W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

1

Does Khan Academy Work?

The effects of Khan Academy usage on student performance and encouragement designs that

worked

Li Chu, Aniruddh Nautiyal, Saifullah Rais & Hilary Yamtich

Date: April 26, 2018

Abstract: Encouragement involving parents improves compliance influencing performance by

~16%

We ran an experiment to assess the causal effects of Khan Academy usage on student performance. A

randomized control trial is conducted on a sample of 103 grade 6/7 charter school students based in

California, USA. A by-product of our encouragement design sheds light on the effectiveness of parental

involvement in increasing activity on these self-learning environments. While the intent to treat effect was

a 10% improvement in student performance, compliers showed 16% improvement in scores. The key

limitations include the limited sample size and the ability to generalize these findings across different

grades, schools and other MOOC offerings. Further work could evaluate the long-term effects of these

encouragement designs and the effects of variable treatment intensity.

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

2

Statement of Purpose

Schools across the United States and worldwide are using free or paid online ed-tech tools such

as Khan Academy to supplement educational programs and improve student achievement.

Schools and teachers integrate Khan Academy into their instructional programs in different

ways, and there are observational studies showing correlations between time spent by students

using Khan Academy and improved student outcomes. These studies do nothing to address the

actual causal effects of Khan usage: likely, students who spend more time doing any program

related to academics will show improved outcomes, when the time spent is self-selected. The

purpose of this experiment is to determine the actual effect of using Khan Academy when that

use is not self-selected. Does spending time on Khan Academy improve student outcomes?

Preliminary observational work done by SRI Education indicates that students who use Khan

more show higher than predicted test performance. This is purely a correlation, and can clearly

be explained by various underlying variables: students who are more motivated to learn, or more

interested in math, or concerned about their academic performance are more likely to choose to

use Khan, just as they are more likely to choose to use any educational resource provided to

them, and they are also more likely to show better than expected growth on assessments.

The observational studies conducted suggest a relationship, but this relationship can be explained

by many non-causal factors. Our aim with this experiment is to understand whether there is any

causal effect of Khan Academy usage.

A necessary component of our project is also to develop a way to effectively encourage students

to use Khan when assigned to do so. To this end, different encouragement strategies were

explored in order to ensure that students assigned to the treatment (of using KA) actually

received the treatment. This led us to develop and assess the effectiveness of two different

encouragement designs.

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

3

EXPERIMENT DESIGN

Pilot

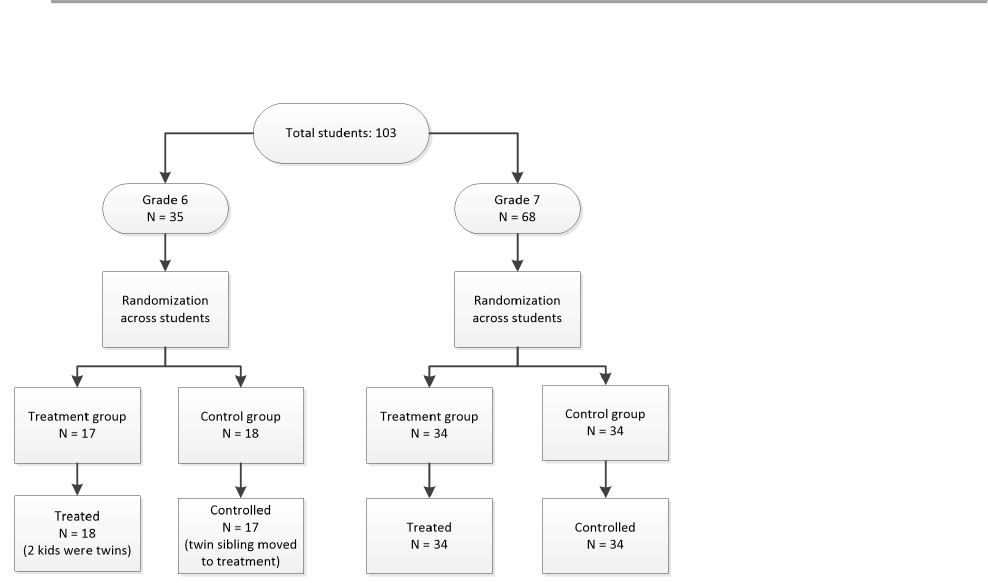

To conduct this experiment, we had access to 103 middle school students at a charter school in

Oakland, California. The pilot experiment involving a pre- and post-test design in which all

students were randomly assigned either to control or treatment.

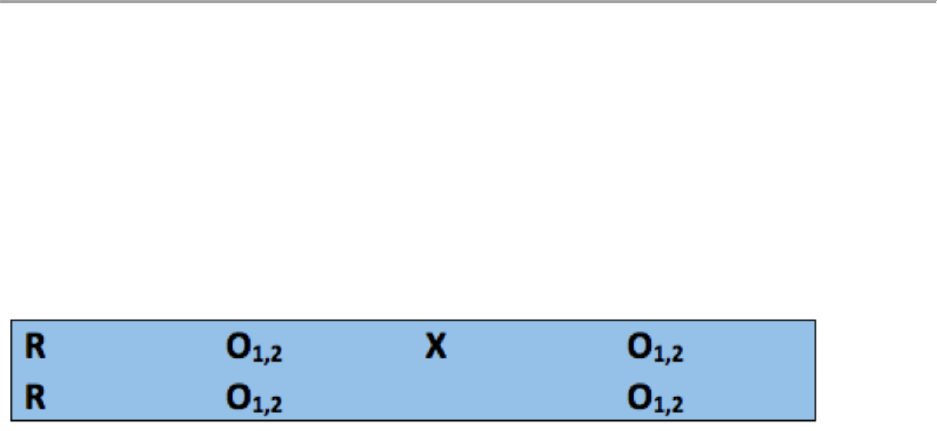

Figure 1: Pilot Design Diagram

The first outcome measure was the student exposure to Khan Academy (KA), which could be

measured in various ways (minutes spent on KA, problems solved, skills mastered, etc;). All this

data was available for each student who used KA either before or during the experiment. The

second outcome measure of the pilot study was the NWEA (Northwest Evaluation Association)

MAP (Measure of Academic Progress) computer-adaptive test scores. These measures were

available for students in both treatment and control both before and after the treatment was

administered.

The primary treatment for the project during the pilot phase was sending study materials and

assignment reminders to the students in the treatment group. These were given twice per week,

for a period of 4 weeks, the student’s math teacher, overseeing the treatment disbursement for

the classes of both the grades - 6 and 7. The students could do these exercises or view the videos

from their Chromebook either at school, or a computer at home. These could be tracked by the

KA’s portal, as long as the student was logged into into their KA account.

The control group did not receive any of the above assignments, study materials or reminders.

The control group students had a KA account, so they technically had access to the same content,

except they did not have access to the specific directions about what they should do on KA. One

of the available time slots for the students to work on the assignments or videos was the common

activities slot, wherein the students were assembled into a common hall and could work on one

of 5 optional activities, which included KA.

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

4

Figure 2: Sample Assignment for Pilot Study Treatment

Figure 1: Sample Assignment for Pilot Study Treatment

The scope of the experiment was limited to the school’s students accessible by the middle school

Math teacher. All the students who were enrolled into grade 6 and 7 were incorporated as the

subjects of the study. This was done to maximize the sample size as much as possible, using all

the students available at hand. There was substantial heterogeneity among the students across

racial and socio-economic backgrounds.

Main Experiment

Based on the results from the pilot study, the treatment in the main experiment involved a

different form of encouragement. Due to time limitations, the main experimental design involved

only a post-test, as shown below:

Figure 3: Experimental Design Diagram

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

5

In this case, the first outcome variable was the time spent on KA (as before, measured by

minutes on the portal, problems solved, assignments completed, or even a binary variable about

whether or not the student used KA at all). The second outcome variable in this case was a

teacher-created post-test based on the KA assignments.

After the pilot study was concluded, the main experiment’s treatment strategy was changed to

have a stronger enforcement, improved compliance and reduced spillover. To this effect, the

experiment was done over the Spring break, which allowed students to be isolated from the

school environment. In this experiment, all students in both treatment and control received the

same assignments in their KA portal, but treatment group students received aggressive

encouragement directed at their parents.

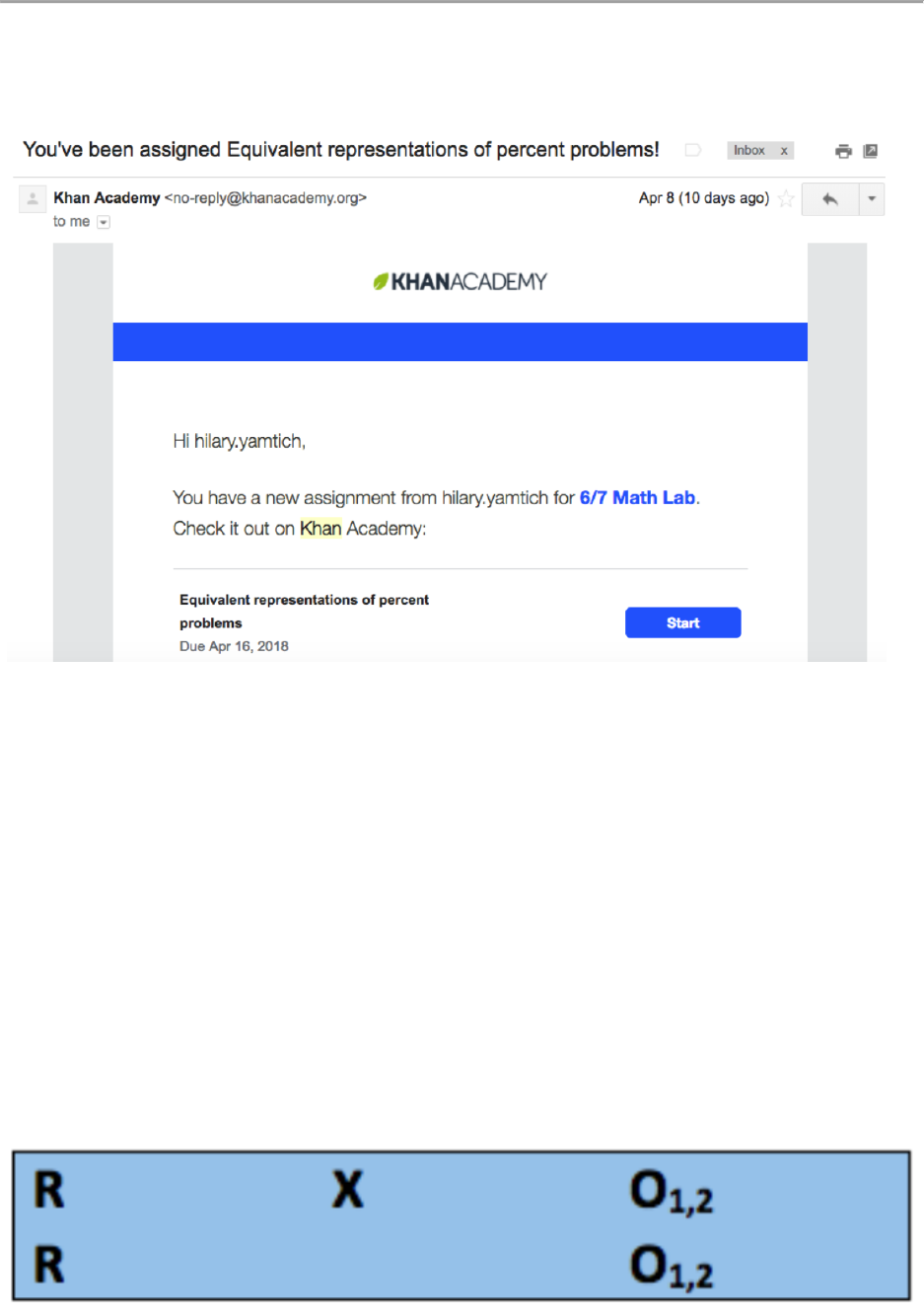

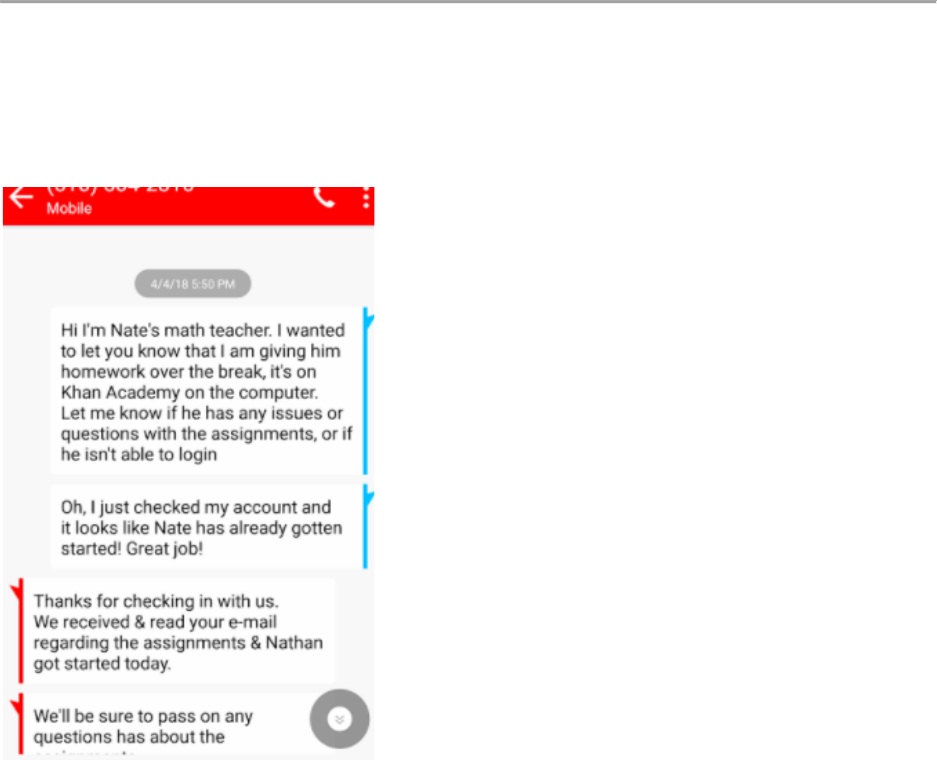

For the 2 week duration of the experiment during which students were not attending class, the

treatment included at least 3 emails and text reminders to the parents about their child’s

assignment status, and 2 updates about whether the student completed the assignment or not. Due

to the online assignment features, the parent updates could be delivered almost in real-time, or

within 24 hours, so that the parents of students who completed assignments received a text

update from their child’s teacher within 24 hours. Parents of students who did not complete

assignments received 2 updates stating that their student still had not started work on the

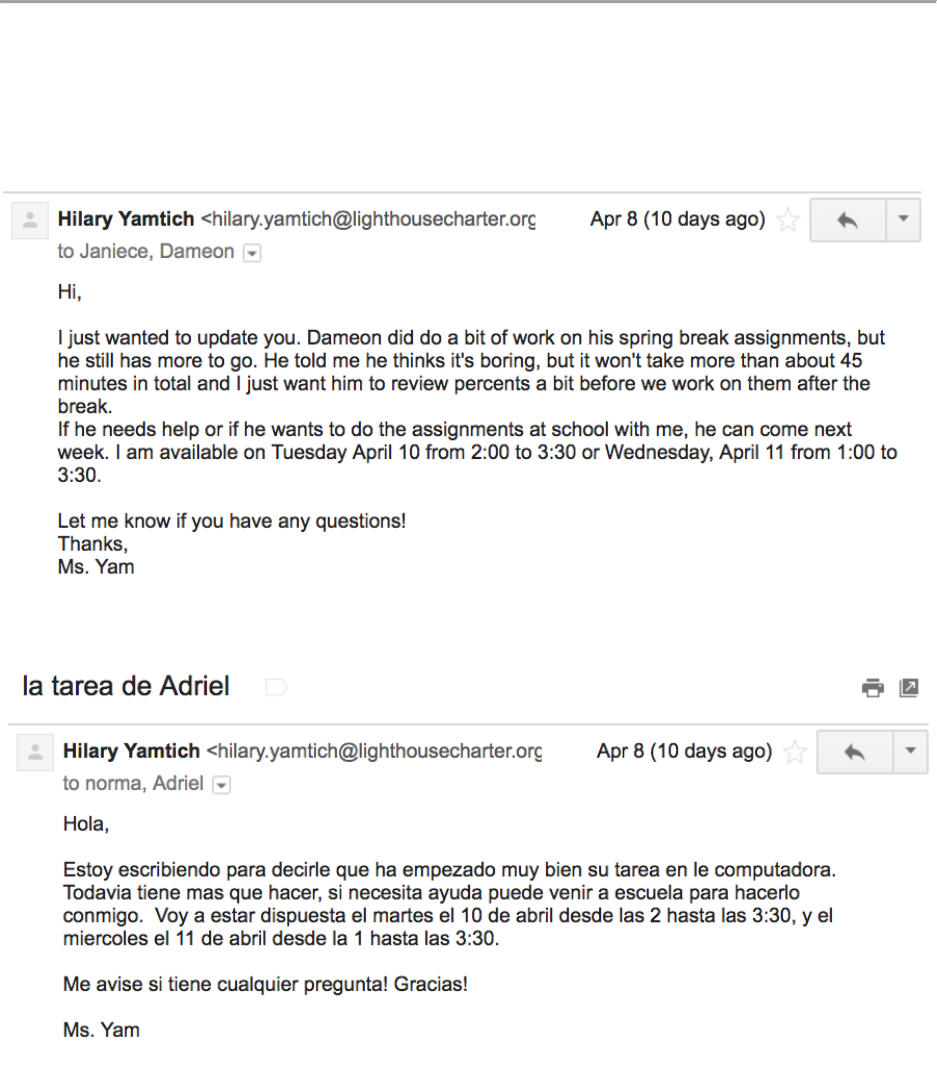

assignments. The treatment communication was delivered in Spanish or English depending upon

the preferred language of communication indicated by parents, and was from the personal email

and cell-phone of their child’s math teacher (i.e. not a stranger or unknown cell-phone number.)

Often, students in the treatment group needed support learning how to access Khan at home, so

additional communication between teacher and parents was focused on giving clear directions so

that students knew how to access and complete the assignments. Students in the treatment group

were also given the option to come to school on one of two teacher work days to use a school

computer to complete the assignments (this was implemented to further increase compliance.)

The overall aim of the encouragement was to ensure that students had no obstacles to completing

their assignments.

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

6

Figure 4: Sample Treatment Email (English)

Figure 5: Sample Treatment Email (Spanish)

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

7

Figure 6: Sample Treatment Text

Randomization Engineering

For both the pilot and the main experiment, treatment assignment was conducted at the

individual student level. This was done partly due to the fact that the sample size was limited to

students in a single middle school, which was separated into only 6 math classes. Clustering at

the class level would have resulted in a very low-powered experiment. The treatment was

administered at an individual level: students were not working on KA during class time but

rather during study halls or at home.

For the pilot study, the randomization was done in R environment using the sample function.

Each of the two grades, 6 and 7 were randomized independently. Prior to randomization,

blocking was done to have roughly equal sized treatment and control groups within each grade.

For the main experiment, the randomization was conducted in the same way. Blocking by grade

level, the sample function was used to assign roughly equal treatment and control groups within

each grade level. Students were re-assigned to either treatment or control for the experiment, so

the treatment and control groups were not the same as for the pilot. In both the cases, the

randomization was done blindly and only once, without rerunning or discarding randomizations

against covariate balance checks.

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

8

Figure 7: Treatment Assignment Flow-chart

Measurement of Variables

The measurement variables throughout the pilot and the main experiment, were collected from

two sources. Most of the variables tracking the metrics of videos, assignments or usage of KA by

the students were extracted through the KA portal which keeps track of the usage activity of all

the students who have accepted the Math teacher as their coach. Before someone could send the

students any guided assignments or study material, they had to be accepted as a ‘coach’ by the

student from the student’s KA account. Thus, a follow up campaign was done during the start of

pilot study to make sure all the students have accepted the invitation from the Math teacher to be

their coach. This was required to effectively reach out to the students and distribute the

treatments or reminders through KA. The second set of variables were collected through

miscellaneous sources from school that had recorded information about the students.

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

9

Figure 8: Description of Each Variable in the Data-set

Variable

Source

Description

Khan_ID

KA

Unique ID to identify subjects

already_active

KA

1 = using khan (before pilot study)

0 = otherwise

home_computer

School

1 = subject has computer at home

0 = no computer at home

subsidized_lunch

School

LunchStatus (F = free, R = reduced, P = paid)

fluent_english

School

english language learner status (EO = ?, RFEP = ?, EL = ?)

treated_exp1

Pilot

study

1=Subject in treatment group during pilot study,

0=Subject in control group during pilot study

winter_score

School

winter MAP score

spring_score

School

spring MAP score

Pilot_Khan_Total

KA

Total time (in mins) spent on Khan portal during pilot study

Pilot_Khan_Total_

questions

KA

No. of questions solved on Khan portal during pilot study

Pilot_Khan_Video

KA

Total time (in mins) spent on Khan videos during pilot study

Pilot_Khan_Skill

KA

Total time (in mins) spent on Khan skills practice during pilot study

Main_Khan_Total

KA

Total time (in mins) spent on Khan portal during main experiment

Main_Khan_Total_

questions

KA

No. of questions solved on Khan portal during main study

Main_Khan_Video

KA

Total time (in mins) spent on Khan videos during main experiment

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

10

Main_Khan_Skill

KA

Total time (in mins) spent on Khan skills practice during main

experiment

Test_score

Teacher

Test score (out of 10 possible points) on post-experiment test

Week_After_Khan

KA

Students’ usage of KA during the week after experiment

Week_After_Test

Teacher

Test scores on a quiz covering similar material 1 week after the end of

the experiment

The Analysis Phase: Concrete steps to avoid fishing

The aim of the main experiment is to investigate if there is relationship between the

encouragement treatment stimulus and the resulting output metrics of the students. Although

there are are various ways to track the latter, tracking the usage time on KA’s portal is a natural

choice to measure the effectiveness of the encouragement. This can be total minutes spent by the

student on KA portal during the duration of the experiment, or can be a specific subset as time

spent on watching videos, or practicing skills. The second measure of the students’ output metric

is a test score, either standardized or in-school prepared and administered, or number of

questions solved by each subject on KA portal.

The covariates used in the main experiment are those described above, which basically are

intended to capture the variation across the group of students. These include: whether the child

has a computer at home, whether they had previously used KA before the experiments, whether

they speak fluent English and whether they come from a low-income family. Another important

covariate is their baseline test score, which stands in for their overall level of academic

achievement. Controlling for this is essential so that we aren’t comparing high performing kids

in either group to low performing kids in either group.

MODELING CHOICES: LEAST SQUARES REGRESSION AND 2SLS

The main model for analyzing outcome variables discussed above, was selected as simple

regression, with different covariates included. One of the reasons was to keep the interpretation

simple and intuitive, especially with multiple covariates involved.

In order to estimate the complier average causal effect (CACE), we use an IV estimator in the

form of our random assignment. As we know, any instrument must meet three requirements:

● Relevance: instrument Z has a causal effect on X

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

11

● Independence: Z does not share common causes with the outcome Y

● Exclusion restriction: Z affects the outcome Y only through X

While the pilot experiment did not meet the relevance assumption (encouragement did not

increase Khan usage), the main experiment took care of the shortfall. While the independence

assumption is taken care of by the randomized control, exclusion restriction remains the weakest

assumption. There are multiple reasons which could lead to better scores than merely MOOC

activity. Past performance could be one such reason. Therefore, we need to reduce the effects of

the same by using Spring MAP scores as a covariate.

RESULTS

Key findings from both experiments can be summarized as follows:

● Student email encouragement has no effect on activity

● Parent involvement makes all the difference

● Parent-assisted encouragement designs influence performance by 10%

● Complying students saw an improvement of 16% in test scores

● Effects of encouragement are short-lived and not sustained past the end of the

encouragement

Pilot Study

The main conclusion of our pilot study was that simply giving students assignments in KA

through their email had no effect on their time spent on KA.

Figure 9: Intent to treat shows statistically insignificant effects on KA usage

The outcome variable for the regression shown below is the time spent on KA. The coefficient of

treated_exp1 variable indicates the treatment effect on the outcome. It is not statistically

significant.

Two-sided non-compliance and spill-over distorted results. This was due to the fact that students

were using KA in a public setting. This could have influenced students in control to use KA as a

result of their friends being exposed to the treatment. During the pilot, Khan Academy usage was

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

12

essentially self-selected: students disregarded the email-based encouragement and chose to use

Khan based on their own personal factors. Assignment to treatment did not have any effect on a

students’ Khan usage.

Because of this, we cannot use the pilot experiment to answer the question of whether or not

Khan usage affects a students’ outcomes. The regression below shows the effects of being

assigned to treatment on the post-treatment MAP score, and here we see no statistically

significant effect:

Figure 10: Intent to treat shows statistically insignificant effects on Spring MAP scores

Main Experiment

The results of the pilot experiment led to more careful design of the main experiment, and the

improved design enabled an analysis of the effects of Khan usage on test scores.

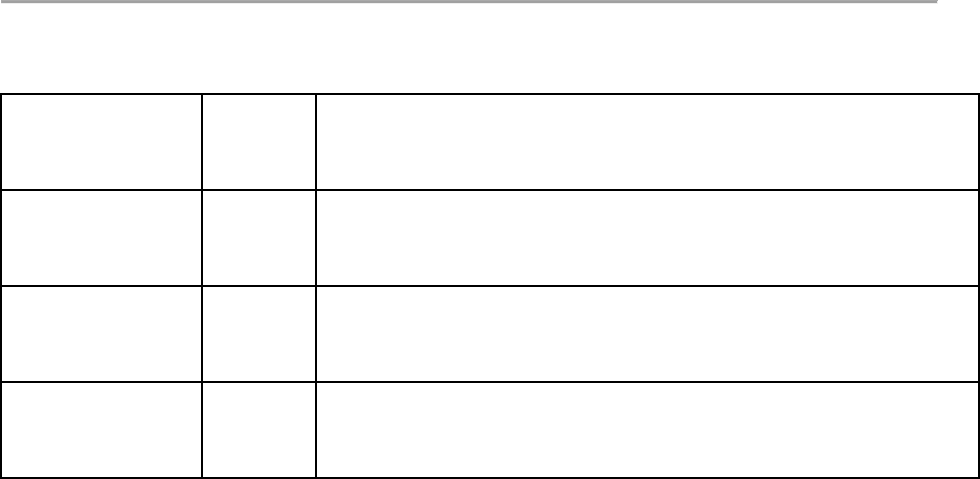

The first component of the analysis is the covariate balance checks:

Figure 11: Grade 7 looks balanced on most covariates except english fluency

Figure 12: Grade 6 has imbalance on computer access at home and english fluency as well

Due to the small sample size, we observe some imbalances between treatment and control groups

at both grade levels, most notably with regards to the baseline MAP test score (winter_score),

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

13

which shows that in both grades the treatment group had significantly lower baseline test scores.

(With MAP scores, 6 points can be an entire year, so an average of 199 vs 210 is a significant

difference). For Grade 6, we saw imbalance in english fluency and home computer access. For

Grade 7, home computer access was well balanced but English fluency remained a concern. As

there was no bias in the assignment methodology, we believe that the covariate imbalances can

be addressed by including these covariates in the regressions that analyze the results.

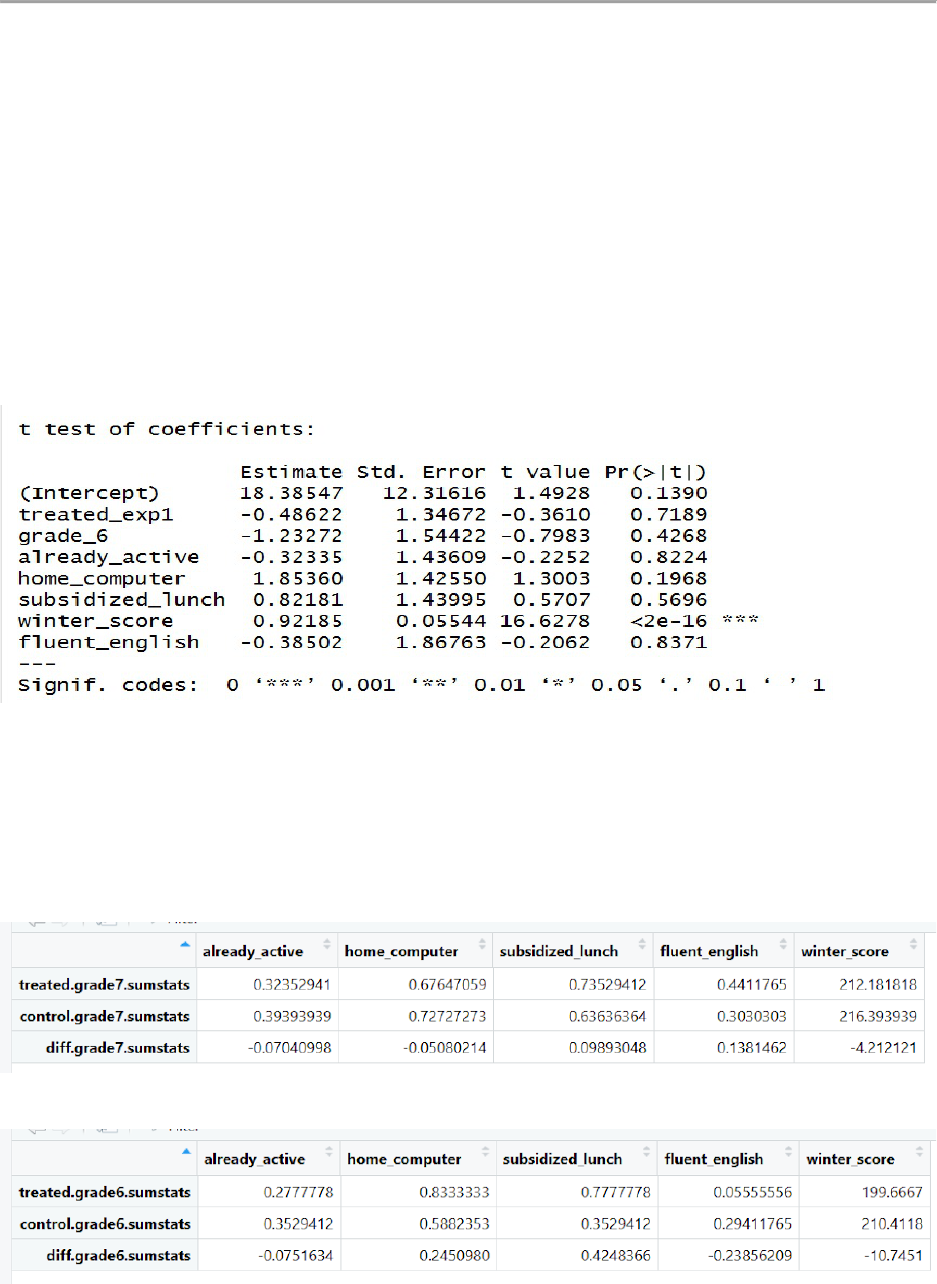

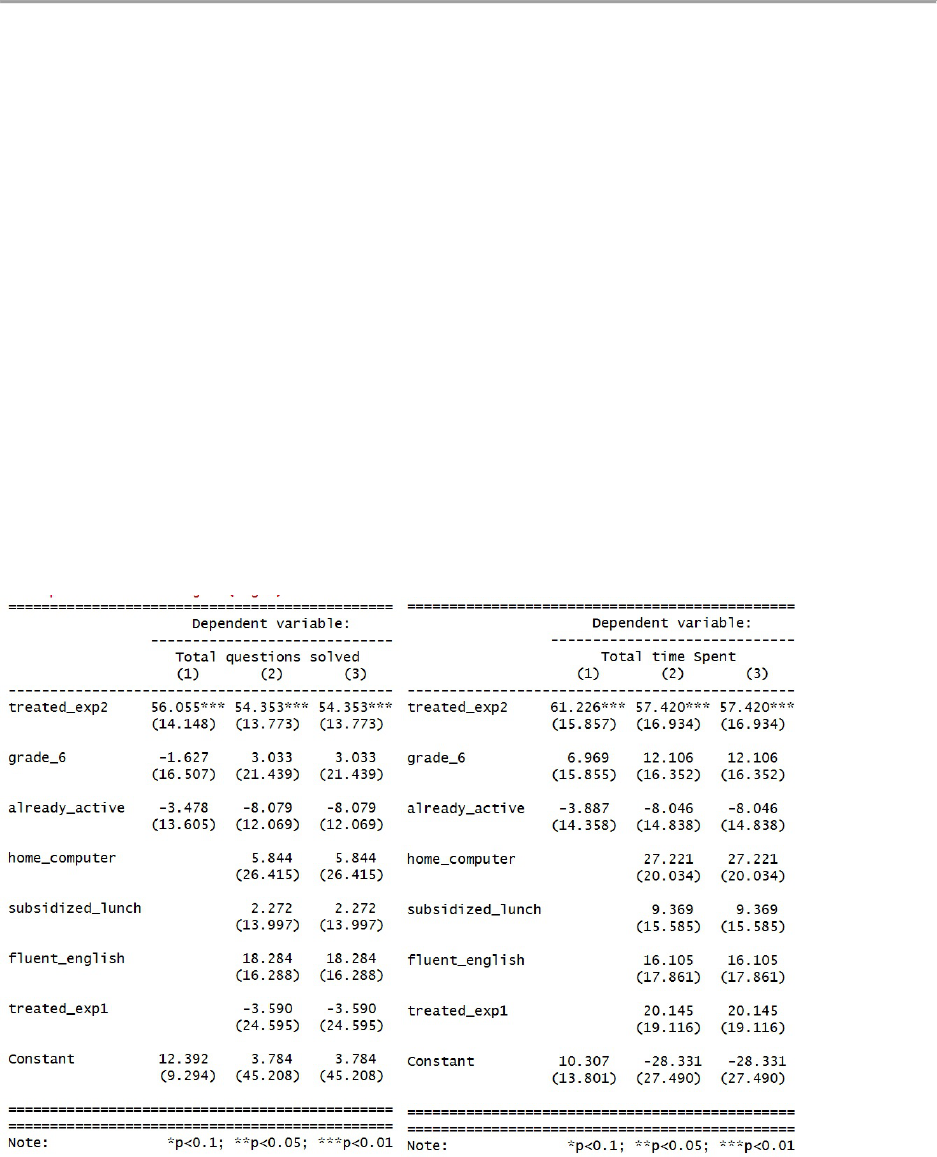

The regressions below show the effects of assignment to treatment on the number of problems

solved by each student on Khan and the total minutes spent by each student on Khan. When

controlling for background factors (i.e. family income and English language proficiency),

assignment to treatment resulted in students spending almost 1 more hour using Khan and

solving about 54 more problems on Khan than students not assigned to treatment. These effects

are highly statistically significant with p-values of less than 0.01. This means that the parental

encouragement was highly effective in terms of getting students to use Khan Academy.

Figure 13: Assignment to treatment increased activity (in time and questions)

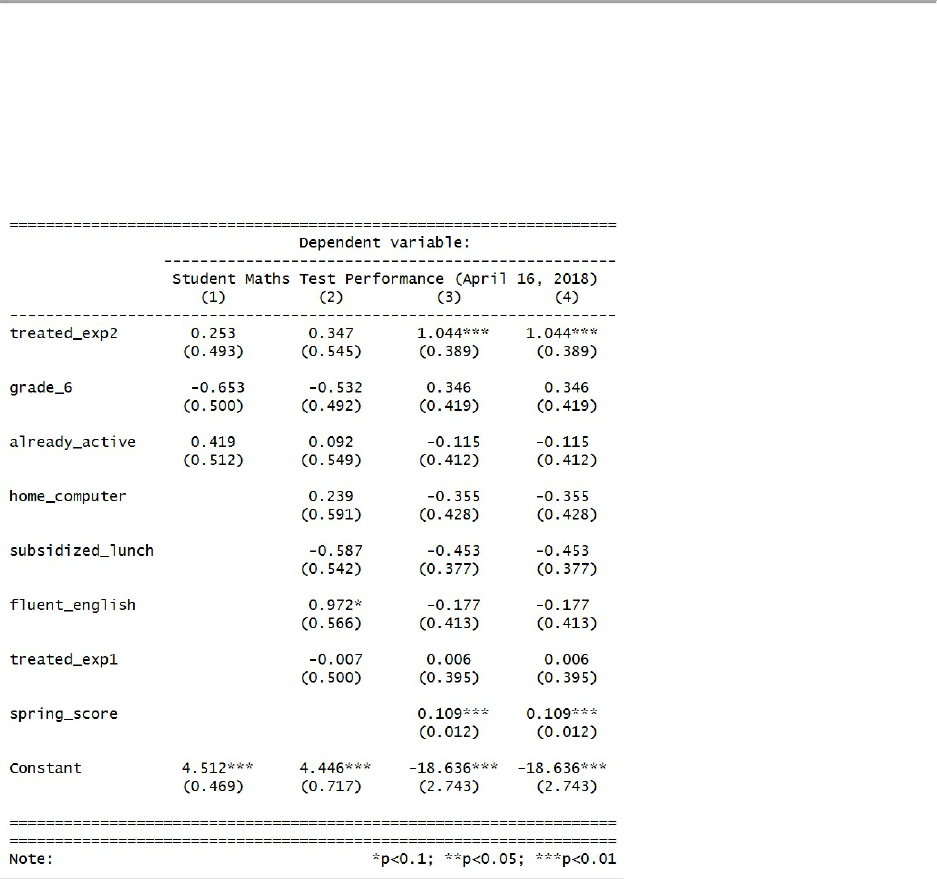

Now that Khan Academy activity was no longer self-selected but in fact randomly assigned

based on treatment assignment, meaningful results can be achieved by looking at the effect of

assignment to treatment on the outcome measure of test scores. Please note the importance of

using Spring MAP scores as covariates to remove the effects of strong math aptitude prior to the

experiment. As the covariate balance check had highlighted imbalance, there was a need to

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

14

control for this factor. Also, expectations from KA usage should be realistic and we did not

expect previous aptitude to be substituted by two weeks of MOOC activity.

Figure 14: 10% positive effect of Intent-to-treat on test scores

Having found a significant intent-to-treat effect, it was logical to evaluate the complier average

causal effect. After all, understanding the effects of these MOOC programs on the performance

of (complying) students could direct teachers to focus on building more effective encouragement

designs and could increase student motivation to comply. Although we saw a comparatively

higher compliance rate in the main experiment as compared to the pilot study (75% vs 35%), we

were far from 100% compliance rates. Grade 6 saw almost 94% compliance rates with Grade 7

students bringing down the overall compliance rates (65%).

For this analysis, the assignment to treatment variable is an instrumental variable to explain the

effects on test scores of using Khan. Using Khan is defined as a boolean variable (used_khan)

indicating that the student completed at least one allocated assignment.

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

15

Figure 15: Calculating the CACE using the 2SLS approach

The biggest advantage of 2SLS methods is their ability manage as many covariates as needed,

provided these covariates are present in the both the stages of the regression.

We have seen versions of IV with covariates in ‘Inputs and Impacts in Charter Schools: KIPP

Lynn’ (Joshua D. Angrist et al., 2010)

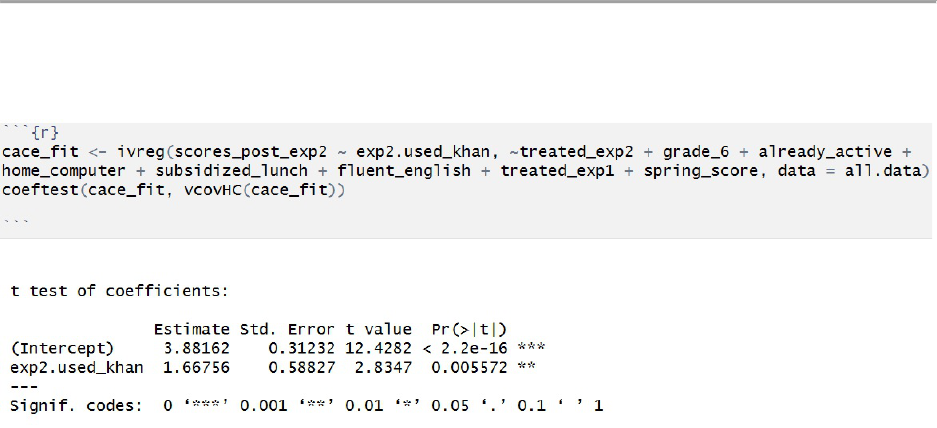

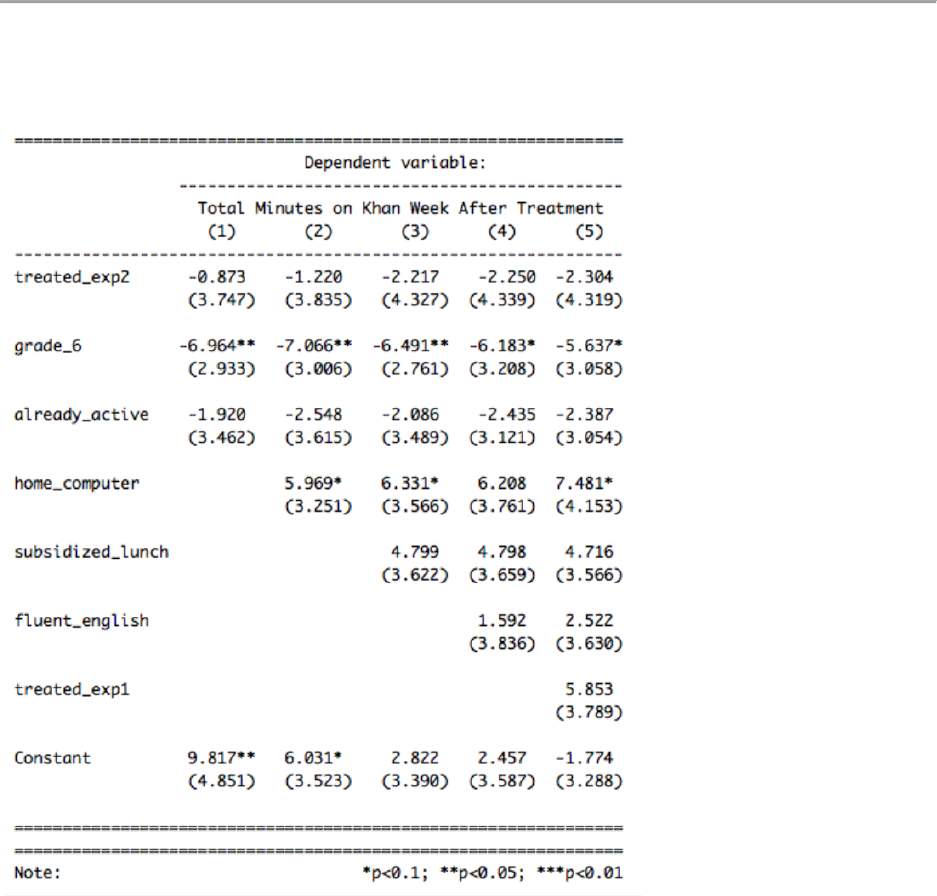

Lasting Effects?

Using data about student time on Khan Academy and student performance for the week

following the experiment, we analyze the lasting effects of the treatment. The regression below

shows that students who were in the treatment group spent about the same amount of time on

Khan Academy in the week following the treatment as students in the control group did. This

shows that the treatment didn’t necessarily cause students to develop a habit of increased Khan

usage. This indicates that continued encouragement to use Khan is necessary for students to

maintain their increased usage.

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

16

Figure 16: Encouragement effect wears off after encouragement ends

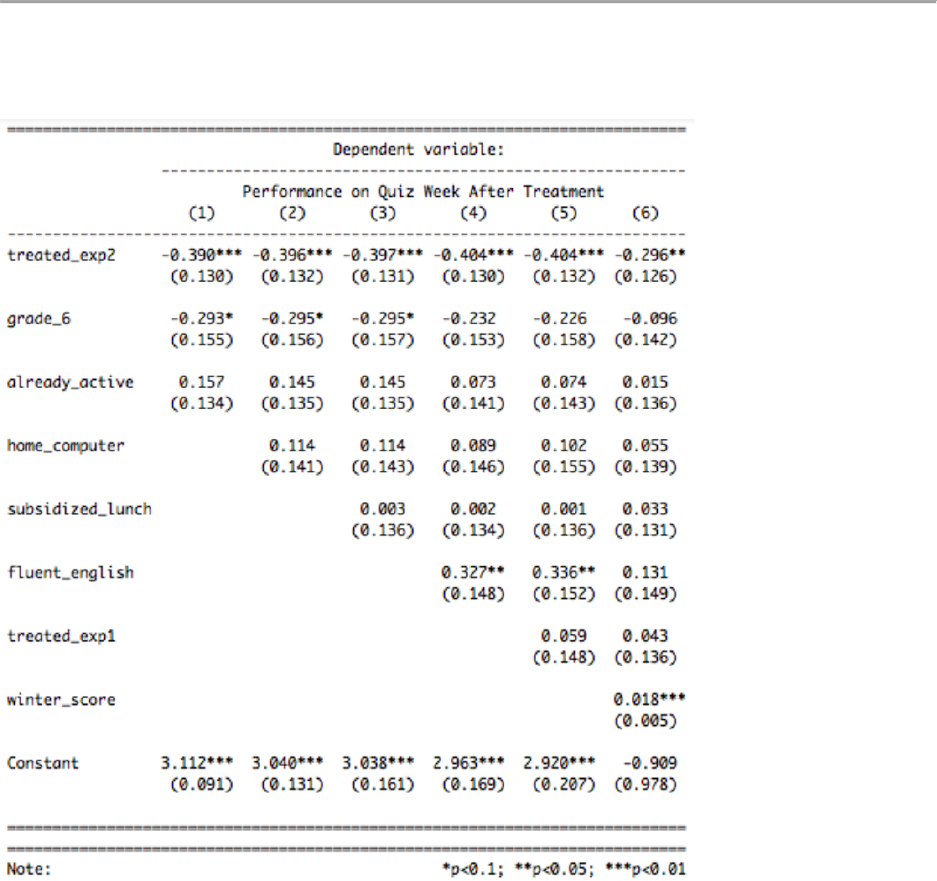

Additionally, the treatment effects on test score outcomes wore off after 1 week. As shown in the

regression below, students in the treatment group earned lower scores on a follow-up teacher-

created assessment that was administered 1 week after treatment ended. Their scores were lower

than the scores of control group students by about 0.3 points, which is statistically significant but

not perhaps practically significant (0.3 / 10 = 3%).

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

17

Figure 17: No lasting impact on test scores after end of treatment

LIMITATIONS

The conclusions of this experiment are limited by various factors. First, the small number of

students means that the experiment was low-powered. If the same experiment were conducted

with a larger sample of students, it might be possible to capture more of a treatment effect.

Second, this experiment would be best conducted with clustering at the school level to prevent

spill-over, which occurred in the main experiment and would have been another reason to

underestimate the treatment effect.

FURTHER WORK

The results of this experiment suggest that spending more time on Khan Academy can improve

at students’ performance on teacher-created assessments that are aligned to the material covered

on Khan Academy. We believe that the generalizability and long-term effects of the treatment

are yet to be confirmed. In terms of generalizability, it would be interesting to see the varying

W241: Does Khan Academy Work?

18

effect of the parent-involved encouragement design across different grades along with the

performance improvement. As the experiments were conducted on a single campus, there were

serious threats to the non-interference assumption. We required the Spring break to reduce

spillovers between control and treatment subjects. To test long-term effects, we may need a

multi-campus experiment clustered at a campus rather than a grade level. Other reasons to

examine the generalizability of these conclusions is that this experiment occurred at a small

charter school where all parents know all of their students’ teachers; in a different school setting

the parent encouragement could be less effective depending upon the strength of the

relationships between parents and teachers.

Also, we believe that we are yet to evaluate the performance effect of different levels of activity

on the KA platform. As the amount of time spent suffered from self-selection bias, we were left

with evaluating the compliance as a boolean variable (used_khan). There are studies conducted

by Powers & Swinton (2010) which evaluated activity on an ordinal scale. Angrist et al. (1995)

extended the LATE to ordered treatment variables and it would be a worthwhile exercise to

understand the effects in light of varying treatment intensities. In order to evaluate this, we

would need to randomly assign levels of activity, rather than leaving this up to self-selection.

REFERENCES

1. Murphy, R., Gallagher, L., Krumm, A ., Mislevy, J., & Haer, A. (2014). Research on the Use of

Khan Academy in Schools. Menlo Park, CA: SRI Educa on. [here]

2. Joshua D. Angrist et al. (2010). Inputs and Impacts in Charter Schools: KIPP Lynn [here]

3. Power & Swinton (1982, 1984). The Impact of Self-Study on GRE Test Performance

4. Joshua D. Angrist, Victor Lavy et al. (2006). Multiple Experiments For The Causal Link Between

The Quantity and Quality of Children

5. Joshua D. Angrist et al. (1995). Two Stage Least Square Estimation of Average Causal Effects in

Models with Variable Treatment intensity