Global Business Languages

Volume 2 Cultures and Cross-Cultural Awareness in

the Professions

Article 4

May 2010

Business Negotiations between the Americans and

the Japanese

Yumi Adachi

Weber State University

Follow this and additional works at: h9p://docs.lib.purdue.edu/gbl

Copyright © 2010 by Purdue Research Foundation. Global Business Languages is produced by Purdue CIBER. h9p://docs.lib.purdue.edu/gbl

8is is an Open Access journal. 8is means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely

read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. 8is journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

Recommended Citation

Adachi, Yumi (2010) "Business Negotiations between the Americans and the Japanese," Global Business Languages: Vol. 2 , Article 4.

Available at: h9p://docs.lib.purdue.edu/gbl/vol2/iss1/4

Global Business Languages (1997)

Yumi Adachi

Weber State University

BUSINESS NEGOTIATIONS BETWEEN THE

AMERICANS AND THE JAPANESE

INTRODUCTION

Culture in the business world is not the same as general culture.

1

Even native speakers of the language learn business manners and

practices, and cooperative culture when they actually engage in a real life

setting. It is not sufficient in business for foreigners to understand only

the general culture of the target language, since culture and language

cannot be separated (King), yet language study by itself is inadequate.

Language is constructed with a strong influence exerted by the culture.

Indeed, when studying language, it is incumbent upon us to study the

culture of the target language (Bloch).

Even though culture cannot explain everything (Fallows), and the

business world shares a common ground regardless of culture (Bloch),

fundamental features of the Japanese cultural values result in a different

negotiation discourse from that of English. The purpose of this paper is

to study how culture and language differences influence business nego-

tiations between Americans and Japanese, and to demonstrate how busi-

ness foreign language courses can better accomplish teaching these dif-

ferences.

AMERICAN CULTURE VS. JAPANESE CULTURE

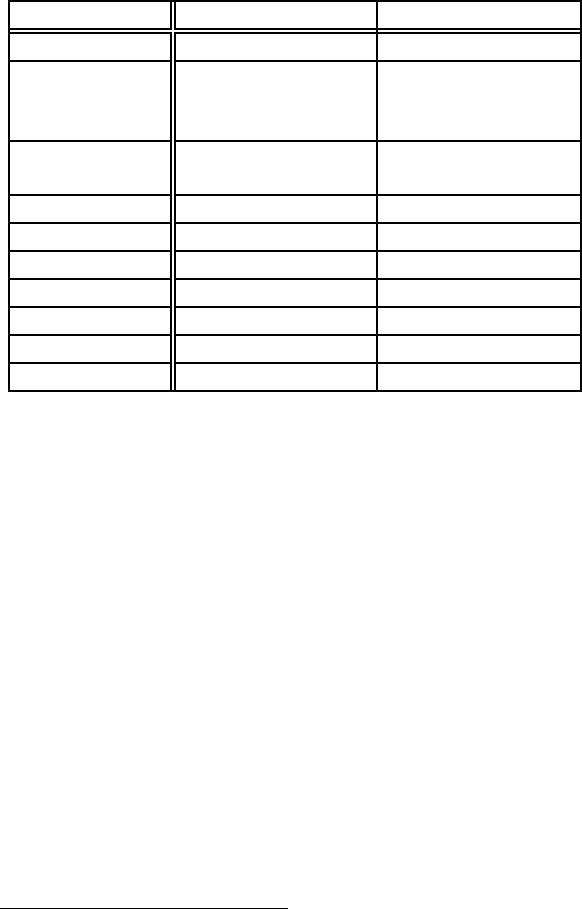

The Training Management Corporation has identified ten crucial cul-

tural values. Table 1 shows the comparison of American and Japanese

cultures’ values for each variable.

1

A version of this paper was presented at the Association for Global Business National

Conference of 1996, and appeared in the proceedings.

20 ADACHI

Table 1

Cultural value differences between Americans and Japanese

2

Variables American Japanese

Nature Control over nature Harmony with nature

Time Present and short-

time future orienta-

tion

Past and long-time

future orientation

Action Doing for the sake of

success

Doing and Being part

of an organization

Communication low context high context

Space private space public space

Power equality emphasis hierarchy emphasis

Individualism high individualism low individualism

Competitiveness competitive cooperative

Structure low structure high structure

Formality informal formal

The Japanese put their highest social priority on harmony because 1)

Japan’s geographical characteristics—a country surrounded by an

ocean—emphasizes its isolation; 2) Japan has the densest population per

square foot of any country in the world, which creates an unavoidable

close proximity of persons to each other; and 3) Japan is a homogeneous

society (McCreary). Fulfilling one’s position in a harmonious way, or in

other words, not destroying the harmony of the society by taking an in-

appropriate position in relation to others, is important for Japanese peo-

ple. The Japanese try to avoid conflict between parties in order to keep

harmony. Also, Japanese society is described as a strong vertical society

(Nakane; Graham and Sano; McCreary; March). Sempai-Kohai [senior-

junior] relationships determine the role of a person in most situations,

and this hierarchical system controls Japanese social life and individual

activity (Nakane; McCreary).

Equality, a horizontal relationship, is strongly valued in the United

States but it is less important in Japan (Graham and Sano). Americans

emphasize equality of power, therefore there is less adherence to hierar-

chy, and rank levels may be bypassed to get the work done more effec-

tively or efficiently. On the other hand, the Japanese see power in the

2

Training Management Cooperation (D-4; D-6).

BUSINESS NEGOTIATIONS 21

context of hierarchy. When the Japanese conduct a business negotiation,

the first thing that they do is to find out their position. They want to know

who has the higher social status and where they themselves need to fit in

among the people involved in the negotiation. The relative power rela-

tionship is first determined by the size of the companies. If the compa-

nies have a similar status, they move on to see who has the higher title,

and they want to know who is older. There are clear lines drawn among

social levels in Japanese culture. The Japanese do not feel comfortable

until they find out where they stand in terms of relative power, therefore

they have a hard time accepting the concept of equal power between the

parties in the business scene.

The concept of time also varies from culture to culture. For instance,

Americans think in a time frame that emphasizes the present and the

short-term future, while the Japanese think in a long-term range. These

conceptual differences cause different perspectives between CEOs in the

United States and in Japan. American CEOs try to improve and maxi-

mize their companies’ profits in their limited time frame of contract

terms with a company rather than considering long-term cooperation as

success. On the other hand, Japanese CEOs see companies as eternal

structures, and consider themselves as history-makers for companies.

They even imagine how companies will be in a hundred years. This does

not mean that the Japanese do not care about making immediate or short-

term time profits. However, they see current profits as a long-term bene-

fit rather than in a one-time-only benefit.

Fundamental social structures make the Japanese language an other-

controlled and other-controlling language (McCreary). Japanese is often

cited as an “indirect language,” unlike English, which is a self-controlled

language. Indirectness is not only important, but in fact critical for Japa-

nese people in order to maintain harmony and/or save face. Even though

the Japanese have strong opinions, views, and issues on a topic, they

usually avoid stating them directly, preferring to use roundabout phrases

and softened statements. By leaving room for the other side to disagree

with issues and to take those disagreements into account in making their

own statements, the Japanese avoid offense (Gakken).

Americans think that the Japanese spend more than enough time ex-

changing information, as mentioned before. For Americans, standards of

cooperation and assertiveness are not the same as for the Japanese. In

other words, the Japanese do not think that an American’s maximum

22 ADACHI

cooperative effort is sufficient when compared to their own acceptable

level of cooperation. The term collaboration may also be interpreted and

handled in different ways between the two cultures even though both

American and Japanese negotiators like to use a collaborative style. It is

also true that the Japanese interpret American assertiveness as aggres-

siveness, since an American’s standard of assertiveness is stronger than

what the Japanese consider reasonable.

JAPANESE NEGOTIATION STYLE

The Japanese decision-making process is more group oriented; each

member of the group prefers a more passive mode of decision making

(Stewart et al.). The members of group-oriented decision-making try to

avoid on-the-spot decisions while Americans try to get to the point as

quickly as possible (Shinnittetsu).

There are four stages to a negotiation process in general: 1) nontask

sounding; 2) task-related exchange of information; 3) persuasion; and 4)

concessions and agreement. The Japanese spend much time on stages one

and two while Americans do not spend much time on these stages

(Graham and Sano). Since so many people live in such a limited space in

Japan, knowing the negotiators on the other side is important. Unlike

Americans, the Japanese try to get as much information regarding the

other negotiators before they actually conduct the negotiation (McCreary;

Graham and Sano).

While Americans recognize that a deal is a deal and consider it a firm

commitment, the Japanese see a deal more as an intention within the

context of a long-term relationship, where the relationship takes prece-

dence over the terms of the deal (Graham and Sano; McCreary; March).

From an American’s perspective, the Japanese make negotiations more

ambiguous due to the fact that they do not want to jeopardize a relation-

ship over just one deal. It is not always necessary for the Japanese to

reach an agreement at the end of a discussion. If they cannot reach an

agreement, they may change the subject, or ignore the matter (Jones).

They do not want their inter-personal relationship to be interrupted by an

issue. Establishing one’s position within a group is more important as

well as the relationship with the other side of negotiators. Roger Fisher

and William Ury emphasize the importance of focusing on the issues

over the positions, and separating people from the issues in their book

Getting to Yes: Negotiation Agreement Without Giving In. The American

BUSINESS NEGOTIATIONS 23

negotiation process and strategies reflect this. However, these principles

are not the first priorities of the Japanese.

Americans also think that the Japanese do not clarify details at the

negotiation table, and that they leave an opportunity for behind-the-

scenes negotiation. This Japanese negotiation process is often perceived

as dishonest negotiating by Americans, who put all the information on

the table and expect negotiations to be straightforward (Graham and

Sano). In addition, the Japanese put more weight on their trust of the

other party rather than on the information on the table. This misappre-

hension can be explained by priority differences on making an agreement

between the two cultures. While Americans negotiate issues point by

point and reach an overall agreement, the Japanese make an overall

agreement first, then get into details (March).

When complications occur during a negotiation process, reactions of

Americans and Japanese show a sharp contrast. March (168) summarizes

their reaction differences as follows:

Japanese

1. Are less concerned with the pressure of deadlines;

2. Retreat into vague statements or silence;

3. Require frequent referrals to superiors or the head office;

4. Appear to slow down as complications develop;

5. Quickly feel threatened or victimized by aggressive tactics or

a stressful situation.

Western

1. Are more conscious of time and feel the pressure of dead-

lines;

2. Become aggressive and/or express frustration sooner;

3. Often have more authority for on-the-spot decisions;

4. Fail to understand, or else misinterpret, Japanese non-verbal

behavior;

5. Experience a breakdown in the team organization, with mem-

bers competing to out-argue the Japanese and control their

team.

If either side does not understand their counterparts’ reactions when

complications emerge, no positive result will be produced. Having a ba-

sic knowledge of business counterparts’ culture and their business prac-

24 ADACHI

tices is essential for cross-cultural negotiations. Since any business trans-

action is done using language as a communication tool, we need to

consider how language affects the negotiation process.

ROLE OF LANGUAGE IN NEGOTIATION

Cross-cultural negotiations normally adapt one side of a negotiator’s

language as a primary communication tool unless two nationals have the

same mother tongue. The meaning of a word is not universal even though

the word can be translated well into another language. Even among peo-

ple who use the same language as their native tongue, connotations of the

word are not the same among countries where the language is used

(Odlin). Words and concepts are culturally bound to some extent, and

learning a language involves not only the surface meaning of the word

but also the notion of the word (Omaggio). The Japanese word

“muzukashii” can be translated as “difficult” in English. However, for

Japanese businessmen, it means “out of the question,” while for Ameri-

can businessmen it means “a hard bargain” (Bloch). Americans say “the

customer comes first,” and Japanese say “okyaku-sama” [honored cus-

tomer], but their definition of a customer is not the same. For Americans,

“customer” refers to a “final consumer” while for the Japanese it implies

a buyer who is on the other side of the negotiation table and not neces-

sarily a consumer. The word “okyaku-sama” is also used as a personal

pronoun in Japanese (Suzuki). It is presumed that non-native speakers

easily transfer the native language’s definitions of the word into a target

language. This could cause misunderstanding between the parties who do

not share the common ground underlying the notion of the word.

Even if the actual meaning of the word is the same, different cultures

and languages might handle it divergently. It has been frustrating to

Americans that the Japanese word for “yes” does not mean “yes” as

Americans know it. Since the Japanese want to maintain harmony in any

situation and avoid conflict, they try not to use “no” as much as possible.

Instead of saying “no” directly, the Japanese use many other ways to say

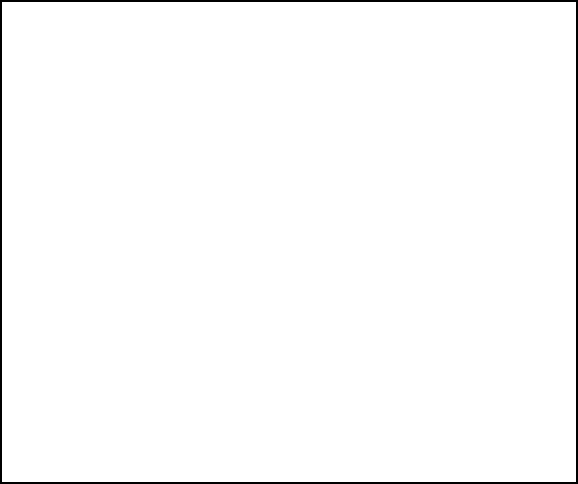

“no.” Keiko Ueda described the Japanese way to say “no” in “Sixteen

ways the Japanese Avoid Saying No” (see table 2; qtd. in Graham and

Sano 24). The Japanese naturally can interpret these signals correctly

(March), however non-native speakers of Japanese have difficulty under-

standing these signals that indicate “no” nuances unless they are not only

linguistically competent but also completely bicultural.

BUSINESS NEGOTIATIONS 25

Table 2

Sixteen ways the Japanese avoid saying no

1. Vague “no”

2. Vague and ambiguous “yes” or “no”

3. Silence

4. Counter question

5. Tangential responses

6. Exiting (leaving)

7. Lying (equivocation or making an excuse—sickness, previ-

ous obligation, etc.)

8. Criticizing the question itself

9. Refusing the question

10. Conditional “no”

11. “Yes, but . . .”

12. Delaying answer (e.g., “We will write you a letter.”)

13. Internally “yes,” externally “no”

14. Internally “no,” externally “yes”

15. Apology

16. The equivalent of the English “no”—primarily used in filling

out forms, not in conversation

If the Japanese were only to use these signals when they speak Japa-

nese, it would not be a big problem. However, they use these tactics even

when they conduct a negotiation in English. In that case, it becomes a

problem. As mentioned earlier, a native language’s framework of lan-

guage use is easily applied to a foreign language. Even when a negotia-

tion is conducted in English, Americans should be aware of these signals

used to indicate “no,” because they could appear frequently during the

course of the negotiation.

These nuances are very difficult to show and to explain sentence by

sentence without an entire discourse and a context. In fact, many exam-

ples may not make any sense when they are translated into English. Nev-

ertheless, it is important enough to have knowledge of this unconven-

tional use of “no,” and to try to understand what is the real meaning of

the message being sent.

A concept of “amae” [dependency] is one of characteristics of the

Japanese mentality (Doi). Since utilization of language reflects the men-

26 ADACHI

tality of its users, some attention should be given to how “amae” appears

in the Japanese language. While the Japanese are weak at handling the

aggressive mode of conversation, they easily accept interdependency. An

American should not say “I can make more money if you do . . .”

because the expression “I cannot make any money unless you do . . .”

may bring better concessions from the Japanese. Adopting this tactic is

much easier than comprehending the ambiguous signals of indicating

“no,” although developing a sense of “amae” is not as easy for Ameri-

cans.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE OPERATION OF

BUSINESS LANGUAGE COURSES

There has been much discussion about how to teach business lan-

guage effectively. Role-playing and simulations are commonly used to

create more authentic business situations in classroom activities. Yet if

these language practice activities are conducted without an appropriate

knowledge of a counterparts’ business culture, then the classroom

learned language cannot have practical functions in real life. Model dia-

logues such as introducing oneself to business counterparts, making ap-

pointments, confirming orders, etc. along with appropriate language ex-

pressions can provide practical exercises. However, the ability to handle

a language within a limited framework (e.g. typical scenes of general

business practices) is still no different from the memorization level even

if it requires higher levels of syntax and semantics. More seriously, if

these dialogues are between students who are non-native speakers of the

target language, limitations might be reached too soon. When two

Americans are engaging in a negotiation simulation in Japanese, there is

a good chance that they will use an American style of negotiation rather

than that of the Japanese, even though they may have been taught about

the Japanese way of handling such a negotiation.

As mentioned in previous sections, language can come alive when it

is used appropriately within a cultural norm. Students ideally should have

access to a native speaker who has real business experience. Even though

it is not practical to involve native-speaking business people in a class-

room on a regular basis, there might be some alternative solutions.

Adjustments can be made in the training of language instructors who

teach business language courses. Unfortunately, not many language in-

structors have ever engaged in a real business negotiation. Motoko

BUSINESS NEGOTIATIONS 27

Tabuse suggested that language teachers should take business related

courses. However, there are always gaps between theory and practice.

Besides having good knowledge of language and business principles, it is

suggested that instructors who teach business language courses have

some experience outside of academia. In fact, there is a national aware-

ness in Japan that school teachers, regardless of their teaching subjects,

do not know much about the world outside their classrooms (“Kyooshi ni

Yutakana Shakai Keiken wo” 3). To remedy this, the Center for Eco-

nomics and Public Relations in Japan has for the last 13 years sent school

teachers for short-term internship programs in the private sector. The

Board of Education in Sendai, Miyagi in Japan has also sent its district’s

new school teachers to private sector positions as a part of its training

program for the last 7 years (“Kyooshi ni Yutakana Shakai Keiken wo”

3; “Okayku ni Osowaru Shin’nin Sensee” 26). Teachers who participated

in the programs experienced culture shock since there were deep gaps

between school culture and business culture.

Many overseas internship programs exist for college students. Lan-

guage instructors who teach business language need to be encouraged to

participate in similar internship programs, or at least need to be given an

opportunity to have training or work experience outside of school set-

tings. If instructors themselves have first-hand experience in what busi-

ness settings involve, they can teach business language in a more authen-

tic way.

Another solution, which is more economical and time saving, is to

reconsider the characteristics of teaching assistants. Traditionally teach-

ing assistantships in foreign language programs are given to graduate

students who are majoring in Foreign Language, Linguistics, Literature,

Education, or Communication. Business Administration graduate stu-

dents are hardly considered. However, if business language courses are

offered, students in that area can be a great resource. Many of them have

had business experience in Japan prior to entering an MBA program. It

might be time to develop a new type of team-teaching in which a lan-

guage teacher takes charge of linguistic aspects of a language that is used

in the business scene, and a person who has engaged in or intends to en-

gage in business as a profession takes charge of how and to what degree

those language uses are practically applied in business situations.

28 ADACHI

CONCLUSION

Comprehending a target culture is a never-ending study (Phillips).

Despite that, the instructors of business language courses as well as stu-

dents in that program must be familiar with business practice differences

across cultures in order to make their foreign language skills useful in a

real life setting. This article has discussed basic differences of negotia-

tion styles between Americans and the Japanese. Each case of negotia-

tion varies from situation to situation, but knowing the general rules can

help Americans understand the Japanese way of acting and thinking.

Language teachers can help students by teaching them the appropriate

styles and forms of the language that lead to better business communica-

tion.

Language in a business situation also involves special attention to

codes as part of reading signals. Understanding cultural connotations is a

crucial aspect of conversation. Misunderstanding one word could cause a

big loss in business. It is not an easy task for Americans to read and un-

derstand the ambiguous expressions that are commonly used in Japanese.

However, being aware of these signals can improve communications

with their Japanese business counterparts.

Since the purpose of taking foreign language courses has been ex-

panded, classroom instruction and teacher training needs to be adjusted

to meet the new demand. Many students who study foreign languages

seek more practical uses of the language rather than merely academic

purposes. Especially in business language courses, instructors need to

have more experience outside the classroom in order to provide better

instruction.

REFERENCES

Bloch, Brian. “The Language-Culture Connection in International Busi-

ness.” Foreign Language Annals 29 (1996): 27–36.

Clancy, Patricia M. “The Acquisition of Communicative Style in Japa-

nese.” Language Socialization Across Culture. Ed. Bambi B. Schief-

felin and Elinor Ochs. New York: Cambridge UP, 1986. 213–50.

Doi, Takeo. The Anatomy of Dependence. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha In-

ternational, 1973.

BUSINESS NEGOTIATIONS 29

Fallows, James M. More Like Us: Making America Great Again. Bos-

ton: Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

Fisher, Roger and William Ury. Getting to Yes: Negotiation Agreement

Without Giving In. New York: Penguin, 1981.

Gakken. Japan as It Is. 2nd ed. Tokyo, Japan: Gakken, 1990.

Graham, John L., and Yoshihiro Sano. Smart Bargaining: Doing Busi-

ness with the Japanese. Cambridge: Ballinger, 1984.

Jones, Kimberly. “Masked Negotiation in a Japanese Work Setting.” The

Discourse of Negotiation: Studies of Language in the Workplace. Ed.

Alan Firth. Oxford, UK: Pergamon, 1995. 141–58.

King, Charlotte P. “A Linguistic and a Culture Competence: Can They

Live Happily Together?” Foreign Language Annals 23 (1990):

65–70.

“Kyooshi ni Yutakana Shakai Keiken wo” [Give Rich Real Life Experi-

ences to Teachers]. Yomiuri-Shinbun 7 June 1996: 3.

March, Robert M. The Japanese Negotiator. New York: Kodansha In-

ternational, 1988.

McCreary, Don R. Japanese-U.S. Business Negotiations: A Cross-Cul-

tural Study. New York: Praeger, 1986.

Nakane, Chie. Japanese Society. Berkeley: U of California P, 1970.

Odlin, Terence. Language Transfer: Cross-Linguistic Influence in Lan-

guage Learning. New York: Cambridge UP, 1989.

“Okayku ni Osowaru Shin’nin Sensee” [New Teachers Learn from the

Customers]. Yomiuri-Shinbun 12 June 1996: 26.

Omaggio, Alice C. Teaching Language in Context: Proficiency-

Oriented Instruction. Boston: Heinle & Heinle, 1986.

Phillips, June K. “Paradigm Shifts and Directions of the Tilt.” The Ca-

nadian Modern Language Review 50 (1993): 144–49.

Shinnittetsu. Nippon: The Land and Its People. Tokyo, Japan: Shinnit-

tetsu, 1992.

Stewart, Lea P., William B. Gudykunst, Stella Ting-Toomy, and

Tsukasa Nishida. “The Effect of Decision-Making Style on Openness

30 ADACHI

and Satisfaction within Japanese Organizations.” Communication

Monographs 53 (1986): 236–51.

Suzuki, Takao. “Jishoo-shi to Tashoo-shi no Hikaku” [Comparative

Studies of Self-Pronoun and Addressing-Pronoun]. Nichi-ei go hi-

kaku kooza: Vol. 5. Bunka to shakai [Series of Comparative Study

between Japanese and English: Vol. 5. Culture and Society]. Ed.

Tetsuya Kunihiro. Tokyo, Japan: Taishuukan, 1982. 17–59.

Tabuse, Motoko. “Toward a More Effective Business Japanese Pro-

gram.” Global Business Languages (1996): 127–41.

Training Management Cooperation. Doing Business Internationally: The

Cross-Cultural Challenges. New Jersey: Princeton Training P, 1992.