Ozlem Kazan Kizilkurt

1

, Taha Kizilkurt

2

, Medine Yazici Gulec

3

, Ferzan Ergun Giynas

3

,

Gokhan Polat

2

, Onder Ismet Kilicoglu

2

, Huseyin Gulec

3

DOI: 10.14744/DAJPNS.2020.00070

Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and

Neurological Sciences 2020;33:109-119

How to cite this article: Kizilkurt OK, Kizilkurt T, Yazici Gulec M, Ergun Giynas F, Polat G, Kilicoglu OI, Gulec H. Quality of life after lower extremity

amputation due to diabetic foot ulcer: the role of prosthesis-related factors, body image, self-esteem, and coping styles. Dusunen Adam The

Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2020;33:109-119.

Quality of life after lower extremity amputation due

to diabetic foot ulcer: the role of prosthesis-related

factors, body image, self-esteem, and coping styles

1

Uskudar University, Department of Psychiatry, NPIstanbul Neuropsychiatry Hospital, Istanbul - Turkey

2

Istanbul University, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Istanbul - Turkey

3

University of Health, Sciences Erenkoy Mental Research and Training Hospital, Istanbul - Turkey

Correspondence: Ozlem Kazan Kizilkurt, Ahmet Tevfik Ileri Street No:18, 34768 Umraniye/Istanbul - Turkey

E-mail: [email protected]

Received: December 19, 2019; Revised: February 03, 2020; Accepted: March 30, 2020

ABSTRACT

Objective: The purpose of this study was to identify clinical and psychosocial factors that predict an individual’s subjective

quality of life after having undergone a lower limb amputation secondary to diabetic foot ulcer.

Method: The study sample comprised 65 patients who underwent amputation because of an infected diabetic foot ulcer. Short

Form 36, The Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scale, Coping Attitudes Evaluation Scale, Multidimensional Scale of

Perceived Social Support, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and Amputee Body Image Scale were administered as questionnaires.

Stepwise linear regression analysis was conducted to assess the factors predicting quality of life.

Results: Quality of life was negatively correlated with depression, anxiety, body image, activity limitation, and dysfunctional

coping strategies and positively correlated with perceived social support, satisfaction with prosthesis, self-esteem, and

problem-focused coping style. Regression analysis showed satisfaction with prosthesis and body perception, problem-focused

coping strategies, dysfunctional coping strategies, and self-esteem to be the factors with the highest predictive power for the

physical component of quality of life, while body perception, problem-focused, and dysfunctional coping strategies were the

strongest predictors for the mental component of quality of life.

Conclusion: Impaired body image and self-esteem, less usage of problem-focused and high usage of dysfunctional coping

strategies, in addition to low satisfaction with the prosthesis were the strongest predictors for poor quality of life. Factors

associated with better quality of life after the amputation were investigated in this study, which may support future

development of post-amputation rehabilitation strategies for lower limb amputees.

Keywords: Amputation, body image, coping strategies, diabetes, self-esteem

RESEARCH ARTICLE

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic foot ulcers are often considered complications

requiring long periods of challenging treatment;

additionally, they may cause anxiety due to the potential

necessity of amputation (1). Although the psychological

status of mobile amputees is known to be better than

that of diabetic foot ulcer patients, extremity amputation

Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2020;33:109-119110

remains an important medical issue and the

psychosocial adaptation of individuals after extremity

amputation involves significant difficulties (2). It is

generally accepted that lower extremity complications

due to diabetic foot ulcer negatively affect a person’s

quality of life, predisposing the patient to psychiatric

symptoms (1,3,4). Depression and anxiety symptoms

that emerge after amputation have been reported to

make significant contributions to a reduced quality of

life (5). In addition, it is reported that although

depression and anxiety are relatively high in a period of

up to 2 years post-amputation, they appear to decline

thereafter to general population norms (6).

After amputation, patients can experience a distorted

body image, decreased self-esteem, social isolation, and

increased dependency on others (7). During the post-

amputation period, perceived social support, adaptation

to the prosthesis, amputation type, presence of phantom

and stump pain, self-esteem, and body image issues are

among the factors reported to affect quality of life and

psychosocial functionality significantly (8,9). Different

coping strategies have been shown to have different

outcomes on adaptation after amputation. Problem-

focused strategies are associated with positive

psychosocial adaptation (10), while emotion-focused

and passive strategies are associated with negative

psychosocial outcomes (11).

We believe that evaluating and detecting the

conditions negatively affecting individuals’ quality of

life after amputation are important in ensuring

appropriate rehabilitation practices. Our first

hypothesis was that the presence of stump and

phantom pain or additional medical disease and the

level and type of prosthesis would have an impact on

quality of life. Secondly, we assumed that depression

and anxiety scores, body image, self-esteem, coping

methods, perceived social support, as well as post-

prosthetic activity restriction and satisfaction with

prosthesis will be factors associated with quality of life.

According to this hypothesis, we predicted that people

with high depression and anxiety scores, distorted

body image, low self-esteem, and poor perceived social

support would have lower quality of life. In addition,

we thought that the quality of life of patients with

activity restriction after receiving the prosthesis who

were not satisfied with the device would be worse off.

We hypothesized that the use of problem-focused

coping methods would affect the quality of life

positively and the use of emotion-focused and

dysfunctional coping methods would have a negative

impact. A number of studies published in the past

evaluated difficulties incurred in the post-amputation

period. These studies typically included individuals

who underwent amputation for various reasons.

Considering the fact that individuals with diabetic foot

ulcers are a homogeneous group with similar

characteristics and a quality of life that is lower than in

the normal population due to the nature of the disease,

we aimed to evaluate the factors affecting the quality

of life of individuals undergoing lower extremity

amputation due to diabetic foot ulcer. We investigated

the effects of clinical variables, perceived social

support, coping attitudes, self-esteem, body image,

and prosthesis adaptation on the quality of life of these

patients.

METHOD

Participants

Patients being followed up at the prosthesis clinics were

invited to participate in the study with a consecutive

approach for 6 months. In total, 65 patients who had

undergone amputation because of an infected diabetic

foot ulcer were included in the study and face-to-face

interviews were performed by the psychiatrists who

conducted the study and orthopedic specialists who

performed clinical follow-up. Measurements were

administered 1-8 years (median 3 years) after fitting the

prosthesis. All prostheses used by patients were of the

socket type. Exclusion criteria were mental retardation,

serious mental conditions that would prevent

participants from being interviewed and completing the

scales (e.g., serious psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder,

organic mental disorder), and physical illnesses at level

IV and above according to the American Society of

Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System

(12). The sample size was calculated using the G-power

3.1 program by Heinrich Heine University, Dusseldorf.

A total of 64 participants were needed for a large effect

size of 0.30, a significance level of 0.05, a verification

power (1-β) of 0.8, and 10 predictive variables

(depression, anxiety, body image, self-esteem, perceived

social support, problem focused-emotional focused and

dysfunctional coping mechanisms, activity restriction,

satisfaction with prosthesis). Ten independent variables

predicted to have an impact on quality of life were

determined in the light of the earlier literature

investigating factors affecting quality of life.

Ethical considerations

All participants gave written informed consent to be

included in the research. Ethical approval for this study

Kazan Kizilkurt et al. Quality of life after lower extremity amputation due to diabetic foot ulcer: the role of prosthesis-related factors, body image... 111

was obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee of

the University of Health Sciences’ Erenkoy Mental

Research and Training Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables were evaluated with a data

form prepared specifically for this study.

Short Form 36 (SF-36): SF-36 was used to assess the

patients’ quality of life and to measure an individual’s

state of health based on 8 dimensions: physical function,

pain, role limitations due to physical problems, general

perception of health, role limitations due to emotional

problems, social function, energy/vitality, and mental

health. For each parameter, higher scores indicate a

better health state (13). Two summary measures were

further calculated from the item scores using the

procedures recommended by the developers: a Physical

Component (PCS) and a Mental Component (MCS)

score (14). The first four dimensions of the scale form

part of the PCS score and the last four dimensions

comprise the MCS score (15). The reliability and validity

of the scale in the Turkish population were confirmed

by Kocyigit et al. (16).

The Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis

Experience Scales (TAPES): TAPES is a multifactorial

assessment tool for lower limb amputees fitted with

prosthesis developed by Gallagher and MacLachlan

(17). It is a 54-item self-report questionnaire comprising

nine factor-analytically derived subscales assessing

three dimensions of psychosocial adjustment (general

adjustment, social adjustment, and adjustment to

limitation), three dimensions of activity restriction

(functional restriction, social restriction, and athletic

activity restriction), and three dimensions of prosthesis

satisfaction (weight satisfaction, functional satisfaction,

and esthetic satisfaction). In addition, phantom and

residual limb pain experiences and other medical

problems unrelated to the amputation are assessed. In

this study, TAPES was used to evaluate the activity

restriction after prosthesis fitting, satisfaction with the

prosthesis, and residual stump and phantom pain. The

reliability and validity of the TAPES in the Turkish

population were studied by Topuz et al. (18).

Coping Attitudes Evaluation Scale (COPE): COPE,

used to assess patients’ coping attitudes, was developed

by Carver et al. (19). Reliability and validity of the

COPE scale in the Turkish population were assessed by

Agargun et al. (20). COPE is a 60-item scale with 15

subscales. Five of these 15 subscales represent problem-

focused attitudes: active coping, planning, suppression

of competing activities, restraint coping, and seeking of

instrumental social support; 5 represent emotion-

focused coping attitudes: seeking of emotional social

support, positive reinterpretation, acceptance, humor,

and turning to religion; and the remaining five subscales

represent dysfunctional coping attitudes: focus on and

venting of emotions, behavioral disregard, substance

use, denial, and mental disregard (19,21). Carver et al.

(19) stated that it is not appropriate to divide coping

strategies into only problem-focused and emotion-

focused. They criticized researchers for viewing factors

other than problem-focused coping as variations on

emotion-focused coping, stating that the “nature of this

diversity would seem to deserve further scrutiny.” In

addition, while developing the COPE scale, they pointed

out that some of the strategies that had been included in

emotion-focused coping strategies so far were more

incompatible, making it appropriate to consider them as

dysfunctional coping methods (19). Therefore, in our

study we evaluated coping methods under three

headings as problem-focused, emotion-focused, and

dysfunctional coping strategies (22,23).

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social

Support (MSPSS): The MSPSS is a 12-item scale

measuring three sources of perceived support, namely,

family, friends, and significant other. It is a brief, easy-

to-administer self-report questionnaire containing

twelve items rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale

with scores ranging from ‘very strongly disagree’ (1) to

‘very strongly agree’ (7). The MSPSS has proven to be

psychometrically sound in diverse samples and to have

good internal and test-retest reliability and robust

factorial validity (24). A reliability and validity study of

the MSPSS in the Turkish population was conducted by

Eker (25).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES): The RSES

scale developed by Rosenberg (26) consists of 12

subcategories. Only the first subscale including 10 items

was used in this study to assess general personal self-

esteem. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale

from 0 (strongly agree) to 3 (strongly disagree), producing

a cumulative score from 0 to 30, whereby high mean

scores (computed) indicate high self-esteem (26). The

reliability and validity of the scale in the Turkish

population was examined by Cuhadaroglu et al. (27).

Amputee Body Image Scale (ABIS): The ABIS is a

5-point Likert-type self-assessment scale that contains

20 questions. Items in the scale query an individual’s

perceptions and experiences regarding her/his own

body. High scores represent a distortion of body image

(28). The reliability and validity of the ABIS in the

Turkish population was confirmed by Safaz et al. (29).

Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2020;33:109-119112

Patient Health Questionnaire-Somatic, Anxiety,

and Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-SADS): Patients’

somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were

assessed with the PHQ-SADS evaluation form. The

PHQ-SADS is a self-report questionnaire, consisting of

a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) subscale that

assesses nine domains of major depressive disorder and

a General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) subscale that

rates seven basic symptoms of anxiety (30). The

reliability and validity of the PHQ-SADS in the Turkish

population was studied by Yazici Gulec et al. (31).

Statistical Analysis

Mean, standard deviation, median, and the lowest and

highest frequency and percentage values were used for

descriptive statistics and the distribution of the variables

was analyzed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Factors affecting quality of life after having undergone a

lower limb amputation were collected from the literature

and examined in this study. The Mann-Whitney U test

was performed to analyze the differences in quality of

life for categorical independent variables including

stump pain, phantom pain, level of the prosthesis used,

and comorbid medical diseases. Spearman correlation

analysis was carried out to assess the relationship

between qualitative independent data. Stepwise linear

regression analysis was conducted to assess the factors

predicting the quality of life. In all models where the

MCS and PCS scores were treated as dependent

variables, factors correlated with quality of life were

treated as independent variables. The analyses were

performed using SPSS version 22.0.

RESULTS

Sixty-five patients were included in the study, of whom

41.5% were women, 9.2% were single, 78.5% were

married, 12.3% were either divorced or widowed. Of

the patients, 38.5% were primary school graduates,

35.4% had completed middle school and 26.2% had a

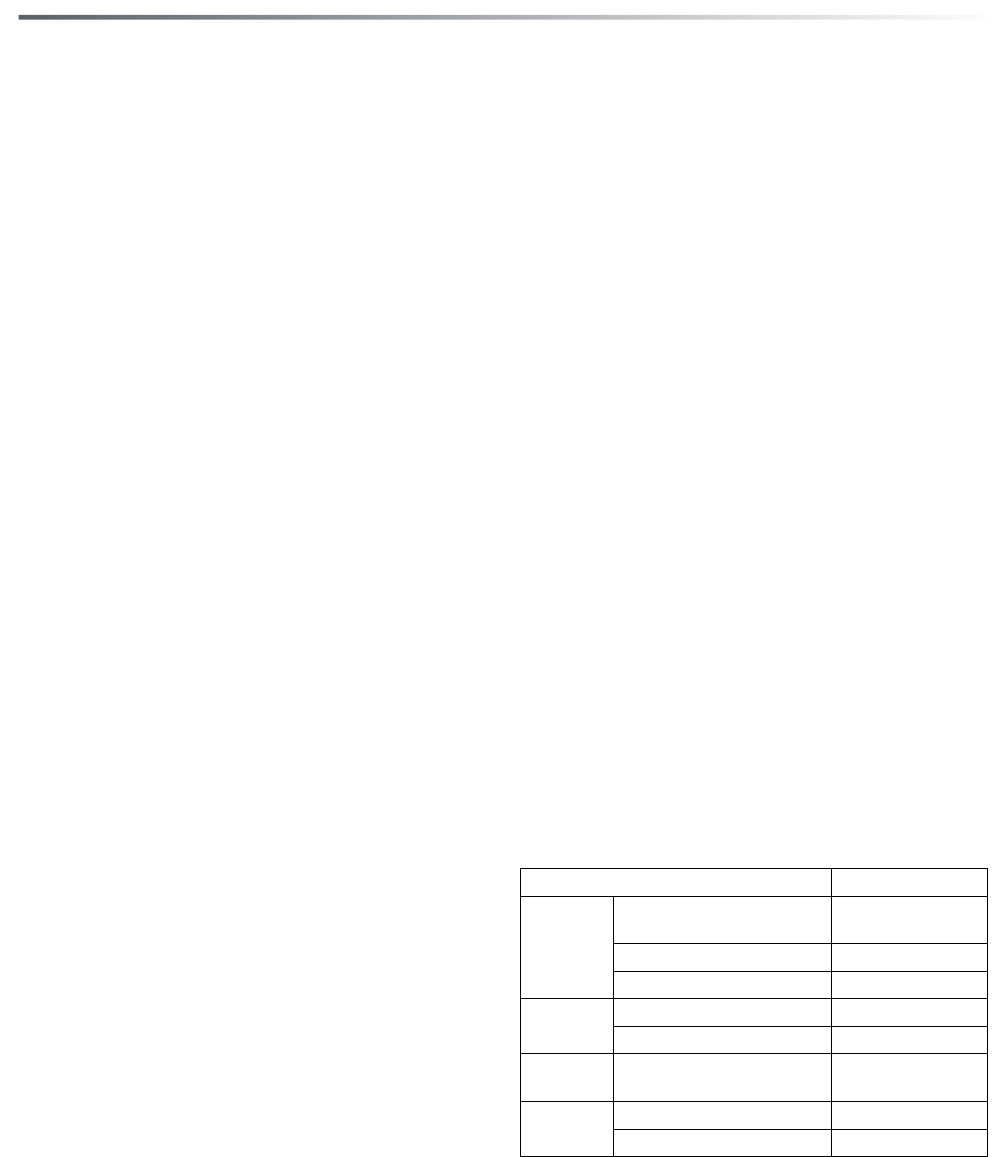

high school degree. Tables 1 and 2 report clinical data

and descriptive statistics for the quality of life

assessments. When the norm values in the quality of

life domains were evaluated for the Turkish population

(32), all domains in our study were below the average

(Table 2).

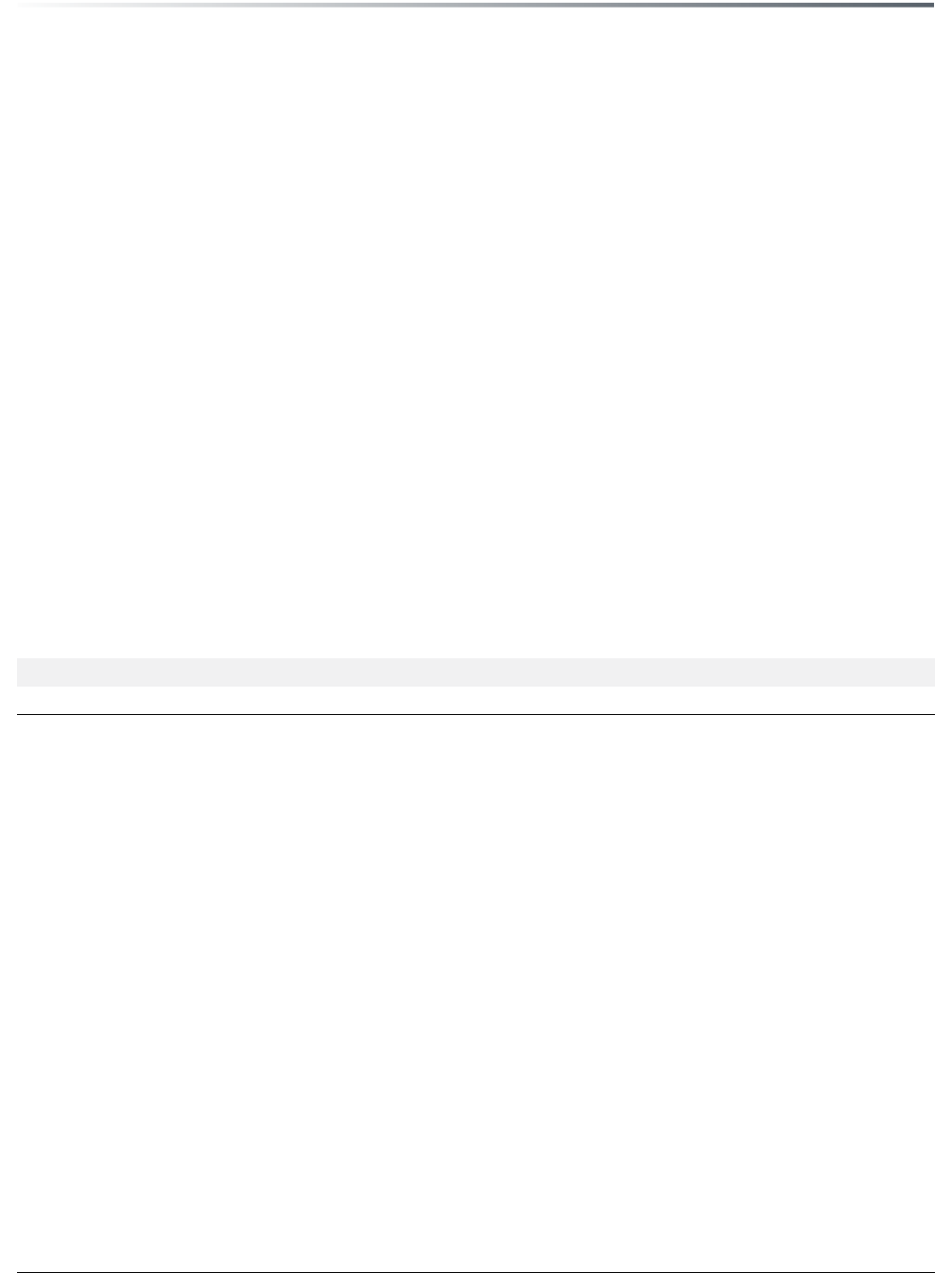

Table 1: Descrptve statstcs of clncal features, RSES, ABIS, MSPSS, GAD-7, PHQ-9, and TAPES scores (n=65)

Median Mean SD n %

Age 58.0 57.8 7.6

DM duration (Years) 8.0 9.4 4.9

GAD-7 (Anxiety) 6.0 6.0 4.7

PHQ-9 (Depression) 8.0 8.7 6.8

RSES (Self-esteem) 18.0 18.7 5.4

ABIS (Body image) 56.0 56.2 12.1

MSPSS

MSPSS family 22.0 21.1 6.1

MSPSS friends 19.0 18.2 6.8

MSPSS others 16.0 16.9 6.6

MSPSS total 58.0 56.2 17.6

Prosthetic duration (Years) 3.0 3.6 2.04

Prosthesis type

Below the knee 48 73.8

Above the knee 17 26.2

Having stump pain 16 24.6

Having phantom pain 17 26.2

TAPES Part 1

Activity restriction 24.0 23.3 5.9

Satisfaction with the prosthesis 35.0 33.3 8.4

SD: Standard deviation, DM: Diabetes mellitus, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7, ABIS: Amputee Body Image Scale,

RSES: Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale, MSPSS: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, TAPES: Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales,

PCS: Physical component summary, MCS: Mental component summary

Kazan Kizilkurt et al. Quality of life after lower extremity amputation due to diabetic foot ulcer: the role of prosthesis-related factors, body image... 113

Comparative analysis (Mann-Whitney U test) was

first established statistically. The patient group was

divided into two subgroups according to the presence or

not of phantom and stump pain. A significant difference

in the PCS and MSC scores was found between groups:

PCS and MCS scores in the subgroup suffering from

stump and phantom pain were significantly lower than

those in the patient group without such pain (p<0.01).

Then, the patient group was divided into two subgroups

according to the level of the prosthesis. PCS and MCS

scores in the group having a prosthesis fitted above the

knee were found to be significantly lower than scores in

the group with a prosthesis fitted below the knee

(transtibial amputation) (p<0.01). In addition, 40% of

patients had comorbid medical diseases. PCS (p=0.011)

and MCS (p=0.006) scores showed significant

differences between groups with and without a

comorbid disease, and the life quality scores in the

group with comorbid medical diseases were lower.

After comparative analysis, correlation analysis

(Spearman analysis) was used for numerical variables.

No significant correlations were found between age,

duration of diabetes diagnosis, years of using prosthesis,

and PCS and MCS scores (p>0.05). A negative

correlation was observed between PHQ-9 and also

GAD-7 scores and PCS and MCS scores separately.

Higher depression scores were associated with lower

PCS and MCS scores (p<0.001). Similarly, PCS and

MCS scores showed a decrease as anxiety scores

increased (p<0.001). A negative correlation was

observed between body image and quality of life, and

higher ABIS scores were associated with lower PCS and

MCS scores (p<0.001). In addition, it was found that

perceived social support and self-esteem scores

correlated positively with quality of life scores. Higher

MSPSS scores (p<0.001) and RSES scores (p<0.001)

were associated with higher PCS and MCS scores. In

addition, as activity limitation increased, quality of life

was negatively affected. A significant positive correlation

was noted between the total score for prosthesis

satisfaction and quality of life (p<0.001). No significant

correlations were found between the emotion-focused

coping score and the quality-of-life subscales (p>0.05).

In contrast, it was observed that quality of life scores

were positively correlated with problem-focused coping

strategies scores (p<0.001) and negatively related with

dysfunctional coping strategies scores (p<0.001). The

quality of life was better with increasing use of problem-

focused coping strategies, while greater use of

dysfunctional coping strategies was associated with

poor quality of life (Table 3).

Independent effects of the predictors associated with

quality of life according to correlation analysis were

examined using a multivariate regression model. In two

separate analyses with PCS and MCS scores as

dependent variables, PHQ-9, GAD-7, MSPSS, ABIS,

RSES, problem-focused and dysfunctional coping

strategies, activity restriction, and satisfaction with

prosthesis were taken as independent variables.

Regression analysis showed that patients’ PCS scores

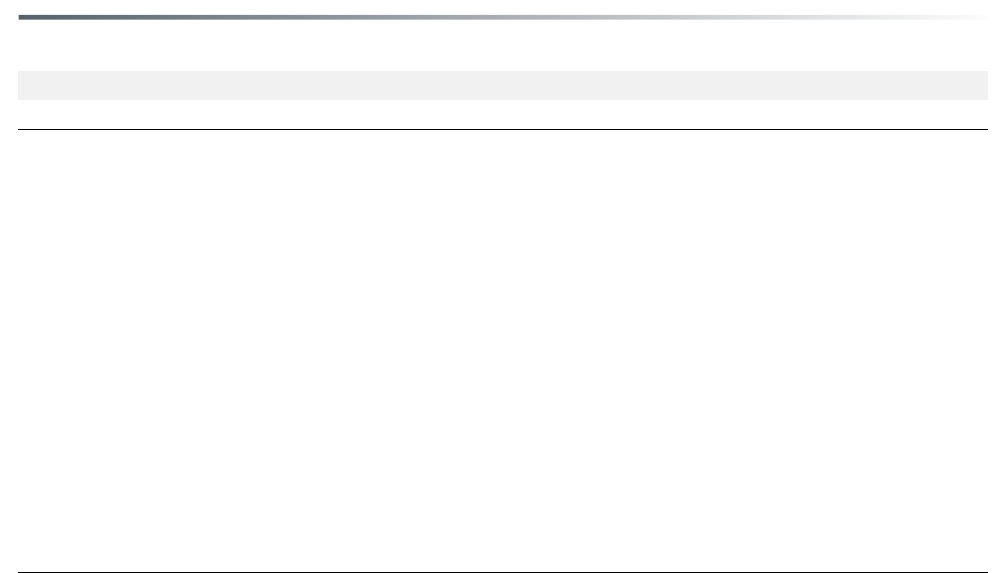

Table 2: Descrptve statstcs of COPE and SF-36 scores (n=65)

Median Mean SD

COPE

Problem-focused coping 57.0 56.2 8.5

Emotion-focused coping 56.0 56.6 7.4

Dysfunctional coping 56.0 53.3 10.9

SF-36

Physical functioning 50.0 45.3 33.1

Role limitations (physical problems) 25.0 38.5 40.3

Role limitations (emotional problems) 33.3 36.9 41.7

Energy 50.0 49.6 17.5

Mental health 52.0 51.4 16.1

Social functioning 62.5 59.8 20.3

Pain 67.5 65.7 20.3

General health status 45.0 47.8 5.5

PCS 39.1 39.3 9.1

MCS 39.6 39.8 8.9

SD: Standard deviation, COPE: Coping Attitudes Evaluation Scale, SF-36: Short Form-36, PCS: Physical component summary, MCS: Mental component summary

Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2020;33:109-119114

were significantly correlated negatively with ABIS

scores (β=−0.34, p=0.01) and dysfunctional coping

strategies (β=−0.43, p<0.001), positively with

satisfaction with the prosthesis (β=0.27, p=0.01), RSES

scores (β=0.27, p<0.001), and problem-focused coping

strategies (β=0.23, p=0.01), and the combination of

these factors explained 78% of the variability of the

patients’ PCS scores. The regression model for the MCS

scores correlated negatively with ABIS scores (β=−0.32,

p=0.01) and dysfunctional coping strategies (β=−0.47,

p<0.001) and positively with problem-focused coping

strategies (β=0.31, p<0.001). These three significant

variables explained 80% of the variance observed in the

patients’ MCS scores (Tables 4,5).

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to investigate the

factors affecting the quality of life of patients

undergoing amputation of a lower extremity following

complications arising from diabetes mellitus. Our

results were consistent with those of previous studies

conducted in this field (33) and revealed that both the

physical and mental quality of life after lower limb

amputation were reduced compared to the normal

population (32). The results of our study supported our

first hypothesis: The presence of stump and phantom

pain, additional medical diseases, and the level of

prosthetics were found to be factors related to quality

of life. With regard to our second hypothesis, we have

seen that many aspects are supported by the results of

our study. It was observed that depression and anxiety

scores, body perception, self-esteem, perceived social

support, problem-focused and dysfunctional coping

strategies, post-prosthetic activity restriction, and

prosthetic satisfaction were related to quality of life.

According to our results, the only factor that differed

from our hypothesis was the use of emotion-focused

coping strategies, which was not found not be related to

the quality of life. Regression analysis was performed to

Table 3: Spearman correlaton analyss between PHQ-9, GAD-7, ABIS, RSES, MSPSS, COPE subgroups, Actvty

restrcton, Satsfacton wth the prosthess scores and PCS and MCS scores

PHQ-9 GAD-7 ABIS RSES MSPSS Problem- Emotion- Dysfunctional Activity Satisfaction

total focused focused Coping restriction with the

coping coping prosthesis

PCS

r -0.51 -0.49 -0.72 0.29 0.38 0.43 -0.07 -0.56 -0.69 0.61

p <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.53 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001

MCS

r -0.59 -0.49 -0.61 0.53 0.48 0.57 0.04 -0.62 -0.63 0.54

p <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.76 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001

Spearman correlation analysis, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7, ABIS: Amputee Body Image Scale, RSES: Rosenberg Self

Esteem Scale, MSPSS: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, PCS: Physical component summary, MCS: Mental component summary

Table 4: Stepwse multple regresson analyss model of the varables that affect MSC scores (p<0.05)

MCS

B t p R² Adjusted R² F

Model 1

ABIS -5.58 -10.36 <0.001 0.63 0.62 107.40

Model 2

ABIS -3.71 -6.23 <0.001 0.73 0.73 85.63

Dysfunctional coping -3.26 -4.92 <0.001

Model 3

ABIS -2.27 -3.67 0.01 0.79 0.79 80.47

Dysfunctional coping -3.67 -6.25 <0.001

Problem focused coping 3.09 4.41 <0.001

Stepwise Multiple Regression Analysis, ABIS: Amputee Body Image Scale, MCS: Mental component summary

Kazan Kizilkurt et al. Quality of life after lower extremity amputation due to diabetic foot ulcer: the role of prosthesis-related factors, body image... 115

observe the predictive effects of these related factors,

and body image, problem-focused and dysfunctional

coping strategies, self-esteem, and satisfaction with the

prosthesis were all observed to have a significant effect

on the physical component of quality of life.

Furthermore, body image and problem-focused and

dysfunctional coping strategies were found to be the

factors with the highest predictive power for the mental

component of quality of life.

Firstly, it was observed that patients with stump and

phantom pain had reduced quality of life. In the

literature, in addition to studies showing that phantom

pain and stump pain are not an important determinant

for the quality of life (34), there are also articles arguing

that these two types of pain have important effects on

both physical and mental quality of life (35,36). It is

known that stump pain causes activity restriction as a

result of negative effects on mobility and rehabilitation

(6). We think that this activity restriction, which is an

important factor for life quality, may explain the

importance of stump pain for quality of life. In addition,

phantom limb pain in some patients may gradually

disappear over the course of a few months or up to one

year even when untreated, but some patients suffer from

phantom limb pain for decades (37). The average period

of prosthesis use in our sample group was three years.

We found no relationship between the duration of

prosthesis use and quality of life. This result suggests

that phantom pain may have an impact on the quality of

life even after years have passed since fitting the

prosthesis. We think that the negative effect of phantom

pain on quality of life in patients with long-term

prosthesis use can be evaluated as an important data

point in the rehabilitation process. In our study, it was

found that the patients who had undergone transtibial

amputation had a better quality of life than others with

higher-level amputations, and this result is compatible

with the data in the literature (38). Patients with

transtibial amputation level are far more mobile than

those with transfemoral amputation, and rates of using

crutches are higher after transfemoral amputation

(39,40). This is probably one of the reasons why the

results of individual domains of the quality of life

displayed significantly higher scores in individuals with

transtibial amputations compared to patients with a

higher level of amputation.

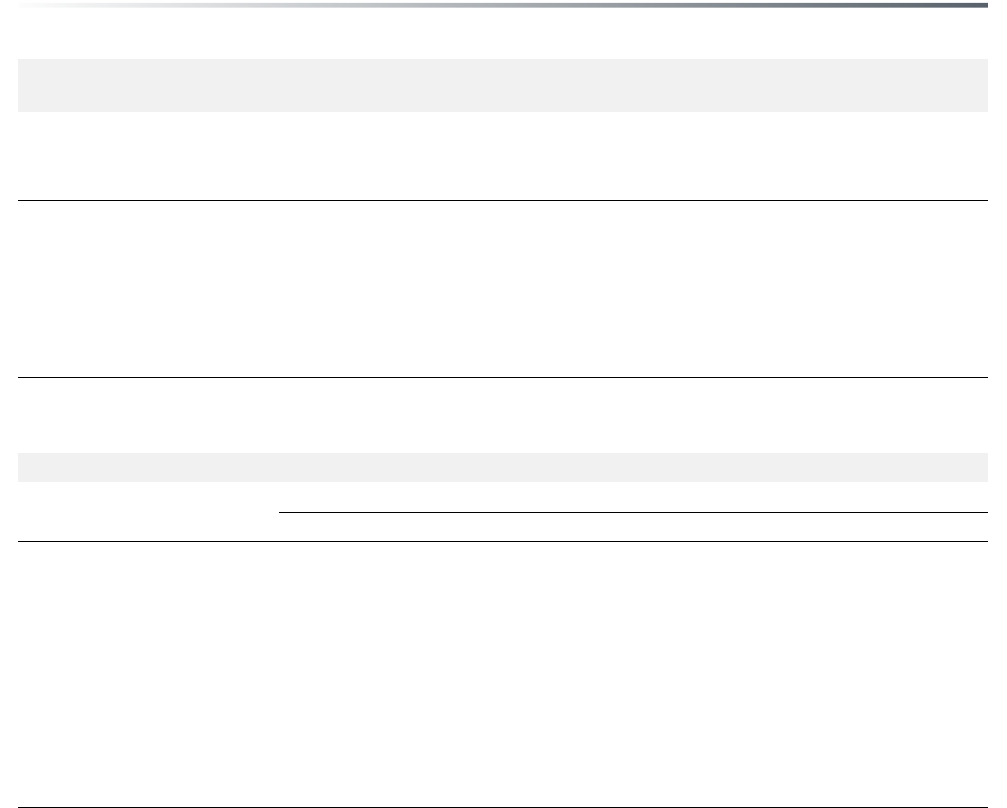

Table 5: Stepwse multple regresson analyss model of the varables that affect PSC scores (p<0.05)

PCS

B t p R² Adjusted R² F

Model 1

ABIS -5.64 -10.07 <0.001 0.62 0.61 101.43

Model 2

ABIS -4.01 -6.13 <0.001 0.69 0.68 69.70

Dysfunctional coping -2.83 -3.89 <0.001

Model 3

ABIS -1.90 -2.17 0.03 0.74 0.73 57.82

Dysfunctional coping -3.35 -4.85 <0.001

Satisfaction with the prosthesis 3.50 3.35 <0.001

Model 4

ABIS -2.46 -2.75 0.01 0.76 0.74 46.68

Dysfunctional coping -3.30 -4.90 <0.001

Satisfaction with the prosthesis 3.81 3.69 <0.001

RSES -2.63 -2.05 0.04

Model 5

ABIS -2.41 -2.81 0.01 0.78 0.76 42.14

Dysfunctional coping -3.42 -5.29 <0.001

Satisfaction with the prosthesis 2.83 2.68 0.01

Self-esteem -4.33 -3.10 <0.001

Problem focused coping 2.39 2.57 0.01

Stepwise Multiple Regression Analysis, ABIS: Amputee Body Image Scale, RSES: Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale, PCS: Physical components summary

Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2020;33:109-119116

One of the most important factors affecting

functional and life quality results of amputee

rehabilitation is compatible with the patient’s

prosthesis satisfaction (41). Patient dissatisfaction with

the artificial limb can create major problems for the

individual on a physical, psychological, and social

level, and can directly impact health-related life quality

(42). Individuals using a suitable prosthesis can regain

their mobility more quickly and are more likely to

adapt to the amputation successfully (43). Their self-

confidence increases as they gain functional

independence and the adaptation to their social

environment and working life are also affected

positively (44). Similar to our work, Matsen et al. (45)

found that quality of life in people with a lower-

extremity amputation correlated with the comfort,

function, and appearance of the prosthesis. In addition,

a positive correlation has been determined in the

literature between prosthesis satisfaction and quality

of life and positive adaptation to extremity loss (6,46).

Asano et al. (5) found that problems with prosthetics

after lower limb amputation are an important

predictive factor for quality of life. In our study,

satisfaction with the prosthesis was measured using

the three subscales functional satisfaction, esthetic

satisfaction, and weight satisfaction. Prosthesis

satisfaction covering these three areas was found to be

correlated with both physical and mental quality of life

scores, but it was predictive only for the physical

component. No study in the literature investigated the

predictive power of quality of life for physical and

mental components separately, but the importance of

mobility for physical functioning has been reported in

other studies (5,47). When the important effect of

prosthesis satisfaction on mobilization is taken into

consideration, it is thought that its predictive power

for the physical component may be related to this

situation. Considering that a prosthesis is a means of

replacing a natural limb, the importance of patient

satisfaction with the device is evidently of utmost

importance (7).

The loss of a limb causes emotional stress and

inevitably requires examining the patient’s capacity to

cope with this stressful situation (48). Problem-

focused coping was also found to be a major predictor

of psychological and physical quality of life in our

study. There are results similar to our findings in the

literature. In their study with 63 individuals with lower

limb amputation due to diabetes and peripheral

vascular disease, Pereira et al. (49) showed that

satisfaction with life was positively associated with

active and planning coping. In our study, emotion-

focused coping methods were found to be unrelated to

the quality of life, thus not supporting our hypothesis.

In contrast, a limited number of studies in the literature

showed that emotion-focused and passive strategies

have been associated with poor psychosocial outcomes

(50). We think that the reason may be that the coping

methods used in the literature are problem-oriented

and emotion-oriented, while in our study, the coping

assessment tool used also included dysfunctional

strategies. These dysfunctional coping methods

comprise some of the methods that are routinely

evaluated in emotional coping methods, but are more

incompatible. We think that the negative relationship

of emotion-focused coping in the literature with

psychosocial adjustment and quality of life may be

related to these incompatible coping strategies that we

determined in the dysfunctional coping strategies

group. Desmond and MacLachlan (50), evaluating 3

coping strategies, namely, problem solving, seeking

social support, and avoidance, found avoidance to be

associated with poor psychosocial adaptation to

amputation. Likewise, in our study the use of

dysfunctional coping strategies was similar in effect to

the non-adaptive nature of avoidance-type coping, and

it was found to be a negative predictor for the physical

and mental components of quality of life. The

international literature has already documented that

coping strategies focused on active resolution are more

effective in decreasing the level of restriction in

physical activities and in the adjustment to amputation

(51,52). Coping strategies are important not only to

minimize the negative effects of lower extremity

amputation but also for the amputee’s psychological

well-being (53). In the light of this information, which

is also parallel to our results, we think that evaluating

coping mechanisms as an important parameter

especially in a rehabilitation program may have

positive effects on patients’ quality of life and general

well-being.

Emotions created by breaking up the integrity of the

body cause a distorted body image, leading to

inadequate and negative feelings about the body and

decreased self-esteem (7,54). It is well known that our

way of perceiving our bodies has a major effect on our

social lives, psychological and physical states, and the

overall quality of our lives (55). When individuals’

perceptions of their bodies are distorted after

amputation, they experience greater difficulties carrying

out the bodily movements required for daily activities

and struggle to accept their new body image; this can

Kazan Kizilkurt et al. Quality of life after lower extremity amputation due to diabetic foot ulcer: the role of prosthesis-related factors, body image... 117

lead to rejection of the prosthesis and difficulties in

functional adaptation (56). It has been stated that the

deterioration in the body image perception of the

amputated person may affect their lives physically,

socially, and psychologically, as they do not conform to

the esthetic perception accepted by the majority of

social media users and society (57). Holzer et al. (9)

found that body image was distorted in patients who

had undergone amputation, and the physical and

mental components of their quality of life was negatively

affected. In our study, it was observed that the

perception of body image was an important predictive

factor for both physical and mental quality of life.

Similar to our results, Rybarczyk et al. (8) stated that

body image is an independent predictor of quality of

life. Helping amputees to integrate into society

successfully requires their amputation-associated body

image distortions to be addressed during rehabilitation,

and understanding the impact of body image is critical

for appropriate rehabilitation interventions (8).

Studies have also indicated that self-perception and

evaluating one’s body are a significant source of self-

esteem (58). Although many studies show that self-

esteem decreases after amputation (7,28), few studies

trace the relationship between self-esteem and quality of

life. One study investigating the relationship between

self-esteem and quality of life reported a weak

correlation between these two variables (9). In contrast,

we observed that decreased self-esteem was a significant

predictor of a poor physical component of quality of

life. In a study with patients undergoing mastectomy, a

procedure that similarly leads to the feeling of mutilation

of the body, self-esteem was also reported to be

decreased, which was a significant predictive factor for

impaired health-associated quality of life (59). Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy (CBT) was introduced as a method

to increase individuals’ adaptation to chronic health

states. CBT is advocated in helping patients recognize

and adjust their distorted thinking patterns and non-

productive behaviors by focusing on their emotional,

cognitive, and behavioral responses (60). Studies have

shown that CBT is effective in improving self-esteem,

body image, and quality of life among patients with

chronic diseases (61,62). A recent study examining the

beneficial effect of CBT on self-esteem and quality of

life among elder amputees demonstrated that self-

esteem and life quality significantly improved among

these individuals (60).

There are some limitations of our study. First of all,

due to its cross-sectional design, it was not possible to

establish cause-effect relationships. There was no

longitudinal follow-up before and after amputation and

non-amputee diabetic foot patients were not included in

the study as a comparison group. Secondly, in parallel

with amputation, the effect of diabetes mellitus itself on

the quality of life should be taken into consideration, as

all negative effects on quality of life are unlikely to be

attributable to the amputation. Comorbid medical and

psychiatric disorders were not considered as a

confounding factor on outcome. Eventually, when this

study examined the effect of medical diseases and

psychiatric burdens such as depression, anxiety, and

somatization on the outcome, it was observed that these

burdens had no predictive power on the outcome.

In conclusion, the results of our study emphasize the

significance of multiple physical and psychosocial

aspects in the successful adaptation of patients after

amputation. This study investigated the variables

affecting the quality of life of individuals in orthopedic

practice, applying a biopsychosocial approach. It has

shown that patients’ existing schemas of coping styles,

self-esteem, and body perception have a greater impact

on the outcome than their physical variables and

psychological burdens such as depression and anxiety.

Furthermore, the importance of multidisciplinary

evaluation of patients is evident, both during

amputation, which is a traumatic process, and during

rehabilitation. We suggest that rehabilitation after

amputation should be a multifactorial process including

physical functional adaptation and psychosocial

schemes.

Contribution Categories Author Initials

Category 1

Concept/Design

O.K.K., T.K., M.Y.G., F.E.G.,

G.P., I.O.K., H.G.

Data acquisition T.K., G.P.

Data analysis/Interpretation O.K.K., H.G.

Category 2

Drafting manuscript O.K.K., T.K., F.E.G., G.P.

Critical revision of manuscript M.Y.G., I.O.K., H.G.

Category 3 Final approval and accountability

O.K.K., T.K., M.Y.G., F.E.G.,

G.P., O.I.K., H.G.

Other

Technical or material support N/A

Supervision N/A

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethical approval for this study was

obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee of the University of

Health Sciences’ Erenkoy Mental Research and Training Hospital,

Istanbul, Turkey.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent of all patients was

obtained.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Conflict of Interest: There in no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure: There is no any financial support.

Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2020;33:109-119118

REFERENCES

1. Ragnarson Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. Health-related quality of

life in patients with diabetes mellitus and foot ulcers. J Diabetes

Complications 2000; 14:235-241.

2. Carrington AL, Mawdsley SK, Morley M, Kincey J, Boulton AJ.

Psychological status of diabetic people with or without lower

limb disability. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1996; 32:19-25.

3. Willrich A, Pinzur M, McNeil M, Juknelis D, Lavery L. Health

related quality of life, cognitive function, and depression in

diabetic patients with foot ulcer or amputation. A preliminary

study. Foot Ankle Int 2005; 26:128-134.

4. Boutoille D, Féraille A, Maulaz D, Krempf M. Quality of life with

diabetes-associated foot complications: comparison between

lower-limb amputation and chronic foot ulceration. Foot Ankle

Int 2008; 29:1074-1078.

5. Asano M, Rushton P, Miller WC, Deathe BA. Predictors of quality

of life among individuals who have a lower limb amputation.

Prosthet Orthot Int 2008; 32:231-243.

6. Horgan O, MacLachlan M. Psychosocial adjustment to lower-

limb amputation: a review. Disabil Rehabil 2004; 26:837-850.

7. Grossman EF. The Gestalt approach to people with amputations.

J Appl Rehabil Couns 1990; 21:16-19.

8. Rybarczyk B, Nyenhuis D, Nicholas JJ, Cash SM, Kaiser J. Body

image, perceived social stigma, and the prediction of psychosocial

adjustment to leg amputation. Rehabil Psychol 1995; 40:95-110.

9. Holzer LA, Sevelda F, Fraberger G, Bluder O, Kickinger W,

Holzer G. Body image and self-esteem in lower-limb amputees.

PLoS One 2014; 9:e92943.

10. Dunn DS. Well-being following amputation: Salutary effects of

positive meaning, optimism, and control. Rehabil Psychol 1996;

41:285-302.

11. Livneh H, Antonak RF, Gerhardt J. Psychosocial adaptation to

amputation: the role of sociodemographic variables, disability-

related factors and coping strategies. Int J Rehabil Res 1999;

22:21-31.

12. Daabiss M. American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical

status classification. Indian J Anaesth 2011; 55:111-115.

13. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health

survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med

Care 1992; 30:473-483.

14. Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski MA, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental

health summary scales: a User’s Manual. Fifth ed., Boston: MA

Health Assessment Lab, New England Medical Center, 1994.

15. Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)

2000; 25:3130-3139.

16. Kocyigit H, Aydemir O, Fisek G, Olmez N, Memis AK. Reliability

and validity of the Short Form 36, Turkish version (KF-36). Ilac

ve Tedavi Dergisi 1999; 12:102-106. (Turkish)

17. Gallagher P, MacLachlan M. Development and psychometric

evaluation of the Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience

Scales (TAPES). Rehabil Psychol 2000; 45:130-154.

18. Topuz S, Ulger O, Yakut Y, Gul Sener F. Reliability and construct

validity of the Turkish version of the Trinity Amputation and

Prosthetic Experience Scales (TAPES) in lower limb amputees.

Prosthet Orthot Int 2011;35:201-206.

19. Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies:

a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989; 56:267-

283.

20. Agargun MY, Besiroglu L, Kiran UK, Ozer OA, Kara H. The

psychometric properties of the COPE inventory in Turkish

sample: a preliminary research. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg 2005;

6:221.

21. Carver CS, Scheier MF. Situational coping and coping dispositions

in a stressful transaction. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994; 66:184-195.

22. Cooper C, Katona C, Orrell M, Livingston G. Coping strategies

and anxiety in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease: the

LASER-AD study. J Affect Disord 2006; 90:15-20.

23. Coolidge FL, Segal DL, Hook JN, Stewart S. Personality disorders

and coping among anxious older adults. J Anxiety Disord 2000;

14:157-172.

24. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The

multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess

1988;52:30-41.

25. Eker D, Arkar H, Yaldiz H. Factorial Structure, Validity, and

Reliability of Revised Form of the Multidimensional Scale of

Perceived Social Support. Turk Psikiyatri Derg 2001; 12:17-25.

(Turkish)

26. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. First ed.,

Princeton, NJ.:Princeton University Press, 1965.

27. Cuhadaroglu F. Self-esteem in Adolescents. Specialization Thesis,

Hacettepe University Medical Faculty Department of Psychiatry,

Ankara. 1986. (Turkish)

28. Breakey JW. Body image: the lower-limb amputee. JPO J

Prosthetics Orthot 1997; 9:58-66.

29. Safaz I, Yilmaz B, Goktepe AS, Yazicioglu K. Turkish version of

the amputee body image scale and relationship with quality of

life. Bulletin Clin Psychopharmacol 2010; 20:79-83.

30. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of

a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;

16:606-613.

31. Yazici Gulec M, Gulec H, Simsek G, Turhan M, Aydin Sunbul

E. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the

Patient Health Questionnaire-Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive

Symptoms. Compr Psychiatry 2012; 53:623-629.

32. Demiral Y, Ergor G, Unal B, Semin S, Akvardar Y, Kivircik B, et

al. Normative data and discriminative properties of short form 36

(SF-36) in Turkish urban population. BMC Public Health 2006;

6:247.

33. Hagberg K, Brånemark R. Consequences of non-vascular trans-

femoral amputation: a survey of quality of life, prosthetic use and

problems. Prosthet Orthot Int 2001; 25:186-194.

34. Sinha R, van den Heuvel WJ, Arokiasamy P. Factors affecting

quality of life in lower limb amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int 2011;

35:90-96.

Kazan Kizilkurt et al. Quality of life after lower extremity amputation due to diabetic foot ulcer: the role of prosthesis-related factors, body image... 119

35. Arena JG, Sherman RA, Bruno GM, Smith JD. The relationship

between situational stress and phantom limb pain: cross-lagged

correlational data from six month pain logs. J Psychosom Res

1990; 34:71-77.

36. van der Schans CP, Geertzen JH, Schoppen T, Dijkstra PU.

Phantom pain and health-related quality of life in lower limb

amputees. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002; 24:429-436.

37. Kaur A, Guan Y. Phantom limb pain: A literature review. Chin J

Traumatol 2018; 21:366-368.

38. Knežević A, Salamon T, Milankov M, Ninković S, Jeremić Knežević

M, Tomašević Todorović S. Assessment of quality of life in patients

after lower limb amputation. Med Pregl 2015; 68:103-108.

39. Burger H, Marincek C, Isakov E. Mobility of persons after

traumatic lower limb amputation. Disabil Rehabil. 1997; 19:272-

277.

40. Raya MA, Gailey RS, Fiebert IM, Roach KE. Impairment

variables predicting activity limitation in individuals with lower

limb amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int 2010; 34:73-84.

41. Schürmann T, Beckerle P, Preller J, Vogt J, Christ O. Theoretical

implementation of prior knowledge in the design of a multi-scale

prosthesis satisfaction questionnaire. Biomed Eng Online 2016;

15:143.

42. Millstein S, Bain D, Hunter GA. A review of employment patterns

of industrial amputees--factors influencing rehabilitation.

Prosthet Orthot Int 1985; 9:69-78.

43. Sansam K, Neumann V, O’Connor R, Bhakta B. Predicting

walking ability following lower limb amputation: a systematic

review of the literature. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41:593-603.

44. Fernández A, Isusi I, Gómez M. Factors conditioning the return

to work of upper limb amputees in Asturias, Spain. Prosthet

Orthot Int 2000; 24:143-147.

45. Matsen SL, Malchow D, Matsen FA 3rd. Correlations with

patients’ perspectives of the result of lower-extremity amputation.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82:1089-1095.

46. Akarsu S, Tekin L, Safaz I, Göktepe AS, Yazicioğlu K. Quality of

life and functionality after lower limb amputations: comparison

between uni- vs. bilateral amputee patients. Prosthet Orthot Int

2013; 37:9-13.

47. Deans SA, McFadyen AK, Rowe PJ. Physical activity and quality

of life: A study of a lower-limb amputee population. Prosthet

Orthot Int 2008; 32:186-200.

48. Copuroglu C, Ozcan M, Yilmaz B, Gorgulu Y, Abay E, Yalniz E.

Acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder following

traumatic amputation. Acta Orthop Belg 2010; 76:90-93.

49. Pereira MG, Ramos C, Lobarinhas A, Machado JC, Pedras S.

Satisfaction with life in individuals with a lower limb amputation:

The importance of active coping and acceptance. Scand J Psychol

2018; 59:414-421.

50. Desmond DM, MacLachlan M. Coping strategies as predictors

of psychosocial adaptation in a sample of elderly veterans with

acquired lower limb amputations. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62:208-216.

51. Andersson M, Deighan F. Coping strategies in conjunction with

amputation: A literature study. Thesis, Division for Health and

Caring Sciences, Karlstads University, Sweden, 2006.

52. Couture M, Desrosiers J, Caron CD. Coping with a lower limb

amputation due to vascular disease in the hospital, rehabilitation,

and home setting. ISRN Rehabil 2012; 179878.

53. Oaksford K, Frude N, Cuddihy R. Positive coping and stress-

related psychological growth following lower limb amputation.

Rehabil Psychol 2005; 50:266-277.

54. Parkes CM. Components of the reaction to loss of a lamb, spouse

or home. J Psychosom Res 1972; 16:343-349.

55. Adamson PA, Doud Galli SK. Modern concepts of beauty. Curr

Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003; 11:295-300.

56. Deusen J Van. Body image of non-clinical and clinical populations

of men: a literature review. Occup Ther Ment Heal 1996; 13:37-

57.

57. Ching S, Thoma A, McCabe RE, Antony MM. Measuring

outcomes in aesthetic surgery: a comprehensive review of the

literature. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 111:469-480.

58. Goldenberg JL, McCoy SK, Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Solomon

S. The body as a source of self-esteem: the effect of mortality

salience on identification with one’s body, interest in sex, and

appearance monitoring. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000; 79:118-130.

59. Mustian KM, Katula JA, Gill DL, Roscoe JA, Lang D, Murphy

K. Tai Chi Chuan, health-related quality of life and self-esteem:

a randomized trial with breast cancer survivors. Support Care

Cancer 2004; 12:871-876.

60. Alavi M, Molavi H, Molavi R. The impact of cognitive behavioral

therapy on self-esteem and quality of life of hospitalized amputee

elderly patients. Nurs Midwifery Stud 2017; 6:162-167.

61. Didarloo A, Alizadeh M. Health-Related Quality of Life and its

Determinants Among Women With Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-

Sectional Analysis. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2016; 5:e28937.

62. Kiani J, Pakizeh A, Ostovar A, Namazi S. Effectiveness of

cognitive behavioral group therapy (CBGT) in increasing the

self esteem & decreasing the hopelessness of β-thalassemic

adolescents. Iran South Med J 2010; 13:241-252. (Persian)