APRIL 2022

Increasing Equity and

Improving Measurement in the

U.S. Unemployment System:

10 Key Insights from the COVID-19 Pandemic

ALEX BELL, THOMAS J. HEDIN, PETER MANNINO,

ROOZBEH MOGHADAM, CARL ROMER, GEOFFREY SCHNORR

AND TILL VON WACHTER

CONTENTS

Summary ..........................................................3

Key Takeaways......................................................4

Changes to Unemployment Insurance During the Pandemic ...........7

Part I: Measuring Equity in Access and Receipt of ...................9

Unemployment Insurance Benets

1. Layos and Long-Term Unemployment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

2. Unequal Access to Unemployment Benets ........................12

3. Unequal Weekly Benet Amounts ................................16

4. UI Benet Exhaustions and Extended UI Programs ..................18

5. Extended Benets Triggers .......................................24

6. Reemployment and Recall Patterns ................................29

Part II: Insights into the Shortcomings of Current Measures of

Unemployment Benets and How to Improve Them

7. Measurement Issues in Initial Claims Data ..........................34

8. Churn and Repeat Layos in the UI System ........................39

9. Improvements in Counting Continuing Claims ......................42

10. Partial UI and Denials: An Overlooked Measurement ................46

Conclusion........................................................49

References ........................................................52

Figure Appendix ...................................................55

The California Policy Lab builds better lives through data-driven policy. We are an independent, nonpartisan research

institute at the University of California with sites at the Berkeley and Los Angeles campuses.

This research publication reects the views of the authors and not necessarily the views of our funders, our sta, our

advisory board, the California Employment Development Department, or the Regents of the University of California.

2 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic had an immense impact on the labor market in California and

the U.S., with unemployment reaching highs not seen since the Great Depression. The

regular Unemployment Insurance (UI) system, as well as federal legislation that created

supplemental UI programs and benet extensions, played a fundamental role in the

country’s economic and public health response. Individual-level data on who applied for and

received UI benets can provide crucial insights into understanding how the crisis evolved,

how well the government’s response worked, and what the implications are for future crises.

The pandemic also brought to the forefront more fundamental issues with our nation’s UI

system, such as pervasive inequities in which workers actually receive benets and large

dierences in benet amounts and durations. While some of these issues have persisted for

decades, a lack of access to individual-level UI data has prevented a deeper understanding

of the extent of the inequities. The crisis also revealed that even the most fundamental

statistics that policymakers rely on have important aws, and basic information on which

workers benet from some of the core UI programs is completely missing, despite the data

being collected every day by UI agencies as they pay benets.

The California Policy Lab (CPL) partnered with the California Employment Development

Department (EDD), which manages unemployment insurance in California, to help bring

greater clarity to policymakers about the impact of the crisis in California. CPL’s rst analysis

was published in April 2020, and through this unique relationship, CPL was able to use

anonymized claims data to track the labor market crisis in close to real-time and to provide

in-depth, detailed insights on the federal government’s response. Through a series of 19

reports, CPL generated new ndings about a range of issues in the California UI system.

CPL’s research also shed light on which demographic groups and types of workers beneted

the most from the dierent program extensions during the pandemic and which workers

fell through the cracks and were unable to access vital UI benets.

By working directly with complicated claims data for more than two years, CPL developed

new, more accurate and timely measures of how many people were relying on the UI

system as compared to the measures that policymakers and the media typically have relied

on. This work directly demonstrated for state and federal policymakers how the measures

they had historically relied on provided a distorted view of the labor market during the

crisis. For example, a 2020 GAO report cited CPL’s research, nding that published claims

data were likely inated (Government Accountability Oce, 2020).

This report highlights ten key insights about the UI system and the labor

market that are based on CPL’s unique partnership with EDD and the

unique data access this partnership provided. The report focuses on six insights

on equity and disparities in access to unemployment insurance benets during the pandemic.

It then documents four insights on measurement issues in the publicly available data and

how access to California’s administrative records allows CPL to overcome these issues. We

also share how these improved measurements can inform policy choices to improve equity.

3 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Part I: Measuring Equity in Access and Receipt of Unemployment

Insurance Benets

1. Workers experienced unequal impacts from the pandemic as

measured by CPL’s new cumulative measures of layos and long-

term unemployment. CPL’s access to UI administrative data allowed us

to, for the rst time, track the impact of the pandemic across demographic

groups using initial claims data. In the rst year of the pandemic, 31% of

Californians in the labor force applied for regular unemployment benets.

Female workers and workers with a high school degree or less had higher

rates of UI claiming than other groups. Of claimants who received benets,

Black, female, and less educated workers claimed UI for longer periods of

time and had higher long-term unemployment rates than other groups.

2. The recipiency rate (which measures how many unemployed

workers are receiving UI benets) increased during the

pandemic. However, there were large disparities across

communities. Publicly available claims data are typically only published

at the state level, which makes it impossible to analyze access to UI across

communities at more detailed geographic levels. Using EDD claims data,

CPL found that California counties with higher incomes and more access

to broadband internet were associated with high recipiency rates, while

areas with a larger share of Hispanic individuals, people with limited English

prociency, and more COVID-19 cases were associated with lower rates.

3. The $600 and $300 UI supplements provided during the

pandemic temporarily helped raise claimants’ incomes above

the “very low” income threshold for single individuals, but

disparities in weekly benet amounts remained. Because of how UI

benets are calculated, males, more educated workers, and White workers

typically receive higher UI benet amounts than other workers. In contrast,

CPL’s research showed that the individuals most impacted by the pandemic

tended to receive smaller weekly UI benet amounts. By measuring benet

amounts with and without these supplements, CPL demonstrated the role

that federal supplements played in raising these workers’ incomes above the

“very low” threshold.

4 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

4. The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation

(PEUC) program and the Extended Benets (EB) program

helped reduce the number of people who ran out of UI

benets during the crisis and these programs were especially

important for less advantaged workers. There is no publicly available

information on which workers beneted from PEUC or EB programs, and

only rudimentary information on average exhaustion rates, severely limiting

the public’s understanding of the impact of these key programs during the

pandemic. CPL’s research showed that 25% of Californians who applied for UI

benets during the pandemic exhausted their benets, which is lower than the

32% national cohort exhaustion rate estimated during previous recessions.

Over half of all claimants in the PEUC program, a key UI benet extension

program, had a high school diploma or less just before the program expired.

Female workers and younger workers also accounted for a larger share of

claimants receiving PEUC near the end of the program.

5. Due to a aw in how states determine if Extended Benets (EB)

are available, California and 38 other states ended their EB

programs while many workers still relied on them. State Extended

benet programs provide a crucial backstop for long-term unemployed

workers during recessions, and CPL’s research shows that in California it

mostly benets workers with a high school degree or less, female workers,

and Hispanic workers. If Congress reformed automatic benets triggers to

align with CPL’s improved Insured Unemployment Rate trigger (which also

counts claimants in extension programs), these 38 states would have been

able to provide claimants who had exhausted state UI benets with an

additional 13 weeks of benets.

6. Re-employment rates one year after the start of the pandemic

had steadily increased, but remained lower for less-educated

workers than during the pre-pandemic expansion period. In

contrast, a higher share of workers returned to their previous

employer and remained in their previous industry. The

employment outcomes of workers receiving UI are typically not visible to

policymakers, but can provide important insight into the pace of recovery

and needs for intervention across types of workers and labor markets.

Using linked employment data, CPL’s research found that 57% of claimants

who were fully separated from their employer at the beginning of the crisis

(Q2, 2020) were employed one year later, in Q2, 2021. In comparison,

71% of people who claimed UI before the pandemic (in Q4, 2018) were

re-employed within a year. Out of all the re-employed workers, 60%

returned to their previous employer, which was substantially larger than

before the pandemic, when 31% of re-employed workers returned to their

previous employer.

5 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Part II: Insights into the Shortcomings of Current Measures of

Unemployment Benets and How to Improve Them

7. Initial claims are one of the most watched measures of

unemployment, yet CPL’s research found that this measure

dramatically overstates the number of individuals entering the UI

system each week. Between early March 2021 and mid October 2021,

there were 2.7 million initial claims for regular UI in California — but during

that same time period, there were only 1.9 million individuals who entered

the regular UI system. In other words, the typical interpretation of the initial

claims measure overstates the number of individuals claiming regular UI by

42% during this time period. CPL created a new measure called Entries into

Paid Unemployment that more accurately measures the number of people

entering (or re-entering) the UI system.

8. CPL’s new measure of Entries into Paid Unemployment based

on actual payments also claries the total amount of churn in

and out of the system. In early May 2021, we found that the share of

people entering the UI system that were reentries — i.e., claimants who

were beginning their second (or more) period of unemployment— was

over 90%. A second measure of churn shows that in 2021, between 30%

and 40% of all claimants who left the UI system returned after four weeks.

Across demographic groups, White workers, female workers, and older

workers were more likely to suer repeated job loss and multiple periods of

unemployment.

9. Dierences between when unemployment is experienced and

when UI claims are certied can give a distorted view of the

number of individuals receiving UI. Ocial UI statistics count the

number of claims certied each week, not the number of people experiencing

unemployment each week. If individuals retroactively certify for benets or

state agencies are delayed in certifying benets for unemployment experienced

in the past, then the published UI measures could provide a distorted view of

the timing of unemployment. CPL’s new metric measures the number of UI

claims based on when unemployment was actually experienced and provides

a more accurate and timely measure of the labor market.

10. Partial and denied UI payments can shed light on how the UI

system interacts with people who are still connected to their

employer. Through most of the pandemic, the share of UI claimants

receiving partial payments hovered between 9% and 11% and the share being

denied payments due to excess earnings was between 5% and 6%, indicating

that many UI claimants continued to work (albeit at reduced amounts) and

received lower benets as a result. Older workers, more educated workers,

and White workers were more likely to receive partial UI payments and

more likely to be denied payments due to excess earnings.

6 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Changes to Unemployment Insurance During the

Pandemic

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and state policy makers

introduced a large number of temporary changes to the UI program in response

to the economic disruption caused by the pandemic. For example, nearly all states

suspended work search requirements at the beginning of the pandemic, but states

re-introduced them at dierent times as the pandemic evolved. Many of these

changes motivated CPL’s research during the pandemic and reviewing the changes

provides important context for several of the insights described in this report.

In the CARES Act (2020), federal policymakers introduced the Pandemic

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program that

provided additional weeks of UI to claimants who used all their regular UI benets.

At its maximum, PEUC provided up to 53 weeks of additional benets. Depending

on local labor market conditions a state program called Extended Benets

(EB) provides additional weeks of benets for those that exhausted PEUC

benets (see Section 5).

Federal policymakers also provided supplemental weekly payments of either $300

or $600 to claimants’ normal Weekly Benet Amounts through the Pandemic

Additional Compensation program and the Federal Pandemic

Unemployment Compensation program (which will be described in more

detail in Section 3).

Finally, a new program called Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA)

provided benets for workers who are normally not eligible for regular UI, such as

self-employed workers.

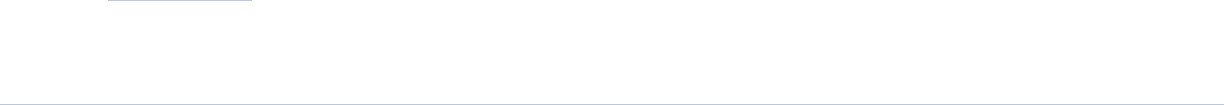

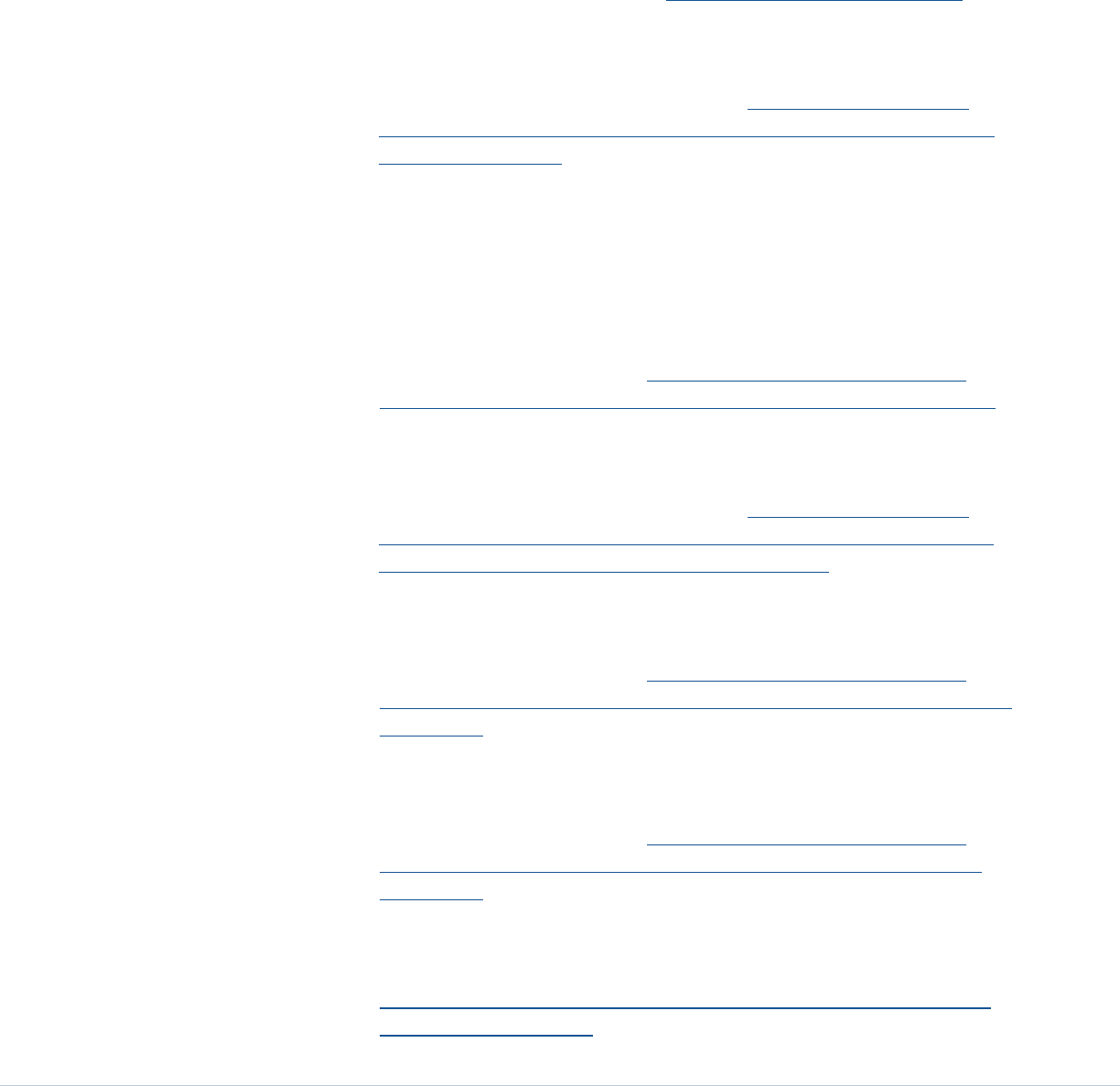

Figure 1 indicates the extent of UI benet use and the importance of extended

benet programs in the pandemic. The role of these benets especially for more

vulnerable workers is analyzed in several sections of this paper. As reected in

the gure, the nal expiration date for all the temporary programs was in early

September 2021.

7 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 1: Total Number of Individuals Paid Benets by Week of Unemployment

Regular UI

(Continuing)

PUA (Expiring)

PEUC (Expiring)

EB (Expiring)

December 26th:

PEUC/PUA Temporarily Expire

September 4th:

PEUC/PUA Expire

September 11th:

Extended Benefits Expire

0

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

Feb 8

, 2020

Mar 7

Apr 4

May 2

May 30

Jun 27

Jul 25

Aug 22

Sep 19

Oct 17

Nov 14

Dec 12

Jan 9

Feb 6

Mar 6

Apr 3

May 1

May 29

Jun 26

Jul 24

Aug 21

Sep 18

, 2021

Week of Unemployment

Individuals Receiving Benefits

Notes: X-axis labels correspond to Saturdays. Data has been adjusted to account for delays in processing and retroactive claims. Figure includes all available

programs for the period 2/2/20-10/2/21.

While CPL’s and other research indicates these programs have successfully

supported workers in the pandemic, the PUA program has been the subject of

controversy due to high reported levels of fraud. As a result, this report (with a

few exceptions) does not analyze the PUA program. Ongoing work by CPL will

shed light on this program in the future.

8 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Part I: Measuring Equity in Access and Receipt of

Unemployment Insurance Benets

1. Layos and Long-Term Unemployment: How the Crisis Impacted

Demographic Groups and Workers Dierently

Issue. The weekly initial claims data released by the Department of Labor (DOL)

is an important indicator of changes in the labor market. Unfortunately, none of

the publicly available initial claims data include demographic characteristics, which

makes it impossible to use the indicator to measure labor market changes by

demographic group or industry. Access to the UI microdata in CA has allowed

CPL, for the rst time, to measure dierences in UI claims across groups during

the pandemic and we have released this data in our UI reports throughout the

crisis

1

(Bell, Hedin, Moghadam, et al., 2021b). Throughout much of the crisis,

initial UI claims were particularly high for less advantaged groups in the labor

market, including female and less educated workers, and in communities with a

higher rate of poverty and higher shares of Black individuals.

Access to the microdata has an additional advantage over the published DOL

data, which is that we can calculate deduplicated cumulative measures of UI use

with both the initial claims and continuing claims data. This allows us to measure

the total number of workers who applied for UI during the crisis. By comparison,

in the publicly available data, the new initial claims series could provide a close

estimate, but would still suer from some duplication from claimants who le

multiple claims.

2,3

Additionally, the publicly available data does not provide the

new initial claims series with demographic or detailed geographic breakdowns.

4

Analyzing California claims data also allows CPL to measure the number of weeks

of payments each recipient received. The DOL publishes data on the distribution

of the number of payments received by recipients, but it does not provide the

detailed demographic distribution that is available in the California microdata. We

can use these two metrics to measure the total impact of the pandemic across

demographic groups in California.

1 Figures 8A and 8B in the June 2021 UI report show initial claims by demographic groups over the course of the crisis. See: https://www.capolicylab.org/wp-

content/uploads/2021/12/June-30th-Analysis-of-Unemployment-Insurance-Claims-in-California-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf

2 This could be the case if the Employment Development Department website experienced crashes from high usage and users resubmit their claims because

they were unsure if their rst claim was received. Alternatively, it could happen if employers submit claims on an employee’s behalf and an employee submits a

claim themselves (Cajner et al., 2020).

3 While the duplication issue will be relatively modest for new initial claims, the duplication with total initial claims will be substantially larger.

4 The DOL does provide demographics for all initial claims, but not the new initial claims, which is what would be needed to account for duplication.

9 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Analysis. Figure 2 shows the rst cumulative measure of UI claiming — the

share of unique people who led for regular UI benets as a share of the

pre-crisis labor force. It shows that through the rst year of the crisis, 31% of

the labor force led for regular UI benets in California. By this measure, less

educated workers have been hit hardest by the pandemic with over half of

workers with a high school degree or less applying for Regular UI benets in the

rst year of the pandemic. The data also illustrate the previously documented

“she-cession” character of the crisis with a higher percentage of female workers

ling for UI benets than male workers (Gupta, 2020).

Racial groups are not included in this gure because of dierences in how racial

and ethnic groups are categorized between the California UI administrative data

and the labor force data from the Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS

asks about race and ethnicity as separate questions so that respondents can

indicate their race and ethnicity separately. The California UI application asks

about race and ethnicity as a combined question where the racial and ethnic

identities cannot be separated. This means the same individual could identify

dierently between the two sources. Therefore, constructing measures across

these two datasets that assumes individuals would identify the same way in each

source is problematic.

FIGURE 2: Unique Individuals Filing for Regular UI Benets, as a Percentage of Group’s Pre-Crisis Labor Force

Note: This gure shows the number of unique individuals with initial claims for regular UI processed between March 15, 2020, and March, 15, 2021 as a share of

the February 2020 labor force.

10 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

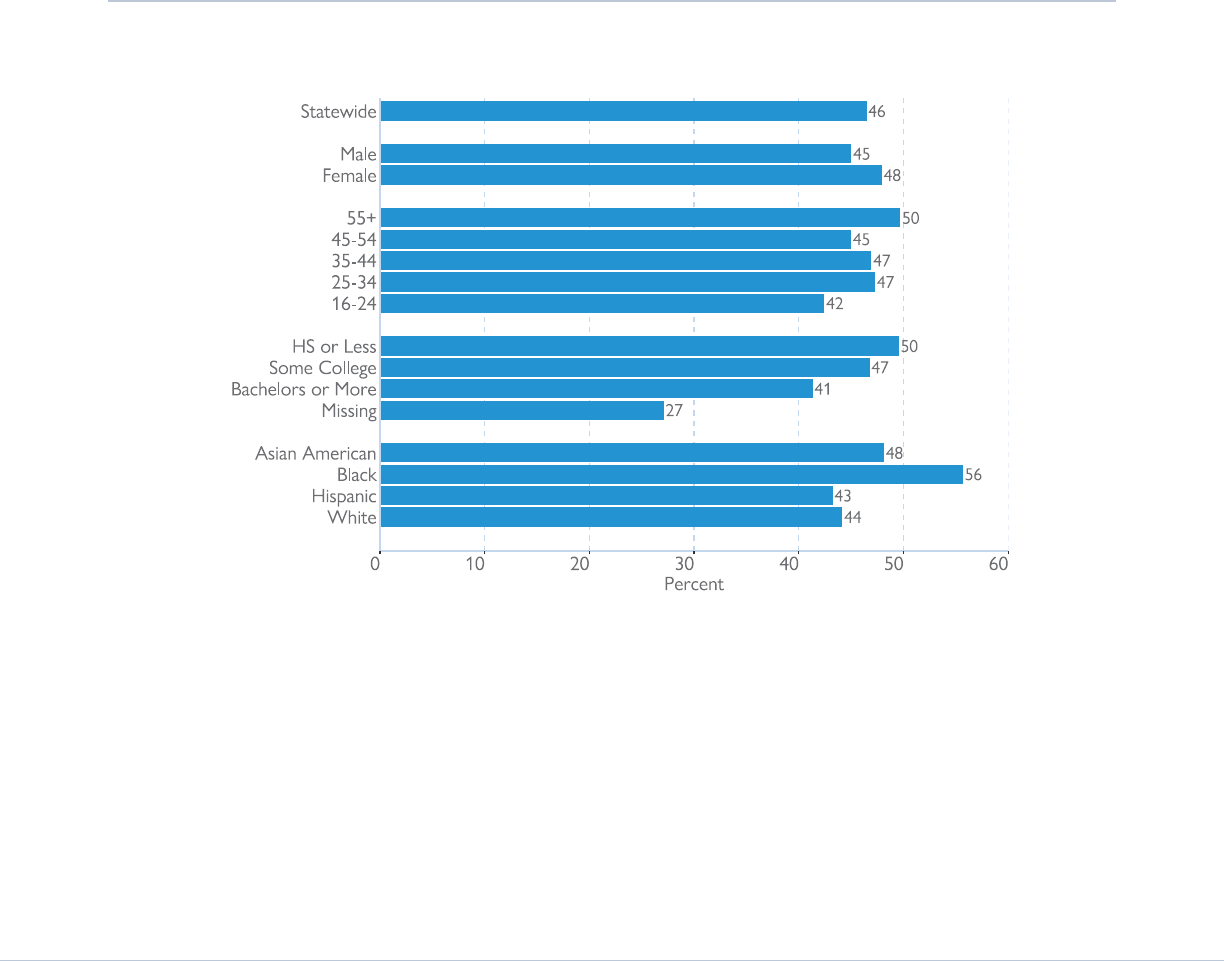

Figure 3 illustrates the second measure of the cumulative impact of the pandemic

on UI claimants — the long-term unemployment rate. Overall, about 46% of

UI recipients received over 26 weeks of UI payments during the rst year of

the pandemic. Typically, the long-term unemployment rate is dened as the

share of the unemployed who have been jobless for over 26 weeks (about six

months). CPL’s modied version of the long-term unemployment rate using the

administrative UI data is the share of UI claimants who received at least one

payment who have received more than 26 weeks of unemployment benets

during the rst year of the crisis. The gure also shows that Black claimants, older

claimants, less educated claimants, and female claimants experienced higher rates

of long-term unemployment than other groups over the rst year of the pandemic.

FIGURE 3: The Share of Regular UI Claimants who Received More than 26 weeks of UI Payments in the First Year of

the Crisis.

Note: Long-term unemployment is dened as receiving more than 26 UI payments during the 52 weeks between March 2020 and March 2021.

11 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

2. Access to Unemployment Benets Increased During the Pandemic,

but There Were Substantial Dierences Across Communities

Issue. The process to receive UI is relatively laborious and requires being able

to access, understand, and complete the applications to apply for benets.

Applicants then have to meet certain requirements such as having earned a

minimum amount of income during a base period (prior to being unemployed)

to be approved to receive benets. Finally, they have to verify that they meet

ongoing requirements, such as looking for work each week to receive payments.

The requirements at each stage and other barriers, such as access to an internet

connection, can aect workers’ ability to receive benets that they might be

eligible for.

The recipiency rate measures the rate at which unemployed workers receive

UI benets. It is a summary measure of unemployed workers’ ability to access

benets and can vary over time, by geography, and by demographic group. The

standard recipiency rate is calculated using the publicly available continuing claims

data from the DOL and the unemployed workers estimate from the Current

Population Survey. One issue with the calculation is that continuing claims data

from the DOL measures the number of claims certied each week, not the

number of claims paid for unemployment experienced in a week. Since claims

can be submitted retroactively and there can be administrative delays in certifying

benets, the number of claims paid for unemployment experienced in a week

and the number of claims certied in a week can be very dierent. This could

be particularly true when there are large changes in the labor market like the

beginning of the pandemic.

We improve on this approach by measuring the number of people who received

UI benets for the week in which they actually experienced unemployment

(Hedin et al., 2020b). This allows us to calculate a recipiency rate measure that

provides a more apples-to-apples comparison of the number of people who

received UI benets for unemployment experienced during a week to the total

number of people who were unemployed during the week. Additionally, most

prior measures of the recipiency rate used U3 unemployment, which is the

standard measure of unemployment that includes people actively looking for

work, as the denominator. During the pandemic, work search requirements were

suspended which allowed “discouraged workers” (workers who were looking

for work in the recent past, but stopped because they could not nd any or

felt it was unsafe to work during the pandemic) to qualify for UI benets. This

group is excluded from the U3 unemployed, so using U3 as the denominator

would overstate the recipiency rate. Our measure of the recipiency rate uses

the alternative U6 unemployment rate, which includes discouraged workers and

therefore will not overstate the recipiency rate (Bell, Hedin, Schnoor, et al., 2021).

5

5 For more details of the U3 and U6 unemployment rates, see:: https://www.bls.gov/lau/stalt.htm

12 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Measuring recipiency rates for regions within California is an important but

dicult task. Although we have precise measures of how many Californians

collected benets from a given geographic area, estimating the number of

unemployed workers in a specic region at a specic time is more cumbersome.

In this analysis, we rely on ocial county-level estimates from the Bureau of Labor

Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics (US Bureau of Labor Statistics,

2021) for our measure of the unemployed. However, estimating recipiency rates

this way is far from ideal because — due to the small sample size of the Current

Population Survey (108,000 people) — the LAUS estimates for unemployment at

the sub-state level rely on certain measures of UI claims themselves.

6

While we

have contrasted the LAUS county unemployment rates to comparable estimates

based on the CPS microdata and found them to be similar, the fact remains that

for many smaller geographic units the estimates are based on small samples so

are prone to statistical noise. For this reason, the county-level estimates of UI

recipiency rates presented below should be interpreted with caution.

7

Analysis. Figure 4 shows how recipiency rates for Regular UI varied within

California before and during the pandemic.

8

Based on the comparisons of UI

claimants to LAUS unemployment rates (re-scaled to mirror U-6), Los Angeles

County has by far the lowest recipiency rate among large counties in California.

The recipiency rate in California increased steadily from about 20% at the start of

the crisis to almost 90% by the end of 2020. This increase coincided with more

unemployed workers, new federal UI programs, and work requirement rules

being suspended. The gure also demonstrates the large geographic variation in

recipiency rates. Before the crisis, recipiency rates across counties were relatively

similar, but during the crisis, the gaps between counties increased substantially.

Finally, the recipiency rate plummeted back to its pre-crisis level of about 20% as

a result of the federal UI programs expiring in September 2021.

6 For more information, see the LAU.S. methodology note: https://www.bls.gov/lau/laumthd.htm.

7 In our ongoing series of policy briefs, we have compared geographic patterns of recipiency rates using the LAU.S. county-level denition of unemployment to

the tract-level unemployment estimates near the start of the pandemic of (Ghitza & Steitz, 2020). We have not detected meaningful dierences in the spatial

correlations using either measure of unemployment.

8 We do not include claimants on the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program for two reasons. First, high reported levels of fraud in the program

raise questions about the accuracy of the data. Second, we want to compare changes in recipiency from the pre-pandemic period and PUA did not exist

before the pandemic, so excluding PUA makes for a better comparison.

13 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 4: The Share of Unemployed or Underemployed (U-6*) in Each California County Who Are Receiving

Regular UI Benets (Jan. 2019–Sept. 2021)

Figure 5 shows county-level correlations

9

of recipiency rates with socioeconomic

indicators just before the federal UI expirations. It indicates that before the

expirations counties with higher rates of COVID-19 deaths saw lower rates of

recipiency, as did those counties with higher shares of Hispanic residents. We

nd that counties with more broadband access had substantially higher rates of

UI recipiency, which points to the importance of technological gaps in access to

UI during the pandemic. We also nd that counties with more residents with

limited English prociency had lower rates of UI recipiency, which is consistent

with reports that language barriers may also have played a role in limiting access

(Hellerstein, 2020). Many of these correlational ndings corroborate the more

qualitative conclusions (Fields-White et al., 2020) on the role that barriers like

stigma, documentation burdens, and the digital divide have played in widening

racial disparities in access to UI. Although an authoritative dissection of the roots

of these dierences is beyond the scope of the current study, a growing body

of quantitative and qualitative evidence (Fields-White et al., 2020; Gould-Werth,

2016; Shaefer, 2010) suggests that both legal eligibility and more nuanced barriers

to accessibility of UI have played important roles in determining UI recipiency rates.

9 All statistically signicant correlations are signicant at the 95% condence level.

Statewide Average

Los Angeles

County

Recipiency rates jumped suddenly

at the start of the pandemic.

Then steadily increased

throughout the fall.

Topping out at

around 90% by

the end of 2020.

Pandemic UI Programs Expire

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Jan 2019 May 2019 Sep 2019 Jan 2020 May 2020 Sep 2020 Jan 2021 May 2021

Recipiency Rate in County

Note: Each dot represents the recipiency rate in each month for each of the 58 counties in California. The size of the dot corresponds to the number of U6

unemployed in each county. The line represents the weighted average recipiency rate in California for each month.

14 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 5: Recipiency Rates Within California, County-Level Correlations

Note: Each dot represents the correlation between the county U*6 recipiency rate for August 2021 and county characteristics from the 2019 American Com-

munity Survey. The error bars represent 95% condence intervals.

In our recent report to the US DOL (Bell et al., 2022), we leverage our

experience with California’s claims-level data to construct similar measures of

access in other states during the pandemic. For each state, we used publicly

available data to calculate rates of rst payments, recipiency rates, and exhaustion

rates. Measures of access varied much more across states than across California’s

58 counties, likely reecting the importance of state-level policy dierences.

Although UI has played a critical role in supporting individuals and stabilizing

communities during the pandemic, serious disparities in access exist across the

nation. Policy dierences (such as diering benet amounts, base periods, and

benet durations) across states likely underlie many of these disparities. For

instance, although states with more Black or low-income residents had higher

rates of UI exhaustion during the pandemic, one of the strongest predictors of

a state’s exhaustion rate was the potential benet duration (how long a worker

could claim UI benets) the state extended to claimants. Though more analysis is

needed to isolate the causal eects of particular policies, this descriptive cross-

state analysis suggests there is likely great scope to equalize access to UI in the

country by harmonizing UI policies.

Share Self-Employed

Non-Citizen, percent

Limited English, share aged 5+

Hispanic, percent

COVID Confirmed Cases, % pop

Percent in poverty

Population share aged 20-24

Black, percent

Agricultural employment, percent

Population, ages 65 plus, percent

SNAP recipient, percent

Means of transportation to work, public transit

Retail trade employment, share

Median Household Income

Broadband access of any type, share

-1 -.8 -.6 -.4 -.2 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1

Correlation With Recipiency Rate

15 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

3. Pre-pandemic labor market inequalities translated to very low UI

benet amounts for more vulnerable workers

Issue. In California most claimants found to be eligible for regular UI are paid

benets equal to 50% of their average weekly earnings in a base period, up to a

maximum of $450 per week. As a result of this benet structure, higher income

workers receive higher absolute weekly benet amounts than lower income

workers. Due to inequalities in labor outcomes across demographic groups, this

also implies that the weekly benets provided by UI will dier across dierent

workers to the detriment of disadvantaged groups. These lower absolute benet

amounts mean that already disadvantaged workers will have a harder time

providing the essentials for their families. The DOL has also recognized the

negative consequences of inadequate benet levels and has made addressing

them a key component of UI reform.

10

Congress mandated that all claimants for regular UI and PUA who were eligible

for benets between March 29th and July 25th, 2020 received an additional $600

weekly benet through the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation

(FPUC) and all claimants for regular UI and PUA eligible for benets between

December 27th, 2020 and September 4th, 2021 received an additional $300

supplement through Pandemic Additional Compensation (PAC). These benet

amounts can be compared to California’s 2020 state income limits, which are

used for eligibility determinations of various government programs.

Analysis. In our UI policy briefs, we have been able to use our unique access

to California UI administrative data to measure how the average weekly benet

amount (WBA) has both changed through the crisis and how it has diered

across demographic groups (Hedin et al., 2020a). The average weekly benet

amount (WBA) for new initial claimants who led for the week ending in

10/16/21 was $330.83 per week. Figure 6 shows how weekly benet amounts

have evolved over the course of the pandemic, and how total benet amounts

(including supplements) relate to the income limits for single person households.

Throughout the whole period, the average WBA without supplements would

have provided an income that was only about half the “Very Low Income”

threshold for a single person household. Due to the $600 supplement and the

later $300 supplement, the average claimant was lifted above the “Very Low

Income” threshold, and for nearly four months at the beginning of the crisis

almost surpassed the “Low Income” threshold. Appendix Figure A1 shows the

evolution of weekly benet amounts across programs for the cohort of claimants

who entered UI in March 2020. On average, PUA recipients had the lowest

and regular UI recipients had the highest benets. Workers receiving extended

benets had lower average benets, especially those that had very long periods of

unemployment..

10 See page 17: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/les/general/budget/2022/CBJ-2022-V1-07.pdf

16 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 6: Average Weekly Benet Amounts of Initial Claimants for Regular Unemployment Insurance

Notes: Data is from March 1, 2020 to October 16, 2021. X-axis labels correspond to Saturdays. Does not include PUA claimants or transitions to extension

programs. Eligibility for FPUC, LWA, and PAC supplements are determined by the week of unemployment, not the week the initial claim was led

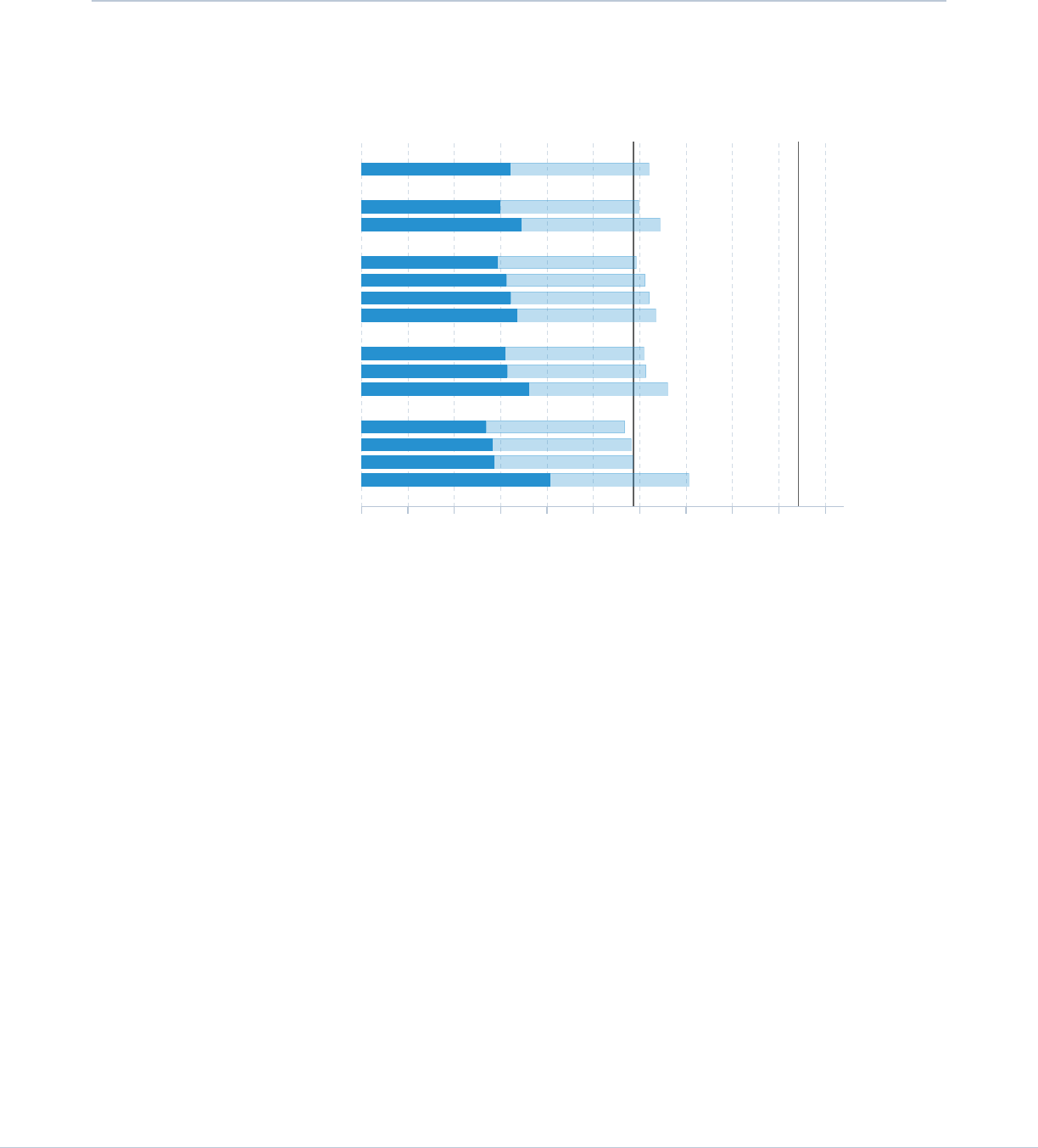

Figure 7 shows how households of dierent demographic groups might fare

under these scenarios. The average WBA for initial claimants over the course

of the pandemic was lower for female workers than it was for male workers.

Lower-educated claimants, younger claimants, claimants in the Retail Trade and

Accommodation & Food Service sectors, and Asian American, Hispanic, and

Black claimants have all seen lower WBAs.

+$600 FPUC Supplement

+$300 LWA

Supplement

+$300 PAC

Supplement

Average WBA (No Supplements)

Single Person HH: Very Low Income Threshold

Single Person HH: Low Income Threshold

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

Mar 14

, 2020

Apr 11

May 9

Jun 6

Jul 4

Aug 1

Aug 29

Sep 26

Oct 24

Nov 21

Dec 19

Jan 16

Feb 13

Mar 13

Apr 10

May 8

Jun 5

Jul 3

Jul 31

Aug 28

Sep 25

Oct 23

, 2021

Processed in Week Ending

1,000

$

17 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

4. Better Measure of UI Benet Exhaustions and Which Workers

Beneted from Extended UI Programs

Issue. Unemployment durations typically increase during recessions because jobs

become more scarce and additional weeks of UI are needed to prevent severe

economic distress among the unemployed. In response, Congress often creates

supplementary UI programs that increase the number of weeks of UI benets

that claimants can receive. Policymakers have to grapple with two questions when

designing these programs: How many additional weeks of benets to provide

and how long to keep the program active. An important input into making these

decisions is to understand who benets from these extended UI programs.

One way of understanding who would benet from these programs is to

measure the rate at which claimants exhaust their benets. These exhaustion

rates are useful in understanding who benets from extended benets programs

because, to a large degree, they reect the degree in which workers were

insured against the length of job loss they experienced (Schmieder et al., 2012). If

exhaustion rates rise during recessions, then a larger number of claimants would

have beneted from programs that increase potential UI durations.

FIGURE 7: Average Weekly Benet Amounts of Initial Claimants for Regular Unemployment Insurance Over the

Course of the COVID-19 Crisis

Notes: Weekly Benet Amounts are the average among all new initial claims (for Regular UI) led between March 15th, 2020 and October 16, 2021. It does not

include new claims led when individuals transition to extension programs. The average benet amount for individuals who either did not self-identify their race

or self-identied as a dierent racial group is not shown.

$405 $705

$285 $585

$281 $581

$267 $567

$359 $659

$313 $613

$309 $609

$334 $634

$321 $621

$311 $611

$292 $592

$344 $644

$298 $598

$320 $620

Single Person HH:

"Very Low Income"

Threshold

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1,000

Average Weekly Benefit Amount + $300 PAC Supplement

Construction

Education Services

Accommodation & Food Services

Retail Trade

Bachelor's Degree or More

Some College or Associate's

High School Degree or Less

White

Asian American

Hispanic

Black

Male

Female

Statewide

Single Person HH:

'Very Low Income'

Threshold

Single Person HH:

'Low Income'

Threshold

18 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

However, exhaustion rates have proven particularly dicult to measure, especially

in the publicly available data from the DOL. Whereas the term “exhaustion” has

at times been used to refer to claimants who exhausted their (regular non-

extension) state UI benets and moved on to extension programs, in this report

we dene exhaustions as those cases in which a claimant has exhausted state UI

benets as well as all available extensions. This is a more meaningful measure for

understanding which groups of workers would have beneted from additional

benet extensions. The data supplied by DOL indicate only the number of

claimants who have exhausted particular UI programs, and so are not well-suited

for research on exhaustions during periods of benet extensions, particularly

when extension programs were abruptly modied.

A second way of understanding who benets from extended benet programs is

to measure which groups of workers received payments through the programs.

Early in the pandemic, Congress created two new UI programs that extended

the duration of benets for regular UI claimants and also expanded eligibility

to include workers who did not traditionally qualify for UI. The Pandemic

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program added additional

weeks of UI for workers who exhausted their regular UI benets and the

Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program expanded UI access to

workers who did not qualify for regular UI benets. Along with these federal

programs, each state has their own Extended Benet (EB) program that provides

additional weeks of UI during periods of high unemployment. While the DOL

provides data on the number of claimants receiving benets through these

programs, it does not provide a demographic breakdown of beneciaries.

Analysis. First, we illustrate how the UI microdata can improve on the

exhaustion measures available in the DOL data. We do this by counting

exhaustions as the co-occurrence of two separate events. The rst event is that a

worker received a nal payment for a particular UI program, and the second is that

another payment does not follow within four weeks.

11

This combination of events

ensures that we are measuring people who received their last payments and then

did not transition to any other programs, overcoming the issue in the publicly

available data where claimants could have transitioned to another program.

12

11 We are considering the expiration of the PEUC and EB programs to be the nal payment for those programs and thus count as exhaustions.

12 The one drawback of this method is that not all claimants who are eligible for the state Extended Benets program are aware that they could actually

transition onto it. This would count as an exhaustion using this method even though the claimant is actually eligible for additional weeks.

19 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

In the California Policy Lab’s recent report to DOL, we put forward two distinct

measures of exhaustion rates (Bell et al., 2022). To mirror the denition of

exhaustion rates that can be operationalized in the DOL data, we rst divide

the number of claimants who exhausted UI in a given week by the total number

of claimants who certied that week. Conceptually, this ratio is dicult to

interpret.

13

A more readily interpretable statistic is what we call the ‘cohort

exhaustion rate,’ dened as the share of UI entrants in a given week who will

eventually exhaust UI.

14

Our cohort measure tends to be higher than the

traditional measure. A potential drawback is that it cannot be implemented

nationally with available data.

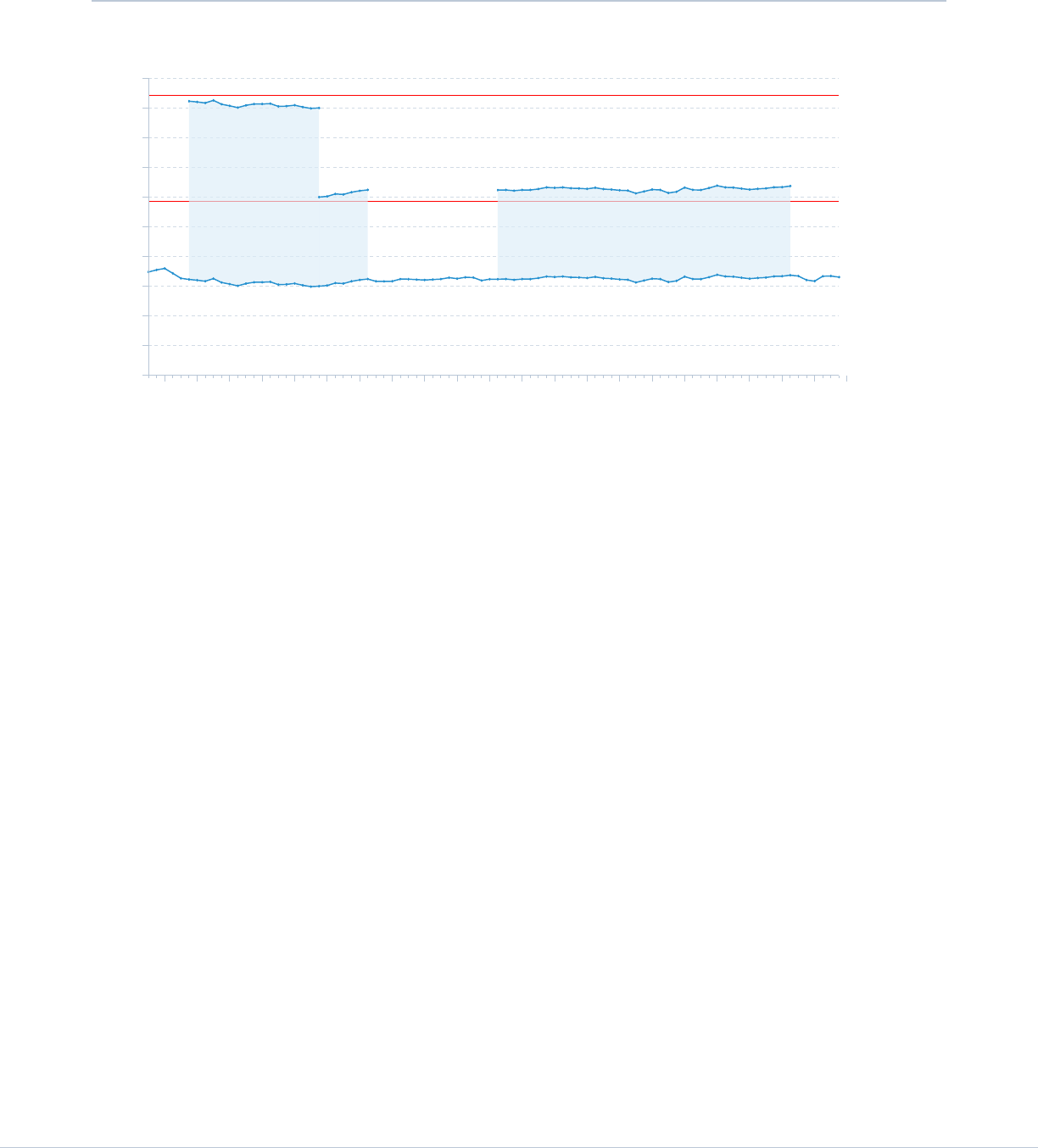

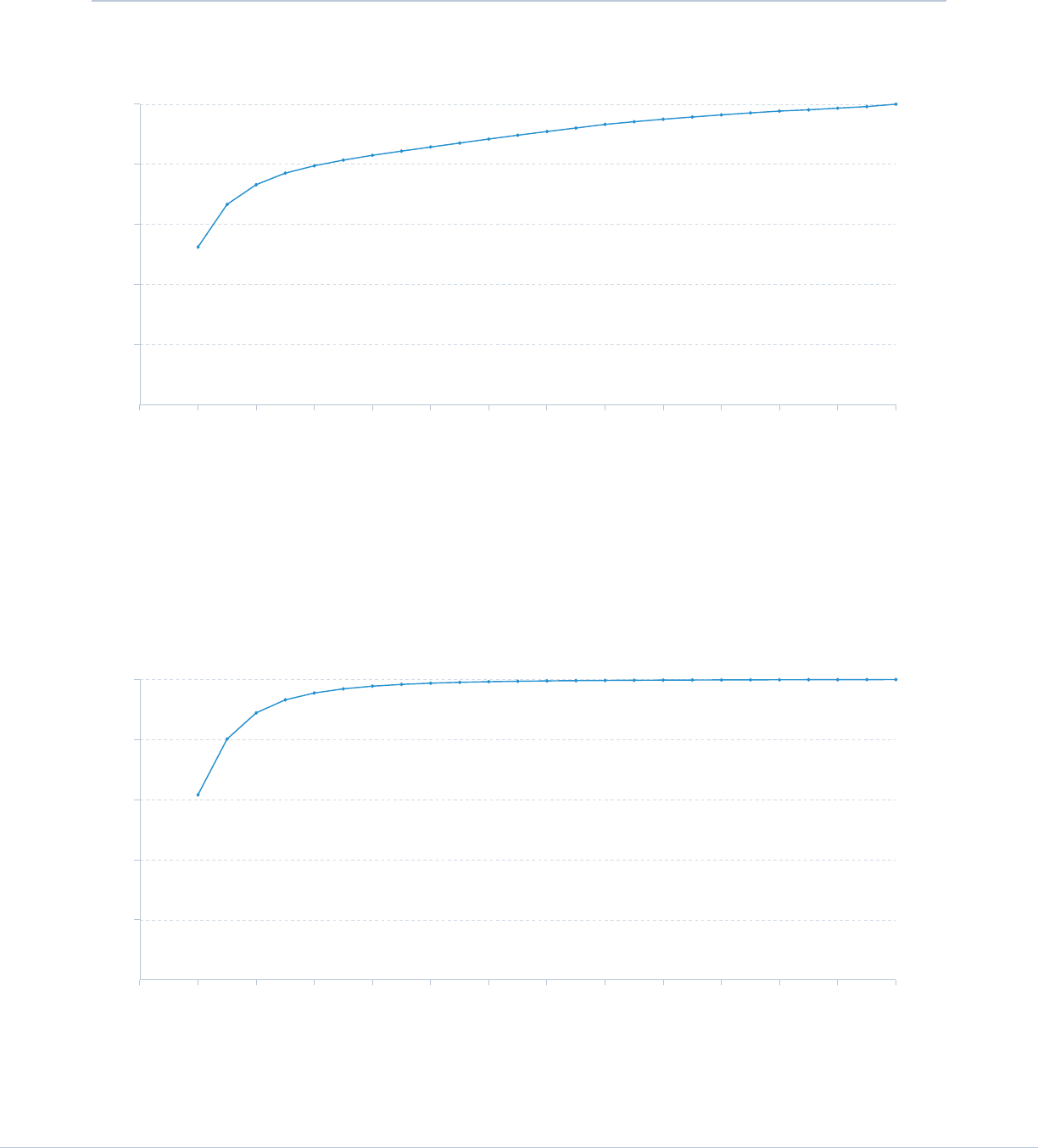

Figure 8 plots how these two denitions of exhaustion rates have evolved in

California during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, the share of California’s

claimants exhausting each week was typically 2–3% and then fell below 1% during

most of the pandemic when the extension programs were active (Panel A). This

initial drop in the exhaustion is driven mostly by claimants entering the UI system

at the beginning of the pandemic. Then in early September 2021, the pandemic-

era expanded unemployment insurance benets (PUA, PEUC, and EB) turned o,

at which point 51.2% of claimants exhausted during the week of September 11th.

A dierent story emerges when analyzing exhaustees as a share of the weekly

entry cohort (Panel B). Among Californians who entered UI at the beginning

of the pandemic, 24% of these claimants exhausted benets as of the end of

October, 2021. This is somewhat lower than what prior literature had found

during past recessions. Nicholson and Needels (2006) look at cohort exhaustion

rates during recession years between 1970 and 2003. They show that the

(national) exhaustion rate for the early 2000s recession was on average 32%. This

might suggest that the extension programs during the pandemic have done a

better job of insuring claimants against long unemployment spells than programs

in previous recessions. It could also reect a dierence between numbers for

California and U.S nationwide estimates. Figure A2 in the appendix compares the

traditional exhaustion rate for Regular UI only to the new exhaustion rate for

all programs. Without the extensions the exhaustion rate for the March 2020

cohort would be nearly 50% — about twice the actual rate.

13 Although each claimant can count at most once in the numerator (during the week of exhaustion), the same individual would count toward the denominator

for multiple weeks (during each week claimed).

14 Because this statistic counts each claimant exactly once in the denominator (during the week of entry), it is more accurate.

20 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Notes: The blue line shows

the share of all claimants

who entered UI each week

and who ultimately received

all the benets they were

eligible for before and during

the pandemic. The gray

dashed line shows the max-

imum number of weeks of

UI each cohort had available

to them. The maximum

number of weeks available

during this period was 92.

All claimants qualied for

the Regular 26 weeks of UI.

Claimants whose benet

year began between sum-

mer 2018 and September

4h 2021 were eligible for

PEUC. Claimants whose

benet year began after May

1st, 2019 were eligible for

Extended Benets.

FIGURE 8: Exhaustion Rates Within California, Weekly Resolution, Jan. 2019–Oct. 2021

Notes: The Y-axis is log

scale to improve readability.

Graph shows the share of

all claimants who received

their nal UI payment each

week before and during the

pandemic.

PANEL B: NUMBER OF CLAIMANTS EXHAUSTING AS A SHARE OF WEEKLY ENTRY COHORT

PANEL A: NUMBER OF CLAIMANTS IN CALIFORNIA EXHAUSTING AS A SHARE OF WEEKLY CONTINUING CLAIMANTS

21 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

An important but understudied question is understanding which demographic

groups and what types of workers benet from extension benet programs. One

way to address this question is to measure the share of all PEUC or EB claimants

that each demographic group accounts for. The second is to measure the share

of all exhaustions that each demographic group accounts for. Neither of these

measures are available in the publicly available DOL data, but we can answer

these questions for California using our access to the UI administrative data.

Figure 9 shows the share of PEUC or EB claimants that each demographic group

accounted for just before the program expirations in September 2021. Overall it

shows that claimants with a high school degree or less, millennials, and Hispanic

claimants made up the largest share of PEUC or EB claimants and thus beneted

the most from the PEUC and EB program in California. Appendix Figure A3

shows the tight relationship between the exhaustion share and the extended

benets program share. Either measure is very informative of who benets from

extension programs, but the data in Figures 9 and 10 are in principle more readily

available.

FIGURE 9: The Share of PEUC or EB Claimants by Demographics Group as of 9/4/2021

Notes: The blue bars show the share of all PEUC and EB claimants that each demographic group accounted for during the week of 9/4/2021

22 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Figure 10 shows the industry composition of PEUC and EB claimants.

Accommodation and Food, Retail Trade, Administrative Services, and Healthcare

& Social Assistance made up the largest shares of all extension claimants. These

industries often employ less educated workers, which is consistent with the

previous nding that most PEUC or EB claimants were workers with a high

school degree or less.

Additionally, along with the composition of workers that would benet from

extended benets programs, we can measure the rate of exhaustion within

demographic groups. Appendix Figure A4 reveals the exhaustion rates by

demographic group. Black claimants, older claimants, and less educated claimants

had higher exhaustion rates than other types of claimants.

FIGURE 10: The Share of PEUC or EB Claimants by Industry as of 9/4/2021

Notes: The blue bars show the share of all PEUC and EB claimants that each industry accounted for during the week of 9/4/2021.

23 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Overall, the exhaustion rate analysis shows that the pandemic UI programs did a

reasonably eective job of insuring workers against their increased unemployment

periods as the cohort exhaustion rate during the pandemic recession was lower

than in previous recessions and was either the same as or lower than prior to

the crisis. The programs were also eective in supporting some, albeit not all, of

the most disadvantaged workers.

To aid in further research on measuring exhaustion rates nationally, we suggest

the DOL collect data across all states on claimants who have exhausted

all UI programs, not just particular programs. Publishing this information

by demographic group would also aid in analyzing disparities in access to

UI. Furthermore, DOL should also publish the demographic and industry

breakdowns of workers receiving extended benet programs, something not

currently available.

5. How an Incomplete Measure of Unemployment Led Many States to

“Turn O” their Extended Benets Programs Prematurely During

the Pandemic

Issue. During the COVID-19 crisis, two forms of benets extensions allowed

unemployed workers in California and other states to claim unemployment

beyond the standard 26 weeks. A special extension program created in the

CARES Act of 2020, PEUC, originally provided 13 weeks (which Congress

increased to 24 on December 27th, 2020, and then to 53 on March 11th,

2021).

15

Claimants who rst exhaust their 26 weeks of regular benets, then their

13–24 weeks under PEUC, have been eligible for an additional 13 to 20 weeks

of unemployment insurance benets, called Extended Benets (EB).

16,17

The EB

program is designed to automatically “trigger” on in each state during times of

unusually high unemployment in that state, when additional relief and stimulus is

most needed, and to trigger o when the labor market has recovered.

15 https://edd.ca.gov/unemployment/pdf/unemployment-benets-chart.pdf

16 Not all claimants who are eligible for PEUC benets meet the monetary eligibility restrictions for receiving Federal-State Extended Benets.

17 Due to the timing of the roll-out of additional PEUC extensions, in certain cases claimants exhausting EB may be eligible to move back to PEUC.

24 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

There are two types of economic triggers that can cause a state’s Extended

Benets period to turn on or o (summarized graphically in Figure 11). The rst

trigger, used in all states, is the Insured Unemployment Rate (IUR) trigger. The

IUR is a measure of the share of the covered labor force that is currently claiming

regular unemployment benets. Importantly, the IUR does not count

claimants receiving benets under an extension program. The IUR

was changed in 1980 to no longer count claimants on EB, as part of a package

of changes to EB that some scholars have suggested “very nearly disabled the

program” (Woodbury, 1996).

18

In all states, when at least 5% of the state’s labor

force is claiming regular benets, EB is triggered on, provided that IUR in the

prior years was suciently low. The latter provision is called the “IUR lookback”

provision.

19,20

When the share falls back below 5% (or the lookback provision

no longer holds), the IUR trigger turns o, and Extended Benets expire.

21

In

recessions when unemployment remains elevated, the lookback provision is often

hard to satisfy.

FIGURE 11: Pathways for EB to Trigger on

Notes: This graphic depicts the ways in which an EB period can trigger on for a state. Possible scenarios in which IUR and TUR do not satisfy the EB trigger

conditions are not illustrated.

18 See also page 10 here on the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1980: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34340.pdf

19 The 5% IUR trigger is satised if the IUR is at least 120% of the IUR in the same period of the prior two years, averaged over the two years. Accounts by

researchers have suggested that the lookback provision, which references the state’s data in the same seasonal period of prior years, arose “primarily due to

the costliness and diculty of seasonally adjusting the weekly claims data for each state” (Wenger & Walters, 2006).

20 In addition, either IUR trigger requires that “[s]tate extended benet payments have not been paid for at least 12 weeks including the current report week, so

that there will have been at least 13 weeks of nonpayment before the week benet payments begin.” See page 10: https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/

ETAH/ETHand401_4th_s01.pdf

21 Typically, there is a lag of a few weeks between when the IUR trigger crosses the threshold and the last week of unemployment for which EB can be paid.

EB is off, and has not

been on during last

12 weeks

IUR>=5.00%

State has 6% non-

lookback IUR

trigger law

State has TUR

trigger law

IUR>=120% of

prior year’s on

same day

IUR>=6.00%

TUR>=110% of

either of last 2

years’ on same day

TUR>=6.50%

TUR>=8.00%

13 Weeks of EB Benefits 20 Weeks of EB Benefits

IUR: 13-week

average of the share

of the covered labor

force claiming

regular non-

extension UI

TUR: 3-month

average

unemployment rate

as estimated by the

Bureau of Labor

Statistics

25 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

The second type of EB trigger is the Total Unemployment Rate (TUR) trigger.

The TUR is derived from monthly surveys of the number of unemployed people

conducted by the Current Population Survey (CPS) run by the Bureau of Labor

Statistics. The TUR trigger is optional and before the crisis only 10 states had it.

By a year into the pandemic, half of all states had adopted it,

22

though the number

of states with TUR triggers has since fallen.

23

If a state adopts a TUR law, there is

only one system of thresholds that it can adopt. The TUR trigger has three levels:

O, TUR Light, and TUR Heavy.

24

A state can move from “O” to “TUR Light”

when TUR reaches at least 6.5%, and can move to “TUR Heavy” when TUR rises

above 8%. Both TUR Light and TUR Heavy turn Extended Benets “on,” with the

dierence between the two being that TUR Light provides 13 weeks of extended

benets (the same amount as the IUR trigger), whereas TUR Heavy provides

20 weeks of benets.

25

Because TUR Heavy provides more weeks of benets, it

supersedes TUR Light or either IUR based trigger in instances when multiple

triggers are satised.

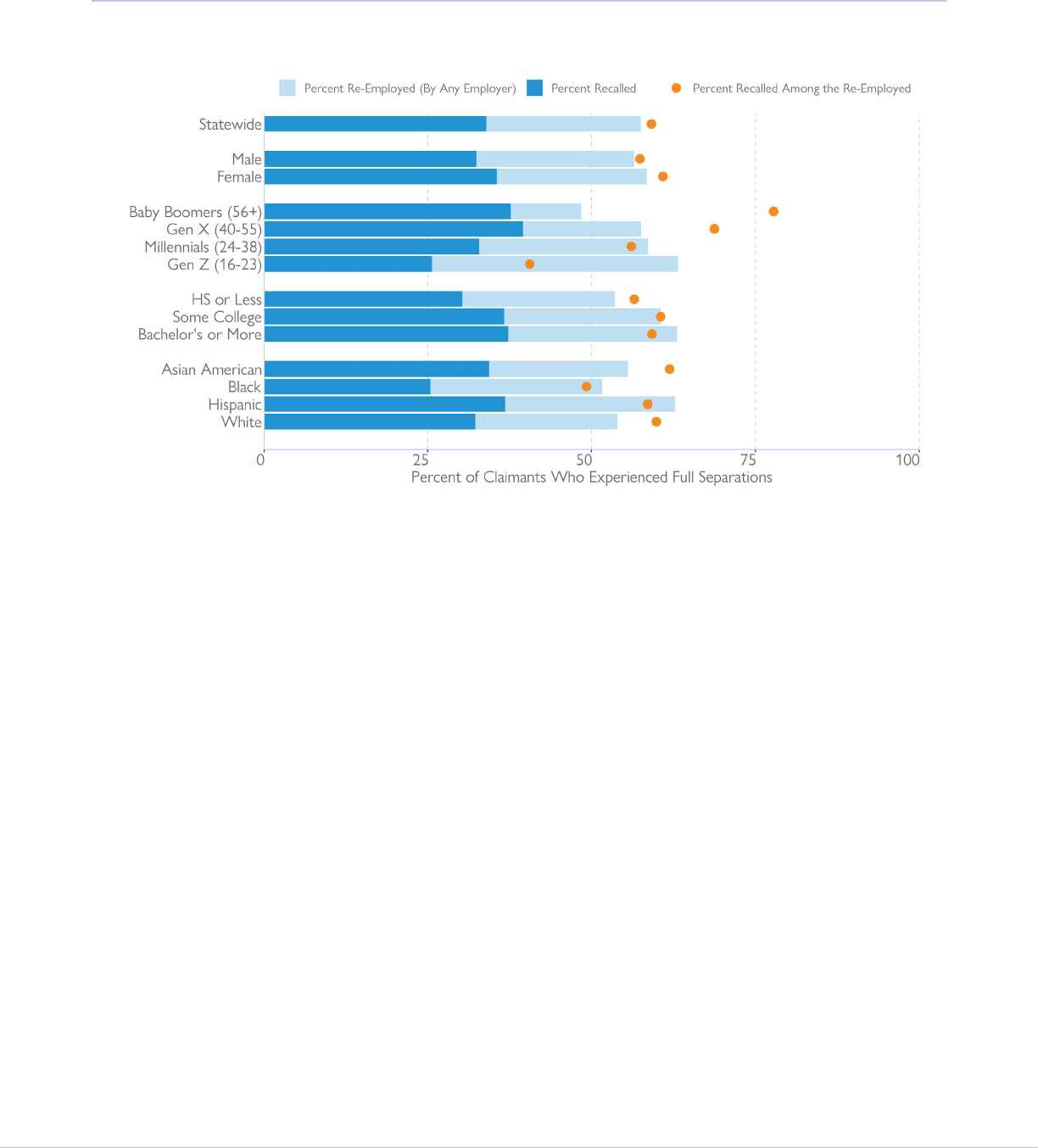

Analysis. During the COVID-19 crisis a large share of unemployed individuals

(particularly those who began claiming benets at the beginning of the crisis)

have remained unemployed long-term, and thus have transitioned from Regular

UI programs to extension programs.

26

As a result, even as regular UI claims

captured by IUR started to fall, a large number of individuals were still depending

on EB. Minnesota provides a clear example of this issue. Figure 12 shows that EB

triggered o in December 2020 because the ocial IUR (not counting claimants

on extension programs) fell below the IUR threshold. However, if claimants who

had transitioned from receiving benets through regular UI to receiving benets

through an extension program were included in the IUR, then the EB program

would have remained on for an additional 9 months (Bell, Hedin, Moghadam, et

al., 2021a).

22 See this article for list of all states who adopted the TUR trigger: https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/2021/03/09/states-should-activate-extended-benet-

triggers/

23 https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/trigger/2022/trig_011622.html

24 In some states, the period we refer to as TUR Heavy is termed High Unemployment Period, or HUP.

25 Both TUR triggers also have “lookback” provisions stipulating the TUR must exceed 110% of either of the prior two years. During most of the Great

Recession period, the lookback period was extended to 3 years. For further information on TUR triggers, see Appendix 2 here https://georeyschnorr.com/

pdf/ui_worker_productivity_oct2020.pdf as well as https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilaws_extended.pdf. The requirement that EB cannot trigger on

again if it was recently triggered on and o also applies to the TUR trigger.

26 CPL’s March report found more than half of all CA UI claimants during the crisis had claimed more than 6 months of benets. See: https://www.capolicylab.

org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/March-18th-Analysis-of-CA-UI-Claims-during-the-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf

26 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Claimants receiving EB have to rst exhaust both their regular UI and PEUC

benets and would therefore be among the workers who have spent the most

time unemployed. This current policy design is most harmful to the people who

have struggled the most to nd employment during the pandemic. Appendix

Figure A5 shows the demographic groups that made up the EB program in

California and thus reveals the workers that are the most impacted by the

premature trigger turn o. It shows that already disadvantaged groups such as

workers with a high school degree or less, females, and Hispanic workers make

up a larger share of EB claimants than other groups and are the most impacted by

prematurely triggering o the EB program.

Figure 13 below shows a map of all the states that were impacted by the awed

IUR trigger. EB would have remained triggered on longer for all the states colored

in red. Table A1 in the appendix shows the number of weeks that each state lost

in EB benets due to the design and shows the number of claimants on EB leading

up to the ocial turn o date. Overall, 39 states (plus the District of Columbia

and Puerto Rico) ended their EB programs earlier than they would have if their

version of IUR had instead included extension claimants. Workers in California

lost out on 15 weeks of EB due to the awed IUR measure.

Official IUR

(Excludes Extensions)

Replicated IUR

(Includes Extensions)

EB Weeks Claimed

(Right axis)

IUR Threshold

Official EB Turn-Off:

December 19, 2020

Official PEUC Turn-Off:

September 4, 2021

If the IUR measure included

claimants on extension programs,

EB would have remained

available for another

9 months in MN.

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

0

5

10

15

Feb 1, 2020

Feb 25

Mar 20

Apr 13

May 7

May 31

Jun 24

Jul 18

Aug 11

Sep 4

Sep 28

Oct 22

Nov 15

Dec 9

Jan 2

Jan 26

Feb 19

Mar 15

Apr 8

May 2

May 26

Jun 19

Jul 13

Aug 6

Aug 30

Sep 23

Oct 17

Nov 10, 2021

|

FIGURE 12: Extended Benets Triggers O Early in Minnesota (01/26/20-11/10/21)

Notes: This gure shows the divergence between Minnesota’s ocial Insured Unemployment Rate (IUR) and that which includes workers reporting unemploy-

ment but paid through extensions. Had the IUR counted extensions, it would not yet have fallen below the 5% threshold used to determine the state’s EB period

until October 2021. The Ocial IUR (dark blue) is as reported in Weekly Trigger Reports. The Replicated IUR with Extensions (orange) is based on authors’

calculations to additionally include PEUC and EB weeks claimed. EB Weeks Claimed (light blue, right axis) is reported on AR539 report from DOL, and indicates

the number of weeks of benets that were claimed that week to be paid under the EB program.

27 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 13: States Where Extended Benets Would Have Remained on Longer If Claimants on Extension Programs

Were Counted Toward a State’s IUR Trigger

Notes: The red states in the map had their EB benets turned o early due to the design of the IUR trigger.

To include all workers who are relying on UI benets (including extended

benets), Congress could pass legislation to include extension claimants in

IUR. Such a reform would update the EB program to be more eective at

automatically providing additional benets in times of elevated unemployment.

■

Aected

D

Not Aected

•

•

.

, .

28 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

6. Reemployment Patterns and Recall to Former Employers has been

Uneven During the Recovery

Issue. In March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic hit California, a wave of new

public health measures closed down restaurants, retail stores, and other outlets

and caused the unemployment rate to rise higher than at any point since the

Great Depression. In Q2 2020, over 2 million workers entered California’s UI

system and were fully separated from their employers (meaning they did not

report any earnings in their rst week of certifying for benets). Using earnings

data from the EDD, CPL measured the quarterly employment outcomes of all

workers covered by UI (Bell, Hedin, Mannino, et al., 2021). Using this data, we

followed the cohort of two million individuals who were unemployed at the

beginning of the pandemic to see how they fared in the labor market a year later

(in Q2 2021).

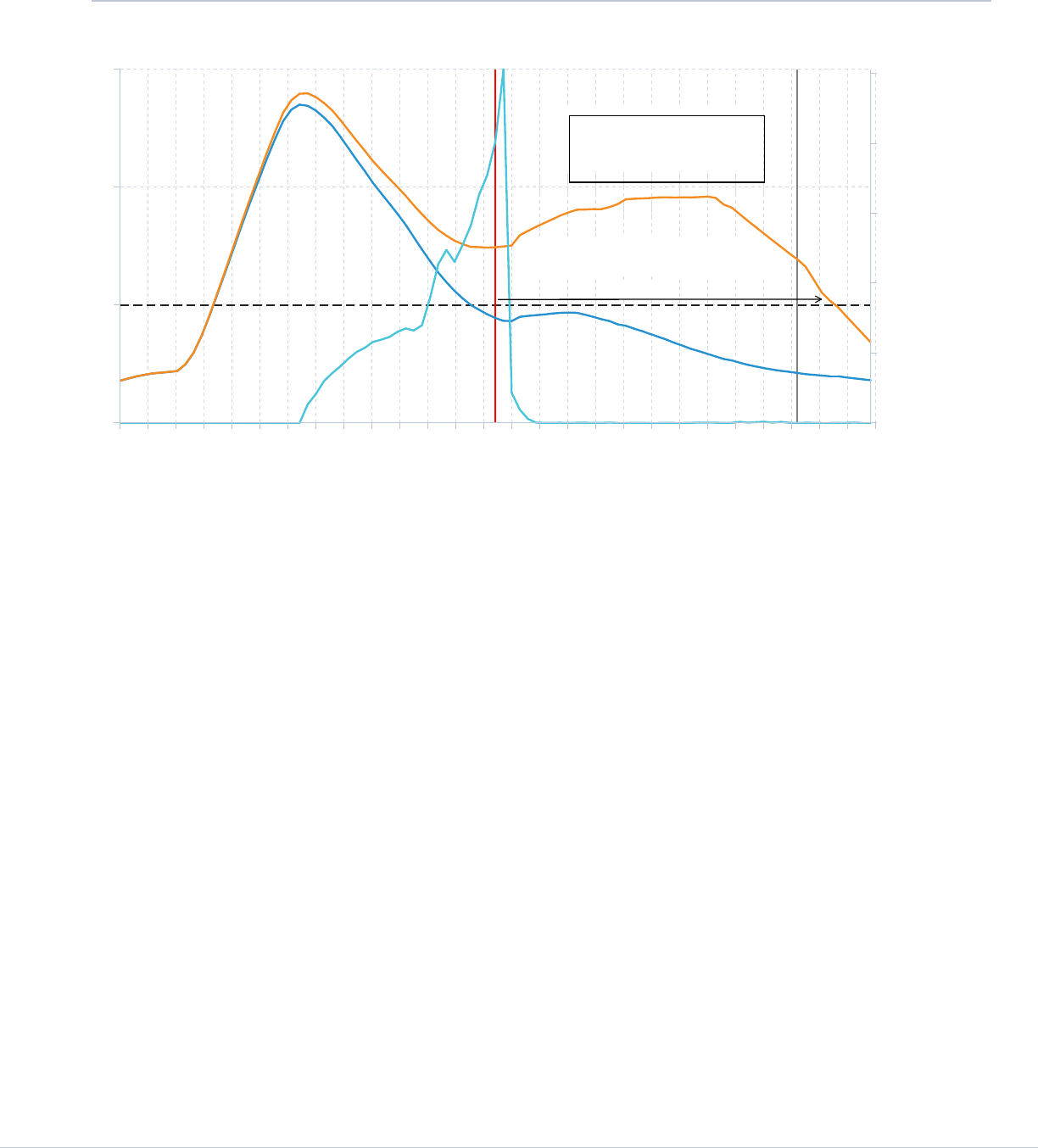

Analysis. Figure 14 shows that of the two million claimants who entered the UI

system during the second quarter of 2020 and who were “fully separated” from

their employers (meaning they did not report any earnings in their rst week

of certifying for benets), 57% were employed four quarters later in Q2 2021,

and 34% had been recalled to a prior employer. Among those that had found

reemployment, the percent recalled to a prior employer was 60%. Compared

to before the pandemic, reemployment after four quarters is substantially lower

but the rate of recall conditional on reemployment is slightly higher. For claimants

who entered the UI system in Q4 2018, 71% were reemployed four quarters later

in Q4 2019 and 31% had been recalled to a prior employer. Among those who

were reemployed only 44% were recalled to a previous employer. Recall played

a much larger role in overall reemployment during the pandemic than during

normal times. Overall, the relatively high rate of recall suggests that workers and

rms have maintained some ties during the job separations of the pandemic.

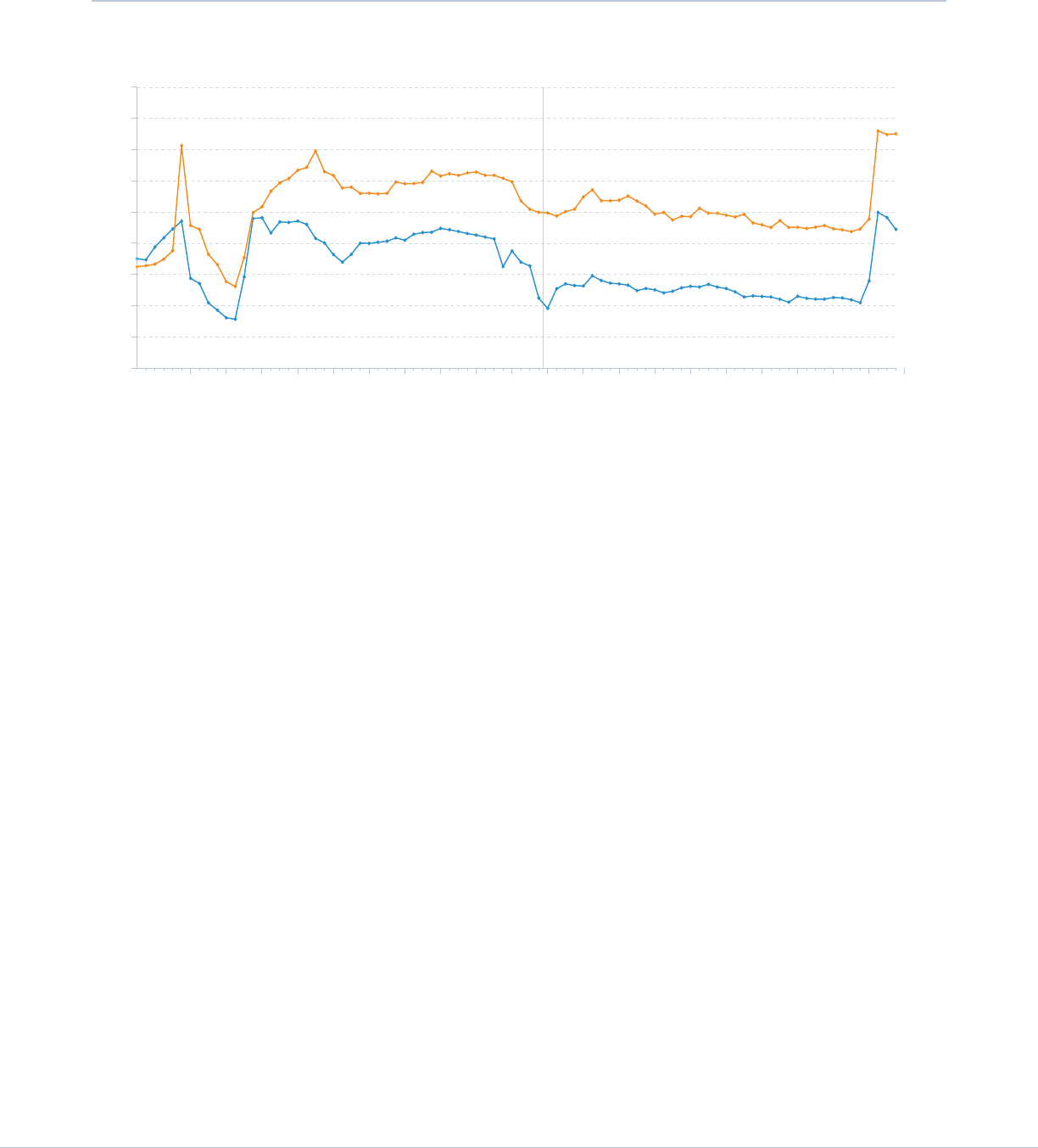

Figure 15 shows how, to some extent, the high rate of recall during the pandemic

was expected by claimants. At the beginning of the pandemic, the share of new

initial claimants reporting that they expected to be recalled to their previous

employer increased substantially and remained elevated through most of the

pandemic. The increase and gradual decrease in claimants expecting recall is

similar to results found using temporary layos from the CPS to measure recall

expectations (Bartik et al., 2020). This rate varied moderately by race and

ethnicity with Hispanic and Asian American claimants expecting recall at higher

rates than other groups. Reemployment rates varied only moderately between

those expecting recall and others (60% vs. 50%). The nal column in Appendix

Table A2 shows how these expectations may have been too optimistic with 40%

of claimants who expected to be recalled actually being recalled (65% among

those reemployed). In contrast, among those not expecting recall, only 20%

returned to their previous employer (39% among those reemployed).

29 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 14: Recall and Re-employment Rates by Demographic Groups

Notes: The denominator for each bar includes all regular UI claimants from that demographic group who led a UI claim during the 2nd quarter of 2020. The

numerator consists of the subset of those claimants who had found any type of employment a year later, and those who became re-employed by their separating

employer.

While 34% of all claimants had been recalled in Q2 2021, substantial

heterogeneity exists across demographic groups, industries, and geographies.

Figure 14 contrasts how our measures of recall and re-employment vary across

demographic groups. Although older workers have had among the lowest rates

of reemployment, their likelihood of recall was among the highest, suggesting

that recall has been more common among longer-tenured workers. Female,

more educated workers, and workers identifying as Hispanic have each seen

relatively high rates of both recall and overall re-employment. These patterns

for older workers and Hispanic workers are also observed before the pandemic,

but prior to the pandemic, workers with a high school degree or less and male

workers had the highest rates of both reemployment and recall. CPL’s December

2021 UI report also examined claimant transitions across industries and found

that a higher share of claimants returned to their previous industry during the

pandemic than they did before the pandemic (Bell, Hedin, Mannino, et al., 2021).

The increased rate at which workers returned to their previous industry is

likely driven, in part, by the increase in workers being recalled to their previous

employers as described above. Appendix Figure A6 shows how this rate of

return varied by demographic group.

30 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 15: Recall Expectations Among New Initial Claimants

Notes: X-axis Labels Correspond to Saturdays. This gure excludes PUA claims. New initial claims exclude additional and transitional claims

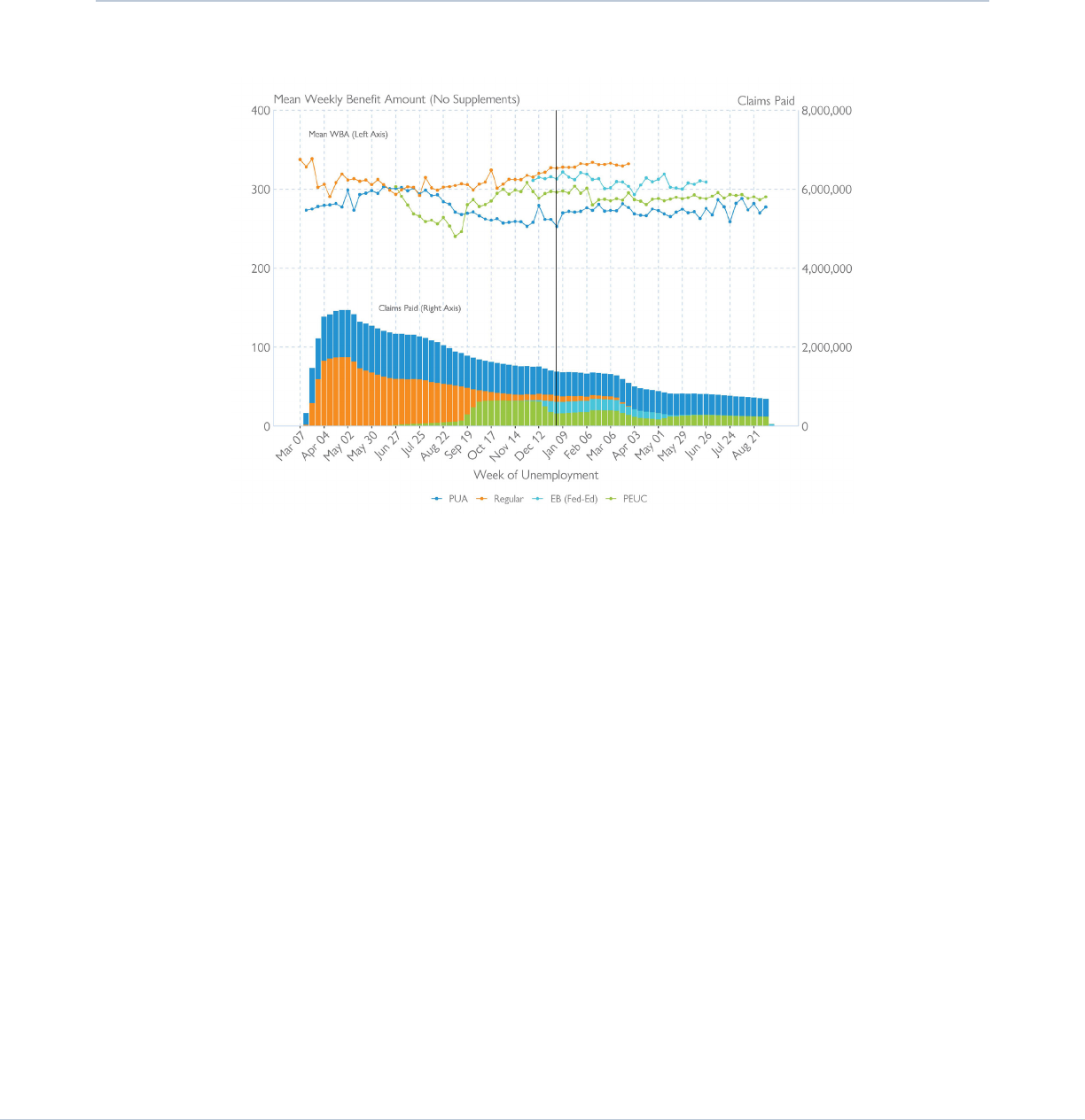

Figure 16 compares rates of recall and re-employment across industries. Workers

in the Education, Manufacturing, Arts & Entertainment, Health Care and Social

Assistance, Management, and Mining, Oil, and Gas industries have all seen rates

of recall of at least 45%. Education, Management, and Mining, Oil, and Gas also

had the highest overall reemployment rates at over 70%. Information also had

a reemployment rate of 70% even though it had a lower recall rate. The three

industries with the lowest rates of both re-employment (<= 55 %) and recall (<=

23%) are Finance and Insurance, Administrative Support and Waste Management,

and Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing.

Before the pandemic, workers from the Construction industry and Transportation

& Warehousing industries had some of the highest reemployment rates, but

during the pandemic workers from those industries saw much lower rates of

reemployment relative to other industries. Conversely, workers from the Mining,

Oil, and Gas industries had some of the highest reemployment rates during the

pandemic, but had relatively lower reemployment rates before the pandemic.

31 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 16: Recall and Re-employment Rates by Major Industry

20% 43%

23% 53%

23% 55%

36% 58%

34% 58%

31% 60%

32% 61%

38% 61%

37% 62%

40% 65%

42% 65%

46% 66%

43% 67%

44% 67%

47% 68%

49% 69%

43% 70%

45% 70%

46% 70%

53% 71%

0 20 40 60 80

Percent of Claimants Who Experienced Full Separations

Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing (a)

Admin. Support, Waste Man. (a)

Finance and Insurance

Other Services

Real Estate and Leasing

Accommodation Food Svc

Prof., Scientific, Techn. Services (a)

Transp and Warehousing

Construction

Retail Trade

Wholesale Trade

Health Care and Social Assistance

Utilities

Public Admin

Arts, Entertainment, Recreation

Manufacturing

Information

Mining, Oil and Gas

Management

Education Services

Percent Recalled Percent Re-Employed (By any Employer)

Notes: The denominator for each bar includes all regular UI claimants from that industry who led a UI claim during the 2nd quarter of 2020 and who were

“fully separated” from their employer (i.e., not just working reduced hours). The numerator consists of the subset of those claimants who had found any type of

employment a year later, and those who became re-employed by their separating employer. Graph excludes claimants whose industry could not be identied.

a) Full Names of Sectors: Administrative Support, Waste Management, and Remediation. Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting. Professional, Scientic, and

Technical Services

As noted previously, a higher share of re-employed workers returned to the

previous industry during the pandemic than before it. Figure 17 reveals which

industries re-employed workers transitioned to when they did not return to

their previous employers. During the pandemic, Admin, Support, and Waste

Management, Retail Trade, and Healthcare & Social Assistance were the industries

that received the highest percent of transitioning workers. Compared to the

pre-pandemic period, Retail Trade, and Healthcare and Social Assistance became

more important destination industries for transitioning workers, while Admin,

Support, and Waste Management became less important. Admin, Support, and

Waste Management includes jobs like janitors, oce clerks, and security guards

that might typically be employed in corporate oces (or retail settings), but the

closing of oces and the increasing prevalence of work from home arrangements

could account for the industry becoming a less popular (though still important)

destination. Construction, which normally contracts during recessions, was also a

less popular destination for transitioning workers during the pandemic.

32 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

FIGURE 17: Industries that Claimants Transitioned to Before and During the Pandemic

Notes: The denominator for each bar includes all regular UI claimants who led a UI claim during the 2nd quarter of 2020 (pandemic) or the 4th quarter of 2018

(pre-pandemic) and were re-employed a year later in a dierent industry. The numerator consists of the subset of those claimants who were employed in that industry.

Geographically, we nd that more auent counties had higher rates of

re-employment. Appendix Figure A7 presents spatial correlations of these

county-level re-employment rates with a variety of socioeconomic factors.

Some of the strongest county-level predictors of re-employment are measures

of economic well-being, including poverty, median household income, fraction

receiving SNAP/CalFresh benets, and access to broadband internet. We also

see the importance of measures of urbanicity, namely the share of workers who

take public transit to work. CPL’s December 2021 report found that before

the pandemic, the fraction receiving SNAP/CalFresh benets was still highly

correlated with reemployment, but median household income, broadband access,

and public transportation were not. On the other hand, the share of employment

in agriculture, the percent non-citizen, and the percent of people with limited

English prociency were more highly correlated with reemployment rates before

the pandemic.

Taken together, these results suggest that by mid-2021, jobless workers had

continued to maintain some ties with their former employers, but pandemic

reemployment rates are lower than pre-pandemic rates.

33 10 KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMICcapolicylab.org

Part II: Insights into the Shortcomings of Current

Measures of Unemployment Benets and How to

Improve Them

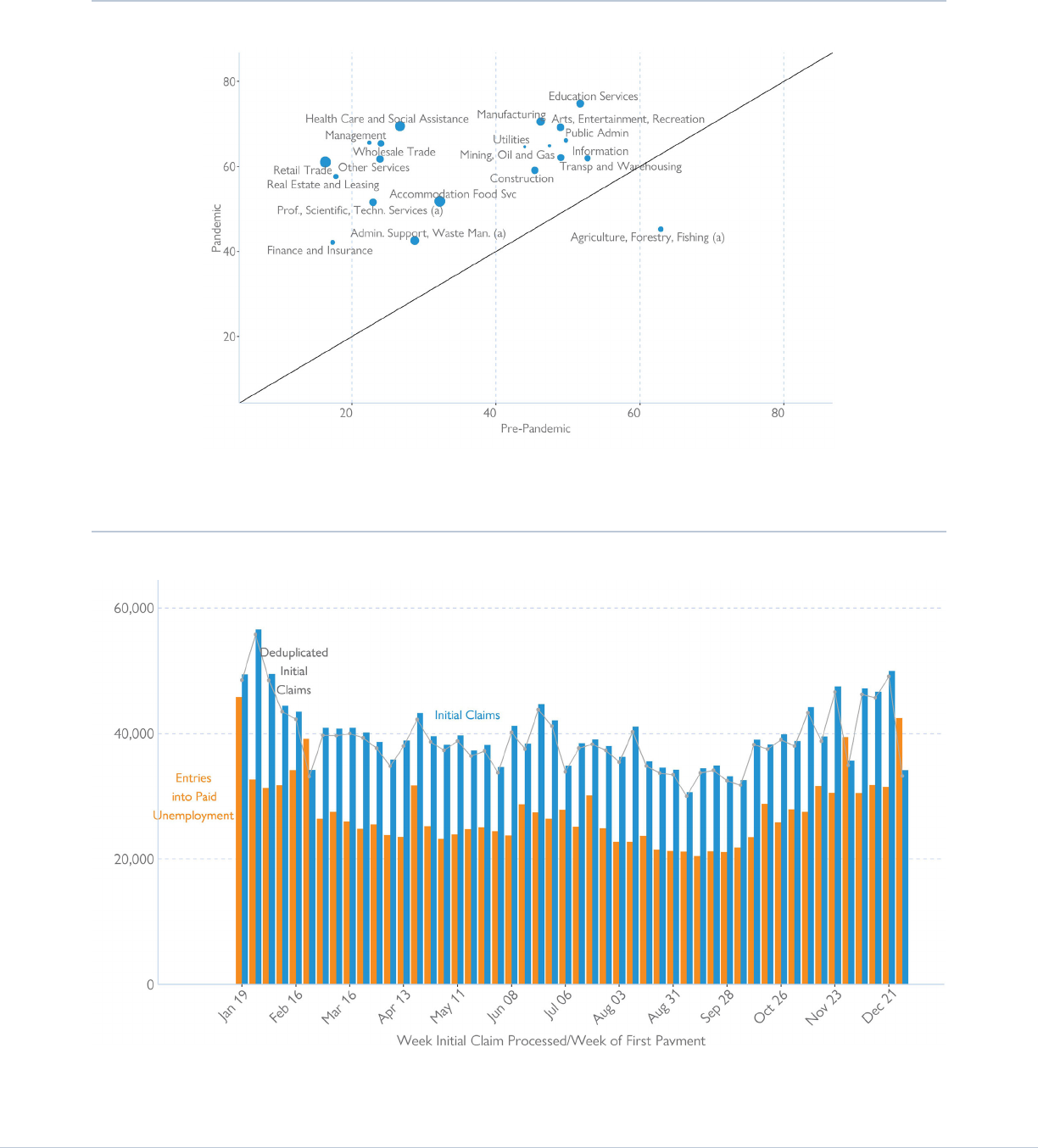

7. Initial Claims Dramatically Overstated the Number of Workers

Entering the UI System During the Pandemic

FIGURE 18: Weekly Initial UI Claims (including PUA) During the COVID-19 Crisis in California. Initial Claims for

regular UI include New Initial and Additional Claims.

Issue. Initial claims are an important leading indicator of changes in the labor

market, however the weekly published numbers provide a misleading view of the

number of newly unemployed workers. For example, despite the gradual decline

in initial claims both in California and nationwide during the course of 2021, initial

claims have not fallen by as much as one might expect, and at the end of August

2021 were still near the peak of the Great Recession. Initial claims for regular

UI are composed of two major components, as illustrated in Figure 18: New

initial claims and additional claims. It shows that the high level of initial claims in

California has been driven by a persistently elevated number of additional claims

processed in each week, while new initial claims have dropped substantially and

are now in line with the levels seen prior to the pandemic.