National behaviour

survey

Findings from Academic Year 2022/23

April 2024

1

Contents

Acknowledgements 3

Table of Figures 4

List of tables 6

Executive Summary 7

Findings 1: School behaviour culture and policy 7

Findings 2: School environment and experience 8

Findings 3: Prevalence and impact of misbehaviour 8

Findings 4: Responding to behaviour 9

Introduction 11

The objective of the NBS 11

Topics covered 11

Methodology 13

School and College Panel 13

Parent, Pupil and Learner Panel 15

Interpreting the findings 17

Data tables 18

Findings 1: School behaviour culture and policy 19

Understanding of behaviour policy 19

Ease of following rules 23

Consistency of application of behaviour policy 26

Visible leadership 27

Approach to managing behaviour 27

Use of data and pupil voice 30

Working with parents and pupils 32

Findings 2: School environment and experience 37

School environment and relationships 37

School belonging 44

School connectedness 46

Motivation to learn 47

2

Wellbeing 48

Findings 3: Frequency and impact of misbehaviour 51

Overall perception of pupil behaviour at school 52

Frequency and impact of misbehaviour 54

Bullying 60

Findings 4: Responding to behaviour 63

Confidence in managing pupil misbehaviour 63

Support and training 66

Interventions and targeted support 69

Teaching assistants 73

Annex 75

Methodology 75

3

Acknowledgements

This report brings together both new data and previously published data. Some drafting

in this report replicates previous publications and internal reports authored by both IFF

Research and Verian. The following authors are gratefully acknowledged for their

contribution to this report.

IFF Research: James Taylor, Aminul Hassan, Jacquie Collins.

Verian: Sarah Hingley, Emily Gaskell, John Morris, Charlotte Man, Eve Milne, Alex

Thornton, Sarah Vasic.

4

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Extent to which school leaders and teachers agree that there is a shared

understanding amongst staff of what good behaviour means (May 2023) ....................... 20

Figure 2: How well pupils thought their school explained the rules on behaviour at the

start of the academic year (May 2023 and June 2022) .................................................... 21

Figure 3: Extent to which school leaders and teachers agree that pupils understand what

will happen if they don’t meet the expected standards of pupil behaviour (May 2023) .... 22

Figure 4: Extent to which pupils agree that they understand what will happen if they don't

meet the expected standards of pupil behaviour (May 2023 and June 2022) .................. 23

Figure 5: How easy school leaders and teachers think it is for pupils to follow (in practice)

school rules on pupil behaviour (May 2023) .................................................................... 24

Figure 6: How easy pupils find it to follow school rules on behaviour (May 2023) ........... 25

Figure 7: Extent to which different activities or interventions form part of the school’s

approach to encourage positive pupil behaviour and minimise misbehaviour (May 2023)

......................................................................................................................................... 28

Figure 8: What pupils report schools do to recognise and reward good behaviour (May

2023) ............................................................................................................................... 30

Figure 9: Pupil confidence that their school will listen to or act on behaviour feedback

(May 2023) ....................................................................................................................... 32

Figure 10: School leader and teacher confidence in communicating with parents about

their child's behaviour (May 2023) ................................................................................... 33

Figure 11: Extent to which school leaders and teachers agree that parents are supportive

of the school’s behaviour rules (May 2023 and June 2022) ............................................. 35

Figure 12: Extent to which pupils and parents agree that they are supportive of the

school’s behaviour rules (May 2023 and June 2022) ....................................................... 36

Figure 13: Frequency of positive behaviour culture experiences in the past week (School

Leaders and Teachers, May 2023) .................................................................................. 39

Figure 14: Frequency of positive behaviour culture experiences in the past week (Pupils,

May 2023) ........................................................................................................................ 41

Figure 15: Frequency of positive behaviour culture experiences in the past week across

survey waves ................................................................................................................... 43

5

Figure 16: Frequency of feelings of enjoyment, safety and belonging at school in the past

week across survey waves (Pupils’ views) ...................................................................... 46

Figure 17: Pupils’ mean score for school connectedness (May 2023) ............................. 47

Figure 18: Ratings of pupil behaviour across survey waves ............................................ 53

Figure 19: Extent to which teachers felt misbehaviour stopped or interrupted teaching or

learning in the past week (May 2023) .............................................................................. 54

Figure 20: Extent to which pupil misbehaviour has had a negative impact on health and

wellbeing across survey waves (Leaders and teachers) .................................................. 60

Figure 21: School leader and teacher confidence in managing misbehaviour in school

across survey waves ....................................................................................................... 64

Figure 22: School leader and teacher confidence in addressing different types of bullying

at their school (May 2023) ............................................................................................... 66

Figure 23: Extent to which school teachers agree that the support they receive from

senior leaders helps them to effectively manage pupils with persistently disruptive

behaviour (May 2023) ...................................................................................................... 68

Figure 24: Interventions, if any, that the school provides where necessary to manage

behaviour (May 2023) ...................................................................................................... 71

Figure 25: School leaders' and teachers' views on timeliness of external specialist

support services (May 2023) ............................................................................................ 72

Figure 26: School leader and teacher views on the importance of teaching assistants in

managing and supporting pupil behaviour (May 2023) .................................................... 74

6

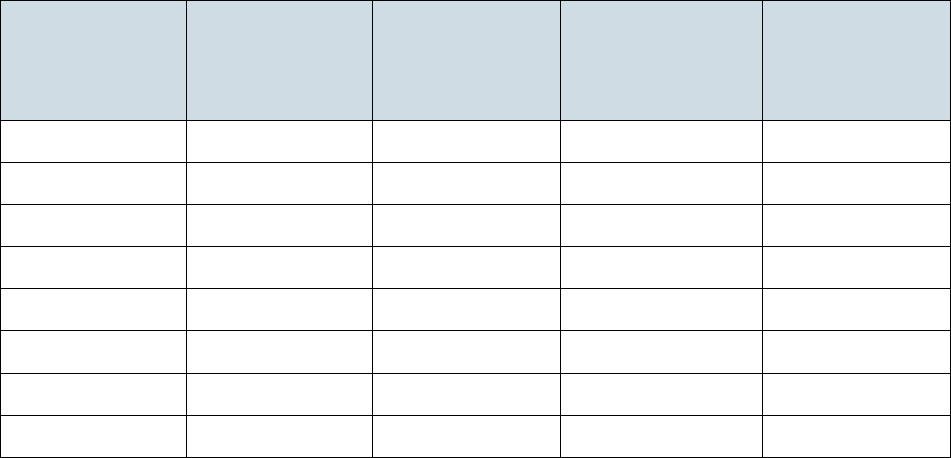

List of tables

Table 1: SCP survey waves achieved sample sizes ........................................................ 14

Table 2: SCP survey waves topic coverage and fieldwork dates ..................................... 14

Table 3: PPLP survey waves achieved sample sizes ...................................................... 16

Table 4: PPLP survey waves topic coverage and fieldwork dates ................................... 17

Table 5: Pupil wellbeing measures (May 2023) ............................................................... 49

Table 6: Frequency of types of pupil misbehaviour in the past week (secondary school

teacher views, May 2023) ................................................................................................ 58

Table 7: Frequency of types of pupil misbehaviour in the past week (pupil views, May

2023) ............................................................................................................................... 58

Table 8: Pupils' experience of being a victim of bullying in the past 12 months (May 2023)

......................................................................................................................................... 61

Table 9: Sampling error in the SCP NBS May 2023 wave ............................................... 76

7

Executive Summary

This report presents the findings from the National Behaviour Survey (NBS) Academic

Year 2022/23. The NBS is designed to provide the Department for Education with termly

survey data related to pupil behaviour in mainstream primary and secondary schools in

England collected from multiple respondent groups (school leaders, teachers, pupils and

parents/carers).

The NBS was delivered via multiple survey waves conducted through the Department for

Education’s omnibus panel surveys (the School and College Panel

1

(SCP) and the

Parent, Pupil and Learner Panel

2

(PPLP)) in November 2022, March 2023, May 2023

and June 2023.

The NBS survey has questions covering a range of topics related to pupil behaviour in

schools. This report is structured in line with these topics, with chapters containing

findings related to:

• School behaviour culture and policy

• School environment and experience

• Frequency and impact of misbehaviour

• Responding to behaviour

Key findings are given below. As in 2021/22, there was divergence between school

leaders, teachers and pupils on their responses to several survey questions relating to

school environment and misbehaviour; school leaders tended to give more positive

responses than teachers, who in turn tended to give more positive responses than pupils.

All survey findings have been compared with 2021/22 (June 2022 timepoint at a

minimum. Where findings have been shown to be statistically significantly different to

previous survey waves, this is commented upon in the text.

Findings 1: School behaviour culture and policy

Key findings include:

• In May 2023, the majority (81%) of school leaders and teachers agreed that there

was a shared understanding amongst staff in their school of what “good

behaviour” means.

1

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-and-college-panel-omnibus-surveys-for-2022-to-2023

2

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/parent-pupil-and-learner-panel-omnibus-surveys-for-2022-to-

2023

8

• In May 2023, the majority of pupils (85%) agreed that they knew how their school

expected them to behave. This is a decrease from 91% in June 2022.

• Almost all school leaders and teachers (98%) reported that rules on behaviour

were applied fairly to pupils at least some of the time (May 2023). However, only

38% of school leaders and 19% of teachers reported this happened ‘all of the

time’. Overall, 89% of pupils reported rules were applied fairly to all pupils at least

some of the time, with 18% reporting this happened ‘all of the time’.

• Overall, 60% of school leaders and teachers agreed that parents are supportive of

the school’s behaviour rules. School leaders were more likely than teachers to

agree parents are supportive of the school's behaviour rules (71% vs 58%).

• Compared with June 2022, the proportion of school leaders and teachers that

disagreed that parents were generally supportive of the school’s behaviour rules

increased from 15% in June 2022 to 20% in May 2023.

Findings 2: School environment and experience

Key findings include:

• In May 2023, 84% of school leaders reported that their school had been calm and

orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ in the past week (versus 59% of teachers). For

pupils, 54% reported that their school had been calm and orderly ‘every day’ or

‘most days’ in the past week. Comparing across survey waves, for school leaders

and teachers this is a decrease from 92% and 70% respectively in June 2022.

• In May 2023, 11% of pupils said that they had enjoyed coming to school ‘every

day’ in the past week, whilst 17% said that they had ‘never’ enjoyed coming to

school in the past week. Comparing across survey waves, the proportion of pupils

reporting that they had enjoyed coming to school ‘every day’ has decreased from

15% in June 2022.

• When asked how often they felt safe at school, 39% of all pupils said that they had

felt safe at school ‘every day’ in the past week in May 2023.

• In May 2023, 71% of pupils felt they were motivated to learn, with 17% who said

that they were ‘very motivated’ and 54% who said they were ‘fairly motivated’.

Findings 3: Prevalence and impact of misbehaviour

Key findings include:

• In May 2023, 82% of school leaders reported that pupil behaviour was either ‘very

good’ or ‘good’ in the past week (versus 55% of teachers). For pupils, 43% said

9

that behaviour had been ‘very good’ or ‘good’ in the past week. Comparing across

survey waves, this is a decrease for all groups compared to June 2022.

• In May 2023, 76% of teachers reported that misbehaviour stopped or interrupted

teaching in at least some lessons in the past week. Comparing across survey

waves, this is an increase from 64% in June 2022.

• On average, in May 2023, teachers reported that for every 30 minutes of lesson

time, 7 minutes were lost due to misbehaviour. This is an increase of 1.5 minutes

from March 2023, when teachers reported that 5.5 minutes were lost per 30

minutes, but is similar to June 2022 when 6.3 minutes were reported to be lost.

• In May 2023, 58% of teachers reported that between 1 to 10 minutes of time were

lost due to misbehaviour per 30 minutes of teaching time. Comparing across

survey waves, the proportion of teachers reporting that more than 10 minutes of

teaching time was lost due to pupil misbehaviour per 30 minutes of lesson time

increased from 10% in June 2022 and March 2023 to 25% in May 2023.

• In May 2023, 73% of school leaders and teachers reported that pupil misbehaviour

had had a negative impact on their health and wellbeing to any extent in the past

week: of these, 12% reported it ‘to a great extent’, 31% ‘to some extent’, and 30%

‘to a small extent’.

• Overall, 22% of pupils said that they had been a victim of bullying for any reason

in the past 12 months. Among pupils who reported that they had been bullied, the

most common perceived reason reported for being bullied was the way they

looked (40% for those bullied in person; 32% for those bullied online).

Findings 4: Responding to behaviour

Key findings include:

• In May 2023, 92% of school leaders and teachers felt at least fairly confident in

personally managing misbehaviour in their school, with 39% feeling ‘very

confident’. School leaders were more likely than teachers to report being ‘very

confident’ in managing misbehaviour (66% vs. 35%). Compared with March 2023,

the proportion of school leaders and teachers reporting being ‘very confident’ has

decreased (from 80% to 66% for leaders; from 47% to 35% for teachers).

• Just under a third of school teachers (31%) and just over a fifth of school leaders

(22%) felt they could not personally access training and development support for

behaviour management relevant to their experience and needs.

• In May 2023, the interventions most commonly used by schools to manage

behaviour were referrals to specialist services (89%) and targeted interventions

such as mentoring and social/emotional learning (88%). These were followed by

10

removal from the classroom as a restorative measure (80%) and by the

involvement of specialised pastoral support staff (76%).

• In May 2023, 18% of school leaders and teachers reported that any external

specialist support provided to manage behaviour was timely (3% ‘very timely’ and

16% ‘fairly timely’) while 52% reported it was not timely (26% ‘not very timely’ and

27% ‘not timely at all’).

11

Introduction

This report presents findings from the National Behaviour Survey (NBS) Academic Year

2022/23. The NBS was delivered via the Department for Education’s omnibus surveys:

the School and College Panel (SCP) and the Parent, Pupil and Learner Panel (PPLP).

This report presents findings from multiple survey waves (7 in total) conducted in

November 2022, March 2023, May 2023 and June 2023.

3

The objective of the NBS

Creating a school culture with high expectations of behaviour is a priority for the

Government. Establishing calm, safe and supportive environments conducive to teaching

benefits both school staff and pupils. No pupil should miss out on education because

they feel unsafe, miss out on learning because their lesson is disrupted, or fall behind

because their needs are not identified and supported.

The NBS is designed to provide the Department for Education (DfE) with a tool to monitor

pupil behaviour in mainstream primary and secondary schools, allowing the department

and wider stakeholders to track perceptions of behaviour over time in a consistent

manner. The termly survey data is collected from multiple respondent groups (school

leaders, teachers, pupils and parents

4

) to allow for triangulation of views and is weighted

to be nationally representative of teachers, schools and pupils (for England).

5

Understanding concerns related to pupil behaviour and engagement is a priority for DfE.

The regular survey data provides evidence to build on our programme of work to support

school leaders and teachers in managing pupil behaviour and to create a positive culture,

including delivery of the £10 million Behaviour Hubs programme.

Topics covered

The NBS survey has questions covering a range of topics related to pupil behaviour in

schools. This report is structured in line with these topics, with chapters containing

findings related to:

3

Data from previous survey waves in November 2022, March 2023, and June 2023 have previously been

published in the omnibus panels survey reports: School and college panel: omnibus surveys for 2022 to

2023 - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) and Parent, pupil and learner panel omnibus surveys for 2022 to 2023 -

GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

4

Where the report uses the term ‘parents’ this is inclusive of parents and carers with parental

responsibility.

5

Leader data are weighted to either schools or teachers depending on the question asked and the parent

data are weighted to pupils (see Methodology section).

12

• School behaviour culture and policy

• School environment and experience

• Frequency and impact of misbehaviour

• Responding to behaviour

13

Methodology

The National Behaviour Survey for the Academic Year 2022/23 was delivered via the

Department for Education’s omnibus panels, the School and College Panel (SCP) and

the Parent, Pupil and Learner Panel (PPLP), in November 2022, March 2023, May 2023

and June 2023. Technical reports have been published for both the SCP

6

and PPLP

7

where further detail on methodology can be found.

The SCP is a survey panel of mainstream school leaders and teachers and the PPLP is a

survey panel of parents, pupils and learners. Both panels have been designed to provide

rapid feedback to the Department for Education on topical educational issues.

School and College Panel

The SCP consists of a group of school leaders

8

and teachers that have agreed to

participate in short regular research surveys on topical education issues. The panellists

for the survey work in the 2022/23 academic year were comprised of existing panellists

that had taken part in the 2021/22 academic year, plus new panellists recruited in

September 2022. All school leaders and teachers were recruited from School Workforce

Census data provided by the Department for Education.

Three SCP survey waves were used to deliver the NBS – 1 in November 2022, 1 in

March 2023 and 1 in May 2023.

The surveys were administered online, with respondents receiving an email invite and

two reminder emails, along with a reminder SMS text. Achieved sample sizes are given

in Table 1.

6

School and College Panel Technical Report 2022 to 2023 academic year (publishing.service.gov.uk)

7

Parent, Pupil and Learner Panel Technical Report (publishing.service.gov.uk)

8

The school leader types for inclusion in the survey were: headteacher, assistant headteacher and deputy

headteacher.

14

Table 1: SCP survey waves achieved sample sizes

Primary

school

Leaders

Secondary

school

Leaders

Total

school

Leaders

Primary

school

Teachers

Secondary

school

Teachers

Total

school

Teachers

SCP

November

2022

wave

a

429

288

717

655

693

1,348

SCP

March

b

2023 wave

311 218 529 1,073 1,157 2,230

SCP NBS

May 2023

wave

c

447 333 780 668 810 1,478

a

Data is for Panel A school leaders and teachers. Whilst college leaders and teachers were included in the

full SCP Nov 2022 wave, the NBS questions in this report were asked of Panel A school leaders and

teachers only.

b

Data is for Panel A school leaders. Whilst college leaders and teachers were included in the full SCP

March 2023 wave, the NBS questions in this report were asked of Panel A school leaders only and all

school teachers.

c

Only leaders and teachers from primary and secondary schools were invited to take part in the NBS May

2023 survey wave.

The surveys’ topic coverage was either specific to behaviour or included a range of topics

of relevance to the wider department. Topic coverage and fieldwork dates are given in

Table 2.

Table 2: SCP survey waves topic coverage and fieldwork dates

Survey topics Fieldwork dates

SCP November 2022

wave

Variety of topics, including

behaviour

7

th

– 14

th

November 2022

SCP March 2023 wave

Variety of topics, including

behaviour

20

th

- 28

th

March 2023

SCP NBS May 2023

wave

Behaviour only 22

nd

- 31

st

May 2023

15

SCP weighting

Two types of weighting were applied to school leader data, depending on whether

questions were asking for school-level or individual-level answers from these

respondents. All school teacher data was weighted to individual-level.

School-level weighting:

• At the analysis stage, for questions reported at the school-level, school leaders’

data was grossed up to the overall population of schools. This process corrects for

the over-sampling of secondary schools (relative to the proportion of the popula-

tion that they represent) so that the findings are representative of all (in scope)

state-funded schools.

• The population data for weighting was drawn from Get Information about Schools

(GIAS).

9

Individual-level weighting:

• For the analysis on an individual rather than school-level, the responses from

school leaders and classroom teachers were combined and weighted together to

the overall population of school leaders and teachers.

• The population data for the individual weighting was taken from the Schools Work-

force Census based on November 2020 data (the most recent available at the

time of fieldwork and analysis).

Parent, Pupil and Learner Panel

The PPLP consisted of:

• pupils in years 7-11 in the 2022/23 academic year (sampled from the National

Pupil Database (NPD) using 2021/22 data).

• pupils and learners in years 12-13 in the 2022/23 academic year (sampled from

the NPD and Individualised Learner Record (ILR) using 2021/22 data).

• parents of pupils in years 1-11 in the 2022/23 academic year (sampled from the

NPD using 2021/22 data).

9

Get Information about Schools - GOV.UK (get-information-schools.service.gov.uk) GIAS is the

Department for Education’s register for several educational organisation types.

16

Four PPLP survey waves were used to deliver the NBS – 1 in November 2022, 1 in

March 2023, 1 in May 2023 and 1 in June 2023.

Table 3 shows the total number of respondents participating in the PPLP survey waves.

The NBS reporting only covers pupils and parents from primary and secondary schools;

colleges are not included in the reporting.

Parents and pupils on the panel were invited to take part in a 10-minute online survey by

email and SMS. A reminder email was sent on day three and five of fieldwork.

Table 3: PPLP survey waves achieved sample sizes

Secondary

Pupils (years

7-11)

Primary

Parents (years

1-6)

Secondary

Parents (years

7-11)

Total Parents

(years 1-11)

PPLP

November

2022 wave

2,245 1,468 1,508 2,976

PPLP March

2023 wave

a

2,978 2,382 2,186 4,568

PPLP NBS

May 2023

wave

b

2,521 NA NA NA

PPLP June

2023 wave

NA 1,678 1,616 3,294

a

Although year 12 and 13 secondary pupils and college learners were included in the full PPLP

March/April 2023 wave, the NBS questions in this report were asked of year 7-11 pupils only.

b

The PPLP NBS May 2023 wave included years 12 and 13. If including just years 7-11, number of

secondary pupils in this wave is 2,126.

The surveys’ topic coverage was either specific to behaviour or included a range of topics

of relevance to the wider department. Topic coverage and fieldwork dates are given in

Table 4 below.

17

Table 4: PPLP survey waves topic coverage and fieldwork dates

Topics Fieldwork dates

PPLP Nov 2022

wave

Variety of topics, including

behaviour

9

th

- 14

th

November 2022

PPLP March

2023 wave

Variety of topics, including

behaviour

22

nd

- 27

th

March 2023

PPLP NBS May

2023 wave

Behaviour only

17

th

– 22

nd

May 2023

PPLP June

2023 wave

Variety of topics, including

behaviour

21

st

– 27

th

June 2023

PPLP weighting

Only a subset of the original panel of parents and secondary aged pupils and learners

took part in each subsequent wave of the survey; however, at each wave, results were

weighted to be representative of pupils in mainstream state schools in England.

Weighting was based on characteristics of the pupils only, as the NPD does not hold

information about parents. As such, the parent survey responses are weighted based on

the characteristics of their child that was sampled from the NPD.

Interpreting the findings

Where school leader responses are weighted to school-level, these findings are reported

as a percentage of schools. Where school leader data is weighted to individual-level,

these findings are reported as a percentage of school leaders.

For all questions, comparisons have been made between the NBS May 2023 and the

NBS June 2022 waves (the last time that all questions were asked).

10

For survey

questions that are asked each term, NBS May 2023 data may additionally be compared

with the last time the question was asked (March 2023 or November 2022 waves).

Differences between respondent sub-groups and between waves are only commented on

in the text however if they are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level i.e.

statistically we can be 95% confident that the differences are ‘real’ differences (and not a

result of the fact that the findings are based on samples of the respondent groups rather

10

The NBS June 2022 surveys took place between 13th June and 4

th

July 2022, at a slightly later point in

the academic year to the NBS May 2023 survey.

18

than a census of all respondent groups). Statistically significant differences between

survey waves have been noted in the report text.

Due to rounding to the nearest whole number, percentages may not total to exactly 100%

or precisely reflect statistics provided in the data tables.

Where averages are referred to in the text, this is the mean average, unless otherwise

stated.

Data tables

An accompanying set of data tables have been published alongside this report. They

include statistical testing, total responses and more detailed responses by key subgroups

by each data set (so contain further statistically significant differences between key

subgroups that are not commented upon in this report, which covers headline findings

only). For further guidance on how to interpret these tables, please see the covering

pages of the data tables.

19

Findings 1: School behaviour culture and policy

Understanding of behaviour policy

School leaders, teachers and pupils were asked a set of questions to explore their

perception of their school’s behaviour culture and understanding of their school’s

behaviour policy. These questions were asked in May 2023.

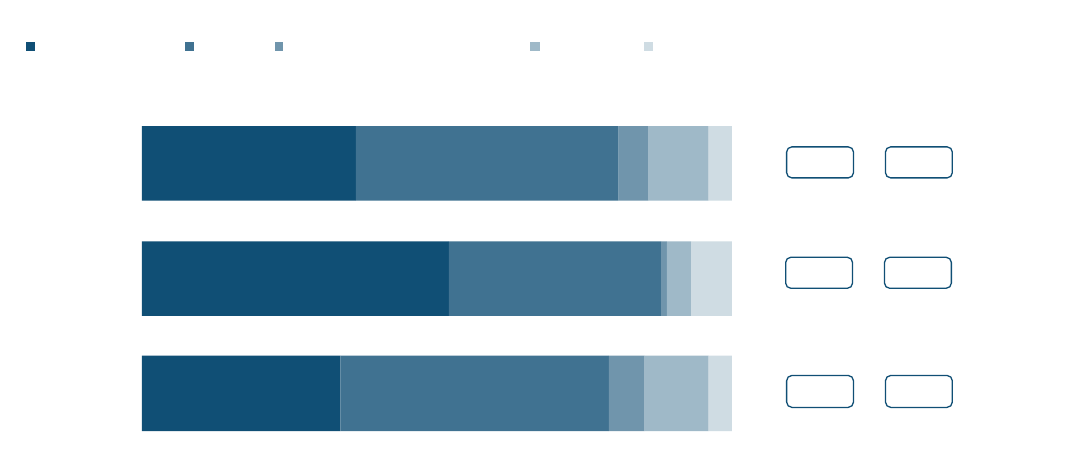

Shared understanding of what good behaviour means

School leaders and teachers were asked about the shared understanding amongst staff

of what was meant by “good behaviour”. The majority (81%) of school leaders and

teachers agreed that there was a shared understanding amongst staff in their school of

what “good behaviour” means. As shown in Figure 1, school leaders were more likely

than teachers to agree there is this shared understanding (88% vs. 79% respectively).

Primary school teachers were more likely than secondary school teachers to agree that

there is a shared understanding amongst staff of what “good behaviour” means (84% vs.

75%).

Key findings:

• In May 2023, the majority (81%) of school leaders and teachers agreed that

there was a shared understanding amongst staff in their school of what “good

behaviour” means.

• In May 2023, the majority of pupils (85%) agreed that they knew how their

school expected them to behave. This is a decrease from 91% in June 2022.

• Almost all school leaders and teachers (98%) reported that rules on behaviour

were applied fairly to pupils at least some of the time (May 2023). However,

only 38% of school leaders and 19% of teachers reported this happened ‘all of

the time’. Overall, 89% of pupils reported rules were applied fairly to all pupils at

least some of the time, with 18% reporting this happened ‘all of the time’.

• Overall, 60% of school leaders and teachers agreed that parents are supportive

of the school’s behaviour rules. School leaders were more likely than teachers

to agree parents are supportive of the school's behaviour rules (71% vs 58%).

• Compared with June 2022, the proportion of school leaders and teachers that

disagreed that parents were generally supportive of the school’s behaviour

rules increased from 15% in June 2022 to 20% in May 2023.

20

Figure 1: Extent to which school leaders and teachers agree that there is a shared

understanding amongst staff of what good behaviour means (May 2023)

Base: All leaders (n=780) and all teachers (n=1,478).

Source: SCP NBS May 2023. Individual weighting. * Indicates a significant difference between leaders and

teachers. ‘Don’t know’ responses (<1% total) not charted. Totals do not match chart exactly due to

rounding. “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement: At my school there is a

shared understanding amongst staff of what is meant by good behaviour.”

Explanation of school rules

Pupils were asked how well their school explained the rules on behaviour at the start of

the academic year. In May 2023, 77% of pupils said that the school had explained the

rules well, of which 30% said the rules were explained ‘very well’ and 47% said they were

explained ‘fairly well’. Conversely, 12% of pupils said that the school had explained the

rules ‘not very well’ and 2% said the school had explained the rules ‘not well at all’ (5%

said that the rules had not been explained to them at all and 3% responded ‘don’t know’).

Pupils in year 7 (84%) were more likely than pupils in year 9 (75%), years 10-11 (75%)

and years 12-13 (72%) to say that the school had explained the rules well.

Compared with June 2022, the proportion of pupils who said that their school explained

the rules on behaviour well decreased from 84% in June 2022 to 77% in May 2023 (see

Figure 2). In particular, the proportion of pupils who said their school explained the rules

on behaviour ‘very well’ fell from 36% in June 2022 to 30% in May 2023.

36

%

52%*

34%

44%

36%

46%*

5%

1%

6%*

10%

4%

11%*

4%

7%*

4%

All leaders and

teachers

Leaders

Teachers

Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree

Total:

Agree

88%*

79%

81%

Total:

Disagree

11%

15

%*

14%

21

Figure 2: How well pupils thought their school explained the rules on behaviour at

the start of the academic year (May 2023 and June 2022)

Base: May 2023 - all pupils year 7-13 (n=2,521). June 2022 – all pupils year 7-13 (n=1,908)

Source: PPLP NBS May 2023. * Indicates a significant difference between timepoints. Totals do not match

chart exactly due to rounding. “At the start of this academic year, how well did your school explain the rules

on behaviour?”

Expectations of behaviour

Pupils were asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the following statement:

“I know how my school expects me to behave”. The majority of pupils (85%) agreed with

this statement, of which 35% responded ‘strongly agree’ and 50% ‘agree’. Just 2% of

pupils disagreed with this statement, while 10% responded ‘neither agree nor disagree’

and 2% ‘don’t know’. The proportion of pupils who agreed with this statement has

decreased from 91% in June 2022 to 85% in May 2023.

School leaders and teachers were asked about pupils’ understanding of what will happen

if they didn’t meet the expected standards of behaviour, and pupils were asked about

their own understanding of what would happen if they didn’t meet the expected standards

of behaviour.

For school leaders and teachers, 78% agreed that pupils understand what will happen if

they do not meet expected standards of pupil behaviour (of which 29% responded

‘strongly agree’ and 49% ‘agree’). School leaders were more likely than teachers to feel

that pupils understand what will happen if they do not meet the expected standards of

behaviour (93% vs. 76%; see Figure 3).

36%*

30%

48%

47%

8%

12%

1%

2%

4%

5%

3%

3%

All pupils June 2022

All pupils May 2023

Very well Fairly well Not very well Not well at all They weren't explained to me Don't know

Total:

Explained

well

84%*

77%

Total: Not

explained

well

9%*

15

%

22

Figure 3: Extent to which school leaders and teachers agree that pupils

understand what will happen if they don’t meet the expected standards of pupil

behaviour (May 2023)

Base: All leaders (n=780) and all teachers (n=1,478).

Source: SCP NBS May 2023. Individual weighting. * Indicates a significant difference between leaders and

teachers. ‘Don’t know’ responses (<1% total) not charted. “To what extent do you agree or disagree with

the following statement: Pupils understand what will happen if they don’t meet the expected standards of

behaviour.”

For pupils, 83% agreed that “I understand what will happen if I don’t meet the expected

standards of behaviour” (32% responded ‘strongly agree’ and 51% ‘agree’). As shown in

Figure 4, 4% of pupils said they disagreed with this statement (of which 3% responded

‘disagree’ and 1% ‘strongly disagree’), 10% said they neither agreed nor disagreed, and

2% reported ‘don’t know’.

Compared with June 2022, the proportion of pupils who agreed that they understand

what will happen if they don’t meet the expected standards of behaviour has decreased

from 87% in June 2022 to 83% in May 2023.

93%*

76%

78%

Total

:

Agree

29%

46%*

26%

49%

47%

50%

9%

4%

9%*

10%

2%

12%*

3%

1%

3%*

All leaders

and teachers

Leaders

Teachers

Strongly agree Agree

Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree

3%

15%*

13

%

Total

:

Disagree

23

Figure 4: Extent to which pupils agree that they understand what will happen if

they don't meet the expected standards of pupil behaviour (May 2023 and June

2022)

Base: May 2023 - all pupils year 7-13 (n=2,521). June 2022 – all pupils year 7-13 (n=1,908).

Source: PPLP NBS May 2023. ^ Indicates a significant difference between timepoints. ‘Don’t know’ (≤2%

of the total) and ‘Prefer not to say’ (≤1% of the total) not charted. “To what extent do you agree or disagree

with the following statements…. – I understand what will happen if I don’t meet the expected standards of

behaviour.”

Parents were asked to what extent they agreed with the statement “[Pupil] understands

what will happen if they don’t meet the expected standards of behaviour”. Overall, 92% of

parents agreed that their child understands what will happen if they don't meet the

expected standards of behaviour (of which 53% responded ‘strongly agree’ and 39%

‘agree’), while 2% disagreed and 1% responded ‘don’t know’. Parents of secondary-aged

pupils were more likely than parents of primary-aged pupils to agree with this statement

(94% vs. 91%).

Ease of following rules

School leaders, teachers, pupils and parents were asked questions about how easy it

was for pupils to understand and follow the school’s rules on behaviour. These questions

were asked in May 2023.

37%^

32%

50%

51%

7%

10%

3%

3%

1%

1%

All pupils June 2022

All pupils May 2023

Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree

Total:

Agree

87%^

83%

Total

:

Disagree

4%

4

%

24

The majority (92%) of school leaders and teachers reported that it was easy for pupils to

understand the school’s rules on behaviour (of which 64% thought it was ‘very easy’ and

29% ‘fairly easy’). School leaders were more likely than teachers to say that it was easy

for pupils to understand the school’s rules (99% vs. 91%) and more likely to say it was

‘very easy’ (77% vs. 61%). Teachers were more likely than school leaders to say that it

was not easy (8% vs. 1% respectively).

Primary school teachers were more likely than secondary school teachers to report that

school rules were easy for their pupils to understand (94% vs. 89%), whilst primary

school leaders were more likely than secondary school leaders to say school rules were

‘very easy’ for pupils to understand (81% vs. 69%).

School leaders and teachers were then asked how easy it was for pupils to follow the

school’s rules on behaviour in practice. As shown in Figure 5, 86% of school leaders and

teachers thought this was easy for pupils. In a similar pattern to understanding rules,

school leaders were more likely than teachers to say it was easy for pupils to follow the

rules (94% vs. 85%) and to think it ‘very easy’ (56% vs. 45%).

Primary school teachers were more likely than secondary school teachers to report that

school rules were easy for their pupils to follow (90% vs. 81%).

Figure 5: How easy school leaders and teachers think it is for pupils to follow (in

practice) school rules on pupil behaviour (May 2023)

Base: All leaders (n=780) and teachers (n=1,478).

Source: SCP NBS May 2023. Individual weighting. * Indicates a significant difference between leaders and

teachers. ‘Don’t know’ responses (<1% total) not charted. Totals do not match chart exactly due to

rounding. “How easy, if at all, do you think it is for pupils to follow (in practice) your school’s rules on pupil

behaviour?”

46%

56%*

45%

40%

38%

40%

11%

6%

12

%

*

2%

1%

2%*

All leaders and

teachers

Leaders

Teachers

Very easy Fairly easy Not very easy Not easy at all

Total:

Easy

94%*

85%

86%

Total:

Not easy

6%

15%*

13%

25

When pupils were asked “how easy are your school’s rules on behaviour to follow?”, 82%

of all pupils said that their school's rules on behaviour are easy to follow, of which 29%

said they are ‘very easy’ to follow and 53% said they are ‘fairly easy’ to follow. As shown

in Figure 6, 16% of all pupils said that the school’s rules are not easy to follow (12% ‘not

very easy’ and 4% ‘not easy at all’) and 2% reported ‘don’t know’.

Pupils in years 12-13 (90%) were more likely than pupils in years 7-9 (81%) and years

10-11 (80%) to say that their school's rules on behaviour are easy to follow. Pupils in

year 9 (20%) and year 10 (20%) were more likely than pupils in year 7 (13%) and years

12-13 (8%) to say that the rules are not easy to follow.

Compared with June 2022, the proportion of pupils who said that their school’s rules are

‘very easy’ to follow has fallen from 33% in June 2022 to 29% in May 2023.

Figure 6: How easy pupils find it to follow school rules on behaviour (May 2023)

Base: All pupils year 7-13 (n=2,521), year 7 pupils (n=412), year 8 pupils (n=414), year 9 pupils (n=433),

year 10 pupils (n=423), year 11 pupils (n=444), year 12 pupils (n=227), year 13 pupils (n=168).

Source: PPLP NBS May 2023. ^ Indicates a significant difference compared to all years except 7 and 12. *

Indicates a significant difference to years 7 and 12-13. Totals do not match chart exactly due to rounding.

“How easy are your school’s rules on behaviour to follow?”

29%

35%

29%

26%

22%

29%

32%

42%^

53%

50%

51%

52%

56%

53%

56%

50%

12%

10%

14%

15%

15%

11%

9%

6%

4%

3%

3%

5%

5%

5%

1%

2%

1%

2%

2%

2%

2%

2%

1%

All pupils

Ye ar 7 pupils

Ye ar 8 pupils

Ye ar 9 pupils

Ye ar 10 pupils

Ye ar 11 pupils

Ye ar 12 pupils

Ye ar

13

pupils

Very easy

Fairly easy Not very easy Not easy at all Don't know

Total

: Easy

85%

82

%

81%

78%

78%

82%

88%

93%

Total: Not easy

13%

16%

17%

20%*

20%*

16%

10%

7%

26

Parents were also asked “how easy does [Pupil] find their school’s rules on behaviour to

follow?” Overall, 89% of parents said that their child found it easy to follow the school's

rules on behaviour, including 57% who said their child found it ‘very easy’ to follow the

rules and 33% who said they found it ‘fairly easy’. Around one in ten parents (9%) said

their child did not find it easy to follow the school’s rules (7% ‘not very easy’ and 3% ‘not

easy at all’). Compared to June 2022, the proportion of parents who said that their child

found it easy to follow the school's rules on behaviour has decreased from 92% in June

2022 to 89% in May 2023.

Consistency of application of behaviour policy

School leaders, teachers and pupils were asked how often the school’s rules on

behaviour are applied fairly to all pupils. These questions were asked in May 2023.

Almost all school leaders and teachers (98%) reported that rules on behaviour were

applied fairly to pupils at least some of the time (with 21% reporting this happened ‘all of

the time’, 57% ‘most of the time’, and 20% ‘some of the time’). Only 1% of school leaders

and teachers indicated that rules on behaviour were ‘never’ applied fairly to all pupils.

Whilst school leaders and teachers agreed that behaviour rules were applied fairly at

least some of the time (100% and 98% respectively), school leaders were more likely

than teachers to report that the rules were applied fairly ‘all of the time’ (38% vs. 19%).

The proportion of teachers who felt that rules were applied fairly to pupils ‘all of the time’

was lower than recorded in 2022 (23%, a drop of 4 percentage points).

Primary school teachers were more likely than secondary school teachers to report that

rules were applied fairly ‘all of the time’ (27% vs. 11%). The same pattern was true

amongst school leaders; primary school leaders were more likely than secondary school

leaders to say rules were applied fairly ‘all of the time’ (46% vs. 24%).

In May 2023, the majority of pupils (89%) thought rules were applied fairly to all pupils at

least some of the time, although only around a fifth (18%) thought this was the case ‘all of

the time’ (44% said they were applied fairly ‘most of the time’ and 27% ‘some of the

time’). Seven per cent of pupils said the school’s rules on behaviour were ‘never’ applied

fairly to all pupils, and 4% responded ‘don’t know’.

When comparing only secondary school leaders and teachers with pupils on responses

to this question in May 2023:

• Secondary school leaders (24%) and pupils (18%) were more likely than

secondary school teachers (11%) to say that the rules on behaviour were applied

fairly to all pupils ‘all of the time’.

27

• Secondary school leaders (66%) and secondary school teachers (59%) were more

likely than pupils (44%) to say the rules on behaviour were applied fairly to all

pupils ‘most of the time’.

• Pupils (7%) were more likely than secondary school teachers (2%) to say that the

rules on behaviour were ‘never’ applied fairly to all pupils (no secondary school

leaders responded ‘never’ to this question).

Visible leadership

School teachers and pupils were asked questions relating to the visibility of the school

leadership team and how often they typically see members of the school leadership team

around the school. These questions were asked in May 2023.

Almost all school teachers (97%) reported seeing members of the school leadership

team around the school at least some days. Half (51%) said they see them ‘every day’,

while around a quarter see them ‘most days’ (23%) or ‘some days’ (23%) and just 3%

stated that they never see members of the school leadership team. This is consistent

with findings from 2022.

For pupils, nearly all pupils (93%) reported seeing members of the school leadership

team around school at least some days; of which 37% said they see them ‘every day’,

33% said they see them ‘most days’ and 23% said they see them ‘some days’. Three per

cent of pupils said they ‘never’ see the school leadership team around school.

Compared with June 2022, the proportion of pupils who said they typically see members

of the school leadership team around school ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ has decreased

from 74% in June 2022 to 70% in May 2023.

When comparing only secondary school teachers with pupils on responses to this

question in May 2023:

• Secondary school teachers (46%) were more likely than pupils (37%) to report

seeing members of the school leadership team around the school ‘every day’.

• Pupils (33%) were more likely than secondary school teachers (24%) to report

seeing members of the school leadership team around the school ‘most days’.

Approach to managing behaviour

School leaders and pupils were asked questions about the school’s approach to

encouraging positive pupil behaviour. These questions were asked in May 2023.

28

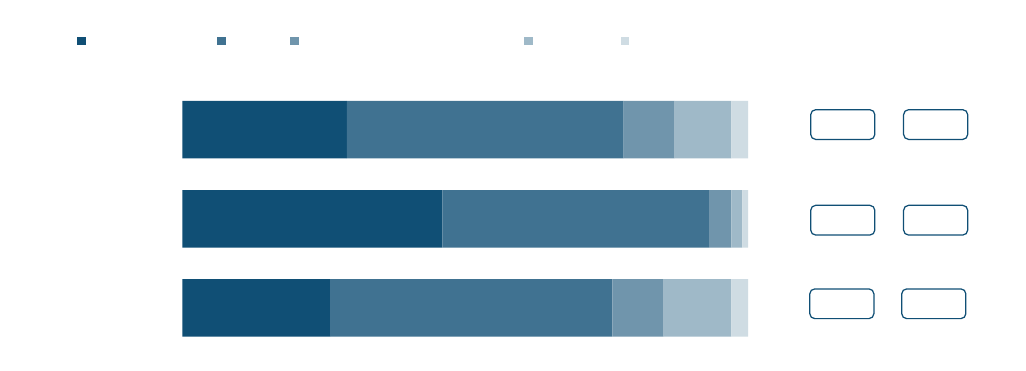

School leaders were asked a set of questions to understand the extent to which different

activities or interventions (from a prompted list) formed part of their school’s approach to

encourage positive pupil behaviour and minimise misbehaviour. As shown in Figure 7, all

the activities or interventions were widely used by schools in May 2023, with 99% of

school leaders reporting ‘staff building supportive relationships with pupils’, ‘staff

modelling positive relationships and expected behaviour’, and ‘understanding and

responding to pupils’ needs’ to at least some extent. A high proportion of school leaders

also reported ‘setting a whole-school approach to behaviour’ (98%), ‘recognising and

rewarding positive behaviour’ (97%), ‘teaching of generic routines to help manage pupil

behaviour’ (96%) and ‘providing appropriate early intervention to pupils who require

additional support with their behaviour’ (94%) to at least some extent. The use of

‘sanctions in response to misbehaviour’ was least commonly used, but still used to at

least some extent by 86% of schools.

Figure 7: Extent to which different activities or interventions form part of the

school’s approach to encourage positive pupil behaviour and minimise

misbehaviour (May 2023)

Base: All leaders (n=780).

Source: SCP NBS May 2023. Schools weighting. ‘Not at all‘ (<1% total) and ‘Don’t know’ responses (<1%

total) not charted. Totals do not match chart exactly due to rounding. “To what extent do the following

elements form part of your school’s approach to encourage positive pupil behaviour and minimise

misbehaviour?”

90%

85%

84%

84%

81%

68%

64%

43%

9%

15%

15%

14%

15%

28%

30%

43%

1%

1%

1%

1%

3%

3%

5%

14%

Staff building supportive

relationships with pupils

Staff modelling positive relationships

and expected behaviour

Understanding and responding

to pupils' needs

Setting a whole-school

approach to behaviour

Recognising and rewarding

positive behaviour

Teaching of generic routines to

help manage pupil behaviour

Providing appropriate early intervention to

pupils who require additional

support with their behaviour

Sanctions in response to misbehaviour

To a great extent To some extent To a small extent

Total: At least

some extent

99%

99%

99%

98%

97%

96%

94%

86%

29

Primary schools were more likely than secondary schools to have adopted the following

interventions to at least some extent:

• Staff modelling positive relationships and expected behaviour (100% vs. 97%)

• Setting a whole school approach (99% vs. 95%)

• Teaching of generic routines to help manage pupil behaviour (97% vs. 90%)

• Providing appropriate early intervention to pupils who require additional support

with their behaviour (96% vs. 86%)

Conversely, secondary schools were more likely than primary schools to have adopted

sanctions in response to misbehaviour (96% vs. 83%).

At the same time, pupils were asked what their school does to recognise or reward good

behaviour, answering from a list presenting six options.

11

As shown in Figure 8, 72% of pupils said that their school uses a behavioural points

system (for example, house points, merits or stickers), 56% said that the school uses

prize ceremonies or special assemblies, while 54% selected verbal praise. Just under

half of pupils (44%) said that the school communicates praise to parents via phone calls

or written correspondence.

Less commonly reported approaches included whole class or year group rewards such

as a popular activity (23%) and positions of responsibility, such as being a prefect (22%).

A small proportion of pupils (4%) said that their school does not recognise or reward

pupils for good behaviour, while 5% did not know what their school did.

Pupils in years 7-9 and 10-11 were more likely than pupils in years 12-13 to say that the

school uses a behavioural points system (74% vs. 59%). Pupils in years 12 to 13 were

more likely than pupils in years 7-9 to say their school uses verbal praise (61% vs. 50%)

and positions of responsibility (32% vs. 18%).

11

Pupils could select multiple response options to this question.

30

Figure 8: What pupils report schools do to recognise and reward good behaviour

(May 2023)

Base: All pupils year 7-13 (n=2,521), year 7 pupils (n=412), year 8 pupils (n=414), year 9 pupils (n=433),

year 10 pupils (n=423), year 11 pupils (n=444), year 12 pupils (n=227), year 13 pupils (n=168).

Source: PPLP NBS May 2023. * Indicates a significant difference compared to years 12-13. “Which of the

following, if any, does your school use to recognise/reward good behaviour at the school?”

Use of data and pupil voice

School leaders and pupils were asked questions to explore the use of data and pupil

feedback on behaviour. These questions were asked in May 2023.

72%

56%

54%

44%

23%

22%

4%

5%

74%*

54%

50%*

44%

23%

18%*

2%

5%

74%*

58%

57%

46%

24%

27%

4%

4%

59%

56%

61%

40%

19%

32%

6%

4%

Behavioural points system

Certificates, prize ceremonies

or special assemblies

Verbal praise

Communicating praise to parents

Whole-class or year group rewards

Positions of responsibility, such as

being a prefect

My school doesn't recognise or

reward pupils for good behaviour

Don't know

All pupils

Ye ar s 7-

9

Ye ar s 10

-11

Ye ar s 12-13

31

School leaders were asked two questions about the recording and use of data on pupils’

behaviour: whether their school systematically records

12

data on pupil behaviour and

whether data on pupil behaviour is used to inform the school’s approach to managing

pupil behaviour.

The vast majority (93%) of schools reported systematically recording data on pupil

behaviour. Four per cent of schools reported that they did not record data but had plans

to do so, 1% reported they currently do not record it but have done so previously, and 2%

did not record it and had no plans to do so.

Systematic recording of data on pupil behaviour was slightly more common among

secondary schools than primary schools (98% vs 92%), though 5% of primary schools

claimed they had plans to record this type of data in the future.

When asked about the use of data, 84% of schools reported using data to inform their

approach to managing pupil behaviour, while 12% of schools did not (4% responded

‘don’t know’). Secondary schools were more likely to use data to inform the school’s

approach to managing pupil behaviour than primary schools (92% vs 82%).

Almost three-quarters of schools (73%) also agreed that pupils’ feedback is taken into

account when reviewing their behaviour policy or approach (of which 20% responded

‘strongly agree’ and 53% ‘agree’) whilst 10% disagreed that this was the case (of which

8% responded ‘disagree’ and 1% ‘strongly disagree’) and 17% neither agreed nor

disagreed.

Pupils were also asked questions in May 2023 about the seeking of feedback on

behaviour, and confidence that any feedback would be utilised.

Overall, 27% of pupils said that their school asks pupils for feedback about behaviour in

their school, whilst 45% said that their school does not do this and 29% did not know.

Compared with June 2022, the proportion of pupils who said their school asks for

feedback on behaviour has increased from 24% in June 2022 to 27% in May 2023.

When asked about their confidence in the school acting on any feedback about

behaviour, 40% of pupils said that they were confident that any feedback they may give

regarding behaviour in school would be listened to or acted upon (of which 7% felt ‘very

confident’ and 34% felt ‘fairly confident’). Almost half of pupils (48%) said they were not

confident that any feedback would be listened to or acted upon (of which 34% felt ‘not

very confident’ and 14% ‘not confident at all’) and 12% of pupils responded ‘don’t know’.

12

In the survey questionnaire, the following explanation was given: ‘by systematically record we mean that

everyone uses the same defined system or process to record aspects of pupil behaviour in a consistent

manner’.

32

As shown in Figure 9, pupils in year 7 (48%) were more likely than pupils in years 9

(38%), 10 (36%), 11 (39%) and 12 (35%) to be confident that any feedback regarding

behaviour would be listened to or acted upon.

Figure 9: Pupil confidence that their school will listen to or act on behaviour

feedback (May 2023)

Base: All pupils year 7-13 (n=2,521), year 7 pupils (n=412), year 8 pupils (n=414), year 9 pupils (n=433),

year 10 pupils (n=423), year 11 pupils (n=444), year 12 pupils (n=227), year 13 pupils (n=168).

Source: PPLP NBS May 2023. * Indicates a significant difference compared to years 9, 10, 11 and 12. ^

Indicates a significant difference to all other years. Totals do not match chart exactly due to rounding. “How

confident are you that any feedback you may give regarding behaviour in your school will be listened to /

acted upon?”

Working with parents and pupils

School leaders, teachers, pupils and parents were asked questions about communication

related to behaviour and parental/pupil support of behaviour rules. These questions were

asked in May 2023.

7%

10%

9%

5%

4%

6%

6%

3%

34%

38%

31%

33%

32%

34%

29%

38%

34%

26%

34%

34%

33%

39%

36%

38%

14%

8%

13%

16%

21%

15%

16%

12%

12%

19%

12%

12%

10%

7%

13%

9%

All pupils

Ye ar 7 pupils

Ye ar 8 pupils

Ye ar 9 pupils

Ye ar 10 pupils

Ye ar 11 pupils

Ye ar 12 pupils

Ye ar 13 pupils

Very confident

Fairly confident

Not very confident Not confident at all Don't know

Total:

Confident

48%*

40%

41%

38%

36%

39%

35%

41%

Total: Not

confident

34

%^

48

%

47

%

50%

54%

53%

52%

50%

33

School leader and teacher confidence in communicating with parents

The majority of school leaders and teachers (89%) reported feeling confident

communicating with parents about their child's behaviour (of which 38% felt ‘very

confident and 50% ‘fairly confident’), whilst 11% reported not feeling confident (of which

9% felt ‘not very confident’ and 2% ‘not confident at all).

As shown in Figure 10, school leaders were more likely than teachers to feel confident

communicating with parents about their child’s behaviour (97% vs. 87%) and were more

likely than teachers to report feeling ‘very confident’ (64% vs. 34%).

Figure 10: School leader and teacher confidence in communicating with parents

about their child's behaviour (May 2023)

Base: All leaders (n=780) and all teachers (n=1,478).

Source: SCP NBS May 2023. Individual weighting. * Indicates a significant difference between leaders and

teachers. ‘Not applicable’ (<1% total) and ‘Prefer not to say’ responses (<1% total) not charted. Totals do

not match chart exactly due to rounding. “In general, how confident, if at all, do you feel communicating

with parents/carers about their child's behaviour?”

Primary school leaders and teachers were more likely to feel confident communicating

with parents about their child’s behaviour than secondary school leaders and teachers

(91% vs. 86%).

89%

97%*

Total:

Confident

87%

38%

64%*

34%

50%

33%

53%*

9%

2%

10%*

2%

3%*

All leaders

and teachers

Leaders

Teachers

Very confident Fairly confident Not very confident Not at all confident

11%

3%

Total: Not

confident

12%*

34

School communication about pupil behaviour

Parents were asked whether their school communicates with them about their child’s

behaviour. Overall, 81% of parents said that the school does communicate with them on

this topic (of which 31% said they receive regular updates and 51% said the school

communicates with them only if there are issues with behaviour), while 16% reported that

the school does not communicate with them about their child’s behaviour and 2%

responded ‘don’t know’. Parents of secondary-aged pupils were more likely than parents

of primary-aged pupils to say they receive regular updates on their child’s behaviour

(37% vs. 26%).

Pupil and parent support of the behaviour rules

School leaders and teachers were asked about parents’ support of the school's

behaviour rules. As shown in Figure 11, in May 2023, 60% of school leaders and

teachers agreed that parents are supportive of the schools’ behaviour rules (of which 8%

responded ‘strongly agree’ and 52% ‘agree’), and 20% disagreed. School leaders were

more likely than teachers to agree parents are supportive of the school's behaviour rules

(71% vs 58%). By phase, primary school leaders and teachers were more likely to agree

that parents were generally supportive of the school’s behaviour rules than secondary

school leaders and teachers (65% vs. 54%).

Compared with June 2022, the proportion of school leaders and teachers that disagreed

parents were generally supportive of the school’s behaviour rules has increased from

15% in June 2022 to 20% in May 2023. Disagreement has increased for both primary

and secondary school leaders and teachers (increasing from 11% in 2022 to 17% in

2023 for primary, and from 20% in 2022 to 24% in 2023 for secondary).

35

Figure 11: Extent to which school leaders and teachers agree that parents are

supportive of the school’s behaviour rules (May 2023 and June 2022)

Base: May 2023 - all leaders (n=780) and all teachers (n=1,478). June 2022 – all leaders (n=786) and all

teachers (n=1,079)

Source: SCP NBS May 2023 and SCP NBS June 2022. Individual weighting. * Indicates a significant

difference between leaders and teachers within the same time period. ^ indicates a significant difference to

June 2022 within the same respondent group. ‘Don’t know’ (≤1% total) not charted. NETs do not match

chart exactly due to rounding. “To what extent do you agree or disagree that parents/carers are generally

supportive of the school’s behaviour rules?”.

Parents were also asked whether they were supportive of the school’s behaviour rules. In

June 2023, the majority of parents (87%) agreed that “I am supportive of the school’s

behaviour rules” (of which 47% responded ‘strongly agree’ and 40% ‘agree’), while 5%

disagreed (4% ‘disagree’ and 1% ‘strongly disagree’) (see Figure 12).

When asked whether they supported the implementation of the school’s behaviour rules,

78% of parents agreed that “I am supportive of how the school's behaviour rules are

implemented” (of which 37% responded ‘strongly agree’ and 40% ‘agree’), while 10%

disagreed (7% ‘disagree’ and 2% ‘strongly disagree’).

Pupils were asked the same questions as parents about their support for the behaviour

rules their school had adopted and whether they supported how they were implemented.

As shown in Figure 12, in May 2023, 49% of pupils agreed that “I am supportive of my

school’s behaviour rules” (of which 15% responded ‘strongly agree’ and 34% ‘agree),

while 29% neither agreed nor disagreed and 18% disagreed (of which 12% responded

8

%

9%

14%*

14%*

7%

9

%

52%

57%

58%*

65%*

51%

56%

19%

18%

13%

11%

20%*

19%*

17%

12%

12%

7%

18%*

13%*

3%

3%

4%

3%

3%

3%

All leaders and

teachers (May 2023)

All leaders and

teachers (June 2022)

Leaders (May 2023)

Leaders (June 2022)

Teachers (May 2023)

Teachers

(June 2022)

Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree

Total:

Agree

66%

71%*

60%

58%

79%*

65%

Total:

Disagree

15%

16%

20%^

21%*

10%

16%*

36

‘disagree’ and 6% ‘strongly disagree’). Compared with June 2022 the proportion of pupils

who agreed they were supportive of their school’s behaviour rules decreased from 58%

in 2022 to 49% in 2023.

Figure 12: Extent to which pupils and parents agree that they are supportive of the

school’s behaviour rules (May 2023 and June 2022)

Base: June 2023 – all parents (n=3294). May 2023 – all pupils year 7-13 (n=2,521). June 2022 – all

parents (n=2,335) and all pupils year 7-13 (n=1,908).

Source: PPLP June 2023, PPLP NBS May 2023, PPLP NBS June 2022, and PPLP June 2022. * Indicates

a significant difference to June 2022 within the same respondent group. ‘Don’t know’ responses (≤3%) not

charted. “I am supportive of the/my school’s behaviour rules.”

When asked whether they were supportive of how their school’s behaviour rules were

implemented, in May 2023, 47% of pupils agreed that they were, while 20% disagreed

and 27% neither agreed nor disagreed. Compared with June 2022, the proportion of

pupils who agreed they were supportive of how their school’s behaviour rules were

implemented decreased from 56% in 2022 to 47% in 2023.

47%

50%

15%

22%

40%

39%

34%

36%

7%

6%

29%

26%

4%

3%

12%

10%

1%

1%

6%

4%

Parents

(June 2023)

Parents

(June 2022)

Pupils

(May

2023

)

Pupils

(June 2022)

Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree

87

%

89%

Total:

Agree

5%

Total

:

Disagree

14%

18%

4%

49%*

58%

37

Findings 2: School environment and experience

This chapter presents findings on how the school environment is perceived by school

leaders, teachers and pupils, as well as pupil and parental perceptions of school

belonging and connectedness, and pupil perceptions of wellbeing.

School environment and relationships

School leaders, teachers and pupils were asked to what extent they agreed with a set of

statements relating to their recent experience of the school’s environment and behaviour

culture. These statements were presented in November 2022, March 2023 and May

2023.

For school leaders in May 2023 (see Figure 13):

• 95% reported that their school was a safe environment for pupils ‘every day’ or

‘most days’ in the past week.

• 84% reported that their school had been calm and orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

Key findings:

• In May 2023, 84% of school leaders reported that their school had been calm

and orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ in the past week (versus 59% of

teachers). For pupils, 54% reported that their school had been calm and orderly

‘every day’ or ‘most days’ in the past week. Comparing across survey waves,

for school leaders and teachers this is a decrease from 92% and 70%

respectively in June 2022.

• In May 2023, 11% of pupils said that they had enjoyed coming to school ‘every

day’ in the past week, whilst 17% said that they had ‘never’ enjoyed coming to

school in the past week. Comparing across survey waves, the proportion of

pupils reporting that they had enjoyed coming to school ‘every day’ has

decreased from 15% in June 2022.

• When asked how often they felt safe at school, 39% of all pupils said that they

had felt safe at school ‘every day’ in the past week in May 2023.

• In May 2023, 71% of pupils felt they were motivated to learn, with 17% who

said that they were ‘very motivated’ and 54% who said they were ‘fairly

motivated’.

38

• 97% reported that school staff had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ or

‘most days’ in the past week.

• 88% reported that pupils had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

• 87% reported that pupils had been respectful to school staff ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

39

Figure 13: Frequency of positive behaviour culture experiences in the past week

(School Leaders and Teachers, May 2023)

Base: All leaders (n=780) and all teachers (n=1,478).

Source: SCP NBS May 2023. Individual weighting. * Indicates a significant difference between leaders and

teachers. ‘Don’t know’ responses (≤1% total) not charted. Totals do not match chart exactly due to

rounding. “Thinking about the past week, how often would you say….?”.

69%*

42%*

76%*

33%*

37%*

27%

41%

21%

55%*

50%*

4%

15%

2%

11%

12%

1%

1%

1%

My school has been a safe

environment for pupils

My school has been

calm and orderly

School staff have been

respectful to each other

Pupils have been

respectful to each other

Pupils have been

respectful to school staff

Every day

Most days Some days Never

97%*

95%*

Total: Every/Most

days

87%*

Leaders

88%*

84%*

49%

20%

63%

16%

18%

33%*

39%

29%*

48%

45%

16%*

30%*

7%*

32%*

32%*

1%

10%*

4%*

4%*

My school has been a safe

environment for pupils

My school has been

calm and orderly

School staff have been

respectful to each other

Pupils have been

respectful to each other

Pupils have been

respectful to school staff

92%

82%

63%

59%

64%

Teacher

s

40

Primary school leaders were more likely than secondary school leaders to report that:

• Their school had been a safe environment for pupils ‘every day’ (75% vs. 58%)

• Their school had been calm and orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ (87% vs. 77%)

• School staff had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ (80% vs. 70%)

• Pupils had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ (92% vs. 82%)

• Pupils had been respectful to school staff ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ (92% vs. 78%)

School teacher views on the same behaviour culture statements were less positive than

school leader views. For every statement, school leaders were significantly more likely

than teachers to say that these positive behaviours happened ‘every day’ in their school

in the past week (or happened ‘every day’ or ‘most days’).

For school teachers in May 2023 (see Figure 13):

• 82% reported that their school was a safe environment for pupils ‘every day’ or

‘most days’ in the past week.

• 59% reported that their school had been calm and orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

• 92% reported that school staff had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ or

‘most days’ in the past week.

• 64% reported that pupils had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

• 63% reported that pupils had been respectful to school staff ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

Primary school teachers were more likely than secondary school teachers to report that:

• Their school had been a safe environment for pupils ‘every day’ or ‘most days’

(87% vs. 78%).

• Their school had been calm and orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ (68% vs. 51%).

• Pupils had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ (71% vs. 56%).

• Pupils had been respectful to school staff ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ (72% vs.

54%).

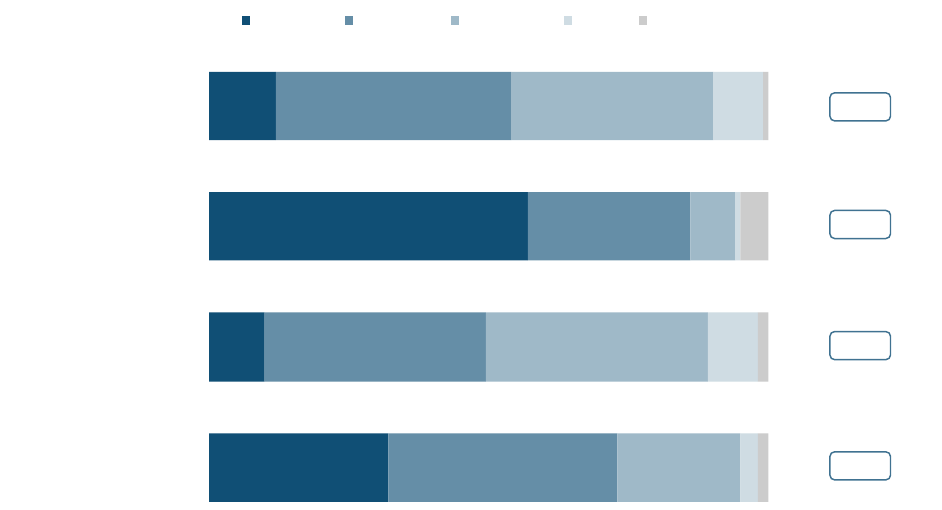

For pupils, in May 2023 (see Figure 14):

41

• 54% reported that their school had been calm and orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

• 86% reported that school staff had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ or

‘most days’ in the past week.

• 49% reported that pupils had been respectful to each other ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

• 72% reported that school staff had been respectful to pupils ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ in the past week.

Figure 14: Frequency of positive behaviour culture experiences in the past week

(Pupils, May 2023)

Base: All pupils year 7-13 (n=2,521).

Source: PPLP NBS May 2023. Totals do not match chart exactly due to rounding. “Thinking about the past

week of term, how often would you say…?”

12%

57%

10%

32%

42%

29%

40%

41%

36%

8%

40%

22%

9%

1%

9%

3%

1%

5%

2%

2

%

My school has been calm

and orderly

School staff have been

respectful to each other

Pupils have been

respectful to each other

School staff have been

respectful to pupils

Every day Most days

Some days Never Don't know

49%

54%

Total: Every/Most

days

72%

86%

42

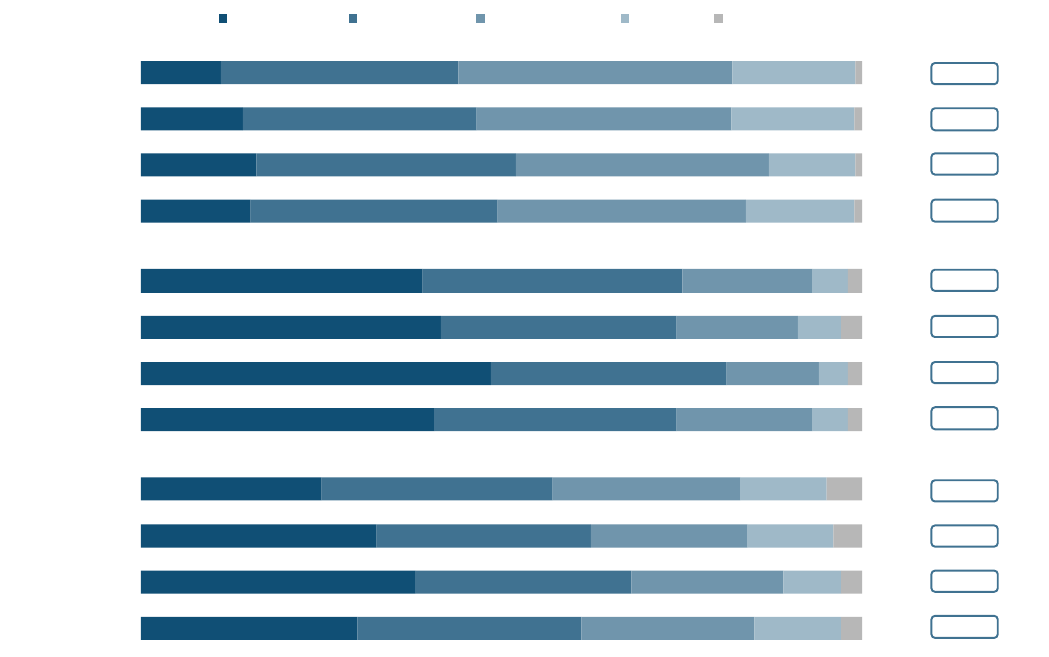

Compared with June 2022

13

(see Figure 15):

• The proportion of school leaders rating all these statements ‘every day’ or ‘most

days’ was significantly lower in May 2023.

• The proportion of school teachers rating all these statements (with the exception

of ‘school staff have been respectful to each other’) ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ was

significantly lower in May 2023.

• The proportion of pupils who said that their school had been calm and orderly

‘every day’ has decreased from 16% in June 2022 to 12% in May 2023.

• The proportion of pupils who said that school staff have been respectful to each

other ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ has increased from 82% in June 2022 to 86% in

May 2023.

13

Comparison does not include ‘Pupils have been respectful to school staff’ or ‘School staff have been

respectful to pupils’ which were not included in the NBS June 2022 survey.

43

Figure 15: Frequency of positive behaviour culture experiences in the past week

across survey waves

Base: May 2023 - all leaders (n=780), all teachers (n=1,478) and all year 7-13 pupils (n=2,521). March

2023 - all leaders (n=529), all teachers (n=2,230) and all year 7-11 pupils (n=2,978). November 2022 - all