Visit the

National Academies Press online, the authoritative source for all books from the

National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of

Medicine, and the National Research Council:

• Download hundreds of free books in PDF

• Read thousands of books online, free

• Sign up to be notified when new books are published

• Purchase printed books

• Purchase PDFs

• Explore with our innovative research tools

Thank you for downloading this free PDF. If you have comments, questions or just want

more information about the books published by the National Academies Press, you may

contact our customer service department toll-free at 888-624-8373,

visit us online, or

send an email to

This free book plus thousands more books are available at

http://www.nap.edu.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. Permission is granted for this material to be

shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this notice appears on the

reproduced materials, the Web address of the online, full authoritative version is retained,

and copies are not altered. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written

permission from the National Academies Press.

ISBN: 0-309-14629-1, 252 pages, 6 x 9, (2010)

This free PDF was downloaded from:

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for

Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

Heather M. Colvin and Abigail E. Mitchell, Editors;

Committee on the Prevention and Control of Viral

Hepatitis Infections; Institute of Medicine

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

Heather M. Colvin and Abigail E. Mitchell, Editors

Committee on the Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infections

Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice

H E PAT I T I S A N D

L I V E R C A N C E R

A National Strategy for Prevention and

Control of Hepatitis B and C

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001

NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing

Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of

the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute

of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their

special competences and with regard for appropriate balance.

This study was supported by Contract 200-2005-13434, TO#16, between the National Acad-

emy of Sciences and the Department of Health and Human Services (with support from the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Office of Minority Health, and the Depart-

ment of Veterans Affairs) and by the Task Force for Child Survival and Development on behalf

of the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommen-

dations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect

the view of the organizations or agencies that provided support for this project.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hepatitis and liver cancer : a national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B

and C / Heather M. Colvin and Abigail E. Mitchell, editors ; Committee on the Prevention

and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infections, Board on Population Health and Public Health

Practice.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-309-14628-9

1. Hepatitis B—United States. 2. Hepatitis C—United States. 3. Liver—Cancer—United

States. I. Colvin, Heather M. II. Mitchell, Abigail E. III. Institute of Medicine (U.S.).

Committee on the Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infections. IV. Institute of

Medicine (U.S.). Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. V. National

Academies Press (U.S.)

[DNLM: 1. Hepatitis B—complications—United States. 2. Hepatitis B—prevention &

control—United States. 3. Hepatitis C—complications—United States. 4. Hepatitis C—

prevention & control—United States. 5. Liver Neoplasms—prevention & control—United

States. 6. Viral Hepatitis Vaccines—therapeutic use—United States. WC 536 H5322 2010]

RA644.H4H37 2010

616.99'436—dc22

2010003194

Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth

Street, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, DC 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in

the Washington metropolitan area); Internet, http://www.nap.edu.

For more information about the Institute of Medicine, visit the IOM home page at www.

iom.edu.

Copyright 2010 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

The serpent has been a symbol of long life, healing, and knowledge among almost all cultures

and religions since the beginning of recorded history. The serpent adopted as a logotype by

the Institute of Medicine is a relief carving from ancient Greece, now held by the Staatliche

Museen in Berlin.

Suggested citation: IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2010. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National

Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National

Academies Press.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

“Knowing is not enough; we must apply.

Willing is not enough; we must do.”

—Goethe

Advising the Nation. Improving Health.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society

of distinguished scholars engaged in scientific and engineering research, dedicated to

the furtherance of science and technology and to their use for the general welfare.

Upon the authority of the charter granted to it by the Congress in 1863, the Acad-

emy has a mandate that requires it to advise the federal government on scientific

and technical matters. Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone is president of the National Academy

of Sciences.

The National Academy of Engineering was established in 1964, under the charter

of the National Academy of Sciences, as a parallel organization of outstanding en-

gineers. It is autonomous in its administration and in the selection of its members,

sharing with the National Academy of Sciences the responsibility for advising the

federal government. The National Academy of Engineering also sponsors engineer-

ing programs aimed at meeting national needs, encourages education and research,

and recognizes the superior achievements of engineers. Dr. Charles M. Vest is presi-

dent of the National Academy of Engineering.

The Institute of Medicine was established in 1970 by the National Academy of

Sciences to secure the services of eminent members of appropriate professions in

the examination of policy matters pertaining to the health of the public. The Insti-

tute acts under the responsibility given to the National Academy of Sciences by its

congressional charter to be an adviser to the federal government and, upon its own

initiative, to identify issues of medical care, research, and education. Dr. Harvey V.

Fineberg is president of the Institute of Medicine.

The National Research Council was organized by the National Academy of Sci-

ences in 1916 to associate the broad community of science and technology with the

Academy’s purposes of furthering knowledge and advising the federal government.

Functioning in accordance with general policies determined by the Academy, the

Council has become the principal operating agency of both the National Academy

of Sciences and the National Academy of Engineering in providing services to the

government, the public, and the scientific and engineering communities. The Coun-

cil is administered jointly by both Academies and the Institute of Medicine. Dr.

Ralph J. Cicerone and Dr. Charles M. Vest are chair and vice chair, respectively, of

the National Research Council.

www.national -academies. org

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

v

COMMITTEE ON THE PREVENTION AND

CONTROL OF VIRAL HEPATITIS INFECTIONS

R. Palmer Beasley (Chair), Ashbel Smith Professor and Dean Emeritus,

University of Texas, School of Public Health, Houston, Texas

Harvey J. Alter, Chief, Infectious Diseases Section, Department of

Transfusion Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Margaret L. Brandeau, Professor, Department of Management Science

and Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California

Daniel R. Church, Epidemiologist and Adult Viral Hepatitis Coordinator,

Bureau of Infectious Disease Prevention, Response, and Services,

Massachusetts Department of Health, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts

Alison A. Evans, Assistant Professor, Department of Epidemiology

and Biostatistics, Drexel University School of Public Health,

Drexel Institute of Biotechnology and Viral Research, Doylestown,

Pennsylvania

Holly Hagan, Senior Research Scientist, College of Nursing, New York

University, New York

Sandral Hullett, CEO and Medical Director, Cooper Green Hospital,

Birmingham, Alabama

Stacene R. Maroushek, Staff Pediatrician, Department of Pediatrics,

Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Randall R. Mayer, Chief, Bureau of HIV, STD, and Hepatitis, Iowa

Department of Public Health, Des Moines, Iowa

Brian J. McMahon, Medical Director, Liver Disease and Hepatitis

Program, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, Anchorage, Alaska

Martín Jose Sepúlveda, Vice President, Integrated Health Services,

International Business Machines Corporation, Somers, New York

Samuel So, Lui Hac Minh Professor, Asian Liver Center, Stanford

University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

David L. Thomas, Chief, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of

Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland

Lester N. Wright, Deputy Commissioner and Chief Medical Officer, New

York Department of Correctional Services, Albany, New York

Study Staff

Abigail E. Mitchell, Study Director

Heather M. Colvin, Program Officer

Kathleen M. McGraw, Senior Program Assistant

Norman Grossblatt, Senior Editor

Rose Marie Martinez, Director, Board on Population Health and Public

Health Practice

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

vii

Reviewers

T

his report has been reviewed in draft form by persons chosen for

their diverse perspectives and technical expertise, in accordance with

procedures approved by the National Research Council’s (NRC’s)

Report Review Committee. The purpose of this independent review is to

provide candid and critical comments that will assist the institution in mak-

ing its published report as sound as possible and to ensure that the report

meets institutional standards for objectivity, evidence, and responsiveness

to the study charge. The review comments and draft manuscript remain

confidential to protect the integrity of the deliberative process. We wish to

thank the following individuals for their review of this report:

Scott Allen, Brown University Medical School

Jeffrey Caballero, Association of Asian Pacific Community Health

Organizations

Colleen Flanigan, New York State Department of Health

James Jerry Gibson, South Carolina Department of Health and

Environmental Control

Fernando A. Guerra, San Antonio Metropolitan Health District

Theodore Hammett, Abt Associates Inc.

Jay Hoofnagle, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and

Kidney Diseases

Charles D. Howell, University of Maryland School of Medicine

Walter A. Orenstein, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Philip E. Reichert, Florida Department of Health

Charles M. Rice III, The Rockefeller University

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

viii REVIEWERS

Tracy Swan, Treatment Action Group

Su Wang, Charles B. Wang Community Health Center

John B. Wong, Tufts Medical Center

Although the reviewers listed above have provided many constructive

comments and suggestions, they were not asked to endorse the conclusions

or recommendations, nor did they see the final draft of the report before

its release. The review of the report was overseen by Bradford H. Gray,

Senior Fellow, The Urban Institute, and Elena O. Nightingale, Scholar-in-

Residence, Institute of Medicine. Appointed by the Institute of Medicine

and the National Research Council, they were responsible for making cer-

tain that an independent examination of the report was carried out in ac-

cordance with institutional procedures and that all review comments were

carefully considered. Responsibility for the final content of the report rests

entirely with the author committee and the institution.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

ix

Acknowledgments

T

he committee acknowledges the valuable contributions made by the

many persons who shared their experience and knowledge with the

committee. The committee appreciates the time and insight of the pre-

senters during the public sessions: John Ward, Dale Hu, Cindy Weinbaum,

and David Bell, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Chris Taylor

and Martha Saly, National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable; Lorren Sandt, Car-

ing Ambassadors Program; Joan Block, Hepatitis B Foundation; Gary

Heseltine, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; William Rogers,

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Tanya Pagán Raggio Ashley,

Health Resources Services Administration; Carol Craig, National Associa-

tion of Community Health Centers; Daniel Raymond, Harm Reduction

Coalition; and Mark Kane, formerly of the Children’s Vaccine Program,

PATH. We are also grateful for the thoughtful written and verbal testimony

provided by members of the public affected by hepatitis B or hepatitis C.

Several persons contributed their expertise for this report. The com-

mittee thanks David Hutton, of the Department of Management Science

and Engineering at Stanford University; Victor Toy, Beverly David, and

Kathleen Tarleton, of IBM; Shiela Strauss, of the New York University

College of Nursing; Ellen Chang and Stephanie Chao, of the Asian Liver

Center at Stanford University; Gillian Haney, of the Massachusetts Depart-

ment of Public Health; and all the State Adult Viral Hepatitis Prevention

Coordinators that provided information to the committee.

This report would not have been possible without the diligent assistance

of Jeffrey Efird and Daniel Riedford, of the Centers for Disease Control and

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

x ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Prevention. We appreciate the assistance of Ronald Valdiserri, of the De-

partment of Veterans Affairs, for providing literature for the report.

The committee thanks the staff members of the Institute of Medicine,

the National Research Council, and the National Academies Press who

contributed to the development, production, and dissemination of this

report. The committee thanks the study director, Abigail Mitchell, and

program officer Heather Colvin for their work in navigating this complex

topic and Kathleen McGraw for her diligent management of the committee

logistics.

This report was made possible by the support of the Division of Viral

Hepatitis and Division of Cancer Prevention and Control of the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human

Services Office of Minority Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and

the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

xi

Contents

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS xvii

SUMMARY 1

The Charge to the Committee, 2

Findings and Recommendations, 2

Surveillance, 3

Knowledge and Awareness, 8

Immunization, 9

Viral Hepatitis Services, 12

Recommendation Outcomes, 17

1 INTRODUCTION 19

Prevalence and Incidence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C

Worldwide, 22

Prevalence and Incidence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C

in the United States, 25

Hepatitis B, 25

Hepatitis C, 28

Liver Cancer and Liver Disease from Chronic Hepatitis B Virus and

Hepatitis C Virus Infections, 29

The Committee’s Task, 30

The Committee’s Approach to Its Task, 32

References, 35

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

xii CONTENTS

2 SURVEILLANCE 41

Applications of Surveillance Data, 43

Outbreak Detection and Control, 44

Resource Allocation, 45

Programmatic Design and Evaluation, 45

Linking Patients to Care, 45

Disease-Specific Issues Related to Viral-Hepatitis Surveillance, 46

Identifying Acute Infections, 47

Identifying Chronic Infections, 51

Identifying Perinatal Hepatitis B, 54

Other Challenges for Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Surveillance

Systems, 56

Infrastructure and Process-Specific Issues with Surveillance, 57

Funding Sources, 58

Program Design, 59

Reporting Systems and Requirements, 59

Capturing Data on At-Risk Populations, 61

Case Evaluation, Followup, and Partner Services, 62

Recommendations, 63

Model for Surveillance, 66

Core Surveillance, 67

Targeted Surveillance, 71

References, 72

3 KNOWLEDGE AND AWARENESS ABOUT CHRONIC

HEPATITIS B AND HEPATITIS C 79

Knowledge and Awareness Among Health-Care and Social-Service

Providers, 80

Hepatitis B, 81

Hepatitis C, 83

Recommendation, 85

Community Knowledge and Awareness, 89

Hepatitis B, 89

Hepatitis C, 93

Recommendation, 96

References, 101

4 IMMUNIZATION 109

Hepatitis B Vaccine, 109

Current Vaccination Recommendations, Requirements, and

Rates, 110

Immunization-Information Systems, 126

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

CONTENTS xiii

Barriers to Hepatitis B Vaccination, 127

Hepatitis C Vaccine, 136

Feasibility of Preventing Chronic Hepatitis C, 136

Need for a Vaccine to Prevent Chronic Hepatitis C, 137

Cost Effectiveness of a Hepatitis C Vaccine, 137

References, 138

5 VIRAL HEPATITIS SERVICES 147

Current Status, 148

Components of Viral Hepatitis Services, 154

Identification of Infected Persons, 154

Prevention, 166

Medical Management, 166

Major Gaps in Services, 170

General Population, 170

Foreign-Born People, 173

Illicit-Drug Users, 175

Pregnant Women, 181

Correctional Settings, 184

Community Health Facilities, 186

Targeting Settings That Serve At-Risk Populations, 189

References, 192

A COMMITTEE BIOGRAPHIES 209

B PUBLIC MEETING AGENDAS 215

BOXES, FIGURES, AND TABLES

Boxes

S-1 Recommendations, 4

2-1 Role of Disease Surveillance, 42

2-2 CDC Acute Hepatitis B Case Definition, 48

2-3 CDC Acute Hepatitis C Case Definition, 49

2-4 CDC Chronic Hepatitis B Case Definition, 52

2-5 CDC Hepatitis C Virus Infection Case Definition

(Past or Present), 53

2-6 CDC Perinatal Hepatitis B Virus Infection Case Definition, 55

3-1 Geographic Regions That Have Intermediate and High Hepatitis B

Virus Endemicity, 81

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

xiv CONTENTS

4-1 Summary of ACIP Hepatitis B Vaccination Recommendations, 112

5-1 Summary of Recommendations Regarding Viral Hepatitis

Services, 148

5-2 Mission Statement of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Division of Viral Hepatitis, 150

5-3 Components of Comprehensive Viral Hepatitis Services, 155

5-4 Summary of CDC At-Risk Populations for Hepatitis B Virus

Infection, 156

5-5 Summary of CDC At-Risk Populations for Hepatitis C Virus

Infection, 158

5-6 Hepatitis B Virus-Specific Antigens and Antibodies Used for

Testing, 160

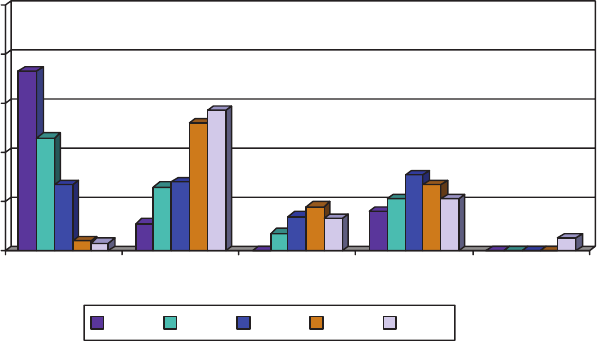

Figures

1-1 Approximate global preventable death rate from selected infectious

diseases and other causes, 2003, 20

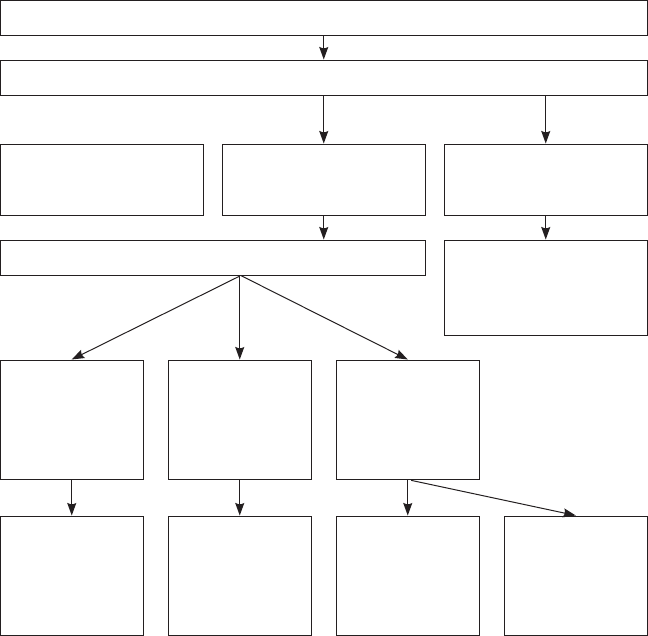

1-2 The committee’s approach to its task, 34

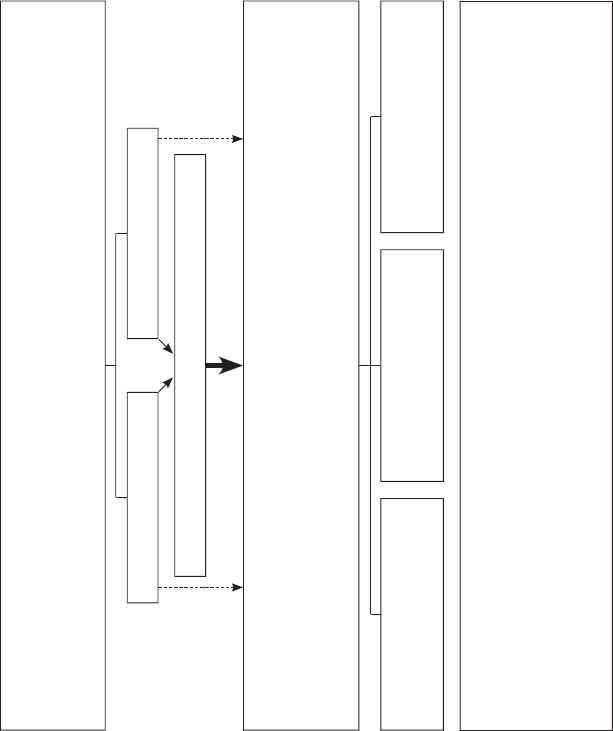

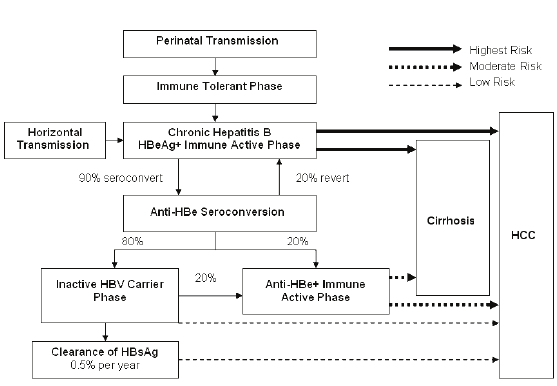

2-1 Natural progression of hepatitis B infection, 46

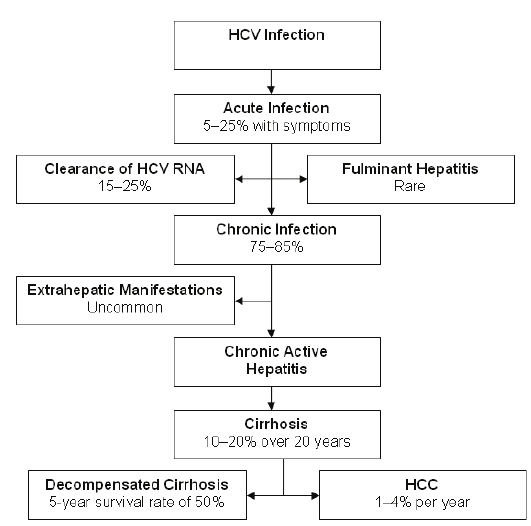

2-2 Natural progression of hepatitis C infection, 47

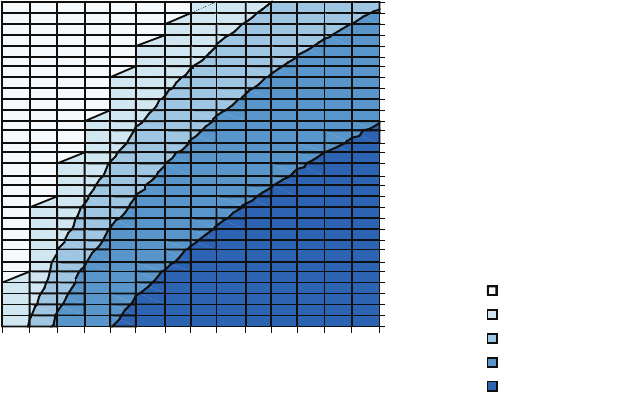

4-1 Estimated cost of adult hepatitis B vaccination per quality adjusted

life year (QALY) gained for different age groups and different rates

of acute hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection incidence, 119

4-2 Trends in private health-insurance coverage, 133

5-1 Hepatitis B services model, 157

5-2 Essential viral hepatitis services for illicit-drug users, 180

Tables

1-1 Key Characteristics of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C, 21

1-2 Burden of Selected Serious Chronic Viral Infections in the United

States, 26

4-1 Hepatitis B Vaccine Schedules for Newborns, by Maternal HBsAg

Status—ACIP Recommendations, 114

4-2 Hepatitis B Immunization Management of Preterm Infants Who

Weigh Less Than 2,000 g, by Maternal HBsAg Status—ACIP

Recommendations, 115

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

CONTENTS xv

4-3 Estimated Chance That an Acute Hepatitis B Infection Becomes

Chronic with Age, 118

4-4 Studies of Hepatitis B Vaccination Rates in Injection-Drug

Users, 122

4-5 Public Health-Insurance Plans, 130

5-1 Summary of Adult Viral Hepatitis Prevention Coordinators

Survey, 153

5-2 Interpretation of Hepatitis B Serologic Diagnostic Test

Results, 161

5-3 Interpretation of Hepatitis C Virus Diagnostic Test Results, 164

5-4 Studies of Association Between Opiate Substitution Treatment and

Hepatitis C Virus Seroconversion, 178

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

xvii

Acronyms and Abbreviations

AASLD American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

ACIP Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

ACOG American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

AIDS acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

ALT alanine aminotransferase

anti-HBc Hepatitis B core antibody

anti-HBs Hepatitis B surface antibody

anti-HCV Hepatitis C antibody

API Asian and Pacific Islander

AST aspartate transaminase

AVHPC adult viral hepatitis prevention coordinators

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CHIP Children’s Health Insurance Program

CI confidence interval

CIA enhanced chemiluminescence

CMS Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

DIS disease intervention specialist

DTaP diptheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis

adsorbed vaccine

DUIT drug user intervention trial

DVH Division of Viral Hepatitis

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

xviii ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

EIA enzyme immunoassay

EIP Emerging Infections Program

EPSDT early periodic screening diagnosis and treatment program

FDA Food and Drug Administration

FEHBP Federal Employee Health Benefit Program

FQHC federally qualified health center

HAV Hepatitis A virus

HBIG Hepatitis B immunoglobulin

HBsAg Hepatitis B surface antigen

HBV Hepatitis B virus

HCC hepatocellular carcinoma

HCV Hepatitis C virus

HCW health-care workers

HDHP high deductable health plan

HIAA Health Insurance Association of America

HIB haemophilus influenzae type B

HIV human immunodeficiency virus

HMO health maintenance organization

HPV human papilloma virus

HRSA Health Resources and Services Administration

IDU injection-drug user

IIS immunization information systems

IOM Institute of Medicine

IPV inactivated polio virus

MMTP methadone maintenance treatment program

NASTAD National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors

NAT nucleic acid test

NCHHSTP National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually

Transmitted Diseases, and Tuberculosis Prevention

NEDSS National Electronic Disease Surveillance System

NETSS National Electronic Telecommunications System for

Surveillance

NGO nongovernmental organization

NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

NIDU non-injection-drug user

NVAC National Vaccine Advisory Committee

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS xix

OB/GYN obstetrician/gynecologist

OMH Office of Minority Health

OR odds ratio

PEI peer education intervention

PHIN Public Health Information Network

POS point of service

PPO preferred provider organization

PY person year

QALY quality adjusted life year

RCT randomized clinical trial

RIBA recombinant immunoblot assay

RNA ribonucleic acid

RSV respiratory syncytial virus

SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration

SARS severe acute respiratory syndrome

SEP syringe exchange program

STD sexually transmitted disease

STRIVE Study To Reduce Intravenous Exposures

TB tuberculosis

TCM traditional Chinese medicine

USPHS US Public Health Service

USPSTF US Preventive Services Task Force

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

vCJD variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

VFC Vaccines for Children

WHO World Health Organization

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

1

Summary

I

n the next 10 years, about 150,000 people in the United States will die

from liver cancer and end-stage liver disease associated with chronic

hepatitis B and hepatitis C. It is estimated that 3.5–5.3 million people—

1–2% of the US population—are living with chronic hepatitis B virus

(HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections. Of those, 800,000 to 1.4 mil-

lion have chronic HBV infections, and 2.7–3.9 million have chronic HCV

infections. Chronic viral hepatitis infections are 3–5 times more frequent

than HIV in the United States.

Because of the asymptomatic nature of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis

C, most people infected with HBV and HCV are not aware that they have

been infected until they have symptoms of cirrhosis or a type of liver cancer,

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), many years later. About 65% and 75% of

the infected population are unaware that they are infected with HBV and

HCV, respectively. Importantly, the prevention of chronic hepatitis B and

chronic hepatitis C prevents the majority of HCC cases because HBV and

HCV are the leading causes of this type of cancer.

Although the incidence of acute HBV infection is declining in the

United States, due to the availability of hepatitis B vaccines, about 43,000

new acute HBV infections still occur each year. Of those new infections,

about 1,000 infants acquire the infection during birth from their HBV-

positive mothers. HBV is also transmitted by sexual contact with an in-

fected person, sharing injection drug equipment, and needlestick injuries.

African American adults have the highest rate of acute HBV infection in

the United States and the highest rates of acute HBV infection occur in the

southern region. People from Asia and the Pacific Islands comprise the larg-

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

2 HEPATITIS AND LIVER CANCER

est foreign-born population that is at risk for chronic HBV infection. The

number of people in the United States who are living with chronic HBV

infection may be increasing as a result of immigration from highly endemic

countries. On the basis of immigration patterns in the last decade, it is esti-

mated that every year 40,000–45,000 people from HBV-endemic countries

enter the United States legally.

There is no vaccine for hepatitis C. HCV is efficiently transmitted by

direct percutaneous exposure to infectious blood. Persons likely to have

chronic HCV infection include those who received a blood transfusion be-

fore 1992 and past or current injection-drug users (IDUs). Most IDUs in the

United States have serologic evidence of HCV infection (that is, they have

been exposed to HCV at some time). While HCV incidence appears to have

declined over the last decade, a large portion of IDUs, who often do not

have access to health-care services, are not identified by current surveillance

systems making interpretation of that trend complicated. African Ameri-

cans and Hispanics have a higher rate of HCV infection than whites.

THE CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

Despite federal, state, and local public health efforts to prevent and

control hepatitis B and hepatitis C, these diseases remain serious health

problems in the United States. Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC) in conjunction with the Department of Health and

Human Services Office of Minority Health, the Department of Veterans

Affairs, and the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable sought guidance from

the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in identifying missed opportunities related

to the prevention and control of HBV and HCV infections. IOM was asked

to focus on hepatitis B and hepatitis C because they are common in the

United States and can lead to chronic disease. The charge to the committee

follows.

The IOM will form a committee to determine ways to reduce new HBV

and HCV infections and the morbidity and mortality related to chronic

viral hepatitis. The committee will assess current prevention and control

activities and identify priorities for research, policy, and action. The com-

mittee will highlight issues that warrant further investigations and oppor-

tunities for collaboration between private and public sectors.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Upon reviewing evidence on the prevention and control of hepatitis B

and hepatitis C, the committee identified the underlying factors that impede

current efforts to prevent and control these diseases. Three major factors

were found:

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

SUMMARY 3

1. There is a lack of knowledge and awareness about chronic viral

hepatitis on the part of health-care and social-service providers.

2. There is a lack of knowledge and awareness about chronic viral

hepatitis among at-risk populations, members of the public, and

policy-makers.

3. There is insufficient understanding about the extent and seriousness

of this public-health problem, so inadequate public resources are

being allocated to prevention, control, and surveillance programs.

That situation has created several consequences:

• Inadequate disease surveillance systems underreport acute and

chronic infections, so the full extent of the problem is unknown.

• At-risk people do not know that they are at risk or how to prevent

becoming infected.

• At-risk people may not have access to preventive services.

• Chronically infected people do not know that they are infected.

• Many health-care providers do not screen people for risk factors

or do not know how to manage infected people.

• Infected people often have inadequate access to testing, social sup-

port, and medical management services.

To address those consequences, the committee offers recommendations

in four categories: surveillance, knowledge and awareness, immunization,

and services for viral hepatitis. The recommendations are discussed below,

and listed in Box S-1.

Surveillance

The viral hepatitis surveillance system in the United States is highly

fragmented and poorly developed. As a result, surveillance data do not pro-

vide accurate estimates of the current burden of disease, are insufficient for

program planning and evaluation, and do not provide the information that

would allow policy-makers to allocate sufficient resources to viral hepatitis

prevention and control programs. The federal government has provided

few resources—in the form of guidance, funding, and oversight—to local

and state health departments to perform surveillance for viral hepatitis.

Additional funding sources for surveillance, such as funding from states

and cities, vary among jurisdictions. The committee found little published

information on or systematic review of viral hepatitis surveillance in the

United States and offers the following recommendation to determine the

current status of the surveillance system:

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

4 HEPATITIS AND LIVER CANCER

BOX S-1

Recommendations

Chapter 2: Surveillance

• 2-1. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should conduct

a comprehensive evaluation of the national hepatitis B and

hepatitis C public-health surveillance system.

• 2-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should develop

specific cooperative viral-hepatitis agreements with all state and

territorial health departments to support core surveillance for

acute and chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

• 2-3. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should support

and conduct targeted active surveillance, including serologic

testing, to monitor incidence and prevalence of hepatitis B virus

and hepatitis C virus infections in populations not fully captured

by core surveillance.

Chapter 3: Knowledge and Awareness about Chronic Hepatitis B

and Hepatitis C

• 3-1. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should work

with key stakeholders (other federal agencies, state and local

governments, professional organizations, health-care organiza-

tions, and educational institutions) to develop hepatitis B and

hepatitis C educational programs for health-care and social-

service providers.

• 3-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should work

with key stakeholders to develop, coordinate, and evaluate inno-

vative and effective outreach and education programs to target

at-risk populations and to increase awareness in the general

population about hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

Chapter 4: Immunization

• 4-1. All infants weighing at least 2,000 grams and born to hepati-

tis B surface antigen-positive women should receive single-

antigen hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin in

the delivery room as soon as they are stable and washed. The

recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization

Practices should remain in effect for all other infants.

• 4-2. All states should mandate that the hepatitis B vaccine se-

ries be completed or in progress as a requirement for school

attendance.

• 4-3. Additional federal and state resources should be devoted to

increasing hepatitis B vaccination of at-risk adults.

• 4-4. States should be encouraged to expand immunization-information

systems to include adolescents and adults.

• 4-5. Private and public insurance coverage for hepatitis B vaccina-

tion should be expanded.

• 4-6. The federal government should work to ensure an adequate,

accessible, and sustainable hepatitis B vaccine supply.

• 4-7. Studies to develop a vaccine to prevent chronic hepatitis C virus

infection should continue.

Chapter 5: Viral Hepatitis Services

• 5-1. Federally funded health-insurance programs—such as Medi-

care, Medicaid, and the Federal Employees Health Benefits

Program—should incorporate guidelines for risk-factor screen-

ing for hepatitis B and hepatitis C as a required core compo-

nent of preventive care so that at-risk people receive serologic

testing for hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus and chronically

infected patients receive appropriate medical management.

• 5-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction

with other federal agencies and state agencies, should provide

resources for the expansion of community-based programs that

provide hepatitis B screening, testing, and vaccination services

that target foreign-born populations.

• 5-3. Federal, state, and local agencies should expand programs to

reduce the risk of hepatitis C virus infection through injection-

drug use by providing comprehensive hepatitis C virus preven-

tion programs. At a minimum, the programs should include

access to sterile needle syringes and drug-preparation equip-

ment because the shared use of these materials has been

shown to lead to transmission of hepatitis C virus.

• 5-4. Federal and state governments should expand services to

reduce the harm caused by chronic hepatitis B and hepati-

tis C. The services should include testing to detect infection,

counseling to reduce alcohol use and secondary transmission,

hepatitis B vaccination, and referral for or provision of medical

management.

• 5-5. Innovative, effective, multicomponent hepatitis C virus preven-

tion strategies for injection-drug users and non-injection-drug

users should be developed and evaluated to achieve greater

control of hepatitis C virus transmission.

• 5-6. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should pro-

vide additional resources and guidance to perinatal hepatitis B

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

SUMMARY 5

BOX S-1

Recommendations

Chapter 2: Surveillance

• 2-1. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should conduct

a comprehensive evaluation of the national hepatitis B and

hepatitis C public-health surveillance system.

• 2-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should develop

specific cooperative viral-hepatitis agreements with all state and

territorial health departments to support core surveillance for

acute and chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

• 2-3. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should support

and conduct targeted active surveillance, including serologic

testing, to monitor incidence and prevalence of hepatitis B virus

and hepatitis C virus infections in populations not fully captured

by core surveillance.

Chapter 3: Knowledge and Awareness about Chronic Hepatitis B

and Hepatitis C

• 3-1. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should work

with key stakeholders (other federal agencies, state and local

governments, professional organizations, health-care organiza-

tions, and educational institutions) to develop hepatitis B and

hepatitis C educational programs for health-care and social-

service providers.

• 3-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should work

with key stakeholders to develop, coordinate, and evaluate inno-

vative and effective outreach and education programs to target

at-risk populations and to increase awareness in the general

population about hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

Chapter 4: Immunization

• 4-1. All infants weighing at least 2,000 grams and born to hepati-

tis B surface antigen-positive women should receive single-

antigen hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin in

the delivery room as soon as they are stable and washed. The

recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization

Practices should remain in effect for all other infants.

• 4-2. All states should mandate that the hepatitis B vaccine se-

ries be completed or in progress as a requirement for school

attendance.

• 4-3. Additional federal and state resources should be devoted to

increasing hepatitis B vaccination of at-risk adults.

• 4-4. States should be encouraged to expand immunization-information

systems to include adolescents and adults.

• 4-5. Private and public insurance coverage for hepatitis B vaccina-

tion should be expanded.

• 4-6. The federal government should work to ensure an adequate,

accessible, and sustainable hepatitis B vaccine supply.

• 4-7. Studies to develop a vaccine to prevent chronic hepatitis C virus

infection should continue.

Chapter 5: Viral Hepatitis Services

• 5-1. Federally funded health-insurance programs—such as Medi-

care, Medicaid, and the Federal Employees Health Benefits

Program—should incorporate guidelines for risk-factor screen-

ing for hepatitis B and hepatitis C as a required core compo-

nent of preventive care so that at-risk people receive serologic

testing for hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus and chronically

infected patients receive appropriate medical management.

• 5-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction

with other federal agencies and state agencies, should provide

resources for the expansion of community-based programs that

provide hepatitis B screening, testing, and vaccination services

that target foreign-born populations.

• 5-3. Federal, state, and local agencies should expand programs to

reduce the risk of hepatitis C virus infection through injection-

drug use by providing comprehensive hepatitis C virus preven-

tion programs. At a minimum, the programs should include

access to sterile needle syringes and drug-preparation equip-

ment because the shared use of these materials has been

shown to lead to transmission of hepatitis C virus.

• 5-4. Federal and state governments should expand services to

reduce the harm caused by chronic hepatitis B and hepati-

tis C. The services should include testing to detect infection,

counseling to reduce alcohol use and secondary transmission,

hepatitis B vaccination, and referral for or provision of medical

management.

• 5-5. Innovative, effective, multicomponent hepatitis C virus preven-

tion strategies for injection-drug users and non-injection-drug

users should be developed and evaluated to achieve greater

control of hepatitis C virus transmission.

• 5-6. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should pro-

vide additional resources and guidance to perinatal hepatitis B

continued

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

6 HEPATITIS AND LIVER CANCER

Recommendation 2-1. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

should conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the national hepatitis B

and hepatitis C public-health surveillance system.

The evaluation should, at a minimum,

• Include assessment of the system’s attributes, including complete-

ness, data quality and accuracy, timeliness, sensitivity, specificity,

predictive value positive, representativeness, and stability.

• Be consistent with CDC’s Updated Guidelines for Evaluating Public

Health Surveillance Systems.

• Be used to guide the development of detailed technical guidance

and standards for viral hepatitis surveillance.

• Be published in a report.

prevention program coordinators to expand and enhance the

capacity to identify chronically infected pregnant women and

provide case-management services, including referral for ap-

propriate medical management.

• 5-7. The National Institutes of Health should support a study of

he effectiveness and safety of peripartum antiviral therapy to

reduce and possibly eliminate perinatal hepatitis B virus trans-

mission from women at high risk for perinatal transmission.

• 5-8. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the De-

partment of Justice should create an initiative to foster partner-

ships between health departments and corrections systems to

ensure the availability of comprehensive viral hepatitis services

for incarcerated people.

• 5-9. The Health Resources and Services Administration should

provide adequate resources to federally funded community

health facilities for provision of comprehensive viral-hepatitis

services.

• 5-10. The Health Resources and Services Administration and the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should provide re-

sources and guidance to integrate comprehensive viral hepatitis

services into settings that serve high-risk populations such as

STD clinics, sites for HIV services and care, homeless shelters,

and mobile health units.

BOX S-1 Continued

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

SUMMARY 7

The committee offers the following recommendations aimed at mak-

ing viral hepatitis surveillance systems more consistent among jurisdictions

and improving their ability to collect and report data on acute and chronic

hepatitis B and hepatitis C more accurately:

Recommendation 2-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

should develop specific cooperative viral-hepatitis agreements with all

state and territorial health departments to support core surveillance for

acute and chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

The agreements should include

• A funding mechanism and guidance for core surveillance

activities.

• Implementation of performance standards regarding revised and

standardized case definitions, specifically through the use of

o Revised case-reporting forms with required, standardized

components.

o Case evaluation and followup.

• Support for developing and implementing automated data-collection

systems, including

o Electronic laboratory reporting.

o Electronic medical-record extraction systems.

o Web-based, Public Health Information Network-compliant re-

porting systems.

Recommendation 2-3. The Centers for Disease Control and Preven-

tion should support and conduct targeted active surveillance, including

serologic testing, to monitor incidence and prevalence

1

of hepatitis B

virus and hepatitis C virus infections in populations not fully captured

by core surveillance.

• Active surveillance should be conducted in specific (sentinel) geo-

graphic regions and populations.

• Appropriate serology, molecular biology, and followup will allow for

distinction between acute and chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

1

Incidence refers to the number of new cases within a specified period of time. Prevalence

refers to the number of existing cases in a specified population at a designated time.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

8 HEPATITIS AND LIVER CANCER

Knowledge and Awareness

The committee found that there is relatively poor awareness about

hepatitis B and hepatitis C among health-care providers, social-service

providers (such as staff of drug-treatment facilities and immigrant-services

centers), and the public, especially important, among members of specific

at-risk populations. Lack of awareness about the prevalence of chronic viral

hepatitis in the United States and the target populations and appropriate

methodology for screening, testing, and medical management of chronic

hepatitis B and hepatitis C probably contributes to continuing transmission;

missing of opportunities for prevention, including vaccination; missing of

opportunities for early diagnosis and medical care; and poor health out-

comes in infected people.

To improve knowledge and awareness among health-care pro-

viders and social-service providers, the committee offers the following

recommendation:

Recommendation 3-1. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

should work with key stakeholders (other federal agencies, state and

local governments, professional organizations, health-care organiza-

tions, and educational institutions) to develop hepatitis B and hepatitis

C educational programs for health-care and social-service providers.

The educational programs should include at least the following

components:

• Information about the prevalence and incidence of acute and chronic

hepatitis B and hepatitis C both in the general US population and

in at-risk populations, particularly foreign-born populations in the

case of hepatitis B, and IDUs and incarcerated populations in the

case of hepatitis C.

• Guidance on screening for risk factors associated with hepatitis B

and hepatitis C.

• Information about hepatitis B and hepatitis C prevention, hepatitis

B immunization, and medical monitoring of chronically infected

patients.

• Information about prevention of HBV and HCV transmission in

hospital and nonhospital health-care settings.

• Information about discrimination and stigma associated with hepa-

titis B and hepatitis C and guidance on reducing them.

• Information about health disparities related to hepatitis B and

hepatitis C.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

SUMMARY 9

To increase knowledge and awareness about hepatitis B and hepatitis

C in at-risk populations and the general population, the committee offers

the following recommendation:

Recommendation 3-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

should work with key stakeholders to develop, coordinate, and evalu-

ate innovative and effective outreach and education programs to target

at-risk populations and to increase awareness in the general population

about hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

The programs should be linguistically and culturally appropriate and

should advance integration of viral hepatitis and liver-health education into

other health programs that serve at-risk populations. They should incorpo-

rate interventions that meet the following goals:

• Promote better understanding of HBV and HCV infections, trans-

mission, prevention, and treatment in the at-risk and general

populations.

• Promote increased hepatitis B vaccination rates among children

and at-risk adults.

• Educate pregnant women and women of childbearing age about

hepatitis B prevention.

• Reduce perinatal HBV infections and improve at-birth immuniza-

tion rates.

• Increase testing rates in at-risk populations.

• Reduce stigmatization of chronically infected people.

• Promote safe injections among IDUs and safe drug use among non-

injection-drug users (NIDUs).

• Provide culturally and linguistically appropriate educational infor-

mation for all persons who have tested positive for chronic HBV

or HCV infections and those who are receiving treatment.

• Encourage notification of close household and sexual contacts of

infected people to be tested for HBV and HCV and encourage

hepatitis B vaccination of close contacts.

Immunization

The longstanding availability of effective hepatitis B vaccines makes

the elimination of new HBV infections possible, particularly in children.

As noted above, about 1,000 newborns are infected by their HBV-positive

mothers at birth each year in the United States, and that number has not

declined in the last decade. To prevent transmission of HBV from moth-

ers to their newborns, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

10 HEPATITIS AND LIVER CANCER

(ACIP) recommends that infants born to mothers who are positive for

hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) receive hepatitis B immune globulin

and a first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours of birth. To

improve adherence to that guideline, the committee offers the following

recommendation:

Recommendation 4-1. All infants weighing at least 2,000 grams and

born to hepatitis B surface antigen-positive women should receive

single-antigen hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin in

the delivery room as soon as they are stable and washed. The recom-

mendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

should remain in effect for all other infants.

The ACIP recommends administration of the hepatitis B vaccine series

to unvaccinated children and young adults under 19 years old. School-entry

mandates have been shown to increase hepatitis B vaccination rates and to

reduce disparities in vaccination rates. Overall, hepatitis B vaccination rates

in school-age children are high (for example, about 80% of states reported

at least 95% hepatitis B vaccine coverage of children in kindergarten in

2006–2007), but there is variability in coverage among states. Additionally,

there are racial and ethnic disparities in childhood vaccination rates—Asian

and Pacific Islander (API), Hispanic, and African American children have

lower vaccination rates than non-Hispanic white children. Regarding vac-

cination of children and adults under 19 years old, the committee offers the

following recommendation:

Recommendation 4-2. All states should mandate that the hepatitis B

vaccine series be completed or in progress as a requirement for school

attendance.

Hepatitis B vaccination for adults is directed at high-risk groups—

people at risk for HBV infection from infected household contact and sex

partners, from injection-drug use, from occupational exposure to infected

blood or body fluids, and from travel to regions that have high or interme-

diate HBV endemicity. Only about half the adults who are at high risk for

HBV infection receive the hepatitis B vaccine. Low coverage of high-risk

adults is attributed to the lack of dedicated vaccine programs; limitations

of funding, insurance coverage, and cost-sharing; and noncompliance of

the involved populations. To increase the rate of hepatitis B vaccination of

at-risk adults, the committee offers the following recommendation:

Recommendation 4-3. Additional federal and state resources should be

devoted to increasing hepatitis B vaccination of at-risk adults.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

SUMMARY 11

• Correctional institutions should offer hepatitis B vaccination to all

incarcerated persons. Accelerated schedules for vaccine administra-

tion should be considered for jail inmates.

• Organizations that serve high-risk populations should offer the

hepatitis B vaccination series.

• Efforts should be made to improve identification of at-risk

adults. Health-care providers should routinely seek risk behav-

ior histories from adult patients through direct questioning and

self-assessment.

• Efforts should be made to increase rates of completion of the vac-

cine series in adults.

• Federal and state agencies should annually determine gaps in hepa-

titis B vaccine coverage among at-risk adults and estimate the

resources needed to fill those gaps.

Immunization-information systems are used for collection and con-

solidation of vaccination data from multiple health-care providers, vaccine

management, adverse-event reporting, and tracking lifespan vaccination

histories. States have made progress on developing and implementing im-

munization-information systems, particularly with regard to collecting vac-

cination data on children. The committee believes that it is also important

to include vaccination data on adolescents and adults in immunization

information systems and offers the following recommendation:

Recommendation 4-4. States should be encouraged to expand

immunization-information systems to include adolescents and adults.

Coverage for hepatitis B vaccination is greater for children and youths

than for adults. Except for Medicaid’s Early Periodic Screening, Diag-

nosis, and Treatment entitlement, public-health insurance often contains

cost-sharing, which may create a barrier to vaccination for some people.

Private health insurance has gaps for vaccination coverage because it does

not universally cover all ACIP-recommended vaccinations for children and

adults. Furthermore, most privately insured persons are required to pay to

receive vaccinations. To reduce barriers to children and adults for hepatitis

B vaccination, the committee offers the following recommendation:

Recommendation 4-5. Private and public insurance coverage for hepa-

titis B vaccination should be expanded.

• Public Health Section 317 should be expanded with sufficient fund-

ing to become the public safety net for underinsured and uninsured

adults to receive the hepatitis B vaccination.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

12 HEPATITIS AND LIVER CANCER

• All private insurance plans should include coverage for all ACIP-

recommended vaccinations. Hepatitis B vaccination should be free

of any deductible so that first-dollar coverage exists for this preven-

tive service.

There has not been a national shortage of the hepatitis B vaccine, how-

ever, temporary supply problems occurred with this vaccine in 2008 (adult

and dialysis formulations of Recombivax HB) and 2009 (pediatric formula-

tions of Recombivax HB and Pediatric Engerix-B). A shortage was avoided

because other manufacturers were able to provide an adequate supply of the

vaccine in adult and dialysis formulations, and CDC released doses of pe-

diatric vaccine from its stockpile. To prevent future supply problems of the

hepatitis B vaccine, the committee offers the following recommendation:

Recommendation 4-6. The federal government should work to ensure

an adequate, accessible, and sustainable hepatitis B vaccine supply.

Efforts are going on to develop a vaccine for hepatitis C, which could

substantially enhance hepatitis C prevention efforts. The committee recog-

nizes the need for a safe, effective, and affordable hepatitis C vaccine and

offers the following recommendation:

Recommendation 4-7. Studies to develop a vaccine to prevent chronic

hepatitis C virus infection should continue.

Viral Hepatitis Services

Health services related to viral hepatitis prevention, risk-factor screen-

ing and serologic testing,

2

and medical management are both sparse and

fragmented among entities at the federal, state, and local levels. The com-

mittee believes that a coordinated approach is necessary to reduce the

numbers of new HBV and HCV infections, illnesses, and deaths associated

with these infections. Comprehensive viral hepatitis services should have

five core components: outreach and awareness, prevention of new infec-

tions, identification of infected people, social and peer support, and medical

management of infected people.

The committee identified major gaps in viral hepatitis services for

the general population and specific groups that are heavily affected by

HBV and HCV infections: foreign-born populations, illicit-drug users, and

2

Risk-factor screening is the process of determining whether a person is at risk for being

chronically infected or becoming infected with HBV or HCV. Serologic testing is laboratory

testing of blood specimens for biomarker confirmation of HBV or HCV infection.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

SUMMARY 13

pregnant women. It also examined venues that provide services to at-risk

groups: correctional facilities, community health facilities, STD and HIV

clinics, shelter-based programs, and mobile health units. The committee

offers recommendations to address major deficiencies for each group and

health-care venue.

General Population

Most people who are chronically infected with HBV or HCV are un-

aware of their infection status. As treatments for chronic hepatitis B and C

improve, it becomes critical to identify chronically infected people. There-

fore, it is important that the general population have access to screening

and testing services so that people who are at risk for viral hepatitis can

be identified. The federal government is the largest purchaser of health

insurance nationally and is well positioned to be the leader in the develop-

ment and enforcement of guidelines to ensure that the people for whom it

provides health care have access to risk-factor screening, serologic testing

for HBV and HCV, and appropriate medical management.

Recommendation 5-1. Federally funded health-insurance programs—

such as Medicare, Medicaid, and the Federal Employees Health Ben-

efits Program—should incorporate guidelines for risk-factor screening

for hepatitis B and hepatitis C as a required core component of pre-

ventive care so that at-risk people receive serologic testing for hepatitis

B virus and hepatitis C virus and chronically infected patients receive

appropriate medical management.

Foreign-Born Populations

Nearly half of US foreign-born people, or 6% of the total US popula-

tion, originate in HBV-endemic countries. Thus, there is a growing urgency

for culturally appropriate programs to provide hepatitis B screening and

related services to this high-risk population. There is a pervasive lack of

knowledge about hepatitis B among Asians and Pacific Islanders, and this

is probably also the case for other foreign-born people in the United States.

The lack of awareness in foreign-born populations from HBV-endemic

countries is compounded by the gaps in knowledge and preventive practice

among health-care and social-service providers, particularly those who

serve a large number of foreign-born, high-risk patients. The committee be-

lieves that the needs of foreign-born people are best met with the approach

outlined in Recommendations 3-1 and 3-2. The community-based approach

as outlined in Recommendation 3-2 would be strengthened by additional

resources to provide screening, testing, and vaccination services.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

14 HEPATITIS AND LIVER CANCER

Recommendation 5-2. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

in conjunction with other federal agencies and state agencies, should

provide resources for the expansion of community-based programs

that provide hepatitis B screening, testing, and vaccination services that

target foreign-born populations.

Illicit-Drug Users

HBV and HCV infection rates in illicit-drug users are high, particularly

in IDUs. HCV is easily transmitted among IDUs, and methods to promote

safe injection can be considered essential for HCV control. However, safe-

injection strategies alone are insufficient to control HCV transmission.

Prevention of HCV infection is a function of multiple factors—safe-injec-

tion strategies, education, testing, and drug treatment—so an integrated

approach that includes all these elements is more likely to be effective in

preventing hepatitis C.

Recommendation 5-3. Federal, state, and local agencies should expand

programs to reduce the risk of hepatitis C virus infection through

injection-drug use by providing comprehensive hepatitis C virus pre-

vention programs. At a minimum, the programs should include access

to sterile needle syringes and drug-preparation equipment because the

shared use of these materials has been shown to lead to transmission

of hepatitis C virus.

Although illicit-drug use is associated with many serious acute and

chronic medical conditions, health-care use among drug users is lower than

among persons who do not use illicit drugs. Health care for both IDUs and

NIDUs is sporadic and typically received in hospital emergency rooms,

corrections facilities, and STD clinics. Given that population’s poor access

to health care and services, it is important to have prevention and care ser-

vices in settings that IDUs and NIDUs are likely to frequent or to develop

programs that will draw them into care.

Recommendation 5-4. Federal and state governments should expand

services to reduce the harm caused by chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis

C. The services should include testing to detect infection, counseling to

reduce alcohol use and secondary transmission, hepatitis B vaccination,

and referral for or provision of medical management.

Studies have shown that the first few years after onset of injection-

drug use constitute a high-risk period in which the rate of HCV infection

can exceed 40%. Preventing the transition from non-injection-drug use

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

SUMMARY 15

to injection-drug use will probably avert many HCV infections. The com-

mittee therefore offers the following research recommendation:

Recommendation 5-5. Innovative, effective, multicomponent hepatitis

C virus prevention strategies for injection-drug users and non-injection-

drug users should be developed and evaluated to achieve greater con-

trol of hepatitis C virus transmission. In particular,

• Hepatitis C prevention programs for persons who smoke or sniff

heroin, cocaine, and other drugs should be developed and tested.

• Programs to prevent the transition from noninjection use of illicit

drugs to injection should be developed and implemented.

Pregnant Women

States and large metropolitan areas are eligible to receive federal fund-

ing to support perinatal hepatitis B prevention programs through CDC’s

National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Comprehen-

sive programs have been shown to be effective not only in identifying HBV-

infected pregnant women but in providing other case-management services

(for example, testing of household and sexual contacts and referral to

medical care). However, most programs are understaffed and underfunded

and cannot offer adequate case-management services.

Recommendation 5-6. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

should provide additional resources and guidance to perinatal hepa-

titis B prevention program coordinators to expand and enhance the

capacity to identify chronically infected pregnant women and provide

case-management services, including referral for appropriate medical

management.

Although an increasing number of effective HBV antiviral suppressive

medications have become available for the management of chronic HBV

infection, very little research has been done on the use of these medications

during the last trimester of pregnancy to eliminate the risk of perinatal

transmission. The committee believes that there is a need to fund research

to guide the effective use of antiviral medications late in pregnancy to

prevent maternofetal HBV transmission, and offers the following research

recommendation:

Recommendation 5-7. The National Institutes of Health should sup-

port a study of the effectiveness and safety of peripartum antiviral

therapy to reduce and possibly eliminate perinatal hepatitis B virus

transmission from women at high risk for perinatal transmission.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

16 HEPATITIS AND LIVER CANCER

Correctional Facilities

Incarcerated populations have higher rates of HBV and HCV infec-

tions than the general population. Screening of all incarcerated people for

risk factors can identify those who need blood tests for infection and, if

appropriate, treatment.

Recommendation 5-8. The Centers for Disease Control and Preven-

tion and the Department of Justice should create an initiative to foster

partnerships between health departments and corrections systems to

ensure the availability of comprehensive viral hepatitis services for

incarcerated people.

Community Health Centers

The Health Resources and Services Administration administers grant

programs across the country to deliver primary care to uninsured and

underinsured people in community health centers, migrant health centers,

homeless programs, and public-housing primary-care programs. In general,

funding of viral hepatitis services at community health centers is inad-

equate. Because community health centers provide primary health care for

many people who are at risk for hepatitis B and hepatitis C, it is important

for them to offer comprehensive viral hepatitis services.

Recommendation 5-9. The Health Resources and Services Adminis-

tration should provide adequate resources to federally funded com-

munity health facilities for provision of comprehensive viral-hepatitis

services.

Other Settings That Target At-Risk Populations

STD and HIV clinics, shelter-based programs, and mobile health units

are settings that serve populations that are at risk for hepatitis B and hepa-

titis C. The populations that use the settings may not have access to care

through traditional health-care venues. Integration of viral hepatitis services

into those settings creates opportunities to identify at-risk clients and to get

them other services that they need.

Recommendation 5-10. The Health Resources and Services Admin-

istration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should

provide resources and guidance to integrate comprehensive viral hepa-

titis services into settings that serve high-risk populations such as STD

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html

SUMMARY 17

clinics, sites for HIV services and care, homeless shelters, and mobile

health units.

RECOMMENDATION OUTCOMES

The committee believes that implementation of its recommendations

would lead to reductions in new HBV and HCV infections, in medical

complications and deaths that result from these viral infections of the liver,

and in total health costs. Advances in three major categories will be needed:

in knowledge and awareness about chronic viral hepatitis among health-

care and social-service providers, the general public, and policy-makers; in

improvement and better integration of viral hepatitis services, including ex-

panded hepatitis B vaccination coverage; and in improvement of estimates

of the burden of disease for resource-allocation purposes.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12793.html