EN EN

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

Brussels, 10.10.2019

SWD(2019) 375 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Evaluation of the Union legislation on blood, tissues and cells

{SWD(2019) 376 final}

Table of Contents

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................. 1

GLOSSARY ........................................................................................................................ 2

1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 7

1.1 Purpose of the Evaluation .................................................................................... 8

1.2 Scope of the Evaluation ....................................................................................... 8

2. BACKGROUND TO THE INTERVENTION ......................................................... 10

2.1 Concerns leading to the intervention ...................................................................... 10

2.2 Baseline and points of comparison ......................................................................... 16

2.2.1 Blood ................................................................................................................ 16

2.2.2 Tissues and Cells .............................................................................................. 17

2.2.3 Situation in Member States that joined after 2004 ........................................... 17

3. STATE OF PLAY ..................................................................................................... 19

3.1 The BTC Sector ...................................................................................................... 19

3.2 Transposition and updating of BTC legislation ...................................................... 21

3.3 Oversight functions at Member State level............................................................. 23

3.4 Monitoring Arrangements....................................................................................... 23

3.5 Support for implementation .................................................................................... 25

4. EVALUATION METHOD ....................................................................................... 26

4.1 Conducting the Evaluation...................................................................................... 26

4.1.1 Evaluation Roadmap ........................................................................................ 26

4.1.2 Stakeholder Consultation ................................................................................. 26

4.1.3 External Study .................................................................................................. 27

4.2 Limitations and robustness of the evaluation findings ........................................... 27

5. ANALYSIS AND ANSWERS TO THE EVALUATION QUESTIONS ................ 29

5.1 Relevance ........................................................................................................... 29

5.1.1 Evaluation question 1a): To what extent is the legislation sufficiently adapted

to, adaptable to, and up-to-date with scientific, technical and epidemiological

developments / innovation? ....................................................................................... 29

5.1.2 Evaluation question 1b) To what extent is the legislation adapted to other

changes in the sector such as commercialisation, internationalisation or other societal

changes? .................................................................................................................... 33

5.1.3 Evaluation question 1c) Are there any gaps in terms of substances of human

origin or activities that are not regulated by the Directives? .................................... 38

5.2 Effectiveness ........................................................................................................... 40

5.2.1 QUESTION 2: To what extent has the legislation increased the quality and

safety of blood and tissues and cells and achieved a high level of human health

protection? ................................................................................................................. 40

5.2.2 QUESTION 3: Has the legislation led to any unintended effects (positive or

negative)? .................................................................................................................. 48

5.2.3 QUESTION 4: What, if any, have been the barriers preventing effective

implementation of the legislation? ............................................................................ 49

5.2.4 QUESTION 5: Are the rules on oversight sufficient to address the increased

internationalisation? .................................................................................................. 51

5.2.5 QUESTION 6: What, if any, are the challenges to maintaining compliance

with the legislation? .................................................................................................. 52

5.2.6 QUESTION 7: To what extent, if any, has the legislation impacted on patient

access to blood, tissues and cells? ............................................................................. 53

5.3 Efficiency ................................................................................................................ 57

5.3.1 Evaluation question 8: How cost-effective has the application of the quality

and safety requirements in the legislation been for operators. Have the benefits

outweighed the costs? ............................................................................................... 58

5.3.2 Evaluation Question 9: Are there particular administrative or other burdens for

specific groups of operators, including downstream users of blood, tissues and cells

as starting materials for medicinal products? ............................................................ 61

5.4 Coherence ............................................................................................................... 64

5.4.1 Evaluation question 12a) To what extent is the legislation on blood and tissues

and cells consistent and coherent within its own provisions? ................................... 65

5.4.2 Evaluation question 12b) To what extent is the legislation coherent and

consistent with other relevant Union legislation? ..................................................... 66

5.4.3 Evaluation question 12c) Are the requirements of the Directives suitable when

blood, tissues and cells are used as starting materials for the manufacture of

medicinal products/medical devices? ........................................................................ 74

5.4.4 Evaluation question 12d): To what extent is the legislation coherent with other

relevant international / third country approaches to the regulation of the quality and

safety of blood and tissues and cells? ....................................................................... 76

5.5 EU Added Value ..................................................................................................... 78

5.5.1 Evaluation Question 13: To what extent has the legislative framework at EU

level added value to the regulation of blood and tissues and cells across the EU-28 in

a manner that could not have been achieved by measures taken at national or global

level? ......................................................................................................................... 78

5.5.2 Question 14. To what extent do stricter national measures pose an obstacle to

exchange of supplies between Member States? ........................................................ 80

6. CONCLUSIONS ........................................................................................................... 82

i) The legislation effectively increased the level of safety and quality of BTC across the

EU ................................................................................................................................. 82

ii) The current rules are no longer up to date with the dynamic BTC sectors .............. 82

iii) Key oversight principles are not sufficiently robust ............................................... 83

iv) Some citizen groups, such as donors and offspring are not adequately protected .. 84

v) The legislation does not keep pace with innovation ................................................. 84

vi) Requirements are insufficient to support sufficiency and a sustainable supply for all

BTC ............................................................................................................................... 85

Were possible areas for simplification identified? ....................................................... 86

Will the issues identified resolve or deteriorate over time? .......................................... 86

ANNEX I: PROCEDURAL INFORMATION ................................................................. 87

ANNEX II: TRANSMISSIONS OF INFECTIONS TO EU PATIENTS BY BLOOD

TRANSFUSION, TREATMENT WITH PLASMA DERIVED MEDICINAL

PRODUCTS AND TISSUES AND CELLS IN THE 1980 AND 1990S. ................ 88

ANNEX III: THE BACKGROUND TO THE REGULATION OF BLOOD AND

BLOOD COMPONENTS IN EUROPE ................................................................... 96

ANNEX IV: THE LEGAL BASIS AND THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK ADOPTED .. 102

Primary Legislation..................................................................................................... 102

Secondary legislation .................................................................................................. 102

Tertiary legislation ...................................................................................................... 104

ANNEX V: BASELINE .................................................................................................. 106

Part A - Blood and Blood components for transfusion ............................................... 106

Part B- Tissues and cells ............................................................................................. 112

ANNEX VI: CASES SENT BY NATIONAL COURTS TO THE EUROPEAN COURT

OF JUSTICE FOR A PRELIMINARY RULING ON QUESTIONS OF UNION

LAW RELATING TO THE BTC SECTORS. ....................................................... 118

ANNEX VII: WRITTEN PARLIAMENTARY QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE

BTC LEGISLATION SINCE 2002 ........................................................................ 124

ANNEX VIII: INTERPRETATION QUESTIONS ARISING IN THE NATIONAL

COMPETENT AUTHORITY (NCA) MEETINGS WITH THE COMMISSION . 127

ANNEX IX: LIST OF PUBLIC HEALTH PROGRAMME ACTIONS FUNDED TO

SUPPORT THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE BTC LEGISLATION ............... 180

ANNEX X: ECDC – SUPPORT FOR EU ACTIVITIES ON SUBSTANCES OF

HUMAN ORIGIN 2012 – 2018 .............................................................................. 186

ANNEX XI: COLLABORATION WITH COUNCIL OF EUROPE ............................. 188

ANNEX XII: STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION SYNOPSIS.................................. 189

1. Consultation Strategy .............................................................................................. 189

2. Consultation Activities and Key messages ............................................................. 192

2.1 Roadmap Feedback ........................................................................................... 192

2.2 Public Consultation ........................................................................................... 193

2.3 Targeted Stakeholder Consultation................................................................... 197

2.4 Stakeholder Event .............................................................................................. 201

3. Representativeness of Stakeholder Participation ................................................. 203

ANNEX XIII: EXAMPLES OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGES IN THE

PROCESSING OF TISSUES AND CELLS ........................................................... 207

ANNEX XIV: EMERGING/INCREASING COMMERCIAL ACTIVITIES ............... 209

ANNEX XV: A NON-EXHAUSTIVE LIST OF CLINICAL OUTCOME REGISTRIES

IN THE BTC SECTORS ......................................................................................... 210

ANNEX XVI: INCONSISTENCIES BETWEEN EU-LEGAL FRAMEWORKS ........ 212

1 | P a g e

List of abbreviations

ATMP

Advanced therapy medicinal products

BTC

Blood, tissues and cells

CoRE SoHO

Consortium of BTC representative societies

DLI

Donor Leukocytes for Infusion

EBA

European Blood Alliance

EBMT

The European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation

ECDC

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

EHA

The European Hematology Association

EHC

The European Haemophilia Consortium

EPA

The European Plasma Alliance

ESHRE

The European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology

FIODS

The International Federation of Blood Donor Organisations

FMT

Faecal Microbiota Transplants

GMP

Good manufacturing practices

GPG

Good Practice Guidelines

HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

IHN

The International Haemovigilance Network

IPFA

The International Plasma Fractionation Association

IPOPI/PLUS

The International Patient Organisation for Primary Immunodeficiencies

ITE

Importing tissue establishments

IVF

In Vitro Fertilisation

MAR

Medically assisted reproduction

MSM

Men having sex with men

NAT

Nucleic Acid Test

OHSS

Ovarian Hyper stimulation Syndrome

PDMP

Plasma derived medicinal products

PMF

Plasma master file

PPTA

The Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association

PRF

Platelet Rich Fibrin

PRP

Platelet rich plasma

RAB

Rapid alert platform for human blood and blood components

RATC

Rapid alert platform for human tissues and cells

SAE

Serious adverse event

SAR

Serious adverse reaction

SARE

Serious adverse reactions and events

SoHO

Substances of Human Origin

TFEU

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

VOC

Volatile organic compounds

VUD

Voluntary and unpaid donation

WMDA

World Marrow Donor Association

WNV

West Nile Virus

2 | P a g e

Glossary

Term

Definition

Advanced Therapy

Medicinal Products

An advanced therapy medicinal product

1

means any of the

following medicinal products for human use:

a gene therapy medicinal product as defined in Part

IV of Annex I to Directive 2001/83/EC,

a somatic cell therapy medicinal product as defined

in Part IV of Annex I to Directive 2001/83/EC,

a tissue engineered product as defined as containing

or consisting of engineered cells or tissues, and

presenting properties for or being used or

administered to human beings with a view to

regenerating, repairing or replacing a human tissue.

Allogeneic use

Cells or tissues removed from one person and applied to

another

2

.

Antibodies

Antibodies are immunoglobulins (Ig). They are large

proteins that are found in blood or other body fluids.

Antibodies are part of the immune system that identify and

neutralise foreign objects, such as bacteria and viruses.

Anticoagulant

An additive that stops or slows blood clotting.

Assisted Reproductive

Technology-ART

All treatments or procedures that include the in vitro

handling of human oocytes and sperm or embryos for the

purpose of establishing a pregnancy. This includes, but is

not limited to, IVF and transcervical embryo transfer,

gamete intra-Fallopian transfer, zygote intra-Fallopian

transfer, tubal embryo transfer, gamete and embryo

cryopreservation, oocyte and embryo donation and

gestational surrogacy. ART does not include assisted

insemination (artificial insemination) using sperm from

either a woman’s partner or sperm donor.

Autologous (transfusion,

donation or use)

Blood

3

: Autologous transfusion shall mean transfusion in

which the donor and the recipient are the same person and

in which pre-deposited blood and blood components are

used.

1

Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 amending Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004.

2

Directive 2004/23/EC.

3

Directive 2002/98/EC.

3 | P a g e

Tissues and cells

4

: Autologous use means cells or tissues

removed from and applied in the same person.

Basocellular Epithelioma

A common type of skin cancer.

Blood Establishments

Blood establishment shall mean any structure or body that

is responsible for any aspect of the collection and testing of

human blood or blood components, whatever their intended

purpose, and their processing, storage, and distribution

when intended for transfusion. This does not include

hospital blood banks

5

.

Bone marrow

See haematopoietic stem cells

Cytapheresis

A procedure for collecting particular cells from a donor or

patient.

Faecal microbiota

transplant – FMT

Fecal microbiota transplantation or FMT is the transfer of

fecal material containing bacteria and natural antibacterial

from a healthy individual into a diseased recipient.

Gametes

Sperm (spermatozoa) and eggs (oocytes).

Good Manufacturing

Practice

Good manufacturing practice shall mean the part of quality

assurance which ensures that products are consistently

produced and controlled to the quality standards appropriate

to their intended use

6

.

Haematopoietic stem cells

Cells in the bone marrow that produce new blood cells.

Haematopoietic stem cells are found in bone marrow and in

blood collected from the umbilical cord after the birth of a

baby. They can also be collected from a donor’s blood

stream if the donor is treated with particular hormones that

cause the cells to move out of the bone marrow into the

blood.

Haemoglobin

A protein found in the red blood cells that is responsible for

carrying oxygen around the body. Haemoglobin picks up

the oxygen in the lungs, and then releases it in the muscles

and other tissues where it is needed. Haemoglobin also

contains iron which is critical for it to work properly.

Haemovigilance

The set of surveillance procedures covering the entire blood

transfusion chain, from the donation and processing of

blood and its components, through to their provision and

4

Directive 2004/23/EC.

5

See: Directive 2002/98/EC.

6

Commission Directive 91/356/EEC.

4 | P a g e

transfusion to patients, and including their follow-up.

Immunodeficiency

A state in which the immune system's ability to fight

infectious disease and cancer is compromised or entirely

absent.

Immunoglobulin

Glycoproteins that are part of the immune system.

Imputability

The likelihood that a serious adverse reaction in a recipient

can be attributed to the tissue or cells applied or that a

serious adverse reaction in a living donor can be attributed

to the donation process

7

.

In vitro fertilisation (IVF)

An assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedure that

involves extracorporeal fertilisation.

Lymphocytes

White blood cells.

Medically assisted

reproduction (MAR)

Reproduction brought about through ovulation induction,

controlled ovarian stimulation, ovulation triggering, ART

procedures, and intrauterine, intracervical, and intravaginal

insemination with semen of donor.

Nucleic acid amplification

technique

A testing method to detect the presence of a targeted area of

a defined nucleic acid (e.g. viral genome) using

amplification techniques such as polymerase chain reaction

or transcription mediated amplification.

Partner Donations

The donation of reproductive cells between a man and a

woman who declare that they have an intimate physical

relationship

8

.

Plasma Derived Medicinal

Products

Medicinal products based on blood constituents which are

prepared industrially by public or private establishments,

such medicinal products including, in particular, albumin,

coagulating factors and immunoglobulins of human origin

9

.

Platelet

Platelets, also called thrombocytes, are a component of

blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is

to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping,

thereby initiating a blood clot.

Platelet Rich Fibrin (PRF)

A fibrin meshwork, in which platelet cytokines, growth

factors, and cells are entrapped and discharged after a

period and can serve as a resorbable film.

Platelet Rich Plasma

Plasma in which the donor’s platelets have been

7

See: Commission Directive 2005/61/EC implementing Directive 2002/98/EC.

8

Commission Directive 2006/17/EC.

9

Directive 2001/83/EC.

5 | P a g e

(PRP)

concentrated.

Reproductive cells

Sperm, eggs and embryos.

Same Surgical Procedure

Processing of human substances (blood, tissues or cells)

from a patient during surgery, within the surgical area.

Serious Adverse Event

Blood

10

: Any untoward occurrence associated with the

collection, testing, processing, storage and distribution, of

blood and blood components that might lead to death or

life-threatening, disabling or incapacitating conditions for

patients or which results in, or prolongs, hospitalisation or

morbidity.

Tissues and cells

11

: Any untoward occurrence associated

with the procurement, testing, processing, storage and

distribution of tissues and cells that might lead to the

transmission of a communicable disease, to death or

lifethreatening, disabling or incapacitating conditions for

patients or which might result in, or prolong, hospitalisation

or morbidity.

Serious Adverse Reaction

Blood

12

: An unintended response in donor or in patient

associated with the collection or transfusion of blood or

blood component that is fatal, life-threatening, disabling,

incapacitating, or which results in, or prolongs,

hospitalisation or morbidity.

Tissues and cells

13

: An unintended response, including a

communicable disease, in the donor or in the recipient

associated with the procurement or human application of

tissues and cells that is fatal, life-threatening, disabling,

incapacitating or which results in, or prolongs,

hospitalisation or morbidity.

Tissue Establishment

Tissue establishment means a tissue bank or a unit of a

hospital or another body where activities of processing,

preservation, storage or distribution of human tissues and

cells are undertaken. It may also be responsible for

procurement or testing of tissues and cells

14

.

Transmissible diseases

Comprises all clinically evident illnesses (i.e. characteristic

medical signs and/or symptoms of disease) resulting from

10

Directive 2002/98/EC.

11

Directive 2004/23/EC.

12

Directive 2002/98/EC.

13

Directive 2004/23/EC.

14

Directive 2004/23/EC.

6 | P a g e

the infection, presence and growth of microorganisms in an

individual or the transmission of genetic conditions to the

offspring. In the context of transplantation, malignancies

and autoimmune diseases may also be transmitted from

donor to recipient.

7 | P a g e

1. INTRODUCTION

In the European Union (EU), millions of blood donations are collected every year by

1,400 blood establishments, enabling the transfusion of millions of blood

components

15

,

16

. Plasma, a blood component, is also used for the manufacture of plasma

derived medicinal products (PDMP). Tissues and cells

17

are handled by over 4,000 tissue

establishments

18

and can also be the starting materials for the manufacture of medicinal

products and medical devices. Several of these substances are exchanged between

Member States.

Blood, tissues and cells (BTC) all come from the same source - donations from human

beings - either during life or after death. They are processed, tested and stored in blood

and tissue establishments before being supplied to hospitals and clinics. In most cases, no

alternative treatments exist to save or enhance human lives. However, these substances

can also cause adverse reactions in patients, including the transmission of disease.

To ensure high levels of public health protection for all stages of the process, the Blood

Directive (2002/98/EC) and the Tissues and Cells Directive (2004/23/EC) were adopted

in 2002 and 2004, respectively, laying down common (minimum) quality and safety

standards at Union level and aiming to facilitate increased exchange of these substances

between Member States. In this report, these two Directives are referred to jointly as ‘the

basic Acts’. Implementing legislation was also adopted to provide technical requirements

for both fields

19

. Since their adoption, some of the implementing Directives have been

amended (see Annex IV).

There has been significant scientific and technological development in the sector and

new risks of transmitting diseases, such as Zika, dengue fever and hepatitis E, have

emerged since the legislation was adopted, more than 15 years ago. The field has also

undergone organisational changes, including an increasing role of commercial players in

a traditionally non-profit sector with a high level of public sector involvement. No

evaluation of the basic Acts has taken place since their adoption. The European

Commission has published several implementation reports for each sub-sector, each

15

Red blood cells, platelets and plasma are components of a blood donation, and each can be transfused to patients.

16

DG SANTE website, introduction to the Commission’s work on blood.

17

Including corneas, bone, skin and heart valves for tissue replacement surgery, stem cells from bone marrow and cord

blood for transplantation and reproductive cells for medically assisted reproduction.

18

DG SANTE website, introduction to the Commission’s work on tissues and cells.

19

Blood: Commission Directive 2004/33/EC as regards technical requirements for blood and blood components,

Directive 2011/38/EU and Directive 2014/110/EU; Commission Directive 2005/61/EC as regards traceability

requirements and notification of serious adverse reactions and events; Commission Directive 2005/62/EC as regards

Community standards and specifications relating to a quality system for blood establishments; Tissues and cells:

Commission Directive 2006/17/EC as regards technical requirements for donation, procurement and testing;

Commission Directive 2006/86/EC as regards traceability requirements, notification of serious adverse reactions and

events and technical requirements for coding, processing, preservation, storage and distribution; Commission Directive

(EU) 2015/566 regarding the procedures for verifying the equivalent standards of quality and safety of imported tissues

and cells; Commission Decision 2010/453/EU on conditions of inspections; Commission Decision 2015/4460 on

agreements with tissue and cell coding organisations.

8 | P a g e

based on information provided by Member States. The most recent reports, published in

April 2016

20

,

21

highlighted a number of gaps and shortcomings.

1.1 Purpose of the Evaluation

The purpose of this evaluation is to provide a comprehensive assessment of the Union

legislation on BTC - the basic Acts and their implementing Directives, examining their

functioning across the EU. The European Commission’s evaluation criteria

22

, i.e.

effectiveness, efficiency, relevance, coherence and EU-added value, are assessed. In

particular, the evaluation assesses the extent to which the BTC legislation met its original

objectives and whether it remains fit for purpose.

1.2 Scope of the Evaluation

This evaluation covers the two basic Acts, Directives 2002/98/EC on blood and

2004/23/EC on tissues and cells, as well as their implementing Directives

5

in all EU

Member States from the date of their entry into force until the end of April 2019. For

those Member States that joined the Union after the entry into force of the Directives, the

evaluation covers the period from their date of accession.

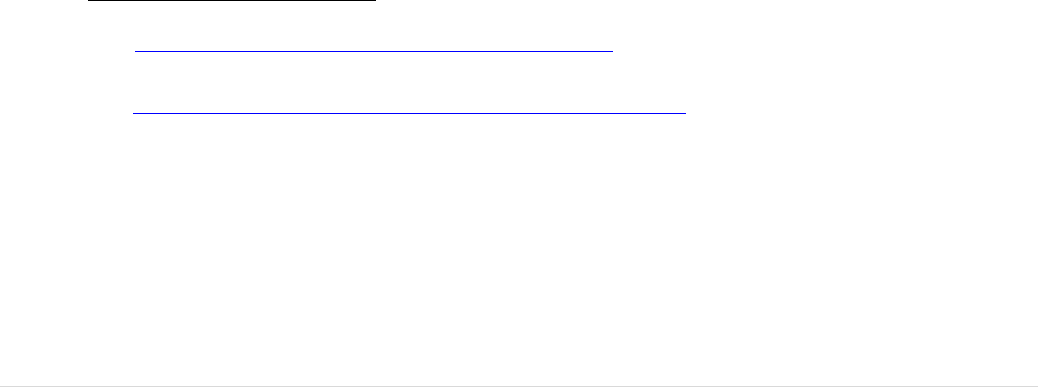

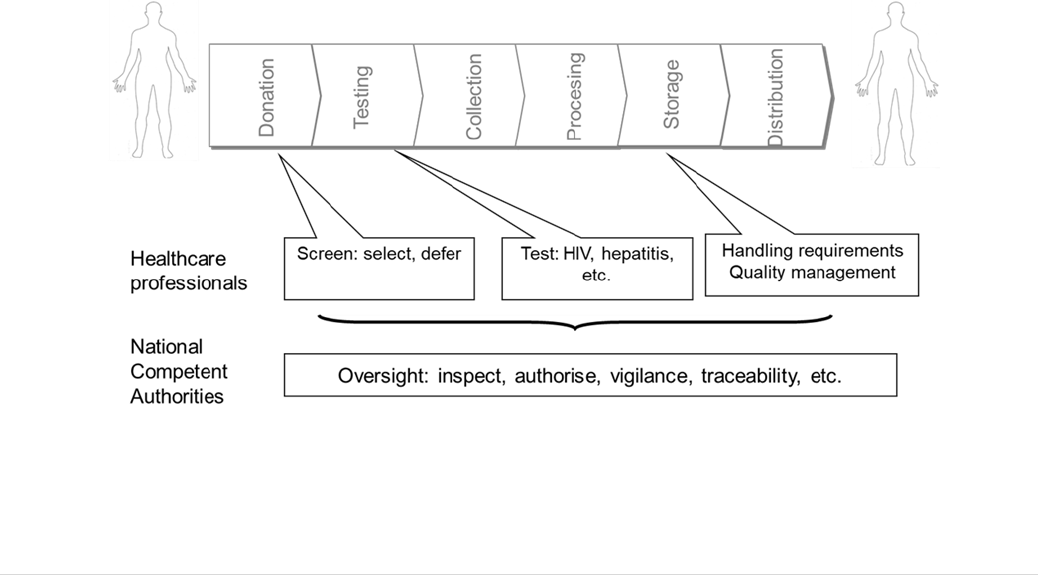

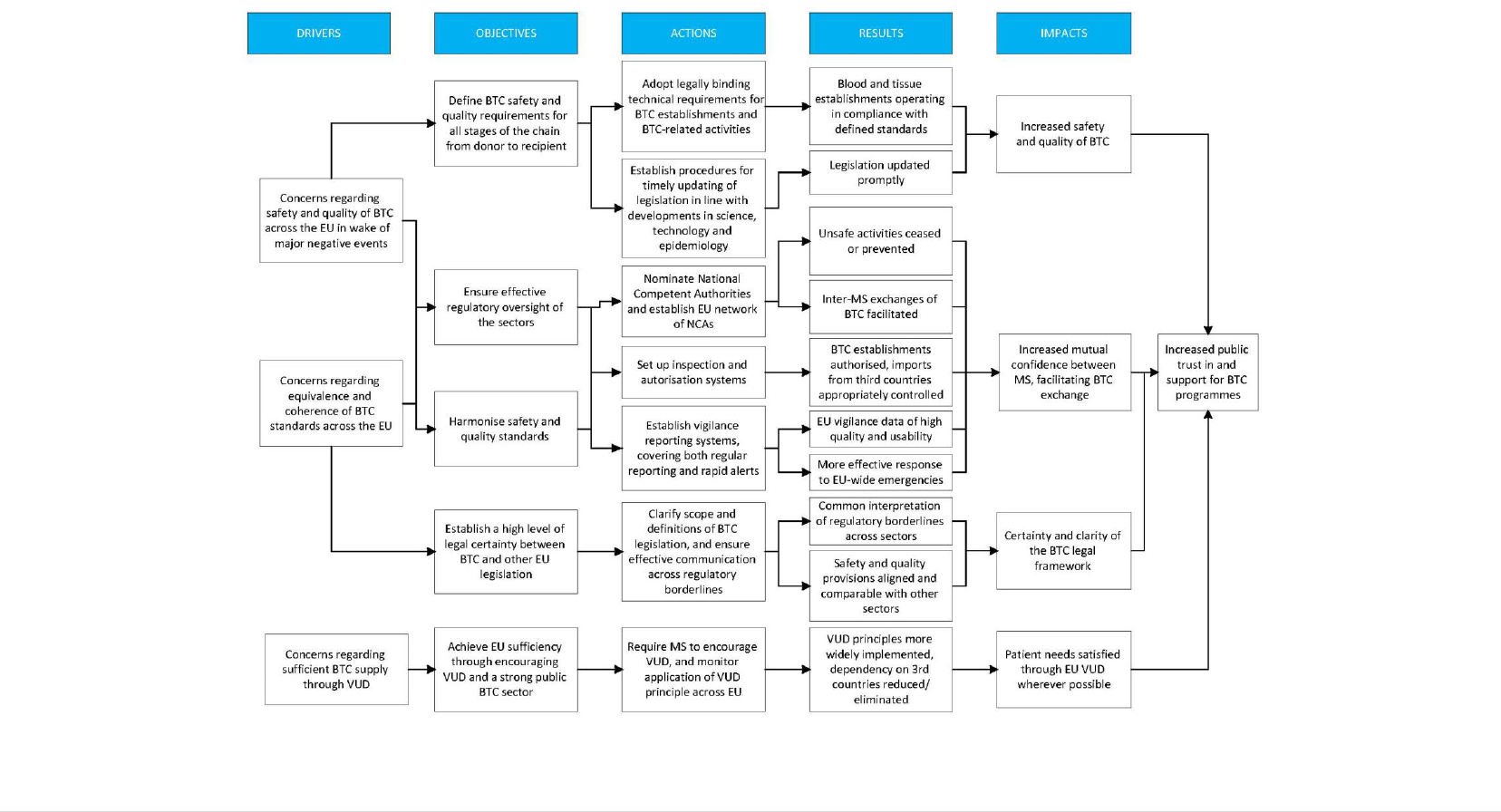

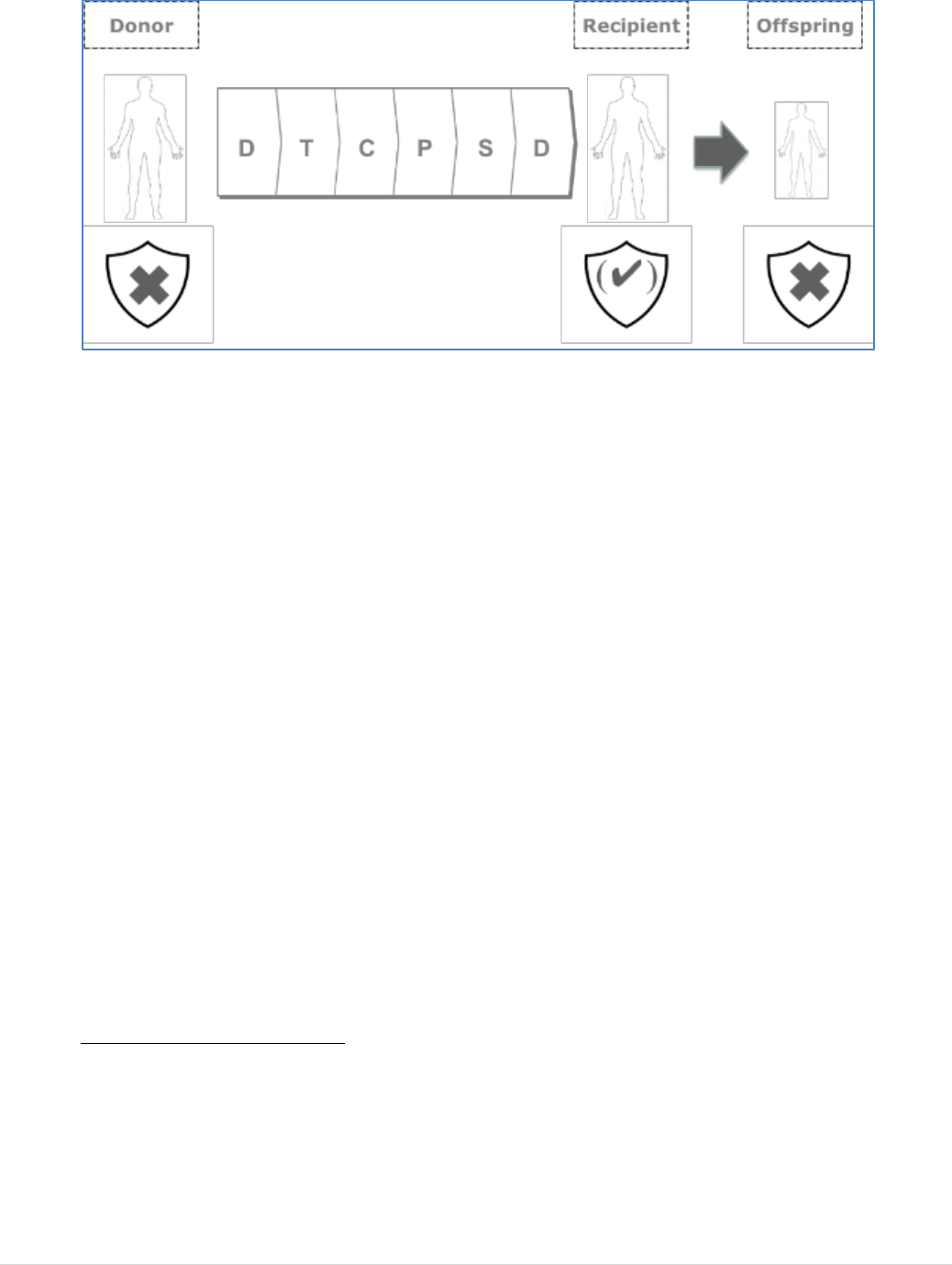

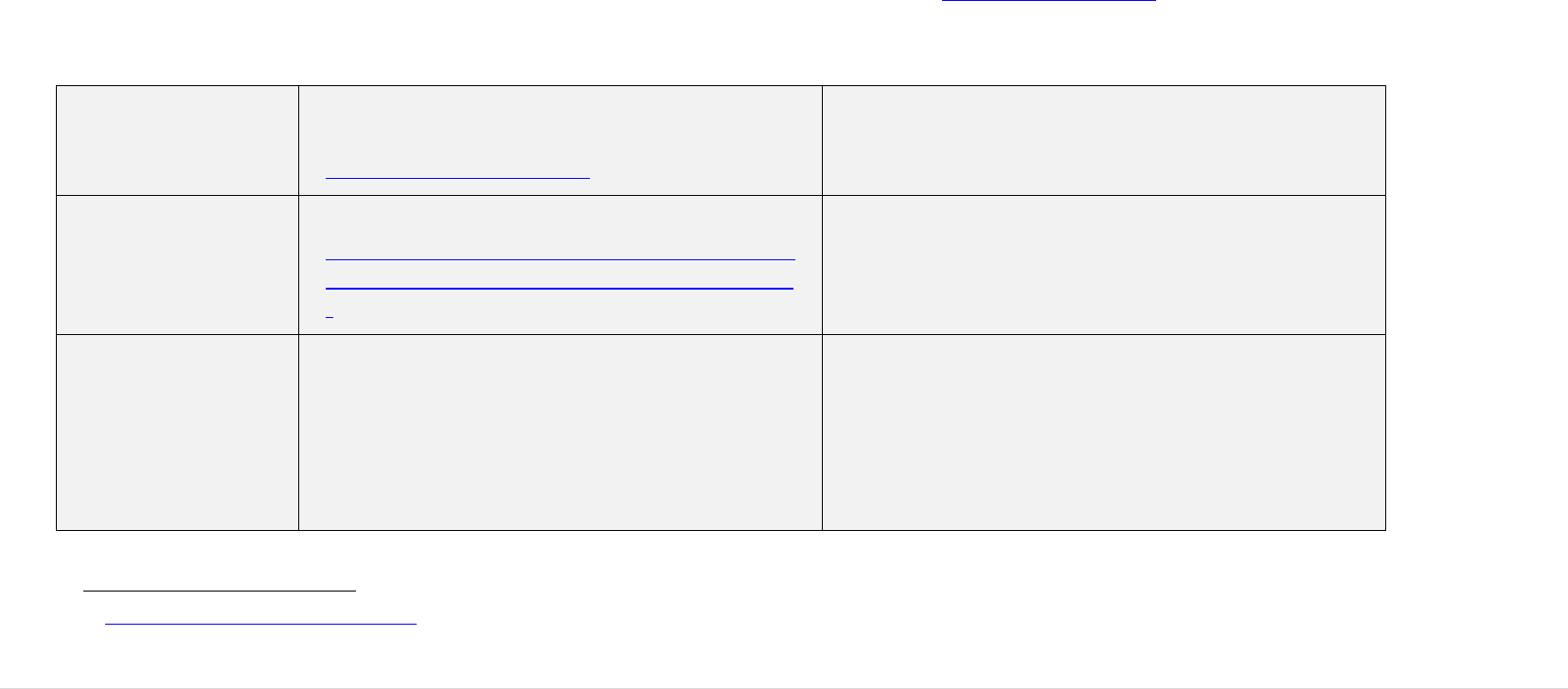

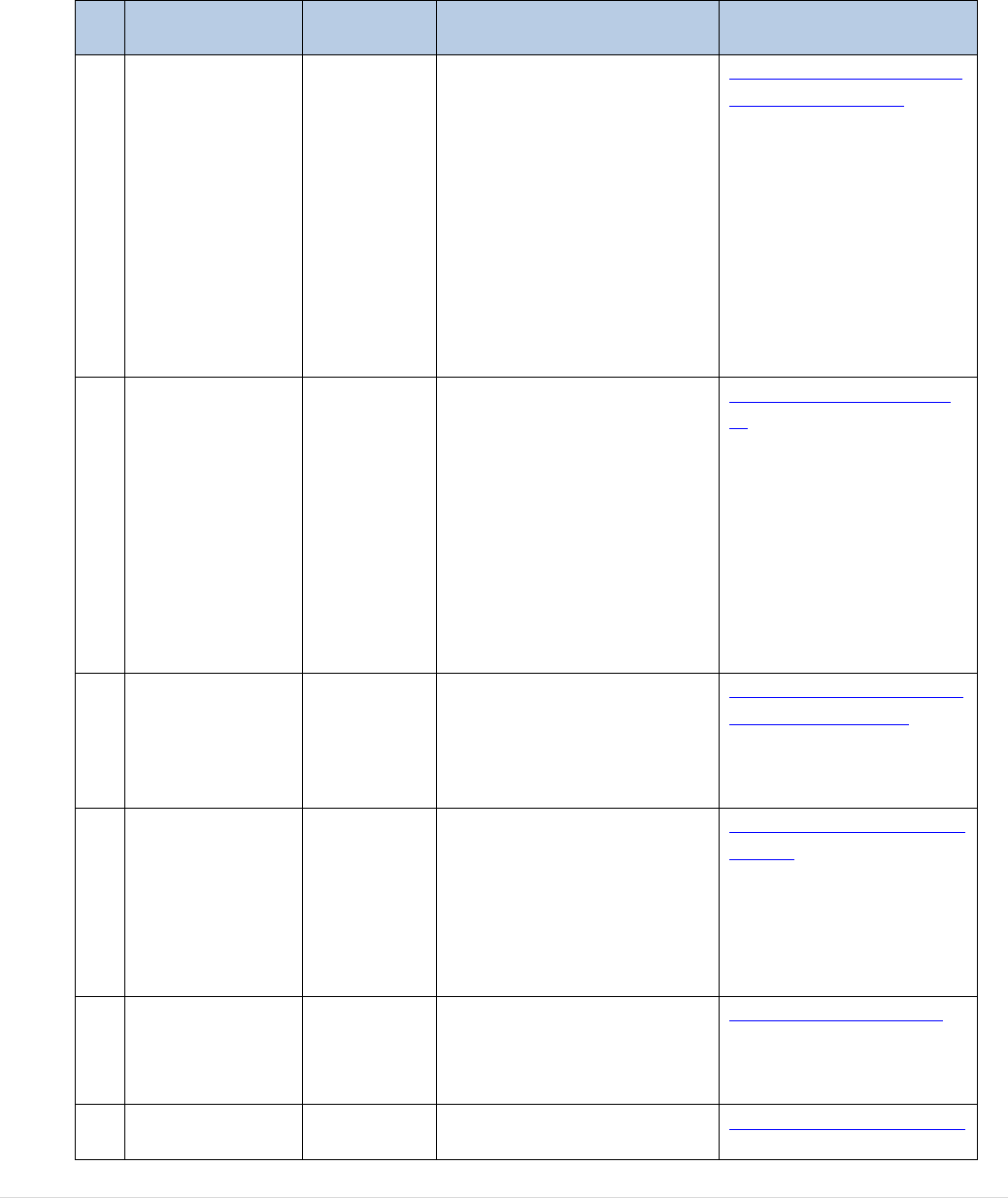

There are many commonalities between the two basic Acts. They have the same legal

basis

23

, similar generic oversight requirements and they aim to mitigate very similar risks

to safety and quality for all stages from donation to distribution for clinical use in a

patient (see Figure 1). Many professionals and authorities work across the two sub-

sectors. For these reasons, one evaluation was conducted to cover both legal frameworks.

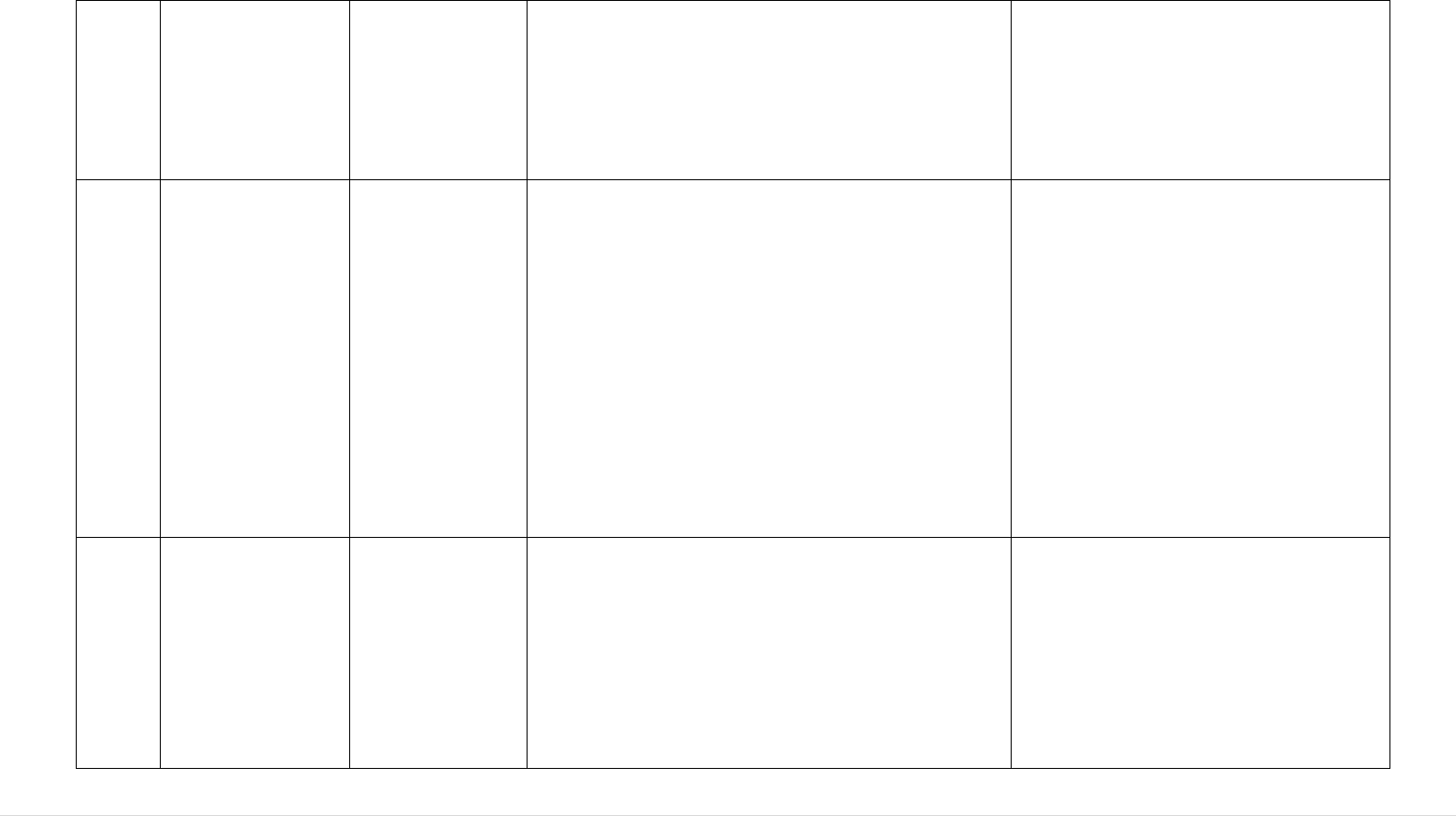

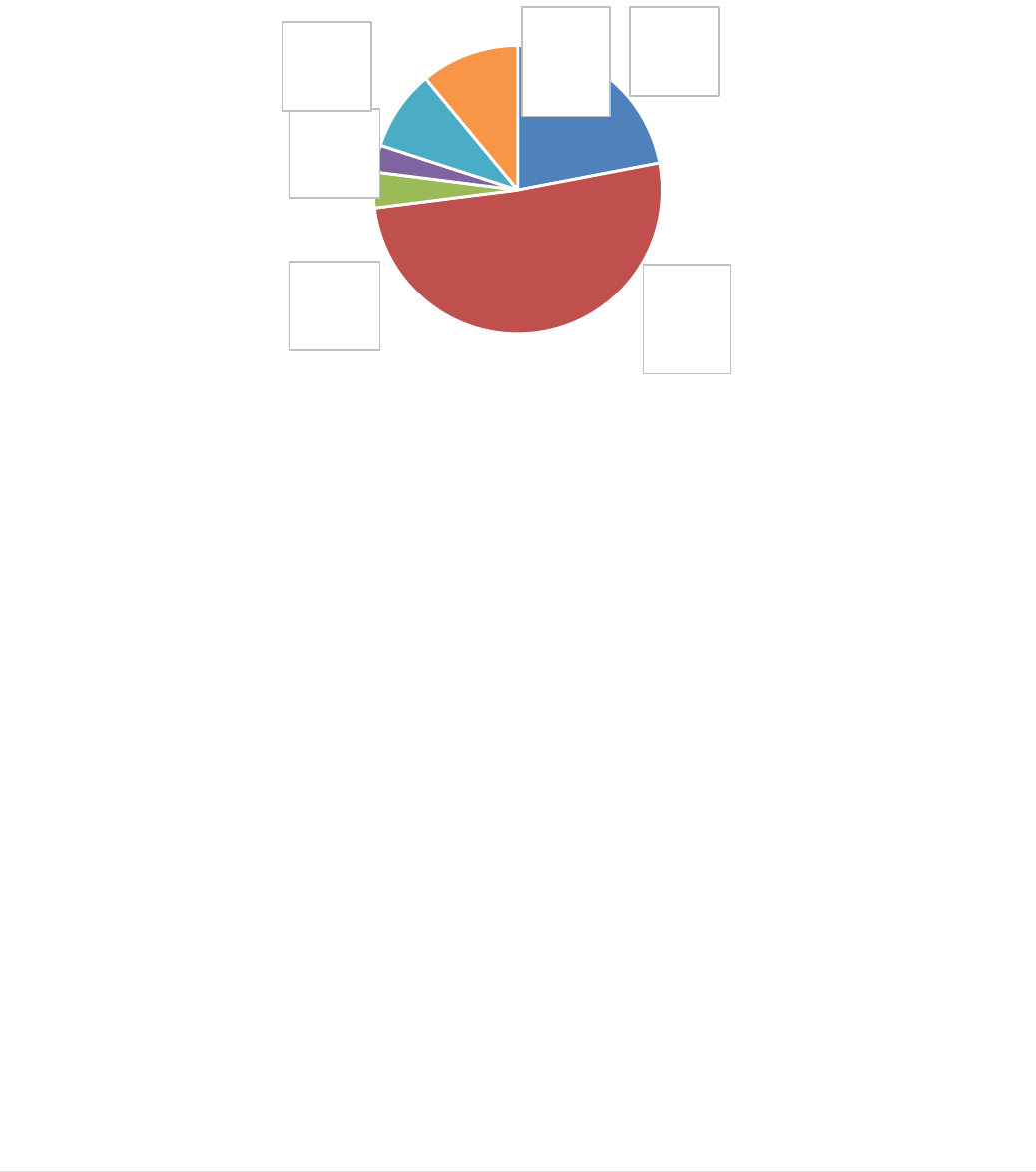

FIGURE 1: THE STEPS FROM BTC DONATION TO CLINICAL APPLICATION

20

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social

Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Implementation of Directive 2002/98/EC and implementing

directives, setting standards of quality and safety for human blood and blood components - COM(2016) 224 final.

21

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social

Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Implementation of Directive 2004/23/EC and implementing

directives, setting standards of quality and safety for human tissues and cells - COM(2016) 223 final.

22

European Commission Better Regulation guidelines.

23

Article 168 (4) (a) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

9 | P a g e

The Human Organs Directive, adopted in 2010 (2010/53/EU), was excluded from the

scope of this evaluation, given that significant shortcomings had not been highlighted, as

they had for BTC, and the quality and safety provisions are significantly different and

less detailed

24

.

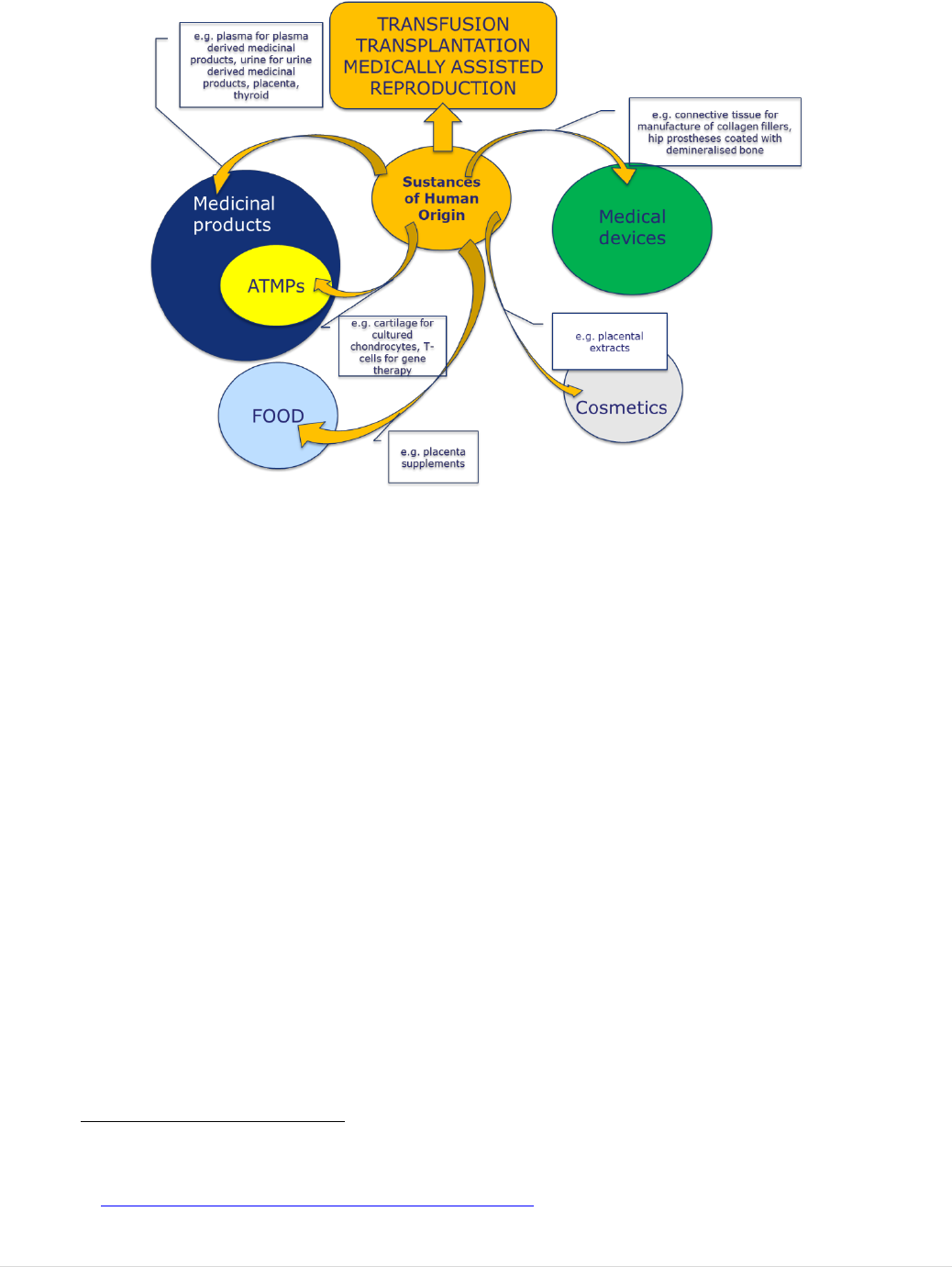

The regulations governing medicinal products, including advanced therapy medicinal

products (ATMPs) adopted in 2007

25

, and governing medical devices, adopted only in

2017

26

, are also excluded from the scope. However, the evaluation does cover the

coherence of the BTC legislation with these frameworks.

In the light of the significant and increasing international exchanges of some BTC with

third countries, the evaluation also considers coherence and similarities/differences with

relevant regulatory frameworks for BTC outside the EU. In particular, the equivalence of

safety and quality of BTC imported into the EU, mostly from the United States of

America (USA), is addressed.

The BTC sector is one where many ethical issues arise, ranging from debates

surrounding the use of technology for the creation of life to consent for donation after

death. EU legal competence to regulate this field is limited, by the Treaty on the

Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)

27

, to safety and quality. Decisions and

policies on the many ethical aspects remain at a Member State level, except where they

have an impact on safety and quality. Where Member States choose to allow particular

practices, such as testing or genetic manipulation of embryos, the safety and quality of

those activities are regulated by these Directives and are included in the scope of this

evaluation. Legal competence for issues related to the organisation of healthcare services

(including BTC services) also remains at the Member State level.

24

Human organs are transported directly from site of donation and procurement to site for transplantation. They do not

pass through dedicated establishments for processing, storage and/or distribution.

25

Regulation 1394/2007.

26

Regulation (EU) 2017/745.

27

Article 168 (4) (a) TFEU stipulates that the Union shall adopt measures setting high standards of quality and safety

of organs and substances of human origin, blood and blood derivatives; these measures shall not prevent any Member

State from maintaining or introducing more stringent protective measures.

10 | P a g e

2. BACKGROUND TO THE INTERVENTION

2.1 Concerns leading to the intervention

Three key concerns prompted the adoption of the blood, tissues and cells policy

intervention.

The first was the spread of infectious diseases by blood transfusion and treatment with

plasma-derived medicinal products, and the equivalent risks it posed for tissues and cells.

The second was the lack of equivalency and coherence of standards for BTC across

Member States. The third was the insufficiency of BTC supply, particularly blood and

plasma for the manufacturing of medicinal products, through voluntary and unpaid

donation (VUD).

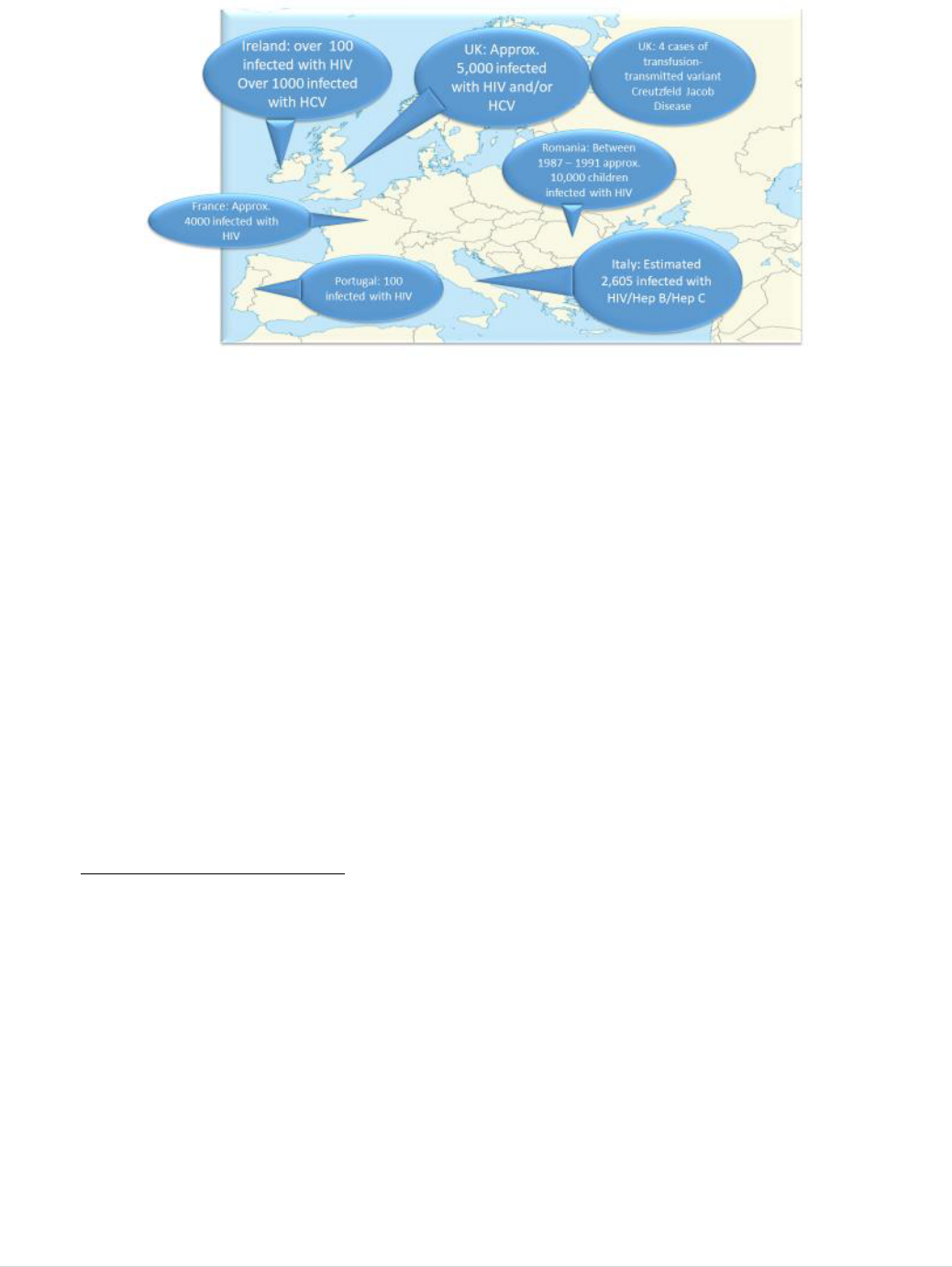

Concern 1 - Widespread concerns due to disease transmission to

patients

The primary driver for taking action in the 80’s and 90’s, was the infection of tens of

thousands of patients across the EU with HIV, and later with hepatitis C, by the

transfusion of blood components and by treatment with plasma-derived medicinal

products. At least 20,000 transmissions of HIV by blood transfusion were recorded in

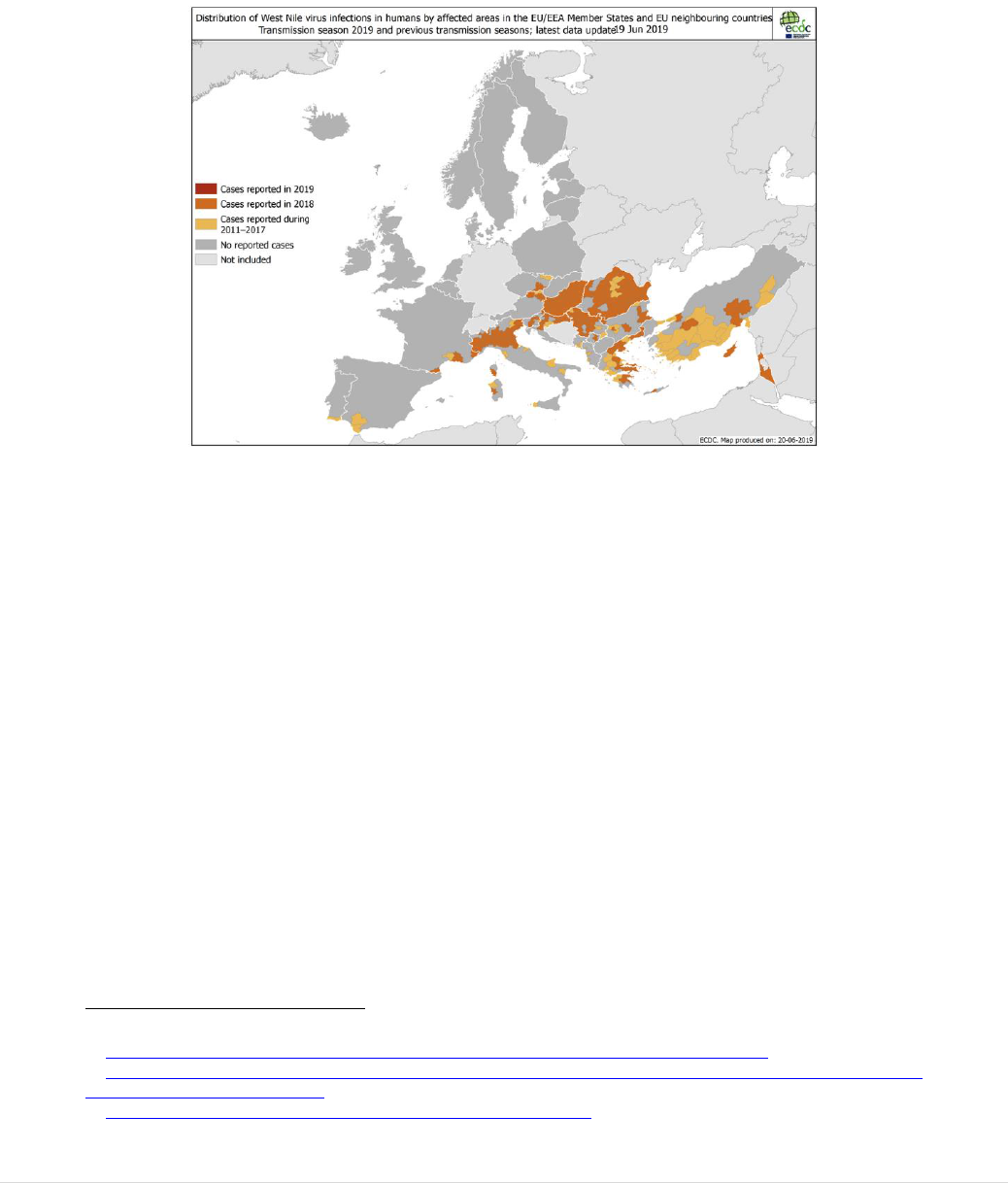

just seven Member States (Figure 2); the total number for the EU is likely to have been

significantly higher.

These events, with a high impact politically and socially, were widely reported in the

media and resulted in court cases and government inquiries in a number of Member

States. In the UK, Germany, Ireland and France, the cases were particularly public and

issues regarding compensation are still the subject of a legal inquiry in the UK today

28

(see also Annexes II and III where more detail is provided).

28

The UK legal inquiry on infected blood can be followed online.

11 | P a g e

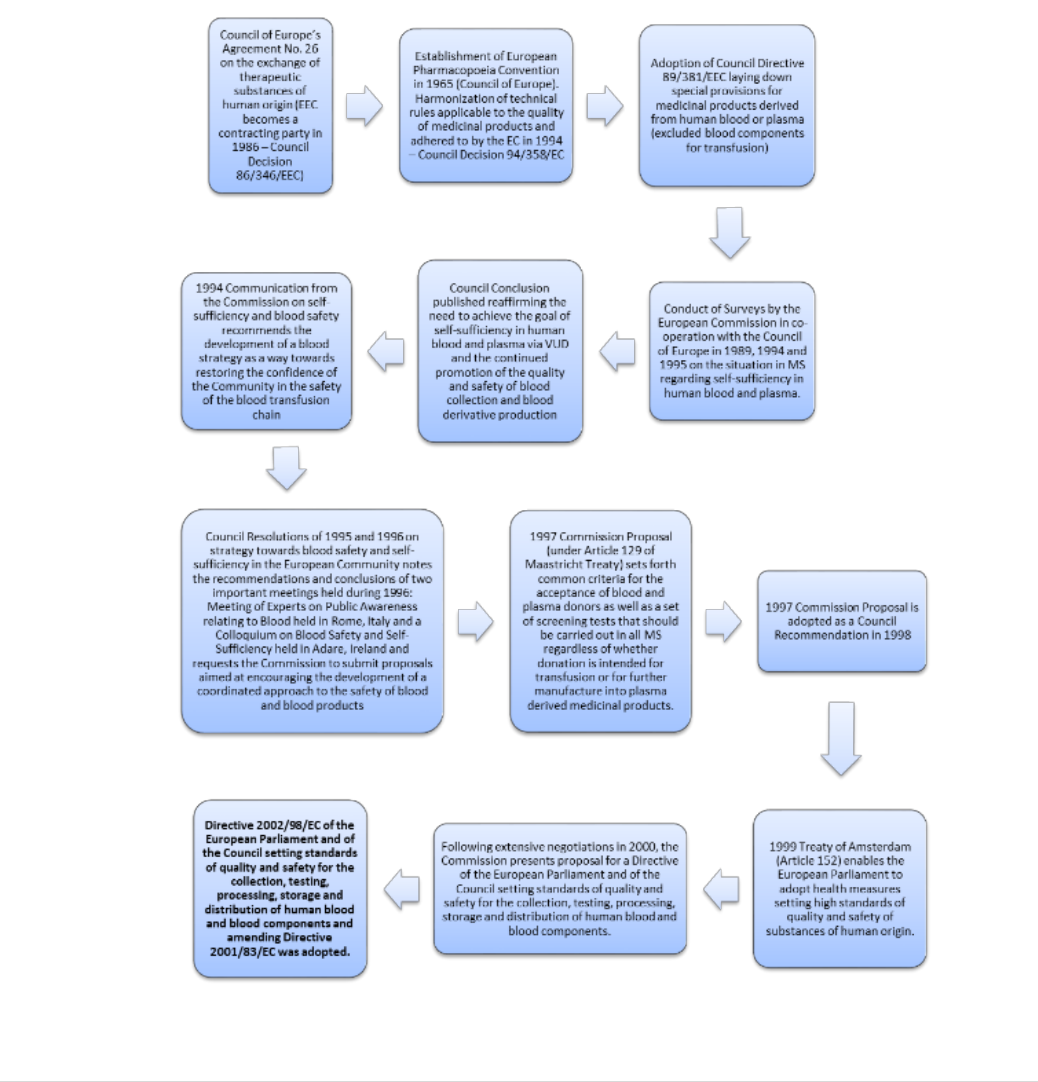

FIGURE 2: EXAMPLES IN THE HISTORY OF CONTAMINATED BLOOD AND BLOOD DERIVATIVES IN

EUROPE PRIOR TO THE ADOPTION OF THE EU BLOOD DIRECTIVE

While infectious transmissions on a scale comparable to blood did not occur for tissues

and cells, the equivalent risks to patients were indeed very real. A number of

scientifically documented sentinel events highlighted that HIV, hepatitis C or Creutzfeldt

Jacob disease transmissions by transplanted tissues and cells had occurred inside or

outside EU and in the latter case continue to emerge due to long incubation times

29

,

30

,

31

.

In the light of these disease transmission concerns, the Treaty of Amsterdam agreed in

1997

32

gives the Union the legal competence to set minimum quality and safety standards

for substances of human origin, while allowing Member States to take more stringent

measures.

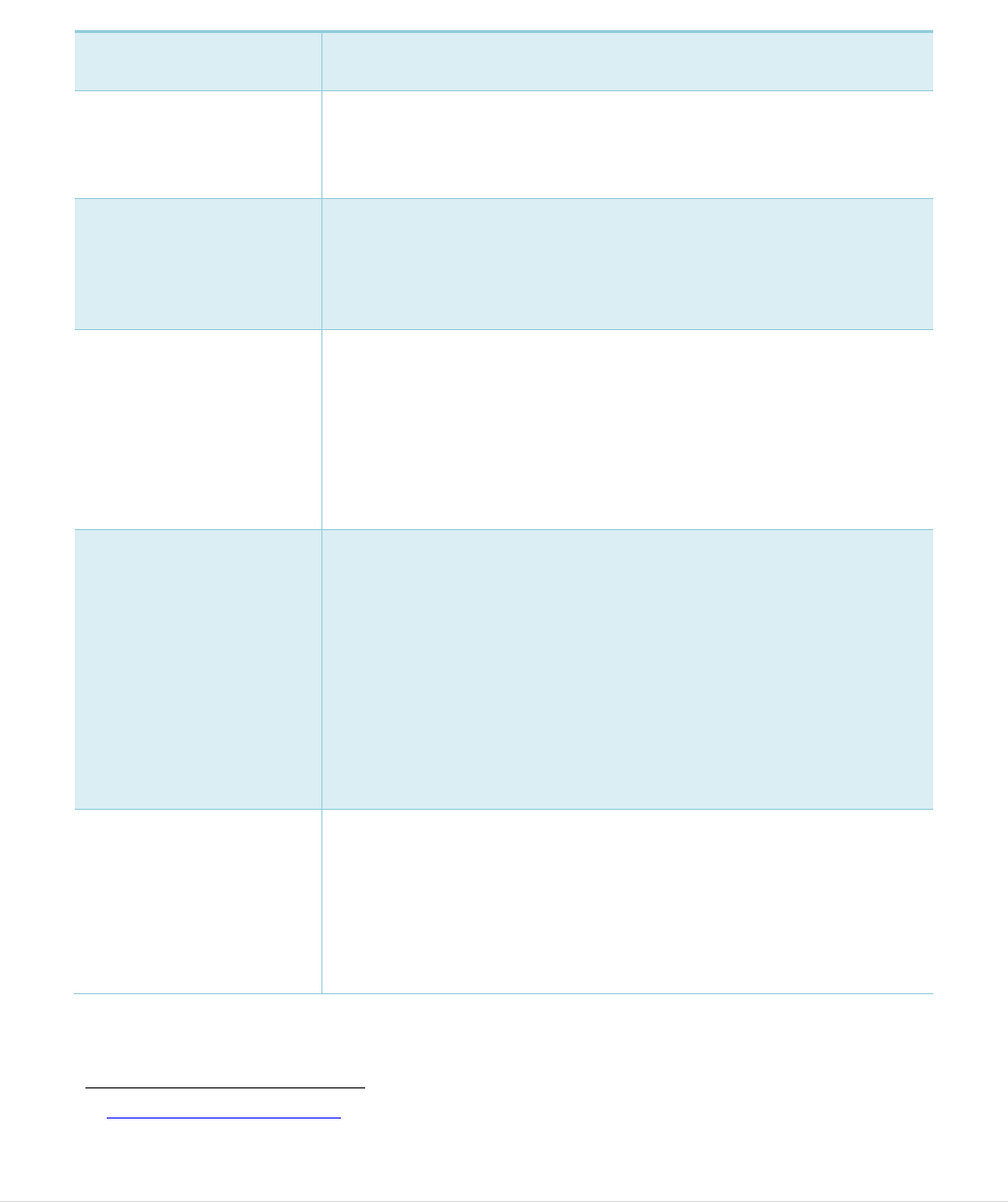

The BTC intervention defined the EU safety and quality requirements for all stages of the

chain from donor to recipient (Objective 1- Safety and quality requirements) and aimed

to ensure effective regulatory oversight of the sectors (Objective 2- Oversight).

To achieve safety and quality of BTC (Objective 1), the following were put in place:

29

Simonds RJ et al. (1992) Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 from a seronegative organ and

tissue donor, NEJM 326 (11): 726-732.

30

Conrad EU et al.(2005) Transmission of the hepatitis C virus by tissue transplantation J Bone Joint Surg 77(2): 214-

224.

31

Over forty transmissions of Creutzfeldt Jacob disease by transplantation of highly processed dura mater (a tissue that

lines the skull) were detected from tissue processed in Germany and mostly exported to Japan. The long incubation

period for this prion disease means that new cases continued to be detected decades later in Japan, with the total

number of infected recipients reaching over 90 according to an update published by the US Centres for Disease Control

in 2008. CDC (2008) Update: Creutzfeldt Jacob disease associated with cadaveric dura mater grafts: Japan 1978 –

2008 MMWR 57(43): 1181.

32

(the now) Article 168 (4) TFEU: ‘By way of derogation from Article 2(5) and Article 6(a) and in accordance with

Article 4(2)(k) the European Parliament and the Council, acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure

and after consulting the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, shall contribute to the

achievement of the objectives referred to in this Article through adopting in order to meet common safety concerns:

a) measures setting high standards of quality and safety of organs and substances of human origin, blood and blood

derivatives; these measures shall not prevent any Member State from maintaining or introducing more stringent

protective measures;’.

12 | P a g e

(i) a set of legally binding quality and safety requirements to address all activities from

donation to distribution, including screening, testing and handling requirements;

(ii) a set of legally binding requirements for blood and tissue establishments addressing

personnel, facilities, quality management etc. and

(iii) processes for the adaptation of the requirements in line with scientific,

technological and epidemiological changes.

To achieve an effective regulatory oversight of the sectors (Objective 2) the basic Acts

included:

(i) the establishment/nomination of Competent Authorities responsible for oversight at

Member State level;

(ii) establishment of a Competent Authority network at EU level;

(iii) set-up of inspection and authorisation systems and

(iv) set-up of vigilance systems (adverse reaction and event reporting and rapid alerts).

The national competent authorities in Member States are required to authorise blood and

tissue establishments, to inspect them at a 2-yearly frequency, to report annually to the

European Commission on serious adverse reactions (where a patient has been harmed),

to report in a similar way on serious adverse events (where an incident posed a risk of

harm to a donor or a patient), and to communicate with each other when more than one

Member State may be involved. For tissues and cells, the authorities must also ensure the

equivalence of imports from third countries in terms of quality and safety to those

provided under EU legislation through the authorisation of ‘Importing Tissue

Establishments’. Finally, Member States are obliged to put penalties in place for non-

compliance and to ensure appropriate data protection.

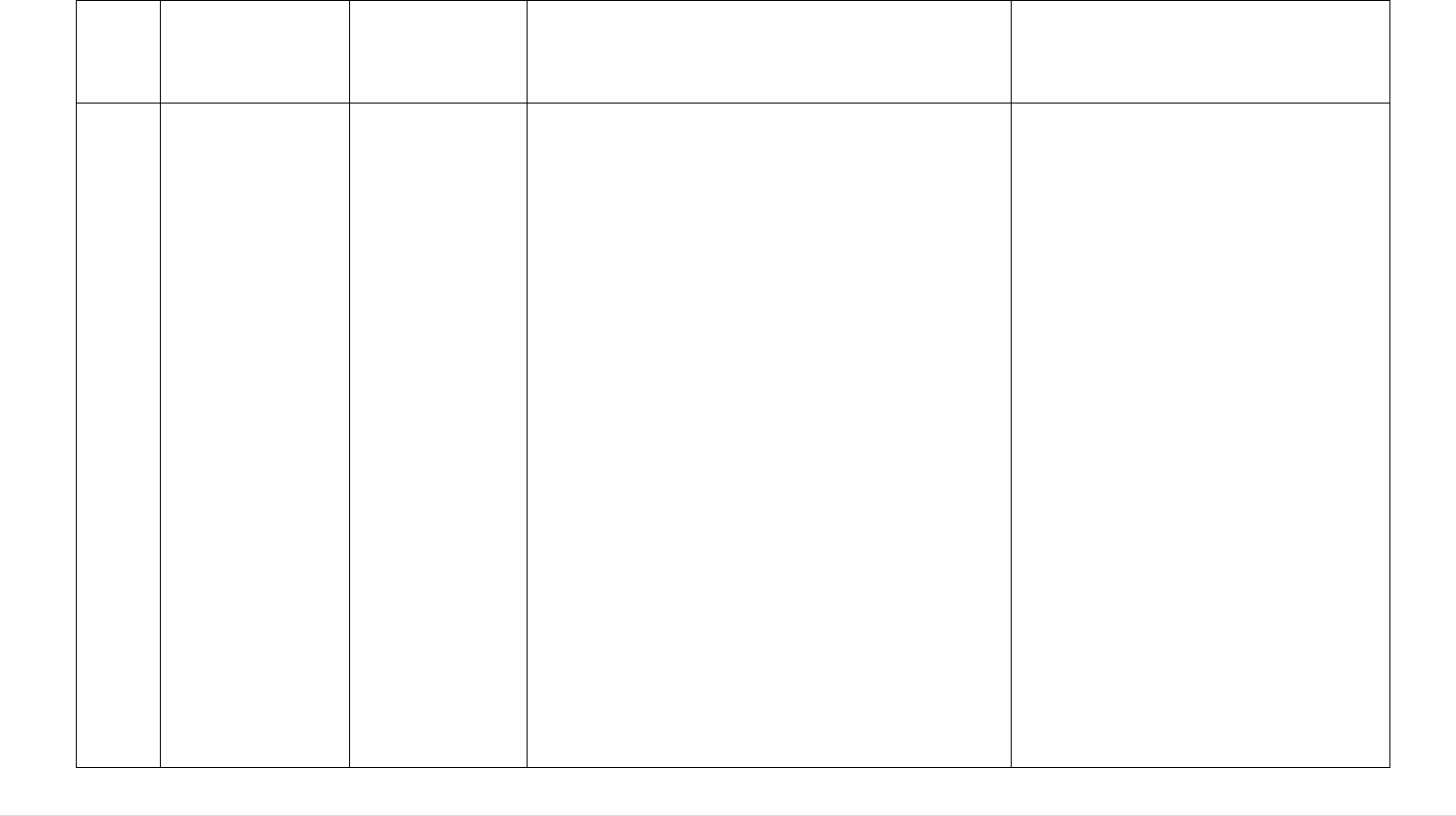

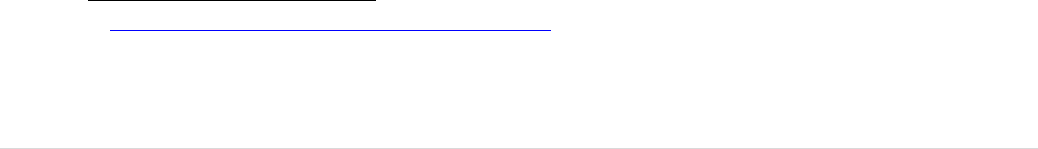

FIGURE 3: OBJECTIVES 1 AND 2 TO ACHIEVE SAFETY AND QUALITY FROM DONOR TO RECIPIENT AND

AND EFFECTIVE OVERSIGHT

13 | P a g e

To mitigate risk and prevent unsafe activities, the European Commission is required to

hold regular meetings with the competent authorities of the Member States to support the

network and facilitate the collection and publication of data and the operation of shared

platforms for information exchange (rapid alerts).

The implementation of the safety and quality and regulatory oversight objectives, and

associated actions, were expected to lead to: (a) increased safety and quality in the chain

from donor to recipient; (b) blood and tissue establishments operating in compliance with

the defined standards; (c) provisions updated promptly in line with technological

developments and new risks; (d) unsafe activities ceased or prevented; (e) vigilance data

feeding quality improvement and increased visibility of risks and (f) risks mitigated

through EU-wide communication and action.

Concern 2 - Lack of equivalency and coherence of standards across EU

Member States

Surveys of blood service organisation and practices across the EU provided evidence of a

wide variation in the standards of safety and quality being applied (see Annexe III).

Movement of plasma and of tissue and cells between Member States was seen as an

urgent problem to tackle because of the high frequency and volumes and concerns

regarding a lack of standardisation and organisational structures, respectively

33

.

Furthermore, Member States applied different rules for the different classification of

substances under national frameworks.

To address these concerns, the intervention aimed to achieve a degree of harmonisation

of safety and quality that facilitates inter-MS exchanges (Objective 3- harmonisation) but

also to stablish a high level of legal certainty at Union level (Objective 4- legal certainty).

The implementation across the EU of the actions for safety and quality requirements, and

for oversight (Objectives 1 and 2), also allow to achieve harmonisation of safety and

quality (Objective 3). Agreed technical requirements and oversight also facilitate the

inter-Member States exchanges, as long as the common minimum standards and the

common oversight obligations are met. These measures aimed to result in increased

mutual trust and confidence between MS, facilitating exchanges.

Legal certainty (Objective 4) was addressed by the scope and definitions provisions of

the basic Acts

34

and through effective communication between authorities for different

sectors within Member States. These aimed to ensure clarity across regulatory

borderlines where BTC are used to manufacture medicines or medical devices or where

the supply of critical devices impacts on the safety or supply of BTC.

33

European Group of Ethics Opinion on Ethical Aspects of Human Tissue Banking.

34

Articles 2 and 3 in both Acts.

14 | P a g e

Concern 3 - Insufficient supply of blood through VUD

Infectious transmissions from donations made by paid plasma donors in the United States

and imported to the EU (mainly to the UK) were reported in the public domain. These

imports, prompted by insufficiency of the local supply, were associated with significantly

higher risks of contamination with hepatitis and HIV

35

,

36

.

This concern led to a call for ensuring community sufficiency through Voluntary and

Unpaid Donations (VUD), a strategy that aimed at avoiding the inclusion of potentially

higher risk donors, motivated by payment, in the donor pool

37

.

Therefore, to achieve EU sufficiency through the encouragement of VUD and a strong

public sector was a priority (Objective 5 - sufficiency).

This was to be achieved by ensuring through legal provisions

38

that Member States

encourage VUD, satisfy patient needs through EU VUD wherever possible and maintain

a high level of safety.

The outcomes expected were good public willingness and awareness to donate

voluntarily, with common understanding of compensation and incentive concepts and a

decreased dependence on third country donations where higher risks might be accepted.

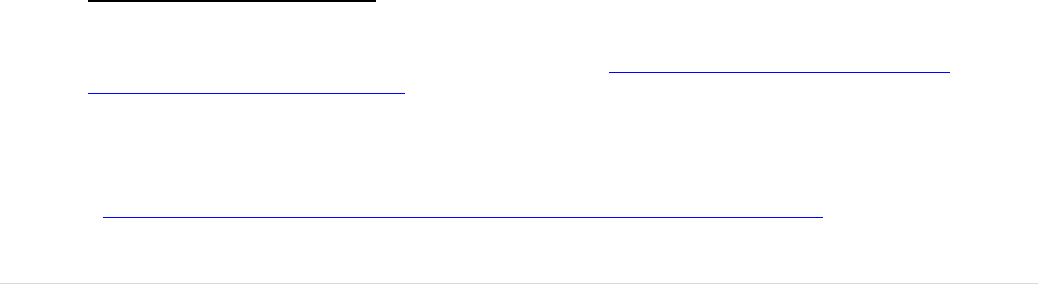

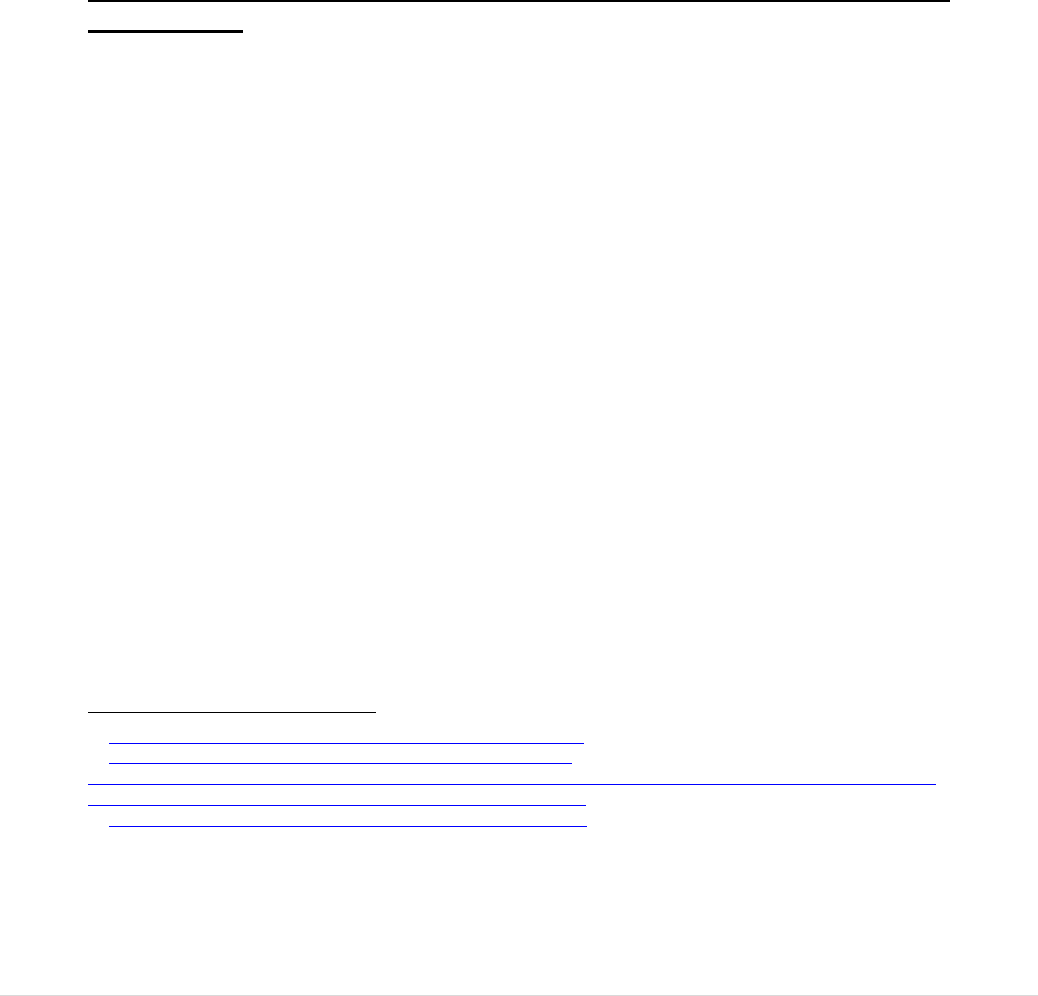

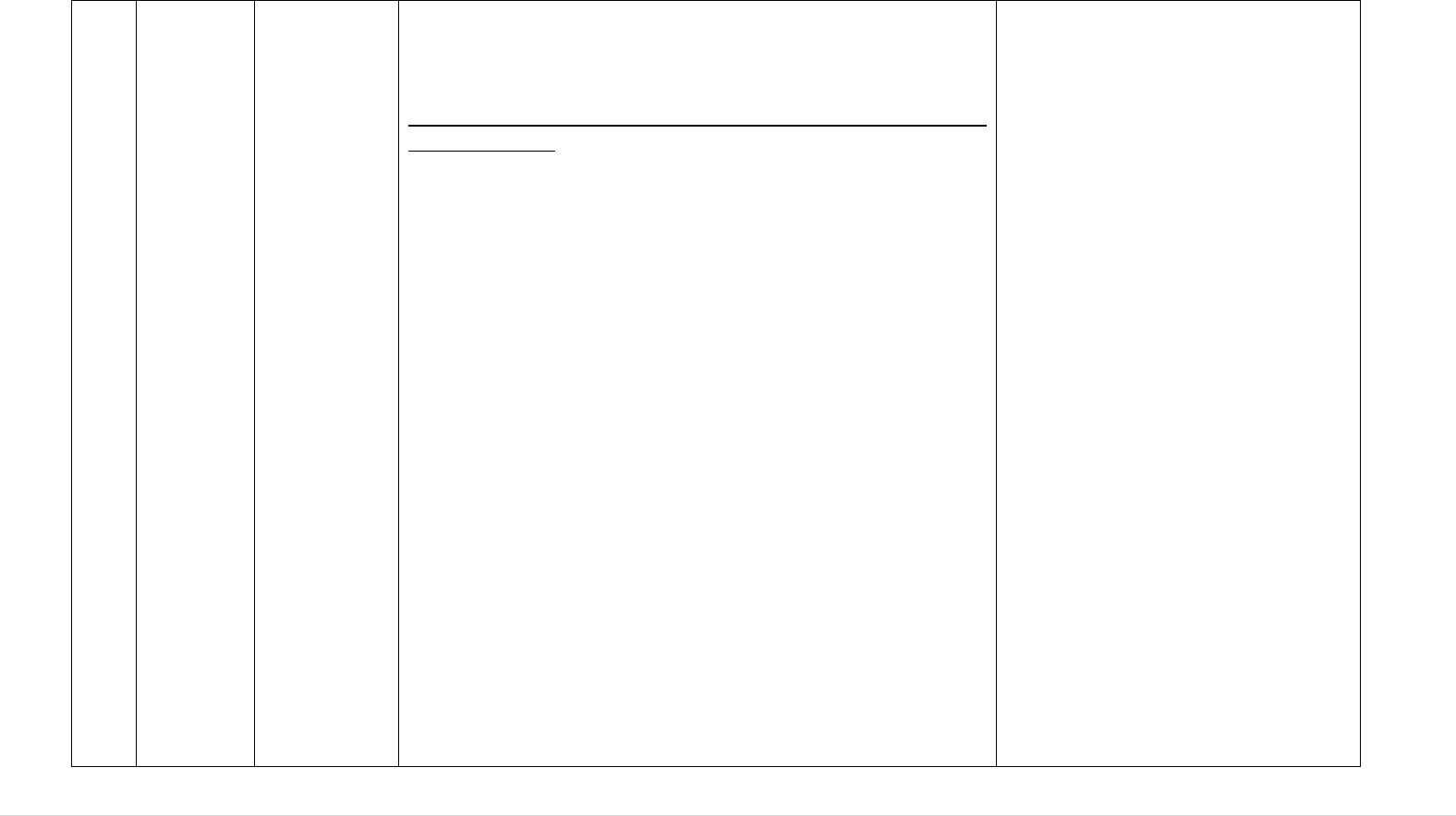

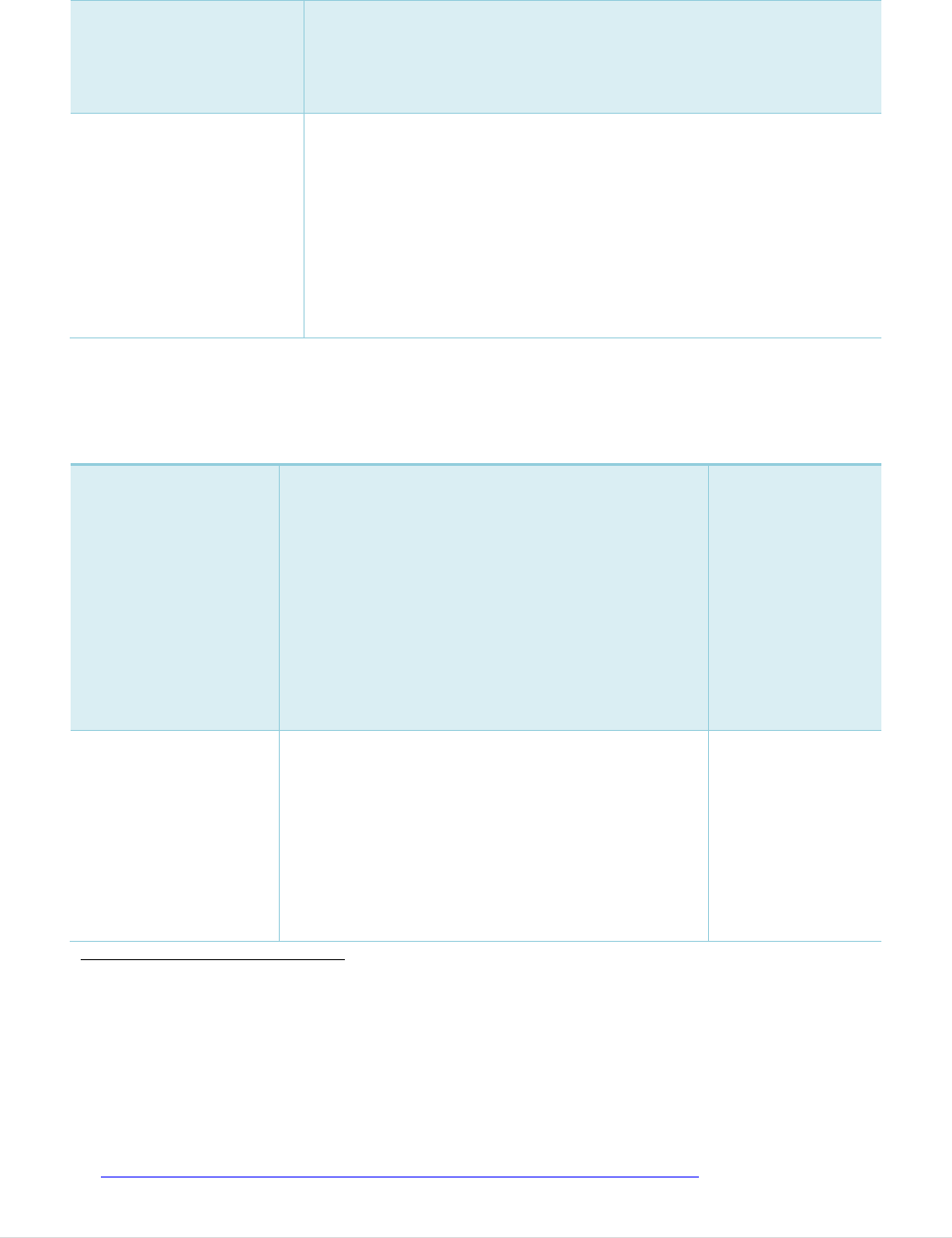

The above highlighted concerns were addressed

by the EU legislation for BTC, which

was adopted with two basic Acts, Directive 2002/98/EC

39

for blood and Directive

2004/23/EC

40

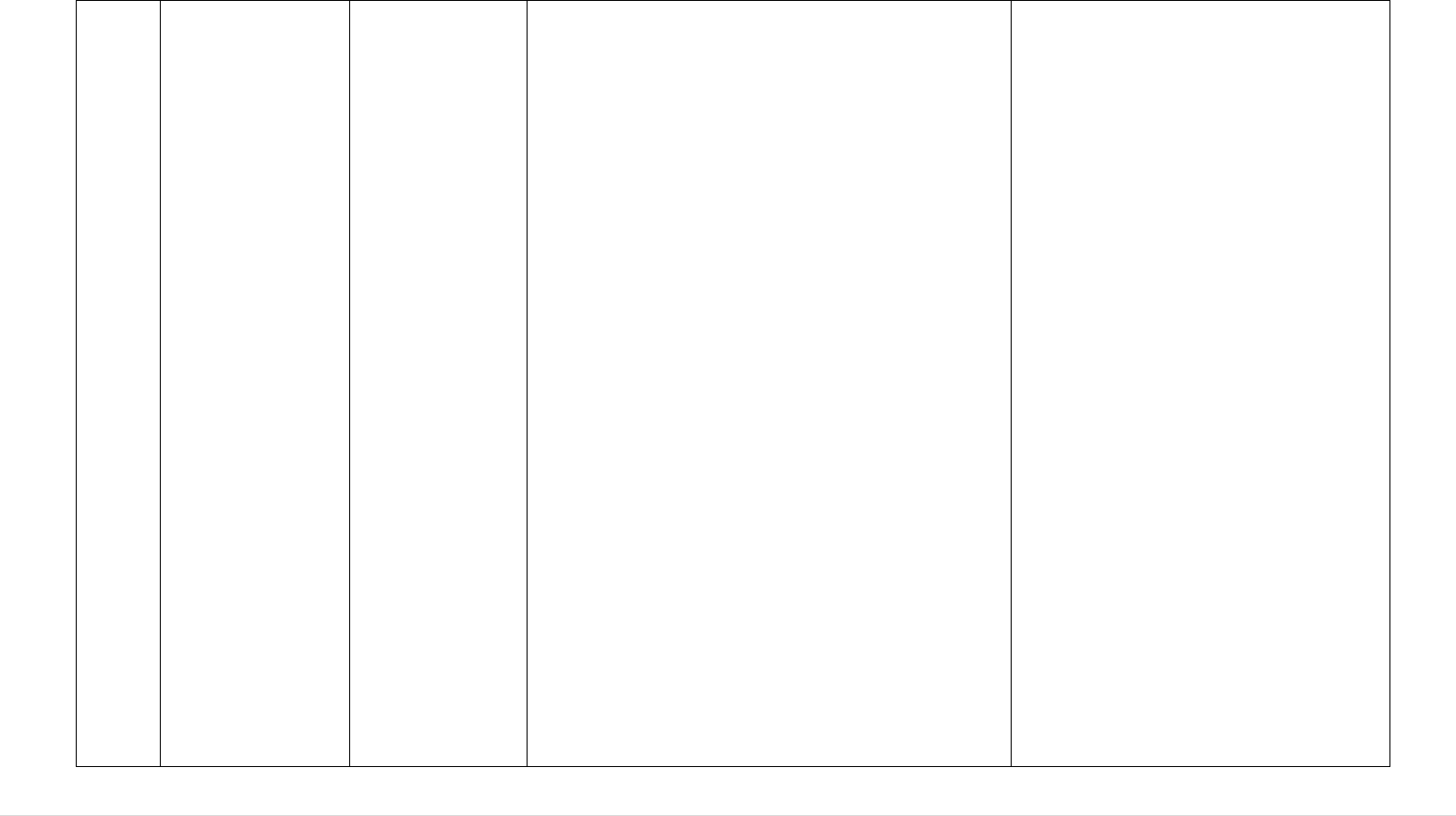

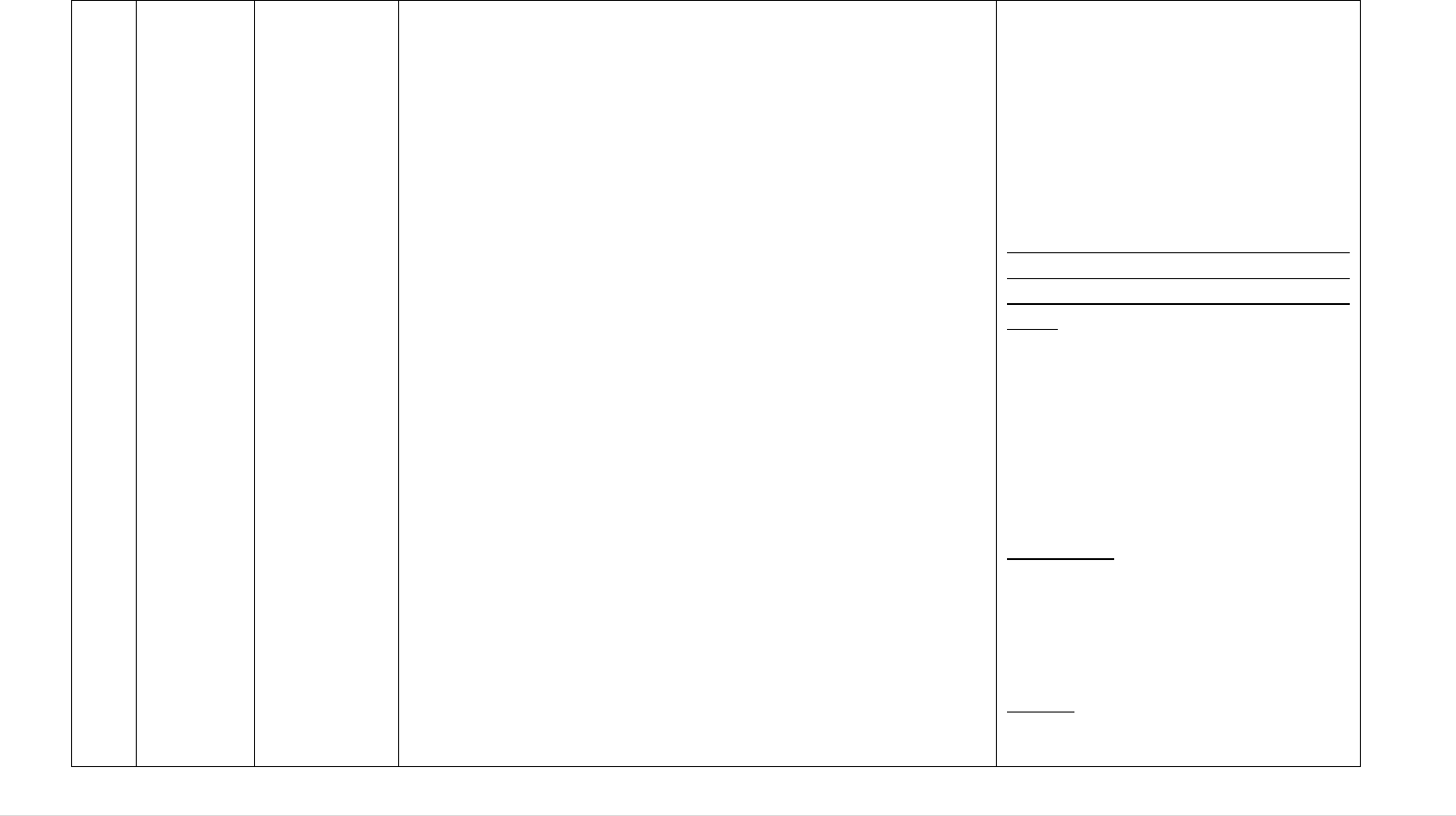

for tissues and cells. Figure 4 provides a summary of the concerns,

objectives, actions and intended outcomes of the intervention (the intervention logic).

The key reports and policy documents that highlighted the concerns, with their key

findings, are described in Annex III. Annex IV provides a full description of the legal

basis for the legislation and the provisions it includes.

35

Eastlund T. (1998) Monetary blood donation incentives and the risk of transfusion-transmitted infection.

Transfusion; 38: 874-82.

36

Van der Poel CL, Seifried E, Schaasberg WP. (2002) Paying for blood donations: still a risk? Vox Sang. 83: 285-

293.

37

Although donors were tested

for infectious HIV and hepatitis, individuals in the early stages of infection have not yet

produced antibodies to the virus (they are in the so-called ‘infectious window-period’) so their infectious status can be

missed by the anti-body tests used.

38

Article 20 in 2002/98/EC and Article 12 in 2004/23/EC.

39

Directive 2002/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 2003 setting standards of quality

and safety for the collection, testing, processing, storage and distribution of human blood and blood components and

amending Directive 2001/83/EC. (OJ L 33, 8.2.2003, p.30).

40

Directive 2004/23/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 on setting standards of

quality and safety for the donation, procurement, testing, processing, preservation, storage and distribution of human

tissues and cells (OJ L 102, 7.4.2004, p. 48).

15 | P a g e

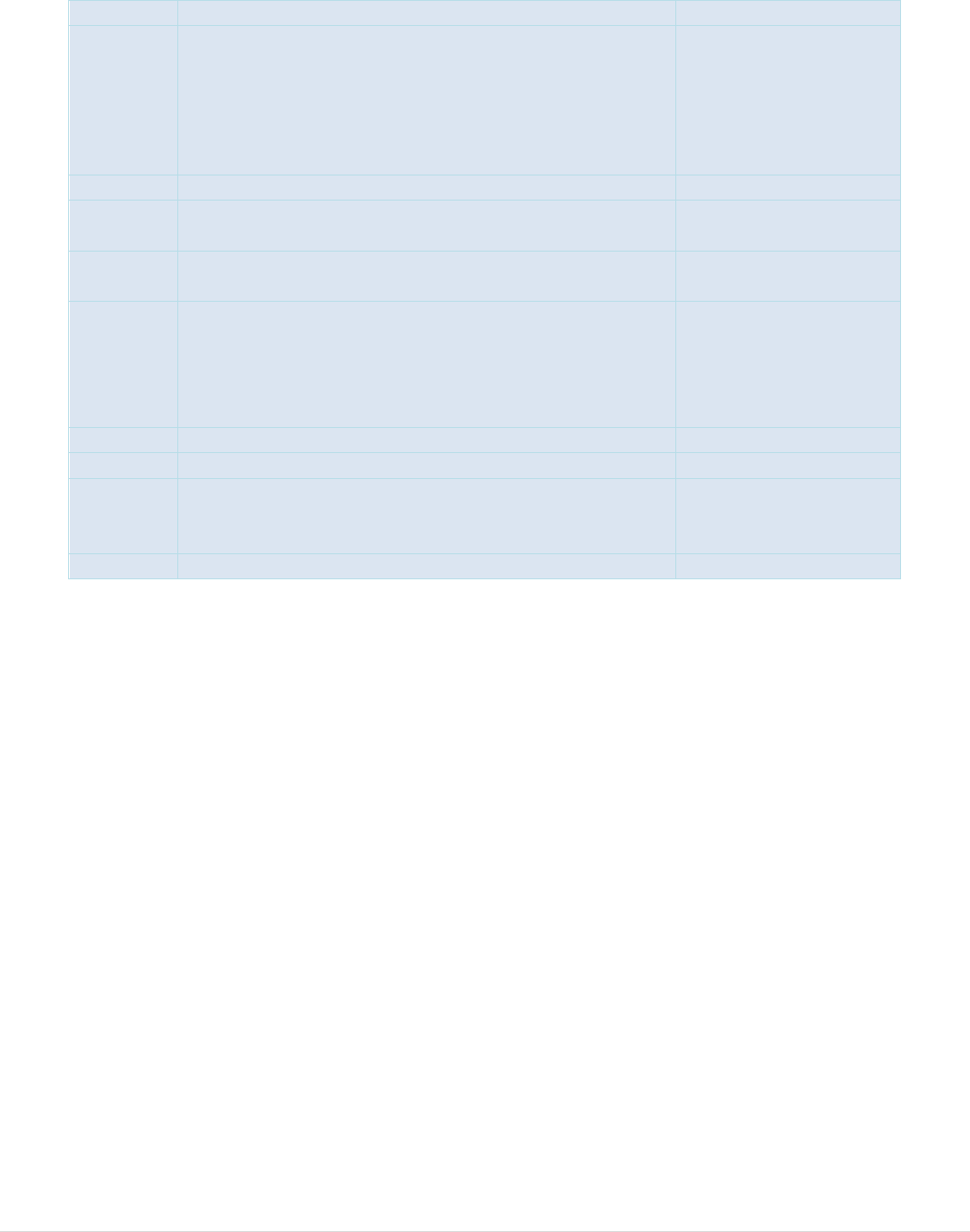

FIGURE 4: A SUMMARY OF THE CONCERNS, OBJECTIVES, ACTIONS AND INTENDED OUTCOMES OF THE INTERVENTION.

16 | P a g e

2.2 Baseline and points of comparison

The baseline used for the evaluation was the situation in fifteen Member States in the

period prior to the adoption of the basic Acts, which was complemented with information

from the 13 new Member States that joined the EU from 2004 onwards. There was no

Impact Assessment carried, out prior to the adoption of the legislation, that describes the

baseline. As many Member States did not have national reporting systems in place

41

,

precise baseline data are limited.

2.2.1 Blood

As early as 1994, the European Commission had raised concerns regarding blood safety

and sufficiency, noting that the donor selection process differed across the Community.

At that time, Directive 89/381/EEC required that testing of blood and plasma, when used

as starting materials for blood derived medicinal products, had to comply with the

recommendations of the Council of Europe, the WHO and the European Pharmacopoeia.

However, as this Directive did not apply to whole blood, to plasma or to blood cells of

human origin for transfusion, divergent testing requirements existed within the

Community for blood donations for transfusion and plasma donations for manufacture of

plasma derived medicinal products.

Licencing and accreditation of blood collection establishments differed widely across the

Member States. Many had no licencing requirements for the collection of blood or

plasma; no standard requirements for collection centres across the country; no routine

and/or unannounced inspections by national authorities nor peer inspections to ensure

that appropriate donor selection procedures were followed.

In 2001, voluntary non-remunerated blood donors were found only in five EU Member

States out of 13. In others, incentives, family replacement

42

and remuneration were

mechanisms used to encourage blood donation

43

. Haemovigilance was required by law in

only 11 countries, and, consequently, infectious transmissions during this time were

likely to have been underestimated.

The first Implementation Report

44

for Directive 2002/98/EC was published in 2006 and

indicated that seven Member States had organised inspections and control measures in

blood establishments in order to ensure compliance with the Directive’s requirements,

41

The situation varied depending on the type of substance but a recent survey of tissue and cell authorities indicated

that over a third of Member States did not have authorities in place for transplanted tissues and cells, and over half for

medically assisted reproduction, that could have gathered such reports. The survey was reported at a meeting of tissue

and cell competent authorities in May 2019.

42

The practice of asking family members to replace donations transfused to their relative by donating blood

themselves. This practice raised concerns from a safety perspective, as donors are not self-selected and, therefore,

might not reveal risk factors.

43

Mascaretti et al. 2004 Comparative analysis of national regulations concerning blood safety across Europe.

Transfusion Medicine, 14,105–111.

44

First report on the application of the Blood Directive from the European Commission, 19 June 2006.

17 | P a g e

confirming that this oversight had not been in place previously. Only nine reported that

donor selection procedures and donation deferral criteria were in place in blood

establishments for all donors of blood and blood components.

See Annex V, Part A, for a full description of the baseline for blood.

2.2.2 Tissues and Cells

Prior to the adoption of the directive there were shortcomings and differences in the

existing national rules, particularly in relation to donor selection and to the circulation of

tissues between countries, which were highlighted in 1998 by the European Group on

Ethics in Science and New Technologies

45

as well as by experts in the areas of organs,

tissues and cells in 2000

46

.

Health ministers from 11 EU Member States met in 2002 and supported a proposed

directive on the therapeutic use of human cells and tissues for transplantation. At that

time, only Spain, France, Belgium, and Denmark had specific legislation for tissue and

cell banks. Most EU countries had regulations only for transplantation of solid organs

47

.

Earlier publications from the UK had already raised concerns about the safety standards

of bone banking

48

,

49

. In addition, there was an increasing degree of uncontrolled tissue

movement between Member States and with third countries

50

.

Prior to the adoption of the basic Act on tissues and cells, or to accession of countries to

the EU, safety and quality rules and oversight were widely lacking

51

. By 2007, 11

Member States had not yet put inspection systems in pace and others had not yet

inspected all tissue establishments or put vigilance reporting procedures in place

52

.

See Annex V, Part B, for a full description of the baseline for tissues and cells.

2.2.3 Situation in Member States that joined after 2004

In three of the Member States that joined the EU after 2004 (Romania, Bulgaria,

Croatia), assessments during the accession process generally demonstrated limited or

45

European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies (European Commission). Ethical aspects of human

tissue banking.

46

At a meeting organised by the Portuguese Presidency of the EU, together with the European Commission described

in Sauer F et al. The Regulation of blood and tissues in the European Union. Pharmaceutical Policy and Law (2005) 6:

47-58.

47

Xavier Bosch. Health ministers support pan-European transplantation standards, The Lancet Vol. 359, ISSUE 9306,

P591, 16 February 2002.

48

Michaud RJ, Drabu KJ. Bone allograft banking in the United Kingdom. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994;76:350.

49

Fehily D & Warwick RW. Safe tissue grafts: Should achieve same standards as for blood transfusion BMJ 1997;

314:1141.

50

Sauer F, Delaney F and Fernandez-Zinke E. The regulation of blood and tissues in the European Union.

Pharmaceuticals Policy and Law 6 (2005) 47-58.

51

Results of a Commission Survey presented to the tissue and cell competent authorities meeting in May 2019.

52

Summary Table of Responses from Competent Authorities: Questionnaire on the transposition and implementation

of the European Tissues and Cells regulatory framework, 06 February 2007.

18 | P a g e

absent oversight functions for BTC, such as an established competent authority,

inspections and authorisation activities. Vigilance programmes were not in place and

many had to upgrade facilities, equipment and quality management in their tissue and

cell services to meet the technical requirements for donation, testing, processing,

preservation, storage and distribution. At least three Member States (Romania, Bulgaria

and Lithuania), also had to change their donor base from paid or replacement donation

53

to VUD

54

,

55

.

Annex V provides more information on the situation prior to the adoption of the BTC

legislation.

53

The term replacement donation refers to systems where there is a request/obligation on the family of a patient

needing transfusion to donate blood in order to replace the blood used from the bank. This system is not considered

compatible with VUD and is considered to put too much pressure on donors and to risk untruthful donor risk

information.

54

WHO Europe (2007) Blood Services in South Eastern Europe – Current Status and Challenges.

55

Skarbalienė A Bikulčienė J (2016) Motivation and retention of voluntary, non-remunerated blood donors. Lithuanian

case. Health Policy and management 2016, 1(9).

19 | P a g e

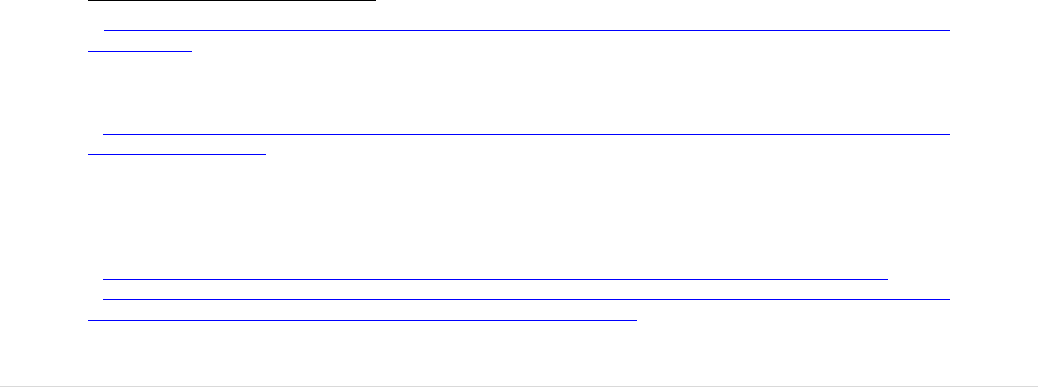

3. STATE OF PLAY

3.1 The BTC Sector

Blood, tissues and cells are collected, processed, stored, tested and supplied for human

application by 1,400 blood establishments

56

and over 4,000 tissue establishments

57

. The

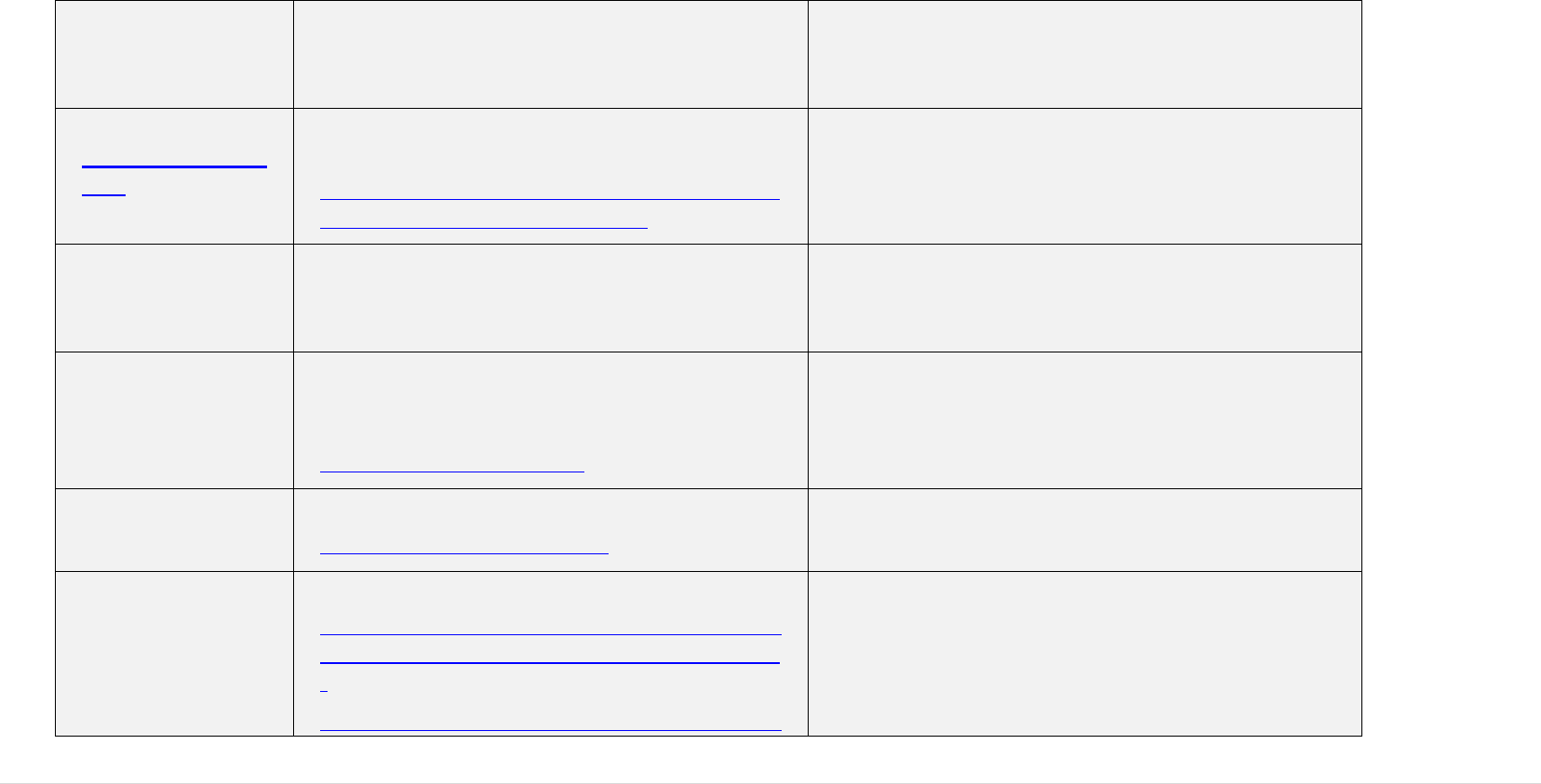

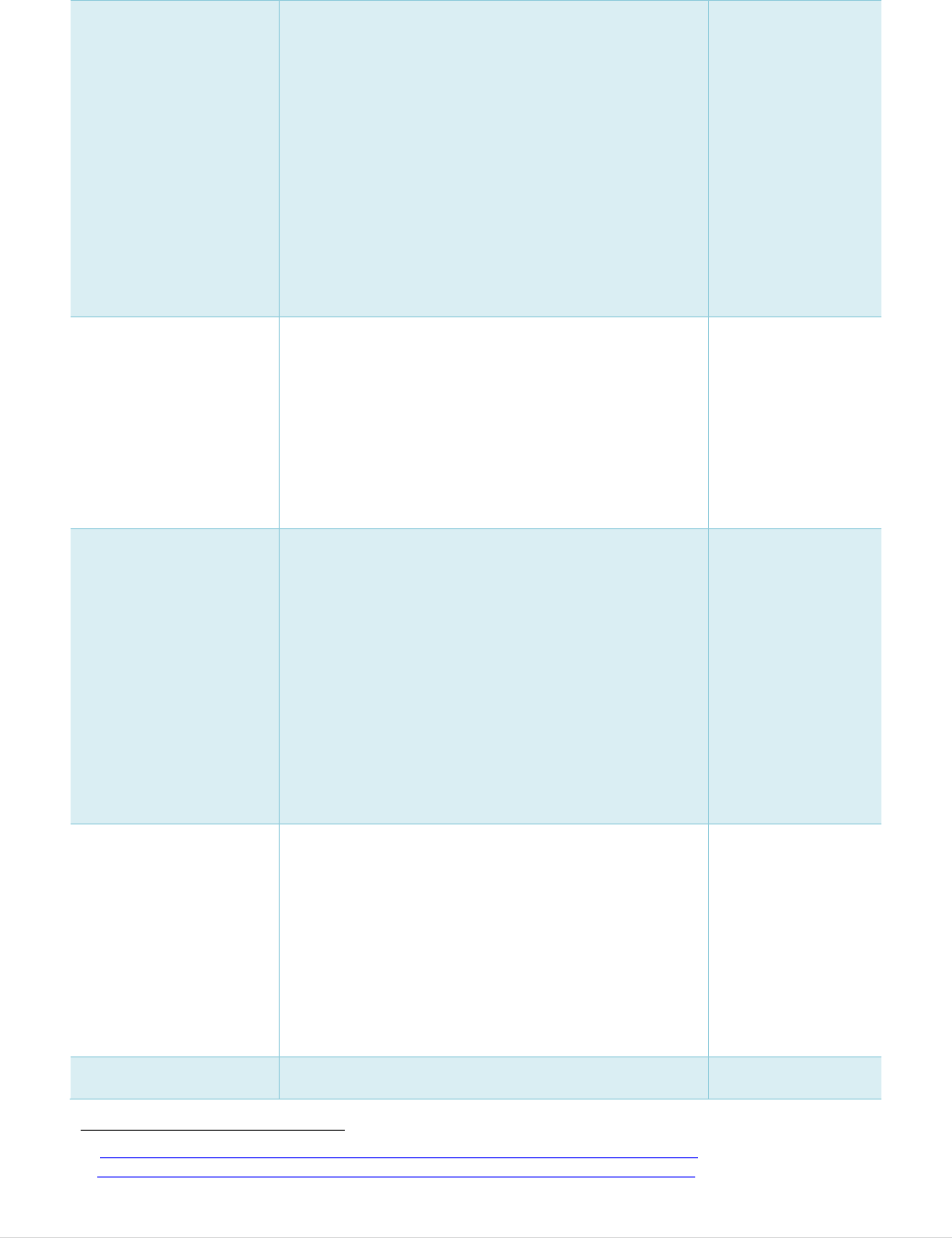

blood sub-sector is broadly divided into blood or blood components for transfusion and

plasma for the manufacture of medicinal products. Tissue establishments are broadly

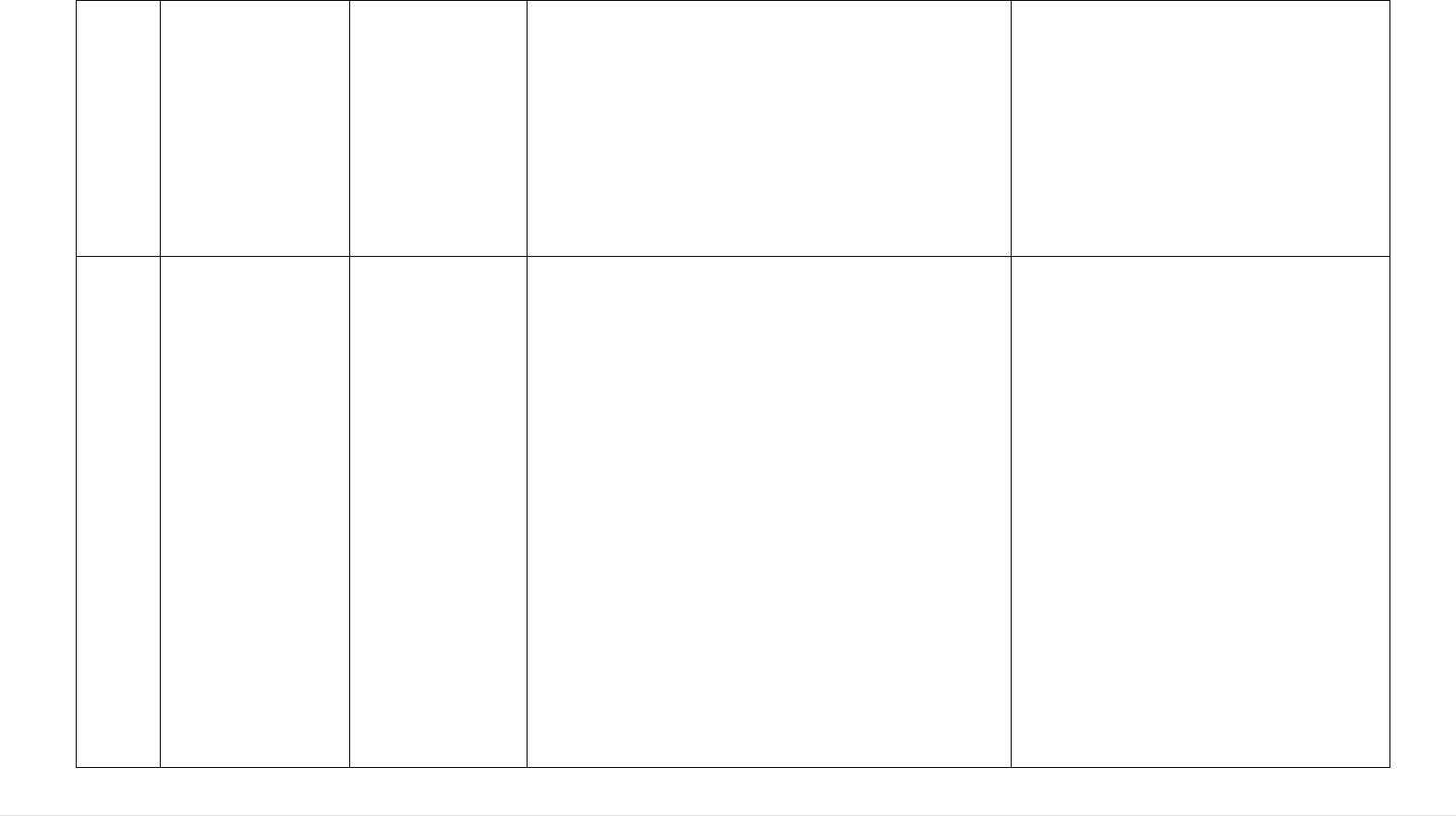

divided in three categories (see Figure 5).

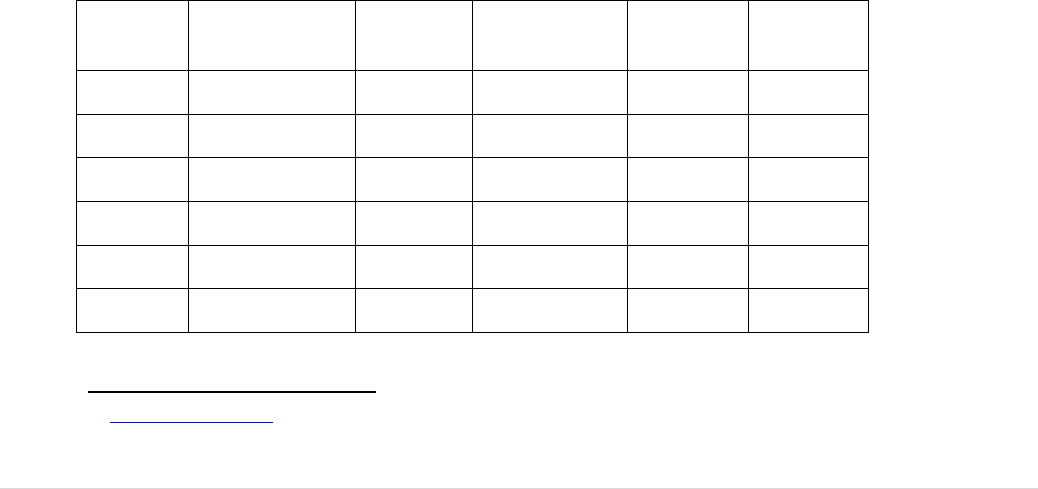

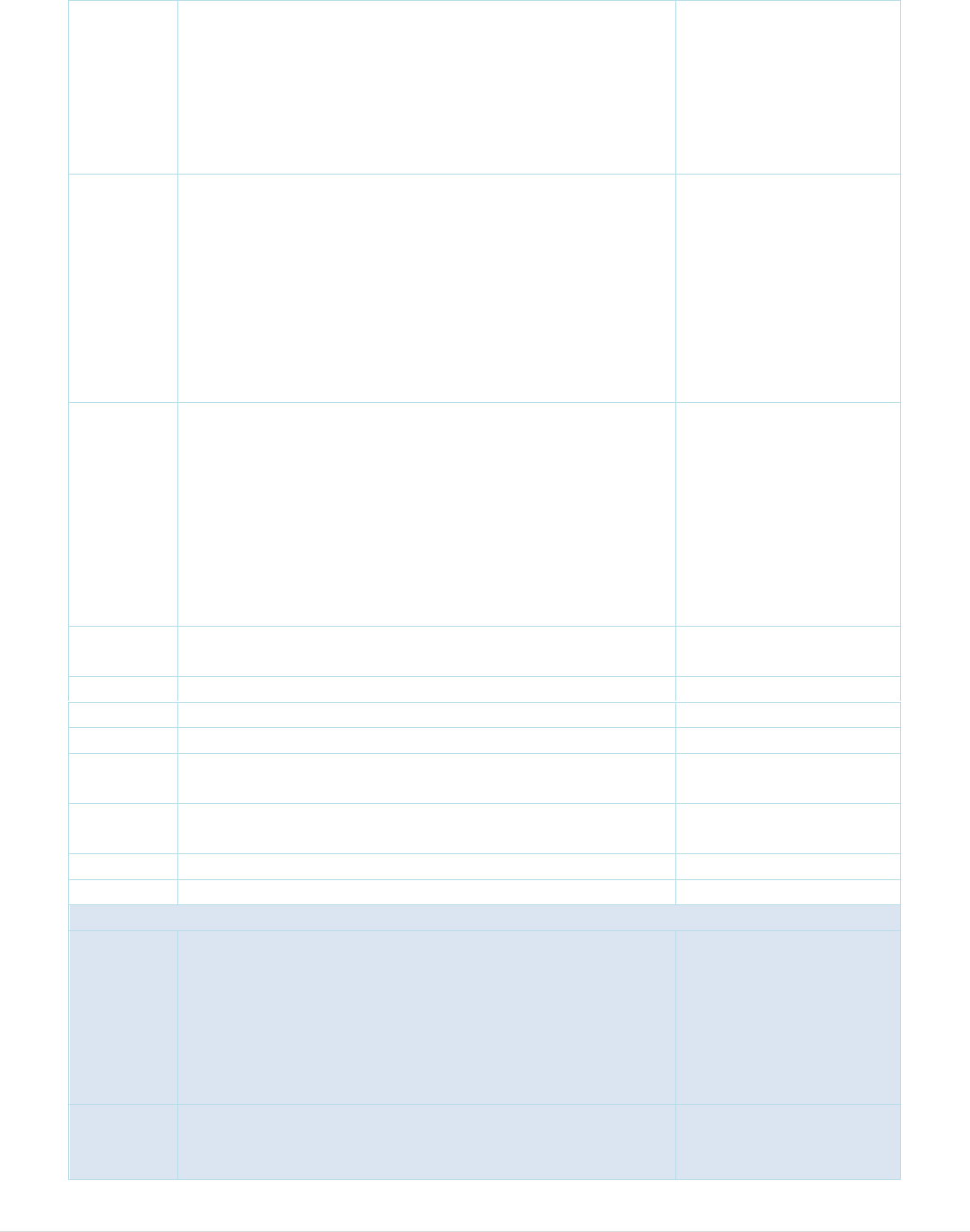

FIGURE 5: THE THREE CATEGORIES OF TISSUE AND CELLS ESTABLISHMENTS

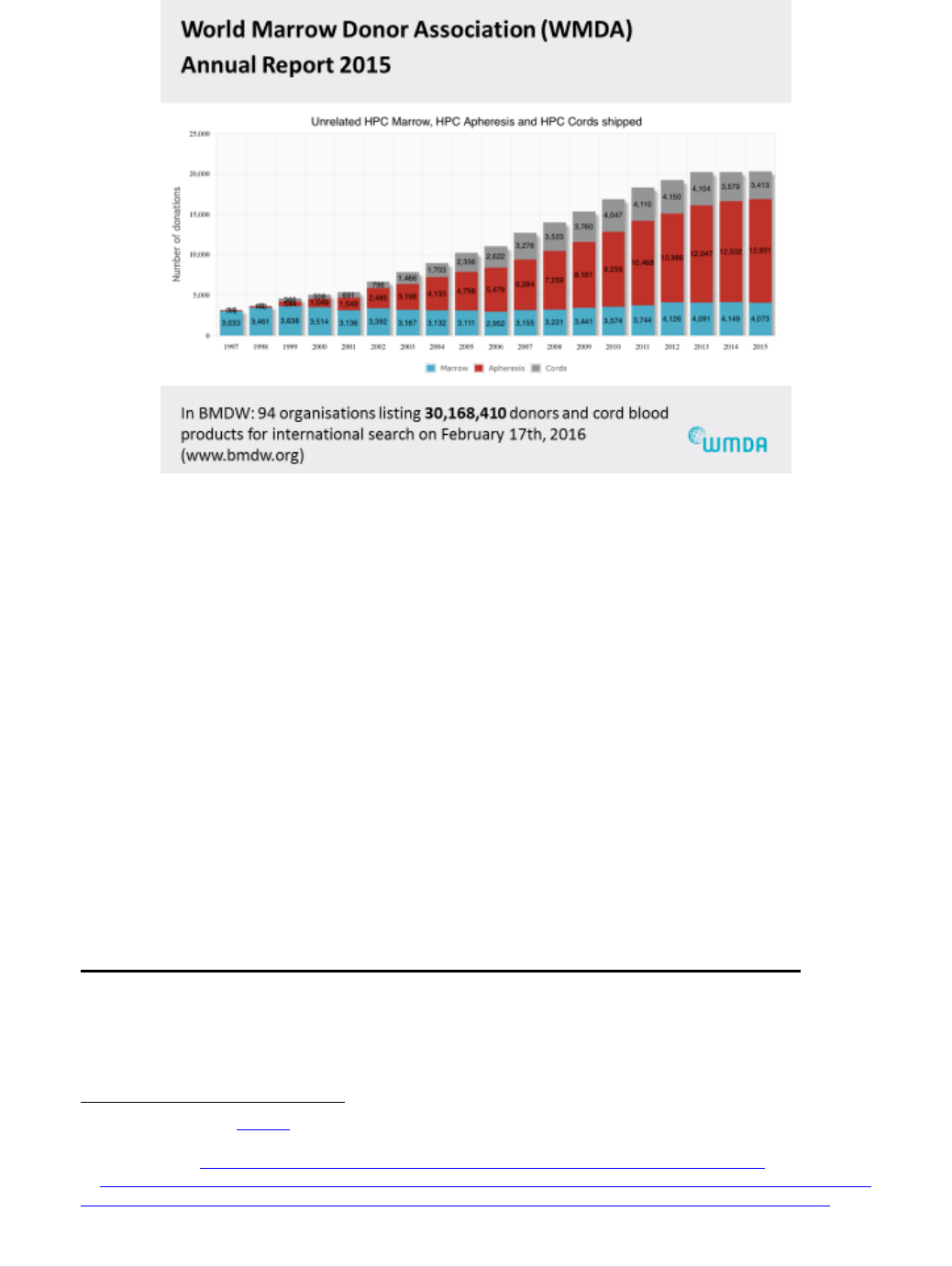

Figure 6 provides aggregated data for the BTC provided by BTC establishments in the

EU. Most blood establishments are national, regional or hospital based and are managed

by the public health sector or by non-profit organisations such as the Red Cross, while

the private sector plays an important role in the collection of plasma for the manufacture

of plasma derived medicinal products. Tissue establishments include banks of corneas,

bone, skin, heart valves, bone marrow and cord blood for transplantation, as well as

sperm banks and clinics for medically assisted reproduction (MAR). Tissue

56

Implementation report published in 2016.

57

See Tissue Establishment Compendium hosted by the European Commission.

20 | P a g e

establishments providing tissues and cells for transplantation are mostly public or non-

profit organisations while sperm banks and MAR clinics are both public and private.

Tissues and cells can also be used as starting materials for medicinal product

manufacture.

FIGURE 6: THE SCALE OF BTC ACTIVITY IN THE EU (DATA FROM 2018 OR MOST RECENT YEAR REPORTED)

Whole blood and blood components, such as platelets and red blood cells, have a limited

shelf life and are rarely exchanged between Member States, with the exception of

emergency or humanitarian situations. Plasma and plasma derived medicinal products

have a longer shelf life and, as plants manufacturing plasma derived medicinal products

exist only in twelve Member States, both plasma (the starting material) and the end

products are frequently exchanged across borders, within the EU and with third

countries. The EU is significantly reliant on importation of plasma from the United States

to meet the needs of patients in the EU for plasma derived medicinal products. The level

of inter-Member State exchange and global movement in general, varies depending on

the type of substance of human origin.

21 | P a g e

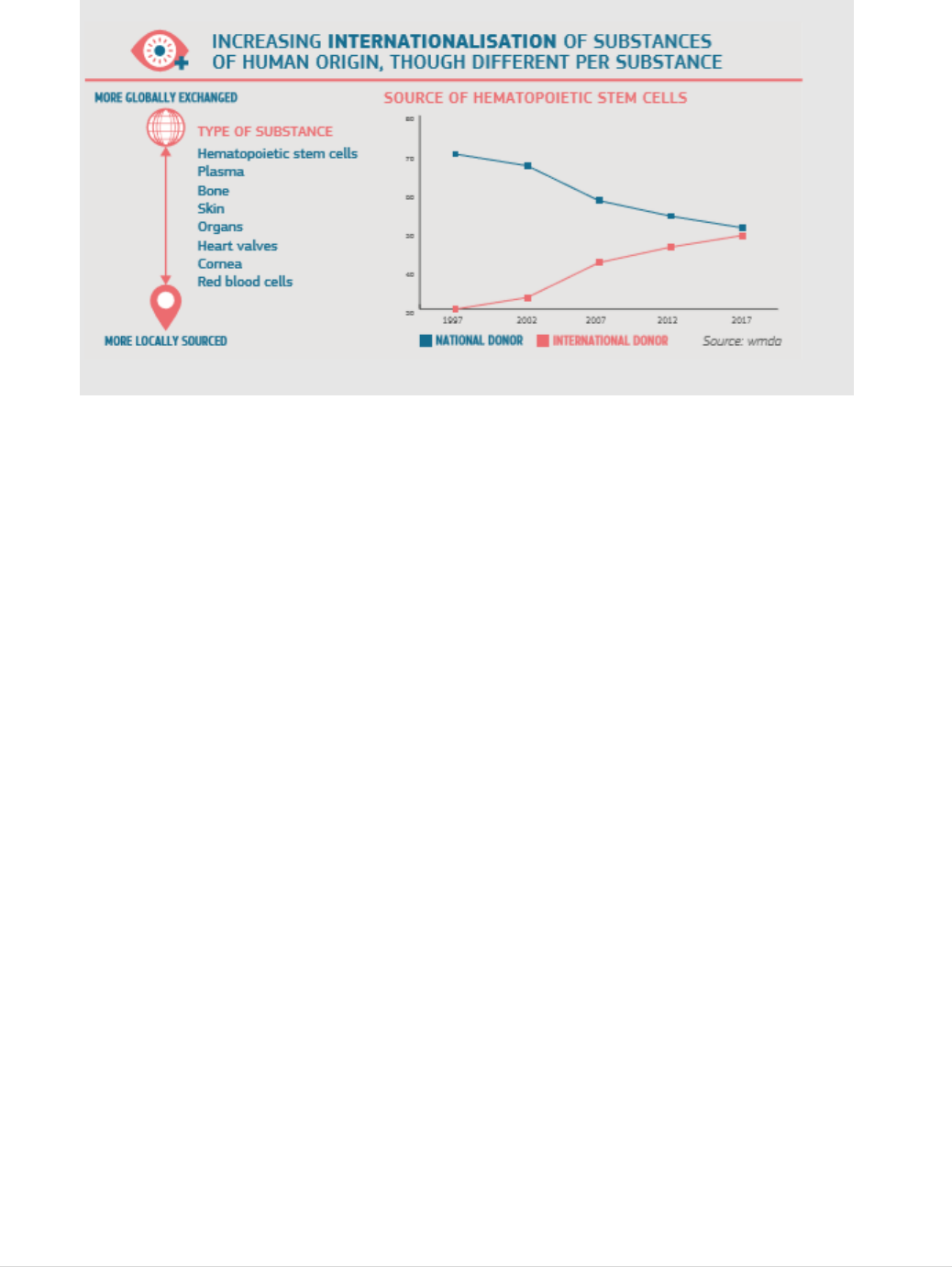

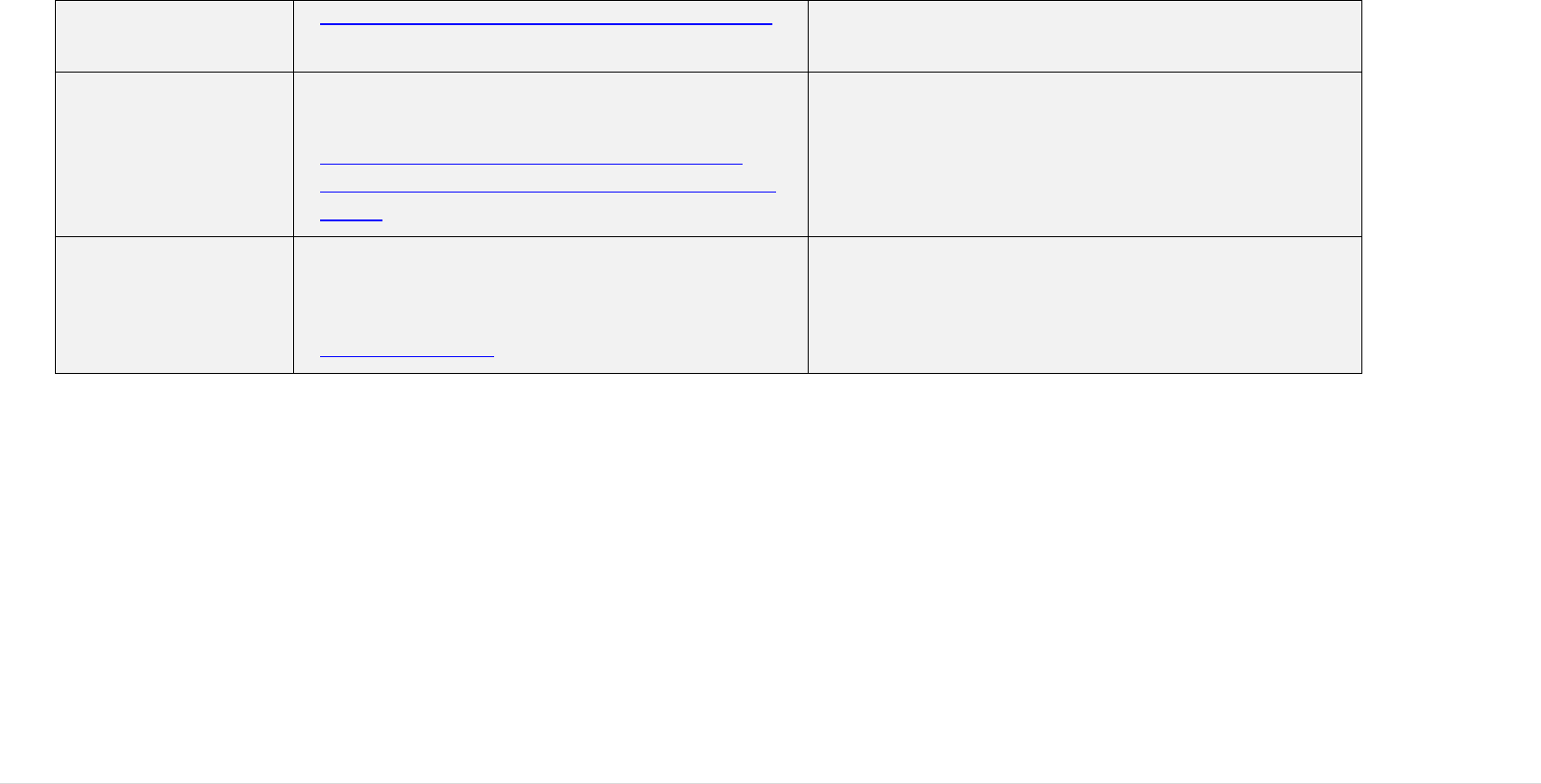

FIGURE 7: LEVELS OF INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE VARY PER SUBSTANCES OF HUMAN ORIGIN

For tissues and cells, specifically, reports indicate significant volumes of human tissues

and cells being exchanged internationally (see Figure 7), with haematopoietic stem cells

(the stem cells in the bone marrow that make new blood cells) being the most exchanged

substance. It is difficult, however, to draw firm conclusions regarding the volume of

imports and exports of human tissues and cells due to the lack of mandatory reporting of

such information at national level and the absence of a harmonised framework for data

collection in the Member States. In addition, some Member States that do gather data on

a national level, and share it on a voluntary basis, do not distinguish between distribution

within the EU and import/export from/to third countries. It is clear, however, that large

quantities of bone and skin are imported from the United States, mostly from commercial

tissue banks, and that increasing numbers of bone marrow donations and other

haematopoietic stem cells circulate globally to facilitate high level donor to recipient

matching, a challenging requirement for successful transplantation in this sub-sector.

There is significant innovation in the sector, both in the way that BTC are processed in

establishments and the way they are used in patients. These innovative approaches are

commonly developed in the broad context of health service planning and they generally

improve patient access to new treatments.

3.2 Transposition and updating of BTC legislation

Most Member States transposed the basic Acts (2002/98/EC and 2004/23/EC) within the

defined deadlines in a complete and satisfactory manner. Between 2004 and 2006,

implementing Directives were adopted for both basic Acts (2004/33/EC, 2005/61/EC,

2005/62/EC for blood and 2006/17/EC and 2006/86/EC for tissues and cells). By 2008,

25 of the 27 Member States reported having transposed the basic Act on blood and all

22 | P a g e

three implementing Directives

58

. By 2009, 26 Member States had completely transposed

Directive 2004/23/EC, 2006/17/EC and 2006/86/EC.

As of February 2019, all current tissue and cell legislation, including more recent

implementing Directives

59

and Decisions

60

, has been transposed satisfactorily, with one

exception

61

. For blood, all legislation has been satisfactorily transposed

62

.

The powers given to the Commission to adapt technical requirements to scientific and

technical progress were used in a small number of specific cases

63

. In general, however,

the speed of technical development and of changing risks in the sectors proved

challenging and many changes are not reflected in the current provisions (see Section

5.1).

There have been some formal complaints to the Commission and a small number of court

cases linked to the legislation. The issues arising have mostly related to blood and blood

components. In particular, cases concerned restrictions applied at national level on the

purchase or import of plasma or plasma derived medicinal products. These restrictions on

imports were linked to the source of the plasma, with Member States that aim to achieve

sufficiency through VUD differentiating between plasma from unpaid donors and plasma

from donors compensated financially

64

.

The classification of certain substances as blood components or medicinal products has

also been the subject of legal discussions, largely resulting from different interpretations

of the scope of the basic act on blood and blood components (see Section 5.4).

Implementing Directive 2004/33/EC requires permanent deferral of prospective donors

whose sexual behaviour puts them at ‘high risk’ of acquiring severe infectious diseases

that can be transmitted by blood. The interpretation of ‘high risk’ led most Member

States to apply permanent exclusion of prospective male blood donors who have sex with

men (MSM). This led to complaints and one national court case that was referred to the

Court of Justice of the EU

65

. The Court ruled that permanent deferral was not a

58

Responses to Commission survey on the implementation of the blood legislation.

59

Blood: Directive 2016/1214 amending Directive 2005/62/EC on good practice guidelines; Tissues and Cells:

Directive 2015/566 on tissue and cell import, Directive 2015/4460 amending Directive 2016/86/EC on the Single

European Code.

60

Decision 2010/453/EU on conditions of inspections.

61

One failure to transpose an amendment to Directive 2006/17/EC (Directive 2012/39/EU) that has been referred to the

European Court of Justice (ECJ).

62

Apart from the most recent amendment, Directive (EU) 2016/1214 amending Directive 2005/62/EC, where 27

Member States have notified transposition and the verification of completeness is ongoing.

63

Blood: Directive 2011/38/EU amending Directive 004/33/EU regarding platelet pH values; Directive 2009/135/EC

amending Directive 2004/33/EC to allow donor eligibility derogations for the Influenza epidemic; Directive

2004/110/EU amending 2004/33/EC to allow testing for West Nile Virus. Tissues and cells: Directive 2012/39/EU

amending Directive 2006/17/EC to update HTLV and ART partner donor testing provisions.

64

Some Member States consider financial compensation as payment and, therefore, as inconsistent with the principle

of VUD described in Article 20 of the basic Act and aim to achieve national sufficiency through unpaid donation only.

Efforts to restrict national use of derived medicinal products to those manufactured from unpaid donors have been

challenged by industry that claims this approach contravenes the free market rules in place for medicinal products.

65

C-528/13, Geoffrey Léger v. Ministre des Affaires sociales, de la Santé et des Droits des Femmes et Établissement

français du sang.

23 | P a g e

proportionate measure. Many Member States have since amended their national rules to

accept MSM donors after one year, or less, since the last exposure to risk.

A full list of court cases, with brief descriptions, is at Annex VI.

The European Parliament also raised questions, mostly concerning the same issues as

those arising for blood in court cases. It also addressed issues such as plasma supply,

VUD and access to BTC treatments. A full list of Parliamentary Questions of relevance

to the BTC legislation is provided at Annex VII.

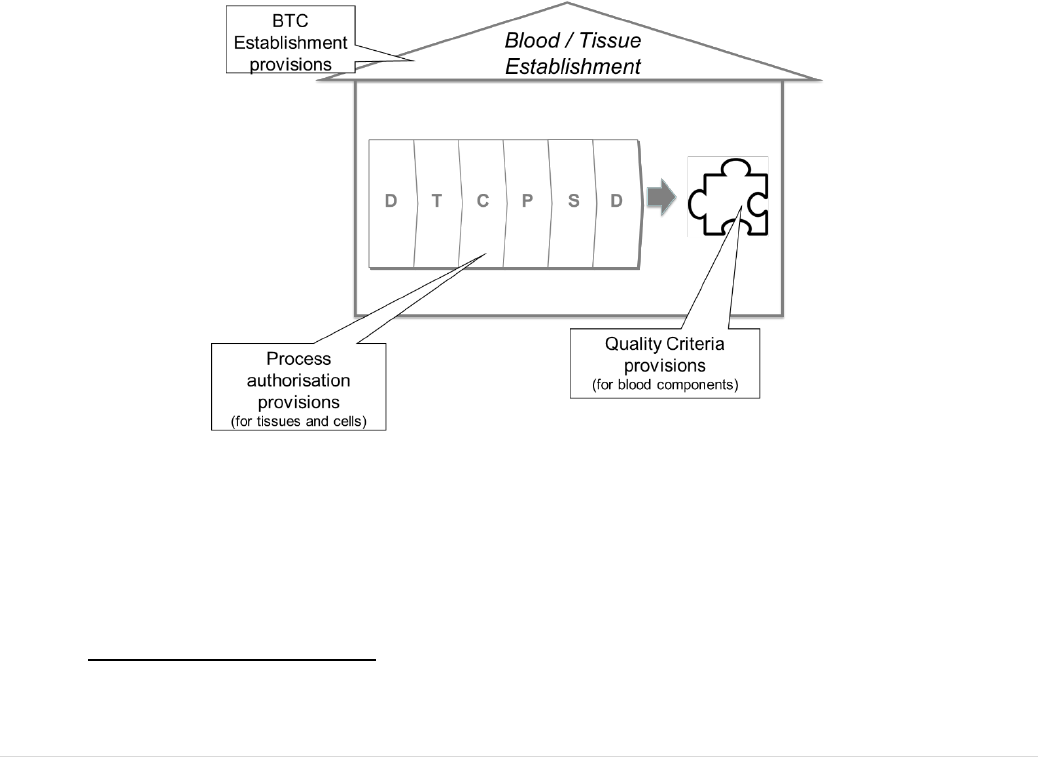

3.3 Oversight functions at Member State level

All Member States have designated one or more competent authorities to carry out the

oversight obligations of the BTC legislation

66

.

The types of organisation designated for

this role vary significantly (see Section 5.2.1.2). The competent authorities inspect and

accredit, designate, authorise or license the blood and tissue establishments. For tissues

and cells, this authorisation is complemented by provisions for authorisation of the

processes applied to the donations at the tissue establishment. For blood, on the other

hand, it includes verification of compliance with defined quality criteria for each blood

component prepared (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8: AUTHORISATION OF ESTABLISHMENTS AND PROCESSES.

3.4 Monitoring Arrangements

66

Study supporting the BTC evaluation, ICF, page 64.

24 | P a g e

Implementation reports have been compiled by the Commission over the years, based on

questionnaires completed by Member State competent authorities. The most recent

reports were published in April 2016

67

,

68

. The gaps and shortcomings identified have

been explored in the evaluation and are described in Section 5 of this report.

Vigilance and surveillance programmes are one of the cornerstones of the safety and

quality framework, allowing the identification and detection of risks and the application

of corrective and preventive measures. Since 2008, in line with obligations defined in the

blood legislation

69

, the EU Member States and Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway have

submitted to the Commission annual vigilance reports. The reports notify serious adverse

reactions (SAR) which occur in recipients of blood and blood components and serious

adverse events (SAE) which occur in the chain from donation to clinical application,

posing a risk of harm. An equivalent provision is included in the tissue and cell

legislation

70

. The Commission, in turn, must send to the competent authorities of the

Member States a summary of the reports received. Definitions for SAR and SAE are

provided in the legislation. The Commission has been working with the BTC competent

authorities over several years to standardise data collection procedures and to improve

both accuracy and comparability of the information submitted. The Commission provides

the Member States with a template, and guidance for its completion, and the summary

reports are published annually

71

. Serious adverse reaction (SAR) reports (per number of

recipients) have stayed relatively stable and low since the adoption of the Directives

(0.03 - 0.05 SAR per recipient for blood and 0.04 - 0.01 for tissues and cells). It is

reported that legislative provisions for vigilance and traceability have helped to prevent

harm to recipients

72

.

The BTC legislation obliges Member States to report to the Commission on a regular

basis on measures taken to encourage VUD and the Commission must inform the

European Parliament and the Council of any necessary further measure it intends to take

at EU level

73

. The Commission has fulfilled this obligation via a questionnaire survey of

Member States on the implementation of the principle of VUD for blood and blood

67

Report from the Commission on the implementation of the Directives 2002/98/EC, 2004/33/EC, 2005/61/EC and

2005/62/EC, 21 April 2016 (Blood);

Report from the Commission on the implementation of Directives 2004/23/EC, 2006/17/EC and 2006/86/EC (tissues

and cells), 21 April 2016.

68

Report from the Commission on the implementation of the Directives 2002/98/EC, 2004/33/EC, 2005/61/EC and

2005/62/EC, 21. April 2016 (Blood).

69

Article 8 of Directive 2005/61/EC provides that Member States shall submit to the Commission an annual report, by

30 June of the following year, on the notification of serious adverse reactions and events (SARE) received by the

competent authority using the formats in Part D of Annex II and C of Annex III.

70

Article 7 and Annexes III, IV and V of Directive 2006/86/EC.

71

The most recent published reports: Summary of the SARE Report for blood for 2017 and Summary of the SARE

Report for tissues and cells for 2017.

72

ICF study, pages 72-73.

73

Article 20 of Directive 2002/98/EC and Article 12 of 2004/23/EC.

25 | P a g e

components and for tissues and cells. The most recent surveys were conducted in 2014

and published in 2016

74

.

The principle of VUD for blood and blood components is recognised in all Member

States, albeit interpreted differently across the EU. It is common practice to provide

refreshments to donors (27 countries) and to give them small tokens such as pin badges,

pens, towels, t-shirts and mugs (24 countries). In around half of the Member States,

donors have their travel costs reimbursed and get time off work in the public and private

sector. In some Member States, donors receive a fixed payment that is not directly related

to actual costs incurred

75

; this is most common in those countries where large quantities

of plasma is collected by private sector companies.

For tissues and cells, the legislative provision also requires encouragement of VUD but is

slightly different to that for blood, allowing ‘compensation’, including for inconvenience.

Although the principle of VUD is mandatory in the large majority of the Member States,

its practical application varies across the EU. Many Member States allow payment of

sperm and egg donors at national level, considering it as compensation.

3.5 Support for implementation

A number of activities and initiatives have supported the implementation of the BTC

legislation since its adoption. The Expert Group of competent authorities responsible for

substances of human origin (CASoHO E01718) meets with the Commission in three

configurations, blood, tissues and cells and organs, once to twice a year each. The

meetings provide a useful forum for increasing standardisation and for joint working

76

.

The EU Public Health Programme has supported the implementation of the BTC

legislation through Joint Actions, Projects and Service Contracts. The outputs have

focused on those areas where legislation has been more challenging to implement or is

most open to interpretation

77

.

Expert support is also provided by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and

Control (ECDC), which was established in 2005 (after the adoption of the two basic BTC

Acts), which has access to the BTC Rapid Alert platforms

78

, and by the Council of

Europe, in particular through a series of Public Health Programme funded Grant

Agreements with defined areas of collaborative work

79

. Although not referenced in BTC

legislation (with the exception of the Council of Europe’s Good Practice Guidelines

74

Commission Staff Working Document on the implementation of the principle of voluntary and unpaid donation for

human blood and blood components and Commission Staff Working Document on the implementation of the principle

of voluntary and unpaid donation for human tissues and cells.

75

Notably Germany, Austria, Hungary and the Czech Republic.

76

A full list of interpretation issues raised in the group and their outcome is summarised at Annex VIII.

77

A full list of Public Health Programme actions in the BTC field is shown at Annex IX.

78

A full list of ECDC working in this field since 2012 is provided at Annex X.

79

Annex XI summarises the work of the Council of Europe in this field and lists the areas of formal collaboration

between DG Sante and the Council of Europe.

26 | P a g e

(GPG)

80

for Blood Establishments that are specifically referenced), the advice and

guidance of both bodies is widely used by BTC professionals and authorities.

4. EVALUATION METHOD

4.1 Conducting the Evaluation

4.1.1 Evaluation Roadmap

A Roadmap was published on 17 January 2017 for a four-week period and the feedback

received from 16 stakeholders was published

81

and taken into account in the conduct of

the evaluation.

4.1.2 Stakeholder Consultation

Stakeholder consultation was one of the key sources of evidence that was used to support

this evaluation. The level of stakeholder engagement in these activities was high and all

the stakeholders mapped in the Roadmap were reached, either through the public events

or by targeted activities (see Annex XII).

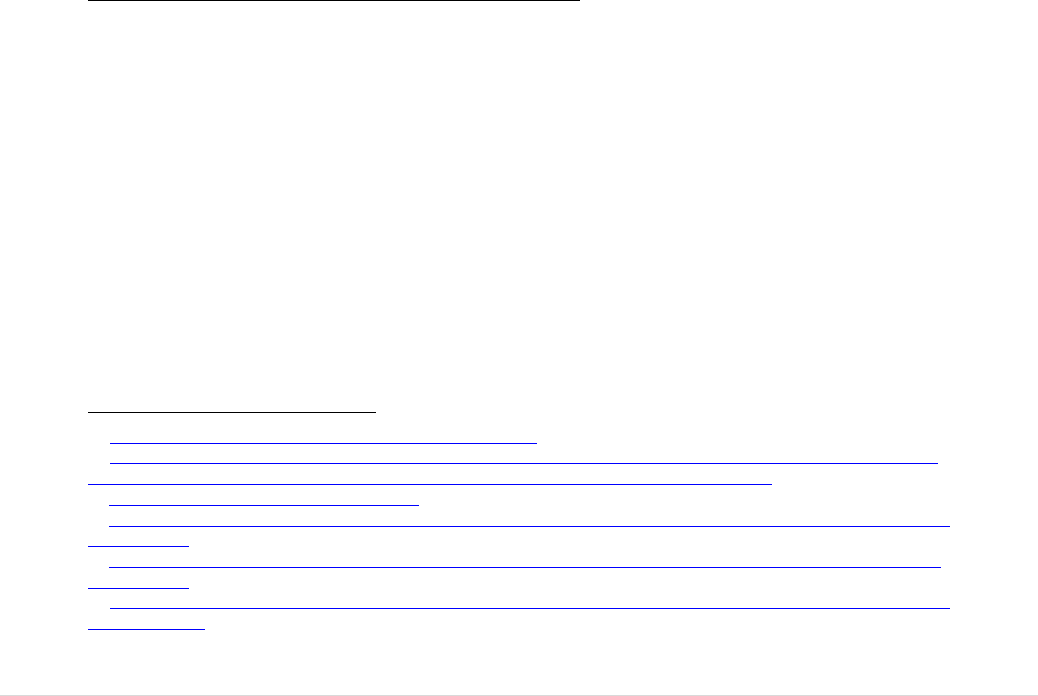

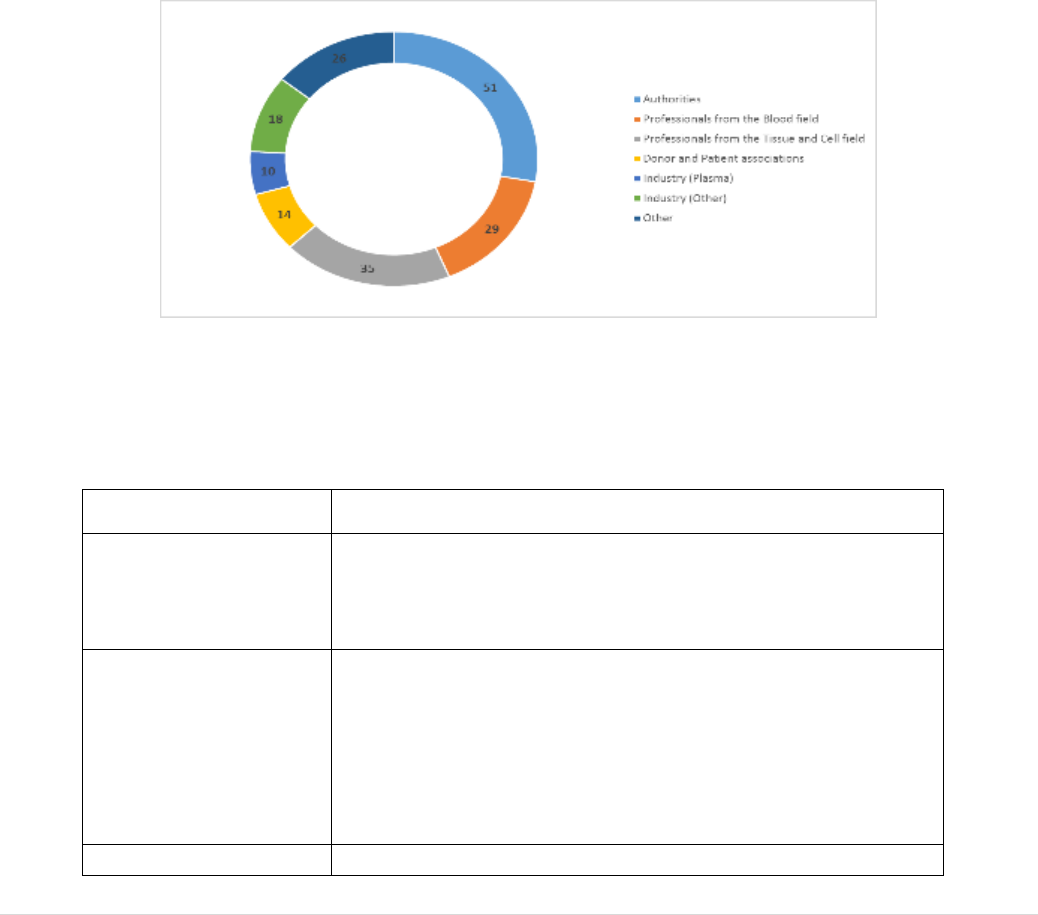

A Public Consultation was launched on 29 May 2017 and ran until 14 September 2017.

Submissions were received from 158 organisations and 43 citizens. A summary of the

outcome, together with the individual submissions, was published

82

. A Stakeholder Event

was held on 20 September 2017 in Brussels. The event attracted a high level of interest,

with over 200 stakeholders attending. A summary of the issues raised was provided in a

published report

83

.

Targeted Consultation was organised to fill any gaps in terms of stakeholders consulted

and to explore certain emerging issues in more depth.

Bilateral Meetings with key stakeholders allowed focused/specific input through

direct interaction. Meetings with relevant EU agencies and with third country

BTC Regulators were also held. Summary minutes were published on the DG

SANTE website.

Multi-lateral topic-specific meetings with selected stakeholders, including donor

and patients associations, industry and professionals working in the sector

84

80

Good Practice Guidelines in the Guide to the Preparation, Use and Quality Assurance of Blood Components 19th

Edition.

81

DG SANTE website.

82

Summary of Responses to the Public Consultation for the Evaluation of the Blood, Tissues and Cells Legislation by

the European Commission 2018.

83

Summary of the Blood, Tissues and Cells Stakeholder Event 20 September 2017.

84

https://ec.europa.eu/health/blood_tissues_organs/consultations/call_adhocstakeholdermeeting_en.

27 | P a g e

together with Member State authorities, were held when more in-depth analysis

of key emerging issues was required. These meetings, and the stakeholders

involved, are listed in Annex XII. Summary minutes were published on the DG

SANTE website.

A Synopsis report of Stakeholder Consultation activities and results is provided at Annex

XII. Numerous stakeholders were also engaged in the activities carried out as part of the

external study described below.

4.1.3 External Study

An external study

85

was commissioned to support this evaluation. This study was largely

desk-based, with a review of over 300 documents, including reports provided by the

Commission, relevant published literature and documents developed by other bodies

(professional associations, international organisations etc.). The contractor also organised

focus groups to address specific topics (including on medically assisted reproduction and

on coherence with other legal frameworks), interviews with experts and targeted surveys

to enhance their evidence gathering and analysis. The outcomes of the consultation

activities organised by the European Commission were also provided as material for use

in the study.

4.2 Limitations and robustness of the evaluation findings

Much of the evidence for the answers provided in this evaluation is considered robust.

There is a rich literature, as evidenced by the bibliography in the external study

supporting the evaluation, and stakeholders, from all sub-sectors, were motivated to share

detailed information and opinions. Many of the issues raised are well documented, either

in Commission monitoring reports, in professional publications or in technical meetings

with stakeholders, organised in the context of the evaluation. The same gaps and

shortcomings raised could be verified from multiple sources.

There were three important limitations to the evidence gathering exercise. Firstly, data

available on the situation in Member States prior to the adoption of the legislation, with

quantified indicators that could be compared to the current situation was limited. This

made measuring the impact of the legislation in a quantitative manner more challenging.

This was exacerbated by the heterogeneous situation across the EU at the time of

adoption in terms of measures already in place and administrative capacity for oversight.

A second important limitation was related to quantifying the costs incurred by the BTC

legislation for the assessment of efficiency. The majority of stakeholders impacted by the

legislation are working in public sector hospitals, clinics and centres often carrying out

85

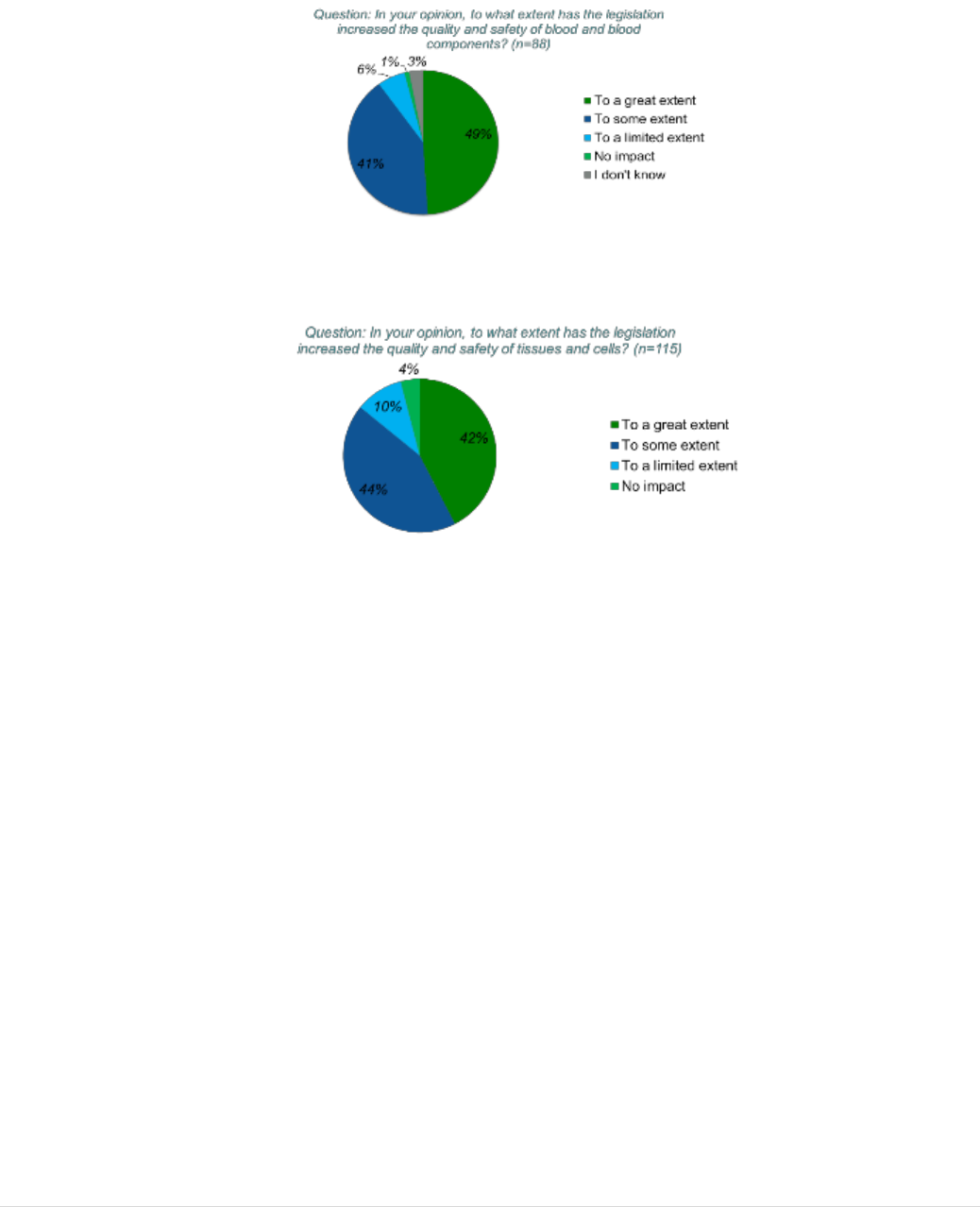

Conducted by ICF Consulting and published together with this report.