1

Title: There is limited evidence supporting the use of the SOS approach to feeding with mixed

results on the effectiveness to improve eating.

Prepared by: Holly Freeman, OTS [email protected]

Alisa Reedy, OTS reedy.alis@uwlax.edu

Ashley Schalow, OTS [email protected]

Date: December 10th, 2015

CLINICAL SCENARIO:

Condition/Problem:

A feeding disorder is characterized by the failure of an infant or child less than six years

of age to eat enough food to gain weight and grow normally over a period of one month or more.

Feeding disorders are more prevalent in infants or children who are born prematurely, had a low

birth weight, or who are developmentally delayed. Some causes for feeding difficulties include:

diseases of the central nervous system, metabolic diseases, sensory defects, anatomical

abnormalities, muscular disorders, heart disease, and gastrointestinal diseases (Encyclopedia of

Mental Health, 2015). Some residual problems that are seen with this condition are dehydration,

poor nutrition, aspiration, pneumonia, repeated upper respiratory infections, and embarrassment

or isolation in social situations involving eating. Due to poor nutrition that may lead to failure to

meet normal weight and growth recommendations, children may be required to have

gastrointestinal tube (g-tube) feedings in order to supplement nutrition (ASHA, 2015). Although

a specific link has not yet been identified, children with Autism seem to be at increased risk for

developing feeding disorders/problems and it is estimated to be as high as 85% (Peterson, 2013).

Incidence/Prevalence:

● “It has been reported that 25%-45% of typically developing children demonstrate feeding

and swallowing problems.”

● “Prevalence is estimated to be 30%-80% for children with developmental disorders.”

● “Significant feeding problems resulting in severe consequences (e.g., growth failure,

susceptibility to chronic illness) have been reported to occur in 3%-10% of children, with

a higher prevalence found in children with physical disabilities” (26%-90%) and medical

illness and prematurity (10%-49%).”

● “It is reported that the prevalence of pediatric dysphasia is increasing due to improved

survival rates of children born prematurely, with low birth weight, and with complex

medical conditions.” (ASHA, 2015)

Impact of the Problem on Occupational Performance:

Areas of occupational performance that may be affected are swallowing/eating because

the child is unable to keep food in the mouth long enough for process of swallowing to take

place. Another area of occupation that is impacted is feeding, meaning that the child is not

interested in eating the food presented to them, and therefore, they will not attempt to bring the

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

2

item to their mouth. The child may lose their energy and drive to participate in mealtimes due to

emotional mental functions that become associated with eating including tension and anxiety.

The social interactions with family at mealtimes may be problematic due to the child’s

unwillingness to partake in normal feeding/eating habits and the struggle for parents to get child

to eat. There may also be an element of embarrassment for the parents when eating in social

situations because eating problems with the child occur. (American Occupational Therapy

Association, 2014).

Intervention:

The Sequential Oral Sensory (SOS) Approach to feeding is a protocol involving sensory

integrative components developed by Dr. Kay Toomey, a pediatric psychologist (Toomey &

Associates, 2015). The protocol for SOS intervention is available only to therapists who have

completed a 5-day training conference. This approach to feeding is considered a transdisciplinary

approach to feeding difficulties because it involves assessing the whole child on the basis of

physical barriers to eating and proper medical treatment, nutritional issues, developmental,

sensory, motor, oral-motor, and cognitive skills that are all involved and needed in the process of

feeding. The SOS protocol is used as an intervention for feeding difficulties over a twelve week

period that uses progression and gradual introduction of foods based on a desensitization

hierarchy that includes aversive and non-aversive foods (Benson et al., 2013). Each therapy

session can last an hour or a few hours.

This SOS approach to feeding is similar to a common behavioral intervention of

systematic desensitization in which the fear of aversive stimuli is replaced with feelings of

relaxation (McLeod, 2008). In systematic desensitization, the aversive or anxiety-provoking

stimuli are presented to the client through a gradual process which begins with less aversive to

more aversive (McLeod, 2008). Children with feeding disorders might find certain textures,

colors, sizes, and temperatures of food as aversive and anxiety-provoking. Even being near the

food could cause a child to cry, engage in inappropriate mealtime behaviors, gag, choke or

vomit. Therefore, the objective of the SOS protocol is increase the child’s willingness and

acceptance to try a variety of foods through a more calm and inviting environment. The child is

led through multiple steps of the protocol starting with selective sensory input that is child-

directed, stomping to the therapy room, participating in pre-meal setup, interacting with the food

in a gradual sequence, and finishing with a clean up routine. This protocol includes gradually

guiding the child through a hierarchy of aversive stimuli, continuous interaction with various

foods, and incorporation of sensory integrative components to help the child become more

comfortable and prepared for trying different foods (Peterson, 2013). See Appendix A for more

details about SOS protocol intervention.

OT Theoretical Basis:

The SOS approach to feeding incorporates several theories and assumptions that can be

closely related to occupational therapy frames of references and theories. These theories include

behavioral approaches and sensory integration (SI).

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

3

The behavioral theories assume that behavior is learned, and therefore, behavior can be

altered or reshaped when it is reinforced. If reinforced, a desired behavior will be more likely to

be performed again (Cole et al, 2008). In the SOS approach, the therapist primarily demonstrates

role-modeling, positive reinforcement, and encouragement of learning through behavioral

approaches (Peterson, 2013). The therapist prompts the child to engage in interaction with the

food by using verbal praise when the child performs a positive behavior with the food. An

example of verbal positive reinforcement that the therapist can say is, “Good job taking a bite.”

Additionally, the therapist also demonstrates modeling of behavior during the SOS

protocol. Each step including sensory preparation, transition to the feeding therapy room, pre-

meal set-up, exposure to food, and clean-up routine includes specific behaviors that the therapist

would need to perform and try to encourage the child to model. For example, during the

transition to the feeding therapy room, the therapist marches and sings, and the child is

encouraged to model the behavior. Lastly, the therapist encourages the child at each food

hierarchy step when the child performs a positive interaction or tolerance for the food. The child

is praised for smelling, touching, or eating the aversive food item and can continue up the

hierarchy if the step is completed (Peterson, 2013).

Sensory integration (SI) is a primary focus of the SOS feeding approach. According to SI,

sensory-motor experiences help a child learn, and if those abilities are impaired, the child cannot

optimally function. Therefore, a child must control the input of sensory stimuli to help the child

modulate and balance the amount of input they are receiving (Case-Smith, 2005). Sensory

integration in the context of the SOS approach to feeding requires that the child practice

appropriate and adaptive responses to food through controlled sensory input before feeding

sessions. It is proposed that the child be an active participant during the therapy process in order

to process the sensory stimuli of the different types of food (Peterson, 2013).

In order to help the child prepare for sensory stimuli and to decrease a child’s sensitivity,

the SOS protocol has the child engage in preparatory activities. These include gross motor

exercises, firm rubbing, vibration, and deep pressure. In the SOS approach, SI is used by

performing gross motor activities on the jungle gym, such as pushing, jumping, running,

swinging or bouncing, singing and marching to help promote vibration in the mouth,

continuation of gross motor exercises, and desensitization of the mouth such as wiping a warm

washcloth around the mouth, blowing bubbles, and hand washing. It is suggested that engaging

in these activities will allow the child to regulate their sensory input and help desensitize the oral

area to increase acceptance and tolerance of a variety of foods (Peterson, 2013).

Science behind the intervention:

The SOS protocol is intended to help address the problem behaviors associated with

eating (Toomey & Associates, 2015). These problem behaviors may emerge as the result of

medical/oral conditions, sensory integration sensitivities, or negative behaviors that are

reinforced during mealtimes (Peterson, 2013). The SOS protocol addresses the child as a whole,

incorporating the child’s organ functioning, muscles, sensory development, behavior, oral-motor

sensations, cognitive level, overall nutrition, and environmental factors (Toomey & Associates,

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

4

2015). The therapist prepares the child for feedings through participation in a play activity,

which is intended to calm a hypersensitive child or alert and improve tone in a hyposensitive

child through heavy work, deep pressure, or oral stimulation by reducing his/her anxious feelings

about food and decrease sensitivity (Peterson, 2013). In addition, the therapist facilitates oral

stimulation through providing pressure to the chest and symmetrical pressure to the face and

mouth, which provides proprioceptive input through oral stimulation (Case-Smith, 1989).

A desensitization approach helps to improve the child’s level of comfort through learning

and exploration of food, where the child begins the intervention through interaction with the

food, in a stress-free environment (Toomey & Associates, 2015). The child progresses through

the intervention from being in the same room as the food to touching/kissing food and finally

tasting/eating food (Toomey & Associates, 2015). The child is presented with foods of various

sizes, color, texture, taste, and temperature throughout the SOS intervention to help reduce the

child’s sensitivity and fear associated with feeding times (Peterson, 2013). It is important that

the child plays a critical role in the feeding intervention, allowing therapy to revolve around a

child’s needs and improving the therapeutic relationship (Peterson, 2013). The aim for the child

at the end of the SOS feeding program is to decrease the level of sensitivity towards foods and

increase the amount of acceptance of new foods (Peterson, 2013).

Why is the intervention appropriate for OT:

The SOS protocol is appropriate for occupational therapy because it falls under the

occupations of swallowing/eating and feeding in the framework (The American Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 2014). Through preparatory methods, such as play and oral stimulation,

occupational therapists are able to prepare a child for the feeding interventions by providing the

child with the necessary stimulation and input that he/she may need (The American Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 2014). The SOS intervention is an occupation-based intervention

because it focuses on increasing a child’s independence during mealtimes by reducing

inappropriate behaviors through desensitization.

The areas under the international classification of function and disability that the SOS

protocol applies to include the health condition, body function and structures, activity,

participation, environmental factors, and personal factors (WHO, 2015). The SOS intervention

applies to the health condition because it addresses a child’s feeding difficulties during

mealtimes. Furthermore, the SOS intervention applies to body function and structures because it

incorporates the child’s oral and swallowing behaviors that may be impeding his/her ability to

swallow food properly. In addition, the SOS protocol is applicable to the area of activity because

it is a feeding intervention that focuses on the child’s occupation of swallowing/eating and

feeding. Throughout the feeding intervention, the SOS protocol requires the child’s participation

during therapy sessions to help decrease sensitivity and increase appropriate mealtime behaviors.

Lastly, the SOS protocol addresses a child’s environmental and personal factors because it

identifies limitations within or surrounding a child that may be affecting a child’s ability to

participate fully throughout mealtime.

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

5

Focused Clinical Question:

● Patient/Client Group: Children 8 months to 8 years with feeding difficulties

● Intervention: SOS approach to feeding

● Comparison Intervention: Applied Behavioral Approach (ABA)

● Outcomes: To increase the number and variety of foods that a child eats

Summary:

● Summarize clinical question: This CAT investigates the effectiveness of the

SOS protocol for improving feeding behaviors in children with feeding

difficulties.

● Search: We searched six databases and located nine articles related to feeding

disorders in children. Of those, we selected and review three articles that were

all case-studies. One article had a strength of 3B and a high rigor. The other two

articles had a strength of 4. However, one article was medium rigor and the other

was high rigor. We selected the three articles reviewed because each of the

studies included the SOS protocol in the intervention and involved children that

were under the age of eight with a feeding difficulty.

● Summary of findings: There is limited and inconclusive information for or

against the SOS protocol.

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE: There is limited evidence supporting the use of the

SOS approach to feeding with mixed results on the effectiveness to improve eating.

Limitation of this CAT: This critically appraised paper (or topic) has been reviewed by

occupational therapy graduate students and the course instructor.

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

6

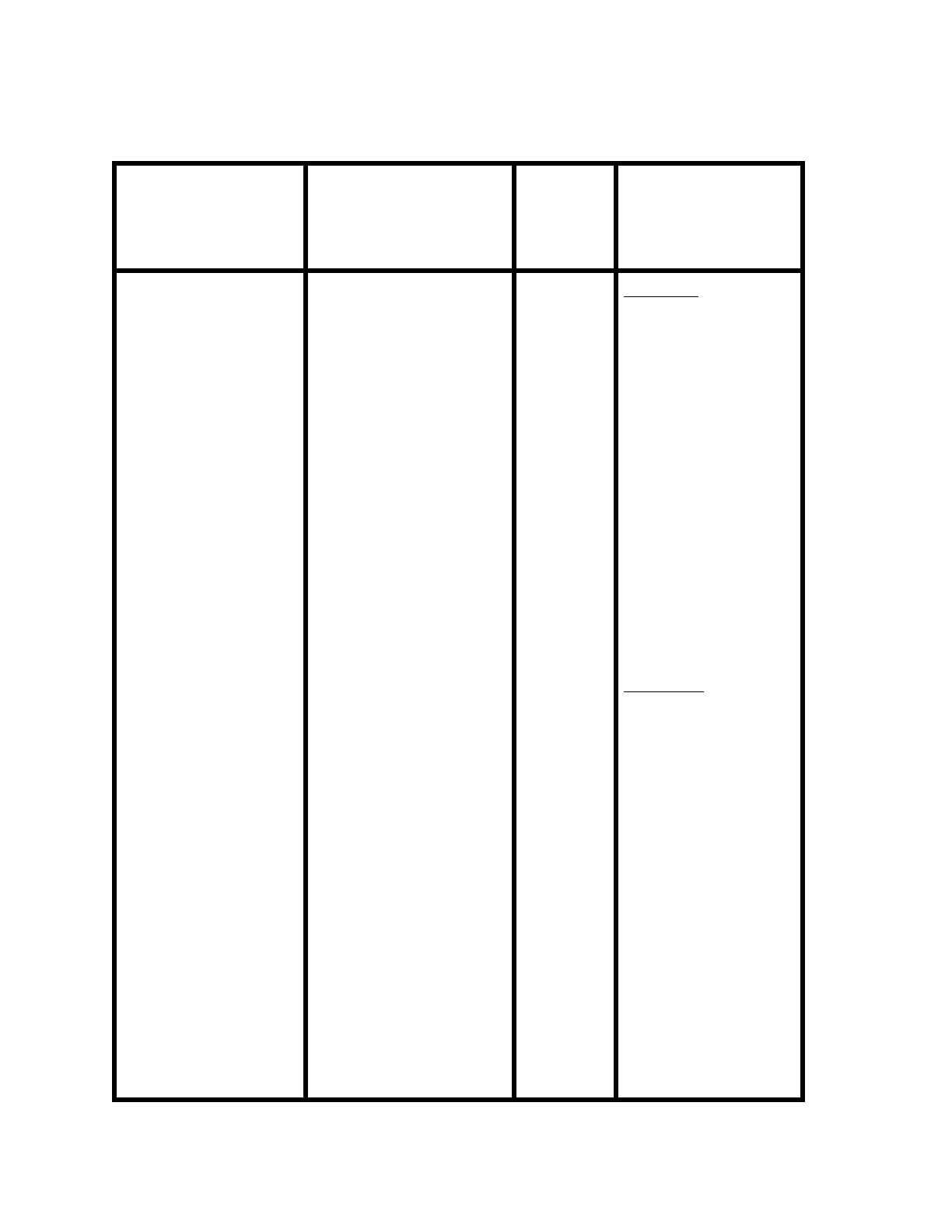

SEARCH STRATEGY:

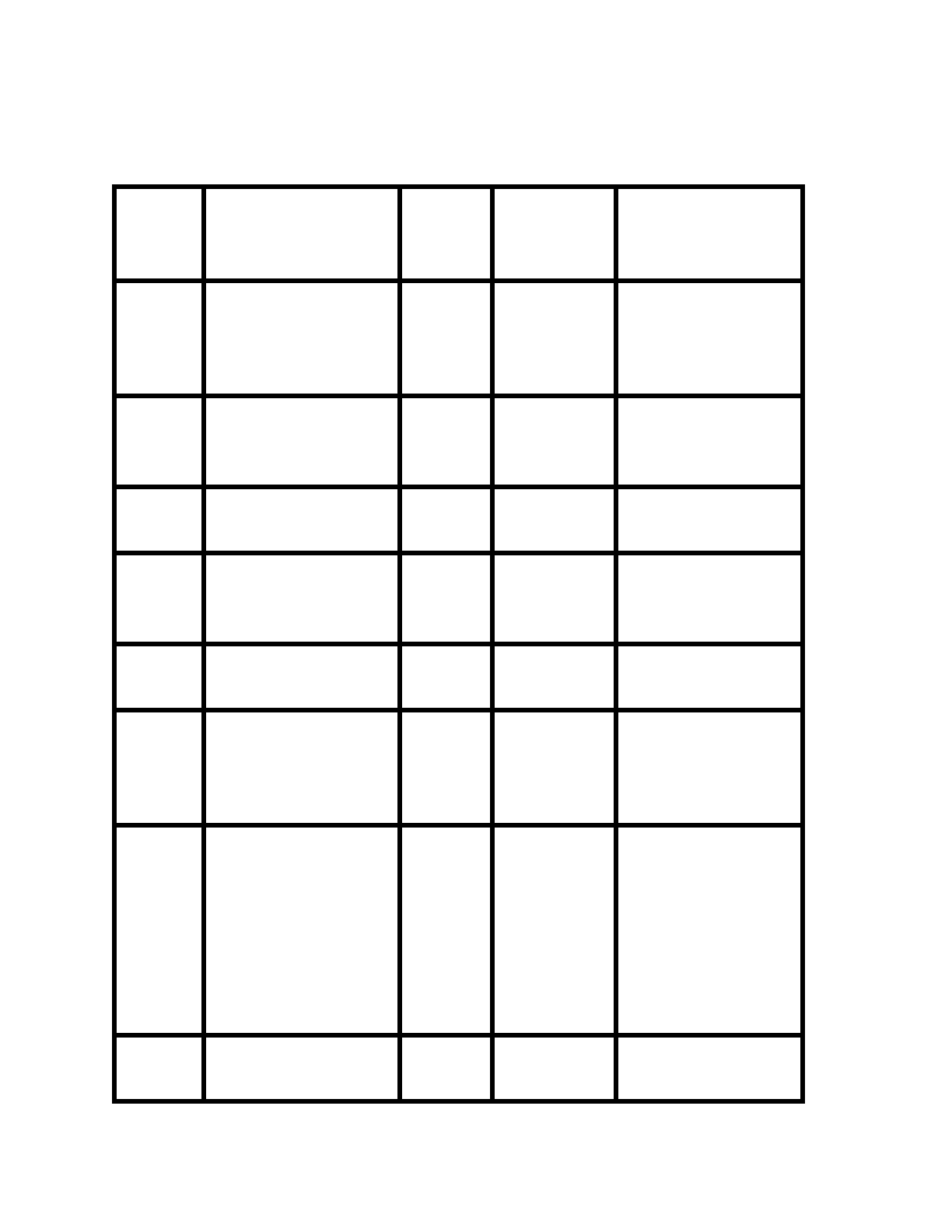

Table 1: Search Strategy

Databases Searched Search Terms Limits

used

Inclusion and

Exclusion Criteria

● Cochrane

● Health

Professions

Data Base via

EBSCO Host

● OT Search

● OT Seeker

● AOTA

● OVID Data

Base

● feeding

● desensitization

● sequential oral

sensory approach

● oral aversion

● feeding therapy

● feeding

difficulties

● problematic

feeding

● premature birth

● sensation

disorders

● pediatric

● eating

● eating behavior

● oral sensory

● intervention

● children

● oral sensory

therapy

● sensory

● Kay Toomey

● Peterson

“+”

“and”

“author”

Inclusion:

● English

● Within the last

10 years

● Includes SOS

protocol or SI

or ABA

interventions

related to

feeding

difficulties

● Population

consisting of

children with

feeding

difficulties

Exclusion:

● Other language

that was not

English

● Article older

than 2005

● Not related to

SOS or ABA

treatment for

feeding

difficulties

● Population that

did not include

children with

feeding

difficulties

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

7

RESULTS OF SEARCH:

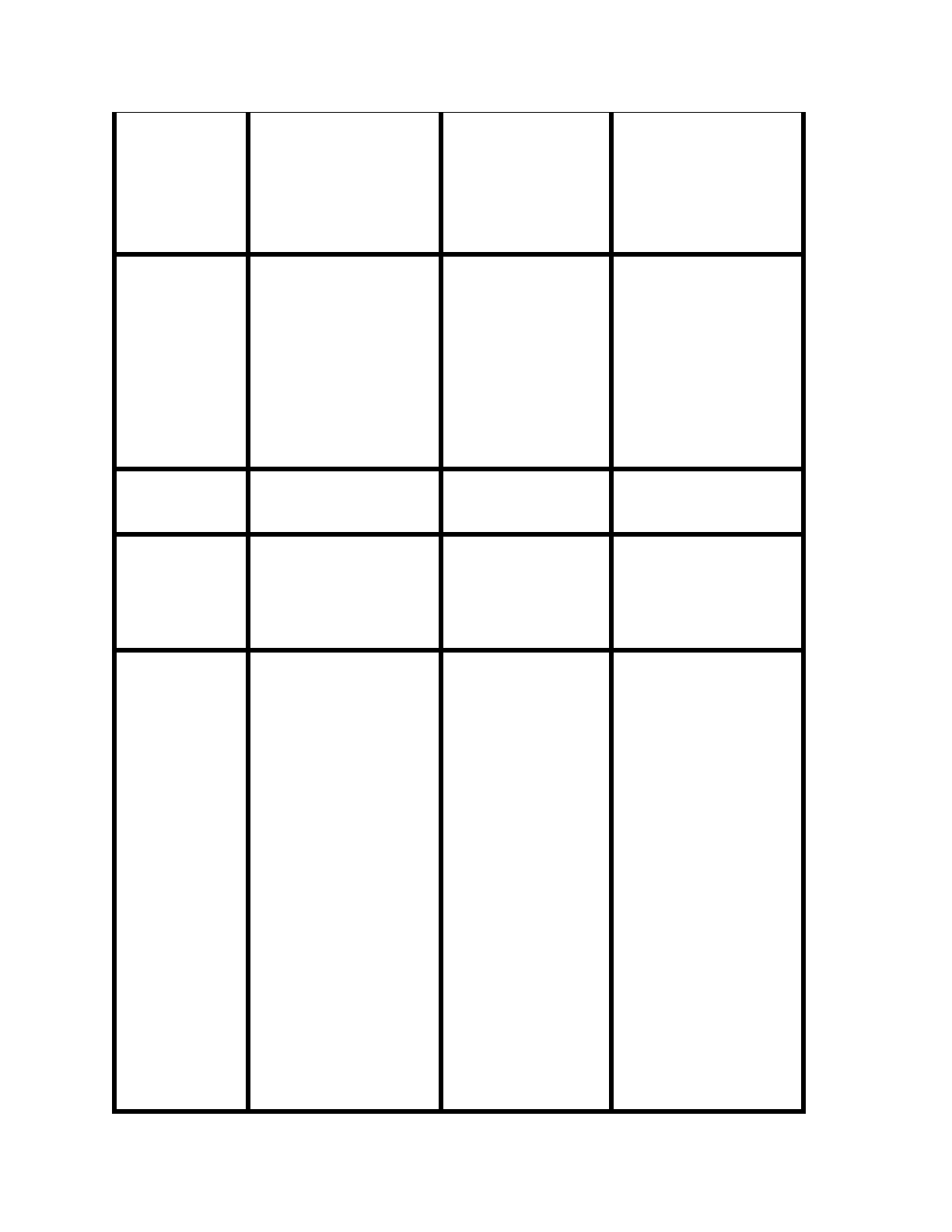

Table 2: Summary of Study Designs of Articles Retrieved

Level

Study Design/

Methodology of

Articles Retrieved

Total

Number

Located

Data Base

Source

Citation (Name, Year)

Level 1a

Systematic Reviews or

Meta-analysis of

Randomized Control

Trials

Level 1b

Individualized

Randomized Control

Trials

Level 2a

Systematic reviews of

cohort studies

Level 2b

Individualized cohort

studies and low quality

RCT’s (PEDro < 6)

Level 3a

Systematic review of

case-control studies

Level

3b

Case-control studies

and non-randomized

controlled trials

I

ProQuest

Dissertations

& Theses

(PQDT)

(Boyd, 2007)

Level 4

Case-series and poor

quality cohort and case-

control studies

III

PUBMED

EBSCOhost

ProQuest

Dissertations

& Theses

(PQDT)

(Addison, 2012)

(Benson, 2013)

(Peterson, 2013)

Level 5

Expert Opinion,

qualitative research,

V

EBSCOhost

(Dobbelsteyn, 2005)

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

8

program descriptions

EBSCOhost

EBSCOhost

EBSCOhost

EBSCOhost

Geggie, 1999)

(Gisel, 1994)

(Ghanizadeh, 2013)

(Toomey, 2011)

STUDIES INCLUDED:

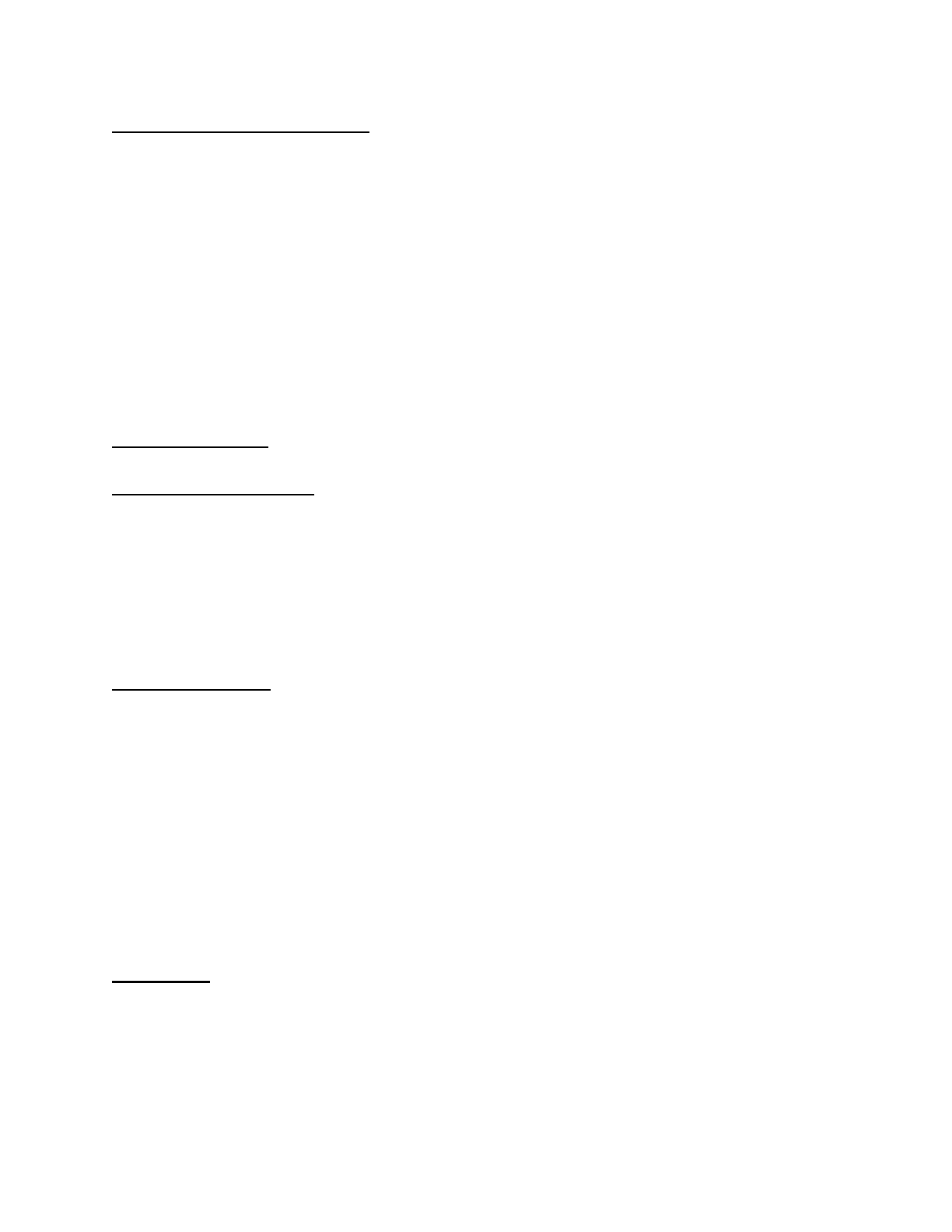

Table 3: Summary of Included Studies

Study 1

Benson, 2013

Study 2

Peterson, K., 2013

Study 3

Boyd, K.L., 2007

Design

Case-series

retrospective repeated-

measures within

subject design

Random control

trial

Quasi-experimental

design

Level of

Evidence

Strength: 4

Strength: 4

Strength: 3B

Rigor Score

SCED: 5/11

SCED: 8/11

SNS:6/8

Population

-34 children (56% M,

44% F) ages 30-92

months

-Mean age= 57.2

months

-Autism (38%), CP

(12%), neurological

impairments (38%),

and no specific

diagnosis (12%)

-6 male, school-

aged children ages

4-6

-Mean age = not

provided

-Issues consuming a

variety of foods and

a diagnosis of ASD

-37 children ages 8-61

months (21 M, 16 F)

-Mean age= 37.23

months

-7 children had GI

feeding tubes

-Other diagnoses

included

gastroesophageal

reflux, oral motor

delays, low tone,

sensory difficulties,

anxiety or trauma

related to food, heart

issues, autism, and

developmental delays.

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

9

-All children were

given therapy in a

group setting at

Toomey and

Associates Inc.

Intervention

Investigated

Effectiveness of the

SOS protocol

intervention leading to

positive trend in

feeding scores in

children with feeding

difficulties.

To determine

whether the SOS

protocol or ABA

behavioral approach

is more effective for

the treatment of

sensory-based

feeding disorders

To examine the

effectiveness of the

SOS protocol with

feeding disorders, as

developed by Dr. Kay

Toomey

Comparison

Intervention

N/A

ABA behavioral

intervention

N/A

Dependent

Variables

-Level of interaction

with the food (25-step

scale)

-Food type

-Food acceptance

-Clean mouth

-Food (gram) intake

-Number of foods

consumed

Outcome

Measures

-25 step scale

developed by Toomey

(feeding score from 1-

25)

-Food (characterized

by hard munchable,

meltable, solid, puree,

or drink)

-Acceptance was

defined as the child

picking up an eating

utensil or using his

fingers to pick up

the bite of food and

placing the entire

bite of food into

mouth within 8

seconds after food

presentation.

-Mouth clean was

defined as the child

having a bite of

food no larger than

a grain of rice in his

mouth 30 seconds

after placing the

-3 day diet histories

done by parents (prior

to and after treatment)

-Initiation of tasting

new food 80-90% of

time

-30 different foods in

food preferences (10

protein, 10 starches, 10

fruits/vegetables)

-Height/weight must

consistently increase

over a 6-12 week

period and following

growth curves

appropriate for age and

condition

-Able to handle age

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

10

food into his mouth.

If the child spit the

food out, this was

not included.

-To measure amount

of food intake, the

therapist measured

the weight of the

food on a scale

before and after the

therapy sessions.

appropriate foods

without negative

behaviors during

mealtimes

-Able to consume

appropriate amount of

fluid for age group

Results

-5 patterns in feeding

scores were found.

- Patterns 1 & 2

showed no positive

trends in feeding scores

(16 children).

-Pattern 3 had 1 or

more food types with a

positive trend in the

last few sessions of the

intervention (7

children).

-Pattern 4 was positive

trend for 1 or more

food

types (5 children).

-Pattern 5 was positive

trend for all food types

(6 children).

-High levels of food

acceptance, clean

mouth, and food

intake were

observed after half

of the participants

received ABA

treatment.

-However, the other

half of the

participants who

received the SOS

treatment did not

achieve any change

throughout

participation in the

program.

-After participants

switched over to the

ABA treatment, it

was observed that

high levels of

acceptance began to

occur across all

areas.

-Children who received

one 12-week SOS

intervention had an

increase in the number

of foods consumed,

which was assessed

with the 3-day diet

history.

-Children who attended

two 12-week

interventions improved

the number of foods

consumed

significantly.

-Children who went on

to attend three or four

12-week sessions did

not have a significant

increase in the number

of foods consumed.

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

11

Effect Size

N/A

N/A

-Group 1: 46% (17/37)

of participants

improved after first 12-

week session.

-Group 2: Additional

22% (8/37) improved

after second 12-week

session.

-After third 12-week

session of SOS

protocol, no significant

improvement was

observed.

Conclusion

The results of this

study were

inconclusive as to

whether the SOS

protocol was an

effective intervention

for improving eating in

children with

neurological disorders.

It was concluded

that the ABA

treatment was

effective at

increasing food

acceptance and

consumption in all 6

of the children,

whereas the SOS

intervention was

not.

It was concluded that

children who attended

one or two 12-week

SOS feeding sessions

significantly improved

the number of foods

consumed. However,

it was found that

children that attended

three or more 12-week

feeding sessions did

not continue to see

significant

improvements in

number of foods

consumed.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE, EDUCATION and FUTURE RESEARCH:

PICO Question:

What is the effectiveness of the Sequential Oral Sensory (SOS) approach in occupational therapy

for improving eating in children ages 8 months-8 years with feeding difficulties compared to

ABA or no treatment?

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

12

Operational Definition of Terms:

SOS: Sequential Oral Sensory approach is a desensitization therapy intervention developed by

Dr. Kay Toomey to address issues with feeding difficulties in children.

ABA: Applied Behavioral Analytic approaches are based on applied behavioral theories which

assume that behavior is learned, and therefore, behavior can be altered or reshaped when it is

reinforced.

Feeding difficulties: Behaviors or medical conditions that lead to a child’s decreased ability to

eat the adequate amount of food to gain weight and grow normally.

Improved eating: Improved eating includes level of interaction with and acceptance of food,

amount of food taken in (gram intake), mouth clean (no packing of food), number of foods

consumed (number and types of food the child eats), and decrease negative behaviors (outbursts,

gagging, crying, and spitting out food).

Overall conclusions:

Results: Similar Findings

● All three studies were single case studies, measuring various aspects of feeding and

eating during the intervention period.

● Each study included children with feeding issues, however, autism was the most common

diagnosis between all studies.

● All studies were similar amongst the intervention (SOS protocol), which measured some

aspect how of children are eating throughout the intervention.

Results: Differences

● The SOS protocol resulted in 46% of participants improving after 12 weeks in the Boyd

study. After 24 weeks, an additional 22% improved from the SOS protocol, but after the

third session (36 weeks) no further improvement was found.

● No other studies saw improvement with SOS even with a variety of measures including

mouth clean, level of acceptance, gram intake, and number of foods consumed.

● In the study conducted by Peterson, it was found that the ABA treatment had more

positive results on feeding difficulties for all of the children involved in the study.

Overall, the findings of these studies reveal inconclusive and limited results as to whether the

SOS protocol is effective for improving eating with children who have eating difficulties.

Boundaries:

There was a total of 77 participants ages 8 months to 8 years in all 3 articles together with

a mean of 4.3 years. Diagnoses differed between studies and included autism, cerebral palsy,

neurological impairments, GI feeding tubes, gastroesophageal reflux, oral motor delays, low

tone, sensory difficulties, anxiety or trauma related to food, heart issues, developmental delays,

and no specific diagnoses. All children displayed some form of feeding difficulty during

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

13

mealtimes. Exclusion criteria varied across studies, when you combine studies, the exclusion

criteria included severe medical issues, failure to thrive, insufficient caloric intake, and any child

who did not fit the diet history criteria.

Implications for practice:

All three articles showed limited evidence of the use of SOS in practice. The SOS

protocol developer, Kay Toomey, has shown minimal support for this intervention. In the study

done by Boyd, the only article that supported the use of SOS, participants were gathered from

Toomey and Associates, Inc. This company was developed by Kay Toomey. Therefore, the

Boyd study may have been influenced by experimenter effects which could be the reason that it

was the only study to show positive results of the SOS protocol. Toomey suggests that there be a

minimum of 12 weeks of SOS therapy before successful results were shown to be effective, and

in the study done by Boyd, the results showed similar findings. Based on the literature reviewed,

ABA has been shown to be more effective for feeding difficulties in children, and one study that

was found provided ABA treatment to every child in the study after effectiveness was

demonstrated. Overall, there is limited research and evidence to determine effectiveness or

ineffectiveness of the SOS protocol. In summary, without a randomized control trial, the

evidence is inconclusive as to whether this treatment approach is a practical use of clinician’s

money and time.

Clinical Bottom Line:

There is limited evidence supporting the use of the SOS approach to feeding with mixed

results on the effectiveness to improve eating.

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

14

APPENDIX A.

The SOS protocol involves a series of steps to help the child become more comfortable

and prepared for trying different foods. Because one of the assumptions to development of eating

difficulties is based on hypersensitivity, the first step in the SOS protocol is to prepare the child

with sensory integrative approaches. According to the protocol, this initial preparation is to

promote organization of the senses and to increase body awareness. The sensory preparation

routine involves playing on jungle gym equipment or an obstacle course to engage the child in

gross motor activities such as running, lifting, pushing, and jumping. The therapist models these

behaviors for the child and praises the child when he or she engages in the modeled behaviors.

However, the therapist allows the child to perform other activities on the jungle gym to enable

the child to create his or her own sensory preparation routine and promote child-directed therapy

(Peterson, 2013).

After about 10 minutes, the sensory preparation period is complete, and the therapist

guides the child into the therapy room or area of intervention. The child is prompted to sing and

march while on the way to the room where eating will take place. The therapist uses modeling to

do so, but if the child does not choose to sing or march, the child may choose to do as they wish.

As the child enters the feeding therapy room, the therapist guides or helps the child sit in his or

her seat in order to engage the child in the pre-meal setup step (Peterson, 2013).

During this stage and throughout the rest of the SOS approach, the therapist sequentially

encourages the child by giving the child positive, non-directive statements, using behavior

modeling, using light physical prompts, and using full physical guidance. An example of a non-

directive statement that the therapist could say is, “Cleaning up is fun!” If the child did not do

what was asked in 10 seconds, the therapist would give the next sequential prompt. Meal time

setup included washing face, washing hands, blowing bubbles with the remainder of the soap,

washing the table, and setting the table. The therapist again modeled the behavior even if the

child did not do meal time setup (Peterson, 2013).

Once the pre-meal setup step is complete, the therapist then introduces the food, in a

hierarchical and gradual manner. Therefore, if twelve foods are to be presented to the child in

each session, the first exposure would include one aversive food, and eleven non-aversive foods.

The preferences of aversive and non-aversive foods of the child would be determined by

interview with the caregiver. The non-aversive foods always included pureed, meltable hard

solids and hard munchable solids. The first food that was presented to the child was a non-

aversive food that was available for the child to interact with for four minutes and then placed on

the food plate within arm’s reach. Each food item after the first presented food contained one

similar property, such as color, taste, texture or size. The therapist encouraged the child to

interact with each food item based on the steps-to-eating hierarchy. For example, food in front of

the child would be lower on the hierarchy than the child touching the food to his or her lips. The

major steps involved in the hierarchy incorporate visual tolerance, indirect interaction, smelling,

touching, tasting, and consuming the food (Peterson, 2013).

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

15

Visual tolerance gradually introduces the child to the food at varying distances in relation

to the child. Indirect interaction encompasses promoting the child to help prepare the food, use

utensils to serve or touch the food, and to touch the food through other objects, such as a napkin.

Smelling consisted of presenting a food with a prominent stench and having the child be near the

food and picking up the food and smelling it. Touching involves the child touching the food

using any body parts including fingers, arms, chest, neck, or tongue. Tasting the food includes

licking with tip of tongue, full tongue, biting a piece and spitting it out, biting a piece and

keeping it in the mouth, and biting the food, chewing it and expelling the food. Eating the food

consisted of chewing the food and swallowing part and spitting out the rest, chewing,

swallowing, and drinking immediately after, and chewing, swallowing without taking a drink.

Throughout the feeding hierarchy session, the therapist used descriptive, positive, and

neutral comments about the child engaging with the food, such as “Johnny can lick the carrot.”

Additionally, the therapist used playfulness to evoke relaxation such as singing, playing with the

food, squishing the food and painting with the food. The therapist would continue with light

physical prompts or full physical guidance if after 30 seconds the child did not engage with the

food. The child was never forced with comply with the behaviors if the child resisted. The

therapist would attempt to place the food as close as the child would allow. If the child required

full physical guidance, the step was failed, and the subsequent step before that one would be

given (Peterson, 2013).

The intention of the SOS protocol is to allow the child to progress through the hierarchy

of steps in order for the child to bite, chew, and swallow the aversive food. To increase

consumption and tolerance of an aversive food, the therapist would present it through different

manners, such as changing the texture of the food. In addition, the aversive food would be

discontinued and a different aversive food would be presented if the child did not interact or

consume the food within six therapy sessions. The first three sessions included presentation of

the same food items in the same order and the same manner, so that the child can be accustomed

to a routine. However in the fourth session, the therapist changed the properties of the food by

altering the shaped, temperature or texture (Peterson, 2013).

Following the feeding intervention, the therapist facilitated a clean-up routine by saying

“All done, time to clean up.” The therapist then asked the child to “blow or throw away” at the

least one food that was used in the eating session by placing it on the lips and spitting the food

into the trashcan. If the child did not comply, the therapist would encourage the child to touch

the food, with or without a napkin, and throw it in the trash. The child was then asked to help

wash the table, throw away the trash, and wash his or her face and hands (Peterson, 2013).

Once the intervention has been administered, the therapist then provides caregiver

training to continue and facilitate the progress of the child with tolerating and accepting different

types of food. Written material on the instructions of the protocol, modeling behaviors, role-

playing, and feedback should be given to the caregivers to help the child maintain a consistency

when interacting with food at home (Peterson, 2013). Children with a sensory processing deficit

have troubles modulating their sensory input and may not be able to identify all the sensory

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

16

properties of an object. They may over-react or under-react to these sensory inputs, and this may

lead to sensitivities to food because the child cannot decipher the sensory information that they

are receiving (Peterson, 2013).

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

17

References

Benson, J. D., Parke, C. S., Gannon, C., & Muñoz, D. (2013). A retrospective analysis of the

sequential oral sensory feeding approach in children with feeding difficulties. Journal of

Occupational Therapy, Schools & Early Intervention, 6(4), 289-300 12p.

doi:10.1080/19411243.2013.860758

Boyd, K. (2007). The effectiveness of the sequential oral sensory approach group feeding

program (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT)

database. Dissertation Abstract International, B 69/01, P. 665 Retrieved October 29th,

2015 from http://search.proquest.com/docview/304762667

Peterson, K.M. (2013) A comparison of the sequential-oral-sensory approach to an applied

behavior analytic approach in the treatment of pediatric feeding disorders (Doctoral

dissertation). Retrieved September 18th, 2015, from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

(PQDT) database.

Related Articles:

Addison, L.R., Piazza C.C., Patel, M.R., Bachmeyer, M.H., Rivas, K.M., Milnes, S.M. and

Oddo, J. (2012). A comparison of sensory integrative and behavioral therapies as

treatment for pediatric feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis, 45, 455-

471 17p. doi:10.1901/jaba.2012.45-455

American Occupational Therapy Association (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework:

Domain and process (3rd ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 68(suppl. 1),

S1-S48. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.682006

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association | ASHA. (2015). Retrieved October 28,

2015, from http://www.asha.org/default.aspx

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT

18

Applied behavioral frames (2008). In M. Cole & E. Tufano (Ed.), Applied theories in

occupational therapy: A practical approach (pp. 125-132). Thorofare, NJ: SLACK,

Incorporated.

Case-Smith, J. (2005). Occupational therapy for children (5th ed.). St Louis: Elsevier.

Dobbelsteyn, C., Marche, D., Blake, K., & Rashid, M. (2005). Early oral sensory experiences and

feeding development in children with CHARGE syndrome: a report of five cases.

Dysphagia (0179051X), 20(2), 89-100 12p.

Geggie, J., Dressler-Mund, D., Creighton, D., & Cormack-Wong, E. (1999). An interdisciplinary

feeding team approach for preterm, high-risk infants and children. Canadian Journal Of

Dietetic Practice & Research,60(2), 72-77 6p.

Ghanizadeh, A. (2013). Parents reported oral sensory sensitivity processing and food preference

in ADHD. Journal Of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 20(5), 426-432 7p.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01830.x

Gisel, E. (1994). Oral sensorimotor therapy: assessment, efficacy and future directions.

Occupational Therapy International, 1(4), 209-232 24p.

McLeod, S. A. (2008). Systematic Desensitization. Retrieved from

www.simplypsychology.org/Systematic-Desensitisation.html

SOS Approach to Feeding. Toomey and Associates, 2015. Web. 29 Oct. 2015.

http://www.sosapproach-conferences.com/about-us/sos-approach-to-feeding

Toomey, K. A., & Ross, E. (2011). SOS Approach to Feeding. Perspectives On Swallowing &

Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia), 20(3), 82-87 6p. doi:10.1044/sasd20.3.82

WHO (2015). International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF).

Retrieved from http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en

Prepared by Holly Freeman, Alisa Reedy and Ashley Schalow (12/10/2015). Available at

www.UWLAX.EDU/OT