Brazilian National

Waterway Transportation

Agency

International

Experience in

Demurrage

Regulation

Federative Republic of Brazil

Jair Bolsonaro

President

Ministry of Infrastructure

Tarcísio Gomes de Freitas

Ministry of Infrastructure

Brazilian National Waterway Transportation Agency –

ANTAQ Collegiate Board of Directors

Eduardo Nery

Director

General

Adalberto Tokarski

Director

Gabriela Coelho

Interim Director

©2020 – ANTAQ

SEPN Quadra 514, Conjunto “E”, Edifício ANTAQ, SDS, 3º andar, 55 61 20296764

CEP: 70760-545, Brasília – DF

Partial non-profit reproduction is permitted, by any means, if the source is cited.

Technical team:

Superintendence of Performance, Development and Sustainability (SDS)

José Renato Ribas Fialho – Superintendent

Development and Studies Management (GDE)

José Gonçalves Moreira Neto – Manager

Specialists in Waterway Transport Services Regulation: Ana Paula Harumi

Higa

Arthur Felipe de Menezes Il Pak Rodrigo

Guimarães Trajano

Formatting: José Antonio Machado do Nascimento

A265e

Brazilian National Waterway Transportation Agency (Brazil).

International experience in demurrage regulation. / National Waterway Transportation Agency. Brasília: ANTAQ, 2021.

78p.:il.

1. Regulation. 2. Demurrage. 3. Maritime carriers. 4. Logistics. I. Brazilian National Waterway Transport Agency (Brazil). II.

Superintendence of Performance, Development and Sustainability (SDS). III. Development and Studies Management (GDE).

CDD: 387.5.

Brazilian National Waterway

Transportation Agency

International Experience

in Demurrage Regulation

Brasilia

2021

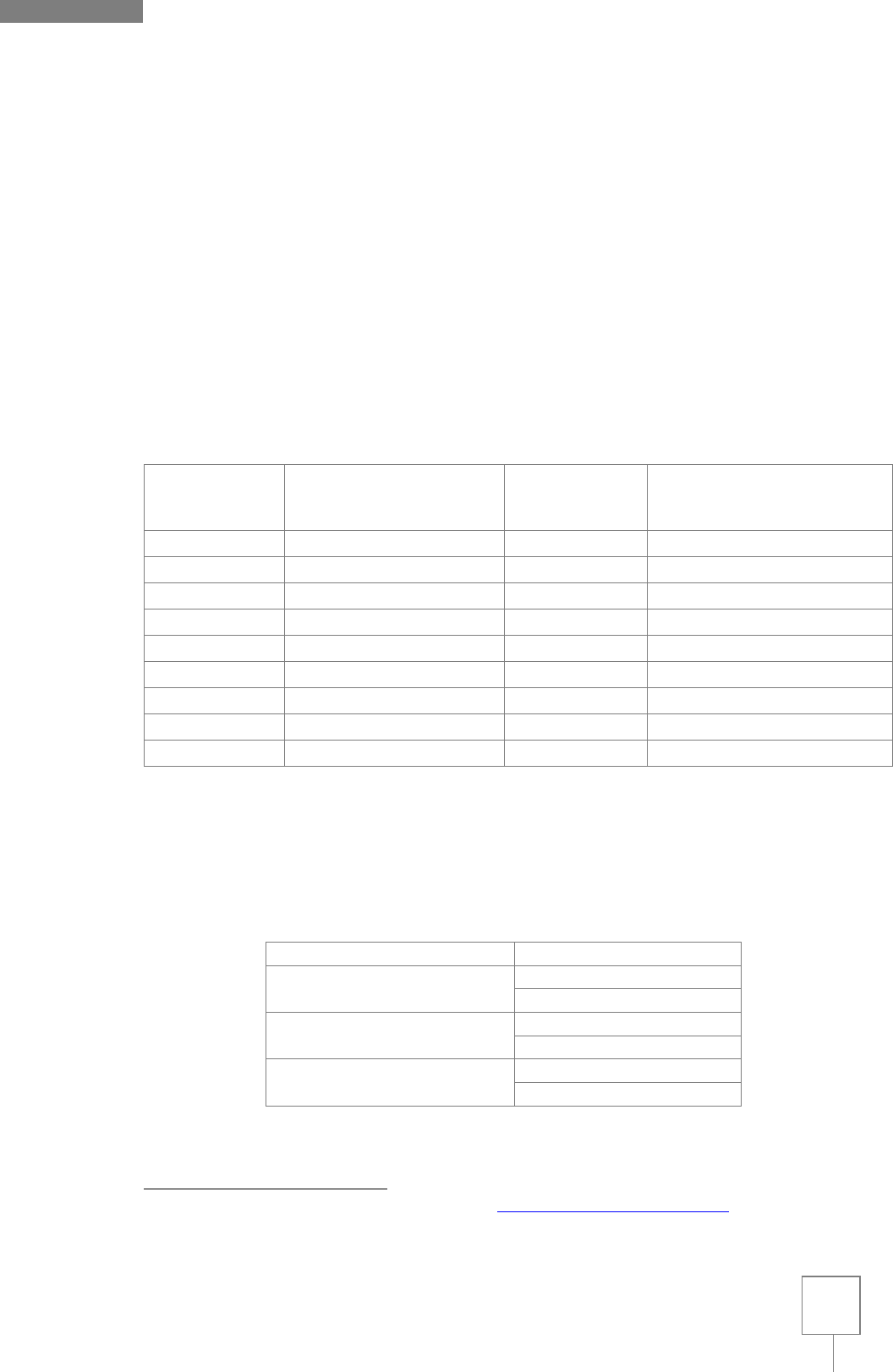

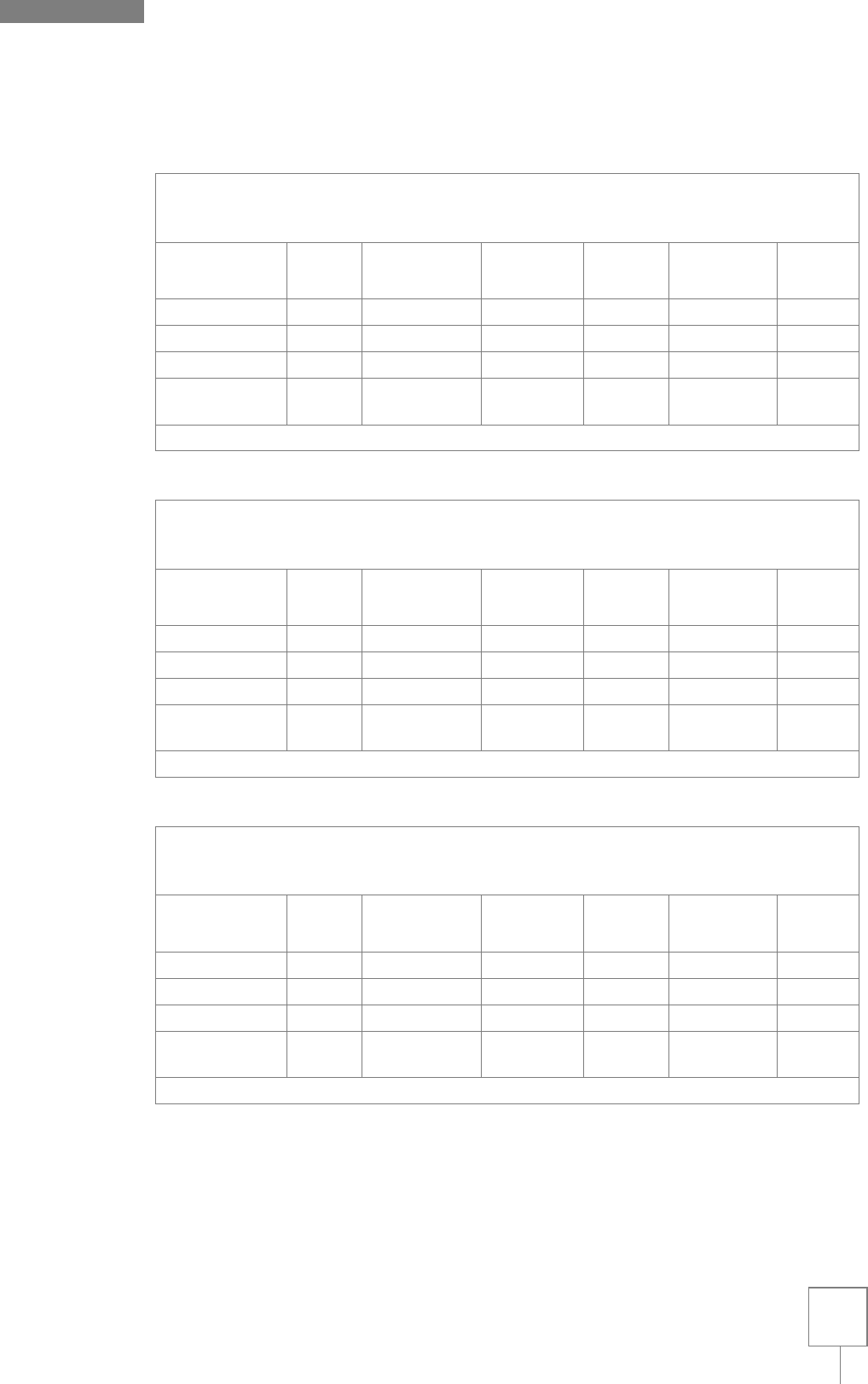

List of figures and tables

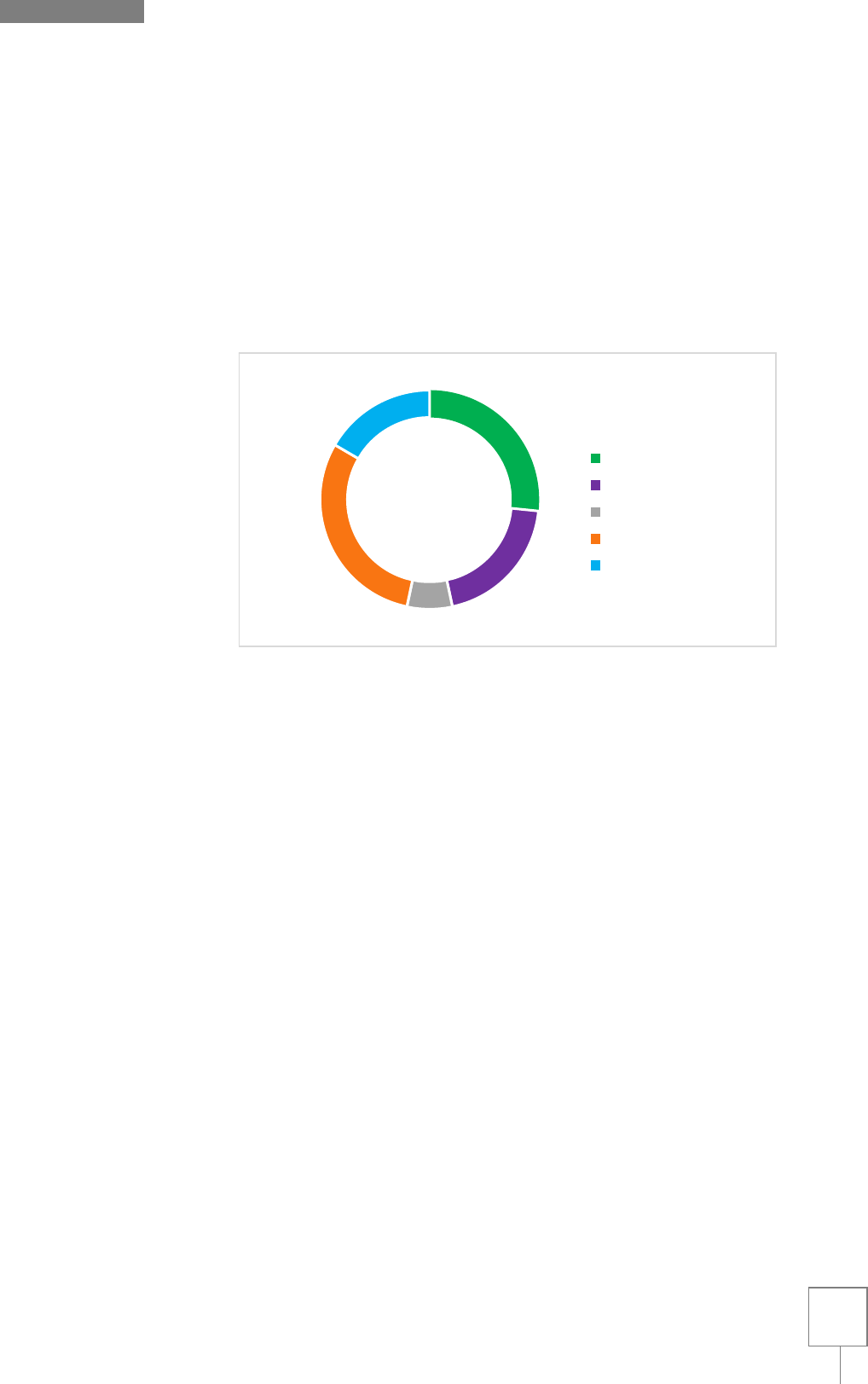

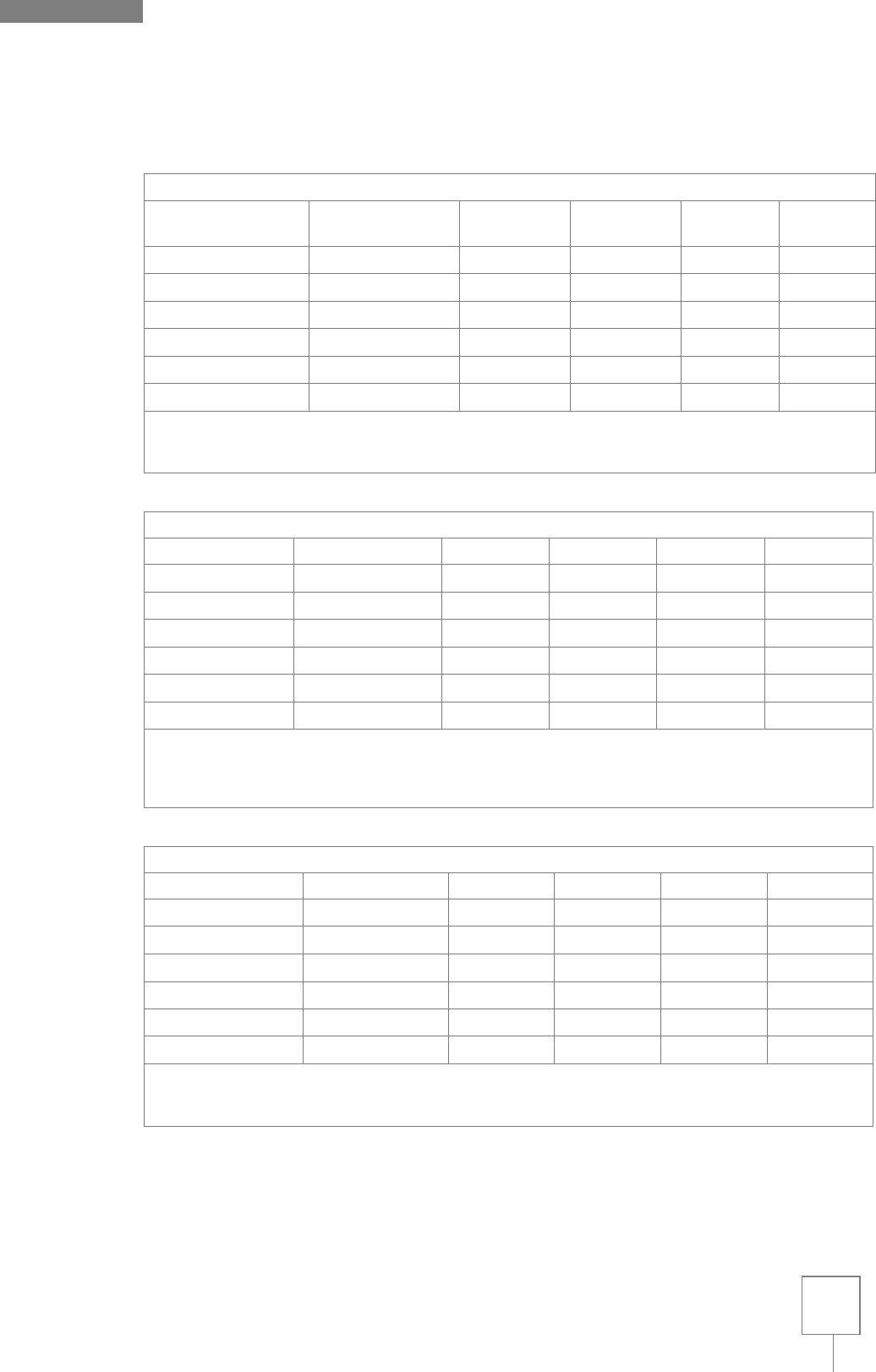

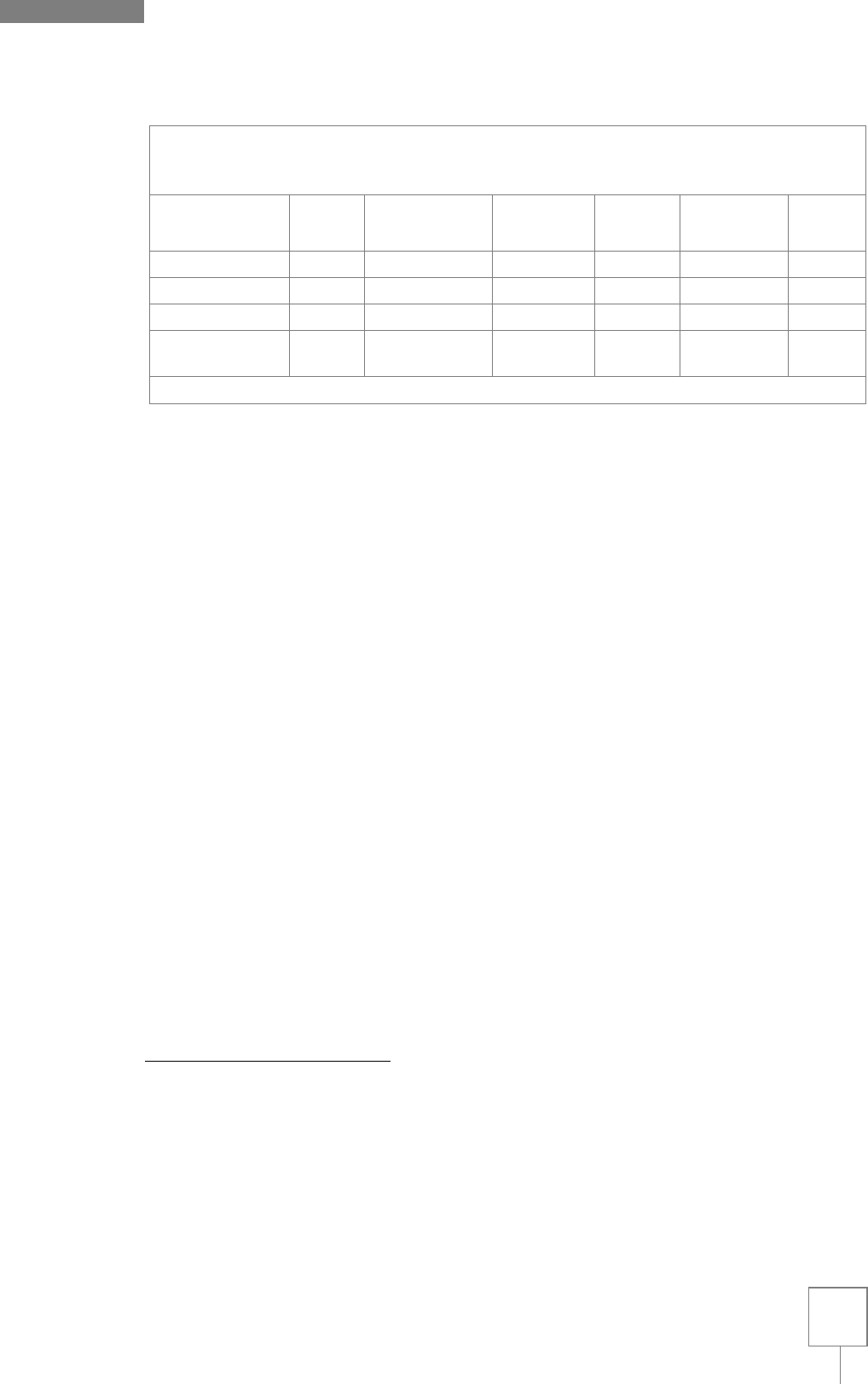

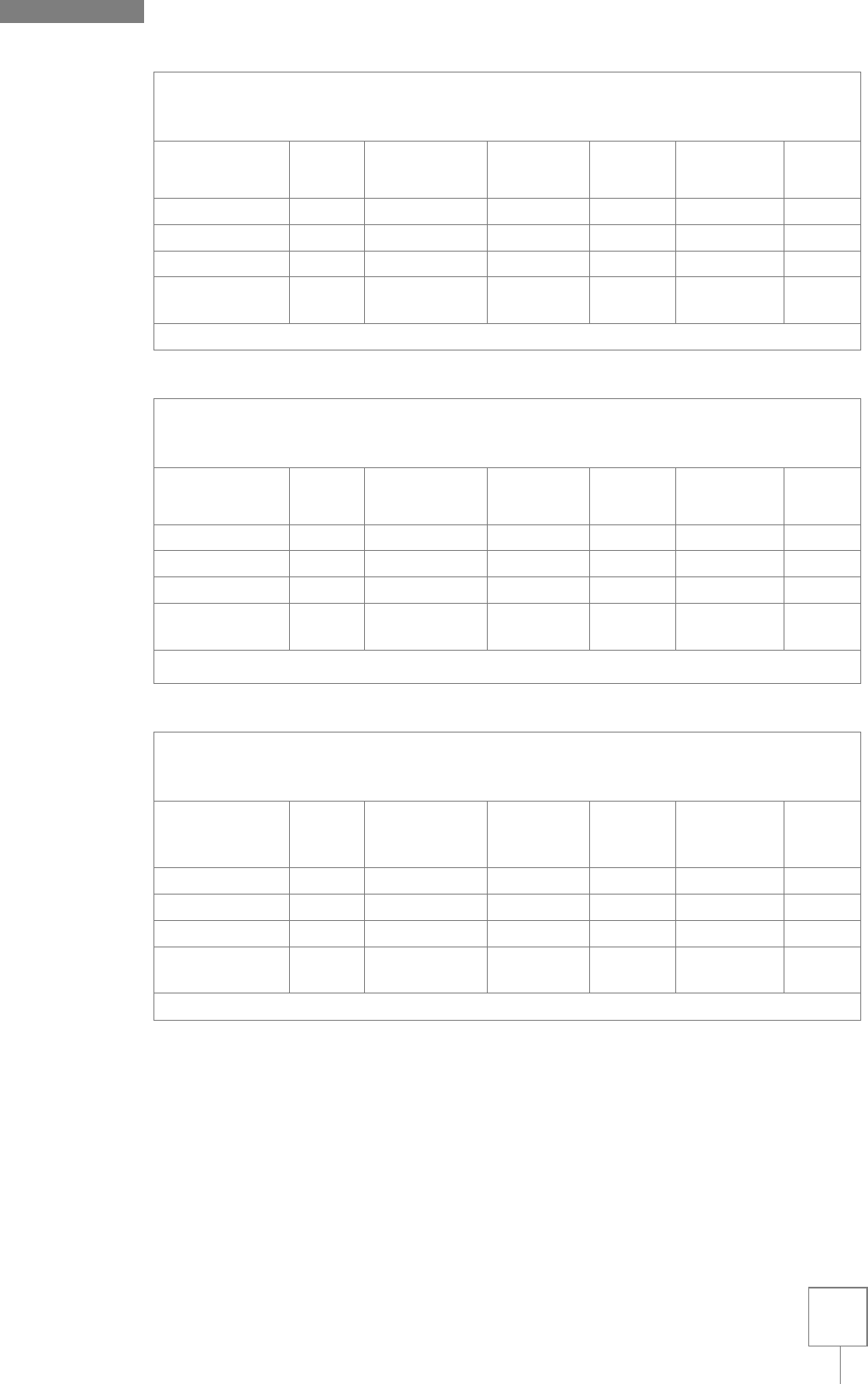

Figure 1 - Contributor profile. Source: Subsidy Collection 03/20 - Preparation 43

GDE/SDS/ANTAQ.

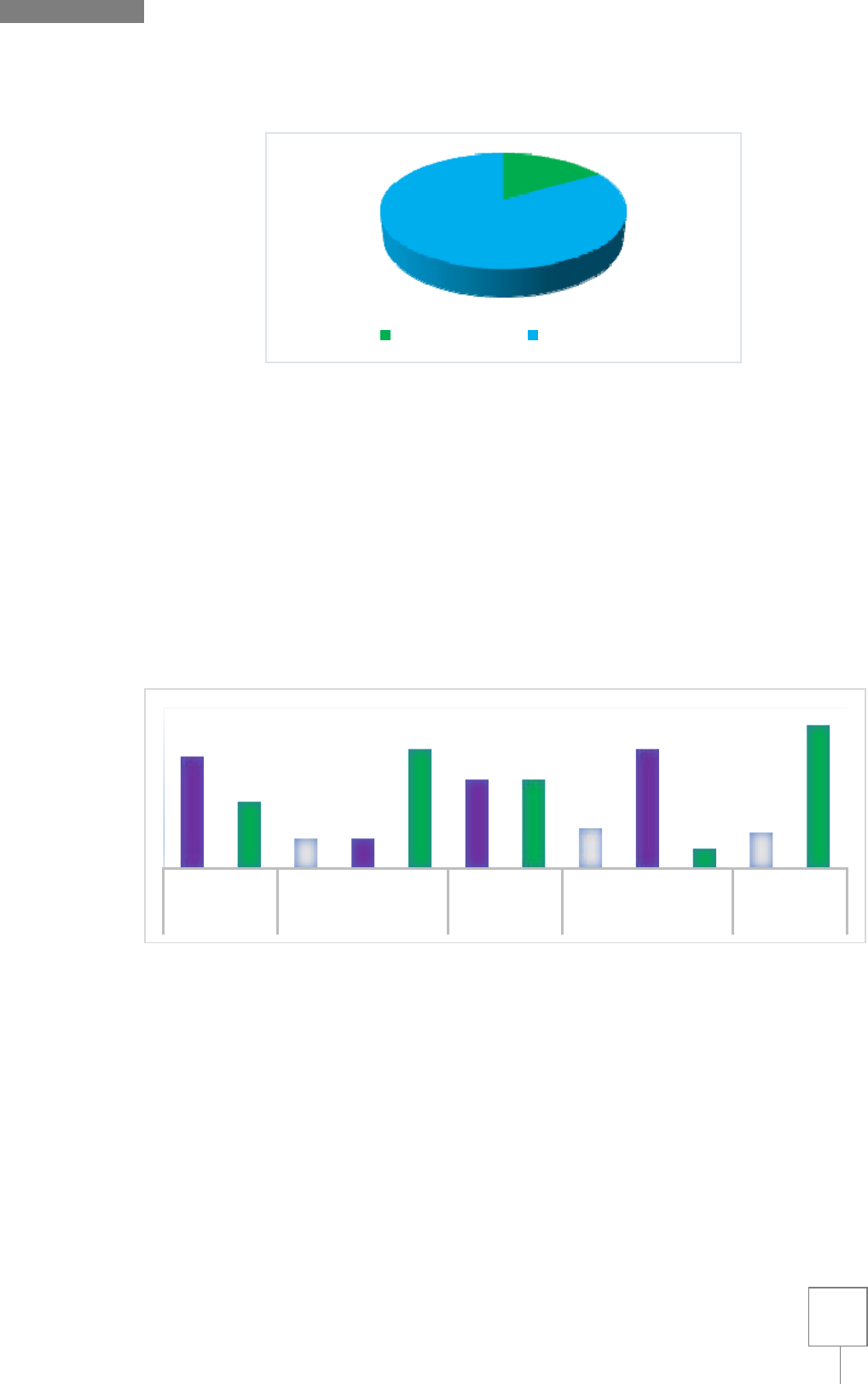

Figure 2 – Legal nature of container demurrage. Source: Taking 44

Grants 03/20 – Preparation GDE/SDS.

Figure 3 – Is the Term of Responsibility an adhesion contract? Source: Taking 44

Grants 03/20 – Preparation GDE/SDS/ANTAQ.

Figure 4 – Favorable to some form of demurrage regulation? Source: Taking 45

Grants 03/20 – Preparation GDE/SDS/ANTAQ.

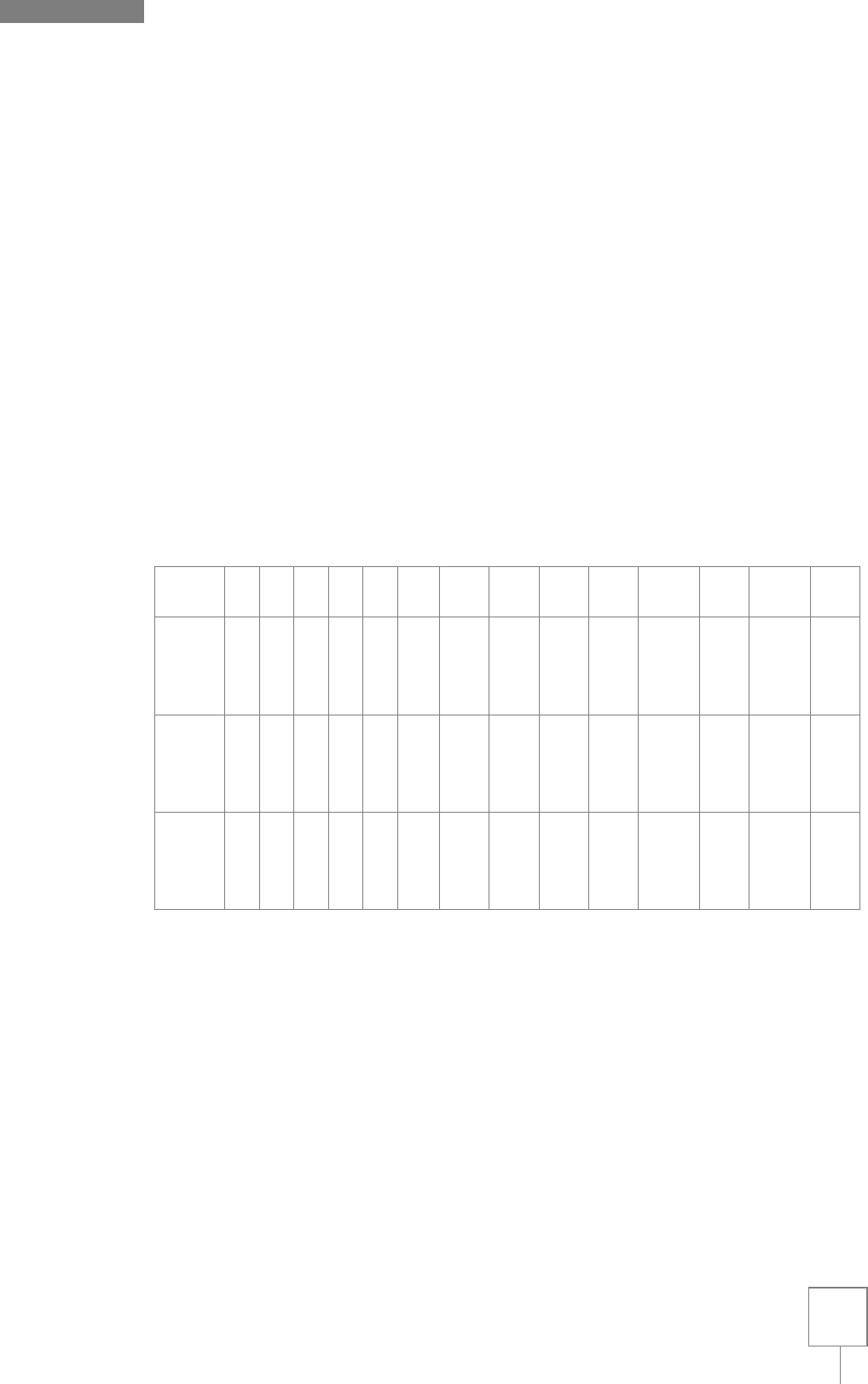

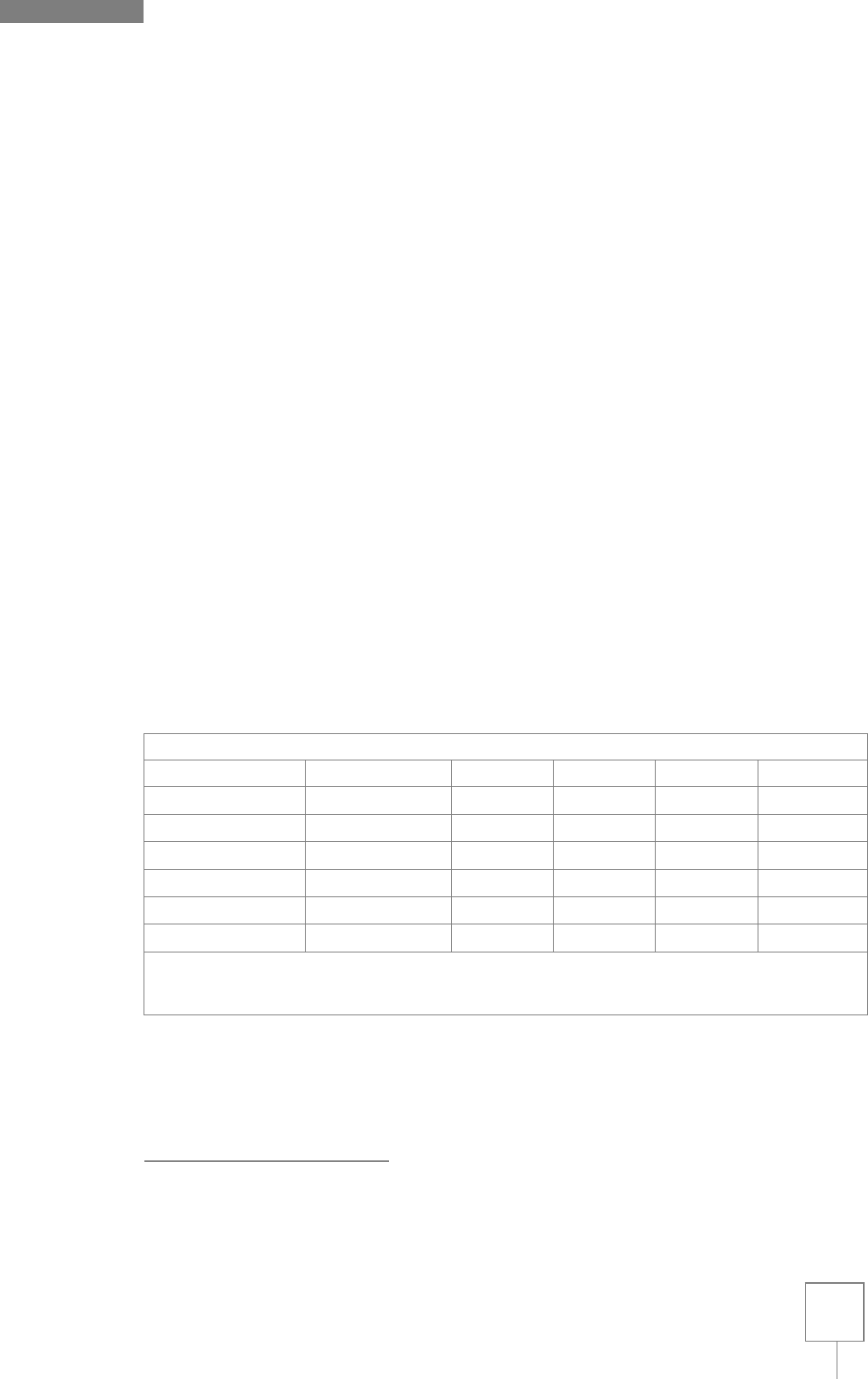

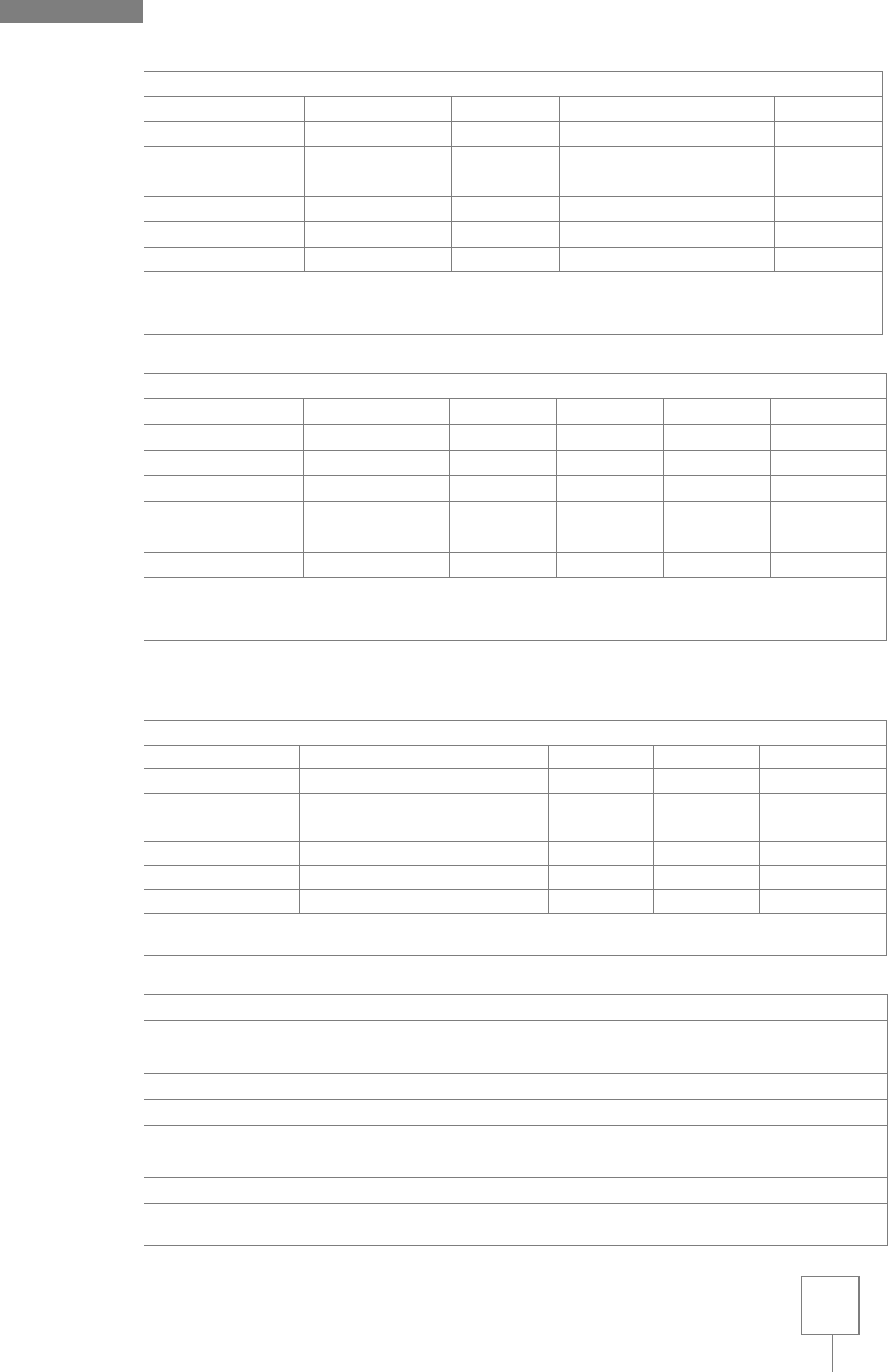

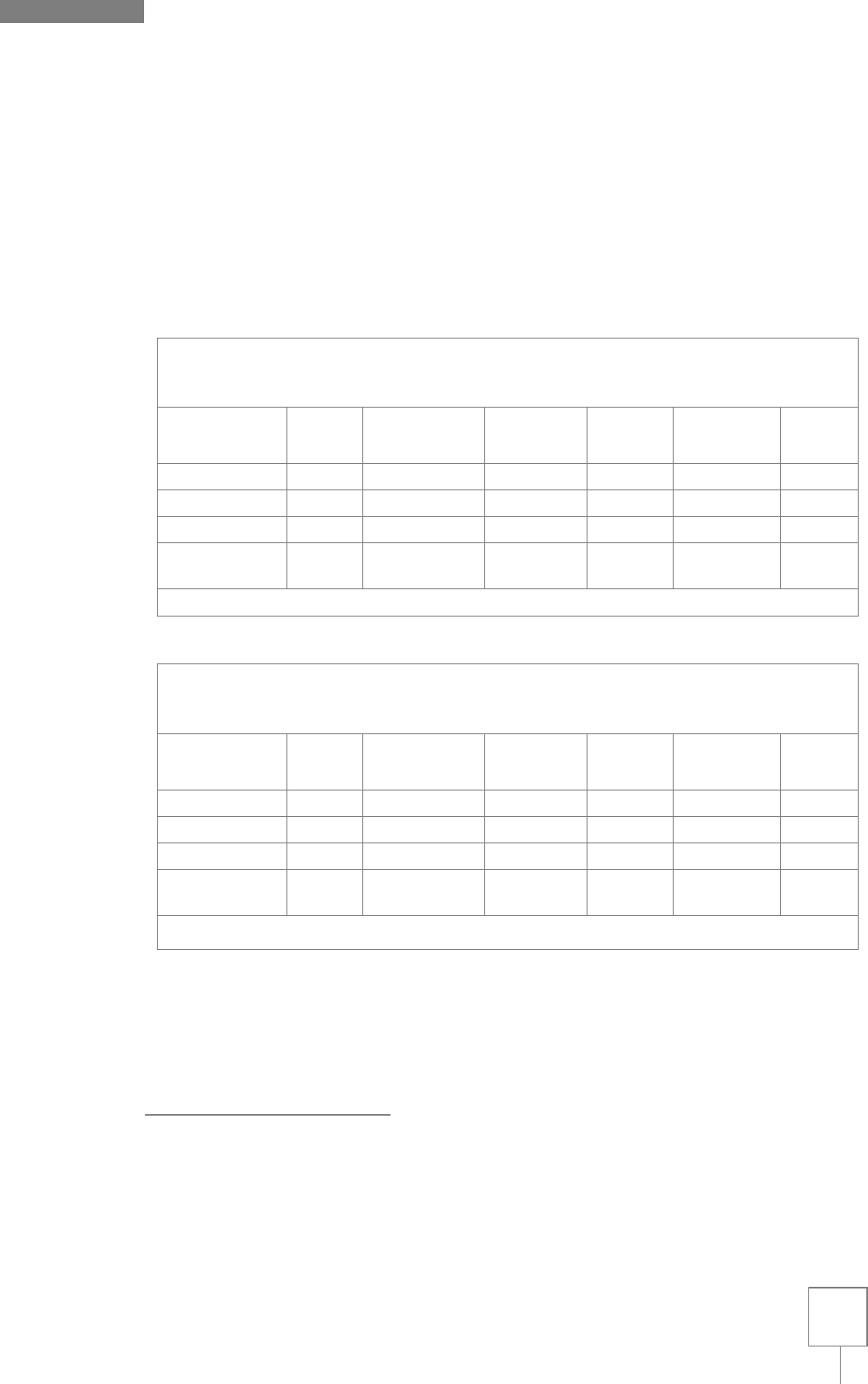

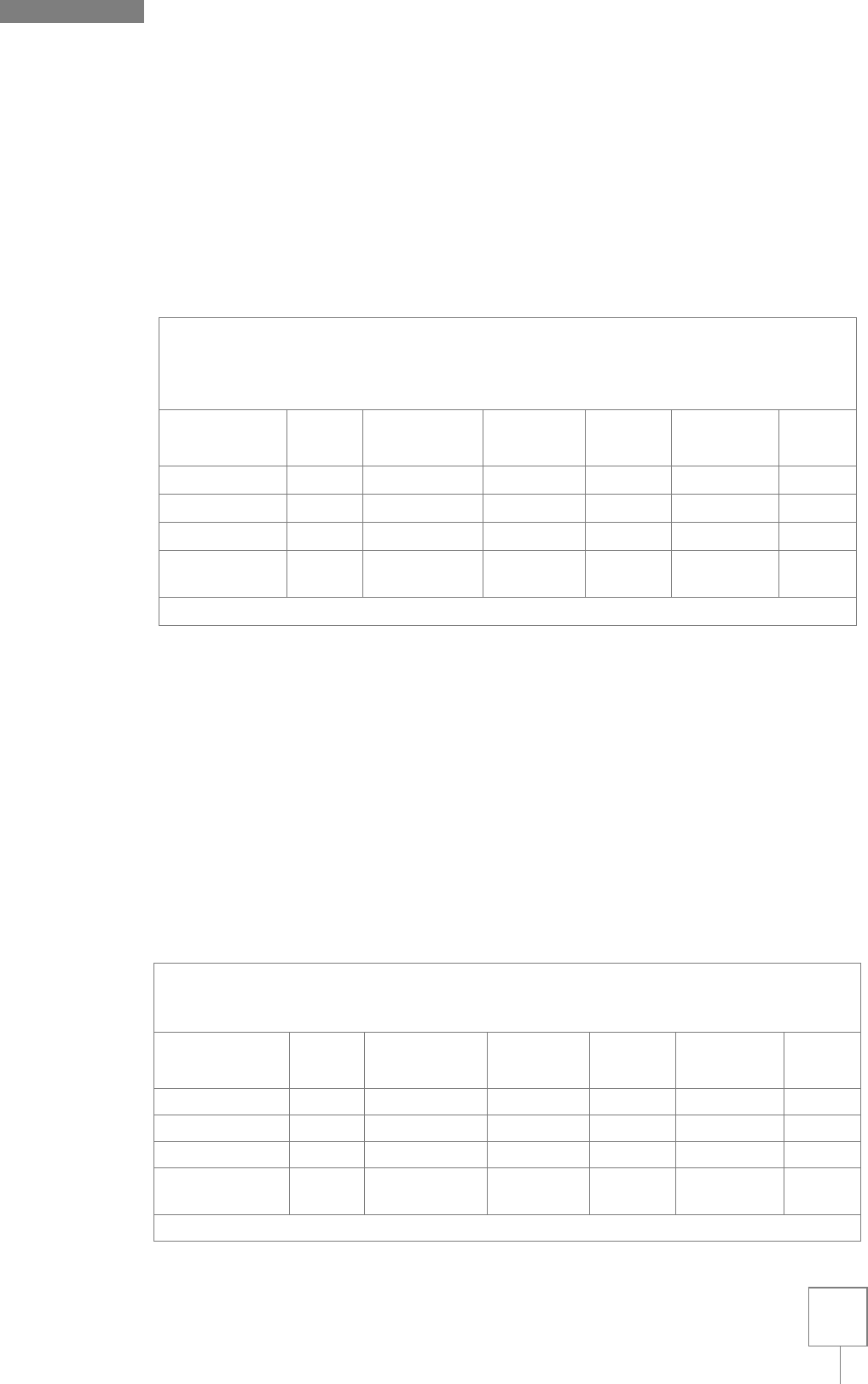

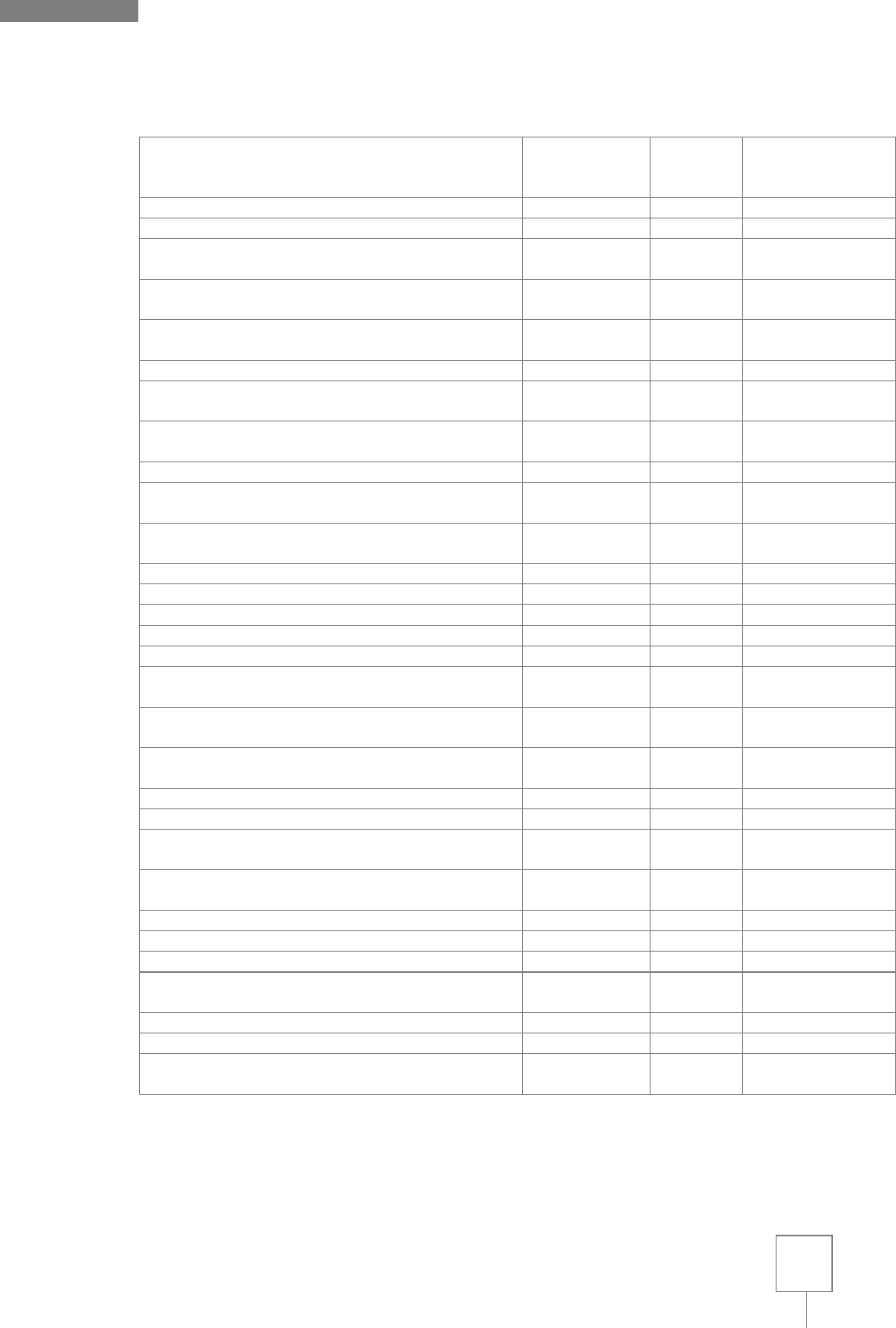

Table 1 – Accumulated movement, in TEU, between Brazilian and foreign ports 47

(2018). Source: ANTAQ. Statistical Yearbook (2018).

Table 2 – Sampling of ports by continent. Source: Preparation GDE/SDS. 47.

Table 3 – Market share and demurrage data source for each 48

maritime carrier. Source: Market share. Available at:

https://alphaliner.axsmarine.com/PublicTop100/. Access on 11/13/2020. Preparation

GDE/SDS.

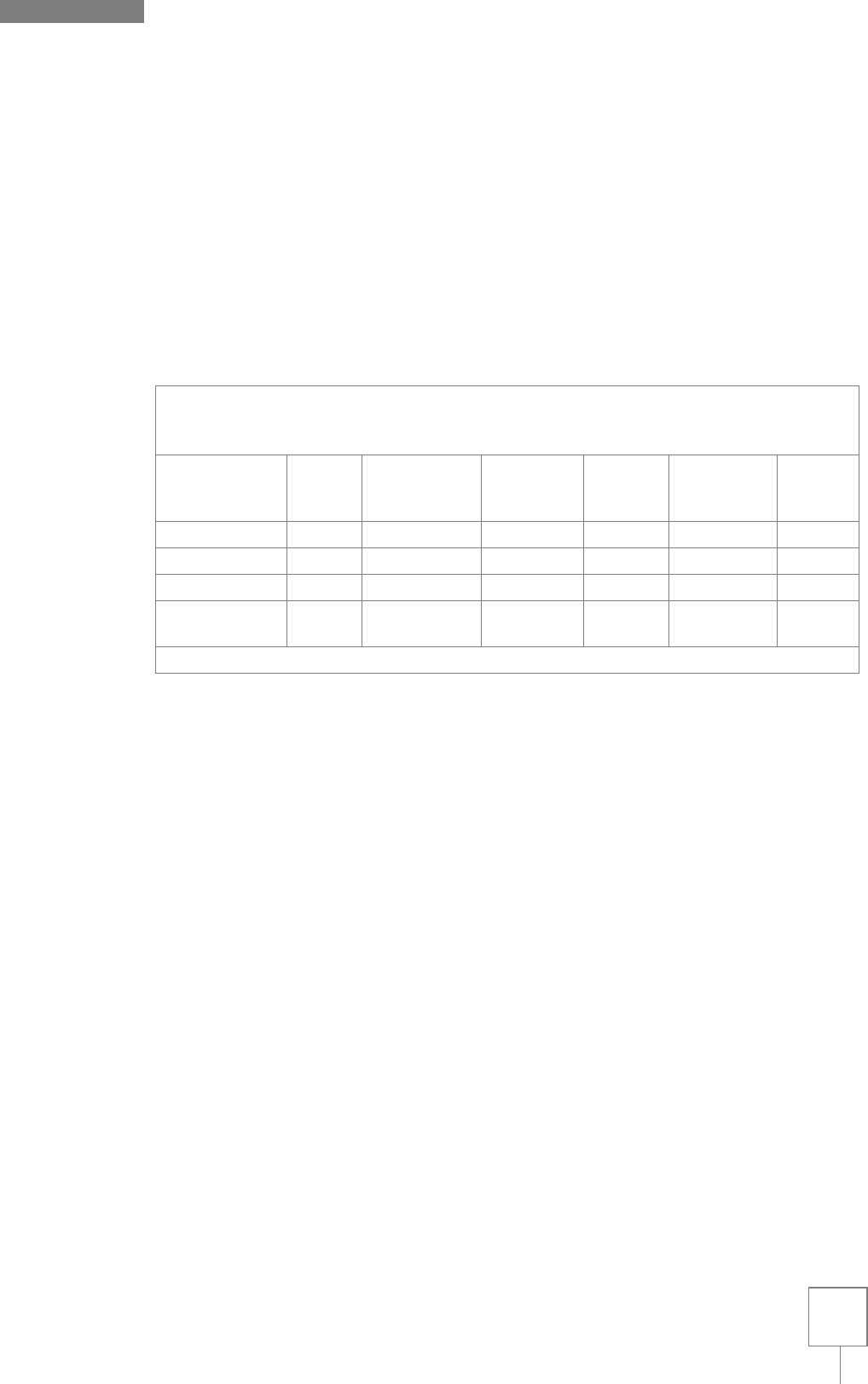

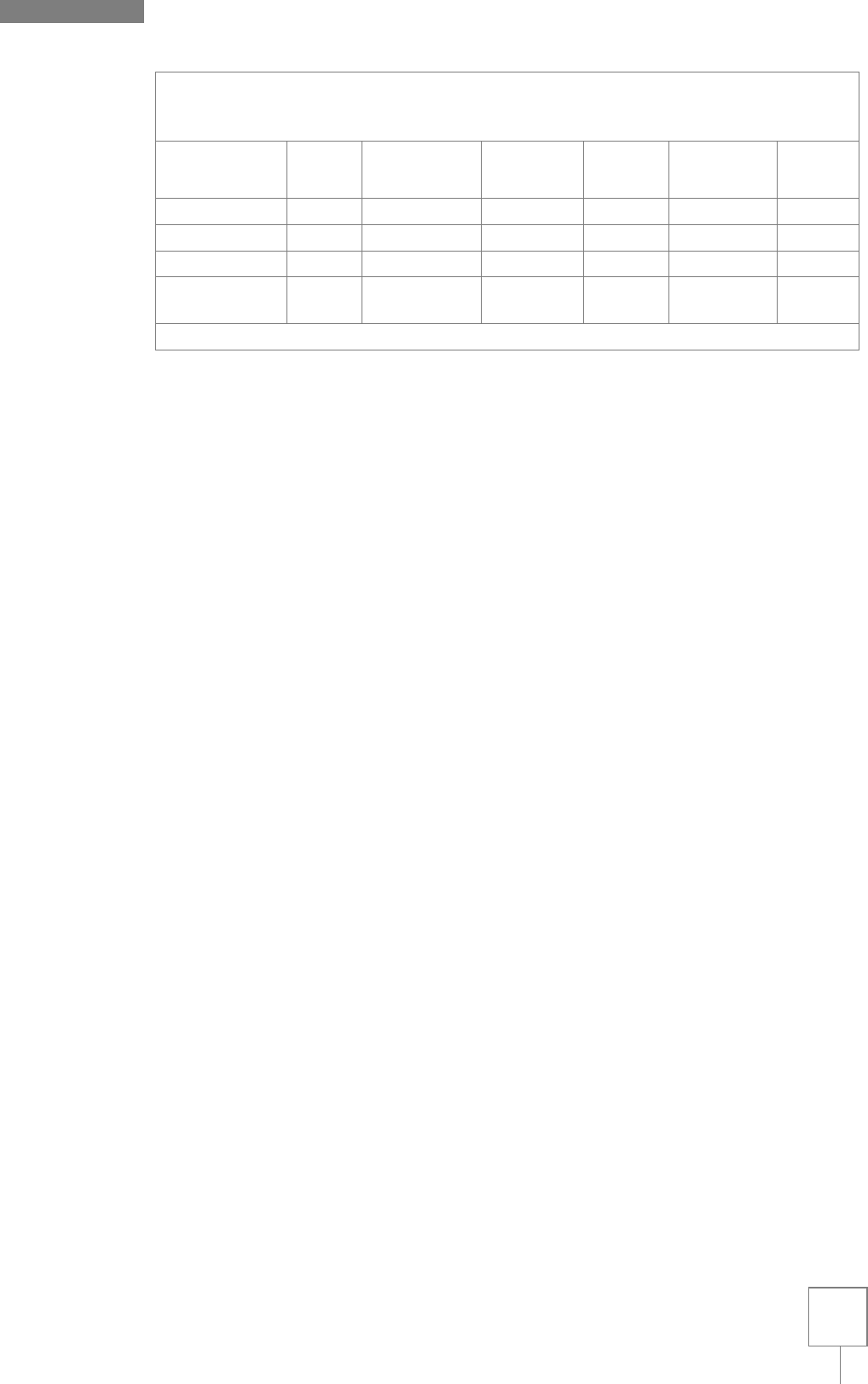

Table 4 – Average Demurrage price per carrier on import on the 14th day 54

(USD/day).

Table 5 – Average Demurrage price per carrier on import on the 14th day 56

(USD/day).

Table 6 – Term of free stay on import, by shipowner. 57

iv

SUMMARY

List of figures and tables IV

1. INTRODUCTION 5

2. LEGAL NATURE OF DEMURRAGE 11

2.1. Origin 11

2.2. Doctrinal differences 16

2.3. Dominant jurisprudence 19

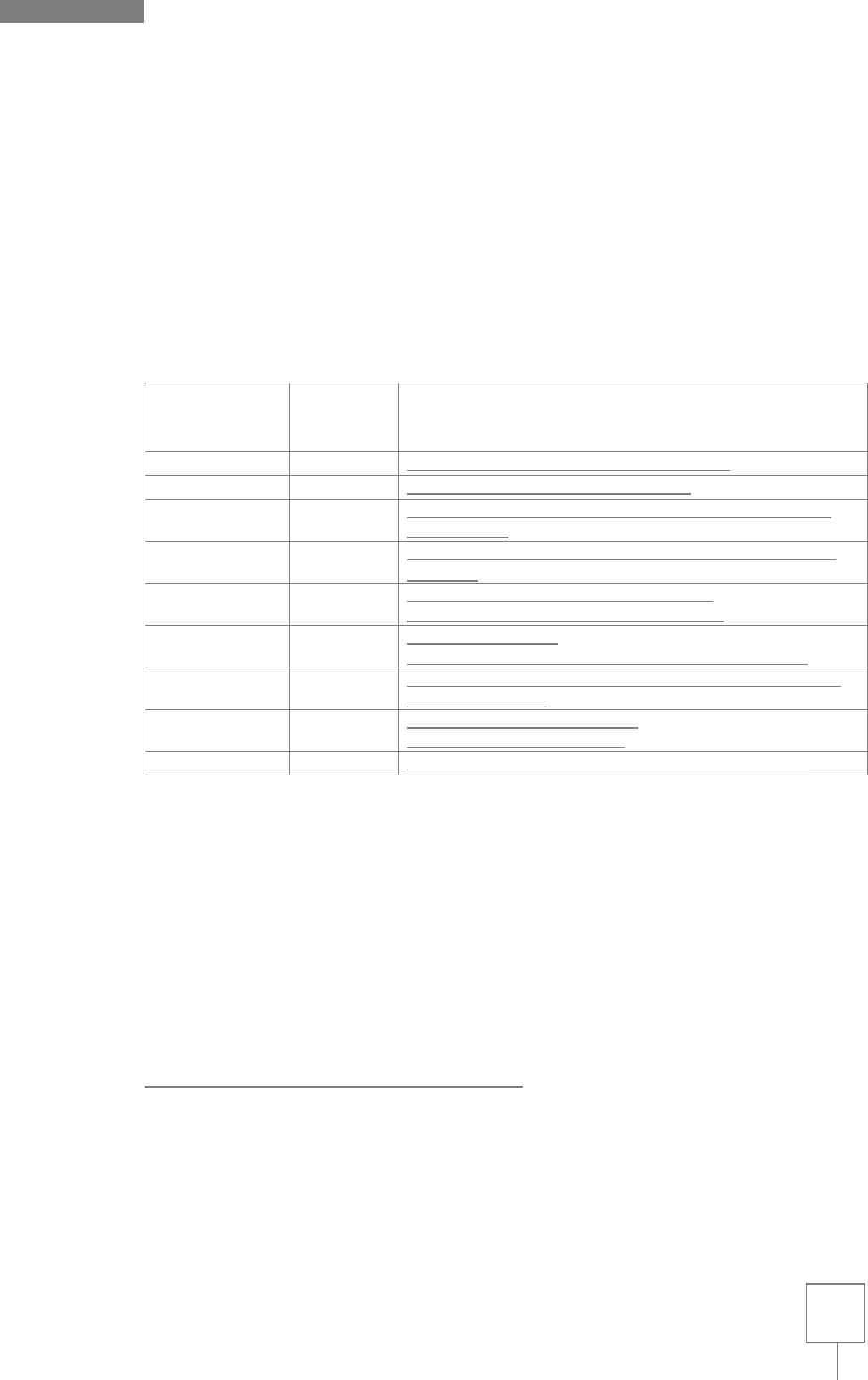

3. INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE 21

3.1. FMC interpretive rule 22

3.2. FIATA recommendations 30

4. DEMURRAGE CHARGE

IN BRAZIL 31

4.1. Term of liability for

container return 32

4.2. Customs broker role 35

4.3. Spread charge on demurrage 38

4.4. Brazilian logistical problems 39

4.5. Positioning of interest groups

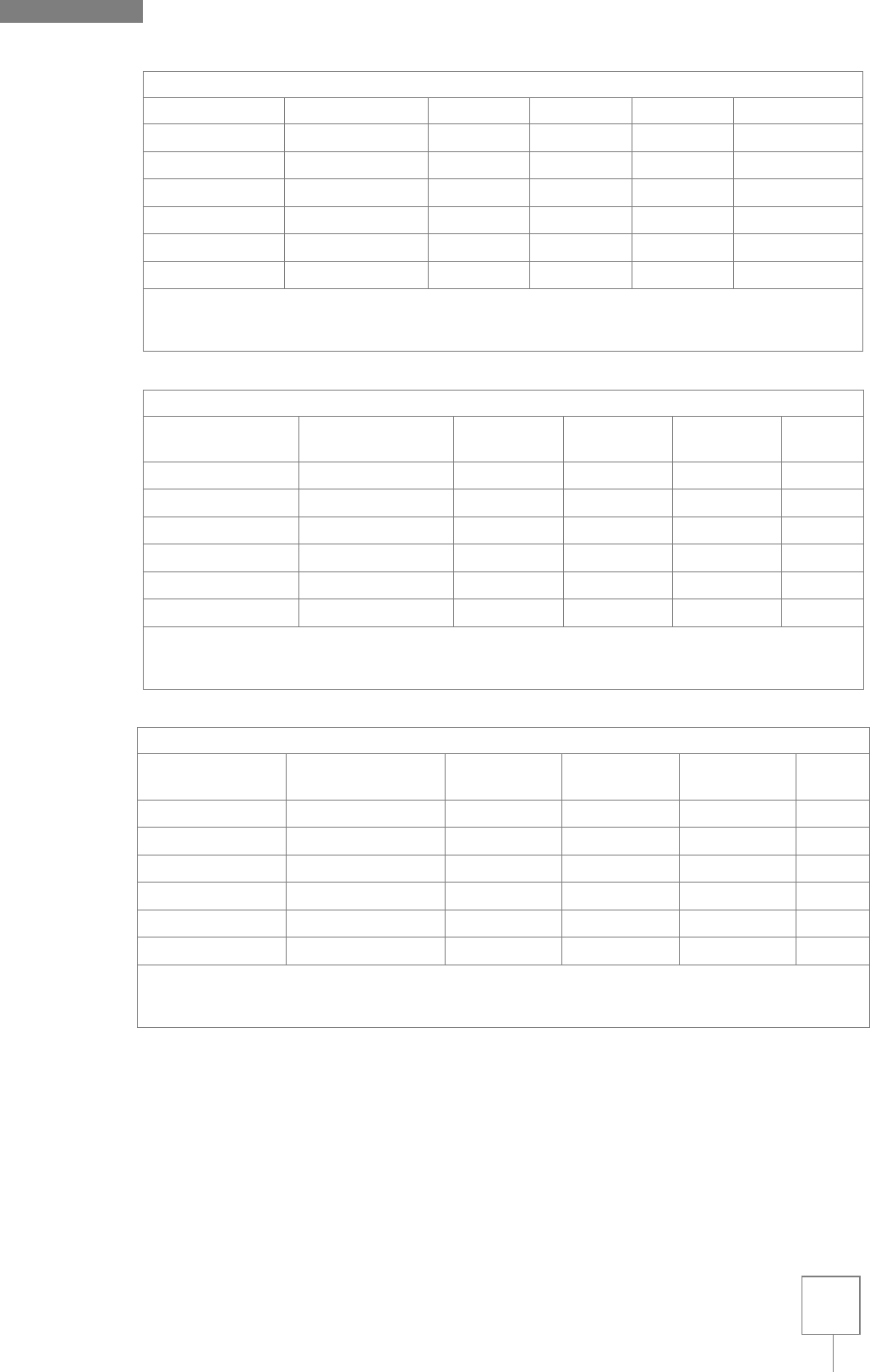

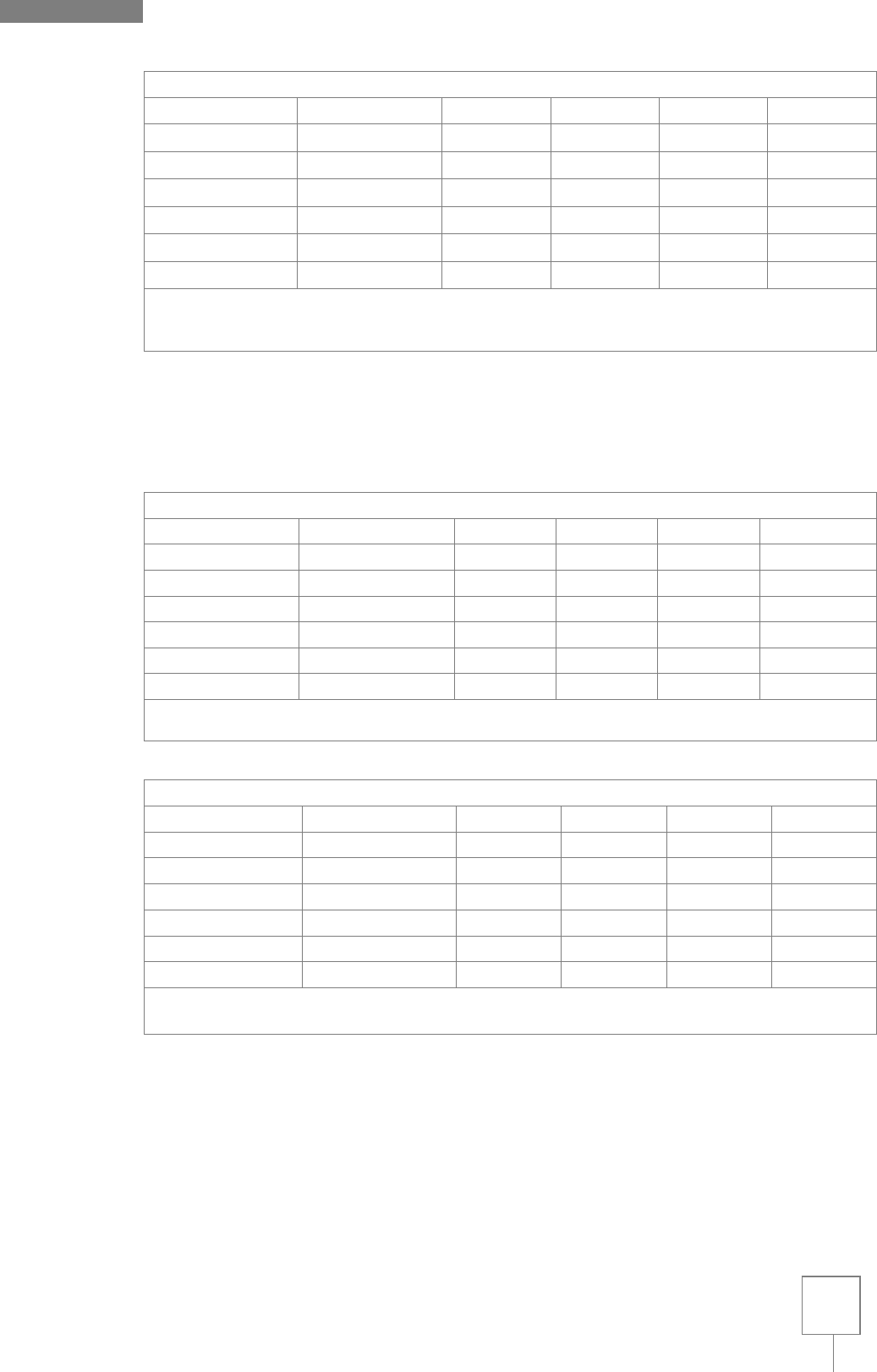

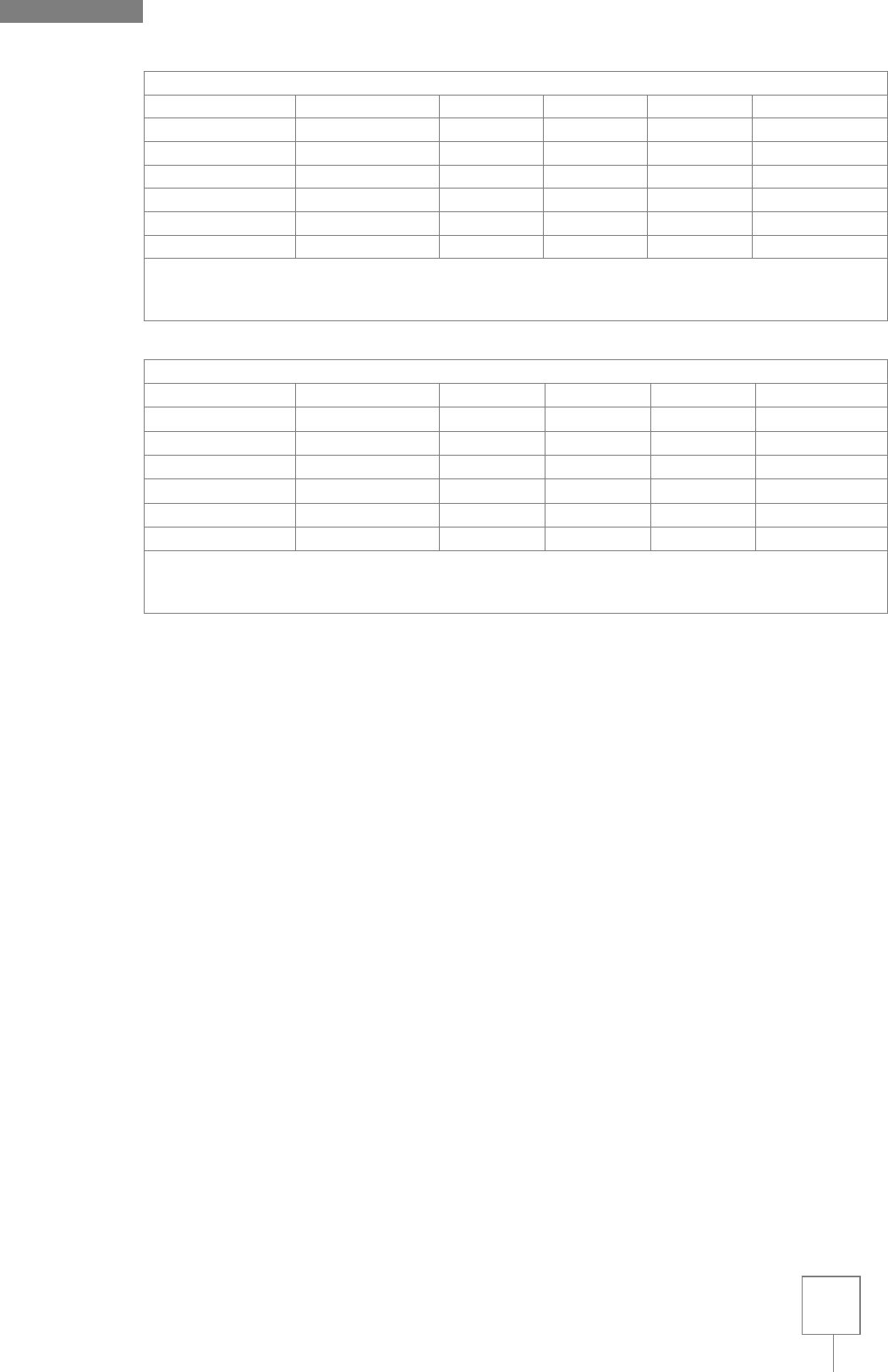

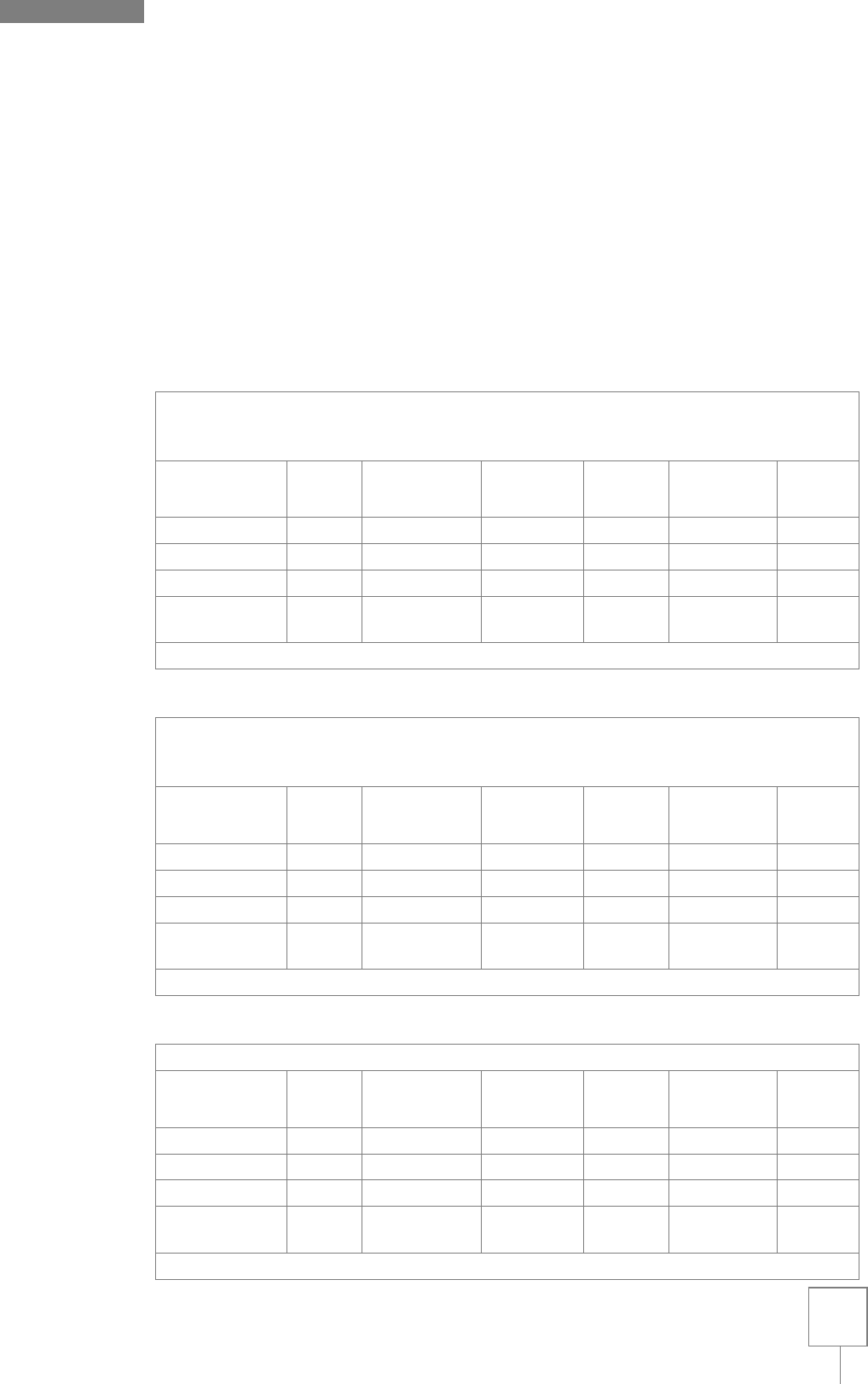

5.5.1. Import demurrage values 54

5.5.2. Export demurrage values 56

5.5.3. Free stay periods on import 57

5.5.4. Free stay periods on export 58

5.6. Comparative analysis of demurrage

values and free stay periods 59

5.6.1. Average demurrage on import 60

5.6.2. Average demurrage on export 62

5.6.3. Free stay on import 64

5.6.4. Free stay on export 66

6. CONCLUSIONS 67

7. REFERENCES 71

8. ATTACHMENTS 76

1 - Interpretive Rule of Demurrage and Detention

under the Maritime Navigation Act – United States

Federal Maritime Commission 76

2 - Quantitative and Summary of Contributions in Subsidy

Collection nº 03/2020

in taking grants

42

Subsidy Collection nº 03/2020 78

5. VALUES COMPARISON 46

5.1. Sampling 47

5.1.1. Ports 47

5.1.2. Maritime carriers 48

5.1.3. Types of containers 48

5.2. Average demurrage

calculation methodology 49

5.3. Methodological observations 50

5.4. Type of research 53

5.5. Demurrage fees and

free stay periods 54

International experience in demurrage regulation

5

1. INTRODUCTION

As Silveira (2018) points out, in the early 1990s, concomitantly with the imports’

explosion caused by the opening of the economy, maritime navigation began to suffer

from the lack of containers. Brazilian importers, used to receiving goods and taking

them to their facilities, used the containers as warehouses taking months to return

them, without incurring any burden. Faced with this situation, some shipowners started

to enforce the “container clause” in the bill of lading, where the free days and days on

demurrage were noted.

The objective, at first, was to promote the awareness of importers for

the quick return of the units used to package the goods, but it soon

became a major source of income, because importers were not able

to spawn the units and return them in time to meet the deadline.

(SILVEIRA, 2018, p.5)

Therefore, the demurrage of containers stems from the imbalance in the movement of

containers in export and import. The logistical bottleneck demanded a positioning by

the carriers to guarantee that the containers would be returned within the agreed

period and that the logistics chain would not be interrupted.

The causes for non-return within the agreed period are numerous, but they become

more relevant when the system does not work optimally. Despite pioneering efforts, a

decade after the opening of the economy it was still necessary to publish articles in the

specialized press that pointed to the institute of container demurrage as a legal

solution for the reinsertion of containers in the logistics chain.

The reasons for the delay in returning the empty unit are the most

varied: delay in starting the procedures with the shipowner;

documentary failures; goods that get stuck in the bureaucracy of

Customs agencies; seizure of imported goods without meeting legal

requirements; commercial disagreements between exporter and

importer, causing the abandonment of the cargo and its forfeiture

decree; lack of space or conditions to receive the goods at the

importer's premises, with the use of the container as packaging; and,

finally, where the cause and consequence of the problem are

confused, some importers, aware of the difficulty in obtaining empty

containers, retain the unit deliberately in order to use it in future

exports.

[...]

International experience in demurrage regulation

6

One of the ways to overcome the lack of containers obstacle is the

awareness of all players in the sector that any problems with the

goods do not affect the cargo unit and cannot harm its immediate

return to the shipowner. The most suitable way to create this culture

in the market is through the charging of container demurrage.

Although the legal provision does not have the force to oblige the

importer to promptly return the cargo safe, there is a clause in the

transportation contracts that obliges the importer to pay a fine for its

unreasonable retention.

[...]

The receipt of amounts as demurrage by itself would already have a

fairly positive effect minimizing the losses caused by the unavailability

of the container, indirectly contributing to moderate eventual

increases in freight. However, it is the long-term effects of demurrage

collection, carried out in an effective, orderly, and permanent way by

all shipowners, which are the most interesting.

The certainty, on the part of importers, that demurrage will be

charge, will contribute to avoid delays in the return of the container.

The importer, fearful of paying the fine, will be more attentive and

diligent, creating mechanisms and procedures to enable the unloading

and return of the container in the shortest possible time. The importer

will be able to differentiate the load from the load unit. Any problems

with the goods will be awaiting solution, prioritizing the delivery of the

empty container, with the immediate request for its unloading by the

importers.

(GAZETA MERCANTIL, 2004, p. 2)

Currently, charging for container demurrage is already a widespread practice in the

Brazilian market, but its legal institute needs to be further discussed. Conceptually, it is

a daily amount agreed by the parties in favor of the owner or possessor of the

container, resulting from the container not being returned within the agreed-upon

period of free time.

It is, in fact, a pre-fixation of the indemnity for the delay in the return

of the container, precisely carried out to avoid uncertainty in the

quantification, as is the case with the conventional penalty clause.

This value works as a means of repression for the user to return the

cargo unit within the deadline provided in the Ocean Bill of Lading

and, in case of non-compliance, early settlement of losses and

damages due to the injured party. (CECAFÉ, 2020 – Subsidy

Collection)

1

1 Subsidy Collection N

º

03/2020/SRG – ANTAQ was carried out from 09/21/2020 to 10/16/2020 and was

later extended until 11/03/2020. Its objective was to send contributions and subsidies for the

implementation of topic 2.2 of the 2020/2021 Biennium Regulatory Agenda, which seeks to develop a

methodology to determine abusive charging for container demurrage.

International experience in demurrage regulation

7

Thus, one of the few consensuses in the analysis of the issue is the dual purpose of

container demurrage: (i) compensation for losses and damages of the maritime carrier

(freight that has not been obtained and logistical losses with the repositioning of

containers, for example); and (ii) to compel the return of the container.

These inherent and inseparable functionalities are responsible for conflicting

understandings as to the legal nature of container demurrage. The purpose of the

indemnity is to compensate for losses and damages and the purpose of the penalty

clause is to compel the return of the container. The discussion is relevant because its

definition has significant consequences for the need to prove intent, the limitation of

amounts, the statute of limitations, tax effects, among others.

It should be noted that there is no law that specifically deals with container demurrage.

In the absence of specific legislation, it is the national jurisprudence that has been

guiding interpretations about the applicable legal regime. In this context, container

demurrage is now charged from users in analogy to the demurrage of ships,

consolidating itself as a specific institute for the maritime transportation of

containerized cargo.

It is worth mentioning that

Lex Maritima

is recognized by Brazilian Legislation as a

criterion for contractual interpretation, as per art. 113, §1, II of the Civil Code and

article 4 of the Law of Introduction to Brazilian Rules of Law

2. However, the

internalization of international usages and customs is not unconditional, as it is limited

the precepts of Brazilian Law, which require the observance of solidary contractual

principles, such as the social function of the contract, objective good faith, and the

principle of contractual justice.

2 As already explained, there has never been a federal legislation in Brazil that specifically deals with the

legal provision and legal obstacles arising from container demurrage charges. In the absence of specific

legislation on the subject, Decree-Law nº 4.657/1942, known as the Law of Introduction to the Norms of

Brazilian Law, expressly provides the content of art. 4, which governs the following: “When the law is

silent, the judge will decide the case according to analogy, customs and general principles of Law” – and

this is what has been effectively constructed by jurisprudence. [...] Our Commercial Code (Law nº

556/1850) includes maritime trade in its second part, but only issues related to the chartering of ships,

being completely silent on the subject of container demurrage, which can even be explained by a temporal

aspect, since the phenomenon of containerization in international maritime transportation effectively

occurred in Brazil after the 1980s – more than a hundred years after the enactment of the Commercial

Code, which, it is worth noting, dates from 1850. (WINTER, 2019, p.42)

International experience in demurrage regulation

8

The statements of maritime carriers, exemplified in the excerpt transcribed below,

emphasize that the transportation of cargo is a private activity, linked to the activity

and performed by parties with equal capacities:

3. The maritime transportation contract reflects a convergence of

wills. It is not an essential public service and the parties, as legitimate

and capable legal entities, are free to choose with whom to contract.

In this sense, contractual freedom is a corollary of the principles of

Private Law applicable to maritime transportation contracts.

(CENTRONAVE, 2020 – Subsidy Collection)

On the other hand, scholars, and advocates of users' rights postulate that the Bill of

Lading (BL) has previously stipulated clauses with no room for negotiation, which

would limit isonomy in the definition of the clauses.

In fact, although the contract of carriage is formally considered a

bilateral contract, it expresses the concrete will of only one of the

parties, the carrier.

The carrier imposes its will through a written contract with printed and

previously stipulated clauses. Hence the term contract of adhesion.

The will of the shipper or the recipient of the cargo is limited to the

adherence to the contractual terms previously stipulated by the

carrier. (CREMONEZE, 2012, pp.33 and 34)

The numerous disputes in all instances of the Brazilian judiciary indicate that the issue

is far from being settled. If on one hand there are those who defend the existence of

isonomy between the parties and the prevalence of the

Pacta Sunt Servanda

principle,

others demand some state regulation as to the values stipulated by the carrier. Faced

with this situation, ANTAQ has been called upon several times to take a stand.

Currently, in addition to the applicable Civil Code provisions, especially those related to

the statute of limitations, we have in force ANTAQ Normative Resolution nº 18/2017

(RN-18), which provides for the rights and duties of users, intermediary agents and

companies that operate in maritime support navigation, port support, cabotage and

long distance, and establish administrative infractions. The normative reserved Section

III (Container demurrage) to address the issue and contributed to reduce information

asymmetry, defining, after extensive discussion with the regulated sector, the concept

of container demurrage and the concept of free time. Furthermore, RN-18 determined

the obligation of transparency and prior knowledge of the amounts charged, in addition

to establishing clear milestones for the start and end dates of the free time.

International experience in demurrage regulation

9

Despite the regulatory advances introduced by RN-18, there are still many disputes and

legal actions regarding the amounts charged for container demurrage. Many users of

waterway transportation services allege the existence of abusive charges. To analyze

the issue, ANTAQ included in its Regulatory Agenda, Biennium 2020/2021, the topic

2.2 – Development of a methodology to determine abusive charges for container

demurrage

(ANTAQ Resolution nº 7.754/2020).

Thus, seeking to support the analysis of the theme, the Department of Research and

Development (GDE/SDS) was asked to conduct the study “International Benchmark of

Demurrage Regulation,” in line with its regulatory competences

3.

This study contributes to the understanding of the international experience on the

charge for container demurrage and aims to map the treatment applied in other

countries to the regulatory problem under analysis, to subsidize the survey of possible

actions and identify effects or impacts not yet detected by the Agency.

As specified in the General Guidelines and the Guidance Guide for the Preparation of

Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) of the Presidency of Brazil

4, the study of international

experience can contribute to the various RIA stages. Example:

Bringing other perspectives on the regulatory problem.

Pointing out approaches and possibilities for action not yet identified

by the agency, body, or entity.

Pointing out impacts of the problem or action alternatives not initially

identified by the agency, body, or entity.

3 According to ANTAQ's Internal Regulations (ANTAQ Resolution N

o

5.585/2014, art. 63, it is up to the

Department of Research and Development– (SDS), [...] to “IV - carry out studies applied to the definitions

of tariffs and prices practiced in cargo handling and storage activities in organized ports and authorized

port facilities and transport of passengers and cargo in navigation, in comparison with the costs and

economic benefits transferred to users by the investments made; V - carry out studies and research that

promote continuous improvement of knowledge of the regulated market, with a view to strengthening the

management quality of operators operating within the scope of the national waterway system; VI - carry

out studies that support the formulation of public policies within the scope of the national waterway

system.”

4 General guidelines and guidance for the preparation of a Regulatory Impact Analysis – AIR/Sub-office of

Analysis and Monitoring of Governmental Policies – Brasília: Presidency of Brazil, 2018.

International experience in demurrage regulation

10

Bringing useful data to analysis.

Anticipating problems observed in action alternatives already tested.

Anticipating unexpected reactions from agents to already tested action

alternatives.

Assisting in the definition of intervention monitoring indicators.

Bringing benchmark performance parameters. (PRESIDENCY OF

BRAZIL, 2018, p. 66)

Therefore, the study presented here aims to identify the international experience in the

regulation of demurrage of containers and analyze the applicability of international

concepts to the Brazilian legal system and the national logistics reality.

Accordingly, the first chapter, entitled “1 – LEGAL NATURE OF DEMURRAGE,”

addresses the origin of the institute, differentiating the demurrage of containers from

that of ships. Then, the doctrinal divergences about the legal nature of demurrage and

the dominant jurisprudence are presented. The chapter discusses the practical effects

of each possible framework.

The following chapter, “2 – INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE,” analyzes the solutions

pointed out by some countries, bringing other perspectives to the issue, with the

suggestions of the International Federation of Freight Forwarders Associations

(FIATA)5

and the regulatory proposal of the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) being especially

analyzed

6.

Then, chapter “3 – CHARACTERISTICS OF DEMURRAGE CHARGE IN BRAZIL” focuses

on specific Brazilian regulatory problems and makes a statistical analysis of the

taxpayers' positions in Subsidy Collection.

Chapter “4 – COMPARISON OF VALUES” compares the demurrage values of containers

and days of free time charged internationally by the main shipowners operating in

Brazil, in comparison with the values charged in the national territory.

5 FIATA is a non-governmental organization that represents freight forwarders and cargo agents in around

150 countries, being a reference source in international policies and regulations that govern the freight

forwarding and logistics industry. (Source: https://fiata.com/who-we-are.html)

6 The FMC is the US waterway transport regulatory agency, whose goal is to ensure that neither the

activities of liner shipping groups nor the laws or regulations of foreign governments impose unfair costs

on US exporters or US consumers of imported goods. (Source: https://www.fmc.gov/about-the-fmc/)

International experience in demurrage regulation

11

Finally, chapter “5 – CONCLUSIONS” presents the main notes of the previous chapters,

making a critical summary of what was presented.

Considering the stipulated objectives, the methodology applied was exploratory

research, gathering information about the international experience in the regulation of

container demurrage to support an analysis in Comparative Law. Therefore, the subject

was investigated, formulating more precise problems and hypotheses, without

intending to end the discussion.

In this sense, the procedural methodology applied was bibliographic research, in which

knowledge and information about the topic were collected from different published

materials, putting different authors, data and points of view into dialogue.

2. LEGAL NATURE OF DEMURRAGE

2.1. Origin

When starting the analysis of the origin of the container

demurrage charge, it's worth emphasizing Collyer's (2007)

etymological analysis. In addition to delving into the meaning of

the term, the text indicates the spread of the fee in several

countries and languages.

Demurrage is a compound word, formed

by agglutination (demur + rage). The definition of the term is based

on demur: period agreed between the contractual parties during

which the owner or operator of the vessel places and keeps it at the

disposal of the charterer (or the consignee of the goods) for loading

and discharge operations during which no payment is owed.

According to this time approach, demurrage is the utilization of a

vessel beyond its stay; it is the extra time used.

This concept can be confirmed by the simple observation of the words

used to indicate demurrage:

överliggetidsersättning

or

överliggedagspenge

, in Scandinavian countries;

overliggeld

, in the

Netherlands;

Überliegegeld

, in Germany;

surestaries

, in France and

Belgium and even

contro-stallie

, in Italy (TIBERG, 1971, p. 2). The

prefix (over, Uber, sur) is evident in all of them, meaning beyond,

over the stay. It is easy to conclude that the intrinsic meaning of the

word carries with it the notion of time, or excess of time. (COLLYER,

2007, pp. 3 and 4)

Its origin goes back to the first charter contracts and is related to the time that the

ship remained in the port beyond the established term.

International experience in demurrage regulation

12

Demurrage was born out of the

Lex Mercatoria

, the uses and customs rooted in customary Maritime Law which is

traditionally applied to delayed vessel return based on charter contracts instrumentalized in the charter party.

However, after the emergence of containers and their widespread use

in global transport, especially in the maritime modal, the first cases of

container demurrage took place, originating from the maritime

transportation contract, not from the charter contracts.

Container demurrage was accepted in our country without ever having

been properly regulated or affirmed in Brazilian Law. It was

introduced by usage and customs and by analogy with the demurrage

of a ship existing in the Commercial Code of 1850. This circumstance

calls for urgent discussion about its application and its effects on

contemporary reality. (WINTER, 2019, p. 10)

The term is currently used both to define delay and to refer to the amount paid

because of the delay. Frequently, the expression is used with different meanings,

which can lead to a confusion of concepts. At the wharf, some relate demurrage with

the occupation of space in the port, describing it as the overextension of time a

container remains in the terminal, and the amount charged if the container does not

return to its owner within the agreed time is known as detention. For others,

demurrage is the amount paid for prolonged use of the container within the port and

detention for prolonged use outside the port. In the present work, the term detention

is not used. In addition, the terms “demurrage” or “container overstay”

7

are

permutable and refer only to the delay in returning the container, with no relation to

the additional stay in port.Although it is relatively easy to adjust the understanding of

the term, defining its legal nature brings many controversies. Even in relation to the

demurrage of ships, which has been charged for centuries now, there is great

disagreement in the doctrine as to its legal nature.

8

7 The concept adopted in this work is that of ANTAQ Normative Resolution N

o

18/2017, art. 2, XX -

container demurrage: amount due to the maritime carrier, the container owner or the forwarding agent for

the days that exceed the agreed period of free time of the container for shipment or for its return.

8 Defending the indemnity character of the demurrage, DINIZ (1998, p. 56); SAMPAIO DE LACERDA (1984,

p. 191); and GILBERTONI (2005, p. 196) apply. Attributing the nature of a fine, KEEDI and MENDONÇA

(2002, p. 100); ANJOS and CAMINHA GOMES (1992, p. 187); and LOSTADO (2000, p. 1) stand out.

International experience in demurrage regulation

13

In comparative Law, French Law and German Law frame the nature of demurrage as a freight supplement if

contemplated in the contract. In the same sense, Portuguese Law expressly sustains the nature of demurrage as a

freight supplement.

In American Law, demurrage has a compensatory nature.

(OCTAVIANO MARTINS, 2015, p. 419)

The French framing of demurrage as a freight supplement is not a consensus and there

are those who understand it as an indemnity, as indicated in the transcript below.

Georges Ripert himself (1954, p. 234), however, states that the legal

nature of demurrages is debatable, but he takes the following

position: “When considering compensation paid by the charterer to

the shipowner for having exceeded the period provided for in the

contract, it must be said that demurrages represent damages.” He

clarifies that French jurisprudence, considering that the term

demurrage can either indicate additional time or compensation, ends

up concluding that demurrage is a supplement to the freight.

Ripert explains that, for the aforementioned jurisprudence to reach

this conclusion, it certainly started from the definition of charter

existing in article 286 of the French Commercial Code: convention or

contract for the leasing of a vessel; thus, if the loading and/or

unloading operation is extended for a certain time beyond the

contracted stay, the rent is extended. Ripert, however, rebels against

this position. He states that “the legal analysis is certainly false” and

goes back to expressing himself in the sense that demurrages are,

legally, “damage and losses fixed conventionally between the parties

for the delay in the performance of the charterer's obligations”

(RIPERT, 1954; apud COLLYER, 2007, p.5)

This issue in English Law has the distinction between a fine and a pre-fixed indemnity

as a peculiarity

9. This interpretation, based on Common Law, indicates that

Salgues (2005, p. 2) sustains the character of a penalty clause in demurrage. In the same sense,

according to Sorrentino, Higa, D'Antonio and Ribeiro (2006, p. 12), and since demurrage is provided for in

the contract, it cannot be attributed to a fine for non-compliance with the obligation. Esteves (1988, p. 61)

maintains, based on the Portuguese legislation referred to above, that demurrage is a freight supplement,

because although it implies delay, demurrage must not be understood as a situation of delay incurred by

the charterer or as a breach of a contractual duty, but a right of the charterer. He also maintains that

demurrage consists, at the same time, of a new term granted to the charterer and an additional amount to

the freight, to be paid in cash. (OCTAVIANO MARTINS, 2015, p. 418)

9 The institute of “pre-fixed indemnity” was not established in the Brazilian legal system. In the Civil Code,

there is the indemnification, corresponding to the compensation for losses and damages (arts. 402 to 405

of the CC) and the penalty clause, whose value cannot exceed the main obligation (arts. 408 to 416 of the

CC). Judicial decisions that understand the demurrage of containers as a pre-fixed indemnity do so based

on uses and customs, internalizing this institute of English Law.

International experience in demurrage regulation

14

demurrage has the nature of a “liquidated indemnity” according to the teachings of

Clive M. SCHMITTHOFF (1980)

10

apud FARIAS (2020):

In English Law, a fixed amount to be paid for breach of contract may be either a pre-fixed indemnity or a fine. (...) With

regard to the treatment of contractual penalty clauses in other legal systems, Peter Benjamin adds that -the extreme

complexity of the French, German and Soviet legislations with regard to penalty clauses, assuming that penalty clauses

are or are not susceptible to modification, each system elaborated its own rule, adopting a series of exceptions that

gave rise to considerable uncertainty in practice. These observations, however, do not apply to Common Law countries,

where the English distinction between pre-fixed damages and fines prevails. (FARIAS, 2020 – Collection of Subsidies)

It is further added that:

In English Law, for a long time, demurrage was the sum or amount paid (under a contract) for the detention of a vessel

in a loading or discharge harbor, beyond the contracted stay. Nowadays, the prevailing understanding, based on Case

Law, is that demurrage is a pre-fixed indemnity for breach of contract (liquidated damages for such a breach), as stated

by John Schofield (2000, p. 317).

It is interesting, however, the understanding of Lord Brandon, of the

House of Lords (apud SCHOFIELD, 2000, p. 315), when judging the

case “President of India v. Lips Maritime Corporation (The Lips).” For

him, demurrage is liability in (or for) liquidated damages, which we

could translate as a (contractual) liability or obligation to indemnify

(according to the pre-fixed amount) the loss or damage caused by the

breach of contract. Other forms used by English Law to conceptualize

demurrage are liquidated damages, agreed additional value for

an allowed detention, e sum payable under and by reason of

a contract for detaining a ship.

However, demurrage should not be confused with damages for

detention. This expression is commonly used to mean compensation

(to be fixed) for detention of the ship, and it can be charged in

addition to demurrage or in replacement of it, although the English

and American courts resist this claim, which will be detailed below. As

a result of what we have said, therefore, we can conclude that

demurrage is a species of the indemnity genus (damages for

detention).

Therefore, demurrage can either mean the time used beyond the

permitted stay, or the agreed amount that must be paid in

compensation for the use, or detention of the ship, beyond the

permitted stay. In the first case it is time, or delay, and in the second,

according to English jurisprudence, it is an (pre-fixed) indemnity for

breach of contract. (COLLYER, 2007, p. 5)

10 SCHMITTOFF, Clive M. Export Trade: The Law and Practice of International Trade, 7th Edition, London,

Ed. Stevens & Sons, 1980, pg. 87.

International experience in demurrage regulation

15

However, it is crucial to note that most Comparative Law considerations and analyses

refer to the demurrage of ships. When it comes to the demurrage of containers,

frequent transpositions of legal concepts are seen in the doctrine and jurisprudence

11,

giving rise to significant distortions in interpretation, since each institute originates

from a completely different contract.

Demurrage of ships should not be confused with demurrage

(detention) of containers.

Despite the many differences between the two institutes, both use the

same terminology in some legal systems (such as Brazil), due to a

common point: lay days, extrapolation of the stay period.

(OCTAVIANO MARTINS, 2015, p. 535)

The demurrage of ships is formalized by the ship charter contract, or departed letter,

being negotiated between the freighter and the charterer of the vessel. Demurrage of

containers, on the other hand, results from the instrumentation of the transportation

contract, which binds the carrier (or its representative) to the service taker (shipper or

consignee).

As an example of imprecision, when referring to the provision of demurrage of

containers in Brazilian legislation, many authors cite the Commercial Code

12 in the

chapter that deals with the nature and form of the charter contract and the letters of

departure.

With all due respect to the historical

Lex Mercatoria

, based on usages

and customs, and to the adoption of the analogy, there is no way,

nowadays, to accept the interpretation that the commercial,

contractual and legal treatment destined to demurrage in cases of

chartering of ships , as well as its consequences, is the same to be

given to container demurrage, as they are, in fact, absolutely different

situations, as will be shown below. (WINTER, 2019 p.26)

11 “Another reason for the legal uncertainty seen in the courts is the confusion of various concepts. This

confusion is often generated by specialists in Maritime Law, in order to protect the interests of their clients

(generally shipowners), which have been causing the distortion of several concepts and, mainly, the

formation of dangerous judicial precedents that do not match the general principles of Private Law, such

as the social function of the contract, the balance between the parties, among others.” (MOYSES FILHO,

Marco Antônio and SILVA, Renã Margalho. In: MARTINS, Eliane M. Octaviano; OLIVEIRA, Paulo Henrique

Reis de (Orgs.). Maritime, port, and customs Law: contemporary issues. Belo Horizonte: Arraes Editores

(2017, p. 371).

12 Commercial Code (arts. 567, nº 5 and nº 6; 591/593, 595, 606, 609, 611, 613 and 627).

International experience in demurrage regulation

16

Therefore, there is no factual support for treating the two concepts as analogous.

Corroborating the arguments raised, the renowned American legal dictionary Black's

Law Dictionary

13 brought in its edition published in 2004, different definitions of ship

and container demurrage. On the demurrage of ships, it defines that it is

“pre-fixed

indemnity due by the charterer to the shipowner for the charterer's inability to load

embark and disembark the cargo at the agreed time”

; and the demurrage of containers

defined as

“charge derived from the late return of maritime containers or other

equipment.”

12. The conclusion is that ship demurrage and container demurrage

are completely different institutes: while in the first case the charge

takes into account that the service has not yet been completed, in the

second the amount charged is based on the incentive to return the

cargo units for a brief resumption of the shipping carrier's logistical

flow, and also to indemnify for the impediment in providing a new

maritime transport service with the respective cargo box.

(CENTRONAVE, 2020, pp. 2 and 3 – Charging of Allowances)

2.2. Doctrinal differences

The legal nature of the demurrage of containers generates great doctrinal and

jurisprudential discussion, as its framework has consequences for the need to prove

intent, the limitation of amounts, the determination of the statute of limitations, tax

effects, among others.

The relevance of investigating the different positions in the doctrine about the legal

nature of demurrage, framing it in one of the existing institutes in the Brazilian positive

system, stems from the dogmatic science of Law, which, according to Tercio Sampaio

Ferraz Jr. (

apud

ROSSI and CASTRO JÚNIOR, 2018, p. 10),

“is thus constructed as a

process of subsumption dominated by a binary schematism, which reduces legal

objects to two possibilities: it is either about this or about that.”

Basically, there are three exponent theories that attempt to determine

the core of container demurrage as: (i) additional freight (or

supplementary freight); (ii) penalty clause, whose terminology is best

used when there is a contractual provision regarding pre-established

amounts (demurrage) or not (detention), due as demurrage (when

there is none, it is preferable to refer to it only as a fine); and (iii)

indemnity. (MARCHIOLI, 2020 – Subsidy Collection)

13 GARNER, Bryan A., Black’s Law Dictionary, Edition 8, U.S.A., Ed. Thomson West, 2004, p. 465, apud

FARIAS, 2020 – Subsidy Collection.

International experience in demurrage regulation

17

The examination of the matter is a challenge for both the factual analysis, since its

presence in maritime transport relations is inevitable due to logistical and

administrative problems in Brazilian ports, and the legal analysis, due to the enormous

confusion regarding doctrinal concepts and the diametrically opposed interests

involved.

Regarding the doctrinal understanding to define the legal regime

applicable to container demurrage, there is a tendency for some

scholars to defend and define the indemnity nature of the institute

without limitation of values, based on the principle of

“Pacta Sunt

Servanda,

” which favors the maritime carrier.

On the other hand, there is part of the specialized doctrine that

understands that container demurrage must be interpreted under the

legal regime of a penalty clause.

Specifically, regarding the framework of the legal regime to be applied

to container demurrage, there have been many doctrinal theses, for

example: freight supplement, lending, fine, lease, pre-fixed indemnity

(penalty clause) and simple indemnity.

Notably, those who defend the interests of shipowners use legal

arguments in favor of the indemnity legal regime, and those who

defend the interests of cargo or importers use the legal grounds for

applying the legal regime of penalty clause. (WINTER, 2019, p. 56).

It is worth remembering that container demurrage collection does not have an express

provision in Brazilian legislation at the level of ordinary law. In the absence of a

positive reference, there are those who defend the analogy with the rules for

demurrage of ships provided for in the Commercial Code of 1850, especially regarding

what must be stated in the charter contract (known as charter party). However, as

highlighted above, the container demurrage originates in the transportation contract

and not in the charter contract.

Given the inapplicability of the Commercial Code, it is within the scope of the Civil

Code, Law Nº 10.406, of January 10, 2002 (CC), that the issue can be settled.

The current that understands demurrage as a penalty clause is based on the fact that

demurrage is an accessory obligation, since there is no demurrage without the main

obligation, which is the transportation contract. From this point of view, it must be

previously fixed in the contract, with a determined deadline and amounts for the delay.

This framework would result in the application of art. 412 of the Civil Code (CC), which

determines the limitation of the value of the sanction imposed in the penalty clause to

that of the main obligation.

International experience in demurrage regulation

18

However, article 408 of the CC provides: “The debtor incurs by right in the penal

clause, provided that, culpably, he fails to fulfill the obligation or constitutes a delay.”

Important information brought by the aforementioned article is that only the culpable

default of the obligation will incur in a penalty clause.

In that regard, the framing of the container demurrage as a penalty clause would

depend on the assessment of the debtor's fault or willful misconduct, which would go

against the grain of international practice. On the other hand, in the agreed penalty

clause (provided for in the contract), it is not necessary for the creditor to claim

damage (art. 416 CC), that is, it would waive the effective proof or settlement of the

damage.

In summary, the text below describes the understanding of the current that defends

that demurrage is a penalty clause:

Notably, it is an ancillary obligation derived from the Maritime Bill of

Lading, which main purpose is to transport the cargo from one point

to another upon payment of freight. As the container is an integral

part of the ship from the moment it is made available to the

consignee, it must be returned within the agreed period of time.

Its character as a penalty clause arises precisely from the prefixation

of an amount already paid to compensate for any damage in the face

of non-compliance with the accessory obligation, that is, the non-

timely return of the container. Hence, arises the penalty, already

predetermined in the contract, either in the Bill of Lading or in the

Term of Commitment to Return the Container, in the exact terms of

article 408 of the Civil Code.

Due precisely to the dynamics of maritime transport, the penalty

clause does not require proof of damage, in order to prevent the

carrier from having to, in each situation, survey and prove, on a case-

by-case basis, its losses, which would really affect its activity, given

the difficult procedure to be carried out on a case-by-case basis.

(WINTER, 2019, p. 67)

The current that defends that container demurrage is an indemnity bases its argument

on the fact that it derives from a contract resulting from a private relationship between

actors with isonomy of decision and based on the autonomy of the parties' will. In

addition, it reinforces the jurisprudential understanding, which, with a large majority,

understands it to be an indemnity.

The aforementioned doctrine has already shown a strong inclination

towards the indemnity nature of demurrage, and national

jurisprudence although in isolated situations it has stated that it is a

lease, a lending, and even a fine, tends to accept a container

demurrage as compensation for the loss of the carrier in not being

able to have the equipment for other international trips for the

transportation of goods, the value of which to be indemnified is pre-

International experience in demurrage regulation

19

adjusted by the parties

International experience in demurrage regulation

20

involved or, as others prefer to say, the demurrage is pre-determined

by the carrier and admitted by the consignee or importer of the

transported goods, which does not change the obligations assumed

since it comes from some form of pact. (SILVEIRA, 2018 p. 36)

By understanding the demurrage of containers as an indemnity, it would fit into art.

402 of the CC and it must be considered that the losses and damages owed to the

creditor cover, in addition to what he lost, what he reasonably failed to profit from.

However, it cannot be forgotten that the amounts owed only include actual losses and

lost profits as a direct and immediate effect of the debtor's non-performance (art. 403

of the CC), that is, the creditor's obligation to prove the losses would be unavoidable.

2.3. Dominant jurisprudence

Currently, the prevailing jurisprudence understands that demurrage collection or

container demurrage has the legal nature of a pre-fixed indemnity for breach of

contract, in order to compensate the owner for the retention of the safe for a longer

period than the one previously agreed upon, regardless of the demonstration of guilt or

injury. Thus, the judgments of the Superior Court of Justice (REsp 1.286.209-SP; AgInt

in AREsp 842151-SP; AgRg in REsp 1451054-PR, among others) stand out, which

understand the legal nature of container demurrage as a pre-fixed indemnity and not

as a penalty clause.

Among the judgments that caused the greatest repercussion in the maritime sector

was the one that decided, in 2016, Special Appeal nº 1.286.209, of which João Otávio

de Noronha was the Minister Rapporteur. By unanimous decision of the Third Panel,

the following amendment was generated:

SPECIAL RESOURCE. ACTION FOR COLLECTION OF CONTAINER

OVERSTAYS (DEMURRAGES). DENIAL OF JURISDICTIONAL

PROVISION. NON-OCCURRENCE. LEGAL NATURE. INDEMNITY.

CONTRACTUAL BREACH. DEBTOR'S LIABILITY. LIMITATION OF

INDEMNITY VALUE.

PACTA SUNT

SERVANDA

. 1. The negative allegation of delivery of full jurisdictional

provision is unreasonable if the Court of origin examined and decided,

in a motivated and sufficient manner, the issues that delimited the

controversy. 2. Demurrages have a legal nature of indemnity, and not

of a penalty clause, which excludes the incidence of art. 412 of the

Civil Code. 3. If the value of the demurrages reaches an excessive

level only due to the negligence of the party obliged to return the

containers, the

Pacta Sunt Servanda

principle must be privileged,

otherwise the Judiciary will reward the wrongful conduct of the debtor

party. 4. Special resource known and provided.

International experience in demurrage regulation

21

With due respect, the main criticisms of the positioning emanated derive from the lack

of differentiation between the charter contract (which gives rise to the demurrage of

ships) and the transportation contract (which gives rise to container demurrage).

The doctrinal quotes by J. C. Sampaio de Lacerda113, Carla Adriana

Comitre Gibertoni

114 and Carlos Rubens Caminha Gomes/Edson

Antônio Miranda

115, all used to support the vote, are clearly directed to

charter contracts, not to maritime cargo transportation contracts (as,

in fact, it occurred in the specific case).

Notably, the wrong direction of the vote remains clear due to the

basis of interpretation used, confusing the demurrage of a ship

(chartering) with the demurrage of a container (transportation

contract – BL or Term of Commitment). (WINTER, 2019, p. 58

)

To exemplify the importance of not exchanging the concepts of demurrage of ships

and containers, it is enough to verify how each contract is carried out and what is the

bargaining power of each party.

Even more attention should be given to these differences in cases

where the “consignee” did not even have prior access to the

transportation contract, or who, due to the requirement to release the

cargo, signed the Container Return Commitment Term by their legal

representative. (WINTER, 2019, p. 59)

Despite the prevailing understanding, one cannot forget the discordant positions. In

this sense, it is worth mentioning the position of Judge Cauduro Padin, of the São

Paulo Court of Justice, when reporting an Appeal involving container demurrage,

especially as it occurred after the STJ judgment (Resp Nº 1.286.209-SP), as shown in

the excerpt below:

Action of obligation to do c.c. damning request. Sea freight transport.

Demurrage overstay. Similar nature to the penalty clause. Anticipation

of loss and damage. Incidence of the sanction value in accordance

with the terms of the liability waiver. Guilty conduct that is equivalent

to the delay/default itself. Exclusion of liability only in fortuitous cases.

Innocence. Non-incidence of the Consumer Protection Code. Sentence

maintenance. Resource not provided.

The argument previously discussed Is extracted from the above decision:

Demurrage has an effect and nature comparable to the penalty clause

and this is a lawful agreement between the parties. It seeks to

achieve the disincentive to the total or partial breach of the obligation

or even to remove the delay in the performance. The clause brings

with it a prior assessment of the losses and damages freely adjusted

by the

International experience in demurrage regulation

22

parties. As a result, it does not depend on proof of damage. (ROSSI

and CASTRO JÚNIOR, 2018, p. 16)

Thus, despite the existence of discordant opinions, Brazil adopted through

jurisprudential decisions, demurrage as a pre-fixed indemnity. Although in Brazil there

is no distinction between pre-fixed indemnity for damages and a penalty clause, as it

exists in the law originating from countries that apply the Common Law, Brazilian

Courts continue to understand that container demurrage should not be treated as a

penalty clause.

Finally, it is noted that despite the prevailing jurisprudence there are still many

complaints from users and those who defend their interests, as can be seen in the

excerpt below.

We realize, with undisguised concern, that the legal nature of

demurrage has been subverted over the years, in such a way that it is

no longer a legitimate protection mechanism for the shipowner

against possible abuses by their container users, to become a

reprehensible form of oppression and undue enrichment. Not all, but

many shipowners profit more from demurrage charges than from the

freights themselves, and the demurrage charge does not serve the

purpose of profit, it serves only to “punish” possible abuses by cargo

consignees regarding the use of containers for longer than is due and

agreed. (CREMONEZE, 2012, apud ROSSI and CASTRO JÚNIOR,

2018, p. 32)

3. INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE

In recent years, the demurrage rate has increased considerably worldwide, and the

free time has decreased. There were indications that shipowners abused demurrage

charges to maximize profits, not necessarily from freight. (ROEMER, 2018)

The increase in demurrage charges generated many disputes, complaints, as well as

legal disputes.

Other factors like port congestion, such as the one that occurred in the United States

between 2014 and 2015, due to climate and labor problems, also partly influenced the

increase in the collection of this fee.

This chapter addresses how the demurrage issue was dealt with by the Federal

Maritime Commission (FMC), as well as the suggestions given by FIATA (International

Federation of Freight

International experience in demurrage regulation

23

Forwarders Associations) for handling commercial disputes around the practice and

charging of demurrage.

3.1. FMC interpretive rule

On May 18

th

2020, the final interpretive rule (FMC, 2020) of the Federal Maritime

Commission (FMC) dealing with container demurrage came into force. This decision

represented an important reference for a problem repeatedly pointed out in

international maritime transportation and related to the high charge for container

demurrage in several ports around the world.

Under this new interpretive rule, the FMC can assess the extent to which the container

demurrage rate and policy fulfill the objective of encouraging the movement of cargo

and promoting the fluidity of transportation. The rule also provides guidance on how

the Commission can apply this principle in the context of cargo (and information)

availability, considering factors related to the content and clarity of shipowners' and

maritime terminals' policies, as well as in relation to the terminology used and the

return of empty containers.

Although the final interpretive rule is the result of Fact-Finding Investigation Nº 28,

from 2018, the FMC's attention to the issue of demurrage dates back to 2014 when

this Commission hosted four regional forums on ports that addressed congestion in the

international maritime chain. Although these forums did not directly address the issue

of demurrage, it was clear that shippers and truck drivers were unhappy with the

demurrage practices and free time stay period of the container.

In 2015, the FMC published a Report on demurrage rules, fees, and practices (FMC,

2015). This Report contained the following definitions

14:

Demurrage is a charge for the use of space; detention is a charge for

the use of equipment. Free time is the grace period for which neither

of these charges will be incurred. Both are meant to compensate for

the use of space and equipment, and to encourage the efficient

movement of cargo by importers, exporters, and drayage providers.

14 It is noteworthy that the definition of container demurrage in the present study is based on the RN-18

and, as explained in Chapter 1, does not cover the costs related to the occupation of space in the port

terminal.

International experience in demurrage regulation

24

While the 2015 FMC Report provided a definition, terms and practices related to

demurrage are not uniform even among shipowners, as noted by the Fact-Finding

Investigation Nº 28 research team, which identified two main approaches used to

determine demurrage charges:

1.

Based on whether the container is (a) on-terminal (inside the gate)

or (b) off-terminal (outside the gate). In this case:

a.

“Demurrage” is a charge for exceeding allotted free time on the

terminal – i.e., between when cargo is off-loaded from a ship until it

moves out the terminal gate. Such “demurrage” may represent use of

terminal space (terminal demurrage) and the use of equipment

(carrier demurrage – i.e., in-port detention).

b.

“Detention” is a charge for use of equipment (containers) beyond

the allotted free time outside the port – i.e., after the full container

has left the port and until the empty container is returned.

2.

Based on whether the container is: (a) being charged for extended

use of terminal space, or (b) for extended use of carrier equipment

(container). In this case:

a.

“Demurrage” is the MTO’s charge for exceeding allotted free time

on the terminal (but not for carrier equipment use). If there is a

carrier charge for use of the container while cargo is on the terminal,

it would be labelled as some form of “detention” – e.g., in-port

detention.

b.

“Detention” is the charge for use of equipment (containers) beyond

the allotted free time – whether at the terminal or outside the port.

(FMC, 2018)

As pointed out in the FMC preliminary Report (2018), the different approaches to the

definition regarding the term and occurrence of demurrage give rise to doubts and

questions, mainly for users of maritime transport:

Under the first approach, it might be less clear to a VOCC’s customer

what it is being charged for – terminal space usage or container

usage, or both. Moreover, because MTOs sometimes collect carrier

demurrage on a VOCC’s behalf, it might not be clear to a customer to

whom their payment goes.

Under the second approach, it is clear the MTO who controls the

terminal is charging for extended use of its asset (terminal space),

and the carrier who controls the container is charging for the use of

its asset (the container).

From the FMC Report (2015), the following main points can be highlighted: the total

average of demurrage and detention prices can be higher for importers than exporters;

demurrage rates are higher than detention rates; US ports have similar rates, except

New York/New Jersey ports that have higher prices; demurrage practices seem to be

more

International experience in demurrage regulation

25

under the control of shipowners than of maritime terminal operators15 (MTOs); the

terminology is not uniform, nor are the circumstances in which these fees are not

charged, get reimbursed, or have another form of mitigation, making comparison in

the sector unfeasible.

The FMC Report (2015) also corroborated the perception that demurrage was not

serving the purpose of speeding up the movement of cargo, which was its original

goal.

It should be noted that the final interpretive rule is the result of a process that began

in December 2016, when a coalition of shippers called the “Coalition for Fair Port

Practices” submitted a petition to the FMC for the adoption of an interpretive rule that

would clarify what “fair and reasonable rules and practices” would be regarding the

assessment of “demurrage,” “detention” and “per diem”:

The Coalition for Fair Port Practices (“Petitioners” or “Coalition”), a

group of 26 trade associations representing importers, exporters,

drayage providers, freight forwarders, Customs brokers, and third-

party logistics providers (“3PLs”), requests that the Federal Maritime

Commission (“FMC” and “Commission”) initiate a rulemaking

proceeding, pursuant to 46 C.F .R. § 502.51, for the purpose of

adopting a rule that will interpret the Shipping Act of 1984, as

amended, and specifically 46 U.S.C. § 41102(c), to clarify what

constitutes “just and reasonable rules and practices” with respect to

the assessment of demurrage, detention, and per diem charges by

ocean common carriers and marine terminal operators when ports are

congested or otherwise inaccessible. Specifically, Petitioners are

proposing a rule for adoption by the Commission and request specific

guidance as to the reasonableness of such charges when port

conditions prevent the timely pick up of cargo or the return of carrier

equipment because of broad circumstances that are beyond the

control of shippers, receivers, or drayage providers. (COALITION,

2016)

For some years now, North American importers and exporters, transportation

intermediaries, and truck drivers complained that shipowners and maritime terminal

operators (MTOs) were adopting unfair demurrage practices that penalized shippers,

intermediaries, and truck drivers for circumstances beyond their control.

Thus, the intermediaries and truck drivers petitioned the Commission to adopt a rule

specifying certain circumstances in which the charge for demurrage

15 As defined by the FMC, MTOs include public port authorities and private terminals.

International experience in demurrage regulation

26

and detention would be unreasonable. They requested that shipowners and terminals

not be allowed to charge for demurrage when cargo and equipment could not be

recovered or returned, and that charging in these situations weakened the incentive for

these companies to seek solutions to port congestion or their own operational

inefficiencies.

Thus, in early March 2018, the FMC approved the initiation of an investigation headed

by Commissioner Rebecca Dye

16, focusing on practices related to demurrage. This

investigation, called Fact-Finding Nº 28, aimed to clarify five main points:

Whether the alignment of commercial, contractual, and cargo interests

increases or worsens the ability to efficiently move cargo through US

ports.

If, and when, the carrier or MTO delivered the cargo to the shipper or

consignee.

What are the demurrage and detention collection practices.

What are the practices regarding delays caused by external events or

stakeholders.

What are the practices regarding dispute settlement.

During the investigation, hearings, field interviews, meetings with industry leaders, and

information gathering were carried out to ascertain the facts. In September 2018, a

preliminary Report was published, and in December 2018 the Final Report was

published.

Among the findings of the investigation and presented in the Final Report (FMC, 2018)

the following points can be highlighted:

Demurrage and detention are valuable charges when applied to

encourage the prompt movement of cargo from ports and maritime

terminals.

The entire international maritime logistics chain can benefit from

transparent, consistent, and reasonable demurrage practices.

16

The FMC's governing body consists of the President and four Commissioners, all appointed by the

President of the United States and confirmed by the US Senate for a four-year term.

International experience in demurrage regulation

27

The performance of the international logistics chain can be improved by

providing information on the status of the cargo.

Standardized and transparent demurrage language would also improve

the international freight system.

Billing practice and dispute settlement process should be clear,

streamlined, and accessible.

There should be explicit guidelines as to the types of evidence that are

relevant to resolving disputes.

In August 2019, Commissioner Dye recommended the FMC to issue an interpretive

rule

17 to implement the general guidelines contained in the Final Report on the

application of demurrage charges. She also recommended that the Commission

establish an Advisory Board of Shippers and continue to support the work of the Supply

Chain Innovation Team in Memphis (FMC, 2019).

According to Commissioner Dye’s recommendation, the suggested interpretive rule

seeks to clarify how the Commission will assess the reasonableness of demurrage and

detention practices. In this sense, the purpose of charging these fees is to serve as a

financial incentive for those interested in the cargo to timely remove it and return the

equipment. However, when the incentives no longer work, as shippers are unable to

collect cargo or return containers within the agreed time frame, the charges must be

suspended.

As for the Advisory Board of Shippers, Commissioner Dye points out that it will allow

the assessment of the implementation of the recommendations of Fact-Finding Nº 28,

as well as contributing to obtain advice from North American importers and exporters

on other matters of the Commission.

In September 2019, the FMC published a proposed interpretive demurrage rule that

received several comments. After analyzing these, the Commission published the final

interpretative rule in May 2020 (FMC, 2020), the full text of which can be viewed in

Attachment I of this Report.

17 Interpretive rule is an agency rule that clarifies or explains existing laws or rules/regulations. An

interpretive rule does not need to satisfy the requirements set out in the Administrative Procedure Act,

e.g., notifying the public and providing an opportunity for comment.

International experience in demurrage regulation

28

The rule sets out a non-exhaustive list of factors that the FMC may consider in the

analysis to assess whether demurrage practices are fair and reasonable, and builds on

the understanding that demurrage charges serve to expedite the movement of cargo in

terminals, as they are an incentive for the various agents acting in the logistics chain to

seek to move with agility in order to give fluidity to transportation. Considering this,

the interpretive rule of the FMC premises that the more the demurrage practices are

aligned with the search for agility and fluidity of transportation, the less they should be

considered unreasonable.

The guidelines adopted by the FMC in the final interpretive rule aim to help shipowners

and MTOs to avoid penalties provided for in the Shipping Act, as well as to increase the

awareness of shippers, intermediaries and truck drivers about their obligations in order

to promote fluidity of the freight system, bring clarification, reduce and speed up

disputes, in addition to increasing competition and innovation in operations and

commercial policies, emphasizing the issue of providing information, especially

regarding cargo availability.

It is worth noting that shipowners and maritime terminals agree that these points are

part of their list of obligations.

With the rule, the FMC can consider whether the regulated entities are providing

adequate information to those responsible for the cargo. Thus, in practice, the

Commission may consider the type of notice and to whom the notice is addressed,

providing the format, method of distribution, timing, and effect. As a result, shipowners

must include in their contracts the obligation to inform consignees when they can

remove the cargo. The alignment of this information between shipowners, MTOs,

intermediaries, and truck drivers contributed to an efficient removal of cargo from the

terminal space.

In addition, the Commission’s guidelines (FMC, 2020) focused on the existence, clarity,

content, and accessibility of dispute settlement and demurrage charging practices.

They also highlighted the issue of terminology used, as investigations found that

demurrage practices and rules were complex, inconsistent, variable, and lacked

transparency. Some of the main points addressed by the FMC are listed below:

a)

The interpretive rule applies to container demurrage practices and

regulations. Thus, for the purposes of the rule demurrage includes

International experience in demurrage regulation

29

all charges, including per day, determined by shipowners, maritime

terminals, or maritime intermediaries for the use of terminal space

(onshore) or container, not included in freight (FMC, 2020).

b)

Historically, the FMC recognizes that demurrage has penal elements that

were established to encourage the prompt movement of cargo off the

pier, but also includes an element compensating for the use of facilities,

security, fire protection, etc., in the case of non-withdrawal in the free

period.

c)

While the focus of the FMC is on the incentive principle and its

applications, the guidelines presented in the interpretive rule also

include other factors that the Commission may consider as contributing

to the reasonableness of the matter. For example, the existence of

accessibility to regulations and the practice of demurrage. This is due to

the fact that, during investigations, it was found that there was a lack of

transparency regarding demurrage practices, including dispute

settlement processes and collection procedures.

d)

Regarding dispute settlement, the FMC considers it important that

information such as contact channels, deadlines and requirements for

conciliation be made available.

e)

A controversial point that emerged in the investigations concerns the

burden of proof, that is who should gather evidence relevant to the

issue of demurrage. The FMC points out that demurrage disputes can be

settled more efficiently if the shipper or truck driver knows in advance

what kind of documentation or other evidence the shipowner or terminal

needs to extend the free period or not charge demurrage fees.

f)

The interpretive rule states that the Commission may consider in the

reasonableness analysis the extent to which the regulated entities have

defined demurrage terms, the accessibility of definitions, and how much

the definitions differ from terms used in other contexts. The FMC

understands that a basic principle of demurrage practices is the clear

definition of the terms used.

International experience in demurrage regulation

30

g)

While not a rule-specific subject, the term “carrier haulage” appeared

many times during the rule-building process. “Carrier haulage” is a

transportation arrangement also referred to as “store door” or “door

move” or “door-to-door” delivery, as we know it in Brazil. In this type of

transportation arrangement, the shipowner is responsible for arranging

the container's transportation from one terminal to another location,

such as a consignee warehouse. The “merchant haulage” is also known

as CY (“container yard”

18) or “port-to-port” transportation. In the latter

case, the shipper makes the arrangements for land transportation.

h)

Some argue that in the case of “door-to-door” transportation, the

shipowner does not charge for demurrage, as he is responsible for

ensuring that the containers are picked up in time from the terminal and

delivered to the appropriate place.

i)

During the investigation, it was recorded that some shipowners charged

demurrage to businessmen who do “port-to-port” arrangements but did

not charge businessmen who do “door-to-door” arrangements. When

shipowners make a “door-to-door” arrangement, they compete with

cargo intermediaries. In this sense, markets tend to be less efficient

when companies have the power to collect unreasonable charges from

their competitors.

j)

The interpretive demurrage rule does not address this specific situation,

but the Commission has concerns about this matter and will seek ways

to appropriately address practices involving “door-to-door” and “port-to-

port” transportation.

In this way, it was possible to verify that the interpretative rule of the FMC consists of

a series of general guidelines about container demurrage, which seek to clarify the

motivation for the charge, in addition to establishing parameters that allow the

evaluation and punctual action of the FMC in each concrete case.

Finally, it's important to highlight that although most of the guidelines are of a general

nature with universal application, special care must be taken to

18 Container yard.

International experience in demurrage regulation

31

internalize the rule in other countries outside the North American reality, considering

the local arrangement of the economic agents involved in the logistics chain, as well as

the current regulatory framework.

3.2. FIATA recommendations19

The FIATA International Federation of Freight Forwarders Associations is a non-

governmental organization that represents, promotes, and protects the interests of the

international freight intermediary industry. FIATA members cover 108 logistics

associations and cargo intermediaries in 97 countries, approximately 6,000 logistics

and freight service providers worldwide.

The FIATA Maritime Transport Working Group has developed a Best Practices Guide to

support both FIATA National Associations and individual members acting as freight

forwarders in commercial disputes (FIATA, 2018).

The guide brings the understanding that, in principle, the demurrage charge has two

main purposes: to compensate the owner for the use of the container, and to

encourage the cargo holder to return the container as soon as possible. On the other

hand, it is the duty of shipowners to grant a realistic free period to the cargo holder so

that he can fill and deliver a container for export, and remove a container, unload it

and return it empty in the case of an import.

In the guide, demurrage is understood as the fee that the cargo holder pays for the

use of the container inside the terminal in addition to the free period, and detention is

the fee that the cargo holder pays for the use of the container outside the terminal or

deposit in addition to the free period. FIATA also presents the concept of “merged

demurrage & detention,” which adds the demurrage and detention periods, combining

them into a single period, which is the same concept adopted in RN-18 and used in this

Report.

The Best Practices Guide released by FIATA (2018) recognizes that demurrage and

detention rates are important and valid instruments for shipowners to ensure the

return of their equipment as soon as possible, and users who exceed the contractual

duration must be billed accordingly.

19 Fact-Finding Nº 28 encouraged FIATA to develop a Best Practices Guide regarding demurrage that was

released in September 2018 (FMC, Final Report, 2018).

International experience in demurrage regulation

32

However, FIATA does not believe that shippers should be subject to unfair or

unreasonable charges of this nature, especially when the delay is due to the owner's

fault.

FIATA suggests that a range of issues related to demurrage and detention be analyzed

and an agreement be negotiated including, but not limited to:

Limit accumulated demurrage to a maximum amount.

Extend the free time period if the terminal is unable to release

/ receive a container within a period equal to the duration of the

inability.

Ensure a level playing field for containers in port-to-port transportation

and negotiate terms to reduce unfair differentiation.

Support the modal shift to more environmentally friendly modes of

transportation, increasing the period of freedom from detention.

Amend the calculation of export demurrage to transfer responsibility for

ship delays to the shipping company.

Make sure that demurrage charges on import shipments are collected

faster, preferably within a week.

Contribute to relieving congestion at the terminal, as well as the on-land

concentration of pickups and deliveries due to larger ships and higher

peaks and allowing cargo holders more flexibility increasing periods of

free time.

Encourage greater data sharing in the maritime logistics chain, which

would lead to greater transparency of information related to these fees.

4. DEMURRAGE CHARGE IN BRAZIL

In addition to the international experience analysis, some singularities of the container

demurrage charge in Brazilian national territory are detailed, such as the Term of

Responsibility for the Return of the Container (or Term of Commitment for the Return

of the Container – TCDC), the adherence of the Customs broker as jointly responsible,

the charging of differentiated values by the cargo agent, and the Brazilian logistical

difficulties that can increase the incidence of collection.

International experience in demurrage regulation

33

4.1. Term of Responsibility for the container's return

Regarding comparative foreign Law, considering that the focus of this

study is container demurrage in Brazil, in which there are practical

operational peculiarities that do not exist in other countries, such as

the requirement to sign the TCDC and some specific regulations of our

legal system, different from Common Law, [...]. (WINTER, 2019, p.

14)

The requirement to sign the Term of Responsibility was created by the carriers to

facilitate the execution of demurrage collection actions, but it is presented as a

document that facilitates the bureaucratic procedures for the release of containers, as

observed in the text below:

By means of this document, whoever signs and delivers it to the

carrier's local agent aims to expedite the release of the cleared cargo