In this report, Hanover Research summarizes approaches that

school districts have used to determine school boundaries and

school assignment processes.

BEST PRACTICES IN DISTRICT

REZONING

Prepared for Portland Public Schools

November 2015

www.hanoverresearch.com

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary and Key Findings ............................................................................... 3

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 3

KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 3

Section I: Best Practices Overview ................................................................................... 5

ENROLLMENT MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES ........................................................................................ 5

CRITERIA FOR DETERMINIG SCHOOL BOUNDARIES AND ASSIGNMENTS .................................................... 9

SCHOOL ASSIGNMENT MECHANISMS ............................................................................................. 10

ADDRESSING SEGREGATION ISSUES ............................................................................................... 16

Redistricting and Inequality ............................................................................................. 16

Department of Education Guidance for Race-Based School Assignment Policies .......... 18

Inter-District Policies ........................................................................................................ 20

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT STRATEGIES ........................................................................................ 21

Section II: Case Studies .................................................................................................. 24

BOSTON PUBLIC SCHOOLS ........................................................................................................... 25

DENVER PUBLIC SCHOOLS ........................................................................................................... 28

SEATTLE PUBLIC SCHOOLS ........................................................................................................... 33

WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLIC SCHOOLS ........................................................................................... 35

Appendix A: Tools and Maps ......................................................................................... 41

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND KEY FINDINGS

INTRODUCTION

Portland Public Schools (PPS) has sought the assistance of Hanover in identifying best

practices for re-drawing school boundaries within urban school districts. This report

summarizes the various approaches that school districts have used to determine school

boundaries and school assignment processes, divided into two sections:

Section I: Best Practices Overview summarizes strategies for projecting school

enrollment and managing over- and under-enrollment, discusses potential criteria to

consider when creating or revising school boundaries, identifies common school

assignment mechanisms, discusses considerations for addressing segregation issues

related to redistricting, and provides an overview of strategies to engage families

and communities in the school boundary review process.

Section II: Case Studies profiles four school districts that have recently undergone

boundary change processes, highlighting criteria used to create new school

boundaries and strategies used to solicit community feedback and communicate

information about policy changes.

KEY FINDINGS

Hanover identified the following key findings related to school district rezoning:

School assignment processes should be feasible, transparent, efficient, and

equitable. Enrollment should not exceed school capacity, families should

understand how assignments are made, and the assignment process should not

disproportionately advantage or disadvantage certain groups.

Many urban school districts have turned to redistricting to address under-

enrollment or overcrowding issues, but neither educators nor researchers have

agreed upon best practices for redistricting. However, common approaches to

redistricting include:

o Using controlled choice mechanisms in which students are assigned to a default

school or set of schools (usually based on location) but may opt-out of the

default school through a specific application process.

o Using economic game theory to inform school assignment mechanisms and/or

hiring economists or consultants to re-design school assignment processes.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

4

o Considering criteria such as sibling enrollment and proximity to schools to

determine school assignments. Additional common criteria that inform school

boundary creation include school capacity, transportation, natural or physical

barriers, diversity and equitable access to high-performing schools, student

achievement, enrollment projections, and feeder patterns.

Districts must be aware of how student assignment mechanisms and redistricting

may have a disproportionate effect on disadvantaged students. High-performing

schools are often unequally distributed throughout districts or may not be

numerous enough to meet existing demand. Many school assignment processes

have the potential to exacerbate inequality because low-income or at-risk students

tend to choose or be zoned for low-performing schools close to their homes.

Districts such as Washington, D.C. and Boston have attempted to address equity

issues by enabling students to access schools outside their neighborhoods, such as

by allocating a certain number of seats at high-performing schools to at-risk, non-

neighborhood students or by creating assignment algorithms that include high-

performing schools as potential choices for all students. Districts should also strive

to improve school quality throughout the system to better serve all students.

Districts have used a variety of strategies to engage the community in revising

school boundaries and assignment systems, such as interactive websites, focus

groups, surveys, community meetings and workgroups, and participatory advisory

committees. Districts also use websites, communications materials in multiple

languages, letters, public service announcements and billboards, school expos and

fairs, community meetings, and published school rankings to inform parents about

policy changes and school choices. However, districts should be aware that the

process of revising school boundaries or school assignment plans is often difficult

due to large demand for high-performing schools and the confusing and complex

nature of school assignments.

Accurate enrollment projections are vital for effective long-term planning and

enrollment management. Districts can ensure accurate projections by using five-

year projections integrated with data from multiple sources, such as local housing

plans, land use, and transportation plans.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

5

SECTION I: BEST PRACTICES OVERVIEW

This section summarizes strategies for projecting school enrollment and managing over- and

under-enrollment, discusses potential criteria to consider when creating or revising school

boundaries, identifies common school assignment mechanisms, discusses considerations for

addressing segregation issues related to redistricting, and provides an overview of strategies

to engage families and communities in the school boundary review process.

ENROLLMENT MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Districts typically use enrollment projections to predict which schools will be over- or under-

enrolled.

1

This may necessitate building new schools or re-drawing school boundaries to

send more students to under-enrolled schools. Accurate enrollment projections are vital

for effective long-term planning. To ensure accuracy of enrollment projections, education

and planning expert Kelley D. Carey recommends the following:

2

Use five-year projections and planning integrated with data from multiple sources.

Districts should look at five-year historical trends to better understand local

demographic cycles, and should not rely on long-term (i.e., twenty-year projections)

for future enrollment predictions, as these projections may be limited by too many

unknown economic and demographic factors. Districts should also take into account

local five-year plans for housing development or other initiatives that may affect

demographics. Carey recommends a “rolling five-year strategy to bring together

programs, demographics, and facilities.”

3

That is, districts should conduct computer

mapping of school zones and students every year, integrated with proven five-year

enrollment projections by grade and school. These data should be combined with

data related to building renovation needs and capacities. Additional data that may

inform enrollment projections include birth rates and cohort survival projections,

local transportation and land use plans, and zoning policies.

4

A full list of data

needed for a five-year planning process is provided in Figure 1.1.

Ensure that planners have skills in computer mapping, demographics analysis, five-

year planning, and involving the public. Educators may not be trained in long-range

planning processes or public engagement strategies.

5

Therefore, districts may need

to hire planners or other demographics experts to ensure the accuracy of

1

Enrollment and Student Assignment Planning Practices. (Hanover Research, 2012).

2

[1] Carey, K.D. “Why Enrollment Projections Go Wrong.” School Superintendents Association, April 2011.

http://www.aasa.org/SchoolAdministratorArticle.aspx?id=18586 [2] Carey, K.D. “Planning for Integration.”

American School Board Journal, 194:10, October 2007.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eue&AN=508004396&site=ehost-live [2] Enrollment

and Student Assignment Planning Practices, Op. cit.

3

Carey, “Why Enrollment Projections Go Wrong.,” Op. cit.

4

Practices for Anticipating District Growth. (Hanover Research, 2015).

5

Carey, K.D. “Why Schools Need Planners.” November 2011. http://www.ocde.us/Facilities/Documents/Why-

Schools-Need-Planners.pdf

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

6

enrollment projections. Districts should also ensure that planners for major

construction or redistricting are able to engage the public in multiple and

meaningful ways.

6

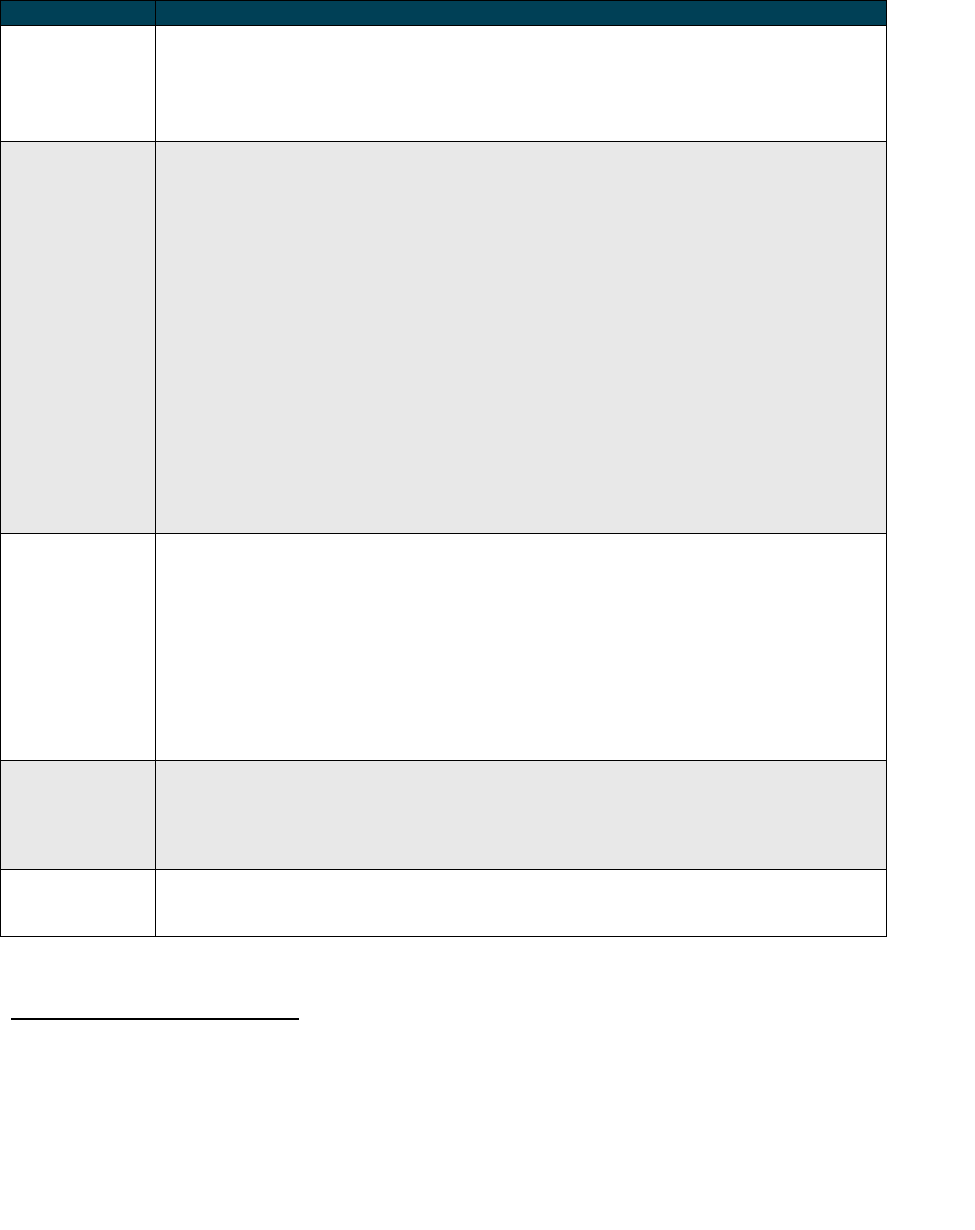

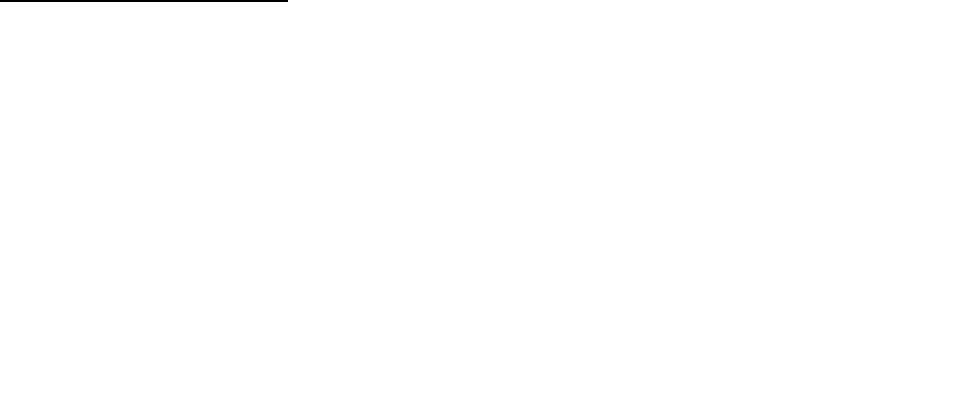

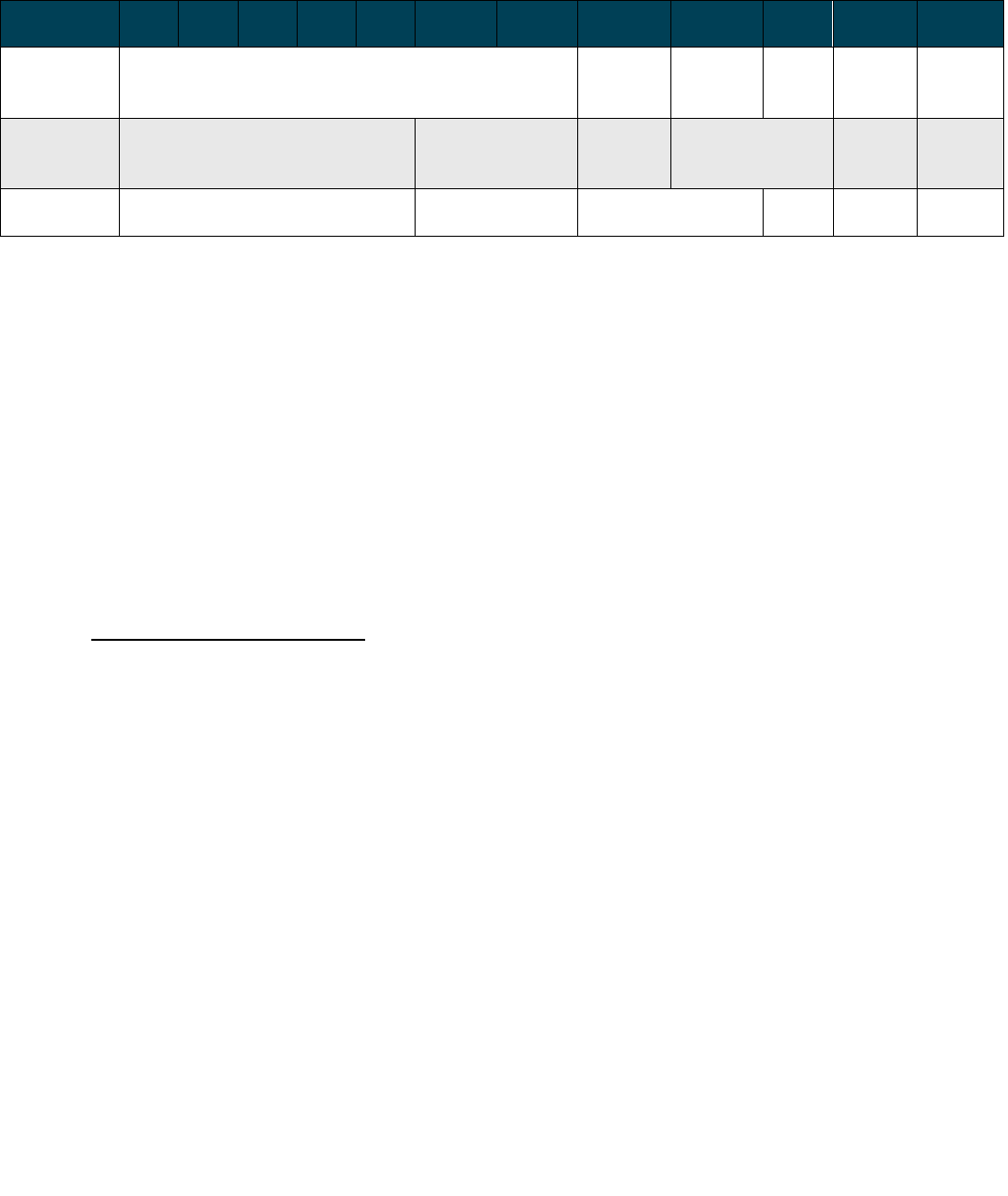

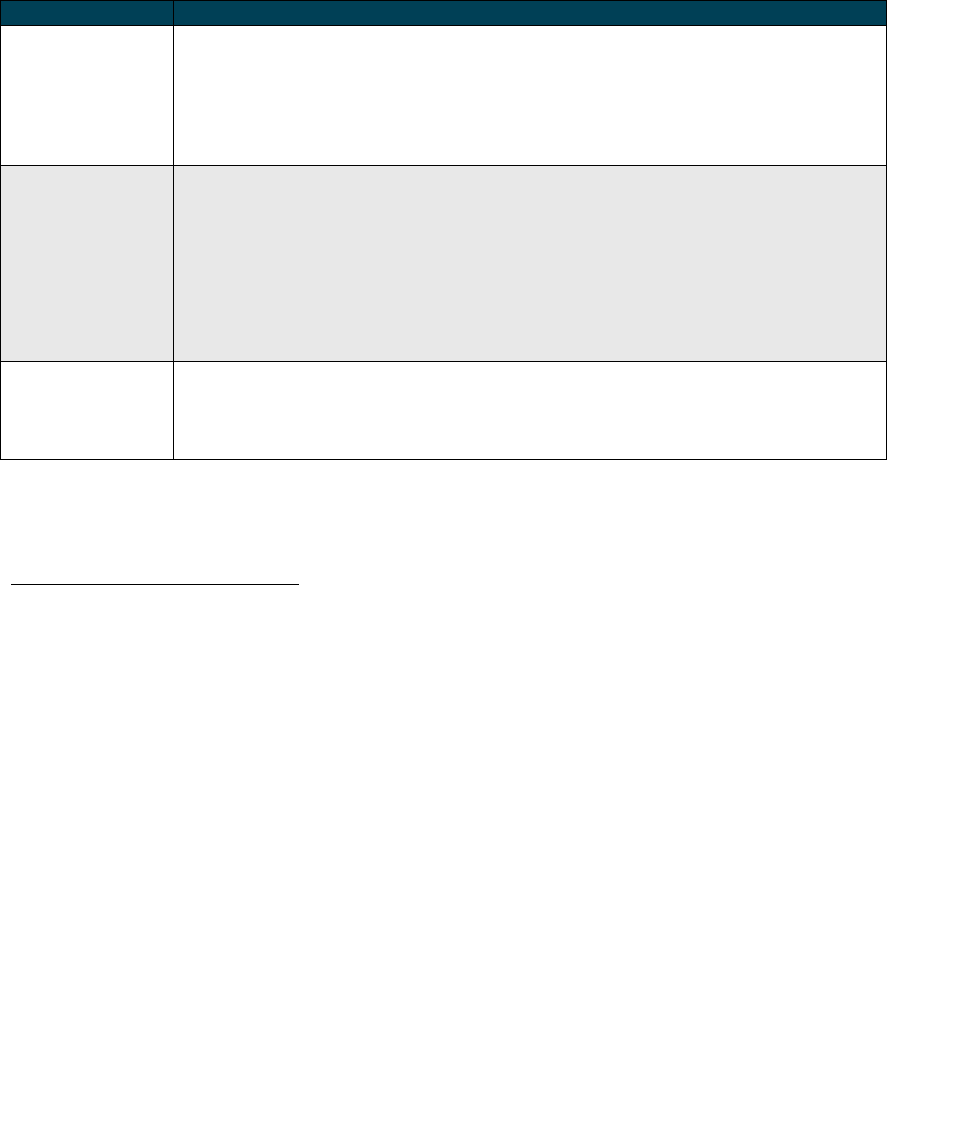

Figure 1.1: Basic Data Needed for Five-Year Enrollment Planning Processes

DATA TYPE

DATA NEEDED

Demographics

data

A demographics map showing land uses and planned developments; and

A demographics map plotting students by their home address for the three school

levels (all maps should be [digital] maps or they will not stay current with street

changes, zone changes, and enrollment changes).

Facilities data

Data on number of standard and portable classrooms at each school site;

Data on number of standard classrooms used at each building. List each standard

classroom with its actual use and how many periods per day that use goes on;

Data on standard classroom uses accepted by the district for all schools and what

uses found are not standard;

Known needs for renovations—not additions—at each school, and estimated costs;

Building and site needs as to life safety code, building code, building integrity, health

security, site preservation, support programs, core programs, special programs, and

desirable options;

Site acreage at each school that is buildable, along with playground area. Identify

site problems with drainage, security, faculty and visitor and student parking, and

bus parking and circulation; and

Area of each core facility: media center, food service, and physical education, for

example, with a comparison to state standards.

Enrollment

data

Enrollment projections by grade for five years at each school;

A school‐zones map with overlays of elementary, middle, and high school zones on a

streets map;

District student transfer policies: Use computer mapping of students overlaid on

attendance zones and [the district] enrollment database to determine how many

students attend a school other than their zoned school at each facility along with

their home school by the map plotting of all students;

Data on how students are assigned to schools and what existing alternatives are;

Cost data

Cost to operate each school per year, not including teachers who will be needed

whether the school is closed or not. It does include payroll costs for principal,

secretaries, media personnel, food‐service personnel and janitors, and utility

expenditures.

Program data

Separate building and site needs including special program needs and wants; and

Special needs of special programs (self‐contained special education, magnet, etc.).

Source: Carey, Kelley D.

7

6

For a more thorough discussion of public engagement strategies, see page 21 of this report.

7

Adapted from Carey, Kelley D. School District Master Planning: A Practical Guide to Demographics and Facilities

Planning, Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011, pp. 18-19, as cited in Practices for Anticipating District Growth,

Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

7

As many urban school districts have experienced enrollment declines in the last decade,

most recent guidance on enrollment management in K-12 schools focuses on addressing

enrollment declines.

8

A 2013 report by Boston Consulting Group recommends the following

strategies for responding to enrollment declines:

9

Understand and manage classroom costs: Districts should be able to disaggregate

spending data to better understand costs on a per-unit basis per student, course,

grade, and teacher. This data can better clarify how specific actions, such as

increasing class sizes at specific schools, would affect costs.

Plan in advance and take action early. Districts should strive to take a multi-year

view of their finances, rather than planning year-to-year. Processes for closing

under-enrolled schools should start early in the year to allow time for engaging

families and preparing students for the change.

Retain your best talent: Districts should retain top teachers, leaders, and staff to

ensure that high-performing schools continue to perform well.

Close severely underutilized schools: Closing low-performing and underutilized

schools can give districts the opportunity to shift students to higher-performing

schools. A study of school closures in Chicago found that students who transferred

from closed low-performing schools to high-performing schools performed better in

math and reading after one year.

10

Enable creative staffing and teaching with technology: Schools may be able to use

online or blended instruction to teach a greater number of students more

efficiently. Schools may also be able to replace some staff, such as librarians, with

non-certified paraprofessionals as a way to save money.

8

[1] McBride, L. et al. “Adapting to Enrollment Declines in Urban School Systems: Managing Costs While Improving

Educational Quality.” Boston Consulting Group, January 16, 2013.

https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/education_public_sector_adapting_enrollment_declines_urb

an_school_systems/#chapter1 [2] DeMoscp, A. “School Districts Get Creative When Enrollment Drops.” District

Administration, July 2013. http://www.districtadministration.com/article/school-districts-get-creative-when-

enrollment-drops [3] “Urban School Districts Can Adapt to Enrollment Declines and Improve Educational Quality

by Taking New Approaches to Cost Management.” Yahoo! Finance, January 16, 2013.

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/urban-school-districts-adapt-enrollment-050100289.html [4] McMilin, E.

“Closing a School Building: A Systematic Approach.” National Clearinghouse for Educational Facilities, September

2010. http://www.ncef.org/pubs/closing.pdf [5] Dillon, N. “The Hardest Choice.” American School Board Journal,

December 2006.

http://web.archive.org/web/20070701073421/http://www.asbj.com/specialreports/1206SpecialReports/S1.html

9

McBride et al., Op. cit.

10

[1] de la Torre, M. and J. Gwyne. “When Schools Close: Effects on Displaced Students in Chicago Public Schools.”

University of Chicago, Urban Education Institute, October 2009.

https://ccsr.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/publications/CCSRSchoolClosings-Final.pdf [2] DeMoscp, Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

8

Shrink fixed costs and convert to variable costs: Districts may be able to reduce

costs by reducing central administration expenses and outsourcing noncore

functions to vendors.

For schools experiencing overcrowding rather than under-enrollment, education

researchers, parent groups, and the National Center for Education Statistics suggest that the

following strategies may alleviate overcrowding issues:

11

Modify how school structures are used: Schools may use portable classrooms or

use non-instructional spaces as temporary classrooms to ease overcrowding.

Create alternate schedules: Staggered lunch schedules, year-round schedules, or

split-day schedules can ease overcrowding by ensuring that not all students are in

the building at the same time.

Lease buildings: Leasing arrangements may be a temporary solution to

overcrowding while districts build new facilities.

Reconfigure existing schools: Redesigning grade configurations may be a potential

solution to overcrowding issues. Some schools in Brooklyn, for example, established

K-3 centers at middle schools that had extra capacity.

12

Build new schools: Educational researchers Ready, Lee, and Welner argue that

building new schools is the best sustainable response to overcrowding concerns.

13

They contend that common approaches such as increasing class sizes, providing

temporary structures, or creating alternative schedules ultimately decrease

educational quality, cause public health problems, and limit students’ ability to

participate in extracurricular activities. However, the authors do acknowledge that

building new facilities is a tremendous cost for districts. Plans for new facilities

should be based on the five-year planning strategies discussed previously in this

section. Districts may be able to build new schools on existing school property or use

innovative financing mechanisms, such as bonds or private sector partnerships, to

support new schools.

14

11

[1] Ready, D.D., V.E. Lee, and K.G. Welner. “Educational Equity and School Structure: School Size, Overcrowding,

and Schools-Within-Schools.” Teachers College Record, 106:10, October 2004.

http://www.colorado.edu/UCB/AcademicAffairs/education/faculty/kevinwelner/Docs/Ready_et_al_Educational_

Equity_School_Structure.pdf [2] “Condition of America’s Public School Facilities: 1999 - Overcrowding.” National

Center for Education Statistics, June 2000.

http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/frss/publications/2000032/index.asp?sectionid=8

12

Woloz, M. “Five Quick and Inexpensive Ways to End Overcrowding.” EPP Monitor, Spring/Summer 2004.

13

Ready, Lee, and Welner, Op. cit.

14

Woloz, Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

9

Many urban school districts have recently turned to redistricting as a strategy to address

overcrowding,

15

but neither educators nor researchers have agreed upon best practices for

redistricting processes. A 2003 study of school boundary and school assignment methods

called for research to assess the effectiveness of school boundary and assignment policies in

districts throughout the country.

16

However, Hanover was unable to identify examples of

such research; most recent research on school boundaries consists of descriptive studies,

case studies, and economic theories, none of which have definitively pointed to the most

effective redistricting strategies or policies. Therefore, rather than making best practice

recommendations, the remainder of this report describes the various approaches school

districts throughout the country have used to determine school boundaries and

assignments. Where applicable, we provide recommendations made by education experts,

associations, or government agencies, but PPS should keep in mind that there is not a

general consensus in the education field regarding best practices for district rezoning.

CRITERIA FOR DETERMINIG SCHOOL BOUNDARIES AND ASSIGNMENTS

District priorities play a large role in creating school boundaries and student assignment

plans. Districts may wish to consider factors such as costs of busing students to school;

desire to maintain neighborhood cohesion; need to ensure that siblings attend the same

schools; and desire to maintain racial and socioeconomic balance across schools.

17

A 2003

study of school boundary and school assignment methods in 15 urban school districts found

that districts considered these and a variety of other criteria to create boundaries for school

assignments.

18

Common considerations included:

School capacity and enrollment;

Natural boundaries or physical barriers such as railroads or highways;

15

[1] Green, E.L. and N. Sherman. “School Boundary Lines Could Change in City.” Baltimore Sun, March 30, 2015.

http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/education/bs-md-ci-school-zones-20150708-story.html [2] Teale,

C. “Alexandria City School Board Moves Forward with Redistricting Plan.” Alexandria Times, May 28, 2015.

http://alextimes.com/2015/05/alexandria-city-school-board-moves-forward-with-redistricting-plan/ [3]

Hennigan, G. “Iowa City School District Backs Off Redistricting Plans.” KCRG-TV9, April 23, 2014.

http://www.kcrg.com/news/local/Iowa-City-School-District-Backs-Off-Redistricting-Plans-151642415.html [4]

Taylor, K. “Race and Class Collide in a Plan for Two Brooklyn Schools.” September 22, 2015.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/23/nyregion/race-and-class-collide-in-a-plan-for-two-brooklyn-schools.html

[5] Lindenbaum, J. “APS Redistricting: Bring on the Trailers.” Curbed Atlanta, April 10, 2012.

http://atlanta.curbed.com/archives/2012/04/10/aps-redistricting-bring-on-the-trailers.php [6] Chesky, M.

“Oklahoma City Public Schools Release Proposed Redistricting Maps.” KOCO 5 News, March 24, 2014.

http://www.koco.com/news/oklahoma-city-public-schools-release-proposed-redistricting-maps/25140844 [7]

Bottalico, B. “No Redistricting for Overcrowded Annapolis School.” Capital Gazette, April 23, 2015.

http://www.capitalgazette.com/news/schools/ph-ac-cn-redistricting-0423-20150423-story.html

16

Brown, A.K. and K.W. Knight. “School Boundary and Student Assignment Procedures in Large, Urban, Public School

Systems.” Education and Urban Society, 37:4, August 2005.

http://search.proquest.com/docview/202706601?accountid=132487

17

Pathak, P.A. “The Mechanism Design Approach to Student Assignment.” Annual Review of Economics, 3, 2011.

http://economics.mit.edu/files/9414

18

Brown and Knight, Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

10

Neighborhood population and size of residential buildings;

Anticipated growth;

Students’ proximity to schools and bus/travel time;

Sibling enrollment at schools;

Census tract and geo-code data;

Existing student feeder patterns;

Districts’ capital plan for school-related facilities and capital expenditures; and

Race,

19

ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other demographic data.

Two of the districts in the study—Boston and Chicago—collaborated with universities to

develop school assignment policies based on quantitative and mapping data. Several

districts commented that the boundary selection process was difficult, emphasizing the

need for flexibility and making compromises.

SCHOOL ASSIGNMENT MECHANISMS

This sub-section summarizes school assignment literature, most of which stems from

economic game theory. This body of literature discusses potential mechanisms for

incorporating student/family preferences and school priorities into students’ school

assignments. School priorities may include geographic or neighborhood considerations, such

as assigning students to schools within a certain walking distance.

In selecting a student assignment mechanism, economists say that schools should

consider:

20

Feasibility: Schools should ensure that enrollment does not exceed school capacity

and only eligible students are enrolled at each school.

Individual choice: If students are assigned at schools that parents or families

consider unacceptable, the family may choose an outside option such as a private or

charter school, home schooling, or another option.

19

The 2007 Supreme Court Case Parents Involved in Community Schools Inc. v. Seattle School District limited the use

of race as a deciding factor for school assignment. For a more detailed discussion of this issue, see page 18.

20

Abdulkadiroglu, A. “School Choice.” In The Handbook of Market Design, (Oxford University Press, 2013).

http://people.duke.edu/~aa88/articles/scsurvey-handbook.pdf

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

11

Efficiency: The school assignment process should promote student welfare to the

greatest extent possible.

The Institute for Innovation in Public School Choice provides similar recommendations,

arguing that school assignment models should be guided by:

21

Transparency: It should be easy to tell how the seats were distributed and what

policies were used in making allocations.

Efficiency: If there are two students applying to the same schools, both students

should get an offer instead of one person getting two offers and the other person

having to wait until the other one chooses.

Equitability: The process should be fair, and no group should be intentionally or

unintentionally disadvantaged.

Public school districts have used a variety of methods for school assignment. As traditional

neighborhood-based student assignments may lead to segregation based on race or

socioeconomic status, schools have explored various methods to offer students access to

schools beyond their neighborhoods.

22

Assignment methods are typically categorized as

comprehensive choice systems or controlled choice systems:

Comprehensive choice system: In this system, families are not assigned to a default

school and can apply to any school in the district.

23

Few districts have implemented

true comprehensive choice systems due to court-ordered desegregation

guidelines.

24

Rather, most rely on controlled choice systems.

Limited or controlled choice system: In this system, students usually have a default

school but can opt out through an application or other process.

25

Students may also

express preferences for schools by submitting rankings or preferences. Controlled

21

Quoted verbatim from “Q&A on School Choice and Enrollment: Neil Dorosin and Gaby Fighetti from The Institute

for Innovation in Public School Choice.” Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, May 19, 2015.

http://www.msdf.org/blog/2015/05/qa-school-choice-enrollment-processes-neil-dorosin-gaby-fighetti-institute-

innovation-public-school-choice/

22

Abdulkadiroglu, Op. cit.

23

Pathak, “The Mechanism Design Approach to Student Assignment,” Op. cit.

24

Abdulkadiroglu, A. and T. Sonmez. “School Choice: A Mechanism Design Approach.” American Economic Review,

93:3, June 2003.

http://www.uibk.ac.at/economics/bbl/lit_se/papierews06_07/abdulkadiroglu_soenmez(200_)_.pdf

25

Pathak, “The Mechanism Design Approach to Student Assignment,” Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

12

choice systems can give parents some options while also maintaining diverse

student bodies.

26

Common controlled choice mechanisms include:

27

Boston mechanism: This method was developed by Cambridge and Boston Public

Schools in the 1980s after eliminating neighborhood zones. In this method, a central

clearinghouse collects students’ school preference rankings and matches students to

schools based on preferences and priority status, attempting to assign as many

students as possible to first-choice schools. Priority status is determined based on

how far away a student lives from a ranked school and whether a student’s sibling

attends the school. Because a number of students often tie for priority at certain

schools, random tie-breaking is used to determine school assignments for students

with equal priority. Variations of the Boston mechanism have been used in school

districts such as Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina; Miami-Dade, Florida;

Minneapolis, Minnesota; Providence, Rhode Island, and Tampa-St. Petersburg

Florida.

28

However, this method is often criticized for its potential for manipulation;

that is, students/families may improve their assignments by misrepresenting their

preferences. Abdulkadiroglu and colleagues, economists who have redesigned

school assignment mechanisms in school districts such as Boston and New York,

provide the following explanation of the Boston mechanism’s limitations:

“Since a student who ranks a school as her second choice loses her priority to

students who rank it as their first choices, it is very risky for the student to

“waste” her first choice at a highly sought after school if she has relatively low

priority. Hence the Boston mechanism gives students and their parents a strong

incentive to misrepresent their preferences by improving the ranking of schools

for which they have high priority.”

29

Gale-Shapley student-optimal stable mechanism (SOM), also known as a student-

proposing deferred acceptance mechanism: In this method, a student “proposes” a

first-choice school, and schools tentatively assign students to first-choice schools

26

Ehlers, L. et al. “School Choice with Controlled Choice Constraints: Hard Bounds versus Soft Bounds.” Journal of

Economic Theory, 153, 2014. https://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/isaemin/EHYY-JET.pdf

27

[1] Abdulkadiroglu, Op. cit. [2] Kesten, O. and M.U. Unver. “A Theory of School-Choice Lotteries.” Theoretical

Economics, 10, 2015. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3982/TE1558/pdf [3] Kesten, O. and M.U. Unver. “A

Theory of School-Choice Lotteries.” May 2010. http://people.duke.edu/~aa88/matchingconference/Kesten.pdf

[4] Abdulkadiroglu and Sonmez, Op. cit. [5] Ehlers et al., Op. cit. [6] Pathak, “The Mechanism Design Approach to

Student Assignment,” Op. cit. [7] Morrill, T. “Two Simple Variations of Top Trading Cycles.” Economic Theory, 60,

2015. [8] Pathak, P.A. and T. Sonmez. “School Admissions Reform in Chicago and England: Comparing

Mechanisms by Their Vulnerability to Manipulation.” American Economic Review, 103:1, 2013.

http://economics.mit.edu/files/9410 [9] Abdulkadiroglu, A. et al. “Changing the Boston School Choice

Mechanism.” National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2006. http://www.nber.org/papers/w11965.pdf

[10] Pathak, P.A. “Lotteries in Student Assignment.” November 2006.

https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/documents/2007_01-16_Pathak_Loitteries.pdf

28

Pathak and Sonmez, Op. cit.

29

Abdulkadiroglu et al., Op. cit., p. 6.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

13

based on priority order (based on location, siblings, test scores, or other priority

criteria). Students not assigned in the next round propose their next best choice.

Schools assign remaining seats while considering students held over from previous

steps and new applicants. Unlike the Boston method, students are assigned

tentatively so that students with higher priorities may be considered in subsequent

steps. Therefore, students do not lose seats to lower priority students and do not

lose priority at a school to those who rank the school as a higher choice. This

mechanism is considered to be “strategy-proof,” or not prone to manipulation like

the Boston mechanism. The outcome of SOM can easily be explained to parents: if a

student does not get into their first-choice school, it is because every enrolled

student at the first-choice school has a higher priority than that student.

30

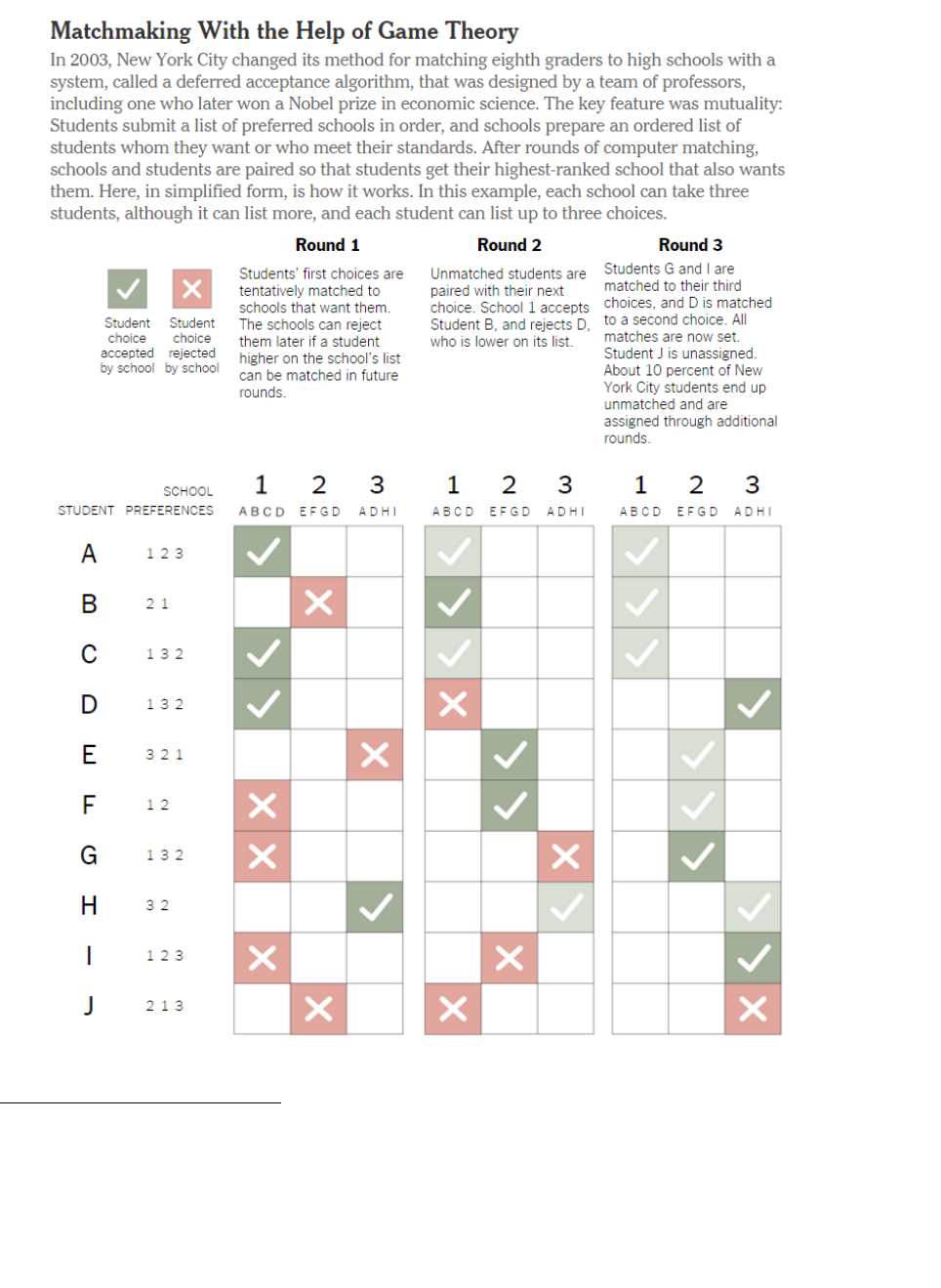

A graphic

representation of the SOM process used by New York City’s public schools is

provided in Figure 1.2 on the following page.

30

Abdulkadiroglu, Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

14

Figure 1.2: New York Times Depiction of New York City’s SOM-Based Student Assignment

Process

Source: New York Times

31

31

Tullis, T. “How Game Theory Helped Improve New York City’s High School Application Process.” New York Times,

December 5, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/07/nyregion/how-game-theory-helped-improve-new-

york-city-high-school-application-process.html?_r=0

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

15

Top trading cycles (TTC) mechanism, also known as the efficient transfer

mechanism: While SOM makes tentative assignments based on student preferences,

TTC makes tentative assignments based on school priorities.

32

Again, priorities may

be related to sibling enrollment, demographic balances, students’ distance from

school, or other criteria of importance to districts. This method consists of cycles in

which one seat at a time is assigned to highest priority students. In each cycle, a

student identifies their preferred school, and each school identifies a student with

the highest priority. Each student is included in one cycle, and each cycle results in a

student being assigned to a seat. If a student is unhappy with their assignment,

priority at one school can be “traded” for priority at another school, depending on

the student’s priority status. This mechanism is also considered to be strategy-proof.

If a student is not accepted to their first-choice school in this method, it is because

every seat at the first-choice school was initially assigned to a higher priority

student, and the student could not be transferred to the first choice because they

did not have enough priority at other schools.

33

Serial dictatorship mechanism, or random priority mechanism: In this mechanism,

the school does not make priority-based assignments. Students are assigned to their

preferred schools (among available schools) one at a time in a randomly drawn

order. This method is considered to be strategy-proof due to its random selection

process. However, students must be able to rank all possible choices for the

mechanism to be strategy-proof. In Chicago’s previous high school assignment

method, students were only able to rank four out of nine possible choices, creating

the need for “strategic calculations on which choices to list and which ones to

drop.”

34

First Preference First mechanism: This method is a hybrid between the Boston

mechanism and SOM. School assignments are based solely on student rankings of

schools. When a student applies to their first-choice school, they are immediately

offered a seat if they qualify. This method was widely used in England, but was

banned in 2007 due to concerns about incentives for parents to distort their

preferences as well as potential unfairness to participants who didn’t attempt to

“game” the system.

35

SOM appears to be the most commonly used and commonly recommended mechanism.

36

In fact, Dr. Lloyd Shapley, an early theoretical contributor to SOM, and Dr. Roth, one of

several economists who developed a version of SOM used in New York City’s public high

32

Abdulkadiroglu, Op. cit.

33

Ibid.

34

Pathak, P.A. “NBER Reporter 2014 Number 1: Research Summary - School Assignment and School Effectiveness.”

National Bureau of Economic Research, 2014. http://www.nber.org/reporter/2014number1/pathak.html

35

[1] Pathak and Sonmez, Op. cit. [2] Pathak, “NBER Reporter 2014 Number 1: Research Summary - School

Assignment and School Effectiveness,” Op. cit.

36

[1] Abdulkadiroglu et al., Op. cit. [2] Sonmez, T. “Policy and Practice Impacts.” 2013.

http://www.tayfunsonmez.net/policy-impact/

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

16

schools, both won a Nobel Prize for the SOM algorithm in 2012.

37

A number of school

districts in the past decade have shifted to SOM due to desires to use assignment systems

less prone to manipulation than the Boston mechanism. Boston Public Schools, for example,

shifted to SOM in 2005 in an effort to “remove ‘incentives to game the system.’”

38

Denver

Public Schools have also shifted to a version of the SOM model,

39

and all schools in England

rely on SOM for public school assignments.

40

Ultimately, developing school assignment

mechanisms, particularly in urban districts, is a complex task for which school districts often

seek the guidance of economists or consultants.

41

ADDRESSING SEGREGATION ISSUES

In addition to considering school priorities and student/family preferences in school

assignment, school districts must be aware of potential equity and segregation issues

associated with redistricting and school choice processes. Although a thorough discussion of

segregation issues in K-12 education is beyond the scope of this report, this section

identifies three areas that PPS may wish to be aware of as it undergoes its rezoning process:

1) potential effects of redistricting on education inequality; 2) U.S. Department of Education

guidance for race-based school assignment policies; and 3) inter-district policies.

REDISTRICTING AND INEQUALITY

School districts should be aware of how the application of student assignment mechanisms

and redistricting may have a disproportionate effect on disadvantaged students. For

example, a 2014 New York Times article about New York City’s SOM school assignment

process says that while the mechanism greatly increased the number of students assigned

to first-choice schools, high-performing schools are still scarce within the district.

42

Low-

income and low-performing children are more likely to be assigned to low-performing

schools, partly because they tend to rank lower-achieving schools as their top choices. The

article’s author explains:

“It seems that most students prefer to go to school close to home, and if nearby

schools are underperforming, students will choose them nevertheless. Researching

other options is labor intensive, and poor and immigrant children in particular may

not get the help they need to do it.”

43

37

[1] Tullis, Op. cit. [2] “The Prize in Economic Sciences 2012 - Stable Matching: Theory, Evidence, and Practical

Design.” Royal Swedism Academy of Sciences, 2012. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-

sciences/laureates/2012/popular-economicsciences2012.pdf

38

Abdulkadiroglu et al., Op. cit., p. 2.

39

[1] Pathak and Sonmez, Op. cit. [2] Pathak, “NBER Reporter 2014 Number 1: Research Summary - School

Assignment and School Effectiveness,” Op. cit.

40

Sonmez, Op. cit.

41

[1] Schulzke, E. “‘Controlled Choice’: Does Mixing Kids Based on Family Income Improve Education?” Desertet News

National, April 10, 2014. http://national.deseretnews.com/article/1265/controlled-choice-does-mixing-kids-

based-on-family-income-improve-education.html [2] Pathak, “The Mechanism Design Approach to Student

Assignment,” Op. cit. [3] Abdulkadiroglu et al., Op. cit.

42

Tullis, Op. cit.

43

Ibid.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

17

In addition, a 2013 study by the Annenberg Institute for School Reform found that a large

number of students in New York City—36,000 each year—do not participate in the high

school choice process, requiring the New York City Department of Education (DOE) to assign

them to schools.

44

The students are usually high-need students, such as new immigrants,

special needs students, previous incarcerated students, homeless youths, or students with

histories of behavioral problems. Unfortunately, these students are disproportionately

assigned to low-performing high schools that are unequipped to serve their unique needs.

The study’s authors argue that the district must improve school performance overall and

more equitably distribute students throughout the city, but they do not make

recommendations for strategies to reduce the number of students left out of the school

choice process.

Rezoning and redistricting process may also negatively affect disadvantaged students and

families. A 2014 study of the redistricting process in a major metropolitan city (not

identified by the study author) found that the process actually increased racial and

socioeconomic segregation in the district.

45

To address over- and under-enrollment in

several schools, the district considered several re-zoning options, including merging over-

and under-capacity schools and re-zoning some white students to a predominantly black

middle school. This option was preferred primarily by African-American families wanting to

preserve their neighborhood schools, as well some middle-class white families already using

these schools. This choice would have also increased racial and socioeconomic diversity

within schools. However, the district ultimately decided to close two predominately black

elementary schools and re-zone these students to other Title I schools. This resulted in a

number of minority and low-income students being zoned out of more academically

competitive schools into lower-performing schools and/or schools further away from their

homes. In addition, many white middle-class families who had previously used the

neighborhood schools were concerned about the district’s lack of commitment to their

neighborhoods and decided to enroll their students in charter schools.

The study’s author makes several broad recommendations to address unequal impacts of

redistricting:

46

Districts may develop strategies to make schools more attractive to middle-class

families who are zoned for, but frequently opt-out of neighborhood schools; and

School districts must work to ensure that minority and low-income students,

families, and communities do not bear the burden of redistricting.

44

Arvidsson, T.S., N. Frutcher, and C. Mokhtar. “Over the Counter, Under the Radar: Inequitably Distributing New York

City’s Late-Enrolling High School Students.” Annenberg Institute for School Reform, 2013.

http://annenberginstitute.org/sites/default/files/OTC_Report.pdf

45

Penn, D. “School Closures and Redistricting Can Reproduce Educational Inequality.” Center for Poverty Research

Policy Brief, 3:5, 2014. http://poverty.ucdavis.edu/sites/main/files/file-

attachments/cpr_penn_redistricting_brief.pdf

46

Quoted almost verbatim from Ibid., p. 2.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

18

However, the author does not provide detailed guidance regarding strategies for making

neighborhood schools more attractive or ensuring that redistricting does not

disproportionately affect disadvantaged students. A 2013 evaluation of New York City’s

school assignment mechanism does provide several recommendations to improve student

outcomes and promote equity within the school choice and assignment process, although

these recommendations are specific to New York City’s needs:

47

Remove residential preferences for school assignment, as well as other screening

procedures that are not essential to the mission of a school. The report’s authors

argue that prioritizing residential preferences is a problem because “parents of

means” can choose a school through purchase of a home in certain neighborhoods,

whereas lower-income families do not have this option.

48

Take significantly greater care to assure that economic, educational, and

residential advantages of students’ parents are not reflected in the quality of

public schools to which students are assigned. Potential strategies include:

o Using student test scores to inform the student assignment policy and achieve a

balanced distribution of students;

o Improving the web-based process by which parents and students express their

preference for schools, such as by providing more information on individual

schools and developing tools to help parents determine the best choice for their

child; and

o Strengthening district-wide policies that enhance the effectiveness of schools and

the teacher workforce.

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION GUIDANCE FOR RACE-BASED SCHOOL ASSIGNMENT POLICIES

The 2007 Supreme Court decision in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle

School District invalidated programs in Seattle and Louisville that considered race as a

primary factor in assigning students to schools, saying that the school districts had not

demonstrated that they had seriously considered race-neutral alternatives to their

policies.

49

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Justice

released guidance to assist K-12 schools in interpreting the Court’s decision.

50

Schools are

47

Whitethurst, G. and S. Whitfield. “School Choice and School Performance in the New York City Public Schools - Will

the Past Be Prologue?” Brookings Institution, October 2013.

http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/reports/2013/10/08-school-choice-in-new-york-city-

whitehurst/school-choice-and-school-performance-in-nyc-public-schools.pdf

48

Ibid., p. 7.

49

“Guidance on the Voluntary Use of Race to Achieve Diversity and Avoid Racial Isolation in Elementary and

Secondary Schools.” U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Jusstice, 2011.

http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/guidance-ese-201111.pdf

50

Ibid.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

19

not prohibited from using race as a consideration for achieving diversity or avoiding racial

isolation in school districts. However, the agencies state that schools must “consider

approaches that do not rely on the race of individual students before adopting

approaches that do.” These approaches may include:

Race-neutral approaches, which take racial impact into account but do not rely on

race as an express criterion; and

Generalized race-based approaches, which use race as an express criterion but do

not treat individual students differently because of race.

Districts may consider the race of individual students only if the district does so “in a

manner that is narrowly tailored to meet a compelling interest,” that is, to meet the goals of

achieving diversity or avoiding racial isolation. Race-based approaches should only be used

if race-neutral or generalized approaches are unable to achieve the district’s compelling

interests. Even when taking race into account, race cannot be the deciding factor in school

assignment.

Finally, the agencies provide a set of key steps for implementing programs to achieve

diversity or avoid racial isolation:

51

Identifying the reason for the district plan:

o Determine how these compelling interests relate to the school district’s mission

and unique circumstances.

o Evaluate how the district will know when compelling interest has been achieved.

Implement the plan:

o Consider whether there are race-neutral approaches the district can use, such as

looking at socioeconomic status or the educational level attained by parents. In

selecting among race-neutral approaches, the district may take into account the

racial impact of various choices. If it’s determined that race-neutral measures

would be unworkable, consider whether using an approach that relies on the

generalized use of racial criteria, such as the racial demographics of feeder

schools or neighborhoods, would help to achieve your goals.

o If race-neutral and generalized race-based approaches would be unworkable to

achieve compelling interest(s), the district may then consider approaches that

take into account the race of individual students. When doing so, evaluate each

51

Quoted almost verbatim from Ibid., p. 8.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

20

student as an individual and do not make the student’s race his or her defining

characteristic. Periodically review the program to determine if the district

continues to need to consider the race of individual students to achieve the

compelling interest. It is important to ensure that race is used to the least extent

needed to workably serve the district’s compelling interest.

General considerations:

o Continue to consider factors that the district ordinarily weighs in student

assignment and other decisions, such as current and projected student

enrollment, travel times, and sibling attendance issues. As the district reviews

these factors in light of changes, such as increased or decreased demand at

school sites, it should also examine its practices to achieve diversity or avoid

racial isolation and modify them if needed.

o The district’s process for students or parents to raise concerns about school

assignments or other school decisions should be open to students or parents

who wish to raise concerns about decisions made pursuant to efforts to achieve

diversity or avoid racial isolation.

o It would be helpful to maintain documents that describe the district’s compelling

interest, and the process the district has followed in arriving at its decisions,

including alternatives considered and rejected and the ways in which the chosen

approach helps to achieve diversity or avoid racial isolation. These documents

will help the district answer questions that may arise about the basis for the

decisions.

INTER-DISTRICT POLICIES

Educational policies to address segregation and inequality by re-configuring boundaries

have generally focused on boundaries within school districts.

52

However, more than 80

percent of racial and ethnic segregation in public schools in the United States is due to

boundaries between school districts rather than within districts.

53

This inequality between

districts has led several researchers and education organizations to argue for the need for

more inter-district desegregation programs.

54

For example, a 2011 report by the National

School Boards Association states that school leaders “may want to consider inter-district

52

Wells, A.S. et al. “Boundary Crossing for Diversity, Equity and Achievement: Inter-District School Desegregation and

Educational Opportunity.” Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice, Harvard Law School, November

2009. http://www.charleshamiltonhouston.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Wells_BoundaryCrossing.pdf

53

[1] Ibid. [2] Siegel-Hawley, G. “Mitigating Milliken? School District Boundary Lines and Desegregation Policy in Four

Southern Metropolitan Areas, 1990-2010.” American Journal of Education, 120:3, May 2014.

54

[1] Wells et al., Op. cit. [2] Siegel-Hawley, Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

21

policies to enhance the size and diversity of the participating student pool.”

55

However,

inter-district policies may be complicated by legal, logistical, and political challenges related

to transportation, resources, and community resistance.

56

Due to PPS’ interest in rezoning within its own district, this report does not provide case

studies of inter-district policies to achieve diverse student bodies. However, case studies of

inter-district desegregation programs are available in recent reports published by the

Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice

57

and the American Journal of

Education.

58

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Parental and community engagement in school decision-making processes is vital,

particularly in redistricting and rezoning processes. The 2003 study of school boundary

processes in 15 school districts identified several promising community engagement

strategies, including:

Focus groups to determine parental preferences for school choice options;

Community meetings and workshops to gather input and convey information;

Attendance boundary committees, consisting of both staff and parents, to

determine school boundaries. These committees were reported by several districts

in Florida:

o Miami-Dade County reported that its committee, composed of 17 non-school-

board members, used a “grassroots, democratic-driven process” for decisions

about boundary changes.

59

Regional superintendents would present information

about schools targeted for boundary changes or reconfiguration, and the

committee made recommendations based on public forums, board meetings,

and analysis of demographic data.

o Palm Beach County reported that its committee served in an advisory capacity to

the Superintendent of Schools. The committee would hold community meetings

to gather input regarding proposed changes to school boundaries. Final

decisions were based on the district’s five-year capital plan; population growth

55

Coleman, A.L., F.M. Negron, Jr., and K.E. Lipper. “Achieving Educational Excellence for All: A Guide to Diversity-

Related Policy Strategies for School Districts.” National School Boards Association, 2011. p. 33.

https://diversitycollaborative.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/document-

library/educexcellenceforall_printfriendly.pdf

56

Coleman, Negron, Jr., and Lipper, Op. cit.

57

Wells et al., Op. cit.

58

Siegel-Hawley, Op. cit.

59

Brown and Knight, Op. cit., p. 405.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

22

data; land use and residential development plans within the municipality; and

criteria such as transportation time, socioeconomic diversity, facility capacity,

and feeder systems and transfers.

o Hillsborough County’s committee consisted of parents, “concerned citizens,”

principals, and other district staff.

60

The committee focused on diversity, student

proximity to schools, student safety, transportation requirements, projected

population growth, community issues, geographic dividers, feeder patterns, and

student needs to make boundary decisions.

Providing the community with demographic information and a set of steps for the

boundary review process. Broward County reported that its school boundary

process occurs annually and lasts throughout almost the whole year. The district

developed a boundary process flowchart and timeline to communicate information

about the process to the public. Steps in the process included data gathering,

boundary conferences, forums, public workshops, scenario development, analysis of

community input, and public hearings.

A 2014 guidance document for Race to the Top grantees provides general recommendations

for engaging the community to improve low-performing schools.

61

These general

engagement strategies can easily be applied to engaging the community the school zoning

and districting process:

Make engagement a priority and establish an infrastructure. Districts can develop

mission statements and plans for engagement or create advisory groups dedicated

to engaging parents and the community. Districts or schools may also wish to create

staff positions for community engagement and/or ensure that hired staff have roots

in the community and have backgrounds in communications or community

organizing.

Communicate proactively in the community. Districts should use a range of

traditional and nontraditional communication tools, such as mailings, newsletters,

blogs, email, open houses, workshops, and events such as barbecues or picnics.

Schools should also make outreach materials accessible by providing materials in

multiple languages, considering parent literacy and technology access, holding

events in safe and welcoming places. Schools should also strive to remove barriers

to participation by offering transportation and/or child care for community meetings

or forums. Finally, districts must ensure that parents and communities are engaged

early on in the process.

60

Ibid., p. 407.

61

“Strategies for Community Engagement in School Turnaround.” Reform Support Network, March 2014.

http://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/implementation-support-unit/tech-assist/strategies-for-community-

engagement-in-school-turnaround.pdf

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

23

Listen to the community and respond to its feedback. Districts can gather feedback

through conversations, public forums, surveys, or focus groups. Districts can show

that that have listened to feedback by taking action in response to community input.

For more information about strategies that individual school districts have used to inform

and engage parents in the school boundary and assignment process see Section II. In

addition, links to tools and maps that districts have used to communicate information about

school boundary changes are provided in Appendix A.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

24

SECTION II: CASE STUDIES

This section profiles four school districts that have recently undergone boundary change

processes: Boston Public Schools, Denver Public Schools, Seattle Public Schools, and

Washington, D.C. Public Schools. We highlight criteria districts have used to create new

school boundaries as well as strategies used to solicit community feedback and

communicate information about policy changes. Figure 2.1 provides demographic

information about each district, although profiled districts were not chosen based on

demographic similarity to PPS.

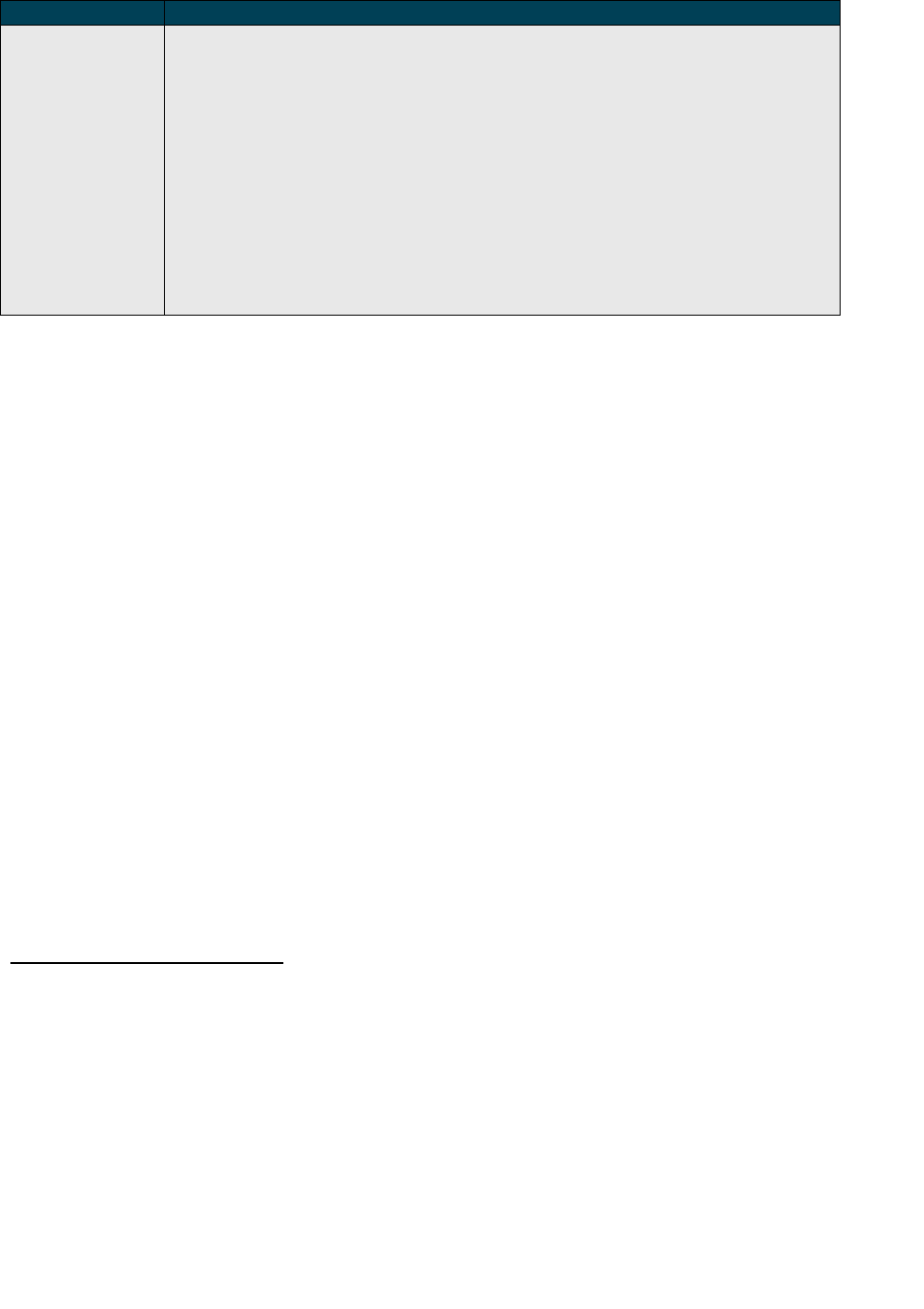

Figure 2.1: Demographic Information for Profiled School Districts

SCHOOL YEAR 2012-2013 DATA

62

BOSTON

DENVER

SEATTLE

WASHINGTON, D.C.

PORTLAND

Land area (square miles)

48.4

153.3

83.9

61.4

152

Population

625,087

634,265

620,778

632,323

460,248

(2010)

Percent of population under 18

17%

22%

16%

17%

19% (2010)

Total public school enrollment

63,780

84,424

49,870

80,231

48,459

School district enrollment

57,100

72,618

49,870

45,557

45,218

Number of district schools

127

162

96

117

78

Charter school enrollment

6,680

11,806

0

34,674

1,764

Number of charter schools

26

41

0

101

8

Percent of students eligible for meal

subsidies

75%

72%

40%

77%

49%

Percent of students bused

52% (2012)

34%

42% (2011)

<1%

Unknown

Source: 21

st

Century School Fund,

63

school district data,

64

and census data

65

Profiled districts have used controlled choice systems that prioritize neighborhood schools.

Denver, Seattle and Washington, D.C. use neighborhood attendance zones to determine

school assignment, although each district provides options for students to access schools

outside their neighborhoods. Boston has eliminated zones altogether, instead

implementing a home-based model that prioritizes access to schools within a one-mile

radius of students’ homes while ensuring that students have the ability to select high-

performing schools if none exist in their neighborhoods. Profiled districts generally rely on

school location and sibling priority to determine school assignments, and also consider

62

Data for PPS is from school year 2014 to 2015.

63

Adapted from “Student-Assignment Policies in Other Cities.” 21st Century School Fund, November 19, 2013. p. 5.

http://dme.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dme/publication/attachments/Policy%20Brief%202%20-

%20Other%20Cities%20Final%20Draft.pdf

64

[1] “About Portland Public Schools.” Portland Public Schools, 2014. http://www.pps.k12.or.us/about-us/ [2] “School

Profiles - Reports.” Portland Public Schools, 2014. http://www.pps.k12.or.us/departments/data-

analysis/9837.htm [3] “Portland Public Schools Enrollment Forecasts.” Portland State University Population

Research Center, August 2014. http://www.pps.k12.or.us/files/data-analysis/PSU-PPS_Report_1314.pdf [4]

“Annual Budget.” Portland Public Schools, June 23, 2014.

http://www.pps.k12.or.us/files/budget/2014_15_PPS_Adopted_Budget1.pdf

65

“Portland (city) QuickFacts.” U.S. Census Bureau, October 14, 2015.

http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/41/4159000.html

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

25

factors such as diversity, physical barriers, transportation, and distribution of at-risk

students when determining school boundaries and priorities.

Districts have used a variety of strategies to engage the community in revising school

boundaries and assignment systems, such as interactive websites, focus groups, surveys,

community meetings and workgroups, and participatory advisory committees. Districts use

websites, communications materials in multiple languages, letters, public service

announcements and billboards, school expos and fairs, community meetings, and published

school rankings to inform parents about policy changes and school choices. Despite

community engagement strategies, however, the process of revising school boundaries or

school assignment plans is often difficult due to large demand for high-performing schools

and the confusing and complex nature of school assignments.

BOSTON PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Boston Public Schools’ (BPS) school assignment process was redesigned in 2004 and again in

2013.

66

As mentioned in Section I, the district switched from the so-called Boston

mechanism to SOM-based assignment in 2004.

In this algorithm, half of schools’ seats were allotted for students with neighborhood or

“walk-zone” priority, while half of seats were allotted for students without neighborhood

priority.

67

From 1989 to 2013, zoning was based on a three-zone system originally

implemented to desegregate the city’s schools. The 2004 re-design process proposed a new

system with four, six, or 12 zones, but BPS chose to retain the three-zone system under the

new assignment algorithm.

68

However, this system was often cumbersome and confusing to

parents—families had to select from approximately two dozen school choices over a large

geographical area. In addition, this system often led to disadvantaged students being

assigned to low-performing schools because these schools were closer to their homes.

69

As part of a mayor-led effort to improve families’ confidence in school choice process and

provide better school options close to families’ homes, the district began searching for a

new school assignment plan in 2012.

70

The mayor appointed a 27-member advisory

committee—divided into data, equality, and community sub-committees—to identify and

propose changes to the existing school assignment system. The committee conducted an

intensive, year-long research process to develop a new plan, working closely with university

66

[1] Abdulkadiroglu et al., Op. cit. [2] Dur, U. et al. “The Demise of Walk Zones in Boston: Priorities vs. Precedence in

School Choice.” October 2014. http://economics.mit.edu/files/10007

67

Dur et al., Op. cit.

68

Vaznis, J. “Boston School Committee Expected to Take Historic Vote on Student Assignment.” Boston Globe, March

13, 2013. http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2013/03/13/boston-school-committee-expected-take-historic-

vote-student-assignment/WNqa3hYG1YNFgkTnEqV8NI/story.html

69

[1] Seligson, S. “Boston School Assignment Plan Marks New Era.” BU Today, March 26, 2013.

http://www.bu.edu/today/2013/boston-school-assignment-plan-marks-new-era/ [2] Seelye, K.Q. “No Division

Required in This School Problem.” New York Times, March 12, 2013.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/13/education/no-division-required-in-this-school-problem.html

70

Vaznis, “Boston School Committee Expected to Take Historic Vote on Student Assignment,” Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

26

researchers and holding over 70 community meetings to solicit feedback on proposed

plans.

71

The new plan, designed by a doctoral student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

is a home-based school assignment model that eliminated zones altogether.

72

The system

still uses an SOM-based assignment algorithm, but does not consider walk-zone priority.

73

Under the new plan, parents receive customized lists of schools to choose from based on

where the family lives. Every school on the list is located within a one-mile radius of the

family’s home, but the list must include at least two top-performing schools (in the top 25

percent) and at least four schools in the top 50 percent of the district’s performance.

74

If

schools within the one-mile radius do not meet these qualifications, the list will include the

next nearest high-performing schools. In addition, lists may include schools further than one

mile if the population of an area exceeds the number of available seats at a school. The

algorithm guarantees a minimum of six choices, but each family typically receives a list of

approximately 10 to 16 schools.

75

Families may rank as many choices as they wish.

In addition to considering school performance and neighborhood, the new plan makes

assignments based on the following priorities:

Sibling priority: Students that have siblings at the same school are given priority;

Feeder patterns: Students attending certain early education or middle schools have

priority at certain pathway/feeder schools; and

English language learning students and students with disabilities: These students

have access to a wider cluster of schools due to program availability.

BPS has used a variety of public outreach strategies to inform families about the new school

assignment method and school choices, including:

76

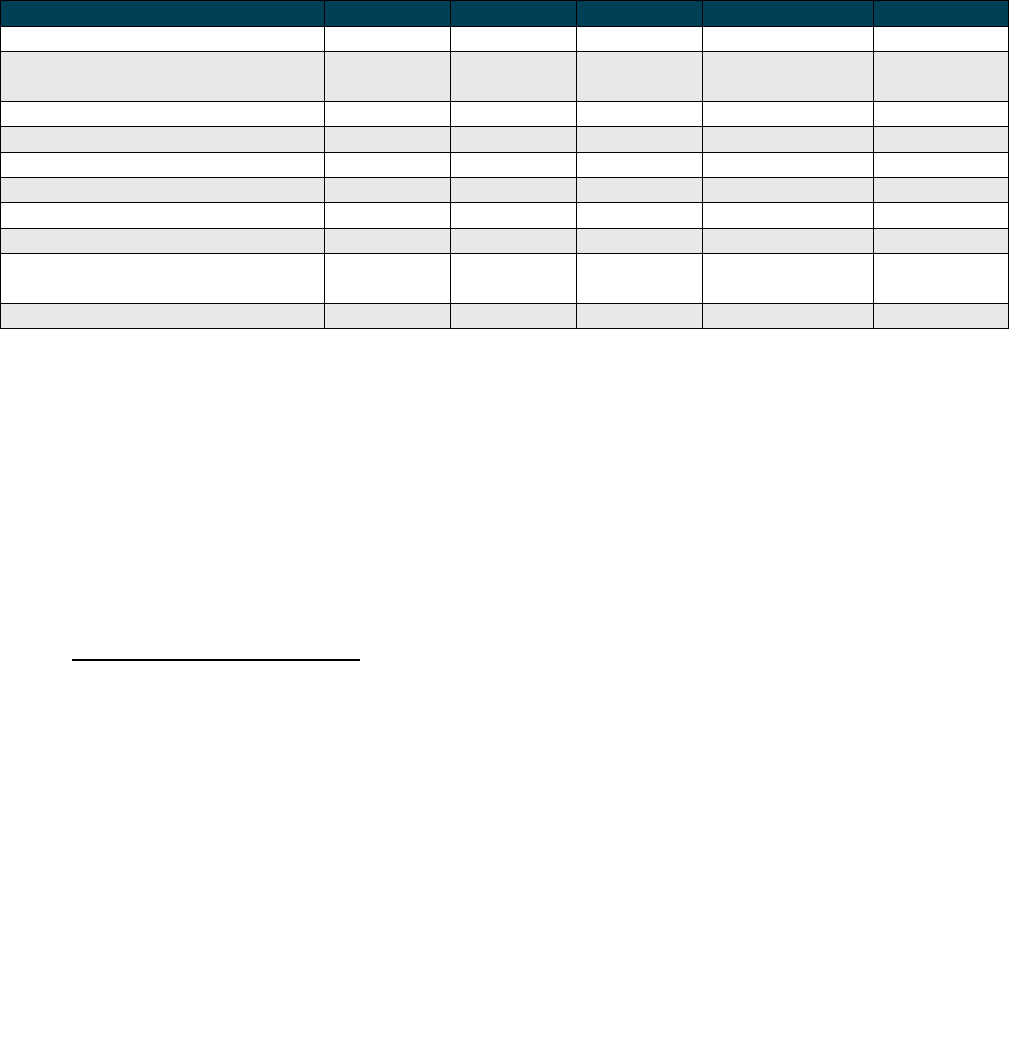

Public service announcements and billboards (see Figure 2.2).

71

[1] Seligson, Op. cit. [2] Seelye, Op. cit.

72

[1] Seelye, Op. cit. [2] “Student Assignment Policy.” Boston Public Schools, 2014.

http://www.bostonpublicschools.org/assignment [3] “How BPS Assigns Students.” Boston Public Schools, 2015.

http://www.bostonpublicschools.org/Page/654 [4] “The Home-Based School Choice Plan.” Boston Public Schools,

2015. http://www.bostonpublicschools.org/Page/1024 [5] “How School Assignment Works In Boston.” WBUR,

November 20, 2014. http://learninglab.wbur.org/topics/how-school-assignment-works-in-boston/

73

Pathak, P.A. and P. Shi. “Demand Modeling, Forecasting, and Counterfactuals: Part 1.” January 2015.

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1401.7359v4.pdf

74

[1] “Student Assignment Policy,” Op. cit. [2] “How School Assignment Works In Boston,” Op. cit.

75

[1] Vaznis, J. “Boston Parents Acclimate to School Choice System.” Boston Globe, January 27, 2014.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/01/27/new-school-assignment-plan-causes-some-confusion-among-

parents/GLORWdD0zdw3SvkAdpnSfM/story.html [2] “Learn about Your School Choices.” Boston Public Schools.

http://www.bostonpublicschools.org/domain/29

76

[1] “Learn about your school choices,” Op. cit. [2] Vaznis, “Boston Parents Acclimate to School Choice System,” Op.

cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

27

A total of 24 informational meetings in neighborhoods throughout the city.

BPS’ school registration website:

77

The website allows parents to view their

customized lists after entering their address and child’s grade. Parents can also

search for schools on a variety of criteria, from location to school hours to uniform

policy.

78

In addition, the BPS’ website explains the school assignment process and

choices in thorough detail.

79

Documents describing the district’s K-8 and high

schools are available in eight languages.

80

BPS’ website provides the following advice

on navigating the registration process:

81

o Apply within the first registration period;

o Select at least five choices;

o List schools in order of true preference; and

o Choose a variety of schools.

Annual school showcases and information sessions: K-8 and high school showcases

provide information about families’ various school options. In addition, school

registration information sessions take place in each neighborhood annually in

November through January.

82

77

“Discover BPS.” Boston Public Schools. http://www.discoverbps.org/

78

Scola, N. “How Boston Is Building the Hotels.com of Public Schools.” Next City, November 14, 2013.

https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/how-boston-is-building-the-hotels.com-of-public-schools

79

“Student Assignment Policy,” Op. cit.

80

“Publications.” Boston Public Schools, 2015. http://www.bostonpublicschools.org/Page/304

81

“When to Make Choices and Register.” Boston Public Schools. http://www.bostonpublicschools.org/Page/653

82

“Learn about your school choices,” Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

28

Figure 2.2: Example of Billboard Sponsored by Boston Public Schools to Advertise New

School Choice Plan and Website

Source: Next City

83

Initial registration under the new system went smoothly,

84

but software glitches led to a

delay in 9,000 students receiving their school assignments; some students did not receive

assignments until just three weeks before classes started. For the 2015 school year, over six

thousand students were assigned to schools that were not their first choices.

85

DENVER PUBLIC SCHOOLS

In 2010, Denver Public Schools began introducing the concept of “shared enrollment

zones”—geographic areas in which students are guaranteed a seat at one of several schools

but not at one particular school.

86

The district’s stated reasons for using shared boundary

zones include:

87

Increasing access to high-performing schools;

Increasing access to transportation options;

83

Scola, Op. cit.

84

Vaznis, “Boston Parents Acclimate to School Choice System,” Op. cit.

85

[1] “Boston Public Schools Superintendent Apologizes For Delayed Release Of School Assignment Lists.”

iSchoolGuide, September 2, 2015. http://www.ischoolguide.com/articles/24224/20150902/boston-public-

schools-superintendent-release-school-assignment.htm [2] Fox, J.C. “BPS Superintendent Chang Pledges Smooth

Start despite Wait-List Woes.” Boston Globe, August 20, 2015.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/08/20/bps-superintendent-chang-pledges-smooth-start-despite-

wait-list-woes/KlTfTS9K0wenIXZH5wVAYM/story.html

86

[1] Robles, Y. and E. Gorski. “Denver Public Schools Looks to Better Integrate Schools through ‘Enrollment Zones.’”

Denver Post, June 13, 2015. http://www.denverpost.com/news/ci_28305017/dps-looks-better-integrate-schools-

through-enrollment-zones [2] “Shared Enrollment Zones.” Denver Public Schools.

http://face.dpsk12.org/community/shared-enrollment-zones/

87

Adapted from “Shared Enrollment Zones,” Op. cit.

Hanover Research | November 2015

© 2015 Hanover Research

29

Prioritizing neighborhood students;

Providing access to different types of school programs; and

Helping schools to better plan for the right number of students.

The district’s superintendent argues that the larger shared zones will promote integration

and school choice within the district, saying:

“The narrower you draw your boundaries, the more likely you are to see schools

that are less diverse. The broader you draw the zone, the more likely you are to

draw greater diversity.”

88

The district uses an “opt-in” school choice process, meaning that students are assigned to

their default neighborhood or zoned schools, unless they decide to participate in the

district’s choice system.

89

Both district schools and charter schools are included in the

school choice process. Families in shared enrollment zones have extra incentive to

participate in the choice process, because their children would otherwise be randomly

assigned to a school within the zone.

Through a centralized, annual application process, either paper or online, families can list up

to five school choices in order of preference.

90

Final assignments are primarily based on

neighborhood and sibling priority. Students are guaranteed a spot at their neighborhood

school, but if a student lists a non-neighborhood school as the first choice, they may lose

their guaranteed spot at their neighborhood school.

91

The district states that it makes

school assignments based on the following priority order:

92

Students who, for various reasons, have a new residence school within Denver and

wish to remain at the current school;

88

Zubrzycki, J. “School Board Moves a Step Away from Neighborhood Middle Schools in Northwest Denver.”

Chalkbeat Colorado, June 18, 2015. http://co.chalkbeat.org/2015/06/18/school-board-moves-another-step-away-

from-neighborhood-middle-schools-in-northwest-denver/#.Vjfv3LerSUk

89

[1] Gross, B., M. DeArmond, and P. Denice. “Common Enrollment, Parents, and School Choice: Early Evidence from

Denver and New Orleans.” Center on Reinventing Public Education, May 2015.

http://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/cpe-report-common-enrollment-denver-nola.pdf [2] Zubrzycki, J. “In