151

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

151

Lisa A. Bero (

1

)

7 Tobacco industry manipulation of

research

(

1

) Funding and support: grants from the American Cancer Society (RPG9714301PBP) and the University of California Tobacco‑

Related Disease Research Program (6RT0025 and 9RT0193) supported this work. Authors would like to thank colleagues who have

collaborated on the studies cited in this paper: Katherine Bryan-Jones, Stanton Glantz, Miki Hong, Christina Mangurian, Theresa

Montini, and Marieka Schotland. Daniel Cook, Susan Dalton, Joshua Dunsby, Michael Givel, Anh Le, Peggy Lopippero, David Rosner

and Theo Tsoukalis for useful input to this manuscript.

(

2

) For example, two contrasting yet complementary histories of cancer in general and smoking in particular are Davies (2007) and

Keating (2009).

This chapter differs in some ways from the others in Volume 2 of Late lessons from early

warnings. The history of 'second hand', 'passive' or 'environmental tobacco smoke' (ETS), to

which non-smokers are exposed overlaps with the history of active smoking. Those affected

include the partners and children of smokers, and the bartenders and other workers who have to

work in smoky environments.

The focus in this chapter is on the strategies used by the tobacco industry to deny, downplay,

distort and dismiss the growing evidence that, like active smoking, ETS causes lung cancer

and other effects in non-smokers. It does not address the history of scientific knowledge about

tobacco and how it was used or not used to reduce lung cancer and other harmful effects

of tobacco smoke. There is much literature on this (

2

) and a table at the end of the chapter

summarises the main dates in the evolution of knowledge in this area.

The chapter concentrates on the 'argumentation' that was used to accept, or reject, the growing

scientific evidence of harm. Who generated and financed the science used to refute data on

adverse health effects? What were the motivations? What kind of science and information, tools

and assumptions were used to refute data on the adverse health of tobacco?

The release of millions of internal tobacco industry documents due to law suits in the US has

given insights into the inner workings of the tobacco industry and revealed their previously

hidden involvement in manipulating research. However, this insight is not available for most

corporate sectors. The chapter discusses the possibilities of 'full disclosure' of funding sources

and special interests in research and risk assessment in order to secure independence and

prevent bias towards particular viewpoints.

While smoking bans are now being introduced in more and more countries, other industries are

drawing inspiration from tobacco company strategies, seeking to maintain doubt about harm in

order to keep hazardous products in the marketplace.

The chapter also includes a summary of the tobacco industry's role in shaping risk assessment in

the US and Europe to serve its own interests.

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

152

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

7.1 Introduction

This chapter describes the strategies that the

tobacco industry has used to influence the design,

conduct and publication of scientific research on

second-hand smoke; and how the tobacco industry

used this research in attempts to influence policy.

It represents an expansion of an earlier article,

'Tobacco industry manipulation of research' by Bero

(2005).

The primary motivation of the tobacco industry

has been to generate controversy about the health

risks of its products. The industry has used several

strategies including:

1. funding and publishing research that supports

its position;

2. suppressing and criticising research that does

not support its position;

3. changing the standards for scientific research;

4. disseminating interest group data or

interpretation of risks via the lay (non-academic)

press and directly to policymakers.

The strategies used by the tobacco industry have

remained remarkably constant since the early 1950s

when the industry focused on refuting data on the

harmful effects of active smoking, through to the

1990s, when the industry was more concerned with

refuting data on the harmful effects of second-hand

smoke. Tobacco industry lawyers and executives,

rather than scientists, have controlled the design,

conduct and dissemination of this research.

When data on risk appear to be controversial,

users of the data should investigate the sources of

controversy. This can be done only if interest group

involvement in all steps of the risk determination

process is transparent and fully disclosed. Since the

tobacco industry's efforts to manipulate research are

international endeavours and are shared by other

corporate interests, individuals around the world

should be aware of the strategies that the industry

has used to influence data on risk.

Communicating accurate information on risk is

essential to risk perception and risk management.

Research findings, often from basic science,

epidemiology and exposure or engineering research,

provide the basis for information on risk. These

research findings or 'facts' are, however, subject

to interpretation and the social construction of

the evidence (Krimsky, 1992). Research evidence

has a context. The roles of framing, problem

definition and choice of language influence risk

communication (Nelkin, 1985). Furthermore,

scientific uncertainties allow for a wide range of

interpretation of the same data. Since data do not

'speak for themselves' interest groups can play a

critical role in generating and communicating the

research evidence on risk.

An interest group is an organised group with

a specific viewpoint that protects its position

(Lowi, 1979). Interest groups are not exclusively

business organisations; they can comprise all kinds

of organisations that may attempt to influence

governments (Walker, 1991; Truman, 1993). Therefore,

interest groups can be expected to select and interpret

the evidence about a health risk to support their

predefined policy position (Jasanoff, 1996). For

example, public health interest groups are likely to

communicate risks in a way that emphasises harm

and, therefore, encourages regulation or mitigation of

risk (Wallack et al., 1993). Industry interest groups are

likely to communicate risks in a way that minimises

harm and reduces the chance that their product is

regulated or restricted in any way. Disputes about

whether a risk should be regulated or not are

sometimes taken to the legal system for resolution

(Jasanoff, 1995). Thus, interest groups often have two

major goals: to influence policy-making and litigation.

Beginning in the 1970s, the tobacco industry

influenced the collection, interpretation and

dissemination of data on risks of exposure to

second-hand smoke. The analysis below suggests

that this was history repeating itself; in the 1950s,

the tobacco industry had used similar strategies to

manipulate information on the risks of smoking.

Moreover, other corporate interest groups appear to

use similar tactics (Special Issue, 2005; White et al.,

2009).

Many of the strategies available to interest groups —

for example sponsoring, publishing and criticising

research — are costly. Industry might therefore be

expected to dominate examples of such activities

because corporate interest groups are more likely to

have the resources to launch expensive, coordinated

efforts. In contrast, public health groups, which tend

to act independently, are less likely to command

such resources (Montini and Bero, 2001).

Industry examples may also predominate because

some interest group activities have come to light

through the documents released during the

'discovery' process in law suits. For example, the

asbestos and tobacco industries were required to

release large amounts of internal correspondence

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

153

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

when they were sued by groups attempting to show

that they were harmed by industry products.

7.2 Scientific community knowledge

about the hazards of second‑hand

smoke exposure

Environmental tobacco smoke, or second-hand

smoke, is a complex mixture of thousands of gases

and fine particles emitted by burning tobacco

products and from smoke exhaled by smokers, as

well as smoke that escapes while the smoker inhales

and some vapour-phase related compounds that

diffuse from tobacco products. During the 1970s

and 1980s, data on the harmful effects of exposure

to second-hand smoke began to be published in

the scientific literature. Seminal epidemiological

studies in 1981 demonstrated that second-hand

smoke exposure was associated with lung cancer

(Hirayama, 1981). United States Surgeon General

and National Academy of Sciences reports in 1986

concluded that second-hand smoke was a cause of

disease (US DHHS, 1986; NRC, 1986).

A landmark European epidemiological study on

lung cancer and second-hand smoke was initiated

by the International Agency for Research on

Cancer (IARC) in 1988 and published in 1998. The

publication reported a 16 % increase in lung cancer

risk for non-smoking spouses of smokers and a 17 %

increase for non-smokers who were exposed in the

workplace (IARC, 1998).

In 1992, the US Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) released a risk assessment classifying ETS

as a Group A human carcinogen (US EPA, 1992).

The tobacco industry criticised the methodology of

the US EPA risk assessment for its study selection

and statistical analysis. The industry also criticised

the epidemiological design of the studies included

in the risk assessment, the ways that these studies

controlled for bias and confounding, and measured

ETS exposure (Bero and Glantz, 1993). The EPA

revised the report in response to valid criticisms

and the report was approved by the Scientific

Advisory Board. The report was improved but the

sheer volume of tobacco industry comments that

required consideration probably delayed its release.

Although the science was valid, the tobacco industry

successfully attacked the US EPA risk assessment in

court on procedural grounds (Flue-Cured Tobacco

Co-op vs. US EPA, 1998) and the tobacco industry

had similar procedural objections to the report of

Australia's National Health and Medical Research

Council, 'The health effects of passive smoking'

(NHMRC, 1997).

In 1997 the California EPA published the final

report of a risk assessment entitled 'Health Effects

of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke'

(Cal-EPA, 1997). The California risk assessment was

more comprehensive than the US EPA's assessment

because it examined the association of second-hand

smoke exposure, lung cancer and respiratory

illness, as well as cardiovascular, developmental,

reproductive and childhood respiratory effects.

The California EPA risk assessment also addressed

criticisms brought by the tobacco industry against

the US EPA risk assessment. The California risk

assessment was the result of a collaborative effort

between the Office of Environmental Health Hazard

Assessment (OEHHA) and the Air Resources Board

(ARB), two of the six constituent organisations of

the California EPA. The Scientific Review Panel that

endorsed the report concluded that second-hand

smoke is 'a toxic air contaminant' that 'has a major

impact on public health' (Cal-EPA, 1997).

In June 2005 the California Scientific Review Panel

approved an updated draft report on Identification

of Environmental Tobacco Smoke as a Toxic Air

Contaminant (Cal-EPA, 2005). The report concluded

that second-hand smoke exposure is causally

associated with developmental effects (e.g. inhibited

foetal growth, sudden infant death syndrome,

pre-term delivery), respiratory effects (e.g. asthma,

acute and chronic respiratory symptoms in children,

middle ear infections in children), carcinogenic

effects (e.g. lung cancer, nasal sinus cancer, breast

cancer in younger, premenopausal women) and

cardiovascular effects (e.g. heart disease mortality,

acute and chronic heart disease, morbidity).

The growing evidence documenting the adverse

health effects of second-hand smoke was clearly a

threat to the tobacco industry as early as the 1970s.

Restrictions on smoking could lead to reduced daily

consumption of cigarettes and a decline in sales. The

tobacco industry responded with its own science to

the independently generated data on tobacco-related

adverse health effects.

7.3 Tobacco industry strategies to

subvert scientific knowledge

Policymaking is facilitated by consensus (Kingdon,

1984; Mazmanian and Sabatier, 1989; Sabatier,

1991). Scientific research, on the other hand, is

characterised by uncertainty. The uncertainty

that is familiar to scientists poses problems when

decision-making occurs in a public forum. Thus, it

is often to the benefit of corporate interest groups to

generate controversy about evidence of a product's

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

154

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

health risks because such controversy is likely to

slow or prevent regulation of that product. Similarly,

scientific debate over the data and methods used

in risk assessment, for example, can hinder the

development of the risk assessment (Stayner, 1999).

The release of previously secret internal tobacco

industry documents as a result of the Master

Settlement Agreement in 1998 has given the

public health community insights into the tobacco

industry's motives, strategies, tactics and data (Bero,

2003). These documents show that for decades the

industry has been motivated to generate controversy

about the health risks of its products. They have

also revealed that the industry was concerned about

maintaining its credibility as it manipulated research

on tobacco (Bero, 2003).

The strategies used by the tobacco industry have

remained remarkably constant since the early

1950s. During the 1950s and 1960s, the tobacco

industry focused on refuting data on the adverse

effects of active smoking. The industry applied the

same tools it developed during that period when

it subsequently refuted data on the adverse effects

of second-hand smoke exposure during the 1970s

through the 1990s.

A 1978 report prepared by the Roper Organization

for The Tobacco Institute noted that the industry's

best strategy for countering public concern about

passive smoking was to fund and disseminate

scientific research that countered research produced

by other sources:

'The strategic and long-run antidote to

the passive smoking issue is, as we see it,

developing and widely publicizing clear-cut,

credible, medical evidence that passive

smoking is not harmful to the non-smoker's

health' (Roper Organization, 1978).

Philip Morris promoted international research

related to passive smoking in order to stimulate

controversy, as described in the notes of a meeting

of the UK [Tobacco] Industry on Environmental

Tobacco Smoke, London, 17 February 1988:

'In every major international area (USA,

Europe, Australia, Far East, South America,

Central America and Spain) we are proposing,

in key countries, to set up a team of scientists

organized by one national coordinating

scientist and American lawyers, to review

scientific literature or carry out work on ETS to

keep the controversy alive' (emphasis added)

(Boyse, 1988).

The tobacco industry organised teams of scientific

consultants all over the world with the main goal

of stimulating controversy about the adverse health

effects of second-hand smoke (Barnoya and Glantz,

2006; Chapman, 1997; Muggli et al., 2001; Grüning

et al., 2006; Assunta et al., 2004).

A variety of studies show that industry sponsorship

of research is associated with outcomes that are

favourable for the industry (Lexchin et al., 2003;

Barnes and Bero, 1998; Barnes and Bero, 1997).

One possible explanation for this bias in outcome

is that industry-sponsored research is poorly

designed or of worse 'methodological quality'

than non-industry-sponsored research. However,

there is no consistent association between industry

sponsorship and methodological quality (Lexchin

et al., 2003).

Factors other than study design can affect the

outcome of research, including:

• theframingorsocialconstructionoftheresearch

question;

• theconductofthestudy;

• thepublication(ornot)ofthestudyfindings.

The tobacco industry has manipulated these

other factors in a variety of ways. First, by using

its funding mechanisms to attempt to control the

research agenda and types of questions asked

about tobacco. Second, the industry's lawyers and

executives have been involved in the design and

conduct of industry-supported research. Third, the

tobacco industry has sponsored publications of its

own funded research, and suppressed research not

favourable to the industry.

Box 7.1 summarises the range of strategies that the

tobacco industry has used for decades to manipulate

information on the risks of tobacco. These strategies

are described in more detail in the remainder of this

section.

7.3.1 Strategy 1: fund research that supports the

interest group's position

The first element in the tobacco industry's strategy

to influence data on risk has been to sponsor

research designed to produce findings that are

favourable to the industry.

Funding research can stimulate controversy in

multiple ways. First, it can put the research agenda

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

155

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

Box 7.1 Tobacco industry strategies to manipulate data on risk

1. Fund research that supports the interest group position.

2. Hide industry involvement in research.

3. Publish research that supports the interest group position.

4. Suppress research that does not support the interest group position.

5. Criticise research that does not support the interest group position.

6. Change scientific standards.

7. Disseminate interest group data or interpretation of risk in the lay press.

8. Disseminate interest group data or interpretation of risk directly to policymakers.

in the control of the interest group. Second, it can

produce data to refute research on risk conducted

by others. In addition to stimulating controversy,

funding research serves other useful purposes for the

tobacco industry. The research can be disseminated

directly to policymakers and the lay press. It can

provide good public relations for the tobacco industry

by establishing it as a philanthropic body that funds

scientific research. Similarly, funding research can

increase the industry's credibility. One of the criteria

that the Philip Morris Worldwide Scientific Affairs

Programme considered when deciding whether to

fund a research application was whether the research

would enhance the credibility of the company

(Malone and Bero, 2003).

The US tobacco industry funded research through its

trade association, The Tobacco Institute (Bero et al.,

1995; Hanauer et al., 1995), internally (e.g. internal

company research), externally (e.g. by supporting

the research of scientific consultants) and through

sponsored research organisations. Tobacco industry

lawyers and executives were involved in selecting

which research to fund. Most of the research did not

undergo any form of independent scientific peer

review but was funded on the basis of its potential

to protect the interests of the companies.

Lawyer involvement in research

In the mid-1990s, internal tobacco industry

documents were circulated by industry

whistle-blowers. By 1998, the availability of tobacco

industry documents increased exponentially as

a result of the settlement of a suit by the State of

Minnesota and Blue Cross/Blue Shield against the

major tobacco companies. The Master Settlement

Agreement between the attorneys general of 46 states

and Brown & Williamson/British American Tobacco,

Lorillard, Philip Morris, RJ Reynolds, the Council

for Tobacco Research and The Tobacco Institute

released millions of additional documents to the

public. These documents provide an unprecedented

look at how tobacco industry lawyers were involved

in the design, conduct and dissemination of tobacco

industry-sponsored research (Bero, 2003). By

involving lawyers in research, the tobacco industry

protected their research activities from public

discovery and kept their lawyers informed about

science relevant to litigation.

The internal tobacco industry documents include

descriptions of research that was funded directly by

law firms. For example, the law firms of Covington

and Burling, and Jacob and Medinger, both of

which represent a number of tobacco company

clients, funded research on tobacco (Bero et al.,

1995). Lawyers selected which projects would be

funded. The supported projects included reviews

of the scientific literature on topics ranging from

addiction to lung retention of particulate matter.

The law firms also funded research on factors

potential confounding the adverse health effects

associated with smoking. For example, projects

examined genetic factors associated with lung

disease or the influence of stress and low-protein

diets on health (Bero et al., 1995). Thus, some of the

research funded by law firms served the purpose of

deflecting attention away from tobacco as a health

hazard and protecting the tobacco companies from

litigation.

Other research was funded directly by the tobacco

companies but lawyers were involved in selecting

and disseminating these projects. For example,

tobacco companies funded individuals to serve

as consultants to prepare expert testimony for

Congressional hearings, attend scientific meetings,

review scientific literature or conduct research on

the health effects of tobacco or second-hand smoke

(Hanauer et al., 1995). At one tobacco company,

Brown & Williamson, the legal department

controlled the dissemination of internal scientific

reports (Hanauer et al., 1995). The lawyers at Brown

& Williamson developed methods for screening

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

156

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

scientific reports from their affiliated companies

in order to ensure that scientific information

related to tobacco and health would be protected

from discovery by legal privileges. In a memo

dated 17 February 1986, J. K. Wells, the Brown &

Williamson corporate counsel, outlined one method

for protecting industry produced research data:

'The only way BAT [British American Tobacco]

can avoid having information useful to

plaintiff found at B&W is to obtain good legal

counsel and cease producing information in

Canada, Germany, Brazil and other places that

is helpful to plaintiffs' (Wells and Pepples,

1986).

Although tobacco industry public statements

claimed that the tobacco companies were funding

objective research to gather facts about the health

effects of smoking, lawyer involvement in the

research served to control the scientific debate on

issues related to smoking and health and protect

from discovery scientific documents that were

potentially damaging to the industry.

Research organisations

The tobacco industry also formed research funding

organisations, which gave the appearance that

the research they supported was independent of

influence from the industry.

The Council for Tobacco Research (CTR) was

formed by United States tobacco companies in 1954

as the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC).

The industry stated publicly that it was forming

the TIRC to fund independent scientific research

to determine whether there was a link between

smoking and lung cancer. However, internal

documents from Brown & Williamson Tobacco

Company have shown that the TIRC was actually

formed for public relations purposes, to convince

the public that the hazards of smoking had not been

proven (Glantz et al., 1996).

Research that is sponsored by federal organisations

or large foundations is typically peer reviewed

by other researchers before funding is approved.

Although the Council for Tobacco Research had

a Scientific Advisory Board consisting of well

respected researchers, not all of the research

funded by the CTR was peer reviewed by this

board. Beginning in 1966, tobacco industry lawyers

became directly responsible for many of the funding

decisions of the CTR. Between 1972 and 1991, the

CTR awarded at least USD 14 636 918 in special

project funding (Bero et al., 1995). Lawyers were not

only involved in selecting projects for funding but

also in designing the research and disseminating the

results (Bero et al., 1995).

The research funded by CTR, although initially useful

for public relations, became increasingly important

for the tobacco industry's activities in legislative and

legal settings. This evolution is described in a memo

dated 4 April 1978 from Ernest Pepples, Brown &

Williamson's vice president and general counsel,

to J. E. Edens, chairman and CEO of Brown &

Williamson Tobacco Company:

'Originally, CTR was organized as a public

relations effort. … The research of CTR

also discharged a legal responsibility. …

There is another political need for research.

Recently it has been suggested that CTR or

industry research should enable us to give

quick responses to new developments in the

propaganda of the avid anti-smoking groups.

… Finally, the industry research effort has

included special projects designed to find

scientists and medical doctors who might

serve as industry witnesses in lawsuits or in a

legislative forum' (Pepples, 1978).

The Pepples memo gives insight into why lawyers

became increasingly involved in the selection of

research projects for CTR.

The Center for Indoor Air Research (CIAR) was

formed by Philip Morris, R. J. Reynolds Tobacco

Company and Lorillard Corporation in 1988 (CIAR,

1988). The founding companies were joined by

Svenska Tobaks A.B., a Swedish domestic tobacco

company in 1994 (CIAR, 1994). The stated mission

of CIAR was 'to create a focal point organisation

of the highest caliber to sponsor and foster quality,

objective research in indoor air issues including

environmental tobacco smoke, and to effectively

communicate research findings to a broad scientific

community' (CIAR, 1989). CIAR's mission statement

was modified in 1992 to eliminate the words

referrring to environmental tobacco smoke (CIAR,

1992a; CIAR, 1992b). The elimination of research on

second-hand smoke from the mission statement was

followed by a shift in the research agenda of CIAR

to one that would prevent it investigating the health

effects of second-hand smoke.

Similar to the CTR, CIAR awarded 'peer-reviewed'

projects, which were reviewed by a Science Advisory

Board, and 'special-reviewed' projects, which

reviewed by its Board of Directors consisting of

tobacco company executives (Barnes and Bero, 1996).

From 1989 to 1993, CIAR awarded USD 11 209 388

for peer-reviewed projects and USD 4 022 723 for

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

157

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

special-reviewed projects (Barnes and Bero, 1996).

Seventy per cent of the peer-reviewed projects funded

by CIAR examined indoor air pollutants other than

tobacco smoke. Thus, the industry appeared to be

financing peer-reviewed projects through CIAR to

enhance its credibility, to provide good publicity and

to divert attention away from second-hand smoke as

an indoor air pollutant.

In contrast to the peer-reviewed projects, almost

two-thirds of CIAR's special-reviewed projects were

related to second-hand smoke (Barnes and Bero,

1996). In addition, most special-reviewed projects

studied exposure rather than health effects. It is

therefore possible that the tobacco industry was

funding research through CIAR to develop data it

could use to support its frequent claim that persons

are not exposed to sufficient levels of passive smoke

to cause any serious adverse health effects (Tobacco

Institute, 1986).

The tobacco industry may have also been funding

special-reviewed research through CIAR to develop

scientific data that it could use in legislative and

legal settings. Six CIAR-funded investigators

have testified at government hearings. All of the

statements submitted by them supported the tobacco

industry position that second-hand smoke exposure

is not harmful to health. Data from two of CIAR's

special-reviewed projects were presented at hearings

held by the United States Occupational Safety

and Health Administration (OSHA) regarding its

proposed indoor air quality regulation. Data from

a third special-reviewed project was presented at a

Congressional hearing related to a proposed ban on

smoking on commercial aircrafts. One CIAR-funded

study was investigated extensively by the United

States Congressional Subcommittee on Health and

the Environment after it was cited in testimony before

numerous government agencies. The CIAR-funded

study had concluded that, with good building

ventilation, clean air could be maintained with

moderate amounts of smoking (Turner et al., 1992)

and was used to support testimony that indoor

smoking restrictions are not necessary. However, the

Congressional Subcommittee found that data for this

study had been altered and fabricated. An earlier

CIAR-funded study by the same organisation was

also severely compromised because The Tobacco

Institute selected the sites where passive smoking

levels were measured for the study (Barnes and Bero,

1996).

The Center for Indoor Air Research was disbanded

as part of the US Master Settlement Agreement in

1998. However, in 2000, Philip Morris re-created an

external research programme called the 'Philip Morris

External Research Program' (PMERP) with a structure

similar to that of CIAR. Like CIAR, PMERP's grant

review panel consisted of a cohort of external peer

reviewers, a science advisory board, and an internal,

anonymous review and approval committee. Three

of the six advisory board members had a previous

affiliation with CIAR. The majority of the named

reviewers also had previous affiliations with the

tobacco industry (Hirschhorn et al., 2001).

Research is an international endeavour

The tobacco industry applied the strategy of

covertly funding research on an international scale.

In Latin America and Asia, tobacco companies,

working through the law firm Covington and

Burling, developed a network of physician and

scientist consultants to prepare and present data

to refute claims about the harms of second-hand

smoke (Assunta et al., 2004; Barnoya and Glantz,

2002). In Germany, tobacco companies and the

German Association of the Cigarette Industry

developed a similar team of consultants and funded

research through various foundations and research

organisations (Grüning et al., 2006). In many cases,

the industry employed the next strategy discussed

below: hiding its support for the research.

In summary, funding research serves multiple

purposes for the tobacco industry. The research

that is directly related to tobacco has been used to

refute scientific findings suggesting that the product

is harmful and sustain controversy about adverse

effects. Tobacco industry-supported research has

been used to prepare the industry for litigation or

legislative challenges. The industry may also have

funded research not directly related to tobacco in

order to generate good publicity, enhance industry

credibility and to distract from tobacco products as a

health problem.

7.3.2 Strategy 2: hide industry involvement in

research

A defining characteristic of the tobacco industry's

response to independent evidence of the harms of

second-hand smoke has been attempts to hide its

involvement in refuting this evidence. In both of

the cases described below, tobacco companies were

secretly involved in generating data to suggest

that second-hand smoke was not harmful and

suppressing data suggesting that it was.

Philip Morris European research programme on

second-hand smoke

As early as 1968, executives at Philip Morris began

planning a new biological research facility that

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

158

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

would focus on examining the effects, including

carcinogenic effects, of second-hand smoke

exposure in various animal species. In 1970,

Philip Morris purchased a research facility in

Germany, Institut für Industrielle und Biologische

Forschung GmbH (INBIFO) (Diethhelm et al.,

2004). Philip Morris hired Ragnar Rylander, a

Swedish university professor, as the coordinator

of INBIFO. Rylander communicated INBIFO's

research findings to Philip Morris executives

in the United States, who would then decide

whether to disseminate the research more

widely or keep it secret. Research that remained

unpublished included studies providing evidence

that 'sidestream smoke' (which enters the air

from a burning cigarette, cigar or pipe) is more

toxic than 'mainstream smoke' (which is inhaled

directly) (Diethhelm et al., 2004). Published

research included an epidemiological study

suggesting an association between lung cancer and

green tea, a finding that would be useful to the

tobacco industry in distracting from the harms of

second-hand smoke (Tewes et al., 1990).

One of the most striking features of the INBIFO

programme was that its coordinator, Ragnar

Rylander, had long-standing and secret links to

the tobacco industry. Thus, he conferred a false

sense of credibility to the programme. Professor

Rylander's association with the tobacco industry

was investigated by an official university committee,

the Fact Finding Commission of the University of

Geneva. The committee concluded that Rylander

was acting as a sponsored agent of the tobacco

industry, rather than as an independent researcher

when he testified as a scientific expert, organised

scientific congresses and directed research at

INBIFO (Fact Finding Commission, 2004). An

extensive analysis of internal tobacco industry

documents found that Rylander took no initiatives

'in the area of [second-hand smoke research] without

first consulting extensively with his contacts within

the tobacco industry'(Fact Finding Commission,

2004).

Tobacco industry creation and dissemination of

a study on second-hand smoke

The tobacco industry's development of the Japanese

Spousal Smoking Study provides another example

of industry involvement in designing, conducting

and disseminating research, and its efforts to hide

this involvement.

In 1981, Takeshi Hirayama published an influential

study showing an association of second-hand smoke

exposure and lung cancer (Hirayama, 1981). The

Hirayama study has been voted the most influential

paper ever on second-hand smoke (Chapman,

2005) and was the most frequently cited study

in regulatory hearings on smoking restrictions

(Montini et al., 2002). In these hearings, tobacco

industry representatives have argued that the

Hirayama study is flawed due to misclassification

bias (Bero and Glantz, 1993; Schotland and Bero,

2002). Furthermore, analysis of internal tobacco

industry documents by Hong and Bero (2002) has

shown how the tobacco industry hid its involvement

in creating a study, the Japanese Spousal

Smoking Study, to support its arguments about

misclassification bias.

The tobacco industry documents reveal that

although the Japanese Spousal Smoking Study

was undertaken by named Japanese investigators,

project management was conducted by Covington

and Burling (a tobacco industry law firm), the

research was supervised by a tobacco industry

scientist and a tobacco industry consultant assisted

in reviewing the study design and interpreting

the data (Hong and Bero, 2002). The documents

show that the tobacco companies that funded

the study did not want any of these individuals

named as co-authors on any of the resulting

scientific publications. Although the tobacco

companies considered using the Center for Indoor

Air Research (CIAR) as 'a cover' to fund the study,

three companies agreed to fund the study directly.

Progress reports for the study were prepared on

Covington and Burling stationery. When the study

was prepared for publication, the tobacco industry

consultant was the sole author (Lee, 1995). The

publication acknowledged 'financial support from

several companies of the tobacco industry' (Lee,

1995). This acknowledgement tells the reader little

about who was actually involved in the design,

conduct and publication of the study. The hidden

roles of the tobacco company lawyers and scientist

raise questions about who was accountable for the

research (Hong and Bero, 2002).

The analysis of tobacco industry documents (Hong

and Bero, 2002) was noticed by Dr E. Yano, one

of the Japanese investigators who was originally

involved in the Japanese Spousal Smoking study.

Dr Yano had been unaware that Dr Lee had

published the study. He had retained the original

data from the study and has reported that Dr Lee's

published analysis excluded data that did not

support misclassification bias (Yano, 2005). Dr Yano

demonstrated that using the full data from the

Japanese Spousal Smoking Study changes the

conclusion of Lee's published report. After 10 years,

the scientific community was able to obtain data that

had been suppressed by the tobacco industry.

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

159

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

7.3.3 Strategy 3: publish research that supports the

interest group position

Research has little impact unless it can be cited. The

tobacco industry has realised that funding research

that supports its interests must be followed by the

dissemination of such research in scientific literature.

The tobacco industry uses several vehicles to publish

the findings of its sponsored research, including

funding the publication of symposia proceedings,

books, journal articles and letters to the editors of

medical journals. To suggest that the research it funds

meets scientific standards and that there is substantial

support for its position, the tobacco industry then

cites its industry-funded, non-peer-reviewed

publications in scientific and policy arenas.

Symposium proceedings

Scientific meetings or symposia often result in

the publication of books or journal articles that

summarise the research presented there. The

pharmaceutical industry, for example, publishes

reports of symposia containing poor quality and

unbalanced articles favourable to particular drugs

(Bero et al., 1992; Rochon, 1994). The tobacco industry

has sponsored numerous symposia on second-hand

smoke (Bero et al., 1994) and paid for scientific

consultants to organise and attend these meetings

(Barnoya and Glantz, 2002, 2006; Muggli et al., 2001).

Between 1965 and 1993, reports on 11 symposia on

passive smoking were published. Six were published

as special issues of medical journals, while five were

published independently as books. None of the

symposia was peer reviewed; six were sponsored

by the tobacco industry or its affiliates such as the

Center for Indoor Air Research, The Tobacco Institute

and Fabriques de Tabac Reunies. Two of the six

industry-sponsored symposia did not explicitly

acknowledge industry sponsorship. The tobacco

industry sometimes sponsored conferences through

independent organisations so that their sponsorship

would be hidden (Bero et al., 1995; Bero et al., 1994).

The symposia on passive smoking were attended by

an international group of scientists and held across

the world, including Europe, the United States,

Canada, Japan and Argentina. One symposium report

was published in Spanish. CTR special projects were

often used to support scientists to prepare talks for

conferences and to send scientists to conferences

(Glantz et al., 1996).

On the surface, articles from symposia look like

articles from peer-reviewed journals. To test the

hypothesis that symposium articles on second-hand

smoke differ in content from articles on second-hand

smoke appearing in scientific journals, Bero et al.

(1994) compared the symposia articles to a random

sample of articles on passive smoking from the

scientific literature and to two consensus reports on

the health effects of passive smoking (US DHHS,

1986; NRC, 1986). Of the symposium articles,

41 % (122/297) were reviews, compared with 10 %

(10/100) of journal articles. Symposia articles were

significantly more likely than journal articles to

agree with the tobacco industry position that

tobacco is not harmful (46 % compared to 20 %),

less likely to assess the health effects of passive

smoking (22 % compared to 49 %), less likely to

disclose their source of funding (22 % compared

to 60 %), and more likely to be written by tobacco

industry-affiliated authors (35 % compared to 6 %).

Symposium authors published a lower proportion of

peer-reviewed articles than consensus report authors

(71 % compared to 81 %) and were more likely to be

affiliated with the tobacco industry (50 % compared

to 0 %) (Bero et al., 1994).

Symposia proceedings can potentially influence

policy because they are often cited as if they are

peer-reviewed articles and balanced reviews of

the scientific literature, with no disclosure of

their industry sponsorship. For example, tobacco

industry-sponsored symposia on second-hand

smoke have been used to attempt to refute both

peer-reviewed journal articles and risk assessments

of second-hand smoke (Bero and Glantz, 1993;

Schotland and Bero, 2002; Chapman et al., 1990).

Symposia articles have also been cited in tobacco

industry public relations materials and the press

(e.g. Tobacco Institute, 1986); and as the consensus

of a gathering 'of leading experts from around the

world' who disagree with the published literature on

passive smoking (Johnston and Sullum, 1994).

In summary, tobacco industry-sponsored symposia

articles on second-hand smoke consist, in large part,

of review articles that reach different conclusions

about the health effects of passive smoking than

peer-reviewed journal articles or consensus reports.

Furthermore, symposia are more likely to publish

research that discusses issues that distract from

tobacco as a health problem. The tobacco industry

affiliations of symposia authors suggest that industry

control over publication and research funding is

likely to influence the presentation of findings.

Quality of tobacco industry-funded symposium

publications

When policymakers, judges, lawyers, journalists

and scientists are presented with tobacco

industry-sponsored symposium articles, they must

decide whether to incorporate these publications into

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

160

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

their deliberations. Although the lack of balance and

peer review suggests that tobacco industry-sponsored

literature may lack scientific rigour, the issue of peer

review and study quality is a contentious subject.

Methodological quality is determined by the presence

or absence of study design characteristics aimed at

reducing bias, such as blinding, follow-up, controlling

for confounding and controlling for selection bias.

Barnes and Bero (1997) assessed the methodological

quality of the research presented at symposia.

As articles from pharmaceutical industry

sponsored symposia have been found to be of poor

methodological quality (Rochon, 1994; Cho and

Bero, 1996) it was hypothesised that articles from

tobacco industry-sponsored symposia would be

poorer in methodological quality than peer-reviewed

journal articles. Other characteristics of articles were

evaluated that might be associated with quality, such

as disclosure of the source of research sponsorship

and the study's conclusions, topics and design.

Original research articles on the health effects of

second-hand smoke published in peer-reviewed

journals were compared to those published in

non-peer-reviewed symposium proceedings from

1980 to 1994.

The study found that peer-reviewed articles were

better quality than symposium articles independent

of their source of funding, their conclusions on the

health effects of second-hand smoke and the type of

study design. Peer-reviewed articles received higher

scores than symposium articles for most of the criteria

evaluated by the quality assessment instrument.

Quality of tobacco industry-sponsored review

articles

Policymakers and clinicians often rely on review

articles to provide accurate and up-to-date

overviews of a topic of interest (Montini and Bero,

2001). As already noted, a large proportion of

symposium articles are reviews of the health effects

of second-hand smoke (Bero et al., 1994) and are

frequently cited in response to government requests

for information (Bero and Glatz, 1993; Montini

et al., 2002; Schotland and Bero, 2002). In view of

their importance in guiding policy, it is somewhat

disconcerting that published review articles often

reach markedly different conclusions about the

adverse health effects of second-hand smoke.

Barnes and Bero (1998) conducted a study to evaluate

the quality of review articles on the health effects

of passive smoking and to determine whether

the conclusions of review articles are primarily

associated with their quality or with other article

characteristics. The a priori hypotheses were that

review articles concluding that passive smoking is not

harmful would tend to be poor in quality, published

in non-peer-reviewed symposium proceedings

and written by investigators with tobacco industry

affiliations. The topic of the review and the year

of publication were also reviewed as potential

confounding factors.

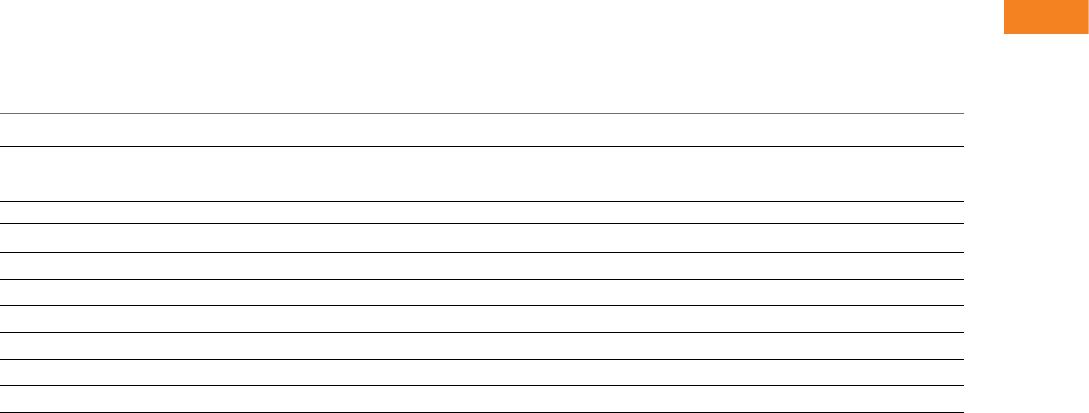

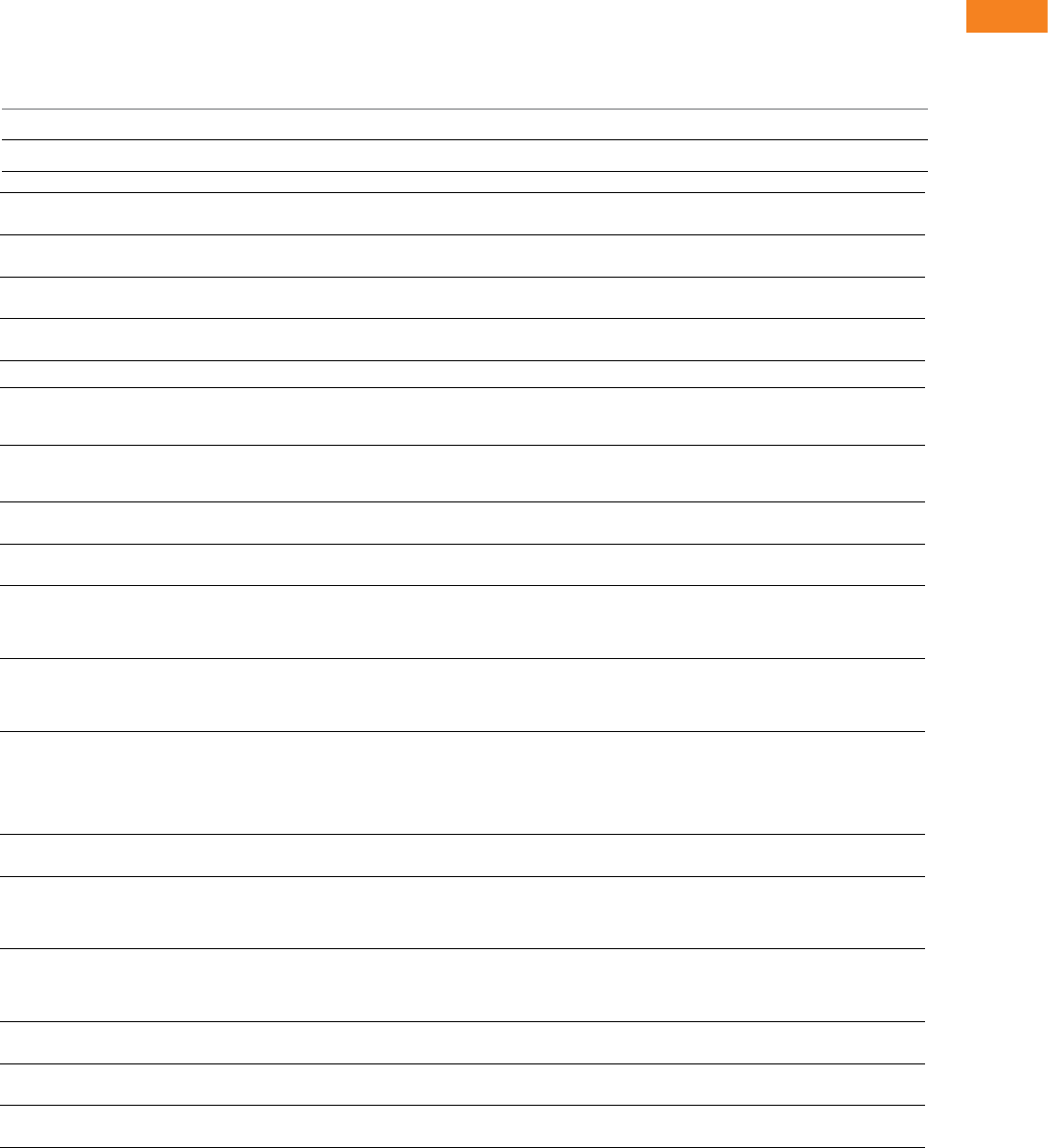

In the sample of 106 review articles, the only factor

associated with concluding that passive smoking is

not harmful was whether the author of the review

article was affiliated with the tobacco industry

(Barnes and Bero, 1998). As shown in Table 7.1,

review articles concluding that passive smoking is

not harmful were about 90 times more likely to be

funded by the tobacco industry than those concluding

that second-hand smoke is harmful. Methodological

quality, peer-review status, outcomes studied

in the reviews, and year of publication were not

associated with the conclusions of the articles. Thus,

sponsorship of review articles by the tobacco industry

appears to influence the conclusions of these articles,

independent of methodological quality.

The tobacco industry has argued that independent

reviews of second-hand smoke are flawed because

studies with statistically significant results are more

likely to be published than studies with statistically

non-significant results (Dickersin et al., 1992; Shook,

Hardy and Bacon, 1993). The industry argues that

publication bias — the tendency to publish work

with statistically significant results — prevents the

identification of all relevant studies for reviews of the

health effects of second-hand smoke (e.g. Armitage,

1993). Bero et al. (2004) conducted a preliminary

Photo: © istockphoto/Richard Clark

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

161

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

Table 7.1 Factors associated with review articles concluding that passive smoking is not

harmful to health: multiple logistic regression analysis

Factor Odds ratio (95 % CI) P value

Quality score 1.5 (< 0.1–67.5) 0.83

Not peer reviewed v. peer reviewed 1.3 (0.3–5.4) 0.70

Tobacco industry sponsored v. not tobacco industry sponsored 88.4 (16.4–476.5) < 0.001

Outcomes — lung cancer v. other clinical outcomes 1.6 (0.2–10.3) 0.63

Heart disease v. other clinical outcomes 1.6 (0.2–14.7) 0.67

Year of publication 1.1 (0.9–1.3) 0.45

Source: Barnes and Bero, 1998.

study of publication bias showing that statistically

non-significant studies are published: approximately

20 % of the published peer-reviewed articles on passive

smoking present statistically non-significant findings.

By interviewing investigators studying second-hand

smoke and health effects, Misakian and Bero

(1998) determined that studies with statistically

non-significant results take about two years longer to

be published than those with statistically significant

results. For studies conducted in humans, only

statistical significance was predictive of time to

publication, not study design or sample size. Thus,

the tobacco industry's argument that statistically

non-significant results are not published is invalid.

Since statistically non-significant results are published

but take longer to be published than statistically

significant results, reviews of research should attempt

to include unpublished data and be periodically

updated. Reviews conducted by the Cochrane

Collaboration, for example, attempt to identify

unpublished studies and include them in reviews

if they meet quality standards. Cochrane reviews,

which are published online, are also regularly

updated (Bero and Rennie, 1995).

7.3.4 Strategy 4: suppress research that does not

support the interest group position

Interest groups are eager to fund and publish

research that supports their position and hesitant

to publicise research that does not. In some

cases, tobacco industry lawyers and editors have

edited their externally funded scientific research

publications; in other cases they have prevented

publication of the research (Hong and Bero, 2002;

Muggli et al., 2001; Barnoya and Glantz, 2002).

Editing has included attempts to obscure evidence

on adverse health effects by using the code word

'zephyr' for 'cancer' in internal memos about health

effects research (Glantz et al., 1996; BAT, 1956).

Research conducted internally by tobacco companies

or through industry-controlled research organisations

is likely to be suppressed if it is unfavourable to

the industry. For example, the German tobacco

industry-supported research organisation, INBIFO,

did not publish its research showing that sidestream

smoke is more toxic than mainstream smoke

(Grüning et al., 2006).

Tobacco companies have also conducted internal

research on the use of chemical additives to reduce,

mask or otherwise alter the visibility, odour, irritation

or emission of second-hand smoke. Some of these

studies showed that the additives increased emissions

of toxins such as carbon monoxide or the carcinogenic

substances, N'-nitrosoniornicotine and benzo(a)

pyrene (Conolly et al., 2000). Virtually none of this

research has been published in scientific literature,

however, and data on additives is not typically

available to public health policymakers.

7.3.5 Strategy 5: criticise research that does not

support the interest group position

Another strategy that the tobacco industry has used

to stimulate controversy about research on risk has

been to criticise research that is not favourable to

its position. Science is improved by constructive

criticism. However, the tobacco industry has misused

legitimate means of scientific debate, such as letters

to the editor of scientific journals and editorials.

The tobacco industry has also used less legitimate

methods to criticise research, including attacking the

integrity of researchers or obtaining data through

lawsuits and reanalysing it using inappropriate

techniques (Barnes et al., 1995).

In order to get its views into public commentary on

risk assessments (Bero and Glantz, 1993; Schotland

and Bero, 2002) or the lay press (Chapman et al.,

1990), the tobacco industry has frequently cited

letters to the editor as if they were peer-reviewed

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

162

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

journal articles. Letter authors affiliated to the tobacco

industry often fail to disclose their affiliation. These

findings support the suggestions by a number of

journal editors that letter writers should disclose

potential conflicts of interest and that journals should

peer review letters (Rennie, 1993).

As mentioned above, the tobacco industry has

maintained large teams of international scientific

consultants (Chapman, 1997; Muggli et al., 2001;

Barnoya and Glantz, 2002). A major goal of the

tobacco industry's scientific consultancy programme

was to refute data about the harmful effects of

tobacco. Industry consultants were paid to criticise

independent research on tobacco and second-hand

smoke via participation in scientific conferences;

publications such as conference proceedings, journal

articles and books; media appearances; testimony at

tobacco litigation trials; forming a scientific society on

indoor air; and preparing statements for government

committees. The industry consultant programmes

were international and were used to discredit

research conducted by non-industry scientists around

the world (Chapman, 1997; Muggli et al., 2001;

Barnoya and Glantz, 2002).

7.3.6 Strategy 6: changing scientific standards

As described above, the tobacco industry has devoted

enormous resources to attacking and refuting

individual scientific studies. In addition, the industry

has attempted to manipulate scientific methods and

regulatory procedures for its benefit. The tobacco

industry has influenced the debate around 'sound

science' (Ong and Glantz, 2001), standards for

risk assessment (Hirschhorn and Bialous, 2001),

international standards for tobacco and tobacco

products (Bialous and Yach, 2001) and laws related to

data access and quality (Baba et al., 2005).

The tobacco industry has played a major role in

developing ventilation standards for indoor air

quality and in establishing international standards

for tobacco and tobacco products. The International

Organization for Standardization (ISO) develops

international standards for tobacco and tobacco

products, including the measurement of tar and

nicotine yield. The tobacco industry, working through

the Cooperation Centre for Scientific Research

Relative to Tobacco (CORESTA) gathered scientific

evidence for ISO and suggested the standards

that were adopted (Bialous and Yach, 2001). These

standards incorrectly imply that there are health

benefits from low-tar and low-nicotine products

(Djordjevic et al., 1995). The tobacco industry

has also been involved in developing ventilation

standards for over 20 years. The industry influenced

the development of ventilation standards by the

American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air

Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) by generating

data and presenting it to the committee (Bialous and

Glantz, 2002). This resulted in a standard that ignores

the health effects of second-hand smoke exposure,

concentrating instead on a 'comfort' standard.

In the early 1990s, the tobacco industry launched a

public relations campaign about 'sound science' and

'good epidemiological practices' (GEP) and used this

rhetoric to criticise government reports, particularly

on the harms of environmental tobacco smoke. All

scientists agree that research should be rigorously

conducted. But the 'sound science' and 'GEP'

campaigns were public relations efforts controlled

by industry executives and lawyers to promote

unreasonably high standards of proof about the harm

caused by the industry's products. For example,

'sound science' rhetoric argues that epidemiological

studies can never establish evidence of harm because

they cannot 'prove' causality. This approach ignores

the fact that a comprehensive assessment of risk

involves considering all the evidence related to a

toxin, not just the epidemiology (Ong and Glantz,

2001).

The tobacco industry also developed a campaign

to criticise the technique of risk assessment of low

doses of a variety of toxins (Hirschhorn and Bialous,

2001). The tobacco industry worked with the

chemical, petroleum, plastics and chlorine industries

to develop its criticisms of risk assessment. In fact,

the first version of GEP was drafted by the Chemical

Manufacturers Association. After about ten years, by

the late 1990s, the industry's 'sound science' public

relations campaign ended. The tobacco industry

then turned to advancing the 'sound science' concept

through legislation (Baba et al., 2005).

One major goal of the tobacco industry has been to

obtain data from independent studies and reanalyse

it using 'sound science' criteria to reach different

conclusions. Philip Morris, for example, used a

three-step strategy to obtain data:

1. asking the researchers for the data directly;

2. litigation;

3. encouraging the enactment of policies that release

data (Baba et al., 2005).

The industry's efforts resulted in 'sound science

legislation': laws that influenced access to data and

standards for data analysis.

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

163

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

In 1998, the United States Congress enacted a data

access law as a rider to the Fiscal Year 1999 Omnibus

Appropriations Act (US Congress, 1999). The law,

for the first time, made all data produced under

federally funded research studies available on

request through the Freedom of Information Act

(FOIA) (Zacaroli, 1998). Two years after the adoption

of the data access provision, another amendment

was added to the 2001 Omnibus Appropriations

Act. The Data Quality Act (2000) requires the

Office of Management and Budget to develop

government-wide standards for data quality in the

form of guidelines. Individual federal agencies must

promulgate their own conforming guidelines based

on OMB's model and adopt standards that 'ensure

and maximise the quality, objectivity, utility and

integrity of information disseminated' by federal

agencies (OMB Watch, 2002). The standards to be

adopted were created by the industry sponsors, not

independent researchers.

While the public had an opportunity to comment

on implementing the laws, these amendments

were initially passed and adopted without a

legislative hearing, committee review or debate

(Renner, 2002). The scientific, academic research

and public health communities voiced concerns

during the public comment period about

potential problems with confidentiality of medical

information, discouragement of research subjects,

misinterpretation of incomplete or prematurely

released data sets, delay of research, protection of

national security information, and administrative

and financial burdens (AAAS, 1999). The research

community was also concerned that these measures

were supported by industry groups seeking to

contest environmental and other regulations

(Zacaroli, 1998).

Although the tobacco industry intended to hide

its involvement in the data access and quality acts,

internal industry documents reveal that these policies

were driven by tobacco industry efforts to coordinate

corporate interests. Tobacco industry strategies to

advance sound science legislation included (Baba

et al., 2005):

• demonstratingthatthepubliccaresaboutthe

issue by sponsoring a poll on issues of data access

and rules of epidemiological studies that can be

made public;

• leveragingalliesandgroupsthathavealready

taken a stand on the issue;

• usingscientistsandtechnicalconferencestofocus

on the issue;

• encouragingasmallgroupofmembersof

Congress to take a stand on the issue;

• encouragingtheAdministrationtotakeastand

for sound science;

• mobilisingalliedindustries(i.e.fishing,utilities,

waterworks) to lobby their local representatives;

• helpingtoorganisecoalitionsforother

epidemiological issues coming up soon

(e.g. fishing industry, mercury, methyline

chloride);

• educatingandmobilisingthebusiness

community on sound science v. junk science and

the federal legislative/regulatory process;

• usingstatestogenerateaction—conducting

briefings in states on epidemiological studies

and the need for uniform standards and

encouraging the passage of state laws;

• developingbroadbipartisansupportfor

'freedom of information' with regards to the data

behind regulations and laws;

• leveraginglobbyiststocontactkeylegislative

members;

• briefingthemedia;

• briefingbusinesscoalitionsontheneedfordata

access;

• usingtheCongressionalScienceCommitteeto

influence Congress.

Together, the data access and data quality acts

provide a mechanism for challenging the scientific

merit of data outside scientific journals and other

channels of scientific review (McGarity, 2004;

Kaiser, 1997). As scientists, legal experts and

environmentalists have pointed out, however,

the data access and data quality riders have the

potential to block agencies from using emerging

science from non-industry sources and to slow the

regulatory process (Kaiser, 2003; Hornstein, 2003;

Shapiro, 2004). The laws can be used to prevent

future policies and to repeal existing policies that

do not meet the data quality standards. The laws

could shift the scientific standards of data used for

policy purposes to favour standards promulgated

by industry. Finally, access to data and quality

standards are not applied equitably; they only apply

to data generated with government funding, not

industry funding.

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

164

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

Panel 7.1 Shaping risk assessment in the US and the EU: the role of the tobacco industry

Katherine Smith, Anna Gilmore and Gary Fooks

The interest of Philip Morris in shaping risk assessment was precipitated by the US EPA risk assessment

of environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), which resulted in ETS being categorised as a class A human

carcinogen (Hirschhorn and Bialous, 2001). Philip Morris challenged the assessment as part of its broader

'sound science' campaign (Ong and Glantz, 2001). This involved lobbying for laws requiring that:

• epidemiological studies meet a particular set of criteria or standards before they can officially inform

policy decisions;

• epidemiological data used in publicly funded studies be made available through freedom of information

requests.

Although the tobacco industry's campaign was ultimately unsuccessful in overturning the EPA's

classification of ETS, it did manage to place 'a cloud over its validity' until 2002 (Muggli et al., 2004),

leading to delays in subsequent introduction of protective legislation. Further, Philip Morris had some

success in introducing data access laws and shaping the Data Quality Act (2000) (Baba et al., 2005).

Philip Morris believed that a similar campaign might be even more effective in Europe, where officials had

not yet taken up the scientific threat of ETS to the same extent. From the mid-1990s onwards, therefore,

it focused its campaign more heavily on Europe. Here, informed by what the Chemical Manufacturers

Association had termed 'good epidemiological practice' (GEP), Philip Morris concentrated on lobbying for a

mandatory set of criteria or standards that epidemiological studies would have to meet before they could

be officially considered by policymakers in Europe (Ong and Glantz, 2001). The Philip Morris standards for

'good epidemiological practice' included a requirement for evidence relating to relative risks of less than

2.0 to be disregarded as too weak to warrant policy intervention.

As of late 2000 Ong and Glantz (2001) concluded that, despite the efforts of Philip Morris, 'no European

Union resolution on GEP had been produced'. As far as we are aware, this remains the case.

British American Tobacco (BAT) managers studied the Philip Morris campaigns carefully and from

1995 onwards considered lobbying for a mandatory requirement for 'structured risk assessment' in

EU policymaking because they believed it could be used to prevent the introduction of public smoking

restrictions (Smith et al., 2010; BAT, 1995 and 1996). By this stage, the industry was well aware

of the negative health impacts of second-hand smoke and was simultaneously trying to influence

the evidence-base on this issue. BAT managers believed that 'a legislated demand for structured

risk assessment', governed by strict 'rules for the assessment of epidemiological and animal data'

would 'remove the possibility of introducing public smoking restrictions that are based on risk claims'

(BAT, 1995).

Our analysis of BAT's internal documents has not yet established precisely what BAT managers meant

when they used the term 'structured risk assessment'. All of the documents with titles indicating that they

include detailed information on this issue have been redacted (

3

).

A 1995 BAT document makes it clear that the company's interpretation of 'risk assessment' involved a

set of 'rules for the assessment of epidemiologic and animal data', which BAT managers believed would,

if applied, make it 'apparent that ETS has not been proven to be a cause of disease in non-smokers'

(BAT, 1995).

BAT managers wanted to use risk assessment as a way of limiting officials' discretion. For example, a

document discussing the company's efforts to influence risk assessment says: 'The challenge will be

to persuade government departments to subordinate policy or judgemental considerations in favour of

scientific rigour in risk assessment' (Gretton, undated [circa 1995]).

(

3

) See for example BAT (1991 and 1996). The Legacy Tobacco Documents Library website, which hosts these documents, states that

the term 'redacted', 'Indicates whether the document contains words or sentences that were erased (redacted) by the tobacco

company due to confidentiality issues (i.e. trade secrets, attorney/client privileges) before the document was publicly released'

(University of California, 2011).

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

165

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

Panel 7.1 Shaping risk assessment in the US and the EU: the role of the tobacco industry

(cont.)

In practice, this constituted a way of undermining the precautionary principle as a basis for policy

decisions.

The key innovation of BAT's European campaign was the decision to focus on promoting risk assessment

within a framework of 'cost-benefit analysis', a term that BAT used interchangeably with business

impact assessment (see Smith et al., 2010). This had the additional effect of embedding economic

considerations into the risk assessment process, which would also require interventions to protect the

public against particular risks to be justified on the basis of economic costs (BAT, 1996; European Policy

Centre, 1997).

BAT initially sought advice on how to shape risk assessment in the EU from the US advisers to Philip

Morris, Covington and Burling (Covington and Burling, 1996). They advised BAT that although there was

little interest in risk assessment within the European Commission at the time it might be possible to

include 'structured risk assessment' in detailed guidance for business impact assessments, which had been

flagged as a priority for the European Commission in 1996.

BAT was aware that a campaign for regulatory reform with known links to the tobacco industry was

unlikely to succeed (Honour, 1996). It had been advised to work through a 'front group' and to recruit

other companies with similar interests, such as other large firms in regulated sectors (MacKenzie-Reid,

1995). Following this advice, BAT approached the European Policy Centre (a prominent Brussels‑based

think tank with strong links to the Commission) to lobby for regulatory reforms on its behalf (Smith et al.,

2010). BAT and the European Policy Centre then jointly set about recruiting other business interests to this

campaign (Smith et al., 2010). These companies, which included large corporations from the oil, chemical

and pharmaceuticals sectors, established an invitation‑only sub‑group within the European Policy Centre,

known as the Risk Forum (Smith et al., 2010).

These efforts contributed to certain amendments to the Treaty on European Union (EU, 1997), placing a

legal duty on the Commission to 'consult widely' and to minimise the potential 'burden' of policy changes

on 'economic operators' and others (EU, 1997). BAT interpreted this to mean that business impact

assessment and risk assessment were now mandatory within EU policymaking. The company perceived

this as 'an important victory' (BAT, undated).

The guidelines for EU officials on how to undertake impact assessment have been revised several times

since and now incorporate guidance on undertaking risk assessment (European Commission, 2009).

In 2006–2007, under pressure to open up to civil society organisations and other members of the

European Policy Centre (which was under new leadership), the coalition of companies involved in the

think tank's Risk Forum left and established a separate organisation called the European Risk Forum. This

group describes itself as 'an expert led, not-for-profit think tank' (European Risk Forum, 2008a), despite

solely representing corporate interests, virtually all of which are connected to the chemical and tobacco

industries. This was confirmed via personal correspondence from the Forum's chair, Dirk Hudig, in February

2010. The European Risk Forum is now actively encouraging the European Commission to adopt a more

structured approach to risk assessment and risk management (European Risk Forum, 2008b), although it

remains unclear precisely what this involves.

Recent analyses suggest that these corporate efforts have been somewhat successful in redefining

policymakers' understandings of and responses to risks, including those that limit use of the precautionary

principle in the EU (Löfstedt, 2004) and the United Kingdom (Dodds, 2006). However, as risk assessment

continues to be actively debated in Brussels, it is not yet possible to assess the success of the BAT or Philip

Morris campaigns.

It is of course legitimate for corporate interests to contribute to discussions on assessing scientific evidence

and weighing up risks. However, it is important to ensure that this influence is transparent, is not excessive

in comparison to other stakeholders, and does not compromise public welfare.

Lessons from health hazards | Tobacco industry manipulation of research

166

Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation

7.3.7 Strategy 7: disseminate interest group data

or interpretation of risk in the lay press

While the tobacco industry appears to have

recognised the importance of publishing work that

supports its position in the scientific literature,

the industry also seems aware of the need to get

research data directly into the hands of the public

and policymakers. How, then, were the public

and other stakeholders involved in generating,

presenting, understanding, communicating and

using science to refute data on the adverse health

effects of tobacco?

The important role of the media in communicating

risk has been extensively studied (Nelkin, 1985;

Raymond, 1985). The tobacco industry has been

active in stimulating controversy in lay print media

about the health effects of second-hand smoke. In

a cross-sectional sample of 180 North American

newspaper and 95 magazine articles reporting on

second-hand smoke research between 1981 and

1995, Kennedy and Bero (1999) found that 66 % of

newspaper articles and 55 % of magazine articles