CHAPMAN LAW REVIEW

!

CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY | FOWLER SCHOOL OF LAW | ONE UNIVERSITY DRIVE | ORANGE,

CALIFORNIA 92866

WWW.CHAPMANLAWREVIEW.COM

Citation: F. E. Guerra-Pujol, Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death

Foretold, 23 CHAP. L. REV. 99 (2020).

--For copyright information, please contact [email protected].

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

99

Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political

Death Foretold

F. E. Guerra-Pujol

*

PROLOGUE ................................................................................... 99

ACT I: A BEAUTIFUL IDEA .......................................................... 101

ACT II: MILLS TO THE RESCUE ................................................... 106

ACT III: DEATH BY COMMITTEE ................................................. 110

EPILOGUE .................................................................................. 121

PROLOGUE

This symposium issue of the Chapman Law Review is

devoted to various landmark laws enacted by the 91st Congress,

including the National Environmental Policy Act,

1

the Organized

Crime Control Act,

2

the Bank Secrecy Act,

3

the Controlled

Substances Act,

4

and the Housing and Urban Development Act.

5

This Article, by contrast, will explore what could have been: The

Family Assistance Act of 1970 (“H.R. 16311”). Had this historic

bill been enacted into law, it would have authorized a negative

income tax, thus providing a minimum guaranteed income to all

poor families with children.

6

In the words of Daniel Patrick

Moynihan, “Family Assistance was income redistribution, and by

any previous standards it was massive.”

7

Although it passed the

House by a wide margin, and although there were sufficient

* F.E. Guerra-Pujol is a professor at University of Central Florida. He earned his J.D.

from Yale Law School and his B.A. from University of California, Santa Barbara. Thanks to

Caroline Cordova, Jillian Friess, and Antonella Vitulli for their comments and suggestions.

1 Pub. L. No. 91-190, 83 Stat. 852 (1970).

2 Pub. L. No. 91-452, 84 Stat. 922 (1970).

3 Pub. L. No. 91-508, 84 Stat. 1118 (1970).

4 Pub. L. No. 91-513, 84 Stat. 1242 (1970).

5 Pub. L. No. 91-609, 84 Stat. 1770 (1970).

6 VINCENT J. BURKE & VEE BURKE, NIXON’S GOOD DEED: WELFARE REFORM 108–09

(1974). This book was the brainchild of Vince Burke, the urban affairs and social welfare

reporter for the Los Angeles Times. See id. at xv. His wife Vee completed the book after

Vince died of cancer in 1973. See id. at xvi.

7 DANIEL P. MOYNIHAN, THE POLITICS OF A GUARANTEED INCOME 385, 385 (1973).

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

100 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

votes to clear the Senate, the guaranteed income bill never made

it to the floor of that august body.

8

Given that the 91st Congress enacted so many historic laws,

why did H.R. 16311 end in failure? The history of the Family

Assistance Act has received a great deal of scholarly attention.

Previous studies, for example, have surveyed the legislative

history of the guaranteed income bill,

9

scrutinized the economics

of the bill,

10

dissected liberal and conservative opposition to the

bill,

11

or emphasized the spillover effects of the Vietnam conflict

on the bill.

12

This Article, by contrast, will narrate the fate of

H.R. 16311 in the form of a three-act legislative morality play. To

this end, this Article is structured as follows:

Act I will introduce the hero of our story, the idea of a

guaranteed income via a negative income tax, and retrace the

intellectual origins of this idea. Next, Act II will spotlight the

shrewd tactics of the second-most powerful man in Washington,

D.C., Representative Wilbur D. Mills, the chairman of the House

Ways and Means Committee, who skillfully shepherded the

guaranteed income bill through the House of Representatives.

Last, Act III will introduce the villain of our story, Senator

Russell D. Long, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.

I make no apologies about casting Senator Long as the villain.

This pro-segregation Dixiecrat, who once referred to welfare

mothers as “Brood Mares,”

13

used his position of power to thwart

the bill at every turn. A brief epilogue concludes.

Although the hero of our story is an idea, not a person, its fate

will be no less dramatic than that of a traditional flesh-and-bones

protagonist. At the time, many social liberals and welfare advocates

8 For a comprehensive legislative history of H.R. 16311, see CONGRESSIONAL

QUARTERLY, Welfare Reform: Disappointment for the Administration, in 1970 CONGRESSIONAL

QUARTERLY ALMANAC 1030 (1970).

9 See generally M. KENNETH BOWLER, THE NIXON GUARANTEED INCOME PROPOSAL:

SUBSTANCE AND PROCESS IN POLICY CHANGE 6 (1974); Leland G. Neuberg, Emergence and

Defeat of Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan (FAP) (U.S. Basic Income Guarantee, Working

Paper No. 66, 2004).

10 See Jonathan H. Hamilton, Optimal Tax Theory: The Journey from the Negative

Income Tax to the Earned Income Tax Credit, 76 S. ECON. J. 860 (2010); see also D. Lee

Bawden, Glen G. Cain & Leonard J. Hausman, The Family Assistance Plan: An Analysis

and Evaluation, 19 PUB. POL’Y 323, 352–53 (1971); Aaron Wildavsky & Bill Cavala, The

Political Feasibility of Income by Right, 18 PUB. POL’Y 321 (1970), reprinted in AARON

WILDAVSKY, THE REVOLT AGAINST THE MASSES 71–100 (2003).

11 See BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 106; see also MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at

384–85; see also Hamilton, supra note 10, at 871–73.

12 See Felicia Kornbluh, Who Shot FAP? The Nixon Welfare Plan and the

Transformation of American Politics, 1 SIXTIES: J. HIST., POL. & CULTURE 125, 125 (2008).

13 See 114 CONG. REC. 10,543 (1968) (remarks by Hon. Walter F. Mondale); see also

MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 518–19. For a more forgiving, or nuanced, view of Senator Russell’s

racist perspectives, see MICHAEL S. MARTIN, RUSSELL LONG: A LIFE IN POLITICS 115–16 (2014).

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 101

complained the bill’s proposed annual stipend was too low, while at

the same time many fiscal conservatives and so-called Dixiecrats

(Southern Democrats) thought the plan was too costly.

14

Moreover,

how can a guaranteed income bill help the poor without distorting

work incentives or increasing taxes on everyone else? These are, of

course, mutually incompatible goals. Hence, with apologies to the

late Latin American literary giant Gabriel García Márquez, the title

of this legislative play.

15

ACT I: A BEAUTIFUL IDEA

The first act of a dramatic work is usually used for exposition

and to establish who the main characters are.

16

At some point

during the first act, an inciting incident or conflict situation will

occur. This incident calls the main character, or protagonist, of

the story to action. The hero will have to make a decision—one

that will change his life forever.

The hero of our three-act play is not a person, however, but

rather an idea: a guaranteed minimum income to all persons via

a negative income tax. The idea of a guaranteed income has an

illustrious pedigree. Historical figures as diverse as Bertrand

Russell, Edward Bellamy, and Thomas Paine—polymath,

utopian planner, and patriot alike—all advocated for some form

of universal basic income in their day.

17

But it was the

conservative economist and future Nobel Laureate, Milton

Friedman, along with his wife Rose Friedman, who coined the

term “negative income tax” in a best-selling book, Capitalism and

Freedom, and in the popular press.

18

14 The bill’s proposed annual stipend for a family of four was $1,600, or about

$10,000 in 2020 dollars. See infra text accompanying notes 29–30.

15 GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ, CHRONICLE OF A DEATH FORETOLD (Gregory Rabassa

trans., First Vintage International ed. 2003). The Nobel Prize in Literature 1982 was

awarded to Gabriel García Márquez “for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic

and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a

continent’s life and conflicts.” The Nobel Prize in Literature 1982, NOBEL PRIZE,

http://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1982/summary/ [http://perma.cc/7WHV-U4N6]

(last visited Feb. 28, 2020). Unlike the great García Márquez, however, I will tell the story of

the Family Assistance Act in a linear fashion.

16 See, e.g., DAVID TROTTIER, THE SCREENWRITER’S BIBLE: A COMPLETE GUIDE TO

WRITING, FORMATTING, AND SELLING YOUR SCRIPT 5–7 (3d ed. 1998).

17 See BERTRAND RUSSELL, THE PROPOSED ROADS TO FREEDOM, 109–10 (2004); see

also Thomas Paine, Agrarian Justice (1797), in JOHN CUNLIFFE & GUIDO ERREYGERS,

EDS., THE ORIGINS OF UNIVERSAL GRANTS 3–16 (2004); EDWARD BELLAMY, LOOKING

BACKWARD: 2000–1887 (Daniel H. Borus ed., 1995).

18 See MILTON FRIEDMAN, CAPITALISM AND FREEDOM 191–94 (40th Anniversary ed.

2002); see also Milton Friedman, Negative Income Tax—I (1968), in MILTON FRIEDMAN,

BRIGHT PROMISES DISMAL PERFORMANCE: AN ECONOMIST’S PROTEST 348–50 (William R. Allen

ed., 1972); Milton Friedman, Negative Income Tax—II (1968), in id. at 351–53. Professor

Friedman would be awarded “The Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel” in

1976. The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, COLUMBIA

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

102 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

Although the idea of a reverse income tax predates

Friedman,

19

it was Milton and Rose Friedman who brought this

unorthodox idea to a popular audience and made it palatable to

social conservatives. If Capitalism and Freedom was destined to

become Friedman’s most famous work,

20

the negative income tax

chapter of his book put forth one of his most original, provocative,

and beautiful ideas.

21

In summary, Friedman proposed that the

federal income tax should be graduated—not only upward, but also

downward. Under Friedman’s proposed negative income tax

scheme, a person without any income would receive a modest

guaranteed income of $300 per year.

22

Later, Friedman would

revise this amount upward, recommending a minimum guaranteed

income of $1,500 for a family of four.

23

Friedman’s negative income

tax thus inspired the 1970 guaranteed minimum income bill: “Had

it not been for Friedman’s endorsement of the basic principles

underlying Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan (FAP) . . . it is unlikely

that FAP would ever have left the White House.”

24

But if the hero of our story is Milton and Rose Friedman’s

negative income tax idea, what is the inciting incident or call to

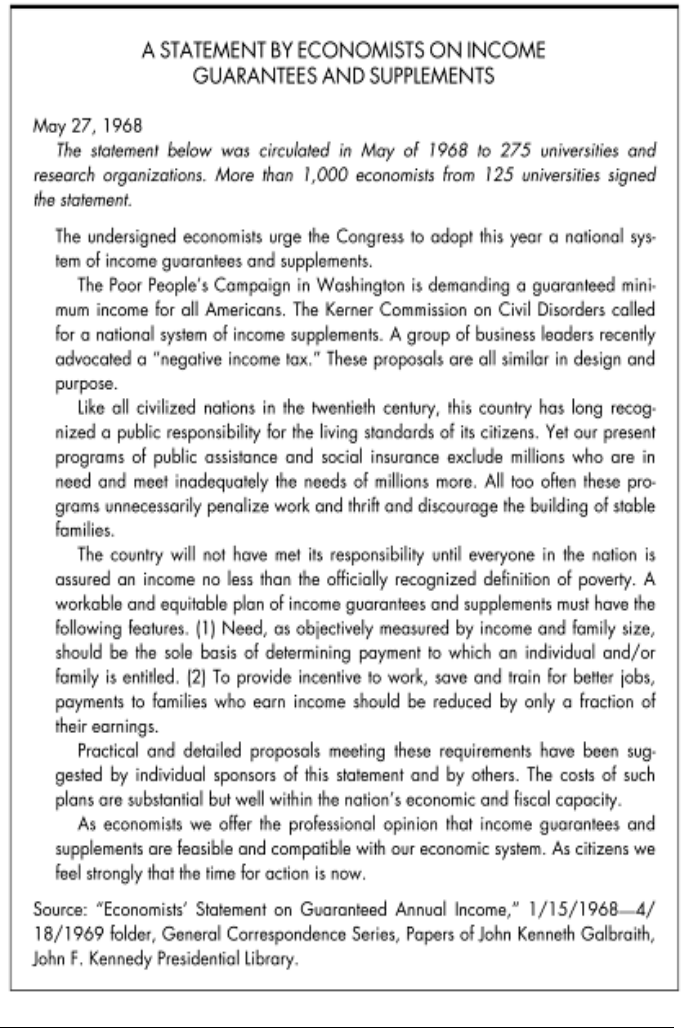

action of our doomed legislative tale? One possibility is a May 27,

1968 letter, which was signed by over 1,000 North American

academic economists, calling on Congress to enact “a workable and

equitable plan of income guarantees . . . .”

25

This letter, which was

co-authored by a group of leading economists—including such

ECON., http://econ.columbia.edu/faculty/nobel-laureates/the-sveriges-riksbank-prize-in-economic-

sciences-in-memory-of-alfred-nobel/ [http://perma.cc/96HA-S2KD]. Although Milton Friedman’s

name appears as the sole author on the front cover of Capitalism and Freedom, he wrote

this book in collaboration with his wife, Rose D. Friedman. See LANNY EBENSTEIN,

MILTON FRIEDMAN: A BIOGRAPHY 140 (2007).

19 See BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 140–41. As an historical aside, the first

Anglo-American person to propose a negative income tax as the mechanism for

providing a guaranteed income was Lady Juliet Rhys-Williams. See Peter Sloman,

Beveridge’s Rival: Juliet Rhys-Williams and the Campaign for Basic Income, 1942–55,

30 CONTEMP. BRIT. HIST. 203, 203–04 (2016); see also Evelyn L. Forget, Canada: The

Case for Basic Income, in MATTHEW C. MURRAY & CAROLE PATEMAN, EDS., BASIC

INCOME WORLDWIDE: HORIZONS OF REFORM 83 (2012).

20 According to the University of Chicago Press, for example, Capitalism and Freedom

has been translated into eighteen languages and has sold over 500,000 copies since its initial

publication in 1962. See FRIEDMAN, CAPITALISM AND FREEDOM, supra note 18.

21 Friedman was one of the most (if not the most) prominent North American

economists at the time. See, for example, the cover of the December 19, 1969 issue of Time

Magazine, which is included in Appendix A to this Article.

22 See FRIEDMAN, CAPITALISM AND FREEDOM, supra note 18, at 192.

23 See Friedman, Negative Income Tax—I, supra note 18, at 349.

24 See MARTIN ANDERSON, WELFARE: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF WELFARE REFORM

IN THE UNITED STATES 78–79 (1978).

25 The letter, along with the list of 1,228 economists who signed the letter, is found

in Income Maintenance Programs: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Fiscal Policy of the J.

Econ. Comm., 90th Cong. 676–90 (1968). The text of this letter is included in Appendix B

to this Article.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 103

luminaries as James Tobin (Yale), Paul Samuelson (MIT), and

John Kenneth Galbraith (Harvard)—openly called for a national

system of income guarantees and made the front page of

The New York Times.

26

Alas, curiously absent from this massive

list of signatures was Milton Friedman’s.

Why did Friedman demur from the May 1968 letter? Why

did he not join his own colleagues in support of his own cause?

The most likely reason Friedman jumped off this basic income

bandwagon is the letter’s choice of words; it omits any reference

to the words “negative income tax.” Moreover, the May letter not

only calls for a guaranteed income, it also calls for supplements to

this income. In other words, the letter seems to imply that existing

social welfare programs should co-exist with a guaranteed income.

Friedman, by contrast, supported a guaranteed income concept

only if it replaced all, or most, existing social entitlements.

27

Here, then, is an alternative inciting incident: President

Richard M. Nixon’s historic speech on August 8, 1969, calling for

a guaranteed income. Between the historic Apollo 11 lunar

mission (July 16–24, 1969) and the Woodstock Music Festival in

Bethel, New York (August 15–18, 1969), Nixon delivered a televised

address announcing one of the most radical and revolutionary

poverty-relief proposals in our nation’s history: a uniform,

unconditional, and guaranteed minimum income for all poor

households in the United States.

28

Under Nixon’s anti-poverty plan,

a poor family of four would receive an annual cash stipend of

$1,600—no strings attached—the equivalent of $10,600 in today’s

inflation-adjusted dollars.

29

In some respects, the proposal Nixon described in his

nationwide address would fall far short of his lofty rhetoric; in

other respects, however, Nixon’s speech understated the radical

nature of his plan.

30

Overall, Nixon’s guaranteed income bill, or

“family assistance plan” (“FAP”), had three internal

contradictions—time bombs that would eventually cause his plan to

26 See Economists Urge Assured Income, N.Y. TIMES, May 28, 1968, at 1. For

additional background and a chronology of events leading up to the 1968 petition, see

BRIAN STEENSLAND, THE FAILED WELFARE REVOLUTION: AMERICA’S STRUGGLE OVER

GUARANTEED INCOME POLICY 64–70 (2008).

27 For alternative explanations of Friedman’s demurral, see Milton Friedman, The

Case for the Negative Income Tax: A View from the Right, PROC. NAT’L SYMP. ON

GUARANTEED INCOME 49–55 (1966), reprinted in Collected Works of Milton Friedman

Project (Robert Leeson & Charles G. Palm, eds.), HOOVER INST. ARCHIVES,

http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/objects/57681 [http://perma.cc/6WKA-7WRV].

28 Address to the Nation on Domestic Programs, 324 PUB. PAPERS 640–41 (Aug. 8, 1969).

29 See Ian Webster, $1600 in 1970, CPI INFLATION CALCULATOR,

http://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1970?amount=1600 [http://perma.cc/448X-LE53].

30 See BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 108–10.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

104 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

self-destruct. First, Nixon’s welfare reform plan was a half-hearted

one. His plan abolished only one welfare program (“AFDC”), not the

welfare state in toto as Friedman, William F. Buckley, Jr., and

other conservative proponents of a basic income had called for.

31

At

that time, for example, the Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare (“HEW”) was one of the largest agencies in the entire

federal government, with 107,000 employees, a budget of nearly $60

billion, 135 advisory boards, and more than 270 programs, covering

everything from family planning to Social Security.

32

Instead of

dismantling this bureaucratic behemoth, Nixon’s bill left HEW

totally intact.

33

This omission would later cause Friedman, the

intellectual author of the negative income tax, as well as

Buckley, Jr., James J. Kilpatrick, and other leading conservative

commentators, to withdraw their support of Nixon’s guaranteed

income plan.

34

Second, instead of showcasing the basic income aspect of his

plan, Nixon buried it in the middle of his speech. Worse yet, Nixon

bundled his guaranteed income proposal with several other

cumbersome legislative proposals, including a costly revenue

sharing proposal in which, in Nixon’s words, “a set portion of the

revenues from Federal income taxes [would] be remitted directly

to the States . . . .”

35

In short, instead of using a negative income

tax to replace existing welfare programs, Nixon was simply

tacking his proposal on top of these existing programs.

Third, Nixon refused to call a spade a spade. He was

unwilling to utter the words “negative income tax,” and denied

that he was proposing a guaranteed income. Instead, he coined

the term “family assistance,” called his plan a “floor,” and tried

to sell it as “workfare.”

36

Although Nixon told the nation, “What

I am proposing is that the Federal Government build a

foundation under the income of every American family with

dependent children that cannot care for itself—and wherever in

31 In the words of President Nixon, “Under [my] plan, the so-called ‘adult categories’

of aid—aid to the aged, the blind, the disabled—would be continued . . . .” See Address to

the Nation on Domestic Programs, 324 PUB. PAPERS 640 (Aug. 8, 1969).

32 See Robert Sherrill, The Real Robert Finch Stands Up, N.Y. TIMES, July 5, 1970,

at 122; see also MICHAEL KONCEWICZ, THEY SAID NO TO NIXON: REPUBLICANS WHO STOOD

UP TO THE PRESIDENT’S ABUSES OF POWER 122 (2018).

33 See COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS, THE FAMILY ASSISTANCE ACT OF 1970,

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS ON H.R. 16311, H.R. NO. 91-904, at 6.

34 See infra Act III.

35 Address to the Nation on Domestic Programs, 324 PUB. PAPERS 643 (Aug. 8, 1969).

According to one scholar, the real purpose of this revenue sharing proposal was to make

sure that no current welfare recipient would be worse off under Nixon’s guaranteed

income plan than under the status quo. See Neuberg, supra note 9, at 37.

36 See BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 111–12.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 105

America that family may live.”

37

He then made the following

clarification: “This national floor . . . is not a ‘guaranteed

income.’ Under the guaranteed income proposal, everyone would

be assured a minimum income, regardless of how much he was

capable of earning, regardless of what his need was, regardless

of whether or not he was willing to work.”

38

This subterfuge was no doubt motivated by politics. After all,

how else could Nixon get conservative members of Congress to go

along with his revolutionary guaranteed income proposal? As

Vincent and Vee Burke wrote in their classic study Nixon’s Good

Deed, “In public affairs the content of a proposal can be less

important than the way it is perceived. Sometimes the label is

the most important ingredient.”

39

But at the same time, calling

his guaranteed income proposal “family assistance” invited a

fundamental moral dispute over whose responsibility it was to

provide support to children—the government or parents.

40

Furthermore, the label chosen must bear some relation to

the content of one’s proposal. The work requirement in Nixon’s

proposal was riddled with exemptions,

41

while the guaranteed

income aspect of the bill would more than double the number of

families eligible for government assistance.

42

Perhaps Nixon

would be able to fool some members of Congress with his

“workfare” subterfuge, but as we shall see in Act III, he would

not be able to fool all of them.

Given these internal contradictions, our dramatic question

now boils down to this: will Nixon’s call for a guaranteed

income—now disguised as a “family assistance plan”—be enacted

by the 91st Congress, or will this bill die in committee? Either

way, Nixon’s FAP would unleash an epic, multi-year intellectual

battle between competing political principles and conflicting

ideological worldviews—between social liberals committed to the

cause of eradicating poverty and fiscal conservatives opposed to

government hand-outs and guaranteed minimum incomes.

The remainder of our story will mostly unfold in the bowels of

Congress, specifically, in two of its most powerful congressional

committees—the House Ways and Means Committee and the

37 Address to the Nation on Domestic Programs, 324 PUB. PAPERS 640 (Aug. 8, 1969).

38 Id. at 640–41.

39 BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 119.

40 See id. at 161.

41 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS, THE FAMILY ASSISTANCE ACT OF 1970, REPORT

OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS ON H.R. 16311, H.R. NO. 91-904, at 4.

42 See BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 110.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

106 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

Senate Finance Committee.

43

The guaranteed income bill was

referred to these committees because it was, technically

speaking, a tax measure.

44

Therefore, our leading protagonists will

now include two Southern Democrats: Wilbur Mills, the chairman

of the House Ways and Means Committee, and Russell Long, the

chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.

45

In their committees

rested the fate of guaranteed income. Even though the 91st

Congress was controlled by the Democratic Party, and even

though the bill was promoted by a Republican president, the

concept of a guaranteed income “was neither a conservative nor a

liberal measure in the meanings intended by those terms.”

46

Would Democrats give Nixon a legislative victory? Would

Republicans support a massive income redistribution bill?

ACT II: MILLS TO THE RESCUE

The second act, or middle section of a dramatic work, typically

portrays a “rising conflict”—one in which the protagonist attempts

to resolve the conflict created by the turning point in the first act,

only to find himself in an ever-worsening situation.

47

Act II of

Nixon’s guaranteed income bill, however, does not follow this

tried-and-tested formulaic blueprint. Far from suffering an initial

reversal of fortune, H.R. 16311 sailed through the House Ways

and Means Committee by an overwhelming margin (21 to 3) and

then sped through the full House of Representatives by a

considerable margin (243 to 155).

48

These early legislative successes in the 91st Congress were

due in large part to the skillful maneuvering and strategic

tactics of Congressman Wilbur D. Mills, an Arkansas Democrat

who was born in the town of Kensett, Arkansas (population 905)

and who was first elected to Congress in 1939.

49

Although his

political career would soon come to a crashing end,

50

at this

43 See Top Congressional Committees, OPENSECRETS.ORG, http://www.opensecrets.org/

revolving/top.php?display=C [http://perma.cc/NH85-2DZ5].

44 See MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 352 (“Technically it was a tax bill, part of the

social security system. . . . If approved it would be a permanent statute, financed by

automatic claims on the Treasury.”).

45 See MILLS, Wilbur Daigh, BIOGRAPHICAL DIRECTORY U.S. CONGRESS,

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=M000778 [http://perma.cc/K5R9-3SSC];

see also LONG, Russell Billiu, BIOGRAPHICAL DIRECTORY U.S. CONGRESS,

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=L000428 [http://perma.cc/A4EL-C57F].

46 See MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 440.

47 See, e.g., TROTTIER, supra note 16, at 15.

48 See CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 1032.

49 See MILLS, Wilbur Daigh, supra note 45.

50 See Richard D. Lyons, Mills Quits as Chairman; Young Democrats Advance, N.Y.

TIMES, Dec. 11, 1974, at 93; see also Laura Smith, In 1974, a stripper known as the “Tidal

Basin Bombshell” took down the most powerful man in Washington, TIMELINE (Sept. 18, 2017),

http://timeline.com/wilbur-mills-tidal-basin-3c29a8b47ad1 [http://perma.cc/B9YZ-4BRC].

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 107

time, Congressman Mills was still the chairman of the House

Ways and Means Committee,

51

and was thus considered to be

the second-most powerful man in Washington, D.C., or in the

memorable words of one fellow Congressman, “I never vote

against God, motherhood, or Wilbur Mills.”

52

Mills’s power and influence were in large part a function of

the committee he chaired since 1958, the House Ways and Means

Committee. In brief, the Origination Clause of the Constitution

requires that all bills regarding taxation must originate in the

House of Representatives,

53

and the internal rules of the House,

in turn, dictate that all taxation bills must pass through Ways

and Means.

54

To this day, the Ways and Means Committee is still

the chief tax-writing committee of the House, and the members of

this key committee may not serve on any other House committee

unless they are granted a waiver from their party’s congressional

leadership.

55

So, when the original version of Nixon’s guaranteed

income bill was first introduced into the 91st Congress on

October 3, 1969, the first draft of the bill (H.R. 14173) was

referred to Ways and Means.

56

Between October 15 and November 13, 1969, the House

Ways and Means Committee held eighteen days of public

hearings on the bill.

57

But then, on November 13, Chairman

Mills abruptly concluded the public phase of his hearings and

proceeded behind a special closed-door session.

58

This was the

first of two pivotal procedural moves Chairman Mills would

make. Rather than drag out consideration of Nixon’s

guaranteed income bill and provide a public forum for

opponents of the bill to raise their objections, the bill would

remain under closed-door consideration until March of 1970.

51 See Lyons, supra note 50, at 1. Before his political downfall, Congressman Mills would

become the longest-serving chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. See Kay C. Goss,

Wilbur Daigh Mills, CALS (Apr. 23, 2019), http://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/wilbur-

daigh-mills-1715/ [http://perma.cc/2LUA-KQGD].

52 Smith, supra note 50.

53 See U.S. CONST. art. I, § 7, cl. 1.

54 See Jurisdiction and Rules: Jurisdiction of the Committee on Ways and Means,

WAYS & MEANS COMM., http://waysandmeans.house.gov/about/jurisdiction-and-rules

[http://perma.cc/8SPW-VRLR].

55 See id.

56 See CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 1031. A few days after Nixon’s

guaranteed income bill was introduced in Congress, Chairman Mills called the first round of

public hearings to order on October 15, 1969. See id. at 1032. In addition to Nixon’s income bill,

the committee also considered a proposal to increase Social Security benefits (“H.R. 14080”). Id.

57 See id. at 1031.

58 For a helpful historical overview of closed-door activities in Congress, see WALTER J.

OLESZEK, CONG. RESEARCH SERV., R42108, CONGRESSIONAL LAWMAKING: A PERSPECTIVE ON

SECRECY AND TRANSPARENCY 2–5 (2011), http://fas.org/sgp/crs/secrecy/R42108.pdf

[http://perma.cc/9758-JN47].

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

108 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

Chairman Mills had “indicated strong reservations about

[Nixon’s] plan” on the final day of public hearings on

November 13, 1969.

59

His hesitation was not surprising. After all,

he was a Southern Democrat or “Dixiecrat,” and for various

reasons, the South overwhelmingly opposed Nixon’s radical

proposal.

60

Nevertheless, by April of 1970, Mills not only

ultimately voted in favor of the bill, he also helped steer it

through the House.

61

What happened behind closed doors

between November 13, 1969, the last day of public hearings, and

April 16, 1970, the day the full House of Representatives

approved the measure? In short, why did Chairman Mills change

his mind?

One reason for Mills’s change of heart might have had to do with

the changing winds of politics. On January 2, 1968, the outgoing

president, Lyndon B. Johnson, had appointed a twelve-member

presidential commission to study the feasibility of a negative income

tax.

62

This blue-ribbon committee, chaired by Ben W. Heineman,

issued its report on November 12, 1969.

63

At this time, the House

Ways and Means Committee was still holding public hearings on

Nixon’s guaranteed income bill.

64

Although the Heineman

commission’s negative income tax proposal ended up being more

generous than Nixon’s FAP bill, the commission supported Nixon’s

plan in principle.

65

Also, because the commission was appointed by a

Democrat president, Heineman’s report gave Nixon’s guaranteed

income bill a boost by putting “the national Democratic party more or

less on record as favoring a proposal very like that of the president.”

66

Furthermore, in addition to the basic income guarantee, Nixon’s

proposal incorporated other “liberal” features that would have

appealed to progressives, including a complete federal take-over of

social welfare.

67

Another reason for Mills’s change of heart was

opportunism: Mills rewrote the bill to his liking. Most everyone

at the time agreed that the current welfare system was broken,

59 See CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 1032.

60 See BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 146–50. When the bill went to the floor of

the House on April 16, 1970, congressmen from the eleven states that made up the Old

Confederacy voted against the bill by an overwhelming margin of 79 to 17. Id. at 147.

61 See id. at 162.

62 See POVERTY AMID PLENTY: THE AMERICAN PARADOX 78 (1969).

63 See Jack Rosenthal, Income Aid Plan Based on Need Proposed by Presidential

Panel, N.Y. TIMES, Nov. 13, 1969, at 1.

64 See CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 1031.

65 Under the Heineman plan, for example, the guaranteed income floor for a family

of four would be $2,400, while under Nixon’s plan it was $1,600. See MOYNIHAN, supra

note 7, at 361.

66 Id. at 364. For other possible reasons, see id. at 398–438.

67 See id. at 134.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 109

so “[i]f Congress spurned the Family Assistance Plan it would

be responsible for perpetuating the discredited welfare

system.”

68

Furthermore, as Vincent and Vee Burke note in their

history of Nixon’s bill, although the term “negative income tax”

was coined by the conservative economist Friedman, the idea of

a guaranteed income was a Democratic idea.

69

But at the same time, Mills and his fellow Democrats had to

grapple with the following dilemma: if they supported Nixon’s FAP,

then Nixon would win a big legislative victory. Mills solved this

problem by rewriting the bill to his own liking and making it his

own. Specifically, he made two significant changes to the bill: (1) he

added a new food stamp subsidy to the bill, and (2) he diverted a

greater share of federal funds to the states.

70

As originally

drafted, the bill required those states whose welfare programs

paid out higher benefits to families than under Nixon’s proposal

(forty-two states in all) to pay the difference.

71

Now, under Mills’s

revised bill, the federal government would agree to pay each

state thirty percent of any additional benefits the states paid out

to existing welfare recipients.

72

With these revisions, H.R. 16311

or “The Family Assistance Act of 1970” was approved by the

House Ways and Means Committee on February 26, 1970.

73

Mills’s Committee then reported a clean bill to the full House of

Representatives on March eleventh.

74

Next, Chairman Mills, who “was known for his excessive

caution, [his] fastidiousness about legislative details, and his

moderation,” had another procedural tactic up his sleeve.

75

Once

his bill was reported out of Ways and Means, he proposed a

“closed rule” in order to prevent members of the House from

offering any amendments to the bill on the floor.

76

(An “open

68 See BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 122.

69 See id. at 123.

70 See id. at 152.

71 See id. at 115.

72 See CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 1032.

73 MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 425.

74 See COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS, THE FAMILY ASSISTANCE ACT OF 1970,

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS ON H.R. 16311, H.R. NO. 91-904. Only

three members of Ways and Means voted against the bill: Al Ullman (D., Oregon), Phil M.

Landrum (D., Georgia), and Omar Burleson (D., Texas). Among other things, the three

dissenters objected to providing a minimum income to the poor: “We do not concur that

the cash incentive approach to welfare is either proven or sound.” See CONGRESSIONAL

QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 1033.

75 See Smith, supra note 50.

76 See Family Assistance Act of 1970: Hearing on H.R. 16311 Before the Comm. on

Rules, 91st Cong. 162 (1970).

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

110 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

rule,” by contrast, would have permitted any member of the

House to propose any amendment to any part of that Act.

77

)

One member of Congress, David W. Dennis protested that

members were being asked to adopt one of the most far-reaching

measures ever to come before it without the possibility “of being

usefully heard or of changing a single thing on the floor.”

78

Representative Dennis said the closed rule procedure treated the

members “as the idiot children of the whole political process,”

while another opponent of the bill, H. Allen Smith, said an open

rule would have permitted an effort on the floor by some

members to raise the $1,600 federal minimum benefit.

79

After the

bill is passed, Smith said, the $1,600 will “start growing and from

then on the sky will be the limit.”

80

Wilbur Mills, however, did not back down. On behalf of the

House Ways and Means Committee, Chairman Mills made his

closed rule resolution “‘to provide for an orderly procedure’” for

consideration of H.R. 16311.

81

Although the vote on April 15, 1970

to adopt the closed rule was a close one (205 to 183), Mills

prevailed.

82

The next day the bill went before the entire House of

Representatives, and it passed by a two-to-one margin.

83

In short, Chairman Mills used his power and influence to

write up his own bill and steer it through Ways and Means and

the floor of the House, but his swift and skillful maneuvering

may have created a false sense of security among proponents of

the guaranteed income bill. A series of events would conspire to

kill the measure in the Senate Finance Committee, the

“graveyard” of H.R. 16311.

84

This historic bill would never make

it out of this critical committee.

ACT III: DEATH BY COMMITTEE

The third act of a dramatic work usually features a climax or

showdown, followed by the resolution of the story’s conflict

situation.

85

The showdown, in turn, is the most consequential

moment of the story—the sequence in which the conflict is

brought to its most intense point and where the dramatic

77 See About, HOUSE COMMITTEE ON RULES, http://archives115-democrats-

rules.house.gov/about [http://perma.cc/D88C-6D2G].

78 CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 5.

79 Id.

80 Id.

81 Id. at 4.

82 Id.

83 Id.

84 BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 213.

85 See TROTTIER, supra note 16, at 16.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 111

question posed by the story is answered, leaving the protagonist

with a new sense of who they really are.

86

Once H.R. 16311 was approved by the House in April of

1970, Nixon’s guaranteed income bill went to the Senate.

87

The

fateful showdown will thus take place in the august halls and

stately corridors of the United States Senate. In summary, this

conflict will consist of a titanic intellectual battle between

competing political principles and conflicting ideological

worldviews—between social liberals committed to the cause of

eradicating poverty, and fiscal conservatives opposed to

government hand-outs and guaranteed minimum incomes.

Victim to these powerful and irreconcilable political forces, the

bill would languish in committee for months until its final defeat

on November 20, 1970.

88

Why does our guaranteed minimum income story end this

way? What happened between April 16, 1970, when H.R. 16311

sailed through the House, and November 20, 1970, when the

guaranteed income bill finally died in committee? It turns out,

however, that most commentators and scholars have been asking

the wrong question.

89

Instead of asking, what killed the income

bill, we should be asking who killed it?

Among the leading culprits is the Chairman of the Senate

Finance Committee, the junior senator from the State of

Louisiana, Russell B. Long. He delayed consideration of the bill

for months on end, tenaciously outmaneuvered supporters of the

bill on the floor of the Senate, and defeated the bill in the waning

days of the 91st Congress.

90

This yellow dog Dixiecrat, renowned

for his “sheer cleverness and cunning,” was the last scion of the

legendary Huey P. Long, the populist politician who was

assassinated in 1935.

91

Russell B. Long was appointed to the Senate Finance

Committee in 1953, where he served as chairman of the

committee from 1966 to 1981.

92

Like Wilbur Mills in the House,

Chairman Long was a powerful political force to be reckoned

with. In the words of one Congressman, “In the heyday of the

86 Id. at 16–17.

87 CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 2.

88 Id.

89 See, e.g., Kornbluh, supra note 12, at 136; Neuberg, supra note 9; MOYNIHAN,

supra note 7, at 385; BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 186–87.

90 See generally Alan Ehrenhalt, Senate Finance: The Fiefdom of Russell Long, 35

CONG. Q. WKLY. REP. 1905 (1977).

91 See id.

92 See The Russell Long Chair, LSU LAW, http://www.law.lsu.edu/ccls/about/

russelllongchair/ [http://perma.cc/66NB-W5RW].

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

112 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

Southern chairmen, [Long] was at the top of the list of big, strong

figures representing the South who were national leaders that

every president had to deal with. . . . Nothing could happen

without them.”

93

Chairman Long called the Senate Finance Committee to

order on April 29, 1970.

94

Would history be made? Would the

Senate Finance Committee rise to the occasion? After all, during

the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, Chairman Long was his

party’s Senate floor leader, who helped enact many of President

Johnson’s “Great Society” poverty-relief programs, including the

creation of the Medicare program in 1965.

95

But as we shall soon

see, it was one thing to provide services to the poor; a guaranteed

income was a whole different ball game.

Not a single senator spoke a single sentence in support of the

guaranteed income bill.

96

The guaranteed income bill was dead on

arrival,

97

or in the words of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, “The hearings

were a calamity. The senators had all but made up their minds that

[H.R. 16311] would provide disincentives to work . . . .”

98

Indeed, by

the second day of hearings, Chairman Long was asking, “Why don’t

we junk the whole thing and start all over again?”

99

The then-Secretary of HEW, Robert H. Finch, testified before

the members of the Senate Finance Committee during this first

round of hearings.

100

His testimony lasted three days, and during

these three days, leading Democrats and Republicans on the

Committee voiced their opposition to the bill. Social liberals like

Abraham A. Ribicoff did not like the bill because they thought

the $1,600 benefit level was set too low, while fiscal conservatives

like John J. Williams did not like the bill because they thought it

was too costly.

101

In the end, H.R. 16311 would die a slow and

painful death, death by delay. Although some last-ditch efforts

were made to save the bill in the final days of the 91st Congress,

it was a classic tale of too little, too late.

102

93 See John H. Cushman, Jr., Russell B. Long, 84, Senator Who Influenced Tax Laws, N.Y.

TIMES (May 11, 2003), http://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/11/us/russell-b-long-84-senator-who-

influenced-tax-laws.html [http://perma.cc/MMY4-5QP4] (quoting Representative Billy Tauzin).

94 See MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 453.

95 See Karen Sparks, Russell Billiu Long, ENCYC. BRITANNICA (Oct. 30, 2019),

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Russell-Billiu-Long [http://perma.cc/T9S5-HSPR].

96 See MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 473.

97 Id. at 453.

98 Id. at 469.

99 CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 6.

100 See id. at 5.

101 Id.

102 Id. at 12.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 113

What happened? What went wrong?

In chapter five of his book, The Politics of a Guaranteed

Income, Moynihan identifies three political blocs the guaranteed

income bill would have to win over in order to become enacted

into law: “The Liberal Democrats,” “The Conservative

Republicans,” and the “Southerners.”

103

From a purely

Machiavellian or political perspective, it might not have been in

the interest of Democrats to allow a Republican president to

outdo them in social policy.

104

For their part, most conservatives

supported the idea of welfare reform and might be expected to

support the president’s bill out of loyalty to the president. But

what about the third bloc identified by Moynihan, Southerners?

In the House, congressmen from the eleven states that made up the

Old Confederacy voted against the bill by a margin of 79 to 17.

105

That the Senate Finance Committee was chaired by Russell

B. Long, a Dixiecrat out of Louisiana, thus did not bode well for

H.R. 16311.

106

Even before he had called his committee to order

to debate the merits of H.R. 16311, Chairman Long had criticized

the bill’s cost and perverse incentive structure in a speech on the

floor of the Senate on April 23, 1970:

Senators should be aware that the welfare bill before the

Finance Committee today does not solve the problem—it

just makes it cost $4 billion more. Under the bill, a fully

employed father of a family of four with low earnings could

increase his family’s total income if he quit work . . . .

107

Furthermore, Chairman Long was not alone in seeing the

bill in moral terms. Another member of the Senate Finance

Committee, Herman Talmadge, a Georgia Democrat who was the

bill’s staunchest opponent, framed guaranteed income as “a work

dis-incentive.”

108

In his view, a guaranteed income “would

undermine the best qualities of this nation.”

109

Senators Long

and Talmadge were traditional Democrats; they saw themselves

as representing “the working man.”

110

Furthermore, if Chairman Long was opposed to the

guaranteed income bill as a matter of first moral principles,

many Republican members of the committee were also worried

103 See MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 352–75.

104 Id. at 441.

105 BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 147. Southern Democrats opposed the bill 60 to

11, while Southern Republicans opposed it 19 to 6. Id.

106 See MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 393.

107 Id. at 459.

108 Id. at 378.

109 Id.

110 Id. at 362.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

114 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

about the mechanical nuts and bolts of the bill. During the second

day of hearings (April 30, 1970), Senator John J. Williams, a

former chicken-feed dealer who was set to retire from politics at

the end of the 91st Congress, pointed out a potential problem with

the guaranteed income bill.

111

Based on a series of flawed and

misleading cost-benefit calculations, Senator Williams, the

ranking member of Senate Finance, concluded that the bill

contained perverse anti-work incentives: people would rationally

choose not to work under the bill.

112

Stated in simple terms, the problem was this: persons who

received a guaranteed income were also eligible to receive

additional welfare benefits from the government, such as

Medicaid, food stamps, and public housing, but those additional

benefits would be lost in their entirety if one’s income exceeded a

certain threshold.

113

At the margin, an increase in earnings of

one dollar would result in a decrease of income of more than one

dollar for many individuals.

114

Would the Senate Finance Committee tinker with the bill or

try to fix these problems, or would those problems be used as a

pretext for inaction? Now that Nixon had proposed and the

House had passed a guaranteed income bill, four possible

strategies were available to the members of the Senate Finance

Committee: cooperate, deny, realign, or outbid.

115

The most vocal

champion of the strategy to outbid the President was Senator

Fred Harris, a Democrat from Oklahoma. Although Senator

Harris supported the idea of a guaranteed income in principle, he

would repeatedly try to outbid Mills and the House’s guaranteed

income bill, though he ended up voting against the bill.

116

Why?

Because the House bill did not go far enough. For him, the glass

was half-empty.

Another possibility was cooperation. Senator Abraham

Ribicoff, for example, a liberal Democrat from Connecticut, was

willing to swallow his political pride and cooperate with the

President and the House to get some form of guaranteed income

enacted into law.

117

Indeed, when it became clear that the bill

might die in committee, Ribicoff offered an amendment to

salvage the bill, proposing a “twelve-month period of ‘field

111 See BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 155.

112 See id. at 154–56.

113 See id.

114 See id. at 156.

115 MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 446–52.

116 See id. at 451–52.

117 Id. at 453.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 115

testing,’”

118

and President Nixon issued a public statement

supporting Ribicoff’s amendment.

119

Yet another possibility was realignment. After all, it was

Nixon, a polarizing Republican president, who was proposing one

of the most radical income redistribution programs in United

States history, and it was the House of Representatives, which

was controlled by the Democratic Party, that had just approved a

bill based on Nixon’s historic proposal. But in the end, most of the

members of the Senate Finance Committee would choose to defect.

Simply put, they were openly opposed to the bill on moral grounds.

Why? Because many senators thought that a guaranteed income

would destroy the moral dignity of work—an ethic that was at the

very foundation of Chairman Long’s own worldview.

After this disastrous start in the Senate Finance Committee,

it became clear that no member of Long’s committee supported

H.R. 16311. In fact, Chairman Long suspended the hearings on

the third day and asked Secretary Finch to submit a revised bill

to the committee.

120

Alas, Finch was put in an impossible

position, for there was no way of solving the work incentive

problem to everyone’s satisfaction. On the one hand, eliminating

Medicaid, food stamps, and public housing was not politically

feasible. Democrats would not allow that to happen, and

Democrats were the majority party. A cutoff would have to be

drawn somewhere. But where? Any cutoff line would produce a

perverse incentive effect.

Worse yet, in the days and weeks after Chairman Long had

suspended the hearings, a series of external events would conspire

to doom whatever slim chances the bill may have still had in the

Senate. Among other things, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Nixon’s

leading spokesman and political strategist in favor of the bill,

would privately offer to resign; Robert Finch would suffer a mental

health breakdown and would resign as Secretary of HEW; and last

but not least, after several conservative voices would begin to turn

against the bill, President Nixon himself would begin to waver.

The cumulative effect of these tumultuous events—along with

Chairman Long’s shrewd delay tactics—would conspire against

H.R. 16311, putting the fate of this historic bill into jeopardy.

First, one of Nixon’s domestic-policy advisors, Daniel Patrick

Moynihan, quietly offered his resignation on May thirteenth in

118 Id. at 520.

119 Id. at 521.

120 See CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 6; see also Frank C. Porter, Hill

Unit Sends Welfare Bill Back to Finch for Overhaul, WASH. POST, May 2, 1970, at A5.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

116 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

order to resume his academic position at Harvard in the fall.

121

According to one historian, Nixon asked Moynihan to stay until

the summer in order “to help get [the guaranteed income bill]

through the Senate.”

122

But with Moynihan’s impending

departure, the bill would lose one of its most eloquent supporters.

Second, another champion of the bill, Secretary of HEW

Robert Finch, would resign from his post after suffering a mental

health breakdown in May 1970.

123

According to Haldeman, Finch

had agreed to resign as early as June 5, 1970.

124

(For what it is

worth, Nixon may have flirted with the idea of appointing

Moynihan as Finch’s replacement at HEW. Although Moynihan

expressed an interest in serving as Secretary of HEW,

125

Nixon

eventually appointed Boston-native Elliott Richardson to this

position.) But Finch’s departure and Moynihan’s impending

resignation were not the only bad omens. One of the intellectual

authors of the negative income tax, the conservative economist

Friedman, openly withdrew his public support of the bill and

applauded Senator Long’s decision to suspend the hearings.

126

121 STEPHEN HESS, THE PROFESSOR AND THE PRESIDENT: DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN

IN THE NIXON WHITE HOUSE 129 (2015).

122 Id. This account is confirmed by a diary entry of H.R. Haldeman. Haldeman, who

served as President Nixon’s Chief of Staff, kept a daily diary throughout his entire career in

the Nixon White House (January 18, 1969 to April 30, 1973). An abridged version of these

diaries was published as The Haldeman Diaries after Haldeman’s death. See H. R. Haldeman

Diaries, RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBR. & MUSEUM, http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/h-r-

haldeman-diaries [http://perma.cc/ATK8-BT5D] [hereinafter Haldeman Diaries]. According to

Haldeman’s entry for May 13, 1970:

[Nixon] met privately with Moynihan, who said he feels he has to leave. Wants

to go July 1, but President got him to stay until August. Will then return to

Harvard—on grounds his two years will be up soon and he wants to start the

fall semester. President appears more relieved than concerned to have him go,

and this timing should work out pretty well because he always said he was

only here for two years.

Haldeman Diaries (May 13, 1970), http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/virtuallibrary/

documents/haldeman-diaries/37-hrhd-journal-vol05-19700513.pdf [http://perma.cc/XPB2-RCWR].

123 Haldeman’s May 21, 1970 diary entry states that “[Nixon was] concerned

regarding Finch’s health problem, and [is] now convinced he should move out of HEW.

Wants Tkach to sell [Finch] on the basis of health. [Finch] is going to Florida to try to

recuperate.” Haldeman Diaries (May 21, 1970), http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/

virtuallibrary/documents/haldeman-diaries/37-hrhd-journal-vol05-19700521.pdf

[http://perma.cc/KHY9-PX32].

124 Haldeman’s June 5, 1970 diary entry begins with the words “Finch day.”

Haldeman then goes on to write: “Ehrlichman and I met with [Finch] in morning, and I

made pitch regarding need for him to move out of HEW now. . . . He was obviously ready

for it, and went along completely. He felt it should be done as fast as possible—so we went

to work on a successor.” Haldeman Diaries 1 (June 5, 1970), http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/

sites/default/files/virtuallibrary/documents/haldeman-diaries/37-hrhd-journal-vol05-19700605.pdf

[http://perma.cc/838V-9ZQ4].

125 Id. at 2.

126 See Milton Friedman, Welfare: Back to the Drawing Board, NEWSWEEK, May 18,

1970, at 89.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 117

In his Newsweek column of May 18, 1970, Friedman identified

several problems with the House version of his negative income

tax proposal.

127

But the most fundamental objection Friedman

raised was this: “A negative income tax—which is what the Family

Assistance plan is—makes sense only if it replaces at least some of

our present rag bag of programs. It makes no sense if it is simply

piled on other programs.”

128

Moreover, Friedman was not the only

conservative public intellectual to defect. On April 15, 1970, the

conservative commentator William F. Buckley explained in his

nationally-syndicated newspaper column why he too was casting a

“reluctant ‘nay’” against the bill.

129

Although Buckley was at first

open to the idea of a guaranteed income, he had now decided that

Nixon’s bill was a bad idea.

130

According to Buckley, the bill was

adding a new and costly welfare program on top of existing social

welfare programs, such as public housing, Medicaid, etc., instead

of sweeping these old programs away.

131

In addition, Buckley saw

through the bill’s watered-down work requirement, disparaging

it as “merely . . . boob-bait for conservatives.”

132

Another leading conservative commentator, James J. Kilpatrick,

went even further. In his syndicated “Conservative View” column of

January 15, 1970, Kilpatrick not only retracted his initial praise of

Nixon’s proposal; he referred to welfare recipients as “parasites”:

If the Nixon plan were adopted, the present $5 billion in annual

federal payments would at least double. . . . Instead of 9.6 million

persons on welfare, we would have nearly 22 million. . . . These would

be the permanent poor feeding like parasites on the body politic unto

the end of time.

133

To make matters worse, Nixon himself may have turned

against his own guaranteed income bill. According to his loyal

Chief of Staff, H. R. Haldeman, by July of 1970 Nixon had come

to the realization that his bill was too costly. The entry in

Haldeman’s diary for Monday, July 13, 1970 states, “Regarding

Family Assistance Plan, [Nixon] wants to be sure it’s killed by

Democrats and that we make big play for it—but don’t let it pass,

127 Id. According to Friedman, one problem with Chairman Mill’s version of the bill

was his decision to reinsert food stamps into the plan instead of abolishing the food stamp

program altogether. The other problem, which echoed Senator Williams’s objection during

the initial Senate Finance hearings, had to do with the phasing out of state supplemental

payments under the House bill. Instead of phasing out these supplemental payments

incrementally as the income of an eligible family went up, these payments were phased

out too drastically. Id.

128 Id.

129 MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 370.

130 Id.

131 Id.

132 Id.

133 BURKE & BURKE, supra note 6, at 134.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

118 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

can’t afford it.”

134

Although Haldeman’s diary entry does not

specify whether the bill was too costly in political terms (the

potential loss of support from working class voters), or too costly

in financial terms (the bill’s price tag), or both, Chairman Long’s

delay tactics, Finch’s abrupt resignation, and Moynihan’s

impending departure would conspire to defeat the bill by the end

of the year.

135

In any case, on the same day that Chairman Long suspended

the hearings (May 2, 1970), President Nixon appointed a special

committee to revise the guaranteed income bill.

136

The revisions,

which were announced on June tenth, were a mishmash of costly

measures that would fail to appease social liberals or mollify

social conservatives.

137

Among other things, the food stamp

program was expanded.

138

Additionally, “[t]he penalty for

‘Refusal to Register for or Accept Employment or Training’ was

increased from $300 to $500.”

139

A “hold harmless” provision was

added, such that no state would be required to spend more on

welfare than under the existing system.

140

But the most

significant change to the bill was a proposed comprehensive,

compulsory, single-payer Family Health Insurance Program,

which would have been “the nation’s first federally subsidized

system of health insurance for the poor.”

141

In short, instead of streamlining or simplifying the

guaranteed income bill, HEW had decided to superimpose a grab

bag of costly programs and cumbersome requirements on the old

134 Haldeman Diaries (July 13, 1970), http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/

virtuallibrary/documents/haldeman-diraries/37-hrhd-journal-vol05-19700713

[http://perma.cc/57PJ-A9FA].

135 In public, however, Nixon continued to profess his support of the bill. On

August 28, 1970, for example, Nixon agreed to a proposal by Senator Abraham A. Ribicoff

(D., Conn.) to test the plan for one year in three areas of the country. “In a statement

issued at San Clemente, Calif., Mr. Nixon said, ‘The present legislation is too far

advanced, the need for reform is too great,’ for time to run out on the proposal.”

CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 5–6. In addition, Nixon invited several key

members of the Senate Finance Committee and their wives to the “Western White House”

in San Clemente, California, and to an official State Dinner at the Hotel Del Coronado in

San Diego, California on September 3, 1970, including three Democrats—Chairman

Russell Long (D., La.), Harry Byrd (D., Va.), and Abraham Ribicoff (D., Conn.), and three

Republicans—Wallace Bennett (R., Utah), Jack Miller (R., Iowa), and Paul Fannin (R.,

Ariz.). Richard Nixon, President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary, RICHARD NIXON

PRESIDENTIAL LIBR. & MUSEUM (Sept. 3, 1970), http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/sites/

default/files/virtuallibrary/documents/PDD/1970/035%20September%201-15%201970.pdf

[http://perma.cc/N85Z-EVWN].

136 MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 490.

137 See Neuberg, supra note 9.

138 MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 493.

139 Id. at 495.

140 See ADMINISTRATIVE CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES: RECOMMENDATIONS

AND REPORTS 83 (1979).

141 MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 490.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 119

system.

142

When the hearings finally resumed on July 21, 1970,

Chairman Long concluded, to no one’s surprise: “In significant

respects the new plan is a worse bill—and a more costly bill than

the measure which passed the House.”

143

Suffice it to say, Long’s

committee would never report this now-monstrous bill to the floor

of the Senate. Instead, the chairman devised a devious strategy to

kill the measure: unceasing delay via endless public scrutiny.

144

In fact, when the Senate Finance hearings resumed in

July 1970, Chairman Long had decided from the get-go to further

delay consideration of the revised bill until after the midterm

elections.

145

The Senate, in the cynical words of Senator Long,

would be able to “give the plan more thoughtful consideration in

the public interest if the bill came up in November.”

146

More

importantly, in contrast to the bill’s swift and stealthy approval

in Wilbur Mills’s Ways and Means Committee, consideration of

the bill in the Senate Finance Committee remained open to the

public. By extending the hearings for weeks on end and inviting

dozens of witnesses to testify before the committee, the sundry

imperfections of the bill came to the fore.

Long’s devious delay tactics would seal H.R. 16311’s fate.

Long’s committee called over two dozen public officials

representing a wide variety of local and state governments, as

well as a long laundry list of representatives from the business

world, labor unions, and other public interest groups.

147

The

142 Id. at 503.

143 Id. at 506.

144 Or, in the words of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, “Delay now became an open tactic of

those opposed to [the guaranteed income bill] and time the greatest enemy of those who

supported it.” Id. at 512.

145 Recall that Chairman Long had suspended the hearings on May 1, 1970.

CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 6–7.

146 Id. at 5. For his part, Moynihan had been hoping for Senate action before

Congress recessed on October fifteenth for the midterm election campaign. See

MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 521.

147 CONGRESSIONAL QUARTERLY, supra note 8, at 9–13. In all, the following

individuals representing the following organizations testified before the Senate Finance

Committee between July 21 and September 10, 1970: James D. Hodgson, Secretary of

Labor; John O. Wilson, Director, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Office of

Economic Opportunity (“OEO”) (Wilson was asked to testify on the New Jersey graduated

work incentive project being conducted by the OEO); Keith E. Marvin, Associate Director,

Office of Policy and Special Studies, General Accounting Office; John V. Lindsay, Mayor of

New York City; W. D. Eberle, President of American Standard and Co-Chairman of

Common Cause (a new citizens’ lobby formed by the leaders of the National Urban

Coalition); Leonard Lesser, Committee for Community Affairs (a nonprofit corporation

representing community organizations of the poor); Harold W. Watts, Professor of

Economics and Director, Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin; Mrs.

Richard M. Lansburgh, President, Day Care and Child Development Council of America

Inc.; Mrs. Edward F. Ryan, National Congress of Parents and Teachers; Andrew J.

Biemiller, Director of legislation, AFL-CIO; Whitney M. Young Jr., Executive Director,

National Urban League, and President, National Association of Social Workers; John E.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

120 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

cumulative effect of all this nitpicking public testimony was to

slow down the bill’s momentum and reinforce the senators’

various biases against the bill. Given the sheer number of witnesses

and the diversity of opinion expressed by them, the bill suffered a

death by a thousand cuts in Chairman Long’s Finance Committee.

Unable to survive the glare of public scrutiny or the paralysis of the

delay, H.R. 16311 would eventually die in committee.

148

The irony of the situation is that President Nixon probably

had enough votes in the full Senate to get his guaranteed income

bill approved. According to Moynihan, at least sixty senators

would have voted for the bill had it reached the floor of the

Senate.

149

If there were only a way to get the bill to the floor of

the Senate.

With time running out and just a few weeks left in the 91st

Congress, Senators Ribicoff and Bennett signaled their intention to

offer a guaranteed income bill as a floor amendment to a different

bill that would reach the full Senate, an omnibus Social Security bill

providing a ten percent across-the-board increase in Social Security

payments.

150

But in addition to the Ribicoff-Bennett amendment,

many other controversial legislative proposals were added to the

Social Security bill, including a supplemental authorization for

additional foreign aid as well as a new protectionist trade policy

with import quotas on foreign goods.

151

These additional

amendments would seal the fate of the guaranteed income bill.

When Chairman Long introduced the Social Security bill on

December sixteenth, Senators Ribicoff and Bennett announced their

intention to offer their guaranteed income amendment to the bill the

next day during floor debate. The Vice President was even put on

alert in case of a tie.

152

Alas, it was not to be. A filibuster broke out

Cosgrove, U.S. Catholic Conference, testifying for the Conference, the National Council of

Churches and the Synagogue Council of America; Howard Rourke, Director of the

Department of Social Services, Ventura County, California, testifying for the National

Association of Counties; Carl B. Stokes, Mayor of Cleveland, testifying for the National

League of Cities and the U.S. Conference of Mayors; Karl T. Schlotterbeck, U.S. Chamber

of Commerce; A. L. Bolton Jr., President of Bolton-Emerson Inc., Lawrence, Mass.,

representing the National Association of Manufacturers; William C. Fitch, Executive

Director, National Council on the Aging; Frederick S. Jaffe, Vice President, Planned

Parenthood-World Population; Warren E. Hearnes, Governor of Missouri and chairman of

the National Governors’ Conference; Tom McCall, Governor of Oregon; George McGovern,

a U.S. Senator from South Dakota; Joseph C. Wilson, Chairman of the board, Xerox

Corporation, testifying for the Committee for Economic Development. Id.

148 The final vote in the Senate Finance Committee was 10 to 6 against the bill. Id. at 13.

Since Chairman Long was able to cast his vote last, he voted for the bill knowing full well that

it lacked sufficient votes to be reported out of committee. Id.

149 MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 518, 525.

150 Id. at 537.

151 Id. at 537–38.

152 Id. at 538.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 121

over the foreign aid amendment, and another filibuster was

threatened over the import quotas.

153

In the end, the Ribicoff-Bennett

amendments were never voted on.

154

Their last-ditch efforts failed.

Time ran out, and the bill perished in the Senate on the last days of

the 91st Congress.

155

Guaranteed income was dead.

EPILOGUE

This Article retold the story of H.R. 16311, “The Family

Assistance Act of 1970,” the historic guaranteed income bill

proposed by President Nixon in the summer of 1969 and enacted

by the House in April of 1970, only to die in the Senate in the last

days of the 91st Congress. To provide structure to this story, this

Article presented the rise and fall of the guaranteed income bill in

three dramatic acts featuring such dramatis personae as Milton

and Rose Friedman, Wilbur Mills, and Russell Long, all of whom

played leading roles in this legislative morality play. Here,

however, I want to conclude this compelling story by asking a

normative question. Specifically, why should the ill-fated history of

H.R. 16311 matter to us today? After all, this political theater took

place several generations ago; the leading players are all dead.

What lessons, if any, can we learn from this legislative debacle?

A lot! Given the resurgence of Universal Basic Income

(“UBI”) proposals in our day,

156

the rise and fall of H.R. 16311

offers a compelling case study into the politics of guaranteed

income. As Moynihan taught us long ago, “income redistribution

goes to the heart of politics: who gets what and how . . . .”

157

So, if

you are a proponent of UBI or are merely sympathetic to this

idea, you will want to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

But, by the same token, if you are opposed to UBI or are just

skeptical of this idea, the story of H.R. 16311 provides an

instructive political playbook for how to defeat such proposals.

Although the idea of a basic income or UBI can be located “at

almost any point on a spectrum ranging from a prudent and cautious

[i.e., incremental] reform of welfare payments to a climactic abolition

153 Id.

154 Although the Senate unanimously approved the omnibus Social Security bill—without

the import quotas, foreign aid, or guaranteed income amendments—on December 29, 1970, the

bill died in conference committee. Id. at 538 n.1.

155 Id.

156 See, e.g., Howard Reed & Stewart Lansley, Universal Basic Income: An Idea Whose

Time Has Come?, COMPASS (May 23, 2016), http://www.compassonline.org.uk/wp-

content/uploads/2016/05/UniversalBasicIncomeByCompass-Spreads.pdf

[http://perma.cc/9E38-BC3K]; see also Jurgen De Wispelaere & Lindsay Stirton, The

Many Faces of Universal Basic Income, 75 POL. Q. 266, 266 (2004).

157 Id. at 355.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

122 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

of the wage system,”

158

in the end H.R. 16311 was negatively framed

by its opponents in moral terms: the bill paid people not to work. As a

result, the leading lesson of this affair is: any realistic UBI proposal

must somehow find a way of passing an impossible political test

before it will ever be enacted into law. How can a government provide

a meaningful income to the poor, let alone a universal income to all

persons, without distorting work incentives and without breaking the

bank, so to speak?

Stated bluntly, what is the optimal amount of income that

each person should be entitled to? Consider for the last time “The

Family Assistance Act of 1970.” Was the proposed $1,600 annual

cash stipend for a family of four—the centerpiece of the bill—too

generous and costly, or was it too stingy and miserly? This

inherent contradiction, not to mention the delicate questions of

race and class looming in the background, cursed H.R. 16311

from the get-go; this contradiction also bedevils all universal

basic income schemes today. Supporters of contemporary UBI

schemes should take this inherent tension to heart. Unless they

can solve this puzzle (how to finance such schemes without

distorting the incentive to work), any attempt to enact a

universal basic income is most likely doomed to fail.

158 MOYNIHAN, supra note 7, at 441.

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 123

Appendix A

159

159 TIME MAGAZINE, Dec. 19, 1969 (noting the presence of Milton Friedman on the cover).

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

124 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 23:1

Appendix B

160

160 Income Maintenance Programs: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Fiscal Policy

of the J. Econ. Comm., 90th Cong. 676–90 (1968).

Do Not Delete 5/22/20 8:52 AM

2020] Guaranteed Income: Chronicle of a Political Death Foretold 125

Appendix C

161

161 Richard M. Nixon, Remarks at the Opening Session of the White House Conference

on Children, 6 WEEKLY COMPILATION OF PRESIDENTIAL DOCUMENTS 1677, 1683 (Week

Ending Saturday, Dec. 19, 1970).