Report No. CDOT-2007-9

Final Report

EFFECTIVENESS OF LEDGES IN CULVERTS

FOR SMALL MAMMAL PASSAGE

Carron Meaney, Mark Bakeman, Melissa Reed-Eckert, and Eli Wostl

June 2007

COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

RESEARCH BRANCH

The contents of this report reflect the views of the

author(s), who is (are) responsible for the facts and

accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents

do not necessarily reflect the official views of the

Colorado Department of Transportation or the

Federal Highway Administration. This report does

not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation.

Technical Report Documentation

1. Report No.

CDOT-2007-9

2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No.

5. Report Date June 2007 4. Title and Subtitle

Effectiveness of Ledges in Culverts for Small Mammal Passage

6. Performing Organization Code

7. Author(s) Carron A. Meaney, Mark Bakeman, Melissa Reed-Eckert,

and Eli Wostl

8. Performing Organization Report

No.

10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) 9. Performing Organization Name and Address

Meaney & Company

and Walsh Environmental Scientists and Engineers, LLC

11. Contract or Grant No.

32.41

13. Type of Report and Period

Covered

Final

12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address

Colorado Department of Transportation - Research Branch

4201 E. Arkansas Ave.

Denver, CO 80222

14. Sponsoring Agency Code

15. Supplementary Notes

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration

16. Abstract

Ledges were installed in six culverts in Boulder County, Colorado, to test their ability to facilitate small

mammal movement under roads and to determine whether Preble’s meadow jumping mice (Zapus

hudsonius preblei) would use such ledges. Ledge use was measured by recording photographs of mammals

on the ledge with motion-detecting cameras. Ledges connected to the streambank with removable ramps,

which served as a proxy for rendering the ledges accessible in order to test whether there was more usage

when the ramps were on (ledges accessible) than when they were off (ledges inaccessible). Nine mammal

species were captured using the ledges in 705 photographs during the study spanning two summers, 2005

and 2006. Preble’s meadow jumping mouse was photographed on the ledge only once during the pilot and

three times during the active study. There were 443 photographs of mammals on the ledge with ramps on

and 262 photographs with ramps off. Significant differences were found among the six culverts and

between ramp conditions. The ledges appear to present desirable passageways even with the ramps off, to

the extent that small mammals will climb up concrete walls to access them. Culvert dimensions and

vegetative cover did not show statistical correlations with the number of photographs, possibly because of

the small number of culverts.

The present study employed temporary wooden ledges. As a result of the positive findings in this study, the

testin

g of permanent retrofits is recommended. Such ledge retrofits are simple, easy, and inexpensive ($17

to $20 per linear foot plus shipping and installation). They could be developed locally, which would

eliminate transportation costs. Recommendations resulting from the current study can be summarized as

follows: 1) expand the study to additional culverts and continue use of ledges in the most active culverts of

the present study, especially in Z. h. preblei habitat, to better determine factors affecting use by Preble’s, 2)

develop an appropriate permanent ledge retrofit design locally, or consider installation of pre-built steel

ledges and test their utility in Colorado, and 3) proactively begin discussions with the Colorado Department

of Transportation engineers for construction/installation of new culverts that contain built-in ledges.

17. Keywords

ramps, mitigation, habitat fragmentation, corridors,

ecoculverts, Preble's meadow jumping mouse

18. Distribution Statement

No restrictions. This document is available to

the public through the National Technical

Information Service,

Springfield, VA 22161

19. Security Classif. (of this report)

Unclassified

20. Security Classif. (of this page)

Unclassified

21. No. of Pages

44

22. Price

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72) Reproduction of completed page authorized

EFFECTIVENESS OF LEDGES IN CULVERTS FOR

SMALL MAMMAL PASSAGE

By

Carron Meaney,¹ Senior Ecologist, Mark Bakeman,² President, Melissa

Reed-Eckert,³ Ecologist, and Eli Wostl,

4

Biologist

Report No. 2007-09

Prepared by ¹Walsh Environmental Scientists and Engineers, LLC,

4888 Pearl E. Circle, Suite 100, Boulder, Colorado 80301, ²Ensight

Technical Services, Incorporated, ³Bear Canyon Consulting, LLC, and

4

University of Colorado

Sponsored by the

Colorado Department of Transportation

In Cooperation with the

U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

June 2007

Colorado Department of Transportation

Research Branch

4201 E. Arkansas Ave.

Denver, CO 80222

(303) 757-9506

ii

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Boulder County Transportation Department staff, Bill Eliasen and Dave

Webster, helped with processing Boulder County utilities permits and addressing

floodplain issues. Colorado Department of Transportation staff Dennis Allen provided

permits, Chris Kelly supported maintenance coordination, Roland Wostl championed the

research project from the beginning, and Roberto DeDios guided its process with Patricia

Martinek picking up at the end. Bob Crifasi, Duane Myers, Rich Koopman, Randy

Rhodes, and Robert Clyncke coordinated permission from ditch companies. Daniel

Fernandez provided assistance with data analysis. We also wish to thank the members of

the Study Panel for their interest and comments, namely Roland Wostl, Roberto DeDios,

Judy DeHaven, Francis (Yates) Opperman, Jeff Peterson, Richard Willard, and Alison

Deans Michael.

iii

Executive Summary

Transportation corridors present a number of problems for wildlife that live in their

vicinity or that require crossings for dispersal or migration. One of the ecological impacts

of roads is an increase in fragmentation of small mammal habitat and populations.

Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei), a federally threatened

species that occurs along the Front Range of Colorado, has experienced habitat

fragmentation by roads including interstate highways. It is of particular value to search

for solutions that can reduce this fragmentation and facilitate movement of small

mammals under roadways.

Temporary ledges were installed in six culverts to investigate small mammal movement

under roads. Small mammal ledge use was measured by recording mammal passage with

motion-detecting cameras. Ledges were connected to the streambank with removable

ramps in order to test whether there was more usage when the ramps were on (ledges

accessible) than when they were off (ledges inaccessible). The study tested whether

Preble’s meadow jumping mouse made use of the ledges, and whether they and other

small mammals used the ledges more when they were accessible.

A total of 12 mammal species were photographed or observed using the culverts

(including the culvert bottom) during the study spanning two summers, 2005 and 2006.

Nine species used the installed ledges as documented in 705 photographs of small

mammals on the ledge. Z. h. preblei individuals were photographed on the ledge once

during the pilot and three times during the active study. There were 443 photographs of

mammals on the ledge when the ramps were on and 262 photographs when the ramps

were off. Both an analysis-of-variance and a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test were

used to determine whether there was an effect due to differences in culverts and to

whether the ramps were on or off over the ten two-week time periods of the two-year

study. Significant differences among culverts and between ramp conditions were found

iv

by both types of analyses. In addition to utilizing the ledges with the ramps on, the ledges

present desirable passageways even with the ramps off, to the extent that small mammals

will clamber their way up concrete walls to access them. Culvert dimensions and

vegetative cover did not show statistical correlations with the number of mammals on the

ledge, possibly because of the small number of culverts (six).

This study employed temporary wooden ledges. As a result of the positive findings, the

implementation of permanent retrofit ledges, at $17 to $20 per linear foot plus

installation, is strongly encouraged. A permanent retrofit ledge design can be developed

in Colorado, and involvement of Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT)

engineers is strongly encouraged. The development of culverts with built-in ledges, as

used in Europe, is also encouraged.

Implementation Statement

The present study tests the concept of temporary wooden ledges in culverts that will not

withstand long-term use. The testing of permanent retrofits made of a durable material

such as metal is recommended. Roscoe Steel and Culvert Company in Montana has

developed permanent retrofit installations for sale (www.roscoebridge.com). They have

installed these retrofits in 11 culverts in Montana on Highway 93. The ledge retrofits are

simple, easy, and inexpensive ($17 to $20 per linear foot plus shipping and installation).

Such retrofits could be developed locally, which would eliminate the transportation costs

for shipping steel ledges from Montana to Colorado.

Other than this recommended materials specification change, the design, general

construction, testing, and methodology components appear to have worked very well. No

anticipated changes are recommended in these factors. A change is recommended in

terms of the number of culverts used. The current study used only six.

v

The current study demonstrates that ledges are readily used by small mammals; however,

the data are equivocal on use by Preble’s meadow jumping mouse. Further testing with

larger sample sizes (more culverts) can serve to better determine whether Preble’s will

use the ledges on a regular basis. An excellent opportunity to test permanent retrofit

ledges has recently been provided by a Biological Opinion from the U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service (USFWS), dated December 28, 2006. In this letter, addressed to Larry

Svoboda of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, USFWS has included the

installation of four permanent ledges as a conservation measure for off-site mitigation for

a wastewater treatment plant to be constructed in the town of Eldorado Springs, Boulder

County, Colorado. Included in this project are four of the same ditches employed in the

current study.

Ecoculverts, used in Europe, have raised dry ledges on each side of the water to allow for

animal movement (Veenbaas and Brandjes 1999, cited in Forman et al. 2003). This is an

excellent approach, and is highly recommended for consideration by CDOT.

The recommendations resulting from the current study can be summarized as follows:

• Expand the study to include additional culverts and continue the use of ledges in

the most active culverts of the present study, especially in Preble’s meadow

jumping mouse habitat, to better determine factors affecting use by Preble’s;

• Develop an appropriate permanent ledge retrofit design locally, or consider

installation of Roscoe Steel ledges and test their utility in Colorado; and

• Proactively begin discussions with CDOT engineers for construction/installation

of new culverts that contain built-in ledges.

vi

Table of Contents

Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1

Methods............................................................................................................................... 5

Results............................................................................................................................... 10

Discussion......................................................................................................................... 21

Conclusions and Recommendations................................................................................. 27

References......................................................................................................................... 29

Appendix A - Photographs of the Culverts Used in the Study........................................A-1

List of Tables

Table A. Culverts used in the study…..................………………………………….…....10

Table B. Species observed using culverts during the project and number of

photographs taken during experimental portion of the study…………………………....12

vii

List of Figures

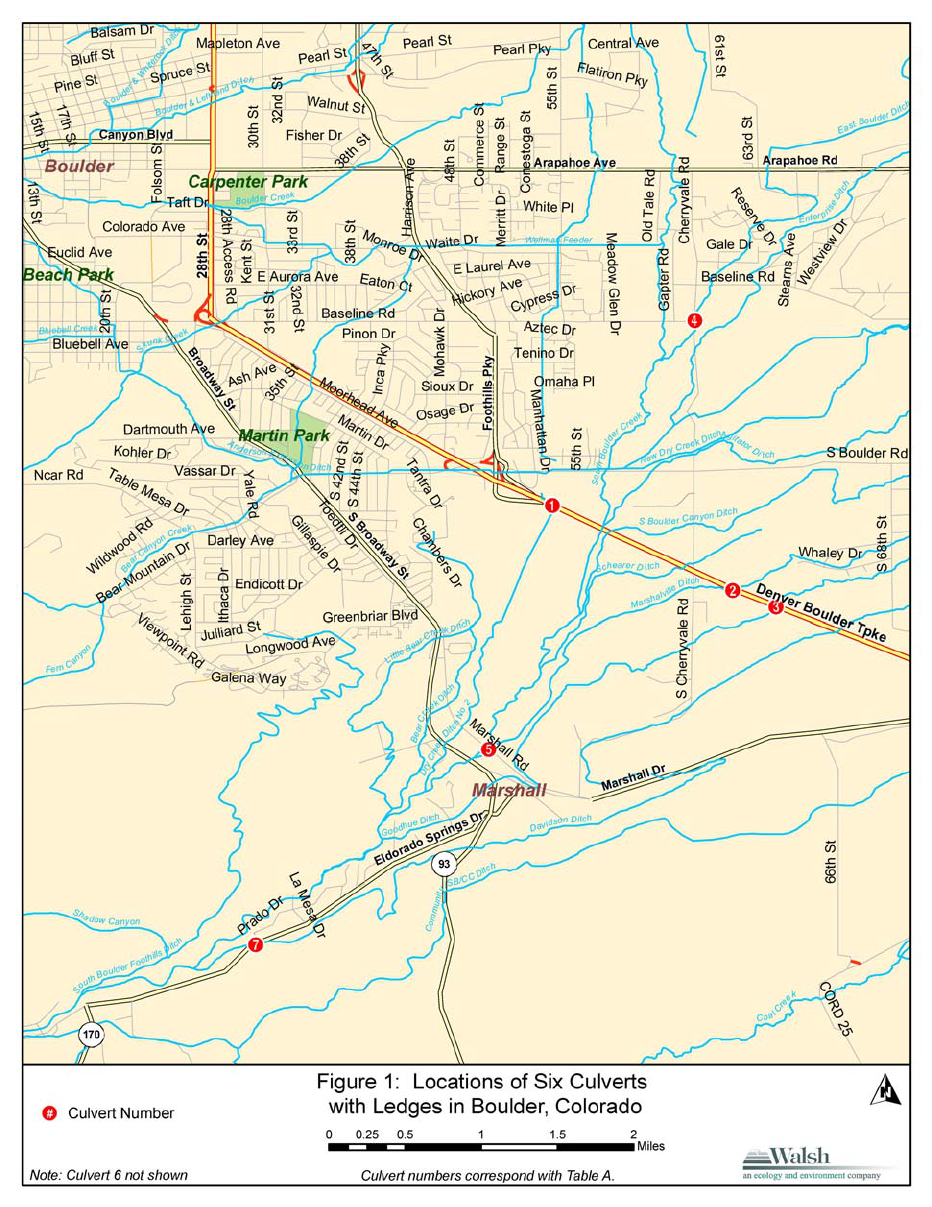

Figure 1. Locations of six culverts with ledges in Boulder, Colorado….……………….11

Figure 2. Photographs of various mammal species captured by remote-sensing cameras in

culverts…………………………………………………………….………………….….13

Figure 3. Number of photographs of mammals on the ledge with ramps on and off…....14

Figure 4. Number of photographs of mammals on the ledges at six different culverts

……………………………………………………………………....…………….…...…15

Figure 5. Species richness of small mammals photographed at six culverts..…….……..16

Figure 6. Number of photographs of mammals on the ledge with ramps on and off in

2005 and 2006……………….……………………………………………………….…..17

Figure 7. Mammal species on the ledge with the ramp on and off………………………18

Figure 8. Number of photographs of mammals on the ledges in the ten periods from June

through September, 2005, and May through September, 2006………………………….19

Figure 9. Three events of Preble’s meadow jumping mice on ledges photographed during

the study…………………………………………………………………..……………..20

viii

Introduction

Transportation corridors present a number of problems for wildlife that live in their

vicinity or that require crossings for dispersal or migration. It has been estimated that

approximately one-fifth of the U.S. land area is directly affected ecologically by the

system of public roads (Forman 2000). Ecological impacts are due to loss of habitat

patches; formation of barriers that isolate habitat patches and result in fragmentation;

creation of disturbance due to noise, light, and air pollution; and road-kill mortality (van

Bohemen 2004). The current study is focused on the problem caused by fragmentation to

small mammal populations and presents one solution to this problem.

Populations of small mammals are fragmented by roads and highways that bisect the

habitat and drainages along which they occur (Forman and Alexander 1998; Theobald et

al. 1997; Trombulak and Frissell 2000). This may be due to dispersal abilities, low

probability of surviving highway crossings, or behavioral avoidance of open highway

expanses (Conrey and Mills 2001). Roads inhibit the movement of rodents (Clark et al.

2001; Kozel and Fleharty 1979) and affect their community structure and density (Adams

and Geiss 1983). Preliminary results suggest that movement is hindered more by wider

(four-lane) than narrower (two-lane) road crossings.

Species differ in their ability to negotiate roadway crossings: Red-backed voles

(Clethrionomys gapperi) and chipmunks (Neotamias sp.) are inhibited more than deer

mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) (Conrey and Mills 2001). Some species (prairie voles

[Microtus ochrogaster] and cotton rats [Sigmodon hispidus]) are inhibited even on

narrow dirt roads (Swihart and Slade 1984). In another study, very small percentages of

white-footed mice (P. leucopus) and eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus) crossed the

roadway, suggesting that clearance distance between open habitats was a factor (Oxley et

al. 1974).

1

Whereas these population fragmentation effects can occur in a relatively short time

frame, genetic effects of fragmentation typically occur over a longer time frame, and

have recently been demonstrated. Genetic differentiation occurred in European bank

voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) on either side of a four-lane highway over only 25 years

(Gerlach and Musolf 2000). These population and genetic effects of roadways present a

significant problem to natural populations of small mammals. Because human

populations continue to increase and require expansion of transportation routes through

both new and wider roadways, it is of particular value to search for solutions that can

safely facilitate movement of small mammals under roadways in order to reduce

population and genetic fragmentation.

Passageways under highways via underpasses and drainage culverts were used by many

native mammals in California (Ng et al. 2004). Barrier walls and culverts reduced

roadkill in Florida from 2,411 to 158 in a 12-month period (Dodd et al. 2004). In

Montana, the installation of ledges in culverts facilitated movement of 14 species of small

mammals. Again, species differences were found: deer mice readily used ledges but

meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) required a tube installed underneath the ledge

which they used instead of the ledge (Foresman 2001, 2004).

The riparian-dwelling Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei), a

subspecies that is federally listed as threatened, may be substantially impacted where

roads cross over drainages that they occupy. Populations of this mouse have been

reduced, extirpated, and fragmented by development, grazing, gravel mining, and other

activities. A Recovery Plan for the species was initiated (U.S. Department of Interior

2003), Critical Habitat has been determined, and efforts are underway all along the

Colorado Front Range to conduct research on their populations (Meaney et al. 2002,

2003) and to develop plans to protect populations of this subspecies. However, in

February 2005 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) issued a 12-month finding

2

on a petition to delist the mouse. The decision on whether to delist the mouse has been

postponed and is now anticipated in June 2007.

In Colorado Springs, Colorado, the construction of a large (65-meter [m]-long) culvert

along Pine Creek at an I-25 exit may have fragmented a population of Z. h. preblei. At

that site, animals were successfully trapped in June and August for 4 consecutive years

on both ends of a newly installed culvert. Although the animals were permanently

marked, there was no evidence of jumping mice passing from one end of the culvert to

the other (Meaney and Ruggles 2000). Other drainages occupied by Z. h. preblei also

flow into Monument Creek, which contains the largest population of the subspecies in El

Paso County. All these tributaries are bisected by I-25. Roads can cause small

populations to become fragmented due to reduced connectivity with adjacent

subpopulations (Carr et al. 2002). These smaller subpopulations are at greater risk of

extirpation than are larger interconnected populations.

The installation of ledges in culverts could mitigate this fragmentation effect. At another

site, there is evidence from ongoing Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT)

research near the town of Monument and I-25 that Preble’s meadow jumping mice do, at

least occasionally, use culverts to cross under roads when there is a dry culvert section

available. Both male and female adults and juveniles crossed through a 91-m-long

concrete box culvert under I-25 along Dirty Woman Creek (Ensight 1999). Artificial

cover stations were used to facilitate culvert usage, and jumping mice were found to cross

through the culvert both with and without the cover stations. However, such movements

were rare, with only five individually marked animals making the passage through the

culvert over an eight-year period. Movements occurred during times of high and low

water levels in the culvert; however, there was always at least some portion of the culvert

bottom that was not inundated. Additional data from this drainage have shown that

Preble’s meadow jumping mice have moved under two-lane paved roads, presumably

through corrugated metal culverts. Movement through the I-25 culvert may have been

related to Preble’s population density – in high-density years there was more movement,

and in low-density years there was little detected movement.

3

Below-road passages are common in the landscape; many are designed for road runoff,

drainage culverts, or movement of livestock and people. These passages are used by

animals and can be important linkages and corridors for local wildlife. However, many

could be used more effectively. Both transportation and natural resource agencies have

overlooked these existing passages and their potential for improvement, even though

substantial gains can be realized with relatively little investment (Forman et al. 2003).

The purpose of this study is to determine whether the installation of ledges in culverts

containing water will facilitate the movement of small mammals, including Z. h. preblei,

from one side to the other. The null and alternative hypotheses are:

Ho: Preble’s meadow jumping mouse will not use ledges installed in

culverts.

H

A:

Preble’s meadow jumping mouse will use ledges installed in culverts.

Ho: Small mammals will show no difference in their use of ledges with access to ledges

(access ramps on) versus no access to ledges (access ramps off).

H

A

: Small mammals will show a greater use of culverts with access to ledges than

without access to ledges.

4

Methods

A list was compiled of all culverts in Boulder County, Colorado, that were within 10

kilometers (km) of known or potential populations of Z. h. preblei. The assumption was

made that habitat suitable for this species would also provide habitat for numerous other

small mammal species, as years of trapping surveys have indicated. Researchers located

and examined 48 culverts. Culverts were eliminated from consideration for the following

reasons:

• Permission from the ditch company or adjacent private landowner to

install ledges was denied.

• There was more than one culvert opening and often one of the openings

was dry, allowing easy passage without a ledge.

• The culvert was too small to fit a person and a ledge (typically less than 1

m in height or width or both).

• The culvert did not contain running water for at least two months or

clearly had dry banks for a substantial portion of the season, as was the

case for bridges over streams.

• The water current and depth were deemed too dangerous for working

inside the culvert.

• Extensive barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) or cliff swallow (Petrochelidon

pyrrhonota) nests were present.

• The culvert was gated and access was denied.

5

• The high-water mark suggested the ledge would be flooded during the

active season.

• Excessive development in the vicinity of the culvert existed.

This process of elimination resulted in seven culverts deemed suitable for the project.

One of these culverts was subsequently rejected. The six remaining culverts were

outfitted with wooden ledges (2.54 x 15.24-centimeter [cm] cedar planks, typically 1.83

m long) attached end to end. We glued blocks of wood (5 x 10.16-cm blocks, 30.48 cm

long) to the culvert wall above the high-water line at 1.83-m intervals with Liquid Nails

glue applied with a caulk gun. These served as anchors for the ledge planks, which were

placed on top and screwed into the blocks.

Ledge

Ram

p

Ramps, also made of 2.54 x 15.24-cm cedar planks, were outfitted with hinges and

attached to the end of the ledge. They were angle-cut to provide the best horizontal angle

to reach the bank, and the hinge allowed for the best vertical angle, so that they provided

access from solid ground along the bank to the ledge. During the first year of the study,

the access ramps were taken on and off as a means to make the ledges accessible and

inaccessible, respectively. This was far more cost-effective than removing and replacing

the entire ledge for the 2-week time intervals that defined each sample period. During the

6

second year, both the ramp and first board of the ledge were removed at both ends of the

culvert.

Small mammal movements through the

culverts were assessed with

photographs. Still cameras were

purchased from TrailMaster (Goodson &

Associates, Inc., Lenexa, Kansas). We

employed the TM 550 monitor and

motion-sensitive camera setup, a passive

sensing unit that detects infrared waves

and microwaves (for temperature

differential and movement,

respectively). Monitors recorded all

interruption incidents of the cone-shaped beam. Motion-sensitive cameras allowed for

remote sensing of animals by photographs taken when criteria were met to trigger the

camera.

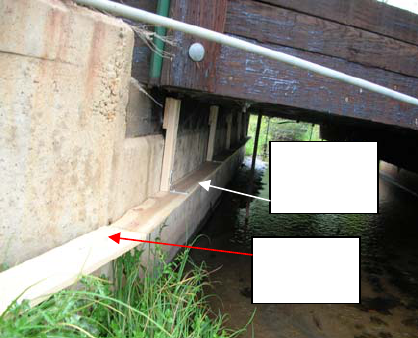

Goodhue Ditch at U.S. 36. Ramp is long and

vegetation is well-developed; ledge not visible

inside culvert. Note green netting for birds.

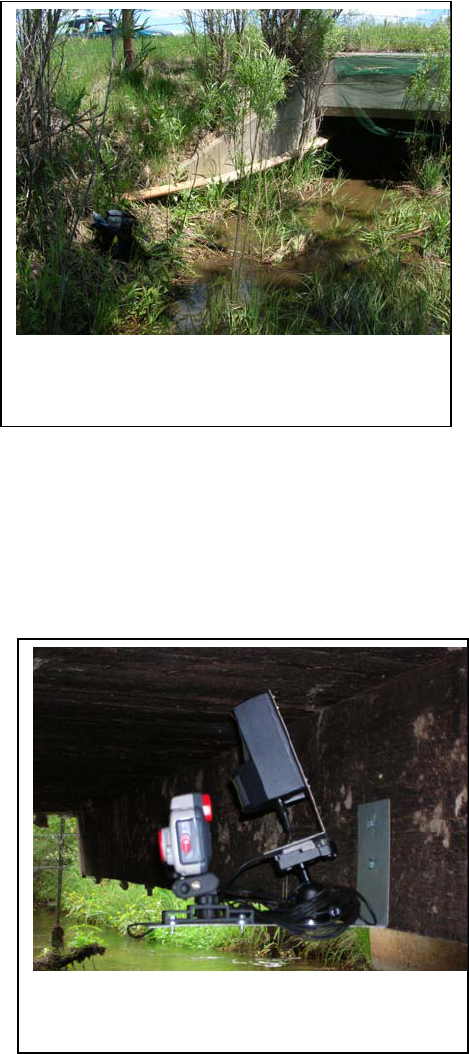

The cameras were attached to the

culvert with the use of 5 x 10.16-cm

wooden blocks glued to the sidewall.

One culvert required suspension of the

camera unit from the culvert ceiling

because of its width, and one had a

wood beam running through the center

that allowed for direct attachment.

Metal L-shaped plates were built and

used to provide a platform to

accommodate the camera and monitor as well as a vertical component for attachment to

the culvert.

Camera (left) and monitor (right) installation.

They are placed on a metal platform attached to the

culvert wall.

7

Cameras and monitors were extensively field-tested for two months prior to the initiation

of the experiment, as settings and angles require much adjusting. The units were placed in

the middle of the culvert, except in Culvert 4 and Culvert 7 due to the small opening or

fast-running (and therefore dangerous) water. This positioning served to avoid

photographing animals that may have entered and turned around, rather than passing all

the way through. Cameras were angled to focus on the ledge. We had hoped to angle the

cameras to pick up the bottom of the culvert as well; however, this was not possible in

most cases. Cameras and monitors were checked weekly and film was replaced as

needed. We employed 200 ASA Fuji film with 24 or 36 exposures.

The experiment ran from June 1 through September 21, 2005 (16 weeks), and from May

2 through September 19, 2006 (20 weeks). Ten two-week periods were defined in 2006

and eight such periods were employed in 2005. A given culvert alternated between

having ramps on for two weeks and ramps off for two weeks, generally within each

month of the summer season. Each culvert was randomly assigned to the ramp on or off

condition for the first period with subsequent alternating conditions per period.

Culvert dimensions (length, width, and height) were measured and water depth was noted

weekly in 2005. Vegetative cover was assessed at each culvert entrance in 2005. Three

adjacent vegetation sampling quadrats were established immediately upstream and

downstream of each culvert. One 5 x 5-m quadrat was situated on each bank and a third

quadrat was defined as the area between the two bank quadrats and centered on the

culvert. Within each quadrat the percent foliar cover (to the nearest 5 percent) of tree,

shrub, forb, and graminoid species was recorded. Regression analysis was used to assess

the relationship of these parameters with the number of photographs of small mammals

on the ledge.

8

The study employed a multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA) (MANOVA) on the

number of photographs of mammals on the ledges during the 10 periods, as well as

various regression analyses on culvert dimensions, vegetation, and water levels. For the

MANOVA, we tested the significance of two factors: the ledges with ramps (on or off),

and culvert. The dependent variable (number of mammals photographed on the ledge)

was square root transformed. When assumptions of the ANOVA test could not be met,

the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed. This test does not require normally distributed

data and tolerates heterogeneous variance.

Small mammals were identified from photographs by their color, relative tail length,

body carriage, and shape. Familiarity with these species from small mammal trapping in

the region facilitated identifications. Shrews were identified only to genus (as Sorex sp.).

9

Results

The seven originally selected culverts are listed in Table A and shown on Figure 1.

Photographs of all the culverts, located in Boulder, Colorado, are provided in Appendix

A. Culvert 6 (South Branch) was eliminated from the study, leaving a sample size of six,

because it was discovered that vehicles driving over the road caused vibrations that

triggered the monitor and camera. Although 530 photographs were taken in both years at

this culvert, only two were of mammals on the ledge and the remainder were blank.

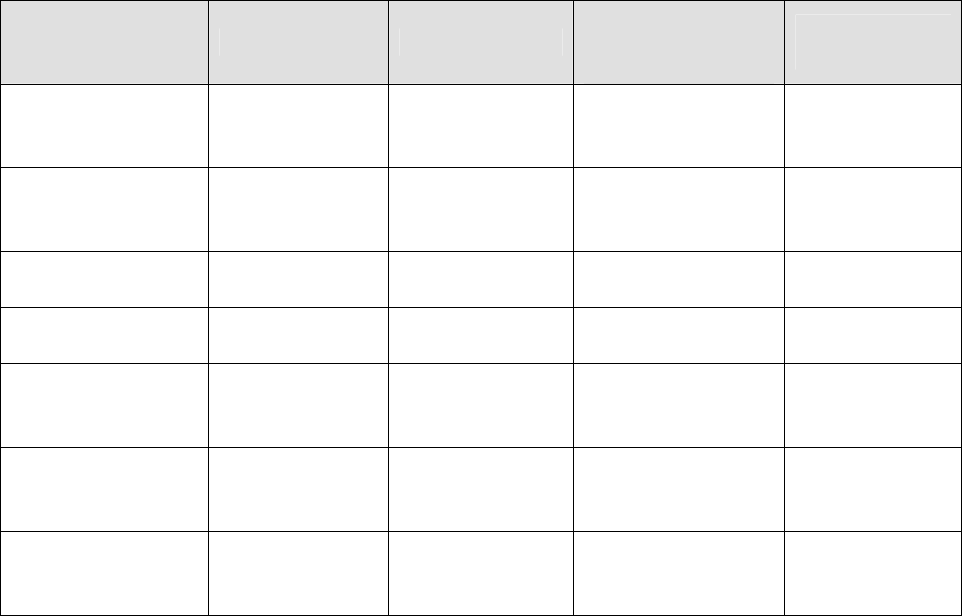

Table A. Culverts used in the study

Culvert Location Culvert Type

1

Culvert

Dimension (m)

Width x Height

Culvert

Length (m)

Culvert 1

Dry Creek No. 2

Ditch

US 36 CBC 1.9 x 1.25 47.5

Culvert 2

Marshallville

Ditch

US 36 CBC 2.4 x 1.3 46.8

Culvert 3

Goodhue Ditch

US 36 CBC 4.9 x 1.2 47

Culvert 4

East Boulder Ditch

Cherryvale

Road

RCC 1 x 1 38.7

Culvert 5

Marshallville

Ditch

Marshall Road CBC 1.85 x 0.9 9

Culvert 6²

South Branch

Crane Hollow

Road

Timber bridge

with concrete

sidewalls

3.8 x 1.2 8.6

Culvert 7

Davidson Ditch

SH 170

(Eldorado

Springs Road)

CBC 3.7 x 1.2 27.2

Notes:

1

CBC = concrete box culvert; RCC = round concrete culvert

Ramp lengths ranged from 1.0 to 3.95 m, and the mean length was 2.34 m.

²Culvert 6 was rejected due to vibrations from cars that triggered the monitor and

camera.

10

Figure 1. Locations of six culverts with ledges in Boulder, Colorado

11

A total of 12 mammal species were photographed or observed using the culverts (on the

ledge, on the wall, or on the bottom of the culvert) and nine species were photographed

using the ledge during the entire project (Table B). Five species of birds were captured by

the camera flying around and sitting on the ledge, as well as numerous spiders and a few

dragonflies.

Table B. Species observed using culverts during the project

Common Name Scientific Name On Ledge?

Mammals

Shrew Sorex sp. Yes

Rock squirrel

Spermophilus variegatus

Yes

Black-tailed prairie dog

Cynomys ludovicianus

No

Deer mouse

Peromyscus maniculatus

Yes

Mexican woodrat

Neotoma mexicana

Yes

Norway rat

Rattus norvegicus

Yes

House mouse

Mus musculus

Yes

Meadow vole

Microtus pennsylvanicus

Yes

Preble’s meadow jumping mouse

Zapus hudsonius preblei

Yes

Coyote

Canis latrans

No

Raccoon

Procyon lotor

Yes

Striped skunk

Mephitis mephitis

No

Birds

Barn swallow

Hirundo rustica

NA

Song sparrow

Melospiza melodia

NA

Brewer’s blackbird

Euphagus cyanocephalus

NA

Belted kingfisher

Ceryle alcyon

NA

Great blue heron

Ardea herodias

NA

Invertebrates

Spider

-

NA

Dragonfly

-

NA

A total of 3,830 events were recorded by the monitors (the beam was triggered by a

movement event) and 2,105 photographs were taken in the six culverts during the 16- and

18-week study over two seasons. Of these, 906 were photographs of animals; the

remainder were blank indicating that the monitor was triggered but the camera did not

capture anything. Of these 906 animal photographs, 722 were of mammals. Of these, 705

were photographs of mammals on the ledges (Figure 2). Many photographs were

triggered by birds flying in and out, and by spiders.

12

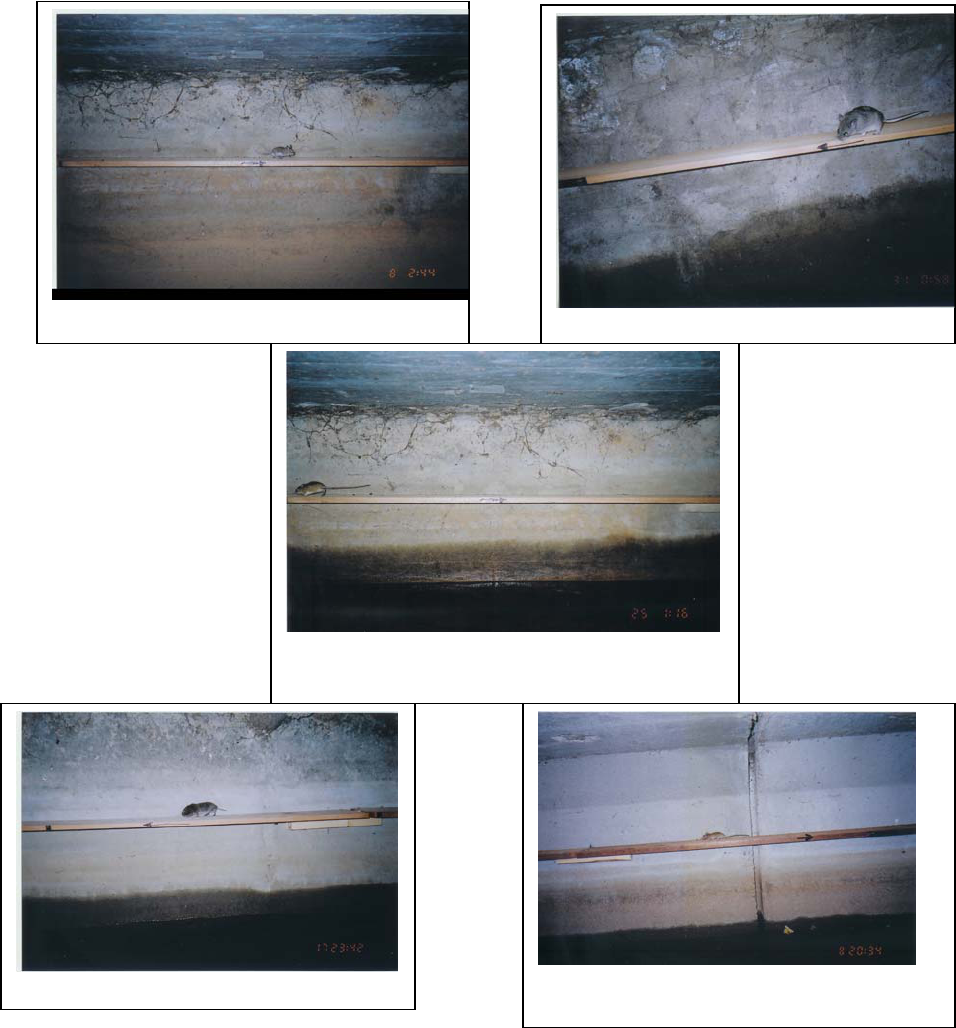

Deer mouse on ledge.

Meadow vole at Davidson Ditch.

House mouse at Marshallville Ditch at

Marshall Road.

Preble’s meadow jumping mouse at

Goodhue Ditch during pilot portion of study.

Mexican woodrat at Davidson Ditch.

Figure 2. Photographs of various mammal species captured by remote-sensing

cameras in culverts

13

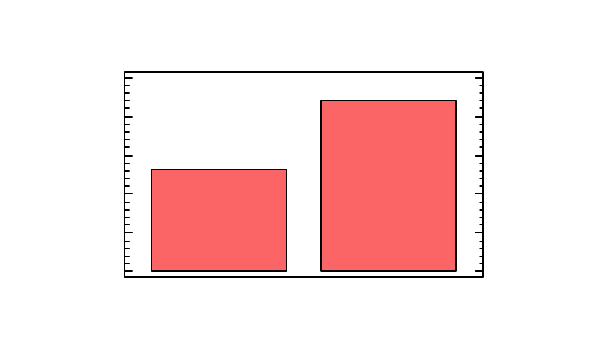

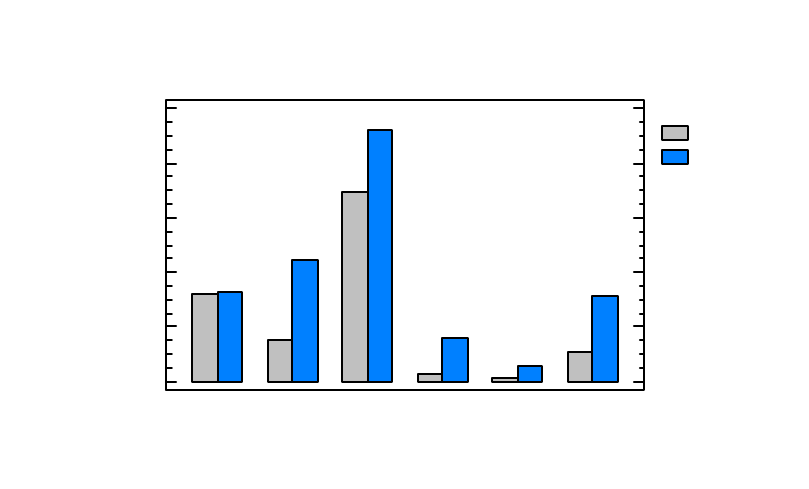

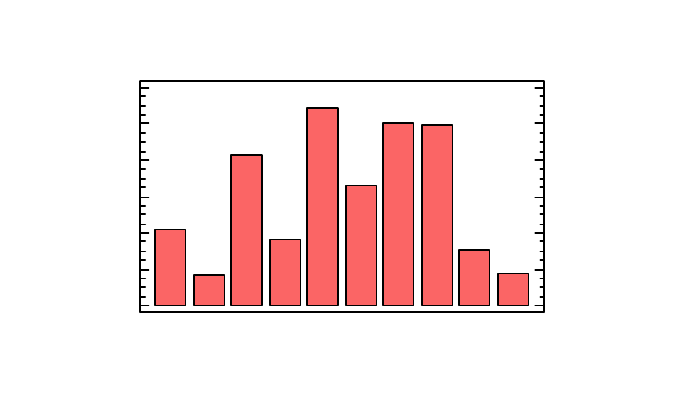

There were more photographs of mammals on the ledges when the ramps were on (443

photographs) versus when they were off (262 photographs) (Figure 3).

Mammals on Ledge

Ramp Condition

0

100

200

300

400

500

Off On

Figure 3. Number of photographs of mammals on the ledges with ramps on and off

The question of interest was whether there was a significant difference in the number of

mammals photographed on the ledge with the ramp on or off. The other factor of note

was the culvert. There were differences among the culverts in their dimensions, the

vegetation at their entrance, and the small mammal communities in the ditches that

passed through the culverts. A MANOVA was used to test the effect of the ramp (were

there more photographed mammals when the ramps were on versus off?) and culvert

(were there differences in the number of photographed mammals among the different

culverts?). The data set was skewed, with most small mammal species showing low to

modest movement numbers, and deer mice typically having values 10 to 50 times that of

the other species.

To better approximate a normal distribution, and to render the discrete data continuous,

the dependent variable (number of mammals on ledge) was square root transformed for

the MANOVA. There were significant effects of culvert and ramp on the number of

mammals on the ledge (F = 10.16 and 9.08, p = 0.0 and 0.0034 for culvert and ramp,

respectively). The interaction between the two factors was not significant (F = 0.15, p =

14

0.9802). However, the data did not meet the assumptions of normality of residuals and

equality of variances, and the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was employed. The

Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences between culverts (H = 29.384, p =

0.000) and between ramp conditions (H = 7.356, p = 0.0067).

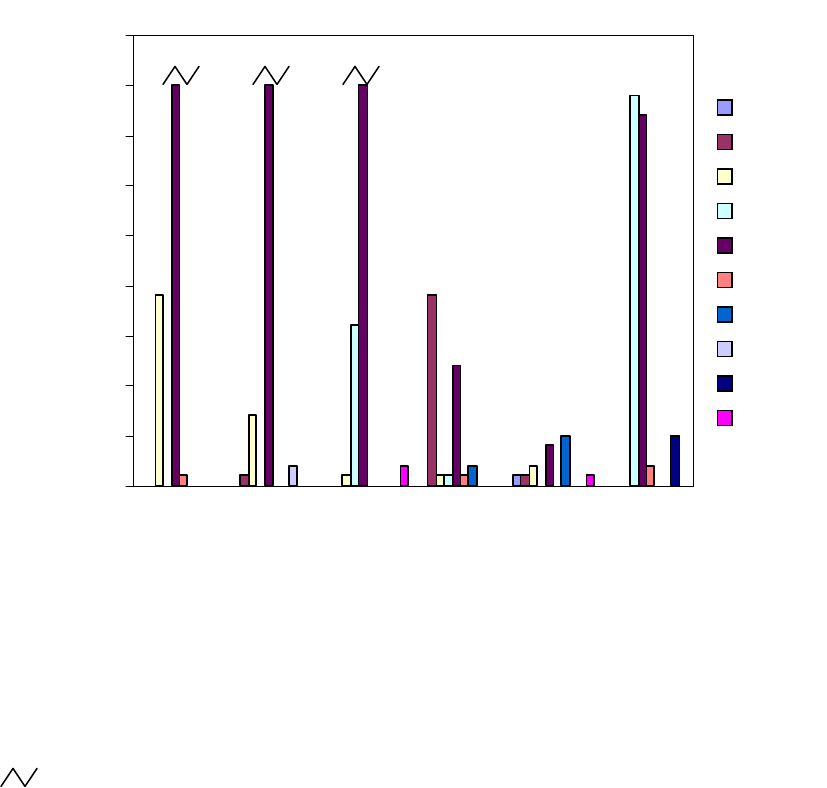

Figure 4 shows the differences among the culverts and ramp conditions. Culvert 3,

Goodhue Ditch, had the greatest amount of overall activity. Culverts 1, 2, and 7 had

medium activity, and Culverts 4 and 5 had the least. Culverts 1, 2, and 3 crossed under

US 36, a four-lane highway with a jersey (concrete highway) barrier. Culvert 4 was very

small, with a 1-m-diameter opening, and Culvert 5 was under a very small two-lane road

in a quiet, rural residential area.

Mammals on Ledge

Cu lve rt

Ramp

Off

On

0

40

80

120

160

200

1

2

3

4

5

7

Figure 4. Number of photographs of mammals on the ledges at six different culverts

In addition to differences in the amount of activity at the different culverts, there were

also differences in small mammal species richness. Although Culvert 3 had the greatest

amount of activity, the activity was due to a high number of deer mice. Culverts 1 and 3

had the lowest species richness, with only three species each. Culverts 4 and 5, with low

overall activity, had the highest richness with five species each. Culvert 2 was relatively

15

high or intermediate on both measures, with a high overall activity level and four species

(Figure 5).

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

123457

Culvert

Mammals on Ledge

Mioc

Mipe

Mumu

Neme

Pema

Prlo

Rano

Sorex sp

Spva

Zahu

Figure 5. Species richness of small mammals photographed at six culverts

Mioc=prairie vole, Mipe=meadow vole, Mumu=house mouse, Neme=Mexican

woodrat, Pema=deer mouse, Prlo=raccoon, Rano=Norway rat, Sorex sp=shrew,

Spva=rock squirrel, Zahu=Preble’s meadow jumping mouse

Notes:

indicates a break in the range for PEMA values

Culvert 1 PEMA = 110 animals

Culvert 2 PEMA = 109 animals

Culvert 3 PEMA = 304 animals

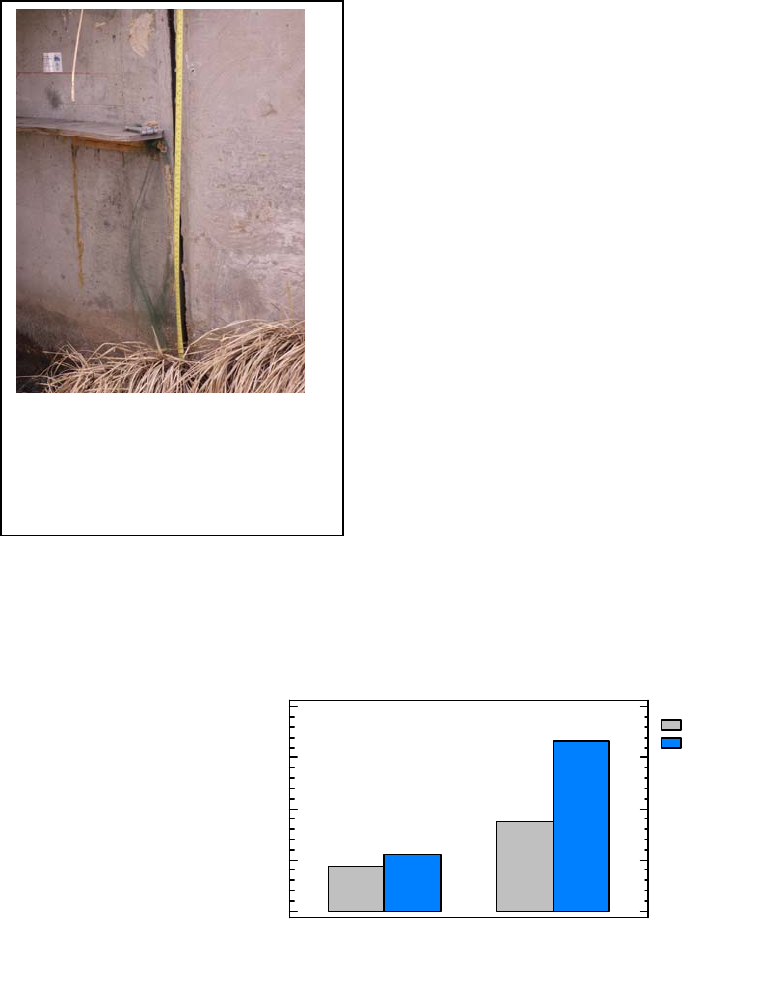

It is noteworthy that small mammals did access ledges when the ramps were off (Figures

3 and 4). However, all six culverts had more activity when the ramps were on than with

the ramps off. The distances that small mammals negotiated from the streambank (solid

ground) to the ramp ranged from 39 to 78 cm and the distance from the ramp to the top of

the culvert ranged from 20 to 80 cm; for those ledges that ended above water rather than

16

solid ground, the lateral distance was 42 to 148 cm. Culvert 1 (Dry Creek No. 2 Ditch)

was one of the two culverts with high activity without the ramp and is shown below.

End of ledge at Dry Creek No.

2 Ditch culvert at U.S. 36. Note

hinge to connect ramp. Distance

from ledge to ground is 54 cm.

Bird nettin

g

is visible.

In 2006, the study ran for an extra month because it

was started in May to capture potential early season

activity, as occurred during the pilot in 2005. With

this larger data set, we looked at the potential

difference in use of ledges with ramps off and on.

The results suggest a small difference, with 87 and

109 animals in 2005 and 174 and 333 animals in

2006 with the ramps off and on, respectively

(Figure 6). These differences represent 11 percent

and 31 percent of the total for 2005 and 2006,

respectively.

Mammals on Ledge

Year

Ramp

Off

On

0

100

200

300

400

2005 2006

Figure 6. Number of photographs of mammals on the ledges with ramps on

and off in 2005 and 2006

17

We evaluated whether certain species had a better ability to access the ledges with the

ramps off (Figure 7). All species accessed the ledges more frequently when the ramp was

on than when it was off. The prairie vole, shrew, and Preble’s meadow jumping mouse

did not access the ledges when the ramps were off, but they also used the ledges

infrequently altogether. Small mammals, and deer mice in particular with their overall

high level of activity, clearly have the ability to walk on the vertical concrete wall.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Mioc Mipe Mumu Neme Pema Prlo Rano Sorex

sp

Spva Zahu

Species

Number Mammals On Ledge

Figure 7. Mammal species on the ledges with the ramps on and off

Mioc=prairie vole, Mipe=meadow vole, Mumu=house mouse, Neme=Mexican

woodrat, Pema=deer mouse, Prlo=raccoon, Rano=Norway rat, Sorex sp=shrew,

Spva=rock squirrel, Zahu=Preble’s meadow jumping mouse

Notes:

indicates a break in the range for PEMA values

PEMA ramp on = 351

PEMA ramp off = 225

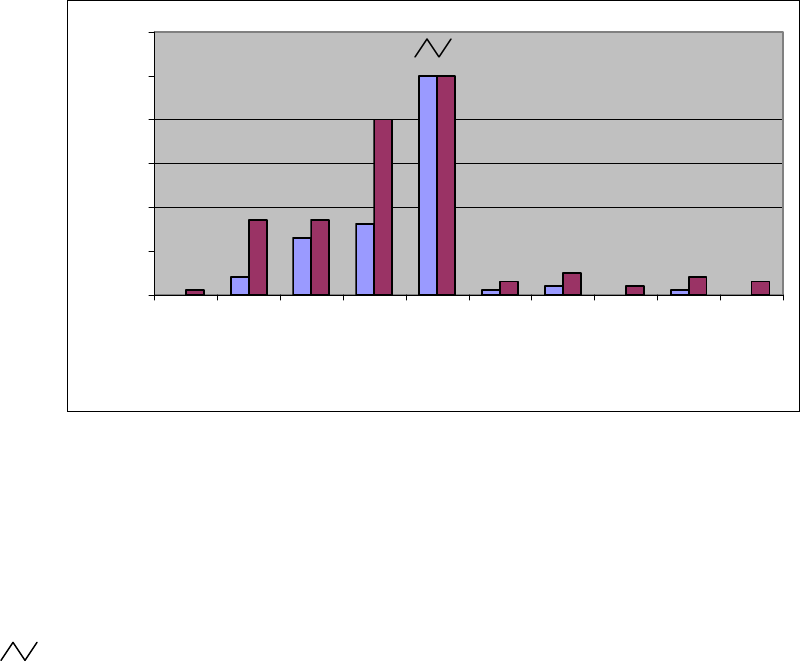

The mammal-on-ledge activity showed some variation and some overall consistency

across periods (Figure 8). The highest activity occurred during Periods 3 through 8, June

through August.

18

Mammals on Ledge

Per iod

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

01

02

03

04

05

06

07

08

09

10

Figure 8. Number of photographs of mammals on the ledges in the ten periods from

June through September 2005, and May through September 2006

We evaluated the culvert dimensions (length, height, and width). Length of the culvert

was assumed to address potential differences in use by small mammals between shorter

(two-lane road) and longer (four-lane road) culverts. Simple regression analysis showed

no significant correlation at the α = 0.05 level between the total number of mammals

photographed on the ledge for each culvert and its length (r

s

= 0.74, p = 0.0958, n = 6),

width (r

s

= 0.78, p = 0.0699), or height (r

s

= 0.72, p = 0.1053), although the correlations

were high.

We evaluated the potential correlation of vegetation at the entrances to the culverts and

the mammal activity on the ledge. We combined percent cover for all six plots at each

culvert (three on the upstream end and three on the downstream end) across all four plant

cover types to determine a total foliar cover value (total foliar cover = tree + shrub + forb

+ grass cover). There was no significant correlation in the number of mammals on the

ledge with percent cover (r

s

= 0.171, p = 0.7454, n = 6).

Four photographs captured Preble’s meadow jumping mouse using the ledges. The first

photograph was taken during the pilot portion of the study in May 2005, on Goodhue

19

Ditch (Culvert 3) under U.S. 36 (Figure 2). Because of the animal photographed in May

2005, the study was started earlier in 2006 (at the beginning of May). Goodhue Ditch

provided excellent habitat, had high overall use of the ledge and low species richness, and

was dominated by deer mice. The second photograph was taken July 21, 2005, on

Marshallville Ditch at Marshall Road (Culvert 5), under a small two-lane road in a rural

residential area where overall activity was low and species richness was high. The third

and fourth photographs were from Goodhue Ditch, taken May 28 and June 16, 2006,

respectively (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Three events of Preble’s meadow jumping mice on ledges photographed

during the study

Note: Clockwise from upper left: July 21, 2005 at Culvert 5; May 28, 2006 at Culvert 3;

and June 16, 2006 at Culvert 3.

20

Discussion

The results of this study show that ledges installed in culverts containing water are

readily used by small mammals as evidenced by 705 photographs documenting small

mammal passage on ledges in six culverts. Furthermore, these culvert ledges are

employed by a broad range of species, including nine species of mammals documented in

this study. Culverts, and more notably culverts with ledges, serve as valuable

passageways in an environment fragmented by roads.

Both the presence or absence of ledges in culverts, and the differences among the six

culverts, significantly affected the number of small mammals that passed through the

culverts (α = 0.05). The culverts were inherently different in type, style, length, and

width. It is likely that certain ditches had higher abundances of small mammals than did

others, and thus some culverts would receive more use as a consequence. In addition,

some of the culverts were frequented by spiders building webs and birds flying in and

out, both of which tripped the cameras and likely precluded capturing small mammals on

film. During the second year, mesh netting was reinforced on the culvert entrances to

prevent use by birds. The higher mammal activity level in 2006 may have been a result.

Culvert 3, on Goodhue Ditch at U.S. 36, had the greatest amount of activity (Figure 4).

Goodhue Ditch provides excellent habitat, with lush vegetation along its banks. It also is

a culvert in which it is possible to see end-to-end. Even at night, this may present a

detectible difference. East Boulder Ditch (Culvert 4) is dark, Marshallville Ditch at U.S.

36 (Culvert 2) is dark and has a bend in it, and Davidson Ditch (Culvert 7) has a bend in

it. None of the small mammal species documented in the photographs are strictly

fossorial, and the degree of ambient light may be a factor in the use of culverts.

The assumption was made that the ramps were necessary to access the ledges.

Interestingly, this was not the case because small mammals accessed the ledges even

when the ramps were off. However, all culverts as well as species showed more use of

the ledges with the ramps on. Small mammals appear to have an ability to climb vertical

21

concrete walls. Whether the animals climbed down onto the ledge from above (20 to 80

cm) or climbed up to it from the closest point along the bank (39 to 78 cm) is not known.

A few photographs captured animals on the concrete wall of the culvert including a shrew

and a deer mouse that was trying to reach a cliff swallow nest above the ledge. It appears

that the ledge was of such utility to these small mammals that they made reasonable

efforts to get to it.

Deer mouse climbing concrete wall toward a cliff swallow nest.

Twelve species of mammals used the culverts in the present study, which was

comparable to use in a study in Montana where 14 species were documented using six

culverts (Foresman 2004). In that study, 14 species also employed the ledges, whereas

only nine species were observed to use the ledges in the current study (Table B). The

Montana study also found differences in use by species, with deer mice readily using the

ledges but voles avoiding them, whereas meadow voles used the ledges in the present

study. The Montana study used ledges constructed of metal grating with a solid metal

edge. Mice always used the solid metal edge, and perhaps voles had no tolerance for the

grating substrate. In the Montana study, tubes were installed (similar to gutter drain

pipes) under the ledges, which facilitated use by voles.

22

The present study documented use by Preble’s meadow jumping mouse once during the

pilot (May 2005) and three times during the study in May, June, and July in two culverts.

The six culverts were selected for their proximity to South Boulder Creek, habitat for the

main population of Preble’s meadow jumping mouse in Boulder County (Meaney et al.

2002, 2003). East Boulder Ditch is also known to be occupied, with densities of 34 to 86

animals per km along the ditch in the stretch immediately adjacent to Culvert 4. That

culvert has the smallest opening of all the culverts, 1 m in diameter, and a length of 38 m.

It is possible that the narrower opening affected the lack of use by Preble’s meadow

jumping mouse. However, the East Boulder Ditch culvert had relatively low use overall,

albeit a high species richness (Figures 4 and 5). Davidson Ditch (Culvert 7) is within

approximately 50 m of a known population of Preble’s meadow jumping mice along

South Boulder Creek; however, none were photographed. Goodhue Ditch (Culvert 3),

with three Preble’s meadow jumping mice, was noteworthy for having the greatest

overall activity (Figure 4) and excellent habitat, albeit low species richness (Figure 5).

Marshallville Ditch at Marshall Road (Culvert 5), also with one photograph of Preble’s,

is a very short culvert in a rural residential neighborhood with a section of mowed lawn

adjacent to the ditch. It had low overall use and high species richness.

It is interesting that the level of activity, measured mostly by deer mice, appeared

inversely correlated with species richness. That is not necessarily typical for small

mammal trapping efforts. Across the 10 periods, activity was generally consistent with

highest activity during the middle of the summer. The increase is likely due to the

addition of the year’s young. The decline in September may be due to reductions in water

levels such that animals may have had some access to dry banks to pass through the

culverts without using the ledges.

A number of studies have found a relationship between culvert use and characteristics

such as culvert dimension. In Spain, length of the culvert was negatively correlated with a

crossing index for small mammals, whereas height, width, and openness were positively

23

correlated with the crossing index, which was determined solely from track plates in and

near the culvert (Yanes et al. 1995). The lack of correlation between small mammal

photographs and culvert dimensions in the present study may be due to a small sample

size of six culverts, in comparison with the Spanish study, which had a sample of 17

culverts (Yanes et al. 1995). Another study, using sooted track plates, found a negative

correlation between culvert use and road width for two of five taxa (coyotes [Canis

latrans] and red squirrels [Tamiasciurus hudsonicus]). Small mammals such as mice,

although the most common culvert users, had been removed from subsequent analyses

because their tracks did not show up on track plates adjacent to the culverts (Clevenger et

al. 2001). In another study, landscape variables were important in determining the

probability and frequency of underpass use, whereas dimension variables were more

important in determining the frequency of use (Haas and Crooks 2001).

Another factor that is generally found to relate directly with culvert use is vegetative

cover and/or height. In Montana, use of culverts increased with percent cover and height

of vegetation, although no statistical analyses were conducted on the six culverts

employed in that study (Foresman 2004). The present study did not show that

relationship, and it is suspected that the small number of culverts is a factor.

Mammals have an excellent ability to learn. This is significant to the present study

because animals had to learn to use the ledges. For example, it is likely that if a mouse

accessed a ledge when the ramps were on, it would then have a greater motivation to

access the ledge when the “ramps off” condition was encountered, having previously

learned the utility of this new passageway. However, it is not known whether all the

photographs taken with ramps off were animals that had previously accessed the ledges

when the ramps were on. Because animals were not marked, it also is not known how

many times a particular individual made use of the ledges, or how many different

individual mammals made use of the ledges.

24

Preble’s meadow jumping mouse is a long-lived small mammal. Whereas deer mice

seldom live one year, Preble’s can live three or four years (Meaney et al. 2002). This

longevity allows for learning to occur. Furthermore, Preble’s are known to travel great

distances. They are excellent dispersers and travel from summering areas to hibernation

sites. These factors combined (i.e., relative longevity and high vagility) suggest a

potential utility of ledges in culverts for Preble’s. However, given that only 3 of the 705

photographs taken during the study documented use by Preble’s, they used the ledges

infrequently. And although long-lived, the majority of individuals will not make it

through one active season. Alternately, if Preble’s are typically 5 percent of the local

small mammal population, and they use the ledges as readily as the other small mammals

that use them, there should have been approximately 35 Preble’s meadow jumping mouse

photos out of the 705 total. However, even if Preble’s movements on ledges are rare,

there still may be tangible benefits of a few animals moving from one side of a culvert to

another, allowing connectivity among adjacent populations. And given the low cost for

installation of permanent ledges, this is a very good value and well worth the effort.

In Australia, a rare small mammal, the mountain pygmy-possum (Burramys parvus), was

experiencing population declines due to fragmentation of its habitat by roads and other

development. By constructing tunnels containing rocks to imitate this marsupial’s habitat

(talus), natural movements were restored and population and survival rates increased

(Mansergh and Scotts 1989, cited in Forman et al. 2003). There is the opportunity for a

similar degree of success with Preble’s meadow jumping mouse.

A telephone survey to evaluate the use and effectiveness of wildlife crossings revealed

that, as of September 2005, there were at least 460 terrestrial and 300 aquatic crossings in

North America. New roads are being planned and constructed with permeability to

wildlife as part of the process (Cramer and Bissonette 2005). Mitigation measures

designed to lessen the impact of roads on wildlife are a necessary and significant

component of a sustainable transportation strategy and, although various techniques are

25

being employed, there is an urgent need for rigorous evaluation of these measures and for

the development and testing of new ones (Forman et al. 2003).

This is an important area of research and will provide “win-win” solutions for the

enhanced mobility of wildlife in the face of growing transportation corridors. Studies are

currently underway to determine how best to proceed with new roadways with

considerations for animal migrations and movement, underpass/overpass locations, and

construction details (Brodziewska 2005). The present study reveals the utility of

retrofitting existing structures for small mammal passage through culverts and a small but

inexpensive benefit for Preble’s meadow jumping mice.

26

Conclusions and Recommendations

This two-year study is the first study to our knowledge that applies an experimental

procedure to evaluate the utility to small mammals of ledges installed in culverts. This

appears to offer a significant and inexpensive means for increasing the permeability of

roadways to small mammals. This research project demonstrates that small mammals

readily make use of ledges in water-filled culverts to pass under roadways.

The testing of permanent retrofits is recommended. The present study tests the concept

with materials that will not withstand long-term use. Roscoe Steel and Culvert Company

in Montana sells permanent retrofit ledges (www.roscoebridge.com). The

recommendation is to implement a working process with CDOT engineers and staff to

assess the potential use of this retrofit equipment in Colorado, and to test its

effectiveness. It was discovered that the ledge construction used in the Montana study

(metal grating with 1-inch-wide diamond-shaped openings) was not optimal because the

lattice openings were too large for small mammals. The final design used #13 flat

galvanized expanded metal mesh (Foresman 2004). These types of engineering details are

significant and require field-testing in Colorado to maximize the benefits. It may also be

more cost-effective to find a local source for permanent retrofit ledges in Colorado. A

further step recommended for implementation is the development and construction of

culverts with pre-installed ledges. These can be directly formed in the concrete.

Another option includes using multiple-cell culverts that are built under roads. One cell

serves as a low-flow channel, and generally conducts water during the growing season.

The other cell(s) are built at a higher grade, and remain dry except during storm events.

The latter cells can be used by small mammals for passage.

27

The study of transportation and wildlife is a relatively new field. Much has been learned,

and much remains to be understood. The presence of roads has negative impacts on many

animals for a variety of reasons and culverts appear to have general positive impact on

animal movement. The use of ledges in culverts that contain water is clearly

demonstrated in the present study to facilitate movement by many species of small

mammals. The main recommendation pursuant to the present study is to initiate a

program to install permanent ledges in culverts where Preble’s populations are bisected

by roads. Although the number of Preble’s meadow jumping mice using the ledges was

small, the authors feel that Preble’s have great potential to use these ledges given time

and sufficient exposure to them. In summary, the recommendations for Colorado are:

• Expand the study to additional culverts and continue use of ledges in the most

active culverts of the present study, especially in Preble’s meadow jumping

mouse habitat, to better determine factors affecting use by Preble’s;

• Develop an appropriate permanent ledge retrofit design locally, or consider

installation of Roscoe Steel ledges and test their utility in Colorado; and

• Proactively begin discussions with CDOT engineers for construction/installation

of new culverts that contain built-in ledges.

28

References

Adams, L.W. and A.D. Geis. 1983. Effects of roads on small mammals. Journal of

Applied Ecology 20:403-415.

Brodziewska, J. 2005. Wildlife tunnels and fauna bridges in Poland: past, present and

future, 1997-2013. Pages 448-460 in Proceedings of the International Conference on

Ecology & Transportation, August 29 - September 2, 2005, San Diego, California.

Carr, L.W., L. Fahrig, and S.E. Pope. 2002. Impacts of landscape transformation by

roads. Pp. 225-243 in Applying Landscape Ecology in Biological Conservation, K.J.

Gutzwiller, ed. Springer, New York.

Clark, B.K., B.S. Clark, L.A. Johnson, and M.T. Hayne. 2001. Influence of roads on the

movements of small mammals. The Southwestern Naturalist 46:338-344.

Clevenger, A.P., B. Chruszcz, and K. Gunson. 2001. Drainage culverts as habitat

linkages and factors affecting passage by mammals. Journal of Applied Ecology 38:1340-

1349.

Conrey, R.C.Y. and L.S. Mills. 2001. Do highways fragment small mammal populations?

Proceedings of the International Conference on Ecology & Transportation, September

24-28, 2001, Keystone, Colorado. Pp. 448-457.

Cramer, P.C. and J.A. Bissonette. 2005. Wildlife crossings in North America: the state of

the science and practice. Pages 442-447 in Proceedings of the International Conference

on Ecology & Transportation, August 29 - September 2, 2005, San Diego, California.

Dodd C.K., Jr., W.J. Barichivich, and L.L. Smith. 2004. Effectiveness of a barrier wall

and culverts in reducing wildlife mortality on a heavily traveled highway in Florida.

Biological Conservation 118(5):619–631.

29

Ensight. 1999. Report on Preble’s meadow jumping mouse movement assessment at

Dirty Woman and Monument Creeks, El Paso County, Colorado. Ensight Technical

Services, Inc., prepared for Colorado Department of Transportation Region 2.

Foresman, K.R. 2001. Small mammal use of modified culverts on the Lolo South Project

of Western Montana. Proceedings of the International Conference on Ecology &

Transportation, September 24-28, 2001, Keystone, Colorado. Pp. 581-582.

Foresman, K.R. 2004. The effects of highways on fragmentation of small mammal

populations and modifications of crossing structures to mitigate such impacts. Final

Report, prepared for State of Montana Department of Transportation, Research Section.

39 pp.

Forman, R.T.T. 2000. Estimate of the area affected ecologically by the road system in the

United States. Conservation Biology 14:31-35.

Forman, R.T.T. and L.E. Alexander. 1998. Roads and their major ecological effects.

Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 29:207-231.

Forman, R.T.T. et al. (Editors). 2003. Road ecology: science and solutions. Island Press,

Washington, D.C. 479 pp.

Gerlach, G. and K. Musolf. 2000. Fragmentation of landscape as a cause for genetic

subdivision in bank voles. Conservation Biology 14:1066-1074.

Haas, D.C. and K.R. Crooks. 2001. Responses of mammals to roadway underpasses

across an urban wildlife corridor, the Puente-Chino Hills, California. Proceedings of the

International Conference on Ecology and Transportation, Keystone, CO, September 24-

28, 2001. Center for Transportation and the Environment, North Carolina State

University, Raleigh, North Carolina. March 2002, 580 pp.

30

Kozel, R.M. and E.D. Fleharty. 1979. Movements of rodents across roads. The

Southwestern Naturalist 24:239-248.

Mansergh, I.M. and D.J. Scotts. 1989. Habitat-continuity and social organization of the

mountain pygmy-possum restored by tunnel. Journal of Wildlife Management 53:701-

707.

Meaney, C.A. and A.K. Ruggles. 2000. Third year monitoring survey for Preble’s

meadow jumping mice, Pine Creek at Academy Boulevard, Colorado Springs, El Paso

County, Colorado. Report submitted to the Colorado Department of Transportation,

October 30.

Meaney, C.A., A.K. Ruggles, N.W. Clippinger, and B.C. Lubow. 2002. The impact of

recreational trails and grazing on small mammals in the Colorado piedmont. The Prairie

Naturalist 34 (3/4):115-136.

Meaney, C.A., A.K. Ruggles, B.C. Lubow, and N.W. Clippinger. 2003. Abundance,

survival, and hibernation of Preble’s meadow jumping mice (Zapus hudsonius preblei) in

Boulder County, Colorado. The Southwestern Naturalist.

Ng, S.J., J.W. Dole, R.M. Sauvajot, S.P.D. Riley, and T.J. Valone. 2004. Use of highway

undercrossings by wildlife in southern California. Biological Conservation 115:499-507.

Oxley, D.J., M.B. Fenton, and G.R. Carmody. 1974. The effects of roads on populations

of small mammals. Journal of Applied Ecology 11:51-59.

Swihart, R.K. and N.A. Slade. 1984. Road crossing in Sigmodon hispidus and Microtus

ochrogaster. Journal of Mammalogy 65:357-360.

31

Theobald, D.M., J.R. Miller, and N.T. Hobbs. 1997. Estimating the cumulative effects of

development on wildlife habitat. Landscape and Urban Planning 39:25-36.

Trombulak, S.C. and C.A. Frissell. 2000. Review of ecological effects of roads on

terrestrial and aquatic communities. Conservation Biology 14:18-30.

U.S. Department of the Interior. 2003. Draft Preble’s Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus

hudsonius preblei) Recovery Plan. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife

Service, Mountain-Prairie Region.

van Bohemen, H.S. 2004. Ecological engineering and civil engineering works. Ph.D.

Thesis, Delft University of Technology. Road and Hydraulic Engineering Institute of the

Directorate-General of Public Works and Water Management in Delft, The Netherlands.

Veenbaas, G. and G.J. Brandjes. 1999. The use of fauna passages along waterways under

motorways. Pp 315-320 in Key Concepts in Landscape Ecology, J.W. Dover and R.G.H.

Bunce, editors. International Association for Landscape Ecology, Preston, England.

Yanes, M., J.M. Velasco, and F. Suarez. 1995. Permeability of roads and railways to

vertebrates: the importance of culverts. Biological Conservation 71:217-222.

32

Appendix A: Photographs of the Culverts Used in the Study.

Culvert 1. Dry Creek Ditch No. 2 at U.S. 36.

Culvert 2. Marshallville at U.S. 36.

A-1

Culvert 3. Goodhue Ditch at U.S. 36. Bird netting visible.

Culvert 4. East Boulder Ditch. This is a round concrete culvert and the smallest diameter

(1 m) of all the culverts.

A-2

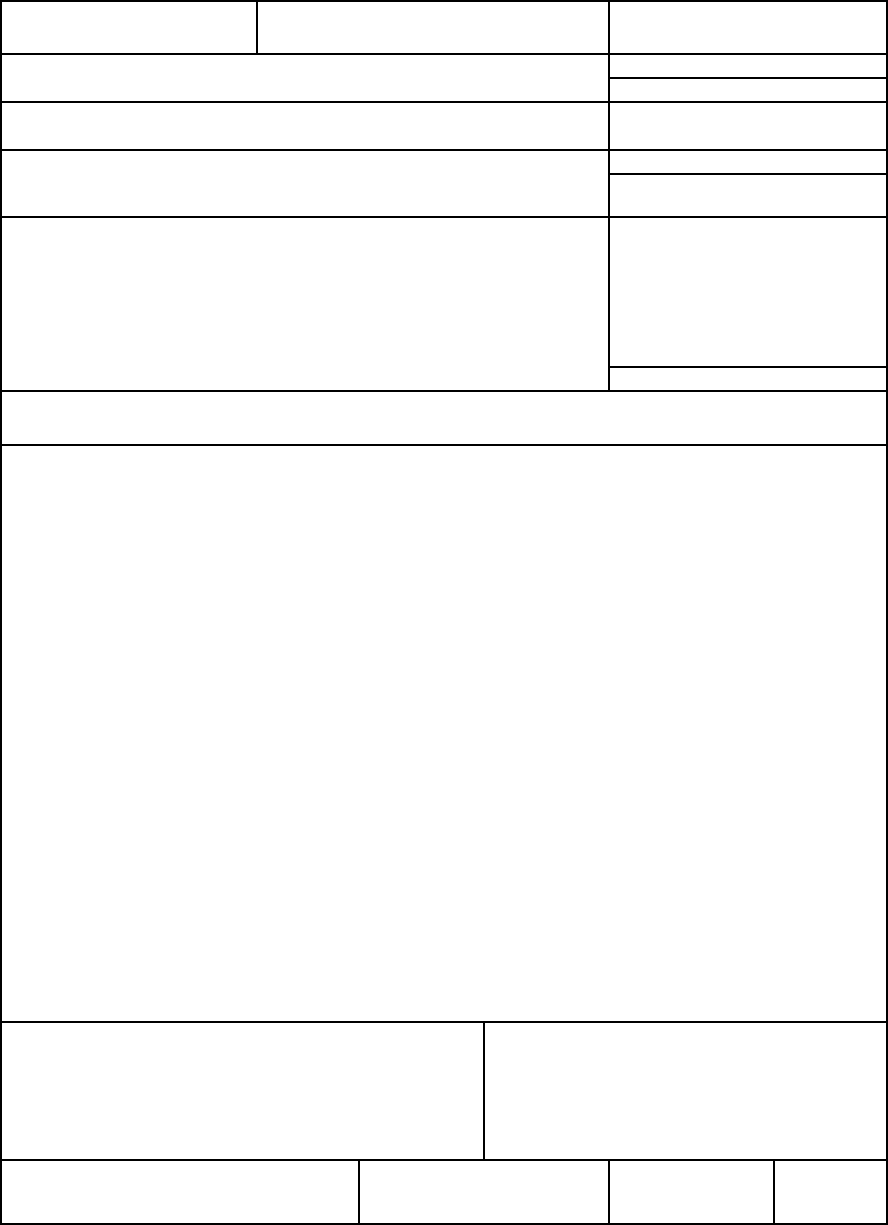

Culvert 5. Marshallville Ditch at Marshall Road. Both ledge and ramp visible at right;

note strap hinge to connect them.

Culvert 6. South Branch of St. Vrain Creek at Crane Hollow Road. This culvert was

eliminated from the study (see text). Ledge is inside culvert, ramp is on wing wall.

A-3

Culvert 7. Davidson Ditch at State Highway 170 in Eldorado Springs.

A-4