HMO

vs

Fee-for-Service

Care

of

Older

Persons

with

Acute

Myocardial

Infarction

David

M.

Carlisle,

MD,

PhD,

Albert

L.

Siu,

MD,

MSPH,

Emmett

B.

Keeler,

PhD,

Elizabeth

A.

McGlynn,

PhD,

Katherine

L.

Kahn,

MD,

Lisa

V.

Rubenstein,

MD,

MSPH,

and

Robert

H.

Brook,

MD,

ScD

Introduction

Methods

Enhanced

competition

within

the

health

care

delivery

system

has

been

en-

couraged

as

a

strategy

to

control

health

care

costs.

One

result

of

this

strategy

has

been

the

rapid

growth

in

the

number

of

individuals

enrolled

in

health

maintenance

organizations

(HMOs).

The

Health

Care

Financing

Administration

(HCFA)

of

the

US

Department

of

Health

and

Human

Services

has

succeeded

in

increasing

the

number

of

elderly

Medicare

beneficiaries

enrolled

in

HMOs

from

521

894

in

1979

to

1.5

million

in

1989.'

Historically,

the

competition

that

has

developed

among

health

plans

has

been

based

on

differences

in

premiums

and

benefit

packages

and

on

public

percep-

tions

about

differences

in

quality.

Al-

though

it

may

be

desirable

for

competition

to

be

based

on

quality,

the

lack

of

objec-

tive

measures

of

quality

of

health

care

has

hindered

the

development

of

such

com-

petition.

Previous

research

has

shown

that

the

quality

of

the

care

delivered

by

HMOs

is

generally

better

than

or

comparable

to

fee-for-service

(FFS)

care.2

However,

only

limited

data

exist

on

the

quality

of

care

received

by

elderly

individuals

en-

rolled

in

HMOs

or

on

the

differences

in

quality

among

individual

health

plans.3,4

This

study

compares

the

quality

of

medical

care

received

by

HMO

and

FFS

elderly

persons

who

had

been

hospitalized

with

an

acute

myocardial

infarction.

How

does

the

quality

of

care

received

by

pa-

tients

from

three

different

HMOs

compare

with

that

received

by

a

nationally

repre-

sentative

sample

of

FFS

patients?

How

does

the

quality

of

care

differ

among

HMOs?

Do

outcome

and

process

mea-

sures

of

quality

of

care

lead

to

similar

con-

clusions?

To

evaluate

the

quality

of

care

re-

ceived

by

Medicare

patients,

we

reviewed

medical

records

of

HMO

and

FFS

pa-

tients

65

years

of

age

or

older

admitted

between

July

1,

1985,

and

June

30,

1986,

with

a

principal

diagnosis

of

acute

myo-

cardial

infarction

(ICD-9-CM5

codes

410.0

through

410.9)

and

signs

or

symptoms

of

a

suspected

acute

myocardial

infarction

at

the

time

of

admission.

We

selected

three

HMOs

from

a

national

consortium

of

12

HMOs

that

had

been

organized

to

evalu-

ate

the

feasibility,

reliability,

and

validity

of

producing

clinically

meaningful

mea-

sures

that

could

be

used

to

compare

qual-

ity

among

health

plans.

The

three

plans

operated

in

separate

states

and

differed

in

size,

geographic

region

served,

and

se-

lected

organizational

characteristics.

We

identified

1469

HMO

admissions

(distributed

among

a

total

of

27

hospitals)

that

met

the

criteria

for

initial

inclusion

in

the

study.

For

each

of

the

three

HMOs,

medical

records

were

stratified

according

to

the

admitting

hospital

and

then

ran-

domly

sampled.

After

oversampling

rec-

ords

from

the

two

smaller

HMOs,

we

se-

lected

459

medical

records

for

review.

Of

these,

90

records

were

excluded

for

the

following

reasons:

39

patients

received

their

initial

care

at

and

were

transferred

The

authors

are

with

the

RAND

Health

Pro-

gram,

Santa

Monica,

Calif.

Drs.

Carlisle,

Siu,

Kahn,

Rubenstein,

and

Brook

are

also

with

the

University

of

California-Los

Angeles.

Requests

for

reprints

should

be

sent

to

David

M.

Carlisle,

MD,

PhD,

RAND,

1700

Main

St,

PO

Box

2138,

Santa

Monica,

CA

90407-2138.

This

paper

was

submitted

to

the

Journal

January

29,

1992,

and

accepted

with

revisions

August

12,

1992.

December

1992,

Vol.

82,

No.

12

EMO

vs

Fee-for-Service

Care

from

a

FFS

hospital

(medical

records

for

these

patients

were

iconsistently

avail-

able);

2

patients

died

in

emergency

depart-

ments;

2

patients

had

incomplete

records;

the

records

of

38

patients

did

not

demon-

strate

signs

or

symptoms

that

were

con-

sistent

with

acute

myocardial

infarction

at

the

time

of

hospital

admission;

and

12

pa-

tients,

upon

detailed

review,

were

deter-

mined

to

have

admission

dates

falling

out-

side

the

sampling

time

frame.

Three

patients

had

more

than

one

reason

for

be-

ing

excluded.

This

resulted

in

a

final

sam-

ple

of

369

admissions

to

a

total

of

27

hos-

pitals

in

the

HMO

group.

The

FFS

sample

was

obtained

from

a

previously

reported

study.6,7

In

that

study

a

sample

of

Medicare

FFS

admissions

was

drawn

from

297

hospitals

(in

five

states)

that

were

selected

to

closely

match

the

nation

in

terms

of

urban-rural

mix,

size,

teaching

status,

ownership,

patient

demo-

graphics,

and

Medicare

and

Medicaid

dis-

tribution.

FFS

patients

from

rural

hospi-

tals

were

excluded

from

this

analysis

because

none

of

our

HMOs

were

in

pri-

marily

rural

areas.

After

we

excluded

these

patients,

1119

patients

remained.

Additional

information

about

the

FFS

sample

is

available

in

an

earlier

publica-

tion.8

We

collected

data

from

hospital

med-

ical

records

using

an

abstraction

tool

de-

veloped

to

collect

process

and

outcome

data

for

patients

with

acute

myocardial

in-

farction.9

For

the

FFS

group,

contracted

peer-review

organizations

in

each

of

the

five

states

received

photocopies

of

each

of

the

admission

records.

Nurses

and

medi-

cal-record

abstractors

specifically

trained

in

the

use

of

this

abstraction

tool

then

ab-

stracted

each

of

the

admission

records.

For

the

HMO

sample,

medical

records

were

photocopied

by

each

HMO

and

sent

to

a

nurse

who

had

previously

abstracted

FFS

records

but

was

unaware

of

the

pur-

pose

of

this

study.

For

both

HMO

and

FFS

samples,

a

nonphysician

reviewer

checked

all

abstraction

forms

for

com-

pleteness,

legibility,

and

internal

consist-

ency.

A

physician

reviewer

then

evalu-

ated

them

to

confirm

the

diagnosis

of

acute

myocardial

infarction.

Abstracted

information

was

used

to

generate

sickness-at-admission

and

quali-

ty-of-care

scales

that

were

designed

to

predict

mortality

at

30

and

180

days

after

admission,

respectively.

Previously

de-

veloped

and

validated

from

the

pooled

FFS

samples,10

the

sickness-at-admission

scales

incorporated

items

from

the

KilliplI

and

Norris12

measures

of

the

severity

of

acute

myocardial

infarction,

the

APACHE

II13

severity-of-illness

scale,

and

measures

of

comorbidity.

(The

Killip,

Norris,

and

APACHE

II

scales

are

based

on

information

obtained

at

the

time

of

hos-

pital

admission,

including

patient

vital

signs,

laboratory

values,

and

components

of

initial

history

and

physical

examina-

tions.)

Measures

such

as

patient

age

and

the

presence

of

chronic

conditions

were

important

predictors

of

long-term

mortal-

ity

and

received

greater

weight

when

in-

corporated

into

our

quality-of-care

index

predicting

mortality

at

180

days.

For

the

HMO

group,

postdischarge

death

data

(30

and

180

days

after

admis-

sion)

were

obtained

from

the

National

Death

Index

maintained

by

the

National

Center

for

Health

Statistics.

For

the

FFS

sample,

similar

data

were

obtained

from

HCFA's

Health

Insurance

Master

File.

Mortality

was

adjusted

for

sickness

at

ad-

mission.

The

quality

of

the

process

of

in-hos-

pital

care

was

assessed

by

a

recently

de-

veloped

and

validated

process-of-care

al-

gorithm14

that

incorporated

93

specific

process-of-care

criteria.

To

generate

these

criteria,

process

measures

were

identified

by

literature

review

and

by

expert

consul-

tation.

These

criteria

were

then

reviewed

by

an

expert

panel

(including

academi-

cians

and

FFS

practitioners)

to

see

if

they

were

clinically

acceptable

and

to

deter-

mine

if

they

were

reliably

recorded

in

the

medical

record.

Internists

and

cardiolo-

gists

from

each

of

the

participating

HMOs

also

reviewed

the

criteria

to

ensure

that

they

remained

valid

within

the

HMO

set-

ting.

No

criteria

were

eliminated

by

HMO

physicians.

Criteria

were

grouped

by

clinical

opinion

and

tested

by

psychometric

anal-

ysis.

This

resulted

in

an

overall

process-

of-care

scale

and

five

process

subscales:

(1)

the

MD

Cognitive

subscale,

which

measures

the

physician's

performance

of

the

patient's

initial

history,

physical

ex-

amination,

and

repeated

clinical

assess-

ment

during

the

hospital

stay;

(2)

the

RN

Cognitive

subscale,

which

measures

the

nurse's

clinical

assessment

of

the

patient;

(3)

the

Technical

Diagnostic

subscale,

which

evaluates

the

use

of

diagnostic

tests

and

procedures

in

the

care

of

the

patient;

(4)

the

Technical

Therapeutic

subscale,

which

evaluates

the

use

of

medications

and

therapeutic

procedures;

and

(5)

the

ICU/Telemetry

subscale,

which

measures

the

appropriate

use

of

the

intensive-care

unit

or

telemetry

monitoring.

Because

pa-

tients

differ

in

terms

of

the

level

of

services

they

need,

each

scale

contains

criteria

that

are

not

applicable

to

all

patients

with

a

myocardial

infarction.

For

example,

using

a

Swan-Ganz

catheter

in

myocardial

in-

farction

patients

with

severe

congestive

heart

failure

and

hypotension

was

consid-

ered

indicated,

but,

in

a

patient

without

these

complications,

invasive

monitoring

was

not

considered

necessary.

As

a

result,

the

number

of

applicable

criteria

varied

from

patient

to

patient.

Performance

on

process

scales

was

scored

by

calculating

compliance

with

applicable

criteria.

Pro-

cess

scores

obtained

in

this

manner

have

been

shown

to

correlate

with

the

proba-

bility

of

death.14

Compliance

with

process

scales

and

the

severity-adjusted

death

rates

for

the

aggregated

HMO

population

of

369

admis-

sions

were

compared

to

the

1119

FFS

ad-

missions.

Intra-HMO

group

comparisons

were

also

performed.

All

scales

were

stan-

dardized

to

have

a

mean

of

0

and

a

stan-

dard

deviation

of

1,

using

as

the

reference

population

the

FFS

sample

that

included

rural

patients.

Thus,

if

a

process

scale

was

reported

as

having

a

value

of

0.54

in

the

HMO

group

and

0.32

in

the

FFS

group,

the

process

score

for

the

HMO

was

0.54

standard

deviations

greater

than

the

ref-

erence

population

(FFS

rural

and

urban

patients)

and

0.22

standard

deviations

greater

than

the

FFS

comparison

used

in

this

analysis.

Differences

in

process

of

care

were

tested

for

significance

using

two-tailed

t

tests.

Resuls

There

was

a

small

difference

between

the

proportions

of

HMO

and

FFS

patients

excluded

from

the

study

(21

and

16%,

re-

spectively,

P

>

.05).

Twenty-six

percent

of

admissions

sampled

from

the

first

HMO

(HM01)

were

excluded,

compared

with

14%

from

HM02

(P

<

.05)

and

20%

from

HM03.

Most

of

the

percentage

difference

between

HM01

and

HM02

was

pro-

duced

by

the

exclusion

of

admitted

pa-

tients

who

had

been

transferred

from

one

hospital

to

the

facility

where

they

received

the

remainder

of

their

care.

HMO

enroll-

ees

were

twice

as

likely

as

their

FFS

coun-

terparts

to

be

transferred

during

the

hos-

pital

admission.

Additionally,

18%

of

admissions

from

HM03

were

excluded

because

they

were

erroneously

coded

with

a

discharge

diagnosis

of

acute

myo-

cardial

infarction.

HMO

patients

were

more

likely

to

be

male

(P

<

.001),

were

less

severely

ill

upon

admission

(P

<

.05),

and

were

dis-

charged

from

the

hospital

earlier

(P

<

.01)

than

their

FFS

counterparts

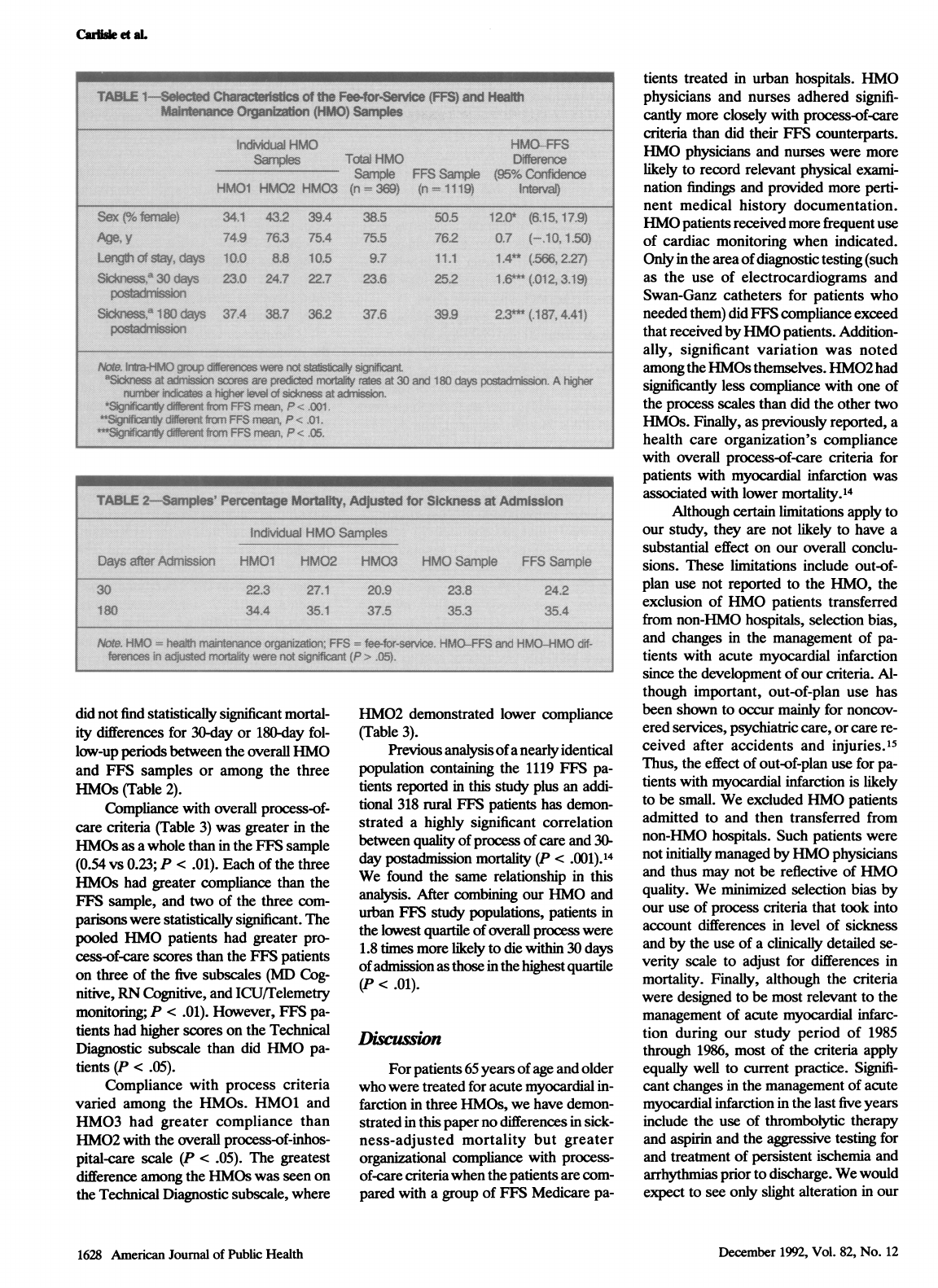

(Table

1).

Af-

ter

adjusting

for

sickness

at

admission,

we

American

Journal

of

Public

Health

1627

December

1992,

Vol.

82,

No.

12

Caiu

et

aL

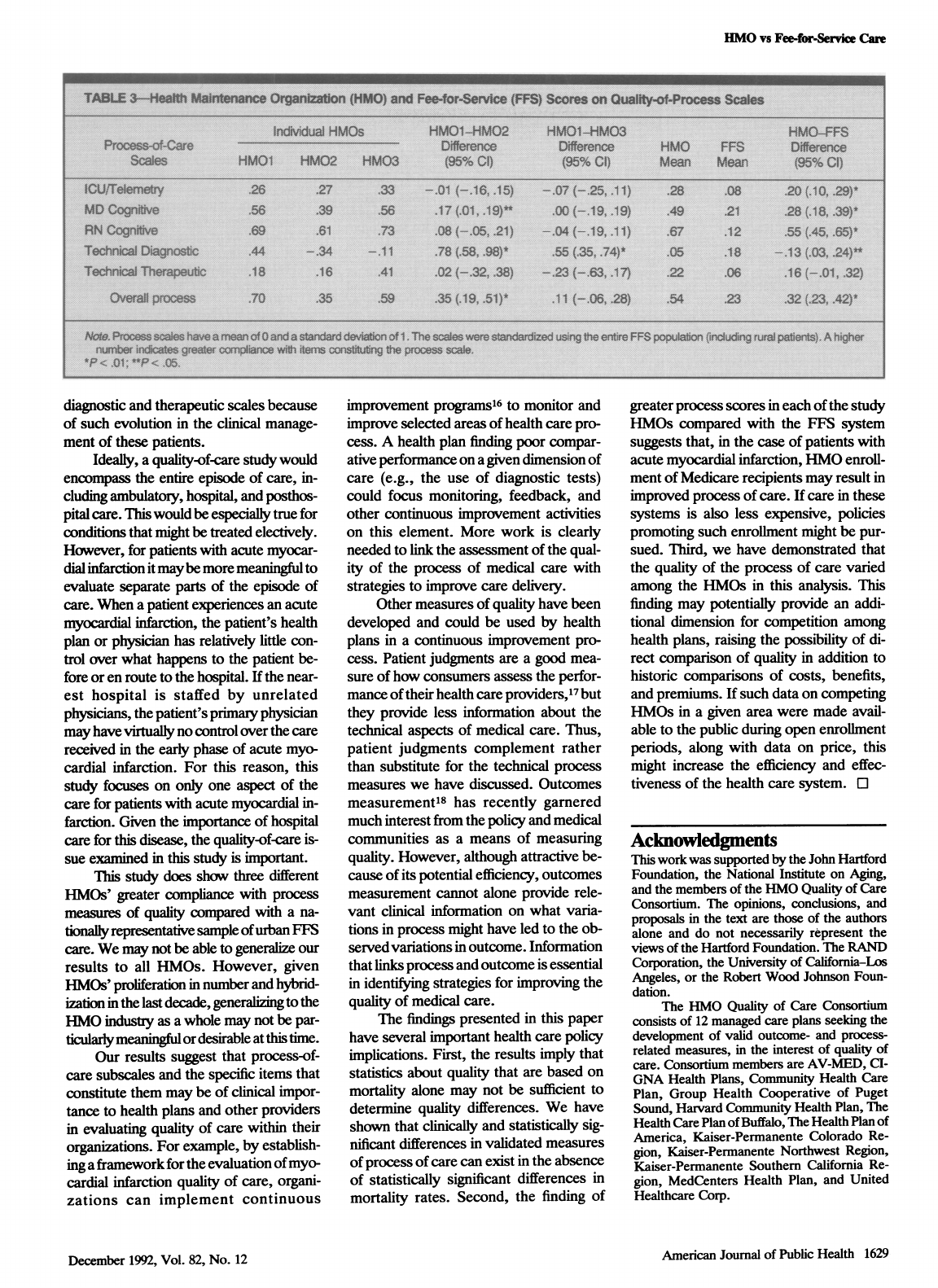

did

not

find

statistically

significant

mortal-

ity

differences

for

30-day

or

180-day

fol-

low-up

periods

between

the

overall

HMO

and

FFS

samples

or

among

the

three

HMOs

(Table

2).

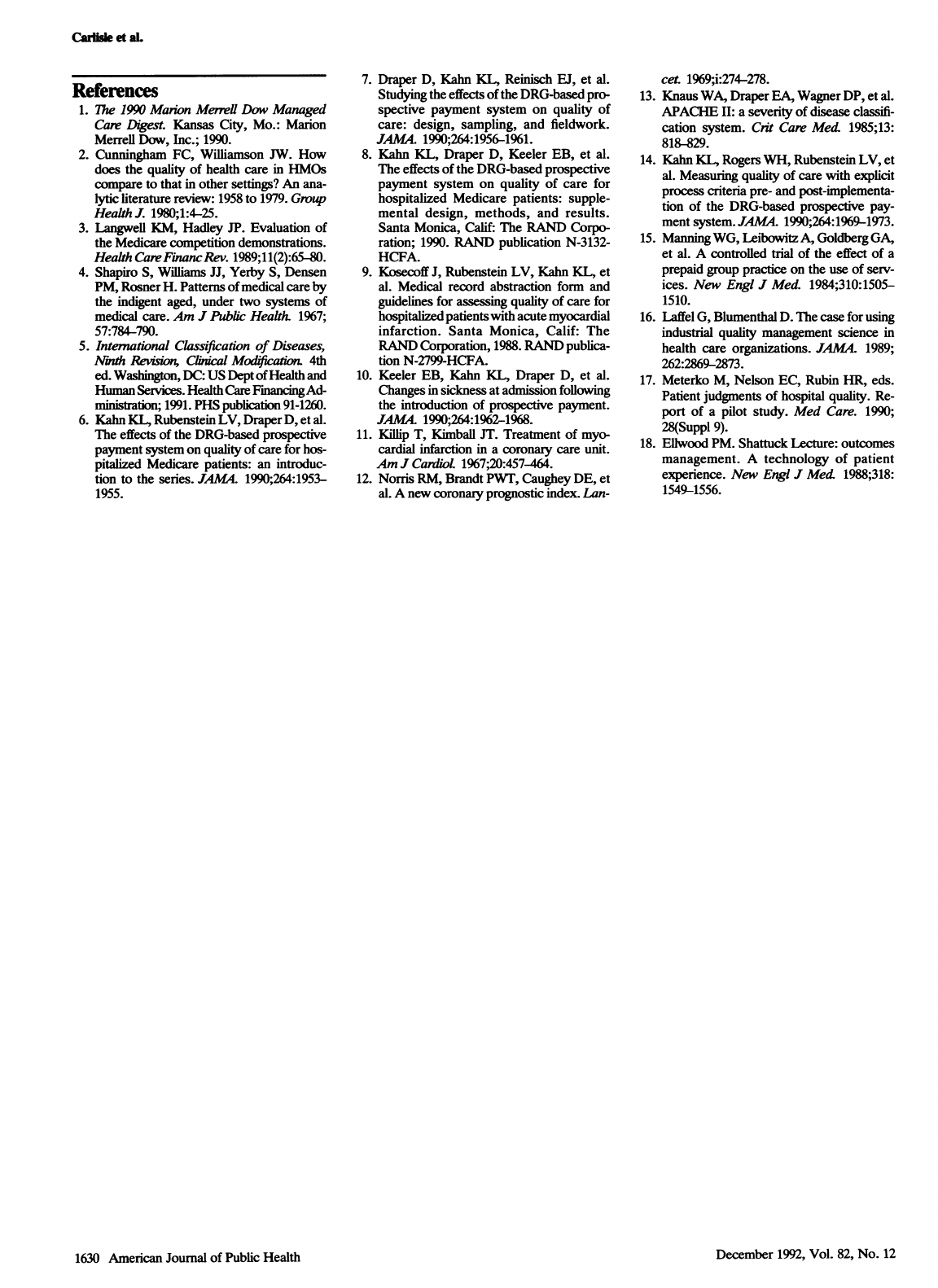

Compliance

with

overall

process-of-

care

criteria

(Table

3)

was

greater

in

the

HMOs

as

a

whole

than

in

the

FFS

sample

(0.54

vs

0.23;

P

<

.01).

Each

of

the

three

HMOs

had

greater

compliance

than

the

FFS

sample,

and

two

of

the

three

com-

parisons

were

statistically

significant.

The

pooled

HMO

patients

had

greater

pro-

cess-of-care

scores

than

the

FFS

patients

on

three

of

the

five

subscales

(MD

Cog-

nitive,

RN

Cognitive,

and

ICU/Telemetry

monitoring;

P

<

.01).

However,

FFS

pa-

tients

had

higher

scores

on

the

Technical

Diagnostic

subscale

than

did

HMO

pa-

tients

(P

<

.05).

Compliance

with

process

criteria

varied

among

the

HMOs.

HM01

and

HM03

had

greater

compliance

than

HM02

with

the

overall

process-of-inhos-

pital-care

scale

(P

<

.05).

The

greatest

difference

among

the

HMOs

was

seen

on

the

Technical

Diagnostic

subscale,

where

HM02

demonstrated

lower

compliance

(Table

3).

Previous

analysis

of

a

nearly

identical

population

containing

the

1119

FFS

pa-

tients

reported

in

this

study

plus

an

addi-

tional

318

rural

FES

patients

has

demon-

strated

a

highly

significant

correlation

between

quality

of

process

of

care

and

30-

day

postadmission

mortality

(P

<

.001).14

We

found

the

same

relationship

in

this

analysis.

After

combining

our

HMO

and

urban

FF5

study

populations,

patients

in

the

lowest

quartile

of

overall

process

were

1.8

times

more

likely

to

die

within

30

days

of

admission

as

those

in

the

highest

quartile

(P

<

.01).

Diwssion

For

patients

65

years

of

age

and

older

who

were

treated

for

acute

myocardial

in-

farction

in

three

HMOs,

we

have

demon-

strated

in

this

paper

no

differences

in

sick-

ness-adjusted

mortality

but

greater

organizational

compliance

with

process-

of-care

criteria

when

the

patients

are

com-

pared

with

a

group

of

FFS

Medicare

pa-

tients

treated

in

urban

hospitals.

HMO

physicians

and

nurses

adhered

signifi-

cantly

more

closely

with

process-of-care

criteria

than

did

their

FFS

counterparts.

HMO

physicians

and

nurses

were

more

likely

to

record

relevant

physical

exami-

nation

findings

and

provided

more

perti-

nent

medical

history

documentation.

HMO

patients

received

more

frequent

use

of

cardiac

monitoring

when

indicated.

Only

in

the

area

of

diagnostic

testing

(such

as

the

use

of

electrocardiograms

and

Swan-Ganz

catheters

for

patients

who

needed

them)

did

FFS

compliance

exceed

that

received

by

HMO

patients.

Addition-

ally,

significant

variation

was

noted

among

the

HMOs

themselves.

HM02

had

significantly

less

compliance

with

one

of

the

process

scales

than

did

the

other

two

HMOs.

Finally,

as

previously

reported,

a

health

care

organization's

compliance

with

overall

process-of-care

criteria

for

patients

with

myocardial

infarction

was

associated

with

lower

mortality.14

Although

certain

limitations

apply

to

our

study,

they

are

not

likely

to

have

a

substantial

effect

on

our

overall

conclu-

sions.

These

limitations

include

out-of-

plan

use

not

reported

to

the

HMO,

the

exclusion

of

HMO

patients

transferred

from

non-HMO

hospitals,

selection

bias,

and

changes

in

the

management

of

pa-

tients

with

acute

myocardial

infarction

since

the

development

of

our

criteria.

Al-

though

important,

out-of-plan

use

has

been

shown

to

occur

mainly

for

noncov-

ered

services,

psychiatric

care,

or

care

re-

ceived

after

accidents

and

injuries.15

Thus,

the

effect

of

out-of-plan

use

for

pa-

tients

with

myocardial

infarction

is

likely

to

be

small.

We

excluded

HMO

patients

admitted

to

and

then

transferred

from

non-HMO

hospitals.

Such

patients

were

not

initially

managed

by

HMO

physicians

and

thus

may

not

be

reflective

of

HMO

quality.

We

minimized

selection

bias

by

our

use

of

process

criteria

that

took

into

account

differences

in

level

of

sickness

and

by

the

use

of

a

clinically

detailed

se-

verity

scale

to

adjust

for

differences

in

mortality.

Finally,

although

the

criteria

were

designed

to

be

most

relevant

to

the

management

of

acute

myocardial

infarc-

tion

during

our

study

period

of

1985

through

1986,

most

of

the

criteria

apply

equally

well

to

current

practice.

Signifi-

cant

changes

in

the

management

of

acute

myocardial

infarction

in

the

last

five

years

include

the

use

of

thrombolytic

therapy

and

aspirin

and

the

aggressive

testing

for

and

treatment

of

persistent

ischemia

and

arrhythmias

prior

to

discharge.

We

would

expect

to

see

only

slight

alteration

in

our

1628

American

Journal

of

Public

Health

December

1992,

Vol.

82,

No.

12

EIMO

vs

Fee-for-Service

Care

diagnostic

and

therapeutic

scales

because

of

such

evolution

in

the

clinical

manage-

ment

of

these

patients.

Ideally,

a

quality-of-care

study

would

encompass

the

entire

episode

of

care,

in-

cluding

ambulatory,

hospital,

and

posthos-

pital

care.

This

would

be

especially

true

for

conditions

that

might

be

treated

electively.

However,

for

patients

with

acute

myocar-

dial

infarction

it

maybe

more

meaningful

to

evaluate

separate

parts

of

the

episode

of

care.

When

a

patient

experiences

an

acute

myocardial

infarction,

the

patient's

health

plan

or

physician

has

relatively

little

con-

trol

over

what

happens

to

the

patient

be-

fore

or

en

route

to

the

hospital.

If

the

near-

est

hospital

is

staffed

by

unrelated

physicians,

the

patient's

primary

physician

may

have

virtualy

no

control

over

the

care

received

in

the

early

phase

of

acute

myo-

cardial

infarction.

For

this

reason,

this

study

focuses

on

only

one

aspect

of

the

care

for

patients

with

acute

myocardial

in-

farction.

Given

the

importance

of

hospital

care

for

this

disease,

the

quality-of-care

is-

sue

examined

in

this

study

is

important.

This

study

does

show

three

different

HMOs'

greater

compliance

with

process

measures

of

quality

compared

with

a

na-

tionally

representative

sample

of

urban

FFS

care.

We

may

not

be

able

to

generalize

our

results

to

all

HMOs.

However,

given

HMOs'

proliferation

in

number

and

hybrid-

ization

in

the

last

decade,

generaizing

to

the

HMO

industry

as

a

whole

may

not

be

par-

ticularly

meanigfl

or

desirable

at

this

time.

Our

results

suggest

that

process-of-

care

subscales

and

the

specific

items

that

constitute

them

may

be

of

clinical

impor-

tance

to

health

plans

and

other

providers

in

evaluating

quality

of

care

within

their

organizations.

For

example,

by

establish-

ing

a

framework

for

the

evaluation

of

myo-

cardial

infarction

quality

of

care,

organi-

zations

can

implement

continuous

improvement

programs16

to

monitor

and

improve

selected

areas

of

health

care

pro-

cess.

A

health

plan

finding

poor

compar-

ative

performance

on

a

given

dimension

of

care

(e.g.,

the

use

of

diagnostic

tests)

could

focus

monitoring,

feedback,

and

other

continuous

improvement

activities

on

this

element.

More

work

is

clearly

needed

to

link

the

assessment

of

the

qual-

ity

of

the

process

of

medical

care

with

strategies

to

improve

care

delivery.

Other

measures

of

quality

have

been

developed

and

could

be

used

by

health

plans

in

a

continuous

improvement

pro-

cess.

Patient

judgments

are

a

good

mea-

sure

of

how

consumers

assess

the

perfor-

mance

of

their

health

care

providers,17

but

they

provide

less

information

about

the

technical

aspects

of

medical

care.

Thus,

patient

judgments

complement

rather

than

substitute

for

the

technical

process

measures

we

have

discussed.

Outcomes

measurement'8

has

recently

garnered

much

interest

from

the

policy

and

medical

communities

as

a

means

of

measuring

quality.

However,

although

attractive

be-

cause

of

its

potential

efficiency,

outcomes

measurement

cannot

alone

provide

rele-

vant

clinical

information

on

what

varia-

tions

in

process

might

have

led

to

the

ob-

servedvariations

in

outcome.

Information

that

links

process

and

outcome

is

essential

in

identifying

strategies

for

improving

the

quality

of

medical

care.

The

findings

presented

in

this

paper

have

several

important

health

care

policy

implications.

First,

the

results

imply

that

statistics

about

quality

that

are

based

on

mortality

alone

may

not

be

sufficient

to

determine

quality

differences.

We

have

shown

that

clinically

and

statistically

sig-

nificant

differences

in

validated

measures

of

process

of

care

can

exist

in

the

absence

of

statistically

significant

differences

in

mortality

rates.

Second,

the

finding

of

greater

process

scores

in

each

of

the

study

HMOs

compared

with

the

FFS

system

suggests

that,

in

the

case

of

patients

with

acute

myocardial

infarction,

HMO

enroll-

ment

of

Medicare

recipients

may

result

in

improved

process

of

care.

If

care

in

these

systems

is

also

less

expensive,

policies

promoting

such

enrollment

might

be

pur-

sued.

Third,

we

have

demonstrated

that

the

quality

of

the

process

of

care

varied

among

the

HMOs

in

this

analysis.

This

finding

may

potentially

provide

an

addi-

tional

dimension

for

competition

among

health

plans,

raising

the

possibility

of

di-

rect

comparison

of

quality

in

addition

to

historic

comparisons

of

costs,

benefits,

and

premiums.

If

such

data

on

competing

HMOs

in

a

given

area

were

made

avail-

able

to

the

public

during

open

enrollment

periods,

along

with

data

on

price,

this

might

increase

the

efficiency

and

effec-

tiveness

of

the

health

care

system.

O

Acknowledgments

This

work

was

supported

by

the

John

Hartford

Foundation,

the

National

Institute

on

Aging,

and

the

members

of

the

HMO

Quality

of

Care

Consortium.

The

opinions,

conclusions,

and

proposals

in

the

text

are

those

of

the

authors

alone

and

do

not

necessarily

represent

the

views

of

the

Hartford

Foundation.

The

RAND

Corporation,

the

University

of

California-Los

Angeles,

or

the

Robert

Wood

Johnson

Foun-

dation.

The

HMO

Quality

of

Care

Consortium

consists

of

12

managed

care

plans

seeking

the

development

of

valid

outcome-

and

process-

related

measures,

in

the

interest

of

quality

of

care.

Consortium

members

are

AV-MED,

CI-

GNA

Health

Plans,

Community

Health

Care

Plan,

Group

Health

Cooperative

of

Puget

Sound,

Haivard

Community

Health

Plan,

The

Health

Care

Plan

of

Buffalo,

The

Health

Plan

of

America,

Kaiser-Permanente

Colorado

Re-

gion,

Kaiser-Permanente

Northwest

Region,

Kaiser-Permanente

Southern

California

Re-

gion,

MedCenters

Health

Plan,

and

United

Healthcare

Corp.

American

Journal

of

Public

Health

1629

December

1992,

Vol.

82,

No.

12

Cailisle

et

aL

References

1.

The

1990

Manon

Merrell

Dow

Managed

Care

Digest.

Kansas

City,

Mo.:

Marion

Meffeil

Dow,

Inc.;

1990.

2.

Cunningham

FC,

Williamson

JW.

How

does

the

quality

of

health

care

in

HMOs

compare

to

that

in

other

settings?

An

ana-

lytic

literature

review:

1958

to

1979.

Group

Health

J.

1980;1:4-25.

3.

Langwell

KM,

Hadley

JP.

Evaluation

of

the

Medicare

competition

demonstrations.

Health

Care

FinancRev.

1989;11(2):65-80.

4.

Shapiro

S,

Williams

JJ,

Yerby

S,

Densen

PM,

Rosner

H.

Patterns

of

medical

care

by

the

indigent

aged,

under

two

systems

of

medical

care.

Am

J

Public

Health.

1967;

57:784-790.

5.

International

Classification

of

Diseases,

Nith

Reision,

Clinical

Modfication.

4th

ed.

Washingto,

DC:

US

Dept

of

Health

and

Human

Services.

Health

Care

FinancingAd-

ministration;

1991.

PHS

publication

91-1260.

6.

Kahn

KL,

Rubenstein

LV,

Draper

D,

et

al.

The

effects

of

the

DRG-based

prospective

payment

system

on

quality

of

care

for

hos-

pitalized

Medicare

patients:

an

introduc-

tion

to

the

series.

JAMA.

1990;264:1953-

1955.

7.

Draper

D,

Kahn

KL,

Reinisch

EJ,

et

al.

Studying

the

effects

of

the

DRG-based

pro-

spective

payment

system

on

quality

of

care:

design,

sampling,

and

fieldwork.

JAMA

1990;264:1956-1961.

8.

Kahn

KL,

Draper

D,

Keeler

EB,

et

al.

The

effects

of

the

DRG-based

prospective

payment

system

on

quality

of

care

for

hospitalized

Medicare

patients:

supple-

mental

design,

methods,

and

results.

Santa

Monica,

Calif:

The

RAND

Corpo-

ration;

1990.

RAND

publication

N-3132-

HCFA.

9.

Kosecoff

J,

Rubenstein

LV,

Kahn

KL,

et

al.

Medical

record

abstraction

form

and

guidelines

for

assessing

quality

of

care

for

hospitalized

patients

with

acute

myocardial

infarction.

Santa

Monica,

Calif:

The

RAND

Corporation,

1988.

RAND

publica-

tion

N-2799-HCFA.

10.

Keeler

EB,

Kahn

KL,

Draper

D,

et

al.

Changes

in

sickness

at

admission

following

the

introduction

of

prospective

payment.

JAMA.

1990;264:1962-1968.

11.

Killip

T,

Kimball

JT.

Treatment

of

myo-

cardial

infarction

in

a

coronary

care

unit.

Am

J

CardioL

1967;20:457-464.

12.

Norris

RM,

Brandt

PWT,

Caughey

DE,

et

al.

A

new

coronary

prognostic

index.

Lan-

cet.

1969;i:274-278.

13.

Knaus

WA,

Draper

EA,

Wagner

DP,

et

al.

APACHE

II:

a

severity

of

disease

classifi-

cation

system.

C,it

Care

Med.

1985;13:

818-829.

14.

Kahn

KL,

Rogers

WH,

Rubenstein

LV,

et

al.

Measuring

quality

of

care

with

explicit

process

criteria

pre-

and

post-implementa-

tion

of

the

DRG-based

prospective

pay-

ment

system.

JAMA.

1990;264:1969-1973.

15.

Manning

WG,

Leibowitz

A,

Goldberg

GA,

et

al.

A

controlled

trial

of

the

effect

of

a

prepaid

group

practice

on

the

use

of

serv-

ices.

New

Engl

J

Med.

1984;310:1505-

1510.

16.

Laffel

G,

Blumenthal

D.

The

case

for

using

industrial

quality

management

science

in

health

care

organizations.

JAMA.

1989;

262:2869-2873.

17.

Meterko

M,

Nelson

EC,

Rubin

HR,

eds.

Patient

judgments

of

hospital

quality.

Re-

port

of

a

pilot

study.

Med

Care.

1990;

28(Suppl

9).

18.

Ellwood

PM.

Shattuck

Lecture:

outcomes

management.

A

technology

of

patient

experience.

New

Engl

J

Med.

1988;318:

1549-1556.

1630

American

Journal

of

Public

Health

December

1992,

Vol.

82,

No.

12