Binghamton University Binghamton University

The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB)

Research Days Posters 2021 Division of Research

2021

Consent During the Growing Age of Virtual Sexuality Consent During the Growing Age of Virtual Sexuality

Phoebe Goldberg

Binghamton University--SUNY

Aubrey Doyen

Binghamton University--SUNY

Skyler Powers

Binghamton University--SUNY

Justin Chen

Binghamton University--SUNY

Brianna Manginelli

Binghamton University--SUNY

See next page for additional authors

Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/research_days_posters_2021

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Goldberg, Phoebe; Doyen, Aubrey; Powers, Skyler; Chen, Justin; Manginelli, Brianna; Adeyemi, Moyosola;

Appel, Rebecca; Kovic, Maya; and Puglisi, Cassandra, "Consent During the Growing Age of Virtual

Sexuality" (2021).

Research Days Posters 2021

. 83.

https://orb.binghamton.edu/research_days_posters_2021/83

This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Division of Research at The Open Repository @

Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Days Posters 2021 by an authorized

administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 has resulted in limited social and sexual interaction. Strict

COVID-19 guidelines and social distancing orders have made meeting potential sexual partners difficult. To engage with

others in a safe manner, individuals have turned to virtual methods which have drawn attention to issues surrounding

consent in a virtual context. While virtual interactions allow for physically safe communication with others, it is important

to recognize risks associated with online sexual interactions such as miscommunication, coercion (Ross et al., 2016),

unwanted sexual solicitations (Naezer, 2017), anxiety and sexual compliance (Drouin et al., 2014), aggressive tendencies

and hostile attitudes (Andrighetto et al., 2019), and fear of personal information and explicit messages or images being

released.

Given the gaps in the literature about consent in virtual sexual encounters, our research aims to better understand what

individuals find uncomfortable in their interactions and how they navigate safe practices by interpreting their

definitions of consent in this context.

When asked what behaviors made them uncomfortable in a virtual setting, participant responses included the

exchanging of unsolicited nude photos, sharing messages without permission, and pushiness.

The question about discomfort in virtual encounters was administered before the direct question about consent in the

context of virtual encounters. Given this sequencing, 7.3% of participants showed a concern or wish for consent

without the survey priming them on this concept, further suggesting a desire for more direct communication and safer

practices in the virtual sphere.

Dating apps feature user agreement policies in an attempt to discourage unsolicited behaviors. Tinder’s community

guidelines read, “Do not engage, or encourage others to engage, in any targeted abuse or harassment against any

other user. This includes sending any unsolicited sexual content to your matches” (Tinder, n.d.). Our participants,

however, still encountered content and forms of conversations that made them uncomfortable.

Additionally, upon review of the Student Code of Conduct for this northeastern university,

regulations for consent in a virtual sexual encounter are nonexistent. We feel that institutions

ultimately hold the responsibility of ensuring safety for its members, and their teachings impact

perceptions of consent, thus leading us to call for the revision of university codes of conduct to

include virtual sexual encounters. Changes like this are not unheard of, as we are aware that

affirmative consent has been added to regulations in recent years, and are therefore feasible in

the foreseeable future.

The study of this behavior is important in order to build on societal regulations. Additionally, our research focuses

on young adults, and therefore can contribute to a cohort bias. Due to the possibility of cohort bias in our study, it

may be valuable to examine a more diverse population of emerging adults, possibly by including these questions

in a nationally distributed survey. With the increase in online sexual interactions, it may also be beneficial to

study which forms of contact are most welcomed for individuals who regard consent as an important part of

virtual sexual interactions.

Due to the gap in the literature and in policy regarding consent in virtual settings, more research is needed

to establish how individuals find safe ways to interact online. Another iteration of the survey will be

released to ask more questions about the role of consent in a virtual space. This survey will address how

participants work towards making their partners feel comfortable in a virtual setting and how they define

consent in virtual interactions.

Procedure:

Participants filled out a survey through Qualtrics about their attitudes and behaviors in regard to an online dating format. Each provided basic

demographic information and answered a series of scaled, checklist or open-ended questions. Codebooks were developed for open-ended

questions and coders outside of the primary research team volunteered to analyze the data in order to minimize bias. For the purpose of this

poster, two questions were analyzed to view sources of discomfort in virtual encounters and definitions of consent in a virtual context.

Survey Questions:

Virtual interactions were defined as “ ...any use of social media, dating apps, texting, direct messaging, etc. all for the purpose of finding a partner

to hook up with or get to know more intimately.”

Participants were then asked to define their virtual interactions through the following questions:

1. “Have you ever felt uncomfortable in an virtual interaction” [Possible Answers: Yes/No/Maybe]

2. “When engaged in a virtual interaction what behaviors make you uncomfortable as the recipient?” [Select all that apply]

3. “Have you ever felt threatened during a virtual interaction in any of the following ways…” [Select all that apply]

4. “What does consent mean in the context of a virtual sexual encounter?” [Open-ended]

Analysis for this poster focused on questions two and four.

Participants:

Participants (N=293) were undergraduate students from a mid-sized northeastern university. The sample was collected

during their Fall 2020 semester from September 28th to October 16th. Responses were omitted for individuals whose

surveys contained incomplete or missing data on a per-question basis. Participants were recruited through the SONA

subject pool and each participant received credit for their completion of the survey. The survey was given out during the

COVID-19 pandemic as there were a large uptick in virtual interactions.

- The mean age of the participants was 18.8 years of age.

- The gender of the participants were 17.2% Male, 81.0% Female, and 1.8% other.

- The participants were 70.5% white, 16.7% Asian/Pacific Islander, 5.5% Black, 4.5% mixed race,

and 2.5% other.

- The participants were 8.4% Hispanic/Latinx and 91.6% not Hispanic/Latinx.

Background

Albury, K., Byron, P., McCosker, A., Pym, T., Walshe, J., Race, K., Salon, D., Wark, T., Botfield, J., Reeders, D., & Dietzel, C. (2019). Safety, risk and wellbeing on dating apps: Final

report. Swinburne University of Technology. https://doi.org/10.25916/5DD324C1B33BB

Andrighetto, L., Riva, P., & Gabbiadini, A. (2019). Lonely hearts and angry minds: Online dating rejection increases male (but not female) hostility. Aggressive Behavior, 45(5), 571–581.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21852

Drouin, M., & Tobin, E. (2014). Unwanted but consensual sexting among young adults: Relations with attachment and sexual motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 412–418.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.001

Naezer, M. (2017). From risky behaviour to sexy adventures: reconceptualising young people’s online sexual activities. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(6), 715–729.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1372632

Ross, J. M., Drouin, M., & Coupe, A. (2016). Sexting Coercion as a Component of Intimate Partner Polyvictimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(11), 2269–2291.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516660300

Tinder. (n.d.). Community guidelines.

https://policies.tinder.com/community-guidelines/intl/en/#:~:text=No%20nudity%2C%20no%20sexually%20explicit,Keep%20it%20clean.&text=Do%20not%20engage%2C%20or

%20encourage,sexual%20content%20to%20your%20matches.

Consent During the Growing Age of Virtual Sexuality

Phoebe Goldberg, Aubrey Doyen, Skyler Powers, Brianna Manginelli, Justin Chen, Moyosola Adeyemi,

Rebecca Appel, Maya Kovic, & Cassandra Puglisi

Mentors: Dr. Sarah Young, Dr. Sean Massey, Dr. Ann Merriwether, & Dr. Melissa Hardesty

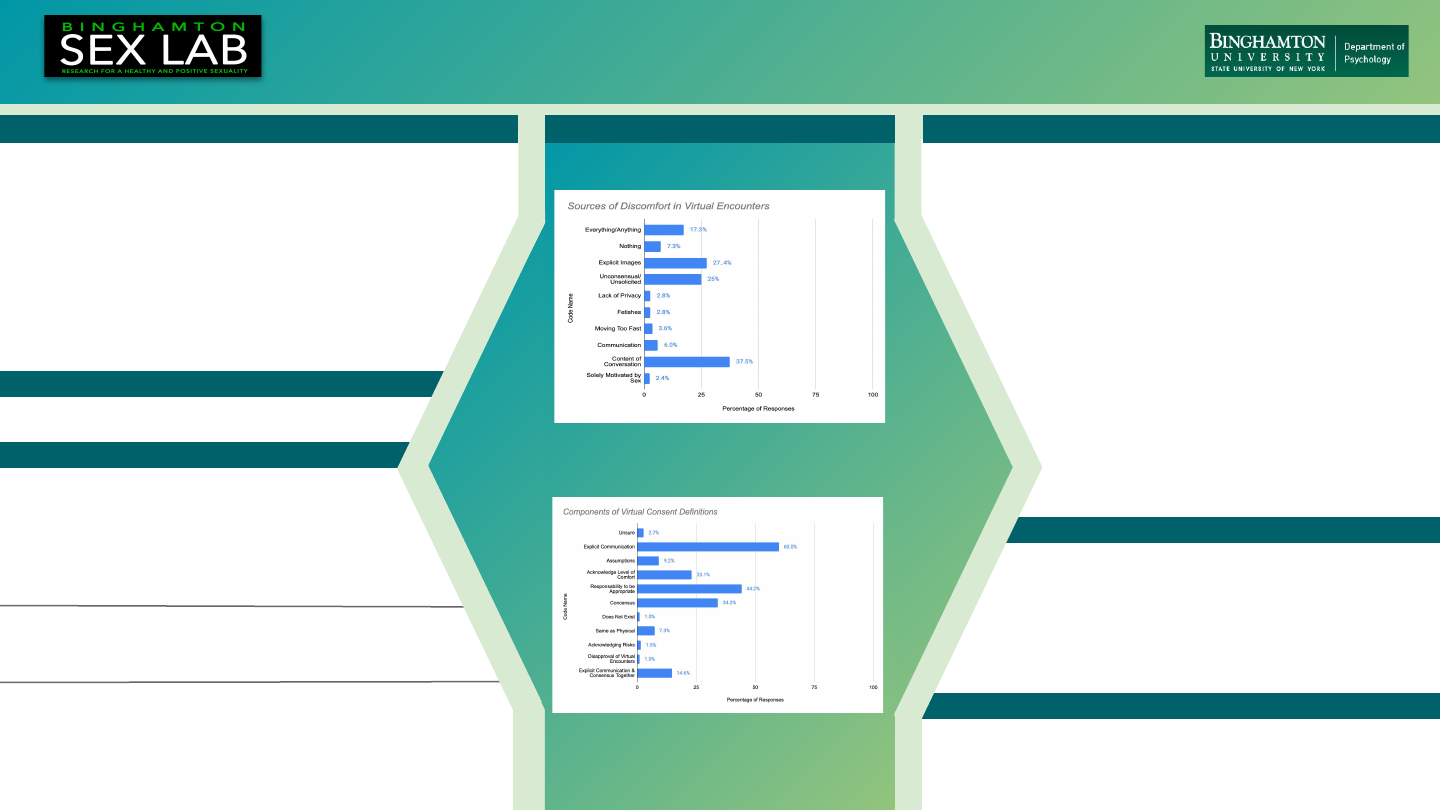

Results

1. When engaged in a virtual interaction what behaviors make you uncomfortable

as the recipient?

2. What does consent mean in the context of a virtual sexual encounter?

Discussion

References

Future Research

Question 2: “When talking to someone virtually that you are

interested in, what sexual behavior would make you feel

uncomfortable?”

- The most frequently mentioned source of discomfort in virtual encounters is the content of conversations (37.5%); this includes dirty

talking, objectification, pressuring, inappropriate jokes, and disrespectful or aggressive speech.

- Explicit imagery (27.4%) and unsolicited behaviors (25%) were also highly identified as uncomfortable.

Research Questions

Methods

A survey was conducted by the Binghamton Human Sexualities Research Lab to better understand the content

of conversations online and what leads to frequent discomfort or aggression. An additional component

focused on how individuals look for signs of consent with potential sexual partners online and if they suggest

obtaining consent as a way to alleviate pressure and establish safe interactions.

The purpose of this study was to understand attitudes about consent in virtual encounters in emerging adults.

Due to a lack of conversation and education about consent in virtual spheres, data collected from this study

can be used to make sexual assault prevention initiatives more comprehensive on college campuses.

Question 4: “What does consent mean in the context of a virtual sexual encounter?”

- One of the most frequently mentioned components of participants’ definitions is

explicit communication, which includes verbal/written permissions, asking

questions, and communications of intentions about relationships.

- Responsibility to be appropriate (44.2%) and consensus among partners (34.2%)

were also highly regarded as components of defining consent.

According to participants’ definitions of consent in the context of virtual encounters, 60.0% of individuals

mentioned a desire for explicit communication of intentions, including the importance of asking questions

about comfort level and sexual behaviors before engaging. Participants found it crucial to act responsibly

in online interactions (44.2%), with frequent responses stating, “not harassing someone,” “allowing an

individual to say no and not feel pressured,” or “not sharing private content.”