CASTES IN INDIA

Their Mechanism, Genesis and

Development

Paper read before

the Anthropology Seminar

of

Dr. A. A. Goldenweizer

at

The Columbia University, New York, U.S.A.

on

9th May 1916

From : Indian Antiquary, May 1917, Vol. XLI

1

CASTES IN INDIA

Many of us, I dare say, have witnessed local, national or international

expositions of material objects that make up the sum total of human

civilization. But few can entertain the idea of there being such a thing as

an exposition of human institutions. Exhibition of human institutions is a

strange idea ; some might call it the wildest of ideas. But as students of

Ethnology I hope you will not be hard on this innovation, for it is not so,

and to you at least it should not be strange.

You all have visited, I believe, some historic place like the ruins of Pompeii,

and listened with curiosity to the history of the remains as it flowed from the

glib tongue of the guide. In my opinion a student of Ethnology, in one sense

at least, is much like the guide. Like his prototype, he holds up (perhaps

with more seriousness and desire of self-instruction) the social institutions

to view, with all the objectiveness humanly possible, and inquires into their

origin and function.

Most of our fellow students in this Seminar, which concerns itself with

primitive versus modern society, have ably acquitted themselves along

these lines by giving lucid expositions of the various institutions, modern

or primitive, in which they are interested. It is my turn now, this evening,

to entertain you, as best I can, with a paper on “Castes in India : Their

mechanism, genesis and development”

I need hardly remind you of the complexity of the subject I intend to

handle. Subtler minds and abler pens than mine have been brought to the

task of unravelling the mysteries of Caste ; but unfortunately it still remains

in the domain of the “unexplained”, not to say of the “un-understood” I am

quite alive to the complex intricacies of a hoary institution like Caste, but I

am not so pessimistic as to relegate it to the region of the unknowable, for

I believe it can be known. The caste problem is a vast one, both theoretically

and practically. Practically, it is an institution that portends tremendous

consequences. It is a local problem, but one capable of much wider mischief,

6

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

for “as long as caste in India does exist, Hindus will hardly intermarry or

have any social intercourse with outsiders ; and if Hindus migrate to other

regions on earth, Indian caste would become a world problem.”

1

Theoretically,

it has defied a great many scholars who have taken upon themselves, as

a labour of love, to dig into its origin. Such being the case, I cannot treat

the problem in its entirety. Time, space and acumen, I am afraid, would

all fail me, if I attempted to do otherwise than limit myself to a phase of

it, namely, the genesis, mechanism and spread of the caste system. I will

strictly observe this rule, and will dwell on extraneous matters only when

it is necessary to clarify or support a point in my thesis.

To proceed with the subject. According to well-known ethnologists, the

population of India is a mixture of Aryans, Dravidians, Mongolians and

Scythians. All these stocks of people came into India from various directions

and with various cultures, centuries ago, when they were in a tribal state.

They all in turn elbowed their entry into the country by fighting with their

predecessors, and after a stomachful of it settled down as peaceful neighbours.

Through constant contact and mutual intercourse they evolved a common

culture that superseded their distinctive cultures. It may be granted that

there has not been a thorough amalgamation of the various stocks that make

up the peoples of India, and to a traveller from within the boundaries of

India the East presents a marked contrast in physique and even in colour

to the West, as does the South to the North. But amalgamation can never

be the sole criterion of homogeneity as predicated of any people. Ethnically

all people are heterogeneous. It is the unity of culture that is the basis of

homogeneity. Taking this for granted, I venture to say that there is no country

that can rival the Indian Peninsula with respect to the unity of its culture.

It has not only a geographic unity, but it has over and above all a deeper

and a much more fundamental unity—the indubitable cultural unity that

covers the land from end to end. But it is because of this homogeneity that

Caste becomes a problem so difficult to be explained. If the Hindu Society

were a mere federation of mutually exclusive units, the matter would be

simple enough. But Caste is a parcelling of an already homogeneous unit,

and the explanation of the genesis of Caste is the explanation of this process

of parcelling.

Before launching into our field of enquiry, it is better to advise ourselves

regarding the nature of a caste I will therefore draw upon a few of the best

students of caste for their definitions of it:

(1) Mr. Senart, a French authority, defines a caste as “a close corporation,

in theory at any rate rigorously hereditary : equipped with a certain

traditional and independent organisation, including a chief and a

council, meeting on occasion in assemblies of more or less plenary

1. Ketkar, Caste, p. 4.

7

CASTES IN INDIA

authority and joining together at certain festivals : bound together

by common occupations, which relate more particularly to marriage

and to food and to questions of ceremonial pollution, and ruling its

members by the exercise of jurisdiction, the extent of which varies,

but which succeeds in making the authority of the community more

felt by the sanction of certain penalties and, above all, by final

irrevocable exclusion from the group”.

(2) Mr. Nesfield defines a caste as “a class of the community which disowns

any connection with any other class and can neither intermarry nor

eat nor drink with any but persons of their own community”.

(3) According to Sir H. Risley, “a caste may be defined as a collection of

families or groups of families bearing a common name which usually

denotes or is associated with specific occupation, claiming common

descent from a mythical ancestor, human or divine, professing to

follow the same professional callings and are regarded by those who

are competent to give an opinion as forming a single homogeneous

community”.

(4) Dr. Ketkar defines caste as “a social group having two characteristics :

(i) membership is confined to those who are born of members and

includes all persons so born ; (ii) the members are forbidden by an

inexorable social law to marry outside the group”.

To review these definitions is of great importance for our purpose. It will

be noticed that taken individually the definitions of three of the writers

include too much or too little : none is complete or correct by itself and all

have missed the central point in the mechanism of the Caste system. Their

mistake lies in trying to define caste as an isolated unit by itself, and not

as a group within, and with definite relations to, the system of caste as a

whole. Yet collectively all of them are complementary to one another, each

one emphasising what has been obscured in the other. By way of criticism,

therefore, I will take only those points common to all Castes in each of the

above definitions which are regarded as peculiarities of Caste and evaluate

them as such.

To start with Mr. Senart. He draws attention to the “idea of pollution”

as a characteristic of Caste. With regard to this point it may be safely said

that it is by no means a peculiarity of Caste as such. It usually originates

in priestly ceremonialism and is a particular case of the general belief in

purity. Consequently its necessary connection with Caste may be completely

denied without damaging the working of Caste. The “idea of pollution” has

been attached to the institution of Caste, only because the Caste that enjoys

the highest rank is the priestly Caste : while we know that priest and purity

are old associates. We may therefore conclude that the “idea of pollution”

is a characteristic of Caste only in so far as Caste has a religious flavour.

8

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

Mr. Nesfield in his way dwells on the absence of messing with those outside

the Caste as one of its characteristics. In spite of the newness of the point

we must say that Mr. Nesfield has mistaken the effect for the cause. Caste,

being a self-enclosed unit naturally limits social intercourse, including

messing etc. to members within it. Consequently this absence of messing

with outsiders is not due to positive prohibition, but is a natural result of

Caste, i.e. exclusiveness. No doubt this absence of messing originally due to

exclusiveness, acquired the prohibitory character of a religious injunction,

but it may be regarded as a later growth. Sir H. Risley, makes no new point

deserving of special attention.

We now pass on to the definition of Dr. Ketkar who has done much

for the elucidation of the subject. Not only is he a native, but he has also

brought a critical acumen and an open mind to bear on his study of Caste.

His definition merits consideration, for he has defined Caste in its relation

to a system of Castes, and has concentrated his attention only on those

characteristics which are absolutely necessary for the existence of a Caste

within a system, rightly excluding all others as being secondary or derivative

in character. With respect to his definition it must, however, be said that

in it there is a slight confusion of thought, lucid and clear as otherwise it

is. He speaks of Prohibition of Intermarriage and Membership by Autogeny

as the two characteristics of Caste. I submit that these are but two aspects

of one and the same thing, and not two different things as Dr. Ketkar

supposes them to be. If you prohibit intermarriage the result is that you

limit membership to those born within the group. Thus the two are the

obverse and the reverse sides of the same medal.

This critical evaluation of the various characteristics of Caste leave no doubt

that prohibition, or rather the absence of intermarriage—endogamy, to be

concise—is the only one that can be called the essence of Caste when rightly

understood. But some may deny this on abstract anthropological grounds, for

there exist endogamous groups without giving rise to the problem of Caste. In

a general way this may be true, as endogamous societies, culturally different,

making their abode in localities more or less removed, and having little to

do with each other are a physical reality. The Negroes and the Whites and

the various tribal groups that go by name of American Indians in the United

States may be cited as more or less appropriate illustrations in support of

this view. But we must not confuse matters, for in India the situation is

different. As pointed out before, the peoples of India form a homogeneous

whole. The various races of India occupying definite territories have more or

less fused into one another and do possess cultural unity, which is the only

criterion of a homogeneous population. Given this homogeneity as a basis,

Caste becomes a problem altogether new in character and wholly absent in

the situation constituted by the mere propinquity of endogamous social or

9

CASTES IN INDIA

tribal groups. Caste in India means an artificial chopping off of the population

into fixed and definite units, each one prevented from fusing into another

through the custom of endogamy. Thus the conclusion is inevitable that

Endogamy is the only characteristic that is peculiar to caste, and if we

succeed in showing how endogamy is maintained, we shall practically have

proved the genesis and also the mechanism of Caste.

It may not be quite easy for you to anticipate why I regard endogamy as

a key to the mystery of the Caste system. Not to strain your imagination

too much, I will proceed to give you my reasons for it.

It may not also be out of place to emphasize at this moment that no

civilized society of today presents more survivals of primitive times than does

the Indian society. Its religion is essentially primitive and its tribal code, in

spite of the advance of time and civilization, operates in all its pristine vigour

even today. One of these primitive survivals, to which I wish particularly to

draw your attention is the Custom of Exogamy. The prevalence of exogamy

in the primitive worlds is a fact too wellknown to need any explanation.

With the growth of history, however, exogamy has lost its efficacy, and

excepting the nearest blood-kins, there is usually no social bar restricting

the field of marriage. But regarding the peoples of India the law of exogamy

is a positive injunction even today. Indian society still savours of the clan

system, even though there are no clans ; and this can be easily seen from

the law of matrimony which centres round the principle of exogamy, for it is

not that Sapindas (blood-kins) cannot marry, but a marriage even between

Sagotras (of the same class) is regarded as a sacrilege.

Nothing is therefore more important for you to remember than the fact

that endogamy is foreign to the people of India. The various Gotras of

India are and have been exogamous : so are the other groups with totemic

organization. It is no exaggeration to say that with the people of India

exogamy is a creed and none dare infringe it, so much so that, in spite of

the endogamy of the Castes within them, exogamy is strictly observed and

that there are more rigorous penalties for violating exogamy than there are

for violating endogamy. You will, therefore, readily see that with exogamy

as the rule there could be no Caste, for exogamy means fusion. But we have

castes ; consequently in the final analysis creation of Castes, so far as India

is concerned, means the superposition of endogamy on exogamy. However,

in an originally exogamous population an easy working out of endogamy

(which is equivalent to the creation of Caste) is a grave problem, and it is

in the consideration of the means utilized for the preservation of endogamy

against exogamy that we may hope to find the solution of our problem.

Thus the superposition of endogamy on exogamy means the creation of caste.

But this is not an easy affair. Let us take an imaginary group that desires

to make itself into a Caste and analyse what means it will have to adopt to

10

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

make itself endogamous. If a group desires to make itself endogamous a

formal injunction against intermarriage with outside groups will be of no

avail, especially if prior to the introduction of endogamy, exogamy had been

the rule in all matrimonial relations. Again, there is a tendency in all groups

lying in close contact with one another to assimilate and amalgamate, and

thus consolidate into a homogeneous society. If this tendency is to be strongly

counteracted in the interest of Caste formation, it is absolutely necessary

to circumscribe a circle outside which people should not contract marriages.

Nevertheless, this encircling to prevent marriages from without creates

problems from within which are not very easy of solution. Roughly speaking,

in a normal group the two sexes are more or less evenly distributed, and

generally speaking there is an equality between those of the same age.

The equality is, however, never quite realized in actual societies. At the

same time to the group that is desirous of making itself into a caste the

maintenance of equality between the sexes becomes the ultimate goal, for

without it. endogamy can no longer subsist. In other words, if endogamy

is to be preserved conjugal rights from within have to be provided for,

otherwise members of the group will be driven out of the circle to take care

of themselves in any way they can. But in order that the conjugal rights be

provided for from within, it is absolutely necessary to maintain a numerical

equality between the marriageable units of the two sexes within the group

desirous of making itself into a Caste. It is only through the maintenance

of such an equality that the necessary endogamy of the group can be kept

intact, and a very large disparity is sure to break it.

The problem of Caste, then, ultimately resolves itself into one of repairing

the disparity between the marriageable units of the two sexes within it. Left

to nature, the much needed parity between the units can be realized only

when a couple dies simultaneously. But this is a rare contingency. The

husband may die before the wife and create a surplus woman, who must be

disposed of, else through intermarriage she will violate the endogamy of the

group. In like manner the husband may survive his wife and be surplus man,

whom the group, while it may sympathise with him for the sad bereavement,

has to dispose of, else he will marry outside the Caste and will break the

endogamy. Thus both the surplus man and the surplus woman constitute a

menace to the Caste if not taken care of, for not finding suitable partners

inside their prescribed circle (and left to themselves they cannot find any,

for if the matter be not regulated there can only be just enough pairs to

go round) very likely they will transgress the boundary, marry outside and

import offspring that is foreign to the Caste.

Let us see what our imaginary group is likely to do with this surplus man

and surplus woman. We will first take up the case of the surplus woman.

11

CASTES IN INDIA

She can be disposed of in two different ways so as to preserve the endogamy

of the Caste.

First: burn her on the funeral pyre of her deceased husband and get

rid of her. This, however, is rather an impracticable way of solving the

problem of sex disparity. In some cases it may work, in others it may not.

Consequently every surplus woman cannot thus be disposed of, because it

is an easy solution but a hard realization. And so the surplus woman (=

widow), if not disposed of, remains in the group : but in her very existence

lies a double danger. She may marry outside the Caste and violate endogamy,

or she may marry within the Caste and through competition encroach upon

the chances of marriage that must be reserved for the potential brides in

the Caste. She is therefore a menance in any case, and something must

be done to her if she cannot be burned along with her deceased husband.

The second remedy is to enforce widowhood on her for the rest of her life.

So far as the objective results are concerned, burning is a better solution

than enforcing widowhood. Burning the widow eliminates all the three evils

that a surplus woman is fraught with. Being dead and gone she creates no

problem of remarriage either inside or outside the Caste. But compulsory

widowhood is superior to burning because it is more practicable. Besides

being comparatively humane it also guards against the evils of remarriage

as does burning; but it fails to guard the morals of the group. No doubt

under compulsory widowhood the woman remains, and just because she is

deprived of her natural right of being a legitimate wife in future, the incentive

to immoral conduct is increased. But this is by no means an insuperable

difficulty. She can be degraded to a condition in which she is no longer a

source of allurement.

The problem of surplus man (= widower) is much more important and

much more difficult than that of the surplus woman in a group that desires

to make itself into a Caste. From time immemorial man as compared with

woman has had the upper hand. He is a dominant figure in every group

and of the two sexes has greater prestige. With this traditional superiority

of man over woman his wishes have always been consulted. Woman, on the

other hand, has been an easy prey to all kinds of iniquitous injunctions,

religious, social or economic. But man as a maker of injunctions is most

often above them all. Such being the case, you cannot accord the same kind

of treatment to a surplus man as you can to a surplus woman in a Caste.

The project of burning him with his deceased wife is hazardous in two

ways : first of all it cannot be done, simply because he is a man. Secondly,

if done, a sturdy soul is lost to the Caste. There remain then only two

solutions which can conveniently dispose of him. I say conveniently, because

he is an asset to the group.

12

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

Important as he is to the group, endogamy is still more important, and

the solution must assure both these ends. Under these circumstances he

may be forced or I should say induced, after the manner of the widow, to

remain a widower for the rest of his life. This solution is not altogether

difficult, for without any compulsion some are so disposed as to enjoy self-

imposed celibacy, or even to take a further step of their own accord and

renounce the world and its joys. But, given human nature as it is, this

solution can hardly be expected to be realized. On the other hand, as is

very likely to be the case, if the surplus man remains in the group as an

active participator in group activities, he is a danger to the morals of the

group. Looked at from a different point of view celibacy, though easy in

cases where it succeeds, is not so advantageous even then to the material

prospects of the Caste. If he observes genuine celibacy and renounces the

world, he would not be a menace to the preservation of Caste endogamy or

Caste morals as he undoubtedly would be if he remained a secular person.

But as an ascetic celibate he is as good as burned, so far as the material

well-being of his Caste is concerned. A Caste, in order that it may be large

enough to afford a vigorous communal life, must be maintained at a certain

numerical strength. But to hope for this and to proclaim celibacy is the same

as trying to cure atrophy by bleeding.

Imposing celibacy on the surplus man in the group, therefore, fails both

theoretically and practically. It is in the interest of the Caste to keep him

as a Grahastha (one who raises a family), to use a Sanskrit technical term.

But the problem is to provide him with a wife from within the Caste. At

the outset this is not possible, for the ruling ratio in a caste has to be one

man to one woman and none can have two chances of marriage, for in a

Caste thoroughly self-enclosed there are always just enough marriageable

women to go round for the marriageable men. Under these circumstances

the surplus man can be provided with a wife only by recruiting a bride

from the ranks of those not yet marriageable in order to tie him down to

the group. This is certainly the best of the possible solutions in the case

of the surplus man. By this, he is kept within the Caste. By this means

numerical depletion through constant outflow is guarded against, and by

this endogamy morals are preserved.

It will now be seen that the four means by which numerical disparity

between the two sexes is conveniently maintained are : (1) burning the widow

with her deceased husband ; (2) compulsory widowhood—a milder form of

burning ; (3) imposing celibacy on the widower and (4) wedding him to a girl

not yet marriageable. Though, as I said above, burning the widow and imposing

celibacy on the widower are of doubtful service to the group in its endeavour

to preserve its endogamy, all of them operate as means. But means, as forces,

when liberated or set in motion create an end. What then is the end that

these means create ? They create and perpetuate endogamy, while caste and

13

CASTES IN INDIA

endogamy, according to our analysis of the various definitions of caste, are

one and the same thing. Thus the existence of these means is identical with

caste and caste involves these means.

This, in my opinion, is the general mechanism of a caste in a system of

castes. Let us now turn from these high generalities to the castes in Hindu

Society and inquire into their mechanism. I need hardly premise that there

are a great many pitfalls in the path of those who try to unfold the past,

and caste in India to be sure is a very ancient institution. This is especially

true where there exist no authentic or written records or where the people,

like the Hindus, are so constituted that to them writing history is a folly,

for the world is an illusion. But institutions do live, though for a long time

they may remain unrecorded and as often as not customs and morals are

like fossils that tell their own history. If this is true, our task will be amply

rewarded if we scrutinize the solution the Hindus arrived at to meet the

problems of the surplus man and surplus woman.

Complex though it be in its general working the Hindu Society, even to

a superficial observer, presents three singular uxorial customs, namely :

(i) Sati or the burning of the widow on the funeral pyre of her deceased

husband.

(ii) Enforced widowhood by which a widow is not allowed to remarry.

(iii) Girl marriage.

In addition, one also notes a great hankering after Sannyasa (renunciation)

on the part of the widower, but this may in some cases be due purely to

psychic disposition.

So far as I know, no scientific explanation of the origin of these customs

is forthcoming even today. We have plenty of philosophy to tell us why these

customs were honoured, but nothing to tell us the causes of their origin and

existence. Sati has been honoured (Cf. A. K. Coomaraswamy, Sati: A Defence

of the Eastern Woman in the British Sociological Review, Vol. VI, 1913)

because it is a “proof of the perfect unity of body and soul” between husband

and wife and of “devotion beyond the grave”, because it embodied the ideal

of wifehood, which is well expressed by Uma when she said, “Devotion to her

Lord is woman’s honour, it is her eternal heaven : and O Maheshvara”, she

adds with a most touching human cry, “I desire not paradise itself if thou

are not satisfied with me !” Why compulsory widowhood is honoured I know

not, nor have I yet met with any one who sang in praise of it, though there

are a great many who adhere to it. The eulogy in honour of girl marriage is

reported by Dr. Ketkar to be as follows : “A really faithful man or woman

ought not to feel affection for a woman or a man other than the one with

whom he or she is united. Such purity is compulsory not only after marriage,

but even before marriage, for that is the only correct ideal of chastity. No

maiden could be considered pure if she feels love for a man other than the one

14

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

to whom she might be married. As she does not know to whom she is going

to be married, she must not feel affection for any man at all before marriage.

If she does so, it is a sin. So it is better for a girl to know whom she has

to love before any sexual consciousness has been awakened in her.”

2

Hence

girl marriage.

This high-flown and ingenious sophistry indicates why these institutions

were honoured, but does not tell us why they were practised. My own

interpretation is that they were honoured because they were practised.

Any one slightly acquainted with rise of individualism in the 18th century

will appreciate my remark. At all times, it is the movement that is most

important; and the philosophies grow around it long afterwards to justify it

and give it a moral support. In like manner I urge that the very fact that

these customs were so highly eulogized proves that they needed eulogy for

their prevalence. Regarding the question as to why they arose, I submit

that they were needed to create the structure of caste and the philosophies

in honour of them were intended to popularize them, or to gild the pill,

as we might say, for they must have been so abominable and shocking to

the moral sense of the unsophisticated that they needed a great deal of

sweetening. These customs are essentially of the nature of means, though they

are represented as ideals. But this should not blind us from understanding

the results that flow from them. One might safely say that idealization of

means is necessary and in this particular case was perhaps motivated to

endow them with greater efficacy. Calling a means an end does no harm,

except that it disguises its real character ; but it does not deprive it of its

real nature, that of a means. You may pass a law that all cats are dogs,

just as you can call a means an end. But you can no more change the

nature of means thereby than you can turn cats into dogs; consequently I

am justified in holding that, whether regarded as ends or as means, Sati,

enforced widowhood and girl marriage are customs that were primarily

intended to solve the problem of the surplus man and surplus woman in a

caste and to maintain its endogamy. Strict endogamy could not be preserved

without these customs, while caste without endogamy is a fake.

Having explained the mechanism of the creation and preservation of

Caste in India, the further question as to its genesis naturally arises. The

question or origin is always an annoying question and in the study of Caste

it is sadly neglected ; some have connived at it, while others have dodged it.

Some are puzzled as to whether there could be such a thing as the origin

of caste and suggest that “if we cannot control our fondness for the word

‘origin’, we should better use the plural form, viz. ‘origins of caste’ ”. As for

myself I do not feel puzzled by the Origin of Caste in India for, as I have

established before, endogamy is the only characteristic of Caste and when

I say Origin of Caste I mean The Origin of the Mechanism for Endogamy.

2. History of Caste in India, 1909, pp. 2-33.

15

CASTES IN INDIA

The atomistic conception of individuals in a Society so greatly popularised—

I was about to say vulgarized—in political orations is the greatest humbug.

To say that individuals make up society is trivial; society is always composed

of classes. It may be an exaggeration to assert the theory of class-conflict,

but the existence of definite classes in a society is a fact. Their basis may

differ. They may be economic or intellectual or social, but an individual in

a society is always a member of a class. This is a universal fact and early

Hindu society could not have been an exception to this rule, and, as a matter

of fact, we know it was not. If we bear this generalization in mind, our study

of the genesis of caste would be very much facilitated, for we have only to

determine what was the class that first made itself into a caste, for class

and caste, so to say, are next door neighbours, and it is only a span that

separates the two. A Caste is an Enclosed Class.

The study of the origin of caste must furnish us with an answer to the

question—what is the class that raised this “enclosure” around itself ? The

question may seem too inquisitorial, but it is pertinent, and an answer to

this will serve us to elucidate the mystery of the growth and development

of castes all over India. Unfortunately a direct answer to this question is

not within my power. I can answer it only indirectly. I said just above that

the customs in question were current in the Hindu society. To be true to

facts it is necessary to qualify the statement, as it connotes universality of

their prevalence. These customs in all their strictness are obtainable only in

one caste, namely the Brahmins, who occupy the highest place in the social

hierarchy of the Hindu society ; and as their prevalence in non-Brahmin castes

is derivative of their observance is neither strict nor complete. This important

fact can serve as a basis of an important observation. If the prevalence of

these customs in the non-Brahmin Castes is derivative, as can be shown

very easily, then it needs no argument to prove what class is the father of

the institution of caste. Why the Brahmin class should have enclosed itself

into a caste is a different question, which may be left as an employment

for another occasion. But the strict observance of these customs and the

social superiority arrogated by the priestly class in all ancient civilizations

are sufficient to prove that they were the originators of this “unnatural

institution” founded and maintained through these unnatural means.

I now come to the third part of my paper regarding the question of the

growth and spread of the caste system all over India. The question I have

to answer is : How did the institution of caste spread among the rest of the

non-Brahmin population of the country ? The question of the spread of the

castes all over India has suffered a worse fate than the question of genesis.

And the main cause, as it seems to me, is that the two questions of spread

and of origin are not separated. This is because of the common belief among

scholars that the caste system has either been imposed upon the docile

16

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

population of India by a law-giver as a divine dispensation, or that it has

grown according to some law of social growth peculiar to the Indian people.

I first propose to handle the law-giver of India. Every country has its

law-giver, who arises as an incarnation (avatar) in times of emergency to set

right a sinning humanity and give it the laws of justice and morality. Manu,

the law-giver of India, if he did exist, was certainly an audacious person. If

the story that he gave the law of caste be credited, then Manu must have

been a dare-devil fellow and the humanity that accepted his dispensation

must be a humanity quite different from the one we are acquainted with. It

is unimaginable that the law of caste was given. It is hardly an exaggeration

to say that Manu could not have outlived his law, for what is that class that

can submit to be degraded to the status of brutes by the pen of a man, and

suffer him to raise another class to the pinnacle ? Unless he was a tyrant

who held all the population in subjection it cannot be imagined that he

could have been allowed to dispense his patronage in this grossly unjust

manner, as may be easily seen by a mere glance at his “Institutes”. I may

seem hard on Manu. but I am sure my force is not strong enough to kill

his ghost. He lives, like a disembodied spirit and is appealed to, and I am

afraid will yet live long. One thing I want to impress upon you is that Manu

did not give the law of Caste and that he could not do so. Caste existed

long before Manu. He was an upholder of it and therefore philosophised

about it, but certainly he did not and could not ordain the present order of

Hindu Society. His work ended with the codification of existing caste rules

and the preaching of Caste Dharma. The spread and growth of the Caste

system is too gigantic a task to be achieved by the power or cunning of an

individual or of a class. Similar in argument is the theory that the Brahmins

created the Caste. After what I have said regarding Manu, I need hardly

say anything more, except to point out that it is incorrect in thought and

malicious in intent. The Brahmins may have been guilty of many things,

and I dare say they were, but the imposing of the caste system on the non-

Brahmin population was beyond their mettle. They may have helped the

process by their glib philosophy, but they certainly could not have pushed

their scheme beyond their own confines. To fashion society after one’s own

pattern ! How glorious ! How hard ! One can take pleasure and eulogize

its furtherance, but cannot further it very far. The vehemence of my attack

may seem to be unnecessary ; but I can assure you that it is not uncalled

for. There is a strong belief in the mind of orthodox Hindus that the Hindu

Society was somehow moulded into the framework of the Caste System and

that it is an organization consciously created by the Shastras. Not only does

this belief exist, but it is being justified on the ground that it cannot but

be good, because it is ordained by the Shastras and the Shastras cannot

be wrong. I have urged so much on the adverse side of this attitude, not

because the religious sanctity is grounded on scientific basis, nor to help

those reformers who are preaching against it. Preaching did not make

17

CASTES IN INDIA

the caste system neither will it unmake it. My aim is to show the falsity of

the attitude that has exalted religious sanction to the position of a scientific

explanation.

Thus the great man theory does not help us very far in solving the spread

of castes in India. Western scholars, probably not much given to hero-

worship, have attempted other explanations. The nuclei, round which have

“formed” the various castes in India, are, according to them : (1) occupation;

(2) survivals of tribal organizations etc. ; (3) the rise of new belief; (4) cross-

breeding and (5) migration.

The question may be asked whether these nuclei do not exist in other

societies and whether they are peculiar to India. If they are not peculiar to

India, but are common to the world, why is it that they did not “form” caste

on other parts of this planet ? Is it because those parts are holier than the

land of the Vedas, or that the professors are mistaken ? I am afraid that

the latter is the truth.

In spite of the high theoretic value claimed by the several authors for

their respective theories based on one or other of the above nuclei, one

regrets to say that on close examination they are nothing more than filling

illustrations— what Matthew Arnold means by “the grand name without

the grand thing in it”. Such are the various theories of caste advanced by

Sir Denzil Ibbetson, Mr. Nesfield, Mr. Senart and Sir H. Risley. To criticise

them in a lump would be to say that they are a disguised form of the Petitio

Principii of formal logic. To illustrate : Mr. Nesfield says that “function and

function only. .. was the foundation upon which the whole system of Castes

in India was built up”. But he may rightly be reminded that he does not very

much advance our thought by making the above statement, which practically

amounts to saying that castes in India are functional or occupational, which

is a very poor discovery ! We have yet to know from Mr. Nesfield why is it

that an occupational group turned into an occupational caste ? I would very

cheerfully have undertaken the task of dwelling on the theories of other

ethnologists, had it not been for the fact that Mr. Nesfield’s is a typical one.

Without stopping to criticize those theories that explain the caste system

as a natural phenomenon occurring in obedience to the law of disintegration,

as explained by Herbert Spencer in his formula of evolution, or as natural

as “the structural differentiation within an organism”—to employ the

phraseology of orthodox apologists—, or as an early attempt to test the laws

of eugenics—as all belonging to the same class of fallacy which regards the

caste system as inevitable, or as being consciously imposed in anticipation

of these laws on a helpless and humble population, I will now lay before

you my own view on the subject.

We shall be well advised to recall at the outset that the Hindu society, in

common with other societies, was composed of classes and the earliest known

18

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

are the (1) Brahmins or the priestly class ; (2) the Kshatriya, or the

military class ; (3) the Vaishya, or the merchant class and (4) the Shudra,

or the artisan and menial class. Particular attention has to be paid to the

fact that this was essentially a class system, in which individuals, when

qualified, could change their class, and therefore classes did change their

personnel. At some time in the history of the Hindus, the priestly class

socially detached itself from the rest of the body of people and through

a closed-door policy became a caste by itself. The other classes being

subject to the law of social division of labour underwent differentiation,

some into large, others into very minute groups. The Vaishya and Shudra

classes were the original inchoate plasm, which formed the sources of

the numerous castes of today. As the military occupation does not very

easily lend itself to very minute sub-division, the Kshatriya class could

have differentiated into soldiers and administrators.

This sub-division of a society is quite natural. But the unnatural thing

about these sub-divisions is that they have lost the open-door character

of the class system and have become self-enclosed units called castes.

The question is : were they compelled to close their doors and become

endogamous, or did they close them of their own accord ? I submit that

there is a double line of answer : Some closed the door : Others found it

closed against them. The one is a psychological interpretation and the

other is mechanistic, but they are complementary and both are necessary

to explain the phenomena of caste-formation in its entirety.

I will first take up the psychological interpretation. The question we

have to answer in this connection is : Why did these sub-divisions or

classes, if you please, industrial, religious or otherwise, become self-

enclosed or endogamous ? My answer is because the Brahmins were so.

Endogamy or the closed-door system, was a fashion in the Hindu society,

and as it had originated from the Brahmin caste it was whole-heartedly

imitated by all the non-Brahmin sub-divisions or classes, who, in their

turn, became endo gamous castes. It is “the infection of imitation” that

caught all these sub-divisions on their onward march of differentiation

and has turned them into castes. The propensity to imitate is a deep-

seated one in the human mind and need not be deemed an inadequate

explanation for the formation of the various castes in India. It is so

deep-seated that Walter Bagehot argues that, “We must not think of

. . . imitation as voluntary, or even conscious. On the contrary it has

its seat mainly in very obscure parts of the mind, whose notions, so far

from being consciously produced, are hardly felt to exist; so far from

being conceived beforehand, are not even felt at the time. The main

seat of the imitative part of our nature is our belief, and the causes

predisposing us to believe this or disinclining us to believe that are

among the obscurest parts of our nature. But as to the imitative nature

19

CASTES IN INDIA

of credulity there can be no doubt.”

3

This propensity to imitate has been made

the subject of a scientific study by Gabriel Tarde, who lays down three laws

of imitation. One of his three laws is that imitation flows from the higher to

the lower or, to quote his own words, “Given the opportunity, a nobility will

always and everywhere imitate its leaders, its kings or sovereigns, and the

people likewise, given the opportunity, its nobility.”

4

Another of Tarde’s laws

of imitation is : that the extent or intensity of imitation varies inversely in

proportion to distance, or in his own words “The thing that is most imitated

is the most superior one of those that are nearest. In fact, the influence

of the model’s example is efficacious inversely to its distance as well as

directly to its superiority. Distance is understood here in its sociological

meaning. However distant in space a stranger may be, he is close by, from

this point of view, if we have numerous and daily relations with him and

if we have every facility to satisfy our desire to imitate him. This law of

the imitation of the nearest, of the least distant, explains the gradual and

consecutive character of the spread of an example that has been set by the

higher social ranks.”

5

In order to prove my thesis—which really needs no proof—that some castes

were formed by imitation, the best way, it seems to me, is to find out whether

or not the vital conditions for the formation of castes by imitation exist in

the Hindu Society. The conditions for imitation, according to this standard

authority are : (1) that the source of imitation must enjoy prestige in the group

and (2) that there must be “numerous and daily relations” among members

of a group. That these conditions were present in India there is little reason

to doubt. The Brahmin is a semi-god and very nearly a demi-god. He sets

up a mode and moulds the rest. His prestige is unquestionable and is the

fountain-head of bliss and good. Can such a being, idolised by scriptures and

venerated by the priest-ridden multitude, fail to project his personality on

the suppliant humanity ? Why, if the story be true, he is believed to be the

very end of creation. Such a creature is worthy of more than mere imitation,

but at least of imitation ; and if he lives in an endogamous enclosure, should

not the rest follow his example ? Frail humanity! Be it embodied in a grave

philosopher or a frivolous housemaid, it succumbs. It cannot be otherwise.

Imitation is easy and invention is difficult.

Yet another way of demonstrating the play of imitation in the formation

of castes is to understand the attitude of non-Brahmin classes towards those

customs which supported the structure of caste in its nascent days until, in

the course of history, it became embedded in the Hindu mind and hangs there

to this day without any support—for now it needs no prop but belief—like

3. Physics and Politics, 1915, p. 60.

4. Laws of Imitation, Tr. by E.C. Parsons, 2nd edition, p. 217.

5. Ibid., p. 224.

20

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

a weed on the surface of a pond. In a way, but only in a way, the status of a

caste in the Hindu Society varies directly with the extent of the observance of

the customs of Sati, enforced widowhood, and girl marriage. But observance

of these customs varies directly with the distance (I am using the word in

the Tardian sense) that separates the caste. Those castes that are nearest

to the Brahmins have imitated all the three customs and insist on the strict

observance thereof. Those that are less near have imitated enforced widowhood

and girl marriage ; others, a little further off, have only girl marriage and

those furthest off have imitated only the belief in the caste principle. This

imperfect imitation, I dare say, is due partly to what Tarde calls “distance”

and partly to the barbarous character of these customs. This phenomenon

is a complete illustration of Tarde’s law and leaves no doubt that the whole

process of caste-formation in India is a process of imitation of the higher by

the lower. At this juncture I will turn back to support a former conclusion

of mine, which might have appeared to you as too sudden or unsupported.

I said that the Brahmin class first raised the structure of caste by the

help of those three customs in question. My reason for that conclusion was

that their existence in other classes was derivative. After what I have said

regarding the role of imitation in the spread of these customs among the

non-Brahmin castes, as means or as ideals, though the imitators have not

been aware of it, they exist among them as derivatives ; and, if they are

derived, there must have been prevalent one original caste that was high

enough to have served as a pattern for the rest. But in a theocratic society,

who could be the pattern but the servant of God ?

This completes the story of those that were weak enough to close their

doors. Let us now see how others were closed in as a result of being closed out.

This I call the mechanistic process of the formation of caste. It is mechanistic

because it is inevitable. That this line of approach, as well as the psychological

one, to the explanation of the subject has escaped my predecessors is entirely

due to the fact that they have conceived caste as a unit by itself and not as

one within a System of Caste. The result of this oversight or lack of sight has

been very detrimental to the proper understanding of the subject matter and

therefore its correct explanation. I will proceed to offer my own explanation

by making one remark which I will urge you to bear constantly in mind. It

is this : that caste in the singular number is an unreality. Castes exist only

in the plural number. There is no such thing as a caste : There are always

castes. To illustrate my meaning : while making themselves into a caste, the

Brahmins, by virtue of this, created non-Brahmin caste; or, to express it in my

own way, while closing themselves in they closed others out. I will clear my

point by taking another illustration. Take India as a whole with its various

communities designated by the various creeds to which they owe allegiance,

to wit, the Hindus, Mohammedans, Jews, Christians and Parsis. Now,

barring the Hindus, the rest within themselves are non-caste communities.

21

CASTES IN INDIA

But with respect to each other they are castes. Again, if the first four enclose

themselves, the Parsis are directly closed out, but are indirectly closed in.

Symbolically, if Group A wants to be endogamous, Group B has to be so by

sheer force of circumstances.

Now apply the same logic to the Hindu society and you have another

explanation of the “fissiparous” character of caste, as a consequence of the

virtue of self-duplication that is inherent in it. Any innovation that seriously

antagonises the ethical, religious and social code of the Caste is not likely

to be tolerated by the Caste, and the recalcitrant members of a Caste are in

danger of being thrown out of the Caste, and left to their own fate without

having the alternative of being admitted into or absorbed by other Castes.

Caste rules are inexorable and they do not wait to make nice distinctions

between kinds of offence. Innovation may be of any kind, but all kinds

will suffer the same penalty. A novel way of thinking will create a new

Caste for the old ones will not tolerate it. The noxious thinker respectfully

called Guru (Prophet) suffers the same fate as the sinners in illegitimate

love. The former creates a caste of the nature of a religious sect and the

latter a type of mixed caste. Castes have no mercy for a sinner who has

the courage to violate the code. The penalty is excommunication and the

result is a new caste. It is not peculiar Hindu psychology that induces

the excommunicated to form themselves into a caste ; far from it. On the

contrary, very often they have been quite willing to be humble members of

some caste (higher by preference) if they could be admitted within its fold.

But castes are enclosed units and it is their conspiracy with clear conscience

that compels the excommunicated to make themselves into a caste. The logic

of this obdurate circumstance is merciless, and it is in obedience to its force

that some unfortunate groups find themselves enclosed, because others in

enclosing, themselves have closed them out, with the result that new groups

(formed on any basis obnoxious to the caste rules) by a mechanical law are

constantly being converted into castes to a bewildering multiplicity. Thus is

told the second tale in the process of Caste formation in India.

Now to summarise the main points of my thesis. In my opinion there

have been several mistakes committed by the students of Caste, which have

misled them in their investigations. European students of Caste have unduly

emphasised the role of colour in the Caste system. Themselves impregnated

by colour prejudices, they very readily imagined it to be the chief factor in the

Caste problem. But nothing can be farther from the truth, and Dr. Ketkar

is correct when he insists that “All the princes whether they belonged to the

so-called Aryan race, or the so-called Dravidian race, were Aryas. Whether

a tribe or a family was racially Aryan or Dravidian was a question which

never troubled the people of India, until foreign scholars came in and began

to draw the line. The colour of the skin had long ceased to be a matter of

22

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR : WRITINGS AND SPEECHES

importance.”

6

Again, they have mistaken mere descriptions for explanation

and fought over them as though they were theories of origin. There are

occupational, religious etc., castes, it is true, but it is by no means an

explanation of the origin of Caste. We have yet to find out why occupational

groups are castes ; but this question has never even been raised. Lastly

they have taken Caste very lightly as though a breath had made it. On the

contrary, Caste, as I have explained it, is almost impossible to be sustained :

for the difficulties that it involves are tremendous. It is true that Caste

rests on belief, but before belief comes to be the foundation of an institution,

the institution itself needs to be perpetuated and fortified. My study of the

Caste problem involves four main points : (1) that in spite of the composite

make-up of the Hindu population, there is a deep cultural unity; (2) that

caste is a parcelling into bits of a larger cultural unit; (3) that there was

one caste to start with and (4) that classes have become Castes through

imitation and excommunication.

Peculiar interest attaches to the problem of Caste in India today; as

persistent attempts are being made to do away with this unnatural institution.

Such attempts at reform, however, have aroused a great deal of controversy

regarding its origin, as to whether it is due to the conscious command of

a Supreme Authority, or is an unconscious growth in the life of a human

society under peculiar circumstances. Those who hold the latter view will,

I hope, find some food for thought in the standpoint adopted in this paper.

Apart from its practical importance the subject of Caste is an all absorbing

problem and the interest aroused in me regarding its theoretic foundations

has moved me to put before you some of the conclusions, which seem to me

well founded, and the grounds upon which they may be supported. I am not,

however, so presumptuous as to think them in any way final, or anything

more than a contribution to a discussion of the subject. It seems to me that

the car has been shunted on wrong lines, and the primary object of the

paper is to indicate what I regard to be the right path of investigation, with

a view to arrive at a serviceable truth. We must, however, guard against

approaching the subject with a bias. Sentiment must be outlawed from the

domain of science and things should be judged from an objective standpoint.

For myself I shall find as much pleasure in a positive destruction of my own

idealogy, as in a rational disagreement on a topic, which, notwithstanding

many learned disquisitions is likely to remain controversial forever. To

conclude, while I am ambitious to advance a Theory of Caste, if it can be

shown to be untenable I shall be equally willing to give it up.

6. History of Caste, p. 82.

Having regard to these close resemblances between Grahasthashram and

Vanaprastha and between Vanaprastha and Sannyas it is difficult to understand

why Manu recognized this third ashram of Vanaprastha in between

Grahasthashram and Sannyas as an ashram distinct and separate from both. As

a matter of fact, there could be only three ashrams: (1) Bramhacharya, (2)

Grahastashram and (3) Sannyas. This seems to be also the view of

Shankaracharya who in his Brahma Sutra in defending the validity of Sannyas

against the Purva Mimansa School speaks only of three ashramas.

Where did Manu get this idea of Vanaprastha Ashrarn? What is his source? As

has been pointed out above, Grahasthashram was not the next compulsory

stage of life after Brahmacharya. A Brahmachari may at once become Sannyasi

without entering the stage of Grahasthashram. But there was also another line of

life which a Brahmachari who did not wish to marry immediately could adopt

namely to become Aranas or Aranamanas. They were Brahmacharies who wish

to continue the life of Study without marrying. These Aranas lived in hermitages

in forests outside the villages or centres of population. The forests where these

Arana ascetics lived were called Aranyas and the philosophical works of these

aranas were called Aranyakas. It is obvious that Manu's Vanaprastha is the

original Arana with two differences (1) he has compelled Arana to enter the

marital state and (2) the arana stage instead of being the second stage is

prescribed as the third stage. The whole scheme of Manu rest in the principle

that marriage is compulsory. A Brahmachari if he wishes to become a Sannyasi

he must become a Vanaprastha and if he wishes to become a Vanaprastha he

must become a Grasthashrami i.e., he must marry. Manu made escape from

marriage impossible. Why?

RIDDLE NO.18

MANU'S MADNESS OR THE BRAHMANIC EXPLANATION OF THE ORIGIN

OF THE MIXED CASTES

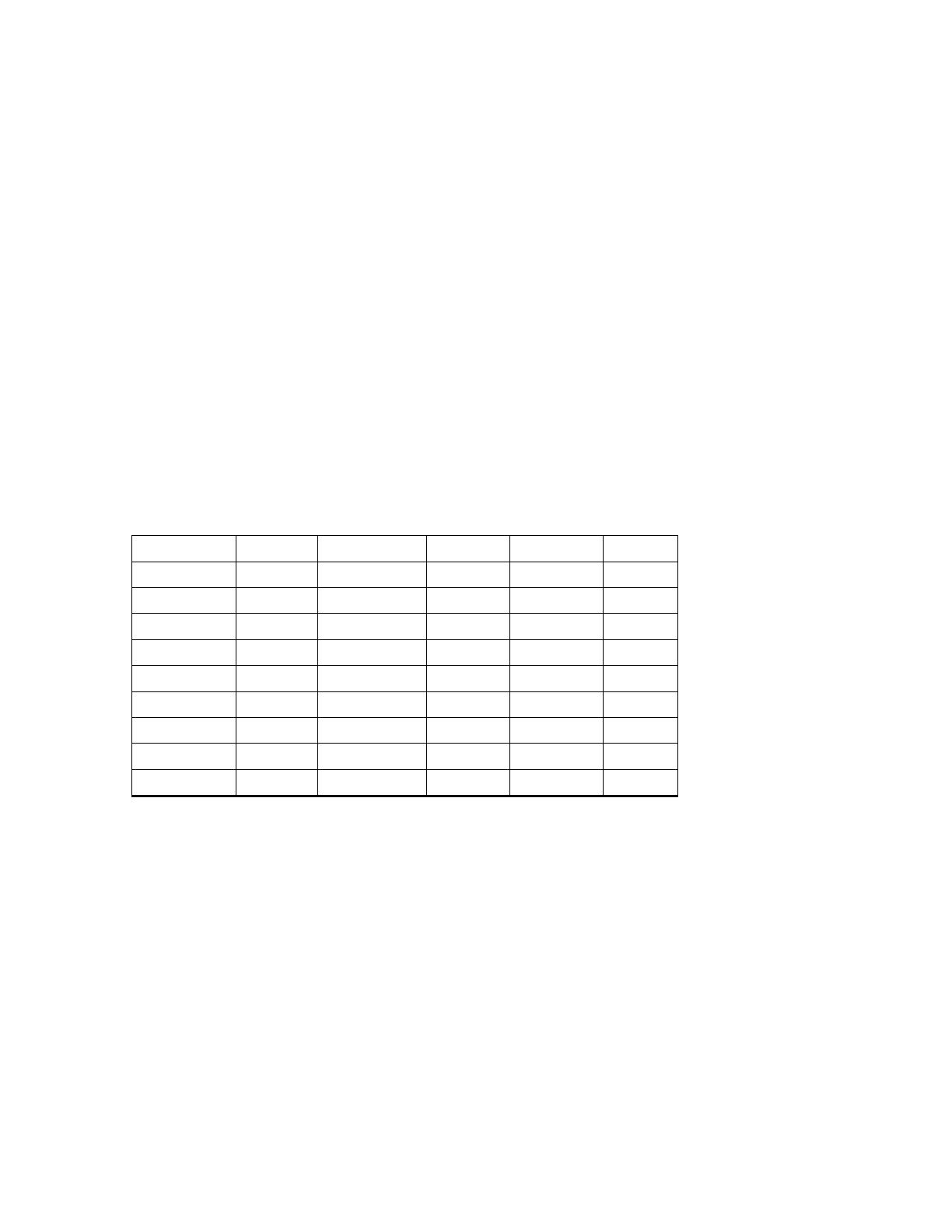

A reader of the Manu Smriti will find that Manu for the purposes of his

discussion groups the various castes under certain specific heads namely (1)

Aryan Castes, (2) Non-Aryan Castes, (3) Vratya Castes, (4) Fallen Castes and

(5) Sankara Castes.

By Aryan Castes he means the four varnas namely Brahmana, Kshatriya,

Vaishya and Shudra. In other words, Manu regards the system of Chatur-varna

to be the essence of Aryanism. By Non-Aryan Castes he means those

communities who do not accept the creed of Chaturvarna and he cites the

community called Dasyu as an illustration of those whom he regards as a Non-

Aryan community. By Vratyas he means those castes who were once believers

in the Chaturvarna but who had rebelled against it. The list of Vratyas given by

Manu includes the following castes:

Vratya Brahmanas

Vratya

Kshatriyas

Vratya Vaishyas

1. Bhrigga Kantaka

1. Jhalla

1. Sudhanvana

2. Avantya

2. Malla

2. Acharya

3. Vatadhana

3. Lacchavi

3. Karusha

4. Phushpada

4. Nata

4. Vijanman

5. Saikha

5. Karana

5. Maitra

6. Khasa

6. Satvata

7. Dravida.

This is about 20-page MS on the origin of the mixed castes '. Through the

original typed MS several handwritten pages are inserted by the author and the

text has been modified with several amendments pasted on the pages.—Ed.

In the list of Fallen Castes Manu includes those Kshatriyas who have become

Shudras by reason of the disuse of Aryan rites and ceremonies and loss of

services of the Brahmin priests. They are enumerated by Manu as under:

1. Paundrakas 7. Paradas

2. Cholas 8. Pahlvas

3. Dravidas 9. Chinas

4. Kambhojas 10. Kiratas

5. Yavanas 11. Daradas

6. Sakas

By Sankara Castes Manu means Castes the members of which are born of

parents who do not belong to the same caste.

These mixed castes he divides into various categories (1) Progeny of different

Aryan Castes which he subdivides into two classes (a) Anuloma and (b)

Pratiloma, (2) Progeny of Anuloma and Pratiloma Castes and (3) Progeny of

Non-Aryan and the Aryan Anuloma and Pratiloma Castes. Those included by

Manu under the head of mixed castes are shown below under different

categories:

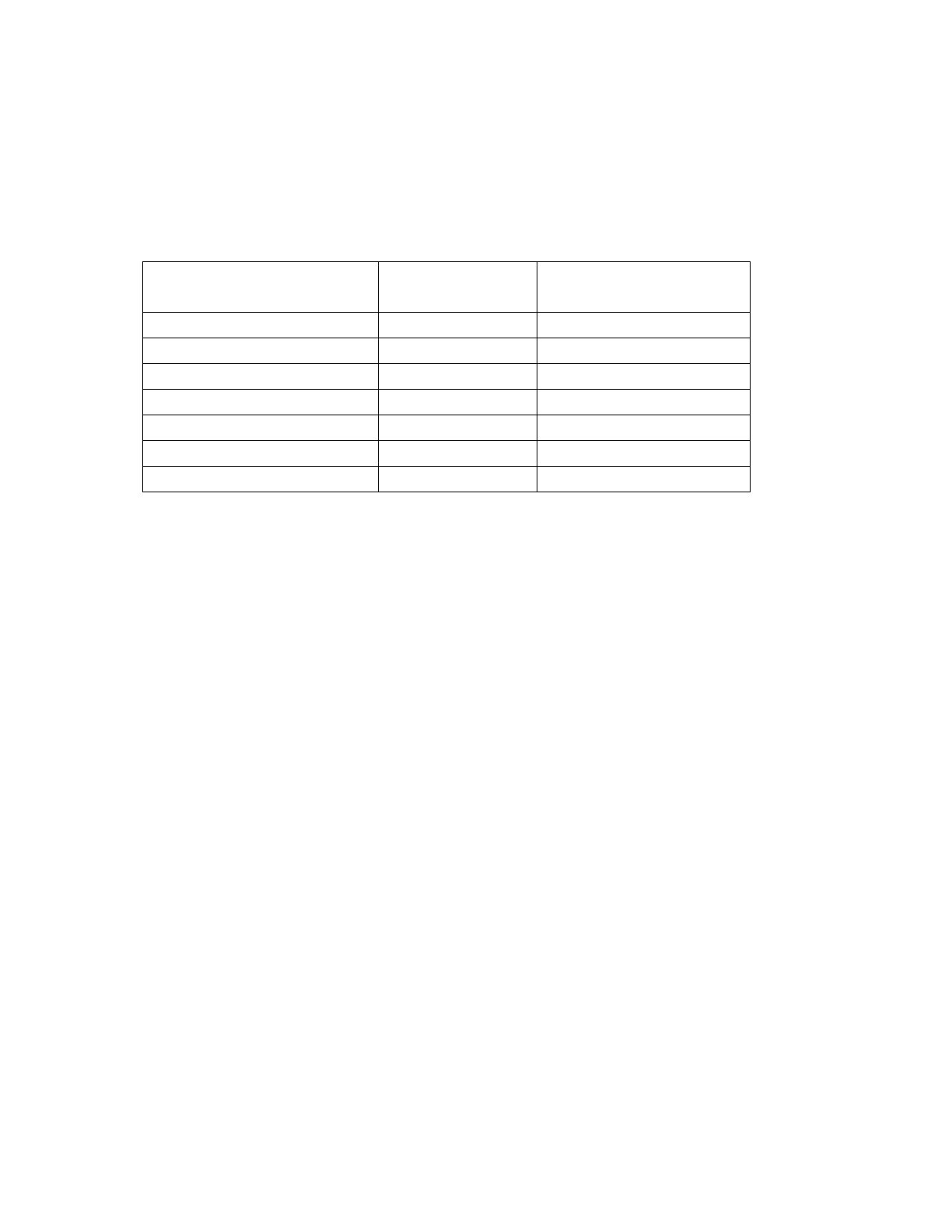

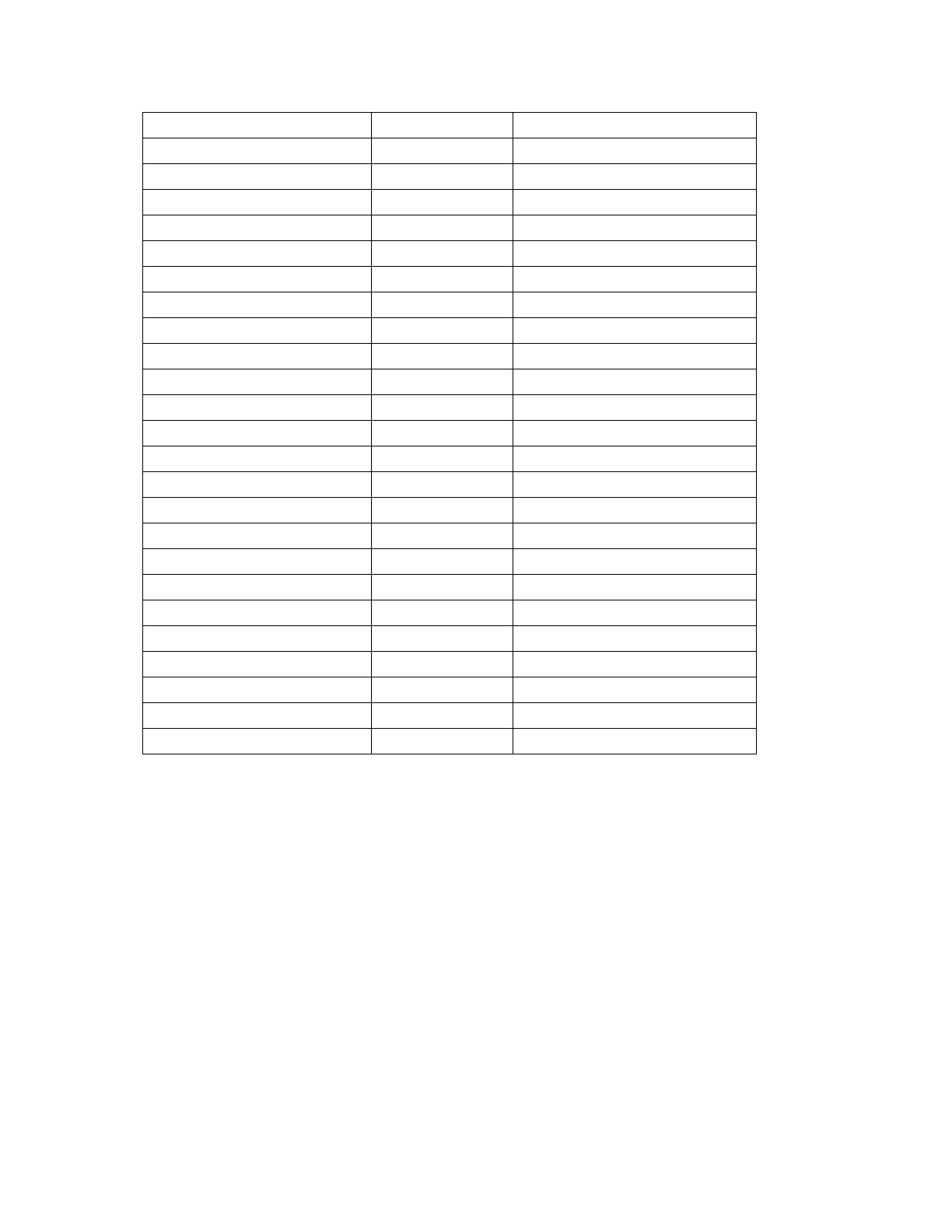

1. PROGENY OF MIXED ARYAN CASTES

Father Mother Progeny known as Anuloma or Pratiloma

Brahman

Kshatriya

?

Brahman

Vaishya

Ambashta

Anuloma

Brahman

Shudra

Nishad

(Parasava)

Anuloma

Kshatriya

Brahman

Suta

Pratiloma

Kshatriya

Vaishya

?

Kshatriya

Shudra

Ugra

Anuloma

Vaishya

Brahman

Vaidehaka

Pratiloma

Vaishya

Kshatriya

Magadha

Pratiloma

Vaishya

Shudra

Karana

Anuloma

Shudra

Brahman

Chandala

Pratiloma

Shudra

Kshatriya

Ksattri

Pratiloma

Shudra

Vaishya

Ayogava

Pratiloma

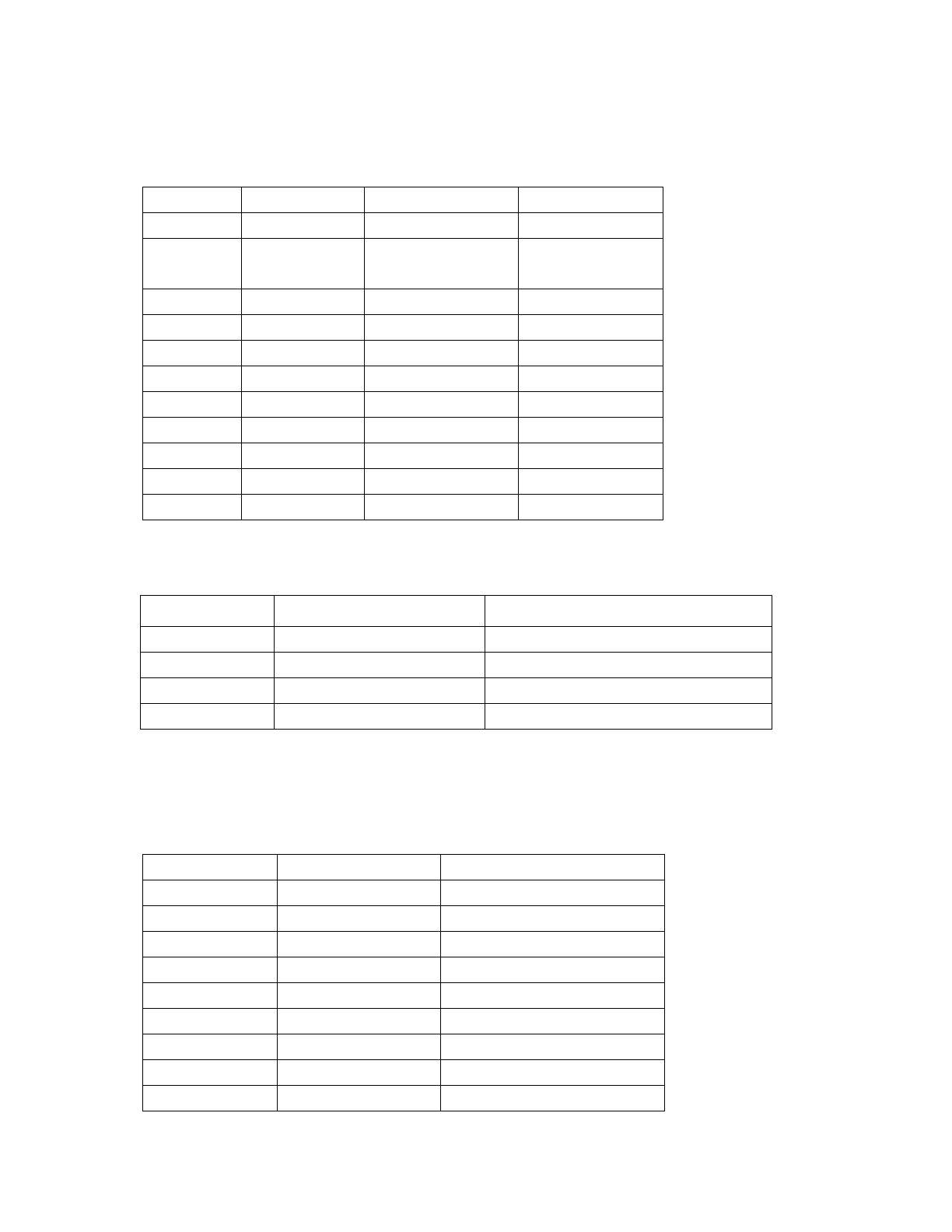

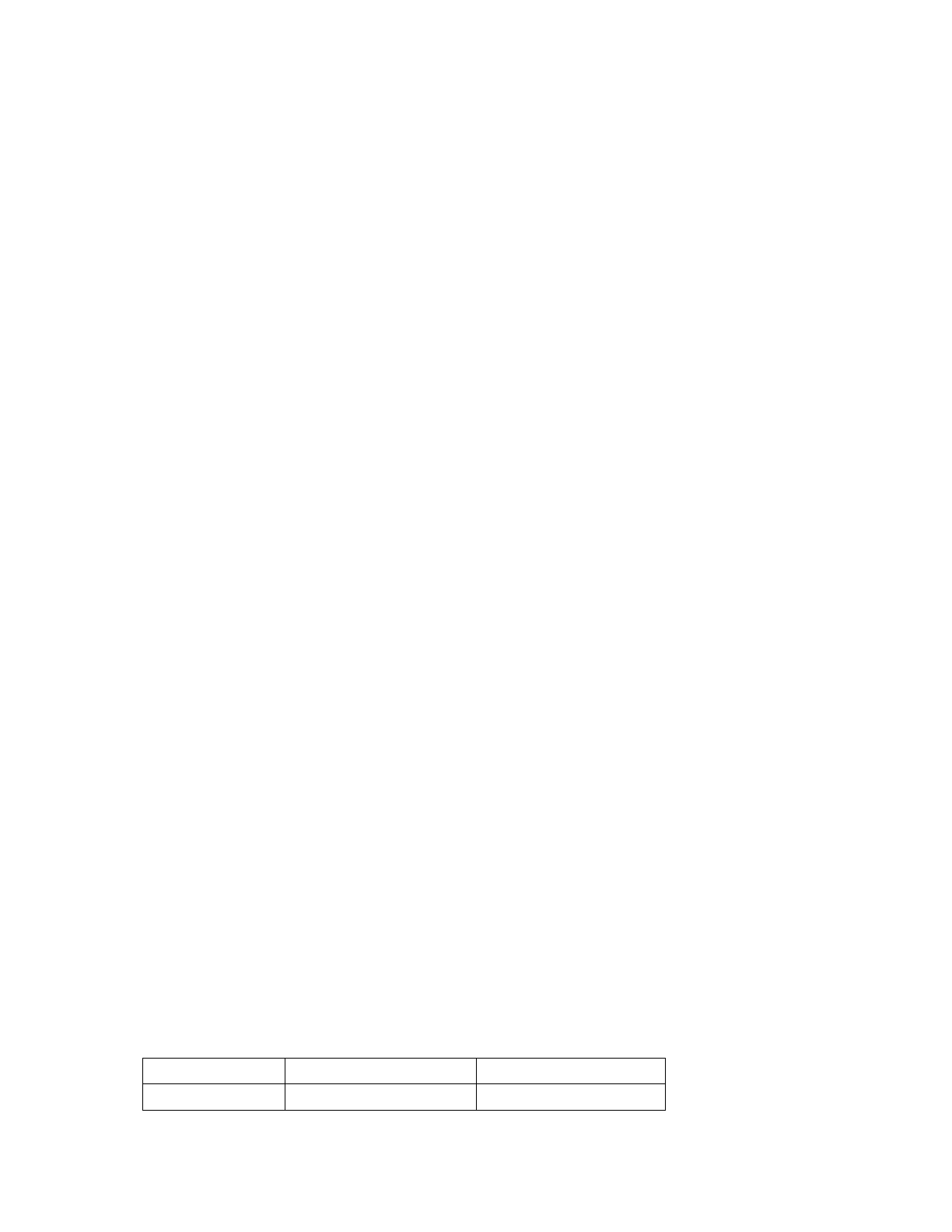

2. PROGENY OF ARYAN CASTES WITH ANULOMA-PRATILOMA CASTES

Father

Mother

Progeny Known As

1. Brahman

Ugra

Avrita

2. Brahman

Ambashta

Dhigvana

3. Brahman

Nishada

Kukutaka

4. Shudra

Abhira

Abhira

2. PROGENY OF MIXED MARRIAGES BETWEEN ANULOMA AND

PRATILOMA CASTES

Father

Mother

Progeny known as

1. Vaideha

Ayogava

Maitreyaka

2. Nishada

Ayogava

Margava (Das)

Kaivarta

3. Nishada

Vaideha

Karavara

4. Vaidehaka

Ambashta

Vena

5. Vaidehaka

Karavara

Andhra

6. Vaidehaka

Nishada

Meda

7. Chandala

Vaideha

Pandusopaka

8. Nishada

Vaideha

Ahindaka

9. Chandala

Pukkassa

Sopaka

10. Chandala

Nishada

Antyavasin

11. Kshattari

Ugra

Swapaka

To Manu's list of Sankar (mixed) Castes additions have been made by his

successors. Among these are the authors of Aushanas Smriti, Baudhayana

Smriti, Vashistha Smriti, Yajnavalkya Smriti and the Suta Sanhita.

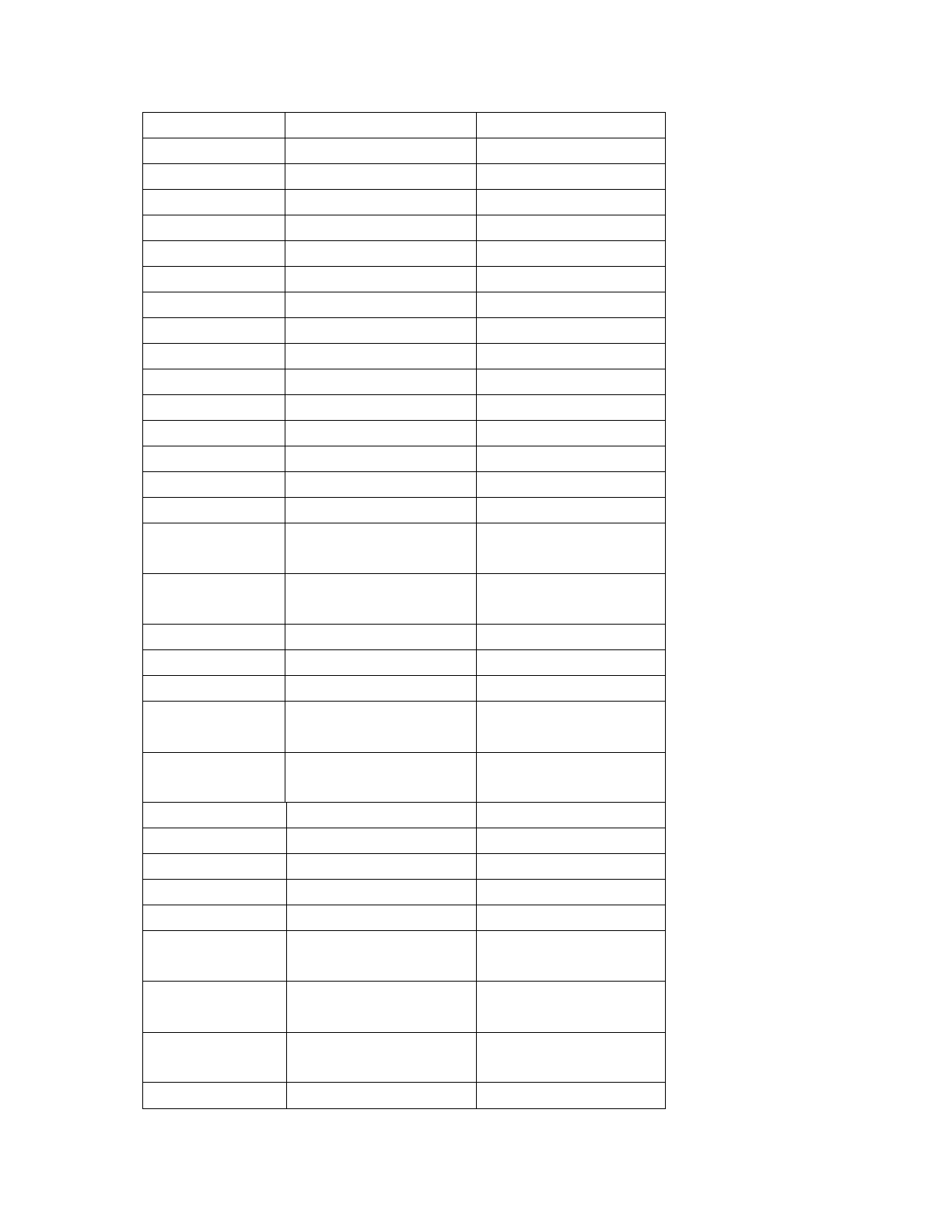

Of these additions four have been made by the Aushanas Smriti. They are

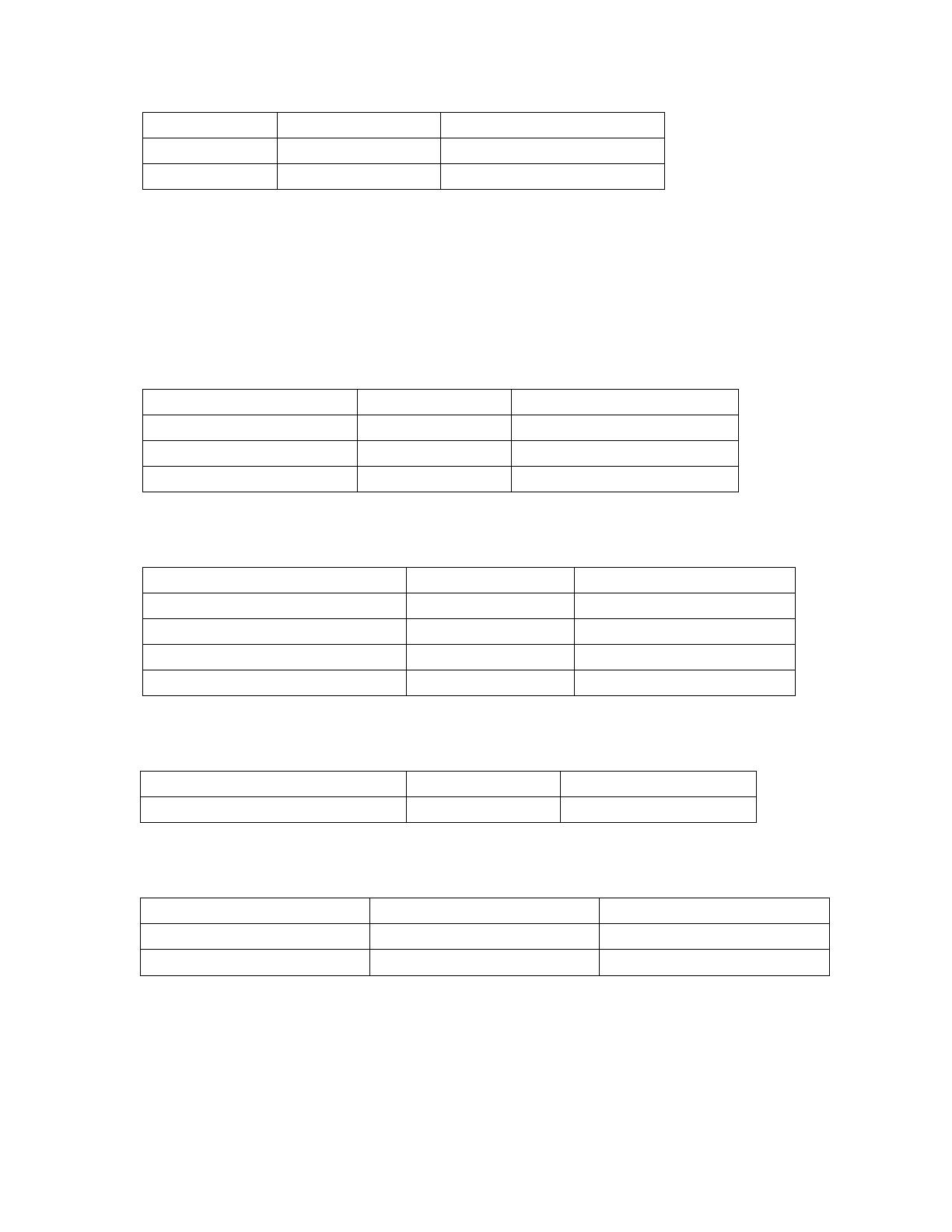

noted below:

Name of the mixed caste Father's caste Mother's caste

1. Pulaksa

Shudra

Kshatriya

2. Yekaj

Pulaksa

Vaishya

3. Charmakarka

Ayogava

Brahmin

4. Venuka

Suta

Brahmin

The following four are added by the Baudhayana Smriti

Name of the mixed caste

Father's caste

Mother's caste

1. Kshatriya

Kshatriya

Vaishya

2. Brahmana

Brahmana

Kshatriya

3. Vaina

Vaidehaka

Ambashta

4. Shvapaka

Ugra

Kshatriya

Vashishta Smriti adds one to the list of Manu, namely:

Name of the Mixed caste

Father’s caste

Mother’s caste

Vaina

Kshatriya

Shudra

The Yajnavalkya Smriti adds two new castes to Manu's list of mixed castes.

Name of mixed caste

Father’s caste

Mother’s caste

1. Murdhavasika

Brahmin

Kshatriya

2. Mahisya

Kshatriya

Vaishya

The Additions made by the author of the Suta Sanhita are on a vast scale. They

number sixty-three castes.

Name of the mixed caste

Father's caste

Mother's caste

1. Ambashteya

Kshatriya

Vaishya

2. Urdhvanapita

Brahman

Vaishya

3. Katkar

Vaishya

Shudra

4. Kumbhkar

Brahman

Vaishya

5. Kunda

Brahman

Married Brahmin

6. Golaka

Brahman

Brahmin Widow

7. Chakri

Shudra

Vaishya

8. Daushantya

Kshatriya

Shudra

9. Daushantee

Kshatriya

Shudra

10. Pattanshali

Shudra

Vaishya

11. Pulinda

Vaishya

Kshatriya

12. Bahyadas

Shudra

Brahmin

13. Bhoja

Vaishya

Kshatriya

14. Mahikar

Vaishya

Vaishya

15. Manavika

Shudra

Shudra

16. Mleccha

Vaishya

Kshatriya

17 Shalika

Vaishya

Kshatriya

18. Shundika

Brahmin

Shudra

19. Shulikha

Kshatriya

Shudra

20. Saparna

Brahman

Kshatriya

21. Agneyanartaka

Ambashta

Ambashta

22. Apitar

Brahman

Daushanti

23. Ashramaka

Dantakevala

Shudra

24. Udabandha

Sanaka

Kshatriya

25. Karana

Nata

Kshatriya

26. Karma

Karana

Kshatriya

27. Karmakar

Renuka

Kshatriya

28. Karmar

Mahishya

Karana

29. Kukkunda

Magadha

Shudra

30. Guhaka

Swapach

Brahman

31. Charmopajivan

Vaidehika

Brahman

32. Chamakar

Ayogava

Brahmani

33. Charmajivi

Nishad

Karushi

34. Taksha

Mahishya

Karana

35. Takshavriti

Ugra

Brahman

36. Dantakavelaka

Chandala

Vaishya

37. Dasyu

Nishad

Ayogava

38. Drumila

Nishad

Kshatriya

39. Nata

Picchalla

Kshatriya

40. Napita

Nishada

Brahmin

41. Niladivarnavikreta

Ayogava

Chirkari

42. Piccahalla

Malla

Kshatriya

43. Pingala

Brahmin

Ayogava

44. Bhaglabdha

Daushanta

Brahmani

45. Bharusha

Sudhanva

Vaishya

46. Bhairava

Nishada

Shudra

47. Matanga

Vijanma

Vaishya

48. Madhuka

Vaidehika

Ayogava

49. Matakar

Dasyu

Vaishya

50. Maitra

Vijanma

Vaishya

51. Rajaka

Vaideha

Brahman

52. Rathakar

Mahishya

Karana

53. Renuka

Napita

Brahman

54. Lohakar

Mahishya

Brahmani

55. Vardhaki

Mahishya

Brahmani

56. Varya

Sudhanva

Vaishya

57. Vijanma

Bharusha

Vaishya

58. Shilp

Mahishya

Karana

59. Shvapach

Chandala

Brahmani

60. Sanaka

Magadha

Kshatriya

61. Samudra

Takashavrati

Vaishya

62. Satvata

Vijanma

Vaishya

63. Sunishada

Nishad

Vaishya

Of the five categories of castes it is easy to understand the explanation given

by Manu as regards the first four. But the same cannot be said in respect of his

treatment of the fifth category namely the Sankar (mixed) caste. There are

various questions that begin to trouble the mind. In the first place Manu's list of

mixed castes is a perfunctory list. It is not an exhaustive list, stating all the

possibilities of Sankar.

In discussing the mixed castes born out of the mixture of the Aryan castes with

the Anuloma-Pratiloma castes, Manu should have specified the names of castes

which are the progeny of each of the four Aryan castes with each of the 12

Anuloma-Pratiloma castes. If he had done so we should have had a list of forty-

eight resulting castes. As a matter of fact he states only the names of four castes

of mixed marriages of this category.

In discussing the progeny of mixed marriages between Anuloma-Pratiloma

castes given the fact that we have 12 of them, Manu should have given the

names of 144 resulting castes. As a matter of fact, Manu only gives a list of I I

castes. In the formation of these I I castes, Manu gives five possible

combinations of 5 castes only. Of these one (Vaideha) is outside the Anuloma-

Pratiloma list. The case of the 8 are not considered at all.

His account of the Sankar castes born out of the Non-Aryan and the Aryan

castes is equally discrepant. We ought to have had first a list of castes resulting

from a combination between the Non-Aryans with each of the four Aryan castes.

We have none of them. Assuming that there was only one Non-Aryan caste—

Dasyu—we ought to have had a list of 12 castes resulting from a conjugation of

Dasyus with each of the Anuloma-Pratiloma castes. As a matter of fact we have

in Manu only one conjugation.

In the discussion of this subject of mixed castes Manu does not consider the

conjugation between the Vratyas and the Aryan castes, the Vratyas and the

Anuloma-Pratiloma castes, the Vratyas and the Non-Aryan castes.

Among these omissions by Manu there are some that are glaring as well as

significant. Take the case of Sankar between Brahmins and Kshatriyas. He does

not mention the caste born out of the Sankar between these two. Nor does he

mention whether the Sankar caste begotten of these two was a Pratiloma or

Anuloma. Why did Manu fail to deal with this question. Is it to be supposed that

such a Sankar did not occur in his time? Or was he afraid to mention it? If so, of

whom was he afraid?

Some of the names of the mixed castes mentioned by Manu and the other

Smritikaras appear to be quite fictitious.

For some of the communities mentioned as being of bastard origin have never

been heard of before Manu. Nor does any one know what has happened to them

since. They are today non-existent without leaving any trace behind. Caste is an

insoluble substance and once a caste is formed it maintains its separate

existence, unless for any special reason it dies out. This can happen but to a few.

Who are the Ayogava, Dhigvana, Ugra, Pukkasa, Svapaka, Svapacha,

Pandusopaka, Ahindaka, Bandika, Malta, Mahikar, Shalika, Shundika, Shulika,

Yekaj, Kukunda to mention only a few. Where are they? What has happened to

them?

Let us now proceed to compare Manu with the rest of Smritikars. Are they

unanimous on the origin of the various mixed castes referred to by them? Far

from it compare the following cases.

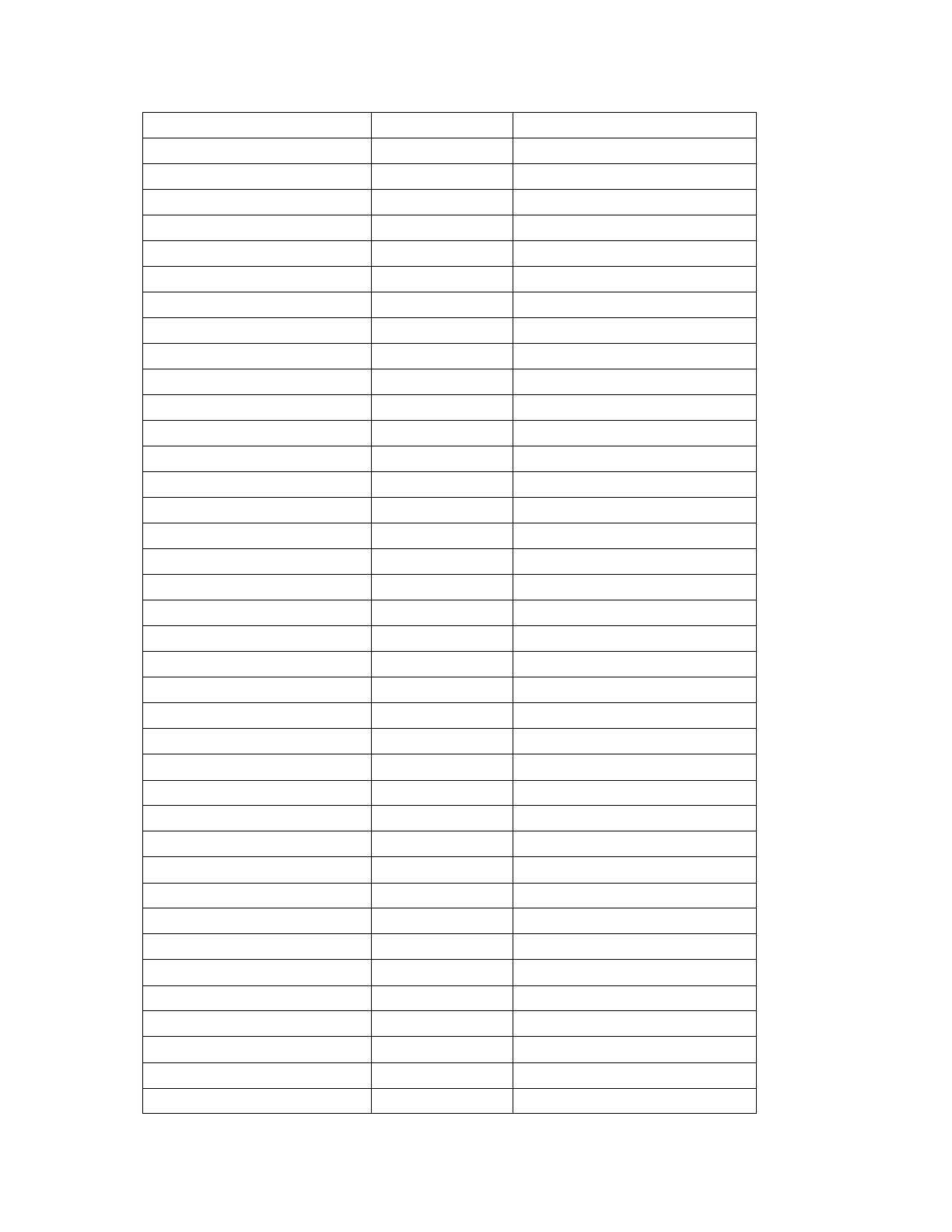

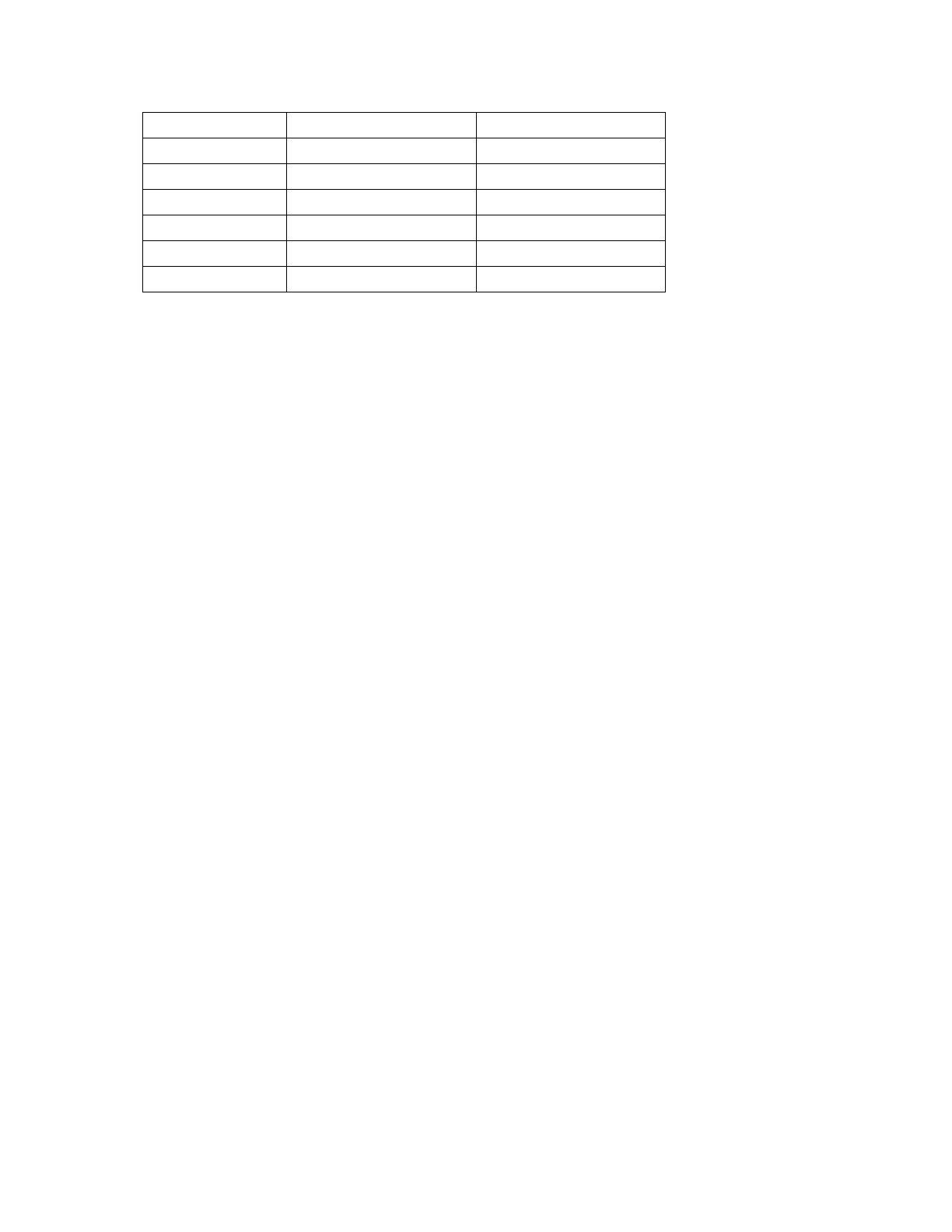

Smriti

Father's caste

Mother's caste

1 AYOGAVA

1. Manu

Shudra

Vaishya

2. Aushanas

Vaishya

Kshatriya

3. Yajnavalkya

Shudra

Vaishya

4. Baudhayana

Vaishya

Kshatriya

5. Agni Purana

Shudra

Kshatriya

11 UGRA

1. Manu

Kshatriya

Shudra

2. Aushanas

Brahman

Shudra

3. Yajnavalkya

Kshatriya

Vaishya

4. Vashishtha

Kshatriya

Vaishya

5. Suta

Vaishya

Shudra

III NISHADA

1. Manu

Brahmana

Shudra

2. Aushanas

Brahmana

Shudra

3. Baudhayana

Brahmana

Shudra

4. Yajnavalkya

Brahmana

Shudra

5. Suta

Sanhita

Brahmana

Vaishya

6. Suta

Sanhita

Brahmana

Shudra

7. Vashishta

Vaishya

Shudra

IV PUKKASA

1. Manu

Nishada

Shudra

2.Brihad-

Vishnu

Shudra

Kshatriya

3.Brihad-

Vishnu

Vaishya

Kshatriya

V MAGADHA

1. Manu

Vaishya

Kshatriya

2. Suta

Vaishya

Kshatriya

3. Baudhayana

Shudra

Vaishya

4. Yajnavalkya

Vaishya

Kshatriya

5.Brihad

Vishnu

Vaishya

Kshatriya

6.Brihad

Vishnu

Shudra

Kshatriya

7.Brihad

Vishnu

Vaishya

Brahman

VI RATHAKAR

1. Aushanas

Kshatriya

Brahmana

2. Baudhayana

Vaishya

Shudra

3. Suta

Kshatriya

Brahmana

VII VAIDEHAKA

1. Manu

Shudra

Vaishya

2. Manu

Vaishya

Brahmana

3. Yajnavalkya

Vaishya

Brahmana

If these different Smritikaras are dealing with facts about the origin and genesis

of the mixed castes mentioned above how can such a wide difference of opinion

exist among them ? The conjugation of two castes can-logically produce a third

mixed caste. But how the conjugation of the same two castes produce a number

of different castes ? But this is exactly what Manu and his followers seem to be

asserting. Consider the following cases:

I. Conjugation of Kshatriya father and Vaishya mother.

1. Baudhyayana says that the caste of the progeny is Kshatriya.

2. Yajnavalkya says it is Mahishya.

3. Suta says it is Ambashta.

II. Conjugation of Shudra father and Kshatriya mother—

1. Manu says the Progeny is Ksattri.

2. Aushanas says it is Pullaksa.

3. Vashishta says it is Vaina.

III. Conjugation of Brahmana father and Vaishya mother.

1. Manu says that the progeny is called Ambashta.

2. Suta once says it is called Urdhava Napita but again says it is called

Kumbhakar.

IV. Conjugation of Vaishya father and Kshatriya mother— 1. Manu says that the

progeny is called Magadha.

2. Suta states that (1) Bhoja, (2) Mleccha, (3) Shalik and (4) Pulinda are the

Progenies of this single conjugation.

V. Conjugation of Kshatriya father and Shudra mother—

1. Manu says that the progeny is called Ugra.

2. Suta says that (1) Daushantya, (2) Daushantee and (3) Shulika are the

progenies of this single conjugation.

VI. Conjugation of Shudra father and Vaishya mother—

1. Manu says the progeny is called Ayogava.

2. Suta says the progeny is (1) Pattanshali and (2) Chakri. Let us take up

another question. Is Manu's explanation of the genesis of the mixed castes

historically true?

To begin with the Abhira. According to Manu the Abhiras are the bastards born

of Brahmin males and Ambashta females. What does history say about them?

History says that the Abhiras (the corrupt form of which is Ahira) were pastoral

tribes which inhabited the lower districts of the North-West as far as Sindh. They

were a ruling independent Tribe and according to the Vishnu Purana the Abhiras

conquered Magadha and reigned there for several years.

The Ambashtasays Manu are the bastards born of Brahmana male and

Vaishya female. Patanjali speaks of Ambashtyas as those who are the natives of

a country called Ambashta. That the Ambashtas were an independent tribe is

beyond dispute. The Ambashtas are mentioned by Megasthenes the Greek

Ambassador at the Court of Chandragupta Maurya as one of the tribes living in

the Punjab who fought against Alexander when he invaded India. The

Ambashtas are mentioned in the Mahabharata. They were reputed for their

political system and for their bravery.

The Andhras says Manu are bastards of second degree in so far as they are

the progeny of Vaidehaka male and Karavara female both of which belong to

bastard castes. The testimony of history is quite different. The Andhras are a

people who inhabited that part of the country which forms the eastern part of the

Deccan Plateau. The Andhras are mentioned by Megasthenes. Pliny the Elder

(77 A.D.) refers to them as a powerful tribe enjoying paramount sway over their

land in the Deccan, possessed numerous villages, thirty walled towns defended

by moats and lowers and supplies their king with an immense army consisting of

1,00,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry and 1,000 elephants.

According to Manu the Magadhas are bastards born of Vaishya male and

Kshatriya female, panini the Grammarian gives quite a different derivation of

'Magadha'. According to him "Magadha'" means a person who comes from the

country known as Magadha. Magadha corresponds roughly to the present Patna

and Gaya districts of Bihar. 'The Magadhas have been mentioned as