Tax Policy Choices

and New York City’s

Competitive Position

Prepared by Donald Boyd

for the Citizens Budget Commission

Citizens Budget Commission

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................1

NEW YORK IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE ...................................................................................................................2

TAXES AND MIGRATION .................................................................................................................................................................7

Lessons from the Literature .....................................................................................................................................................7

Migration in the New York Region .........................................................................................................................................9

NEW YORK CITY PERSONAL INCOME TAX POLICY ........................................................................................................12

NEW YORK CITY PROPERTY TAX POLICY ............................................................................................................................16

A Comparative View of Commercial Property Taxes ....................................................................................................16

Disparities between Commercial and Small Residential Property ...........................................................................18

CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................................................................................................21

APPENDIX A ......................................................................................................................................................................................22

APPENDIX B ......................................................................................................................................................................................25

APPENDIX C ......................................................................................................................................................................................26

APPENDIX D ......................................................................................................................................................................................27

ENDNOTES ........................................................................................................................................................................................29

Citizens Budget Commission

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

1

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this background paper is to help inform tax policy choices that the new mayoral

administration may face. It examines levels of taxation in New York City compared to other cities, and

it reviews research on how taxes affect the local economy and migration patterns. The focus is on the

personal income tax and the real property tax, particularly the tax on commercial property. These are

two elements of tax policy for which New York City has distinctive policies and for which changes may

be considered.

The paper is organized in four sections. The first describes the structure of local taxes in New York City

and compares it to that of other large cities in the United States. The second reviews the literature

on the relationship between taxes and migration of residents and employment, and it presents data

on the current pattern of residential choice and migration in the New York region. The third focuses

on the local personal income tax, indicating how hypothetical increases in the rate structure would

affect household tax burdens. The fourth section focuses on the tax on commercial property indicating

how New York City compares to other large cites in this type of tax and commenting on the possible

implications of an increase.

Citizens Budget Commission

2

NEW YORK IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

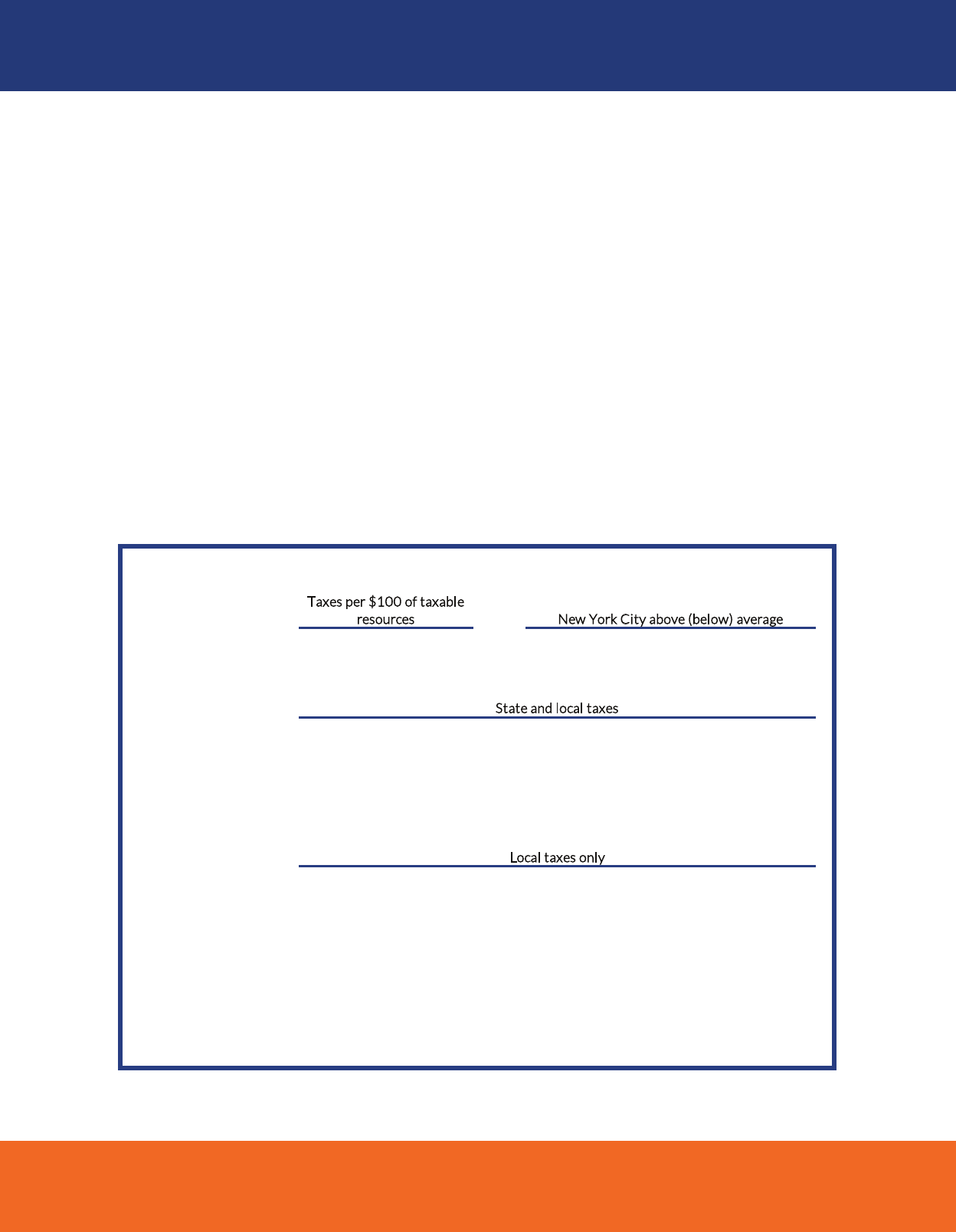

New York City’s taxes are high. A comprehensive and unique study by the New York City Independent

Budget Office used data from 2004 to compare cities with a population over 1 million, computing taxes

as a percentage of taxable resources.

1

It found that New York City’s state and local taxes were the

highest among large cities by far: state and local taxes were 46 percent higher than the average for the

other cities, and local taxes were 90 percent higher than the average for other cities. (See Table 1.) The

combined state and local personal income tax in New York City was more than three times as high in

the other cities, and accounted for three quarters of the difference between New York and the other

cities.

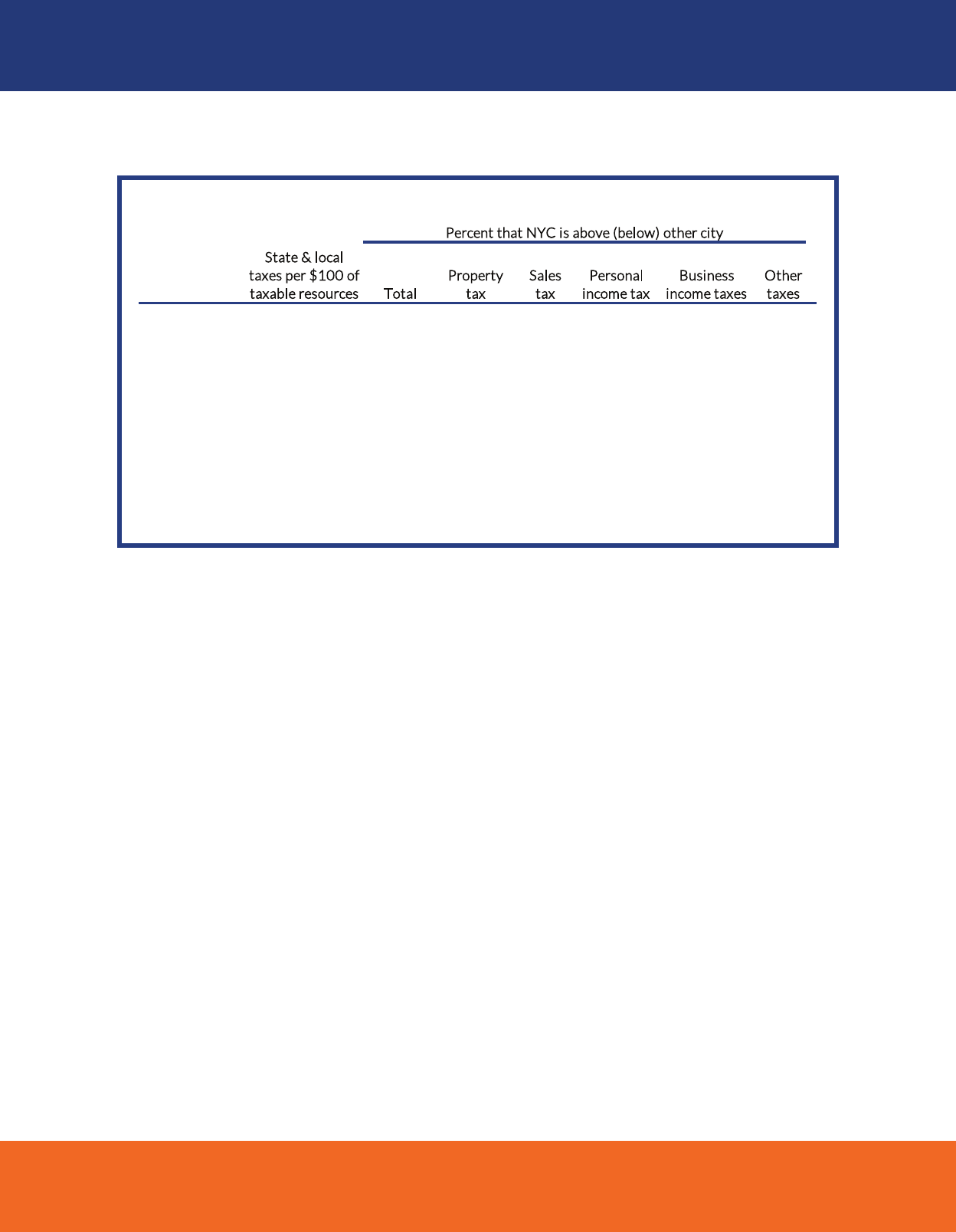

Table 2 shows the state and the local burden for the individual cities. New York City’s taxes were 26

percent higher than the second-highest city, Philadelphia. The personal income tax was much higher

than in the four other cities that had such a tax. Business income taxes were double or even triple the

level in five of the eight other cities. The property tax was higher than in every city but San Antonio. The

sales tax and “other taxes” were typically lower than in other cities.

Average of

other cities New York City

Per $100 of

taxable

resources

Percent of

difference

Percent above

or below

Property tax $ 1.89 $ 2.28 $ 0.39 13.6% 20.6%

Sales tax 1.73 1.56 (0.17) -5.9% -9.8%

Personal income tax 0.95 3.12 2.17

75.9% 228.4%

Business income taxes 0.55 1.06 0.51 17.8% 92.7%

Other taxes 1.04 1.00 (0.04) -1.4% -3.8%

Total $ 6.16 $ 9.02 $ 2.86 100.0% 46.4%

Property tax $ 1.89 $ 2.28 $ 0.39 14.7

% 20.6%

Sales tax 0.52 0.82 0.30 11.3% 57.7%

Personal income tax 0.10 1.11 1.01 38.0% 1010.0%

Business income taxes 0.12 0.71 0.59 22.2% 491.7%

Other taxes 0.33 0.70 0.37

13.9% 112.1%

Total $ 2.96 $ 5.62 $ 2.66 100.0% 89.9%

Source: Author's analysis of informaon in New York City Independent Budget Office, Comparing State and Local Taxes in Large U.S. Cies,

February 2007.

Note: Comparison cies are Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Diego, San Antonio and Dallas.

Table 1: State and Local Taxes in New York City and Average of Other Large U.S. Cities, 2004

Taxes per $100 of taxable

r

esources New York City above (below) average

State and local taxes

Local taxes only

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

3

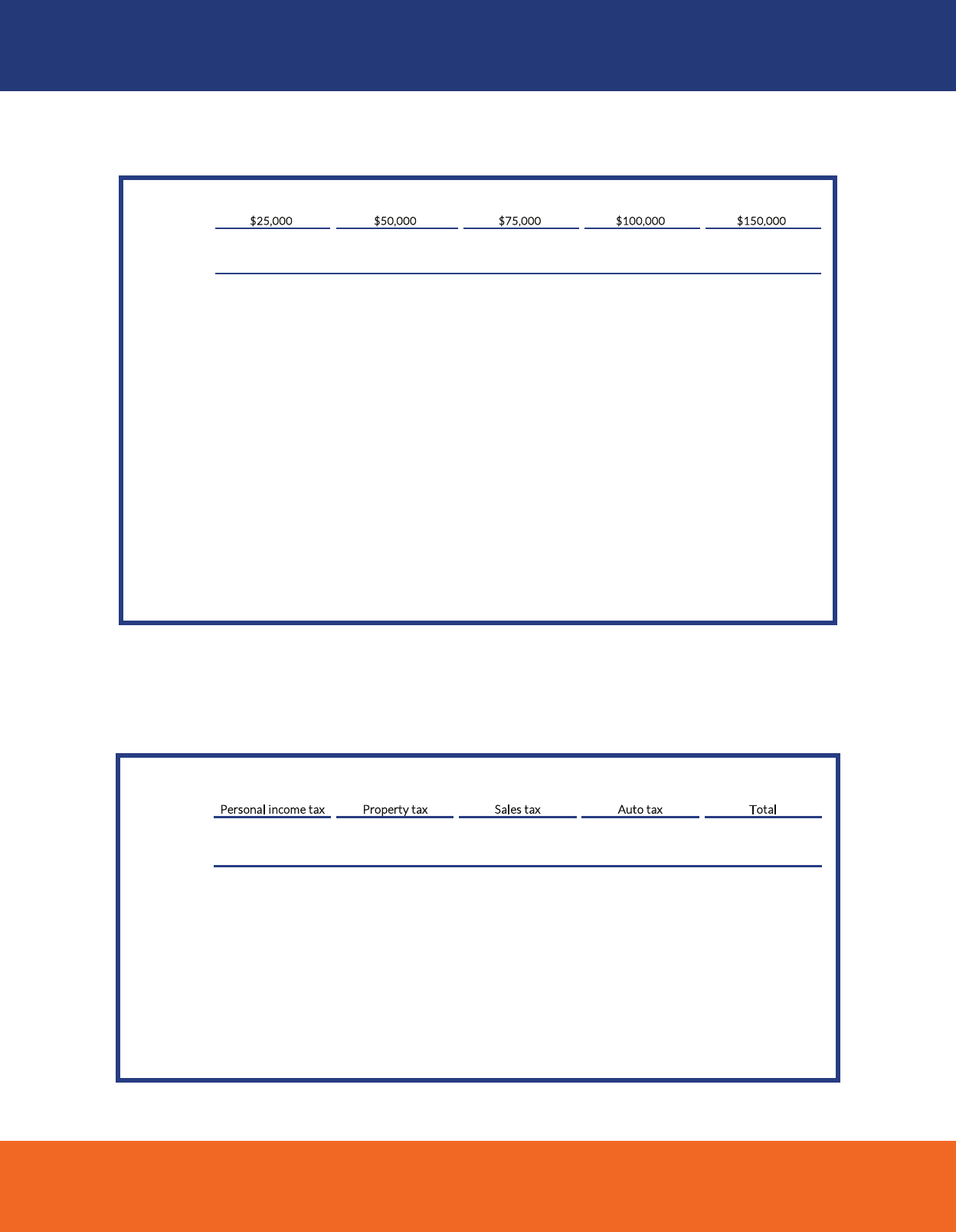

Another comparison of taxes in individual cities is prepared annually by the Chief Financial Officer

of the District of Columbia. It calculates personal income tax, property tax, sales tax, and automobile

taxes on representative households in the District and in the largest city in each state (51 cities in

total) at five income levels ranging from $25,000 to $150,000. The study reasonably varies household

property values among locations (for example, at a given income level a New York City homeowner is

likely to own a more expensive house than a person with the same income in Boise, Idaho), but in other

respects the households are the same from place to place. Depending on the year of the study, the

household is assumed to have either one or two children.

Because this study considers only direct taxes on households, it does not take into account taxes on

businesses that may be borne in part by households or that may affect regional economies in other

ways. For example, the Independent Budget Office study considers all property taxes in New York City,

including taxes on commercial property, which are quite high, whereas the District of Columbia study

only includes homeowner property taxes, which in New York City are quite low. Still, it is a useful way

to examine direct taxes on households, and it is cited widely.

Table 3 shows taxes at each income level, relative to the median for 51 cities, for 21 cities that ranked in

the top 10 for one or more income levels in 2011, the last year for which data are available. New York

City’s ranking rises as income rises: the household with $25,000 of income pays 10.7 percent more in

taxes than a similar household in the median city, earning New York City the 16

th

-highest ranking, but

the New York City household with $150,000 of income pays 41.2 percent more than the median, the

third-highest ranking for this income group. Again, this does not reflect taxes on businesses, some of

which may be passed through to households in the form of higher utility bills, lower wages, or in other

ways. Because these taxes in New York City tend to be higher than in other cities, the indirect effects

could be large.

Table 4 focuses on the highest income households and the ten cities with the highest burden for that

group. New York City ranks number three, behind only Bridgeport and Philadelphia. New York’s

New York City $ 9.02 - - - - - -

Philadelphia 7.16 26.0% 57% 32% 39% -17% 0%

Los Angeles 6.88 31.1 39.0 (6.6) 72.4 53.6 (7.4)

San Antonio 6.73 34.0 (18.0) (37.8) n/a 341.7 (16.7)

Phoenix 6.25 44

.3 20.6 (46.0) 372.7 241.9 104.1

San Diego 6.01 50.1 54.1 (15.7) 93.8 107.8 75.4

Chicago 5.89 53.1 3.2 59.2 250.6 92.7 (20.6)

Houston 5.53 63.1 17.5 (20.4) n/a 171.8 (18.7)

Dallas 5.20 73.5

15.2 (12.8) n/a 158.5 (2.0)

Table 2: State and Local Taxes in New York City and Eight Other U.S. Cities, 2004

Percent that NYC is above (below) other city

Source: Author's analysis of informaon in New York City Independent Budget Office, Comparing State and Local Taxes in Large U.S.

Cies, February 2007.

State & local

t

axes per $100 of

t

axable resources Total

Property

t

ax

Sales

t

ax

Personal

i

ncome tax

Business

i

ncome taxes

Other

t

axes

Citizens Budget Commission

4

high overall ranking is driven by its first-ranked personal income tax, which is 82.6 percent above the

median. Because New York City’s income tax is quite progressive and does not reach its top tax rate

until taxable income hits $500,000, the city’s relative ranking probably would rise if the study were to

include households with income of $500,000 or more.

Bridgeport 25.4% 5 161.1% 1 129.8% 1 100.9% 1 76.4% 1

Philadelphia 52.7 2 77.4 3 62.4 2 58.0 2 49.7 2

New York City 10.7 16 25.3 14 25.7 8 29.1 6 41.2 3

Columbus 14.0 12 53.7

4 41.1 4 38.7 3 36.9 4

Louisville 21.6 8 35.2 7 33.2 5 33.2 4 35.1 5

Baltimore (8.6) 39 28.4 11 26.1 6 27.0 7 28.6 6

Portland, ME (6.5)

33 21.2 15 17.3 13 18.7 10 23.3 7

Newark 1.5 25 95.3 2 48.3 3 31.8 5 20.3 8

Los Angeles 15.9 10 41.4 5 20.6 10 11.7 13 18.3 9

Detroit 10.

6 18 26.2 13 24.2 9 20.5 8 16.5 10

Milwaukee (6.5) 34 26.4 12 19.4 11 19.2 9 15.8 11

Chicago 31.9 4 36.6 6 25.9 7 18.4 11 11.2 14

Providenc

e 6.0 21 34.3 8 17.5 12 9.2 14 5.7 20

Atlanta 25.0 6 1.9 24 3.2 22 0.5 24 2.4 23

Boston 15.5 11 30.5 10 13.2 14 6.3 17 0.6

25

Burlington, VT (3.8) 31 31.0 9 10.5 15 0.6 23 (1.5) 30

Indianapolis 18.3 9 3.3 23 1.2 24 (0.8) 27 (1.7) 31

Birmingham, AL 52.9 1 3.5 22 - 26 (3.1)

28 (3.6) 33

Honolulu 39.5 3 (23.8) 43 (19.9) 39 (16.4) 37 (12.5) 37

Phoenix 23.6 7 (10.2) 33 (17.1) 38 (20.0) 38 (18.5) 40

$

75,000$50,000$25,000

Rank of

51

cities

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank of

51

cities

$

150,000$100,000

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank of

51

cities

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank of

51

cities

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Table 3: State and Local Taxes for Representative Households, Selected Cities, 2011

Source: Natwar M. Gandhi, Tax Rates and Tax Burdens in the District of Columbia - A Naonwide Comparison: 2011, Chief Financial Officer, District of Columbia, September 2012.

Note: Cies shown are those ranked in the top 10 at one or more income levels, ordered by tax at $150,000.

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank of

51

cities

Bridgeport 12.4% 15 213.3% 1 -1.8% 30 128.3% 3 76.4% 1

Philadelphia 52.4 2 82.7 3 (0.3) 28 (37.0) 36 49.7 2

New York City 82.6 1 (9.4) 29 18.7 18 (44.0) 41 41.2 3

Columbus 37.0 6 66.4 4 -

26 (43.0) 39 36.9 4

Louisville 50.0 3 29.3 12 (4.7) 33 9.7 24 35.1 5

Baltimore 37.0 7 39.2 9 (2.8) 31 (43.1) 40 28.6 6

Portland, ME 24.0 9 35.9 10 (29.9)

45 68.6 9 23.3 7

Newark (37.5) 39 148.3 2 (4.6) 32 (65.8) 51 20.3 8

Los Angeles (18.8) 33 63.2 5 18.6 19 96.0 7 18.3 9

Detroit 42.4 5 (11.8) 30 (16.3) 41 (10

.6) 28 16.5 10

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank

of 51

cities

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank

of 51

cities

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank

of 51

cities

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank

of 51

cities

Percent above

(below) median

of 51 cities

Rank

of 51

cities

Table 4: State and Local Taxes on Households with $150,000 Income, Selected Cities, 2011

TotalAuto taxSales taxProperty taxPersonal income tax

Source: Natwar M. Gandhi, Tax Rates and Tax Burdens in the District of Columbia - A Naonwide Comparison: 2011, Chief Financial Officer, District of Columbia,

September 2012.

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

5

Due to changes in methodology over time it is not appropriate to compare tax levels calculated in the

District of Columbia studies from one year to another, but rankings are more robust and provide useful

information. Table 5 shows New York City’s ranking at three income levels for the personal income tax,

sales tax, and total taxes for selected years. For the highest income group, the state and local personal

income tax in New York City was the highest in the nation for all available years. The income tax on

higher income households is the main reason that total state and local taxes on these households in

New York City have long been among the highest in the nation.

1997 20 1 1 NA NA NA 19 4 3

1999 23 1 1 NA NA NA 21 5 4

2001 15 2 1 28 28 28 25 6 5

2003 42 2 1 18 18 18 23 3 2

2005 35 5 1 13 18 16 22 8 2

2007 41 2 1

18 16 16 NA NA NA

2009 40 4 1 15 13 13 16 5 2

2011 40 5 1 16 11 18 16 8 3

T

otal taxesSales taxPersonal income tax

Table 5: Ranking of New York City State and Local Taxes Among 51 Cities, by Income Levels, Selected Years

Source: District of Columbia, Tax Rates and Tax Burdens in the District of Columbia - A Naonwide Comparison. Chief Financial Officer, District of Columbia,

Various Years.

Notes: Methodological changes, parcularly for the sales tax between 1999 and 2001, may have affected rankings. Income levels are

not adjusted for

inflaon.

NA - Denotes a year for which comparave rankings are not reliable.

$25,000 $75,000 $150,000 $25,000 $75,000 $150,000 $25,000 $75,000 $150,000

0.0%

0.5%

1.0%

1.5%

2.0%

2.5%

3.0%

Percentage of Gross City Product

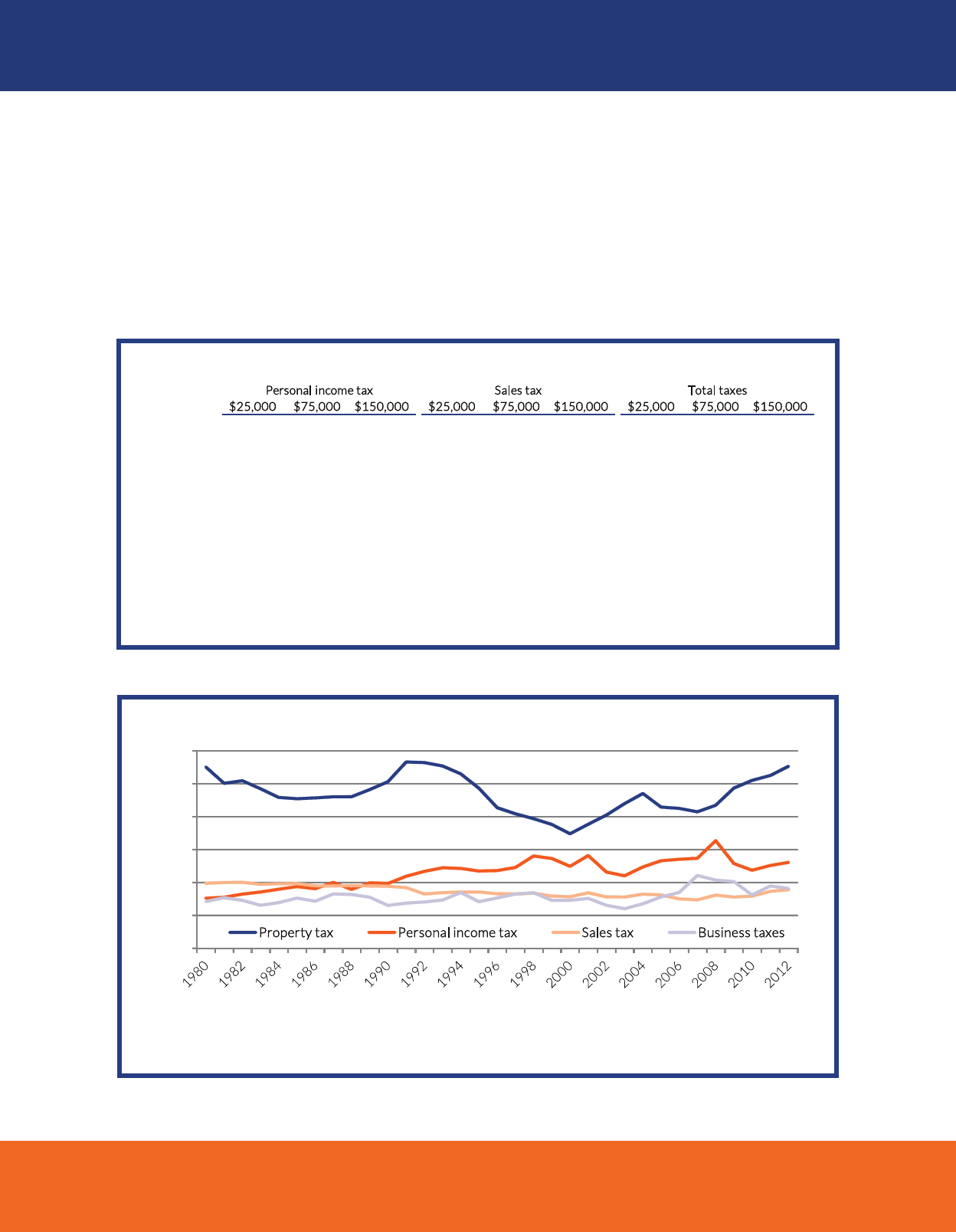

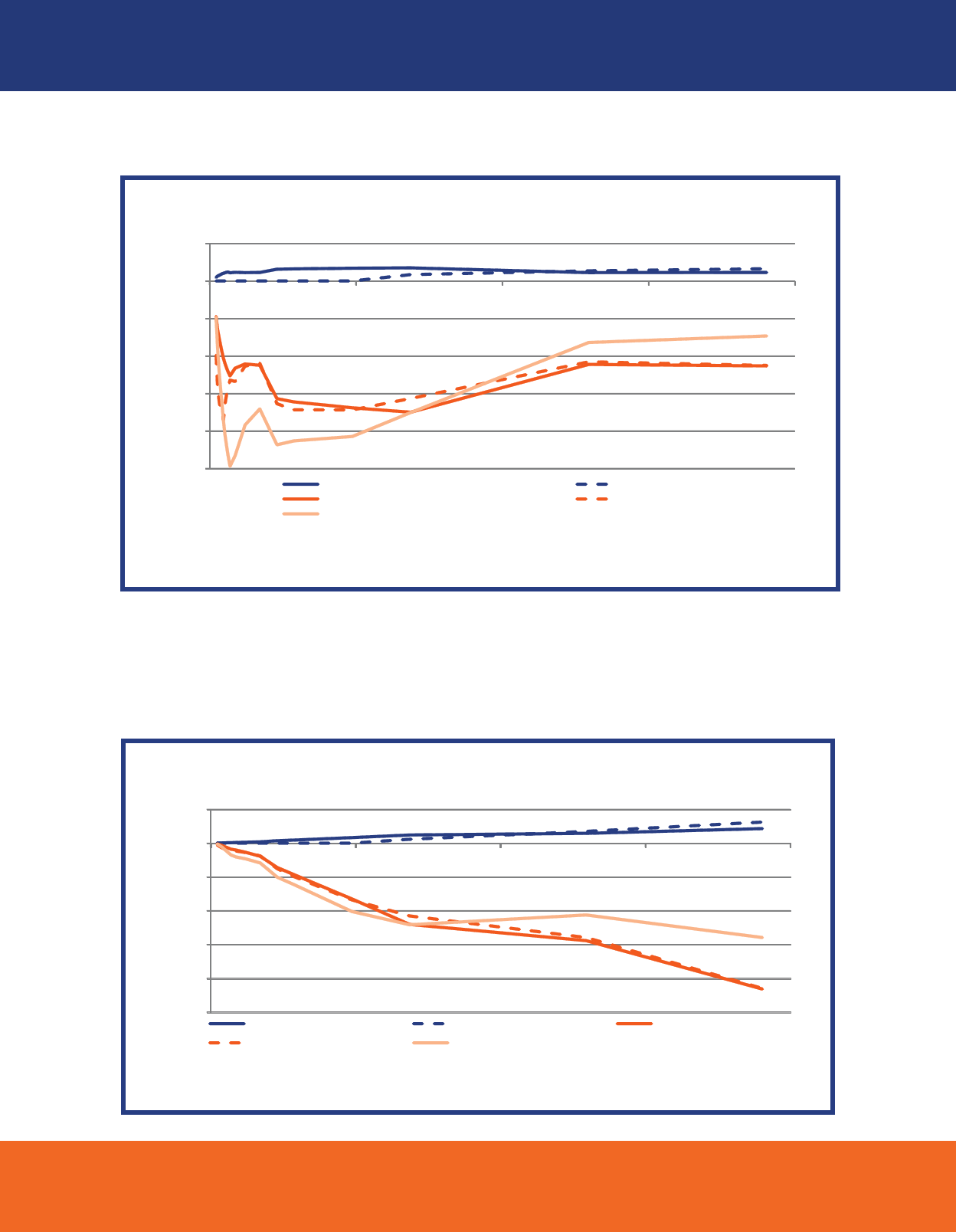

Figure 1: Major New York City Taxes as a Percent of Gross City Product, 1980-2012

Property tax Personal income tax Sales tax Business taxes

Sources: Taxes from NYC Independent Budget Office, hp://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/RevenueSpending/TaxRevenue.xls; Gross City Product

from 1996-2012 from NYC Office of Management and Budget, hp://www.nyc.gov/html/omb/downloads/pdf/ec07_13.pdf; earlier

years esmated by author.

Citizens Budget Commission

6

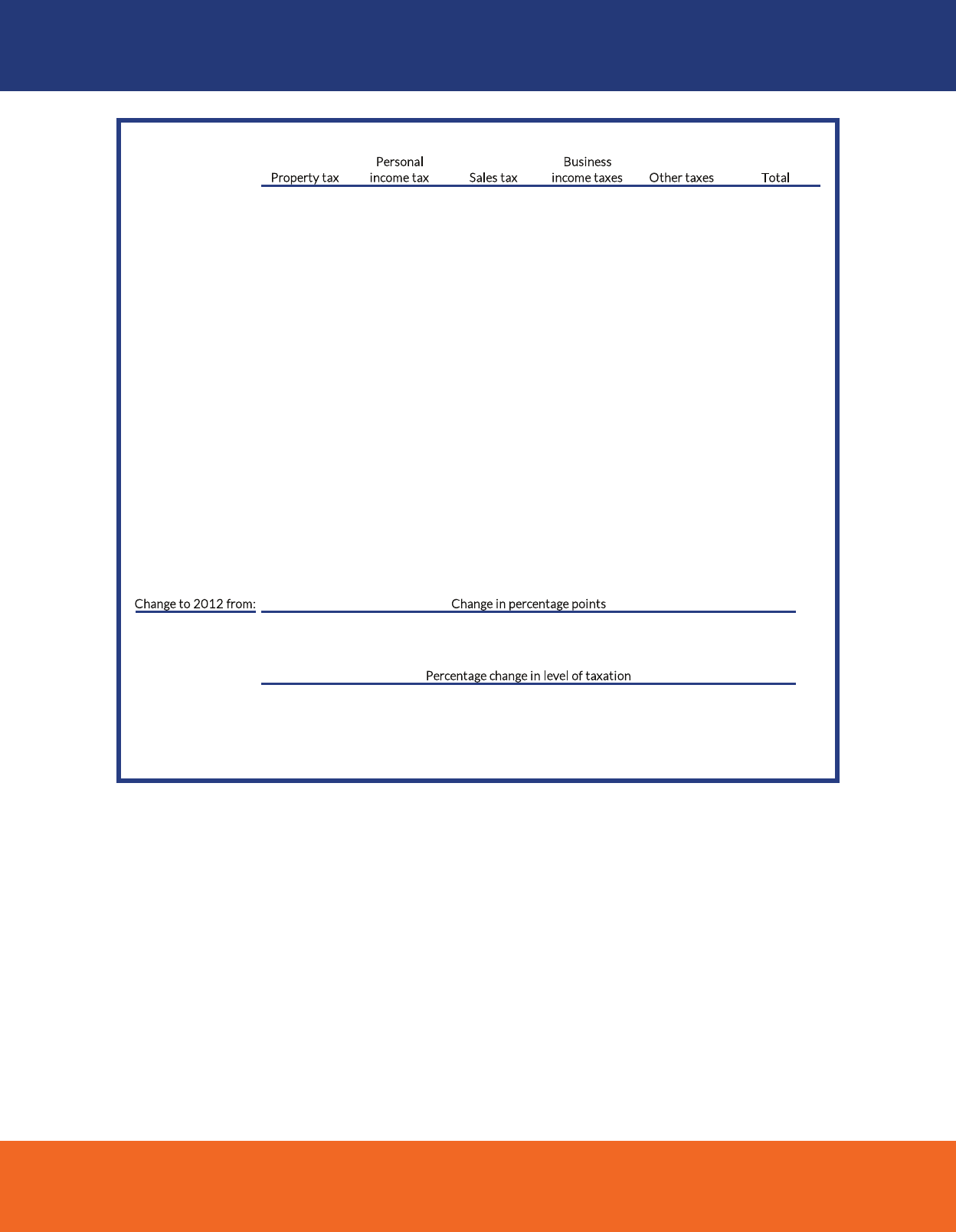

While New York City’s overall taxes have been high relative to other cities for years, there have been

important changes over time. Table 6 shows New York City taxes by major category as a percentage of

gross city product for 1980, 1985, and 1990 through 2012. The table also shows the change to 2012

from the 1991-1994 period average (a previous high point), from the 2000 low point, and from 2002,

the last mayoral changeover year. The 1.3 percentage point increase from 2002 as a share of gross city

product is an increase in the level of taxation of 25 percent. Taxes most likely were depressed in 2002

due to the stock market declines in prior years and to a national recession. But comparisons to 2003 or

2004 also show increases that are considerable, albeit not as large.

Among the taxes, the property tax has shown the greatest variability. (See Figure 1.) Its current level is

well above the low point in 2000 and close to the peak in 1991. The personal income tax has trended

upward with notable variability; its 2012 level is below the peak in 2008 but close to the level of 1998,

1999, and 2005-2007.

1980 2.75% 0.76% 0.98% 0.71% 0.79% 5.99%

1985 2.27% 0.93% 0.98% 0.76% 0.71% 5.66%

1990 2.53% 0.98% 0.94% 0.65% 0.71% 5.80%

1991 2.83% 1.09% 0.92% 0.68% 0.66% 6.18%

1992 2.82% 1.17% 0.82% 0.70% 0.64% 6.15%

1993 2.77% 1.22% 0.84% 0.73% 0.62% 6.18%

1994 2.65% 1.21% 0.85% 0.84% 0.61% 6.17%

1995 2.43% 1.17% 0.85% 0.71% 0.59% 5.75%

1996 2.13% 1.18% 0.82% 0.76% 0.54% 5.44%

1997 2.04% 1.23% 0.82% 0.82% 0.49% 5.39%

1998 1.97% 1.40% 0.83% 0.84% 0.50% 5.54%

1999 1.88% 1.36% 0.79% 0.72% 0.

52% 5.27%

2000 1.74% 1.24% 0.78% 0.73% 0.49% 4.97%

2001 1.88% 1.41% 0.84% 0.75% 0.50% 5.38%

2002 2.02% 1.15% 0.78% 0.65% 0.51% 5.11%

2003 2.20% 1.10% 0.77% 0.60% 0.54% 5.21%

2004 2.35% 1.23% 0.82% 0.67% 0.65% 5.72%

2005 2.14% 1.33% 0.81% 0.78% 0.74% 5.79%

2006 2.12% 1.35% 0.75% 0.85% 0.74% 5.81%

2007 2.07% 1.36% 0.73% 1.10% 0.81% 6.08%

2008 2.17% 1.63% 0.80% 1.03% 0.73% 6.37%

2009 2.43% 1.29% 0.77% 1.01% 0.54% 6.04%

2010 2.55% 1.18% 0.79% 0.81% 0.46% 5.79%

2011 2.62% 1.25% 0.86

% 0.94% 0.51% 6.19%

2012 2.76% 1.30% 0.89% 0.91% 0.55% 6.41%

C

hange to 2012 from:

1991-1994 average (0.00%) 0.13% 0.03% 0.17% (0.09%) 0.24%

2000 lowpoint 1.03% 0.06% 0.11% 0.18% 0.06% 1.43%

2002 0.74% 0.15% 0.11% 0.26% 0.04% 1.30%

1991-1994 average (0.1%) 11.1% 3.2% 22.6% (13.5%) 3.8%

2000 lowpoint 59.0% 4.8% 13.6% 25.0% 12.3% 28.8%

2002 36.7% 12.8% 13.9% 39.4% 8.9% 25.4%

Sources: Taxes from NYC Independent Budget Office, hp://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/RevenueSpending/TaxRevenue.xls; Gross City Product from 1996-2012

from NYC Office of Management and Budget, hp://www.nyc.gov/html/omb/downloads/pdf/ec07_13.pdf; earlier years esmated by author.

Change in percentage points

Percentage change in level of taxation

Table 6: New York City Taxes as Percent of Gross City Product, 1980-2012

Property tax

Personal

i

ncome tax Sales tax

Business

i

ncome taxes Other taxes Total

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

7

TAXES AND MIGRATION

Are New York City’s taxes so high that they are damaging economic growth or causing taxpayers to

flee to other locations? This question is much harder to answer than whether the City’s taxes are

comparatively high, where the answer is clear cut.

This section of the paper seeks to address the harder question in two ways. First it reviews the

economic literature on the topic, focusing particularly on recent studies examining interstate migration

in response to increases in upper-income bracket state tax rates. The implications of these studies

for New York City tax policy must be considered carefully because of the limited parallels between

state and local (especially New York City) circumstances. A second subsection examines the current

situation with respect to outmigration from New York City and other parts of the region and with

respect to the residential decisions of high income earners within the New York region. These data

suggest that: (1) higher-income households in New York City are more likely to migrate out of the area

than similar households in other parts of the New York region, and (2) individuals with high earnings

from jobs in New York City are more likely to opt to commute from suburban counties than those with

lower earnings from jobs in the city.

Lessons from the Literature

Economists have been studying how taxes affect the economy for decades. The research has been

evolving, with data and methods improving, questions becoming more refined, and answers becoming

more nuanced. It is clear that taxes do affect the economy, although there is still enormous variation in

the estimated magnitude of the diverse impacts. This research generally concludes that the employment

and population impacts are likely to be greatest within regions rather than across large geographic

differences, and that the effects depend in part on what tax revenue is spent on, since spending can

have positive economic effects — for example, spending on infrastructure or education could, under

some circumstances, increase private sector productivity.

2

Whether taxes in New York City are so high that further increases would reduce economic growth

so much that the tax increase would not yield a net revenue increase has been debated. One paper

based on data through 2001 found that New York City then was near the peak of its “revenue hills” –

it was nearing the point where tax-rate increases would have large enough negative effects that tax

revenue would actually decline. The paper concluded that New York City had relatively little room to

increase personal income or property tax rates, with somewhat more room to increase the sales tax.

3

Another analysis challenged this finding, arguing that the analysis left out important determinants of

employment in New York City.

4

More recently several studies have examined the relationship between income tax rates and interstate

migration. In the past decade, several states enacted “millionaire” taxes – higher rates on high-income

taxpayers, sometimes starting at thresholds below $1 million. For example, in 2004 New Jersey

raised its rate on taxable income above $500,000 by 2.6 percentage points, from 6.37 percent to 8.97

percent.

5

California and Maryland also adopted increased rates on the highest-income taxpayers, and

several other states have increased top rates as well.

6

Two sets of studies have attempted to analyze millionaire-tax policies specifically. These studies are

summarized below and described more fully in Appendix A.

The first set of studies by Cristobal Young and Charles Varner used progressively better data and

methods to examine the relationship between migration of high-income taxpayers and income tax

rates in New Jersey. Their first study used summary data from New Jersey tax records, with counts

Citizens Budget Commission

8

of the number of half-millionaire households (“HMHs”) in New Jersey and the number of them that

migrated in or out of the state in each year from 2000 to 2007.

7

Thus, the data covered four years

before the tax increase and four years with the tax increase. They found that the average outmigration

rate increased after 2003 (a low year for outmigration) while the average inmigration rate decreased.

8

They then estimated how many HMHs might have been lost due to the tax increase and how much

revenue might have been lost. To develop upper bound estimates, they assumed that the increase

in the outmigration rate from 2003 was attributable to the tax increase, yielding an estimated

HMH outmigration rate increase of 0.2 percent. Similarly, they assumed that the decrease in the

inmigration rate compared to the highest inmigration year before 2004 (which was 2000) was due

to the tax increase, yielding an estimated decrease in inmigration of HMHs annually of 0.4 percent

of HMHs outside New Jersey. They calculated the potential revenue loss under the assumption that

outmigrants and “missing” inmigrants would not be replaced by people already in New Jersey. Under

this assumption, the estimated revenue loss was 4.2 percent of the revenue projected from the tax

increase assuming no migration impact.

In a second study Young and Varner used individual tax records from New Jersey on all taxpayers

with income of $200,000 or more for each year from 2000 through 2007.

9

They compared migration

behavior of taxpayers with incomes between $200,000 and $500,000, who were not subject to the

tax increase, with that of taxpayers with incomes above $500,000. Versions of the statistical analysis

included controls for age, marital status, number of children, and the composition of taxpayer income.

10

The main tax-related conclusions from this analysis were:

• Half-millionaires were more likely to have net outmigration than near-half-millionaires,

whether before or after the tax increase, and the top 0.1 percent of taxpayers were even more

likely to have net outmigration, again regardless of the tax policy.

• The differences in the increase in net outmigration of half-millionaires and of near-half

millionaires after the policy change was not statistically significant.

11

• Increased net outmigration was significantly related to the tax increase for two subgroups of

half-millionaires: (a) those in the top 0.1 percent of taxpayers and who earned all of their income

from investments, and (b) elderly half-millionaires, particularly those in the top 0.1 percent.

Using their results, Young and Varner estimated that the migration effects resulted in a potential loss

of 1.8 percent of an estimated $900 million static revenue gain from the tax increase.

12

This is lower

than their estimate of 4.2 percent in the first study.

A third study by Varner and Young examined the 2005 Mental Health Services Tax in California, which

raised the top rate on income above $1 million by one percentage point.

13

It used a panel data set

on California taxpayers to compare the behavior of taxpayers with income between $500,000 and

$1,000,000 (who did not face the tax increase) with those with incomes above $1,000,000. They found

no difference between how millionaires and near-millionaires responded to the policy change. In other

words, they found no effect of the tax increase on millionaire migration. It is not clear how meaningful

these results are for the New York, New Jersey, Connecticut metropolitan area: it is much harder for

taxpayers in California to move to another state and still access job opportunities and amenities of the

California economy than it is for taxpayers in New York or New Jersey to do so.

Two studies were conducted by staff of the New Jersey Department of the Treasury. These studies

used Internal Revenue Service data to relate interstate outmigration to tax rates, unemployment,

housing prices, and distances between states.

14

They found that outmigration is higher when marginal

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

9

tax rates are greater in the origin state than in a potential destination state. They used the findings to

estimate a seven-year impact on migration and tax revenue due to the New Jersey tax rate increase.

The estimated impact is larger (about 8 to 14 percent of revenue) than in the Young and Varner studies

for two reasons: (1) they find a greater initial migration response, and (2) they assume the higher

migration response persists over time rather than being a one-time response to the tax policy change.

These recent studies are interesting and controversial, but their relevance to income tax policy for

New York City is limited. The situation in New York City differs from that in New Jersey and California

because the tax rate in New York City is already at non-comparable levels for high earners and because

New York City high earners have the option of moving to nearby suburban counties in New York State

where income tax rates are lower, but California and New Jersey taxpayers do not have a similar

option. For these reasons, it may be more instructive to consider the current patterns of migration and

residence within the New York region.

Migration in the New York Region

Nationally people move frequently, but migrate from one state to another infrequently. Between

2010 and 2011, 11.6 percent of the population moved: 7.7 percent moved within the same county,

2.0 percent moved to a different county in the same state, and 1.6 percent moved to a different state.

15

When people do move, housing markets and job opportunities often play a major role.

16

Characteristics

such as marriage, having children present in the home, or owning a house, are major impediments to

moving.

17

Many of these characteristics are associated with people with higher incomes.

The American Community Survey (ACS), a relatively new national data source, permits analysis of

interstate and intraregional migration. For the New York region, it is possible to determine (1) how

much more likely people, and particularly high income individuals, living in New York City are to leave

the region than are similar people living in other parts of the region, and (2) how much more likely are

individuals with high-paying jobs in New York City to choose to live outside the city than those with

lower earnings.

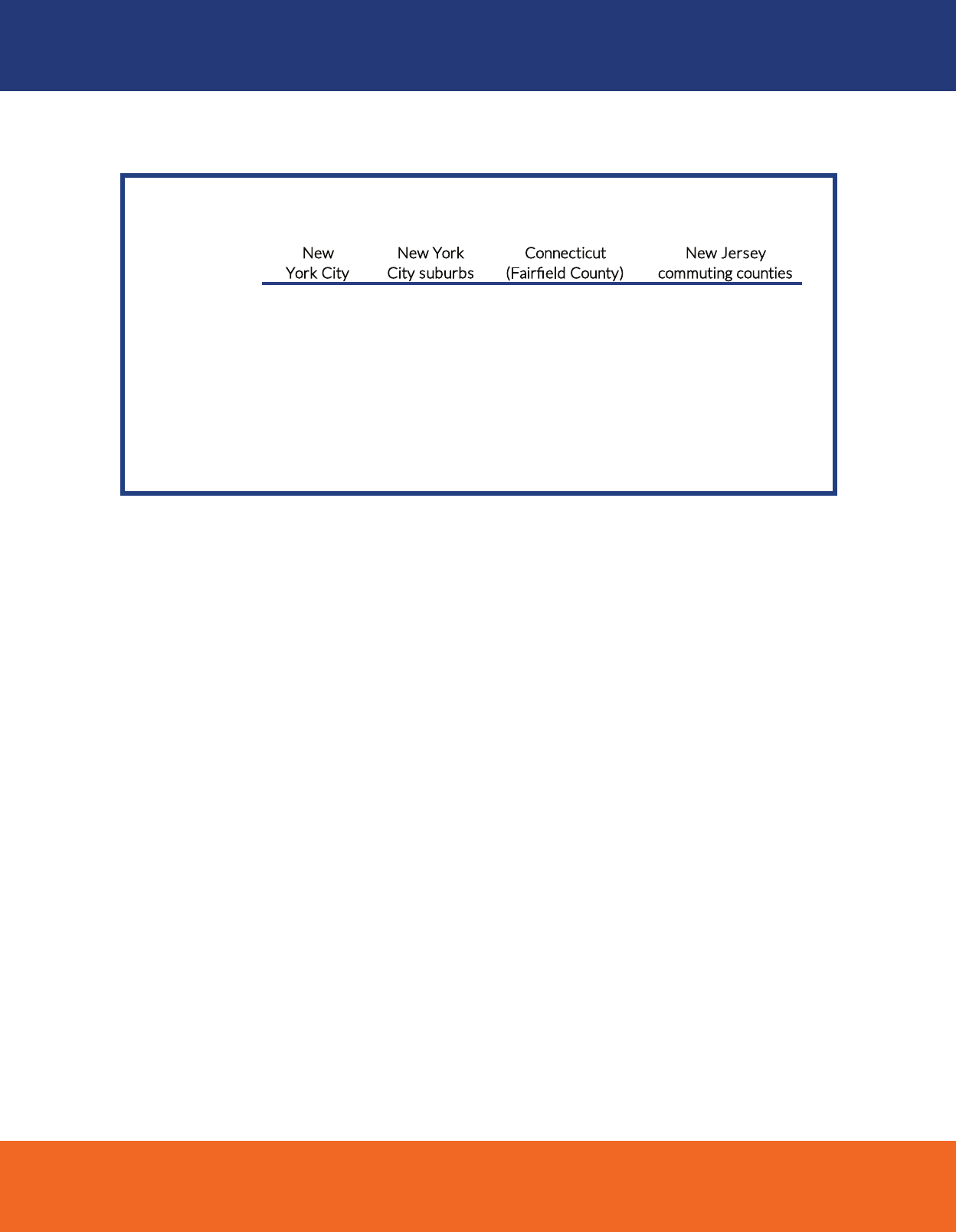

Regional Outmigration. To address the first issue, it is possible to use the ACS for 2007-2011 to

compare regional outmigration for people aged 18 or older who were residents of New York City,

residents of other parts of the region in New York State (Nassau, Rockland, Suffolk, and Westchester

counties), residents of Fairfield County in Connecticut, and residents of the major commuting counties

in New Jersey (Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Middlesex, and Monmouth). Table 7 summarizes the results.The

first point evident from the table is that among the higher-income regional residents, New York City

residents are more likely to move out of their region than residents of the other parts of the region.

For example, 4.0 percent of New York City adults with income of $100,000 - $400,000 outmigrated

compared with only 1.6 percent of adult residents of other New York metropolitan counties, 3.1

percent of adult residents of Fairfield County, and 3.0 percent of adult residents in the New Jersey

counties.

18

The second point is that in other parts of the region higher-income residents are less likely to outmigrate

than residents with income under $100,000, but higher income New York City residents are at least

as likely to outmigrate as city residents with lower incomes. For example, 3.1 percent of residents

of Fairfield County with income of $100,000 -$400,000 outmigrated, compared to 5.8 percent of

residents with incomes up to $100,000; in contrast, in New York City the higher income residents

were at least as likely to move as those with incomes up to $100,000.

19

The people who live in New York City and the people who live in nearby counties may differ in ways that

help explain these different migration rates, but it is possible to control for some of those differences.

Citizens Budget Commission

10

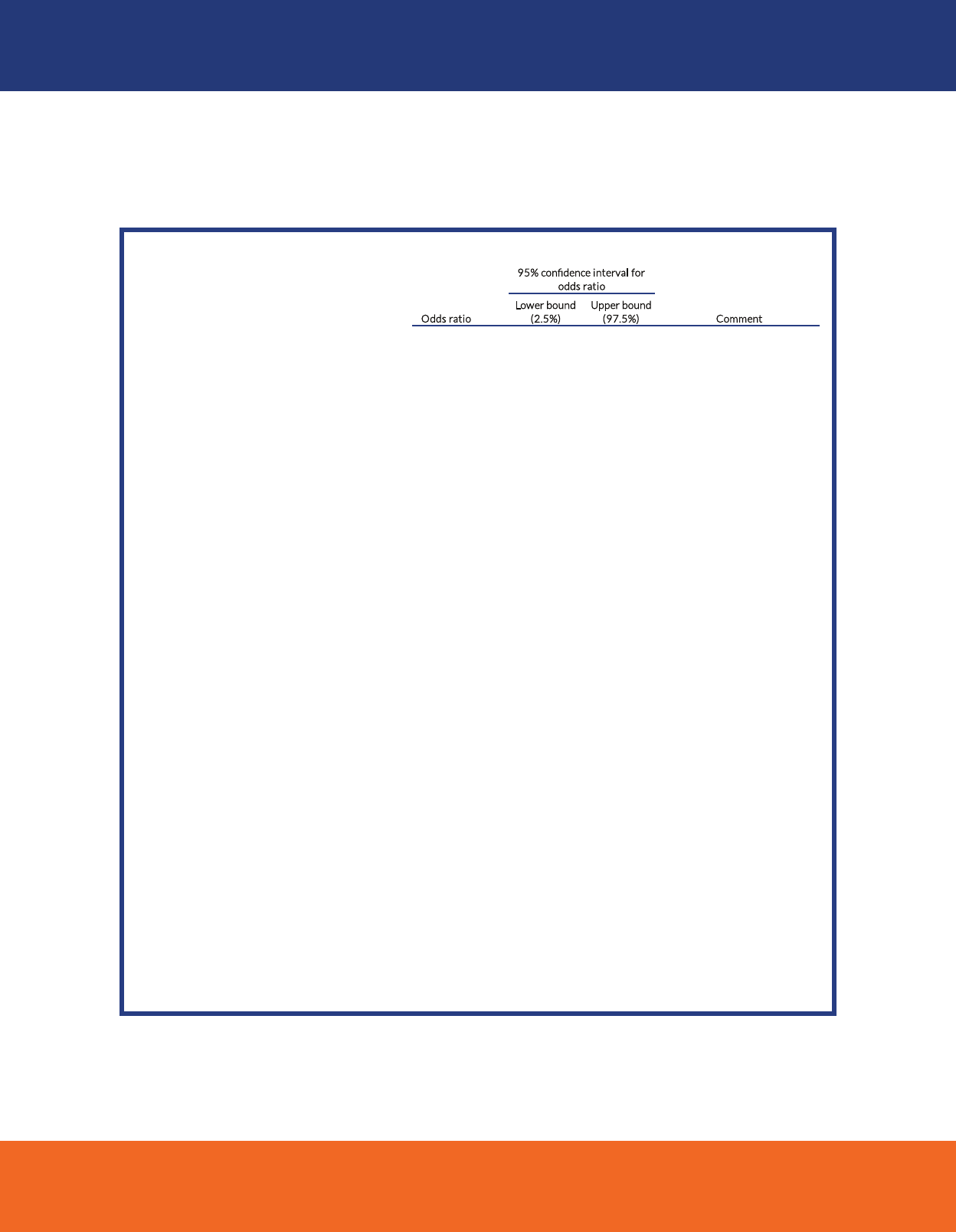

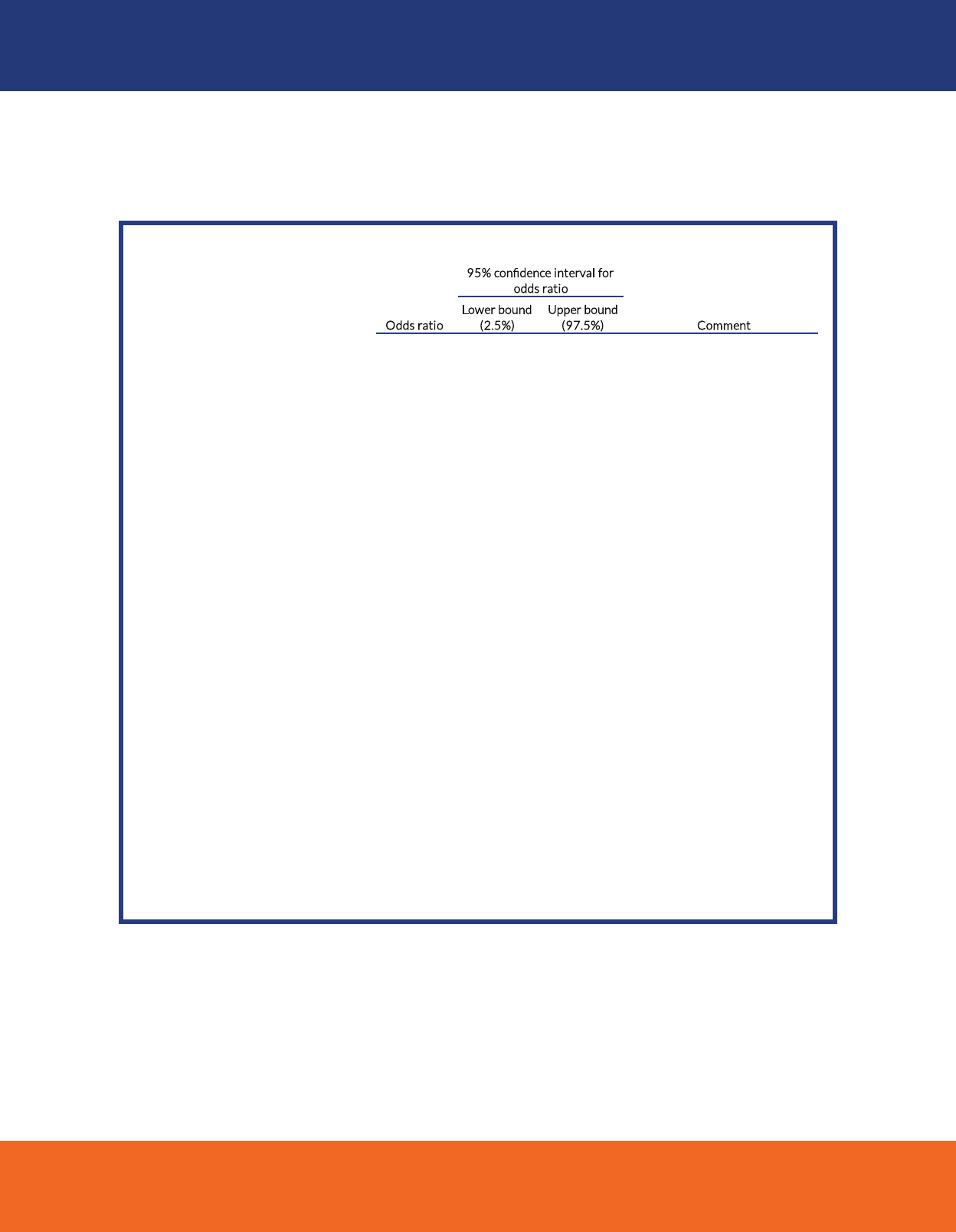

Appendix B presents the results of a logistic regression of outmigration, with independent variables

drawn from those commonly found in prior research. The results generally are consistent with the

academic research – the people most likely to move are those who are unemployed or not in the labor

force, and people with more education; those least likely to move are married or have children present

in the house. However, of particular relevance to tax policy is the finding that after controlling for these

other factors, high-income people (income above $400,000) who live in New York City are more likely

to move than otherwise similar people in the surrounding counties. The appendix presents “odds ratios”

for each variable. For example, the odds ratio for income above $400,000 is 1.9792, or about 2. This

means the probability that someone with income above $400,000 will outmigrate is approximately

twice the probability that someone who is otherwise similar, but with lower income, will outmigrate.

20

If the outmigration probability for someone with a particular set of characteristics and income below

$400,000 was 3 percent, this suggests that an otherwise similar person with income above $400,000

would have an outmigration probability of 6 percent.

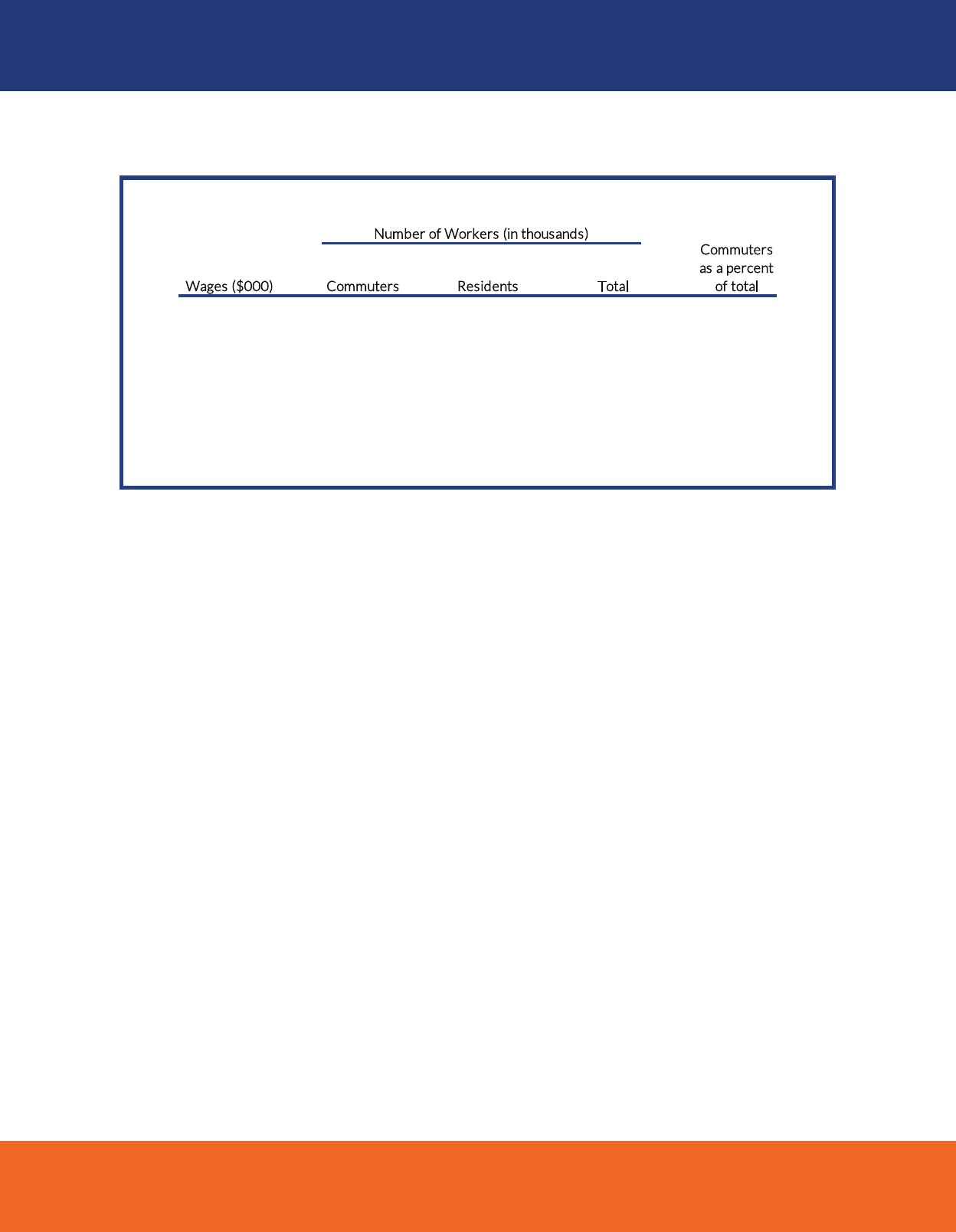

Intraregional Migration. Commuting patterns indicate people’s willingness to live in New York City

versus living in another part of the region. Table 8 shows the number of adults who work in New York

City by whether they are commuters or city residents. On average 21.6 percent of workers commute

to New York City, but the share varies considerably by wage income. In general, higher-wage workers

are more likely to commute than are lower wage workers; 50.6 percent of workers earning $250,000

- $400,000 were commuters, while only 12.2 percent of workers earning less than $50,000 were

commuters. In other words, people with incomes above $50,000 are about two to four times more

likely to commute than people with incomes below $50,000.

These large differences in residential choice cannot be attributed fully to differences in the individuals’

demographic characteristics other than income. Appendix C presents the results of a logistic

regression of commuting. After adjusting for age, marital status, presence of children in the home,

education, and racial and ethnic characteristics, individuals with higher wage income are more likely

to be commuters to New York City than people with similar characteristics but lower wage income.

As with the outmigration regression, the results are presented in terms of odds ratios. The odds ratios

for the higher income groups range from about 2.5 to almost 4, suggesting that after adjusting for

demographic and other differences, higher income individuals are about 2.5 to 4 times more likely to

commute as the lowest income group.

Income ($000)

Up to $100 3.6% 3.8% 5.8% 4.7%

$100-400 4.0% 1.6% 3.1% 3.0%

$400+ 3.5% 1.1% 2.4% 3.1%

Total 3.6% 3.5% 5.3% 4.5%

N

ew

York City

New York

C

ity suburbs

Connecticut

(Fairfield County)

New Jersey

c

ommuting counties

Table 7: Regional Outmigration as a Percent of Residents by County of Origin,

2007-2011

Note: New York City suburbs are Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester and Rockland counes. New Jersey commung

counes are Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Middlesex and Monmouth counes.

Source: Author's analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2007-2011 Five-Year Public Use

Microdata.

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

11

This analysis indicates that higher income individuals are already more likely to opt for suburban

residences than lower income individuals. But it does not necessarily mean that they are even more

likely to do so if tax rates rise. However, it does suggest the likelihood of becoming a commuter will rise

if an accumulation of factors influencing the choice – including taxes – weighs in favor of living outside

the city.

Up to $50 305.3 2,194.8 2,500.1 12.2%

$50-75 183.3 547.3 730.6 25.1

$75-100 145.3 260.0 405.3 35.8

$100-250 224.9 282.4 507.3 44.3

$250-400 24.3 23.8 48.0 50.6

Above $400 38.6 41.9 80.5 48.0

Total 921.7 3,350.

1 4,271.8 21.6%

Table 8: New York City Workers by Commuter Status and Wage Level, 2007-2011

Number of Workers (in thousands)

Source: Author's analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2007-2011 Five-Year Public Use

Microdata.

Wages ($000) Commuters Residents Total

Commuters

as a percent

o

f total

Citizens Budget Commission

12

NEW YORK CITY PERSONAL INCOME TAX POLICY

When assessing different taxes, analysts and policymakers often seek to strike a balance between

goals of equity and adherence to a “benefit” principle of taxation. Concerns for equity favor taxes that

are progressive, meaning higher income households pay a larger share of their income in taxes than do

lower income households. The personal income tax usually scores high on the equity criterion, because

it is largely based on ability to pay and policymakers can control progressivity well by adjusting tax

brackets and other characteristics of the tax. This is especially true for national tax policy, but at the

state and local level varying reliance on income taxes can create competitive disadvantages for states

or cites that depend too heavily on the income tax.

The benefit principle favors taxes that are distributed among residents (and businesses) in proportion to

their consumption of services provided by the government; that is, people should pay in relation to the

extent they receive benefits. The property tax is often seen as scoring well on this criterion, especially

for local governments, because household reliance on core local government services (police, fire, and

sanitation) correlates with the size and value of the property they own or occupy. However, because it

is in many respects a tax on housing, the property tax is also regressive and scores poorly in terms of

equity. Thus, choices between the taxes are a difficult balancing act. This section considers the impact

on progressivity and regional competitiveness of two changes to the New York City personal income

tax. The next section considers New York City’s competitive position with respect to real estate taxes,

particularly commercial real estate taxes. The two income tax policy alternatives are: (1) a 10 percent

across the board surcharge, and (2) a 0.75 percent increase in the top tax rate, from 3.876 percent to

4.626 percent. These options are policies that are near the bounds of past tax increases. New York

City imposed a 14 percent surcharge several times in the past; a 10 percent surcharge is well within

the bounds of historical experience. It would raise more than $800 million annually at current income

levels. The second option, increasing the top rate to 4.626 percent, would exceed the previous highest

top rate in New York City of 4.464 percent in 1998. However, that top rate began at income of $108,000

while this option would take effect at income of $500,000 and would apply to less income. This option

likely would raise more than $750 million annually. It is reasonably consistent with past experience,

similar in revenue magnitude to the surcharge, and a round number (0.75 percent increase).

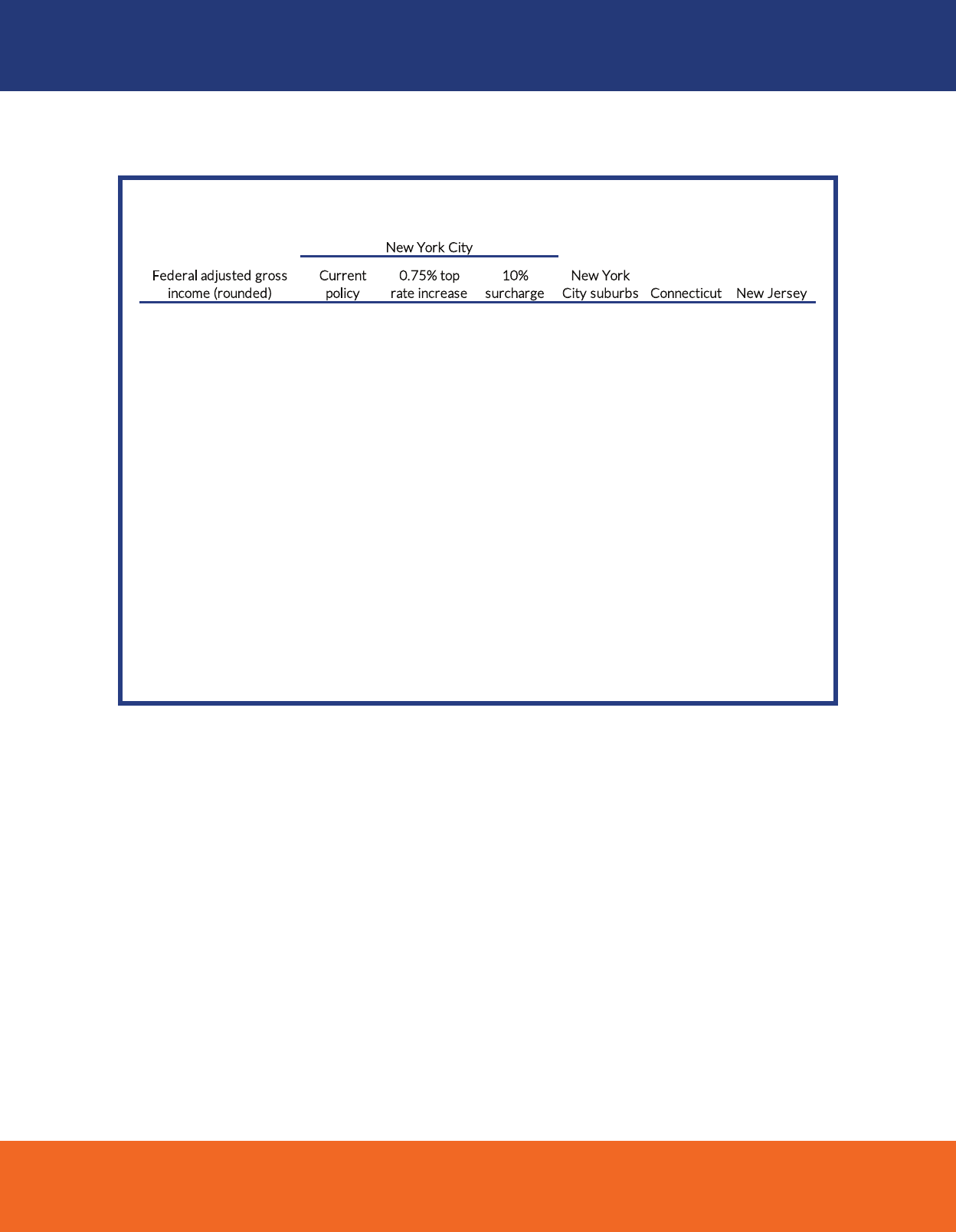

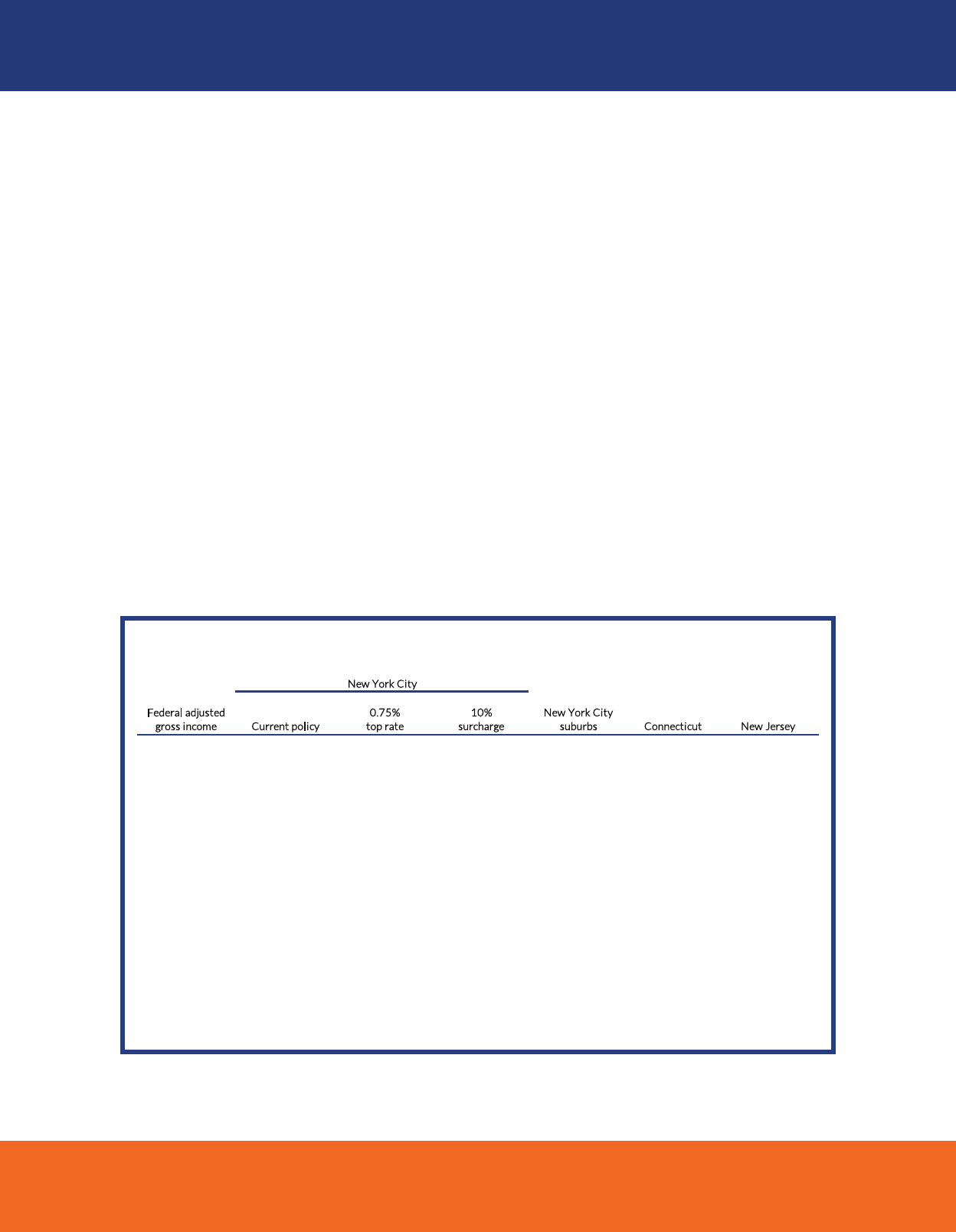

The analysis of the options has two elements. First, it identifies the impact on the combined state and

local tax rate paid by New York City residents at different income levels. The analysis uses 19 different

income levels based on the 10 income categories used in New York State Department of Taxation

and Finance reports and expanded to include more income ranges at the upper level.

21

The income

levels used are based on the midpoint of each reported or interpolated income range, rounded to a

multiple of $1,000; the 19 hypothetical taxpayers are married taxpayers with incomes ranging from

approximately $23,000 to $1.9 million.

The second element of the analysis is a comparison of the state and local tax rates under the two options

to current state and local income tax rates in New York City, in areas of New York State outside New

York City, in New Jersey and in Connecticut. In each case the state and local income tax rate is “net”

income tax taking into account the benefit of deductibility of state and local income taxes against the

federal income tax, for those taxpayers who itemize deductions for their federal taxes. This deduction

lowers federal tax liability, effectively offsetting some of the difference between the City income tax

and income tax in other locations and softening the impact of a local income tax increase. (See Appendix

D for a more detailed description of the method used.)

Table 9 summarizes the results of the analysis. As expected, in comparison to current New York City

rates, the surcharge modestly increases the rate at all income levels. The increase is between one- and

two- tenths of a percentage point across the board. The other option increases the rate only at the

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

13

three highest levels, by between one-tenth and three-tenths of a percentage point.

The impact of the options on competitiveness with other parts of the region is more subtle. Income

tax rates in New York City currently are much higher than in Connecticut, New Jersey, or the rest of

New York State. The rates in New York City at the five highest levels are between 6.2 percent and 9.5

percent; in New Jersey the range at these levels is from 4.6 percent to 5.4 percent; in Connecticut and

other parts of New York from 4.0 to 6.1 percent. Given these large differences under current policy,

the increase in rates in New York City under the two options has only a modest adverse impact on the

differential between New York City and the other areas.

22

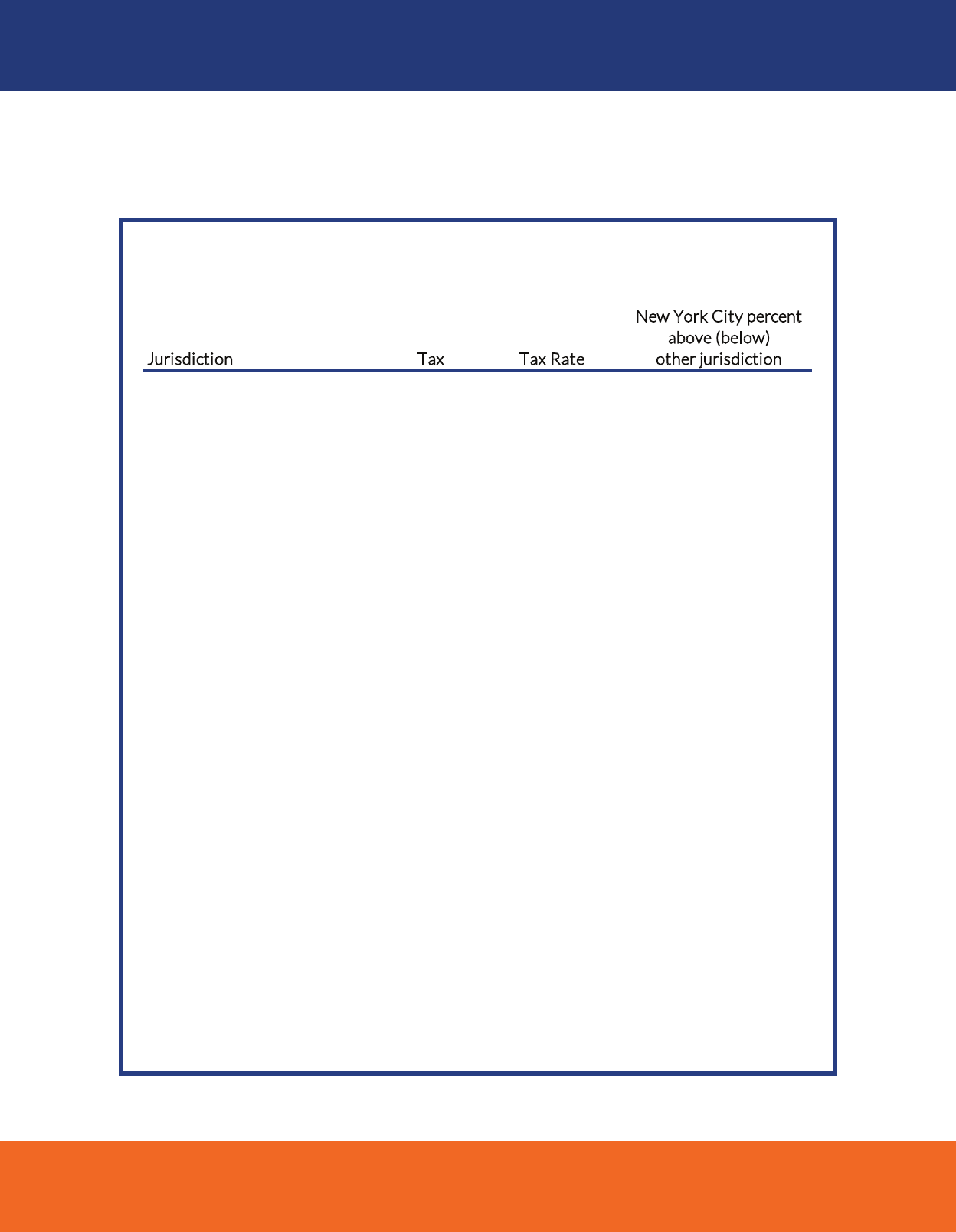

Figure 2 shows the difference in tax rates under the alternative policies. Values above the zero

horizontal line indicate state and local income taxes that are higher than taxes under the current New

York City tax regime. Under the two tax increase options, taxes are higher than under the current tax.

Values below the horizontal line indicate that income taxes under an alternative regime are lower than

current income taxes in New York City. This is the case for all hypothetical taxpayers for New York

outside of New York City, Connecticut, and New Jersey. The differences in tax rates are particularly

large for low- and middle- income taxpayers, but they narrow somewhat for taxpayers with more than

$1 million of income.

Figure 3 shows the tax differentials in actual dollar terms rather than as tax rates. These dollar figures

$23,000 2.0% 2.0% 2.1% 1.0% - % 1.0%

$28,000 2.9 2.9 3.0 1.6 0.1 1.1

$33,000 3.7 3.7 3.8 2.1 0.4 1.2

$38,000 4.1 4.1 4.3 2.4 0.7 1.3

$42,000 4.6

4.6 4.8 2.7 1.1 1.3

$47,000 5.1 5.1 5.3 3.0 1.4 1.4

$52,000 5.5 5.5 5.7 3.3 2.2 1.4

$57,000 5.8 5.8 6.1 3.5 2.8 1.5

$63,000 6.2 6.2

6.4 3.8 3.3 1.5

$70,000 6.6 6.6 6.8 4.0 3.9 1.6

$87,000 6.6 6.6 6.8 4.2 3.9 1.9

$121,000 6.0 6.0 6.2 3.7 3.7 2.1

$171,000 6.1 6.1

6.3 3.9 3.9 2.7

$230,000 7.6 7.6 7.9 4.5 4.3 3.2

$290,000 8.9 8.9 9.2 5.7 5.5 4.7

$490,000 9.5 9.5 9.8 6.1 6.1 5.4

$690,000 8.7 8.8 9.0

5.2 5.5 5.2

$1,300,000 6.2 6.5 6.4 4.0 4.0 4.6

$1,900,000 6.3 6.6 6.5 4.0 4.0 4.8

Source: Author's analysis of hypothecal married-filing-joint taxpayers, as described in text and Appendix D.

Note: Net of savings from deducbility a

gainst federal income tax.

New JerseyConnecticut

New York

C

ity suburbs

10%

s

urcharge

0.75% top

r

ate increase

Current

p

olicy

Federal adjusted gross

i

ncome (rounded)

Table 9: State and Local Income Taxes as a Percent of Federal Adjusted Gross Income,

by Area and Policy Option

New York City

Citizens Budget Commission

14

make clear the impact of the tax policy changes relative to the already existing differences among

jurisdictions. For example, the 10 percent surcharge would raise taxes on a married couple earning

approximately $1.9 million by just under $5,000; the couple already pays approximately $28,000 more

in New York City under the current regime than they would in New Jersey

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

+0

+1

$0 $500 $1,000 $1,500 $2,000

Tax after federal deductibility as % of federal AGI: alternative

regime minus current NYC tax

Note: Net effecve tax rate takes into account deducbility of state and local income taxes against federal tax.

Source: Author's calculaons for hypothecal married taxpayers constructed using data from NYS Department of

Taxaon and Finance.

Federal adjusted gross

income, $ thousands

Figure 2: Difference in Net Effective Income Tax Rates,

Current New York City Policy vs. Other Policy Options

NYC 10% surcharge NYC 0.75% top rate increase

NYS outside NYC Connecticut

New Jersey

($50)

($40)

($30)

($20)

($10)

$0

$10

$0 $500 $1,000 $1,500 $2,000

Alternative regime minus current NYC tax

($ thousands)

Note: Net tax calculaon takes into account deducbility of state and local income taxes against federal tax.

Source: Author's calculaons for hypothecal married taxpayers constructed using data from NYS Department

of Taxaon and Finance.

Federal adjusted gross income, $ thousands

Figure 3: Difference in Net Income Tax Liability,

Current New York City Income Tax vs. Other Policy Options

NYC 10% surcharge NYC 0.75% top rate increase NYS outside NYC

Connecticut New Jersey

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

15

How large would the adverse impacts on the competitiveness of New York City be if either of the

options was pursued? The fact that the increase in tax differentials among jurisdictions is small

relative to already existing differentials, combined with the modest negative impacts found in studies

of state income tax rate changes, might suggest the impacts would not be great. But this is a highly

speculative inference. The situation in New York City is unique. The already high rates, together with

the relatively easy opportunities for intraregional migration (already used by many high earners), make

any predictions about likely outmigration highly uncertain.

Citizens Budget Commission

16

NEW YORK CITY PROPERTY TAX POLICY

This section examines New York City’s current property tax policy and its effects on the competitiveness

of the city for commercial activity. The available comparative data indicate New York City imposes a

property tax on commercial property that is much higher than in most competitive areas, and that

New York City also creates differential rates between commercial and other types of property that are

much greater than in other areas. The policy implication is that these conditions should be considered

in any initiatives to raise more revenue from the property tax.

The analysis in this section relies primarily on annual data published jointly by the Lincoln Institute

of Land Policy and the Minnesota Center on Fiscal Excellence. Their reports compute effective tax

rates for different kinds of properties for the largest city in each state and for the largest 50 cities

in the nation, as well as for selected suburban and rural locations. The analysis takes into account all

property taxes imposed on a parcel of property in a given location, such as county taxes, school taxes,

city taxes or taxes imposed by villages and towns, and special district taxes. It does not generally reflect

special-purpose exemptions or other programs that are available to some properties but not to others.

In the case of New York City it does adjust for the average impact of transitional assessed values and

exemptions.

23

The published data do not include information for key jurisdictions within the New York region that

compete with New York City – notably Mineola and White Plains in New York, Hoboken and Jersey City

in New Jersey, and Stamford, Connecticut. The author has applied the Lincoln Institute methodology

to these locations using data from 2012.

The data for New York City include only the property tax, and do not include the commercial rent tax.

New York City is one of only two jurisdictions in the United States that impose a tax on commercial rent.

(The other is the state of Florida.) The tax was enacted in 1963 when New York City was approaching

a state constitutional limit on the property tax; it was a means to capture some of the growth in real

estate values without exceeding the constitutional cap.

24

The current tax is imposed on commercial

rents on properties in Manhattan south of 96

th

Street. The effective rate is 3.9 percent of gross rent

for properties with gross rent of more than $300,000 annually; the effective rate phases up from zero

to 3.9 percent for properties with gross rent between $250,000 and $300,000. The property tax

equivalent of the commercial rent tax depends on the relationship of rent to property value, which

varies with market conditions. Applying assumptions about market values and rents for Manhattan

office properties that were used by the New York City Department of Finance in early 2013, the

commercial rent tax likely was about 0.7 to 0.9 percent of market value, or about 15 to 20 percent of

the property tax.

25

(Based on market conditions during the 2000’s, this would have ranged from about

10 percent to 25 percent.

26

) Put differently, for properties in Manhattan subject to the commercial

rent tax, the effective tax likely was 15 to 20 percent higher than shown in the tables below.

A Comparative View of Commercial Property Taxes

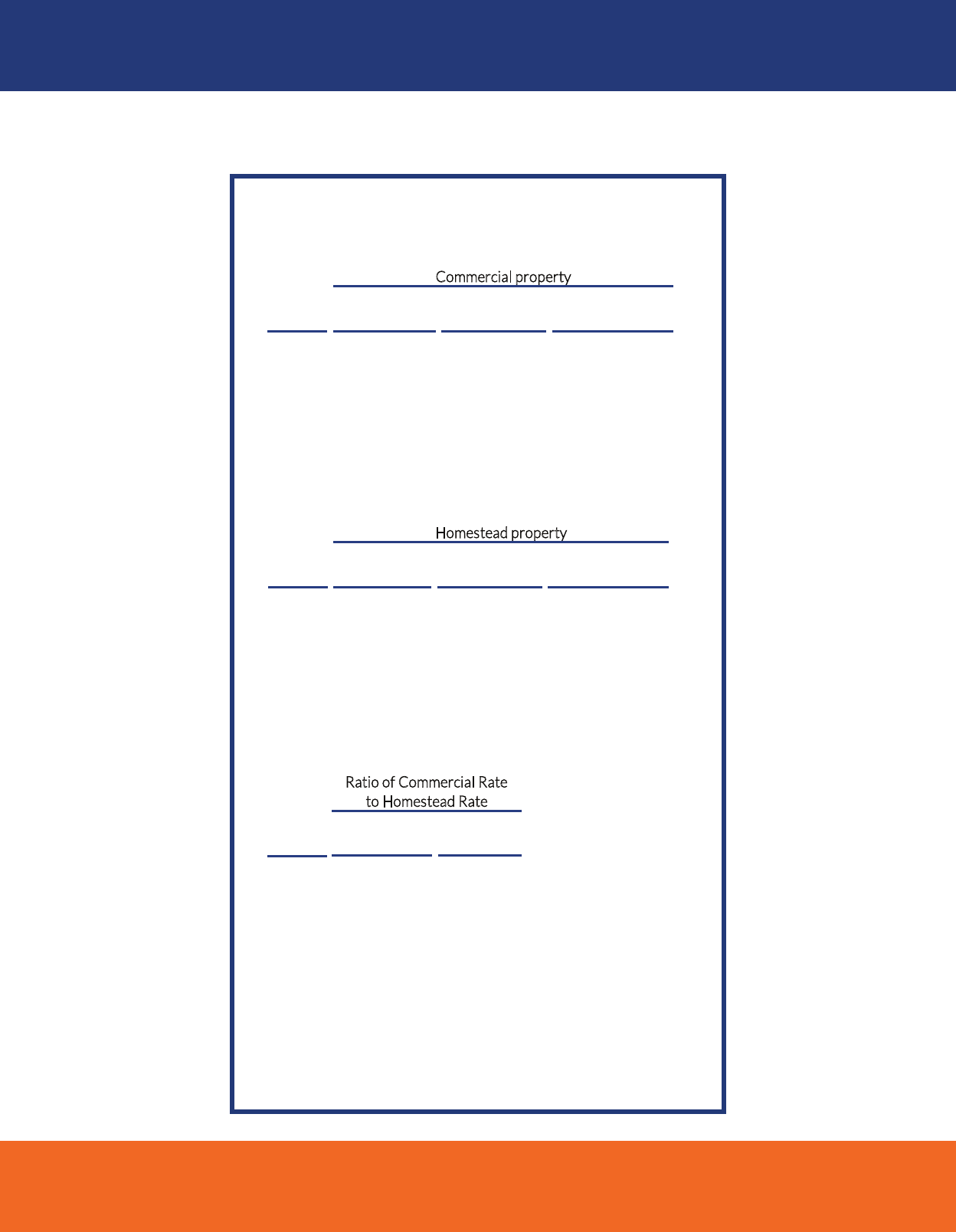

Table 10 shows the property tax on a $25 million commercial property in 2012 in the 15 largest cities

in the nation by population, and in selected jurisdictions in the New York region. The New York City

commercial property tax (not reflecting the commercial rent tax) was second highest among large

cities, behind Chicago. New York’s commercial property tax was 10 percent higher than third-highest

Philadelphia, 35 percent higher than Houston, and 154 percent higher than Los Angeles. It was 51

percent higher than the average for the other 14 of the 15 largest cities – an annual difference of

$327,000 for a $25 million property.

Closer to home, New York was 30 percent higher than the average for the five locations within the

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

17

Jurisdiction

15 largest cities in the U.S.:

Chicago $ 1,166 3.89% (17.3%)

New York City 964 3.21

Philadelphia 876 2.92 10.0%

Dallas 792 2.64 21.6%

San Antonio 761 2.54 26.7%

Houston 717 2.39 34.5%

Austin 693 2.31 39.2%

Phoenix 687 2.29

40.2%

Columbus 687 2.29 40.3%

Indianapolis 571 1.90 68.9%

Jacksonville 526 1.75 83.2%

San Jose 382 1.27 152.2%

Los Angeles 380 1.27 153.8%

San Francisco 351 1.17 174.9%

San Diego 333 1.11 188.9%

Average of largest 15

cities,

excluding NYC

$ 637 2.12% 51.3%

Nearby jurisdictions:

Mineola $ 1,450 4.83% (33.5%)

New York City 964 3.21

White Plains 813 2.71 18.6%

Jersey City 563 1.88 71.2%

Stamford 505 1.68 90.9%

Hoboken 368 1.23 161.8%

Average of nearby jurisdictions,

excluding NYC $ 740 2.47% 3

0.3%

T

ax RateTax

New York City percent

above (below)

other jurisdiction

Table 10: Property Tax on $25 Million Commercial Property,

Selected Locations, 2012

(dollars in thousands)

Source: Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence and Lincoln Instute for Land Policy, 50-State Property Tax

Comparison Study , 2012, and author's analysis.

Notes: Esmates for Mineola, White Plains, Jersey City, Stamford, and Hoboken developed by the author using

methodology of the Minnesota/Linco

ln Instute study.

Citizens Budget Commission

18

region. New York City’s tax is reported as lower than in Mineola, but that is a questionable finding,

because Nassau County appears to have an extraordinarily variable and contentious property tax

system. Many observers believe that the relationship between true market value and the value carried

on the Nassau County assessment roll is inconsistent at best.

27

At the other extreme, a $25 million

commercial property in Hoboken is subject to property tax of $368,000, about $596,000 less, annually,

than in New York City.

It may be surprising to readers to see Chicago higher than New York City in 2012. That is a recent

phenomenon. Table 11 shows the tax rates on commercial property for each year from 2005 through

2012. In every year between 2005 and 2011, the New York tax rate was higher than the Chicago rate.

The recent increase in Chicago reflects, in part, increases in the median level of assessment.

28

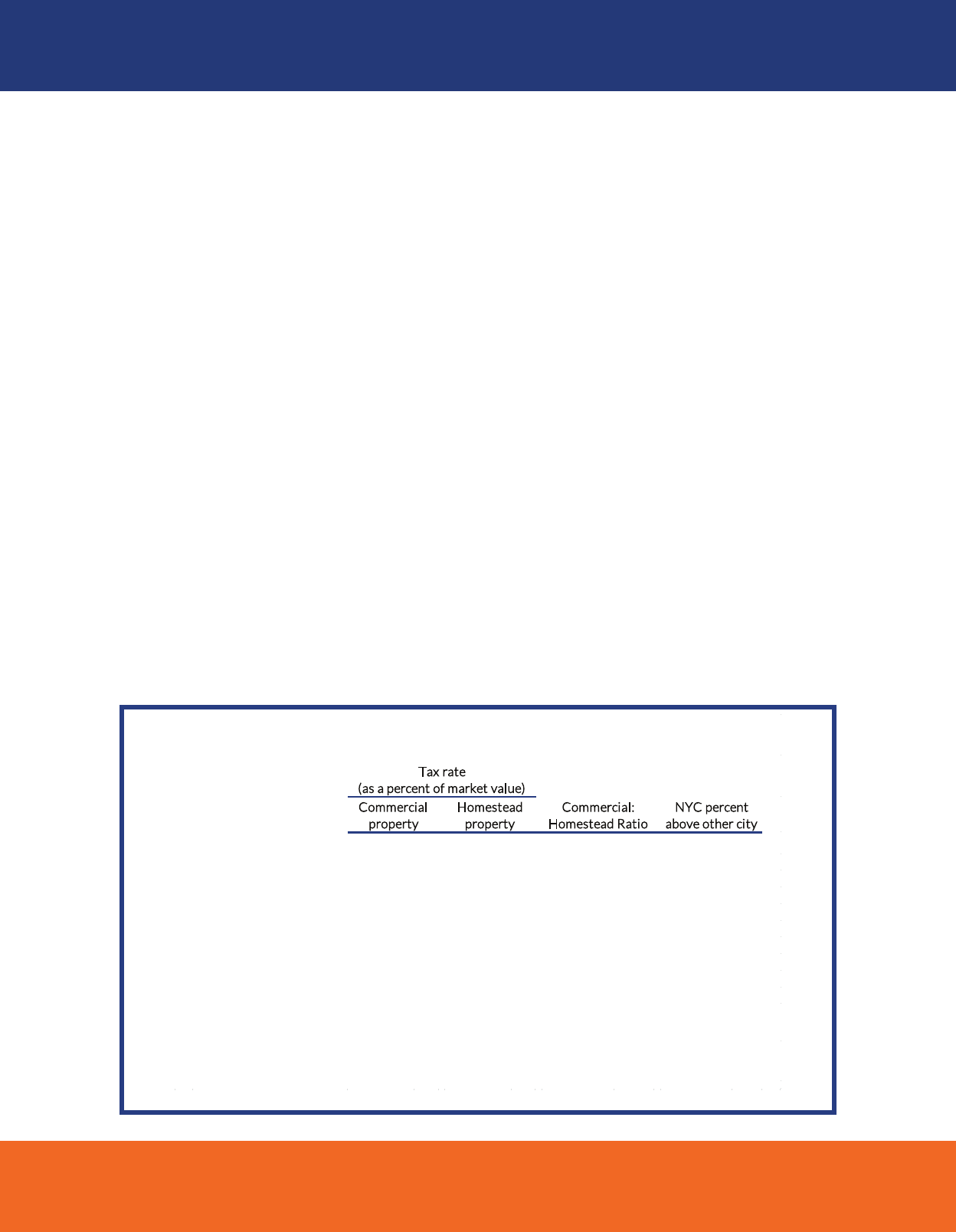

Disparities between Commercial and Small Residential Property

One reason the commercial property tax is so high in New York City is because taxes on small residential

properties (know as Class 1 in New York City) are so low, a longstanding policy in New York. Table 12

shows the effective tax rate on commercial and homeowner properties in New York City, the City’s

ranking among the 50 large cities included in the Lincoln Institute and Minnesota Center analysis,

and the average for large cities, for available years from 1995 through 2012. In a typical year New

York City’s commercial property tax is 50 percent or more above the average for large cities, while the

homeowner property tax generally is 50 percent or more below the average.

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Chicago 3.11% 2.80% 2.41% 2.09% 2.03% 1.79% 2.04% 3.89%

New York City 3.87 3.64 3.29 2.96 3.24 3.31 3.20 3.21

Philadelphia 2.90 3.16 3.04 2.98 3.43 3.40 2.05 2.92

Dallas 2.83 2.72 2.41 2.31 2.38 2.55 2.62

2.64

San Antonio 2.67 2.81 2.41 2.47 2.58 2.49 2.48 2.54

Houston 2.79 2.40 1.99 2.01 2.39 2.34 2.34 2.39

Austin 2.56 2.31 2.10 2.06 2.13 2.27 2.27 2.31

Phoenix 3.34 3.05

3.05 2.35 2.02 2.09 2.10 2.29

Columbus 1.52 1.74 1.89 1.67 1.83 1.96 1.83 2.29

Indianapolis 2.47 2.60 3.28 na 2.62 1.94 3.04 1.90

Jacksonville 1.79 1.71 1.73 1.49 1.58

1.67 1.72 1.75

San Jose 1.16 1.19 1.19 1.22 1.25 1.27 1.29 1.27

Los Angeles 1.20 1.18 1.18 1.19 1.22 1.27 1.25 1.27

San Francisco 1.14 1.14 1.14 1.16 1.16 1.16 1.17

1.17

San Diego 1.11 1.10 1.10 1.08 1.10 1.10 1.11 1.11

Note: Commercial property effecve tax rates are for the highest-value property group examined; year generally is the year of

the tax levy.

Source: Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence and Lincoln Instute for Land Policy, 50-State Property Tax Comparison Study ,

various years.

Table 11: Tax Rates on Large Commercial Property, Selected Cities, 2005-2012

(percent of market value)

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

19

Year

2005 3.87% 1 2.06% 88.0%

2006 3.64 2 2.03 79.4%

2007 3.29 2 1.94 69.4%

2008 2.96 3 1.83 62.2%

2009 3.24 3 1.86 73.7%

2010 3.31 3 1.87 76.5%

2011 3.20 3 1.97 62.8%

2012 3.21 4 2.06 55.8%

Table 12: Property Tax Rates in New York City and Other

Large Cities, by Type of Property, 2005-2012

(percent of market value)

Commercial property

Tax Rate Rank 50 largest cities (below) the average

New York City Average tax rate, NYC percent above

0.59% 46 1.50% (60.5%)

0.54 46 1.44 (62.2%)

0.38 49 1.39 (72.8%)

0.33 49 1.34 (75.4%)

0.59 45 1.38 (57.4%)

0.65 44 1.41 (54.2%)

0.62 47 1.48 (58.1%)

0.63 47 1.51 (58.1%)

Homestead property

RankTax Rate 50 largest cities

NYC percent above

(below) the average

New York City Average tax rate,

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

6.5 1 1.4

6.7 1 1.4

8.7 1 1.4

9.0 1 1.4

5.5 1 1.3

5.1 1 1.3

5.2 1 1.3

5.1 1 1.4

Ratio of Commercial Rate

to Homestead Rate

Ratio Rank largest cities

Average, 50 New York City

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Note: Commercial and homestead property effecve tax rates are for the highest-value

property group examined; year generally is the year of the tax levy.

Source: Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence and Lincoln Instute for Land Policy, 50-

State Property Tax Comparison Study , various years.

Citizens Budget Commission

20

The relationship between commercial and homeowner property tax rates is notably different in New

York City than in other large cities: in a typical year the tax rate on commercial property is 5-6 times

as great as the tax rate on homeowner property. While other large cities also tend to tax commercial

property more heavily than homeowner property, the difference is not as extreme. Table 12 shows that

in most years the rate for commercial property in the average large city is about 40 percent higher than

the effective rate for homeowner property, rather than 5-6 times as great as it is in New York City. New

York City has the highest ratio of commercial property tax rate to homestead tax rate of any large city

in the country, and has held this distinction each year from 2005 through 2012.

The extraordinary extent to which New York City taxes commercial property more than homestead

property is evident in Table 13. It identifies the ten cities, out of the top 50 by population, with the

highest ratio of commercial tax rate to homestead tax rate. New York’s ratio is 9 percent higher than

second-ranking Boston’s. After that the disparity widens dramatically: New York is 39 percent higher

than third-ranked Colorado Springs and 140 percent higher than tenth ranked Kansas City.

What are the implications of the distinctive way in which New York City taxes commercial property?

A 10 percent increase in the tax on commercial property (Class 4) would be roughly comparable in

to the 10 percent surcharge on the personal income tax examined earlier. If the City were to adopt

such an increase it would exacerbate the already-large differences in New York City commercial

property taxes compared to other large cities and to nearby jurisdictions: New York’s commercial

property tax would be 188 percent higher than in Hoboken, 110 percent higher than in Stamford, and

88 percent higher than in Jersey City – again, without considering the impact of the commercial rent

tax, which does not have counterparts in these other locations. Estimating the economic impact of a

commercial property tax increase is not practical, but such a change would be tantamount to taking the

price of a luxury good (a New York City location) that already is substantially more expensive than its

competitors and increasing it further, rather than increasing taxes that are not as far out of line with

those of competitors.

New York City 3.21% 0.63% 5.1

Boston 2.85 0.61 4.7 9.3%

Colorado Springs 1.72 0.47 3.7 38.8%

Denver 2.02 0.57 3.6 43.1%

Washington 2.06 0.64 3.2 57.8%

Mesa 1.92 0.68 2.8

79.6%

Phoenix 2.29 0.86 2.7 89.7%

Tucson 2.48 0.97 2.6 97.8%

Chicago 3.89 1.64 2.4 114.7%

Kansas City 2.92 1.38 2.1 140.3%

Note: Commercial and homestead property effecve tax rates are for the highest-value property group examined; year

generally is the year of the tax levy.

Source: Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence and Lincoln Instute for Land Policy, 50-State Property Tax Comparison

Study , 2012.

Commercial

p

roperty

Homestead

p

roperty

Commercial:

Homestead Ratio

NYC percent

a

bove other city

Tax rate

(as a percent of market value)

Table 13: Tax Rates on Commercial Property Relative to Homestead Property,

Selected Cities, 2012

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

21

CONCLUSION

New York City’s tax burden is far greater than that in other large cities. Higher taxes can, in concept,

cause people to flee a high-tax jurisdiction, potentially reducing the tax base. Empirical research on

migration suggests that people move, or choose not to move, primarily for non-tax reasons such as

to seek employment in better labor markets, to go to less-expensive housing markets, and to take

advantage of opportunities that college degrees provide. Analysis of recent relevant data, however,

suggests that high-income New Yorkers are more likely to outmigrate than are high-income individuals

in neighboring or metropolitan counties in New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey. Similar analysis

suggests that individuals who work in New York City are more likely to be commuters if their wages

are high.

Some people do move for tax reasons. The empirical research on “millionaire taxes” suggests that their

impact on migration has been relatively small. Based on prior research, there is likely to be some “tax

flight” migration from New York City to other locations if the City enacts new increases, but it is not

practical to quantify this impact with any confidence because tax differentials between New York City

and its neighbors already are great and intraregional migration is a very real possibiIty. It is important

to remember that New York City’s income tax already is an outlier. The combined city and state tax

rate is far higher than in neighboring or competitor states, and the personal income tax accounts

for three quarters of the difference between tax burdens in New York City and in other large cities.

Furthermore, the research on tax migration based on New Jersey data examined top marginal rates

that are well below those currently in effect in New York City when combined state and city rates are

taken into account. Thus, the experience in New York City may be different from that in New Jersey.

Although the property tax in New York City, on average, contributes relatively little to the City’s outlier

status, that fact alone is deceptive. The tax on homeowner properties is very low compared with other

large cities – typically ranking the City at or near 50 in an annual study of property tax rates in 50 large

cities. By contrast, the commercial property tax rate is about 5-6 times the homeowner tax rate in

most years, and New York City’s commercial property tax rate is much higher than in most other large

cities and much higher than in potential competitors in the region. In 2012 the commercial rate was

47 percent higher than the average of the other 14 largest cities in the nation and 42 percent higher

than the average for Hoboken, Jersey City, Mineola, Stamford, and White Plains. It was 162 percent

higher than in Hoboken – a difference of $596,000 annually on a property worth $25 million. Further

increases in the commercial property tax would make New York City even more of an outlier.

Policymakers considering raising the personal income tax or the commercial property tax need to be

aware that both taxes are already significantly higher than in other large cities. They are dealing with

uncertainty related to these distinct competitive circumstances and would be well advised to examine

options where New York City is not as far out of line with other cities.

Citizens Budget Commission

22

APPENDIX A

Study

Policy

or trend

examined

Data & methods Authors’ conclusions Comments

Young, Varner,

& Massey

2008; Policy

Research

Institute for

the Region,

Princeton

University

Outmigration

from NJ

2004+ 8.97%

tax rate on

taxable income

above $500k

(for HMH’s –

half-millionaire

households).

Census Bureau annual summary

data by state, for description of

longer-term migration trends

without regard to income levels.

Census ACS person-level

microdata for 2000-2006

combined. Logistic models of

outmigration and inmigration

based on demographic

characteristics.

NJ annual summary of tax data,

with counts of HMHs and of

numbers of in- and outmigrating

HMHs (based on part-year filings),

2000-2007.

Outmigration is driven by low-

income individuals, especially

unemployed and not in labor

force. Elderly and individuals

with children much less likely to

move than others. Outmigration

reflects NJ’s high cost of living.

Number of HMH outmigrants

increased in 2004+, but rate

of outmigration increased only

very slightly. Inmigration slowed

slightly. NJ loses at most ~350

HMHs per year due to the 2004

tax increase, out of 44,000 (0.8%

of HMHs). About $38m annual

loss on average.

CA, MA, NY outmigration

similarly largely driven by low-

income individuals. Tax rates,

climate, and crime do not appear

to explain their outmigration.

In YVM analysis, impacts do

not grow with time.

Implicitly assumes that

when people leave, they

take their jobs and income

with them – the money is

gone.

Authors report their ACS

income data are top-coded

at $300k. However, more-

current ACS data are more

promising: 2007-2011 data

for NY has wages topcoded

at $507k and other income

also has high topcoding.

Highest income in the data

is around $1.3 million.

Cohen, Lai, &

Steindel, 2011,

New Jersey

Dept. of the

Treasury

Interstate

differences in

tax rates.

Hypothetical

1% across-

the-board rate

increase.

Combined

impact of all

changes since

2003: 2004+

HMH increase,

temporary

rate increases,

bracket creep.

IRS annual state-level data on

state-to-state migration: total

number of migrants and their

income, by year, based on tax filing,

1992-2008.

Description of trends.

OLS linear and log-linear models

of state-to-state outmigration

rates, based on differences in tax

rates, unemployment, and housing

prices, and on distances between

states.

When taxes, housing prices, or

unemployment are relatively

higher in the home state,

outmigration is greater.

Clear but modest effects of

tax differentials on interstate

migration.

1% across the board increase

would raise $2.5b revenue, but

lose 4,200 taxpayers and $29m

revenue (1.2% of the increase)

to outmigration.

Cumulative changes from 2003

to 2009 lowered number of

taxpayers by 20,000, with loss of

over $125m in state tax revenue,

partially offsetting increases

from tax changes.

State-level summary data

(as opposed to microdata)

limit the inferences that

can be drawn. Cannot

confidently address HMH

tax questions with these

data.

Assumes outmigration

response to a tax increase

persists forever.

Implicitly assumes that

when people leave, they

take their jobs with them –

the money is gone.

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

23

Study

Policy

or trend

examined

Data & methods Authors’ conclusions Comments

Young &

Varner 2011,

National Tax

Journal

NJ 2004+

8.97% tax rate

on taxable

income above

$500k (for

HMH’s – half-

millionaire

households).

Time-series cross-section

taxpayer-level data on ALL NJ-

1040 tax returns 2000-2007

(without individual linkage

identifier).

Data included outmigrants coded

+1, inmigrants coded -1, and

stayers coded 0.

Difference-in-differences

model - compares inmigration,

outmigration, and non-moving

behavior pre- and post- tax

change, for HMHs and for $200-

500k income households used as

control. Allows estimates of the

“treatment effect” (the effect of

higher 2004+ tax rates).

HMH outmigration increased

after tax was put into effect,

but so did outmigration of

unaffected near-HMHs.

NJ HMH outmigration in a

typical year is about 459 HMHs,

or 1.2% of all HMHs. 1% point

increase in effective tax rate

leads to ~ 0.04% decrease in #

of HMHs.

Groups that are more likely

than average millionaires to

outmigrate in response to tax

increase: those reliant solely on

investment income; those over

age 65; extremely high income

business owners. These groups

are a very small subset of HMHs

and don’t affect totals much.

“Static” estimate was that the

tax increase raised ~$900m.

Model suggests about 70 HMHs

outmigrated because of the tax.

IF they take their jobs/income

with them, revenue loss of

~$16m (1.8% of the increase);

mostly attributable to HMHs

with income above $3m.

Authors also examined

multinomial logit models;

did not change fundamental

conclusions (per

correspondence).

Method forces explanatory

variables to have the same

influence in both directions

– e.g., if elderly people are

more likely to migrate out of

NJ, they also are more likely

to migrate into NJ.

Treats outmigration as one-

time behavioral change in

response to policy change,

rather than occurring year

after year after year. Tax-

averse people leave once,

rather than continually year

after year.

Cohen, Lai, &

Steindel, Feb.

2012, State Tax

Notes

Essentially

same as 2011

report

Same as 2011 report; annual

IRS state-level state-to-state

migration data, updated to 2010.

Essentially same as 2011 report:

“average marginal tax rates have

a small but significant effect on

migration.” Impact of tax changes

from 2004-2009 reduced $1

billion annual static revenue gain

by about $115m (11%).

Implicitly assumes that

when people leave, they

take their jobs with them –

the money is gone.

Cannot distinguish

millionaires.

Assumes outmigration

response to a tax increase

persists forever – people

keep leaving at higher rates,

year after year after year.

Varner &

Young 2012

California’s

Mental Health

Services Tax

(MHST) –

increased top

rate by 1%

for taxable

income above

$1 million, in

2005+.

Longitudinal tax return data for

taxpayers in California who had

adjusted gross income of $500k

or more in any year during 1992-

2009. Panel data with individuals

linked over time.

Difference-in-differences

regression. Control group is those

earning $500k-$1m.

Migration counts at most for

1.2% of annual changes in

millionaire population.

Neither inmigration nor

outmigration shows a tax-flight

effect from the MHST.

Panel nature of data (with

individuals linked over

time) allows improved

identification of migrants,

compared with earlier

studies.

Most million-dollar earners

are having an unusually

good year, and tax may be

transitory.

Citizens Budget Commission

24

Study

Policy

or trend

examined

Data & methods Authors’ conclusions Comments

Cohen, Lai,

& Steindel,

Sep. 2013,

unpublished

draft

NJ 2004+

8.97% tax rate

on taxable

income above

$500k (for

HMH’s – half-

millionaire

households).

Time-series cross-section

taxpayer-level data on ALL NJ-

1040 tax returns 2000-2007

(without individual linkage

identifier).

Replication of Young &

Varner 2011. Also, estimated

outmigration separately (YV

had estimated inmigration and

outmigration together).

Replicated the YV 2011

conclusions with minor

differences.

Separate outmigration

equation suggested that

annual outmigration of HMHs

increased by about 80.

Report argues that near-

millionaires could be affected,

also, out of concern that they

could be HMHs in the future.

Draft provided to me by

study’s authors.

Tax Policy Choices and New York City’s Competitive Position

25

APPENDIX B

Income-related characteristics

Some self-employment income 1.5874 1.4844 1.6959 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Some retirement income 1.0235 0.9554 1.0957

No wage income 0.4256 0.4070 0.4451 LOWERS odds of outmigration

Income above $400,000 1.9792 1.4559 2.6664 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Income above $400,000 & resided in

NYC previous year 2.2937 1.6811 3.1386 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Income above $400,000 & age 65+ 1.2441 0.5836 2.3259

Resided in NYC previous year 0.9572 0.9277 0.9877 LOWERS odds of outmigration

Resided in NYC previous year & age 65+ 0.9674 0.8752 1.0686

Age group:

18-24 0.5044 0.4736 0.5373 LOWERS odds of outmigration

25-4

4 0.4539 0.4255 0.4843 LOWERS odds of outmigration

45-64 0.1397 0.1300 0.1501 LOWERS odds of outmigration

65+ 0.0807 0.0734 0.0887 LOWERS odds of outmigration

Labor force status, compared to working

Unemployed 2.1189 2.0017 2.2418 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Not in labor force 3.5371 3.3776 3.7036 INCREA

SES odds of outmigration

Marital status, compared to single

Married 0.8779 0.8435 0.9138 LOWERS odds of outmigration

Widowed, divorced, or separated 1.4205 1.3488 1.4958 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Person's children are present in the household 0.4521 0.4275 0.4778 LOWERS odds of outmigration

Education, compared to no high school diploma

HS Gra

duate 1.1999 1.1375 1.2661 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Some college 1.4565 1.3794 1.5383 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Associate's degree 1.1659 1.0768 1.2616 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Bachelor's degree 1.7904 1.6912 1.8959 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Master's degree 1.9279 1.8025 2.0621 INCREASE

S odds of outmigration

Professional degree or doctorate 2.7221 2.5089 2.9519 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Male 1.0609 1.0283 1.0945 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Hispanic 0.9102 0.8681 0.9539 LOWERS odds of outmigration

Race, compared to white

Black 1.0414 1.0000 1.0842

Another race, alone 0.8455 0.7871 0.9077

LOWERS odds of outmigration

Multiple races 1.2492 1.1403 1.3658 INCREASES odds of outmigration

Other 0.9104 0.8676 0.9549 LOWERS odds of outmigration

# of individuals (observations) 547,678

McFadden pseudo r-squared= 0.0888

Characteristics Affecting Outmigration: Logistic Regression Results

Data: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2007-2011 Five-Year Public Use Microdata, residents of and outmigrants from: New York City, Nassau, Rockland, Suffolk, and

Westchester Counes in New York; Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Middlesex, and Monmouth Counes in New Jersey; and Fairfield County in Conneccut.

Odds ratio

Lower bound

(

2.5%)

Upper bound

(