Capital Projects & Infrastructure Practice

Collaborative contracting:

Moving from pilot to

scale-up

Despite the early successes of collaborative-contract adopters, the industry

remains hesitant. Five steps can help project owners better envision the

transition toward more collaborative approaches.

January 2020

by Jim Banaszak, Je Billows, Rudi Blankestijn, Matthieu Dussud, and Rebecka Pritchard

© Getty Images

There is mounting evidence that owners of large

capital projects should consider alternatives to

traditional, adversarial contracting practices. More

collaborative agreements and operating models

can be found in integrated project delivery (IPD) or

project alliancing. Under such models, key delivery

partners (usually the owner, engineer or architect,

major equipment manufacturers, and contractors)

work together during a defined preplanning

period to develop the project scope, schedule, and

budget. These partners form a single contract

including a no-fault clause; and operate under a

joint management structure that governs the project

execution.

Early adopters of these collaborative contracts

in industries such as oil and gas, healthcare,

water, and consumer-packaged goods are seeing

improved financial performance for their capital

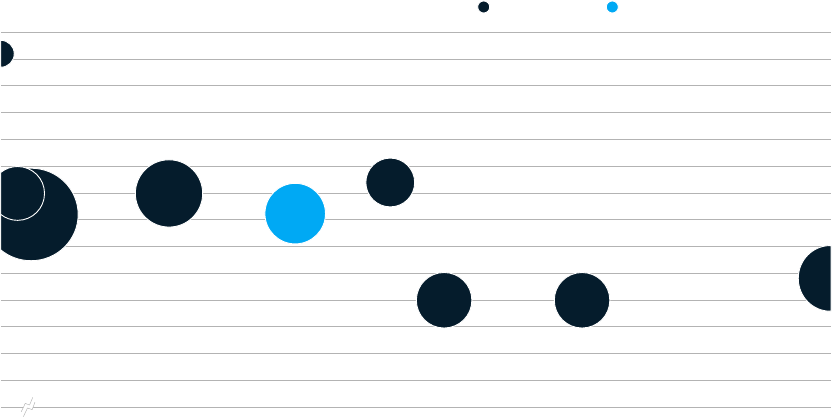

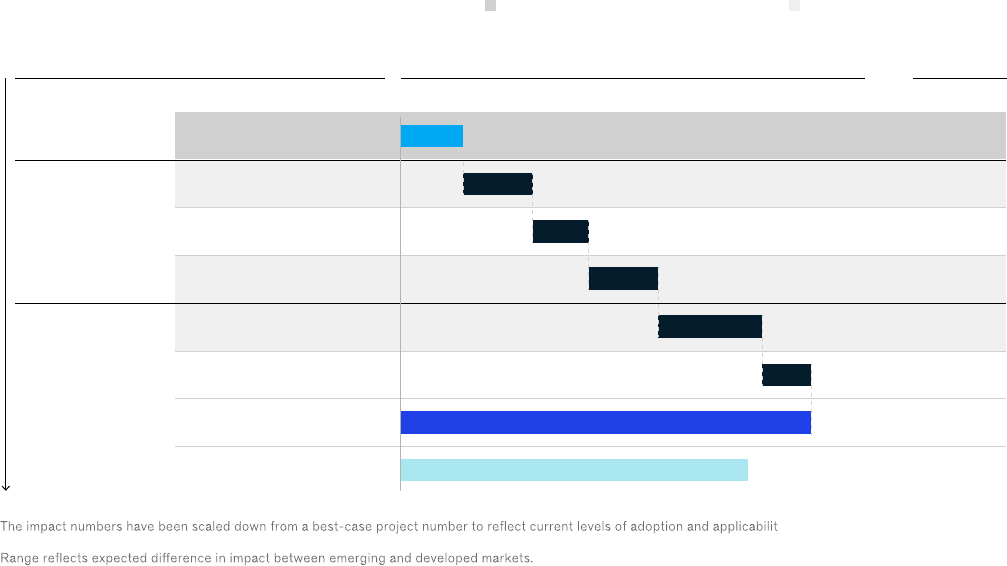

projects during execution. Our analysis of eight

collaborative-contract pilots reveals that these

agreements have resulted in a 15 to 20 percent

improvement in cost and schedule performance

compared with traditional contracts (Exhibit 1).

Despite success in the relatively small number of

implementations to date, project stakeholders

have not widely adopted collaborative contracts.

Many willing industry participants stumble because

they are unfamiliar with what it takes to implement

collaborative models or have difficulties finding the

right partners who agree to this type of structure. In

addition, financing parties often hesitate to approve

anything other than fixed-price agreements,

citing uncertainty and an inability to transfer risk.

Moreover, some public-sector owners are legally

required to award contracts to the lowest qualified

bidder, preventing them from entering into more-

collaborative contract terms.

The result is an inability to shake the status quo—an

adversarial contracting practice in which parties

rush through fixed-price contract negotiations,

opening the door for purposely understated

timelines, long delays, and massive budget overruns.

To break old habits and adopt more-collaborative

contracts, our analysis shows that project owners

must start by fully understanding the elements of a

collaborative contract and the spectrum of possible

collaboration. Then they should assess their own

readiness for collaboration, select the right partners,

and invest, as early as possible in the process, in

building out a detailed project description and

0

0 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34

5.0

10.0

2.5

7.5

12.5

15.0

20.0

25.0

30.0

17.5

22.5

27.5

32.5

35.0

McK CP&I 2020

Collaborative contracting

Exhibit 1 of 3

Early adopters of collaborative contracts are seeing improvements in performance.

Improvements to cost and schedule performance realized in collaborative contracts

Improvement in cost performance, % over conventional

Average performance of early adoptersType of projects

Oil eld

Oshore oil

IndustrialHospital

Average

Hospital system

Oshore oil

Channel deepening

Health system

Improvement in schedule performance, % over conventional

Exhibit 1

Early adopters of collaborative contracts are seeing improvements in performance.

2 Collaborative contracting: Moving from pilot to scale-up

aligning critical partners’ incentives. Finally, owners

can integrate best practices—from a project’s start

through its completion.

The elements of collaborative contracts

A fully collaborative contract, such as those found

in IPD, is founded upon cocreation of the project’s

scope of work, transparency, and joint governance.

These elements translate into four major practices:

partners working together during a defined

preplanning period, a single contract among all key

partners, a no-fault clause, and a joint management

structure.

Defined preplanning period

At the inception of any collaborative-contracting

process, the owner starts by selecting all

critical delivery partners, including an engineer

and architect, the main original equipment

manufacturers (OEMs), and at least one contractor.

This core team then works closely—usually at the

owner’s expense—on a conceptual design, cost

estimate, and schedule. It then negotiates and

finalizes the commercial terms of the contract that

link everyone’s interests through the project’s

completion.

Single contract among all critical delivery

partners

The single and final agreement, signed by all

parties, clearly defines the scope of work, schedule,

coordination guidelines, and the collective

obligations of the partners and by exception

the separate obligations of each partner. It also

defines compensation (actual cost and overhead

recovery) and the profit sharing if the project is

successful. In addition, it outlines detailed voting

rights, representation on the governance board and

execution leadership team, and the change-order

process for the project. (Investing in detailed project

definition during the pre-planning period reduces

the risks of change orders.)

No-fault clause

Most often, collaborative contracts include a

no-fault clause that requires members to forfeit

rights to claim against one another. In contrast to

a traditional lump-sum contract, in which owners

attempt to transfer as much risk as possible to other

parties, the partners within a collaborative contract

have a limited ability to submit claims when they

occur. Instead, all project-related decisions are

binding and made by the governance board.

Joint management structure

During execution, collaborative projects are

typically governed by a joint management

structure or regularly convened board with an

explicit contractual obligation for all parties to

make decisions in the project’s best interest. The

governance board consists of a representative

for each critical delivery partner, and each

representative has a vote in every decision related

to the project. All partners commit to transparency

of their own cost and schedule data, and all parties

share the risk and reward of the project outcome.

Choosing a level of collaboration

We realize some project owners may face

constraints on how they’re able to structure

their agreements. For example, owners run

into procurement constraints, strict lending

requirements, government restrictions, or generally

opposed mind-sets and behaviors. These obstacles,

however, should not stop owners from making

progress on initiatives that would facilitate better

collaboration, such as establishing shared digital

information, tailored incentives, and an integrated

design environment.

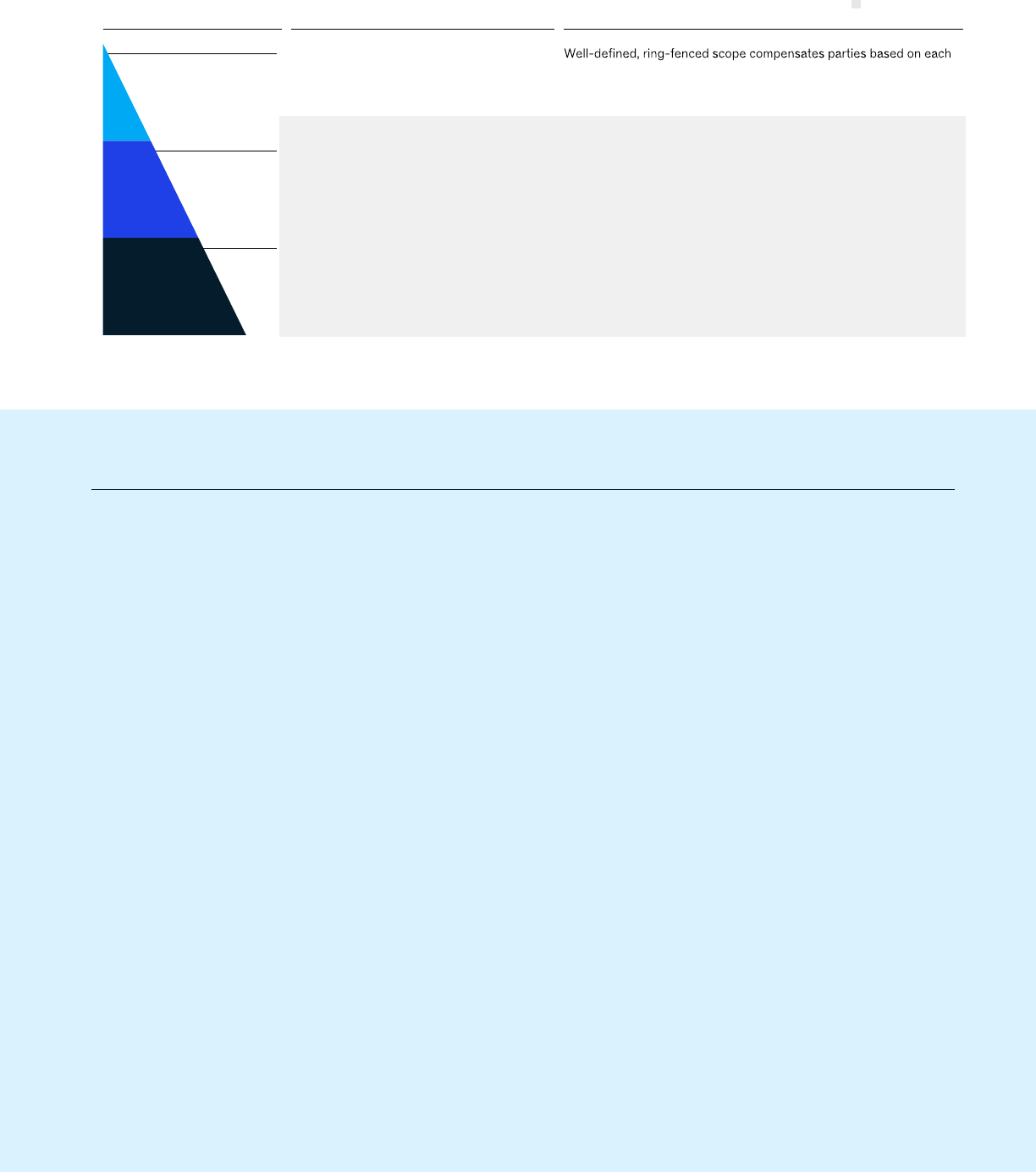

The level of cooperation in a collaborative contract

can be considered along a continuum, with IPD at

one end as the most collaborative and limited risk-

sharing programs or thematic collaboration at the

other (Exhibit 2). (For examples of collaboration, see

sidebar, “Case examples: Incorporating elements of

collaboration into traditional contracts.”)

Implementing a collaborative contract

Transitioning from a transactional approach to

a collaborative model is no easy task. Certain

situations may not be conducive to full collaboration,

some organizations may not be ready, and with

3Collaborative contracting: Moving from pilot to scale-up

Case examples: Incorporating elements of collaboration into traditional contracts

If the most collaborative agreements can’t be implemented, it is often possible to incorporate specic pieces of collaboration into a

traditional project structure. Below are two examples of project owners that benetted from implementing some collaborative practices.

Intermediate level of collaboration

One self-funded high-technology equipment manufacturer needed to expand capacity but had not built a new facility in more than 20

years. Given the degree of sophistication of the required equipment and original, browneld layout of the facility, initial project estimates

were more than 50 percent above the estimated cost limit to make the business plan work. To make the project nancially viable, the

manufacturer set up an integrated team of designers at a single location: OEMs; engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) com-

panies; and major subcontractors. This team used a common data environment and design tools, combined with agile working process-

es, to quickly evaluate more than 70 design concepts. Ultimately, the team landed on a concept that would relocate the facility next to

underutilized existing space, signicantly reducing construction complexity. Under separate contracts with shared milestone incentives,

the team completed the detailed design and successfully executed the project.

Low-level (thematic) collaboration

Sometimes adding just one or two pieces of collaboration is both possible and benecial. An oil and gas company, for example, recently

undertook a self-funded, midsize project for which it signed a long-term reimbursable agreement with an EPC contractor. In this agree-

ment, the company and the contractor collaborated on digital transformation and project-data transparency. In return, the EPC con-

tractor was guaranteed a minimum of three projects over the next four years and earned incentives based on overall project outcomes,

including cost and schedule. This arrangement is similar to a typical “open-book estimate” concept and traditional alliance contract. But

unlike most open-book projects where transparency ends after a project is 30 or 50 percent complete, in this case the books stay open

through the end of the project. As a result, most of the risks stay with the client, but it allows for both full transparency on engineering and

construction costs and guaranteed work for the EPC.

Sidebar

McK CP&I 2020

Collaborative contracting

Exhibit 2 of 3

A range of collaboration options is available to project stakeholders.

Transactional Type or degree of collaboration Description

Traditional two-party contracts

1. Thematic collaboration

eg, digital platforms, data transparency,

and shared services

2. Multiparty contract

ie, all key project participants as signatories

one’s performance

—Contracts require a mature or capable contractor market

Project participants agree to collaborate around specic, well-dened

themes or approaches to deliver project more eciently

All major partners shape project scope, validate cost and schedule

estimates, and share risk and prots

—Owner needs to assess its own structural readiness for collaboration,

Area of opportunity

—To succeed, thematic collaboration requires a clear business case

for each eciency improvement initiative

invest in detailed project denition, select the right partners up

front, align incentives of all partners, and relentlessly invest in trust

and collaborative mind-sets and behaviors

Exhibit 2

A range of collaboration options is available to project stakeholders.

4 Collaborative contracting: Moving from pilot to scale-up

collaboration come real challenges (such as

ambiguous roles). Five steps can help project

owners transition to a collaborative model more

easily.

Assess structural readiness for collaboration

Project owners, as the driving force, must

understand their own structural readiness to

implement a realistic level of collaboration. We

have identified a few essential determinants for

owners to assess their readiness for collaborative

contracting:

— Sophisticated contracting and procurement

capabilities, an existing ecosystem of reliable

engineering and construction (E&C) partners,

and limited regulatory constraints on tender

processes

— Strong organizational capacity and capabilities

(such as for enforcing strict stage gates) and

buy-in across the organization, from executive

leadership to the project team

— Progressive risk-management philosophy, as

well as a willingness to invest up front and take

downside risk (after profit of all partners is

forfeited)

— Agile project culture

— Project portfolio with sufficient volume to

support long-term agreements and flexible

financing arrangements

By knowing where their strengths and

weaknesses lie, owners can better select the

appropriate level of collaboration for their

organization.

Select the right partners up front

An owner assessing potential partners must

first ensure the basics, such as that they have

the right qualifications and expertise. Partners

need relevant experience (such as having

designed similar facilities or local knowledge and

presence), distinct capabilities (so that no two

partners overlap), and general financial health.

Next, assessing the openness, self-orientation,

and support for collaboration among a potential

partner’s project team and senior management is

paramount.

In the end, whether the people are a good

fit is what guarantees trust and a healthy

collective decision-making process. During a

Global Infrastructure Initiative roundtable in

Houston,¹ one oil and gas executive concluded,

“Relationships are what moves the needle.”

Further, owners should be prepared for some of

their potential partners to resist the collaborative

process. Our interviews with one early adopter of

lean IPD revealed that 30 percent of its contractor

population was unwilling to entertain the model

when it was first suggested. Undeterred and

determined to embark on an IPD journey, that

owner selected—and continues to select—

partners willing to work within the boundaries of

collaborative structures.

Invest in detailed project definition

When choosing a contract type, project owners

need to decide early if the projected financial

returns and risk profile warrant the cost of a

higher-quality final investment decision (FID). If

so, a cross-functional team—comprising the core

project stakeholders working closely together to

create a detailed project scope, execution plan,

and cost estimate—increases the likelihood of

a sound FID. While this increases the owner’s

financial commitment up front, this investment

is outweighed by the higher likelihood of

successfully executing the project.

One project for a North American transit agency,

for example, involved a large and complex web

of stakeholders. Initially, the agency used a

traditional contract, intending to transfer risk to a

developer. When potential developers evaluated

this plan, none felt comfortable accepting this

level of risk or submitting an offer.

1

“Houston 2019: Using collaboration to improve performance and predictability in oil, gas, and chemical manufacturing project delivery,” Global

Infrastructure Initiative, November 2019, globalinfrastructureinitiative.com.

5Collaborative contracting: Moving from pilot to scale-up

The transit agency had no choice but to adopt a

collaborative model in which each stakeholder—that

is, the agency, developer, and designer—partnered

up to define the scope, craft design solutions,

negotiate right-of-way approvals, and establish a

target cost for the alliance. The agency assumed

the downside risk of delays that extend past a

certain point, but the developer, designer, and key

subcontractors were given incentives to mitigate

any potential overruns. Where a traditional risk-

transfer model was unacceptable to the private

sector, the agency made this project possible

by adopting a collaborative model that better

distributed the risks.

Align incentives of all partners

Distractions and inefficiencies often occur when

each project stakeholder works toward individual

project goals. Setting up a common incentive pool

that grows or shrinks based on overall project

performance (along with all parties distributing pro

rata compensation) is one approach to facilitate

collaboration among project stakeholders.

This approach was successfully used on an offshore

project. Although each party had a separate

contractual relationship, ranging from reimbursable

to lump sum, the partners had the opportunity

to earn additional profit through a gain-share

agreement—if and when the project came in under

budget and ahead of schedule.

Relentlessly invest in trust

Moving from an adversarial to a collaborative

approach requires persistent investment in not

only building and maintaining trust among delivery

partners but also instilling collaborative behaviors

(such as problem solving, knowledge sharing,

curiosity, and creativity). To succeed, project owners

should define their organizational aspirations and

make those as important as a project’s financial or

schedule goals and enforce reliability and openness,

two of the key dimensions of the “trust equation.”²

Then they must measure their progress against

their goals. Relevant performance indicators can

be scores on engagement surveys by project team

members, number of cross-stakeholder problem-

solving sessions, cost or schedule improvement

opportunities cogenerated by the team, or the

number of digital innovations that were made

possible through collaboration.

Formal mechanisms, such as tying senior leaders’

compensation to organizational alignment goals,

should also be implemented to reinforce the desired

mind-set shifts. Leaders need to understand

their role in overcoming decades of negative

conditioning that make it hard for teams, even

willing ones, to embrace collaboration. Habits are

deeply entrenched, so collaborative teams need

training, feedback, and reinforcement not just at the

beginning but throughout the project life cycle.

Each of these steps is critical, but none can

succeed without a few supporting elements. One

is contractual enforcement; in fact, the former

director of capital projects for a consumer-products

company stated, “Contractual reinforcement is

the secret sauce.” Other essential factors involve

rigorous project- and performance-management

science, including a digital control tower and

war room; agile teams that are accountable for

delivering impact; and finally, a joint execution-

leadership team and project-governance board with

clear authority.

No time to waste

When it comes to the transition away from

transactional contracting practices, project

owners do not have the luxury of time. Major

North American E&C companies have already

reconsidered whether they should bid competitively

on lump-sum contracts at all. As more project

stakeholders take the same path, project owners

that stick to traditional contracts may soon be left

with fewer options and rising prices.

Additionally, those that wait to act risk missing out

on the potential benefits of collaborative contracts

for the entire industry—benefits that are exciting

2

McKinsey’s organizational research defines the “trust equation” as trust = (reliability × credibility × openess) / (self-orientation).

3

For the full report, see “Reinventing construction through a productivity revolution,” McKinsey Global Institute, February 2017.

6 Collaborative contracting: Moving from pilot to scale-up

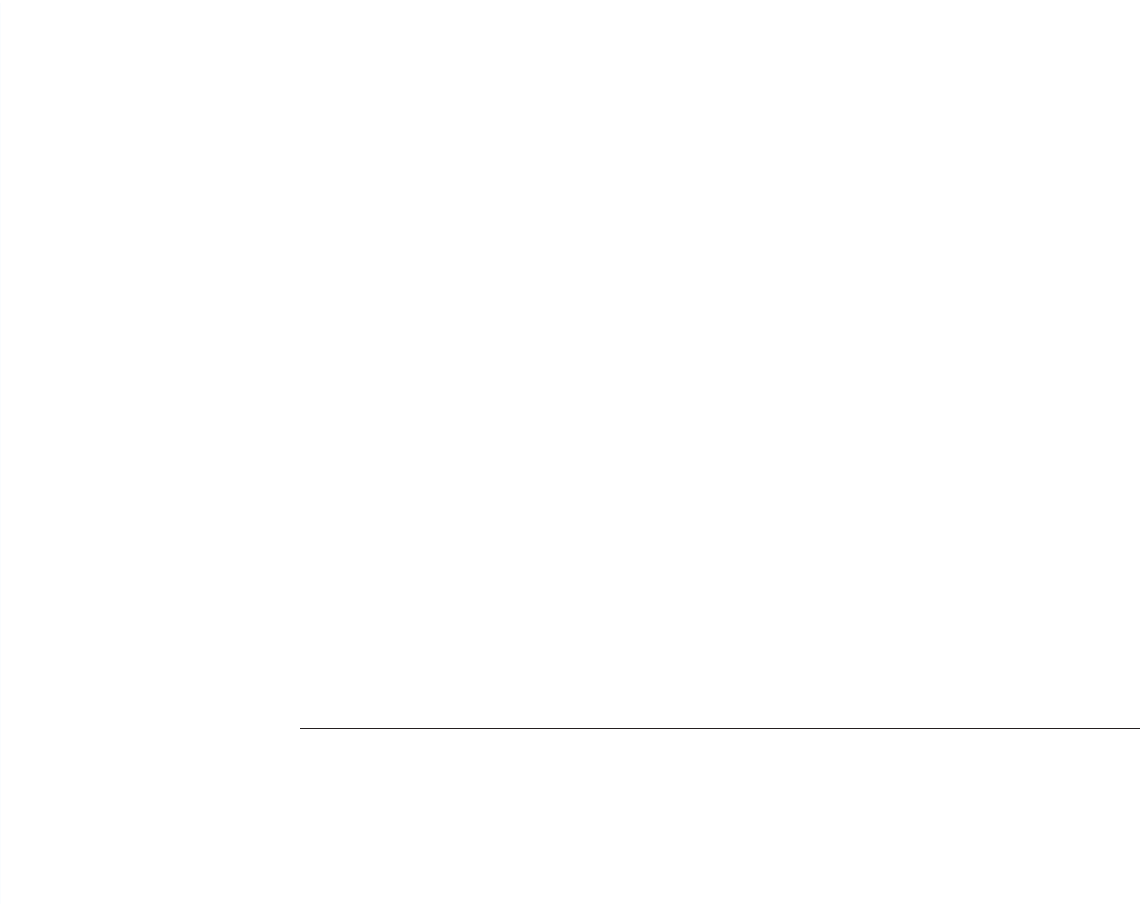

to contemplate (Exhibit 3). A 2017 McKinsey Global

Institute (MGI) report on construction productivity

identified collaborative contracting as one of the

largest opportunities to improve the productivity

of the industry.³ Based on our research, we also

believe that collaborative contracts and practices

serve to enable three of the other levers to improve

productivity: technology adoption, design and

engineering, and on-site execution.

Adoption of digital project tools

Implementing digital tools on projects requires

significant investments in capital, work processes,

and time. E&C contractors and suppliers rarely

make those investments on their own without

knowing that there will be some sort of payoff. That

impediment in the industry would be removed

if project owners proactively invested in digital

infrastructure with a consistent capital program

and a network of committed E&C contractors and

suppliers codeveloping the solution.

Design and engineering

Using a digital design platform is not new to the

industry, but making it transparent and shared

across all parties is a marker of a collaboration. It

creates one source of truth and enables faster

creation of a “digital twin” prior to construction.

When integrated into a database rather than

segregated into distinct disciplinary silos, digital

design deliverables enable more-efficient

cross-party clash detection, along with joint

owner-contractor-supplier design processes and

construction and operability reviews. The results?

Improved engineering quality and accelerated

design releases for construction.

McK CP&I 2020

Collaborative contracting

Exhibit 3 of 3

Collaborative contracts improve project relationships directly and enable productivity

improvements in design, execution, and technology.

Lever

Regulation Enabler

External forces

Industry dynamics

Firm-level

operational factors

Collaboration and contracting

Design and engineering

Procurement and supply-chain

management

On-site execution

Technology

Capability building

Cumulative impact

Gap to total economy

productivity

Global levers to improve construction productivity

Potential global productivity improvement from implementation

of best practices,¹ impact on productivity, %²

Cost savings,

%

7–10

6–7

3–5

4–5

4–6

3–5

27–38

8–9

8–10

7–8

6–10

14–15

50

5–7

48–60

Enabled by collaborative contractsDirectly improved by collaborative contracts

1

y across projects, based on survey

respondents who responded “agree” or “strongly agree” to the questions about implementation of the solutions.

²

Source: McKinsey Global Institute Construction Productivity Survey, n = 210

Exhibit 3

Collaborative contracts improve project relationships directly and enable productivity

improvements in design, execution, and technology.

7Collaborative contracting: Moving from pilot to scale-up

On-site execution

A single source of truth for design, supplier,

and project-management data addresses the

communication gap typically seen between

home-office and on-site teams. This facilitates the

on-time structuring of data into construction work

packages, which improves construction readiness

and enables implementation of advanced

production or construction planning tools.

Furthermore, when teams work in the same place

and from the same project-controls systems

and dataset, it accelerates the on-time release

of forward-looking, actionable data needed

to proactively manage a project. That’s a stark

contrast from traditional structures, in which

project controls gather data from multiple parties,

and typical project-reporting cycles result in data

that’s at least three weeks old—too late for project

leadership to make effective adjustments when

needed.

The value at stake for project owners is enormous.

If just half of the 15 to 20 percent improvement

realized on initial collaborative contracts can be

sustainably achieved, project owners could save

$5 trillion to $7 trillion of the $77 trillion that MGI

believes will be spent on capital projects over the

next ten years. With industry participants becoming

increasingly frustrated with the status quo, now

is the time to make collaborative contracts the

norm and thereby reinvent the owner-contractor

relationship—and the construction industry along

with it.

Copyright © 2020 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

Jim Banaszak is a partner in McKinsey’s Chicago office, Jeff Billows is an expert in the Dallas office, Rudi Blankestijn is a vice

president of CP&I major projects in the Houston office, Matthieu Dussud is an associate partner in the Toronto office, and

Rebecka Pritchard is a specialist in the Atlanta office.

The authors wish to thank Phillip Bernstein, Mark Kuvshinikov, Thibaut Larrat, Peter Trueman, and Homayoun Zarrinkoub for

their contributions to this article.

8 Collaborative contracting: Moving from pilot to scale-up