Working PaPer SerieS

no 1240 / SePtember 2010

monetary Policy,

aSSet PriceS and

conSumPtion in

china

by Tuuli Koivu

WORKING PAPER SERIES

NO 1240 / SEPTEMBER 2010

In 2010 all ECB

publications

feature a motif

taken from the

€500 banknote.

MONETARY POLICY, ASSET PRICES

AND CONSUMPTION IN CHINA

1

by Tuuli Koivu

2

1 The views expressed represent those of the author and not necessarily those of the Bank of Finland. The author is grateful to the participants

in the ECB IPA seminar and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority Conference “ Financial Reforms, Macro Policies and Currency

Internationalization: The Case of China”, and in particular to Alexander Chudik, Kari Heimonen, Cao Honghui,

Aaron Mehrotra, Jukka Pirttilä, Gabor Pula and an anonymous referee for their useful comments.

2 Bank of Finland, European Central Bank and University of Jyväskylä;

e-mail: [email protected]

This paper can be downloaded without charge from http://www.ecb.europa.eu or from the Social Science

Research Network electronic library at http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=1666727.

NOTE: This Working Paper should not be reported as representing

the views of the European Central Bank (ECB).

The views expressed are those of the author

and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB.

© European Central Bank, 2010

Address

Kaiserstrasse 29

60311 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Postal address

Postfach 16 03 19

60066 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Telephone

+49 69 1344 0

Internet

http://www.ecb.europa.eu

Fax

+49 69 1344 6000

All rights reserved.

Any reproduction, publication and

reprint in the form of a different

publication, whether printed or produced

electronically, in whole or in part, is

permitted only with the explicit written

authorisation of the ECB or the author.

Information on all of the papers published

in the ECB Working Paper Series can be

found on the ECB’s website, http://www.

ecb.europa.eu/pub/scientific/wps/date/

html/index.en.html

ISSN 1725-2806 (online)

3

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Abstract

4

Non-technical summary

5

Introduction

6

1 Short overview of the earlier literature

8

2 Data and methodology

10

3 SVAR estimation

12

4 Conclusions

16

References

17

Appendix

20

CONTENTS

4

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Abstract

This paper studies the wealth channel in China. Using the structural vector

autoregression method, we find that a loosening of China’s monetary policy indeed leads

to higher asset prices, which in turn are linked to household consumption. However, the

importance of the wealth channel as a part of the monetary policy transmission

mechanism in China is still limited.

JEL classification: E52, P24

Keywords: China, monetary policy, asset prices

5

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Non-technical Summary

China responded to the global financial and economic crisis by launching a stimulus package in

November 2008. The monetary policy stance was eased, and a large share of investment projects

included in the package was financed by bank credit. The large size of the stimulus package – 13%

of GDP in 2008 – has raised questions about possible unwanted side effects on the economy. In

particular, the role of a loose monetary policy in hastening the return of stock and housing prices to

their rising trends has been discussed.

However, there are no earlier academic studies on the links between monetary policy, asset prices

and the real economy in China. In this study, we aim to fill this gap and contribute to the current

discussion of optimal stimulus policies. Using quarterly data for 1998-2008 we study the impacts of

monetary policy on urban household consumption via both stock and housing prices.

According to our results, monetary policy indeed has an impact on stock and residential prices in

China. As expected, a monetary policy loosening leads to an increase in both types of asset prices.

Furthermore, the link from asset prices to household consumption is found to be positive. However,

this result is not highly robust, which is not surprising in light of the high volatility of the Chinese

stock markets. Earlier studies on the US economy have found that if an increase in asset prices and

thus in household wealth is temporary in nature, its impact on household consumption will be

modest (Lettau, Steindal and Ludvigson, 2002). Furthermore, a very small share of the Chinese

population own more than one apartment, so that an increase in housing prices may actually

encourage some families to save more and thus improve their possibilities to buy an apartment. It

may be the case that very few households will actually benefit from higher housing prices by being

in a position to be able to sell an apartment.

Our results also reveal that the link from monetary policy to household consumption – either

directly or via asset prices – is weak in China. This means that the possibilities of influencing

household behaviour in China via monetary policy are limited, probably due to the fact that Chinese

households have limited access to external finance. For example, because rather few households are

able to finance their housing by mortgage loans, the majority of households are not greatly affected

by monetary policy decisions. It seems that in order to improve the monetary policy transmission

mechanism the financial sector will need further reform.

Our finding that monetary policy does impact asset prices in China needs to be scrutinized. Even

though asset price increases induced by monetary policy measures do not encourage households to

increase their consumption, it is possible that asset prices play a more important role in other

segments of the economy. Therefore, the link from monetary policy, via asset prices, to e.g. fixed

asset investments, which account for nearly 50% of China’s GDP, should be carefully investigated.

6

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Introduction

China’s response to the outbreak of the global financial crisis and subsequent downturn was quick

in autumn 2008. The announced stimulus package - even though amounted to about 13% of annual

GDP - was only one part of a policy package that was put in place to keep the economy on a stable

growth path. The majority of the stimulus policies and related investment projects were financed by

bank credit, which led to a situation in which Chinese banks’ credit stock at the end of 2009 was

30% larger than a year earlier. Naturally, such a pronounced economic stimulus has raised questions

about negative side effects. The rapid recovery of the Chinese stock markets in the summer 2009

was connected with rapid credit growth, and more recently the Chinese authorities have become

concerned about price increases in the real estate market.

2

This paper contributes to the discussion by studying the monetary policy transmission mechanism

in China. In particular, we explore whether monetary policy can have an impact on asset prices,

namely residential property prices and stock prices, and if so whether these price developments are

capable of influencing household consumption. To our knowledge, there are no earlier studies that

estimate links between monetary policy, asset prices and household consumption based on Chinese

data.

According to our results from a structural VAR model, a loosening of monetary policy indeed leads

to higher asset prices in China. Although these positive asset price developments are linked to

higher household consumption, our findings on the wealth channel remain weak. Overall, the

effects of monetary policy on Chinese households’ behaviour are limited.

In addition to the current economic fluctuations, study of the stock and residential property markets

is motivated by their increasing importance in the Chinese economy. Interestingly, developments in

the two asset markets have been uneven over the last decade. In particular, the stock markets have

had a bumpy ride, as share prices experienced several booms and busts right after the opening of the

Shanghai Stock Exchange in 1990 (Figure 1). Subsequently, market performance has been weak –

especially compared to the strong performance of the economy. The weakness of the stock market

was thought to be due mainly to institutional problems such as lack of transparency, low quality of

listed companies, weak minority shareholder rights, limited role of institutional investors, and the

unclear plan to sell state-owned shares.

3

Efforts were made to revive investors’ interest in the stock

markets through institutional reforms touching on some of these problems, which in part led to

another stock market bubble in 2006-2007, as share prices rose fivefold in less than two years,

before the market crashed again. The sharpest monthly drop in the Shanghai A-Index amounted to

almost 25% in October 2008. As mentioned above, the performance of the stock exchanges has

been upbeat since the start of 2009, thanks to stimulus measures and robust economic growth in

China.

Compared to the high volatility of stock markets, developments in Chinese housing prices have

been consistently positive, even though extensive reforms have also targeted this sector (Figure 1).

Liang and Cao (2007) divide the reforms into three subperiods. The last of the three began in 1998,

after which most of the apartments were privatised and the market mechanism was allowed to

2

For example, China raised the minimum down payment on a second house to 40% and tightened land-sale regulations

for developers, by e.g. introducing the first nationwide minimum down payment on land purchases in December 2009.

At the same time, tax regulations on capital gains on house sales were tightened. Since then a number of other

regulatory changes have been implemented in order to cool off price increases in the housing market.

3

An overview of stock market developments in China can be found in e.g. Chen and Shih (2002).

7

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

function. Nowadays 80% of urban residents own their apartment in China.

4

However, the public

sector has maintained its role as a moderator in the real estate market, not least because of its

monopoly in supplying land. Moreover, minor regulatory changes, e.g. in respect of minimum

down payments and land usage, are still common. Housing prices have performed favourably for

many years since the start of the data series in 1998. The strong uptrend ended only in 2008 and

even then the period of declining prices was short-lived; since the spring of 2009, prices have been

on the rise again.

Figure 1. Shanghai A-Index and residential prices in China.

00

1 000

2 000

3 000

4 000

5 000

6 000

7 000

1.19921.19941.19961.19981.20001.20021.20041.20061.20081.2010

Residential market selling prices, RMB/Sq meter

Shanghai A-index

Source: CEIC

In the past, asset prices had virtually no impact on the Chinese economy. The size of the stock

markets compared to the economy was small, and until the second half of the 1990s, apartments

were owned by the public sector. Profound economic reforms have gradually increased the

importance of asset markets in the economy. During the stock market boom in 2007, the number of

stock accounts rose to 139 million (Leung and Yim, 2008).

5

In addition, more and more companies

are obtaining external finance by listing on stock markets. The total capitalisation of Shanghai and

Shenzhen Stock Exchanges, which amounted to just 5% of GDP in the mid-1990s, peaked at more

than 100% of GDP at the end of 2007. The real estate sector is a key segment of the Chinese

economy. The volume of investment in the sector amounts to 10% of GDP on average. However,

the relevance of asset market development for household behaviour is questionable, as only 2.3% of

total household income was classified as property income in 2008 (Figure A1 in the Appendix).

The paper is organised as follows. We first present a short overview of the earlier vast theoretical

and empirical literature on the wealth channel. As mentioned earlier, we are not aware of any papers

that examine whether monetary policy affects household consumption in China via its impacts on

asset prices. After the literature review, we describe the data and methodology for estimating the

links between monetary policy, asset prices and household consumption in China. The third section

4

Financial Times, 22

nd

September 2009: http://blogs.ft.com/dragonbeat//2009/09/22/whats-behind-chinas-skyrocketing-

residential-property-market-subsidies-subsidies-subsidies/?catid=152&SID=google

5

Obviously, a single person or legal entity can hold more than one account. Unfortunately, data on share of population

holding a stock account in China is not available.

8

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

contains a summary of the results, and in the fourth section we conclude and draw some policy

implications.

1. Short overview of the earlier literature

Besides the other monetary policy transmission channels, monetary policy can affect the real

economy also via the ‘wealth channel’, which can be divided into two parts. For the wealth channel

to function, monetary policy must first be capable of affecting the value of wealth, and secondly,

changes in wealth must influence consumption. The existing literature on the wealth channel is vast

and has a long history. Already in 1933, in the aftermath of the economic crisis, Fisher (1933) noted

that a fall in security prices could be a phase of an economic depression. Later on, a theoretical

framework was set out for the channel (de Leeuw and Gramlich, 1969).

In the theoretical literature on the first part of the wealth channel, monetary policy can impact stock

prices in many ways. Monetary policy, which is assumed to have an impact on long-term interest

rates and on the level of economic activity, can influence stock prices by affecting companies’

future earnings and dividend payments. Interest rates also affect the discounted stream of dividends,

and monetary policy has thus been linked to expected stock returns. Furthermore, lower interest

rates are assumed to render shares more attractive than bonds as an outlet for savings and thus to

boost share demand and prices. Expansionary monetary policy should also encourage households to

reduce their money balances, not merely in order to increase their consumption but also to increase

their equity holdings (Mishkin, 1996).

The recent empirical papers confirm these theoretical considerations and find a negative link from a

monetary tightening to stock prices. For example, Bernanke and Kuttner (2005) and Rigobon and

Sack (2004) find that a 25 basis point rise in a short-run interest rate decreases stock prices 1.0-

2.4% in the US market. Bernanke and Kuttner (2005) find that most of the decline in stock prices is

due to the negative impact of tight monetary policy on expected future dividends and expected

future excess returns. In this respect, the role of risk becomes important, as a tightening of monetary

policy can increase either the riskiness of stocks or investors’ risk adversity, thus raising the

expected equity premium. More evidence on the link from monetary policy to stock prices has been

found by Bordo and Wheelock (2004) and Alessi and Detken (2009) who conclude that an increase

in liquidity boosts asset prices in developed economies.

The link from monetary policy to residential prices can be described using the concept of user cost

of capital (Mishkin, 2007). An interest rate hike raises the user cost of capital, causing a decline in

housing demand and prices. As a result, housing construction and thus aggregate demand in the

economy decrease. Expectations of a rise in interest rates may quickly push up the user cost of

capital by lowering the expected real rate of appreciation of residential prices. There is empirical

evidence also on the link from monetary policy to residential prices. Using the structural VAR

methodology, Iacoviello (2000) finds that monetary policy has an impact on housing prices in

Europe. Ahearne, Ammer, Doyle, Kole and Martin (2005) study housing prices in 18 advanced

economies and also get results that confirm the link from monetary policy to housing prices. In

particular, booms in housing prices are often preceded by a period of monetary policy loosening.

Recently, monetary policy credibility has been linked to the wealth channel (Bordo and Wheelock,

2004). Successful monetary policy, that keeps inflation low, can increase the probability of an asset

price bubble.

9

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

The theoretical models dealing with the second part of the wealth channel - the link between asset

prices and consumption - normally rely on the life cycle model by Ando and Modigliani (1963),

which gives aggregate consumption as a function of aggregate expected income and net worth.

6

Modigliani (1971) provides the framework for a large macro model in which monetary policy can

affect asset prices and hence also consumption. Consumers maximise utility subject to a lifetime

resource constraint, and consumption is defined as

[]

)(YHAmpcC

W

+= (1)

where C is consumption, mpc is the marginal propensity to consume, A is real non-human wealth

and H(Y) is the present value of the expected income stream. As one can see from (1), the

importance of the wealth effect on consumption depends largely on the marginal propensity to

consume. Furthermore, the shorter the household’s planning horizon, the stronger the effect from

wealth to consumption (Poterba, 2000).

In the wide selection of empirical papers, the majority conclude that asset prices do influence

consumption.

7

However, estimates of the size of the effect vary considerably. While Modigliani

(1971) suggested that a one dollar increase in wealth boosted consumption by 5 cents, more recent

studies estimate the impact to be smaller (Lettau and Ludvigson, 2004). There are many reasons for

the variation in estimates of the size of the impact (Poterba, 2000, Altissimo et al., 2005). The

wealth effect depends on the liquidity of the asset market and the predictability of prices. In

addition, stock and residential prices influence consumption differently, due to the difference in

ownership distributions. While households’ equity wealth is highly concentrated, real estate wealth

has been more equally distributed among households. As a result, stock prices probably affect a

fairly small share of households while real estate prices are relevant for most households’

behaviour. In addition, if shareholdings are concentrated in pension funds, the marginal propensity

to consume is probably lower than if the equities are owned directly by households. Interestingly,

the nature of the price increases or decreases is also relevant: Lettau and Ludvigson (2004) found

that, while permanent shocks to wealth seem to have a statistically significant effects on household

consumption, most shocks in asset prices are only temporary and do not affect consumption.

Each of the above mentioned papers studies only a single part of the wealth channel. Either they

look at the link from monetary policy to asset prices or they estimate the impact from asset prices to

consumption. They do not explore whether changes in asset prices due to monetary policy have any

impact on consumption. There are few studies that deal with both parts of the wealth channel.

Ludvigson, Steindal and Lettau (2002) summarise the results for the wealth channel from the large

macro models of the US economy. Although the link from monetary policy to the real economy via

asset prices is found to be significant, the importance of the wealth channel in the economy seems

to be moderate. The authors apply a structural VAR to US data and conclude that an increase in

household wealth due to a loosening of monetary policy has a positive, but small and hardly

significant, impact on household consumption.

From the viewpoint of this paper, studies on the wealth channel in emerging economies – and China

in particular – are of course the most relevant ones. However, this literature is very limited. Liang

and Cao (2007) study the impacts of monetary policy on residential prices in China. According to

their long-run results, output growth is the dominating force behind property prices while the

6

Literature surveys on theoretical and empirical work on the impacts of asset prices on the real economy can be found

in e.g. Altissimo et al. (2005) and Poterba (2000).

7

In the empirical literature, household wealth is often measured by asset prices due to data availability.

10

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

influence of bank credit on asset prices is not statistically significant. Funke (2004) studied the

wealth effects from stock prices to private consumption with a panel of 16 emerging countries.

According to his results, a 10% decline in stock prices could cause a 0.2-0.4% decline in private

consumption. The panel data used by Peltonen, Sousa and Vansteenkiste (2008) included 14

emerging economies, including China. Confirming the results by Funke, they found a significant

link from stock prices to consumption. They also found that higher housing prices tend to increase

consumption. In China’s case, stock prices were found to boost consumption although the wealth

effect was the smallest among the countries: a 10% rise in stock prices increased consumption by

0.12%. Residential prices did not have a significant impact on consumption in China.

2. Data and methodology

As mentioned above this study is the first attempt to highlight the dynamics of the relationship

between monetary policy, asset prices and consumption in China. We employ a structural VAR

model with five variables: household income, household consumption, consumer price inflation, an

indicator for monetary policy, and asset prices. The research period runs to the end of 2008 but is

restrictive in starting as late as1998 due to the availability of data. Our data source is the CEIC

database (data details in appendix Table A1). All variables except consumer price inflation are in

real terms and in logs. Furthermore, all the time series except stock prices are seasonally adjusted

using Tramo Seats. The time series are graphed in Figure A2.

Household income and consumption are measured as disposable income and living expenditure per

capita, respectively.

8

The household data are based on urban household surveys. Although we are

restricted to studying the urban areas because of data availability, we assume that the importance of

the wealth channel is very limited in the rural areas, due to the presumably very modest

shareholdings. Furthermore, the residential market in the countryside is still fairly inactive. Inflation

is measured by quarterly changes in the consumer price index.

The selection of a monetary policy indicator is complicated by a fact that there is no consensus on

how to measure China’s monetary policy stance, mainly because of a plethora of policy tools (see

e.g. Geiger 2008). While the studies on the advanced economies typically use a policy interest rate

as the monetary policy indicator, the role of interest rates in the Chinese economy is known to be

very modest (see e.g. Koivu 2008; Laurens and Maino 2007; Mehrotra 2007).

Even if we decide on a quantitative measure for China’s monetary policy we are left with a number

of different monetary aggregates. Using base money, which in China’s case includes currency in

circulation and commercial bank reserves held at the central bank, could obviously be defended by

a fact that it is under authorities’ direct control. However, the frequent changes in commercial

banks’ reserve requirement have made it difficult to interpret changes in base money. While an

increase in base money would otherwise be interpreted as monetary easing, in China’s case a rise

may simply reflect a hike in the reserve requirement and thus a tightening in the monetary policy

stance.

M2 seems to capture much of decision makers’ attention. They set annual growth targets for M2

and the People’s Bank of China (PBC) closely monitors movements in M2 for its quarterly reports.

Furthermore, banks’ reserves, for which the movements are difficult to interpret, as mentioned

8

A number of earlier studies on the wealth channel concentrate on the consumption of nondurable goods and services.

Unfortunately, we are not able to follow this course since quarterly data on the different consumption categories in

China starts from 2002.

11

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

above, are excluded from M2.

9

It is of course somewhat questionable to use such a broad monetary

aggregate as a monetary policy indicator in light of the possible problems related to the

controllability of the aggregate. However, contrary to many advanced economies, we argue that the

Chinese officials actually do control M2 because the public sector still holds a majority ownership

in all the major banks in China.

10

Moreover, even though the credit quotas were abolished in 1998,

the authorities still actively issue direct guidelines regarding banks’ operations under the so-called

window guidance. The use of a broad monetary aggregate can be defended also by a fact that it may

comprehensively capture the impacts of the various policy tools on the economy.

We study the behaviour of two different asset markets – housing and stocks. Like many earlier

studies, we do not have time series data on household wealth in China and so must use asset prices

as a proxy for household wealth. As a first proxy, we use the Shanghai A-share Stock Index.

11

Another proxy that we use for household wealth is the residential property price index.

To study the impacts of monetary policy on asset prices and finally on consumption, we estimate a

structural vector autoregression (VAR) model. The VAR model is preferable in our case, where the

variables endogenously influence each other. A basic reduced form VAR process is presented as:

tptptt

uyAyAy +++=

−−

...

11

, (2)

where y

t

= (y

1t

, … , y

Kt

) contains K endogenous variables. The A

i

are K x K coefficient matrices and

u

t

= (u

1t

, … , u

Kt

) is a K-dimensional process. Errors (u

t

) are assumed to be serially uncorrelated.

The basic VAR model explains the endogenous variables solely by their history. If we want to

model possible contemporaneous relations between the variables, we need a structural form of the

VAR:

....

*

1

*

1 tptptt

ByAyAAy

ε

+++=

−−

(3)

The structural errors, İ

t,

are assumed to be serially and cross-sectionally uncorrelated. The A*

i

(i=1,

…p) are K x K coefficient matrices. The relationship between error terms in the reduced and

structural forms is the following:

tt

BAu

ε

1−

= . (4)

If we write Au

t

= Bİ

t

we essentially decompose the structural errors (İ

t

) into components caused by

the unexplained contemporary reduced-form shocks (u

t

). Since we want to highlight contemporary

relations, we must impose 2K

2

– K(K+1)/2 restrictions on the A and B matrices, to be able to

exactly identify the system. In our case, where K=5, the number of necessary restrictions is 35. We

impose the following restrictions (y indicating household income, c household consumption, ʌ

inflation, m monetary policy and ap asset prices):

9

According to China’s national data definition, M0 comprises currency issued by the PBC less the amount held by

banking institutions. M1 comprises of M0 and demand deposits. M2 comprises M1 and time and savings deposits.

10

The most important exceptions being the foreign-owned banks and the Minsheng Bank.

11

In Mainland China, there are two stock markets. The Shanghai Stock Exchange commenced operations at the end of

1990 and the Shenzhen Stock exchange in the following year. The use of data from the Shanghai A-Index is defended

by a fact that the Shanghai Stock Exchange has always been the leading market by size. As of end-2008, the

capitalisation of the Shanghai Stock Exchange corresponded to 32% and that of Shenzhen 8% of GDP. Furthermore, the

A-shares cover 99% of the capitalisation in the Shanghai Stock Exchange while the B-shares, originally directed at

foreign investors, play only a minor role in the market.

12

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

»

»

»

»

»

»

¼

º

«

«

«

«

«

«

¬

ª

»

»

»

»

»

»

¼

º

«

«

«

«

«

«

¬

ª

=

»

»

»

»

»

»

¼

º

«

«

«

«

«

«

¬

ª

»

»

»

»

»

»

¼

º

«

«

«

«

«

«

¬

ª

ap

t

m

t

t

c

t

y

t

ap

t

m

t

t

c

t

y

t

b

b

b

b

b

u

u

u

u

u

ε

ε

ε

ε

ε

ππ

55

44

33

22

11

0000

0000

0000

0000

0000

1**0*

*1***

00100

00*1*

00*01

where * indicates a parameter that is freely estimated in the system. Following the earlier literature

(see e.g. Ludvigson et al. 2002), household income is presumed to be slow to adjust and is allowed

to react to shocks to consumption, money supply and asset prices only with a lag. However, as

nominal wages take some time to adjust, real income is allowed to react immediately to shocks to

inflation.

Consumption is allowed to react immediately to shocks to real income and inflation. We assume

that asset prices, measured at the end of period, can influence consumption, measured as a flow

over the following period. Along with the general literature on monetary policy transmission

mechanism (see e.g. Bagliano and Favero, 1998), it is assumed that monetary policy can affect

consumption (and all the other variables in the model except asset prices) only after a lag of one

period. We also introduce sticky prices, as is customary in the literature.

It is challenging to construct a monetary policy reaction function for China – in particular because

our monetary policy indicator M2 may in the short run deviate from the authorities’ target. In the

monetary policy literature, it is customary to allow monetary policy to react immediately to shocks

in all other variables and we follow suit (see for example, Bernanke and Mihov, 1998). Although

the PBC has argued that it does not target asset prices in its monetary policy, the Chinese

authorities, as mentioned above, seem to be keen on guiding developments in the real estate and

stock markets, so that it is realistic to allow monetary policy to react to shocks in asset prices

immediately.

Finally, asset prices are allowed to react to all shocks in the economy without delay, except for

shocks to consumption. This assumption is necessary in order to implement a sufficient number of

restrictions in the model. As the theoretical background behind this restriction is admittedly weak

we tested the obtained results by optional models where asset prices were allowed to react

immediately to shocks in consumption. The results remained very much the same.

3. SVAR estimation

We test first test the order of integration of our time series. The results from the Augmented

Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron unit root tests can be found in Tables A2 and A3 in the

Appendix. The number of lags included in the tests was defined by the three information criteria.

We included a trend and a constant in each test in levels and a constant in the tests in differences.

12

According to the ADF test, all the series except the Shanghai A-Index seem to be integrated of

order one.

13

However, the Phillips-Perron test shows all our time series (incl. the stock index) to

definitely be I(1) variables.

12

The test in levels of the Shanghai A-index and consumer price inflation were run with and without a trend.

13

When consumption is tested in differences with 11 lags, as suggested by the Akaike information criteria, the null

hypothesis of a unit root cannot be rejected. However, the high number of lags may be the reason for the result, as the

13

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Next we run cointegration tests to find out whether there are any long-run relationships between the

variables. The results from the Saikkonen-Lütkepohl and Johansen Cointegration tests can be found

in Tables A4 and A5 in the Appendix. As above, the number of lags is decided on the basis of

information criteria, and we introduced a trend and a constant in all our tests. We clearly found

signs of cointegration vectors. However, the number of vectors is highly dependent on the

cointegration test. The reliability of the cointegration test results can be weak due to the shortness of

the time series. It is thus difficult to determine the exact number of cointegrating vectors in our

model. Furthermore, based on theory, we have no strong preference for a specific number of long

run vectors in the system. We thus continue to run VARs in levels without restricting the number of

cointegrating vectors. According to Lütkepohl (2004), this practise does not lead to a

misinterpretation of asymptotic properties of results as long as one allows at least two lags. This

procedure has been followed also by e.g. Bagliano and Favero (2002).

We run the model separately with the stock market index and with residential prices, and include a

constant and a trend in both estimations. The chosen number of lags is two in both systems, based

on the misspecification tests. Also based on the results from the misspecification tests, we include

an impulse dummy in our estimations.

14

We test the models via the Portmanteau and LM tests for autocorrelation of residuals, the Jarque-

Bera tests for non-normality, and ARCH-LM tests, to find possible ARCH effects in the residuals.

Neither of the models seems to have any major problems in passing most of the misspecification

tests (Tables A6 and A7 in the Appendix). In the model with stock prices, there is some indication

of autocorrelation of residuals according to the Portmanteau test, but the result is significant only at

the 10% level. In addition, the results from the LM test, on the existence of residual autocorrelation

in shorter lags, does not signal any problems in the system. In the model with residential prices,

there are no signs of autocorrelation. However, the residuals from the income equation strongly

indicate nonnormality. A closer look at the test results reveals that the failure of the normality test is

due to kurtosis rather than excess skewness. According to Juselius (2006), VAR estimates are more

sensitive to deviations from normality due to skewness than to kurtosis, and so we continue to

report the results.

As China is a transition economy in which monetary policy and asset markets have been in a

process of continuous reform during the research period, it is important to test also the stability of

the model. According to our results from Chow break point and sample split tests, using

bootstrapped p-values, there does not seem to be a problem in this respect. Neither the break point

nor the sample split test find convincing evidence (at least at 5% level) of breaks in the research

period. We also run Cusum tests but do not find any signs of instability.

15

However, the test results

have to be treated cautiously, as the short sample period obviously limits the possibilities for

conducting break tests and reduces their efficiency.

Because the matrix coefficients of the VAR analysis are difficult to interpret as such, we take a

closer look at the dynamics of the system and report the impulse response functions. The resulting

impulse responses of each variable to a shock of one standard deviation in each of the other

variables are reported in Figures A3 and A4 in the Appendix. The responses are reported for 20

null hypothesis can be rejected even at the 1% level when no lags are introduced, as suggested by both Hannan-Quinn

and Schwartz criteria.

14

The impulse dummy for 2003Q4 is introduced because of a pick-up in the CPI due mainly to food prices and can be

considered exogenous to our model.

15

The test results are available from the author.

14

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

quarters using 1,000 bootstrapping replications. The significance of the results can be interpreted

based on the reported 95% Hall bootstrapped percentile confidence intervals.

Most of our results from both specifications are as expected. For example, a positive shock in

income increases consumption, the result being strongly significant. The monetary policy reaction

function also seems to be reasonable. The central bank reduces the money supply in response to a

positive shock in either consumer price inflation or asset prices. Both results remain statistically

significant for more than one year. The link in the opposite direction, from money supply to

consumer price inflation, is also confirmed to accord with results found in the earlier papers on

China’s monetary policy (see, for example, Koivu et al., 2009; Laurens and Maino, 2007).

As expected, a positive shock to income increases stock prices in China. Interestingly, the impact of

an increase in income on residential prices turns negative after less than a year. We assume that this

is related to the supply of new apartments in the market. Fast economic growth leading to a positive

shock in household income is often related to a construction boom in China which, after a lag, leads

to an increase in housing supply and hence lower prices. Overall, the impact is rather small. A 5%

shock to household income translates into a 1% decline in housing prices. The immediate impact of

a consumption shock is negative for both stock and residential prices, reflecting households

choosing to increase consumption instead of investing in stock markets or buying an apartment. As

expected, stock markets benefit faster than the housing sector from an increase in consumption.

Turning now to the wealth channel in China, the impulse response analysis indeed finds a link from

monetary policy to asset prices. As expected, Chinese share prices react quickly and positively to an

increase in liquidity. The size of the impact is economically meaningful. A 1% shock to M2 supply

would imply close to a 10% rise in the Shanghai A-Index. This reaction is statistically significant

for about one year. Later on, the impact of M2 on stock prices turns negative. The positive reaction

of residential prices to a monetary policy shock is slower than the reaction of stock prices, as

expected. Although only borderline significant, the positive impact lasts longer than the reaction of

stock prices to a shock to the money supply.

The results for the second part of the wealth channel – the link from asset price developments to

household consumption –are somewhat less clear. A positive shock in stock prices indeed leads to

an increase in household consumption, but the result is not statistically highly significant. The

positive reaction of consumption to a shock to residential prices takes longer to realise. Actually,

the initial reaction of consumption to a rise in housing prices is negative. Only after a lag of almost

two years does the reaction turn positive and statistically significant.

These results reflect the relatively small role that asset markets still play in households’ income and

consumption in China at the aggregate level. Although the popularity of investing in stocks has

increased over the years, the volume of investment in stocks is probably still very small compared

to bank deposits. Another reason for the rather weak link from stock prices to consumption may be

the high volatility of China’s stock market. As Lettau and Ludvigson (2004) showed, a temporary

increase in wealth may only have a minor impact on consumption.

The result that residential prices first have a negative impact on household consumption is probably

related to a fact that higher prices force some households to save even larger shares of their income

in order to be able to buy an apartment. Probably only a few households are in a position to sell an

apartment and thus benefit from higher prices.

15

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Our results are generally in line with those of Peltonen, Sousa and Vansteenkiste (2008). The

biggest difference is that they did not find a link from residential prices to household consumption

in China whereas our results suggest that a link exists, albeit this is only borderline significant and

is realised only after a two-year lag. Both studies confirm the link from stock prices to consumption.

Finally, we find that the direct link from monetary policy to household consumption is very weak in

both of our specifications.

16

Although the first reaction of consumption to a loosening of monetary

policy is positive, as expected, the result is not statistically significant. After a lag of about half a

year, the impact turns negative. The weak link from monetary policy to household consumption can

be explained by the fact that households are net savers and that household credit

17

only amounted to

around 20% of GDP at the end of 2008. For example, the size of the mortgage market was very

small during the early years of the period studied.

18

Our findings are supported by earlier studies.

For example, Zhang and Wan (2002) found the direct link from monetary policy to household

consumption in China to be weak.

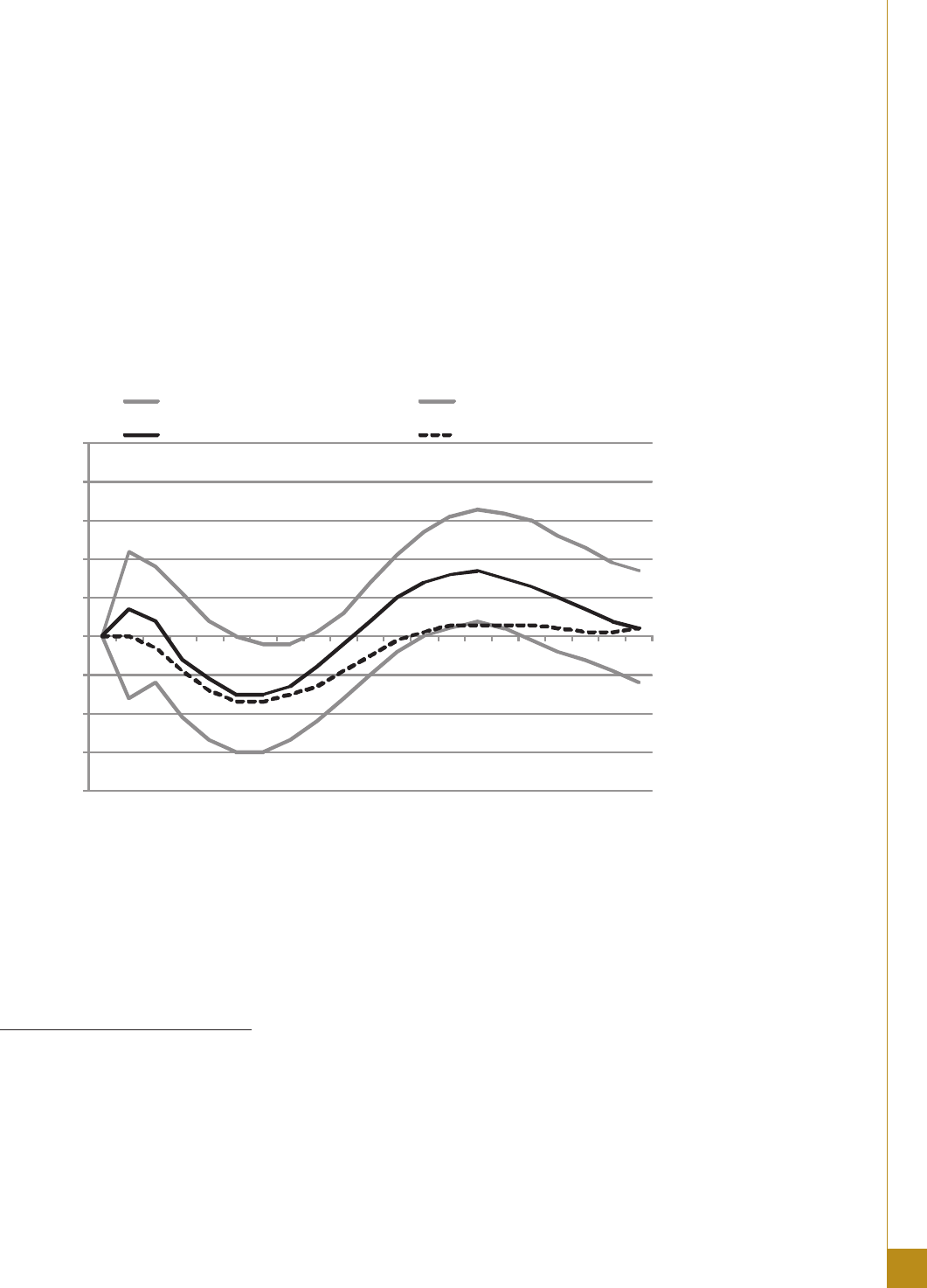

Figure 2. Response of consumption to a shock to money supply via residential prices.

-0,004

-0,003

-0,002

-0,001

0

0,001

0,002

0,003

0,004

0,005

01234567891011121314151617181920

Baseline + one std error Baseline - one std error

Baseline Wealth channel shut down

Our result that a monetary policy loosening increases asset prices - which are, at least to an extent,

linked to higher consumption - need not imply that the wealth channel actually functions in the

Chinese economy. In order to test whether changes in asset prices that are due to monetary policy

have a significant impact on household consumption we use the method by Ludvigson, Steindal and

Lettau (2002). We shut down the wealth channel by restricting to zero both the contemporaneous

and lagged effects from asset prices to consumption. Then we compare the impulse responses of

16

To further test the role of the monetary policy in the Chinese economy, we ran the same estimations by replacing M2

by the real deposit rate. Given households’ high savings rate and the limited investment options outside bank deposits,

the real deposit rate should be a relevant policy variable from the households’ point of view. The authorities set a

ceiling on deposit interest rates in China, which can be exceeded by a maximum 10% . However, on top of the fact that

the estimation had problems in passing some misspecification tests, the interest rate did not have a statistically

significant impact on household income nor consumption.

17

Total of household business loans and consumer loans (incl. mortgages and car loans).

18

The amount of mortgage loans rose from less than 0.2% of GDP at the end of 1997 to 3.4% of GDP already by the

end of 2000. By the end of 2008, the ratio had risen to around 10%.

16

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

consumption to a monetary policy loosening as between the two cases where the wealth channel is

allowed or not allowed to function. If the wealth channel were functioning, there would be a clear

difference between the two impulse responses.

In China’s case, however, we see only a slight difference between the two responses (Figure 2). It

seems that when the wealth channel is not allowed to operate the positive impact of monetary policy

on household consumption is nil in the specification with residential prices. It thus seems that the

wealth channel does work in the right direction in the Chinese economy but only to a very limited

extent. Furthermore, when we test for the existence of a wealth channel via the stock market, we

notice that opening up the possible wealth channel in China does not induce any significant change

in the reaction of household consumption to monetary policy. We thus conclude that the wealth

channel does not function via the stock markets and is very weak via residential prices in China.

4. Conclusions

This paper aims to increase our understanding of the monetary policy transmission channels in

China. In particular, we have tried to answer the question whether monetary policy influences

household consumption via an impact on household wealth. Links through both the housing market

and stock prices are explored.

This is the first attempt to study the wealth channel in China although the question is highly

relevant from the current policy perspective. Active discussions have taken place on the possible

negative side effects of the loose monetary policy that has been implemented, along with the vast

stimulus package, since the outbreak of the global financial and economic crisis in the autumn of

2008. In particular, questions have been raised as to the role of loose monetary policy in causing the

rise in asset prices in China.

This study analyses the wealth channel via stock and housing markets using a structural VAR

model and data for 1998-2008. According to the results, a loosening of monetary policy indeed

leads to higher asset prices in China. Furthermore, urban households’ consumption reacts positively

to a rise in either residential or stock prices, although the effects are fairly weak. After studying

explicitly the existence of the wealth channel, we conclude that changes in asset prices due to

monetary policy do not affect household consumption in a robust manner.

This outcome is not surprising taking into account that even in the advanced economies the

importance of the wealth channel has been estimated to be small. Furthermore, the volatility and

unpredictability of the Chinese stock markets probably reduces the impact of stock prices on

household behaviour (Lettau and Ludvigson, 2004, Ludvigson et al. 2002). Higher housing prices

may even encourage some households to increase their saving in order to be able to afford an

apartment, and only a small proportion of households may be in position to sell an apartment and

thus benefit from higher residential property prices.

Our results can be interpreted as indicating that the possible side effects from loose monetary policy

to the household sector are small and thus not a cause for worry. But, on the other hand, the results

also reveal that the possibilities of affecting households’ decision-making via monetary policy are

very limited in China, as even the direct link from monetary policy to consumption is weak.

Although this outcome is not surprising, taking into account the limited access of households to the

financial sector, it may raise concern among policy makers. In order to make Chinese monetary

policy more effective for the economy, further liberalisation and reform is needed in the financial

sector.

17

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Furthermore, the link from monetary policy to asset prices, found in this paper, is highly relevant

for the current discussion on optimal stimulus policies. The result is supported by the most recent

data (not in our sample): during the period of loose monetary policy asset prices have increased

considerably. Although households seem reluctant to react to changes in asset prices, it may well be

that asset prices play an important role in other parts of the Chinese economy. For example,

developments in fixed asset investment – which covers nearly half of China’s GDP - may follow

asset prices closely, which implies that asset price developments can cause considerable

fluctuations in the real economy. As anecdotal evidence, it seems that price fluctuations in the real

estate market were a key factor behind the slowdown in investment growth in China in the first half

of 2008, albeit this was prior to the global economic downturn. The link between asset prices and

investment would thus seem to warrant further careful investigation.

References

Ahearne, A. G., Ammer, J., Doyle, B. D., Kole, L. S., and Martin, R. F. H. (2005) House Prices and

Monetary Policy: A Cross-Country Study. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

International Finance Discussion Papers, No. 841.

Alessi, L. and Detken, C. (2009) ‘Real Time’ Early Warning Indicators for Costly Asset Price

Boom/Bust Cycles – A Role for Global Liquidity. European Central Bank Working Paper Series,

No. 1039 /March 2009.

Altissimo, F., Georgiou, E., Sastre, T., Valderrama, M. T., Sterne, G., Stocker, M., Weth, M.,

Whelan, K. and Willman, A. (2005) Wealth and Asset Price Effects on Economic Activity.

European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series, No. 29 / June 2005.

Ando and Modigliani (1963) The Life Cycle Hypothesis of Saving: Aggregate Implications and

Tests.” American Economic Review 53, 55-84.

Bagliano, F. C. and Favero, C. A. (1998) Measuring monetary policy with VAR models: An

evaluation. European Economic Review 42, 1069-1112.

Bernanke, B. and Mihov, I. (1998) Measuring Monetary Policy. The Quarterly Journal of

Economics 113, 869-902.

Bernanke, S. B. and Kuttner. K. N. (2005) What Explains the Stock Market’s Reaction to Federal

Reserve Policy? Journal of Finance LX, 1221-1257.

Bordo, M. D. and Wheelock, D. C. (2004) Monetary policy and asset prices: A look at past U.S.

stock market booms. NBER Working Paper 10704.

Chen, C-H. and Shih, H-T. (2002) The Evolution of the Stock Market in China’s Transitional

Economy. Edward Elgar Publishing Lted., UK.

de Leeuw, F. and Gramlich, E. M. (1969) The Channels of Monetary Policy: A Ruther Report on

the Federal Reserve – M.I.T. Model. Journal of Finance 24, 265-290.

Fisher, I. (1933) The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions. Econometrica 1, 337-357.

18

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Funke, N. (2004) Is there a stock market wealth effect in emerging markets? Economic Letters 83,

417-421.

Geiger, M. (2008) Instruments of monetary policy in China and their effectiveness: 1994–2006,

UNCTAD Discussion Paper 187.

Iacoviello, M. (2000) House prices and the macroeconomy in Europe: Results from a structural

VAR analysis. ECB Working Paper, No. 18.

Juselius, K. (2006) The Cointegrated VAR Model Methodology and Applications. Oxford

University Press, Oxford, U.K.

Koivu, T. (2008) Has the Chinese economy become more sensitive to interest rates? Studying credit

demand in China. China Economic Review 20, 455-470.

Koivu, T., Mehrotra, A. and Nuutilainen, R. (2009) An analysis of Chinese money and prices using

a McCallum –type rule. Journal of Chinese Economics and Business Studies 7, 219-235.

Laurens, B. J. and Maino, R. (2007) China: Strengthening Monetary Policy Implementation. IMF

Working Paper No. 07/14.

Lettau, M. and Ludvigson (2004) Understanding Trend and Cycle in Asset Values: Reevaluating

the Wealth Effect on Consumption. The American Economic Review 94, 276-299.

Leung, B. and Yim, J. (2008) Mainland China’s Stock Market Revives, Could It Last? Economic

Focus, Hang Seng Bank, 19 May 2008.

Liang, Q. and Cao, H. (2007) The impact of monetary policy on property prices: Evidence from

China. Journal of Asian Economics 18, 63-75.

Ludvigson, S., Steindal, C. and Lettau, M. (2002) Monetary Policy Transmission through the

Consumption –Wealth Channel. Federal Reserve Bank New York Economic Policy Review, May

2002, 117-133.

Lütkepohl, H. (2004) Vector Autoregressive and Vector Error Correction Models in Lütkepohl, M.

and Krätzig (Eds.) Applied Time Series Econometris. Cambridge University Press, U.K.

Mehrotra, A. (2007) Exchange and Interest Rate Channels during a Deflationary Era – Evidence

from Japan, Hong Kong and China. Journal of Comparative Economics 35, 188-210.

Mishkin, F. S. (1996) The Channels of Monetary Transmission: Lessons for Monetary Policy.

NBER Working Paper 5464.

Mishkin, F. S. (2007) Housing and the Monetary Transmission Mechanism. Finance and

Economics Discussion Series, Federal Reserve Board, 2007-40.

Modigliani, F. (1971) Monetary Policy and Consumption: Linkages via Interest Rate and Wealth

Effects in the FMP Model. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Conference Series 5, 9-84.

19

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Peltonen, T. A., Sousa, R. M. and Vansteenkiste, I. S. (2008) Wealth Effects in Emerging Market

Countries. European Central Bank Working Paper No. 1000.

Poterba, J. M. (2000) Stock Market Wealth and Consumption. Journal of Economic Perspectives 14

(2), 99-118.

Rigobon, R. and Sack, B. (2004) The impact of monetary policy on asset prices. Journal of

Monetary Economics 51, 1553-1575.

Zhang, Y. and Wan, G. H. (2002) Household consumption and monetary policy in China. China

Economic Review 13, 27-52.

20

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

The Appendix

Table A1. Data sources and definitions

Variable Definition Source

Y Disposable

income per

capita: urban

households

Monthly data for 1998-2006

accumulated to quarterly level, deflated

by CPI, seasonally adjusted with Tramo

Seats and in logs.

CEIC

C Urban

household living

expenditure per

capita

Monthly data for 1998-2006

accumulated to quarterly level, deflated

by CPI, seasonally adjusted with Tramo

Seats and in logs.

CEIC

ʌ Inflation Quarterly changes in seasonally CPI

constructed by the author from

month-on-month and 12-month

inflation rates.

CEIC

A Asset prices i) Shanghai A-Share Stock Index,

end of period, deflated by CPI and

in logs.

ii) Residential price index

constructed by the author from year-

on-year changes, seasonally

adjusted with Tramo Seats, deflated

by CPI and in logs.

CEIC

MP Monetary policy

indicator

M2 deflated by CPI, seasonally

adjusted with Tramo Seats and in

logs.

CEIC

21

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

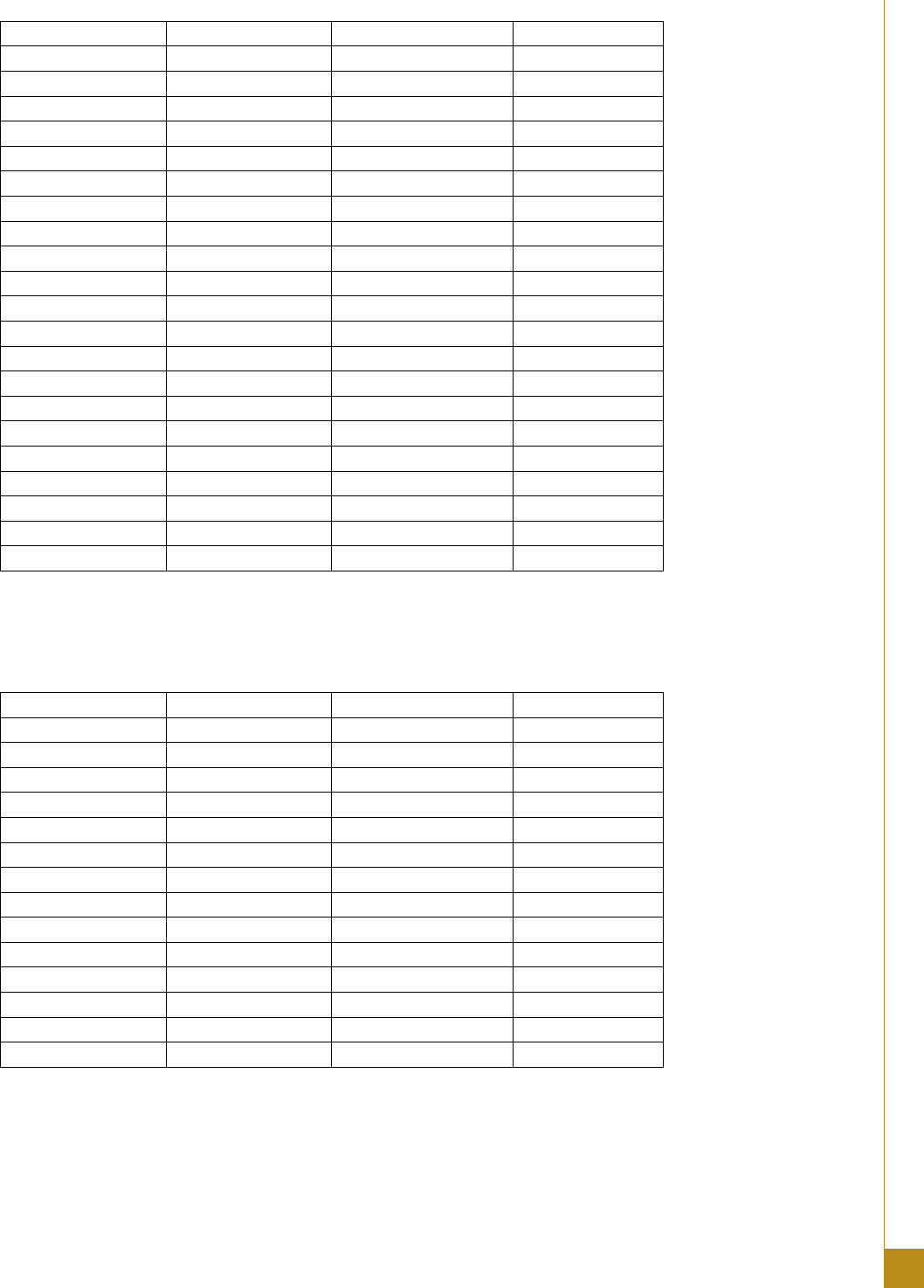

Table A2. Augmented Dickey-Fuller unit root test for 1998-2008

Series Det. term Lags Test stat.

C c, t 12 (AIC) -1.25

C c, t 4 (HQ) -1.05

C c, t 1 (SC) -1.37

dC c 11 (AIC) -1.55

dC c 0 (HQ, SC) -6.94***

Y c, t 0 (AIC, HQ, SC) -2.59

dY c 0 (AIC, HQ, SC) -8.20***

M2 c, t 0 (AIC, HQ, SC) -1.82

dM2 c 0 (AIC, HQ, SC) -6.04***

π c, t 12 (AIC) -3.01

π c, t 10 (HQ) -3.34*

π c, t 3 (SC) -4.34***

π c 11 (AIC) -0.62

π c 3 (HQ, SC) -3.29**

dπ c 10 (AIC, HQ) -3.87***

dπ c 3 (SC) -2.77*

Shanghai c, t 3 (AIC, HQ, SC) -3.48**

Shanghai c 3 (AIC, HQ, SC) -3.62***

dShanghai c 0 (AIC, HQ, SC) -4.64***

res1mid c, t 12 (AIC, HQ, SC) -2.29

dres1mid c 11 (AIC, HQ, SC) -3.47**

* indicates significance at 10% level, ** at 5% level and *** at 1% level.

c indicates a constant and t a trend. Maximum number of lags 12. In parentheses, the specification

criteria: AIC = Akaike, HQ=Hannan-Quinn, SC=Schwarz criteria.

Table A3. Phillips-Perron unit root test for 1998-2008

Series Det. term Bandwith Test stat.

C c, t 4 -1.79

dC c 4 -7.30***

Y c, t 0 -2.60

dY c 11 -9.53***

M2 c, t 3 -1.61

dM2 c 3 -6.66***

π c, t 2 -3.11

π c 3 -2.80*

dπ c 2 -8.21***

Shanghai c, t 4 -2.17

Shanghai c 4 -2.19

dShanghai c 3 -4.75***

res1mid c, t 4 -1.71

dres1mid c 4 -4.20***

* indicates significance at 10% level, ** at 5% level and *** at 1% level. c indicates a constant and

t a trend. The estimation method is Bartlett Kernel, bandwith selected by Newey-West method.

22

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

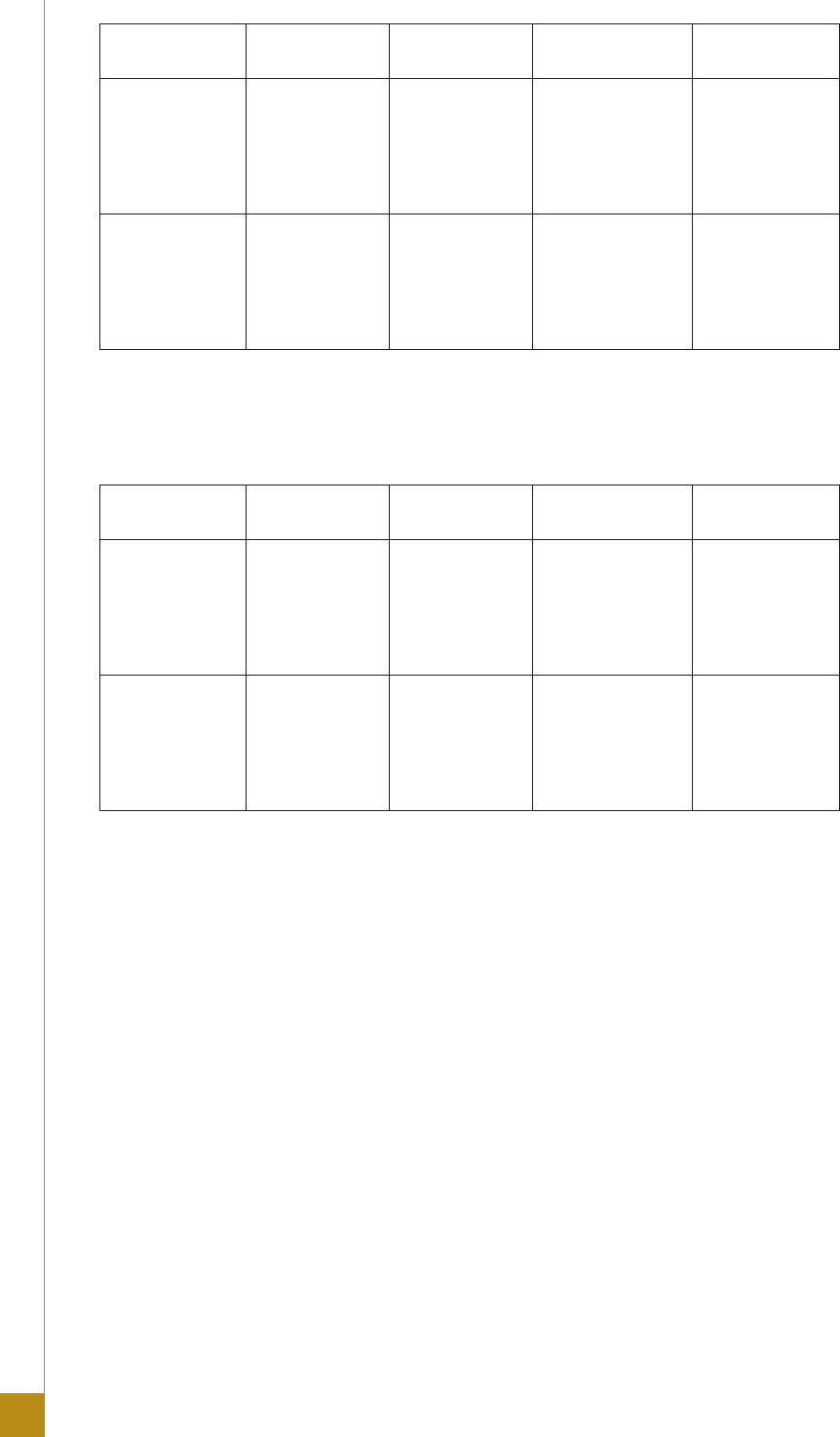

Table A4. Saikkonen-Lütkepohl Cointegration Test

Series Det. term Lags Cointegration

rank

Test

statistic

Y, c, M2, ʌ,

Shanghai

c, t 6 (AIC, HQ) 0

1

2

3

4

75.19***

44.11*

18.45

4.77

0.67

Y, c, M2, ʌ,

real estate

c, t 6 (AIC, HQ,

SC)

0

1

2

3

4

82.99***

48.77**

23.96

12.40

2.61

* indicates significance at 10% level, ** at 5% level and *** at 1% level. c indicates a constant and

t a trend. Maximum number of lags 6. In parentheses, the specification criteria: AIC = Akaike,

HQ=Hannan-Quinn, SC=Schwarz criteria.

Table A5. Johansen Cointegration Test

Series Det. term Lags Cointegration

rank

Test

statistic

Y, c, M2, ʌ,

Shanghai

c, t 6 (AIC, HQ) 0

1

2

3

4

298.78***

141.19***

82.01***

31.51***

9.76

Y, c, M2, ʌ,

real estate

c, t 6 (AIC, HQ,

SC)

0

1

2

3

4

375.79***

235.19***

97.55***

42.45***

5.62

* indicates significance at 10% level, ** at 5% level and *** at 1% level. c indicates a constant and

t a trend. Maximum number of lags 6. In parentheses, the specification criteria: AIC = Akaike,

HQ=Hannan-Quinn, SC=Schwarz criteria.

23

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Table A6. Misspecification tests on baseline model with Shanghai A-Index.

Test Test

statistics

p-value

Portmanteau test for autocorrelation, 16 lags 388.21 .08*

LMF test for autocorrelation

4 lags

1 lags

1.51

1.30

.10

.19

Jarque-Bera test for nonnormality for five system

equations

4.00

0.73

2.47

1.75

4.78

.13

.69

.29

.42

.09*

ARCH LM test for autoregressive conditional

heteroskedasticity, 16 lags, for five system

equations

17.46

18.10

17.74

14.22

7.42

.36

.32

.34

.58

.96

1

Adjusted test statistic

2

LMF Statistic

* indicates significance at 10% level, ** at 5% level and *** at 1% level.

Table A7. Misspecification tests on baseline model with residential prices.

Test Test

statistics

p-value

Portmanteau test for autocorrelation, 16 lags 371.39 .21

LMF test for autocorrelation

4 lags

1 lags

1.29

0.98

.22

.50

Jarque-Bera test for nonnormality for five system

equations

13.87

0.36

3.92

0.56

0.22

.00***

.83

.14

.75

.90

ARCH LM test for autoregressive conditional

heteroskedasticity, 16 lags, for five system

equations

12.71

14.22

14.29

17.52

8.86

.69

.58

.58

.35

.92

1

Adjusted test statistic

2

LMF Statistic

* indicates significance at 10% level, ** at 5% level and *** at 1% level.

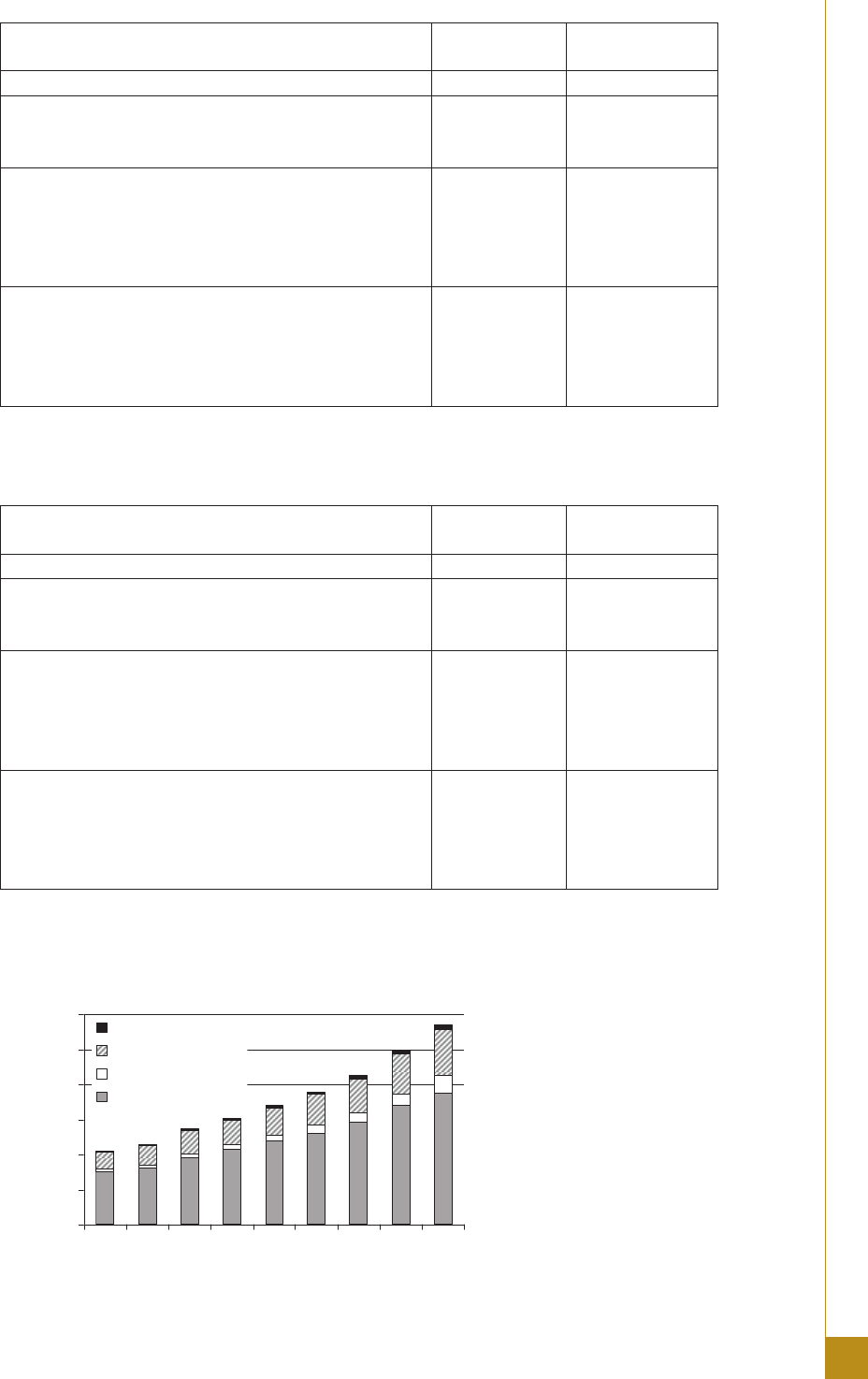

Figure A1. Urban household income by category in China, RMB.

0

3,000

6,000

9,000

12,000

15,000

18,000

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

Property

Transfer

Household Business

Wage

Source: CEIC

24

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Figure A2. The time series used in VAR estimation.

Household income Household consumption

6.8

7

7.2

7.4

7.6

7.8

8

8.2

8.4

8.6

1998Q1 2000Q1 2002Q1 2004Q1 2006Q1 2008Q1

6.8

7

7.2

7.4

7.6

7.8

8

8.2

1998Q1 2000Q1 2002Q1 2004Q1 2006Q1 2008Q1

Inflation M2

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

1998Q1 2000Q1 2002Q1 2004Q1 2006Q1 2008Q1

8

8.5

9

9.5

10

10.5

11

1994Q1 1997Q1 2000Q1 2003Q1 2006Q1 2009Q1

Shanghai A-Index Residential prices

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

8.5

9

1998Q1 2000Q1 2002Q1 2004Q1 2006Q1 2008Q1

4.4

4.5

4.6

4.7

4.8

4.9

5

1998Q1 2000Q1 2002Q1 2004Q1 2006Q1 2008Q1

25

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Figure A3. Impulse response analysis with Shanghai A-Index.

Income -> Income

Cons. -> Income

Inflation -> Income

M2 -> Income

Shanghai-> Income

Income -> Cons.

Cons. -> Cons.

Inflation -> Cons.

M2 -> Cons.

Shanghai-> Cons.

Income -> Inflation

Cons. -> Inflation

Inflation -> Inflation

M2 -> Inflation

Shanghai-> Inflation

Income -> M2

Cons. -> M2

Inflation -> M2

M2 -> M2

Shanghai-> M2

Income-> Shanghai

Cons. -> Shanghai

Inflation -> Shanghai

M2 -> Shanghai

Shanghai->Shanghai

26

ECB

Working Paper Series No 1240

September 2010

Figure A4. Impulse response analysis with residential prices.

Income-> Income

Cons. -> Income

Inflation-> Income

M2 -> Income

Res. prices –> Income

Income-> Cons.

Cons. -> Cons.

Inflation-> Cons.

M2 -> Cons.

Res. prices–> Cons.

Income-> Inflation

Cons. -> Inflation

Inflation-> Inflation

M2 -> Inflation

Res. prices –> Inflation

Income-> M2

Cons. -> M2

Inflation-> M2

M2 -> M2

Res. prices –> M2

Income-> Res. prices

Cons. -> Res. prices

Inflation-> Res. prices

M2 -> Res. prices

Res. prices –> Res.

prices

Working PaPer SerieS

no 1118 / november 2009

DiScretionary

FiScal PolicieS

over the cycle

neW eviDence

baSeD on the eScb

DiSaggregateD aPProach

by Luca Agnello

and Jacopo Cimadomo