Genre analysis of personal statements: Analysis

of moves in application essays to medical and

dental schools

Huiling Ding

*

English Department, Purdue University, 228-8 Arnold Drive, West Lafayette, IN, 47906, United States

Abstract

Despite the important role the personal statement plays in the graduate school application pro-

cesses, little research has been done on its functional features and little instruction has been given

about it in academic writing courses. The author conducted a multi-level discourse analysis on a cor-

pus of 30 medical/dental school application letters, using both a hand-tagged move analysis and a

computerized analysis of lexical features of texts. Five recurrent moves were identified, namely,

explaining the reason to pursue the proposed study, establishing credentials related to the fields of

medicine/dentistry, discussing relevant life experience, stating future career goals, and describing

personality.

Ó 2006 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of The American University.

1. Introduction

The personal statement, or the graduate school application letter, as an academic pro-

motional genre (Bhatia, 1993), serves as one of the most important documents in the grad-

uate school admission process. In the preparation of application materials, the personal

statement poses a challenge to most applicants because of their unfamiliarity with the

conventions of the genre, its discourse community, and its audience expectations.

Research on academic writing has examined a variety of genres such as journal articles,

0889-4906/$30.00 Ó 2006 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of The American University.

doi:10.1016/j.esp.2006.09.004

*

Tel.: +1 765 496 5185.

English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

www.elsevier.com/locate/esp

E

NGLISH FOR

S

PECIFIC

P

URPOSES

abstracts, dissertations, and conference proposals (Badger, 2003; Berkenkotter, 2000;

Brett, 1994; Hyland, 2001, 2003; Kanoksilapatham, 2005; Martı

´

n, 2002; Pinto dos Santos,

2002; Rowley-Jolivet, 2002; Samraj, 2002, 2005; Smith, 1997). An impor tant genre that

has received little attention from researchers, however, is the personal statement for grad-

uate programs. Little is known about this occluded genre in the academy (Swales, 1996)

and college writing instru ctors have no theoretical or practical guidance to assist students

to produce good personal statements, a high-stakes genre for the graduate admission pro-

cess. Graff and Hoberek (1999) attributed the applicants’ lack of knowledge not to the

deficiencies in the applicants but to ‘‘a lack of interest in socializing hopeful members of

the academic family into its parti cular customs, beliefs, and behaviors’’ (p. 242). Genre

study helps to bridge the gap in preparing future practitioners because it connects the rec-

ognition of regularities in discourse types with a broader social and cultural understanding

of language in use, thus unpacking the complex cultural, institutional and disciplinary fac-

tors at play in the production of specific kinds of writing (Freedman & Medway, 1994).

This study was conducted using the framework of genre analys is to explore move struc-

tures, underlying patterns, text-audience relations, and communicative purposes of the

personal statement as a genre.

1.1. Literature review

As a defining treatise in genre theory, Carolyn Miller’s (1984) essay, ‘‘Genre as Social

Action,’’ described genre as a recurrent social action taking place in recurrent rhetorical

situations in particular discourse communities. Swales (1990) further defined genre as

particular forms of discourse with shared ‘‘structure, style, content, and intended audi-

ence,’’ whi ch are used by a specific discourse community to achieve certain communica-

tive purposes through ‘‘socio-rhetorical’’ activities of writing (pp. 8–10). In his latest

book on research genres, Swales (2004) described ‘‘constellations of genres’’ in the forms

of hierarchies, chains, sets, and networks, stressi ng the need to see genres as ‘‘networks

of variably distributed strategic resources’’ (stress original, pp. 13–31). Hyland (2004)

discusses the importance of genre approaches to teaching L2 writing by emphasizing

the role of language in written communication. Other genre studies stress socio-cultural

and disciplinary contexts, textual regularities, the interpretive process of reading, inter-

textual linkage through implicit or explicit reference to other texts and background

knowledge, the social roles of readers and writers, and the dynamics and instability of

genre (Berkenkotter & Huckin, 1993; Bhatia, 1993; Freedman & Medway, 1994; Miller,

1994; Pare

´

& Smart, 1994 ) discussed the pedagogical implication of genre studies in

composition classrooms, focusing on its role as a heuristic tool for invention, its high

relevance to reader expectations, and its nature as social processes of responding to

recurrent contextual sit uations. The analysis of context and audience plays an important

role in genre studies. Pal tridge discussed the two concepts of context and audience in

depth, distinguishing the ‘‘context of culture’’ from ‘‘the context of situation’’ (Paltridge,

2001, pp. 45–62). Swales and Feak (1994) considered genre as a product of many con-

siderations, such as audience, purpose, organization, and presentation, with audience as

the most important factor in their list.

The notion of move (Swales, 1990), defined as a functional unit in a text used for

some identifiable purpose, is often used to identify the textual regularities in certain

genres of writing and to ‘‘describe the functions which particular portions of the text

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 369

realizes in the relationship to the overall task’’ (Connor, Davis, & De Rycker, 1995, p.

463). Contributing to the fulfillment of the overall communicative purpose of the genre,

moves can vary in length and size from several paragraphs to one sentence, but normally

contain at least one proposition (Connor & Mauranen, 1999, p. 51). Move analysis is a

helpful tool in genre studies since moves are semantic and functional units of texts,

which can be identified because of their communicative purposes and linguistic

boundaries.

1.2. Unique features of personal statements as a genre

Many move analyses of promotional genres have been done for genres such as job

application letters , negotiation letters, and grant proposals (Bhatia, 1993; Connor &

Mauranen, 1999; Connor & Upton, 2004; Henry & Roseberry, 2001). Compared with

genres with more rigid structures such as job application letters and research abstracts

for journal articles, the personal statement differs in its lack of prescriptive guidelines,

its allowance for creativity and individuality, its space for narratives and stories, and

its goal both to infor m and to persuade. Moreover, as Hyland (2000) pointed out, dif-

ferent disciplines value different kinds of arguments and set different writing tasks. The

personal statement, as one of the primary written products used to win one’s entry into

most graduate programs in the US, reflects such disciplinary differences in its structure

and communicative purposes. For instance, Brown’s (2004) rhetorical study of psychol-

ogy personal statements highlighted the need for the applicant to provide eviden ce of

disciplinary appropriation and socialization as well as to present oneself as an apprentice

scientist rather than an outsider. Moreover, audience expectations for personal state-

ments as a genre are often ‘‘more shaped by local cultural values and national academic

traditions than is the case with more technical writing’’ (Swales & Feak, 1994, p. 229).

Therefore, the move structure of the personal statement for professional programs such

as law and medicine may differ slightly from that of the personal statement for philos-

ophy, which stresses academic and intellectual preparedness over relevant professional

and practical experiences. One unique feature about personal statements for medical/

dental school is that applicants come with a bachelor or master’s degree from fields

unrelated to med icine/dentistry. They are required to both justify their motivation to

shift from their previous areas of study to medicine/dentistry and to prove their pre-

paredness for medical/dental schools. Given the limit of 5300 characters for personal

statements in the American Medical College Application Service (AMCAS) app lication,

such a constraint on rhetorical space requires the use of well thought out, con cise, clear ,

persuasive, and interesting essays to ‘‘encapsulate the entire [relevant] experience into

words [to] present [one’s] goals, motivations, sincer ity, experience, and background,

[and to] accurately express [one’s] unique, interesting, and likable personality’’ (Kauf-

man, Burnham, & Dowhan, 2003, p. 1).

1.3. Research questions

This text-based, exploratory study serves mainly to examine the genre features of per-

sonal statements written by applicants to medical/dental schools in the US through the

construction and analysis of two small personal statement corpora. More specifically, this

study strives to answer the following two research questions:

370 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

1. What are the moves of successful personal statements used for application to medical/

dental schools?

2. How do unedited unsuccessful personal statements differ from edited and successful

personal statements?

2. Description of the study

2.1. Discourse community

The discourse community that uses the genre of personal statements comprises medical/

dental school admission committees, faculty members, and medical/dental school appli-

cants with diverse academic and professional backgrounds. No matter whether they are

native speakers or non-native speakers, the applicants are involved in composing a com-

pletely new genre to appeal to an unfamiliar audience, namely, medical/dental school

admission committees or privileged professors. Applicants suffer from their unfamili arity

with the conventions of the genre, readers’ expectations, and the need to promote them-

selves as perfect candidates for target programs. In other words, in this rhetorical situa-

tion, the writers are very different from, if not inferior to, their interpretive/evaluative

counterparts in terms of academic and professional backgrounds, power, attitudes, and

knowledge. Such imbalance in power and expertise creates great tension for the applicants,

who have to write to conform to the conventions of the genre and to meet the expectations

of their evaluators.

2.2. Communicative purposes

As a promotional genre, the personal statement serves to capture readers’ attention, to

establish the writer’s competence, to appeal to readers’ needs and expectations, and to

demonstrate the fit between the writer and the field of medicine/dentistry. The communi-

cative purpose of composing the genre is to gain admission to and/or financial support

from target programs. According to existing publications on the personal statement

(Asher, 2000; Curry, 1991; Mumby, 1997; Stewart, 1996), to gain admission, the applicants

have to establish their academic and professional qualifications; demonstrate their abilities

through work experiences; discuss their interests and motivation in studying in the target

field; explain why the target program matches well with their interests and goals and what

contributions they can make to the field; and explain their future study and career plan.

The following are questions frequently asked in personal statement prompts and guide-

lines that the author gathered from over 100 American graduate programs:

1. Why do you choose to study in this program? Why here and now?

2. What is unique and exceptional about you?

3. Why are you qualified? What kind of relevant experience do you have?

4. What is your future study and career plan?

Two professors in charge of admission processes at two medical schools in the mid-west

were contacted and interviewed through phone calls and email correspondences to obtain

insiders’ perspectives on conventions of the genre. Some of the qualities the admission

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 371

committees hope to see in personal statements, according to the professors interviewed,

are evidence of commitment to medicine/dentistry, i.e., intellectual interests in and aca-

demic and research experiences related to medic ine/dentistry; intellectual capacity to suc-

ceed in medical/dental schools, for instance, academic successes and contribution to

research projects; involvement in community services, clinical or health care related expe-

riences; and personal qualities such as maturity, dedication, commitment, empathy, com-

passion, and responsibility. One thing stressed by both professors is the necessity to go

beyond a basic desire to help people. In other words, applicants have to demonstrate their

commitment to the career of physician/dentist through the description and discussion of

specific, concrete first-hand experiences rather than just repeating the cliche

´

s that they

enjoy helping people. They warn against the use of a laundry list of accomplishments

and recommend the selective use of specific illustrative stories to make a strong argument

about the applic ant’s possession of qualities highly desired by medical/dental schools.

The understanding specified above was obtained only through the author’s research

and, in most cases, is not readily available to potential applicants. Most students are likely

to be at a loss when writing the admission essay due to their position as outsiders to the

discourse community they hope to join. Therefore, research on the move structure of the

personal statement should help shed light on its characteristics and better prepare appli-

cants to write this high-stakes document.

3. Methodology

3.1. The corpus: data collection

Thirty online personal statements for medical/dental schools were collected from public

websites, among which 20 were posted as successful and/or edited samples

1

and 10 were

posted as unedited samples.

2

All the personal statements in the corpora were either sub-

mitted to commercial websites providing professional editing services or posted by the tar-

get programs or successful applicants

3

to offer potential candidates some insight into the

features of successful application letters . Commercial websites such as EssayEdge.com or

Accepted.com offer paid editing services. Some websites post both unedited and critiqued

personal statements to demonstrate to browsers the quality of services of the websites,

while others include both unedited and edited versions for advertising purposes. However,

the majority of the personal statements posted on those editing service websites were uned-

ited, perhaps both to promote sales and to avoid plagiarism. As Table 1 shows, the total

1

These personal statements were either edited and posted by commercial websites as well-written samples or

posted by medical/dental programs or applicants as successful essays that won their writers admission into the

target programs. Using percentages of moves separately for edited and successful personal statements, my

examination of the corpus did not find any significant difference between the moves and structures used in those

two types of personal statements or the background (credentials and life experiences) between applicants of edited

and successful personal statements except the relatively higher use of Move 3, Relevant experiences, in the

successful personal statements (see Table 3 for distribution of moves in the personal statements). For

convenience’s sake, I categorize this corpus as one single corpus and refer to it as successful personal statements.

2

The unedited samples were posted in the original state as submitted by applicants interested in using the paid

editing services. No professional editors or writers changed the personal statements to make them better.

3

Please contact the author for more information if you are interested in the sources. Detailed lists of websites

used in this study were omitted due to space constraints.

372 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

words for the two corpora were 13,802 and 6613. The average length of successful personal

statements (692 words) is slightly lon ger than that of unedited ones (661 words).

In the two corpora, nine essays were edited and posted as excellent samples by paid ser-

vices, six were posted as successful application letters by the target programs and five

posted by successful applicants, and 10 were posted unedited and claimed as resulting

in rejection by paid services (see Tabl e 2). Moreover, all the essays were written to apply

for doctoral programs in medicine (24) or dentistry (6). The unedited personal statements

were written by applicants themselves without any assistance from people more familiar

with the genre. In contrast, most of the successful personal stat ements either received paid

services from professionals or were known to have gained the writers entry to their target

programs. According to the statements, the applicants came from very diverse back-

grounds: most of them were native speakers with undergraduate degrees from anthropol-

ogy, Spanish, biology, sociology, mathe matics, and chemistry. Only one applicant

explicitly stated that he had a master’s degree. It was also worth noticing that most per-

sonal statements (9 out of 10) in the unedited corpus did not mention the applicants’ aca-

demic background whereas 13 out of 20 personal statements in the successful corpus

mentioned that explicitly.

Table 2

Number and percentage of personal statements that use different moves and steps

Move/corpus Successful (20 PS) Unedited (10 PS)

Total

a

PS

b

Percentage Total PS Percentage

M1: Explaining reason 41 19 95 20 10 100

S1: Interest 18 12 60 5 1 10

S2: Understanding 16 9 45 9 5 50

S3: Personal/family 7 7 35 6 5 50

M2: Credentials 62 20 100 20 8 80

S1: Academic 15 11 55 7 5 50

S2: Research 12 10 50 6 4 40

S3: Professional 35 19 95 7 8 80

M3: Relevant experience 31 20 100 9 7 70

M4: Stating goal 23 18 90 11 9 90

M5: Personality 8 8 40 7 4 40

Total 151 67

a

Total: total number of moves/steps used in the corpus.

b

PS: total number of personal statements that use the move/step under discussion.

Table 1

Total words and average length of personal statements

Number/corpus Successful Unedited

PS 20 10

Total words 13,802 6613

Range 501–1083 502–792

Average length 692 661

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 373

This project aimed to first examine the moves of successful personal statements and

then compare their rhetorical and linguistic features with the unedited ones. As the

identification of typical moves for medical/dental schools is based on the analysis of

successful personal statements, the corpus size of successful personal statements was

twice that of their unedited counterparts. Two small corpora were constructed to ana-

lyze the moves and rhetorical strategies employed in these two types of essays. The 20

successful personal statements were examined to identify moves regularly used in the

genre of admission essays for medical/dental schools. The 10 unedited essays were ana-

lyzed to identify the differences between successful and unedited essays and to explore

how such differences might contribute to the final success or failure in admission

processes.

3.2. Development of moves

The definition and categorization of moves in the personal statement drew on many

sources. First, to understand the rhetorical objectives of the genre, the author looked

through existing publications on personal statements in general (Asher, 2000; Curry,

1991; Mumby, 1997; Stewart, 1996) and over 100 websites in different tiers of graduate

programs in the US, all of which offer instructions on the writing of personal statements.

Even though different programs have different length and structure requirements, the basic

communicative purpose and rhetorical objective are the same: to gain admission into tar-

get programs by demonstrating one’s academic background, professional qualifications,

and personal strengths.

Second, as Connor and Mauranen (1999) pointed out, the identification of moves in a

text dep ends on both the rhetorical purpose of the texts and the division of the text into

meaningful units on the basis of linguistic clues, which include ‘‘discourse markers (con-

nectors and other metatextual signals) , marked themes, tense and modality changes,

and introduction of new lexical references’’ (p. 52). In this study, explicit text divisions

in the personal statement, namely, the use of section boundaries, paragraph divisions,

and subheadings, served as textual marks for move recognition. As moves served rhetor-

ical purposes, the introduction of new themes (Overall, I feel I am the type of person/Since

that time, I’ve acquired a more realistic view of medicine) and lexical references (I pro-

ceeded to volunteer in the Preceptorship Program/My interest in medicine had started

out with an enjoyment of science/I started investigating dentistry by talking to my dentist)

usually implied the start of a new move. In addition, the identification and counting of T

units

4

helped to break down the text into moves because this examination revealed T units’

rhetorical and communicative purp ose, which in turn helped to locate places for change of

topics and themes. Finally, the analysis of lexical devices also helped to an alyze the moves.

One important tool was the identification of keywords, which , closely related to the move

categories, helped to break down the personal statement into distinct moves. However,

instead of operating by themselves, such use of keywords should alw ays be followed by

4

A T-unit consists of a main clause and any subordinate clause or non-clausal structure attached to or

embedded in it. A sentence may contain several T-units if it is a complex sentence with several main clauses. One

such example is: ‘‘They were messengers from someplace else where the decisions were made and the odds

calculated; they seemed in control of events that I wanted very badly to have control of myself.’’ The semicolon

here signifies the existence of two complete sentences.

374 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

the analysis of the rhetorical intentions of the T-units containing the keywords before

determining whether different moves exist and what kind of moves they are.

One instance was taken from an unedited personal statement to illustrate the process of

dividing texts into moves. Altogether, four different moves were identified in the text. The

use of explicit text division tools, in this case, paragraph division, suggested the existence

of different moves. Linguistic means such as marked themes (so far), tense/modal change

(see below), and new lexical references served as sources for move recognition. The use of

keywords such as medicine, courses, research, clinics, hospital, volunteer, and maturity sug-

gested the introduction of new lexical references and the start of different topics and

themes in the text. To determine whether the change of topics and themes signifies the start

of new moves, the iden tification of keywords should be followed by careful reading and

analysis of the rhetorical intention of the T-units containing those keywords.

When I was fifteen I was stricken with a cryptic illness. After several years of suffer-

ing and many doctors visits I was diagnosed with Systemic Lupus Erythramatosis.

The Lupus diagnosis would change my life in almost every aspect and was the begin-

ning of the path that has led me towards medicine. //

I’ve spent the past year going to school, working, and volunteering and I’ve learned

through various ways that medicine is not only a path that I’m capable of, but one

that I want more than anythi ng in the world. // As a full time student I have success-

fully taken many challenging courses.Ihave been working part time in a psychobiol-

ogy lab learning how to perform research first hand. // It was here that I discovered

that although I love research, in many ways it is too disconnected from the people it

is helping to be my ideal career.//Ispend a great deal of time in the clinics and the

hospital at Boston University Medical Center and there I have observed the patient–

doctor interaction and realized that I want to be involved with the people I’m help-

ing. // My volunteer work, which involved bring healthcare access to the homeless was

also important in that it showed me just how much as a doctor you truly can make a

difference in someone’s life.

Flowerdew (1998) stressed that the trend of corpus-based analyses is not only to study

the lexico-grammatical patterns of texts but also to examine the corpus at functional, rhe-

torical, pragmatic, and textlinguistic levels. Following the method used by Henry and

Roseberry (2001) and Upton and Connor (2001), a multi-level analysis of a textual corpus

was conducted using both a hand-tagged moves-analysis and a computerized analysis of

lexical features of texts. Two types of concordance software were used in the study: Con-

capp was used to compile concordances for keywords related to the moves and Concor-

dance to find out collocations, or words located to the left and right of certain words.

The use of a mixed method approach, namely, both quantitative and qualitative, aimed

to examine the corpus from different perspectives and to reach a richer understanding

of the genre at both the functional and rhetorical levels.

4. Results and findings

4.1. Identification and analysis of moves

The corpus of successful personal statements was analyzed through an iterative pro-

cess until distinct genre moves were identified and clear definitions for each were devel-

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 375

oped. The corpus was reanalyzed and recoded five months later using the final set of

moves, resulting in an 89.3% intracoder reliability rate. The entire corpus was then inde-

pendently coded by a research assistant, with a resulting 82.7% intercoder reliability

rate.

Five moves were identified in the corpus, namely, Explaining the reason to pursue the

proposed study, Establishing credentials related to medicine/dentistry, Discussing relevant

life experiences, Stating career goals, and Describing personality. The order of appearance

of the moves varied in different personal statement s, but most of them were commonly

presented in the two corpora.

Move 1: Explaining the reason to pursue the proposed study shares similar functions

with Swales’ (1990) move for article introductions, namely, Establishing a terrority,

and Connor and Mauranen’s (1999) move for territory for grant proposals. Move 1 con-

sists of three steps: Step 1: Explaining academic or intellectual interest in medicine/den-

tistry describes the way in which the applicant became interested in those fields

through related academic and intellectual pursuits; Step 2: Stating one’s understanding

of medicine/dentistry links the applicant’s understanding of the profession to his/her

experiences, personality, and abilities, and explains how the applicant’s understanding

of the field helped him/her to make the decision to study medicine/dentistry. Step 3:

Describing the motivation to become a doctor/dentist due to personal or family experiences

discusses how the applicant started to consider pursuing the study and what family

events and personal experiences contributed to such a decision. In most personal state-

ments, at least one of these three steps was used. Examples of each of these steps are

provided below.

Move 1, Step 1: Explaining academic or intellectual interest in medicine/dentistry

Throughout high school I have been intrigued by the sciences, but it was not until I

read about late-breaking discoveries and research in the field of genetics that my

interests in science intensified. In my sophomore year at UBC, I first began to seri-

ously consider dentistry as a career.

Move 1, Step 2: Stating understanding of medicine/dentistry

From these opportunities and others I’ve gleaned that the physician’s job involves

more than the application of intelligence. It is a career which demands tenacity, faith,

objectivity and perhaps more importantly, compassion. It is a profession offering

physical as well as mental challenges, direct human-to-human contact when it fre-

quently counts more, a measure of business autonomy and relative prestige, I can

never see the job as becoming boring.

Move 1, Step 3: Describing motivation to become a doctor/dentist due to personal or family

experiences

These crises included the teenage pregnancy of my sister in 1981, and subse-

quent shared parenting responsibility for my nephew, and my mother’s

seven-year battle against cancer. It was through this exposure to cancer that

I gained some limited medical experience and first began thinking about

becoming a physician.

376 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

Move 2: Establishing credentials related to the fields of medicine/dentistry is the most

important move in the personal statement. It describes the applicant’s qualifications and

experiences related to and valued by the fields of medicine and dentistry. Move 2 in this

corpus is realized by three variations: Step 1: Listing academic achievements; Step 2:

Reviewing research experiences related to medicine/dentistry; and Step 3: Discussing profes-

sional experiences in clinical settings.

Move 2, Step 1: Listing academic achievements demonstrates the applicants’ academic pre-

paredness for the proposed study.

After five years of working, I decided to pursue more advanced research training in

the latest techniques of microbiology. Since the fall of 1998, I have been taking sev-

eral Ph.D.-level course s at New York University. My courses at NYU are Biochem-

istry ... and Physiology Basis of Behavior.

Move 2, Step 2: Reviewing research experiences related to medicine, according to the two

interviewed medical school professors, is considered essential for the qualified applicant

because of the research-oriented and performance-based nature of doctoral study in med-

icine/dentistry.

My interest in medicine remained constant through health-related part-time jobs and

a focus on medical sociology in my graduate research. Issues such as drug abuse and

attitudes toward death were among my concerns. During my two years of graduate

school, I co-authored three publications, six research monographs, and five papers

for presentation at professional meetings.

Move 2, Step 3: Discussing professional experiences (volunteer and exposure) in clinical set-

tings goes beyond the cliche

´

story of ‘‘moti vation’’ to show the applicants’ involvement

and experiences in the profession.

I’ve spent time as an EMT on ambulances, in emergency rooms and in an autopsy

room, seeing for myself some of the decisions being made by doctors and the other

many health professionals... I have been employed for the previous year as a Stu-

dent lab assistant in a university medical school observing and interacting with the

medical students and staff.

Move 3: Discussing relevant life experiences deals with the applicant’s community involve-

ment, extracurricular activities, and work experience to offer insight into his/her abilities

and skills related to, but not directly connected with or obtained from the field of medi-

cine/dentistry. Professional experiences, for instance, volunteer work and clinical shadow-

ing, are highly desirable for applic ants. However, not every applicant may have the

opportunity to get such professional involvement. To make up for this lack of clinic-re-

lated experiences, many applicants used their work and volunteer experiences in non-clin-

ical community settings and their people skills to stress their willingness to help others,

which is considered as an important hallmark of medicine/dentistry. Most essays con-

tained at least one move of such experiences.

Since I already volunteered in the community, I broadened the experience by work-

ing with different groups. My work with the elderly, the handicapped and with chil-

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 377

dren caused me to evaluate the different needs of those groups and if I could provide

those needs.

Move 4: Stating future career goals. This move describes the applicant’s intended future

career after graduation, which stresses the goal-orientedness and strong motivation of

the applicant.

I look forward to one day opening my own practice and becoming a well-respected

member of both the communi ty of dentists and the community of patients.

Move 5: Describing personality This move explicitly describes or demonstrates the appli-

cant’s unique experience and personality to distinguish him/herself from the large pool

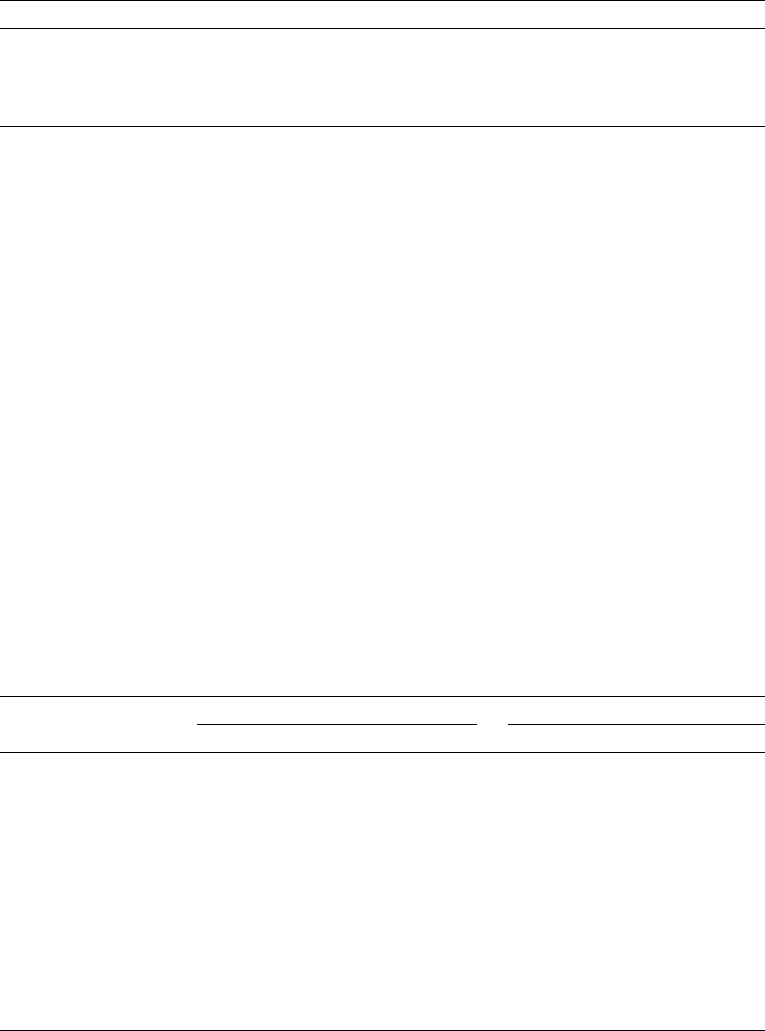

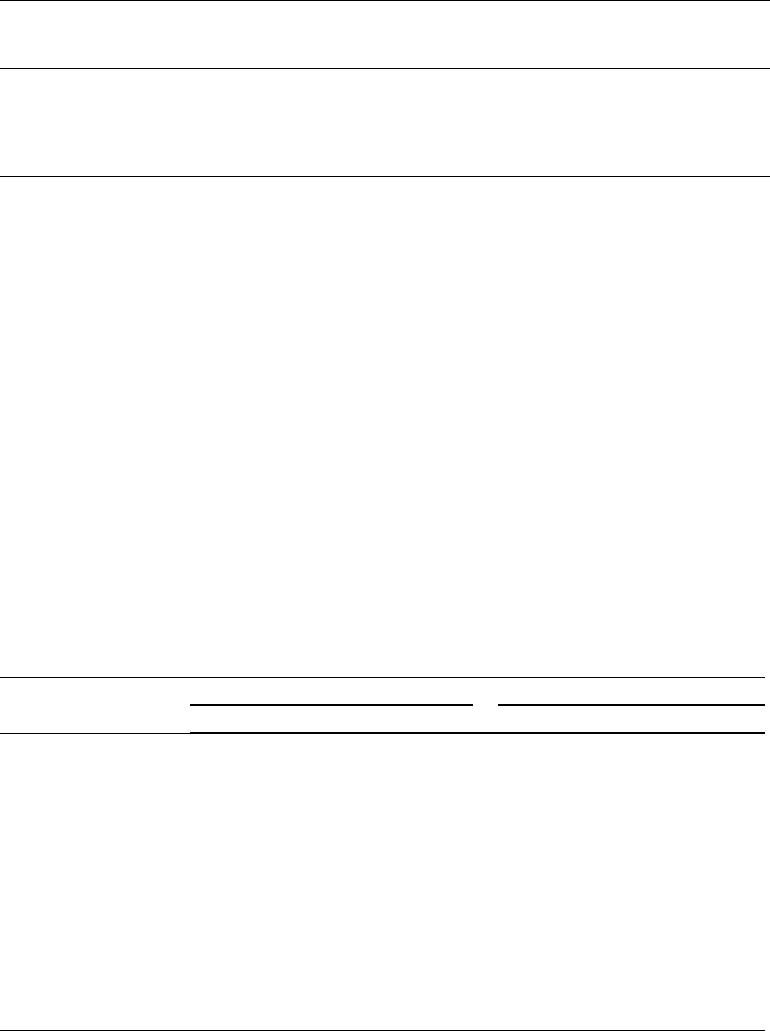

of applicants (see Fig. 1).

I have learned the importance of teamwork and contribution from all team mem-

bers. These experiences have also given me a great deal of confidence in my abilities

and myself... My inherent strong work ethic has resulted in much positive feedback

from employers and colleagues.

Among the five moves identified above, Moves 1, 2, 3, and 4 are the quasi-obligatory

moves whereas Move 5 seems a more elective one. Moves 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the successful

corpus and Moves 1, 2, and 4 of the une dited corpus all occur on average once per state-

ment, with Move 3 of the unedited corpus occurring on average only slightly less fre-

quently at 0.9 times per personal statement. This pattern suggests the importance of

the use of these four moves to meet the genre convention, communicative purpose,

and rhetorical expectations. Table 2 confirms this finding, for in the successful corpus,

Moves 2 and 3 appeared in all the essays at least once and Moves 1 and 4 were used

at least once in 18 and 19 essays (respectively, 90% and 95%). In the unedited corpus,

Move 1 appeared in all the essays at least once, and Moves 2, 3, and 4 were used,

respectively, 80%, 70%, and 90%. In contrast, the average number of Move 5 is well

Move Definition

Move 1: Reason for studying medicine The writer explains reasons for pursuing the proposed study

Step 1: Academic/intellectual

interests

The writer gives reason for academic or intellectual interests

in medicine/dentistry

Step 2: Understanding of the field The writer describes his/her understanding of

medicine/dentistry

Step 3: Personal/family experiences The writer explains the motivation to become a

doctor/dentist due to personal or family experiences

Move 2: Credentials The writer establishes credentials related to the fields of

medicine/dentistry

Step 1: Academic achievements The writer lists academic achievements related to

medicine/dentistry

Step 2: Research experiences

The writer reviews relevant research experiences

Step 3: Professional experiences The writer discusses professional experiences (volunteer

and exposure) in clinical settings

Move 3: Relevant life experiences The writer discusses life experiences valued by the field of

medicine/dentistry, for instance, community volunteering

Move 4: Future career goals The writer states future career goals

Move 5: Personality The writer describes personality either through explicit

statement or through the use of examples

Fig. 1. Moves of personal statements and their definitions.

378 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

below 1 per essay and the move appeared at least once in only 40% of the essays in both

corpora (see Table 2), which suggests its function is more elective. The sequence of the

five moves in su ccessful personal statements is quite variable and to some extent deter-

mined by both the applicants’ life and professional experiences and their way of organiz-

ing their personal statements.

One interesting thing about the move structure is that none of the personal statements

in the two corpora addressed the issue of the applicants’ ‘‘m atch’’ with the target pro-

gram. Explicit explanation of the match between the applicant and the target program

is highly stressed in publications about persona l statements for graduate programs in

general. However, this part is missing in the entire corpora used for this study. The

absence is in part due to the similarity of all medical/dental programs, for they are

not as different as other graduate programs in terms of teaching and research focuses

and strengths. Medical schools adopt similar curriculum and course offering because

they have to prepare students for the Medical Licensing Examination (MLE). Similarly,

dental schools use standard curriculum to prepare students for the National Board Den-

tal Examination (NBDE).

4.2. Move analysis of the corpora

4.2.1. Move frequency and proportion

The average number of each of the moves is listed in Table 3. Although the average

length of successful and unedited personal statements is about the same, the average

number of moves used in each essay is quite different (8.2 vs. 6.1, or 4:3). This ratio

indicates the absence of relevant moves and the overuse of irrelevant details in the

unedited personal statements. The average number of moves demonstrates that, com-

pared with the unedited personal statements, successful personal statements devote

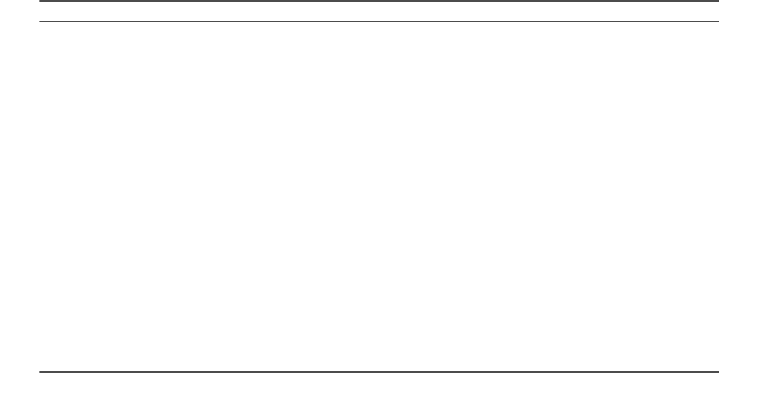

Table 3

Total and average number of moves in the corpora

Move/corpus Successful (20 PS) Unedited (10 PS)

Total Average Percentage

b

Total Average Percentage

M1

a

: Reason 41 2 25 20 2 30

S1: Interest 18 0.9 11 5 0.5 8

S2: Understanding 16 0.8 10 9 0.9 14

S3: Personal/family 7 0.35 4 6 0.6 9

M2: Credentials 62 3.1 38 20 2 30

S1: Academic 15 0.75 9 7 0.7 11

S2: Research 12 0.6 7 6 0.6 9

S3: Professional 35 1.75 21 7 0.7 11

M3: Life experience 31 1.55 19 9 0.9 14

M4: Stating goal 23 1.15 14 11 1.1 16

M5: Personality 8 0.4 4 7 0.7 11

Total number of moves 165 8.2 100 67 6.1 100

a

M: move; S: step.

b

Percentage: the percentage of the move/step under discussion when compared with the total number of moves

in the corpus under discussion.

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 379

more effort to and better develop the first four moves but pay less attention to Move 5,

Describing personalities. The two moves or steps that appear on average more than

once in the successful personal statements are Move 2, Step 3, Stating professional qual-

ifications (1.75 times per essay, or 21% of the total number of moves) and Move 3,

Stating relevant experiences (1.55 times per essay, or 19%). In comparison, most moves

appear less than once in unedited personal statements except Move 4, Stating goals (1.1

times per essay). Judging from the result of the average number of moves per essay,

successful personal statement s pay almost twice as much attention to Move 1, Step

1, Stating intellectual interest (0.9 times per essay and 11%, compared to 0.5 times

and 8% for unedited essays). Successful essays also devote more discussion to the appli-

cants’ credentials (3.1 times per essay and 38%, compared to 2 times and 30% for uned-

ited essays), particularly professional qualifications (more than twice as many), and

relevant experiences (1.55 times per essay and 19%, compared to 0.9 times and 14%

for the unedited essays).

Tables 4 and 5 show, respectively, the average number of moves and steps per essay in

both corpora. The ratios of Move 2, Establishing credentials and M ove 3, Desc ribing rel-

evant life experiences in the successful and unedited corpora were, respectively, 3:2 and 5:3,

which mean s the successful essays devoted more atte ntion and discussion to these two

moves than the unedited ones. Meanwhile, the ratio for Move 5, Describing personality

is 1:2, which suggests the unedited essays tended to rely more on explicit description of

personality whereas the successful ones relied more on facts to suggest the applicants’

character.

As Table 5 shows, the ratios of Move 1, Step 1, Desc ribing academic/intellectual interest

and Move 2, Step 3, Discussing professional experiences of the successful and unedited cor-

pora are both 2:1 whereas that of Move 1, Step 3, Discussing personal/family experiences is

1:2. Thi s implies that successful essays considered academic and intellectual interests in

medicine/dentistry as the reason for pursuing the study. In contrast, unedited essays

stressed family events and personal experiences with diseases as the motivation. Table 5

also shows that successful essays had far more discussion about applicants’ professional

experiences in clinical settings than the unedite d ones (1.75 steps vs. 0.7 steps per essay,

or a ratio of 5:2).

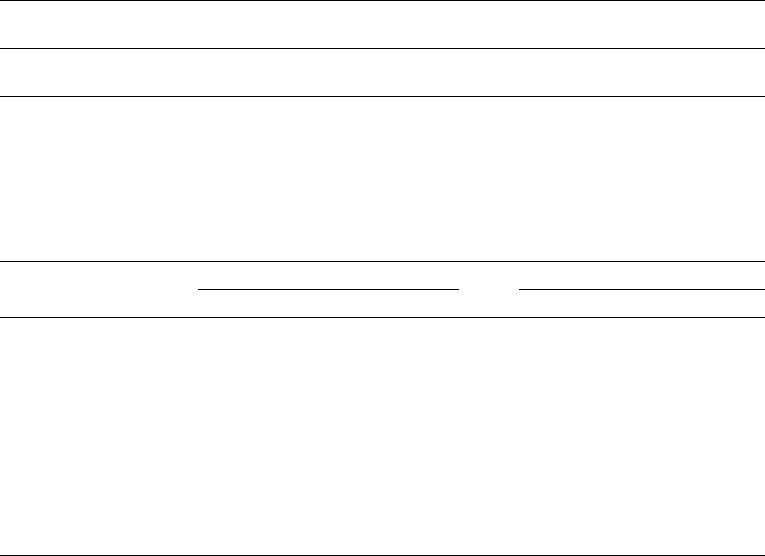

Table 4

Number and ratio of moves in the two corpora

Corpus/moves Move 1 Move 2 Move 3 Move 4 Move 5 Total

Reason

T (A)

a

Credential

T (A)

Life experience

T (A)

Goal

T (A)

Personality

T (A)

Successful (20)

b

41 (2) 62 (3.1) 31 (1.5) 23 (1.1) 8(0.4) 165(8.5)

Unedited (10)

c

20 (2) 20 (2) 9 (0.9) 11(1.1) 7(0.7) 67 (6.7)

S/U ratio

d

1:1 3:2 5:3 1:1 1:2 4:3

a

T: total number of moves in the corpus; A: average number of moves per personal statement.

b

The successful corpus contains 20 personal statements.

c

The unedited corpus contains 10 personal statements.

d

S/U ratio: the ratio of the average number of moves per personal statement in the successful and unedited

corpus.

380 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

4.2.2. T-units for moves

To further explore the differences between the two corpora, T units were counted and

calculated for each move. All the T units in the successful corpus were relevant to the five

moves identified above, whereas only 75% of T units in the unedited corpus were relevant

to the moves (see Table 6). Since the average length of the personal statement was about

the same in the two corpora, this finding suggests the overuse of irrelevant detail and the

lack of attention paid to the rhetorical moves valued by the medical/dental schools in the

unedited essays. One example of an irrelevant detail describes the applicant’s study-abroad

experience without making any explicit connection with the ultimate rhetorical purpose of

the essay.

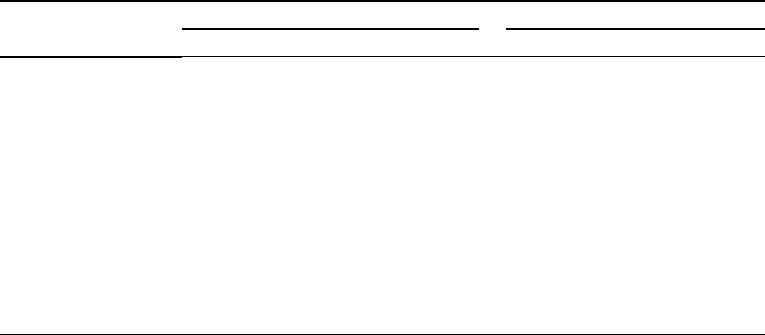

Table 5

Ratio of steps for Moves 1 and 2

Corpus/

steps

M1S1

a

M1S2 M1S3 M2S1 M2S2 M2S3

Interest

T(A)

b

Understand

T (A)

Personal

T (A)

Academic T

(A)

Research

T (A)

Professional

T (A)

Successful

(20)

c

18 (0.9) 16 (0.8) 7 (0.35) 15 (0.75) 12 (0.6) 35 (1.75)

Unedited

(10)

d

5 (0.5) 9 (0.9) 6 (0.6) 7 (0.7) 6 (0.6) 7 (0.7)

S/U ratio

e

2:1 1:1 1:2 1:1 1:1 5:2

a

M: move; S: step.

b

T: total number of steps in the corpus; A: average number of steps per PS.

c

The successful corpus contains 20 personal statements.

d

The unedited corpus contains 10 personal statements.

e

S/U ratio: the ratio of the average number of moves per PS in the successful and unedited corpus.

Table 6

Number of T-units for each move

T unit/corpus Successful (20 PS) Unedited (10 PS)

Total Average Percentage Total Average Percentage

M1

a

: Explaining reason 153 7.7 28 85 8.5 30

S1: Interest 53 2.7 10 4 0.4 1.5

S2: Understanding 58 2.9 10.5 23 2.3 8

S3: Personal/family 42 2.1 7.5 58 5.8 20.5

M2: Credentials 224 11.2 41 70 8.4 25

S1: Academic 61 3 11 17 1.7 6

S2: Research 43 2.2 8 17 1.7 6

S3: Professional 121 6.1 22 36 3.6 13

M3: Relevant experience 63 3.2 11.5 14 1.4 5

M4: Stating goal 46 2.3 8.5 29 2.9 10

M5: Personality 59 3 11 14 1.4 5

Total of relevant T units 545 27.3 100 212 21.2 75

Total number of T units 545 27.3 100 283 28.3 100

a

M: move; S: step; T: total number of T-units in the corpus; A: average number of moves per personal

statement.

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 381

During my junior year in England, I did some serious introspection. My British

friends, though in a friendly manner, challenged my most basic assumptions, and

by doing so, challenged me... Against the background of Englan d’s racial and eco-

nomic crises, and of the Falklands war, my friends and I sharpened our perceptions

of eq uality and civil liberty. In comparing my views with theirs, I strove to distin-

guish opinions that were mere products of my American upbringing from fundamen-

tal convictions about individuals, society, moralit y and justice. My year in England

taught me more than any course on foreign cu ltures or sociology ever could. I left

with a deeper faith in my own beliefs.

A few lines below, the applicant stated, ‘‘I further tested my resolve this past year as

I completed pre-medical courses and conducted a research project in pediatric psychia-

try.’’ He/she devoted long paragraphs to irrelevant details but only one short sentence

to what could have been strong instances of Move 2, Establishing credentials. Because

the study-abroad paragraph took the space of 143 words out of the total of 684 words

(over 1/5 of the length) of this essay, such use of irrelevant details marked a waste of

space that could have been used for sound rhetorical argument and elaboration for

Move 2.

Table 6 also confirmed the finding that Move 2, Establish ing credentials, was the

most developed move in the successful corpus (41% of the total number of T units),

within which pro fessional qualifications (Step 3) stood as the most developed step

(22%). This finding showed that the successful personal statements met the expectations

of the admission committees. As discussed by the two faculty interviewees for this

study, the things that admission committees value most in medical/dental school appli-

cants are evidence of commitment to medicine/dentistry demonstrated by intellectual

interest in and academic/research qualifications related to medicine/dentistry, evidence

of commitment to medicine/dentistry, involvement in community services, and clini-

cal-related experiences. Althou gh all five moves existed in most personal statements,

the qualities closely connected to and valued by the discipline of medicine/dentistry

5

were much more developed in the successful corpus than the unedited one. In terms

of the average number of T-units for each move per essay in the successful and uned-

ited corpora, that of Move 1, Step 1 (Academic interest) is, respectively, 2.7 and 0.4,

that of Move 2, Step 1 (Academic qualifications ) is 3 and 1.7, and that of Move 2, Step

3(Professional experiences) is 6.1 and 3.6 (see Table 6). The decision to focus and elab-

orate on the moves/steps highly valued by the target audience well served the commu-

nicative purpose of the genre, namely, to help the applicant to gain entry to the

discourse community of medicine/dentistry.

In Move 1, Stating reasons for pursuing the study, the three steps took about a similar

number of T units to address those three issues in the successful corpus. In contrast, as

Table 6 shows, the unedited corpus relied more on motivation, or personal experiences

(20.5%), and much less on interest, or related academic/intellectual pursuit (1.5%), as

the reason to study medicine/dentistry. In other words, the unedited corpus stressed per-

sonal experiences rather than academic/intellectual development as the reason for study-

ing medicine. However, as graduate programs expect applicants to demonstrate some

basic understanding about the discipline and academic research (Brown, 2004; Graff &

5

See the findings of my interviews of medical professors above.

382 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

Hoberek, 1999), unedited essays may fail to demonstrate the applicants’ understanding of

the fields due to reliance on personal experience rather than knowledge obtained from aca-

demic and practical work.

One interesting finding for the T-unit analysis is that for Move 5, Describing personality,

although the ratio of the average number of times this move is used per essay is 1:2

between successful and unedited personal statements, the ratio of the average number

of T-units for Move 5 per essay is 3:1.4, or over 2:1 (see Table 6). This finding demon-

strates the importance of the use of T-unit analysis to further examine and supplement

the findings of move analysis: althoug h successful personal statements use fewer moves

in describing the applicants’ personality (Move 5), the average number of T-units used

in those moves is much higher than their unedited counterparts, which implies the use

of more development and elaboration in Move 5, Describing personality, in the successful

personal statements.

4.2.3. Use of stories

Labov and Waletsk y (1967) define a story as one of the methods to recreate a past expe-

rience by matc hing a sequence of verbal paragraphs or passages to a sequence of events

which previously occurred. Because the genre of personal statements discusses one’s past

experiences to establish oneself as a well-qualified applicant for the target program, stories

serve as an important persuasive tool in the genre. Not all stories are directly relevant to

the ultimate goal of the genre, namely, to promote oneself as a competent applicant. Some

stories are told to serve certain purposes, which may eventually help promote the applicant

as a competent candidate. Other stories fail to explicitly state or elaborate on the connec-

tion between those stories and the promotion of the applicant and remain irrelevant to the

rhetorical purpose of the genre. For instance, the personal statement in Appendix A tells

stories about the applicant’s frequent change of school in her early years of education and

the difficulties she experienced in applying to colleges, whic h could have been made highly

relevant to her decision of applying for medical schools through adequate explanation and

good argument. However, little connection is made between the deficienci es in her aca-

demic background and her reason for applying to medical schools. What started as a dis-

advantageous background was never resolved because she did not explain how she

managed to overcome those obstacles and succeed in her academic career. As a result,

her stories remain negative and become irrelevant, even damaging to the rhetorical pur-

pose of her essay.

After the corpora were analyzed and segmented into different moves, stories in all per-

sonal statements were categorized into relevant and irrelevant ones dep ending on whether

they became part of any of the five mo ves, and the T units for all stories were counted in

both corpora. Stories were employed in 12 out of 20 successful personal statements (60%)

and 9 out of 10 unedited personal statements (90%). As Table 7 shows, the average num-

ber of T units devoted to story telling per essay in the unedited corpus was over twice as

many as that in the successful corpus, which demonstrated the unedited essays’ over-reli-

ance on story telling as a persuasive tool. Moreover, whereas successful essays employed

stories highly relevant to the rhetorical purpose of the genre, only half of the stories in the

unedited ones appeared directly relevant to the purpose of app lying for medical/dental

programs.

The unedited personal statements (with 24 stories, or 2.4 stories per essay) relied

much more heavily on story telling than the successful corpus (with 16 stories, or

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 383

0.8 stories per essay) (see Table 8 ). The 16 stories employed in the successful corpus

were used in four moves, with an average of 0.05 per personal statement in Move 1,

Step 1 (Academic interest), 0.2 in Move 1, Step 3 (Personal/family experiences), 0.3 in

Move 2, Step 3 (Professional experiences), 0.1 in Move 3 (Relevant life experiences),

and 0.15 in Move 5 (Personality). In contrast, only 14 out of the 24 stories wer e used

in the moves, with an average of 0.5 move per personal statement in Move 1, Step 3

(Personal/family experiences), 0.4 in Move 2, Step 3 (Professional experiences), and 0.5

in Move 3 (Relevant life experiences). The other 10 stories in the unedited texts

occurred in extraneous materials unrelated to the five moves identi fied in the successful

personal statements. This finding again confirmed the over-reliance of unedited essays

on Move 1, Step 3, Personal/family experiences as the reason for studying medicine/

dentistry instead of stressing the applicants’ intellectual/academic interests in the fields.

Moreover, story telling in the unedited corpus tended to overuse remotely related or

unrelated stories to demonstrate one’s motivation to study medicine/denti stry due to

the applicant’s or family member’s illnesses or death, to stress one’s strong will and

persistence in adversities, or to explain things such as low GPAs, long period of

absence from schools, and lack of relevant academic or professional background.

Instead of quickly resolving the negative experiences to focus on what they learned

Table 7

Number of T-units used in stories

Corpus/T units Successful (20)

a

Successful (20) Unedited (10)

b

Unedited (10)

Total (A)

c

Relevant (A) Total (A) Relevant (A)

Stories 16 16 24 14

T-units 111 (5.6) 111 (5.6) 125 (12.5) 74 (7.4)

a

The successful corpus contains 20 personal statements.

b

The unedited corpus contains 10 personal statements.

c

A: average number of T-units of stories per PS.

Table 8

Number of stories in different moves

Successful (20)

a

Unedited (10)

b

Total Average Total Average

M1: Reason 5 0.25 5 0.5

S1: Interest 1 0.05 0 0

S3: Personal/family 4 0.2 5 0.5

M2: Credentials 6 0.3 4 0.4

S3: Professional 6 0.3 4 0.4

M3: Life experience 2 0.1 5 0.5

M4: Stating goal 0 0 0 0

M5: Personality 3 0.15 0 0

Relevant stories 16 0.8 14 1.4

Stories in the corpus 16 0.8 24 2.4

a

The total number of personal statements for the successful corpus is 20.

b

The total number of personal statements for the unedited corpus is 10.

384 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

from such experiences and to explain why they were capable of undertaking the

demanding task of pursuing medicine/dentistry, the unedited essays tended to dwell

on and give overwhelming information about such negative experiences without making

explicit connection between those experiences and their ultimate communicative pur-

pose: to get admitted to medical/dental schools. As a result, such strategies both wasted

the space of the personal statement and failed to present the applicant positively as

someone who conquered personal adversities and overcame unusual obstacles to

become a qualified candidate for the target program.

One example of an irrelevant story describes the applicant’s father as a farmer without

making connecti on with his/her application to medical schools or the father’s influence on

the applicant’s personality. That story took the space of 224 words out of a total of 730

words (about 1/3 of the essay). Although the applicant later compared physicians to farm-

ers in terms of their long working hours and hard work, the comparison was only remotely

relevant to his rhetorical purpose and did not appear to help strengthen the presentation of

him/herself as a competent candidate for the target program.

I heard the familiar sound of the back door closing gently. My father was return-

ing from driving his dirty, green John Deere tractor in one of our fields. Although

he begins his day at 5:00 a.m. e very morning, he usually returns at around 7:00

p.m. I never really questioned his schedule when I was a child, but as I entered

high school I wondered how my dad could work so hard every day of the week

and still enjoy what he does. He works long hours, becomes filthy from dirt, oil,

and mud, and worst of all, can watch all his hard work go to waste if one day

of bad weather wipes out our crop... His dedication and pride mystified me

throughout high school.

4.2.4. Factors contributing to the differences between the two corpora

One question remaining to be addressed was the cause of the differences in the use of

moves in the two corpora: Why did the unedited essays rely on irrelevant stories? Was it

because of the applicants’ lack of relevant skills and experiences, or was it because of

their ineffective rhetorical strategies and unfamiliarity with the genre? As shown in Table

2, in the successful and unedited corpora, Move 2 was used, respectively, in 100% and

80% of the personal statements, whereas Move 3 was used, respectively, in 100% and

70% of the personal statements. This difference in the use of the two most important

moves in the corpora implied that, compared with successful applicants, the applicants

from the unedited corpus might have fewer profession-related credentials and relevant

life experiences. However, such differences did not justify the over-reliance on stories

(2.4 compared to 0.8 per essay in the successful corpus), the overuse of irrelevant stories

(10 out of 24), or the lack of attention paid to Move 1, Step 1, Academic/intellectual

interests in the unedited corpus (1.5% of T-units compared to 10% in the successful cor-

pus, see Table 7).

As illustrated by the use of irrelevant details in the study-abroad essay, too little atten-

tion was paid to experiences related to medicine/dentistry. The most important informa-

tion about the applicant’s credentials, namely, pre-medical courses and research

experiences, was buried in one short sentence. In addition, only minimal attention was

given to the applicant’s experiences working in medical settings:

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 385

My summer at the Frontier Nursing Service in Kentucky’s Appalachia confirmed

my career choice. It brought me full circle, to life at its beginnings. Although I

thoroughly enjoyed following FNS pediatricians, internists, ob-gyn’s and surgeons,

my adventures as a labor coach were by far the most exhilarating e vents of the

summer.

Instead of using this important clinical experience to illustrate and discuss his/her cre-

dentials, qua lifications, and experiences, the applicant only mentioned and commented on

the experience before moving on to other topics. In contrast, the applicant devoted two

long paragraphs (242 out of a total of 684 words, or over 1/3 of the space) to discussing

his/her interests in journalism and law and his/her study-abroad experiences without mak-

ing explicit connection with the ultimate rhetorical purpose: to apply for medical/dental

programs. Therefore, it is likely that with better genre knowledge and rhetorical decisions,

this applicant could come up with a successful revision that highlights and focuses on his/

her qualifications and experiences related to medicine/dentistry instead of dwelling on

irrelevant ones.

Because of the lack of detai led background information ab out the applicants, it was

hard to come to a solid conclusion as to whether all the other personal statements in

the unedited corpora fell into the same category of ineffective use of rhetorical strate-

gies in composing the admission essay. However, the personal statement analyzed

above did reveal the existence of ineffective rhetorical choices. If enough attention

had been paid to fully develop Moves 2 and 3, the applic ant could have constructed

a highly persuasive argument about him/herself as a competent candidate for the target

program.

The analysis points to both ineffective rhetorical strategies and the relative lack of med-

icine/dentistry-related experiences as the factors contributing to the overuse of irrelevant

details in the unedited corpus. It also suggests the importance of teaching genre conven-

tions and rhetorical principles in helping graduate school applicants to compose strong

personal statements.

4.2.5. Word frequency

While the moves were manually identified and counted, the lexical features were ana-

lyzed through the use of concordance software, Concapp and Concordance. Concor-

dance was used to run the frequency word counts on both corpora to compare the

frequency word list for them. An interesting word is and (443/242, or 22.2 and 24.2

per essay on average in the successful and unedited corpora), which ranks third and

fourth in the two corpora. The use of keyword concordance shows that and is used

in binary phrases, most frequently with two nouns, but also with two verbs and some-

times two adjectives, which confirms Henry and Roseberry’s (2001) finding in their

study of application letters as a promotional genre. Focusing on the use of binary

nouns in the two co rpora, my analysis showed that many cases of the use of and serve

as examples to demonstrate the applicant’s qualifications, relevant experiences, and

desire to pursue medicine or dentistry as a career. The use of binary nouns in the

two corpora was somehow different, however, with more medicine/dentistry-related

phrases used in the successful corpus (18 out of a total of 28, or 64%) and both a

larger number of binary noun phrases and much lower percentage of medicine/

dentistry-related binary noun phrases used in the unedited corpus (9 out of 43, or

386 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

21%).

6

The overuse of noun phrases unrelated to medicine/dentistry suggest ed the inclu-

sion of more irrelevant information in the unedited corpus, which again, confirmed the

finding about the lack of focus on medicine/dentistry-related issues in the unedited

corpus.

5. Discussion

Applicants are faced with a dilemma when applying to medical/dental schools: they

write personal statements to seek entry into the disciplinary community of medicine/den-

tistry. As outsiders to the community, they are expected to say something that is of interest

and relevant to the field of medicine/dentistry and to demonstrate their previous involve-

ment with and understanding of the field. However, such expectations are assumed rather

than explicitly stated. Surrounded by such ambiguities, tensions, and misconceptions,

applicants suffer from this ‘‘don’t ask, don’t tell’’ feature of the application process (Graff

& Hoberek, 1999). In other words, the genre of personal statements becomes a mystified

and occluded genre to the applicants: they have no adequate knowledge of the context,

their audience, and the communicative purpose. Because occluded genres (Askehave &

Swales, 2001; Swales, 1996), for instance, manuscript reviews (Chilton, 1999) and recom-

mendation letters (Precht, 1998), are hidden from public record, hard to obtain, and

understudied, little guidance exists on how to write these texts to meet their multiple

obscure communicative purposes. The person al statement, as one occluded genre, may

present extra barriers for writers when they have to cross cultural, disciplinary, and

linguistic boundaries.

This study serves to bridge the gap discussed above by examining the contexts and

the rhetor ical/linguistic features of the genre of personal statements. It also contributes

to the existing understanding of promotional genres by expanding the application of

move analysis from job application letters to personal statements. Personal statements

share something in common with other promotional genres such as job application let-

ters, namely, the use of the move to promote the candidate (Henry & Roseberry,

2001). Job application letters use other moves

7

mainly to inform the readers of the

applicant’s interest in and condition for applying for the position as well as the referees

and materials supporting his or her application (Henry & Roseberry, 2001, p. 159).

However, the function and development of the rhetor ical move of self-promotion in

personal statements are very different from that in job application letters. Although

both genres of documents are submi tted together with resumes in the application pro-

cesses, they serve different communicative purposes and function differently as rhetor-

ical documents. The promotion move in job application letters serves to highlight

relevant experiences and skills and to obtain a job interview. As one of the first doc-

uments an employer will read in the job search processes, the application letter supple-

ments the information in the resume and helps determine whether the employer will

give the applicant an interview or simply throw the application materials into the trash-

can. Anothe r important feature of the genre is the short amount of time it usually

6

Please contact the author for a complete list of the binary phrases.

7

Opening, Referring to a Job Advertisement; Offering Candidature; Stating Reasons for Applying, Stating

Availability, Stipulating Terms and Conditions of Employment, Naming Referees, Enclosing Documents, Polite

Ending, and Signing off.

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 387

receives from its audience: employers usually scan a resume in 10–30 seconds, and in

most cases they read the cover letter only when the resume does not give them enough

information to offer or decline an interview. Even if cover letters get read, they only

receive 10–20 seconds of review (Donlin; ‘‘Cover letters,’’ 23). In contrast, as one of

the key components in the application package, the personal statement aims to per-

suade the admission committee to offer admission and/or financial support to the

applicant by demonstrating the applicant’s academic, intellectual, and/or professional

qualifications as well as his/her unique personality through the use of narratives, evi-

dence, and examples. Unlike the job application letter, it works as a vital part of the

application package rather than a supplementary one. Because most applicants have

high GPAs, standard test scores, and good recommendations, they need to capture

the reader’s attention and to distinguish themselves from the pool of applicants and

establish their credentials through the description of relevant life experiences and unique

personality instead of just listing them.

Job application letters employ five strategies in the move Promoting the Candidate to

present selected information about the applicants’ qualifications and abilities relevant to

the desired position (Henry & Roseberry, 2001). Rather than using examples to illustrate

the applicant’s skills, these five strategies focus more on highlighting relevant skills and

abilities and stating from which jobs or experiences such abilities are acquired. Therefore,

this promotional move in job applic ation letters tends to look more like those in the uned-

ited personal statements rather than those in the successful ones because of its reliance on

claims of abilities and qualifications rather than good use of narratives to support such

claims.

Unlike job application letters, which use different moves both to inform the audience

and to promote the job candidate, personal statements devote all the five moves to

accomplishing the overall rhetorical task of promoting the applicant as a competent

candidate for the target program. The use of narratives of personal experiences to illus-

trate one’s acad emic, research, and professional qualifications replaces the listing of rel-

evant skills and abilities in job application letters to promote the candidates as

competent applicants. As the two interviewees of this study stressed, personal state-

ments are evaluated as the evidence of the applicant’s commitment to and involvement

in the field of medicine/dentistry. Therefore, description and discussion of first-hand

experience in medicine/dentistry-related settings or human service settings are expected

and valued by the admission committees rather than empty claims of abilities. More-

over, providing the opportunity for app licants to stress their strengths, interest in the

fields, and individuality, the personal statement serves as the only place in the applica-

tion where applicants can personalize their application package and present themselves

as both unique individuals and competent candidates. In other words, job application

letters are more informative whereas personal statements are more descriptive and per-

suasive as promoting genres.

In additi on to the theoretical contributions to genre knowledge, this study has prac-

tical pedagogical implications for writing courses for native and non-nativ e speakers.

Genre-based analysis offers insights that can be applied in the teaching of ESL,

EAP, and ESP courses. It serves as a useful tool for a holistic teaching methodology,

which should be understood as a heuristic description rather than prescription (Bhatia,

1993; Swales, 1990). Through the use of specialized, genre-specific corpora, this study

examined how language is used in particular contexts for particular purposes or in

388 H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392

particular genres, thus contributing to the knowledge for both writing instruction and

professional understanding. The rhetor ical move structure delineated in this study

helps to demystify the writing of personal statements and other related promotional

genres and facilitate the creation of persuasive documents. The rhetorical structure

revealed by move analysis can be presented in writing classrooms to enhance students’

understanding of the genre of personal statements. The move structure can be used to

explicitly teach the disciplinary contexts, audience expectations, and communicative

purposes surrounding the graduate school application processes and to demystify

the writing process. It can also serve as a heuristic tool in writing personal statements

when applicants are asked to use the moves to guide their understanding and analysis

of both the communicative purposes and audience expectations of the target program.

The awareness of the convention of personal statements can empower potential appli-

cants by helping them to think early and start preparing early in the process, thus

greatly enhancing their chance of getting admitted to the target program. Finally,

as a guideline, the move structure provides some systematic assistance to less experi-

enced applicants to meet the expectations of the discourse community they seek to

enter. In short, this study contributes to the understanding of genre knowledge by

defining and describing the rhetorical and lexical featu res of personal statements as

a genre.

6. Limitations and suggestions for future resear ch

This study examined and described the features of graduate applica tion letters to med-

ical/dental programs. Five functional moves were identified: Explaining the reason to pur-

sue the proposed study, Establishing credentials, Describing relev ant life experience, Stating

career goals, and Describing personality. However, there are some limitations in the design

of this study due to practical constraints. Because of the difficulty to get access to private

documents such as the personal statement, the author could only use personal statements

available on public websites. The first drawback is the limited size of the corpus, for the

study of 30 personal statements can only lead to tentative conclusions instead of applicable

generalizations. The second limitation is the lack of cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural

comparison of such genre in this study due to limited sources . Future research should

examine personal statements written in different disciplinary and cultural settings and

make comparison to find out possible disciplinary and cultural influence on personal state-

ment writing.

To conclude, this descriptive study seeks not to confirm or reject hypotheses but rather

to generate hypotheses and stimulate further research for the study of the personal state-

ment as a genre. Therefore, all the findings about personal statements for medical/dental

schools should be tested by future research and compared with the move structure in per-

sonal statements for other graduate programs.

Acknowledgements

I thank Kai Zhang and Xiaoye You, respectively, for their kind help and suggestion at

the research and writing stages of this project.

H. Ding / English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 368–392 389

Appendix A. M ove analysis of a sample unedited personal statement

The original personal statement Moves

All of my life I have been a city girl, but I moved to Santa

Rosa when I was about 13. Up until I was about 16, I

lived there permanently. I used to switch back and forth

from parent to parent all of the time. When I first

started high school, I went to Piner High and, in my

junior year, I went to Montgome ry and, from there, to a

continuation school. I am currently now back at Piner. I

had to basically kick and scream to get back into my

regular high school – as you can see there is some drama

behind the scene.

Story about

education,

remotely

relevant

Applying to college was not an easy thing for me. First, I

had to make the choice of whether I wanted to go or not.

After I went to SMYSP, I knew I wanted to be there –

my big problem was that I did not think I was good

enough. No one in my family even has a high school

diploma. At first I was going to just sett le for a junior

college, but with the pushing of my pals from Stanford,

I decided not to sell myself short.

Personal

history –

academic

background,

not directly

relevant

I really had no confidence in myself. I did not feel so

smart.

Move 5:

describing

personality

I kept telling myself that my chances for getting into

college were slim because I went to a continuation