National Health Statistics Reports

Number 129 October 9, 2019

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

Breast Cancer Screening Among Women by Nativity,

Birthplace, and Length of Time in the United States

by Tainya C. Clarke, Ph.D., M.P.H., National Center for Health Statistics; and Meheret Endeshaw, M.P.H., Denise Duran,

M.P.H., and Mona Saraiya, M.D., M.P.H., National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Abstract

Objective—The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends

biennial mammography screening for women aged 50–74 to reduce mortality from

breast cancer. In the United States, foreign-born women have historically had higher

breast cancer mortality rates than their U.S.-born peers. This report presents national

estimates of mammography screening among women by nativity, birthplace, and

percentage of lifetime living in the United States.

Methods—Combined data were analyzed from 29,951 women aged 50–74 years

who participated in the 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015 National Health Interview

Survey. The percentage of these women who ever had a mammogram and met the

USPSTF recommendations for screening by nativity, birthplace, and percentage of

lifetime in the United States was generated. Estimates were adjusted for selected

demographic, socioeconomic, and health care access and utilization factors and

presented as predictive margins.

Results—Overall, foreign-born women were less likely than U.S.-born women

to have ever had a mammogram (88.3% compared with 94.1%). Foreign-born

women living in the United States for less than 25% of their lifetime were less likely

to have ever had a mammogram (76.4%) or meet the USPSTF recommendations

(55.0%) compared with U.S.-born women. Foreign-born women living in the

United States for 25% or more of their lifetime were also less likely to have ever had a

mammogram (90.9%) compared with U.S.-born women. After adjustment for selected

sociodemographic characteristics, the percentage of foreign-born women who ever

received a mammogram increased but was still lower than that of U.S.-born women.

Foreign-born women residing in the United States for less than 25% of their lifetime

were as likely as U.S.-born women to have met the USPSTF recommendations (72.1%

and 72.4%, respectively), while those residing in the United States for 25% or more of

their lifetime (75.1%) were more likely to do so than U.S.-born women. Dierences

by birthplace were also observed.

Keywords: mammography • acculturation • health disparities • National Health

Interview Survey

Introduction

In the United States, breast cancer

is the most common cancer in women

(excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer)

(1). Although morbidity and mortality

have remained stable, in 2016, the

latest year for which incidence data

are available, 245,299 new cases of

breast cancer were reported among

women, and 41,487 women died of

breast cancer in the United States (2).

For every 100,000 women, 124 cases

of breast cancer were reported, and 20

died of cancer (2). Breast cancer is the

leading cause of cancer-related death

among Hispanic women, and the second-

leading cause among white, black,

Asian or Pacic Islander, and American

Indian or Alaska Native women in

the United States (1). Breast cancer

incidence and mammography receipt

are associated with race and ethnicity,

income or poverty status, education,

health insurance status, and foreign-born

status (3,4). These correlates often lead to

the observed race and ethnicity disparities

in breast cancer-related morbidity and

mortality. Research on breast cancer

screening by birthplace among foreign-

born women residing in the United States

is scarce.

NCHS reports can be downloaded from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm.

Page 2 National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019

More than 43.7 million persons,

accounting for 13.5% of the U.S.

population, are foreign born. This

proportion is expected to grow to about

70 million, or 20% of the population, in

the next 40 years (5,6). Approximately

51% of the foreign-born population in the

United States is female (5,6). Compared

with their U.S.-born counterparts,

foreign-born women often experience an

elevated cancer risk because of lifestyle

changes associated with living in the

United States (7–9). Understanding the

screening experience of foreign-born

women compared with U.S.-born women

is important because immigrant women

may not be exposed to the same level

of public health messaging or screening

opportunities in their home countries

(10–13).

Past studies of breast cancer

screening among foreign-born women

living in the United States have focused

on specic population subgroups (14,15).

Some have looked at language barriers,

and others have looked at adaptation

to western culture (16–18). However,

few have examined the relationship

between mammography receipt and the

birthplace of ethnically diverse foreign-

born women, and none have examined

the percentage of time living in the

United States, as factors aecting the

likelihood of having a mammogram.

Cervical cancer research has shown that

whether a woman is likely to ever be

screened, as well as adhere to screening

recommendations, varies by birthplace

(19).

Although mammography does not

detect all tumors of the breast, it can

often detect breast cancer at an early

stage when treatment is more eective

(20,21). The reduction and stability of

breast cancer mortality and morbidity

rates in North American and European

countries over the past 2 decades have

been attributed to early detection through

mammography and improved treatment

(2–4). The U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force (USPSTF) recommends biennial

mammography screening for women

aged 50–74 who have an average risk of

breast cancer (22).

Using the National Health Interview

Survey (NHIS), this report examines

the percentage of women aged 50–74

who have ever received a mammogram

as well as those who met the USPSTF

recommendations for screening according

to nativity status (U.S. or foreign

born) and percentage of time in the

United States. Compliance with screening

recommendations among foreign-born

women is also described according to

birthplace.

Methods

Data source

Data in this report are from the

combined 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and

2015 NHIS. NHIS is a multipurpose,

cross-sectional health survey of the U.S.

civilian noninstitutionalized population,

based on a stratied multistage sample

of U.S. households (23,24). Data are

collected in person at the respondent’s

home using computer-assisted personal

interviewing, but follow-ups for

completing interviews may be conducted

over the telephone if needed. The survey

consists of both a core set of questions

that remain relatively unchanged from

year to year as well as supplemental

questions that are asked periodically.

Within each household, information

is collected at the family level, then

a sample adult is selected to answer

additional questions about his or her

individual health and health behaviors

such as cancer screening.

Data selected for this study were

restricted to years in which NHIS

elded a cancer supplement. Based on

USPSTF recommendations for breast

cancer screening applicable to the study

period (22,25,26), the analysis was

further restricted to women aged 50–74

at interview (n = 29,951). Final sample

adult response rates varied across survey

years: 69.0% in 2005, 62.6% in 2008,

60.8% in 2010, 61.2% in 2013, and

55.2% in 2015 (27).

Mammography receipt

In NHIS, women aged 30 and

over were asked, “Have you ever

had a mammogram?” Those who

responded “no” were categorized as

never having had a mammogram. Those

who responded “yes” were then asked,

“When did you have your most recent

mammogram?” Current age and time

of most recent screening were used to

calculate the proportion of women who

had a mammogram in the past 2 years for

breast cancer screening out of all women

reporting ever having had a mammogram.

Women who have had a mammogram but

did not have one in the past 2 years, and

those who had never had a mammogram

in their lifetime, were categorized as not

meeting USPSTF recommendations.

Nativity, birthplace, and

percentage of lifetime in

United States

Nativity

Data from the restricted-use NHIS

le, which contains information on the

respondent’s country of birth, were used

to determine nativity and birthplace.

Women who were born in one of the 50

states, the District of Columbia (D.C.),

or Puerto Rico or another U.S. territory

(American Samoa, Guam, Northern

Mariana Islands, and U.S. Virgin

Islands), as well as those born outside

the United States to parents with U.S.

citizenship, were considered to be U.S.-

born. Women not in these categories were

considered foreign born.

Birthplace

Among foreign-born women,

country of birth, geographic proximity,

cultural commonalities, socioeconomic

dierences and similarities, and sample

size guided the creation of the variable

of regional birthplace categories used

for analysis. Mexico was placed in its

own category due to the large number of

foreign-born Mexican persons living in

the United States. Central America and

the Caribbean islands were also presented

separately due to sample size.

Africa and the Middle East were

combined for this analysis due to small

sample size as well as geographic

proximity. Europe (Western Europe) and

Russia (as well as former Union of Soviet

Socialist Republics areas) were combined

due to small sample sizes, some cultural

similarities, and geographic proximity.

The remaining birthplace categories used

in this analysis were South America,

Central Asia (labeled Asia), Southeast

National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019 Page 3

Asia, South Asia (Indian subcontinent),

and Other. Note that, because of small

sample sizes, foreign-born women from

Canada (0.32%) and Oceana and other

unspecied countries or regions (0.08%)

were placed in the Other category.

However, due to their vast socioeconomic

and cultural dierences, this group is

not discussed in statistical comparisons.

The birthplace variable is a geographic

measure of region of birth and is not

intended to indicate legal status or

citizenship.

Percentage of lifetime in United

States

The length of stay or residence in the

United States was calculated by using the

year from the response to the question,

“In what year did {person} come to the

United States to stay?” and subtracting

it from the year of interview. Length of

stay was then divided by the respondent’s

age and multiplied by 100 to determine

the percentage of lifetime living in the

United States. This measure was divided

into two categories: less than 25% and

25% or more of lifetime residing in the

United States. Categorization was based

on previous research on the health-related

behaviors of foreign-born persons living

in the United States (19,28–32). These

studies revealed that persons who spent

less of their life in the United States

showed similar health behaviors and

access and utilization of health care

services compared with non-English-

speaking immigrants.

Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic characteristics

of U.S. women presented in this report

include sex, age group, educational

attainment, poverty status, marital status,

Hispanic or Latino origin, and race. All

characteristics were measured at the time

of the interview. Detailed information on

the categories used for these variables

can be found in Endeshaw et al. (19) and

other sources (33).

Health status and health care

access and utilization

Health status was based on the

question, “Would you say your health

in general is excellent, very good, good,

fair, or poor?” “Excellent” and “very

good” were combined in this analysis, as

were “fair” and “poor.”

Health insurance coverage was

presented as a four-category variable:

private, public, Medicare, and uninsured.

A person was dened as uninsured

if he or she did not have any private

health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid,

state-sponsored or other government-

sponsored health plan, or military plan at

the time of interview. A person was also

dened as uninsured if he or she had only

Indian Health Service coverage or had

only a private plan that paid for one type

of service, such as accidents or dental

care. Public health insurance included

persons on Medicaid, persons with dual

Medicare and Medicaid enrollment, and

persons with military coverage or other

government health insurance coverage.

Persons aged 65 and over with Medicare

coverage only, including Medicare

Advantage plans, were placed in a

separate category.

Usual place of care was based on

a survey question, “Is there a place that

you usually go to when you are sick or

need advice about your health?” For

number of visits to a health care provider,

respondents were asked, “During the

past 12 months, how many times have

you seen a doctor or other health care

professional about your own health at a

doctor’s oce, a clinic, or some other

place?” Respondents were instructed

to exclude overnight hospitalizations,

visits to hospital emergency rooms, home

visits, dental visits, and telephone calls.

U.S. region of current

residence

For region of current U.S. residence,

the 50 states and D.C. were categorized

into nine regions:

● New England—Connecticut, Maine,

Massachusetts, New Hampshire,

Rhode Island, Vermont

● Mid-Atlantic—Delaware, D.C.,

Maryland, New Jersey, New York,

Pennsylvania

● East North Central—Illinois,

Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin

● West North Central—Iowa, Kansas,

Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska,

North Dakota, South Dakota

● South Atlantic—Florida, Georgia,

North Carolina, South Carolina,

Virginia, West Virginia

● East South Central—Alabama,

Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee

● West South Central—Arkansas,

Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas

● Mountain—Arizona, Colorado,

Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico,

Montana, Utah, Wyoming

● Pacic—Alaska, California, Hawaii,

Oregon, Washington

Statistical analyses

Estimates in this report were

calculated using the sample adult

sampling weights and are representative

of the civilian noninstitutionalized

population of U.S. women aged 50–74.

Weights were adjusted to account for

combined survey years. Data weighting

procedures are described in more detail

elsewhere (23,24). Point estimates,

and estimates of their variances, were

calculated using SAS-callable SUDAAN

version 11.0.0 (34,35), a software

package that accounts for the complex

sample design of NHIS. Unless otherwise

specied, the denominator used was

women aged 50–74. Calculations

excluded persons with unknown

information on the variables examined.

Descriptive statistics of the

population (Figure 1, Table 1)

and estimates of ever receiving a

mammogram and meeting the USPSTF

recommendations for screening

(Figure 2) by nativity and percentage

of lifetime in the United States are

unadjusted. Figure 3 and Table 2 present

estimates of mammography receipt

adjusted for age, marital status, poverty

status, U.S. region of current residence,

educational attainment, health status,

health insurance coverage, usual place

for medical care, and number of doctor

visits in the past 12 months; these

are presented as predictive margins

from logistic regression models. The

predictive marginal approach is a

regression-based equivalent of the

common epidemiological technique of

Page 4 National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019

standardization, in which the estimates

are proportionally adjusted according to a

weight for each level of the confounding

factors. The marginal probabilities

obtained reect a weighted average over

the distribution of the confounders and

are equivalent to estimates obtained by

standardizing to the total population

(36). This means that comparisons of

mammography receipt by birthplace

and percentage of lifetime in the

United States were made as though

women in those population subgroups

had the same sociodemographic

characteristics, health status, and selected

indicators of health care access and

utilization. Thus, resulting estimates

should largely reect dierences by

birthplace and percentage of lifetime in

the United States. Because correlation

analyses showed that race and ethnicity

were highly correlated with birthplace,

they were not included in the group of

sociodemographic variables used for

standardization.

Signicant dierences in

demographic characteristics and

mammography receipt among U.S.

women by nativity, birthplace, and

percentage of lifetime living in the

United States were compared using

two-sided t tests at the 0.05 level and

assuming consistency, asymptotic

normality, and asymptotic independence

of the estimates (37). Terms such as

“more likely” and “less likely” indicate a

statistically signicant dierence. Terms

such as “not signicantly dierent”

indicate that no statistically detectable

dierences were found between the

estimates being compared. In this report,

estimates that do not meet National

Center for Health Statistics standards of

reliability as specied in the “National

Center for Health Statistics Data

Presentation Standards for Proportions”

(38) are denoted by an asterisk (*).

Results

Birthplace

Among women aged 50–74, the

majority were born in one of the 50

states, D.C., or a U.S. territory, or

abroad to parents who were U.S. citizens

(86.9%); 13.1% were born in other

countries (Figure 1). Among foreign-born

women, 20.4% were born in Mexico,

18.3% in Europe, 13.5% in Southeast

Asia, 13.1% in the Caribbean, and the

remainder in other specied regions

(Table 1).

Sociodemographic

characteristics

The distribution of selected

sociodemographic characteristics

examined in this study diered by

nativity and percentage of lifetime in the

United States (Table 2). The percentage

of foreign-born Hispanic women (38.9%)

was more than eight times that of U.S.-

born Hispanic women (4.8%). Hispanic

women also constituted the largest

proportion of foreign-born women,

regardless of the length of time in the

United States (43.5% for less than 25% of

their lifetime and 37.8% for 25% or more

of lifetime). More non-Hispanic black

women were born in the United States

(11.8%) than abroad (7.9%). The

percentage of foreign-born Asian women

(26.5%) was more than twentyfold higher

than the percentage of U.S.-born Asian

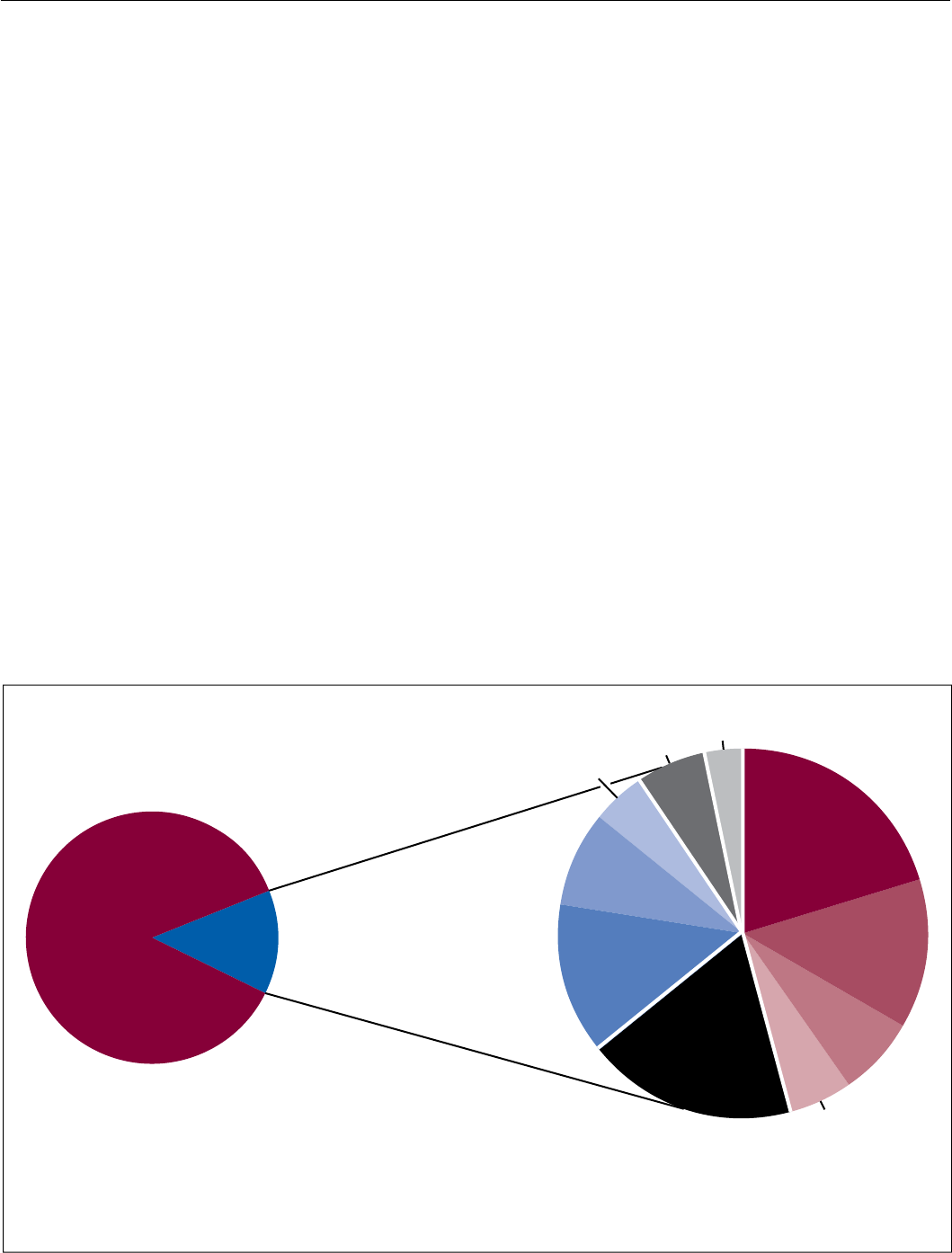

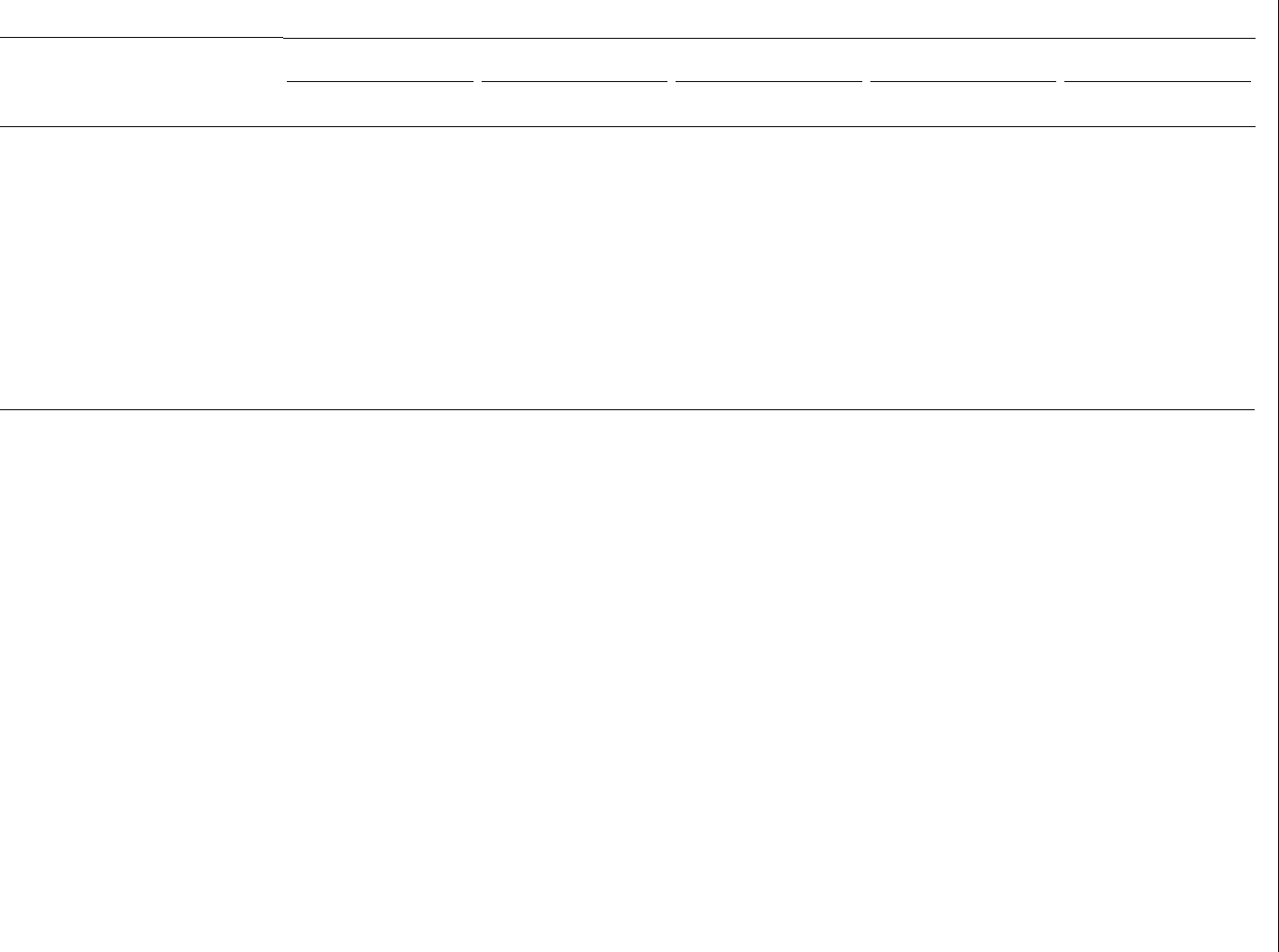

Figure 1. Percent distribution of women aged 50–74, by birthplace: United States, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015

13.1

U.S. born

86.9

NOTES: The denominator used for analysis is the number of U.S. women aged 50–74. Women born in the United States or born abroad to parents who were U.S. citizens are categorized

as U.S. born. If born abroad to parents who were non-U.S. citizens, country of birth, geographic proximity, cultural commonalities, socioeconomic differences and similarities, and sample

size are used to categorize participants by birthplace. South Asia, also known as the Indian subcontinent, includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and

Sri Lanka. Europe includes Russia and former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics areas. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015.

Other

3.3

Europe

18.3

Mexico

20.4

Caribbean

13.1

South

America

7.1

Central

America

5.4

Africa and

Middle East

5.9

Other

3.3

Southeast

Asia

13.5

Central Asia

8.3

South Asia

4.9

National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019 Page 5

women (0.8%). Compared with U.S.-

born women, foreign-born women were

more likely to be currently married or

living with a partner (66.7% compared

with 62.9%), have less than a high school

education (30.2% compared with 11.1%),

and live below the federal poverty level

(16.7% compared with 9.2%).

Foreign-born women residing in the

United States for less than 25% of their

lifetime were more likely to have less

than a high school education (38.3%) and

less likely to have some college education

(13.7%) compared with U.S.-born

women (11.1% and 31.2%, respectively).

Foreign-born women living in the

United States for less than 25% of their

lifetime were more likely to be living

below the federal poverty level (24.1%)

and at 100%–199% of the federal poverty

level (28.5%), but less likely to live at

400% or more of the federal poverty

level (17.6%) compared with U.S.-born

women.

Health status and health care

access and utilization

Compared with U.S.-born women,

foreign-born women were less likely

to have excellent or very good health

(43.6% compared with 51.7%), more

likely to have fair or poor health (22.3%

compared with 18.6%), more than

twice as likely to be uninsured (17.8%

compared with 7.4%), and more likely

to have public health insurance (19.8%

compared with 13.5%) and Medicare

only or Medicare Advantage (10.6%

compared with 9.3%). This pattern held

true regardless of percentage of lifetime

in the United States. Foreign-born women

were more than twice as likely to not

have a usual place of care compared with

U.S.-born women (11.8% compared with

5.8%). Foreign-born women were more

likely than U.S.-born women to have

had no visit to a health care provider

(14.1% compared with 8.4%) or only one

visit (15.8% compared with 12.5%) in the

past 12 months.

Foreign-born women living in the

United States for less than 25% of their

lifetime were more likely to have fair

or poor health (25.7%) compared with

U.S.-born women (18.6%). Foreign-

born women living in the United States

for less than 25% of their lifetime were

also less likely to have Medicare only

or Medicare Advantage than U.S.-born

women (6.7% compared with 9.3%). On

the contrary, foreign-born women living

in the United States for 25% or more of

their lifetime were more likely to have

Medicare only or Medicare Advantage

(11.5%) compared with U.S.-born

women.

Foreign-born women living in the

United States for less than 25% of their

lifetime were more than four times as

likely to be uninsured (33.5%) compared

with U.S.-born women (7.4%). Foreign-

born women living in the United States

for less than 25% of their lifetime were

more likely to not have a usual place of

care (22.2%) compared with U.S.-born

women (5.8%). They were also more

likely to have no visits to a health care

provider in the past 12 months (23.2%)

compared with U.S.-born women (8.4%).

U.S. region of current

residence

The population distribution of

U.S.-born women diered from foreign-

born women when compared with the

region of current U.S. residence. While

the majority of U.S.-born women were

distributed across ve of the nine regions

examined (Mid-Atlantic [15.2%], East

North Central [17.0%], South Atlantic

[18.1%], West South Central [11.0%],

and Pacic [12.4%]), more than two-

thirds of foreign-born women in the

United States resided in the Mid-Atlantic

(20.8%), South Atlantic (16.2%), and

Pacic (32.1%) regions. No dierence

in distribution was observed among the

nine regions of current U.S. residence for

foreign-born women by percentage of

lifetime in the United States.

Mammography screening

U.S. born compared with foreign

born

Unadjusted estimates—Overall,

foreign-born women were less likely

than U.S.-born women to have ever had

a mammogram (88.3% compared with

94.1%) (Figure 2). Foreign-born women

who resided in the United States for

less than 25% of their lifetime were less

likely to have ever had a mammogram

than U.S.-born women (76.4% compared

with 94.1%). Foreign-born women who

spent more than 25% of their lives living

in the United States were also less likely

to have ever had a mammogram (90.9%)

compared with U.S.-born women.

However, the percentage point dierence

was less than that of foreign-born women

who resided in the United States for less

than 25% of their lifetime.

Foreign-born women were less likely

than U.S.-born women to have met the

USPSTF recommendation of having had

a mammogram in the past 2 years (68.8%

compared with 73.0%). Foreign-born

women who spent less than 25% of their

lifetime living in the United States were

also less likely than U.S.-born women to

have met the USPSTF recommendation

for screening (55.0% compared with

73.0%). No statistically signicant

dierence was found between foreign-

born women who spent 25% or more of

their lifetime living in the United States

(71.8%) and U.S.-born women.

Adjusted estimates—After

adjustment, the dierences in the

percentage of women ever screened were

attenuated. Overall, foreign-born women

(91.4%)—both those who resided in the

United States for less than 25% of their

lifetime (87.6%) and those who lived

in the United States for 25% or more of

their lifetime (92.5%)—remained less

likely than U.S.-born women (93.9%)

to have ever had a mammogram

(Figure 3). However, the percentage point

dierences were smaller. With regard

to meeting USPSTF recommendations

for screening, no signicant dierence

was observed between U.S.-born women

(72.4%) and foreign-born women

(74.4%), particularly those who resided

in the United States for less than 25%

of their lifetime (72.1%). Although the

percentage point dierence was relatively

small, foreign-born women who lived

in the United States for 25% or more of

their lifetime (75.1%) were more likely to

have met the USPSTF recommendations

compared with U.S.-born women.

U.S. born compared with foreign

born by birthplace

Unadjusted estimates—Foreign-

born women from Mexico (85.8%),

the Caribbean (87.3%), South America

Page 6 National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019

(89.4%), Africa and the Middle East

(86.1%), Central Asia (82.8%), Southeast

Asia (89.2%), and South Asia (83.7%)

were less likely than those born in the

United States (94.1%) to have ever had

a mammogram, while the dierences for

those born in Central America (93.3%)

and Europe (92.4%) were not statistically

signicant (Table 3).

Dierences in meeting the

USPSTF recommendations for breast

cancer screening were also observed

by birthplace. Foreign-born women

from Mexico (65.1%), Central Asia

(59.6%), and South Asia (60.9%) were

less likely to have met the USPSTF

recommendations compared with U.S.-

born women. However, no signicant

dierence was found in the percentage

of those who met the USPSTF

recommendations for screening among

women born in the Caribbean (72.3%),

Central America (72.6%), South America

(67.3%), Africa and the Middle East

(66.2%), Southeast Asia (72.8%), and

Europe (72.9%) compared with U.S.-born

women (73.0%).

Adjusted estimates—After

adjustment, dierences by birthplace

resulted in a change in pattern for some

groups (Table 3). The percentage of

women who had ever had a mammogram

was still lower among those born in

Central Asia (84.1%), Southeast Asia

(88.8%), and South Asia (81.5%)

compared with U.S.-born women

(93.9%). However, there was no longer a

signicant dierence in ever receiving a

mammogram between U.S.-born women

and women from Mexico (93.7%), the

Caribbean (91.8%), South America

(93.3%), and Africa and the Middle East

(88.4%), while women from Central

America (96.6%) were more likely to

have ever been screened compared with

U.S.-born women.

U.S.-born women were less likely to

have met the USPSTF recommendations

compared with foreign-born women from

Mexico (81.4%), the Caribbean (78.6%),

and Central America (82.8%). However,

women born in Central Asia (61.6%)

and South Asia (58.4%) remained

less likely to have met the USPSTF

recommendations compared with U.S.-

born women.

Discussion

In this report, unadjusted estimates

show signicant dierences in

mammography receipt between foreign-

born and U.S.-born women. After

adjusting for several sociodemographic

characteristics—including education,

age, marital status, and usual place of

care, which are usually some of the

most prominent factors associated with

mammography receipt (39–41)—the

dierence in ever having a mammogram

between foreign-born women residing

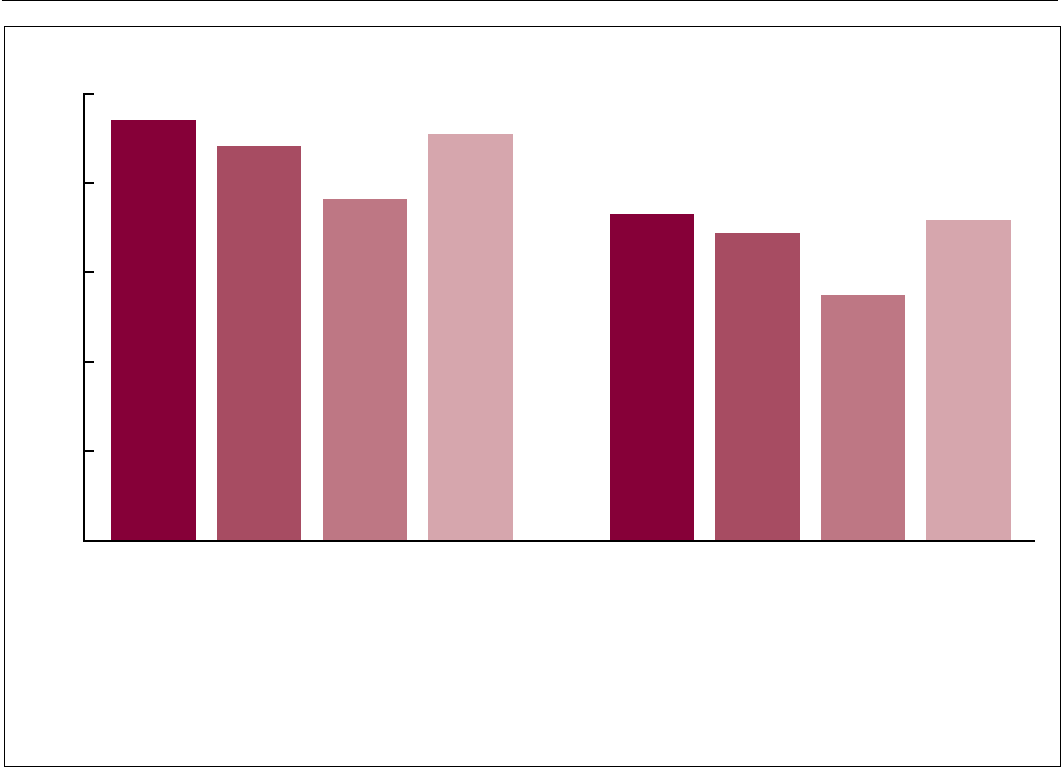

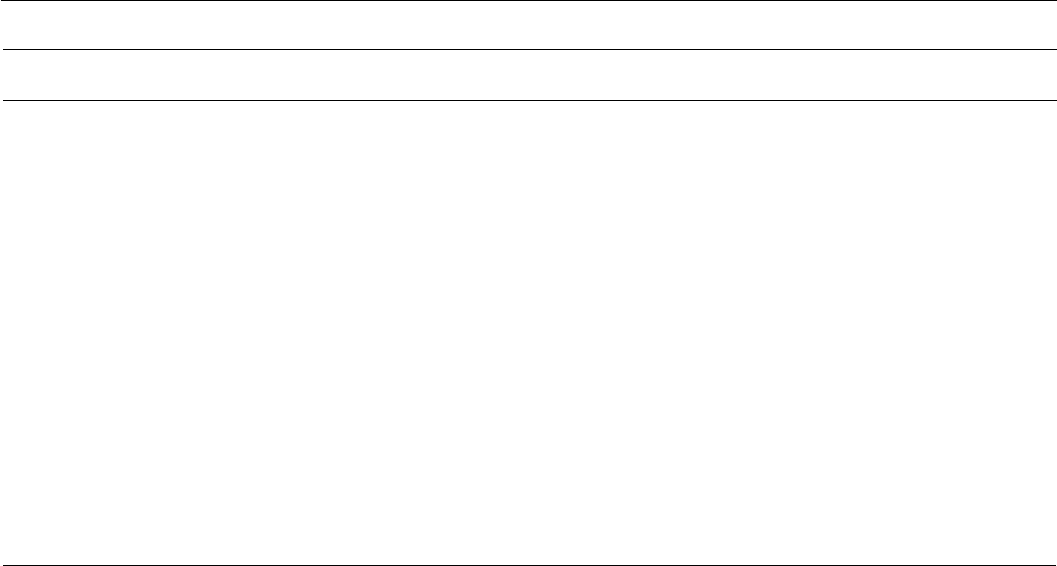

Figure 2. Unadjusted estimates of mammography receipt among women aged 50–74, by nativity and percentage of lifetime in United States:

National Health Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015

0

20

40

60

80

100

Foreign born

with 25% or

more of

lifetime

in U.S.

Foreign born

with less

than 25%

of lifetime

in U.S.

Foreign bornU.S. born Foreign born

with 25% or

more of

lifetime

in U.S.

Foreign born

with less

than 25%

of lifetime

in U.S.

Foreign bornU.S. born

94.1

1

88.3

1

76.4

1

90.9

73.0

1

68.8

1

55.0

71.8

1

Significantly different from U.S. born, p < 0.05.

NOTES: The denominator used for analysis is the number of U.S. women aged 50–74. A mammogram is a radiograph of the breast that can be used to check for breast cancer in

women who have no signs or display no symptoms of the disease. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for breast cancer with mammography every 2 years

for women aged 50–74. Country of birth, number of years residing in the United States, and current age are used to determine nativity and percentage of time in the United States.

Women born in the United States or born abroad to parents who were U.S. citizens are categorized as U.S. born.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015.

Percent

Ever had a mammogram

Met U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

recommended mammography screening

National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019 Page 7

in the United States for less than 25%

of their lifetime and U.S.-born women

was reduced by more than 10 percentage

points (76.4% compared with 94.1%

narrowed to 87.6% compared with

93.9%), although the dierence remained

statistically signicant. A similar pattern

was seen for the likelihood of meeting

the USPSTF recommendations among

foreign-born women who spent less

than 25% of their lifetime compared

with women born in the United States.

After adjustment, those who spent 25%

or more of their lifetime in the United

States were slightly more likely than

U.S.-born women to have met the

USPSTF recommendations, although this

dierence was still signicantly dierent.

Adjustment for sociodemographic

characteristics also aected dierences in

mammography receipt by birthplace. The

dierences in lifetime mammography

receipt between U.S.-born women and

foreign-born women from Mexico, the

Caribbean, South America, and Africa

and the Middle East were attenuated and

no longer signicant. Adjustment resulted

in women from some foreign-born

regions being more likely to have met the

USPSTF recommendations for screening

compared with U.S.-born women, while

for others, dierences in receipt of

recommended mammography compared

with U.S.-born women were attenuated

and no longer signicant.

Previous studies have shown that

morbidity and mortality associated

with breast cancer is reduced by

routine screening (12,42). Some studies

have found that in the absence of

cultural barriers, foreign-born women

may be more receptive to physician

recommendations compared with U.S.-

born women (43). However, this analysis

shows that foreign-born women from

predominantly Spanish-speaking regions

such as Mexico and Central America

had a higher prevalence of adherence

to USPSTF recommendations for

mammography compared with U.S.-born

women, while foreign-born women from

other countries did not. The reduced

dierence in foreign-born women

from Spanish-speaking regions after

adjustment may be explained, in part, by

targeted health care and mammography

programs in some states (44–52). The

inability to further assess dierences by

birthplace and percentage of lifetime

in the United States due to sample size

precludes further assumptions related to

mammography screening and birthplace

in this report. However, these ndings

may inform future research.

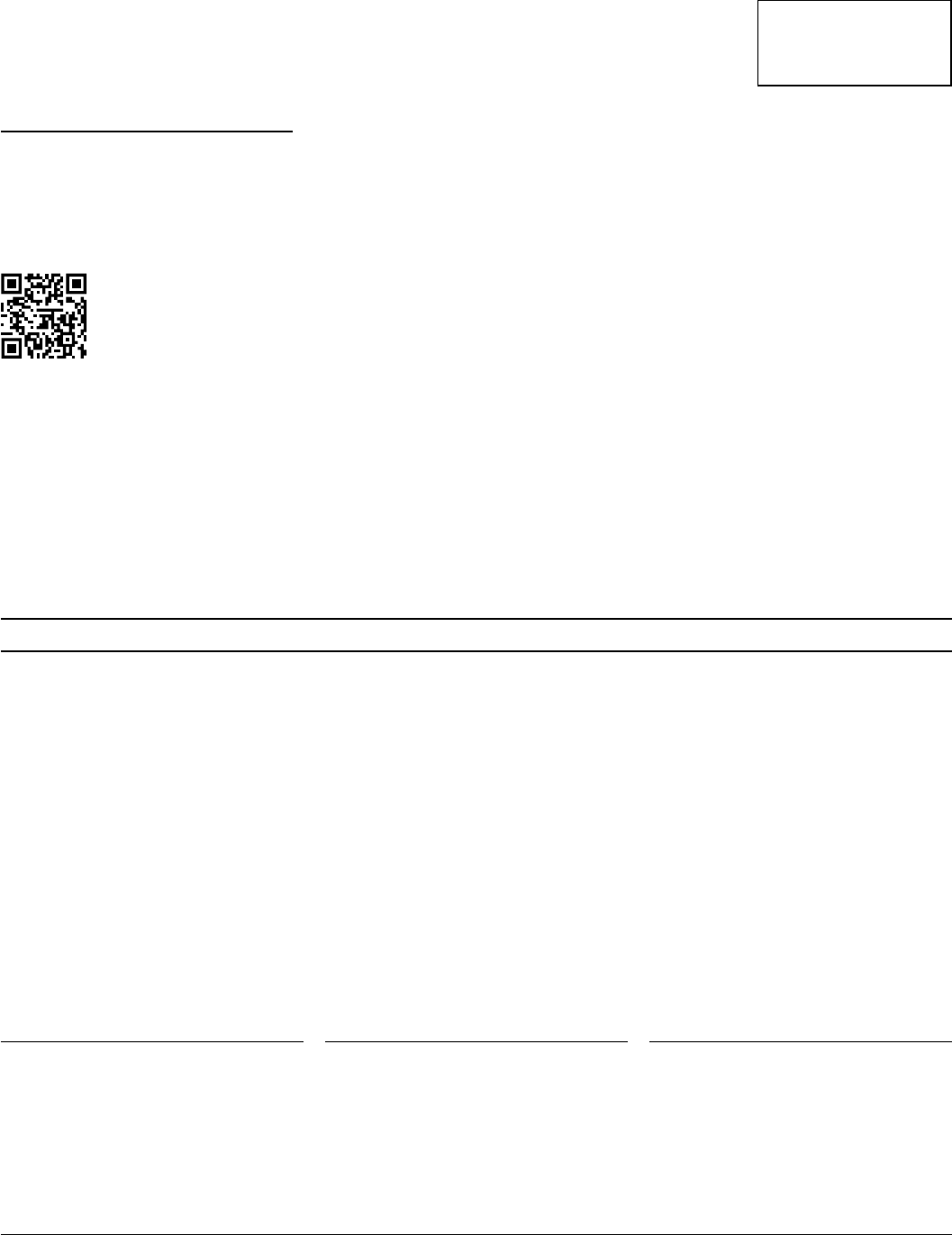

The reduced dierences in having

ever been screened and meeting the

1

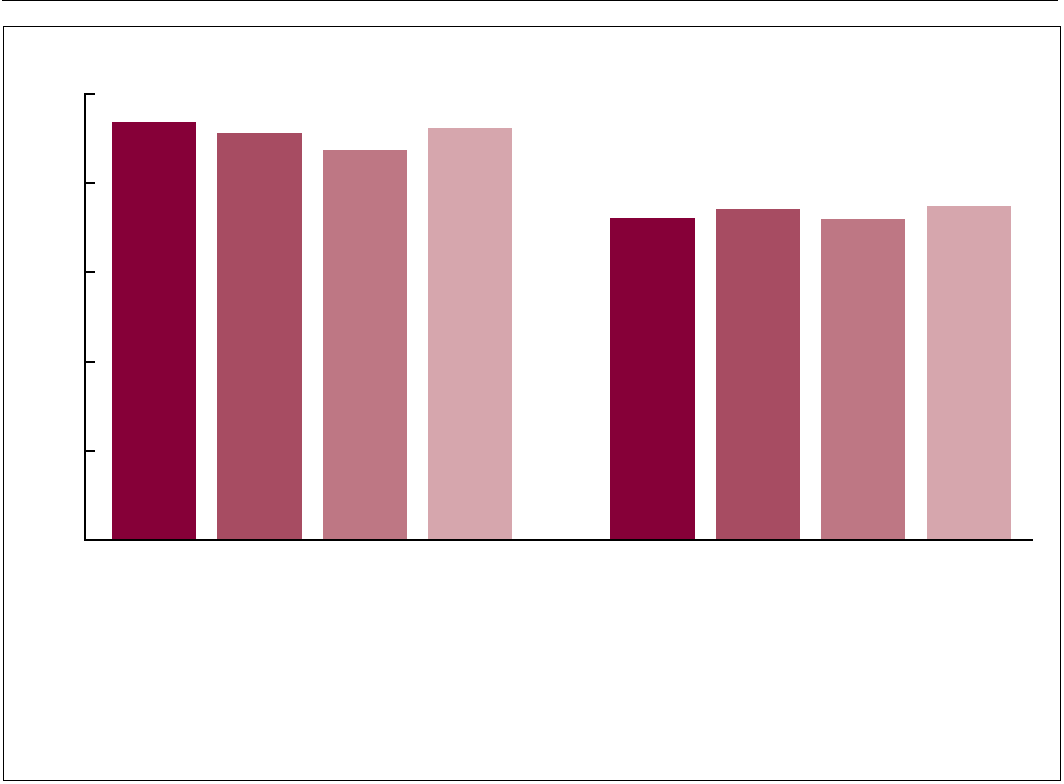

Significantly different from U.S. born, p < 0.05.

NOTES: The denominator used for analysis is the number of U.S. women aged 50–74. Estimates are adjusted for age, marital status, income, U.S. region of current residence,

education, health status, health insurance coverage, usual place for medical care, and number of doctor visits in the past 12 months. A mammogram is a radiograph of the breast that

can be used to check for breast cancer in women who have no signs or display no symptoms of the disease. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for breast

cancer with mammography every 2 years for women aged 50–74. Country of birth, number of years residing in the United States, and current age are used to determine nativity and

percentage of time in the United States. Women born in the United States or born abroad to parents who were U.S. citizens are categorized as U.S. born.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015.

Percent

Ever had a mammogram

Met U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

recommended mammography screening

Foreign born

with 25% or

more of

lifetime

in U.S.

Foreign born

with less

than 25%

of lifetime

in U.S.

Foreign bornU.S. born Foreign born

with 25% or

more of

lifetime

in U.S.

Foreign born

with less

than 25%

of lifetime

in U.S.

Foreign bornU.S. born

0

20

40

60

80

100

93.9

1

91.4

1

87.6

1

92.5

72.4

74.4

72.1

1

75.1

Figure 3. Predicted marginal distributions of mammography receipt among women aged 50–74, by nativity and percentage of time in

United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015

Page 8 National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019

USPSTF recommendations among

foreign-born women who have lived

in the United States for 25% or more

of their lifetime after adjustment is

supported by research that suggests

time spent in the United States can be

used as an indirect measure or proxy

of acculturation. In their report titled,

“Assimilation Today,” Myers and Pitkin

suggested that evidence showed the

latest immigrants to the United States

were quickly adapting to their new

home and following in the footsteps of

migrants from early U.S. history (53).

Other research has shown that the length

of time spent in the United States is

highly correlated with English language

adoption (28,29). These studies also

reported that the adoption of English

in everyday communication among

Spanish-speaking persons was shown to

predict breast cancer screening.

In summary, after adjustment for

potential confounders, regardless of

the percentage of lifetime in the United

States, foreign-born women were still

less likely to ever have received a

mammogram. However, this pattern

diered to some extent by birthplace.

After adjustment, foreign-born women

who resided in the United States for less

than 25% of their lifetime were as likely

as U.S.-born women to have met the

USPSTF recommendations for breast

cancer screening. Although the relative

dierence was small, foreign-born

women who resided in the United States

for 25% or more of their lifetime were

more likely than U.S.-born women to

have met the USPSTF recommendations.

This was also true of women from

Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central

America.

The data in this report have some

limitations. Responses are dependent on

participants’ recall of ever receiving, and

recent receipt of, a mammogram, as well

as their willingness to accurately report

information on socioeconomic factors

and health care access and utilization.

Due to small sample size, and to increase

the precision of mammography estimates

at very detailed levels, data were used

from ve periodic cancer supplements

spanning 11 years. While sampling errors

are signicantly reduced by combining

data across years, limitations are also

associated with this estimation procedure

because it only provides an average

across the years. However, preliminary

analysis using Joinpoint software showed

no signicant trend in ever having

received a mammogram across the survey

years within the sample (54,55). Lastly,

despite combining data across years,

small sample sizes prevented some group

dierences from reaching statistical

signicance as well as examining

the interaction between percentage

of lifetime in the United States and

birthplace on mammography receipt.

A major strength of these analyses

is that the data were from a nationally

representative sample of civilian

noninstitutionalized adults living in the

United States, allowing for population

estimates. Although data were pooled

across years, the consistency of the

questions examined from NHIS allows

for a large enough sample size to permit

subgroup analyses. Because both foreign-

and U.S.-born women in this study

received the same survey instrument,

comparisons between these two groups

are more likely to accurately measure the

dierences due to birthplace, compared

with using multiple national surveys

with dierent questions and sampling

methods. Analytically, estimating and

interpreting adjusted predictions and

marginal eects make the results more

tangible and provide a more accurate

picture of relative dierences. Compared

with the direct standardization approach,

the predictive marginal approach permits

the use of a larger number of variables in

the standardization process.

These ndings may inform other

research on the potential relationship

with, and impact of, nativity, percentage

of lifetime in the United States, and

birthplace, and the likelihood of engaging

in recommended preventive cancer

screening.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Breast cancer statistics.

Available from: https://www.cdc.

gov/cancer/breast/statistics/index.

htm.

2. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working

Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics

Data Visualizations Tool, based on

November 2018 submission data

(1999–2016). Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention; National

Cancer Institute. 2019. Available

from: https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/

USCS/DataViz.html.

3. White A, Thompson TD, White MC,

Sabatino S, de Moor J, Doria-Rose

PV, et al. Cancer screening test use—

United States, 2015. MMWR Morb

Mortal Wkly Rep. 66(8):201–6. 2017.

4. Clarke TC, Endeshaw M, Duran D,

Saraiya M. QuickStats: Percentage of

U.S. women aged 50–74 years who

never had a mammogram, by place

of birth and length of residence in

the United States—National Health

Interview Survey, 2013 and 2015.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

66(11):309. 2017.

5. Zong J, Batalova J, Hallock J.

Frequently requested statistics

on immigrants and immigration

in the United States. Migration

Policy Institute. 2018. Available

from: https://www.migrationpolicy.

org/article/frequently-requested-

statistics-immigrants-and-

immigration-united-states-7.

6. Migration Policy Institute. U.S.

immigrant population by state and

county. Available from: https://www.

migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-

hub/charts/us-immigrant-population-

state-and-county.

7. Khan F, Ruterbusch JJ, Gomez

SL, Schwartz K. Dierences in the

cancer burden among foreign-born

and US-born Arab Americans living

in metropolitan Detroit. Cancer Causes

Control 24(11):1955–61. 2013.

8. Kato I, Yee CL, Ruterbusch J,

Schwartz K. Patterns of cancer in

rst generation immigrants from the

Arab League and other countries. J

Registry Manag 36(3):71–6; quiz

101–2. 2009.

9. Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and

disparities in socioeconomic and

behavioural characteristics, life

expectancy, and cause-specic

mortality of native-born and

foreign-born populations in the

United States, 1979–2003. Int J

Epidemiol 35(4):903–19. 2006.

10. Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay

J, Forman D. Global cancer

transitions according to the Human

Development Index (2008–2030):

National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019 Page 9

A population-based study. Lancet

Oncol 13(8):790–801. 2012.

11. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram

I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal

A. Global cancer statistics 2018:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence

and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer

J Clin 68(6):394–424. 2018.

12. Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Dunn

NA, Muller JM, Pyke CM, Baade

PD. The descriptive epidemiology

of female breast cancer: An

international comparison of

screening, incidence, survival

and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol

36(3):237–48. 2012.

13. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay

J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global

cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J

Clin 65(2):87–108. 2015.

14. John EM, Phipps AI, Davis A, Koo

J. Migration history, acculturation,

and breast cancer risk in Hispanic

women. Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev 14(12):2905–13.

2005.

15. Engelman KK, Cupertino AP, Daley

CM, Long T, Cully A, Mayo MS,

et al. Engaging diverse underserved

communities to bridge the

mammography divide. BMC Public

Health 11:47. 2011.

16. Lubetkin EI, Zabor EC, Brennessel

D, Kemeny MM, Hay JL. Beyond

demographics: Dierences in patient

activation across new immigrant,

diverse language subgroups. J

Community Health 39(1):40–9.

2014.

17. Brown WM, Consedine NS, Magai

C. Time spent in the United States

and breast cancer screening

behaviors among ethnically diverse

immigrant women: Evidence for

acculturation? J Immigr Minor

Health 8(4):347–58. 2006.

18. Alexandraki I, Mooradian AD.

Barriers related to mammography

use for breast cancer screening

among minority women. J Natl Med

Assoc 102(3):206–18. 2010.

19. Endeshaw M, Clarke T, Senkomago

V, Saraiya M. Cervical cancer

screening among women by

birthplace and percent of lifetime

living in the United States. J Low

Genit Tract Dis 22(4):280–7 2018.

20. Jemal A, Ward E, Thun MJ.

Recent trends in breast cancer

incidence rates by age and tumor

characteristics among U.S. women.

Breast Cancer Res 9(3):R28. 2007.

21. Wun LM, Feuer EJ, Miller BA.

Are increases in mammographic

screening still a valid explanation

for trends in breast cancer incidence

in the United States? Cancer Causes

Control 6(2):135–44. 1995.

22. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Screening for breast cancer: U.S.

Preventive Services Task Force

Recommendation Statement. Ann

Intern Med 151(10):716–26. 2009.

23. Botman SL, Moore TF, Moriarity

CL, Parsons VL. Design and

estimation for the National Health

Interview Survey, 1995–2004.

National Center for Health Statistics.

Vital Health Stat 2(130). 2000.

24. Parsons VL, Moriarity C, Jonas K,

Moore TF, Davis KE, Tompkins

L. Design and estimation for the

National Health Interview Survey,

2006–2015. National Center for

Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat

2(165). 2014.

25. Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A,

Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey

L. Screening for breast cancer:

An update for the U.S. Preventive

Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med

151(10):727–37. 2009.

26. U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force. Breast cancer: Screening.

2016. Available from: https://www.

uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/

Page/Document/UpdateSummary

Final/breast-cancer-screening1.

27. National Center for Health Statistics.

2015 National Health Interview

Survey (NHIS) public use data

release: Survey description.

Hyattsville, MD. 2016. Available

from: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/

Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_

Documentation/NHIS/2015/

srvydesc.pdf.

28. O’Malley AS, Kerner J, Johnson

AE, Mandelblatt J. Acculturation

and breast cancer screening among

Hispanic women in New York City.

Am J Public Health 89(2):219–27.

1999.

29. Mandelblatt JS, Gold K, O’Malley

AS, Taylor K, Cagney K, Hopkins

JS, Kerner J. Breast and cervix

cancer screening among multiethnic

women: Role of age, health,

and source of care. Prev Med

28(4):418–25. 1999.

30. Gorman BK, Read JG, Krueger PM.

Gender, acculturation, and health

among Mexican Americans. J Health

Soc Behav 51(4):440–57. 2010.

31. Lee S, Nguyen HA, Tsui J. Interview

language: A proxy measure

for acculturation among Asian

Americans in a population-based

survey. J Immigr Minor Health

13(2):244–52. 2011.

32. Samuel PS, Pringle JP, James NW

4th, Fielding SJ, Faireld KM.

Breast, cervical, and colorectal

cancer screening rates amongst

female Cambodian, Somali, and

Vietnamese immigrants in the USA.

Int J Equity Health 8(30). 2009.

33. U.S. Census Bureau. How the

U.S. Census Bureau measures

poverty. 2014. Available from:

https://www.census.gov/library/

visualizations/2014/demo/poverty_

measure-how.html.

34. SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT

(version 9.3) [computer software].

2012.

35. RTI International. SUDAAN (release

11.0.0) [computer software]. 2012

36. Sato T, Matsuyama Y. Marginal

structural models as a tool for

standardization. Epidemiology

14(6):680–6. 2003.

37. Schenker N, Gentleman JF.

On judging the signicance of

dierences by examining the overlap

between condence intervals. The

American Statistician 55(3):182–6.

2001.

38. Parker JD, Talih M, Malec DJ,

Beresovsky V, Carroll M, Gonzalez

JF Jr, et al. National Center for

Health Statistics data presentation

standards for proportions. National

Center for Health Statistics. Vital

Health Stat 2(175). 2017.

39. Dallo FJ, Kindratt TB. Disparities in

vaccinations and cancer screening

among U.S.- and foreign-born

Arab and European American

non-Hispanic white women. Womens

Health Issues 25(1):56–62. 2015.

40. Theme Filha MM, Leal MD, Oliveira

EF, Esteves-Pereira AP, Gama SG.

Page 10 National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019

Regional and social inequalities

in the performance of Pap test and

screening mammography and their

correlation with lifestyle: Brazilian

National Health Survey. Int J Equity

Health 15(1):136. 2016.

41. Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler

RJ, Breen N, Tangka F, Shaw KM.

Disparities in mammography use

among US women aged 40–64 years,

by race, ethnicity, income, and health

insurance status, 1993 and 2005.

Med Care 46(7):692–700. 2008.

42. Oenger KC, Fontham ET,

Etzioni R, Herzig A, Michaelson

JS, Shih YC, et al. Breast cancer

screening for women at average

risk: 2015 guideline update from the

American Cancer Society. JAMA

314(15):1599–614. 2015.

43. Julliard K, Vivar J, Delgado C, Cruz

E, Kabak J, Sabers H. What Latina

patients don’t tell their doctors: A

qualitative study. Ann Fam Med

6(6):543–9. 2008.

44. Health Resources and Services

Administration, Bureau of Primary

Health Care. Public Health Service

Act [42 USC 254b], Section 330(b).

Available from: https://www.hrsa.

gov/advisorycommittees/shortage/

Meetings/20100922/section330mua.

pdf.

45. Health Resources and Services

Administration, Rural Health

Information Hub. Federally qualied

health centers (FQHCs) and the

Health Center Program. Available

from: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.

org/topics/federally-qualied-health-

centers.

46. United States–Mexico Border Health

Commission. Border lives: Health

status in the United States–Mexico

border region. 2010. Available from:

https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/assets/

940-3105/health-status-in-the-united-

states-mexico-border-region.pdf.

47. Cleveland Clinic. Three reasons why

we opened a Hispanic clinic: A new

model of patient-centered care. 2015.

Available from: https://consultqd.

clevelandclinic.org/3-reasons-why-

we-opened-a-hispanic-clinic/.

48. Oce of Minority Health. State and

territorial eorts to reduce health

disparities: Findings of a 2016

survey by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services Oce

of Minority Health. Washington,

DC: U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services. 2018. Available

from: https://minorityhealth.hhs.

gov/assets/PDF/OMH-Health-

Disparities-Report-State-and-

Territorial-Eorts-October-2018.pdf.

49. Coronado GD, Beresford SA,

McLerran D, Jimenez R, Patrick

DL, Ornelas I, et al. Multilevel

intervention raises Latina

participation in mammography

screening: Findings from ¡Fortaleza

Latina! Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev 25(4):584–92.

2016.

50. Lairson DR, Kim J, Byrd T, Salaiz

R, Shokar NK. Cost-eectiveness

of community interventions for

colorectal cancer screening: Low-

income Hispanic population. Health

Promot Pract 19(6):863–72. 2018.

51. Luque JS, Logan A, Soulen G,

Armeson KE, Garrett DM, Davila

CB, Ford ME. Systematic review of

mammography screening educational

interventions for Hispanic women

in the United States. J Cancer Educ

34(3):412–22. 2019.

52. New York State Department of

Public Health. Public health works!

2017. Available from:

https://www.health.ny.gov/

prevention/public_health_works/.

53. Myers D, Pitkin J. Assimilation

today: New evidence shows the

latest immigrants to America are

following in our history’s footsteps.

Washington, DC: Center for

American Progress. 2010. Available

from: https://cdn.americanprogress.

org/wp-content/uploads/

issues/2010/09/pdf/immigrant_

assimilation.pdf.

54. National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint

Regression Program (Version

4.5.0.1) [computer software]. 2017.

55. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ,

Midthune DN. Permutation tests

for joinpoint regression with

applications to cancer rates. Stat Med

19(3):335–51. 2000.

National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019 Page 11

Table 1. Percent distribution of women aged 50–74, by birthplace: United States, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015

Birthplace Sample size Percent of total population

Relative percent among

foreign-born women

United States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25,707 86.9 …

Mexico . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,022 2.7 20.4

Caribbean. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 694 1.7 13.1

Central America . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 283 0.7 5.4

South America . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 340 0.9 7.1

Europe . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 577 2.4 18.3

Central Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 328 1.1 8.3

Southeast Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 559 1.8 13.5

South Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137 0.6 4.9

Africa and Middle East . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182 0.8 5.9

Other. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122 0.4 3.3

Total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29,951 100.0 100.2

... Category not applicable

NOTES: The denominator used for analysis is the number of U.S. women aged 50–74. Women born in the United States or born abroad to parents who were U.S. citizens are categorized as U.S. born.

If born abroad to parents who were non-U.S. citizens, country of birth, geographic proximity, cultural commonalities, socioeconomic differences and similarities, and sample sizes are used to catego-

rize participants by birthplace. South Asia, also known as the Indian subcontinent, includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Europe includes Russia

and former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics areas. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015.

Page 12 National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics and health care access and utilization among women aged 50–74, by nativity and percentage of lifetime in United States: National Health

Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015

Characteristic

Total U.S. born Foreign born

Less than 25% of

lifetime in United States

25% or more of lifetime

in United States

Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE) Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE) Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE) Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE) Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE)

All women. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29,951 100.0 (0.0) 25,707 86.9 (0.3) 4,244

1

13.1 (0.4) 792

1

2.4 (0.1) 3,452

1

10.7 (0.3)

Age group

50–59 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13,945 50.4 (0.4) 11,867 49.9 (0.4) 2,078

1

53.8 (1.0) 400

1

55.2 (2.1) 1,678

1

53.5 (1.1)

60–69 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11,620 36.8 (0.4) 10,076 37.2 (0.4) 1,544

1

34.0 (0.9) 297 35.4 (2.0) 1,247

1

33.6 (1.0)

70–74 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,386 12.8 (0.2) 3,764 12.9 (0.3) 622 12.2 (0.6) 95

1

9.4 (1.1) 527 12.9 (0.7)

Race and ethnicity

2

Hispanic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,772 9.3 (0.3) 1,731 4.8 (0.2) 2,041

1

38.9 (1.1) 406

1

43.5 (2.2) 1,635

1

37.8 (1.2)

Non-Hispanic white. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19,679 73.6 (0.5) 18,874 80.8 (0.4) 805

1

26.0 (1.1) 109

1

19.3 (2.1) 696

1

27.5 (1.1)

Non-Hispanic black. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,644 11.2 (0.3) 4,299 11.8 (0.3) 345

1

7.9 (0.7) 73

1

8.8 (1.2) 272

1

7.7 (0.8)

Non-Hispanic Asian . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,274 4.2 (0.2) 247 0.8 (0.1) 1,027

1

26.5 (1.0) 202

1

27.9 (2.0) 825

1

26.2 (1.1)

Other or mixed race . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 582 1.6 (0.1) 556 1.8 (0.1) 26

1

0.7 (0.2) * * 24

1

0.8 (0.2)

Marital status

Never married . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,816 6.4 (0.2) 2,421 6.4 (0.2) 395 6.4 (0.4) 69 5.8 (0.8) 326 6.5 (0.5)

Currently married or living with partner. . . . . . . . . . 14,420 63.4 (0.4) 12,235 62.9 (0.4) 2,185

1

66.7 (0.9) 401 63.1 (2.0) 1,784

1

67.6 (1.0)

Formerly married . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12,570 30.2 (0.3) 10,932 30.7 (0.4) 1,638

1

26.9 (0.8) 311 31.1 (1.9) 1,327

1

25.9 (0.9)

Education

Less than high school. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,711 13.6 (0.3) 3,228 11.1 (0.3) 1,483

1

30.2 (0.9) 325

1

38.3 (2.1) 1,158

1

28.5 (0.9)

High school graduate or GED. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8,481 29.2 (0.4) 7,557 30.2 (0.4) 924

1

22.9 (0.9) 165

1

23.2 (1.9) 759

1

22.9 (1.0)

Some college . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8,879 29.6 (0.3) 8,098 31.2 (0.4) 781

1

18.7 (0.8) 109

1

13.7 (1.5) 672

1

19.8 (0.9)

College degree . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7,695 27.6 (0.4) 6,701 27.5 (0.4) 994 28.2 (0.9) 161 24.8 (2.0) 833 28.9 (1.0)

Poverty status

3

Less than 100% of poverty level. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,328 10.2 (0.2) 3,362 9.2 (0.2) 966

1

16.7 (0.7) 235

1

24.1 (1.9) 731

1

15.0 (0.8)

100%–199% of poverty level . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5,936 17.1 (0.3) 4,910 16.5 (0.3) 1,026

1

21.1 (0.7) 233

1

28.5 (2.0) 793

1

19.5 (0.8)

200%–399% of poverty level . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8,758 29.5 (0.4) 7,574 29.4 (0.4) 1,184 29.9 (0.9) 204 29.8 (2.0) 980 29.9 (1.0)

400% or more of poverty level . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10,929 43.2 (0.5) 9,861 44.9 (0.5) 1,068

1

32.3 (1.0) 120

1

17.6 (2.0) 948

1

35.6 (1.1)

Health status

Excellent or very good . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14,465 50.7 (0.4) 12,734 51.7 (0.5) 1,731

1

43.6 (1.0) 296

1

39.9 (2.1) 1,435

1

44.5 (1.1)

Good. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9,086 30.2 (0.3) 7,650 29.7 (0.4) 1,436

1

34.1 (0.9) 272

1

34.4 (2.0) 1,164

1

34.0 (1.0)

Fair or poor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6,386 19.1 (0.3) 5,314 18.6 (0.3) 1,072

1

22.3 (0.8) 224

1

25.7 (1.8) 848

1

21.5 (0.9)

Health insurance coverage

4

Private. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18,598 67.5 (0.4) 16,704 69.8 (0.4) 1,894

1

51.8 (1.0) 243

1

34.3 (2.2) 1,651

1

55.6 (1.1)

Public . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5,247 14.3 (0.3) 4,230 13.5 (0.5) 1,017

1

19.8 (0.8) 223

1

25.5 (1.9) 794

1

18.5 (0.8)

Medicare only and Medicare Advantage. . . . . . . . . 3,248 9.5 (0.2) 2,736 9.3 (0.2) 512

1

10.6 (0.6) 55

1

6.7 (0.9) 457

1

11.5 (0.6)

Uninsured . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,775 8.7 (0.2) 1,975 7.4 (0.2) 800

1

17.8 (0.8) 264

1

33.5 (2.1) 536

1

14.3 (0.8)

Usual place of care

None. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,103 6.6 (0.2) 1,585 5.8 (0.2) 518

1

11.8 (0.6) 174

1

22.2 (1.8) 344

1

9.4 (0.7)

Has a usual place. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27,587 93.4 (0.2) 23,897 94.2 (0.2) 3,690

1

88.2 (0.6) 613

1

77.8 (1.8) 3,077

1

90.6 (0.7)

See footnotes at end of table.

National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019 Page 13

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics and health care access and utilization among women aged 50–74, by nativity and percentage of lifetime in United States: National Health

Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015—Con.

Characteristic

Total U.S. born Foreign born

Less than 25% of

lifetime in United States

25% or more of lifetime

in United States

Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE) Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE) Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE) Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE) Sample size

Percent

distribution (SE)

Visits to health care provider

None. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,829 9.2 (0.2) 2,213 8.4 (0.2) 616

1

14.1 (0.7) 173

1

23.2 (1.9) 443

1

12.0 (0.7)

1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,796 12.9 (0.3) 3,172 12.5 (0.3) 624

1

15.8 (0.8) 119 14.7 (1.5) 505

1

16.1 (0.8)

2 or 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7,747 27.0 (0.3) 6,637 26.9 (0.4) 1,110 28.0 (0.9) 187 25.1 (1.9) 923 28.6 (1.0)

4 or more . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14,984 50.9 (0.4) 13,186 52.2 (0.4) 1,798

1

42.1 (0.9) 293

1

37.0 (2.0) 1,505

1

43.3 (1.1)

U.S. region of current residence

New England . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,020 5.5 (0.5) 1,812 5.5 (0.5) 208 5.1 (0.6) 33

1

3.5 (0.8) 175 5.5 (0.7)

Mid-Atlantic. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,315 16.0 (1.1) 3,499 15.2 (1.0) 816

1

20.8 (2.1) 138 18.9 (2.8) 678

1

21.3 (2.0)

East North Central . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,860 15.6 (0.7) 3,613 17.0 (0.7) 247

1

7.0 (0.9) 51

1

8.4 (1.6) 196

1

6.8 (0.9)

West North Central. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,499 7.2 (0.4) 2,409 7.9 (0.4) 90

1

2.1 (0.3) 24

1

3.1 (0.8) 66

1

1.8 (0.3)

South Atlantic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,958 17.9 (0.7) 4,231 18.1 (0.7) 727 16.2 (1.3) 151 18.0 (2.1) 576

1

5.7 (1.3)

East South Central . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,868 6.1 (0.3) 1,829 6.9 (0.4) 39

1

1.2 (0.3) * * 30

1

1.2 (0.3)

West South Central. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,295 10.8 (0.5) 2,858 11.0 (0.5) 437 9.8 (0.6) 102 10.7 (1.6) 335 9.6 (0.7)

Mountain. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,538 6.1 (0.3) 2,269 6.2 (0.4) 269 5.6 (0.6) 36 5.3 (1.1) 233 5.7 (0.5)

Pacic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,598 14.9 (0.4) 3,187 12.4 (0.4) 1,411

1

32.1 (2.2) 248

1

30.9 (2.2) 1,163

1

32.4 (1.4)

* Estimate does not meet NCHS standards of reliability.

1

Signicantly different from U.S. born, p < 0.05.

2

Hispanic refers to persons who are of Hispanic or Latino origin and may be of any race or combination of races. Non-Hispanic refers to persons who are not of Hispanic or Latino origin, regardless of race.

3

Based on family income and family size using the U.S. Census Bureau poverty thresholds for 2004, 2007, 2009, 2012, and 2014.

4

A person is dened as uninsured if he or she did not have any private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, state-sponsored or other government–sponsored health plan, or military plan at the time of interview. A person is also dened as uninsured if he or she

had only Indian Health Service coverage or had only a private plan that paid for one type of service, such as accidents or dental care. Public health insurance includes persons with Medicaid, dual Medicare and Medicaid enrollment, or military or other government

health insurance coverage. Women aged 65 and over with only Medicare coverage including Medicare Advantage plans were placed in a separate category.

NOTES: Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Estimates were weighted using the Sample Adult weight. Unless indicated, unknowns for the columns were not included in the denominators

when calculating percentages, but they were included in the category of All women. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding. Country of birth, number of years residing in the United States, and current age are used to determine nativity and percentage of

time in the United States. Women born in the United States or born abroad to parents who were U.S. citizens are categorized as U.S. born. SE is standard error.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015.

Page 14 National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019

Table 3. Estimates of mammography receipt among women aged 50–74, by birthplace: United States, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015

Birthplace Ever had a mammogram

Met U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

mammography screening recommendations

Unadjusted estimates Percent (standard error)

United States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94.1 (0.2) 73.0 (0.4)

Mexico . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

85.8 (1.5)

1

65.1 (2.0)

Caribbean. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

87.3 (1.4) 72.3 (2.0)

Central America . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93.3 (1.7) 72.6 (3.5)

South America . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

89.4 (2.0) 67.3 (3.6)

Africa and Middle East . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

86.1 (3.2) 66.2 (4.8)

Central Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

82.8 (2.6)

1

59.6 (3.5)

Southeast Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

89.2 (1.8) 72.8 (2.6)

South Asia

2

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

83.7 (3.9)

1

60.9 (5.4)

Europe

3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92.4 (1.4) 72.9 (2.4)

Adjusted estimates

4

United States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93.9 (0.2) 72.4 (0.4)

Mexico . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93.7 (0.8)

1

81.4 (1.4)

Caribbean. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91.8 (1.1)

1

78.6 (2.0)

Central America . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

96.6 (0.9)

1

82.8 (2.3)

South America . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93.3 (1.5) 74.7 (2.6)

Africa and Middle East . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88.4 (2.8) 69.6 (4.4)

Central Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

84.1 (2.3)

1

61.6 (3.4)

Southeast Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

88.8 (1.6) 73.6 (2.2)

South Asia

2

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

81.5 (4.0)

1

58.4 (5.3)

Europe

3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92.3 (1.3) 72.5 (2.3)

1

Signicantly different from U.S.-born women, p < 0.05.

2

Also known as the Indian subcontinent; includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

3

Includes Russia and former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics areas.

4

Adjusted for age, marital status, income, U.S. region of current residence, education, health status, health insurance coverage, usual place for medical care, and number of doctor visits in the

past 12 months.

NOTES: The denominator used for analysis is the number of U.S. women aged 50–74. A mammogram is a radiograph of the breast that can be used to check for breast cancer in women who have no

signs or display no symptoms of the disease. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for breast cancer with mammography every 2 years for women aged 50–74. For women

born abroad to parents who were non-U.S. citizens, country of birth, geographic proximity, cultural commonalities, socioeconomic differences and similarities, and sample size are used to categorize

participants by birthplace.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2015.

National Health Statistics Reports Number 129 October 9, 2019

For more NCHS NHSRs, visit:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/nhsr.htm.

For e-mail updates on NCHS publication releases, subscribe online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/govdelivery.htm.

For questions or general information about NCHS: Tel: 1–800–CDC–INFO (1–800–232–4636) • TTY: 1–888–232–6348

Internet: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs • Online request form: https://www.cdc.gov/info

DHHS Publication No. 2020–1250 • CS310396

FIRST CLASS MAIL

POSTAGE & FEES PAID

CDC/NCHS

PERMIT NO. G-284

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

3311 Toledo Road, Room 4551, MS P08

Hyattsville, MD 20782–2064

OFFICIAL BUSINESS

PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE, $300

Suggested citation

Clarke TC, Endeshaw M, Duran D, Saraiya M.

Breast cancer screening among women by

nativity, birthplace, and length of time in the

United States. National Health Statistics

Reports; no 129. Hyattsville, MD: National

Center for Health Statistics. 2019.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in

the public domain and may be reproduced

or copied without permission; citation as to

source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Jennifer H. Madans, Ph.D., Acting Director

Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Acting Associate

Director for Science

Division of Health Interview Statistics

Stephen J. Blumberg, Ph.D., Director

Anjel Vahratian, Ph.D., M.P.H., Associate

Director for Science