Australian Journal of Teacher Education Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Volume 43 Issue 1 Article 1

2018

Effective Behaviour Management Strategies for Australian Effective Behaviour Management Strategies for Australian

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students: A Literature Review Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students: A Literature Review

Linda L. Llewellyn

James Cook University

Helen J. Boon

James Cook University

Brian E. Lewthwaite

James Cook University

Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte

Part of the Education Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Llewellyn, L. L., Boon, H. J., & Lewthwaite, B. E. (2018). Effective Behaviour Management Strategies for

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students: A Literature Review.

Australian Journal of

Teacher Education, 43

(1). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n1.1

This Journal Article is posted at Research Online.

https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/vol43/iss1/1

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 1

Effective Behaviour Management Strategies for Australian

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students: A Literature Review

Linda Llewellyn

Helen Boon

Brian Lewthwaite

James Cook University

Abstract: This paper reports findings from a systematic literature

review conducted to identify effective behaviour management

strategies which create a positive learning environment for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander students. The search criteria employed

resulted in 103 documents which were analysed in response to this

focus. Results identified eight themes underpinning strategies for

effective behaviour management. Despite the suggested actions, the

review highlights that little empirical research has been conducted to

validate effective classroom behaviour management strategies;

strategies which may also be used to inform teacher education.

Considering the high representation of Indigenous students in

statistics related to behaviour infringements and other negative school

outcomes, this review affirms the urgent need for research to

investigate and establish empirically what constitutes effective

behaviour management for Indigenous students.

Introduction

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) students are perpetually

overrepresented in every negative indicator associated with schooling such as discipline

events (Perso, 2012), suspensions (Mills & McGregor, 2014; Partington, Waugh & Forrest,

2001; Stehbens, Anderson & Herbert, 1999), low attendance (Auditor General of

Queensland, 2012; Keddie, Gowlett, Mills, Monk & Renshaw, 2013), exclusions (Partington

et al., 2001; Perso, 2012), low retention (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011; Bain, 2011)

and performance (Perso, Kenyon & Darrough, 2012; Stehbens et al., 1999). This

overrepresentation persists despite a decade’s focus on targeted interventions nationally on

Indigenous education to reduce Indigenous disadvantage and increase educational outcomes

(Auditor General of Queensland, 2012; Ministerial Council on Education Employment

Training and Youth Affairs, 2008). These negative indicators and perpetuating inequities in

Indigenous student performance are usually attributed in the public discourse to student

qualities rather than school system features (Gillan, 2008; Griffiths, 2011).

In response, Campbell (2000) claims that national agendas and strategies are more

likely to fail because they do not meet the diverse requirements and expectations of

Indigenous students and their communities. Griffith (2011) states that “Indigenous education

programs in Australia are overwhelmingly designed with good intentions and with laudable

goals, but with little reference to the evidence base or to the ‘big picture’ of competing

programs and the actual needs of Indigenous people” (p. 69). The Melbourne Declaration

also asserts that any attempt to ameliorate these negative propensities in Indigenous students’

education should be grounded in Indigenous students’ cultural norms (Ministerial Council on

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 2

Education Employment Training and Youth Affairs, 2008). This implies that the reasons for

the failure of education initiatives is thought to be attributed to the mismatch between

classroom and home (Malin, 1990a) and the failure of educators to listen to Indigenous

communities (Bond, 2010; Yunkaporta & McGinty, 2009). Perso (2012) maintains that what

is needed to address these issues is increased teacher awareness of Indigenous cultural norms

that, accordingly, lead to adjusted classroom practice. Teacher education in culturally

responsive strategies might lead to ameliorating this problem; otherwise, if left unaddressed,

inequity and disadvantage will likely be perpetuated (Bazron, Osher & Fleischman, 2005).

Behaviour Management Resources Prominent in the Local Context

In North Queensland, where this multi-phase study is situated, initial teacher

education places unquestioned emphasis on six behaviour management resources that have

been implemented without rigorous evaluation of their efficacy for Indigenous students. The

six resources are (1) Behaviour Management Skill Training Handbook, better known as the

“Microskills” (Richmond, 1996), later re-packaged as (2) The Essential Skills for Classroom

Management (Education Queensland, 2007); (3) numerous works by Bill Rogers (Rogers,

1990; 1994; 2001; 2008); (4) Classroom Profiling by Mark Davidson (Davidson & Goldman,

2004; Jackson, Simincini & Davidson, 2013), which records teacher and student behaviours,

allowing teachers to reflect on their strategies; (5) the work of John Hattie (2009; 2012) and

(6) the work of Robert Marzano (2003; 2007). Evident within this resource base is that only

one of these resources explicitly gives any consideration to Indigeneity and the plight of

Indigenous students (K. Ahmat, personal communication, June 1, 2015; M. Davidson,

personal communication, November 13, 2014). Despite this single reference, any benefits of

such assertions for Indigenous students are not supported by empirical evidence. Teacher

education appropriately requires preservice teachers’ exposure to evidence-based practices.

The shortcoming of these suggested practices is the lack of empirical evidence with

consideration of the influence of the socio-political context in informing responsive

behaviour management practices. The dilemma in addressing this concern in teacher

education is that it appears that there is little empirically-based research that provides any

evidence of what works in positively influencing learning outcomes (Lewthwaite et al., 2015;

Price & Hughes, 2009) and assists in positive behaviour management practice for Indigenous

students. Many argue for empirically-based research to investigate culturally located

behaviour management practices that contribute to Indigenous students’ school success

(Castagno & Brayboy, 2008; Griffiths, 2011; Perso, 2012). In response to this assertion, this

literature review seeks to understand what is stated in the published literature on effective

behaviour management strategies for Australian Indigenous students.

Literature Review Methodology

The literature review was conducted using Randolph’s (2009) approach for

conducting a systematic review of the literature. This involved a five-step process including:

(1) problem formulation; (2) data collection; (3) data evaluation; (4) analysis and

interpretation and, finally, (5) presentation.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 3

Problem Identification

As detailed in the introductory section to this paper, the aim of this review was to

identify in the literature specific teacher actions, or behaviours, that have been effective in

supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander classroom behaviour due to them being

overrepresented in negative school indicators related to behaviour.

Data Evaluation

Systematic protocols were used in conducting all stages of the review (Randolph,

2009). The following data bases were used in the search: One search, the university library

search engine, Informit, the Indigenous database hosted by Informit, ProQuest, the

Australasian Education Directory, AiATSIS Indigenous Studies bibliography, Education in

video, EdiTLib Digital Library, Educational Research Abstracts online, Educational

Resources Information Centre, and ScienceDirect. In response to the search term behaviour

AND/OR classroom management in the Title/Abstract or Keywords, almost two million

results were obtained. Filters were added to restrict the search to studies that mentioned

Indigenous or marginalised context. The following keyword combinations were used:

behavio(u)r support AND /OR Classroom management AND/OR behavio(u)r management

AND/OR Indigenous AND/OR marginalised AND school. The terms ‘classroom’,

‘behaviour’, ‘support’ and ‘management’ were used in the search. For this review ‘behaviour

management’ will be used, which encompasses behaviour support practices, similar to

Richmond (2002a, 2002b) and others (Ministerial Advisory Committee for Educational

Renewal, 2005; Papatheodorou, 1998). This excludes other classroom factors such as staff,

furniture and resources, which may be included by authors using the term ‘classroom

management’ (Emmer, Evertson, Clements & Worsham, 1997; Jackson et al., 2013;

Marzano, 2003; Miranda & Eschenbrenner, 2013; Pinto, 2013). Data collection stopped when

saturation point was reached; “a point where no new articles come to light” (Randolph, 2009,

p. 7).

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The initial search identified 339 publications. Of these, 235 were excluded after

reading the abstract on the basis of the criteria detailed above, or due to duplication. The

remaining 104 were fully reviewed. Fifteen further publications, mainly books, were

identified from internet searches or reference lists in other publications. Three articles or

book sections were not available through these searches and were therefore not included.

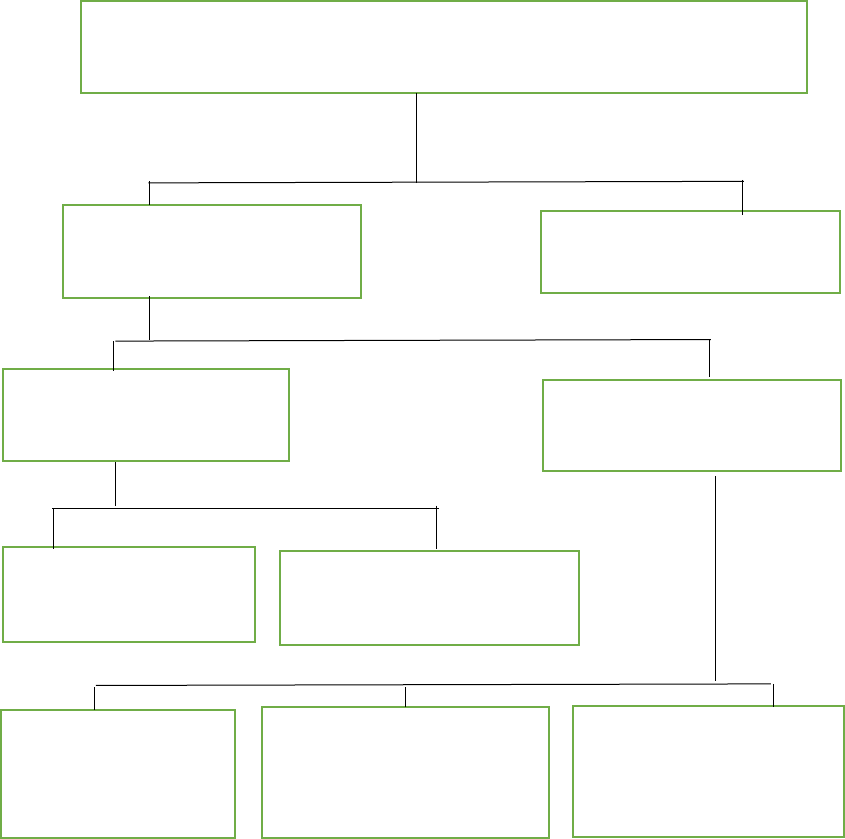

Figure 1 below illustrates the exclusion criteria and search process. The literature was

classified into (1) international non-empirical publications, (2) international empirical studies,

(3) Australian non-empirical publications, (4) Australian empirical studies on curriculum and/

or pedagogy, which covered behaviour management implicitly and (5) Australian empirical

studies explicitly on behaviour management.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 4

Figure 1: Structure of the literature review

International Non-Empirical Publications

Practical suggestions for developing teacher understanding about the needs of

Indigenous and marginalised students tended to dominate this category. Attention was

directed to broader social and political contexts and teacher beliefs and understanding of

these contexts. ‘Culturally Responsive Classroom Management’ (CRCM) (Weinstein, Curran

& Tomlinson-Clarke, 2003; Weinstein, Tomlinson-Clarke & Curran, 2004), which has

become a standard reference in this area, was widely cited within the literature (Gay, 2006;

Milner & Tenore, 2010; Miranda & Eschenbrenner, 2013; Monroe, 2006; Perso, 2012; Pinto,

2013; Ullicci, 2009). These articles drew from previous empirically-based work of the

authors and others (Bowers & Flinders, 1990; Delpit, 1995 ; Doyle, 1986; Gay, 2000;

Ladson-Billings, 1994; Weinstein, 1998). Weinstein and colleagues developed five essential

components of CRCM: recognition of one’s own ethnocentrism; knowledge of students’

cultural backgrounds; an understanding of the broader social, economic and political context;

an ability and willingness to use culturally responsive management strategies and a

commitment to building caring classrooms (Weinstein et al., 2004). Weinstein et al. also

All publications that mention behaviour and / or classroom

management in schools (>1,900,000)

Indigenous or

marginalised context (104)

No mention of Indigenous

or marginalised context

International publications

(43)

Australian publications

(61)

(1). International Non-

Empirical publications

(10)

(3). Australian Non-

Empirical

Publications (40)

(2). International

Empirical Publications (33)

(5). Australian Empirical

publications- behaviour

discussed explicitly (6)

(4). Australian Empirical

publications- behaviour

discussed implicitly (15)

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 5

listed classroom management techniques perceived to create a culturally responsive

classroom. Laura Pinto’s book, “From Discipline to Culturally Responsive Engagement”

(Pinto, 2013) emphasised the need for consideration of context in classroom management

practices and teacher examination of personal history and biases. She goes beyond these

personal and epistemological issues and identified strategies based on her observations over

long periods of time in culturally diverse classrooms. Although these practices have obvious

merit in informing practice, her assertions are not empirically evaluated.

In other non-empirical publications, Miranda and Eschenbrenner (2013) included

details of how marginalised students are disproportionally disciplined in American schools.

They identify a racial gap where students of colour receive more suspensions and exclusions

than white students for similar offences, which is a socially unjust practice. They suggested

rethinking classroom management using socially just practices, because the problem is often

seen to be the child without looking at the operative agenda and actions of the school.

Drawing from this premise, Brantlinger and Danforth (2006) argued that by their

unquestioned actions, teachers implicitly teach students about power and subordination. In

the context of the American Native populations, the literature encouraged educators to

understand the uniqueness of each native population. Specific practices for creating a positive

learning environment are recommended including extended wait time, providing

opportunities for group work and use of humour (Morgan, 2010). Bazron et al. (2005) listed

several strategies that increased student cooperation such as group work, increased wait time

and detailed social instruction. In brief, this body of literature introduced epistemological

ideas of power differences due to cultural and political contexts, cultural differences between

teachers and students and teacher ethnocentrism, which may impact on teacher behaviour

management choices (Pinto, 2013; Weinstein et al., 2003). Also mentioned was teacher

awareness of their shortcomings and willingness to learn (Pinto, 2013). However, research

evidence to support these claims was missing, and thus draws into question the efficacy of

these claims for pre-service and in-service teacher education.

International Empirical Studies

The identified international empirical literature was largely based in the United States,

with research predominantly in urban schools. As well, remote Indigenous (Canadian First

Peoples and American Indian) contexts featured occasionally. Some information came from

discussions of pedagogy, but most of these studies examined Indigenous or marginalised

student behaviour explicitly. Evidence showed that Indigenous and marginalised students are

disproportionally represented in discipline events, punished more severely and more likely to

be suspended from school (Sheets & Gay, 1996; Skiba, Michael, Nardo & Peterson, 2002).

Recurrent themes identified by the researchers that detailed successful evidence-based

behaviour management strategies working with Indigenous and marginalised students

included:

a. knowledge of self and other and power relations in the socio-historical political

context without a deficit notion of difference,

b. knowing students and their culture,

c. particular teacher qualities,

d. positive relationships,

e. culturally responsive pedagogy,

f. proactive behaviour management,

g. culturally appropriate reactive behaviour management and

h. connections with family and community.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 6

Knowledge of Self and Other and Power Relations

Evident within the literature was that teachers need to be aware that schools exist in

an historical and political climate that may influence the perceptions of student and teacher

behaviour (Bondy, Ross, Gallingane & Hambacher, 2007). Therefore, there is a fundamental

need for teachers to have an understanding of the ‘Self and Other’ and the power relations

that either consciously or unconsciously operate in schools. Of particular importance was

attention to whether teachers possess a deficit notion of difference; that is, when someone

differs from the self, attributing those differences to a lack of understanding (Bishop,

Berryman, Cavanagh & Teddy, 2007; Milner, 2008; Milner & Tenore, 2010; Monroe, 2009;

Schlosser, 1992; Sheets & Gay, 1996). Successful teachers - whether or not the teachers were

from the same culture as the children - understood their own cultural background and

similarities and differences from the cultures of the children (Milner, 2008). Some teachers

explained race, culture and power in discussion with students to help them understand how

the dominant culture can replicate power imbalances in the classroom (Bliss, 2006; Milner,

2011; Ullicci, 2009).

Knowing Students and Their Culture

Successful teachers get to know their students and their backgrounds, which reduces

behaviours inappropriate to the context (Schlosser, 1992). There are commonalities and

differences among communities and students, and teachers must take the time to know each

student and each community. For example, American Indian students in one community

preferred to hear a story to the end before stopping to discuss it (Hammond, Dupoux &

Ingalls, 2004). Inuit and American Indian students were comforted by touch under very

different cultural expectations than urban mainstream students (Kleinfeld, 1975). Also,

Latino and African American students reacted differently from middle class ‘white’ students

when in confrontation situations with their teachers (Milner & Tenore, 2010; Sheets & Gay,

1996). In all, authors indicated that a cultural mismatch between the expectations of teachers

and students could lead to misunderstanding of student behaviour; a “lack of cultural

synchronization” (Monroe, 2006; Monroe & Obidah, 2004). Effective teachers understood

that cultural context strongly mediates definitions of appropriate behaviour (Monroe &

Obidah, 2004) and knew that they could not make one set of rules or strategies and assume

everyone knew how to meet them (Milner, 2011). These teachers also understood that

students were not ‘bad’; they were learning behaviour in the new context (Monroe, 2006,

2009), or expressing a need (Milner, 2011).

Particular Teacher Qualities

A third theme identified was the personal qualities of the teacher in fostering positive

behaviour management. The term ‘warm demander’, used by Kleinfeld (1975), is a “teacher

stance that communicates both warmth and a nonnegotiable demand for student effort and

mutual respect” (Bondy & Ross, 2008, p. 54; cf. Lewthwaite & McMillan, 2010). An African

American teacher used cultural humour and demonstrations of emotion and affect, with a

tough and no-nonsense style (Monroe & Obidah, 2004). Successful teachers combined a

sense of humour, with setting boundaries and following through, creating an atmosphere

reflective of family, but using firm redirections (Milner, 2008; Ullicci, 2009). Such a teacher

is a reflective practitioner, always committed to evaluating and re-evaluating practice

(Lewthwaite & McMillan, 2010). Related personal qualities included: not taking student

behaviour personally; being agentic, that is, being able to solve problems that come his/ her

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 7

way (Bishop et al., 2007) or having an internal locus of control (Kennedy, 2011); and

regulation of own teacher emotions (Sutton, Maudrey-Camino & Knight, 2009). The personal

qualities recommended by these authors required teachers to accept responsibility for their

behaviour and recognise the impact their behaviour has on students.

Positive Relationships

The literature indicated that students were more likely to behave well for teachers

they liked (Milner, 2011; Sheets & Gay, 1996), so successful teachers possessed an ability to

create effective relationships with and among students. Having less distance in relationships

contributed to that situation. These teachers shared with students a few personal matters

(Kennedy, 2011; Milner, 2008, 2011; Schlosser, 1992; Sheets & Gay, 1996); stressed that the

class was their ‘family’ or ‘community’ at school, and expected students to respect and value

others in a caring classroom (Bondy et al., 2007; Brown, 2003; Milner, 2011; Ullicci, 2009).

Bondy et al. (2007) noted:

Teachers with a naive conception of care may create an ambiguous rather than

a supportive psychological environment. That is they may believe they care

about students and value a culture of respect but may lack the knowledge

necessary to explicitly teach the skills of respectful behavior or to insist on

respectful behavior in culturally appropriate ways (Bondy et al., 2007, p. 346).

Table 1 details successful teacher strategies for creating a caring environment for students

from Indigenous cultures identified through international empirical studies.

Strategies to create a caring environment

Sources

Giving culturally appropriate social instruction

(Baydala et al., 2009)

Using clear and consistent expectations

(Bondy & Ross, 2008)

Creating physical environment that welcomes and displays

culture

(Brown, 2003; Ullicci, 2009)

Using humour

(Milner, 2008; Ullicci, 2009)

Treating students with respect, not shouting, threatening or

demeaning

(Ullicci, 2009)

Not using punishment

(Noguera, 2003)

Using communication process that are understood by the

student to communicate respect

(Bondy et al., 2007; Brown, 2003)

Communicating expectations of success

(Bishop et al., 2007; Bondy et al.,

2007; Lewthwaite & McMillan, 2010)

Treating students fairly as they see it

(Milner, 2008)

Giving students a sense of control

(Castagno & Brayboy, 2008; Milner,

2008)

Table 1: Successful teacher strategies for Indigenous students

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

Culturally informed teaching strategies were commonly identified as means by which

inappropriate behaviours were minimised and subsequently contributed to more settled

classrooms. These strategies included increased wait time after asking questions or making

requests (Lewthwaite & McMillan, 2010; Winterton, 1977); opportunities for group work

(Hammond et al., 2004; McCarthy & Benally, 2003); scaffolded learning (Bondy & Ross,

2008); opportunities for movement (Boykin, 2001; Monroe, 2006); flexibility (Monroe,

2006); storytelling (Milner, 2008) and activity based learning (McCarthy & Benally, 2003).

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 8

Proactive Behaviour Management

Proactive behaviour management strategies were also identified to decrease disruption

(Sanford & Evertson, 2006). These included, making behaviour expectations clear

(Anderson, Evertson & Emmer,1980; Bondy & Ross, 2008; Bondy et al., 2007; Kennedy,

2011; Lewthwaite & McMillan, 2010; McCarthy & Benally, 2003) and teaching students

how to meet expectations (Anderson et al., 1980).

Reactive Behaviour Management

Reactive strategies were suggested to be implemented after inappropriate behaviour

has occurred. Importantly, reactive interventions should be chosen and implemented in a way

that suits the cultures of the students (Baydala et al., 2009; Bazron et al., 2005; Hammond et

al., 2004; Monroe, 2006; Sheets & Gay, 1996). Table 2 lists further recommendations for

reactive behaviour management.

Reactive strategies

Source

Not make every infraction a serious offense

(Ullicci, 2009)

Calmly deliver consequences

(Bondy et al., 2007).

Look for reasons behind the behaviour and find

ways to meet student needs

(Kennedy, 2011)

Be consistent

(Milner, 2008)

Do not take student behaviour personally

(Kennedy, 2011)

Refrain from holding grudges

(Milner, 2008)

Table 2: Reactive strategies

While policies of zero tolerance may have been seen as a solution, they did not work

to change student behaviour (Noguera, 2003; Nolan, 2007). Zero tolerance approaches came

from a reaction to extreme violence in schools (Skiba & Peterson, 1999a). Nolan’s findings

were consistent with mainstream literature on this issue (Jeffers, 2008; Skiba & Peterson,

1999a, 1999b). Too often schools failed to address the reasons for behaviour and used

suspension to address behaviour concerns and this led to the overrepresentation of

marginalised and first peoples or American Indian students mentioned earlier (Noguera,

2003; Sheets & Gay, 1996; Skiba et al., 2002).

Connections with Families and Communities

Making connections with families and communities was deemed to be critical because

teachers and families may have different standards and expectations about what is appropriate

behaviour in schools (Cary, 2000). In two rural American Indian reservations, the typical

classroom management style where teachers micro-managed the behaviour of individual

students did not fit with cultural values of encouraging students to self-manage for the benefit

of the group. In this case, listening to parents offered the researcher insights into more

culturally appropriate behaviour management strategies for their students. (Hammond et al.,

2004). Different cultures may see the role of parents in schools differently. Monroe (2009)

found that all of the effective teachers made attempts to reach out to families and support

them. Sometimes teachers felt that racial difference between families and teachers hindered

these relationships, but that did not stop them trying.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 9

One international study (Bishop et al., 2007), which used qualitative and quantitative

methods, actually measured student outcomes in New Zealand as a result of the enactment of

teaching practices, including those associated with behaviour. The practices implemented

drew from conversations with Maori students as to what they saw as effective practice. An

Effective Teaching Profile (ETP) was created, guided by the experiences of Maori students,

families, their teachers and principals. Quantitative observations that counted teacher

frequency of use of the strategies were used and student numeracy and literacy outcomes

were measured. The outcomes showed statistical benefits for Maori students. Behaviours

demonstrated by teachers who managed behaviour effectively included: caring and high

expectations; classroom management that promotes learning; discursive learning; successful

learning strategies and sharing learning outcomes and achievements with students to increase

Maori student achievement. Essential to this ETP, was a need to reject deficit paradigms

about differences, and a commitment to reflective practice. This study provides an effective

framework for investigation, as it uses mixed methods and provides evidence of utility.

The eight categories summarised, although valuable, cannot be applied to an

Australian context without consideration of Aboriginal and Torres-Strait Islander contexts

and opinions.

Australian Non-Empirical Publications

Before describing the themes that emerged from this body of literature, two points

must be made. First, there are two very distinct cultures in Australia. Most of this literature is

written for an Aboriginal context and is often assumed to apply to the Torres Strait Islander

culture as well. Little is written by Torres Strait Islander people, or from a Torres Strait

Islander perspective (Nakata, 1995a, 1995b, 2007; Osborne, 1996). Also, within these two

cultures each cultural or family group has its own practices (Bamblett, 1985), so students

come from diverse backgrounds. Indigenous students cannot all be grouped together (Nakata,

2007); but they may share some common traits (Gollan & Malin, 2012; Harris & Malin,

1995).

Second, historical antecedents must be considered by a reader who negotiates

information describing Indigenous cultures in Australia (Osborne, 1996). An attitude of

deficit theorising ignores historical antecedents and places the problems with students and

families rather than the systems or schools or teachers (Griffiths, 2011). “One must

acknowledge also that Aboriginal attitudes, and often Aboriginal living conditions have been

determined by two hundred years of white cultural and economic dominance of Aboriginal

cultural values, which are alien to non-Aboriginal society” (Bamblett, 1985, p. 35). This has

resulted in transgenerational trauma to Australian Indigenous peoples (Aitkinson, 2002;

Ralph, Hamaguchi, & Cox, 2006), including children (Milroy, 2005). Accurate recounting of

history (Bottoms, 2013; Christie, 1987b; Shaw, 2009) helps to situate information about

education in communities.

Often the literature in this section was based on personal experience and in-depth

understanding from Indigenous and non-Indigenous authors. Information in this section is

consistent with the themes from international authors, so these same categories will be used

in presenting the Australian literature.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 10

Knowledge of Self and Other and Power Relations

In this context authors emphasised that teachers did not need to be from the same

culture as their students to be culturally competent (Osborne, 1996), with a caveat that a

teacher must get to know the culture, as it may differ from their own and cause cultural

misunderstanding (Ionn, 1995; Osborne, 1996), which includes behaviour. Christie (1985)

explained some difference between cultures: ‘meaningful’ experiences hold value for the

Yolgnu people while ‘purposeful’ experiences hold value for Western culture. The difference

is an approach to getting things done. A meaningful experience holds importance and

significance for the individual, while a purposeful experience is about setting and achieving

goals under an assumption that we are in control of the world (Christie, 1985). When we use

our own standards to judge others, Yolgnu can see Westerners as greedy and Westerners can

see Yolgnu as lazy (Christie, 1985). School is dependent on purposeful behaviour that comes

from a Western view that the world can be controlled.

Meaningful behaviour is a different sort of activity altogether. It is not a watered

down version or a pale imitation of purposeful behaviour. It is behaviour that is

directed at developing and maintaining the meaningfulness of one’s life and, in

fact, personally controlled goal directed, purposeful activity will interfere with

the practise of meaningful behaviour (Christie, 1985, p. 8).

One way to value Indigenous cultures in Australia has been referred to as ‘two way

learning’ (Purdie, Milgate & Bell, 2011; Rogers, 1994) or ‘both ways education’ (Harrison,

2005). Two-way learning recognises that Indigenous epistemologies must be included in

education, whereas, both ways education is about “a two-way exchange or reciprocity

between people” (Harrison, 2005, p. 874). For a Western teacher that means learning and

accepting that Western ways do not always need to be paramount (Rogers, 1994).

Knowing Students and their Culture

Australian authors strongly emphasised the importance of having knowledge of the

students and their cultural background and behaviours that may be different from those

expected in classrooms. For example, and most importantly, Aboriginal children are raised

with more autonomy than Western children (Bamblett, 1985; Berry & Hudson, 1997; Guider,

1991; Harris, 1987b; Harrison, 2008, 2011; Howard, 1995; Ionn, 1995; Ngarritjan-Kessaris,

1995) and this behaviour may be misunderstood by teachers. Because value is placed on

giving, students may not use ‘please’ or ‘thank you’, but express needs directly. This is not a

‘lack of manners’, but an example of a different values system in operation (Berry & Hudson,

1997; Harrison, 2011; Howard, 1995; Ionn, 1995). Time may be perceived and used

differently (Ngarritjan-Kessaris, 1995). Shared ownership of possessions is valued (Bamblett,

1985; Berry & Hudson, 1997) and cooperation between people is valued more than obedience

to a particular person (Bamblett, 1985; Christie, 1987a). Importantly, students may be

motivated to engage in school work by relationship and community rather than work ethic or

authority (Bamblett, 1985; Berry & Hudson, 1997; Groome, 1995; Harrison, 2008, 2011;

Howard, 1995; Linkson, 1999; Nichol & Robinson, 2010; Perso et al., 2012; Shaw, 2009).

Particular Teacher Qualities

It was suggested that successful teachers use reflective practice (Guider, 1991; Perso,

2012) and do not take student behaviour personally (Berry & Hudson, 1997). They teach

about race, culture and power and school culture (Appo, 1994; Christie, 1987a; Groome,

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 11

1995; Harris, 1987b; Harrison, 2005; Linkson, 1999; Osborne, 1996; Sarra, 2011b). They are

warm demanders (Fanshawe, 1976, 1999; Guider, 1991; Osborne, 1996) with expectations of

success (Griffiths, 2011; Hones, 2005; Sarra, 2011b) and have a sense of humour (Gollan &

Malin, 2012; Harrison, 2011; Ngarritjan-Kessaris, 1995).

Positive Relationships

Effective teachers understand that relationship comes before work (Christie, 1987a;

Howard, 1995; Linkson, 1999), that respect is earned, not based on authority (Bamblett,

1985; Christie, 1987a) and give students a sense of control (West, 1995). They treat students

with respect and communicate in culturally appropriate ways (Perso, 2012), and tell students

a little about themselves (Berry & Hudson, 1997; Byrne & Munns, 2012). Importantly, they

avoid ‘spotlighting’ or ‘shaming’ students, allowing them ‘save face’ (Bissett, 2012;

Osborne, 1996; West, 1995). They also avoid bossing and sarcasm (Harrison, 2008; Howard,

1995) and confrontation (Harrison, 2008; Osborne, 1996). Effective teachers also recognise

and use real-life strengths and skills of their students (Clarke & Dunlap, 2008; Dockett,

Mason & Perry, 2006; Howard, 1995; Perso et al., 2012; Sarra, 2011b).

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

This construct is covered in detail in Australian non-empirical literature. Effective

teachers prevent behaviour that is inappropriate to the context by understanding that students

need the big picture context (Garvis, 2006; Harrison, 2008; Sarra, 2011a) and that students

may not want to learn something new until they are confident in foundational understandings

and skills (Berry & Hudson, 1997; Harrison, 2008, 2011; West, 1995). They employ group

work (Garvis, 2006; Harris, 1987b); use persistence, repetition, rote learning and memory

(Garvis, 2006; Harris, 1987b); relate tasks to real-life (Harris, 1987b) use concrete learning

rather than abstract (Hughes, More & Williams, 2004) and use storytelling, observation and

imitation rather than verbal instruction (Garvis, 2006; Harris, 1987b; Harrison, 2008; Sarra,

2011a; West, 1995) or exposition (Harrison, 2008). They also use learning support and

scaffolding (West, 1995) and avoid over talking (Berry & Hudson, 1997; Christie, 1980;

Harris, 1987b) and too many direct questions; particularly ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions (Berry

& Hudson, 1997; Christie, 1980; Harris, 1987a, 1987b; Harrison, 2008; Ionn, 1995; Linkson,

1999; West, 1995).

Proactive Behaviour Management Strategies

Proactive behaviour management strategies are preventative measures that are put in

place before behaviour inappropriate to the context happens. These include encouraging a

strong sense of self in students (Appo, 1994; Garvis, 2006; Groome, 1995; Hones, 2005;

Milgate & Giles-Brown, 2013; Sarra, 2011b; West, 1995) and giving clear expectations and

how to achieve them (Harrison, 2011; Sarra, 2011b). Teachers must meet student needs in

health (Dockett et al., 2006), belonging and attention (Harrison, 2011). Classrooms should

cater for movement, noise and flexibility (Nichol & Robinson, 2010). Indigenous role models

also help (Dockett et al., 2006; Hones, 2005).

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 12

Reactive Behaviour Management

Reactive strategies are measures taken after behaviour inappropriate for the context

happens. There are many reactive strategies documented as valuable in working with

Australian Indigenous students. These include using restrained power, not an ‘I’m the boss’

approach (Christie, 1987a; Groome, 1995; Harrison, 2008), also avoiding the Western way of

gaining justice and punish to vindicate the wronged (Christie, 1987a; Groome, 1995;

Harrison, 2008). Give rewards for appropriate behaviour rather than punishing hard (Christie,

1987a; Harrison, 2011). The rewards should be consistent and short-lived (Christie, 1987a)

and group rewards rather than individual (Harrison, 2008, 2011). Defuse quickly and calmly

and when calm, talk about responsibility to the group (Christie, 1987a). Above all, avoid

escalating the conflict (Christie, 1987a; Groome, 1995; Nichol & Robinson, 2010). Harrison

(2008) suggests avoiding suspensions because students may be seeking this.

Connections with Families and Communities

In this group of publications, links with family and community are emphasised to

connect with families and create a team approach to teaching students behaviour appropriate

for the context (Bamblett, 1985; Budby, 1994; Clarke, 2000; Dockett et al., 2006; Guider,

1991; Milgate & Giles-Brown, 2013; Osborne, 1996; Perso, 2012; Sims, O'Connor & Forrest,

2003, Shipp, 2013). Suggestions include making an environment where parents feel

comfortable or meet away from school (Sims et al., 2003) and taking the long way around

when talking with parents to make a connection first (Harrison, 2008). Also, while it may not

always be possible Sims et al. (2003) advise staff to learn culturally appropriate

communication and some language features of the community.

The suggestions that emerged from these Australian publications were grouped in the

same themes as those used in international empirical literature. Many useful suggestions were

made for teacher practice. Since these suggestions are not based in empirical evidence

however, their capacity to inform teacher education is questionable.

Australian Empirical Literature

Behaviour Discussed Implicitly

The literature in this category comprised empirical studies from the Australian

context. These studies contained implicit discussions about behaviour while examining

pedagogy (Munns, O'Rourke & Bodkin-Andrews, 2013; Rahman, 2010; Yunkaporta &

McGinty, 2009), disadvantage (Keddie et al., 2013), curriculum (Munns et al., 2013;

Simpson & Clancy, 2012), the hidden curriculum (Rahman, 2010), Indigenous voice (Bond,

2010; Colman-Dimon, 2000), teacher characteristics (Fanshawe, 1989), classroom discourse

(Thwaite, 2007), student mobility (Nelson & Hay, 2010) and humour (Hudspith, 1995). As

these studies investigated other pedagogical topics, conclusions were made that relate

specifically to behaviour management. These findings, again, correspond to the themes that

have been identified in the previous sections.

Understanding of Self and Other and Power Relations

Keddie et al. (2013) observed curricular and non-curricular activities and interviewed

administration, teaching and ancillary staff in one school that catered well for the needs of

Indigenous students. They highlighted the need for teachers to have an understanding of the

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 13

Self and Other, and power relations without a deficit notion of difference. This means that

cultural differences between the teacher and student should not be taken as a lack on the part

of the student. This comes with a warning against treating all Indigenous cultures as a

homogeneous group against a dominant white norm (Keddie et al., 2013). Keddie called this

‘cultural reductionism’, and warned that cultural homogeneity can lead to “further ‘othering’

of non-dominant cultures” (Keddie et al., 2013, p. 94). What works at one time in one context

may not work in another context or another time (Keddie et al., 2013). Hughes, More and

Williams (2004) recommend that teachers focus on individuals and learning strengths, rather

than making generalisations based upon students’ cultural backgrounds. Rahman (2010)

discussed the ‘hidden curriculum’ and how students who are comfortable negotiating the

different context of schooling perform better than those who have not learned to play the

‘game’ of schooling.

Knowing Students and Their Culture

In order to avoid behaviours arising from cultural mismatch, authors identified that

effective teachers get to know their students and their cultures (Yunkaporta & McGinty,

2009). Hughes et al. (2004) observed and interviewed effective teachers in four schools

teaching prepared units and observed the students. They identified particular learning

strengths of Indigenous students and compared Indigenous and Western cultures in their

discussion (Hughes et al., 2004), some of these comparisons have been supported by others

(Hudsmith, 1992; Malin, 1990a, 1990b; Simpson & Clancy, 2012; Yunkaporta & McGinty,

2009). Indigenous students may respond better to indirect questioning rather than direct

questions (Hughes et al., 2004; Thwaite, 2007,) which may be seen as rude (Simpson &

Clancy, 2012). Students may make little eye contact; it is impolite (Hughes et al., 2004, p.

234) and they can be attentive without making eye contact (Thwaite, 2007). Kinship is

important, children may be shared between homes (Hughes et al., 2004). They may engage in

holistic thinking rather than empirical thinking and they may use symbolic language rather

than literal (Hughes et al., 2004). ‘Being’ is more important than ‘doing’ and children may

focus on immediate gratification rather than deferred gratification (Hughes et al., 2004). Time

is circular and without boundaries rather than linear and quantified and students may have a

spontaneous lifestyle rather than a structured lifestyle. Students may be group oriented rather

than individualistic with ownership (Hughes et al., 2004). Pathways through school may be

complex and multifaceted. Nelson and Hay (2010) recommended engaging and re-engaging

with students in open flexible ways rather than making moral judgements about their reasons

for diverse pathways (Nelson & Hay, 2010). Some schools did this better than others (Nelson

& Hay, 2010).

Another cultural difference commonly identified is that Aboriginal children are self-

reliant, self-regulated, observant, and practical (Malin, 1990b; Rahman, 2010). Malin (1990b)

observed children in several Aboriginal and Western families and at school and reported that

Aboriginal children seek help from peers as much as from adults, approach new tasks

cautiously to avoid making mistakes and are emotionally and physically resilient. Aboriginal

students are raised with more autonomy in the home (Malin, 1990a). In the classroom this

autonomy may be mistaken by the teacher as slowness or disobedience (Malin, 1990b). When

the teacher asks them to come, students think they have time to finish what they are currently

doing and may exercise their autonomy to do so (Malin, 1990b). Malin (1990b) observed that

students felt shame at their wrong being made public and reported that students perceived

racist discrimination. Students would like time to reflect and think and see the whole before

engaging in it (Malin, 1990b).

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 14

Particular Teacher Qualities.

Teacher qualities that reduced conflict in the classroom included expressions of

caring, through the words and body language of the teacher, which are noticed, no matter

how small (Hughes et al., 2004). Another characteristic that was noted through research that

looked at teacher effectiveness was personal warmth rather than professional distance

(Fanshawe, 1989). Teachers had to set aside their deficit notion of difference to embrace

Aboriginal ways of knowing (Yunkaporta & McGinty, 2009). Effective teachers were willing

to learn from cultural groups of the children in the class (Simpson & Clancy, 2012) and they

had interest in the wider lives of the children (Bond, 2010).

Hudspith (1995) researched the use of humour in classes with predominantly

Aboriginal students. It was found that unsuccessful or ‘discordant’ teachers used humour to

“reinforc[e] social and political distance” (Hudspith, 1995, p. 21) from groups. Effective or

‘positive’ teachers had a positive ‘tone’ in the room (Hudspith, 1995). In one lesson, 71% of

the humour was directed towards the whole class, not towards individual students (Hudspith,

1995), which is considered to be an effective teaching strategy with Aboriginal students who

avoid being shamed. Effective teachers also directed humour towards themselves; relating

stories of personal failings with humour (Hudspith, 1995). This delighted Aboriginal students

(Hudspith, 1995). Aboriginal students liked teachers who were funny, had a good sense of

humour and were easy to talk to (Hudspith, 1995). These teachers explained humour and did

not use sarcasm (Hudspith, 1995).

Positive Teacher Relationships

Relationships with individual teachers were significant in student perceptions of

schools and schooling (Nelson & Hay, 2010; Rahman, 2010), which impacts on student

behaviour. Munns et al. (2013) researched sociological and psychological understanding of

student motivation and engagement in eight exemplary schools in terms of Indigenous

student performance, attendance and behavioural data and observations. Students with high

self-concept were identified through quantitative data and interviewed, as were

Administrators, liaison staff and teachers identified as having high empathy, association and

success with Indigenous students. Interview data showed that relationships between teachers

and students were paramount in schools that have success with Indigenous students (Munns

et al., 2013). In these schools teachers saw students as important, responsible and able to

achieve (Munns et al., 2013).

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

Student behaviour and engagement were improved when staff worked in Indigenous

ways (Rahman, 2010; Yunkaporta & McGinty, 2009). Teachers did this by linking

curriculum to local Indigenous pedagogies, lore, language and landscape and ways of

thinking and problem solving in design and technology (Yunkaporta & McGinty, 2009).

Students worked well in Indigenous learning circles, but also when working autonomously

and creatively (Yunkaporta & McGinty, 2009). Other suggestions include detailed

scaffolding, so students like to participate, even in direct questioning (Thwaite, 2007).

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 15

Proactive Behaviour Management

Recommendations for proactive behaviour management have emanated from research

that used qualitative observation or action research methods. They include: that teachers

avoid spotlighting students (Thwaite, 2007) and provide social support as the key pedagogy

to shifting to self-direction (Yunkaporta & McGinty, 2009). Teachers should learn how to

frame requests in a way that will engage students (Simpson & Clancy, 2012). One example

cited was an Aboriginal teacher aide who used cultural knowledge and student strengths to

frame a request in a way that was successful. A teacher had requested that students sit in a

particular place, but they refused. The teacher aide created a meaningful context for children

by describing the seat as a car, and framed the request as an invitation to join her (Simpson &

Clancy, 2012).

Reactive Behaviour Management

Reactive behaviour management (measures taken after inappropriate behaviour

happens) was not mentioned in this category of literature.

Connections with Families and Communities

Munns et al. (2013) examined 52 schools, and using quantitative records, selected

four that were successful in enhancing social and academic outcomes for Aboriginal students.

Using case studies of these schools they identified that schools that were successful with

Indigenous students had close links with communities. Hilary Bond (2004) listened to elders

on Mornington Island. Her thesis titled “We’re the mob you should be listening to” related

information from elders in the community. The elders expressed that school gave them no

voice in curriculum and they wanted to have input (Bond, 2004). According to Colman-

Dimon (2000), who used qualitative methods students enjoyed their schooling and felt

optimistic about their futures when parents and community members played an active and

decision-making role in the school. “It is vital that education be improved through a process

of attentive listening rather than an imposition of inappropriate pedagogy, curriculum and

lack of meaningful personal relationships with the community” (Colman-Dimon, 2000, p.

43).

Behaviour Discussed Explicitly

Only five studies specifically focused on behaviour management for Indigenous

students (Edwards-Groves & Murray, 2008; Gillan, 2008; Malin, 1990a; Partington et al.,

2001; Stehbens et al., 1999). Merridy Malin (1990a) observed the children of two Aboriginal

families and two ‘Anglo’ families at home and at school in a five-year ethnographic study in

Adelaide. As a starting point for investigation into inequalities in the classroom, her work has

been widely referenced by others (Howard, 1995; Ionn, 1995, Rahman, 2010). She observed

that socialisation at home for Aboriginal children was very different from that of the Anglo

children (Malin, 1990a), which is consistent with theme (b) knowing students and their

culture. Aboriginal families monitored children indirectly, selectively attending to some

behaviour without the “direct and overt verbal monitoring, directing and persuading” (Malin,

1990a, p. 314), which characterised the Anglo style of parenting. Aboriginal parents used less

than half the number of controlling statements than Anglos and they did not expect

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 16

compliance immediately (Malin, 1990a). When observing the children at school Malin

identified the ideology of the teacher as a source of concern. The teacher harboured lower

expectations for Aboriginal students and when stressed, she also used disparaging

descriptions of them. Malin also warned that “‘treating all students the same' is a dangerous

creed because it is not easy to carry out nor is it appropriate. Even when students are from the

same cultural group, their different personalities, skills and life experiences demand different

responses” (Malin, 1990a, p. 327). Reflecting findings mentioned previously (e.g. Hughes et

al., 2004; Keddie et al., 2013), Malin recommended that teachers become aware of their own

cultural orientations and uncover and challenge their unconscious ideology to be “sensitive to

the students’ respective personalities and propensities and respond accordingly” (Malin,

1990a, p. 327).

Sandra Hudsmith observed two teachers who were known to be successful in their

classroom interactions with Aboriginal students using field notes, audio and video recordings

and interviews. Previously there had been a wide range of behaviour problems with these

children, but with these teachers, misbehaviours in the class were rare. These teachers

incorporated an Aboriginal learning style in their teaching and pedagogy and had extensive

knowledge of their students (Hudsmith, 1992). They highlighted and valued students’

experiences and autonomy and used these in curriculum with an Aboriginal socio-linguistic

etiquette, such as circle talking, where everyone sat on the floor to discuss an issue. Both

teachers attempted to expose the hidden aspects of school culture that generate

misunderstanding between teachers and students. They trained students to use mainstream

language conventions and behaviours for other classrooms. Students were affirmed in their

Aboriginality, and their individual needs were taken into account. Students could go to the

library when they chose, which supported their autonomy. They just had to let the teacher

know, not ask for permission. Older children were encouraged to tutor younger ones, which

made use of the cultural value of helping others and reflected home norms. The teachers

developed positive affirming relationships and through their personal qualities extended the

boundaries of their role. Each class had visited the teacher’s home as an excursion and the

teachers regularly stepped out of their official role to share some aspect of themselves or used

humour. These teachers exemplified “sensitivity, respect and allegiance to common

goals…[by] catering for Aboriginal student differences and needs, while focusing student

creativity and energy towards self-enhancing goals” (Hudsmith, 1992, p. 11). Parents were

involved in their classrooms and teachers took an interest in the lives of students outside of

school. Her work offers detailed, evidence-based insights into the personal characteristics,

classsroom pedagogies and routines of two effective teachers. Unfortunately, it did not focus

on reactive strategies.

Stehbens et al. (1999) examined factors that may contribute to high rates of

suspension for Indigenous students in New South Wales by examining suspension data and

speaking with Aboriginal students, staff, parents and non-Indigenous teachers. Echoing other

authors (e.g. Keddie et al., 2013; Nelson & Hay, 2010) they were critical of schooling as a

way to replicate the “dominant mainstream” (Stehbens et al., 1999, p. 11) where children who

did not assimilate are treated to address the “personal deficit within the child or his or her

family” (Stehbens et al., 1999, p. 11) and if children did not change, they were suspended or

excluded from education. Stehbens et al., argued that behaviour management policies and

programs helped to achieve this assimilation or exclusion process. We need to consider

cultural differences in what is ‘unacceptable’ behaviour. They identified factors that

contributed to the problem, but offered little in the way of solutions. A parent suggested that

while some behaviour is extreme, staff should try to be more tolerant and accepting (Stehbens

et al., 1999) and one staff member saw inflexibility as a problem (Stehbens et al., 1999).

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 17

Partington, Waugh and Forrest (2001) investigated the reasons for higher

representation of Indigenous students in suspensions and exclusions in one Western

Australian school. They examined policy and student and staff perceptions, highlighting

student resistance to alienation (Partington et al., 2001). Their study uncovered reasons for

inequalities in student referrals and suggested some ways to combat the inequality. School

rules were few and not taught (Partington et al., 2001). Among the teachers, there was not a

consistent approach to discipline. Some teachers ignored the underlying causes of behaviour

and used the system to escalate students out of the classroom. Partington et al. (2001)

suggested two explanations for Indigenous student misbehaviour from the literature. The first

explanation was cultural misunderstanding, where teachers misinterpreted behaviour that was

culturally acceptable. Cultural conflict occurred when Indigenous students, steeped in their

home culture, were unfamiliar with the school culture (Partington et al., 2001). Partington et

al., (2001) identified the historical relations of power and racism. Students had a perception

of racist discrimination. A teacher who was not aware of history could exercise power in the

belief that they expected obedience, and if they did not get this they took punitive action

(Partington et al., 2001). Partington et al. offered some solutions based on getting to know

students and relationship:

Culturally appropriate strategies for classroom management are not a bag of

tricks that can be produced as needed. Rather, the relationships among the

various components of culture must be understood and applied in appropriate

contexts so they are seen by students to be relevant and meaningful (Partington

et al., 2001, pp. 74-75).

Each student must be considered in terms of his or her learning strengths, preferences

and needs (Partington et al., 2001). Qualities of effective teachers in creating positive

learning environments included: effective communication, creating good rapport with

students, and demonstrating willingness to negotiate. They also suggested a “framework of

collaboration and more egalitarian teacher-student relationships” (Partington et al., 2001, p.

78). They recommended using fewer worksheets, and in the use of reactive strategies they

found that effective teachers examined the motivations, contexts and interactions when

responding to an incident; they dealt with an incident in isolation from previous student

incidents; used defusing strategies; looked for the antecedents of behaviour, not simply

blaming students; and employed restrained use of power where procedures were set, but not

followed blindly (Partington et al., 2001).

Edwards-Groves and Murray (2008) in a small study, interviewed boys who had

previous negative school experiences and were situated in a short term residential centre.

They used novel data collection methods that included informal discussions, participant

observation, photo interviews, creating together and writing poetry. These methods allowed

for connection between the boys and the researcher in culturally appropriate ways. The

students perceived that teachers and other class members in mainstream schools lacked

“cultural, social and political knowledge and understanding about Aboriginality” (Edwards-

Groves & Murray, 2008, p. 175). In the alternative setting, student needs were met in a

culturally appropriate way and the boys expressed their satisfaction (Edwards-Groves &

Murray, 2008). The authors suggested “renewed scrutiny on classroom interactions and more

importantly still offers teachers impetus for changing the perspectives of the ‘racialized

marginalised other’ so that the ways of being an Aboriginal student in Australian classrooms

can be perceived as relevant, just and balanced” (Edwards-Groves & Murray, 2008, p. 175).

Gillan (2008) examined the language and practice of behaviour management policy in

a Western Australian primary school and discussed how it excluded Noongar students and

families. Following interviews with Indigenous staff, students and families he recommended

changes to school practice and policy development that reflect the themes used previously.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 18

After thorough investigation, he recommended that teachers get to know Noongar child-

rearing practices and culture (Gillan, 2008). Students preferred flexible teachers with a sense

of humour who sought harmonious relationships with students (Gillan, 2008). He

recommended group work, active learning and repetition as teaching strategies to make a

more supportive learning environment (Gillan, 2008). He suggested allowing for movement

(Gillan, 2008). Moreover, he suggested talking to a student one on one away from the class,

and listening to the point of view of the Noongar student (Gillan, 2008). Further, he

recommended early contact with families when students are in trouble and case by case

negotiating with parents over suspension matters to seek a culturally appropriate solution

(Gillan, 2008). He suggested seeking positive communication early on to create relationship

with families (Gillan, 2008). These suggestions were not accompanied by evidence of their

utility when implemented.

While the research in this section detailed a number of issues and suggested some

specific strategies to positively influence Aboriginal and/ or Torres Strait Islander student

behaviour, there was little evidence of the utility of the strategies in classrooms. It is evident

that more research needs to be conducted to explore the effectiveness of these strategies in

supporting Indigenous students and, in turn, for them to be incorporated into teacher training

programs and professional development for classroom teachers.

Discussion and Summary

This review systematically summarised the published literature on behaviour

management for Indigenous students. In so doing the literature was divided into empirical

studies and others emanating from Australia and elsewhere. Specific teacher strategies that

positively influence the behaviour of Indigenous students resulted in eight themes that

emerged initially from international research but were reflected across all publications. These

were: (a) knowledge of self and other and power relations in the socio-historical political

context without a deficit notion of difference, (b) knowing students and their culture, (c)

particular teacher qualities, (d) positive relationships, (e) culturally responsive pedagogy, (f)

proactive behaviour management, (g) culturally appropriate reactive behaviour management

and (h) connections with family and community.

At the start of this review emphasis was placed on the resources currently used in

preservice teacher education and schools in North Queensland where this study is situated.

Although there is widespread use of these resources and they are considered professionally to

be of sound effect, they pale in comparison to what the international literature is saying about

effective behaviour management practices for Indigenous students because they lack any

consideration of students’ cultural context. Evidence-based research into culturally

appropriate behaviour management practices would enhance the efficacy of these claims and

augment the worthiness of these current resources.

Further to this, most of the national and international studies were grounded in

qualitative research methods. Of the international studies, three (Baydala et al., 2009; Bishop

et al., 2007; Boykin, 2001) used quantitative methods which included the use of

psychological tests (Baydala et al., 2009). Boykin (2001) used several survey instruments to

measure the impact of movement on student achievement. Of all the studies identified, only

six examined behaviour management explicitly in the context of Australian Indigenous

students. While their findings reflected the propositions and themes endorsed in the non-

empirical publications and the empirical studies from overseas, they provided little evidence

of the efficacy of their strategies within the socio-cultural context. Empirical studies

conducted in Australia have not been generalised because they have not been validated

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 19

quantitatively in the way that Bishop et al. (2007) determined the effectiveness of their

Aotearoa New Zealand Effective Teaching Profile for Maori students.

Overall, the limited number of studies in this area supports the claim that “There is a

need to empirically validate the generalisability of [Hattie’s (2003)] findings to Aboriginal

students to tease out facets of quality teaching that are salient to Aboriginal students,

elucidate their perspectives of teacher quality and test the influence of specific facets of

quality teaching on academic outcomes [for Aboriginal students] and the consequences of the

findings for developing interventions for Aboriginal primary school students” (Craven,

Bodkin-Andrews & Yeung, 2007, p. 4).

Conclusion

Behaviour management strategies suggested for Aboriginal students in Australia, and

those commonly practiced in North Queensland where this study is centred, lack empirical

evidence that validates what works and for whom (Craven et al., 2007; Griffiths, 2011). They

also lack the inclusion of the voice of Torres Strait Islanders (Nakata, 2007; Osborne, 1996).

Empirically based evidence is needed to inform policy and practice (Craven et al., 2007;

Griffiths, 2011). In addition, there is no empirical data about how teacher beliefs and

strategies support the behaviour of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. This is an

important gap in the literature that needs to be addressed in order to provide teacher

education in the most appropriate pedagogy for Indigenous students (Bishop et al., (2007)

This review suggests important ways to direct a multi-phase study to (1) identify from

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and their families’ behaviour management

practices that positively influence classroom interactions, (2) develop a statistically validated

instrument that can be used to evaluate and inform teacher’s practice and (3) test the

enactment of such strategies on students’ behaviour and learning outcomes. In doing so, the

study will provide empirical evidence for informing pre-service teachers as to what works for

creating a positive learning environment for our region’s Indigenous students.

References

Aitkinson, J. (2002). Voices in the wilderness: Restoring justice to traumatised peoples.

University of New South Wales Law Journal, 25(1), 233-241.

Anderson, M. L., Evertson, C. M., & Emmer, E. T. (1980). Dimensions in classroom

management derived from recent research. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 12(4), 343-

362. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027800120407

Appo, N. (1994). Providing an ideal environment for our children: A personal view.

Aboriginal Child at School, 22(3), 3-4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0310582200005253

Auditor General of Queensland. (2012). Improving student attendance. Brisbane,

Queensland: The State of Queensland, Queensland Audit Office.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2011). Census of population and housing: Characteristics of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2011, education. Retrieved from

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Latestproducts/2076.0Main%20Features302

011?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=2076.0&issue=2011&num=&view

=

Bain, C. (2011). Indigenous retention: What can be learned from Queensland. In N. Purdie,

G. Milgate & H. R. Bell (Eds.), Two way teaching and learning (pp. 71-89).

Camberwell, Australia: ACER Press.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 20

Bamblett, P. (1985). Koories in the classroom. Aboriginal Child at School, 13(5), 34-37.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0310582200014048

Baydala, L., Rasmussed, C., Birch, J., Sherman, J., Charchun, J., Kennedy, M., & Bisanz, J.

(2009). Self-beliefs and behavioural development as related to academic achievement

in Canadian Aboriginal children. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 24(1), 19-

33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573509332243

Bazron, B., Osher, D., & Fleischman, S. (2005). Creating culturally responsive schools.

Educational Leadership, 63(1).

Berry, R., & Hudson, J. (1997). Making the jump: A resource book for teachers of Aboriginal

students. Broome, Australia: Catholic Education Office, Kimberly Region.

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Cavanagh, T., & Teddy, T. (2007). Te Kotahitanga phase 3

Whanaungatanga: Establishing a culturally responsive pedagogy of relations in

mainstream secondary school classrooms. Ministry of Education, New Zealand.

Bissett, S. Z. (2012). Bala ga lili: Meeting Indigenous learners halfway. Australian Journal of

Environmental Education, 28(2), 78-91. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2013.2

Bliss, B. A. (2006). Disciplinary power and extra-classroom public life. [Doctoral

disseration]. University of Delaware, Delaware.

Bond, H. (2004). 'We're the mob you should be listening to': Aboriginal elders talk about

community-school relationships on Mornington Island. [Doctoral dissertation], James

Cook University, Townsville, Australia. Retrieved from

https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/971/

Bond, H. (2010). "We're the mob you should be listening to": Aboriginal elders at

Mornington Island speak up about productive relationships with visiting teachers. The

Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 39(1), 40-53.

https://doi.org/10.1375/S1326011100000909

Bondy, E., & Ross, D. D. (2008). The teacher as warm demander. Educational Leadership,

66(1), 54-58.

Bondy, E., Ross, D. D., Gallingane, C., & Hambacher, E. (2007). Creating environments of

success and resilience: Culturally responsive classroom managment and more. Urban

Education, 42(4), 326-348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085907303406

Bottoms, T. (2013). Conspiracy of silence: Queensland's frontier killing times. Sydney,

Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Bowers, C. A., & Flinders, D. J. (1990). Responsive teaching: An ecological approach to

classroom patterns of language, culture, and thought. New York, N.Y. : Teachers

College Press.

Boykin, W. A. (2001). The effects of movement expressiveness in story content and learning

context on the analogical reasoning performance of African American children.

Journal of Negro Education, 70(1), 72-83.

Brantlinger, E., & Danforth, S. (2006). Critical theory perspective on social class, race,

gender, and classroom management. In C. M. Evertson & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.),

Handbook of Classroom management: Research, practice and contemporary issues

(pp. 157-179). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Brown, D. (2003). Urban teachers' use of culturally responsive management strategies.

Theory Into Practice, 42(4), 277-282. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4204_3

Budby, J. (1994). Aboriginal and Islander views: Aboriginal parental involvement in

education. Aboriginal Child at School, 22(2), 123-128.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0310582200006325

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 21

Byrne, M., & Munns, G. (2012). From the big picture to the indivdual student: The

importance of classroom relationship. In Q. Beresford, G. Partington & G. Gower

(Eds.), Reform and resistance in Aboriginal education (pp. 304-334). Crawley,

Australia: UWA Publishing.

Campbell, S. (2000). The reform agenda for vocational education and training: Implications

for Indigenous Australians. Discussion Paper. Centre for Aboriginal Economic and

policy Research: Australian National University. Retrieved from

http://caepr.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/Publications/DP/2000_DP202.pdf

Cary, S. (2000). Working with second languge learners: Answers to teachers' top ten

questions. Portsmouth, NH: Hinemann.

Castagno, A., & Brayboy, B. M. (2008). Culturally responsive schooling for Indigenous

youth: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 941- 993.

https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308323036

Christie, M. J. (1980). Keeping the teacher happy. Aboriginal Child at School, 8(4), 3-7.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0310582200011111

Christie, M. J. (1985). Aboriginal modes of behaviour in white Australia. Aboriginal Child at

School, 13(5). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0310582200014012

Christie, M. J. (1987a). Discipline. In M. Christie, S. Harris & D. McClay (Eds.), Teaching

Aboriginal children: Milingimbi and beyond (pp. 118-123). Mount Lawley,

Australia: Institute of Applied Aboriginal Studies, Western Australian College of Advanced

Education.

Christie, M. J. (1987b). A history of Milingimbi. In M. J. Christie, S. Harris & D. McClay

(Eds.), Teaching Aboriginal children: Milingimbi and beyond (pp. 1-5). Mount

Lawley, W.A.: The Institute of Applied Aboriginal Studies, Western Australia

College of Advanced Education.

Clarke, M. (2000). Direction and support for new Non-Aboriginal teachers in remote

Aboriginal community schools in the Northern Territory. Australian Journal of

Indigenous Education, 28(2), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100001587

Clarke, S., & Dunlap, G. (2008). A descriptive analysis of intervention research published in

the Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions: 1999 Through 2005. Journal of

Positive Behavior Interventions, 10(1), 67-71.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300707311810

Colman-Dimon, H. (2000). Relationships with the school: Listening to the voice of a remote

Aboriginal community. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 28(1), 34-

47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100001277

Craven, R. S., Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Yeung, A. S. (2007). A model for seeding success for

Aboriginal students. Paper presented at the meeting of Australian Association for

Research in Education, Freemantle.

Davidson, M., & Goldman, M. (2004). "Oh behave"...Reflecting teachers' behaviour

mangement practices to teachers. Paper presented at the Australian Vocational

Education and Training Research Association National Conference (7th), Canberra.

Delpit, L. (1995 ). Other people's children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York,

N.Y.: The New Press.

Dockett, S., Mason, T., & Perry, B. (2006). Successful transition to school for Australian

Aboriginal children. Childhood Education, 82(2), 139-144.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2006.10521365

Doyle, W. (1986). Classroom organization and management. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.),

Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 392-431). New York, N.Y.: Macmillan.

Education Queensland. (2007). The essential skills for classroom management. Brisbane,

Australia: Queensland Government.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education

Vol 43, 1, January 2018 22

Edwards-Groves, C., & Murray, C. (2008). Enabling voice: Perceptions of schooling from

rural Aboriginal youth at risk of entering the juvenile justice system. Australian

Journal of Indigenous Education, 37, 165-177.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100016203

Emmer, E. T., Evertson, C. M., Clements, B. S., & Worsham, M., E. (1997). Classroom

management for secondary teachers (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn &

Bacon.

Fanshawe, J. P. (1976). Possible characteristics of an effective teacher of adolescent