AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 1

Should the Federal Reserve Issue a

Central Bank Digital Currency?

By Paul H. Kupiec August 2021

During Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s July 2021 congressional testimony, several

elected members encouraged Powell to fast-track the issuance of a Federal Reserve digital cur-

rency. Chairman Powell indicated he is not convinced there is a need for a Fed digital currency.

But he also indicated that Fed staff are actively studying the issue and that his opinion could

change based on their findings and recommendations. In this report, I explain how a new Fed-

eral Reserve digital currency would interface with the existing payment system and review the

policy issues associated with introducing a Fed digital currency.

The Bank for International Settlements defines

“central bank digital currency” as “a digital payment

instrument, denominated in the national unit of

account, that is a direct liability of the central

bank” (BIS 2020). In his semiannual appearance

before Congress, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome

Powell indicated that the Fed was studying the idea

of creating a new dollar-based central bank digital

currency (USCBDC) (Lee 2021). The design of

USCBDC has important implications for the US finan-

cial system. To facilitate the policy discussion, I

discuss how a US digital currency relates to existing

forms of dollar-based money, the payments sys-

tem, competing privately issued stablecoins, and

the policy issues associated with USCBDC design.

Central Bank Money, Digital Money,

and Efficiency of Payments Systems

At present, the Federal Reserve issues two types of

central bank money—paper Federal Reserve notes

and digital Federal Reserve deposits (Board of

Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2021b).

Digital deposits are money recorded in (electronic)

ledger entries with no physical form. Digital Fed-

eral Reserve deposits can only be held by financial

institutions (primarily banks) eligible for master

accounts at a Federal Reserve bank.

Most businesses and consumers are not eligible

to own Federal Reserve master accounts, so they

cannot own Federal Reserve digital deposits under

current arrangements. They can own central bank

money in the form of paper Federal Reserve notes

or hold “bank money”—US dollar-denominated

digital currency in the form of bank deposits that

are exchangeable at par into paper Federal Reserve

notes. Unlike central bank digital money, bank-

issued digital deposits can be subject to default

losses if the bank issuing deposits fails. However,

bank deposits up to $250,000 per depositor are

fully insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation (FDIC), and the maximum effective

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 2

insurance coverage on bank deposits can be increased

simply by keeping deposit accounts in multiple banks.

The infrastructure for settling domestic trans-

actions between financial institutions using cen-

tral bank digital deposits is well-developed, fast,

reliable, and inexpensive.

1

Domestic transfers of

central bank digital deposits can settle in real time

or end of day depending on the settlement system

used.

2

Settlement systems for international trans-

fers of central bank deposits are reliable if more

expensive than domestic transfers. However, efforts

are underway to reduce international transactions

costs (FSB 2020b).

1

For example, Fedwire, the Federal Reserve System for transferring bank master account balances, charges institutions a monthly fee

for access and transactions fees that depend on the volume of transactions. The FRB (2021) details the current Fedwire ACH fee schedule.

2

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2021a) explains the Federal Reserve’s Fedwire Fund Services.

3

Venmo is an example of a state-licensed money transfer service that offers settlement times faster than standard ACH transactions do.

The transfer of digital bank money is the primary

mechanism used to settle retail transactions in the

US. Transfers of bank retail digital deposits are

inexpensive but historically have taken longer to

settle than central bank digital deposit transfers.

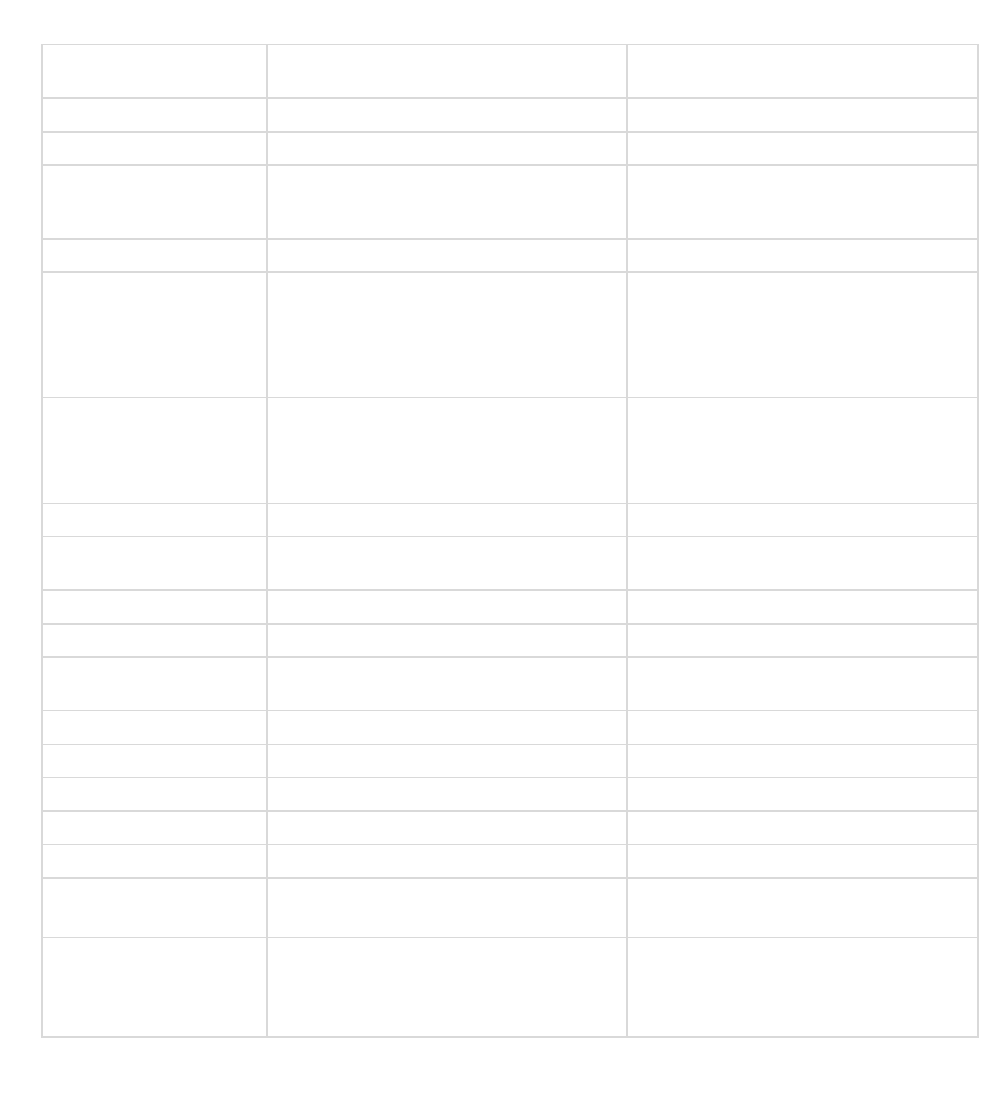

Table 1 provides the fees and settlement times

associated with Automated Clearing House (ACH)

domestic deposit transfers for a sample of US

banks. New real-time processing systems are now

available (Clearing House 2021) for settling bank

retail digital transactions (Zelle 2021). In addition,

popular online money transfer services

3

linked to

bank accounts offer, for a fee, a faster settlement

Terminology

A short description of some industry-specific terminology is below.

Stablecoins. Stablecoins are a class of cryptocurrencies that attempts to maintain a fixed

exchange rate with a designated fiat currency or basket of fiat currencies by holding reserve

assets that can be used to buy and sell coins on cryptocurrency exchanges to maintain

the target exchange rate peg.

Federal Reserve Master Account. Eligible institutions may have one master account at

a designated Federal Reserve bank that is both a record of financial transactions that reflects

the financial rights and obligations of an account holder and of the Federal Reserve bank

with respect to each other and the place where opening and closing balances are deter-

mined (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2021c).

Automated Clearing House (ACH). The ACH is an electronic funds transfer system run

by NACHA, formerly called the National Automated Clearing House Association, since

1974. This payment system provides ACH transactions for use with payroll, direct deposit,

tax refunds, consumer bills, tax payments, and many more payment services in the US.

Blockchain. Blockchain is a decentralized, distributed, public digital ledger consisting of

historical transactions processed and recorded in uniform sequential groups of transac-

tions called blocks. Each block of transactions is processed across many computers using

cryptographic methods that make it difficult to falsify a record or alter records retroactively.

Permissioned Blockchain. This blockchain network has limited access to a shared dis-

tributed ledger. Controlling access to ledger transaction processing and record verifica-

tion allows ledger security to be maintained with more efficient cryptographic methods.

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 3

time than standard ACH transfers (Venmo 2021).

The volume of transactions settled in real time will

undoubtedly increase over time.

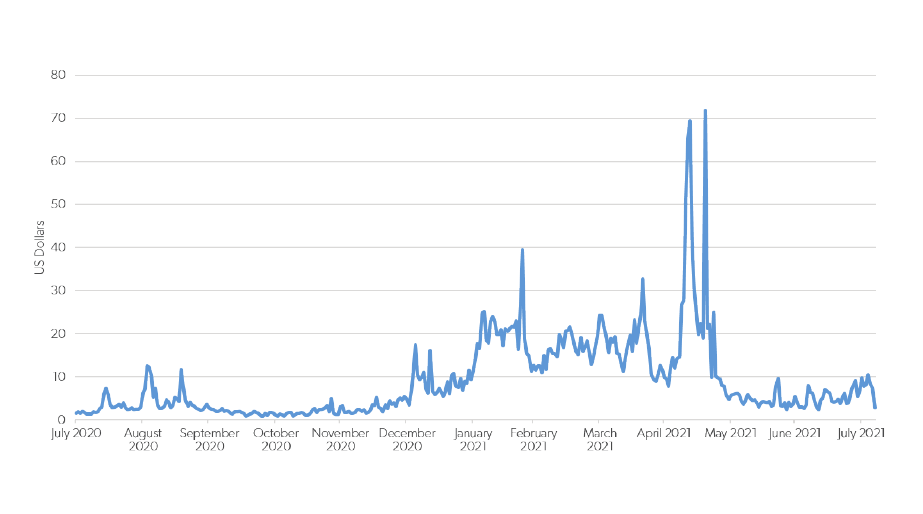

In contrast, the processing of cryptocurrency

transactions is costly in computing resources and

electricity consumption (McDonald 2021), and trans-

actions fees and settlement timing vary according

to the volume of transactions and the public

computing resources processing the distributed

ledger. Figure 1 shows the average daily cost of pro-

Table 1. Electronic Bank Deposit Transfer Fees and Settlement Times at Selected Banks

Financial Institution

Transfer Fee

Cost (Both Directions Unless Specified)

Approximate Delivery Times*

Alliant Credit Union

$0

One business day

Ally Bank

$0

Three business days

American Express National

Bank

$0

One to three business days; three or more

business days for transfers initiated at the

bank where the funds should

arrive

Axos Bank

$0

Three to five business days

Bank of America

To Bank of America account: $0

From Bank of America account (three busi-

ness days):

$3

From Bank of America account (next day):

$10

Three business days; option for next

-day

delivery

Bank5 Connect

To Bank5 Connect account: $0

From Bank5 Connect account (standard de-

livery): $0

From Bank5 Connect account (next day):

$3

Up to three business days; option

for next-

day delivery

Barclays

$0

Two to three business days

Boeing Emp

loyees Credit

Union

$0

Two to three business days; option for free

next

-day delivery

Capital One 360 Bank

$0

Two business days

Chase

$0

One to two business days

Citibank

$0

Three business days; option for free n

ext-

day delivery

Discover Bank

$0

Up to four business days

Navy Federal Credit Union

$0

Two to three business days

PNC Bank

$0

Three business days

Synchrony Bank

$0

Up to three business days

TD Bank

$0

One to three business days

US Bank

To US Bank account: $0

From US Bank account:

Up to $3

Three business days; option for free next

-

day delivery (incoming transfers only)

Wells Fargo

$0

To Wells Fargo account: Three business

days

From Wells Fargo acc

ount: Two business

days

Note: * These are typical outgoing and incoming transfer times when initiated through online banking, according to each financial institution’s

disclosures and general policies. Delays can occur due to holding periods, sending after daily cutoff times, initial service setup, and other reasons.

This list includes only personal accounts, not business accounts.

Source: Burnette and Tierney (2021).

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 4

cessing a stablecoin transaction on the Ethereum-

distributed blockchain ledger over the past year.

These costs, while much higher on average than

the costs of domestically transferring bank deposit

balances, are mostly lower than the cost of trans-

ferring bank deposits internationally.

USCBDC, Stablecoins, and Competing

Digital Currencies

One rationale for so-called stablecoin cryptocur-

rencies like Facebook’s proposed Diem is the claim

that they will bring down the cost of processing

transactions, especially when transactions are inter-

national and involve countries with less-developed

financial infrastructures (Libra Association Mem-

bers 2020). Reportedly, Diem balances will be

maintained and transactions processed using some

type of “permissioned” distributed ledger that

could make transactions processing more efficient

than bitcoin’s blockchain process (Auer, Monnet, and

Shin 2021). Diem’s transactions processing system

is still being developed, so Diem transactions costs

are yet to be determined.

Notwithstanding Diem representations regarding

transactions costs, any transaction cost reductions

achieved by privately issued stablecoins settled using

distributed ledger systems would likely be under-

cut by the cost savings achievable with centralized

USCBDC transactions processing. This presumes

of course that international ownership of USCBDC

would be legal and widely used.

Proponents of private stablecoin cryptocurren-

cies and USCBDC argue that both would provide

the unbanked with a new, more affordable way to

access to the banking and payment system. As dis-

cussed below, unless USCBDC pays interest,

USCBDC account holders will likely face costs to

maintain USCBDC accounts and transfer balances

to reimburse the costs intermediaries must expend

to maintain and transfer USCBDC balances. While

USCBDC payments processing will likely be less

expensive than the cost of maintaining and trans-

acting in private stablecoins, the unbanked would

still face costs unless subsidy programs were cre-

ated to defray the costs for targeted individuals.

Similar subsidy programs could be used to alleviate

the “unbanked problem” (FDIC 2012) using digital

bank deposit accounts, so it is unclear why a

USCBDC is a better solution for giving the unbanked

access to the payment system.

In sum, there is not a strong case for creating

USCBDC based on the cost and efficiency of domes-

tic payment transaction processing, especially con-

sidering the efficiency improvements that will

come with expanded real-time processing systems

for digital bank deposits. Moreover, the allure of the

anonymity once associated with privately issued

Figure 1. Average Daily Cost to Process a Stablecoin Transaction on the Ethereum-Distributed

Blockchain Ledger

Source: YCharts (2021).

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 5

cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and Ethereum is

being eroded as private cryptocurrency users are

increasingly required to comply with anti–money

laundering and terrorist finance laws in the US and

other developed countries.

The Financial Stability Board has opined that,

unless they are properly regulated, privately issued

stablecoins can threaten financial stability (FSB

2020a). One argument favoring USCBDC is that it

would prevent privately issued stablecoins from

becoming systemically important pseudo-currencies.

When recently questioned about the Fed’s plans

regarding a USCBDC, Fed Chairman Powell

responded, “You wouldn’t need stablecoins, you

wouldn’t need cryptocurrencies, if you had a digital

US currency. I think that’s one of the stronger

arguments in its favor” (US House Committee on

Financial Services 2021). Others (Adler and Pollock

2021) focus on digital currency competition among

central banks, arguing that the Fed will be forced

to issue its own digital currency to prevent China’s

digital currency from undermining the US dollar’s

international reserve currency status. Rightly or

wrongly, senior Fed officials (Quarles 2021) are,

however, skeptical of this argument.

USCBDC Demand

If the Fed were to issue USCBDC, current features

of our monetary system will likely generate demand

for this new digital currency. Many businesses

must maintain large uninsured bank deposit bal-

ances to meet payroll and other expenses. These

bank deposits are exposed to losses should the

bank holding the deposits fail. USCBDC may be an

attractive alternative for some uninsured deposi-

tors because USCBDC eliminates the risk of loss

due to bank failure.

Money market mutual funds (MMFs) are another

potential source of USCBDC demand. On behalf of

their account holders, MMFs invest large amounts

in short-term debt instruments such as Treasury

bills, commercial paper, and repurchase agreements.

Depending on MMF investments, account holders

can be exposed to losses from defaults or prema-

ture investment liquidations. During periods of

financial stress and elevated default risk, MMF

account holders will likely prefer the certainty of a

USCBDC deposit over an investment in a MMF.

A third source of potential USCBDC demand is

international investors. Currently, deposit insur-

ance protections for digital bank money only apply

to deposits in domestically chartered and insured

depository institutions and a few domestic

branches of foreign banks with “grandfathered”

insurance coverage. Dollar deposits in foreign

banks are not protected by FDIC insurance and are

subject to loss should the foreign bank fail.

USCBDC Design

The framers of the Federal Reserve Act never envi-

sioned USCBDC, so it is an open issue whether the

Fed has the legal authority to issue a new Fed digi-

tal currency. In response to members of Congress’

questions about the need for explicit authorizing

legislation, the chairman admitted he was unsure

of the Fed’s legal standing regarding USCBDC but

further stated that, under his chairmanship, the

Fed would not undertake such a step without strong

congressional support, even if the Fed’s legal staff

could justify USCBDC based on existing authorities.

Two designs could be used to issue USCBDC. In

one, the Fed would accept dollars and issue a digi-

tal dollar token with a unique digital identifier. The

digital token would then trade and settle using

some type of distributed public ledger technology.

The integrity of this type of digital currency relies

on a large number of independent processors to

verify the authenticity of a transaction and ensure

that token owners cannot spend the same token twice.

Digital currencies of this design are not well suited for

retail transactions because transactions are expen-

sive to process in volume using a public distributed

ledger and payees may face significant delays and

uncertain fees to verify the transfer of funds.

An alternative USCBDC design is more suitable

for processing retail transactions. It uses a single

private ledger controlled by the Fed to process and

record USCBDC transactions. Under this approach,

USCBDC purchasers could have their own individ-

ual deposit accounts at a Federal Reserve bank, or,

more likely, USCBDC accounts would be issued by

financial intermediaries who would in turn have a

USCBDC account at the Fed. Retail accounts

would be established and managed by qualified

financial intermediaries who would be required to

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 6

back each dollar of USCBDC they issue with a dol-

lar deposit in the intermediary’s Federal Reserve

USCBDC account. In other words, USCBDC inter-

mediaries would have to back their USCBDC accounts

with a 100 percent investment in Federal Reserve

master account balances.

If individuals were allowed to open USCBDC

accounts held directly at a Federal Reserve bank,

the Fed would be responsible for complying with

all the regulations associated with retail deposit

accounts, such as meeting know-your-customer

anti–money laundering and terrorism finance

requirements and maintaining an internet portal in

which perhaps millions of customers could view

their account balances and transfer funds. If, alter-

natively, USCBDC is issued using intermediaries,

the intermediary will interface with the retail cus-

tomer and be responsible for enforcing all regula-

tions associated with deposit intermediaries, pro-

cessing transactions, and maintaining customer

balance information while only reporting the inter-

mediaries’ net USCBDC transactions to the Fed for

processing. Financial intermediaries will almost

certainly be involved should the Fed decide to issue

USCBDC.

Every dollar of USCBDC created is a liability of

the Fed and must be matched by assets of equiva-

lent value on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

In the case of Federal Reserve notes and central

bank reserve balances, the offsetting liabilities are

US Treasury securities, agency mortgage-backed

securities, collateralized loans to depository insti-

tutions, and loans to other financial intermediaries

made through crisis-related special purpose lend-

ing programs. The proceeds of USCBDC deposits

could be used to purchase similar assets unless

Congress intervenes to restrict or expand the assets

the Fed is allowed to purchase using USCBDC

receipts.

USCBDC issuance will directly affect banks and

MMFs. The bulk of the dollar balances used to pur-

chase USCBDC will come directly from bank deposit

accounts and MMF accounts. Deposits are typically

a bank’s cheapest source of funding and the pri-

mary instrument banks use to fund loans and other

investments. If USCBDC are purchased using bank

deposits, banks will have to contract their loans

and security investments or replace lost deposits

with a more expensive source of funding. Either

way, the cost of bank credit could substantially

increase should USCBDC prove popular with bank

depositors.

Similarly, MMF account holders may withdraw

balances to purchase USCBDC. Withdrawals will

affect MMFs’ ability to purchase commercial paper

and other short-term liabilities that are an important

source of funding for many large business and cor-

porations. Should a significant volume of USCBDC

purchases come at the expense of MMF account

balances, interest rates could increase on short-term

marketable paper issued by private-sector firms.

One of the most important issues surrounding

USCBDC design is the payment of interest. Should

the Fed be permitted to pay interest on USCBDC,

and, if so, at what rate?

One option is to prohibit USCBDC from paying

interest. Paper money—Federal Reserve notes—

pays no interest, and before the passage of the

Dodd-Frank Act, bank transaction account balances

were prohibited from paying interest. At present,

only depository institutions are allowed to earn

interest on balances held in Federal Reserve mas-

ter accounts. Government-sponsored enterprises

and primary dealers can have Fed master accounts

but do not earn interest on these account balances.

If USCBDC intermediaries were given the same

status as other non-depository master account

holders, the no-interest convention would be con-

sistent with current practice. However, prohibiting

interest would limit the retail demand for

USCBDC, as USCBDC account holders would

likely be required to pay intermediaries to main-

tain USCBDC accounts and process transactions.

The Federal Reserve may prefer paying interest

on USCBDC balances if the Fed is allowed to vary

the interest rate on these balances and the rate is

allowed to differ from the rate the Fed pays on

depository institution master account balances.

Under this design, the Fed would acquire a new

instrument that could be used to control MMF bal-

ances and bank reserves. This additional instru-

ment could enhance the Fed’s ability to attain its

monetary targets, but it would also disrupt the tra-

ditional business models of banks and MMFs.

The interest rate earned on USCBDC will likely

be an important factor that determines institutional

investor interest in USCBDC under normal condi-

tions. If USCBDC pays no interest, institutional

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 7

balances will likely remain bifurcated between unin-

sured bank deposits and MMF accounts because it

will be costly to maintain USCBDC balances and

process transactions, whereas uninsured bank

deposits typically generate nonpecuniary benefits

for account holders and MMF balances generate

marginal account holder returns. Other things

equal, higher USCBDC interest rates will draw

larger balances from MMFs and uninsured bank

deposits into USCBDC.

Suppose the Fed were to issue USCBDC and set

the interest rate above the overnight reverse repur-

chase rate (0.05 percent as of July 30, 2021, according

to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis) but below

the interest rate it pays banks on bank reserves

held at the Fed (currently 0.15 percent). This

USCBDC interest rate would likely attract some

institutional money and drain account balances

from both MMFs and large uninsured bank depos-

its. This in turn would reduce the volume of Fed

overnight reverse repurchase agreements and

reduce bank reserves, reducing banks’ and MMFs’

capacity to fund private-sector credit. Conversely,

negative USCBDC interest rates or any rate below

the overnight reverse repurchase rate would signif-

icantly diminish the appeal of USCBDC.

On issues of financial stability, the availability of

USCBDC could cause panicked uncontrolled disin-

termediation in a financial crisis. Facing an elevated

risk of default losses, uninsured bank depositors

and MMF account holders would likely pull their

balances from banks and MMFs to purchase

USCBDC regardless of interest rates because

USCBDC has no default risk. In a financial crisis,

private-sector financial institutions would likely

hemorrhage funds as investors ran to the safety of

USCBDC.

Conclusion

The dominant form of money in the US is digital

money in the form of bank deposits. Fast, reliable,

and inexpensive systems are in place to process

domestic digital bank deposit transactions. Inter-

national digital deposit transfers are more expen-

sive, but plans are underway to improve the effi-

ciency of these systems. There are no compelling

reasons to believe that USCBDC would increase

the speed and reduce the cost of domestic transac-

tions processing relative to the systems used to

process bank digital deposits.

The design of a USCBDC has

important implications for the finan-

cial system and private-sector credit

availability.

The international availability of a USCBDC

would undermine the competitiveness of privately

issued stablecoins and likely prevent them from

becoming a financial stability threat. Federal Reserve

officials discount arguments that a USCBDC is

necessary to defend the reserve currency status of

the US dollar, but competition among central bank

digital currencies could become an important con-

sideration in the future.

The design of a USCBDC has important impli-

cations for the financial system and private-sector

credit availability. If issued, USCBDC almost cer-

tainly will use a private central ledger controlled by

the Fed and employ regulated intermediaries to

interact with USCBDC retail accounts.

Decisions regarding USCBDC interest payments

are a crucial design issue. Prohibiting USCBDC

from paying interest, while consistent with the lack

of interest earned on paper currency, will limit the

appeal of USCBDC under normal conditions.

USCBDC balances will entail transactions fees that

may make USCBDC appear to be the most expen-

sive form of dollar-denominated “money.” If

USCBDC is allowed to earn interest, the USCBDC

interest rate will be a new monetary policy instru-

ment that the Fed can use to regulate the level of

reserves in the financial system. Regardless, the

availability of USCBDC will introduce a new finan-

cial stability concern: In a financial crisis, the finan-

cial disintermediation caused by an uncontrolled

run into USCBDC will severely disrupt the availa-

bility of private-sector credit.

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 8

About the Author

Paul H. Kupiec is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he studies economic issues

related to banking and financial services.

References

Adler, Howard, and Alex Pollock. 2021. “Why a Fed Digital Dollar Is a Bad Idea.” RealClearMarkets. July 22. https://www.realclear-

markets.com/articles/2021/07/22/why_a_fed_digital_dollar_is_a_bad_idea_786639.html.

Auer, Raphael, Cyril Monnet, and Hyun Song Shin. 2021. “Permissioned Distributed Ledgers and the Governance of Money.” Working

Paper. Bank for International Settlements. January 27. https://www.bis.org/publ/work924.htm.

BIS (Bank for International Settlements). 2020. “Central Bank Digital Currencies: Foundational Principles and Core Features.”

October 9. https://www.bis.org/publ/othp33.pdf.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2021a. “Fedwire Funds Services.” May 7. https://www.federalreserve.gov/

paymentsystems/fedfunds_about.htm.

———. 2021b. “Financial Accounting Manual for Federal Reserve Banks. July 2021.” July. https://www.federalreserve.

gov/aboutthefed/files/BSTfinaccountingmanual.pdf.

———. 2021c. https://www.federalreserve.gov/.

Burnette, Margarette, and Spencer Tierney. 2021. “What It Costs to Transfer Money Between Banks.” NerdWallet. June 10.

https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/banking/ach-transfer-costs.

Clearing House. 2021. “The RTP Network: For All Financial Institutions.” https://www.theclearinghouse.org/payment-

systems/rtp/institution.

Diem. 2020. “White Paper v2.0.” April. https://www.diem.com/en-us/white-paper/#cover-letter.

FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation). 2012. “2011 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.”

September. https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2012_unbankedreport.pdf.

FRB (Federal Reserve Banks). 2021. “FedACH Services 2021 Fee Schedule.” https://www.frbservices.org/resources/fees/ach-2021.html.

FSB (Financial Stability Board). 2020a. “Addressing the Regulatory, Supervisory and Oversight Challenges Raised by ‘Global

Stablecoin’ Arrangements.” April 14. https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P140420-1.pdf.

———. 2020b. “FSB Delivers a Roadmap to Enhance Cross-Border Payments.” Press Release. October 13. https://www.fsb.org/

2020/10/fsb-delivers-a-roadmap-to-enhance-cross-border-payments/.

Khatwani, Sudhir. 2020. “Bitcoin Transaction Fees: A Beginner’s Guide for 2020.” Money Mongers. May 30. https://themoney-

mongers.com/bitcoin-transaction-fees/.

Lee, Isabelle. 2021. “Fed Chair Jerome Powell Says Cryptocurrencies and Stablecoins Won’t Be Needed Once the US Has a Digital

Currency.” Business Insider. July 14. https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/markets/fed-chair-jerome-powell-says-cryptocurrencies-

and-stablecoins-wont-be-needed-once-the-us-has-a-digital-currency/ar-AAM9YJ7.

McDonald, Oonagh. 2021. Cryptocurrencies: Money, Trust and Regulation. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Agenda Publishing. October 7.

Quarles, Randal K. 2021. “Parachute Pants and Central Bank Money.” Utah Bankers Association Convention. Sun Valley, Utah. June 28.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/quarles20210628a.htm

US House Committee on Financial Services. 2021. “Virtual Hearing: Monetary Policy and the State of the Economy.” YouTube. July 14.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gj9ygZHNemY.

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE 9

Venmo. 2021. “Fees.” https://venmo.com/about/fees/.

YCharts. 2021. “Ethereum Average Transaction Fee.” https://ycharts.com/indicators/ethereum_average_transaction_fee.

Zelle. 2021. “What Is Zelle?” https://www.zellepay.com/support/what-is-zelle.

Robert Doar, President; Michael R. Strain, Director of Economic Policy Studies; Stan Veuger, Editor, AEI Economic Perspectives

AEI Economic Perspectives

is a publication of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a nonpartisan, not-for-

profit, 501(c)(3)

educational organization. The views expressed in AEI publications are those of the authors. AEI does not take institutional p

os

itions

on any issues.

© 202

1 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. All rights reserved. For more information on

AEI Economic

Perspectives

, please visit www.aei.org/feature/aei-economic-perspectives/.