Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Recommendations and Reports November 11, 2005 / Vol. 54 / No. RR-13

INSIDE: Continuing Education Examination

depardepar

depardepar

depar

tment of health and human sertment of health and human ser

tment of health and human sertment of health and human ser

tment of health and human ser

vicesvices

vicesvices

vices

Centers for Disease Control and PreventionCenters for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and PreventionCenters for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Good Laboratory Practices

for Waived Testing Sites

Survey Findings from Testing Sites Holding

a Certificate of Waiver Under the Clinical

Laboratory Improvement Amendments

of 1988 and Recommendations

for Promoting Quality Testing

MMWR

CONTENTS

Introduction......................................................................... 1

Background ......................................................................... 2

Surveys of Waived Testing Sites ........................................... 4

Recommended Good Laboratory Practices ........................... 8

Conclusions ....................................................................... 19

Acknowledgments ............................................................. 19

References......................................................................... 19

Terms and Abbreviations Used in this Report ..................... 22

Continuing Education Activity ......................................... CE-1

The MMWR series of publications is published by the

Coordinating Center for Health Information and Service,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA 30333.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Julie L. Gerberding, MD, MPH

Director

Dixie E. Snider, MD, MPH

Chief Science Officer

Tanja Popovic, MD, PhD

Associate Director for Science

Coordinating Center for Health Information

and Service

Steven L. Solomon, MD

Director

National Center for Health Marketing

Jay M. Bernhardt, PhD, MPH

Director

Division of Scientific Communications

Maria S. Parker

(Acting) Director

Mary Lou Lindegren, MD

Editor, MMWR Series

Suzanne M. Hewitt, MPA

Managing Editor, MMWR Series

Teresa F. Rutledge

(Acting) Lead Technical Writer-Editor

David C. Johnson

Project Editor

Beverly J. Holland

Lead Visual Information Specialist

Lynda G. Cupell

Malbea A. LaPete

Visual Information Specialists

Quang M. Doan, MBA

Erica R. Shaver

Information Technology Specialists

SUGGESTED CITATION

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Good laboratory

practices for waived testing sites; survey findings from testing

sites holding a certificate of waiver under the Clinical Laboratory

Improvement Amendments of 1988 and Recommendations

for Promoting Quality Testing. MMWR 2005;54(No. RR-13):

[inclusive page numbers].

Vol. 54 / RR-13 Recommendations and Reports 1

Good Laboratory Practices for Waived Testing Sites

Survey Findings from Testing Sites Holding a Certificate of Waiver

Under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments

of 1988 and Recommendations for Promoting Quality Testing

Prepared by

Devery Howerton, PhD, Nancy Anderson, MMSc, Diane Bosse, MS, Sharon Granade, Glennis Westbrook

Division of Public Health Partnerships, National Center for Health Marketing, Coordinating Center for Health Information and Service

Summary

Under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), simple, low-risk tests can be waived and per-

formed with no routine regulatory oversight in physicians’ offices and various other locations. Since CLIA was implemented,

waived testing has steadily increased in the United States. Surveys conducted during 1999–2004 by the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services and studies funded by CDC during 1999–2003 evaluated testing practices in sites holding a CLIA Certificate

of Waiver (CW). Although study findings indicate CW sites generally take measures to perform testing correctly, they raise quality

concerns about practices that could lead to errors in testing and poor patient outcomes. These issues are probably caused, in part,

by high personnel turnover rates, lack of understanding about good laboratory practices, and inadequate training. This report

summarizes study findings and provides recommendations developed by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Advisory Commit-

tee for conducting quality waived testing. These recommendations include considerations before introducing waived testing, such

as management responsibility for testing, regulatory requirements, safety, physical and environmental requirements, benefits and

costs, staffing, and documentation. They also cover good laboratory practices for the three phases of testing: 1) before testing (test

ordering and specimen collection), 2) during testing (control testing, test performance, and result interpretation and recording),

and 3) after testing (result reporting, documentation, confirmatory testing, and biohazard waste disposal). They are intended to

be used by those who would benefit from improving their knowledge of good laboratory practices. Continued monitoring of

waived testing, with a focus on personnel education and training, is needed to improve practices and enhance patient safety as

waived testing continues to increase.

devices that are waived from most federal oversight require-

ments (and are thus designated as waived tests), including

requirements for personnel qualifications and training, qual-

ity control (QC) (unless specified as required in the test sys-

tem instructions), proficiency testing (PT), and routine quality

assessment.

Advances in technology have made tests simpler, contribut-

ing to this shift in testing. In the past, tests such as prothrom-

bin time, cholesterol, and glucose either used complex manual

methodologies or were performed using sizable instrumenta-

tion suitable for use by highly trained personnel in traditional

clinical laboratory settings. Many tests can now be performed

using compact or hand held devices by personnel with lim-

ited experience and training. These advances have enabled more

testing to be performed in emergency departments, hospital

rooms, and physicians’ offices and in nontraditional testing

sites such as community counseling centers, pharmacies, nurs-

ing homes, ambulances, and health fairs. Since the 1992

inception of the program implementing the Clinical Labora-

tory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), the num-

bers of waived tests and the sites that perform them have

Introduction

Laboratory testing plays a critical role in health assessment,

health care, and ultimately, the public’s health. Test results

contribute to diagnosis and prognosis of disease, monitoring

of treatment and health status, and population screening for

disease. Laboratory testing affects persons in every life stage,

and almost everyone will experience having one or more labo-

ratory tests conducted during their lifetime. An estimated 7–10

billion laboratory tests are performed each year in the United

States (1,2), and laboratory test results influence approximately

70% of medical decisions (2–4). Increasingly, these decisions

are based on simple tests performed at the point-of-care using

The material in this report originated in the Coordinating Center for

Health Information and Service, Steven L. Solomon, MD, Director;

National Center for Health Marketing, Jay M. Bernhardt, PhD,

Director; and the Division of Public Health Partnerships, Robert

Martin, DrPH, Director.

Corresponding author: Devery Howerton, PhD, National Center for

Health Marketing, Coordinating Center for Health Information and

Service; 4770 Buford Hwy NE, MS G-23, Atlanta, GA, 30341. Telephone:

770-488-8126; Fax: 770-488-8275; Email: [email protected].

2 MMWR November 11, 2005

increased dramatically. This trend is expected to continue as

laboratory testing technology continues to evolve.

The purpose of this report is to highlight quality issues iden-

tified in waived testing sites on the basis of surveys conducted

on-site by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

(CMS) during 1999–2004 and studies of waived testing prac-

tices funded through CDC during 1999–2003. In addition,

this report presents recommendations developed by the Clini-

cal Laboratory Improvement Advisory Committee (CLIAC)

for improving the quality of waived testing. By following these

recommendations, errors that could potentially lead to

patient harm and the associated morbidity and mortality can

be prevented.

Background

CLIA Requirements for Waived Testing

All facilities in the United States that perform laboratory

testing on human specimens for health assessment or the

diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of disease are regulated

under CLIA (5). The CLIA program is administered by CMS

and is implemented through three federal agencies—CDC,

CMS, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). When

CLIA was implemented in 1992, CLIAC was chartered to

provide scientific and technical advice and guidance to the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) about

laboratory standards and their impact on medical and labora-

tory practice. The committee consists of 20 members selected

by the HHS secretary from authorities knowledgeable in the

fields of laboratory medicine, pathology, public health, and

clinical practice and includes consumer representatives and

an industry liaison. CLIAC also includes three ex officio mem-

bers from CDC, CMS, and FDA.

By law, CLIA regulations are based on a complexity model,

with more complicated testing subject to more stringent

requirements (6). The three categories of testing for CLIA pur-

poses are waived, moderate complexity (including the provider-

performed microscopy procedures [PPMP] subcategory), and

high complexity. Facilities performing only waived tests have

no routine oversight and no personnel requirements and are

only required to obtain a Certificate of Waiver (CW), pay bien-

nial certificate fees, and follow manufacturers’ test instructions.

Tests can be waived under CLIA if they are determined to

be “simple tests with an insignificant risk of an erroneous result”

(5). Eight tests were included in the 1992 CLIA regulations

(a ninth test was subsequently added) as meeting these crite-

ria and later, the FDA Modernization Act of 1997 clarified

that tests cleared by FDA for home use are automatically

waived. An additional route to waiver exists through a process

in which FDA evaluates studies and other information sub-

mitted by manufacturers to demonstrate that a test meets the

waiver criteria of being simple and having a low risk for error.

Approximately 1,600 test systems representing at least 76

analytes are waived under CLIA (Table 1).

Scope of Waived Testing

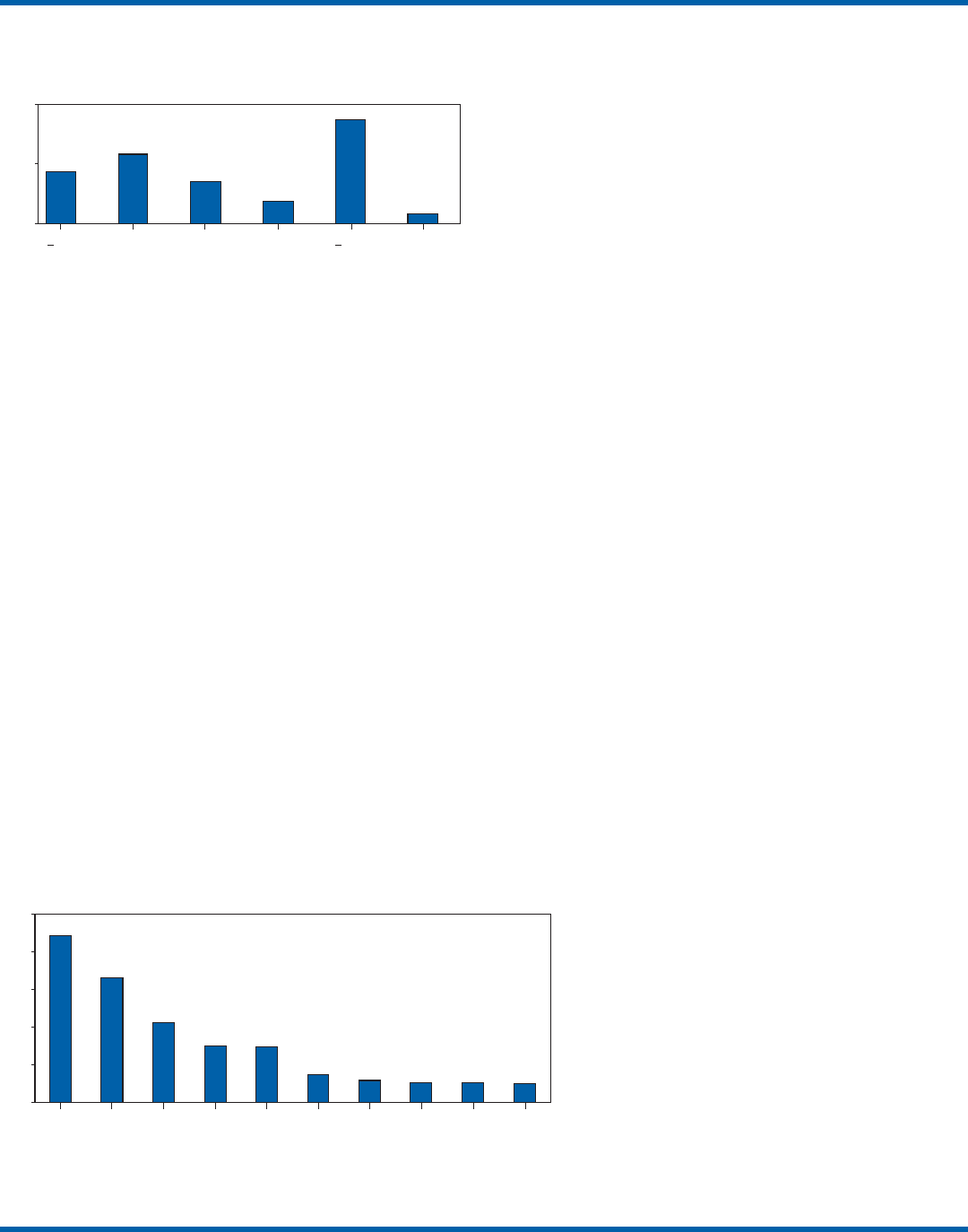

Sites performing only waived tests comprise 58% (105,138)

of the approximately 180,000 laboratory testing sites in the

United States (Table 1, Figure 1). Waived testing performed

in these sites is often wellness testing, screening tests, or other

critical testing that introduces a large population of persons

into the health-care setting. Although the testing performed

in CW sites accounts for <10% of the total U.S. testing vol-

ume, this percentage has been increasing each year since the

CLIA program began (Table 1). Most testing is not waived

and is typically performed in hospital or reference laborato-

ries (Certificate of Compliance and Certificate of Accredita-

tion), which comprise 20% of the total number of testing

sites (Figure 1). The remaining testing sites (22%) have PPMP

certificates, meaning that in addition to waived tests, direct

microscopic examinations of certain specimens can be per-

formed as part of the patient’s examination by that patient’s

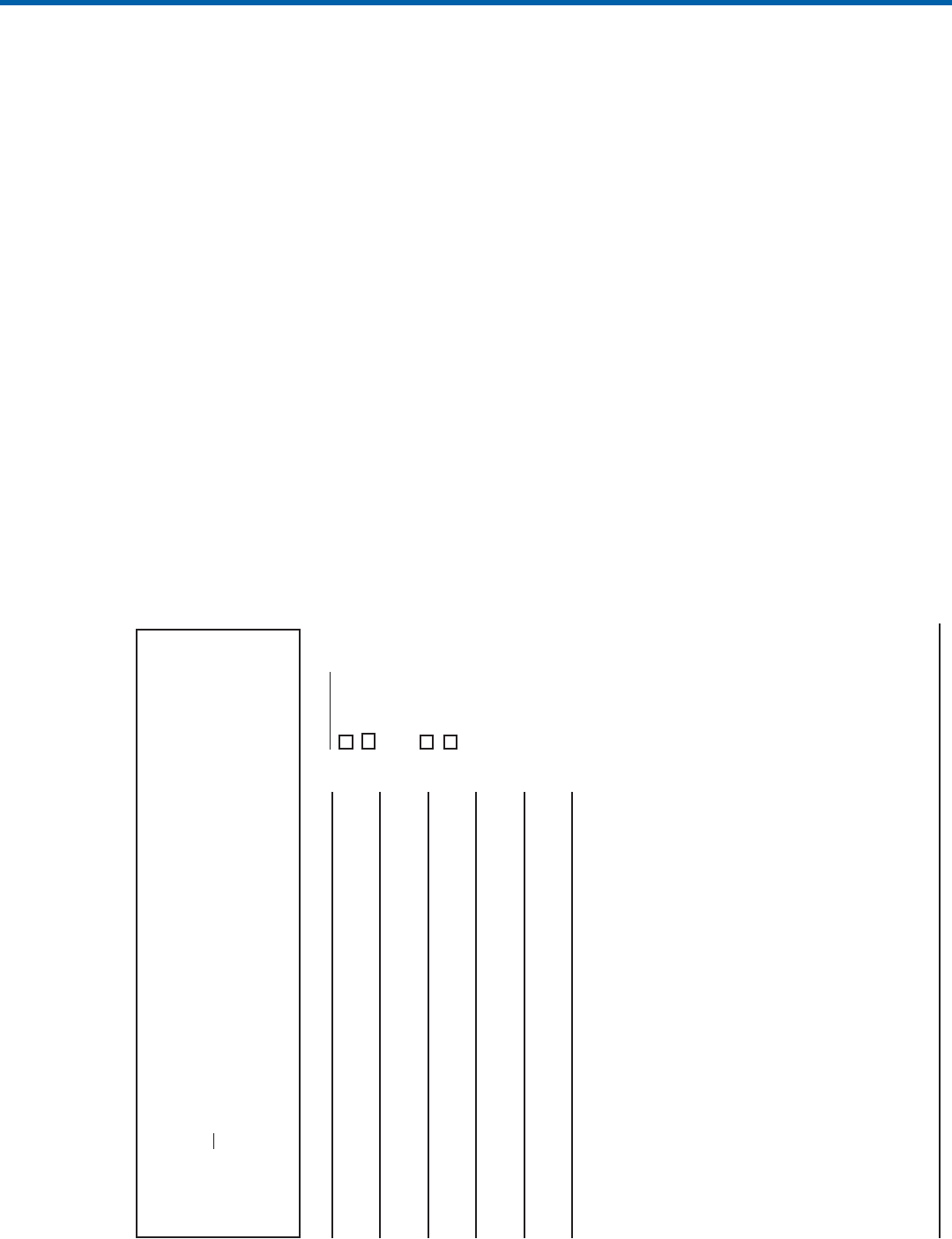

TABLE 1. Increases in waived analytes and test systems, Certificate of Waiver laboratories, and Medicare Part B reimbursed waived

testing, 1993–2004

Waived testing measurement parameter 1993 1998 2000 2003 2004

No. of analytes for which waived test systems are available 9 40 53 74 76

No. of waived test systems* 203 608 832 1,495 1,638

No. of laboratories with a Certificate of Waiver

†

67,294 78,825 85,944 102,123 105,138

Percentage of laboratories with a Certificate of Waiver

†

44% 50% 52% 57% 58%

No. of Medicare Part B reimbursed waived tests NA

§

NA 14,663,751 20,781,297 23,041,693

Percentage of Medicare Part B reimbursed laboratory testing that is waived NA NA 6.5% 7.8% 8.1%

Medicare Part B payment amount for waived tests NA NA $69,765,453 $112,247,706 $128,169,398

* Numbers reflect multiple names under which individual tests are marketed and might include waived tests no longer sold.

†

Does not include Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) exempt laboratories in New York and Washington.

§

Not available.

Source: CDC and Food and Drug Administration CLIA Test categorization databases; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Part B

Utilization for CLIA-covered Laboratory Services; and CMS On-line Survey, Certification, and Reporting database.

Vol. 54 / RR-13 Recommendations and Reports 3

physician or midlevel health-care practitioner. An increasing

shift toward waived testing has resulted in a corresponding

increase in health-care expenditures for this testing. Medicare

Part B, the federal medical insurance program for persons aged

>65 years and certain disabled persons, covers diagnostic labo-

ratory testing. Payment data for 2004, provided by CMS, in-

dicated that of the $3,494,840,086 spent on reimbursed

laboratory testing for that year, $128,169,398 (3.7%) was for

waived tests. The volume of Medicare Part B reimbursed

waived laboratory testing in 2004 represented 8% of the total

reimbursed testing volume for that year, a 57% increase over

the volume in 2000 (Table 1).

Patient Safety Concerns Related

to Waived Testing

Efforts to reduce medical errors, improve health-care qual-

ity, and increase patient safety have been gaining national

attention. A report issued in 1999 by the Institute of Medi-

cine (IOM) presented a national agenda to address these

issues and recommended strategies for change that included

the implementation of safe practices at the health-care deliv-

ery level (7). As described in the IOM report, errors most

often occur when multiple contributing factors converge, and

preventing errors and improving patient safety require a sys-

tems approach. Five years after this seminal report, small but

consequential changes have occurred that have shifted the

focus to improving systems, engaging stakeholders, and moti-

vating health-care providers to adopt new safe practices (8).

Although by law waived tests should have insignificant risk

for erroneous results, these tests are not completely error-proof

and are not always used in settings that employ a systems

approach to quality and patient safety. Errors can occur any-

where in the testing process, particularly when the

manufacturer’s instructions are not followed and when test-

ing personnel are not familiar with all aspects of the test sys-

tem and how testing is integrated into the facility’s workflow.

Although data have not been systematically collected on

patient outcomes with waived testing, adverse events can

occur (9). Some waived tests have potential for serious health

impacts if performed incorrectly. For example, results from

waived tests can be used to adjust medication dosages, such as

prothrombin time testing in patients undergoing anticoagu-

lant therapy and glucose monitoring in diabetics. In addition,

erroneous results from diagnostic tests, such as those for

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, can have

unintended consequences.

The lack of oversight and requirements for personnel quali-

fications and training for an increasingly large number of CW

sites is a concern and could contribute to errors and patient

harm. During 1999–2001, CMS conducted on-site surveys

of a representative sample of CW sites in 10 states to assess

the quality of testing in these sites. These pilot surveys identi-

fied quality issues that could result in medical errors (10).

Contributing factors included inadequate training in good

laboratory practices and high turnover rates of testing person-

nel. As a result, during 2002–2004, CMS conducted nation-

wide on-site surveys of CW facilities to collect additional data

that would provide an assessment of testing, promote good

laboratory practices and encourage improvement through

educational outreach, and make recommendations on the basis

of cumulative survey findings. The data collected from these

surveys, along with data on waived testing practices gathered

through CDC-funded studies conducted during 1999–2003

by the state health departments of Arkansas, New York, and

Washington (collectively referred to as the Laboratory Medi-

cine Sentinel Monitoring Network [LMSMN]), support the

initial CMS findings of gaps in good laboratory practices in

these sites (11–16). In addition, a 2001 report issued by the

HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG), following their in-

vestigation of CLIA certification and enrollment processes,

identified the lack of routine on-site visits to CW sites by

surveyors representing state agencies and private sector accredi-

tation organizations as presenting vulnerabilities in these sites.

The OIG report indicated that approximately half of the state

respondents reported problems related to quality issues with

the waived laboratories in their states (e.g., failure to follow

manufacturers’ instructions or failure to identify incorrect

results and performing unauthorized testing) (17). The con-

cerns noted by states were similar to those identified in the

CMS pilot studies.

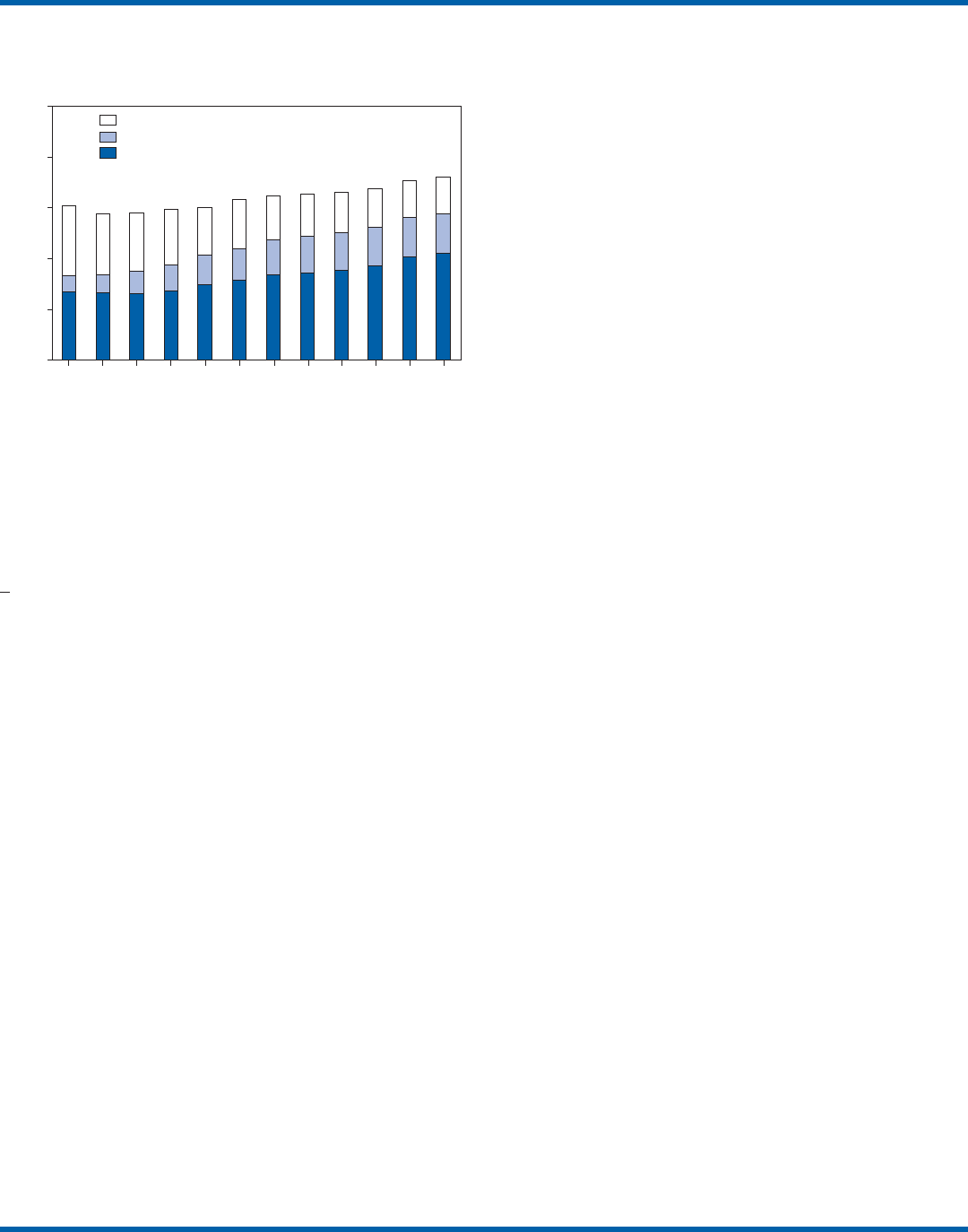

FIGURE 1. Number of Clinical Laboratory Improvement

Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) certified laboratories, by

certificate type and year, 1993–2004

Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services On-line Survey,

Certification, and Reporting database.

0

50

100

150

200

250

1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003

1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004

Year

Number (in thousands)

Certificate of Accreditation/Certificate of Compliance

Provider performed Microscopy Procedures Certificate

Certificate of Waiver

4 MMWR November 11, 2005

CLIAC Response

An initial CMS report of its 2002–2003 survey findings,

presented to CLIAC in 2004, supported earlier concerns about

the quality of testing practices and the need for education and

training of testing personnel in CW sites. In response, the

committee recommended publication of the 2002–2004 CMS

data in conjunction with other data pertinent to waived test-

ing performance along with recommendations for good labo-

ratory practices for waived testing sites. This information

would then be available to provide guidance to physicians,

nurses, and other health-care providers in CW facilities. As a

result, a workgroup was appointed to consider practices asso-

ciated with the waived testing process and their impact on the

quality of waived testing. This workgroup was comprised of

key stakeholders in waived testing (i.e., CLIAC members;

physicians; nurses; laboratorians; manufacturers; distributors;

and representatives from CDC, CMS, and FDA). In its evalu-

ations, the workgroup considered existing practice guidelines

from professional organizations, waived testing recommen-

dations from CMS, personal and professional experience, and

publications related to waived testing. The workgroup’s find-

ings were presented to CLIAC for its deliberations at the Feb-

ruary 2005 meeting, at which time CLIAC provided

recommendations to HHS concerning good laboratory prac-

tices for waived testing sites. CLIAC supported publication

of the recommendations, along with the data from the studies

of CW sites, and suggested the publication could serve as a

comprehensive source document that could be used to

develop additional educational tools appropriate for specific

target audiences.

Surveys of Waived Testing Sites

Methods

During 2002–2004, approximately 150 CMS and state

agency surveyors conducted on-site surveys nationwide using

a questionnaire at 4,214 sites performing testing under a CLIA

CW. Surveyors self-selected CW sites on the basis of test vol-

ume, location, and facility types. Different facilities were sur-

veyed each year so that no repetition exists among CW sites

represented in the CMS data in this report. LMSMN obtained

additional waived testing data from 1999–2003. Within

LMSMN, the Washington State Department of Health

established the Pacific Northwest Sentinel Network

(PNWSN), which included approximately 650 waived and

nonwaived laboratories in Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Wash-

ington. The Arkansas Sentinel Network (ASN) consisted of

94 local health units integrated into the state health agency

(mostly waived testing sites) and approximately 600 waived

and nonwaived laboratories in Arkansas and surrounding

states. PNWSN and ASN gathered data about waived testing

practices through questionnaires mailed to network members

(11). The New York Sentinel Network (NYSN) consisted of

approximately 600 limited service laboratories (facilities other

than physician office laboratories [POLs] that perform only

waived tests and PPMP). NYSN collected its data through

on-site surveys during which waived testing practices were

assessed by surveyor observation and record reviews (11).

Survey Findings

Demographics

CMS surveyed 4,214 CW sites during April 15, 2002–

November 12, 2004. This included 897 sites in 2002, 1,575

sites in 2003, and 1,742 sites in 2004. Of the CW facility

types surveyed, POLs compose the largest percentage (47%),

followed by skilled nursing facilities (14%) (Table 2). The

CW sites surveyed estimated performing a broad range of

annual test volumes (Figure 2). Of the facilities surveyed by

TABLE 2. Percentage of facilities with a Certificate of Waiver

(CW), by type of facility, from the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services (CMS) surveyed sites, 2002–2004, and all

CW sites, February 25, 2004

CMS surveyed All CW

sites %* sites

†

%*

Facility type (n = 4,214) (n = 109,820)

Physician office 47 46

Nursing facility 14 13

Ambulatory surgery center 4 3

End-stage renal disease dialysis center 4 3

Home health agency 3 8

Community clinic 3 2

Pharmacy 2 3

School (student health) 2 1

Industrial 2 1

Hospital 1 1

Other practitioner 1 1

Ancillary test site 1 1

Ambulance 1 2

Independent 1 1

Mobile unit 1 1

Intermediate care (mentally retarded) 1 1

Rural health clinic/Federally qualified

health center 1 1

Hospice <1 1

Health fair <1 <1

Blood bank <1 <1

Health maintenance organization <1 <1

Comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation <1 <1

Public health laboratory <1 <1

Insurance <1 <1

Other 9 9

Invalid/Missing data 2 0

* Totals might not equal 100% because of rounding.

†

Data from CMS On-line Survey, Certification, and Reporting database.

Vol. 54 / RR-13 Recommendations and Reports 5

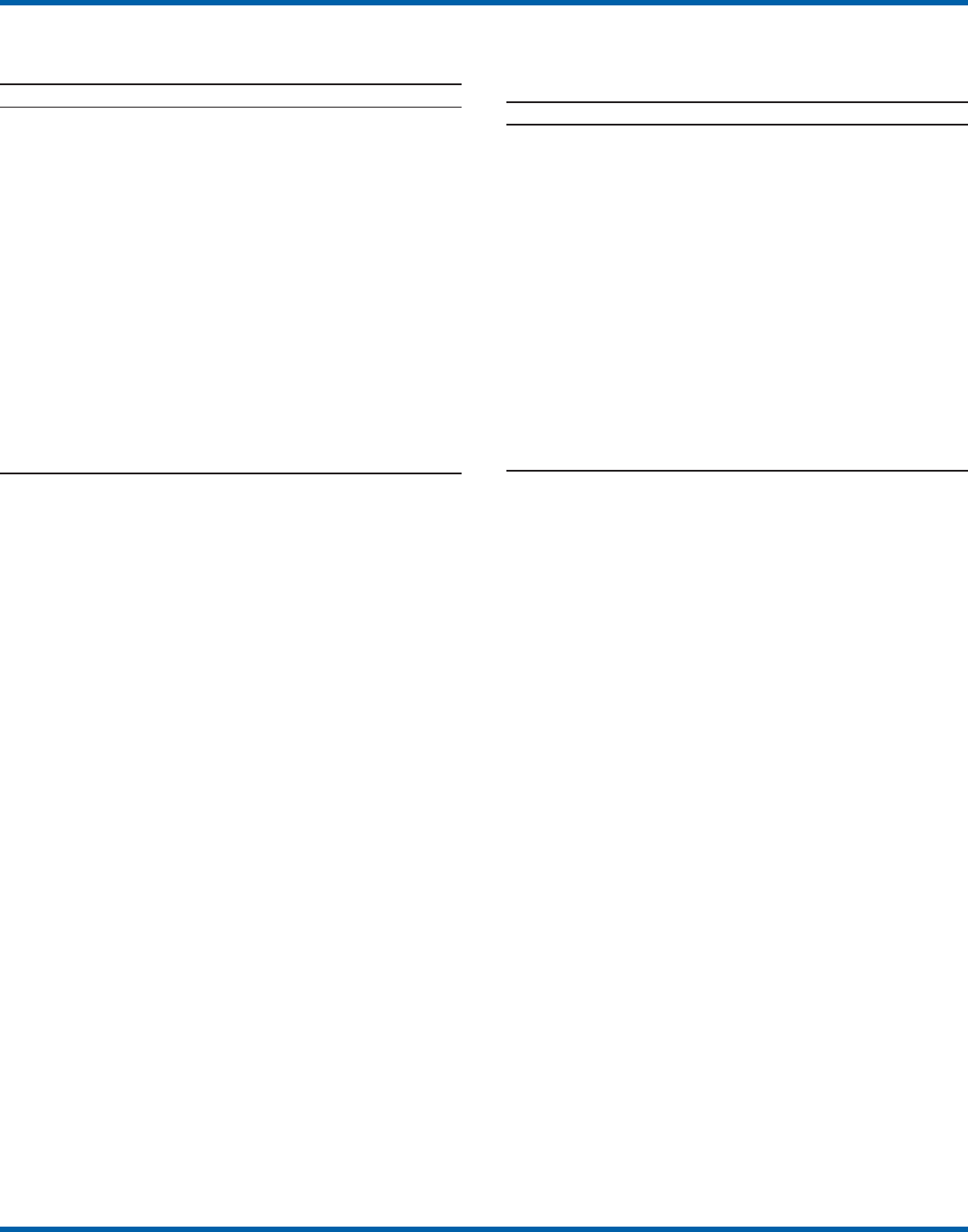

CMS during 2003–2004 (2002 data not available), 90%

reported that they performed no more than five different

waived tests, and 99% performed no more than 10 different

waived tests. Although the exact volume of each test performed

per site is not known, on the basis of the number of sites

testing for each analyte, the five most commonly performed

waived tests were identified as glucose, dipstick urinalysis,

fecal occult blood, urine human chorionic gonadotropin

(hCG) (visual color comparison), and group A streptococcal

antigen (direct test from throat swabs) (Figure 3). This corre-

lates with data for the top five waived tests identified through

the LMSMN, especially for POLs (11). Although not among

the most commonly performed, waived tests are available for

certain infectious diseases of public health significance and

were reportedly performed by CW sites in the CMS surveys

(influenza, 46 sites; HIV, four; and Lyme disease, one).

Personnel and Training

Under CLIA, no education or training is required for the

director or testing personnel in CW sites. The educational

background and qualifications for directors and testing per-

sonnel at CW sites were collected as part of the CMS surveys

and by LMSMN (PNWSN and NYSN). The CMS surveys

indicated that in 69% of CW sites, physicians served as direc-

tors, followed by nurses (17%) (Table 3). Similarly, 59% of

the PNWSN CW site directors were physicians, with the

remaining 41% having other backgrounds or degrees (12).

For CW testing personnel, according to the CMS data, the

top four categories were nurses (46%), medical assistants

(25%), physicians (9%), and high school graduates (7%)

(Table 3). NYSN reported that registered nurses (RNs) and

licensed practical nurses (LPNs) served as testing personnel in

84% of the limited service laboratories they surveyed (13).

Trained laboratorians (i.e., medical technologists and medical

laboratory technicians) accounted for 2% of laboratory direc-

tors and testing personnel in the CW sites surveyed by CMS

and a smaller percentage in the limited service laboratories

surveyed by the NYSN (13).

CMS surveys indicated that 43% of CW sites experienced a

change in testing personnel during the preceding 12 months.

Among the top categories of testing personnel in the PNWSN,

turnover rates were highest for medical assistants (17%), fol-

lowed by LPNs (13%), RNs (9%), and physicians (2%) (14).

Although the majority of CW sites in the CMS surveys (90%)

reported that new personnel were trained, fewer sites (85%)

evaluated staff to ensure competency. Data identifying who pro-

vided training were not submitted for all sites in the surveys.

However, according to the CW sites that provided this infor-

mation for 2003–2004 (Table 4), nurses most frequently pro-

vided waived test training (33%), followed by the manufacturer

or sales representatives (15%). Findings from a PNWSN study

indicated that the highest percentage of personnel were initially

trained by another employee (25%) or trained themselves by

using instructions provided with the waived test system (17%)

(15). Another PNWSN study indicated that most

training (77%) took place in a day or less (14).

Comments from this study reflected the thinking

that training is not always necessary or that mini-

mal time should be spent on training because per-

sons have been trained in school or on other jobs.

The time spent on training was not captured as

part of the CMS surveys.

Testing Practices

The CMS surveys indicated that the majority

of the CW sites were aware of and followed some

practices for ensuring the accuracy and reliability

of their testing. However, lapses in quality were

identified at certain sites, some of which could

result in patient harm. In some instances, CW

sites were determined to be performing testing

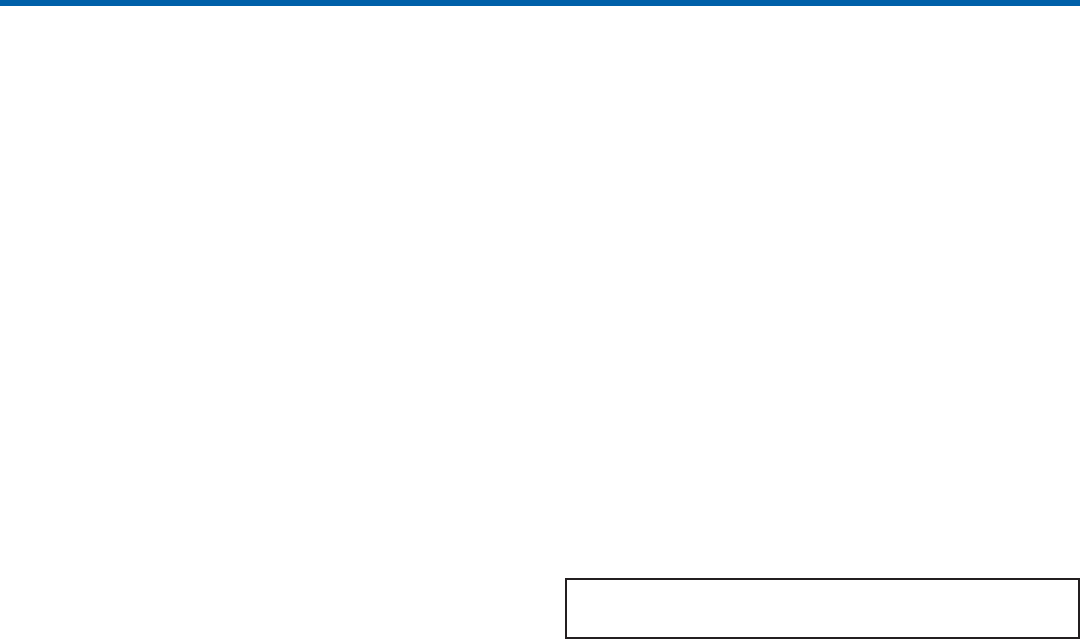

FIGURE 2. Estimated annual number of tests for Certificate of

Waiver (CW) sites, from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services surveyed sites, 2002–2004*

* N = 4,214.

0

20

40

101 500– 501 1,000–

1,001–1,500

No response<100

>1,501

Number of tests

% of CW sites

FIGURE 3. Percentage of Certificate of Waiver sites that perform specific

waived tests, by selected test, from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services surveyed sites, 2003–2004*

* N = 3,317. 2002 data not available.

0

10

20

30

40

50

Glucose Dipstick

urinalysis

Fecal

occult

blood

Urine

hCG

Group

A strep

antigen

Hemoglobin Cholesterol HDL

cholesterol

Triglyceride Prothrombin

time

Test

Percentage

6 MMWR November 11, 2005

that was an imminent and serious threat to the public’s health

because they were performing nonwaived testing in the

absence of CLIA-required quality measures. The CMS sur-

veys indicated that 5% of CW sites were conducting tests that

were not waived, the most frequently performed nonwaived

procedures (72%) being direct microscopic examinations (e.g.,

potassium hydroxide preparations, wet mounts, or urine sedi-

ment examinations). Surveyed CW testing sites also reported

performing various other nonwaived tests (e.g., urine and

throat cultures, Rh antigen testing, and the use of glucometers

to perform diagnostic glucose tolerance testing [an intended

use not specified in manufacturers’ instructions]). When per-

forming nonwaived tests, surveyors noted that, in some

instances, the sites were not meeting CLIA requirements for

qualified personnel, QC, PT, or test system maintenance. In

addition, these sites did not have adequate records of their

testing activities, including test system procedures, training

records, or other documentation.

Of the CW facilities CMS surveyed, 12% did not have the

most recent instructions for the waived test systems they were

using, and 21% of the sites reported they did not routinely

check the product insert or instructions for changes to the

information (Table 5). On the basis of manufacturer’s instruc-

tions, 21% of the CW sites did not perform QC testing as

specified, and 18% of the sites did not use correct terminol-

ogy or units of measure when reporting results. Among other

quality deficiencies identified were failure to adhere to proper

expiration dates for the test system, reagents, or control mate-

rials (6%) and failure to adhere to the storage conditions as

described in the product insert (3%). Six percent of CW sites

did not perform follow-up confirmatory tests as specified in

the instructions for certain waived tests (e.g., group A strep-

tococcal antigen), and 5% did not perform function checks

or calibration checks to ensure the test system was operating

correctly. Findings from the LMSMN studies were similar to

the CMS findings for these quality deficiencies (11).

Although not usually specified in the product insert (and

therefore not a CLIA requirement), proper documentation

and recordkeeping of patient and testing information are also

important elements of good laboratory practices. CMS sur-

veys indicated that 45% of CW sites did not document the

name, lot number, and expiration dates for tests performed;

TABLE 3. Percentage of Certificate of Waiver site directors and

testing personnel, from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services surveyed sites, 2002–2004

Personnel category %

Site directors (n = 3,788 responses*)

Physician (MD, DO, DPM, DDS)

†

69

Nurse (LPN, RN, NP, midwife) 17

Administrator/Nursing home administrator 3

Medical technologist/Medical laboratory technician 2

Pharmacist 2

High school, GED 1

Emergency medical technician/Paramedic 1

PhD, MS, BS degree (diverse majors) <1

Medical assistant <1

Other

§

4

Testing personnel (n = 5,511 responses*)

Nurse (LPN, RN, NP, Midwife) 46

Medical assistant 25

Physician (MD, DO, DPM, DDS) 9

High school, GED 7

Medical technologist/Medical laboratory technician 2

Emergency medical technician/Paramedic 2

Nursing assistant 1

Pharmacist 1

Physician assistant 1

Other

¶

6

* All sites did not provide this information, and some sites responded with

multiple answers for each category. For example, for the site director, a

site could have responded with Medical Technologist and Bachelor of

Science degree for the same person. For testing personnel, some sites

indicated multiple personnel types. All responses were included in the

data.

†

MD=Doctor of Medicine; DO=Doctor of Osteopathy; DPM=Doctor of

Podiatric Medicine; DDS=Doctor of Dental Surgery; LPN=licensed practical

nurse; RN=registered nurse; NP=nurse practitioner; GED=general

equivalency diploma; PhD=Doctor of Philosophy; MS=Master of Science;

and BS=Bachelor of Science.

§

Others identified as site directors were chiropractors, social workers/

counselors, physician assistants, fire chiefs, military trained personnel,

naturopaths, optometrists, physical therapists, and nutritionists.

¶

Other testing personnel were radiology technicians, patient-care

technicians, phlebotomists, hemodialysis technicians, chiropractors,

nutritionists, surgical technicians, office managers, patients/clients (self-

testing), nuclear medical technicians, social workers/counselors, medical/

nursing/pharmacy students, respiratory therapists, community-health

representatives, naturopaths, clerical staff, cardiac technicians, home

health assistants, and certified rehabilitation technicians.

TABLE 4. Number and percentage of training providers for

Certificate of Waiver testing personnel, by type of training

provider, from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

surveyed sites,* 2003–2004

Training provider No. (%)

Nurse 699 (33)

Manufacturer/Sales representative 329 (15)

Physician 220 (10)

In-service/Training coordinator 152 (7)

Other employees 144 (7)

Self-trained/Video 98 (5)

Director/Medical director 97 (5)

Medical assistant 92 (4)

Supervisor/Manager 42 (2)

Office manager 52 (2)

Laboratory director 49 (2)

Laboratory personnel 39 (2)

Hospital laboratory staff 37 (2)

Medical technologist/Medical laboratory technician 37 (2)

Laboratory consultant 19 (1)

Emergency medical technician/Paramedic 24 (1)

Pharmacist 23 (1)

Physician assistant 6 (<1)

Other 93 (4)

Physician testing only

†

54 (2)

Training not documented 51 (2)

* N = 2,139 sites. A total of 3,317 sites were surveyed. However, all sites

did not provide information on training sources, and some sites identified

more than one training provider. All responses were included in the data.

†

Sites did not specify who provided training to these physicians.

Vol. 54 / RR-13 Recommendations and Reports 7

35% did not maintain logs with records of their QC testing;

31% did not maintain a log or record of tests performed; and

9% did not require a requisition or test orders documented in

a patient chart before performing a test (Table 5). NYSN

observed similar findings but noted increased compliance with

state requirements for documentation/recordkeeping when

laboratories had formal affiliations with New York State-

licensed laboratories (11).

Discussion

The findings from the CMS surveys and LMSMN studies

indicated that the majority of CW testing sites performed test-

ing correctly and provided reliable service. However, in CW

sites, most directors and testing personnel did not have for-

mal laboratory training or testing experience, there was a high

turnover of personnel, and lapses in following manufacturers’

instructions and instituting practices to ensure the quality of

the testing were noted. The survey findings indicated that 485

(12%) of the 4,214 CW sites surveyed did not have the cur-

rent manufacturers’ instructions available, and 701 (21%) of

the 3,317 sites surveyed during 2003–2004 did not check to

be sure there had been no changes to the instructions. Test

system instructions can change over time and CW sites some-

times switch test systems that could have different instruc-

tions. CMS survey results also indicated that, in varying

proportions, when CW sites had the current instructions, they

did not follow critical steps in the testing process (e.g., per-

forming QC testing, reporting results correctly, adhering to

expiration dates and appropriate storage requirements, and

performing test system function checks or calibration checks).

This is a concern because the only CLIA requirement for per-

forming waived testing is to follow the manufacturer’s instruc-

tions. Neglecting to follow instructions could cause inaccurate

test results that could lead to incorrect diagnoses, inappropri-

ate or unnecessary medical treatment, and poor patient

outcomes.

CMS surveys indicated that certain CW sites (5%) were per-

forming testing more complex than waived testing without tak-

ing required measures to ensure quality. In certain CW sites,

nonwaived microscopic examinations were being performed by

personnel who lacked the education and training needed to

develop the interpretive and judgment skills necessary to accu-

rately perform these procedures. In addition, measures such as

QC, PT, adequate documentation, and monitoring are required

to ensure the accuracy and reliability of nonwaived test results.

Although direct microscopic examinations can be conducted

by a physician or midlevel health-care practitioner as part of a

patient examination, testing must be conducted under a CLIA

PPMP certificate.

The quality issues identified through these surveys might

have been caused, in part, by high turnover rates of testing

personnel in CW sites, inadequate training with respect to

waived testing, and lack of understanding of good laboratory

practices, including the importance of following all aspects of

the manufacturers’ instructions. Although the study results

indicated that most testing personnel were trained, they were

often trained for minimum periods by persons who did not

have formal education or training in clinical laboratory test-

ing and who might not have understood the importance of

measures to ensure quality testing. Certain testing personnel

also were self-trained. In addition, when testing personnel were

not evaluated to determine their competency level following

training or on an ongoing basis, no assessment was conducted

to determine whether the training was effective. The data dem-

onstrate a need for educational information among CW site

directors and testing personnel about the importance of fol-

lowing manufacturers’ instructions, adhering to expiration

dates, performing QC testing, and proper documentation and

recordkeeping. One of the recommendations in the 2001 OIG

TABLE 5. Number and percentage of quality deficiencies related

to following manufacturer’s instructions and documentation in

Certificate of Waiver sites, from the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services surveyed sites,* 2002–2004

No. of (% of

Quality deficiencies sites sites)

Following manufacturer’s instructions

†

The site did not

Have current manufacturer’s instructions 485 (12)

Routinely check new product inserts for changes

§

701 (21)

Based on manufacturer’s instructions,

the site did not

Perform quality control testing 866 (21)

Report test results with terminology or units

described in package insert 744 (18)

Adhere to proper expiration dates 267 (6)

Perform required confirmatory tests 265 (6)

Perform function checks or calibration 195 (5)

Adhere to storage and handling instructions 135 (3)

Perform instrument maintenance 125 (3)

Use appropriate specimen for each test 81 (2)

Add required reagents in the prescribed order 24 (1)

Documentation

¶

The site did not

Document the name, lot number, and expiration

date for all tests performed

§

1,493 (45)

Maintain a quality-control log

§

1,151 (35)

Maintain a log of tests performed 1,318 (31)

Require test requisition (or patient chart) before

performing a test

§

304 (9)

Keep the test report in the patient’s chart

§

56 (2)

Check patient identification

§

31 (1)

* N = 4,214 sites.

†

Required for waived testing under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement

Amendments of 1988 (CLIA).

§

2003–2004 data only (n = 3,317).

¶

Not required for waived testing under CLIA.

8 MMWR November 11, 2005

report was that CMS should provide educational outreach to

directors of waived and PPMP laboratories about the CLIA

requirements (17).

The findings in the 2002–2004 CMS surveys are subject to

at least three limitations, and caution should be used in

extrapolating the survey data to make generalizations about

waived testing. First, the CMS surveys were not intended to

be a scientific study of a random sample of CW sites. Waived

testing data were collected by CMS to provide an assessment

of testing practices, promote good laboratory practices, and

encourage improvement through educational outreach.

Although surveyors attempted to include a wide variety of

CW sites in the sample, the sites were self-selected by survey-

ors and selection was based, to some degree, on convenience

to the surveyors and willingness of the sites to participate in

the voluntary surveys. However, few sites refused to partici-

pate in the surveys. Overall, the sites represent a nationwide

sample and the distribution of CW facility types is similar to

the distribution of CW facility types in the United States

(Table 2). In addition, the 2002–2004 CMS survey findings

resulted in the same general conclusions as the earlier CMS

pilot studies, which were conducted on a random sample of

laboratories (10). Second, the CMS data were collected and

entered into the database by a large number of persons, intro-

ducing variability. Although training was provided before the

surveys were conducted, the intent of the survey questions

was subject to individual interpretation. Because the phrasing

of some questions differed slightly from 2002 to 2003–2004,

in certain cases, the meanings of the questions also changed.

Finally, the CMS surveys did not assess the frequency of erro-

neous test results in CW sites or whether lapses in following

manufacturers’ instructions directly affected test results or

patient outcomes. Similar limitations to these were identified

in the LMSMN studies (11).

The findings of the CMS and LMSMN studies are strik-

ingly similar. Even though the majority of CW sites meet the

CLIA requirement to follow manufacturers’ instructions for

test performance, and many sites follow additional good labo-

ratory practices, over the years these studies have demonstrated

that a persistent percentage of CW sites do not meet minimal

requirements and are not aware of recommended practices to

help ensure quality testing. Because surveying all CW sites is

not feasible, the proposed actions to improve and promote

quality testing in CW sites emphasize the importance of edu-

cation and training for CW site directors and testing person-

nel. To provide a guide that can be adapted for use, either in

part or as a whole, by persons or facilities considering the

initiation of waived testing and personnel performing waived

testing, CLIAC provided recommendations for good labora-

tory practices. By implementing these recommendations, CW

sites could improve quality, reduce testing errors, and enhance

patient safety.

Recommended Good

Laboratory Practices

Overview

These recommendations are intended to promote the use

of good laboratory practices by physicians, nurses, and other

providers of waived testing in a variety of CW sites. They

were developed on the basis of recommendations and other

resources that provided additional information for promot-

ing patient safety and the quality of CLIAC waived testing in

laboratories or nontraditional testing sites (18–22). These rec-

ommendations address decisions that need to be made and

steps to be taken as a facility begins offering waived testing or

adds a new waived test. They also address developing proce-

dures and training CW personnel and describe recommended

practices for each phase of the total testing process, or path of

workflow, including the important steps or activities before,

during, and after testing. The activities that occur in each of

these phases are critical to providing quality testing (Table 6).

Considerations Before Introducing

Waived Testing or Offering

a New Waived Test

Forethought, planning, and preparation are critical to initi-

ating high-quality waived testing in any type of setting. This

section describes factors to consider before opening a waived

testing site or offering an additional waived test. Questions to

address include the following:

• Management responsibility for testing. Who will be

responsible and accountable for testing oversight at the

CW site, and does this person have the appropriate train-

ing for making decisions on testing?

• Regulatory requirements. What federal, state, and local

regulations apply to testing, and is the site adequately pre-

pared to comply with all regulations?

TABLE 6. Activities within each phase of the total testing

process

Before testing During testing After testing

Control testing/checks

Test performance

Results interpretation

Recording results

Test ordering

Patient identification,

preparation

Specimen collection,

handling

Preparing materials,

equipment, and

testing area

Reporting results

Documenting

Confirmatory testing

Patient follow-up

Disease reporting

Biohazard

waste disposal

Vol. 54 / RR-13 Recommendations and Reports 9

• Safety. What are the safety considerations for persons con-

ducting testing and those being tested?

• Testing space and facilities. What are the physical and

environmental requirements for testing?

• Benefits and costs. How will the care offered in the site

benefit by introduction of testing or the addition of a

new test, and what will it cost?

• Staffing. How will introduction of testing affect the cur-

rent work flow, are there sufficient personnel to conduct

testing, and how will they be trained and maintain test-

ing competency?

• Documents and records. What written documentation

will be needed, and how will test records be maintained?

Management Responsibility

Each testing site should identify at least one person respon-

sible for testing oversight and decision-making, later referred

to as the CW site director. In POLs, this might be a physician

or someone in a senior management position who has the

appropriate background and knowledge to make decisions

about laboratory testing. Ideally, the person signing the CW

application (CMS Form 116) is responsible for management

of the testing operations. The management staff should dem-

onstrate a commitment to the quality of testing service by

complying with applicable regulatory requirements and pro-

moting good laboratory practices.

Regulatory Requirements

CLIA certification. Each site offering only waived testing

that is not included under any other type of CLIA certificate

must obtain a CLIA CW before testing patient specimens.

Certain sites offering waived testing can be certified as part of

a larger health-care organization that holds a CLIA Certifi-

cate of Compliance or Certificate of Accreditation. In addi-

tion, certain public health testing sites offering only waived

testing can be included under a limited public health or

mobile testing exception. A valid CLIA certificate is required

for Medicare reimbursement.

To apply for a CLIA certificate, CMS Form 116 (http://

www.cms.hhs.gov/clia/cliaapp.asp) must be completed and

sent to the state agency for the state in which the testing site is

located. This form asks for specific information, including

the type of testing site (laboratory type), hours of operation,

estimated total annual volume of waived testing, and the total

number of persons involved in performing waived testing. The

form must be signed by the facility owner or the facility direc-

tor. Specific state agencies and contacts are available at

http://www.cms.hhs.gov/clia/ssa-map.asp. The state agency

will process the application and send an invoice for the regis-

tration fee. If additional assistance is required, contact the

appropriate CMS regional office (http://www.cms.hhs.gov/

clia/ro-map.asp).

CLIA requirements that apply to testing sites operating

under a CW include the following:

• Renew the CW every 2 years.

• Perform only waived tests. Waived tests include test sys-

tems cleared by FDA for home use, and simple, low-risk

tests categorized as waived under CLIA. Sometimes a test

that can be performed using different specimens or pro-

cedures might be waived only for certain specimen types

or procedures. Because the list of waived tests is constantly

being revised as new test systems are added, the most cur-

rent information about waived tests and appropriate speci-

mens is available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/

cdrh/cfdocs/cfCLIA/search.cfm.

• Follow the instructions in the most current manufacturer’s

product insert, without modification, when performing

the test. Changes to the timing of the test or physical

alteration of the test components (e.g., cutting test cards

or strips to increase the number of specimens tested per

kit) are examples of modifications. If modified, tests are

no longer waived tests and become subject to the more

stringent CLIA requirements for nonwaived testing.

• Permit announced or unannounced on-site inspections

by CMS representatives.

State and local regulations. States and local jurisdictions

vary as to the extent to which they regulate laboratory testing.

Some states and localities have specific regulations for testing,

some require licensure of personnel who perform testing, and

some have phlebotomy requirements. State and local jurisdic-

tions often regulate biohazard safety, including handling and

disposal of medical waste. The person responsible for testing

oversight should ensure that all state and local requirements

are met. These requirements might be more or less stringent

than federal requirements. When state or local regulations

governing laboratory testing are more stringent than the fed-

eral CLIA requirements, they supersede what is required

under CLIA.

Safety requirements. The Occupational Safety and Health

Administration (OSHA) and individual state standards require

employers to provide a safe and healthy work environment

for employees. Each CW site must comply with OSHA stan-

dards pertinent to workplace hazards (23). Regulatory require-

ments for all OSHA standards, including specific information

for medical and dental offices (24), are available at http://

www.osha.gov and by telephone, 800-321-6742.

The OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard applies to sites

where workers have potential occupational exposure to blood

and infectious materials (25). The requirements for compli-

ance with this standard include, but are not limited to:

10 MMWR November 11, 2005

• A written plan for exposure control, including

postexposure evaluation and follow-up for the employee

in the event of an “exposure incident;”

• Use of Universal Precautions, an approach to infection

control in which all human blood and certain human body

fluids are treated as if known to be infectious for HIV,

hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and other bloodborne

pathogens. Universal Precautions is one component of

Standard Precautions, a broader approach designed to

reduce the risk for transmission of microorganisms from

both recognized and unrecognized sources of infection in

hospitals;

• Use of safer, engineered needles and sharps;

• Use of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves

and protective eyewear;

• Provision of hepatitis B vaccination at no cost for those with

possible occupational exposure who want to be vaccinated;

• Safety training for handling blood, exposure to bloodborne

pathogens, and other infectious materials; and

• Equipment for the safe handling and disposal of

biohazardous waste (e.g., properly labeled or color-coded

sharps containers and biohazard trash bags and bins).

Additional safety practices for performing testing are:

• Prohibit eating, drinking, or applying makeup in areas

where specimens are collected and where testing is being

performed (i.e., where hand-to-mouth transmission of

pathogens can occur);

• Prohibit storage of food in refrigerators where testing sup-

plies or specimens are stored;

• Provide hand-washing facilities or antiseptic hand-

washing solutions; and

• Post safety information for employees and patients.

Specific information on the Bloodborne Pathogens Stan-

dard and needlestick prevention is available at http://www.

osha.gov/SLTC/bloodbornepathogens/index.html.

CDC and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

(CLSI) (formerly NCCLS) have also published information

about biosafety and precautions for preventing transmission

of bloodborne pathogens in the workplace (26–30).

Privacy and confidentiality requirements. The Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

established federal privacy standards to protect patients’ medi-

cal records and other health information provided to health

plans, doctors, hospitals, and other health-care providers.

Under HIPAA, CW sites are required to establish policies and

procedures to protect the confidentiality of health informa-

tion about their patients, including patient identification, test

results, and all records of testing. These medical records and

other individually identifiable health information must be

protected, whether on paper, in computers, or communicated

orally. In addition, CW sites should be aware that applicable

state laws that provide more stringent privacy protections for

patients supersede HIPAA. Additional information on HIPAA

is available at http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa.

Physical Requirements for Testing

Testing should be performed in a separate designated area

where adequate space to safely conduct testing and maintain

patient privacy is available. In addition, some tests have spe-

cific environmental requirements described in the

manufacturer’s product insert that need to be met to ensure

reliable test results. Meeting these environmental conditions

can be challenging in nontraditional settings (e.g., health fairs)

or community outreach venues (e.g., shopping malls, meet-

ing rooms, parks, parking lots, mobile vans, and buses). Fac-

tors to consider include:

• Humidity — Unusually high, low, or extreme fluctua-

tions in humidity can cause deterioration of reagents and

test components, affect the rate of chemical reactions and

specimen interaction, or make test endpoints blurred and

difficult to read.

• Temperature — Temperature ranges for storage of test

components and controls and for test performance are

defined by the manufacturer to maintain test integrity.

Extreme temperatures can degrade reagents and test com-

ponents, impact reaction times, cause premature expira-

tion of test kits, and affect the test results.

• Lighting — Inadequate lighting can negatively affect speci-

men collection, test performance, and interpretation of

test results.

• Work space — Work surfaces should be stable and level

and be able to be adequately disinfected; work space should

be adequate in size for patient confidentiality, ease of speci-

men collection, test performance, and storage of supplies

and records.

Benefit and Cost Considerations

Evaluating the benefits of a particular test. Evaluate the

test system, its intended use, performance characteristics, and

the population to be tested when assessing whether to intro-

duce waived testing or a new waived test. Information for this

evaluation can be obtained from the test manufacturer’s prod-

uct insert (Table 7) or by speaking with the manufacturer’s

technical representatives. Specific considerations include:

• Intended use – Be aware of the intended medical use for

which FDA approved the test system as explained in the

product insert. This section describes what is being mea-

sured by the test, the type of specimen for which it is

approved, and whether it is a quantitative or qualitative

measurement.

Vol. 54 / RR-13 Recommendations and Reports 11

• Performance characteristics — Assess the information on

performance provided by the test manufacturer or pub-

lished data. Review data that includes the test’s accuracy,

precision, sensitivity, specificity, and interferences.

• Patient population — Consider the population that will

be tested before offering a test. Some tests have not been

evaluated for use in specific age groups (e.g., pediatric

populations). The predictive value for certain types of test

results in a specific patient population depends on the

test’s sensitivity, specificity, and the prevalence of the con-

dition in the population. For example, when testing for a

certain condition or disease in a low-prevalence popula-

tion, the predictive value of a positive result will be low

compared with the predictive value of a negative result.

Refer to the product insert for limitations for use in par-

ticular patient populations.

• Need for supplemental testing or patient follow up —

Some waived tests provide preliminary results as part of a

multitest series (e.g., rapid HIV testing) or results that

must be considered in conjunction with other medical

information. These test results might require additional

testing before a definitive test result is obtained, and

patients might need posttest counseling about the mean-

ing of the test result. Assess the potential need for addi-

tional time, documentation, and staffing and a mechanism

to refer additional testing to another laboratory when

offering such tests.

• Test system considerations — Consider the simplicity of

operating the test system, length of time to obtain a result,

and the level of technical support provided by the manu-

facturer or distributor. Sales restrictions, such as special

training requirements, development of a quality assurance

program, or provision of information to patients, might

apply to some waived tests and require additional plan-

ning and resources.

Cost considerations. A fiscal assessment of testing is part

of a good management program. Before offering a new test,

consider the level of reimbursement and factors that contrib-

ute to total test cost. These factors include:

• Test kits or instruments, supplies not provided with the

test, control and calibration materials, inventory require-

ments for anticipated test volume (including seasonal test-

ing), and the shelf life of test components and supplies.

• Equipment maintenance, such as repairs or preventive

maintenance contracts.

• Additional safety and biohazard equipment.

• Personnel training, competency assessment, and the

potential need for additional personnel.

• Recordkeeping and information systems.

• Required supplemental/confirmatory testing.

• Regulatory compliance.

• Resource needs to manage public health reporting, if

required nationally or by the state.

Personnel Considerations

Personnel competency and turnover are important factors

affecting the quality and reliability of waived testing results.

No CLIA requirements exist for waived testing personnel quali-

fications; however, applicable state or local personnel regula-

tions must be met. Personnel issues to consider include:

• Is staffing adequate?

— Determine whether employees have sufficient time and

skills to reliably perform all activities needed for test-

ing in addition to their other duties.

— Be aware that temporary or parttime personnel might

be less proficient in performing testing.

— Evaluate staff for color-blindness because this can limit

their ability to interpret test results based on color end-

points.

• How much training will be needed?

— Take into account the staff turnover rate and the

ongoing need to provide training for new personnel.

— Factor in the time and resources for adequate training

and competency evaluation of staff before they per-

form testing.

— Consider how testing personnel will maintain compe-

tency, especially when testing volume is low.

Developing Procedures and Training

Personnel

After the decision is made to offer waived testing, it is good

practice to develop written policies and procedures so that

responsibilities and testing instructions are clearly described

for the testing personnel and facility director. The testing pro-

cedures form the basis of training for testing personnel. These

procedures should be derived from the manufacturer’s instruc-

tions and should be in a language understandable to testing

personnel.

Written Test Procedures

To comply with CLIA requirements and provide accurate

testing, CW sites must adhere to the manufacturer’s current

testing instructions. These instructions, as outlined in the prod-

uct insert, include directions for specimen collection and han-

dling, control procedures, test and reagent preparation, and

instructions for test performance, interpretation, and report-

ing (Table 7). In addition, certain manufacturers provide quick

reference instructions formatted as cards or small signs con-

taining essential steps in conducting a test. Quick reference

instructions should be clearly posted where testing is per-

12 MMWR November 11, 2005

TABLE 7. Components of the manufacturer’s product insert*

Component Information provided

Describes the test purpose, the substance being detected or measured, test methodology, appropriate specimen type and the

Food and Drug Administration-cleared conditions for use. Might address whether the test is to be used for diagnosis or screen-

ing the target population and whether it is for professional use or self-testing.

Explains what the test detects and a short history of the methodology, including the disease process or health condition being

detected or monitored. Might include the response to disease (e.g., development of IgM antibodies), the symptoms and their

severity, and the disease prevalence. Includes literature citations as applicable.

States the methodology used in the test. Details the technical aspects (chemical, physical, physiologic, or biologic reactions) of

the test, and explains how the components of the test system interact with the patient specimen to detect or measure a specific

substance.

Alerts the user of practices or conditions that might affect the test and warns of potential hazards (e.g., handling infectious

specimens or toxic reagents). Frequent precautions include directions to not mix components from different lot numbers, to not

use products past expiration dates, and the need for safe disposal of biohazardous waste. Might address conditions for

specimen acceptability.

Specifies conditions for storing reagents and test systems to protect their stability. Includes recommended temperature ranges

and, as applicable, physical requirements (e.g., protection from humidity and light). Also addresses the stability of reagents and

test systems when opened or after reconstitution and/or mixing. Describes indicators of reagent deterioration.

Lists the reagents and materials supplied in the test system kit and the concentration and major ingredients used to make the

reagents.

Lists materials needed to perform the test but not provided in the test system kit.

Details the procedures for specimen collection, handling, storage, and stability, including, as applicable, instructions for

performing a fingerstick, appropriate anticoagulant or swab type, and directions for specimen preparation. Might address

conditions for specimen acceptability.

Provides step-by-step instructions for performing the test and frequently includes visual aids (e.g., pictures or graphs). Critical

information (e.g., the order of reagent addition, timing of test steps, mixing and temperature requirements, and reading of the

test results) is included.

Describes how to read and interpret the test results and often includes visual aids. Alerts the user when the results are invalid

and gives instructions on what to do when the results cannot be interpreted. Might include precautions against reporting results

unless supplementary/confirmatory testing is performed.

Explains what aspects of the test system are monitored by QC procedures and provides instructions on how to perform QC.

Includes recommendations on how frequently QC should be performed, acceptable QC results, and what to do when QC values

are not acceptable. Might include specific information about external QC and, as applicable, internal procedural QC.

Describes conditions that might influence the test results or for which the test is not designed. Limitations could include:

• possible interferences from medical conditions, drugs, or other substances.

• warning that the test is not approved for use with alternate specimen types or in alternate populations (e.g., pediatric).

• indications of the need for additional testing that might be more specific or more sensitive.

• warning that the test does not differentiate between active infection and carrier states.

• statement that the test result should be considered in the context of clinical signs and symptoms, patient history, and other test

results.

Describes the test result the user should expect (positive/negative or within/outside of a reference interval). Explains, as

applicable, how results can vary depending on disease prevalence and the season of the year. Might include a brief description

of studies conducted to derive this information.

Details the results of studies conducted to evaluate test performance. Included are data used to determine accuracy, precision,

sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility of the test and results of cross-reactivity studies with interfering substances.

* Product inserts vary in format, but the majority contain the information described above. Some information might appear in different sections than listed

above because of format variations between manufacturers. Certificate of Waiver site directors and testing personnel should read this information for a

complete understanding of each test.

Intended use

Summary

Test principle

Precautions

Storage/Stability

Reagents and

materials supplied

Materials required

but not provided

Specimen collection

and preparation

Test procedure

Interpretation of

results

Quality control (QC)

Limitations

Expected values

Performance

characteristics

Vol. 54 / RR-13 Recommendations and Reports 13

formed. The specific test system name should be on the quick

reference instructions to avoid confusion.

A comprehensive procedure manual is a valuable resource

for CW sites. Although product inserts can be used as test

procedures, these instructions will typically need to be supple-

mented with testing information that is unique to the CW

site’s operations and workflow (31). A procedure manual can

also include examples of forms used (e.g., charts to record

daily test kit storage temperatures, infectious disease report-

ing forms, or logs for recording control testing and test results)

and check lists for personnel training. New testing procedures

should be reviewed and signed by the CW site director before

incorporating them into the procedure manual. The manual

should be updated as tests or other aspects of the testing ser-

vice change and should be reviewed by the director whenever

changes are made. When procedures are no longer used, they

should be removed from the manual and retained with a

notation of the dates during which they were in service.

When writing procedures for each CW site, it might be

helpful to:

• Use a template with standard component headings to

facilitate writing a new procedure and promote ease of

use when performing testing;

• List all materials needed and how to prepare them before

testing;

• Include instructions for patient preparation and specimen

collection;

• Highlight key steps in the procedure (e.g., test incuba-

tion time);

• List test limitations;

• Describe actions to take when the test does not perform

as expected;

• Integrate control procedures with the steps for perform-

ing patient testing to assure control testing is performed;

• Include established reference intervals and critical values

for the test; and

• Describe how to record and report results and how to

handle critical values.

Personnel Training

Trained and competent testing personnel are essential to

good quality testing and patient care. Data from CDC and

CMS surveys demonstrate that waived testing sites are subject

to a high rate of personnel turnover. Personnel should be

trained and competent in each test they will perform before

reporting patient results (32,33). In addition, training should

include aspects of safety (including Universal Precautions) and

QC. The CW site director or other person responsible for

overseeing testing should ensure that testing personnel receive

adequate training and are competent to perform the proce-

dures for which they are responsible. Training checklists are

helpful to ensure the training process is comprehensive and

documented.

The training process. Training should be provided by a

qualified person (e.g., experienced co-worker, facility expert,

or outside consultant) with knowledge of the test performance,

good laboratory practices, and the ability to evaluate the effi-

cacy of the training. On-the-job training should include the

following steps:

1. The trainee reads the testing instructions.

2. The trainer demonstrates the steps for performing the test.

3. The trainee performs the test while the trainer observes.

4. The trainer evaluates test performance, provides feedback

and additional instruction, and follow-up evaluations to

ensure effective training.

5. Both trainer and trainee document completion of training.

Training resources. Resources for training are available from

various sources. Tools for training continue to evolve and are

not limited to traditional methods. Instructional videos, work-

shops, computer-based programs, and other methods can be

used. The manufacturer’s test system instructions and instru-

ment operating manuals should be the primary resource for

information and training in CW sites. Other sources for train-

ing on waived testing or specific tests include:

• Manufacturers and distributors who often provide tech-

nical assistance, product updates or notifications, and lim-

ited training.

• Professional organizations that can provide workshops or

other training tools.

• State health departments or other government agencies

that can provide limited training.

Competency Assessment

To ensure testing procedures are performed consistently and

accurately, periodic evaluation of competency is recommended,

with retraining, as needed, on the basis of results of the compe-

tency assessment (32). Assessment activities should be conducted

in a positive manner with an emphasis on education and pro-

moting good testing practices. Competency can be evaluated

by methods such as observation, evaluating adequacy of docu-

mentation, or the introduction of mock specimens by testing

control materials or previously tested patient specimens. Exter-

nal quality assessment or evaluation programs, such as volun-

tary PT programs, are another resource for assessment.

Additional Measures to Help Testing Staff

Ensure Reliable Results

The CW site director or person overseeing testing should pro-

mote quality testing and encourage staff to ask questions and

seek help when they have concerns. Recommendations include:

14 MMWR November 11, 2005

• Identifying a resource person or expert (e.g., a consultant

or manufacturer’s technical representative), available

either off-site or on-site, to answer questions and be of

assistance.

• Posting telephone numbers for manufacturers’ technical

assistance representatives.

• Designating an appropriately trained person, who under-

stands the responsibilities and impact of changing from

one test system to another, to discuss new products with

sales representatives. Uninformed personnel might mis-

takenly use a promotional test kit, provided by a distribu-

tor or manufacturer’s representative, for patient testing

without realizing the consequences of test substitution.

Recommended Practices Before Testing

Preparations before performing patient testing are a critical

element in producing quality results. Paying attention to test

orders, properly identifying and preparing the patient, col-

lecting a good quality specimen, and setting up the test sys-

tem and testing area all contribute to reliable test results.

Test Orders, Patient Identification,

and Preparation

Before collecting the specimen, confirm the test(s) ordered and

the patient’s identification and verify that pretest instructions or

information, as applicable, have been provided. This includes:

• Test orders — CW sites performing various waived tests

should routinely confirm that the written test order is

correct. If there is a question, check with the ordering