Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for

Children at Risk Children at Risk

Volume 11

Issue 1

Implementation in Real World Settings:

The Untold Challenges

Article 10

2020

Planting the Seeds of College and Career Readiness in Preschool Planting the Seeds of College and Career Readiness in Preschool

Betty Coneway

West Texas A & M University

Sang K. Hwang

West Texas A & M University

Jill Goodrich

Opportunity School

, jillgoodrich@opportunityschool.com

Lyonghee Kim

West Texas A & M University

Emilee Egbert

emileeegber[email protected]

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Coneway, Betty; Hwang, Sang K.; Goodrich, Jill; Kim, Lyonghee; and Egbert, Emilee (2020) "Planting the

Seeds of College and Career Readiness in Preschool,"

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing

Policy for Children at Risk

: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 10.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58464/2155-5834.1411

Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

The Journal of Applied Research on Children is brought

to you for free and open access by CHILDREN AT RISK at

DigitalCommons@The Texas Medical Center. It has a "cc

by-nc-nd" Creative Commons license" (Attribution Non-

Commercial No Derivatives) For more information, please

contact [email protected].tmc.edu

Planting the Seeds of College and Career Readiness in Preschool Planting the Seeds of College and Career Readiness in Preschool

Acknowledgements Acknowledgements

We want to thank the West Texas A & M University Center for Learning Disabilities for their ongoing

support of this research project.

This new research is available in Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk:

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

Planting the Seeds of College and Career Readiness in Preschool

Introduction

It is well-documented that in 2020, 65% of all jobs require further

schooling or training beyond high school.

1

This may include specialized

vocational education, military service, or professional preparation

programs that may not require a 4-year university degree but do involve a

significant amount of training, study, or apprenticeship experiences.

2

Therefore, it remains critical that children develop the requisite skills and

personal motivation for college and career readiness. Yet, the negative

effects of poverty can be one of the greatest barriers to students’

attainment of post-secondary success.

3

When educational achievement of the American citizenry is

examined, the disparities are significant. According to Hanushek et al,

4

the

achievement gap between children living in poverty and those from higher-

income families has failed to close over the past 50 years. These authors

assert that achievement inequalities between students’ educational

experiences and their socioeconomic background should be addressed

through targeted policies and practices aimed at this disparity, particularly

the need for high-quality teachers working with disadvantaged students.

4

Despite attempts to close these achievement and opportunity gaps,

children who are born into low-income families often remain in the bottom

two-fifths of the income distribution as adults.

5

Guilfoyle

6

argued that

college and career success begins during preschool and reports that the

first educational experiences young children receive are crucial to their

future success. Early childhood educators must then be equipped with

resources to assist young students in envisioning the broader goals of

college and career readiness to help them develop their “college-going

identity”.

7

The long-term educational goal of attending college may seem like

an obvious aspiration for children growing up in families from upper or

middle social classes. However, this quintessential goal may not be a

fundamental concept for students coming from underprivileged

backgrounds. When a child is young and impressionable, families

influence the development of their educational values and inspire their

overall academic development. In fact, Dubow et al

8 (p243)

reported that the

“beneficial effects of parental educational level when the child is young are

not limited to academic achievement throughout the school years, but

have long-term implications for positive outcomes into middle adulthood.”

Many families rely on schools not only to educate their children, but to

encourage and motivate them toward college attainment or professional

1

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

career pathways. Educators then have a responsibility to develop

strategies that allow students to explore options for post-high school

education and ensure rich opportunities for lifelong learning and future

goal setting. The changing nature of today’s global workplace demands

that students develop the college and career readiness competencies

necessary for post-secondary success.

9

However, according to Adams,

10

more than half of all students in public schools in the United States,

especially those from underrepresented minorities, do not meet the

readiness benchmarks to attend college.

Rural communities have both unique and complex identities.

11

Schools in rural areas tend to be strongly connected to the community and

typically have positive and supportive school cultures.

12

Even though rural

communities share many positive attributes, they also face significant

challenges, such as poverty, shifting demographics, educational

accountability, school consolidation, and the effects of economic changes.

12,13

Williams and Mann

14

explained that many rural communities have

high rates of concentrated poverty, especially among African Americans.

Research data supports the idea that access to high-quality early

educational experiences can be leveraged to improve the post-secondary

outcomes for children starting at an early age.

15

How, then, can these challenges be addressed so more students

from lower income or rural populations aspire for career readiness beyond

high school? For parents and children to see purpose in their daily

educational tasks, they must trust that the work is meaningful, understand

that they are not toiling in vain, and know that post-secondary success is

attainable. Additionally, some students growing up in poverty may not

embrace the dream of going to college or may develop an attitude of

hopelessness about their academic future.

16

The developmental approach to understanding readiness for post-

secondary experiences asserts that there are many social, emotional, and

cognitive factors that influence individual decisions and outcomes.

7

One

effective process identified by Bouffard and Savitz-Romer

7 (p41)

is the

development of students’ “future-oriented identities.”

While there are many

strategies that may affect this identity development, the current study was

designed to investigate the following research questions: 1) How have the

core beliefs of the No Excuses University (NEU) framework influenced the

participants’ perceptions of future educational opportunities? 2) How has

the NEU framework impacted the overall culture of achievement at the

research site?

Literature Review

2

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

Traditionally, college and career readiness proficiencies were

directed toward the development of core academic skills. However, other

abilities, such as soft skills, critical thinking, motivation, and technological

expertise can also influence student’s chances of reaching their full

potential.

2

Conley

17

noted the 4 keys to college and career readiness: 1)

cognitive strategies, 2) content knowledge, 3) learning skills and

techniques, and 4) transition knowledge and skills. These last 2 keys may

especially affect students from families and communities typically

underrepresented in higher education as they transition to life beyond high

school.

17

Consequently, students from economically disadvantaged

backgrounds may require supportive systems and programs to overcome

barriers and help them obtain equitable access to positive post-secondary

experiences.

3

To uphold the school’s mission of ensuring that children from low-

income families or students at risk of delays receive high-quality early

education,

18

the leadership team at the research site intentionally

employed the theoretical framework of organizational culture to positively

enhance the school’s philosophy. As Schein

19

explained, the ethos of an

organization relies on the perceptions, values, interactions, and

expectations of the group. By adopting a framework focused on future-

oriented success, the nonprofit preschool sought to purposefully influence

the beliefs of its faculty/staff, parents, and students by offering

opportunities for cultural evolution. The belief that all stakeholders provide

unique contributions to the organizations’ culture is an important

component of this transformational work.

20

NEU provides support by instilling a “culture of universal

achievement” for all students.

21

The NEU framework, originally conceived

at the elementary school level, is intended to support students, their

families, and the school by building a culture of college and career

readiness.

21

NEU is a nation-wide network of schools unified in the

conviction that all students have the right to be academically successful

and well-prepared for college and/or professional careers if that is the path

they choose. Its founder, Damen Lopez, who had a vision of what might

be done to enhance student performance,

22

launched NEU in 2004.

Founders of the framework believe that for children to embrace

their own potential and develop a hope-filled future story, it must become

their personal dream and not be a goal that is simply handed to them or

forced upon them. NEU explains that for this seed of hope to take root, it

must be planted early and watered often.

22

Therefore, college readiness is

not a topic relegated solely to high schools; in fact, experts believe that

high school may even be too late to begin implanting the goal of attending

college.

3

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

The model encompasses 6 distinctive systems: a culture of

universal achievement, collaboration, standards alignment, assessment,

data management, and intervention.

23

When schools exhibit a well-

developed culture of universal achievement, every member of the school’s

staff believes that each student is capable of meeting academic standards

and that the school has the power to make this achievement happen.

21

As

they collaborate around the core beliefs, schools align their standards as a

team, plan for assessment, and manage the data. Eventually schools

pursue data-driven interventions for academic achievement and begin

implementing social and emotional interventions for their students. The

NEU movement has influenced schools, school districts, students, and

families through the belief that every child deserves the opportunity to be

educated in a way that prepares them for college and professional

careers.

21

This model has influenced the lives of more than 150,000

students in 22 states and continues to receive national attention.

24

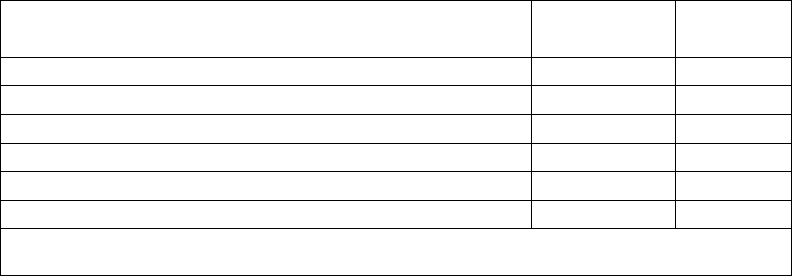

Table 1

breaks down the 207 schools participating in NEU network at the time this

article was written.

24

Table 1: NEU Network of Participating Schools

a

Early

Childhood

Elementary

School

Middle

(Intermediate)

School

High

School

Academy

Others

(K-8 School,

Preparatory

School, etc.)

Number

of

Schools

1

157

20

7

9

13

Total

207 Schools

a

Data adapted from the No Excuses University Network of Schools.

24

Curry noted the 2 overarching beliefs that the NEU framework is

based upon: 1) “Every child has the right to be educated in a way that

prepares them for college or post-secondary training that leads to a living

wage career, and 2) It is the responsibility of the adults in the school and

community to create and maintain exceptional systems in order to make

this a reality”.

25

These belief statements, communicated through the NEU

framework, reiterate that all students need a plan for their life after high

school, whether it be military service, vocational trade school, or a

specialized training program.

25

This future-oriented message is then

embedded throughout the daily routines of the school.

To transform the school culture and implant the idea of attending

college, NEU schools are encouraged to hang college pennants and teach

university songs and chants to connect students to a specific university or

4

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

college. According to Schein,

19

displaying artifacts, one of three levels of

an organization’s culture, is a highly visible practice. The next level of

organizational culture conveys a deeper meaning through addressing the

espoused beliefs and values of the school. This level of social validation is

noted as an expectation of the way things are done within the school

culture.

19

The third level of an organization’s culture has to do with the

underlying assumptions of the work being done in the organization.

19

Muhammad

26

further demonstrated that college and career readiness is

not only about strategies or programs, but also includes expectations,

attitudes, and the underlying culture of beliefs. NEU encourages schools

to offer their students the possibility of attending college by nurturing the

hope and then creating exceptional systems to ensure that their dreams

become reality.

23

A review of literature on this topic unearthed 2 studies investigating

the implementation of the NEU framework in elementary schools. One is

Devor’s study on the creation of a culture of universal achievement

through implementing the NEU framework.

27

To identify how academic

qualities are developed in students at an early age through a healthy

college-ready culture, Devor

27

examined teacher and principal perceptions

of how a culture of college and career readiness is achieved at the

elementary school level, noting that staff members’ belief that every

student can succeed was the dominant characteristic for success. Devor

27

concluded that early exposure to the ideal of attending college would

support students as they continued throughout their school experiences.

Another study conducted by Alonso

9

investigated trends within

NEU’s 6 exceptional systems and their relationship to student academic

achievement. Alonso pointed out that research on college and career

readiness had most often been conducted at the middle and high school

levels; however, her study investigated the impact of the NEU framework

on student’s academic achievement and social behavior at the elementary

school level. She found that promoting college and career readiness

through the NEU approach had a positive impact on students’ reading and

writing scores and on their social behaviors. Alonso concluded that these

6 systems helped to address the academic achievement gap between

elementary students from diverse backgrounds, especially children from

low-income families.

Ayala

28

reported that the first elementary school in Texas to

implement the NEU framework was San Jacinto Elementary, an under-

performing school in Amarillo, Texas. After learning about the framework,

the school’s administration implemented the 6 exceptional systems

identified by NEU and in 3 years the school went from being labeled

unacceptable to exemplary by the state education agency.

28

The founders

5

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

of NEU share that their goal is to revolutionize public education one school

at a time.

28

While a few research studies have been conducted to examine the

influences of the NEU program at elementary schools, no formal studies

were found that investigated the use of these structures in preschools.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to discover how the core beliefs

of the NEU framework have influenced the participants and the culture of

achievement at one nonprofit preschool.

Context of the Study

Within the local public-school district where this study was

conducted, 68.5% of students are classified as economically

disadvantaged

29

; therefore, finding ways to positively enhance the

educational outcomes for children of poverty is a critical need for this

community. At the research site, 80% of families are considered

economically disadvantaged and receive either free or reduced meals.

The average annual income of families at the school is reported as

$27,482 (Jill Goodrich, M.B.A., email communication, October 20, 2020)

30

.

Breaking this cycle of poverty and building a strong foundation of high-

quality early education has been a foundational goal of the school for over

50 years.

31

The research site, one of only two early childhood programs

currently accredited by the National Association for the Education of

Young Children (NAEYC) in this southern US rural city, seeks to embody

the principle that each family and child is unique and deserves high-quality

early education. As part of the accreditation process, the school must

uphold the 10 NAEYC program standards to ensure high quality. These

standards purport that childcare facilities and preschools are some of a

child’s first communities and thus have the important responsibility of

encouraging life-long goals and aspirations.

32

To promote this ideal, the

administrators and leaders of the target school investigated ways to

accomplish this goal and discovered the NEU framework.

In 2012, as NEU was expanding throughout the country, the

leadership of the nonprofit preschool wondered if a preschool could

become an NEU campus? They questioned if preschool was too young to

start planting the seeds of college and career readiness. They did not

think it was, so through dedication, hard work, and partnerships, they

seized the unique chance to positively affect the lives of young students

and their families by becoming the first preschool in the country to become

part of the NEU network of schools.

6

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

In June of 2012, 8 teachers from the preschool, 2 campus

administrators, and the executive director attended the Turnaround

Institute in Dallas to learn more about the NEU approach. At this institute,

teachers discovered ways to develop these future-oriented concepts in the

minds of preschoolers. From helping young learners understand the

different levels of education and the symbolism associated with colleges

and universities, these educators began to envision other ways to

jumpstart future-oriented dreams for the students and families they serve.

These teachers agreed that the NEU approach was a good fit to enhance

the longstanding history and philosophy of helping children achieve their

full potential. Therefore, in the fall of 2013, the school in the study became

the first NEU preschool, outside a public-school system, in the United

States to implement the framework.

Sharing the vision continues as information about NEU is

disseminated through parent orientation meetings and is regularly

included in handbooks and special brochures. NEU is part of the new-

employee orientation and is a topic that program development specialists

work on with new teachers joining the faculty. Every 2 years, team

members attend the NEU convention to learn new strategies.

Methodology

This research study used a mixed-methods case study design to

explore the participants’ perceptions of the influence of the NEU approach

at a nonprofit preschool program located in a rural hub city. Johnson and

Onwuegbuzie

33

pointed out that both quantitative and qualitative research

can be useful in educational research and a mixed-methods approach

allows researchers to benefit from the strengths and minimize the

weaknesses of both. This design was selected to collect both objective

quantitative data through the online surveys and subjective qualitative

data through informal discussions and semi-structured interviews.

Including survey data allows for replication of the study in other settings,

while the open-ended nature of the questions, follow-up discussions, and

face-to-face interviews helped describe the lived experiences of the study

participants in more detail.

34

Analyses of both data sets enhanced and

enriched the conclusions drawn from this study.

Participants

7

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

The research site school serves an average of 150 children per

year from ages 0 to 5 and provides affordable, high-quality early childhood

education for children from many low-income families. The purposeful

sample for this investigation included faculty/staff members, parents of the

preschool students, and young students attending this program.

Participants included 18 preschool faculty/staff members, 37 parents, and

31 preschool students. Adult participants responded electronically to

questions through an online survey. Preschool students were asked to

respond to survey questions in a face-to-face interview at the school with

their parents by their side.

Data Collection

The research team recruited adults by sending letters and email

messages to potential participants who were at least 18 years old, letting

them know that they would be receiving an email containing a link to the

informed consent form and survey questions. The school posted

information about the research study on the school’s Facebook page, on

its website, and in its newsletters. School administrators supplied

information to families and faculty members via email messages,

announcements, notes, and flyers. After notification, the potential adult

participants received a link to their specific survey questions. After

opening the link, they were able to consent to take part in the research

and submit their survey responses electronically.

Surveys for faculty, staff, and administration asked participants to

provide information about how they first learned about NEU and provided

a venue to share how the core beliefs of the NEU program have

influenced the culture of achievement at the school. Parents were asked

to reflect on how the NEU philosophy has affected them and their families

and were encouraged to suggest ways to improve the NEU program at the

school.

To collect data from the preschool students, research team

members visited the school and asked parents if they would give their

permission for a researcher to ask their child questions about the NEU

program. After parents gave verbal permission, they read and signed the

informed permission form. A researcher then asked the young student if

they were willing to answer a few questions. They were then prompted to

share their ideas and perceptions of attending college and their future

plans using the approved protocol questions. Some children eagerly

answered all the questions. A few young students were comfortable

answering questions at first, but then changed their minds; others

answered by whispering their responses to their parents, who relayed the

8

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

child’s answers to the research team member. The brief student

responses were recorded, transcribed, and entered into the Qualtrics

online software system to be analyzed alongside the adult participant

data. Data collection took over a semester to complete and yielded 86

completed responses.

Findings

Adult Faculty/Staff and Parent Survey Analysis

The faculty/staff members and parents were asked how they had

learned about the NEU program. The results of the survey showed that

83.9% of the parent participants and 93.75% of the faculty/staff had

learned about the NEU approach from the school or through their local

school district. When they first heard about the NEU initiative, 92.9% of

parents and 86.7% of the faculty/staff members were excited about the

idea and 83.3% of parents believed that the NEU philosophy was positive.

Overall, the adult participants perceived an increase in conversations

about college with their children as shown in this comment made by one

participant: “One thing that I have seen personally is my own children

talking about college. They never say ‘if’ I go to college, they always say

‘when’ I go to college” (Faculty/Staff Participant 8). One faculty member

noted that the NEU framework reflects the school’s motto: “[NEU] is a

great fit with our motto of “Good Beginnings Never End” (Faculty/Staff

Participant 11).

Findings revealed that 56.5% of parents believed knowledge about

college and career readiness would be helpful for their child’s success

later in life. Additionally, 17.4% of the parent participants felt as though the

NEU philosophy would better prepare their child for college and 13%

believed that these attitudes could provide positive educational

opportunities in the future. Parents said they more often talked about

college and career goals at home in response to receiving the NEU

information. In addition, 72% of the parent participants responded that

their children seemed to be more interested in going to college because of

their participation in these activities. For example, parent participant 5

responded, “We talk about him going on to kindergarten and how each

year he will learn different things”; while parent participant 3 described

conversations with her son by saying, “We talk about what college he

wants to attend to become a doctor.”

9

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

Data revealed that 53.8% of faculty/staff believed that NEU

principles could help students value their personal strengths and validate

how they might use their strengths in the future. Furthermore, 46.2% of

the faculty/staff participants credited the NEU program with helping

students learn that higher education is attainable and is one way they

could achieve long-term goals.

Regarding suggestions to improve the NEU program at the school,

39.1% of parents responded that the framework was good just the way it

was, while 26% of parents suggested improved communication with

parents about the NEU framework. Some suggested that vocational

career education be added to strengthen the approach. Faculty/staff

suggested more assistance in helping students achieve short-term

academic goals, additional guidance in providing motivation and hope to

students, and further information about different college or career choices.

In general, 44.4% of faculty/staff members responded that the NEU

program was a positive influence on the faculty/staff, and 33.3% agreed

that the program provided a positive influence on their children. Overall,

77.7% of the faculty/staff participants believed the NEU approach has

helped create a positive school culture that promotes college and career

readiness.

Student Survey Analysis

Student responses were examined to find out about young

children’s beliefs about college and/or career choices in their future. Even

though the responses were brief, their ideas were clear. In response to a

question about their thoughts on college, 75% of students responded

positively and 70.8% of the child participants said they were interested in

going to college. Examples of their responses included: “Going to college

is cool” and “I think I am going to do it!” (selected child participants).

Most student participants agreed that going to college would offer

some benefit to their life, including making money (32.5%), developing

knowledge and skills (22.5%), and fostering friendships (12.5%).

Approximately 45% of students responded that their teacher encouraged

them to go to college, and mentioned a variety of career choices for what

they would like to become when they grow up such as a firefighter, police

officer, doctor, veterinarian, or teacher. Interestingly, 70.9% of students

responded that family members of theirs had gone to college or graduated

from college.

Discussion

10

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

The findings from this study suggest that preschool is not too early to

begin shaping students’ identities for future success and developing the

self-efficacy skills to seek out post-secondary opportunities to fit their

unique interests and talents. This can be accomplished by creating a

culture of college and career readiness; providing ongoing training and

support for faculty, parents, and students; and addressing the ongoing

challenges of implementing this framework.

The Culture of College and Career Readiness

Helping students and families embrace the importance of post-

secondary success is one purpose of the NEU message. By facilitating

students’ development of self-efficacy skills, they may become more

willing and able to take risks and persevere to reach college or career

goals.

7

To cultivate this identity, students must understand and believe

that a myriad of college opportunities or career paths are open to them.

The NEU message of universal achievement can influence the

college- and career-readiness culture at a school. Communicating a

philosophy that upholds educational achievement and lifelong learning for

all not only influences the students’ futures, but this positive and

motivational message can also encourage the adults in the school to

complete their post-secondary education or seek ongoing training

opportunities. Exposure to the positive message of universal achievement

helps motivate students, teachers, staff, and parents to seek or complete

educational opportunities.

Ongoing Training and Support

Preschool leaders may benefit from these research-based findings

when making decisions on training their faculty and staff about college and

career readiness concepts. This understanding can be beneficial to in-

service educators working in the field of early education and teacher

educators preparing the next generation of early childhood educational

professionals. NEU provides one model for improved communication

about the development of long-term educational goals for all students.

Whatever framework or model is adopted, we assert that cultivating ways

to motivate young preschool students and their families toward long-term

academic achievement is both worthy and attainable.

Across the country there is a need for high-quality, well-trained

teachers in schools serving at-risk and diverse populations. Both in-

service and pre-service educators at all levels must be taught to honor

cultural diversity and uphold equity in their classrooms. Providing well-

11

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

developed methods of support for addressing these sensitive issues can

give teachers confidence as they fight some of the negative outcomes of

generational or situational poverty. As Kaiser and Rasminsky

35 (p21)

explained, “Equitable means ensuring that you consider each child’s

strengths, context, and needs and provide all children with the

opportunities that will support them in reaching their potential.” The NEU

framework is a resource that can aid educators in helping all children

explore possibilities and accomplish what they want for their unique

futures.

The data reveal that the faculty and staff at the school may benefit

from additional and more robust training and support to articulate the NEU

message more clearly. High staff turnover and limited time to train new

staff members may affect this implementation. When staff are hired, the

leadership team must train them on many procedures and sometimes

there is not enough time to fully explain the NEU framework. Therefore,

developing a strategic employee onboarding process is critical to this

work. Having a consistent orientation process can provide better support

for new employees and lead to more coherence in programming.

The research study provided parent participants with a venue to

express their opinions and provide input and ideas about the NEU

framework at the preschool level. The findings show that parents

appreciate positive and motivating messages being dispensed to their

students. However, only 17.4% of the parent participants reported that the

NEU philosophy would help to better prepare their child for college, and

only 13% believed that these attitudes could provide positive educational

opportunities in the future. These low percentages may reveal that parents

may not be hearing the message consistently or do not have a clear

understanding of what the culture of universal achievement can mean for

their children. Since the majority (80%) of families at the research site are

economically disadvantaged, the parents may not currently have the

capacity to envision college for their child. London

36

explained that many

immigrant families or first-generation college students often have identity

conflicts when balancing the expectations of their traditional family role

and educational advancement.

Untold Challenges

While the findings from this study shed light on several positive

results from implementing a framework for college and career readiness in

a preschool setting, the results did not address the questions, resistance,

and ongoing coordination of implementing this program. As a rule, early

12

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

childhood educators have not traditionally focused on the concept of post-

secondary educational readiness. In fact, some may argue that it is not

developmentally appropriate to include college readiness as a learning

objective in preschool settings. Therefore, early childhood advocates may

dismiss this concept as something unimportant to the early learning

community. However, we must continue to encourage educational

advancement and achievement at all levels. In a faltering economy,

helping individuals advance their education to create economic stability

within their families is a valuable message to convey.

While initially sharing ideas about the NEU framework with the

preschool faculty and staff of the research site, the program administrators

and leadership team had to address several concerns and respond to

ongoing questions from their staff. One critical misconception that needed

clarification was the concept that the “no excuses” message is meant as a

reminder for the adult facilitators in the field of education, and is not

targeted at the children or their families.

When the NEU initiative was first launched at the preschool, the

majority of faculty and staff members did not have college degrees and

this caused some to feel cautious or inhibited when they were asked to

talk about college or post-secondary plans with students and families.

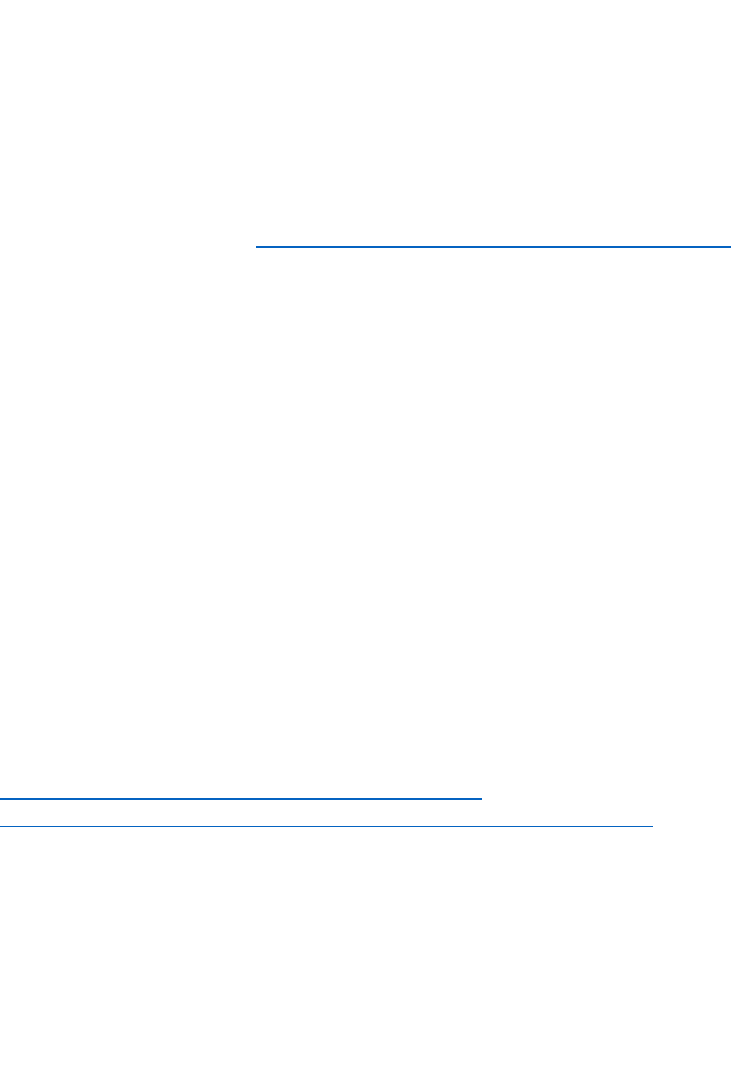

Table 2 provides information about the educational levels of the

faculty/staff at the time of the research study along with current statistics.

Table 2: Research Site Faculty/Staff Educational Background

a

Educational Level

Spring

2018

Fall

2020

Master’s degree

9%

7%

Bachelor’s degree

16%

15%

Associate degree

9%

24%

Child development associate (CDA) credential

24%

15%

Working on degree or credential completion

33%

22%

High school diploma

9%

17%

a

Data provided by the research site Executive Director (Jill Goodrich, M.B.A., email

communication, October 20, 2020)

30

The most notable increase can be seen in the percentage of

faculty/staff who have completed an associate degree. As a result of the

NEU message promoting education as a pathway out of poverty, there

13

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

has been an increase in faculty/staff at the research site who have

become interested in pursuing or continuing their educational goals.

Several faculty members were inspired to begin a degree program, while

others were motivated to complete an associate or bachelor’s degree. All

current administrators, directors, and supervisors at the research site have

an associate degree or higher. Through their ongoing efforts, the school

continues to support the community-wide effort to break the cycle of

poverty through education.

Initiatives and supportive communication over the past 7 years

have helped develop a clearer understanding of the NEU goals. The

preschool teachers now embrace the potential benefits for their students,

while exploring ways to embed the concept that every child, regardless of

their background, deserves the opportunity to be prepared for a future that

may include college if that is the path they choose. The current

expectation for preschool teachers is for them to have an earned college

degree or to be actively pursuing a degree in the field of early childhood

education. Program directors must consistently share this expectation with

prospective employees during the hiring and interview process.

Other challenges affecting the ongoing implementation of this or

any program initiative are the increased standards from regulatory and

accrediting bodies and the time needed to implement and document the

mandated requirements. In this environment, the focus sometimes shifts

to the immediate requirements, and some of the higher ideals may

become overshadowed. Addressing this challenge requires that we

remain focused on the principles that contribute to the long-term mission,

values, and goals of the organization.

18

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study is subject to a few limitations. One limitation was the

small sample size. The researchers realize that a larger group of

participants and more robust quantitative data would make the findings

from this study richer. Since NEU has been implemented in many schools

across the nation, the research could be extended to determine the

influence of the NEU program on the stakeholders and the culture of

achievement at other NEU schools. Additionally, this study was conducted

in a rural area; therefore, the findings may not generalize to urban areas,

where there are more programs that focus on post-secondary education,

so replication of this study in a large urban area would be beneficial.

14

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

Out of the 6 distinctive systems outlined in the NEU framework, this

study documented the influence of the “culture of universal achievement”

and “collaboration” systems. Hence, we recommend further research to

investigate strategies focusing on the other NEU systems, which would

include collecting and analyzing data regarding standards alignment,

assessment, data management, and intervention requirements in early

childhood education.

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that preschoolers are not too

young to begin understanding college and career readiness skills. Even

the youngest 4- and 5-year-old participants were able to explain the

benefits of attending college due to their exposure to the tenets of NEU.

Acknowledging that developing one’s self-identity as a “college goer”

takes many exposures and ongoing dialogue, Mattern et al.

2 (p10)

pointed

out that students need to receive encouragement and positive feedback

“early and often.” Therefore, preschool is not too early to begin planting

and tending the seeds of college and career readiness.

The “Culture of Universal Achievement” is a belief that “each

student is capable of meeting academic standards in reading, writing, and

math, and that the school has the power to make that opportunity a

reality.”

21

The system of “Collaboration” validates that purposeful and

action-oriented collaboration can reap great rewards.

21

Collaboration was

noted in this study by the data collected from the various perspectives of

participants. Findings were verified by the faculty, staff, administrators,

parents, and students. By embracing these systemic beliefs, schools can

shift the negative cycle of poverty to a cycle of achievement for all

students.

Even though there are many challenges to overcome, the culture of

college and career readiness can permeate the preschool environment to

motivate all stakeholders to attain post-secondary success. Positive and

intentional efforts to build a culture of success communicates that all

individuals of any age or background can be well prepared for a promising

and bright future.

15

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

References

1. Carnevale AP, Smith N, Strohl J. Recovery: Job Growth and Education

Requirements Through 2020. Georgetown University Center on

Education and the Workforce. https://1gyhoq479ufd3yna29x7ubjn-

wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-

content/uploads/2014/11/Recovery2020.FR_.Web_.pdf. Published

June 2013. Accessed October 30, 2020.

2. Mattern K, Burrus J, Camara W, et al. Broadening the Definition of

College and Career Readiness: A Holistic Approach. ACT Research

Report Series. 2014(5). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED555591.pdf.

Published 2014. Accessed October 30, 2020.

3. Lowery-Hart R, Crowley C, Herrera J. No excuses: a systemic

approach to student poverty. Diversity & Democracy. 2017;20(4).

https://www.aacu.org/diversitydemocracy/2017/fall/lowery-hart.

Published December 3, 2017. Accessed October 30, 2020.

4. Hanushek EA, Peterson PE, Talpey LM, Woessmann L. The

achievement gap fails to close. Education Next. 2019;19(3).

https://www.educationnext.org/achievement-gap-fails-close-half-

century-testing-shows-persistent-divide/. Updated March 19, 2019.

Accessed October 30, 2020.

5. Haskins R, Isaacs JB, Sawhill IV. Getting Ahead or Losing Ground:

Economic Mobility in America. Brookings Report.

https://www.brookings.edu/research/getting-ahead-or-losing-ground-

economic-mobility-in-america/. Published February 20, 2008.

Accessed October 30, 2020.

6. Guilfoyle C. For college and career success, start with

preschool. Policy Priorities. 2013;19(4):1-7.

7. Bouffard SM, Savitz-Romer M. Ready, willing, and able. Educ

Leadership. 2012;69(7):40–43.

http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-

leadership/apr12/vol69/num07/Ready,-Willing,-and-Able.aspx.

Accessed October 30, 2020.

8. Dubow EF, Boxer P, Huesmann RL. Long-term effects of parents'

education on children's educational and occupational success:

mediation by family interactions, child aggression, and teenage

aspirations. Merrill Palmer Q. 2009;55(3):224-249.

doi:10.1353/mpq.0.0030.

9. Alonso M. Culture of College Readiness in No Excuses University

Elementary Schools: Patterns and Trends Within Six Exceptional

Systems and the Relationship to Student Academic Achievement in

16

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

Reading and Writing and Social Behavior in the Classroom

[dissertation]. La Verne, CA: University of La Verne; 2017.

10. Adams C. SAT-ACT performance for 2015 graduates called

“disappointing”. Education Week. 2015;35(3):6.

11. Wieczorek D, Manard C. Instructional leadership challenges and

practices of novice principals in rural schools. J Res Rural Educ.

2018;34(2). https://jrre.psu.edu/sites/default/files/2019-06/34-2_0.pdf.

Accessed October 30, 2020.

12. Bushnell M. Imagining rural life: schooling as a sense of place. J Res

Rural Educ. 1999;15(2):80-89. http://sites.psu.edu/jrre/wp-

content/uploads/sites/6347/2014/02/15-2_5.pdf. Accessed October 30,

2020.

13. Harmon HL, Schafft K. Rural school leadership for collaborative

community development. Rural Educator. 2009;30(3):4-9.

14. Williams DT, Mann TL, eds. Early Childhood Education in Rural

Communities: Access and Quality Issues. Fairfax, VA: Frederick D.

Patterson Research Institute; 2011.

15. Workman S, Ullrich, R. Quality 101: Identifying the core components of

a high-quality early childhood program. Center for American Progress.

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-

childhood/reports/2017/02/13/414939/quality-101-identifying-the-core-

components-of-a-high-quality-early-childhood-program/. Published

February 13, 2017. Accessed October 30, 2020.

16. Jensen E. Teaching with Poverty in Mind: What Being Poor Does to

Kids’ Brains and What Schools Can Do About It. Alexandria, VA: ASCD;

2009.

17. Conley DT. The four key dimensions of college and career readiness.

In: College and Career Ready: Helping All Students Success Beyond

High School. 2012:17-52. doi:10.1002/9781118269411.

18. Opportunity School website. Educational philosophy.

https://www.opportunityschool.com/EducationalPhilosophy. Accessed

October 30, 2020.

19. Schein E. Organizational Culture and Leadership. 4th ed. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

20. Covey SR, Covey S, Summers M, Hatch DK. The Leader in Me. 2nd ed.

New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2014.

21. No Excuses University. What we believe.

https://noexcusesu.com/about/what-we-believe/. Published 2018.

Accessed October 30, 2020.

22. No Excuses University. Who we are. https://noexcusesu.com/about/.

Published 2018. Accessed October 30, 2020.

23. Lopez D. No Excuses University: How Six Exceptional Systems Are

17

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020

Revolutionizing Our Schools. Kindle Edition: TurnAround Schools

Publishing; 2013.

24. No Excuses University. No Excuses University. NEU Network.

https://noexcusesu.com/network/. Published 2019. Accessed October

30, 2020.

25. Curry D. No Excuses University. Panhandle PBS.

https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=no+excuses+university&docid=

608019364546084915&mid=47F73A4FB272E30D264747F73A4FB27

2E30D2647&view=detail&FORM=VIRE. Published September 25,

2014. Accessed November 2, 2020.

26. Muhammad A. Transforming School Culture: How to Overcome Staff

Division. 2nd ed. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree; 2017.

27. Devor E. Teacher and Principal Perceptions of How a Culture of

College Readiness is Achieved at the Elementary School Level.

[dissertation]. La Verne, CA: University of La Verne; 2016.

28. Ayala S. Leading with no excuses: Damen and Dan Lopez. Point Loma

Nazarene University Viewpoint. https://viewpoint.pointloma.edu/alumni-

in-focus-leading-with-no-excuses-damen-and-dan-lopez/. Published

October 17, 2012. Accessed November 2, 2020.

29. Texas Education Agency (TEA). 2018-2019 Texas academic

performance report: district detail for Amarillo ISD.

https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/tapr/2019/srch.html?srch=D.

Published December 2019. Accessed November 2, 2020.

30. Opportunity School Statistical Report for 2019. Email communication

from Executive Director, Jill Goodrich, September 2020.

31. Opportunity School website. History.

https://www.opportunityschool.com/History. Accessed November 2,

2020.

32. National Association of Education for Young Children (NAEYC). The

10 NAEYC program standards. https://www.naeyc.org/our-

work/families/10-naeyc-program-standards. Accessed November 2,

2020.

33. Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research

paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33(7):14-26.

34. Scoles, J, Huxham M, McArthur J. Mixed-methods research in

education: exploring students' response to a focused feedback

initiative. SAGE Res Methods Cases Part 1. 2014.

https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/978144627305013514690. Accessed

November 2, 2020.

35. Kaiser B, Rasminsky JS. Valuing diversity: Developing a deeper

understanding of all young children's behavior. Teaching Young

Children. December 2019/January 2020;13(2).

18

Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, Vol. 11 [2020], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2155-5834.1411

https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/tyc/dec2019/valuing-diversity-

developing-understanding-behavior. Accessed November 2, 2020.

36. London HB. Breaking away: a study of first-generation college students

and their families. Am J Educ. 1989;97(2):144-170.

19

Coneway et al.: Planting the Seeds

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2020