Measuring and Evaluating

Indirect Benefits

Framework and Guidance

For Use When Developing and Reporting NYSERDA Initiatives

October 2023

2

Tale of Contents

List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... 3

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ 3

Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................. 4

Glossary of Terminology ......................................................................................................... 5

1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6

1.1 Framework Objectives .................................................................................................................. 6

1.2 Market Transformation Indirect Benefits Evaluation Challenges .................................................. 7

1.3 Indirect Benefits Estimation ........................................................................................................... 8

2 Indirect Benefits Framework ...........................................................................................12

2.1 Stage 1. Initiative Planning (Pre-Filing) ....................................................................................... 14

Key Activity. Clarify Market Transformation Theory ............................................................ 14

2.1.1.1 Market Definition .............................................................................................. 14

2.1.1.2 Causal Logic/Pathways of Influence ................................................................. 15

2.1.1.3 Hypothesized Market Outcomes and Effects .................................................... 16

Key Activity. Create Logic Model and Evaluability Map ...................................................... 16

Key Activity. Develop Benefits Forecast with Documented Assumptions...........................

16

2.2

Stage 2. Initiative Year 1 ............................................................................................................. 17

Key Activity. Review Initiative Documentation .................................................................... 18

Key Activity. Develop Evaluation Plan ................................................................................

18

2.2.2.1 R

esearch Questions ......................................................................................... 18

2.2.2.2 Market Progress Indicators ............................................................................... 19

2.2.2.3 Causality .......................................................................................................... 20

2.2.2.4 Research Methods and Data Sources .............................................................. 21

2.2.2.5 Timeline ........................................................................................................... 21

2.2.2.6 Analysis Plan .................................................................................................... 21

2.2.2.7 Considerations by Program Type ..................................................................... 23

Key Activity. Coordinate with Internal and External Stakeholders ...................................... 25

2.2.3.1 Co

ordination within NYSERDA ......................................................................... 25

2.2.3.2 Coordination with External Stakeholders .......................................................... 27

Key Activity. Characterize Baseline Conditions and Forecast ............................................ 27

2.2.4.1 B

aseline Conditions .......................................................................................... 27

2.2.4.2 Baseline Forecast............................................................................................. 28

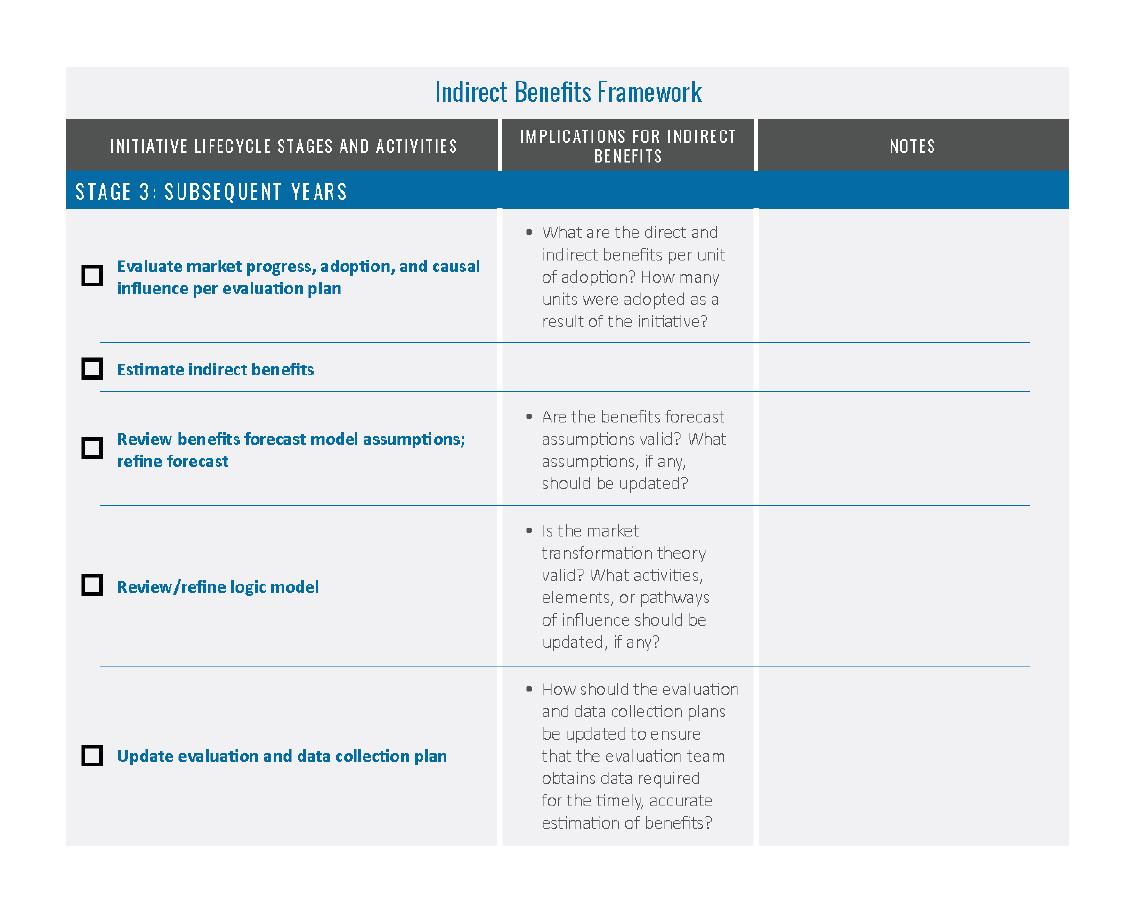

2.3 Stage 3. Subsequent Initiative Years (Annual Evaluation Activities) .......................................... 31

Key Activity. Assess Market Adoption and Causal Influence .............................................. 31

2.3.1.1 M

arket Adoption ............................................................................................... 31

2.3.1.2 Causal Influence .............................................................................................. 33

Key Activity. Perform Analysis and Estimate Indirect Benefits ........................................... 37

3

2.3.2.1 Example: Industrial Energy Management Practices .......................................... 38

2.3.2.2 Top-Down Methods .......................................................................................... 40

2.3.2.3 Avoiding Double-Counting ................................................................................ 41

Key Activity. Review Benefits Forecast Model Assumptions and Refine Forecast ............ 43

Key Activity. Review/Refine Logic Model ............................................................................ 43

Key Activity. Update Evaluation Plan ..................................................................................

43

3 Bibli

ography .....................................................................................................................44

Appendix A. Indirect Benefits Evaluation Tools ................................................................. A-1

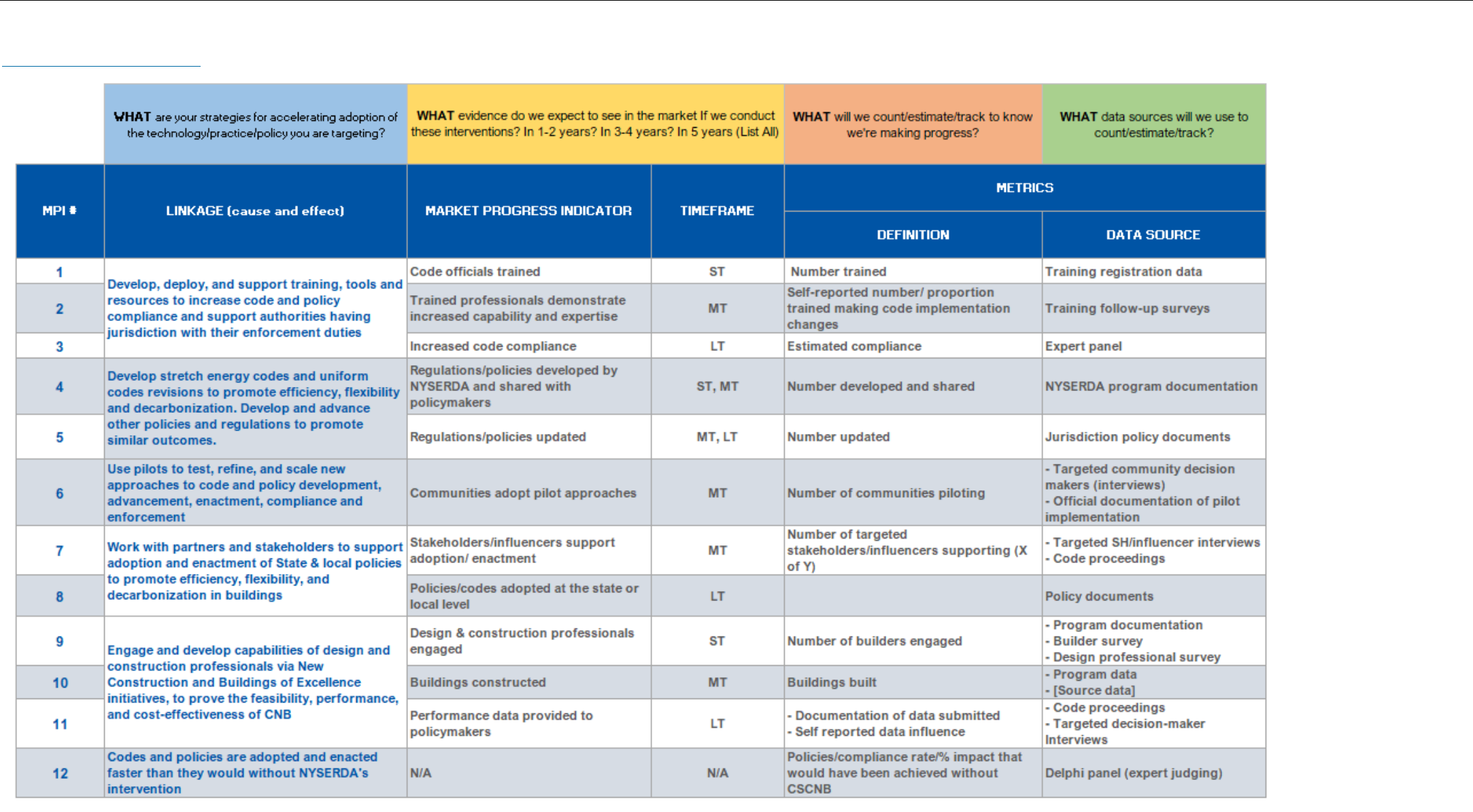

Appendix B. Evaluability Map: Codes and Standards for Carbon Neutral Buildings ....... B-1

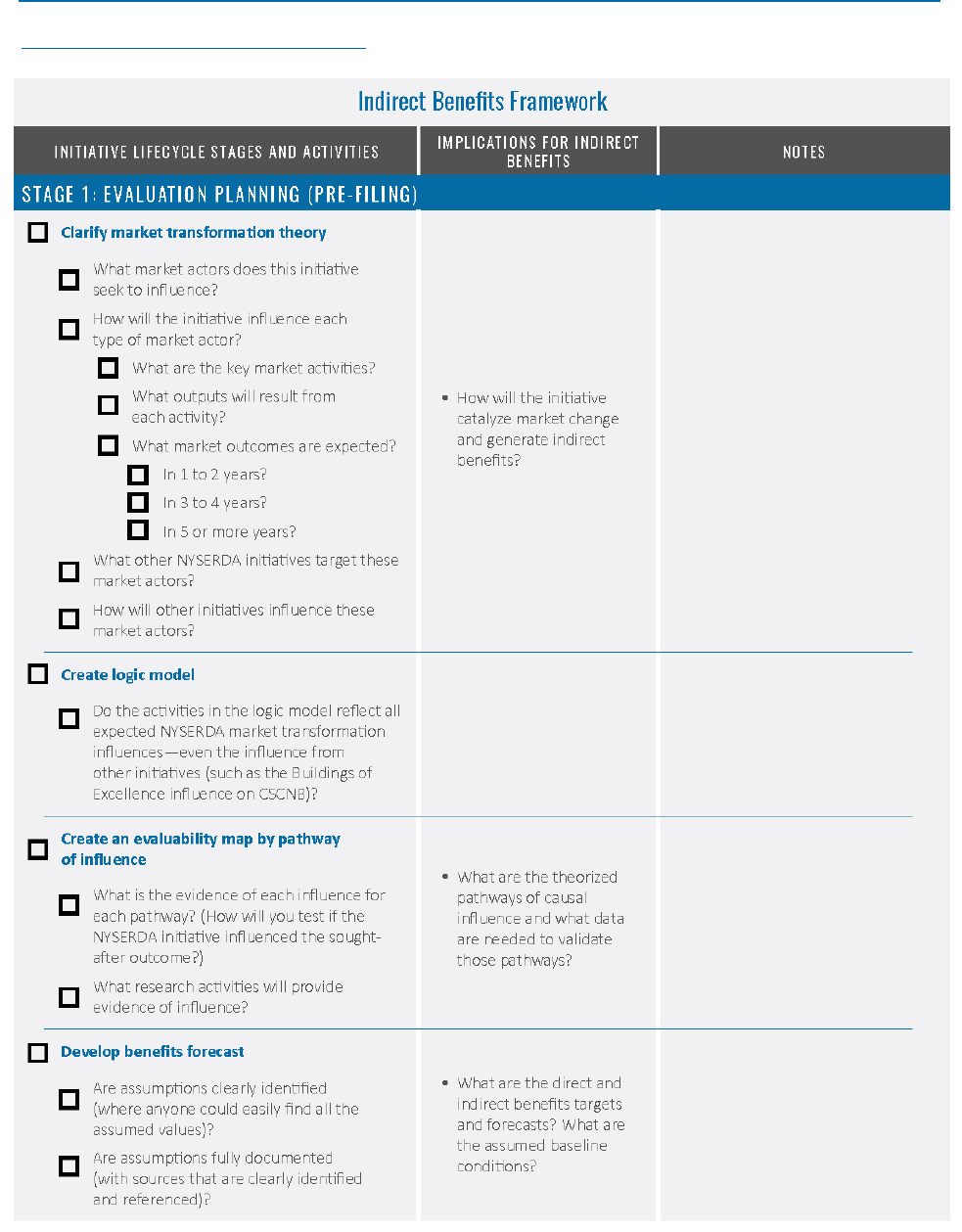

Appendix C. Indirect Benefits Evaluation Checklist ........................................................... C-1

List of Figures

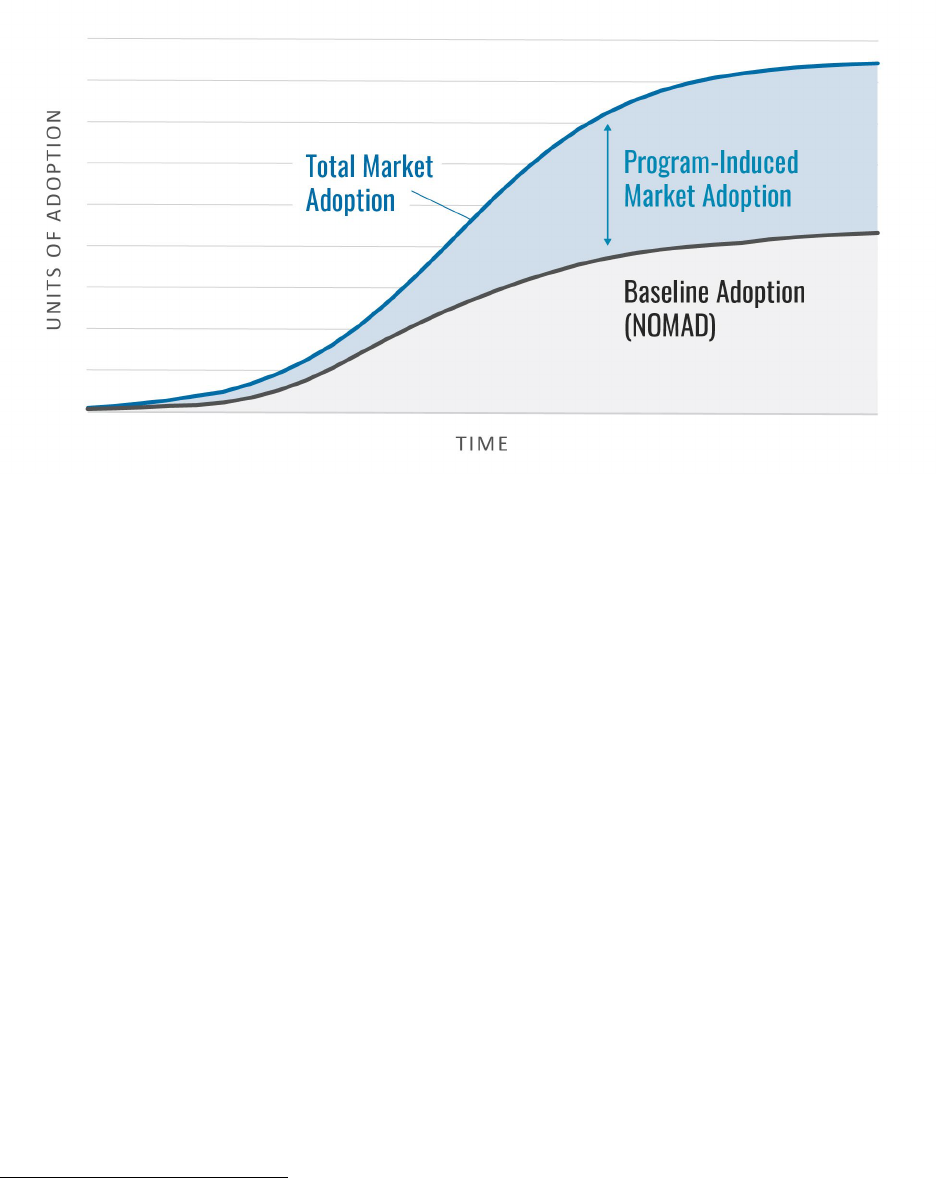

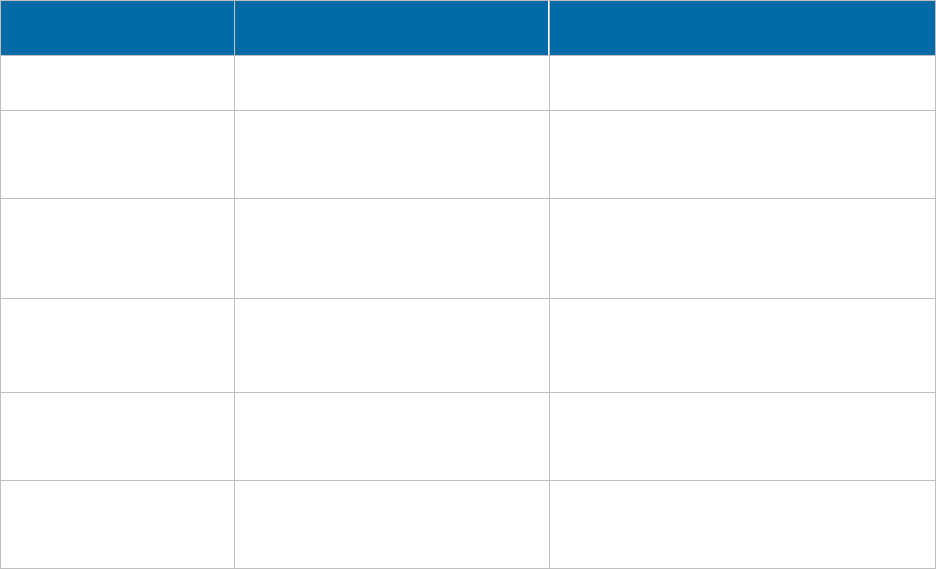

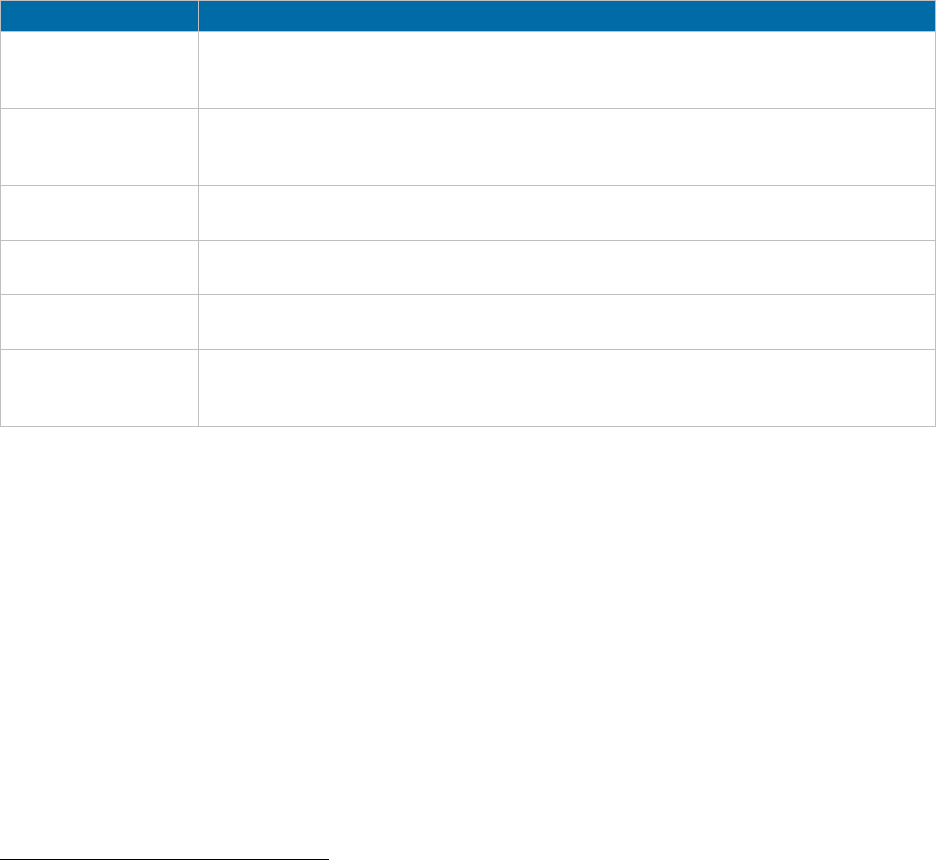

Figure 1. Total, Program-Induced, and Baseline Adoptions over Time ......................................10

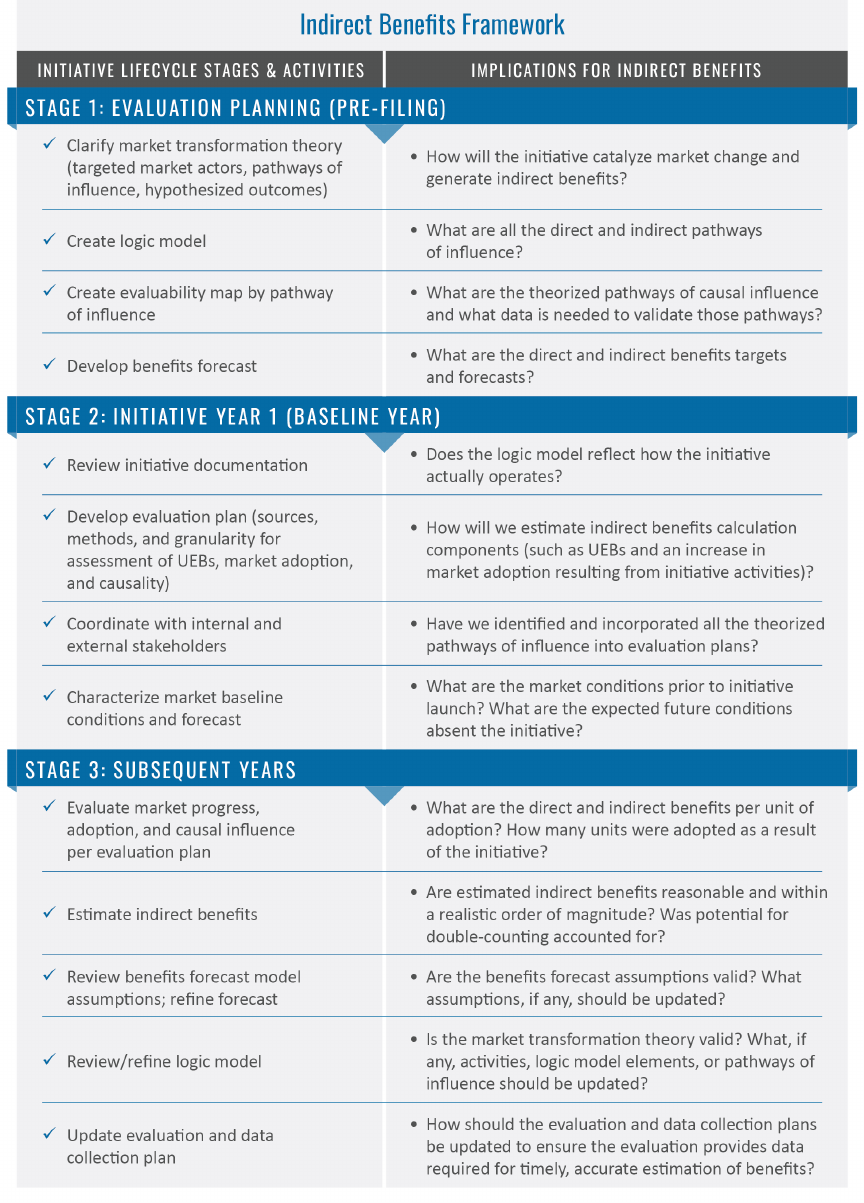

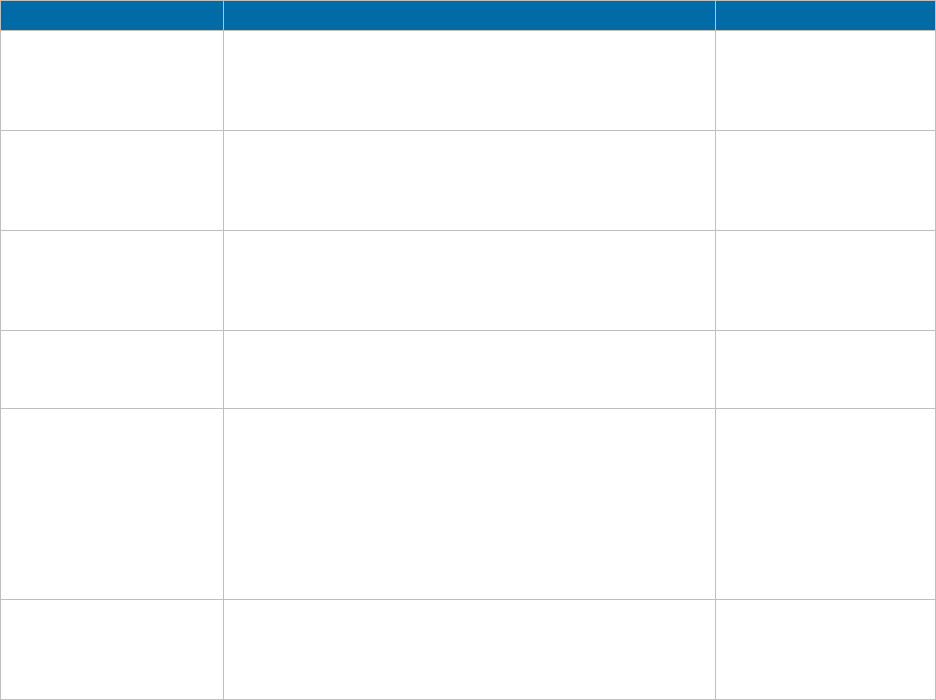

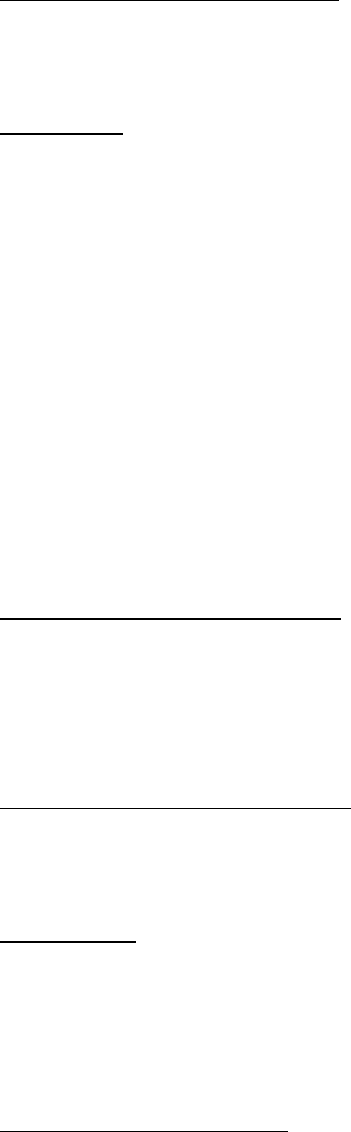

Figure 2. NYSERDA Initiative Lifecycle and Key Questions Informing Indirect Benefits

Evaluation ...................................................................................................................12

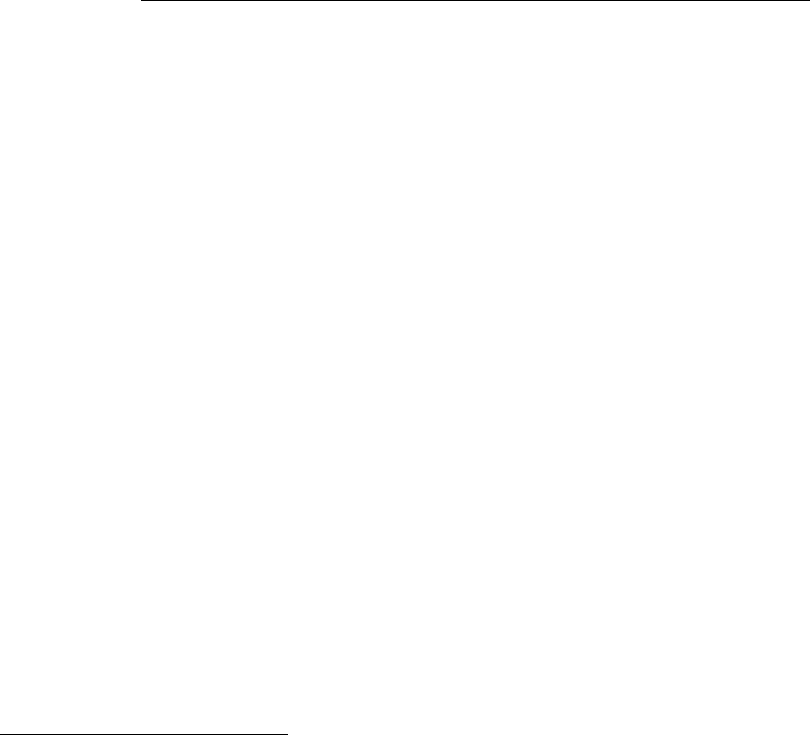

Figure 3. Key Activities and Purpose for Each Lifecycle Stage ..................................................13

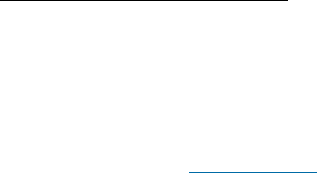

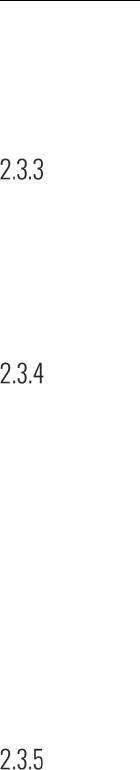

Figure 4. Baseline Forecast Decision Tree ................................................................................29

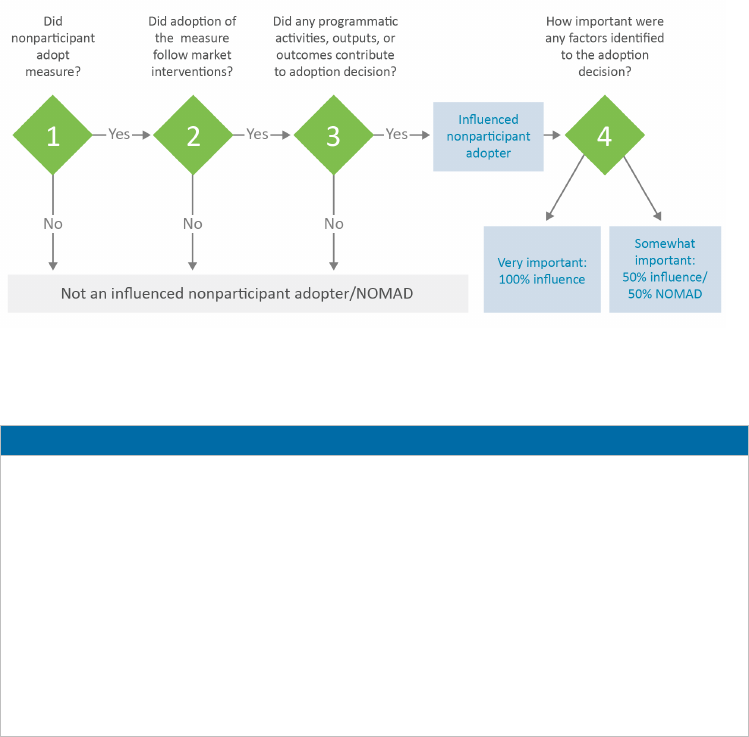

Figure 5. Program Influence Assessment Approach .................................................................36

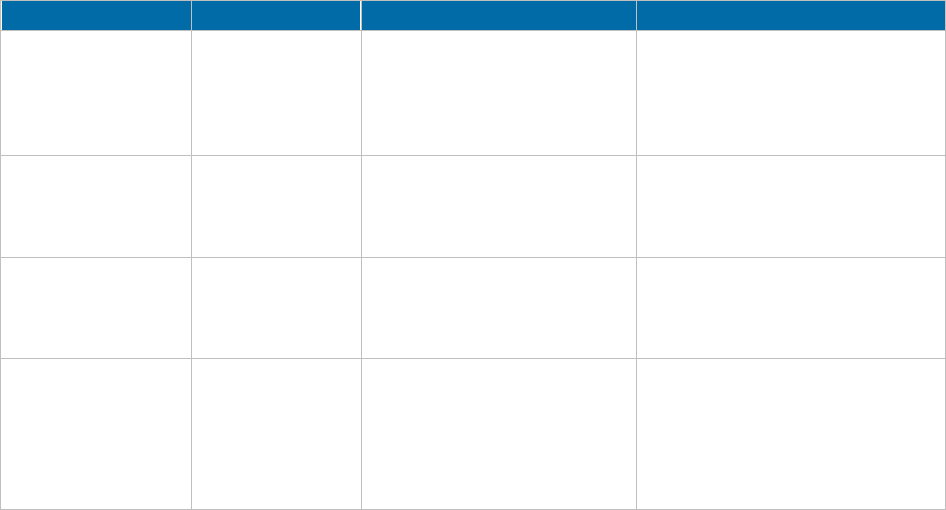

List of Tables

Table 1. Example Research Questions .....................................................................................19

Table 2. Example Market Effects, Indicators, and Research Approach .....................................20

Table 3. Program Typology .......................................................................................................23

Table 4. Market Adoption Estimation Sources ...........................................................................31

Table 5. Causality Assessment Sources and Methods ..............................................................34

Table 6. Example Questions to Substantiate the Influence of Market Transformation

Program Interventions ................................................................................................36

Table 7. Summary of Indirect Benefits Estimation Activities by Roadmap Step .........................38

4

Acronyms and Abbreviations

BAB Budget and Benefits

CEF Clean Energy Fund

CSCNB Codes and Standards for Carbon Neutral Buildings

EM&V Evaluation, Measurement, and Verification

EMP Energy Management Practices

EMT Energy Management Technology

MPI Market Progress Indicator

MPTA Metrics, Tracking, and Performance Assessment

NEEA Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance

NOMAD Naturally Occurring Market Adoption

NYSERDA New York State Energy Research and Development Authority

OsEM On-site Energy Manager

SEM Strategic Energy Management

UEB Unit Energy Benefit

5

Glossary of Terminology

Baseline market adoption or Market adoption that would have occurred in the absence of a market

naturally occurring market transformation program.

adoption (NOMAD):

Direct benefits: Benefits that result from measures, projects, or practices implemented

with direct NYSERDA assistance.

Direct influence participant Units of adoption by participant end users, during or after program

adoption: engagement, not associated with incentives or direct support from

NYSERDA. (Contributes to NYSERDA indirect benefits.)

Direct involvement Units of adoption associated with incentives or direct support from

participant adoption: NYSERDA, as part of direct end-user engagement with the program.

(Contributes to NYSERDA direct benefits.)

Indirect benefits: Energy savings and other benefits resulting from measure adoption

associated with indirect program influence.

Leveraged funds: Private-sector investment mobilized by the initiative that otherwise

would not have occurred.

Market transformation: The strategic process of intervening in a market to create lasting change

in market behavior by removing identified barriers or exploiting

opportunities to accelerate the adoption of all cost-effective energy

efficiency as a matter of standard practice.

Midstream initiatives: NYSERDA’s collaboration with retailers and distributors to increase the

availability and promotion of energy-efficient equipment and reduce the

final price to consumers.

Measure: An

y product, service, technology, or practice that is intended to produce

clean energy or energy efficiency benefits.

Nonparticipant adoption: Units of adoption by targeted end users who have adopted the technology

or practice but have not engaged directly with NYSERDA. (Contributes

to NYSERDA indirect benefits.)

Program-induced

market adoption: The number of measure units adopted that were influenced by the

program activities.

Total market adoption: The units of a measure adopted or implemented by both program

participants and nonparticipants.

Upstream initiatives: NYSERDA’s collaboration with manufacturers and producers of energy-

efficient equipment to increase the availability and promotion of energy-

efficient equipment and reduce the final price to consumers.

Unit energy benefits: Energy savings (MWh or MMBtu) or renewable energy (MWh) per end

user resulting from the measure adoption.

6

1 Introduction

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) has deployed

approximately 80 market transformation initiatives as part of its Clean Energy Fund (CEF) portfolio and

expects to add more initiatives in the future. NYSERDA has set targets—in terms of energy efficiency

(MWh, MMBtu), renewable energy (MWh), carbon reduction (CO2e metric tons), and leveraged funds

(dollars)—for the expected direct and indirect benefits impacts of each initiative in the portfolio. With

these market transformation initiatives, NYSERDA aims to create sustained market change that will

substantially accelerate and increase the long-term market adoption of clean, energy-efficient

technologies and practices. In many cases, indirect benefits targets exceed expected direct benefits.

NYSERDA tracks the direct benefits for each initiative that result from energy projects implemented with

NYSERDA assistance. Indirect benefits arise from NYSERDA’s influence to spur adoption without

NYSERDA’s assistance and are not directly tracked by the initiatives.

NYSERDA will estimate direct benefits for each initiative using appropriate impact evaluation methods.

Estimating initiative-specific indirect benefits, however, typically relies upon a combination of (1) impact

(measurement and verification) evaluation activities to determine unit energy savings and the renewable

energy and carbon reduction impacts associated with technologies and practices, and (2) market

evaluation activities to estimate the increase in market adoption induced by the initiative, beyond the

participant adoption resulting from direct NYSERDA involvement. While market diffusion and

associated indirect impacts generally occur over the mid-to-long term, it is critical that NYSERDA have

specific plans in place at the start of each initiative to capture the data necessary for credible, defensible

analysis and quantification of indirect benefits as they are realized. An indirect benefits framework is also

necessary to ensure consistency and transparency among evaluation, measurement, and verification

(EM&V) contractors’ data collection and analysis efforts.

1.1 Framework Objectives

Indirect benefits are critically important to NYSERDA being able to achieve its CEF goals. Indirect

benefits comprise a substantial proportion of NYSERDA’s energy efficiency, electrification, and

renewable energy goals (estimated at nearly 50% of NYSERDA’s 105 TBtu contribution to the State’s

acquired energy efficiency savings in 2030). There are several objectives of the indirect benefits

framework:

Ensure a solid foundation for the credible evaluation of indirect benefits in two ways:

• Outline a common approach to estimating indirect benefits that conforms with market

transformation program evaluation best practices.

• Provide a resource for NYSERDA and evaluators to plan, design, and implement market

evaluation activities in a manner that helps to ensure timely collection of the data required to

reliably estimate and claim indirect benefits.

Provide guidelines on how to identify and avoid or adjust double-counting of indirect benefits.

Create a well-documented methodological approach that can help NYSERDA communicate with

stakeholders.

7

This document is an update to the NYSERDA indirect benefits evaluation framework developed in 2018,

consistent with the New York State Department of Public Service’s evaluation guidance document;

1

the

Clean Energy Advisory Council’s Metrics, Tracking, and Performance Assessment (MPTA) Working

Group’s document, Market Transformation Metrics and EM&V Coordination Report;

2

and other

documented best practices for evaluating market transformation programs cited herein. This update builds

on the original framework in four ways:

Highlights approaches to ensure that evaluations fully capture large, transformative impacts that

may not be captured by program-level evaluations

Expands the discussion of unit energy benefits (UEBs), including estimation approaches and the

importance of using values that are appropriate for market projection

Increases the usability of the framework by presenting key evaluation activities at each stage of

the program lifecycle and adding two practical tools to support indirect benefits evaluation

Updates content to reflect changes in the CEF portfolio and associated benefits

The framework and tools outlined below will help NYSERDA ensure that it achieves reliable indirect

benefits evaluation results that are comparable across programs,

3

evaluators, and program implementers.

By employing the framework, NYSERDA can easily compare, analyze, and aggregate evaluations from

different EM&V vendors across different sectors, programs, and delivery methods. This framework is

intended to provide general methodological guidance and serve as a reference document; it is not a

specific evaluation plan.

1.2 Market Transformation Indirect Benefits Evaluation Challenges

Whereas the methods and protocols for evaluating direct energy savings impacts from traditional utility

resource acquisition programs are well-established and documented in numerous EM&V protocols,

4

the

market transformation impact evaluation body of knowledge is less formal and not as well-established.

However, best practices for evaluating market transformation programs are reasonably well-documented

in the California Energy Efficiency Evaluation Protocols and several other papers and public documents

on this subject.

5

They are also addressed to some extent in impact evaluation frameworks under the topic

of market effects estimation.

One key difference between resource acquisition and market transformation program evaluations is that

resource acquisition studies seek to measure and verify energy savings associated with technology

measures and practices among known customer program participants, while market transformation studies

must estimate adoption of the targeted technology or practice among a population of end users who are

1

See DPS 2016.

2

See MPTA 2018.

3

In this document, programs and initiatives are used interchangeably.

4

For example, see NREL 2004, NREL 2002, and EM&V Working Group 2012.

5

See TecMarket Works 2006, Rosenberg and Hoefgen 2009, Vine 2013, NMR 2019, and SAG 2022.

8

typically unknown to the program administrator. In both cases, statistical methods are used to estimate

measure adoption and savings. However, the nonparticipating end users for market transformation

programs are different from those for resource acquisition programs in two ways:

The program administrator of a market transformation program often has no direct relationship

with the end user, which has three implications:

• The administrator does not have access to customer data, including contact information and

energy consumption data.

• There is a less compelling reason for end users to provide information to evaluators because

they have not explicitly signed up or participated in anything.

• UEB estimates must be based on secondary sources (verified or evaluated values, if possible)

or on market-representative studies of the energy savings associated with the technology or

practice in question; measurement and verification of nonparticipating market adoptees is

unlikely to be an option.

End users who have adopted the technology or practice promoted by the market transformation

initiative are unlikely to be able to directly attribute actions or motivations to program

interventions because the influence is typically indirect and designed to permanently change

market practices at large, such as by working to change building codes, product standards, and the

practices of market actors and decision-makers.

In

fact, market transformation programs are defined by strategically removing market barriers and

exploiting market opportunities and points of leverage to achieve lasting, structural market changes that

effectively change standard practice.

6

This characteristic of market transformation programs has

implications for the methods used to establish program causality. More specifically, because market

transformation programs deliberately seek points of market leverage to influence end users, it is not

reasonable, as it is for resource acquisition programs, to expect an end user to be able to directly attribute

their adoption decision to an initiative activity. This framework discusses the different methods required

to establish appropriate market transformation program causality, known as program-induced market

adoption.

1.3 Indirect Benefits Estimation

The evaluation of indirect benefits typically relies on estimating two key components:

The change in market adoption induced by the initiative

The savings (or other benefit) impact of the adopted technology or practice

6

See ACEEE 2018.

9

The following equation shows the relationship between these variables and indirect benefits:

Indirect Benefits =

(Program-Induced Market Adoption * UEB) - Direct Benefits

Where:

Indirect Benefits = Energy savings and other benefits resulting from measure

7

adoption associated

with indirect program influence

Program-Induced = The number of measure units adopted that were

Market Adoption influenced by program activities

UEB = Unit energy benefits; energy savings (MWh or MMBtu) or renewable

energy (MWh) per end user resulting from adopting the measure

Direct Benefits = Energy savings (MWh or MMBtu) or renewable energy (MWh) resulting

from measure adoption associated with direct program engagement

Protocols for estimating energy impacts for a wide range of technologies and practices are

comprehensively addressed in numerous documents and are not the focus of this framework. It is

important to note, however, that direct benefits impact evaluations, which focus on participant impacts,

may not produce UEBs that represent the market or market segments at large. The importance of

identifying UEBs that can be extrapolated to the market is discussed in the

Key Activity. Develop

Evaluation Plan section.

Figure 1 illustrates the concept of program-induced market adoption. The graphic depicts an increase in

the market adoption of a technology or practice over time:

The blue line represents total market adoption.

The grey area represents baseline market adoption (also known as naturally occurring market

adoption, or NOMAD). NOMAD is the market adoption that would have occurred in absence of

the market transformation program. It is important to acknowledge that the NOMAD curve is a

counterfactual set of values, making it challenging to estimate.

The light blue area—the difference the between total market adoption and NOMAD—is program-

induced market adoption.

7

This document uses “measure” as a generic term that refers to products, services, technologies, or practices (or any

combination thereof) promoted through a Market Development initiative.

10

Figure 1. Total, Program-Induced, and Baseline Adoptions over Time

The f

ollowing equation describes the concept presented in Figure 1 and represents a general approach to

estimating market transformation program-induced market adoption:

Program-Induced Market Adoption =

Total Market Adoption – NOMAD

Total market adoption comprises adoption by both program participants and nonparticipants, as shown in

the expanded equation:

Program-Induced Market Adoption =

Participant Adoption + Nonparticipant Adoption – NOMAD

NYSERDA counts benefits resulting from direct program engagement as direct benefits, and it counts

benefits resulting from participant adoption that occurs outside of direct program engagement as indirect

benefits. This distinction has evaluation implications: market evaluators must assess ongoing adoption

among nonparticipants (that is, the general target market) as well as adoption among direct participants

that occurs during and after direct involvement has ceased. In this framework, we refer to end-user

adoption using three terms:

8

Direct involvement participant adoption: Units of adoption associated with direct end-user

engagement with the program. (Contributes to NYSERDA direct benefits.)

Direct influence participant adoption: Additional units of adoption by participant end users not

associated with the incentives or direct support from NYSERDA, including adoption by former

participants who are no longer engaged with NYSERDA. (Contributes to NYSERDA indirect

benefits.)

8

Heschong Mahone Group (2008) originally developed this nomenclature to describe these three types of market

adoption in evaluating market effects for the Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance’s (NEEA) Integrated Design

Labs initiative, which intended to accelerate the market adoption of commercial integrated design practices.

11

Nonparticipant adoption: Units of adoption by targeted end users who have adopted the

technology or practice but have not engaged directly with NYSERDA. (Contributes to

NYSERDA indirect benefits.)

The next section of this document describes the indirect benefits evaluation framework and discusses the

planning and evaluation activities that support indirect benefits estimation at each stage of an initiative’s

lifecycle. The appendix of this framework includes links to three practical tools that help initiative teams

ensure that evaluations include the activities necessary to comprehensively assess indirect benefits: (1) an

Indirect Benefits Evaluation Checklist, (2) an Evaluability Mapping Tool, and (3) an Initiative Typology

and Associated Evaluation Considerations guide.

12

2 Indirect Benefits Framework

This section presents a framework and roadmap to estimate indirect benefits. It begins by introducing

the framework and continues with a discussion of the required activities for each stage of an initiative’s

lifecycle.

This framework will assist NYSERDA program management teams and evaluators with ensuring the

evaluability and reliable measurement of impacts resulting from CEF program investments. Figure 2

summarizes three lifecycle stages of initiatives funded by NYSERDA’s CEF, along with the key research

questions to answer at each stage to ensure evaluability and reliable measurement of indirect benefits.

Figure 2. NYSERDA Initiative Lifecycle and Key Questions Informing Indirect Benefits

Evaluation

F

igure 3 identifies specific activities that must be completed at each lifecycle stage, along with the

purpose of each activity with respect to indirect benefits evaluation. Appendix A includes a more detailed

checklist that program teams can use to help ensure they are completing the steps necessary to estimate

indirect benefits. The sections that follow provide detail on best practices and methods for each stage and

activity. The Stage 2. Initiative Year 1 section identifies methodological considerations for different

program types.

13

Figure 3. Key Activities and Purpose for Each Lifecycle Stage

14

2.1 Stage 1. Initiative Planning (Pre-Filing)

The evaluability of indirect benefits begins at the initiative planning stage, with NYSERDA’s

development of the program theory, logic model, and benefits forecast. Evaluators use the hypothesized

pathways of market influence documented in the program theory and logic model to assess the influence

and impact of the initiative. In addition, a well-documented benefits forecast allows evaluators to identify

assumptions that should be validated to estimate indirect benefits.

Key Activity. Clarify Market Transformation Theory

To determine indirect benefits, an evaluator depends on the program theory, which explains the theory of

market change, and on the logic model, which documents the program’s intended targeted activities,

outputs, and outcomes. Together, the program theory and logic model describe the current market

situation (barriers, opportunities, and existing [if any] programs targeting the same market), a theory and

strategy for how the program’s market interventions will induce sustained market changes that will

accelerate market adoption (pathways of market influence), and the outcomes that are expected over the

short, medium, and long term. The program theory and logic model provide the basis upon which the

evaluator can assess market progress and the impact of the initiative and validate the theory of market

transformation.

As part of its CEF investment plan, NYSERDA has developed program theories and logic models for

Market Development and Innovation and Research initiatives, along with key market progress indicators

(MPIs) and the data sources expected to be used for the assessment. The evaluator should be able to

identify direct and indirect impacts from examining the program theory and logic model, and an

evaluation plan for indirect benefits should include a logic model that highlights or annotates the primary

pathways of influence.

To

develop credible estimates of indirect benefits, it is necessary to identify three key components of the

market transformation theory, each discussed below:

Market definition and targeted market actors

Causal logic/pathways of influence

Hypothesized market outcomes and effects

2.1.1.1

Market Definition

Because market transformation programs seek to change markets, evaluations must be structured to

measure program-induced market changes.

9

Generally, a market is defined as of a set of entities that

supply a product or service and the buyers of that product or service. While there is no universally

accepted taxonomy of energy efficiency markets, there is consensus about the characteristics that

delineate and define markets. If a clean energy technology or practice share the following list of

characteristics, they are likely in the same market:

9

This discussion is adapted from TecMarket Works 2004.

15

Same or similar product functions or categories of functions (for example, HVAC,

water heating, appliances, and energy management systems)

Overlapping distribution chains

Same or competing manufacturers

Same or competing service providers

Demographically or firmographically similar buyers

NYSERDA’s CEF portfolio includes a mix of initiatives that target a single market (such as Greenhouse

Lighting and Systems Engineering) and those that target multiple markets. For example, NYSERDA’s

New Construction initiative operates in the residential homebuilding market and in the commercial and

multifamily building markets. These markets are distinct because they have different suppliers of building

services—designers, builders, and real estate professionals. In addition, the CEF portfolio includes

initiatives that target overlapping markets. For example, the New Construction and the Codes and

Standards for Carbon Neutral Buildings (CSCNB) initiatives both seek to influence the practices of

building owners and developers, as well as those of design and construction professionals.

Because market effects and the associated indirect benefits must be estimated at the market level, it is an

essential first step to identify the discrete market(s) that the initiative seeks to transform and which

population it will measure to estimate adoption. In addition, for initiatives that target the same market,

NYSERDA should consider the extent to which each initiative’s activities may contribute to market

transformation and evaluation research efforts should be deliberately coordinated. Initiatives that target

the same market should acknowledge other relevant programs or initiatives in the program theory and

logic model.

Market tr

ansformation strategies typically seek to accelerate end-user adoption of the desired technology

or practice by targeting multiple market actors engaged on the supply and demand sides of the technology

or practice, and may also seek to influence codes, standards, and local policies and practices. In addition

to identifying the market(s) each initiative seeks to transform, it is also important for NYSERDA and the

evaluator to create an inventory of the market actors to engage for each initiative. NYSERDA’s Compiled

Investment Plan (2023) includes a list of the market participants targeted by each initiative. This

information allows NYSERDA and market evaluators to identify the markets and the specific market

actors who are targeted by more than one initiative. Market actors who are not directly involved with the

program are often difficult to reach for research purposes; this mapping will enable NYSERDA to

identify research activities that can benefit from coordination between the market evaluations (such as for

commercial building manager surveys or interviews).

2.1.1.2

Causal Logic/Pathways of Influence

The program theory and logic model must include the theorized linkages and causality between initiative

activities and outputs and the hypothesized market outcomes. An example using the CSCNB initiative is

provided in Appendix

B.

16

2.1.1.3

Hypothesized Market Outcomes and Effects

The initiative logic model should identify the anticipated short- and long-term market outcomes

expected to result from the initiative market interventions. To establish which market changes to

assess, the evaluator must first identify hypothesized market effects resulting from interventions.

These hypothesized outcomes must be sufficiently clear to develop associated, measurable MPIs.

When a key goal of the market intervention is to attract additional outside investment (leveraged funds),

the logic model should identify that investment as an output, along with the market actor(s) who are

hypothesized to make those investments. Doing so will ensure that the evaluation research plan includes

an investigation of stimulated investment with directly targeted market actors. The Compiled Investment

Plan identifies leveraged funds’ targets as direct benefits only, representing direct private investments

made by initiative participants.

Key Activity. Create Logic Model and Evaluability Map

Logic models document initiative resources, activities, outputs, and outcomes. A logic model should also

include context about any relevant NYSERDA or external initiatives to capture the complete state of the

market. A logic model is critical for defensible market transformation program evaluations because it

documents the theorized pathways of market influence and outcomes, along with a holistic accounting of

relevant market actors, which informs potential savings while avoiding double-counting. While the logic

model provides a roadmap for the initiative and a framework for its market evaluation, two additional

elements are required to ensure the evaluability of indirect benefits: MPIs and the identification of data

sources to assess MPIs and initiative influence. MPIs allow for an objective measurement over time of

the market status and its progress toward desired initiative goals.

Best practice in market transformation initiative and evaluation planning includes developing MPIs for

each theorized pathway of influence and identifying viable data sources to assess the MPIs and causality.

Appendix A includes an Evaluability Mapping Tool that the program and evaluation teams can use to

ensure that the evaluation fully assesses all pathways of influence.

Appendix B

provides an e

xample evaluability map for NYSERDA’s CSCNB initiative.

Key Activity. Develop Benefits Forecast with Documented Assumptions

In addition to the program theory, logic model, and MPIs, NYSERDA develops forecasts for direct and

indirect benefits during the planning stage for each initiative in its CEF Market Development portfolio.

These forecasts are documented in a Budget and Benefits (BAB) workbook,

10

which NYSERDA updates

annually for each initiative using implementation experience and research conducted as part of its market

and impact evaluations.

10

See NYSERDA 2017.

17

The assumptions used to develop the forecast must be clearly identified with documented sources and

calculations—particularly for market size, market baseline, and UEBs. The evaluator(s) should review

these assumptions annually and make sure they are updated as needed to reflect the best available data. A

BAB workbook includes several sections:

Cover page summarizing key inputs and considerations, date that NYSERDA began influencing

the market, and a list of other programs that target the same market (if applicable)

Definition of the market and “unit of adoption” (how to count instances of measure adoption)

• Unit of adoption could be a building, a system, an appliance, or a single or set of

business practices.

• This definition should include calculations and data sources to support a market size

estimation and forecast.

• This definition should also include market segments, if needed (such as large business or

small business), and rationale. For example, UEBs for certain equipment installed at large

businesses are expected to differ from those installed at small businesses.

Adoption rates

• NOMAD (historic and forecasted), ideally for each market segment and measure combination

• Direct impacts claimed by programs

UEBs and extrapolation considerations

• UEBs developed from small sample sizes should be noted and updated as more impact

evaluation research is completed, especially for measures with high variability.

• UEBs must correspond to the unit of adoption. For example, the UEB for a single heat pump

system should not be used if the unit of adoption is a whole multifamily building.

Adjustments for other program or external influences

• Explanation of how double-counting may occur and where else the savings are being reported

• Calculations and sources used to quantify the size of indirect benefits’ overlap

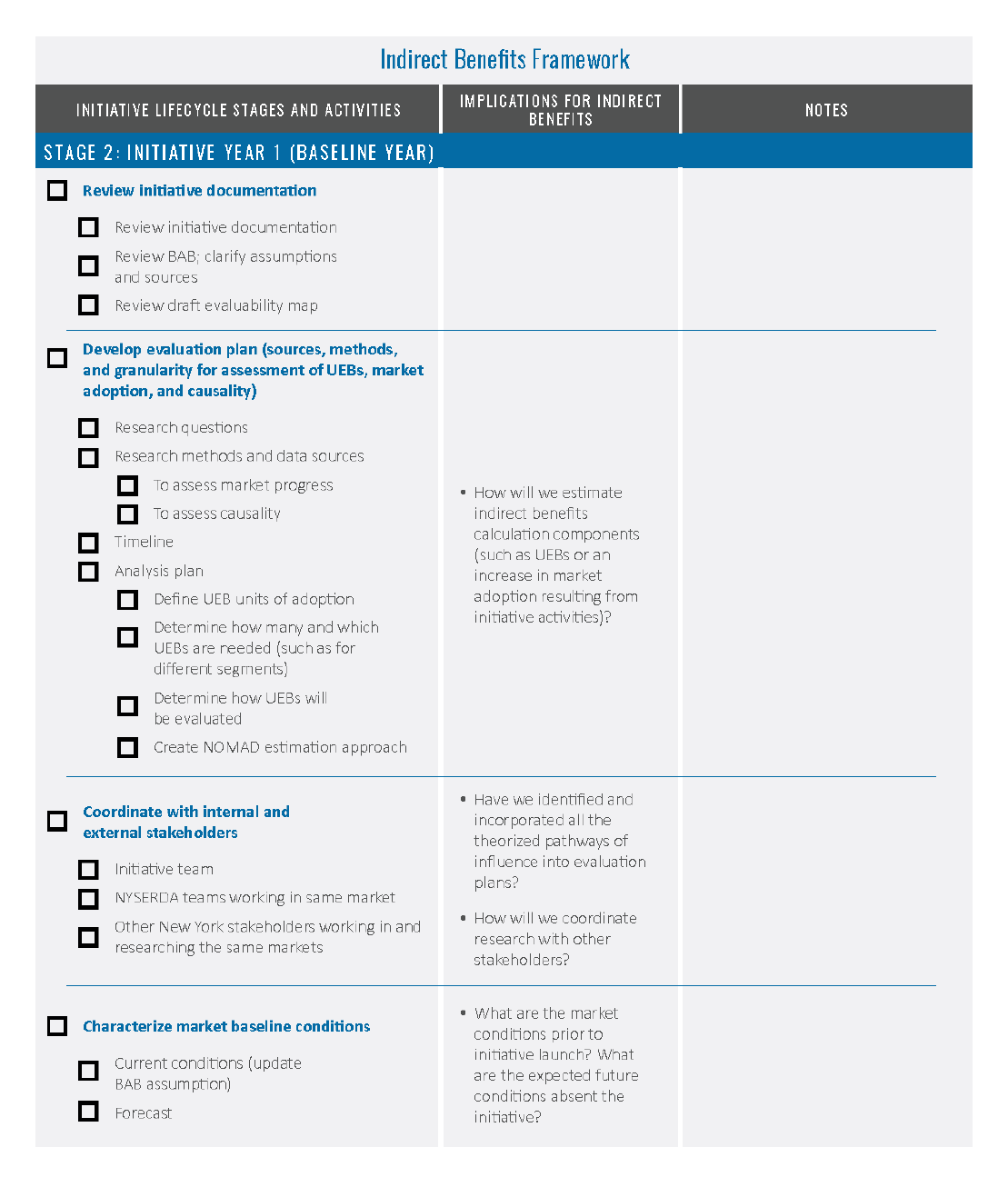

2.2 Stage 2. Initiative Year 1

During the initial year of initiative funding, NYSERDA works with a third-party evaluation contractor

to develop or refine an evaluation plan for each initiative. NYSERDA typically drafts an evaluation plan

and asks evaluators to propose methods and modifications, where appropriate, as part of the evaluator

solicitation process. The draft plan should include a task to estimate indirect benefits. This section of the

framework begins with an overview of the evaluation plan elements that are necessary to evaluate indirect

benefits and introduces an initiative typology with associated evaluation planning considerations. Next,

it discusses the importance of coordinating plans with internal and external stakeholders. It concludes

with a discussion of the baseline assessment, which the evaluator typically completes during the

initiative’s first year.

18

Key Activity. Review Initiative Documentation

To ensure that the evaluation plan includes all research necessary to evaluate indirect benefits, the

evaluation team should begin by reviewing initiative documentation, including the program theory, logic

model, and BAB workbook. During this review, evaluators should verify the clarity of several elements:

Hypothesized causal linkages between program activities and outcomes, which will determine

the research approach to establishing causality

Hypothesized initiative outcomes that correspond with measurable MPIs

UEBs assumed in the BAB and documented source(s) of those values

Definition of what constitutes “adoption” (such as which types of equipment, which practices,

or which combination of technologies and practices)

NYSERDA creates a BAB workbook for each initiative that documents how it estimated indirect benefits

for the CEF plan. The market evaluator and impact evaluator should collaborate to carefully review the

initiative BAB workbook and underlying BAB estimation algorithms and assumptions, flag any questions

or issues with respect to the assumptions, and incorporate research to update the assumptions in the

evaluation plan, as needed.

Once the evaluator has clarified any questions about the program theory, logic model, and BAB

assumptions, it must develop or refine an evaluation plan that identifies research questions and methods,

data sources, and the timing for each evaluation activity required to estimate program-induced market

adoption and benefits. This section of the roadmap is focused on essential evaluation plan components,

while the

Stage

3. Subsequent Initiative Years (Annual Evaluation Activities) section discusses research

methods and considerations for executing the evaluation plan.

Key Activity. Develop Evaluation Plan

NYSERDA drafts evaluation plans for its CEF initiatives and asks third-party evaluators to elaborate

on those draft plans as part of the proposal selection process. Once an evaluation contractor is selected,

one of the first tasks is to finalize the evaluation plan. To ensure the evaluability of indirect benefits,

evaluation plans should include all the components described below. At the conclusion of each program

year, it is best practice for the evaluation team to review the evaluation plan and revise it as necessary

to reflect the development and evolution of the initiative strategy.

2.2.2.1

Research Questions

At the most fundamental level, estimating indirect benefits requires estimating two values: units of

program-induced market adoption and UEBs. The research questions associated with quantifying these

values are common to all market transformation program evaluations. However, other research questions

will vary according to the specific program theory and type of initiative. Table 1 shows research questions

that are common to all market transformation program evaluations, along with examples of initiative-

specific research questions.

19

Table 1. Example Research Questions

Common Research

Questions

Initiative-Dependent Research Questions

What market progress is

being achieved?

• Are the outcomes specified in the logic model observable?

• Is there evidence to support the causality between activities and outcomes

hypothesized in the program theory and logic model?

What is total market

adoption by

nonparticipants?

• How many units have been shipped, installed, or purchased?

• What proportion of targeted end users have adopted the technology or practice?

• What proportion of targeted end users have changed their behavior, and to what

degree have they changed their behavior?

What proportion of market

adoption was the result of

program interventions?

a

Naturally Occurring Market Adoption

• What is the baseline market adoption forecast?

Program Causality

• Is there evidence to support the causality between initiative activities and market

adoption?

• Of the units adopted/installed, what proportion can be traced to specific initiative

activities or outputs (such as participating supply chain market actors, training,

and other materials or resources provided to the market)?

• What proportion of end users changed their behavior as the result of initiative

activities or outputs?

• Of the entities that adopt the approach or set of practices, what proportion did so

because of specific initiative activities or outputs?

• Which and what proportion of projects or measures implemented can be traced to

specific initiative activities or outputs?

• Did other initiatives contribute to market adoption?

How much participant

market adoption has the

program influenced?

• Among program participants, how many additional units have been adopted or

installed since participating in the program?

What is the estimated

impact of adoption?

• What are the energy saving, carbon reduction, and other impact per unit of

adoption, by end user segment and/or measure characteristics?

a

Note that the evaluation plan should identify initiative-specific research questions based on the type of program

and its specific theory of change.

a

There are often multiple programs influencing market adoption. For example,

NYSERDA may have multiple programs that address the same market, and NYSERDA, utility, and government

programs may all seek to influence the adoption of energy-efficient technologies or practices in a particular market.

Various approaches can be used to estimate or assign the impact of each program. These approaches are discussed in

the Assessing Causality When Multiple Programs Exist and Avoiding Double-Counting sections of this document.

2.2.2.2

Market Progress Indicators

Quantifying market adoption is foundational to estimating indirect benefits and is an important indicator

of market progress. However, given the long-term nature of market transformation initiatives, indirectly

influenced market adoption may not be observable for several years and may continue for years after the

initiative activities have ended. For these reasons, it is crucial that market evaluators focus early market

progress evaluation research on expected shorter-term market progress outcomes, as indicated in the

initiative logic model.

20

MPIs are important for estimating program-induced adoption: in order to credibly substantiate causality

between program activities and outcomes, the evidence of that causality must be well-documented from

early program stages.

The evaluation plan should specify, for each hypothesized outcome, the associated MPI or evidence of

market progress and the method that will be used to evaluate that indicator or obtain that evidence. Table

2 lists examples of typical MPIs and associated research methods.

Table 2. Example Market Effects, Indicators, and Research Approach

Market

Effect/Outcome

Market Progress Indicator Research Approach

Increased awareness

among target audience(s)

Awareness of technology or practice

• Target audience survey

Increased availability

Supply chain decisions (such as

production decisions or retailer

buying decisions)

• Supply-side market actor interviews or

surveys

• Shelf surveys, web scraping

Targeted market actor(s)

promote the technology or

practice

Salespeople communicate benefits

and value proposition and marketing

materials reflect benefits and value

proposition

• Mystery shopping

• Marketing materials review

• Market actor interviews

Increased market

capability or capacity

Number of service providers offering

technology or services and number

of certified building operators

• Industry association data and interviews

• Market actor interviews

• Business databases (such as Data Axle)

Voluntary standard

upgraded to reflect

technology or practice

Voluntary standard adopted

• Direct observation

• Interviews with standards-setting

organization

Increased stringency of

energy code

Adoption of energy code developed

and/or advocated by initiative

activities

• Direct observation

• Interviews with targeted codes

organizations and policy makers

2.2.2.3

Causality

In addition to identifying how an evaluator will measure each MPI, it is critical that the market evaluation

plan specify the approach the evaluator will use to establish causality between the initiative activities

and the observed outcomes. It is important to identify both the research activities (for example, surveys,

interviews, or expert judging) and the specific methods the evaluator will use to establish causality (for

example, the sampling approach, specific survey and/or interview questions, expert judging methods,

experimental methods, or historical tracing). There are several benefits from defining these methods

as part of the evaluation plan:

Research instruments for the market and impact evaluations can be coordinated and designed

to include the necessary questions in the first survey wave, allowing causal linkages to be

documented from the earliest stages of the initiative.

Program teams can review the sampling approach and confirm that targeted market actors

are adequately represented in research efforts.

21

Program teams can vet the methods to establish causality with stakeholders before finalizing

the research plan.

Methods for assessing causal influence are discussed in Stage 3. Subsequent Initiative Years (Annual

Evaluation Activities).

2.2.2.4

Research Methods and Data Sources

The evaluation plan must specify the research activities, methods, and data sources the evaluator will

conduct and use to inform each research question. Research activities typically comprise a variety of

secondary and primary research efforts and may include industry data, when available, and interviews or

surveys with end users and market actors. The evaluation plan should also describe the sampling approach

for primary research activities, including the sample frame, stratification, sample size, and confidence and

precision (per the Uniform Methods Project).

11

Stage 3. Subsequent Initiative Years (Annual Evaluation

Activities) further describes typical methods.

After determining specific research activities and data sources, the market evaluator and NYSERDA

project manager should determine whether opportunities exist to coordinate this research with impact

evaluations, evaluations for other initiatives operating in the same market, and/or with top-down market

evaluation activities (such as statewide baseline and market assessment studies).

2.2.2.5

Timeline

The evaluation plan must also include the timing for each planned research activity. This component of

the plan will help to ensure a logical sequence of research activities and will facilitate coordination with

other evaluation efforts.

2.2.2.6

Analysis Plan

To ensure that the research will provide all information necessary to estimate indirect benefits, the market

evaluation plan should include an analysis plan with the initiative-specific algorithms and approaches that

will be used to estimate program-induced market adoption. The evaluation plan should fully specify all

UEBs, estimation algorithms, data sources, and unit of adoption so that these variables are determined

prior to the beginning of data collection. Doing this will help to ensure that the evaluator collects the

data needed to calculate indirect benefits from the outset.

When developing the analysis plan and initiative-specific algorithms, the evaluator should consider and

verify several elements with the NYSERDA project manager:

11

See NREL 2018.

22

Units of Adoption Definition. To estimate indirect benefits, the evaluation team must clearly

define the measure(s) or actions associated with the benefits. This may seem obvious in the

case of a specific technology, such as a heat pump space heater or a heat pump water heater.

However, in other cases it may not be so obvious to determine what constitutes a unit of adoption.

For example, in the case of the Energy Management Practices (EMP) initiative, benefits are

associated with and driven by implementing a combination of strategic energy management

(SEM) practices at New York State industrial facilities. As part of the original evaluation plan,

the evaluation team used the Consortium for Energy Efficiency’s SEM minimum elements

and developed a corresponding market survey questionnaire and scoring rubric as the basis to

estimate the number of facilities adopting SEM.

12

The EMP impact evaluation, however, found

energy savings at facilities that had not adopted all the Consortium for Energy Efficiency

minimum elements—leading the evaluation team to revise the definition of units of adoption.

Unit Energy Benefits. To quantify indirect savings, evaluators must assign a savings value (unit

energy savings) to the technology, practice, or combination thereof being promoted by the market

transformation initiative.

13

The UEB value or values assumed for planning should be included in

the initiative BAB with documented source(s). The initiative evaluation plan should specify the

approach and research activities to evaluate or update those assumptions. If the evaluation team

plans to use initiative impact evaluation results (direct impacts) to update the UEB values, then

the impact evaluation should be designed to produce estimates of savings based on a statistically

representative sample of the target market.

Note that impact evaluations focused on quantifying direct impacts achieved by program

participants may not produce UEB values that can be projected to estimate indirect market

benefits if they are not based on the same unit of adoption or if the sample of participants does

not represent the target market. In that case, the evaluation plan should include another approach

to evaluating UEBs, such as secondary research or a market-wide impact study, like the New

York Department of Public Service’s current study for heat pumps.

Different UEB Values by Type of End User. The existence of different UEB values for different

types of end users (such as large versus medium industrial firms or residential versus commercial

users) will have implications for the research plan. Programs that assume or evaluate different

unit benefit values for more than one end-user type should also calculate program-induced market

adoption for each type of end user. For example, the On-site Energy Manager (OsEM) description

in the Industrial Focus Area of the Compiled Investment Plan and the corresponding BAB

workbook specify different measure savings values for medium and large facilities, so the market

evaluation team should estimate program-induced market adoption separately for each of those

two end-user types. In addition, if the evaluation team plans to use initiative impact evaluation

results to update the UEBs, then it should design the impact evaluation to estimate savings based

on a statistically representative sample of each end-user segment.

12

See CEE n.d.

13

This discussion is focused on energy savings but is applicable to renewable energy and carbon dioxide

reduction as well.

23

UEB Values for Multiple Measures. Several NYSERDA initiatives encourage end users to adopt

multiple measures, some of which may produce overlapping or synergistic benefits. For example,

a facility that adopts SEM may also hire an OsEM. To develop an indirect benefits analysis plan,

the market evaluator must understand whether to estimate UEB values for different combinations

of measures or for each measure individually. If there are different UEB values for each measure

or combination of measures, the evaluator should estimate program-induced market adoption

separately for each measure or measure combination. Similar to the discussion on multiple end

users, if the evaluation team plans to use initiative impact evaluation results (direct impacts) to

update the UEBs, then the impact evaluation plan should include details of how to estimate

statistically reliable savings for various measure combinations.

2.2.2.7

Considerations by Program Type

NYSERDA’s portfolio includes a wide variety of market transformation programs. Although the indirect

benefits evaluation framework is broadly applicable to NYSERDA’s portfolio, the recommended and

practical evaluation methods vary by program type. Table 3 presents a program typology showing six

program types, their characteristics, and example initiatives.

Table 3. Program T

ypology

Program Type

Key Characteristics

Example Initiatives

1. Clean Energy

Products or

Technologies

(midstream/upstream)

Increase market availability and attractiveness by providing

incentives and other resources to midstream and upstream

market actors

Heat Pump Phase 2

2. Enabling

Technologies

Advance the market uptake of technologies that enable

decarbonization by providing support to technology

providers and resources to end users to reduce soft costs

and support the business case for adoption

Energy Management

Technology (EMT);

Advancing Agricultural

Energy Technologies

3. New Construction

Provide technical assistance, design tools, and financial

incentives to building owners, developers, and builders to

overcome initial design challenges, costs, and risks

associated with high-performance building

New Construction

4. Codes and Standards

Support the adoption of more stringent product standards

and energy codes, and increase compliance and

enforcement

CSCNB; Product and

Appliance Standards

5. Training, Technical

Services, Practices,

and Challenges

Provide resources and/or encouragement to end users to

support their successful adoption or implementation of

clean energy practices, leading to further adoption beyond

direct program engagement

EMP; Clean Green

Campuses (formerly

Rev Campus

Challenge); Clean

Energy Communities;

Building Operations and

Maintenance

Partnerships

6. Innovation and

Research

Invest in research, business support, product development

support, demonstration projects, and contracts with

incubators

ClimateTech

Commercialization

Support; NextGen

Buildings

24

There are important indirect benefits evaluation methodological considerations for each program type.

Key considerations are highlighted below, and Appendix A includes a summary reference guide: Initiative

Typology and Associated Evaluation Considerations.

Type 1. Clean Energy Products or Technologies (midstream/upstream)

These initiatives work primarily with supply chain market actors to increase the availability, affordability,

and promotion of a product or technology. The market adoption for these initiatives is best assessed

and tracked using sales or shipment data and assortment data. Initiative causality and influence are

best assessed via interviews with targeted market actors. End-user surveys are useful to assess end-user

awareness, motivations, barriers, and attitudes, but cannot be relied upon to estimate initiative influence

because end users do not have insight into the supply chain interventions that drove changes in product

availability or recommendations from vendors.

Type 2. Enabling Technologies

These initiatives seek to advance market uptake of technologies that enable decarbonization by providing

support to technology providers and resources to end users to reduce soft costs and support the business

case for technology adoption. Market adoption of these enabling technologies can be estimated using

sales or installation data obtained from vendors. Evaluators can assess causality via surveys of targeted

vendors and end-use decision-makers using questions that investigate adoption and implementation

influences. Note that end-user research is useful to gain insights into decision-making, but end users may

not be aware of NYSERDA’s indirect influence on decisions via market interventions targeted to vendors.

Type 3. New Construction

Through its New Construction initiative, NYSERDA aims to increase the adoption of high-performance

building practices and technologies by providing technical assistance, design tools, and financial

incentives to building owners, developers, and builders to overcome initial design challenges, costs,

and risks. The market adoption of high-performance buildings and practices can be estimated using

building permit data and/or data gathered from builder surveys. Evaluators can assess causality via

surveys of targeted market actors and decision-makers using questions that investigate adoption and

implementation influences. Note that nonparticipating builders may not be aware of NYSERDA’s

influence on the increased market demand for or supply of high-performance building practices.

Type 4. Codes and Standards

Through its Codes and Standards initiatives, NYSERDA aims to influence federal, state, and regional

regulations to adopt new or improved energy efficiency requirements or increase compliance with

existing regulations. Product sales, shipment, and/or installation data are key to estimating indirect

benefits impacts from efficient and clean equipment standards; evaluators can use building permit

and construction data and code compliance estimates to estimate impacts from Codes and Standards

initiatives. To assess causality, evaluators must examine the influence of NYSERDA interventions on

codes and standards adoption processes, which can be accomplished via interviews with decision-makers

and influencers, document review, and historical tracing.

25

Type 5. Training, Technical Services, Practices, and Challenges

These initiatives provide resources and encouragement to end users to identify, provide experience

in, or otherwise support the successful adoption and implementation of clean energy technologies and

practices, with the objective of influencing additional adoption beyond direct program engagement.

These initiatives may also target and support service and technology providers and industry associations

as points of market leverage to transform standard practice. Service providers or associations can be good

sources for assessing market adoption and tracking data, as well as for assessing initiative influence.

For initiatives where the primary engagement is with end users, evaluators may need to rely on end-user

surveys to estimate and track market adoption, as well as to substantiate the influence of initiative

activities and resources. The best way to design end-user surveys that assess influence is discussed

in the Stage 3. Subsequent Initiative Years (Annual Evaluation Activities) section.

Type 6. Innovation and Research

NYSERDA’s Innovation and Research portfolio includes initiatives to accelerate the development and

commercialization of innovative technologies, solutions, and market approaches designed to advance

decarbonization. These initiatives focus on providing resources to early- and mid-stage companies,

investors, manufacturers, entrepreneurs, solution adopters, and policy makers and regulators.

14

Given

their early-stage nature, these initiatives do not currently have indirect benefits targets. Nonetheless, it is

important that the program teams document and assess the program theory, strategies, baseline conditions,

and hypothesized market impacts of these programs: this will ensure the future evaluability of indirect

benefits for successful initiatives.

Key Activity. Coordinate with Internal and External Stakeholders

Before finalizing the evaluation plan, the evaluation team should communicate with internal and external

stakeholders about proposed evaluation activities in order to coordinate related research activities that

may be planned or under consideration by NYSERDA or external stakeholders.

2.2.3.1

Coordination within NYSERDA

The market evaluation team should share and coordinate evaluation activities with program management,

impact evaluation, and reporting, as well as with any other NYSERDA teams working in the same

markets. Specifically, the market evaluator should communicate with these internal stakeholders:

Initiative Management Team. The evaluator should review the proposed evaluability map

with the initiative management team to ensure that all the theorized pathways of influence are

represented and that the data collection and sampling plans fully represent market activities. For

some initiatives where NYSERDA executives have the most complete knowledge about market

influence activities, such as CSCNB, it is important to obtain executive-level feedback regarding

the evaluability map.

15

14

See NYSERDA 2022.

15

Cadmus facilitated two workshops with NYSERDA executives and selected initiative managers (on April 12, 2022 and

April 20, 2022) to discuss indirect benefits and needs for this revised framework. This example surfaced in those

workshops.

26

After reviewing the BAB, the market evaluator should clarify questions regarding indirect

benefits planning assumptions and estimates with the person who developed the BAB. The

program team updates benefits estimates annually, using findings from the evaluation, so it is

important that the evaluation plan includes any research required to update planning assumptions.

Initiative Impact Evaluation Team. The impact evaluation and market evaluation teams should

share pre-final evaluation plans with each other to ensure consistency of definitions (unit of

adoption and targeted market), and to ensure that any research required to support each other’s

analysis is identified, planned, and coordinated.

16

In the EMP initiative, for example, the market

evaluator needs the impact evaluator to collect data from direct participants about adoption at

nonparticipating company facilities. Another important area of coordination is evaluating the

UEBs used to estimate indirect benefits. The two evaluation teams must assess and agree on

whether impact evaluation results can be used to update the UEB assumptions in the BAB and

on the important characteristics that drive UEBs, such as customer or facility size or type.

Other NYSERDA Teams. The evaluation team should share the pre-final evaluation plan

with other NYSERDA teams that are working on programs or research activities in the same

or overlapping market(s). Communication and coordination between teams working in same

markets provides several benefits:

• Al

lows for identifying, coordinating, and streamlining activities that may be targeting the

same end users or market actors

• Provides the information necessary to ensure that the research fully captures

NYSERDA’s influence

• Provides the information needed to avoid double-counting of indirect benefits

o When multiple initiatives target the same market, the default practice should be that the

last initiative to enter the market accounts for savings claimed by existing initiatives.

For example, NYSERDA’s Residential New Construction and Buildings of Excellence initiatives have

arguably contributed to the success and impact of the NYSERDA’s Codes and Standards initiative.

Deliberate conversations between the Codes and Standards initiative evaluator and the Residential New

Construction and Buildings of Excellence initiatives teams would allow the evaluator to design market

actor interview guides that better capture the influence of those programs on policymakers’ willingness

to adopt codes with building requirements that are similarly stringent to those in the successful new

construction programs.

16

In 2021, NYSERDA began soliciting proposals for joint impact and market evaluations, which should eventually

diminish the required coordination since a single team will be planning both evaluations.

27

2.2.3.2

Coordination with External Stakeholders

The evaluator should also coordinate with other program administrators (utilities or municipalities)

or energy advocacy entities (such as the Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships, NEEA, and the

Association of Energy Service Professionals) conducting studies in the same markets. Coordination

may not be possible, but it offers several potential benefits, including streamlining activities, maintaining

consistency with research approaches, if appropriate, and staggering the timing for research that targets

the same market actors or end users.

Key Activity. Characterize Baseline Conditions and Forecast

As discussed previously and illustrated in Figure 1, program-induced market adoption is the difference

between total adoption and adoption that would have occurred absent program intervention (NOMAD).

To estimate these values, the evaluator must begin by establishing current practice and the level of market

adoption prior to initiative market intervention. The evaluator should review NYSERDA’s estimate of the

pre-initiative market adoption, conducted as part of the BAB. In addition, to determine what part of total

market adoption over time is program induced, the evaluator must use one or more approaches:

Develop a baseline (NOMAD) forecast prior to market intervention.

Include questions in a representative survey of market adopters designed to detect and

quantify program influence.

Include questions in market actor surveys to assess program influence.

This section addresses methods to assess baseline conditions and to develop a NOMAD forecast, while

Stage 3. Subsequent Initiative Years (Annual Evaluation Activities) addresses the latter two approaches.

2.2.4.1

Baseline Conditions

Market transformation program evaluation best practices call for conducting research to characterize the

market prior to market intervention. Baseline market characterization comprises straightforward market

research approaches and typically includes several research activities:

Secondary research and interviews with supply-side market actors (such as manufacturers,

distributors, builders, installers, service providers, and industry organizations) to characterize

the structure of the supply chain; determine the mix of current products and services; quantify

the market size and volume moving through various channels, along with prices and industry

trends; and identify potential opportunities and points of leverage.

Interviews and surveys with supply-side market actors and end users to understand their

awareness and perceptions, motivations, preferences, and barriers to adoption.

Primary and secondary research activities to quantify baseline levels for MPIs.

28

2.2.4.2

Baseline Forecast

As opposed to baseline market characterization, which describes the current state of the market at the

time it is conducted, a baseline forecast requires the evaluator to establish a counterfactual estimate of

what would happen without program intervention. A counterfactual estimate, by definition, cannot be

substantiated by observation because it describes a scenario that never occurs if the initiative is

implemented. As such, baseline forecasts necessarily have a high level of uncertainty, raising the

questions of whether to develop them and what makes them worthwhile.

When and Why a Baseline Forecast is Advisable

It is generally advisable to develop a baseline forecast for market transformation programs when

indirect benefits are significant

17

and when the evaluator can determine and implement a reasonable

method for determining those benefits within the evaluation budget. As mentioned previously, one

defining characteristic of a market transformation program is that it produces lasting structural changes

in the market and accelerates the adoption of energy-efficient technologies and practices so that they

become standard practice. Once structural market changes have occurred, particularly on the supply

side of the market (such as widespread availability and new or more stringent standards), it can become

increasingly challenging, if not inappropriate, to attribute additional market adoption of the technology

or practice in question to the market transformation initiative that induced those structural market

changes. NEEA’s experience with its CFL market transformation initiative, described below,

provides an illustrative example of this challenge.

In

the late 1990s NEEA invested in an initiative to transform the residential lighting market, focused

on working with supply-side market actors to increase the market availability of high-quality CFLs at

an affordable price. After several years of working toward those goals, product availability and quality

had increased substantially, but CFL market saturation remained low. In 2002, however, the West Coast

energy crisis prompted a spike in CFL sales. Following this dramatic increase, evaluators were challenged

to establish that a high proportion of market adoption was attributable to program activities. Without

historical context and evidence of NEEA’s influence on manufacturers, retailers, and product quality,

it appeared that the increase in market adoption was attributable to the energy crisis. However, detailed

documentation and evaluation of the initiative’s logic model revealed that the CFLs would not have

been available for purchase during the energy crisis if not for NEEA’s extensive market interventions.

18

An industry forecast dating from the start of the initiative would have loaned additional credibility to

program causality and likely would have resulted in lower estimated NOMAD and higher estimated

indirect benefits.

17

“Significant” is used here in the context of the total expected benefits for the portfolio. For example, an analysis

of NYSERDA’s CEF portfolio indirect benefits forecast as of May 20, 2022 found that two initiatives (Product and

Appliance Standards and EMT) were forecasted to deliver approximately 50% of indirect energy efficiency benefits

(MMBtu energy savings). NYSERDA could consider setting a threshold for which programs require a baseline

forecast, using this or another analysis of contribution to indirect benefits.

18

NEEA’s CFL and other initiative market progress evaluations are well-documented and publicly available on the

NEEA website:

www.neea.org.

29

Baseline Forecasting Methods

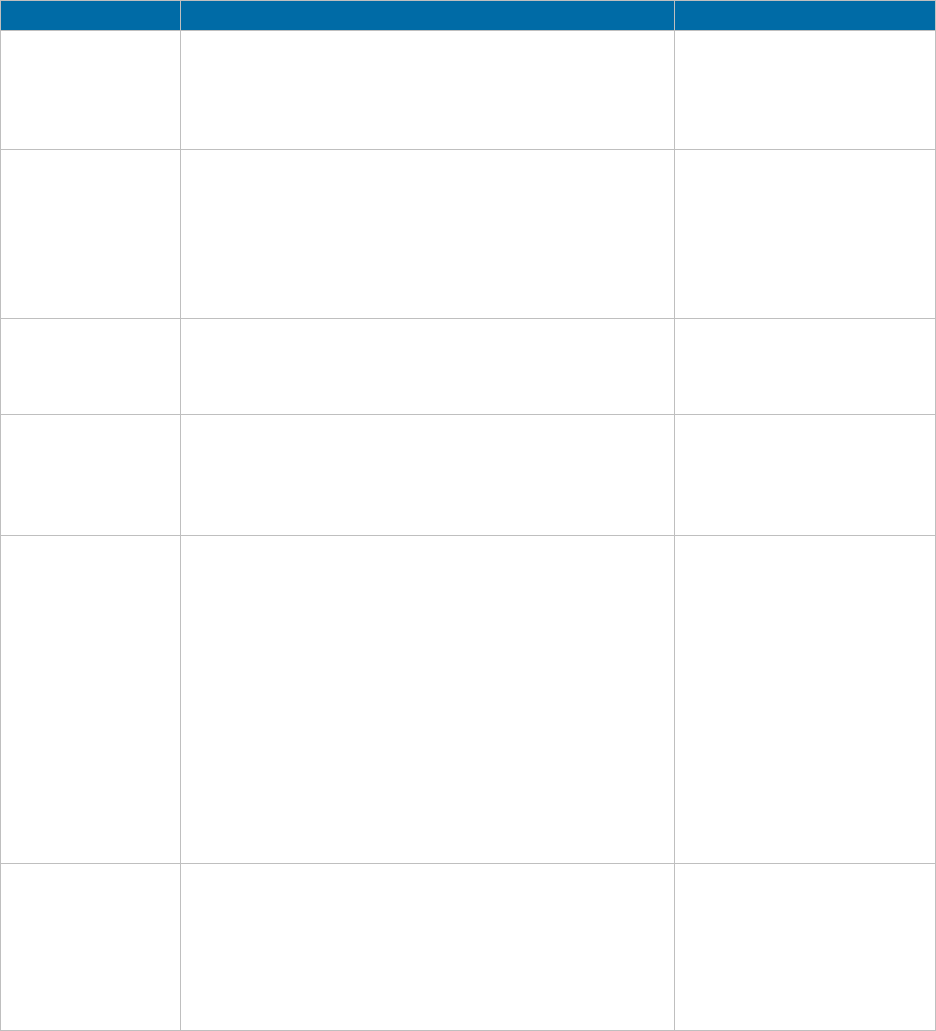

There are three primary methods to develop baseline forecasts of market adoption: industry forecasts,

econometric modeling, and structured expert judging (such as a Delphi panel). Each of these methods

is described in more detail below. Figure 4 presents a decision tree as guidance for determining the

most appropriate method.

Figure 4. Baseline Forecast Decision Tree

a

“Significant” is used here in the context of the total expected benefits for the portfolio.

Industry Forecasts

Industry forecasts, if they exist, generally serve as the best approach to establishing a credible

baseline forecast. Industry forecasts represent the collective expectations of the market actors who are

most knowledgeable about the market because they participate in it as manufacturers, distributors, and

retailers. These market actors have a strong interest in producing the most accurate forecast possible.

Industry forecasts are most likely to be available for specific technologies but are unlikely to exist

for practices or management approaches. If forecasts do exist, they may not be publicly available;

however, industry partnerships and relationships should help NYSERDA to identify and gain access

to existing forecasts.

Econometric Modeling

If industry forecasts are not available, but historical sales or production data are available, it may

be possible to develop a forecast using econometric modeling. This approach uses historical sales

or production data, combined with economic variables, to develop a model that predicts the pattern

of past sales with a reasonable degree of accuracy, using a model that may look like the following:

Sales t =

f (weather, economic variables, time)

Like industry forecasts, historical sales or production data are only likely to exist for discrete technologies

but may be expensive to acquire or be unavailable. The other significant drawback to using econometric

models is that they cannot factor in anticipated future changes—even those that may be known to industry

experts, such as changes in a policy, market, or technology, or an updated production cost.

30

Structured

Expert Judging (Delphi Panel)

For programs with significant forecasted indirect benefits,

19

if industry forecasts are not available,

structured expert judging is a good method to develop a credible NOMAD forecast.

In general, this approach involves assembling a panel of individuals with close working knowledge

of the targeted market. The Delphi technique is a widely used and accepted expert judging method for

forecasting by gathering information and converging opinions to gain consensus. With this method,

researchers convene a panel of experts to provide individual forecasts of market adoption, often through

a web-based tool. Experts—who represent diverse perspectives—provide forecasts and accompanying

explanations individually. Anonymous results are shared with the group, and panelists are invited to