A STUDY TO DETERMINE WHETHER THE CALIFORNIA CRITICAL THINKING

SKILLS TEST WILL DISCRIMINATE BETWEEN THE CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS OF

FIRST SEMESTER STUDENTS AND FOURTH SEMESTER STUDENTS AT A TWO

YEAR COMMUNITY TECHNICAL COLLEGE.

By

Thomas F. Raykovich

A Research Paper

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degree of

Education Specialist

With a Major in

Counseling and Psychological Services

Approved 6 Semester Credits

__________________________

Field Study Chair

Field Study Committee Members:

__________________________

__________________________

The Graduate College

University of Wisconsin-Stout

January 2000

The Graduate College

University of Wisconsin-Stout

Menomonie, WI 54751

ABSTRACT

Raykovich Thomas F.

A STUDY TO DETERMINE WHETHER THE CALIFORNIA CRITICAL THINKING

SKILLS TEST WILL DISCRIMINATE BETWEEN THE CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS OF

FIRST SEMESTER STUDENTS AND FOURTH SEMESTER STUDENTS AT A TWO YEAR

COMMUNITY TECHNICAL COLLEGE.

Education Specialist in Counseling & Psychological Services Dr. Thomas Modahl January

2000 37 pages

American Psychological Association (APA) Publication Manual

From a historical perspective, the general public has largely accepted the claims of

quality made by institutions of higher learning (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991). Overall, the

view of most individuals concerning post secondary education has been very positive. In recent

years, however, the perception of higher learning has become more critical and cynical.

In response to the public=s growing aversion toward many colleges and universities, the

federal government, state government, and many accrediting associations have strongly

suggested, and in some cases required, that institutions of higher learning assess the educational

outcomes of students to document and improve the quality of their academic offerings (Ewell,

1991).

Nicolet Area Technical College, a public community college serving approximately

1500 students annually, is located in rural Northcentral Wisconsin. The College has developed

an assessment plan which proposes to determine to whether Nicolet College is fulfilling its

Mission, Vision, Values, and Goals, and to refine and enhance the programs and services of the

institution. The assessment plan will provide the college staff with the detailed information

needed to continually improve the quality of educational programs, services, and facilities. It

was decided that a major component of this assessment plan would include the assessment of

critical thinking skills. The California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) was chosen as the

College=s test pilot instrument for evaluating critical thinking ability. This decision was based,

in part, on the CCTST manual=s description of the test which indicates the CCTST was

specifically developed to measure the Askills@ dimension of critical thinking, targeting core

critical thinking abilities regarded to be essential elements in a college education. The purpose

of this Causal Comparative study seeks to determine if the California Critical Thinking Test will

detect differences in critical thinking skills between first and fourth semester program students

attending Nicolet Area Technical College.

The subjects for this study were two groups of Nicolet Area Technical College students

enrolled in programs of substantial length (45 credit hours minimum). One group consisted of

students enrolled in first semester classes and the other of students enrolled in their fourth

semester, preparing to graduate. The first group, consisting of fifty-three students enrolled in

various general education courses, were administered the California Critical Thinking Test

shortly after enrollment. The second group administered the test, consisted of fifty students who

had applied for graduation in December 1999. A t-Test for Independent Samples was the

statistic of choice to accept or reject the null hypotheses.

Null: There will be no significant difference between California Critical Thinking Skills

Test scores of matriculating Nicolet Area Technical College students and those preparing to

graduate.

The findings will be used to determine if this test is an appropriate measure to use in

assessing the critical thinking skills of students attending Nicolet Area Technical College.

Should it be found that the California Critical Thinking Test is an appropriate measure, Nicolet

students, chosen at random, will be pre-tested (during enrollment) and tested again when

applying for graduation.

The results of this study indicate the average mean test score of Nicolet College students

enrolled in their fourth semester was significantly higher on the California Critical Thinking

Skills Test (CCTST) than the average mean test score earned by first semester Nicolet College

students. Additionally, there was a statistically significant increase in the mean test scores of

fourth semester students on the Analysis, Evaluation, Deductive and Inductive sub-scale areas of

the CCTST.

Contents

Page

List of Tables .................................................................................................................................vi

Chapter I Introduction..................................................................................................................... 1

Statement of Problem.......................................................................................................... 4

Purpose of the Study ........................................................................................................... 4

Definition of Terms............................................................................................................. 5

Chapter II Review of Literature ...................................................................................................... 8

Chapter III Design of Study.......................................................................................................... 21

The Population .................................................................................................................. 21

Description of the measuring Instrument.......................................................................... 22

Data Collection.................................................................................................................. 23

Statistical Procedure..........................................................................................................24

Limitations ........................................................................................................................25

Summary ........................................................................................................................... 25

Chapter IV Results ........................................................................................................................26

Introduction.......................................................................................................................26

Data Analysis ....................................................................................................................26

Chapter V Summary...................................................................................................................... 34

Summary ........................................................................................................................... 34

Conclusions.......................................................................................................................35

Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 36

6

Precautions ....................................................................................................................... .38

Recommendations.............................................................................................................40

7

Figures

Figure

Page

1. Total Critical Thinking Scores

First and fourth semester student comparison................................................................... 27

2. Analysis

First and fourth semester student comparison................................................................... 28

3. Evaluation

First and fourth semester student comparison................................................................... 29

4. Inference

First and fourth semester student comparison................................................................... 30

5. Deductive

First and fourth semester student comparison................................................................... 31

6. Inductive

First and fourth semester student comparison................................................................... 32

7. Percentile scores for over-all critical thinking and individual sub-scales

First and fourth semester student comparison................................................................... 33

1

CHAPTER I

Introduction

From a historical perspective, the general public has largely accepted the claims of

quality made by institutions of higher learning (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991). Overall, the

view of most individuals concerning post secondary education has been very positive. In recent

years, however, the perception of higher learning has become more critical and cynical. Several

blue ribbon advisory panels have issued reports criticizing the quality of higher education and

have called for colleges and universities to assess student performance in relation to the

colleges= institutional objectives (Osterlind, 1997). According to the Wingspread Group

(1993), AEducation is in trouble and with it our nation=s hope for the future@ (p.24). The report

goes on to challenge the higher education community to improve the intellectual ability of its

students. The spirit of this challenge is evident in the groups conclusion: AA generation ago, we

told educators we wanted more people with a college credential and more research-based

knowledge. Educators responded accordingly. Now we need to ask for different things.

Students must value achievement, not simply seek a credential.@ (Wingspread Group, 1993, p.

24). A 20-year review into the effects of college education on student learning concluded that

the evidence concerning the net effects of college on the development of general cognitive skills

is minimal and rather limited in scope (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991).

The Resource Group on Adult Literacy and Lifelong Learning (1991), states in its interim

report to the National Education Goals Panel that very limited information is available on the

ability of college graduates to solve problems, communicate, or to think critically.

According to Lopez (1998), Associate Director of the North Central Association of

Colleges and Schools Commission on Institutions of Higher Education (NCA), public and

2

private two-year, four-year, and doctoral institutions face a major challenge in addressing the

assessment of student learning.

In response to the public=s growing aversion toward many colleges and universities,

federal and state governments, and many accrediting associations have strongly suggested, and in

some cases required, that institutions of higher learning assess the educational outcomes of

students to document and improve the quality of their academic offerings (Ewell, 1991). Studies

have found that a high percentage of America=s post secondary institutions, a number as high as

82 %, have indeed initiated some form of outcomes assessment (El-Khawas, 1990). Even

though there is widespread use of outcomes assessment being conducted in American higher

education, there is little evidence available concerning what college students know and what

skills they possess. Almost all institutions of higher learning have incorporated some form of

survey or questionnaire that probes student attitudes about their educational experiences.

Evaluation teams have been highly critical of this form of self reported data, however, since the

surveys do not focus on what the student has actually accomplished, nor do they

assess learning (Lopez, 1998).

There are various ways to assess student learning, such as standardized tests, portfolios,

and locally developed tests. In choosing an assessment instrument, Lopez (1998) stressed the

importance of sound methodology and measures. The instrument should measure factors the

college feels students are to know, and the scores derived should be appropriate and logical

inferences about student learning (Lopez, 1998).

The North Central Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Institutions of

Higher Education (NCA) is a membership organization made up of educational institutions in the

3

nineteen-state North Central region. The association is committed to developing and

maintaining high standards of educational excellence. In order for Nicolet College to be a

member of the North Central Association, it has to meet all twenty General Institutional

Requirements. General Institutional Requirement Number Sixteen emphasizes the importance of

the Aassessment of student academic achievement including the general education component of

the program and is linked to expected learning outcomes@ (AHandbook of Accreditation,@ 1997,

p. 23-24). The Commission believes that the assessment of student academic achievement is

imperative in evaluating overall institutional effectiveness (AHandbook of Accreditation,@

1997).

Nicolet Area Technical College, a public community college serving approximately

1500 students annually, is located in rural Northcentral Wisconsin. The College has developed

an assessment plan which proposes to determine whether Nicolet College is fulfilling its

Mission, Vision, Values, and Goals, and to refine and enhance the programs and services of the

institution. The assessment plan will provide the college staff with the detailed information

needed to continually improve the quality of educational programs, services, and facilities. It

was decided that a major component of this assessment plan would include the assessment of

critical thinking skills. The California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) was chosen as the

College=s test pilot instrument for evaluating critical thinking ability. This decision was based,

in part, on the CCTST manual=s description of the test which indicates the CCTST was

specifically developed to measure the Askills@ dimension of critical thinking, targeting core

critical thinking abilities regarded to be essential elements in a college education.

4

Statement of the Problem

Research shows the assessment of student academic achievement is key to the

improvement of student learning, in aiding educational institutions with issues related to

accountability, and in documenting the importance of higher education. According to Nicolet

College=s Assessment Plan (1995), critical thinking is a key element in the process of student

learning. The College, therefore, has identified a need to assess critical thinking ability and is

considering the California Critical Thinking Skills Test as the instrument to help it accomplish

this objective. In order to make that decision, however, more information is needed to help the

College determine if this test is appropriate for its population of students.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this Causal Comparative study seeks to determine if the California

Critical Thinking Test will detect differences in critical thinking skills between first and fourth

semester students enrolled in two year programming at Nicolet Area Technical College.

Null Hypothesis

There will be no significant difference in the scores on the California Critical Thinking

Skills Test between students who are enrolling and students who are preparing to graduate from

Nicolet Area Technical College.

Alternate Hypothesis

5

Students who are preparing to graduate from Nicolet Area Technical College will have

significantly higher scores on the California Critical Thinking Skills Test than students who have

just enrolled.

Definition of Terms

General Institutional Requirements (GIR)

: Define institutional parameters, establish a

threshold of institutional development, and mirror the North Central Association=s basic

expectations of all affiliated institutions of higher education (Handbook of Accreditation

[HOA],@ 1997)..

Critical Thinking: AThe process of personal, self regulatory judgement. This process

gives reasoned consideration to evidence, context, conceptualizations, methods, and criteria @

(The American Philosophical Association Delphi Report, 1990). Thus defined as the cognitive

process which effects problem-solving and decision-making.

General Education: Although every educational institution has it=s own definition of

general education, according to the Nicolet Area Technical College Assessment Plan (1990), the

mission of general education at Nicolet Area Technical College is to:

Provide an educational base of knowledge that is designed to foster customary skills,

intellectual concepts and attitudes that all educated individuals should possess. General

education furnishes explicit instruction in important lifelong skills needed for success in

career, home, community, and the larger society. This commitment to general education

6

is found in the essential competencies for all graduates from the college which have

become known as core abilities (p.4).

Core Abilities:

Address broad cognitive skills and perceptions that are transferrable and

go beyond the framework of a specific class. Nicolet=s core abilities are: Educational program

competence, solid foundation skills, effective communications, critical thinking skills, self-

directed inquiry and growth, self awareness and esteem, community commitment, and global

awareness and sensitivity (Nicolet Area Technical College Assessment Plan, 1995).

The following are definitions of the five California Critical Thinking Skills (CCTST)

sub-scales, as defined in the CCTST Manual, (Facione, Facione, Blohm, Howard and Giancarlo,

1998):

Analysis:

To comprehend and express the meaning or significance of a wide variety of experiences,

situations, data, events, judgements, conventions, beliefs, rules, procedures, or criteria.

Analysis also means to identify the intended and actual inferential relationships among

statements, questions, concepts, descriptions, or other forms of representation intended to

express beliefs, judgements, experiences, reasons, information, or opinions (Facione, et

al., 1998, p.5).

Evaluation:

To assess the credibility of statements or other representations which are accounts or a

description of a person=s perception, experience, situation, judgement, belief, or opinion;

and to assess the logical strength of the actual or intended inferential relationships among

statements, descriptions, questions or other forms of representations. To state the results

7

of one=s reasoning; to justify that reasoning in terms of the evidential, conceptual,

methodological, criteriological, and contextual considerations upon which one=s results

were based; and to present one=s reasoning in the form of cogent arguments (Facione, et

al., 1998, p.5).

Inference:

To identify and secure elements needed to draw reasonable conclusions; to form

conjectures and hypotheses, to consider relevant information and to deduce the

consequences flowing from the data, statements, principles, evidence, judgements,

beliefs, opinions, concepts, descriptions, questions, or other forms of representation@

(Facione, et al., 1998, p. 5-6).

Matriculate: To enroll, especially in a college or university, as a candidate for a degree

(Thorndike & Barnhart, 1983).

Substantial Length: Student must be enrolled for at least 45 credit hours to be considered

in an academic program of substantial length (AHandbook of Accreditation,@ 1997).

8

CHAPTER II

Review of Literature

Institutional Accreditation

In American institutions, accreditation is a uniquely voluntary process. Voluntary

accreditation has two basic purposes: Quality assurance and institutional and program

involvement. Institutional accreditation evaluates and accredits an educational institution as a

whole. It assesses educational activities, governance, financial stability, admissions, student

services, institutional services, student academic achievement, institutional effectiveness, and

relationships with constituencies outside the institution (AHandbook of Accreditation [HOA],@

1997).

Six regional agencies provide institutional accreditation, those being: Middle States, New

England, North Central, Northwest, Southern, and Western. Although they function independent

of one another, these six regional associations cooperate with and accept one another=s

accreditation (AHOA,@ 1997).

9

The primary purposes of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools

Commission of Institutions of Higher Education are the public=s determination of institutional

quality and the encouragement of continual institutional self-improvement. In this process, the

Commission has organized the issues of institutional evaluation into broad areas called Criteria

for Accreditation. It is important to note that the Commission sets high expectations for its

members in all five Criteria for Accreditation areas and all of these Criteria must be to met to

satisfy full accreditation requirements (AHOA,@ 1997).

Criteria 3 and 4 deal with whether the institution can accomplish its stated purposes

and improve its educational effectiveness. While the Commission cannot guarantee that an

institution will accomplish its purposes, it does represent the best peer judgement about the

institution=s future at the time of the evaluation. In choosing to be part of NCA, an institution

seeks not only external validation, but also accepts responsibility for improving educational

offerings. In order to meet this criteria, it will need to have the necessary resources to maintain

strengths, correct weaknesses, and respond to changing societal educational needs (AHOA,@

1997).

In 1989, The Commission adopted its current assessment initiative. Through this

initiative, educational institutions interested in learning whether they are accomplishing what

they claim to be accomplishing inevitably find ways in which they can improve (AHOA,@ 1997).

Recently, the Commission has determined that an effective program for assessing student

academic achievement is an imperative piece of the puzzle in support of an institution=s claims

of

10

educational effectiveness. Although the measurement of learning outcomes is only one aspect

of an overall effective educational program, NCA recognizes the importance of assessment data

in contributing to successful decision making within an institution, especially in faculty and

curriculum development. The Commission also indicated that unless an institution is prepared

to integrate assessment into the institutional budgeting process, even the best plan will fail. Thus

the long-range success of assessment of student learning and its ability to enhance educational

quality depends on several factors including: Governing board support, appropriate leadership

support, sufficient resources for ongoing assessment, funding, and an appropriate avenue for

ways in which assessment information can influence institutional priorities (AHOA,@ 1997).

The Nicolet Area Technical College Assessment Plan

According to the Executive Summary of the Assessment Plan of Nicolet Area Technical

College (1995), AThe overriding purpose of the Assessment Plan is to determine to what degree

Nicolet College is fulfilling its mission, vision, values, and goals and to strengthen the programs

and services of the College@ (p. ii).

Nicolet College Mission: In service to people of Northern Wisconsin, we deliver

superior community college education that transforms lives and enriches

communities...

Nicolet College Vision: To be a model college recognized for educational excellence and

valued as a vital resource by the people of Northern Wisconsin...

Nicolet College Values: We believe in the worth and dignity of the individual, and we

therefore commit to treating each person with kindness and respect. We honor individual

11

freedom of inquiry and individual and group contributions to governance. We value

education as a life-long process. We value our students, and we strive to empower them

to realize their educational goals. We value our staff and board, and we strive to support

one another in our common efforts to contribute fully to the success of Nicolet College.

We value our communities, and we strive to enrich them by being responsive to their

needs through partnerships (Nicolet Area Technical College Catalog, 1998, p.3-5).

The Executive Summary of the Assessment Plan of Nicolet Area Technical College

(1995) indicates the assessment plan will provide the college with detailed information needed to

improve educational programs, services, and facilities. Nicolet College=s Assessment Plan is

linked to its mission, goals, and objectives as outlined in the following Assessment Plan goals:

1. Validate that programs and services are delivered as are represented by publications.

2. Increase the awareness and expectations for quality in all educational endeavors.

3. Incorporate results into future planning, policy decisions, and resource allocation.

4. Develop measurable outcomes and set program standards.

5. Publicly promote exemplary programs and services and to increase information

throughout the college district to stimulate interest and confidence in college

operations.

6. Create a culture where stakeholders are part of and committed to improving the

quality of teaching and learning at Nicolet Area Technical College.

Assessment

The concept of assessment has changed from one which was added on to instruction from

12

the outside to periodically check on its effectiveness, to a comprehensive process of

continuous improvement where the use of evidence and discipline are part of the delivery of

instruction itself. Ewell (as cited in IEASSA, 1994), states the whole point of assessment

according to most practitioners is institutional improvement.

According to Allen, et al., (1985) an appropriate assessment program will contribute to

student growth and development, resulting in increased competence, self knowledge, self esteem,

and confidence. Allen stresses, that students at Alverno College have found their assessment

program Ato be one of the most distinctive and powerful parts of learning@ (p.54).

For over 60 years, educational institutions have been examined in an effort to determine

their effectiveness (Morgan & Welker, 1991). In the mid-1970's, numerous reports emphasized

the need for the development of excellence in the educational experience. The mid-1980's

stressed increased accountability in higher education, accurate measurement of institutional

effectiveness, and evidence that educational institutions were accomplishing their stated

objectives. One of the main obstacles to determining institutional effectiveness has been that

few colleges have common criteria for determining institutional effectiveness (Cameron, 1978).

According to a report by the Institutional Effectiveness and Assessment of Student

Academic Achievement (IEASSA) (1994), there are two core indicators from the Wisconsin

Technical College System which speak directly to the assessment of student achievement.

1. Identification of Student Functional Skills at Entry

The proportion of an entering student cohort for which the institution has

13

information describing functional skills in reading, mathematics, written and oral

communication, and technical fields. Standardized or local tests administered to

students at entry that include the determination of functional skills in reading,

mathematics, and written and oral communication. Also desirable are tests of

applied skills for students in specific technical fields (p. 4).

Basically all colleges in the Wisconsin Technical College System collect data from

entering students in the areas of reading, writing, and mathematics. Applied skills are typically

not assessed at entry and this is an area that, according to the Wisconsin Technical College

System, needs to be further developed. It should be noted that Nicolet College does have

an applied writing (essay) component.

2. Student Knowledge and Skills at Exit

The knowledge and skills achieved by students at the time of exit from college in

some or all of the following areas: reading, mathematics, written and oral

communication, general education and applied technology. Different methods are

used at exit to collect data from students documenting knowledge and skills in

basic education, general education, and applied technology. Possible methods of

assessment include pre-and post-tests, portfolio performance evaluation,

demonstrated competency or practical application, assessment of verbal and non-

verbal communication skills, assessment of critical thinking and problem-solving

skills, student description of achievement and competencies, and competency

based grading (p.4).

Colleges periodically collect student outcome data at exit, especially to satisfy

14

requirements of self study for accreditation. Common practice does not exist among the

Wisconsin Technical College System. Again, it has been recommended that this process be

further developed (IEASSA, 1994).

Implementation of the Wisconsin Instructional Design System (WIDS) requires that all

courses and programs determine competencies and/or outcomes that accompany appropriate

measures of learner mastery. Outcomes must relay to learners what primary skills, knowledge,

and attitudes they will learn; be measurable and observable; and require learning at the

application level or higher. General education competencies and core abilities need to be

measured in all courses (IEASSA, 1994).

According to the Executive Summary of the Assessment Plan of Nicolet Area Technical

College, (1994), general education and core abilities are defined as follows:

The mission of general education at Nicolet College is to provide an

educational core of knowledge that is intended to impart common skills,

intellectual concepts, and attitudes that every educated person should possess.

General education provides explicit instruction in the essential lifelong skills

required for success in career, home, community, and the larger society.

Core abilities are the broadest outcomes, skills, or purposes that are

addressed throughout a course or program rather than in one specific unit or

lesson. Core abilities address broad knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are

transferrable and go beyond the context of a specific course. Core abilities are

institutional outcomes for students. Core abilities are imbedded in the curriculum

and are assessed simultaneously with lesson, unit, or course outcomes (p. 4).

15

Critical Thinking

According to Toulmin, Rieke, and Janik, (1979), the ability to think critically is one of

the most crucial survival skills in society today. The lack of these skills can keep people from

participating effectively in a democratic society.

After decades of ignoring the heart of education, the eighties witnessed a growth in the

process of inquiry, learning, and thinking rather than the accumulation of disjointed skills and

information. Through conferences and position papers, the critical thinking movement gained

momentum throughout the decade. This movement lead to the development of lesson plans

incorporating critical thinking instruction in elementary, and secondary schools, as well as in

college level courses in critical thinking. Critical thinking related publications and staff

development programs are now major growth areas. Critical thinking is no longer characterized

as a cottage industry (The American Philosophical Association, 1990) .

From a historical perspective, the areas of philosophy, psychology, and education, have

accepted a myriad of individual, often overlapping definitions of the words Acritical thinking.@

There seems to be as many definitions of critical thinking as there are authors on the subject. In

1987, as the need for a clear consensus definition of critical thinking became ever apparent, the

Committee on Pre-College Philosophy of the American Philosophical Society (APS) began

making inquires into the construct of critical thinking and its assessment. Using the Delphi

methodology, a facilitator conducted an anonymous, two-year intercommunication between 46

critical thinking experts drawn from the fields of philosophy, psychology, and education. These

experts, located from across the United States and Canada, did reach the first consensus

definition, and this research has been called the Delphi Report (Facione, 1990).

16

The Delphi report was successful in identifying a specific definition for critical thinking

and also in the description of a critical thinker. According to Facione, (1990), it would be

impossible to understand the teaching of critical thinking without a profile of the consummate

critical thinker. The Delphi Report consensus definition regarding critical thinking, as well as

its interpretation of the ideal critical thinker is as follows:

We understand critical thinking to be purposeful , self-regulatory judgement

which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference as well as

explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or

contextual considerations upon which that judgement was based. Critical thinking

is essential as a tool of inquiry... Critical thinking is a pervasive and self-

rectifying human phenomenon. The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive,

well-informed, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgements,

willing to reconsider, clear about the issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent

in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria,

focused on inquiry, and persistent in seeking results which are as precise as the

subject and the circumstances of inquiry permit... (Facione, 1990)

The above definition is intended to be a guide to curriculum development and the

assessment of critical thinking. For example, in applying this definition to writing curriculum for

college students in specific programs, it may be helpful to substitute Aautomotive technician, or

computer programmer@ in place of Aideal critical thinker@ (Facione & Facione, 1994).

The Executive Summary of the Assessment Plan of Nicolet Area Technical College

(1995, p 5), identifies critical thinking skills through students possessing and demonstrating core

17

ability skills in the following:

synthesis comparison

creativity analysis

logic skepticism

evaluation evolution/adaptation

One of the most frequently cited reasons for the failure of education in America is the

inability of American students to read and think critically. A study conducted by the National

Commission on Excellence in Education reported that many 17-year-old=s do not possess the

higher level intellectual abilities we expect from them. An alarming 40 % cannot draw

inferences from written material and only one-fifth can write a convincing essay. Further, the

Study notes that all subject matter contributes to the development of critical thinking (AA Nation

at Risk,@ 1983).

It is getting increasingly more important to know how to use resources to discover new

information or to problem solve in an age where access to knowledge is general and immediate

(Clarke & Biddle, 1993). Clarke and Brittle, (1993) also argue that the test of today=s

curriculum is to teach students to govern their own minds, and that if thinking strategies were

taught and demonstrated in the academic disciplines, high school and college students could

better understand the classroom experience and control and direct intellectual work. AInstructors

in the academic disciplines could and should therefore teach them as surely as they teach the

subject knowledge those strategies have produced@ (p.12).

Although there is agreement on the importance of critical thinking in higher education,

there is debate as to how these skills should be taught (MacAdam, 1995). Talaska (1992), has

compiled a number of essays by many scholars representing diverse contemporary theoretical

18

views of critical reasoning. He identified two central questions:

1. Is critical thinking a general skill apart from content or knowledge context?

2. Should critical thinking be taught as a skill in itself or integrated with other teaching

and learning programs?

Learning must be active rather than passive. Critical thinking cannot be taught by a

teacher standing at the chalk board, but must be learned by the students themselves working

cooperatively or individually (Clark & Biddle, 1993).

According to Barnes, (as cited in Paul, 1992) extensive content coverage through lecture

and mindless memorization combined with passive students, perpetuate lower order thinking and

learning that many students currently associate with going to school. Students need to take an

active role in thinking to conclusion in order to achieve higher order learning. Many students

leave school with fragmentary opinions and undisciplined beliefs, leading to limited intellectual

ability, morality, as well as motivational level.

Critical Thinking Standardized Assessment

According to the new Roget=s Thesaurus (Chapman, 1992, p. 842), a synonym for the

word Acritical@ is Acrucial.@ Critical thinking skills are crucial to human development and

society; therefore, developing an appropriate test to assess critical thinking is a monumentally

important task, according to Ennis, (1993). Although there are many tests available that require

some form of critical thinking, there are few that measure critical thinking as their primary

objective. The shortage of critical thinking tests is rather unfortunate; many more are needed to

fit various testing situations and purposes of critical thinking testing. In choosing a critical

19

thinking assessment instrument, Ennis, (1993), advises that one not depend solely on claims

made by test authors and publishers; he recommends the following questions be considered:

1. Is the test based upon a defensible conception of critical thinking?

2. How comprehensive is the coverage of this conception?

3. Does it seem to do a good job assessing the level of your students?

There are many ways of assessing critical thinking skills including: standardized tests,

locally developed (customized) tests, portfolios, essays, and performance/competency

assessment. This assessment can be done longitudinally or cross sectionally (Ennis, 1993).

In terms of standardized critical thinking skills test instruments, Ennis (1993) indicated

almost all are of a multiple choice format which he believes to be an advantage for institutions in

terms of cost, efficiency; and time, however, he cautions that they may lack comprehensiveness.

He indicated the need for additional research and development in this area.

California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST)

According to Facione and Facione (1994), prior to the development of the CCTST there

were only three test instruments available for assessing critical thinking skills at the college

level. Each of these instruments however were developed based upon different theoretical

constructs. This difference limits the potential for establishing concurrent validity between them.

Before the Delphi Project there was not a clear definition of critical thinking. The

CCTST was the first assessment tool to derive its construct validity from this well honed

definition. The CCTST first published in 1992, is an objectively scored standardized instrument

that assesses the cognitive skills dimension of critical thinking. It is a a timed (45 minute), 34

item, multiple choice test which, according to the manual Atargets those critical thinking skills

20

regarded to be essential elements in a college education@(p.1). There are five scores one can

obtain from this assessment instrument: an overall critical thinking score, and five sub-scores.

These five sub-scores are analysis, evaluation, inference, deductive reasoning, and inductive

reasoning (Facione, et al.)

According to a review by McMorris in The Twelfth Mental Measurements

Yearbook, (as cited in Conoley & Impaira, 1995), The California Critical Thinking Skills Test

does not have the history, reliability, or number of norm reference groups like the Watson-Glaser

Critical Thinking Appraisal. McMorris felt that there was great potential for misinterpretation,

as there is not mention in the manual of standard error of measurement, information on

difference scores, or the need for interpretation by a qualified counselor/psychometrist.

Another concern was the single college norm reference group represented by a California state

college. Obviously, one would have a rather difficult time using this norm reference group to

compare students at a rural Northern Wisconsin community college. In a second review,

Michael (as cited in Conoley & Impaira, 1995), felt the CCTST appeared to possess substantial

content validity, probably more that its competitors, due to the collective wisdom of the scholars

who contributed to its development. To summarize, both reviewers had areas where they felt

the test was strong, and, conversely, they felt there were also areas of significant weakness. The

CCTST seems to have exceptional potential; however, as recommended, it appears that more

psychometric research is needed to permit widespread use of this test instrument in both college

undergraduate and graduate programs.

Summary

Critical thinking is likely to continue to be a significant component of secondary

21

and postsecondary education. Current literature seems to indicate that there is, has

been, and continues to be debate not only on the definition of critical thinking, but on

teaching/learning and the assessment of critical thinking skills as well.

The area of critical thinking is a topic that we need to continue to research. The

assessment of student gains is imperative to improving teaching and learning and overall

institutional effectiveness, not to mention obtaining and maintaining accreditation from the North

Central Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Institutions of Higher Education.

CHAPTER III

Design of the Study

In an effort to determine if the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) will

identify differences in critical thinking skills between first and fourth semester program students

attending Nicolet Area Technical College, a causal-comparative study was conducted. The

study was conducted comparing matriculating Nicolet College students and students preparing

22

for graduation. The Null and Alternate Hypotheses follow:

Null Hypothesis

There will be no significant difference in the scores on the California Critical Thinking

Skills Test between students who are enrolling and students who are preparing to graduate from

Nicolet Area Technical College.

Alternate Hypothesis

Students who are preparing to graduate from Nicolet Area Technical College will have

significantly higher scores on the California Critical Thinking Skills Test than students who have

just enrolled.

Population

The sample population for this study consisted of 103 students enrolled in programming

of substantial length (2 years, or 45 credits) at Nicolet Area Technical College. Of this sample,

53 were incoming (first semester) students, and 50 were students preparing for graduation. The

incoming students were taking general education courses and were administered the test

instrument during class time under their instructor=s direction. The other group of students were

chosen at random and were required to take the examination under the direction of the Nicolet

College Assessment committee upon application for graduation.

Description of the Measurement Instrument

The California Critical Thinking Skills Test provides percentile ranking scores.

Percentiles can be obtained for an overall critical thinking score, and/or for the following sub-

scales: Analysis, Evaluation, Inference, Deduction, and Induction. There are three norm

reference groups, including a sample group comprised of 781 college students (Facione, et al.,

23

1998).

An alternate form method was used to calculate the reliability of the CCTST. The

CCTST manual estimates the reliability to be at 0.78. Although this is less than .80 which is

suggested for internal consistency on tests intended to measure a single ability, it should be noted

that the CCTST assesses numerous factors (Facione, et al., 1998). According to Norris and

Ennis (1990), reliability ratings of .65 - .75 are adequate on multiple factor test instruments,

since on these tests there is no theoretical reason for the test items to correlate highly with one

another.

According to Facione, et al., (1998), the specified domain used to determine content

validity is essentially the definition of critical thinking as outlined by the Delphi group. The

CCTST manual states that each of the items chosen for inclusion in the test was based upon a

theoretical relationship to the Delphi critical thinking conceptualization. The CCTST manual

cites several studies involving the CCTST as the primary research tool which support that the

test measures precisely what it purports to measure, thus supporting its case for construct

validity. The issue of face validity is addressed by the nature of the questions asked, in that s

students must make judgements, draw inferences, evaluate reasoning, and justify their inferences

and evaluations. Face validity was further supported by student responses to the test, by faculty

committees who have adopted the CCTST as the instrument of choice for student placement, as

well as, by a number of research projects examining critical thinking issues that have chosen to

use the CCTST in their project. In terms of criterion validity, the CCTST has been found to

correlate with college level grade point average, the Graduate Record Examination, and with

SAT Verbal and Math scores (Facione, et al., 1998).

24

Nicolet College students will be administered Form A or Form B (equivalent forms) of

the CCTST and these scores will be compared to a CCTST norm group consisting of 781

college students from a comprehensive, urban, state university. It should be noted that none of

these students had completed a course in critical thinking. Their college experience ranged from

completing no semester units, to completing enough units to qualify for graduation. The mean

age of the students was 22 with a standard deviation of 4.457 (Facione, et al.,1998).

The CCTST manual did not provide information regarding specific reading level

requirements. According to the Gamco Readability Analysis which employs the Fry Readability

Formula, samples taken from random reading passages were at the 12

th

, 14

th

and 17

th

plus grade

levels.

Data Collection

The California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) was given to first semester students

during the month of October, 1999, as a pre-test indicator of the participants= critical thinking

ability. The CCTST was also administered during the month of December 1999, to students

who had essentially completed their two-year programs and had applied for graduation.

Statistical Procedure

This section will address the procedure that will be used in making a decision to accept or

reject the null.

Null Hypothesis

There will be no significant difference in the scores on the California Critical Thinking

25

Skills Test between students who are enrolling and students who are preparing to graduate from

Nicolet Area Technical College.

Alternate Hypothesis

Students who are preparing to graduate from Nicolet Area Technical College will have

significantly higher scores on the California Critical Thinking Skills Test than students who have

just enrolled.

Data taken from the California Critical Thinking Skills Test was statistically analyzed

and the index of choice used to find the significance of the difference between the means of the

two samples was the t-test for independent samples. The predetermined level at which the null

hypothesis will be rejected, or the level of significance, will be set at .05, as according to Ary,

Lucy, and Razavieh, (1985), AThe most commonly used levels of significance in the field of

education are the .05 and .01 levels@ (p.155). At the .05 level of significance, the null

hypothesis will be rejected only if the estimated probability of the observed relationship being a

chance occurrence is five in one hundred, thus greatly limiting the chances of

committing a type I error (Ary, Lucy, & Razavieh, 1985).

Limitations

This study is limited by the geographical area of the population used in the study.

Students involved in the study were mainly from rural Northcentral Wisconsin. Caution should

be taken when generalizing the results of this study with other geographic areas.

26

Summary

Historically, people have, in general, accepted the premise that attending a college or

university would result in an improvement in one=s ability to think critically. The trend recently

however, has taken a more cynical turn, as students are graduating from post secondary

institutions of higher learning without possessing the basic life skills necessary to obtain and

maintain employment. Governing agencies such as the North Central Association of Colleges

and Schools Commission on Institutions of Higher Education have responded to these concerns

and have set forth specific criteria for measuring core abilities. In examining ways to assess

these broad cognitive skills, many colleges and universities have adopted entrance/exit testing

procedures, including the assessment of critical thinking skills.

Nicolet Area Technical College=s Assessment committee has expressed a desire to adopt

an assessment program to measure student outcomes related to core abilities. Part of this plan

seeks to address critical thinking skills. This study was devised to aid Nicolet College in

determining whether the California Critical Thinking Skills instrument would be an appropriate

measure for assessing the critical thinking growth provided through the Nicolet College

experience.

CHAPTER IV

Results

Introduction

27

The purpose of this causal-comparative study was to test the following null hypothesis:

There will be no significant difference in the scores on the California Critical Thinking Skills

Test (CCTST) between matriculating students and students who are preparing to graduate from

Nicolet Area Technical College.

The subjects for this study were 103 Nicolet Area Technical College students. Fifty-three

of which were first semester (incoming) students and 50 were fourth semester (outgoing)

students. These students were administered the California Critical Thinking Skills Test. Critical

thinking scores were obtained in six areas on the CCTST. These scores consisted of an over-all

critical thinking score and five sub-scale scores in the areas of analysis, evaluation, inference,

deductive reasoning, and inductive reasoning. The first three scales-analysis, evaluation, and

inference-make up a major portion of critical thinking theory as identified by the Delphi group

(Facione, 1990). The last two-inductive and deductive reasoning-are more traditional critical

thinking characterizations.

Data Analysis

Since the purpose of this study focused on whether the CCTST would discriminate

between the critical thinking skills of students attending Nicolet College enrolled in their first

semester and those enrolled in their fourth semester, a statistical analysis was conducted on the

total mean scores of these two groups. The following data was compiled using a t-test for

independent samples.

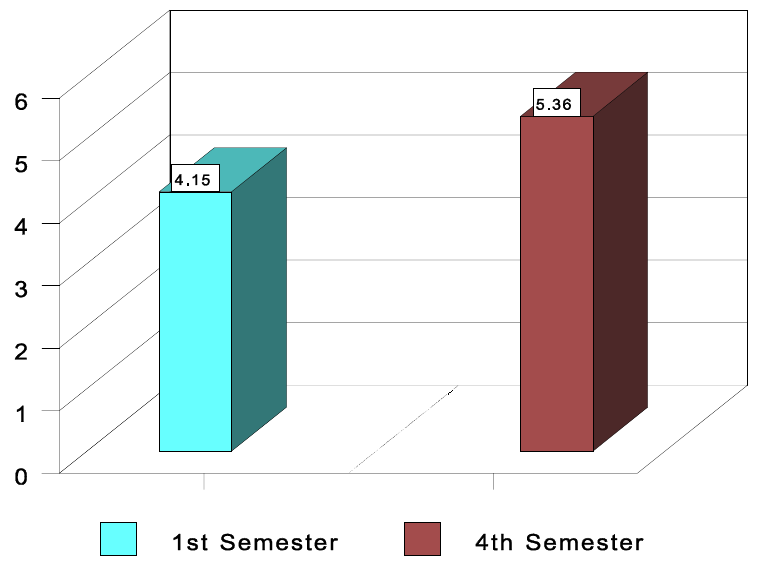

The null hypothesis was rejected and the alternate hypothesis was accepted by this

researcher. To determine significance, the probability level was set at the .05 level. It was

28

found that the CCTST mean score for the group of students who were preparing to graduate from

Nicolet College (14.06) was significantly higher than the scores on the CCTST obtained by

students who were in their first semester (11.21), (t-value of 3.87, df = 101, p<.05).

(see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Total Critical Thinking Scores on the California Critical

Thinking Skills Test for First and Fourth Semester Comparison

Mean Score

While not having been addressed by the null hypothesis, as an area of interest to this

researcher, data analysis was done on the five sub-tests of the CCTST. Again the level of

significance was set at .05 for the t-value analysis of each sub-scale.

n=53 n=50

29

It was found that there was a statistically significant difference in the total mean test

scores between first and fourth semester Nicolet College students on the California Critical

Thinking Skills Test in the Analysis Sub-scale (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Analysis

There was a statistically significant difference between the total mean test scores of first

semester students and fourth semester Nicolet College students on the California Critical

n=50 n=53

30

Thinking Skills Test - Evaluation Sub-scale (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Evaluation

Although it was found that there was a difference between the total mean scores of first

semester students and fourth semester Nicolet College students on the California Critical

n=50 n=53

31

Thinking Skills Test - Inference Sub-scale, this difference was not statistically significant

(Figure 4).

Figure 4

Inference

There was a statistically significant difference between the total mean test scores of first

n=53 n=50

32

and fourth semester Nicolet College students on the California Critical Thinking Skills -

Deductive Sub-scale (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Deductive

n=53 n=50

33

A statistically significant difference was found between the mean test scores of first

semester and fourth semester Nicolet College students on the California Critical Thinking Skills

Test - Inductive Sub-scale (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Inductive

n=53 n=50

34

Additional information that may prove helpful in further defining the critical thinking

abilities of first and fourth semester Nicolet College students, as assessed by the California

Critical Thinking Skills Test, was obtained by comparing student raw scores to a norm group

representation derived from the California Critical Thinking Skills Test Manual (Norm Group

1). This norm group consisted of 781 college students enrolled at a comprehensive, urban state

university. None of the students in this norm group had completed a formal critical thinking

course and were typically of junior standing, although some had completed no collegiate work

and others were qualified for graduation (Facione, et al., 1998, p. 10). The percentiles in Figure

7 were obtained by converting Nicolet College student total raw scores to percentiles based

upon a comparison to this norm group.

Figure 7

Percentiles

n=50

35

According to Figure 7, Nicolet College student=s critical thinking skills are typically

below the average mean scores of the norm group represented by the test publisher.

Chapter V

Summary

Historically the general population has accepted claims made by institutions of higher

learning regarding the value of higher education. Today, however, students, parents, employers,

accrediting institutions, and colleges are questioning whether students are getting real value for

their money, (i.e. Are students receiving what has been promised to them in terms of a quality

education?) In an effort to substantiate claims of quality, the Wisconsin

Technical College

System has instituted an educational guarantee called the Guaranteed Retraining Policy. This

policy states that:

The Wisconsin Technical College System guarantees up to six free credits of

additional instruction within the same occupational program to Wisconsin graduates of a

vocational diploma or associate degree program if: Within 90 days after initial

employment, the graduates employer certifies to the District Board that the graduate lacks

the entry-level job skills and specifies in writing the specific areas of deficiency (Nicolet

Area Technical College Catalog, 1998, p.7).

In order to define and measure student learning, improve the teaching and learning

process and overall institutional effectiveness, and to meet Northcentral Association (NCA)

accreditation mandates, Nicolet College has formed an Assessment Committee. One of the

initial charges of this committee is to identify and determine the appropriateness of various

n=53

36

assessment procedures and instruments for use in the Nicolet Assessment Program. Because

NCA has identified critical thinking as an important factor to consider in assessing student

learning, this study was undertaken to aid Nicolet College in selecting an appropriate instrument

for assessing students= critical thinking skills.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate the average mean test score of Nicolet College students

enrolled in their fourth semester was significantly higher on the California Critical Thinking

Skills Test (CCTST) than the mean test score earned by first semester Nicolet College students.

Through additional research, it was found that on the five (CCTST) sub-scales, the total

mean scores of fourth semester students were significantly higher than those of first semester

students, with the exception of the Inference Sub-scale. It should be noted that although a

statistically significant difference between the scores of first and fourth semester students was

not found on the Inference sub-scale, this sub-scale did yield a higher mean score for the fourth

semester students.

Although the overall mean test scores for Nicolet College students was below that of the

test publisher=s norm group most closely representing Nicolet College students (Group 1), there

are some fundamental differences among these two groups of college students that need to be

addressed. The Group 1 test norms consist of college students attending an urban four-year,

liberal arts university located in California, as opposed to Nicolet College which is a small, rural,

Midwestern, community technical college . Additionally, most of the students in Norm Group 1

are reported to be of junior (5-6 semester) standing, whereas Nicolet students were in their 1

st

or 4

th

semesters. This research could however indicate that although there was an improvement

in critical thinking ability between 1

st

and 4

th

semester Nicolet College students, there may be

37

room for further growth.

Discussion

In related research done by the author of the CCTST, four quasi-experimental studies

were conducted to explore the attributes of the CCTST. A pretest/posttest, case/control study

design was utilized to gather data to determine the CCTST=s validity and reliability, to assess

instrumentation effects, and to measure student gain scores after a course in critical thinking.

Cases were students enrolled in one of four course offerings in critical thinking. Controls

consisted of students who had not taken a critical thinking course, but took the course

AIntroduction to Philosophy.@ The total number of students participating in the study was 1673.

Like the Nicolet study, the test was administered in college classrooms within a 45-minute time

frame. Results of this study indicate that significant gains in the CCTST total score were

observed in the case group (students who took a critical thinking skills course) as compared to

the control group who took the course AIntroduction to Philosophy@ (Facione & Facione, 1994).

If it is the goal of Nicolet College to improve student critical thinking abilities, this

research would seem to suggest that Nicolet College may want to identify current critical

thinking courses, adapt curriculum and incorporate at least one of these classes, or at minimum,

infuse portions of these identified courses into the core program curriculum to ensure that critical

thinking skills are a part of all the Nicolet College educational offerings. Another possibility

would be to require that all Nicolet College students take an actual critical thinking course.

38

In somewhat conflicting research, Harris and Clemmons, (1990), conducted a study to

determine an appropriate test of critical thinking to screen college freshman. The study took

place at a comprehensive university with an enrollment of 14,000 students. Matriculating

students with entry level test scores in English, math, and reading below certain cut scores were

required to engage in remedial instruction. This remedial program of study included a

mandatory three semester hour critical thinking course. Through preliminary research, it was

found that the Watson Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (WGCTA) and California Critical

Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) met their standardized test requirements. If either test proved to

be a good predictor, it would possibly be used as a placement test allowing students to Atest out@

of the critical thinking course. Prediction was based upon the extent to which students scoring

above the median on the pre-test were also above the median on their overall course grade

(Harris & Clemmons, 1996).

To help minimize variables, all sections of the course were taught by the same professor

using the same lesson plans, course materials, and course evaluations. A comparison between

pre-test scores and course grades was then made. Fifty percent of those who placed above the

median on the CCTST pre-test, and 61.5 of those who placed above the median on the WGCTA

pre-test, also completed the course above the median. The difference of the mean scores for

both the CCTST and the WGCTA were found to be statistically insignificant, suggesting that the

course had little effect on the students= critical thinking abilities.

With only half (CCTST) or slightly more than half (WGCTA) of those above the

median on the pre-test also in the top half in terms of course grades, the notion that doing

well on the pre-test indicates a likelihood of doing well in the course is reduced to about

39

the same odds as a coin-toss.

Because of the results of the study, the university did not feel confident that either test

was appropriate for placement purposes, therefore they chose to delay making a decision

regarding a critical thinking skills screening assessment instrument until further research is

conducted (Harris and Clemmons, 1990).

In regards to the above study, and of particular interest to this researcher, was the mean

score for the developmental students on the CCTST of 10.9. While this score is significantly

below the mean of the norm group reported by the CCTST test publisher (15), it is important to

note that this norm group probably did not include a significant number of students enrolled

in remedial education. This researcher was not surprised, therefore, to see a mean score

significantly below that reported by the test publisher. Also, because these students were in

remedial education, one would question whether many of them possessed the reading level

necessary to comprehend the CCTST. As noted in chapter III of this study, according to the Fry

Readability Formula, the CCTST contains passages written at the 17

th

grade level equivalent.

An additional factor for consideration regarding this study was the relationship between course

content and content of the tests. Was the content of these tests the same, or at minimum, highly

similar to what was being taught in the critical thinking course? If not, this study basically

compared apples to oranges.

Precautions

In terms of the Nicolet study, there were several confounding variables which should be

addressed, since they may have had an impact on the findings of this study. These potential

limitations include:

40

$ Students not taking the test seriously (random guessing).

$ Limited sample size.

$ The use of a single assessment instrument to assess critical thinking ability.

$ Outside factors that may be influencing a growth in critical thinking ability, such as

maturation, employment, health, major life changes, etc.

$ One may be an exceptional critical thinker at college entrance, therefore there may not be a

significant amount of growth in this area as a result of the Nicolet College educational

process.

$ The lack of an improved score on the critical thinking examination may, or may not, be the

result of a poor or ineffective test instrument.

$ Limited geographical area of the population used in this study.

$ Through the process of attrition, students ill-prepared for the rigors of post-secondary

education either drop out or fail. In all likelihood, some of these students were part of the

first semester group. There is a high probability that students who make it to the fourth

semester are good students, possessing at least a moderate level of critical thinking ability,

thus emphasizing the importance of pre-and post-testing the same students.

$ The CCTST requires a rather high reading level, up to and beyond the 17

th

grade

equivalent; therefore, it is possible that students who took this test instrument may

not have had the reading ability necessary to comprehend some of the reading passages.

$ The test starts out with items that appeared to be very difficult. According to many student

responses, the test=s first question seemed extremely difficult, which fostered negative

41

feelings almost immediately, causing several students to simply quit or guess. It would seem

that a transition from basic to more complex material would have been more appropriate.

$ According to several students taking the test, the literary topics were not very interesting,

especially to the typical student enrolled in technical college programming. The test,

therefore, seemed to be better suited to liberal arts students.

Recommendations

Considering the preceding study results, related research, and precautions, the following

recommendations are made for consideration in the adoption of a critical thinking skills

assessment instrument for use in a program designed to pre/post test students at Nicolet College.

1. Further research should be conducted to include a greater population of Nicolet

college students. Ideally, this study could be cross-validated by the testing of students

throughout the Wisconsin Technical College System for comparison purposes.

2. For the sake of expediting the study, incoming and exiting students were assessed

concurrently and inferences regarding growth in critical thinking were then made. It seems

that a more valid research method for measuring growth in critical thinking ability would be to

conduct a longitudinal study pre-and post-testing the same sample of students.

3. Although research determined the California Critical Thinking Skills Test did

discriminate between the scores of first and fourth semester Nicolet College students, further

research is warranted using additional critical thinking assessment instruments, such as the

Watson Glaser Critical thinking Appraisal and Cornell Critical Thinking Test. Comparisons

should be made and a recommendation for adoption of the most appropriate test for

42

assessing Nicolet College students should then be made based on this data.

4. In light of the Nicolet College Mission Statement which stresses the delivery of

Asuperior community college education,@ Nicolet may want to consider developing a course

specific to critical thinking to further develop it=s students critical thinking abilities. This course

could be a requirement for all program students, or identify critical thinking type courses

taught at Nicolet College, and if students are not mandated to take one of these courses, infuse

critical thinking components from these courses into all program curriculum.

REFERENCES

Allen, J. A., (1985). Student assessment-as-learning at Alverno College. Milwaukee,

WI: Alverno Publications.

The American Philosophical Association. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of

expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. The Delphi Report

.

ERIC Doc. No. ED 315-423, 80.

A nation at risk: The imperative for education reform. (1983). [Pamphlet]. Washington,

DC: USGPO, 9.

Ary, D., Jacobs, L., & Asghar, R. (1985). Introduction to research in education, 3rd.

Edition. New York, NY: CBS College Publishing.

Barnes, C.A. (1977). Critical thinking: Educational imperative. New Directions

for Community Colleges, 21,

3-24.

Cameron, K. S. (1978). Measuring organizational effectiveness in institutions of higher

education. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23

, 604-632.

Chapman. (1992). The New Roget=s Thesaurus. Thomas Y. Crowell Company, Inc.

43

842.

Clarke, J. H., & Biddle, A. W. (Eds.). (1993). Teaching critical thinking: reports from

across the curriculum (prentice hall studies in writing and culture). Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall. 12.

Conoley, J. & Impara, J. (1995). Review of the California critical thinking skills test.

The Twelfth Mental Measurements Yearbook. Lincoln, NB: The University on Nebraska Press,

143-145.

El-Khawas, E. (1990). Campus trends, higher educational panel report, No. 90.

Washington, D.C.: American Counsel on Education. ED 322 846.

Ennis, R.H. (1993). Critical thinking assessment. Theory Into Practice, 32(3), 179-

186.

Executive summary of the assessment plan of Nicolet Area Technical College. (1995,

March). Rhinelander, WI: Nicolet College

Faacione, P.A. (1990). Critical thinking : A statement of expert consensus for

purposes of educational assessment and instruction. The Delphi Report. ERIC Doc. No. TM

014423.

Facione, P.A., Facione N. C., Blohm, S., Howard, K., & Giancarlo, C. (1998). The

California critical thinking skills test manual. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press.

Facione, N.C. & Facione, P.A. (1994). The California critical thinking skills test and

the National League for Nursing accreditation requirement in critical thinking. Millbrae, CA:

The California Academic Press.

Handbook of accreditation. (2

nd

ed.).(1997). North Central Association

44

of Colleges and Schools Commission on Institutions of Higher Education. Chicago, IL.

Harris, J. C. & Clemmons, S. (1996). Utilization of Standardized Critical Thinking Tests

with Developmental Freshmen

. ERIC Doc. No. ED 412825.

Institutional effectiveness and assessment of student academic achievement

(1994,

November). [Pamphlet]. Wisconsin Technical College System.

Interim report on adult literacy and lifelong learning. Measuring progress toward the

national education goals: Potential indicators and measurement strategies. (1991). Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. ED 334 278.

Lopez, C.L. (1998). Assessment of student learning. Liberal Education. 36-43.

MacAdam, B., & Kemp, B. (1989). Bibliographic instruction and critical inquiry in the

undergraduate curriculum. Reference Librarian, 24, 233-244.

Morgan & Welker (1991). One step beyond what the literature says on institutional

effectiveness of community, junior, and technical colleges. Community College Review,

19(1), 25.

Nicolet Area Technical College Catalog (1998). [Catalog]. Rhinelander, WI: Nicolet

Area Technical College.

Osterlind, S.J. (1997). A national review of scholastic achievement in general education,

how

are we doing and why should we care. 25(8) 2.

Pascarella, E.T., & Terenzini, P.T. (1991). How college affects students: Findings and

insights

from twenty years of research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Paul, R. (1992) Critical thinking: what, why, and how. In C.A. Barnes, Critical

Thinking: Educational Imperative. New Directions for Community Colleges

, Spring, 1977, 3-

45

24.

Talaska, R. A. (1992). Critical reasoning in contemporary culture

. Albany, NY: State

University of New York Press, 5-27.

Thorndike, E.L. & Barnhart, C.L. (1983). Scott Foresman Advanced Dictionary.

Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman and Company.

Toulmin, S., Rieke, R., & Janik, A. (1979). An introduction to reasoning

. New York:

MacMillan.

Wingspread Group on Higher Education. (1993). An American imperative:Higher

expectations for higher education: An open letter to those concerned about the American future.

Johnson Foundation. ISBN.