793

PRIVACY HARMS

DANIELLE KEATS CITRON

*

& DANIEL J. SOLOVE

**

ABSTRACT

The requirement of harm has significantly impeded the enforcement of

privacy law. In most tort and contract cases, plaintiffs must establish that they

have suffered harm. Even when legislation does not require it, courts have taken

it upon themselves to add a harm element. Harm is also a requirement to

establish standing in federal court. In Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins and TransUnion

LLC v. Ramirez, the Supreme Court ruled that courts can override

congressional judgment about cognizable harm and dismiss privacy claims.

Case law is an inconsistent, incoherent jumble with no guiding principles.

Countless privacy violations are not remedied or addressed on the grounds that

there has been no cognizable harm.

Courts struggle with privacy harms because they often involve future uses of

personal data that vary widely. When privacy violations result in negative

consequences, the effects are often small—frustration, aggravation, anxiety,

inconvenience—and dispersed among a large number of people. When these

minor harms are suffered at a vast scale, they produce significant harm to

individuals, groups, and society. But these harms do not fit well with existing

cramped judicial understandings of harm.

This Article makes two central contributions. The first is the construction of

a typology for courts to understand harm so that privacy violations can be

tackled and remedied in a meaningful way. Privacy harms consist of various

different types that have been recognized by courts in inconsistent ways. Our

*

Jefferson Scholars Foundation Schenck Distinguished Professor in Law, Caddell and

Chapman Professor of Law, University of Virginia School of Law; Vice President, Cyber

Civil Rights Initiative; 2019 MacArthur Fellow.

**

John Marshall Harlan Research Professor of Law, George Washington University Law

School.

We would like to thank research assistants Kimia Favagehi, Katherine Grabar, Jean Hyun,

Austin Mooney, Julia Schur, and Rebecca Weitzel. Many scholars provided extremely helpful

feedback, including Kenneth Abraham, Alessandro Acquisti, Rachel Bayefsky, Ryan Calo,

Ignacio Cofone, Bob Gellman, Woodrow Hartzog, Chris Hoofnagle, Lauren Scholz, Lior

Strahelivitz, Ari Waldman, Benjamin Zipursky, the participants at our workshop at the

Privacy Law Scholars Conference, and students in Neil Richards’s Advanced Privacy Law

and Theory class at Washington University School of Law. Jackson Barnett and fellow editors

at the Boston University Law Review provided superb feedback during our delightful editing

process.

794 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

typology of privacy harms elucidates why certain types of privacy harms should

be recognized as cognizable.

This Article’s second contribution is providing an approach to when privacy

harm should be required. In many cases, harm should not be required because

it is irrelevant to the purpose of the lawsuit. Currently, much privacy litigation

suffers from a misalignment of enforcement goals and remedies. We contend that

the law should be guided by the essential question: When and how should

privacy regulation be enforced? We offer an approach that aligns enforcement

goals with appropriate remedies.

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 795

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 796

I. COGNIZABLE HARMS: THE LEGAL RECOGNITION OF

PRIVACY HARMS ................................................................................. 799

A. Standing ....................................................................................... 800

B. Harm in Causes of Action ............................................................ 807

1. Contract Law ......................................................................... 807

2. Tort Law ................................................................................ 808

3. Statutory Causes of Action .................................................... 810

C. Harm in Regulatory Enforcement Actions .................................. 813

II. THE CHALLENGES OF PRIVACY HARMS .............................................. 816

A. Aggregation of Small Harms ....................................................... 816

B. Risk: Unknowable and Future Harms ......................................... 817

C. Individual vs. Societal Harms ...................................................... 818

III. REALIGNING PRIVACY ENFORCEMENT AND REMEDIES ...................... 819

A. The Goals of Enforcement ........................................................... 820

B. Aligning Remedies with Goals ..................................................... 820

1. The Problem of Misalignment ............................................... 820

2. The Value of Private Enforcement ........................................ 821

3. An Approach for Realignment .............................................. 822

IV. THE IMPORTANCE OF PROPERLY RECOGNIZING PRIVACY HARMS ..... 826

A. Properly Identifying the Interests at Stake .................................. 826

B. The Expressive Value of Recognizing Harm ............................... 828

C. Legislative and Regulatory Agenda ............................................. 829

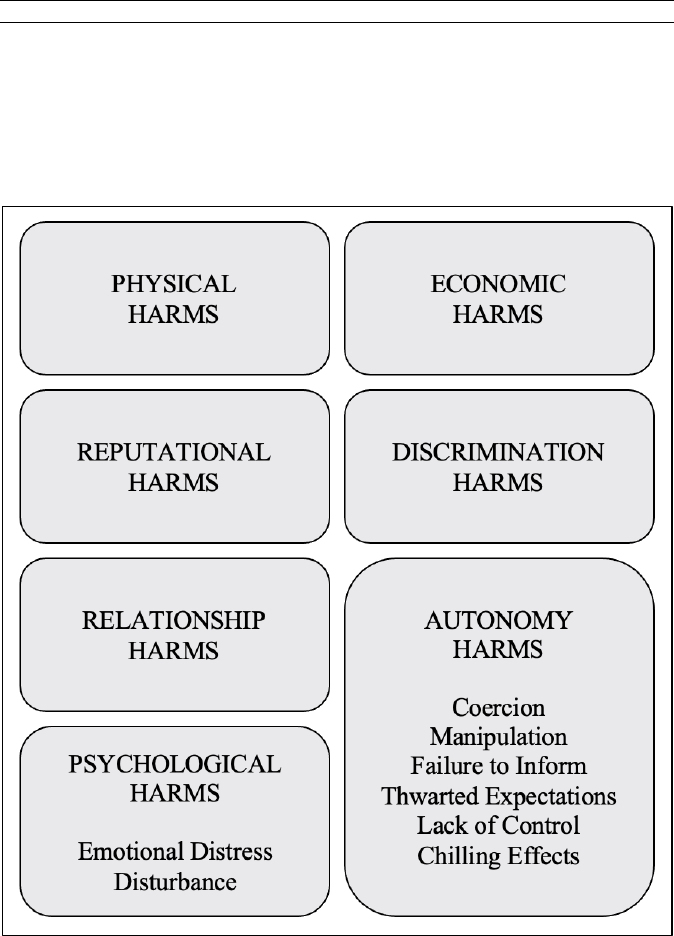

V. A TYPOLOGY OF PRIVACY HARMS ...................................................... 830

A. Physical Harms ........................................................................... 831

B. Economic Harms ......................................................................... 834

C. Reputational Harms ..................................................................... 837

D. Psychological Harms ................................................................... 841

1. Emotional Distress ................................................................ 841

2. Disturbance ............................................................................ 844

E. Autonomy Harms ......................................................................... 845

1. Coercion ................................................................................ 846

2. Manipulation ......................................................................... 846

3. Failure to Inform ................................................................... 848

4. Thwarted Expectations .......................................................... 849

5. Lack of Control ..................................................................... 853

6. Chilling Effects ...................................................................... 854

F. Discrimination Harms ................................................................. 855

G. Relationship Harms ..................................................................... 859

CONCLUSION ................................................................................................... 861

796 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

INTRODUCTION

Harm has become one of the biggest challenges in privacy law.

1

The law’s

treatment of privacy harms is a jumbled, incoherent mess. Countless privacy

violations are left unremedied not because they are unworthy of being addressed

but because of the law’s failure to recognize harm.

2

As Ryan Calo has observed,

“courts and some scholars require a showing of harm in privacy out of

proportion with other areas of law.”

3

Privacy law in the United States is a sprawling patchwork of various types of

law, from contract and tort to statutes and other bodies of law.

4

As these laws

are enforced, especially in the courts, harm requirements stand as a major

impediment.

5

When cases are dismissed due to the lack of harm, wrongdoers

escape accountability.

6

The message is troubling—privacy commitments

enshrined in legislation and common law can be ignored.

In several ways, harm emerges as a gatekeeper in privacy cases. Harm is an

element of many causes of action.

7

Courts, however, refuse to recognize privacy

harms that do not involve tangible financial or physical injury.

8

But privacy

harms more often involve intangible injuries, which courts address

inconsistently and with considerable disarray.

9

Many privacy violations involve

1

Jacqueline D. Lipton, Mapping Online Privacy, 104 NW. U. L. REV. 477, 508 (2010)

(“Delineating remediable harms has been a challenge for law and policy makers since the

early days of the Internet.”).

2

Id. at 505 (explaining monetary damages compensate economic harm, but “[c]ourts and

legislatures have been slow to compensate plaintiffs for nonmonetary harms resulting from a

privacy incursion”).

3

Ryan Calo, Privacy Harm Exceptionalism, 12 COLO. TECH. L.J. 361, 361 (2014); see also

Ryan Calo, Privacy Law’s Indeterminacy, 20 THEORETICAL INQUIRIES L. 33, 48 (2019)

(“[C]ourts . . . do not understand privacy loss as a cognizable injury, even as they recognize

ephemeral harms in other contexts.”).

4

DANIEL J. SOLOVE & PAUL M. SCHWARTZ, INFORMATION PRIVACY LAW 2 (7th ed. 2021).

(“Information privacy law is an interrelated web of tort law, federal and state constitutional

law, federal and state statutory law, evidentiary privileges, property law, contract law, and

criminal law.”).

5

Calo, Privacy Harm Exceptionalism, supra note 3, at 362 (explaining, for example, that

in Federal Aviation Administration v. Cooper, the Supreme Court’s reading of the Privacy

Act to require “‘actual damages’ limited to pecuniary or economic harm” prevented plaintiff

from recovery (quoting Fed. Aviation Admin. v. Cooper, 566 U.S. 284, 292 (2012))).

6

Id. (citing instances where, absent a finding of cognizable harm, privacy actions were

dismissed for lack of standing).

7

Id. at 361 (noting harm is a “prerequisite to recovery in many contexts”).

8

Danielle Keats Citron, The Privacy Policymaking of State Attorneys General, 92 NOTRE

DAME L. REV. 747, 798-99 (2016) [hereinafter Citron, Privacy Policymaking] (“For most

courts, privacy and data security harms are too speculative and hypothetical, too based on

subjective fears and anxieties, and not concrete and significant enough to warrant

recognition.”).

9

Lipton, supra note 1, at 504-05 (explaining that economic loss is “readily cognizable”

but intangible harms like shame, embarrassment, ridicule, and humiliation are more difficult

to quantify).

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 797

broken promises or thwarted expectations about how people’s data will be

collected, used, and disclosed.

10

The downstream consequences of these

practices are often hard to determine in the here and now. Other privacy

violations involve flooding people with unwanted advertising or email spam. Or

people’s expectations may be betrayed, resulting in their data being shared with

third parties that may use it in detrimental ways—although precisely when and

how is unknown.

For many privacy harms, the injury may appear small when viewed in

isolation, such as the inconvenience of receiving an unwanted email or

advertisement or the failure to honor people’s expectations that their data will

not be shared with third parties. But when done by hundreds or thousands of

companies, the harm adds up. Moreover, these small harms are dispersed among

millions—and sometimes billions—of people.

11

Over time, as people are

individually inundated by a swarm of small harms, the overall societal impact is

significant. Yet these types of injuries do not fit well into judicial conceptions

of harm, which have an individualistic focus and heavily favor tangible physical

and financial injuries that occur immediately.

Some statutory laws recognize government agency or state attorney general

enforcement that is less constrained by judicial conceptions of harm, but these

enforcers have limited resources so they can only bring a handful of actions each

year.

12

To fill the anticipated enforcement gap, legislators have often included

statutory private rights of action.

13

The financial rewards of litigating and

winning cases work like a bounty system, encouraging private parties to enforce

the law.

14

To address the difficulties in establishing privacy harms, several

privacy statutes contain statutory damages provisions, which allow people to

recover a minimum amount of money without having to prove harm.

15

10

Id. at 498-99 (noting “the greatest harms in the present age often come from

unauthorized uses of private information online” including the improper collection,

aggregation, processing, and dissemination of information).

11

See, e.g., Brian Fung, T-Mobile Says Data Breach Affects More than 40 Million People,

CNN BUS. (Aug. 18, 2021, 8:07 AM), https://www.cnn.com/2021/08/18/tech/t-mobile-data-

breach/index.html [https://perma.cc/L6XV-6PUN] (reporting that one data breach “affect[ed]

as many as 7.8 million postpaid subscribers, 850,000 prepaid customers and ‘just over’ 40

million past or prospective customers who have applied for credit with T-Mobile”).

12

Citron, Privacy Policymaking, supra note 8, at 799 (“Federal authorities cannot attend

to most privacy and security problems because their resources are limited and their duties ever

expanding. Simply put, federal agencies have too few resources and too many

responsibilities.” (footnote omitted)).

13

See infra notes 109-12 and accompanying text (listing several examples of federal and

state privacy laws with private rights of action).

14

See Crabill v. Trans Union, L.L.C., 259 F.3d 662, 665 (7th Cir. 2001) (“The award of

statutory damages could also be thought a form of bounty system, and Congress is permitted

to create legally enforceable bounty systems for assistance in enforcing federal laws . . . .”).

15

See infra notes 113-16 and accompanying text (explaining that, for example, under Fair

Credit Reporting Act, a person who willfully violates any part of the statute is liable for at

least $100 in damages, and listing other statutes which do not require a showing of harm).

798 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

Courts, however, have wrought havoc on legislative plans for statutory

damages in privacy cases by adding onerous harm requirements. In Doe v.

Chao,

16

for example, the Supreme Court held that a statutory damages provision

under the federal Privacy Act of 1974 would only impose such damages if

plaintiffs established “actual” damages.

17

As a second punch, the Court held in

Federal Aviation Administration v. Cooper

18

that emotional distress alone was

insufficient to establish actual damages under the Privacy Act.

19

In a variation

of this theme, in Senne v. Village of Palatine,

20

the Seventh Circuit held that a

plaintiff had to prove harm to recover under a private right of action for a

violation of the federal Driver’s Privacy Protection Act (“DPPA”) even though

the provision lacked any harm requirement.

21

Courts have also injected harm as a gatekeeper to the enforcement of the law

through modern standing doctrine. The Supreme Court has held that plaintiffs

cannot pursue cases in federal court unless they have suffered an “injury in

fact.”

22

Specifically in the privacy law context, in 2016, the Supreme Court

concluded in Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins,

23

a case involving the Fair Credit Reporting

Act (“FCRA”), that courts could deny standing to plaintiffs seeking to recover

under private rights of action in statutes.

24

The court stated that, even if a

legislature granted plaintiffs a right to recover without proving harm, courts

could require a plaintiff to prove harm to establish standing.

25

Due to judicial intervention, the requirement of privacy harm is inescapable.

Even when legislation does not require proof of harm, courts exert their will to

add it in, turning the enforcement of privacy law into a far more complicated

task than it should be. Privacy harm is a conceptual mess that significantly

impedes U.S. privacy law from being effectively enforced. Even when

16

540 U.S. 614 (2004).

17

Id. at 616 (holding “[p]laintiffs must prove some actual damages to qualify for a

minimum statutory award”).

18

566 U.S. 284 (2012).

19

Id. at 299-304 (holding “the Privacy Act does not unequivocally authorize an award of

damages for mental or emotional distress” and adopting narrow interpretation of actual

damages limited to pecuniary harm).

20

784 F.3d 444 (7th Cir. 2015).

21

Id. at 448.

22

Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Env’t Servs. (TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 181 (2000)

(declaring that injury-in-fact requirement is met only by showing “injury to the plaintiff”).

23

578 U.S. 330 (2016).

24

Id. at 341 (holding that plaintiffs alleging “bare procedural violation” of FCRA do not

satisfy injury-in-fact requirement of Article III and thus lack standing).

25

Id. at 337-38 (noting that Congress does not have power to give plaintiffs statutory right

to sue unless those plaintiffs also satisfy Article III standing requirements).

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 799

organizations have engaged in clear wrongdoing, privacy harm requirements

often result in cases being dismissed.

26

In this Article, we clear away the fog so that privacy harms can be better

understood and appropriately addressed.

27

We set forth a typology that explains

why particular harms should be legally cognizable. We show how concepts and

doctrines in other areas of law can be applied in the context of privacy harms.

In addition to the issue of what should constitute cognizable privacy harm,

we also examine the issue of when privacy harm should be required. In many

cases, harm should not be required because it is irrelevant to the purpose of the

lawsuit. The overarching question that the law should ask is: When and how

should various privacy laws be enforced? This question brings into focus the

underlying source of the law’s current malaise: the misalignment of enforcement

goals and remedies. We propose an approach that aligns enforcement goals with

appropriate remedies.

Properly recognizing privacy harm is not just essential for litigation. It is

essential for its expressive value as well as for legislation and regulatory

enforcement. Appropriately identifying the interests at stake is essential for the

law to balance and protect them.

This Article has five parts. Part I discusses when the law requires cognizable

harm in order to enforce privacy regulation. Part II examines several challenges

that make it difficult to recognize certain types of privacy harms. Part III

examines when privacy harm should be required in privacy litigation and how

the law should better align enforcement goals and remedies. Part IV discusses

the importance of recognizing privacy harm. Part V sets forth a typology of

privacy harms, explaining why each involves an impairment of important

interests, how the law tackles them, and why the law should do so.

I. COGNIZABLE HARMS: THE LEGAL RECOGNITION OF PRIVACY HARMS

Requirements to establish harm are major hurdles in privacy cases. Harms

involve injuries, setbacks, losses, or impairments to well-being.

28

They leave

people or society worse off than before their occurrence.

29

Frequently,

26

E.g., Senne, 784 F.3d at 448 (holding that even though defendant’s display of plaintiff’s

personal information amounted to a disclosure under DPPA, plaintiff could not recover absent

finding of harm).

27

Previously, we wrote an article about data breach harms. Daniel J. Solove & Danielle

Keats Citron, Risk and Anxiety: A Theory of Data-Breach Harms, 96 TEX. L. REV. 737 (2018)

[hereinafter Solove & Citron, Risk and Anxiety]. We write separately on privacy harms

because they are quite different. Data breach harms often involve either anxiety or a risk of

future identity theft or fraud. Privacy harms are more varied than data breach harms and

involve many other dimensions that pose challenges for the law.

28

A taxonomy of privacy developed by one of us (Solove) has focused on privacy

problems. DANIEL J. SOLOVE, UNDERSTANDING PRIVACY (2008). Problems are broader than

harms. Problems are undesirable states of affairs. Harms are a subset of problems.

29

JOEL FEINBERG, 1 THE MORAL LIMITS OF THE CRIMINAL LAW: HARM TO OTHERS 28, 34-

36 (1984) (defining harms as “setbacks to interest” and noting that “[t]he test . . . of whether

800 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

establishing harm is a prerequisite to enforcement for privacy violations in the

judicial system. A cognizable harm is harm that the law recognizes as suitable

for intervention.

30

Through harm requirements, courts have made the enforcement of privacy

laws difficult and, at times, impossible. They have added requirements for harm

via standing.

31

They have required harm for statutes that do not require such a

showing.

32

They have mandated proof of harm even for statutes that include

statutory damages, undercutting the purpose of these provisions.

33

They have

adopted narrow conceptions of cognizable harm to exclude many types of harm,

including emotional injury and dashed expectations.

34

Because courts lack a

theory of privacy harms or any guiding principles, they have made a mess of

things. This Part discusses the varied ways that harm is involved in privacy

cases.

A. Standing

To pursue a lawsuit in federal court, a plaintiff must have standing. Standing

is based on Article III of the U.S. Constitution, which states that courts are

limited to hearing “cases” or “controversies.”

35

In a series of cases starting in the

second half of the twentieth century, the Supreme Court placed harm at the

such an invasion has in fact set back an interest is whether that interest is in a worse condition

than it would otherwise have been in had the invasion not occurred at all”).

30

Id. at 34 (“It is only when an interest is thwarted through an invasion by self or others,

that its possessor is harmed in the legal sense . . . .”); see also OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES, THE

COMMON LAW 64 (Mark DeWolfe Howe ed., Harvard Univ. Press 1963) (1881) (“The

business of the law of torts is to fix the dividing lines between those cases in which a man is

liable for harm which he has done, and those in which he is not. But it cannot enable him to

predict . . . . [a]ll the rules that the law can lay down beforehand are rules for determining

conduct which will be followed by liability if it is followed by harm,—that is, the conduct

which a man pursues at his peril.”); Thomas C. Grey, Accidental Torts, 54 VAND. L. REV.

1225, 1272 (2001) (discussing Holmes’s harm-based approach).

31

See, e.g., Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Env’t Servs. (TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167,

181 (2000) (holding proof of harm is necessary to satisfy “injury in fact” requirement in

Article III standing).

32

See, e.g., Senne v. Village of Palatine, 784 F.3d 444, 448 (7th Cir. 2015) (denying

plaintiff recovery on grounds that plaintiff did not prove harm even though statute plaintiff

was suing under lacked harm requirement).

33

See, e.g., Doe v. Chao, 540 U.S. 614, 627 (2004) (refusing to award plaintiff minimum

statutory damages under Privacy Act of 1974 on grounds that plaintiff did not sufficiently

show harm resulting in “actual damages”).

34

See, e.g., Fed. Aviation Admin. v. Cooper, 566 U.S. 284, 299 (2012) (adopting narrow

interpretation of “actual damages” such that only proven pecuniary harm suffices).

35

U.S. CONST. art. III, § 2.

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 801

center of standing doctrine.

36

State courts generally do not require proof of

standing.

37

The Supreme Court has developed a rather tortured body of standing doctrine,

which is restrictive in its view of harm as well as muddled and contradictory.

Under contemporary standing doctrine, plaintiffs must allege an “injury in

fact.”

38

The injury must be “concrete and particularized” and “actual or

imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical.”

39

If a plaintiff lacks standing to bring

a claim, a federal court cannot hear it.

40

Three cases decided during the past decade focused on privacy issues. In

2013, in Clapper v. Amnesty International,

41

a group of lawyers, journalists, and

activists challenged the constitutionality of surveillance by the National Security

Agency (“NSA”). The plaintiffs contended that because they were

communicating with foreign people whom the NSA was likely to deem

suspicious, they feared their communications would be wiretapped. The

plaintiffs took measures to avoid governmental surveillance that would pierce

attorney-client confidentiality, including spending time and money to travel in

person to talk to clients.

42

The Court held that the plaintiffs lacked standing

because they failed to prove that they were actually under government

surveillance or that such surveillance was “certainly impending.”

43

The

plaintiffs’ “speculation” about being under surveillance was insufficient.

44

In a

36

E.g., Friends of the Earth, 528 U.S. at 181.

37

Peter N. Salib & David K. Suska, The Federal-State Standing Gap: How to Enforce

Federal Law in Federal Court Without Article III Standing, 26 WM. & MARY BILL RTS. J.

1155, 1160 (2018) (“State courts are not subject to Article III and its standing requirement.”).

38

Friends of the Earth, 528 U.S. at 180-81 (citing Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504

U.S. 555, 560-61 (1992)) (noting that to satisfy Article III’s standing requirements, plaintiff

must show injury in fact, causation, and redressability).

39

Id. at 180.

40

Id. (“[The Court has] an obligation to assure [itself] that [plaintiff] had Article III

standing at the outset of the litigation”).

41

568 U.S. 398 (2013).

42

Id. at 415 (“Respondents claim . . . the threat of surveillance sometimes compels them

to avoid certain e-mail and phone conversations, to ‘tal[k] in generalities rather than

specifics,’ or to travel so that they can have in-person conversations.” (second alteration in

original)). For a thoughtful analysis of Clapper, see Neil M. Richards, The Dangers of

Surveillance, 126 HARV. L. REV. 1934 (2013).

43

Clapper, 568 U.S. at 422.

44

The Clapper case comes with a dose of cruel irony. Although the government

diminished the plaintiffs’ concerns about surveillance by arguing that the plaintiffs could not

prove that they were subject to it, the government knew the answer all along (it was surely

engaging in such surveillance), but because the program was classified as a state secret, the

plaintiffs did not and could not know for sure that they were being subject to surveillance. See

Seth F. Kreimer, “Spooky Action at a Distance”: Intangible Injury in Fact in the Information

Age, 18 U. PA. J. CONST. L. 745, 756-57 (2016) (describing the Bush Administration as

engaging in a “strategy of deep secrecy” which resulted in details of surveillance only being

known by a “charmed circle of initiates” who would not face legal scrutiny).

802 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

footnote, the Court noted that, “in some instances,” a “‘substantial risk’ that the

harm will occur” would be sufficient to confer standing to a plaintiff.

45

The

Court never explained what would constitute a “substantial risk.”

Although Clapper had a significant impact on data breach cases, a subsequent

case took center stage for standing in privacy cases. In 2016, in Spokeo, Inc. v.

Robins, the Supreme Court attempted to elaborate on the types of harm that

could be sufficient to establish standing.

46

The Court focused on whether

statutory violations involving personal data constituted harm sufficient to

establish standing. The plaintiff alleged that Spokeo, a site supplying

information about people’s backgrounds, violated the federal FCRA when it

published incorrect data about him.

47

Spokeo’s profiles were used by employers

to investigate prospective hires, an activity regulated by the FCRA. The FCRA

mandates that firms take reasonable steps to ensure the accuracy of data in

people’s profiles.

48

The plaintiff’s dossier was riddled with falsehoods,

including that he was wealthy and married, had children, and worked in a

professional field.

49

According to the plaintiff, these errors hurt his employment

chances by indicating that he was overqualified for positions he sought or that

he might not be able to relocate because he had a family.

50

Although the district court held that the plaintiff properly sued under the

FCRA’s private right of action, it nevertheless held the plaintiff lacked standing

because he had not suffered an injury based on the erroneous information

included in his credit report.

51

The Ninth Circuit reversed on the grounds that

the statute resolved the question of whether a cognizable injury existed: the

FCRA explicitly allowed plaintiffs to sue for any violation of its provisions.

52

45

Clapper, 568 U.S. at 414 n.5 (citing Monsanto Co. v. Geertson Seed Farms, 561 U.S.

139, 153 (2010)). In Susan B. Anthony List v. Driehaus, the Court, quoting Clapper, held that

“[a]n allegation of future injury may suffice if the threatened injury is ‘certainly impending,’

or there is a ‘substantial risk’ that the harm will occur.” 573 U.S. 149, 158 (2014).

46

578 U.S. 330, 340-42 (2016) (noting that history and “judgment of Congress” are

meaningful in determining whether intangible harm amounts to injury in fact).

47

Id. at 333-34 (describing website as “people search engine” and explaining Robins’s

claim that site violated his (and other similarly situated individuals’) rights under the FCRA

when it published false information).

48

15 U.S.C. § 1681e(b) (mandating that consumer reporting agencies “follow reasonable

procedures to assure maximum possible accuracy of the information concerning the individual

about whom the report relates”).

49

Spokeo, 578 U.S. at 336.

50

Id. at 350 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting).

51

Id. at 336.

52

Robins v. Spokeo, Inc., 742 F.3d 409, 411-14 (9th Cir. 2014), vacated, 578 U.S. 330

(2016); see also 15 U.S.C. § 1681n (imposing civil liability for willful violations); Id. § 1681o

(imposing civil liability for negligent violations).

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 803

The Supreme Court took up the case, issuing an opinion purporting to clarify

standing doctrine but instead creating significant confusion.

53

Instead of

deferring to congressional judgment for when plaintiffs could sue for violations

of the FCRA, the Court added harm into the equation through standing.

54

Reversing and remanding the case to the Ninth Circuit, the Court explained that

harm must be “concrete” and that “intangible harm” could be sufficient in some

cases to establish injury.

55

According to the Court, a “risk of real harm” could

satisfy the concreteness inquiry because long-standing common law has

“permitted recovery by certain tort victims even if their harms may be difficult

to prove or measure.”

56

The question would turn on “whether an alleged

intangible harm has a close relationship to a harm that has traditionally been

regarded as providing a basis for a lawsuit in English or American courts.”

57

Unfortunately, the common law invoked by the Court points in different

directions. The Court’s discussion of “intangible harm” ended up creating

further confusion rather than clarity.

The Court confounded matters in yet another way—it instructed courts to

assess “the judgment of Congress” to figure out “whether an intangible harm

constitutes injury in fact.”

58

The Court began by noting:

[W]e said in Lujan that Congress may “elevat[e] to the status of legally

cognizable injuries concrete, de facto injuries that were previously

inadequate in law.” Similarly, Justice Kennedy’s concurrence in that case

explained that “Congress has the power to define injuries and articulate

chains of causation that will give rise to a case or controversy where none

existed before.”

59

Although Congress could independently define “concrete injury” in a way

that enlarged the concept, the Court also said that Congress could deviate only

so much:

Congress’ role in identifying and elevating intangible harms does not mean

that a plaintiff automatically satisfies the injury-in-fact requirement

whenever a statute grants a person a statutory right and purports to

authorize that person to sue to vindicate that right. Article III standing

requires a concrete injury even in the context of a statutory violation. For

that reason, Robins could not, for example, allege a bare procedural

53

Spokeo, 578 U.S. at 337-42 (deciding even where Congress created private right of

action for statutory violations, plaintiffs must show concrete and particularized harm to satisfy

injury-in-fact requirement of Article III standing).

54

Id. at 337-40.

55

Id. at 340-42.

56

Id. at 341.

57

Id.

58

Id. at 340-41.

59

Id. at 341 (first quoting Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 578 (1992); and

then quoting Lujan, 504 U.S. at 580 (Kennedy, J., concurring)).

804 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

violation, divorced from any concrete harm, and satisfy the injury-in-fact

requirement of Article III.

60

As to how far Congress could deviate from courts in defining injuries, the

Court failed to provide a clear answer. As an example, the Court noted that

courts could reject a “bare procedural violation” of a statute as an injury, but this

example was muddled with further explanation: “[T]he violation of a procedural

right granted by statute can be sufficient in some circumstances to constitute

injury in fact. In other words, a plaintiff in such a case need not allege any

additional harm beyond the one Congress has identified.”

61

The Court thus said on one hand that a mere violation of a procedural right

can be sufficient for concrete injury without any additional harm. But, on the

other hand, a “bare procedural violation, divorced from any concrete harm”

cannot satisfy the harm requirement.

62

So, how are courts to distinguish between

when a violation of a procedural right is a concrete injury and when it is not?

The Court tried to explain its reasoning by noting that Congress passed the

FCRA “to curb the dissemination of false information,” so bare procedural

violations would not support standing if they did not operate to prevent such

inaccuracies.

63

The Court explained that consumers may not be able to sue a

consumer reporting agency for failing to provide notice required by the statute

if the information in their dossiers was accurate. The Court further complicated

matters by stating that “not all inaccuracies cause harm or present any material

risk of harm.”

64

The example provided by the Court was an incorrect zip code.

The Court explained, “It is difficult to imagine how the dissemination of an

incorrect zip code, without more, could work any concrete harm.”

65

The Court remanded the case to the Ninth Circuit to examine “whether the

particular procedural violations alleged in this case entail a degree of risk

sufficient to meet the concreteness requirement.”

66

The Court noted that it was

not taking a particular position about whether Robins properly alleged an

injury.

67

In the wake of Spokeo, courts issued a contradictory mess of decisions

regarding privacy harm and standing. On remand, the Ninth Circuit concluded

that Robins had suffered harm, justifying standing.

68

The court applied a test

60

Id.

61

Id. at 341-42.

62

Id. at 341.

63

Id. at 342.

64

Id.

65

Id.

66

Id. at 343 (Thomas, J., concurring).

67

See id. at 343 (majority opinion) (“We take no position as to whether the Ninth Circuit’s

ultimate conclusion¾that Robins adequately alleged an injury in fact¾was correct.”).

68

Robins v. Spokeo, Inc. (Spokeo II), 867 F.3d 1108, 1118 (9th Cir. 2017) (“We are

satisfied that Robins has alleged injuries that are sufficiently concrete for the purposes of

Article III.”), cert. denied, 138 S. Ct. 931 (2018).

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 805

from the Second Circuit that assessed whether a statutory provision was

designed to protect people’s concrete interests and whether those interests were

at risk of harm in a particular case.

69

Other courts have extracted a two-prong

test from the wreckage, first looking to a “historical inquiry” that “asks whether

an intangible harm ‘has a close relationship’ to one that historically has provided

a basis for a lawsuit,” and second, looking to a “congressional inquiry” that

“acknowledges that Congress’s judgment is ‘instructive and important’ because

that body ‘is well positioned to identify intangible harms that meet minimum

Article III requirements.’”

70

In the lower courts, no clear principles have emerged to guide the harm

inquiry for standing in privacy cases. Rather than a simple circuit split or other

clear disagreement in approach, courts have produced a jumbled mess by

grasping at inconsistent parts of Spokeo.

71

Predictably, courts have reached

opposing conclusions as to the very same or similar FCRA violations. In Dutta

v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance,

72

the Ninth Circuit concluded that

an employer’s alleged FCRA violation—failing to provide the plaintiff with a

copy of his inaccurate credit report before disqualifying him from the hiring

process—was not a harm because the correct information in the credit report

prevented him from getting a job anyway.

73

By contrast, in Long v. Southeastern

Pennsylvania Transportation Authority,

74

the Third Circuit found the plaintiffs

had standing to sue an employer under the FCRA for its alleged failure to

provide them with copies of their fully accurate background checks before

rejecting them for a job.

75

As the Third Circuit stated in another case involving a FCRA violation,

In some cases, we have appeared to reject the idea that the violation of a

statute can, by itself, cause an injury sufficient for purposes of Article III

standing. But we have also accepted the argument, in some circumstances,

69

See id. at 1113 (citing Strubel v. Comenity Bank, 842 F.3d 181, 190 (2d Cir. 2016))

(holding the two-prong Strubel test “best elucidates the concreteness standards articulated by

the Supreme Court in Spokeo II” and applying it to Robins’s alleged harm).

70

Long v. Se. Pa. Transp. Auth., 903 F.3d 312, 321 (3d Cir. 2018) (quoting Spokeo, 578

U.S. at 341).

71

Jackson Erpenbach, Note, A Post-Spokeo Taxonomy of Intangible Harms, 118 MICH. L.

REV. 471, 473 (2019) (describing inconsistent findings of standing for intangible harms as

evidence of “significant confusion in the lower courts” caused by Spokeo).

72

895 F.3d 1166 (9th Cir. 2018).

73

Id. at 1175-76 (holding plaintiff “plausibly [pled] a violation of [FCRA]” by alleging

State Farm disqualified him before providing copy of his credit report but “fail[ed] to

demonstrate actual harm or a substantial risk of such harm” because disqualification was

based on report’s accurate information).

74

Long, 903 F.3d 312.

75

Id. at 316-17, 322-24 (finding “the use of Plaintiffs’ personal information . . . without

Plaintiffs being able to see or respond to it” was “sufficient concrete harm” to establish

standing).

806 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

that the breach of a statute is enough to cause a cognizable injury—even

without economic or other tangible harm.

76

Similarly, the Sixth Circuit declared when it dismissed a case for lack of

standing, “It’s difficult, we recognize, to identify the line between what

Congress may, and may not, do in creating an ‘injury in fact.’ Put five smart

lawyers in a room, and it won’t take long to appreciate the difficulty of the task

at hand.”

77

In its coup de grâce, the Supreme Court in 2021 revisited standing and the

FCRA in TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez.

78

TransUnion incorrectly labeled the

plaintiffs as potential terrorists in their credit reports. The Court held that only

the plaintiffs whose credit reports had been disclosed to businesses had standing;

plaintiffs whose credit reports had not yet been disseminated had not suffered a

concrete injury.

79

As the Court pithily concluded, “No concrete harm, no

standing.”

80

To determine whether harm is concrete, the Court reiterated the position it

had previously espoused in Spokeo: “Central to assessing concreteness is

whether the asserted harm has a ‘close relationship’ to a harm traditionally

recognized as providing a basis for a lawsuit in American courts . . . .”

81

Yet

still, the Court provided scant guidance about how close the relationship must

be to traditionally recognized harm. Another difficulty with this test is that harm

traditionally has not been required at all for violations of individual private

rights, as Justice Thomas pointed out in his dissent.

82

Additionally, the harms

that courts have recognized have evolved considerably in the common law.

83

Pointing to tradition means that the target is constantly moving.

76

In re Horizon Healthcare Servs. Inc. Data Breach Litig., 846 F.3d 625, 635 (3d Cir.

2017) (footnote omitted).

77

Hagy v. Demers & Adams, 882 F.3d 616, 623 (6th Cir. 2018).

78

141 S. Ct. 2190, 2200-02 (2021) (determining class action plaintiffs’ standing on claims

arising from TransUnion’s FCRA violations).

79

Id. at 2200 (holding 1,853 class members whose “misleading credit reports [were

provided] to third-party businesses” had “demonstrated concrete reputational harm and thus

had Article III standing,” while the remaining 6,332 did not).

80

Id. For more background about TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez and our extensive critique

of the decision, see Daniel J. Solove & Danielle Keats Citron, Standing and Privacy Harms:

A Critique of TransUnion v. Ramirez, 101 B.U. L. REV. ONLINE 62 (2021) [hereinafter Solove

& Citron, Standing and Privacy Harms].

81

TransUnion, 141 S. Ct. at 2200 (citing Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins, 578 U.S. 530, 341

(2016)).

82

See id. at 2217 (Thomas, J., dissenting) (“Where an individual sought to sue someone

for a violation of his private rights, . . . the plaintiff needed only to allege the violation. Courts

typically did not require any showing of actual damage.” (citation omitted))).

83

Solove & Citron, Standing and Privacy Harms, supra note 80, at 67-68 (critiquing

TransUnion’s reliance on “messy and inconsistent” common law that “is constantly

evolving”).

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 807

In the end, applying this test is difficult because the tradition of the common

law is complicated, nuanced, and ever-shifting. The Court in TransUnion

appeared to have a different conception of the tradition in mind, and other courts

will likely interpret the tradition in diverging ways. Ultimately, looking for a

close relationship to traditionally recognized harms leaves the door open for

courts to reach wildly different conclusions in cases. Standing doctrine in

privacy litigation will thus remain muddled and inconsistent.

B. Harm in Causes of Action

For plaintiffs in federal court, standing is just the first harm hurdle. The

second is showing harm as an element of claims alleged in the lawsuit.

Additionally, in state courts, although there is no constitutional standing

requirement,

84

most causes of action nevertheless have harm as one of the

elements. Different types of causes of action recognize cognizable harm

differently.

1. Contract Law

Contract law might seem to be a relevant body of law to regulate many

privacy issues, as many privacy violations involve organizations breaking

promises made in privacy policies.

85

These policies could be deemed contracts

or at least be subject to the doctrine of promissory estoppel. But, on the main,

courts have been reluctant to recognize privacy policies as contracts.

86

84

Salib & Suska, supra note 37, at 1169-72 (explaining states have “comparatively lax”

standing requirements because Article III does not apply (citing ASARCO Inc. v. Kadish, 490

U.S. 605, 617 (1989))).

85

See Bernard Chao, Privacy Losses as Wrongful Gains, 106 IOWA L. REV. 555, 559-64

(2021) (detailing various privacy policy violations by, inter alia, tech companies, retailers,

automobile producers, and nonprofits).

86

Courts have decided surprisingly few cases involving contract law theories for privacy

notices. Of those cases, few have held that privacy policies amount to enforceable contracts.

A group of academics published an empirical analysis of cases and concluded that many

courts were holding that privacy notices were contracts. See Oren Bar-Gill, Omri Ben-Shahar

& Florencia Marotta-Wurgler, Searching for the Common Law: The Quantitative Approach

of the Restatement of Consumer Contracts, 84 U. CHI. L. REV. 7, 28 (2017) (concluding that

“privacy policies are typically recognized as contracts”). These academics used their study

as part of their project with the American Law Institute, the Restatement of Consumer

Contracts. See id. at 8. However, Gregory Klass critiqued the study, finding that the cases

were incorrectly evaluated. See Gregory Klass, Empiricism and Privacy Policies in the

Restatement of Consumer Contract Law, 36 YALE J. ON REGUL. 45, 50, 67 (2019) (rejecting

Bar-Gill et al.’s conclusions because majority of cases upon which they relied did not classify

privacy policies as contracts and were decisions on motions to dismiss in federal district

courts). Klass found “little support” for any “trend towards contractual enforcement of privacy

notices.” See id. at 50 (quoting RESTATEMENT OF THE L. CONSUMER CONTS. § 1 Reporters’

Notes 15 (AM. L. INST., Discussion Draft No. 4 2017)). A subsequent analysis of the Bar-Gill

study sided with Klass. Adam J. Levitin, Nancy S. Kim, Christina L. Kunz, Peter Linzer,

Patricia A. McCoy, Juliet M. Moringiello, Elizabeth A. Renuart & Lauren E. Willis, The

Faulty Foundation of the Draft Restatement of Consumer Contracts, 36 YALE J. ON REGUL.

808 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

Even if privacy policies were contracts, the plaintiffs would still lose due to

the absence of cognizable harm. Under contract law, courts typically require

harm amounting to economic loss.

87

Failing to fulfill promises made in privacy

policies and thus betraying people’s expectations has not counted as a

cognizable harm.

88

For example, in Smith v. Trusted Universal Standards in

Electronic Transactions, Inc.,

89

the court stated that the “[p]laintiff

must . . . plead loss flowing from the breach [of contract] to sustain a claim.”

90

In Rudgayzer v. Yahoo! Inc.,

91

the court held that “[m]ere disclosure of

[personal] information . . . without a showing of actual harm[] is insufficient” to

support a breach of contract claim.

92

2. Tort Law

Most tort claims require that plaintiffs establish harm.

93

As tort law developed

in the nineteenth century, a lively debate centered on whether tort law concerned

the recognition of wrongs or, alternatively, the redress of harms.

94

In The

Common Law, Oliver Wendell Holmes argued that tort law provided remedies

for activities “not because they are wrong, but because they are harms.”

95

Modern tort law has largely embraced the Holmesian approach.

96

The privacy torts grew out of Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis’s influential

article in 1890, The Right to Privacy.

97

Warren and Brandeis primarily took a

447, 450 (2019) (noting authors’ own review of cases in which Klass disagreed with Bar-Gill

et al. led them to “conclude[] that Professor Klass’s readings were uniformly correct”).

87

Thomas B. Norton, Note, The Non-contractual Nature of Privacy Policies and a New

Critique of the Notice and Choice Privacy Protection Model, 27 FORDHAM INTELL. PROP.

MEDIA & ENT. L.J. 181, 193-94, 193 n.57 (citing numerous cases to show damages are “an

essential element of a breach of contract claim”).

88

See Joel R. Reidenberg, Privacy Wrongs in Search of Remedies, 54 HASTINGS L.J. 877,

881-84, 892-93 (2003) (framing thwarted expectations as privacy wrong and discussing lack

of judicial remedies for such wrongs).

89

No. 09-cv-04567, 2010 WL 1799456 (D.N.J. May 4, 2010).

90

Id. at *10.

91

No. 5:12-cv-01399, 2012 WL 5471149 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 9, 2012).

92

Id. at *6.

93

See JOHN C.P. GOLDBERG & BENJAMIN ZIPURSKY, RECOGNIZING WRONGS 28 (2020)

(“Every tort involves a person injuring another person in some way, or failing to prevent

another’s injury: every tort is an injury-inclusive wrong.”).

94

See John C.P. Goldberg, Unloved: Tort in the Modern Legal Academy, 55 VAND. L.

REV. 1501, 1505 n.15 (2002) (describing debates in nineteenth century concerning tort’s status

as a substantive area of law or merely “part of civil procedure and/or remedies”).

95

HOLMES, supra note 30, at 130.

96

See GOLDBERG & ZIPURSKY, supra note 93, at 5-6, 44 (noting Holmesian pragmatism,

including concept that purpose of tort law is to compensate victims for losses, is modern view

of many academics). There is a robust and important literature on tort law as the recognition

of wrongs. See generally id.

97

Samuel D. Warren & Louis D. Brandeis, The Right to Privacy, 4 HARV. L. REV. 193

(1890); see also Danielle Keats Citron, Mainstreaming Privacy Torts, 98 CALIF. L. REV. 1805,

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 809

rights-based approach rather than a harms-based approach to privacy,

conceiving of privacy as the protection of “individuals’ ability to develop their

‘inviolate’ personalities without unwanted interference.”

98

The judicial

development of the privacy torts can be attributed to William Prosser, the

leading torts scholar of the twentieth century, who played an enormous role in

mainstreaming and legitimizing the privacy torts.

99

Prosser made the turn to harm explicitly and clearly, and courts followed suit.

In 1960, in an article entitled Privacy, Prosser summed up a scattered body of

case law to identify four torts: (1) “Intrusion upon the plaintiff’s seclusion”;

(2) “Public disclosure of embarrassing private facts about the plaintiff”;

(3) “Publicity which places the plaintiff in a false light in the public eye”;

(4) “Appropriation, for the defendant’s advantage, of the plaintiff’s name or

likeness.”

100

As chief reporter on the influential American Law Institute’s

Restatement (Second) of Torts, Prosser added the four categories of privacy torts

to the Restatement.

101

Prosser followed the Holmesian harms-based approach in

constructing the privacy torts.

102

After Prosser’s article and the Restatement,

courts readily embraced the privacy torts.

103

Although Prosser strengthened the

privacy torts, his work ossified them.

104

No new privacy torts have been created

in the years following Prosser’s shining the spotlight on them.

1820-21 (2010) [hereinafter Citron, Privacy Torts] (“Shortly after the publication of The Right

to Privacy, courts adopted privacy torts in the manner that Warren and Brandeis suggested.”

(citing Edward J. Bloustein, Privacy as an Aspect of Human Dignity: An Answer to Dean

Prosser, 39 N.Y.U. L. REV. 962, 977, 979 (1964))).

98

Citron, Privacy Torts, supra note 97, at 1820 (quoting Warren & Brandeis, supra note

97, at 205).

99

Id. at 1809-10 (discussing Prosser’s theory of four privacy torts in Restatement (Second)

of Torts and its subsequent adoption by courts); Neil M. Richards & Daniel J. Solove,

Prosser’s Privacy Law: A Mixed Legacy, 98 CALIF. L. REV. 1887, 1888-90, 1917 (2010)

[hereinafter Richards & Solove, Prosser’s Privacy Law].

100

William L. Prosser, Privacy, 48 CALIF. L. REV. 383, 388-89 (1960) (identifying four

privacy torts from “over three hundred cases in the books”).

101

Richards & Solove, Prosser’s Privacy Law, supra note 99, at 1890 (“[Prosser] was also

the chief reporter for the Second Restatement of Torts, in which he codified his scheme for

tort privacy.”).

102

Citron, Privacy Torts, supra note 97, at 1821-24 (discussing Prosser’s adoption of

“Holmes’s focus on specific injuries caused by particular conduct”).

103

Richards & Solove, Prosser’s Privacy Law, supra note 99, at 1903-04 (observing

Prosser’s work on privacy torts in the span of four decades “transformed” privacy law “from

a curious minority rule to . . . a doctrine recognized by the overwhelming majority of

jurisdictions”).

104

Id. at 1904-07 (arguing Prosser’s efforts to ensure acceptance of his theory “fossilized

[tort privacy] and eliminated its capacity to change and develop”); see also G. EDWARD

WHITE, TORT LAW IN AMERICA: AN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY 175-76 (1980) (describing

development of Prosser’s privacy torts as “[a] classification made seemingly for convenience”

in 1941 that ultimately, by 1971, had become “synonymous with law”).

810 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

Today, nearly all states recognize most of the privacy torts.

105

Courts rarely

question the existence of harm or the fact that the basis of harm for many privacy

torts is pure emotional distress. In fact, they tend to presume the existence of

harm.

106

And yet while the privacy torts handily address the privacy problems

of Warren and Brandeis’s time, such as invasions of privacy by the media, this

is not the case for modern privacy problems involving the collection, use, and

disclosure of personal data. Because courts cling rigidly to the elements of the

privacy torts as set forth in the Restatement, the privacy torts have little

application to contemporary privacy issues.

107

Other mainstream torts have been invoked to address privacy issues, such as

intentional infliction of emotional distress, breach of confidentiality, and

negligence. These torts are often limited by harm requirements, making it

difficult for plaintiffs to obtain redress. For example, the intentional infliction of

emotional distress tort requires proof of “severe emotional distress,” which can

be difficult to establish.

108

3. Statutory Causes of Action

Many state and federal privacy statutes provide for private rights of action.

Typically, the assumption is that a private right of action is a legislative

recognition of harm, though no rule or doctrine commands that all private rights

of action in statutes redress harm. Some might be there to facilitate private

enforcement of a law or to deter violations.

Countless federal and state privacy laws have private rights of action. At the

federal level, notable laws with private rights of action include the Telephone

Consumer Protection Act (“TCPA”), the Electronic Communications Privacy

Act, the Video Privacy Protection Act (“VPPA”), the FCRA, and the Cable

105

Richards & Solove, Prosser’s Privacy Law, supra note 99, at 1904 (“Today, due in

large part to Prosser’s influence, his ‘complex’ of four torts is widely accepted and recognized

by almost every state.” (citing ROBERT M. O’NEIL, THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND CIVIL

LIABILITY 77 (2001))).

106

Solove & Citron, Risk and Anxiety, supra note 27, at 768-70.

107

Citron, Privacy Policymaking, supra note 8, at 798 (“Overly narrow interpretations of

the privacy torts—intrusion on seclusion, public disclosure of private fact, false light, and

misappropriation of image—have prevented their ability to redress data harms.”); Citron,

Privacy Torts, supra note 97, at 1826-31 (arguing privacy torts fail to address modern data

breaches and leaks and preclude recovery with high burdens of proof).

108

See RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS § 46 (AM. L. INST. 1965) (recognizing liability

for “[o]ne who by extreme and outrageous conduct intentionally or recklessly causes severe

emotional distress to another”). This tort was of particular interest to Prosser, who wrote a

key article about it in 1939. William L. Prosser, Intentional Infliction of Mental Suffering: A

New Tort, 37 MICH. L. REV. 874 (1939). In the first edition of his treatise on tort law, published

in 1941, Prosser noted that “the law has been slow to accept the interest in peace of mind as

entitled to independent legal protection, even against intentional invasions. It is not until

comparatively recent years that there has been any general admission that the infliction of

mental distress, standing alone, may serve as the basis of an action, apart from any other tort.”

WILLIAM L. PROSSER, HANDBOOK OF THE LAW OF TORTS 54 (1941).

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 811

Communications Policy Act, among others.

109

At the state level, the California

Consumer Privacy Act has a private right of action, but only for data security

breaches.

110

Several state unfair and deceptive acts and practices laws (called

“UDAP” laws) have private rights of action.

111

The Illinois Biometric

Information Privacy Act (“BIPA”) also has a private right of action.

112

Congress has recognized statutory damages for these private rights.

113

Under

the FCRA, the federal law at issue in Spokeo,

114

any person who willfully

violates “any requirement” in the statute is liable in an amount equal to the sum

of damages sustained by the consumer or “damages of not less than $100 and

not more than $1,000.”

115

There is no harm requirement in the Wiretap Act, the

109

Telephone Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 102-243, 105 Stat. 2399 (1991)

(codified as amended at 47 U.S.C. § 277(c)(5)); Electronic Communications Privacy Act,

Pub. L. No. 99-508, 100 Stat. 1854 (1986) (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. §§ 2520

(Wiretap Act), 2707 (Stored Communications Act)); Video Privacy Protection Act, Pub. L.

No. 100-618, 102 Stat. 3196 (1998) (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. § 2710(c)); Fair Credit

Reporting Act, Pub. L. No. 91-508, 84 Stat. 1114 (1970) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C.

§§ 1681n, 1681o) (providing cause of action to any consumer harmed by willful or negligent

violation, respectively); Cable Communications Policy Act, Pub. L. No. 98-549, 98 Stat. 2795

(1984) (codified as amended at 47 U.S.C. § 551(f)). For a more complete list of federal laws

with private rights of action, see DANIEL J. SOLOVE & PAUL M. SCHWARTZ, PRIVACY LAW

FUNDAMENTALS 160-61 (5th ed. 2019).

110

California Consumer Privacy Act, CAL. CIV. CODE § 1798.150 (West 2022) (providing

private right to of action to “[a]ny consumer” for breach of personal information “as a result

of the business’s violation of the duty to implement and maintain reasonable security

procedures”).

111

See Citron, Privacy Policymaking, supra note 8, at 798 (discussing applicability of

private UDAP actions to privacy claims). Many UDAP laws require or have been interpreted

to require a showing of injury. Id. at 754. Almost half of state UDAP laws restrict claims for

intangible injuries. See CAROLYN CARTER, CONSUMER PROTECTION IN THE STATES: A 50-

STATE EVALUATION OF UNFAIR AND DECEPTIVE PRACTICES LAWS 2, 40 (2018),

https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/udap/udap-report.pdf [https://perma.cc/R9UY-RGWZ]

(noting that twenty-one states do not recognize intangible injuries under UDAP laws, and

twenty-two require economic loss).

112

Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act, 740 ILL. COMP. STAT. 14/20 (2022)

(providing private right of action to “[a]ny person aggrieved by a violation of this Act”).

113

The meaning of a private right of action with statutory damages is debatable. Is a private

right of action a recognition of harm, with the statutory damages being imposed because harm

can be difficult for plaintiffs to establish? Or is the purpose of the statutory damages to enable

recovery in the absence of any harm because of other goals? Either way, the presence of

statutory damages means that courts do not have to hold bench or jury trials on the question

of recovery—lawmakers have supplied their judgment as to the appropriate extent of redress.

114

15 U.S.C. § 1681a(d)(1)(A)-(C), 1681b (regulating creation and use of consumer

reports by consumer reporting agencies for credit transactions, insurance, licensing,

consumer-initiated business transactions, and employment); see also Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins,

578 U.S. 330, 334-35 (2016) (discussing § 1681a(d)(1)(A)-(C) and § 1681b).

115

15 U.S.C. § 1681n(a)(1)(A).

812 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

Stored Communications Act, the DPPA, the VPPA, and the Cable

Communications Policy Act.

116

The Supreme Court has complicated recovery under these private rights of

action by forcing plaintiffs to prove harm even though the statutes provide for

statutory damages. For example, the Supreme Court has made recovery of

damages under the federal Privacy Act exceedingly difficult. In Doe v. Chao,

the U.S. Department of Labor improperly disclosed the Social Security Numbers

of people filing for benefits under the Black Lung Benefits Act. A group of

plaintiffs sued under the Privacy Act. The lead plaintiff stated that he was

“torn . . . all to pieces” by the disclosure and was “greatly concerned and

worried.”

117

The U.S. Supreme Court held that the statutory damages provision

under the Privacy Act was only available if plaintiffs established actual

damages.

118

In a subsequent case, Federal Aviation Administration v. Cooper, the

Supreme Court held that emotional distress alone could not amount to actual

damages under the Privacy Act of 1974.

119

Justice Sotomayor dissented, joined

by Justices Ginsburg and Breyer. They argued that Congress passed the Privacy

Act to protect against an agency’s disclosure of personal information that could

result in “substantial harm, embarrassment, inconvenience, or unfairness to any

individual.”

120

The result of the Court’s holding was that a “federal agency could

intentionally or willfully forgo establishing safeguards to protect against

embarrassment and no successful private action could be taken against it for the

harm Congress identified.”

121

The overall effect of Chao and Cooper has been to drastically limit the

enforcement of the Privacy Act through private rights of action. Plaintiffs now

have to prove willful conduct as well as establish harm, and they are forbidden

from using emotional distress, which is a common type of harm in privacy

cases.

122

Congress created the private right of action with statutory damages as

an enforcement mechanism in the law, but the Court effectively nullified it. The

Privacy Act now has few enforcement actions.

Even when federal statutes do not mention having to prove damages, some

courts have taken it upon themselves to add a requirement of harm. Consider

116

Wiretap Act, 18 U.S.C. §§ 2510-2522; Stored Communications Act, 18 U.S.C.

§§ 2701-2709; Driver’s Privacy Protection Act, 18 U.S.C. §§ 2721-2725; Video Privacy

Protection Act, 18 U.S.C. § 2710; Cable Communications Policy Act, 47 U.S.C. §§ 521-573.

117

Doe v. Chao, 540 U.S. 614, 617-18 (2004).

118

Id. at 614; see Calo, Privacy Harm Exceptionalism, supra note 3, at 362-63 (discussing

the Court’s refusal to recognize emotional harm as a basis for statutory damages under Privacy

Act).

119

566 U.S. 284, 299 (2012) (“[The Court] adopt[s] an interpretation of ‘actual damages’

limited to proven pecuniary or economic harm.”).

120

Id. at 309 (Sotomayor, J., dissenting) (quoting 5 U.S.C. § 552a(e)(10)) (discussing

requirements for agencies under Privacy Act).

121

Id.

122

Calo, Privacy Harm Exceptionalism, supra note 3, at 362-63.

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 813

Senne v. Village of Palatine. In that case, the Seventh Circuit held that a plaintiff

could not pursue a private cause of action for a violation of the DPPA because

the plaintiff could not demonstrate injury.

123

The Village of Palatine had a

practice of including identifying information, such as people’s height and

weight, on parking tickets placed under their windshield wipers. Although the

Village’s practice was a clear DPPA violation, the court concluded that “we need

to balance the utility (present or prospective) of the personal information on a

parking ticket against the potential harm.”

124

The court acknowledged that “the

Act does not state that a permissible use can be offset by the danger that the use

will result in a crime or tort,” yet it created a harm requirement anyway.

125

The

court struck down the right to sue under the DPPA because the plaintiff failed to

provide evidence of harm, such as “stalking or any other crime (such as identity

theft),” “tort (such as invasion of privacy),” disclosure over the Internet, or the

involvement of “highly sensitive information” like a social security number.

126

Through interpretations like these, coupled with standing, courts are

undercutting the enforcement of privacy laws by creating harm requirements out

of whole cloth. Courts are generally supposed to be deferential to the legislative

policy goals, striking down laws only when they traduce a constitutional

boundary or infringe upon a right. But courts are trading deference for activism,

undermining laws in an underhanded way. Harm requirements are being

invented to prevent the enforcement of privacy protections.

To sum up, courts have blocked statutory private rights of action by:

(1) adding a requirement for harm via standing; (2) interpreting statutes with

statutory damages in ways that require proof of harm to obtain statutory

damages, thus undercutting the purpose of statutory damages provisions;

(3) interpreting statutory private rights of action to require harm even when they

do not have a harm requirement; and (4) adopting narrow conceptions of

cognizable harm to exclude many types of harm.

The enforcement of privacy laws is a challenging issue, and unfortunately,

courts are making a mess of things. Courts often lack a theory of privacy harms

or any guiding principles. As Lauren Scholz observes, in many cases, the

“analysis as to why a harm is not present is often superficial or absent.”

127

Decisions involving harm lack a coherent vision; they are creating mischief

rather than good policy.

C. Harm in Regulatory Enforcement Actions

Regulators are often much less constrained by harm requirements. In many

cases, the laws that they enforce do not require harm. The enforcement of

123

Senne v. Village of Palatine, 784 F.3d 444, 448 (7th Cir. 2015).

124

Id. at 447.

125

Id.

126

Id. at 448.

127

Lauren Henry Scholz, Privacy Remedies, 94 IND. L.J. 653, 662-63 (2019).

814 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 102:793

statutes by regulators often occurs outside of the judicial system, so the issue of

harm never arises.

128

However, there are circumstances where harm is a requirement for regulators

to enforce, most notably Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) enforcement of

“unfair” acts or practices. Since the mid-1990s, the FTC has used its

enforcement power under section 5 of the FTC Act to address privacy issues.

129

Section 5 of the FTC Act prohibits “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or

affecting commerce.”

130

A “deceptive” act or practice is a “representation,

omission or practice that is likely to mislead a consumer . . . . acting reasonably

in the circumstances . . . . to the consumer’s detriment.”

131

There is no mention

of harm in this definition, though it does indicate that the deception must be to

the “detriment” of the consumer.

The definition of unfairness is much more directly focused on harm. An

“unfair” act or practice is one that “causes or is likely to cause substantial injury

to consumers which is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and

not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.”

132

This definition explicitly includes “likely” harm. The FTC recognizes traditional

harms (and risks of such harms) such as economic and physical harms, but “more

subjective types of harm” such as emotional harm are usually not considered

substantial for unfairness purposes.

133

On the other hand, the FTC is able to

focus on harm to consumers generally, which allows it to look to harm in a

broader manner than most tort and contracts cases, which involve specific

individuals.

Although regulators are less constrained by the requirement of harm, they are

often limited in resources and must be highly selective about the matters they

enforce.

134

State attorneys general vary considerably on how actively they

128

See, e.g., A Brief Overview of the Federal Trade Commission’s Investigative, Law

Enforcement, and Rulemaking Authority, FTC, https://www.ftc.gov/about-ftc/what-we-

do/enforcement-authority [https://perma.cc/LQD3-YA7L] (last updated May 2021) (noting

that FTC may initiate enforcement action using either administrative or judicial process).

129

See Ryan P. Blaney, David A. Munkittrick & Brooke Gottlieb, Federal Trade

Commission Enforcement of Privacy, in PROSKAUER ON PRIVACY: A GUIDE TO PRIVACY AND

DATA SECURITY LAW IN THE INFORMATION AGE § 4:1 (Kristen J. Mathews ed., 2016)

(identifying section 5 as FTC’s primary means for taking action against privacy violations);

FTC, PREPARED STATEMENT OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION: OVERSIGHT OF THE

FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION 4 (2018), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public

_statements/1423835/p180101_commission_testimony_re_oversight_senate_11272018_0.p

df [https://perma.cc/Y7TJ-2STS] (“Beginning in the mid-1990s, with the development of the

Internet as a commercial medium, the FTC expanded its focus on privacy . . . .”).

130

15 U.S.C. § 45(a)(1).

131

FTC, FTC POLICY STATEMENT ON DECEPTION (1983), appended to Cliffdale Assocs.,

Inc., 103 F.T.C. 110, 174 (1984).

132

15 U.S.C. § 45(n); see also FTC, FTC POLICY STATEMENT ON UNFAIRNESS (1980),

appended to Int’l Harvester Co., 104 F.T.C. 949, 1070 (1984).

133

FTC POLICY STATEMENT ON UNFAIRNESS, supra note 132, at 1073.

134

Citron, Privacy Policymaking, supra note 8, at 799.

2022] PRIVACY HARMS 815

enforce; some are aggressive whereas others have not brought any enforcement

actions under many privacy laws that they are authorized to enforce.

135

Because of these limitations, many privacy laws rely upon private litigants

for enforcement. The TCPA is a prime example of this type of enforcement

mechanism. The law restricts unsolicited commercial telemarketing calls,

robocalls, and faxes, and it is enforced by the Federal Communications

Commission (“FCC”) and state attorneys general.

136

To augment this

enforcement, the law includes a private right of action with statutory damages

of $500 for each violation and $1,500 for each knowing or willful violation.

137

Because the TCPA enforcement process is tedious and time-consuming and

because many TCPA cases involve small matters that do not make splashy

headlines, FCC enforcement has been modest.

138

In one year, for example, there

were 47,704 complaints, but the FCC only issued twenty-three citations.

139

In

practice, private litigation has become the primary source of TCPA

enforcement.

140

Litigation by private parties thus supplements enforcement by regulatory

agencies and state attorneys general, and in a number of instances, private

litigation serves as the primary enforcement mechanism of a law. Based on this

enforcement role, private parties enforcing a law through private litigation are

often referred to as “private attorneys general.”

141

As the Seventh Circuit aptly

explained:

The award of statutory damages could also be thought a form of bounty

system, and Congress is permitted to create legally enforceable bounty

systems for assistance in enforcing federal laws, provided the bounty is a

reward for redressing an injury of some sort (though not necessarily an

injury to the bounty hunter).

142

And these cases typically require a showing of harm, which is often the death

knell if plaintiffs cannot show financial or physical harm.

135

Id. at 755 (“In the past fifteen years, a core group of states have taken the lead on

privacy enforcement: California, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts,

New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, and

Washington.”).

136

See 47 U.S.C. § 227(c)(3); see also Spencer Weber Waller, Daniel B. Heidtke & Jessica

Stewart, The Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991: Adapting Consumer Protection to

Changing Technology, 26 LOY. CONSUMER L. REV. 343, 358 (2014).

137

47 U.S.C. § 227(c)(5).

138

Waller et al., supra note 136, at 376-78.

139

Id. at 378.

140

Id. at 375 (“Private parties have largely been responsible for enforcement of the

TCPA.”).

141