Policy Implementation Challenges and Barriers to Access

Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Faced By People

With Disabilities: An Intersectional Analysis of Policy

Actors’ Perspectives in Post-Conflict Northern Uganda

Muriel Mac-Seing

1,2*

ID

, Emmanuel Ochola

3

ID

, Martin Ogwang

4

ID

, Kate Zinszer

1,2

ID

, Christina Zarowsky

1,2,5

ID

Abstract

Background: Emerging from a 20-year armed conflict, Uganda adopted several laws and policies to protect the rights

of people with disabilities, including their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) rights. However, the SRH rights of

people with disabilities continue to be infringed in Uganda. We explored policy actors’ perceptions of existing pro-

disability legislation and policy implementation, their perceptions of potential barriers experienced by people with

disabilities in accessing and using SRH services in post-conflict Northern Uganda, and their recommendations on

how to redress these inequities.

Methods: Through an intersectionality-informed approach, we conducted and thematically analysed 13 in-depth

semi-structured interviews with macro level policy actors (national policy-makers and international and national

organisations); seven focus groups (FGs) at meso level with 68 health service providers and representatives of disabled

people’s organisations (DPOs); and a two-day participatory workshop on disability-sensitive health service provision

for 34 healthcare providers.

Results: We identified four main themes: (1) legislation and policy implementation was fraught with numerous

technical and financial challenges, coupled with lack of prioritisation of disability issues; (2) people with disabilities

experienced multiple physical, attitudinal, communication, and structural barriers to access and use SRH services; (3)

the conflict was perceived to have persisting impacts on the access to services; and (4) policy actors recommended

concrete solutions to reduce health inequities faced by people with disabilities.

Conclusion: This study provides substantial evidence of the multilayered disadvantages people with disabilities face

when using SRH services and the difficulty of implementing disability-focused policy in Uganda. Informed by an

intersectionality approach, policy actors were able to identify concrete solutions and recommendations beyond the

identification of problems. These recommendations can be acted upon in a practical road map to remove different

types of barriers in the access to SRH services by people with disabilities, irrespective of their geographic location in

Uganda.

Keywords: Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis, People With Disabilities, Sexual and Reproductive Health, Health

Equity, Policy Implementation, Uganda

Copyright: © 2022 The Author(s); Published by Kerman University of Medical Sciences. This is an open-access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original work is properly cited.

Citation:

Mac-Seing M, Ochola E, Ogwang M, Zinszer K, Zarowsky C. Policy implementation challenges and

barriers to access sexual and reproductive health services faced by people with disabilities: an intersectional analysis

of policy actors’ perspectives in post-conflict Northern Uganda.

Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(7):1187–1196.

doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2021.28

*Correspondence to:

Muriel Mac-Seing

Email:

muriel.k.f.mac-seing@umontreal.ca

Article History:

Received: 19 December 2020

Accepted: 28 March 2021

ePublished: 13 April 2021

Original Article

Full list of authors’ affiliations is available at the end of the article.

2022, 11(7), 1187–1196

doi

Background

More than 180 Member States have ratified the United

Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with

Disabilities (CRPD), which aims to promote, protect and

ensure the fundamental human rights of people with

disabilities.

1

The CRPD was adopted in 2006 and came

into force in 2008 after two decades of negotiation among

international organisations, activists, disabled people’s

organisations (DPOs), and governments.

2

According to the

CRPD, people with disabilities are people “who have a long

term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments

which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their

full and effective participation in society on an equal basis

with others.”

3

Worldwide, one person in seven is estimated

to live with some form of disability, with 80% of them living

in low and middle resource income countries.

4

In 2019, the

UN report on the realisation of the Sustainable Development

Goals stated that despite improvement in development,

people with disabilities continue to experience exclusion and

face numerous barriers to their full participation.

5

In sub-Saharan Africa, Uganda cited as an exemplary

disability rights promoter,

6,7

was among the first countries

to ratify the CRDP in 2008.

1

One fifth of its population was

estimated to live with some disability.

8

In 1995, Uganda

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–11961188

Implications for policy makers

• An intersectionality-informed analysis goes beyond describing a problem. It enables policy actors and researchers to examine intersecting social

identities, diverse sources of knowledge, and multilevel factors, and to consciously explore complex policy issues for transformative policy

solutions.

• Pro-disability policy implementation challenges are multiple and people with disabilities still experience physical, attitudinal, communication,

and structural barriers to access and use sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services in post-conflict Northern Uganda.

• Policy actors, including health service providers, disabled people’s organisations (DPOs), national and international organisations, and national

policy-makers, proposed numerous recommendations and solutions which can be applied within the normative space created by the recent

adoption of the 2019 Disability Act.

• The combination of these recommendations contributes to redress situations of social inequity and injustice, and advances Uganda’s progress

towards the Sustainable Development Goals for universal health coverage.

Implications for the public

The fundamental rights of people with disabilities, including their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) rights, continue to be violated despite the

existence of many laws and policies adopted to promote the rights of people with disabilities in Uganda. The study found that multiple forms of

barriers and policy implementation challenges still exist, preventing people with disabilities from accessing and using SRH services. Many actionable

solutions at individual, community and national levels exist and can be implemented to redress historic health inequities and injustice. People with

and without disabilities, health service providers, civil society organisations (CSOs) and policy-makers have a renewed opportunity to contribute to

concretely ‘leave no one behind’, as promoted by the Sustainable Development Goals.

Key Messages

enacted its Constitution, and in 2005 it was amended,

providing a legal space for the promotion of people with

disabilities’ rights. In the following years, several legal

instruments that contain sections or articles related to the

rights of people with disabilities were adopted. Among

these, Uganda approved the Parliamentary Election Statute

in 1996 and the Local Government Act in 1997. These laws,

respectively, make provision for people with disabilities to be

elected to Parliament, and at the district and subcounty levels.

6

In 2003, the National Council for Disability (NCD) Act was

adopted and specified the role of this national body in the

promotion, monitoring, and advocacy of equal opportunities

for Ugandans with disabilities.

9

Three years later, Uganda

further adopted a Disability Act with sections related to

such as accessibility, social services, and health, including

access to reproductive health and user-friendly health facility

materials.

10

In September 2019, Uganda updated this Act with

a more comprehensive version, referencing the CRPD and

using a similar definition of disability.

11

Emerging from a 20-year armed conflict which most affected

its Northern region, Uganda had to rebuild a weakened health

system. It witnessed high levels of sexual and gender-based

violence and unwanted pregnancies as well as poor access to

safe motherhood

12,13

and reproductive healthcare.

14

Despite

an arsenal of well-intentioned legal tools adopted over several

years to promote and protect the human rights of people with

disabilities, including their sexual and reproductive health

(SRH) rights, people with disabilities continue to have limited

access to routinely accessible SRH services in Uganda. Studies

examining SRH service utilisation reported ongoing physical

and costs barriers,

15,16

attitudinal challenges,

15

and multilayered

discrimination and inequities

17

experienced by people with

disabilities. The 2018 Guttmacher-Lancet Commission also

highlighted that people with disabilities constitute a group

‘with specific disadvantages’ and are ‘subjected to harmful

stereotypes and myths’ which contribute to their heightened

risk of physical and sexual abuse.

18

Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis (IBPA)

can critically address social inequities and multiple

discriminations experienced by people with disabilities.

19

It provides a flexible framework to enable policy actors,

researchers, and group advocates to examine diverse sources

of knowledge, intersecting multiple social identities and

multilevel factors, and to explore complex policy issues

for transformative policy solutions, beyond describing the

problem.

20

Intersectionality addresses the interrelationships

among multiple social identities, social inequities, power

dynamics, context, and complexity.

21

Principles promoted in

the IBPA are the importance of acknowledging intersecting

social categories, a multilevel analysis, power structures, the

context, the diversity of sources of knowledge, reflexivity, and

social justice and equity.

22

Before critical studies started to

be interested in intersectionality to highlight inequality and

multiple oppressions experienced by marginalised groups,

23-27

Black feminists and lesbians of the Combahee River Collective

were already embracing core concepts of this framework and

approach in their struggle in the 1970s.

28

Intersectionality

was first coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw to address the

multiple discriminations faced by African American women

workers who were protected by neither anti-racism nor anti-

sexism legislation.

24,29

The study reported here aimed to understand and document

how policy actors perceive the relationships among legislation

and health policy and the utilisation of SRH services by

people with disabilities in the post-conflict Northern region

of Uganda. We were interested in exploring policy actors’

understanding of existing pro-disability legislation and policy

implementation, their perceptions of possible discriminations

experienced by people with disabilities in accessing and using

SRH services, and their recommendations on how to redress

these inequities. This paper reports the qualitative findings

on the perceptions of policy actors at meso and macro

levels, drawing from a larger body of evidence from a mixed

methods study which also involved women and men with

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–1196

1189

disabilities (micro level). Perspectives of women and men

with disabilities have been reported previously.

17

Methods

The qualitative study methods are reported in detail elsewhere

and summarised here.

17

From November 2017 to April 2018,

we conducted our study in the districts of Gulu, Amuru, and

Omoro in the Northern region and in Kampala, the capital of

Uganda. To assess the rigour of our qualitative research, we

followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative

Research.

30

Study Participants

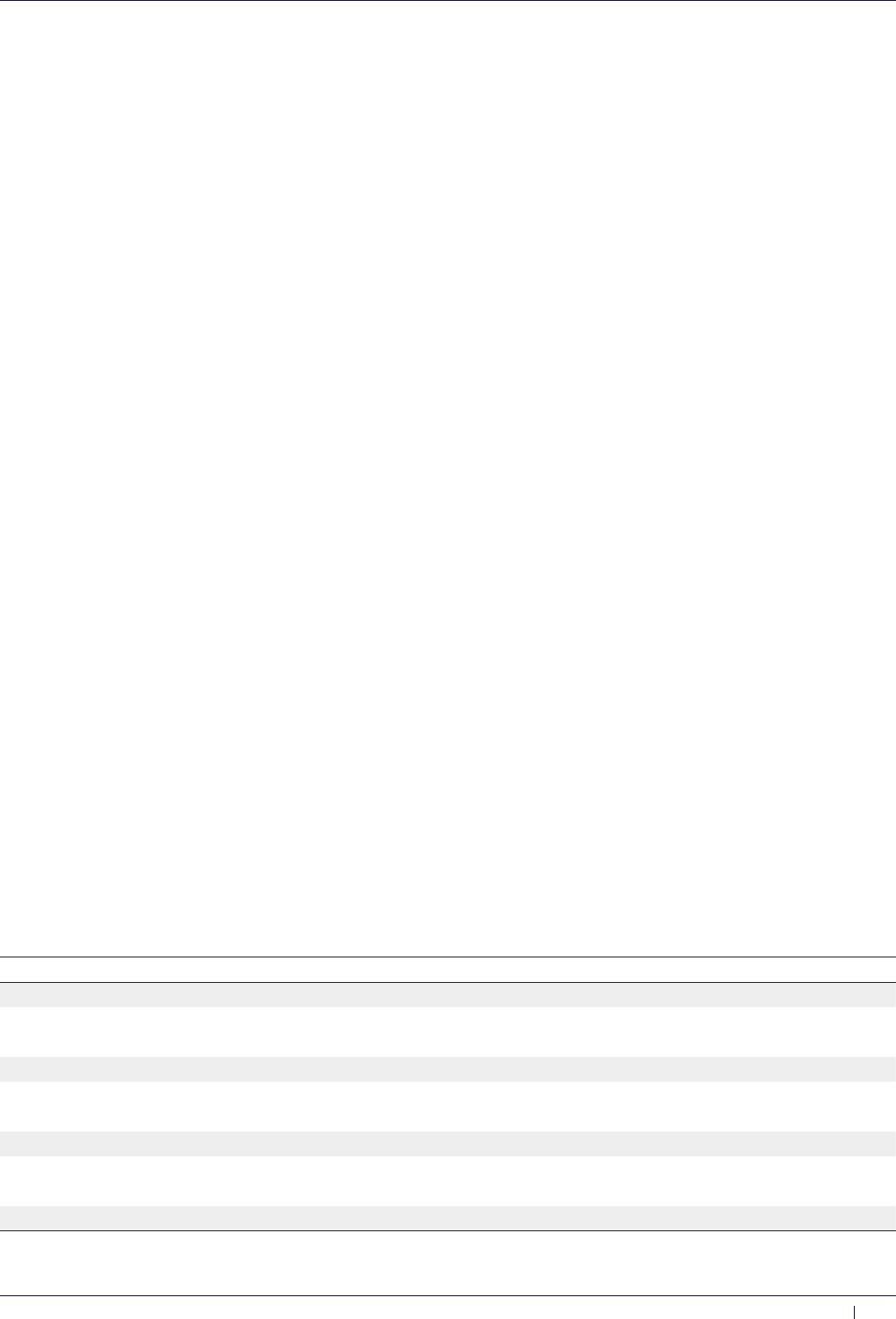

A total of 115 people participated in the study: at the national

level, 13 policy actors took part in in-depth semi-structured

interviews; and at the community level, 68 health service

providers and DPO representatives participated in seven

focus groups (FGs) of the Northern districts of Gulu, Amuru,

and Omoro. Additionally, 34 health service providers and

managers participated in a 2-day participatory workshop

on disability-sensitive health service provision (Table 1).

Participants were purposefully recruited, following a snow-

ball approach in which initially recruited study respondents

recommended other potentially relevant policy actors that

could speak to the research objectives.

31

National policy

actors based in the capital of Kampala were selected based

on different types of organisations they belonged to and who

were knowledgeable of disability and SRH related policy and

programmatic processes in Uganda. Health service providers

were recruited from seven health facilities, with a balance of

gender and public and private-not-for-profit health facilities.

Recruitment of study participants continued until saturation

was reached.

32

Data Collection

We used in-depth semi-structured interviews, FGs,

and a participatory workshop to triangulate findings.

32

These techniques were selected to further increase the

trustworthiness of qualitative research process.

32

For fine-

tuning of data collection tools, we first discussed them among

the research team, and pre-tested each tool in FGs and with

sign language interpreters to improve comprehension. The

IBPA framework informed this research and was adapted in

our interview and FG guidelines, which included two sets of

questions

20

: The first set constituted of descriptive questions

related to the identification of problems related to SRH use

among people with disabilities and information on policy

implementation processes. The second set was composed

of transformative questions related to solutions aimed at

reducing inequities and addressing problems identified.

Individual and group interviews were conducted in English,

and research assistants translated concurrently questions and

answers in Luo, when needed. For the few participants with

hearing impairments, we hired locally qualified Ugandan sign

language interpreters who were fluent in English, Luo and sign

language. Each individual or group interview lasted around

60 minutes and was audio recorded with the permission of

study participants.

Consistent with the transformative component of the

IBPA emphasising the search for solutions, we organised a

2-day participatory workshop on disability-sensitive service

provision, following the numerous requests we received

from interviewed health service providers. The workshop

objective was to discuss the barriers people with disabilities

encountered when seeking SRH services and the solutions

to address concretely these problems. It was organised

for health service providers and managers of seven health

facilities of three districts. On the first day, the preliminary

findings of the study and the existing pro-disability policies

and legislation in Uganda were presented. Two women,

one with a physical impairment and another with a mental

impairment, and two men, one with a hearing impairment

and the second with a vision impairment, were invited as

experts to share their experiences and recommendations on

how to improve accessibility and service delivery. On the

second day, a deaf trainer and a hearing trainer who knew

sign language facilitated a series of hands-on sessions for

participants to learn the basics of Uganda sign language in

relation to health and SRH services. With the permission

of workshop participants, we documented the outcomes of

group discussions and exchanges.

To ensure confidentiality, all citations from study

Table 1. Sample Characteristics

Source Total Women (%) Men(%) Disabled (%)

6

7 5 2 2

68 7 (9)

60 26 1

8 2 6 6

19 (56) 0 (0)

27 16 11 0

7 0

115 12 (10)

Note

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–11961190

respondents have been depersonalised and are referred to

in this paper by their professional function only. For health

service providers, the FG number is specified.

Analysis

Informed by the intersectional framework, a thematic

analysis was adopted due to its flexible approach as well as the

opportunity this type of analysis provides us in managing “a

large data set” in a more structured manner.

33

Our thematic

analysis following specific steps which are described in detail

elsewhere,

17

and briefly summarised here. Relevant themes

emerged after a series of iterative activities which included

listening to all recordings, reading a couple of times all

interview transcripts, and writing down analytical memos

along the process. Transcripts were coded through QDA

Miner 5.0.31 (Provalis) following an inductive and deductive

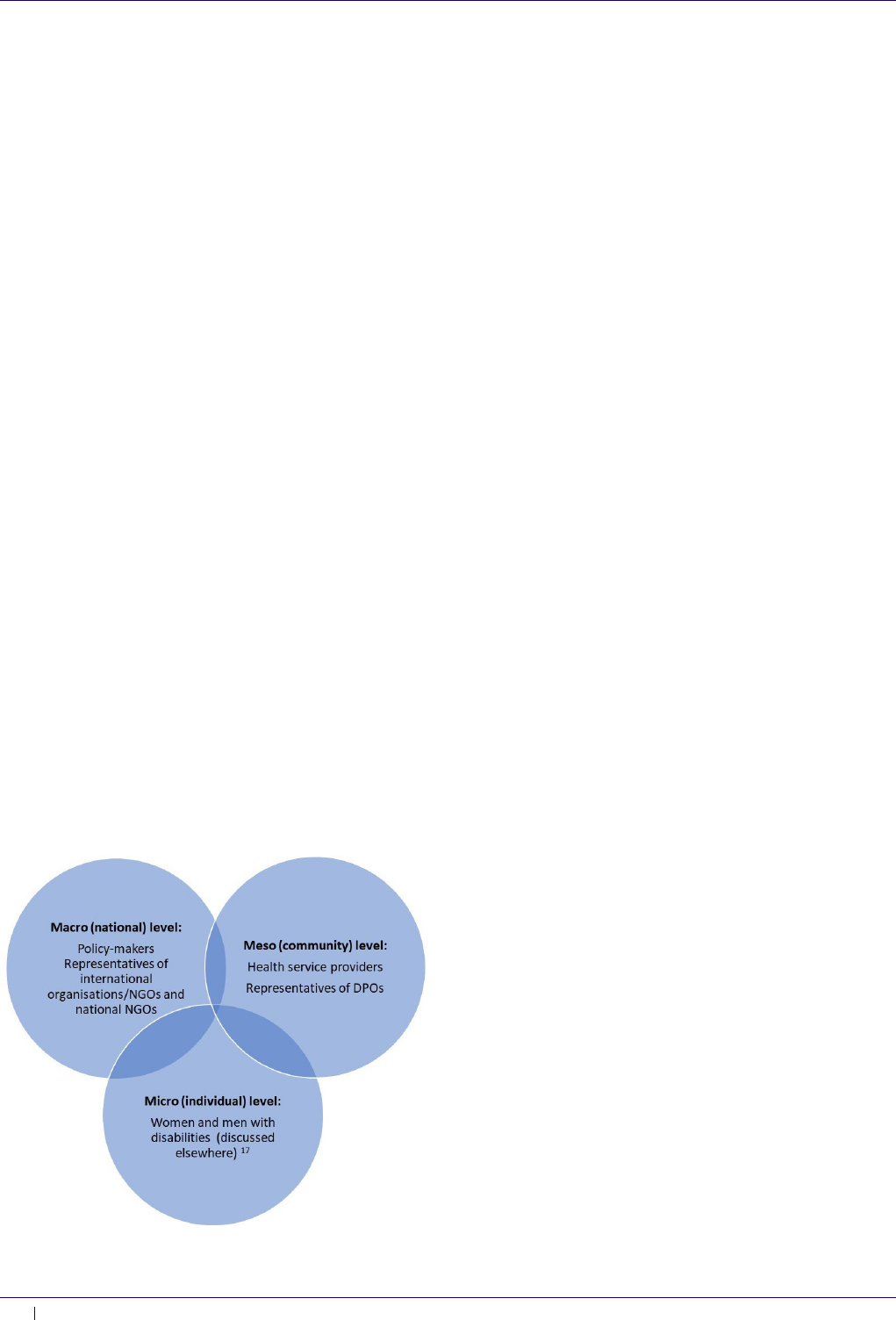

approach. Our analysis was guided by the key principles of the

IBPA framework of intersecting social categories, multilevel

analysis (Figure), power structures, time and space (context),

diverse sources of knowledge, reflexivity, and equity and

social justice.

22

Specifically, when identifying themes, we

were attentive to how policy actors answered descriptive and

transformative questions posed during individual and group

interviews as well as during the workshop.

22

Results

We report here the findings of the perceptions of health service

providers and representatives of DPOs, at meso level, and

those of policy-makers and representatives of international

organisations/non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

and national NGOs, at macro level. They complement the

findings of a larger body of evidence on the perceptions

and recommendations of women and men with different

types of impairments, at micro level, which highlighted the

intersectional discriminations experienced by people with

disabilities when using different types of SRH services.

17

Although we interviewed diverse policy actors at meso and

macro levels, they shared several common narratives around

the relationships between pro-disability legislation and policy

and the use of SRH services by people with disabilities in the

post-conflict Northern region of Uganda.

This study identified four major themes across policy

actors, levels, and districts, as follows: (1) policy and

legislation application challenges; (2) acknowledgment of the

existence of multiple barriers faced by people with disabilities

in accessing and using SRH services; (3) lingering impacts of

the conflict on people with disabilities’ access to services; and

(4) multilevel recommendations to remove barriers.

Policy and Legislation Application Challenges

Policy actors mentioned several challenges related to the

implementation and enforcement of pro-disability policy and

legislation in Uganda. Central to a lack of enforcement is a

widespread lack of awareness and training on disability issues

among policy executors, particularly health professionals,

of existing key policy and laws which focus on the rights of

people with disabilities. To some health service providers, this

implementation gap was illustrated by inaccessible services

and infrastructures.

“It’s unfortunate that most of these things [policies]

stop at Kampala or in offices. They [policy-makers] don’t

come to the ground…. Myself, I have even never seen the

[Disability] Act … This is something that they should also

consider if it must work out very well … because we should

work with references … It was not availed….We also try to

improvise. It is there, though it’s not [up] to standard. But

it is a requirement that we should at least create accessible

[structures] … It’s not very functional because some of our

clients … are still crawling” (Health service provider, FG9,

Omoro).

Awareness was identified as essential in the pathway to

policy implementation; however, a lack of prioritisation and

budgeting were also identified as detrimental to an effective

response to disability issues from ministry to local levels.

The deficient financial capacity at governmental level was

perceived to be influenced by policy-makers’ worldviews and

their lack of sensitivity towards disability issues.

“I mean the issue of mindset has affected most of our

implementation. If I showed you the percentage for the

[disability] budget … Like the law (…) it should be backed

by resources, financially. If it is a government building, let’s

make sure it’s accessible. That means you need money to

change … Of the Ministry, I think it’s 0.1, is it 1% or something

less than 1%?” (Government policy-maker, Kampala).

Although Uganda has adopted many policies promoting

the rights of people with disabilities, policy actors insisted

on the importance of supervision and monitoring: “There is

no committee in place to supervise the policies that have been

approved, so it is upon the organisation to take it on or not”

(Health service provider, FG4, Gulu). According to policy

actors, the 2006 Disability Act was not substantial enough

to hold the Government imputable to its policy intent:

“People have raised the issue that the Act has so many things

missing … [The Act] doesn’t hold the Government accountable”

(Government policy-maker, Kampala). They further

Figure. Multilevel Analysis of Policy Actors. Abbreviations: DPOs, disabled

people’s organisations; NGOs, non-governmental organisations.

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–1196

1191

mentioned that the NCD and the civil society organisations

(CSOs) were not fully playing their role of advocacy for and

monitoring of accessible services for people with disabilities:

“It’s the role of disability unions and umbrellas to ensure that they

engage institutions so that they can sign some memorandum

of understanding … help push for disability-friendly services”

(National NGO representative, Kampala).

Acknowledgment of the Existence of Multiple Barriers Faced

by People With Disabilities in Accessing and Using SRH

Services

Irrespective of their background and function, policy actors

at both community and national levels reported similar

barriers regarding the access to and utilisation of SRH services

experienced by people with disabilities. Four types of barriers

were identified: physical, attitudinal, communication, and

structural (related to systems, policies, and norms). According

to respondents, the lack of accessible equipment and

infrastructure, such as toilets, was prevalent and prevented

people with disabilities, especially women, from having optimal

access to maternal and reproductive health services. Health

service providers were frank about the physical accessibility

gaps that they observed in their health facility, prompting

some of them to revisit their service delivery approach.

“Especially in our … maternity ward. You find that it is

very hard to deliver them. Sometimes, we prefer to deliver

them down on the floor. Sometimes, if you have the energy,

you, as the medical person, you have to lift her up on the

bed. She delivers. Again, you lift her down or you use a

trolley to push her … In case of an operation….We don’t

have the equipment for people with [physical] disabilities

like [involving] lower limbs. There is no way you can help

her… [For] most of them, we deliver them on the floor. The

delivery bed is made for normal people … .That is one of

the challenges we’re having” (Health service provider, FG4,

Gulu).

At the attitudinal level, participants reported that for many

health service providers in Uganda, people with disabilities

were perceived to be sexually inactive and incapable of

entertaining sexual activities or having children. This

common perception lead health staff to believe that people

with disabilities did not need to use any SRH services.

This ableist attitude could deny people with disabilities the

possibility of receiving SRH services like anyone else.

“[The] majority of them [health service providers]

do not think disabled people are clients for reproductive

health services … They imagine they might not need these

services … I just asked them a question and I said: ‘If I come

here with a wheelchair, rolling into your health centre, what

will you see?,’ they told me: ‘We see a wheelchair!’ ‘So, you

don’t see the person?!’ … I said ‘It’s just your work to check

whether the baby is lying there [she was pregnant at that

time], and not to look at my disability. It’s the leg that is

disabled … My womb is okay!’” (Government policy-maker

with a disability, Kampala).

According to representatives of DPOs, most of whom were

also people living with different impairments, the negative

and discriminatory attitudes of health service providers were

of concern. Often, these attitudes acted as deterrents among

people with disabilities to seek care for health conditions

that would necessitate medical attention. Moreover, DPO

representatives questioned the professional ethics of health

staff when they were providing SRH services.

“I don’t know whether that is part of their code of conduct,

but most of them are arrogant to clients at the hospital. This

is a big barrier because most of our persons with disabilities

would not want to go to [the] hospital where they are shouted

at. In most cases, our health service providers do not know

how to take care of [people with disabilities]. I think [that is] a

very big barrier in accessing sexual health [and] reproductive

services” (DPO representative, Gulu).

When further probed, most policy actors mentioned

the communication barriers which people with hearing

impairments faced. In Uganda, sign language is officially

recognised. According to the Disability Act, sign language

should be “introduced into the curriculum of medical

personnel.”

10

Interviewed health service providers reported

receiving no training in this regard during their professional

training or continued education opportunities. The inability of

health service providers to communicate health information

or instructions to people with hearing impairments led to

sub-optimal provision of SRH care. These situations could

be detrimental to people with disabilities and frustrating to

health service providers who needed to find alternatives to

understand the needs of people with hearing impairments.

“Last week, we received one [patient who was a] deaf

person. The problem was how to help? Because they use sign

language … but none of us has been trained … I was trying

to handle, doing signs … but I know [figured out] what she

wanted because she came with a paper for HIV test … But

when I wanted to talk to her, she cannot understand … I took

her to the [HIV] counsellor, [but] I don’t know how they

handled it” (Health service provider, FG6, Omoro).

At a structural level, one of the most important barriers

policy actors reported was the lack of disability data collection

and monitoring of service delivery. Although the Ministry of

Health included a specific column on disability (Yes/No) in

the patient registry book made available throughout health

facilities in the country, this information was seldom or

inconsistently collected. Most of health service providers did

not receive any training on how to obtain and use data on

disability nor did analyse the information collected when this

was done.

“We realised that we are not capturing our data well. And

if [it] is captured … we are not reporting … As you report

something, you should be able to analyse, and you put in

practice … At least, there should be a strategy where … even

in the district level, [and at] the facility [level], we should

be able to generate the number of people who are having

disability, so … it can help with planning. We don’t know

how many clients we have who are disabled” (Health service

provider, FG9, Omoro).

During the workshop, participants had the opportunity

to learn directly from people with disabilities who acted as

experts in their SRH care trajectory. The four people with

disabilities explained who they were in their community, what

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–11961192

happened to them when seeking health services, and how

they were often mistreated by health service providers. They

also described the multiple barriers they faced. While sharing

their stories, they also made sure that health staff recognised

their strengths and resilience, beyond their impairments and

the limitations they were facing due to systemic obstacles,

at environmental, attitudinal, and communication levels.

According to workshop participants, this workshop helped

them to be more reflexive and enabled them to better

understand the situations of people with disabilities.

“I want to apologise. We have been working on people with

different disabilities, but we didn’t know what you people

were going through. I want you to forgive me and us, the

health workers … I would like to tell you that we shall see

that we change the quality of care because disability can

come to anyone, any time. So, I want you not to think that

you are different from us. We shall make a change, I promise”

(Workshop participant, health manager, Gulu).

Lingering Impacts of the Conflict on People With Disabilities’

Access to Services

For many respondents, the impacts of the conflict were

still vivid despite the end of the conflict through a signed

agreement between the Government and the Lord’s Resistance

Army rebels in 2006.

34

According to them, the armed

conflict contributed to “the breakdown of the formal system”

(International NGO representative, Kampala), and generated

widespread disabilities and trauma for Northern Ugandans.

It affected family structure, with persisting sequelae to date.

Others mentioned the high level of gender-based violence

which occurred during the conflict. Many young women and

girls became “child mothers,” after being raped “in the bush,” a

term referencing the period in rebel captivity (Health service

provider, FG3, Amuru). These situations were compounded

by limited access to SRH services: “Access to all health services

or reproductive health services for people with disabilities is

[was] not easily accessible. And it’s worst in Northern Uganda.

This is [was] due to war” (National NGO representative,

Kampala).

Policy actors believed that the impacts of the conflict

were “worse for people with disabilities” (International NGO

representative, Kampala), especially “women with disabilities

in the North [who] are still recovering from war” (Government

policy-maker, Kampala). In the context of insecurity due

to armed conflict, families, in some instances, had to save

their own lives amid the fighting, leaving their relatives with

disabilities behind: “So, if you’re disabled and you have all these

sorts of needs, and the family has to decide between running

away to safety and helping you to access a service?” (National

NGO representative, Kampala). Paradoxically, while the

conflict created different forms of hardship for people with

and without disabilities, camps that were erected to cater

for internally displaced Northern Ugandan populations also

became a source of support considered as “[one stop] shop

centre[s]” (Health service provider, FG9, Omoro) where all

services such as food, education, and healthcare were provided

for free, for all. However, as the conflict ceased, many NGOs

stopped providing their humanitarian services, and people,

including many with disabilities, had to fend for themselves

and survive without any support.

“But after that [the conflict], people were dispersed…

They are now coming from different places. [This situation

has] created distance from points of service delivery. If a

crippled person has to move for more than 10 km to seek for

healthcare, that has become very hard. I would say that this

is negative to them because it is not very easy for them now

to access services, as it used to [be in the camps]” (Health

service provider, FG9, Omoro).

Based on the accounts of a few policy actors, a life spent

in camps not only provided immediate benefits such as

accessible and free services but also generated long-term

social negative consequences. According to them, people lost

their social compass and became dependent upon external

sources to receive services. This situation might have created

other social consequences given the lack of accessible services

of proximity, including healthcare.

“The post-war effect in Northern Uganda has been there.

[There] is still [a] dependency syndrome. We had so many

NGOs which were supporting the household activities. Most

NGOs have gone away, so people have [feel] the effects now.

People resorted to drinking…. We have child-headed families

because of … loss of parents … loss of dear ones” (Heath

service provider, FG3, Amuru).

Multilevel Recommendations to Remove Barriers

At both community and national levels, policy actors

described in detail the multiple barriers people with

disabilities encountered when using health and SRH services.

On the other hand, policy actors also identified specific

recommendations to redress these barriers and better promote

the rights of people with disabilities as enshrined in adopted

policies and laws. Policy actors were reflective about their

shortcomings, but they also went beyond listing problems.

They felt the urgency to instill measures in their institution

and capitalise on the strengths of people with disabilities to

induce change.

“My recommendation goes to the Quality Assurance team

[of the hospital] … Concerning people with disabilities,

much has not yet been done. So, I would advise that we

get a committee that looks at the welfare of persons with

disabilities, to see that this kind of training should be

continuous. And disabled who are doing good things like

these ones [people with disabilities invited in the workshop as

experts] should be used as role models to the other disabled

persons” (Workshop participant, health service provider,

Gulu).

Given the intersectoral and multilayered nature of

barriers to access SRH services and policy and legislation

implementation challenges identified, policy actors

acknowledged that solutions did not lie at a single location, nor

could they be addressed by only one actor. Rather, respondents

recommended solutions targeting specific policy actors. At

the micro level, people with disabilities and their families

were named, highlighting the importance of empowerment

and the exercise of the basic rights of people with disabilities.

At the meso level, both health service providers and local

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–1196

1193

CSOs were mentioned as playing a crucial role in concretely

removing barriers and in defending the rights of people

with disabilities they served. Respondents argued that at the

macro level, the Government and elected bodies held a prime

position of being held accountable and responsible for putting

in place actionable measures such as devoting financial

and technical resources to mainstream disability in service

delivery, including SRH services. The NCD was pinpointed as

pivotal in monitoring the Government’s policy and legislation

focusing on the promotion and protection of disability rights.

National and international CSOs identified the need for

more research and disability data collection and analysis for

improved planning of services for people with disabilities.

Table 2 summarises the main recommendations made by

policy actors at community and national levels during the

interviews, FGs, and participatory workshop, targeting the

three levels of actors at micro, meso, and macro levels.

Discussion

This paper emphasises the plurality of voices, the exploration of

both problems and solutions, and the triangulation of methods.

An important finding of this study is the convergence of views

collected from policy actors at community and national levels,

who identified multiple policy implementation challenges

and barriers to SRH service use experienced by disabled

users. From the study findings, we highlight learnings which

emerged from our approach of using both an intersectional

analysis and a participatory workshop to validate and

enrich study findings. Study respondents referred to the

principles of intersectionality related to knowledge, power,

multilevel analysis, and the importance of context, equity, and

reflexivity. Specifically, we address the following three points

of discussion: (1) how diverse sources of knowledge and the

reflexivity of policy actors can lead to new insight about their

privileges and the discrimination and barriers faced by people

with disabilities; (2) the importance of the post-conflict

context in understanding policy implementation challenges

and the experiences of barriers to access among people with

disabilities; and (3) the capacity of policy actors to propose

transformative solutions to redress health inequities faced by

people with disabilities.

First, through an intersectionality-informed analysis,

we were able to analyse the different voices of different

groups of policy actors. The study methodology capitalised

on their distinctive social positions to shed light on their

understanding of the relationships among legislation, policy

and its implementation, and the use of SRH services by people

with disabilities. Their views corroborated the perceptions

of people with disabilities reported previously.

17

People

with disabilities experienced multiple physical, attitudinal,

Table 2. Main Areas of Recommendations Proposed for and by Policy Actors to Improve the Access to and Utilisation of SRH Services by People With Disabilities

Levels Recommendations

At micro level

“Awareness-raising is needed at all

levels from family, health staff to policy-makers”

“Using people with disabilities

themselves, train them. Use them to target their membership, that would be key”

At meso level

“The

delivery beds... When I went to the Midwifery Day in Fort Portal, Karamoja district, they came with a bed that I have

never seen… those are the beds [for] the use for people with disabilities… They [policy-makers] could come to the

hospital, [and] find out if there are people who are interested in learning sign language… We wait for these things to be

integrated into our curriculums”

“… to create a network of people working in the

area of disability so that we can have a unified voice to address the issues, not only health issues but other social issues

that affect people with disabilities”

At macro level

“The Government needs to [have a] committee in action on the

implementation of the existing laws. The Government must ensure that the accessibility must be universal… to all…

They should widen their scope of consultations when they are coming up with their policies and guidelines… so that you

can be in position to intersect, and also ensure that the needs of all the categories of people, whom you have consulted,

are taken care of”

“One priority is to mainstream disability at all levels of MCH

[maternal and child health] and SRH, in all levels, but don’t separate people with disabilities. It should be integrated,

data collected, and with a budget!”

[There are] too many small disability organisations, and poorly coordinated. The

NCD is not strong because too small…. Competition disadvantages, this decreases their bargaining power… If they are

together at the same time, they have more power to ask for change. So, they need to be strong and give a united voice

from all categories of people with disabilities for advocacy and lobbying”

“The role of research… is to make sure you collect the

appropriate and relevant data [which can] inform the service institutions so that they create the demand of services for

[people with] disabilities”

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–11961194

communication, and structural barriers. In particular, the

sister study to this paper identified inequitable access to

SRH services in health facilities and numerous intersectional

discriminations related to gender, disability, and experience

of violence.

17

These barriers faced by people with disabilities

have been discussed in the literature regarding Uganda,

15,16,35

other sub-Saharan African countries,

36-39

and globally.

40

Furthermore, the interviewed policy actors were reflexive

about their privilege, and the effects of oppression created by

their inconsideration of the needs of people with disabilities.

They recognised the effects that these internalised biases had

on the experiences of access to and use of SRH services by

users with disabilities.

41,42

According to the IBPA principles,

acknowledging the diverse sources of knowledge and

highlighting the reflexivity of policy actors enable them

to reflect upon the power and privilege they own.

42

This

realisation is a further step toward health equity and acts as a

catalyst toward social justice.

42

Second, the post-conflict context in Northern Uganda

was considered in our analysis. Our findings showed that

time spent in the camps during and after the armed conflict

and the post-conflict period has heavily affected Ugandans.

The post-conflict continues to disadvantage people with

disabilities in the Northern region, up to the current day.

In an intersectionality approach, time and space (context)

are key components in analysis.

42,43

Literature has reported

that the armed conflict in Uganda has caused limited access

to and poor quality of maternal and reproductive health

services,

14

while sexual and gender-based violence aggravated

the physical and psychological health of women.

12

According

to a systematic review on the long-term effects of armed

conflicts, such as in Uganda, findings reported two types of

effects, direct and indirect. Direct long-term effects included

the experience of violence of all forms, disability, illnesses,

injuries, and torture. The indirect long-term effects were

characterised by limited access to healthcare and education as

well as social marginalisation.

44

Specifically, a study conducted

among people with disabilities in the Gulu region reported

the negative effect the conflict had on the psychological and

emotional health of people with disabilities who shared their

traumatic experiences and difficult coping strategies.

45

These

findings also reported difficulties in accessing healthcare

services, including rehabilitation, such as assistive devices,

and mental health services.

45

Literature further mentioned

that people with disabilities, especially women, faced

discrimination and lacked access to health facilities upon

return home, coupled with economic challenges.

46

Third, policy actors identified recommendations

to the numerous barriers to SRH service utilisation

experienced by people with disabilities, disability-focused

policy implementation challenges, and multipronged

recommendations addressed to policy actors at micro, meso,

and macro levels. In an intersectionality-informed analysis,

exploring alternatives and solutions is as important as

identifying problems which need to be addressed.

20

Reflecting

upon and consciously proposing solutions is integral to a

transformative process and contributes to eventually reaching

equity and social justice. For example, the recommendation

made by policy actors to allocate more budget on disability

issues and to reinforce the position of the NCD found an

echo in the revised 2019 Disability Act.

11

Whereas the 2006

Disability Act did not include the scope of the NCD, the 2019

iteration of the Act specified its roles and funds, in addition

to making the provision for representatives of the Council to

work at the district level to enhance the presentation of people

with disabilities in the community. Through the participatory

workshop, health service providers and managers discovered

the strengths of people with disabilities and that they could

be experts in helping them devise health services to be more

accessible and act as role models for others. While policy

actors used to consider people with disabilities as weak and

not capable, Intersectionality enabled them to acknowledge

the multiple social categories a person/group may have,

recognising that they may be simultaneously privileged in one

context and be disadvantaged in another one.

42

Limitations

Given the richness of information elicited from different

groups of policy actors, we were not able to report them all in

a single manuscript. Comprehensive description and analyses

from people with disabilities at individual level have been

reported elsewhere,

17

and the perceptions of policy actors

at meso and macro levels are reported separately here. The

contrasting of convergent or divergent views of policy actors

will subsequently be discussed more in detail. We also did not

include the views of policy actors located in other Northern

districts which have been affected by the armed conflict. This

inclusion may have expanded the depth of data collected

and the richness of description to analyse. With more time

and resources, this expansion would be possible. Given the

convergence of problems and recommendations reported

by study respondents, social desirability could have been a

bias. However, respondents were clear about the observed

multiple barriers faced by people with disabilities and the

policy implementation challenges. They demonstrated the

readiness to address these issues, collectively. Finally, to

reduce the limitations of translation when it was used, we

elaborated a glossary of research and SRH terms in English

and Luo for consistency. Both research assistants were present

during all interviews to support one another for translation

when needed. At the end of each day of interviews, the

research team met and debriefed about the interview process,

including translation, for improvement purposes.

Conclusion

This study reveals the multilayered perceptions of policy actors

at meso and macro levels of the relationships among pro-

disability policy and legislation and the use of SRH services

by people with disabilities in three post-conflict Northern

districts of Uganda. The study findings intersect with and

complement the perceptions and recommendations provided

by people with disabilities at micro level. An intersectionality-

informed analysis emphasised the importance of going beyond

the identification of problems by concomitantly searching for

solutions. With the recent adoption of the revised Disability

Act in 2019, Uganda has renewed its commitment to remove

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–1196

1195

barriers structurally and better protect the rights of people

with disabilities. This creates a normative space for actions

such as those recommended by the participants in our study.

Concrete recommendations included empowering people

with disabilities, families, and their organisations through

awareness-creation and capacity-building, at micro level. At

meso level, policy actors recommended training of health

service providers on disability-sensitive services such as sign

language, improving physical, attitudinal, and communication

accessibility in health facilities, and collecting and analysing

data on disability more systematically. At macro level, more

accountability of policy-makers, active monitoring, and

enforcing of policy implementation with disability budgeting

were identified. The proposed solutions targeting three

levels of policy actors, vertically, and various types of groups,

horizontally, are within the reach and capacity of Government

policy-makers, CSOs’ managers, health decision-makers,

DPO leaders, and people with disabilities. As suggested by

the UN report on the Sustainable Development Goals for

people with disabilities,

5

the recommendations can constitute

the foundation for a hands-on road map to health equity

by removing multiple barriers to access to and use of SRH

services by people with disabilities, irrespective of their

geographic location in Uganda.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study research assistants, Bryan Eryong and

Emma Ajok, and all study participants and stakeholders.

We are grateful to the St-Mary’s Hospital Lacor for its

collaboration during fieldwork.

Ethical issues

This study received ethics approval from the Centre de recherche du Centre

hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CR-CHUM) (17.127-CÉR, 1 August

2017); the Research Ethics Committee in Sciences and Health of the Université

de Montréal (CERCES-20-074-D, 13 May 2020), following a change of research

affiliation in Canada; the Lacor Hospital Institutional and Research Ethics

Committee (LHIREC - 019/07/2017); and the Uganda National Council for

Science and Technology (SS-4451, 14 November 2017).

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MMS conceptualised the manuscript and collected and analysed the data. All

authors contributed to, reviewed, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the MoCHeLaSS (Mother Child health Lacor-South Sudan)/

IDRC/IMCHA Project for its support. The MoCHeLaSS Project was carried out

with the aid of a grant from the Innovating for Maternal and Child Health in Africa

initiative- a partnership of Global Affairs Canada (GAC), the Canadian Institutes

of Health Research (CIHR) and Canada’s International Development Research

Centre (IDRC). MMS received a doctoral training scholarship from the Fonds

de Recherche du Québec – Santé [0000256736] and a doctoral award from

the International Development Research Centre: [Grant Number 108544-010].

The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis,

and interpretation, or writing and preparation of the manuscript, or decision to

publish.

Authors’ affiliations

1

Social and Preventive Medicine Department, School of Public Health,

Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada.

2

Centre de recherche en

santé publique (CReSP), Université de Montréal et CIUSSS du Centre-Sud-

de-l’Île-de-Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada.

3

Public Health Department, St-

Mary’s Hospital, Lacor, Uganda.

4

Institutional Direction Department, St-Mary’s

Hospital, Lacor, Uganda.

5

School of Public Health, University of Western Cape,

Bellville, South Africa.

References

1. UN. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://

treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-

15&chapter=4&clang=_en. Accessed July 11, 2020. Published 2020.

2. Kanter AS. The promise and challenge of the United Nations Convention

on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Syracuse Journal of International

Law and Commerce. 2006;34:287-321.

3. United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

(CRPD). United Nations; 2006. https://www.un.org/development/

desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/

convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html. Accessed

July 13, 2020.

4. World Health Organization (WHO), The World Bank. World Report on

Disability. Malta: WHO; 2011.

5. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA).

Disability and Development Report: Realizing the Sustainable

Development Goals By, for and with Persons with Disabilities 2018. New

York: DESA; 2019.

6. Millward H, Ojwang VP, Carter JA, Hartley S. International guidelines and

the inclusion of disabled people. The Ugandan story. Disabil Soc. 2005;

20(2):153-167. doi:10.1080/09687590500059101

7. Lang R, Murangira A. Disability Scoping Study: Commissioned by DFID

Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Department for Internal Development; 2009.

8. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), ICF. Uganda Demographic Health

Survey 2016. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS, ICF; 2018.

9. Yokoyama A. A comparative analysis of institutional capacities for

implementing disability policies in East African countries: functions of

National Councils for Disability. Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development.

2012;23(2):22-40. doi:10.5463/dcid.v23i2.106

10. Republic of Uganda. Persons with Disabilities Act. Republic of Uganda;

2006.

11. The Republic of Uganda Parliament. The Persons with Disabilities Act,

20192019:46.

12. Liebling-Kalifani H, Ojiambo-Ochieng R, Marshall A, Were-Oguttu J,

Musisi S, Kinyanda E. Violence against women in Northern Uganda:

the neglected health consequences of war. J Int Womens Stud.

2008;9(3):174-192.

13. Roberts B, Odong VN, Browne J, Ocaka KF, Geissler W, Sondorp E. An

exploration of social determinants of health amongst internally displaced

persons in northern Uganda. Confl Health. 2009;3:10. doi:10.1186/1752-

1505-3-10

14. Chi PC, Bulage P, Urdal H, Sundby J. Perceptions of the effects of armed

conflict on maternal and reproductive health services and outcomes in

Burundi and Northern Uganda: a qualitative study. BMC Int Health Hum

Rights. 2015;15:7. doi:10.1186/s12914-015-0045-z

15. Ahumuza SE, Matovu JK, Ddamulira JB, Muhanguzi FK. Challenges

in accessing sexual and reproductive health services by people with

physical disabilities in Kampala, Uganda. Reprod Health. 2014;11:59.

doi:10.1186/1742-4755-11-59

16. Apolot RR, Ekirapa E, Waldman L, et al. Maternal and newborn health

needs for women with walking disabilities; “the twists and turns”: a case

study in Kibuku District Uganda. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):43.

doi:10.1186/s12939-019-0947-9

17. Mac-Seing M, Zinszer K, Eryong B, Ajok E, Ferlatte O, Zarowsky C. The

intersectional jeopardy of disability, gender and sexual and reproductive

health: experiences and recommendations of women and men with

disabilities in Northern Uganda. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;

28(2):1772654. doi:10.1080/26410397.2020.1772654

18. Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress-sexual and

reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher-Lancet

Commission. Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2642-2692. doi:10.1016/s0140-

6736(18)30293-9

19. Frohmader C, Ortoleva S. The Sexual and Reproductive Rights of

Women and Girls with Disabilities. Paper presented at: ICPD International

Conference on Population and Development Beyond; 2014.

20. Hankivsky O, Grace D, Hunting G, et al. An intersectionality-based policy

analysis framework: critical reflections on a methodology for advancing

equity. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:119. doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0119-x

Mac-Seing et al

International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2022, 11(7), 1187–11961196

21. Collins PH, Bilge S. Intersectionality. Cambridge, UK: Polity; 2016.

22. Hankivsky O. An Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis Framework.

Vancouver, BC: Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon

Fraser University; 2012.

23. Mitchell D Jr. Intersectionality & Higher Education. New York, NY: Peter

Lang; 2014.

24. Carbado DW, Crenshaw KW, Mays VM, Tomlinson B. Intersectionality:

mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Rev. 2013;10(2):303-312.

doi:10.1017/s1742058x13000349

25. Cho S, Crenshaw KW, McCall L. Toward a field of intersectionality

studies: theory, applications, and praxis. Signs. 2013;38(4):785-810.

doi:10.1086/669608

26. Chun JJ, Lipsitz G, Shin Y. Intersectionality as a social movement

strategy: Asian immigrant women advocates. Signs. 2013;38(4):917-940.

doi:10.1086/669575

27. Erevelles N, Minear A. Unspeakable offenses: untangling race and

disability in discourses of intersectionality. J Lit Cult Disabil Stud. 2010;

4(2):127-145. doi:10.3828/jlcds.2010.11

28. Combahee River Collective. The Combahee River Collective Statement.

Combahee River Collective; 1977.

29. Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black

feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and

antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 1989;140(1):139-167.

30. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative

research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups.

Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

31. Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam Pract. 1996;

13(6):522-525. doi:10.1093/fampra/13.6.522

32. Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing Qualitative Research. SAGE

Publications; 2016.

33. Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis:

striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;

16(1):1609406917733847. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847

34. Advisory Consortium on Conflict Sensitivity (ACCS). Northern Uganda

Conflict Analysis. ACCS; 2013.

35. Nampewo Z. Young women with disabilities and access to HIV/AIDS

interventions in Uganda. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25(50):121-127.

doi:10.1080/09688080.2017.1333895

36. Casebolt MT. Barriers to reproductive health services for women with

disability in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the literature.

Sex Reprod Healthc. 2020;24:100485. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2020.100485

37. Mac-Seing M, Zarowsky C. Une méta-synthèse sur le genre, le handicap

et la santé reproductive en Afrique subsaharienne. Sante Publique.

2017;29(6):909-919. doi:10.3917/spub.176.0909

38. Trani JF, Browne J, Kett M, et al. Access to health care, reproductive

health and disability: a large scale survey in Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med.

2011;73(10):1477-1489. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.040

39. Hanass-Hancock J. Disability and HIV/AIDS - a systematic review of

literature on Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:34. doi:10.1186/1758-2652-

12-34

40. Groce N. HIV/AIDS and Disability: Capturing Hidden Voices: Global

Survey on HIV/AIDS and Disability. New Haven: Global Health Division,

Yale School of Public Health, Yale University; 2004.

41. Nixon SA. The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: implications for

health. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1637. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-

7884-9

42. Hankivsky O. Intersectionality 101. http://vawforum-cwr.ca/sites/default/

files/attachments/intersectionallity_101.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2020.

Published 2014.

43. Hulko W. The time- and context-contingent nature of intersectionality and

interlocking oppressions. Affilia. 2009;24(1):44-55.

44. Kadir A, Shenoda S, Goldhagen J. Effects of armed conflict on child health

and development: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210071.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210071

45. Mulumba M, Nantaba J, Brolan CE, Ruano AL, Brooker K, Hammonds

R. Perceptions and experiences of access to public healthcare by

people with disabilities and older people in Uganda. Int J Equity Health.

2014;13:76. doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0076-4

46. Hollander T, Gill B. Every day the war continues in my body: examining

the marked body in postconflict Northern Uganda. Int J Transit Justice.

2014;8(2):217-234. doi:10.1093/ijtj/iju007