DIGITAL DECAY?

Tracing Change Over Time Among

English-Language Islamic State

Sympathizers on Twitter

BY

Audrey Alexander

October 2017

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publisher.

© 2017 by Program on Extremism

Program on Extremism

2000 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Suite 2210

Washington, DC 20006

www.extremism.gwu.edu

Digital Decay? • iii

CONTENTS

Author’s Notes and About the Author · v

Executive Summary · vii

Introduction · 1

Background · 5

Method and Design · 11

Analysis of English-Language IS-Sympathizers on Twitter · 15

Conclusion · 45

List of Figures

1. IS Infographic · 1

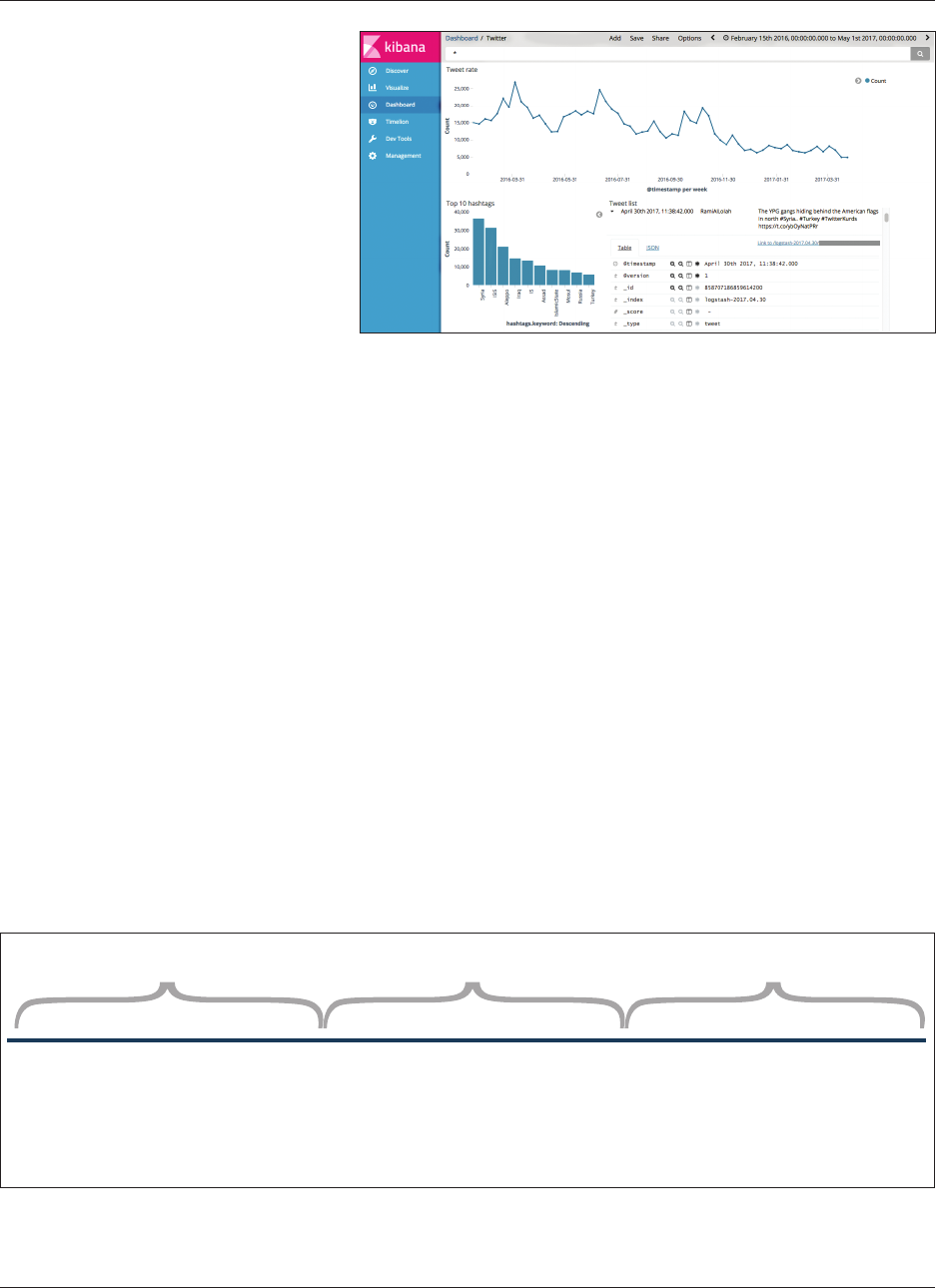

2. Kibana’s Dashboard · 12

3. Breakdown of Time Segments · 12

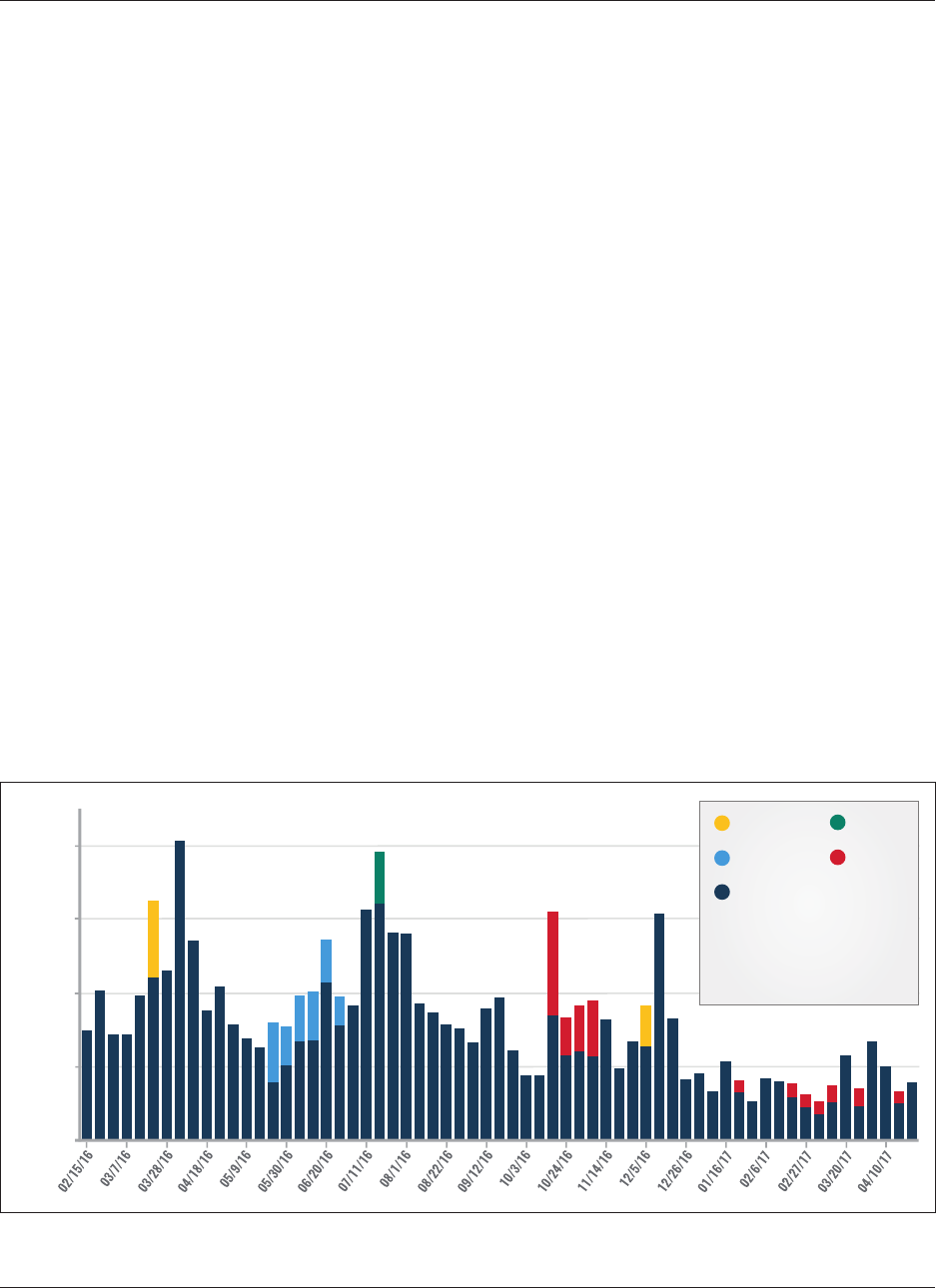

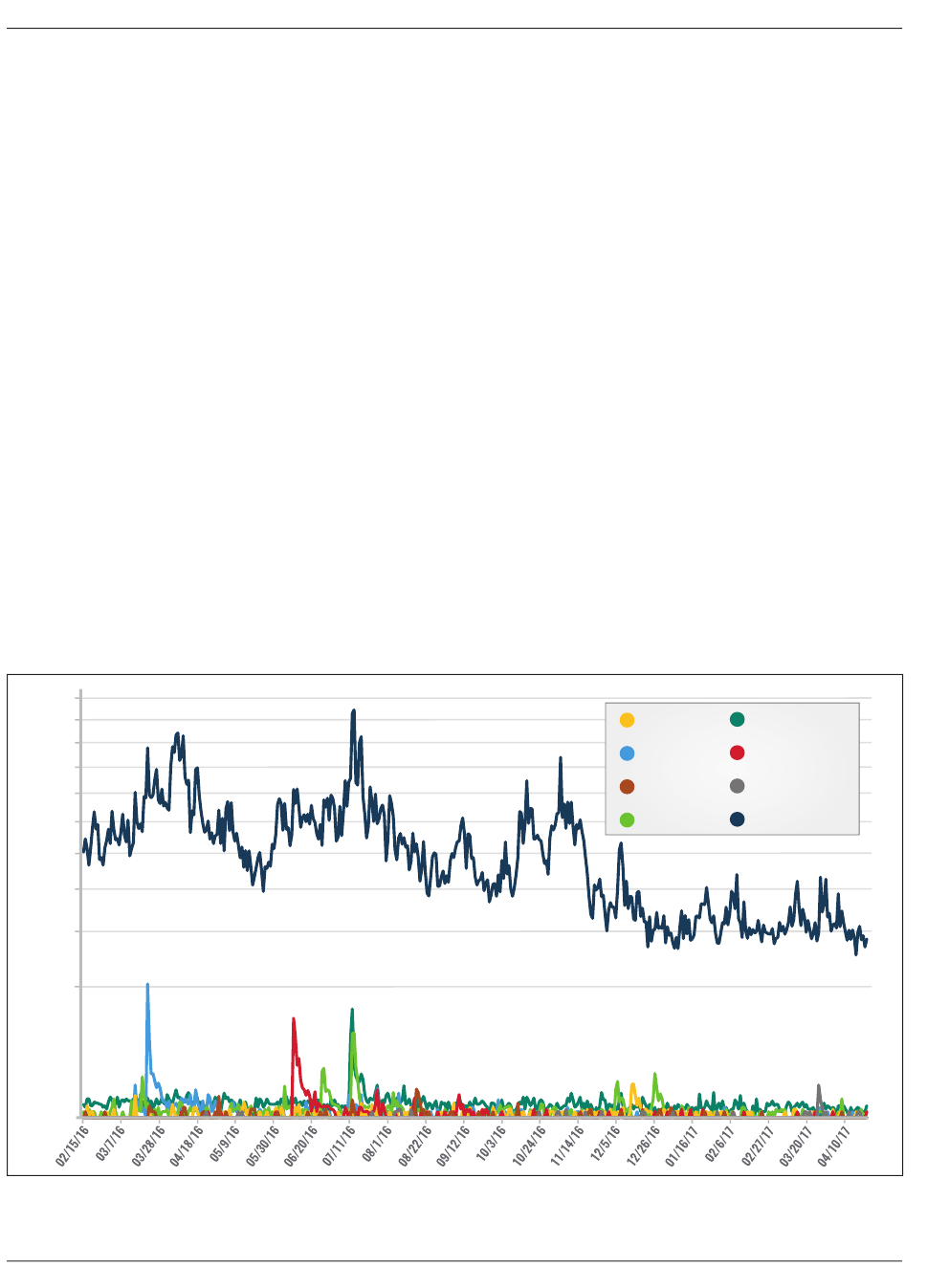

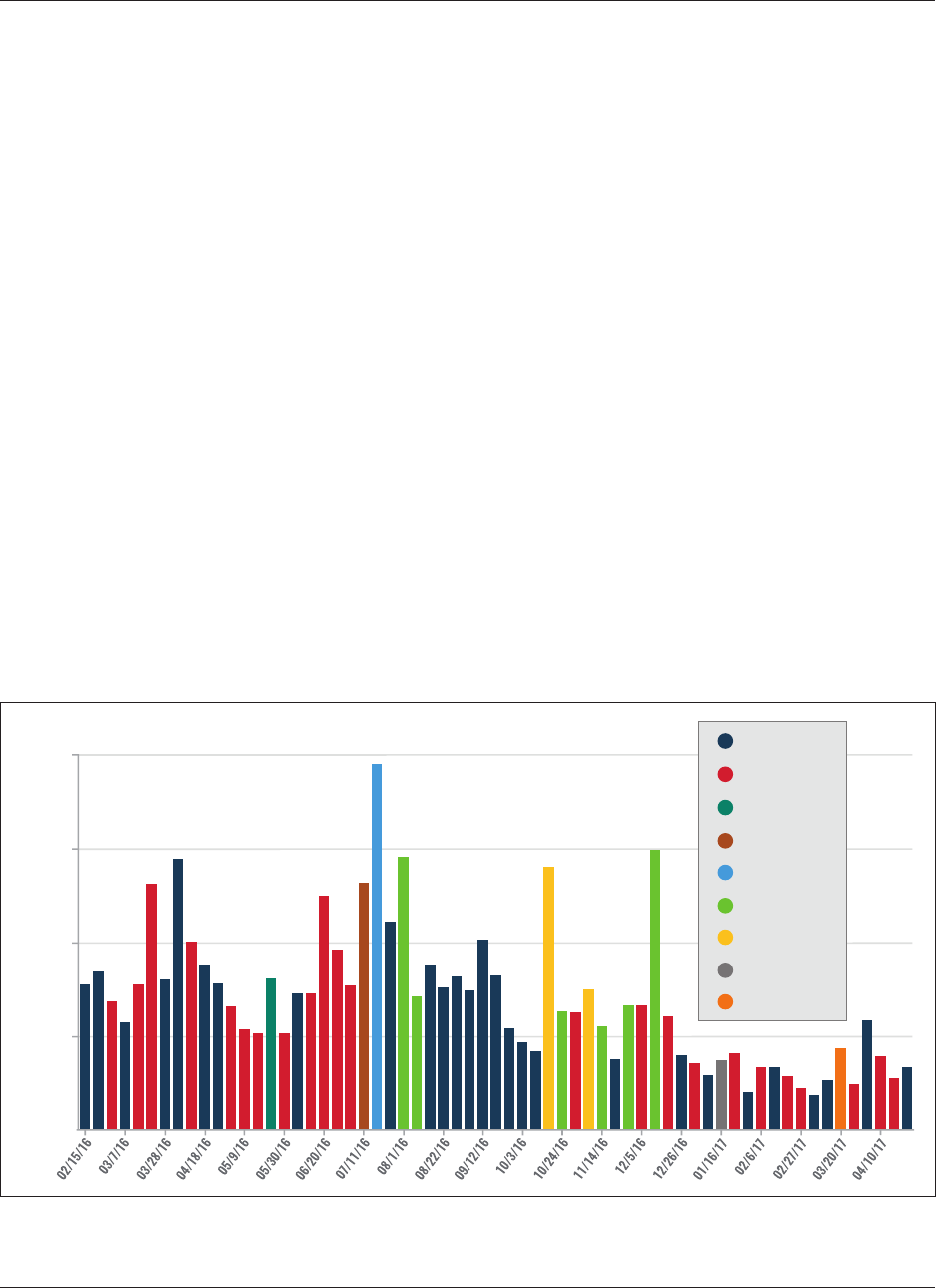

4. Twee t Cou nt Per Week · 15

5. Twee t Frequenc y a nd Unique Sc reen Na mes By We ek · 17

6. Duration of Account Activity · 17

7. Follower Count by Chronological Segment · 18

8. Tracing Username Mentions by English-Language IS Sympathizers · 20

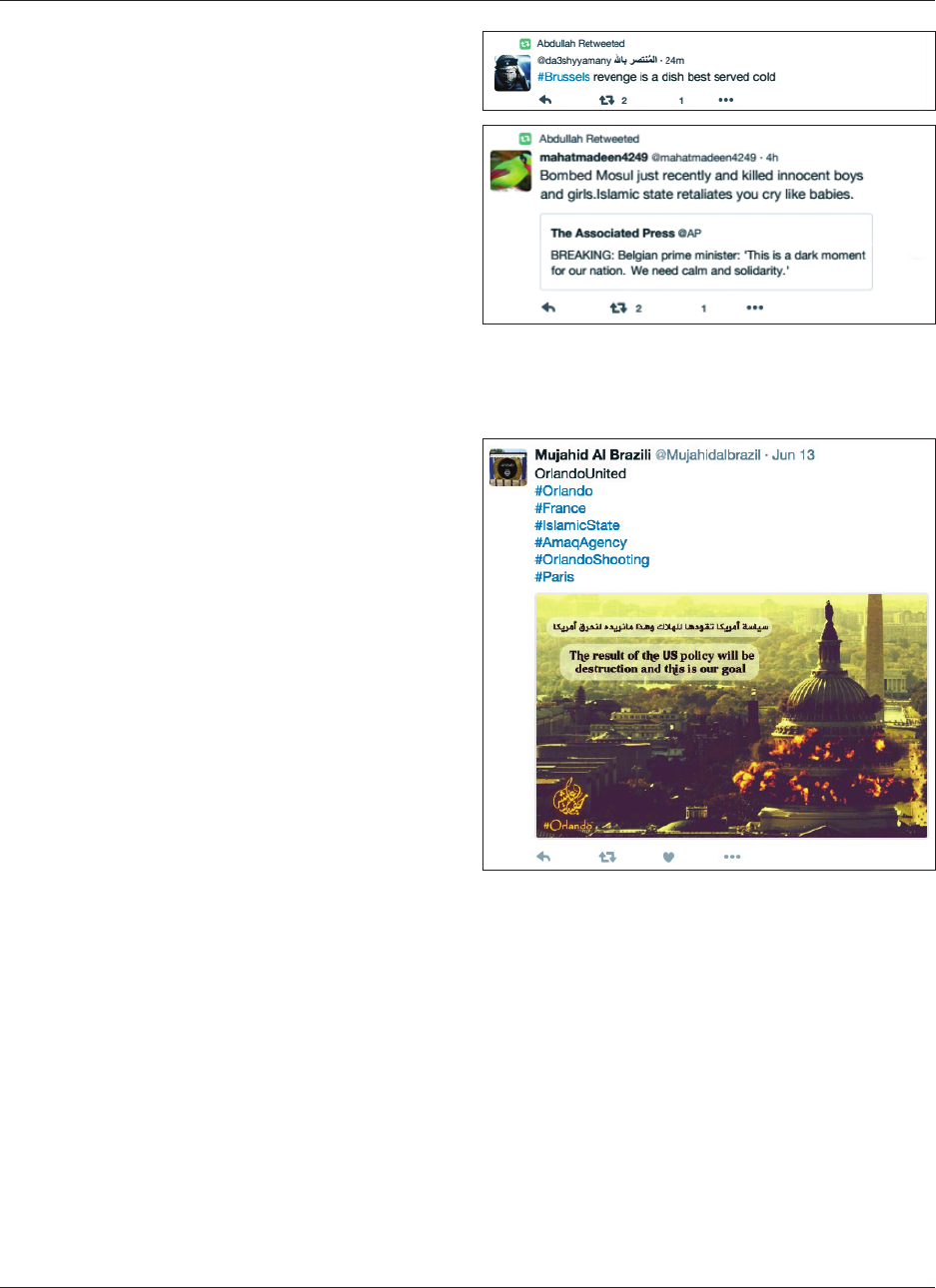

9. Example Tweets · 23

10. Twit ter Accounts · 24

11. Example Tweet · 24

12. Tracking Military Engagements Over Time · 25

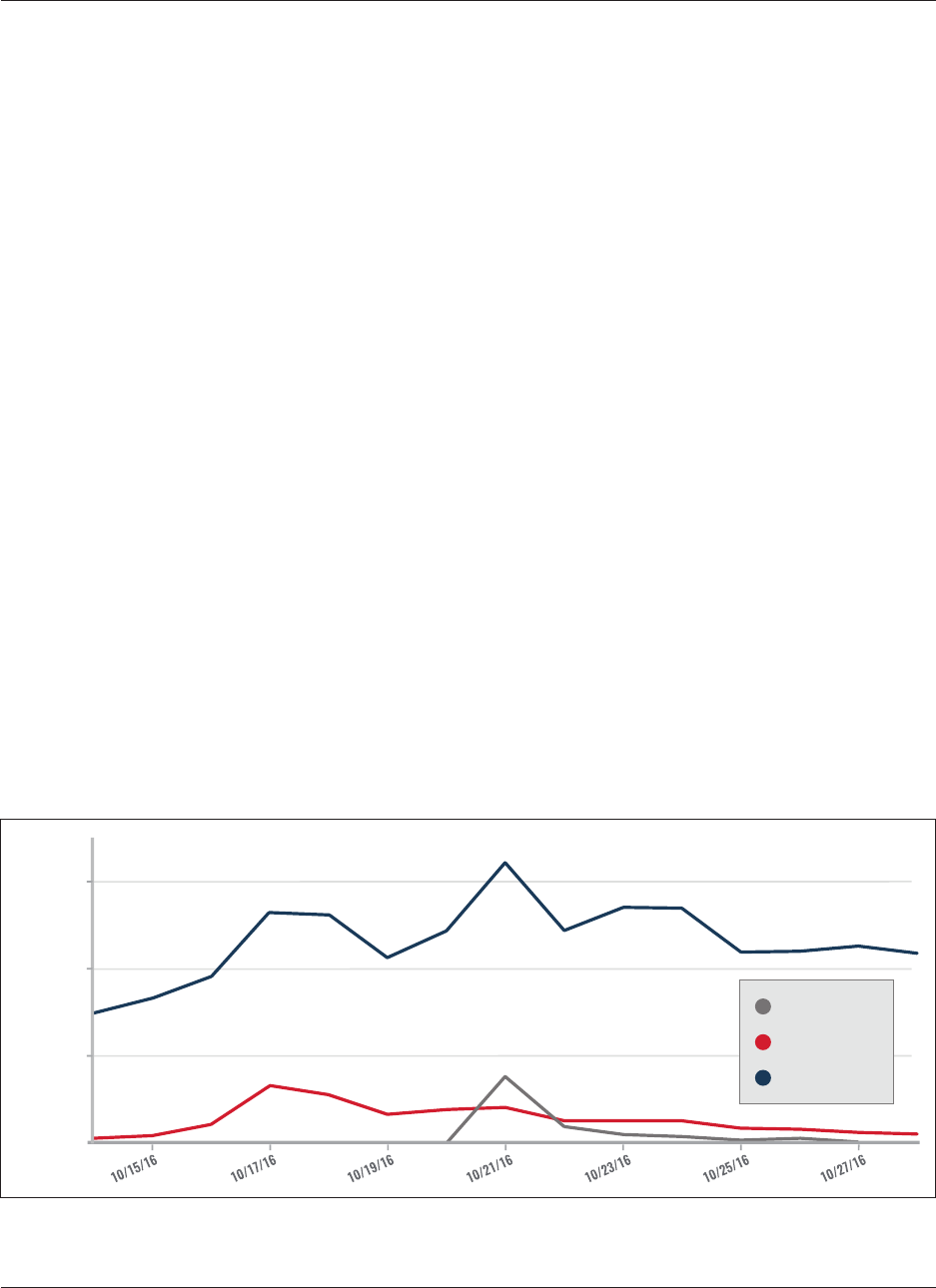

13. Two-Week Snapshot of Mosu l a nd K irk uk (Oc tober 14 to 28, 2016) · 26

14. Top 3 Hashtags Per Week Highlighting Prevalence of Key Batt les · 28

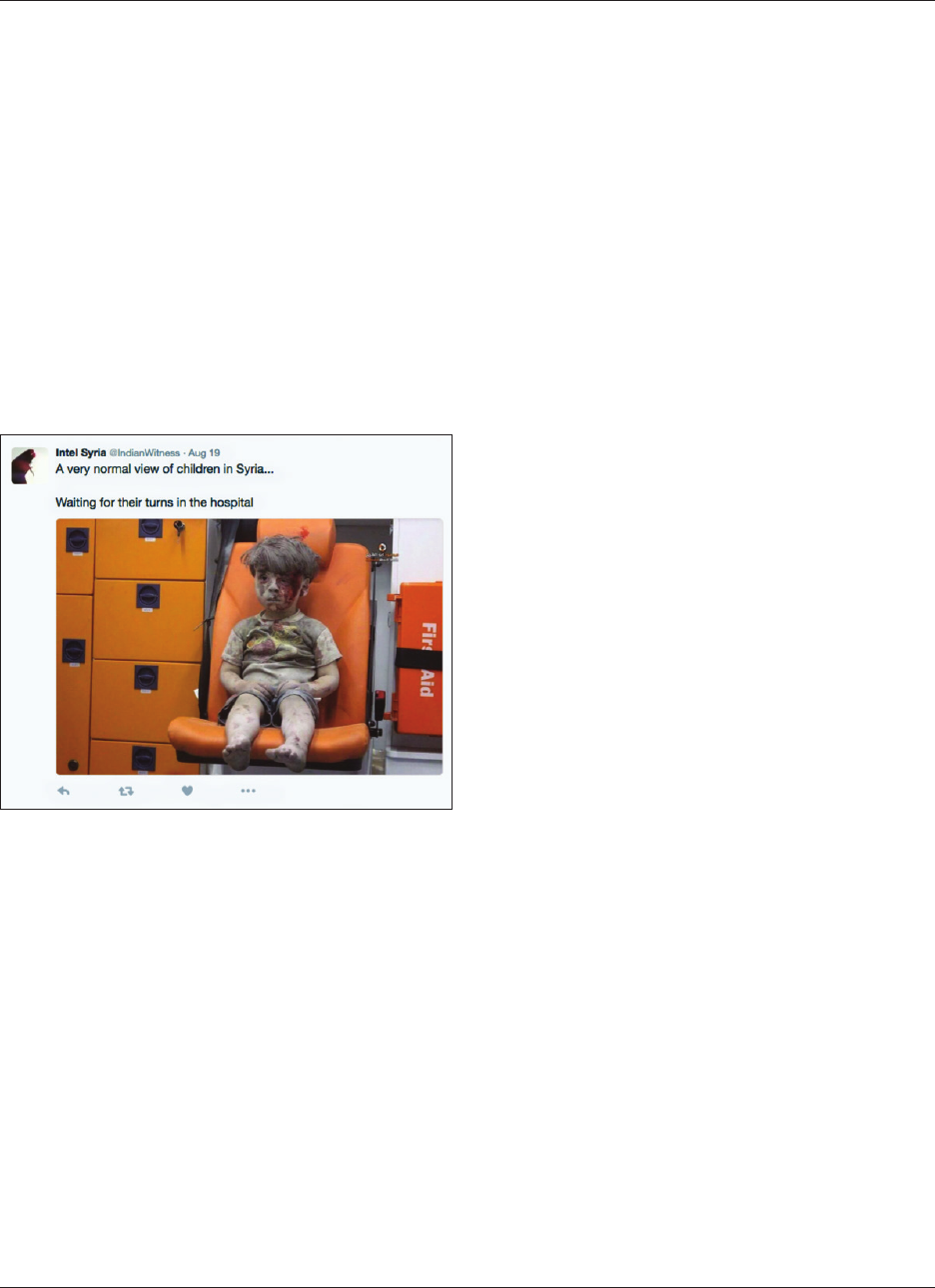

15. Tracing Attacks Over Time · 30

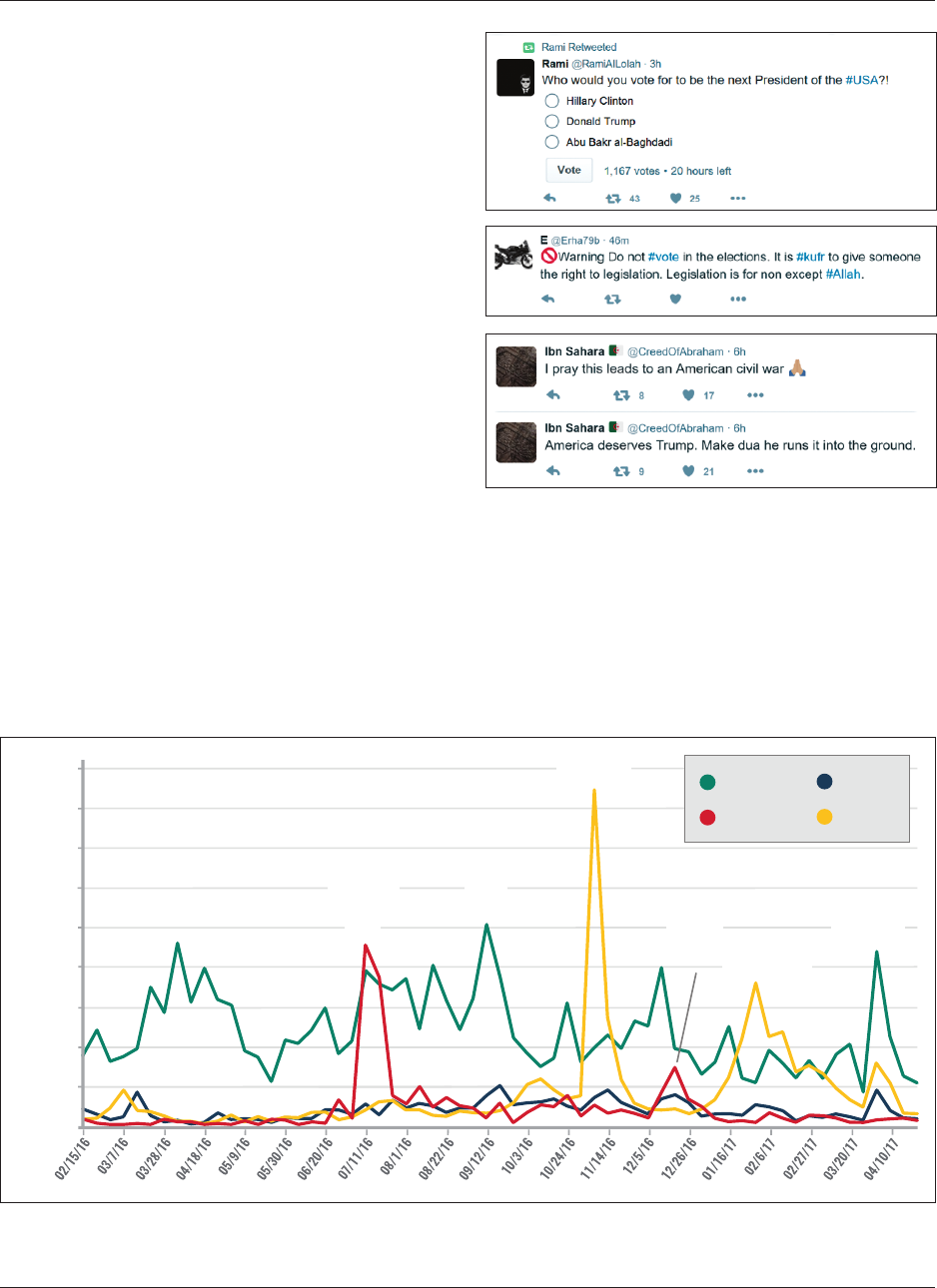

16. Example Tweets · 31

17. Example Tweet · 31

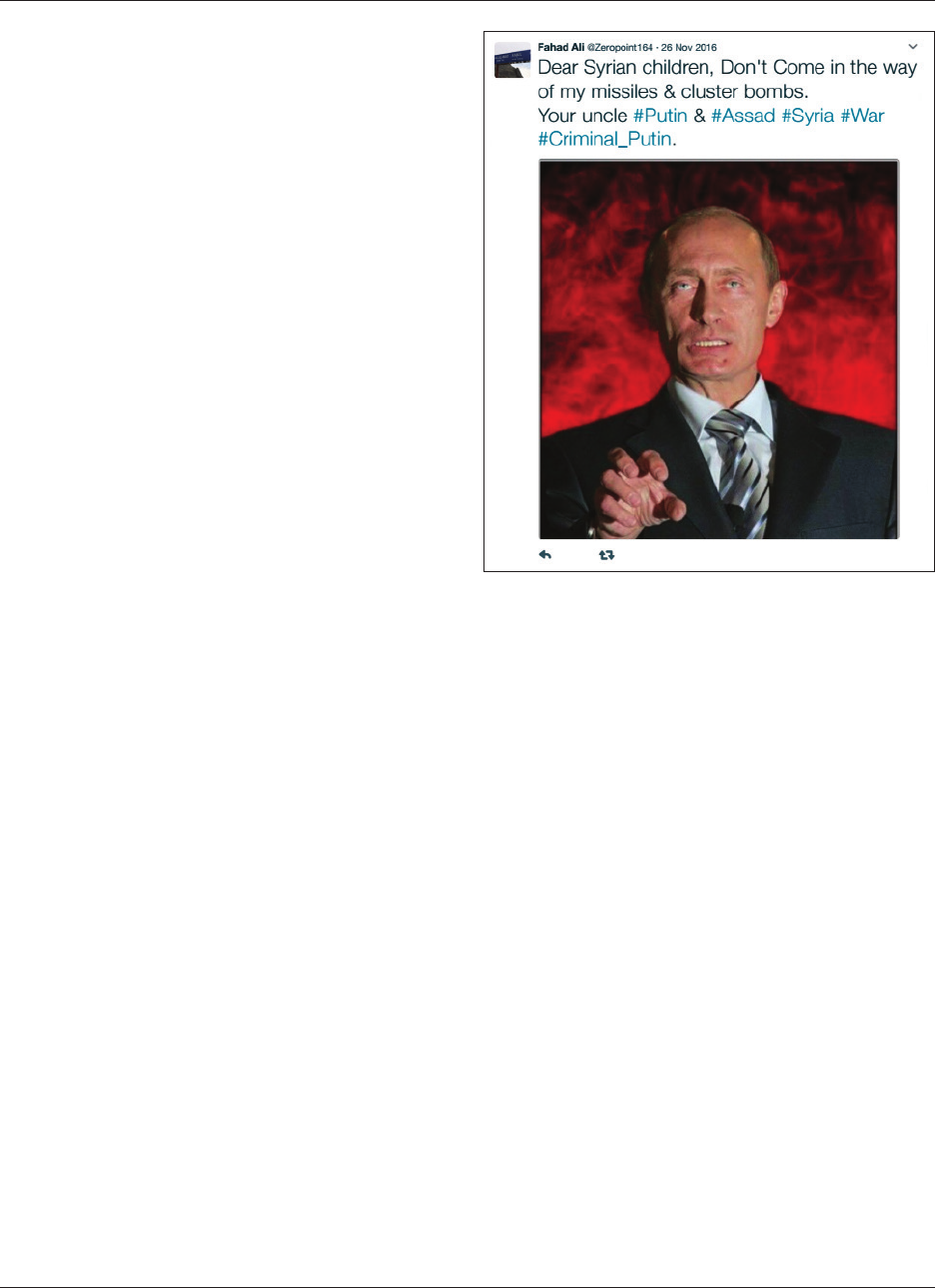

18. Example Tweet · 33

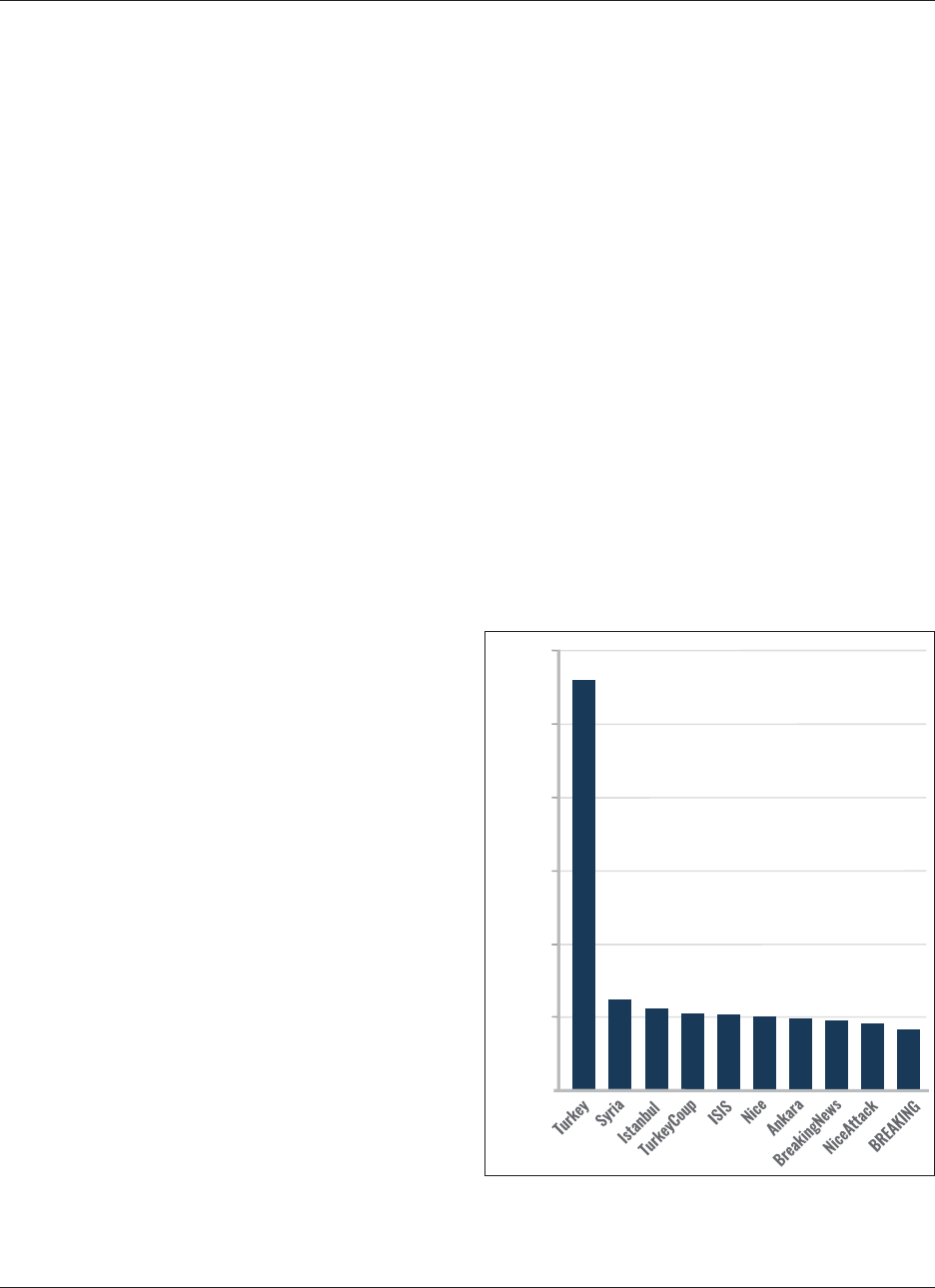

19. Top 10 Hashtags on July 15 and July 16, 2016 · 34

20. Example Tweet · 35

21. Twe et Referencing A nt i-US St ate L eaders · 35

22. Example Tweet · 36

23. Example Tweet · 37

24. Top Hashtag Per Week · 38

Digital Decay? • v

AUTHOR’S NOTES

First and foremost, the author would like to thank Daniel Kerchner, and the team at Scholarly Technology Group (STG) of

the George Washington University Libraries, for their immeasurable contributions to this project since December 2015.

This report was made possible by the Program’s team of Research Assistants, particularly Alex Theodosiou; Sarah

Metz, Eleanor Anderson, Samantha Weirman, Mattisen Stonhouse, Adib Milani, Tanner Wrape, Mario Ayoub, Scott

Backman, Jenna Hopkins, and Elizabeth Yates also contributed to this report.

The author would also like to thank Dr. Ali Fisher for his constructive feedback, and Larisa Baste for formatting

this report.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Audrey Alexander specializes in the role of digital communications technologies in terrorism and studies the radicaliza-

tion of women. As a Research Fellow at the Program on Extremism at The George Washington University, she authored

Cruel Intentions: Female Jihadists in America and published articles in , the Washington Post , and Lawfare blog.

In this role, Alexander also maintains a database of nearly 3,000 pro-Islamic State social media accounts. Before joining

the Program on Extremism, she worked at King’s College London’s International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation

(ICSR) and with the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD). Alexander holds a Masters in Terrorism, Security & Society

from the War Studies Department at King’s College.

The Program on Extremism

The Program on Extremism at George Washington University provides analysis on issues related to violent

and non-violent extremism. The Program spearheads innovative and thoughtful academic inquiry, producing

empirical work that strengthens extremism research as a distinct field of study. The Program aims to develop

pragmatic policy solutions that resonate with policymakers, civic leaders, and the general public.

Digital Decay? • vii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Until 2016, Twitter was the online platform of choice for

English-language Islamic State (IS) sympathizers. As a

result of Twitter’s counter-extremism policies - includ-

ing content removal - there has been a decline in activity

by IS supporters. This outcome may suggest the com-

pany’s efforts have been effective, but a deeper analysis

reveals a complex, nonlinear portrait of decay. Such ob-

servations show that the fight against IS in the digital

sphere is far from over. In order to examine this change

over time, this report collects and reviews 845,646

tweets produced by 1,782 English-language pro-IS ac-

counts from February 15, 2016 to May 1, 2017.

This study finds that:

Twitter’s policies hinder sympathizers on the plat-

form, but counter-IS practitioners should not over-

state the impact of these measures in the broader

fight against the organization online.

‐ Most accounts lasted fewer than 50 days, and

the network of sympathizers failed to draw

the same number of followers over time.

‐ The decline in activity by English-language IS

sympathizers is caused by Twitter suspensions

and IS’ strategic shift from Twitter to messag-

ing platforms that offer encryption services.

‐ Silencing IS adherents on Twitter may pro-

duce unwanted side effects that challenge law

enforcement’s ability to detect and disrupt

threats posed by violent extremists.

The rope connecting IS’ base of sympathizers to

the organization’s top-down, central infrastruc-

ture is beginning to fray as followers stray from the

agenda set for them by strategic communicators.

While IS’ battlefield initiatives are a unify-

ing theme among adherents on Twitter, the

organization’s strategic messaging output about

these fronts receive varying degrees of attention

from sympathizers.

Terrorist attacks do little to sustain the conver-

sation among supporters on Twitter, despite sub-

stantive attention from IS leadership, central pro-

paganda, and even Western mass media.

‐ Over time, there has been a decline in tweets

following major attacks. This suggests that at-

tacks in the West have diminishing effects in

mobilizing support.

Current events – such as the attempted coup in

Tu r ke y a n d t h e 2 016 U. S . pre side nt i a l e le c t i on – a r e

among the most popular topics within the sample.

‐ Events unrelated directly to IS cause some of

the greatest spikes in activity.

‐ These discussions are ongoing despite

Twitter’s policies.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

‐ English-language IS sympathizers on Twitter

defy straightforward analysis and convenient

solutions.

‐ They are skilled problem-solvers in the digital

sphere. Rather than ruminating over losses,

angered adherents fight to be heard, either on

Twitter or other digital platforms.

‐ Counter-IS practitioners must show a similar

willingness to adapt and explore alternative

ventures.

‐ While some collaboration is beneficial, the

government cannot rely predominantly on

the efforts of tech companies to counter IS

and its supporters.

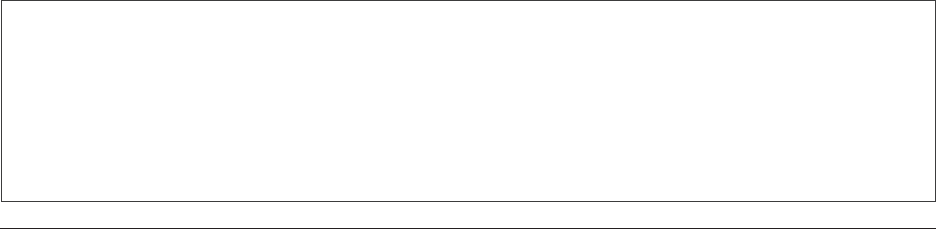

In May 2017, a pro-IS English-language infographic en-

titled “Failure of the Media War on the Islamic State” by

Yaqeen Media Foundation

1

circulated among some of the

movement’s sympathizers on social media (Figure 1).

With a healthy level of skepticism, the graphic highlights

the complexity of the ‘media war’ between IS and its ad-

versaries. On one hand, the image alludes to IS’ dynamic

media strategy, made to amplify the organization’s voice

through coordinated “campaigns” that disseminate con-

tent on “famous websites such as Twitter and Facebook.”

Simultaneously, however, the graphic touts in the bottom

left-hand corner that “More than 1,000 new accounts are

made by Islamic State supporters each day on Twitter.”

Figures from Twitter’s tenth #Transparency Report suggest

the company’s effort to suspend accounts for violations

related to the promotion of terrorism far exceeds a rate

of 1,000 accounts per day, challenging the infographic’s

evaluation of their opponents’ ‘failure’ in the fight against

IS on Twitter.

2

In light of these discrepancies, perhaps

binary measures of success and failure, like winning and

losing, have limited utility in the discourse surrounding

the fight against IS online.

Several conventional markers indicate that the foothold

of the self-styled caliphate is faltering on the ground in

Syria and Iraq. IS has lost considerable territory, putting

a tremendous strain on the organization’s internal rev-

enue streams, while casualties and a decrease in foreign

fighter travel continue to deplete its pool of combatants.

3

The decline in central media output is a symptom, and

perhaps also a cause, of depletion in the physical world.

4

Despite these setbacks, IS sympathizers continue to wage

Digital Decay? • 1

INTRODUCTION

IS Infographic

2 • The George Washington University Program on Extremism

Introduction

a protracted struggle in the digital sphere using a wealth

of digital communications technologies. Thus, the orga-

nization’s presence in the virtual theater is hard to gauge.

IS is strategically adept on social media because of slick

branding, masterful distribution, and effective agen-

da-setting.

5

On a strategic level, the group demonstrates

extraordinary dexterity in navigating the changing me-

dia landscape online.

6

From Facebook and Twitter to

Telegram and Tor, sympathizers fluidly cross between

broad-based platforms and more private, protected chan-

nels.

7

Reaping the benefit of a “two-tier production line”

of “official” and “user generated” content, IS’ propaganda is

accessible to a broad swathe of sympathizers.

8

Moreover,

the multi-lingual approach IS implements “has a clear

objective: targeting non-Arabic

speaking potential recruits.”

9

The

reach of these media products is

optimized by a mix of coordinat-

ed campaigns and the organic ral-

lying of IS’ online supporters.

Despite its competencies, IS is

vulnerable in the digital domain.

Much like the militant wings of

the organization, considerable

challenges confront IS’ networks

online. Due to the prosecution of IS supporters in the

West and targeted strikes on select f ighters in IS-held

territory, operational security is a growing concern

among many sympathizers. IS’ most prolific online re-

cruiter, British hacker Junaid Hussain, was reportedly

killed in 2015 after leaving an Internet cafe in Raqqa,

IS’ de facto capital.

10

A multitude of legal documents and

news media demonstrate the utility of virtual commu-

nications for investigating authorities in mapping the

international network of IS recruiters and recruits.

11

In addition to the actions of the military and law en-

forcement, public and private sector initiatives target IS

in the digital sphere and make it more difficult for ad-

herents to access information and communicate freely.

Existing approaches continue to yield mixed results, re-

lying predominantly on counter-messaging campaigns

and content-based regulation.

12

As it pertains to this report, Twitter regulates content

by suspending accounts that violate the company’s pol-

icies regarding the promotion of terrorism.

13

In the

‘Countering Violent Extremism’ section of the com-

pany’s tenth #Transparency Report, Twitter announced

the suspension of a total of 636,248 accounts between

August 1, 2015 and December 31, 2016.

14

According to

an official blog post published in early 2016, Twitter’s

terrorism-related suspensions were “primarily related

to ISIS.”

15

The company claims to investigate “accounts

similar to those reported” and “leverage[s] proprietary

spam-fighting tools to surface other potentially violat-

ing accounts for review.”

16

Twitter’s efforts to counter

extremism in the virtual sphere extend beyond con-

tent regulation and range from official preservation

requests from law enforcement

to the collaborative promotion

of counter-messaging efforts.

17

In December 2016, the company

announced a hashing-centric in-

formation-sharing partnership

with Facebook, Microsoft, and

YouTube to more effectively f lag

problematic materials with algo-

rithms to “help curb the spread

of extremist content online.”

18

While these indicators suggest IS’ presence has deteri-

orated online, policy makers, law enforcement officials,

and private companies have a limited and largely anec-

dotal understanding of how pro-IS online networks re-

spond to duress in the digital arena. Consequently, this

report will examine how an important cross-section of

English-language IS sympathizers on Twitter adapt to on-

line and offline initiatives aimed at weakening the wider

movement. After reviewing relevant literature, the report

examines change over time in a sample of 845,646 tweets

produced by 1,782 English-language pro-IS accounts on

Twitter between February 15, 2016, and May 1, 2017.

19

This 63-week dataset is among the largest time-bound

samples on the subject, but it only represents a snapshot

of IS’ activity on Twitter. The Program on Extremism

(PoE) collected this corpus of tweets with the support of

software developers in the Scholarly Technology Group

This report will examine how

an important cross-section of

English-language IS sympathizers

on Twitter adapt to online and

offline initiatives aimed at

weakening the wider movement.

Digital Decay? • 3

Audrey Alexander

(STG)

20

of the George Washington University Libraries.

This report is also part of an ongoing initiative tracking

the online efforts of IS in the West.

Despite some limitations, namely the applicability of the

findings to the wider conflict online and offline, this

unique resource offers an opportunity to examine shifts

in activity among English-language IS sympathizers on

Twitter. After contextualizing the broader fight against IS,

the background chapter discusses the synergistic interplay

between the physical, digital, and strategic elements of the

movement. The method chapter articulates PoE’s original

data collection process, identifies key caveats, and punc-

tuates the particular scope, transferability, and reliability

of the findings. The subsequent analysis of the data is split

into two overall sections. The first of these examines the

primary research question, namely: ‘How have Twitter’s

counter-extremism policies affected English-language IS

sympathizers on the platform?’ The second section poses

three supplementary questions to investigate how this de-

mographic of supporters engages with battles in Iraq and

Syria, terrorist attacks, and other current events. These

inquiries probe how English-language IS sympathizers

engage with matters in the physical world, especially con-

sidering the internal and external dynamics that guide

their behavior on Twitter. In tandem, these sections hint

that the dissipation of accessible communication channels

threatens the cohesion of IS’ sympathizers in the West.

Focusing on a small sliver of the broader population of

IS supporters worldwide, this report paints a complex

portrait of the struggle between English-language adher-

ents on Twitter, and the social media company’s efforts to

silence IS’ calls to support the self-proclaimed caliphate.

Rather than focusing exclusively on the numerical decline

in tweet frequency or the plummeting number of pro-

IS accounts, the following discussion strives to unpack

change over time and interrogate the implications for the

broader fight against IS in the digital sphere. Although

findings suggest that the term ‘decay’ best descibes the

effects of Twitter’s policy on the English-language IS

community on Twitter, growing evidence reveals that the

‘media war’ between IS and its adversaries is not nearing a

definitive end, it is just changing.

Notes

1. SITE Enterprise. 2017. “Yaqeen Media Center.” https://ent.

siteintelgroup.com/index.php?option=

com_customproperties&task=tag&tagId=209&

phpMyAdmin=31b32de8000cb1c40d5792b21dc9961a.

2. Tw it t er ’s te nt h #Transparency Report explains, “a total of 376,890

accounts were suspended for violations related to promotion

of terrorism” between July 1 and December 31, 2016. This

amounts to a rate of approximately 2,060 accounts per day.

“Government TOS Reports - July to December 2016.” 2017.

https://transparency.twitter.com/en/gov-tos-reports.html.

3. Jacob Shapiro, “A predictable failure: the political economy of

the decline of the Islamic State,”

9:9, 2016; Stefan Heißner, Peter R. Neumann, John

Holland-McCowan, Rajan Basra, “Caliphate in Decline: An

Estimate of Islamic State’s Financial Fortunes,” Report by the

International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, 2017;

Lucy Pasha-Robinson, “ISIS loves ‘10,000 fighters and a quar-

ter of territory in 18 months,’” Independent, October 17, 2016.

4. Milton, Daniel. 2016. ‘Communication Breakdown:

Unraveling the Islamic State’s Media Efforts.’ Combating

Terrorism Center at West Point.

5. Koerner, Brendan. 2016. “Why ISIS Is Winning

the Social Media War—And How to Fight Back.”

WIRED, April. https://www.wired.com/2016/03/

isis-winning-social-media-war-heres-beat/.

6. Prucha, Nico. 2016. “IS and the Jihadist Information Highway

– Projecting Influence and Religious Identity via Telegram.”

Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6), p.52 http://www.terrorismana-

lysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/556.

7. Alkhouri, Laith, and Alex Kassirer. 2016. “Tech for Jihad:

Dissecting Jihadists’ Digital Toolbox.” Flashpoint. https://

www.flashpoint-intel.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/

Tech ForJihad.p df.

8. Prucha, Nico. 2016. “IS and the Jihadist Information

Highway – Projecting Influence and Religious Identity via

Tel eg ram .” Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6), p.54 http://www.

terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/556.

9. Prucha, Nico. 2016. “IS and the Jihadist Information Highway

– Projecting Influence and Religious Identity via Telegram.”

Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6), p.54 http://www.terrorismana-

lysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/556.

10. Goldman, Adam, and Eric Schmitt. 2016. “One by One, ISIS

Social Media Experts Are Killed as Result of F.B.I. Program.” The

New York Times, November 24. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/

11/24/world/middleeast/isis-recruiters-social-media.html.

11. United States v. Munir Abdulkader (2016), Sentencing

Memorandum; United States v. David Daoud Wright (2017),

Second Superseding Indictment. Wilber, Del Quentin. 2017.

“Here’s How the FBI Tracked down a Tech-Savvy Terrorist

Recruiter for the Islamic State.” Los Angeles Times, April 13.

4 • The George Washington University Program on Extremism

Introduction

http://www.latimes.com/politics/la-fg-islamic-state-recruit-

er-20170406-story.html; Hughes, Seamus, and Alexander

Meleagrou-Hitchens. 2017. “The Threat to the United States

from the Islamic State’s Virtual Entrepreneurs” 10

(3). https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-threat-to-the-unit-

ed-states-from-the-islamic-states-virtual-entrepreneurs;

12. Google’s Jigsaw, for example, attempts to counter online

extremism with the Redirect Method, which, according to its

website, diverts supporters to “curated YouTube videos” that

confront IS’ recruitment themes. “The Redirect Method -

Jigsaw.” 2017. http://redirectmethod.org.

13. In the official ‘Twitter Rules,’ the company identifies “Violent

threats (direct or indirect)” as grounds for temporarily locking

and/or permanently suspending accounts, explaining, “You

may not make threats of violence or promote violence, in-

cluding threatening or promoting terrorism.” - “The Twitter

Rules.” 2017. Twitter Help Center. https://help.twitter.com/

articles/18311?lang=en.

14. “Government TOS Reports - July to December 2016.” 2017.

https://transparency.twitter.com/en/gov-tos-reports.html.

15. Please note that Twitter made this assertion prior to the

timeframe used in PoE’s report. Although subsequent

suspensions likely continued the trend, PoE cannot confirm

what percentage of the total number of suspensions relate

to IS specifically. “Combating Violent Extremism.” 2016.

Twitter Blogs. February 5. https://blog.twitter.com/2016/

combating-violent-extremism.

16. “Combating Violent Extremism.” 2016. Tw it t er Bl og s. February

5. https://blog.twitter.com/2016/combating-violent-extremism.

17. “Guidelines for Law Enforcement.” 2017. Twitter Help

Center. Accessed September 11. https://help.twitter.

com/articles/41949?lang=en. See also, “An Update

on Our Efforts to Combat Violent Extremism.” 2016.

Twitter Blogs. August 18. https://blog.twitter.com/2016/

an-update-on-our-efforts-to-combat-violent-extremism.

18. “Partnering to Help Curb the Spread of Terrorist Content

Online.” 2016. Twitter Blogs. December 5. https://blog.twitter.

com/2016/partnering-to-help-curb-the-spread-of-terrorist-

content-online.

19. In this context, accounts are distinguished by username rather

than ID number. For more information, this report articulates

the precise logistics of PoE’s approach in the method section.

20. For more information about the Scholarly Technology Group,

see https://library.gwu.edu/scholarly-technology.

Digital Decay? • 5

BACKGROUND

Although several jihadi groups gained online traction

prior to and during the Syrian civil war,

1

Abu Bakr

al-Baghdadi and his pool of supporters set a precedent

by expertly blending the online and offline battlefield.

Arguably more so than its jihadi predecessors and com-

petitors, IS and its media department “embraced the pop-

ularity of social media and other methods of reaching new

audiences,” moving away from hierarchical websites and

forums.

2

In this way, al-Baghdadi, the supposed ‘Caliph’

and a man of few words, encouraged the movement to

speak for itself.

Some analysts rightly question whether the effects of

social media are exaggerated,

3

but counter-terrorism

scholars and practitioners broad-

ly agree that digital communica-

tions technology, especially social

media, are a means by which IS

and its adherents engage with

each other.

4

Using a versatile

media apparatus, IS “managed to

leverage a combination of official

and unofficial actors in support

of its propaganda mission.”

5

This

method helped facilitate a global

movement, posing a real but amorphous threat to entities

inside and outside IS-controlled territory.

As IS gained traction in Syria and Iraq, social media re-

search revealed a burgeoning relationship between ac-

tivity on the ground and a broad base of sympathizers

worldwide. Works like #GreenBirds: Measuring Importance

by the

International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation

(ICSR) and ‘Tweeting the Jihad’ by Jytte Klausen laid

the foundation for research using social media as a lens

to examine the networks of Western foreign fighters.

6

Both studies articulate the relevance of actors outside

IS-controlled territory. Where ICSR emphasizes the in-

fluence of unofficial clerical authorities as ‘dissemina-

tors’ who inform foreign fighters, Klausen suggests that

organizations within extremist networks play a role in

driving jihadist networks.

7

Moreover, Klausen’s study

contends that official IS accounts are vital and tightly in-

tegrated with other types of Twitter profiles, indicating a

more centralized communication strategy.

8

These works,

among others,

9

illuminate how social media affords IS the

opportunity to implement top-down and bottom-up re-

cruitment procedures.

The nature of IS’ central communications continues to

evolve, especially since the group conducts targeted me-

dia initiatives in an effort to mobilize its base of sup-

porters worldwide. In

, Craig Whiteside succinctly

notes that for IS, “controlling the

message is a goal unto itself.”

10

In

pursuit of that aim, “the official

content put out by the Islamic

State is an amalgamation of prod-

ucts from a number of separate,

geographically-centered media

bureaus spread across the group’s

territory.”

11

Anecdotally, IS has

advanced targeted recruitment

by tailoring content to reach a

broader audience. The creation of

which publishes content in multiple languages, including

English, is a testament to IS’ desire to cast a wide net.

12

The

production of non-Arabic content “remains a high prior-

ity for IS” in addition to the continued stream of propa-

ganda targeting Arabic speaking sympathizers.

13

In 2017,

the pro-IS Yaqeen Media Foundation reports that “Islamic

State media [are] spread in more than 40 languages.”

14

Jihadists disseminate these messages across a range of

digital platforms: while some mediums are broad-based

and far-reaching, like Facebook and Twitter, others are

more insular and protected, like Telegram and Kik.

In Documenting the Virtual Caliphate: Understanding Islamic

, a report published in 2015, Charlie

Winter identifies several themes in IS’ ‘brand’ including

The nature of IS’ central

communications continues to

evolve, especially since the

group conducts targeted media

initiatives in an eort to mobilize

its base of supporters worldwide.

6 • The George Washington University Program on Extremism

Background

brutality, mercy, victimhood, war, belonging, and utopia-

nism.

15

Winter notes that IS’ propaganda output had “in-

creased significantly since June 2014.”

16

Multiple analyses

suggest that IS’ top-down propaganda effort reached its

height around July and August 2015.

17

In some instances,

changes in territory correlate with shifts in the aggre-

gate number of media products; this point is increasingly

apparent in the wake of significant losses. Aaron Zelin

notes, “there may be two reasons” for a decline in central

media output: “the killing of IS media operatives, and/

or the loss in territory.”

19

In Communication Breakdown:

, Daniel Milton

traces change over time in IS’ official propaganda dissem-

ination, observing a substantial decline in visual media

products from August 2015 to August 2016.

20

Using official, unofficial, and grassroots communication

channels, IS is often credited with ‘winning the war on

social media.’

21

Although this assertion has some validity,

precise measures of success and failure in the digital arena

are context dependent and difficult to operationalize. IS

uses an interconnected network to disseminate informa-

tion that is always changing and reconfiguring without

relying on the typical hierarchal structure, which is si-

multaneously beneficial and detrimental.

22

IS communi-

cators undoubtedly weathered numerous blows, but this

is not the same as defeat. In his discussion on official pro-

paganda, Milton notes, “setbacks suggest that the efficacy

of the media arm is not a foregone conclusion, but a sub-

jective reality contingent on a wide array of other factors

such as counterterrorism pressure, battlefield conditions,

and personnel availability.”

23

The subsequent discussion

about the dissemination efforts of IS sympathizers on

Twitter must adopt an equally nuanced approach and ac-

count for the major variables that may influence behavior

in the digital sphere.

Nico Prucha aptly articulates the predominant factors

contributing to the early 2016 shift among IS adherents

from Twitter to Telegram. In

Highway, Prucha highlights the dialectical process where-

by Twitter’s growing efficacy in banning sympathizers

led IS followers to pursue alternative means of commu-

nication in other, less regulated spaces.

24

The necessity of

this move is best illustrated by IS’ nostalgia for Twitter;

Prucha explains, “IS media operatives and sympathizers

miss” the platform and some of the group’s media outlets

“called for a return to Twitter.”

25

Furthermore, evidence

suggests that contemporary messaging campaigns “coor-

dinate distribution” on a “multiplatform zeitgeist,” which

often targets Twitter, highlighting the enduring impor-

tance of the medium.

26

Ultimately, despite the increased

operational security afforded by Telegram, the transition

to a platform other than Twitter impedes IS’ ability to ex-

pand online.

27

Despite setbacks, IS uses social media and other commu-

nications technology, to praise, claim, incite, and facilitate

violent activity outside IS-controlled territory. A 2017 re-

port confirms that since 2011, states in Europe and North

America are attractive targets for jihadi operatives.

28

Based on such activity in the United States alone, evidence

suggests that there is no monolithic digital footprint for

an IS sympathizer; they are just as idiosyncratic online as

they are in the real world, and use various forms of so-

cial media to participate in the movement.

29

Moreover,

although some social media platforms prove to be more

commonplace than others within the jihadisphere, sym-

pathizers do not necessarily use them in the same way.

In February 2016, for example, after tracking Safya

Yassin’s various Twitter, Google+, and Facebook accounts

over the span of several months, authorities arrested the

Missouri resident for transmitting threats to injure fed-

eral government employees.

30

In spite of multiple account

suspensions on Twitter, Yassin created new profiles to

disseminate content bolstering IS’ message of violent ji-

had.

31

On August 24, 2015, prior to her arrest, the FBI re-

corded Yassin tweeting personal information, including

the names, locations, and phone numbers, of three federal

employees listed under the title, “Wanted to Kill.”

32

By

January 27, 2016, the FBI identified 97 Twitter accounts

that were “likely” linked to Yassin.

33

Although Yassin’s po-

tential trajectory for physical mobilization and operation-

al links to IS remain unknown, her prolific presence on

social media, namely Twitter, has facilitative significance

because she amplified IS’ violent rhetoric to her sizable

base of followers.

Digital Decay? • 7

Audrey Alexander

In contrast, the case of attempted Garland shooter Elton

Simpson demonstrates a drastically different use of

Twitter (among other platforms) by an IS sympathizer. In

the U.S. On May 3, 2015, Simpson and Nadir Soofi, his

accomplice, drove from Arizona to Texas to attack the

Muhammad Art Exhibit and Contest with assault rifles;

both men were killed by law enforcement before breach-

ing the venue. Before the plot, Simpson had “direct con-

tact” with at least two jihadists abroad “using Twitter di-

rect message and SureSpot.”

34

Although the nature of such

communications vary, links to prolific IS-recruiter Junaid

Hussain and Mohamed Abdullahi Hassan (Mujahid

Miski), the notorious U.S.-linked member of Al-Shabaab,

are suggestive of a more operational connection to for-

malized jihadist groups.

35

On the day of the attack, using

the handle @atawaakul, Simpson allegedly alluded to an

emerging plot on Twitter, creating the hashtag “#texasat-

tack.”

36

According to news reports, Simpson also encour-

aged supporters on Twitter to follow @_AbuHu55ain,

an account tied to Junaid Hussain.

37

Shortly thereafter,

Hussain’s account tweeted statements suggesting that he

had prior knowledge of the attack.

38

Ultimately, Simpson’s

use of Twitter drastically differed from that of Safya

Yassin, demonstrating variance in IS sympathizers’ use of

social media platforms.

Even though IS sympathizers in the West use social me-

dia as a means to connect with the self-proclaimed ca-

liphate, whether operational or ideological, engagement

in the digital sphere varies. The geographic location of

the sympathizer may also influence the channel of en-

gagement which users pursue. Though not empirically

proven, IS sympathizers in the UK, for example, may be

less inclined to download jihadi propaganda than their

counterparts in the US due to differing laws on extremist

content. Admittedly, patterns of participation are likely

defined by operational security considerations, but exist-

ing laws and ease of engagement may factor into sympa-

thizers’ cost-benefit analysis of various means of digital

communications.

In response to the proliferation of violent extremists

online, Western governments, particularly the U.S. and

U.K., have relied much on the participation of tech com-

panies in the fight against IS in the digital domain. In the

U.S. for example, the ‘Madison Valleywood Project’ en-

courages tech and entertainment companies to assist in

the fight against terrorism with counternarratives and

stringent enforcement of their respective terms of ser-

vice.

39

While it is a necessary step to curb the dissemina-

tion of media products that advocate for violent agendas,

the precise impact of such attempts is difficult to quantify.

Even so, it is imperative to discuss the measures used by

tech companies to counter IS online.

The most prevalent contemporary approaches are con-

tent-based regulation and counter-messaging. Such pol-

icies range from stand-alone initiatives by one company

to collaborative engagement by several others. Despite

more recent partnerships with Facebook, Microsoft, and

YouTube, Twitter’s efforts to counter violent extremism

online focus on content-based regulation via account

suspension.

40

Though commendable, Twitter’s approach

produces mixed results. One study suggests that suspen-

sion efforts yield some success, particularly as returning

accounts fail to gain relative traction after suspension.

41

On the other hand, IS sympathizers create new accounts

every day and continue to demonstrate tremendous agili-

ty across multiple platforms. Consequently, the efficacy of

one tech company in silencing IS on its site may produce

negative results across other channels of communication.

Digital communications technologies remain instru-

mental in the exchange of ideas between IS supporters

on a global stage. But still, the flux in communications

between IS-central and its international base of support-

ers is subject to changing tides in the physical and digital

arena. In his discussion about IS media, Whiteside notes,

IS’ “desire to expand required an intensity and quantity

of messaging that might have invited failure due to a lack

of control.”

42

Similarly, although social media affords IS

innumerable opportunities for growth and mobilization,

these channels pose critical challenges to those who seek

to direct and advance the movement inside and outside

IS-controlled territory. In a recent analysis, Bryan Price

and Muhammad al-`Ubaydi highlight IS-central’s effort

to limit its fighters’ use of social media on the ground in

Iraq and Syria.

43

The authors explain, “This is not the first

time [IS] has warned against the use of social media by its

rank-and-file,” but the most recent endeavor in May 2017

8 • The George Washington University Program on Extremism

Background

is “its most forceful attempt to date.”

44

Like IS-central,

sympathizers worldwide adapt to initiatives that target

the movement online and offline, but little is known of

the impact these counter-IS measures have on IS’ online

diaspora. The subsequent study and analysis works to

unpack these dynamics using a sizable sample of English-

language IS sympathizers on Twitter.

Notes

1. Zelin, Aaron. 2013. “The State of Global Jihad Online.”

Washington, DC: New America Foundation. Prucha, Nico,

and Ali Fisher. 2013. “Tweeting for the Caliphate: Twitter

as the New Frontier for Jihadist Propaganda | Combating

Terrorism Center at West Point.”CTC Sentinel, 6 (6). https://

ctc.usma.edu/posts/tweeting-for-the-caliphate-twitter-as-the

-new-frontier-for-jihadist-propaganda.

2. Whiteside, Craig. 2016. “Lighting the Path:the Evolution of

the Islamic State Media Enterprise (2003-2016).” International

Centre for Counter-Terrorism - The Hague. Zelin, Aaron. 2013.

“The State of Global Jihad Online.” Washington, DC: New

America Foundation. Prucha, Nico, and Ali Fisher. 2013.

3. Gilsinan, Kathy. 2015. “Is ISIS’s Social-Media Power

Exaggerated?” The Atlantic, February 23. https://www.

theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/02/

is-isiss-social-media-power-exaggerated/385726/.

4. Taylor, Harriet. “Most Young Terrorist Recruitment Is

Linked to Social Media, Said DOJ Official,” October 5, 2016.

http://www.cnbc.com/2016/10/05/most-young-terrorist-

recruitment-is-linked-to-social-media-said-doj-official.

html.; Rose, Steve. “The Isis Propaganda War: A Hi-Tech

Media Jihad.” The Guardian, October 7, 2014, sec. World

news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/07/

isis-media-machine-propaganda-war.

5. Milton, Daniel. 2016. ‘Communication Breakdown:

Unraveling the Islamic State’s Media Efforts’. Combating

Terrorism Center at West Point, p.V.

6. Carter, Joseph, Shiraz Maher, and Peter Neumann. 2014.

“#Greenbirds: Measuring Importance and Influence in

Syrian Foreign Fighter Networks.” International Centre for

the Study of Radicalisation. http://icsr.info/wp-content/

uploads/2014/04/ICSR-Report-Greenbirds-Measuring-

Importance-and-Infleunce-in-Syrian-Foreign-Fighter-

Networks.pdf. Jytte Klausen. 2015. ‘Tweeting the Jihad: Social

Media Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and

Iraq’, , 38:1.

7. Carter, Joseph, Shiraz Maher, and Peter Neumann. 2014.

“#Greenbirds: Measuring Importance and Influence in Syrian

Foreign Fighter Networks.” International Centre for the Study

of Radicalisation. http://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/

ICSR-Report-Greenbirds-Measuring-Importance-and-

Infleunce-in-Syrian-Foreign-Fighter-Networks.pdf; Jytte

Klausen. 2015. ‘Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media Networks of

Wester n Foreign Fighters i n Sy ria and Iraq,’

Ter ro ri sm , 38:1, p.19.

8. Jytte Klausen. 2015. ‘Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media

Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq,’

, 38:1, p.19.

9. Bodine-Baron, Elizabeth, Todd C. Helmus, Madeline

Magnuson, Zev Winkelman. 2016. “Examining ISIS Support

and Opposition on Twitter.” RAND Corporation. Berger,

J.M., and Jonathan Morgan. 2015. “The ISIS Twitter Census:

Defining and Describing the Population of ISIS Supporters on

Twitter.” Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/

wp-content/uploads/2016/06/isis_twitter_census_berger_

morgan.pdf.

10. Whiteside, Craig. 2016. “Lighting the Path: The Evolution of

the Islamic State Media Enterprise (2003-2016).” International

Centre for Counter-Terrorism - The Hague, p.26.

11. Milton, Daniel. 2016. ‘Communication Breakdown:

Unraveling the Islamic State’s Media Efforts.’ Combating

Terrorism Center at West Point, p.IV-V.

12. Joscelyn, Thomas. 2015. “Graphic Promotes the Islamic State’s

Prolific Media Machine.” . Accessed

November 25. http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/

2015/11/graphic-promotes-islamic-states-prolific-media-

machine.php. Also cited in Whiteside, Craig. 2016. “Lighting

the Path: The Evolution of the Islamic State Media Enterprise

(2003-2016).” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism -

The Hague, p.18.

13. Prucha, Nico. 2016. “IS and the Jihadist Information

Highway – Projecting Influence and Religious Identity via

Teleg ra m.” Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6), p.52 http://www.

terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/556.

14. Naturally, pro-IS propaganda infographics are not reliable

sources for statics. Even so, this example highlights IS’

eagerness to demonstrate its global reach. “Failure of the

Media War on the Islamic State” infographic. Yaqeen Media

Foundation, 2016.

15. Winter, Charlie. 2015. “‘Documenting the Virtual ‘Caliphate’:

Understanding Islamic State’s Propaganda,’” Quilliam Foundation.

16. Winter, Charlie. 2015. “‘Documenting the Virtual ‘Caliphate’:

Understanding Islamic State’s Propaganda,’” Quilliam Foundation.

17. In the month of Shawwal (July 17 to August 15, 2015),

IS-central released 892 unique items of propaganda. This,

according to Winter, was its peak. (This is compared to 570

individual media products between January 30 to February

28 in February, 2017.) Winter, Charlie. 2015. “Fishing and

Ultraviolence.” 2017. BBC News. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/

resources/idt-88492697-b674-4c69-8426-3edd17b7daed;

Lakomy, Miron. 2017. “Cracks in the Online “Caliphate”:

How the Islamic State is Losing Ground in the Battle for

Cyberspace.” Perspectives on Terrorism, 11 (3), p.47; Winter,

Charlie. 2017. “ICSR Insight: The ISIS Propaganda Decline”

Digital Decay? • 9

Audrey Alexander

. March 23; Milton also notes that IS released 700 official

video products in August 2015, only 200 were released

in August 2016. Milton, Daniel. 2016. ‘Communication

Breakdown: Unraveling the Islamic State’s Media Efforts’.

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point.

18. http://icsr.info/2017/03/icsr-insight-isis-propaganda-

decline/

19. Zelin, Aaron. 2015. “ICSR Insight - The Decline in Islamic

State Media Output / ICSR.” . December 4. http://icsr.

info/2015/12/icsr-insight-decline-islamic-state-media-output/.

20. Milton, Daniel. 2016. ‘Communication Breakdown:

Unraveling the Islamic State’s Media Efforts.’ Combating

Terrorism Center at West Point. p.21.

21. Mazzetti, Mark, and Michael R. Gordon. 2015. “ISIS Is

Winning the Social Media War, U.S. Concludes.” The

New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/13/

world/middleeast/isis-is-winning-message-war-us-

concludes.html. Koerner, Brendan. 2016. “Why ISIS

Is Winning the Social Media War—And How to Fight

Back.” WIRED, April. https://www.wired.com/2016/03/

isis-winning-social-media-war-heres-beat/.

22. Fischer, Ali. 2014. “Eye of the Swarm: The Rise of

ISIS and the Media Mujahedeen.”

Diplomacy. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/

eye-swarm-rise-isis-and-media-mujahedeen.

23. Milton, Daniel. 2016. ‘Communication Breakdown:

Unraveling the Islamic State’s Media Efforts.’ Combating

Terrorism Center at West Point, p.50.

24. Prucha, Nico. 2016. “IS and the Jihadist Information Highway

– Projecting Influence and Religious Identity via Telegram.”

Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6), p.54 http://www.terrorismana-

lysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/556.

25. Prucha, Nico. 2016. “IS and the Jihadist Information Highway

– Projecting Influence and Religious Identity via Telegram.”

Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6), p.54 http://www.terrorismana-

lysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/556.

26. Prucha, Nico. 2016. “IS and the Jihadist Information Highway

– Projecting Influence and Religious Identity via Telegram.”

Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6), p.54 http://www.terrorismana-

lysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/556.

27. Prucha, Nico. 2016. “IS and the Jihadist Information Highway

– Projecting Influence and Religious Identity via Telegram.”

Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6), p.56 http://www.terrorismana-

lysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/556.

28. Vidino, Lorenzo, Francesco Marone, and Eva Entenmann.

2017. “Fear Thy Neighbor Radicalization and Jihadists Attacks

in the West.” Program on Extremism, p.15-16.

29. Alexander, Audrey. 2017. “How to Fight ISIS Online.” Foreign

, April 7. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/

middle-east/2017-04-07/how-fight-isis-online.

30. United States v. Safya Roe Yassin, Criminal Complaint and

Affidavit (2016).

31. United States v. Safya Roe Yassin, Criminal Complaint and

Affidavit (2016).

32. United States v. Safya Roe Yassin, Criminal Complaint and

Affidavit (2016).

33. United States v. Safya Roe Yassin, Criminal Complaint and

Affidavit (2016).

34. Using a mix of evidence, Hughes and Meleagrou-Hitchens link

Elton Simpson to Junaid Hussain and Mohamed Abdullahi

Hassan (Mujahid Miski). For more information about the

nature of these communications, see: “Virtual Entrepreneurs”

Hughes, Seamus, and Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens. 2017.

“The Threat to the United States from the Islamic State’s

Virtual Entrepreneurs.” CTC Sentinel 10 (3). https://www.

ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-threat-to-the-united-states-from-

the-islamic-states-virtual-entrepreneurs.

35. “Virtual Entrepreneurs” Hughes, Seamus, and Alexander

Meleagrou-Hitchens. 2017. “The Threat to the United States

from the Islamic State’s Virtual Entrepreneurs.” CTC Sentinel

10 (3). https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-threat-to-the-

united-states-from-the-islamic-states-virtual-entrepreneurs.

36. Callimachi, Rukmini. 2015. “Clues on Twitter Show Ties

Between Texas Gunman and ISIS Network.” The New York

Times, May 11, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/

05/12/us/twitter-clues-show-ties-between-isis-and-garland-

texas-gunman.html. See also the account linked to Elton

Simpson, Sharia is Light (@atawaakul). “The bro with me and

myself have given bay’ah to Amirul Mu’mineen. May Allah accept

us as mujahideen. Make dua #texasattack,” May 3, 2015. Tweet.

37. Callimachi, Rukmini. 2015. “Clues on Twitter Show Ties

Between Texas Gunman and ISIS Network.” The New York

Times, May 11, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/

05/12/us/twitter-clues-show-ties-between-isis-and-garland-

texas-gunman.html.

38. “Virtual Entrepreneurs” Hughes, Seamus, and Alexander

Meleagrou-Hitchens. 2017. “The Threat to the United States

from the Islamic State’s Virtual Entrepreneurs.”

10 (3). https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-threat-to-the-

united-states-from-the-islamic-states-virtual-entrepreneurs.

39. Kang, Cecilia, and Matt Apuzzo. 2016. “U.S. Asks Tech and

Entertainment Industries Help in Fighting Terrorism.” The

New York Times, February 24. https://www.nytimes.com/

2016/02/25/technology/tech-and-media-firms-called-to-

white-house-for-terrorism-meeting.html.

40. “Partnering to Help Curb the Spread of Terrorist Content

Online.” 2016. Twitter Bl ogs. December 5. https://blog.

twitter.com/2016/partnering-to-help-curb-the-spread-of-

terrorist-content-online. Government TOS Reports - July to

December 2016.” 2017. https://transparency.twitter.com/en/

gov-tos-reports.html.

10 • The George Washington University Program on Extremism

Background

41. Berger, J.M., and Heather Perez. 2016. “The Islamic State’s

Diminishing Returns on Twitter: How suspensions are limit-

ing the social networks of English-speaking ISIS supporters.”

Program on Extremism. https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.

edu/files/downloads/Berger_Occasional%20Paper.pdf.

42. Whiteside, Craig. 2016. “Lighting the Path: The Evolution of

the Islamic State Media Enterprise (2003-2016).” International

Centre for Counter-Terrorism - The Hague, p.26.

43. Price, Bryan, and Muhammad al-‘Ubaydi. 2017. “CTC

Perspectives: The Islamic State’s Internal Rifts and Social Media

Ban.” . https://ctc.usma.

edu/posts/ctc-perspectives-the-islamic-states-internal-rifts-

and-social-media-ban.

44. Price, Bryan, and Muhammad al-‘Ubaydi. 2017. “CTC

Perspectives: The Islamic State’s Internal Rifts and Social Media

Ban.” . https://ctc.usma.

edu/posts/ctc-perspectives-the-islamic-states-internal-rifts-

and-social-media-ban.

Digital Decay? • 11

METHOD AND DESIGN

Similar to any study that uses social media as a means to

understand a movement, the following investigation faces

inherent limitations on the scope, transferability, and re-

liability of the dataset. By focusing on English-language

sympathizers on Twitter, a small but substantive sliver of

IS’ online activity, this report adds to a growing body of

research that uses social media as a lens to comprehend

the mobilization efforts of violent extremists worldwide.

From the outset of the project, the author has made a con-

certed effort to implement a design that strives to miti-

gate the effects of such drawbacks. In short, this report

presents analysis on a sample of data gleaned from the

Program on Extremism’s (PoE) broader initiative exam-

ining IS’ use of social media. The following section pro-

vides an in-depth description of the Program’s general

approach to data collection, and then identifies the par-

ticular segment of content interrogated in this report.

Design for Broader Initiative:

Tracking IS’ Use of Social Media in the West

PoE first launched the project investigating the various ef-

forts of English-speaking IS sympathizers on Twitter after

the publication of its December 2015 report

From Retweets to Raqqa. The approach uses a two-step data

collection method to build a substantive, time-bound cor-

pus of tweets by English-language accounts; as of May

2017, the resource contained about one million tweets from

nearly 3,000 accounts. While not a comprehensive snap-

shot of English-language activity on Twitter, this content

allows PoE to cross-examine a spectrum of questions about

IS supporters’ use of social media in the West.

Inspired by a range of studies on the efforts of IS in the

digital sphere, the Program’s mixed method approach

yields a wealth of data apt for qualitative and quantita-

tive analyses. Since the project’s conception, research as-

sistants,

1

under the supervision of PoE fellows and asso-

ciates,

2

have been using open source practices to collect

a snowball sample of English-language accounts exud-

ing pro-IS sentiment via organic content and retweets.

3

When Twitter accounts satisfy the study’s predetermined

criteria,

4

researchers document the user’s name, handle,

link, location, and bio in a spreadsheet and archive digital

records in select circumstances.

5

Although focusing on English-language sympathizers on

Tw i t t er i n h eren t l y l i m i t s t he t r a n s fe r a bi l i t y o f t he s t u d y, t h e

author adopted this approach to build a manageable dataset

and streamline language requirements for the various cod-

ers identifying pro-IS accounts. Moreover, the connection

between IS in Iraq and Syria and its diaspora of sympathiz-

ers in the West requires rigorous examination, creating an

opportunity for more targeted analysis. On Twitter espe-

cially, this approach remains relevant due to IS’ prioritiza-

tion of non-Arabic content, particularly in English.

6

With the support of software developers in the Scholarly

Technology Group (STG)

7

of the George Washington

University Libraries, PoE collects and analyzes con-

tent produced by the running list of IS sympathizers on

Twitter. These accounts are difficult to monitor because

of Twitter’s ongoing efforts to suspend users that violate

their terms of service. To complement manual record

keeping, PoE uses software to archive content produced

by this sample of Twitter accounts around the clock.

Several times a week,

8

the author adds the latest iteration

of newly identified pro-IS handles to a running list of ac-

counts monitored by

Social Feed Manager (SFM),

9

open

source software developed by GWU Libraries. SFM cap-

tures raw data using Twitter’s Application Programming

Interface (API).

10

Every 30 minutes, SFM harvests tweets

posted by accounts that are still active.

11

In addition to the

sheer number of tweets collected by SFM, PoE benefits

from SFM’s collection of each tweet’s complete metadata -

providing investigators access to a wealth of information

that is not visible on Twitter’s web or mobile interface.

12

By saving the tweets as structured data, SFM captures it

in a form that is well-suited for quantitative analysis.

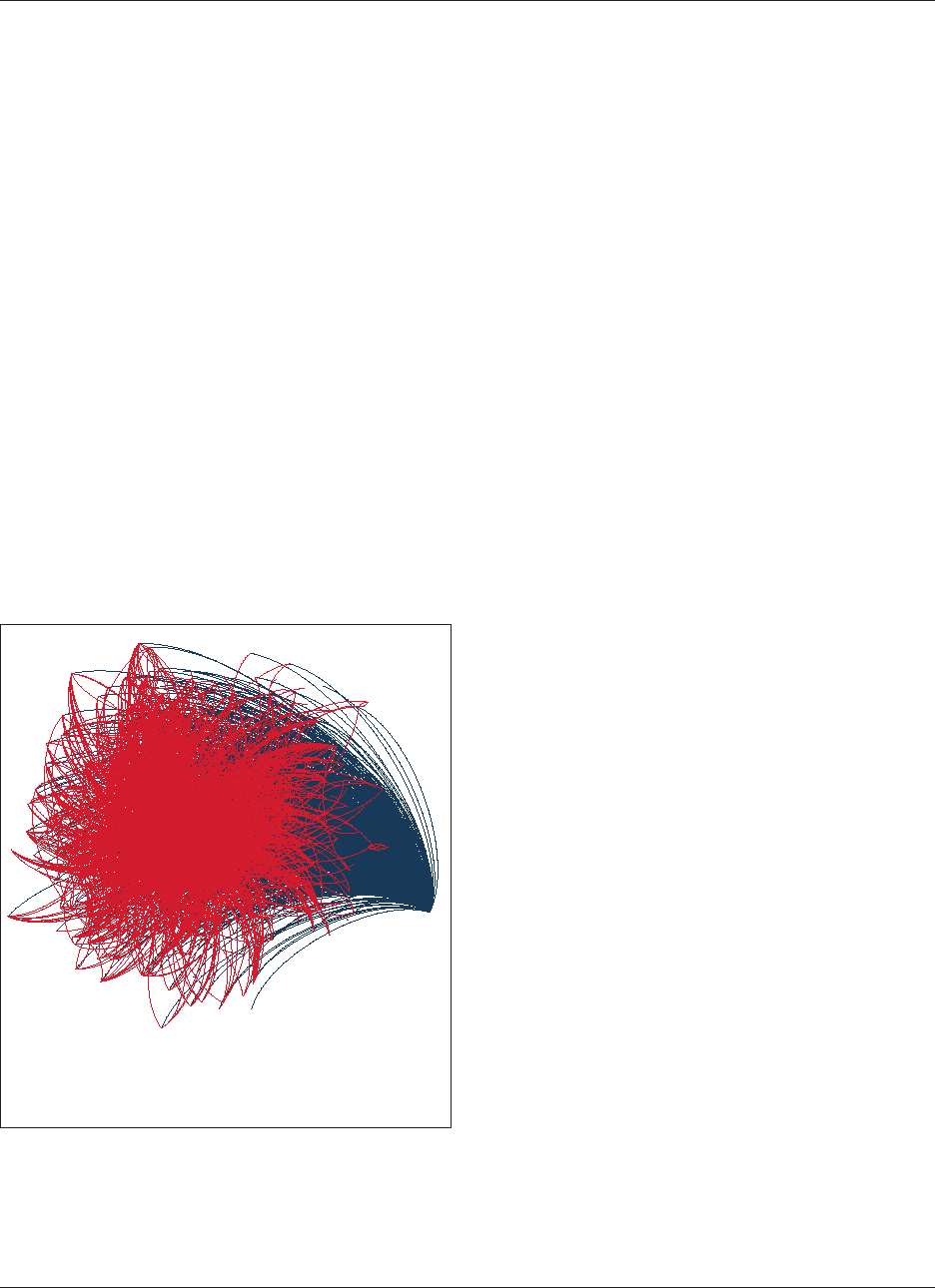

Next, STG maintains a flow of PoE data from SFM

to a data exploration environment where researchers

12 • The George Washington University Program on Extremism

Method and Design

can interact with the data using the

Kibana interface. The Kibana interface

is part of an ElasticStack (Elasticsearch,

Logstash, Kibana) server that has been

customized for examining social me-

dia data,

13

making it easy for analysts to

see graphics such as ‘tweet frequency’ or

‘top-ten hashtags’ (See Kibana image).

ElasticStack is a general-purpose frame-

work for exploring data and provides

support for loading, querying, analyz-

ing, and visualizing. SFM’s ElasticSearch

receives a continual stream of tweets as

they are collected by SFM, allowing PoE

to investigate the data in exciting ways

using custom analytics.

Method Employed in This Report

Rather than focusing on the full dataset, which includes a

sharp increase at the beginning due to project implementa-

tion, this report conducts a comprehensive analysis of a

63-week section of tweets ranging from February 15, 2016

at 00:00:00 to May 1, 2017 at 00:00:00. This sample con-

tains 845,646 tweets produced by 1,782 unique accounts of

English-language IS sympathizers on Twitter.

14

The au-

thor selected this time series because it encapsulates a sus-

tained period of account collection that lasts over one year.

This sample also divides neatly into three chronological

21-week segments (see Figure 3), which allows the parti-

tioning of data for comparative analysis of the first, second,

and third part of the dataset.

15

Despite efforts to mitigate these challenges, the most nota-

ble impediments to the comprehensiveness of the sample

stem from project design and implementation. The conti-

nuity of account selection, for example, is imperfect due

to the schedule of staff and volunteer research assistants

who could not devote the same amount of time to data

collection every day during the 63-week period. Twitter’s

regulations and efforts to suspend accounts that violate

their terms of service also appears to curb the quantity

February 15, 2016

February 22, 2016

February 29, 2016

March 7, 2016

March 14, 2016

March 21, 2016

March 28, 2016

April 4, 2016

April 11, 2016

April 18, 2016

April 25, 2016

May 2, 2016

May 9, 2016

May 16, 2016

May 23, 2016

May 30, 2016

June 6, 2016

June 13, 2016

June 20, 2016

June 27, 2016

July 4, 2016

July 11, 2016

July 18, 2016

July 25, 2016

August 1, 2016

August 8, 2016

August 15, 2016

August 22, 2016

August 29, 2016

September 5, 2016

September 12, 2016

September 19, 2016

September 26, 2016

October 3, 2016

October 10, 2016

October 17, 2016

October 24, 2016

October 31, 2016

November 7, 2016

November 14, 2016

November 21, 2016

November 28, 2016

December 5, 2016

December 12, 2016

December 19, 2016

December 26, 2016

January 2, 2017

January 9, 2017

January 16, 2017

January 23, 2017

January 30, 2017

February 6, 2017

February 13, 2017

February 20, 2017

February 27, 2017

March 6, 2017

March 13, 2017

March 20, 2017

March 27, 2017

April 3, 2017

April 10, 2017

April 17, 2017

April 24, 2017

February 15, 2016—July 11, 2016 July 11, 2016—December 5, 2016 December 5, 2016—May 1, 2017

SEGMENT A SEGMENT B SEGMENT C

Breakdown of Time Segments

Digital Decay? • 13

Audrey Alexander

and visibility of pro-IS content available for collection and

analysis. Additionally, while Twitter’s metadata provides

investigators countless opportunities, some useful vari-

ables like location and gender setting of each account is ei-

ther unattainable or unreliable. Such barriers and caveats

receive additional attention in subsequent analysis.

Despite key constraints and the narrow scope of the study,

this dataset allows PoE to test for digital decay over time

among a select demographic of IS supporters on Twitter.

After presenting some initial observations and the decline

in tweet frequency, this report poses one primary and

three supplementary questions to examine how English-

language IS sympathizers on Twitter fare in the face of

online and offline initiatives aimed at weakening the

wider movement.

16

The author selected these questions

from a running list of relevant inquiries that demand

further examination. Using Kibana, the above mentioned

data visualization interface, and a range of tools including

Python, Google Sheets, and Gephi, the study presents the

data and a wide range of findings that pertain to the lim-

inal space between IS’ centralized and decentralized ef-

forts on Twitter. Though dense and technical at times, the

following discussion presents key findings in a nuanced

but accessible way. Many of the graphs, for example, use

the square root on the y-axis to more clearly demonstrate

the relationship of different variables. In other instances,

observations are cross-examined with existing research

to highlight the data’s convergence and divergence with

existing lines of logic.

Notes

1. Special thanks to all the Research Assistants who helped build

PoE’s Twitter database, including: Adib Milani, Armand Jhala,

William Kiely, Graham Raby, Jacob Chereskin, Alexander

Bierman, Helen Powell, Sarah Kells, Nick Gallucci, Dillon

McGreal, Marco Olimpio, Ethan Santangelo, Jessie Gimpel,

Andrea Moneton, Sneha Bolisetty, Tinshan Fullop, Andrew

Walsh, Cole Swaffield, Sam Riccardi, Dan Heesemann.

2. PoE Research Fellows include Bennett Clifford and Katerina

Papatheodorou, and Research Associates include Prachi Vyas

and Sarah Gilkes.

3. In an effort to standardize the project’s data collection

process, research assistants receive extensive training and

ongoing supervision.

4. To be transparent, the author will further explain the account

selection criteria in the appendix.

5. Researchers archive accounts in a shared storage drive if they

meet at least one of the following benchmarks: If the user is

likely (or certainly) an American, if the user provides com-

mentary on U.S. domestic events or Western foreign policy,

if their kunya (a nom de guerre) contains “al-Amriki” (“the

American”), if they locate themselves within the U.S., if they

claim to be in ISIS-controlled territory, if he/she posts original

pro-ISIS content useful for media purposes, if the account has

more than 350 followers.

6. Fernandez, Alberto. 2015. “Here to Stay and growing:Combat-

ing ISIS Propaganda Networks.” The Brookings Project on U.S.

Relations with the Islamic World U.S.-Islamic World Forum

Papers 2015. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/

wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IS-Propaganda_Web_English.pdf.

7. For more information about the Scholarly Technology

Group, see https://library.gwu.edu/scholarly-technology.

8. In some instances, accounts are shut down between the time

they are added to PoE’s dataset and fed into SFM. Consequently,

the number of unique accounts in PoE’s social media database

is greater than the number of accounts monitored by SFM.

Though unfortunate, the author does not believe this limitation

undermines the dataset as the majority of accounts are repre-

sented in both the social media database and SFM.

9. For more information on Social Feed Manager (SFM), visit

https://gwu-libraries.github.io/sfm-ui/

10. An Application Programming Interface (API) is a set of com-

mands, functions, protocols, and objects that programmers

can use to create software or interact with an external system.

11. In these cases, PoE’s manual collection method and record keep-

ing complement SFM’s automated process. For example, Twitter

limits the amount of data that it provides through the API, but

PoE’s screenshots helps capture content SFM cannot collect. In

some instances, PoE preserves records of accounts that are shut

down after researchers add it to the internal database but before

it is added to SFM. When a new account is added to SFM, the

Tw it t er AP I prov i de s SFM w i t h da t a in J SON for m at f or t he

account’s most recent 3,200 Tweets. Upon subsequent harvests,

SFM captures any new content produced by the user so long as

the account is active and public. If the account is made protected

(private), deactivated by the user, or suspended by Twitter, SFM

cannot harvest new content from the account.

12. For a description of the metadata contained in a tweet, see

https://dev.twitter.com/overview/api/tweets

13. The ELK Stack is a collection of three open-source products:

Elasticsearch, Logstash, and Kibana. Elasticsearch is a NoSQL

database that is based on the Lucene search engine. Logstash

is a log pipeline tool that accepts inputs from various sources,

executes different transformations, and exports the data to

various targets. Lastly, Kibana is a visualization layer that

works on top of Elasticsearch.

14 • The George Washington University Program on Extremism

Method and Design

14. For the sake of clarity, the number of accounts is calculated

using the number of unique usernames rather than unique

Twitter ID numbers.

15. Segment A spans from February 15, 2016 to July 11, 2016;

Segment B spans from July 11, 2016 to December 5, 2016;

Segment C spans from December 5, 2016 to May 1, 2017.

16. Question 1: How have Twitter’s counter-extremism policies

affected English-language IS sympathizers on the platform?;

Question 2: How do English-language IS sympathizers engage

with on-the-ground IS activity over time?; Question 3: How

do terrorist attacks drive discourse among English-language

IS sympathizers on Twitter?; Question 4: How do current

events influence the activity of English-language IS sympa-

thizers on Twitter?

Digital Decay? • 15

ANALYSIS OF ENGLISH-LANGUAGE IS SYMPATHIZERS ON TWITTER

Digital Decay? • 15

Due to the relative anonymity afforded by Twitter, it is

challenging to speculate about the entities operating be-

hind the 1,782 accounts discussed in this report. Even so,

the data suggest that there is tremendous diversity among

English-language sympathizers on Twitter, with accounts

tweeting from nearly every time zone.

1

For the most part,

accounts adopt demographically ambiguous usernames,

though some allude to factors like gender, nationality, and

familial status, hinting at a disparate array of IS adherents

that defy categorization. In every instance, it is difficult to

discern the authenticity of pro-IS accounts, and thus, the

sincerity of the actors operating them.

IS’ international base of adherents uses multiple lan-

guages to engage with and support the organization

online. Despite emphasizing content produced by

English-language sympathizers on Twitter, PoE’s data

demonstrates the diversity of users on the platform.

Unsurprisingly, over 87 percent of the sample set English

as the primary language of their account; however, tweets

posted by these accounts are not exclusively in English.

2

The other 13 percent represent 16 different languages

ranging from German

and Danish to Indonesian

and Chinese. Indonesian

makes up about 2.7 per-

cent of accounts, the

second most common

language in the dataset.

Somewhat surprisingly,

accounts with Arabic as

their primary language

amassed less than half

a percent. Within the

content produced by this

swathe of accounts tweet-

ing in English, the trans-

literation of Arabic words,

Islamic terms, and jihadi

phraseology are standard.

Accounts that employ

colloquial transliteration and words like ‘coconuts’

3

and

’

4

hark on religiopolitical concepts, actively defin-

ing membership to the English-language IS communi-

ty on Twitter. This demographic, and trends regarding

their use of Twitter over time, receive in-depth analysis

in the following discussion.

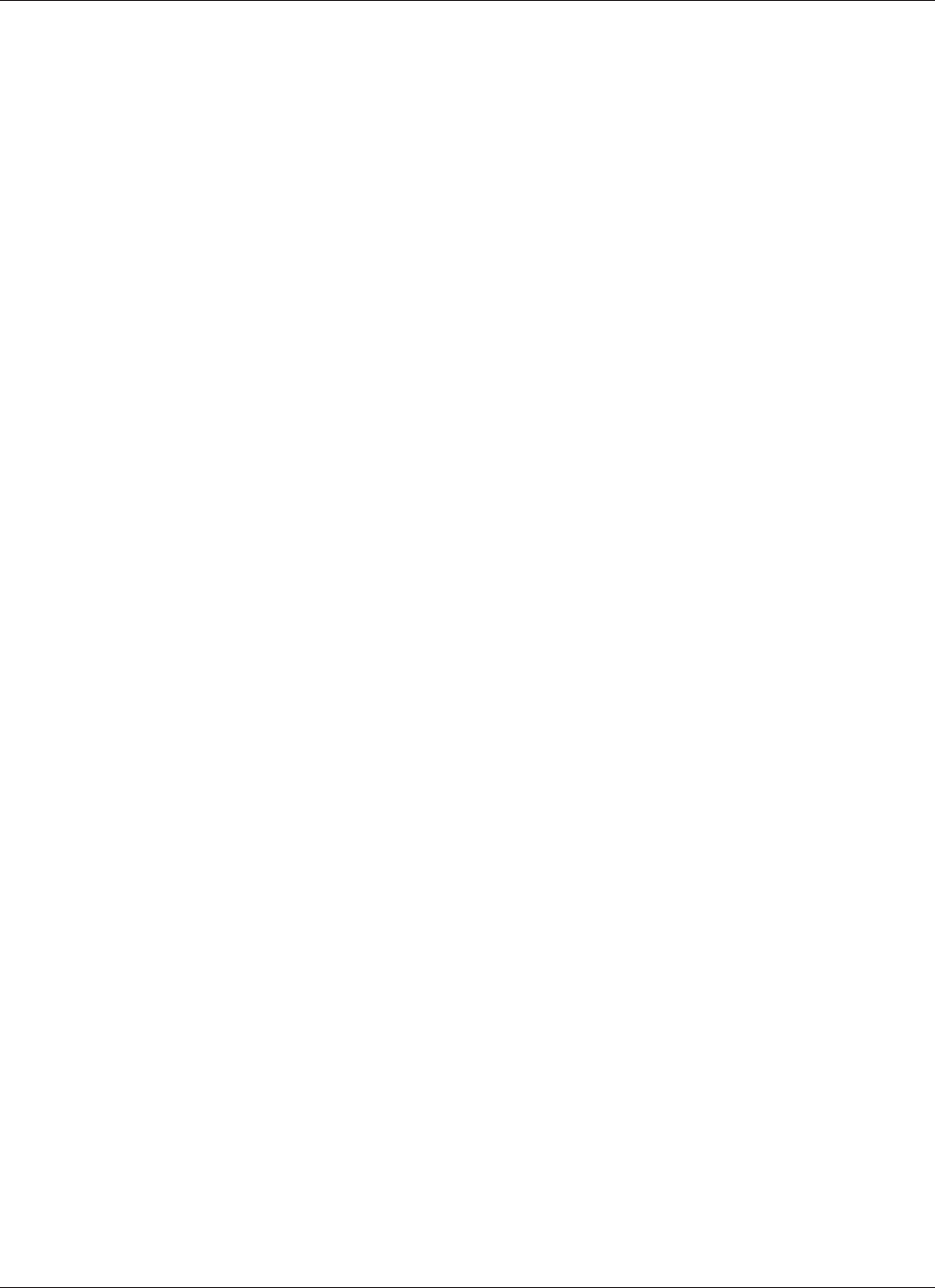

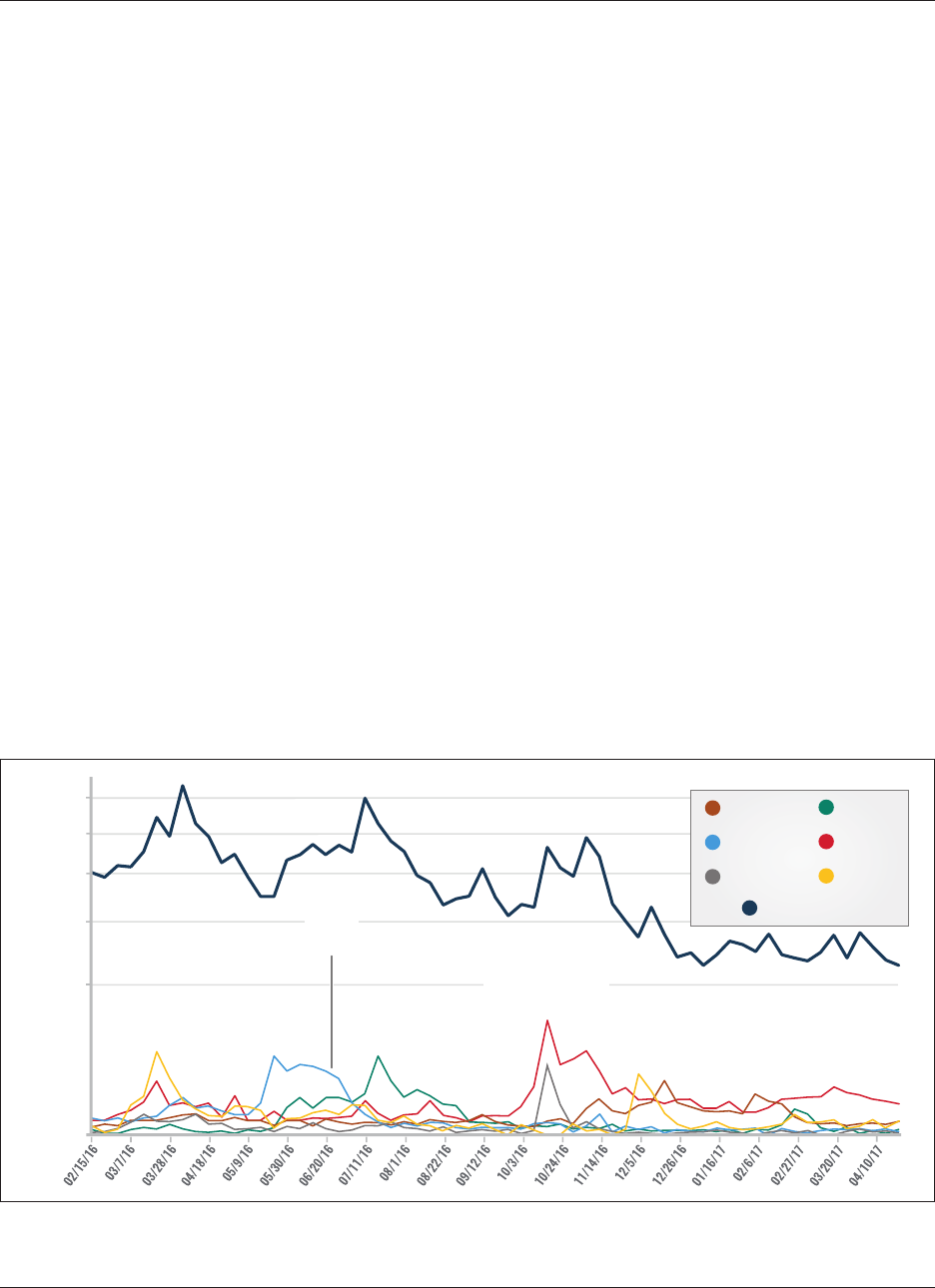

There are many ways to examine change over time in online

networks. This graph (Figure 4) demonstrates one initial

finding: despite notable fluctuations from week to week,

there is a dramatic decline in tweet frequency by English-

language IS sympathizers on Twitter. From the most active

week to the least active week, there is a 76 percent fall in the

number of tweets per week.

5

Though interesting, the sheer

amount of content disseminated by English-language sym-

pathizers on Twitter is only one measure of change over

time. This numerical decline is not a wholly reliable indi-

cator in isolation: for example, accounts with fewer tweets

may still be more impactful if they are seen by a greater

number of followers. As Ali Fisher notes in a blog post on

interpreting data about IS online, “this type of tactical-level

data can indicate success” in the online fight against IS, but

30,000

20,000

10,000

0

Tweet Count

Trendline for Tweet Count

Tweet Count Per Week

16 • The George Washington University Program on Extremism

Analysis of English-Language IS Sympathizers on Twitter

a more “robust interpretation of data at the strategic level”

is necessary.

6

With this point in mind, the subsequent sec-

tions strive to provide a mix of tactical-, operational-, and

strategic-level analyses.

The following discussion breaks into two analytical sec-

tions. The first strives to answer the question, ‘How have

Tw it te r’s c ou nte r- ex t re mi sm p olic ie s a f fe cted Eng li sh-

language IS sympathizers on the platform?’ With the ini-

tial findings in mind, the second section pursues three al-

ternative paths of inquiry to probe how English-language

IS sympathizers engage with matters in the real world,

especially in light of internal and external dynamics that

guide their behavior on Twitter. Even though it is difficult

to ascertain the precise impact of each cause, particularly

as the various factors may accentuate each other’s effects,

this report strives to determine the key elements shaping

activity by English-language IS sympathizers on Twitter.

Section 1: Key Question and Analysis

How have Twitter’s counter-extremism policies aected

English-language IS sympathizers on the platform?

Twitter’s mounting efforts to suspend accounts that

threaten or promote terrorism correlate with the decline

in tweet frequency found in PoE’s sample of English-

language IS sympathizers. As cited in the introduction,

Twitter “suspended a total of 636,248 accounts” between

August 1, 2015, and December 31, 2016.

7

These users

hailed from multiple extremist persuasions but an of-

ficial blogpost from Twitter asserted that the accounts

were “primarily related to ISIS.”

8

Although Twitter does

not necessarily report its rates of suspension, the compa-

ny published total figures on three separate occasions.

9

The estimates derived from these numbers and the cor-

responding dates reveal a substantial increase in the av-

erage number of accounts suspended per day, particularly

in 2016.

10

With these approximations alone, it is hard to

deduce the precise strategy or chronological implemen-

tation of a more robust initiative to suspend accounts.

Additionally, in a similar fashion to the decline in tweet

frequency, a numerical decline in accounts does not nec-

essarily translate to a reduction in reach.

As articulated in the methodology section, PoE strived to

maintain a consistent level of effort to supply SFM with

a continuous stream of English-language IS sympathiz-

ers’ accounts. This process became increasingly difficult

over the span of several months as accounts that met the

predetermined criteria began to disappear. Anecdotally,

the project manager noticed that a growing number of

accounts became inactive, likely due to suspension, with-

in the short window of time between account selection

and adding the new accounts to SFM.

11

As a result, PoE’s

data collection method may have inadvertently biased the

sample against exceptionally short-lived accounts, partic-

ularly those lasting only a few hours. While difficult to

parse out, it is crucial to consider how this might affect

the following analysis, especially in the context of coordi-

nated media campaigns utilizing Twitter.

Accounts, Tweet Frequency, and

Duration of Activity

Throughout the 63-week period used in this study, SFM

recorded content by 1,782 unique usernames . In the first

third of the dataset, SFM gleaned data from an average of

307 accounts per week. By the last third of the time se-

ries, this average dropped by nearly fifty percent as SFM

collected data from about 155 accounts per week. These

figures give little insight on the enduring centrality or

connectivity of the movement (or perhaps lack thereof),

but receive additional attention later in the discussion.

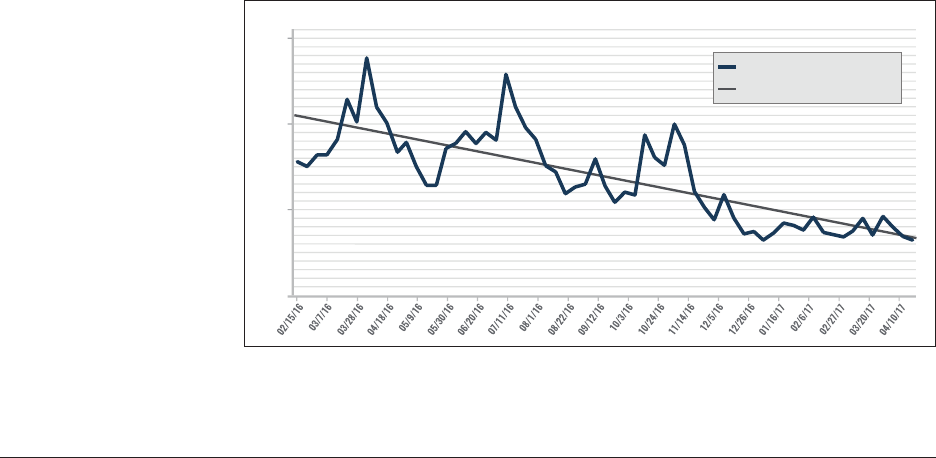

The fall in tweet frequency relates to the decline in the

number of active accounts collected by SFM each week

(See Figure 5).

12

During the 63-week period, 1,782 distinct

usernames tweeted at an average rate of approximately 56

tweets per week. In the last third of the dataset, the aver-

age number of tweets per week by account fell compared

to the first two-thirds of the time series. Although this

change was not dramatic, an observation supported by

basic calculations and likely subject to the pull of outliers,

it might suggest that English-language IS sympathizers on

Twitter share less content per week over time. One con-

tributing factor might be the migration of users to other

platforms, but no singular cause has led to this decline.

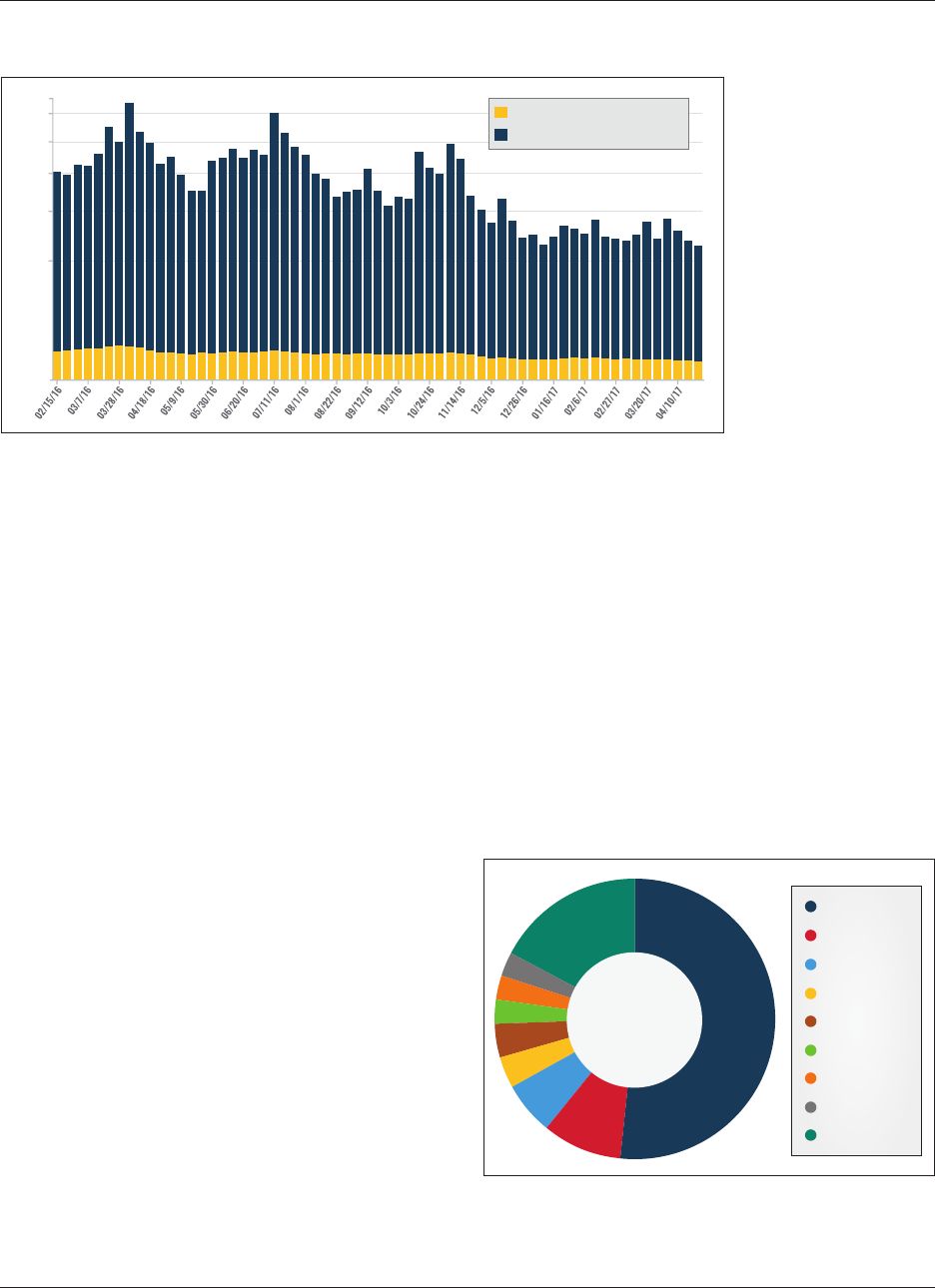

The duration of account activity is another factor that

requires consideration. In this context, a user’s ‘duration

Digital Decay? • 17

Audrey Alexander

of activity’ is quantified by the number of days between

an account’s first and last tweet. Twitter’s API does not

discern the date or time at which the company suspends

accounts, nor does it identify accounts that were created

and then subsequently abandoned by their respective us-

ers. Consequently, this measurement allows the study to

grasp the chronological span of sympathizers that actively

use the platform to share content. While overwhelmingly

skewed by outliers, the average lifespan for this sample

of English-language pro-IS accounts on Twitter was 251

days. It is critical to note, however, that dispersion of lifes-

pan is highly concentrated (see Figure 6). Approximately

51.7 percent of accounts did not remain active longer than

50 days. On the other hand, however, a substantive portion

of accounts lasted over a year, suggesting that Twitter’s at-

tempts to detect and suspend pro-IS account may be miss-

ing some long-term users. One possible explanation for

long-standing users relates to the data collection meth-

od, as researchers are more likely to identify accounts the

longer they are open.

13

Ultimately, accounts that opted to

leave the platform are likely included in this breakdown,

although multiple factors- including the threat of suspen-

sion- likely affect user activity in this regard.

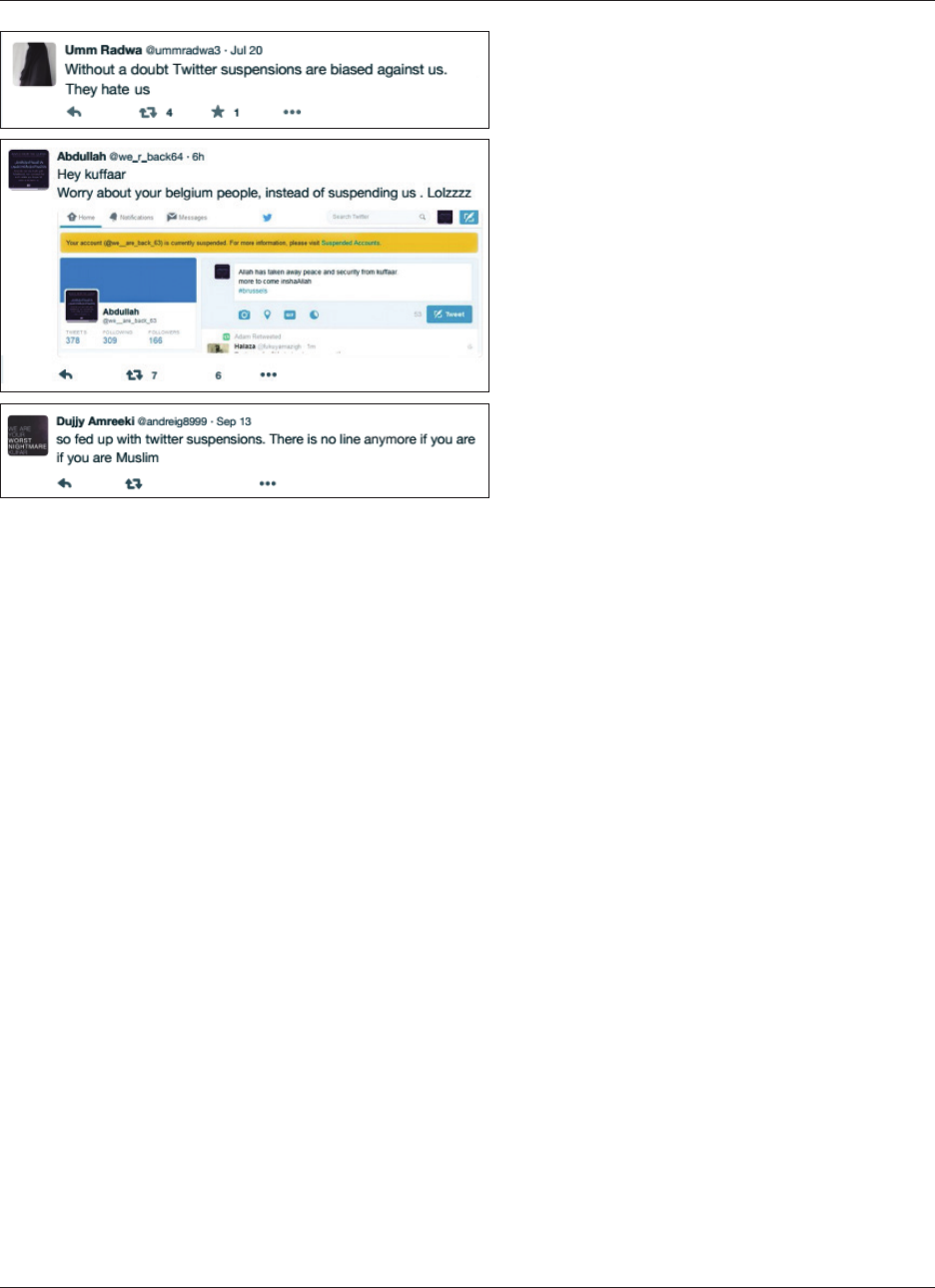

In order to maintain their presence on Twitter, some

English language IS sympathizers appeared to have created

multiple accounts at the same time to avoid shutdowns. On

February 17, 2016, for example, four separate accounts were

fashioned from a core handle,

14

possibly from the same

individual. One account (@erhabi35) survived only eight

days, whereas another account (@Erhabi39) stayed active

for 62 days. Although the study attempted to annotate cases

where the same individual controlled multiple accounts, as

the trend is common, quantitative figures are generally not

reliable due to the relative anonymity Twitter affords users.

It is hard to ascertain whether users that demonstrate simi-

lar behavioral patterns are simply individuals attempting to

inoculate their digital presence against suspensions or are

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

Unique Count of Screen Name

Number of Tweets

0-50 Days

51-100 Days

101-150 Days

151-200 Days

201-250 Days

251-300 Days

301-350 Days

351-400 Days

*Over 401 Days

51.7%

16.9%

4.0%

6.1%

9.5%

shows how the relationship

per week changed over

like several others in the

represent the relationship

Tweet Frequency and Unique Screen Names By Week

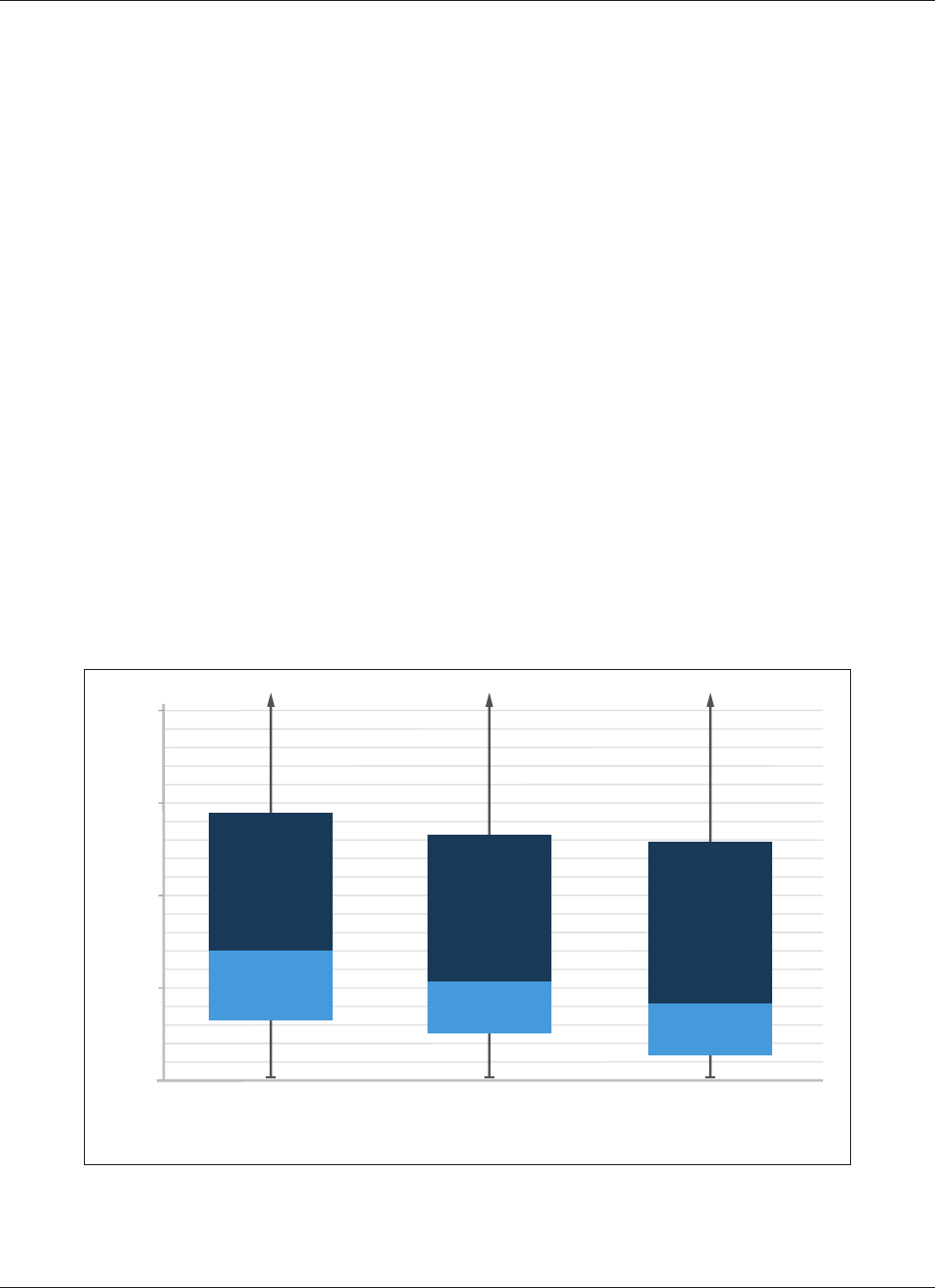

(Figure 6) This chart depicts the duration of account activity,

meaning the number of days a pro-IS Twitter account was