The Impact of New Jersey's County Line Primary Ballots

on Election Outcomes, Politics, and Policy

Julia Sass Rubin, Ph.D.

Forthcoming, Seton Hall Law Review

Julia Sass Rubin is the Associate Dean of Academic Programs, Director of the Public

Policy Program, and an Associate Professor at the Edward J. Bloustein School of

Planning and Public Policy, Rutgers University - New Brunswick

2

This article examines New Jersey’s unique county line primary ballots; specifically, how

the county line ballots affect primary election outcomes, and how that, in turn, impacts

the state’s political system. Primary elections are particularly important in New Jersey

because the majority of the state’s counties and legislative districts are dominated by

one of the two major parties.

1

With general election outcomes largely a foregone

conclusion in much of the state, the real contests happen in the primaries.

The article proceeds as follows: The first section describes the county line ballot and the

mechanisms through which it may affect voting behavior. The second section examines

the impact of the county line ballot on primary election outcomes. The third section

describes how parties award the county line and the resulting candidate choices

available to voters. The article concludes with a discussion of how the county line

primary ballot affects New Jersey politics and policy.

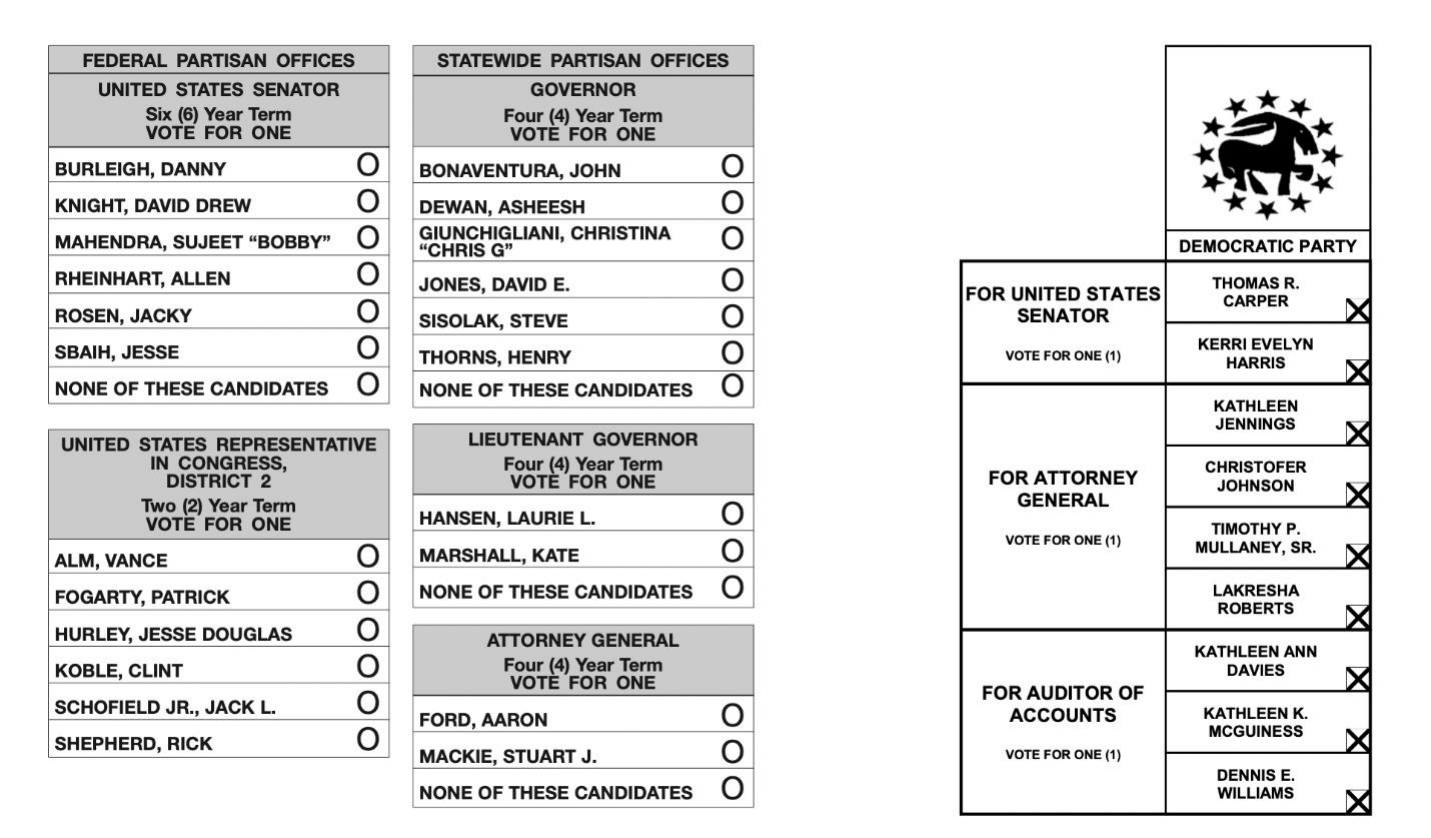

I. New Jersey’s Unique Primary Ballot

New Jersey’s county line primary ballots are very different from primary ballots in other

states.

2

A review of primary ballots in the largest counties in all fifty states and the

District of Columbia found that, outside of New Jersey, primary ballots are organized by

the electoral position being sought, such as Senator or Governor. Most states list

candidates beneath the position they are seeking (see Figure 1, Elko County, Nevada

ballot). In a few states, candidates appear to the right of the position they are seeking

1

See Matt Friedman. N.J. advocates push commission to draw more competitive legislative districts, NJ.Com,

February 18, 2011. https://www.nj.com/news/2011/02/commission_based_on_nj_politic.html

2

See Julia Sass Rubin. Toeing the Line: New Jersey Primary Ballots Enable Party Insiders to Pick Winners. NJ

Policy Perspective, June 29, 2020. https://njppprevious.wpengine.com/reports/toeing-the-line-new-jersey-primary-

ballots-enable-party-insiders-to-pick-winners

3

(see Figure 1, Sussex County, Delaware ballot). These ballot designs make it relatively

easy for voters to identify which candidates are running for each electoral position.

Insert Figure 1 here

By contrast, county line primary ballots, which are used by both the Democratic and

Republican parties in nineteen of New Jersey’s twenty-one counties, are organized

around a group of candidates endorsed by the county parties. These groups of party-

endorsed candidates are referred to as the “county line,” “party line,” or organization

line” because they are presented on the ballot as a vertical or horizontal line of names,

usually with a candidate included for every position on the ballot in that election cycle.

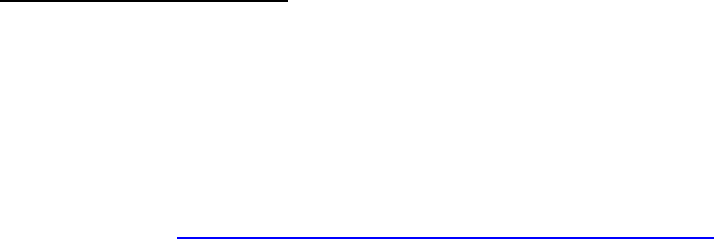

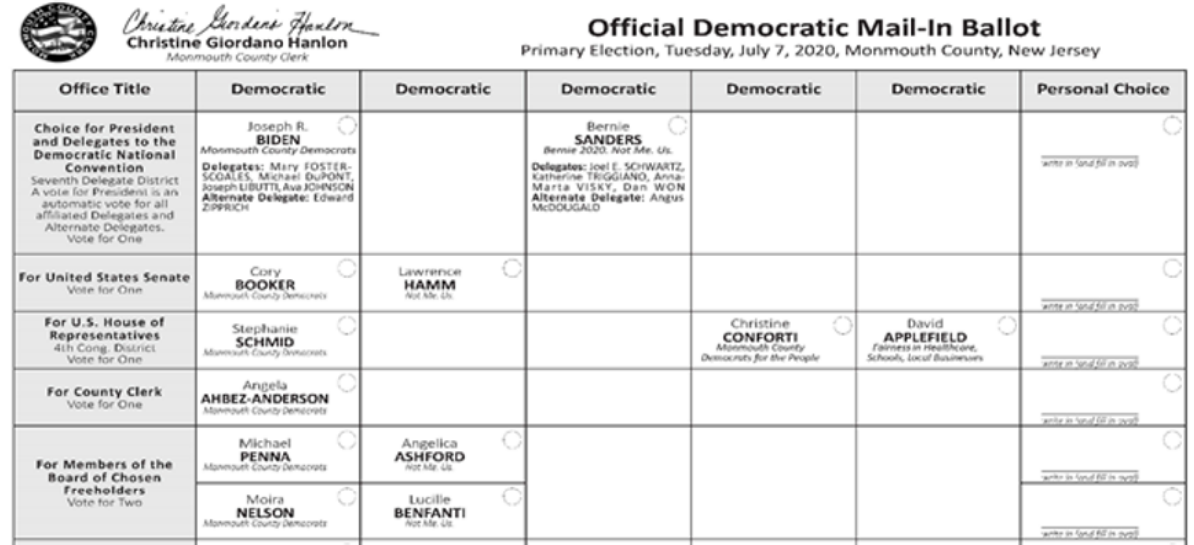

Figure 2 shows a 2020 New Jersey Democratic primary ballot from Monmouth County.

The seven county line candidates are in column one. The remaining six candidates are

scattered across the other four, mostly empty, columns. There is no obvious logic as to

why each of the non-endorsed candidates is in a particular column. Column two

includes a candidate for the U.S. Senate and two candidates for County Commissioner

(previously called Freeholder). Column three includes a candidate for President and his

delegates. Columns four and five each include a single candidate for the U.S. House of

Representatives.

Insert Figure 2 here

This ballot design provides multiple advantages for candidates who appear on the

county line. First, the county line is easy for voters to find on the ballot. The inclusion of

4

candidates for every position makes it visually distinct. It also usually has prime ballot

position, in the first or second column or row.

Candidates on the county line are further advantaged by the placement of candidates

for the highest position on the ballot that cycle at the head of the line -- such as Joseph

Biden in the Monmouth example. While voters may not know the names of candidates

running for county commissioner or county clerk, they generally know who is running for

president, governor, or US senator. These better-known candidates lend familiarity and

legitimacy to the other county line candidates.

Candidates not on the county line appear in different columns or rows and are often

separated from the county line by additional blank columns or rows, such as the two

columns between Stephanie Schmid, the county line candidates for US House of

Representatives on the Monmouth ballot, and her two challengers Christine Conforti

and David Applefield. In extreme examples, candidates on the county line are separated

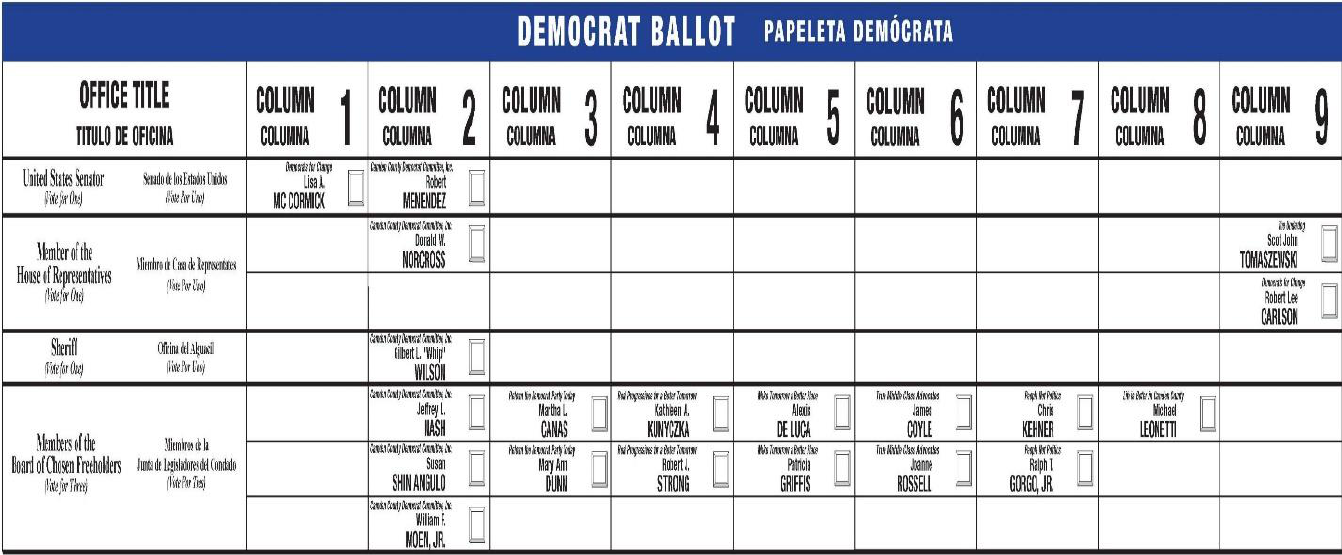

from their challengers by multiple columns or rows. For example, on the 2018 Camden

County Democratic primary ballot shown in Figure 3, Donald Norcross, the county line

candidate for US House of Representatives, is separated from his challengers by six

blank columns. This can make the non-county line candidates more difficult for voters to

find on the ballot, a placement that has colloquially come to be known as “ballot

Siberia.”

Insert Figure 3 here

5

Candidates not on the county line also may be placed in the same column or row as

their opponents. For example, on the 2018 Camden County Democratic primary ballot,

two candidates running against each other for the US House of Representative both

appear in column 9.

Designing primary ballots in this way creates murky contest boundaries that make it

difficult for voters to determine which candidates are running for each office.

3

This

results in voters not realizing that some positions are contested, benefiting the

candidates on the county line, who are easier to locate on the ballot. By confusing

voters, the county line ballots also encourage overvotes and undervotes.

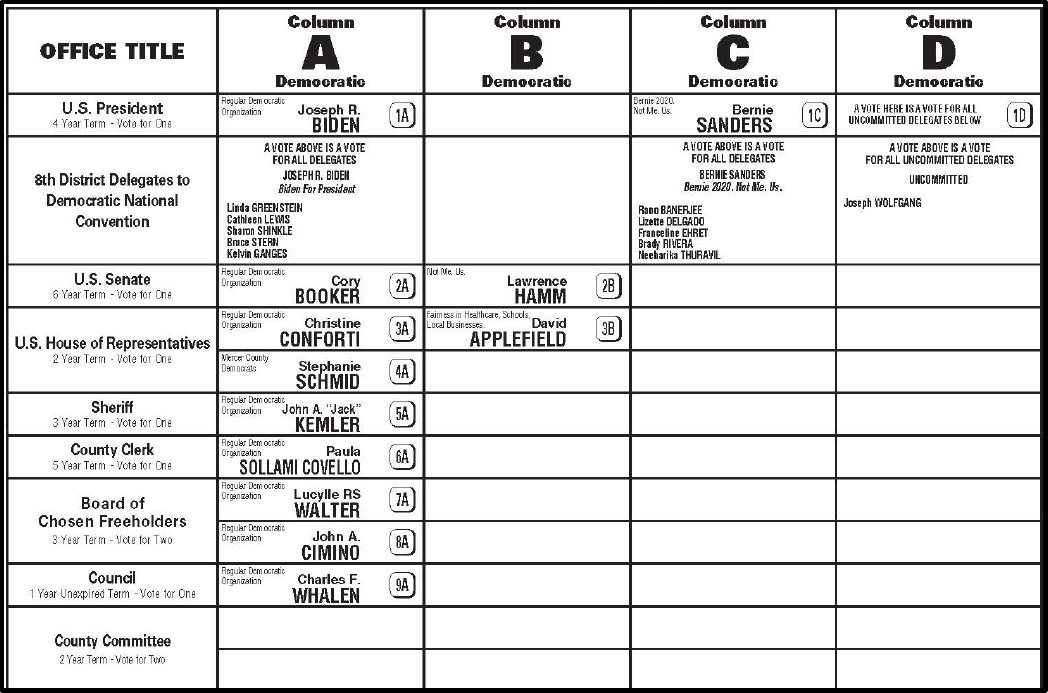

The 2020 primary election provided examples of both outcomes. The Mercer County

Democratic primary ballot shown in figure 4, listed two of the three candidates for the

US House of Representatives 4

th

Congressional District in column A, which is the

county line, one below the other. The third candidate appeared in column B.

4

Insert Figure 4 here

New Jersey primary voters are encouraged by the county parties, and conditioned by

years of practice, to vote for all the candidates on a county line regardless of the ballot

instructions. In this case, placing both Christine Conforti and Stephanie Schmid on the

same column encouraged voters to vote for both even though the ballot instructed them

3

See Andrea Cordova McCadney, Lawrence Norden and Whitney Quesenbery, Common Ballot Design Flaws and

How to Fix Them, The Brennan Center. February 3, 2020. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-

reports/common-ballot-design-flaws-and-how-fix-them.

4

Article VII of Mercer County Democratic Committee Constitution and Bylaws states that “Any candidate failing to be

endorsed shall have the option of choosing to run in the same column as the endorsed candidate(s) but without the

party slogan only if the unendorsed candidate received at least forty percent (40%) of the vote of the registered

delegates in any ballot in which a candidate received the endorsement of the Convention.” See

https://www.mercerdemocrats.com/_files/ugd/f6fae7_3f3c588f8c354170aca934a23017a381.pdf page 6.

6

to vote for only one candidate. This ballot design resulted in a 32.4% overvote in this

Congressional contest, leading to all the overvotes being discarded.

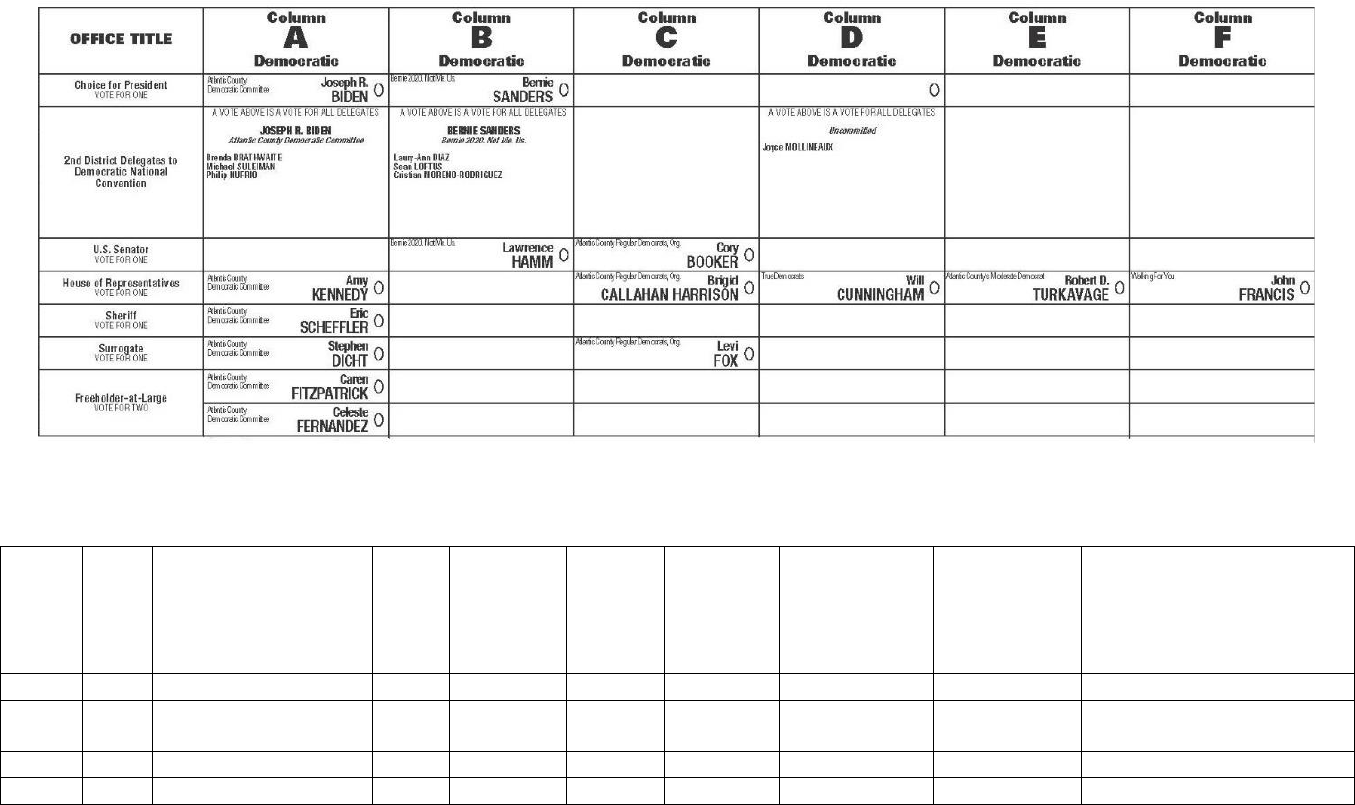

In contrast, the Atlantic County Democratic primary ballot shown in Figure 5 resulted in

substantial undervotes, with the number of Democratic votes cast for the U.S. Senate

totaling only 81% of the votes cast for President and only 82% of the votes cast for U.S.

House of Representatives. In every other county, the total votes for U.S. Senate

exceeded the number cast for the U.S. House of Representatives and equaled at least

97% of the total votes cast for President.

Insert Figure 5 here

The undervotes in the Atlantic County example likely reflect the lack of a Senate

candidate on the county line in column A. Cory Booker, the incumbent senator running

for reelection, was endorsed by all the county parties but chose not to run on the line in

Atlantic County. Instead, Senator Booker appeared on the primary ballot in column J,

above his friend Brigid Callahan Harrison, who was running for the US House of

Representatives and did not receive the Atlantic County party’s endorsement. Nearly

twenty percent of the Democratic voters in this primary left the US Senate position on

their ballots blank. Conditioned to vote for everyone on the line, they may have been

reluctant to vote for candidates not on the county line or may not even have realized

that they could do so.

7

II. Impact of the County Line on New Jersey Primary Election Outcomes

To evaluate the impact of the county line primary ballot on election outcomes, Diez

examined New Jersey legislative election outcomes for incumbents from 2003 to 2019.

5

I updated his data to include the 2021 and 2023 legislative primary elections.

Between 2003 and 2023, 1033 incumbent NJ state legislators ran for reelection; 227 of

them had a challenger.

6

In 208 of those 227 contested primaries, incumbents were

awarded the county line in all the counties in their district that used a county line ballot.

In 19 of the 227 contested primaries, incumbents were denied the county line in at least

one of the counties in their district.

Of the 208 incumbents who ran on the county line in all the counties in their district, 205

won renomination and three were defeated.

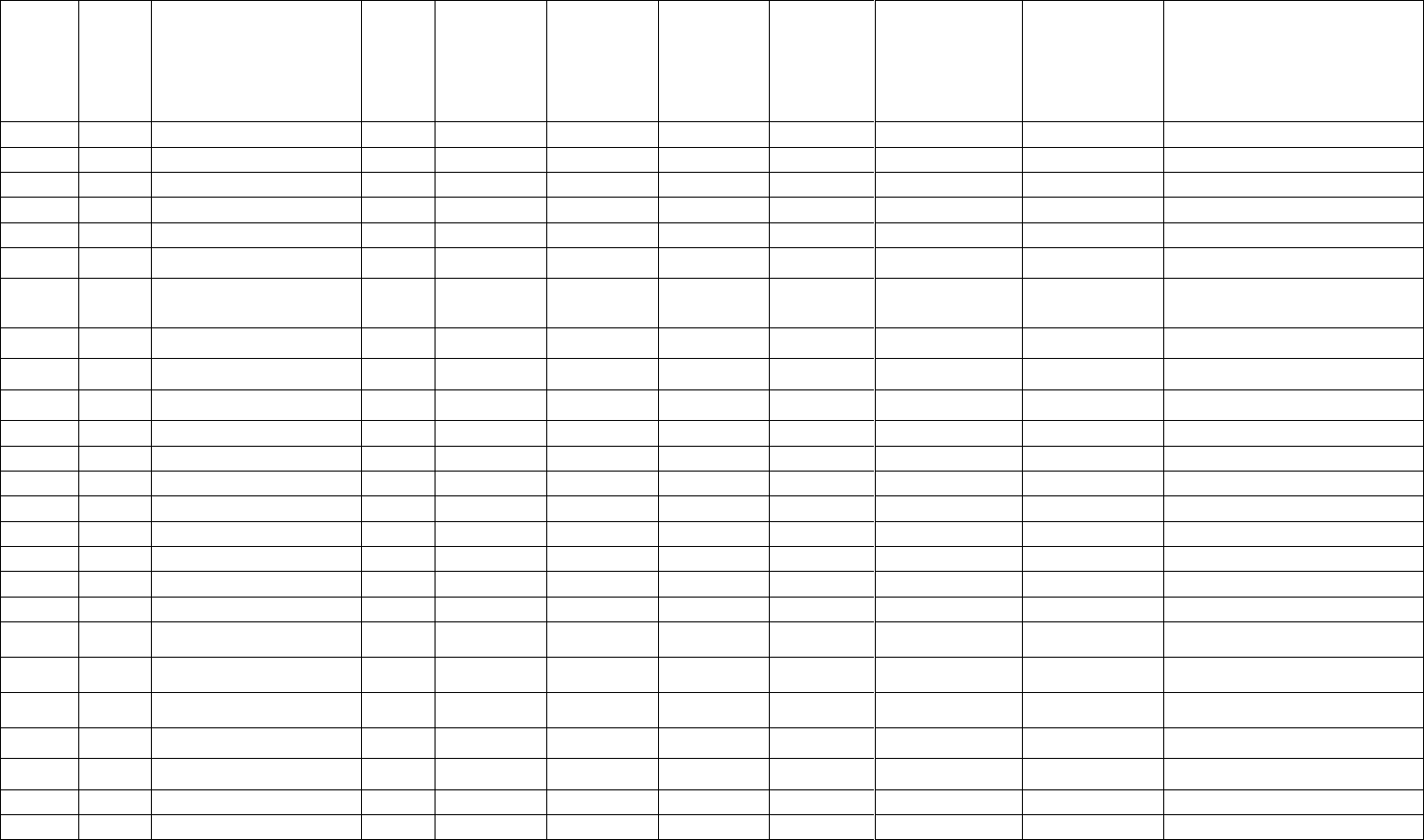

Insert Figure 6 here

Of the 19 incumbents denied the county line in at least one county in their legislative

district, nine won their primaries and ten were defeated. Only two of those nine won

while running off the county line in every county in their district – Nia Gill in 2003 and

Ronald Rice in 2007. The other seven had the county line in at least one of the counties

in their district. For example, Robert Auth and Deanne DeFuccio lost the county line in

Passaic in their 2021 reelection bid for the Republican nomination for the 39th NJ

Assembly District. However, they kept the county line in Bergen, which was the larger

5

Francisco Diez, The Likely Advantages of the Line, Communication Workers of America analysis, July 29, 2019.

This analysis was not published but was shared with the author.

6

Incumbent is defined as having served in the prior term in the same capacity in at least some of the same

counties. This includes incumbents whose district number changed post redistricting and those who ran against

other incumbents post redistricting.

8

portion of their district. They lost their races in Passaic but still won the primary because

they won in Bergen.

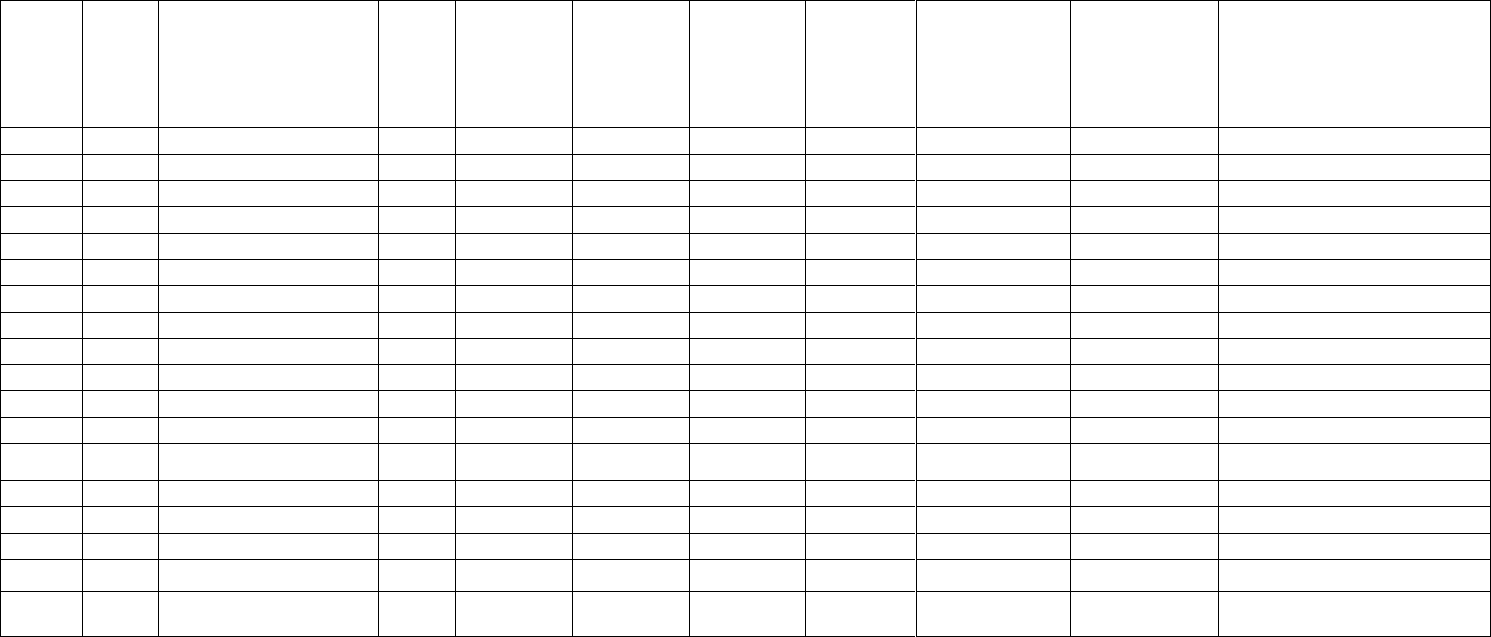

Insert Figure 7 here

Two of the ten incumbents who lost after losing the county line in at least one county in

their district had the county line in other counties in their district. Both won the counties

where they were on the county line.

Insert Figure 8 here

No incumbent on the county line in all the counties in their district has lost a primary

election since 2009. This fourteen-year period encompasses seven legislative election

cycles. In contrast, in the other 49 states, 1,145 state legislative incumbents lost primary

elections over that time period.

7

To quantify the impact of the county line on primary election outcomes, I analyzed the

results of congressional and senatorial primary election contests held between 2002

and 2022 in which political parties in different counties endorsed different primary

candidates.

8

For example, in the 2020 primary, two candidates split the Republican

party endorsements in the two counties that made up the 3rd Congressional District.

Kate Gibbs was endorsed and given the line by the Burlington County Republican party

and David Richter was endorsed and given the line by the Ocean County Republican

7

In the 48 states that hold their state legislative elections in even-numbered years, 1,121 state legislators lost primary

elections between 2010 and 2022. Source: https://news.ballotpedia.org/2022/10/21/a-closer-look-at-the-229-

incumbents-who-lost-state-legislative-primaries/. In Virginia, the only other state besides New Jersey to hold its state

legislative elections in odd-numbered years, 24 state legislative incumbents lost their primary elections between 2011

and 2023. Source: https://ballotpedia.org/Incumbents_defeated_in_state_legislative_elections,_2023#Virginia

8

The historical election results are from the New Jersey Voter Information Portal, Department of State, Division of

Elections https://www.state.nj.us/state/elections/election-information-results.shtml.

9

party. Gibbs received 57% of the vote when she was on the county line in Burlington

and 22% when she was not on the county line in Ocean. Richter received 78% of the

vote when he was on the county line in Ocean and 43% when he was not on the county

line in Burlington. The difference in how Gibbs and Richter performed when they were

on the county line versus when their opponent was on the county line was 35

percentage points.

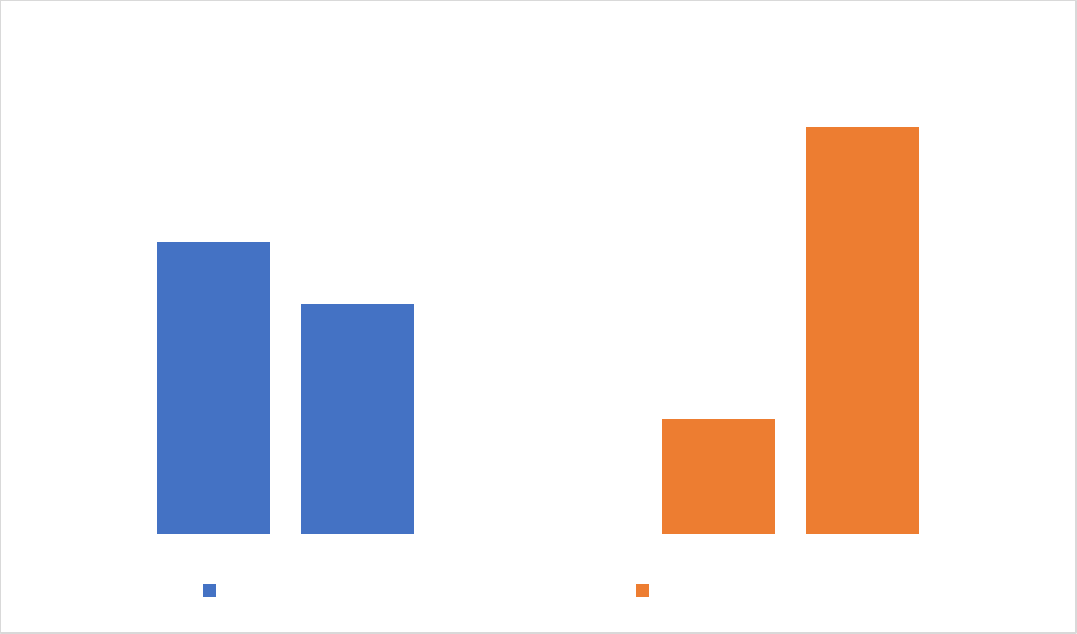

Insert Figure 9 here

Between 2002 and 2022, 45 congressional and senatorial candidates appeared on the

county line in at least one county and had at least one opponent on the county line in a

different county.

9

Every one of those 45 candidates performed substantially better when

they were on the county line than when their opponent was on the county line. The

average margin in performance for those 45 candidates between being on the county

line and having their opponent on the county line was 38 percentage points.

Insert Figure 10 here

Only three of those 45 candidates were incumbents – Senator Frank Lautenberg, who

split county endorsements with Congressman Rob Andrews in the 2008 Democratic

senatorial primary, and Congressmen Bill Pascrell and Steven Rothman, who split

endorsements with each other in the 2012 Democratic primary for the 9

th

congressional

9

For contests with more than two counties, a candidate’s percentage of the total vote was averaged for all the

counties in which that candidate was on the county line versus their percentage of the total vote for all the

counties in which one of their opponents was on the county line. Counties that did not use a county line ballot in

that election contest were excluded from the averages.

10

district.

10

The small number of incumbents is not surprising as incumbents, particularly

those at the federal level, generally maintain county party support for their reelections.

Although incumbency did not protect state legislators who lost the county line, we might

expect congressional incumbents to have greater name recognition with primary voters,

which could help counter the impact of the county line. In each of the three federal

primaries that included incumbents, however, being on the county line provided a

greater advantage than incumbency. Lautenberg, Pascrell, and Rothman lost every

county in which their opponent was on the county line and won every county in which

they were on the county line.

Insert Figure 11 here

III. Awarding the County Line and New Jersey Politics

The county line is awarded to candidates endorsed by the county Democratic and

Republican parties. In theory, the endorsement decisions are made by county

committee members, two Democrats and two Republicans elected in each precinct by

primary voters who belong to those parties.

11

The county committee members are

meant to represent the voters of their political party who live in their home precincts in

determining which candidates to endorse for local, county, and state-level positions.

10

Pascrell and Rothman competed against each other after New Jersey lost a Congressional District following the

2010 census. Prior to redistricting, Rothman had represented the 9

th

Congressional District consisting of Bergen,

Hudson, and a small part of Passaic County, while Pascrell had represented the 8

th

, consisting of Passaic and Essex

counties. Post redistricting, parts of both of their former districts ended up in the new 9

th

Congressional District, which

consisted of Bergen, Hudson, and Passaic counties. Rothman and Pascrell split county endorsements, with Rothman

receiving the county line in Bergen and Hudson counties and Pascrell, who had represented a much larger portion of

Passaic than Rothman, receiving the county line in Passaic.

11

County committee members are elected during primaries and serve for two-, three- or four-year terms, depending

on the bylaws of their county party.

11

In practice, the endorsement process varies substantially by county and between

election cycles. A few county party bylaws mention a specific endorsement process.

Most county party bylaws, however, are silent on this issue.

In some counties, the party endorsement process includes a vote by county committee

members.

12

Municipal party committees, made up of the county committee members in

each municipality, decide on endorsements for mayor and city council. The entire

county committee meets at county nominating conventions to determine county-wide

endorsements (e.g., county elected positions, state legislature, congress, governor, and

president). In other counties, the endorsement decisions are made solely by the county

party chair, sometimes after consultation with the chairs of the municipal party

committees in that county.

13

,

14

Even in counties that hold county nominating conventions at which all county committee

members vote, the endorsement process is vulnerable to influence by the county party

chairs. In some counties, convention votes cast by individual committee members are

not secret, which can create pressure to vote in ways that align with the wishes of the

county party chair.

15

Pleasing the county party chair is important because the chair determines which county

committee members may run for election on the county line, along with the other

12

The number of county committees that allow a vote varies by year, based on the preferences of the county party

chairs.

13

See Colleen O’Dea, Some NJ Congressional Primary Candidates Argue Party-Line Politics Are Unfair. NJ

Spotlight, May 14, 2018. https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2018/05/18-05-13-some-nj-congressional-primary-

candidates-argue-party-line-politics-are-unfair/

14

County party chairs are elected by members of the county committee. They must reside in the county but do not

have to be county committee members themselves. See Brett M. Pugach, The County Line: The law and politics of

ballot positioning in New Jersey. Rutgers University Law Review, Volume 72, Issue 3, Spring.

15

See O’Dea. Also see Max Pizarro, LIVE BLOG: Union County Democratic Committee Special Convention,

February 21, 2018. https://www.insidernj.com/live-blog-union-county-democratic-committee-special-convention/

12

endorsed candidates. If the chair removes a committee member from the county line, it

can be much more difficult for that committee member to be reelected. This happens

regularly. In Union County, for example, the Democratic County party chair Nicholas

Scutari removed a large number of county committee members from the county line in

2019 after they supported his opponent in the 2018 chair election.

16

Scutari knew which

committee members voted for him versus his opponent because they had to sign their

names to their ballots.

17

Another reason that county committee members may act in accordance with the wishes

of the county party chair is that they or their family members may be municipal or county

employees and fear losing those jobs as retribution from the county party chairs.

18

Retribution is a particular concern when the party chair also holds other positions of

power. Scutari, for example, is Union County Democratic Party Chair; represents part of

Union County in the New Jersey State Senate; has served as Senate President since

2021; and is the prosecutor for the Union County City of Linden. Similarly, Shaun

Golden, the Republican party chair of Monmouth County, serves as the elected county

sheriff.

In addition to their ability to influence the votes of county committee members, county

party chairs can also influence endorsement decisions by withholding information

regarding the endorsement process from candidates they do not support or by

16

See Maryanne Disporto, Charlie Sweeney, Paul Bentsen, Joanne Wrobleski, Patricia Brandt, Nancy Yewaisis,

Joseph Wrobleski, Phil Laskowski, Harry Brandt, Maria Santiago, Patrick Murphy, Judith Gottlieb, Robin Dexter-

Meyer, Robert Ellenport, Michael Altmann, Leslie Romano, Denise Hessler, Dario Valdivia, Paul Bentsen, Joanne

Wrobleski, Mark Boulanger, Gail Sweeney, Jerry Fogle, and Nancy Sheridan. Union County Dem Chair Wages War

on Opponents in Local Towns. Tap Into Clark. May 28, 2019. https://www.tapinto.net/towns/clark/articles/union-

county-dem-chair-wages-war-on-opponents-in-local-townset all

17

See Pizarro, 2018.

18

See Disporto et al, 2019.

13

implementing county convention rules that are challenging for those candidates to

navigate. In Somerset County, for example, some of the 2021 Democratic candidates

for state assembly were excluded from consideration because of a requirement that

they be nominated from the convention floor. Chris Fistonich, one of those candidates,

described his experience:

The Somerset County Democratic Committee (SCDC) has a screening process

to vet candidates... They held their nominating convention on March 4th, 2021.

With no public notice in any newspaper or any public facing publication…As a

candidate for the 16th Assembly District, I reached out to Somerset County party

leadership in February, formally announcing my intention to seek the

endorsement of the SCDC. I was told that I had “missed screening.” Later that

week I finally learned when the convention would be and was instructed that I

would require a member of the SCDC to nominate me, and another member to

second the nomination in order to speak and to be eligible to earn votes at the

convention. Delegates were forbidden from nominating or seconding multiple

candidates, already reducing the pool of delegates who might consider

nominating the myriad candidates running for the Assembly seat. Contact

information was provided for the voting delegates that I might seek their support.

A dozen of the email addresses bounced back from being either out of date or

erroneously written out. More than half a dozen delegates were excited about my

candidacy: a bold, progressive vision backed by technical expertise. Many

agreed that more scientists are needed in our state government. Several

indicated they would be happy to vote for me. Zero delegates, however, would

nominate me or second my nomination. One cited a “conflict of interest.” Another

cited “fear of blowback from party leadership, especially Peg [Schaffer].” Yet

another mentioned in no uncertain terms that they were “discouraged from

nominating a non-Somerset resident.” I would not get to speak at the convention

due to these insurmountable restrictions and roadblocks.”

19

Even in counties that allow county committee members to participate in the candidate

endorsement process and to vote a secret ballot, county committee decisions can be

overruled by the county party chair, who has the power under New Jersey law to

19

Chris Fistonich, personal communication with author, March 6, 2021.

14

determine who will be on the county line.

20

In 2021, for example, the Middlesex County

Democratic party chair Kevin McCabe overruled the Edison municipal committee

endorsements for mayor and city council and awarded the county line to other

candidates.

21

Candidates are aware of the power of the county line to determine primary election

outcomes. Many drop out of the primary if they do not receive the party’s endorsements.

This is particularly the case for county-level and state legislative positions, candidates

for which tend to be less well known to the voters. This includes incumbents. In 2021,

for example, Assembly Majority Whip Nickolas Chiaravalloti did not seek reelection to a

fourth term in the state Assembly after losing the county line.

22

Chiaravalloti said that he

decided to retire because “the prospect of winning a Democratic primary off an

organization line was too daunting.”

23

The difficulty of winning when not on the county line may explain New Jersey’s low

percentage of contested primary elections, particularly for the state legislature and

county positions. In 2021, for example, only 10 percent of the state legislative positions

20

See Brett M. Pugach, The County Line: The law and politics of ballot positioning in New Jersey. Rutgers University

Law Review, Volume 72, Issue 3, Spring. “The practical effect of receiving the endorsement of the county committee

is that it leads to the endorsed candidates having their names listed on the same column or row of the ballot, with the

same ballot slogan under each of their names…The slogan used by county committee-endorsed candidates is often

owned by a corporation, which grants permission for the slogan’s use to the slate of candidates endorsed by the

county committee. This is because New Jersey law requires that those who wish to use a ballot slogan containing the

name of another person or an incorporated association must receive the written consent of such person or entity. For

all practical purposes, the county chair and the county’s political machine, or those under their close direction, will

control the corporation that owns the slogan. Furthermore, all endorsed candidates will be featured on the same line

of the ballot with that same slogan. Technically, the county line itself is controlled by the campaign manager of the

candidates (usually two or more [county commissioner] candidates) who file a joint petition with the county clerk, and

not by the county chair; however, in practice, the county chair will control who that campaign manager is” (p. 654).

21

Insider NJ, Bhagia Hits Back After McCabe Awards Edison Line to Joshi. April 7, 2021.

https://www.insidernj.com/bhagia-hits-back-after-mccabe-awards-edison-line-to-joshi/

22

By long-standing tradition, the county line for the two state assembly positions in Chiaravalloti’s district is allocated

by the mayors of Bayonne and Jersey City. See Peter D’Auria, Chiaravalloti will seek re-election without the county

line, Mar. 30, 2021,https://www.nj.com/hudson/2021/03/chiaravalloti-will-seek-re-election-without-the-county-line.html.

23

See David Wildstein (2021, April 19). Chiaravalloti drops bid for re-election after losing party support. New Jersey

Globe. https://newjerseyglobe.com/legislature/chiaravalloti-drops-bid-for-re-election-after-losing-party-support/s

15

were contested in the primary. Two years later, following redistricting that saw the

retirement of a historically large number of incumbents, the percentage of contested

primaries increased only minutely to 11.3%.

24

This is one of the lowest percentages

nationally.

25

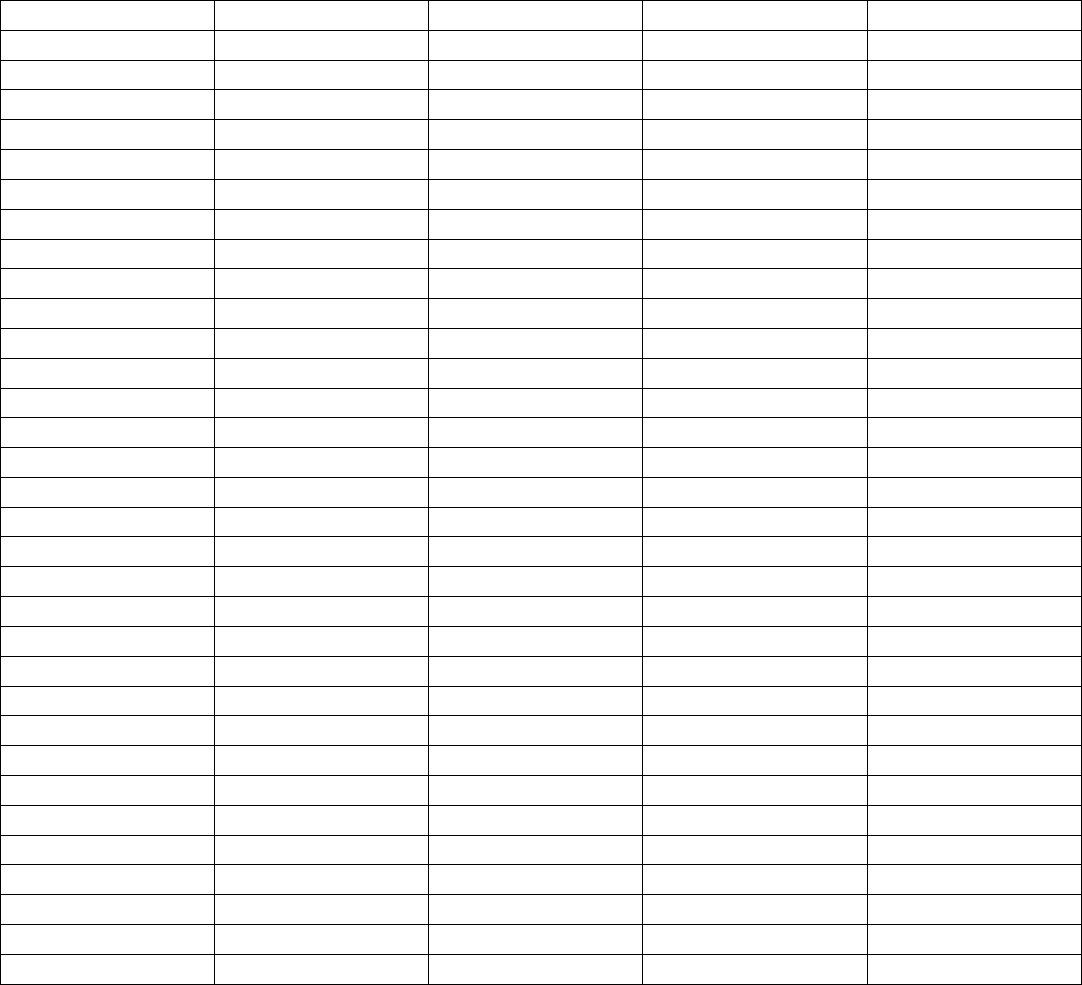

Insert Figure 12 here

The power of the county party chairs to determine who receives the county line also

contributes to the state’s relatively low percentages of women in elected office. Unlike

33 other states, New Jersey has never had a female US Senator. Only one woman has

served as governor and only seven women have served in Congress (with two of those

seven elected in the last eight years). New Jersey ranks 27

th

nationally for the

percentage of women in municipal office and 21

st

nationally for the percentage of

women in the state legislature.

26

As Jean Sinzdak, Associate Director of the Rutgers Center for American Women and

Politics, observed “Valuable [county] line slots are frequently taken by people who

emerge from the networks of the party chairs, limiting the ability of outsiders to break

24

In 2023, 28 out of 240 state legislative positions did not have an incumbent running in the primary. Seven

incumbents retired from the New Jersey State Senate before the primary and two others were redistricted into the

same district. Twenty incumbents retired from the New Jersey Assembly before the primary. In comparison, there

were only fifteen seats without an incumbent running in 2011, the first year after the 2010 redistricting, and an

average of 8.4 open seats for the five election cycles in between 2011 and 2023. See Ballotpedia

https://ballotpedia.org/New_Jersey_State_Senate_elections,_2023

25

In 2021, 24 out of 240 state legislative seats (120 Republican and 120 Democratic) were contested in the primary

In 2023, 27 out of 240 state legislative seats were contested in the primary. According to Ballotpedia, twenty percent

of the legislative primaries held in 2022 were contested, ranging from 1.7% in Alaska to 60% in California. The

national percentage of contested even-year state legislative primaries held during the prior decade ranged from 16 to

19%. See Ballotpedia https://ballotpedia.org/Contested_state_legislative_primaries,_2022 Direct comparisons across

states are challenging because Ballotpedia calculates the number of contested primaries using the number of

primaries rather than the number of contested seats. Because New Jersey ballots ask voters to select up to two

candidates for the state Assembly, Ballotpedia treats both candidates as one primary. As a result, Ballotpedia does

not differentiate whether one or both seats are contested.

26

See Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP). 2023. “New Jersey.” New Brunswick, NJ: Center for

American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

https://cawp.rutgers.edu/facts/state-state-information/new-jersey (Accessed August 15, 2023)

16

through…And as the network of insiders in the state’s political system is already

overwhelmingly male, New Jersey remains trapped in a negative feedback loop that

privileges the emergence of male candidates and disadvantages women.”

27

IV. Impact of the county line on New Jersey Politics and Policy

The impact of the county line on New Jersey politics and policy extends well beyond the

candidate choices available to voters. Elected officials are aware of the importance of

the line for their reelection and the power of county party chairs to award the line. If an

elected official does not do as the county chair wants, they can lose the line and almost

surely lose the primary, ending or severely curtailing their political careers. In such an

environment, it is the county party chairs rather than the voters that elected officials

must please to be elected and to stay in office. This gives the county party chairs

substantial power to shape the state’s politics and public policy.

The chairs determine not only who is elected to the state legislature but, through their

ongoing influence over those state legislators, they also shape whom the legislators

elect Senate President and Assembly Speaker. These are very powerful positions that

decide which legislators serve as committee chairs and vice-chairs and which bills are

posted for consideration. The Senate President and Assembly Speaker also control

27

See Jean Sinzdak, In national politics, women are rising. In New Jersey, they’re treading water. NJ.Com,

December 8, 2020. https://www.nj.com/opinion/2020/12/in-national-politics-women-are-rising-in-new-jersey-theyre-

treading-water-opinion.html. As of August 2023, only 10 of New Jersey’s 42 county party chairs are women,

representing 28.4% of all chair positions (see Women in New Jersey Government 2023, Center for American Women

and Politics https://cawp.rutgers.edu/women-new-jersey-government).

17

well-funded political action committees they can use to support their own reelection as

well as that of other political candidates.

28

Governors, US Senators, and Congresspeople must also court the county party chairs

to receive the county line and win their respective primaries. For example former

Governor John Corzine and Governor Phil Murphy, both wealthy investment bankers,

made substantial donations to county party organizations to win the chairs’

endorsements.

29

By early October 2016, months before any formal county party

endorsement processes took place and more than seven months before the primary

election, Murphy had secured the support of many North Jersey Democratic county

party chairs and Jersey City Mayor Steve Fulop and Senate President Steve Sweeney,

Murphy’s main primary opponents, had both dropped out of the race.

30

Matthew Hale, a

political science professor at Seton Hall University, observed that this showed “how

important county chairs are, and how important backroom politics in New Jersey is.”

31

28

See Julia Sass Rubin, Can Progressives Change New Jersey? The American Prospect, June 26, 2020

https://prospect.org/politics/can-progressives-change-new-jersey/ “The leadership of the state Senate and General

Assembly is critical in New Jersey. No legislation can advance without the blessing of the Senate president and

Assembly Speaker. They decide committee assignments, determine committee leadership, and have final say as to

which committee a bill is referred, which bills are heard and voted on in committee, and which bills are voted on by

the full Senate and Assembly after clearing committee. They also control legislative leadership PACs that raise their

own contributions and help fund the election and re-election of their allies. Legislators who are in their good graces

receive committee chairmanships that provide them with additional resources to hire staff and enable them to

generate contributions from the groups that hope to move legislation through their committees. In contrast, legislators

who upset the leadership risk losing committee positions and the ability to advance legislation” (p.7).

29

See David Kocieniewski, G.O.P. Says Corzine's Cash Makes Him the New Boss, The New York Times, Feb. 18,

2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/18/nyregion/gop-says-corzines-cash-makes-him-the-new-boss.html and

Brent Johnson, Phil Murphy nabs another county endorsement in 2017 governor's race, NJ.Com, Oct. 18, 2016,

https://www.nj.com/politics/2016/10/phil_murphy_nabs_another_county_endorsement_in_201.html

30

See Herb Jackson and Charles Stile, Fulop won't run for governor, endorses Murphy, Asbury Park Pres,

September 28, 2016 https://www.app.com/story/news/politics/new-jersey/2016/09/28/fulop-murphy-nj-

governor/91219024/ and Matt Friedman, Sweeney out of NJ governor’s race, setting up Murphy as 2017 front-

runner, Politico, October 6, 2016, https://www.politico.com/states/new-jersey/story/2016/10/sweeney-will-not-

run-for-governor-in-2017-106135.

31

See Brent Johnson, Phil Murphy nabs another county endorsement in 2017 governor's race, NJ.Com, Oct. 18,

2016, https://www.nj.com/politics/2016/10/phil_murphy_nabs_another_county_endorsement_in_201.html

18

This system of backroom politics is part of a transactional political culture that hinders

transparency and accountability and feeds what former state senator William Schluter

termed soft corruption, “when people who hold public office figure out how to game the

system in ways that enrich them and their cronies without breaking any laws”

32

It also

has enabled political machines to maintain power in the state even as they have been

weakened in much of the rest of the country.

33

Eliminating the county line primary ballots would not resolve every problem with New

Jersey’s political system. However, it would dramatically rebalance the power away

from the county party chairs and toward the voters, opening opportunities for much

needed reforms.

32

See William E. Schluter, Soft corruption: How unethical conduct undermines good government and what to do

about it. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017, page 2.

33

See Julia Sass Rubin, Can progressives Change New Jersey? The American Prospect, June 26, 2020,

https://prospect.org/politics/can-progressives-change-new-jersey/ and David Kocieniewski, G.O.P. Says Corzine's

Cash Makes Him the New Boss, The New York Times, Feb. 18, 2005,

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/18/nyregion/gop-says-corzines-cash-makes-him-the-new-boss.html

Figure 2: Monmouth County 2020 Democratic primary ballot

Figure 3: Camden County 2018 Democratic primary ballot

Figure 4: Mercer County 2020 Democratic primary ballot

Figure 5: Atlantic County 2020 Democratic primary ballot

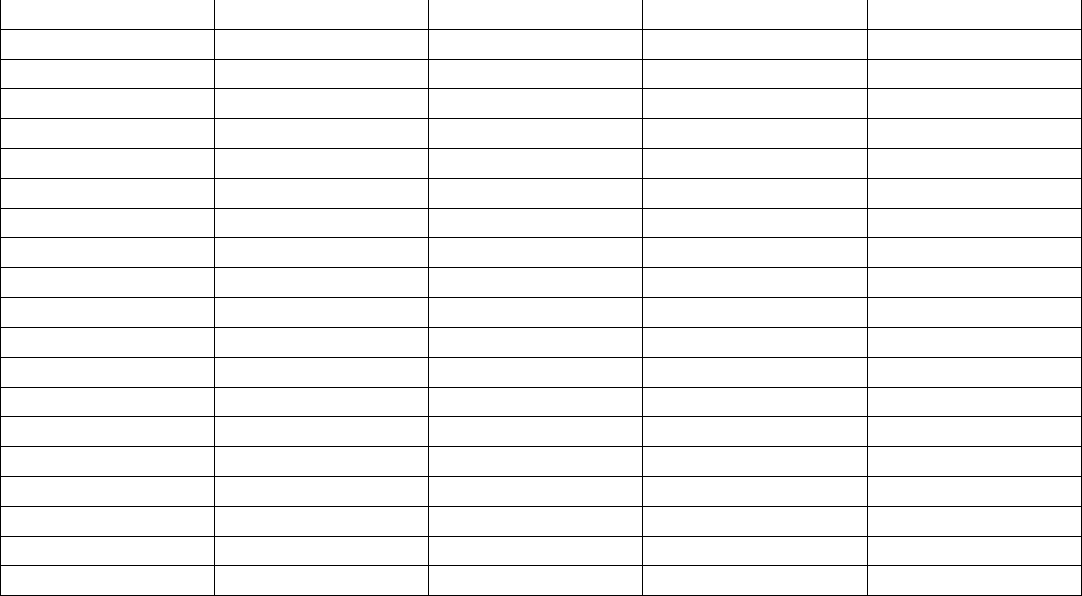

Figure 6: New Jersey incumbent legislators who lost primary while on county line in all counties, 2003-23

Year

Incumbent

Party

Chamber

District

Number

of

Counties

in

District

County

Had county

line

Won County

1

2003

Joseph V. Doria

D

Assembly

31

1

Hudson

Yes

No

2

2003

Elba Perez-

Cinciarelli

D

Assembly

31

1

Hudson

Yes

No

3

2009

Marcia A. Karrow

R

Senate

23

2

Hunterdon

Yes

No

Warren

No (1)

No

(1) Warren County did not use a county line ballot in 2009.

(2) 2003 to 2019 data courtesy of Francisco Diez analysis for CWA.

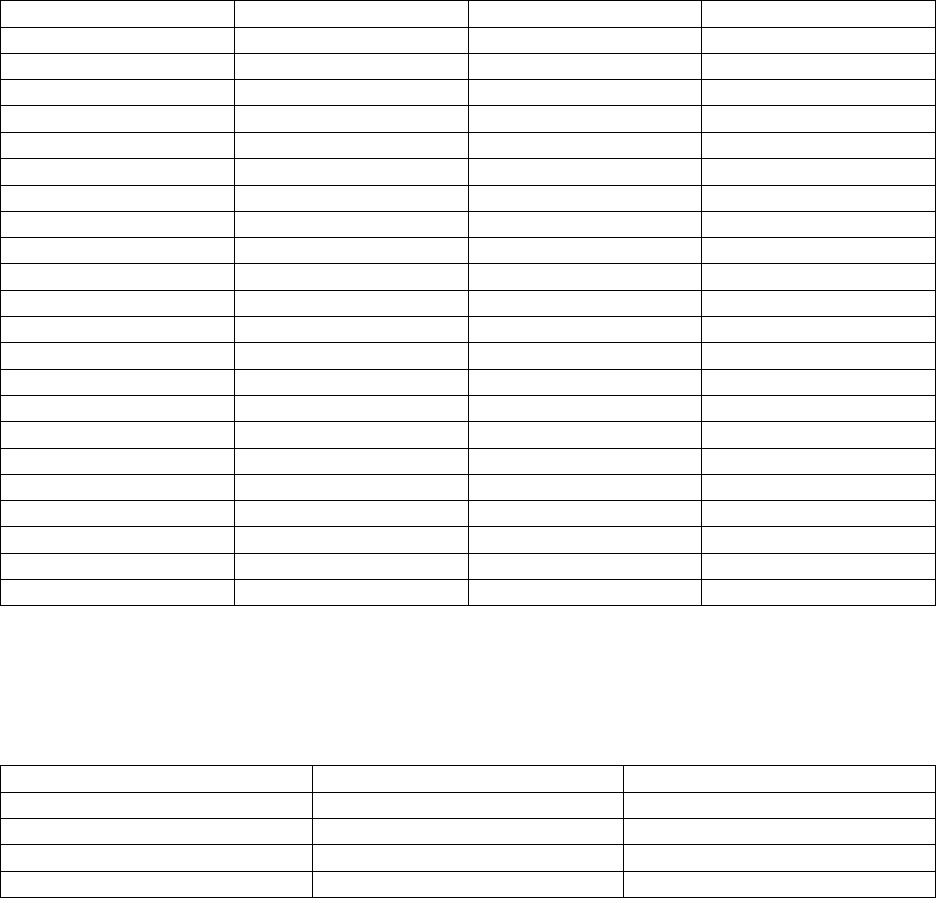

Figure 7: New Jersey incumbent legislators who won primary after losing at least one county line, 2003-23

Year

Incumbent

Party

Chamber

District

Number

of

Counties

in

District

Won

District?

County

Had county

line

Won County

1

2003

Nia H. Gill

D

34

Senate

2

Yes

Essex

No

Yes

Passaic

No

Yes

2

2007

Ronald L. Rice

D

28

Senate

1

Yes

Essex

No

Yes

3

2007

David C. Russo

R

40

Assembly

3

Yes

Bergen

No

Yes

Essex

Yes

Yes

Passaic

Yes

Yes

4

2017

Samuel D.

Thompson

R

12

Senate

4

Yes

Burlington

No

Yes

Middlesex

No

No

Monmouth

Yes

Yes

Ocean

Yes

Yes

5

2017

Ronald S. Dancer

R

12

Assembly

4

Yes

Burlington

No

Yes

Middlesex

No

Yes

Monmouth

Yes

Yes

Ocean

Yes

Yes

6

2017

Robert D. Clifton

R

12

Assembly

4

Yes

Burlington

No

Yes

Middlesex

No

No

Monmouth

Yes

Yes

Ocean

Yes

Yes

7

2021

Jay Webber

R

26

Assembly

3

Yes

Essex

No (1)

Yes

Morris

Yes

Yes

Passaic

No (1)

Yes

8

2021

Robert Auth

R

39

Assembly

2

Yes

Bergen

Yes

Yes

Passaic

No

No

9

2021

Deanne DeFuccio

R

39

Assembly

2

Yes

Bergen

Yes

Yes

Passaic

No

No

(1) Voters were instructed to vote for two candidates for the Assembly, but only one Assembly candidate (BettyLou DeCroce) appeared on the Essex and Passaic county

lines.

(2) 2003 to 2019 data courtesy of Francisco Diez analysis for CWA

Figure 8: New Jersey incumbent legislators who lost primary after losing at least one county line, 2003-23

Year

Incumbent

Party

Chamber

District

Number

of

Counties

in

District

Won

District?

County

Had county

line

Won County

1

2003

Arline Friscia

D

19

Assembly

1

No

Middlesex

No

No

2

2005

Joseph Azzolina

R

13

Assembly

2

No

Middlesex

Yes

Yes

Monmouth

No

No

3

2005

Anthony Chiappone

D

31

Assembly

1

No

Hudson

No

No

4

2007

Craig A. Stanley

D

28

Assembly

1

No

Essex

No

No

5

2007

Oadline D. Truitt

D

28

Assembly

1

No

Essex

No

No

6

2007

Wilfredo Caraballo

D

29

Assembly

2

No

Essex

No

No

Union

No

No

7

2019

Joe Howarth

R

8

Assembly

3

No

Atlantic

No

No

Burlington

No

No

Camden

No

No

8

2021

Serena Dimaso

R

13

Assembly

1

No

Monmouth

No

No

9

2021

BettyLou DeCroce

R

26

Assembly

3

No

Essex

Yes

Yes

Morris

No

No

Passaic

Yes

Yes

10

2023

Nia H. Gill (1)

D

27

Senate

2

No

Essex

No

No

Passaic

No

No

(1) From January 2002 to January 2024, Senator Nia Gill represented the 34

th

legislative district in the New Jersey State Senate. As of June 2023, the 34

th

district included

parts of Essex and Passaic Counties. Following the 2022 redistricting, Senator Gill’s hometown of Montclair was moved into the 27

th

legislative district. Prior to

redistricting, the 27

th

legislative district included parts of Essex and Morris Counties. After redistricting, the 27

th

district included parts of Essex and Passaic Counties. In

the 2023 primary, Gill ran against another incumbent, Senator Richard Codey, who had represented the 27

th

legislative district prior to redistricting.

(2) 2003 to 2019 data courtesy of Francisco Diez analysis for CWA

Figure 9: New Jersey 3

rd

Congressional District 2020 Republican primary

Gibbs

56

Gibbs

22

Richter

44

Richter

78

Gibbs has county line Richter has county line

Figure 10: Impact of county line, US House & Senate, 2002 – 2022

Year

Candidate

Margin

Contest/Party

Incumbent

2002

Allen

+31

Senate/Republican

No

2002

Forester

+44

Senate/Republican

No

2002

Matheussen

+31

Senate/Republican

No

2006

Sires

+47

CD13/Democrat

No

2006

Vas

+47

CD13/Democrat

No

2008

Kelly

+34

CD3/Republican

No

2008

Myers

+46

CD3/Republican

No

2008

Lance

+42

CD7/Republican

No

2008

Hatfield

+39

CD7/Republican

No

2008

Whitman

+27

CD7/Republican

No

2008

Pennacchio

+27

Senate/Republican

No

2008

Sabrin

+13

Senate/Republican

No

2008

Zimmer

+27

Senate/Republican

No

2008

Andrews

+36

Senate/Democrat

No

2008

Lautenberg

+33

Senate/Democrat

Yes

2012

Shober

+72

CD 2/Democrat

No

2012

Hughes

+79

CD 2/Democrat

No

2012

Little

+24

CD 6/Republican

No

2012

Cullari

+24

CD 6/Republican

No

2012

Pascrell

+64

CD 9/Democrat

Yes, redistricted

2012

Rothman

+64

CD 9/Democrat

Yes, redistricted

2012

Payne

+22

CD 10/Democrat

No

2012

Gill

+36

CD 10/Democrat

No

2014

Watson Coleman

+57

CD 12/Democrat

No

2014

Greenstein

+48

CD 12/Democrat

No

2014

Chivukula

+52

CD 12/Democrat

No

2014

Goldberg

+27

Senate/Republican

No

2014

Pezzullo

+33

Senate/Republican

No

2014

Sabrin

+15

Senate/Republican

No

2016

Keady

+58

CD 3/Democrat

No

2016

Lavergne

+58

CD 3/Democrat

No

2018

Singh

+37

CD 2/Republican

No

2018

Fiocchi

+34

CD 2/Republican

No

2020

Kennedy

+25

CD 2/Democrat

No

2020

Harrison

+20

CD 2/Democrat

No

2020

Schmid

+40

CD 4/Democrat

No

2020

Gibbs

+35

CD 3/Democrat

No

2020

Richter

+35

CD 3/Democrat

No

2020

Mehta

+41

Senate/Republican

No

2020

Singh

+50

Senate/Republican

No

2022

Pallotta

+13

CD 5/Republican

No

2022

De Gregorio

+17

CD 5/Republican

No

2022

Tayfun

+33

CD 11/Republican

No

2022

DeGroot

+38

CD 11/Republican

No

Figure 11:

2008 Democratic primary for US Senate percentage of total vote by candidate**

County

Frank Lautenberg

Robert Andrews

Donald Cresitellow

Atlantic

45%

50%

4%

Bergen

79%

17%

5%

Burlington

42%

52%

6%

Camden

16%

80%

3%

Cape May

45%

50%

5%

Cumberland

46%

47%

6%

Essex

76%

21%

3%

Gloucester

17%

80%

3%

Hudson

75%

22%

4%

Hunterdon

59%

34%

8%

Mercer

74%

22%

4%

Middlesex

62%

29%

9%

Monmouth

66%

22%

11%

Morris

65%

24%

11%

Ocean

58%

33%

9%

Passaic

79%

14%

7%

Salem*

32%

60%

9%

Somerset

65%

25%

10%

Sussex*

53%

30%

17%

Union

68%

28%

5%

Warren*

47%

31%

22%

*Salem, Sussex and Warren counties did not use a county line ballot for the 2008 Democratic

primary

2012 Democratic primary for CD 9 percentage of total vote by candidate**

County

Bill Pascrell

Steve Rothman

Bergen

27%

73%

Hudson

26%

74%

Passaic

90%

10%

**(Vote % of candidate on county line shown in bold)

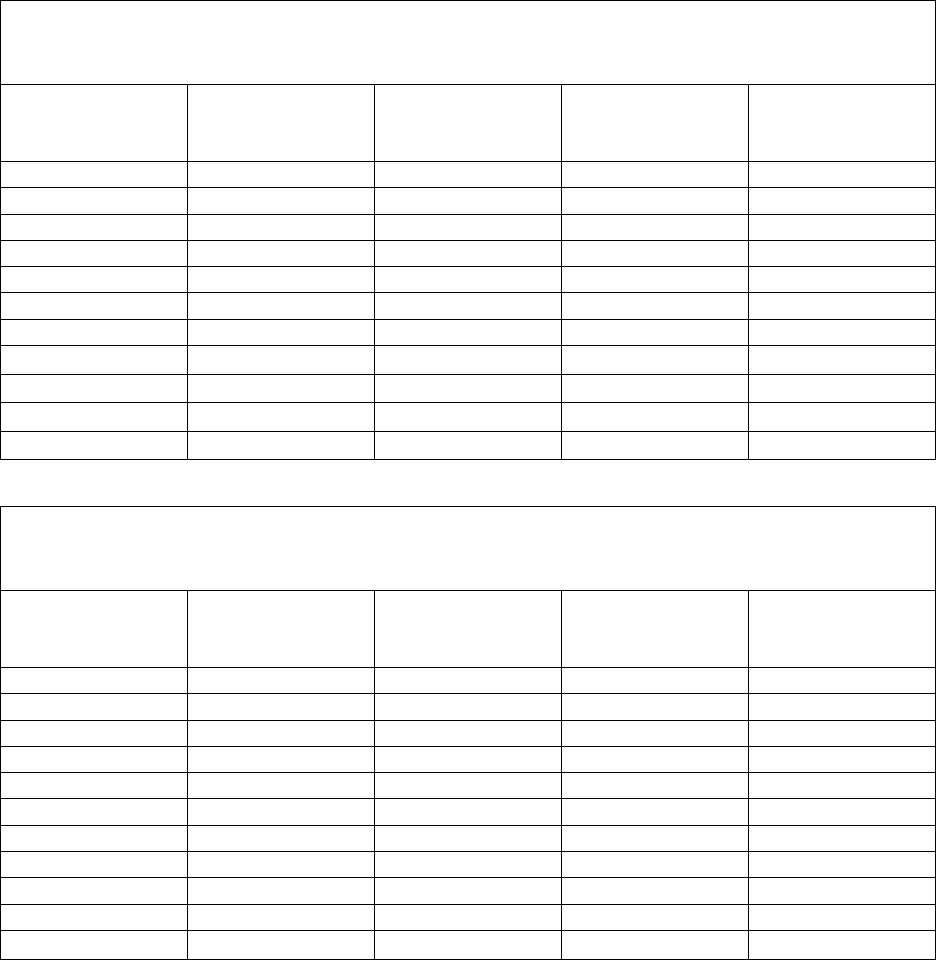

Figure 12: Contested New Jersey legislative primaries, 2021 and 2023

2021

Assembly

District

Party

Number of

Seats

Challenged

Senate District

Party

10

Rep

2

2

Rep

12

Rep

1

16

Rep

13

Rep

1

18

Dem

16

Dem

1

20

Dem

18

Dem

2

24

Rep

20

Dem

2

28

Dem

21

Rep

1

37

Dem

26

Rep

2

30

Rep

1

37

Dem

2

39

Rep

2

2023

Assembly

District

Party

Number of

Seats

Challenged

Senate District

Party

3

Rep

1

3

Rep

3

Dem

2

3

Dem

4

Rep

2

4

Rep

12

Rep

1

18

Dem

14

Rep

1

19

Dem

20

Dem

2

20

Dem

24

Rep

2

23

Dem

26

Rep

2

26

Rep

27

Dem

2

27

Dem

28

Dem

1

31

Dem

31

Dem

1