Fiscal Policies

for Diet and Prevention of

Noncommunicable

Diseases

Technical Meeting Report

5–6 May 2015, Geneva, Switzerland

Fiscal Policies

for Diet and Prevention of

Noncommunicable

Diseases

Technical Meeting Report

5–6 May 2015, Geneva, Switzerland

4 5

© World Health Organization 2016

All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on

the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health

Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264;

fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]).

Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for

sale or for non-commercial distribution–should be addressed to WHO Press through

the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/index.html).

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication

do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World

Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area

or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there

may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specic companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not

imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization

in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and

omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial

capitalletters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to

verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material

is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied.

Theresponsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader.

In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising

fromitsuse.

Printed by WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland.

Layout design: Eddy Hill Design

WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Fiscal policies for diet and prevention of noncommunicable diseases:

technical meeting report, 5-6 May 2015, Geneva, Switzerland.

1.Diet. 2.Food Habits. 3.Chronic Disease. 4.Health Behavior. 5.Taxes.

6.HealthPolicy. 7.Meeting Abstracts. I.World Health Organization.

ISBN 978 92 4 151124 7 (NLM classication: WT 500)

4 5

Contents

Acknowledgements 6

Abbreviations 7

Glossary 8

Executive summary 9

1. Introduction 10

2. Overview of noncommunicable diseases and the role

of scal policies to promote healthy diets 11

3. Rationale and evidence of scal policies 12

Rationale for scal policies on diet 12

Existing evidence on scal policies for diet 13

4. Country experiences and lessons learned 14

5. Implications for design and implementation of scal policies 19

A typology for consideration 19

Fiscal policies and price elasticity 20

Health and substitution eects of scal policies 21

Overcoming barriers to scal policies 21

Nutrient proling 22

Policy development 23

Earmarking of tax revenues 23

6. Conclusions 24

7. Recommendations 26

References 27

Annex 1. List of participants 30

Annex 2. Meeting programme 34

Figures

Figure 1: Pathways for the effect of fiscal policy interventions 12

Figure 2: Summary of main findings of meta-review 13

Figure 3: Types of taxes 19

Figure 4: Different tax base options for beverages 20

Figure 5: Fiscal policy development and implementation framework 23

Contents

6 7

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

Acknowledgements

The meeting report was prepared by Temo Waqanivalu and Leo Nederveen

withsupport from Doris Oppong and Paulina Sosa of the Department of Prevention

ofNoncommunicable Diseases.

Sta in the WHO regional oces and colleagues from the WHO departments

of Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases, and Nutrition for Health and

Development, participated in the organization of the meeting and provided

valuablecontributions to the meeting report.

WHO also wishes to thank the authors of the background paper provided to the

meeting, in particular Dr Anne Marie Thow and Dr Shauna Downs of the Menzies

Centre for Health Policy, University of Sydney, Australia.

Photos: Front cover: Gutsulyak (background, also back cover, p. 7), Mariyana M (also p. 8, 26),

Xiaorui (also p. 8, 26), Irina Rogova (also p. 8, 25), Billion Photos (also p. 8, 22, 26), Zelenskaya

(also p. 8, 11, 26), 5second Studio (also back cover, p. 9, 11), Claudio Divizia (also p. 9, 11, 25),

Yuttana Samol (alsop.9, 22, 25), Worananphoto (also p. 9, 25). Back cover: Yellow Cat (also

p. 5), Kanchana P (also p. 5), Andrey Popov, Niwat Chaiyawoot, BillionPhotos (also p. 20, 30),

AfricaStudio (also p. 5), Claudio Divizia (alsop.5, 21, 26), Ultimathule (also p. 5, 23), Africa

Studio. Page 33: Martin Good / all Shutterstock.

6 7

Abbreviations

CN Combined nomenclature

DALY Disability-adjusted life year

DKr Danish krone

EU European Union

FINI Food Insecurity and Nutrition Incentives

GAP Global Action Plan on Noncommunicable Diseases

HIP Health Incentive Pilot

ICN2 2nd International Conference on Nutrition

MRA Mauritius Revenue Authority

NCD Noncommunicable disease

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PAHO Pan American Health Organization

PHPT Public health product tax

SNAP Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme

SSB Sugar-sweetened beverage

USA United States of America

VAT Value added tax

WHO World Health Organization

Abbreviations

8 9

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

Glossary

Ad valorem tax:

Method for charging a duty, fee, or tax according to the

value of goods and services, instead of by a xed rate, or

by weight or quantity.

Fiscal policy:

A government’s revenue (taxation) and spending policy.

This report focuses on non-trade related taxes and

subsidies related to food, as non-discriminatory scal

policy approaches.

Noncommunicable diseases:

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) – also known

as chronic diseases – are not passed from person

to person. They are of long duration and, generally,

slow progression. The four main types of NCDs are:

cardiovascular diseases (such as heart attacks and

stroke); cancers; chronic respiratory diseases (such as

chronic obstructed pulmonary disease and asthma); and

diabetes.

Non-sugar sweetener:

A food additive (other than a mono- or disaccharide

sugar), which imparts a sweet taste to a food.

Technological purposes for this functional class includes:

sweetener, intense sweetener, bulk sweetener. It should

be noted that products like sugars, honey and other

food ingredients that can be used to sweeten are not

associated with the term “sweetener”.

Nutrient proling:

The science of classifying or ranking foods according

to their nutritional composition for reasons related to

preventing disease and promoting health.

Price elasticity of demand:

The degree to which demand for a good or service varies

with its price.

Regressivity:

The extent to which the burden of a tax is higher for

people on lower incomes, and/or represents a smaller

percentage of a higher income earner.

Specic excise:

A set amount of tax charged on a given amount

ofproduct.

Substitution:

An eect caused by a rise in price that induces a

consumer (whose income has remained the same)

tobuy more of a relatively lower-priced good and less

ofahigher-priced one.

Sugar-sweetened beverages:

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are beverages

containing added caloric sweeteners, such as sucrose,

high-fructose corn syrup, or fruit-juice concentrates.

These include, but are not limited to, carbonates, fruit

drinks, sports drinks, energy and vitamin water drinks,

sweetened iced tea, and lemonade.

Value-added tax:

Tax on each stage of production that adds value to

aproduct or process.

Sources: World Health Organization ( www.who.int ); Online Business

Dictionary ( ww w.businessdictionary.com );

Using price policies to promote healthier diets. Copenhagen:

WHORegional Office for Europe; 2015.

8 9

Executive summary

The Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of

Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020 proposes that

“as appropriate to national context, countries consider

the use of economic tools that are justified by evidence,

and may include taxes and subsidies, to improve access

to healthy dietary choices and create incentives for

behaviours associated with improved health outcomes

and discourage the consumption of less healthy options”.

The Comprehensive Implementation Plan on Maternal,

Infant and Young Child Nutrition 2012 also considers

that “trade measures, taxes and subsidies are an important

means of guaranteeing access and enabling healthy

dietary choices”.

To address the increasing number of requests from

Member States for guidance on how to design scal

policies on diet, WHO convened a technical meeting

of global experts in scal policies on 5–6 May 2015 in

Geneva. The main objectives of the meeting were to

review evidence and existing guidance, discuss country

case studies and provide considerations with regards to

the scope, design and implementation of eective scal

policies on diet. The meeting consisted of presentations

and discussions during plenary and in working groups

on the evidence, country experiences and technical

aspects of policy design and implementation.

It was concluded that there is reasonable and increasing

evidence that appropriately designed taxes on sugar-

sweetened beverages would result in proportional

reductions in consumption, especially if aimed at raising

the retail price by 20% or more. There is similar strong

evidence that subsidies for fresh fruits and vegetables

that reduce prices by 10–30% are eective in increasing

fruit and vegetable consumption. Greater eects on

thenet energy intake and weight may be accomplished

by combining subsidies on fruit and vegetables and

taxation of target foods and beverages. Vulnerable

populations, including low-income consumers, are

most price-responsive and, in terms of health, benet

most from changes in the relative prices of foods

andbeverages.

Consistent with the evidence on tobacco taxes, specic

excise taxes – as opposed to sales or other taxes – based

on a percentage of retail price, are likely to be most

eective. In countries with strong tax administration,

taxes that are calculated based on nutrient content

can have greater impact. A proper situation analysis,

good political advocacy, appropriate objective setting

and evaluation, should be part of the multidisciplinary

development and implementation of such policies.

It is also important in this process to be proactive in

counteracting the industry arguments and eorts to

oppose the development and implementation of tax

measures or attenuate their eects.

There are evidence gaps that could be addressed, with

more countries developing and implementing such scal

policies. Lack of standards or criteria for determining

exactly what to tax is a challenge experienced by

countries and the development of a nutrient prole

model for designing and implementing scal policies

was recommended. In addition, there was a call for

a manual on developing and implementing scal

policiesfor diet.

Executive summary

10 11

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

The Global Action Plan for the Prevention and

Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020

(GAP) (1)provides a roadmap and a menu of policy

options for Member States and other stakeholders

to take coordinated and coherent action to reduce

mortality from noncommunicable diseases (NCDs)

and exposure to risk factors. Under Objective 3 of GAP,

one of the policy options is to “consider economic tools

that are justied by evidence, and may include taxes and

subsidies, that create incentives for behaviours associated

with improved health outcomes, improve the aordability

and encourage consumption of healthier food products and

discourage the consumption of less healthy options”.

Furthermore, the Comprehensive Implementation Plan

on Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition 2012 (2)

states under Action 3: “Trade measures, taxes and subsidies

are an important means of guaranteeing access and

enabling healthy dietary choices. They can be powerful tools

when associated with adequate information for consumers

through nutrition labelling and responsible food marketing,

and with social marketing and promotion of healthy diets

and healthy lifestyles”. In November 2014, during the

Second International Conference on Nutrition (ICN2),

Member States adopted the Rome Declaration (3) and

a Framework for Action (4) which called governments

and partners to “identify opportunities to achieve global

food and nutrition targets, through trade and investment

policies”.

As part of these global mandates to prevent NCDs,

improve nutrition, and address the increasing demand

from Member States for guidance on how to design

scal policies on diet, WHO organized an expert technical

meeting on 5–6 May 2015 in Geneva.

The specic objectives of the meeting were to:

• Review existing evidence of taxes on sugar-sweetened

beverages (SSBs) and other foods and beverages

high in sugar, salt and fat, including the health and

economic impact;

• Present and review evidence from countries with

experience in the taxing of SSBs and other foods and

beverages high in sugar, salt and fat;

• Review and discuss modalities on policy options of

taxes on SSBs and other foods and beverages high in

sugar, salt and fat, including scope, tax rate, tax base

and use of tax revenue.

The expected output of the technical meeting was to

provide considerations based on evidence with regards

to the scope, design and implementation of eective

scal policies on sugar-sweetened beverages and other

foods and beverages high in saturated fats, trans-fatty

acids, free sugars and/or salt. The meeting convened

global experts in public health or health economics

with experience in scal policies for health, particularly

in relation to diet and tobacco. These included country

experts, a politician, academic researchers, and

civil society organization representatives. The WHO

Secretariat consisted of sta from the departments of

Nutrition for Health and Development and of Prevention

of Noncommunicable Diseases.

Dr Oleg Chestnov, Assistant Director-General

Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health

welcomed the participants and opened the meeting

by describing it as another milestone in the work on

NCD prevention. Dr Sirpa Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, Senior

Adviser of the Ministry of Social Aairs and Health of

Finland, and Dr Franco Sassi, Senior Health Economist

of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD), were elected as co-chairs, and

Professor Jamie Chriqui of the University of Illinois at

Chicago as rapporteur. A full list of participants can be

found in Annex 1.

The meeting consisted of panel presentations and

discussions on the evidence of scal policies, country

experiences and technical aspects of policy design

and implementation. Two working groups discussed

opportunities and challenges for scal policies and

aspects of good scal policy design, particularly with

respect to target foods, type of tax, tax structure, price

elasticity, substitution eects and implications for

revenue generations. This was followed by a plenary

discussion to reach consensus on the conclusions

and recommendations. The meeting programme

canbefound in Annex 2.

1. Introduction

10 11

Noncommunicable diseases, including diabetes

and obesity, are a major challenge for health and

development, particularly in developing countries,

where 85% of premature deaths occur. The 2013 World

Health Assembly endorsed the Global Action Plan on

Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020 (1) which

includes a set of actions for Member States, international

partners and the WHO Secretariat to prevent NCDs,

promote healthy diets and physical activity, and to attain

the nine voluntary global NCD targets by 2025. The nine

targets include halting the rise in diabetes and obesity

in adults and adolescents as well as the increase of

childhood overweight and obesity by 2025.

In 2014, 39% of adults worldwide aged 18 years and

older (38% of men and 40% of women) were overweight

(dened as body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25). Between

1980 and 2014, the worldwide prevalence of obesity

nearly doubled, with 11% of men and 15% of women

– i.e.more than half a billion adults – being classied

as obese. In2013, an estimated 42 million children

aged under 5 years (6.3%) were overweight, an increase

from around 5% in 2000 to 6% in 2010 and 6.3% in

2013,with the highest rates of increase being observed

in Africa and Asia. Diabetes was directly responsible

for 1.5million deaths in 2012 and 89 million DALYs.

The global prevalence of diabetes (dened as a fasting

plasma glucose value ≥7.0 mmol/L [126 mg/dl] or being

on medication for raised blood glucose) was estimated

to be 9% in 2014 (5). Excess consumption of calorie-

dense foods containing high levels of saturated fats,

trans-fatty acids, free sugars and/or salt either alone, or in

combination with insucient physical activity, contribute

to obesity and diabetes, as well as other NCDs. National

dietary surveys indicate that foods and beverages high

in free sugars can be a major source of discretionary

calories in the diet, particularly in the case of children,

adolescents and young adults.

Fiscal policies to improve diet – particularly taxation and

subsidies – are key population-based policy interventions

to reduce the consumption of calorie-dense foods and

address obesity and diabetes. They form part of the

menu of policy options of GAP and are being considered

by an increasing number of countries to promote

healthy diets, especially after experiencing progress in

implementing tobacco taxation. There is increasingly

clear evidence that taxes and subsidies inuence

purchasing behaviour, notably when applied to sugar-

sweetened beverages and this contributes signicantly

towards addressing the obesity and diabetes epidemic,

especially when part of comprehensive multisectoral

population-basedinterventions.

2. Overview of noncommunicable

diseases and the role of scal

policies to promote healthy diets

2. Overview of noncommunicable diseases and the role of scal policies to promote healthy diets

12 13

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

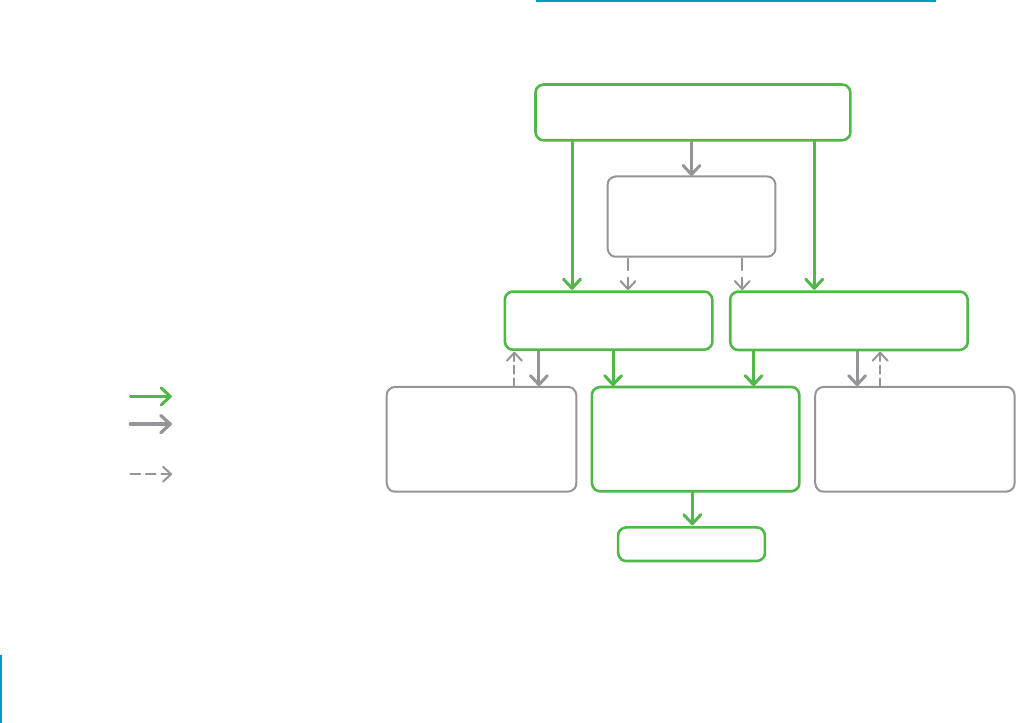

There are strong economic and health rationales for

using scal tools: scal interventions play a key role in

correcting for market failure; they can create incentives

to reduce dietary risk factors for NCDs and generate

revenues for the government. Estimates from recent

economic research show that the prices of foods

and beverages eect purchase and consumption

signicantly. Fiscal policy intervention has been

proposed primarily as a mechanism to inuence

consumer behaviour at the point of purchase. By

incentivising consumers to purchase healthier foods (or

disincentivising the purchase of less healthy foods), scal

interventions aim to change consumption of these foods

at the individual and household level, and to thus reduce

diet-related risk factors for NCDs (Figure 1).

Fiscal policy interventions can also work through

changing incentives for the production and manufacture

of healthy, relative to less healthy, foods. As taxes

increase, the purchase price of certain foods increases

and consumers thus reduce their purchases. As a

consequence, industry may produce less of the

food in question. Similarly, a subsidy decreases the

cost for consumers and can lead to increased

consumption, thus triggering increases in

supply to meet the rising demand. Taxes and

subsidies can also incentivise the food industry

to reformulate foods to improve the nutritional

quality of their products.

An additional benet of scal policy interventions,

highlighted in the literature, is revenue generation

and the potential to designate (hypothecate)

these funds for health promoting purposes.

Rationale for scal policies on diet

Source: Fiscal policy options with potential for improving diets for the prevention of

noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) (draft). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

3. Rationale and evidence

ofscalpolicies

As such, the use of scal policies should be considered a key

component of a comprehensive strategy for the promotion

of healthy diet and the prevention and control of NCDs.

The main scal policy interventions that have been proposed

for NCD prevention are: taxes on SSBs, unhealthy nutrients

(saturated/trans fats, salt and sugar) and/or unhealthy foods

(dened through nutrient proling); and subsidies on fruits,

vegetables and/or other healthy foods.

The fundamentals to the eect of scal policies on diet and

the basics of price elasticities include:

a) demand for SSBs is generally elastic, with price elasticities

around -0.9 to -1.3;

b) price elasticity is higher among low-income consumers,

in younger people and people with overweight, which

iscorrelated with income;

c) high consumers of SSBs are also likely to be more

price-responsive.

Figure 1: Pathways for the eect of scal policy

interventions

Eect on consumers

Secondary eect

(on industry and revenue)

Possible amplication eect

Tax and/or subsidy – incentives for substitution

with healthier foods and beverages

Increased purchase and

consumption ofhealthy foods

Financial implications

for manufacturers and

producers – incentive for

increased production

Decreased diet-related risk

factors for NCDs (e.g. body

weight; blood pressure;

bloodcholesterol)

Decreased NCD risk

Financial implications for

manufacturers and producers

– incentive for decreased

production andreformulation

Decreased purchase and

consumption of lesshealthyfoods

Revenue generation:

potentialhealth care/

healthpromotion funds

12 13

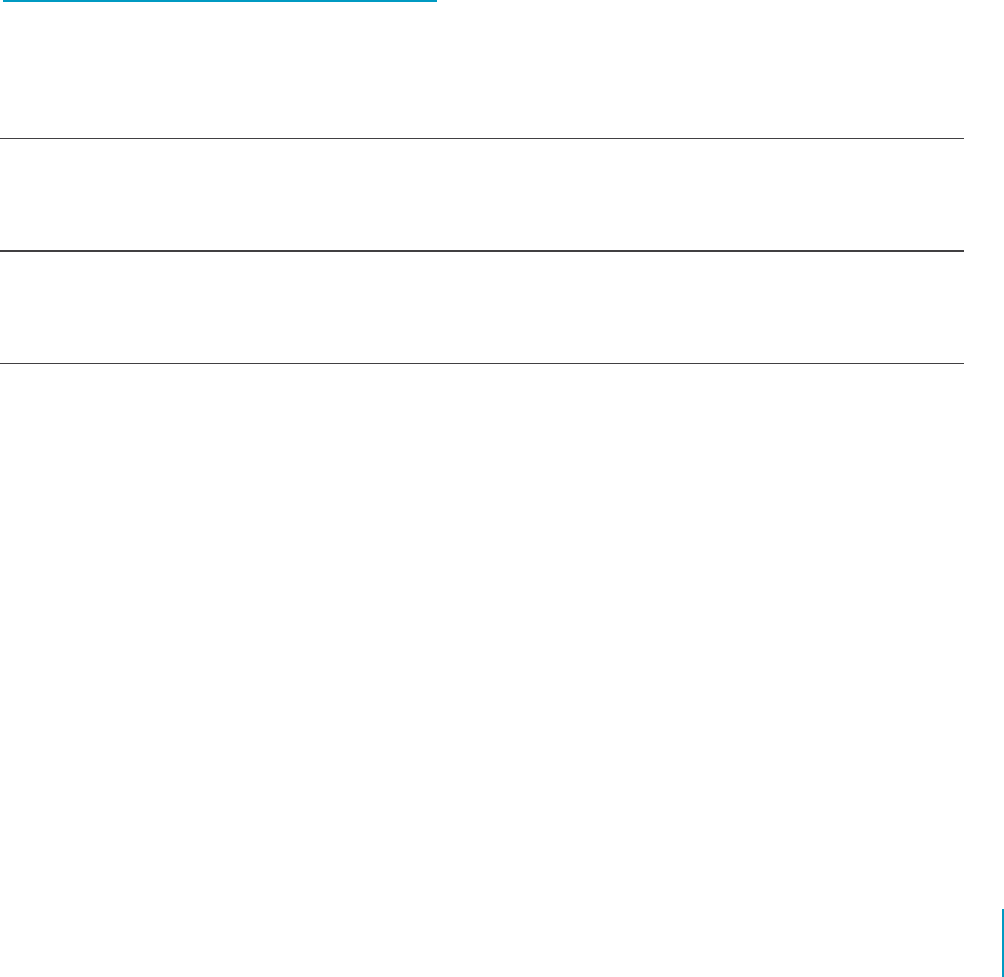

Growing evidence shows that appropriately designed

scal policies, when implemented with other policy

actions, have considerable potential for promoting

healthier diets. These will improve weight outcomes

and other diet-related risk factors, and will contribute,

ultimately, both to the prevention of NCDs and to the

reduction of the NCD health and economic burden.

A meta-review of 11 recent systematic reviews on the

eectiveness of scal policy interventions for improving

diets and preventing NCDs (6) showed that the evidence

was strongest and most consistent for the eectiveness

of SSB taxes in the range of 20–50% in reducing

consumption, and of fruit and vegetable subsidies in

the range of 10–30% in increasing consumption. While

evidence is mixed on the net eect of fruit and vegetable

subsidies on net caloric intake and weight, overall diet

quality improves thus leading to improvements in health

outcomes. There is also growing evidence for the likely

eectiveness of combinations of taxes and subsidies,

particularly as a mechanism to reduce potential

substitution with unhealthy foods. These combination

interventions can be designed using modelling that

is both eective and revenue neutral. All the reviews

concluded that taxes and subsidies were eective at

changing the consumption and purchasing of target

foods, with the strongest and most consistent eects

seen for SSB taxes and fruit and vegetable subsidies

(Figure 2). The greatest impact was on lower-income,

less-educated younger populations, and populations

atgreater risk of obesity.

Existing evidence on scal policies for diet

Current evidence is based mainly on intervention

studies and modelling. The most accurate and eective

objectives for price policies focus on their upstream

potential to inuence purchasing and consumption

behaviour, rather than on downstream eects, such as

body weight or disease which are also inuenced by

a large number of other factors. One of the evidence

gaps that needs to be lled is research quantifying the

impact of SSB tax on improving weight outcomes and

other diet-related risk factors. In many of the countries

implementing scal policies formal evaluations are

lacking, and when more countries introduce similar

measures, longitudinal research work could be one way

to address this evidence gap. Monitoring and evaluation

eorts are critical in documenting the eectiveness

of the taxes in achieving their objectives in terms of

revenue and its use, impact on purchase patterns,

consumption, and product composition for targeted

products and close substitutes. In addition, monitoring

and evaluation highlight the relevant health outcomes

of tax implementation, while identifying unanticipated

eects - such as a substitution to non-sugar sweeteners.

3. Rationale and evidence ofscalpolicies

Source: Fiscal policy options with potential for improving diets for the prevention of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) (draft).

Geneva:WorldHealth Organization; 2015.

Figure 2: Summary of main ndings of meta-review

of systematic reviews on scal policies on diet

Food/ beverage taxes Nutrient-focused taxes Subsidies

Eect on

consumption

Strongest evidence for SSB taxes – reduce

consumption by same percentage as

taxrate.

Reduce consumption of target but may

increase consumption of non-target

nutritients; may apply to core foods;

better if paired with subsidy.

Subsidies increase healthy food intake.

Strongest evidence for fruit and vegetable

subsidies.

Eects on body

weight/disease

outcomes

Substitution will aect total calorie

intake. Most eective to target sugar-

sweetened beverages. Limited evidence

for disease outcomes.

Disease outcome aected by substitution

– nutrient prole taxes less likely to have

unintented eects than single nutrient-

based taxes.

Subsidies may also increase total calorie

intake and body weight. Very likely to

reduce dietary NCD risk factors.

Dierential

eects

May be most eective for low-income

populations; may have greater eect on

those who consumemost.

May be more likely to have regressive

eects as more likely to apply to

corefoods.

Mixed socioeconomic status eects

for population subsidies, may benet

wealthy. Targeted low-income

subsidieseective.

14 15

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

There were important insights from each of the country

presentations: Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Finland, France,

Hungary, Mauritius, Mexico, Philippines, Thailand and

the United States of America. Fiscal measures – in

particular food taxation – are being implemented with

promising results; however, the objectives of many

countries focus more on economical benets rather

than on public health. Some of the challenges faced in

implementation include a lack of appropriate capacity

for tax administration, tax set at low levels that prove

inecient in inuencing behavioural choices, and a lack

of monitoring and evaluation of the health impact. It

was established from all presentations that countries

attempting to progress scal policies face considerable

political and industry opposition.

Denmark

Denmark’s tax on saturated fat – implemented on 1

October 2011 and abolished on 1 January 2013 – proved

to be ecient in reducing the intake of saturated fat

as well as in improving other dietary measures and

reducing mortality from NCDs. The tax was paid on

the weight of saturated fat in foods and on saturated

fat used for the production of foods when the content

of saturated fat exceeded 2.3 g/100 g. The excise tax

amounted to DKr 16.00 (€2.15) per kilogram of saturated

fat, plus an additional 25% VAT.

Weaknesses in design, the lack of a coordinated voice

from public health organizations and a lack of public

documentation of the aggregated eects on health and

the overall eects on the economy, gave opponents

of the tax – for example the food industry and trade

organizations – free play to create negative publicity and

to initiate EU jurisdictional actions against it (7–14).

The lessons learned from Denmark are that:

• potential health eects should be estimated before

implementation of a tax, and real health and

consumption eects measured and documented after.

These would include the measuring of potential and

adverse substitution eects;

4. Country experiences

andlessons learned

• health professionals and organizations should be

consulted during the design of the tax to ensure

acoordinated voice;

• total welfare eects on the economy should be analysed

and discussed;

• anti-competitiveness of a tax should be analysed before

implementation to avoid lawsuits; and

• the design of a tax should be clear and logical and based

on clear public health rationale.

Ecuador

In light of the dramatic increases in overweight and

obesity rates across the Ecuadorian population (15), the

government has implemented interventions in the eld of

food regulation. Ecuador is the rst country in Latin America

to implement a trac light front-of-pack food labelling. This

regulation went into eect ocially on 29 August 2014 (16).

The Ecuadorian government made the political decision

to levy a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages and foods

high in fat, sugar and salt (“junk food”). However, the

technical aspect of this proposal faced challenges which

made the tax dicult to implement – the main challenge

being a lack of standard criteria for determining what food

products to tax based on nutrient content. Also, as this was

a public announcement, the national media distorted the

information, stating that certain traditional preparations

consumed in Ecuador would be considered as junk food

because of their high fat content. In order to clarify the

dierence, the energy density criteria (17) were used as

well as denitions developed by the University of Sao Paulo

research group. Nevertheless, application ofthese criteria

was not considered feasible (18).

Egypt

Egypt applies a sales tax on industrial goods with a general

rate of 10%, and specic rates for some goods (excise tax).

The government imposed reduced tax rates, or exemptions,

for specic goods, the purchase of which they considered

essential or desirable. This was put in place without

consideration of the resulting negative health eects

this may have on the consumer, such aswith sugar and

hydrogenated oils.

14 15

To date, the government of Egypt has not adopted taxes

on unhealthy food as a tool to reduce its consumption.

On the contrary, it has imposed low tax rates on some

unhealthy foods, such as sugar, which has tax rates

less than 60 Egyptian pounds per ton. With certain

products, the government has reduced tax rates due to

manufacturers pressure, as, for example, with carbonated

beverages where the excise tax rate was changed from a

two-tiered rate (50% and 60% of the producer price) into

a single sales tax of 25%.

Finland

Finland has a long history of using price policies to

inuence food consumption. Since 1948, free school

meals, paid by tax income, have been oered to all pupils

at elementary schools (19) and university students have

benetted from subsidized meals if nutritional quality

criteria are met (20). Moreover, since 2009, EU school

milk subsidies have not been given to products high in

fat or salt. Since 2011, excise duties have been levied

on sweets, chocolate and non alcoholic beverages (Act

1127/2010). The taxes are primarily levied to generate

revenue for government nance purposes, but potential

health and consumption impacts are acknowledged. The

tax rates were increased in 2012 and 2014.

The current excise tax is €0.95 per kilogram for sweets

and ice cream. For non-alcoholic beverages the tax is

€0.11 per litre; however, beverages containing more than

0.5% sugar pay €0.22 per litre. Products are identied by

CN/Custom tari headings and small-scale production

and exported products are exempted (21).

1

From 2010 to 2013, a Sugar Tax Working Group, set up

by the Ministry of Finance, assessed the suitability and

impact of three tax models: 1) a tax model based on

sugar content; 2) a tax model similar to existing excise

duty on sweets; and 3) a tax model combining the

two. The Working Group found that the combination

model would be optimal in terms of health promotion,

while the excise duty model would be the most

straightforward in terms of practical implementation.

Both the sugar tax and the combination model would

impose a signicant administrative burden on taxpayers

falling within the sphere of the tax (22).

The impact of the tax on purchase, consumption and

health has not been formally evaluated; however

according to unocial reports it has led to decreased

sales and consumption of non alcoholic beverages and

sweets. At the same time, there have been concerns

raised by the industry that a tax targeting such specic

products is unfairly discriminating against particular

manufacturers in the food industry, and therefore

distorting competition.

France

In 2011, France adopted a levy on beverages and liquid

preparations for human consumption that contained

added sugar or other sweeteners. The amount of the

contribution was set at €7.16 per hectolitre, and was

increased to €7.5 per hectolitre in 2015. Since 2013,

thetotal of the contribution is allocated to the National

Social Health Insurance.

According to the Nutrinet

2

study for the General

Directorate of Health of 2013, consumption of sodas

hasdecreased, particularly in young people, low-income

groups and households with adolescents. There is a

need for more detailed impact assessments and eects

on children, dierent socioeconomic groups and on

substitution.

In 2014, the revenue raised by tax was approximately

€300 million. The tax has appeared to have a positive

eect on purchase patterns from a public health

perspective and is generally well accepted by

thepopulation.

Hungary

A public health product tax (PHPT) was introduced in

2011 taxing non-staple food products that carry proven

health risks when consumed. The objectives of the PHPT

were: to encourage healthier eating habits by increasing

the availability of healthy choices; to encourage

reformulation; and to increase revenues for public health.

The PHPT is a specic excise tax on a per unit measure,

based on sugar, salt and methylxantine content in pre-

packaged food products. The tax-related administrative

burden for enterprises is minimal.

The rst impact assessment, conducted one year later,

found that 26–32% of consumers had decreased their

intake of products subject to PHPT. Price increase was

the major driving force, although a high percentage of

consumers (22–38%, depending on food categories)

had reduced their intake due to an increased health

consciousness. Consumers with bad self perceived

health status were, on average, twice as likely to decrease

consumption of foods subject to PHPT compared with

those of good health. Moreover, of the responding

food producers, 40% had carried out reformulation of

their products, 30% had totally removed unfavourable

4. Country experiences andlessons learned

1

On 29 September 2015, a Finnish Financial Parliamentary Committee decided to end the tax on sweets that has been in force since 2011.

www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/finland-tax-on-chocolate-and-sweets-to-be-eliminated-2017

2

https://www.etude-nutrinet-sante.fr/fr/common/login.aspx

16 17

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

components in their products, and 70% had decreased

the quantity of unfavourable components in their

products (23).

In conclusion, PHPT has achieved its public health aims.

The population has reduced its consumption of products

subject to PHPT; food manufacturers have started

reformulation, and the estimated tax revenue has been

almost fully realized.

The second impact assessment of 2014 sought to

determine whether changes in consumption would be

maintained in the long term and how they would be

inuenced by nutritional and socioeconomic status. The

assessment also aimed to obtain information on product

substitution. Initial results showed that consumers of

unhealthy food products responded to the tax by: a)

choosing a cheaper, often healthier product (7–16%

of those surveyed); b) consumed less of the unhealthy

product (5–16%); or c) changed to another brand of the

product (5–11%) or substituted some other food (often

a healthier alternative). Most people (59–73%) who

reduced their consumption after introduction of the tax,

consumed less in 2014 than in previous years, suggesting

that the reduction in unhealthy food consumption has

been sustained.

Mauritius

Mauritius is a sugar producing country. The share

of sugar production in the Mauritian economy

has consequently declined over the years and in

relative terms dwindled to about 3.5% of the gross

domestic product in 2003 (from 25% in the 1970s).

Sugar production nevertheless remains an important

contributor to the country’s economy, with sugar exports

representing approximately 19% of foreign exchange

earnings.

Irrespective of the signicance of sugar to the economy,

in February 2013, the government took the decision

to introduce an excise duty on the sugar content of

“soft drinks”. “Soft drinks” subject to tax in Mauritius

include: any aerated beverage (such as colas); any syrup

for dilution; and any fruit squash, cordial or fruit drink

(including blends and juice with added sugar). The excise

duty excludes bottled water; pure fruit juice, and blends

thereof; pure vegetable juice, and blends thereof; and

dairy milk, and products thereof.

The rate of the excise duty was set at 2 Mauritian cents

per gram of sugar. This was increased to 3 cents per gram

from 1 January 2014.

For imported products, the tax is collected by the

Mauritius Revenue Authority (MRA) (Mauritian customs)

at the time the product is being cleared from customs.

For locally produced products, the tax is collected by

the MRA at the time the product leaves the factory. The

importer, or the local manufacturer, has to produce a

certicate from an accredited laboratory, or the Mauritius

Standard Bureau, indicating the sugar content for

customs clearance. In addition, the MRA also carries out

post-control audit checks on a risk management basis.

The excise duty collected is 330 million Mauritian rupees

(US$9.2 million). Its impact on the sale of soft drinks has

not been assessed.

Mexico

The prevalence of overweight and obesity reached 71%

among adults and 30% in children and adolescents in

Mexico (24, 25). The proportion of adults with diabetes

was estimated at 14% in 2006 (26). In 2012, Mexico had

the highest worldwide consumption of sugar-sweetened

beverages: 160 litres per capita (27). In addition, recent

evidence shows that 71% of the consumption of added

sugars comes from SSBs and 23% from non-basic energy

dense foods (28).

In this context, on January 2014 Mexico implemented

two taxes: 1) a 1 peso per litre excise tax on any

non-alcoholic beverage with added sugar (powder,

concentrates or ready-to-drink), which is paid by the

producer and represents about a 10% increase in price;

and, 2) an 8% ad valorem tax on the purchase price

for a list of non-essential energy-dense foods (snacks,

confectionery products, chocolate and other products

derived from cacao, puddings, ans, ice cream, candies,

peanut butter), that contain 275 calories per 100 grams

or more. This tax is paid by the producer or the retailer.

The SSB tax was proposed by the government to the

congress as a means of reducing the negative eects

of SSB consumption on overweight and obesity, and

the direct and indirect associated costs. Factors that

enabled the approval and implementation of the tax

were: evidence provided by experts on nutrition; high

obesity and diabetes rates; high consumption of SSBs

and non essential high energy dense foods; economics

(price elasticities overall and by income level, potential

substitutes, revenue estimation); the active presence

of the civil society (advocacy, campaigns, mapping

key supporters of the initiative); and interest from

thegovernment.

After implementation of the tax, studies have been

conducted to evaluate the eects on consumer prices

and purchases. Preliminary results show a complete pass

through to consumer prices for SSBs in urban areas, but

incomplete for rural areas and heterogeneous for the

16 17

non essential high-energy dense foods (29). Preliminary

results also show that household purchases have

decreased during 2014 (30).

A study by the Mexican Public Health Institute and

University of North Carolina on the impact of rst year

of introduction of the excise tax on sugar-sweetened

beverages in Mexico concluded that “relative to the

counterfactual in 2014, purchases of taxed beverages

decreased by an average of 6%, and decreased at an

increasing rate up to a 12% decline by December 2014.

All three socioeconomic groups reduced purchases of

taxed beverages, but reductions were higher among the

households of low socioeconomic status, averaging a 9%

decline during 2014, and up to a 17% decrease by December

2014 compared with pre-tax trends” (31, 32).

Philippines

In 2009, the Philippines ranked 11th worldwide in the

consumption of soft drinks (about 1.6 billion litres) which

prompted a lawmaker and health initiatives advocate

in congress to initiate and le a bill imposing an excise

tax on sugar-sweetened beverages to help curb its

consumption and lower the risk of obesity, diabetes

and related illnesses. At the same time, the bill was to

generate tax revenues that would be allocated towards

government health initiatives. These included: providing

medicines and medical assistance for the indigenous

diabetic patients; the promotion of community-

based obesity prevention programmes; diabetes

prevention campaigns and other diet-related health

awareness programmes; funding for research and other

development programmes related to food and nutrition;

providing access to potable water; and establishing

sports facilities in communities and public schools to

promote health and wellness.

The aim of curbing SSBs consumption is supported by

a study (33) that shows that imposing a tax that would

increase the price of SSBs by 20% would reduce overall

consumption by 24%. The ling of the bill in October

2013 sparked negative reactions, not only from the

beverage and sugar industries, but also from some

government agencies and political gures directly

impacted.

Although there is inuence from stakeholders in

deterring the bill within congress, there remains great

optimism that, with the strong support received from

various Philippine and international health organizations

and agencies – including the World Health Organization

– it will be progressed with a positive outcome.

Thailand

Economic growth in Thailand has led to higher incomes

andan increase in consumption of SSBs as Thailand

becomes an emerging market for many ready-to-drink

beverages. Existing taxation is ad valorem and does not

consider the health promotion value. The current tax of

beverages without sugar is US$0.025/440 ml, while the

taxon beverages with sugar is US$0.012/440 ml.

The food system in Thailand includes many dierent food

items, manufacturers and sellers. Tax increases do not always

translate into higher prices. Compared with high-income

countries, Thailand has a smaller proportion of commercial

processed foods and beverages, cheaper retail prices of SSBs

and relatively high prices of fast food. Healthy alternatives

are not always available.

Fiscal policy development and implementation is

dicult due to the many competing policy priorities and

an increasing inuence of international trade treaties

on policies. Human resources for stewardship and

implementation are limited and are coupled with a lack of

verication mechanisms, particularly on food composition

and retail prices. There is also insucient monitoring and

enforcement capacity and limited preparedness of local

governments to administer tax policies.

United States of America: California and Vermont

In the USA, the state of California has been a leader in

establishing public policies to regulate the sale of soda and

other sugar-sweetened beverages. State legislation to ban

the sale of SSBs on school campuses was rst introduced in

1999, and was fully enacted by 2005. Since 2002, California

has considered establishing a tax on SSBs ve times. In 2012,

two cities in California – Richmond and El Monte – voted to

tax SSBs; however, the two-thirds threshold for success was

not achieved. In 2014, two further Californian cities – Berkeley

and San Francisco – similarly voted for an SSB tax. Berkeley

achieved a 75% vote for implementation, well above the 50%

threshold for success and thus became the rst USA city to

pass a tax measure, imposing a 1 cent per ounce tax on SSBs.

In 2014, California was the rst state in the USA to consider

legislation to require warning labels on SSBs.

There was much opposition to these two legislations and two

fundamental lessons emerged from the political campaigns.

The rst was that, using the same well-nanced scare

tactics made famous by the tobacco industry, the beverage

industry, similarly, will do everything it can to prevent tax

implementation; the second is that, as California has shown,

industry can be defeated.

Much of legislative action on SSBs in the USA is at the state

or local (city, county) level. The state of Vermont is another

4. Country experiences andlessons learned

18 19

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

example of a recent attempt to introduce a state excise tax

on SSBs, proposing a tax doubling the existing penny-per-

ounce (US$1 per almost 3 litres). Given very low SSB prices

in the USA, this translated into a tax burden of, onaverage,

approximately 50%. One of the challenges for economists

is to predict the response of consumers (i.e. price elasticity)

when taxes are very high, and have not been evaluated

based on prior data. Another is to anticipate the tax pass-

through rate (i.e. how much the tax gets passed into the

price). Economic theory predicts a perfect pass-through

(i.e. a 1 cent excise tax increases retail price by 1 cent).

The rst year, data from Berkeley suggested that the tax

pass-through might be initially less than 1 cent, indicating

that prices increase less than the amount of an excise tax

imposed (34).

Cross-price elasticity data are very limited and unstable, with

much variation across studies. Most studies predict a shift

primarily to bottled water and juice, while diet beverages

have a positive cross-price elasticity with SSBs (35). This is

likely the result of the underlying data where promotions

are usually the same for both diet and regular beverages

(e.g. all products of a brand on sale). Shifts to food and the

overall eect on diet should be also considered.

In the USA, the ongoing market trend is for a signicant

reduction in SSB consumption (36), much higher

purchases of bottled water, shifts away from soda towards

water and new healthier (less caloric) beverages (37). Per

capita consumption of SSBs is still very high, which justies

policy action such as taxes. It is likely to have an eect

on SSB consumption per se, since the campaign to pass

a tax (even if unsuccessful) helps to educate consumers,

encourages the industry to reformulate products, and

reduces SSB consumption.

United States of America: Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Programme

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

provides food-purchasing assistance for low- and no-

income people living in the USA. The eect of providing

nancial incentives to participants of the SNAP at the

point-of-sale was recently evaluated in a randomized

control trial. Known as the Healthy Incentive Pilot (HIP),

the study showed that a 30% subsidy of targeted fruit

and vegetable purchases increased their consumption,

by SNAP participants, by 26% (38). This would be

predicted by price elasticity data from prior research

(39). There was no eect on total energy intake and no

change in SSB and “junk food” intake. No cost-benet

analysis was done in this evaluation, but it is unlikely that

the intervention would be shown to save money.

There are also incentive programmes, known as “double-

buck programmes”, that provide a match to SNAP benets

for fruit and vegetable purchases at farmers’ markets (40).

These, mostly privately-run, programmes give low-income

consumers “double bucks” (or “health bucks”) coupons that

double the value of food stamps at farmers’ markets and

occasionally grocery stores for buying fruits and vegetables.

The Food Insecurity and Nutrition Incentive (FINI) grant

programme, authorized in the Agricultural Act of 2014, will

provide US$100 million over 5 years to support projects

that increase purchases of fruits and vegetables among

SNAP participants by providing incentives at the point of

purchase (41).

Using price policies to promote healthier diets

inEurope

In 2015, the WHO European Region published a document

on the use of price policies to promote healthy diets (42).

Thedocument provides information on the use of price policies

to promote healthy diets and explores policy developments

from around the WHO European Region. Itexamines the

economic theory underpinning the use of subsidies and

taxation and explores the currently available evidence.

The publication includes several case studies from WHO

European Member States where price policies have been

introduced, including Denmark, Finland, France, Hungary and

the EU School Fruit Scheme.

Specic factors to consider in the design of eective

price policies include possible substitution eects, the tax

mechanism chosen, price pass-through, and impact on

health inequalities. Price policies can also be implemented to

inuence supply-side factors. Comprehensive monitoring and

evaluation, using carefully selected indicators, is essential in

using price policies.

The document concludes that scal policies are an important

tool in tackling unhealthy diets and NCDs and that there is

signicant scope in the future for countries across Europe

to advance their implementation. From the evidence, taxes

on sugar-sweetened beverages and targeted subsidies on

fruit and vegetables emerge as the policy options with the

greatest potential to induce positive changes in consumption;

however there is also demonstrable positive impact with

other approaches. Experience with the implementation of

such policies in the Region has shown that they are feasible

and can inuence consumption and purchasing patterns

as intended, and have a signicant impact on dietary and

health-related behaviour. The revenue raised has, in some

cases, beensuccessfully ring fenced for the health budget.

Continued monitoring and evaluation is considered

important, particularly in terms of establishing baseline data

atthe outsetin order to monitor the eects ofthe policy.

18 19

When designing scal policies on diet, key questions

toconsider are (42–44):

1. What type of tax to apply?

2. What tax structure to implement?

3. What products to tax?

4. What are the implications for revenue generation

anddiet/nutrition-related programming?

Excise tax is tax levied on manufacture, sale, use, or

distribution. It may also include a xed fee or levy on a

purveyor. A special value added tax (VAT) applies to the

production and distribution of goods. It is considered a

consumption tax because the ultimate cost is borne by

the consumer at point of purchase.

A tax can be specic or ad valorem. A specic tax is levied

on the basis of product size or amount. An ad valorem

tax is a percentage of the product value (Figure3).

Consistent with the evidence on tobacco taxes, specic

excise taxes (where a set amount of tax is charged on a

given quantity of the product or specic ingredient) are

likely to be most eective. This is because they reduce

incentives to switch down to cheaper options, in that

they increase the price of all products aected by the tax

in the same way. They also provide more stable revenues,

are not subject to industry price manipulation and are

easier to administer. Inorder to prevent the impact of

specic taxes from being eroded over time, it is essential

that they be adjusted regularly to, at least, keep up with

ination and reduce aordability of the taxed product by

accounting for income growth as well.

In countries with strong tax administration, taxes that

are calculated based on nutrient content (e.g. SSB taxes

based on sugar content) can have the greatest impact,

as they dierentiate between options based on nutrient

content within a product category and can be used to

incentivise consumers to substitute to alternatives while

simultaneously encouraging producers to reformulate

their products. In countries where tax administration is

not as strong, simpler tax systems (e.g. a volume-based

SSB tax) may be more appropriate.

WHO’s tobacco taxation experience

Since 2009, WHO has been working closely with

Member States to improve and increase their excise

taxes on tobacco products and to reduce their

aordability. There are dierent types of indirect taxes

applicable on tobacco products. It is important to

focus on excise taxes (specic, ad valorem and mixed)

as a public health policy rather than other taxes in

order to increase the relative price of the targeted

product eectively and to reduce consumption.

One of the main conclusions derived, and lessons

learned, from tobacco taxation is the importance of

implementing specic excise taxes, or a mixed system,

relying more on the specic excise component.

These taxes lead to higher prices, reduce gaps within

products – therefore reducing risk of substitution –

and are easier to administer. However, specic excise

taxes need to be adjusted to ination – and ideally

to income as well – in order to eectively reduce

aordability and discourage consumption over time.

Additionally, tax policies have to be accompanied by

a system that closely monitors products throughout

the supply chain (track and trace). This will reduce the

chance of products ending in the illicit market.

5. Implications for design and

implementation of scal policies

A typology for consideration

5. Implications for design and implementation of scal policies

Figure 3: Types of taxes

Excise Tax VAT

Specic

+

Ad valorem

+ +

20 21

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

The responsiveness of consumers to price changes (price elasticity) for the food

and beverage products that may be taxed is central in the design of taxes for

health promotion. When consumers can substitute alternative products, their

response to price increases will be greater; but not all substitutions are likely to

be desirable. Carefully designing the tax base (range of products to be taxed)

will help to prevent undesirable substitutions, and possibly steer substitutions

towardshealthyalternatives (Figure 4).

Fiscal policies and price elasticity

In most cases, however, the demand for foods and

beverages is typically inelastic (i.e. consumers are not

very responsive to price changes). This should not be

viewed, per se, as hindering the pursuit of public health

goals. It simply means that the tax rate will have to be

high enough to reduce the consumption of the taxed

products to an extent that will generate meaningful

health eects. A low price elasticity also makes the tax

more likely to be passed on to consumers by suppliers

(i.e. prices will increase at the point of consumption).

Moreover, tax revenues will be larger than in the case

of products with a more elastic demand, providing

greater opportunities for funding other health

promotion activities.

There are areas in which taxation practice is not

entirely in line with theory and some of these

deviations might be desirable from a public health

point of view. For instance, there is a broad consensus

on excise taxes (particularly, specic excises regularly

adjusted for ination) being the scal tool of choice in

the pursuit of public health goals, at least in the area

of food and non-alcoholic beverages.

However, the public health community has also

called for the use of positive scal incentives, for

instance to stimulate the consumption of healthy

foods. This goal could be pursued via the indirect tax

system through rate dierentiation in value added

orsales taxes.

All/most beverages

All sweetened beverages

Only SSBs

Selected SSBs

Figure 4: Dierent tax base options for beverages

20 21

Health and substitution

effectsof scal policies

The overall health eects of food and beverage taxes

depend on the price elasticities of demand, which

are composed of the income and substitution eects.

The size of the substitution eect depends on the

extent to which there are available substitutes, for

example from SSBs to water, milk, unsweetened 100%

fruit juice and beverages with non caloric sweeteners.

Close substitutes give rise to a large substitution

eect. The income eect depends on the extent

to which consumers are able, or willing, to change

behaviour. Lack of behavioural change might imply

that consumers feel burdened by the tax and have less

money to buy either unhealthy or healthy foods.

It is important to consider the tax base since the overall

health eects of the tax depends on the availability

of substitutes for dierent types of consumers.

Consumers might substitute to a healthier type of

product, to another type of unhealthy product, to a

cheaper brand or store. Correct design of the tax and

correct choice of the tax base could minimize any

potential adverse unexpected health eects of food

and beverage taxes (45–48).

Vulnerable populations, including low-income

consumers, young people, and those most at risk

of obesity, are most responsive to changes in the

relative prices of foods and beverages. Well-designed

taxes targeting non-core foods with close, healthier

(untaxed) substitutes may result in greater behaviour

change and would minimize tax regressivity.

There is potential for taxes to be further supported

by complementary subsidies targeted to low-

incomepopulations.

Overcoming barriers

toscalpolicies

Countries experience great challenges in policy

implementation from the undue pressure of the food

and beverage industries. Oppositional arguments

against taxes are usually either false or greatly overstated.

Common myths relate to the impact on jobs, businesses,

those on a low income, and tax avoidance. As has been

conrmed by recent studies in California and Illinois in

the USA, SSB taxes are likely to lead to a net increase

in jobs, in spite of a small decrease in jobs in the

beverage sector (49). This occurs because consumers

redirect their purchases towards untaxed products thus

stimulating growth in other non-beverage sectors. A

study conducted in the USA between 1997 and 2009

found that, contrary to predictions from the tobacco

industry, there was an increase, rather than a decrease,

in the number of convenience stores. This was due to

consumers shifting to buying other products and thus

creating more demand for those products.

Low-income populations have the largest health benet

from taxes, because their pre-tax SSB consumption

is high and post-tax reductions in consumption are

relatively large. The benets for these populations are

even higher if tax revenues are used for targeted obesity

prevention and health promotion programmes and if

targeted subsidies for healthier options exist. There is

likely to be little tax avoidance and evasion in response

to an SSB tax. The strength of governance and presence

of informal distribution networks have a greater eect

than tax and price levels in driving tax avoidance and

evasion.

The role of civil society and health professionals is critical,

not only to counteract undue pressure from food and

beverage companies, but also to monitor scal policies

and ensure their appropriate implementation.

Regarding opposition to taxes, fundamental lessons

are to be learned from the experience of countries

implementing SSB taxes. Firstly, the beverage industry

will do everything it can to avoid taxes, using the same

well-nanced – and well recognized – scare tactics

used by the tobacco industry. In 2014, for example,

the beverage industry spent more than US$10 million

ghting SSB tax measures in Berkeley and San Francisco,

outspending proponents by 18:1, with 99% of funds

provided by corporate interests outside of California.

Tactics ranged from buying television and radio

advertisements, paying for advertising billboards, lawn

signs and advertising space in subway stations (including

5. Implications for design and implementation of scal policies

22 23

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

the oor space) as well as paying members of the

community to go from house to house canvassing

support. Claims were made that the tax was unfair to

poorer people; that it would harm small businesses;

and that revenues would not be spent as promised.

It was also stated that the government should not

interfere with the personal choices of consumers.

A further lesson learned is that, regardless of pressure

and nance from industry, any opposition to taxation

can be overcome with a well-planned campaign

involving a broad coalition of supporters (from

community leaders and health-oriented organizations

to grassroots people and organizations), the ability to

respond to the beverage industry’s propaganda, and

sucient resources. The objective would be to inform

populations of the truth of potential harm caused by

the products. The experiences from countries such as

the USA (in particular the city of Berkeley in California)

and Mexico prove how policies can be progressed

even amidst greatindustryopposition.

As countries around the world enact these policies,

an ever-greater movement to support other countries

to do the same will be created. As with the tobacco

industry, the beverage industry is concerned that

rates of SSB consumption are dropping. However, as

an increasing number of taxes, warning labels, and

other policies are enacted around the world, this

drop may continue and, as a result, diets will become

morehealthy.

Nutrient proling

Health-related taxes applied to foods and beverages

must dene the foods to which the tax applies, and

this often requires some form of nutritional criteria

underpinning the tax. Lack of such criteria or standards

for determining exactly what to tax is a challenge

experienced by many countries. The development of a

nutrient prole model is, therefore, considered important

in identifying the categories of foods subject to the tax

and the nutrient thresholds that apply, thus providing a

tool for countries to implement scal policies.

Nutrient proling is the science of classifying or ranking

foods according to their nutritional composition for

reasons related to preventing disease and promoting

health. Nutrient proling can be used for various

applications, including the marketing of foods to

children; health and nutrition claims; product labelling

logos or symbols; information and education; provision

of food to public institutions; and the use of economic

tools to orient food consumption.

The initial request for WHO to initiate nutrient proling

came in 2007 when the rst technical meeting was

held to review the existing evidence on the eects

of marketing of food and non-alcoholic beverages

to children. The ad hoc development of models by

dierent stakeholders was leading to inconsistencies

andconfusion for target audiences and consumers.

In 2010, WHO prepared guiding principles and a

framework manual for the development and adoption

of nutrient prole models. The main lesson learned from

pre-testing the manual was that it is easier to adapt an

existing model than to develop an entirely new model.

WHO will review and update the manual after country

eld-testing.

Regional nutrient proling models for regulating the

marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to

children have already been developed in the WHO

European and American Regions, and are in the process

of being developed in the Eastern Mediterranean

Region, and the South-East Asia and Western Pacic

Regions. WHO aims to prepare a global nutrient prole

model for: the marketing of food to children; school

food procurement; scal policies; and product labelling

(i.e.front-of-pack labelling).

22 23

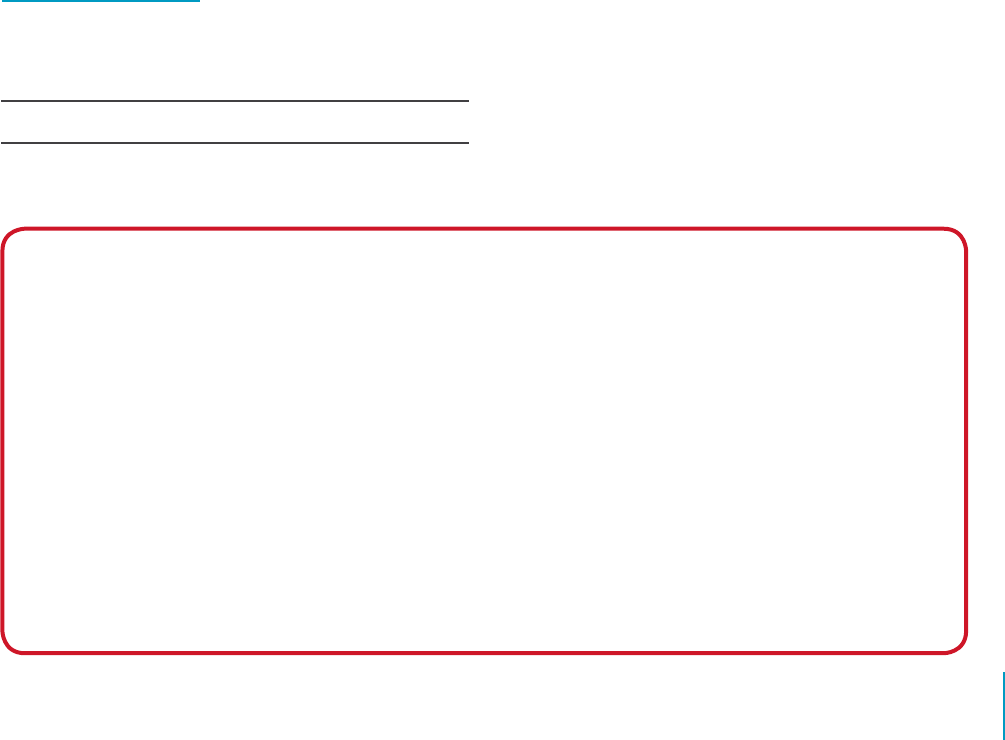

Policy development

The importance of a good policy development process

needs to be reinforced when developing scal policies

(Figure 5). An assessment, using all existing relevant

information, should inform appropriate objective-setting

and advocacy and use key policy champions and the

broad coalition of partners for both political buy-in and

for countering industry challenges. Nutrient proling – or

similar tools – need to be developed to dene products

to be taxed as a key part of the multidisciplinary drafting

of the policy. In implementation, tax structure and

administrative issues should be considered as well as

the monitoring of purchases and consumption, while

planning for evaluation and consideration for earmarking

of tax for health is further discussed. Evaluation of the

impact of the policy on purchasing, consumption,

revenues, and, ultimately, health outcomes (e.g. obesity)

is needed, so some consideration for longitudinal

design should be given. Policy coherence is needed to

ensure maximum impact of scal policies on diet. The

requirement of warning labels on taxed products – as

an education strategy and to limit the marketing of

taxed products particularly for children – were discussed

asexamples.

Earmarking of tax revenues

The earmarking of tax revenues is used in many

countries, including in connection with taxes for health

promotion. Earmarking may be aimed at strengthening

health promotion actions, for example by funding

education campaigns or healthy food subsidies, or at

limiting the regressive impact of taxation (when the

impact is indeed regressive). In all cases, earmarking will

improve the transparency of the taxation process and

use of revenues, which will increase the acceptability of

the tax by politicians and the general public. Whenthe

objective of the tax policy is health, rather than solely

economics, it may be easier to discuss earmarking

forhealth in that context.

5. Implications for design and implementation of scal policies

Evidence-gathering

(nance, health,

industry)

Tax environment –

learn from Tobacco

Policy Rationale

Policy Objective

(health and

economic)

Policy coherence

(marketing

restriction etc.)

Public awareness,

education and

support

Tools to dene

products to include

Options of tax

measure

Industry challenges

Key policy

champions

Tax infrastructure

Administrative issues

Enforcement

Purchasing/

consumption

Consider earmarking

of tax for health

Planning evaluation

Systems to support -

monitoring revenue

andconsumption

- longitudinal evaluation of

the impact on purchasing,

consumption, revenues,

health outcomes

(e.g.obesity)

1. Assessment

Figure 5: Fiscal policy development and implementation framework

2. Design

3. Implementation

4. Evaluation

24 25

Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of NoncommunicableDiseases

At the end of the meeting the following conclusions were made:

• Growing evidence shows that appropriately designed

scal policies, when implemented with other policy

actions, have considerable potential for promoting

healthier diets. They will also improve weight

outcomes and other diet-related risk factors, and will

ultimately contribute to the prevention and reduction

of the health and economic burden of NCDs. The

use of scal policies should therefore be considered

a key component of a comprehensive strategy for

prevention and control of NCDs.

• The evidence for meaningful health eects is

strongest for taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages,

with suggestions that SSB prices would need to be

raised by 20%, or more. Such taxes lead to more than

proportional reductions in SSB consumption and net

reductions in caloric intake, and thus contribute to

improving nutrition and reducing overweight, obesity

and NCDs.

• Similarly strong evidence shows that subsidies for

fresh fruits and vegetables, that reduce prices by

10–30%, are eective in increasing fruit and vegetable

consumption. While evidence is mixed on the net

eect of fruit and vegetable subsidies on net caloric

intake and weight, overall diet quality improves, with

a resulting improvement in health outcomes. Greater

eects on the net energy intake and weight may be

accomplished by combining subsidies on fruit and

vegetables and taxation of target foods.

• Taxation of other target foods and beverages,

particularly those high in saturated fats, trans fatty

acids, free sugars and/or salt appears promising,

withexisting evidence clearly showing that

increases in the prices of target options reduces

their consumption. Evidence will emerge from

countries that have recently implemented such taxes

showing the impact on health and other outcomes –

forexample NCDmortality.

• Vulnerable populations, including low-income

consumers, young people, and those at most risk of

obesity, are most responsive to changes in the relative

prices of foods and beverages. It is benecial to target

non-core foods and foods for which good healthier

alternatives are available.

• Consistent with the evidence on tobacco taxes,

specic excise taxes (where a set amount of tax is

charged on a given quantity of the product or specic

ingredient), as opposed to sales or other taxes based

on a percentage of retail price, are likely to be most

eective. This is because they reduce incentives to

switch down to cheaper options, in that they increase

the price of all products aected by the tax in the

same way. In order to prevent the impact of specic

taxes from being eroded over time, it is essential that

they be regularly adjusted to keep in line with ination

and to reduce aordability of the taxed product by

accounting for income growth as well.

• In countries with strong tax administration, taxes that

are calculated based on nutrient content (e.g. SSB

taxes based on sugar content) can have the greatest

impact, as they dierentiate between options based

on nutrient content within a product category and

can be used to incentivise consumers to substitute

to alternatives while simultaneously encouraging

producers to reformulate their products. In countries

where tax administration is not as strong, simpler tax

systems (e.g. a volume-based SSB tax) may be more

appropriate.

• Earmarking of tax revenues may be challenging in

some countries, but dedicating some, or all, of the

revenues generated by these taxes for eorts to

improve the health care system, encourage healthier

diets through health promotion and nutrition

education campaigns, increase physical activity, as

well as to build capacity for eective tax administrative

processes (i.e. for monitoring and enforcement)