). However, only provider-to-patient

services are eligible for Medicaid coverage. The literature on telehealth for SUD among pediatric

populations is limited and varied in scope and quality. This report includes relevant findings for

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

3

telehealth for SUD among adult populations where appropriate, as well as information on mental

health services delivered via telehealth for pediatric patients.

This study will support fulfillment of the requirements of section 1009(d) of the

Substance Use–Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients

and Communities Act (SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act), Public Law No. 115-271,

which requires the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to provide a

report “identifying best practices and potential solutions for reducing barriers to using services

delivered via telehealth to furnish services and treatment for SUDs among pediatric populations

under Medicaid.”

Pursuant to section 1009(d) of the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, the

research questions guiding this work are:

1. What are the best practices, barriers and potential solutions for using services

delivered via telehealth to diagnose and provide services and treatment for children

with SUD, including OUD?

2. What are the differences, if any, in furnishing services and treatment for children with

SUD using services delivered via telehealth and using services delivered in person

with respect to:

• utilization rates;

• costs;

• avoidable inpatient admissions and readmissions;

• quality of care; and

• patient, family, and provider satisfaction.

To answer these questions, RTI conducted an environmental scan, met with key

informants via phone, and conducted two in-person case studies. RTI used qualitative analysis

methods to analyze the data and identify themes. This report presents the findings from each

component of the study.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

4

[This page intentionally left blank]

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

5

DATA AND METHODS

DATA COLLECTION

Data collection includes findings from the environmental scan, discussions with key

informants, and case studies. The objective of the environmental scan was to assess the current

state of the literature on SUD services delivered via telehealth to help answer our research

questions and inform the discussions with key informants and with case study participants. Key

informant interviews supplemented the environmental scan by ensuring that we identified newer

information and programs, provided the opportunity for more in-depth discussion of key topics,

and helped to identify possible case study sites. The objective of the case studies was to learn

from on-the-ground experiences of those who administer and use telehealth in the field. Even

when literature or documented guidance exists for key topics, firsthand accounts and

explanations add clarity and provide a broader context for the published information, address

emerging issues, and provide concrete examples of challenges and solutions.

Environmental Scan

The scan included a literature review that identified and synthesized findings from peer-

reviewed journals; gray literature; issue briefs; Federal, state, and local government reports; and,

conference proceedings and presentations. Where possible, we focused on publications from

2012 through May 2019. Earlier publications were included if they provided key insights not

available in the more recent literature. To conduct the literature review, we developed a list of

keywords from the research questions. MLS-trained librarians provided input on the keywords

and assisted in searches. We then obtained relevant articles for review and analysis using the

following process.

Search Parameters

We performed a literature search of the four major databases listed below for peer-

reviewed and gray literature published from 2012 to date:

• PubMed

• Web of Science (includes Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation

Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science, and Conference Proceedings

Citation Index-Social Science & Humanities)

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

6

• PsycINFO

• New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Database (to 2016)

Each database was queried for the intersection of:

• telehealth AND pediatric populations

• telehealth AND opioids OR substance abuse OR behavioral health

• telehealth AND other terms.

Below are the search parameters.

• Telehealth: telehealth OR "tele-health" OR telemental OR "tele-mental" OR

telemedicine OR "tele-medicine" OR telerehabilitation OR "tele-rehabilitation" OR

teleconsultation* OR "tele-consultation*" OR "remote consultation*"

• Pediatric population: pediatric* OR pediatrician* OR child* OR youth* OR

adolescent* OR teen* OR school* OR college* OR university* OR "young adult*"

OR "transition age"

• Opioids, substance abuse, behavioral health: opioid* OR opiate* OR heroin OR

fentanyl OR OxyContin OR Vicodin OR hydrocodone OR oxycodone OR narcotic*

OR behavioral OR "substance us*" OR "substance abuse*" OR "drug abuse*" OR

"drug us*" OR addiction OR “mental health” OR alcohol

• Other terms: Medicaid OR barrier* OR quality OR utilization OR cost OR costs OR

economic* OR financial* OR finance* OR financing OR satisfaction OR

readmission* OR admission* OR "best practice*"

In addition to the searches listed above, we conducted targeted Google searches to

identify changes in policies around telehealth for this population, relevant Medicaid policies, and

specific telehealth applications such as school-based health.

All publications were downloaded to an EndNote database. We identified 215

unduplicated articles. Two analysts from the research team reviewed abstracts for each and

identified 189 articles for full review. Each member of the team participated in reviewing a

selection of the articles which included reading the entire article and extracting information to be

recorded into a tracking form.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

7

Discussions with Key Informants

To supplement the findings from the environmental scan, we conducted semi-structured

discussions via telephone with nine key informants and categorized findings based on themes

and research questions. Specifically, the results are presented by the best practices, barriers and

solutions, and differences in in-person versus telehealth service delivery for SUD treatment in

pediatric patient populations.

Potential key informants were identified based on the findings of the environmental scan

and a review of professional organizations. From this potential list, informants were categorized

based on several criteria, including the following:

• Experience with telehealth for behavioral health services

• Geography

• Type of behavioral health services provided

• Diversity of role at organization

A discussion guide was developed to support the interview and included probing sub-

questions to prompt the informant to provide their unique perspective on different topics

(Appendix A). The perspectives represented included the following:

• Researchers

• Clinicians

• Health care administrators

The key informant discussions were conducted to help us gain a better understanding of

policies that influence treatment of the pediatric population with SUD via telehealth and

reimbursement aspects, such as coverage by Medicaid and private payers. The RTI team

developed a semi-structured discussion guide to support the discussions that covered the key

research questions. The guide was designed to take advantage of the unique perspectives of each

selected informant.

Key Informant and Program Characteristics

Discussions were held with nine key informants covering a variety of perspectives,

including the following non-mutually exclusive categories:

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

8

• five physicians, three of whom were psychiatrists

• three nurses

• three researchers with university faculty appointments

• three government officials

• three acting as administrators in a provider organization

Three university medical centers were represented as well as two private provider organizations.

Two separate state governments were represented. At least one respondent was also associated

with each of the following:

• Indian Health Service

• Telehealth Resource Center funded by the Health Resources & Services

Administration

• American Telemedicine Association

The key informants’ backgrounds in telehealth were varied, ranging from only very

recent experience to more than 20 years of experience with telehealth. One clinician worked for

20+ years in pediatric care and then transitioned into the role of clinical information technology

liaison where they have been developing and running the telemedicine program for the past 7

years. Another stakeholder reported using telehealth for pediatric behavioral health services for

more than 20 years and provided a unique perspective on how telehealth has evolved in their

state. One administrator had worked for more than 24 years within their current state’s

department of public health and has been the point of contact for all telehealth-related activities

since the department established an office dedicated to telehealth. One administrator wrote their

provider organization’s first policy on telehealth and has since continued to expand it.

Four of the key informants had experience providing clinical pediatric MH/SUD services

face-to-face and using telehealth, including one in a school-based telehealth program. The rest

were either administrators associated with such programs or had related policy roles.

Case Studies

In order to gain additional perspective from providers in the field, we conducted in-

person discussions with staff from selected provider organizations. These visits helped to address

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

9

gaps and supplement findings from the literature and the key informant interviews. Based on

results from the environmental scan and key informant interviews, we developed an interview

guide for providers, administrators and community partners/stakeholders (Appendix B).

We identified potential provider sites based on several criteria, including:

• Experience with telehealth for pediatric populations

• Experience with telehealth for delivering MH/SUD treatment services

• Geography (rural vs. urban and U.S. regions)

• Setting (e.g., outpatient clinic, Federally Qualified Health Center)

• Type of telehealth in use (provider-to-provider or provider-to-patient)

Sites were contacted by phone or email to discuss the possibility of a site visit following a

script explaining the purpose of the visit and what they might expect during the visit. During the

site visit, we spoke with different stakeholders involved in the telehealth program(s). These

included providers, administrators, and other representatives of the organization delivering the

telehealth services. When feasible, we also met with stakeholders from partner organizations

who may have been directly or indirectly involved with the telehealth program. In addition, we

briefly reviewed the telehealth technology and setting firsthand. We recognized that

organizations’ time was very limited and that meeting with us could have been disruptive;

therefore, we worked with each site to plan a visit that would minimize any burden. We were on-

site for no longer than one day during regular business hours, and our team consisted of two staff

and a representative from ASPE.

The two case study sites that we visited are university medical centers with Health

Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)-funded Telehealth Resource Centers. Both sites

have a broad portfolio of telehealth activities, including programs that provide services to

pediatric patients with mental disorders. Descriptions of the two case study sites are provided in

Appendix B.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

10

DATA ANALYSIS

All study data were analyzed using qualitative analytic methods. Results from the

literature review were analyzed by identifying themes relevant to the research questions.

Qualitative data from key informant and in-person discussions were also analyzed thematically.

The results of each of the three data sources are organized by primary research question.

The key informant and in-person case studies reflect on the environmental scan results when

appropriate. We also highlight innovative programs and approaches to the use of telehealth

identified in the literature and in discussions with key stakeholders and providers.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

11

[This page intentionally left blank]

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

12

RESULTS

OVERVIEW OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN RESULTS

Overall, the environmental scan highlighted the knowledge gaps in the field about the use

of telehealth for SUD services for the pediatric population. Much of the evidence base for the use

of telehealth with pediatric patients comes from treatment of mental disorders. Most of the

evidence found regarding use of telehealth for SUD services is based on adult populations, and it

is unclear the extent to which these experiences would be similar among a pediatric population.

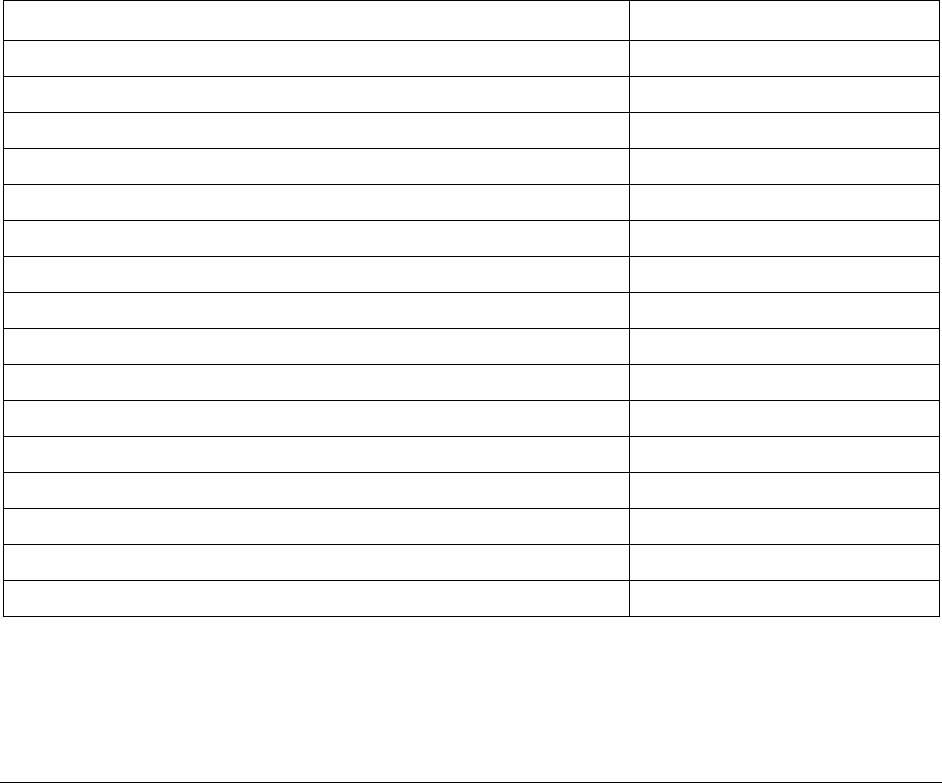

Exhibit 1 summarizes differences in the evidence base by modality, funding sources,

barriers and facilitators. We have categorized the strength of evidence as scant (very little or no

information about this topic), emerging (several resources about the topic, but not enough to gain

a consensus) or strong (many resources about this topic over a period of time).

Exhibit 1. Summary of Evidence from Available Literature

Category State of Evidence

Research Question 1. Best practices, barriers and solutions

Telehealth best practices

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Scant

SUD treatment with adult populations

Emerging

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Scant

Barriers/issues for using telehealth treatment/services for SUD

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Emerging

SUD treatment with adult populations

Strong

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Emerging

Facilitators to address barriers

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Emerging

SUD treatment with adult populations

Strong

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Emerging

Research Question #2: Telehealth vs. in-person

Utilization rates

Utilization rates for adult or pediatric populations with SUD

Scant

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

13

Exhibit 1. Summary of Evidence from Available Literature (continued)

Category State of Evidence

Costs

Costs for treatment of adult or pediatric populations with SUD

Scant

Avoidable inpatient admissions and readmissions

Avoidable inpatient admissions and Readmissions for adult or

pediatric SUD

Scant

Quality of care

SUD treatment for pediatric populations

Scant

SUD treatment for adult populations with SUD

Scant

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Emerging

Patient and family satisfaction

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Scant

SUD treatment with adult populations

Emerging

Other treatment focus with adult or pediatric populations

Strong

Provider satisfaction

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Scant

SUD treatment with adult populations

Scant

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Emerging

Examples of programs

Telehealth in schools

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Emerging

SUD treatment with adult populations

Emerging

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Emerging

Teleconsultations in the emergency department

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Scant

SUD treatment with adult populations

Scant

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Emerging

Family-based treatment approaches

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Strong

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Emerging

Provider to provider use of telehealth to augment face-to-face care

SUD treatment with pediatric populations

Scant

SUD treatment with adult populations

Emerging

Other treatment focus with pediatric populations

Scant

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

14

ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN AND DISCUSSION RESULTS BY QUESTION

What Are the Best Practices, Barriers and Potential Solutions for Using Services Delivered

Via Telehealth to Diagnose and Provide Services and Treatment for Children With SUD,

Including OUD? (Research Question #1)

Best Practices

As telehealth use has grown, some best practices have been formalized and disseminated

in the form of handbooks or guidelines. These are not specific to SUD for pediatric populations

and apply to telehealth generally or to pediatric telehealth generally (American Academy of

Pediatrics, 2017). Some of these resources offer broad guidance—for example, the United

Kingdom’s National Health Service released a guide on telehealth capabilities aimed at

demonstrating value to public officials (National Health Services, 2016). Other telehealth best

practices are tailored to specific treatment programs, such as enhancing access to medication

assisted treatment (MAT) and frequent contact with support systems for OUD treatment (Knopf,

2013). Although best practices are still evolving and emerging, there are a few general principles

for telehealth that will apply to telehealth for behavioral health.

Organizational Readiness

One of the best practices frequently noted in the literature involves ensuring

organizational readiness. These activities include planning, understanding the current state of the

organization’s culture and infrastructure and its particular needs. Planning should begin with an

early assessment of the needs of the community and the capability of telehealth to address any

gaps or issues (California Telehealth Resource Center, 2014). Factors such as the existing

technology available, how technology might be adapted for future programs, and quality

assurance should all be considered and addressed early on (Molfenter, Brown, O'Neill,

Kopetsky, & Toy, 2018; V. Perry, 2016). In addition, planning should include how telehealth

will be integrated into clinical and administrative workflows (Molfenter et al., 2018). This

includes identifying how care will be scheduled, coordinated and delivered (Gagnon, Duplantie,

Fortin, & Landry, 2006). This also includes mechanisms for identifying emergency and non-

emergency communications (Tofighi, Grossman, Sherman, Nunes, & Lee, 2016).

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

15

Engagement

Involving clinical and administrative staff in the decision to implement telehealth and

develop related policies and protocols can improve their engagement and perceptions of

telehealth. Often, administrative staff such as telehealth coordinators at originating and distant

sites maintain communication and work together closely on tasks such as coordinating

scheduling, relaying laboratory results, and following up with providers and patients. In addition,

administrative engagement at the leadership level can help facilitate buy-in and engagement.

Provider engagement and buy-in are needed to support telehealth uptake. One way to do

that is to get provider involvement in identifying and developing clinical practice guidelines and

outlining the ways in which telehealth is appropriate (Myers et al., 2017). Initiatives are more

likely to have an impact on care outcomes and facilitate access to care when providers champion

telehealth use. In rural Alabama, for example, a community organized a child telepsychiatry

program using distance learning equipment available at the county technical high school. To

accomplish this, providers in the community had to work with state Medicaid officials to

understand reimbursement policies, as well as arrange for services from the University of

Alabama Department of Psychiatry to be furnished. Their program now provides weekly services

to children with a range of diagnoses (Merrell & Doarn, 2013).

Barriers and Solutions to Overcome Them

The literature includes discussion of several barriers to telehealth use, including the need

for technology investment, technology acceptance, and challenges associated with ongoing

service delivery.

Technology Investment

Barriers.

Although specific equipment needs vary across telehealth programs, all programs need

internet connectivity. Broadband gaps throughout the United States mean that some areas are

more likely than others to have sufficient connectivity to support telehealth (Federal

Communications Commission, n.d.-a). Applications such as videoconferencing require more

bandwidth and a faster connection than what is consistently available throughout the country

(California Telehealth Resource Center, 2014; McGinty, Saeed, Simmons, & Yildirim, 2006). A

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

16

strong internet connection is needed to prevent quality issues such as lagging or skipping while

providing services. In addition, high network use by a telehealth application may interfere with

other staff members' work, particularly if the organization uses cloud-based services. Current

industry standards recommend that small physician practices and rural health clinics have

internet capability in line with U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) broadband

internet benchmarks. Broadband download speeds are generally 25 Mbps for streaming ultra HD

4k video. Accounting for at least that capacity would allow for EHRs, videoconferencing, and

other uses of technology (Federal Communications Commission, 2019a; HealthIT.gov, 2019a).

This is in line with the bandwidth needed to stream high-quality video generally.

Solutions.

There are a number of initiatives aimed at increasing broadband capability throughout the

country which may ameliorate these concerns (Federal Communication Commission, 2010). For

example, the FCC has allocated funds to expand broadband access (Federal Communications

Commission, 2019b) and 4G access throughout the country (Federal Communications

Commission, n.d.-b). In addition, efforts have been made to support broadband adoption through

launching the Broadband Deployment Advisory Committee (Federal Communications

Commission, 2019c) and developing, reviewing and revising rules to promote streamlining the

process to transition to modern broadband networks. These initiatives may reduce the cost of

increasing the bandwidth necessary for telehealth interventions.

Technology Acceptance

Barriers.

Lack of access to technology and low technology competency across providers and

patients are barriers to telehealth (Muench, n.d.; K. Perry, Gold, & Shearer, 2019). In addition,

interruptions, technological complexity or other challenges in the visit can reduce technology

acceptance for both providers and patients (Boudreaux, Haskins, Harralson, & Bernstein, 2015;

Tofighi et al., 2016).

Solutions.

Organizations can help promote technology acceptance and combat issues by providing

initial training and technical support for both patients and providers (Batastini, King, Morgan, &

McDaniel, 2016).

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

17

Some provider associations have started being proactive to encourage technology use and

assuage concerns. For example, the American Telemedicine Association maintains directories of

their members, allowing practitioners the opportunity to communicate with their peers (Becevic,

Boren, Mutrux, Shah, & Banerjee, 2015). The National Frontier and Rural—Addiction

Technology Transfer Center holds an annual summit for telehealth training during which

providers can interact in person (Reynolds & Maughan, 2015).

Telehealth can greatly reduce initial visit wait times for patients seeking mental health

services in rural clinics by making additional providers available, which can influence patient

acceptance. Thorough planning for integration into provider workflow (organizational readiness)

can help support efficiency and reduce interruption to workflow, both of which are critical to

physician buy-in and the ultimate success of initiatives (Gagnon et al., 2006).

Supporting Ongoing Service Delivery

Barriers.

Ongoing service delivery can be challenging due to workforce shortages and capacity

issues and the need for coordination. In the past, telehealth educational services were scheduled

as far a year in advance because of demand (HealthIT.gov, 2019b; Kraetschmer, Deber, Dick, &

Jennett, 2009). In addition, telehealth services across organizations require coordination and

information sharing, which may be difficult due to interoperability concerns.

Solutions.

Identification of systems and processes to support coordination within and across

organizations may help address the barriers associated with capacity (Luxton, Pruitt, &

Osenbach, 2014). In one model, remote providers can more quickly perform initial diagnostic

assessments and help plan for ongoing medication maintenance (Johnston & Yellowlees, 2016).

The Office of the National Coordinator is embarking on efforts to improve interoperability to

enhance data sharing across organizations, including for technologies to enable services

delivered via telehealth (The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information

Technology, 2015).

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

18

What Are the Differences, If Any, in Furnishing Services and Treatment for Children With

SUD Using Services Delivered Via Telehealth and Using Services Delivered in Person?

(Research Question #2)

For the general population, the literature indicates no significant difference between

services delivered via telehealth and face-to-face services. Limited information is available about

telehealth use for pediatrics, particularly for those patients with SUD.

Utilization Rates

Although there were no studies comparing the rates of service utilization for SUDs for a

pediatric population between telehealth and face-to-face encounters, a few studies analyzed

service utilization rates for broader health care services. In a systematic review of school-based

telehealth studies for acute and chronic illness, utilization was equal or higher in schools with

telehealth for students with special health care needs or medical complexities (Sanchez, Reiner,

Sadlon, Price, & Long, 2019). In another national study of Medicaid beneficiaries of all ages,

rural patients used telehealth more than urban patients, particularly for psychotropic medication

management (Talbot et al., 2018).

Costs

Although there was information available about financing, information specific to the

total cost of care and treatment was limited. Some publications mentioned that telehealth reduced

transfers to other facilities and reduced the use of transportation overall, but few showed

quantifiable results on the costs of telehealth models.

There are a number of business models to support telehealth, depending on the specific

application used (Chen, Cheng, & Mehta, 2013). However, there is no clearly established best

practice approach to compare cost between services delivered via telehealth and face-to-face

care. For example, the cost of equipment (e.g., computers or higher-speed internet) should be

included in any comparison if that equipment is only used for the telehealth intervention.

However, its inclusion in a cost assessment is less clear if the equipment is used for non-

telehealth purposes (Bounthavong et al., 2016).

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

19

Avoidable Inpatient Admissions and Readmissions

There was limited information available about how telehealth for pediatric patients with

SUD impacts avoidable inpatient admissions and readmissions. Some studies show decreases in

urgent care or emergency room settings with use of telehealth interventions. In one study, 67

percent of parents of patients with varying acute health concerns would have visited an urgent

care center, emergency room, or retail clinic had the telehealth intervention not been available

(Vyas, Murren-Boezem, & Solo-Josephson, 2018). However, in a claims data analysis for a large

national health plan, use of direct-to-consumer telehealth by pediatric patients was associated

with greater use of both urgent care and emergency department visits (Ray, Shi, Poon, Uscher-

Pines, & Mehrotra, 2019; Talbot et al., 2018). One current program estimates a reduction in

downstream costs (Williams & Vance, 2019).

Quality of Care

Overall, the quality of telehealth care is similar to that of face-to-face care. This appears

to be true, both generally and in behavioral health, specifically (Lin et al., 2019). In one

retrospective review study, telehealth was associated with similar MAT outcomes in comparison

to face-to-face care (Zheng et al., 2017). In another, telehealth was associated with similar

treatment retention rates compared to face-to-face care (Fleischman et al., 2016).

With respect to quality as a process (Hanefield, Powell-Jackson, & Balabanova, 2017),

telehealth can help overcome issues of distant providers not being able to engage with local

resources or conduct assessments. An effectiveness review of telemental health in 2013 by Hilty

and colleagues found that telehealth is effective for behavioral health diagnosis and assessment

across many populations (adult, pediatric, geriatric, and minority) and for disorders in many

settings (e.g., emergency, home health), and appears to be comparable with in-person care (Hilty

et al., 2013). A recent review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) found

a large volume of research reporting that telehealth interventions produced positive results when

used in the clinical areas of chronic conditions and behavioral health, and when used for

providing communication or counseling and monitoring or management (Totten et al., 2016).

These review articles suggest that using telehealth for behavioral health services provides quality

similar to in-person services.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

20

Telehealth does create new challenges for quality of service delivery. Some areas lack

access to broadband, high-speed internet with stable connectivity (Bashir, 2018). Poor

connectivity can cause poor quality audio and video, disconnections, and slowed information

exchange (Celio et al., 2017; Cunningham, Connors, Lever, & Stephan, 2013). For pediatric

patients, it is important to ensure that they can see and be seen on the computer screen; this

entails making sure that webcams are set to the appropriate height, and that a staff member is

present to provide flexible or moveable technology (Goldschmidt, 2016; Stiles-Shields, Corden,

Kwasny, Schueller, & Mohr, 2015). For home-based services, some patients and families may

not have access to technology to participate in telehealth (Fischer et al., 2017).

Additional quality of care measures related to patient and family satisfaction are

discussed below.

Patient, Family, and Provider Satisfaction

Patients and Families

Telehealth use and satisfaction is influenced by individuals’ access to technology,

knowledge of available resources, and willingness to interact with the technology. For pediatric

patients, this includes both the patient and their caregiver. Some patients and their families may

face digital and cultural barriers (Bashir, 2018), and it may be difficult for those with limited

technology skills to adopt treatment approaches delivered via telehealth (Batastini et al., 2016).

Patient and family experiences may vary across demographics. For example, Schmeida

and McNeal (2007) found that older, low-income individuals were likely to search for Medicare

and Medicaid information online and young, highly-educated, and wealthy individuals were

more likely to use the internet in general. College graduates, young adults and those from high-

income households have extremely high levels of internet use and 80 percent of users have

searched for health information online in general (Pew Research Center, 2019b). Patients with

more than a high school education were more likely to use services delivered via telehealth than

those without a high school education (Lowery, Bronstein, Benton, & Fletcher, 2014).

Computer-based treatments for OUD have been shown to be more effective for patients

who are employed, suffering from anxiety, or are ambivalent about continuing substance use

than for other populations (Kim, 2015). Goldschmidt (2016) found that patients and families

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

21

using telehealth for cognitive behavioral therapy needed support to ensure that they knew how to

use the technology, that they were aware of camera placement, and that they removed

distractions during therapy.

Beyond patient demographics, other factors may influence use and effectiveness of

telehealth. In a clinical trial of a remote Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment

(SBIRT) program implemented in an emergency department setting, researchers found several

factors that could hinder use, including complications with provider engagement, delays in warm

handoffs to other remote behavioral health interventions, and disruptions from other medical

staff during the encounter, as well as family members and friends. Overall, the evidence

indicates that patients and caregivers had positive perceptions about telehealth. Despite the

challenges with SBIRT, the feedback and acceptance ratings from participants were generally

favorable, and the study ultimately concluded that a remote SBIRT application held great

promise. In addition, in a regional survey of patients across specialties, the majority found that

lack of physical touch was not a barrier and they were satisfied with the care received via

telehealth (Becevic et al., 2015; Vyas et al., 2018). Two additional studies—one of patients

diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and their caregivers and one of

parents with children with varying acute health concerns—reported a high degree of satisfaction

with care via telehealth (McCarty, Stoep, Violette, & Myers, 2015). Several other treatment

studies were found where patients with complex psychological problems (e.g., adult substance

use, PTSD), reported high rates of client satisfaction (Frueh, Henderson, & Myrick, 2005; King,

Brooner, Peirce, Kolodner, & Kidorf, 2014; Luxton, Pruitt, O'Brien, & Kramer, 2015; Martinez

et al., 2018; McKellar et al., 2012).

Providers

Telehealth satisfaction and uptake is also influenced by provider factors such as training

and technology acceptance. In a comprehensive survey study across provider types, providers

indicated that they were able to treat patients with telehealth and were satisfied with care

delivery via this mode (Becevic et al., 2015). However, from a long-term perspective, another

pilot study found that after 10 months, only two of 12 rural providers were using the telehealth

methods for which they trained. The physicians cited difficulty with the infrastructure needed to

implement telehealth as a key barrier (SAMHSA, 2016). Providers may also be wary of

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

22

becoming credentialed (a process that involves a facility’s acceptance of a remote providers

medical credentials) at facilities they plan to serve only through telehealth.

A state-wide telepsychiatry intervention in Wyoming found that telehealth produced

noticeable results only when a range of providers were included and involved (Hilt et al., 2015).

Hilt (2017) found that ensuring that providers understand how to use technology is key to

provider engagement and satisfaction (Hilt, 2017).

Provider Organizations.

Telehealth also necessitates changes within the organizations through which care is delivered.

Provider organizations vary in size, complexity and resources. Thus, the ability to accommodate a

change in care delivery such as telehealth varies. Some organizational challenges include

credentialing, billing, technical barriers, and workflow.

Care delivery across organizations has implications for credentialing (McSwain &

Marcin, 2014). Facilities require that providers delivering services in their locations be

credentialed to ensure that services are within their scope of practice. Although the use of

delegated credentialing has increased, providers may not wish to undertake the credentialing

process for multiple organizations. And while there have been some strides to streamline

credentialing for telehealth purposes, it remains an issue (LeRouge & Garfield, 2013).

Although Medicaid, Medicare, and private payers have expanded payment for services

delivered via telehealth over time, the variability of requirements between states related to

coverage and payment remain a barrier. States vary with respect to policies around

reimbursement for telehealth and the conditions under which telehealth encounters are

reimbursable (Center for Connected Health Policy, n.d.-a). In addition, recent legislation, as

discussed in the next section, has changed certain payment policies for Medicare telehealth

services, such as what is considered a permissible originating site (site at which the beneficiary is

located) for certain services, which CMS implemented in 2019 (Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services, 2019). Members from provider organizations perceive that billing for

services delivered via telehealth in general is a challenge (N. M. Antoniotti, Drude, & Rowe,

2014). This is, in part, due to lack of training on how to manage these claims, perceptions that

these claims may be audited more frequently, and changes in billing codes and modifiers (N. M.

Antoniotti et al., 2016).

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

23

Although patient visits are largely similar regardless of modality, there are a few

workflow differences between services delivered via telehealth and face-to-face visits that

organizations must accommodate. These include identifying when to refer and schedule

telehealth visits (Lambert, Gale, Hartley, Croll, & Hansen, 2016). Other workflow considerations

include streamlining data entry to save time and promote information sharing (Langkamp,

McManus, & Blakemore, 2015). Identifying staff and processes to manage telehealth visits is an

important part of telehealth uptake and use.

DELIVERY OF PEDIATRIC BEHAVIORAL HEALTH TREATMENT VIA

TELEHEALTH

Program Examples

Telehealth in the Emergency Department: Reducing Transfers

Telehealth delivery methods in emergency departments can be used to bring expertise

quickly and prevent unnecessary transfers to different institutions. The literature search did not

yield resources addressing SUD in pediatric patients specifically; however, just as services

delivered via telehealth can be used for diagnosis and treatment planning for other areas (Burke

& Hall, 2015), it can also be used for this application. Some potential outcomes include patient

and provider satisfaction and reducing transfers without degradation of care (Burke & Hall,

2015). Telehealth has been successful in reducing or eliminating the time psychiatric patients

wait in an emergency department for an inpatient bed by facilitating the development of a

tailored treatment plan (Deslich, Thistlethwaite, & Coustasse, 2013).

Telehealth Supplementing in-Person Visits: Enhancing Care

Telehealth delivery methods can supplement in-person visits by establishing links

between providers and pediatric patients when ongoing in-person care is infeasible. This is of

particular importance for those who might not be able to travel due to their location in a

childcare center, preschool, school, or juvenile detention facility (Burke & Hall, 2015). When

used as part of an enhanced medical home, some reported advantages of this model for the

pediatric population include fewer school absences for the children; less money spent by parents

on travel; less time away from employment for parents; and less crowding in emergency

departments where there may be a lack of pediatric expertise.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

24

Telehealth in the School Setting: Meeting the Population in the Community

Delivering services via telehealth while school-aged patients are at school allows patients

to receive care where they are during the day. In addition, school-based telehealth can help

connect patients and families with community resources that can help them manage their health

(Reynolds & Maughan, 2015). School-based services delivered via telehealth have shown

promising results to improve social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes among school-aged

children in need of a school psychologist, especially in rural settings where psychologist travel

time is a real concern (Bice-Urbach & Kratochwill, 2016). Teachers, students, and counselors

had favorable perceptions of telehealth. This mirrors an experience of using telehealth delivery

methods to address behavioral problems in the schools, where teachers had positive impressions

and there was a notable decrease in on-task behavior after implementation (Fischer et al., 2017).

Other school-based health clinics served as a medical home for patients who received a

variety of services delivered via telehealth for specialty care, including psychiatric care (RTI

International, 2016). In order for school-based interventions to be successful, communication and

coordination with school administration and teachers is important (Bice-Urbach & Kratochwill,

2016). One school-based telepsychiatry intervention emphasized the importance of

communication and coordination between different providers, staff, and parents (Cunningham et

al., 2013). Students had positive perceptions of telehealth used in this way. Similarly, in a

telehealth intervention designed for pediatric obesity, the importance of coordination was

identified as a key factor for success (Slusser, Whitley, Izadpanah, Kim, & Ponturo, 2016).

Telehealth to Support Family-Based Treatment Approaches

Family-based treatment approaches view SUD as a disease that includes the entire family

system. Thus, therapeutic approaches involve treating the individual and his or her family system

in tandem (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2004; Kuhn & Laird, 2014; Lammers et al.,

2019; Sherr, 2018). Family-based treatment has been shown to be more effective than

approaches that focus on the patient alone (Crum & Comer, 2016). These approaches are often

used in face-to-face care (Allen et al., 2016; Donelan et al., 2019; Kaslow, Broth, Smith, &

Collins, 2012). In studies of the use of telehealth for substance use treatment and prevention,

interventions via telehealth demonstrated equal or better outcomes to face-to-face interventions

(Danaher et al., 2018; Donelan et al., 2019). Some considerations with this approach include

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

25

ensuring the entire family is engaged with technology and ensuring connectivity at home for

home-based interventions (Crum & Comer, 2016). In another study of non-pediatric patients

with chronic disease at the Veterans Administration, patients found that incorporating family

members in care planning with telehealth had similar satisfaction rates as incorporating them

using face-to-face interaction (Bashir, 2018).

In a family-based approach using telehealth for a behavioral intervention focused on diabetes

management, outcomes were similar between telehealth and face-to-face cohorts, but patients

reported greater satisfaction with their provider in the telehealth cohort (Freeman, Duke, &

Harris, 2013). Project ECHO: Supporting Provider to Provider Education

The primary focus of telehealth financing has been on reimbursing direct services from

remote providers to patients. Provider to provider training is not covered by most payers,

including under Medicare and Medicaid. However, one of the most promising telehealth

approaches is the use of telehealth to connect providers with training, expertise, and/or

certification in areas that are relevant to the patients they are treating. This is of particular

importance for pediatric SUD, where there is a dearth of providers.

Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) is a telehealth program

focused on building capacity at the local level. This effort virtually links specialists at an

academic “hub” to providers in local communities—the “spokes” of the model. Connections

occur by providing remote training and specialist consultations. Specifically, the spokes

participate in weekly teleECHO clinics, which are virtual grand rounds, combined with

mentoring and patient case presentations facilitated by the hub. As of 2017, this model is in use

in more than 130 hubs across the United States, as well as 23 other countries (Lewiecki et al.,

2017). Many of the studies we reviewed were based on the ECHO model or were working

directly with the model, and reported an increase in the number of MAT-prescribing providers in

rural communities. Some communities integrated support for the Drug Addiction Treatment Act

(DATA 2000) waiver for prescribing medications for OUD with training to further support spoke

providers (Quest, Merrill, Roll, Saxon, & Rosenblatt, 2012).

One of the challenges affecting provider participation is the lack of funding for the time

providers spend attending and participating in these types of telehealth activities. Project ECHO

has addressed this concern by holding TeleECHO clinics at or near lunchtimes for the local

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

26

providers and by offering Continuing Education Units as an incentive (American Medical

Association, 2016; University of New Mexico, 2016). In some cases, Project ECHO participation

is covered by grant funding or included as time to be covered by the provider organization under

employment contracts. Although these efforts may be effective in some cases, some providers

may still choose not to take advantage of telehealth training in the absence of specific

reimbursement for their time.

In one study, sites noted that funding for TeleECHO is a challenge. Payers including

Medicaid do not reimburse for provider to provider communication and training. Often, such

programs have been initiated with grant funding and face a sustainability challenge after the

grant ends (Dunlap et al., 2018).

POLICY AND REIMBURSEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Many of the resources we reviewed called for regulatory changes to promote the uptake

of telehealth delivery methods to treat SUDs. Policies supporting the use of telehealth more

generally were not unique to pediatric patients. Some articles examined regulatory issues as a

component of payment policy, for example focusing on variation in licensure requirement.

Telehealth Policies that Influence Delivery of SUD Treatment

Our environmental scan found that many of the policies explicitly focused on telehealth

delivery methods for SUD treatment emphasized the treatment of OUD and MAT in particular.

The majority of resources describing these policies either reflected adult populations or did not

make any age distinctions. Telehealth-delivered MAT for OUD is not as prevalent as the use of

telehealth in other behavioral health services due to some unique considerations. Methadone is

only available from federally designated opioid treatment providers who typically require in-

person visits. Naltrexone requires a 7- to 10-day period of abstinence prior to start, which is often

a challenge without local provider support. Limitations on prescribing controlled substances is

recognized as a barrier for the provision of MAT via telehealth. For pediatric patients, MAT is

uncommon. Methadone and naltrexone are not approved for patients under age 18 (although an

exception can be made for methadone if the patient has had two documented unsuccessful

attempts at detoxification and has parental consent). Buprenorphine products are allowed for

patients 16 or older.

Reducing Barriers to Using Telehealth for Pediatric Populations

Final Report

27

Regardless, many of the policies are likely to have a similar influence on treatment for

pediatric patient populations delivered via telehealth. Other policies we describe below do apply

specifically to services delivered via telehealth for pediatric populations. Finally, some policies

apply similarly to all medical conditions while others are particular to both mental and substance

use disorders.

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (Pub. L. No. 115-334), commonly known as

the Farm Bill, includes key provisions for the use of telehealth to address SUD in rural

communities. These include increasing the annual budget for U.S. Department of Agriculture

Distance Learning and Telemedicine grants from $75 million to $82 million, and requiring 20

percent of all financial assistance for telehealth projects to be set aside for programs that address

SUD. In addition, this Act addresses connectivity concerns by increasing Federal resources for

broadband expansion projects in rural parts of the country. This includes creating a Federal

advisory committee to study opportunities for and barriers to rural broadband expansion.

The Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment

for Patients and Communities Act of 2018 (“SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act”, Pub.

L. 115-271) includes a number of provisions to support services delivered via telehealth. For

example, the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act amended section 1834(m) of the

Social Security Act (Pub. L. 74-271) to change certain payment policies for Medicare telehealth

services, as described in section 3.4.2.

The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008 (“Ryan Haight

Act”, Pub. L. 110-425) modified the Controlled Substances Act (CSA, Pub. L. 91-513), placing

challenges on the ability of telehealth providers to prescribe controlled substances. The Ryan