Walden University Walden University

ScholarWorks ScholarWorks

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection

3-27-2024

Destigmatizing Mental Health Treatment Among Law Destigmatizing Mental Health Treatment Among Law

Enforcement O6cers Amidst the Blue Wall of Silence Enforcement O6cers Amidst the Blue Wall of Silence

Jason Yerk

Walden University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations

Part of the Criminology Commons

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an

authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Walden University

College of Psychology and Community Services

This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by

Jason R. Yerk

has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by

the review committee have been made.

Review Committee

Dr. Grace Telesco, Committee Chairperson,

Criminal Justice Faculty

Dr. Nancy Blank, Committee Member,

Criminal Justice Faculty

Chief Academic Officer and Provost

Sue Subocz, Ph.D.

Walden University

2024

Abstract

Destigmatizing Mental Health Treatment Among Law Enforcement Officers Amidst the

Blue Wall of Silence

by

Jason R. Yerk

MA, American Military University, 2015

BS, Southwest Florida College, 2012

Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Criminal Justice

Walden University

May 2024

Abstract

Law enforcement officers are continuously presented with high risk/high stress

encounters throughout their career. However, mental health issues among police officers

are often minimized or overlooked, so the danger of burnout, depression, heightened

anxiety, along with PTSD are substantially increased. This qualitative study examined the

perceived obstacles and challenges that officers face based on the officers’ lived

experiences that prevent them from seeking mental health treatment. The study also

investigated how, if at all, stigmatization plays a role in preventing them from seeking

mental health treatment. Labeling theory was the framework used for this study. The

research employed purposeful sampling with 11 law enforcement officers who served in

the Southwest Florida region. Semistructured interviews with participants were

conducted using snowball sampling. Data was analyzed using Saldana’s (2011) coding

process and included two research questions focused on the perceived obstacles and

challenges that officers faced based on their lived experiences that prevent them from

seeking mental health treatment (RQ1) and how stigmatization played a role in

preventing or keeping officers from seeking mental health treatment (RQ2). Themes

identified throughout the study included scheduling issues, self-medication, fear of forced

evaluations, perceived loss of dependability, perceived weakness, and perceived loss of

advancement. This research has illustrated some of the obstacles that prevent officers

from seeking mental health treatment and provides law enforcement agencies with

information for positive social change to alter the negative perception of stigma as it

relates to officer self-seeking mental health assistance.

Destigmatizing Mental Health Treatment Among Law Enforcement Officers Amidst the

Blue Wall of Silence

by

Jason R. Yerk

MA, American Military University, 2015

BS, Southwest Florida College, 2012

Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Criminal Justice

Walden University

May 2024

Dedication

This dissertation is dedicated to the brave men and women of law enforcement

who continually battle the demons both externally and internally in order to keep us all

safe. May this dissertation help reduce the stigma related to mental health treatment so

that officers don't have to endure the pain in silence.

Acknowledgments

To my wife, Dr. Melanie Yerk, thank you for being my greatest fan and supporter

throughout this entire process. It was your encouragement and support that made over

coming any and all of life’s obstacles possible throughout this journey. It was your

encouragement and belief in me that made this journey possible, and I cannot express

how grateful I am for your unconditional support.

To Dr. Grace Telesco, it has been a blessing and an honor to have you as my

dissertation chair guiding me through this process. Your expertise both in field and as a

doctoral chair has been invaluable throughout the dissertation process. Thank you for the

countless hours of questions and guidance you have provided as you have remained the

calm within the storm. I am forever grateful that you were my dissertation chair.

To Dr. Blank, thank you for all your qualitative expertise throughout this doctoral

journey. I appreciate all your feedback and assistance throughout the process.

i

Table of Contents

List of Tables .......................................................................................................................v

List of Figures .....................................................................................................................vi

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Study....................................................................................1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................1

Background ....................................................................................................................3

Problem Statement .........................................................................................................4

Purpose Statement..........................................................................................................5

Purpose of Study ............................................................................................................6

Research Questions ........................................................................................................7

Theoretical Framework ..................................................................................................7

Nature of Study ..............................................................................................................8

Definitions......................................................................................................................8

Assumptions...................................................................................................................9

Scope and Delimitations ..............................................................................................11

Limitations ...................................................................................................................11

Significance..................................................................................................................12

Summary ......................................................................................................................13

Chapter 2: Literature Review .............................................................................................14

Introduction ..................................................................................................................14

Literature Search Strategy............................................................................................15

Theoretical Foundations...............................................................................................16

ii

Police Mental Health Issues .........................................................................................19

Police Stress .......................................................................................................... 19

Organizational Stress ............................................................................................ 22

Personal Stress ...................................................................................................... 30

Anxiety.................................................................................................................. 32

Depression............................................................................................................. 34

Police Suicide........................................................................................................ 36

Subcultural Stigma .......................................................................................................39

Self-Stigma............................................................................................................ 39

Organizational Stigma........................................................................................... 42

Strategy and Solutions .................................................................................................45

Organizational Support ......................................................................................... 45

Peer Support .......................................................................................................... 48

EAP ................................................................................................................... 52

Summary and Conclusion ............................................................................................53

Chapter 3: Research Method..............................................................................................59

Introduction ..................................................................................................................59

Research Design and Rationale....................................................................................60

RQs ................................................................................................................... 61

Research Design.................................................................................................... 61

Phenomenon.......................................................................................................... 62

Methodology ................................................................................................................62

iii

Population ............................................................................................................. 62

Participant Selection ............................................................................................. 62

Participant Recruitment Strategy .......................................................................... 63

Instrumentation ..................................................................................................... 64

Data Collection ..................................................................................................... 65

Data Analysis Plan ................................................................................................ 66

Role of Researcher .......................................................................................................67

Reflexivity (Managing Relationships) .........................................................................67

Ethical Assurances .......................................................................................................68

Issues of Trustworthiness.............................................................................................69

Credibility ............................................................................................................. 70

Transferability ....................................................................................................... 70

Dependability ........................................................................................................ 71

Confirmability ....................................................................................................... 71

Summary ......................................................................................................................72

Chapter 4: Results ..............................................................................................................73

Introduction ..................................................................................................................73

Participants...................................................................................................................74

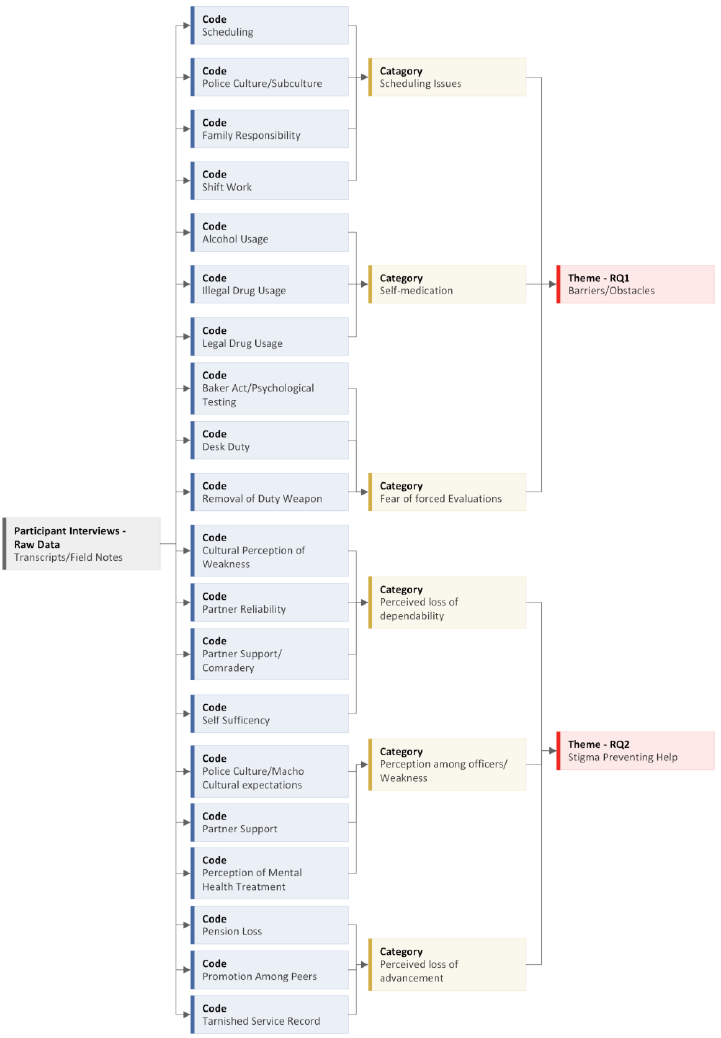

Data Analysis ...............................................................................................................75

Results ..........................................................................................................................79

RQ1 ................................................................................................................... 81

RQ2 ................................................................................................................... 84

iv

Summary ......................................................................................................................88

Chapter 5: Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations ............................................89

Interpretation of the Findings.......................................................................................89

RQ1 ................................................................................................................... 89

RQ2 ................................................................................................................... 92

Limitations of the Study...............................................................................................94

Recommendations for Future Research .......................................................................95

Recommendations for Practice ....................................................................................96

Implications..................................................................................................................97

Implications for Positive Social Change ............................................................... 97

Implications for Practice ....................................................................................... 98

Theoretical Implications ....................................................................................... 99

Conclusion .................................................................................................................100

References ........................................................................................................................102

Appendix A: Qualitative Instrument................................................................................111

Appendix B: Recruitment Flyer .......................................................................................113

1

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Study

Introduction

The profession of law enforcement has long been known to be an occupation in

which officers are continuously presented with high risk/high stress encounters

throughout their career. While officers are exposed to such dangerous and violent

encounters, it is understood that putting their life at risk while in service is a very real and

dangerous expectation of their chosen profession (Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019). These

high stress levels and exposure to traumatic stress along with potential deadly encounters

are key factors in officers physical and mental well-being (Soomro & Yanos, 2018). Due

to the over-exposure of these high stress/risk incidents, officers suffer from a higher rate

of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and thoughts of suicide than the general public or

professions without traumatic exposure (Soomro & Yanos, 2018; Velazquez &

Hernandez, 2019).

This continual exposure to fatal encounters in 2022 led to 247 in the line of duty

deaths, with officers having an average of 15 years of service (The Officer Down

Memorial Page [ODMP], 2022). This nationwide statistic states that 38% were felonious

in nature while the reaming 62% were incidents such as vehicle accidents, vehicle

pursuit, or duty related illnesses (ODMP, 2022). In comparison, during the same year

(2022), there were 161 reported officer involved suicides, where the deceased had an

average of 16.5 years of service (Blue H.E.L.P., 2022). Officer deaths by suicide are

expected to be higher as these are only reported numbers that are not mandated by federal

reporting regulations (Blue H.E.L.P., 2022).

2

Mental health issues among police officers are often minimized or overlooked, so

the danger of burnout, depression, heightened anxiety, along with posttraumatic stress

disorder (PTSD) are substantially increased (Hartford Courant, 2022). During times when

stress is heightened by outside factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, police officers

are particularly vulnerable due to altered social/societal norms (Stogner et al., 2020). On

average, 25% of police officers have had suicidal thoughts due to their continual

exposure to traumatic experiences in the performance of their duties (Hartford Courant,

2022). These statistics increased during the pandemic when they were deemed “essential

workers” with minimal personal protection equipment and ever-changing threats based

on the virus (Hartford Courant, 2022; Stogner et al., 2020).

In addition to work-based traumatic exposures, research has shown that there is a

negative stigma associated with officers who speak out and seek assistance for mental

health treatment (Bikos, 2020; Hartford Courant, 2022; Soomro & Yanos, 2018). This

stigma is present due to the police subcultural belief that if officers need to seek outside

assistance, then they are perceived as weak and unable to be trusted as backup in future

high stress dangerous situations (Soomro & Yanos, 2018). This warrior mentality not to

display any signs of weakness is engrained in officers from the beginning of their careers

when they are told that any outward displays of weakness or loss of control, both

physically and mentally, could jeopardize their future career path (Soomro & Yanos,

2018). This developed sense of masculinity is created through the police subculture due

to the intensity of work and traumatic exposure in an effort for officers to cope with the

immense pressure they face daily (Bikos, 2020).

3

Chapter 1 introduces the study as well as present the background as it relates to

police officers suffering from a higher risk of mental health disorders and suicide based

on the attached stigma within the police subculture. This chapter will also addresses the

blue wall of silence that perpetuates this stigma of weakness inside the subculture for

those that seek help. In addition, Chapter 1 includes the problem statement, purpose of

study, research questions, theoretical framework, nature of study, definitions,

assumptions, scope and delimitations, limitations, significance of study, as well as the

summary.

Background

The research focusing on police officers’ mental health has clearly indicated that

there is a greater chance of officers developing mental health disorders such as PTSD,

depression, or thoughts of suicide than the general public (Soomro & Yanos, 2018;

Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019; Violanti et al., 2021). With known heightened mental

health symptoms, there is also a negative stigma that spreads throughout the police

subculture where seeking help is perceived as a weakness that could be perceived by

other officers that they are not suitable backup, or something is wrong with them

(Soomro & Yanos, 2018). In addition to these consequences, there is an institutional fear

of being removed from certain high-risk units, being overlooked for promotion, or even

forced out of law enforcement completely (Bikos, 2020).

The primary objective of this research was to understand the stigma that police

officers face within the subculture of policing, whether it is self-imposed, social, or

organizational in nature when seeking mental health treatment. Each of these stigmas

4

highlights that officers often do not seek mental health treatment in fear of a perceived

perception of weakness, which is the number one reason officers avoid seeking treatment

(Wheeler et al., 2018). Reducing these subcultural stigmas is expected to promote

psychological wellness, mitigate mental illness among officers, and reduce officer suicide

(Ramchand et al., 2018).

This study was designed to help close the gap by destigmatizing mental health

treatment among those who suffer from any number of mental health issues due to their

continual exposure to traumatic stress while performing their duties. The hope is that

officers who self-seek mental health assistance will be destigmatized by other officers

and supported by the organizational subculture, which will increase officer mental well-

being. Researchers have not fully addressed the mental health stigma attached to seeking

mental health treatment and the impact of the subculture of policing on officers’ self-

seeking perspective. Thus, this study helps fill the gap by obtaining the perspectives of

the officers themselves on help seeking behaviors.

Problem Statement

The subculture of law enforcement includes a stigma around seeking mental

health help, which, according to Wheeler et al. (2018), causes officers not to self-seek

mental health assistance in fear of been perceived as weak and unable to handle job

related duties. Continuous exposure to traumatic stress without the proper coping

mechanisms could cause long term mental health related issues that manifest into

physical illness throughout the officer’s career (Wheeler et al., 2018). Additional research

(Bikos, 2020; Hartford Courant, 2022; Soomro & Yanos, 2018) has indicated that

5

officers choose not to self-report and seek help for mental health problems due to the

well-found fear of perceived weakness or professional consequences they may face from

both their peers and organization.

The law enforcement subculture is based on principals of masculinity where

showing emotional control is considered a form of strength. This type of organizationally

instilled values perpetuates the stigma related to self-seeking mental health treatment as a

form of weakness that will cause officers to internalize traumatic stress (Velazquez &

Hernandez, 2019). Within the law enforcement subculture, officers express this

masculinity by imposing dominance and a defensive solidarity among peers to comply

with organizational norms due to the strong influence agencies have over their officers

(Habersaat et al., 2021). As a result, officers are prone to depersonalization or emotional

numbing, which could also have a negative impact on an officer’s ability to maintain

interpersonal friendships or intimate partner relationships (Velazquez & Hernandez,

2019). A gap in the literature was identified relating to how officers’ willingness to seek

mental health treatment is related to the stigma from the subculture’s blue wall of silence.

Purpose Statement

In this qualitative study, I examined the perceived obstacles and challenges that

officers face based on the officers’ lived experiences that prevent them from seeking

mental health treatment. I also investigated how, if at all, stigmatization plays a role in

preventing them from seeking mental health treatment.

6

Purpose of Study

In response to the apparent need for law enforcement officers to self-seek mental

health assistance, the purpose of this study was to analyze the stigmas and obstacles to

asking for mental health treatment that exist within the law enforcement subculture and to

identify potential pathways for officers to obtain mental health treatment that they deem

as acceptable. Throughout the study, I examined the perceived obstacles and challenges

that officers face based on their lived experiences that prevent them from seeking mental

health treatment, and the role that stigmatization plays in preventing or keeping officers

from seeking mental health treatment was explored based on officers’ lived experiences.

The mental health stigmas that are prominent in law enforcement subculture,

including self-stigma and organizational stigma, were thoroughly examined throughout

this study. I also conducted a thorough analysis of the problems associated with police

work. These included police stress, organizational stress, personal stress, anxiety,

depression, and police suicide. Strategies and solutions that have been implemented by

law enforcement agencies throughout the nation were evaluated for effectiveness and

acceptance by officers. These approaches allowed me to provide strategic

recommendations for successful agency implementation of mental health services and

programs to support law enforcement officers’ mental health (see Hartford Courant,

2022; Stogner et al., 2020; Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019).

My goal is to provide officers with a more comfortable avenue to self-seek

mental-health treatment to combat the stressors brought on by the continuous traumatic

stress exposures they encounter during their careers. By contributing to this literature, it

7

is expected that officers will have access to fundamental methods to positively change the

police subculture to provide a positive experience to self-seek mental health assistance

for traumatic stress. This opportunity for both individual officers and organizations could

lead to increased organizational support for officers by promoting positives mental health

outcomes, thus reducing stress disorders, depression, forced retirement, or even suicide

(Ramchand et al., 2018).

Research Questions

The following research questions (RQs) were used to understand the subcultural

stigma related to officers’ help seeking behaviors for mental health in the field of law

enforcement.

RQ1: What are the perceived obstacles and challenges that officers face based on

their lived experiences that prevent them from seeking mental health treatment?

RQ2: Based on the lived experiences of officers, how, if at all, does stigmatization

play a role in preventing or keeping them from seeking mental health treatment?

Theoretical Framework

Labeling theory was the framework used for this study. This sociology of

deviance study was based on the work of Becker in 1963 and his perception of

sociological theory where he observed deviants and their behavior (Becker, 1997).

Labeling theory is an approach including agents of social control and the stigmatic

stereotypes that they assign to groups or individuals in ways that could alter their

behavior (Becker, 1997). According to Becker (1997), there are consequences related to

external constructs or judgments that alter the way an individual views their self- concept.

8

This view is relevant as it imposes a self-fulfilling prophecy that indicates that the

behavioral patterns conducted by offenders are likely to promote wrongdoing or alter

other individual behavior (Payne et al., 2018).

Nature of Study

To address the RQs in this qualitative phenomenological study, I conducted

purposeful sampling to include active law enforcement officers in the southwest Florida

region. Interviews were conducted using both in-person and Zoom interviews with

current officers of varied levels of law enforcement experience. Memoing was also used

to record my perceptions of the how the participants displayed nonverbal communication

during the questioning along with any other pertinent information observed. Interviews

were conducted with 11 participants when saturation was reached. The use of a

qualitative methodology provides the researcher with the opportunity to understand the

participants’ lived experiences by assessing their responses to open ended questions,

which are presented in a semistructured interview design (Rubin & Rubin, 2011). To best

ascertain in-depth information about self-seeking mental assistance from the sample, the

qualitative methodology was appropriate for this research.

Definitions

Mental health treatment: This encompasses a wide range of interventions and

support aimed at improving mental well-being. It includes therapy, counseling,

medication, and other forms of professional assistance for mental health conditions

(Payne et al., 2018).

9

Peer support programs: These programs involve trained peers or colleagues

offering emotional and psychological support to police officers facing mental health

challenges. Peer support can help reduce stigma by providing a more relatable source of

assistance (Payne et al., 2018).

Police officers: Members of law enforcement agencies responsible for

maintaining public order, enforcing laws, and ensuring the safety of communities (Payne

et al., 2018).

Resilience: The ability to bounce back from adversity and maintain mental well-

being in the face of stress or trauma. Resilience-building programs are often implemented

to help police officers better cope with the challenges of their profession (Payne et al.,

2018).

Stigma: Stigma refers to negative attitudes, beliefs, and stereotypes that lead to

discrimination and social exclusion. In the context of mental health treatment among

police officers, stigma often involves societal or internalized biases against seeking help

for mental health issues (Payne et al., 2018).

Stigmatization: The act of treating someone unfairly or negatively because of their

mental health condition or their decision to seek mental health treatment (Payne et al.,

2018).

Assumptions

The subculture of law enforcement does not lend itself to an open platform where

officers feel comfortable to self-seek assistance and discuss their mental health concerns

with other officers or supervisors. This is based on the negative stigma on mental illness

10

within law enforcement and on those who self-seek mental health assistance. The

assumptions below include the attitudes held by officers toward self-seeking mental

health assistance and directly relate to the theoretical context that is explored in the

literature review found in Chapter 2:

1. Police officers are less likely to discuss their continual exposure to

traumatic and stressful incidents that cause mental health concerns more

so than the general public (Rief & Clinkinbeard, 2021).

2. Police officers understand that mental health concerns such as anxiety or

depression could escalate and lead to officer involved suicide (Violanti et

al., 2018).

3. The police subculture is known to include feelings of suspicion and

skepticism, and, therefore, officers are concerned that if they speak to

someone confidentially, their mental health issues could be shared within

their agency (Violanti et al., 2018).

4. Police officers are more reluctant to discuss mental health concerns with

individuals who are not familiar with the police subculture and the stigmas

attached to the police culture (Lambert et al., 2021).

5. Due to the negative stigma officers present within police culture, officers

are concerned they may be placed on administrative leave and pushed into

forced medical retirement for not being mentally fit for duty (Bullock &

Garland, 2017).

11

These assumptions represent my anecdotal experience, which is also supported by

the literature (see Bullock & Garland, 2017; Lambert et al., 2021; Rief & Clinkinbeard,

2021; Violanti et al., 2018).

Scope and Delimitations

The purpose of this study was to analyze the stigmas and obstacles that exist

within the law enforcement subculture and identify potential pathways for mental health

treatment that they may deem as acceptable. Researchers have suggested that continued

exposure to traumatic stress has an impact on mental health for police officers and that

there is a negative stigma associated with receiving treatment (Grupe, 2023; Stuart, 2017;

Yasuhara et al., 2019).

This study focused on police officers located in the southwest region of Florida

who had a varied levels of experience in law enforcement. I conducted in-person

interviews or Zoom interviews if face-to-face was not available with 11 officers or until

saturation is attained. The participants of this study were selected using purposive

sampling from a sample population in the southwest Florida regain. The inclusion criteria

for this study ensured that all the participants had been exposed to similar traumatic stress

events based on population demographics and geographic locations. These inclusion

criteria were assumed to be relevant in order to assure that shared experiences reported

would include those that are most accurate and detailed.

Limitations

Possible limitations to this research were the participants’ willingness to remain

truthful due to the negative stigma as it related to self-seeking mental health assistance

12

within the subculture of law enforcement. Possibilities existed that the participants would

not fully believe the confidential nature of the research, and, therefore, answers could

have been skewed in order to conform to the police subculture that seeking mental health

assistance is a sign of weakness as not to disrupt the status quo.

Another potential limitation of the research was that a vast number of officers

may have chosen not to participate in the study due to variety of reasons based on the

police subculture and negative stigma associated with the topic of research. This study

was limited to voluntary participants who were willing to speak out, despite the stigma

associated with the research, to attain valid saturation.

Significance

To promote positive social change, I hope to provide police officers and law

enforcement agencies information to alter the negative perception of stigma as it relates

to officer self-seeking mental health assistance. Allowing agencies to have the ability to

understand how self-stigma is viewed within the subculture could facilitate change in the

methods used for officers to self-seek mental health assistance. The long-term benefit of

the expected results of the study can be used to eliminate both self and organizational

stigmas associated with helping seeking behaviors for mental health within the field of

law enforcement through the implementation of policy change.

I expected to uncover information including ways to reduce the negative stigma

within the field of law enforcement and improving the overall mental health crisis within

policing. This improvement of mental health could also increase officer productivity

levels due to the increased treatment of mental health issues.

13

Summary

A vast amount of research has pointed to a negative mental health stigma related

to police officers who self-seek mental health assistance within the subculture of law

enforcement. This is based on officers’ well-founded fear of becoming labeled by fellow

officers as weak along with the organization’s perception of being incapable of doing

their job thus being forced to retire or quit. This study addressed the gap in the research

on barriers to seeking mental health treatment including the stigmas characteristic of

police subculture. The focus of Chapter 2 is an in-depth literature review related to the

negative stigmas and the impact they have on officers’ help seeking behaviors for mental

health treatment.

14

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Introduction

The profession of law enforcement is one of the most challenging and stressful

occupations due to the repeated exposure to death, violence, and acute and chronic

stressful events at work. There has been a direct correlation between job-related trauma

and stress and PTSD, substance abuse, depression, and suicide or suicide ideation in law

enforcement officers. These combined factors negatively impact the mental and physical

well-being of law enforcement officers and cause them to exhibit far more mental health

symptoms than that of civilian employees (Craig et al., 2018). These exposures cause

police officers to experience elevated stress levels and increase their risk of mental health

consequences such as burnout, anxiety, depression, somatization, and PTSD (Violanti et

al., 2018). In addition, research has shown that working under the stressful conditions

that law enforcement officers do increases the risk for new mental health conditions to

emerge and exacerbates preexisting mental health issues (Rief & Clinkinbeard, 2021).

In addition to the job stressors, police officers are subject to administrative and

organizational pressures that exist in police subcultures. Historically, officers who have

sought treatment have been labeled, ostracized, and treated as outsiders within their own

organization (Paoline III & Gau, 2022). This subculture that exists within law

enforcement agencies is created by both self-stigma that officers personally feel and

organizational stigma that results from the negative stigma from law enforcement

organizations and environmental factors related to officers seeking mental health

treatment (Grupe, 2023). Research involving law enforcement agencies throughout the

15

nation has identified that police organizations are unknowingly promoting stigmas that

deter officers from seeking mental health treatment. Despite the apparent need for

emotional and mental health support, a large percentage of law enforcement officers do

not seek mental health treatment due to the fear of being labeled and the negative stigmas

associated with seeking treatment (Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019).

This literature review was conducted to further explore the primary causes for law

enforcement officers’ stressors, mental health symptoms, stigmas associated with seeking

mental health treatment, and the analysis of programs that have been implemented

throughout agencies to support officer mental health. The stressors examined include

police work-stress and organizational stress. The primary mental health symptoms

analyzed include anxiety, depression, and police suicide. The stigmas that examined

include subculture stigma, which encompasses self-stigma and organizational stigma.

The mental health support programs explored include organizational support and training,

peer support programs, and employee assistance programs (EAP).

Literature Search Strategy

To effectively examine research and data that had been previously collected and

analyzed regarding the apprehensions officers have with seeking mental health treatment

and support, a thorough literature review was conducted. This primarily involved the

review of information from a variety of databases housed within the Walden University

Library.

Once related research articles were identified, they were evaluated for appropriate

and relevant content and academic rigor and validity. In addition to the research articles

16

that were evaluated from the Walden University Library, a thorough review of

dissertations that were published by Walden University doctoral graduates was

conducted. The criteria for the dissertation review included similar content to this

literature review and recency of publication. All publications reviewed had a focus on

recency with a target of a publication date no more than 5 years prior to the literature

review. Due to the limited number of published articles related to law enforcement

officers’ mental health, associated stigmas, and current programs available through

internal agencies, it was necessary to use some literary resources outside of that target

time-period. Discretion was used to determine appropriateness, applicability, and validity

of the resources.

The following search terms were used in this literature review when seeking

research articles to evaluate police officer mental health, police mental health stigma,

officer stigma and seeking mental health, self-stigma, police organizational stigma,

police anxiety, police depression, police suicide, police traumatic experiences, traumatic

stress, PTSD, police stress, peer to peer support, organizational support, employee

assistance program (EAP), and law enforcement mental health support.

Theoretical Foundations

Law enforcement officers hold one of the most challenging positions in society

today, as they face extreme situations frequently while protecting and serving their

communities. The impact that these repeated exposures to crime and terrible acts of

violence would have on the officers’ mental health seems evident. However, despite the

apparent need, a large percentage of officers do not seek mental health treatment due to

17

the labeling and stigmas associated with seeking treatment (Abdullah & Brown, 2020).

The labeling theory founded by Becker in the 1960s is evident in law enforcement

agencies’ perceptions of mental health treatment for officers across the nation. The roots

of the labeling theory according to Becker (1997) trace back to both conflict theory and

symbolic interactionism. The conflict theory aspect determines who is labeled and who

makes the decision to label others. The symbolic interactionism perspective of the

labeling theory focuses on the perceptions and evaluation of a person’s behavior (Craig et

al., 2018).

The founder of the labeling theory, Becker, wrote a book about the theory entitled

“Outsiders” in which he discussed how those who were labeled were considered to be

outsiders. He used this term to describe those who were labeled as being outside of the

“normal” members of a specific group. Becker (1997) explained that these individuals

who were labeled as being outsiders were treated differently and often ostracized from

the group. Applying the labeling theory to law enforcement agencies’ perspectives of

mental health treatment, it is evident that officers may be labeled as weak, incapable,

inferior, or somehow less competent to perform their duties than officers who do not seek

mental health treatment (Augustyn et al., 2019).

Due to the labeling associated with mental health treatment that exists in many

law enforcement agencies, many officers elect not to seek treatment. In many situations

where officers have sought treatment, they are labeled, ostracized, and treated as

outsiders within their own organization (Augustyn et al., 2019). This subculture that

exists within law enforcement agencies is created by both self-stigma that officers

18

personally feel and organizational stigma that exists throughout the organization.

Researchers have hypothesized that “defensive projection” may be a driving factor in this

labeling and stigmatization of officers who seek treatment (Zoubaa et al., 2020).

According to Zoubaa et al. (2020), defensive projection occurs when an

undiagnosed person who exhibits mental health symptoms but has not sought treatment

endorses more stigma as a result. These individuals project their own defensive responses

to mental health treatment onto others who do seek treatment because they also need

treatment but fear the consequences and stigmas of doing so. Research findings have

indicated that a greater emphasis be placed on normalizing mental health treatment in

order to reduce instances where people reject others, often when they are struggling with

accepting aspects of themselves. These antistigma interventions are recommended to

reduce labeling and stigmatization that occurs when officers seek mental health treatment

(Zoubaa et al., 2020).

The labeling theory is evident throughout law enforcement agencies across the

nation and has created a culture of both self-stigma and organizational stigma to exist.

Although the nature of the job of police officers clearly exposes them to extreme

situations involving violence and crime on a frequent basis, agencies have not adopted

sufficient support mechanisms to provide officers with mental health treatment that is

safe to seek (Craig et al., 2018). Instead, many agencies label officers as incapable and

either remove them from their positions or deny them promotions if they have sought

mental health treatment (Zoubaa et al., 2020). This internal stigma and labeling that exists

19

in most agencies aligns with the labeling theory and the challenges that it causes

individuals once they are perceived as outsiders (Becker, 1997).

Police Mental Health Issues

Police Stress

Law enforcement has been deemed as one of the most challenging and stressful

occupations worldwide due to acute and chronic stressful events at work, exposure to

violence and death, and the physical and psychological demands placed on the officers.

These repeated exposures negatively impact the mental and physical health of officers

and often lead to impaired psychosocial well-being, poor physical health, self-harm, and

poor functioning (Duran et al., 2018). In addition, PTSD has been increasingly reported

by law enforcement officers and has stemmed primarily from stress of the role,

administrative and organizational pressure, and physical and psychological stressors. The

results of a research study indicated that officers who demonstrate higher active or lower

passive coping skills are better able to cope with the stressors of the job. Those with low

active and high passive coping skills are more likely to be impacted by PTSD (Violanti et

al., 2018).

Research has indicated that the success of a law enforcement agency is dependent

upon the appropriate understanding of the stressors within the organization. There are

two generally accepted source of stressors in law enforcement. According to Lambert et

al. (2021), these include operational stressors, which are comprised of the job content,

and organizational stressors, which is the job context. Operational stressors include the

pressure to make critical decisions quickly and effectively, perform in life-threatening

20

situations, and have repeated exposure to violence and death. Organizational stressors

include lack of agency support, demanding shifts that often include nights and weekends,

overtime requirements, poor relationships resulting from the job schedule and physical

and emotional demands of the job, training deficiencies, and sometimes challenged

relationships with coworkers and supervisors (Duran et al., 2018).

Research studies have identified two primary coping strategies used by law

enforcement officers. According to Allison et al. (2022), these include problem-focused

coping and emotion-focused coping strategies. Problem-focused coping strategies

directly address the source of the stress, whereas emotion-focused coping strategies

incorporate distraction and acceptance techniques to manage stress. Research studies

have proven that officers who use problem-focused coping demonstrate better coping

skills and have a better overall wellbeing (Allison et al. 2022). Those who use the

emotion-focused coping strategy report more psychological distress and increased

smoking and alcohol consumption. Additional coping strategies that researchers have

identified include simply seeking social support from coworkers, supervisors, and family

members. It is also recommended that officers get an adequate amount of high-quality

sleep each day to assist with stress management (Duran et al., 2018).

Law enforcement officers have also demonstrated better coping skills and job

satisfaction rates when they feel that their psychological contract fulfilment has been met.

A psychological contract is the trust between the law enforcement officer and his or her

colleagues and supervisors. Research has indicated a direct correlation between positive

psychological contract fulfilment and job satisfaction rates, decreased work-related

21

anxiety and depression, and an increased level of trust and fairness between employees. If

employees feel as though there is a psychological contract breach, there is an imbalance

in the employment relationship, which increases psychological stressors at work (Duran

et al., 2018).

A study was conducted in the southern region of the United States that focused on

the impacts of the internal and external work environment and personal character traits on

police officer stress (Paoline III & Gau, 2022).. The study involved 349 officers who

worked at the street-level in the southern United States. The findings of the study

indicated that the officers’ perceived danger, cynicism toward the public, and suspicion

of citizens all contributed to increased office stress. The findings also indicated that

support from law enforcement supervisors mitigated stress levels and had a direct

correlation of officers’ abilities to cope with job stressors. Based on the findings of their

study, the researchers recommended that police administrators understand the impact that

they have on their officers’ abilities to cope with stress. In addition, it is recommended

that law enforcement trainers and supervisors provide new officers with a variety of

patrol areas and avoid prolonged assignments in higher-stress environments when

possible (Paoline III & Gau, 2022).

Officers experience acute stress as an innate factor of their police professions,

which impacts their psychological and physiological responses to stress. Much research

has been conducted regarding the psychological, cognitive, and behavioral results of

stressors; however, limited research exists regarding the impacts of stress on officers’

physiological responses to stress. A study was conducted to examine the autonomic,

22

endocrine, and musculoskeletal responses to acute stress (Anderson et al., 2019). The

study involved both humans and animals and clearly indicated a positive correlation

between high levels of acute stress and skill decay in these areas. The research also

indicated that training exercises that were designed to be evidence-informed and robust

can mitigate skill decay in officers and ultimately improve officer safety (Anderson et al.,

2019).

According to Stogner et al., (2020) it is evident that law enforcement is one of the

most mentally taxing professions due to the threats of violence, rotating and

nontraditional shifts, need for continuous hypervigilance, and often a lack of support

from the communities that they serve. In addition to the existing stressors, the COVID-19

pandemic only added to the stress of being police officers. Agencies required officers to

enforce COVID-19 restrictions within their communities while continuing to perform

their normal duties. The added stress impacted the mental health of officers, and there

was a notable impact on officer resiliency, misconduct, and overall mental health. The

impacts of the pandemic were comparable to the HIV epidemic that surfaced in the 1990s

and the 911 aftermath in 2001 (Stogner et al., 2020).

Organizational Stress

The law enforcement profession has been noted as one of the most high-risk and

high-stress occupations due to the dangerous situations that officers face frequently as

they risk their lives to protect and serve their communities. The continued exposure to

these types of situations causes police officers to experience elevated stress levels and

increases their risk of mental health consequences such as burnout, anxiety, depression,

23

somatization, and PTSD. In addition, research has shown that working under the stressful

conditions that law enforcement officers do increases the risk for new mental health

conditions to emerge and exacerbates preexisting mental health issues. Despite the

apparent stressors that first responders have at the police and organizational level and the

emotional and mental strain that is caused by the nature of the job, a large percentage of

law enforcement officers do not seek mental health treatment. A study was conducted to

identify the reasons behind officers’ apprehension to seek mental health treatment

(Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019) The study focused on the type of duty-related trauma

that law enforcement officers face, the level of influence that mental health stigma has

among officer culture, and the intervention strategies that are currently in place to support

their mental and emotional health of police officers (Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019).

According to Velazquez & Hernandez (2019) their research concluded that there

is a strong, negative stigma from law enforcement organizations and environmental

factors related to officers seeking mental health treatment. In addition, the researchers

identified a direct correlation between job-related trauma and stress and PTSD, substance

abuse, depression, and suicide or suicide ideation. The research identified the

organizational factors having the most negative impact on officers’ mental health to be

environmental factors of the job, abiding by law enforcement and social culture

ideologies, and the continuous exposures to crime and violence on the job. Although the

researchers identified the long-term results of these ideologies and negative exposures to

materialize in PTSD, substance abuse, depression, or even suicide, it was found that law

24

enforcement agencies throughout the nation are unknowingly promoting stigmas that

deter officers from seeking mental health treatment (Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019).

The researchers identified that despite the apparent need for officers to seek

mental and emotional treatment, there are apparent barriers to doing so. In addition to the

stigma-related apprehensions that officers have, they also face other barriers including

delaying treatment, difficulty in pursuing treatment, not fully emerging in prescribed

regimens, and often never identifying the symptoms of mental health issues. The

researchers concluded that there are two great areas of need in order to bridge the gap that

exists between the officer’s needs and the treatment currently being sought. Those

include reducing the stigma associated with officers’ self-seeking mental health treatment

and the identification of police officer trauma-related mental health (Velazquez &

Hernandez, 2019).

One of the greatest challenges that officers face today is the organizational stress

associated with the job that, in addition to the innate demands of the law enforcement

profession, include expectations of officers by the internal agencies. One of the

expectations is that law enforcement officers are unbreakable, both physically and

mentally. This causes an unrealistic expectation for officers to avoid seeking mental

health treatment despite the obvious need for such support in a profession such as this.

Researchers Bullock and Garland examined the findings of qualitative study focusing on

mental health stigmas within the law enforcement profession. They identified that there

was an extremely high amount of pressure throughout internal agencies to avoid mental

health treatment. They found that those who sought treatment were often isolated,

25

alienated, demoted, or held back from promotions. In addition, they identified an internal

stigma for seeking mental health treatment and identified a strong correlation between the

sociological framework for Goffman and the modified labeling theory where officers

were labelled for seeking mental health treatment. The labels included weakness,

inferiority, inability to complete their police duties, and mental instability (Bullock &

Garland, 2017).

Despite the challenging mental and physical requirements of police work, the

expectation by the internal agency for the officer to remain unaffected by the continuous

exposure to violence and crime causes a great deal of stress. As a result of this unrealistic

expectation to not need any emotional or mental support and the high demands of the job

that take a toll on one’s mental health, officers often choose to self-medicate through the

use of alcohol, cigarettes, or other vices that are not healthy for their bodies or minds.

Internal pressure often causes officers to internalize their stress which leads to physical

challenges for the officers as well (Bullock & Garland, 2017).

Organizational stress exists in many aspects of the law enforcement profession,

some including internal agency stressors. One strong internal stressor for officers is the

trust associated with the political agendas of many in the industry. Whether it is

perceived or factual, many officers believe that there are agendas among other officers

and management to advance and there is often concern that he or she may be a casualty

of these agendas. A study was conducted to examine the effects of trust within law

enforcement agencies. The focus was on management trust, supervisor trust, and

coworker trust. The study assessed the impact of the level of trust on job autonomy,

26

perceptions of training and preparation, perceived dangers of the job, and overload and

underload of work associated with the job. The population sample for this study included

827 police officers from two districts (Lambert et al., 2021).

The findings of the study indicated that the most significant trust relationships for

offers involved their co-workers and their direct supervisor. There was a strong

relationship between the trust of these groups and the officers and their corresponding

stress levels. The trust relationship with higher-level managers had less significance on

the associated job stress. Perceptions of the job as being dangerous and the work overload

had strong positive implications for officer stress levels, whereas role underload

demonstrated insignificant effects. The overall outcomes of the study indicated that in

order to reduce stress and improve the mental health of law enforcement officers, it is

essential that agencies foster relationships that build trust among coworkers and

supervisors. In addition, increasing the officers’ job autonomy, providing higher quality

and quantity of training, and reducing work overload and perceptions of the job being

dangerous have all proven to reduce stress and improve the overall mental health of law

enforcement officers (Lambert et al., 2021).

Additional studies have been conducted to allow law enforcement agencies

greater insight into how to assist with mitigating organizational stress and improve

overall mental health. A study was conducted to assess the current knowledge held by

public safety personnel including law enforcement officers of available programs and to

assess the associated stigmas of self-seeking mental health assistance. The study involved

the use of questionnaires and categorized the public safety personnel into various

27

categories in order to compare the knowledge and stigmas among departments (Krakauer

et al., 2020).

The findings of the study indicated that corrections officers reported the greatest

level of knowledge of mental health programs available to them and the least amount of

stigma for seeking mental health treatment. Firefighters and law enforcement officers

reported the lowest level of knowledge regarding mental health support available to them

and the highest rates for internal agency stigma. The researchers concluded that agencies

need to greatly improve their communication to public safety personnel regarding the

available mental health services that are available to them internally. They also concluded

that by communicating the available support and not villainizing it that there should be a

reduction in the negative perception of such services and the associated stigmas. The

researchers recommended that internal agencies strategically integrate mental health

services and programs throughout their units to better support officers and to reduce the

negative stigmas associated. They also noted that there should be no internal

ramifications for seeking treatment, such as loss of promotion, alienation, or negative

treatment as a result (Krakauer et al., 2020).

Smith (2021) investigated factors related to organizational stress, excessive

heightened emotional exhaustion, and increased organizational cynicism among law

enforcement officers. The study involved 281 active police officers and spanned a period

of three months. Officers were provided with online surveys and were asked to provide

open-ended responses to questions. The results of the data were analyzed, and the two

significant factors that were identified as contributors to organizational stress, emotional

28

exhaustion, and organizational cynicism was organizational support and employee voice

climate (Smith et al., 2021).

Through the completion of this study, the researchers identified that officers

contributed exhibited excessive organization cynicism, experienced emotional

exhaustion, and felt increased levels of organizational stress to the lack of organizational

support and a feeling of their voice not being heard. The study revealed that by increasing

organizational support and improving the employee voice climate that officers should

exhibit a healthier attitude toward the organization and demonstrate an increased level of

confidence in the members of their leadership teams. It is recommended by the

researchers that law enforcement agencies across the globe identify areas of stress that

are impacting their officers and remediate those with a change in behavior within the

organization. They concluded that failure to do so may result in employee dissatisfaction,

decreased well-being, and poor job performance. The researchers also theorized that by

improving organizational support and creating a positive employee voice climate,

turnover may be reduced, and officer mental health and job performance is expected to

improve (Smith et al., 2021).

Despite the apparent stressors that first responders have at the police and

organizational level and the emotional and mental strain that is caused by the nature of

the job, a large percentage of law enforcement officers do not seek mental health

treatment. A study was conducted to identify the reasons behind officers’ apprehension to

seek mental health treatment. The study focused on the type of duty-related trauma that

law enforcement officers face, the level of influence that mental health stigma has among

29

officer culture, and the intervention strategies that are currently in place to support their

mental and emotional health of police officers (Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019).

The findings of this research study concluded that there is a strong, negative

stigma from law enforcement organizations and environmental factors related to officers

seeking mental health treatment. In addition, the researchers identified a direct correlation

between job-related trauma and stress and PTSD, substance abuse, depression, and

suicide or suicide ideation. The research identified the organizational factors having the

most negative impact on officers’ mental health to be environmental factors of the job,

abiding by law enforcement and social culture ideologies, and the continuous exposures

to crime and violence on the job. Although the researchers identified the long-term results

of these ideologies and negative exposures to materialize in PTSD, substance abuse,

depression, or even suicide, it was found that law enforcement agencies throughout the

nation are unknowingly promoting stigmas that deter officers from seeking mental health

treatment (Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019).

The researchers identified that despite the apparent need for officers to seek

mental and emotional treatment there are apparent barriers to doing so. In addition to the

stigma-related apprehensions that officers have, they also face other barriers including

delaying treatment, difficulty in pursuing treatment, not fully emerging in prescribed

regimens, and often never identifying the symptoms of mental health issues. The

researchers concluded that there are two great areas of need in order to bridge the gap that

exists between the officer’s needs and the treatment currently being sought. Those

include reducing the stigma associated with officers’ self-seeking mental health treatment

30

and the identification of police officer trauma-related mental health (Velazquez &

Hernandez, 2019).

Personal Stress

Law enforcement officers face a tremendous amount of stress which stem from

the nature of the job as well as organizational stress caused by agency’s interactions

with officers and bureaucracy (Krakauer et al., 2020). In a sample of 832 officers

from two different police departments in the Midwest, Rief & Clinkinbeard (2021) found

that in addition to the general stress of police work, officers also face personal stress,

some of which is caused by their perception of whether they “fit” into the organization

or even the law enforcement profession itself. The research examined the correlation

between law enforcement officer’s perceptions of “fit” in their organizations and the

outcome of stress. The findings of the study indicated that there was a strong correlation

between officers perceived organizational fit and their stress levels. For those who did not

feel as though they do fit in their organization or in the profession, there was a high level

of stress exhibited. Additionally, there was a positive correlation between the

organizational fit and overall job satisfaction and turnover rates.

Rief and Clinkinbeard (2021) concluded that if officers felt that they were a good

fit for the organization and the profession, their stress level was mitigated significantly.

Conversely, those who felt as though they did not belong either in the organization, the

profession, or both, exhibited much higher levels of stress, sometimes as much as twice

as those who perceived themselves as being a good fit. The researchers noted that

perceived stress and organizational fit were both strong predictors of turnover

31

contemplation and overall job satisfaction. Based on their findings, the researchers

strongly recommend that agencies prioritize organizational culture and ensure that it is

inclusive and supportive of the officers who are employed there.

Stressors that officers face are often internalized and ultimately cause them a great

deal of personal stress. As a result of this continuous internalization of stress and repeated

exposures to stressful situations due to the police work and the organizational stressors,

law enforcement officers develop personal health issues at a greater rate than the general

population (Violanti et al., 2018). A study was conducted that analyzed the personal

stress of police offers and the corresponding adverse health conditions and mortality rates

over a period of 68 years. The researchers who conducted this study analyzed health and

mortality rates of police officers from 1950 to 2018 and analyzed 1,853 police deaths that

spanned across that time-period (Violanti et al., 2021).

The findings of this research study indicated that law enforcement officers had

significantly higher mortality rates resulting from adverse health conditions. The most

prominent conditions noted that led to the increased officer mortality rates included

circulatory system diseases, cirrhosis of the liver, mental disorders, and malignant

neoplasms. The study also concluded that officers who were white males were the most

prone to adverse health conditions that led to their mortality. Black male and female

officers of all races demonstrated lower mortality rates resulting from adverse health

conditions. The authors concluded that continuous exposure to stressors caused adverse

health conditions to develop. These conditions ultimately led to the death of the officers

at a much higher rate than was evidenced in the general population (Violanti et al., 2021).

32

The law enforcement profession exposes officers to violent and volatile situations

on a continual basis. The stress that results from that repeated exposure materializes in

the physical and mental health of officers (Violanti et al., 2021). A research study was

conducted to further analyze the relationship between police offers’ self-reported stress

and their corresponding health reports. The study also assessed the correlation between

dysfunctions in the basal cortisol profiles and their relationship to social desirability. The

study involved 77 policy offers who completed questionnaires that measured perceived

stress and mental and somatic health symptoms as well as social desirability. In addition,

saliva samples were provided for cortisol concentration analysis (Habersaat et al., 2021).

The findings of this study indicated a strong correlation between officer stress and

adverse health conditions and symptoms. The results of the saliva analysis indicated a

strong correlation between the dysregulation of the hypothalmic-pituitaryadrenal. This

verified the hypothesis that officers who seek social approval by inflating one’s capacities

(pretending) causes increased work-related stress and causes the officer to be more prone

to stress-related disease. The researchers strongly recommend that law enforcement

agencies become aware of the impacts of the stress that police work and the

organizational stress associated with the position has on an officer’s personal stress level

and overall mental and physical well-being (Habersaat et al., 2021).

Anxiety

The repeated exposures to violence, crime, death, and life-threatening situations

that are part of the law enforcement profession predispose officers to higher levels of

anxiety and mental health issues. Conditions such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD are

33

far more prevalent in law enforcement officers and first responders compared to other

professions. A survey was administered in 2017 that included 2,004 police officers,

paramedics, EMTs, and firefighters and focused on the self-identification of mental

health symptoms. The results of the survey indicated that 85-percent of those surveyed

reported having experienced mental health related symptoms. Despite the large

percentage of respondents who acknowledged the symptoms, only 34-percent of the

respondents stated that they have been diagnosed as having a mental disorder (Axelrod,

2018).

The research report indicated that the stigma of weakness when seeking mental

health treatment is the primary reason for first responders to avoid mental health

treatment. This fear of being ostracized or treated differently due to the stigmas that are

associated with mental health treatment adds to the anxiety that the officers already have.

Licensed psychologist Stephanie Conn indicated that although there have been

improvements made regarding officers seeking assistance for anxiety and mental health

issues due to generational changes, a stigma of weakness still exists. Conn recommends

that agencies encourage officers to recognize the anxieties that they are experiencing and

to voice their need for mental health treatment (Axelrod, 2018).

Conn recommended that agencies adopt a model that encompasses three common

mental health resources to include EAPs, peer support, and critical incident stress

management. Although Conn felt that all three resources are needed, she strongly

recommended the peer support and critical incident stress management models for law

enforcement officers who are experiencing anxiety and other mental health symptoms.

34

Conn provided a strong rationale for these support systems to be offered through law

enforcement agencies where officers are employed. She felt that the officers would be

more encouraged to seek assistance if their agencies were offering and promoting these

resources among the organization. She theorized that this would assist the officers with

their anxiety and would reduce some of the current stigmas associated with mental health

treatment (Axelrod, 2018).

Depression

Due to the nature of the law enforcement profession and the continuous exposures

that officers have with traumatic incidents, extreme violence, and crime, the risk for

officers to develop depression is of great concern. A study involving 242 police officers

from Buffalo, New York, were evaluated over a period of 10 years (2004-2014) to

identify factors that predispose officers to depression. Personality characteristics

including coping abilities, hardiness, social support, and protective factors were

examined. The study revealed that officers with previous depression symptoms and/or

diagnosis had a 95% probability of experiencing recurring depression after entering the

profession of law enforcement. The study indicated that for officers who were free of

depression prior to entering the profession, there was a 23% chance that they would

experience onset depression as a result of being a police officer (Jenkins et al., 2018).

The study also analyzed the personality characteristics of officers and compared

those with the propensity for the onset of depression. The findings of the study indicated

that officers who demonstrated strong coping skills, hardiness, and had social support

were less likely to experience depression. Conversely, officers who passive coping skills

35

and who experienced neuroticism were far more likely to experience the onset of

depression as a result of their professional experiences (Jenkins et al., 2018).

Depression affects approximately 6.7% of adults in the United States. This

statistic is more than double for that for police officers due to sustained exposures to

critical incidents that they face on a continuous basis. Some reports indicate that 16 to

23% of police offers exhibit depressive tendencies. Research indicates that depression

resulting from occupational-related stress can be mitigated through the use of effective

coping skills and hardiness of an officer. Those who demonstrated positive coping

behaviors which included planning, acceptance, and seeking support demonstrated fewer

symptoms of distress and corresponding depression. Officers who possess negative

coping behaviors which include self-blame, disengagement, and denial are more likely to

experience psychological distress and depression. The strongest personality trait that was

noted to correlate with positive coping skills is an officer’s hardiness. This is the set of

beliefs or attitudes about oneself that provide motivation and courage to allow the officer

to endure stressful situations and transition problematic events into opportunities (Allison

et al., 2019).

A study involving heart rate and physical activity monitoring was conducted to