CIMA’S Official Learning System

CIMA Certificate in Business Accounting,

2006 Syllabus

Fundamentals of

Management

Accounting

Janet Walker

CIMA Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier

Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK

30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA

First edition 2006

Copyright # 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system

or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher

Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights

Department in Oxford, UK: phone (+44) (0) 1865 843830; fax (+44) (0) 1865 853333;

visiting the Elsevier web site at http://elsevier.com/locate/permissions, and selecting

Obtaining permission to use Elsevier material

Notice

No responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to persons

or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use

or operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material

herein.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 978 0 7506 8031 8

ISBN-10: 0 7506 8031 8

Typeset by Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd, Pondicherry, India

www.integra-india.com

Printed and bound in Great Britain

06 07 08 09 10 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For information on all CIMA publications

visit our web site at books.elsevier.com

Contents

The CIMA Learning System xi

How to use your CIMA Learning System xi

Guide to the Icons used within this Text xii

Study technique xii

Computer-based assessment xiv

Fundamentals of Management Accounting and computer-based assessment xv

Learning Outcomes and Indicative Syllabus Content xvi

1 Basic Aspects of Cost Accounting 3

Learning Outcomes 3

1.1 Introduction 3

1.2 Why organisations need costing systems 3

1.3 What is meant by ‘cost’? 4

1.4 Cost units 4

1.4.1 Composite cost units 5

1.5 Cost centres 6

1.6 Cost objects 6

1.7 Classification of costs 7

1.7.1 Classification of costs according to their nature 7

1.7.2 Classification of costs according to their purpose:

direct costs and indirect costs 8

1.8 Elements of cost 9

1.9 Cost behaviour 12

1.9.1 Fixed cost 12

1.9.2 Variable cost 14

1.9.3 Semi-variable cost 15

1.9.4 Analysing semi-variable costs 16

1.9.5 Using historical data 18

1.9.6 The importance of time scale in analysing cost behaviour 18

1.10 Summary 19

Revision Questions 21

Solutions to Revision Questions 27

iii

2006.1

2 Accounting for the Value of Inventories 33

Learning Outcomes 33

2.1 Introduction 33

2.2 Valuing inventory at cost 33

2.3 First in, first out (FIFO) 34

2.4 Last in, first out (LIFO) 35

2.5 Cumulative weighted average (AVCO) 35

2.6 Comparison of FIFO, LIFO and AVCO 36

2.6.1 Historical cost compared with economic cost and economic value 37

2.7 Inventory valuation and the effect on gross profit 37

2.8 Periodic weighted average 38

2.9 Materials documentation 39

2.9.1 Perpetual inventory system 39

2.9.2 Recording the receipt of goods 39

2.9.3 Recording the movement of inventory items 39

2.10 Summary 40

Revision Questions 41

Solutions to Revision Questions 45

3 The Analysis of Overhead 53

Learning Outcomes 53

3.1 Introduction 53

3.2 What is an overhead cost? 53

3.2.1 Definition 53

3.2.2 Functional analysis of overhead costs 54

3.3 Overhead allocation and apportionment 54

3.4 Absorption of overheads into saleable cost units 56

3.4.1 General principles 56

3.4.2 Applying the overhead absorption rate 57

3.4.3 Other absorption bases 57

3.4.4 Selecting the most appropriate absorption rate 58

3.5 Predetermined overhead absorption rates 59

3.5.1 Under- or over-absorption of overheads 59

3.5.2 The reasons for under- or over-absorption 61

3.5.3 The problems caused by under- or over-absorption of overheads 61

3.6 Illustrative example 61

3.6.1 Solution 62

3.7 Reciprocal servicing 64

3.7.1 Taking account of reciprocal servicing 64

3.7.2 The usefulness of reapportioned service centre costs 65

3.8 Activity based costing (ABC) 66

3.9 The use of cost information in pricing decisions 66

3.9.1 Marginal cost pricing 66

3.9.2 Full cost-plus pricing 67

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING C1

iv

CONTENTS

2006.1

3.9.3 Example: full-cost pricing to achieve a specified return on sales 67

3.9.4 Example: full-cost pricing to achieve a specified return on investment 68

3.9.5 Second example: full-cost pricing to achieve a specified return

on investment 68

3.10 Summary 69

Revision Questions 71

Solutions to Revision Questions 79

4 Cost–Volume–Profit Analysis 87

Learning Outcomes 87

4.1 Introduction 87

4.2 Breakeven or cost–volume–profit analysis 87

4.2.1 The concept of contribution 88

4.2.2 Calculating the breakeven point 88

4.3 The margin of safety 88

4.4 The contribution to sales (C/S) ratio 89

4.5 Drawing a basic breakeven chart 90

4.6 The contribution breakeven chart 92

4.7 The profit–volume chart 92

4.7.1 The advantage of the profit–volume chart 93

4.8 The limitations of breakeven (or CVP) analysis 94

4.9 The economist’s breakeven chart 95

4.10 Using CVP analysis to evaluate proposals 96

4.11 Limiting factor analysis 98

4.11.1 Decisions involving a single limiting factor 98

4.12 Summary 102

Revision Questions 103

Solutions to Revision Questions 111

5 Standard Costing and Variance Analysis 119

Learning Outcomes 119

5.1 Introduction 119

5.2 What is a standard cost? 120

5.3 Performance levels 121

5.3.1 A standard 121

5.3.2 Ideal standard 122

5.3.3 Attainable standard 122

5.3.4 Current standard 122

5.4 Setting standard costs 122

5.4.1 Standard material price 122

5.4.2 Standard material usage 123

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

v

CONTENTS

2006.1

5.4.3 Standard labour rate 123

5.4.4 Standard labour times 123

5.4.5 Variable production overhead costs 123

5.5 Updating standards 123

5.6 Standard costing in the modern business environment 124

5.7 What is variance analysis? 124

5.8 Variable cost variances 124

5.8.1 Direct material cost variances 125

5.8.2 The direct material price variance and inventory (stock) valuation 126

5.8.3 Direct labour cost variances 127

5.8.4 Variable overhead cost variances 128

5.9 Sales variances 129

5.9.1 Sales price variance 129

5.9.2 Sales volume contribution variance 130

5.10 Summary 130

Revision Questions 131

Solutions to Revision Questions 137

6 Further Standard Costing 145

Learning Outcomes 145

6.1 Introduction 145

6.2 Reconciling actual contribution with budgeted contribution 145

6.3 Idle time variances 148

6.4 Interpreting variances 149

6.4.1 The reasons for variances 149

6.4.2 The significance of variances 150

6.5 Standard hour 152

6.6 Labour incentive schemes 153

6.6.1 Bonus schemes 153

6.6.2 Piecework systems 154

6.6.3 Guaranteed minimum wage 155

6.6.4 Differential piece rate 155

6.6.5 Piecework hours 156

6.6.6 Group incentive schemes 156

6.7 Summary 157

Revision Questions 159

Solutions to Revision Questions 163

7 Integrated Accounting Systems 171

Learning Outcomes 171

7.1 Introduction 171

7.2 An integrated accounting system 171

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING C1

vi

CONTENTS

2006.1

7.3 Accounting for the cost of labour 172

7.3.1 Deductions from employees’ wages 172

7.3.2 Overtime premium 172

7.3.3 Bonus earnings 173

7.3.4 Idle time 173

7.3.5 Example: analysis of labour costs 173

7.4 Integrated accounts in operation 174

7.4.1 Example: the main accounting entries in an integrated system 174

7.4.2 Accounting for under- or over-absorbed overheads 176

7.4.3 Example: integrated accounts 177

7.5 Standard cost bookkeeping 184

7.6 Recording variances in the ledger accounts 184

7.6.1 General rules for recording variances 184

7.6.2 The income statement (profit and loss account) 185

7.7 Standard cost bookkeeping: an example 185

7.8 Valuing material inventory (stock) at actual cost 192

7.8.1 Which inventory (stock) valuation method is generally preferred? 193

7.9 Summary 193

Revision Questions 195

Solutions to Revision Questions 203

8 Specific Order Costing 209

Learning Outcomes 209

8.1 Introduction 209

8.2 Job costing 209

8.2.1 Job cost sheets and databases 210

8.2.2 Collecting the direct costs of each job 210

8.2.3 Attributing overhead costs to jobs 212

8.2.4 A worked example 213

8.2.5 Preparing ledger accounts for job costing systems 214

8.3 Batch costing 218

8.3.1 Example: batch costing 218

8.4 Contract costing 220

8.4.1 Architect’s certificates and progress payments 220

8.4.2 Retention money 220

8.4.3 Contract accounts 220

8.4.4 Accounting for contract materials 221

8.4.5 Accounting for plant used on the contract 221

8.4.6 Cost classification in contract costing 221

8.4.7 Calculating contract profit and preparing balance sheet entries 222

8.4.8 Contract costing: a worked example 222

8.4.9 Accounting for a loss-making contract 226

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

vii

CONTENTS

2006.1

8.4.10 Contract costing: a second example 227

8.4.11 Contract costing: a final example 230

8.5 Summary 232

Revision Questions 233

Solutions to Revision Questions 239

9 Process Costing 247

Learning Outcomes 247

9.1 Introduction 247

9.2 Process accounts 247

9.3 Losses in process 249

9.4 Abnormal losses and gains 250

9.5 Closing work in progress: the concept of equivalent units 252

9.6 Previous process costs 256

9.7 Opening work in progress 256

9.8 Process costing: a further example 258

9.9 Contrasting process costing and specific order costing 260

9.10 Summary 260

Revision Questions 263

Solutions to Revision Questions 271

10 Presenting Management Information 281

Learning Outcomes 281

10.1 Introduction 281

10.2 Subjective and objective classification 281

10.2.1 Responsibility centres 282

10.2.2 Reporting management accounting information 282

10.3 Coding of costs 282

10.3.1 Composite codes 282

10.3.2 The advantages of a coding system 283

10.3.3 The requirements for an efficient coding system 284

10.4 Preparing financial statements that inform management 284

10.4.1 Value added 284

10.4.2 Contribution 285

10.4.3 Gross margin 286

10.5 Managerial reports in a service organisation 287

10.5.1 Establishing a suitable cost unit 287

10.5.2 Establishing the cost per unit 287

10.5.3 The instantaneous and perishable nature of services 287

10.5.4 Managerial reporting in a charity: example 291

10.6 Summary 292

Revision Questions 293

Solutions to Revision Questions 297

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING C1

viii

CONTENTS

2006.1

11 Financial Planning and Control 303

Learning Outcomes 303

11.1 Introduction 303

11.2 The purposes of budgeting 303

11.2.1 Budgetary planning and control 304

11.2.2 What is a budget? 304

11.2.3 The budget period 304

11.2.4 Strategic planning, budgetary planning and operational

planning 305

11.3 The preparation of budgets 305

11.3.1 Coordination: the budget committee 306

11.3.2 Participative budgeting 306

11.3.3 Information: the budget manual 306

11.3.4 Early identification of the principal budget factor 307

11.3.5 The interrelationship of budgets 307

11.3.6 Using computers in budget preparation 308

11.3.7 The master budget 308

11.4 Preparation of functional budgets 309

11.4.1 Budget interrelationships 311

11.5 The cash budget 311

11.5.1 Preparing cash budgets 312

11.5.2 Interpretation of the cash budget 313

11.6 A complete exercise 315

11.7 Rolling budgets 322

11.8 Budgets for non-operating functions 322

11.8.1 Incremental budgeting 323

11.8.2 Zero-based budgeting 323

11.9 Budgetary control information 323

11.9.1 Budget centres 324

11.9.2 Budgetary control reports 324

11.10 Fixed and flexible budgets 325

11.10.1 Flexible budgets: an example 325

11.10.2 Preparing a flexible budget 325

11.10.3 The total budget variance 327

11.10.4 Using flexible budgets for planning 328

11.10.5 Flexible budgets: another example 328

11.10.6 Extrapolating outside the relevant range 331

11.10.7 Example: producing a flexible budget control statement 331

11.11 Using budgets as a basis for rewards 333

11.11.1 Example 333

11.11.2 Factors to consider in the design of budget reward schemes 333

11.12 Summary 334

Revision Questions 335

Solutions to Revision Questions 343

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

ix

CONTENTS

2006.1

Preparing for the Assessment 349

Format of the assessment 349

Revision technique 349

How to tackle the assessment 353

Revision Questions 355

Solutions to Revision Questions 387

Mock Assessment 1 421

Mock Assessment 2 451

Index 479

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING C1

x

2006.1

CONTENTS

The CIMA

Learning System

How to use your CIMA Learning System

This Fundamentals of Management Accounting Learning System has been devised as a resource for

students attempting to pass their CIMA computer-based assessment, and provides:

a detailed explanation of all syllabus areas;

extensive ‘practical’ materials;

generous question practice, together with full solutions;

a computer-based assessment preparation section, complete with computer-based

assessment standard questions and solutions.

This Learning System has been designed with the needs of home-study and distance-

learning candidates in mind. Such students require very full coverage of the syllabus topics,

and also the facility to undertake extensive question practice. However, the Learning

System is also ideal for fully taught courses.

The main body of the text is divided into a number of chapters, each of which is

organised on the following pattern:

Detailed learning outcomes expected after your studies of the chapter are complete. You

should assimilate these before beginning detailed work on the chapter, so that you can

appreciate where your studies are leading.

Step-by-step topic coverage. This is the heart of each chapter, containing detailed explanatory

text supported where appropriate by worked examples and exercises. You should work

carefully through this section, ensuring that you understand the material being explained

and can tackle the examples and exercises successfully. Remember that in many cases

knowledge is cumulative: if you fail to digest earlier material thoroughly, you may

struggle to understand later chapters.

Question practice. The test of how well you have learned the material is your ability to

tackle assessment-standard questions. Make a serious attempt at producing your own

answers, but at this stage do not be too concerned about attempting the questions in

computer-based assessment conditions. In particular, it is more important to absorb the

material thoroughly than to observe the time limits that would apply in the actual

computer-based assessment.

Solutions. Avoid the temptation merely to ‘audit’ the solutions provided. It is an illusion

to think that this provides the same benefits as you would gain from a serious attempt of

xi

2006.1

your own. However, if you are struggling to get started on a question you should read

the introductory guidance provided at the beginning of the solution, where provided,

and then make your own attempt before referring back to the full solution.

Having worked through the chapters you are ready to begin your final preparations for

the computer-based assessment. The final section of this CIMA Learning System provides

you with the guidance you need. It includes the following features:

A brief guide to revision technique.

A note on the format of the computer-based assessment. You should know what to

expect when you tackle the real computer-based assessment, and in particular the

number of questions that you will be required to attempt.

Guidance on how to tackle the computer-based assessment itself.

A table mapping revision questions to the syllabus learning outcomes allowing you to

quickly identify questions by subject area.

Revision questions. These are of computer-based assessment standard and should be

tackled in computer-based assessment conditions, especially as regards the time allocation.

Solutions to the revision questions.

Two mock computer-based assessments. You should plan to attempt these just before

the date of the real computer-based assessment. By this stage your revision should be

complete and you should be able to attempt the mock computer-based assessment within

the time constraints of the real computer-based assessment.

If you work conscientiously through this CIMA Learning System according to the

guidelines above you will be giving yourself an excellent chance of success in your

computer-based assessment. Good luck with your studies!

Guide to the Icons used within this text

Key term or definition

Assessment tip or topic likely to appear in the computer-based assessment

Exercise

Question

Solution

Comment or Note

Formula to learn

Study technique

Passing exams is partly a matter of intellectual ability, but however accomplished you are

in that respect you can improve your chances significantly by the use of appropriate study

and revision techniques. In this section we briefly outline some tips for effective study

THE CIMA LEARNING SYSTEM

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING C1

xii

2006.1

during the earlier stages of your approach to the computer-based assessment. Later in the

text we mention some techniques that you will find useful at the revision stage.

Planning

To begin with, formal planning is essential to get the best return from the time you spend

studying. Estimate how much time in total you are going to need for each paper you are

studying for the Certificate in Business Accounting. Remember that you need to allow

time for revision as well as for initial study of the material. The amount of notional study

time for any paper is the minimum estimated time that students will need to achieve the

specified learning outcomes in the syllabus. This time includes all appropriate learning

activities, for example, face-to-face tuition, private study, directed home study, learning in

the workplace, revision time, etc. You may find it helpful to read Better Exam Results: a

Guide for Business and Accounting Students by S.A. Malone, Elsevier, ISBN: 075066357X. This

book will provide you with proven study techniques. Chapter by chapter it covers the

building blocks of successful learning and examination techniques.

The notional study time for the Certificate in Business Accounting Paper

Fundamentals of Management Accounting is 130 hours. Note that the standard amount

of notional learning hours attributed to one full-time academic year of approximately

30 weeks is 1,200 hours.

By way of example, the notional study time might be made up as follows:

Hours

Face-to-face study: up to 40

Personal study: up to 65

‘Other’ study – e.g. learning in the workplace, revision, etc.: up to

25

130

Note that all study and learning-time recommendations should be used only as a

guideline and are intended as minimum amounts. The amount of time recommended for

face-to-face tuition, personal study and/or additional learning will vary according to the

type of course undertaken, prior learning of the student, and the pace at which different

students learn.

Now split your total time requirement over the weeks between now and the assessment.

This will give you an idea of how much time you need to devote to study each week.

Remember to allow for holidays or other periods during which you will not be able to

study (e.g. because of seasonal workloads).

With your study material before you, decide which chapters you are going to study in

each week, and which weeks you will devote to revision and final question practice.

Prepare a written schedule summarising the above – and stick to it!

It is essential to know your syllabus. As your course progresses you will become more

familiar with how long it takes to cover topics in sufficient depth. Your timetable may

need to be adapted to allocate enough time for the whole syllabus.

THE CIMA LEARNING SYSTEM

2006.1

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

xiii

Tips for effective studying

1. Aim to find a quiet and undisturbed location for your study, and plan as far as possible

to use the same period of time each day. Getting into a routine helps to avoid wasting

time. Make sure that you have all the materials you need before you begin so as to

minimise interruptions.

2. Store all your materials in one place, so that you do not waste time searching for items

every time you want to begin studying. If you have to pack everything away after each

study period, keep your study materials in a box, or even a suitcase, which will not be

disturbed until the next time.

3. Limit distractions. To make the most effective use of your study periods you should be

able to apply total concentration, so turn off all entertainment equipment, set your

phones to message mode, and put up your ‘do not disturb’ sign.

4. Your timetable will tell you which topic to study. However, before diving in and

becoming engrossed in the finer points, make sure you have an overall picture of all the

areas that need to be covered by the end of that session. After an hour, allow yourself a

short break and move away from your Learning System. With experience, you will learn

to assess the pace you need to work at.

5. Work carefully through a chapter, making notes as you go. When you have covered a

suitable amount of material, vary the pattern by attempting a practice question. When

you have finished your attempt, make notes of any mistakes you made.

6. Make notes as you study, and discover the techniques that work best for you. Your

notes may be in the form of lists, bullet points, diagrams, summaries, ‘mind maps’, or

the written word, but remember that you will need to refer back to them at a later date,

so they must be intelligible. If you are on a taught course, make sure you highlight any

issues you would like to follow up with your lecturer.

7. Organise your paperwork. Make sure that all your notes, calculations etc. can be

effectively filed and easily retrieved later.

Computer-based assessment

CIMA uses computer-based assessment (CBA) for all subjects for the Certificate in

Business Accounting. The website says:

Objective questions are used. The most common type is ‘multiple choice’, where you

have to choose the correct answer from a list of possible answers, but there are a variety of

other objective question types that can be used within the system. These include true/false

questions, matching pairs of text and graphic, sequencing and ranking , labelling diagrams

and single and multiple numeric entry.

Candidates answer the questions by either pointing and clicking the mouse, moving

objects around the screen, typing numbers, or a combination of these responses. Try the

online demo at www.cimaglobal.com to see how the technology works.

The CBA system can ensure that a wide range of the syllabus is assessed, as a pre-

determined number of questions from each syllabus area (dependent upon the syllabus

weighting for that particular area) are selected in each assessment.

In every chapter of this Learning System we have introduced these types of questions

but obviously we have to label answers A, B, C etc. rather than using click boxes. For

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING C1

xiv

THE CIMA LEARNING SYSTEM

2006.1

convenience we have retained quite a lot of questions where an initial scenario leads to a

number of sub-questions. There will be questions of this type in the CBA but they will

rarely have more than three sub-questions. In all such cases examiners will ensure that the

answer to one part does not hinge upon a prior answer.

For further CBA practice, CIMA E-Success CD’s will be available from www.

cimapublishing.com from September 2006.

Fundamentals of Management Accounting and

Computer-based Assessment

The assessment for Fundamentals of Management Accounting is a two-hour computer-

based assessment comprising 50 compulsory questions, with one or more parts. Single

part questions are generally worth 1–2 marks each, but two and three part questions may

be worth 4 or 6 marks. There will be no choice and all questions should be attempted if

time permits. CIMA are continuously developing the question styles within the CBA

system and you are advised to try the on-line website demo at www.cimaglobal.com, to

both gain familiarity with assessment software and examine the latest style of questions

being used.

Syllabus (2006) – Paper C01 Fundamentals of

Management Accounting

Syllabus Outline

The syllabus comprises:

Topic and Study Weighting

A Cost Determination 25%

B Cost Behaviour and Break-even Analysis 10%

C Standard Costing 15%

D Cost and Accounting Systems 30%

E Financial Planning and Control 20%

Learning Aims

This syllabus aims to test student’s ability to:

explain and use concepts and processes to determine product and service costs;

explain direct, marginal and absorption costs and their use in pricing;

apply CVP analysis and interpret the results;

apply a range of costing and accounting systems;

explain the role of budgets and standard costing within organisations;

prepare and interpret budgets, standard costs and variance statements.

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

xv

THE CIMA LEARNING SYSTEM

2006.1

Assessment Strategy

There will be a computer-based assessment of 2 hours duration, comprising 50 compulsory

questions, each with one or more parts.

A variety of objective test question types and styles will be used within the assessment.

Learning Outcomes and Indicative Syllabus Content

A Cost Determination – 25%

Learning Outcomes

On completion of their studies students should be able to:

(i) explain why organisations need to know how much things cost and why they need

costing systems;

(ii) explain the idea of a ‘cost object’;

(iii) explain the concept of a direct cost and an indirect cost;

(iv) explain why the concept of ‘cost’ is not as simple as it first seems;

(v) distinguish between the historic cost of an asset and the economic value of an asset

to an organisation;

(vi) apply first-in-first-out (FIFO), last-in-first-out (LIFO) and average cost (AVCO)

methods of accounting for stock, calculating stock values and related gross profit;

(vii) explain why first-in-first-out (FIFO) is essentially a historic cost method, while last-

in-first-out (LIFO) approximates economic cost;

(viii) prepare cost statements for allocation and apportionment of overheads, including

reciprocal service departments;

(ix) calculate direct, variable and full costs of products, services and activities using

overhead absorption rates to trace indirect costs to cost units;

(x) explain the use of cost information in pricing decisions, including the calculation of

‘full cost’ based prices to generate a specified return on sales or investment.

Indicative Syllabus Content:

Classification of costs and the treatment of direct costs (specifically attributable to a cost

object) and indirect costs (not specifically attributable) in ascertaining the cost of a ‘cost

object’ (e.g. a product, service, activity, customer).

Cost measurement: historic versus economic costs.

Accounting for the value of materials on FIFO, LIFO and AVCO bases.

Overhead costs: allocation, apportionment, re-apportionment and absorption of overhead

costs. Note: The repeated distribution method only will be used for reciprocal service

department costs.

Full-cost pricing to achieve specified return on sales or return on investment.

THE CIMA LEARNING SYSTEM

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING C1

xvi

2006.1

B Cost Behaviour and Break-even Analysis – 10%

Learning Outcomes

On completion of their studies students should be able to:

(i) explain how costs behave as product, service or activity levels increase or decrease;

(ii) distinguish between fixed, variable and semi-variable costs;

(iii) explain step costs and the importance of time-scales in their treatment as either

variable or fixed;

(iv) estimate the fixed and variable elements of cost using the high-low method and ‘line

of best fit’ method;

(v) explain the contribution concept and its use in CVP analysis;

(vi) calculate and interpret the break-even point, profit target, margin of safety and

profit/volume ratio for a single product or service;

(vii) prepare break-even charts and profit/volume graphs for a singe product or service;

(viii) calculate the profit maximising sales mix for a multi-product company that has

limited demand for each product and one other constraint or limiting factor.

Indicative Syllabus Content:

Fixed, variable and semi-variable costs.

Step costs and the importance of time-scale in analysing cost behaviour.

High-low and graphical methods to establish fixed and variable components of a semi-

variable cost. Note: regression analysis is not required.

Contribution concept.

Break-even charts, profit volume graphs, break-even point, profit target, margin of

safety, contribution/sales ratio.

Limiting factor analysis.

C Standard Costing – 15%

Learning Outcomes

On completion of their studies students should be able to:

(i) explain the difference between ascertaining costs after the event and planning by

establishing ‘standard costs’ in advance;

(ii) explain why planned ‘standard costs’, prices and volumes are useful in setting a

benchmark for comparison and so allowing managers’ attention to be directed to

areas of the business that are performing below or above expectation;

(iii) prepare ‘standard costs’ for the material, labour and variable overhead elements of

cost in a product or service;

(iv) calculate variances for materials, labour, variable overhead, sales prices and sales

volumes;

(v) prepare a statement that reconciles budgeted contribution margin with actual

contribution margin;

THE CIMA LEARNING SYSTEM

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

xvii

2006.1

(vi) interpret statements of variances for variable costs, sales prices and sales volumes

including possible inter-relations between cost variances, sales price and volume

variances, and cost and sales variances;

(vii) describe the possible use of standard labour costs in designing incentive schemes for

factory and office workers.

Indicative Syllabus Content:

Principles of standard costing.

Preparation of standards for the variable elements of cost: material, labour, variable

overhead.

Variances: materials – total, price and usage; labour – total, rate and efficiency; variable

overhead – total, expenditure and efficiency; sales – price, contribution margin volume.

Note: Candidates will be expected to calculate the sales contribution margin volume

variance.

Reconciliation of budget and actual contribution margin.

Piecework and the principles of incentive schemes based on standard hours ‘produced’

versus actual hours taken. Note: the details of a specific incentive scheme will be

provided.

D Costing and Accounting Systems – 30%

Learning Outcomes

On completion of their studies students should be able to:

(i) explain the principles of production accounts and the integration of the cost

accounts with the financial accounting system;

(ii) prepare a set of integrated accounts, given opening balances and appropriate

transactional information, and show standard cost variances;

(iii) compare and contrast job, batch, contract and process costing;

(iv) prepare ledger accounts for job, batch and process costing systems;

(v) prepare ledger accounts for contract costs;

(vi) explain the difference between subjective and objective classifications of expenditure

and the importance of tracing costs both to products/services and to responsibility

centres;

(vii) design coding systems that facilitate both subjective and objective classification of

costs;

(viii) prepare financial statements that provide relevant management information;

(ix) explain why gross revenue, net revenue, value-added, contribution margin, gross

margin, marketing expense, general and administration expense, etc. might be

highlighted in management reporting;

(x) compare and contrast managerial reports in a range of organisations including

commercial enterprises, charities and government undertakings.

THE CIMA LEARNING SYSTEM

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING C1

xviii

2006.1

Indicative Syllabus Content:

Integrated ledgers including over and under absorption of production overhead.

The treatment of variances as period entries in integrated ledger systems.

Job, batch, process and contract costing. Note: Only the average cost method will be

examined for process costing but candidates must be able to deal with differing degrees

of completion of opening and closing stocks, normal and abnormal gains and losses, and

the treatment of scrap value.

Subjective, objective and responsibility classifications and design of coding systems to

facilitate these analyses.

Cost accounting statements for management information in production and service

companies and not-for-profit organisations.

E Financial Planning and Control – 20%

Learning Outcomes

On completion of their studies students should be able to:

(i) explain why organisations set out financial plans in the form of budgets, typically for

a financial year;

(ii) prepare functional budgets for material usage and purchase, labour and overheads,

including budgets for capital expenditure and depreciation;

(iii) prepare a ‘master budget’; profit and loss account, balance sheet and cash flow

statement, based on the functional budgets;

(iv) interpret budget statements and advise managers on financing projected cash

shortfalls and/or investing projected cash surpluses;

(v) prepare a flexible budget based on the actual levels of sales and production and

calculate appropriate variances;

(vi) compare and contrast fixed and flexible budgets;

(vii) explain the use of budgets in designing reward strategies for managers.

Indicative Syllabus Content:

Budgeting for planning and control.

Budget preparation, interpretation and use of the ‘master’ budget.

Reporting of actual against budget.

Fixed and flexible budgeting.

Budget variances.

Interpretation and use of budget statements and budget variances.

THE CIMA LEARNING SYSTEM

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

xix

2006.1

1

Basic Aspects of Cost

Accounting

Basic Aspects of

Cost Accounting

1.1 Introduction

In this chapter we will look at some of the fundamental concepts of the framework of cost

accounting. You will learn some basic principles which underpin all of the material in your

Fundamentals of Management Accounting syllabus.

1.2 Why organisations need costing systems

An organisation’s costing system is the foundation of the internal financial information

system for managers. It provides the information that management needs to plan and

control the organisation’s activities and to make decisions about the future. Examples of

1

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

"

explain why organisations need to know how much products, processes and services

cost and why they need costing systems;

"

explain the idea of a ‘cost object’;

"

explain the concept of a direct cost and an indirect cost;

"

explain why the concept of cost needs to be qualified as direct, full, marginal, etc. in

order to be meaningful;

"

explain how costs behave as product, service or activity levels increase or decrease;

"

distinguish between fixed, variable and semi-variable costs;

"

explain step costs and the importance of time-scales in their treatment as either

variable or fixed;

"

compute the fixed and variable elements of a semi-variable cost using the high–low

method and ’line of best fit’ method.

3 2006.1

the type of information provided by a costing system and the uses to which it might be put

include the following.

Actual unit costs for the latest period; could be used for cost control by comparing

with a predetermined unit standard cost, which would also be provided by the costing

system. Could also be used as the basis for planning future unit costs and for

decisions about pricing and production levels. For example, a manager cannot make a

decision about the price to be charged to a customer without information which tells

the manager how much it costs to produce and distribute the product to the

customer.

Actual costs of operating a department for the latest period; could be used for cost control

by comparing with a predetermined budget for the department. Could also be used as the

basis for planning future budgeted costs and for decisions such as outsourcing. For

example, a manager might be considering the closure of the packing department and

instead outsourcing the packing operations to another organisation. In order to make this

decision the manager needs to know, among other things, the actual cost of operating the

packing department.

The forecast costs to be incurred at different levels of activity. Could be used for

planning, for decision making and as a part of cost control by comparing the actual costs

with the forecasts. For example, a manager cannot make a well-informed decision about

the appropriate production level for the forthcoming period unless information is

available about the costs that will be incurred at various possible output levels.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of the information that is provided by a costing

system. However it should serve to demonstrate that organisations need costing systems

that will provide the basic information that management requires for planning, control

and decision-making.

1.3 What is meant by ‘cost’?

The word ‘cost’ can be used in two contexts. It can be used as a noun, for example, when

we are referring to the cost of an item. Alternatively, it can be used as a verb, for example,

we can say that we are attempting to cost an activity, when we are undertaking the tasks

necessary to determine the costs of carrying out the activity.

The word ‘cost’ can rarely stand alone and should always be qualified as to its nature and

limitations. You will be seeing throughout this text that there are many different types of

cost and that each has its usefulness and limitations in different circumstances.

1.4 Cost units

The CIMA Terminology defines a cost unit as ‘a unit of product or service in relation

to which costs are ascertained’.

This means that a cost unit can be anything for which it is possible to ascertain the

cost. The cost unit selected in each situation will depend on a number of factors,

including the purpose of the cost ascertainment exercise and the amount of information

available.

STUDY MATERIAL C1

4

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

Cost units can be developed for all kinds of organisations, whether manufacturing,

commercial or public service based. Some examples from the CIMA Terminology are as

follows:

Industry sector Cost unit

Brick-making 1000 bricks

Electricity Kilowatt-hour (KwH)

Professional services Chargeable hour

Education Enrolled student

Activity Cost unit

Credit control Account maintained

Selling Customer call

Exercise 1.1

Can you think of at least one other cost unit which could be used for each of these

industries and activities? For example, in controlling the costs of the selling activity we

might monitor the cost per order taken.

The above list is not exhaustive. A cost unit can be anything which is measurable

and useful for cost control purposes. For example, with brick-making, 1,000 bricks is

suggested as a cost unit. It would be possible to determine the cost per brick but perhaps

in this case a larger measure is considered more suitable and useful for control purposes.

Notice that this list of cost units contains both tangible and intangible items. Tangible

items are those which can be seen and touched, for example the 1,000 bricks. Intangible

items cannot be seen and touched and do not have physical substance but they can be

measured, for example a chargeable hour of accounting service.

1.4.1 Composite cost units

The cost units for services are usually intangible and they are often composite cost units,

that is, they are often made up of two parts. For example, if we were attempting to

monitor and control the costs of a delivery service we might measure the cost per tonne

delivered. However, ‘tonne delivered’ would not be a particularly useful cost unit because

it would not be valid to compare the cost per tonne delivered from London to Edinburgh

with the cost per tonne delivered from London to Brighton. The former journey is

much longer and it will almost certainly cost more to deliver a tonne over the longer

distance.

Composite cost units assist in overcoming this problem. We could perhaps use a ‘tonne-

mile’ instead. This means that we would record and monitor the cost of carrying one tonne

for one mile. The cost per tonne-mile would be a comparable measure whatever the length

of journey and this is therefore a valid and useful cost unit for control purposes.

Other examples of composite cost units might be as follows:

Business Cost unit

Hotel Bed night

Bus company Passenger mile

Hospital In-patient day

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

5

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

Exercise 1.2

Can you think of some other examples of composite cost units that could be used in these

organisations and in other types of organisation?

1.5 Cost centres

A cost centre is a production or service location, a function, an activity or an item of

equipment for which costs are accumulated.

A cost centre is used as a ‘collecting place’ for costs. The cost of operating the cost

centre is determined for the period, and then this total cost is related to the cost units

which have passed through the cost centre.

For instance, an example of a production cost centre could be the machine shop in

a factory. The production overhead cost for the machine shop might be £100,000 for

the period. If 1,000 cost units have passed through this cost centre we might say

that the production overhead cost relating to the machine shop was £100 for

each unit.

A cost centre could also be a service location, a function, an activity or an item of

equipment. Examples of these might be as follows but you should try to think of some

others:

Type of cost centre Examples

Service location Stores, canteen

Function Sales representative

Activity Quality control

Item of equipment Packing machine

If you are finding it difficult to see how a sales representative could be used as a cost

centre, then work carefully through the following points.

1. What are the costs which might be incurred in ‘operating’ a sales representative for one

period?

Examples might be the representative’s salary cost, the cost of running a company

car, the cost of any samples given away by the representative and so on. Say these

amount to £40,000.

2. Once we have determined this cost, the next thing we need to know is the number of

cost units that can be related to the sales representative.

The cost unit selected might be £100 of sales achieved. If the representative has

achieved £400,000 of sales, then we could say that the representative’s costs

amounted to £10 per £100 of sales. The representative has thus been used as a cost

centre or collecting place for the costs, which have then been related to the cost

units.

1.6 Cost objects

A cost object is anything for which costs can be ascertained. The CIMA Terminology contains

the following description: ‘For example a product, service, centre, activity, customer or

distribution channel in relation to which costs are ascertained.’

STUDY MATERIAL C1

6

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

All of the cost units and cost centres we have described earlier in this chapter are

therefore types of cost object. We have seen the quality control activity being treated as a

cost centre, and thus as a cost object.

Exercise 1.3

Notice that CIMA’s examples of cost objects include a customer. Can you think of costs

that might be attributed to a supermarket which is a customer and is treated as a cost

object by a supplier of processed foods?

Solution

Costs that you might have thought of include the following.

The cost of the food products supplied to the customer.

The cost of delivering the food products to the customer.

The cost of funding the credit taken by the customer.

The cost of holding any inventories for the supermarket.

The salary cost of the account manager responsible for the supermarket’s account.

The cost of dealing with the customer’s queries.

1.7 Classification of costs

Costs can be classified in many different ways. It is necessary to be able to classify all

costs, that is, to be able to arrange them into logical groups, in order to devise an

efficient system to collect and analyse the costs. The classifications selected and the level

of detail used in the classification groupings will depend on the purpose of the

classification exercise.

The CIMA Terminology defines classification as the ‘arrangement of items in logical

groups by nature, purpose or responsibility’.

1.7.1 Classification of costs according to their nature

This means grouping costs according to whether they are materials, labour or expense

cost.

Material costs include the cost of obtaining the materials and receiving them within the

organisation. The cost of having the materials brought to the organisation is known as

carriage inwards.

Labour costs are those costs incurred in the form of wages and salaries, together with

related employment costs. In the United Kingdom, there is an additional cost borne by the

employer in respect of employees which is paid to the government: this is called National

Insurance. These costs are documented internally, the amount of the wages and salary

costs being determined by reference to agreed rates of pay and attendance time and output

measures, depending on the method of remuneration being used.

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

7

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

Expense costs are external costs such as rent, business rates, electricity, gas, postages,

telephones and similar items which will be documented by invoices from suppliers.

Within each of these classifications there is a number of subdivisions; for example,

within the materials classification the subdivisions might include the following:

(a) Raw materials, that is, the basic raw material used in manufacture.

(b) Components, that is, complete parts that are used in the manufacturing process.

(c) Consumables, that is, cleaning materials, etc.

(d) Maintenance materials, that is, spare parts for machines, lubricating oils, etc.

This list of subdivisions is not exhaustive, and there may even be further subdivisions

of each of these groups. For example, the raw materials may be further divided according

to the type of raw material, for example, steel, plastic, glass, etc.

Exercise 1.4

Can you think of some possible subdivisions for the costs that are classified as labour costs

and as expense costs?

1.7.2 Classification of costs according to their purpose:

direct costs and indirect costs

When costs are classified having regard to their purpose, they are grouped according to the

reason for which they have been incurred. The broadest classification of this type is to

divide costs into direct costs and indirect costs.

A direct cost is one that can be clearly identified with the cost object we are trying to

cost. For example, suppose that a furniture maker is determining the cost of a wooden

table. The manufacture of the table has involved the use of timber, screws and metal

drawer handles. These items are classified as direct materials. The wages paid to the machine

operator, assembler and finisher in actually making the table would be classified as direct

labour costs. The designer of the table may be entitled to a royalty payment for each table

made, and this would be classified as a direct expense.

Other costs incurred would be classified as indirect costs. They cannot be directly

attributed to a particular cost unit, although it is clear that they have been incurred in the

production of the table. Examples of indirect production costs are as follows:

Cost incurred Cost classification

Lubricating oils and cleaning

materials

Indirect material

Salaries of supervisory labour Indirect labour

Factory rent and power Indirect expense

It is important for you to realise that a particular cost may sometimes be a direct cost

and sometimes an indirect cost. It depends on the cost object we are trying to cost.

For example, the salary of the machining department supervisor is a direct cost of that

department because it can be specifically identified with the department. However, it is an

indirect cost of each of the cost units processed in the machining department because it

cannot be specifically identified with any particular cost unit.

STUDY MATERIAL C1

8

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

Exercise 1.5

State whether each of the following costs would be a direct cost or an indirect cost of the

quality control activity which is undertaken in a company’s factory.

The salary of the quality control supervisor.

The rent of the factory.

The depreciation of the quality testing machine.

The cost of the samples destroyed during testing.

The insurance of the factory.

Solution

The salary of the quality control supervisor is a direct cost of the quality control activity

because it can be specifically attributed to this cost object.

The rent of the factory is an indirect cost of the quality control activity because it cannot

be specifically attributed to this cost object but must also be attributed to other activities

undertaken in the factory.

The depreciation of the quality testing machine is a direct cost of the quality control

activity because it can be specifically attributed to this cost object.

The cost of the samples destroyed during testing is a direct cost of the quality control

activity because it can be specifically attributed to this cost object.

The insurance of the factory is an indirect cost of the quality control activity because it

cannot be specifically attributed to this cost object but must also be attributed to other

activities undertaken in the factory.

In a later chapter we will return to consider the classification of costs by

responsibility.

1.8 Elements of cost

The elements of cost are the constituent parts of cost which make up the total cost of a

cost object.

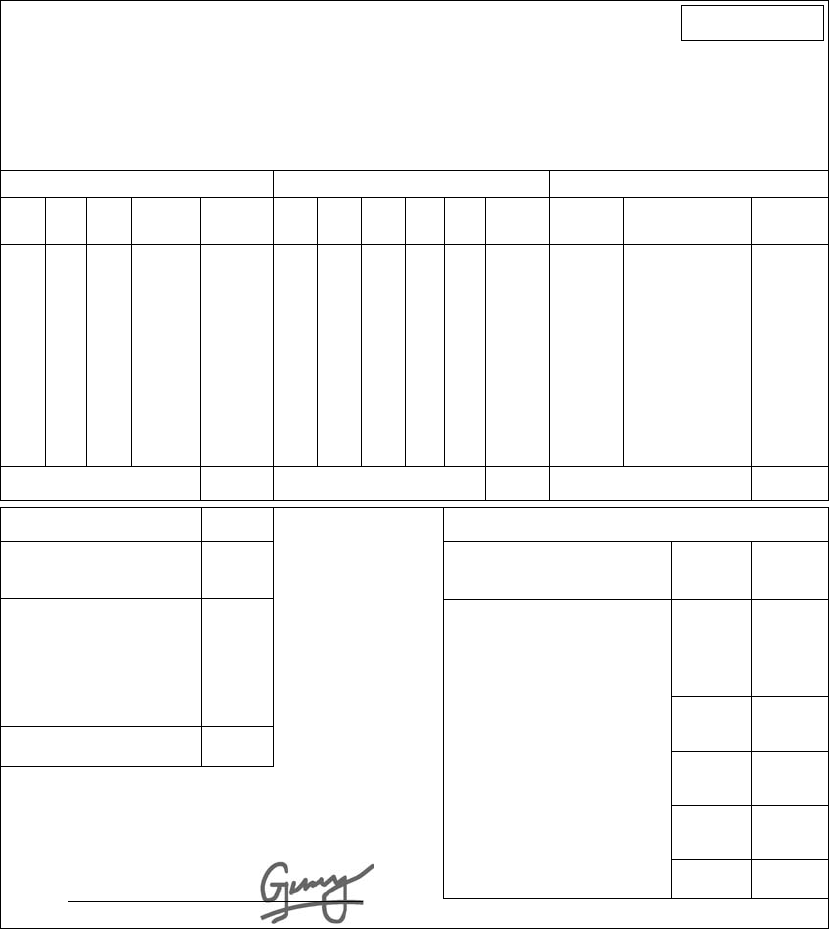

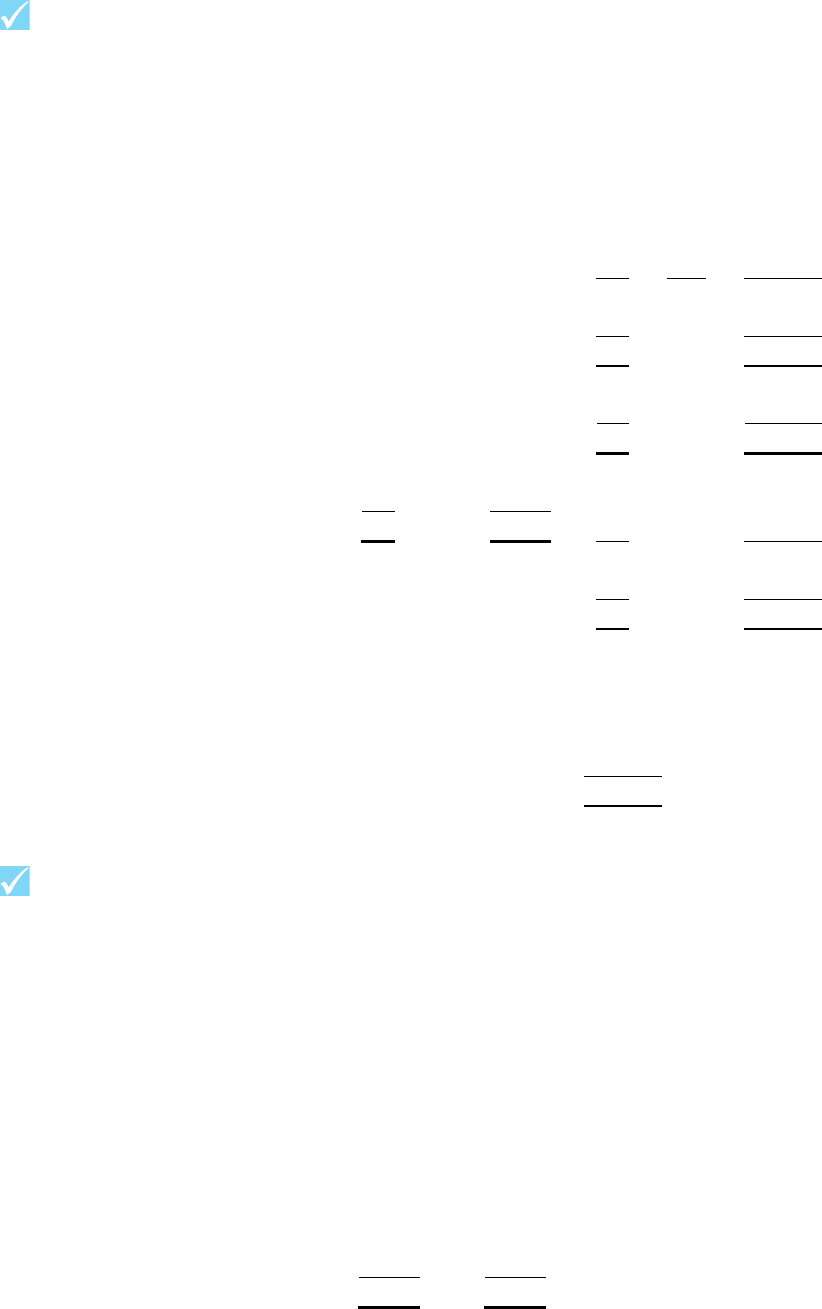

In Figure 1.1, the outline cost statement for a single cost unit shows you how the total

or full cost for a unit might be built up. Notice in particular that a number of subtotals can

be highlighted before the total cost figure is determined.

The usefulness of each of these subtotals depends on the management action that is to

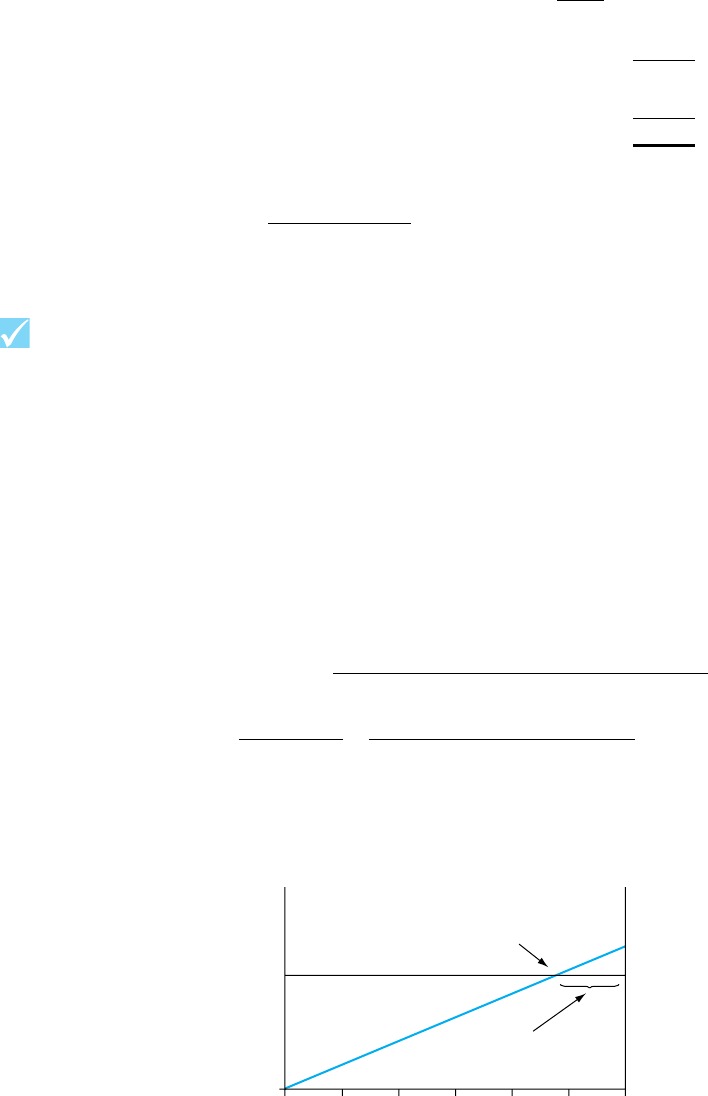

be taken based on each of the totals.

Suppose that the cost analysis in Figure 1.1 has been provided by the management

accountant to help us to decide on the selling price to be charged for a luxury wall-

mounted hairdryer: the type that is fixed to the wall for customers’ use in hotel bedrooms.

You have been negotiating with the procurement manager of a chain of hotels in an

attempt to secure a contract to supply a batch of hairdryers. It is very important that you

should win this contract because it is likely that, once this first order has been fulfilled

successfully, the hotel chain will place future orders for hairdryers and for your company’s

other products, when refurbishing its other hotels. Furthermore, other hotel chains may

become interested in your company’s products once they discover that this major chain is

one of your customers.

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

9

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

Unfortunately, the hotel’s procurement manager is working within the constraints of a

very strict budget and has made it clear that the highest price that the hotel is prepared to

pay is £25 per hairdryer. The analysis in Figure 1.1 shows that your company’s normal

selling price is considerably higher than this.

The company cannot afford to sell its hairdryers for £25 each if they cost £40 to

produce and sell. Or can it?

Let us look at the sort of costs that might be incurred in manufacturing and selling a

hairdryer, and how each cost would be classified in terms of the above analysis of the

elements of cost.

Direct materials. This is the material that actually becomes part of the finished hairdryer. It

would include the plastic for the case and the packaging materials. If we make another

batch of hairdryers then we will need to purchase another batch of these and other

direct materials.

Direct labour. This is the labour cost incurred directly as a result of making one hairdryer.

If we make another batch of hairdryers then we will need to pay more direct labour cost.

Direct expenses. These are expenses caused directly as a result of making one more batch

of hairdryers. For example, the company might be required to pay the designer of the

hairdryer a royalty of £2 for each hairdryer produced.

The three direct costs are summed to derive the prime cost or total direct cost of

a hairdryer. This is one measure of cost but there are still other costs to be added:

production overheads and other overheads.

Production overheads are basically the same three costs as for direct cost, but they are

identified as indirect costs because they cannot be specifically identified with any particular

hairdryer or batch of hairdryers. Indirect costs must be shared out over all the cost objects

using a fair and equitable basis.

In a later chapter you will see how indirect costs can be shared over all the

production for the period.

Figure 1.1 The build-up of cost

STUDY MATERIAL C1

10

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

Indirect materials are those production materials that do not actually become part of the

finished product. This might include the cleaning materials and lubricating oils for the

machinery. The machines must be clean and lubricated in order to carry out production, but

it will probably not be necessary to spend more on these materials in order to manufacture a

further batch. This cost is therefore only indirectly related to the production of this batch.

Indirect labour is the production labour cost which cannot be directly associated with the

production of any particular batch. It would include the salaries of supervisors who are

overseeing the production of hairdryers as well as all the other products manufactured in

the factory.

Indirect expenses are all the other production overheads associated with running the

factory, including factory rent and rates, heating and lighting, etc. These indirect costs

must be shared out over all of the batches produced in a period.

The share of indirect production costs is added to the prime cost to derive the total

production cost of a hairdryer. This is another measure of cost but there are still more

costs to be added: a share of the other overheads.

Selling and distribution overhead includes the sales force salaries and commission, the cost of

operating delivery vehicles and renting a storage warehouse, etc. These are indirect costs

which are not specifically attributable to a particular cost unit.

Administration overhead includes the rent on the administrative office building, the

depreciation of office equipment, postage and stationery costs, etc. These are also indirect

costs which are not specifically attributable to a particular cost unit.

Now that you understand the nature of each of the cost elements which make up the

full cost we can think a bit more about the price to be charged to the hotel chain.

Exercise 1.6

Which of the above costs would be incurred as a result of making another hairdryer?

Solution

The direct cost of £22 would definitely be incurred if another hairdryer was produced.

This is the extra material that would have to be bought, the extra labour costs that would

have to be paid and the extra expenses for royalties that would be incurred.

The £16 production overhead cost would not be incurred additionally if another

hairdryer was produced. This is the share of costs that would be incurred anyway, such as

the cleaning materials, the factory rent and the supervisors’ salaries.

The £2 share of selling, distribution and administration overhead would probably not

be incurred if another hairdryer was produced. This includes the office costs, the

depreciation on the delivery vehicles and the rent of warehousing facilities. This sort of

cost would not increase as a result of producing another hairdryer or batch of hairdryers.

However, there may be some incremental or extra selling and distribution costs, for

example we would probably be entitled to a sales commission for all our hard work in

winning the sale, and there would be some costs involved in delivering the goods to the

hotel chain. For the sake of our analysis let us suppose that this incremental cost amounts

to £1 per hairdryer, rather than the full amount of £2 shown in the cost analysis.

You can see from the discussion in this exercise that in fact the only extra or

incremental cost to be incurred in producing another hairdryer is £23 (£22 direct cost plus

assumed £1 incremental selling and distribution costs).

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

11

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

Therefore it may be possible to sell to the hotel chain for £25 per hairdryer, and still be

better off than if the sale was not made at all! At least the extra £2 per hairdryer (£25 – £23

extra cost) would contribute towards the costs which are being incurred anyway – the

production overheads, administration overheads, etc.

This discussion has illustrated that the concept of cost needs to be qualified if it is to be

meaningful. We need to know to which cost we are referring when we state something

like, ‘The cost is £40’.

The £40 cost quoted is the full cost, which includes a fair share of all costs incurred on

behalf of the cost object. In our discussion we derived the marginal or incremental cost of

£23 which would be incurred as a direct result of making and selling another hairdryer.

Therefore we have seen that different costs are useful in different circumstances and we

must always qualify what we mean by ‘cost’. Do we mean the direct cost, the marginal

cost, the full cost or some other measure of cost?

When we consider the full cost in this example there is a profit of £10 on this particular

cost unit if it is sold for £50. This is referred to as a profit margin on sales of 20 per cent

(10=50) and a profit mark-up on full cost of 25 per cent (10=40). These are the ‘strictly

correct’ definitions of margin and mark-up. However, in practice, the two terms tend to be

used interchangeably.

The important thing in an assessment question is that you should establish whether

profit is to be calculated as a percentage of cost, or as a percentage of selling price.

1.9 Cost behaviour

Many factors affect the level of costs incurred; for instance inflation will cause costs to

increase over a period of time. In management accounting, when we talk about cost

behaviour we are referring to the way in which costs are affected by fluctuations in the

level of activity.

The level of activity can be measured in many different ways. For example, we can

record the number of units produced, miles travelled, hours worked, meals served,

percentage of capacity utilised and so on.

An understanding of cost behaviour patterns is essential for many management tasks,

particularly in the areas of planning, decision-making and control. It would be impossible

for managers to forecast and control costs without at least a basic knowledge of the way in

which costs behave in relation to the level of activity.

In this section we will look at the most common cost behaviour patterns and we will

consider some examples of each.

1.9.1 Fixed cost

The CIMA Terminology defines a fixed cost as a ‘cost incurred for an accounting

period, that, within certain output or turnover limits, tends to be unaffected by

fluctuations in the levels of activity (output or turnover)’.

Another term that can be used to refer to a fixed cost is a period cost. This highlights

the fact that a fixed cost is incurred according to the time elapsed, rather than according to

the level of activity.

STUDY MATERIAL C1

12

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

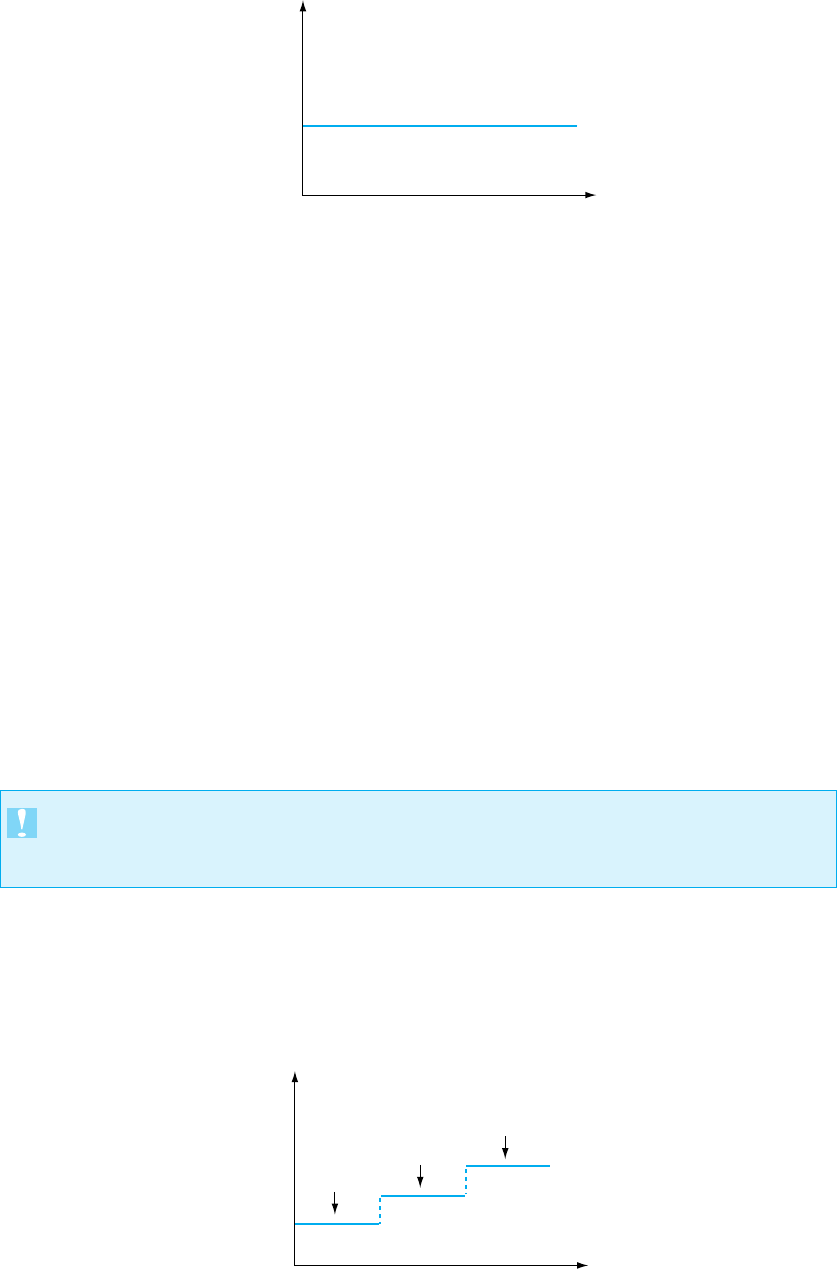

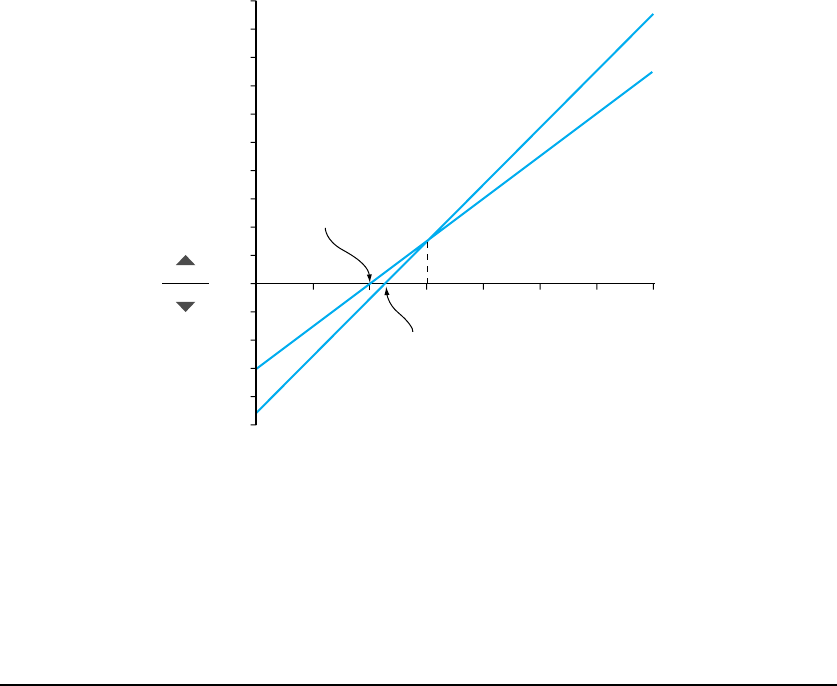

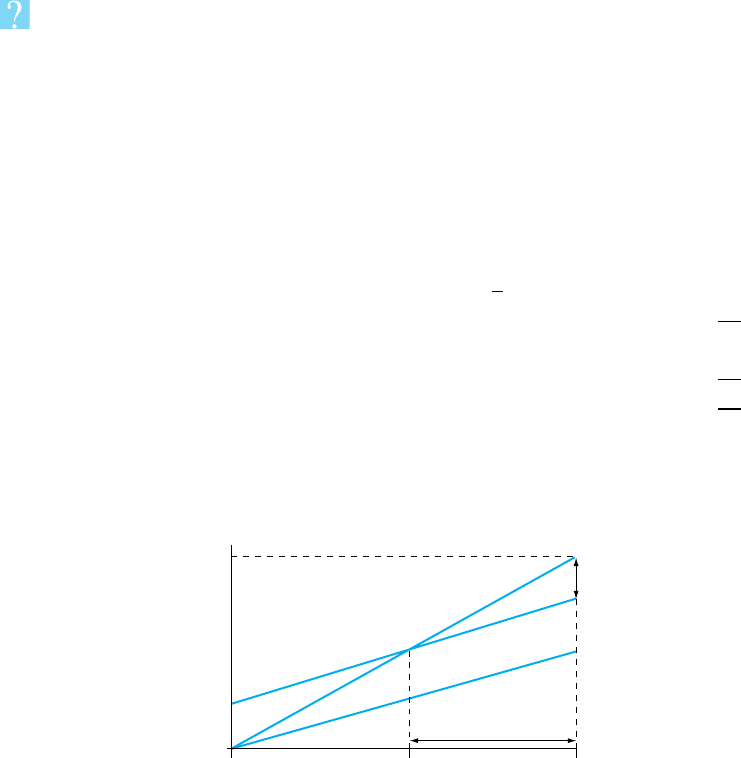

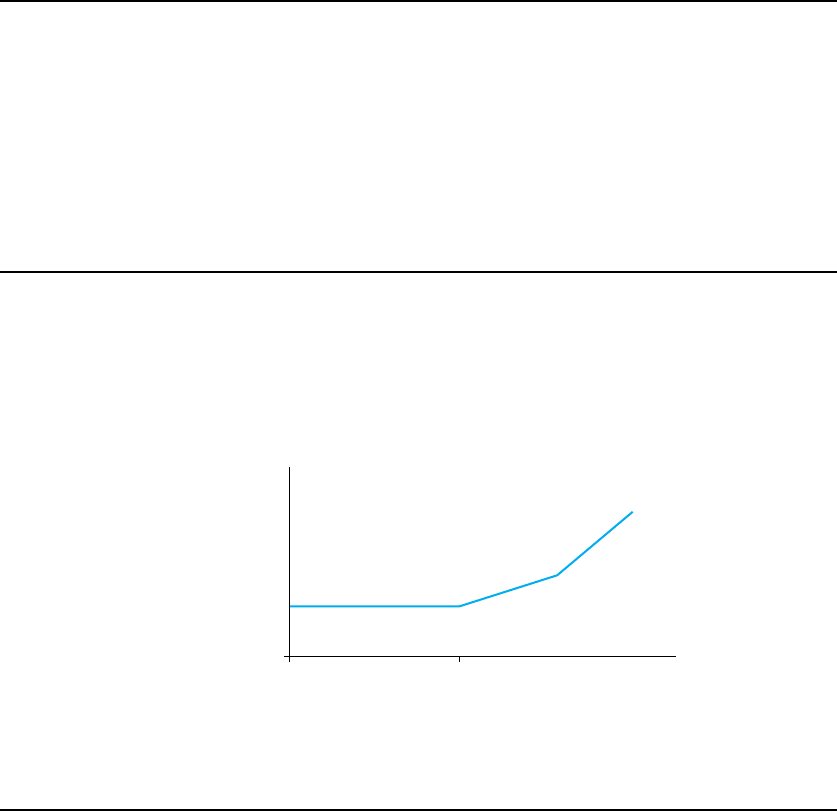

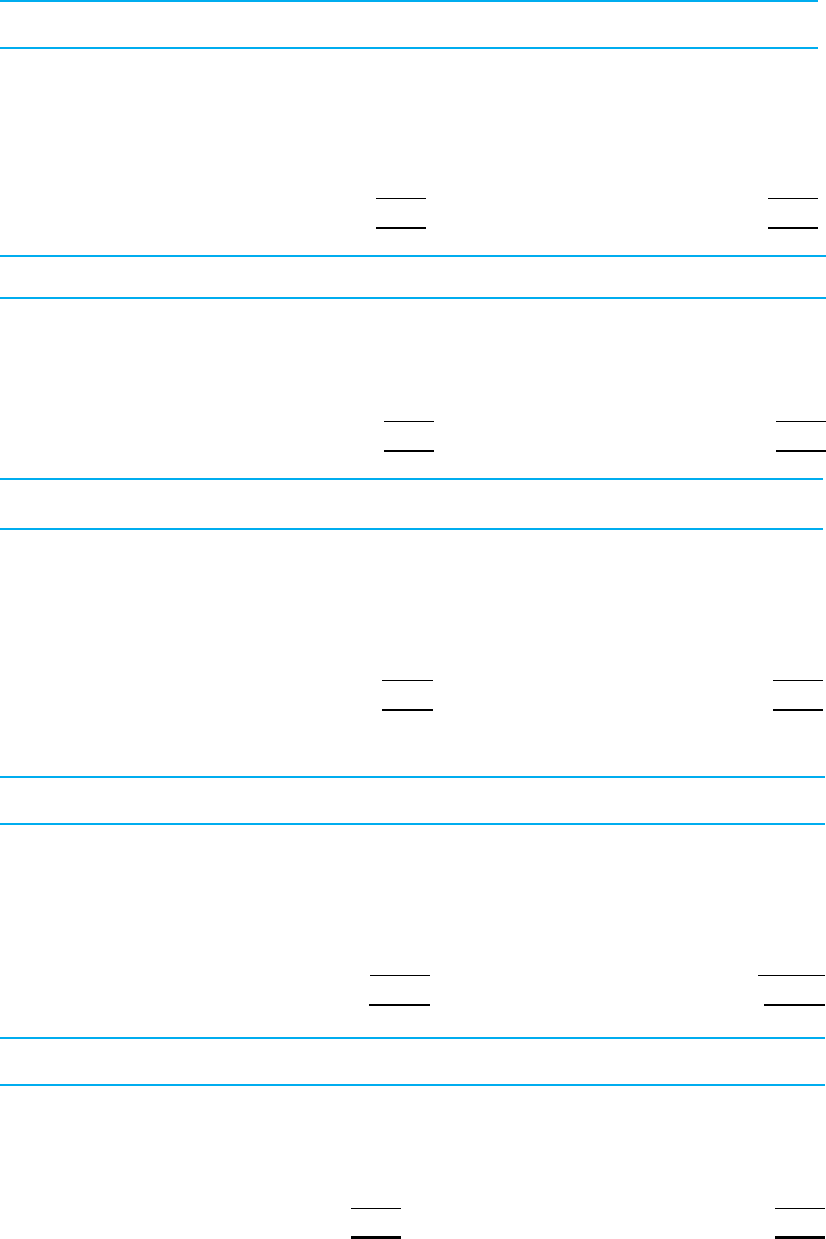

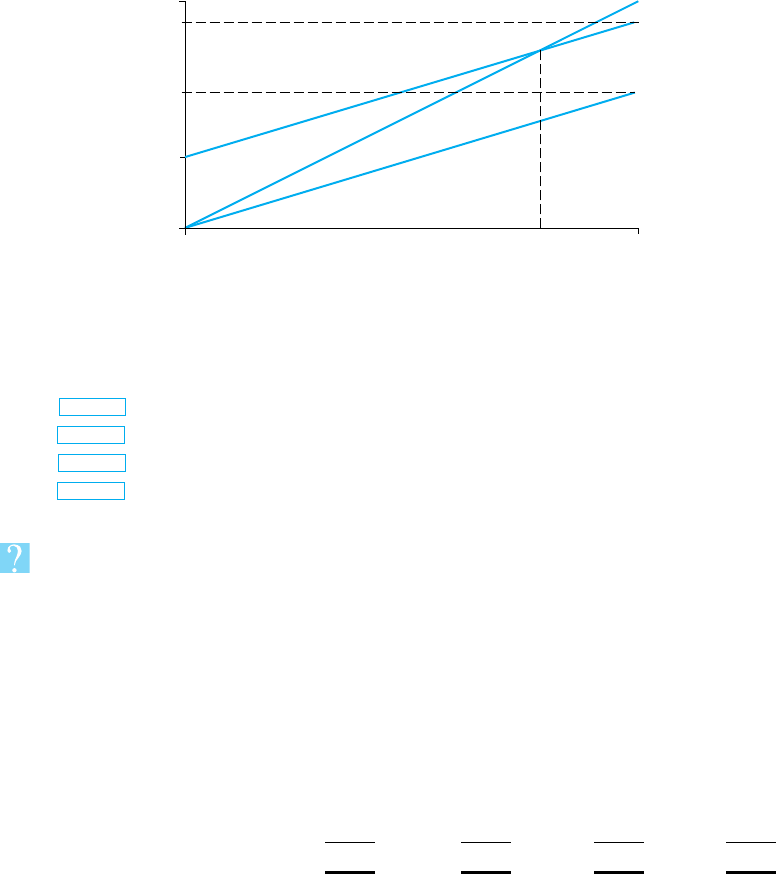

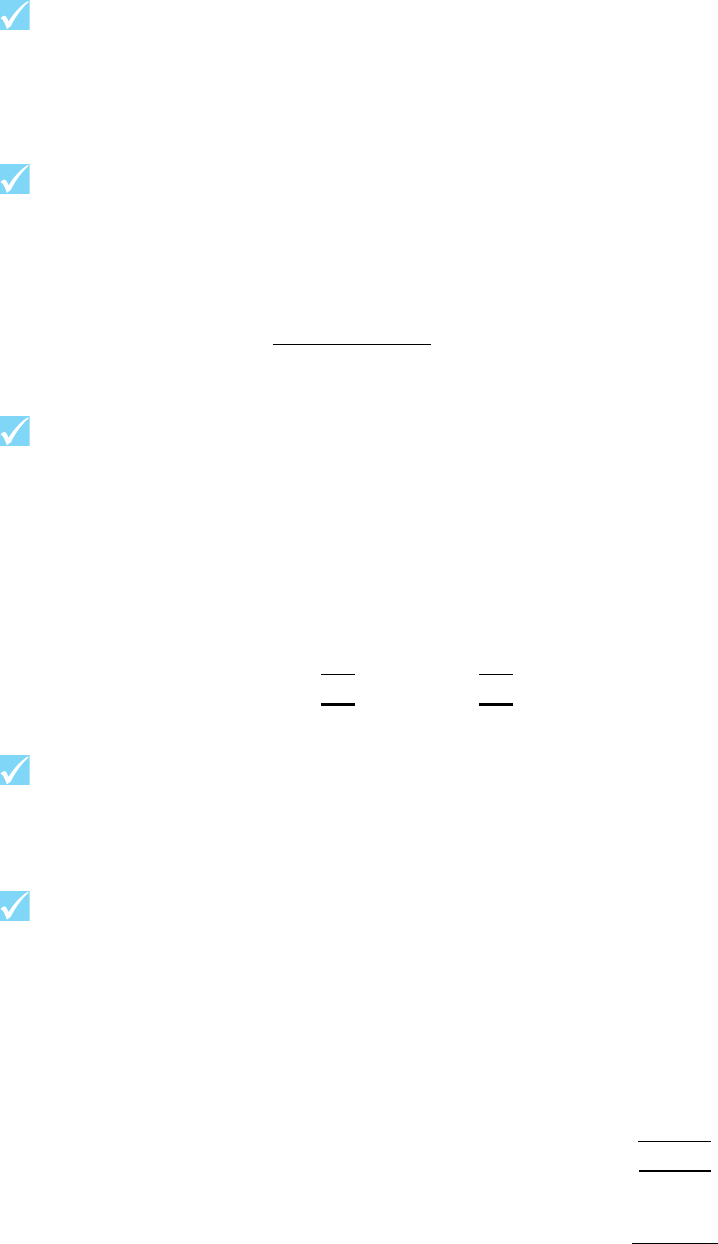

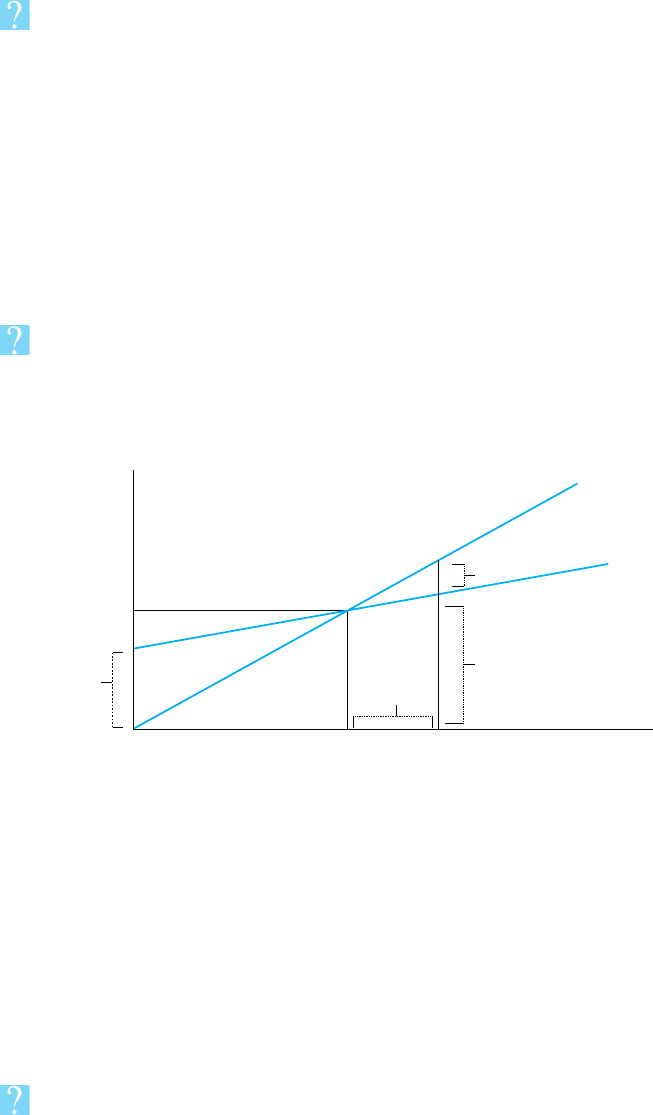

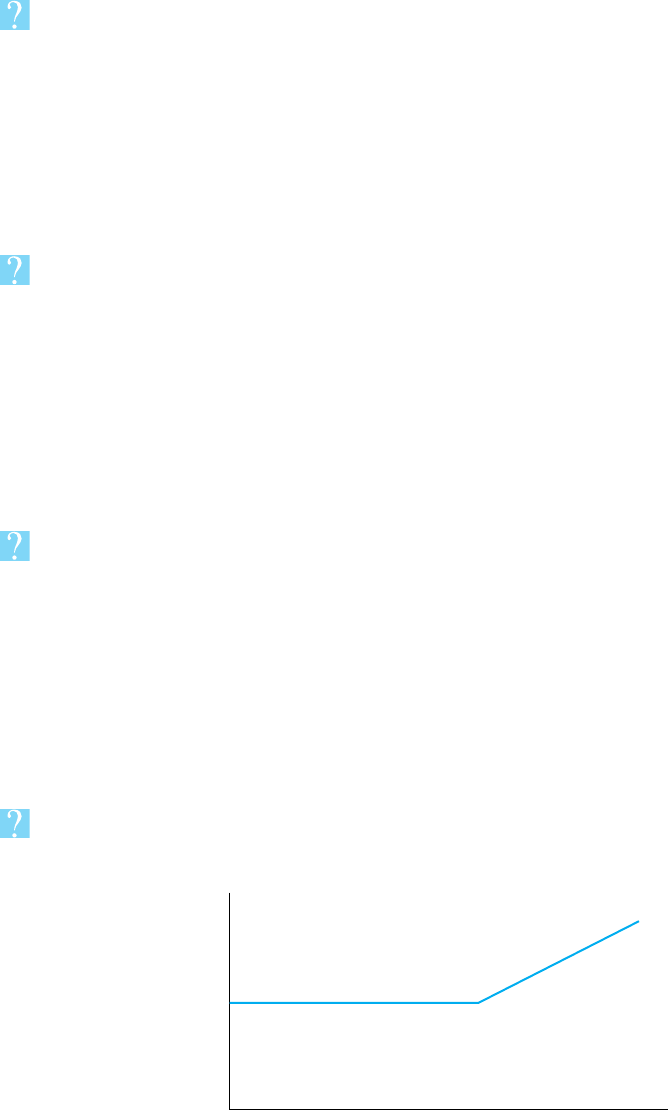

A fixed cost can be depicted graphically as shown in Figure 1.2.

Examples of fixed costs are rent, rates, insurance and executive salaries.

The graph shows that the cost is constant (in this case at £5,000) for all levels of activity.

However, it is important to note that this is only true for the relevant range of activity.

Consider, for example, the behaviour of the rent cost. Within the relevant range it is

possible to expand activity without needing extra premises and therefore the rent cost

remains constant. However, if activity is expanded to the critical point where further

premises are needed, then the rent cost will increase to a new, higher level.

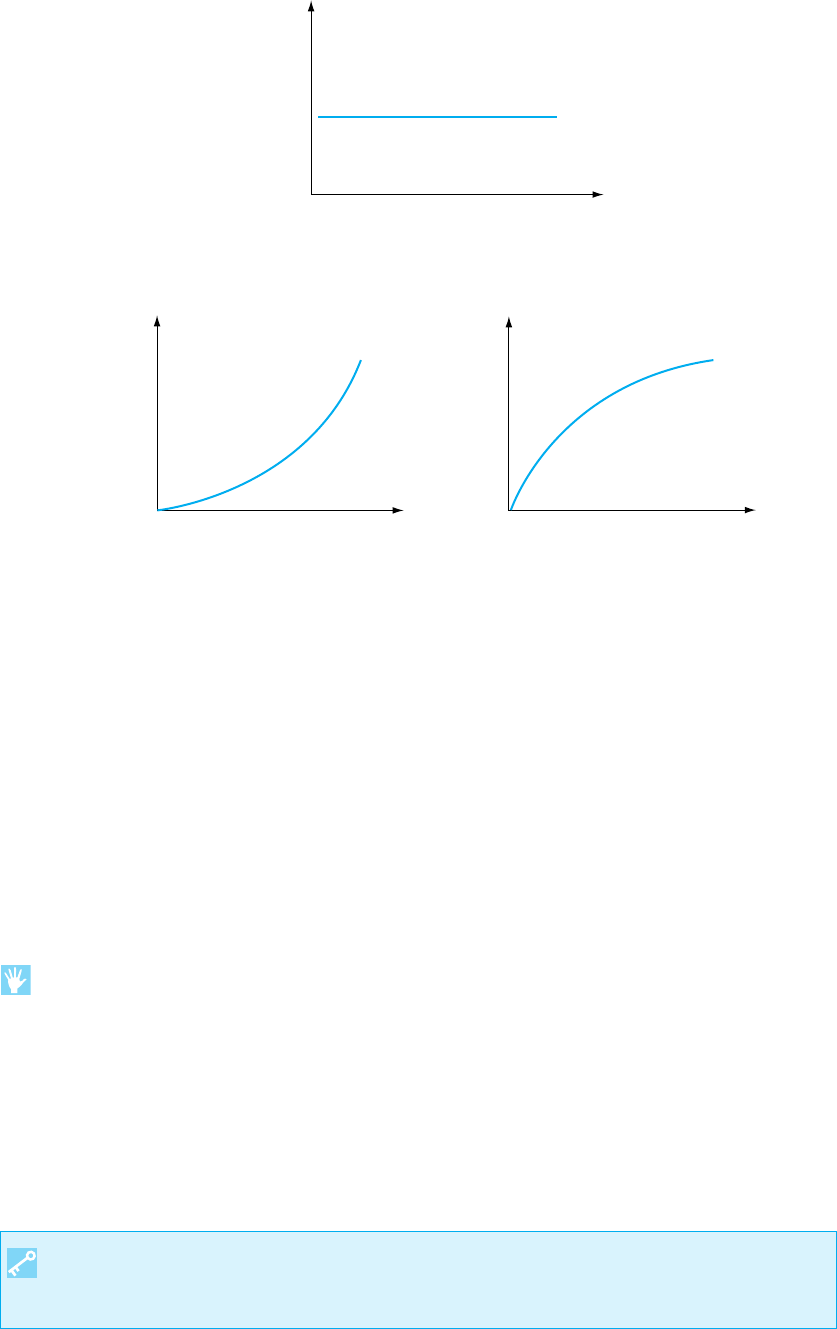

This cost behaviour pattern can be described as a stepped fixed cost or step cost ( Figure 1.3).

The cost is constant within the relevant range for each activity level but when a critical

level of activity is reached, the total cost incurred increases to the next step.

The possibility of changes occurring in cost behaviour patterns means that it is

unreliable to predict costs for activity levels which are outside the relevant range. For

example our records might show the cost incurred at various activity levels between

100 units and 5,000 units. We should therefore try to avoid using this information as

the basis for forecasting the level of cost which would be incurred at an activity of, say,

6,000 units, which is outside the relevant range.

This warning does not only apply to fixed costs: it is never wise to attempt to

predict costs for activity levels outside the range for which cost behaviour patterns

have been established.

When you are drawing or interpreting graphs of cost behaviour patterns, it is important

that you pay great attention to the label on the vertical axis. In Figures 1.2 and 1.3 the

graphs depicted the total cost incurred. If the vertical axis had been used to represent the

fixed cost per unit, then it would look as shown in Figure 1.4.

Total fixed

cost, £

Activity leve

l

5,000

Figure 1.2 Fixed cost

Total

cost, £

Relevant

range 1

Activity leve

l

Relevant

range 2

Relevant

range 3

Figure 1.3 Stepped fixed cost

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

13

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

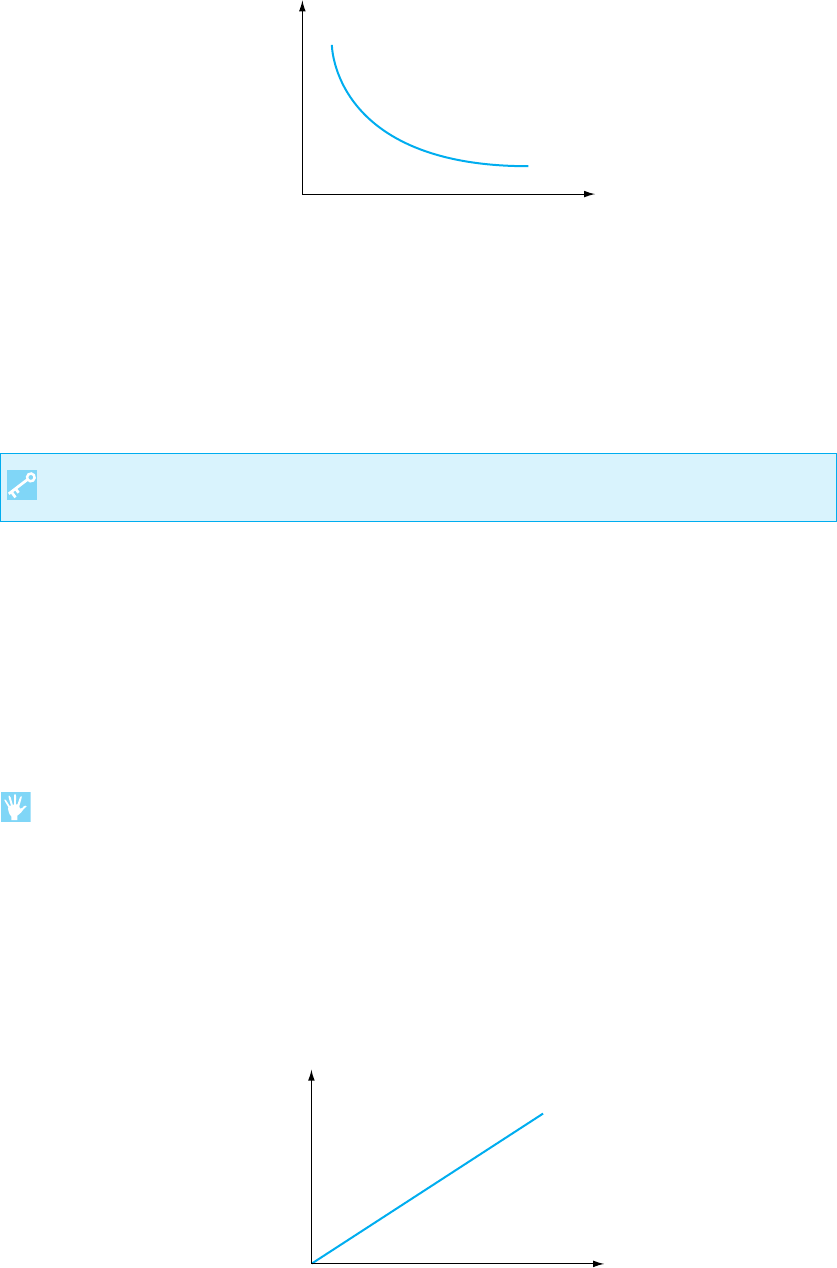

The fixed cost per unit reduces as the activity level is increased. This is because the same

amount of fixed cost is being spread over an increasing number of units.

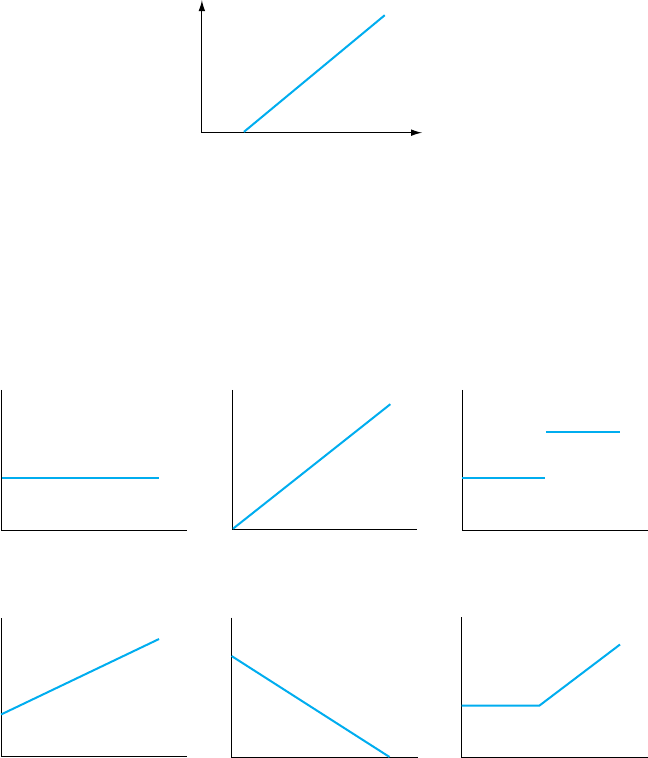

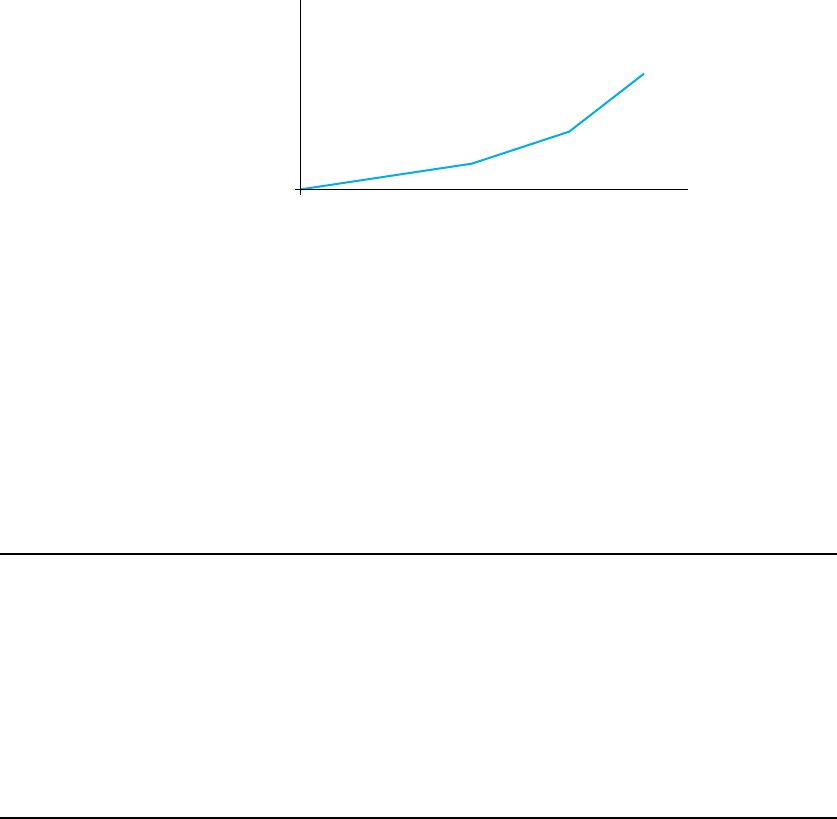

1.9.2 Variable cost

The CIMA Terminology defines a variable cost as a ‘cost that varies with a measure of

activity’.

Examples of variable costs are direct material, direct labour and variable overheads.

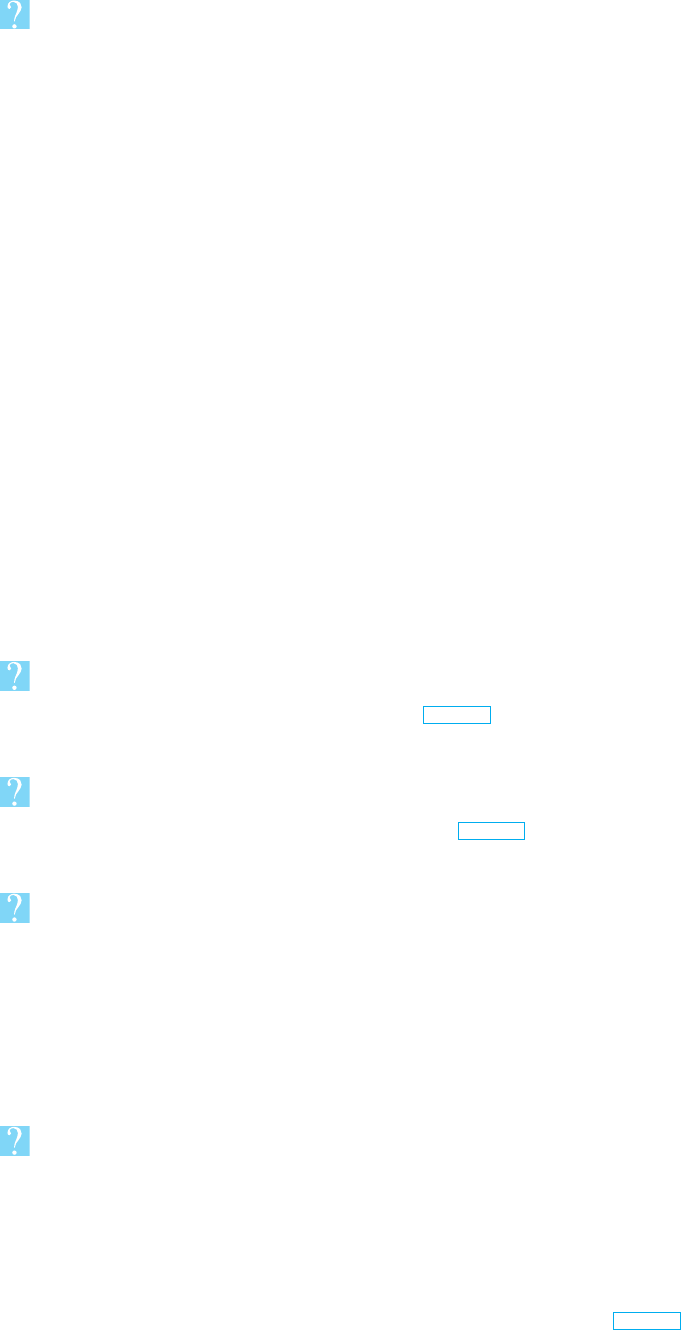

Figure 1.5 depicts a linear variable cost. It is a straight line through the origin, which

means that the cost is nil at zero activity level. When activity increases, the total variable

cost increases in direct proportion, that is, if activity goes up by 10 per cent, then the total

variable cost also increases by 10 per cent, as long as the activity level is still within the

relevant range.

The gradient of the line will depend on the amount of variable cost per unit.

Exercise 1.7

Figure 1.5 depicts the total variable cost at each activity level. Can you draw a sketch graph

of the variable cost per unit?

Your graph of variable cost per unit should look like Figure 1.6. The straight line parallel

to the horizontal axis depicts a constant variable cost per unit, within the relevant range.

In most assessment situations, and very often in practice, variable costs are assumed

to be linear. Although many variable costs do approximate to a linear function, this

Fixed cost

p

er unit, £

Activity leve

l

Figure 1.4 Fixed cost per unit

Total variable

cost, £

Activity leve

l

Figure 1.5 Linear variable cost

STUDY MATERIAL C1

14

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

assumption may not always be realistic. A variable cost may be non-linear as depicted in

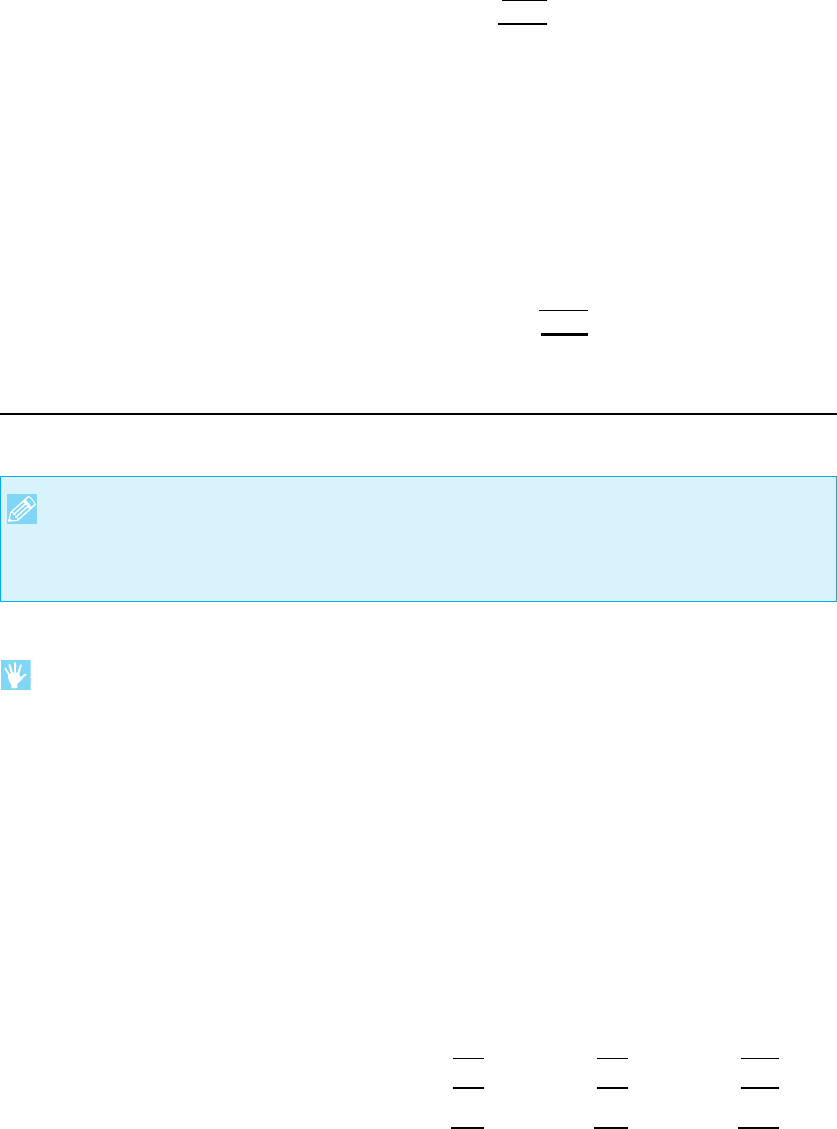

either of the diagrams in Figure 1.7.

These costs are sometimes called curvilinear variable costs.

The graph of cost A becomes steeper as the activity level increases. This indicates that

each successive unit of activity is adding more to the total variable cost than the previous

unit. An example of a variable cost which follows this pattern could be the cost of direct

labour where employees are paid an accelerating bonus for achieving higher levels of

output. The graph of cost B becomes less steep as the activity level increases. Each

successive unit of activity adds less to total variable cost than the previous unit. An

example of a variable cost which follows this pattern could be the cost of direct material

where quantity discounts are available.

Exercise 1.8

Can you think of other variable costs which might follow the behaviour patterns depicted

in Figure 1.7?

The important point is that managers should be aware of any assumptions that have

been made in estimating cost behaviour patterns. They can then use the information which

is based on these assumptions with a full awareness of its possible limitations.

1.9.3 Semi-variable cost

A semi-variable cost is also referred to as a semi-fixed or mixed cost. The CIMA

Terminology defines it as a ‘cost containing both fixed and variable components and

thus partly affected by a change in the level of activity’.

Variable cost

per unit, £

Activity leve

l

Figure 1.6 Variable cost per unit

Total

varlable

cost, £

Total

varlable

cost, £

Activity level Activity leve

l

Cost A Cost B

Figure 1.7 Non-linear variable costs

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

15

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

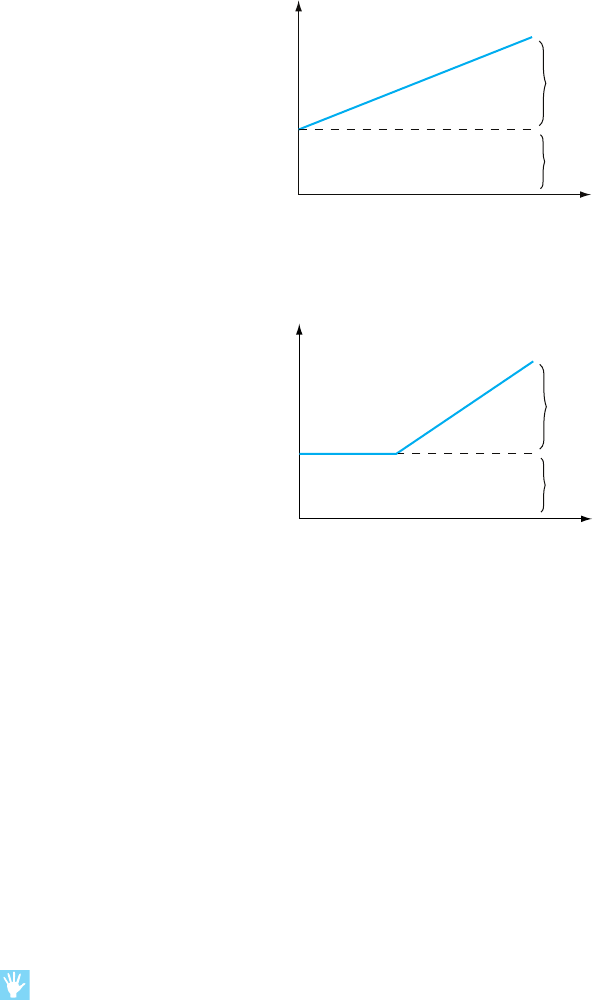

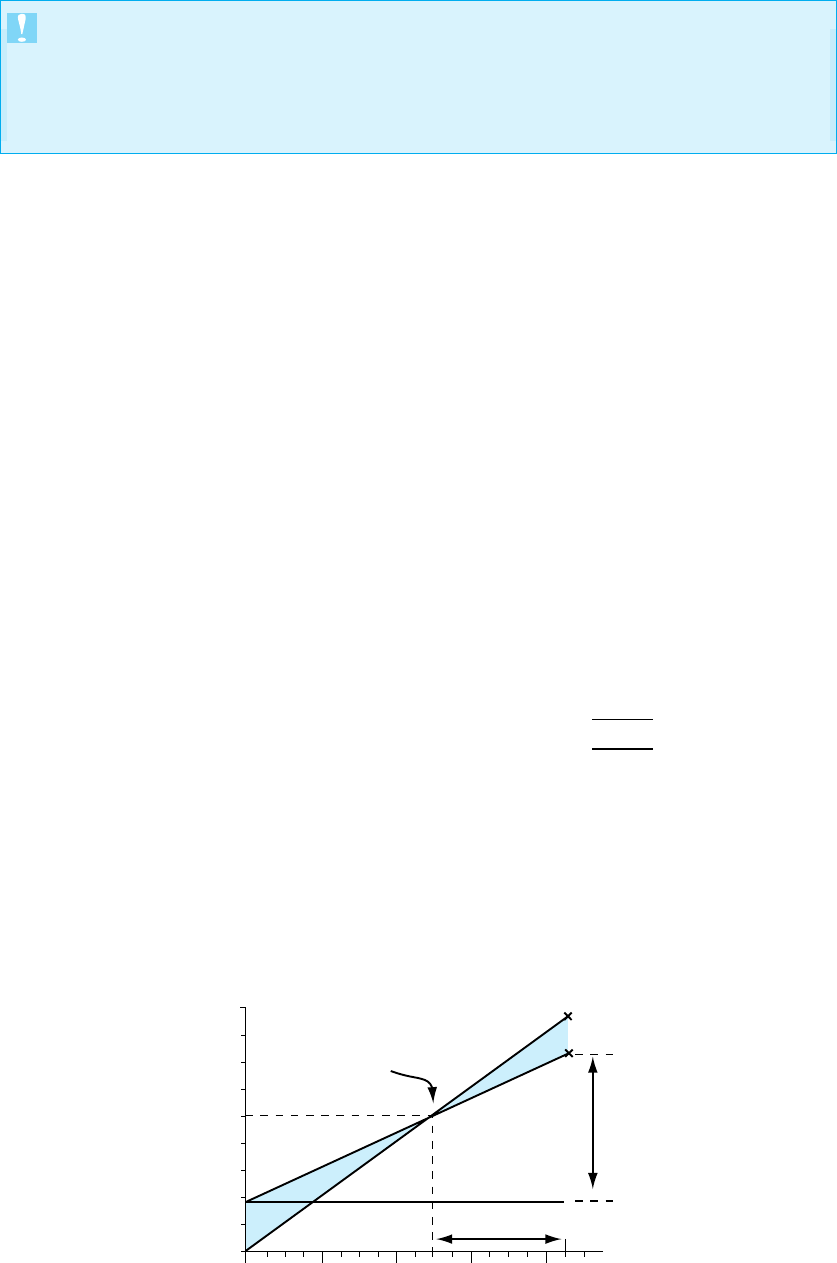

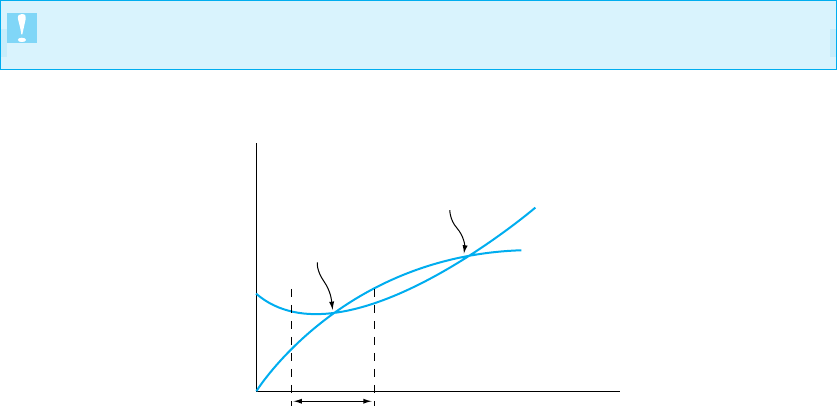

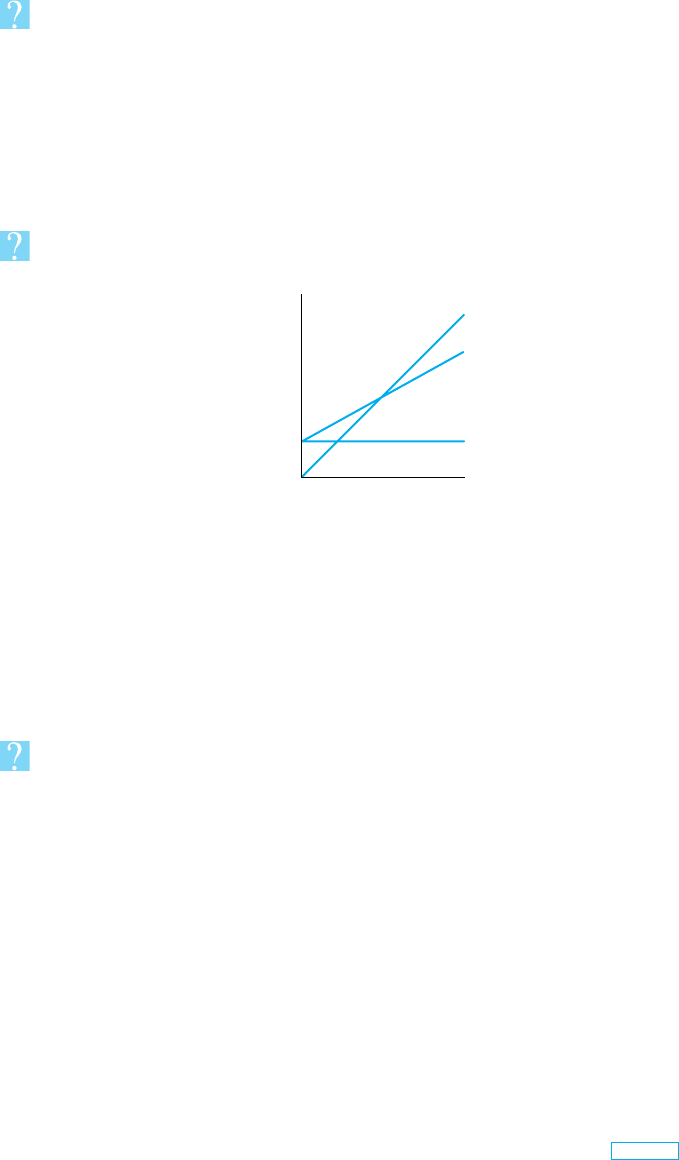

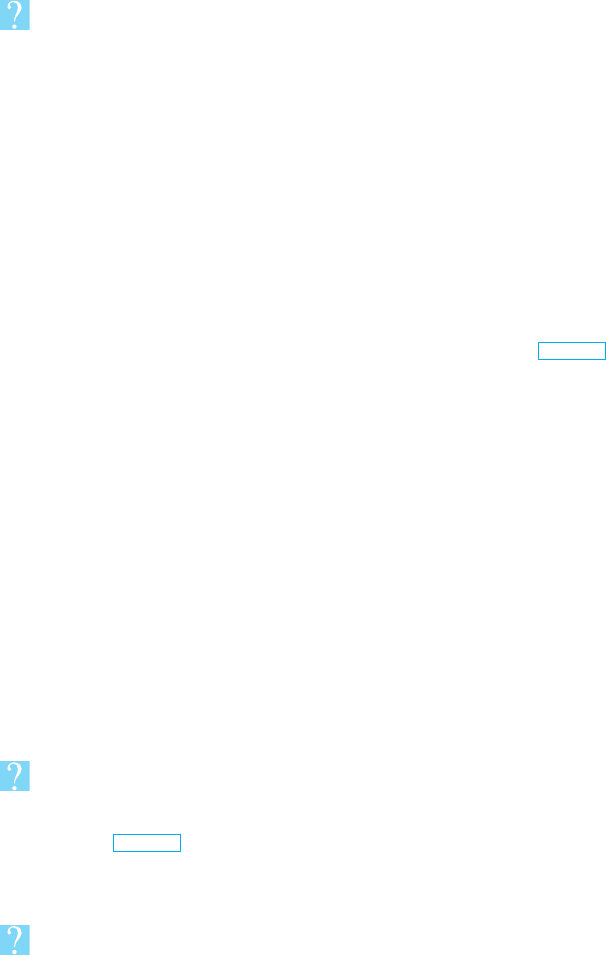

A graph of a semi-variable cost might look like Figure 1.8.

Examples of semi-variable costs are gas and electricity. Both of these expenditures

consist of a fixed amount payable for the period, with a further variable amount which is

related to the consumption of gas or electricity.

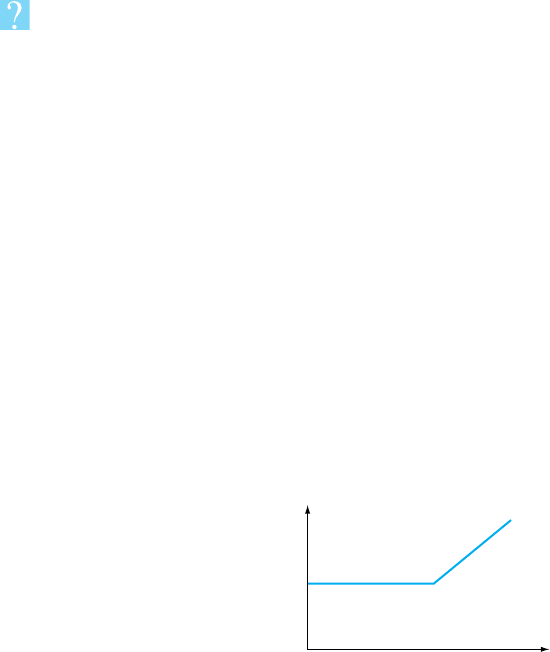

Alternatively a semi-variable cost behaviour pattern might look like Figure 1.9.

This cost remains constant up to a certain level of activity and then increases as the

variable cost element is incurred. An example of such a cost might be the rental cost of a

photocopier where a fixed rental is paid and no extra charge is made for copies up to a

certain number. Once this number of copies is exceeded, a constant charge is levied for

each copy taken.

Exercise 1.9

Can you think of other examples of semi-variable costs with behaviour patterns like those

indicated in Figures 1.8 and 1.9?

1.9.4 Analysing semi-variable costs

The semi-variable cost behaviour pattern depicted in Figure 1.8 is most common in

practice and in assessment situations.

When managers have identified a semi-variable cost they will need to know how much

of it is fixed and how much is variable. Only when they have determined this will they be

able to estimate the cost to be incurred at relevant activity levels. Past records of costs and

their associated activity levels are usually used to carry out the analysis. Your Fundamentals

Total cost, £

Activity level

Fixed cost

Variable cos

t

Figure 1.8 Semi-variable cost

Total cost, £

Variable cos

t

Fixed cost

Activity level

Figure 1.9 Semi-variable cost

STUDY MATERIAL C1

16

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

2006.1

of Management Accounting syllabus requires you to know how to use two common methods

of separating the fixed and variable elements:

(a) The high–low method.

(b) The ‘line of best fit’ method.

The high–low method

This method picks out the highest and lowest activity levels from the available data and

investigates the change in cost which has occurred between them. The highest and lowest

points are selected to try to use the greatest possible range of data. This improves the

accuracy of the result.

Example: the high–low method

A company has recorded the following data for a semi-variable cost:

Activity level Cost incurred

Month (units) (£)

January 1,800 36,600

February 2,450 41,150

March 2,100 38,700

April 2,000 38,000

May 1,750 36,250

June 1,950 37,650

The highest activity level occurred in February and the lowest in May. Since the amount of fixed cost incurred in

each month is constant, the extra cost resulting from the activity increase must be the variable cost.

Activity level

(units) £

February 2,450 41,150

May

1,750 36,250

Increase

700 4,900

The extra variable cost for 700 units is £4,900. We can now calculate the variable cost per unit:

Variable cost ¼

£4;900

700

¼ £7 per unit

Substituting back in the data for February, we can determine the amount of fixed cost:

February £

Total cost 41,150

Variable cost (2,450 units £7)

17,150

Therefore, fixed cost per month

24,000

Now that the fixed and variable cost elements have been identified, it is possible to estimate the total

cost for any activity level within the range 1,750 units to 2,450 units.

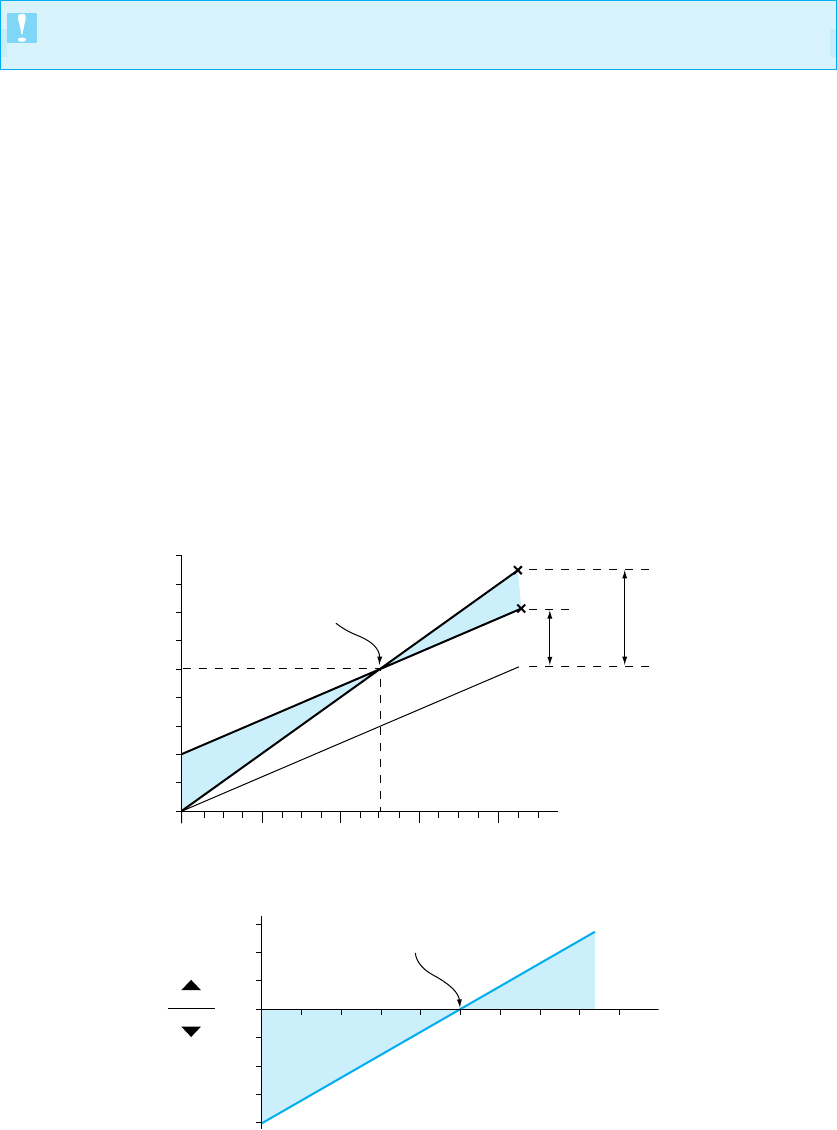

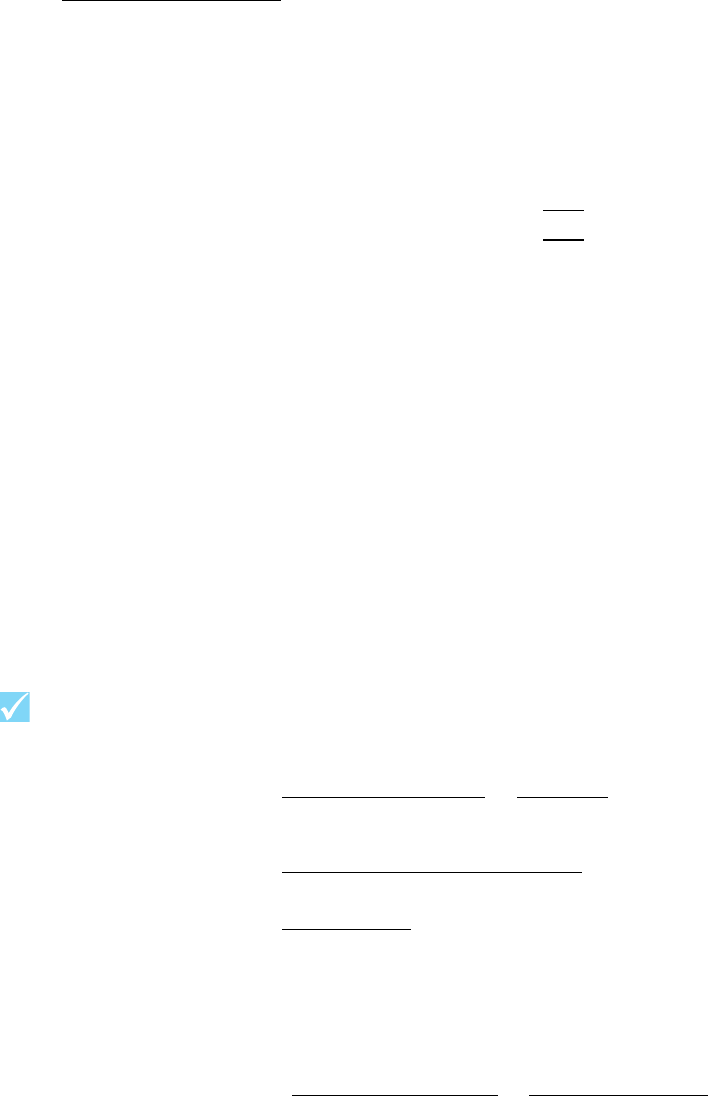

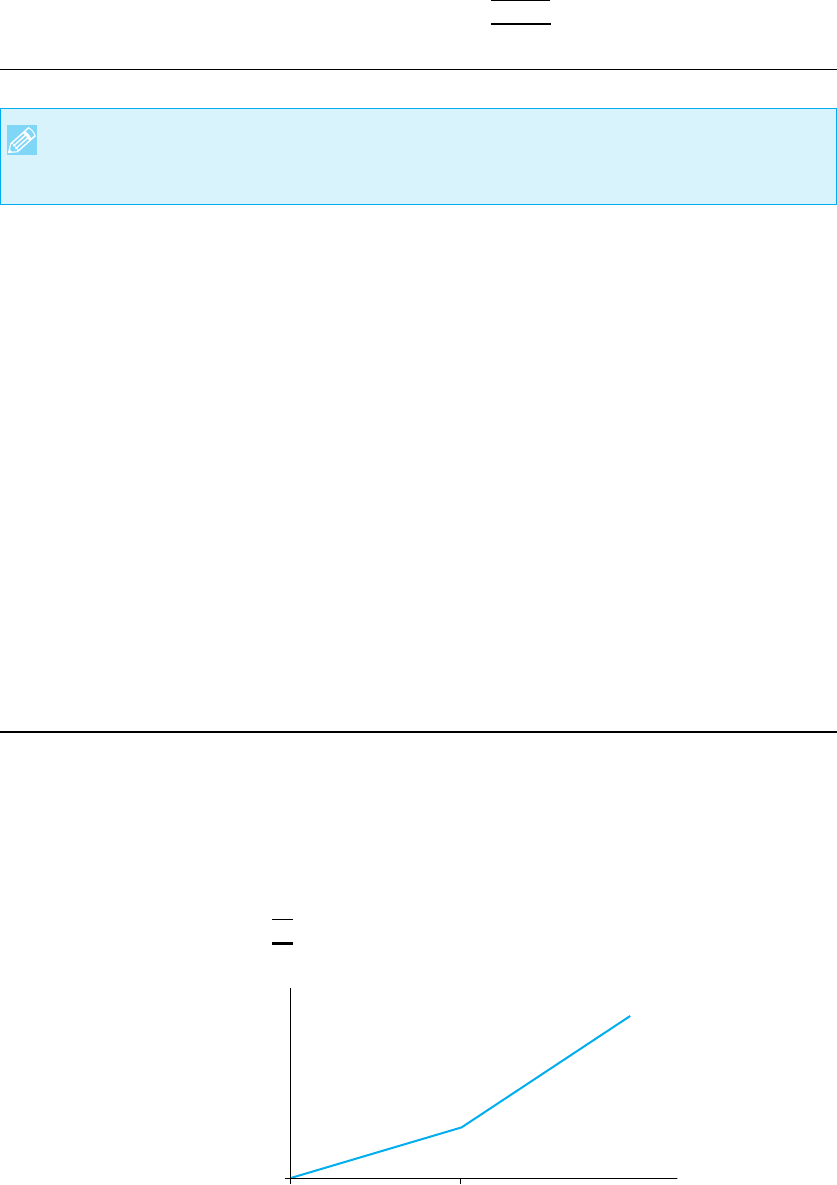

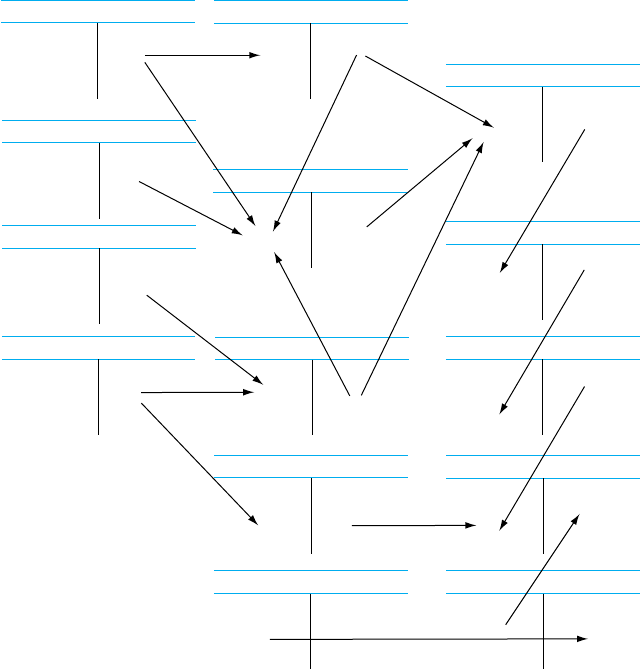

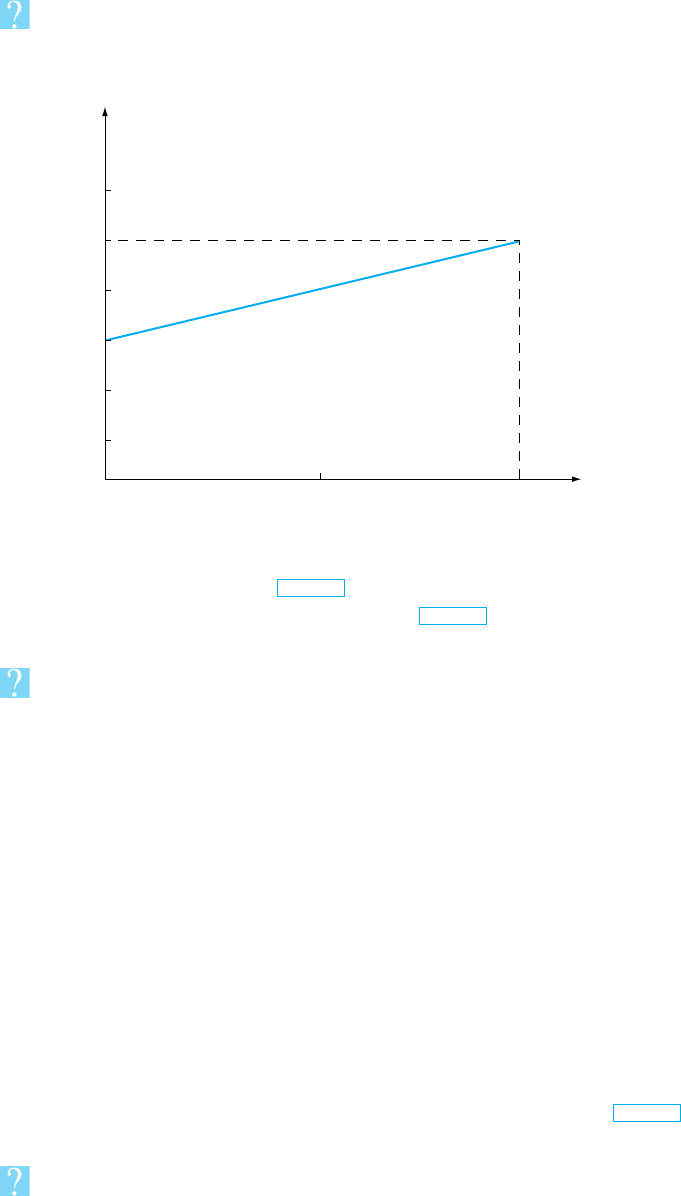

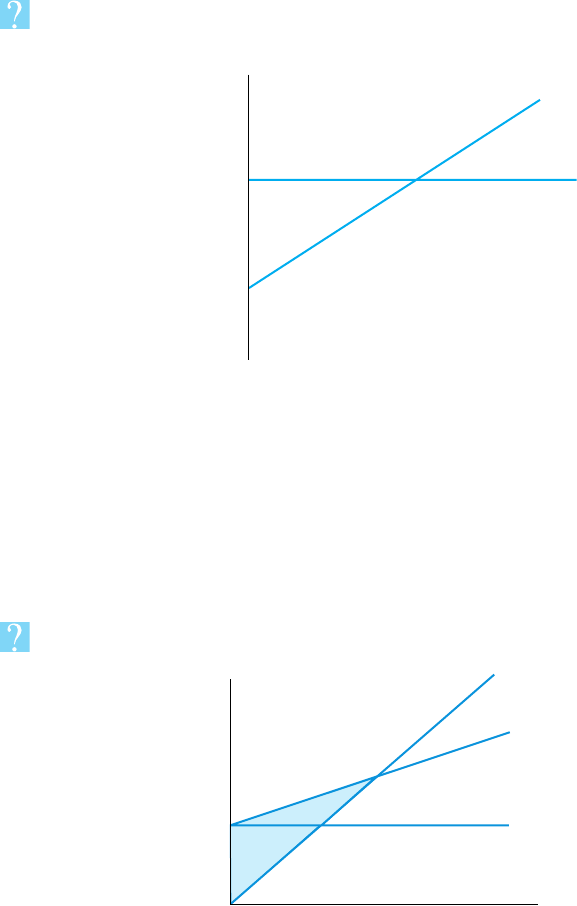

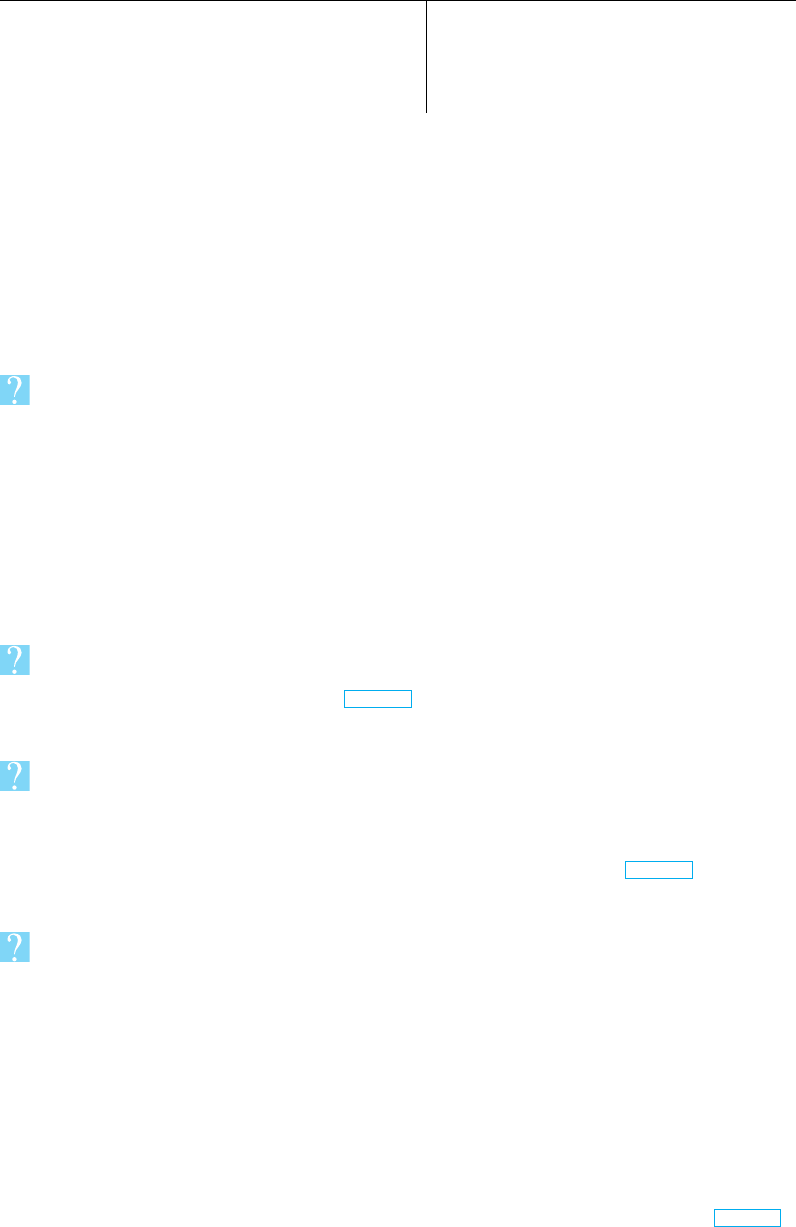

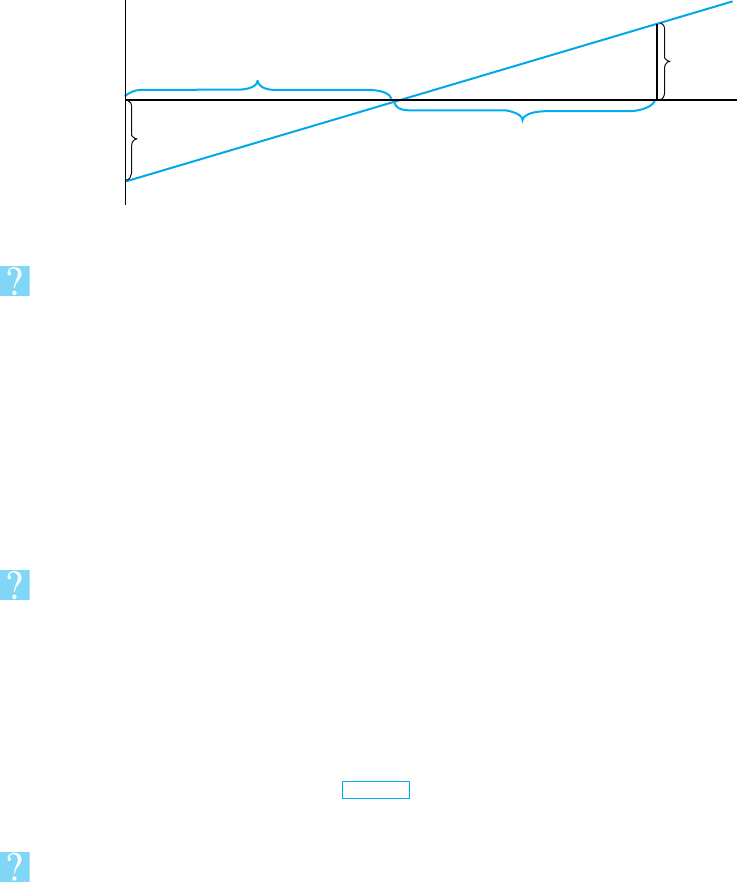

The scattergraph method

This method takes account of all available historical data and it is simple to use.

However, it is very prone to inaccuracies that arise due to subjectivity and the likelihood

of human error.

FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

17

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

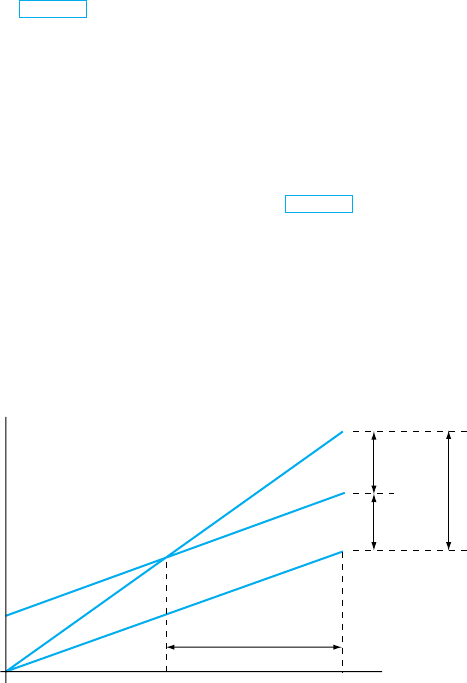

2006.1

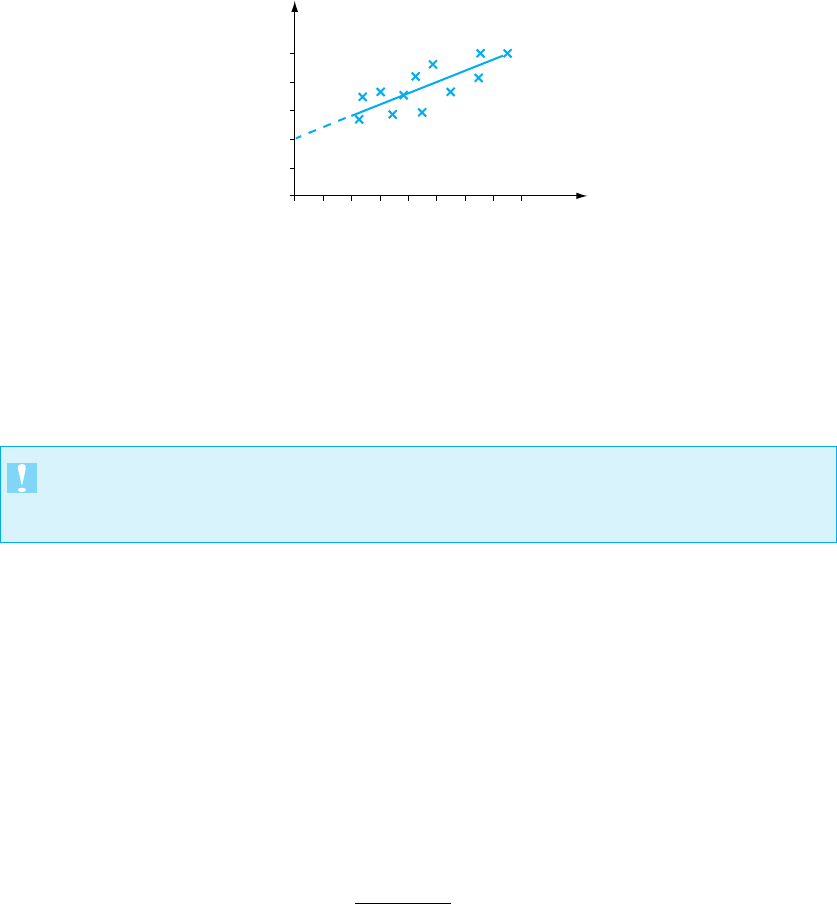

1. First a scattergraph is drawn which plots all available pairs of data on a graph.

2. Then a line of best fit is drawn by eye. This is the line which, in the judgement of the

user, appears to be the best representation of the gradient of the sets of points on the

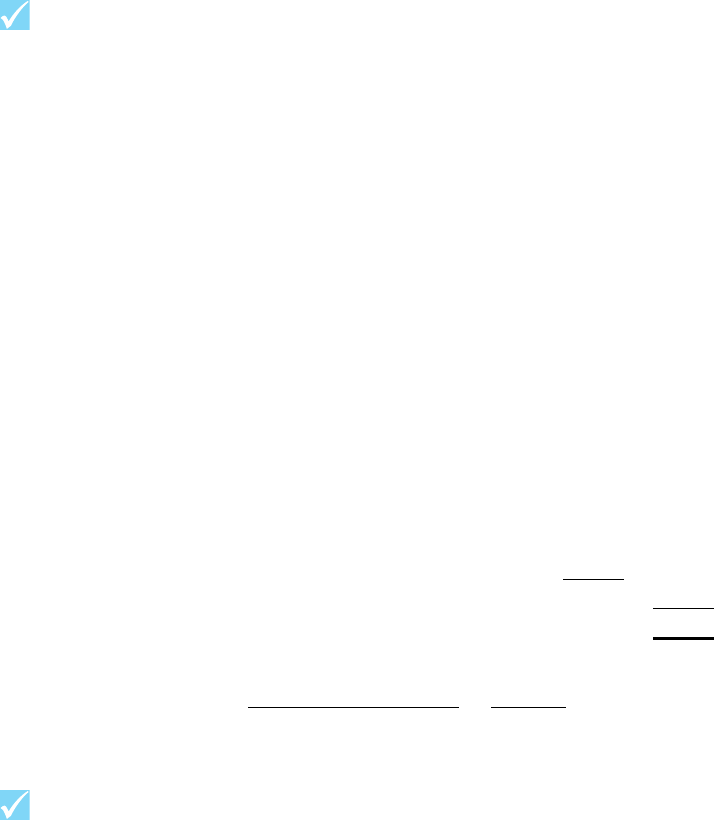

graph. This is demonstrated in Figure 1.10.

The inaccuracies involved in drawing the line of best fit should be obvious to you.

If you had been presented with this set of data, your own line of best fit might have

been slightly different from ours.

3. The point where the extrapolation of this line cuts the vertical axis (the intercept) is

then read off as the total fixed cost element. The variable cost per unit is given by the

gradient of the line.

From Figure 1.10, the fixed cost contained within this set of data is adjudged to

be £200.

The variable cost is calculated as follows:

Cost for zero units ¼ £200

Cost for 150 units ¼ £500

Gradient (i.e. variable cost) ¼

500 200

150 0

¼ £2 per unit

1.9.5 Using historical data

The main problem which arises in the determination of cost behaviour is that the

estimates are usually based on data collected in the past. Events in the past may not be

representative of the future and managers should be aware of this if they are using the

information for planning and decision-making purposes.

1.9.6 The importance of time scale in analysing cost

behaviour

It is important to think about the time period under consideration when we are analysing

cost behaviour patterns. For example, over a long period of time all costs might be

considered to be variable.

Total cost, £

Activity leve

l

16012080400

0

100

200

300

400

500

Figure 1.10 Scattergraph

STUDY MATERIAL C1

18

2006.1

BASIC ASPECTS OF COST ACCOUNTING

Over a number of years, if activity reduces an organisation can move to smaller

premises to reduce rent costs and they can reduce the number of supervisors to reduce

supervisor salary cost. Thus costs which we might normally classify as fixed costs are, in

the longer term, becoming more variable in relation to the level of activity.

However in the shorter term costs such as rent and supervisors’ salaries are fixed. If

demand for a product reduces, the expenditure on rent and on supervisors’ salaries cannot

be reduced immediately in response to the reduction in output. Such decisions require

planning and consideration of factors such as whether the reduction in output is